User login

Caution urged for antidepressant use in bipolar depression

Although patients with bipolar disorder commonly experience depressive symptoms, clinicians should be very cautious about treating them with antidepressants, especially as monotherapy, experts asserted in a recent debate on the topic as part of the European Psychiatric Association (EPA) 2020 Congress.

At the Congress, which was virtual this year because of the COVID-19 pandemic, psychiatric experts said that clinicians should also screen patients for mixed symptoms that are better treated with mood stabilizers. These same experts also raised concerns over long-term antidepressant use, recommending continued use only in patients who relapse after stopping antidepressants.

Isabella Pacchiarotti, MD, PhD, Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental, Barcelona, Spain, argued against the use of antidepressants in treating bipolar disorder; Guy Goodwin, PhD, however, took the “pro” stance.

Goodwin, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Oxford in the UK, admitted that there is a “paucity of data” on the role of antidepressants in bipolar disorder.

Nevertheless, there are “circumstances that one really has to treat with antidepressants simply because other things have been tried and have not worked,” he told conference attendees.

Challenging, Controversial Topic

The debate was chaired by Eduard Vieta, MD, PhD, chair of the Department of Psychiatry and Psychology at the University of Barcelona Hospital Clinic, Spain.

Vieta said the question over whether antidepressants should be used in the depressive phase of bipolar illness is “perhaps the most challenging ... especially in the area of bipolar disorder.”

At the beginning of the presentation, Vieta asked the audience for their opinion in order to have a “baseline” for the debate: among 164 respondents, 73% were in favor of using antidepressants in bipolar depression.

“Clearly there is a majority, so Isabella [Dr Pacchiarotti] is going to have a hard time improving these numbers,” Vieta noted.

Up first, Pacchiarotti began by noting that this topic remains “an area of big controversy.” However, the real question “should not be the pros and cons of antidepressants but more when and how to use them.»

Of the three phases of bipolar disorder, acute depression «poses the greatest difficulties,» she added.

This is because of the relative paucity of studies in the area, the often heated debates on the specific role of antidepressants, the discrepancy in conclusions between meta-analyses, and the currently approved therapeutic options being associated with “not very high response rates,” Pacchiarotti said.

The diagnostic criteria for unipolar and bipolar depression are “basically the same,” she noted. However, it’s important to be able to distinguish between the two conditions, as up to one fifth of patients with unipolar depression suffer from undiagnosed bipolar disorder, she explained.

Moreover, several studies have identified key symptoms in bipolar depression, such as hyperphagia and hypersomnia, increased anxiety, and psychotic and psychomotor symptoms.

As previously reported by Medscape Medical News, a task force report was released in 2013 by the International Society for Bipolar Disorder (ISBD) on antidepressant use in bipolar disorders. Pacchiarotti and Goodwin were among the report’s authors, which concluded that available evidence on this issue is methodologically weak.

This is largely because of a lack of placebo-controlled studies in this patient population (bipolar depression, alongside suicidal ideation, is often an exclusion criteria in clinical antidepressant trials).

Many guidelines consequently do not consider antidepressants to be a first-line option as monotherapy in bipolar depression, although some name the drugs as second- or third-line options.

In 2013, the ISBD recommended that antidepressant monotherapy should be “avoided” in bipolar I disorder; and in bipolar I and II depression, the treatment should be accompanied by at least two concomitant core manic symptoms.

“What Has Changed?”

Antidepressants should be used “only if there is a history of a positive response,” whereas maintenance therapy should be considered if a patient relapses into a depressive episode after stopping the drugs, the report notes.

Pacchiarotti noted that since the recommendations were published nothing has changed, noting that antidepressant efficacy in bipolar depression “remains unproven.”

The issue is not whether antidepressants are effective in bipolar depression but rather are there subpopulations where these medications are helpful or harmful, she added.

The key to understanding the heterogeneity of responses to antidepressants, she said, is the concept of a bipolar spectrum and a dimensional approach to distinguishing between bipolar disorder and unipolar depression.

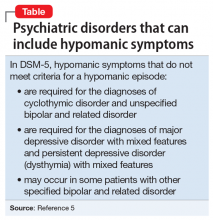

In addition, the definition of a mixed episode in the DSM-IV-TR differs from that of an episode with mixed characteristics in the DSM-5, which Pacchiarotti said offers a better understanding of the phenomenon while seemingly disposing with the idea of mixed depression.

Based on previous research, there is some suggestion that a depressive state exists between major depressive disorder and bipolar I disorder with mixed features, and hypomania state between bipolar II and I disorder, also with mixed features.

Pacchiarotti said the role of antidepressants in the treatment of bipolar depression remains “controversial” and there is a need for both short- and long-term studies of their use in both bipolar I and bipolar II disorder with real-world inclusion criteria.

The concept of a bipolar spectrum needs to be considered a more “dimensional approach” to depression, with mixed features seen as a “transversal” contraindication for antidepressant use, she concluded.

In Favor — With Caveats

Taking the opposite position and arguing in favor of antidepressant use, albeit cautiously, Goodwin said previous work has shown that stable patients with bipolar disorder experience depression of variable severity about 50% of the time.

The truth is that patients do not have a depressive episode for extended periods but instead have depressive symptoms, he said. “So how we manage and treat depression really matters.”

In an analysis, Goodwin and his colleagues estimated that the cost of bipolar disorder is approximately £12,600 ($16,000) per patient per year, of which only 30.6% is attributable to healthcare costs and 68.1% to indirect costs. This means the impact on the patient is also felt by society.

He agreed with Pacchiarotti’s assertion of a bipolar spectrum and the need for a dimensional approach.

“All the patients along the spectrum have the symptoms of depression and they differ in the extent to which they show symptoms of mania, which will include irritability,” he added.

Goodwin argued that there is no evidence to suggest that the depression experienced at one end of the scale is any different from that at the other. However, safety issues around antidepressant use “really relate to the additional symptoms you see with increasing evidence of bipolarity.”

In addition, the whole discussion is confounded by comorbidity, “with symptoms that sometimes coalesce into our concept of borderline personality disorder” or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, he said.

Goodwin said there is “very little doubt” that antidepressants have an effect vs placebo. “The argument is over whether the effect is large and whether we should regard it as clinically significant.”

He noted that previous studies have shown a range of effect sizes with antidepressants, but the “massive” confidence intervals mean that “one is free to believe pretty much what one likes.”

The only antidepressant medication that is statistically significantly different from placebo is fluoxetine combined with olanzapine. However, that conclusion is based on “little data,” said Goodwin.

In terms of long-term management, there is “extremely little” randomized data for maintenance treatment with antidepressants in bipolar disorder. “So this does not support” long-term use, he added.

Still, although choice of antidepressant remains a guess, there is “just about support” for using them, Goodwin noted.

He urged clinicians not to dismiss antidepressant use, but to use them only where there is a clinical need and for as little time as possible. Patients with bipolar disorder should continue to take antidepressants if they relapse after they come off these medications.

However, all of that sits “in contrast” to how they’re currently used in clinical practice, Goodwin said.

Caution Urged

After the debate, the audience was asked to vote again. This time, The remaining 12% voted against the practice.

Summarizing the discussion, Vieta said that “we should be cautious” when using antidepressants in bipolar depression. However, “we should be able to use them when necessary,” he added.

Although their use as monotherapy is not best practice, especially in bipolar I disorder, there may be a subset of bipolar II patients in whom monotherapy “might still be acceptable; but I don’t think it’s a good idea,” Vieta said.

He added that clinicians should very carefully screen for mixed symptoms, which call for the prescription of other drugs, such as olanzapine and fluoxetine.

“The other important message is that we have to be even more cautious in the long term with the use of antidepressants, and we should be able to use them when there is a comorbidity” that calls for their use, Vieta concluded.

Pacchiarotti reported having received speaker fees and educational grants from Adamed, AstraZeneca, Janssen-Cilag, and Lundbeck. Goodwin reported having received honoraria from Angellini, Medscape, Pfizer, Servier, Shire, and Sun; having shares in P1vital Products; past employment as medical director of P1vital Products; and advisory board membership for Compass Pathways, Minerva, MSD, Novartis, Lundbeck, Sage, Servier, and Shire. Vieta has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Although patients with bipolar disorder commonly experience depressive symptoms, clinicians should be very cautious about treating them with antidepressants, especially as monotherapy, experts asserted in a recent debate on the topic as part of the European Psychiatric Association (EPA) 2020 Congress.

At the Congress, which was virtual this year because of the COVID-19 pandemic, psychiatric experts said that clinicians should also screen patients for mixed symptoms that are better treated with mood stabilizers. These same experts also raised concerns over long-term antidepressant use, recommending continued use only in patients who relapse after stopping antidepressants.

Isabella Pacchiarotti, MD, PhD, Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental, Barcelona, Spain, argued against the use of antidepressants in treating bipolar disorder; Guy Goodwin, PhD, however, took the “pro” stance.

Goodwin, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Oxford in the UK, admitted that there is a “paucity of data” on the role of antidepressants in bipolar disorder.

Nevertheless, there are “circumstances that one really has to treat with antidepressants simply because other things have been tried and have not worked,” he told conference attendees.

Challenging, Controversial Topic

The debate was chaired by Eduard Vieta, MD, PhD, chair of the Department of Psychiatry and Psychology at the University of Barcelona Hospital Clinic, Spain.

Vieta said the question over whether antidepressants should be used in the depressive phase of bipolar illness is “perhaps the most challenging ... especially in the area of bipolar disorder.”

At the beginning of the presentation, Vieta asked the audience for their opinion in order to have a “baseline” for the debate: among 164 respondents, 73% were in favor of using antidepressants in bipolar depression.

“Clearly there is a majority, so Isabella [Dr Pacchiarotti] is going to have a hard time improving these numbers,” Vieta noted.

Up first, Pacchiarotti began by noting that this topic remains “an area of big controversy.” However, the real question “should not be the pros and cons of antidepressants but more when and how to use them.»

Of the three phases of bipolar disorder, acute depression «poses the greatest difficulties,» she added.

This is because of the relative paucity of studies in the area, the often heated debates on the specific role of antidepressants, the discrepancy in conclusions between meta-analyses, and the currently approved therapeutic options being associated with “not very high response rates,” Pacchiarotti said.

The diagnostic criteria for unipolar and bipolar depression are “basically the same,” she noted. However, it’s important to be able to distinguish between the two conditions, as up to one fifth of patients with unipolar depression suffer from undiagnosed bipolar disorder, she explained.

Moreover, several studies have identified key symptoms in bipolar depression, such as hyperphagia and hypersomnia, increased anxiety, and psychotic and psychomotor symptoms.

As previously reported by Medscape Medical News, a task force report was released in 2013 by the International Society for Bipolar Disorder (ISBD) on antidepressant use in bipolar disorders. Pacchiarotti and Goodwin were among the report’s authors, which concluded that available evidence on this issue is methodologically weak.

This is largely because of a lack of placebo-controlled studies in this patient population (bipolar depression, alongside suicidal ideation, is often an exclusion criteria in clinical antidepressant trials).

Many guidelines consequently do not consider antidepressants to be a first-line option as monotherapy in bipolar depression, although some name the drugs as second- or third-line options.

In 2013, the ISBD recommended that antidepressant monotherapy should be “avoided” in bipolar I disorder; and in bipolar I and II depression, the treatment should be accompanied by at least two concomitant core manic symptoms.

“What Has Changed?”

Antidepressants should be used “only if there is a history of a positive response,” whereas maintenance therapy should be considered if a patient relapses into a depressive episode after stopping the drugs, the report notes.

Pacchiarotti noted that since the recommendations were published nothing has changed, noting that antidepressant efficacy in bipolar depression “remains unproven.”

The issue is not whether antidepressants are effective in bipolar depression but rather are there subpopulations where these medications are helpful or harmful, she added.

The key to understanding the heterogeneity of responses to antidepressants, she said, is the concept of a bipolar spectrum and a dimensional approach to distinguishing between bipolar disorder and unipolar depression.

In addition, the definition of a mixed episode in the DSM-IV-TR differs from that of an episode with mixed characteristics in the DSM-5, which Pacchiarotti said offers a better understanding of the phenomenon while seemingly disposing with the idea of mixed depression.

Based on previous research, there is some suggestion that a depressive state exists between major depressive disorder and bipolar I disorder with mixed features, and hypomania state between bipolar II and I disorder, also with mixed features.

Pacchiarotti said the role of antidepressants in the treatment of bipolar depression remains “controversial” and there is a need for both short- and long-term studies of their use in both bipolar I and bipolar II disorder with real-world inclusion criteria.

The concept of a bipolar spectrum needs to be considered a more “dimensional approach” to depression, with mixed features seen as a “transversal” contraindication for antidepressant use, she concluded.

In Favor — With Caveats

Taking the opposite position and arguing in favor of antidepressant use, albeit cautiously, Goodwin said previous work has shown that stable patients with bipolar disorder experience depression of variable severity about 50% of the time.

The truth is that patients do not have a depressive episode for extended periods but instead have depressive symptoms, he said. “So how we manage and treat depression really matters.”

In an analysis, Goodwin and his colleagues estimated that the cost of bipolar disorder is approximately £12,600 ($16,000) per patient per year, of which only 30.6% is attributable to healthcare costs and 68.1% to indirect costs. This means the impact on the patient is also felt by society.

He agreed with Pacchiarotti’s assertion of a bipolar spectrum and the need for a dimensional approach.

“All the patients along the spectrum have the symptoms of depression and they differ in the extent to which they show symptoms of mania, which will include irritability,” he added.

Goodwin argued that there is no evidence to suggest that the depression experienced at one end of the scale is any different from that at the other. However, safety issues around antidepressant use “really relate to the additional symptoms you see with increasing evidence of bipolarity.”

In addition, the whole discussion is confounded by comorbidity, “with symptoms that sometimes coalesce into our concept of borderline personality disorder” or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, he said.

Goodwin said there is “very little doubt” that antidepressants have an effect vs placebo. “The argument is over whether the effect is large and whether we should regard it as clinically significant.”

He noted that previous studies have shown a range of effect sizes with antidepressants, but the “massive” confidence intervals mean that “one is free to believe pretty much what one likes.”

The only antidepressant medication that is statistically significantly different from placebo is fluoxetine combined with olanzapine. However, that conclusion is based on “little data,” said Goodwin.

In terms of long-term management, there is “extremely little” randomized data for maintenance treatment with antidepressants in bipolar disorder. “So this does not support” long-term use, he added.

Still, although choice of antidepressant remains a guess, there is “just about support” for using them, Goodwin noted.

He urged clinicians not to dismiss antidepressant use, but to use them only where there is a clinical need and for as little time as possible. Patients with bipolar disorder should continue to take antidepressants if they relapse after they come off these medications.

However, all of that sits “in contrast” to how they’re currently used in clinical practice, Goodwin said.

Caution Urged

After the debate, the audience was asked to vote again. This time, The remaining 12% voted against the practice.

Summarizing the discussion, Vieta said that “we should be cautious” when using antidepressants in bipolar depression. However, “we should be able to use them when necessary,” he added.

Although their use as monotherapy is not best practice, especially in bipolar I disorder, there may be a subset of bipolar II patients in whom monotherapy “might still be acceptable; but I don’t think it’s a good idea,” Vieta said.

He added that clinicians should very carefully screen for mixed symptoms, which call for the prescription of other drugs, such as olanzapine and fluoxetine.

“The other important message is that we have to be even more cautious in the long term with the use of antidepressants, and we should be able to use them when there is a comorbidity” that calls for their use, Vieta concluded.

Pacchiarotti reported having received speaker fees and educational grants from Adamed, AstraZeneca, Janssen-Cilag, and Lundbeck. Goodwin reported having received honoraria from Angellini, Medscape, Pfizer, Servier, Shire, and Sun; having shares in P1vital Products; past employment as medical director of P1vital Products; and advisory board membership for Compass Pathways, Minerva, MSD, Novartis, Lundbeck, Sage, Servier, and Shire. Vieta has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Although patients with bipolar disorder commonly experience depressive symptoms, clinicians should be very cautious about treating them with antidepressants, especially as monotherapy, experts asserted in a recent debate on the topic as part of the European Psychiatric Association (EPA) 2020 Congress.

At the Congress, which was virtual this year because of the COVID-19 pandemic, psychiatric experts said that clinicians should also screen patients for mixed symptoms that are better treated with mood stabilizers. These same experts also raised concerns over long-term antidepressant use, recommending continued use only in patients who relapse after stopping antidepressants.

Isabella Pacchiarotti, MD, PhD, Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental, Barcelona, Spain, argued against the use of antidepressants in treating bipolar disorder; Guy Goodwin, PhD, however, took the “pro” stance.

Goodwin, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Oxford in the UK, admitted that there is a “paucity of data” on the role of antidepressants in bipolar disorder.

Nevertheless, there are “circumstances that one really has to treat with antidepressants simply because other things have been tried and have not worked,” he told conference attendees.

Challenging, Controversial Topic

The debate was chaired by Eduard Vieta, MD, PhD, chair of the Department of Psychiatry and Psychology at the University of Barcelona Hospital Clinic, Spain.

Vieta said the question over whether antidepressants should be used in the depressive phase of bipolar illness is “perhaps the most challenging ... especially in the area of bipolar disorder.”

At the beginning of the presentation, Vieta asked the audience for their opinion in order to have a “baseline” for the debate: among 164 respondents, 73% were in favor of using antidepressants in bipolar depression.

“Clearly there is a majority, so Isabella [Dr Pacchiarotti] is going to have a hard time improving these numbers,” Vieta noted.

Up first, Pacchiarotti began by noting that this topic remains “an area of big controversy.” However, the real question “should not be the pros and cons of antidepressants but more when and how to use them.»

Of the three phases of bipolar disorder, acute depression «poses the greatest difficulties,» she added.

This is because of the relative paucity of studies in the area, the often heated debates on the specific role of antidepressants, the discrepancy in conclusions between meta-analyses, and the currently approved therapeutic options being associated with “not very high response rates,” Pacchiarotti said.

The diagnostic criteria for unipolar and bipolar depression are “basically the same,” she noted. However, it’s important to be able to distinguish between the two conditions, as up to one fifth of patients with unipolar depression suffer from undiagnosed bipolar disorder, she explained.

Moreover, several studies have identified key symptoms in bipolar depression, such as hyperphagia and hypersomnia, increased anxiety, and psychotic and psychomotor symptoms.

As previously reported by Medscape Medical News, a task force report was released in 2013 by the International Society for Bipolar Disorder (ISBD) on antidepressant use in bipolar disorders. Pacchiarotti and Goodwin were among the report’s authors, which concluded that available evidence on this issue is methodologically weak.

This is largely because of a lack of placebo-controlled studies in this patient population (bipolar depression, alongside suicidal ideation, is often an exclusion criteria in clinical antidepressant trials).

Many guidelines consequently do not consider antidepressants to be a first-line option as monotherapy in bipolar depression, although some name the drugs as second- or third-line options.

In 2013, the ISBD recommended that antidepressant monotherapy should be “avoided” in bipolar I disorder; and in bipolar I and II depression, the treatment should be accompanied by at least two concomitant core manic symptoms.

“What Has Changed?”

Antidepressants should be used “only if there is a history of a positive response,” whereas maintenance therapy should be considered if a patient relapses into a depressive episode after stopping the drugs, the report notes.

Pacchiarotti noted that since the recommendations were published nothing has changed, noting that antidepressant efficacy in bipolar depression “remains unproven.”

The issue is not whether antidepressants are effective in bipolar depression but rather are there subpopulations where these medications are helpful or harmful, she added.

The key to understanding the heterogeneity of responses to antidepressants, she said, is the concept of a bipolar spectrum and a dimensional approach to distinguishing between bipolar disorder and unipolar depression.

In addition, the definition of a mixed episode in the DSM-IV-TR differs from that of an episode with mixed characteristics in the DSM-5, which Pacchiarotti said offers a better understanding of the phenomenon while seemingly disposing with the idea of mixed depression.

Based on previous research, there is some suggestion that a depressive state exists between major depressive disorder and bipolar I disorder with mixed features, and hypomania state between bipolar II and I disorder, also with mixed features.

Pacchiarotti said the role of antidepressants in the treatment of bipolar depression remains “controversial” and there is a need for both short- and long-term studies of their use in both bipolar I and bipolar II disorder with real-world inclusion criteria.

The concept of a bipolar spectrum needs to be considered a more “dimensional approach” to depression, with mixed features seen as a “transversal” contraindication for antidepressant use, she concluded.

In Favor — With Caveats

Taking the opposite position and arguing in favor of antidepressant use, albeit cautiously, Goodwin said previous work has shown that stable patients with bipolar disorder experience depression of variable severity about 50% of the time.

The truth is that patients do not have a depressive episode for extended periods but instead have depressive symptoms, he said. “So how we manage and treat depression really matters.”

In an analysis, Goodwin and his colleagues estimated that the cost of bipolar disorder is approximately £12,600 ($16,000) per patient per year, of which only 30.6% is attributable to healthcare costs and 68.1% to indirect costs. This means the impact on the patient is also felt by society.

He agreed with Pacchiarotti’s assertion of a bipolar spectrum and the need for a dimensional approach.

“All the patients along the spectrum have the symptoms of depression and they differ in the extent to which they show symptoms of mania, which will include irritability,” he added.

Goodwin argued that there is no evidence to suggest that the depression experienced at one end of the scale is any different from that at the other. However, safety issues around antidepressant use “really relate to the additional symptoms you see with increasing evidence of bipolarity.”

In addition, the whole discussion is confounded by comorbidity, “with symptoms that sometimes coalesce into our concept of borderline personality disorder” or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, he said.

Goodwin said there is “very little doubt” that antidepressants have an effect vs placebo. “The argument is over whether the effect is large and whether we should regard it as clinically significant.”

He noted that previous studies have shown a range of effect sizes with antidepressants, but the “massive” confidence intervals mean that “one is free to believe pretty much what one likes.”

The only antidepressant medication that is statistically significantly different from placebo is fluoxetine combined with olanzapine. However, that conclusion is based on “little data,” said Goodwin.

In terms of long-term management, there is “extremely little” randomized data for maintenance treatment with antidepressants in bipolar disorder. “So this does not support” long-term use, he added.

Still, although choice of antidepressant remains a guess, there is “just about support” for using them, Goodwin noted.

He urged clinicians not to dismiss antidepressant use, but to use them only where there is a clinical need and for as little time as possible. Patients with bipolar disorder should continue to take antidepressants if they relapse after they come off these medications.

However, all of that sits “in contrast” to how they’re currently used in clinical practice, Goodwin said.

Caution Urged

After the debate, the audience was asked to vote again. This time, The remaining 12% voted against the practice.

Summarizing the discussion, Vieta said that “we should be cautious” when using antidepressants in bipolar depression. However, “we should be able to use them when necessary,” he added.

Although their use as monotherapy is not best practice, especially in bipolar I disorder, there may be a subset of bipolar II patients in whom monotherapy “might still be acceptable; but I don’t think it’s a good idea,” Vieta said.

He added that clinicians should very carefully screen for mixed symptoms, which call for the prescription of other drugs, such as olanzapine and fluoxetine.

“The other important message is that we have to be even more cautious in the long term with the use of antidepressants, and we should be able to use them when there is a comorbidity” that calls for their use, Vieta concluded.

Pacchiarotti reported having received speaker fees and educational grants from Adamed, AstraZeneca, Janssen-Cilag, and Lundbeck. Goodwin reported having received honoraria from Angellini, Medscape, Pfizer, Servier, Shire, and Sun; having shares in P1vital Products; past employment as medical director of P1vital Products; and advisory board membership for Compass Pathways, Minerva, MSD, Novartis, Lundbeck, Sage, Servier, and Shire. Vieta has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New long-term data for antipsychotic in pediatric bipolar depression

The antipsychotic lurasidone (Latuda, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals) has long-term efficacy in the treatment of bipolar depression (BD) in children and adolescents, new research suggests.

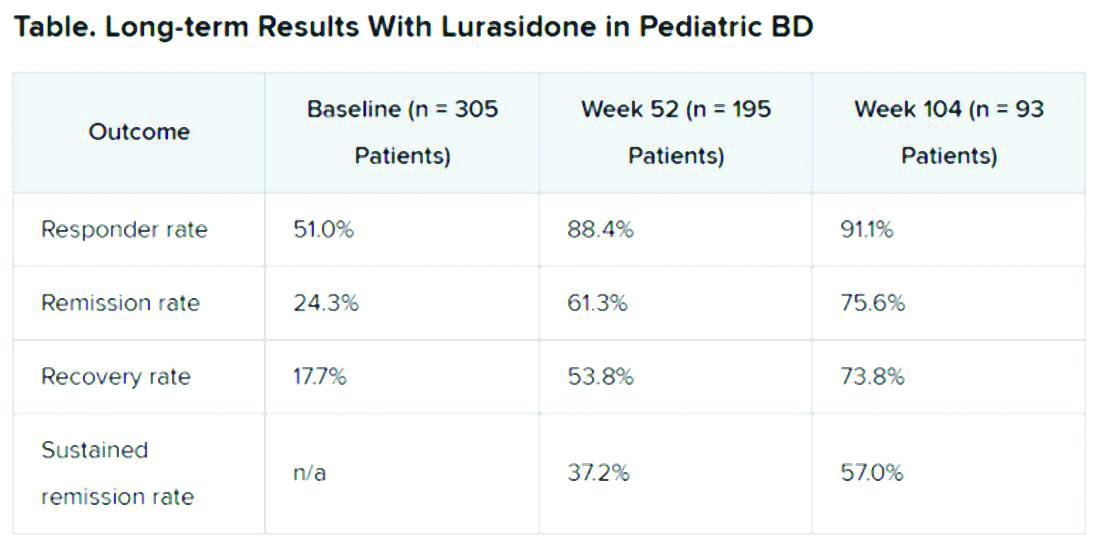

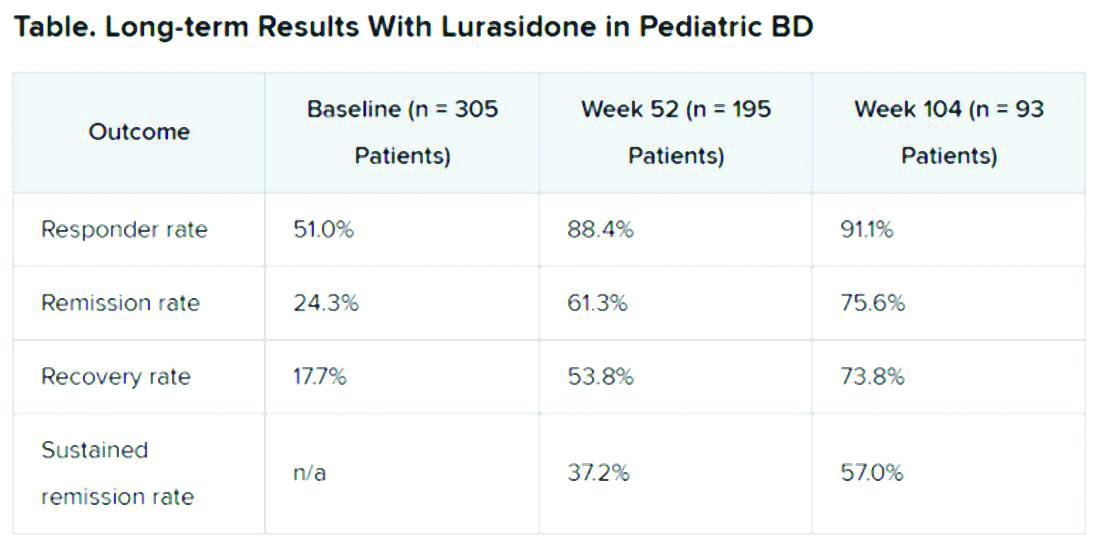

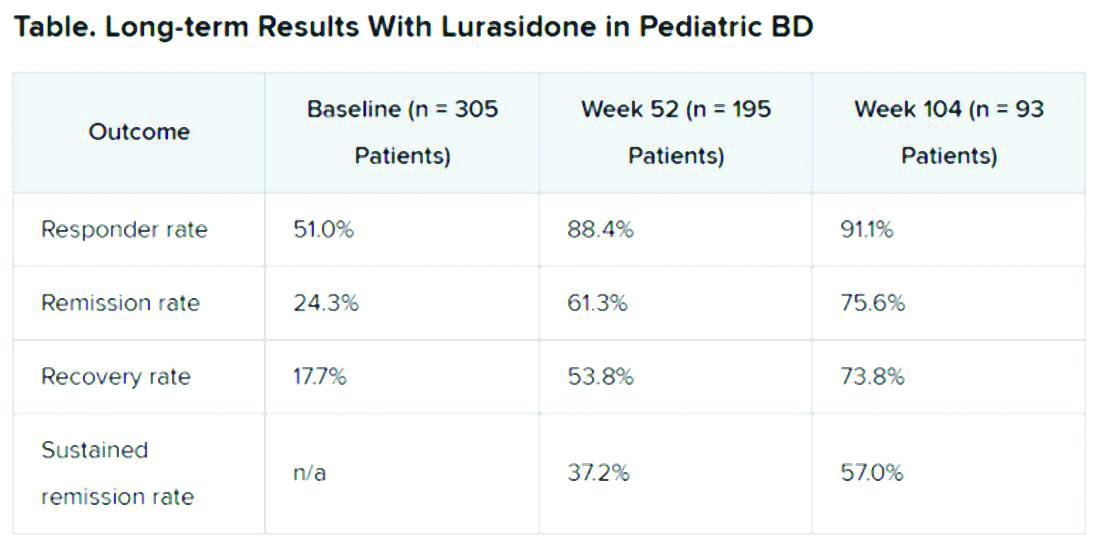

In an open-label extension study involving patients aged 10-17 years, up to 2 years of treatment with lurasidone was associated with continued improvement in depressive symptoms. There were progressively higher rates of remission, recovery, and sustained remission.

Coinvestigator Manpreet K. Singh, MD, director of the Stanford Pediatric Mood Disorders Program, Stanford (Calif.) University, noted that early onset of BD is common. Although in pediatric populations, prevalence has been fairly stable at around 1.8%, these patients have “a very limited number of treatment options available for the depressed phases of BD,” which is often predominant and can be difficult to identify.

“A lot of youths who are experiencing depressive symptoms in the context of having had a manic episode will often have a relapsing and remitting course, even after the acute phase of treatment, so because kids can be on medications for long periods of time, a better understanding of what works ... is very important,” Dr. Singh said in an interview.

The findings were presented at the virtual American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology (ASCP) 2020 annual meeting.

Long-term Efficacy

The Food and Drug Administration approved lurasidone as monotherapy for BD in children and adolescents in 2018. The aim of the current study was to evaluate the drug’s long-term efficacy in achieving response or remission in this population.

A total of 305 children who completed an initial 6-week double-blind study of lurasidone versus placebo entered the 2-year, open-label extension study. In the extension, they either continued taking lurasidone or were switched from placebo to lurasidone 20-80 mg/day. Of this group, 195 children completed 52 weeks of treatment, and 93 completed 104 weeks of treatment.

Efficacy was measured with the Children’s Depression Rating Scale, Revised (CDRS-R) and the Clinical Global Impression, Bipolar Depression Severity scale (CGI-BP-S). Functioning was evaluated with the clinician-rated Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS); on that scale, a score of 70 or higher indicates no clinically meaningful functional impairment.

Remission criteria were met if a patient achieved a CDRS-R total score of 28 or less, a Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) total score of 8 or less, and a CGI-BP-S depression score of 3 or less.

Recovery criteria were met if a patient achieved remission and had a CGAS score of at least 70.

Sustained remission, a more stringent outcome, required that the patient meet remission criteria for at least 24 consecutive weeks.

In addition, there was a strong inverse correlation (r = –0.71) between depression severity, as measured by CDRS-R total score, and functioning, as measured by the CGAS.

“That’s the cool thing: As the depression symptoms and severity came down, the overall functioning in these kids improved,” Dr. Singh noted.

“This improvement in functioning ends up being much more clinically relevant and useful to clinicians than just showing an improvement in a set of symptoms because what brings a kid – or even an adult, for that matter – to see a clinician to get treatment is because something about their symptoms is causing significant functional impairment,” she said.

“So this is the take-home message: You can see that lurasidone ... demonstrates not just recovery from depressive symptoms but that this reduction in depressive symptoms corresponds to an improvement in functioning for these youths,” she added.

Potential Limitations

Commenting on the study, Christoph U. Correll, MD, professor of child and adolescent psychiatry, Charite Universitatsmedizin, Berlin, Germany, noted that BD is difficult to treat, especially for patients who are going through “a developmentally vulnerable phase of their lives.”

“Lurasidone is the only monotherapy approved for bipolar depression in youth and is fairly well tolerated,” said Dr. Correll, who was not part of the research. He added that the long-term effectiveness data on response and remission “add relevant information” to the field.

However, he noted that it is not clear whether the high and increasing rates of response and remission were based on the reporting of observed cases or on last-observation-carried-forward analyses. “Given the naturally high dropout rate in such a long-term study and the potential for a survival bias, this is a relevant methodological question that affects the interpretation of the data,” he said.

“Nevertheless, the very favorable results for cumulative response, remission, and sustained remission add to the evidence that lurasidone is an effective treatment for youth with bipolar depression. Since efficacy cannot be interpreted in isolation, data describing the tolerability, including long-term cardiometabolic effects, will be important complementary data to consider,” Dr. Correll said.

The study was funded by Sunovion Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Singh is on the advisory board for Sunovion, is a consultant for Google X and Limbix, and receives royalties from American Psychiatric Association Publishing. She has also received research support from Stanford’s Maternal Child Health Research Institute and Department of Psychiatry, the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute on Aging, Johnson and Johnson, Allergan, PCORI, and the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation. Dr. Correll has been a consultant or adviser to and has received honoraria from Sunovion, as well as Acadia, Alkermes, Allergan, Angelini, Axsome, Gedeon Richter, Gerson Lehrman Group, Intra-Cellular Therapies, Janssen/J&J, LB Pharma, Lundbeck, MedAvante-ProPhase, Medscape, Neurocrine, Noven, Otsuka, Pfizer, Recordati, Rovi, Sumitomo Dainippon, Supernus, Takeda, and Teva.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The antipsychotic lurasidone (Latuda, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals) has long-term efficacy in the treatment of bipolar depression (BD) in children and adolescents, new research suggests.

In an open-label extension study involving patients aged 10-17 years, up to 2 years of treatment with lurasidone was associated with continued improvement in depressive symptoms. There were progressively higher rates of remission, recovery, and sustained remission.

Coinvestigator Manpreet K. Singh, MD, director of the Stanford Pediatric Mood Disorders Program, Stanford (Calif.) University, noted that early onset of BD is common. Although in pediatric populations, prevalence has been fairly stable at around 1.8%, these patients have “a very limited number of treatment options available for the depressed phases of BD,” which is often predominant and can be difficult to identify.

“A lot of youths who are experiencing depressive symptoms in the context of having had a manic episode will often have a relapsing and remitting course, even after the acute phase of treatment, so because kids can be on medications for long periods of time, a better understanding of what works ... is very important,” Dr. Singh said in an interview.

The findings were presented at the virtual American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology (ASCP) 2020 annual meeting.

Long-term Efficacy

The Food and Drug Administration approved lurasidone as monotherapy for BD in children and adolescents in 2018. The aim of the current study was to evaluate the drug’s long-term efficacy in achieving response or remission in this population.

A total of 305 children who completed an initial 6-week double-blind study of lurasidone versus placebo entered the 2-year, open-label extension study. In the extension, they either continued taking lurasidone or were switched from placebo to lurasidone 20-80 mg/day. Of this group, 195 children completed 52 weeks of treatment, and 93 completed 104 weeks of treatment.

Efficacy was measured with the Children’s Depression Rating Scale, Revised (CDRS-R) and the Clinical Global Impression, Bipolar Depression Severity scale (CGI-BP-S). Functioning was evaluated with the clinician-rated Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS); on that scale, a score of 70 or higher indicates no clinically meaningful functional impairment.

Remission criteria were met if a patient achieved a CDRS-R total score of 28 or less, a Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) total score of 8 or less, and a CGI-BP-S depression score of 3 or less.

Recovery criteria were met if a patient achieved remission and had a CGAS score of at least 70.

Sustained remission, a more stringent outcome, required that the patient meet remission criteria for at least 24 consecutive weeks.

In addition, there was a strong inverse correlation (r = –0.71) between depression severity, as measured by CDRS-R total score, and functioning, as measured by the CGAS.

“That’s the cool thing: As the depression symptoms and severity came down, the overall functioning in these kids improved,” Dr. Singh noted.

“This improvement in functioning ends up being much more clinically relevant and useful to clinicians than just showing an improvement in a set of symptoms because what brings a kid – or even an adult, for that matter – to see a clinician to get treatment is because something about their symptoms is causing significant functional impairment,” she said.

“So this is the take-home message: You can see that lurasidone ... demonstrates not just recovery from depressive symptoms but that this reduction in depressive symptoms corresponds to an improvement in functioning for these youths,” she added.

Potential Limitations

Commenting on the study, Christoph U. Correll, MD, professor of child and adolescent psychiatry, Charite Universitatsmedizin, Berlin, Germany, noted that BD is difficult to treat, especially for patients who are going through “a developmentally vulnerable phase of their lives.”

“Lurasidone is the only monotherapy approved for bipolar depression in youth and is fairly well tolerated,” said Dr. Correll, who was not part of the research. He added that the long-term effectiveness data on response and remission “add relevant information” to the field.

However, he noted that it is not clear whether the high and increasing rates of response and remission were based on the reporting of observed cases or on last-observation-carried-forward analyses. “Given the naturally high dropout rate in such a long-term study and the potential for a survival bias, this is a relevant methodological question that affects the interpretation of the data,” he said.

“Nevertheless, the very favorable results for cumulative response, remission, and sustained remission add to the evidence that lurasidone is an effective treatment for youth with bipolar depression. Since efficacy cannot be interpreted in isolation, data describing the tolerability, including long-term cardiometabolic effects, will be important complementary data to consider,” Dr. Correll said.

The study was funded by Sunovion Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Singh is on the advisory board for Sunovion, is a consultant for Google X and Limbix, and receives royalties from American Psychiatric Association Publishing. She has also received research support from Stanford’s Maternal Child Health Research Institute and Department of Psychiatry, the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute on Aging, Johnson and Johnson, Allergan, PCORI, and the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation. Dr. Correll has been a consultant or adviser to and has received honoraria from Sunovion, as well as Acadia, Alkermes, Allergan, Angelini, Axsome, Gedeon Richter, Gerson Lehrman Group, Intra-Cellular Therapies, Janssen/J&J, LB Pharma, Lundbeck, MedAvante-ProPhase, Medscape, Neurocrine, Noven, Otsuka, Pfizer, Recordati, Rovi, Sumitomo Dainippon, Supernus, Takeda, and Teva.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The antipsychotic lurasidone (Latuda, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals) has long-term efficacy in the treatment of bipolar depression (BD) in children and adolescents, new research suggests.

In an open-label extension study involving patients aged 10-17 years, up to 2 years of treatment with lurasidone was associated with continued improvement in depressive symptoms. There were progressively higher rates of remission, recovery, and sustained remission.

Coinvestigator Manpreet K. Singh, MD, director of the Stanford Pediatric Mood Disorders Program, Stanford (Calif.) University, noted that early onset of BD is common. Although in pediatric populations, prevalence has been fairly stable at around 1.8%, these patients have “a very limited number of treatment options available for the depressed phases of BD,” which is often predominant and can be difficult to identify.

“A lot of youths who are experiencing depressive symptoms in the context of having had a manic episode will often have a relapsing and remitting course, even after the acute phase of treatment, so because kids can be on medications for long periods of time, a better understanding of what works ... is very important,” Dr. Singh said in an interview.

The findings were presented at the virtual American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology (ASCP) 2020 annual meeting.

Long-term Efficacy

The Food and Drug Administration approved lurasidone as monotherapy for BD in children and adolescents in 2018. The aim of the current study was to evaluate the drug’s long-term efficacy in achieving response or remission in this population.

A total of 305 children who completed an initial 6-week double-blind study of lurasidone versus placebo entered the 2-year, open-label extension study. In the extension, they either continued taking lurasidone or were switched from placebo to lurasidone 20-80 mg/day. Of this group, 195 children completed 52 weeks of treatment, and 93 completed 104 weeks of treatment.

Efficacy was measured with the Children’s Depression Rating Scale, Revised (CDRS-R) and the Clinical Global Impression, Bipolar Depression Severity scale (CGI-BP-S). Functioning was evaluated with the clinician-rated Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS); on that scale, a score of 70 or higher indicates no clinically meaningful functional impairment.

Remission criteria were met if a patient achieved a CDRS-R total score of 28 or less, a Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) total score of 8 or less, and a CGI-BP-S depression score of 3 or less.

Recovery criteria were met if a patient achieved remission and had a CGAS score of at least 70.

Sustained remission, a more stringent outcome, required that the patient meet remission criteria for at least 24 consecutive weeks.

In addition, there was a strong inverse correlation (r = –0.71) between depression severity, as measured by CDRS-R total score, and functioning, as measured by the CGAS.

“That’s the cool thing: As the depression symptoms and severity came down, the overall functioning in these kids improved,” Dr. Singh noted.

“This improvement in functioning ends up being much more clinically relevant and useful to clinicians than just showing an improvement in a set of symptoms because what brings a kid – or even an adult, for that matter – to see a clinician to get treatment is because something about their symptoms is causing significant functional impairment,” she said.

“So this is the take-home message: You can see that lurasidone ... demonstrates not just recovery from depressive symptoms but that this reduction in depressive symptoms corresponds to an improvement in functioning for these youths,” she added.

Potential Limitations

Commenting on the study, Christoph U. Correll, MD, professor of child and adolescent psychiatry, Charite Universitatsmedizin, Berlin, Germany, noted that BD is difficult to treat, especially for patients who are going through “a developmentally vulnerable phase of their lives.”

“Lurasidone is the only monotherapy approved for bipolar depression in youth and is fairly well tolerated,” said Dr. Correll, who was not part of the research. He added that the long-term effectiveness data on response and remission “add relevant information” to the field.

However, he noted that it is not clear whether the high and increasing rates of response and remission were based on the reporting of observed cases or on last-observation-carried-forward analyses. “Given the naturally high dropout rate in such a long-term study and the potential for a survival bias, this is a relevant methodological question that affects the interpretation of the data,” he said.

“Nevertheless, the very favorable results for cumulative response, remission, and sustained remission add to the evidence that lurasidone is an effective treatment for youth with bipolar depression. Since efficacy cannot be interpreted in isolation, data describing the tolerability, including long-term cardiometabolic effects, will be important complementary data to consider,” Dr. Correll said.

The study was funded by Sunovion Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Singh is on the advisory board for Sunovion, is a consultant for Google X and Limbix, and receives royalties from American Psychiatric Association Publishing. She has also received research support from Stanford’s Maternal Child Health Research Institute and Department of Psychiatry, the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute on Aging, Johnson and Johnson, Allergan, PCORI, and the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation. Dr. Correll has been a consultant or adviser to and has received honoraria from Sunovion, as well as Acadia, Alkermes, Allergan, Angelini, Axsome, Gedeon Richter, Gerson Lehrman Group, Intra-Cellular Therapies, Janssen/J&J, LB Pharma, Lundbeck, MedAvante-ProPhase, Medscape, Neurocrine, Noven, Otsuka, Pfizer, Recordati, Rovi, Sumitomo Dainippon, Supernus, Takeda, and Teva.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ASCP 2020

Atopic dermatitis in adults, children linked to neuropsychiatric disorders

according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology, held virtually.

“The risk increase ranges from as low as 5% up to 59%, depending on the outcome, with generally greater effects observed among the adults,” Joy Wan, MD, a postdoctoral dermatology fellow at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said in her presentation. The risk was independent of other atopic disease, gender, age, and socioeconomic status.

Dr. Wan and colleagues conducted a cohort study of patients with AD in the United Kingdom using data from the Health Improvement Network (THIN) electronic records database, matching AD patients in THIN with up to five patients without AD, similar in age and also registered to general practices. The researchers validated AD disease status using an algorithm that identified patients with a diagnostic code and two therapy codes related to AD. Outcomes of interest included anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, ADHD, schizophrenia, and autism. Patients entered into the cohort when they were diagnosed with AD, registered by a practice, or when data from a practice was reported to THIN. The researchers stopped following patients when they developed a neuropsychiatric outcome of interest, left a practice, died, or when the study ended.

“Previous studies have found associations between atopic dermatitis and anxiety, depression, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. However, many previous studies had been cross-sectional and they were unable to evaluate the directionality of association between atopic dermatitis and neuropsychiatric outcomes, while other previous studies have relied on the self-report of atopic dermatitis and outcomes as well,” Dr. Wan said. “Thus, longitudinal studies, using validated measures of atopic dermatitis, and those that include the entire age span, are really needed.”

Overall, 434,859 children and adolescents under aged 18 with AD in the THIN database were matched to 1,983,589 controls, and 644,802 adults with AD were matched to almost 2,900,000 adults without AD. In the pediatric group, demographics were mostly balanced between children with and without AD: the average age ranged between about 5 and almost 6 years. In pediatric patients with AD, there was a higher rate of allergic rhinitis (6.2% vs. 4%) and asthma (13.5% vs. 9.3%) than in the control group.

For adults, the average age was about 48 years in both groups. Compared with patients who did not have AD, adults with AD also had higher rates of allergic rhinitis (15.2% vs. 9.6%) and asthma (19.9% vs. 12.6%).

After adjusting for age, gender, socioeconomic status, asthma, and allergic rhinitis, Dr. Wan and colleagues found greater rates of bipolar disorder (hazard ratio, 1.34; 95% confidence interval, 1.09-1.65), obsessive-compulsive disorder (HR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.21-1.41), anxiety (HR, 1.09; 95% CI, 1.07-1.11), and depression (HR, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.04-1.08) among children and adolescents with AD, compared with controls.

In the adult cohort, a diagnosis of AD was associated with an increased risk of autism (HR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.30-1.80), obsessive-compulsive disorder (HR, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.40-1.59), ADHD (HR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.13-1.53), anxiety (HR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.15-1.18), depression (HR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.14-1.16), and bipolar disorder (HR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.04-1.21), after adjusting for age, gender, socioeconomic status, asthma, and allergic rhinitis.

One reason for the increased associations among the adults, even for ADHD and autism, which are more characteristically diagnosed in childhood, Dr. Wan said, is that, since they looked at incident outcomes, “many children may already have had these prevalent comorbidities at the time of the entry in the cohort.”

She noted that the study may have observation bias or unknown confounders, but she hopes these results raise awareness of the association between AD and neuropsychiatric disorders, although more research is needed to determine how AD severity affects neuropsychiatric outcomes. “Additional work is needed to really understand the mechanisms that drive these associations, whether it’s mediated through symptoms of atopic dermatitis such as itch and poor sleep, or potentially the stigma of having a chronic skin disease, or perhaps shared pathophysiology between atopic dermatitis and these neuropsychiatric diseases,” she said.

The study was funded by a grant from Pfizer. Dr. Wan reports receiving research funding from Pfizer paid to the University of Pennsylvania.

according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology, held virtually.

“The risk increase ranges from as low as 5% up to 59%, depending on the outcome, with generally greater effects observed among the adults,” Joy Wan, MD, a postdoctoral dermatology fellow at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said in her presentation. The risk was independent of other atopic disease, gender, age, and socioeconomic status.

Dr. Wan and colleagues conducted a cohort study of patients with AD in the United Kingdom using data from the Health Improvement Network (THIN) electronic records database, matching AD patients in THIN with up to five patients without AD, similar in age and also registered to general practices. The researchers validated AD disease status using an algorithm that identified patients with a diagnostic code and two therapy codes related to AD. Outcomes of interest included anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, ADHD, schizophrenia, and autism. Patients entered into the cohort when they were diagnosed with AD, registered by a practice, or when data from a practice was reported to THIN. The researchers stopped following patients when they developed a neuropsychiatric outcome of interest, left a practice, died, or when the study ended.

“Previous studies have found associations between atopic dermatitis and anxiety, depression, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. However, many previous studies had been cross-sectional and they were unable to evaluate the directionality of association between atopic dermatitis and neuropsychiatric outcomes, while other previous studies have relied on the self-report of atopic dermatitis and outcomes as well,” Dr. Wan said. “Thus, longitudinal studies, using validated measures of atopic dermatitis, and those that include the entire age span, are really needed.”

Overall, 434,859 children and adolescents under aged 18 with AD in the THIN database were matched to 1,983,589 controls, and 644,802 adults with AD were matched to almost 2,900,000 adults without AD. In the pediatric group, demographics were mostly balanced between children with and without AD: the average age ranged between about 5 and almost 6 years. In pediatric patients with AD, there was a higher rate of allergic rhinitis (6.2% vs. 4%) and asthma (13.5% vs. 9.3%) than in the control group.

For adults, the average age was about 48 years in both groups. Compared with patients who did not have AD, adults with AD also had higher rates of allergic rhinitis (15.2% vs. 9.6%) and asthma (19.9% vs. 12.6%).

After adjusting for age, gender, socioeconomic status, asthma, and allergic rhinitis, Dr. Wan and colleagues found greater rates of bipolar disorder (hazard ratio, 1.34; 95% confidence interval, 1.09-1.65), obsessive-compulsive disorder (HR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.21-1.41), anxiety (HR, 1.09; 95% CI, 1.07-1.11), and depression (HR, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.04-1.08) among children and adolescents with AD, compared with controls.

In the adult cohort, a diagnosis of AD was associated with an increased risk of autism (HR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.30-1.80), obsessive-compulsive disorder (HR, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.40-1.59), ADHD (HR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.13-1.53), anxiety (HR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.15-1.18), depression (HR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.14-1.16), and bipolar disorder (HR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.04-1.21), after adjusting for age, gender, socioeconomic status, asthma, and allergic rhinitis.

One reason for the increased associations among the adults, even for ADHD and autism, which are more characteristically diagnosed in childhood, Dr. Wan said, is that, since they looked at incident outcomes, “many children may already have had these prevalent comorbidities at the time of the entry in the cohort.”

She noted that the study may have observation bias or unknown confounders, but she hopes these results raise awareness of the association between AD and neuropsychiatric disorders, although more research is needed to determine how AD severity affects neuropsychiatric outcomes. “Additional work is needed to really understand the mechanisms that drive these associations, whether it’s mediated through symptoms of atopic dermatitis such as itch and poor sleep, or potentially the stigma of having a chronic skin disease, or perhaps shared pathophysiology between atopic dermatitis and these neuropsychiatric diseases,” she said.

The study was funded by a grant from Pfizer. Dr. Wan reports receiving research funding from Pfizer paid to the University of Pennsylvania.

according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology, held virtually.

“The risk increase ranges from as low as 5% up to 59%, depending on the outcome, with generally greater effects observed among the adults,” Joy Wan, MD, a postdoctoral dermatology fellow at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said in her presentation. The risk was independent of other atopic disease, gender, age, and socioeconomic status.

Dr. Wan and colleagues conducted a cohort study of patients with AD in the United Kingdom using data from the Health Improvement Network (THIN) electronic records database, matching AD patients in THIN with up to five patients without AD, similar in age and also registered to general practices. The researchers validated AD disease status using an algorithm that identified patients with a diagnostic code and two therapy codes related to AD. Outcomes of interest included anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, ADHD, schizophrenia, and autism. Patients entered into the cohort when they were diagnosed with AD, registered by a practice, or when data from a practice was reported to THIN. The researchers stopped following patients when they developed a neuropsychiatric outcome of interest, left a practice, died, or when the study ended.

“Previous studies have found associations between atopic dermatitis and anxiety, depression, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. However, many previous studies had been cross-sectional and they were unable to evaluate the directionality of association between atopic dermatitis and neuropsychiatric outcomes, while other previous studies have relied on the self-report of atopic dermatitis and outcomes as well,” Dr. Wan said. “Thus, longitudinal studies, using validated measures of atopic dermatitis, and those that include the entire age span, are really needed.”

Overall, 434,859 children and adolescents under aged 18 with AD in the THIN database were matched to 1,983,589 controls, and 644,802 adults with AD were matched to almost 2,900,000 adults without AD. In the pediatric group, demographics were mostly balanced between children with and without AD: the average age ranged between about 5 and almost 6 years. In pediatric patients with AD, there was a higher rate of allergic rhinitis (6.2% vs. 4%) and asthma (13.5% vs. 9.3%) than in the control group.

For adults, the average age was about 48 years in both groups. Compared with patients who did not have AD, adults with AD also had higher rates of allergic rhinitis (15.2% vs. 9.6%) and asthma (19.9% vs. 12.6%).

After adjusting for age, gender, socioeconomic status, asthma, and allergic rhinitis, Dr. Wan and colleagues found greater rates of bipolar disorder (hazard ratio, 1.34; 95% confidence interval, 1.09-1.65), obsessive-compulsive disorder (HR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.21-1.41), anxiety (HR, 1.09; 95% CI, 1.07-1.11), and depression (HR, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.04-1.08) among children and adolescents with AD, compared with controls.

In the adult cohort, a diagnosis of AD was associated with an increased risk of autism (HR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.30-1.80), obsessive-compulsive disorder (HR, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.40-1.59), ADHD (HR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.13-1.53), anxiety (HR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.15-1.18), depression (HR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.14-1.16), and bipolar disorder (HR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.04-1.21), after adjusting for age, gender, socioeconomic status, asthma, and allergic rhinitis.

One reason for the increased associations among the adults, even for ADHD and autism, which are more characteristically diagnosed in childhood, Dr. Wan said, is that, since they looked at incident outcomes, “many children may already have had these prevalent comorbidities at the time of the entry in the cohort.”

She noted that the study may have observation bias or unknown confounders, but she hopes these results raise awareness of the association between AD and neuropsychiatric disorders, although more research is needed to determine how AD severity affects neuropsychiatric outcomes. “Additional work is needed to really understand the mechanisms that drive these associations, whether it’s mediated through symptoms of atopic dermatitis such as itch and poor sleep, or potentially the stigma of having a chronic skin disease, or perhaps shared pathophysiology between atopic dermatitis and these neuropsychiatric diseases,” she said.

The study was funded by a grant from Pfizer. Dr. Wan reports receiving research funding from Pfizer paid to the University of Pennsylvania.

FROM SID 2020

Dietary intervention cuts mood swings, other bipolar symptoms

A nutritional intervention with a focus on fatty acids appears to reduce mood swings in patients with bipolar disorder (BD) when used as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy, early research suggests.

In a single-center study, patients with BD who received a diet consisting of high omega-3 plus low omega-6 fatty acids (H3-L6), in addition to usual care, showed significant reductions in mood variability, irritability, and pain, compared with their counterparts who received a diet with usual levels of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids commonly consumed in regular U.S. diets.

“Our findings need replication and validation in other studies,” study coinvestigator Erika Saunders, MD, professor and chair of the department of psychiatry and behavioral health at Penn State Health, Hershey, said in an interview.

“While we got really exciting findings, it’s far from confirmatory or the last word on the subject. The fatty acids do two broad things. They incorporate into the membranes of neurons in the brain and they also create signaling molecules throughout the brain and the body that interact with the immune system and the inflammatory system. And we suspect that it is through those mechanisms that this composition of fatty acids is having an effect on mood stability, but lots more work needs to be done to figure that out,” Dr. Saunders added.

The findings were presented at the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology 2020 Virtual Conference.

Fewer mood swings

Many patients with bipolar disorder do not achieve complete mood stability with medication, making the need for additional treatments imperative, she added.

“We were interested in looking at treatments that improved mood stability in bipolar disorder that are well tolerated by patients and that can be added to pharmacological treatments. We studied this particular nutritional intervention because biologically it does some of the same things that effective medications for bipolar disorder do and it has been investigated as an effective treatment for conditions like migraine headaches, which has a lot of overlap and comorbidity with bipolar disorder.”

The researchers randomized 41 patients with BD to receive the nutritional intervention of high omega-3 plus low omega-6 (H3-L6) and 41 patients with BD to receive a control diet of usual US levels of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids.

The patients were aged 20-75 years (mean age, 43.5 +/– 13.9 years) and 83% were women. They had similar mean levels of mood symptoms and pain.

All patients received group-specific study foods and oils, as well as intensive dietary counseling from a dietitian, access to a website with recipes, and guidance for eating in restaurants. All participants were blinded to the composition of the food that they were eating.

Both the interventional diet and the control diet were tailored for the purposes of the study, noted coinvestigator Sarah Shahriar, a research assistant at Penn State.

“The interventional group had more fatty fish such as salmon and tuna, while the control group had more white fish and fish with less fatty acid content. The interventional group also received a different type of cooking oil, which was a blend of olive and macadamia-nut oil, which was specially formulated by a research nutritional service at the University of North Carolina,” Ms. Shahriar said in an interview.

“They also decreased their red meat consumption and received specially formulated snack foods, which were specifically prepared by [the university’s] research nutritional service. It is important to point out that these diets were for a very specific purpose. We are not saying in any way shape or form that this particular nutritional intervention is good in general,” she added.

After 12 weeks, significant reductions were seen in mood variability, energy, irritability, and pain in the H3-L6 group (P < .001). The only symptom that was significantly lowered in the control group was impulsive thoughts (P = .004).

“The best message for doctors to tell their patients at this point is one of general nutritional health and the importance of nutrition in overall body and brain health, and that [this] can be a very important component of mood,” Dr. Saunders said.

Diet matters

“Highly unsaturated fatty acids are important components of neuronal cell membranes and in cell signaling,” Jessica M. Gannon, MD, University of Pittsburgh, who was not part of the study, said in an interview.

“Omega-6 fatty acids are precursors to proinflammatory compounds. Omega-3 fatty acids eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid are thought to be competitive inhibitors of omega-6 and thought to have anti-inflammatory effects. Supplementation with omega-3 has been explored in cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and in rheumatologic disorders as well as in a host of psychiatric disorders, including bipolar disorders, where a possible treatment effect has been suggested,” Dr. Gannon said.

Dietary interventions targeting not only increasing omega-3 but also decreasing consumption of omega-6 rich foods could be both effective and attractive to patients invested in a healthy lifestyle for promotion of mental health, especially when they are not optimally controlled by prescribed medications, she added.

“This study suggests that such an intervention could prove beneficial, although significant patient support may be necessary to assure adherence to the diet. I would agree that future studies would be worth pursuing,” Dr. Gannon said.

The investigators and Dr. Gannon have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

A nutritional intervention with a focus on fatty acids appears to reduce mood swings in patients with bipolar disorder (BD) when used as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy, early research suggests.

In a single-center study, patients with BD who received a diet consisting of high omega-3 plus low omega-6 fatty acids (H3-L6), in addition to usual care, showed significant reductions in mood variability, irritability, and pain, compared with their counterparts who received a diet with usual levels of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids commonly consumed in regular U.S. diets.

“Our findings need replication and validation in other studies,” study coinvestigator Erika Saunders, MD, professor and chair of the department of psychiatry and behavioral health at Penn State Health, Hershey, said in an interview.

“While we got really exciting findings, it’s far from confirmatory or the last word on the subject. The fatty acids do two broad things. They incorporate into the membranes of neurons in the brain and they also create signaling molecules throughout the brain and the body that interact with the immune system and the inflammatory system. And we suspect that it is through those mechanisms that this composition of fatty acids is having an effect on mood stability, but lots more work needs to be done to figure that out,” Dr. Saunders added.

The findings were presented at the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology 2020 Virtual Conference.

Fewer mood swings

Many patients with bipolar disorder do not achieve complete mood stability with medication, making the need for additional treatments imperative, she added.

“We were interested in looking at treatments that improved mood stability in bipolar disorder that are well tolerated by patients and that can be added to pharmacological treatments. We studied this particular nutritional intervention because biologically it does some of the same things that effective medications for bipolar disorder do and it has been investigated as an effective treatment for conditions like migraine headaches, which has a lot of overlap and comorbidity with bipolar disorder.”

The researchers randomized 41 patients with BD to receive the nutritional intervention of high omega-3 plus low omega-6 (H3-L6) and 41 patients with BD to receive a control diet of usual US levels of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids.

The patients were aged 20-75 years (mean age, 43.5 +/– 13.9 years) and 83% were women. They had similar mean levels of mood symptoms and pain.

All patients received group-specific study foods and oils, as well as intensive dietary counseling from a dietitian, access to a website with recipes, and guidance for eating in restaurants. All participants were blinded to the composition of the food that they were eating.

Both the interventional diet and the control diet were tailored for the purposes of the study, noted coinvestigator Sarah Shahriar, a research assistant at Penn State.

“The interventional group had more fatty fish such as salmon and tuna, while the control group had more white fish and fish with less fatty acid content. The interventional group also received a different type of cooking oil, which was a blend of olive and macadamia-nut oil, which was specially formulated by a research nutritional service at the University of North Carolina,” Ms. Shahriar said in an interview.

“They also decreased their red meat consumption and received specially formulated snack foods, which were specifically prepared by [the university’s] research nutritional service. It is important to point out that these diets were for a very specific purpose. We are not saying in any way shape or form that this particular nutritional intervention is good in general,” she added.

After 12 weeks, significant reductions were seen in mood variability, energy, irritability, and pain in the H3-L6 group (P < .001). The only symptom that was significantly lowered in the control group was impulsive thoughts (P = .004).

“The best message for doctors to tell their patients at this point is one of general nutritional health and the importance of nutrition in overall body and brain health, and that [this] can be a very important component of mood,” Dr. Saunders said.

Diet matters

“Highly unsaturated fatty acids are important components of neuronal cell membranes and in cell signaling,” Jessica M. Gannon, MD, University of Pittsburgh, who was not part of the study, said in an interview.

“Omega-6 fatty acids are precursors to proinflammatory compounds. Omega-3 fatty acids eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid are thought to be competitive inhibitors of omega-6 and thought to have anti-inflammatory effects. Supplementation with omega-3 has been explored in cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and in rheumatologic disorders as well as in a host of psychiatric disorders, including bipolar disorders, where a possible treatment effect has been suggested,” Dr. Gannon said.

Dietary interventions targeting not only increasing omega-3 but also decreasing consumption of omega-6 rich foods could be both effective and attractive to patients invested in a healthy lifestyle for promotion of mental health, especially when they are not optimally controlled by prescribed medications, she added.

“This study suggests that such an intervention could prove beneficial, although significant patient support may be necessary to assure adherence to the diet. I would agree that future studies would be worth pursuing,” Dr. Gannon said.

The investigators and Dr. Gannon have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

A nutritional intervention with a focus on fatty acids appears to reduce mood swings in patients with bipolar disorder (BD) when used as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy, early research suggests.

In a single-center study, patients with BD who received a diet consisting of high omega-3 plus low omega-6 fatty acids (H3-L6), in addition to usual care, showed significant reductions in mood variability, irritability, and pain, compared with their counterparts who received a diet with usual levels of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids commonly consumed in regular U.S. diets.

“Our findings need replication and validation in other studies,” study coinvestigator Erika Saunders, MD, professor and chair of the department of psychiatry and behavioral health at Penn State Health, Hershey, said in an interview.

“While we got really exciting findings, it’s far from confirmatory or the last word on the subject. The fatty acids do two broad things. They incorporate into the membranes of neurons in the brain and they also create signaling molecules throughout the brain and the body that interact with the immune system and the inflammatory system. And we suspect that it is through those mechanisms that this composition of fatty acids is having an effect on mood stability, but lots more work needs to be done to figure that out,” Dr. Saunders added.

The findings were presented at the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology 2020 Virtual Conference.

Fewer mood swings

Many patients with bipolar disorder do not achieve complete mood stability with medication, making the need for additional treatments imperative, she added.

“We were interested in looking at treatments that improved mood stability in bipolar disorder that are well tolerated by patients and that can be added to pharmacological treatments. We studied this particular nutritional intervention because biologically it does some of the same things that effective medications for bipolar disorder do and it has been investigated as an effective treatment for conditions like migraine headaches, which has a lot of overlap and comorbidity with bipolar disorder.”

The researchers randomized 41 patients with BD to receive the nutritional intervention of high omega-3 plus low omega-6 (H3-L6) and 41 patients with BD to receive a control diet of usual US levels of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids.

The patients were aged 20-75 years (mean age, 43.5 +/– 13.9 years) and 83% were women. They had similar mean levels of mood symptoms and pain.

All patients received group-specific study foods and oils, as well as intensive dietary counseling from a dietitian, access to a website with recipes, and guidance for eating in restaurants. All participants were blinded to the composition of the food that they were eating.

Both the interventional diet and the control diet were tailored for the purposes of the study, noted coinvestigator Sarah Shahriar, a research assistant at Penn State.

“The interventional group had more fatty fish such as salmon and tuna, while the control group had more white fish and fish with less fatty acid content. The interventional group also received a different type of cooking oil, which was a blend of olive and macadamia-nut oil, which was specially formulated by a research nutritional service at the University of North Carolina,” Ms. Shahriar said in an interview.

“They also decreased their red meat consumption and received specially formulated snack foods, which were specifically prepared by [the university’s] research nutritional service. It is important to point out that these diets were for a very specific purpose. We are not saying in any way shape or form that this particular nutritional intervention is good in general,” she added.

After 12 weeks, significant reductions were seen in mood variability, energy, irritability, and pain in the H3-L6 group (P < .001). The only symptom that was significantly lowered in the control group was impulsive thoughts (P = .004).

“The best message for doctors to tell their patients at this point is one of general nutritional health and the importance of nutrition in overall body and brain health, and that [this] can be a very important component of mood,” Dr. Saunders said.

Diet matters

“Highly unsaturated fatty acids are important components of neuronal cell membranes and in cell signaling,” Jessica M. Gannon, MD, University of Pittsburgh, who was not part of the study, said in an interview.