User login

Pandemic-related stress causing health issues in many Americans

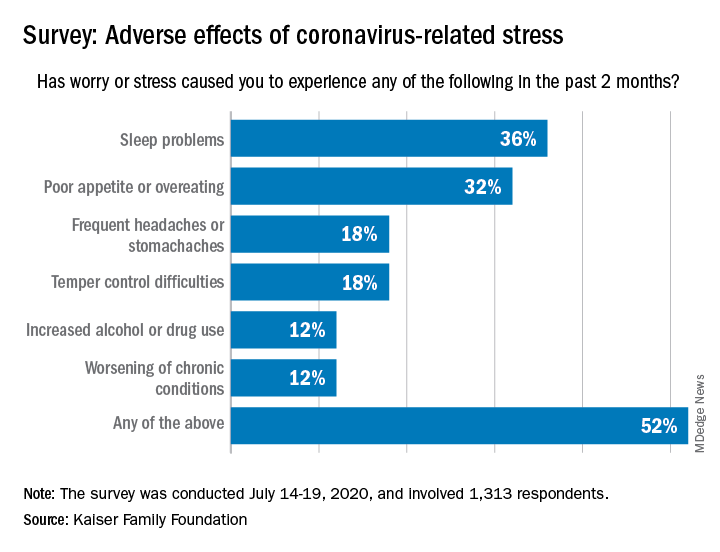

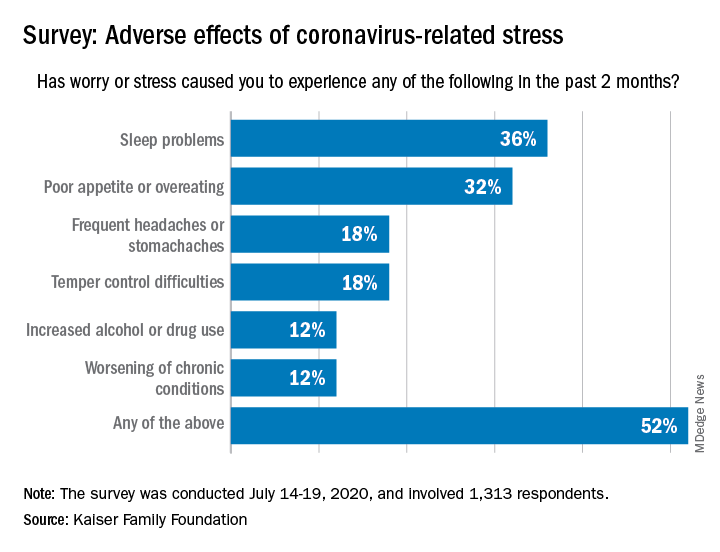

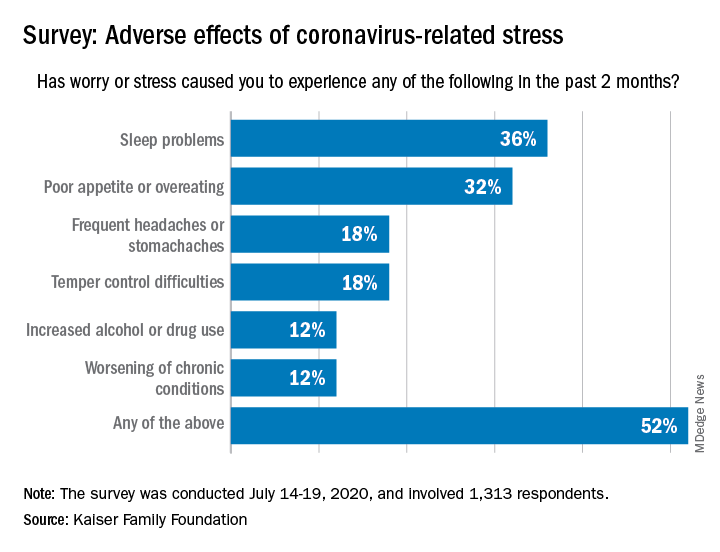

Over the last 2 months, more than half of Americans have experienced some sort of adverse effect caused by stress related to the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a survey from the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF).

More than a third (36%) of the 1,313 respondents said they either had difficulty sleeping, falling asleep, or sleeping too much, KFF said in its latest Health Tracking Poll, conducted July 14-19, 2020. That was followed by poor appetite or overeating, which was mentioned by 32% of those surveyed.

Other adverse effects included frequent headaches or stomachaches (18%), temper-control issues (18%), increased drug or alcohol use (12%), and worsening of chronic conditions such as diabetes or hypertension (12%). Altogether, 52% of Americans have had at least one of these issues in the past 2 months, Liz Hamel and associates at KFF reported.

breaking down to 26% reporting a major impact and 28% reporting a minor impact (figures have been rounded), they said.

“As life with the coronavirus pandemic wears on, Americans increasingly say it is taking a negative toll on their mental health,” the investigators wrote. Earlier polls showed that pandemic-related stress was having an impact on mental health for 39% of respondents in May, compared with 45% in early April and 32% in March.

In the July poll, Black adults were much more likely to report a negative mental health impact (68%) than were Hispanics or Whites, who were both at 51%. Age was also a factor: The youngest group of respondents (ages 18-29 years) had the highest negative-impact rate (62%), and the oldest group (65 years and older) had the lowest (47%), they said.

When it came to reporting the adverse effects of stress or worry, however, the situation was somewhat different. Hispanics had the highest rate of such effects at 63%, while Blacks had a rate of 57% and 47% of Whites reported issues with sleep, eating, temper, and other problems, Ms. Hamel and associates reported.

Over the last 2 months, more than half of Americans have experienced some sort of adverse effect caused by stress related to the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a survey from the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF).

More than a third (36%) of the 1,313 respondents said they either had difficulty sleeping, falling asleep, or sleeping too much, KFF said in its latest Health Tracking Poll, conducted July 14-19, 2020. That was followed by poor appetite or overeating, which was mentioned by 32% of those surveyed.

Other adverse effects included frequent headaches or stomachaches (18%), temper-control issues (18%), increased drug or alcohol use (12%), and worsening of chronic conditions such as diabetes or hypertension (12%). Altogether, 52% of Americans have had at least one of these issues in the past 2 months, Liz Hamel and associates at KFF reported.

breaking down to 26% reporting a major impact and 28% reporting a minor impact (figures have been rounded), they said.

“As life with the coronavirus pandemic wears on, Americans increasingly say it is taking a negative toll on their mental health,” the investigators wrote. Earlier polls showed that pandemic-related stress was having an impact on mental health for 39% of respondents in May, compared with 45% in early April and 32% in March.

In the July poll, Black adults were much more likely to report a negative mental health impact (68%) than were Hispanics or Whites, who were both at 51%. Age was also a factor: The youngest group of respondents (ages 18-29 years) had the highest negative-impact rate (62%), and the oldest group (65 years and older) had the lowest (47%), they said.

When it came to reporting the adverse effects of stress or worry, however, the situation was somewhat different. Hispanics had the highest rate of such effects at 63%, while Blacks had a rate of 57% and 47% of Whites reported issues with sleep, eating, temper, and other problems, Ms. Hamel and associates reported.

Over the last 2 months, more than half of Americans have experienced some sort of adverse effect caused by stress related to the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a survey from the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF).

More than a third (36%) of the 1,313 respondents said they either had difficulty sleeping, falling asleep, or sleeping too much, KFF said in its latest Health Tracking Poll, conducted July 14-19, 2020. That was followed by poor appetite or overeating, which was mentioned by 32% of those surveyed.

Other adverse effects included frequent headaches or stomachaches (18%), temper-control issues (18%), increased drug or alcohol use (12%), and worsening of chronic conditions such as diabetes or hypertension (12%). Altogether, 52% of Americans have had at least one of these issues in the past 2 months, Liz Hamel and associates at KFF reported.

breaking down to 26% reporting a major impact and 28% reporting a minor impact (figures have been rounded), they said.

“As life with the coronavirus pandemic wears on, Americans increasingly say it is taking a negative toll on their mental health,” the investigators wrote. Earlier polls showed that pandemic-related stress was having an impact on mental health for 39% of respondents in May, compared with 45% in early April and 32% in March.

In the July poll, Black adults were much more likely to report a negative mental health impact (68%) than were Hispanics or Whites, who were both at 51%. Age was also a factor: The youngest group of respondents (ages 18-29 years) had the highest negative-impact rate (62%), and the oldest group (65 years and older) had the lowest (47%), they said.

When it came to reporting the adverse effects of stress or worry, however, the situation was somewhat different. Hispanics had the highest rate of such effects at 63%, while Blacks had a rate of 57% and 47% of Whites reported issues with sleep, eating, temper, and other problems, Ms. Hamel and associates reported.

AHA statement addresses genetic testing for CVD

A new scientific statement from the American Heart Association recommends that genetic testing for inherited cardiovascular disease should be reserved for four specific types of heart diseases – cardiomyopathies, thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections, arrhythmias, and familial hypercholesterolemia – and should enlist skilled geneticists and genetic counselors in the care team.

The guidance comes in a scientific statement published online in the journal Circulation: Genomic and Precision Medicine.

Kiran Musunuru, MD, PhD, MPH, ML, chair of the writing group for the scientific statement, described in an interview the rationale for publishing the statement at this time. “There was no prior single statement that summarized best practices for the whole gamut of inherited cardiovascular diseases in adults, only statements for individual diseases,” he said in an interview. “With genetic testing seeing explosive growth in the past few years, both in the clinical setting and with direct-to-consumer testing, we felt that cardiovascular practitioners would benefit from having a single document to serve as a general resource on genetic testing.”

The statement describes two types of patients who would be suitable for genetic testing for cardiovascular disease (CVD), Dr. Musunuru noted: “Patients who have been diagnosed with or are strongly suspected to have a cardiovascular disease that is often inherited and family members of patients who have been diagnosed with an inherited cardiovascular disease and found by genetic testing to have a mutation that is felt to be the cause of the disease.”

The statement also spells out two crucial elements for genetic testing: thorough disease-specific phenotyping – that is, using genetic information to identify the individual’s disease characteristics and a comprehensive family history that spans at least three generations. Testing should only proceed after patients has had genetic counseling and made a shared decision with their doctors.

“Genetic counseling is absolutely essential both before genetic testing to educate patients on what genetic testing entails and what potential results to expect, as well as the risks of testing; and after genetic testing, to review the results of the genetic testing and explain the potential consequences for the patient’s health and the health of family members, including children,” Dr. Musunuru said.

The process should involve board-certified geneticists or at least cardiovascular specialists well-versed in genetics and genetic counselors, the statement noted. The latter are “critical” in the care team, Dr. Musunuru said.

After the decision is made to do genetic testing, the next step is to decide the scope of the testing. That can range from targeted sequencing of a single gene or a few genes linked to the disease to large gene panels; the latter “may not increase the likelihood of clinically actionable results in adult patients,” Dr. Musunuru and colleagues wrote.

But genetic testing is no guarantee to identify a cause or confirm a diagnosis of CVD, the statement noted. “The yield for any genetic testing for any inherited cardiovascular disease remains <100%, usually much less than 100%,” the writing committee stated.

Dr. Musunuru explained that the results can sometimes be inconclusive. “In many cases, genetic testing reveals a mutation that is uninterpretable, what we call a variant of uncertain significance,” he said. “It is not clear whether the mutation increases the risk of disease or is entirely benign, which makes it very challenging to counsel patients as to whether anything should be done about the mutation.”

Even in a diagnosed patient the test results can be uncertain. “This makes it challenging to explain why the patient has the disease and whether any of the family members are at risk,” Dr. Musunuru said.

According to the statement, providers should encourage patients with a confirmed or likely pathogenic variant for CVD to share that information with “all of their at-risk relative,” the statement noted, suggesting “family letters” given to patients are a way to navigate HIPAA’s privacy limits.

The statement was written on behalf of the American Heart Association’s Council on Genomic and Precision Medicine; Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; and Council on Clinical Cardiology.

Dr. Musunuru and writing group members have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

SOURCE: Musunuru K et al. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2020 Jul 23. doi: 10.1161/HCG.0000000000000067.

A new scientific statement from the American Heart Association recommends that genetic testing for inherited cardiovascular disease should be reserved for four specific types of heart diseases – cardiomyopathies, thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections, arrhythmias, and familial hypercholesterolemia – and should enlist skilled geneticists and genetic counselors in the care team.

The guidance comes in a scientific statement published online in the journal Circulation: Genomic and Precision Medicine.

Kiran Musunuru, MD, PhD, MPH, ML, chair of the writing group for the scientific statement, described in an interview the rationale for publishing the statement at this time. “There was no prior single statement that summarized best practices for the whole gamut of inherited cardiovascular diseases in adults, only statements for individual diseases,” he said in an interview. “With genetic testing seeing explosive growth in the past few years, both in the clinical setting and with direct-to-consumer testing, we felt that cardiovascular practitioners would benefit from having a single document to serve as a general resource on genetic testing.”

The statement describes two types of patients who would be suitable for genetic testing for cardiovascular disease (CVD), Dr. Musunuru noted: “Patients who have been diagnosed with or are strongly suspected to have a cardiovascular disease that is often inherited and family members of patients who have been diagnosed with an inherited cardiovascular disease and found by genetic testing to have a mutation that is felt to be the cause of the disease.”

The statement also spells out two crucial elements for genetic testing: thorough disease-specific phenotyping – that is, using genetic information to identify the individual’s disease characteristics and a comprehensive family history that spans at least three generations. Testing should only proceed after patients has had genetic counseling and made a shared decision with their doctors.

“Genetic counseling is absolutely essential both before genetic testing to educate patients on what genetic testing entails and what potential results to expect, as well as the risks of testing; and after genetic testing, to review the results of the genetic testing and explain the potential consequences for the patient’s health and the health of family members, including children,” Dr. Musunuru said.

The process should involve board-certified geneticists or at least cardiovascular specialists well-versed in genetics and genetic counselors, the statement noted. The latter are “critical” in the care team, Dr. Musunuru said.

After the decision is made to do genetic testing, the next step is to decide the scope of the testing. That can range from targeted sequencing of a single gene or a few genes linked to the disease to large gene panels; the latter “may not increase the likelihood of clinically actionable results in adult patients,” Dr. Musunuru and colleagues wrote.

But genetic testing is no guarantee to identify a cause or confirm a diagnosis of CVD, the statement noted. “The yield for any genetic testing for any inherited cardiovascular disease remains <100%, usually much less than 100%,” the writing committee stated.

Dr. Musunuru explained that the results can sometimes be inconclusive. “In many cases, genetic testing reveals a mutation that is uninterpretable, what we call a variant of uncertain significance,” he said. “It is not clear whether the mutation increases the risk of disease or is entirely benign, which makes it very challenging to counsel patients as to whether anything should be done about the mutation.”

Even in a diagnosed patient the test results can be uncertain. “This makes it challenging to explain why the patient has the disease and whether any of the family members are at risk,” Dr. Musunuru said.

According to the statement, providers should encourage patients with a confirmed or likely pathogenic variant for CVD to share that information with “all of their at-risk relative,” the statement noted, suggesting “family letters” given to patients are a way to navigate HIPAA’s privacy limits.

The statement was written on behalf of the American Heart Association’s Council on Genomic and Precision Medicine; Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; and Council on Clinical Cardiology.

Dr. Musunuru and writing group members have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

SOURCE: Musunuru K et al. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2020 Jul 23. doi: 10.1161/HCG.0000000000000067.

A new scientific statement from the American Heart Association recommends that genetic testing for inherited cardiovascular disease should be reserved for four specific types of heart diseases – cardiomyopathies, thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections, arrhythmias, and familial hypercholesterolemia – and should enlist skilled geneticists and genetic counselors in the care team.

The guidance comes in a scientific statement published online in the journal Circulation: Genomic and Precision Medicine.

Kiran Musunuru, MD, PhD, MPH, ML, chair of the writing group for the scientific statement, described in an interview the rationale for publishing the statement at this time. “There was no prior single statement that summarized best practices for the whole gamut of inherited cardiovascular diseases in adults, only statements for individual diseases,” he said in an interview. “With genetic testing seeing explosive growth in the past few years, both in the clinical setting and with direct-to-consumer testing, we felt that cardiovascular practitioners would benefit from having a single document to serve as a general resource on genetic testing.”

The statement describes two types of patients who would be suitable for genetic testing for cardiovascular disease (CVD), Dr. Musunuru noted: “Patients who have been diagnosed with or are strongly suspected to have a cardiovascular disease that is often inherited and family members of patients who have been diagnosed with an inherited cardiovascular disease and found by genetic testing to have a mutation that is felt to be the cause of the disease.”

The statement also spells out two crucial elements for genetic testing: thorough disease-specific phenotyping – that is, using genetic information to identify the individual’s disease characteristics and a comprehensive family history that spans at least three generations. Testing should only proceed after patients has had genetic counseling and made a shared decision with their doctors.

“Genetic counseling is absolutely essential both before genetic testing to educate patients on what genetic testing entails and what potential results to expect, as well as the risks of testing; and after genetic testing, to review the results of the genetic testing and explain the potential consequences for the patient’s health and the health of family members, including children,” Dr. Musunuru said.

The process should involve board-certified geneticists or at least cardiovascular specialists well-versed in genetics and genetic counselors, the statement noted. The latter are “critical” in the care team, Dr. Musunuru said.

After the decision is made to do genetic testing, the next step is to decide the scope of the testing. That can range from targeted sequencing of a single gene or a few genes linked to the disease to large gene panels; the latter “may not increase the likelihood of clinically actionable results in adult patients,” Dr. Musunuru and colleagues wrote.

But genetic testing is no guarantee to identify a cause or confirm a diagnosis of CVD, the statement noted. “The yield for any genetic testing for any inherited cardiovascular disease remains <100%, usually much less than 100%,” the writing committee stated.

Dr. Musunuru explained that the results can sometimes be inconclusive. “In many cases, genetic testing reveals a mutation that is uninterpretable, what we call a variant of uncertain significance,” he said. “It is not clear whether the mutation increases the risk of disease or is entirely benign, which makes it very challenging to counsel patients as to whether anything should be done about the mutation.”

Even in a diagnosed patient the test results can be uncertain. “This makes it challenging to explain why the patient has the disease and whether any of the family members are at risk,” Dr. Musunuru said.

According to the statement, providers should encourage patients with a confirmed or likely pathogenic variant for CVD to share that information with “all of their at-risk relative,” the statement noted, suggesting “family letters” given to patients are a way to navigate HIPAA’s privacy limits.

The statement was written on behalf of the American Heart Association’s Council on Genomic and Precision Medicine; Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; and Council on Clinical Cardiology.

Dr. Musunuru and writing group members have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

SOURCE: Musunuru K et al. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2020 Jul 23. doi: 10.1161/HCG.0000000000000067.

FROM CIRCULATION: GENOMIC AND PRECISION MEDICINE

A Multidisciplinary Ambulation Protocol to Reduce Postoperative Venous Thromboembolism After Colorectal Surgery

From the Department of Surgery, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO.

Abstract

Background: Patients undergoing colorectal surgery are at high risk for postoperative venous thromboembolism (VTE). Early ambulation has been encouraged to lower rates of VTE, but evidence demonstrating its effectiveness outside of a bundle is limited.

Objective: To create a multidisciplinary ambulation protocol in an effort to reduce postoperative VTE.

Methods: A single-center, retrospective, comparative study of patients who underwent colectomy or proctectomy was conducted. Outcomes of patients operated on prior to protocol implementation were compared with a cohort after implementation. The intervention studied was the implementation of a multidisciplinary ambulation protocol. The primary endpoint was postoperative VTE.

Results: There was no difference between the pre-intervention group (n = 1762) and the postintervention group (n = 253) in terms of sex, race, origin, emergency status, operative time, and the majority of medical comorbidities (with the exception of smoking status and congestive heart failure). After the protocol was implemented, ambulation rates on postoperative days 0, 1, and 2 improved from 36.4%, 47.3%, and 50.2% to 36.8%, 74.7%, and 82.6%, respectively The VTE rate in the pre-intervention group was 2.7% versus a rate of 0.4% in the postintervention group (P = 0.02).

Conclusion: Creation of an ambulation protocol is associated with a significant reduction in VTE. Commitment from patients, families, nurses, physician extenders, and physicians is critical to the success of the program.

Keywords: VTE; pulmonary embolism; deep vein thrombosis; postoperative; quality improvement.

Postoperative venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a significant source of morbidity, mortality, and cost.1,2 Colorectal surgery patients are at particularly high risk for VTE due to positioning during surgery, pelvic dissection, and other conditions often found in these patients, such as cancer and inflammatory bowel disease.3 A National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) analysis demonstrated an overall rate of VTE in colorectal surgery patients of 2.4%, although other studies have demonstrated rates up to 9%, even in those receiving appropriate chemoprophylaxis.4-6 Many of these VTEs occur in the postdischarge setting. In a NSQIP study of colorectal surgery patients, the rate of VTE between discharge and 30 days was 0.47%.7 The cost burdenfor a postoperative VTE has been estimated to be more than $18,000.8

Studies from NSQIP have identified multiple factors associated with VTE in colorectal surgery patients, but NSQIP does not record ambulation as a standard variable.9 Multiple strategies have been implemented to reduce postoperative VTE. Often, these studies focus on increasing compliance with appropriate chemoprophylaxis, risk stratification, or bundling multiple strategies.10,11 However, despite the fact that postsurgical ambulation is widely encouraged and recommended by the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons clinical practice guidelines, there is little evidence demonstrating the role of ambulation alone in the reduction of VTE.4,12 The purpose of this study was to create a multidisciplinary protocol to increase postoperative ambulation and evaluate its effect on VTE.

Methods

Setting

This study was conducted at a single academic tertiary care center.

Patients and Outcome Measures

All patients undergoing colectomy or proctectomy by surgeons in the section of colon and rectal surgery at a single institution between January 2011 and March 2017 were included. Colectomy and proctectomy were defined by CPT codes 44140, 44141, 44143, 44144, 44145, 44146, 44147, 44150, 44151, 44155, 44156, 44157, 44158, 44160, 44204, 44205, 44206, 44207, 44208, 44210, 44211, 44212, 44213, 45110, 45111, 45112, 45113, 45114, 45116, 45119, 45120, 45121, 45123, 45126, 45160, 45395, and 45397. The primary outcome of VTE within 30 days, including deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), was measured using institution-specific data from NSQIP in both the pre-intervention and postintervention setting. The occurrence of both DVT and PE in 1 patient was counted as a single event of VTE. Ambulation rate on postoperative day (POD) 0, 1, and 2 was calculated by NSQIP in the pre-intervention setting (our institution-specific NSQIP recorded ambulation data for an unrelated project) and by review of the electronic health record in the postintervention setting, as this institution-specific variable was no longer being collected. Ambulation was defined as getting out of bed and taking at least 1 step. The threshold for ambulating each day was once on POD 0 and twice on PODs 1 and 2. Patients with missing ambulation data were excluded from the analysis. Both prior to and throughout the intervention, all patients were given VTE chemoprophylaxis with either low-dose unfractionated heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin prior to induction of anesthesia, with chemoprophylaxis extending an additional 21 days after discharge (unless specifically contraindicated); sequential compression devices; and standard orders to ambulate 3 times daily from POD 0 as part of the standard Enhanced Recovery After Surgery protocol.

Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using univariate analysis. Chi-square test and univariate logistic regression were used to determine the association between ambulation rates and VTE in the pre-intervention group. Chi-square test was also used to compare ambulation and VTE rates between the pre-intervention and postintervention groups. Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle fidelity (the degree to which a PDSA cycle is carried out in accordance with the guiding principles of its use) was measured by recording the ambulation rates both before and after the intervention.13 Statistical analysis was performed using SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). This study was reviewed by the Washington University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board and deemed to be quality improvement, not human subjects research, and therefore did not require formal approval.

Baseline Outcome Rates

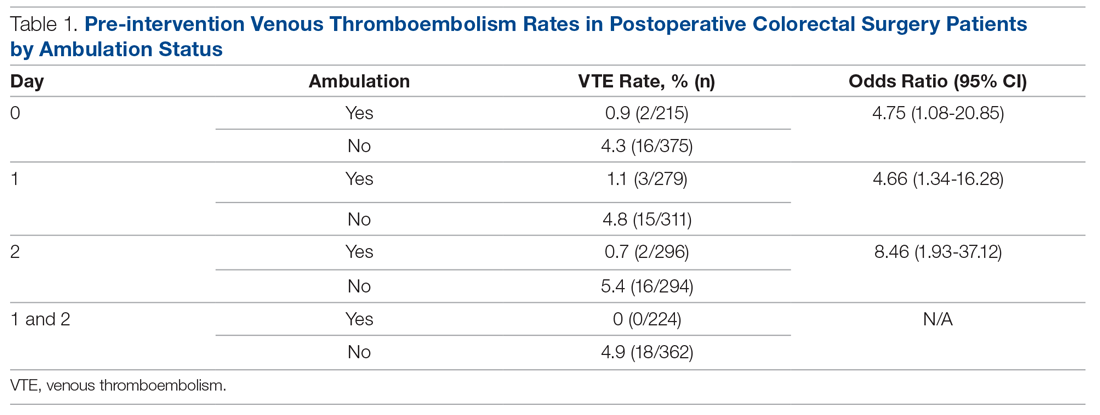

A total of 1762 patients were identified during the pre-intervention period. The overall VTE rate in the pre-intervention group was 2.7% (n = 48), with 39 DVTs (2.2%) and 13 PEs (0.7%). Pre-intervention ambulation data were available on 590 patients. Baseline ambulation rates on PODs 0, 1, and 2 were 36.4% (213/590), 47.3% (279/590), and 50.2% (296/590), respectively. Patients who did not ambulate on POD 0 had a VTE rate of 4.3%, as compared to 0.9% in those who did ambulate (Table 1). Patients who did not ambulate twice on POD 1 had a VTE rate of 4.8%, compared to 1.1% in those who did ambulate (odds ratio [OR], 4.66; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.34 to 16.28). Patients who did not ambulate twice on POD 2 had a VTE rate of 5.4%, compared to 0.7% in those who did. Finally, those who ambulated twice on both PODs 1 and 2 had a 0% rate of VTE, compared to 4.9% in those who did not ambulate on both PODs.

Ambulation Protocol

After baseline outcome rates had been established, a multidisciplinary team of medical assistants, nurses, nurse practitioners, and physicians worked together to identify all processes that involved postoperative ambulation. Given the significant differences in VTE rates between patients who ambulated and those that did not, we created a multidisciplinary ambulation protocol using the PDSA method.14 Multiple points of patient contact were chosen for intervention, and the ambulation protocol was implemented in June 2018 and continued for 7 months.

Patients were observed from their initial office visit with a surgeon, during the preoperative education encounter, and in the operating room and on the surgical ward until discharge. Representatives from multiple disciplines who encountered patients at various times in the process, including medical assistants, patient care technicians, nurses, nurse practitioners, physical therapists, and physicians, participated in a kick-off meeting to identify difficulties they encounter when encouraging patient ambulation. The following 4 areas were identified.

Barriers to Patient Ambulation

Patient Expectations. Patients did not appear to have a clear expectation of what their ambulation goals were postoperatively, despite the fact that each patient is given an operative pathway booklet that includes their goals for each day, including ambulation. The consensus was that patients were overwhelmed with the amount of information and, oftentimes, the severity of their diagnosis, so the information regarding ambulation was not retained. Nurses commented that patients frequently stated that they did not think their surgeon wanted them to get out of bed postoperatively.

Electronic Orders. There was confusion within the nursing staff regarding orders in the electronic health record compared to physician expectations. Orders stated patients should ambulate 3 times daily, but did not specify on which postoperative day this should start. Often, nursing verbal sign-out from the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU) would be an order for bedrest, despite no clear origin of this order. This created confusion among the nursing staff as to what the appropriate ambulation orders should be.

Nursing Workflow. The initial state of the nursing workflow was not conducive to evaluating for, or assisting with, ambulation. With no set time to assist and evaluate patients for ambulation, it turned into a task nurses needed to accomplish when they had extra time. With increasing demands of charting in the electronic health record, nurses often had to skip ambulation in order to accomplish other tasks.

Family Expectations. In addition to patient expectations, family members often had expectations that were not congruent with the planned postoperative course. Nurses stated family members would often tell them that they did not feel that their family member should be ambulating so soon after surgery. Often these family members had not attended preoperative education sessions with the patient. This was compounded by the uncertainty among the nursing staff regarding what exactly the ambulation orders were.

Interventions

Targeted interventions were created to address these 4 barriers to ambulation identified by staff.

Preoperative Education. Although all elective patients received a printed operative pathway booklet describing daily goals, including ambulation, patients still did not have a sufficient understanding of what was expected of them. The education session was modified to increase the time spent on both the expectation for and the rationale behind ambulation. That section of the education session ended with a verbal commitment and read-back of the expectations for ambulation by the patient.

Clarification of Electronic Orders. Postoperative orders within the colorectal standard pathway were changed, including specific time frames and frequency, to match the information provided in the patient education booklet. These orders were for ambulation within 4 hours of arrival to the floor, and the orders also noted that no patient should be on bedrest unless explicitly stated. From POD 1, all patients were to ambulate at least twice daily for the remainder of the hospital stay (patients were encouraged to walk 4 times daily, but we set a minimum expectation of twice daily for the order set). These orders were clarified with in-person meetings with the nursing staff and leadership from the PACU and the colorectal surgical ward.

Adjusted Nursing Workflow. Nurses were interviewed and asked to create a plan regarding how they could better incorporate ambulation into their daily workflow. Ambulation assessment was incorporated into the twice-per-shift recording of vital signs and patient safety assessment. This was recorded into the electronic health record at the same time as the patients’ vital signs. This allowed nurses to keep track of which patients would need extra assistance in ambulation and which patients were doing well on their own with the assistance of family. It also helped focus the resources of physical therapy and the single ambulation technician on the floor and to assist patients who needed more assistance.

Creation of Ambulation Encouragement Signs. The authors discovered that despite patients being told preoperatively about ambulation expectations, friends and family are not always included in these conversations. As nurses frequently cited both patients and family as reasons patients thought they should not walk, multiple signs inviting patients to take an active role in their recovery by ambulating were created and placed around the unit. The signs outlined the expectations of being out of bed and taking at least 1 step on the day of surgery and walking at least 4 times per day thereafter. In addition, we addressed frequently asked questions around issues such as walking with intravenous poles and urinary catheters. The posters were signed by all staff colorectal surgeons.

Results

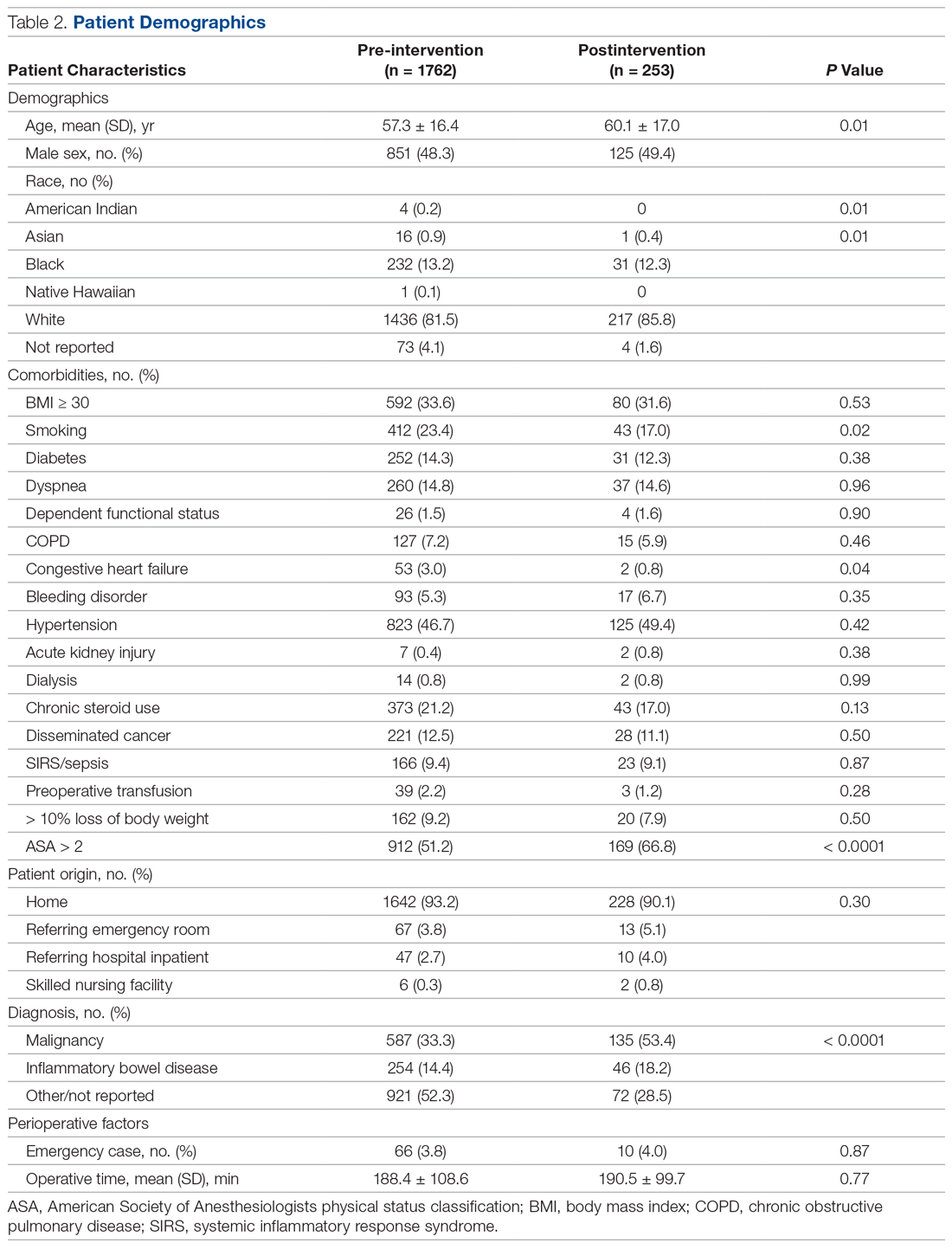

Over the course of 7 months (June 2018 to December 2018), 253 postintervention patients were identified (Table 2). There was no difference between the pre-intervention group (n = 1762) and the postintervention group in terms of sex, race, origin, emergency status, operative time, and the majority of medical comorbidities (with the exception of smoking status and congestive heart failure). The postintervention group was slightly older (60 versus 57 years) and had a higher percentage of patients with an American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status score greater than 2 (66.8% versus 51.2%). The postintervention group also had higher rates of both malignancy (53.4% versus 33.3%) and inflammatory bowel disease (18.2% versus 14.4%).

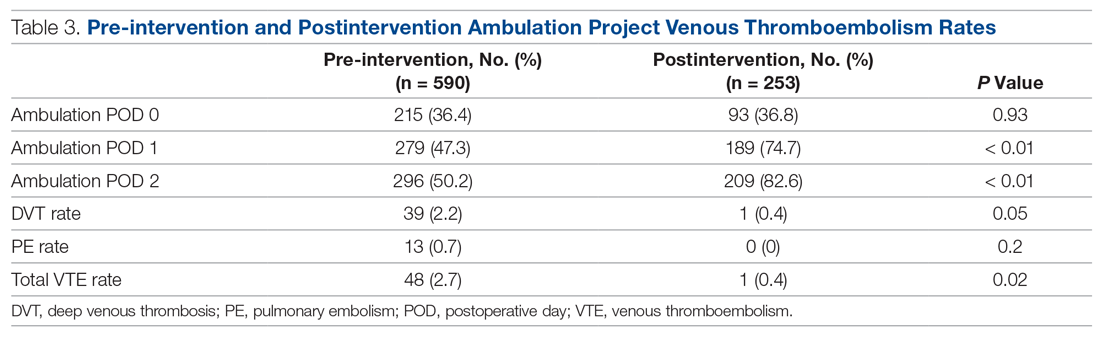

The fidelity of the PDSA cycle was measured by pre-intervention and postintervention ambulation rates. Ambulation rates on POD 0, 1, and 2 improved from 36.4%, 47.3%, and 50.2% to 36.8%, 74.7%, and 82.6%, respectively (Table 3). The VTE rate decreased from 2.7% to 0.4% (P = 0.02), with 1 DVT and 0 PEs. It should be noted that the only patient who developed a VTE postintervention did not ambulate on PODs 0, 1, or 2.

Discussion

Postoperative VTE is a severe complication for postoperative colorectal surgery patients. Previous studies have demonstrated that increasing ambulation is associated with a lower rate of overall complications, and, when incorporated into a bundle, is associated with decreased rates of VTE.11,15 However, this is the first study to our knowledge demonstrating that creation of an ambulation protocol alone is associated with a decrease in VTE.

Analysis of pre-intervention data demonstrated a strong association between ambulation and an absence of VTE. No patient who ambulated on PODs 0, 1, and 2 developed a VTE. Based on those results, we moved forward with creating the ambulation protocol. While ambulation stayed stable on POD 0, there were 60% and 65% increases on PODs 1 and 2, respectively. Nurses cited late arrival to the floor for second and third start cases as the primary difficulty in getting patients to ambulate more on POD 0.

We believe the key to the success of the ambulation protocol was its multidisciplinary nature. Certainly, the easiest way to create an ambulation protocol is to change the postoperative orders to state patients must walk 4 times per day. However, if the nursing staff is unable or unwilling to carry out these orders, the orders serve little purpose. In order to make lasting changes, all stakeholders in the process must be identified. In our case, stakeholders included surgery and nursing leadership, surgeons, nurse practitioners, nurses, medical assistants, physical therapists, patient care technicians, and patients. This is where we utilized kaizen, a core principle of Lean methodology that empowers employees at the level of the work being carried out to propose ideas for improvement.16 From the beginning of the patient experience, the health care practitioners who were carrying out each step of the process were best able to identify the problems and create solutions. In addition, stakeholders were given regular updates regarding how their efforts were increasing ambulation rates and the results at the end of the study period.

This study also demonstrates that, in a health care system increasingly focused on both quality and cost, significant improvements in quality can be made without increasing cost or resource utilization. Early in the process, it was proposed that the only way to increase the ambulation rate would be to increase the number of physical therapists, nurses, and nursing assistants. However, after identifying the root causes of the problem, the solutions had more to do with improving workflow and fixing problem areas identified by the staff.

In addition to having a positive effect on the outcome studied, collaborative projects such as this between physicians and nurses may lead to increased nursing job satisfaction. A meta-analysis of 31 studies identified nurse-physician collaboration and autonomy as 2 factors that correlate most strongly with nursing satisfaction.17 A Cochrane review also suggests that practice-based interprofessional collaboration may lead to improved health care processes and outcomes.18

This study has several limitations. Pre-intervention ambulation rates were abstracted from institution-specific NSQIP data, and missing data were excluded from analysis. Also, due to the retrospective collection of the pre-intervention data, the distance of ambulation could not be quantified. The bar for ambulation is low, as patients were only required to get out of bed and walk 1 step. However, we feel that getting out of bed and taking even 1 step is substantially better than complete bedrest. It is likely that once patients cross the threshold of taking 1 step, they are more likely to ambulate. An area of future study may be to more precisely define the relationship between the quantity of ambulation in steps and its effect on VTE. Finally, we acknowledge that while there is no direct increase in costs, implementing an ambulation protocol does take time from all who participate in the project.

Conclusion

Creation of an ambulation protocol is associated with a decrease in postoperative VTE rates in colorectal surgery patients. A multidisciplinary approach is critical to identify the underlying problems and propose effective solutions. Further studies are required to better correlate the distance of ambulation and its effect on VTE. However, this study shows that even a minimum of 1 step is associated with decreased VTE rates.

Corresponding author: Aneel Damle, MD, MBA, Colon & Rectal Surgery Associates, 3433 Broadway St. NE, Suite 115, Minneapolis, MN 55413; adamle@CRSAL.org.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Gangireddy C, Rectenwald JR, Upchurch GR, et al. Risk factors and clinical impact of postoperative symptomatic venous thromboembolism. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:341-342.

2. Newhook TE, LaPar DJ, Walters DM, et al. Impact of postoperative venous thromboembolism on postoperative morbidity, mortality, and resource utilization after hepatectomy. Am Surg. 2015;81:1216-1223.

3. Bergqvist D. Venous thromboembolism: a review of risk and prevention in colorectal surgery patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1620-1628.

4. Fleming F, Gaertner W, Ternent CA, et al. The American society of colon and rectal surgeons clinical practice guideline for the prevention of venous thromboembolic disease in colorectal surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2018;61:14-20.

5. McLeod RS, Geerts WH, Sniderman KW, et al. Canadian Colorectal Surgery DVT Prophylaxis Trial investigators. Subcutaneous heparin versus low-molecular-weight heparin as thromboprophylaxis in patients undergoing colorectal surgery: results of the Canadian colorectal DV prophylaxis trial: a randomized, double-blind trial. Ann Surg. 2001;233:438-444.

6. Shapiro R, Vogel JD, Kiran RP. Risk of postoperative venous thromboembolism after laparoscopic and open colorectal surgery: an additional benefit of the minimally invasive approach? Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:1496-1502.

7. Dimick JB, Chen SL, Taheri PA, et al. Hospital costs associated with surgical complications: a report from the private-sector National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199:531-537.

8. Fleming FJ, Kim MJ, Salloum RM, et al. How much do we need to worry about venous thromboembolism after hospital discharge? A study of colorectal surgery patients using the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53:1355-1360.

9. ACS NSQIP. User guide for the 2016 ACS NSQIP participant use data file (PUF). 2017. www.facs.org/~/media/files/quality%20programs/nsqip/nsqip_puf_userguide_2016.ashx Accessed July 10, 2020.

10. Caprini JA. Risk assessment as a guide for the prevention of the many faces of venous thromboembolism. Am J Surg. 2010;199(1 Suppl):S3-S10.

11. Cassidy MR, Rosenkranz P, McAney D. Reducing postoperative venous thromboembolism complications with a standardized risk-stratified prophylaxis protocol and mobilization protocol. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218:1095-1104.

12. Lau BD, Streiff MB, Kraus PS, et al. No evidence to support ambulation for reducing postoperative venous thromboembolism. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;219:1101-1103.

13. McNicholas C, Lennox L, Woodcock T, et al. Evolving quality improvement support strategies to improve Plan–Do–Study–Act cycle fidelity: a retrospective mixed-methods study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019;28:356-365.

14. Taylor MJ, McNicholas C, Nicolay C, et al. Systematic review of the application of the plan–do–study–act method to improve quality in healthcare. BMC Qual Saf. 2014;23:290-298.

15. Nevo Y, Shaltiel T, Constantini N, et al. Effect of ambulation and physical activity on postoperative complications. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;223(Suppl 1):S61.

16. Mazzocato P, Stenfors-Hayes T, von Thiele Schwarz U, et al. Kaizen practice in healthcare: a qualitative analysis of hospital employees’ suggestions for improvement. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e012256.

17. Zangaro GA, Soeken KL. A meta-analysis of studies of nurses’ job satisfaction. Res Nursing Health. 2007;30:445-458.

18. Reeves S, Pelone F, Harrison R, et al. Interprofessional collaboration to improve professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;6(6):CD000072.

From the Department of Surgery, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO.

Abstract

Background: Patients undergoing colorectal surgery are at high risk for postoperative venous thromboembolism (VTE). Early ambulation has been encouraged to lower rates of VTE, but evidence demonstrating its effectiveness outside of a bundle is limited.

Objective: To create a multidisciplinary ambulation protocol in an effort to reduce postoperative VTE.

Methods: A single-center, retrospective, comparative study of patients who underwent colectomy or proctectomy was conducted. Outcomes of patients operated on prior to protocol implementation were compared with a cohort after implementation. The intervention studied was the implementation of a multidisciplinary ambulation protocol. The primary endpoint was postoperative VTE.

Results: There was no difference between the pre-intervention group (n = 1762) and the postintervention group (n = 253) in terms of sex, race, origin, emergency status, operative time, and the majority of medical comorbidities (with the exception of smoking status and congestive heart failure). After the protocol was implemented, ambulation rates on postoperative days 0, 1, and 2 improved from 36.4%, 47.3%, and 50.2% to 36.8%, 74.7%, and 82.6%, respectively The VTE rate in the pre-intervention group was 2.7% versus a rate of 0.4% in the postintervention group (P = 0.02).

Conclusion: Creation of an ambulation protocol is associated with a significant reduction in VTE. Commitment from patients, families, nurses, physician extenders, and physicians is critical to the success of the program.

Keywords: VTE; pulmonary embolism; deep vein thrombosis; postoperative; quality improvement.

Postoperative venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a significant source of morbidity, mortality, and cost.1,2 Colorectal surgery patients are at particularly high risk for VTE due to positioning during surgery, pelvic dissection, and other conditions often found in these patients, such as cancer and inflammatory bowel disease.3 A National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) analysis demonstrated an overall rate of VTE in colorectal surgery patients of 2.4%, although other studies have demonstrated rates up to 9%, even in those receiving appropriate chemoprophylaxis.4-6 Many of these VTEs occur in the postdischarge setting. In a NSQIP study of colorectal surgery patients, the rate of VTE between discharge and 30 days was 0.47%.7 The cost burdenfor a postoperative VTE has been estimated to be more than $18,000.8

Studies from NSQIP have identified multiple factors associated with VTE in colorectal surgery patients, but NSQIP does not record ambulation as a standard variable.9 Multiple strategies have been implemented to reduce postoperative VTE. Often, these studies focus on increasing compliance with appropriate chemoprophylaxis, risk stratification, or bundling multiple strategies.10,11 However, despite the fact that postsurgical ambulation is widely encouraged and recommended by the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons clinical practice guidelines, there is little evidence demonstrating the role of ambulation alone in the reduction of VTE.4,12 The purpose of this study was to create a multidisciplinary protocol to increase postoperative ambulation and evaluate its effect on VTE.

Methods

Setting

This study was conducted at a single academic tertiary care center.

Patients and Outcome Measures

All patients undergoing colectomy or proctectomy by surgeons in the section of colon and rectal surgery at a single institution between January 2011 and March 2017 were included. Colectomy and proctectomy were defined by CPT codes 44140, 44141, 44143, 44144, 44145, 44146, 44147, 44150, 44151, 44155, 44156, 44157, 44158, 44160, 44204, 44205, 44206, 44207, 44208, 44210, 44211, 44212, 44213, 45110, 45111, 45112, 45113, 45114, 45116, 45119, 45120, 45121, 45123, 45126, 45160, 45395, and 45397. The primary outcome of VTE within 30 days, including deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), was measured using institution-specific data from NSQIP in both the pre-intervention and postintervention setting. The occurrence of both DVT and PE in 1 patient was counted as a single event of VTE. Ambulation rate on postoperative day (POD) 0, 1, and 2 was calculated by NSQIP in the pre-intervention setting (our institution-specific NSQIP recorded ambulation data for an unrelated project) and by review of the electronic health record in the postintervention setting, as this institution-specific variable was no longer being collected. Ambulation was defined as getting out of bed and taking at least 1 step. The threshold for ambulating each day was once on POD 0 and twice on PODs 1 and 2. Patients with missing ambulation data were excluded from the analysis. Both prior to and throughout the intervention, all patients were given VTE chemoprophylaxis with either low-dose unfractionated heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin prior to induction of anesthesia, with chemoprophylaxis extending an additional 21 days after discharge (unless specifically contraindicated); sequential compression devices; and standard orders to ambulate 3 times daily from POD 0 as part of the standard Enhanced Recovery After Surgery protocol.

Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using univariate analysis. Chi-square test and univariate logistic regression were used to determine the association between ambulation rates and VTE in the pre-intervention group. Chi-square test was also used to compare ambulation and VTE rates between the pre-intervention and postintervention groups. Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle fidelity (the degree to which a PDSA cycle is carried out in accordance with the guiding principles of its use) was measured by recording the ambulation rates both before and after the intervention.13 Statistical analysis was performed using SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). This study was reviewed by the Washington University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board and deemed to be quality improvement, not human subjects research, and therefore did not require formal approval.

Baseline Outcome Rates

A total of 1762 patients were identified during the pre-intervention period. The overall VTE rate in the pre-intervention group was 2.7% (n = 48), with 39 DVTs (2.2%) and 13 PEs (0.7%). Pre-intervention ambulation data were available on 590 patients. Baseline ambulation rates on PODs 0, 1, and 2 were 36.4% (213/590), 47.3% (279/590), and 50.2% (296/590), respectively. Patients who did not ambulate on POD 0 had a VTE rate of 4.3%, as compared to 0.9% in those who did ambulate (Table 1). Patients who did not ambulate twice on POD 1 had a VTE rate of 4.8%, compared to 1.1% in those who did ambulate (odds ratio [OR], 4.66; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.34 to 16.28). Patients who did not ambulate twice on POD 2 had a VTE rate of 5.4%, compared to 0.7% in those who did. Finally, those who ambulated twice on both PODs 1 and 2 had a 0% rate of VTE, compared to 4.9% in those who did not ambulate on both PODs.

Ambulation Protocol

After baseline outcome rates had been established, a multidisciplinary team of medical assistants, nurses, nurse practitioners, and physicians worked together to identify all processes that involved postoperative ambulation. Given the significant differences in VTE rates between patients who ambulated and those that did not, we created a multidisciplinary ambulation protocol using the PDSA method.14 Multiple points of patient contact were chosen for intervention, and the ambulation protocol was implemented in June 2018 and continued for 7 months.

Patients were observed from their initial office visit with a surgeon, during the preoperative education encounter, and in the operating room and on the surgical ward until discharge. Representatives from multiple disciplines who encountered patients at various times in the process, including medical assistants, patient care technicians, nurses, nurse practitioners, physical therapists, and physicians, participated in a kick-off meeting to identify difficulties they encounter when encouraging patient ambulation. The following 4 areas were identified.

Barriers to Patient Ambulation

Patient Expectations. Patients did not appear to have a clear expectation of what their ambulation goals were postoperatively, despite the fact that each patient is given an operative pathway booklet that includes their goals for each day, including ambulation. The consensus was that patients were overwhelmed with the amount of information and, oftentimes, the severity of their diagnosis, so the information regarding ambulation was not retained. Nurses commented that patients frequently stated that they did not think their surgeon wanted them to get out of bed postoperatively.

Electronic Orders. There was confusion within the nursing staff regarding orders in the electronic health record compared to physician expectations. Orders stated patients should ambulate 3 times daily, but did not specify on which postoperative day this should start. Often, nursing verbal sign-out from the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU) would be an order for bedrest, despite no clear origin of this order. This created confusion among the nursing staff as to what the appropriate ambulation orders should be.

Nursing Workflow. The initial state of the nursing workflow was not conducive to evaluating for, or assisting with, ambulation. With no set time to assist and evaluate patients for ambulation, it turned into a task nurses needed to accomplish when they had extra time. With increasing demands of charting in the electronic health record, nurses often had to skip ambulation in order to accomplish other tasks.

Family Expectations. In addition to patient expectations, family members often had expectations that were not congruent with the planned postoperative course. Nurses stated family members would often tell them that they did not feel that their family member should be ambulating so soon after surgery. Often these family members had not attended preoperative education sessions with the patient. This was compounded by the uncertainty among the nursing staff regarding what exactly the ambulation orders were.

Interventions

Targeted interventions were created to address these 4 barriers to ambulation identified by staff.

Preoperative Education. Although all elective patients received a printed operative pathway booklet describing daily goals, including ambulation, patients still did not have a sufficient understanding of what was expected of them. The education session was modified to increase the time spent on both the expectation for and the rationale behind ambulation. That section of the education session ended with a verbal commitment and read-back of the expectations for ambulation by the patient.

Clarification of Electronic Orders. Postoperative orders within the colorectal standard pathway were changed, including specific time frames and frequency, to match the information provided in the patient education booklet. These orders were for ambulation within 4 hours of arrival to the floor, and the orders also noted that no patient should be on bedrest unless explicitly stated. From POD 1, all patients were to ambulate at least twice daily for the remainder of the hospital stay (patients were encouraged to walk 4 times daily, but we set a minimum expectation of twice daily for the order set). These orders were clarified with in-person meetings with the nursing staff and leadership from the PACU and the colorectal surgical ward.

Adjusted Nursing Workflow. Nurses were interviewed and asked to create a plan regarding how they could better incorporate ambulation into their daily workflow. Ambulation assessment was incorporated into the twice-per-shift recording of vital signs and patient safety assessment. This was recorded into the electronic health record at the same time as the patients’ vital signs. This allowed nurses to keep track of which patients would need extra assistance in ambulation and which patients were doing well on their own with the assistance of family. It also helped focus the resources of physical therapy and the single ambulation technician on the floor and to assist patients who needed more assistance.

Creation of Ambulation Encouragement Signs. The authors discovered that despite patients being told preoperatively about ambulation expectations, friends and family are not always included in these conversations. As nurses frequently cited both patients and family as reasons patients thought they should not walk, multiple signs inviting patients to take an active role in their recovery by ambulating were created and placed around the unit. The signs outlined the expectations of being out of bed and taking at least 1 step on the day of surgery and walking at least 4 times per day thereafter. In addition, we addressed frequently asked questions around issues such as walking with intravenous poles and urinary catheters. The posters were signed by all staff colorectal surgeons.

Results

Over the course of 7 months (June 2018 to December 2018), 253 postintervention patients were identified (Table 2). There was no difference between the pre-intervention group (n = 1762) and the postintervention group in terms of sex, race, origin, emergency status, operative time, and the majority of medical comorbidities (with the exception of smoking status and congestive heart failure). The postintervention group was slightly older (60 versus 57 years) and had a higher percentage of patients with an American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status score greater than 2 (66.8% versus 51.2%). The postintervention group also had higher rates of both malignancy (53.4% versus 33.3%) and inflammatory bowel disease (18.2% versus 14.4%).

The fidelity of the PDSA cycle was measured by pre-intervention and postintervention ambulation rates. Ambulation rates on POD 0, 1, and 2 improved from 36.4%, 47.3%, and 50.2% to 36.8%, 74.7%, and 82.6%, respectively (Table 3). The VTE rate decreased from 2.7% to 0.4% (P = 0.02), with 1 DVT and 0 PEs. It should be noted that the only patient who developed a VTE postintervention did not ambulate on PODs 0, 1, or 2.

Discussion

Postoperative VTE is a severe complication for postoperative colorectal surgery patients. Previous studies have demonstrated that increasing ambulation is associated with a lower rate of overall complications, and, when incorporated into a bundle, is associated with decreased rates of VTE.11,15 However, this is the first study to our knowledge demonstrating that creation of an ambulation protocol alone is associated with a decrease in VTE.

Analysis of pre-intervention data demonstrated a strong association between ambulation and an absence of VTE. No patient who ambulated on PODs 0, 1, and 2 developed a VTE. Based on those results, we moved forward with creating the ambulation protocol. While ambulation stayed stable on POD 0, there were 60% and 65% increases on PODs 1 and 2, respectively. Nurses cited late arrival to the floor for second and third start cases as the primary difficulty in getting patients to ambulate more on POD 0.

We believe the key to the success of the ambulation protocol was its multidisciplinary nature. Certainly, the easiest way to create an ambulation protocol is to change the postoperative orders to state patients must walk 4 times per day. However, if the nursing staff is unable or unwilling to carry out these orders, the orders serve little purpose. In order to make lasting changes, all stakeholders in the process must be identified. In our case, stakeholders included surgery and nursing leadership, surgeons, nurse practitioners, nurses, medical assistants, physical therapists, patient care technicians, and patients. This is where we utilized kaizen, a core principle of Lean methodology that empowers employees at the level of the work being carried out to propose ideas for improvement.16 From the beginning of the patient experience, the health care practitioners who were carrying out each step of the process were best able to identify the problems and create solutions. In addition, stakeholders were given regular updates regarding how their efforts were increasing ambulation rates and the results at the end of the study period.

This study also demonstrates that, in a health care system increasingly focused on both quality and cost, significant improvements in quality can be made without increasing cost or resource utilization. Early in the process, it was proposed that the only way to increase the ambulation rate would be to increase the number of physical therapists, nurses, and nursing assistants. However, after identifying the root causes of the problem, the solutions had more to do with improving workflow and fixing problem areas identified by the staff.

In addition to having a positive effect on the outcome studied, collaborative projects such as this between physicians and nurses may lead to increased nursing job satisfaction. A meta-analysis of 31 studies identified nurse-physician collaboration and autonomy as 2 factors that correlate most strongly with nursing satisfaction.17 A Cochrane review also suggests that practice-based interprofessional collaboration may lead to improved health care processes and outcomes.18

This study has several limitations. Pre-intervention ambulation rates were abstracted from institution-specific NSQIP data, and missing data were excluded from analysis. Also, due to the retrospective collection of the pre-intervention data, the distance of ambulation could not be quantified. The bar for ambulation is low, as patients were only required to get out of bed and walk 1 step. However, we feel that getting out of bed and taking even 1 step is substantially better than complete bedrest. It is likely that once patients cross the threshold of taking 1 step, they are more likely to ambulate. An area of future study may be to more precisely define the relationship between the quantity of ambulation in steps and its effect on VTE. Finally, we acknowledge that while there is no direct increase in costs, implementing an ambulation protocol does take time from all who participate in the project.

Conclusion

Creation of an ambulation protocol is associated with a decrease in postoperative VTE rates in colorectal surgery patients. A multidisciplinary approach is critical to identify the underlying problems and propose effective solutions. Further studies are required to better correlate the distance of ambulation and its effect on VTE. However, this study shows that even a minimum of 1 step is associated with decreased VTE rates.

Corresponding author: Aneel Damle, MD, MBA, Colon & Rectal Surgery Associates, 3433 Broadway St. NE, Suite 115, Minneapolis, MN 55413; adamle@CRSAL.org.

Financial disclosures: None.

From the Department of Surgery, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO.

Abstract

Background: Patients undergoing colorectal surgery are at high risk for postoperative venous thromboembolism (VTE). Early ambulation has been encouraged to lower rates of VTE, but evidence demonstrating its effectiveness outside of a bundle is limited.

Objective: To create a multidisciplinary ambulation protocol in an effort to reduce postoperative VTE.

Methods: A single-center, retrospective, comparative study of patients who underwent colectomy or proctectomy was conducted. Outcomes of patients operated on prior to protocol implementation were compared with a cohort after implementation. The intervention studied was the implementation of a multidisciplinary ambulation protocol. The primary endpoint was postoperative VTE.

Results: There was no difference between the pre-intervention group (n = 1762) and the postintervention group (n = 253) in terms of sex, race, origin, emergency status, operative time, and the majority of medical comorbidities (with the exception of smoking status and congestive heart failure). After the protocol was implemented, ambulation rates on postoperative days 0, 1, and 2 improved from 36.4%, 47.3%, and 50.2% to 36.8%, 74.7%, and 82.6%, respectively The VTE rate in the pre-intervention group was 2.7% versus a rate of 0.4% in the postintervention group (P = 0.02).

Conclusion: Creation of an ambulation protocol is associated with a significant reduction in VTE. Commitment from patients, families, nurses, physician extenders, and physicians is critical to the success of the program.

Keywords: VTE; pulmonary embolism; deep vein thrombosis; postoperative; quality improvement.

Postoperative venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a significant source of morbidity, mortality, and cost.1,2 Colorectal surgery patients are at particularly high risk for VTE due to positioning during surgery, pelvic dissection, and other conditions often found in these patients, such as cancer and inflammatory bowel disease.3 A National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) analysis demonstrated an overall rate of VTE in colorectal surgery patients of 2.4%, although other studies have demonstrated rates up to 9%, even in those receiving appropriate chemoprophylaxis.4-6 Many of these VTEs occur in the postdischarge setting. In a NSQIP study of colorectal surgery patients, the rate of VTE between discharge and 30 days was 0.47%.7 The cost burdenfor a postoperative VTE has been estimated to be more than $18,000.8

Studies from NSQIP have identified multiple factors associated with VTE in colorectal surgery patients, but NSQIP does not record ambulation as a standard variable.9 Multiple strategies have been implemented to reduce postoperative VTE. Often, these studies focus on increasing compliance with appropriate chemoprophylaxis, risk stratification, or bundling multiple strategies.10,11 However, despite the fact that postsurgical ambulation is widely encouraged and recommended by the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons clinical practice guidelines, there is little evidence demonstrating the role of ambulation alone in the reduction of VTE.4,12 The purpose of this study was to create a multidisciplinary protocol to increase postoperative ambulation and evaluate its effect on VTE.

Methods

Setting

This study was conducted at a single academic tertiary care center.

Patients and Outcome Measures

All patients undergoing colectomy or proctectomy by surgeons in the section of colon and rectal surgery at a single institution between January 2011 and March 2017 were included. Colectomy and proctectomy were defined by CPT codes 44140, 44141, 44143, 44144, 44145, 44146, 44147, 44150, 44151, 44155, 44156, 44157, 44158, 44160, 44204, 44205, 44206, 44207, 44208, 44210, 44211, 44212, 44213, 45110, 45111, 45112, 45113, 45114, 45116, 45119, 45120, 45121, 45123, 45126, 45160, 45395, and 45397. The primary outcome of VTE within 30 days, including deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), was measured using institution-specific data from NSQIP in both the pre-intervention and postintervention setting. The occurrence of both DVT and PE in 1 patient was counted as a single event of VTE. Ambulation rate on postoperative day (POD) 0, 1, and 2 was calculated by NSQIP in the pre-intervention setting (our institution-specific NSQIP recorded ambulation data for an unrelated project) and by review of the electronic health record in the postintervention setting, as this institution-specific variable was no longer being collected. Ambulation was defined as getting out of bed and taking at least 1 step. The threshold for ambulating each day was once on POD 0 and twice on PODs 1 and 2. Patients with missing ambulation data were excluded from the analysis. Both prior to and throughout the intervention, all patients were given VTE chemoprophylaxis with either low-dose unfractionated heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin prior to induction of anesthesia, with chemoprophylaxis extending an additional 21 days after discharge (unless specifically contraindicated); sequential compression devices; and standard orders to ambulate 3 times daily from POD 0 as part of the standard Enhanced Recovery After Surgery protocol.

Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using univariate analysis. Chi-square test and univariate logistic regression were used to determine the association between ambulation rates and VTE in the pre-intervention group. Chi-square test was also used to compare ambulation and VTE rates between the pre-intervention and postintervention groups. Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle fidelity (the degree to which a PDSA cycle is carried out in accordance with the guiding principles of its use) was measured by recording the ambulation rates both before and after the intervention.13 Statistical analysis was performed using SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). This study was reviewed by the Washington University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board and deemed to be quality improvement, not human subjects research, and therefore did not require formal approval.

Baseline Outcome Rates

A total of 1762 patients were identified during the pre-intervention period. The overall VTE rate in the pre-intervention group was 2.7% (n = 48), with 39 DVTs (2.2%) and 13 PEs (0.7%). Pre-intervention ambulation data were available on 590 patients. Baseline ambulation rates on PODs 0, 1, and 2 were 36.4% (213/590), 47.3% (279/590), and 50.2% (296/590), respectively. Patients who did not ambulate on POD 0 had a VTE rate of 4.3%, as compared to 0.9% in those who did ambulate (Table 1). Patients who did not ambulate twice on POD 1 had a VTE rate of 4.8%, compared to 1.1% in those who did ambulate (odds ratio [OR], 4.66; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.34 to 16.28). Patients who did not ambulate twice on POD 2 had a VTE rate of 5.4%, compared to 0.7% in those who did. Finally, those who ambulated twice on both PODs 1 and 2 had a 0% rate of VTE, compared to 4.9% in those who did not ambulate on both PODs.

Ambulation Protocol

After baseline outcome rates had been established, a multidisciplinary team of medical assistants, nurses, nurse practitioners, and physicians worked together to identify all processes that involved postoperative ambulation. Given the significant differences in VTE rates between patients who ambulated and those that did not, we created a multidisciplinary ambulation protocol using the PDSA method.14 Multiple points of patient contact were chosen for intervention, and the ambulation protocol was implemented in June 2018 and continued for 7 months.

Patients were observed from their initial office visit with a surgeon, during the preoperative education encounter, and in the operating room and on the surgical ward until discharge. Representatives from multiple disciplines who encountered patients at various times in the process, including medical assistants, patient care technicians, nurses, nurse practitioners, physical therapists, and physicians, participated in a kick-off meeting to identify difficulties they encounter when encouraging patient ambulation. The following 4 areas were identified.

Barriers to Patient Ambulation

Patient Expectations. Patients did not appear to have a clear expectation of what their ambulation goals were postoperatively, despite the fact that each patient is given an operative pathway booklet that includes their goals for each day, including ambulation. The consensus was that patients were overwhelmed with the amount of information and, oftentimes, the severity of their diagnosis, so the information regarding ambulation was not retained. Nurses commented that patients frequently stated that they did not think their surgeon wanted them to get out of bed postoperatively.

Electronic Orders. There was confusion within the nursing staff regarding orders in the electronic health record compared to physician expectations. Orders stated patients should ambulate 3 times daily, but did not specify on which postoperative day this should start. Often, nursing verbal sign-out from the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU) would be an order for bedrest, despite no clear origin of this order. This created confusion among the nursing staff as to what the appropriate ambulation orders should be.

Nursing Workflow. The initial state of the nursing workflow was not conducive to evaluating for, or assisting with, ambulation. With no set time to assist and evaluate patients for ambulation, it turned into a task nurses needed to accomplish when they had extra time. With increasing demands of charting in the electronic health record, nurses often had to skip ambulation in order to accomplish other tasks.

Family Expectations. In addition to patient expectations, family members often had expectations that were not congruent with the planned postoperative course. Nurses stated family members would often tell them that they did not feel that their family member should be ambulating so soon after surgery. Often these family members had not attended preoperative education sessions with the patient. This was compounded by the uncertainty among the nursing staff regarding what exactly the ambulation orders were.

Interventions

Targeted interventions were created to address these 4 barriers to ambulation identified by staff.

Preoperative Education. Although all elective patients received a printed operative pathway booklet describing daily goals, including ambulation, patients still did not have a sufficient understanding of what was expected of them. The education session was modified to increase the time spent on both the expectation for and the rationale behind ambulation. That section of the education session ended with a verbal commitment and read-back of the expectations for ambulation by the patient.

Clarification of Electronic Orders. Postoperative orders within the colorectal standard pathway were changed, including specific time frames and frequency, to match the information provided in the patient education booklet. These orders were for ambulation within 4 hours of arrival to the floor, and the orders also noted that no patient should be on bedrest unless explicitly stated. From POD 1, all patients were to ambulate at least twice daily for the remainder of the hospital stay (patients were encouraged to walk 4 times daily, but we set a minimum expectation of twice daily for the order set). These orders were clarified with in-person meetings with the nursing staff and leadership from the PACU and the colorectal surgical ward.

Adjusted Nursing Workflow. Nurses were interviewed and asked to create a plan regarding how they could better incorporate ambulation into their daily workflow. Ambulation assessment was incorporated into the twice-per-shift recording of vital signs and patient safety assessment. This was recorded into the electronic health record at the same time as the patients’ vital signs. This allowed nurses to keep track of which patients would need extra assistance in ambulation and which patients were doing well on their own with the assistance of family. It also helped focus the resources of physical therapy and the single ambulation technician on the floor and to assist patients who needed more assistance.

Creation of Ambulation Encouragement Signs. The authors discovered that despite patients being told preoperatively about ambulation expectations, friends and family are not always included in these conversations. As nurses frequently cited both patients and family as reasons patients thought they should not walk, multiple signs inviting patients to take an active role in their recovery by ambulating were created and placed around the unit. The signs outlined the expectations of being out of bed and taking at least 1 step on the day of surgery and walking at least 4 times per day thereafter. In addition, we addressed frequently asked questions around issues such as walking with intravenous poles and urinary catheters. The posters were signed by all staff colorectal surgeons.

Results

Over the course of 7 months (June 2018 to December 2018), 253 postintervention patients were identified (Table 2). There was no difference between the pre-intervention group (n = 1762) and the postintervention group in terms of sex, race, origin, emergency status, operative time, and the majority of medical comorbidities (with the exception of smoking status and congestive heart failure). The postintervention group was slightly older (60 versus 57 years) and had a higher percentage of patients with an American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status score greater than 2 (66.8% versus 51.2%). The postintervention group also had higher rates of both malignancy (53.4% versus 33.3%) and inflammatory bowel disease (18.2% versus 14.4%).

The fidelity of the PDSA cycle was measured by pre-intervention and postintervention ambulation rates. Ambulation rates on POD 0, 1, and 2 improved from 36.4%, 47.3%, and 50.2% to 36.8%, 74.7%, and 82.6%, respectively (Table 3). The VTE rate decreased from 2.7% to 0.4% (P = 0.02), with 1 DVT and 0 PEs. It should be noted that the only patient who developed a VTE postintervention did not ambulate on PODs 0, 1, or 2.

Discussion

Postoperative VTE is a severe complication for postoperative colorectal surgery patients. Previous studies have demonstrated that increasing ambulation is associated with a lower rate of overall complications, and, when incorporated into a bundle, is associated with decreased rates of VTE.11,15 However, this is the first study to our knowledge demonstrating that creation of an ambulation protocol alone is associated with a decrease in VTE.

Analysis of pre-intervention data demonstrated a strong association between ambulation and an absence of VTE. No patient who ambulated on PODs 0, 1, and 2 developed a VTE. Based on those results, we moved forward with creating the ambulation protocol. While ambulation stayed stable on POD 0, there were 60% and 65% increases on PODs 1 and 2, respectively. Nurses cited late arrival to the floor for second and third start cases as the primary difficulty in getting patients to ambulate more on POD 0.

We believe the key to the success of the ambulation protocol was its multidisciplinary nature. Certainly, the easiest way to create an ambulation protocol is to change the postoperative orders to state patients must walk 4 times per day. However, if the nursing staff is unable or unwilling to carry out these orders, the orders serve little purpose. In order to make lasting changes, all stakeholders in the process must be identified. In our case, stakeholders included surgery and nursing leadership, surgeons, nurse practitioners, nurses, medical assistants, physical therapists, patient care technicians, and patients. This is where we utilized kaizen, a core principle of Lean methodology that empowers employees at the level of the work being carried out to propose ideas for improvement.16 From the beginning of the patient experience, the health care practitioners who were carrying out each step of the process were best able to identify the problems and create solutions. In addition, stakeholders were given regular updates regarding how their efforts were increasing ambulation rates and the results at the end of the study period.

This study also demonstrates that, in a health care system increasingly focused on both quality and cost, significant improvements in quality can be made without increasing cost or resource utilization. Early in the process, it was proposed that the only way to increase the ambulation rate would be to increase the number of physical therapists, nurses, and nursing assistants. However, after identifying the root causes of the problem, the solutions had more to do with improving workflow and fixing problem areas identified by the staff.