User login

Low-risk TAVR loses ground at 2 years in PARTNER 3

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) continued to show superiority over surgical replacement in terms of the primary composite endpoint in low-surgical-risk patients at 2 years of follow-up in the landmark randomized PARTNER 3 trial, but the between-group differences favoring the transcatheter procedure in some key outcomes have narrowed considerably, Michael J. Mack, MD, reported in a video presentation of his research during the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation, which was presented online this year. ACC organizers chose to present parts of the meeting virtually after COVID-19 concerns caused them to cancel the meeting.

“On the basis of 1-year data, many physicians were counseling patients that TAVR outcomes were better than surgery. Now we see that the outcomes are roughly the same at 2 years,” said Dr. Mack, who is medical director of cardiothoracic surgery and chairman of the Baylor Scott & White The Heart Hospital – Plano (Tex.) Research Center.

PARTNER 3 randomized 1,000 patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis with a tricuspid valve and a very low mean Society of Thoracic Surgeons risk score of 1.9% to TAVR with the Sapien 3 valve or surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR). The 1-year results presented at ACC 2019 caused a huge stir, with the primary composite outcome of death, stroke, or cardiovascular rehospitalization occurring in 8.5% of TAVR patients and 15.6% of the SAVR group, representing a 48% relative risk reduction and a resounding win for TAVR (N Engl J Med. 2019 May 2;380:1695-705). At 2 years, the difference in the composite outcome remained statistically significant, but the gap had closed: 11.5% with TAVR and 17.4% with SAVR for a 37% relative risk reduction.

Moreover, the between-group difference in stroke, which at 1 year was significantly in favor of TAVR at 1.2% versus 3.3%, was no longer significant at 2 years, with rates of 2.4% versus 3.6%. Nor was the difference in mortality significant: 2.4% with TAVR, 3.2% with SAVR.

What was a statistically significant between-group difference at 2 years – and an eye-catching one at that – involved the cumulative incidence of valve thrombosis confirmed by CT or echocardiography: 2.6% in the TAVR arm, compared with 0.7% with SAVR, with most of these unwanted events coming in year 2.

The good news was there was no echocardiographic evidence of deterioration in valve structure or function in either study arm at 2 years. The mean gradients and aortic valve areas remained unchanged in both arms between 1 and 2 years, as did the frequency of mild or moderate paravalvular leak. Prospective follow-up will continue annually out to 10 years.

“I think it’s way too early to expect to see a signal, but I think it’s somewhat comforting at this point that there’s no signal of early structural valve deterioration,” Dr. Mack said.

Discussant Howard C. Hermann, MD, commented: “I guess the biggest concern in looking at the data is the increase in stroke and valve thrombosis, both numerically and relative to SAVR, between years 1 and 2.”

Dr. Mack offered a note of reassurance regarding the valve thrombosis findings: The rates he presented were based upon the now-outdated second Valve Academic Research Consortium (VARC-2) definition, per study protocol. When he and his coinvestigators recalculated the valve thrombosis rates using the contemporary VARC-3 definition of valve deterioration and bioprosthetic valve failure, the incidence was very low and not significantly different in the two study arms, at roughly 1%.

Dr. Hermann, professor of medicine and director of the cardiac catheterization laboratories at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, had a question: As a clinician taking care of TAVR patients, what clinical or hemodynamic findings should prompt an imaging study looking for valve thrombus or deterioration that might prompt initiating oral anticoagulation?

“If there’s a change in hemodynamics, an increasing valve gradient, if there’s increasing paravalvular leak, or if there’s a change in symptoms, that should prompt an imaging study. Only with confirmation of valve thrombosis on an imaging study should anticoagulation be considered. Oral anticoagulation is not benign: Of the six clinical events associated with valve thrombosis in the study, two were related to anticoagulation,” Dr. Mack replied.

“Regarding whether patients should receive warfarin or a novel anticoagulant, I don’t think we have evidence that there’s benefit to anything other than warfarin at the current time,” he added.

Dr. Mack reported receiving research support from Edwards Lifesciences, the sponsor of PARTNER 3, as well as from Abbott, Gore, and Medtronic.

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) continued to show superiority over surgical replacement in terms of the primary composite endpoint in low-surgical-risk patients at 2 years of follow-up in the landmark randomized PARTNER 3 trial, but the between-group differences favoring the transcatheter procedure in some key outcomes have narrowed considerably, Michael J. Mack, MD, reported in a video presentation of his research during the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation, which was presented online this year. ACC organizers chose to present parts of the meeting virtually after COVID-19 concerns caused them to cancel the meeting.

“On the basis of 1-year data, many physicians were counseling patients that TAVR outcomes were better than surgery. Now we see that the outcomes are roughly the same at 2 years,” said Dr. Mack, who is medical director of cardiothoracic surgery and chairman of the Baylor Scott & White The Heart Hospital – Plano (Tex.) Research Center.

PARTNER 3 randomized 1,000 patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis with a tricuspid valve and a very low mean Society of Thoracic Surgeons risk score of 1.9% to TAVR with the Sapien 3 valve or surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR). The 1-year results presented at ACC 2019 caused a huge stir, with the primary composite outcome of death, stroke, or cardiovascular rehospitalization occurring in 8.5% of TAVR patients and 15.6% of the SAVR group, representing a 48% relative risk reduction and a resounding win for TAVR (N Engl J Med. 2019 May 2;380:1695-705). At 2 years, the difference in the composite outcome remained statistically significant, but the gap had closed: 11.5% with TAVR and 17.4% with SAVR for a 37% relative risk reduction.

Moreover, the between-group difference in stroke, which at 1 year was significantly in favor of TAVR at 1.2% versus 3.3%, was no longer significant at 2 years, with rates of 2.4% versus 3.6%. Nor was the difference in mortality significant: 2.4% with TAVR, 3.2% with SAVR.

What was a statistically significant between-group difference at 2 years – and an eye-catching one at that – involved the cumulative incidence of valve thrombosis confirmed by CT or echocardiography: 2.6% in the TAVR arm, compared with 0.7% with SAVR, with most of these unwanted events coming in year 2.

The good news was there was no echocardiographic evidence of deterioration in valve structure or function in either study arm at 2 years. The mean gradients and aortic valve areas remained unchanged in both arms between 1 and 2 years, as did the frequency of mild or moderate paravalvular leak. Prospective follow-up will continue annually out to 10 years.

“I think it’s way too early to expect to see a signal, but I think it’s somewhat comforting at this point that there’s no signal of early structural valve deterioration,” Dr. Mack said.

Discussant Howard C. Hermann, MD, commented: “I guess the biggest concern in looking at the data is the increase in stroke and valve thrombosis, both numerically and relative to SAVR, between years 1 and 2.”

Dr. Mack offered a note of reassurance regarding the valve thrombosis findings: The rates he presented were based upon the now-outdated second Valve Academic Research Consortium (VARC-2) definition, per study protocol. When he and his coinvestigators recalculated the valve thrombosis rates using the contemporary VARC-3 definition of valve deterioration and bioprosthetic valve failure, the incidence was very low and not significantly different in the two study arms, at roughly 1%.

Dr. Hermann, professor of medicine and director of the cardiac catheterization laboratories at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, had a question: As a clinician taking care of TAVR patients, what clinical or hemodynamic findings should prompt an imaging study looking for valve thrombus or deterioration that might prompt initiating oral anticoagulation?

“If there’s a change in hemodynamics, an increasing valve gradient, if there’s increasing paravalvular leak, or if there’s a change in symptoms, that should prompt an imaging study. Only with confirmation of valve thrombosis on an imaging study should anticoagulation be considered. Oral anticoagulation is not benign: Of the six clinical events associated with valve thrombosis in the study, two were related to anticoagulation,” Dr. Mack replied.

“Regarding whether patients should receive warfarin or a novel anticoagulant, I don’t think we have evidence that there’s benefit to anything other than warfarin at the current time,” he added.

Dr. Mack reported receiving research support from Edwards Lifesciences, the sponsor of PARTNER 3, as well as from Abbott, Gore, and Medtronic.

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) continued to show superiority over surgical replacement in terms of the primary composite endpoint in low-surgical-risk patients at 2 years of follow-up in the landmark randomized PARTNER 3 trial, but the between-group differences favoring the transcatheter procedure in some key outcomes have narrowed considerably, Michael J. Mack, MD, reported in a video presentation of his research during the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation, which was presented online this year. ACC organizers chose to present parts of the meeting virtually after COVID-19 concerns caused them to cancel the meeting.

“On the basis of 1-year data, many physicians were counseling patients that TAVR outcomes were better than surgery. Now we see that the outcomes are roughly the same at 2 years,” said Dr. Mack, who is medical director of cardiothoracic surgery and chairman of the Baylor Scott & White The Heart Hospital – Plano (Tex.) Research Center.

PARTNER 3 randomized 1,000 patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis with a tricuspid valve and a very low mean Society of Thoracic Surgeons risk score of 1.9% to TAVR with the Sapien 3 valve or surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR). The 1-year results presented at ACC 2019 caused a huge stir, with the primary composite outcome of death, stroke, or cardiovascular rehospitalization occurring in 8.5% of TAVR patients and 15.6% of the SAVR group, representing a 48% relative risk reduction and a resounding win for TAVR (N Engl J Med. 2019 May 2;380:1695-705). At 2 years, the difference in the composite outcome remained statistically significant, but the gap had closed: 11.5% with TAVR and 17.4% with SAVR for a 37% relative risk reduction.

Moreover, the between-group difference in stroke, which at 1 year was significantly in favor of TAVR at 1.2% versus 3.3%, was no longer significant at 2 years, with rates of 2.4% versus 3.6%. Nor was the difference in mortality significant: 2.4% with TAVR, 3.2% with SAVR.

What was a statistically significant between-group difference at 2 years – and an eye-catching one at that – involved the cumulative incidence of valve thrombosis confirmed by CT or echocardiography: 2.6% in the TAVR arm, compared with 0.7% with SAVR, with most of these unwanted events coming in year 2.

The good news was there was no echocardiographic evidence of deterioration in valve structure or function in either study arm at 2 years. The mean gradients and aortic valve areas remained unchanged in both arms between 1 and 2 years, as did the frequency of mild or moderate paravalvular leak. Prospective follow-up will continue annually out to 10 years.

“I think it’s way too early to expect to see a signal, but I think it’s somewhat comforting at this point that there’s no signal of early structural valve deterioration,” Dr. Mack said.

Discussant Howard C. Hermann, MD, commented: “I guess the biggest concern in looking at the data is the increase in stroke and valve thrombosis, both numerically and relative to SAVR, between years 1 and 2.”

Dr. Mack offered a note of reassurance regarding the valve thrombosis findings: The rates he presented were based upon the now-outdated second Valve Academic Research Consortium (VARC-2) definition, per study protocol. When he and his coinvestigators recalculated the valve thrombosis rates using the contemporary VARC-3 definition of valve deterioration and bioprosthetic valve failure, the incidence was very low and not significantly different in the two study arms, at roughly 1%.

Dr. Hermann, professor of medicine and director of the cardiac catheterization laboratories at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, had a question: As a clinician taking care of TAVR patients, what clinical or hemodynamic findings should prompt an imaging study looking for valve thrombus or deterioration that might prompt initiating oral anticoagulation?

“If there’s a change in hemodynamics, an increasing valve gradient, if there’s increasing paravalvular leak, or if there’s a change in symptoms, that should prompt an imaging study. Only with confirmation of valve thrombosis on an imaging study should anticoagulation be considered. Oral anticoagulation is not benign: Of the six clinical events associated with valve thrombosis in the study, two were related to anticoagulation,” Dr. Mack replied.

“Regarding whether patients should receive warfarin or a novel anticoagulant, I don’t think we have evidence that there’s benefit to anything other than warfarin at the current time,” he added.

Dr. Mack reported receiving research support from Edwards Lifesciences, the sponsor of PARTNER 3, as well as from Abbott, Gore, and Medtronic.

FROM ACC 2020

Fellowship Burnout: What can we do to identify those at risk and minimize the impact?

Jeff is a high-performing first-year gastroenterology fellow who started with eagerness and enthusiasm. He seemed to enjoy talking to patients, wrote thorough notes, and often participated during case discussions at morning report. He initiated a quality improvement project and joined a hospital committee. Over the past few months, he has interacted less with his peers in the fellow’s office and stayed late to complete his patient encounters. He now frequently arrives late to work, is unprepared for rounds, and forgets to place important orders. One day, you notice him shuffling through several papers when the attending asks him a question about his patient. Later that day, he snapped at a nurse who paged to ask a question about a patient who just had a colonoscopy. When you ask him how he is doing, he becomes tearful and reports that he is under a lot of stress between work and home and does not feel the work he is doing is meaningful.

Introduction

The above scenario is all too familiar. Gastroenterology training can be a stressful period in an individual’s life. Long hours, steep learning curves for new cognitive and mechanical skill sets, as well as managing personal relationships and responsibilities at home all contribute to the stress of training and finding appropriate work-life balance. These stressors can result in burnout. The last decade has brought about a renewed emphasis on mitigating the impact of occupational burnout and improving trainee lifestyle through interventions such as work-hour restrictions, resiliency training, instruction on the importance of sleep, and team-building activities.

The problem

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines occupational burnout as chronic work-related stress, which may be characterized by feelings of energy depletion, mental distance from one’s job or feelings of negativity toward it, and reduced professional efficacy. Occupational burnout has been identified as an increasing problem both in practicing providers and trainees. Surveys in gastroenterologists show rates of burnout ranging between 37% and 50%,1 with trainees and early-career physicians disproportionately affected.1,2Physicians along the entire training spectrum are more likely to report high emotional exhaustion, high depersonalization, and burnout than a population control sample.2

Several individual factors identified for those at increased risk for burnout include younger age, not being married, and being male.2 Individuals spending less than 20% of their time working on activities they find meaningful and productive were more likely to show evidence of burnout.1

Symptoms of burnout can have a profound impact on trainees’ work performance, personal interactions, and the learning environment as a whole. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) annual survey of trainees asks them how strongly they agree or disagree on various components of burnout such as how meaningful they find their work, if they have enough time to think and reflect, if they feel emotionally drained at work, and if they feel worn out and weary after work. The intent of these questions is to provide anonymous feedback to training programs to help identify year to year trends and intervene early to prevent occupational burnout from becoming an increasing issue.

The solution

Considerations for any intervention should take several factors into account: the impact it may have on training and the development of a competent physician in their individualized specialty, the sustainability of the intervention, and whether it is something that will be accepted by the invested parties.

One method proposed for preventing burnout during fellowship has been designated as the three R’s: relaxation, reflection, and regrouping.3

- Relax. In order to relax, trainees need ways to decompress. Activities such as exercise and social events can be helpful. Within our own program the fellows have started their own group exercise program, playing wallyball weekly before clinical duties. We also encourage use of vacation days and build comradery by organizing potluck dinners for major holidays, graduation parties at the program director’s house, and an end-of-the-year golf outing in which trainees play against staff followed by a discussion regarding the state of the program. More recently we have added one half-day per a quarter for morale and team building. During this first year, the activities in which trainees have collectively decided to participate include an escape room, a rock-climbing facility, and laser tag. The addition of more team-building days has been well received by our program’s trainees and the simple addition of these team-building days has resulted in the trainees interacting more together outside of work, particularly in the form of group dinners.

Walter Reed National Military Medical Center fellows gathering for wallyball. - Reflect. They describe reflection as a necessary checkpoint which typically occurs every 6 months.3 These “checkpoints” provide an opportunity to provide feedback to the fellow as well as check in on their well-being and receive feedback about the program. We give frequent feedback to fellows in the form of spot, rotational, and mid-/end-of-year feedback. Additionally, we have developed a unique feedback system in which the trainees meet at the end of the year to discuss collective feedback for the staff and the program. This feedback is collated by the chief fellow and given to the program director as anonymous feedback, which is then passed to the individual staff.

- Regroup. Finally, regrouping to form new strategies.3 This regrouping provides an opportunity to improve on areas in which the trainee may have a deficiency and build on their strengths. To facilitate regrouping, we identify a mentor within the department and occasionally in other departments to meet regularly with the trainee. A successful mentor ensures effective regrouping and can help the trainee avoid pitfalls that they may have experienced in similar situations.

Moving forward

Occupational burnout is a systemic problem within the medical field, with trainees disproportionately affected. It is imperative that training programs continue to work toward creating a culture that prevents development of burnout. Along with the ideas presented here, the ACGME has launched AWARE, which is a suite of resources directed specifically at the GME community, with a goal of mitigating stress and preventing burnout. No one approach will be universally applicable but continued awareness and efforts to address this on an individual and programmatic level should be encouraged.

Dr. Ordway is a chief fellow, Dr. Tritsch and Dr. Singla are associate program directors, and Dr. Torres the program director, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Md.

References

1. Barnes EL et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64(2):302-6.

2. Dyrbye LN et al. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):443-51.

3. Waldo OA. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(11):1303-6.

Jeff is a high-performing first-year gastroenterology fellow who started with eagerness and enthusiasm. He seemed to enjoy talking to patients, wrote thorough notes, and often participated during case discussions at morning report. He initiated a quality improvement project and joined a hospital committee. Over the past few months, he has interacted less with his peers in the fellow’s office and stayed late to complete his patient encounters. He now frequently arrives late to work, is unprepared for rounds, and forgets to place important orders. One day, you notice him shuffling through several papers when the attending asks him a question about his patient. Later that day, he snapped at a nurse who paged to ask a question about a patient who just had a colonoscopy. When you ask him how he is doing, he becomes tearful and reports that he is under a lot of stress between work and home and does not feel the work he is doing is meaningful.

Introduction

The above scenario is all too familiar. Gastroenterology training can be a stressful period in an individual’s life. Long hours, steep learning curves for new cognitive and mechanical skill sets, as well as managing personal relationships and responsibilities at home all contribute to the stress of training and finding appropriate work-life balance. These stressors can result in burnout. The last decade has brought about a renewed emphasis on mitigating the impact of occupational burnout and improving trainee lifestyle through interventions such as work-hour restrictions, resiliency training, instruction on the importance of sleep, and team-building activities.

The problem

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines occupational burnout as chronic work-related stress, which may be characterized by feelings of energy depletion, mental distance from one’s job or feelings of negativity toward it, and reduced professional efficacy. Occupational burnout has been identified as an increasing problem both in practicing providers and trainees. Surveys in gastroenterologists show rates of burnout ranging between 37% and 50%,1 with trainees and early-career physicians disproportionately affected.1,2Physicians along the entire training spectrum are more likely to report high emotional exhaustion, high depersonalization, and burnout than a population control sample.2

Several individual factors identified for those at increased risk for burnout include younger age, not being married, and being male.2 Individuals spending less than 20% of their time working on activities they find meaningful and productive were more likely to show evidence of burnout.1

Symptoms of burnout can have a profound impact on trainees’ work performance, personal interactions, and the learning environment as a whole. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) annual survey of trainees asks them how strongly they agree or disagree on various components of burnout such as how meaningful they find their work, if they have enough time to think and reflect, if they feel emotionally drained at work, and if they feel worn out and weary after work. The intent of these questions is to provide anonymous feedback to training programs to help identify year to year trends and intervene early to prevent occupational burnout from becoming an increasing issue.

The solution

Considerations for any intervention should take several factors into account: the impact it may have on training and the development of a competent physician in their individualized specialty, the sustainability of the intervention, and whether it is something that will be accepted by the invested parties.

One method proposed for preventing burnout during fellowship has been designated as the three R’s: relaxation, reflection, and regrouping.3

- Relax. In order to relax, trainees need ways to decompress. Activities such as exercise and social events can be helpful. Within our own program the fellows have started their own group exercise program, playing wallyball weekly before clinical duties. We also encourage use of vacation days and build comradery by organizing potluck dinners for major holidays, graduation parties at the program director’s house, and an end-of-the-year golf outing in which trainees play against staff followed by a discussion regarding the state of the program. More recently we have added one half-day per a quarter for morale and team building. During this first year, the activities in which trainees have collectively decided to participate include an escape room, a rock-climbing facility, and laser tag. The addition of more team-building days has been well received by our program’s trainees and the simple addition of these team-building days has resulted in the trainees interacting more together outside of work, particularly in the form of group dinners.

Walter Reed National Military Medical Center fellows gathering for wallyball. - Reflect. They describe reflection as a necessary checkpoint which typically occurs every 6 months.3 These “checkpoints” provide an opportunity to provide feedback to the fellow as well as check in on their well-being and receive feedback about the program. We give frequent feedback to fellows in the form of spot, rotational, and mid-/end-of-year feedback. Additionally, we have developed a unique feedback system in which the trainees meet at the end of the year to discuss collective feedback for the staff and the program. This feedback is collated by the chief fellow and given to the program director as anonymous feedback, which is then passed to the individual staff.

- Regroup. Finally, regrouping to form new strategies.3 This regrouping provides an opportunity to improve on areas in which the trainee may have a deficiency and build on their strengths. To facilitate regrouping, we identify a mentor within the department and occasionally in other departments to meet regularly with the trainee. A successful mentor ensures effective regrouping and can help the trainee avoid pitfalls that they may have experienced in similar situations.

Moving forward

Occupational burnout is a systemic problem within the medical field, with trainees disproportionately affected. It is imperative that training programs continue to work toward creating a culture that prevents development of burnout. Along with the ideas presented here, the ACGME has launched AWARE, which is a suite of resources directed specifically at the GME community, with a goal of mitigating stress and preventing burnout. No one approach will be universally applicable but continued awareness and efforts to address this on an individual and programmatic level should be encouraged.

Dr. Ordway is a chief fellow, Dr. Tritsch and Dr. Singla are associate program directors, and Dr. Torres the program director, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Md.

References

1. Barnes EL et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64(2):302-6.

2. Dyrbye LN et al. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):443-51.

3. Waldo OA. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(11):1303-6.

Jeff is a high-performing first-year gastroenterology fellow who started with eagerness and enthusiasm. He seemed to enjoy talking to patients, wrote thorough notes, and often participated during case discussions at morning report. He initiated a quality improvement project and joined a hospital committee. Over the past few months, he has interacted less with his peers in the fellow’s office and stayed late to complete his patient encounters. He now frequently arrives late to work, is unprepared for rounds, and forgets to place important orders. One day, you notice him shuffling through several papers when the attending asks him a question about his patient. Later that day, he snapped at a nurse who paged to ask a question about a patient who just had a colonoscopy. When you ask him how he is doing, he becomes tearful and reports that he is under a lot of stress between work and home and does not feel the work he is doing is meaningful.

Introduction

The above scenario is all too familiar. Gastroenterology training can be a stressful period in an individual’s life. Long hours, steep learning curves for new cognitive and mechanical skill sets, as well as managing personal relationships and responsibilities at home all contribute to the stress of training and finding appropriate work-life balance. These stressors can result in burnout. The last decade has brought about a renewed emphasis on mitigating the impact of occupational burnout and improving trainee lifestyle through interventions such as work-hour restrictions, resiliency training, instruction on the importance of sleep, and team-building activities.

The problem

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines occupational burnout as chronic work-related stress, which may be characterized by feelings of energy depletion, mental distance from one’s job or feelings of negativity toward it, and reduced professional efficacy. Occupational burnout has been identified as an increasing problem both in practicing providers and trainees. Surveys in gastroenterologists show rates of burnout ranging between 37% and 50%,1 with trainees and early-career physicians disproportionately affected.1,2Physicians along the entire training spectrum are more likely to report high emotional exhaustion, high depersonalization, and burnout than a population control sample.2

Several individual factors identified for those at increased risk for burnout include younger age, not being married, and being male.2 Individuals spending less than 20% of their time working on activities they find meaningful and productive were more likely to show evidence of burnout.1

Symptoms of burnout can have a profound impact on trainees’ work performance, personal interactions, and the learning environment as a whole. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) annual survey of trainees asks them how strongly they agree or disagree on various components of burnout such as how meaningful they find their work, if they have enough time to think and reflect, if they feel emotionally drained at work, and if they feel worn out and weary after work. The intent of these questions is to provide anonymous feedback to training programs to help identify year to year trends and intervene early to prevent occupational burnout from becoming an increasing issue.

The solution

Considerations for any intervention should take several factors into account: the impact it may have on training and the development of a competent physician in their individualized specialty, the sustainability of the intervention, and whether it is something that will be accepted by the invested parties.

One method proposed for preventing burnout during fellowship has been designated as the three R’s: relaxation, reflection, and regrouping.3

- Relax. In order to relax, trainees need ways to decompress. Activities such as exercise and social events can be helpful. Within our own program the fellows have started their own group exercise program, playing wallyball weekly before clinical duties. We also encourage use of vacation days and build comradery by organizing potluck dinners for major holidays, graduation parties at the program director’s house, and an end-of-the-year golf outing in which trainees play against staff followed by a discussion regarding the state of the program. More recently we have added one half-day per a quarter for morale and team building. During this first year, the activities in which trainees have collectively decided to participate include an escape room, a rock-climbing facility, and laser tag. The addition of more team-building days has been well received by our program’s trainees and the simple addition of these team-building days has resulted in the trainees interacting more together outside of work, particularly in the form of group dinners.

Walter Reed National Military Medical Center fellows gathering for wallyball. - Reflect. They describe reflection as a necessary checkpoint which typically occurs every 6 months.3 These “checkpoints” provide an opportunity to provide feedback to the fellow as well as check in on their well-being and receive feedback about the program. We give frequent feedback to fellows in the form of spot, rotational, and mid-/end-of-year feedback. Additionally, we have developed a unique feedback system in which the trainees meet at the end of the year to discuss collective feedback for the staff and the program. This feedback is collated by the chief fellow and given to the program director as anonymous feedback, which is then passed to the individual staff.

- Regroup. Finally, regrouping to form new strategies.3 This regrouping provides an opportunity to improve on areas in which the trainee may have a deficiency and build on their strengths. To facilitate regrouping, we identify a mentor within the department and occasionally in other departments to meet regularly with the trainee. A successful mentor ensures effective regrouping and can help the trainee avoid pitfalls that they may have experienced in similar situations.

Moving forward

Occupational burnout is a systemic problem within the medical field, with trainees disproportionately affected. It is imperative that training programs continue to work toward creating a culture that prevents development of burnout. Along with the ideas presented here, the ACGME has launched AWARE, which is a suite of resources directed specifically at the GME community, with a goal of mitigating stress and preventing burnout. No one approach will be universally applicable but continued awareness and efforts to address this on an individual and programmatic level should be encouraged.

Dr. Ordway is a chief fellow, Dr. Tritsch and Dr. Singla are associate program directors, and Dr. Torres the program director, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Md.

References

1. Barnes EL et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64(2):302-6.

2. Dyrbye LN et al. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):443-51.

3. Waldo OA. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(11):1303-6.

Can drinking more water prevent urinary tract infections?

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 23-year-old nonpregnant woman, whom you treated 3 times in the past year for cystitis, comes to you for follow-up. She wants to know what she can do to prevent another urinary tract infection other than taking prophylactic antibiotics. Should you recommend that this patient increase her daily water intake to prevent recurrent cystitis?

Urinary tract infection (UTI) is the most common bacterial infection encountered in the ambulatory setting. Half of all women report having had at least 1 UTI by the time they are 32 years old.2 Recurrence is also common, with 27% of women having 1 recurrence within 6 months of their first episode.2

Because of growing antimicrobial resistance, the World Health Organization has urged using novel antimicrobial-sparing approaches to infectious diseases.3 Physicians have long recommended behavioral, nonantimicrobial strategies for prevention of recurrent uncomplicated cystitis. Such behavioral recommendations include drinking fluids liberally, urinating after intercourse, not delaying urination, wiping front to back, and avoiding tight-fitting underwear. However, these behavior modification strategies have been studied largely in case-control trials that have yet to find an association between behavior modification and reduced risk of UTI.2 Although unproven as a prevention strategy, increasing daily fluid intake has long been a recommendation because of the belief that it helps to dilute and clear bactiuria.4 This study is the first non–case-control trial to examine the association between increased fluid intake and decreased UTIs.1

STUDY SUMMARY

RCT looks at whether more water leads to fewer UTIs

Hooton and colleagues1 conducted an open-label, randomized controlled trial (RCT) of premenopausal women with recurrent UTIs and low baseline fluid intake and compared increased fluid intake (an additional 1.5 L/d) with no additional fluids. Participants were provided three 500-mL bottles of water per day and were followed for 1 year. Screened women were included if they had 3 or more symptomatic UTIs in the previous year, 1 culture-confirmed UTI, self-reported fluid intake < 1.5 L /d, and were otherwise in good health. Fluid intake was verified by 24-hour urine collection, requiring a volume < 1.2 L and urine osmolality of ≥ 500 mOsm/kg. Exclusion criteria included a history of pyelonephritis within the past year, interstitial cystitis, pregnancy, or current symptoms of UTI.

The primary outcome was frequency of UTI during the study period, defined as 1 urinary symptom and at least 103 CFU/mL uropathogens in a urine culture. Secondary outcomes included the number of antimicrobial agents used, time to first UTI, mean time interval between cystitis episodes, and adverse events.1

A total of 140 participants were randomized with 70 in the water group and 70 in the control group. The mean age of the participants was 35.7 years, and the mean number of reported cystitis episodes was 3.3 in the 12 months prior to the study. By the end of the 12-month study period, mean daily fluid intake had increased by 1.7 L above baseline in the water group. During the 12-month study period, the mean (SD) number of cystitis episodes was 1.7 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.5-1.8) in the water group compared with 3.2 (95% CI, 3-3.4) in the control group, with a difference in means of 1.5 (95% CI, 1.2-1.8; P < .001).

The mean number of antimicrobial agents used for UTI was 1.9 (95% CI, 1.7-2.2) in the water group and 3.6 (95% CI, 3.3-4) in the control group. The median time to first UTI episode was 148 days in the water group compared with 93.5 days in the control group (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.51; 95% CI, 0.36-0.74; P < .001) and the difference in means for the time interval between UTI episodes was 58.4 days (95% CI, 39.4-77.4; P < .001). No serious adverse events were reported.1

Continue to: WHAT'S NEW

WHAT’S NEW

Proof that increased fluid intake reduces the risk of recurrent UTI

Increasing daily fluid intake is a long-held but previously unproven recommendation. This is the first RCT to show increased daily water intake can reduce the risk of recurrent cystitis in premenopausal patients at high risk for UTI and with low fluid intake. No additional risk of adverse events was found.

CAVEATS

Is there a risk of overhydration?

The study did not address the effect of increasing water intake in women who do not have low-volume fluid intake. Case reports of overhydration emphasize the need to be cautious when making recommendations to hydrate.5 It is not known if physicians should screen for fluid intake at baseline to identify those (with low intake) who would be eligible for this intervention.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

It’s unclear whether the strategy will work without monitoring

The intervention is both low-risk and low-cost to the patient. However, the intervention was supported by home delivery of water and monthly monitoring interventions that are not typical in normal care. Although the clinical intervention of drinking more fluids (primarily water) appears sound, it is not known whether a physician’s recommendation would result in the same adherence and risk reduction as water delivery and monitoring.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Hooton TM, Vecchio M, Iroz A, et al. Effect of increased daily water intake in premenopausal women with recurrent urinary tract infections: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:1509-1515.

2. Hooton TM. Clinical practice. Uncomplicated urinary tract infection. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1028-1037.

3. WHO. Antimicrobial resistance: global report on surveillance. April 2014. www.who.int/drugresistance/documents/surveillancereport/en/. Accessed March 23, 2020.

4. Fasugba O, Mitchell BG, McInnes E, et al. Increased fluid intake for the prevention of urinary tract infection in adults and children in all settings: a systematic review. J Hosp Infect. 2020;104:68-77.

5. Lee LC, Noronha M. When plenty is too much: water intoxication in a patient with a simple urinary tract infection. BMJ Case Rep. 2016. doi:10.1136/bcr-2016-216882.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 23-year-old nonpregnant woman, whom you treated 3 times in the past year for cystitis, comes to you for follow-up. She wants to know what she can do to prevent another urinary tract infection other than taking prophylactic antibiotics. Should you recommend that this patient increase her daily water intake to prevent recurrent cystitis?

Urinary tract infection (UTI) is the most common bacterial infection encountered in the ambulatory setting. Half of all women report having had at least 1 UTI by the time they are 32 years old.2 Recurrence is also common, with 27% of women having 1 recurrence within 6 months of their first episode.2

Because of growing antimicrobial resistance, the World Health Organization has urged using novel antimicrobial-sparing approaches to infectious diseases.3 Physicians have long recommended behavioral, nonantimicrobial strategies for prevention of recurrent uncomplicated cystitis. Such behavioral recommendations include drinking fluids liberally, urinating after intercourse, not delaying urination, wiping front to back, and avoiding tight-fitting underwear. However, these behavior modification strategies have been studied largely in case-control trials that have yet to find an association between behavior modification and reduced risk of UTI.2 Although unproven as a prevention strategy, increasing daily fluid intake has long been a recommendation because of the belief that it helps to dilute and clear bactiuria.4 This study is the first non–case-control trial to examine the association between increased fluid intake and decreased UTIs.1

STUDY SUMMARY

RCT looks at whether more water leads to fewer UTIs

Hooton and colleagues1 conducted an open-label, randomized controlled trial (RCT) of premenopausal women with recurrent UTIs and low baseline fluid intake and compared increased fluid intake (an additional 1.5 L/d) with no additional fluids. Participants were provided three 500-mL bottles of water per day and were followed for 1 year. Screened women were included if they had 3 or more symptomatic UTIs in the previous year, 1 culture-confirmed UTI, self-reported fluid intake < 1.5 L /d, and were otherwise in good health. Fluid intake was verified by 24-hour urine collection, requiring a volume < 1.2 L and urine osmolality of ≥ 500 mOsm/kg. Exclusion criteria included a history of pyelonephritis within the past year, interstitial cystitis, pregnancy, or current symptoms of UTI.

The primary outcome was frequency of UTI during the study period, defined as 1 urinary symptom and at least 103 CFU/mL uropathogens in a urine culture. Secondary outcomes included the number of antimicrobial agents used, time to first UTI, mean time interval between cystitis episodes, and adverse events.1

A total of 140 participants were randomized with 70 in the water group and 70 in the control group. The mean age of the participants was 35.7 years, and the mean number of reported cystitis episodes was 3.3 in the 12 months prior to the study. By the end of the 12-month study period, mean daily fluid intake had increased by 1.7 L above baseline in the water group. During the 12-month study period, the mean (SD) number of cystitis episodes was 1.7 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.5-1.8) in the water group compared with 3.2 (95% CI, 3-3.4) in the control group, with a difference in means of 1.5 (95% CI, 1.2-1.8; P < .001).

The mean number of antimicrobial agents used for UTI was 1.9 (95% CI, 1.7-2.2) in the water group and 3.6 (95% CI, 3.3-4) in the control group. The median time to first UTI episode was 148 days in the water group compared with 93.5 days in the control group (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.51; 95% CI, 0.36-0.74; P < .001) and the difference in means for the time interval between UTI episodes was 58.4 days (95% CI, 39.4-77.4; P < .001). No serious adverse events were reported.1

Continue to: WHAT'S NEW

WHAT’S NEW

Proof that increased fluid intake reduces the risk of recurrent UTI

Increasing daily fluid intake is a long-held but previously unproven recommendation. This is the first RCT to show increased daily water intake can reduce the risk of recurrent cystitis in premenopausal patients at high risk for UTI and with low fluid intake. No additional risk of adverse events was found.

CAVEATS

Is there a risk of overhydration?

The study did not address the effect of increasing water intake in women who do not have low-volume fluid intake. Case reports of overhydration emphasize the need to be cautious when making recommendations to hydrate.5 It is not known if physicians should screen for fluid intake at baseline to identify those (with low intake) who would be eligible for this intervention.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

It’s unclear whether the strategy will work without monitoring

The intervention is both low-risk and low-cost to the patient. However, the intervention was supported by home delivery of water and monthly monitoring interventions that are not typical in normal care. Although the clinical intervention of drinking more fluids (primarily water) appears sound, it is not known whether a physician’s recommendation would result in the same adherence and risk reduction as water delivery and monitoring.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 23-year-old nonpregnant woman, whom you treated 3 times in the past year for cystitis, comes to you for follow-up. She wants to know what she can do to prevent another urinary tract infection other than taking prophylactic antibiotics. Should you recommend that this patient increase her daily water intake to prevent recurrent cystitis?

Urinary tract infection (UTI) is the most common bacterial infection encountered in the ambulatory setting. Half of all women report having had at least 1 UTI by the time they are 32 years old.2 Recurrence is also common, with 27% of women having 1 recurrence within 6 months of their first episode.2

Because of growing antimicrobial resistance, the World Health Organization has urged using novel antimicrobial-sparing approaches to infectious diseases.3 Physicians have long recommended behavioral, nonantimicrobial strategies for prevention of recurrent uncomplicated cystitis. Such behavioral recommendations include drinking fluids liberally, urinating after intercourse, not delaying urination, wiping front to back, and avoiding tight-fitting underwear. However, these behavior modification strategies have been studied largely in case-control trials that have yet to find an association between behavior modification and reduced risk of UTI.2 Although unproven as a prevention strategy, increasing daily fluid intake has long been a recommendation because of the belief that it helps to dilute and clear bactiuria.4 This study is the first non–case-control trial to examine the association between increased fluid intake and decreased UTIs.1

STUDY SUMMARY

RCT looks at whether more water leads to fewer UTIs

Hooton and colleagues1 conducted an open-label, randomized controlled trial (RCT) of premenopausal women with recurrent UTIs and low baseline fluid intake and compared increased fluid intake (an additional 1.5 L/d) with no additional fluids. Participants were provided three 500-mL bottles of water per day and were followed for 1 year. Screened women were included if they had 3 or more symptomatic UTIs in the previous year, 1 culture-confirmed UTI, self-reported fluid intake < 1.5 L /d, and were otherwise in good health. Fluid intake was verified by 24-hour urine collection, requiring a volume < 1.2 L and urine osmolality of ≥ 500 mOsm/kg. Exclusion criteria included a history of pyelonephritis within the past year, interstitial cystitis, pregnancy, or current symptoms of UTI.

The primary outcome was frequency of UTI during the study period, defined as 1 urinary symptom and at least 103 CFU/mL uropathogens in a urine culture. Secondary outcomes included the number of antimicrobial agents used, time to first UTI, mean time interval between cystitis episodes, and adverse events.1

A total of 140 participants were randomized with 70 in the water group and 70 in the control group. The mean age of the participants was 35.7 years, and the mean number of reported cystitis episodes was 3.3 in the 12 months prior to the study. By the end of the 12-month study period, mean daily fluid intake had increased by 1.7 L above baseline in the water group. During the 12-month study period, the mean (SD) number of cystitis episodes was 1.7 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.5-1.8) in the water group compared with 3.2 (95% CI, 3-3.4) in the control group, with a difference in means of 1.5 (95% CI, 1.2-1.8; P < .001).

The mean number of antimicrobial agents used for UTI was 1.9 (95% CI, 1.7-2.2) in the water group and 3.6 (95% CI, 3.3-4) in the control group. The median time to first UTI episode was 148 days in the water group compared with 93.5 days in the control group (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.51; 95% CI, 0.36-0.74; P < .001) and the difference in means for the time interval between UTI episodes was 58.4 days (95% CI, 39.4-77.4; P < .001). No serious adverse events were reported.1

Continue to: WHAT'S NEW

WHAT’S NEW

Proof that increased fluid intake reduces the risk of recurrent UTI

Increasing daily fluid intake is a long-held but previously unproven recommendation. This is the first RCT to show increased daily water intake can reduce the risk of recurrent cystitis in premenopausal patients at high risk for UTI and with low fluid intake. No additional risk of adverse events was found.

CAVEATS

Is there a risk of overhydration?

The study did not address the effect of increasing water intake in women who do not have low-volume fluid intake. Case reports of overhydration emphasize the need to be cautious when making recommendations to hydrate.5 It is not known if physicians should screen for fluid intake at baseline to identify those (with low intake) who would be eligible for this intervention.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

It’s unclear whether the strategy will work without monitoring

The intervention is both low-risk and low-cost to the patient. However, the intervention was supported by home delivery of water and monthly monitoring interventions that are not typical in normal care. Although the clinical intervention of drinking more fluids (primarily water) appears sound, it is not known whether a physician’s recommendation would result in the same adherence and risk reduction as water delivery and monitoring.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Hooton TM, Vecchio M, Iroz A, et al. Effect of increased daily water intake in premenopausal women with recurrent urinary tract infections: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:1509-1515.

2. Hooton TM. Clinical practice. Uncomplicated urinary tract infection. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1028-1037.

3. WHO. Antimicrobial resistance: global report on surveillance. April 2014. www.who.int/drugresistance/documents/surveillancereport/en/. Accessed March 23, 2020.

4. Fasugba O, Mitchell BG, McInnes E, et al. Increased fluid intake for the prevention of urinary tract infection in adults and children in all settings: a systematic review. J Hosp Infect. 2020;104:68-77.

5. Lee LC, Noronha M. When plenty is too much: water intoxication in a patient with a simple urinary tract infection. BMJ Case Rep. 2016. doi:10.1136/bcr-2016-216882.

1. Hooton TM, Vecchio M, Iroz A, et al. Effect of increased daily water intake in premenopausal women with recurrent urinary tract infections: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:1509-1515.

2. Hooton TM. Clinical practice. Uncomplicated urinary tract infection. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1028-1037.

3. WHO. Antimicrobial resistance: global report on surveillance. April 2014. www.who.int/drugresistance/documents/surveillancereport/en/. Accessed March 23, 2020.

4. Fasugba O, Mitchell BG, McInnes E, et al. Increased fluid intake for the prevention of urinary tract infection in adults and children in all settings: a systematic review. J Hosp Infect. 2020;104:68-77.

5. Lee LC, Noronha M. When plenty is too much: water intoxication in a patient with a simple urinary tract infection. BMJ Case Rep. 2016. doi:10.1136/bcr-2016-216882.

PRACTICE CHANGER

Advise premenopausal women with recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs) and low-volume fluid intake to increase their water intake by at least 1.5 liters daily to reduce the frequency of UTIs.1

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

A: Based on a single, high-quality randomized controlled trial.

Hooton TM, Vecchio M, Iroz A, et al. Effect of increased daily water intake in premenopausal women with recurrent urinary tract infections: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:1509-1515.

Paranoid delusions • ideas of reference • sleep problems • Dx?

THE CASE

A 58-year-old married Asian woman with no apparent psychiatric history presented to the emergency department (ED) in an acute state with ideas of reference, paranoid delusions, and multiple, vague somatic symptoms.

Based on information in the patient’s medical record, there had been suspicion of an underlying psychiatric disorder 6 years earlier. At that time, the patient had presented to her primary care provider (PCP) with vague somatic complaints, including diffuse body pain, dry cough, chills, weakness, facial numbness, and concerns about infections. A physical examination and work-up did not reveal the source of her complaints. Unfortunately, the patient’s complaints increased in number and severity over time.

Her medical records also indicated that she had been assessed for depression severity using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), with scores of 0 (4 years earlier) and 3 (3 years earlier). The scores suggested that she was not suffering from depression.

During this time, the patient also saw a psychiatrist; however, it was unclear whether her symptoms met the criteria for delusional disorder or schizophrenia because she did not exhibit negative symptoms or sensory hallucinations. In addition, the patient was extremely high-functioning in the community—she participated in dance classes and other social events—and had the equivalent of a medical degree from another country. Based on chart review, when she went to the psychiatrist 3 years prior to her current presentation, there were no antipsychotics prescribed.

In the weeks leading up to her current presentation, the patient reported that she was struggling with sleep, sometimes spending days in bed and other times needing unspecified medication obtained overseas to help her sleep. Her husband reported that she had become increasingly withdrawn and stopped attending her dance classes and social events.

The patient believed the government was trying to poison her via radiation and that unknown people were trying to harm her via an online messaging application. Immediately prior to her arrival in the ED, the police were called to pull her away from oncoming traffic because she ran into the road to find the assassins that were stalking her.

During this recent visit to the ED, the patient presented with labile affect, rapid speech, and anxious and angry mood. She complained about darkened spots on her arm (inflicted through radiation by the media), vaginal bleeding, paralysis below the waist (although she was pacing around), and unspecific pain around her belly. Physical examination revealed no obvious signs of head trauma, intact extraocular movements, no coughing or wheezing, regular heart rate and rhythm, a nontender abdomen to palpation, and normal bowel sounds. No focal neurological deficits were appreciated. She had no rashes, bruises, or skin abrasions on her abdomen or upper extremities.

Continue to: The patient tried to...

The patient tried to leave the ED, saying that her third eye could see the radiation. She required medication and 4-point restraints.

Her initial laboratory work-up for heavy metals, Lyme disease, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), syphilis, delirium, and drug use were all negative. She also underwent head imaging studies that were also found to be negative. Her mental status exam was notable for a tangential thought process, preservation of delusions with loose associations, labile mood, and dysphoric affect. The patient demonstrated limited insight and judgment, although she was fully oriented to person, place, and time, which suggested against delirium at the time of evaluation.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Based on the patient’s current presentation and in light of her medical history, the health care team arrived at a

DISCUSSION

Schizophrenia is a severe, lifelong mental disorder characterized by at least 2 symptoms of delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech, disorganized or catatonic behavior, or negative symptoms for at least 6 months, with significant social, occupational, and functional deterioration. Current models attribute the neurodevelopmental deregulation of the brain in patients with schizophrenia to dopaminergic hyperactivity and hypofunction of the glutamatergic neurotransmitter system, explaining why its onset is usually in adolescence or young adulthood.1,2 However, 23% of patients present with symptoms after age 40, with 7% of patients being diagnosed between the ages of 51 and 60.3

Late-onset vs early-onset schizophrenia. LOS is often a missed diagnosis because the clinical presentation is different from early-onset schizophrenia (EOS). Although the prodromal symptoms of EOS and LOS are similar and include marked isolation that subsequently progresses to suspiciousness and ideas of reference,4 patients with EOS often also have prodromal negative symptoms. These prodromal negative symptoms associated with EOS may include loss of motivation, social passivity, and disorganized behavior. These symptoms are hypothesized to be caused by dopaminergic dysregulation in the anterior cingulate cortex. EOS is characterized by the patient experiencing more negative symptoms than LOS, which is characterized by the patient experiencing more positive symptoms.

Continue to: Patients with late-onset schizophrenia...

Patients with LOS typically do not exhibit negative symptoms because remodeling and myelination of neuronal circuitry matures by late adulthood, and thus becomes more resistant to impairment of motivational processes in the anterior cingulate gyrus.4,5,6

LOS is characterized by paranoid personality with predominantly positive symptoms, likely due to disruptions in

Other features of LOS include a high female:male ratio and symptomatic improvement with antipsychotics.7,10 Studies show that the LOS ratio of women:men can range from 2.2:1 to 22.5:1, which could be explained by the effect of dopaminergic-modulating estrogen from different sex-specific aging brain patterns.8,11,12 Finally, patients with LOS are less likely to seek care for sensory deficits than their age-equivalent counterparts.8,10 Fortunately, many of the characteristics of LOS predict good prognosis: Patients are usually female, display positive symptoms, have acute onset of symptoms, and are married with social support.10

Diagnosing LOS

LOS can be challenging to diagnose because of its atypical presentation compared with EOS, relative rarity in the population, and its propensity to be confused with progressive Alzheimer disease/dementia, delusional disorder, and major depressive disorder with psychotic features.3,6 Patients with no prior psychiatric history often do not have ready access to psychiatrists and depend on PCPs and other clinicians to identify mental health issues. A careful history, including familial involvement, utilization of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) test, and evaluation of environmental factors, are crucial to arriving at the proper diagnosis.

Continue to: Differential diagnosis

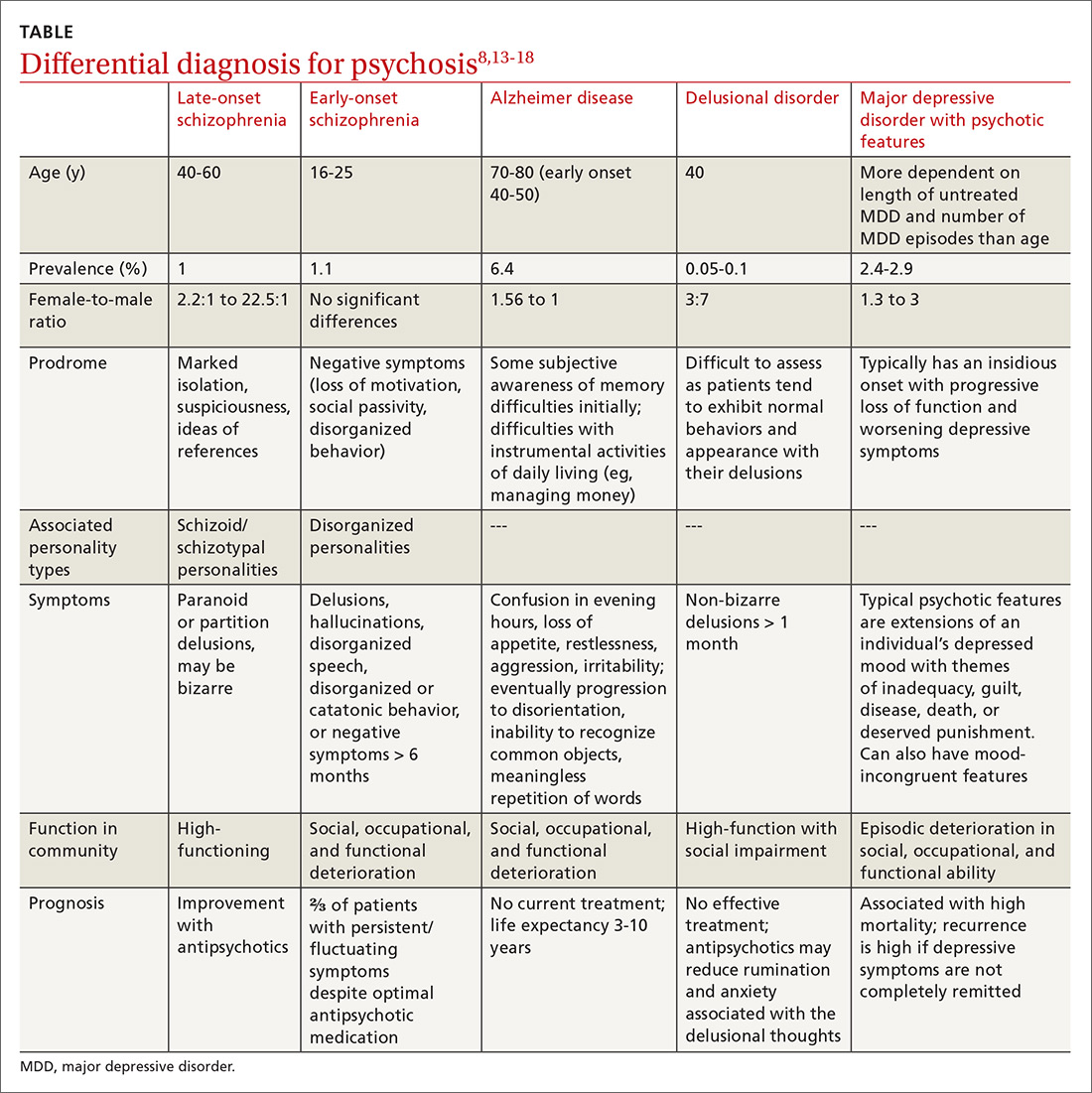

Differential diagnosis. When psychosis appears later in life, it is important to consider a broad differential (TABLE13-18), which includes the following:

Alzheimer disease. LOS can be easily differentiated from psychosis associated with Alzheimer disease or dementia through findings from neuropsychologic assessments and brain imaging. The initial first-line assessment for Alzheimer disease includes determining time course of daily living impairment and memory with follow-up brain imaging. Magnetic resonance imaging of patients with Alzheimer disease shows clear atrophy of the medial temporal lobes and general brain atrophy.19 Other than hypoperfusion in the frontal and temporal area, brain imaging of patients with LOS will not reveal any pathology.1

Delusional disorder and LOS are often more challenging to differentiate because symptoms can overlap, and many of the negative symptoms that would otherwise help clinicians diagnose schizophrenia in a younger population are absent in LOS. The milder symptoms of LOS may also lead clinicians to favor a diagnosis of delusional disorder. However, the following differences can help physicians differentiate between LOS and delusional disorder. Delusional disorder20-22:

- often will include paranoid beliefs, but these beliefs will not be bizarre, and the patient’s daily functioning will not be impaired, whereas patients with schizophrenia would have an increase in isolation and impairment in functioning that tends to be distinct from baseline.

- is more rare than schizophrenia. Delusional disorder has a prevalence of 0.05% to 0.1% compared to 1% for schizophrenia.

Major depressive disorder (MDD) with psychotic features. Major depressive disorder with psychotic features is an important differential to consider in this setting because the treatment intervention can be considerably different. Among patients who have MDD with psychotic features, a significant mood component is present, and treatment typically focuses on optimizing a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI); depending on severity, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) also may be warranted.19

Continue to: For patients with LOS...

For patients with LOS, optimizing an antipsychotic medication is the typical course of treatment, and ECT would likely have less of an impact than it does with MDD with psychotic features.

Other. Finally, in an acute setting, other differential diagnoses for mental status changes (depending on clinical findings) might include:

- drug/medication use

- delirium

- nutrient deficiencies

- acute head trauma

- chronic subdural hematoma

- syphilis

- Lyme disease

- HIV encephalitis

- heavy metal toxicity.

Treatment involves antipsychotics—especially certain ones

Antipsychotic medications are utilized for the treatment of patients with LOS. A Cochrane review concluded that there are no trial-based evidence guidelines for the treatment of patients with LOS, and that physicians should continue with their current practice and use clinical judgment and prescribing patterns to guide their selection of antipsychotic medications.22,23 Pearlson et al24 found that 76% of patients with schizophrenia achieved at least partial remission and 48% achieved full remission with antipsychotic treatment.

The preferred treatment for patients with schizophrenia is low doses of newer antipsychotics (atypical or second-generation antipsychotics [SGAs]) because they are less likely to cause extrapyramidal symptoms/adverse effects than first-generation antipsychotics. Examples of SGAs include aripiprazole, risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, and ziprasidone.

Effective treatment for LOS includes antipsychotics at a quarter to one-half of the usual therapeutic doses. In patients with very late-onset schizophrenia, doses should be started at a tenth of therapeutic dose.1,23 Physicians should titrate up carefully, as needed.

Continue to: As with any significant mental illness...

As with any significant mental illness, to improve clinical outcomes, family support may help patients’ medication adherence and ensure they attend scheduled medical appointments.

Our patient was eventually stabilized on long-acting injectable risperidone, 25 mg, with improvement in symptoms. Unfortunately, she was not convinced that her symptoms were psychiatric in nature and did not continue with her medications as an outpatient.

The patient’s nonadherence to her medication regimen led to 2 more hospitalizations with similar presentations over the following 2 years. On her most recent discharge, she was stabilized on oral olanzapine, 10 mg every night at bedtime, with close outpatient follow-up and family education.

THE TAKEAWAY

The prodromal phase of patients with LOS is similar to patients with EOS and includes withdrawal and isolation from others, making it difficult for physicians to evaluate and treat patients. Patients with LOS predominantly experience positive symptoms that may include delusions and hallucinations. Brain imaging studies can help rule out progressive dementia diseases. A neuropsychological evaluation can assess the patient’s functional level and types of delusions, which helps to differentiate LOS from other late-age psychoses. Treatment with SGAs make for a good prognosis; however, this requires patients to be adherent to treatment.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sandy Chan, MD, Department of Internal Medicine, UMass Memorial Medical Center, 55N Lake Avenue, Worcester, MA 01605; Sandy.Chan@umassmemorial.org

1. Howard R, Rabins P, Seeman M, et al. Late-onset schizophrenia and very-late-onset schizophrenia-like psychosis: an international crisis. Am J Psychiatry 2000;157:172-178.

2. Pickard B. Progress in defining the biological causes of schizophrenia. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2011;13:e25.

3. Jeste D, Symonds L, Harris M, et al. Nondementia nonpraecox dementia praecox? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1997;5:302-317.

4. Gourzis P, Katrivanou A, Beratis S. Symptomatology of the initial prodromal phase of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2002;28:415-429.

5. Dolan R, Fletcher P, Frith C, et al. Dopaminergic modulation of impaired cognitive activation in the anterior cingulate cortex in schizophrenia. Nature. 1995;378:180-182.

6. Skokou M, Katrivanou A, Andriopoulos I, et al. Active and prodromal phase symptomatology of young-onset and late-onset paranoid schizophrenia. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment. 2012;5:150-159.

7. Riecher-Rossler A, Loffler W, Munk-Jorgensen P. What do we really know about late-onset schizophrenia? Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1997;247:195-208.

8. Lubman D, Castle D. Late-onset schizophrenia: make the right diagnosis when psychosis emerges after age 60. Current Psychiatry. 2002;1:35-44.

9. Howard R, Castle D, Wessely S, et al. A comparative study of 470 cases of early-onset and late-onset schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;163:352-357.

10. Harris M, Jeste D. Late-onset schizophrenia: an overview. Schizophr Bull. 1988;14:39-55.

11. Castle D, Murray R. The epidemiology of late-onset schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1993;19:691-700.

12. Lindamer L, Lohr J, Harris M, Jeste D. Gender, estrogen, and schizophrenia. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1997;33:221-228.

13. Gaudiano BA, Dalrymple KL, Zimmerman M. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of psychotic versus non-psychotic major depression in a general psychiatric outpatient clinic. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26:54-64.

14. Saha S, Chant D, Welham J, et al. A systematic review of the prevalence of schizophrenia. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e141.

15. Gao S, Hendrie H, Hall K. The relationships between age, sex, and the incidence of dementia and Alzheimer Disease. JAMA Psychiatry. 1998;55:809-815.

16. Reitz C, Brayne C, Mayeux R. Epidemiology of Alzheimer Disease. Nature Reviews Neurology. 2011;7:137-152

17. Winokur G. Delusional Disorder (Paranoia). Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1977;18:511-521.

18. Scheltens P, Leys D, Huglo D, et al. Atrophy of medial temporal lobes on MRI in “probable” Alzheimer’s disease and normal ageing: diagnostic value and neuropsychological correlates. J Neurol, Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1992;55:967-972.

19. Copeland J, Dewey M, Scott A, et al. Schizophrenia and delusional disorder in older age: community prevalence, incidence, comorbidity, and outcome. Schizophr Bull. 1998;24:153-161.

20. Kendler K. Demography of paranoid psychosis (delusional disorder): a review and comparison with schizophrenia and affective illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1982;39:890-902.

21. McGrath J, Saha S, Chant D, et al. Schizophrenia: a concise overview of incidence, prevalence, and mortality. Epidemiol Rev. 2008;30:67.

22. Essali A, Ali G. Antipsychotic drug treatment for elderly people with late-onset schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(2):CD004162.

23. Sweet R, Pollock B. New atypical antipsychotics- experience and utility in the elderly. Drugs Aging. 1998;12:115-127.

24. Pearlson G, Kreger L, Rabins P, et al. A chart review study of late-onset and early-onset schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry.1989;146:1568-1574.

THE CASE

A 58-year-old married Asian woman with no apparent psychiatric history presented to the emergency department (ED) in an acute state with ideas of reference, paranoid delusions, and multiple, vague somatic symptoms.

Based on information in the patient’s medical record, there had been suspicion of an underlying psychiatric disorder 6 years earlier. At that time, the patient had presented to her primary care provider (PCP) with vague somatic complaints, including diffuse body pain, dry cough, chills, weakness, facial numbness, and concerns about infections. A physical examination and work-up did not reveal the source of her complaints. Unfortunately, the patient’s complaints increased in number and severity over time.

Her medical records also indicated that she had been assessed for depression severity using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), with scores of 0 (4 years earlier) and 3 (3 years earlier). The scores suggested that she was not suffering from depression.

During this time, the patient also saw a psychiatrist; however, it was unclear whether her symptoms met the criteria for delusional disorder or schizophrenia because she did not exhibit negative symptoms or sensory hallucinations. In addition, the patient was extremely high-functioning in the community—she participated in dance classes and other social events—and had the equivalent of a medical degree from another country. Based on chart review, when she went to the psychiatrist 3 years prior to her current presentation, there were no antipsychotics prescribed.

In the weeks leading up to her current presentation, the patient reported that she was struggling with sleep, sometimes spending days in bed and other times needing unspecified medication obtained overseas to help her sleep. Her husband reported that she had become increasingly withdrawn and stopped attending her dance classes and social events.

The patient believed the government was trying to poison her via radiation and that unknown people were trying to harm her via an online messaging application. Immediately prior to her arrival in the ED, the police were called to pull her away from oncoming traffic because she ran into the road to find the assassins that were stalking her.

During this recent visit to the ED, the patient presented with labile affect, rapid speech, and anxious and angry mood. She complained about darkened spots on her arm (inflicted through radiation by the media), vaginal bleeding, paralysis below the waist (although she was pacing around), and unspecific pain around her belly. Physical examination revealed no obvious signs of head trauma, intact extraocular movements, no coughing or wheezing, regular heart rate and rhythm, a nontender abdomen to palpation, and normal bowel sounds. No focal neurological deficits were appreciated. She had no rashes, bruises, or skin abrasions on her abdomen or upper extremities.

Continue to: The patient tried to...

The patient tried to leave the ED, saying that her third eye could see the radiation. She required medication and 4-point restraints.

Her initial laboratory work-up for heavy metals, Lyme disease, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), syphilis, delirium, and drug use were all negative. She also underwent head imaging studies that were also found to be negative. Her mental status exam was notable for a tangential thought process, preservation of delusions with loose associations, labile mood, and dysphoric affect. The patient demonstrated limited insight and judgment, although she was fully oriented to person, place, and time, which suggested against delirium at the time of evaluation.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Based on the patient’s current presentation and in light of her medical history, the health care team arrived at a

DISCUSSION

Schizophrenia is a severe, lifelong mental disorder characterized by at least 2 symptoms of delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech, disorganized or catatonic behavior, or negative symptoms for at least 6 months, with significant social, occupational, and functional deterioration. Current models attribute the neurodevelopmental deregulation of the brain in patients with schizophrenia to dopaminergic hyperactivity and hypofunction of the glutamatergic neurotransmitter system, explaining why its onset is usually in adolescence or young adulthood.1,2 However, 23% of patients present with symptoms after age 40, with 7% of patients being diagnosed between the ages of 51 and 60.3

Late-onset vs early-onset schizophrenia. LOS is often a missed diagnosis because the clinical presentation is different from early-onset schizophrenia (EOS). Although the prodromal symptoms of EOS and LOS are similar and include marked isolation that subsequently progresses to suspiciousness and ideas of reference,4 patients with EOS often also have prodromal negative symptoms. These prodromal negative symptoms associated with EOS may include loss of motivation, social passivity, and disorganized behavior. These symptoms are hypothesized to be caused by dopaminergic dysregulation in the anterior cingulate cortex. EOS is characterized by the patient experiencing more negative symptoms than LOS, which is characterized by the patient experiencing more positive symptoms.

Continue to: Patients with late-onset schizophrenia...

Patients with LOS typically do not exhibit negative symptoms because remodeling and myelination of neuronal circuitry matures by late adulthood, and thus becomes more resistant to impairment of motivational processes in the anterior cingulate gyrus.4,5,6

LOS is characterized by paranoid personality with predominantly positive symptoms, likely due to disruptions in

Other features of LOS include a high female:male ratio and symptomatic improvement with antipsychotics.7,10 Studies show that the LOS ratio of women:men can range from 2.2:1 to 22.5:1, which could be explained by the effect of dopaminergic-modulating estrogen from different sex-specific aging brain patterns.8,11,12 Finally, patients with LOS are less likely to seek care for sensory deficits than their age-equivalent counterparts.8,10 Fortunately, many of the characteristics of LOS predict good prognosis: Patients are usually female, display positive symptoms, have acute onset of symptoms, and are married with social support.10

Diagnosing LOS