User login

Hypertension goes unmedicated in 40% of adults

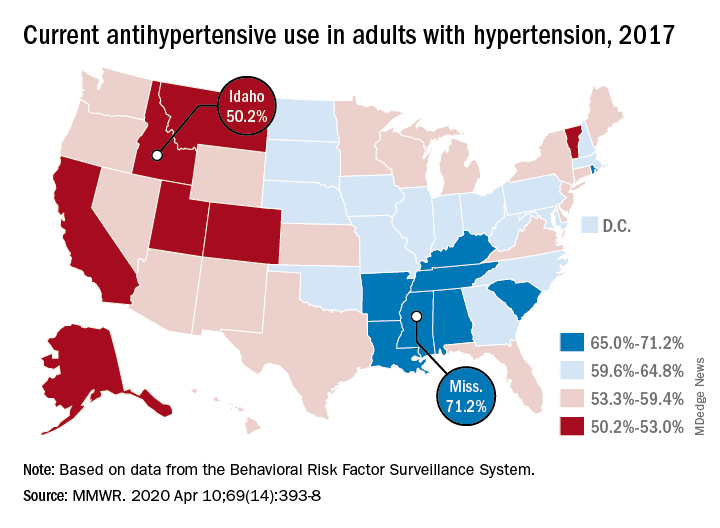

Roughly 30% of adults in the United States had hypertension in 2017, and just under 60% of those adults reported using antihypertensive medication, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

There is, however, quite a bit of variation from those age-standardized national figures when state-level data are considered.

In Alabama and West Virginia, the prevalence of hypertension in 2017 was 38.6%, the highest in the country, with Arkansas (38.5%) and Mississippi (38.2%) not far behind. Meanwhile, Minnesota came in with a lowest-in-the-nation rate of 24.3%, which was nearly matched by Colorado at 24.8%, Claudine M. Samanic, PhD, and associates wrote in the MMWR.

There was also a considerable gap between the states in hypertensive adults’ self-reported use of antihypertensive drugs, which was generally higher in the states with a greater prevalence of disease, they noted.

Adults in Mississippi were the most likely (71.2%) to be taking medication, along with those in Alabama (70.5%) and Arkansas (69.3%). Idaho occupied the other end of the scale with a rate of 50.2%, while Montana and Vermont were slightly better at 51.7%, based on survey data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.

“Prevalence of antihypertensive medication use was higher in older age groups, highest among blacks, and higher among women [64.0%] than men [56.7%]. This overall gender difference has been reported previously, but the reasons are unclear,” wrote Dr. Samanic and associates at the CDC’s National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

The BRFSS data for 2017 are based on based on interviews with 450,016 adults. Respondents were asked, “Have you ever been told by a doctor, nurse, or other health professional that you have high blood pressure?” and were considered to have hypertension if they answered yes.

SOURCE: Samanic CM et al. MMWR. 2020 Apr 10;69(14):393-8.

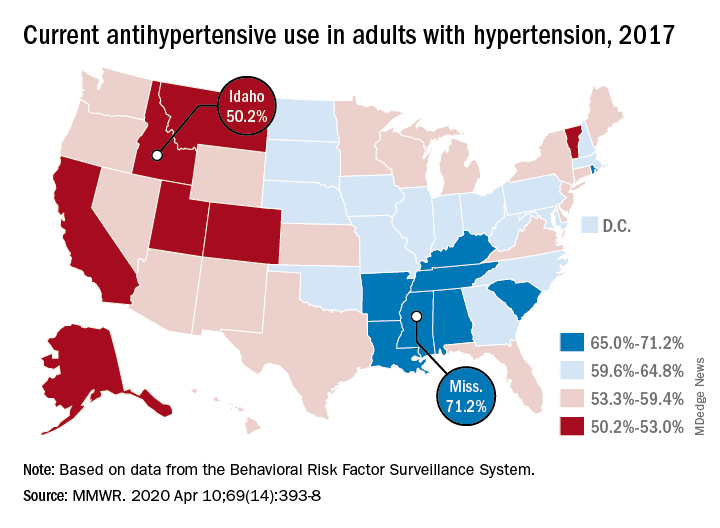

Roughly 30% of adults in the United States had hypertension in 2017, and just under 60% of those adults reported using antihypertensive medication, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

There is, however, quite a bit of variation from those age-standardized national figures when state-level data are considered.

In Alabama and West Virginia, the prevalence of hypertension in 2017 was 38.6%, the highest in the country, with Arkansas (38.5%) and Mississippi (38.2%) not far behind. Meanwhile, Minnesota came in with a lowest-in-the-nation rate of 24.3%, which was nearly matched by Colorado at 24.8%, Claudine M. Samanic, PhD, and associates wrote in the MMWR.

There was also a considerable gap between the states in hypertensive adults’ self-reported use of antihypertensive drugs, which was generally higher in the states with a greater prevalence of disease, they noted.

Adults in Mississippi were the most likely (71.2%) to be taking medication, along with those in Alabama (70.5%) and Arkansas (69.3%). Idaho occupied the other end of the scale with a rate of 50.2%, while Montana and Vermont were slightly better at 51.7%, based on survey data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.

“Prevalence of antihypertensive medication use was higher in older age groups, highest among blacks, and higher among women [64.0%] than men [56.7%]. This overall gender difference has been reported previously, but the reasons are unclear,” wrote Dr. Samanic and associates at the CDC’s National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

The BRFSS data for 2017 are based on based on interviews with 450,016 adults. Respondents were asked, “Have you ever been told by a doctor, nurse, or other health professional that you have high blood pressure?” and were considered to have hypertension if they answered yes.

SOURCE: Samanic CM et al. MMWR. 2020 Apr 10;69(14):393-8.

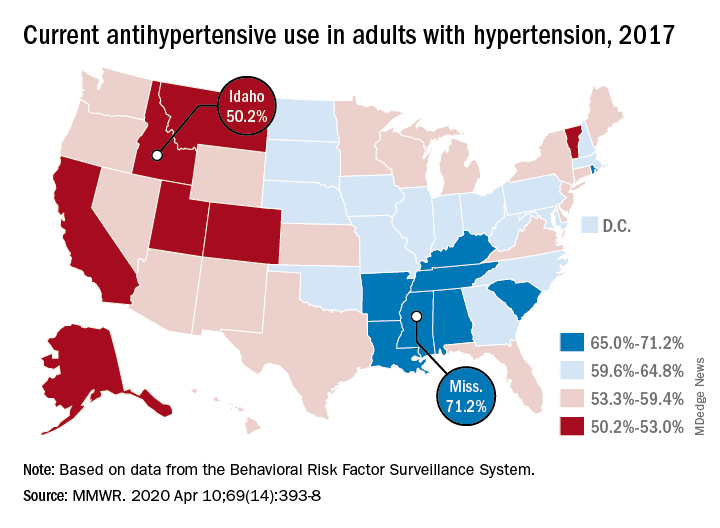

Roughly 30% of adults in the United States had hypertension in 2017, and just under 60% of those adults reported using antihypertensive medication, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

There is, however, quite a bit of variation from those age-standardized national figures when state-level data are considered.

In Alabama and West Virginia, the prevalence of hypertension in 2017 was 38.6%, the highest in the country, with Arkansas (38.5%) and Mississippi (38.2%) not far behind. Meanwhile, Minnesota came in with a lowest-in-the-nation rate of 24.3%, which was nearly matched by Colorado at 24.8%, Claudine M. Samanic, PhD, and associates wrote in the MMWR.

There was also a considerable gap between the states in hypertensive adults’ self-reported use of antihypertensive drugs, which was generally higher in the states with a greater prevalence of disease, they noted.

Adults in Mississippi were the most likely (71.2%) to be taking medication, along with those in Alabama (70.5%) and Arkansas (69.3%). Idaho occupied the other end of the scale with a rate of 50.2%, while Montana and Vermont were slightly better at 51.7%, based on survey data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.

“Prevalence of antihypertensive medication use was higher in older age groups, highest among blacks, and higher among women [64.0%] than men [56.7%]. This overall gender difference has been reported previously, but the reasons are unclear,” wrote Dr. Samanic and associates at the CDC’s National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

The BRFSS data for 2017 are based on based on interviews with 450,016 adults. Respondents were asked, “Have you ever been told by a doctor, nurse, or other health professional that you have high blood pressure?” and were considered to have hypertension if they answered yes.

SOURCE: Samanic CM et al. MMWR. 2020 Apr 10;69(14):393-8.

FROM THE MMWR

AHA updates management when CAD and T2DM coincide

Patients with stable coronary artery disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus could benefit from a “plethora of newly available risk-reduction strategies,” but their “adoption into clinical practice has been slow” and inconsistent, prompting an expert panel organized by the American Heart Association to collate the range of treatment recommendations now applicable to this patient population in a scientific statement released on April 13.

“There are a number of things to consider when treating patients with stable coronary artery disease [CAD] and type 2 diabetes mellitus [T2DM], with new medications and trials and data emerging. It’s difficult to keep up with all of the complexities,” which was why the Association’s Councils on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health and on Clinical Cardiology put together a writing group to summarize and prioritize the range of lifestyle, medical, and interventional options that now require consideration and potential use on patients managed in routine practice, explained Suzanne V. Arnold, MD, chair of the writing group, in an interview.

The new scientific statement (Circulation. 2020 Apr 13; doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000766), aimed primarily at cardiologists but also intended to inform primary care physicians, endocrinologists, and all other clinicians who deal with these patients, pulls together “everything someone needs to think about if they care for patients with CAD and T2DM,” said Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School in Boston and vice chair of the statement-writing panel in an interview. “There is a lot to know,” he added.

The statement covers antithrombotic therapies; blood pressure control, with a discussion of both the appropriate pressure goal and the best drug types used to reach it; lipid management; glycemic control; lifestyle modification; weight management, including the role of bariatric surgery; and approaches to managing stable angina, both medically and with revascularization.

“The goal was to give clinicians a good sense of what new treatments they should consider” for these patients, said Dr. Bhatt, who is also director of interventional cardiovascular programs at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, also in Boston. Because of the tight associations between T2DM and cardiovascular disease in general including CAD, “cardiologists are increasingly involved in managing patients with T2DM,” he noted. The statement gives a comprehensive overview and critical assessment of the management of these patients as of the end of 2019 as a consensus from a panel of 11 experts .

The statement also stressed that “substantial portions of patients with T2DM and CAD, including those after an acute coronary syndrome, do not receive therapies with proven cardiovascular benefit, such as high-intensity statins, dual-antiplatelet therapy, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin II receptor blockers, and glucose-lowering agents with proven cardiovascular benefits.

“These gaps in care highlight a critical opportunity for cardiovascular specialists to assume a more active role in the collaborative care of patients with T2DM and CAD,” the statement said. This includes “encouraging cardiologists to become more active in the selection of glucose-lowering medications” for these patients because it could “really move the needle,” said Dr. Arnold, a cardiologist with Saint Luke’s Health System in Kansas City, Mo. She was referring specifically to broader reliance on both the SGTL2 (sodium-glucose cotransporter 2) inhibitors and the GLP-1 (glucagonlike peptide-1) receptor agonists as top choices for controlling hyperglycemia. Based on recent evidence drugs in these two classes “could be considered first line for patients with T2DM and CAD, and would likely be preferred over metformin,” Dr. Arnold said in an interview. Although the statement identified the SGLT2 inhibitors as “the first drug class [for glycemic control] to show clear benefits on cardiovascular outcomes,” it does not explicitly label the class first-line and it also skirts that designation for the GLP-1 receptor agonist class, while noting that metformin “remains the drug most frequently recommended as first-line therapy in treatment guidelines.”

“I wouldn’t disagree with someone who said that SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists are first line,” but prescribing patterns also depend on familiarity, cost, and access, noted Dr. Bhatt, which can all be issues with agents from these classes compared with metformin, a widely available generic with decades of use. “Metformin is safe and cheap, so we did not want to discount it,” said Dr. Arnold. Dr. Bhatt recently coauthored an editorial that gave an enthusiastic endorsement to using SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with diabetes (Cell Metab. 2019 Nov 5;30[5]:47-9).

Another notable feature of the statement is the potential it assigns to bariatric surgery as a management tool with documented safety and efficacy for improving cardiovascular risk factors. However, the statement also notes that randomized trials “have thus far been inadequately powered to assess cardiovascular events and mortality, although observational studies have consistently shown cardiovascular risk reduction with such procedures.” The statement continues that despite potential cardiovascular benefits “bariatric surgery remains underused among eligible patients,” and said that surgery performed as Roux-en-Y bypass or sleeve gastrectomy “may be another effective tool for cardiovascular risk reduction in the subset of patients with obesity,” particularly patients with a body mass index of at least 35 kg/m2.

“While the percentage of patients who are optimal for bariatric surgery is not known, the most recent NHANES [National Health and Nutrition Examination Study] study showed that less than 0.5% of eligible patients underwent bariatric surgery,” Dr. Arnold noted. Bariatric surgery is “certainly not a recommendation for everyone, or even a majority of patients, but bariatric surgery should be on our radar,” for patients with CAD and T2DM, she said.

Right now, “few cardiologists think about bariatric surgery,” as a treatment option, but study results have shown that “in carefully selected patients treated by skilled surgeons at high-volume centers, patients will do better with bariatric surgery than with best medical therapy for improvements in multiple risk factors, including glycemic control,” Dr. Bhatt said in the interview. “It’s not first-line treatment, but it’s an option to consider,” he added, while also noting that bariatric surgery is most beneficial to patients relatively early in the course of T2DM, when its been in place for just a few years rather than a couple of decades.

The statement also notably included a “first-line” call out for icosapent ethyl (Vascepa), a novel agent approved in December 2019 for routine use in U.S. patients, including those with CAD and T2DM as long as their blood triglyceride level was at least 150 mg/dL. Dr. Bhatt, who led the REDUCE-IT study that was pivotal for proving the safety and efficacy of icosapent ethyl (N Engl J Med. 2019 Jan 3;380[1]:11-22), estimated that anywhere from 15% to as many as half the patients with CAD and T2DM might have a triglyceride level that would allow them to receive icosapent ethyl. One population-based study in Canada of nearly 200,000 people with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease found a 25% prevalence of the triglyceride level needed to qualify to receive icosapent ethyl under current labeling, he noted (Eur Heart J. 2020 Jan 1;41[1]:86-94). However, the FDA label does not specify that triglycerides be measured when fasting, and a nonfasting level of about 150 mg/dL will likely appear for patients with fasting levels that fall as low as about 100 mg/dL, Dr. Bhatt said. He hoped that future studies will assess the efficacy of icosapent ethyl in patients with even lower triglyceride levels.

Other sections of the statement also recommend that clinicians: Target long-term dual-antiplatelet therapy to CAD and T2DM patients with additional high-risk markers such as prior MI, younger age, and tobacco use; prescribe a low-dose oral anticoagulant along with an antiplatelet drug such as aspirin for secondary-prevention patients; promote a blood pressure target of less than 140/90 mm Hg for all CAD and T2DM patients and apply a goal of less than 130/80 mm Hg in higher-risk patients such as blacks, Asians, and those with cerebrovascular disease; and reassure patients that “despite a modest increase in blood sugars, the risk-benefit ratio is clearly in favor of administering statins to people with T2DM and CAD.”

Dr. Arnold had no disclosures. Dr. Bhatt has been an adviser to Cardax, Cereno Scientific, Medscape Cardiology, PhaseBio; PLx Pharma, and Regado Biosciences, and he has received research funding from numerous companies including Amarin, the company that markets icosapent ethyl.

Patients with stable coronary artery disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus could benefit from a “plethora of newly available risk-reduction strategies,” but their “adoption into clinical practice has been slow” and inconsistent, prompting an expert panel organized by the American Heart Association to collate the range of treatment recommendations now applicable to this patient population in a scientific statement released on April 13.

“There are a number of things to consider when treating patients with stable coronary artery disease [CAD] and type 2 diabetes mellitus [T2DM], with new medications and trials and data emerging. It’s difficult to keep up with all of the complexities,” which was why the Association’s Councils on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health and on Clinical Cardiology put together a writing group to summarize and prioritize the range of lifestyle, medical, and interventional options that now require consideration and potential use on patients managed in routine practice, explained Suzanne V. Arnold, MD, chair of the writing group, in an interview.

The new scientific statement (Circulation. 2020 Apr 13; doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000766), aimed primarily at cardiologists but also intended to inform primary care physicians, endocrinologists, and all other clinicians who deal with these patients, pulls together “everything someone needs to think about if they care for patients with CAD and T2DM,” said Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School in Boston and vice chair of the statement-writing panel in an interview. “There is a lot to know,” he added.

The statement covers antithrombotic therapies; blood pressure control, with a discussion of both the appropriate pressure goal and the best drug types used to reach it; lipid management; glycemic control; lifestyle modification; weight management, including the role of bariatric surgery; and approaches to managing stable angina, both medically and with revascularization.

“The goal was to give clinicians a good sense of what new treatments they should consider” for these patients, said Dr. Bhatt, who is also director of interventional cardiovascular programs at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, also in Boston. Because of the tight associations between T2DM and cardiovascular disease in general including CAD, “cardiologists are increasingly involved in managing patients with T2DM,” he noted. The statement gives a comprehensive overview and critical assessment of the management of these patients as of the end of 2019 as a consensus from a panel of 11 experts .

The statement also stressed that “substantial portions of patients with T2DM and CAD, including those after an acute coronary syndrome, do not receive therapies with proven cardiovascular benefit, such as high-intensity statins, dual-antiplatelet therapy, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin II receptor blockers, and glucose-lowering agents with proven cardiovascular benefits.

“These gaps in care highlight a critical opportunity for cardiovascular specialists to assume a more active role in the collaborative care of patients with T2DM and CAD,” the statement said. This includes “encouraging cardiologists to become more active in the selection of glucose-lowering medications” for these patients because it could “really move the needle,” said Dr. Arnold, a cardiologist with Saint Luke’s Health System in Kansas City, Mo. She was referring specifically to broader reliance on both the SGTL2 (sodium-glucose cotransporter 2) inhibitors and the GLP-1 (glucagonlike peptide-1) receptor agonists as top choices for controlling hyperglycemia. Based on recent evidence drugs in these two classes “could be considered first line for patients with T2DM and CAD, and would likely be preferred over metformin,” Dr. Arnold said in an interview. Although the statement identified the SGLT2 inhibitors as “the first drug class [for glycemic control] to show clear benefits on cardiovascular outcomes,” it does not explicitly label the class first-line and it also skirts that designation for the GLP-1 receptor agonist class, while noting that metformin “remains the drug most frequently recommended as first-line therapy in treatment guidelines.”

“I wouldn’t disagree with someone who said that SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists are first line,” but prescribing patterns also depend on familiarity, cost, and access, noted Dr. Bhatt, which can all be issues with agents from these classes compared with metformin, a widely available generic with decades of use. “Metformin is safe and cheap, so we did not want to discount it,” said Dr. Arnold. Dr. Bhatt recently coauthored an editorial that gave an enthusiastic endorsement to using SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with diabetes (Cell Metab. 2019 Nov 5;30[5]:47-9).

Another notable feature of the statement is the potential it assigns to bariatric surgery as a management tool with documented safety and efficacy for improving cardiovascular risk factors. However, the statement also notes that randomized trials “have thus far been inadequately powered to assess cardiovascular events and mortality, although observational studies have consistently shown cardiovascular risk reduction with such procedures.” The statement continues that despite potential cardiovascular benefits “bariatric surgery remains underused among eligible patients,” and said that surgery performed as Roux-en-Y bypass or sleeve gastrectomy “may be another effective tool for cardiovascular risk reduction in the subset of patients with obesity,” particularly patients with a body mass index of at least 35 kg/m2.

“While the percentage of patients who are optimal for bariatric surgery is not known, the most recent NHANES [National Health and Nutrition Examination Study] study showed that less than 0.5% of eligible patients underwent bariatric surgery,” Dr. Arnold noted. Bariatric surgery is “certainly not a recommendation for everyone, or even a majority of patients, but bariatric surgery should be on our radar,” for patients with CAD and T2DM, she said.

Right now, “few cardiologists think about bariatric surgery,” as a treatment option, but study results have shown that “in carefully selected patients treated by skilled surgeons at high-volume centers, patients will do better with bariatric surgery than with best medical therapy for improvements in multiple risk factors, including glycemic control,” Dr. Bhatt said in the interview. “It’s not first-line treatment, but it’s an option to consider,” he added, while also noting that bariatric surgery is most beneficial to patients relatively early in the course of T2DM, when its been in place for just a few years rather than a couple of decades.

The statement also notably included a “first-line” call out for icosapent ethyl (Vascepa), a novel agent approved in December 2019 for routine use in U.S. patients, including those with CAD and T2DM as long as their blood triglyceride level was at least 150 mg/dL. Dr. Bhatt, who led the REDUCE-IT study that was pivotal for proving the safety and efficacy of icosapent ethyl (N Engl J Med. 2019 Jan 3;380[1]:11-22), estimated that anywhere from 15% to as many as half the patients with CAD and T2DM might have a triglyceride level that would allow them to receive icosapent ethyl. One population-based study in Canada of nearly 200,000 people with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease found a 25% prevalence of the triglyceride level needed to qualify to receive icosapent ethyl under current labeling, he noted (Eur Heart J. 2020 Jan 1;41[1]:86-94). However, the FDA label does not specify that triglycerides be measured when fasting, and a nonfasting level of about 150 mg/dL will likely appear for patients with fasting levels that fall as low as about 100 mg/dL, Dr. Bhatt said. He hoped that future studies will assess the efficacy of icosapent ethyl in patients with even lower triglyceride levels.

Other sections of the statement also recommend that clinicians: Target long-term dual-antiplatelet therapy to CAD and T2DM patients with additional high-risk markers such as prior MI, younger age, and tobacco use; prescribe a low-dose oral anticoagulant along with an antiplatelet drug such as aspirin for secondary-prevention patients; promote a blood pressure target of less than 140/90 mm Hg for all CAD and T2DM patients and apply a goal of less than 130/80 mm Hg in higher-risk patients such as blacks, Asians, and those with cerebrovascular disease; and reassure patients that “despite a modest increase in blood sugars, the risk-benefit ratio is clearly in favor of administering statins to people with T2DM and CAD.”

Dr. Arnold had no disclosures. Dr. Bhatt has been an adviser to Cardax, Cereno Scientific, Medscape Cardiology, PhaseBio; PLx Pharma, and Regado Biosciences, and he has received research funding from numerous companies including Amarin, the company that markets icosapent ethyl.

Patients with stable coronary artery disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus could benefit from a “plethora of newly available risk-reduction strategies,” but their “adoption into clinical practice has been slow” and inconsistent, prompting an expert panel organized by the American Heart Association to collate the range of treatment recommendations now applicable to this patient population in a scientific statement released on April 13.

“There are a number of things to consider when treating patients with stable coronary artery disease [CAD] and type 2 diabetes mellitus [T2DM], with new medications and trials and data emerging. It’s difficult to keep up with all of the complexities,” which was why the Association’s Councils on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health and on Clinical Cardiology put together a writing group to summarize and prioritize the range of lifestyle, medical, and interventional options that now require consideration and potential use on patients managed in routine practice, explained Suzanne V. Arnold, MD, chair of the writing group, in an interview.

The new scientific statement (Circulation. 2020 Apr 13; doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000766), aimed primarily at cardiologists but also intended to inform primary care physicians, endocrinologists, and all other clinicians who deal with these patients, pulls together “everything someone needs to think about if they care for patients with CAD and T2DM,” said Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School in Boston and vice chair of the statement-writing panel in an interview. “There is a lot to know,” he added.

The statement covers antithrombotic therapies; blood pressure control, with a discussion of both the appropriate pressure goal and the best drug types used to reach it; lipid management; glycemic control; lifestyle modification; weight management, including the role of bariatric surgery; and approaches to managing stable angina, both medically and with revascularization.

“The goal was to give clinicians a good sense of what new treatments they should consider” for these patients, said Dr. Bhatt, who is also director of interventional cardiovascular programs at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, also in Boston. Because of the tight associations between T2DM and cardiovascular disease in general including CAD, “cardiologists are increasingly involved in managing patients with T2DM,” he noted. The statement gives a comprehensive overview and critical assessment of the management of these patients as of the end of 2019 as a consensus from a panel of 11 experts .

The statement also stressed that “substantial portions of patients with T2DM and CAD, including those after an acute coronary syndrome, do not receive therapies with proven cardiovascular benefit, such as high-intensity statins, dual-antiplatelet therapy, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin II receptor blockers, and glucose-lowering agents with proven cardiovascular benefits.

“These gaps in care highlight a critical opportunity for cardiovascular specialists to assume a more active role in the collaborative care of patients with T2DM and CAD,” the statement said. This includes “encouraging cardiologists to become more active in the selection of glucose-lowering medications” for these patients because it could “really move the needle,” said Dr. Arnold, a cardiologist with Saint Luke’s Health System in Kansas City, Mo. She was referring specifically to broader reliance on both the SGTL2 (sodium-glucose cotransporter 2) inhibitors and the GLP-1 (glucagonlike peptide-1) receptor agonists as top choices for controlling hyperglycemia. Based on recent evidence drugs in these two classes “could be considered first line for patients with T2DM and CAD, and would likely be preferred over metformin,” Dr. Arnold said in an interview. Although the statement identified the SGLT2 inhibitors as “the first drug class [for glycemic control] to show clear benefits on cardiovascular outcomes,” it does not explicitly label the class first-line and it also skirts that designation for the GLP-1 receptor agonist class, while noting that metformin “remains the drug most frequently recommended as first-line therapy in treatment guidelines.”

“I wouldn’t disagree with someone who said that SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists are first line,” but prescribing patterns also depend on familiarity, cost, and access, noted Dr. Bhatt, which can all be issues with agents from these classes compared with metformin, a widely available generic with decades of use. “Metformin is safe and cheap, so we did not want to discount it,” said Dr. Arnold. Dr. Bhatt recently coauthored an editorial that gave an enthusiastic endorsement to using SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with diabetes (Cell Metab. 2019 Nov 5;30[5]:47-9).

Another notable feature of the statement is the potential it assigns to bariatric surgery as a management tool with documented safety and efficacy for improving cardiovascular risk factors. However, the statement also notes that randomized trials “have thus far been inadequately powered to assess cardiovascular events and mortality, although observational studies have consistently shown cardiovascular risk reduction with such procedures.” The statement continues that despite potential cardiovascular benefits “bariatric surgery remains underused among eligible patients,” and said that surgery performed as Roux-en-Y bypass or sleeve gastrectomy “may be another effective tool for cardiovascular risk reduction in the subset of patients with obesity,” particularly patients with a body mass index of at least 35 kg/m2.

“While the percentage of patients who are optimal for bariatric surgery is not known, the most recent NHANES [National Health and Nutrition Examination Study] study showed that less than 0.5% of eligible patients underwent bariatric surgery,” Dr. Arnold noted. Bariatric surgery is “certainly not a recommendation for everyone, or even a majority of patients, but bariatric surgery should be on our radar,” for patients with CAD and T2DM, she said.

Right now, “few cardiologists think about bariatric surgery,” as a treatment option, but study results have shown that “in carefully selected patients treated by skilled surgeons at high-volume centers, patients will do better with bariatric surgery than with best medical therapy for improvements in multiple risk factors, including glycemic control,” Dr. Bhatt said in the interview. “It’s not first-line treatment, but it’s an option to consider,” he added, while also noting that bariatric surgery is most beneficial to patients relatively early in the course of T2DM, when its been in place for just a few years rather than a couple of decades.

The statement also notably included a “first-line” call out for icosapent ethyl (Vascepa), a novel agent approved in December 2019 for routine use in U.S. patients, including those with CAD and T2DM as long as their blood triglyceride level was at least 150 mg/dL. Dr. Bhatt, who led the REDUCE-IT study that was pivotal for proving the safety and efficacy of icosapent ethyl (N Engl J Med. 2019 Jan 3;380[1]:11-22), estimated that anywhere from 15% to as many as half the patients with CAD and T2DM might have a triglyceride level that would allow them to receive icosapent ethyl. One population-based study in Canada of nearly 200,000 people with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease found a 25% prevalence of the triglyceride level needed to qualify to receive icosapent ethyl under current labeling, he noted (Eur Heart J. 2020 Jan 1;41[1]:86-94). However, the FDA label does not specify that triglycerides be measured when fasting, and a nonfasting level of about 150 mg/dL will likely appear for patients with fasting levels that fall as low as about 100 mg/dL, Dr. Bhatt said. He hoped that future studies will assess the efficacy of icosapent ethyl in patients with even lower triglyceride levels.

Other sections of the statement also recommend that clinicians: Target long-term dual-antiplatelet therapy to CAD and T2DM patients with additional high-risk markers such as prior MI, younger age, and tobacco use; prescribe a low-dose oral anticoagulant along with an antiplatelet drug such as aspirin for secondary-prevention patients; promote a blood pressure target of less than 140/90 mm Hg for all CAD and T2DM patients and apply a goal of less than 130/80 mm Hg in higher-risk patients such as blacks, Asians, and those with cerebrovascular disease; and reassure patients that “despite a modest increase in blood sugars, the risk-benefit ratio is clearly in favor of administering statins to people with T2DM and CAD.”

Dr. Arnold had no disclosures. Dr. Bhatt has been an adviser to Cardax, Cereno Scientific, Medscape Cardiology, PhaseBio; PLx Pharma, and Regado Biosciences, and he has received research funding from numerous companies including Amarin, the company that markets icosapent ethyl.

FROM CIRCULATION

Pandemic necessitates new strategies to treat migraine

Patients with migraine who are unable to continue preventive procedures such as onabotulinumtoxinA injections during the COVID-19 pandemic may be at risk of worsening migraine, according to an article published March 30 in Headache. To address this scenario, including monoclonal antibodies against calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) or the CGRP receptor, the authors said.

“This is a particularly vulnerable time for individuals with migraine and other disabling headache disorders, with many physical and mental stressors, increased anxiety, and changes in daily routine which may serve as triggering factors for worsening headache,” said lead author Christina L. Szperka, MD, director of the pediatric headache program at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and colleagues.

Acute treatment

The authors described potential treatment regimens based on their experience as headache specialists and the experiences of their colleagues. For acute therapy options, NSAIDs, triptans, and neuroleptics may be used in combination when needed. Medications within the same drug category should not be combined, however, and triptans, dihydroergotamine, and lasmiditan should not be coadministered within 24 hours. Since the 2015 American Headache Society guideline for the acute treatment of migraine, the Food and Drug Administration has approved additional acute migraine medications, including ubrogepant, rimegepant, and lasmiditan, the authors said. The agency also cleared several neuromodulation devices for the acute treatment of migraine.

Although few drugs have been studied as treatments for unusually prolonged severe headaches, headache doctors often recommend NSAIDs before patients seek care at an emergency department or infusion center, the authors said. NSAID options include indomethacin, ketorolac, naproxen, nabumetone, diclofenac, and mefenamic acid. Neuroleptics also may be used. “Long-acting triptan medications can be used as bridge therapies, as is often done in the treatment of menstrually related migraine or in the treatment of medication overuse headache,” they said. “We propose a similar strategy can be trialed as a therapeutic option for refractory or persistent migraine.”

The authors also described the use of antiepileptics and corticosteroids, as well as drugs that may treat specific symptoms, such as difficulty sleeping (hydroxyzine or amitriptyline), neck or muscle pain (tizanidine), and aura with migraine (magnesium). Clinicians should avoid the use of opioids and butalbital, they said.

Preventive treatment

“While the injection of onabotulinumtoxinA is an effective treatment for chronic migraine, the procedure can put the patient and the provider at higher risk of COVID-19 given the close contact encounter,” wrote Dr. Szperka and colleagues. “We believe that other migraine preventive treatments should be utilized first when possible.” Since the publication of a guideline on preventive migraine therapies in 2012, the FDA has approved additional preventive therapies, including the anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies erenumab‐aooe, galcanezumab‐gnlm, fremanezumab‐vfrm, and eptinezumab‐jjmr. “The first three are intended for self‐injection at home, with detailed instructions available for each product on its website,” they said.

Among angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), candesartan has evidence of efficacy and tolerability in migraine prevention. Lisinopril has been considered possibly effective. “There has been recent concern in the media about the possibility of these medications interfering with the body’s response to COVID‐19,” the authors said, although this theoretical concern was not based on experimental or clinical data. “For patients in need of a new preventive therapy, the potential for benefit with an ACE/ARB must be weighed against the theoretical increased risk of infection.”

In addition, studies indicate that melatonin may prevent migraine with few side effects and that zonisamide may be effective in patients who have an inadequate response to or experience side effects with topiramate.

Policy changes and telehealth options

Effectively treating patients with migraine during the pandemic requires policy changes, according to the authors. “Migraine preventive prior authorization restrictions need to be lifted for evidence‐based, FDA‐approved therapies; patients need to be able to access these medications quickly and easily. Patients should not be required to fail older medications,” they said. “Similarly, in order to permit the transition of patients from onabotulinumtoxinA to anti‐CGRP [monoclonal antibodies], insurers should remove the prohibition against simultaneous coverage of these drug classes.” Insurers also should loosen restrictions on the off-label use of acute and preventive medication for adolescents, Dr. Szperka and coauthors suggest.

“In the era of COVID‐19, telehealth has become an essential modality for most headache specialists, given the need for providers to take significant precautions for both their patients and themselves, limiting touch or close contact,” they said. Patients with headache may warrant additional screening for COVID-19 as well. “As headache has been reported as an early symptom of COVID‐19, patients with worsening or new onset severe headache should be reviewed for exposure risk and any other symptoms which may be consistent with COVID‐19 infection,” the authors said.

There was no direct funding for the report. Dr. Szperka and a coauthor receive salary support from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Szperka also has received grant support from Pfizer, and her institution has received compensation for her consulting work for Allergan. Several coauthors disclosed consulting and serving on speakers’ bureaus for and receiving research support from various pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Szperka CL et al. Headache. 2020 Mar 30. doi: 10.1111/head.13810.

Patients with migraine who are unable to continue preventive procedures such as onabotulinumtoxinA injections during the COVID-19 pandemic may be at risk of worsening migraine, according to an article published March 30 in Headache. To address this scenario, including monoclonal antibodies against calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) or the CGRP receptor, the authors said.

“This is a particularly vulnerable time for individuals with migraine and other disabling headache disorders, with many physical and mental stressors, increased anxiety, and changes in daily routine which may serve as triggering factors for worsening headache,” said lead author Christina L. Szperka, MD, director of the pediatric headache program at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and colleagues.

Acute treatment

The authors described potential treatment regimens based on their experience as headache specialists and the experiences of their colleagues. For acute therapy options, NSAIDs, triptans, and neuroleptics may be used in combination when needed. Medications within the same drug category should not be combined, however, and triptans, dihydroergotamine, and lasmiditan should not be coadministered within 24 hours. Since the 2015 American Headache Society guideline for the acute treatment of migraine, the Food and Drug Administration has approved additional acute migraine medications, including ubrogepant, rimegepant, and lasmiditan, the authors said. The agency also cleared several neuromodulation devices for the acute treatment of migraine.

Although few drugs have been studied as treatments for unusually prolonged severe headaches, headache doctors often recommend NSAIDs before patients seek care at an emergency department or infusion center, the authors said. NSAID options include indomethacin, ketorolac, naproxen, nabumetone, diclofenac, and mefenamic acid. Neuroleptics also may be used. “Long-acting triptan medications can be used as bridge therapies, as is often done in the treatment of menstrually related migraine or in the treatment of medication overuse headache,” they said. “We propose a similar strategy can be trialed as a therapeutic option for refractory or persistent migraine.”

The authors also described the use of antiepileptics and corticosteroids, as well as drugs that may treat specific symptoms, such as difficulty sleeping (hydroxyzine or amitriptyline), neck or muscle pain (tizanidine), and aura with migraine (magnesium). Clinicians should avoid the use of opioids and butalbital, they said.

Preventive treatment

“While the injection of onabotulinumtoxinA is an effective treatment for chronic migraine, the procedure can put the patient and the provider at higher risk of COVID-19 given the close contact encounter,” wrote Dr. Szperka and colleagues. “We believe that other migraine preventive treatments should be utilized first when possible.” Since the publication of a guideline on preventive migraine therapies in 2012, the FDA has approved additional preventive therapies, including the anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies erenumab‐aooe, galcanezumab‐gnlm, fremanezumab‐vfrm, and eptinezumab‐jjmr. “The first three are intended for self‐injection at home, with detailed instructions available for each product on its website,” they said.

Among angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), candesartan has evidence of efficacy and tolerability in migraine prevention. Lisinopril has been considered possibly effective. “There has been recent concern in the media about the possibility of these medications interfering with the body’s response to COVID‐19,” the authors said, although this theoretical concern was not based on experimental or clinical data. “For patients in need of a new preventive therapy, the potential for benefit with an ACE/ARB must be weighed against the theoretical increased risk of infection.”

In addition, studies indicate that melatonin may prevent migraine with few side effects and that zonisamide may be effective in patients who have an inadequate response to or experience side effects with topiramate.

Policy changes and telehealth options

Effectively treating patients with migraine during the pandemic requires policy changes, according to the authors. “Migraine preventive prior authorization restrictions need to be lifted for evidence‐based, FDA‐approved therapies; patients need to be able to access these medications quickly and easily. Patients should not be required to fail older medications,” they said. “Similarly, in order to permit the transition of patients from onabotulinumtoxinA to anti‐CGRP [monoclonal antibodies], insurers should remove the prohibition against simultaneous coverage of these drug classes.” Insurers also should loosen restrictions on the off-label use of acute and preventive medication for adolescents, Dr. Szperka and coauthors suggest.

“In the era of COVID‐19, telehealth has become an essential modality for most headache specialists, given the need for providers to take significant precautions for both their patients and themselves, limiting touch or close contact,” they said. Patients with headache may warrant additional screening for COVID-19 as well. “As headache has been reported as an early symptom of COVID‐19, patients with worsening or new onset severe headache should be reviewed for exposure risk and any other symptoms which may be consistent with COVID‐19 infection,” the authors said.

There was no direct funding for the report. Dr. Szperka and a coauthor receive salary support from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Szperka also has received grant support from Pfizer, and her institution has received compensation for her consulting work for Allergan. Several coauthors disclosed consulting and serving on speakers’ bureaus for and receiving research support from various pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Szperka CL et al. Headache. 2020 Mar 30. doi: 10.1111/head.13810.

Patients with migraine who are unable to continue preventive procedures such as onabotulinumtoxinA injections during the COVID-19 pandemic may be at risk of worsening migraine, according to an article published March 30 in Headache. To address this scenario, including monoclonal antibodies against calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) or the CGRP receptor, the authors said.

“This is a particularly vulnerable time for individuals with migraine and other disabling headache disorders, with many physical and mental stressors, increased anxiety, and changes in daily routine which may serve as triggering factors for worsening headache,” said lead author Christina L. Szperka, MD, director of the pediatric headache program at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and colleagues.

Acute treatment

The authors described potential treatment regimens based on their experience as headache specialists and the experiences of their colleagues. For acute therapy options, NSAIDs, triptans, and neuroleptics may be used in combination when needed. Medications within the same drug category should not be combined, however, and triptans, dihydroergotamine, and lasmiditan should not be coadministered within 24 hours. Since the 2015 American Headache Society guideline for the acute treatment of migraine, the Food and Drug Administration has approved additional acute migraine medications, including ubrogepant, rimegepant, and lasmiditan, the authors said. The agency also cleared several neuromodulation devices for the acute treatment of migraine.

Although few drugs have been studied as treatments for unusually prolonged severe headaches, headache doctors often recommend NSAIDs before patients seek care at an emergency department or infusion center, the authors said. NSAID options include indomethacin, ketorolac, naproxen, nabumetone, diclofenac, and mefenamic acid. Neuroleptics also may be used. “Long-acting triptan medications can be used as bridge therapies, as is often done in the treatment of menstrually related migraine or in the treatment of medication overuse headache,” they said. “We propose a similar strategy can be trialed as a therapeutic option for refractory or persistent migraine.”

The authors also described the use of antiepileptics and corticosteroids, as well as drugs that may treat specific symptoms, such as difficulty sleeping (hydroxyzine or amitriptyline), neck or muscle pain (tizanidine), and aura with migraine (magnesium). Clinicians should avoid the use of opioids and butalbital, they said.

Preventive treatment

“While the injection of onabotulinumtoxinA is an effective treatment for chronic migraine, the procedure can put the patient and the provider at higher risk of COVID-19 given the close contact encounter,” wrote Dr. Szperka and colleagues. “We believe that other migraine preventive treatments should be utilized first when possible.” Since the publication of a guideline on preventive migraine therapies in 2012, the FDA has approved additional preventive therapies, including the anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies erenumab‐aooe, galcanezumab‐gnlm, fremanezumab‐vfrm, and eptinezumab‐jjmr. “The first three are intended for self‐injection at home, with detailed instructions available for each product on its website,” they said.

Among angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), candesartan has evidence of efficacy and tolerability in migraine prevention. Lisinopril has been considered possibly effective. “There has been recent concern in the media about the possibility of these medications interfering with the body’s response to COVID‐19,” the authors said, although this theoretical concern was not based on experimental or clinical data. “For patients in need of a new preventive therapy, the potential for benefit with an ACE/ARB must be weighed against the theoretical increased risk of infection.”

In addition, studies indicate that melatonin may prevent migraine with few side effects and that zonisamide may be effective in patients who have an inadequate response to or experience side effects with topiramate.

Policy changes and telehealth options

Effectively treating patients with migraine during the pandemic requires policy changes, according to the authors. “Migraine preventive prior authorization restrictions need to be lifted for evidence‐based, FDA‐approved therapies; patients need to be able to access these medications quickly and easily. Patients should not be required to fail older medications,” they said. “Similarly, in order to permit the transition of patients from onabotulinumtoxinA to anti‐CGRP [monoclonal antibodies], insurers should remove the prohibition against simultaneous coverage of these drug classes.” Insurers also should loosen restrictions on the off-label use of acute and preventive medication for adolescents, Dr. Szperka and coauthors suggest.

“In the era of COVID‐19, telehealth has become an essential modality for most headache specialists, given the need for providers to take significant precautions for both their patients and themselves, limiting touch or close contact,” they said. Patients with headache may warrant additional screening for COVID-19 as well. “As headache has been reported as an early symptom of COVID‐19, patients with worsening or new onset severe headache should be reviewed for exposure risk and any other symptoms which may be consistent with COVID‐19 infection,” the authors said.

There was no direct funding for the report. Dr. Szperka and a coauthor receive salary support from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Szperka also has received grant support from Pfizer, and her institution has received compensation for her consulting work for Allergan. Several coauthors disclosed consulting and serving on speakers’ bureaus for and receiving research support from various pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Szperka CL et al. Headache. 2020 Mar 30. doi: 10.1111/head.13810.

FROM HEADACHE

‘We’re in great distress here,’ infusion center CMO says

Count Vikram Sengupta, MD, among the slew of health care workers feeling overwhelmed by the impact that COVID-19 is having on the delivery of health care in Manhattan and its surrounding boroughs.

“Nobody in the country is suffering like New York City,” said Dr. Sengupta, chief medical officer of Thrivewell Infusion, which operates three stand-alone infusion centers in the region: a four-chair center in Crown Heights, a 10-chair center in Borough Park, Brooklyn, and an eight-chair center in Manhasset. “We have 30%-50% of all cases in the country. I’ve been reading the news, and some people think this thing is going away. We’re in great distress here. There need to be new strategies moving forward. The whole world has changed. Our whole approach to ambulatory care has changed.”

In early March 2020, when it became clear that New York hospitals would face a tidal wave of citizens infected with COVID-19, Thrivewell began to receive an influx of referrals originating from concerned patients, providers, payers, and even large integrated health care systems, all in an effort to help prevent infectious exposure through infusion in hospital-based settings. “We are trying to accommodate them as swiftly as possible,” said Dr. Sengupta, who was interviewed for this story on April 9. “There’s been a huge uptick from that standpoint. We’ve made sure that we’ve kept our facilities clean by employing standards that have been released by the CDC, as well as by the major academic centers who are dealing with this firsthand, and also with guidance from the National Infusion Center Association.”

He and his colleagues launched a pop-up infusion center in the Bronx to help offload Montefiore Medical Center, “because they’re so overwhelmed with COVID-19 patients that they need help taking care of the autoimmune patients,” Dr. Sengupta said. “That’s the role we’re playing. We’ve made our resources available to these centers in a very flexible way in order to ensure that we do the best thing we can for everybody.”

Thrivewell is also deploying a mobile infusion unit to recovered COVID-19 patients who require an infusion for their autoimmune disease, in order to minimize the risk of contamination and transmission in their stand-alone centers. The RV-sized unit, about the size of a Bloodmobile, is equipped with infusion chairs and staffed by a physician and nurse practitioner. “The objective is continuant care and reduction of cross-contamination, and also, on a broader health care systems level, to ensure that we as ambulatory infusion center providers can offload an overburdened system,” he said.

Dr. Sengupta, who has assisted on COVID-19 inpatient wards at New York University as a volunteer, is also leading a trial of a stem cell-derived therapy developed by Israel-based Pluristem Therapeutics, to treat New York–area patients severely ill from COVID-19 infection. “There are reports from Wuhan, China, in which clinicians are delivering IV mesenchymal stem cells to patients who are on mechanical ventilators, and the patients are getting better,” he said. “I have initiated a study in which we have three cohorts: One is the outpatient setting in which we are trying to treat COVID-19 patients who have hypoxia but have been turned away from overwhelmed EDs and need some therapy. We will be converting one of our infusion centers to conduct this trial. We are also going to be administering this [stem cell-derived therapy] to COVID-19 patients in ICUs, in EDs, and on med-surg floors throughout the city.”

Count Vikram Sengupta, MD, among the slew of health care workers feeling overwhelmed by the impact that COVID-19 is having on the delivery of health care in Manhattan and its surrounding boroughs.

“Nobody in the country is suffering like New York City,” said Dr. Sengupta, chief medical officer of Thrivewell Infusion, which operates three stand-alone infusion centers in the region: a four-chair center in Crown Heights, a 10-chair center in Borough Park, Brooklyn, and an eight-chair center in Manhasset. “We have 30%-50% of all cases in the country. I’ve been reading the news, and some people think this thing is going away. We’re in great distress here. There need to be new strategies moving forward. The whole world has changed. Our whole approach to ambulatory care has changed.”

In early March 2020, when it became clear that New York hospitals would face a tidal wave of citizens infected with COVID-19, Thrivewell began to receive an influx of referrals originating from concerned patients, providers, payers, and even large integrated health care systems, all in an effort to help prevent infectious exposure through infusion in hospital-based settings. “We are trying to accommodate them as swiftly as possible,” said Dr. Sengupta, who was interviewed for this story on April 9. “There’s been a huge uptick from that standpoint. We’ve made sure that we’ve kept our facilities clean by employing standards that have been released by the CDC, as well as by the major academic centers who are dealing with this firsthand, and also with guidance from the National Infusion Center Association.”

He and his colleagues launched a pop-up infusion center in the Bronx to help offload Montefiore Medical Center, “because they’re so overwhelmed with COVID-19 patients that they need help taking care of the autoimmune patients,” Dr. Sengupta said. “That’s the role we’re playing. We’ve made our resources available to these centers in a very flexible way in order to ensure that we do the best thing we can for everybody.”

Thrivewell is also deploying a mobile infusion unit to recovered COVID-19 patients who require an infusion for their autoimmune disease, in order to minimize the risk of contamination and transmission in their stand-alone centers. The RV-sized unit, about the size of a Bloodmobile, is equipped with infusion chairs and staffed by a physician and nurse practitioner. “The objective is continuant care and reduction of cross-contamination, and also, on a broader health care systems level, to ensure that we as ambulatory infusion center providers can offload an overburdened system,” he said.

Dr. Sengupta, who has assisted on COVID-19 inpatient wards at New York University as a volunteer, is also leading a trial of a stem cell-derived therapy developed by Israel-based Pluristem Therapeutics, to treat New York–area patients severely ill from COVID-19 infection. “There are reports from Wuhan, China, in which clinicians are delivering IV mesenchymal stem cells to patients who are on mechanical ventilators, and the patients are getting better,” he said. “I have initiated a study in which we have three cohorts: One is the outpatient setting in which we are trying to treat COVID-19 patients who have hypoxia but have been turned away from overwhelmed EDs and need some therapy. We will be converting one of our infusion centers to conduct this trial. We are also going to be administering this [stem cell-derived therapy] to COVID-19 patients in ICUs, in EDs, and on med-surg floors throughout the city.”

Count Vikram Sengupta, MD, among the slew of health care workers feeling overwhelmed by the impact that COVID-19 is having on the delivery of health care in Manhattan and its surrounding boroughs.

“Nobody in the country is suffering like New York City,” said Dr. Sengupta, chief medical officer of Thrivewell Infusion, which operates three stand-alone infusion centers in the region: a four-chair center in Crown Heights, a 10-chair center in Borough Park, Brooklyn, and an eight-chair center in Manhasset. “We have 30%-50% of all cases in the country. I’ve been reading the news, and some people think this thing is going away. We’re in great distress here. There need to be new strategies moving forward. The whole world has changed. Our whole approach to ambulatory care has changed.”

In early March 2020, when it became clear that New York hospitals would face a tidal wave of citizens infected with COVID-19, Thrivewell began to receive an influx of referrals originating from concerned patients, providers, payers, and even large integrated health care systems, all in an effort to help prevent infectious exposure through infusion in hospital-based settings. “We are trying to accommodate them as swiftly as possible,” said Dr. Sengupta, who was interviewed for this story on April 9. “There’s been a huge uptick from that standpoint. We’ve made sure that we’ve kept our facilities clean by employing standards that have been released by the CDC, as well as by the major academic centers who are dealing with this firsthand, and also with guidance from the National Infusion Center Association.”

He and his colleagues launched a pop-up infusion center in the Bronx to help offload Montefiore Medical Center, “because they’re so overwhelmed with COVID-19 patients that they need help taking care of the autoimmune patients,” Dr. Sengupta said. “That’s the role we’re playing. We’ve made our resources available to these centers in a very flexible way in order to ensure that we do the best thing we can for everybody.”

Thrivewell is also deploying a mobile infusion unit to recovered COVID-19 patients who require an infusion for their autoimmune disease, in order to minimize the risk of contamination and transmission in their stand-alone centers. The RV-sized unit, about the size of a Bloodmobile, is equipped with infusion chairs and staffed by a physician and nurse practitioner. “The objective is continuant care and reduction of cross-contamination, and also, on a broader health care systems level, to ensure that we as ambulatory infusion center providers can offload an overburdened system,” he said.

Dr. Sengupta, who has assisted on COVID-19 inpatient wards at New York University as a volunteer, is also leading a trial of a stem cell-derived therapy developed by Israel-based Pluristem Therapeutics, to treat New York–area patients severely ill from COVID-19 infection. “There are reports from Wuhan, China, in which clinicians are delivering IV mesenchymal stem cells to patients who are on mechanical ventilators, and the patients are getting better,” he said. “I have initiated a study in which we have three cohorts: One is the outpatient setting in which we are trying to treat COVID-19 patients who have hypoxia but have been turned away from overwhelmed EDs and need some therapy. We will be converting one of our infusion centers to conduct this trial. We are also going to be administering this [stem cell-derived therapy] to COVID-19 patients in ICUs, in EDs, and on med-surg floors throughout the city.”

Infusion center directors shuffle treatment services in the era of COVID-19

It’s anything but business as usual for clinicians who oversee office-based infusion centers, as they scramble to maintain services for patients considered to be at heightened risk for severe illness should they become infected with COVID-19.

“For many reasons, the guidance for patients right now is that they stay on their medications,” Max I. Hamburger, MD, a managing partner at Rheumatology Associates of Long Island (N.Y.), said in an interview. “Some have decided to stop the drug, and then they call us up to tell us that they’re flaring. The beginning of a flare is tiredness and other things. Now they’re worried: Are they tired because of the disease, or are they tired because they have COVID-19?”

With five office locations located in a region considered to be the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, Dr. Hamburger and his colleagues are hypervigilant about screening patients for symptoms of the virus before they visit one of the three practice locations that provide infusion services. This starts with an automated phone system that reminds patients of their appointment time. “Part of that robocall now has some questions like, ‘Do you have any symptoms of COVID-19?’ ‘Are you running a fever?’ ‘Do you have any reason to worry about yourself? If so, please call us.’ ” The infusion nurses are also calling the patients in advance of their appointment to check on their status. “When they get to the office location, we ask them again about their general health and check their temperature,” said Dr. Hamburger, who is also founder and executive chairman of United Rheumatology, which is a nationwide rheumatology care management services organization with 650 members in 39 states. “We’re doing everything we can to talk to them about their own state of health and to question them about what I call extended paranoia: like, ‘Who are you living with?’ ‘Who are you hanging out with?’ ‘What are all the six degrees of separation here?’ I want to know what the patient’s husband did last night. I want to know where their kids were over this past week, et cetera. We do everything we can to see if there’s anybody who might have had the slightest [contact with someone who has COVID-19]. Because if I lose my infusion nurse, then I’m up the creek.”

The infusion nurse wears scrubs, a face mask, and latex gloves. She and her staff are using hand sanitizer and cleaning infusion equipment with sanitizing wipes as one might do in a surgical setting. “Every surface is wiped down between patients, and the nurse is changing gloves between patients,” said Dr. Hamburger, who was founding president of the New York State Rheumatology Society before retiring from that post in 2017. “Getting masks has been tough. We’re doing the best we can there. We’re not gloving patients but we’re masking patients.”

As noted in guidance from the American College of Rheumatology and other medical organizations, following the CDC’s recommendation to stay at home during the pandemic has jump-started conversations between physicians and their patients about modifying the time interval between infusions. “If they have been doing well for the last 9 months, we’re having a conversation such as ‘Maybe instead of getting your Orencia every 4 weeks, maybe we’ll push it out to 5 weeks, or maybe we’ll push the Enbrel out to 10 days and the Humira out 3 weeks, et cetera,” Dr. Hamburger said. “One has to be very careful about when you do that, because you don’t want the patient to flare up because it’s hard to get them in, but it is a natural opportunity to look at this. We’re seeing how we can optimize the dose, but I don’t want to send the message that we’re doing this because it changes the patient’s outcome, because there’s zero evidence that it’s a good thing to do in terms of resistance.”

At the infusion centers operated by the Johns Hopkins division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Baltimore, clinicians are not increasing the time interval between infusions for patients at this time. “We’re keeping them as they are, to prevent any flare-ups. Our main goal is to keep patients in remission and out of the hospital,” said Alyssa M. Parian, MD, medical director of the infusion center and associate director of the university’s GI department. “With Remicade specifically, there’s also the risk of developing antibodies if you delay treatment, so we’re basically keeping everyone on track. We’re not recommending a switch from infusions to injectables, and we also are not speeding up infusions, either. Before this pandemic happened, we had already tried to decrease all Remicade infusions from 2 hours to 1 hour for patient satisfaction. The Entyvio is a pretty quick, 30-minute infusion.”

To accommodate patients during this era of physical distancing measures recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Dr. Parian and her infusion nurse manager Elisheva Weiser converted one of their two outpatient GI centers into an infusion-only suite with 12 individual clinic rooms. As soon as patients exit the second-floor elevator, they encounter a workstation prior to entering the office where they are screened for COVID-19 symptoms and their temperature is taken. “If any symptoms or temperature comes back positive, we’re asking them to postpone their treatment and consider COVID testing,” she said.

Instead of one nurse looking after four patients in one room during infusion therapy, now one nurse looks after two patients who are in rooms next to each other. All patients and all staff wear masks while in the center. “We always have physician oversight at our infusion centers,” Dr. Parian said. “We are trying to maintain a ‘COVID-free zone.’ Therefore, no physicians who have served in a hospital ward are allowed in the infusion suite because we don’t want any carriers of COVID-19. Same with the nurses. Additionally, we limit the staff within the suite to only those who are essential and don’t allow anyone to perform telemedicine or urgent clinic visits in this location. Our infusion center staff are on a strict protocol to not come in with any symptoms at all. They are asked to take their temperature before coming in to work.”

She and her colleagues drew from recommendations from the joint GI society message on COVID-19, the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation, and the International Organization for the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IOIBD) to inform their approach in serving patients during this unprecedented time. “We went as conservative as possible because these are immunosuppressed patients,” she said. One patient on her panel who receives an infusion every 8 weeks tested positive for COVID-19 between infusions, but was not hospitalized. Dr. Parian said that person will only be treated 14 days after the all symptoms disappear. “That person will wear a mask and will be infused in a separate room,” she said.

In Aventura, Fla., Norman B. Gaylis, MD, and his colleagues at Arthritis & Rheumatic Disease Specialties are looking into shutting down their infusion services during the time period that local public health officials consider to be the peak level of exposure to COVID-19. “We’ve tried to work around that, and bring people in a little early,” said Dr. Gaylis, medical director of rheumatology and infusion services at the practice. “We’ve done our best to mitigate the risk [of exposure] as much as possible.” This includes staggering their caseload by infusing 5 patients at a time, compared with the 15 patients at a time they could treat during prepandemic conditions. “Everyone is at least 20 feet apart,” said Dr. Gaylis, who is a member of the American College of Rheumatology Board of Directors. “While we don’t have the kind of protective garments you might see in an ICU, we still are gowning, gloving, and masking our staff, and trying to practice sterile techniques as much as we can.”

The pandemic has caused him to reflect more broadly on the way he and his colleagues deliver care for patients on infusion therapy. “We see patients who really want their treatment because they feel it’s helpful and beneficial,” he said. “There are also patients who may truly be in remission who could stop [infusion therapy]. We could possibly extend the duration of their therapy, try and push it back.”

Dr. Gaylis emphasized that any discussion about halting infusion therapy requires clinical, serological, and ideally even MRI evidence that the disease is in a dormant state. “You wouldn’t stop treatment in someone who is showing signs in their blood that their disease is still active,” he said. “You’re using all those parameters in that conversation.”

In his clinical opinion, now is not the time to switch patients to self-injectable agents as a perceived matter of convenience. “I don’t really think that’s a good idea because self-injectables are different,” Dr. Gaylis said. “You’re basically switching treatment patterns. The practicality of getting a specialty pharmacy to switch, the insurance companies to cover it, and determine copay for it, is a burden on patients. That’s why I’m against it, because you’re starting a whole new process and problem.”

One patient tested positive for COVID-19 about 3 weeks after an infusion at the facility. “That does lead to a point: Have my staff been tested? We have not had the tests available to us,” Dr. Gaylis said. “One provider had a contact with someone with COVID-19 and stayed home for 2 weeks. That person tested negative. Soon we are going to receive a kit that will allow us to measure IgM and IgG COVID-19 antibodies. Because we’re going to be closed for 2 weeks, measuring us now would be a great way to handle it.”

In rural Western Kentucky, Christopher R. Phillips, MD, and his colleagues at Paducah Rheumatology have arranged for “drive-by” injections for some of their higher-risk patients who require subcutaneous administration of biologic agents. “We have them call us when they’re in the parking lot, and we give them the treatment while they sit in their car,” said Dr. Phillips, who chairs the ACR Insurance Subcommittee and is a member of the ACR COVID-19 Practice and Advocacy Task Force.

For patients who require infusions, they’ve arranged three chairs in the clinic to be at least 6 feet apart, and moved the fourth chair into a separate room. “My infusion nurse knows these patients well; we’re a small community,” he said. “She checks in with them the day before to screen for any symptoms of infection and asks them to call when they get here. A lot of them wait in their car to be brought in. She’ll bring them in, screen for infection symptoms, and check their temperature. She and the receptionist are masked and gloved, and disinfect aggressively between patients. The other thing we are trying to be on top of is making sure that everyone’s insurance coverage is active when they come in, in light of the number of people who have been laid off or had changes in their employment.”

Dr. Phillips has considered increasing the infusion time interval for some patients, but not knowing when current physical distancing guidelines will ease up presents a conundrum. “If I have a patient coming in today, and their next treatment is due in a month, I don’t know how to say that, if we stretch the infusion to 2 months, that things are going to be better,” he said. “For some very well-controlled patients and/or high-risk patients, that is something we’ve done: stretch the interval or skip a treatment. For most patients, our default is to stick with the normal schedule. We feel that, for most patients who have moderate to severe underlying rheumatic disease, the risk of disease flare and subsequent need for steroids may be a larger risk than the treatment itself, though that is an individualized decision.”

To date, Dr. Phillips has not treated a patient who has recovered from COVID-19, but the thought of that scenario gives him pause. “There is some literature suggesting these patients may asymptomatically shed virus for some time after they’ve clinically recovered, but we don’t really know enough about that,” he said. “If I had one of those patients, I’d probably be delaying them for a longer period of time, and I’d be looking for some guidance from the literature on postsymptomatic viral shedding.”

In the meantime, the level of anxiety that many of his patients express during this pandemic is palpable. “They really are between a rock and a hard place,” Dr. Phillips said. “If they come off their effective treatment, they risk flare of a disease that can be life or limb threatening. And yet, because of their disease and their treatment, they’re potentially at increased risk for serious illness if they become infected with COVID-19. We look for ways to try to reassure patients and to comfort them, and work with them to make the best of the situation.”

It’s anything but business as usual for clinicians who oversee office-based infusion centers, as they scramble to maintain services for patients considered to be at heightened risk for severe illness should they become infected with COVID-19.

“For many reasons, the guidance for patients right now is that they stay on their medications,” Max I. Hamburger, MD, a managing partner at Rheumatology Associates of Long Island (N.Y.), said in an interview. “Some have decided to stop the drug, and then they call us up to tell us that they’re flaring. The beginning of a flare is tiredness and other things. Now they’re worried: Are they tired because of the disease, or are they tired because they have COVID-19?”

With five office locations located in a region considered to be the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, Dr. Hamburger and his colleagues are hypervigilant about screening patients for symptoms of the virus before they visit one of the three practice locations that provide infusion services. This starts with an automated phone system that reminds patients of their appointment time. “Part of that robocall now has some questions like, ‘Do you have any symptoms of COVID-19?’ ‘Are you running a fever?’ ‘Do you have any reason to worry about yourself? If so, please call us.’ ” The infusion nurses are also calling the patients in advance of their appointment to check on their status. “When they get to the office location, we ask them again about their general health and check their temperature,” said Dr. Hamburger, who is also founder and executive chairman of United Rheumatology, which is a nationwide rheumatology care management services organization with 650 members in 39 states. “We’re doing everything we can to talk to them about their own state of health and to question them about what I call extended paranoia: like, ‘Who are you living with?’ ‘Who are you hanging out with?’ ‘What are all the six degrees of separation here?’ I want to know what the patient’s husband did last night. I want to know where their kids were over this past week, et cetera. We do everything we can to see if there’s anybody who might have had the slightest [contact with someone who has COVID-19]. Because if I lose my infusion nurse, then I’m up the creek.”

The infusion nurse wears scrubs, a face mask, and latex gloves. She and her staff are using hand sanitizer and cleaning infusion equipment with sanitizing wipes as one might do in a surgical setting. “Every surface is wiped down between patients, and the nurse is changing gloves between patients,” said Dr. Hamburger, who was founding president of the New York State Rheumatology Society before retiring from that post in 2017. “Getting masks has been tough. We’re doing the best we can there. We’re not gloving patients but we’re masking patients.”

As noted in guidance from the American College of Rheumatology and other medical organizations, following the CDC’s recommendation to stay at home during the pandemic has jump-started conversations between physicians and their patients about modifying the time interval between infusions. “If they have been doing well for the last 9 months, we’re having a conversation such as ‘Maybe instead of getting your Orencia every 4 weeks, maybe we’ll push it out to 5 weeks, or maybe we’ll push the Enbrel out to 10 days and the Humira out 3 weeks, et cetera,” Dr. Hamburger said. “One has to be very careful about when you do that, because you don’t want the patient to flare up because it’s hard to get them in, but it is a natural opportunity to look at this. We’re seeing how we can optimize the dose, but I don’t want to send the message that we’re doing this because it changes the patient’s outcome, because there’s zero evidence that it’s a good thing to do in terms of resistance.”

At the infusion centers operated by the Johns Hopkins division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Baltimore, clinicians are not increasing the time interval between infusions for patients at this time. “We’re keeping them as they are, to prevent any flare-ups. Our main goal is to keep patients in remission and out of the hospital,” said Alyssa M. Parian, MD, medical director of the infusion center and associate director of the university’s GI department. “With Remicade specifically, there’s also the risk of developing antibodies if you delay treatment, so we’re basically keeping everyone on track. We’re not recommending a switch from infusions to injectables, and we also are not speeding up infusions, either. Before this pandemic happened, we had already tried to decrease all Remicade infusions from 2 hours to 1 hour for patient satisfaction. The Entyvio is a pretty quick, 30-minute infusion.”