User login

Dual vs Triple Therapy Following ACS or PCI in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation

Study Overview

Objective. To compare the benefit of apixaban with a vitamin K antagonist and compare aspirin with placebo in patients with atrial fibrillation who had acute coronary syndrome or underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and were planning to take a P2Y12 inhibitor.

Design. Multicenter, international, open-label, prospective randomized controlled trial with a 2-by-2 factorial design.

Setting and participants. 4614 patients who had an acute coronary syndrome or had undergone PCI and were planning to take a P2Y12 inhibitor.

Intervention. Patients were assigned by means of an interactive voice-response system to receive apixaban or a vitamin K antagonist and to receive aspirin or matching placebo for 6 months.

Main outcome measures. The primary outcome was major or clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding. Secondary outcomes included death or hospitalization and a composite of ischemic events.

Main results. At 6 months, major or clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding had occurred in 10.5% of the patients receiving apixaban, as compared to 14.7% of those receiving a vitamin K antagonist (hazard ratio [HR], 0.69; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.58-0.81, P < 0.001 for both noninferiority and superiority), and in 16.1% of the patients receiving aspirin, as compared with 9.0% of those receiving placebo (HR 1.89; 95% CI, 1.59-2.24; P < 0.001). Patients in the apixaban group had a lower incidence of death or hospitalization than those in the vitamin K antagonist group (23.5% versus 27.4%; HR 0.83; 95% CI, 0.74-0.93; P = 0.002) and similar incidence of ischemic events.

Conclusion. Among patients with atrial fibrillation and recent acute coronary syndrome or PCI treated with a P2Y12 inhibitor, an antithrombotic regimen that included apixaban without aspirin resulted in less bleeding and fewer hospitalizations without significant differences in the incidence of ischemic events than the regimens that included a vitamin K antagonist, aspirin, or both.

Commentary

PCI is performed in about 20% of patients with atrial fibrillation. These patients require dual antiplatelet therapy to prevent ischemic events, combined with long-term anticoagulation to prevent stroke due to atrial fibrillation. Because the combination of anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy is associated with a higher risk of bleeding, balancing the risk and benefit of dual antiplatelet therapy and anticoagulation in this population is crucial.

Previous studies have assessed the risk and benefit associated with anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy. When warfarin plus clopidogrel (double therapy) was compared with warfarin, aspirin, and clopidogrel (triple therapy) in patients with acute coronary syndromes and stable ischemic coronary disease undergoing PCI, use of clopidogrel without aspirin (double therapy) was associated with a significant reduction in bleeding complications (19.4% versus 44.4%, HR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.26-0.20; P < 0.0001) without increasing thrombotic events.1 Recent studies have compared triple therapy with warfarin to double therapy using direct oral anticoagulants (DOAC). The PIONEER AF-PCI study, which compared low-dose rivaroxaban (15 mg once daily) plus a P2Y12 inhibitor to vitamin K antagonist plus dual antiplatelet therapy, found that the rates of clinically significant bleeding were lower in the low-dose rivaroxaban group compared to the triple-therapy group with a vitamin K antagonist (16.8% versus 26.7%; HR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.47-0.76; P < 0.001).2 Similarly, the RE-DUAL PCI studied dabigatran and showed that the dual therapy group with dabigatran had a lower incidence of major or clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding events during follow-up compared to triple therapy including a vitamin K antagonist (15.4% versus 26.9%; HR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.42-0.63; P < 0.001).3

In this context, Lopes at al investigated the clinical question of dual therapy versus triple therapy by performing a well-designed randomized clinical trial. In this trial with a 2-by-2 factorial design, the authors studied the effect of apixaban compared to vitamin K antagonist and the effect of aspirin compared to placebo. Major or clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding occurred in 10.5% of patients receiving apixaban, as compared to 14.7% of those receiving a vitamin K antagonist (HR 0.69; 95% CI, 0.58-0.81; P < 0.001). The incidence of major or clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding was higher in patients receiving aspirin than in those receiving placebo (16.1% versus 9.0%; HR, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.59-2.24; P < 0.001). Patients in the apixaban group had a lower incidence of death or hospitalization than those in the vitamin K antagonist group (23.5% versus 27.4%; HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.74-0.93; P = 0.002). The incidence of ischemic events was similar between the apixaban group and vitamin K antagonist group and between the aspirin group and placebo group.

The strengths of this current study include the large number of patients it enrolled. Taking the results from the PIONEER-AF, RE-DUAL PCI, and AUGUSTUS trials, it is clear that DOAC reduces the risk of bleeding compared to vitamin K antagonist. In addition, the AUGUSTUS trial was the first that evaluated the effect of aspirin in patients treated with DOAC and antiplatelet therapy. Aspirin was associated with increased risk of bleeding, with a similar rate of ischemic events compared to placebo.

The AUGUSTUS trial has several limitations. Although the incidence of ischemic events was similar between the apixaban group and the vitamin K antagonist group, the study was not powered to evaluate for individual ischemic outcomes. However, there was no clear evidence of an increase in harm. Since more than 90% of P2Y12 inhibitors used were clopidogrel, the safety and efficacy of combining apixaban with ticagrelor or prasugrel will require further study.

Applications for Clinical Practice

In patients with atrial fibrillation and a recent acute coronary syndrome or PCI treated with a P2Y12 inhibitor, dual therapy with a P2Y12 inhibitor and DOAC should be favored over a regimen that includes a vitamin K antagonist and/or aspirin.

—Taishi Hirai, MD, University of Missouri Medical Center, and John Blair, MD, University of Chicago Medical Center

1. Dewilde WJM, Oirbans T, Verheugt FWA, et al. Use of clopidogrel with or without aspirin in patients taking oral anticoagulant therapy and undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: an open-label, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9872):1107-1115.

2. Gibson CM, Mehran R, Bode C, et al. Prevention of bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing PCI. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2423-2434.

3. Cannon CP, Bhatt DL, Oldgren J, et al. Dual antithrombotic therapy with dabigatran after PCI in atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1513-1524.

Study Overview

Objective. To compare the benefit of apixaban with a vitamin K antagonist and compare aspirin with placebo in patients with atrial fibrillation who had acute coronary syndrome or underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and were planning to take a P2Y12 inhibitor.

Design. Multicenter, international, open-label, prospective randomized controlled trial with a 2-by-2 factorial design.

Setting and participants. 4614 patients who had an acute coronary syndrome or had undergone PCI and were planning to take a P2Y12 inhibitor.

Intervention. Patients were assigned by means of an interactive voice-response system to receive apixaban or a vitamin K antagonist and to receive aspirin or matching placebo for 6 months.

Main outcome measures. The primary outcome was major or clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding. Secondary outcomes included death or hospitalization and a composite of ischemic events.

Main results. At 6 months, major or clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding had occurred in 10.5% of the patients receiving apixaban, as compared to 14.7% of those receiving a vitamin K antagonist (hazard ratio [HR], 0.69; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.58-0.81, P < 0.001 for both noninferiority and superiority), and in 16.1% of the patients receiving aspirin, as compared with 9.0% of those receiving placebo (HR 1.89; 95% CI, 1.59-2.24; P < 0.001). Patients in the apixaban group had a lower incidence of death or hospitalization than those in the vitamin K antagonist group (23.5% versus 27.4%; HR 0.83; 95% CI, 0.74-0.93; P = 0.002) and similar incidence of ischemic events.

Conclusion. Among patients with atrial fibrillation and recent acute coronary syndrome or PCI treated with a P2Y12 inhibitor, an antithrombotic regimen that included apixaban without aspirin resulted in less bleeding and fewer hospitalizations without significant differences in the incidence of ischemic events than the regimens that included a vitamin K antagonist, aspirin, or both.

Commentary

PCI is performed in about 20% of patients with atrial fibrillation. These patients require dual antiplatelet therapy to prevent ischemic events, combined with long-term anticoagulation to prevent stroke due to atrial fibrillation. Because the combination of anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy is associated with a higher risk of bleeding, balancing the risk and benefit of dual antiplatelet therapy and anticoagulation in this population is crucial.

Previous studies have assessed the risk and benefit associated with anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy. When warfarin plus clopidogrel (double therapy) was compared with warfarin, aspirin, and clopidogrel (triple therapy) in patients with acute coronary syndromes and stable ischemic coronary disease undergoing PCI, use of clopidogrel without aspirin (double therapy) was associated with a significant reduction in bleeding complications (19.4% versus 44.4%, HR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.26-0.20; P < 0.0001) without increasing thrombotic events.1 Recent studies have compared triple therapy with warfarin to double therapy using direct oral anticoagulants (DOAC). The PIONEER AF-PCI study, which compared low-dose rivaroxaban (15 mg once daily) plus a P2Y12 inhibitor to vitamin K antagonist plus dual antiplatelet therapy, found that the rates of clinically significant bleeding were lower in the low-dose rivaroxaban group compared to the triple-therapy group with a vitamin K antagonist (16.8% versus 26.7%; HR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.47-0.76; P < 0.001).2 Similarly, the RE-DUAL PCI studied dabigatran and showed that the dual therapy group with dabigatran had a lower incidence of major or clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding events during follow-up compared to triple therapy including a vitamin K antagonist (15.4% versus 26.9%; HR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.42-0.63; P < 0.001).3

In this context, Lopes at al investigated the clinical question of dual therapy versus triple therapy by performing a well-designed randomized clinical trial. In this trial with a 2-by-2 factorial design, the authors studied the effect of apixaban compared to vitamin K antagonist and the effect of aspirin compared to placebo. Major or clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding occurred in 10.5% of patients receiving apixaban, as compared to 14.7% of those receiving a vitamin K antagonist (HR 0.69; 95% CI, 0.58-0.81; P < 0.001). The incidence of major or clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding was higher in patients receiving aspirin than in those receiving placebo (16.1% versus 9.0%; HR, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.59-2.24; P < 0.001). Patients in the apixaban group had a lower incidence of death or hospitalization than those in the vitamin K antagonist group (23.5% versus 27.4%; HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.74-0.93; P = 0.002). The incidence of ischemic events was similar between the apixaban group and vitamin K antagonist group and between the aspirin group and placebo group.

The strengths of this current study include the large number of patients it enrolled. Taking the results from the PIONEER-AF, RE-DUAL PCI, and AUGUSTUS trials, it is clear that DOAC reduces the risk of bleeding compared to vitamin K antagonist. In addition, the AUGUSTUS trial was the first that evaluated the effect of aspirin in patients treated with DOAC and antiplatelet therapy. Aspirin was associated with increased risk of bleeding, with a similar rate of ischemic events compared to placebo.

The AUGUSTUS trial has several limitations. Although the incidence of ischemic events was similar between the apixaban group and the vitamin K antagonist group, the study was not powered to evaluate for individual ischemic outcomes. However, there was no clear evidence of an increase in harm. Since more than 90% of P2Y12 inhibitors used were clopidogrel, the safety and efficacy of combining apixaban with ticagrelor or prasugrel will require further study.

Applications for Clinical Practice

In patients with atrial fibrillation and a recent acute coronary syndrome or PCI treated with a P2Y12 inhibitor, dual therapy with a P2Y12 inhibitor and DOAC should be favored over a regimen that includes a vitamin K antagonist and/or aspirin.

—Taishi Hirai, MD, University of Missouri Medical Center, and John Blair, MD, University of Chicago Medical Center

Study Overview

Objective. To compare the benefit of apixaban with a vitamin K antagonist and compare aspirin with placebo in patients with atrial fibrillation who had acute coronary syndrome or underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and were planning to take a P2Y12 inhibitor.

Design. Multicenter, international, open-label, prospective randomized controlled trial with a 2-by-2 factorial design.

Setting and participants. 4614 patients who had an acute coronary syndrome or had undergone PCI and were planning to take a P2Y12 inhibitor.

Intervention. Patients were assigned by means of an interactive voice-response system to receive apixaban or a vitamin K antagonist and to receive aspirin or matching placebo for 6 months.

Main outcome measures. The primary outcome was major or clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding. Secondary outcomes included death or hospitalization and a composite of ischemic events.

Main results. At 6 months, major or clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding had occurred in 10.5% of the patients receiving apixaban, as compared to 14.7% of those receiving a vitamin K antagonist (hazard ratio [HR], 0.69; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.58-0.81, P < 0.001 for both noninferiority and superiority), and in 16.1% of the patients receiving aspirin, as compared with 9.0% of those receiving placebo (HR 1.89; 95% CI, 1.59-2.24; P < 0.001). Patients in the apixaban group had a lower incidence of death or hospitalization than those in the vitamin K antagonist group (23.5% versus 27.4%; HR 0.83; 95% CI, 0.74-0.93; P = 0.002) and similar incidence of ischemic events.

Conclusion. Among patients with atrial fibrillation and recent acute coronary syndrome or PCI treated with a P2Y12 inhibitor, an antithrombotic regimen that included apixaban without aspirin resulted in less bleeding and fewer hospitalizations without significant differences in the incidence of ischemic events than the regimens that included a vitamin K antagonist, aspirin, or both.

Commentary

PCI is performed in about 20% of patients with atrial fibrillation. These patients require dual antiplatelet therapy to prevent ischemic events, combined with long-term anticoagulation to prevent stroke due to atrial fibrillation. Because the combination of anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy is associated with a higher risk of bleeding, balancing the risk and benefit of dual antiplatelet therapy and anticoagulation in this population is crucial.

Previous studies have assessed the risk and benefit associated with anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy. When warfarin plus clopidogrel (double therapy) was compared with warfarin, aspirin, and clopidogrel (triple therapy) in patients with acute coronary syndromes and stable ischemic coronary disease undergoing PCI, use of clopidogrel without aspirin (double therapy) was associated with a significant reduction in bleeding complications (19.4% versus 44.4%, HR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.26-0.20; P < 0.0001) without increasing thrombotic events.1 Recent studies have compared triple therapy with warfarin to double therapy using direct oral anticoagulants (DOAC). The PIONEER AF-PCI study, which compared low-dose rivaroxaban (15 mg once daily) plus a P2Y12 inhibitor to vitamin K antagonist plus dual antiplatelet therapy, found that the rates of clinically significant bleeding were lower in the low-dose rivaroxaban group compared to the triple-therapy group with a vitamin K antagonist (16.8% versus 26.7%; HR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.47-0.76; P < 0.001).2 Similarly, the RE-DUAL PCI studied dabigatran and showed that the dual therapy group with dabigatran had a lower incidence of major or clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding events during follow-up compared to triple therapy including a vitamin K antagonist (15.4% versus 26.9%; HR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.42-0.63; P < 0.001).3

In this context, Lopes at al investigated the clinical question of dual therapy versus triple therapy by performing a well-designed randomized clinical trial. In this trial with a 2-by-2 factorial design, the authors studied the effect of apixaban compared to vitamin K antagonist and the effect of aspirin compared to placebo. Major or clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding occurred in 10.5% of patients receiving apixaban, as compared to 14.7% of those receiving a vitamin K antagonist (HR 0.69; 95% CI, 0.58-0.81; P < 0.001). The incidence of major or clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding was higher in patients receiving aspirin than in those receiving placebo (16.1% versus 9.0%; HR, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.59-2.24; P < 0.001). Patients in the apixaban group had a lower incidence of death or hospitalization than those in the vitamin K antagonist group (23.5% versus 27.4%; HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.74-0.93; P = 0.002). The incidence of ischemic events was similar between the apixaban group and vitamin K antagonist group and between the aspirin group and placebo group.

The strengths of this current study include the large number of patients it enrolled. Taking the results from the PIONEER-AF, RE-DUAL PCI, and AUGUSTUS trials, it is clear that DOAC reduces the risk of bleeding compared to vitamin K antagonist. In addition, the AUGUSTUS trial was the first that evaluated the effect of aspirin in patients treated with DOAC and antiplatelet therapy. Aspirin was associated with increased risk of bleeding, with a similar rate of ischemic events compared to placebo.

The AUGUSTUS trial has several limitations. Although the incidence of ischemic events was similar between the apixaban group and the vitamin K antagonist group, the study was not powered to evaluate for individual ischemic outcomes. However, there was no clear evidence of an increase in harm. Since more than 90% of P2Y12 inhibitors used were clopidogrel, the safety and efficacy of combining apixaban with ticagrelor or prasugrel will require further study.

Applications for Clinical Practice

In patients with atrial fibrillation and a recent acute coronary syndrome or PCI treated with a P2Y12 inhibitor, dual therapy with a P2Y12 inhibitor and DOAC should be favored over a regimen that includes a vitamin K antagonist and/or aspirin.

—Taishi Hirai, MD, University of Missouri Medical Center, and John Blair, MD, University of Chicago Medical Center

1. Dewilde WJM, Oirbans T, Verheugt FWA, et al. Use of clopidogrel with or without aspirin in patients taking oral anticoagulant therapy and undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: an open-label, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9872):1107-1115.

2. Gibson CM, Mehran R, Bode C, et al. Prevention of bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing PCI. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2423-2434.

3. Cannon CP, Bhatt DL, Oldgren J, et al. Dual antithrombotic therapy with dabigatran after PCI in atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1513-1524.

1. Dewilde WJM, Oirbans T, Verheugt FWA, et al. Use of clopidogrel with or without aspirin in patients taking oral anticoagulant therapy and undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: an open-label, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9872):1107-1115.

2. Gibson CM, Mehran R, Bode C, et al. Prevention of bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing PCI. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2423-2434.

3. Cannon CP, Bhatt DL, Oldgren J, et al. Dual antithrombotic therapy with dabigatran after PCI in atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1513-1524.

Patient-Reported Outcomes in Multiple Sclerosis: An Overview

From the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy & Clinical Practice, Geisel School of Medicine, Hanover, NH (Ms. Manohar and Dr. Oliver), the Department of Community & Family Medicine, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, NH (Ms. Perkins, Ms. Laurion, and Dr. Oliver), and the Multiple Sclerosis Specialty Care Program, Concord Hospital, Concord, NH (Dr. Oliver).

Abstract

- Background: Patient-reported outcomes (PROs), including patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) and patient-reported experience measures (PREMs), can be used to assess perceived health status, functioning, quality of life, and experience of care. Complex chronic illnesses such as multiple sclerosis (MS) affect multiple aspects of health, and PROs can be applied in assessment and decision-making in MS care as well as in research pertaining to MS.

- Objective: To provide a general review of PROs, with a specific focus on implications for MS care.

- Methods: Evidence synthesis of available literature on PROs in MS care.

- Results: PROs (including PROMs and PREMs) have historically been utilized in research and are now being applied in clinical, improvement, and population health settings using learning health system approaches in many disease populations, including MS. Many challenges complicate the use of PROs in MS care, including reliability, validity, and interpretability of PROMs, as well as feasibility barriers due to time and financial constraints in clinical settings.

- Conclusion: PROs have the potential to better inform clinical care, empower patient-centered care, inform health care improvement efforts, and create the conditions for coproduction of health care services.

Keywords: PRO; PROM; patient-reported outcome measure; patient-reported experience measure; quality of life; patient-centered care.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a disabling, complex, chronic, immune-mediated disorder of the central nervous system (CNS). MS causes inflammatory and degenerative damage in the CNS, which disrupts signaling pathways.1 It is most commonly diagnosed in young adults and affects 2.3 million people worldwide.2 People with MS experience very different disease courses and a wide range of neurological symptoms, including visual, somatic, mental health, sensory, motor, and cognitive problems.1-3 Relapsing-remitting MS, the most common form, affects 85% of those with MS and is characterized by periods of relapse (exacerbation) and remission.1 Other forms of MS (primary progressive and secondary progressive MS) are characterized by progressive deterioration and worsening symptom severity without exacerbations. Disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) can reduce the frequency of exacerbations and disability progression, but unfortunately there is no cure for MS. Treatment is focused on increasing quality of life, minimizing disability, and maximizing wellness.

Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) describe the perceived health status, function, and/or experience of a person as obtained by direct self-report. Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) are validated PROs that can be used to inform clinical care,4 and have demonstrated effectiveness in improving patient-provider communication and decision-making.5-7 PROMs are currently used in some MS clinical trials to determine the impact of experimental interventions,8-10 and are also being used to inform and improve clinical care in some settings. Especially for persons with MS, they can provide individualized perspectives about health experience and outcomes.11 In more advanced applications, PROMs can be used to improve face-to-face collaborations between clinicians and patients and to inform patient-centered systems of care.12-14 PROMs can also be used to inform systems-level improvement for entire patient populations.15,16

In this article, we review current applications of PROs and PROMs in the care of persons with MS, as well as current limitations and barriers to their use.

At a recent visit to her neurologist, Marion reviews her health diary, in which she has been tracking her fatigue levels throughout the day and when she has to visit the bathroom. The PRO diary also helps her remember details that she might not otherwise be able to recall at the time of her clinic visit. They review the diary entrees together to develop a shared understanding of what Marion has been experiencing and identify trends in the PRO data. They discuss symptom management and use the PRO information from the diary to help guide adjustments to her physical therapy routine and medication regimen.

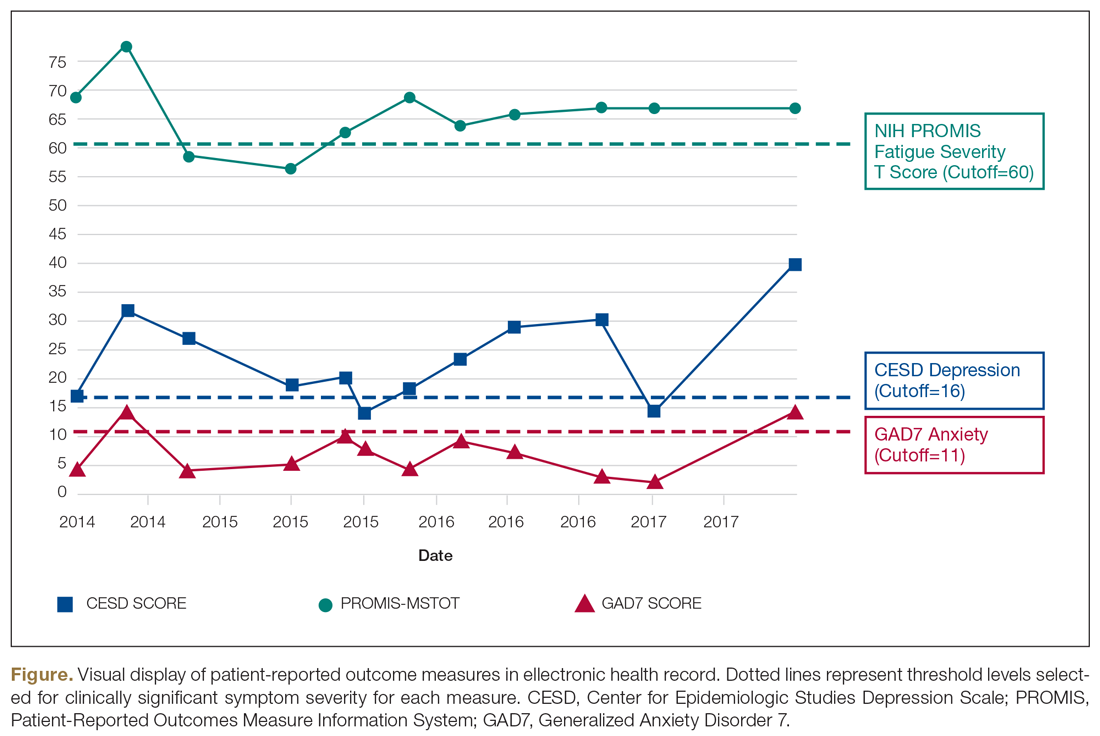

Part of Marion’s “PRO package” includes the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), a validated depression screening and symptom severity questionnaire that she completes every 3 months. Although she denies being depressed, she has noticed that her CES-D scores in recent months have been consistently increasing. This prompts a discussion about mental health in MS and a referral to work on depression with the MS mental health specialist. Marion and the mental health specialist use CES-D measures at baseline and during treatment to set a remission target and to track progress during treatment. Marion finds this helpful because she says it is hard for her to “wrap my hands around depression… it’s not something that there is a blood test or a MRI for.” Marion is encouraged by being able to see her CES-D scores change as her depression severity decreases, and this helps motivate her to keep engaged in treatment.

PROs and PROMs: General Applications

PROs are measures obtained directly from an individual without a priori interpretation by a clinician.9,17 PROs capture individual perspectives on symptoms, capability, disability, and health-related quality of life.9 With increasing emphasis on patient-centered care,18 individual perspectives and preferences elicited using PROMs may be able to inform better quality of care and patient-centered disease treatment and management.19-21

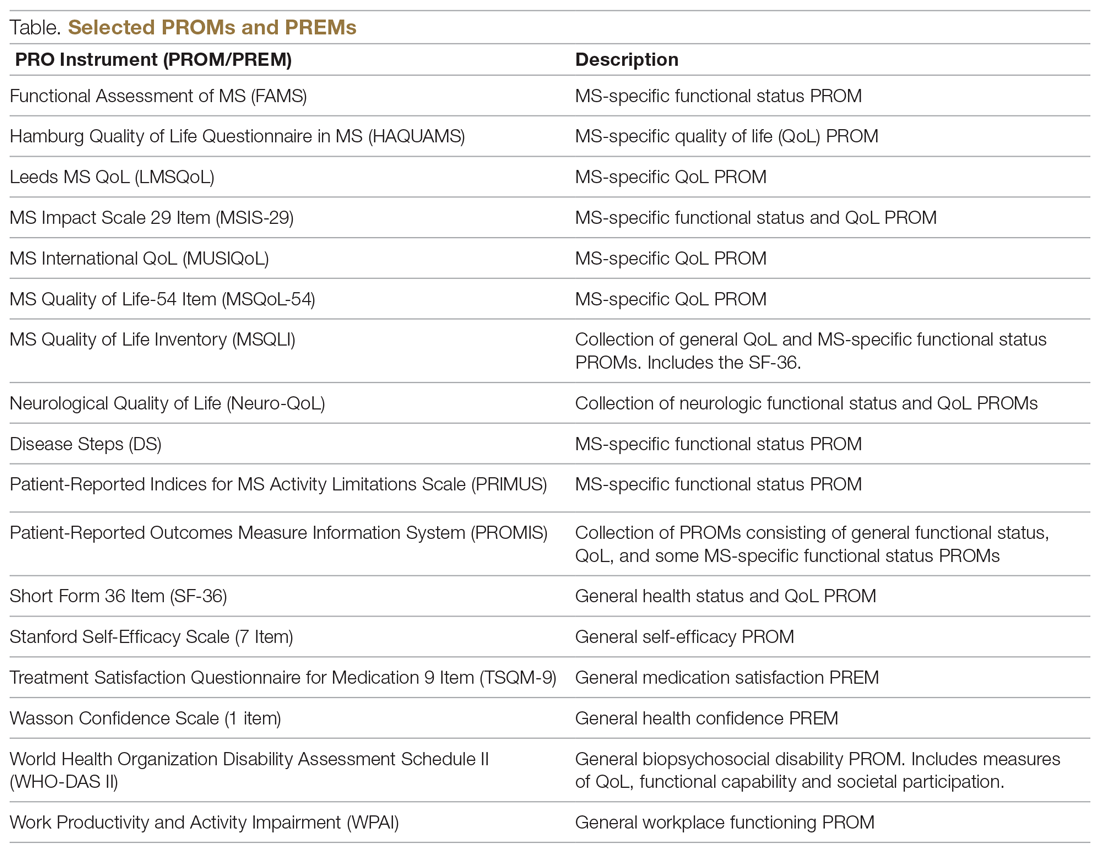

PROMs are standardized, validated questionnaires used to assess PROs and can be generic or condition-specific. Generic PROMs can be used in any patient population. The SF-3622 is a set of quality of life measures that assess perceived ability to complete physical tasks and routine activities, general health status, fatigue, social functioning, pain, and emotional and mental health.23 Condition-specific PROMs can be used for particular patient populations and are helpful in identifying changes in health status for a specific disease, disability, or surgery. For example, the PDQ-39 assesses 8 dimensions of daily living, functioning, and well-being for people with Parkinson’s disease.24

PROMs have been used in some MS clinical trials and research studies to determine the effectiveness of experimental treatments from the viewpoint of study participants.9,25,26 PROs can also be utilized in clinical care to facilitate communication of needs and track health outcomes,27 and can inform improvement in outcomes for health systems and populations. They can also be used to assess experience of care,28 encouraging a focus on high-quality outcomes through PRO-connected reimbursement mechanisms,29 and provide aggregate data to evaluate clinical practice, population health outcomes, and the effectiveness of public policies.27

Patient-reported experience measures (PREMs) assess patient satisfaction and experience of health care.30,31 CollaboRATE32 is a PREM that assesses the degree of shared decision-making occurring between patients and clinicians during clinical care. PREMs are currently used for assessing self-efficacy and in shared decision-making and health care improvement applications. PREMs have yet to be developed specifically for persons with MS.

PROMs in MS Care

Generic PROMs have shown that persons with MS are disproportionately burdened by poor quality of life.33-35 Other generic PROMs, like the SF-36,36 the Sickness Impact Profile,37 and versions of the Health Utilities Index,38 can be used to gather information on dysfunction and to determine quality and duration of life modified by MS-related dysfunction and disability. MS-specific PROMs are used to assess MS impairments, including pain, fatigue, cognition, sexual dysfunction, and depression.12,39-42 PROMs have also been used in MS clinical trials, including the Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale-29 (MSIS-29),43,44 the Leeds MS QoL (LMSQoL),45,46 the Functional Assessment of MS (FAMS),47 the Hamburg Quality of Life Questionnaire in MS (HAQUAMS),48 the MS Quality of Life-54 (MSQoL-54),49 the MS International QoL (MUSIQoL),50 and the Patient-Reported Indices for MS Activity Limitations Scale (PRIMUS).51

Condition-specific PROMs are more sensitive to changes in health status and functioning for persons with MS compared to generic PROMs. They are also more reliable during MS remission and relapse periods.44,52 For example, the SF-36 has floor and ceiling effects in MS populations—a high proportion of persons with MS are scored at the maximum or minimum levels of the scale, limiting discriminant capability.22 As a result, a “combined approach” using both generic and MS-specific measures is often recommended.53 Some MS PROMs (eg, MSQoL-54) include generic questions found in the SF-36 as well as additional MS-specific questions or scales.

The variety of PROMs available (see Table for a selected listing) introduces a significant challenge to using them—limited generalizability and difficulty comparing PROs across MS studies. Efforts to establish common PROMs have been undertaken to address this problem.54 The National Institute of Neurologicical Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) sponsored the development of a neurological quality of life battery, the Neuro-QOL.55 Neuro-QOL measures the physical, mental, and social effects of neurological conditions in adults and children with neurological disorders and has the capability to facilitate comparisons across different neurological conditions. Additionally, the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measure Information System (PROMIS) has been developed to assess physical, mental, and social effects of chronic disease. PROMIS has a hybrid design that includes generic and MS-specific measures (such as PROMIS FatigueMS).56 PROMIS can be used to assess persons with MS as well as to compare the MS population with other populations with chronic illness.

PROMs have varying levels of reliability and validity. The Evaluating the Measure of Patient-Reported Outcomes57 study evaluated the development process of MS PROMs,43 and found that the MSIS-29 and LMSQoL had the highest overall reliability among the most common MS PROMs. However, both scored poorly on validity due to lack of patient involvement during development. This questions the overall capability of existing MS PROMs to accurately and consistently assess PROs in persons with MS.

“Feed-Forward” PROMs

Oliver and colleagues16 have described “feed-forward” PROM applications in MS care in a community hospital setting using a learning health system approach. This MS clinic uses feed-forward PROs to inform clinical care—PRO data are gathered before the clinic visit and analyzed ahead of or during the clinic visit by the clinician. Patients are asked to arrive early and complete a questionnaire comprised of PROMs measuring disability, functioning, quality of life, cognitive ability, pain, fatigue, sleep quality, anxiety, and depression. Clinicians score the PROMs and input scores into the electronic health record before the clinical encounter. During the clinic visit, PROM data is visually displayed so that the clinician and patient can discuss results and use the data to better inform decision-making. The visual data display contains longitudinal information, displaying trends in health status across multiple domains, and includes specified thresholds for clinically active symptom levels (Figure).16 Longitudinal monitoring of PROM data allows for real-time assessment of goal-related progress throughout treatment. As illustrated previously by Marion’s case study, the use of real-time feed-forward PROM data can strengthen the partnership between patient and clinician as well as improve empowerment, engagement, self-monitoring, and adherence.

PRO Dashboards

Performance dashboards are increasingly used in health care to visually display clinical and PRO data for individual patients, systems, and populations over time. Dashboards display a parsimonious group of critically important measures to give clinicians and patients a longitudinal view of PRO status. They can inform decision-making in clinical care, operations, health care improvement efforts, and population health initiatives.58 Effective dashboards allow for user customization with meaningful measures, knowledge discovery for analysis of health problems, accessibility of health information, clear visualization, alerts for unexpected data values, and system connectivity.59,60 Appropriate development of PRO dashboards requires meaningful patient and clinician involvement via focus groups and key informant interviews, Delphi process approaches to prioritize and finalize selection of priority measures, iterative building of the interface with design input from key informants and stakeholders (co-design), and pilot testing to assess feasibility and acceptability of use.61-63

Other Applications of PROs/PROMs in MS

Learning Health Systems

The National Quality Forum (NQF) and the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services have adopted PROs for use in quality measurement.64-66 This includes a movement towards the use of LHS, defined as a health system in which information from patients and clinicians is systematically collected and synthesized with external evidence to inform clinical care, improvement, and research.67-70 Often a LHS is undertaken as a collaborative effort between multiple health care centers to improve quality and outcomes of care.70 The MS Continuous Quality Improvement Collaborative (MS-CQI), the first multi-center systems-level health care improvement research collaborative for MS,71 as well as IBD Qorus and the Cystic Fibrosis Care Center Network utilize LHS approaches.72-77

IBD Qorus is a LHS developed by the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation that uses performance dashboards to better inform clinical care for people with inflammatory bowel disease. It also employs system-level dashboards for performance benchmarking in quality improvement initiatives and aggregate-level dashboards to assess population health status.78,79 MS-CQI uses a LHS approach to inform the improvement of MS care across multiple centers using a comprehensive dashboard, including PROMs, for benchmarking and to monitor system and population health status. MS-CQI collects PROMs using a secure online platform that can be accessed by persons with MS and their clinicians and also includes a journaling feature for collecting qualitative information and for reference and self-monitoring.71

MS Research

PROMs are used in clinical and epidemiological research to evaluate many aspects of MS, including the FAMS, the PDSS, the Fatigue Impact Scale (FIS), and others.80-82 For example, the PROMIS FatigueMS and the Fatigue Performance Scale have been used to assess the impact of MS-related fatigue on social participation.83 Generic and MS-specific PROMs have been used to assess pain levels for people with MS,84-87 and multiple MS-specific PROMs, like PRIMUS and MSQoL-54,43 as well as the SF-3639 include pain assessment scales. PROMs have also been used to assess MS-related bladder, bowel, and sexual dysfunction. Urgency, frequency, and incontinence affect up to 75% of patients with MS,88 and many PROMs, such as the LMSQoL, MUSIQoL, and the MSQoL-54, are able to evaluate bladder control and sexual functioning.43,89

PROMs are employed in MS clinical trials to help assess the tolerability and effectiveness of DMTs.90,91 PROs have been used as secondary endpoints to understand the global experience of a DMT from the patient perspective.92-94 There are 15 FDA-approved DMTs for MS, and clinical trials for 6 of these have used PROMs as an effectiveness end point.54,91,95,96 However, most DMT clinical trials are powered for MRI, relapse rate, or disease progression primary outcomes rather than PROMs, often resulting in underpowered PROM analyses.97 In addition, many PROMs are not appropriate for use in DMT clinical trials.98,99

In order to bridge the gap between clinical research and practice, some industry entities are championing “patient-focused drug development” approaches. The Accelerated Cure Project for MS has launched iConquerMS, which collects PROMs from persons with MS to further PRO research in MS and follows 4700 individuals with MS worldwide.100 In 2018, the American College of Physicians announced a collaboration with an industry partner to share data to inform DMT clinical trials and develop and validate PROMs specifically designed for DMT clinical trials.101

Population Health

Registries following large cohorts of people with MS have the potential to develop knowledge about disease progression, treatment patterns, and outcomes.102 The Swedish EIMS study has identified associations between pre-disease body mass index and MS prognosis,102 alcohol and tobacco consumption affecting MS risk,103,104 and exposure to shift work at a young age and increased MS risk.105 The North American Research Committee on MS83,106,107 and iConquerMS registries are “PROM-driven” and have been useful in identifying reductions in disease progression in people using DMTs.107,108 The New York State MS Consortium has identified important demographic characteristics that influence MS progression.109,110 PROs can also be used to determine risk of MS-related mortality111 and decline in quality of life.112,113 Limitations of these approaches include use of different PROMs, inconsistencies in data collection processes, and different follow-up intervals used across registries.102

Patient-Centered Care

The Institute of Medicine defines patient-centeredness as “care that is respectful and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values and ensures that patient values guide all clinical decisions.”114 PROs are useful for identifying a patient’s individual health concerns and preferences, something that is needed when treating a highly variable chronic health condition like MS. The use of PROs can help clinicicans visualize the lived experience of persons with MS and identify personal preferences,115 as well as improve self-monitoring, self-management, self-efficacy, adherence, wellness, and coping ability.116 At the system level, PROs can inform improvement initiatives and patient-centered care design efforts.117-120

Selecting PROMs

Initiatives from groups like the COnsensus-based Standards for the Selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN)121 and the International Society for Quality of Life Research (ISOQOL)108 offer guidance on selecting PROs. The NINDS has promoted common data collection between clinical studies of the brain and nervous system.122 General guidance from these sources recommends first considering the outcome and target population, selecting PROMs to measure the outcome through a synthesis of the available evidence, assessing validity and reliability of selected PROMs, and using standard measures that can be compared across studies or populations.108,121 Other factors include feasibility, acceptability, and burden of use for patients, clinicians, and systems, as well as literacy, cultural, and linguistic factors.123

The NQF recommends that consideration be given to individual patient needs, insurance factors, clinical setting constraints, and available resources when selecting PROMs.124 To maximize response rate, PROMs that are sensitive, reliable, valid, and developed in a comparative demographic of patients are advised.125 ISOQOL has released a User’s Guide and several companion guides on implementing and utilizing PROMs.108,126,127 Finally, PRO-Performance Measures (PRO-PMs) are sometimes used to assess whether PROMs are appropriately contributing to performance improvement and accountability.124

The Cons of PROs

PROs can disrupt busy clinical care environments and overextend clinical staff.125 Online collection of PROs outside of clinical encounters can relieve PRO-related burden, but this requires finding and funding appropriate secure online networks to effectively collect PROs.128 In 2015, only 60% of people seen for primary care visits could access or view their records online, and of those, only 57% used messaging for medical questions or concerns.129 Ideally, online patient portal or mobile health apps could synchronize directly to electronic health records or virtual scribes to transfer patient communications into clinical documentation.130 There has been limited success with this approach in European countries131 and with some chronic illness conditions in the United States.74

Electronic health technologies, including mobile health (mHealth) solutions, have improved the self-monitoring and self-management capability of patients with MS via information sharing in patient networks, assistive technologies, smartphone applications, and wearable devices.132,133 A recent study found that communication modes included secure online patient portal use (29%) and email use (21%), and among those who owned tablets or smartphones, 46% used mHealth apps.134 Social media use has been associated with increased peer/social/emotional support and increased access to health information, as well as clinical monitoring and behavior change.134,135 Individuals using mHealth apps are younger, have comorbidities, and have higher socioeconomic and education levels,135,136 suggesting that inequities in mHealth access exist.

Questionnaires can be time-consuming and cause mental distress if not appropriately facilitated.137 Decreasing questionnaire length and providing the option for PROMs to be delivered and completed online or outside of the clinic context can reduce burden.138 Additionally, while some people are consistent in sharing their PROs, others struggle with using computers, especially while experiencing severe symptoms, forget to complete PROMs, or simply do not have internet access due to financial or geographic constraints.139 A group of disabled and elderly persons with MS reported barriers to internet use due to visual deficits, small website font sizes, and distracting color schemes.140

Interpretability

Interpreting PROMs and displays of longitudinal PROM data can be a challenge for persons with MS and their clinicians. There is little standardization in how PROMs are scored and presented, and there is often confusion about thresholds for clinical significance and how PROM scores can be compared to other PROMs.141,142 While guidelines exist for implementing PRO scores in clinical settings,126,143 there are few that aid PROM interpretation. As a result, clinicians often seek research evidence for PROMs used in other similar patient populations as a benchmark,142-144 or compare them to other patients seen in their clinical practice.

Longitudinal PRO data are usually displayed in simple line graphs.145,146 Overall, line graphs have been found to have the highest ease of understanding by both patients and clinicians, but sometimes can be confusing.147 For example, upward trending lines are usually viewed as improvement and downward trending lines as decline; however, upward trending scores on a PROM can indicate decline, such as increasing fatigue severity. Annotation of visual displays can help. Patients and clinicians find that employing thresholds and color coding is useful, and better than “stoplight” red-yellow-green shading schemes or red-circle formats to indicate data that warrant attention.142

PROs are not free of risk for error, especially if they are used independently of other information sources, such as clinical interview, examination, and diagnostic testing, or if they are utilized too frequently, too infrequently, or are duplicated in practice. If a PRO instrument is employed too frequently, score changes may reflect learning effects rather than actual clinical status. Conversely, if used too infrequently, PRO information will not be timely enough to inform real-time clinical practice. Duplication of PRO assessments (eg, multiple measures of the same PRO for the same patient on the same day) or use of multiple PRO measures to assess the same aspect (eg, 2 measures used to assess fatigue) could introduce unnecessary complexity and confusion to interpretation of PRO results.

PRO measures also can be biased or modified by clinical status and/or perceptions of people with MS at the time of assessment. For example, cognitive impairment, whether at baseline state or due to a cognitive MS relapse event, could impact patients’ ability to understand and respond to PRO assessments, producing erroneous results. However, when used appropriately, PROs targeting cognitive dysfunction may be able to detect onset of cognitive events or help to measure recovery from them. Finally, PROs measure perceived (self-reported) status, which may not be an accurate depiction of actual status.

All of these potential pitfalls support the argument that PROs should be utilized to augment the clinical interview, examination, and diagnostic (objective) testing aspects of comprehensive MS care. In this way, PROs can be correlated with other information sources to deepen the shared understanding of health status between a person with MS and her clinician, increasing the potential to make better treatment decisions and care plans together in partnership.

Value and Cost

National groups such as the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) are working with regulatory bodies, funding agencies, insurance providers, patient advocacy groups, researchers, providers, and specialty groups to investigate how PROMs can be implemented into value-based health care reforms, including value-based reimbursement.148 However, practical PRO implementation requires considerable time and resources, and many methodological and operational questions must be addressed before widespread adoption and reimbursement for PROMs will be feasible.148,149

Summary

PROs can generate valuable information about perceived health status, function, quality of life, and experience of care using self-reported sources. Validated PRO assessment tools include PROMs and PREMs. PROs are currently utilized in research settings (especially PROMs) but are also being used in clinical practice, quality improvement initiatives, and population health applications using LHS approaches. PROs have the advantages of empowering and informing persons with MS and clinicians to optimize patient-centered care, improve systems of care, and study population health outcomes. Barriers include PROM validity, reliability, comparability, specificity, interpretability, equity, time, and cost. Generic PROMs and PREMs, and some MS-specific PROMs, can be used for persons with MS. Unfortunately, no PREMs have been developed specifically for persons with MS, and this is an area for future research. With appropriate development and utilization in LHS applications, PROs can inform patient-centered clinical care, system-level improvement initiatives, and population health research, and have the potential to help facilitate coproduction of health care services.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank Ann Cabot, DO, of the MS Specialty Care Program at Concord Hospital and (especially) peer mentors from a peer outreach wellness program for people with MS (who have asked to remain anonymous) for interviews conducted with their permission to inform the case study described in this article. The case study used in this manuscript has been de-identified, with some aspects modified from actual, and the person in the case study is fictitiously named.

Corresponding author: Brant Oliver, PhD, MS, MPH, APRN-BC, Department of Community & Family Medicine, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, NH 03756; brant.j.oliver@dartmouth.edu.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Goldenberg MM. Multiple sclerosis review. PT. 2012;37:175-184.

2. Doshi A, Chataway J. Multiple sclerosis, a treatable disease. Clin Med. 2016;16(Suppl 6):s53-s9.

3. Perrin Ross A. Management of multiple sclerosis. Am J Managed Care. 2013;19(16 Suppl):s301-s306.

4. Batalden M, Batalden P, Margolis P, et al. Coproduction of healthcare service. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25:509-517.

5. Chen J, Ou L, Hollis SJ. A systematic review of the impact of routine collection of patient reported outcome measures on patients, providers and health organisations in an oncologic setting. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:211.

6. Knaup C, Koesters M, Schoefer D, et al. Effect of feedback of treatment outcome in specialist mental healthcare: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatr. 2009;195:15-22.

7. Dudgeon D. The impact of measuring patient-reported outcome measures on quality of and access to palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(S1):S76-s80.

8. Snyder CF, Herman JM, White SM, et al. When using patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice, the measure matters: a randomized controlled trial. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:e299-e306.

9. Guidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims: draft guidance. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:79.

10. de Jong MJ, Huibregtse R, Masclee AAM, et al. Patient-reported outcome measures for use in clinical trials and clinical practice in inflammatory bowel diseases: a systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:648-663.

11. Roman D, Osborne-Stafsnes J, Amy CH, et al. Early lessons from four ‘aligning forces for quality’ communities bolster the case for patient-centered care. Health Affairs. 2013;32:232-241.

12. Ehde DM, Alschuler KN, Sullivan MD, et al. Improving the quality of depression and pain care in multiple sclerosis using collaborative care: The MS-care trial protocol. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2018;64:219-229.

13. Lavallee DC, Chenok KE, Love RM, et al. Incorporating patient-reported outcomes into health care to engage patients and enhance care. Health Affairs. 2016;35:575-582.

14. Schick-Makaroff K, Thummapol O, Thompson S, et al. Strategies for incorporating patient-reported outcomes in the care of people with chronic kidney disease (PRO kidney): a protocol for a realist synthesis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:648-663.

15. Nelson EC, Dixon-Woods M, Batalden PB, et al. Patient focused registries can improve health, care, and science. BMJ. 2016;354:i3319.

16. Oliver BJ, Nelson EC, Kerrigan CL. Turning feed-forward and feedback processes on patient-reported data into intelligent action and informed decision-making: case studies and principles. Med Care. 2019;57 Suppl 1:S31-s37.

17. Deshpande PR, Rajan S, Sudeepthi BL, Abdul Nazir CP. Patient-reported outcomes: A new era in clinical research. Perspect Clin Res. 2011;2:137-144.

18. Epstein RM, Street RL, Jr. The values and value of patient-centered care. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9:100-103.

19. Payne SA. A study of quality of life in cancer patients receiving palliative chemotherapy. Soc Sci Med. 1992;35:1505-1509.

20. Borgaonkar MR, Irvine EJ. Quality of life measurement in gastrointestinal and liver disorders. Gut. 2000;47:444-454.

21. Macdonell R, Nagels G, Laplaud DA, et al. Improved patient-reported health impact of multiple sclerosis: The ENABLE study of PR-fampridine. Multiple Sclerosis. 2016;22:944-954.

22. Hobart J, Freeman J, Lamping D, et al. The SF-36 in multiple sclerosis: why basic assumptions must be tested. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;71:363-370.

23. Lins L, Carvalho FM. SF-36 total score as a single measure of health-related quality of life: Scoping review. SAGE Open Med. 2016;4:2050312116671725.

24. Parkinson’s Disease Society of the United Kingdom. The Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire (PDQ-39). https://www.parkinsons.org.uk/professionals/resources/parkinsons-disease-questionnaire-pdq-39. Accessed October 20, 2019.

25. Basch E. The missing voice of patients in drug-safety reporting. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:865-869.

26. Calvert M, Brundage M, Jacobsen PB, et al. The CONSORT Patient-Reported Outcome (PRO) extension: implications for clinical trials and practice. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:184.

27. Black N. Patient reported outcome measures could help transform healthcare. BMJ. 2013;346:f167.

28. Franks P, Fiscella K, Shields CG, et al. Are patients’ ratings of their physicians related to health outcomes? Ann Fam Med. 2005;3:229-234.

29. Hostetter M, Klein S. Using patient-reported outcomes to improve health care quality. The Commonwealth Fund 2019. www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/newsletter-article/using-patient-reported-outcomes-improve-health-care-quality. Accessed October 24, 2019.

30. Charlotte Kingsley SP. Patient-reported outcome measures and patient-reported experience measures. BJA Education. 2017;17:137-144.

31. Weldring T, Smith SM. Patient-Reported outcomes (PROs) and patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). Health Services Insights. 2013;6:61-68.

32. Elwyn G, Barr PJ, Grande SW, et al. Developing CollaboRATE: A fast and frugal patient-reported measure of shared decision making in clinical encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;93:102-107.

33. Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology. 1983;33:1444-1452.

34. Rudick RA, Miller D, Clough JD, et al. Quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Comparison with inflammatory bowel disease and rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Neurol. 1992;49:1237-1242.

35. Benito-Leon J, Morales JM, Rivera-Navarro J, Mitchell A. A review about the impact of multiple sclerosis on health-related quality of life. Disabil Rehabil. 2003;25:1291-1303.

36. RAND Corporation. 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36). [https://www.rand.org/health-care/surveys_tools/mos/36-item-short-form.html. Accessed October 20, 2019.

37. Bergner M, Bobbitt RA, Carter WB, Gilson BS. The sickness impact profile: development and final revision of a health status measure. Medical Care. 1981;19:787-805.

38. Horsman J, Furlong W, Feeny D, Torrance G. The Health Utilities Index (HUI): concepts, measurement properties and applications. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:54.

39. Kinkel RP, Laforet G, You X. Disease-related determinants of quality of life 10 years after clinically isolated syndrome. Int J MS Care. 2015;17:26-34.

40. Baumstarck-Barrau K, Simeoni MC, Reuter F, et al. Cognitive function and quality of life in multiple sclerosis patients: a cross-sectional study. BMC Neurology. 2011;11:17.

41. Samartzis L, Gavala E, Zoukos Y, et al. Perceived cognitive decline in multiple sclerosis impacts quality of life independently of depression. Rehabil Res Pract. 2014;2014:128751.

42. Vitkova M, Rosenberger J, Krokavcova M, et al. Health-related quality of life in multiple sclerosis patients with bladder, bowel and sexual dysfunction. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36:987-992.

43. Khurana V, Sharma H, Afroz N, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in multiple sclerosis: a systematic comparison of available measures. Eur J Neurol. 2017;24:1099-1107.

44. Hobart J, Lamping D, Fitzpatrick R, et al. The Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale (MSIS-29): a new patient-based outcome measure. Brain. 2001;124(Pt 5):962-973.

45. Lily O, McFadden E, Hensor E, et al. Disease-specific quality of life in multiple sclerosis: the effect of disease modifying treatment. Multiple Sclerosis. 2006;12:808-813.

46. Ford HL, Gerry E, Tennant A, et al. Developing a disease-specific quality of life measure for people with multiple sclerosis. Clin Rehabil. 2001;15:247-258.

47. Cella DF, Dineen K, Arnason B, et al. Validation of the functional assessment of multiple sclerosis quality of life instrument. Neurology. 1996;47:129-139.

48. Gold SM, Heesen C, Schulz H, et al. Disease specific quality of life instruments in multiple sclerosis: validation of the Hamburg Quality of Life Questionnaire in Multiple Sclerosis (HAQUAMS). Multiple Sclerosis. 2001;7:119-130.

49. Vickrey BG, Hays RD, Harooni R, et al. A health-related quality of life measure for multiple sclerosis. Qual Life Res. 1995;4:187-206.

50. Simeoni M, Auquier P, Fernandez O, et al. Validation of the Multiple Sclerosis International Quality of Life questionnaire. Multiple Sclerosis. 2008;14:219-230.

51. Doward LC, McKenna SP, Meads DM, et al. The development of patient-reported outcome indices for multiple sclerosis (PRIMUS). Multiple Sclerosis. 2009;15:1092-1102.

52. Ozakbas S, Akdede BB, Kosehasanogullari G, et al. Difference between generic and multiple sclerosis-specific quality of life instruments regarding the assessment of treatment efficacy. J Neurol Sci. 2007;256:30-34.

53. Cella DF, Wiklund I, Shumaker SA, Aaronson NK. Integrating health-related quality of life into cross-national clinical trials. Qual Life Res. 1993;2:433-440.

54. Nowinski CJ, Miller DM, Cella D. Evolution of patient-reported outcomes and their role in multiple sclerosis clinical trials. Neurotherapeutics. 2017;14:934-944.

55. Cella D, Nowinski C, Peterman A, et al. The neurology quality-of-life measurement initiative. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92(10 Suppl):S28-S36.

56. HealthMeasures: PROMIS. http://www.healthmeasures.net/explore-measurement-systems/promis. Accessed October 20, 2019.

57. Valderas JM, Ferrer M, Mendivil J, et al. Development of EMPRO: a tool for the standardized assessment of patient-reported outcome measures. Value Health. 2008;11:700-708.

58. Bach K, Martling C, Mork PJ, et al. Design of a clinician dashboard to facilitate co-decision making in the management of non-specific low back pain. J Intelligent Helath Syst. 2019;52:269-284.

59. Karami M, Safdari R, Rahimi A. Effective radiology dashboards: key research findings. Radiology Management. 2013;35:42-45.

60. Dowding D, Randell R, Gardner P, et al. Dashboards for improving patient care: review of the literature. Int J Med Informatic. 2015;84:87-100.

61. Mlaver E, Schnipper JL, Boxer RB, et al. User-centered collaborative design and development of an inpatient safety dashboard. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2017;43:676-685.

62. Dowding D, Merrill J, Russell D. Using feedback intervention theory to guide clinical dashboard design. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2018;2018:395-403.

63. Hartzler AL, Izard JP, Dalkin BL, et al. Design and feasibility of integrating personalized PRO dashboards into prostate cancer care. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;23:38-47.

64. Lavallee DC, Chenok KE, Love RM, et al. Incorporating patient-reported outcomes into health care to engage patients and enhance care. Health Affairs. 2016;35:575-582.

65. U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement Model. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/CJR. Accessed August 3, 2019.

66. National Quality Forum. Patient-reported outcomes: Accessed August 3, 2019. http://www.qualityforum.org/Patient-Reported_Outcomes.aspx. Accessed October 20, 2019.

67. Institute of Medicine Roundtable on Evidence-Based Medicine. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. In: Olsen LA, Aisner D, McGinnis JM, eds. The Learning Healthcare System: Workshop Summary. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US).National Academy of Sciences; 2007.

68. About Learning Health Systems: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. https://www.ahrq.gov/learning-health-systems/about.html. Accessed August 3, 2019.

69. Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2013.

70. Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001.

71. Oliver BJ, for the MS-CQI Investigators. The Multiple Sclerosis Continuous improvement collaborative: the first coproduction learning health system improvement science research collaborative for multiple sclerosis. The International Society for Quality in Health Care (ISQua) Annual International Conference; October 2019; Cape Town, South Africa.

72. Britto MT, Fuller SC, Kaplan HC, et al. Using a network organisational architecture to support the development of Learning Healthcare Systems. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27:937-946.

73. Care Centers: Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. https://www.cff.org/Care/Care-Centers/. Accessed August 3, 2019.

74. Schechter MS, Fink AK, Homa K, Goss CH. The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation patient registry as a tool for use in quality improvement. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(Suppl 1):i9-i14.

75. Mogayzel PJ, Dunitz J, Marrow LC, Hazle LA. Improving chronic care delivery and outcomes: the impact of the cystic fibrosis Care Center Network. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(Suppl 1):i3-i8.

76. Godfrey MM, Oliver BJ. Accelerating the rate of improvement in cystic fibrosis care: contributions and insights of the learning and leadership collaborative. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(Suppl 1):i23-i32.

77. Nelson EC, Godfrey MM. Quality by Design: A Clinical Microsystems Approach. San Francisco, California: Jossey-Bass; 2007.

78. Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation.Quality of Care: IBD Qorus: https://www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/research/ibd-qorus. Accessed October 23, 2019.

79. Johnson LC, Melmed GY, Nelson EC, et al. Fostering collaboration through creation of an ibd learning health system. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:406-468.

80. Fernandez-Munoz JJ, Moron-Verdasco A, Cigaran-Mendez M, et al. Disability, quality of life, personality, cognitive and psychological variables associated with fatigue in patients with multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 2015;132:118-124.

81. Flachenecker P, Kumpfel T, Kallmann B, et al. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis: a comparison of different rating scales and correlation to clinical parameters. Multiple Sclerosis. 2002;8:523-526.

82. Tellez N, Rio J, Tintore M, et al. Does the Modified Fatigue Impact Scale offer a more comprehensive assessment of fatigue in MS? Multiple Sclerosis. 2005;11:198-202.

83. Salter A, Fox RJ, Tyry T, et al. The association of fatigue and social participation in multiple sclerosis as assessed using two different instruments. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019;31:165-72.

84. Solaro C, Trabucco E, Messmer Uccelli M. Pain and multiple sclerosis: pathophysiology and treatment. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2013;13:320.

85. Jawahar R, Oh U, Yang S, Lapane KL. A systematic review of pharmacological pain management in multiple sclerosis. Drugs. 2013;73:1711-1722.

86. Rintala A, Hakkinen A, Paltamaa J. Ten-year follow-up of health-related quality of life among ambulatory persons with multiple sclerosis at baseline. Qual Life Res. 2016;25:3119-3127.

87. Tepavcevic DK, Pekmezovic T, Stojsavljevic N, et al. Change in quality of life and predictors of change among patients with multiple sclerosis: a prospective cohort study. Qual Life Res. 2014;23:1027-1037.

88. DasGupta R, Fowler CJ. Bladder, bowel and sexual dysfunction in multiple sclerosis: management strategies. Drugs. 2003;63:153-166.

89. Marck CH, Jelinek PL, Weiland TJ, et al. Sexual function in multiple sclerosis and associations with demographic, disease and lifestyle characteristics: an international cross-sectional study. BMC Neurology. 2016;16:210.

90. Gajofatto A, Benedetti MD. Treatment strategies for multiple sclerosis: When to start, when to change, when to stop? World J Clinical Cases. 2015;3:545-555.

91. National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Disease-modifying therapies for MS. 2018.

92. Rudick RA, Panzara MA. Natalizumab for the treatment of relapsing multiple sclerosis. Biologics. 2008;2:189-199.

93. Cohen JA, Cutter GR, Fischer JS, et al. Benefit of interferon beta-1a on MSFC progression in secondary progressive MS. Neurology. 2002;59:679-687.

94. Patti F, Pappalardo A, Montanari E, et al. Interferon-beta-1a treatment has a positive effect on quality of life of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: results from a longitudinal study. J Neurol Sci. 2014;337:180-185.

95. Novartis. Exploring the efficacy and safety of Siponimod in patients with secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (EXPAND). Available from clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01665144. NLM identifier: NCT01665144.

96. Singal AG, Higgins PD, Waljee AK. A primer on effectiveness and efficacy trials. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2014;5:e45.

97. Jongen PJ. Health-related quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis: impact of disease-modifying drugs. CNS Drugs. 2017;31:585-602.

98. Coretti S, Ruggeri M, McNamee P. The minimum clinically important difference for EQ-5D index: a critical review. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2014;14:221-233.

99. Clinical Review Report: Ocrelizumab (Ocrevus). CADTH Common Drug Review. 2018:Appendix 4, Validity of Outcome Measures.

100. iCounquer MS; Empowering patients: how individuals with ms are contributing to the fight to find a cure: 2018. https://www.iconquerms.org/empowering-patients-how-individuals-ms-are-contributing-fight-find-cure. Accessed October 23, 2019.

101. K M. Accelerated Cure Project Announces Collaboration with EMD Serono to Advance Patient-Focused Drug Development in Multiple Sclerosis2018. https://www.iconquerms.org/accelerated-cure-project-announces-collaboration-emd-serono-advance-patient-focused-drug-development. Accessed October 24, 2019.

102. Bebo BF Jr, Fox RJ, Lee K, et al. Landscape of MS patient cohorts and registries: Recommendations for maximizing impact. Multiple Sclerosis. 2018;24:579-586.

103. Hedstrom AK, Hillert J, Olsson T, Alfredsson L. Alcohol as a modifiable lifestyle factor affecting multiple sclerosis risk. JAMA Neurology. 2014;71:300-305.

104. Hedstrom AK, Baarnhielm M, Olsson T, Alfredsson L. Tobacco smoking, but not Swedish snuff use, increases the risk of multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2009;73:696-701.

105. Hedstrom AK, Akerstedt T, Hillert J, et al. Shift work at young age is associated with increased risk for multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2011;70:733-741.

106. Hadjimichael O, Vollmer T, Oleen-Burkey M. Fatigue characteristics in multiple sclerosis: the North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis (NARCOMS) survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6:100.

107. Fox RJ, Salter AR, Tyry T, et al. Treatment discontinuation and disease progression with injectable disease-modifying therapies: findings from the North American research committee on multiple sclerosis database. Int J MS Care. 2013;15:194-201.

108. Reeve BB, Wyrwich KW, Wu AW, et al. ISOQOL recommends minimum standards for patient-reported outcome measures used in patient-centered outcomes and comparative effectiveness research. Qual Life Res. 2013;22:1889-1905.

109. Jacobs LD, Wende KE, Brownscheidle CM, et al. A profile of multiple sclerosis: the New York State Multiple Sclerosis Consortium. Multiple Sclerosis. 1999;5:369-376.

110. Weinstock-Guttman B, Jacobs LD, Brownscheidle CM, et al. Multiple sclerosis characteristics in African American patients in the New York State Multiple Sclerosis Consortium. Multiple Sclerosis. 2003;9:293-298.

111. Raffel J, Wallace A, Gveric D, et al. Patient-reported outcomes and survival in multiple sclerosis: A 10-year retrospective cohort study using the Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale-29. PLoS Med. 2017;14:e1002346.

112. Vaughn CB, Kavak KS, Dwyer MG, et al. Fatigue at enrollment predicts EDSS worsening in the New York State Multiple Sclerosis Consortium. Multiple Sclerosis. 2018:1352458518816619.

113. Alroughani RA, Akhtar S, Ahmed SF, Al-Hashel JY. Clinical predictors of disease progression in multiple sclerosis patients with relapsing onset in a nation-wide cohort. Int J Neuroscience. 2015;125:831-837.

114. Dolan JG, Veazie PJ, Russ AJ. Development and initial evaluation of a treatment decision dashboard. BMC Med Inform Decision Mak. 2013;13:51.

115. Stuifbergen AK, Becker H, Blozis S, et al. A randomized clinical trial of a wellness intervention for women with multiple sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84:467-476.

116. Finkelstein J, Martin C, Bhushan A, et al. Feasibility of computer-assisted education in patients with multiple sclerosis. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Symposium on Computer-Based Medical Systems. Bethesda, MD; 2004.

117. Batalden P. Getting more health from healthcare: quality improvement must acknowledge patient coproduction—an essay by Paul Batalden. BMJ. 2018;362:k3617.

118. Batalden PB, Davidoff F. What is “quality improvement” and how can it transform healthcare? Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;16:2-3.

119. Ovretveit J, Zubkoff L, Nelson EC, et al. Using patient-reported outcome measurement to improve patient care. Int J Qual Health Care. 2017;29:874-879.

120. Prodinger B, Taylor P. Improving quality of care through patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs): expert interviews using the NHS PROMs Programme and the Swedish quality registers for knee and hip arthroplasty as examples. BMC Health Services Res. 2018;18:87.

121. Prinsen CA, Vohra S, Rose MR, et al. How to select outcome measurement instruments for outcomes included in a “Core Outcome Set” – a practical guideline. Trials. 2016;17:449.

122. NINDS. NINDS Common Data Elements: Streamline Your Neuroscience Clinical Research National Institute of Health. https://www.commondataelements.ninds.nih.gov/#page=Default. Accessed October 23, 2019.

123. Francis DO, McPheeters ML, Noud M, et al. Checklist to operationalize measurement characteristics of patient-reported outcome measures. Systematic Rev. 2016;5:129.

124. National Quality Forum. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) in performance measurement. 2013. https://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2012/12/Patient-Reported_Outcomes_in_Performance_Measurement.aspx. Accessed October 15, 2019.

125. Dawson J, Doll H, Fitzpatrick R, et al. The routine use of patient reported outcome measures in healthcare settings. BMJ. 2010;340:c186.

126. Aaronson N ET, Greenlhalgh J, Halyard M, et al. User’s guide to implementation of patient reported outcomes assessment in clinical practice. International Society for Quality of Life. 2015.

127. Chan EKH, Edwards TC, Haywood K, et al. Implementing patient-reported outcomes mesaures in clinical practice: a companion guide to the ISOQOL user’s guide. Qual Life Res. 2018;28:621-627.

128. Snyder CF, Wu AW, Miller RS, et al. The role of informatics in promoting patient-centered care. Cancer J. 2011;17:211-218

129. Osborn R, Moulds D, Schneider EC, et al. Primary care physicians in ten countries report challenges caring for patients with complex health needs. Health Affairs. 2015;34:2104-2112.

130. Wu AW, Kharrazi H, Boulware LE, Snyder CF. Measure once, cut 0wice--adding patient-reported outcome measures to the electronic health record for comparative effectiveness research. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(8 Suppl):S12-S20.

131. Trojano M, Bergamaschi R, Amato MP, et al. The Italian multiple sclerosis register. Neurol Sci. 2019;40:155-165.

132. Moorhead SA, Hazlett DE, Harrison L, et al. A new dimension of health care: systematic review of the uses, benefits, and limitations of social media for health communication. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15:e85.

133. Luigi L, Francesco B, Marcello M, et al. e-Health and multiple sclerosis: An update. Multiple Sclerosis J. 2018;24:1657-1664.

134. Marrie RA, Leung S, Tyry T, et al. Use of eHealth and mHealth technology by persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Dis. 2019;27:13-19.

135. Giunti G, Kool J, Rivera Romero O, Dorronzoro Zubiete E. Exploring the specific needs of persons with multiple sclerosis for mhealth solutions for physical activity: mixed-methods study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2018;6:e37.

136. Spooner KK, Salemi JL, Salihu HM, Zoorob RJ. eHealth patient-provider communication in the United States: interest, inequalities, and predictors. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2017;24(e1):e18-e27.

137. Safdar N, Abbo LM, Knobloch MJ, Seo SK. Research methods in healthcare epidemiology: survey and qualitative research. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37:1272-1277.

138. Rolstad S, Adler J, Rydén A. Response burden and questionnaire length: is shorter better? A review and meta-analysis. Value Health. 2011;14:1101-1108.

139. Chiu C, Bishop M, Pionke JJ, et al. Barriers to the accessibility and continuity of health-care services in people with multiple sclerosis: a literature review. Int J MS Care. 2017;19:313-321.

140. Atreja A, Mehta N, Miller D, et al. One size does not fit all: using qualitative methods to inform the development of an Internet portal for multiple sclerosis patients. AMIA Annu Symp Proc Symp. 2005:16-20.

141. Snyder CF, Blackford AL, Brahmer JR, et al. Needs assessments can identify scores on HRQOL questionnaires that represent problems for patients: an illustration with the Supportive Care Needs Survey and the QLQ-C30. Qual Life Res. 2010;19:837-845.

142. de Vet HC, Terwee CB. The minimal detectable change should not replace the minimal important difference. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:804-805.

143. Snyder CF, Aaronson NK, Choucair AK, et al. Implementing patient-reported outcomes assessment in clinical practice: a review of the options and considerations. Qual Life. 2012;21:1305-1314.

144. Myla DG, Melanie DW, Robert WM, et al. Identification and validation of clinically meaningful benchmarks in the 12-item Multiple Sclerosis Walking Scale. Multiple Sclerosis J. 2017;23:1405-1414.

145. van Munster CEP, Uitdehaag BMJ. Outcome measures in clinical trials for multiple sclerosis. CNS Drugs. 2017;31:217-236.

146. Snyder CF, Jensen R, Courtin SO, Wu AW. PatientViewpoint: a website for patient-reported outcomes assessment. Quality Life Res. 2009;18:793-800.

147. Snyder CF, Smith KC, Bantug ET, et al. What do these scores mean? Presenting patient-reported outcomes data to patients and clinicians to improve interpretability. Cancer. 2017;123:1848-1859.

148. Squitieri L, Bozic KJ, Pusic AL. The role of patient-reported outcome measures in value-based payment reform. Value Health. 2017;20:834-836.

149. Boyce MB, Browne JP. The effectiveness of providing peer benchmarked feedback to hip replacement surgeons based on patient-reported outcome measures—results from the PROFILE trial: a cluster randomised controlled study. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e008325.

From the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy & Clinical Practice, Geisel School of Medicine, Hanover, NH (Ms. Manohar and Dr. Oliver), the Department of Community & Family Medicine, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, NH (Ms. Perkins, Ms. Laurion, and Dr. Oliver), and the Multiple Sclerosis Specialty Care Program, Concord Hospital, Concord, NH (Dr. Oliver).

Abstract

- Background: Patient-reported outcomes (PROs), including patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) and patient-reported experience measures (PREMs), can be used to assess perceived health status, functioning, quality of life, and experience of care. Complex chronic illnesses such as multiple sclerosis (MS) affect multiple aspects of health, and PROs can be applied in assessment and decision-making in MS care as well as in research pertaining to MS.

- Objective: To provide a general review of PROs, with a specific focus on implications for MS care.

- Methods: Evidence synthesis of available literature on PROs in MS care.

- Results: PROs (including PROMs and PREMs) have historically been utilized in research and are now being applied in clinical, improvement, and population health settings using learning health system approaches in many disease populations, including MS. Many challenges complicate the use of PROs in MS care, including reliability, validity, and interpretability of PROMs, as well as feasibility barriers due to time and financial constraints in clinical settings.

- Conclusion: PROs have the potential to better inform clinical care, empower patient-centered care, inform health care improvement efforts, and create the conditions for coproduction of health care services.

Keywords: PRO; PROM; patient-reported outcome measure; patient-reported experience measure; quality of life; patient-centered care.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a disabling, complex, chronic, immune-mediated disorder of the central nervous system (CNS). MS causes inflammatory and degenerative damage in the CNS, which disrupts signaling pathways.1 It is most commonly diagnosed in young adults and affects 2.3 million people worldwide.2 People with MS experience very different disease courses and a wide range of neurological symptoms, including visual, somatic, mental health, sensory, motor, and cognitive problems.1-3 Relapsing-remitting MS, the most common form, affects 85% of those with MS and is characterized by periods of relapse (exacerbation) and remission.1 Other forms of MS (primary progressive and secondary progressive MS) are characterized by progressive deterioration and worsening symptom severity without exacerbations. Disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) can reduce the frequency of exacerbations and disability progression, but unfortunately there is no cure for MS. Treatment is focused on increasing quality of life, minimizing disability, and maximizing wellness.