User login

FDA grants priority review to quizartinib

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has accepted for priority review a new drug application (NDA) for the FLT3 inhibitor quizartinib.

With this NDA, Daiichi Sankyo is seeking approval for quizartinib to treat adults with relapsed/refractory FLT3-ITD acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

The FDA grants priority review to applications for products that are expected to provide significant improvements in the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of serious conditions.

The FDA aims to take action on a priority review application within 6 months rather than the standard 10 months.

The FDA is expected to make a decision on the quizartinib NDA by May 25, 2019.

In addition to priority review, quizartinib has breakthrough therapy designation and fast track designation from the FDA.

Trial results

The NDA for quizartinib is supported by results from the phase 3 QuANTUM-R study. Topline results from this study were presented at the 23rd Congress of the European Hematology Association in June, and new analyses are set to be presented at the 2018 ASH Annual Meeting in December (abstract 563).

QuANTUM-R enrolled adults with FLT3-ITD AML (at least 3% FLT3-ITD allelic ratio) who had refractory disease or had relapsed within 6 months of their first complete response (CR).

Patients were randomized to receive once-daily treatment with quizartinib (n=245) or a salvage chemotherapy regimen (n=122)—low-dose cytarabine (LoDAC, n=29); combination mitoxantrone, etoposide, and cytarabine (MEC, n=40); or combination fludarabine, cytarabine, and idarubicin (FLAG-IDA, n=53).

Patients who responded to treatment could proceed to hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT), and those in the quizartinib arm could resume quizartinib after HSCT.

In all, 241 patients received quizartinib, and 94 received salvage chemotherapy—LoDAC (n=22), MEC (n=25), and FLAG-IDA (n=47). Of the 28 patients in the chemotherapy group who were not treated, most withdrew consent.

Thirty-two percent of quizartinib-treated patients and 12% of the chemotherapy group went on to HSCT.

Efficacy

The median follow-up was 23.5 months. The efficacy results include all randomized patients.

The overall response rate was 69% in the quizartinib arm and 30% in the chemotherapy arm. The composite CR rate was 48% in the quizartinib arm and 27% in the chemotherapy arm. This includes:

- The CR rate (4% and 1%, respectively)

- The rate of CR with incomplete platelet recovery (4% and 0%, respectively)

- The rate of CR with incomplete hematologic recovery (40% and 26%, respectively).

The median event-free survival was 6.0 weeks in the quizartinib arm and 3.7 weeks in the chemotherapy arm (hazard ratio=0.90, P=0.1071).

The median overall survival was 6.2 months in the quizartinib arm and 4.7 months in the chemotherapy arm (hazard ratio=0.76, P=0.0177). The 1-year overall survival rate was 27% and 20%, respectively.

Safety

The safety results include only patients who received their assigned treatment.

Grade 3 or higher hematologic treatment-emergent adverse events occurring in at least 5% of patients (in the quizartinib and chemotherapy groups, respectively) included:

- Thrombocytopenia (35% and 34%)

- Anemia (30% and 29%)

- Neutropenia (32% and 25%)

- Febrile neutropenia (31% and 21%)

- Leukopenia (17% and 16%).

Grade 3 or higher non-hematologic treatment-emergent adverse events occurring in at least 5% of patients (in the quizartinib and chemotherapy groups, respectively) included:

- Sepsis/septic shock (16% and 18%)

- Hypokalemia (12% and 9%)

- Pneumonia (12% and 9%)

- Fatigue (8% and 1%)

- Dyspnea (5% for both)

- Hypophosphatemia (5% for both).

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has accepted for priority review a new drug application (NDA) for the FLT3 inhibitor quizartinib.

With this NDA, Daiichi Sankyo is seeking approval for quizartinib to treat adults with relapsed/refractory FLT3-ITD acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

The FDA grants priority review to applications for products that are expected to provide significant improvements in the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of serious conditions.

The FDA aims to take action on a priority review application within 6 months rather than the standard 10 months.

The FDA is expected to make a decision on the quizartinib NDA by May 25, 2019.

In addition to priority review, quizartinib has breakthrough therapy designation and fast track designation from the FDA.

Trial results

The NDA for quizartinib is supported by results from the phase 3 QuANTUM-R study. Topline results from this study were presented at the 23rd Congress of the European Hematology Association in June, and new analyses are set to be presented at the 2018 ASH Annual Meeting in December (abstract 563).

QuANTUM-R enrolled adults with FLT3-ITD AML (at least 3% FLT3-ITD allelic ratio) who had refractory disease or had relapsed within 6 months of their first complete response (CR).

Patients were randomized to receive once-daily treatment with quizartinib (n=245) or a salvage chemotherapy regimen (n=122)—low-dose cytarabine (LoDAC, n=29); combination mitoxantrone, etoposide, and cytarabine (MEC, n=40); or combination fludarabine, cytarabine, and idarubicin (FLAG-IDA, n=53).

Patients who responded to treatment could proceed to hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT), and those in the quizartinib arm could resume quizartinib after HSCT.

In all, 241 patients received quizartinib, and 94 received salvage chemotherapy—LoDAC (n=22), MEC (n=25), and FLAG-IDA (n=47). Of the 28 patients in the chemotherapy group who were not treated, most withdrew consent.

Thirty-two percent of quizartinib-treated patients and 12% of the chemotherapy group went on to HSCT.

Efficacy

The median follow-up was 23.5 months. The efficacy results include all randomized patients.

The overall response rate was 69% in the quizartinib arm and 30% in the chemotherapy arm. The composite CR rate was 48% in the quizartinib arm and 27% in the chemotherapy arm. This includes:

- The CR rate (4% and 1%, respectively)

- The rate of CR with incomplete platelet recovery (4% and 0%, respectively)

- The rate of CR with incomplete hematologic recovery (40% and 26%, respectively).

The median event-free survival was 6.0 weeks in the quizartinib arm and 3.7 weeks in the chemotherapy arm (hazard ratio=0.90, P=0.1071).

The median overall survival was 6.2 months in the quizartinib arm and 4.7 months in the chemotherapy arm (hazard ratio=0.76, P=0.0177). The 1-year overall survival rate was 27% and 20%, respectively.

Safety

The safety results include only patients who received their assigned treatment.

Grade 3 or higher hematologic treatment-emergent adverse events occurring in at least 5% of patients (in the quizartinib and chemotherapy groups, respectively) included:

- Thrombocytopenia (35% and 34%)

- Anemia (30% and 29%)

- Neutropenia (32% and 25%)

- Febrile neutropenia (31% and 21%)

- Leukopenia (17% and 16%).

Grade 3 or higher non-hematologic treatment-emergent adverse events occurring in at least 5% of patients (in the quizartinib and chemotherapy groups, respectively) included:

- Sepsis/septic shock (16% and 18%)

- Hypokalemia (12% and 9%)

- Pneumonia (12% and 9%)

- Fatigue (8% and 1%)

- Dyspnea (5% for both)

- Hypophosphatemia (5% for both).

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has accepted for priority review a new drug application (NDA) for the FLT3 inhibitor quizartinib.

With this NDA, Daiichi Sankyo is seeking approval for quizartinib to treat adults with relapsed/refractory FLT3-ITD acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

The FDA grants priority review to applications for products that are expected to provide significant improvements in the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of serious conditions.

The FDA aims to take action on a priority review application within 6 months rather than the standard 10 months.

The FDA is expected to make a decision on the quizartinib NDA by May 25, 2019.

In addition to priority review, quizartinib has breakthrough therapy designation and fast track designation from the FDA.

Trial results

The NDA for quizartinib is supported by results from the phase 3 QuANTUM-R study. Topline results from this study were presented at the 23rd Congress of the European Hematology Association in June, and new analyses are set to be presented at the 2018 ASH Annual Meeting in December (abstract 563).

QuANTUM-R enrolled adults with FLT3-ITD AML (at least 3% FLT3-ITD allelic ratio) who had refractory disease or had relapsed within 6 months of their first complete response (CR).

Patients were randomized to receive once-daily treatment with quizartinib (n=245) or a salvage chemotherapy regimen (n=122)—low-dose cytarabine (LoDAC, n=29); combination mitoxantrone, etoposide, and cytarabine (MEC, n=40); or combination fludarabine, cytarabine, and idarubicin (FLAG-IDA, n=53).

Patients who responded to treatment could proceed to hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT), and those in the quizartinib arm could resume quizartinib after HSCT.

In all, 241 patients received quizartinib, and 94 received salvage chemotherapy—LoDAC (n=22), MEC (n=25), and FLAG-IDA (n=47). Of the 28 patients in the chemotherapy group who were not treated, most withdrew consent.

Thirty-two percent of quizartinib-treated patients and 12% of the chemotherapy group went on to HSCT.

Efficacy

The median follow-up was 23.5 months. The efficacy results include all randomized patients.

The overall response rate was 69% in the quizartinib arm and 30% in the chemotherapy arm. The composite CR rate was 48% in the quizartinib arm and 27% in the chemotherapy arm. This includes:

- The CR rate (4% and 1%, respectively)

- The rate of CR with incomplete platelet recovery (4% and 0%, respectively)

- The rate of CR with incomplete hematologic recovery (40% and 26%, respectively).

The median event-free survival was 6.0 weeks in the quizartinib arm and 3.7 weeks in the chemotherapy arm (hazard ratio=0.90, P=0.1071).

The median overall survival was 6.2 months in the quizartinib arm and 4.7 months in the chemotherapy arm (hazard ratio=0.76, P=0.0177). The 1-year overall survival rate was 27% and 20%, respectively.

Safety

The safety results include only patients who received their assigned treatment.

Grade 3 or higher hematologic treatment-emergent adverse events occurring in at least 5% of patients (in the quizartinib and chemotherapy groups, respectively) included:

- Thrombocytopenia (35% and 34%)

- Anemia (30% and 29%)

- Neutropenia (32% and 25%)

- Febrile neutropenia (31% and 21%)

- Leukopenia (17% and 16%).

Grade 3 or higher non-hematologic treatment-emergent adverse events occurring in at least 5% of patients (in the quizartinib and chemotherapy groups, respectively) included:

- Sepsis/septic shock (16% and 18%)

- Hypokalemia (12% and 9%)

- Pneumonia (12% and 9%)

- Fatigue (8% and 1%)

- Dyspnea (5% for both)

- Hypophosphatemia (5% for both).

Harnessing the power of urine tests in pain care

SAN DIEGO – Clinicians have few tools to in their patients. However, addiction specialist and internist Edwin Salsitz, MD, says an inexpensive and simple tool, the urine test, can provide an impressive amount of useful information.

“The urine drug test, or another matrix for testing, gives one of the only objective factors we have to see how a patient is doing, if they’re following the treatment plan,” said Dr. Salsitz, of Mount Sinai Beth Israel, New York, in a presentation at Pain Care for Primary Care, a symposium offered by the American Pain Society and the Global Academy for Medical Education.

Dr. Salsitz offered these tips about urine tests in pain care:

Consider urine tests before beginning opioid therapy

Dr. Salsitz pointed to this 2016 recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: “When prescribing opioids for chronic pain, clinicians should use urine drug testing before starting opioid therapy and consider urine drug testing at least annually to assess for prescribed medications as well as other controlled prescription drugs and illicit drugs.” As Dr. Salsitz puts it, these tests “can help identify misuse, which hopefully hasn’t gotten to addiction yet.”

Ask the patient what the urine test will reveal

Dr. Salsitz likes to tell patients: “If you tell me the truth, no matter what’s in the urine, it’s going to be OK. I’m not going to stop prescribing or do anything harmful to you.” But, he tells patients, if they lie, “you’re going to start breaking the trust between us. Once you do that, it becomes a problem. I don’t know what’s true or not.” In some cases, he said, patients will fess up to drug use that wouldn’t have shown up in the urine tests because it didn’t happen recently enough. “We’ll talk about whether it’s a problem,” he said.

Begin with an immunoassay panel test (IA)

The CDC recommends using an immunoassay panel first in most situations. “You can do this in the office,” Dr. Salsitz said, using a dipstick-style test. Or you can “send it out to a lab, and they’ll do the same thing.”

Understand what IA tests do and don’t do

Standard 5-drug IA screening tests detect marijuana, cocaine, amphetamine/methamphetamine, PCP, and opiates (morphine/codeine). Keep in mind, Dr. Salsitz said, that opiates and opioids aren’t the same. That means IA tests don’t pick up oxycodone use, for example, he said. More sophisticated (and more expensive) tests can distinguish between types of drugs (for example, morphine vs. codeine) and can detect drugs that aren’t included in the IA tests.

Don’t make assumptions about positive or negative tests

A positive drug test for cocaine doesn’t necessarily mean the person is addicted, Dr. Salsitz said. “It just means they used that molecule in the last 3 days. It’s up to you to figure out what it actually means.” And if a patient’s urine fails to show that he or she is taking a prescribed medication, that doesn’t necessarily indicate that the drug is being illegally diverted. The patient could have run out of the drug or lost insurance coverage, Dr. Salsitz said.

Be aware that patients may fake urine tests

“Cheating is a huge problem,” Dr. Salsitz said. “Is it their urine or not their urine?” Many kits promise to help people provide fake urine, and some have even provided fake penises to foil observed urine collection. What to do? Alternative tests that rely on hair, saliva, and even sweat are available, Dr. Salsitz said, and these make cheating more difficult. However, they have various limitations. Saliva, for example, only tells you what patients are using now, not what they used days ago, he said, and it’s not sensitive for marijuana.

Dr. Salsitz reported no disclosures.

The Global Academy for Medical Education, which offered the Pain Care for Primary Care symposium, and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

SAN DIEGO – Clinicians have few tools to in their patients. However, addiction specialist and internist Edwin Salsitz, MD, says an inexpensive and simple tool, the urine test, can provide an impressive amount of useful information.

“The urine drug test, or another matrix for testing, gives one of the only objective factors we have to see how a patient is doing, if they’re following the treatment plan,” said Dr. Salsitz, of Mount Sinai Beth Israel, New York, in a presentation at Pain Care for Primary Care, a symposium offered by the American Pain Society and the Global Academy for Medical Education.

Dr. Salsitz offered these tips about urine tests in pain care:

Consider urine tests before beginning opioid therapy

Dr. Salsitz pointed to this 2016 recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: “When prescribing opioids for chronic pain, clinicians should use urine drug testing before starting opioid therapy and consider urine drug testing at least annually to assess for prescribed medications as well as other controlled prescription drugs and illicit drugs.” As Dr. Salsitz puts it, these tests “can help identify misuse, which hopefully hasn’t gotten to addiction yet.”

Ask the patient what the urine test will reveal

Dr. Salsitz likes to tell patients: “If you tell me the truth, no matter what’s in the urine, it’s going to be OK. I’m not going to stop prescribing or do anything harmful to you.” But, he tells patients, if they lie, “you’re going to start breaking the trust between us. Once you do that, it becomes a problem. I don’t know what’s true or not.” In some cases, he said, patients will fess up to drug use that wouldn’t have shown up in the urine tests because it didn’t happen recently enough. “We’ll talk about whether it’s a problem,” he said.

Begin with an immunoassay panel test (IA)

The CDC recommends using an immunoassay panel first in most situations. “You can do this in the office,” Dr. Salsitz said, using a dipstick-style test. Or you can “send it out to a lab, and they’ll do the same thing.”

Understand what IA tests do and don’t do

Standard 5-drug IA screening tests detect marijuana, cocaine, amphetamine/methamphetamine, PCP, and opiates (morphine/codeine). Keep in mind, Dr. Salsitz said, that opiates and opioids aren’t the same. That means IA tests don’t pick up oxycodone use, for example, he said. More sophisticated (and more expensive) tests can distinguish between types of drugs (for example, morphine vs. codeine) and can detect drugs that aren’t included in the IA tests.

Don’t make assumptions about positive or negative tests

A positive drug test for cocaine doesn’t necessarily mean the person is addicted, Dr. Salsitz said. “It just means they used that molecule in the last 3 days. It’s up to you to figure out what it actually means.” And if a patient’s urine fails to show that he or she is taking a prescribed medication, that doesn’t necessarily indicate that the drug is being illegally diverted. The patient could have run out of the drug or lost insurance coverage, Dr. Salsitz said.

Be aware that patients may fake urine tests

“Cheating is a huge problem,” Dr. Salsitz said. “Is it their urine or not their urine?” Many kits promise to help people provide fake urine, and some have even provided fake penises to foil observed urine collection. What to do? Alternative tests that rely on hair, saliva, and even sweat are available, Dr. Salsitz said, and these make cheating more difficult. However, they have various limitations. Saliva, for example, only tells you what patients are using now, not what they used days ago, he said, and it’s not sensitive for marijuana.

Dr. Salsitz reported no disclosures.

The Global Academy for Medical Education, which offered the Pain Care for Primary Care symposium, and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

SAN DIEGO – Clinicians have few tools to in their patients. However, addiction specialist and internist Edwin Salsitz, MD, says an inexpensive and simple tool, the urine test, can provide an impressive amount of useful information.

“The urine drug test, or another matrix for testing, gives one of the only objective factors we have to see how a patient is doing, if they’re following the treatment plan,” said Dr. Salsitz, of Mount Sinai Beth Israel, New York, in a presentation at Pain Care for Primary Care, a symposium offered by the American Pain Society and the Global Academy for Medical Education.

Dr. Salsitz offered these tips about urine tests in pain care:

Consider urine tests before beginning opioid therapy

Dr. Salsitz pointed to this 2016 recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: “When prescribing opioids for chronic pain, clinicians should use urine drug testing before starting opioid therapy and consider urine drug testing at least annually to assess for prescribed medications as well as other controlled prescription drugs and illicit drugs.” As Dr. Salsitz puts it, these tests “can help identify misuse, which hopefully hasn’t gotten to addiction yet.”

Ask the patient what the urine test will reveal

Dr. Salsitz likes to tell patients: “If you tell me the truth, no matter what’s in the urine, it’s going to be OK. I’m not going to stop prescribing or do anything harmful to you.” But, he tells patients, if they lie, “you’re going to start breaking the trust between us. Once you do that, it becomes a problem. I don’t know what’s true or not.” In some cases, he said, patients will fess up to drug use that wouldn’t have shown up in the urine tests because it didn’t happen recently enough. “We’ll talk about whether it’s a problem,” he said.

Begin with an immunoassay panel test (IA)

The CDC recommends using an immunoassay panel first in most situations. “You can do this in the office,” Dr. Salsitz said, using a dipstick-style test. Or you can “send it out to a lab, and they’ll do the same thing.”

Understand what IA tests do and don’t do

Standard 5-drug IA screening tests detect marijuana, cocaine, amphetamine/methamphetamine, PCP, and opiates (morphine/codeine). Keep in mind, Dr. Salsitz said, that opiates and opioids aren’t the same. That means IA tests don’t pick up oxycodone use, for example, he said. More sophisticated (and more expensive) tests can distinguish between types of drugs (for example, morphine vs. codeine) and can detect drugs that aren’t included in the IA tests.

Don’t make assumptions about positive or negative tests

A positive drug test for cocaine doesn’t necessarily mean the person is addicted, Dr. Salsitz said. “It just means they used that molecule in the last 3 days. It’s up to you to figure out what it actually means.” And if a patient’s urine fails to show that he or she is taking a prescribed medication, that doesn’t necessarily indicate that the drug is being illegally diverted. The patient could have run out of the drug or lost insurance coverage, Dr. Salsitz said.

Be aware that patients may fake urine tests

“Cheating is a huge problem,” Dr. Salsitz said. “Is it their urine or not their urine?” Many kits promise to help people provide fake urine, and some have even provided fake penises to foil observed urine collection. What to do? Alternative tests that rely on hair, saliva, and even sweat are available, Dr. Salsitz said, and these make cheating more difficult. However, they have various limitations. Saliva, for example, only tells you what patients are using now, not what they used days ago, he said, and it’s not sensitive for marijuana.

Dr. Salsitz reported no disclosures.

The Global Academy for Medical Education, which offered the Pain Care for Primary Care symposium, and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM PAIN CARE FOR PRIMARY CARE

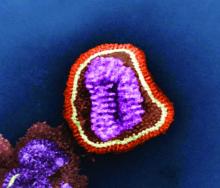

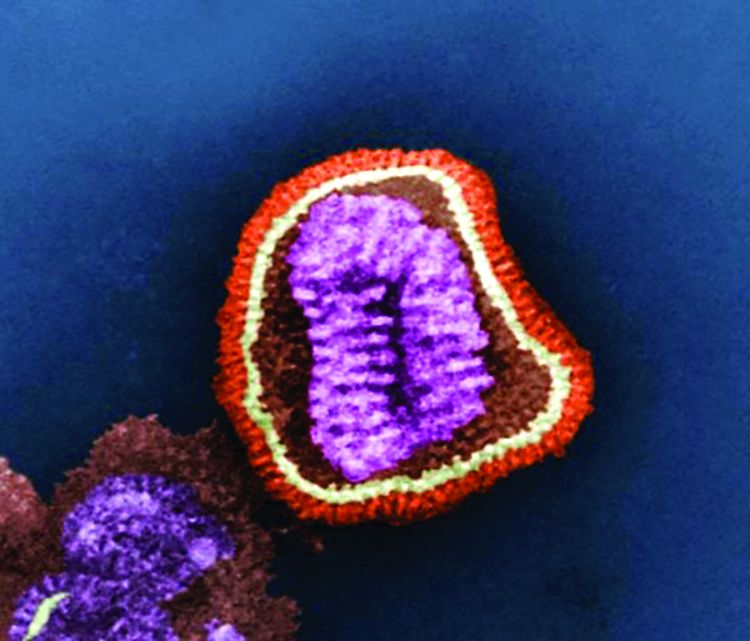

The powerful virus inflammatory response

Inflammation is a double-edged sword. Controlled and modest proinflammatory responses can enhance host immunity against viruses and decrease bacterial colonization and infection, whereas excessive uncontrolled proinflammatory responses may increase the susceptibility to bacterial colonization and secondary infection to facilitate disease pathogenesis. The immune system produces both proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. It is a balanced response that is key to maintaining good health.

Viral upper respiratory tract infections (URIs) are caused by rhinoviruses, coronaviruses, enteroviruses, respiratory syncytial viruses, influenza A and B viruses, parainfluenza viruses, adenoviruses, and human metapneumoviruses. Viruses are powerful. In the nose, they induce hypersecretion of mucus, slow cilia beating, up-regulate nasal epithelial cell receptors to facilitate bacterial attachment, suppress neutrophil function, and cause increased release of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines. All these actions by respiratory viruses promote bacterial overgrowth in the nasopharynx and thereby facilitate bacterial superinfections. In fact, progression in pathogenesis of the common bacterial respiratory infections – acute otitis media, acute sinusitis, acute conjunctivitis, and pneumonia – almost always is preceded by a viral URI. Viruses activate multiple target cells in the upper respiratory tract to produce an array of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines. The symptoms of a viral URI resolve coinciding with an anti-inflammatory response and adaptive immunity.

In recent work, we found a higher frequency of viral URIs in children who experienced more frequent acute otitis media (AOM). We sought to understand why this might occur by comparing levels of inflammatory cytokines/chemokines in the nose during viral URI that did not precipitate AOM versus when a viral URI precipitated an AOM episode. When a child had a viral URI but did not go on to experience an AOM, the child had higher proinflammatory responses than when the viral URI precipitated an AOM. When differences of levels of proinflammatory cytokines/chemokines were compared in otitis-prone and non–otitis-prone children, lower nasal responses were associated with higher otitis-prone classification frequency (Clin Infect Dis. 2018. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy750).

The powerful virus and the inflammatory response it can induce also play a major role in allergy and asthma. Viral URIs enhance allergic sensitization to respiratory viruses, such as influenza and respiratory syncytial virus, cause cytopathic damage to airway epithelium, promote excessive proinflammatory cytokine/chemokine production, and increase the exposure of allergens and irritants to antigen-presenting cells. Viral infections also may induce the release of epithelial mediators and cytokines that may propagate eosinophilia. Viral URIs, particularly with respiratory syncytial virus and rhinovirus, are the most common causes of wheezing in children, and they have important influences on the development of asthma. Studies have shown that viral infections trigger up to 85% of asthma exacerbations in school-aged children.

Because this column is being published during the winter, a brief discussion of influenza as a powerful virus is appropriate. Influenza occurs in winter outbreaks of varying extent every year. The severity of the influenza season reflects the changing nature of the antigenic properties of influenza viruses, and their spread depends on susceptibility of the population. Influenza outbreaks typically peak over a 2-3 week period and last for 2-3 months. Most outbreaks have attack rates of 10%-20% in children. There may be variations in disease severity caused by different influenza virus types. The symptoms are caused by excessive proinflammatory cytokine/chemokine production in the nose and lung.

Influenza and other viruses can precipitate the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), a manifestation of extreme immune dysregulation resulting in organ dysfunction that clinically resembles bacterial sepsis. In this syndrome, tissues remote from the original insult display the cardinal signs of inflammation, including vasodilation, increased microvascular permeability, and leukocyte accumulation. SIRS is another example of the double-edged sword of inflammation.

The onset and progression of SIRS occurs because of dysregulation of the normal inflammatory response, usually with an increase in both proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, initiating a chain of events that leads to organ failure.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He reported having no conflicts of interest. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Inflammation is a double-edged sword. Controlled and modest proinflammatory responses can enhance host immunity against viruses and decrease bacterial colonization and infection, whereas excessive uncontrolled proinflammatory responses may increase the susceptibility to bacterial colonization and secondary infection to facilitate disease pathogenesis. The immune system produces both proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. It is a balanced response that is key to maintaining good health.

Viral upper respiratory tract infections (URIs) are caused by rhinoviruses, coronaviruses, enteroviruses, respiratory syncytial viruses, influenza A and B viruses, parainfluenza viruses, adenoviruses, and human metapneumoviruses. Viruses are powerful. In the nose, they induce hypersecretion of mucus, slow cilia beating, up-regulate nasal epithelial cell receptors to facilitate bacterial attachment, suppress neutrophil function, and cause increased release of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines. All these actions by respiratory viruses promote bacterial overgrowth in the nasopharynx and thereby facilitate bacterial superinfections. In fact, progression in pathogenesis of the common bacterial respiratory infections – acute otitis media, acute sinusitis, acute conjunctivitis, and pneumonia – almost always is preceded by a viral URI. Viruses activate multiple target cells in the upper respiratory tract to produce an array of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines. The symptoms of a viral URI resolve coinciding with an anti-inflammatory response and adaptive immunity.

In recent work, we found a higher frequency of viral URIs in children who experienced more frequent acute otitis media (AOM). We sought to understand why this might occur by comparing levels of inflammatory cytokines/chemokines in the nose during viral URI that did not precipitate AOM versus when a viral URI precipitated an AOM episode. When a child had a viral URI but did not go on to experience an AOM, the child had higher proinflammatory responses than when the viral URI precipitated an AOM. When differences of levels of proinflammatory cytokines/chemokines were compared in otitis-prone and non–otitis-prone children, lower nasal responses were associated with higher otitis-prone classification frequency (Clin Infect Dis. 2018. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy750).

The powerful virus and the inflammatory response it can induce also play a major role in allergy and asthma. Viral URIs enhance allergic sensitization to respiratory viruses, such as influenza and respiratory syncytial virus, cause cytopathic damage to airway epithelium, promote excessive proinflammatory cytokine/chemokine production, and increase the exposure of allergens and irritants to antigen-presenting cells. Viral infections also may induce the release of epithelial mediators and cytokines that may propagate eosinophilia. Viral URIs, particularly with respiratory syncytial virus and rhinovirus, are the most common causes of wheezing in children, and they have important influences on the development of asthma. Studies have shown that viral infections trigger up to 85% of asthma exacerbations in school-aged children.

Because this column is being published during the winter, a brief discussion of influenza as a powerful virus is appropriate. Influenza occurs in winter outbreaks of varying extent every year. The severity of the influenza season reflects the changing nature of the antigenic properties of influenza viruses, and their spread depends on susceptibility of the population. Influenza outbreaks typically peak over a 2-3 week period and last for 2-3 months. Most outbreaks have attack rates of 10%-20% in children. There may be variations in disease severity caused by different influenza virus types. The symptoms are caused by excessive proinflammatory cytokine/chemokine production in the nose and lung.

Influenza and other viruses can precipitate the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), a manifestation of extreme immune dysregulation resulting in organ dysfunction that clinically resembles bacterial sepsis. In this syndrome, tissues remote from the original insult display the cardinal signs of inflammation, including vasodilation, increased microvascular permeability, and leukocyte accumulation. SIRS is another example of the double-edged sword of inflammation.

The onset and progression of SIRS occurs because of dysregulation of the normal inflammatory response, usually with an increase in both proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, initiating a chain of events that leads to organ failure.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He reported having no conflicts of interest. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Inflammation is a double-edged sword. Controlled and modest proinflammatory responses can enhance host immunity against viruses and decrease bacterial colonization and infection, whereas excessive uncontrolled proinflammatory responses may increase the susceptibility to bacterial colonization and secondary infection to facilitate disease pathogenesis. The immune system produces both proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. It is a balanced response that is key to maintaining good health.

Viral upper respiratory tract infections (URIs) are caused by rhinoviruses, coronaviruses, enteroviruses, respiratory syncytial viruses, influenza A and B viruses, parainfluenza viruses, adenoviruses, and human metapneumoviruses. Viruses are powerful. In the nose, they induce hypersecretion of mucus, slow cilia beating, up-regulate nasal epithelial cell receptors to facilitate bacterial attachment, suppress neutrophil function, and cause increased release of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines. All these actions by respiratory viruses promote bacterial overgrowth in the nasopharynx and thereby facilitate bacterial superinfections. In fact, progression in pathogenesis of the common bacterial respiratory infections – acute otitis media, acute sinusitis, acute conjunctivitis, and pneumonia – almost always is preceded by a viral URI. Viruses activate multiple target cells in the upper respiratory tract to produce an array of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines. The symptoms of a viral URI resolve coinciding with an anti-inflammatory response and adaptive immunity.

In recent work, we found a higher frequency of viral URIs in children who experienced more frequent acute otitis media (AOM). We sought to understand why this might occur by comparing levels of inflammatory cytokines/chemokines in the nose during viral URI that did not precipitate AOM versus when a viral URI precipitated an AOM episode. When a child had a viral URI but did not go on to experience an AOM, the child had higher proinflammatory responses than when the viral URI precipitated an AOM. When differences of levels of proinflammatory cytokines/chemokines were compared in otitis-prone and non–otitis-prone children, lower nasal responses were associated with higher otitis-prone classification frequency (Clin Infect Dis. 2018. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy750).

The powerful virus and the inflammatory response it can induce also play a major role in allergy and asthma. Viral URIs enhance allergic sensitization to respiratory viruses, such as influenza and respiratory syncytial virus, cause cytopathic damage to airway epithelium, promote excessive proinflammatory cytokine/chemokine production, and increase the exposure of allergens and irritants to antigen-presenting cells. Viral infections also may induce the release of epithelial mediators and cytokines that may propagate eosinophilia. Viral URIs, particularly with respiratory syncytial virus and rhinovirus, are the most common causes of wheezing in children, and they have important influences on the development of asthma. Studies have shown that viral infections trigger up to 85% of asthma exacerbations in school-aged children.

Because this column is being published during the winter, a brief discussion of influenza as a powerful virus is appropriate. Influenza occurs in winter outbreaks of varying extent every year. The severity of the influenza season reflects the changing nature of the antigenic properties of influenza viruses, and their spread depends on susceptibility of the population. Influenza outbreaks typically peak over a 2-3 week period and last for 2-3 months. Most outbreaks have attack rates of 10%-20% in children. There may be variations in disease severity caused by different influenza virus types. The symptoms are caused by excessive proinflammatory cytokine/chemokine production in the nose and lung.

Influenza and other viruses can precipitate the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), a manifestation of extreme immune dysregulation resulting in organ dysfunction that clinically resembles bacterial sepsis. In this syndrome, tissues remote from the original insult display the cardinal signs of inflammation, including vasodilation, increased microvascular permeability, and leukocyte accumulation. SIRS is another example of the double-edged sword of inflammation.

The onset and progression of SIRS occurs because of dysregulation of the normal inflammatory response, usually with an increase in both proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, initiating a chain of events that leads to organ failure.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He reported having no conflicts of interest. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Malignant olecranon bursitis in the setting of multiple myeloma relapse

Multiple myeloma is the most common plasma cell neoplasm, with an estimated 24,000 cases occurring annually.1 Symptomatic multiple myeloma most commonly presents with one or more of the cardinal CRAB phenomena of hypercalcemia, renal dysfunction, anemia, or lytic bone lesions.2 Less commonly, patients may present with plasmacytomas (focal lesions of malignant plasma cells), which may involve bony or soft tissues.1

Plasma cell neoplasms occasionally involve the joints, including the elbows, typically as plasmacytomas. The elbow is an unusual but reported location of plasmacytomas.3,4 A case of multiple myeloma and amyloid light-chain (AL) amyloidosis has been reported, with manifestations including pseudomyopathy, bone marrow plasmacytosis, and bilateral trochanteric bursitis.5Bursitis is defined as inflammation of the synovial-fluid–containing sacs that lubricate joints. The olecranon bursa is commonly affected. Etiologies include infection, inflammatory disease, trauma, and malignancy. Furthermore, there is an association between bursitis and immunosuppression.6,7 The most common modes of therapy used to treat bursitis are nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, corticosteroid injections, and surgical management.

Trochanteric bursitis has been attributed to multiple myeloma in one previous case report, but we are not aware of any previous cases of olecranon bursitis caused by multiple myeloma. Here, we present the case of a 46-year-old man with heavily pretreated multiple myeloma and amyloidosis who developed left olecranon bursitis contemporaneously with disease relapse; flow cytometric analysis of the bursal fluid demonstrated an abnormal plasma cell population, establishing the etiology.

Case presentation and summary

A 46-year-old man with a longstanding history of multiple myeloma developed swelling of the left elbow that was initially painless in September 2016. He had been diagnosed with IgA kappa multiple myeloma and AL deposition in 2011. Over the course of his disease, he was treated with the following sequence of therapies: cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone, followed by melphalan-conditioned autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplant; lenalidomide and dexamethasone; carfilzomib and dexamethasone; pomalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone; and bortezomib, lenalidomide, dexamethasone, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and etoposide, followed by second melphalan-conditioned autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplant. In addition to treatment with numerous novel and chemotherapeutic agents, his disease course was notable for amyloid deposition in the liver, bone marrow, and kidneys, which resulted in dialysis dependence.

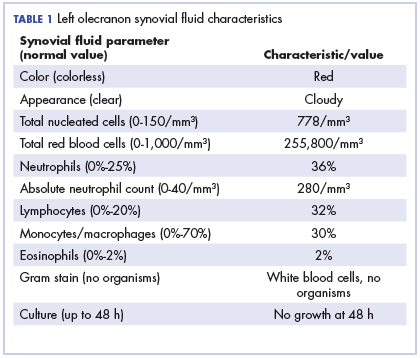

After the second autologous transplant, he achieved a very good partial response and experienced about 9 months of remission, after which laboratory evaluation indicated recurrence of IgA kappa monoclonal protein and free kappa light-chains, which increased slowly over several months without focal symptoms, cytopenias, or decline in organ function (Figure 1).

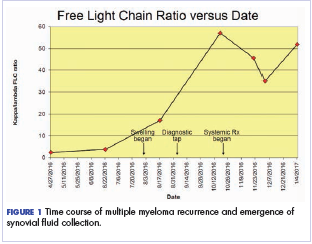

Twelve months after his second transplant, he presented in September 2016 with 4 weeks of left elbow swelling, with the appearance suggesting a fluid collection over the left olecranon process (Figure 2). The fluid collection was not painful unless bumped or pushed. The maximum pain level was 1-2 on a scale of 0-10. His daughter drained the fluid collection on 2 occasions, but it reaccumulated over 2 to 3 days. He reported no fevers, chills, or sweats. He did not have any redness at the site. He did not report any systemic symptoms.

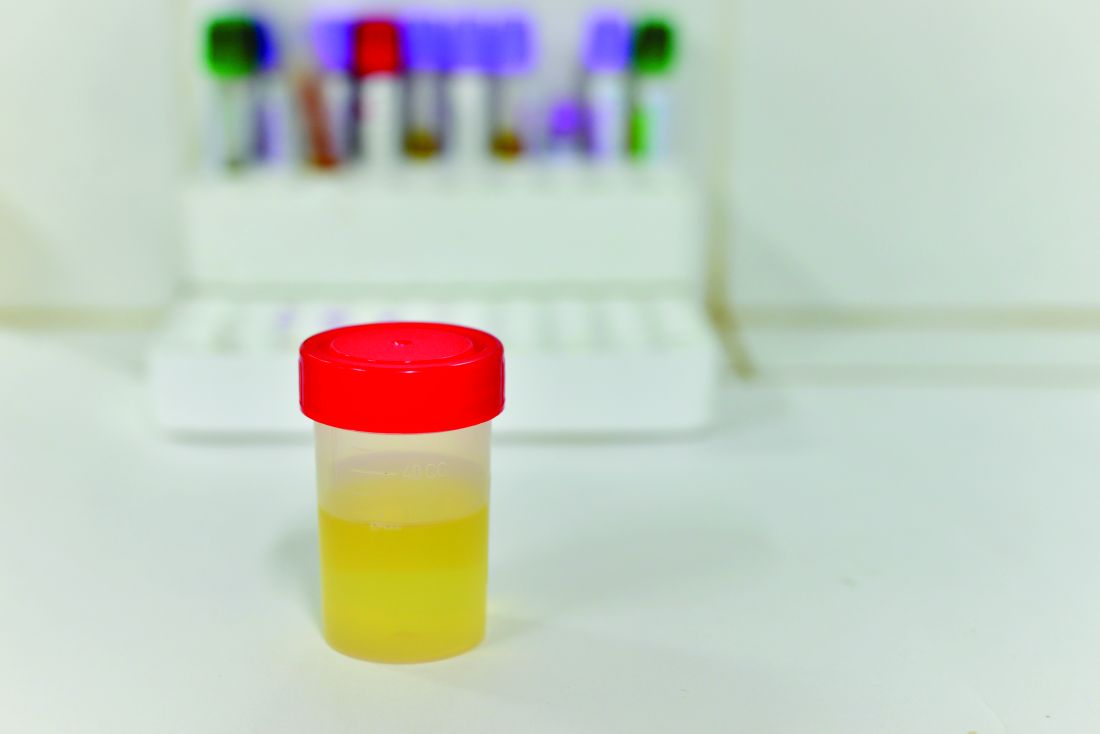

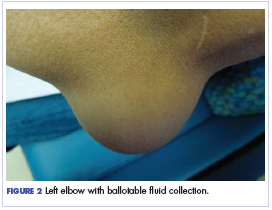

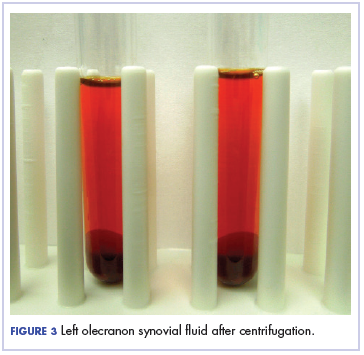

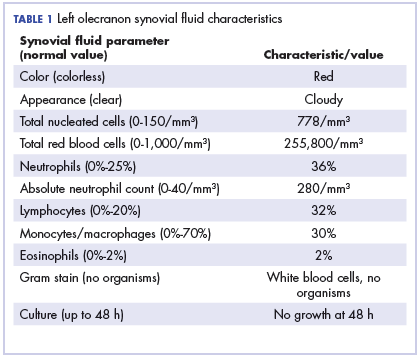

Physical examination of the left elbow demonstrated a ballotable fluid collection associated with the olecranon, with no associated warmth, tenderness, or erythema. Bursal fluid was sampled, yielding orange-colored serous fluid with bland characteristics (Figure 3). Microbiologic studies were negative (Table 1). We did not suspect a malignant cause initially.

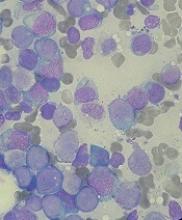

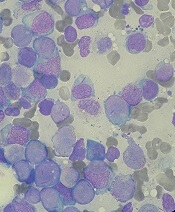

The fluid collection persisted despite treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and serial drainage procedures approximately twice per week. It became more erythematous and uncomfortable. We repeated diagnostic sampling at 13 months post-transplant. Cytospin revealed scant plasma cells. A multiparametric 8-color flow cytometric analysis was performed on the bursal fluid. It demonstrated the presence of a small abnormal population of plasma cells (0.04%). The abnormal plasma cells showed expression of CD138 and bright CD38 with aberrant expression of CD56, dim CD45, and loss of CD19, CD81 and CD27. They did not express CD117 or CD20 (Figure 4).

Because of the patient’s discomfort and his history of multidrug-refractory multiple myeloma, we obtained computed tomography imaging of the axial and appendicular skeleton, which demonstrated diffuse small lytic lesions, none larger than 3 mm, including the left elbow joint. The patient began systemic treatment with ixazomib, pomalidomide, and dexamethasone and then received radiation therapy of 20 Gy in 4 fractions to the left olecranon area. The bursal fluid collection remained stable in size but required periodic, though less frequent, drainage procedures. Unfortunately, the patient only tolerated 2 cycles of systemic therapy before experiencing hypercalcemia, exacerbation of hepatic amyloidosis, and a decline in performance status. He died 17 months after the transplant.

Discussion

Our patient experienced left olecranon bursitis simultaneously with relapse of multiple myeloma and AL amyloidosis. Evaluation for infectious causes was negative, and the bursal fluid did not have strongly inflammatory characteristics. Furthermore, a small plasma cell population was isolated from the fluid. Imaging did not reveal an underlying dominant lytic lesion. Although we do not have direct pathologic confirmation, the clinical scenario and flow cytometry findings support our interpretation that the patient’s bursitis was caused by or at least related to underlying multiple myeloma. While reactive plasma cells are also CD38 positive and CD138 positive, they maintain the expression of CD19 and CD45 without aberrant expression of CD56 or CD117 and do not show loss of expression of CD81 or CD27. In this situation, we suspect that either a plasmacytoma involving the soft tissue of the bursa or amyloid infiltration of the synovium may have occurred. Anti-myeloma therapies and radiation therapy did not result in control of the bursitis, though it should be noted that the patient’s highly refractory disease progressed despite treatment with a combination of later-generation immunomodulatory imide and proteasome inhibitor therapies.

Cases of malignant bursitis have been reported several times in the literature, though nearly all of the instances involved connective tissue or metastatic tumors. Tumor histologies include osteochondroma,8,9 malignant fibrous histiocytoma,10 synovial sarcoma,11 and metastatic breast cancer.12

Hematologic malignancies are more rare causes of bursitis; our literature search identified a report of 2 cases of non-Hodgkin lymphoma mimicking rheumatoid arthritis. The joints were the knee and elbow. Synovial fluid from one case was clear and yellow, with leukocytosis with a neutrophilic predominance (similar to our case). In both cases, pathology confirmed lymphomatous infiltration of the synovium.13 Notably, we identified a case of a previously healthy 35-year-old woman with bilateral trochanteric bursitis. Biopsy of tissue from the right trochanteric bursa demonstrated positive birefringence, diagnostic of AL amyloidosis. The patient also had a biclonal paraprotein accompanied by calvarial lytic lesions. She was treated with a corticosteroid pulse and bisphosphonates, followed by autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant. 5 Our case shares features with the above case, including the relatively young age of the patient and the presence of AL amyloidosis.

Our patient wished to avoid a surgical biopsy procedure, and therefore we utilized flow cytometry of the bursal fluid to establish that the etiology of fluid collection was consistent with his concurrent relapse of multiple myeloma. We believe that we are reporting the second case of multiple myeloma-associated bursitis and the first case associated with multiple myeloma relapse; to our knowledge, it is the first to be diagnosed with the aid of flow cytometry.

Because of our patient’s reliance on hemodialysis beginning one year prior to his presentation with olecranon bursitis, we entertain “dialysis elbow” within the differential diagnosis. Dialysis elbow is a relatively uncommon complication of dialysis, in which patients develop olecranon bursitis on the same side as the hemodialysis access after a prolonged (months to years) duration of hemodialysis. Serositis and mechanical forces are the hypothesized etiologies14; infectious and rheumatologic causes were excluded from the reported cases. Nevertheless, we favor a malignant cause based upon the flow cytometry findings indicating involvement by immunophenotypically abnormal plasma cells.

Our patient was treated initially with serial drainage and nonsteroidals, which had little impact. After diagnosis of a plasma cell population in the fluid, we offered local treatment with radiation and systemic treatment of multiple myeloma, which offered better but suboptimal control. Possible treatments for olecranon bursitis include surgery, corticosteroid injections, anti-inflammatories, and serial drainage. Nonsurgical management may be more effective than surgical management, and corticosteroid injection carries significant risks. On the other hand, serial drainage does not confer additional infection risk in cases with aseptic etiology.15 We combined conservative measures as well as treatment of the underlying disease, but we believe that our patient did not derive significant benefit because of the refractory nature of his disease; he also expressed a preference to avoid surgical intervention.

Conclusion

Bursitis is a rare but thought-provoking potential manifestation of multiple myeloma and AL amyloidosis; we believe that our patient’s bursitis was related to plasma cell neoplasia based upon co-occurrence with disease relapse. His bursitis turned out to be an early indicator of impending systemic relapse. In this particular case, in which the patient wished to avoid surgical intervention, flow cytometry was of great value, and we believe that our case is the first report of malignant bursitis being diagnosed by flow cytometry. Our patient’s case shares similarities with other biopsy-confirmed cases of malignant bursitis, but we were able to avoid the need for surgical biopsy or bursal stripping.

The authors thank Jennifer Wilham MT (ASCP), Pat Byrd MT (ASCP), and Darlene Mann MT (ASCP) for their technical support.

1. Teras LR, DeSantis CE, Cerhan JR, Morton LM, Jemal A, Flowers CR. 2016 US lymphoid malignancy statistics by World Health Organization subtypes. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(6):443-459.

2. Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, Palumbo A, et al. International Myeloma Working Group updated criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(12):e538–e548.

3. Gozzetti A, Coviello G, Fabbri A, et al. Unusual localizations of plasmacytoma. Leuk Res. 2011;35(7):e104-e105.

4. Kivioja AH, Karaharju EO, Elomaa I, Böhling TO. Surgical treatment of myeloma of bone. Eur J Cancer. 1992;28(11):1865-1869.

5. Santos MS, Soares B, Mendes O, Carvalho CM, Casimiro RF. Multiple myeloma-amyloidosis presenting as pseudomyopathy. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2011;51(6):651-654. 6. Blackwell JR, Hay BA, Bolt AM, May SM. Olecranon bursitis: a systematic overview. Shoulder Elbow. 2014;6(3):182-190.

7. Reilly D, Kamineni S. Olecranon bursitis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25(1):158-167.

8. De Groote J, Geerts B, Mermuys K, Verstraete K. Osteochondroma of the proximal humerus with frictional bursitis and secondary synovial osteochondromatosis. JBR-BTR. 2015;98(1):45-47. 9. Kumar R, Anjana, Kundan M. Retrocalcaneal bursitis due to rare calcaneal osteochrondroma in adult male: excision and outcome. J Orthop Case Rep. 2016;6(2):16-19.

10. Yoon PW, Jang WY, Yoo JJ, Yoon KS, Kim HJ. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma at the site of an alumina-on-alumina-bearing total hip arthroplasty mimicking infected trochanteric bursitis. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(2):324.e9-324.e12.

11. Hutchison CW, Kling DH. Malignant synovioma. Am J Cancer. 1940;40(1):8-84.

12. Hutchings C, Hull R. Metastatic bone disease presenting as trochanteric bursitis. J R Soc Med. 1997;90(12):685-686.

13. Dorfman HD, Siegel HL, Perry MC, Oxenhandler R. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the synovium simulating rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1987;30(2):155-161.

14. Chao CT, Wu MS. Dialysis elbow. QJM. 2012;105(5):485-486.

15. Sayegh ET, Strauch RJ. Treatment of olecranon bursitis: a systematic review. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2014;134(11):1517-1536.

Multiple myeloma is the most common plasma cell neoplasm, with an estimated 24,000 cases occurring annually.1 Symptomatic multiple myeloma most commonly presents with one or more of the cardinal CRAB phenomena of hypercalcemia, renal dysfunction, anemia, or lytic bone lesions.2 Less commonly, patients may present with plasmacytomas (focal lesions of malignant plasma cells), which may involve bony or soft tissues.1

Plasma cell neoplasms occasionally involve the joints, including the elbows, typically as plasmacytomas. The elbow is an unusual but reported location of plasmacytomas.3,4 A case of multiple myeloma and amyloid light-chain (AL) amyloidosis has been reported, with manifestations including pseudomyopathy, bone marrow plasmacytosis, and bilateral trochanteric bursitis.5Bursitis is defined as inflammation of the synovial-fluid–containing sacs that lubricate joints. The olecranon bursa is commonly affected. Etiologies include infection, inflammatory disease, trauma, and malignancy. Furthermore, there is an association between bursitis and immunosuppression.6,7 The most common modes of therapy used to treat bursitis are nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, corticosteroid injections, and surgical management.

Trochanteric bursitis has been attributed to multiple myeloma in one previous case report, but we are not aware of any previous cases of olecranon bursitis caused by multiple myeloma. Here, we present the case of a 46-year-old man with heavily pretreated multiple myeloma and amyloidosis who developed left olecranon bursitis contemporaneously with disease relapse; flow cytometric analysis of the bursal fluid demonstrated an abnormal plasma cell population, establishing the etiology.

Case presentation and summary

A 46-year-old man with a longstanding history of multiple myeloma developed swelling of the left elbow that was initially painless in September 2016. He had been diagnosed with IgA kappa multiple myeloma and AL deposition in 2011. Over the course of his disease, he was treated with the following sequence of therapies: cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone, followed by melphalan-conditioned autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplant; lenalidomide and dexamethasone; carfilzomib and dexamethasone; pomalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone; and bortezomib, lenalidomide, dexamethasone, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and etoposide, followed by second melphalan-conditioned autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplant. In addition to treatment with numerous novel and chemotherapeutic agents, his disease course was notable for amyloid deposition in the liver, bone marrow, and kidneys, which resulted in dialysis dependence.

After the second autologous transplant, he achieved a very good partial response and experienced about 9 months of remission, after which laboratory evaluation indicated recurrence of IgA kappa monoclonal protein and free kappa light-chains, which increased slowly over several months without focal symptoms, cytopenias, or decline in organ function (Figure 1).

Twelve months after his second transplant, he presented in September 2016 with 4 weeks of left elbow swelling, with the appearance suggesting a fluid collection over the left olecranon process (Figure 2). The fluid collection was not painful unless bumped or pushed. The maximum pain level was 1-2 on a scale of 0-10. His daughter drained the fluid collection on 2 occasions, but it reaccumulated over 2 to 3 days. He reported no fevers, chills, or sweats. He did not have any redness at the site. He did not report any systemic symptoms.

Physical examination of the left elbow demonstrated a ballotable fluid collection associated with the olecranon, with no associated warmth, tenderness, or erythema. Bursal fluid was sampled, yielding orange-colored serous fluid with bland characteristics (Figure 3). Microbiologic studies were negative (Table 1). We did not suspect a malignant cause initially.

The fluid collection persisted despite treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and serial drainage procedures approximately twice per week. It became more erythematous and uncomfortable. We repeated diagnostic sampling at 13 months post-transplant. Cytospin revealed scant plasma cells. A multiparametric 8-color flow cytometric analysis was performed on the bursal fluid. It demonstrated the presence of a small abnormal population of plasma cells (0.04%). The abnormal plasma cells showed expression of CD138 and bright CD38 with aberrant expression of CD56, dim CD45, and loss of CD19, CD81 and CD27. They did not express CD117 or CD20 (Figure 4).

Because of the patient’s discomfort and his history of multidrug-refractory multiple myeloma, we obtained computed tomography imaging of the axial and appendicular skeleton, which demonstrated diffuse small lytic lesions, none larger than 3 mm, including the left elbow joint. The patient began systemic treatment with ixazomib, pomalidomide, and dexamethasone and then received radiation therapy of 20 Gy in 4 fractions to the left olecranon area. The bursal fluid collection remained stable in size but required periodic, though less frequent, drainage procedures. Unfortunately, the patient only tolerated 2 cycles of systemic therapy before experiencing hypercalcemia, exacerbation of hepatic amyloidosis, and a decline in performance status. He died 17 months after the transplant.

Discussion

Our patient experienced left olecranon bursitis simultaneously with relapse of multiple myeloma and AL amyloidosis. Evaluation for infectious causes was negative, and the bursal fluid did not have strongly inflammatory characteristics. Furthermore, a small plasma cell population was isolated from the fluid. Imaging did not reveal an underlying dominant lytic lesion. Although we do not have direct pathologic confirmation, the clinical scenario and flow cytometry findings support our interpretation that the patient’s bursitis was caused by or at least related to underlying multiple myeloma. While reactive plasma cells are also CD38 positive and CD138 positive, they maintain the expression of CD19 and CD45 without aberrant expression of CD56 or CD117 and do not show loss of expression of CD81 or CD27. In this situation, we suspect that either a plasmacytoma involving the soft tissue of the bursa or amyloid infiltration of the synovium may have occurred. Anti-myeloma therapies and radiation therapy did not result in control of the bursitis, though it should be noted that the patient’s highly refractory disease progressed despite treatment with a combination of later-generation immunomodulatory imide and proteasome inhibitor therapies.

Cases of malignant bursitis have been reported several times in the literature, though nearly all of the instances involved connective tissue or metastatic tumors. Tumor histologies include osteochondroma,8,9 malignant fibrous histiocytoma,10 synovial sarcoma,11 and metastatic breast cancer.12

Hematologic malignancies are more rare causes of bursitis; our literature search identified a report of 2 cases of non-Hodgkin lymphoma mimicking rheumatoid arthritis. The joints were the knee and elbow. Synovial fluid from one case was clear and yellow, with leukocytosis with a neutrophilic predominance (similar to our case). In both cases, pathology confirmed lymphomatous infiltration of the synovium.13 Notably, we identified a case of a previously healthy 35-year-old woman with bilateral trochanteric bursitis. Biopsy of tissue from the right trochanteric bursa demonstrated positive birefringence, diagnostic of AL amyloidosis. The patient also had a biclonal paraprotein accompanied by calvarial lytic lesions. She was treated with a corticosteroid pulse and bisphosphonates, followed by autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant. 5 Our case shares features with the above case, including the relatively young age of the patient and the presence of AL amyloidosis.

Our patient wished to avoid a surgical biopsy procedure, and therefore we utilized flow cytometry of the bursal fluid to establish that the etiology of fluid collection was consistent with his concurrent relapse of multiple myeloma. We believe that we are reporting the second case of multiple myeloma-associated bursitis and the first case associated with multiple myeloma relapse; to our knowledge, it is the first to be diagnosed with the aid of flow cytometry.

Because of our patient’s reliance on hemodialysis beginning one year prior to his presentation with olecranon bursitis, we entertain “dialysis elbow” within the differential diagnosis. Dialysis elbow is a relatively uncommon complication of dialysis, in which patients develop olecranon bursitis on the same side as the hemodialysis access after a prolonged (months to years) duration of hemodialysis. Serositis and mechanical forces are the hypothesized etiologies14; infectious and rheumatologic causes were excluded from the reported cases. Nevertheless, we favor a malignant cause based upon the flow cytometry findings indicating involvement by immunophenotypically abnormal plasma cells.

Our patient was treated initially with serial drainage and nonsteroidals, which had little impact. After diagnosis of a plasma cell population in the fluid, we offered local treatment with radiation and systemic treatment of multiple myeloma, which offered better but suboptimal control. Possible treatments for olecranon bursitis include surgery, corticosteroid injections, anti-inflammatories, and serial drainage. Nonsurgical management may be more effective than surgical management, and corticosteroid injection carries significant risks. On the other hand, serial drainage does not confer additional infection risk in cases with aseptic etiology.15 We combined conservative measures as well as treatment of the underlying disease, but we believe that our patient did not derive significant benefit because of the refractory nature of his disease; he also expressed a preference to avoid surgical intervention.

Conclusion

Bursitis is a rare but thought-provoking potential manifestation of multiple myeloma and AL amyloidosis; we believe that our patient’s bursitis was related to plasma cell neoplasia based upon co-occurrence with disease relapse. His bursitis turned out to be an early indicator of impending systemic relapse. In this particular case, in which the patient wished to avoid surgical intervention, flow cytometry was of great value, and we believe that our case is the first report of malignant bursitis being diagnosed by flow cytometry. Our patient’s case shares similarities with other biopsy-confirmed cases of malignant bursitis, but we were able to avoid the need for surgical biopsy or bursal stripping.

The authors thank Jennifer Wilham MT (ASCP), Pat Byrd MT (ASCP), and Darlene Mann MT (ASCP) for their technical support.

Multiple myeloma is the most common plasma cell neoplasm, with an estimated 24,000 cases occurring annually.1 Symptomatic multiple myeloma most commonly presents with one or more of the cardinal CRAB phenomena of hypercalcemia, renal dysfunction, anemia, or lytic bone lesions.2 Less commonly, patients may present with plasmacytomas (focal lesions of malignant plasma cells), which may involve bony or soft tissues.1

Plasma cell neoplasms occasionally involve the joints, including the elbows, typically as plasmacytomas. The elbow is an unusual but reported location of plasmacytomas.3,4 A case of multiple myeloma and amyloid light-chain (AL) amyloidosis has been reported, with manifestations including pseudomyopathy, bone marrow plasmacytosis, and bilateral trochanteric bursitis.5Bursitis is defined as inflammation of the synovial-fluid–containing sacs that lubricate joints. The olecranon bursa is commonly affected. Etiologies include infection, inflammatory disease, trauma, and malignancy. Furthermore, there is an association between bursitis and immunosuppression.6,7 The most common modes of therapy used to treat bursitis are nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, corticosteroid injections, and surgical management.

Trochanteric bursitis has been attributed to multiple myeloma in one previous case report, but we are not aware of any previous cases of olecranon bursitis caused by multiple myeloma. Here, we present the case of a 46-year-old man with heavily pretreated multiple myeloma and amyloidosis who developed left olecranon bursitis contemporaneously with disease relapse; flow cytometric analysis of the bursal fluid demonstrated an abnormal plasma cell population, establishing the etiology.

Case presentation and summary

A 46-year-old man with a longstanding history of multiple myeloma developed swelling of the left elbow that was initially painless in September 2016. He had been diagnosed with IgA kappa multiple myeloma and AL deposition in 2011. Over the course of his disease, he was treated with the following sequence of therapies: cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone, followed by melphalan-conditioned autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplant; lenalidomide and dexamethasone; carfilzomib and dexamethasone; pomalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone; and bortezomib, lenalidomide, dexamethasone, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and etoposide, followed by second melphalan-conditioned autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplant. In addition to treatment with numerous novel and chemotherapeutic agents, his disease course was notable for amyloid deposition in the liver, bone marrow, and kidneys, which resulted in dialysis dependence.

After the second autologous transplant, he achieved a very good partial response and experienced about 9 months of remission, after which laboratory evaluation indicated recurrence of IgA kappa monoclonal protein and free kappa light-chains, which increased slowly over several months without focal symptoms, cytopenias, or decline in organ function (Figure 1).

Twelve months after his second transplant, he presented in September 2016 with 4 weeks of left elbow swelling, with the appearance suggesting a fluid collection over the left olecranon process (Figure 2). The fluid collection was not painful unless bumped or pushed. The maximum pain level was 1-2 on a scale of 0-10. His daughter drained the fluid collection on 2 occasions, but it reaccumulated over 2 to 3 days. He reported no fevers, chills, or sweats. He did not have any redness at the site. He did not report any systemic symptoms.

Physical examination of the left elbow demonstrated a ballotable fluid collection associated with the olecranon, with no associated warmth, tenderness, or erythema. Bursal fluid was sampled, yielding orange-colored serous fluid with bland characteristics (Figure 3). Microbiologic studies were negative (Table 1). We did not suspect a malignant cause initially.

The fluid collection persisted despite treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and serial drainage procedures approximately twice per week. It became more erythematous and uncomfortable. We repeated diagnostic sampling at 13 months post-transplant. Cytospin revealed scant plasma cells. A multiparametric 8-color flow cytometric analysis was performed on the bursal fluid. It demonstrated the presence of a small abnormal population of plasma cells (0.04%). The abnormal plasma cells showed expression of CD138 and bright CD38 with aberrant expression of CD56, dim CD45, and loss of CD19, CD81 and CD27. They did not express CD117 or CD20 (Figure 4).

Because of the patient’s discomfort and his history of multidrug-refractory multiple myeloma, we obtained computed tomography imaging of the axial and appendicular skeleton, which demonstrated diffuse small lytic lesions, none larger than 3 mm, including the left elbow joint. The patient began systemic treatment with ixazomib, pomalidomide, and dexamethasone and then received radiation therapy of 20 Gy in 4 fractions to the left olecranon area. The bursal fluid collection remained stable in size but required periodic, though less frequent, drainage procedures. Unfortunately, the patient only tolerated 2 cycles of systemic therapy before experiencing hypercalcemia, exacerbation of hepatic amyloidosis, and a decline in performance status. He died 17 months after the transplant.

Discussion

Our patient experienced left olecranon bursitis simultaneously with relapse of multiple myeloma and AL amyloidosis. Evaluation for infectious causes was negative, and the bursal fluid did not have strongly inflammatory characteristics. Furthermore, a small plasma cell population was isolated from the fluid. Imaging did not reveal an underlying dominant lytic lesion. Although we do not have direct pathologic confirmation, the clinical scenario and flow cytometry findings support our interpretation that the patient’s bursitis was caused by or at least related to underlying multiple myeloma. While reactive plasma cells are also CD38 positive and CD138 positive, they maintain the expression of CD19 and CD45 without aberrant expression of CD56 or CD117 and do not show loss of expression of CD81 or CD27. In this situation, we suspect that either a plasmacytoma involving the soft tissue of the bursa or amyloid infiltration of the synovium may have occurred. Anti-myeloma therapies and radiation therapy did not result in control of the bursitis, though it should be noted that the patient’s highly refractory disease progressed despite treatment with a combination of later-generation immunomodulatory imide and proteasome inhibitor therapies.

Cases of malignant bursitis have been reported several times in the literature, though nearly all of the instances involved connective tissue or metastatic tumors. Tumor histologies include osteochondroma,8,9 malignant fibrous histiocytoma,10 synovial sarcoma,11 and metastatic breast cancer.12

Hematologic malignancies are more rare causes of bursitis; our literature search identified a report of 2 cases of non-Hodgkin lymphoma mimicking rheumatoid arthritis. The joints were the knee and elbow. Synovial fluid from one case was clear and yellow, with leukocytosis with a neutrophilic predominance (similar to our case). In both cases, pathology confirmed lymphomatous infiltration of the synovium.13 Notably, we identified a case of a previously healthy 35-year-old woman with bilateral trochanteric bursitis. Biopsy of tissue from the right trochanteric bursa demonstrated positive birefringence, diagnostic of AL amyloidosis. The patient also had a biclonal paraprotein accompanied by calvarial lytic lesions. She was treated with a corticosteroid pulse and bisphosphonates, followed by autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant. 5 Our case shares features with the above case, including the relatively young age of the patient and the presence of AL amyloidosis.

Our patient wished to avoid a surgical biopsy procedure, and therefore we utilized flow cytometry of the bursal fluid to establish that the etiology of fluid collection was consistent with his concurrent relapse of multiple myeloma. We believe that we are reporting the second case of multiple myeloma-associated bursitis and the first case associated with multiple myeloma relapse; to our knowledge, it is the first to be diagnosed with the aid of flow cytometry.

Because of our patient’s reliance on hemodialysis beginning one year prior to his presentation with olecranon bursitis, we entertain “dialysis elbow” within the differential diagnosis. Dialysis elbow is a relatively uncommon complication of dialysis, in which patients develop olecranon bursitis on the same side as the hemodialysis access after a prolonged (months to years) duration of hemodialysis. Serositis and mechanical forces are the hypothesized etiologies14; infectious and rheumatologic causes were excluded from the reported cases. Nevertheless, we favor a malignant cause based upon the flow cytometry findings indicating involvement by immunophenotypically abnormal plasma cells.

Our patient was treated initially with serial drainage and nonsteroidals, which had little impact. After diagnosis of a plasma cell population in the fluid, we offered local treatment with radiation and systemic treatment of multiple myeloma, which offered better but suboptimal control. Possible treatments for olecranon bursitis include surgery, corticosteroid injections, anti-inflammatories, and serial drainage. Nonsurgical management may be more effective than surgical management, and corticosteroid injection carries significant risks. On the other hand, serial drainage does not confer additional infection risk in cases with aseptic etiology.15 We combined conservative measures as well as treatment of the underlying disease, but we believe that our patient did not derive significant benefit because of the refractory nature of his disease; he also expressed a preference to avoid surgical intervention.

Conclusion

Bursitis is a rare but thought-provoking potential manifestation of multiple myeloma and AL amyloidosis; we believe that our patient’s bursitis was related to plasma cell neoplasia based upon co-occurrence with disease relapse. His bursitis turned out to be an early indicator of impending systemic relapse. In this particular case, in which the patient wished to avoid surgical intervention, flow cytometry was of great value, and we believe that our case is the first report of malignant bursitis being diagnosed by flow cytometry. Our patient’s case shares similarities with other biopsy-confirmed cases of malignant bursitis, but we were able to avoid the need for surgical biopsy or bursal stripping.

The authors thank Jennifer Wilham MT (ASCP), Pat Byrd MT (ASCP), and Darlene Mann MT (ASCP) for their technical support.

1. Teras LR, DeSantis CE, Cerhan JR, Morton LM, Jemal A, Flowers CR. 2016 US lymphoid malignancy statistics by World Health Organization subtypes. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(6):443-459.

2. Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, Palumbo A, et al. International Myeloma Working Group updated criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(12):e538–e548.

3. Gozzetti A, Coviello G, Fabbri A, et al. Unusual localizations of plasmacytoma. Leuk Res. 2011;35(7):e104-e105.

4. Kivioja AH, Karaharju EO, Elomaa I, Böhling TO. Surgical treatment of myeloma of bone. Eur J Cancer. 1992;28(11):1865-1869.

5. Santos MS, Soares B, Mendes O, Carvalho CM, Casimiro RF. Multiple myeloma-amyloidosis presenting as pseudomyopathy. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2011;51(6):651-654. 6. Blackwell JR, Hay BA, Bolt AM, May SM. Olecranon bursitis: a systematic overview. Shoulder Elbow. 2014;6(3):182-190.

7. Reilly D, Kamineni S. Olecranon bursitis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25(1):158-167.

8. De Groote J, Geerts B, Mermuys K, Verstraete K. Osteochondroma of the proximal humerus with frictional bursitis and secondary synovial osteochondromatosis. JBR-BTR. 2015;98(1):45-47. 9. Kumar R, Anjana, Kundan M. Retrocalcaneal bursitis due to rare calcaneal osteochrondroma in adult male: excision and outcome. J Orthop Case Rep. 2016;6(2):16-19.

10. Yoon PW, Jang WY, Yoo JJ, Yoon KS, Kim HJ. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma at the site of an alumina-on-alumina-bearing total hip arthroplasty mimicking infected trochanteric bursitis. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(2):324.e9-324.e12.

11. Hutchison CW, Kling DH. Malignant synovioma. Am J Cancer. 1940;40(1):8-84.

12. Hutchings C, Hull R. Metastatic bone disease presenting as trochanteric bursitis. J R Soc Med. 1997;90(12):685-686.

13. Dorfman HD, Siegel HL, Perry MC, Oxenhandler R. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the synovium simulating rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1987;30(2):155-161.

14. Chao CT, Wu MS. Dialysis elbow. QJM. 2012;105(5):485-486.

15. Sayegh ET, Strauch RJ. Treatment of olecranon bursitis: a systematic review. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2014;134(11):1517-1536.

1. Teras LR, DeSantis CE, Cerhan JR, Morton LM, Jemal A, Flowers CR. 2016 US lymphoid malignancy statistics by World Health Organization subtypes. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(6):443-459.

2. Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, Palumbo A, et al. International Myeloma Working Group updated criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(12):e538–e548.

3. Gozzetti A, Coviello G, Fabbri A, et al. Unusual localizations of plasmacytoma. Leuk Res. 2011;35(7):e104-e105.

4. Kivioja AH, Karaharju EO, Elomaa I, Böhling TO. Surgical treatment of myeloma of bone. Eur J Cancer. 1992;28(11):1865-1869.

5. Santos MS, Soares B, Mendes O, Carvalho CM, Casimiro RF. Multiple myeloma-amyloidosis presenting as pseudomyopathy. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2011;51(6):651-654. 6. Blackwell JR, Hay BA, Bolt AM, May SM. Olecranon bursitis: a systematic overview. Shoulder Elbow. 2014;6(3):182-190.

7. Reilly D, Kamineni S. Olecranon bursitis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25(1):158-167.

8. De Groote J, Geerts B, Mermuys K, Verstraete K. Osteochondroma of the proximal humerus with frictional bursitis and secondary synovial osteochondromatosis. JBR-BTR. 2015;98(1):45-47. 9. Kumar R, Anjana, Kundan M. Retrocalcaneal bursitis due to rare calcaneal osteochrondroma in adult male: excision and outcome. J Orthop Case Rep. 2016;6(2):16-19.

10. Yoon PW, Jang WY, Yoo JJ, Yoon KS, Kim HJ. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma at the site of an alumina-on-alumina-bearing total hip arthroplasty mimicking infected trochanteric bursitis. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(2):324.e9-324.e12.

11. Hutchison CW, Kling DH. Malignant synovioma. Am J Cancer. 1940;40(1):8-84.

12. Hutchings C, Hull R. Metastatic bone disease presenting as trochanteric bursitis. J R Soc Med. 1997;90(12):685-686.

13. Dorfman HD, Siegel HL, Perry MC, Oxenhandler R. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the synovium simulating rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1987;30(2):155-161.

14. Chao CT, Wu MS. Dialysis elbow. QJM. 2012;105(5):485-486.

15. Sayegh ET, Strauch RJ. Treatment of olecranon bursitis: a systematic review. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2014;134(11):1517-1536.

Pot for chronic pain? The jury is still out

SAN DIEGO – Is pot a valid alternative to opioids for patients with chronic pain? The verdict on the use of medical marijuana is still hazy, a pain specialist told primary care colleagues. “There’s some evidence for pain, but it’s not extensive,” said Timothy Furnish, MD, of the University of California at San Diego.

Still, he said, studies suggest that the expanding legal use of medical marijuana isn’t boosting opioid use or worsening traffic accident rates. (JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178[5]:667-72; Am J Public Health. 2016 Nov;106[11]:2032-7) And, he said, two things are clear: “There is no one who has overdosed and died specifically from marijuana ... and compared to opioids, cannabinoids have a relatively good safety profile.”

Dr. Furnish spoke in a presentation at Pain Care for Primary Care, a symposium held by the American Pain Society and Global Academy for Medical Education.

Thirty-three states and the District of Columbia allow – or will soon allow – the medical use of marijuana, although their laws and policies vary widely. The newest states to join the list are Utah, Missouri, and Oklahoma, where voters passed medical marijuana measures this year.

Ten states and the District of Columbia also allow the recreational use of marijuana.

However, most states in the South, including Texas and Georgia, don’t allow medical marijuana. The other states that continue to forbid it are in the Midwest and Rocky Mountain regions.

How does cannabis fare against pain? Dr. Furnish pointed to a 2011 systematic review of 18 randomized trials in noncancer chronic pain that showed that “overall there is evidence that cannabinoids are safe and modestly effective in neuropathic pain with preliminary evidence of efficacy in fibromyalgia and rheumatoid arthritis” (Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011 Nov;72[5]:735-44).

More recently, a 2018 systematic review and meta-analysis of 104 studies found that “it seems unlikely that cannabinoids are highly effective medicines” for chronic noncancer pain (Pain. 2018 Oct;159[10]:1932-54).