User login

Daniel Claassen, MD, on working with patients experiencing levodopa-induced dyskinesia

How do we recognize and explain the necessity for a peak dose to patients with levodopa-induced dyskinesia (LID)?

The way I usually do it with my patients is I draw a graph. On the X axis I have time; on the Y axis I have levodopa levels. Then I show them on the graph a sinusoidal wave, displaying how, if they take their medication at 8 in the morning, the medication will grow in terms of concentration and then it will wear off.

With the sinusoidal wave I'm able to illustrate that at the peak a patient may have what we call "peak-dose dyskinesia." Typically for patients that's anywhere from 30 minutes to 45 minutes after they take their carbidopa/levodopa medication.

In terms of recognizing those symptoms, I usually spend some time with a patient describing what dyskinesia looks or feels like. There are certain cases where patients are unaware of their dyskinetic movements, when instead their caregiver, spouse, or partner are the ones actually recognizing the movements.

Typically, we talk about facial movements or lip/jaw movements and we can talk about upper extremity truncal writhing or hyperkinetic movements.

Sometimes, I'll have the patient come to the clinic having not taken their medication and then we evaluate them and have them take their medicine. About 30-45 minutes later we reevaluate the patient, which is when we can see the movements and have the patient look at themselves in the mirror to see what we're talking about, or at least explain movements to the caregiver.

Ultimately what we are trying to do is link the timing of medication and the timing of these side effects to help the patient and their family member understand the nature of what these symptoms are and when they're happening in relation to the medication that they're taking.

How can practitioners assess patients as their LID might become unpredictable?

I think the first step is to recognize that there are certain patients with Parkinson disease who are more likely to have adverse responses to levodopa. They're typically younger and they usually have other symptoms they are concerned about.

For example, it is very common for the patient to describe feeling stressed. I have had a number of patients tell me that when they're having anxiety or stress-related issues, such as at work or in their interpersonal relationships, that their dyskinesia might come on and progress a little bit more suddenly or unpredictably outside of that window when we typically expect it to peak.

Other triggers could be food. For instance, if a patient has changed their diet or changed the timing of their food intake, there may be issues related to gastric emptying or gastrointestinal symptoms that may influence the onset of these symptoms.

What we try to do is recognize the movements and then associate them with the environment or the timing behind the medication. When these things happen outside of the regular time when they're accustomed to getting them, we talk about these as unpredictable movements.

The other side effect is that patients can often have dystonia, or a forced muscle contraction. We are not only focused on the dyskinesia movement; dystonic movements are important as well.

Overall, I think practitioners can explain to patients the difference between these predictable and unpredictable movements. Additionally, we must help patients better recognize their symptoms and maybe the triggers for them, so that they may better manage them over time.

What are some aspects of LID that are most important to discuss with patients before a treatment?

The most important thing to talk about is the rationale for why a person would want to initiate levodopa or another medication.

Usually when a clinician is talking with a patient about pharmacotherapy they explain symptoms and how the individuals quality of life would improve if we treat them with levodopa.

We spend time explaining that the dose that's going to be required to get optimal control of their symptoms may differ in one person from another. And part of that dose selection is the fact that we're going to have to balance between not enough medication to too much medication.

So, I think the most important thing to discuss with patients is developing a strategy to come up with an individualized plan for medication management and explain to the patients the idea of on and off, explaining the idea of things that could interfere with medication, such as food or timing of medication use because of sleeping or changes to their day.

Basically, we are trying to give patients the framework for why we're dosing at certain times of the day regularly, why we're starting at a certain dose, and why we gradually increase the dose until we find resolution of their symptoms. We might explain why we may gradually reduce the dose if they are having symptoms like LID, and then why we may add other medications if they are experiencing LID. Also, we explain how and why we might not reduce the dose if a dose reduction would likely trigger worse symptoms.

Our aim is to give patients an outline of on/off factors that can affect drug availability and explain the long-term treatment goal, which is to optimize their motor symptoms to give them the best quality of life.

How do we recognize and explain the necessity for a peak dose to patients with levodopa-induced dyskinesia (LID)?

The way I usually do it with my patients is I draw a graph. On the X axis I have time; on the Y axis I have levodopa levels. Then I show them on the graph a sinusoidal wave, displaying how, if they take their medication at 8 in the morning, the medication will grow in terms of concentration and then it will wear off.

With the sinusoidal wave I'm able to illustrate that at the peak a patient may have what we call "peak-dose dyskinesia." Typically for patients that's anywhere from 30 minutes to 45 minutes after they take their carbidopa/levodopa medication.

In terms of recognizing those symptoms, I usually spend some time with a patient describing what dyskinesia looks or feels like. There are certain cases where patients are unaware of their dyskinetic movements, when instead their caregiver, spouse, or partner are the ones actually recognizing the movements.

Typically, we talk about facial movements or lip/jaw movements and we can talk about upper extremity truncal writhing or hyperkinetic movements.

Sometimes, I'll have the patient come to the clinic having not taken their medication and then we evaluate them and have them take their medicine. About 30-45 minutes later we reevaluate the patient, which is when we can see the movements and have the patient look at themselves in the mirror to see what we're talking about, or at least explain movements to the caregiver.

Ultimately what we are trying to do is link the timing of medication and the timing of these side effects to help the patient and their family member understand the nature of what these symptoms are and when they're happening in relation to the medication that they're taking.

How can practitioners assess patients as their LID might become unpredictable?

I think the first step is to recognize that there are certain patients with Parkinson disease who are more likely to have adverse responses to levodopa. They're typically younger and they usually have other symptoms they are concerned about.

For example, it is very common for the patient to describe feeling stressed. I have had a number of patients tell me that when they're having anxiety or stress-related issues, such as at work or in their interpersonal relationships, that their dyskinesia might come on and progress a little bit more suddenly or unpredictably outside of that window when we typically expect it to peak.

Other triggers could be food. For instance, if a patient has changed their diet or changed the timing of their food intake, there may be issues related to gastric emptying or gastrointestinal symptoms that may influence the onset of these symptoms.

What we try to do is recognize the movements and then associate them with the environment or the timing behind the medication. When these things happen outside of the regular time when they're accustomed to getting them, we talk about these as unpredictable movements.

The other side effect is that patients can often have dystonia, or a forced muscle contraction. We are not only focused on the dyskinesia movement; dystonic movements are important as well.

Overall, I think practitioners can explain to patients the difference between these predictable and unpredictable movements. Additionally, we must help patients better recognize their symptoms and maybe the triggers for them, so that they may better manage them over time.

What are some aspects of LID that are most important to discuss with patients before a treatment?

The most important thing to talk about is the rationale for why a person would want to initiate levodopa or another medication.

Usually when a clinician is talking with a patient about pharmacotherapy they explain symptoms and how the individuals quality of life would improve if we treat them with levodopa.

We spend time explaining that the dose that's going to be required to get optimal control of their symptoms may differ in one person from another. And part of that dose selection is the fact that we're going to have to balance between not enough medication to too much medication.

So, I think the most important thing to discuss with patients is developing a strategy to come up with an individualized plan for medication management and explain to the patients the idea of on and off, explaining the idea of things that could interfere with medication, such as food or timing of medication use because of sleeping or changes to their day.

Basically, we are trying to give patients the framework for why we're dosing at certain times of the day regularly, why we're starting at a certain dose, and why we gradually increase the dose until we find resolution of their symptoms. We might explain why we may gradually reduce the dose if they are having symptoms like LID, and then why we may add other medications if they are experiencing LID. Also, we explain how and why we might not reduce the dose if a dose reduction would likely trigger worse symptoms.

Our aim is to give patients an outline of on/off factors that can affect drug availability and explain the long-term treatment goal, which is to optimize their motor symptoms to give them the best quality of life.

How do we recognize and explain the necessity for a peak dose to patients with levodopa-induced dyskinesia (LID)?

The way I usually do it with my patients is I draw a graph. On the X axis I have time; on the Y axis I have levodopa levels. Then I show them on the graph a sinusoidal wave, displaying how, if they take their medication at 8 in the morning, the medication will grow in terms of concentration and then it will wear off.

With the sinusoidal wave I'm able to illustrate that at the peak a patient may have what we call "peak-dose dyskinesia." Typically for patients that's anywhere from 30 minutes to 45 minutes after they take their carbidopa/levodopa medication.

In terms of recognizing those symptoms, I usually spend some time with a patient describing what dyskinesia looks or feels like. There are certain cases where patients are unaware of their dyskinetic movements, when instead their caregiver, spouse, or partner are the ones actually recognizing the movements.

Typically, we talk about facial movements or lip/jaw movements and we can talk about upper extremity truncal writhing or hyperkinetic movements.

Sometimes, I'll have the patient come to the clinic having not taken their medication and then we evaluate them and have them take their medicine. About 30-45 minutes later we reevaluate the patient, which is when we can see the movements and have the patient look at themselves in the mirror to see what we're talking about, or at least explain movements to the caregiver.

Ultimately what we are trying to do is link the timing of medication and the timing of these side effects to help the patient and their family member understand the nature of what these symptoms are and when they're happening in relation to the medication that they're taking.

How can practitioners assess patients as their LID might become unpredictable?

I think the first step is to recognize that there are certain patients with Parkinson disease who are more likely to have adverse responses to levodopa. They're typically younger and they usually have other symptoms they are concerned about.

For example, it is very common for the patient to describe feeling stressed. I have had a number of patients tell me that when they're having anxiety or stress-related issues, such as at work or in their interpersonal relationships, that their dyskinesia might come on and progress a little bit more suddenly or unpredictably outside of that window when we typically expect it to peak.

Other triggers could be food. For instance, if a patient has changed their diet or changed the timing of their food intake, there may be issues related to gastric emptying or gastrointestinal symptoms that may influence the onset of these symptoms.

What we try to do is recognize the movements and then associate them with the environment or the timing behind the medication. When these things happen outside of the regular time when they're accustomed to getting them, we talk about these as unpredictable movements.

The other side effect is that patients can often have dystonia, or a forced muscle contraction. We are not only focused on the dyskinesia movement; dystonic movements are important as well.

Overall, I think practitioners can explain to patients the difference between these predictable and unpredictable movements. Additionally, we must help patients better recognize their symptoms and maybe the triggers for them, so that they may better manage them over time.

What are some aspects of LID that are most important to discuss with patients before a treatment?

The most important thing to talk about is the rationale for why a person would want to initiate levodopa or another medication.

Usually when a clinician is talking with a patient about pharmacotherapy they explain symptoms and how the individuals quality of life would improve if we treat them with levodopa.

We spend time explaining that the dose that's going to be required to get optimal control of their symptoms may differ in one person from another. And part of that dose selection is the fact that we're going to have to balance between not enough medication to too much medication.

So, I think the most important thing to discuss with patients is developing a strategy to come up with an individualized plan for medication management and explain to the patients the idea of on and off, explaining the idea of things that could interfere with medication, such as food or timing of medication use because of sleeping or changes to their day.

Basically, we are trying to give patients the framework for why we're dosing at certain times of the day regularly, why we're starting at a certain dose, and why we gradually increase the dose until we find resolution of their symptoms. We might explain why we may gradually reduce the dose if they are having symptoms like LID, and then why we may add other medications if they are experiencing LID. Also, we explain how and why we might not reduce the dose if a dose reduction would likely trigger worse symptoms.

Our aim is to give patients an outline of on/off factors that can affect drug availability and explain the long-term treatment goal, which is to optimize their motor symptoms to give them the best quality of life.

David Charles, MD, and Thomas Davis, MD, on updates on levodopa-induced dyskinesia treatment and research

David Charles, MD, and Thomas Davis, MD, of the Vanderbilt University Department of Neurology, recently spoke with Neurology Reviews about the treatment pipeline and latest research in levodopa-induced dyskinesia in Parkinson's disease.

How is the treatment pipeline advancing for different types of levodopa-induced dyskinesia (LID)?

Dr. Thomas Davis: Dyskinesia has traditionally been hard to quantify, and we have been lacking any US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved anti-dyskinesia drugs. The pipeline has historically been strongest for wearing-off because it is easier to measure on time than to quantify involuntary movements.

The Unified Dyskinesia Rating Scale (UDysRS), released in 2008 by the Movement Disorder Society, provided a standardized scale that allowed dyskinesia clinical trials to move forward. The UDysRS was used as the primary outcome for the extended release amantadine capsule study. This was important because it demonstrated the possibility of a successful clinical trial design to get a drug approved for dyskinesia, which will encourage others to test more potential new treatments.

What is the status of research on deep brain stimulation (DBS) for Parkinson's disease, and when might it be considered?

Dr. David Charles: This is one of the areas of research that we're focused on here at Vanderbilt. All 3 of the FDA-approved device manufacturers have been conducting research in technology refinement and improvements. These advances include not only patient programmers and physician programmers, but also new sensing capability and lead designs. Some of the manufacturers now have leads that allow the physician to steer the current in one direction or another, where traditionally the current has been delivered in a circumferential contact that's shaped like a cylinder, where the energy is transmitted 360 degrees from the lead. The new designs allow you to steer the current hopefully toward areas that provide more efficacy and away from areas that cause side effects. Even more exciting is the emerging sensing capability that may allow the development of stimulating technology that is responsive to fluctuating symptoms. There is keen research interest in understanding whether a device could detect a specific neuronal firing pattern and then respond with an individually tailored stimulation to improve symptoms as needed. Will the next generation of deep brain stimulating devices detect the pattern and deliver energy in a more targeted and precise way, responsive to what it's sensing from the patient's brain? I think that's an area of research that's really exciting.

In regard to when it might be considered: The ability to steer the current is already available in 2 of the 3 systems that are on the market today. Having current that is steerable in all 3 will be coming in the not too distant future. The available devices already have improved programming platforms for health care providers as well.

Our research at Vanderbilt is focused on DBS in early-stage Parkinson's disease. There is a paper published in Neurology that reports Class II evidencet hat DBS applied in early-stage Parkinson's disease slows the progression of tremor. This is exciting because none of the available treatments change the progression of disease—they're currently accepted as symptomatic therapies only. In this publication, we report that participants receiving DBS in the very earliest stages of Parkinson's disease it may slow the progression of rest tremor. We now have approval from the FDA to conduct a large-scale phase 3, multicenter, clinical trial of DBS in early-stage Parkinson's disease, with the primary endpoint focused on slowing progression of tremor, a cardinal feature of the disease. This upcoming trial is approved by the FDA as a pivotal trial, meaning that the findings could potentially be used to change the labeling of DBS devices. Our goal is to obtain Class I evidence of slowing the progression of tremor or other elements of the disease.

Dr. Thomas Davis: If you are a device manufacturer for DBS it is natural for you to aim to make better devices, better batteries, better programming, and better electrodes than your competitor. That's really where the industry-based research is right now. Clinicians are still determining which device is the best candidate, where the best target in the brain is, and when to use DBS.

When would a health care practitioner decide to try frequent smaller dosages or immediate-release formulations of dopaminergic drugs to control levodopa-induced dyskinesia (LID), compared with non-dopaminergic treatments that are available? What are some pros and cons of each approach?

Dr. David Charles: If you have a patient who's already on levodopa, it's not uncommon that—separate from the way we prescribe the medicine—the patients experiment with their medicine to some degree. At the very least, people occasionally forget to take a dose and they feel the effect of a missed dose. They may take an extra dose or an extra half dose, particularly if they feel that the last dose isn't working as well, or in the event they have some special occasion coming up.

Over time, patients and physicians learn that sometimes smaller, more frequent dosing of levodopa can be a helpful strategy for certain individuals. One advantage is that it's the medication that the patient is already taking, and they're just simply breaking tablets. Many pharmacies will break tablets for patients so they can take some smaller doses more frequently. Obviously, there can be downsides to that, such as it becoming harder to remember to take more frequent doses.

Dr. Thomas Davis: I would agree that the biggest advantage of taking more frequent, smaller doses is that it's cheaper than adding an adjunct or moving to a more invasive therapy. More frequent smaller doses of levodopa also generally has no side effects because if you're taking 2 carbidopa/levodopa 3 times a day and you're tolerating it, but you're having peak dose problems, you can then switch to 1.5 tablets 4 times a day. It involves more work and planning, but it's no more total medication than the patient is taking already, so this strategy usually does not have any unexpected side effects. It really boils down to how much work the patient wants to put in, how adherent they are to medication dosing, and whether they want to add another medication.

Most of the adjunctive medications to treat motor fluctuations are approved to improve on-time in Parkinson's disease patients with wearing off. These include the monoamine oxidase inhibitors, COMT inhibitors, and adenosine A2A antagonists. For treatment of dyskinesia, only the extended release capsule formulation of amantadine has FDA approval, although all formulations are approved for Parkinson's disease and are used clinically to dampen dyskinesia. How long to try these strategies before moving to one of the more advanced therapies, like DBS or jejunal infusion of levodopa, is not clear. It's great to have options, but it makes the decisions a lot harder.

Dr. David Charles: Dr. Davis raised the question of what medicine to choose, and what's your next choice in a patient who's having wearing-off dyskinesia or LID and so forth. There is an increasing number of options for those mid-stage patients. The pitfall is feeling that you have to try every available medication and combination before moving to a more advanced therapy. The physician risks churning through the various combinations for so long that the benefit of an advanced therapy becomes shortened or lost altogether.

Take epilepsy, for example. In operative candidates, surgery is often more beneficial when applied earlier. There's solid data to support that adding on multiple anti-epileptics medications is not always helpful. Continuing to add or change medications can actually diminish returns, particularly in a person who could receive benefit from surgery for epilepsy.

I get the sense that the same may be true for dyskinesia. In clinical practice, we often receive DBS referrals when a patient's community-based physician has tried various medications and combination therapies until the point that the patient and the physician have become totally frustrated. By the time they are referred, the patient may benefit from DBS, but not nearly as well and as for long as they could have if they had received it earlier. We as physicians have to be mindful that while we have these increasing number of options—which is a good thing for both patients and physicians—that we don't continue to use them to the point that it takes away the option of more advanced therapies for appropriate candidates.

Metabotropic glutamate (mGlu) receptors have been receiving attention as potential therapeutic targets for LID. How do these compare with other receptors such as N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) and alpha-amino-3-hydroxyl-5-

Dr. Thomas Davis: NMDA and AMPA are traditional ionotropic receptors, meaning that they are ligand gated, that they are almost exclusively excitatory, and that they generally have to do with the flow of potassium.

mGlu receptors are protein coupled receptors. They have more elaborate action and may be either excitatory or inhibitory. Though mGlu, NMDA, and AMPA are completely different, they are all activated by glutamate. Pharmacologically utilizing the mGlu receptors is a relatively new and novel idea. Specifically, mGlu-5 receptors have received the most attention as potentially having an anti-parkinsonian effect and possibly dampening dyskinesia. The mGlu-5 receptors are an attractive target because they are concentrated in the striatum, as opposed to other glutamatergic receptors that are more diffusely located. It was felt that mGlu-5 modulators would be more specific and have less of the potential adverse effects of other glutamates. Most drugs that we think of affecting glutamate, like amantadine and memantine (used for Alzheimer's disease), have some NMDA antagonist effect, but this is relatively mild.

David Charles, MD, and Thomas Davis, MD, of the Vanderbilt University Department of Neurology, recently spoke with Neurology Reviews about the treatment pipeline and latest research in levodopa-induced dyskinesia in Parkinson's disease.

How is the treatment pipeline advancing for different types of levodopa-induced dyskinesia (LID)?

Dr. Thomas Davis: Dyskinesia has traditionally been hard to quantify, and we have been lacking any US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved anti-dyskinesia drugs. The pipeline has historically been strongest for wearing-off because it is easier to measure on time than to quantify involuntary movements.

The Unified Dyskinesia Rating Scale (UDysRS), released in 2008 by the Movement Disorder Society, provided a standardized scale that allowed dyskinesia clinical trials to move forward. The UDysRS was used as the primary outcome for the extended release amantadine capsule study. This was important because it demonstrated the possibility of a successful clinical trial design to get a drug approved for dyskinesia, which will encourage others to test more potential new treatments.

What is the status of research on deep brain stimulation (DBS) for Parkinson's disease, and when might it be considered?

Dr. David Charles: This is one of the areas of research that we're focused on here at Vanderbilt. All 3 of the FDA-approved device manufacturers have been conducting research in technology refinement and improvements. These advances include not only patient programmers and physician programmers, but also new sensing capability and lead designs. Some of the manufacturers now have leads that allow the physician to steer the current in one direction or another, where traditionally the current has been delivered in a circumferential contact that's shaped like a cylinder, where the energy is transmitted 360 degrees from the lead. The new designs allow you to steer the current hopefully toward areas that provide more efficacy and away from areas that cause side effects. Even more exciting is the emerging sensing capability that may allow the development of stimulating technology that is responsive to fluctuating symptoms. There is keen research interest in understanding whether a device could detect a specific neuronal firing pattern and then respond with an individually tailored stimulation to improve symptoms as needed. Will the next generation of deep brain stimulating devices detect the pattern and deliver energy in a more targeted and precise way, responsive to what it's sensing from the patient's brain? I think that's an area of research that's really exciting.

In regard to when it might be considered: The ability to steer the current is already available in 2 of the 3 systems that are on the market today. Having current that is steerable in all 3 will be coming in the not too distant future. The available devices already have improved programming platforms for health care providers as well.

Our research at Vanderbilt is focused on DBS in early-stage Parkinson's disease. There is a paper published in Neurology that reports Class II evidencet hat DBS applied in early-stage Parkinson's disease slows the progression of tremor. This is exciting because none of the available treatments change the progression of disease—they're currently accepted as symptomatic therapies only. In this publication, we report that participants receiving DBS in the very earliest stages of Parkinson's disease it may slow the progression of rest tremor. We now have approval from the FDA to conduct a large-scale phase 3, multicenter, clinical trial of DBS in early-stage Parkinson's disease, with the primary endpoint focused on slowing progression of tremor, a cardinal feature of the disease. This upcoming trial is approved by the FDA as a pivotal trial, meaning that the findings could potentially be used to change the labeling of DBS devices. Our goal is to obtain Class I evidence of slowing the progression of tremor or other elements of the disease.

Dr. Thomas Davis: If you are a device manufacturer for DBS it is natural for you to aim to make better devices, better batteries, better programming, and better electrodes than your competitor. That's really where the industry-based research is right now. Clinicians are still determining which device is the best candidate, where the best target in the brain is, and when to use DBS.

When would a health care practitioner decide to try frequent smaller dosages or immediate-release formulations of dopaminergic drugs to control levodopa-induced dyskinesia (LID), compared with non-dopaminergic treatments that are available? What are some pros and cons of each approach?

Dr. David Charles: If you have a patient who's already on levodopa, it's not uncommon that—separate from the way we prescribe the medicine—the patients experiment with their medicine to some degree. At the very least, people occasionally forget to take a dose and they feel the effect of a missed dose. They may take an extra dose or an extra half dose, particularly if they feel that the last dose isn't working as well, or in the event they have some special occasion coming up.

Over time, patients and physicians learn that sometimes smaller, more frequent dosing of levodopa can be a helpful strategy for certain individuals. One advantage is that it's the medication that the patient is already taking, and they're just simply breaking tablets. Many pharmacies will break tablets for patients so they can take some smaller doses more frequently. Obviously, there can be downsides to that, such as it becoming harder to remember to take more frequent doses.

Dr. Thomas Davis: I would agree that the biggest advantage of taking more frequent, smaller doses is that it's cheaper than adding an adjunct or moving to a more invasive therapy. More frequent smaller doses of levodopa also generally has no side effects because if you're taking 2 carbidopa/levodopa 3 times a day and you're tolerating it, but you're having peak dose problems, you can then switch to 1.5 tablets 4 times a day. It involves more work and planning, but it's no more total medication than the patient is taking already, so this strategy usually does not have any unexpected side effects. It really boils down to how much work the patient wants to put in, how adherent they are to medication dosing, and whether they want to add another medication.

Most of the adjunctive medications to treat motor fluctuations are approved to improve on-time in Parkinson's disease patients with wearing off. These include the monoamine oxidase inhibitors, COMT inhibitors, and adenosine A2A antagonists. For treatment of dyskinesia, only the extended release capsule formulation of amantadine has FDA approval, although all formulations are approved for Parkinson's disease and are used clinically to dampen dyskinesia. How long to try these strategies before moving to one of the more advanced therapies, like DBS or jejunal infusion of levodopa, is not clear. It's great to have options, but it makes the decisions a lot harder.

Dr. David Charles: Dr. Davis raised the question of what medicine to choose, and what's your next choice in a patient who's having wearing-off dyskinesia or LID and so forth. There is an increasing number of options for those mid-stage patients. The pitfall is feeling that you have to try every available medication and combination before moving to a more advanced therapy. The physician risks churning through the various combinations for so long that the benefit of an advanced therapy becomes shortened or lost altogether.

Take epilepsy, for example. In operative candidates, surgery is often more beneficial when applied earlier. There's solid data to support that adding on multiple anti-epileptics medications is not always helpful. Continuing to add or change medications can actually diminish returns, particularly in a person who could receive benefit from surgery for epilepsy.

I get the sense that the same may be true for dyskinesia. In clinical practice, we often receive DBS referrals when a patient's community-based physician has tried various medications and combination therapies until the point that the patient and the physician have become totally frustrated. By the time they are referred, the patient may benefit from DBS, but not nearly as well and as for long as they could have if they had received it earlier. We as physicians have to be mindful that while we have these increasing number of options—which is a good thing for both patients and physicians—that we don't continue to use them to the point that it takes away the option of more advanced therapies for appropriate candidates.

Metabotropic glutamate (mGlu) receptors have been receiving attention as potential therapeutic targets for LID. How do these compare with other receptors such as N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) and alpha-amino-3-hydroxyl-5-

Dr. Thomas Davis: NMDA and AMPA are traditional ionotropic receptors, meaning that they are ligand gated, that they are almost exclusively excitatory, and that they generally have to do with the flow of potassium.

mGlu receptors are protein coupled receptors. They have more elaborate action and may be either excitatory or inhibitory. Though mGlu, NMDA, and AMPA are completely different, they are all activated by glutamate. Pharmacologically utilizing the mGlu receptors is a relatively new and novel idea. Specifically, mGlu-5 receptors have received the most attention as potentially having an anti-parkinsonian effect and possibly dampening dyskinesia. The mGlu-5 receptors are an attractive target because they are concentrated in the striatum, as opposed to other glutamatergic receptors that are more diffusely located. It was felt that mGlu-5 modulators would be more specific and have less of the potential adverse effects of other glutamates. Most drugs that we think of affecting glutamate, like amantadine and memantine (used for Alzheimer's disease), have some NMDA antagonist effect, but this is relatively mild.

David Charles, MD, and Thomas Davis, MD, of the Vanderbilt University Department of Neurology, recently spoke with Neurology Reviews about the treatment pipeline and latest research in levodopa-induced dyskinesia in Parkinson's disease.

How is the treatment pipeline advancing for different types of levodopa-induced dyskinesia (LID)?

Dr. Thomas Davis: Dyskinesia has traditionally been hard to quantify, and we have been lacking any US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved anti-dyskinesia drugs. The pipeline has historically been strongest for wearing-off because it is easier to measure on time than to quantify involuntary movements.

The Unified Dyskinesia Rating Scale (UDysRS), released in 2008 by the Movement Disorder Society, provided a standardized scale that allowed dyskinesia clinical trials to move forward. The UDysRS was used as the primary outcome for the extended release amantadine capsule study. This was important because it demonstrated the possibility of a successful clinical trial design to get a drug approved for dyskinesia, which will encourage others to test more potential new treatments.

What is the status of research on deep brain stimulation (DBS) for Parkinson's disease, and when might it be considered?

Dr. David Charles: This is one of the areas of research that we're focused on here at Vanderbilt. All 3 of the FDA-approved device manufacturers have been conducting research in technology refinement and improvements. These advances include not only patient programmers and physician programmers, but also new sensing capability and lead designs. Some of the manufacturers now have leads that allow the physician to steer the current in one direction or another, where traditionally the current has been delivered in a circumferential contact that's shaped like a cylinder, where the energy is transmitted 360 degrees from the lead. The new designs allow you to steer the current hopefully toward areas that provide more efficacy and away from areas that cause side effects. Even more exciting is the emerging sensing capability that may allow the development of stimulating technology that is responsive to fluctuating symptoms. There is keen research interest in understanding whether a device could detect a specific neuronal firing pattern and then respond with an individually tailored stimulation to improve symptoms as needed. Will the next generation of deep brain stimulating devices detect the pattern and deliver energy in a more targeted and precise way, responsive to what it's sensing from the patient's brain? I think that's an area of research that's really exciting.

In regard to when it might be considered: The ability to steer the current is already available in 2 of the 3 systems that are on the market today. Having current that is steerable in all 3 will be coming in the not too distant future. The available devices already have improved programming platforms for health care providers as well.

Our research at Vanderbilt is focused on DBS in early-stage Parkinson's disease. There is a paper published in Neurology that reports Class II evidencet hat DBS applied in early-stage Parkinson's disease slows the progression of tremor. This is exciting because none of the available treatments change the progression of disease—they're currently accepted as symptomatic therapies only. In this publication, we report that participants receiving DBS in the very earliest stages of Parkinson's disease it may slow the progression of rest tremor. We now have approval from the FDA to conduct a large-scale phase 3, multicenter, clinical trial of DBS in early-stage Parkinson's disease, with the primary endpoint focused on slowing progression of tremor, a cardinal feature of the disease. This upcoming trial is approved by the FDA as a pivotal trial, meaning that the findings could potentially be used to change the labeling of DBS devices. Our goal is to obtain Class I evidence of slowing the progression of tremor or other elements of the disease.

Dr. Thomas Davis: If you are a device manufacturer for DBS it is natural for you to aim to make better devices, better batteries, better programming, and better electrodes than your competitor. That's really where the industry-based research is right now. Clinicians are still determining which device is the best candidate, where the best target in the brain is, and when to use DBS.

When would a health care practitioner decide to try frequent smaller dosages or immediate-release formulations of dopaminergic drugs to control levodopa-induced dyskinesia (LID), compared with non-dopaminergic treatments that are available? What are some pros and cons of each approach?

Dr. David Charles: If you have a patient who's already on levodopa, it's not uncommon that—separate from the way we prescribe the medicine—the patients experiment with their medicine to some degree. At the very least, people occasionally forget to take a dose and they feel the effect of a missed dose. They may take an extra dose or an extra half dose, particularly if they feel that the last dose isn't working as well, or in the event they have some special occasion coming up.

Over time, patients and physicians learn that sometimes smaller, more frequent dosing of levodopa can be a helpful strategy for certain individuals. One advantage is that it's the medication that the patient is already taking, and they're just simply breaking tablets. Many pharmacies will break tablets for patients so they can take some smaller doses more frequently. Obviously, there can be downsides to that, such as it becoming harder to remember to take more frequent doses.

Dr. Thomas Davis: I would agree that the biggest advantage of taking more frequent, smaller doses is that it's cheaper than adding an adjunct or moving to a more invasive therapy. More frequent smaller doses of levodopa also generally has no side effects because if you're taking 2 carbidopa/levodopa 3 times a day and you're tolerating it, but you're having peak dose problems, you can then switch to 1.5 tablets 4 times a day. It involves more work and planning, but it's no more total medication than the patient is taking already, so this strategy usually does not have any unexpected side effects. It really boils down to how much work the patient wants to put in, how adherent they are to medication dosing, and whether they want to add another medication.

Most of the adjunctive medications to treat motor fluctuations are approved to improve on-time in Parkinson's disease patients with wearing off. These include the monoamine oxidase inhibitors, COMT inhibitors, and adenosine A2A antagonists. For treatment of dyskinesia, only the extended release capsule formulation of amantadine has FDA approval, although all formulations are approved for Parkinson's disease and are used clinically to dampen dyskinesia. How long to try these strategies before moving to one of the more advanced therapies, like DBS or jejunal infusion of levodopa, is not clear. It's great to have options, but it makes the decisions a lot harder.

Dr. David Charles: Dr. Davis raised the question of what medicine to choose, and what's your next choice in a patient who's having wearing-off dyskinesia or LID and so forth. There is an increasing number of options for those mid-stage patients. The pitfall is feeling that you have to try every available medication and combination before moving to a more advanced therapy. The physician risks churning through the various combinations for so long that the benefit of an advanced therapy becomes shortened or lost altogether.

Take epilepsy, for example. In operative candidates, surgery is often more beneficial when applied earlier. There's solid data to support that adding on multiple anti-epileptics medications is not always helpful. Continuing to add or change medications can actually diminish returns, particularly in a person who could receive benefit from surgery for epilepsy.

I get the sense that the same may be true for dyskinesia. In clinical practice, we often receive DBS referrals when a patient's community-based physician has tried various medications and combination therapies until the point that the patient and the physician have become totally frustrated. By the time they are referred, the patient may benefit from DBS, but not nearly as well and as for long as they could have if they had received it earlier. We as physicians have to be mindful that while we have these increasing number of options—which is a good thing for both patients and physicians—that we don't continue to use them to the point that it takes away the option of more advanced therapies for appropriate candidates.

Metabotropic glutamate (mGlu) receptors have been receiving attention as potential therapeutic targets for LID. How do these compare with other receptors such as N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) and alpha-amino-3-hydroxyl-5-

Dr. Thomas Davis: NMDA and AMPA are traditional ionotropic receptors, meaning that they are ligand gated, that they are almost exclusively excitatory, and that they generally have to do with the flow of potassium.

mGlu receptors are protein coupled receptors. They have more elaborate action and may be either excitatory or inhibitory. Though mGlu, NMDA, and AMPA are completely different, they are all activated by glutamate. Pharmacologically utilizing the mGlu receptors is a relatively new and novel idea. Specifically, mGlu-5 receptors have received the most attention as potentially having an anti-parkinsonian effect and possibly dampening dyskinesia. The mGlu-5 receptors are an attractive target because they are concentrated in the striatum, as opposed to other glutamatergic receptors that are more diffusely located. It was felt that mGlu-5 modulators would be more specific and have less of the potential adverse effects of other glutamates. Most drugs that we think of affecting glutamate, like amantadine and memantine (used for Alzheimer's disease), have some NMDA antagonist effect, but this is relatively mild.

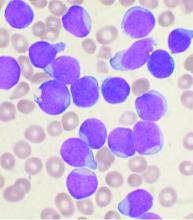

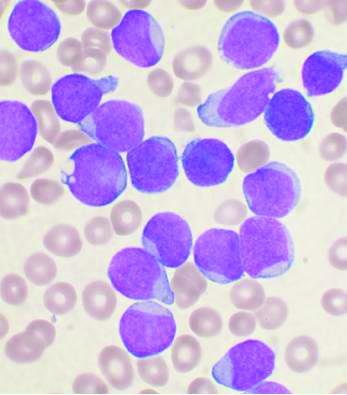

COVID-19: Adjusting practice in acute leukemia care

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic poses significant risks to leukemia patients and their providers, impacting every aspect of care from diagnosis through therapy, according to an editorial letter published online in Leukemia Research.

One key concern to be considered is the risk of missed or delayed diagnosis due to the pandemic conditions. An estimated 50%-75% of patients with acute leukemia are febrile at diagnosis and this puts them at high risk of a misdiagnosis of COVID-19 upon initial evaluation. As with other oncological conditions (primary mediastinal lymphoma or lung cancer, for example), which often present with a cough with or without fever, their symptoms “are likely to be considered trivial after a negative SARS-CoV-2 test,” with patients then being sent home without further assessment. In a rapidly progressing disease such as acute leukemia, this could lead to critical delays in therapeutic intervention.

The authors, from the Service and Central Laboratory of Hematology, Lausanne (Switzerland) University Hospital, also discussed the problems that might occur with regard to most standard forms of therapy. In particular, they addressed potential impacts of the pandemic on chemotherapy, bone marrow transplantation, maintenance treatments, supportive measures, and targeted therapies.

Of particular concern, “most patients may suffer from postponed chemotherapy, due to a shortage of isolation beds and blood products or the wish to avoid immunosuppressive treatments,” the authors noted, warning that “delay in chemotherapy initiation may negatively affect prognosis, [particularly in patients under age 60] with favorable- or intermediate-risk disease.”

With regard to stem cell transplantation, the authors detail the many potential difficulties with regard to procedures involving both donors and recipients, and warn that in some cases, delay in transplant could result in the reappearance of a significant minimal residual disease, which has a well-established negative impact on survival.

The authors also noted that blood product shortages have already begun in most affected countries, and how, in response, transfusion societies have called for conservative transfusion policies in strict adherence to evidence-based guidelines for patient’s blood management.

“COVID-19 will result in numerous casualties. Acute leukemia patients are at a higher risk of severe complications,” the authors stated. In particular, physicians should especially be aware of how treatment for acute leukemia may have “interactions with other drugs used to treat SARS-CoV-2–related infections/complications such as antibiotics, antiviral drugs, and various other drugs that prolong QTc or impact targeted-therapy pharmacokinetics,” they concluded.

The authors reported that they received no government or private funding for this research, and that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Gavillet M et al. Leuk. Res. 2020. doi.org/10.1016/j.leukres.2020.106353.

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic poses significant risks to leukemia patients and their providers, impacting every aspect of care from diagnosis through therapy, according to an editorial letter published online in Leukemia Research.

One key concern to be considered is the risk of missed or delayed diagnosis due to the pandemic conditions. An estimated 50%-75% of patients with acute leukemia are febrile at diagnosis and this puts them at high risk of a misdiagnosis of COVID-19 upon initial evaluation. As with other oncological conditions (primary mediastinal lymphoma or lung cancer, for example), which often present with a cough with or without fever, their symptoms “are likely to be considered trivial after a negative SARS-CoV-2 test,” with patients then being sent home without further assessment. In a rapidly progressing disease such as acute leukemia, this could lead to critical delays in therapeutic intervention.

The authors, from the Service and Central Laboratory of Hematology, Lausanne (Switzerland) University Hospital, also discussed the problems that might occur with regard to most standard forms of therapy. In particular, they addressed potential impacts of the pandemic on chemotherapy, bone marrow transplantation, maintenance treatments, supportive measures, and targeted therapies.

Of particular concern, “most patients may suffer from postponed chemotherapy, due to a shortage of isolation beds and blood products or the wish to avoid immunosuppressive treatments,” the authors noted, warning that “delay in chemotherapy initiation may negatively affect prognosis, [particularly in patients under age 60] with favorable- or intermediate-risk disease.”

With regard to stem cell transplantation, the authors detail the many potential difficulties with regard to procedures involving both donors and recipients, and warn that in some cases, delay in transplant could result in the reappearance of a significant minimal residual disease, which has a well-established negative impact on survival.

The authors also noted that blood product shortages have already begun in most affected countries, and how, in response, transfusion societies have called for conservative transfusion policies in strict adherence to evidence-based guidelines for patient’s blood management.

“COVID-19 will result in numerous casualties. Acute leukemia patients are at a higher risk of severe complications,” the authors stated. In particular, physicians should especially be aware of how treatment for acute leukemia may have “interactions with other drugs used to treat SARS-CoV-2–related infections/complications such as antibiotics, antiviral drugs, and various other drugs that prolong QTc or impact targeted-therapy pharmacokinetics,” they concluded.

The authors reported that they received no government or private funding for this research, and that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Gavillet M et al. Leuk. Res. 2020. doi.org/10.1016/j.leukres.2020.106353.

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic poses significant risks to leukemia patients and their providers, impacting every aspect of care from diagnosis through therapy, according to an editorial letter published online in Leukemia Research.

One key concern to be considered is the risk of missed or delayed diagnosis due to the pandemic conditions. An estimated 50%-75% of patients with acute leukemia are febrile at diagnosis and this puts them at high risk of a misdiagnosis of COVID-19 upon initial evaluation. As with other oncological conditions (primary mediastinal lymphoma or lung cancer, for example), which often present with a cough with or without fever, their symptoms “are likely to be considered trivial after a negative SARS-CoV-2 test,” with patients then being sent home without further assessment. In a rapidly progressing disease such as acute leukemia, this could lead to critical delays in therapeutic intervention.

The authors, from the Service and Central Laboratory of Hematology, Lausanne (Switzerland) University Hospital, also discussed the problems that might occur with regard to most standard forms of therapy. In particular, they addressed potential impacts of the pandemic on chemotherapy, bone marrow transplantation, maintenance treatments, supportive measures, and targeted therapies.

Of particular concern, “most patients may suffer from postponed chemotherapy, due to a shortage of isolation beds and blood products or the wish to avoid immunosuppressive treatments,” the authors noted, warning that “delay in chemotherapy initiation may negatively affect prognosis, [particularly in patients under age 60] with favorable- or intermediate-risk disease.”

With regard to stem cell transplantation, the authors detail the many potential difficulties with regard to procedures involving both donors and recipients, and warn that in some cases, delay in transplant could result in the reappearance of a significant minimal residual disease, which has a well-established negative impact on survival.

The authors also noted that blood product shortages have already begun in most affected countries, and how, in response, transfusion societies have called for conservative transfusion policies in strict adherence to evidence-based guidelines for patient’s blood management.

“COVID-19 will result in numerous casualties. Acute leukemia patients are at a higher risk of severe complications,” the authors stated. In particular, physicians should especially be aware of how treatment for acute leukemia may have “interactions with other drugs used to treat SARS-CoV-2–related infections/complications such as antibiotics, antiviral drugs, and various other drugs that prolong QTc or impact targeted-therapy pharmacokinetics,” they concluded.

The authors reported that they received no government or private funding for this research, and that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Gavillet M et al. Leuk. Res. 2020. doi.org/10.1016/j.leukres.2020.106353.

FROM LEUKEMIA RESEARCH

Noninvasive fibrosis scores not sensitive in people with fatty liver disease and T2D

Noninvasive fibrosis scores, which are widely used to predict advanced fibrosis in people with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), do not do a good job of picking up advanced fibrosis in patients with underlying diabetes, according to a new study.

Advanced fibrosis is associated with an increased risk of cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease, and liver failure. Underlying diabetes is a risk factor for both advanced fibrosis and death in patients with NAFLD.

While liver biopsy remains the gold standard for detecting advanced fibrosis, high costs and risks limit its use. Noninvasive scores such as the AST/ALT ratio; AST to platelet ratio index (APRI); fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) index; and NAFLD fibrosis score (NFS) have gained popularity in recent years, as they offer the compelling advantage of using easily and cheaply attained clinical and laboratory measures to assess likelihood of disease.

But their accuracy has come into question, particularly for people with diabetes.

In research published in the Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, Amandeep Singh, MD, and colleagues at the Cleveland Clinic looked at their center’s records for 1,157 patients with type 2 diabetes (65% women, 88% white, 85% with obesity) who had undergone a liver biopsy for suspected advanced fibrosis between 2000 and 2015. Biopsy results revealed that a third of the cohort (32%) was positive for advanced fibrosis.

The investigators then pulled patients’ laboratory results for AST, ALT, cholesterol, triglycerides, fasting glucose, hemoglobin A1c, bilirubin, albumin, platelet count, alkaline phosphatase, albumin, and lipid levels, all collected within a year of biopsy. After plugging these into the algorithms of four different scoring systems for advanced fibrosis, they compared results with results from the biopsies.

The scores of AST/ALT greater than 1.4, APRI of at least 1.5, NFS greater than 0.676, and FIB-4 index greater than 2.67 had high specificities of 84%, 97%, 70%, and 93%, respectively, but sensitivities of only 27%, 17%, 64%, and 44%. Even when the cutoff measures were tightened, the scoring systems still missed a lot of disease. This suggests, Dr. Singh and colleagues wrote, that “the presence of diabetes could decrease the predictive value of these scores to detect advanced disease in NAFLD patients.” Reliable noninvasive biomarkers are “urgently needed” for this patient population.

In an interview, Dr. Singh advised that clinicians continue to use current noninvasive scores in patients with diabetes – preferably the NFS – “until we have a better scoring system.” If clinicians suspect advanced fibrosis based on lab tests and clinical data, then “liver biopsy should be considered,” he said.

The investigators described among the limitations of their study its retrospective, single-center design, with patients who were mostly white and from one geographic region.

Dr. Singh and colleagues reported no conflicts of interest or outside funding for their study.

jensmith@mdedge.com

SOURCE: Singh A et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2020 Mar 11. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001339.

Noninvasive fibrosis scores, which are widely used to predict advanced fibrosis in people with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), do not do a good job of picking up advanced fibrosis in patients with underlying diabetes, according to a new study.

Advanced fibrosis is associated with an increased risk of cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease, and liver failure. Underlying diabetes is a risk factor for both advanced fibrosis and death in patients with NAFLD.

While liver biopsy remains the gold standard for detecting advanced fibrosis, high costs and risks limit its use. Noninvasive scores such as the AST/ALT ratio; AST to platelet ratio index (APRI); fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) index; and NAFLD fibrosis score (NFS) have gained popularity in recent years, as they offer the compelling advantage of using easily and cheaply attained clinical and laboratory measures to assess likelihood of disease.

But their accuracy has come into question, particularly for people with diabetes.

In research published in the Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, Amandeep Singh, MD, and colleagues at the Cleveland Clinic looked at their center’s records for 1,157 patients with type 2 diabetes (65% women, 88% white, 85% with obesity) who had undergone a liver biopsy for suspected advanced fibrosis between 2000 and 2015. Biopsy results revealed that a third of the cohort (32%) was positive for advanced fibrosis.

The investigators then pulled patients’ laboratory results for AST, ALT, cholesterol, triglycerides, fasting glucose, hemoglobin A1c, bilirubin, albumin, platelet count, alkaline phosphatase, albumin, and lipid levels, all collected within a year of biopsy. After plugging these into the algorithms of four different scoring systems for advanced fibrosis, they compared results with results from the biopsies.

The scores of AST/ALT greater than 1.4, APRI of at least 1.5, NFS greater than 0.676, and FIB-4 index greater than 2.67 had high specificities of 84%, 97%, 70%, and 93%, respectively, but sensitivities of only 27%, 17%, 64%, and 44%. Even when the cutoff measures were tightened, the scoring systems still missed a lot of disease. This suggests, Dr. Singh and colleagues wrote, that “the presence of diabetes could decrease the predictive value of these scores to detect advanced disease in NAFLD patients.” Reliable noninvasive biomarkers are “urgently needed” for this patient population.

In an interview, Dr. Singh advised that clinicians continue to use current noninvasive scores in patients with diabetes – preferably the NFS – “until we have a better scoring system.” If clinicians suspect advanced fibrosis based on lab tests and clinical data, then “liver biopsy should be considered,” he said.

The investigators described among the limitations of their study its retrospective, single-center design, with patients who were mostly white and from one geographic region.

Dr. Singh and colleagues reported no conflicts of interest or outside funding for their study.

jensmith@mdedge.com

SOURCE: Singh A et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2020 Mar 11. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001339.

Noninvasive fibrosis scores, which are widely used to predict advanced fibrosis in people with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), do not do a good job of picking up advanced fibrosis in patients with underlying diabetes, according to a new study.

Advanced fibrosis is associated with an increased risk of cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease, and liver failure. Underlying diabetes is a risk factor for both advanced fibrosis and death in patients with NAFLD.

While liver biopsy remains the gold standard for detecting advanced fibrosis, high costs and risks limit its use. Noninvasive scores such as the AST/ALT ratio; AST to platelet ratio index (APRI); fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) index; and NAFLD fibrosis score (NFS) have gained popularity in recent years, as they offer the compelling advantage of using easily and cheaply attained clinical and laboratory measures to assess likelihood of disease.

But their accuracy has come into question, particularly for people with diabetes.

In research published in the Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, Amandeep Singh, MD, and colleagues at the Cleveland Clinic looked at their center’s records for 1,157 patients with type 2 diabetes (65% women, 88% white, 85% with obesity) who had undergone a liver biopsy for suspected advanced fibrosis between 2000 and 2015. Biopsy results revealed that a third of the cohort (32%) was positive for advanced fibrosis.

The investigators then pulled patients’ laboratory results for AST, ALT, cholesterol, triglycerides, fasting glucose, hemoglobin A1c, bilirubin, albumin, platelet count, alkaline phosphatase, albumin, and lipid levels, all collected within a year of biopsy. After plugging these into the algorithms of four different scoring systems for advanced fibrosis, they compared results with results from the biopsies.

The scores of AST/ALT greater than 1.4, APRI of at least 1.5, NFS greater than 0.676, and FIB-4 index greater than 2.67 had high specificities of 84%, 97%, 70%, and 93%, respectively, but sensitivities of only 27%, 17%, 64%, and 44%. Even when the cutoff measures were tightened, the scoring systems still missed a lot of disease. This suggests, Dr. Singh and colleagues wrote, that “the presence of diabetes could decrease the predictive value of these scores to detect advanced disease in NAFLD patients.” Reliable noninvasive biomarkers are “urgently needed” for this patient population.

In an interview, Dr. Singh advised that clinicians continue to use current noninvasive scores in patients with diabetes – preferably the NFS – “until we have a better scoring system.” If clinicians suspect advanced fibrosis based on lab tests and clinical data, then “liver biopsy should be considered,” he said.

The investigators described among the limitations of their study its retrospective, single-center design, with patients who were mostly white and from one geographic region.

Dr. Singh and colleagues reported no conflicts of interest or outside funding for their study.

jensmith@mdedge.com

SOURCE: Singh A et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2020 Mar 11. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001339.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY

AASLD: Liver transplants should proceed despite COVID-19

In liver transplant recipients or patients with autoimmune hepatitis on immunosuppressive therapy, acute cellular rejection or disease flare should not be presumed in the face of active coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), according to the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD).

Signs that would normally be interpreted as flare or rejection need to be considered more cautiously now because the virus attacks the liver, and elevated aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, and slightly elevated bilirubin are common, ranging from a prevalence of 14% to 53% in COVID-19 patients. Acute liver injury is possible, especially in more severe cases, the group said.

The advice comes from a recently released document from AASLD, called “Clinical Insights for Hepatology and Liver Transplant Providers During the Covid-19 Pandemic,” to help hepatologists and liver transplant providers negotiate the pandemic, according to the latest data. It’s a far-ranging work that contains a lot of now familiar steps for providers to take to protect themselves and patients from the virus, but also much advice specific to liver medicine.

For instance, the group said it’s important to keep in mind that experimental treatments for the infection, including statins, remdesivir, and tocilizumab, can be hepatotoxic. Abnormal liver biochemistries are not a contraindication, but liver biochemistries need to be followed regularly in COVID-19 patients, especially those treated with remdesivir or tocilizumab, regardless of baseline values.

Also, lopinavir/ritonavir is a potent inhibitor of cytochrome P450 enzymes involved with calcineurin inhibitor metabolism, so if it’s used, AASLD said to reduce tacrolimus dosages to 1/20–1/50 of baseline.

The group cautioned against anticipatory adjustments to immunosuppressive drugs or dosages in patients without COVID-19, but if immunosuppressed liver disease patients do get the infection, prednisone doses should be reduced but kept above 10 mg/day to avoid adrenal insufficiency. In the setting of lymphopenia, fever, or worsening COVID-19 pneumonia, it advised reduction of azathioprine and mycophenolate dosages and reduction of, but not stopping, calcineurin inhibitors.

Liver transplants should not be postponed. However, to minimize exposure to the hospital environment, AASLD advised to “consider evaluating only patients with HCC [hepatocellular carcinoma] or those patients with severe disease and high MELD [model for end-stage liver disease] scores who are likely to benefit from immediate liver transplant.”

“An argument that has been put forward to justify deferring some transplants is concern about immunosuppressing patients during the COVID-19 pandemic,” the group said, but “data suggest the innate immune response may be the main driver for pulmonary injury due to COVID-19 and [that] immunosuppression may be protective. ... Posttransplant immunosuppression was not a risk factor for mortality associated with” the severe acute respiratory syndrome pandemic in 2003-2004 or the ongoing Middle East respiratory syndrome pandemic, both also caused by coronaviruses.

AASLD advised against reducing immunosuppression or stopping mycophenolate for asymptomatic patients after transplant, but COVID-19 prevention measures should be emphasized, including frequent hand washing and staying away from large crowds.

People who test positive for COVID-19 are ineligible for organ donation. Bronchoalveolar lavage is the most sensitive test (93%), followed by nasal swabs (63%) and pharyngeal swabs (32%).

In general, the group said elective procedures should be postponed, but urgent ones, such as biliary surgery and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts for bleeding varices, in addition to liver transplants, should not.

Also, HCC patients “should not wait until the pandemic abates to undergo [surveillance] imaging because the prospective duration of the pandemic is unknown. ... An arbitrary delay of 2 months is reasonable” for imaging based on patient and facility circumstances, but otherwise, “proceed with HCC treatments rather than delaying them due to the pandemic,” the group said.

As for who to bring into the office for an initial consult, “consider seeing in person only new adult and pediatric patients with urgent issues and clinically significant liver disease (e.g., jaundice, elevated ALT or AST above 500 U/L, recent onset of hepatic decompensation),” AASLD said.

In liver transplant recipients or patients with autoimmune hepatitis on immunosuppressive therapy, acute cellular rejection or disease flare should not be presumed in the face of active coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), according to the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD).

Signs that would normally be interpreted as flare or rejection need to be considered more cautiously now because the virus attacks the liver, and elevated aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, and slightly elevated bilirubin are common, ranging from a prevalence of 14% to 53% in COVID-19 patients. Acute liver injury is possible, especially in more severe cases, the group said.

The advice comes from a recently released document from AASLD, called “Clinical Insights for Hepatology and Liver Transplant Providers During the Covid-19 Pandemic,” to help hepatologists and liver transplant providers negotiate the pandemic, according to the latest data. It’s a far-ranging work that contains a lot of now familiar steps for providers to take to protect themselves and patients from the virus, but also much advice specific to liver medicine.

For instance, the group said it’s important to keep in mind that experimental treatments for the infection, including statins, remdesivir, and tocilizumab, can be hepatotoxic. Abnormal liver biochemistries are not a contraindication, but liver biochemistries need to be followed regularly in COVID-19 patients, especially those treated with remdesivir or tocilizumab, regardless of baseline values.

Also, lopinavir/ritonavir is a potent inhibitor of cytochrome P450 enzymes involved with calcineurin inhibitor metabolism, so if it’s used, AASLD said to reduce tacrolimus dosages to 1/20–1/50 of baseline.

The group cautioned against anticipatory adjustments to immunosuppressive drugs or dosages in patients without COVID-19, but if immunosuppressed liver disease patients do get the infection, prednisone doses should be reduced but kept above 10 mg/day to avoid adrenal insufficiency. In the setting of lymphopenia, fever, or worsening COVID-19 pneumonia, it advised reduction of azathioprine and mycophenolate dosages and reduction of, but not stopping, calcineurin inhibitors.

Liver transplants should not be postponed. However, to minimize exposure to the hospital environment, AASLD advised to “consider evaluating only patients with HCC [hepatocellular carcinoma] or those patients with severe disease and high MELD [model for end-stage liver disease] scores who are likely to benefit from immediate liver transplant.”

“An argument that has been put forward to justify deferring some transplants is concern about immunosuppressing patients during the COVID-19 pandemic,” the group said, but “data suggest the innate immune response may be the main driver for pulmonary injury due to COVID-19 and [that] immunosuppression may be protective. ... Posttransplant immunosuppression was not a risk factor for mortality associated with” the severe acute respiratory syndrome pandemic in 2003-2004 or the ongoing Middle East respiratory syndrome pandemic, both also caused by coronaviruses.

AASLD advised against reducing immunosuppression or stopping mycophenolate for asymptomatic patients after transplant, but COVID-19 prevention measures should be emphasized, including frequent hand washing and staying away from large crowds.

People who test positive for COVID-19 are ineligible for organ donation. Bronchoalveolar lavage is the most sensitive test (93%), followed by nasal swabs (63%) and pharyngeal swabs (32%).

In general, the group said elective procedures should be postponed, but urgent ones, such as biliary surgery and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts for bleeding varices, in addition to liver transplants, should not.

Also, HCC patients “should not wait until the pandemic abates to undergo [surveillance] imaging because the prospective duration of the pandemic is unknown. ... An arbitrary delay of 2 months is reasonable” for imaging based on patient and facility circumstances, but otherwise, “proceed with HCC treatments rather than delaying them due to the pandemic,” the group said.

As for who to bring into the office for an initial consult, “consider seeing in person only new adult and pediatric patients with urgent issues and clinically significant liver disease (e.g., jaundice, elevated ALT or AST above 500 U/L, recent onset of hepatic decompensation),” AASLD said.

In liver transplant recipients or patients with autoimmune hepatitis on immunosuppressive therapy, acute cellular rejection or disease flare should not be presumed in the face of active coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), according to the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD).

Signs that would normally be interpreted as flare or rejection need to be considered more cautiously now because the virus attacks the liver, and elevated aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, and slightly elevated bilirubin are common, ranging from a prevalence of 14% to 53% in COVID-19 patients. Acute liver injury is possible, especially in more severe cases, the group said.

The advice comes from a recently released document from AASLD, called “Clinical Insights for Hepatology and Liver Transplant Providers During the Covid-19 Pandemic,” to help hepatologists and liver transplant providers negotiate the pandemic, according to the latest data. It’s a far-ranging work that contains a lot of now familiar steps for providers to take to protect themselves and patients from the virus, but also much advice specific to liver medicine.

For instance, the group said it’s important to keep in mind that experimental treatments for the infection, including statins, remdesivir, and tocilizumab, can be hepatotoxic. Abnormal liver biochemistries are not a contraindication, but liver biochemistries need to be followed regularly in COVID-19 patients, especially those treated with remdesivir or tocilizumab, regardless of baseline values.

Also, lopinavir/ritonavir is a potent inhibitor of cytochrome P450 enzymes involved with calcineurin inhibitor metabolism, so if it’s used, AASLD said to reduce tacrolimus dosages to 1/20–1/50 of baseline.

The group cautioned against anticipatory adjustments to immunosuppressive drugs or dosages in patients without COVID-19, but if immunosuppressed liver disease patients do get the infection, prednisone doses should be reduced but kept above 10 mg/day to avoid adrenal insufficiency. In the setting of lymphopenia, fever, or worsening COVID-19 pneumonia, it advised reduction of azathioprine and mycophenolate dosages and reduction of, but not stopping, calcineurin inhibitors.

Liver transplants should not be postponed. However, to minimize exposure to the hospital environment, AASLD advised to “consider evaluating only patients with HCC [hepatocellular carcinoma] or those patients with severe disease and high MELD [model for end-stage liver disease] scores who are likely to benefit from immediate liver transplant.”

“An argument that has been put forward to justify deferring some transplants is concern about immunosuppressing patients during the COVID-19 pandemic,” the group said, but “data suggest the innate immune response may be the main driver for pulmonary injury due to COVID-19 and [that] immunosuppression may be protective. ... Posttransplant immunosuppression was not a risk factor for mortality associated with” the severe acute respiratory syndrome pandemic in 2003-2004 or the ongoing Middle East respiratory syndrome pandemic, both also caused by coronaviruses.

AASLD advised against reducing immunosuppression or stopping mycophenolate for asymptomatic patients after transplant, but COVID-19 prevention measures should be emphasized, including frequent hand washing and staying away from large crowds.

People who test positive for COVID-19 are ineligible for organ donation. Bronchoalveolar lavage is the most sensitive test (93%), followed by nasal swabs (63%) and pharyngeal swabs (32%).

In general, the group said elective procedures should be postponed, but urgent ones, such as biliary surgery and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts for bleeding varices, in addition to liver transplants, should not.

Also, HCC patients “should not wait until the pandemic abates to undergo [surveillance] imaging because the prospective duration of the pandemic is unknown. ... An arbitrary delay of 2 months is reasonable” for imaging based on patient and facility circumstances, but otherwise, “proceed with HCC treatments rather than delaying them due to the pandemic,” the group said.

As for who to bring into the office for an initial consult, “consider seeing in person only new adult and pediatric patients with urgent issues and clinically significant liver disease (e.g., jaundice, elevated ALT or AST above 500 U/L, recent onset of hepatic decompensation),” AASLD said.

COVID-19 experiences from the ob.gyn. front line

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to spread across the United States, several members of the Ob.Gyn. News Editorial Advisory Board shared their experiences.

Catherine Cansino, MD, MPH, who is an associate clinical professor in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of California, Davis, discussed the changes COVID-19 has had on local and regional practice in Sacramento and northern California.