User login

Enhanced team-based CVD care found to benefit diabetes patients

PHOENIX, ARIZ. – Diabetes patients in China who were enrolled in a team-based care intervention with clinical decision support systems significantly reduced their hemoglobin A1c, systolic blood pressure, and LDL cholesterol over 18 months, compared with those who received team-based care alone.

The finding comes from the Diabetes Complication Control in Community Clinics (D4C), a cluster randomized trial conducted in 38 community health centers in Xiamen, China.

“Diabetes has become a major public health challenge worldwide, especially in low- and middle-income countries where populations are large and growing and health care resources are limited,” Jiang He, MD, PhD, said at the Epidemiology and Prevention/Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health meeting.

According to Dr. He, chair and professor of epidemiology at Tulane School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine, New Orleans, the prevalence of diabetes has increased rapidly in recent decades in China, from 2.5% in 1994 to 11.6% in 2010. “It was estimated that 114 million Chinese adults had diabetes in 2010,” he said. “Hyperglycemia, high blood pressure, and elevated LDL cholesterol are major risk factors for cardiovascular disease and premature death. The majority of patients with diabetes have multiple uncontrolled CVD risk factors due to suboptimal care. Diabetes and its complications further strain an already overburdened and overwhelmed health care system, especially tertiary care facilities, in China. On the other hand, community health centers are underutilized.”

In D4C, Dr. He and colleagues set out to evaluate changes in CVD risk factors among patients with diabetes after implementing a team-based care model at community health centers in Xiamen, China. They compared the effectiveness of team-based care with clinical decision support systems versus team-based care alone on CVD risk factor control among patients with diabetes at these community health centers.

The study population consisted of 10,942 patients aged 50 years and older with uncontrolled diabetes and at least one of the following three additional CVD risk factors: systolic BP of at least 140 mm Hg and/or diastolic BP of at least 90 mm Hg; LDL cholesterol of at least 100 mg/dL, or clinical atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD). At the intervention clinics, team-based care was delivered by a team of primary care physicians, nurses, and diabetes specialists. The researchers trained the primary care physicians and nurses, and a clinical decision support system was integrated with guideline-based treatment algorithms for controlling glycemia, blood pressure, and lipids.

At the enhanced care control clinics, team-based care was delivered by a team of primary care physicians, nurses, and diabetes specialists. The city health commission trained the primary care physicians and nurses. The intervention lasted for 18 months in both groups.

Dr. He, the D4C study chair, reported findings from 10,942 patients: 5,394 in the intervention group and 5,548 in the enhanced care group. The mean baseline age was similar between the intervention group and the enhanced care group (a mean of 63 years), as was body mass index (a mean of 24.9 kg/m2), hemoglobin A1c (a mean of 8.8 vs. 8.7%, respectively), LDL cholesterol (121.2 vs. 121.1 mg/dL), systolic blood pressure (136.6 vs. 136.9 mm Hg), and diastolic blood pressure (79.7 vs. 79.8 mm Hg).

The researchers found patients in both groups experienced significant reductions in HbA1c, LDL cholesterol, and BP over the 18-month follow-up, but those in the intervention group fared better in all measures. Specifically, the mean change in HbA1c from baseline was –.85% in the intervention group, compared with –.66% in the enhanced care group, while the change in LDL was –19 mg/dL, compared with –12.8 mg/dL, respectively; the change in systolic blood pressure was –8.9 mm Hg vs. –7.7 mm Hg, and the change in 10-year ASCVD risk was .57% vs. .28% (P < .0001 for all associations).

The researchers also observed that the proportions of controlled HbA1c, LDL, and blood pressure at 18 months were higher in the intervention group, compared with the enhanced care group. Specifically, 38% of patients in the intervention group achieved glycemic control, compared with 35% of those in the enhanced care group (P =. 0006), while 48% vs. 39%, respectively, achieved control of LDL cholesterol (P < .0001), and 78% vs. 75% achieved control of blood pressure (P = .0009). In addition, 15% vs. 12% achieved control of all three risk factors at 18 months (P < .0001).

“Implementing team-based care with a clinical decision support system is an effective and sustainable strategy for diabetes control in primary care settings,” Dr. He said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the American Heart Association. “This implementation strategy could be scaled up within primary care settings in China and other low- to middle-income countries to improve CVD risk factor control in patients with diabetes.”

In an interview, session moderator Joshua J. Joseph, MD, of Ohio State University, Columbus, pointed out that since only 12%-15% of study participants achieved control of all three CVD risk factors, “that leaves a great opportunity for [figuring out] how to we get the other 88% or 85% of patients to target levels. That’s going to be important as we think about cardiovascular disease prevention in type 2 diabetes. The more we can use team-based care along with clinical decision support tools, the more we will continue to improve the lives of patients.”

The study was supported by the Xiamen City Health Commission. Dr. He reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: He J et al. EPI/LIFESTYLE 2020, session 7A, abstract 17.

PHOENIX, ARIZ. – Diabetes patients in China who were enrolled in a team-based care intervention with clinical decision support systems significantly reduced their hemoglobin A1c, systolic blood pressure, and LDL cholesterol over 18 months, compared with those who received team-based care alone.

The finding comes from the Diabetes Complication Control in Community Clinics (D4C), a cluster randomized trial conducted in 38 community health centers in Xiamen, China.

“Diabetes has become a major public health challenge worldwide, especially in low- and middle-income countries where populations are large and growing and health care resources are limited,” Jiang He, MD, PhD, said at the Epidemiology and Prevention/Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health meeting.

According to Dr. He, chair and professor of epidemiology at Tulane School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine, New Orleans, the prevalence of diabetes has increased rapidly in recent decades in China, from 2.5% in 1994 to 11.6% in 2010. “It was estimated that 114 million Chinese adults had diabetes in 2010,” he said. “Hyperglycemia, high blood pressure, and elevated LDL cholesterol are major risk factors for cardiovascular disease and premature death. The majority of patients with diabetes have multiple uncontrolled CVD risk factors due to suboptimal care. Diabetes and its complications further strain an already overburdened and overwhelmed health care system, especially tertiary care facilities, in China. On the other hand, community health centers are underutilized.”

In D4C, Dr. He and colleagues set out to evaluate changes in CVD risk factors among patients with diabetes after implementing a team-based care model at community health centers in Xiamen, China. They compared the effectiveness of team-based care with clinical decision support systems versus team-based care alone on CVD risk factor control among patients with diabetes at these community health centers.

The study population consisted of 10,942 patients aged 50 years and older with uncontrolled diabetes and at least one of the following three additional CVD risk factors: systolic BP of at least 140 mm Hg and/or diastolic BP of at least 90 mm Hg; LDL cholesterol of at least 100 mg/dL, or clinical atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD). At the intervention clinics, team-based care was delivered by a team of primary care physicians, nurses, and diabetes specialists. The researchers trained the primary care physicians and nurses, and a clinical decision support system was integrated with guideline-based treatment algorithms for controlling glycemia, blood pressure, and lipids.

At the enhanced care control clinics, team-based care was delivered by a team of primary care physicians, nurses, and diabetes specialists. The city health commission trained the primary care physicians and nurses. The intervention lasted for 18 months in both groups.

Dr. He, the D4C study chair, reported findings from 10,942 patients: 5,394 in the intervention group and 5,548 in the enhanced care group. The mean baseline age was similar between the intervention group and the enhanced care group (a mean of 63 years), as was body mass index (a mean of 24.9 kg/m2), hemoglobin A1c (a mean of 8.8 vs. 8.7%, respectively), LDL cholesterol (121.2 vs. 121.1 mg/dL), systolic blood pressure (136.6 vs. 136.9 mm Hg), and diastolic blood pressure (79.7 vs. 79.8 mm Hg).

The researchers found patients in both groups experienced significant reductions in HbA1c, LDL cholesterol, and BP over the 18-month follow-up, but those in the intervention group fared better in all measures. Specifically, the mean change in HbA1c from baseline was –.85% in the intervention group, compared with –.66% in the enhanced care group, while the change in LDL was –19 mg/dL, compared with –12.8 mg/dL, respectively; the change in systolic blood pressure was –8.9 mm Hg vs. –7.7 mm Hg, and the change in 10-year ASCVD risk was .57% vs. .28% (P < .0001 for all associations).

The researchers also observed that the proportions of controlled HbA1c, LDL, and blood pressure at 18 months were higher in the intervention group, compared with the enhanced care group. Specifically, 38% of patients in the intervention group achieved glycemic control, compared with 35% of those in the enhanced care group (P =. 0006), while 48% vs. 39%, respectively, achieved control of LDL cholesterol (P < .0001), and 78% vs. 75% achieved control of blood pressure (P = .0009). In addition, 15% vs. 12% achieved control of all three risk factors at 18 months (P < .0001).

“Implementing team-based care with a clinical decision support system is an effective and sustainable strategy for diabetes control in primary care settings,” Dr. He said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the American Heart Association. “This implementation strategy could be scaled up within primary care settings in China and other low- to middle-income countries to improve CVD risk factor control in patients with diabetes.”

In an interview, session moderator Joshua J. Joseph, MD, of Ohio State University, Columbus, pointed out that since only 12%-15% of study participants achieved control of all three CVD risk factors, “that leaves a great opportunity for [figuring out] how to we get the other 88% or 85% of patients to target levels. That’s going to be important as we think about cardiovascular disease prevention in type 2 diabetes. The more we can use team-based care along with clinical decision support tools, the more we will continue to improve the lives of patients.”

The study was supported by the Xiamen City Health Commission. Dr. He reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: He J et al. EPI/LIFESTYLE 2020, session 7A, abstract 17.

PHOENIX, ARIZ. – Diabetes patients in China who were enrolled in a team-based care intervention with clinical decision support systems significantly reduced their hemoglobin A1c, systolic blood pressure, and LDL cholesterol over 18 months, compared with those who received team-based care alone.

The finding comes from the Diabetes Complication Control in Community Clinics (D4C), a cluster randomized trial conducted in 38 community health centers in Xiamen, China.

“Diabetes has become a major public health challenge worldwide, especially in low- and middle-income countries where populations are large and growing and health care resources are limited,” Jiang He, MD, PhD, said at the Epidemiology and Prevention/Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health meeting.

According to Dr. He, chair and professor of epidemiology at Tulane School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine, New Orleans, the prevalence of diabetes has increased rapidly in recent decades in China, from 2.5% in 1994 to 11.6% in 2010. “It was estimated that 114 million Chinese adults had diabetes in 2010,” he said. “Hyperglycemia, high blood pressure, and elevated LDL cholesterol are major risk factors for cardiovascular disease and premature death. The majority of patients with diabetes have multiple uncontrolled CVD risk factors due to suboptimal care. Diabetes and its complications further strain an already overburdened and overwhelmed health care system, especially tertiary care facilities, in China. On the other hand, community health centers are underutilized.”

In D4C, Dr. He and colleagues set out to evaluate changes in CVD risk factors among patients with diabetes after implementing a team-based care model at community health centers in Xiamen, China. They compared the effectiveness of team-based care with clinical decision support systems versus team-based care alone on CVD risk factor control among patients with diabetes at these community health centers.

The study population consisted of 10,942 patients aged 50 years and older with uncontrolled diabetes and at least one of the following three additional CVD risk factors: systolic BP of at least 140 mm Hg and/or diastolic BP of at least 90 mm Hg; LDL cholesterol of at least 100 mg/dL, or clinical atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD). At the intervention clinics, team-based care was delivered by a team of primary care physicians, nurses, and diabetes specialists. The researchers trained the primary care physicians and nurses, and a clinical decision support system was integrated with guideline-based treatment algorithms for controlling glycemia, blood pressure, and lipids.

At the enhanced care control clinics, team-based care was delivered by a team of primary care physicians, nurses, and diabetes specialists. The city health commission trained the primary care physicians and nurses. The intervention lasted for 18 months in both groups.

Dr. He, the D4C study chair, reported findings from 10,942 patients: 5,394 in the intervention group and 5,548 in the enhanced care group. The mean baseline age was similar between the intervention group and the enhanced care group (a mean of 63 years), as was body mass index (a mean of 24.9 kg/m2), hemoglobin A1c (a mean of 8.8 vs. 8.7%, respectively), LDL cholesterol (121.2 vs. 121.1 mg/dL), systolic blood pressure (136.6 vs. 136.9 mm Hg), and diastolic blood pressure (79.7 vs. 79.8 mm Hg).

The researchers found patients in both groups experienced significant reductions in HbA1c, LDL cholesterol, and BP over the 18-month follow-up, but those in the intervention group fared better in all measures. Specifically, the mean change in HbA1c from baseline was –.85% in the intervention group, compared with –.66% in the enhanced care group, while the change in LDL was –19 mg/dL, compared with –12.8 mg/dL, respectively; the change in systolic blood pressure was –8.9 mm Hg vs. –7.7 mm Hg, and the change in 10-year ASCVD risk was .57% vs. .28% (P < .0001 for all associations).

The researchers also observed that the proportions of controlled HbA1c, LDL, and blood pressure at 18 months were higher in the intervention group, compared with the enhanced care group. Specifically, 38% of patients in the intervention group achieved glycemic control, compared with 35% of those in the enhanced care group (P =. 0006), while 48% vs. 39%, respectively, achieved control of LDL cholesterol (P < .0001), and 78% vs. 75% achieved control of blood pressure (P = .0009). In addition, 15% vs. 12% achieved control of all three risk factors at 18 months (P < .0001).

“Implementing team-based care with a clinical decision support system is an effective and sustainable strategy for diabetes control in primary care settings,” Dr. He said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the American Heart Association. “This implementation strategy could be scaled up within primary care settings in China and other low- to middle-income countries to improve CVD risk factor control in patients with diabetes.”

In an interview, session moderator Joshua J. Joseph, MD, of Ohio State University, Columbus, pointed out that since only 12%-15% of study participants achieved control of all three CVD risk factors, “that leaves a great opportunity for [figuring out] how to we get the other 88% or 85% of patients to target levels. That’s going to be important as we think about cardiovascular disease prevention in type 2 diabetes. The more we can use team-based care along with clinical decision support tools, the more we will continue to improve the lives of patients.”

The study was supported by the Xiamen City Health Commission. Dr. He reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: He J et al. EPI/LIFESTYLE 2020, session 7A, abstract 17.

REPORTING FROM EPI/LIFESTYLE 2020

Comorbidities more common in hospitalized COVID-19 patients

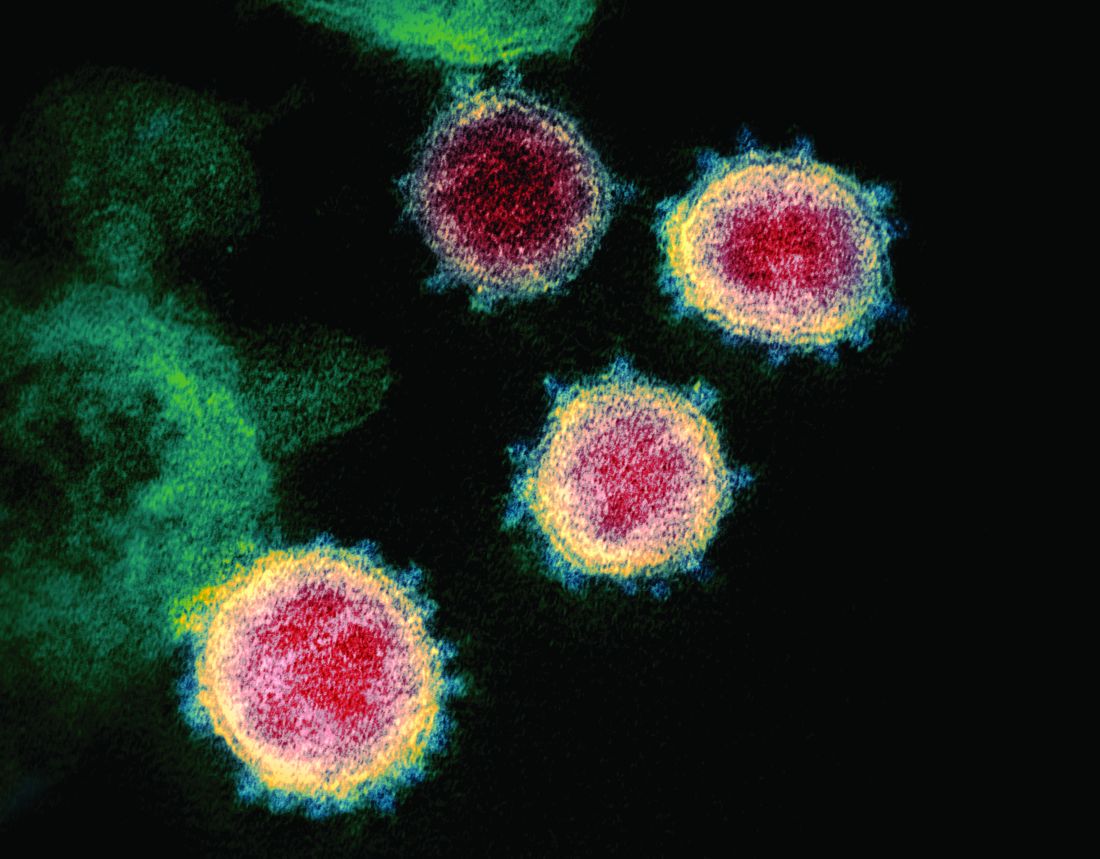

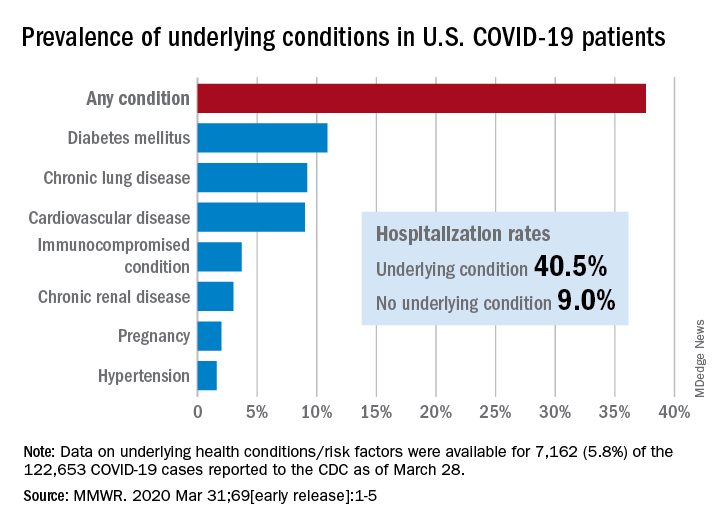

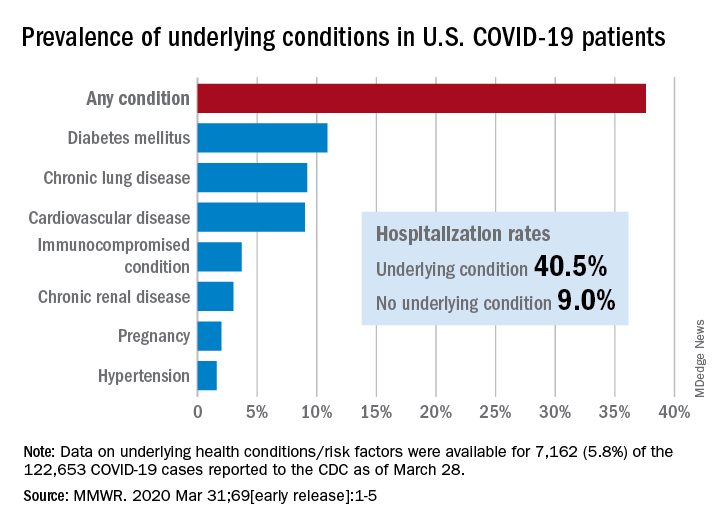

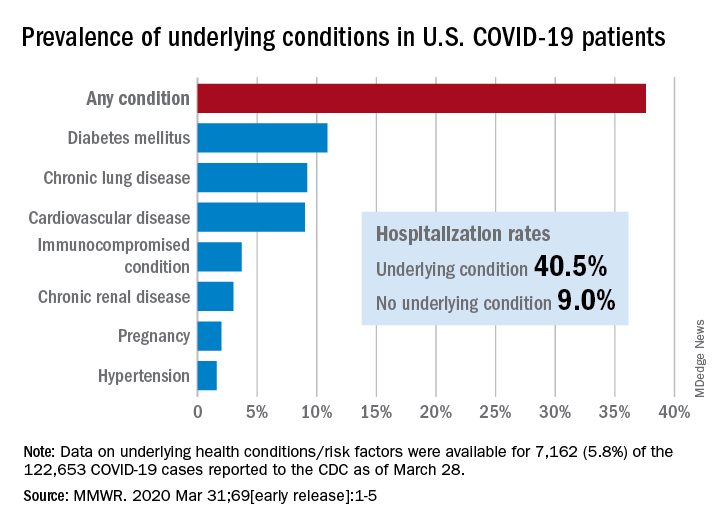

Greater prevalence of underlying health conditions such as diabetes and chronic lung disease was seen among nearly 7,200 Americans hospitalized with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Of the 122,653 laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 cases reported to the CDC as of March 28, the COVID-19 Response Team had access to data on the presence or absence of underlying health conditions and other recognized risk factors for severe outcomes from respiratory infections for 7,162 (5.8%) patients.

“Among these patients, higher percentages of patients with underlying conditions were admitted to the hospital and to an ICU than patients without reported underlying conditions. These results are consistent with findings from China and Italy,” Katherine Fleming-Dutra, MD, and associates said in the MMWR.

Individuals with underlying health conditions/risk factors made up 37.6% of all COVID-19 patients in the study but represented a majority of ICU (78%) and non-ICU (71%) hospital admissions. In contrast, 73% of COVID-19 patients who were not hospitalized had no underlying conditions, Dr. Fleming-Dutra and the CDC COVID-19 Response Team reported.

With a prevalence of 10.9%, diabetes mellitus was the most common condition reported among all COVID-19 patients, followed by chronic lung disease (9.2%) and cardiovascular disease (9.0%), the investigators said.

Another look at the data shows that 40.5% of those with underlying conditions were hospitalized, compared with 9.0% of the 4,470 COVID-19 patients without any risk factors.

“Strategies to protect all persons and especially those with underlying health conditions, including social distancing and handwashing, should be implemented by all communities and all persons to help slow the spread of COVID-19,” the response team wrote.

SOURCE: Fleming-Dutra K et al. MMWR. 2020 Mar 31;69 (early release):1-5.

Greater prevalence of underlying health conditions such as diabetes and chronic lung disease was seen among nearly 7,200 Americans hospitalized with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Of the 122,653 laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 cases reported to the CDC as of March 28, the COVID-19 Response Team had access to data on the presence or absence of underlying health conditions and other recognized risk factors for severe outcomes from respiratory infections for 7,162 (5.8%) patients.

“Among these patients, higher percentages of patients with underlying conditions were admitted to the hospital and to an ICU than patients without reported underlying conditions. These results are consistent with findings from China and Italy,” Katherine Fleming-Dutra, MD, and associates said in the MMWR.

Individuals with underlying health conditions/risk factors made up 37.6% of all COVID-19 patients in the study but represented a majority of ICU (78%) and non-ICU (71%) hospital admissions. In contrast, 73% of COVID-19 patients who were not hospitalized had no underlying conditions, Dr. Fleming-Dutra and the CDC COVID-19 Response Team reported.

With a prevalence of 10.9%, diabetes mellitus was the most common condition reported among all COVID-19 patients, followed by chronic lung disease (9.2%) and cardiovascular disease (9.0%), the investigators said.

Another look at the data shows that 40.5% of those with underlying conditions were hospitalized, compared with 9.0% of the 4,470 COVID-19 patients without any risk factors.

“Strategies to protect all persons and especially those with underlying health conditions, including social distancing and handwashing, should be implemented by all communities and all persons to help slow the spread of COVID-19,” the response team wrote.

SOURCE: Fleming-Dutra K et al. MMWR. 2020 Mar 31;69 (early release):1-5.

Greater prevalence of underlying health conditions such as diabetes and chronic lung disease was seen among nearly 7,200 Americans hospitalized with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Of the 122,653 laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 cases reported to the CDC as of March 28, the COVID-19 Response Team had access to data on the presence or absence of underlying health conditions and other recognized risk factors for severe outcomes from respiratory infections for 7,162 (5.8%) patients.

“Among these patients, higher percentages of patients with underlying conditions were admitted to the hospital and to an ICU than patients without reported underlying conditions. These results are consistent with findings from China and Italy,” Katherine Fleming-Dutra, MD, and associates said in the MMWR.

Individuals with underlying health conditions/risk factors made up 37.6% of all COVID-19 patients in the study but represented a majority of ICU (78%) and non-ICU (71%) hospital admissions. In contrast, 73% of COVID-19 patients who were not hospitalized had no underlying conditions, Dr. Fleming-Dutra and the CDC COVID-19 Response Team reported.

With a prevalence of 10.9%, diabetes mellitus was the most common condition reported among all COVID-19 patients, followed by chronic lung disease (9.2%) and cardiovascular disease (9.0%), the investigators said.

Another look at the data shows that 40.5% of those with underlying conditions were hospitalized, compared with 9.0% of the 4,470 COVID-19 patients without any risk factors.

“Strategies to protect all persons and especially those with underlying health conditions, including social distancing and handwashing, should be implemented by all communities and all persons to help slow the spread of COVID-19,” the response team wrote.

SOURCE: Fleming-Dutra K et al. MMWR. 2020 Mar 31;69 (early release):1-5.

FROM MMWR

SARS serum neutralizing antibodies may inform the treatment of COVID-19

The immune responses of specific antibodies were maintained in more than 90% of recovered SARS-CoV patients for 2 years, raising the likelihood that the similarly behaving SARS-CoV-2 might provoke the same response, according to an online communication published in the Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection.

The authors cited a cohort study of convalescent SARS-CoV patients (56 cases, from the Beijing hospital of the Armed Forces Police, China) that showed that specific IgG antibodies and neutralizing antibodies were highly correlated, peaking at month 4 after the onset of disease and decreasing gradually thereafter.

This and other studies suggest that the immune responses of specific antibodies were maintained in more than 90% of recovered SARS-CoV patients for 2 years, according to the authors.

However, of particular concern is the fact that only 11.8% of patients acquire specific SARS-CoV Abs in the early period after recovery at day 7, not reaching 100% until day 90, which highlights the importance of the detection of antibody titers for convalescent COVID-19 patients, according to the authors. “Otherwise, these patients with low titers of antibodies may not be efficient for the clearance of SARS-CoV-2.”

The authors also cited a recent study that showed how neutralizing antibody from a convalescent SARS patient could block the SARS-CoV-2 from entering into target cells in vitro, and suggested that previous experimental SARS-CoV vaccines and neutralizing antibodies could provide novel preventive and therapeutic options for COVID-19.

“These experiences from SARS-CoV are expected to have some implications for the treatment, management and surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 patients,” the authors concluded.

SOURCE: Lin Q et al. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020 Mar 25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmii.2020.03.015.

The immune responses of specific antibodies were maintained in more than 90% of recovered SARS-CoV patients for 2 years, raising the likelihood that the similarly behaving SARS-CoV-2 might provoke the same response, according to an online communication published in the Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection.

The authors cited a cohort study of convalescent SARS-CoV patients (56 cases, from the Beijing hospital of the Armed Forces Police, China) that showed that specific IgG antibodies and neutralizing antibodies were highly correlated, peaking at month 4 after the onset of disease and decreasing gradually thereafter.

This and other studies suggest that the immune responses of specific antibodies were maintained in more than 90% of recovered SARS-CoV patients for 2 years, according to the authors.

However, of particular concern is the fact that only 11.8% of patients acquire specific SARS-CoV Abs in the early period after recovery at day 7, not reaching 100% until day 90, which highlights the importance of the detection of antibody titers for convalescent COVID-19 patients, according to the authors. “Otherwise, these patients with low titers of antibodies may not be efficient for the clearance of SARS-CoV-2.”

The authors also cited a recent study that showed how neutralizing antibody from a convalescent SARS patient could block the SARS-CoV-2 from entering into target cells in vitro, and suggested that previous experimental SARS-CoV vaccines and neutralizing antibodies could provide novel preventive and therapeutic options for COVID-19.

“These experiences from SARS-CoV are expected to have some implications for the treatment, management and surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 patients,” the authors concluded.

SOURCE: Lin Q et al. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020 Mar 25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmii.2020.03.015.

The immune responses of specific antibodies were maintained in more than 90% of recovered SARS-CoV patients for 2 years, raising the likelihood that the similarly behaving SARS-CoV-2 might provoke the same response, according to an online communication published in the Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection.

The authors cited a cohort study of convalescent SARS-CoV patients (56 cases, from the Beijing hospital of the Armed Forces Police, China) that showed that specific IgG antibodies and neutralizing antibodies were highly correlated, peaking at month 4 after the onset of disease and decreasing gradually thereafter.

This and other studies suggest that the immune responses of specific antibodies were maintained in more than 90% of recovered SARS-CoV patients for 2 years, according to the authors.

However, of particular concern is the fact that only 11.8% of patients acquire specific SARS-CoV Abs in the early period after recovery at day 7, not reaching 100% until day 90, which highlights the importance of the detection of antibody titers for convalescent COVID-19 patients, according to the authors. “Otherwise, these patients with low titers of antibodies may not be efficient for the clearance of SARS-CoV-2.”

The authors also cited a recent study that showed how neutralizing antibody from a convalescent SARS patient could block the SARS-CoV-2 from entering into target cells in vitro, and suggested that previous experimental SARS-CoV vaccines and neutralizing antibodies could provide novel preventive and therapeutic options for COVID-19.

“These experiences from SARS-CoV are expected to have some implications for the treatment, management and surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 patients,” the authors concluded.

SOURCE: Lin Q et al. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020 Mar 25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmii.2020.03.015.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF MICROBIOLOGY, IMMUNOLOGY AND INFECTION

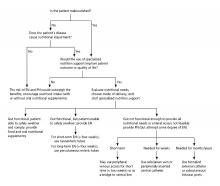

Which tube placement is best for a patient requiring enteral nutrition?

Comparative advantages of EN tubes

Case

A 68-year-old diabetic nonverbal female presents to the ED because of “seizure” 1 hour ago. On exam, her blood glucose is 200. She is unable to speak and has dysphagia because of a stroke she sustained last month. The patient’s husband adds that she hasn’t been eating and drinking sufficiently in the past couple of days. Imaging was negative for any acute intracranial bleeds or lesions. Labs showed a serum sodium level of 150 milliequivalents/L. D5W is started, and the following day, the patient has a sodium level of 154 milliequivalents/L.

Brief overview

Many hospitalized patients are unable to maintain hydration and/or nutritional status by mouth and will need enteral nutrition. Variables such as past medical history, swallowing ability, history of aspiration, prognosis, and functional capacity of each gastrointestinal segment will determine the best option for enteral nutrition for each patient. Each type of enteral tube feeding has advantages, disadvantages, and complications.

Overview of the data

Enteral nutrition should be started within 24-48 hours in a critically ill patient who is unable to maintain intake according to the American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition.1 This can be provided through a nasogastric (NG) tube, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube, PEG tube with jejunal extension (PEG-J), or a percutaneous endoscopic jejunal (PEJ) tube.1

NG tubes are often the first method deployed because of their low cost and convenience. They are also suitable for the patient who requires this type of feeding for less than 4 weeks. However, NG tubes do require some patient cooperation (to place and maintain)and are contraindicated in some patients with orofacial trauma, upper GI tumors, inadequate lower esophageal sphincter tone, and gastroparesis.2

Another option is a PEG tube, which is a good alternative for patients who are sedated; ventilated; or have neurodegenerative processes, stroke with dysphagia, or head and neck cancers. These are typically recommended when enteral nutrition will be needed for more than 4 weeks. Disadvantages of PEG tubes include tube obstruction or displacement, gastroesophageal reflux, and leakage of gastric content around the percutaneous site or into the peritoneum.

PEG-J tubes, PEJ tubes, or jejunostomy tubes are best suited for patients with GI dysmotility, patients who have unsuccessfully undergone the aforementioned methods, patients with histories of partial gastrectomies, or patients with gastric or pancreatic cancers/multiple traumas. The PEG-J tube extends into the distal duodenum; because it is longer and more narrow, it is more likely to coil and occlude the flow of nutrients during feedings.2,3 Jejunal feeding methods incorporate a continuous pump controlled infusion; if set too rapidly, this could cause dumping syndrome. A benefit of jejunal nutrition is a lower risk of aspiration, compared with other enteral tubes.4

It is best to appraise the selected method for its efficacy and patient preference. The American College of Gastroenterology recommends starting with orogastric or nasogastric feeds, and switching to postpyloric or jejunal feeds for those intolerant to or at high risk for aspiration.5 The most important aspect is early enteral nutrition in hospitalized patients unable to maintain oral nutrition.

Application of the data to the original case

This is a severely hypernatremic diabetic patient unable to swallow. On day 2 of her hospitalization, the clinical team provided the patient with an NG tube for increased free-water intake to gradually decrease her serum sodium. By hospital day 4, the patient’s sodium had normalized. Considering the patient’s long-term prognosis and dysphagia, discussions were held with the patient and husband for PEG tube placement. The patient received a PEG tube and was subsequently discharged 2 days later.

Bottom line

Enteral nutrition is a common need among hospitalized patients. Modality of enteral nutrition will depend on the patient’s past medical history, anticipated duration, and preferences.

Dr. Basnet is the hospitalist program director for Apogee Physicians Group at Eastern New Mexico Medical Center in Roswell. Ms. Tayes is a third-year medical student at Burrell College of Osteopathic Medicine in Las Cruces, N.M., with interests in surgery, internal medicine, and emergency medicine. Ms. Gallivan is a third-year medical student at Burrell College of Osteopathic Medicine, with interests in cardiothoracic surgery, general surgery, and internal medicine.

References

1. Boullata JI et al. ASPEN Safe Practices for Enteral Nutrition Therapy. J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2016;1-89.

2. Kirby DF et al. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on tube feeding for enteral nutrition. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:1282.

3. Lazarus BA et al. Aspiration associated with long-term gastric versus jejunal feeding: A critical analysis of the literature. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1990;71:46.

4. Alkhawaja S et al. Postpyloric versus gastric tube feeding for preventing pneumonia and improving nutritional outcomes in critically ill adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Aug 4;(8):CD008875.

5. McCalve SA et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Nutrition therapy in the hospitalized patient. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:315-34. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.28.

Additional reading

Bellini LM. Nutrition Support in Advanced Lung Disease. UptoDate. https://www-uptodate-com.ezproxy.ad.bcomnm.org/contents/nutritional-support-in-advanced-lung-disease?. Published April 20, 2018.

Commercial Formulas for the Feeding Tube. The Oral Cancer Foundation. https://oralcancerfoundation.org/nutrition/commercial-formulas-feeding-tube/. Published June 5, 2018.

Marik Z. Immunonutrition in critically ill patients: A systematic review and analysis of the literature. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(11). doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1213-6.

Wischmeyer PE. Enteral nutrition can be given to patients on vasopressors. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(1):122-5. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003965.

Comparative advantages of EN tubes

Comparative advantages of EN tubes

Case

A 68-year-old diabetic nonverbal female presents to the ED because of “seizure” 1 hour ago. On exam, her blood glucose is 200. She is unable to speak and has dysphagia because of a stroke she sustained last month. The patient’s husband adds that she hasn’t been eating and drinking sufficiently in the past couple of days. Imaging was negative for any acute intracranial bleeds or lesions. Labs showed a serum sodium level of 150 milliequivalents/L. D5W is started, and the following day, the patient has a sodium level of 154 milliequivalents/L.

Brief overview

Many hospitalized patients are unable to maintain hydration and/or nutritional status by mouth and will need enteral nutrition. Variables such as past medical history, swallowing ability, history of aspiration, prognosis, and functional capacity of each gastrointestinal segment will determine the best option for enteral nutrition for each patient. Each type of enteral tube feeding has advantages, disadvantages, and complications.

Overview of the data

Enteral nutrition should be started within 24-48 hours in a critically ill patient who is unable to maintain intake according to the American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition.1 This can be provided through a nasogastric (NG) tube, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube, PEG tube with jejunal extension (PEG-J), or a percutaneous endoscopic jejunal (PEJ) tube.1

NG tubes are often the first method deployed because of their low cost and convenience. They are also suitable for the patient who requires this type of feeding for less than 4 weeks. However, NG tubes do require some patient cooperation (to place and maintain)and are contraindicated in some patients with orofacial trauma, upper GI tumors, inadequate lower esophageal sphincter tone, and gastroparesis.2

Another option is a PEG tube, which is a good alternative for patients who are sedated; ventilated; or have neurodegenerative processes, stroke with dysphagia, or head and neck cancers. These are typically recommended when enteral nutrition will be needed for more than 4 weeks. Disadvantages of PEG tubes include tube obstruction or displacement, gastroesophageal reflux, and leakage of gastric content around the percutaneous site or into the peritoneum.

PEG-J tubes, PEJ tubes, or jejunostomy tubes are best suited for patients with GI dysmotility, patients who have unsuccessfully undergone the aforementioned methods, patients with histories of partial gastrectomies, or patients with gastric or pancreatic cancers/multiple traumas. The PEG-J tube extends into the distal duodenum; because it is longer and more narrow, it is more likely to coil and occlude the flow of nutrients during feedings.2,3 Jejunal feeding methods incorporate a continuous pump controlled infusion; if set too rapidly, this could cause dumping syndrome. A benefit of jejunal nutrition is a lower risk of aspiration, compared with other enteral tubes.4

It is best to appraise the selected method for its efficacy and patient preference. The American College of Gastroenterology recommends starting with orogastric or nasogastric feeds, and switching to postpyloric or jejunal feeds for those intolerant to or at high risk for aspiration.5 The most important aspect is early enteral nutrition in hospitalized patients unable to maintain oral nutrition.

Application of the data to the original case

This is a severely hypernatremic diabetic patient unable to swallow. On day 2 of her hospitalization, the clinical team provided the patient with an NG tube for increased free-water intake to gradually decrease her serum sodium. By hospital day 4, the patient’s sodium had normalized. Considering the patient’s long-term prognosis and dysphagia, discussions were held with the patient and husband for PEG tube placement. The patient received a PEG tube and was subsequently discharged 2 days later.

Bottom line

Enteral nutrition is a common need among hospitalized patients. Modality of enteral nutrition will depend on the patient’s past medical history, anticipated duration, and preferences.

Dr. Basnet is the hospitalist program director for Apogee Physicians Group at Eastern New Mexico Medical Center in Roswell. Ms. Tayes is a third-year medical student at Burrell College of Osteopathic Medicine in Las Cruces, N.M., with interests in surgery, internal medicine, and emergency medicine. Ms. Gallivan is a third-year medical student at Burrell College of Osteopathic Medicine, with interests in cardiothoracic surgery, general surgery, and internal medicine.

References

1. Boullata JI et al. ASPEN Safe Practices for Enteral Nutrition Therapy. J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2016;1-89.

2. Kirby DF et al. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on tube feeding for enteral nutrition. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:1282.

3. Lazarus BA et al. Aspiration associated with long-term gastric versus jejunal feeding: A critical analysis of the literature. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1990;71:46.

4. Alkhawaja S et al. Postpyloric versus gastric tube feeding for preventing pneumonia and improving nutritional outcomes in critically ill adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Aug 4;(8):CD008875.

5. McCalve SA et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Nutrition therapy in the hospitalized patient. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:315-34. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.28.

Additional reading

Bellini LM. Nutrition Support in Advanced Lung Disease. UptoDate. https://www-uptodate-com.ezproxy.ad.bcomnm.org/contents/nutritional-support-in-advanced-lung-disease?. Published April 20, 2018.

Commercial Formulas for the Feeding Tube. The Oral Cancer Foundation. https://oralcancerfoundation.org/nutrition/commercial-formulas-feeding-tube/. Published June 5, 2018.

Marik Z. Immunonutrition in critically ill patients: A systematic review and analysis of the literature. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(11). doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1213-6.

Wischmeyer PE. Enteral nutrition can be given to patients on vasopressors. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(1):122-5. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003965.

Case

A 68-year-old diabetic nonverbal female presents to the ED because of “seizure” 1 hour ago. On exam, her blood glucose is 200. She is unable to speak and has dysphagia because of a stroke she sustained last month. The patient’s husband adds that she hasn’t been eating and drinking sufficiently in the past couple of days. Imaging was negative for any acute intracranial bleeds or lesions. Labs showed a serum sodium level of 150 milliequivalents/L. D5W is started, and the following day, the patient has a sodium level of 154 milliequivalents/L.

Brief overview

Many hospitalized patients are unable to maintain hydration and/or nutritional status by mouth and will need enteral nutrition. Variables such as past medical history, swallowing ability, history of aspiration, prognosis, and functional capacity of each gastrointestinal segment will determine the best option for enteral nutrition for each patient. Each type of enteral tube feeding has advantages, disadvantages, and complications.

Overview of the data

Enteral nutrition should be started within 24-48 hours in a critically ill patient who is unable to maintain intake according to the American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition.1 This can be provided through a nasogastric (NG) tube, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube, PEG tube with jejunal extension (PEG-J), or a percutaneous endoscopic jejunal (PEJ) tube.1

NG tubes are often the first method deployed because of their low cost and convenience. They are also suitable for the patient who requires this type of feeding for less than 4 weeks. However, NG tubes do require some patient cooperation (to place and maintain)and are contraindicated in some patients with orofacial trauma, upper GI tumors, inadequate lower esophageal sphincter tone, and gastroparesis.2

Another option is a PEG tube, which is a good alternative for patients who are sedated; ventilated; or have neurodegenerative processes, stroke with dysphagia, or head and neck cancers. These are typically recommended when enteral nutrition will be needed for more than 4 weeks. Disadvantages of PEG tubes include tube obstruction or displacement, gastroesophageal reflux, and leakage of gastric content around the percutaneous site or into the peritoneum.

PEG-J tubes, PEJ tubes, or jejunostomy tubes are best suited for patients with GI dysmotility, patients who have unsuccessfully undergone the aforementioned methods, patients with histories of partial gastrectomies, or patients with gastric or pancreatic cancers/multiple traumas. The PEG-J tube extends into the distal duodenum; because it is longer and more narrow, it is more likely to coil and occlude the flow of nutrients during feedings.2,3 Jejunal feeding methods incorporate a continuous pump controlled infusion; if set too rapidly, this could cause dumping syndrome. A benefit of jejunal nutrition is a lower risk of aspiration, compared with other enteral tubes.4

It is best to appraise the selected method for its efficacy and patient preference. The American College of Gastroenterology recommends starting with orogastric or nasogastric feeds, and switching to postpyloric or jejunal feeds for those intolerant to or at high risk for aspiration.5 The most important aspect is early enteral nutrition in hospitalized patients unable to maintain oral nutrition.

Application of the data to the original case

This is a severely hypernatremic diabetic patient unable to swallow. On day 2 of her hospitalization, the clinical team provided the patient with an NG tube for increased free-water intake to gradually decrease her serum sodium. By hospital day 4, the patient’s sodium had normalized. Considering the patient’s long-term prognosis and dysphagia, discussions were held with the patient and husband for PEG tube placement. The patient received a PEG tube and was subsequently discharged 2 days later.

Bottom line

Enteral nutrition is a common need among hospitalized patients. Modality of enteral nutrition will depend on the patient’s past medical history, anticipated duration, and preferences.

Dr. Basnet is the hospitalist program director for Apogee Physicians Group at Eastern New Mexico Medical Center in Roswell. Ms. Tayes is a third-year medical student at Burrell College of Osteopathic Medicine in Las Cruces, N.M., with interests in surgery, internal medicine, and emergency medicine. Ms. Gallivan is a third-year medical student at Burrell College of Osteopathic Medicine, with interests in cardiothoracic surgery, general surgery, and internal medicine.

References

1. Boullata JI et al. ASPEN Safe Practices for Enteral Nutrition Therapy. J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2016;1-89.

2. Kirby DF et al. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on tube feeding for enteral nutrition. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:1282.

3. Lazarus BA et al. Aspiration associated with long-term gastric versus jejunal feeding: A critical analysis of the literature. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1990;71:46.

4. Alkhawaja S et al. Postpyloric versus gastric tube feeding for preventing pneumonia and improving nutritional outcomes in critically ill adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Aug 4;(8):CD008875.

5. McCalve SA et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Nutrition therapy in the hospitalized patient. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:315-34. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.28.

Additional reading

Bellini LM. Nutrition Support in Advanced Lung Disease. UptoDate. https://www-uptodate-com.ezproxy.ad.bcomnm.org/contents/nutritional-support-in-advanced-lung-disease?. Published April 20, 2018.

Commercial Formulas for the Feeding Tube. The Oral Cancer Foundation. https://oralcancerfoundation.org/nutrition/commercial-formulas-feeding-tube/. Published June 5, 2018.

Marik Z. Immunonutrition in critically ill patients: A systematic review and analysis of the literature. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(11). doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1213-6.

Wischmeyer PE. Enteral nutrition can be given to patients on vasopressors. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(1):122-5. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003965.

Ten Tips for a Crisis: Lessons from a Soldier

A few days ago, I had a heartfelt conversation with my good friend Dr Omayra Mansfield. Dr Mansfield has been an Emergency Department Physician for more than 12 years. She is also the wife of another physician and the mother of two young children, the recently appointed Chief Medical Officer at a hospital at AdventHealth, and one of the first graduates of the Physician Leader Development Course I teach.

“During the leadership course, you always provided examples of how physicians are like soldiers,” she began. She reminded me of my words describing how both doctors and soldiers are part of a professional body, how both have a cherished ethos and a set of directing values to guide both their path and their actions as a very special part of our society, and how of all the professions in our society, the military and medicine are the only two that deal in life and death, albeit in very different ways.

She had certainly paid attention in our seminars. Now, as she and her team faced the COVID-19 pandemic, she realized their daily challenges are expanding and they are now going to war. The leadership discussions that had sparked so much debate in our colloquia had now become real.

Dr Mansfield explained that beyond caring for patients, one of her key concerns was the physical and emotional well-being of the clinical staff at her hospital: the physicians, nurses, technicians, and clinicians under her care. Getting to her point, she asked if I might have any suggestions based on my time and experiences in combat that might be helpful to her as she “cared for her troops” as they faced the battle ahead.

Her request was a good one. Lessons from my military past immediately rushed to my mind. I started scribbling and came up with a Top Ten list of recommendations for anyone going into a tough fight. Here’s what I sent to her:

- Find a battle-buddy. On the first day of Army basic training, drill sergeants pair new recruits with one another. That’s primarily for accountability purposes throughout the weeks of training—to ensure soldiers hold each other responsible for getting to the right place, at the right time, in the right uniform—but it’s also part of a larger psychological dynamic related to building teams and mutual support within organizations. Your battle-buddy is charged with keeping you out of trouble, having your back, and being there when you need it most. In combat, battle-buddies do all those things and then some; they protect you from harm in so many other ways. Healthcare providers during this crisis will sometimes feel all alone, and they need to rely on someone else to help them when times get really tough. Having a battle-buddy—for those at the healthcare team level, of course, but also among those at the level of clinical director, hospital administrator, CMO, or even CEO—will help get you through the tough times and provide sanity when you need it the most. So my first piece of advice: Find a battle-buddy.

- Plan and prepare for things you don’t expect will happen. During a preparatory training exercise for our unit’s deployment to Iraq during the surge, when we thought the exercise was about to end, the trainers surprised us with a final crisis we had to solve. According to the scenario, Al Qaida had blown up a major bridge in our area, causing dire logistical problems for the security forces and challenges to the population as they brought their goods to market. I remember my initial reaction: “They don’t have the strength to do that. This’ll never happen,” I said to the Chief of Staff under my breath, as we started developing the required drill to counter the action and please the trainers. I quickly forgot about that lesson, until after we deployed. Two weeks into our 15-month tour in Iraq, the enemy blew the exact bridge that was part of the scenario, causing the exact problems that were predicted. Because we had prepared for the unexpected, we were able to quickly repair the bridge, reestablish the logistics flow, and satisfy the worried population. The lesson: Teams can hope for the best, but it’s always important to prepare for the worst—a lack of equipment, a key member of the team not being available to contribute, an overwhelming surge of patients—and then develop a plan to mitigate it. Take time to reflect, and ask yourself, What is the worst that can happen, what can the “enemy” do to disrupt our lives, and how do we prepare to counter it?

- Get everyone into the fight. In every organizations, it’s often true that some people take on too much and try and do it all themselves, others do only what they’re told to do, there’s the unique few who want to contribute but don’t know how they can to help, and then there’s some who even attempt to avoid contributing at all. It’s important for leaders to know who on their team fits each of these categories. It’s even more critical for leaders to be able to find ways to relieve the overworked, assign tasks to those who might not know their role, bring those who want to contribute into the fold, and cross-train teams to help relieve those who are exhausted. Leaders must look across their “battlespace” and ensure everyone is contributing. Leaders assign everyone tasks and do their best to level—and lighten—the load of the overworked.

- “Fatigue makes cowards of us all.” During any type of crisis, the body and mind will rapidly break down from lack of sleep, emotional strain, or overwhelming stress. While a 12-hour shift in a hospital is exceedingly tough even during normal operations, the COVID-19 crisis will demand dramatically more of all the members of any healthcare team. For that reason, leaders must incorporate rest cycles, team rotations, and half-days away from the hospitals even when all hands are on deck, as well as consider reducing shift times, if possible. Many who have experienced the disease in hot spots say this is really tough, but not attempting to plan for this will cause eventual breakdown and dysfunction. Take a break, do all you can to maintain a modicum of balance, and get away for a while.

- Take time to huddle. Communication and information are always key, but especially critical during any crisis. One technique that has proven valuable, beyond meetings and shift changes, is a preshift and postshift huddle. Different from the formal passing of critical information, the huddle is a brief opportunity for teams to pass informal information, look each other in the eye, and perhaps even pray together. As a two-star general, I did that every morning in combat with my small team of sergeants, captains, and privates before we left the headquarters to visit units, and it gave us all the power of knowing we had shared information, and we had a common operating picture. It gave us strength. During a crisis, all kinds of communication, formal and informal, are key.

- This ain’t peacetime. In a crisis, the enemy gets a vote. If leaders don’t find ways to counter the enemy’s action (and fast!), they’ll be behind the curve! It’s important to find the techniques and procedures that are bureaucratic (or even dumb) and overturn or eliminate them quickly. Decisions must be made with alacrity and with an understood flow, and people must be assigned responsibilities and held accountable to make things happen. In a crisis, speed in action will almost always trump perfection in understanding. Stay calm but ensure that those who might not understand this come around to the dynamics associated with the threat. A crisis isn’t the time for business as usual.

- Force adaptation—don’t wait ’til things are over to adjust. In a crisis, faults and disconnects in techniques and procedures often bubble to the surface and cause consternation. Don’t wait for a break in the action to adjust and find new ways to do things because a break in the action will usually never happen. The military has an expression: “Those who adapt the fastest on the battlefield win.” Find ways to look for and then publicize your methods of adaptation to the team, pin the rose on someone to ensure the changes are made, and then have someone make a historical record so other teams might also learn from your scar tissue. Lessons from the fight must be incorporated by the organization, or they’re not “lessons learned.”

- Talkin’ ain’t fightin’. During a crisis, it’s important to establish techniques of verbal shorthand between the members of a team, and everyone must know their responsibilities and required actions. In the military, this is called a battle drill; in medicine, you know it as a code. In these situations, leaders must find ways to pass information quickly, and the reaction should be immediate response. In a crisis, normal process must take on the dynamics of a “code.” All members of the team must understand that there are just times when things can’t be explained, but it’s also important that leaders know when to use this abbreviated format. Explain when you can, but act when you must.

- Cherish your teams. Every single team will experience things that human beings aren’t designed or meant to handle—even those in the medical profession, who likely thought they had seen it all. There will be repeated and overwhelming trauma, with the expected emotional reactions. The approach during these situations requires empathy, humility, emotional understanding, and validation. Praise your team at every opportunity, find ways to turn mistakes into learning opportunities, but most importantly be human and find ways to provide memories that your team can cherish and look back upon. Give them memories.

- Leaders don’t have the right to have a bad day. In 2004, after a 12-month deployment in Iraq, our unit was on our way home. We had been a long time away from our families, and we had experienced some tough fighting. A third of our unit had already returned to their families in Germany when we were told we would be extended because of a changing situation on the ground. A wave of frustration went through our 18,000 soldiers. Our commander then pulled us together, communicated our new mission, and told us he was also disappointed, but it was time we had to show our grit by getting those soldiers who had already returned to Europe back, unpack our equipment, and return to the fight. Then he said something I will always remember: “It’s tough, but understand your soldiers are looking at you to lead in this crisis … and leaders don’t have the right to have a bad day.” He didn’t mean we couldn’t be frustrated, or disappointed, or emotional, or even pissed off. He meant we just couldn’t show it when others were around. That’s one of the toughest things about leading during a crisis: The unimaginable is expected of leaders. And leaders have to be ready to lead.

All this advice may seem like philosophical musings rather than pragmatic thoughts for a crisis, but hopefully this advice will make a difference as healthcare providers tackle the issues ahead. Stay healthy, mitigate risks, but know that the calm provided by leaders will make a difference.

A few days ago, I had a heartfelt conversation with my good friend Dr Omayra Mansfield. Dr Mansfield has been an Emergency Department Physician for more than 12 years. She is also the wife of another physician and the mother of two young children, the recently appointed Chief Medical Officer at a hospital at AdventHealth, and one of the first graduates of the Physician Leader Development Course I teach.

“During the leadership course, you always provided examples of how physicians are like soldiers,” she began. She reminded me of my words describing how both doctors and soldiers are part of a professional body, how both have a cherished ethos and a set of directing values to guide both their path and their actions as a very special part of our society, and how of all the professions in our society, the military and medicine are the only two that deal in life and death, albeit in very different ways.

She had certainly paid attention in our seminars. Now, as she and her team faced the COVID-19 pandemic, she realized their daily challenges are expanding and they are now going to war. The leadership discussions that had sparked so much debate in our colloquia had now become real.

Dr Mansfield explained that beyond caring for patients, one of her key concerns was the physical and emotional well-being of the clinical staff at her hospital: the physicians, nurses, technicians, and clinicians under her care. Getting to her point, she asked if I might have any suggestions based on my time and experiences in combat that might be helpful to her as she “cared for her troops” as they faced the battle ahead.

Her request was a good one. Lessons from my military past immediately rushed to my mind. I started scribbling and came up with a Top Ten list of recommendations for anyone going into a tough fight. Here’s what I sent to her:

- Find a battle-buddy. On the first day of Army basic training, drill sergeants pair new recruits with one another. That’s primarily for accountability purposes throughout the weeks of training—to ensure soldiers hold each other responsible for getting to the right place, at the right time, in the right uniform—but it’s also part of a larger psychological dynamic related to building teams and mutual support within organizations. Your battle-buddy is charged with keeping you out of trouble, having your back, and being there when you need it most. In combat, battle-buddies do all those things and then some; they protect you from harm in so many other ways. Healthcare providers during this crisis will sometimes feel all alone, and they need to rely on someone else to help them when times get really tough. Having a battle-buddy—for those at the healthcare team level, of course, but also among those at the level of clinical director, hospital administrator, CMO, or even CEO—will help get you through the tough times and provide sanity when you need it the most. So my first piece of advice: Find a battle-buddy.

- Plan and prepare for things you don’t expect will happen. During a preparatory training exercise for our unit’s deployment to Iraq during the surge, when we thought the exercise was about to end, the trainers surprised us with a final crisis we had to solve. According to the scenario, Al Qaida had blown up a major bridge in our area, causing dire logistical problems for the security forces and challenges to the population as they brought their goods to market. I remember my initial reaction: “They don’t have the strength to do that. This’ll never happen,” I said to the Chief of Staff under my breath, as we started developing the required drill to counter the action and please the trainers. I quickly forgot about that lesson, until after we deployed. Two weeks into our 15-month tour in Iraq, the enemy blew the exact bridge that was part of the scenario, causing the exact problems that were predicted. Because we had prepared for the unexpected, we were able to quickly repair the bridge, reestablish the logistics flow, and satisfy the worried population. The lesson: Teams can hope for the best, but it’s always important to prepare for the worst—a lack of equipment, a key member of the team not being available to contribute, an overwhelming surge of patients—and then develop a plan to mitigate it. Take time to reflect, and ask yourself, What is the worst that can happen, what can the “enemy” do to disrupt our lives, and how do we prepare to counter it?

- Get everyone into the fight. In every organizations, it’s often true that some people take on too much and try and do it all themselves, others do only what they’re told to do, there’s the unique few who want to contribute but don’t know how they can to help, and then there’s some who even attempt to avoid contributing at all. It’s important for leaders to know who on their team fits each of these categories. It’s even more critical for leaders to be able to find ways to relieve the overworked, assign tasks to those who might not know their role, bring those who want to contribute into the fold, and cross-train teams to help relieve those who are exhausted. Leaders must look across their “battlespace” and ensure everyone is contributing. Leaders assign everyone tasks and do their best to level—and lighten—the load of the overworked.

- “Fatigue makes cowards of us all.” During any type of crisis, the body and mind will rapidly break down from lack of sleep, emotional strain, or overwhelming stress. While a 12-hour shift in a hospital is exceedingly tough even during normal operations, the COVID-19 crisis will demand dramatically more of all the members of any healthcare team. For that reason, leaders must incorporate rest cycles, team rotations, and half-days away from the hospitals even when all hands are on deck, as well as consider reducing shift times, if possible. Many who have experienced the disease in hot spots say this is really tough, but not attempting to plan for this will cause eventual breakdown and dysfunction. Take a break, do all you can to maintain a modicum of balance, and get away for a while.

- Take time to huddle. Communication and information are always key, but especially critical during any crisis. One technique that has proven valuable, beyond meetings and shift changes, is a preshift and postshift huddle. Different from the formal passing of critical information, the huddle is a brief opportunity for teams to pass informal information, look each other in the eye, and perhaps even pray together. As a two-star general, I did that every morning in combat with my small team of sergeants, captains, and privates before we left the headquarters to visit units, and it gave us all the power of knowing we had shared information, and we had a common operating picture. It gave us strength. During a crisis, all kinds of communication, formal and informal, are key.

- This ain’t peacetime. In a crisis, the enemy gets a vote. If leaders don’t find ways to counter the enemy’s action (and fast!), they’ll be behind the curve! It’s important to find the techniques and procedures that are bureaucratic (or even dumb) and overturn or eliminate them quickly. Decisions must be made with alacrity and with an understood flow, and people must be assigned responsibilities and held accountable to make things happen. In a crisis, speed in action will almost always trump perfection in understanding. Stay calm but ensure that those who might not understand this come around to the dynamics associated with the threat. A crisis isn’t the time for business as usual.

- Force adaptation—don’t wait ’til things are over to adjust. In a crisis, faults and disconnects in techniques and procedures often bubble to the surface and cause consternation. Don’t wait for a break in the action to adjust and find new ways to do things because a break in the action will usually never happen. The military has an expression: “Those who adapt the fastest on the battlefield win.” Find ways to look for and then publicize your methods of adaptation to the team, pin the rose on someone to ensure the changes are made, and then have someone make a historical record so other teams might also learn from your scar tissue. Lessons from the fight must be incorporated by the organization, or they’re not “lessons learned.”

- Talkin’ ain’t fightin’. During a crisis, it’s important to establish techniques of verbal shorthand between the members of a team, and everyone must know their responsibilities and required actions. In the military, this is called a battle drill; in medicine, you know it as a code. In these situations, leaders must find ways to pass information quickly, and the reaction should be immediate response. In a crisis, normal process must take on the dynamics of a “code.” All members of the team must understand that there are just times when things can’t be explained, but it’s also important that leaders know when to use this abbreviated format. Explain when you can, but act when you must.

- Cherish your teams. Every single team will experience things that human beings aren’t designed or meant to handle—even those in the medical profession, who likely thought they had seen it all. There will be repeated and overwhelming trauma, with the expected emotional reactions. The approach during these situations requires empathy, humility, emotional understanding, and validation. Praise your team at every opportunity, find ways to turn mistakes into learning opportunities, but most importantly be human and find ways to provide memories that your team can cherish and look back upon. Give them memories.

- Leaders don’t have the right to have a bad day. In 2004, after a 12-month deployment in Iraq, our unit was on our way home. We had been a long time away from our families, and we had experienced some tough fighting. A third of our unit had already returned to their families in Germany when we were told we would be extended because of a changing situation on the ground. A wave of frustration went through our 18,000 soldiers. Our commander then pulled us together, communicated our new mission, and told us he was also disappointed, but it was time we had to show our grit by getting those soldiers who had already returned to Europe back, unpack our equipment, and return to the fight. Then he said something I will always remember: “It’s tough, but understand your soldiers are looking at you to lead in this crisis … and leaders don’t have the right to have a bad day.” He didn’t mean we couldn’t be frustrated, or disappointed, or emotional, or even pissed off. He meant we just couldn’t show it when others were around. That’s one of the toughest things about leading during a crisis: The unimaginable is expected of leaders. And leaders have to be ready to lead.

All this advice may seem like philosophical musings rather than pragmatic thoughts for a crisis, but hopefully this advice will make a difference as healthcare providers tackle the issues ahead. Stay healthy, mitigate risks, but know that the calm provided by leaders will make a difference.

A few days ago, I had a heartfelt conversation with my good friend Dr Omayra Mansfield. Dr Mansfield has been an Emergency Department Physician for more than 12 years. She is also the wife of another physician and the mother of two young children, the recently appointed Chief Medical Officer at a hospital at AdventHealth, and one of the first graduates of the Physician Leader Development Course I teach.

“During the leadership course, you always provided examples of how physicians are like soldiers,” she began. She reminded me of my words describing how both doctors and soldiers are part of a professional body, how both have a cherished ethos and a set of directing values to guide both their path and their actions as a very special part of our society, and how of all the professions in our society, the military and medicine are the only two that deal in life and death, albeit in very different ways.

She had certainly paid attention in our seminars. Now, as she and her team faced the COVID-19 pandemic, she realized their daily challenges are expanding and they are now going to war. The leadership discussions that had sparked so much debate in our colloquia had now become real.

Dr Mansfield explained that beyond caring for patients, one of her key concerns was the physical and emotional well-being of the clinical staff at her hospital: the physicians, nurses, technicians, and clinicians under her care. Getting to her point, she asked if I might have any suggestions based on my time and experiences in combat that might be helpful to her as she “cared for her troops” as they faced the battle ahead.

Her request was a good one. Lessons from my military past immediately rushed to my mind. I started scribbling and came up with a Top Ten list of recommendations for anyone going into a tough fight. Here’s what I sent to her:

- Find a battle-buddy. On the first day of Army basic training, drill sergeants pair new recruits with one another. That’s primarily for accountability purposes throughout the weeks of training—to ensure soldiers hold each other responsible for getting to the right place, at the right time, in the right uniform—but it’s also part of a larger psychological dynamic related to building teams and mutual support within organizations. Your battle-buddy is charged with keeping you out of trouble, having your back, and being there when you need it most. In combat, battle-buddies do all those things and then some; they protect you from harm in so many other ways. Healthcare providers during this crisis will sometimes feel all alone, and they need to rely on someone else to help them when times get really tough. Having a battle-buddy—for those at the healthcare team level, of course, but also among those at the level of clinical director, hospital administrator, CMO, or even CEO—will help get you through the tough times and provide sanity when you need it the most. So my first piece of advice: Find a battle-buddy.

- Plan and prepare for things you don’t expect will happen. During a preparatory training exercise for our unit’s deployment to Iraq during the surge, when we thought the exercise was about to end, the trainers surprised us with a final crisis we had to solve. According to the scenario, Al Qaida had blown up a major bridge in our area, causing dire logistical problems for the security forces and challenges to the population as they brought their goods to market. I remember my initial reaction: “They don’t have the strength to do that. This’ll never happen,” I said to the Chief of Staff under my breath, as we started developing the required drill to counter the action and please the trainers. I quickly forgot about that lesson, until after we deployed. Two weeks into our 15-month tour in Iraq, the enemy blew the exact bridge that was part of the scenario, causing the exact problems that were predicted. Because we had prepared for the unexpected, we were able to quickly repair the bridge, reestablish the logistics flow, and satisfy the worried population. The lesson: Teams can hope for the best, but it’s always important to prepare for the worst—a lack of equipment, a key member of the team not being available to contribute, an overwhelming surge of patients—and then develop a plan to mitigate it. Take time to reflect, and ask yourself, What is the worst that can happen, what can the “enemy” do to disrupt our lives, and how do we prepare to counter it?

- Get everyone into the fight. In every organizations, it’s often true that some people take on too much and try and do it all themselves, others do only what they’re told to do, there’s the unique few who want to contribute but don’t know how they can to help, and then there’s some who even attempt to avoid contributing at all. It’s important for leaders to know who on their team fits each of these categories. It’s even more critical for leaders to be able to find ways to relieve the overworked, assign tasks to those who might not know their role, bring those who want to contribute into the fold, and cross-train teams to help relieve those who are exhausted. Leaders must look across their “battlespace” and ensure everyone is contributing. Leaders assign everyone tasks and do their best to level—and lighten—the load of the overworked.

- “Fatigue makes cowards of us all.” During any type of crisis, the body and mind will rapidly break down from lack of sleep, emotional strain, or overwhelming stress. While a 12-hour shift in a hospital is exceedingly tough even during normal operations, the COVID-19 crisis will demand dramatically more of all the members of any healthcare team. For that reason, leaders must incorporate rest cycles, team rotations, and half-days away from the hospitals even when all hands are on deck, as well as consider reducing shift times, if possible. Many who have experienced the disease in hot spots say this is really tough, but not attempting to plan for this will cause eventual breakdown and dysfunction. Take a break, do all you can to maintain a modicum of balance, and get away for a while.

- Take time to huddle. Communication and information are always key, but especially critical during any crisis. One technique that has proven valuable, beyond meetings and shift changes, is a preshift and postshift huddle. Different from the formal passing of critical information, the huddle is a brief opportunity for teams to pass informal information, look each other in the eye, and perhaps even pray together. As a two-star general, I did that every morning in combat with my small team of sergeants, captains, and privates before we left the headquarters to visit units, and it gave us all the power of knowing we had shared information, and we had a common operating picture. It gave us strength. During a crisis, all kinds of communication, formal and informal, are key.

- This ain’t peacetime. In a crisis, the enemy gets a vote. If leaders don’t find ways to counter the enemy’s action (and fast!), they’ll be behind the curve! It’s important to find the techniques and procedures that are bureaucratic (or even dumb) and overturn or eliminate them quickly. Decisions must be made with alacrity and with an understood flow, and people must be assigned responsibilities and held accountable to make things happen. In a crisis, speed in action will almost always trump perfection in understanding. Stay calm but ensure that those who might not understand this come around to the dynamics associated with the threat. A crisis isn’t the time for business as usual.

- Force adaptation—don’t wait ’til things are over to adjust. In a crisis, faults and disconnects in techniques and procedures often bubble to the surface and cause consternation. Don’t wait for a break in the action to adjust and find new ways to do things because a break in the action will usually never happen. The military has an expression: “Those who adapt the fastest on the battlefield win.” Find ways to look for and then publicize your methods of adaptation to the team, pin the rose on someone to ensure the changes are made, and then have someone make a historical record so other teams might also learn from your scar tissue. Lessons from the fight must be incorporated by the organization, or they’re not “lessons learned.”

- Talkin’ ain’t fightin’. During a crisis, it’s important to establish techniques of verbal shorthand between the members of a team, and everyone must know their responsibilities and required actions. In the military, this is called a battle drill; in medicine, you know it as a code. In these situations, leaders must find ways to pass information quickly, and the reaction should be immediate response. In a crisis, normal process must take on the dynamics of a “code.” All members of the team must understand that there are just times when things can’t be explained, but it’s also important that leaders know when to use this abbreviated format. Explain when you can, but act when you must.