User login

Rapid recovery pathway for pediatric PSF/AIS patients

An important alternative amidst the opioid crisis

Clinical question

In pediatric postoperative spinal fusion/adolescent idiopathic scoliosis patients, do alternatives to traditional opioid-based analgesic pain regimens lead to improved clinical outcomes?

Background

Traditional care for pediatric postoperative spinal fusion (PSF) patients has included late mobilization most often because of significant pain that requires significant opioid administration. This has led to side effects of heavy opioid use, primarily nausea/vomiting and sleepiness.

In the United States, prescribers have become more aware of the pitfalls of opioid use given that more people now die of opioid misuse than breast cancer. An approach of multimodal analgesia with early mobilization has been shown to have decreased length of stay (LOS) and improve patient satisfaction, but data on clinical outcomes have been lacking.

Study design

Single-center quality improvement (QI) project.

Setting

Urban, 527-bed, quaternary care, free-standing children’s hospital.

Synopsis

Based on the recognition that multiple “standards” of care were utilized in the postoperative management of PSF patients, a QI project was undertaken. The primary outcome measured was functional recovery, as measured by average LOS and pain scores at the first 6:00 am after surgery then on postoperative days 1, 2, and 3.

Process measures were: use of multimodal agents (gabapentin and ketorolac) and discontinuation of patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) before postoperative day 3. Balancing measures were 30-day readmissions or ED revisit. Patients were divided into three groups by analyzing outcomes in three consecutive time periods: conventional management (n = 134), transition period (n = 104), and rapid recovery pathway (n = 84). In the conventional management time period, patients received intraoperative methadone and postoperative morphine/hydromorphone PCA. During the transition period, plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycles with ketorolac and gabapentin pilots were instituted and assessed. Finally, a rapid recovery pathway (RRP) was designed and published as a web-based algorithm. Standardized entry order sets were developed to maintain compliance and consistency among health care professionals, and a transition period was allowed to reach the highest possible percentage of patients adhering to multimodal analgesia regimen.

Adherence to the multimodal regimen led to 90% of patients receiving ketorolac on postoperative day 1, 100% receiving gabapentin on night of surgery, 86% off of IV PCA by postoperative day 3, and 100% order set adherence after full implementation of the RRP. LOS decreased from 5.7 to 4 days after RRP implementation. Pain scores also showed significant improvement on postoperative day 0 (average pain score, 3.8 vs. 4.9) and postoperative day 1 (3.8 vs. 5). Balancing measures of 30-day readmissions or ED visits after discharge was 2.9% and rose to 3.6% after full implementation.

Bottom line

Multimodal analgesia – including preoperative gabapentin and acetaminophen, intraoperative methadone and acetaminophen, and postoperative PCA diazepam, gabapentin, acetaminophen, and ketorolac – results in decreased length of stay and improved self-reported daily pain scores.

Citation

Muhly WT et al. Rapid recovery pathway after spinal fusion for idiopathic scoliosis. Pediatrics. 2016 Apr;137(4):e20151568.

Dr. Giordano is a pediatric neurosurgery hospitalist and assistant professor in pediatrics at Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York.

An important alternative amidst the opioid crisis

An important alternative amidst the opioid crisis

Clinical question

In pediatric postoperative spinal fusion/adolescent idiopathic scoliosis patients, do alternatives to traditional opioid-based analgesic pain regimens lead to improved clinical outcomes?

Background

Traditional care for pediatric postoperative spinal fusion (PSF) patients has included late mobilization most often because of significant pain that requires significant opioid administration. This has led to side effects of heavy opioid use, primarily nausea/vomiting and sleepiness.

In the United States, prescribers have become more aware of the pitfalls of opioid use given that more people now die of opioid misuse than breast cancer. An approach of multimodal analgesia with early mobilization has been shown to have decreased length of stay (LOS) and improve patient satisfaction, but data on clinical outcomes have been lacking.

Study design

Single-center quality improvement (QI) project.

Setting

Urban, 527-bed, quaternary care, free-standing children’s hospital.

Synopsis

Based on the recognition that multiple “standards” of care were utilized in the postoperative management of PSF patients, a QI project was undertaken. The primary outcome measured was functional recovery, as measured by average LOS and pain scores at the first 6:00 am after surgery then on postoperative days 1, 2, and 3.

Process measures were: use of multimodal agents (gabapentin and ketorolac) and discontinuation of patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) before postoperative day 3. Balancing measures were 30-day readmissions or ED revisit. Patients were divided into three groups by analyzing outcomes in three consecutive time periods: conventional management (n = 134), transition period (n = 104), and rapid recovery pathway (n = 84). In the conventional management time period, patients received intraoperative methadone and postoperative morphine/hydromorphone PCA. During the transition period, plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycles with ketorolac and gabapentin pilots were instituted and assessed. Finally, a rapid recovery pathway (RRP) was designed and published as a web-based algorithm. Standardized entry order sets were developed to maintain compliance and consistency among health care professionals, and a transition period was allowed to reach the highest possible percentage of patients adhering to multimodal analgesia regimen.

Adherence to the multimodal regimen led to 90% of patients receiving ketorolac on postoperative day 1, 100% receiving gabapentin on night of surgery, 86% off of IV PCA by postoperative day 3, and 100% order set adherence after full implementation of the RRP. LOS decreased from 5.7 to 4 days after RRP implementation. Pain scores also showed significant improvement on postoperative day 0 (average pain score, 3.8 vs. 4.9) and postoperative day 1 (3.8 vs. 5). Balancing measures of 30-day readmissions or ED visits after discharge was 2.9% and rose to 3.6% after full implementation.

Bottom line

Multimodal analgesia – including preoperative gabapentin and acetaminophen, intraoperative methadone and acetaminophen, and postoperative PCA diazepam, gabapentin, acetaminophen, and ketorolac – results in decreased length of stay and improved self-reported daily pain scores.

Citation

Muhly WT et al. Rapid recovery pathway after spinal fusion for idiopathic scoliosis. Pediatrics. 2016 Apr;137(4):e20151568.

Dr. Giordano is a pediatric neurosurgery hospitalist and assistant professor in pediatrics at Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York.

Clinical question

In pediatric postoperative spinal fusion/adolescent idiopathic scoliosis patients, do alternatives to traditional opioid-based analgesic pain regimens lead to improved clinical outcomes?

Background

Traditional care for pediatric postoperative spinal fusion (PSF) patients has included late mobilization most often because of significant pain that requires significant opioid administration. This has led to side effects of heavy opioid use, primarily nausea/vomiting and sleepiness.

In the United States, prescribers have become more aware of the pitfalls of opioid use given that more people now die of opioid misuse than breast cancer. An approach of multimodal analgesia with early mobilization has been shown to have decreased length of stay (LOS) and improve patient satisfaction, but data on clinical outcomes have been lacking.

Study design

Single-center quality improvement (QI) project.

Setting

Urban, 527-bed, quaternary care, free-standing children’s hospital.

Synopsis

Based on the recognition that multiple “standards” of care were utilized in the postoperative management of PSF patients, a QI project was undertaken. The primary outcome measured was functional recovery, as measured by average LOS and pain scores at the first 6:00 am after surgery then on postoperative days 1, 2, and 3.

Process measures were: use of multimodal agents (gabapentin and ketorolac) and discontinuation of patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) before postoperative day 3. Balancing measures were 30-day readmissions or ED revisit. Patients were divided into three groups by analyzing outcomes in three consecutive time periods: conventional management (n = 134), transition period (n = 104), and rapid recovery pathway (n = 84). In the conventional management time period, patients received intraoperative methadone and postoperative morphine/hydromorphone PCA. During the transition period, plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycles with ketorolac and gabapentin pilots were instituted and assessed. Finally, a rapid recovery pathway (RRP) was designed and published as a web-based algorithm. Standardized entry order sets were developed to maintain compliance and consistency among health care professionals, and a transition period was allowed to reach the highest possible percentage of patients adhering to multimodal analgesia regimen.

Adherence to the multimodal regimen led to 90% of patients receiving ketorolac on postoperative day 1, 100% receiving gabapentin on night of surgery, 86% off of IV PCA by postoperative day 3, and 100% order set adherence after full implementation of the RRP. LOS decreased from 5.7 to 4 days after RRP implementation. Pain scores also showed significant improvement on postoperative day 0 (average pain score, 3.8 vs. 4.9) and postoperative day 1 (3.8 vs. 5). Balancing measures of 30-day readmissions or ED visits after discharge was 2.9% and rose to 3.6% after full implementation.

Bottom line

Multimodal analgesia – including preoperative gabapentin and acetaminophen, intraoperative methadone and acetaminophen, and postoperative PCA diazepam, gabapentin, acetaminophen, and ketorolac – results in decreased length of stay and improved self-reported daily pain scores.

Citation

Muhly WT et al. Rapid recovery pathway after spinal fusion for idiopathic scoliosis. Pediatrics. 2016 Apr;137(4):e20151568.

Dr. Giordano is a pediatric neurosurgery hospitalist and assistant professor in pediatrics at Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York.

Staying up to date on screening may cut risk of death from CRC

according to the results of a large retrospective case-control study.

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

The findings signify “potentially modifiable” screening failures in a population known for relatively high uptake of colorectal cancer screening, wrote Chyke A. Doubeni, MD, MPH, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and his associates in Gastroenterology. Strikingly, 76% of patients who died from colorectal cancer were not current on screening versus 55% of cancer-free patients, they said. Being up to date on screening decreased the odds of dying from colorectal cancer by 62% (odds ratio, 0.38; 95% confidence interval, 0.33-0.44), even after adjustment for race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, comorbidities, and frequency of contact with primary care providers, they added.

Colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, and fecal testing are effective and recommended screening techniques that help prevent deaths from colorectal cancer. Therefore, most such deaths are thought to result from “breakdowns in the screening process,” the researchers wrote. However, interval cancers and missed lesions also play a role, and no prior study has examined detailed screening histories and their association with colorectal cancer mortality.

Accordingly, the researchers reviewed medical records and registry data for 1,750 enrollees in the Kaiser Permanente Northern and Southern California systems who died from colorectal cancer during 2002-2012 and were part of the health plan for at least 5 years before their cancer diagnosis. They compared these patients with 3,486 cancer-free controls matched by age, sex, study site, and numbers of years enrolled in the health plan. Patients were considered up to date on screening if they were screened at intervals recommended by the 2008 multisociety colorectal cancer screening guidelines – that is, if they had received a colonoscopy within 10 years of colorectal cancer diagnosis or sigmoidoscopy or barium enema within 5 years of it. For fecal testing, the investigators used a 2-year interval based on its efficacy in clinical trials.

Among patients who died from colorectal cancer, only 24% were up to date on screening versus 45% of cancer-free-patients, the investigators determined. Furthermore, 68% of patients who died from colorectal cancer were never screened or were not screened at appropriate intervals, compared with 53% of cancer-free patients.

Additionally, while 8% of colorectal cancer deaths occurred in patients who had not followed up on abnormal screening results, only 2% of controls who had received abnormal screening results had failed to follow up.

“In two health systems with high rates of screening, we observed that most patients dying from colorectal cancer had potentially modifiable failures of the screening process,” the researchers concluded. “This study suggests that, even in settings with high screening uptake, access to and timely uptake of screening, regular rescreening, appropriate use of testing given patient characteristics, completion of timely diagnostic testing when screening is positive, and improving the effectiveness of screening tests, particularly for right colon cancer, remain important areas of focus for further decreasing colorectal cancer deaths.”

The National Institutes of Health funded the work. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest except that one coinvestigator is editor in chief of the journal Gastroenterology.

SOURCE: Doubeni CA et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Sep 27. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.09.040.

Screening for colorectal cancer (CRC) is a major success story – one of only two cancers (the other being cervical cancer) with an A recommendation for screening from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Multiple randomized trials for two CRC screening modalities, stool-based tests and sigmoidoscopy, have shown significant reductions in CRC incidence and mortality.

Within this context, Doubeni et al. examined the association of CRC screening with death from CRC in a real-world HMO setting. Their study is notable for several reasons. First, it showed a highly protective effect on CRC mortality of being up to date with screening (odds ratio, 0.38; 95% confidence interval, 0.33-0.44). Second, it examined CRC screening as a process, with various steps of that process related to CRC mortality. Finally, methodologically, the study’s utilization of electronic medical records and cancer registry linkages highlights the importance of integrated data systems in the efficient performance of epidemiologic research.

Of note, screening was primarily stool-based tests (fecal occult blood test/fecal immunochemical test ) and sigmoidoscopy, in contrast to most of the U.S., where colonoscopy is predominant. Randomized trials of these modalities show mortality reductions of 15%-20% (FOBT/FIT) and 25%-30% (sigmoidoscopy), respectively. Therefore, some of the reported effect is likely due to selection bias, with healthier persons more likely to choose screening.

It would be of interest to see similar studies performed in a colonoscopy-predominant screening setting and with the effect on CRC incidence as well as mortality examined.

Paul F. Pinsky, PhD, chief of the Early Detection Research Branch, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD. He has no conflicts of interest.

Screening for colorectal cancer (CRC) is a major success story – one of only two cancers (the other being cervical cancer) with an A recommendation for screening from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Multiple randomized trials for two CRC screening modalities, stool-based tests and sigmoidoscopy, have shown significant reductions in CRC incidence and mortality.

Within this context, Doubeni et al. examined the association of CRC screening with death from CRC in a real-world HMO setting. Their study is notable for several reasons. First, it showed a highly protective effect on CRC mortality of being up to date with screening (odds ratio, 0.38; 95% confidence interval, 0.33-0.44). Second, it examined CRC screening as a process, with various steps of that process related to CRC mortality. Finally, methodologically, the study’s utilization of electronic medical records and cancer registry linkages highlights the importance of integrated data systems in the efficient performance of epidemiologic research.

Of note, screening was primarily stool-based tests (fecal occult blood test/fecal immunochemical test ) and sigmoidoscopy, in contrast to most of the U.S., where colonoscopy is predominant. Randomized trials of these modalities show mortality reductions of 15%-20% (FOBT/FIT) and 25%-30% (sigmoidoscopy), respectively. Therefore, some of the reported effect is likely due to selection bias, with healthier persons more likely to choose screening.

It would be of interest to see similar studies performed in a colonoscopy-predominant screening setting and with the effect on CRC incidence as well as mortality examined.

Paul F. Pinsky, PhD, chief of the Early Detection Research Branch, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD. He has no conflicts of interest.

Screening for colorectal cancer (CRC) is a major success story – one of only two cancers (the other being cervical cancer) with an A recommendation for screening from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Multiple randomized trials for two CRC screening modalities, stool-based tests and sigmoidoscopy, have shown significant reductions in CRC incidence and mortality.

Within this context, Doubeni et al. examined the association of CRC screening with death from CRC in a real-world HMO setting. Their study is notable for several reasons. First, it showed a highly protective effect on CRC mortality of being up to date with screening (odds ratio, 0.38; 95% confidence interval, 0.33-0.44). Second, it examined CRC screening as a process, with various steps of that process related to CRC mortality. Finally, methodologically, the study’s utilization of electronic medical records and cancer registry linkages highlights the importance of integrated data systems in the efficient performance of epidemiologic research.

Of note, screening was primarily stool-based tests (fecal occult blood test/fecal immunochemical test ) and sigmoidoscopy, in contrast to most of the U.S., where colonoscopy is predominant. Randomized trials of these modalities show mortality reductions of 15%-20% (FOBT/FIT) and 25%-30% (sigmoidoscopy), respectively. Therefore, some of the reported effect is likely due to selection bias, with healthier persons more likely to choose screening.

It would be of interest to see similar studies performed in a colonoscopy-predominant screening setting and with the effect on CRC incidence as well as mortality examined.

Paul F. Pinsky, PhD, chief of the Early Detection Research Branch, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD. He has no conflicts of interest.

according to the results of a large retrospective case-control study.

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

The findings signify “potentially modifiable” screening failures in a population known for relatively high uptake of colorectal cancer screening, wrote Chyke A. Doubeni, MD, MPH, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and his associates in Gastroenterology. Strikingly, 76% of patients who died from colorectal cancer were not current on screening versus 55% of cancer-free patients, they said. Being up to date on screening decreased the odds of dying from colorectal cancer by 62% (odds ratio, 0.38; 95% confidence interval, 0.33-0.44), even after adjustment for race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, comorbidities, and frequency of contact with primary care providers, they added.

Colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, and fecal testing are effective and recommended screening techniques that help prevent deaths from colorectal cancer. Therefore, most such deaths are thought to result from “breakdowns in the screening process,” the researchers wrote. However, interval cancers and missed lesions also play a role, and no prior study has examined detailed screening histories and their association with colorectal cancer mortality.

Accordingly, the researchers reviewed medical records and registry data for 1,750 enrollees in the Kaiser Permanente Northern and Southern California systems who died from colorectal cancer during 2002-2012 and were part of the health plan for at least 5 years before their cancer diagnosis. They compared these patients with 3,486 cancer-free controls matched by age, sex, study site, and numbers of years enrolled in the health plan. Patients were considered up to date on screening if they were screened at intervals recommended by the 2008 multisociety colorectal cancer screening guidelines – that is, if they had received a colonoscopy within 10 years of colorectal cancer diagnosis or sigmoidoscopy or barium enema within 5 years of it. For fecal testing, the investigators used a 2-year interval based on its efficacy in clinical trials.

Among patients who died from colorectal cancer, only 24% were up to date on screening versus 45% of cancer-free-patients, the investigators determined. Furthermore, 68% of patients who died from colorectal cancer were never screened or were not screened at appropriate intervals, compared with 53% of cancer-free patients.

Additionally, while 8% of colorectal cancer deaths occurred in patients who had not followed up on abnormal screening results, only 2% of controls who had received abnormal screening results had failed to follow up.

“In two health systems with high rates of screening, we observed that most patients dying from colorectal cancer had potentially modifiable failures of the screening process,” the researchers concluded. “This study suggests that, even in settings with high screening uptake, access to and timely uptake of screening, regular rescreening, appropriate use of testing given patient characteristics, completion of timely diagnostic testing when screening is positive, and improving the effectiveness of screening tests, particularly for right colon cancer, remain important areas of focus for further decreasing colorectal cancer deaths.”

The National Institutes of Health funded the work. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest except that one coinvestigator is editor in chief of the journal Gastroenterology.

SOURCE: Doubeni CA et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Sep 27. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.09.040.

according to the results of a large retrospective case-control study.

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

The findings signify “potentially modifiable” screening failures in a population known for relatively high uptake of colorectal cancer screening, wrote Chyke A. Doubeni, MD, MPH, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and his associates in Gastroenterology. Strikingly, 76% of patients who died from colorectal cancer were not current on screening versus 55% of cancer-free patients, they said. Being up to date on screening decreased the odds of dying from colorectal cancer by 62% (odds ratio, 0.38; 95% confidence interval, 0.33-0.44), even after adjustment for race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, comorbidities, and frequency of contact with primary care providers, they added.

Colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, and fecal testing are effective and recommended screening techniques that help prevent deaths from colorectal cancer. Therefore, most such deaths are thought to result from “breakdowns in the screening process,” the researchers wrote. However, interval cancers and missed lesions also play a role, and no prior study has examined detailed screening histories and their association with colorectal cancer mortality.

Accordingly, the researchers reviewed medical records and registry data for 1,750 enrollees in the Kaiser Permanente Northern and Southern California systems who died from colorectal cancer during 2002-2012 and were part of the health plan for at least 5 years before their cancer diagnosis. They compared these patients with 3,486 cancer-free controls matched by age, sex, study site, and numbers of years enrolled in the health plan. Patients were considered up to date on screening if they were screened at intervals recommended by the 2008 multisociety colorectal cancer screening guidelines – that is, if they had received a colonoscopy within 10 years of colorectal cancer diagnosis or sigmoidoscopy or barium enema within 5 years of it. For fecal testing, the investigators used a 2-year interval based on its efficacy in clinical trials.

Among patients who died from colorectal cancer, only 24% were up to date on screening versus 45% of cancer-free-patients, the investigators determined. Furthermore, 68% of patients who died from colorectal cancer were never screened or were not screened at appropriate intervals, compared with 53% of cancer-free patients.

Additionally, while 8% of colorectal cancer deaths occurred in patients who had not followed up on abnormal screening results, only 2% of controls who had received abnormal screening results had failed to follow up.

“In two health systems with high rates of screening, we observed that most patients dying from colorectal cancer had potentially modifiable failures of the screening process,” the researchers concluded. “This study suggests that, even in settings with high screening uptake, access to and timely uptake of screening, regular rescreening, appropriate use of testing given patient characteristics, completion of timely diagnostic testing when screening is positive, and improving the effectiveness of screening tests, particularly for right colon cancer, remain important areas of focus for further decreasing colorectal cancer deaths.”

The National Institutes of Health funded the work. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest except that one coinvestigator is editor in chief of the journal Gastroenterology.

SOURCE: Doubeni CA et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Sep 27. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.09.040.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point: Being up to date on screening was associated with a significant reduction in the risk of dying from colon cancer.

Major finding: Being up to date on screening decreased the odds of dying from colorectal cancer by 62% (odds ratio, 0.38; 95% confidence interval, 0.33-0.44).

Study details: Retrospective cohort study of 1,750 patients who died from colorectal cancer during 2002-2012 and 3,486 matched controls.

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health funded the work. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest except that one coinvestigator is editor in chief of Gastroenterology.

Source: Doubeni CA et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Sep 27. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.09.040.

Expert highlights rare causes of stroke to keep in mind

ATLANTA – According to Peter Berlit, MD, clinicians should .

Other factors include combination of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, exclusive involvement of intracranial vessels, systemic signs, and lab tests indicating inflammation.

At the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association, Dr. Berlit, secretary general of the German Society of Neurology in Berlin, discussed the diagnosis and management of rare causes of stroke.

Giant cell arteritis (GCA)

One of the rare causes of stroke, GCA can be diagnosed when three of five criteria are met: being 50 years of age or older, having a newly developed headache, tenderness of the superficial temporal artery, elevated sedimentation rate of at least 50 mm per hour, and GCA in a biopsy specimen from the temporal artery.

“What we fear most is sudden blindness due to involvement of arteries serving the eyes, which appears in up to 30% of GCA patients,” said Dr. Berlit, who formerly chaired the department of neurology at Alfried Krupp Hospital, Essen, Germany. “Stroke occurs in approximately 2% of GCA patients, so it’s a lot rarer.” GCA can also be diagnosed by ultrasound. One meta-analysis of 23 studies using halo, stenosis, and occlusion as ultrasound criteria found a sensitivity of 87% and a specificity of 96% (Ann Intern Med. 2005;142[5]:359-69). “You can also use 3-Tesla MRI with the use of contrast agent, which shows inflammation of the temporal artery, but also other large vessels including the aortic arch,” he said. “The treatment of GCA has changed since the end of 2017 and involves starting with prednisolone 1 mg/kg body weight.” After a dose of 30 mg for 4 weeks, reduce the dose by 2.5 mg every 2 weeks. After reaching the dose of 15 mg daily, reduce by 1 mg per month. “The recommended steroid-sparing treatment is subcutaneous tocilizumab at a dose of 162 mg weekly or every other week, combined with a prednisone taper for a minimum of 26 weeks,” he said. Supportive therapies include pantoprazole 20 mg, aspirin 100 mg, calcium, vitamin D, and bisphosphonates.

Primary angiitis of the central nervous system (PACNS)

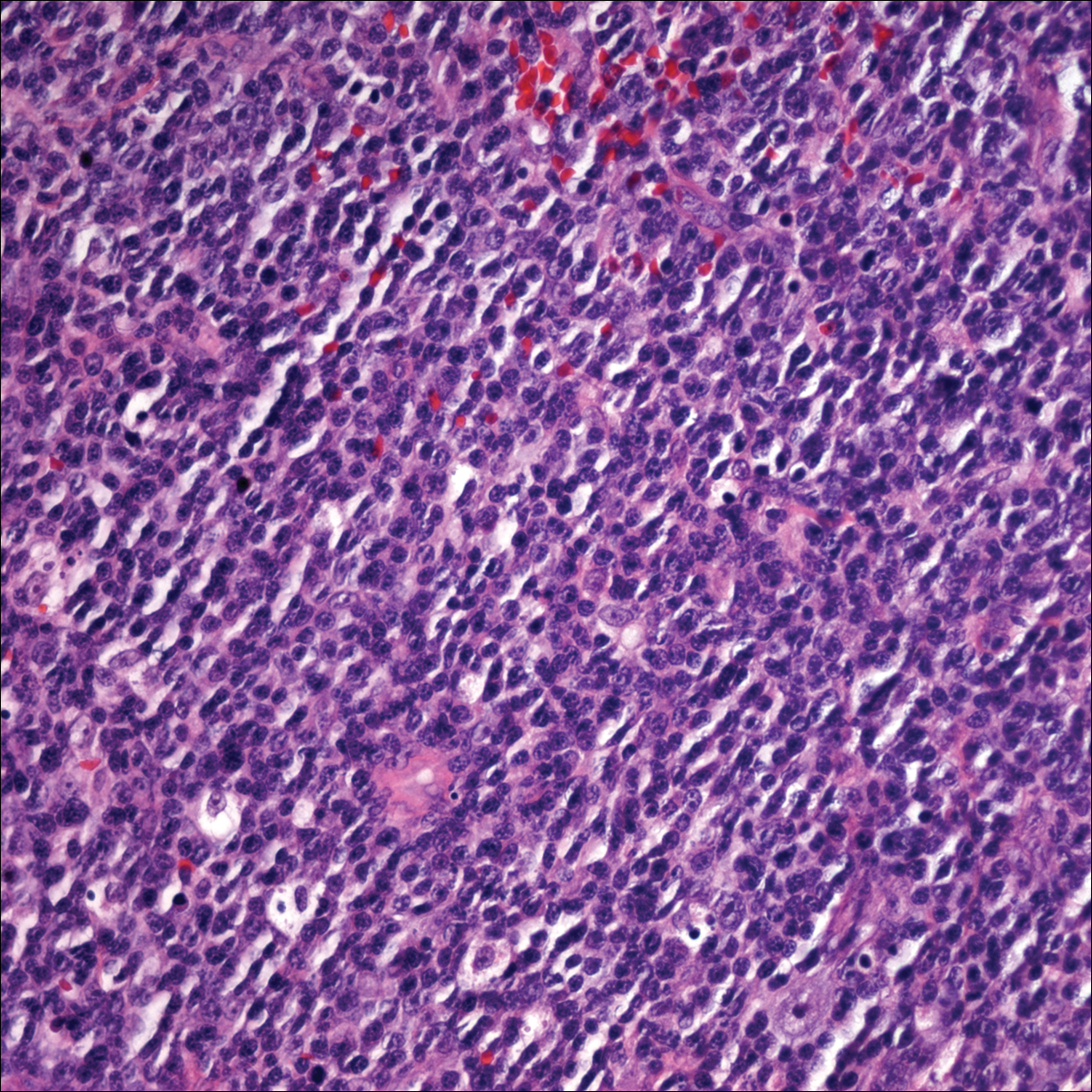

Next, Dr. Berlit discussed diagnostic criteria for PACNS, an acquired neurological deficit unexplained after complete evaluation. “You should have a diagnostic cerebral angiogram or biopsy demonstrating vasculitis,” he said. “There should be no evidence of systemic vasculitis or any other conditions that could mimic the angiogram findings. Usually you have abnormal CSF findings, including pleocytosis and protein elevation, and a biopsy demonstrating vasculitis.”

MRI studies in suspected vasculitis include fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR), diffusion imaging with apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) maps, gradient ECHO, MR angiography, and contrast-enhanced imaging. “These usually show multifocal lesions of different ages, and hemorrhages occur in about 10% of lesions,” Dr. Berlit said. “Leptomeningeal enhancement is an indicator of good treatment response.”

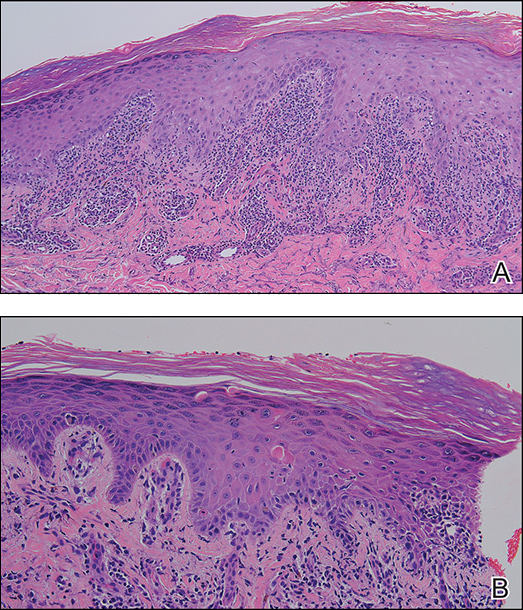

A brain and leptomeningeal biopsy demonstrating the angiitis remains the preferred method for diagnosis of PACNS. “Open biopsies out of recent MRI lesions are especially diagnostic,” he said. “If there are no lesions accessible for surgery in noneloquent brain areas, a biopsy from the right frontal lobe is recommended.” The histologic findings of PACNS consist of granulomatous inflammation, fibrinoid necrosis of vessel walls, or exclusively lymphocytic cellular infiltrates. “The treatment of choice in PACNS is the combination of steroids and cyclophosphamide pulse therapy,” he said. “There are also data showing that rituximab or methotrexate might be treatment options. With a relapse rate of 25% and a reduced survival rate, a close follow-up of suspected PACNS is mandatory.”

Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS)

Another rare cause of stroke is RCVS, which typically presents as thunderclap headaches with or without neurologic symptoms. MRI may be normal, but symmetric border zone infarctions and small subarachnoid hemorrhages are possible. Catheter, CT, or MR angiography show segmental arterial vasoconstriction. “You always have to exclude cerebral aneurysm,” Dr. Berlit said. “There is reversibility of RCVS within 3 months.” RCVS is often associated with a long list of drugs, including phenylpropanolamine, Methergine (methylergonovine), bromocriptine, lisuride, SSRIs, triptans, isometheptene, tacrolimus, cyclophosphamide, erythropoietin, intravenous immunoglobulins, erythrocyte concentrates, nasal sprays, cocaine, ecstasy, amphetamines, cannabis, and LSD. “After stopping responsible medications, treatment involves a course of nimodipine,” he said.

Moyamoya disease (MMD)

Dr. Berlit closed his presentation by discussing MMD, a rare occlusive cerebrovascular disorder characterized by progressive stenosis or occlusion of the intracranial portion of the internal carotid artery and proximal cerebral arteries with an extensive network of fine collaterals. “This is an idiopathic vasculopathy with remarkable regional and racial differences worldwide; it’s most frequently found in Asians, especially in Japan and Korea,” he said. “In Europe, there is about one-tenth the incidence, compared with that of Japan. In Asian MMD, about 15% of cases follow an autosomal dominant inheritance. The collaterals in MMD present histologically as a thin media, a fragmented elastic laminae, and the formation of microaneurysms. There is no inflammation.”

MMD diagnostic criteria include stenosis or occlusion of the terminal portion of the internal carotid artery and at the proximal portion of the anterior and middle cerebral arteries. Abnormal vascular networks are present in the basal ganglia and angiographic findings present bilaterally. Cases with unilateral angiographic findings are considered probable. Clinicians should exclude the following conditions: arteriosclerosis, autoimmune disease, brain neoplasm, history of cranial irradiation, Down syndrome, head trauma, neurofibromatosis, and meningitis. “If the angiographic pattern is resembled by one of these conditions, this is called moyamoya syndrome,” Dr. Berlit noted. “MMD is a progressive disorder. Within a few months you can see occlusion of the middle cerebral artery and the anterior cerebral artery, so you have to treat these patients.”

In patients who are white, MMD presents with lower rates of hemorrhage, but in Asians, microbleeds occur in up to 44% of patients and hemorrhages in up to 65% patients. “Both subarachnoidal and intracerebral hemorrhages occur, especially in connection with pregnancy and delivery,” he said. “The risk of both cerebral ischemia and hemorrhagic complications increases with stages of MMD.”

Direct or indirect intracranial bypass surgery is recommended in stages 3 or more, and has been shown to significantly reduce the 5-year stroke risk. To date, Dr. Berlit and his associates have treated 86 hemispheres in 56 patients. The average age of the patients was 42 years, 70% were female, and the average follow-up was 39 months. All intracranial bypasses were open on follow-up, and a decrease of the typical moyamoya vessels was observed in 81% of patients.

Dr. Berlit reported having no financial disclosures.

ATLANTA – According to Peter Berlit, MD, clinicians should .

Other factors include combination of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, exclusive involvement of intracranial vessels, systemic signs, and lab tests indicating inflammation.

At the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association, Dr. Berlit, secretary general of the German Society of Neurology in Berlin, discussed the diagnosis and management of rare causes of stroke.

Giant cell arteritis (GCA)

One of the rare causes of stroke, GCA can be diagnosed when three of five criteria are met: being 50 years of age or older, having a newly developed headache, tenderness of the superficial temporal artery, elevated sedimentation rate of at least 50 mm per hour, and GCA in a biopsy specimen from the temporal artery.

“What we fear most is sudden blindness due to involvement of arteries serving the eyes, which appears in up to 30% of GCA patients,” said Dr. Berlit, who formerly chaired the department of neurology at Alfried Krupp Hospital, Essen, Germany. “Stroke occurs in approximately 2% of GCA patients, so it’s a lot rarer.” GCA can also be diagnosed by ultrasound. One meta-analysis of 23 studies using halo, stenosis, and occlusion as ultrasound criteria found a sensitivity of 87% and a specificity of 96% (Ann Intern Med. 2005;142[5]:359-69). “You can also use 3-Tesla MRI with the use of contrast agent, which shows inflammation of the temporal artery, but also other large vessels including the aortic arch,” he said. “The treatment of GCA has changed since the end of 2017 and involves starting with prednisolone 1 mg/kg body weight.” After a dose of 30 mg for 4 weeks, reduce the dose by 2.5 mg every 2 weeks. After reaching the dose of 15 mg daily, reduce by 1 mg per month. “The recommended steroid-sparing treatment is subcutaneous tocilizumab at a dose of 162 mg weekly or every other week, combined with a prednisone taper for a minimum of 26 weeks,” he said. Supportive therapies include pantoprazole 20 mg, aspirin 100 mg, calcium, vitamin D, and bisphosphonates.

Primary angiitis of the central nervous system (PACNS)

Next, Dr. Berlit discussed diagnostic criteria for PACNS, an acquired neurological deficit unexplained after complete evaluation. “You should have a diagnostic cerebral angiogram or biopsy demonstrating vasculitis,” he said. “There should be no evidence of systemic vasculitis or any other conditions that could mimic the angiogram findings. Usually you have abnormal CSF findings, including pleocytosis and protein elevation, and a biopsy demonstrating vasculitis.”

MRI studies in suspected vasculitis include fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR), diffusion imaging with apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) maps, gradient ECHO, MR angiography, and contrast-enhanced imaging. “These usually show multifocal lesions of different ages, and hemorrhages occur in about 10% of lesions,” Dr. Berlit said. “Leptomeningeal enhancement is an indicator of good treatment response.”

A brain and leptomeningeal biopsy demonstrating the angiitis remains the preferred method for diagnosis of PACNS. “Open biopsies out of recent MRI lesions are especially diagnostic,” he said. “If there are no lesions accessible for surgery in noneloquent brain areas, a biopsy from the right frontal lobe is recommended.” The histologic findings of PACNS consist of granulomatous inflammation, fibrinoid necrosis of vessel walls, or exclusively lymphocytic cellular infiltrates. “The treatment of choice in PACNS is the combination of steroids and cyclophosphamide pulse therapy,” he said. “There are also data showing that rituximab or methotrexate might be treatment options. With a relapse rate of 25% and a reduced survival rate, a close follow-up of suspected PACNS is mandatory.”

Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS)

Another rare cause of stroke is RCVS, which typically presents as thunderclap headaches with or without neurologic symptoms. MRI may be normal, but symmetric border zone infarctions and small subarachnoid hemorrhages are possible. Catheter, CT, or MR angiography show segmental arterial vasoconstriction. “You always have to exclude cerebral aneurysm,” Dr. Berlit said. “There is reversibility of RCVS within 3 months.” RCVS is often associated with a long list of drugs, including phenylpropanolamine, Methergine (methylergonovine), bromocriptine, lisuride, SSRIs, triptans, isometheptene, tacrolimus, cyclophosphamide, erythropoietin, intravenous immunoglobulins, erythrocyte concentrates, nasal sprays, cocaine, ecstasy, amphetamines, cannabis, and LSD. “After stopping responsible medications, treatment involves a course of nimodipine,” he said.

Moyamoya disease (MMD)

Dr. Berlit closed his presentation by discussing MMD, a rare occlusive cerebrovascular disorder characterized by progressive stenosis or occlusion of the intracranial portion of the internal carotid artery and proximal cerebral arteries with an extensive network of fine collaterals. “This is an idiopathic vasculopathy with remarkable regional and racial differences worldwide; it’s most frequently found in Asians, especially in Japan and Korea,” he said. “In Europe, there is about one-tenth the incidence, compared with that of Japan. In Asian MMD, about 15% of cases follow an autosomal dominant inheritance. The collaterals in MMD present histologically as a thin media, a fragmented elastic laminae, and the formation of microaneurysms. There is no inflammation.”

MMD diagnostic criteria include stenosis or occlusion of the terminal portion of the internal carotid artery and at the proximal portion of the anterior and middle cerebral arteries. Abnormal vascular networks are present in the basal ganglia and angiographic findings present bilaterally. Cases with unilateral angiographic findings are considered probable. Clinicians should exclude the following conditions: arteriosclerosis, autoimmune disease, brain neoplasm, history of cranial irradiation, Down syndrome, head trauma, neurofibromatosis, and meningitis. “If the angiographic pattern is resembled by one of these conditions, this is called moyamoya syndrome,” Dr. Berlit noted. “MMD is a progressive disorder. Within a few months you can see occlusion of the middle cerebral artery and the anterior cerebral artery, so you have to treat these patients.”

In patients who are white, MMD presents with lower rates of hemorrhage, but in Asians, microbleeds occur in up to 44% of patients and hemorrhages in up to 65% patients. “Both subarachnoidal and intracerebral hemorrhages occur, especially in connection with pregnancy and delivery,” he said. “The risk of both cerebral ischemia and hemorrhagic complications increases with stages of MMD.”

Direct or indirect intracranial bypass surgery is recommended in stages 3 or more, and has been shown to significantly reduce the 5-year stroke risk. To date, Dr. Berlit and his associates have treated 86 hemispheres in 56 patients. The average age of the patients was 42 years, 70% were female, and the average follow-up was 39 months. All intracranial bypasses were open on follow-up, and a decrease of the typical moyamoya vessels was observed in 81% of patients.

Dr. Berlit reported having no financial disclosures.

ATLANTA – According to Peter Berlit, MD, clinicians should .

Other factors include combination of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, exclusive involvement of intracranial vessels, systemic signs, and lab tests indicating inflammation.

At the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association, Dr. Berlit, secretary general of the German Society of Neurology in Berlin, discussed the diagnosis and management of rare causes of stroke.

Giant cell arteritis (GCA)

One of the rare causes of stroke, GCA can be diagnosed when three of five criteria are met: being 50 years of age or older, having a newly developed headache, tenderness of the superficial temporal artery, elevated sedimentation rate of at least 50 mm per hour, and GCA in a biopsy specimen from the temporal artery.

“What we fear most is sudden blindness due to involvement of arteries serving the eyes, which appears in up to 30% of GCA patients,” said Dr. Berlit, who formerly chaired the department of neurology at Alfried Krupp Hospital, Essen, Germany. “Stroke occurs in approximately 2% of GCA patients, so it’s a lot rarer.” GCA can also be diagnosed by ultrasound. One meta-analysis of 23 studies using halo, stenosis, and occlusion as ultrasound criteria found a sensitivity of 87% and a specificity of 96% (Ann Intern Med. 2005;142[5]:359-69). “You can also use 3-Tesla MRI with the use of contrast agent, which shows inflammation of the temporal artery, but also other large vessels including the aortic arch,” he said. “The treatment of GCA has changed since the end of 2017 and involves starting with prednisolone 1 mg/kg body weight.” After a dose of 30 mg for 4 weeks, reduce the dose by 2.5 mg every 2 weeks. After reaching the dose of 15 mg daily, reduce by 1 mg per month. “The recommended steroid-sparing treatment is subcutaneous tocilizumab at a dose of 162 mg weekly or every other week, combined with a prednisone taper for a minimum of 26 weeks,” he said. Supportive therapies include pantoprazole 20 mg, aspirin 100 mg, calcium, vitamin D, and bisphosphonates.

Primary angiitis of the central nervous system (PACNS)

Next, Dr. Berlit discussed diagnostic criteria for PACNS, an acquired neurological deficit unexplained after complete evaluation. “You should have a diagnostic cerebral angiogram or biopsy demonstrating vasculitis,” he said. “There should be no evidence of systemic vasculitis or any other conditions that could mimic the angiogram findings. Usually you have abnormal CSF findings, including pleocytosis and protein elevation, and a biopsy demonstrating vasculitis.”

MRI studies in suspected vasculitis include fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR), diffusion imaging with apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) maps, gradient ECHO, MR angiography, and contrast-enhanced imaging. “These usually show multifocal lesions of different ages, and hemorrhages occur in about 10% of lesions,” Dr. Berlit said. “Leptomeningeal enhancement is an indicator of good treatment response.”

A brain and leptomeningeal biopsy demonstrating the angiitis remains the preferred method for diagnosis of PACNS. “Open biopsies out of recent MRI lesions are especially diagnostic,” he said. “If there are no lesions accessible for surgery in noneloquent brain areas, a biopsy from the right frontal lobe is recommended.” The histologic findings of PACNS consist of granulomatous inflammation, fibrinoid necrosis of vessel walls, or exclusively lymphocytic cellular infiltrates. “The treatment of choice in PACNS is the combination of steroids and cyclophosphamide pulse therapy,” he said. “There are also data showing that rituximab or methotrexate might be treatment options. With a relapse rate of 25% and a reduced survival rate, a close follow-up of suspected PACNS is mandatory.”

Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS)

Another rare cause of stroke is RCVS, which typically presents as thunderclap headaches with or without neurologic symptoms. MRI may be normal, but symmetric border zone infarctions and small subarachnoid hemorrhages are possible. Catheter, CT, or MR angiography show segmental arterial vasoconstriction. “You always have to exclude cerebral aneurysm,” Dr. Berlit said. “There is reversibility of RCVS within 3 months.” RCVS is often associated with a long list of drugs, including phenylpropanolamine, Methergine (methylergonovine), bromocriptine, lisuride, SSRIs, triptans, isometheptene, tacrolimus, cyclophosphamide, erythropoietin, intravenous immunoglobulins, erythrocyte concentrates, nasal sprays, cocaine, ecstasy, amphetamines, cannabis, and LSD. “After stopping responsible medications, treatment involves a course of nimodipine,” he said.

Moyamoya disease (MMD)

Dr. Berlit closed his presentation by discussing MMD, a rare occlusive cerebrovascular disorder characterized by progressive stenosis or occlusion of the intracranial portion of the internal carotid artery and proximal cerebral arteries with an extensive network of fine collaterals. “This is an idiopathic vasculopathy with remarkable regional and racial differences worldwide; it’s most frequently found in Asians, especially in Japan and Korea,” he said. “In Europe, there is about one-tenth the incidence, compared with that of Japan. In Asian MMD, about 15% of cases follow an autosomal dominant inheritance. The collaterals in MMD present histologically as a thin media, a fragmented elastic laminae, and the formation of microaneurysms. There is no inflammation.”

MMD diagnostic criteria include stenosis or occlusion of the terminal portion of the internal carotid artery and at the proximal portion of the anterior and middle cerebral arteries. Abnormal vascular networks are present in the basal ganglia and angiographic findings present bilaterally. Cases with unilateral angiographic findings are considered probable. Clinicians should exclude the following conditions: arteriosclerosis, autoimmune disease, brain neoplasm, history of cranial irradiation, Down syndrome, head trauma, neurofibromatosis, and meningitis. “If the angiographic pattern is resembled by one of these conditions, this is called moyamoya syndrome,” Dr. Berlit noted. “MMD is a progressive disorder. Within a few months you can see occlusion of the middle cerebral artery and the anterior cerebral artery, so you have to treat these patients.”

In patients who are white, MMD presents with lower rates of hemorrhage, but in Asians, microbleeds occur in up to 44% of patients and hemorrhages in up to 65% patients. “Both subarachnoidal and intracerebral hemorrhages occur, especially in connection with pregnancy and delivery,” he said. “The risk of both cerebral ischemia and hemorrhagic complications increases with stages of MMD.”

Direct or indirect intracranial bypass surgery is recommended in stages 3 or more, and has been shown to significantly reduce the 5-year stroke risk. To date, Dr. Berlit and his associates have treated 86 hemispheres in 56 patients. The average age of the patients was 42 years, 70% were female, and the average follow-up was 39 months. All intracranial bypasses were open on follow-up, and a decrease of the typical moyamoya vessels was observed in 81% of patients.

Dr. Berlit reported having no financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ANA 2018

Health Care Barriers and Quality of Life in Central Centrifugal Cicatricial Alopecia Patients

The etiology of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA), a clinical and histological pattern of hair loss on the central scalp, has been well studied. This disease is chronic and progressive, with extensive follicular destruction and eventual burnout.1,2 Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia is most commonly seen in patients of African descent and has been shown to be 1 of the 5 most common dermatologic diagnoses in black patients.3,4 The top 5 dermatologic diagnoses within this population include acne vulgaris (28.4%), dyschromia (19.9%), eczema (9.1%), alopecia (8.3%), and seborrheic dermatitis (6.7%).4 The incidence rate of CCCA is estimated to be 5.6%.3,5 Most patients are women, with onset between the second and fourth decades of life.6

Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia treatment efficacy is inversely correlated with disease duration. The primary goal of treatment is to prevent progression. Efforts are made to stimulate regrowth in areas that are not permanently scarred. When patients present with a substantial amount of scarring hair loss, dermatologists often are limited in their ability to achieve a cosmetically acceptable pattern of growth. Generally, hair is connected to a sense of self-worth in black women, and any type of hair loss has been shown to lead to frustration and decreased self-esteem.7 A 1994 study showed that 75% (44/58) of women with androgenetic alopecia had decreased self-esteem and 50% (29/58) had social challenges.8

The purpose of this pilot study was to determine the personal, historical, logistical, or environmental factors that preclude women from obtaining medical care for CCCA and to investigate how CCCA affects quality of life (QOL) and psychological well-being.

Methods

The investigators designed a survey study of adult, English-speaking, black women diagnosed with CCCA at the Northwestern University Department of Dermatology (Chicago, Illinois) between 2011 and 2017. Patients were selected from the electronic data warehouse compiled by the Department of Dermatology and were included if they fulfilled the following criteria: evaluated in the dermatology department between September 1, 2011, and September 30, 2017, by any faculty physician; diagnosed with CCCA; and aged 18 years or older. Patients were excluded if they did not speak English, as interpreters were not available. All patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria provided signed informed consent prior to participation. All surveys were disseminated in the office or via telephone from fall 2016 to spring 2017 and took 10 to 15 minutes to complete. The research was approved by the authors’ institutional review board (IRB ID STU00203449).

Survey Instrument

The

Data Analysis

Analyses were completed using data analysis software JMP Pro 13 from SAS and a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Continuous data were presented as mean, SD, median, minimum, and maximum. Categorical data were presented as counts and percentages. Nine QOL items were aggregated into a self-esteem category (questions 30–38).

Cronbach α, a statistical measure of internal consistency and how closely related items are in a group, was used to evaluate internal consistency reliability; values of 0.70 or greater indicate acceptable reliability.

Results

Of 501 individuals contacted, 34 completed the survey (7% completion rate). Nonrespondents included 7 who refused to participate and 460 who could not be contacted. All respondents self-identified as black women. Median age at time of survey administration was 46 years (range, 28–79 years); median age at CCCA diagnosis was 42 years (range, 15–73 years). Respondents did not significantly differ in age from nonrespondents (P=.46). The majority of respondents had an associate’s degree, bachelor’s degree, or advanced degree of education (master of arts, doctor of medicine, doctor of jurisprudence, doctor of philosophy); however, 8 women reported completing some college, 1 reported completing high school, and 1 reported no schooling. Three respondents had no health insurance.

Initial Hair Loss Discovery

The majority of respondents (22/34 [65%]) were first to notice their hair loss, while 5 (15%) reported hairstylists as the initial observers. Twelve respondents (35%) initially went to a physician to learn why they were losing hair; 6 (18%) instead utilized hairstylists or the Internet. Fifteen women (44%) waited more than 1 month up to 6 months after noticing hair loss before seeing a physician instead of going immediately within a 4-week period, and 16 (47%) waited 1 year or more.

Nondermatologist Consultation

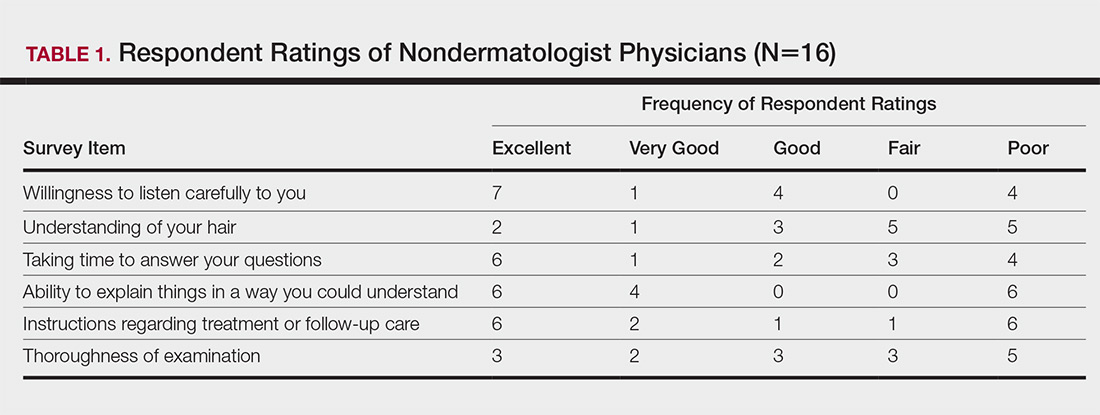

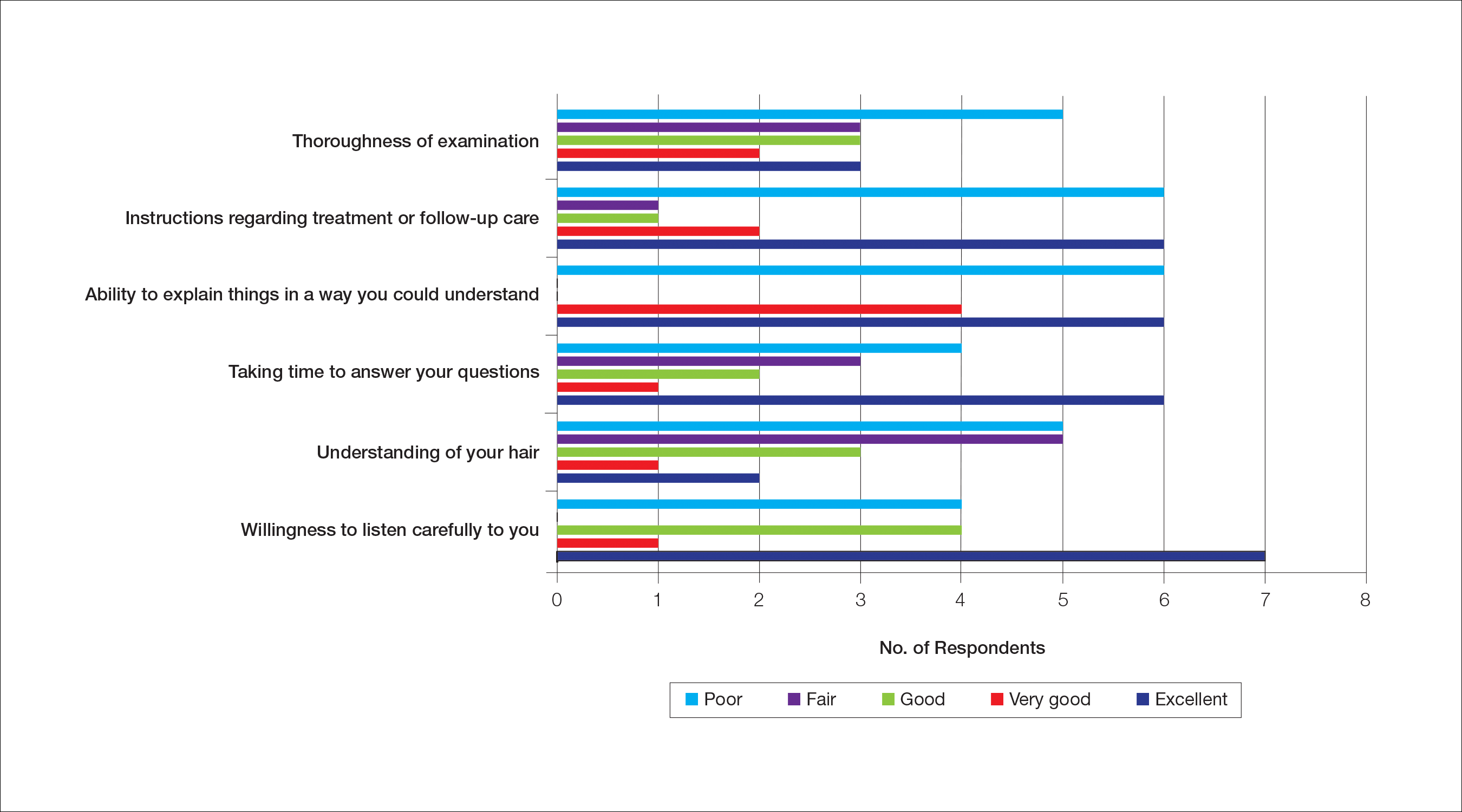

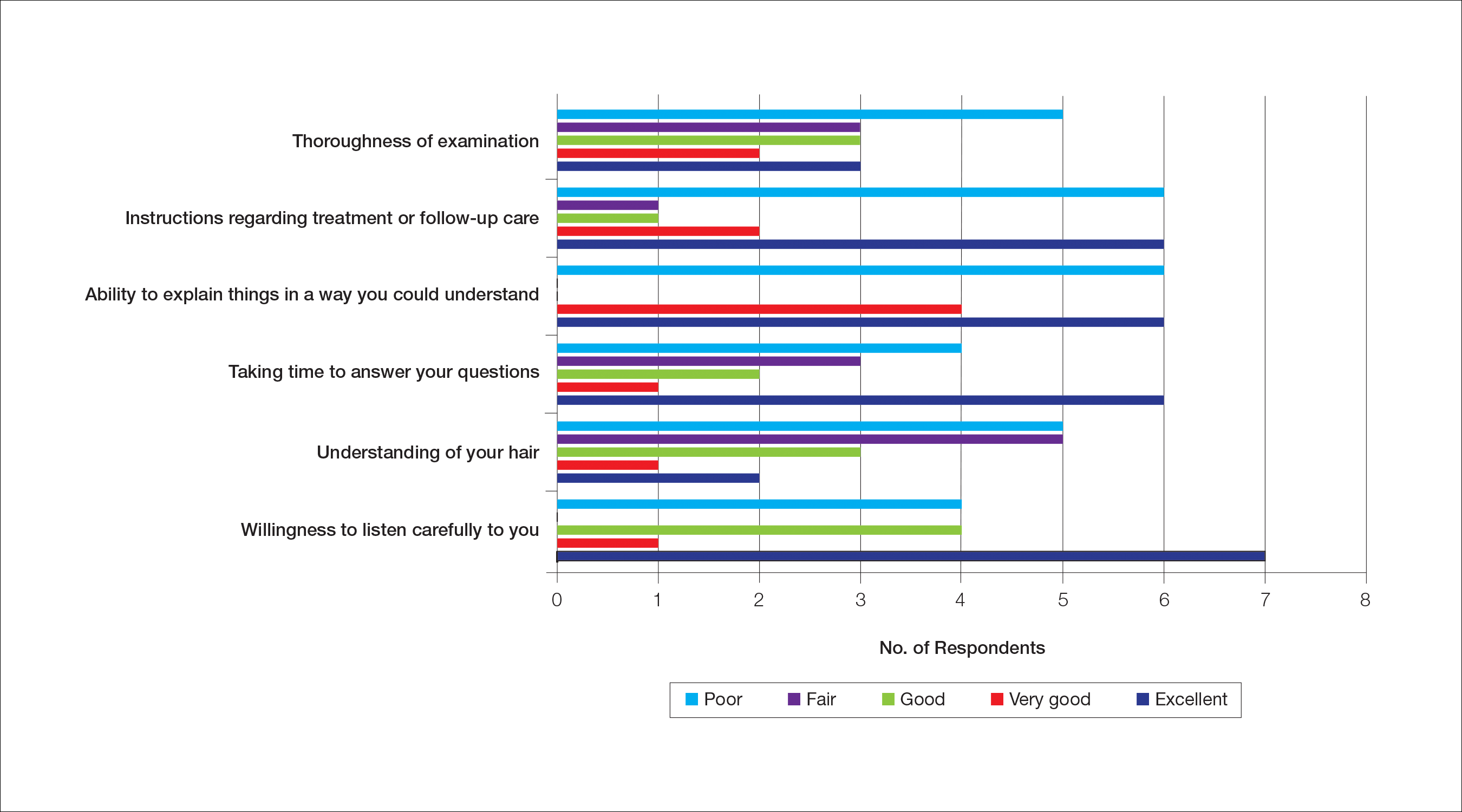

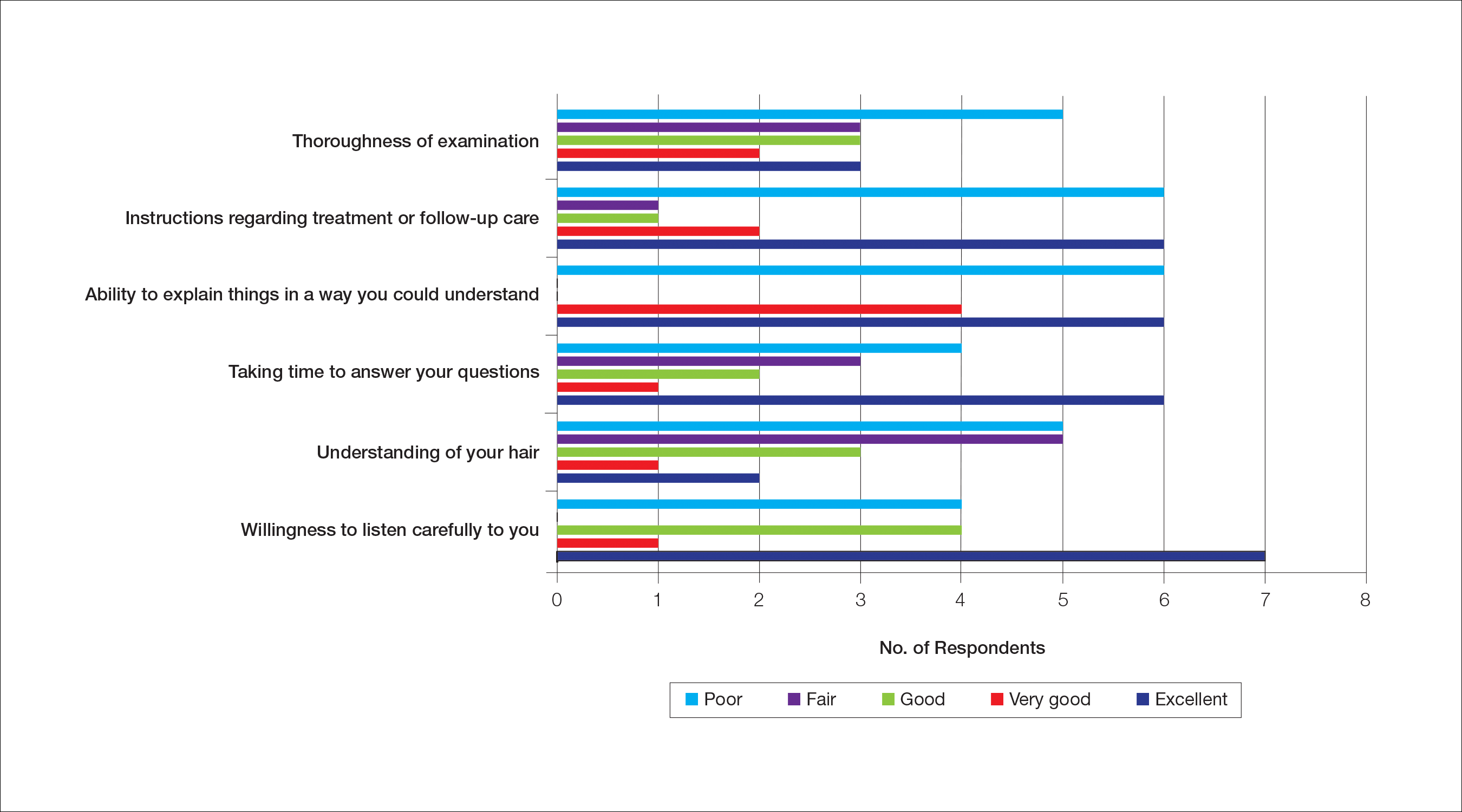

Almost half (16/34 [47%]) of the women went to a nondermatologist physician regarding their hair loss; of them, half (8/16 [50%]) reported their physician did not examine the scalp, 3 (19%) reported their physician offered a biopsy, and none of them reported that their physician diagnosed them with CCCA. The median patient rating of their nondermatologist physician interactions was good (3 on a 5-point scale). Table 1 and Figure 1 show responses to individual items.

Dermatologist Consultation

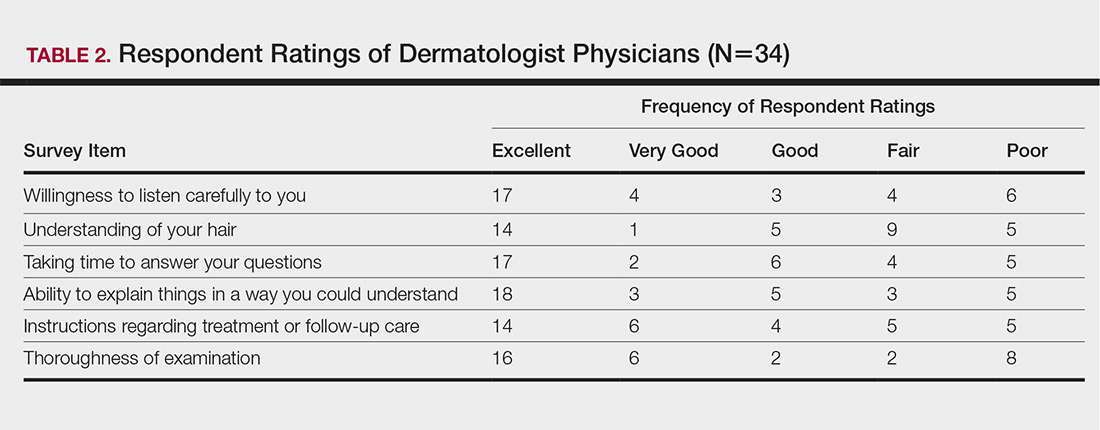

All 34 respondents presented to a dermatologist. The majority of respondents (22/34 [65%]) saw either 1 or 2 dermatologists for their hair loss. Three (9%) reported their dermatologist did not examine their scalp. Twelve respondents (35%) reported their dermatologist did not offer a biopsy. Twenty-one respondents (62%) reported a CCCA diagnosis from the first dermatologist they saw. Twenty-three respondents (68%) were diagnosed by dermatologists with expertise in hair disorders. Sixteen (47%) were diagnosed by dermatologists within a skin-of-color center. Fourteen (41%) initial dermatology consultations were race concordant.

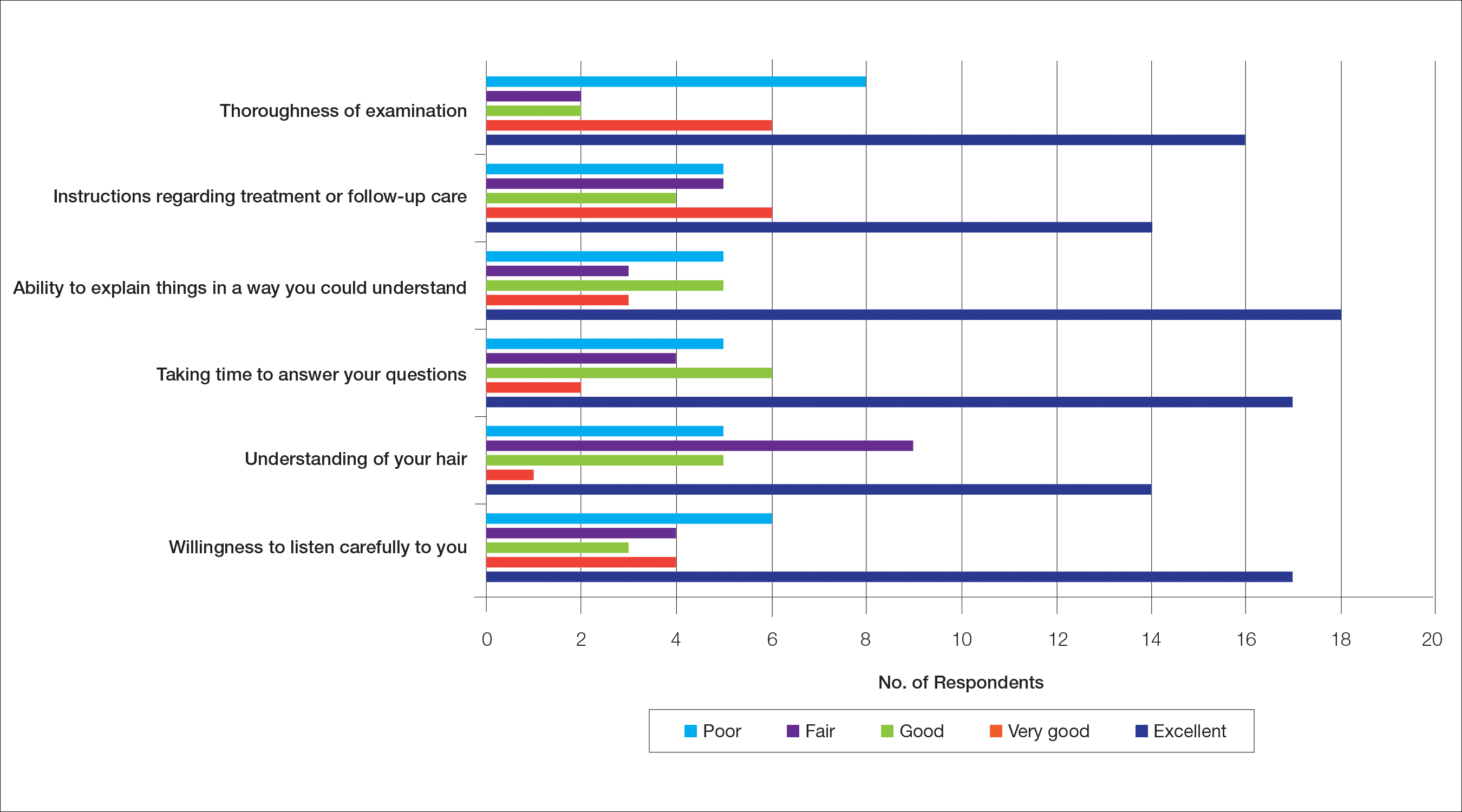

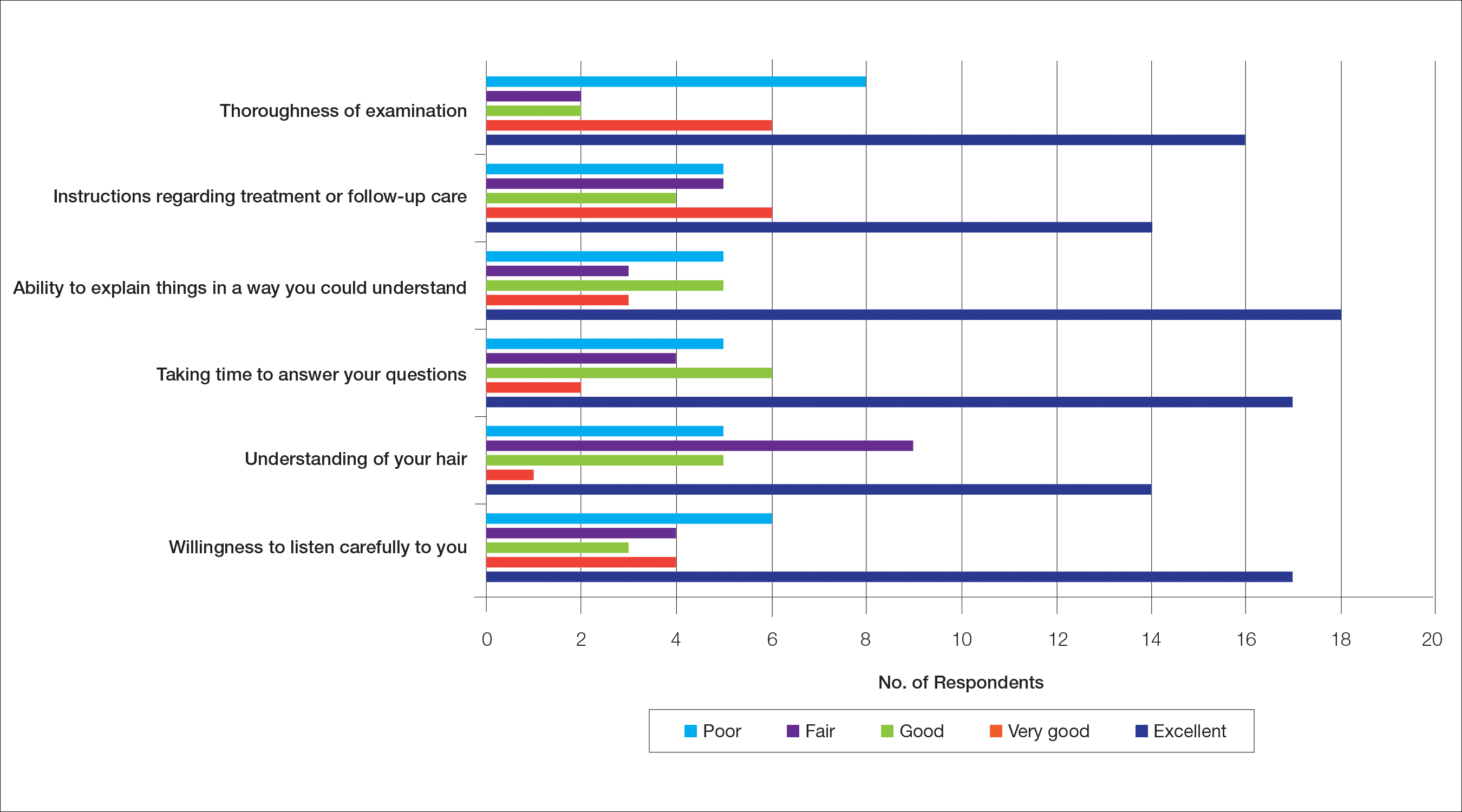

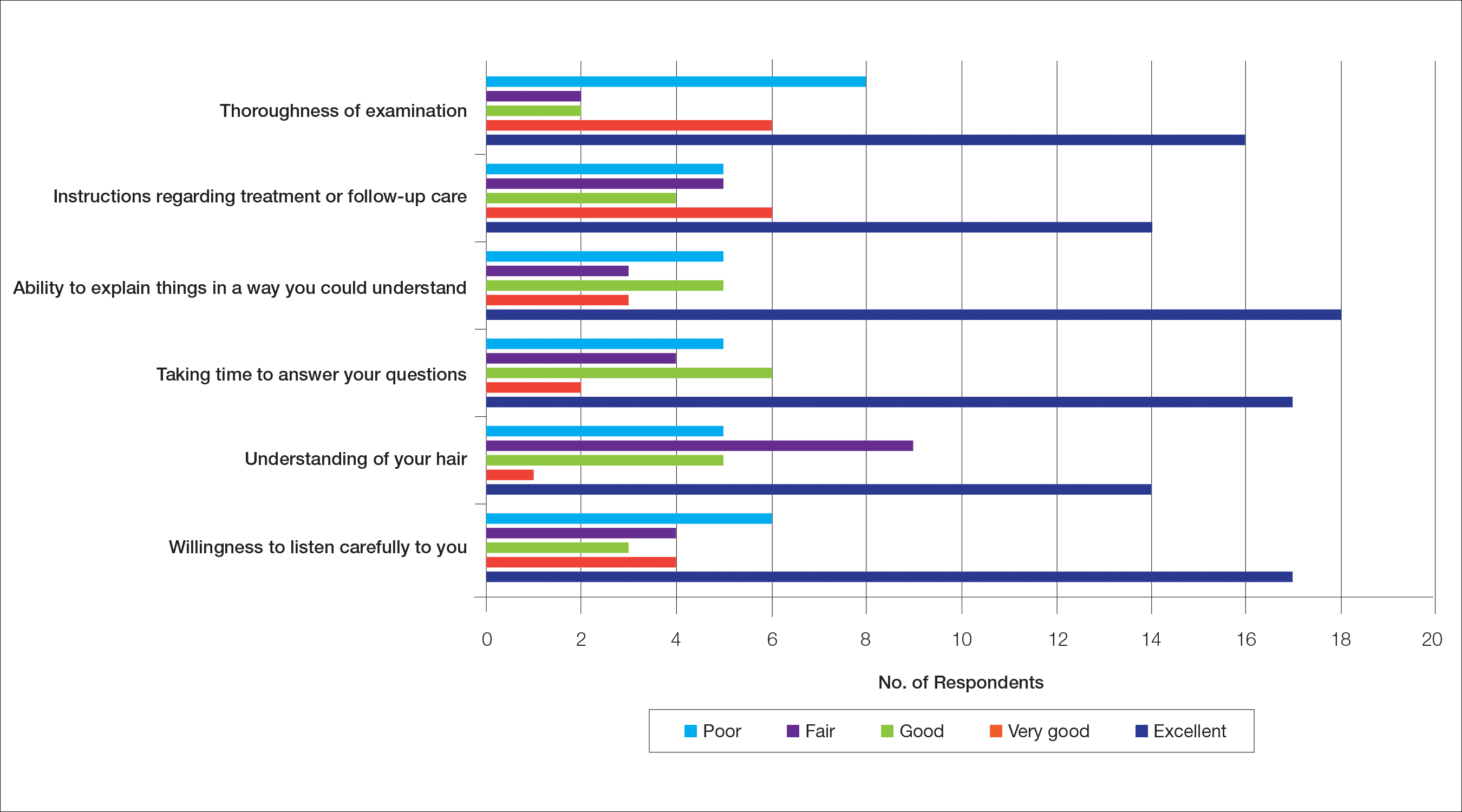

The median patient rating of their dermatologist interactions was excellent (5 on a 5-point scale). Table 2 and Figure 2 show responses to individual items. Respondents saw an average of 3 different providers, both dermatologists and otherwise.

Waiting to See a Dermatologist

Nearly all respondents (31/34 [91%]) recommended that other women with hair loss immediately go see a dermatologist.

Barriers to Care

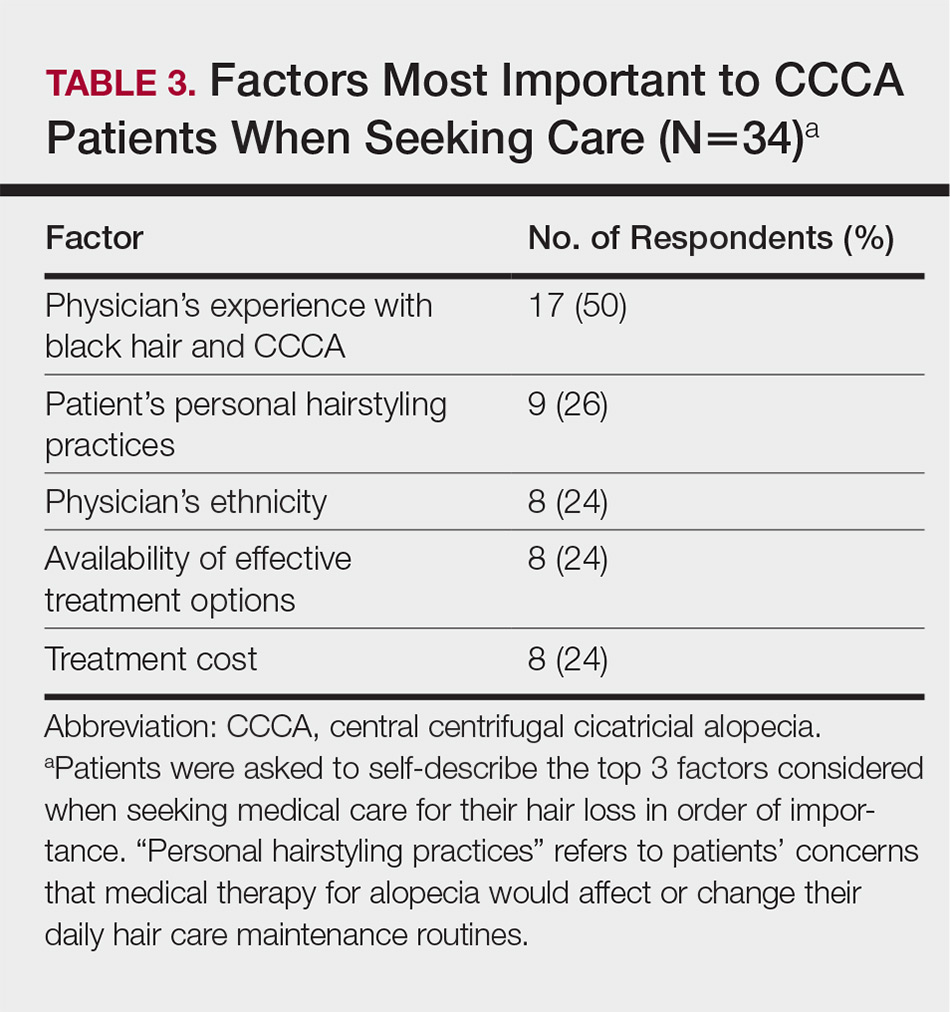

The top 5 factors reported as most important when initially seeking care included the physician’s experience with black hair and CCCA, the patient’s personal hairstyling practices, the physician’s ethnicity, availability of effective treatment options, and treatment cost. Table 3 shows frequency counts for these freely reported factors.

Quality of Life

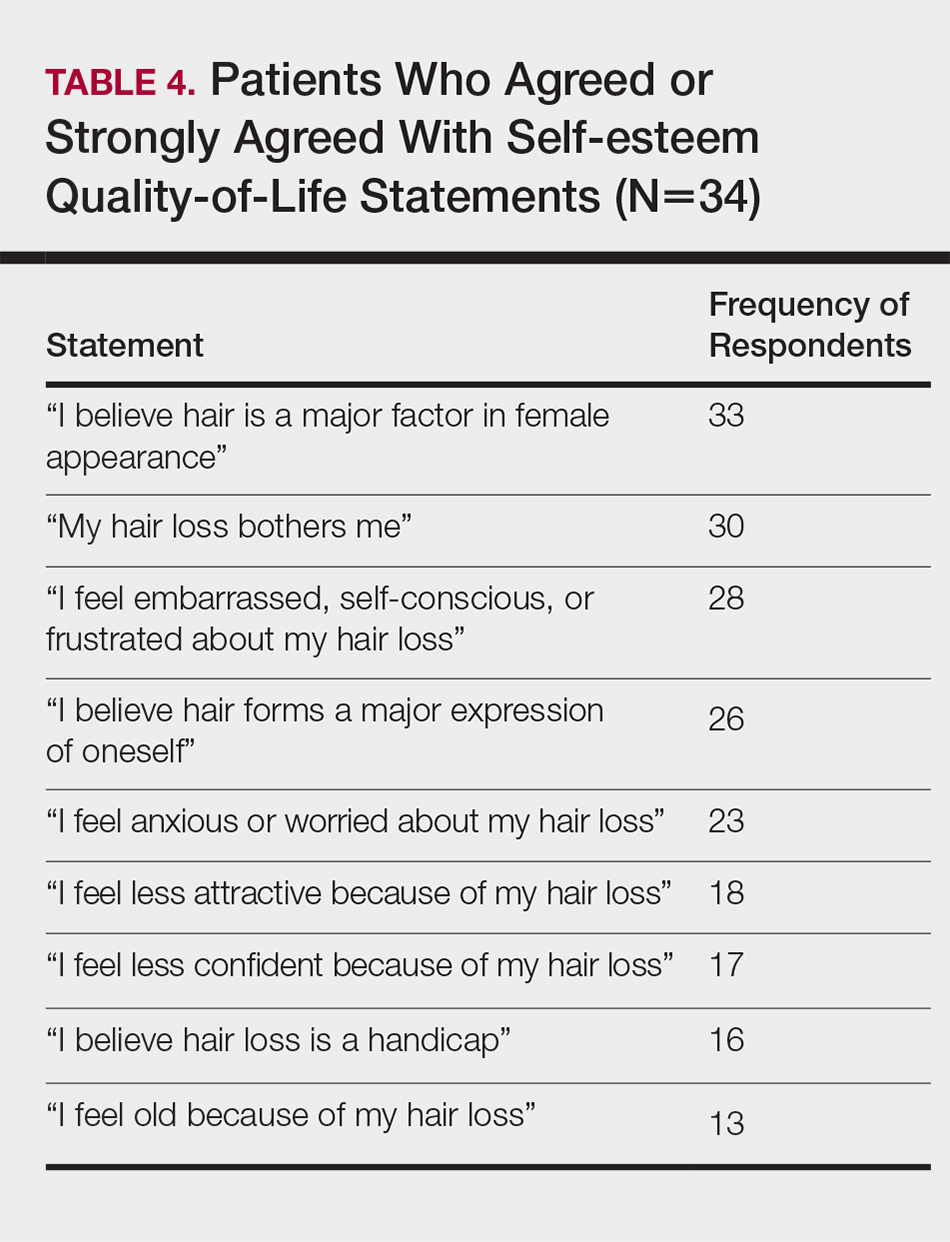

The median score on 9 aggregated self-esteem items was 4 on a 5-point scale, representing an agree response to statements such as “I feel embarrassed, self-conscious, or frustrated about my hair loss” (28/34 [82%]) and “My hair loss bothers me” (28/34 [82%])(Table 4). Cronbach α for self-esteem survey items was 0.7826.

For the nonaggregated items, many respondents strongly disagreed with statements pertaining to activities of daily living, including “I take care of where I sit or stand at social gatherings due to my hair loss” (18/34 [53%]), “My hair loss makes it difficult for me to go to the grocery store” (29/34 [85%]), “My hair loss makes it difficult for me to attend faith-based activities” (30/34 [88%]), “My hair loss makes it difficult for me to exercise” (23/34 [68%]), “My hair loss makes it difficult for me to go to work and/or school” (24/34 [71%]), “My hair loss makes it difficult for me to go out with a significant other” (24/34 [71%]), “My hair loss makes it difficult for me to spend time with family” (27/34 [79%]), and “My hair loss makes it difficult for me to go to a hairstylist” (16/34 [47%]).

Comment

The majority of respondents were first to discover their hair loss. Harbingers of CCCA hair loss include paresthesia, tenderness, and itch,6 symptoms that are hard to ignore. Unfortunately, many patients notice hair thinning years after the scarring process has begun and a notable amount of hair has already been lost.6,9

Fifteen percent of respondents learned about their hair loss from their hairstylist. Women of African descent often maintain hairstyles that require frequent interactions with a hair care professional.7,10 As a result, hairstylists are at the forefront of early alopecia detection and are a valued resource in the black community. Open dialogue between dermatologists and hair care professionals could funnel women with hair loss into treatment before extensive damage.

Fifteen women (44%) recalled a waiting period of several months before seeking medical assistance, and 16 (47%) reported waiting 1 year or more. However, 91% of respondents indicated that women with hair loss should immediately see a physician for evaluation, thus patient experiences underscore the importance of early treatment. In our experience, many patients wait years before presenting to a physician. Some work with their hairstylists first to address the issue, while others do not realize how notable the loss has become. Some have a negative experience with one provider or are told there is nothing that can be done and then wait many years to see a second provider. Proper education of patients, physicians, and hairstylists is important in the identification and prompt treatment of this condition.

It is perhaps to be expected that patients rated interactions with dermatologists as excellent and very good more frequently than interactions with nondermatologists, which may be due to an absence of thorough hair evaluation with nondermatologists. Respondents reported that only half of nondermatologist providers actually examined their scalp during an initial encounter. However, both physician groups had the lowest frequencies of excellent and very good ratings on “understanding of your hair” (Tables 1 and 2). Patients with hair loss seek immediate answers, and often it is the specialist that can give them a firm diagnosis as opposed to a primary care provider. The fact that dermatologists and nondermatologists alike scored poorly on patient-perceived understanding of CCCA indicates an area for improvement within patient-physician interactions and physician knowledge.

The top 5 factors important to respondents when obtaining medical care included the physician’s experience with black hair and CCCA, the patient’s personal hairstyling practices, the physician’s ethnicity, availability of effective treatment options, and treatment cost. Patients with CCCA seeing dermatologists may discern a lack of experience with ethnic hair that leads patients to doubt their physicians’ ability to provide adequate care and decreased shared decision-making.11,12 These patient perceptions are not unfounded; a 2008 study showed that dermatology residents are not uniformly trained in diseases pertaining to patients with skin of color.13 Thus, incorporation of education on skin of color in dermatology training programs is critical.

Finally, hair loss patients often have concerns regarding how medical therapeutics could adversely affect personal hair care regimens, including washing and hairstyling practices. Current research demonstrates that patients consider treatment effectiveness and ability to be integrated into daily routines after establishing medical care.14 The present study shows that some CCCA patients contemplate how well a therapy will work before seeking medical care, demonstrating that patients continue to have these concerns after establishing medical care. Consideration of treatment effectiveness is important for both patients and providers, as there is minimal evidence behind current CCCA management practices. The ability for treatments to be easily integrated into daily hair care habits is important to maintain patient compliance.

Participants’ median self-esteem scores indicate the effect of CCCA on morale and self-perception. Items scrutinizing this construct had acceptable internal consistency reliability. It is interesting to note that activities of daily living were not impacted by hair loss. Examination of self-esteem is important in the alopecia population because the effect of hair loss on mental status is well documented.15-17 Low self-esteem has been reported as a prospective risk factor for clinical depression.18-20 In black patients, clinical depression rates surpass those of Hispanics and non-Hispanic white individuals.21 Dermatologists must consider the psychological status of all patients, particularly populations at risk for severe disease.

Limitations of this study include the small (34 participants) and mostly highly educated sample size, limited survey validity, and potential patient bias. Because many patients changed their address and/or telephone number in the time between CCCA diagnosis and the present study, we were left with a small pilot study, which minimizes the impact of our findings. Furthermore, our survey was created by a single expert’s opinion and modeling from preexisting alopecia questionnaires16; full validity procedures analyzing face, content, and criterion validity were not undertaken. Finally, the majority of respondents were patients of one of the study’s authors (S.S.L.P.), which could influence survey responses. The fact that some providers were hair experts and some were race concordant with their patients also could potentially affect the responses received, which was not analyzed in the present study. Future studies with more respondents from multiple providers would help clarify our preliminary findings.

Conclusion

Analysis of barriers to care and QOL in patients with skin of color is an essential addition to dermatologic discourse. Alopecia is particularly important to investigate, as prior research has found it to be one of the top 5 diagnoses made in patients with skin of color.3,4 Alopecia has been shown to negatively affect QOL.15,22,23 This study, although limited by small sample size, suggests CCCA also is a contributor to self-esteem challenges, similar to other forms of hair loss. Patient-physician interactions and personal hairstyling practices are prominent barriers to care for CCCA patients, demonstrating the need for quality education on skin of color and cultural competency in dermatology residencies across the country.

- Ogunleye TA, McMichael A, Olsen EA. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: what has been achieved, current clues for future research. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:173-181.

- Sperling LC. Scarring alopecia and the dermatopathologist. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:333-342.

- Halder RM, Grimes PE, McLaurin CI, et al. Incidence of common dermatoses in a predominantly black dermatologic practice. Cutis. 1983;32:388, 390.

- Alexis AF, Sergay AB, Taylor SC. Common dermatologic disorders in skin of color: a comparative practice survey. Cutis. 2007;80:387-394.

- Olsen EA, Callender V, McMichael A, et al. Central hair loss in African American women: incidence and potential risk factors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:245-252.

- Gathers RC, Lim HW. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: past, present, and future. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:660-668.

- Gathers RC, Mahan MG. African american women, hair care, and health barriers. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:26-29.

- Van Der Donk J, Hunfeld JA, Passchier J, et al. Quality of life and maladjustment associated with hair loss in women with alopecia androgenetica. Social Sci Med. 1994;38:159-163.

- Sperling LC, Sau P. The follicular degeneration syndrome in black patients. ‘hot comb alopecia’ revisited and revised. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:68-74.

- Gathers RC, Jankowski M, Eide M, et al. Hair grooming practices and central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:574-578.

- Harvey VM, Ozoemena U, Paul J, et al. Patient-provider communication, concordance, and ratings of care in dermatology: results of a cross-sectional study. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22. pii: 13030/qt06j6p7gh.

- Laveist TA, Nuru-Jeter A. Is doctor-patient race concordance associated with greater satisfaction with care? J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43:296-306.

- Nijhawan RI, Jacob SE, Woolery-Lloyd H. Skin of color education in dermatology residency programs: does residency training reflect the changing demographics of the United States? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:615-618.

- Suchonwanit P, Hector CE, Bin Saif GA, et al. Factors affecting the severity of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:E338-E343.

- Williamson D, Gonzalez M, Finlay AY. The effect of hair loss on quality of life. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:137-139.

- Fabbrocini G, Panariello L, De Vita V, et al. Quality of life in alopecia areata: a disease-specific questionnaire. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:E276-E281.

- Ramos PM, Miot HA. Female pattern hair loss: a clinical and pathophysiological review. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:529-543.

- Sowislo JF, Orth U. Does low self-esteem predict depression and anxiety? a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol Bull. 2013;139:213-240.

- Steiger AE, Allemand M, Robins RW, et al. Low and decreasing self-esteem during adolescence predict adult depression two decades later. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2014;106:325-338.

- Wegener I, Geiser F, Alfter S, et al. Changes of explicitly and implicitly measured self-esteem in the treatment of major depression: evidence for implicit self-esteem compensation. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;58:57-67.

- Pratt LAB, Brody DJ. Depression in the U.S. Household Population, 2009-2012. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2014. NCHS Data Brief, No. 172. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db172.pdf. Published December 2014. Accessed November 19, 2018.

- Schmidt S, Fischer TW, Chren MM, et al. Strategies of coping and quality of life in women with alopecia. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:1038-1043.

- Hunt N, McHale S. The psychological impact of alopecia. Br Med J. 2005;331:951-953.

The etiology of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA), a clinical and histological pattern of hair loss on the central scalp, has been well studied. This disease is chronic and progressive, with extensive follicular destruction and eventual burnout.1,2 Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia is most commonly seen in patients of African descent and has been shown to be 1 of the 5 most common dermatologic diagnoses in black patients.3,4 The top 5 dermatologic diagnoses within this population include acne vulgaris (28.4%), dyschromia (19.9%), eczema (9.1%), alopecia (8.3%), and seborrheic dermatitis (6.7%).4 The incidence rate of CCCA is estimated to be 5.6%.3,5 Most patients are women, with onset between the second and fourth decades of life.6

Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia treatment efficacy is inversely correlated with disease duration. The primary goal of treatment is to prevent progression. Efforts are made to stimulate regrowth in areas that are not permanently scarred. When patients present with a substantial amount of scarring hair loss, dermatologists often are limited in their ability to achieve a cosmetically acceptable pattern of growth. Generally, hair is connected to a sense of self-worth in black women, and any type of hair loss has been shown to lead to frustration and decreased self-esteem.7 A 1994 study showed that 75% (44/58) of women with androgenetic alopecia had decreased self-esteem and 50% (29/58) had social challenges.8

The purpose of this pilot study was to determine the personal, historical, logistical, or environmental factors that preclude women from obtaining medical care for CCCA and to investigate how CCCA affects quality of life (QOL) and psychological well-being.

Methods

The investigators designed a survey study of adult, English-speaking, black women diagnosed with CCCA at the Northwestern University Department of Dermatology (Chicago, Illinois) between 2011 and 2017. Patients were selected from the electronic data warehouse compiled by the Department of Dermatology and were included if they fulfilled the following criteria: evaluated in the dermatology department between September 1, 2011, and September 30, 2017, by any faculty physician; diagnosed with CCCA; and aged 18 years or older. Patients were excluded if they did not speak English, as interpreters were not available. All patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria provided signed informed consent prior to participation. All surveys were disseminated in the office or via telephone from fall 2016 to spring 2017 and took 10 to 15 minutes to complete. The research was approved by the authors’ institutional review board (IRB ID STU00203449).

Survey Instrument

The

Data Analysis

Analyses were completed using data analysis software JMP Pro 13 from SAS and a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Continuous data were presented as mean, SD, median, minimum, and maximum. Categorical data were presented as counts and percentages. Nine QOL items were aggregated into a self-esteem category (questions 30–38).

Cronbach α, a statistical measure of internal consistency and how closely related items are in a group, was used to evaluate internal consistency reliability; values of 0.70 or greater indicate acceptable reliability.

Results

Of 501 individuals contacted, 34 completed the survey (7% completion rate). Nonrespondents included 7 who refused to participate and 460 who could not be contacted. All respondents self-identified as black women. Median age at time of survey administration was 46 years (range, 28–79 years); median age at CCCA diagnosis was 42 years (range, 15–73 years). Respondents did not significantly differ in age from nonrespondents (P=.46). The majority of respondents had an associate’s degree, bachelor’s degree, or advanced degree of education (master of arts, doctor of medicine, doctor of jurisprudence, doctor of philosophy); however, 8 women reported completing some college, 1 reported completing high school, and 1 reported no schooling. Three respondents had no health insurance.

Initial Hair Loss Discovery

The majority of respondents (22/34 [65%]) were first to notice their hair loss, while 5 (15%) reported hairstylists as the initial observers. Twelve respondents (35%) initially went to a physician to learn why they were losing hair; 6 (18%) instead utilized hairstylists or the Internet. Fifteen women (44%) waited more than 1 month up to 6 months after noticing hair loss before seeing a physician instead of going immediately within a 4-week period, and 16 (47%) waited 1 year or more.

Nondermatologist Consultation

Almost half (16/34 [47%]) of the women went to a nondermatologist physician regarding their hair loss; of them, half (8/16 [50%]) reported their physician did not examine the scalp, 3 (19%) reported their physician offered a biopsy, and none of them reported that their physician diagnosed them with CCCA. The median patient rating of their nondermatologist physician interactions was good (3 on a 5-point scale). Table 1 and Figure 1 show responses to individual items.

Dermatologist Consultation

All 34 respondents presented to a dermatologist. The majority of respondents (22/34 [65%]) saw either 1 or 2 dermatologists for their hair loss. Three (9%) reported their dermatologist did not examine their scalp. Twelve respondents (35%) reported their dermatologist did not offer a biopsy. Twenty-one respondents (62%) reported a CCCA diagnosis from the first dermatologist they saw. Twenty-three respondents (68%) were diagnosed by dermatologists with expertise in hair disorders. Sixteen (47%) were diagnosed by dermatologists within a skin-of-color center. Fourteen (41%) initial dermatology consultations were race concordant.

The median patient rating of their dermatologist interactions was excellent (5 on a 5-point scale). Table 2 and Figure 2 show responses to individual items. Respondents saw an average of 3 different providers, both dermatologists and otherwise.

Waiting to See a Dermatologist

Nearly all respondents (31/34 [91%]) recommended that other women with hair loss immediately go see a dermatologist.

Barriers to Care

The top 5 factors reported as most important when initially seeking care included the physician’s experience with black hair and CCCA, the patient’s personal hairstyling practices, the physician’s ethnicity, availability of effective treatment options, and treatment cost. Table 3 shows frequency counts for these freely reported factors.

Quality of Life

The median score on 9 aggregated self-esteem items was 4 on a 5-point scale, representing an agree response to statements such as “I feel embarrassed, self-conscious, or frustrated about my hair loss” (28/34 [82%]) and “My hair loss bothers me” (28/34 [82%])(Table 4). Cronbach α for self-esteem survey items was 0.7826.

For the nonaggregated items, many respondents strongly disagreed with statements pertaining to activities of daily living, including “I take care of where I sit or stand at social gatherings due to my hair loss” (18/34 [53%]), “My hair loss makes it difficult for me to go to the grocery store” (29/34 [85%]), “My hair loss makes it difficult for me to attend faith-based activities” (30/34 [88%]), “My hair loss makes it difficult for me to exercise” (23/34 [68%]), “My hair loss makes it difficult for me to go to work and/or school” (24/34 [71%]), “My hair loss makes it difficult for me to go out with a significant other” (24/34 [71%]), “My hair loss makes it difficult for me to spend time with family” (27/34 [79%]), and “My hair loss makes it difficult for me to go to a hairstylist” (16/34 [47%]).

Comment

The majority of respondents were first to discover their hair loss. Harbingers of CCCA hair loss include paresthesia, tenderness, and itch,6 symptoms that are hard to ignore. Unfortunately, many patients notice hair thinning years after the scarring process has begun and a notable amount of hair has already been lost.6,9

Fifteen percent of respondents learned about their hair loss from their hairstylist. Women of African descent often maintain hairstyles that require frequent interactions with a hair care professional.7,10 As a result, hairstylists are at the forefront of early alopecia detection and are a valued resource in the black community. Open dialogue between dermatologists and hair care professionals could funnel women with hair loss into treatment before extensive damage.

Fifteen women (44%) recalled a waiting period of several months before seeking medical assistance, and 16 (47%) reported waiting 1 year or more. However, 91% of respondents indicated that women with hair loss should immediately see a physician for evaluation, thus patient experiences underscore the importance of early treatment. In our experience, many patients wait years before presenting to a physician. Some work with their hairstylists first to address the issue, while others do not realize how notable the loss has become. Some have a negative experience with one provider or are told there is nothing that can be done and then wait many years to see a second provider. Proper education of patients, physicians, and hairstylists is important in the identification and prompt treatment of this condition.

It is perhaps to be expected that patients rated interactions with dermatologists as excellent and very good more frequently than interactions with nondermatologists, which may be due to an absence of thorough hair evaluation with nondermatologists. Respondents reported that only half of nondermatologist providers actually examined their scalp during an initial encounter. However, both physician groups had the lowest frequencies of excellent and very good ratings on “understanding of your hair” (Tables 1 and 2). Patients with hair loss seek immediate answers, and often it is the specialist that can give them a firm diagnosis as opposed to a primary care provider. The fact that dermatologists and nondermatologists alike scored poorly on patient-perceived understanding of CCCA indicates an area for improvement within patient-physician interactions and physician knowledge.

The top 5 factors important to respondents when obtaining medical care included the physician’s experience with black hair and CCCA, the patient’s personal hairstyling practices, the physician’s ethnicity, availability of effective treatment options, and treatment cost. Patients with CCCA seeing dermatologists may discern a lack of experience with ethnic hair that leads patients to doubt their physicians’ ability to provide adequate care and decreased shared decision-making.11,12 These patient perceptions are not unfounded; a 2008 study showed that dermatology residents are not uniformly trained in diseases pertaining to patients with skin of color.13 Thus, incorporation of education on skin of color in dermatology training programs is critical.