User login

Circadian rhythm changes linked to future Parkinson’s disease risk

a new study suggests. “We found that men with abnormal circadian rhythms had three times the risk of developing Parkinson’s disease over an 11-year follow-up period,” lead author, Yue Leng, MD, University of California, San Francisco, said in an interview.

“If confirmed to be a risk factor for Parkinson’s disease, then circadian rhythmicity could be a promising intervention target and will open new opportunities for the prevention and management of Parkinson’s disease,” the researchers concluded.

The study was published online in JAMA Neurology on June 15.

Circadian disruption is very common in neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s disease, but there isn’t much information on how it may predict the disease, Dr. Leng explained. “We wanted to see whether circadian abnormalities may predict Parkinson’s disease,” she said. “Parkinson’s disease has a long prodromal phase where brain changes have started to occur but no clinical symptoms have become evident. It would be useful to be able to identify these patients, and maybe changes in circadian rhythms may help us to do that,” she added.

For the study, the researchers analyzed data from 2,930 community-dwelling men aged 65 years or older (mean age, 76 years) who participated in the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study, in which they underwent comprehensive sleep and rest-activity rhythms assessment. “Patterns of rest and activity were measured with an actigraph device, which is worn on the wrist like a watch and captures movements which are translated into a rest-activity rhythm model – one of the most commonly used and evidence-based measures of circadian rhythm,” Dr. Leng said. Men were asked to wear the actigraphs continuously for a minimum of three 24-hour periods.

Results showed that 78 men (2.7%) developed Parkinson’s disease during the 11-year follow-up. After accounting for all covariates, the risk of Parkinson’s disease increased with decreasing circadian amplitude (strength of the rhythm) with an odds ratio of 1.77 per each decrease by one standard deviation; mesor (mean level of activity) with an odds ratio of 1.64; or robustness (how closely activity follows a 24-hour pattern) with an odds ratio of 1.54.

Those in the lowest quartile of amplitude, mesor, or robustness had approximately three times the risk of developing Parkinson’s disease compared with those in the highest quartile of amplitude. The association remained after further adjustment for nighttime sleep disturbances.

“It has previously been shown that daytime napping has been linked to risk of developing Parkinson’s disease. Now we have shown that abnormalities in the overall 24-hour circadian rest activity rhythm are also present in the prodromal phase of Parkinson’s disease, and this association was independent of several confounders, including nighttime sleep disturbances,” Dr. Leng said.

“This raises awareness of the importance of circadian rhythm in older individuals and changes in their 24-hour pattern of behavior could be an early signal of Parkinson’s disease,” she said.

“This study does not tell us whether these circadian changes are causal for Parkinson’s or not,” Dr. Leng noted.

Future studies are needed to explore underlying mechanisms and to determine whether circadian disruption itself might contribute to the development of Parkinson’s disease, the researchers said.

“If there is a causal link, then using techniques to improve circadian rhythm could help to prevent or slow the onset of Parkinson’s disease,” Dr. Leng suggested. There are many established therapies that act on circadian rhythm including bright light therapy, melatonin, and chronotherapy, she added.

Support for this study was provided by the National Institute on Aging (NIA); the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases; the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; and the Weill Pilot Award. Dr. Leng reported grants from the NIA and the University of California, San Francisco, Weill Institute for Neurosciences during the conduct of the study; and grants from Global Brain Health Institute, the Alzheimer’s Association, and the Alzheimer’s Society outside the submitted work.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

a new study suggests. “We found that men with abnormal circadian rhythms had three times the risk of developing Parkinson’s disease over an 11-year follow-up period,” lead author, Yue Leng, MD, University of California, San Francisco, said in an interview.

“If confirmed to be a risk factor for Parkinson’s disease, then circadian rhythmicity could be a promising intervention target and will open new opportunities for the prevention and management of Parkinson’s disease,” the researchers concluded.

The study was published online in JAMA Neurology on June 15.

Circadian disruption is very common in neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s disease, but there isn’t much information on how it may predict the disease, Dr. Leng explained. “We wanted to see whether circadian abnormalities may predict Parkinson’s disease,” she said. “Parkinson’s disease has a long prodromal phase where brain changes have started to occur but no clinical symptoms have become evident. It would be useful to be able to identify these patients, and maybe changes in circadian rhythms may help us to do that,” she added.

For the study, the researchers analyzed data from 2,930 community-dwelling men aged 65 years or older (mean age, 76 years) who participated in the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study, in which they underwent comprehensive sleep and rest-activity rhythms assessment. “Patterns of rest and activity were measured with an actigraph device, which is worn on the wrist like a watch and captures movements which are translated into a rest-activity rhythm model – one of the most commonly used and evidence-based measures of circadian rhythm,” Dr. Leng said. Men were asked to wear the actigraphs continuously for a minimum of three 24-hour periods.

Results showed that 78 men (2.7%) developed Parkinson’s disease during the 11-year follow-up. After accounting for all covariates, the risk of Parkinson’s disease increased with decreasing circadian amplitude (strength of the rhythm) with an odds ratio of 1.77 per each decrease by one standard deviation; mesor (mean level of activity) with an odds ratio of 1.64; or robustness (how closely activity follows a 24-hour pattern) with an odds ratio of 1.54.

Those in the lowest quartile of amplitude, mesor, or robustness had approximately three times the risk of developing Parkinson’s disease compared with those in the highest quartile of amplitude. The association remained after further adjustment for nighttime sleep disturbances.

“It has previously been shown that daytime napping has been linked to risk of developing Parkinson’s disease. Now we have shown that abnormalities in the overall 24-hour circadian rest activity rhythm are also present in the prodromal phase of Parkinson’s disease, and this association was independent of several confounders, including nighttime sleep disturbances,” Dr. Leng said.

“This raises awareness of the importance of circadian rhythm in older individuals and changes in their 24-hour pattern of behavior could be an early signal of Parkinson’s disease,” she said.

“This study does not tell us whether these circadian changes are causal for Parkinson’s or not,” Dr. Leng noted.

Future studies are needed to explore underlying mechanisms and to determine whether circadian disruption itself might contribute to the development of Parkinson’s disease, the researchers said.

“If there is a causal link, then using techniques to improve circadian rhythm could help to prevent or slow the onset of Parkinson’s disease,” Dr. Leng suggested. There are many established therapies that act on circadian rhythm including bright light therapy, melatonin, and chronotherapy, she added.

Support for this study was provided by the National Institute on Aging (NIA); the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases; the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; and the Weill Pilot Award. Dr. Leng reported grants from the NIA and the University of California, San Francisco, Weill Institute for Neurosciences during the conduct of the study; and grants from Global Brain Health Institute, the Alzheimer’s Association, and the Alzheimer’s Society outside the submitted work.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

a new study suggests. “We found that men with abnormal circadian rhythms had three times the risk of developing Parkinson’s disease over an 11-year follow-up period,” lead author, Yue Leng, MD, University of California, San Francisco, said in an interview.

“If confirmed to be a risk factor for Parkinson’s disease, then circadian rhythmicity could be a promising intervention target and will open new opportunities for the prevention and management of Parkinson’s disease,” the researchers concluded.

The study was published online in JAMA Neurology on June 15.

Circadian disruption is very common in neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s disease, but there isn’t much information on how it may predict the disease, Dr. Leng explained. “We wanted to see whether circadian abnormalities may predict Parkinson’s disease,” she said. “Parkinson’s disease has a long prodromal phase where brain changes have started to occur but no clinical symptoms have become evident. It would be useful to be able to identify these patients, and maybe changes in circadian rhythms may help us to do that,” she added.

For the study, the researchers analyzed data from 2,930 community-dwelling men aged 65 years or older (mean age, 76 years) who participated in the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study, in which they underwent comprehensive sleep and rest-activity rhythms assessment. “Patterns of rest and activity were measured with an actigraph device, which is worn on the wrist like a watch and captures movements which are translated into a rest-activity rhythm model – one of the most commonly used and evidence-based measures of circadian rhythm,” Dr. Leng said. Men were asked to wear the actigraphs continuously for a minimum of three 24-hour periods.

Results showed that 78 men (2.7%) developed Parkinson’s disease during the 11-year follow-up. After accounting for all covariates, the risk of Parkinson’s disease increased with decreasing circadian amplitude (strength of the rhythm) with an odds ratio of 1.77 per each decrease by one standard deviation; mesor (mean level of activity) with an odds ratio of 1.64; or robustness (how closely activity follows a 24-hour pattern) with an odds ratio of 1.54.

Those in the lowest quartile of amplitude, mesor, or robustness had approximately three times the risk of developing Parkinson’s disease compared with those in the highest quartile of amplitude. The association remained after further adjustment for nighttime sleep disturbances.

“It has previously been shown that daytime napping has been linked to risk of developing Parkinson’s disease. Now we have shown that abnormalities in the overall 24-hour circadian rest activity rhythm are also present in the prodromal phase of Parkinson’s disease, and this association was independent of several confounders, including nighttime sleep disturbances,” Dr. Leng said.

“This raises awareness of the importance of circadian rhythm in older individuals and changes in their 24-hour pattern of behavior could be an early signal of Parkinson’s disease,” she said.

“This study does not tell us whether these circadian changes are causal for Parkinson’s or not,” Dr. Leng noted.

Future studies are needed to explore underlying mechanisms and to determine whether circadian disruption itself might contribute to the development of Parkinson’s disease, the researchers said.

“If there is a causal link, then using techniques to improve circadian rhythm could help to prevent or slow the onset of Parkinson’s disease,” Dr. Leng suggested. There are many established therapies that act on circadian rhythm including bright light therapy, melatonin, and chronotherapy, she added.

Support for this study was provided by the National Institute on Aging (NIA); the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases; the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; and the Weill Pilot Award. Dr. Leng reported grants from the NIA and the University of California, San Francisco, Weill Institute for Neurosciences during the conduct of the study; and grants from Global Brain Health Institute, the Alzheimer’s Association, and the Alzheimer’s Society outside the submitted work.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

Management of race in psychotherapy and supervision

On the Friday evening after the public execution of George Floyd, we were painfully reminded of the urgency to address the inadequate management of race, racism, and anti-blackness in medical education, residency training, and postgraduate continuing medical education.

The reminder did not originate from the rioting that was occurring in some cities, though we could feel the ground shifting beneath our feet as civic protests that began in U.S. cities spread around the globe. Instead, it occurred during a webinar we were hosting for psychiatry residents focused on techniques for eliminating blind spots in the management of race in clinical psychotherapy supervision. (Dr. Jessica Isom chaired the webinar, Dr. Flavia DeSouza and Dr. Myra Mathis comoderated, and Dr. Ebony Dennis and Dr. Constance E. Dunlap served as discussants.)

Our panel had presented an ambitious agenda that included reviewing how the disavowal of bias, race, racism, and anti-blackness contributes to ineffective psychotherapy, undermines the quality of medical care, and perpetuates mental health disparities. We spent some time exploring how unacknowledged and unexamined conscious and unconscious racial stereotypes affect interpersonal relationships, the psychotherapeutic process, and the supervisory experience. Our presentation included a clinical vignette demonstrating how racism, colorism, and anti-blackness have global impact, influencing the self-esteem, identity formation, and identity consolidation of immigrants as they grapple with the unique form of racism that exists in America. Other clinical vignettes demonstrated blind spots that were retroactively identified though omitted in supervisory discussions. We also discussed alternative interventions and interpretations of the material presented.1-5

Because 21st-century trainees are generally psychologically astute and committed to social justice, we did two things. First, before the webinar, we provided them access to a prerecorded explanation of object relations theorist Melanie Klein’s paranoid-schizoid and depressive positions concepts, which were applied to theoretically explain the development of race, specifically the defenses used by early colonists that contributed to the development of “whiteness” and “blackness” as social constructs, and their influence on the development of the U.S. psyche. For example, as early colonists attempted to develop new and improved identities distinct from those they had in their homelands, they used enslaved black people (and other vulnerable groups) to “other.” What we mean here by othering is the process of using an other to project one’s badness into in order to relieve the self of uncomfortable aspects and feelings originating within the self. If this other accepts the projection (which is often the case with vulnerable parties), the self recognizes, that is, identifies (locates) the bad they just projected in the other, who is now experienced as a bad-other. This is projection in action. If the other accepts the projection and behaves accordingly, for example, in a manner that reflects badness, this becomes projective identification. Conversely, if the other does not accept these projections, the self (who projects) is left to cope with aspects of the self s/he might not have the capacity to manage. By capacity, we are speaking of the Bionian idea of the ability to experience an extreme emotion while also being able to think. Without the ego strength to cope with bad aspects of the self, the ego either collapses (and is unable to think) or further projection is attempted.6-8

We have seen this latter dynamic play out repeatedly when police officers fatally shoot black citizens and then claim that they feared for their lives; these same officers have been exonerated by juries by continuing to portray the deceased victims as threatening, dangerous objects not worthy of living. We are also seeing a global movement of black and nonblack people who are in touch with a justified rage that has motivated them to return these projections by collectively protesting, and in some cases, by rioting.

Back to the webinar

In anticipating the residents’ curiosity, impatience, and anger about the lack of progress, the second thing we did was to show a segment from the “Black Psychoanalysts Speak” trailer. In the clip played, senior psychoanalyst Kirkland C. Vaughans, PhD, shares: “The issue of race so prompts excessive anxiety that it blocks off our ability to think.”

We showed this clip to validate the trainees’ frustrations about the difficulty the broader establishment has had with addressing this serious, longstanding public health problem. We wanted these young psychiatrists to know that there are psychoanalysts, psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers who have been committed to this work, even though the contributions of this diverse group have curiously been omitted from education and training curricula.9

So, what happened? What was the painful reminder? After the formal panel presentations, a black male psychiatry resident recounted his experience in a clinical supervision meeting that had occurred several days after the murder of George Floyd. In short, a patient had shared his reactions to yet another incident of fatal police use of force and paused to ask how the resident physician, Dr. A., was doing. The question was experienced as sincere concern about the psychiatrist’s mental well-being. The resident was not sure how to answer this question since it was a matter of self-disclosure, which was a reasonable and thoughtful consideration for a seasoned clinician and, certainly, for a novice therapist. The supervisor, Dr. B., seemingly eager to move on, to not think about this, responded to the resident by saying: “Now tell me about the patient.” In other words, what had just been shared by the resident – material that featured a patient’s reaction to another killing of a black man by police and the patient’s expressed concern for his black psychiatrist, and this resident physician appropriately seeking space in supervision to process and receive guidance about how to respond – all of this was considered separate (split off from) and extraneous to the patient’s treatment and the resident’s training. This is a problem. And, unfortunately, this problem or some variation of it is not rare.

Why is this still the state of affairs when we have identified racism as a major health concern and our patients and our trainees are asking for help?

Rethinking a metaphor

Despite calls to action over the last 50 years to encourage medicine to effectively address race and racism, deficits remain in didactic education, clinical rotations, and supervisory experiences of trainees learning how to do psychodynamic psychotherapy.8-10 Earlier that evening, we used the metaphor of a vehicular blind spot to capture what we believe occurs insupervision. Like drivers, supervisors generally have the ability to see. However, there are places (times) and positions (stances) that block their vision (awareness). Racism – whether institutionalized, interpersonally mediated, or internalized – also contributes to this blindness.

As is true of drivers managing a blind spot, what is required is for the drivers – the supervisors – to lean forward or reposition themselves so as to avoid collisions, maintain safety, and continue on course. We use this metaphor because it is understood that any clinician providing psychodynamic supervision to psychiatry residents, regardless of professional discipline, has the requisite skills and training.10-13

Until May 25, we thought eliminating blind spots would be effective. But, in the aftermath of the police killing of George Floyd, our eyes have been opened.

Hiding behind the blue wall of silence is an establishment that has looked the other way while black and brown women, men, and children have come to live in fear as a result of the state-sanctioned violence that repeatedly occurs across the nation. Excessive police use of force is a public health issue of crisis magnitude. However, the house of medicine, like many other established structures in society, has colluded with the societal constructs that have supported law enforcement by remaining willfully blind, often neutral, and by refusing to make the necessary adjustments, including connecting the dots between police violence and physical and mental health.

For example, racism has never been listed even in the index of the American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.14 Being the victim of police use of force is not generally regarded as an adverse childhood experience, even though communities that are heavily policed experience harassment by law enforcement on a regular basis. The 12 causes of trauma listed on the website15 of the National Child Traumatic Stress Network – bullying, community violence, complex trauma, disasters, early childhood trauma, intimate partner violence, medical trauma, physical abuse, refugee trauma, sexual abuse, terrorism and violence, and traumatic grief – do not include maltreatment, abuse, or trauma resulting from interactions with members of law enforcement. Much of the adverse childhood experiences literature focuses on white, upper middle class children and on experiences within the home. When community level experiences, such as discrimination based on race or ethnicity, are included, as in the Philadelphia ACES study,16 as many as 40% reported ACE scores of greater than 4 for community level exposures.

As psychiatrists, we recognize the psychic underpinnings and parallels between the psychic projections onto black and brown people and the actual bullets pumped into the bodies of black and brown people; there is a lurid propensity to use these others as repositories. Those who have the privilege of being protected by law enforcement and the ability to avoid being used as containers for the psychic projections and bullets of some police officers also have the privilege of compartmentalizing and looking the other way when excessive acts of force – projections and projectiles – are used on other human beings. This partly explains why the injuries and deaths of black and brown people caused by police officers’ excessive use of force have continued even though these unjustified deaths are widely televised and disseminated via various social media platforms.

Prior to the death of George Floyd on May 25, other than the American Public Health Association, the National Medical Association (NMA) was the only major medical organization to issue a call to consider police use of force as a public health issue. In its July 2016 press release, provided in the aftermath of the death of Freddie Gray while in the custody of Baltimore police officers, the NMA summarized the scope of injuries citizens sustain during “the pre-custody (commission of a crime, during a fight, chase, and apprehension, during a siege or hostage situation, or during restraint or submission), custody (soon after being admitted to jail, during interrogation, during incarceration, or legal execution), and post-custody (revenge by police or rival criminals or after reentry into the community)” periods. It is noteworthy that the scope of these injuries is comparable to those encountered in a combat zone.17,18 According to the NMA:

“Injuries sustained by civilians at the hands of law enforcement include gunshot wounds, skull fractures, cervical spine injuries, facial fractures, broken legs, blunt trauma orbital floor fractures, laryngeal cartilage fractures, shoulder dislocations, cuts and bruises, concussions, hemorrhage, choking (positional or due to upper body holds), abdominal trauma, hemothorax, and pneumothorax. Complications of such injuries include posttraumatic brain swelling, infections following open fractures and lacerations, hydrocephalus due to blood or infection, as well as subdural and epidural hematomas and, in the most severe cases, death.”

In addition, there are multiple emotional and psychiatric sequelae of these injuries for the victims, families, upstanders, bystanders, and those viewing these images via various social media platforms. Increasingly, many are experiencing retraumatization each time a new death is reported. How do we explain that we are turning away from this as physicians and trainers of physicians? Seeing and not seeing – all of the methods used to avert one’s gaze and look the other way (to protect the psyches of nonmarginalized members of society from being disturbed and possibly traumatized) – these key defense mechanisms creep into consulting rooms and become fertile ground for the enactment described above.

Yet, there is reason to believe in change. It’s not simply because we are mental health professionals and that’s what we do. With the posting of position statements issued by major corporations and a growing number of medical organizations, many of us are experiencing a mixture of hope, anger, and sadness. Hope that widespread awareness will continue to tilt the axis of our country in a manner that opens eyes – and hearts – so that real work can be done; and anger and sadness because it has taken 400 years to receive even this level of validation.

In the meantime, we are encouraged by a joint position statement recently issued by the APA and the NMA, the first joint effort by these two medical organizations to partner and advocate for criminal justice reform. We mention this statement because the NMA has been committed to the needs of the black community since its inception in 1895, and the APA has as its mission a commitment to serve “the needs of evolving, diverse, underrepresented, and underserved patient populations” ... and the resources to do so. This is the kind of partnership that could transform words into meaningful action.19,20

Of course, resident psychiatrist Dr. A. had begun supervision with the discussion of his dyadic experience with his patient, which is set in the context of a global coronavirus pandemic that is disproportionately affecting black and brown people. And, while his peers are marching in protest, he and his fellow trainees deserve our support as they deal with their own psychic pain and prepare to steady themselves. For these psychiatrists will be called to provide care to those who will consult them once they begin to grapple with the experiences and, in some cases, traumas that have compelled them to take action and literally risk their safety and lives while protesting.

That evening, the residents were hungry for methods to fill the gaps in their training and supervision. In some cases, we provided scripts to be taken back to supervision. For example, the following is a potential scripted response for the supervisor in the enactment described above:

Resident speaking to supervisor: This is a black patient who, like many others, is affected by the chronic, repeated televised images of black men killed by police. I am also a black man.

I think what I have shared is pertinent to the patient’s care and my experience as a black male psychiatrist who will need to learn how to address this in my patients who are black and for other racialized groups, as well as with whites who might have rarely been cared for by a black man. Can we discuss this?

We also anticipated that some residents would need to exercise their right to request reassignment to another supervisor. And, until we do better at listening, seeing, and deepening our understanding, outside and inside the consulting room and in supervision, more residents might need to steer around those who have the potential to undermine training and adversely affect treatment. But, as a professional medical community in crisis, do we really want to proceed in such an ad hoc fashion?

Dr. Dunlap is a psychiatrist and psychoanalyst, and clinical professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at George Washington University. She is interested in the management of “difference” – race, gender, ethnicity, and intersectionality – in dyadic relationships and group dynamics; and the impact of racism on interpersonal relationships in institutional structures. Dr. Dunlap practices in Washington and has no disclosures.

Dr. Dennis is a clinical psychologist and psychoanalyst. Her interests are in gender and ethnic diversity, health equity, and supervision and training. Dr. Dennis practices in Washington and has no disclosures.

Dr. DeSouza is a PGY-4 psychiatry resident and public psychiatry fellow in the department of psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. Her professional interests include health services development and delivery in low- and middle-income settings, as well as the intersection of mental health and spirituality. She has no disclosures.

Dr. Isom is a staff psychiatrist at the Codman Square Health Center in Dorchester, Mass., and Boston Medical Center. Her interests include racial mental health equity and population health approaches to community psychiatry. She has no disclosures.

Dr. Mathis is an addictions fellow in the department of psychiatry at Yale University and former programwide chief resident at Yale. Her interests include the intersection of racial justice and mental health, health equity, and spirituality. She has no disclosures.

References

1. Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity. A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md.: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2001.

2. Banaji MR and Greenwald AG. Blindspot: Hidden Biases of Good People. New York: Delacorte Press, 2013.

3. Anekwe ON. Voices in Bioethics. 2014.

4. Soute BJ. The American Psychoanalyst Magazine. 2017 Winter/Spring.

5. Powell DR. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 2019 Jan 8. doi: 10.1177/000306511881847.

6. Allen TW. The Invention of the White Race. London: Verso, 1994.

7. Klein M. Int J Psychoanal. 1946;27(pt.3-4):99-100.

8. Bion WR. (1962b). Psychoanal Q. 2013 Apr;82(2):301-10.

9. Black Psychoanalysts Speak trailer.

10. Thomas A and Sillen S. Racism and Psychiatry. New York: Brunner/Mazel, 1972.

11. Jones BE et al. Am J Psychiatry. 1970 Dec;127(6):798-803.

12. Sabshin M et al. Am J Psychiatry. 1970 Dec;126(6):787-93.

13. Medlock M et al. Am J Psychiatry. 2017 May 9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp-rj.2016.110206.

14. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5). Arlington, Va.: American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

15. “What is Child Trauma?” The National Child Traumatic Stress Network.

16. The Philadelphia Project. Philadelphia ACE Survey.

17. “Addressing law enforcement violence as a public health issue.” Washington: American Public Health Association. 2018 Nov 13. Policy# 20811.

18. National Medical Association position statement on police use of force. NMA 2016.

19. “APA and NMA jointly condemn systemic racism in America.” 2020 Jun 16.

20. APA Strategic Plan. 2015 Mar.

On the Friday evening after the public execution of George Floyd, we were painfully reminded of the urgency to address the inadequate management of race, racism, and anti-blackness in medical education, residency training, and postgraduate continuing medical education.

The reminder did not originate from the rioting that was occurring in some cities, though we could feel the ground shifting beneath our feet as civic protests that began in U.S. cities spread around the globe. Instead, it occurred during a webinar we were hosting for psychiatry residents focused on techniques for eliminating blind spots in the management of race in clinical psychotherapy supervision. (Dr. Jessica Isom chaired the webinar, Dr. Flavia DeSouza and Dr. Myra Mathis comoderated, and Dr. Ebony Dennis and Dr. Constance E. Dunlap served as discussants.)

Our panel had presented an ambitious agenda that included reviewing how the disavowal of bias, race, racism, and anti-blackness contributes to ineffective psychotherapy, undermines the quality of medical care, and perpetuates mental health disparities. We spent some time exploring how unacknowledged and unexamined conscious and unconscious racial stereotypes affect interpersonal relationships, the psychotherapeutic process, and the supervisory experience. Our presentation included a clinical vignette demonstrating how racism, colorism, and anti-blackness have global impact, influencing the self-esteem, identity formation, and identity consolidation of immigrants as they grapple with the unique form of racism that exists in America. Other clinical vignettes demonstrated blind spots that were retroactively identified though omitted in supervisory discussions. We also discussed alternative interventions and interpretations of the material presented.1-5

Because 21st-century trainees are generally psychologically astute and committed to social justice, we did two things. First, before the webinar, we provided them access to a prerecorded explanation of object relations theorist Melanie Klein’s paranoid-schizoid and depressive positions concepts, which were applied to theoretically explain the development of race, specifically the defenses used by early colonists that contributed to the development of “whiteness” and “blackness” as social constructs, and their influence on the development of the U.S. psyche. For example, as early colonists attempted to develop new and improved identities distinct from those they had in their homelands, they used enslaved black people (and other vulnerable groups) to “other.” What we mean here by othering is the process of using an other to project one’s badness into in order to relieve the self of uncomfortable aspects and feelings originating within the self. If this other accepts the projection (which is often the case with vulnerable parties), the self recognizes, that is, identifies (locates) the bad they just projected in the other, who is now experienced as a bad-other. This is projection in action. If the other accepts the projection and behaves accordingly, for example, in a manner that reflects badness, this becomes projective identification. Conversely, if the other does not accept these projections, the self (who projects) is left to cope with aspects of the self s/he might not have the capacity to manage. By capacity, we are speaking of the Bionian idea of the ability to experience an extreme emotion while also being able to think. Without the ego strength to cope with bad aspects of the self, the ego either collapses (and is unable to think) or further projection is attempted.6-8

We have seen this latter dynamic play out repeatedly when police officers fatally shoot black citizens and then claim that they feared for their lives; these same officers have been exonerated by juries by continuing to portray the deceased victims as threatening, dangerous objects not worthy of living. We are also seeing a global movement of black and nonblack people who are in touch with a justified rage that has motivated them to return these projections by collectively protesting, and in some cases, by rioting.

Back to the webinar

In anticipating the residents’ curiosity, impatience, and anger about the lack of progress, the second thing we did was to show a segment from the “Black Psychoanalysts Speak” trailer. In the clip played, senior psychoanalyst Kirkland C. Vaughans, PhD, shares: “The issue of race so prompts excessive anxiety that it blocks off our ability to think.”

We showed this clip to validate the trainees’ frustrations about the difficulty the broader establishment has had with addressing this serious, longstanding public health problem. We wanted these young psychiatrists to know that there are psychoanalysts, psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers who have been committed to this work, even though the contributions of this diverse group have curiously been omitted from education and training curricula.9

So, what happened? What was the painful reminder? After the formal panel presentations, a black male psychiatry resident recounted his experience in a clinical supervision meeting that had occurred several days after the murder of George Floyd. In short, a patient had shared his reactions to yet another incident of fatal police use of force and paused to ask how the resident physician, Dr. A., was doing. The question was experienced as sincere concern about the psychiatrist’s mental well-being. The resident was not sure how to answer this question since it was a matter of self-disclosure, which was a reasonable and thoughtful consideration for a seasoned clinician and, certainly, for a novice therapist. The supervisor, Dr. B., seemingly eager to move on, to not think about this, responded to the resident by saying: “Now tell me about the patient.” In other words, what had just been shared by the resident – material that featured a patient’s reaction to another killing of a black man by police and the patient’s expressed concern for his black psychiatrist, and this resident physician appropriately seeking space in supervision to process and receive guidance about how to respond – all of this was considered separate (split off from) and extraneous to the patient’s treatment and the resident’s training. This is a problem. And, unfortunately, this problem or some variation of it is not rare.

Why is this still the state of affairs when we have identified racism as a major health concern and our patients and our trainees are asking for help?

Rethinking a metaphor

Despite calls to action over the last 50 years to encourage medicine to effectively address race and racism, deficits remain in didactic education, clinical rotations, and supervisory experiences of trainees learning how to do psychodynamic psychotherapy.8-10 Earlier that evening, we used the metaphor of a vehicular blind spot to capture what we believe occurs insupervision. Like drivers, supervisors generally have the ability to see. However, there are places (times) and positions (stances) that block their vision (awareness). Racism – whether institutionalized, interpersonally mediated, or internalized – also contributes to this blindness.

As is true of drivers managing a blind spot, what is required is for the drivers – the supervisors – to lean forward or reposition themselves so as to avoid collisions, maintain safety, and continue on course. We use this metaphor because it is understood that any clinician providing psychodynamic supervision to psychiatry residents, regardless of professional discipline, has the requisite skills and training.10-13

Until May 25, we thought eliminating blind spots would be effective. But, in the aftermath of the police killing of George Floyd, our eyes have been opened.

Hiding behind the blue wall of silence is an establishment that has looked the other way while black and brown women, men, and children have come to live in fear as a result of the state-sanctioned violence that repeatedly occurs across the nation. Excessive police use of force is a public health issue of crisis magnitude. However, the house of medicine, like many other established structures in society, has colluded with the societal constructs that have supported law enforcement by remaining willfully blind, often neutral, and by refusing to make the necessary adjustments, including connecting the dots between police violence and physical and mental health.

For example, racism has never been listed even in the index of the American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.14 Being the victim of police use of force is not generally regarded as an adverse childhood experience, even though communities that are heavily policed experience harassment by law enforcement on a regular basis. The 12 causes of trauma listed on the website15 of the National Child Traumatic Stress Network – bullying, community violence, complex trauma, disasters, early childhood trauma, intimate partner violence, medical trauma, physical abuse, refugee trauma, sexual abuse, terrorism and violence, and traumatic grief – do not include maltreatment, abuse, or trauma resulting from interactions with members of law enforcement. Much of the adverse childhood experiences literature focuses on white, upper middle class children and on experiences within the home. When community level experiences, such as discrimination based on race or ethnicity, are included, as in the Philadelphia ACES study,16 as many as 40% reported ACE scores of greater than 4 for community level exposures.

As psychiatrists, we recognize the psychic underpinnings and parallels between the psychic projections onto black and brown people and the actual bullets pumped into the bodies of black and brown people; there is a lurid propensity to use these others as repositories. Those who have the privilege of being protected by law enforcement and the ability to avoid being used as containers for the psychic projections and bullets of some police officers also have the privilege of compartmentalizing and looking the other way when excessive acts of force – projections and projectiles – are used on other human beings. This partly explains why the injuries and deaths of black and brown people caused by police officers’ excessive use of force have continued even though these unjustified deaths are widely televised and disseminated via various social media platforms.

Prior to the death of George Floyd on May 25, other than the American Public Health Association, the National Medical Association (NMA) was the only major medical organization to issue a call to consider police use of force as a public health issue. In its July 2016 press release, provided in the aftermath of the death of Freddie Gray while in the custody of Baltimore police officers, the NMA summarized the scope of injuries citizens sustain during “the pre-custody (commission of a crime, during a fight, chase, and apprehension, during a siege or hostage situation, or during restraint or submission), custody (soon after being admitted to jail, during interrogation, during incarceration, or legal execution), and post-custody (revenge by police or rival criminals or after reentry into the community)” periods. It is noteworthy that the scope of these injuries is comparable to those encountered in a combat zone.17,18 According to the NMA:

“Injuries sustained by civilians at the hands of law enforcement include gunshot wounds, skull fractures, cervical spine injuries, facial fractures, broken legs, blunt trauma orbital floor fractures, laryngeal cartilage fractures, shoulder dislocations, cuts and bruises, concussions, hemorrhage, choking (positional or due to upper body holds), abdominal trauma, hemothorax, and pneumothorax. Complications of such injuries include posttraumatic brain swelling, infections following open fractures and lacerations, hydrocephalus due to blood or infection, as well as subdural and epidural hematomas and, in the most severe cases, death.”

In addition, there are multiple emotional and psychiatric sequelae of these injuries for the victims, families, upstanders, bystanders, and those viewing these images via various social media platforms. Increasingly, many are experiencing retraumatization each time a new death is reported. How do we explain that we are turning away from this as physicians and trainers of physicians? Seeing and not seeing – all of the methods used to avert one’s gaze and look the other way (to protect the psyches of nonmarginalized members of society from being disturbed and possibly traumatized) – these key defense mechanisms creep into consulting rooms and become fertile ground for the enactment described above.

Yet, there is reason to believe in change. It’s not simply because we are mental health professionals and that’s what we do. With the posting of position statements issued by major corporations and a growing number of medical organizations, many of us are experiencing a mixture of hope, anger, and sadness. Hope that widespread awareness will continue to tilt the axis of our country in a manner that opens eyes – and hearts – so that real work can be done; and anger and sadness because it has taken 400 years to receive even this level of validation.

In the meantime, we are encouraged by a joint position statement recently issued by the APA and the NMA, the first joint effort by these two medical organizations to partner and advocate for criminal justice reform. We mention this statement because the NMA has been committed to the needs of the black community since its inception in 1895, and the APA has as its mission a commitment to serve “the needs of evolving, diverse, underrepresented, and underserved patient populations” ... and the resources to do so. This is the kind of partnership that could transform words into meaningful action.19,20

Of course, resident psychiatrist Dr. A. had begun supervision with the discussion of his dyadic experience with his patient, which is set in the context of a global coronavirus pandemic that is disproportionately affecting black and brown people. And, while his peers are marching in protest, he and his fellow trainees deserve our support as they deal with their own psychic pain and prepare to steady themselves. For these psychiatrists will be called to provide care to those who will consult them once they begin to grapple with the experiences and, in some cases, traumas that have compelled them to take action and literally risk their safety and lives while protesting.

That evening, the residents were hungry for methods to fill the gaps in their training and supervision. In some cases, we provided scripts to be taken back to supervision. For example, the following is a potential scripted response for the supervisor in the enactment described above:

Resident speaking to supervisor: This is a black patient who, like many others, is affected by the chronic, repeated televised images of black men killed by police. I am also a black man.

I think what I have shared is pertinent to the patient’s care and my experience as a black male psychiatrist who will need to learn how to address this in my patients who are black and for other racialized groups, as well as with whites who might have rarely been cared for by a black man. Can we discuss this?

We also anticipated that some residents would need to exercise their right to request reassignment to another supervisor. And, until we do better at listening, seeing, and deepening our understanding, outside and inside the consulting room and in supervision, more residents might need to steer around those who have the potential to undermine training and adversely affect treatment. But, as a professional medical community in crisis, do we really want to proceed in such an ad hoc fashion?

Dr. Dunlap is a psychiatrist and psychoanalyst, and clinical professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at George Washington University. She is interested in the management of “difference” – race, gender, ethnicity, and intersectionality – in dyadic relationships and group dynamics; and the impact of racism on interpersonal relationships in institutional structures. Dr. Dunlap practices in Washington and has no disclosures.

Dr. Dennis is a clinical psychologist and psychoanalyst. Her interests are in gender and ethnic diversity, health equity, and supervision and training. Dr. Dennis practices in Washington and has no disclosures.

Dr. DeSouza is a PGY-4 psychiatry resident and public psychiatry fellow in the department of psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. Her professional interests include health services development and delivery in low- and middle-income settings, as well as the intersection of mental health and spirituality. She has no disclosures.

Dr. Isom is a staff psychiatrist at the Codman Square Health Center in Dorchester, Mass., and Boston Medical Center. Her interests include racial mental health equity and population health approaches to community psychiatry. She has no disclosures.

Dr. Mathis is an addictions fellow in the department of psychiatry at Yale University and former programwide chief resident at Yale. Her interests include the intersection of racial justice and mental health, health equity, and spirituality. She has no disclosures.

References

1. Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity. A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md.: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2001.

2. Banaji MR and Greenwald AG. Blindspot: Hidden Biases of Good People. New York: Delacorte Press, 2013.

3. Anekwe ON. Voices in Bioethics. 2014.

4. Soute BJ. The American Psychoanalyst Magazine. 2017 Winter/Spring.

5. Powell DR. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 2019 Jan 8. doi: 10.1177/000306511881847.

6. Allen TW. The Invention of the White Race. London: Verso, 1994.

7. Klein M. Int J Psychoanal. 1946;27(pt.3-4):99-100.

8. Bion WR. (1962b). Psychoanal Q. 2013 Apr;82(2):301-10.

9. Black Psychoanalysts Speak trailer.

10. Thomas A and Sillen S. Racism and Psychiatry. New York: Brunner/Mazel, 1972.

11. Jones BE et al. Am J Psychiatry. 1970 Dec;127(6):798-803.

12. Sabshin M et al. Am J Psychiatry. 1970 Dec;126(6):787-93.

13. Medlock M et al. Am J Psychiatry. 2017 May 9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp-rj.2016.110206.

14. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5). Arlington, Va.: American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

15. “What is Child Trauma?” The National Child Traumatic Stress Network.

16. The Philadelphia Project. Philadelphia ACE Survey.

17. “Addressing law enforcement violence as a public health issue.” Washington: American Public Health Association. 2018 Nov 13. Policy# 20811.

18. National Medical Association position statement on police use of force. NMA 2016.

19. “APA and NMA jointly condemn systemic racism in America.” 2020 Jun 16.

20. APA Strategic Plan. 2015 Mar.

On the Friday evening after the public execution of George Floyd, we were painfully reminded of the urgency to address the inadequate management of race, racism, and anti-blackness in medical education, residency training, and postgraduate continuing medical education.

The reminder did not originate from the rioting that was occurring in some cities, though we could feel the ground shifting beneath our feet as civic protests that began in U.S. cities spread around the globe. Instead, it occurred during a webinar we were hosting for psychiatry residents focused on techniques for eliminating blind spots in the management of race in clinical psychotherapy supervision. (Dr. Jessica Isom chaired the webinar, Dr. Flavia DeSouza and Dr. Myra Mathis comoderated, and Dr. Ebony Dennis and Dr. Constance E. Dunlap served as discussants.)

Our panel had presented an ambitious agenda that included reviewing how the disavowal of bias, race, racism, and anti-blackness contributes to ineffective psychotherapy, undermines the quality of medical care, and perpetuates mental health disparities. We spent some time exploring how unacknowledged and unexamined conscious and unconscious racial stereotypes affect interpersonal relationships, the psychotherapeutic process, and the supervisory experience. Our presentation included a clinical vignette demonstrating how racism, colorism, and anti-blackness have global impact, influencing the self-esteem, identity formation, and identity consolidation of immigrants as they grapple with the unique form of racism that exists in America. Other clinical vignettes demonstrated blind spots that were retroactively identified though omitted in supervisory discussions. We also discussed alternative interventions and interpretations of the material presented.1-5

Because 21st-century trainees are generally psychologically astute and committed to social justice, we did two things. First, before the webinar, we provided them access to a prerecorded explanation of object relations theorist Melanie Klein’s paranoid-schizoid and depressive positions concepts, which were applied to theoretically explain the development of race, specifically the defenses used by early colonists that contributed to the development of “whiteness” and “blackness” as social constructs, and their influence on the development of the U.S. psyche. For example, as early colonists attempted to develop new and improved identities distinct from those they had in their homelands, they used enslaved black people (and other vulnerable groups) to “other.” What we mean here by othering is the process of using an other to project one’s badness into in order to relieve the self of uncomfortable aspects and feelings originating within the self. If this other accepts the projection (which is often the case with vulnerable parties), the self recognizes, that is, identifies (locates) the bad they just projected in the other, who is now experienced as a bad-other. This is projection in action. If the other accepts the projection and behaves accordingly, for example, in a manner that reflects badness, this becomes projective identification. Conversely, if the other does not accept these projections, the self (who projects) is left to cope with aspects of the self s/he might not have the capacity to manage. By capacity, we are speaking of the Bionian idea of the ability to experience an extreme emotion while also being able to think. Without the ego strength to cope with bad aspects of the self, the ego either collapses (and is unable to think) or further projection is attempted.6-8

We have seen this latter dynamic play out repeatedly when police officers fatally shoot black citizens and then claim that they feared for their lives; these same officers have been exonerated by juries by continuing to portray the deceased victims as threatening, dangerous objects not worthy of living. We are also seeing a global movement of black and nonblack people who are in touch with a justified rage that has motivated them to return these projections by collectively protesting, and in some cases, by rioting.

Back to the webinar

In anticipating the residents’ curiosity, impatience, and anger about the lack of progress, the second thing we did was to show a segment from the “Black Psychoanalysts Speak” trailer. In the clip played, senior psychoanalyst Kirkland C. Vaughans, PhD, shares: “The issue of race so prompts excessive anxiety that it blocks off our ability to think.”

We showed this clip to validate the trainees’ frustrations about the difficulty the broader establishment has had with addressing this serious, longstanding public health problem. We wanted these young psychiatrists to know that there are psychoanalysts, psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers who have been committed to this work, even though the contributions of this diverse group have curiously been omitted from education and training curricula.9

So, what happened? What was the painful reminder? After the formal panel presentations, a black male psychiatry resident recounted his experience in a clinical supervision meeting that had occurred several days after the murder of George Floyd. In short, a patient had shared his reactions to yet another incident of fatal police use of force and paused to ask how the resident physician, Dr. A., was doing. The question was experienced as sincere concern about the psychiatrist’s mental well-being. The resident was not sure how to answer this question since it was a matter of self-disclosure, which was a reasonable and thoughtful consideration for a seasoned clinician and, certainly, for a novice therapist. The supervisor, Dr. B., seemingly eager to move on, to not think about this, responded to the resident by saying: “Now tell me about the patient.” In other words, what had just been shared by the resident – material that featured a patient’s reaction to another killing of a black man by police and the patient’s expressed concern for his black psychiatrist, and this resident physician appropriately seeking space in supervision to process and receive guidance about how to respond – all of this was considered separate (split off from) and extraneous to the patient’s treatment and the resident’s training. This is a problem. And, unfortunately, this problem or some variation of it is not rare.

Why is this still the state of affairs when we have identified racism as a major health concern and our patients and our trainees are asking for help?

Rethinking a metaphor

Despite calls to action over the last 50 years to encourage medicine to effectively address race and racism, deficits remain in didactic education, clinical rotations, and supervisory experiences of trainees learning how to do psychodynamic psychotherapy.8-10 Earlier that evening, we used the metaphor of a vehicular blind spot to capture what we believe occurs insupervision. Like drivers, supervisors generally have the ability to see. However, there are places (times) and positions (stances) that block their vision (awareness). Racism – whether institutionalized, interpersonally mediated, or internalized – also contributes to this blindness.

As is true of drivers managing a blind spot, what is required is for the drivers – the supervisors – to lean forward or reposition themselves so as to avoid collisions, maintain safety, and continue on course. We use this metaphor because it is understood that any clinician providing psychodynamic supervision to psychiatry residents, regardless of professional discipline, has the requisite skills and training.10-13

Until May 25, we thought eliminating blind spots would be effective. But, in the aftermath of the police killing of George Floyd, our eyes have been opened.

Hiding behind the blue wall of silence is an establishment that has looked the other way while black and brown women, men, and children have come to live in fear as a result of the state-sanctioned violence that repeatedly occurs across the nation. Excessive police use of force is a public health issue of crisis magnitude. However, the house of medicine, like many other established structures in society, has colluded with the societal constructs that have supported law enforcement by remaining willfully blind, often neutral, and by refusing to make the necessary adjustments, including connecting the dots between police violence and physical and mental health.

For example, racism has never been listed even in the index of the American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.14 Being the victim of police use of force is not generally regarded as an adverse childhood experience, even though communities that are heavily policed experience harassment by law enforcement on a regular basis. The 12 causes of trauma listed on the website15 of the National Child Traumatic Stress Network – bullying, community violence, complex trauma, disasters, early childhood trauma, intimate partner violence, medical trauma, physical abuse, refugee trauma, sexual abuse, terrorism and violence, and traumatic grief – do not include maltreatment, abuse, or trauma resulting from interactions with members of law enforcement. Much of the adverse childhood experiences literature focuses on white, upper middle class children and on experiences within the home. When community level experiences, such as discrimination based on race or ethnicity, are included, as in the Philadelphia ACES study,16 as many as 40% reported ACE scores of greater than 4 for community level exposures.

As psychiatrists, we recognize the psychic underpinnings and parallels between the psychic projections onto black and brown people and the actual bullets pumped into the bodies of black and brown people; there is a lurid propensity to use these others as repositories. Those who have the privilege of being protected by law enforcement and the ability to avoid being used as containers for the psychic projections and bullets of some police officers also have the privilege of compartmentalizing and looking the other way when excessive acts of force – projections and projectiles – are used on other human beings. This partly explains why the injuries and deaths of black and brown people caused by police officers’ excessive use of force have continued even though these unjustified deaths are widely televised and disseminated via various social media platforms.

Prior to the death of George Floyd on May 25, other than the American Public Health Association, the National Medical Association (NMA) was the only major medical organization to issue a call to consider police use of force as a public health issue. In its July 2016 press release, provided in the aftermath of the death of Freddie Gray while in the custody of Baltimore police officers, the NMA summarized the scope of injuries citizens sustain during “the pre-custody (commission of a crime, during a fight, chase, and apprehension, during a siege or hostage situation, or during restraint or submission), custody (soon after being admitted to jail, during interrogation, during incarceration, or legal execution), and post-custody (revenge by police or rival criminals or after reentry into the community)” periods. It is noteworthy that the scope of these injuries is comparable to those encountered in a combat zone.17,18 According to the NMA:

“Injuries sustained by civilians at the hands of law enforcement include gunshot wounds, skull fractures, cervical spine injuries, facial fractures, broken legs, blunt trauma orbital floor fractures, laryngeal cartilage fractures, shoulder dislocations, cuts and bruises, concussions, hemorrhage, choking (positional or due to upper body holds), abdominal trauma, hemothorax, and pneumothorax. Complications of such injuries include posttraumatic brain swelling, infections following open fractures and lacerations, hydrocephalus due to blood or infection, as well as subdural and epidural hematomas and, in the most severe cases, death.”

In addition, there are multiple emotional and psychiatric sequelae of these injuries for the victims, families, upstanders, bystanders, and those viewing these images via various social media platforms. Increasingly, many are experiencing retraumatization each time a new death is reported. How do we explain that we are turning away from this as physicians and trainers of physicians? Seeing and not seeing – all of the methods used to avert one’s gaze and look the other way (to protect the psyches of nonmarginalized members of society from being disturbed and possibly traumatized) – these key defense mechanisms creep into consulting rooms and become fertile ground for the enactment described above.

Yet, there is reason to believe in change. It’s not simply because we are mental health professionals and that’s what we do. With the posting of position statements issued by major corporations and a growing number of medical organizations, many of us are experiencing a mixture of hope, anger, and sadness. Hope that widespread awareness will continue to tilt the axis of our country in a manner that opens eyes – and hearts – so that real work can be done; and anger and sadness because it has taken 400 years to receive even this level of validation.

In the meantime, we are encouraged by a joint position statement recently issued by the APA and the NMA, the first joint effort by these two medical organizations to partner and advocate for criminal justice reform. We mention this statement because the NMA has been committed to the needs of the black community since its inception in 1895, and the APA has as its mission a commitment to serve “the needs of evolving, diverse, underrepresented, and underserved patient populations” ... and the resources to do so. This is the kind of partnership that could transform words into meaningful action.19,20

Of course, resident psychiatrist Dr. A. had begun supervision with the discussion of his dyadic experience with his patient, which is set in the context of a global coronavirus pandemic that is disproportionately affecting black and brown people. And, while his peers are marching in protest, he and his fellow trainees deserve our support as they deal with their own psychic pain and prepare to steady themselves. For these psychiatrists will be called to provide care to those who will consult them once they begin to grapple with the experiences and, in some cases, traumas that have compelled them to take action and literally risk their safety and lives while protesting.

That evening, the residents were hungry for methods to fill the gaps in their training and supervision. In some cases, we provided scripts to be taken back to supervision. For example, the following is a potential scripted response for the supervisor in the enactment described above:

Resident speaking to supervisor: This is a black patient who, like many others, is affected by the chronic, repeated televised images of black men killed by police. I am also a black man.

I think what I have shared is pertinent to the patient’s care and my experience as a black male psychiatrist who will need to learn how to address this in my patients who are black and for other racialized groups, as well as with whites who might have rarely been cared for by a black man. Can we discuss this?

We also anticipated that some residents would need to exercise their right to request reassignment to another supervisor. And, until we do better at listening, seeing, and deepening our understanding, outside and inside the consulting room and in supervision, more residents might need to steer around those who have the potential to undermine training and adversely affect treatment. But, as a professional medical community in crisis, do we really want to proceed in such an ad hoc fashion?

Dr. Dunlap is a psychiatrist and psychoanalyst, and clinical professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at George Washington University. She is interested in the management of “difference” – race, gender, ethnicity, and intersectionality – in dyadic relationships and group dynamics; and the impact of racism on interpersonal relationships in institutional structures. Dr. Dunlap practices in Washington and has no disclosures.

Dr. Dennis is a clinical psychologist and psychoanalyst. Her interests are in gender and ethnic diversity, health equity, and supervision and training. Dr. Dennis practices in Washington and has no disclosures.

Dr. DeSouza is a PGY-4 psychiatry resident and public psychiatry fellow in the department of psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. Her professional interests include health services development and delivery in low- and middle-income settings, as well as the intersection of mental health and spirituality. She has no disclosures.

Dr. Isom is a staff psychiatrist at the Codman Square Health Center in Dorchester, Mass., and Boston Medical Center. Her interests include racial mental health equity and population health approaches to community psychiatry. She has no disclosures.

Dr. Mathis is an addictions fellow in the department of psychiatry at Yale University and former programwide chief resident at Yale. Her interests include the intersection of racial justice and mental health, health equity, and spirituality. She has no disclosures.

References

1. Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity. A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md.: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2001.

2. Banaji MR and Greenwald AG. Blindspot: Hidden Biases of Good People. New York: Delacorte Press, 2013.

3. Anekwe ON. Voices in Bioethics. 2014.

4. Soute BJ. The American Psychoanalyst Magazine. 2017 Winter/Spring.

5. Powell DR. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 2019 Jan 8. doi: 10.1177/000306511881847.

6. Allen TW. The Invention of the White Race. London: Verso, 1994.

7. Klein M. Int J Psychoanal. 1946;27(pt.3-4):99-100.

8. Bion WR. (1962b). Psychoanal Q. 2013 Apr;82(2):301-10.

9. Black Psychoanalysts Speak trailer.

10. Thomas A and Sillen S. Racism and Psychiatry. New York: Brunner/Mazel, 1972.

11. Jones BE et al. Am J Psychiatry. 1970 Dec;127(6):798-803.

12. Sabshin M et al. Am J Psychiatry. 1970 Dec;126(6):787-93.

13. Medlock M et al. Am J Psychiatry. 2017 May 9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp-rj.2016.110206.

14. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5). Arlington, Va.: American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

15. “What is Child Trauma?” The National Child Traumatic Stress Network.

16. The Philadelphia Project. Philadelphia ACE Survey.

17. “Addressing law enforcement violence as a public health issue.” Washington: American Public Health Association. 2018 Nov 13. Policy# 20811.

18. National Medical Association position statement on police use of force. NMA 2016.

19. “APA and NMA jointly condemn systemic racism in America.” 2020 Jun 16.

20. APA Strategic Plan. 2015 Mar.

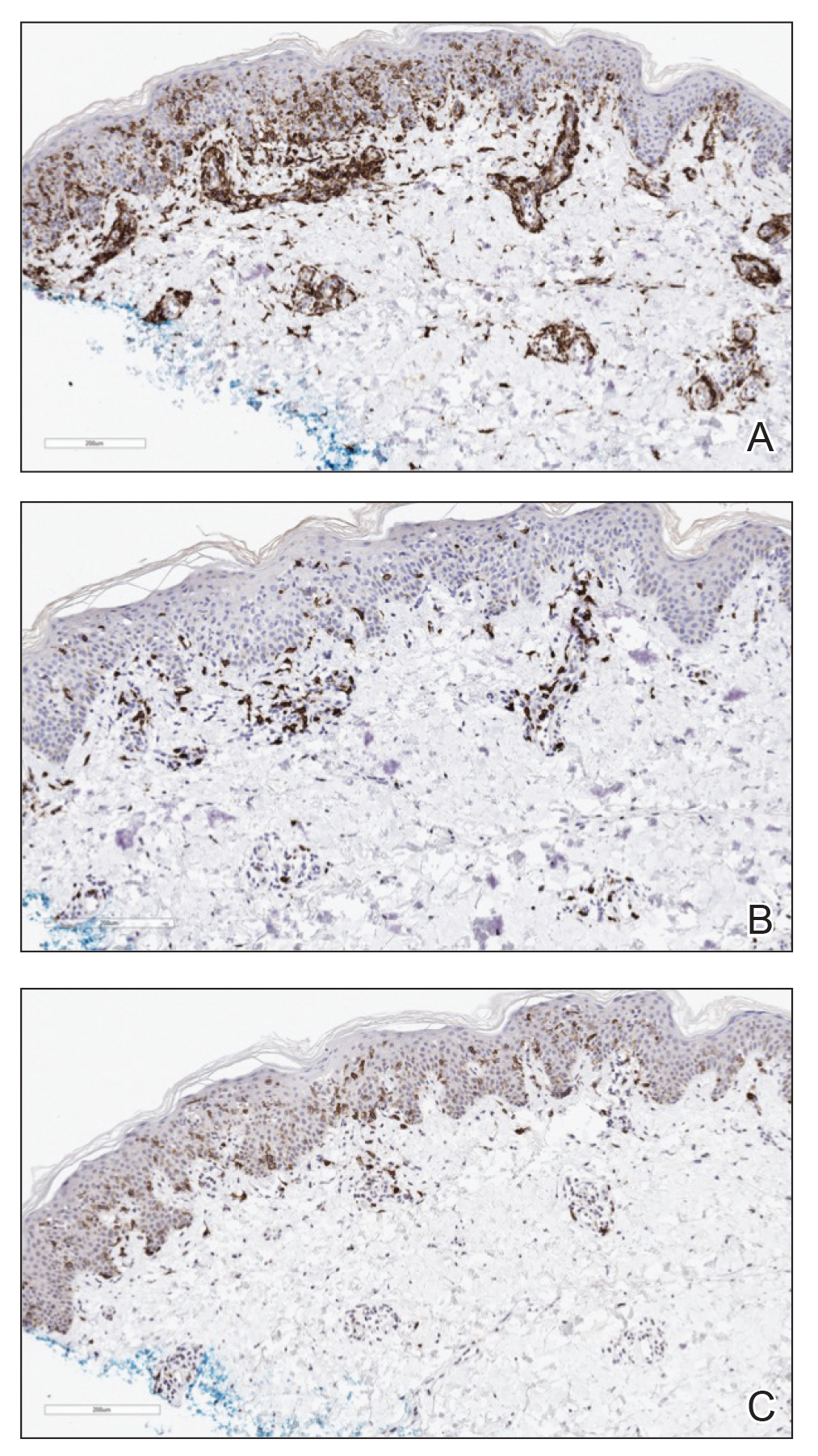

Study evaluates number of needed to refer, biopsy for diagnosing a melanoma

At the same time, the number needed to refer to diagnose non-melanoma skin cancer was 4 and the number needed to biopsy was 1.5.

The findings come from a retrospective review of 707 patients referred to a tertiary medical center dermatology practice for suspicious lesions, presented in a poster session at the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology

“Multiple studies in the dermatology literature have looked at the number needed to treat (NNT) as a quality metric for dermatology clinics, where a lower number is ‘better,’” the study’s first author, Nikolai Klebanov, MD, said in an interview following the virtual meeting. “Our particular study is unique in that we estimated both the number needed to refer and number needed to biopsy to closely examine the process of referrals for suspicious lesions from primary care settings to specialists. We also looked closely at the underlying patient-centered characteristics, which could be used by all clinicians to streamline the referral process by reducing the volume of low-risk referrals.”

Dr. Klebanov, of the department of dermatology at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and his associates reviewed 707 unique patient visits to the department during July 2015–February 2016. They calculated the number needed to refer and biopsy for melanoma as the ratio of biopsy-proven melanoma diagnoses among benign and dysplastic nevi and seborrheic keratoses. For nonmelanoma skin cancer, they used the ratio of basal and squamous cell carcinoma among actinic keratoses and seborrheic keratoses.

Of the 707 patients, 54% were female, and males were slightly older than females (a mean of 58 vs. 54 years, respectively). The researchers found that lesions were more commonly benign among all age groups, while the frequency of premalignant and malignant lesions such as actinic keratoses, nonmelanoma skin cancer, and melanoma was highest for males and increased with age. Nevi were the most common benign diagnosis among patients 39 years of age and younger, while seborrheic keratoses were more common among patients aged 40 years and older.

The researchers found that the number needed to treat for melanoma was 31.5 and the number needed to biopsy was 7.5, which represents a 4.2-fold difference. Meanwhile, the number needed to refer for nonmelanoma skin cancer was 4, and the number needed to biopsy was 1.5, which represents a 2.7-fold difference. Despite variable rates of skin cancer between demographics, the biopsy rate ranged between 18% and 30%, for a mean of 23.4%.

“We found that most young patients referred for a ‘suspicious lesion’ on clinical prebiopsy assessment by the dermatologist were determined to actually have a benign nevus, and that older patients were most likely to have a seborrheic keratosis as the underlying lesion,” Dr. Klebanov said. “Among the minority of patients in each demographic group who were selected for biopsy, those lesions which were found to be benign were also largely nevi and keratoses. Even by being mindful of just the patient’s age, primary care providers can follow patients clinically with a tailored differential diagnosis in mind before referral, and dermatologists can reduce the number of biopsies they perform on patients who are being referred.”

He added that he and his colleagues were surprised that despite very low rates of skin cancer in young patients, and thus different pretest probabilities of cancer, biopsy rates across demographics were consistently around 20%. “We also found a disproportionate number of female patients younger than age 40 who were referred for suspicious lesions, while in the older age groups, the ratio of males to females was approximately equal.”

Dr. Klebanov acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its single-center, retrospective design, and that information was not collected on patients’ family history of skin cancer, Fitzpatrick skin type, nor the clinical course of the lesion while it was followed by the primary care office. “The nuanced differences in these factors may certainly play a role in decisions for individual patients,” he said.

The study’s principal investigator was Hensin Tsao MD, PhD, clinical director of the MGH Melanoma & Pigmented Lesion Center The work was supported by the Alpha Omega Alpha Carolyn Kuckein Research Fellowship. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Klebanov N et al. AAD 20. Abstract 15881.

At the same time, the number needed to refer to diagnose non-melanoma skin cancer was 4 and the number needed to biopsy was 1.5.

The findings come from a retrospective review of 707 patients referred to a tertiary medical center dermatology practice for suspicious lesions, presented in a poster session at the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology

“Multiple studies in the dermatology literature have looked at the number needed to treat (NNT) as a quality metric for dermatology clinics, where a lower number is ‘better,’” the study’s first author, Nikolai Klebanov, MD, said in an interview following the virtual meeting. “Our particular study is unique in that we estimated both the number needed to refer and number needed to biopsy to closely examine the process of referrals for suspicious lesions from primary care settings to specialists. We also looked closely at the underlying patient-centered characteristics, which could be used by all clinicians to streamline the referral process by reducing the volume of low-risk referrals.”

Dr. Klebanov, of the department of dermatology at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and his associates reviewed 707 unique patient visits to the department during July 2015–February 2016. They calculated the number needed to refer and biopsy for melanoma as the ratio of biopsy-proven melanoma diagnoses among benign and dysplastic nevi and seborrheic keratoses. For nonmelanoma skin cancer, they used the ratio of basal and squamous cell carcinoma among actinic keratoses and seborrheic keratoses.

Of the 707 patients, 54% were female, and males were slightly older than females (a mean of 58 vs. 54 years, respectively). The researchers found that lesions were more commonly benign among all age groups, while the frequency of premalignant and malignant lesions such as actinic keratoses, nonmelanoma skin cancer, and melanoma was highest for males and increased with age. Nevi were the most common benign diagnosis among patients 39 years of age and younger, while seborrheic keratoses were more common among patients aged 40 years and older.

The researchers found that the number needed to treat for melanoma was 31.5 and the number needed to biopsy was 7.5, which represents a 4.2-fold difference. Meanwhile, the number needed to refer for nonmelanoma skin cancer was 4, and the number needed to biopsy was 1.5, which represents a 2.7-fold difference. Despite variable rates of skin cancer between demographics, the biopsy rate ranged between 18% and 30%, for a mean of 23.4%.

“We found that most young patients referred for a ‘suspicious lesion’ on clinical prebiopsy assessment by the dermatologist were determined to actually have a benign nevus, and that older patients were most likely to have a seborrheic keratosis as the underlying lesion,” Dr. Klebanov said. “Among the minority of patients in each demographic group who were selected for biopsy, those lesions which were found to be benign were also largely nevi and keratoses. Even by being mindful of just the patient’s age, primary care providers can follow patients clinically with a tailored differential diagnosis in mind before referral, and dermatologists can reduce the number of biopsies they perform on patients who are being referred.”

He added that he and his colleagues were surprised that despite very low rates of skin cancer in young patients, and thus different pretest probabilities of cancer, biopsy rates across demographics were consistently around 20%. “We also found a disproportionate number of female patients younger than age 40 who were referred for suspicious lesions, while in the older age groups, the ratio of males to females was approximately equal.”

Dr. Klebanov acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its single-center, retrospective design, and that information was not collected on patients’ family history of skin cancer, Fitzpatrick skin type, nor the clinical course of the lesion while it was followed by the primary care office. “The nuanced differences in these factors may certainly play a role in decisions for individual patients,” he said.