User login

ASH expands late-breaking abstract session

An additional presentation has been added to the late-breaking abstract session of the 2018 ASH Annual Meeting.

The session was expanded from six abstracts to seven this year because of a record number of “exciting” submissions, according to ASH Secretary Robert A. Brodsky, MD, of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland.

“We received 98 late-breaking abstracts, which is a record,” Dr. Brodsky said.

“They were so exciting this year that we added a seventh, and, quite frankly, we could have added several more, but we just didn’t have time in the meeting.”

Dr. Brodsky discussed this year’s late-breaking abstracts during a recent press briefing.

Abstract LBA-1 reports results of rivaroxaban thromboprophylaxis in cancer patients with an increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE). Compared to placebo, rivaroxaban significantly reduced VTE and VTE-related death during treatment but not over the entire study period.

Abstract LBA-2 describes a phase 3, randomized trial comparing daratumumab plus lenalidomide and dexamethasone to lenalidomide and dexamethasone in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma who are ineligible for transplant. The addition of daratumumab reduced the risk of disease progression or death by 45%.

Abstract LBA-3 details results with HemoTypeSC, a test used to detect sickle cell trait and sickle cell disease. The test correctly identified all phenotypes in the 1,000 children studied.

Abstract LBA-4 describes a randomized, phase 3 study comparing ibrutinib plus rituximab to fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab in younger patients with untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Investigators found that ibrutinib plus rituximab provided significantly better progression-free and overall survival than the three-drug combination.

Abstract LBA-5 details a strategy for direct oral anticoagulant use in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing surgery. Investigators say the strategy is likely to be “practice-changing” and incorporated into guidelines.

Abstract LBA-6 covers a trial of emapalumab in patients with primary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Emapalumab, which was recently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, produced responses in most of the 34 patients studied and had a favorable safety profile, according to investigators.

Abstract LBA-7 reports the discovery of a recurrent mutation in BCL2 that confers resistance to venetoclax in patients with progressive CLL. Investigators say this mutation could be a biomarker of CLL relapse.

An additional presentation has been added to the late-breaking abstract session of the 2018 ASH Annual Meeting.

The session was expanded from six abstracts to seven this year because of a record number of “exciting” submissions, according to ASH Secretary Robert A. Brodsky, MD, of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland.

“We received 98 late-breaking abstracts, which is a record,” Dr. Brodsky said.

“They were so exciting this year that we added a seventh, and, quite frankly, we could have added several more, but we just didn’t have time in the meeting.”

Dr. Brodsky discussed this year’s late-breaking abstracts during a recent press briefing.

Abstract LBA-1 reports results of rivaroxaban thromboprophylaxis in cancer patients with an increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE). Compared to placebo, rivaroxaban significantly reduced VTE and VTE-related death during treatment but not over the entire study period.

Abstract LBA-2 describes a phase 3, randomized trial comparing daratumumab plus lenalidomide and dexamethasone to lenalidomide and dexamethasone in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma who are ineligible for transplant. The addition of daratumumab reduced the risk of disease progression or death by 45%.

Abstract LBA-3 details results with HemoTypeSC, a test used to detect sickle cell trait and sickle cell disease. The test correctly identified all phenotypes in the 1,000 children studied.

Abstract LBA-4 describes a randomized, phase 3 study comparing ibrutinib plus rituximab to fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab in younger patients with untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Investigators found that ibrutinib plus rituximab provided significantly better progression-free and overall survival than the three-drug combination.

Abstract LBA-5 details a strategy for direct oral anticoagulant use in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing surgery. Investigators say the strategy is likely to be “practice-changing” and incorporated into guidelines.

Abstract LBA-6 covers a trial of emapalumab in patients with primary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Emapalumab, which was recently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, produced responses in most of the 34 patients studied and had a favorable safety profile, according to investigators.

Abstract LBA-7 reports the discovery of a recurrent mutation in BCL2 that confers resistance to venetoclax in patients with progressive CLL. Investigators say this mutation could be a biomarker of CLL relapse.

An additional presentation has been added to the late-breaking abstract session of the 2018 ASH Annual Meeting.

The session was expanded from six abstracts to seven this year because of a record number of “exciting” submissions, according to ASH Secretary Robert A. Brodsky, MD, of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland.

“We received 98 late-breaking abstracts, which is a record,” Dr. Brodsky said.

“They were so exciting this year that we added a seventh, and, quite frankly, we could have added several more, but we just didn’t have time in the meeting.”

Dr. Brodsky discussed this year’s late-breaking abstracts during a recent press briefing.

Abstract LBA-1 reports results of rivaroxaban thromboprophylaxis in cancer patients with an increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE). Compared to placebo, rivaroxaban significantly reduced VTE and VTE-related death during treatment but not over the entire study period.

Abstract LBA-2 describes a phase 3, randomized trial comparing daratumumab plus lenalidomide and dexamethasone to lenalidomide and dexamethasone in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma who are ineligible for transplant. The addition of daratumumab reduced the risk of disease progression or death by 45%.

Abstract LBA-3 details results with HemoTypeSC, a test used to detect sickle cell trait and sickle cell disease. The test correctly identified all phenotypes in the 1,000 children studied.

Abstract LBA-4 describes a randomized, phase 3 study comparing ibrutinib plus rituximab to fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab in younger patients with untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Investigators found that ibrutinib plus rituximab provided significantly better progression-free and overall survival than the three-drug combination.

Abstract LBA-5 details a strategy for direct oral anticoagulant use in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing surgery. Investigators say the strategy is likely to be “practice-changing” and incorporated into guidelines.

Abstract LBA-6 covers a trial of emapalumab in patients with primary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Emapalumab, which was recently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, produced responses in most of the 34 patients studied and had a favorable safety profile, according to investigators.

Abstract LBA-7 reports the discovery of a recurrent mutation in BCL2 that confers resistance to venetoclax in patients with progressive CLL. Investigators say this mutation could be a biomarker of CLL relapse.

Immunotherapy may hold the key to defeating virally associated cancers

Infection with certain viruses has been causally linked to the development of cancer. In recent years, an improved understanding of the unique pathology and molecular underpinnings of these virally associated cancers has prompted the development of more personalized treatment strategies, with a particular focus on immunotherapy. Here, we describe some of the latest developments.

The link between viruses and cancer

Suspicions about a possible role of viral infections in the development of cancer were first aroused in the early 1900s. The seminal discovery is traced back to Peyton Rous, who showed that a malignant tumor growing in a chicken could be transferred to a healthy bird by injecting it with tumor extracts that contained no actual tumor cells.1

The infectious etiology of human cancer, however, remained controversial until many years later when the first cancer-causing virus, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), was identified in cell cultures from patients with Burkitt lymphoma. Shortly afterward, the Rous sarcoma virus was unveiled as the oncogenic agent behind Rous’ observations.2Seven viruses have now been linked to the development of cancers and are thought to be responsible for around 12% of all cancer cases worldwide. The burden is likely to increase as technological advancements make it easier to establish a causal link between viruses and cancer development.3

In addition to making these links, researchers have also made significant headway in understanding how viruses cause cancer. Cancerous transformation of host cells occurs in only a minority of those who are infected with oncogenic viruses and often occurs in the setting of chronic infection.

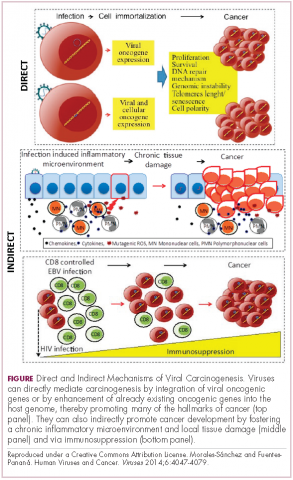

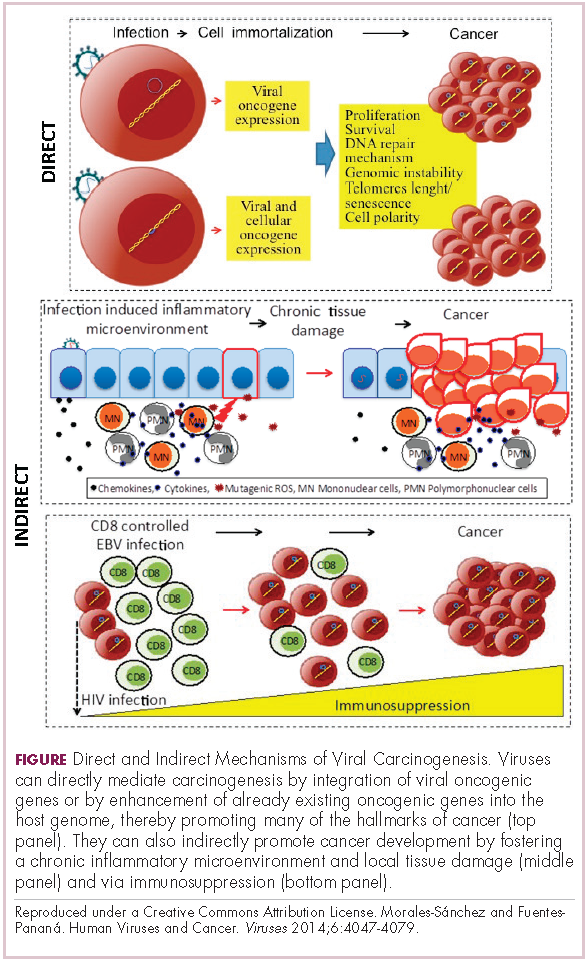

Viruses can mediate carcinogenesis by direct and/or indirect mechanisms (Figure 1). Many of the hallmarks of cancer, the key attributes that drive the transformation from a normal cell to a malignant one, are compatible with the virus’s needs, such as needing to avoid cell death, increasing cell proliferation, and avoiding detection by the immune system.

Viruses hijack the cellular machinery to meet those needs and they can do this either by producing viral proteins that have an oncogenic effect or by integrating their genetic material into the host cell genome. When the latter occurs, the process of integration can also cause damage to the DNA, which further increases the risk of cancer-promoting changes occurring in the host genome.

Viruses can indirectly contribute to carcinogenesis by fostering a microenvironment of chronic inflammation, causing oxidative stress and local tissue damage, and by suppressing the antitumor immune response.4,5

Screening and prevention efforts have helped to reduce the burden of several different virally associated cancers. However, for the substantial proportion of patients who are still affected by these cancers, there is a pressing need for new therapeutic options, particularly since genome sequencing studies have revealed that these cancers can often have distinct underlying molecular mechanisms.

Vaccines lead the charge in HPV-driven cancers

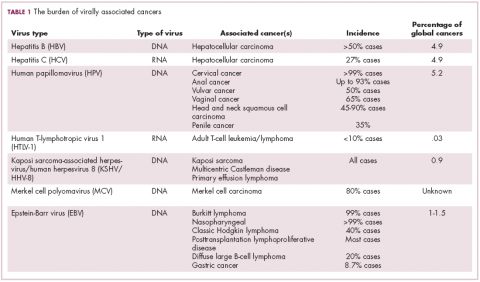

German virologist Harald zur Hausen received the Nobel Prize in 2008 for his discovery of the oncogenic role of human papillomaviruses (HPVs), a large family of more than 100 DNA viruses that infect the epithelial cells of the skin and mucous membranes. They are responsible for the largest number of virally associated cancer cases globally – around 5% (Table 1).

A number of different cancer types are linked to HPV infection, but it is best known as the cause of cervical cancer. The development of diagnostic blood tests and prophylactic vaccines for prevention and early intervention in HPV infection has helped to reduce the incidence of cervical cancer. Conversely, another type of HPV-associated cancer, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), has seen increased incidence in recent years.

HPVs are categorized according to their oncogenic potential as high, intermediate, or low risk. The high-risk HPV16 and HPV18 strains are most commonly associated with cancer. They are thought to cause cancer predominantly through integration into the host genome. The HPV genome is composed of 8 genes encoding proteins that regulate viral replication and assembly. The E6 and E7 genes are the most highly oncogenic; as the HPV DNA is inserted into the host genome, the transcriptional regulator of E6/E7 is lost, leading to their increased expression. These genes have significant oncogenic potential because of their interaction with 2 tumor suppressor proteins, p53 and pRb.6,7

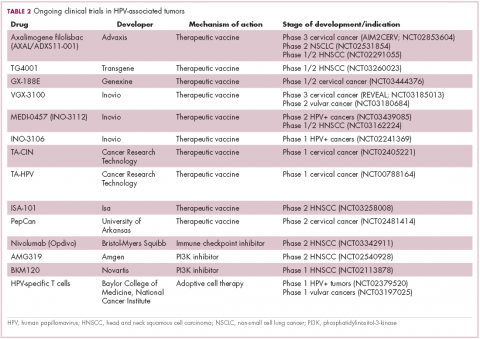

The largest investment in therapeutic development for HPV-positive cancers has been in the realm of immunotherapy in an effort to boost the anti-tumor immune response. In particular, there has been a focus on the development of therapeutic vaccines, designed to prime the anti-tumor immune response to recognize viral antigens. A variety of different types of vaccines are being developed, including live, attenuated and inactivated vaccines that are protein, DNA, or peptide based. Most developed to date target the E6/E7 proteins from the HPV16/18 strains (Table 2).8,9

Other immunotherapies are also being evaluated, including immune checkpoint inhibitors, antibodies designed to target one of the principal mechanisms of immune evasion exploited by cancer cells. The combination of immune checkpoint inhibitors with vaccines is a particularly promising strategy in HPV-associated cancers. At the European Society for Medical Oncology Congress in 2017, the results of a phase 2 trial of nivolumab in combination with ISA-101 were presented.

Among 24 patients with HPV-positive tumors, the majority oropharyngeal cancers, the combination elicited an overall response rate (ORR) of 33%, including 2 complete responses (CRs). Most adverse events (AEs) were mild to moderate in severity and included fever, injection site reactions, fatigue and nausea.14

Hepatocellular carcinoma: a tale of two viruses

The hepatitis viruses are a group of 5 unrelated viruses that causes inflammation of the liver. Hepatitis B (HBV), a DNA virus, and hepatitis C (HCV), an RNA virus, are also oncoviruses; HBV in particular is one of the main causes of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most common type of liver cancer.

The highly inflammatory environment fostered by HBV and HCV infection causes liver damage that often leads to cirrhosis. Continued infection can drive permanent damage to the hepatocytes, leading to genetic and epigenetic damage and driving oncogenesis. As an RNA virus, HCV doesn’t integrate into the genome and no confirmed viral oncoproteins have been identified to date, therefore it mostly drives cancer through these indirect mechanisms, which is also reflected in the fact that HCV-associated HCC predominantly occurs against a backdrop of liver cirrhosis.

HBV does integrate into the host genome. Genome sequencing studies revealed hundreds of integration sites, but most commonly they disrupted host genes involved in telomere stability and cell cycle regulation, providing some insight into the mechanisms by which HBV-associated HCC develops. In addition, HBV produces several oncoproteins, including HBx, which disrupts gene transcription, cell signaling pathways, cell cycle progress, apoptosis and other cellular processes.15,16

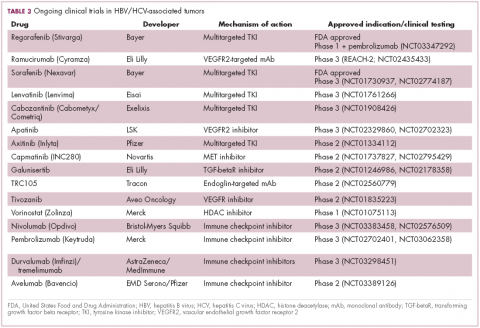

Multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have been the focal point of therapeutic development in HCC. However, following the approval of sorafenib in 2008, there was a dearth of effective new treatment options despite substantial efforts and numerous phase 3 trials. More recently, immunotherapy has also come to the forefront, especially immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Last year marked the first new drug approvals in nearly a decade – the TKI regorafenib (Stivarga) and immune checkpoint inhibitor nivolumab (Opdivo), both in the second-line setting after failure of sorafenib. Treatment options in this setting may continue to expand, with the TKIs cabozantinib and lenvatinib and the immune checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab and the combination of durvalumab and tremelimumab hot on their heels.17-20 Many of these drugs are also being evaluated in the front-line setting in comparison with sorafenib (Table 3).

At the current time, the treatment strategy for patients with HCC is independent of etiology, however, there are significant ongoing efforts to try to tease out the implications of infection for treatment efficacy. A recent meta-analysis of patients treated with sorafenib in 3 randomized phase 3 trials (n = 3,526) suggested that it improved overall survival (OS) among patients who were HCV-positive, but HBV-negative.21

Studies of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2-targeting monoclonal antibody ramucirumab, on the other hand, suggested that it may have a greater OS benefit in patients with HBV, while regorafenib seemed to have a comparable OS benefit in both subgroups.22-25 The immune checkpoint inhibitors studied thus far seem to elicit responses irrespective of infection status.

A phase 2 trial of the immune checkpoint inhibitor tremelimumab was conducted specifically in patients with advanced HCC and chronic HCV infection. The disease control rate (DCR) was 76.4%, with 17.6% partial response (PR) rate. There was also a significant drop in viral load, suggesting that tremelimumab may have antiviral effects.26,27,28

Adoptive cell therapy promising in EBV-positive cancers

More than 90% of the global population is infected with EBV, making it one of the most common human viruses. It is a member of the herpesvirus family that is probably best known as the cause of infectious mononucleosis. On rare occasions, however, EBV can cause tumor development, though our understanding of its exact pathogenic role in cancer is still incomplete.

EBV is a DNA virus that doesn’t tend to integrate into the host genome, but instead remains in the nucleus in the form of episomes and produces several oncoproteins, including latent membrane protein-1. It is associated with a range of different cancer types, including Burkitt lymphoma and other B-cell malignancies. It also infects epithelial cells and can cause nasopharyngeal carcinoma and gastric cancer, however, much less is known about the molecular underpinnings of these EBV-positive cancer types.26,27Gastric cancers actually comprise the largest group of EBV-associated tumors because of the global incidence of this cancer type. The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network recently characterized gastric cancer on a molecular level and identified an EBV-positive subgroup as a distinct clinical entity with unique molecular characteristics.29

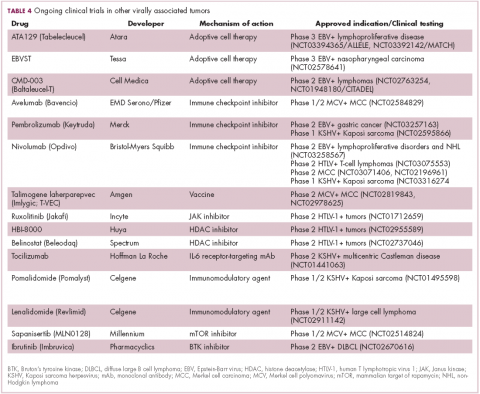

The focus of therapeutic development has again been on immunotherapy, however in this case the idea of collecting the patients T cells, engineering them to recognize EBV, and then reinfusing them into the patient – adoptive cell therapy – has gained the most traction (Table 4).

Two presentations at the American Society of Hematology annual meeting in 2017 detailed ongoing clinical trials of Atara Biotherapeutics’ ATA129 and Cell Medica’s CMD-003. ATA129 was associated with a high response rate and a low rate of serious AEs in patients with posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder; ORR was 80% in 6 patients treated after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, and 83% in 6 patients after solid organ transplant.30

CMD-003, meanwhile, demonstrated preliminary signs of activity and safety in patients with relapsed extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, according to early results from the phase 2 CITADEL trial. Among 6 evaluable patients, the ORR was 50% and the DCR was 67%.31

Newest oncovirus on the block

The most recently discovered cancer-associated virus is Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCV), a DNA virus that was identified in 2008. Like EBV, virtually the whole global adult population is infected with MCV. It is linked to the development of a highly aggressive and lethal, though rare, form of skin cancer – Merkel cell carcinoma.

MCV is found in around 80% of MCC cases and in fewer than 10% of melanomas and other skin cancers. Thus far, several direct mechanisms of oncogenesis have been described, including integration of MCV into the host genome and the production of viral oncogenes, though their precise function is as yet unclear.32-34

The American Cancer Society estimates that only 1500 cases of MCC are diagnosed each year in the United States.35 Its rarity makes it difficult to conduct clinical trials with sufficient power, yet some headway has still been made.

Around half of MCCs express the programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) on their surface, making them a logical candidate for immune checkpoint inhibition. In 2017, avelumab became the first FDA-approved drug for the treatment of MCC. Approval was based on the JAVELIN Merkel 200 study in which 88 patients received avelumab. After 1 year of follow-up the ORR was 31.8%, with a CR rate of 9%.36

Genome sequencing studies suggest that the mutational profile of MCV-positive tumors is quite different to those that are MCV-negative, which could have therapeutic implications. To date, these implications have not been delineated, given the challenge of small patient numbers, however an ongoing phase 1/2 trial is evaluating the combination of avelumab and radiation therapy or recombinant interferon beta, with or without MCV-specific cytotoxic T cells in patients with MCC and MCV infection.

The 2 other known cancer-causing viruses are human T-lymphotropic virus 1 (HTLV-1), a retrovirus associated with adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATL) and Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus (KSHV). The latter is the causative agent of Kaposi sarcoma, often in combination with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), a rare skin tumor that became renowned in the 1980s as an AIDS-defining illness.

The incidence of HTLV-1- and KSHV-positive tumors is substantially lower than the other virally associated cancers and, like MCC, this makes studying them and conducting clinical trials of novel therapeutic options a challenge. Nonetheless, several trials of targeted therapies and immunotherapies are underway.

1. Rous PA. Transmissible avain neoplasm. (Sarcoma of the common fowl). J Exp Med. 1910;12(5):696-705.

2. Epstein MA, Achong BG, Barr YM. Virus particles in cultured lymphoblasts from Burkitt's lymphoma. Lancet. 1964;1(7335):702-703.

3. Mesri Enrique A, Feitelson MA, Munger K. Human viral oncogenesis: a cancer hallmarks analysis. Cell Host & Microbe. 2014;15(3):266-282.

4. Santana-Davila R, Bhatia S, Chow LQ. Harnessing the immune system as a therapeutic tool in virus-associated cancers. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(1):106-112.

5. Tashiro H, Brenner MK. Immunotherapy against cancer-related viruses. Cell Res. 2017;27(1):59-73.

6. Brianti P, De Flammineis E, Mercuri SR. Review of HPV-related diseases and cancers. New Microbiol. 2017;40(2):80-85.

7. Tulay P, Serakinci N. The route to HPV-associated neoplastic transformation: a review of the literature. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2016;26(1):27-39.

8. Smola S. Immunopathogenesis of HPV-associated cancers and prospects for immunotherapy. Viruses. 2017;9(9).

9. Rosales R, Rosales C. Immune therapy for human papillomaviruses-related cancers. World Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2014;5(5):1002-1019.

10. Miles B, Safran HP, Monk BJ. Therapeutic options for treatment of human papillomavirus-associated cancers - novel immunologic vaccines: ADXS11-001. Gynecol Oncol Res Pract. 2017;4:10.

11. Miles BA, Monk BJ, Safran HP. Mechanistic insights into ADXS11-001 human papillomavirus-associated cancer immunotherapy. Gynecol Oncol Res Pract. 2017;4:9.

12. Huh W, Dizon D, Powell M, Landrum L, Leath C. A prospective phase II trial of the listeria-based human papillomavirus immunotherapy axalimogene filolisbac in second and third-line metastatic cervical cancer: A NRG oncology group trial. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting on Women's Cancer; March 12-15, 2017, 2017; National Harbor, MD.

13. Petit RG, Mehta A, Jain M, et al. ADXS11-001 immunotherapy targeting HPV-E7: final results from a Phase II study in Indian women with recurrent cervical cancer. Journal for Immunotherapy of Cancer. 2014;2(Suppl 3):P92-P92.

14. Glisson B, Massarelli E, William W, et al. Nivolumab and ISA 101 HPV vaccine in incurable HPV-16+ cancer. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(suppl_5):v403-v427.

15. Ding X-X, Zhu Q-G, Zhang S-M, et al. Precision medicine for hepatocellular carcinoma: driver mutations and targeted therapy. Oncotarget. 2017;8(33):55715-55730.

16. Ringehan M, McKeating JA, Protzer U. Viral hepatitis and liver cancer. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2017;372(1732):20160274.

17. Abou-Alfa G, Meyer T, Cheng AL, et al. Cabozantinib (C) versus placebo (P) in patients (pts) with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) who have received prior sorafenib: results from the randomized phase III CELESTIAL trial. J Clin Oncol. 2017;36(Suppl 4S):abstr 207.

18. Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018.

19. Zhu AX, Finn RS, Cattan S, et al. KEYNOTE-224: Pembrolizumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma previously treated with sorafenib. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(Suppl 4S):Abstr 209.

20. Kelley RK, Abou-Alfa GK, Bendell JC, et al. Phase I/II study of durvalumab and tremelimumab in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): Phase I safety and efficacy analyses. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2017;35(15_suppl):4073-4073.

21. Jackson R, Psarelli E-E, Berhane S, Khan H, Johnson P. Impact of Viral Status on Survival in Patients Receiving Sorafenib for Advanced Hepatocellular Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Phase III Trials. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2017;35(6):622-628.

22. Kudo M. Molecular Targeted Agents for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Current Status and Future Perspectives. Liver Cancer. 2017;6(2):101-112.

23. zur Hausen H, Meinhof W, Scheiber W, Bornkamm GW. Attempts to detect virus-secific DNA in human tumors. I. Nucleic acid hybridizations with complementary RNA of human wart virus. Int J Cancer. 1974;13(5):650-656.

24. Bruix J, Qin S, Merle P, et al. Regorafenib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib treatment (RESORCE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10064):56-66.

25. Bruix J, Tak WY, Gasbarrini A, et al. Regorafenib as second-line therapy for intermediate or advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: multicentre, open-label, phase II safety study. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(16):3412-3419.

26. Neparidze N, Lacy J. Malignancies associated with epstein-barr virus: pathobiology, clinical features, and evolving treatments. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2014;12(6):358-371.

27. Ozoya OO, Sokol L, Dalia S. EBV-Related Malignancies, Outcomes and Novel Prevention Strategies. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2016;16(1):4-21.

28. Sangro B, Gomez-Martin C, de la Mata M, et al. A clinical trial of CTLA-4 blockade with tremelimumab in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2013;59(1):81-88.

29. The Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;513:202.

30. Prockop S, Li A, Baiocchi R, et al. Efficacy and safety of ATA129, partially matched allogeneic third-party Epstein-Barr virus-targeted cytotoxic T lymphocytes in a multicenter study for post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder. Paper presented at: 59th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Hematology; December 9-12, 2017, 2017; Atlanta, GA.

31. Kim W, Ardeshna K, Lin Y, et al. Autologous EBV-specific T cells (CMD-003): Early results from a multicenter, multinational Phase 2 trial for treatment of EBV-associated NK/T-cell lymphoma. Paper presented at: 59th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Hematology; December 9-12, 2017, 2017; Atlanta, GA.

32. Schadendorf D, Lebbé C, zur Hausen A, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: Epidemiology, prognosis, therapy and unmet medical needs. European Journal of Cancer. 2017;71:53-69.

33. Spurgeon ME, Lambert PF. Merkel cell polyomavirus: a newly discovered human virus with oncogenic potential. Virology. 2013;435(1):118-130.

34. Tello TL, Coggshall K, Yom SS, Yu SS. Merkel cell carcinoma: An update and review: Current and future therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(3):445-454.

35. American Cancer Society. Key Statistics for Merkel Cell Carcinoma. 2015; https://www.cancer.org/cancer/merkel-cell-skin-cancer/about/key-statistics.html#written_by. Accessed March 7th, 2017.

36. Kaufman HL, Russell J, Hamid O, et al. Avelumab in patients with chemotherapy-refractory metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma: a multicentre, single-group, open-label, phase 2 trial. The Lancet Oncology.17(10):1374-1385.

Infection with certain viruses has been causally linked to the development of cancer. In recent years, an improved understanding of the unique pathology and molecular underpinnings of these virally associated cancers has prompted the development of more personalized treatment strategies, with a particular focus on immunotherapy. Here, we describe some of the latest developments.

The link between viruses and cancer

Suspicions about a possible role of viral infections in the development of cancer were first aroused in the early 1900s. The seminal discovery is traced back to Peyton Rous, who showed that a malignant tumor growing in a chicken could be transferred to a healthy bird by injecting it with tumor extracts that contained no actual tumor cells.1

The infectious etiology of human cancer, however, remained controversial until many years later when the first cancer-causing virus, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), was identified in cell cultures from patients with Burkitt lymphoma. Shortly afterward, the Rous sarcoma virus was unveiled as the oncogenic agent behind Rous’ observations.2Seven viruses have now been linked to the development of cancers and are thought to be responsible for around 12% of all cancer cases worldwide. The burden is likely to increase as technological advancements make it easier to establish a causal link between viruses and cancer development.3

In addition to making these links, researchers have also made significant headway in understanding how viruses cause cancer. Cancerous transformation of host cells occurs in only a minority of those who are infected with oncogenic viruses and often occurs in the setting of chronic infection.

Viruses can mediate carcinogenesis by direct and/or indirect mechanisms (Figure 1). Many of the hallmarks of cancer, the key attributes that drive the transformation from a normal cell to a malignant one, are compatible with the virus’s needs, such as needing to avoid cell death, increasing cell proliferation, and avoiding detection by the immune system.

Viruses hijack the cellular machinery to meet those needs and they can do this either by producing viral proteins that have an oncogenic effect or by integrating their genetic material into the host cell genome. When the latter occurs, the process of integration can also cause damage to the DNA, which further increases the risk of cancer-promoting changes occurring in the host genome.

Viruses can indirectly contribute to carcinogenesis by fostering a microenvironment of chronic inflammation, causing oxidative stress and local tissue damage, and by suppressing the antitumor immune response.4,5

Screening and prevention efforts have helped to reduce the burden of several different virally associated cancers. However, for the substantial proportion of patients who are still affected by these cancers, there is a pressing need for new therapeutic options, particularly since genome sequencing studies have revealed that these cancers can often have distinct underlying molecular mechanisms.

Vaccines lead the charge in HPV-driven cancers

German virologist Harald zur Hausen received the Nobel Prize in 2008 for his discovery of the oncogenic role of human papillomaviruses (HPVs), a large family of more than 100 DNA viruses that infect the epithelial cells of the skin and mucous membranes. They are responsible for the largest number of virally associated cancer cases globally – around 5% (Table 1).

A number of different cancer types are linked to HPV infection, but it is best known as the cause of cervical cancer. The development of diagnostic blood tests and prophylactic vaccines for prevention and early intervention in HPV infection has helped to reduce the incidence of cervical cancer. Conversely, another type of HPV-associated cancer, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), has seen increased incidence in recent years.

HPVs are categorized according to their oncogenic potential as high, intermediate, or low risk. The high-risk HPV16 and HPV18 strains are most commonly associated with cancer. They are thought to cause cancer predominantly through integration into the host genome. The HPV genome is composed of 8 genes encoding proteins that regulate viral replication and assembly. The E6 and E7 genes are the most highly oncogenic; as the HPV DNA is inserted into the host genome, the transcriptional regulator of E6/E7 is lost, leading to their increased expression. These genes have significant oncogenic potential because of their interaction with 2 tumor suppressor proteins, p53 and pRb.6,7

The largest investment in therapeutic development for HPV-positive cancers has been in the realm of immunotherapy in an effort to boost the anti-tumor immune response. In particular, there has been a focus on the development of therapeutic vaccines, designed to prime the anti-tumor immune response to recognize viral antigens. A variety of different types of vaccines are being developed, including live, attenuated and inactivated vaccines that are protein, DNA, or peptide based. Most developed to date target the E6/E7 proteins from the HPV16/18 strains (Table 2).8,9

Other immunotherapies are also being evaluated, including immune checkpoint inhibitors, antibodies designed to target one of the principal mechanisms of immune evasion exploited by cancer cells. The combination of immune checkpoint inhibitors with vaccines is a particularly promising strategy in HPV-associated cancers. At the European Society for Medical Oncology Congress in 2017, the results of a phase 2 trial of nivolumab in combination with ISA-101 were presented.

Among 24 patients with HPV-positive tumors, the majority oropharyngeal cancers, the combination elicited an overall response rate (ORR) of 33%, including 2 complete responses (CRs). Most adverse events (AEs) were mild to moderate in severity and included fever, injection site reactions, fatigue and nausea.14

Hepatocellular carcinoma: a tale of two viruses

The hepatitis viruses are a group of 5 unrelated viruses that causes inflammation of the liver. Hepatitis B (HBV), a DNA virus, and hepatitis C (HCV), an RNA virus, are also oncoviruses; HBV in particular is one of the main causes of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most common type of liver cancer.

The highly inflammatory environment fostered by HBV and HCV infection causes liver damage that often leads to cirrhosis. Continued infection can drive permanent damage to the hepatocytes, leading to genetic and epigenetic damage and driving oncogenesis. As an RNA virus, HCV doesn’t integrate into the genome and no confirmed viral oncoproteins have been identified to date, therefore it mostly drives cancer through these indirect mechanisms, which is also reflected in the fact that HCV-associated HCC predominantly occurs against a backdrop of liver cirrhosis.

HBV does integrate into the host genome. Genome sequencing studies revealed hundreds of integration sites, but most commonly they disrupted host genes involved in telomere stability and cell cycle regulation, providing some insight into the mechanisms by which HBV-associated HCC develops. In addition, HBV produces several oncoproteins, including HBx, which disrupts gene transcription, cell signaling pathways, cell cycle progress, apoptosis and other cellular processes.15,16

Multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have been the focal point of therapeutic development in HCC. However, following the approval of sorafenib in 2008, there was a dearth of effective new treatment options despite substantial efforts and numerous phase 3 trials. More recently, immunotherapy has also come to the forefront, especially immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Last year marked the first new drug approvals in nearly a decade – the TKI regorafenib (Stivarga) and immune checkpoint inhibitor nivolumab (Opdivo), both in the second-line setting after failure of sorafenib. Treatment options in this setting may continue to expand, with the TKIs cabozantinib and lenvatinib and the immune checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab and the combination of durvalumab and tremelimumab hot on their heels.17-20 Many of these drugs are also being evaluated in the front-line setting in comparison with sorafenib (Table 3).

At the current time, the treatment strategy for patients with HCC is independent of etiology, however, there are significant ongoing efforts to try to tease out the implications of infection for treatment efficacy. A recent meta-analysis of patients treated with sorafenib in 3 randomized phase 3 trials (n = 3,526) suggested that it improved overall survival (OS) among patients who were HCV-positive, but HBV-negative.21

Studies of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2-targeting monoclonal antibody ramucirumab, on the other hand, suggested that it may have a greater OS benefit in patients with HBV, while regorafenib seemed to have a comparable OS benefit in both subgroups.22-25 The immune checkpoint inhibitors studied thus far seem to elicit responses irrespective of infection status.

A phase 2 trial of the immune checkpoint inhibitor tremelimumab was conducted specifically in patients with advanced HCC and chronic HCV infection. The disease control rate (DCR) was 76.4%, with 17.6% partial response (PR) rate. There was also a significant drop in viral load, suggesting that tremelimumab may have antiviral effects.26,27,28

Adoptive cell therapy promising in EBV-positive cancers

More than 90% of the global population is infected with EBV, making it one of the most common human viruses. It is a member of the herpesvirus family that is probably best known as the cause of infectious mononucleosis. On rare occasions, however, EBV can cause tumor development, though our understanding of its exact pathogenic role in cancer is still incomplete.

EBV is a DNA virus that doesn’t tend to integrate into the host genome, but instead remains in the nucleus in the form of episomes and produces several oncoproteins, including latent membrane protein-1. It is associated with a range of different cancer types, including Burkitt lymphoma and other B-cell malignancies. It also infects epithelial cells and can cause nasopharyngeal carcinoma and gastric cancer, however, much less is known about the molecular underpinnings of these EBV-positive cancer types.26,27Gastric cancers actually comprise the largest group of EBV-associated tumors because of the global incidence of this cancer type. The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network recently characterized gastric cancer on a molecular level and identified an EBV-positive subgroup as a distinct clinical entity with unique molecular characteristics.29

The focus of therapeutic development has again been on immunotherapy, however in this case the idea of collecting the patients T cells, engineering them to recognize EBV, and then reinfusing them into the patient – adoptive cell therapy – has gained the most traction (Table 4).

Two presentations at the American Society of Hematology annual meeting in 2017 detailed ongoing clinical trials of Atara Biotherapeutics’ ATA129 and Cell Medica’s CMD-003. ATA129 was associated with a high response rate and a low rate of serious AEs in patients with posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder; ORR was 80% in 6 patients treated after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, and 83% in 6 patients after solid organ transplant.30

CMD-003, meanwhile, demonstrated preliminary signs of activity and safety in patients with relapsed extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, according to early results from the phase 2 CITADEL trial. Among 6 evaluable patients, the ORR was 50% and the DCR was 67%.31

Newest oncovirus on the block

The most recently discovered cancer-associated virus is Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCV), a DNA virus that was identified in 2008. Like EBV, virtually the whole global adult population is infected with MCV. It is linked to the development of a highly aggressive and lethal, though rare, form of skin cancer – Merkel cell carcinoma.

MCV is found in around 80% of MCC cases and in fewer than 10% of melanomas and other skin cancers. Thus far, several direct mechanisms of oncogenesis have been described, including integration of MCV into the host genome and the production of viral oncogenes, though their precise function is as yet unclear.32-34

The American Cancer Society estimates that only 1500 cases of MCC are diagnosed each year in the United States.35 Its rarity makes it difficult to conduct clinical trials with sufficient power, yet some headway has still been made.

Around half of MCCs express the programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) on their surface, making them a logical candidate for immune checkpoint inhibition. In 2017, avelumab became the first FDA-approved drug for the treatment of MCC. Approval was based on the JAVELIN Merkel 200 study in which 88 patients received avelumab. After 1 year of follow-up the ORR was 31.8%, with a CR rate of 9%.36

Genome sequencing studies suggest that the mutational profile of MCV-positive tumors is quite different to those that are MCV-negative, which could have therapeutic implications. To date, these implications have not been delineated, given the challenge of small patient numbers, however an ongoing phase 1/2 trial is evaluating the combination of avelumab and radiation therapy or recombinant interferon beta, with or without MCV-specific cytotoxic T cells in patients with MCC and MCV infection.

The 2 other known cancer-causing viruses are human T-lymphotropic virus 1 (HTLV-1), a retrovirus associated with adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATL) and Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus (KSHV). The latter is the causative agent of Kaposi sarcoma, often in combination with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), a rare skin tumor that became renowned in the 1980s as an AIDS-defining illness.

The incidence of HTLV-1- and KSHV-positive tumors is substantially lower than the other virally associated cancers and, like MCC, this makes studying them and conducting clinical trials of novel therapeutic options a challenge. Nonetheless, several trials of targeted therapies and immunotherapies are underway.

Infection with certain viruses has been causally linked to the development of cancer. In recent years, an improved understanding of the unique pathology and molecular underpinnings of these virally associated cancers has prompted the development of more personalized treatment strategies, with a particular focus on immunotherapy. Here, we describe some of the latest developments.

The link between viruses and cancer

Suspicions about a possible role of viral infections in the development of cancer were first aroused in the early 1900s. The seminal discovery is traced back to Peyton Rous, who showed that a malignant tumor growing in a chicken could be transferred to a healthy bird by injecting it with tumor extracts that contained no actual tumor cells.1

The infectious etiology of human cancer, however, remained controversial until many years later when the first cancer-causing virus, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), was identified in cell cultures from patients with Burkitt lymphoma. Shortly afterward, the Rous sarcoma virus was unveiled as the oncogenic agent behind Rous’ observations.2Seven viruses have now been linked to the development of cancers and are thought to be responsible for around 12% of all cancer cases worldwide. The burden is likely to increase as technological advancements make it easier to establish a causal link between viruses and cancer development.3

In addition to making these links, researchers have also made significant headway in understanding how viruses cause cancer. Cancerous transformation of host cells occurs in only a minority of those who are infected with oncogenic viruses and often occurs in the setting of chronic infection.

Viruses can mediate carcinogenesis by direct and/or indirect mechanisms (Figure 1). Many of the hallmarks of cancer, the key attributes that drive the transformation from a normal cell to a malignant one, are compatible with the virus’s needs, such as needing to avoid cell death, increasing cell proliferation, and avoiding detection by the immune system.

Viruses hijack the cellular machinery to meet those needs and they can do this either by producing viral proteins that have an oncogenic effect or by integrating their genetic material into the host cell genome. When the latter occurs, the process of integration can also cause damage to the DNA, which further increases the risk of cancer-promoting changes occurring in the host genome.

Viruses can indirectly contribute to carcinogenesis by fostering a microenvironment of chronic inflammation, causing oxidative stress and local tissue damage, and by suppressing the antitumor immune response.4,5

Screening and prevention efforts have helped to reduce the burden of several different virally associated cancers. However, for the substantial proportion of patients who are still affected by these cancers, there is a pressing need for new therapeutic options, particularly since genome sequencing studies have revealed that these cancers can often have distinct underlying molecular mechanisms.

Vaccines lead the charge in HPV-driven cancers

German virologist Harald zur Hausen received the Nobel Prize in 2008 for his discovery of the oncogenic role of human papillomaviruses (HPVs), a large family of more than 100 DNA viruses that infect the epithelial cells of the skin and mucous membranes. They are responsible for the largest number of virally associated cancer cases globally – around 5% (Table 1).

A number of different cancer types are linked to HPV infection, but it is best known as the cause of cervical cancer. The development of diagnostic blood tests and prophylactic vaccines for prevention and early intervention in HPV infection has helped to reduce the incidence of cervical cancer. Conversely, another type of HPV-associated cancer, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), has seen increased incidence in recent years.

HPVs are categorized according to their oncogenic potential as high, intermediate, or low risk. The high-risk HPV16 and HPV18 strains are most commonly associated with cancer. They are thought to cause cancer predominantly through integration into the host genome. The HPV genome is composed of 8 genes encoding proteins that regulate viral replication and assembly. The E6 and E7 genes are the most highly oncogenic; as the HPV DNA is inserted into the host genome, the transcriptional regulator of E6/E7 is lost, leading to their increased expression. These genes have significant oncogenic potential because of their interaction with 2 tumor suppressor proteins, p53 and pRb.6,7

The largest investment in therapeutic development for HPV-positive cancers has been in the realm of immunotherapy in an effort to boost the anti-tumor immune response. In particular, there has been a focus on the development of therapeutic vaccines, designed to prime the anti-tumor immune response to recognize viral antigens. A variety of different types of vaccines are being developed, including live, attenuated and inactivated vaccines that are protein, DNA, or peptide based. Most developed to date target the E6/E7 proteins from the HPV16/18 strains (Table 2).8,9

Other immunotherapies are also being evaluated, including immune checkpoint inhibitors, antibodies designed to target one of the principal mechanisms of immune evasion exploited by cancer cells. The combination of immune checkpoint inhibitors with vaccines is a particularly promising strategy in HPV-associated cancers. At the European Society for Medical Oncology Congress in 2017, the results of a phase 2 trial of nivolumab in combination with ISA-101 were presented.

Among 24 patients with HPV-positive tumors, the majority oropharyngeal cancers, the combination elicited an overall response rate (ORR) of 33%, including 2 complete responses (CRs). Most adverse events (AEs) were mild to moderate in severity and included fever, injection site reactions, fatigue and nausea.14

Hepatocellular carcinoma: a tale of two viruses

The hepatitis viruses are a group of 5 unrelated viruses that causes inflammation of the liver. Hepatitis B (HBV), a DNA virus, and hepatitis C (HCV), an RNA virus, are also oncoviruses; HBV in particular is one of the main causes of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most common type of liver cancer.

The highly inflammatory environment fostered by HBV and HCV infection causes liver damage that often leads to cirrhosis. Continued infection can drive permanent damage to the hepatocytes, leading to genetic and epigenetic damage and driving oncogenesis. As an RNA virus, HCV doesn’t integrate into the genome and no confirmed viral oncoproteins have been identified to date, therefore it mostly drives cancer through these indirect mechanisms, which is also reflected in the fact that HCV-associated HCC predominantly occurs against a backdrop of liver cirrhosis.

HBV does integrate into the host genome. Genome sequencing studies revealed hundreds of integration sites, but most commonly they disrupted host genes involved in telomere stability and cell cycle regulation, providing some insight into the mechanisms by which HBV-associated HCC develops. In addition, HBV produces several oncoproteins, including HBx, which disrupts gene transcription, cell signaling pathways, cell cycle progress, apoptosis and other cellular processes.15,16

Multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have been the focal point of therapeutic development in HCC. However, following the approval of sorafenib in 2008, there was a dearth of effective new treatment options despite substantial efforts and numerous phase 3 trials. More recently, immunotherapy has also come to the forefront, especially immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Last year marked the first new drug approvals in nearly a decade – the TKI regorafenib (Stivarga) and immune checkpoint inhibitor nivolumab (Opdivo), both in the second-line setting after failure of sorafenib. Treatment options in this setting may continue to expand, with the TKIs cabozantinib and lenvatinib and the immune checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab and the combination of durvalumab and tremelimumab hot on their heels.17-20 Many of these drugs are also being evaluated in the front-line setting in comparison with sorafenib (Table 3).

At the current time, the treatment strategy for patients with HCC is independent of etiology, however, there are significant ongoing efforts to try to tease out the implications of infection for treatment efficacy. A recent meta-analysis of patients treated with sorafenib in 3 randomized phase 3 trials (n = 3,526) suggested that it improved overall survival (OS) among patients who were HCV-positive, but HBV-negative.21

Studies of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2-targeting monoclonal antibody ramucirumab, on the other hand, suggested that it may have a greater OS benefit in patients with HBV, while regorafenib seemed to have a comparable OS benefit in both subgroups.22-25 The immune checkpoint inhibitors studied thus far seem to elicit responses irrespective of infection status.

A phase 2 trial of the immune checkpoint inhibitor tremelimumab was conducted specifically in patients with advanced HCC and chronic HCV infection. The disease control rate (DCR) was 76.4%, with 17.6% partial response (PR) rate. There was also a significant drop in viral load, suggesting that tremelimumab may have antiviral effects.26,27,28

Adoptive cell therapy promising in EBV-positive cancers

More than 90% of the global population is infected with EBV, making it one of the most common human viruses. It is a member of the herpesvirus family that is probably best known as the cause of infectious mononucleosis. On rare occasions, however, EBV can cause tumor development, though our understanding of its exact pathogenic role in cancer is still incomplete.

EBV is a DNA virus that doesn’t tend to integrate into the host genome, but instead remains in the nucleus in the form of episomes and produces several oncoproteins, including latent membrane protein-1. It is associated with a range of different cancer types, including Burkitt lymphoma and other B-cell malignancies. It also infects epithelial cells and can cause nasopharyngeal carcinoma and gastric cancer, however, much less is known about the molecular underpinnings of these EBV-positive cancer types.26,27Gastric cancers actually comprise the largest group of EBV-associated tumors because of the global incidence of this cancer type. The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network recently characterized gastric cancer on a molecular level and identified an EBV-positive subgroup as a distinct clinical entity with unique molecular characteristics.29

The focus of therapeutic development has again been on immunotherapy, however in this case the idea of collecting the patients T cells, engineering them to recognize EBV, and then reinfusing them into the patient – adoptive cell therapy – has gained the most traction (Table 4).

Two presentations at the American Society of Hematology annual meeting in 2017 detailed ongoing clinical trials of Atara Biotherapeutics’ ATA129 and Cell Medica’s CMD-003. ATA129 was associated with a high response rate and a low rate of serious AEs in patients with posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder; ORR was 80% in 6 patients treated after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, and 83% in 6 patients after solid organ transplant.30

CMD-003, meanwhile, demonstrated preliminary signs of activity and safety in patients with relapsed extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, according to early results from the phase 2 CITADEL trial. Among 6 evaluable patients, the ORR was 50% and the DCR was 67%.31

Newest oncovirus on the block

The most recently discovered cancer-associated virus is Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCV), a DNA virus that was identified in 2008. Like EBV, virtually the whole global adult population is infected with MCV. It is linked to the development of a highly aggressive and lethal, though rare, form of skin cancer – Merkel cell carcinoma.

MCV is found in around 80% of MCC cases and in fewer than 10% of melanomas and other skin cancers. Thus far, several direct mechanisms of oncogenesis have been described, including integration of MCV into the host genome and the production of viral oncogenes, though their precise function is as yet unclear.32-34

The American Cancer Society estimates that only 1500 cases of MCC are diagnosed each year in the United States.35 Its rarity makes it difficult to conduct clinical trials with sufficient power, yet some headway has still been made.

Around half of MCCs express the programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) on their surface, making them a logical candidate for immune checkpoint inhibition. In 2017, avelumab became the first FDA-approved drug for the treatment of MCC. Approval was based on the JAVELIN Merkel 200 study in which 88 patients received avelumab. After 1 year of follow-up the ORR was 31.8%, with a CR rate of 9%.36

Genome sequencing studies suggest that the mutational profile of MCV-positive tumors is quite different to those that are MCV-negative, which could have therapeutic implications. To date, these implications have not been delineated, given the challenge of small patient numbers, however an ongoing phase 1/2 trial is evaluating the combination of avelumab and radiation therapy or recombinant interferon beta, with or without MCV-specific cytotoxic T cells in patients with MCC and MCV infection.

The 2 other known cancer-causing viruses are human T-lymphotropic virus 1 (HTLV-1), a retrovirus associated with adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATL) and Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus (KSHV). The latter is the causative agent of Kaposi sarcoma, often in combination with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), a rare skin tumor that became renowned in the 1980s as an AIDS-defining illness.

The incidence of HTLV-1- and KSHV-positive tumors is substantially lower than the other virally associated cancers and, like MCC, this makes studying them and conducting clinical trials of novel therapeutic options a challenge. Nonetheless, several trials of targeted therapies and immunotherapies are underway.

1. Rous PA. Transmissible avain neoplasm. (Sarcoma of the common fowl). J Exp Med. 1910;12(5):696-705.

2. Epstein MA, Achong BG, Barr YM. Virus particles in cultured lymphoblasts from Burkitt's lymphoma. Lancet. 1964;1(7335):702-703.

3. Mesri Enrique A, Feitelson MA, Munger K. Human viral oncogenesis: a cancer hallmarks analysis. Cell Host & Microbe. 2014;15(3):266-282.

4. Santana-Davila R, Bhatia S, Chow LQ. Harnessing the immune system as a therapeutic tool in virus-associated cancers. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(1):106-112.

5. Tashiro H, Brenner MK. Immunotherapy against cancer-related viruses. Cell Res. 2017;27(1):59-73.

6. Brianti P, De Flammineis E, Mercuri SR. Review of HPV-related diseases and cancers. New Microbiol. 2017;40(2):80-85.

7. Tulay P, Serakinci N. The route to HPV-associated neoplastic transformation: a review of the literature. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2016;26(1):27-39.

8. Smola S. Immunopathogenesis of HPV-associated cancers and prospects for immunotherapy. Viruses. 2017;9(9).

9. Rosales R, Rosales C. Immune therapy for human papillomaviruses-related cancers. World Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2014;5(5):1002-1019.

10. Miles B, Safran HP, Monk BJ. Therapeutic options for treatment of human papillomavirus-associated cancers - novel immunologic vaccines: ADXS11-001. Gynecol Oncol Res Pract. 2017;4:10.

11. Miles BA, Monk BJ, Safran HP. Mechanistic insights into ADXS11-001 human papillomavirus-associated cancer immunotherapy. Gynecol Oncol Res Pract. 2017;4:9.

12. Huh W, Dizon D, Powell M, Landrum L, Leath C. A prospective phase II trial of the listeria-based human papillomavirus immunotherapy axalimogene filolisbac in second and third-line metastatic cervical cancer: A NRG oncology group trial. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting on Women's Cancer; March 12-15, 2017, 2017; National Harbor, MD.

13. Petit RG, Mehta A, Jain M, et al. ADXS11-001 immunotherapy targeting HPV-E7: final results from a Phase II study in Indian women with recurrent cervical cancer. Journal for Immunotherapy of Cancer. 2014;2(Suppl 3):P92-P92.

14. Glisson B, Massarelli E, William W, et al. Nivolumab and ISA 101 HPV vaccine in incurable HPV-16+ cancer. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(suppl_5):v403-v427.

15. Ding X-X, Zhu Q-G, Zhang S-M, et al. Precision medicine for hepatocellular carcinoma: driver mutations and targeted therapy. Oncotarget. 2017;8(33):55715-55730.

16. Ringehan M, McKeating JA, Protzer U. Viral hepatitis and liver cancer. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2017;372(1732):20160274.

17. Abou-Alfa G, Meyer T, Cheng AL, et al. Cabozantinib (C) versus placebo (P) in patients (pts) with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) who have received prior sorafenib: results from the randomized phase III CELESTIAL trial. J Clin Oncol. 2017;36(Suppl 4S):abstr 207.

18. Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018.

19. Zhu AX, Finn RS, Cattan S, et al. KEYNOTE-224: Pembrolizumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma previously treated with sorafenib. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(Suppl 4S):Abstr 209.

20. Kelley RK, Abou-Alfa GK, Bendell JC, et al. Phase I/II study of durvalumab and tremelimumab in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): Phase I safety and efficacy analyses. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2017;35(15_suppl):4073-4073.

21. Jackson R, Psarelli E-E, Berhane S, Khan H, Johnson P. Impact of Viral Status on Survival in Patients Receiving Sorafenib for Advanced Hepatocellular Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Phase III Trials. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2017;35(6):622-628.

22. Kudo M. Molecular Targeted Agents for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Current Status and Future Perspectives. Liver Cancer. 2017;6(2):101-112.

23. zur Hausen H, Meinhof W, Scheiber W, Bornkamm GW. Attempts to detect virus-secific DNA in human tumors. I. Nucleic acid hybridizations with complementary RNA of human wart virus. Int J Cancer. 1974;13(5):650-656.

24. Bruix J, Qin S, Merle P, et al. Regorafenib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib treatment (RESORCE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10064):56-66.

25. Bruix J, Tak WY, Gasbarrini A, et al. Regorafenib as second-line therapy for intermediate or advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: multicentre, open-label, phase II safety study. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(16):3412-3419.

26. Neparidze N, Lacy J. Malignancies associated with epstein-barr virus: pathobiology, clinical features, and evolving treatments. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2014;12(6):358-371.

27. Ozoya OO, Sokol L, Dalia S. EBV-Related Malignancies, Outcomes and Novel Prevention Strategies. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2016;16(1):4-21.

28. Sangro B, Gomez-Martin C, de la Mata M, et al. A clinical trial of CTLA-4 blockade with tremelimumab in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2013;59(1):81-88.

29. The Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;513:202.

30. Prockop S, Li A, Baiocchi R, et al. Efficacy and safety of ATA129, partially matched allogeneic third-party Epstein-Barr virus-targeted cytotoxic T lymphocytes in a multicenter study for post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder. Paper presented at: 59th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Hematology; December 9-12, 2017, 2017; Atlanta, GA.

31. Kim W, Ardeshna K, Lin Y, et al. Autologous EBV-specific T cells (CMD-003): Early results from a multicenter, multinational Phase 2 trial for treatment of EBV-associated NK/T-cell lymphoma. Paper presented at: 59th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Hematology; December 9-12, 2017, 2017; Atlanta, GA.

32. Schadendorf D, Lebbé C, zur Hausen A, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: Epidemiology, prognosis, therapy and unmet medical needs. European Journal of Cancer. 2017;71:53-69.

33. Spurgeon ME, Lambert PF. Merkel cell polyomavirus: a newly discovered human virus with oncogenic potential. Virology. 2013;435(1):118-130.

34. Tello TL, Coggshall K, Yom SS, Yu SS. Merkel cell carcinoma: An update and review: Current and future therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(3):445-454.

35. American Cancer Society. Key Statistics for Merkel Cell Carcinoma. 2015; https://www.cancer.org/cancer/merkel-cell-skin-cancer/about/key-statistics.html#written_by. Accessed March 7th, 2017.

36. Kaufman HL, Russell J, Hamid O, et al. Avelumab in patients with chemotherapy-refractory metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma: a multicentre, single-group, open-label, phase 2 trial. The Lancet Oncology.17(10):1374-1385.

1. Rous PA. Transmissible avain neoplasm. (Sarcoma of the common fowl). J Exp Med. 1910;12(5):696-705.

2. Epstein MA, Achong BG, Barr YM. Virus particles in cultured lymphoblasts from Burkitt's lymphoma. Lancet. 1964;1(7335):702-703.

3. Mesri Enrique A, Feitelson MA, Munger K. Human viral oncogenesis: a cancer hallmarks analysis. Cell Host & Microbe. 2014;15(3):266-282.

4. Santana-Davila R, Bhatia S, Chow LQ. Harnessing the immune system as a therapeutic tool in virus-associated cancers. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(1):106-112.

5. Tashiro H, Brenner MK. Immunotherapy against cancer-related viruses. Cell Res. 2017;27(1):59-73.

6. Brianti P, De Flammineis E, Mercuri SR. Review of HPV-related diseases and cancers. New Microbiol. 2017;40(2):80-85.

7. Tulay P, Serakinci N. The route to HPV-associated neoplastic transformation: a review of the literature. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2016;26(1):27-39.

8. Smola S. Immunopathogenesis of HPV-associated cancers and prospects for immunotherapy. Viruses. 2017;9(9).

9. Rosales R, Rosales C. Immune therapy for human papillomaviruses-related cancers. World Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2014;5(5):1002-1019.

10. Miles B, Safran HP, Monk BJ. Therapeutic options for treatment of human papillomavirus-associated cancers - novel immunologic vaccines: ADXS11-001. Gynecol Oncol Res Pract. 2017;4:10.

11. Miles BA, Monk BJ, Safran HP. Mechanistic insights into ADXS11-001 human papillomavirus-associated cancer immunotherapy. Gynecol Oncol Res Pract. 2017;4:9.

12. Huh W, Dizon D, Powell M, Landrum L, Leath C. A prospective phase II trial of the listeria-based human papillomavirus immunotherapy axalimogene filolisbac in second and third-line metastatic cervical cancer: A NRG oncology group trial. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting on Women's Cancer; March 12-15, 2017, 2017; National Harbor, MD.

13. Petit RG, Mehta A, Jain M, et al. ADXS11-001 immunotherapy targeting HPV-E7: final results from a Phase II study in Indian women with recurrent cervical cancer. Journal for Immunotherapy of Cancer. 2014;2(Suppl 3):P92-P92.

14. Glisson B, Massarelli E, William W, et al. Nivolumab and ISA 101 HPV vaccine in incurable HPV-16+ cancer. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(suppl_5):v403-v427.

15. Ding X-X, Zhu Q-G, Zhang S-M, et al. Precision medicine for hepatocellular carcinoma: driver mutations and targeted therapy. Oncotarget. 2017;8(33):55715-55730.

16. Ringehan M, McKeating JA, Protzer U. Viral hepatitis and liver cancer. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2017;372(1732):20160274.

17. Abou-Alfa G, Meyer T, Cheng AL, et al. Cabozantinib (C) versus placebo (P) in patients (pts) with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) who have received prior sorafenib: results from the randomized phase III CELESTIAL trial. J Clin Oncol. 2017;36(Suppl 4S):abstr 207.

18. Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018.

19. Zhu AX, Finn RS, Cattan S, et al. KEYNOTE-224: Pembrolizumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma previously treated with sorafenib. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(Suppl 4S):Abstr 209.

20. Kelley RK, Abou-Alfa GK, Bendell JC, et al. Phase I/II study of durvalumab and tremelimumab in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): Phase I safety and efficacy analyses. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2017;35(15_suppl):4073-4073.

21. Jackson R, Psarelli E-E, Berhane S, Khan H, Johnson P. Impact of Viral Status on Survival in Patients Receiving Sorafenib for Advanced Hepatocellular Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Phase III Trials. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2017;35(6):622-628.

22. Kudo M. Molecular Targeted Agents for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Current Status and Future Perspectives. Liver Cancer. 2017;6(2):101-112.

23. zur Hausen H, Meinhof W, Scheiber W, Bornkamm GW. Attempts to detect virus-secific DNA in human tumors. I. Nucleic acid hybridizations with complementary RNA of human wart virus. Int J Cancer. 1974;13(5):650-656.

24. Bruix J, Qin S, Merle P, et al. Regorafenib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib treatment (RESORCE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10064):56-66.

25. Bruix J, Tak WY, Gasbarrini A, et al. Regorafenib as second-line therapy for intermediate or advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: multicentre, open-label, phase II safety study. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(16):3412-3419.

26. Neparidze N, Lacy J. Malignancies associated with epstein-barr virus: pathobiology, clinical features, and evolving treatments. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2014;12(6):358-371.

27. Ozoya OO, Sokol L, Dalia S. EBV-Related Malignancies, Outcomes and Novel Prevention Strategies. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2016;16(1):4-21.

28. Sangro B, Gomez-Martin C, de la Mata M, et al. A clinical trial of CTLA-4 blockade with tremelimumab in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2013;59(1):81-88.

29. The Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;513:202.

30. Prockop S, Li A, Baiocchi R, et al. Efficacy and safety of ATA129, partially matched allogeneic third-party Epstein-Barr virus-targeted cytotoxic T lymphocytes in a multicenter study for post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder. Paper presented at: 59th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Hematology; December 9-12, 2017, 2017; Atlanta, GA.

31. Kim W, Ardeshna K, Lin Y, et al. Autologous EBV-specific T cells (CMD-003): Early results from a multicenter, multinational Phase 2 trial for treatment of EBV-associated NK/T-cell lymphoma. Paper presented at: 59th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Hematology; December 9-12, 2017, 2017; Atlanta, GA.

32. Schadendorf D, Lebbé C, zur Hausen A, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: Epidemiology, prognosis, therapy and unmet medical needs. European Journal of Cancer. 2017;71:53-69.

33. Spurgeon ME, Lambert PF. Merkel cell polyomavirus: a newly discovered human virus with oncogenic potential. Virology. 2013;435(1):118-130.

34. Tello TL, Coggshall K, Yom SS, Yu SS. Merkel cell carcinoma: An update and review: Current and future therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(3):445-454.

35. American Cancer Society. Key Statistics for Merkel Cell Carcinoma. 2015; https://www.cancer.org/cancer/merkel-cell-skin-cancer/about/key-statistics.html#written_by. Accessed March 7th, 2017.

36. Kaufman HL, Russell J, Hamid O, et al. Avelumab in patients with chemotherapy-refractory metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma: a multicentre, single-group, open-label, phase 2 trial. The Lancet Oncology.17(10):1374-1385.

Ins and outs of SCD treatment to be covered at ASH

Sickle cell disease (SCD) will take center stage at the 2018 ASH Annual Meeting, according to a recent press briefing.

During the briefing, ASH President Alexis A. Thompson, MD, highlighted four “abstracts to watch” that focus on SCD.

These abstracts cover a pilot study of gene therapy, long-term outcomes of haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplant (haplo-HSCT), mortality rates in SCD patients prescribed opioids, and outcomes with hydroxyurea (HU) among patients in sub-Saharan Africa.

“These are all quite different aspects of work being done,” said Dr. Thompson, of Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago in Illinois.

Gene therapy

In the pilot study of gene therapy (abstract 1023), investigators used a microRNA-adapted short hairpin RNA lentiviral vector targeting BCL11A for autologous gene therapy in SCD patients.

Preclinical research had shown that this approach could induce fetal hemoglobin in human erythroid cells and “largely” attenuate the hematologic effects of SCD in a murine model, according to investigators.

Initial results from the pilot study suggest this approach is feasible in humans as well. In the first patient infused, investigators observed “rapid” induction of fetal hemoglobin and “marked attenuation of hemolysis in the early phase of autologous reconstitution.”

“We’re looking forward to seeing this initial presentation on their findings with this first administration to humans,” Dr. Thompson said.

Haplo-HSCT

In another study (abstract 162), investigators assessed long-term health-related quality of life in high-risk SCD patients who underwent familial haplo-HSCT.

The patients received myeloablative conditioning and familial haplo-HSCT using CD34 enrichment and mononuclear cell (CD3) addback.

Two years from haplo-HSCT, patients had significant improvements in emotional and physical health-related quality of life, among other outcomes of interest, including neurocognitive outcomes.

Opioid use

A third study (abstract 315) indicates that opioid use is not associated with in-hospital mortality in SCD patients.

This is interesting in the context of the national opioid epidemic, Dr. Thompson said.

Investigators looked at data from the National Inpatient Sample and found no significant increase in in-hospital mortality in SCD patients from 1998 through 2013. This can be compared to the 350% increase in non-SCD opioid prescription-related deaths from 1999 through 2013.

“It should alleviate many concerns about patients with sickle cell who, for legitimate reasons, may require high doses of opioids,” Dr. Thompson said. “While I think we’re being very mindful about opioid use in this patient population, they certainly do need these high doses, but there does not seem to be an extraordinary risk of death associated with their use.”

HU in sub-Saharan Africa

Dr. Thompson said a fourth study worth watching is REACH (abstract 3), a trial of HU in 635 children in sub-Saharan Africa.

The study provides the first prospective data showing the feasibility, safety, and benefits of HU use in this population, according to investigators.

The findings are “quite encouraging,” Dr. Thompson said.

She added that the results looked “very similar” to the United States experience and demonstrated effective clinical trial design and execution in a lower-resource country.

Sickle cell disease (SCD) will take center stage at the 2018 ASH Annual Meeting, according to a recent press briefing.

During the briefing, ASH President Alexis A. Thompson, MD, highlighted four “abstracts to watch” that focus on SCD.

These abstracts cover a pilot study of gene therapy, long-term outcomes of haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplant (haplo-HSCT), mortality rates in SCD patients prescribed opioids, and outcomes with hydroxyurea (HU) among patients in sub-Saharan Africa.

“These are all quite different aspects of work being done,” said Dr. Thompson, of Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago in Illinois.

Gene therapy

In the pilot study of gene therapy (abstract 1023), investigators used a microRNA-adapted short hairpin RNA lentiviral vector targeting BCL11A for autologous gene therapy in SCD patients.

Preclinical research had shown that this approach could induce fetal hemoglobin in human erythroid cells and “largely” attenuate the hematologic effects of SCD in a murine model, according to investigators.

Initial results from the pilot study suggest this approach is feasible in humans as well. In the first patient infused, investigators observed “rapid” induction of fetal hemoglobin and “marked attenuation of hemolysis in the early phase of autologous reconstitution.”

“We’re looking forward to seeing this initial presentation on their findings with this first administration to humans,” Dr. Thompson said.

Haplo-HSCT

In another study (abstract 162), investigators assessed long-term health-related quality of life in high-risk SCD patients who underwent familial haplo-HSCT.

The patients received myeloablative conditioning and familial haplo-HSCT using CD34 enrichment and mononuclear cell (CD3) addback.

Two years from haplo-HSCT, patients had significant improvements in emotional and physical health-related quality of life, among other outcomes of interest, including neurocognitive outcomes.

Opioid use

A third study (abstract 315) indicates that opioid use is not associated with in-hospital mortality in SCD patients.

This is interesting in the context of the national opioid epidemic, Dr. Thompson said.

Investigators looked at data from the National Inpatient Sample and found no significant increase in in-hospital mortality in SCD patients from 1998 through 2013. This can be compared to the 350% increase in non-SCD opioid prescription-related deaths from 1999 through 2013.

“It should alleviate many concerns about patients with sickle cell who, for legitimate reasons, may require high doses of opioids,” Dr. Thompson said. “While I think we’re being very mindful about opioid use in this patient population, they certainly do need these high doses, but there does not seem to be an extraordinary risk of death associated with their use.”

HU in sub-Saharan Africa

Dr. Thompson said a fourth study worth watching is REACH (abstract 3), a trial of HU in 635 children in sub-Saharan Africa.

The study provides the first prospective data showing the feasibility, safety, and benefits of HU use in this population, according to investigators.

The findings are “quite encouraging,” Dr. Thompson said.

She added that the results looked “very similar” to the United States experience and demonstrated effective clinical trial design and execution in a lower-resource country.

Sickle cell disease (SCD) will take center stage at the 2018 ASH Annual Meeting, according to a recent press briefing.

During the briefing, ASH President Alexis A. Thompson, MD, highlighted four “abstracts to watch” that focus on SCD.

These abstracts cover a pilot study of gene therapy, long-term outcomes of haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplant (haplo-HSCT), mortality rates in SCD patients prescribed opioids, and outcomes with hydroxyurea (HU) among patients in sub-Saharan Africa.

“These are all quite different aspects of work being done,” said Dr. Thompson, of Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago in Illinois.

Gene therapy

In the pilot study of gene therapy (abstract 1023), investigators used a microRNA-adapted short hairpin RNA lentiviral vector targeting BCL11A for autologous gene therapy in SCD patients.

Preclinical research had shown that this approach could induce fetal hemoglobin in human erythroid cells and “largely” attenuate the hematologic effects of SCD in a murine model, according to investigators.