User login

Command hallucinations, but is it really psychosis?

CASE Frequent hospitalizations

Ms. D, age 26, presents to the emergency department (ED) after drinking a bottle of hand sanitizer in a suicide attempt. She is admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit, where she spends 50 days, followed by a transfer to a step-down unit, where she spends 26 days. Upon discharge, her diagnosis is schizoaffective disorder–bipolar type.

Shortly before this, Ms. D had intentionally ingested 20 vitamin pills to “make her heart stop” after a conflict at home. After ingesting the pills, Ms. D presented to the ED, where she stated that if she were discharged, she would kill herself by taking “better pills.” She was then admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit, where she spent 60 days before being moved to an extended-care step-down facility, where she resided for 42 days.

HISTORY A challenging past

Ms. D has a history of >25 psychiatric hospitalizations with varying discharge diagnoses, including schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, borderline personality disorder (BPD), and borderline intellectual functioning.

Ms. D was raised in a 2-parent home with 3 older half-brothers and 3 sisters. She was sexually assaulted by a cousin when she was 12. Ms. D recalls one event of self-injury/cutting behavior at age 15 after she was bullied by peers. Her family history is significant for schizophrenia (mother), alcohol use disorder (both parents), and bipolar disorder (sister). Her mother, who is now deceased, was admitted to state psychiatric hospitals for extended periods.

Her medication regimen has changed with nearly every hospitalization but generally has included ≥1 antipsychotic, a mood stabilizer, an antidepressant, and a benzodiazepine (often prescribed on an as-needed basis). Ms. D is obese and has difficulty sleeping, hypothyroidism, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), hypertension, and iron deficiency anemia. She receives medications to manage each of these conditions.

Ms. D’s previous psychotic symptoms included auditory command hallucinations. These occurred under stressful circumstances, such as during severe family conflicts that often led to her feeling abandoned. She reported that the “voice” she heard was usually her own instructing her to “take pills.” There was no prior evidence of bizarre delusions, negative symptoms, or disorganized thoughts or speech.

During episodes of decompensation, Ms. D did not report symptoms of mania, sustained depressed mood, or anxiety, nor were these symptoms observed. Although Ms. D endorsed suicidal ideation with a plan, intent, and means, during several of her previous ED presentations, she told clinicians that her intent was not to end her life but rather to evoke concern in her family members.

Continue to: After her mother died...

After her mother died when Ms. D was 19, she began to have nightmares of wanting to hurt herself and others and began experiencing multiple hospitalizations. In 2010, Ms. D was referred to an assertive community treatment (ACT) program for individuals age 16 to 27 because of her inability to participate in traditional community-based services and her historical need for advanced services, in order to provide psychiatric care in the least restrictive means possible.

Despite receiving intensive ACT services, and in addition to the numerous inpatient psychiatric hospitalizations, over 7 years, Ms. D accumulated 8 additional general-medical hospitalizations and >50 visits to hospital EDs and urgent care facilities. These hospitalizations typically followed arguments at home, strained family dynamics, and not feeling wanted. Ms. D would ingest large quantities of prescription or over-the-counter medications as a way of coping, which often occurred while she was residing in a step-down facility after hospital discharge.

[polldaddy:10528342]

The authors’ observations

The treatment team decided to transition Ms. D to an LTSR with full continuum of treatment. While some clinicians might be concerned with potential iatrogenic harm of LTSR placement and might instead recommend less restrictive residential support and an IOP. However, in Ms. D’s case, her numerous admissions to EDs, urgent care facilities, and medical and psychiatric hospitals, her failed step-down facility placements, and her family conflicts and poor dynamics limited the efficacy of her natural support system and drove the recommendation for an LTSR.

Previously, Ms. D’s experience with ACT services had centered on managing acute crises, with brief periods of stabilization that insufficiently engaged her in a consistent and meaningful treatment plan. Ms. D’s insurance company agreed to pay for the LTSR after lengthy discussions with the clinical leadership at the ACT program and the LTSR demonstrated that she was a high utilizer of health care services. They concluded that Ms. D’s stay at the LTSR would be less expensive than the frequent use of expensive hospital services and care.

EVALUATION A consensus on the diagnosis

During the first few weeks of Ms. D’s admission to the LTSR, the treatment team takes a thorough history and reviews her medical records, which they obtained from several past inpatient admissions and therapists who previously treated Ms. D. The team also collects collateral information from Ms. D’s family members. Based on this information, interviews, and composite behavioral observations from the first few weeks of Ms. D’s time at the LTSR, the psychiatrists and treatment team at the LTSR and ACT program determine that Ms. D meets the criteria for a primary diagnosis of BPD. Previous discharge diagnoses of schizoaffective disorder–bipolar type (Table 11), schizophrenia, or bipolar disorder could not be affirmed.

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

During Ms. D’s LTSR placement, it became clear that her self-harm behaviors and numerous visits to the ED and urgent care facilities involved severe and intense emotional dysregulation and maladaptive behaviors. These behaviors had developed over time in response to acute stressors and past trauma, and not as a result of a sustained mood or psychotic disorder. Before her LTSR placement, Ms. D was unable to use more adaptive coping skills, such as skills building, learning, and coaching. Ms. D typically “thrived” with medical attention in the ED or hospital, and once the stressor dissipated, she was discharged back to the same stressful living environment associated with her maladaptive coping.

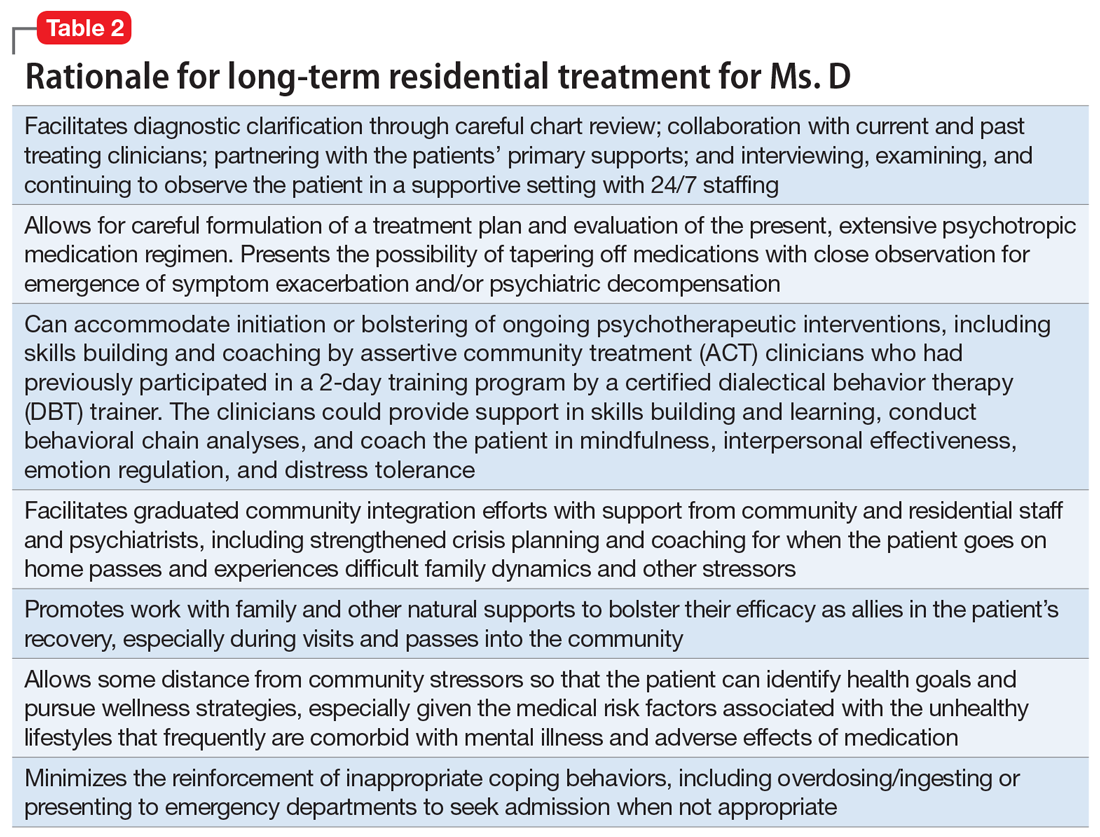

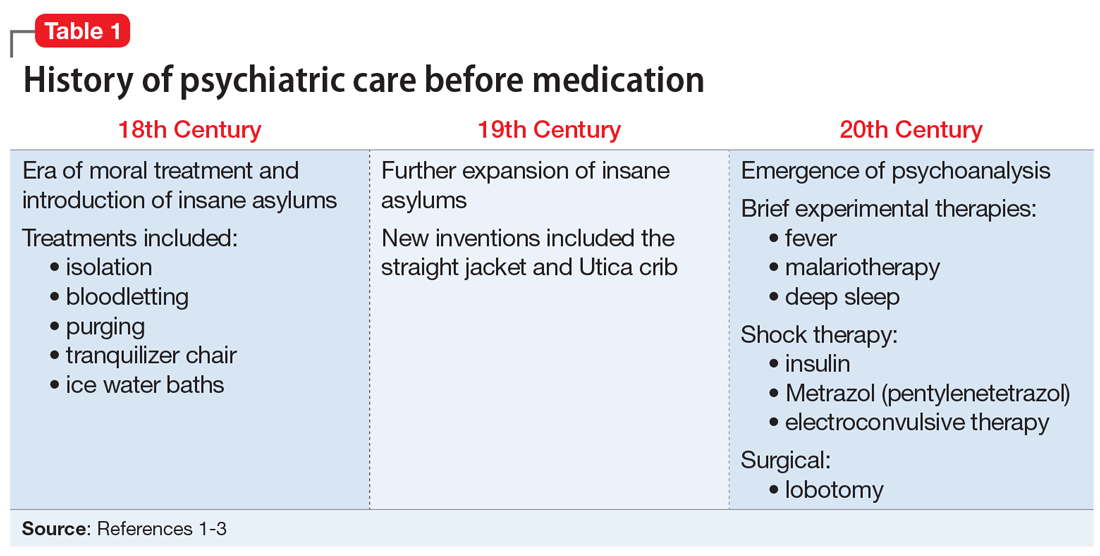

Table 2 outlines the rationale for long-term residential treatment for Ms. D.

TREATMENT Developing more effective skills

Bolstered by a clearer diagnostic formulation of BPD, Ms. D’s initial treatment goals at the LTSR include developing effective skills (eg, mindfulness, interpersonal effectiveness, emotion regulation, and distress tolerance) to cope with family conflicts and other stressors while she is outside the facility on a therapeutic pass. Ms. D’s treatment focuses on skills learning and coaching, and behavior chain analyses, which are conducted by her therapist from the ACT program.

Ms. D remains clinically stable throughout her LTSR placement, and benefits from ongoing skills building and learning, coaching, and community integration efforts.

[polldaddy:10528348]

The authors’ observations

Several systematic reviews2-5 have found that there is a lack of high-quality evidence for the use of various psychotropic medications for patients with BPD, yet polypharmacy is common. Many patients with BPD receive ≥2 medications and >25% of patients receive ≥4 medications, typically for prolonged periods. Stoffers et al4 suggested that FGAs and antidepressants have marginal effects of for patients with BPD; however, their use cannot be ruled out because they may be helpful for comorbid symptoms that are often observed in patients with BPD. There is better evidence for SGAs, mood stabilizers, and omega-3 fatty acids; however, most effect estimates were based on single studies, and there is minimal data on long-term use of these agents.4

Continue to: A recent review highlighted...

A recent review highlighted 2 trends in medication prescribing for individuals with BPD3:

- a decrease in the use of benzodiazepines and antidepressants

- an increase in or preference for mood stabilizers and SGAs, especially valproate and quetiapine.

In terms of which medications can be used to target specific symptoms, the same researchers also noted from previous studies3:

- The prior use of SSRIs to target affective dysregulation, anxiety, and impulsive- behavior dyscontrol

- mood stabilizers (notably anticonvulsants) and SGAs to target “core symptoms” of BPD, including affective dysregulation, impulsive-behavioral dyscontrol, and cognitive-perceptual distortions

- omega-3 fatty acids for mood stabilization, impulsive-behavior dyscontrol, and possibly to reduce self-harm behaviors.

TREATMENT Medication adjustments

The treatment team reviews the lack of evidence for the long-term use of psychotropic medications in the treatment of BPD with Ms. D and her relatives,2-5 and develops a medication regimen that is clinically appropriate for managing the symptoms of BPD, while also being mindful of adverse effects.

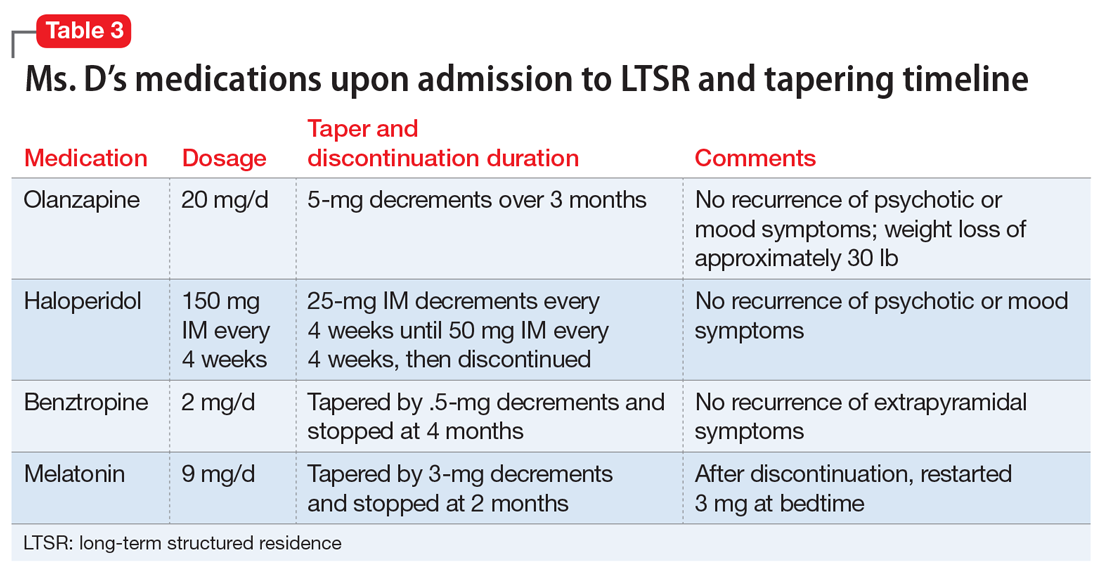

When Ms. D was admitted to the LTSR from the hospital, her psychotropic medication regimen included haloperidol, 150 mg IM every month; olanzapine, 20 mg at bedtime; benztropine, 1 mg twice daily; and melatonin, 9 mg at bedtime.

Following discussions with Ms. D and her older sister, the team initiates a taper of olanzapine because of metabolic concerns. Ms. D has gained >40 lb while receiving this medication and had hypertension. Olanzapine was tapered and discontinued over the course of 3 months with no reemergence of sustained mood or psychotic symptoms (Table 3). During this period, Ms. D also participates in dietary counselling, follows a portion-controlled regimen, and loses >30 lb. Her wellness plan focuses on nutrition and exercise to improve her overall physical health.

Continue to: Six months into her stay...

Six months into her stay at the LTSR, Ms. D remains clinically stable and is able to leave the LTSR placement to go on home passes. At this time, the team begins to taper the haloperidol long-acting injection. One month prior to discharge from the LTSR, haloperidol is discontinued entirely. The treatment team simultaneously tapers and discontinues benztropine. No recurrence of extrapyramidal symptoms is observed by staff or noted by the patient.

A treatment plan is developed to address Ms. D’s medical conditions, including hypothyroidism, GERD, and obesity. Ms. D does not appear to have difficulty sleeping at the LTSR, so melatonin is tapered by 3-mg decrements and stopped after 2 months. However, shortly thereafter, she develops insomnia, so a 3-mg dose is re-initiated, and her complaints abate. Her primary care physician discontinues hydrochlorothiazide, an antihypertensive medication.

Ms. D’s medication regimen consists of melatonin, 3 mg at bedtime; pantoprazole, 40 mg before breakfast, for GERD; senna, 8.6 mg at bedtime, and polyethylene glycol, 17 gm/d, for constipation; levothyroxine, 125 mcg/d, for hypothyroidism; metoprolol extended-release, 50 mg/d, for hypertension; and ferrous sulfate, 325 mg/d, for iron deficiency anemia.

OUTCOME Improved functioning

After 11 months at the LTSR, Ms. D is discharged home. She continues to receive outpatient services in the community through the ACT program, meeting with her therapist for cognitive-behavioral therapy, skills building and learning, and integration.

Approximately 9 months later, Ms. D is re-started on an SSRI (sertraline, 50 mg/d, which is increased to 100 mg/d 9 months later) to target symptoms of anxiety, which primarily manifest as excessive worrying. Hydroxyzine, 50 mg 3 times daily as needed, is added to this regimen, for breakthrough anxiety symptoms. Hydroxyzine is prescribed instead of a benzodiazepine to avoid potential addiction and abuse.

Continue to: Oral ziprasidone...

Oral ziprasidone, 20 mg/d twice daily, is initiated during 2 brief inpatient psychiatric admissions; however, it is successfully tapered within 1 week of discharge, in partnership with the ACT program.

In the 23 months after her discharge, Ms. D has had 1 ED visit and 2 brief inpatient psychiatric hospitalizations, which is markedly fewer encounters than she had in the 2 years before her LTSR placement. She has also lost an additional 30 lb since her LTSR discharge through a healthy diet and exercise.

Ms. D is now considering transitioning to living independently in the community through a residential supported housing program.

Bottom Line

Psychotic symptoms in patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD) are typically fleeting and mostly occur in the context of intense interpersonal conflicts and real or imagined abandonment. Long-term structured residence placement for patients with BPD can allow for careful formulation of a treatment plan, and help patients gain effective skills to cope with difficult family dynamics and other stressors, with the ultimate goal of gradual community integration.

Related Resource

- National Education Alliance for Borderline Personality Disorder. https://www.borderlinepersonalitydisorder.org.

Drug Brand Names

Benztropine • Cogentin

Haloperidol • Haldol

Hydrochlorothiazide • Microzide, HydroDiuril

Hydroxyzine • Vistaril

Levothyroxine • Synthroid,

Metoprolol ER • Toprol XL

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Pantoprazole • Protonix

Polyethylene glycol • MiraLax, Glycolax

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Senna • Senokot

Sertraline • Zoloft

Valproate • Depakene, Depakote

Ziprasidone • Geodon

1. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Hancock-Johnson E, Griffiths C, Picchioni M. A focused systematic review of pharmacological treatment for borderline personality disorder. CNS Drugs. 2017;31:345-356.

3. Starcevic V, Janca A. Pharmacotherapy of borderline personality disorder: replacing confusion with prudent pragmatism. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2018;31(1):69-73.

4. Stoffers J, Völlm BA, Rücker G, et al. Pharmacological interventions for borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;6:CD005653. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005653.pub2.

5. Stoffers-Winterling JM, Storebo OJ, Völlm BA, et al. Pharmacological interventions for borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;3:CD012956. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012956.

CASE Frequent hospitalizations

Ms. D, age 26, presents to the emergency department (ED) after drinking a bottle of hand sanitizer in a suicide attempt. She is admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit, where she spends 50 days, followed by a transfer to a step-down unit, where she spends 26 days. Upon discharge, her diagnosis is schizoaffective disorder–bipolar type.

Shortly before this, Ms. D had intentionally ingested 20 vitamin pills to “make her heart stop” after a conflict at home. After ingesting the pills, Ms. D presented to the ED, where she stated that if she were discharged, she would kill herself by taking “better pills.” She was then admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit, where she spent 60 days before being moved to an extended-care step-down facility, where she resided for 42 days.

HISTORY A challenging past

Ms. D has a history of >25 psychiatric hospitalizations with varying discharge diagnoses, including schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, borderline personality disorder (BPD), and borderline intellectual functioning.

Ms. D was raised in a 2-parent home with 3 older half-brothers and 3 sisters. She was sexually assaulted by a cousin when she was 12. Ms. D recalls one event of self-injury/cutting behavior at age 15 after she was bullied by peers. Her family history is significant for schizophrenia (mother), alcohol use disorder (both parents), and bipolar disorder (sister). Her mother, who is now deceased, was admitted to state psychiatric hospitals for extended periods.

Her medication regimen has changed with nearly every hospitalization but generally has included ≥1 antipsychotic, a mood stabilizer, an antidepressant, and a benzodiazepine (often prescribed on an as-needed basis). Ms. D is obese and has difficulty sleeping, hypothyroidism, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), hypertension, and iron deficiency anemia. She receives medications to manage each of these conditions.

Ms. D’s previous psychotic symptoms included auditory command hallucinations. These occurred under stressful circumstances, such as during severe family conflicts that often led to her feeling abandoned. She reported that the “voice” she heard was usually her own instructing her to “take pills.” There was no prior evidence of bizarre delusions, negative symptoms, or disorganized thoughts or speech.

During episodes of decompensation, Ms. D did not report symptoms of mania, sustained depressed mood, or anxiety, nor were these symptoms observed. Although Ms. D endorsed suicidal ideation with a plan, intent, and means, during several of her previous ED presentations, she told clinicians that her intent was not to end her life but rather to evoke concern in her family members.

Continue to: After her mother died...

After her mother died when Ms. D was 19, she began to have nightmares of wanting to hurt herself and others and began experiencing multiple hospitalizations. In 2010, Ms. D was referred to an assertive community treatment (ACT) program for individuals age 16 to 27 because of her inability to participate in traditional community-based services and her historical need for advanced services, in order to provide psychiatric care in the least restrictive means possible.

Despite receiving intensive ACT services, and in addition to the numerous inpatient psychiatric hospitalizations, over 7 years, Ms. D accumulated 8 additional general-medical hospitalizations and >50 visits to hospital EDs and urgent care facilities. These hospitalizations typically followed arguments at home, strained family dynamics, and not feeling wanted. Ms. D would ingest large quantities of prescription or over-the-counter medications as a way of coping, which often occurred while she was residing in a step-down facility after hospital discharge.

[polldaddy:10528342]

The authors’ observations

The treatment team decided to transition Ms. D to an LTSR with full continuum of treatment. While some clinicians might be concerned with potential iatrogenic harm of LTSR placement and might instead recommend less restrictive residential support and an IOP. However, in Ms. D’s case, her numerous admissions to EDs, urgent care facilities, and medical and psychiatric hospitals, her failed step-down facility placements, and her family conflicts and poor dynamics limited the efficacy of her natural support system and drove the recommendation for an LTSR.

Previously, Ms. D’s experience with ACT services had centered on managing acute crises, with brief periods of stabilization that insufficiently engaged her in a consistent and meaningful treatment plan. Ms. D’s insurance company agreed to pay for the LTSR after lengthy discussions with the clinical leadership at the ACT program and the LTSR demonstrated that she was a high utilizer of health care services. They concluded that Ms. D’s stay at the LTSR would be less expensive than the frequent use of expensive hospital services and care.

EVALUATION A consensus on the diagnosis

During the first few weeks of Ms. D’s admission to the LTSR, the treatment team takes a thorough history and reviews her medical records, which they obtained from several past inpatient admissions and therapists who previously treated Ms. D. The team also collects collateral information from Ms. D’s family members. Based on this information, interviews, and composite behavioral observations from the first few weeks of Ms. D’s time at the LTSR, the psychiatrists and treatment team at the LTSR and ACT program determine that Ms. D meets the criteria for a primary diagnosis of BPD. Previous discharge diagnoses of schizoaffective disorder–bipolar type (Table 11), schizophrenia, or bipolar disorder could not be affirmed.

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

During Ms. D’s LTSR placement, it became clear that her self-harm behaviors and numerous visits to the ED and urgent care facilities involved severe and intense emotional dysregulation and maladaptive behaviors. These behaviors had developed over time in response to acute stressors and past trauma, and not as a result of a sustained mood or psychotic disorder. Before her LTSR placement, Ms. D was unable to use more adaptive coping skills, such as skills building, learning, and coaching. Ms. D typically “thrived” with medical attention in the ED or hospital, and once the stressor dissipated, she was discharged back to the same stressful living environment associated with her maladaptive coping.

Table 2 outlines the rationale for long-term residential treatment for Ms. D.

TREATMENT Developing more effective skills

Bolstered by a clearer diagnostic formulation of BPD, Ms. D’s initial treatment goals at the LTSR include developing effective skills (eg, mindfulness, interpersonal effectiveness, emotion regulation, and distress tolerance) to cope with family conflicts and other stressors while she is outside the facility on a therapeutic pass. Ms. D’s treatment focuses on skills learning and coaching, and behavior chain analyses, which are conducted by her therapist from the ACT program.

Ms. D remains clinically stable throughout her LTSR placement, and benefits from ongoing skills building and learning, coaching, and community integration efforts.

[polldaddy:10528348]

The authors’ observations

Several systematic reviews2-5 have found that there is a lack of high-quality evidence for the use of various psychotropic medications for patients with BPD, yet polypharmacy is common. Many patients with BPD receive ≥2 medications and >25% of patients receive ≥4 medications, typically for prolonged periods. Stoffers et al4 suggested that FGAs and antidepressants have marginal effects of for patients with BPD; however, their use cannot be ruled out because they may be helpful for comorbid symptoms that are often observed in patients with BPD. There is better evidence for SGAs, mood stabilizers, and omega-3 fatty acids; however, most effect estimates were based on single studies, and there is minimal data on long-term use of these agents.4

Continue to: A recent review highlighted...

A recent review highlighted 2 trends in medication prescribing for individuals with BPD3:

- a decrease in the use of benzodiazepines and antidepressants

- an increase in or preference for mood stabilizers and SGAs, especially valproate and quetiapine.

In terms of which medications can be used to target specific symptoms, the same researchers also noted from previous studies3:

- The prior use of SSRIs to target affective dysregulation, anxiety, and impulsive- behavior dyscontrol

- mood stabilizers (notably anticonvulsants) and SGAs to target “core symptoms” of BPD, including affective dysregulation, impulsive-behavioral dyscontrol, and cognitive-perceptual distortions

- omega-3 fatty acids for mood stabilization, impulsive-behavior dyscontrol, and possibly to reduce self-harm behaviors.

TREATMENT Medication adjustments

The treatment team reviews the lack of evidence for the long-term use of psychotropic medications in the treatment of BPD with Ms. D and her relatives,2-5 and develops a medication regimen that is clinically appropriate for managing the symptoms of BPD, while also being mindful of adverse effects.

When Ms. D was admitted to the LTSR from the hospital, her psychotropic medication regimen included haloperidol, 150 mg IM every month; olanzapine, 20 mg at bedtime; benztropine, 1 mg twice daily; and melatonin, 9 mg at bedtime.

Following discussions with Ms. D and her older sister, the team initiates a taper of olanzapine because of metabolic concerns. Ms. D has gained >40 lb while receiving this medication and had hypertension. Olanzapine was tapered and discontinued over the course of 3 months with no reemergence of sustained mood or psychotic symptoms (Table 3). During this period, Ms. D also participates in dietary counselling, follows a portion-controlled regimen, and loses >30 lb. Her wellness plan focuses on nutrition and exercise to improve her overall physical health.

Continue to: Six months into her stay...

Six months into her stay at the LTSR, Ms. D remains clinically stable and is able to leave the LTSR placement to go on home passes. At this time, the team begins to taper the haloperidol long-acting injection. One month prior to discharge from the LTSR, haloperidol is discontinued entirely. The treatment team simultaneously tapers and discontinues benztropine. No recurrence of extrapyramidal symptoms is observed by staff or noted by the patient.

A treatment plan is developed to address Ms. D’s medical conditions, including hypothyroidism, GERD, and obesity. Ms. D does not appear to have difficulty sleeping at the LTSR, so melatonin is tapered by 3-mg decrements and stopped after 2 months. However, shortly thereafter, she develops insomnia, so a 3-mg dose is re-initiated, and her complaints abate. Her primary care physician discontinues hydrochlorothiazide, an antihypertensive medication.

Ms. D’s medication regimen consists of melatonin, 3 mg at bedtime; pantoprazole, 40 mg before breakfast, for GERD; senna, 8.6 mg at bedtime, and polyethylene glycol, 17 gm/d, for constipation; levothyroxine, 125 mcg/d, for hypothyroidism; metoprolol extended-release, 50 mg/d, for hypertension; and ferrous sulfate, 325 mg/d, for iron deficiency anemia.

OUTCOME Improved functioning

After 11 months at the LTSR, Ms. D is discharged home. She continues to receive outpatient services in the community through the ACT program, meeting with her therapist for cognitive-behavioral therapy, skills building and learning, and integration.

Approximately 9 months later, Ms. D is re-started on an SSRI (sertraline, 50 mg/d, which is increased to 100 mg/d 9 months later) to target symptoms of anxiety, which primarily manifest as excessive worrying. Hydroxyzine, 50 mg 3 times daily as needed, is added to this regimen, for breakthrough anxiety symptoms. Hydroxyzine is prescribed instead of a benzodiazepine to avoid potential addiction and abuse.

Continue to: Oral ziprasidone...

Oral ziprasidone, 20 mg/d twice daily, is initiated during 2 brief inpatient psychiatric admissions; however, it is successfully tapered within 1 week of discharge, in partnership with the ACT program.

In the 23 months after her discharge, Ms. D has had 1 ED visit and 2 brief inpatient psychiatric hospitalizations, which is markedly fewer encounters than she had in the 2 years before her LTSR placement. She has also lost an additional 30 lb since her LTSR discharge through a healthy diet and exercise.

Ms. D is now considering transitioning to living independently in the community through a residential supported housing program.

Bottom Line

Psychotic symptoms in patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD) are typically fleeting and mostly occur in the context of intense interpersonal conflicts and real or imagined abandonment. Long-term structured residence placement for patients with BPD can allow for careful formulation of a treatment plan, and help patients gain effective skills to cope with difficult family dynamics and other stressors, with the ultimate goal of gradual community integration.

Related Resource

- National Education Alliance for Borderline Personality Disorder. https://www.borderlinepersonalitydisorder.org.

Drug Brand Names

Benztropine • Cogentin

Haloperidol • Haldol

Hydrochlorothiazide • Microzide, HydroDiuril

Hydroxyzine • Vistaril

Levothyroxine • Synthroid,

Metoprolol ER • Toprol XL

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Pantoprazole • Protonix

Polyethylene glycol • MiraLax, Glycolax

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Senna • Senokot

Sertraline • Zoloft

Valproate • Depakene, Depakote

Ziprasidone • Geodon

CASE Frequent hospitalizations

Ms. D, age 26, presents to the emergency department (ED) after drinking a bottle of hand sanitizer in a suicide attempt. She is admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit, where she spends 50 days, followed by a transfer to a step-down unit, where she spends 26 days. Upon discharge, her diagnosis is schizoaffective disorder–bipolar type.

Shortly before this, Ms. D had intentionally ingested 20 vitamin pills to “make her heart stop” after a conflict at home. After ingesting the pills, Ms. D presented to the ED, where she stated that if she were discharged, she would kill herself by taking “better pills.” She was then admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit, where she spent 60 days before being moved to an extended-care step-down facility, where she resided for 42 days.

HISTORY A challenging past

Ms. D has a history of >25 psychiatric hospitalizations with varying discharge diagnoses, including schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, borderline personality disorder (BPD), and borderline intellectual functioning.

Ms. D was raised in a 2-parent home with 3 older half-brothers and 3 sisters. She was sexually assaulted by a cousin when she was 12. Ms. D recalls one event of self-injury/cutting behavior at age 15 after she was bullied by peers. Her family history is significant for schizophrenia (mother), alcohol use disorder (both parents), and bipolar disorder (sister). Her mother, who is now deceased, was admitted to state psychiatric hospitals for extended periods.

Her medication regimen has changed with nearly every hospitalization but generally has included ≥1 antipsychotic, a mood stabilizer, an antidepressant, and a benzodiazepine (often prescribed on an as-needed basis). Ms. D is obese and has difficulty sleeping, hypothyroidism, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), hypertension, and iron deficiency anemia. She receives medications to manage each of these conditions.

Ms. D’s previous psychotic symptoms included auditory command hallucinations. These occurred under stressful circumstances, such as during severe family conflicts that often led to her feeling abandoned. She reported that the “voice” she heard was usually her own instructing her to “take pills.” There was no prior evidence of bizarre delusions, negative symptoms, or disorganized thoughts or speech.

During episodes of decompensation, Ms. D did not report symptoms of mania, sustained depressed mood, or anxiety, nor were these symptoms observed. Although Ms. D endorsed suicidal ideation with a plan, intent, and means, during several of her previous ED presentations, she told clinicians that her intent was not to end her life but rather to evoke concern in her family members.

Continue to: After her mother died...

After her mother died when Ms. D was 19, she began to have nightmares of wanting to hurt herself and others and began experiencing multiple hospitalizations. In 2010, Ms. D was referred to an assertive community treatment (ACT) program for individuals age 16 to 27 because of her inability to participate in traditional community-based services and her historical need for advanced services, in order to provide psychiatric care in the least restrictive means possible.

Despite receiving intensive ACT services, and in addition to the numerous inpatient psychiatric hospitalizations, over 7 years, Ms. D accumulated 8 additional general-medical hospitalizations and >50 visits to hospital EDs and urgent care facilities. These hospitalizations typically followed arguments at home, strained family dynamics, and not feeling wanted. Ms. D would ingest large quantities of prescription or over-the-counter medications as a way of coping, which often occurred while she was residing in a step-down facility after hospital discharge.

[polldaddy:10528342]

The authors’ observations

The treatment team decided to transition Ms. D to an LTSR with full continuum of treatment. While some clinicians might be concerned with potential iatrogenic harm of LTSR placement and might instead recommend less restrictive residential support and an IOP. However, in Ms. D’s case, her numerous admissions to EDs, urgent care facilities, and medical and psychiatric hospitals, her failed step-down facility placements, and her family conflicts and poor dynamics limited the efficacy of her natural support system and drove the recommendation for an LTSR.

Previously, Ms. D’s experience with ACT services had centered on managing acute crises, with brief periods of stabilization that insufficiently engaged her in a consistent and meaningful treatment plan. Ms. D’s insurance company agreed to pay for the LTSR after lengthy discussions with the clinical leadership at the ACT program and the LTSR demonstrated that she was a high utilizer of health care services. They concluded that Ms. D’s stay at the LTSR would be less expensive than the frequent use of expensive hospital services and care.

EVALUATION A consensus on the diagnosis

During the first few weeks of Ms. D’s admission to the LTSR, the treatment team takes a thorough history and reviews her medical records, which they obtained from several past inpatient admissions and therapists who previously treated Ms. D. The team also collects collateral information from Ms. D’s family members. Based on this information, interviews, and composite behavioral observations from the first few weeks of Ms. D’s time at the LTSR, the psychiatrists and treatment team at the LTSR and ACT program determine that Ms. D meets the criteria for a primary diagnosis of BPD. Previous discharge diagnoses of schizoaffective disorder–bipolar type (Table 11), schizophrenia, or bipolar disorder could not be affirmed.

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

During Ms. D’s LTSR placement, it became clear that her self-harm behaviors and numerous visits to the ED and urgent care facilities involved severe and intense emotional dysregulation and maladaptive behaviors. These behaviors had developed over time in response to acute stressors and past trauma, and not as a result of a sustained mood or psychotic disorder. Before her LTSR placement, Ms. D was unable to use more adaptive coping skills, such as skills building, learning, and coaching. Ms. D typically “thrived” with medical attention in the ED or hospital, and once the stressor dissipated, she was discharged back to the same stressful living environment associated with her maladaptive coping.

Table 2 outlines the rationale for long-term residential treatment for Ms. D.

TREATMENT Developing more effective skills

Bolstered by a clearer diagnostic formulation of BPD, Ms. D’s initial treatment goals at the LTSR include developing effective skills (eg, mindfulness, interpersonal effectiveness, emotion regulation, and distress tolerance) to cope with family conflicts and other stressors while she is outside the facility on a therapeutic pass. Ms. D’s treatment focuses on skills learning and coaching, and behavior chain analyses, which are conducted by her therapist from the ACT program.

Ms. D remains clinically stable throughout her LTSR placement, and benefits from ongoing skills building and learning, coaching, and community integration efforts.

[polldaddy:10528348]

The authors’ observations

Several systematic reviews2-5 have found that there is a lack of high-quality evidence for the use of various psychotropic medications for patients with BPD, yet polypharmacy is common. Many patients with BPD receive ≥2 medications and >25% of patients receive ≥4 medications, typically for prolonged periods. Stoffers et al4 suggested that FGAs and antidepressants have marginal effects of for patients with BPD; however, their use cannot be ruled out because they may be helpful for comorbid symptoms that are often observed in patients with BPD. There is better evidence for SGAs, mood stabilizers, and omega-3 fatty acids; however, most effect estimates were based on single studies, and there is minimal data on long-term use of these agents.4

Continue to: A recent review highlighted...

A recent review highlighted 2 trends in medication prescribing for individuals with BPD3:

- a decrease in the use of benzodiazepines and antidepressants

- an increase in or preference for mood stabilizers and SGAs, especially valproate and quetiapine.

In terms of which medications can be used to target specific symptoms, the same researchers also noted from previous studies3:

- The prior use of SSRIs to target affective dysregulation, anxiety, and impulsive- behavior dyscontrol

- mood stabilizers (notably anticonvulsants) and SGAs to target “core symptoms” of BPD, including affective dysregulation, impulsive-behavioral dyscontrol, and cognitive-perceptual distortions

- omega-3 fatty acids for mood stabilization, impulsive-behavior dyscontrol, and possibly to reduce self-harm behaviors.

TREATMENT Medication adjustments

The treatment team reviews the lack of evidence for the long-term use of psychotropic medications in the treatment of BPD with Ms. D and her relatives,2-5 and develops a medication regimen that is clinically appropriate for managing the symptoms of BPD, while also being mindful of adverse effects.

When Ms. D was admitted to the LTSR from the hospital, her psychotropic medication regimen included haloperidol, 150 mg IM every month; olanzapine, 20 mg at bedtime; benztropine, 1 mg twice daily; and melatonin, 9 mg at bedtime.

Following discussions with Ms. D and her older sister, the team initiates a taper of olanzapine because of metabolic concerns. Ms. D has gained >40 lb while receiving this medication and had hypertension. Olanzapine was tapered and discontinued over the course of 3 months with no reemergence of sustained mood or psychotic symptoms (Table 3). During this period, Ms. D also participates in dietary counselling, follows a portion-controlled regimen, and loses >30 lb. Her wellness plan focuses on nutrition and exercise to improve her overall physical health.

Continue to: Six months into her stay...

Six months into her stay at the LTSR, Ms. D remains clinically stable and is able to leave the LTSR placement to go on home passes. At this time, the team begins to taper the haloperidol long-acting injection. One month prior to discharge from the LTSR, haloperidol is discontinued entirely. The treatment team simultaneously tapers and discontinues benztropine. No recurrence of extrapyramidal symptoms is observed by staff or noted by the patient.

A treatment plan is developed to address Ms. D’s medical conditions, including hypothyroidism, GERD, and obesity. Ms. D does not appear to have difficulty sleeping at the LTSR, so melatonin is tapered by 3-mg decrements and stopped after 2 months. However, shortly thereafter, she develops insomnia, so a 3-mg dose is re-initiated, and her complaints abate. Her primary care physician discontinues hydrochlorothiazide, an antihypertensive medication.

Ms. D’s medication regimen consists of melatonin, 3 mg at bedtime; pantoprazole, 40 mg before breakfast, for GERD; senna, 8.6 mg at bedtime, and polyethylene glycol, 17 gm/d, for constipation; levothyroxine, 125 mcg/d, for hypothyroidism; metoprolol extended-release, 50 mg/d, for hypertension; and ferrous sulfate, 325 mg/d, for iron deficiency anemia.

OUTCOME Improved functioning

After 11 months at the LTSR, Ms. D is discharged home. She continues to receive outpatient services in the community through the ACT program, meeting with her therapist for cognitive-behavioral therapy, skills building and learning, and integration.

Approximately 9 months later, Ms. D is re-started on an SSRI (sertraline, 50 mg/d, which is increased to 100 mg/d 9 months later) to target symptoms of anxiety, which primarily manifest as excessive worrying. Hydroxyzine, 50 mg 3 times daily as needed, is added to this regimen, for breakthrough anxiety symptoms. Hydroxyzine is prescribed instead of a benzodiazepine to avoid potential addiction and abuse.

Continue to: Oral ziprasidone...

Oral ziprasidone, 20 mg/d twice daily, is initiated during 2 brief inpatient psychiatric admissions; however, it is successfully tapered within 1 week of discharge, in partnership with the ACT program.

In the 23 months after her discharge, Ms. D has had 1 ED visit and 2 brief inpatient psychiatric hospitalizations, which is markedly fewer encounters than she had in the 2 years before her LTSR placement. She has also lost an additional 30 lb since her LTSR discharge through a healthy diet and exercise.

Ms. D is now considering transitioning to living independently in the community through a residential supported housing program.

Bottom Line

Psychotic symptoms in patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD) are typically fleeting and mostly occur in the context of intense interpersonal conflicts and real or imagined abandonment. Long-term structured residence placement for patients with BPD can allow for careful formulation of a treatment plan, and help patients gain effective skills to cope with difficult family dynamics and other stressors, with the ultimate goal of gradual community integration.

Related Resource

- National Education Alliance for Borderline Personality Disorder. https://www.borderlinepersonalitydisorder.org.

Drug Brand Names

Benztropine • Cogentin

Haloperidol • Haldol

Hydrochlorothiazide • Microzide, HydroDiuril

Hydroxyzine • Vistaril

Levothyroxine • Synthroid,

Metoprolol ER • Toprol XL

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Pantoprazole • Protonix

Polyethylene glycol • MiraLax, Glycolax

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Senna • Senokot

Sertraline • Zoloft

Valproate • Depakene, Depakote

Ziprasidone • Geodon

1. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Hancock-Johnson E, Griffiths C, Picchioni M. A focused systematic review of pharmacological treatment for borderline personality disorder. CNS Drugs. 2017;31:345-356.

3. Starcevic V, Janca A. Pharmacotherapy of borderline personality disorder: replacing confusion with prudent pragmatism. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2018;31(1):69-73.

4. Stoffers J, Völlm BA, Rücker G, et al. Pharmacological interventions for borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;6:CD005653. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005653.pub2.

5. Stoffers-Winterling JM, Storebo OJ, Völlm BA, et al. Pharmacological interventions for borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;3:CD012956. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012956.

1. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Hancock-Johnson E, Griffiths C, Picchioni M. A focused systematic review of pharmacological treatment for borderline personality disorder. CNS Drugs. 2017;31:345-356.

3. Starcevic V, Janca A. Pharmacotherapy of borderline personality disorder: replacing confusion with prudent pragmatism. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2018;31(1):69-73.

4. Stoffers J, Völlm BA, Rücker G, et al. Pharmacological interventions for borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;6:CD005653. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005653.pub2.

5. Stoffers-Winterling JM, Storebo OJ, Völlm BA, et al. Pharmacological interventions for borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;3:CD012956. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012956.

Polypharmacy in older adults

Mrs. B, age 66, presents to the emergency department with altered mental status, impaired gait, and tremors. Her son says she has had these symptoms for 3 days. He adds that she has been experiencing more knee pain than usual, and began taking naproxen, 220 mg twice daily, approximately 1 week ago.

Mrs. B’s medical history includes coronary artery disease (CAD), gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), hip fracture, osteoarthritis, and osteoporosis. She also has a history of insomnia and bipolar disorder.

Further, Mrs. B reports that 2 months ago, after watching a television program about mental health, she began taking ginkgo biloba, 60 mg/d by mouth for “memory,” and kava kava, 100 mg by mouth 3 times a day for “anxiety.” She did not tell her physician or pharmacist that she began using these supplements because she believes that “natural supplements wouldn’t affect her prescription medications.”

In addition to naproxen, gingko biloba, and kava kava, Mrs. B takes the following medications orally:

Mrs. B’s blood pressure is 132/74 mm Hg (at goal for her age) and her laboratory workup is unremarkable, except for the following results: serum creatinine level of 1.1 mg/dL, blood urea nitrogen/serum creatinine ratio of 40, and creatinine clearance rate of approximately 85 mL/min. An electrocardiogram shows normal sinus rhythm with a QTc of 489 ms. A lithium serum concentration level, drawn randomly, is 1.6 mEq/mL, suggesting lithium toxicity.

Although there is no consensus definition of polypharmacy, the most commonly referenced is concurrent use of ≥5 medications.1 During the last 2 decades, the percentage of adults who report receiving polypharmacy has markedly increased, from 8.2% to 15%.2 Geriatric patients, defined as those age >65, typically receive ≥5 prescription medications.2 Polypharmacy is associated with increased1:

- mortality

- adverse drug reactions

- falls

- length of hospital stay

- readmission rates.

Older adults are particularly vulnerable to the negative outcomes associated with polypharmacy because both increasing age and number of medications received are positively correlated with the risk of adverse events.3 However, the use of multiple medications may be clinically appropriate and necessary in patients with multiple chronic conditions. Recent research suggests that in addition to prescription medications, over-the-counter (OTC) medications and dietary supplements also pose polypharmacy concerns for geriatric patients.3 Here we discuss the risks of OTC medications and dietary supplements for older patients who may be receiving polypharmacy, and highlight specific agents and interactions to watch for in these individuals based on Mrs. B’s case.

Continue to: Factors that increase the risks of OTC medications

Factors that increase the risks of OTC medications

Although older adults account for only 15% of the present population, they purchase 40% of all OTC medications.4 These patients may inadvertently use OTC medications containing unnecessary or potentially harmful active ingredients because of unfamiliarity with the specific product, variability among products, or decreased health literacy. According to research presented at a 2010 Institute of Medicine Workshop on Safe Use Initiative and Health Literacy, many patients have a limited understanding of OTC medication indications and therapeutic duplication.5 For example, researchers found that almost 70% of patients thought they could take 2 products containing the same ingredient.5 Most patients were not able to determine the active ingredients or maximum daily dose of an OTC medication. Patients who were older, had lower literacy, or were African American were more likely to misunderstand medication labeling.5 Additional literature suggests that up to 20% of medical admissions can be attributed to adverse effects of OTC medications.6

Misconceptions regarding dietary supplements

The use of alternative and complementary medicine also is on the rise among geriatric patients.7-9 A recent study found that 70% of older adults in the United States consumed at least 1 dietary supplement in the past 30 days, with 29% consuming ≥4 natural products. Women consumed twice as many supplements as men.10

The perceived safety of natural medicines and dietary supplements is a common and potentially dangerous misconception.11 Because patients typically assume dietary supplements are safe, they often do not report their use to their clinicians, especially if clinicians do not explicitly ask them about supplement use.12 This is especially concerning because the FDA does not have the authority to review or regulate natural medicines or dietary supplements.13,14

With no requirements or regulations regarding quality control of these products, the obvious question is: “How do patients know what they’re ingesting?” The uncertainty regarding the true composition of dietary supplements is a cause for concern because federal regulations do not provide a standard way to verify the purity, quality, and safety. As a result, there is a dearth of information regarding drug–dietary supplement interactions and drug–dietary supplement–disease state interactions.8,15

What to watch for

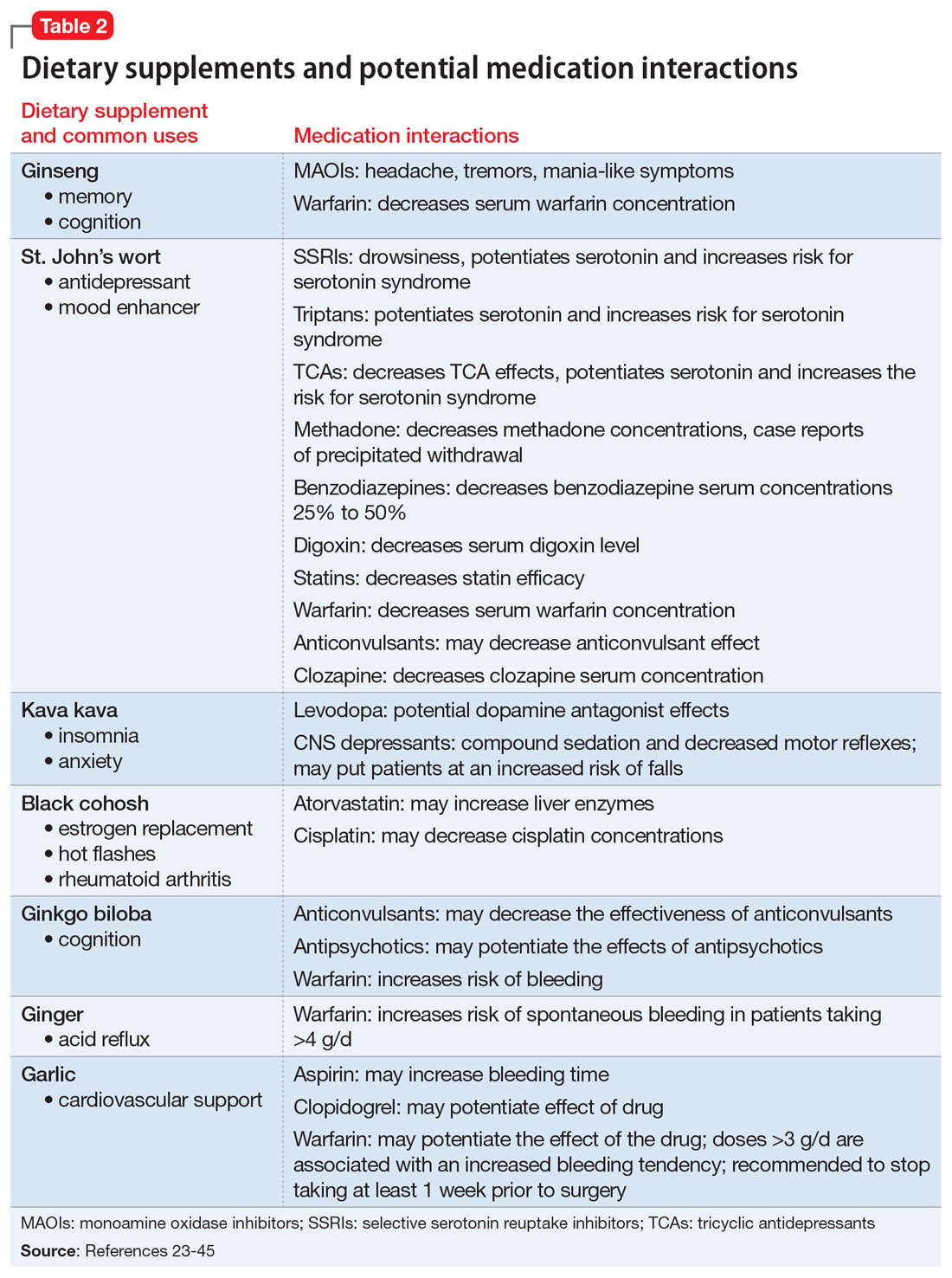

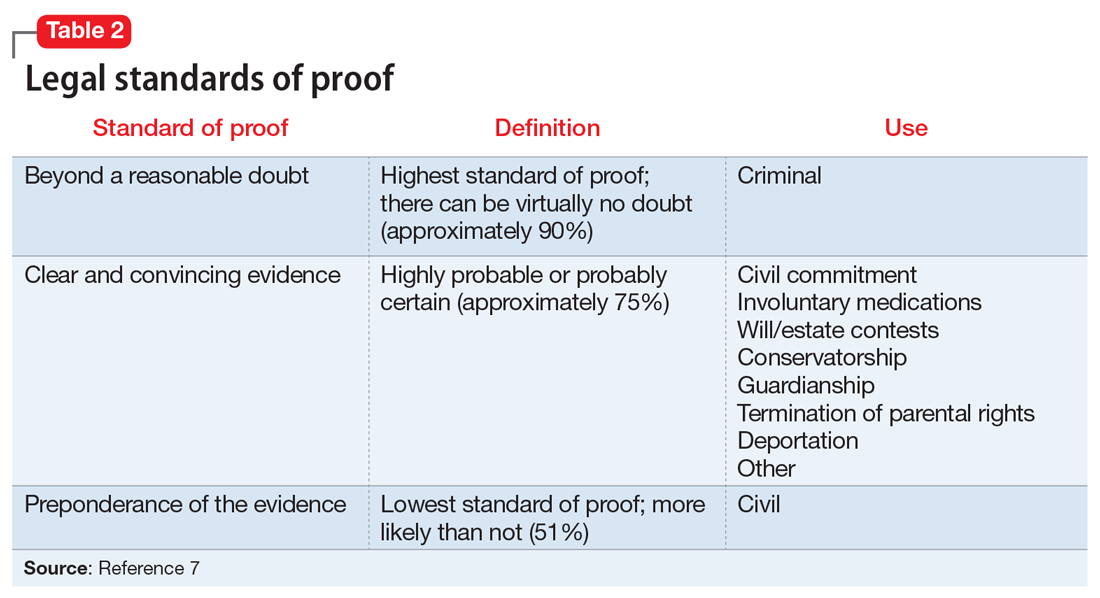

Table 116-22 outlines OTC medication classes and potential medication and/or disease state interactions. Table 223-45 outlines potential interactions between select dietary supplements, medications, and disease states. Here we discuss several of these potential interactions based on the medications that Mrs. B was taking.

Continue to: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). All OTC NSAIDs, except aspirin and salicylates, increase the risk for lithium toxicity by decreasing glomerular filtration rate and promoting lithium reabsorption in the kidneys.16 Additionally, NSAIDs increase the risk of developing gastric ulcers and may initiate or exacerbate GERD by suppressing gastric prostaglandin synthesis. Gastric prostaglandins facilitate the formation of a protective lipid-layer in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract.18,46-48 For Mrs. B, the naproxen she was taking resulted in lithium toxicity.

Ginkgo biloba is a plant used most commonly for its reported effect on memory. However, many drug–dietary supplement interactions have been associated with ginkgo biloba that may pose a problem for geriatric patients who receive polypharmacy.49 Mrs. B may have experienced decreased effectiveness of omeprazole and increased sedation or orthostatic hypotension with trazodone.

Kava kava is a natural sedative that can worsen cognition, increase the risk of falls, and potentially cause hepatotoxicity.50 The sedative effects of kava kava are thought to be a direct result of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) modulation via the blockage of voltage-gated sodium ion channels.51 In Mrs. B’s case, when used in combination with diphenhydramine and trazodone, kava kava had the potential to further increase her risk of sedation and falls.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease medications. Older adults may be at an increased risk of GERD due to diseases that affect the esophagus and GI tract, such as diabetes, Parkinson’s disease, and Alzheimer’s disease. Medications may also contribute to gastric reflux by loosening the esophageal tone. Nitrates, benzodiazepines, anticholinergics, antidepressants, and lidocaine have been implicated in precipitating or exacerbating GERD.52

Numerous OTC products can be used to treat heartburn. Calcium carbonate supplements are typically recommended as first-line agents to treat occasional heartburn; histamine-2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs) and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) generally are reserved for patients who experience heartburn more frequently.47 Per the American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults, H2RAs were removed from the “avoid” list for patients with dementia or cognitive impairment due to a lack of strong evidence; however, H2RAs remain on the “avoid” list for patients with delirium.17 Low-dose H2RAs can be used safely in geriatric patients who have renal impairment. Although PPIs are not listedon the Beers Criteria, they have been associated with an increased risk of dementia, osteoporosis, and infections.53,54 There is robust evidence to support bone loss and fractures associated with chronic use of PPIs. However, the data linking PPI use and dementia is controversial due to multiple confounders identified in the studies, such as concomitant use of benzodiazepines.48 PPIs should be prescribed sparingly and judiciously in geriatric patients, and the need for continued PPI therapy should frequently be reassessed.48 Mrs. B’s use of omeprazole, a PPI, may put her at an increased risk for hip fracture compounded by an elevated fall risk associated with other medications she was taking.

Continue to: Trazodone

Trazodone causes sedative effects via anti-alpha 1 activity, which is thought to be responsible for orthostasis and may further increase the risk of falls.51 Mrs. B’s use of trazodone may have increased her risk of sedation and falls.

Antihistaminergic medications are associated with sedation, confusion, cognitive dysfunction, falls, and delirium in geriatric patients. Medications that act on histamine receptors can be particularly detrimental in the geriatric population because of their decreased clearance, smaller volume of distribution, and decreased tolerance.17,18

Anticholinergic medications. Although atropine and benztropine are widely recognized as anticholinergic agents, other medications, such as digoxin, paroxetine, and colchicine, also demonstrate anticholinergic activity that can cause problematic central and peripheral effects in geriatric patients.55 Central anticholinergic inhibition can lead to reduced cognitive function and impairments in attention and short-term memory. The peripheral effects of anticholinergic medications are similar to those of antihistamines and may include, but are not limited to, dry eyes and mouth via increased inhibition of acetylcholine-mediated muscle contraction of salivary glands.55 These effects can be compounded by the use of OTC medications that exhibit anticholinergic activity.

Diphenhydramine causes sedation through its activity on cholinergic and histaminergic receptors. Patients may not be aware that many OTC cough-and-cold combination products (such as NyQuil, Theraflu, etc.) and OTC nighttime analgesic products (such as Tylenol PM, Aleve PM, Motrin PM, etc.) contain diphenhydramine. For a geriatric patient, such as Mrs. B, diphenhydramine may increase the risk of falls and worsen cognition.

Teach patients to disclose everything they take

Polypharmacy can be detrimental to older patients’ health due to the increased risk of toxicity caused by therapeutic duplication, drug–drug interactions, and drug-disease interactions. Most patients are unable to navigate the nuances of medication indications, maximum dosages, and therapeutic duplications. Older adults frequently take OTC medications and have the greatest risk of developing adverse effects from these medications due to decreased renal and hepatic clearance, increased drug sensitivity, and decreased volume of distribution. Dietary supplements pose a unique risk because they are not FDA-regulated and their purity, quality, and content cannot be verified. Educating patients and family members about the importance of reporting all their prescription medications, OTC medications, and dietary supplements to their pharmacists and clinicians is critical in order to identify and mitigate the risks associated with polypharmacy in geriatric patients.

Continue to: CASE

CASE CONTINUED

Mrs. B is diagnosed with lithium toxicity due to a drug–drug interaction with naproxen. Her lithium is held, and IV fluids are administered. Her symptoms resolve over the next few days. Mrs. B and her son are taught about the interaction between lithium and NSAIDs, and she is counseled to avoid all OTC NSAIDs other than aspirin. Her clinician recommends taking acetaminophen because it will not interact with her medications and is the recommended OTC treatment for mild or moderate pain in geriatric patients.17,56

Next, the clinician addresses Mrs. B’s GERD. Although Mrs. B had been taking PPIs twice daily, her physician recommends decreasing the omeprazole frequency to once daily to minimize adverse effects and pill burden. She also decreases Mrs. B’s aspirin from 325 to 81 mg/d because evidence suggests that when used to prevent CAD, lower-dose aspirin is effective as high-dose aspirin and has fewer adverse effects.57 Finally, she advises Mrs. B to stop taking ginkgo biloba and kava kava and to always check with her primary care physician or pharmacist before beginning any new medication, dietary supplement, or vitamin.

Mrs. B agrees to first check with her clinicians before following advice from mass media. A follow-up appointment is scheduled for 2 weeks to assess renal function, a lithium serum concentration, and adherence to her simplified medication regimen.

Related Resources

- US Department of Health and Human Services. National Institutes of Health. MedlinePlus. Herbs and supplements. https://medlineplus.gov/druginfo/herb_All.html.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. https://nccih.nih.gov/.

Drug Brand Names

Atorvastatin • Lipitor

Atropine • Atropen

Benztropine • Cogentin

Clozapine • Clozaril

Clopidogrel • Plavix

Colchicine • Colcrys, Gloperba

Digoxin • Cardoxin, Digitek

Lidocaine • Lidoderm, Xylocaine Viscous

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Methadone • Methadose

Morphine • Kadian, Morphabond

Paroxetine • Paxil

Trazodone • Desyrel

Warfarin • Coumadin, Jantoven

1. Masnoon N, Shakib S, Kalisch-Ellett, et al. What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17:230.

2. Kantor ED, Rehm CD, Haas JS, et al. Trends in prescription drug use among adults in the United States from 1999-2012. JAMA. 2015;314(17):1818-1831.

3. Maher RL, Hanlon J, Hajjar ER. Clinical consequences of polypharmacy in elderly. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13(1):57-65.

4. Maiese DR. Healthy People 2010-leading health indicators for women. Womens Health Issues. 2002;12(4):155-164.

5. National Academy of Sciences. Institute of Medicine (US) Roundtable on Health Literacy. The Safe Use Initiative and Health Literacy: workshop summary. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK209756/. Published 2010. Accessed January 22, 2020.

6. Caranasos GJ, Stewart RB, Cluff LE. Drug-induced illness leading to hospitalisation. JAMA. 1974;228(6):713-717.

7. Agbabiaka T. Prevalence of drug–herb and drug-supplement interactions in older adults: a cross-sectional survey. Br J Gen Pract. 2018;68(675):e711-e717. doi: 10.3399/bjgp18X699101.

8. Agbabiaka T, Wider B, Watson L, et al. Concurrent use of prescription drugs and herbal medicinal products in older adults: a systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2017;34(12):891-905.

9. de Souza Silva JE, Santos Souza CA, da Silva TB, et al. Use of herbal medicines by elderly patients: a systematic review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2014;59(2):227-233.

10. Gahche J, Bailey RL, Potischman N, et al. Dietary supplement use was very high among older adults in the United States in 2011-2014. J Nutr. 2017;147(10):1968-1976.

11. Nisly NL, Gryzlak BM, Zimmerman MB et al. Dietary supplement polypharmacy: an unrecognized public health problem? Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2010;7(1):107-113.

12. Kennedy J, Wang CC, Wu CH. Patient disclosure about herb and supplement use among adults in the US. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2008;5(4):451-456.

13. Dickinson A. History and overview of DSHEA. Fitoterapia. 2011;82(1):5-10.

14. Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994. Public Law 103-417,103rd Congress. https://www.congress.gov/bill/103rd-congress/senate-bill/784. Accessed February 20, 2020.

15. US Department of Health & Human Services. National Institute on Aging. Dietary supplements. https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/dietary-supplements. Reviewed November 30, 2017. Accessed January 22, 2020.

16. Ragheb M. The clinical significance of lithium-nonsteroidal. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1990;10(5):350-354.

17. 2019 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2019 Updated AGS Beers Criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(4):674-694.

18. Cho H, Myung J, Suh HS, et al. Antihistamine use and the risk of injurious falls or fracture in elderly patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2018;29(10):2163-2170.

19. Manlucu J, Tonelli M, Ray JG, et al. Dose-reducing H2 receptor antagonists in the presence of low glomerular filtration rate: a systematic review of the evidence. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20(11):2376-2384.

20. Sudafed [package insert]. Fort Washington, PA: McNeil Consumer Healthcare Division; 2018.

21. US National Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem Compound Summary: Dextromethorphan; CID=5360696. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/5360696. Accessed January 22, 2020.

22. Hedya SA, Swoboda HD. Lithium toxicity. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499992/. Updated August 14, 2019. Accessed January 22, 2020.

23. US Department of Health & Human Services. National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Herb-drug interactions: what the science says. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/providers/digest/herb-drug-interactions-science. Published September 2015. Accessed January 22, 2020.

24. Shader RI, Greenblatt DJ. Bees, ginseng and MAOIs revisited. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1988;8(4):235.

25. Chua YT. Interaction between warfarin and Chinese herbal medicines. Singapore Med J. 2015;56(1):11-18.

26. Bonetto N, Santelli L, Battistin L, et al. Serotonin syndrome and rhabdomyolysis induced by concomitant use of triptans, fluoxetine and hypericum. Cephalalgia. 2007;27(12):1421-1423.

27. Henderson L, Yue QY, Bergquist C, et al. St John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum): drug interactions and clinical outcomes. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;54(4):349-356.

28. Johne A, Schmider J, Brockmöller J, et al. Decreased plasma levels of amitriptyline and its metabolites on comedication with an extract from St John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum). J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;22(1):46-54.

29. Eich-Höchli D, Oppliger R, Golay KP, et al. Methadone maintenance treatment and St John’s wort: a case report. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2003;36(1):35-37.

30. Johne A, Brockmöller J, Bauer S, et al. Pharmacokinetic interaction of digoxin with an herbal extract from St John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum). Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1999;66(4):338-345.

31. Andrén L, Andreasson A, Eggertsen R. Interaction between a commercially available St John’s wort product (Movina) and atorvastatin in patients with hypercholesterolemia. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63(10):913-916.

32. Van Strater AC. Interaction of St John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum) with clozapine. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;27(2):121-124.

33. Nöldner M, Chatterjee SS. Inhibition of haloperidol-induced catalepsy in rats by root extracts from Piper methysticum F. Phytomedicine. 1999;6(4):285-286.

34. Boerner RJ, Klement S. Attenuation of neuroleptic-induced extrapyramidal side effects by kava special extract WS 1490. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2004;154(21-22):508-510.

35. Schelosky L, Raffauf C, Jendroska K, et al. Kava and dopamine antagonism. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1995;58(5):639-640.

36. Singh YN. Potential for interaction of kava and St. John’s wort with drugs. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;100(1-2):108-113.

37. Patel NM, Derkits R. Possible increase in liver enzymes secondary to atorvastatin and black cohosh administration. J Pharm Prac. 2007;20(4):341-346.

38. Rockwell S, Liu Y, Higgins SA. Alteration of the effects of cancer therapy agents on breast cancer cells by the herbal medicine black cohosh. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;90(3):233-239.

39. Granger AS. Ginkgo biloba precipitating epileptic seizures. Age Ageing. 2001;30(6):523-525.

40. Mohutsky MA, Anderson GD, Miller JW, et al. Ginkgo biloba: evaluation of CYP2C9 drug interactions in vitro and in vivo. Am J Ther. 2006;13(1):24-31.

41. Zhang XY, Zhou DF, Zhang PY, et al. A double-blind, placebo controlled trial of extract of Ginkgo biloba added to haloperidol in treatment-resistant patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(11):878-883.

42. Atmaca M, Tezcan E, Kuloglu M, et al. The effect of extract of ginkgo biloba addition to olanzapine on therapeutic effect and antioxidant enzyme levels in patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59(6):652-656.

43. Doruk A, Uzun O, Ozsahin A. A placebo-controlled study of extract of ginkgo biloba added to clozapine in patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(4):223-237.

44. Vaes LP. Interactions of warfarin with garlic, ginger, ginkgo, or ginseng: nature of the evidence. Ann Pharmacother. 2000;34(12):1478-1482.

45. Kanji S, Seely D, Yazdi F, et al. Interactions of commonly used dietary supplements with cardiovascular drugs: a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2012;1:26.

46. Wallace JL. Pathogenesis of NSAID-induced gastroduodenal mucosal injury. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;15(5):691-703.

47. Triadafilopoulos G, Sharma R. Features of symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease in elderly patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92(11):2007-2011.

48. Haastrup PF, Thompson W, Søndergaard J, et al. Side effects of long-term proton pump inhibitor use: a review. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2018;123(2):114-121.

49. Diamond BJ, Bailey MR. Ginkgo biloba: indications, mechanisms and safety. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2013;36:73-83.

50. White CM. The pharmacology, pharmacokinetics, efficacy, and adverse events associated with kava. J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;58(11):1396-1405.

51. Gleitz J, Beile A, Peters T. (+/-)-Kavain inhibits veratridine-activated voltage-dependent Na(+)-channels in synaptosomes prepared from rat cerebral cortex. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34(9):1133-1138.

52. Kahrilas PJ. Gastroesophageal reflux disease and its complications. In: Feldman M, ed. Sleisenger & Fordtran’s Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders Company; 1998:498-516.

53. Haenisch B, von Holt K, Wiese B, et al. Risk of dementia in elderly patients with the use of proton pump inhibitors. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015;265(5):419-428.

54. Sheen E, Triadafilopoulos G. Adverse effects of long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56(4):931-950.

55. Pitkälä KH, Suominen MH, Bell JS, et al. Herbal medications and other dietary supplements. A clinical review for physicians caring for older people. Ann Medicine. 2016;48(8):586-602.

56. American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Osteoarthritis Guidelines. Recommendations for the medical management of osteoarthritis of the hip and knee: 2000 update. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43(9):1905-1915.

57. Vandvik PO, Lincoff AM, Core JM, et al. Primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease: Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e637S-e668S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2306.

Mrs. B, age 66, presents to the emergency department with altered mental status, impaired gait, and tremors. Her son says she has had these symptoms for 3 days. He adds that she has been experiencing more knee pain than usual, and began taking naproxen, 220 mg twice daily, approximately 1 week ago.

Mrs. B’s medical history includes coronary artery disease (CAD), gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), hip fracture, osteoarthritis, and osteoporosis. She also has a history of insomnia and bipolar disorder.

Further, Mrs. B reports that 2 months ago, after watching a television program about mental health, she began taking ginkgo biloba, 60 mg/d by mouth for “memory,” and kava kava, 100 mg by mouth 3 times a day for “anxiety.” She did not tell her physician or pharmacist that she began using these supplements because she believes that “natural supplements wouldn’t affect her prescription medications.”

In addition to naproxen, gingko biloba, and kava kava, Mrs. B takes the following medications orally:

Mrs. B’s blood pressure is 132/74 mm Hg (at goal for her age) and her laboratory workup is unremarkable, except for the following results: serum creatinine level of 1.1 mg/dL, blood urea nitrogen/serum creatinine ratio of 40, and creatinine clearance rate of approximately 85 mL/min. An electrocardiogram shows normal sinus rhythm with a QTc of 489 ms. A lithium serum concentration level, drawn randomly, is 1.6 mEq/mL, suggesting lithium toxicity.

Although there is no consensus definition of polypharmacy, the most commonly referenced is concurrent use of ≥5 medications.1 During the last 2 decades, the percentage of adults who report receiving polypharmacy has markedly increased, from 8.2% to 15%.2 Geriatric patients, defined as those age >65, typically receive ≥5 prescription medications.2 Polypharmacy is associated with increased1:

- mortality

- adverse drug reactions

- falls

- length of hospital stay

- readmission rates.

Older adults are particularly vulnerable to the negative outcomes associated with polypharmacy because both increasing age and number of medications received are positively correlated with the risk of adverse events.3 However, the use of multiple medications may be clinically appropriate and necessary in patients with multiple chronic conditions. Recent research suggests that in addition to prescription medications, over-the-counter (OTC) medications and dietary supplements also pose polypharmacy concerns for geriatric patients.3 Here we discuss the risks of OTC medications and dietary supplements for older patients who may be receiving polypharmacy, and highlight specific agents and interactions to watch for in these individuals based on Mrs. B’s case.

Continue to: Factors that increase the risks of OTC medications

Factors that increase the risks of OTC medications

Although older adults account for only 15% of the present population, they purchase 40% of all OTC medications.4 These patients may inadvertently use OTC medications containing unnecessary or potentially harmful active ingredients because of unfamiliarity with the specific product, variability among products, or decreased health literacy. According to research presented at a 2010 Institute of Medicine Workshop on Safe Use Initiative and Health Literacy, many patients have a limited understanding of OTC medication indications and therapeutic duplication.5 For example, researchers found that almost 70% of patients thought they could take 2 products containing the same ingredient.5 Most patients were not able to determine the active ingredients or maximum daily dose of an OTC medication. Patients who were older, had lower literacy, or were African American were more likely to misunderstand medication labeling.5 Additional literature suggests that up to 20% of medical admissions can be attributed to adverse effects of OTC medications.6

Misconceptions regarding dietary supplements

The use of alternative and complementary medicine also is on the rise among geriatric patients.7-9 A recent study found that 70% of older adults in the United States consumed at least 1 dietary supplement in the past 30 days, with 29% consuming ≥4 natural products. Women consumed twice as many supplements as men.10

The perceived safety of natural medicines and dietary supplements is a common and potentially dangerous misconception.11 Because patients typically assume dietary supplements are safe, they often do not report their use to their clinicians, especially if clinicians do not explicitly ask them about supplement use.12 This is especially concerning because the FDA does not have the authority to review or regulate natural medicines or dietary supplements.13,14

With no requirements or regulations regarding quality control of these products, the obvious question is: “How do patients know what they’re ingesting?” The uncertainty regarding the true composition of dietary supplements is a cause for concern because federal regulations do not provide a standard way to verify the purity, quality, and safety. As a result, there is a dearth of information regarding drug–dietary supplement interactions and drug–dietary supplement–disease state interactions.8,15

What to watch for

Table 116-22 outlines OTC medication classes and potential medication and/or disease state interactions. Table 223-45 outlines potential interactions between select dietary supplements, medications, and disease states. Here we discuss several of these potential interactions based on the medications that Mrs. B was taking.

Continue to: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). All OTC NSAIDs, except aspirin and salicylates, increase the risk for lithium toxicity by decreasing glomerular filtration rate and promoting lithium reabsorption in the kidneys.16 Additionally, NSAIDs increase the risk of developing gastric ulcers and may initiate or exacerbate GERD by suppressing gastric prostaglandin synthesis. Gastric prostaglandins facilitate the formation of a protective lipid-layer in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract.18,46-48 For Mrs. B, the naproxen she was taking resulted in lithium toxicity.

Ginkgo biloba is a plant used most commonly for its reported effect on memory. However, many drug–dietary supplement interactions have been associated with ginkgo biloba that may pose a problem for geriatric patients who receive polypharmacy.49 Mrs. B may have experienced decreased effectiveness of omeprazole and increased sedation or orthostatic hypotension with trazodone.

Kava kava is a natural sedative that can worsen cognition, increase the risk of falls, and potentially cause hepatotoxicity.50 The sedative effects of kava kava are thought to be a direct result of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) modulation via the blockage of voltage-gated sodium ion channels.51 In Mrs. B’s case, when used in combination with diphenhydramine and trazodone, kava kava had the potential to further increase her risk of sedation and falls.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease medications. Older adults may be at an increased risk of GERD due to diseases that affect the esophagus and GI tract, such as diabetes, Parkinson’s disease, and Alzheimer’s disease. Medications may also contribute to gastric reflux by loosening the esophageal tone. Nitrates, benzodiazepines, anticholinergics, antidepressants, and lidocaine have been implicated in precipitating or exacerbating GERD.52

Numerous OTC products can be used to treat heartburn. Calcium carbonate supplements are typically recommended as first-line agents to treat occasional heartburn; histamine-2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs) and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) generally are reserved for patients who experience heartburn more frequently.47 Per the American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults, H2RAs were removed from the “avoid” list for patients with dementia or cognitive impairment due to a lack of strong evidence; however, H2RAs remain on the “avoid” list for patients with delirium.17 Low-dose H2RAs can be used safely in geriatric patients who have renal impairment. Although PPIs are not listedon the Beers Criteria, they have been associated with an increased risk of dementia, osteoporosis, and infections.53,54 There is robust evidence to support bone loss and fractures associated with chronic use of PPIs. However, the data linking PPI use and dementia is controversial due to multiple confounders identified in the studies, such as concomitant use of benzodiazepines.48 PPIs should be prescribed sparingly and judiciously in geriatric patients, and the need for continued PPI therapy should frequently be reassessed.48 Mrs. B’s use of omeprazole, a PPI, may put her at an increased risk for hip fracture compounded by an elevated fall risk associated with other medications she was taking.

Continue to: Trazodone

Trazodone causes sedative effects via anti-alpha 1 activity, which is thought to be responsible for orthostasis and may further increase the risk of falls.51 Mrs. B’s use of trazodone may have increased her risk of sedation and falls.

Antihistaminergic medications are associated with sedation, confusion, cognitive dysfunction, falls, and delirium in geriatric patients. Medications that act on histamine receptors can be particularly detrimental in the geriatric population because of their decreased clearance, smaller volume of distribution, and decreased tolerance.17,18

Anticholinergic medications. Although atropine and benztropine are widely recognized as anticholinergic agents, other medications, such as digoxin, paroxetine, and colchicine, also demonstrate anticholinergic activity that can cause problematic central and peripheral effects in geriatric patients.55 Central anticholinergic inhibition can lead to reduced cognitive function and impairments in attention and short-term memory. The peripheral effects of anticholinergic medications are similar to those of antihistamines and may include, but are not limited to, dry eyes and mouth via increased inhibition of acetylcholine-mediated muscle contraction of salivary glands.55 These effects can be compounded by the use of OTC medications that exhibit anticholinergic activity.

Diphenhydramine causes sedation through its activity on cholinergic and histaminergic receptors. Patients may not be aware that many OTC cough-and-cold combination products (such as NyQuil, Theraflu, etc.) and OTC nighttime analgesic products (such as Tylenol PM, Aleve PM, Motrin PM, etc.) contain diphenhydramine. For a geriatric patient, such as Mrs. B, diphenhydramine may increase the risk of falls and worsen cognition.

Teach patients to disclose everything they take