User login

Combo produces disappointing PFS, promising OS in metastatic colorectal cancer

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – An immunochemotherapy regimen produced mixed results in a phase 2 trial of patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer.

The regimen – avelumab and cetuximab plus oxaliplatin, leucovorin, and 5-fluorouracil (mFOLFOX6) – failed to meet the primary endpoint for progression-free survival (PFS) but was associated with “promising” yet “preliminary” overall survival, according to Joseph Tintelnot, MD, of University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (Germany).

Dr. Tintelnot presented these results from the AVETUX trial (NCT03174405) at the annual meeting of the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer.

The trial enrolled 43 patients with previously untreated, metastatic colorectal cancer, and 39 of them had wild-type RAS and BRAF mutations. Among those 39 patients, the median age was 62 years (range, 29-82 years), 13 patients were female, and 36 patients had left-sided tumors.

A total of 30 patients had liver metastasis, 12 had lung metastasis, and 18 had lymph node metastasis. Most patients (n = 36) had microsatellite stable tumors, 2 were microsatellite instability high, and 1 was microsatellite instability low.

Patients received IV cetuximab at 250 mg/m2 over 60-90 minutes (day 1 and 8), with a first dose of 400 mg/m2; mFOLFOX6 according to local standard – IV oxaliplatin at 85 mg/m2 IV (day 1), IV leucovorin at 400 mg/m2 IV (day 1), and IV bolus 5-fluorouracil at 400 mg/m2 (day 1) and IV at 2,400 mg/m2 (days 1-3); and IV avelumab at 10 mg/kg over 60-90 minutes (day 1 from cycle 2 onward).

The median number of treatment cycles was 8 (range, 1-34) for oxaliplatin, 13 (range, 1-35) for 5-fluorouracil, 12 (range, 1-35) for cetuximab, and 16 (range, 0-34) for avelumab. The median duration of cetuximab/avelumab treatment was 5.4 months (range, 0.7-18.4 months).

The study’s primary endpoint was 12-month PFS, and the researchers expected the PFS to rise from 40% to 57%. Unfortunately, the 12-month PFS was 40%, so the primary endpoint was not met.

However, the treatment produced a “very high” overall response rate at 81% (30/37), according to Dr. Tintelnot. A total of 4 patients achieved a complete response, 26 had a partial response, 4 had stable disease, and 3 progressed.

Dr. Tintelnot also noted a “promising” but “preliminary” overall survival rate – 84% at a median follow-up of 16.2 months. He said these results suggest PFS may not be the ideal endpoint for this combination.

Dr. Tintelnot said the combination was safe, with no unexpected toxicities. The most common grade 3-4 adverse events were infection of catheter, device, urinary tract, etc. (32%); abdominal pain, diarrhea, etc. (24%); skin reaction (21%); anemia, blood disorders, and hemolytic-uremic syndrome (18%); administration, infusion-related, and allergic reactions (16%); cognitive disturbance, meningism, syncope, and psychiatric disorders (16%); and peripheral sensory polyneuropathy and paresthesia (16%).

Dr. Tintelnot and colleagues also conducted translational research evaluating programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression and serial circulating tumor DNA in patients on this trial.

The team found no clear correlation between PFS and T-cell diversification, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, or tumor proportion score. Dr. Tintelnot said this suggests classical predictive factors for PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor treatment have a limited role with this combination.

The researchers did find that circulating tumor mutations might help predict early relapse with the regimen. The team identified 26 patients with mutations detectable in their blood. There was an immediate decline of circulating tumor mutations after treatment initiation, and reemergence of mutation clones was associated with progression.

Lastly, the researchers found that avelumab, cetuximab, and mFOLFOX6 suppressed the development of epidermal growth factor receptor–resistant subclones. There were no epidermal growth factor receptor mutations detected during follow-up.

This research was sponsored by AIO-Studien-gGmbH. Dr. Tintelnot disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Tintelnot J et al. SITC 2019, Abstract O16.

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – An immunochemotherapy regimen produced mixed results in a phase 2 trial of patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer.

The regimen – avelumab and cetuximab plus oxaliplatin, leucovorin, and 5-fluorouracil (mFOLFOX6) – failed to meet the primary endpoint for progression-free survival (PFS) but was associated with “promising” yet “preliminary” overall survival, according to Joseph Tintelnot, MD, of University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (Germany).

Dr. Tintelnot presented these results from the AVETUX trial (NCT03174405) at the annual meeting of the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer.

The trial enrolled 43 patients with previously untreated, metastatic colorectal cancer, and 39 of them had wild-type RAS and BRAF mutations. Among those 39 patients, the median age was 62 years (range, 29-82 years), 13 patients were female, and 36 patients had left-sided tumors.

A total of 30 patients had liver metastasis, 12 had lung metastasis, and 18 had lymph node metastasis. Most patients (n = 36) had microsatellite stable tumors, 2 were microsatellite instability high, and 1 was microsatellite instability low.

Patients received IV cetuximab at 250 mg/m2 over 60-90 minutes (day 1 and 8), with a first dose of 400 mg/m2; mFOLFOX6 according to local standard – IV oxaliplatin at 85 mg/m2 IV (day 1), IV leucovorin at 400 mg/m2 IV (day 1), and IV bolus 5-fluorouracil at 400 mg/m2 (day 1) and IV at 2,400 mg/m2 (days 1-3); and IV avelumab at 10 mg/kg over 60-90 minutes (day 1 from cycle 2 onward).

The median number of treatment cycles was 8 (range, 1-34) for oxaliplatin, 13 (range, 1-35) for 5-fluorouracil, 12 (range, 1-35) for cetuximab, and 16 (range, 0-34) for avelumab. The median duration of cetuximab/avelumab treatment was 5.4 months (range, 0.7-18.4 months).

The study’s primary endpoint was 12-month PFS, and the researchers expected the PFS to rise from 40% to 57%. Unfortunately, the 12-month PFS was 40%, so the primary endpoint was not met.

However, the treatment produced a “very high” overall response rate at 81% (30/37), according to Dr. Tintelnot. A total of 4 patients achieved a complete response, 26 had a partial response, 4 had stable disease, and 3 progressed.

Dr. Tintelnot also noted a “promising” but “preliminary” overall survival rate – 84% at a median follow-up of 16.2 months. He said these results suggest PFS may not be the ideal endpoint for this combination.

Dr. Tintelnot said the combination was safe, with no unexpected toxicities. The most common grade 3-4 adverse events were infection of catheter, device, urinary tract, etc. (32%); abdominal pain, diarrhea, etc. (24%); skin reaction (21%); anemia, blood disorders, and hemolytic-uremic syndrome (18%); administration, infusion-related, and allergic reactions (16%); cognitive disturbance, meningism, syncope, and psychiatric disorders (16%); and peripheral sensory polyneuropathy and paresthesia (16%).

Dr. Tintelnot and colleagues also conducted translational research evaluating programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression and serial circulating tumor DNA in patients on this trial.

The team found no clear correlation between PFS and T-cell diversification, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, or tumor proportion score. Dr. Tintelnot said this suggests classical predictive factors for PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor treatment have a limited role with this combination.

The researchers did find that circulating tumor mutations might help predict early relapse with the regimen. The team identified 26 patients with mutations detectable in their blood. There was an immediate decline of circulating tumor mutations after treatment initiation, and reemergence of mutation clones was associated with progression.

Lastly, the researchers found that avelumab, cetuximab, and mFOLFOX6 suppressed the development of epidermal growth factor receptor–resistant subclones. There were no epidermal growth factor receptor mutations detected during follow-up.

This research was sponsored by AIO-Studien-gGmbH. Dr. Tintelnot disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Tintelnot J et al. SITC 2019, Abstract O16.

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – An immunochemotherapy regimen produced mixed results in a phase 2 trial of patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer.

The regimen – avelumab and cetuximab plus oxaliplatin, leucovorin, and 5-fluorouracil (mFOLFOX6) – failed to meet the primary endpoint for progression-free survival (PFS) but was associated with “promising” yet “preliminary” overall survival, according to Joseph Tintelnot, MD, of University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (Germany).

Dr. Tintelnot presented these results from the AVETUX trial (NCT03174405) at the annual meeting of the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer.

The trial enrolled 43 patients with previously untreated, metastatic colorectal cancer, and 39 of them had wild-type RAS and BRAF mutations. Among those 39 patients, the median age was 62 years (range, 29-82 years), 13 patients were female, and 36 patients had left-sided tumors.

A total of 30 patients had liver metastasis, 12 had lung metastasis, and 18 had lymph node metastasis. Most patients (n = 36) had microsatellite stable tumors, 2 were microsatellite instability high, and 1 was microsatellite instability low.

Patients received IV cetuximab at 250 mg/m2 over 60-90 minutes (day 1 and 8), with a first dose of 400 mg/m2; mFOLFOX6 according to local standard – IV oxaliplatin at 85 mg/m2 IV (day 1), IV leucovorin at 400 mg/m2 IV (day 1), and IV bolus 5-fluorouracil at 400 mg/m2 (day 1) and IV at 2,400 mg/m2 (days 1-3); and IV avelumab at 10 mg/kg over 60-90 minutes (day 1 from cycle 2 onward).

The median number of treatment cycles was 8 (range, 1-34) for oxaliplatin, 13 (range, 1-35) for 5-fluorouracil, 12 (range, 1-35) for cetuximab, and 16 (range, 0-34) for avelumab. The median duration of cetuximab/avelumab treatment was 5.4 months (range, 0.7-18.4 months).

The study’s primary endpoint was 12-month PFS, and the researchers expected the PFS to rise from 40% to 57%. Unfortunately, the 12-month PFS was 40%, so the primary endpoint was not met.

However, the treatment produced a “very high” overall response rate at 81% (30/37), according to Dr. Tintelnot. A total of 4 patients achieved a complete response, 26 had a partial response, 4 had stable disease, and 3 progressed.

Dr. Tintelnot also noted a “promising” but “preliminary” overall survival rate – 84% at a median follow-up of 16.2 months. He said these results suggest PFS may not be the ideal endpoint for this combination.

Dr. Tintelnot said the combination was safe, with no unexpected toxicities. The most common grade 3-4 adverse events were infection of catheter, device, urinary tract, etc. (32%); abdominal pain, diarrhea, etc. (24%); skin reaction (21%); anemia, blood disorders, and hemolytic-uremic syndrome (18%); administration, infusion-related, and allergic reactions (16%); cognitive disturbance, meningism, syncope, and psychiatric disorders (16%); and peripheral sensory polyneuropathy and paresthesia (16%).

Dr. Tintelnot and colleagues also conducted translational research evaluating programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression and serial circulating tumor DNA in patients on this trial.

The team found no clear correlation between PFS and T-cell diversification, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, or tumor proportion score. Dr. Tintelnot said this suggests classical predictive factors for PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor treatment have a limited role with this combination.

The researchers did find that circulating tumor mutations might help predict early relapse with the regimen. The team identified 26 patients with mutations detectable in their blood. There was an immediate decline of circulating tumor mutations after treatment initiation, and reemergence of mutation clones was associated with progression.

Lastly, the researchers found that avelumab, cetuximab, and mFOLFOX6 suppressed the development of epidermal growth factor receptor–resistant subclones. There were no epidermal growth factor receptor mutations detected during follow-up.

This research was sponsored by AIO-Studien-gGmbH. Dr. Tintelnot disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Tintelnot J et al. SITC 2019, Abstract O16.

REPORTING FROM SITC 2019

Disentangling sleep problems and bipolar disorder

COPENHAGEN – Sleep spindle density is diminished in euthymic patients with bipolar disorder, suggesting that this sleep architecture abnormality might offer potential for early differentiation of bipolar from unipolar depression, Philipp S. Ritter, MD, said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

“Hopefully in the future our finding, if replicated, might have clinical utility. It might be a kind of soft biomarker that could be used in early detection, or, in people having their first depressive episode, you could perhaps use this to risk-stratify. And if you see there’s a great reduction in spindle density then a patient might have a higher likelihood of a bipolar disorder, so you might not want to treat with antidepressants that have a high switch rate,” explained Dr. Ritter, a psychiatrist at Technical University of Dresden (Germany).

Sleep spindles are a specific sleep architecture formation evident on the sleep EEG. They are sudden high-amplitude bursts occurring in stage N2 sleep. They are thought to be associated with sensory gating and memory processes. Other investigators have repeatedly demonstrated that patients with schizophrenia, as well as their asymptomatic first-degree relatives, have a reduced density of fast spindles greater than 13 Hz, compared with the general population. In contrast, patients with unipolar depression do not display this polysomnographic abnormality.

These findings prompted Dr. Ritter and his coinvestigators to conduct an all-night polysomnographic study in 24 euthymic patients with bipolar disorder and 25 healthy controls. The bipolar patients demonstrated a reduced density and mean frequency of fast sleep spindles, but not slow spindles (Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018 Aug;138[2]:163-72).

These sleep spindle findings implicate thalamic dysfunction as a potential neurobiologic mechanism in bipolar disorder, since spindles are generated in the thalamus and spun off in thalamocortical feedback loops, Dr. Ritter observed.

Which came first: the chicken (bipolar disorder) or the egg (sleep disturbance)?

Sleep problems are a prominent issue in patients with bipolar disorder, even when they are euthymic.

“Anybody who deals with bipolar patients knows that sleep is a constant issue. You are always talking to your patients about their sleep. They’re sleeping too much, or not enough, or they’re sleeping just about right but it’s unsatisfactory. They do not sleep well. And if there’s something that disrupts their sleep, it can precipitate episodes,” Dr. Ritter said.

He wondered whether sleep problems are an intrinsic part of the bipolar illness, or a byproduct of the stress of having a severe mental disorder, perhaps a medication side effect, or whether the disordered sleep actually precedes the clinical expression of the mood disorder. So he and his coinvestigators turned to a Munich-based cohort sample of 3,021 adolescents and young adults assessed via the standardized Composite International Diagnostic Interview four times during 10 years of prospective follow-up.

Among 1,943 participants in the epidemiologic study who were free of major mental disorders at entry, the presence of sleep disturbance at baseline as quantified using the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised doubled the risk of developing bipolar disorder within the next 10 years. After the researchers controlled for potential confounders, including parental mood disorder, gender, age, and a history of alcohol or cannabis dependence, poor sleep quality at baseline remained independently associated with a 1.75-fold increased chance of subsequently developing bipolar disorder (J Psychiatr Res. 2015 Sep;68:76-82).

“This is a little bit higher, actually, than the odds ratio usually found for depressive disorders,” said Dr. Ritter.

he added.

Dr. Ritter reported having no financial conflicts regarding these studies.

COPENHAGEN – Sleep spindle density is diminished in euthymic patients with bipolar disorder, suggesting that this sleep architecture abnormality might offer potential for early differentiation of bipolar from unipolar depression, Philipp S. Ritter, MD, said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

“Hopefully in the future our finding, if replicated, might have clinical utility. It might be a kind of soft biomarker that could be used in early detection, or, in people having their first depressive episode, you could perhaps use this to risk-stratify. And if you see there’s a great reduction in spindle density then a patient might have a higher likelihood of a bipolar disorder, so you might not want to treat with antidepressants that have a high switch rate,” explained Dr. Ritter, a psychiatrist at Technical University of Dresden (Germany).

Sleep spindles are a specific sleep architecture formation evident on the sleep EEG. They are sudden high-amplitude bursts occurring in stage N2 sleep. They are thought to be associated with sensory gating and memory processes. Other investigators have repeatedly demonstrated that patients with schizophrenia, as well as their asymptomatic first-degree relatives, have a reduced density of fast spindles greater than 13 Hz, compared with the general population. In contrast, patients with unipolar depression do not display this polysomnographic abnormality.

These findings prompted Dr. Ritter and his coinvestigators to conduct an all-night polysomnographic study in 24 euthymic patients with bipolar disorder and 25 healthy controls. The bipolar patients demonstrated a reduced density and mean frequency of fast sleep spindles, but not slow spindles (Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018 Aug;138[2]:163-72).

These sleep spindle findings implicate thalamic dysfunction as a potential neurobiologic mechanism in bipolar disorder, since spindles are generated in the thalamus and spun off in thalamocortical feedback loops, Dr. Ritter observed.

Which came first: the chicken (bipolar disorder) or the egg (sleep disturbance)?

Sleep problems are a prominent issue in patients with bipolar disorder, even when they are euthymic.

“Anybody who deals with bipolar patients knows that sleep is a constant issue. You are always talking to your patients about their sleep. They’re sleeping too much, or not enough, or they’re sleeping just about right but it’s unsatisfactory. They do not sleep well. And if there’s something that disrupts their sleep, it can precipitate episodes,” Dr. Ritter said.

He wondered whether sleep problems are an intrinsic part of the bipolar illness, or a byproduct of the stress of having a severe mental disorder, perhaps a medication side effect, or whether the disordered sleep actually precedes the clinical expression of the mood disorder. So he and his coinvestigators turned to a Munich-based cohort sample of 3,021 adolescents and young adults assessed via the standardized Composite International Diagnostic Interview four times during 10 years of prospective follow-up.

Among 1,943 participants in the epidemiologic study who were free of major mental disorders at entry, the presence of sleep disturbance at baseline as quantified using the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised doubled the risk of developing bipolar disorder within the next 10 years. After the researchers controlled for potential confounders, including parental mood disorder, gender, age, and a history of alcohol or cannabis dependence, poor sleep quality at baseline remained independently associated with a 1.75-fold increased chance of subsequently developing bipolar disorder (J Psychiatr Res. 2015 Sep;68:76-82).

“This is a little bit higher, actually, than the odds ratio usually found for depressive disorders,” said Dr. Ritter.

he added.

Dr. Ritter reported having no financial conflicts regarding these studies.

COPENHAGEN – Sleep spindle density is diminished in euthymic patients with bipolar disorder, suggesting that this sleep architecture abnormality might offer potential for early differentiation of bipolar from unipolar depression, Philipp S. Ritter, MD, said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

“Hopefully in the future our finding, if replicated, might have clinical utility. It might be a kind of soft biomarker that could be used in early detection, or, in people having their first depressive episode, you could perhaps use this to risk-stratify. And if you see there’s a great reduction in spindle density then a patient might have a higher likelihood of a bipolar disorder, so you might not want to treat with antidepressants that have a high switch rate,” explained Dr. Ritter, a psychiatrist at Technical University of Dresden (Germany).

Sleep spindles are a specific sleep architecture formation evident on the sleep EEG. They are sudden high-amplitude bursts occurring in stage N2 sleep. They are thought to be associated with sensory gating and memory processes. Other investigators have repeatedly demonstrated that patients with schizophrenia, as well as their asymptomatic first-degree relatives, have a reduced density of fast spindles greater than 13 Hz, compared with the general population. In contrast, patients with unipolar depression do not display this polysomnographic abnormality.

These findings prompted Dr. Ritter and his coinvestigators to conduct an all-night polysomnographic study in 24 euthymic patients with bipolar disorder and 25 healthy controls. The bipolar patients demonstrated a reduced density and mean frequency of fast sleep spindles, but not slow spindles (Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018 Aug;138[2]:163-72).

These sleep spindle findings implicate thalamic dysfunction as a potential neurobiologic mechanism in bipolar disorder, since spindles are generated in the thalamus and spun off in thalamocortical feedback loops, Dr. Ritter observed.

Which came first: the chicken (bipolar disorder) or the egg (sleep disturbance)?

Sleep problems are a prominent issue in patients with bipolar disorder, even when they are euthymic.

“Anybody who deals with bipolar patients knows that sleep is a constant issue. You are always talking to your patients about their sleep. They’re sleeping too much, or not enough, or they’re sleeping just about right but it’s unsatisfactory. They do not sleep well. And if there’s something that disrupts their sleep, it can precipitate episodes,” Dr. Ritter said.

He wondered whether sleep problems are an intrinsic part of the bipolar illness, or a byproduct of the stress of having a severe mental disorder, perhaps a medication side effect, or whether the disordered sleep actually precedes the clinical expression of the mood disorder. So he and his coinvestigators turned to a Munich-based cohort sample of 3,021 adolescents and young adults assessed via the standardized Composite International Diagnostic Interview four times during 10 years of prospective follow-up.

Among 1,943 participants in the epidemiologic study who were free of major mental disorders at entry, the presence of sleep disturbance at baseline as quantified using the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised doubled the risk of developing bipolar disorder within the next 10 years. After the researchers controlled for potential confounders, including parental mood disorder, gender, age, and a history of alcohol or cannabis dependence, poor sleep quality at baseline remained independently associated with a 1.75-fold increased chance of subsequently developing bipolar disorder (J Psychiatr Res. 2015 Sep;68:76-82).

“This is a little bit higher, actually, than the odds ratio usually found for depressive disorders,” said Dr. Ritter.

he added.

Dr. Ritter reported having no financial conflicts regarding these studies.

REPORTING FROM ECNP 2019

Office of Inspector General

Question: Which one of the following statements is incorrect?

A. Office of Inspector General (OIG) is a federal agency of Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) that investigates statutory violations of health care fraud and abuse.

B. The three main legal minefields for physicians are false claims, kickbacks, and self-referrals.

C. Jail terms are part of the penalties provided by law.

D. OIG is also responsible for excluding violators from participating in Medicare/Medicaid programs, as well as curtailing a physician’s license to practice.

E. A private citizen can file a qui tam lawsuit against an errant practitioner or health care entity for fraud and abuse.

Answer: D. Health care fraud, waste, and abuse consume some 10% of federal health expenditures despite well-established laws that attempt to prevent and reduce such losses. The Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) Office of Inspector General, as well as the Department of Justice and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services are charged with enforcing these and other laws like the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act. Their web pages, referenced throughout this article, contain a wealth of information for the practitioner.

The term “Office of Inspector General” (OIG) refers to the oversight division of a federal or state agency charged with identifying and investigating fraud, waste, abuse, and mismanagement within that department or agency. There are currently 73 separate federal offices of inspectors general, which employ armed and unarmed criminal investigators, auditors, forensic auditors called “audigators,” and a variety of other specialists. An Act of Congress in 1976 established the first OIG under HHS. Besides being the first, HHS-OIG is also the largest, with a staff of approximately 1,600. A majority of resources goes toward the oversight of Medicare and Medicaid, as well as programs under other HHS institutions such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institutes of Health, and the Food and Drug Administration.1

HHS-OIG has the authority to seek civil monetary penalties, assessments, and exclusion against an individual or entity based on a wide variety of prohibited conduct affecting federal health care programs. Stiff penalties are regularly assessed against violators, and jail terms are not uncommon; however, it has no direct jurisdictions over physician licensure or nonfederal programs. The government maintains a pictorial list of its most wanted health care fugitives2 and provides an excellent set of Physician Education Training Materials on its website.3

False Claims Act (FCA)

In the health care arena, violation of FCA (31 U.S.C. §§3729-3733) is the foremost infraction. False claims by physicians can include billing for noncovered services such as experimental treatments, double billing, billing the government as the primary payer, or regularly waiving deductibles and copayments, as well as quality of care issues and unnecessary services. Wrongdoing also includes knowingly using another patient’s name for purposes of, say, federal drug coverage, billing for no-shows, and misrepresenting the diagnosis to justify services, as well as other claims. In the modern doctor’s office, the EMR enables easy check-offs on a preprinted form as documentation of actual work done. However, fraud is implicated if the information is deliberately misleading such as for purposes of upcoding. Importantly, physicians are liable for the actions of their office staff, so it is prudent to oversee and supervise all such activities. Naturally, one should document all claims that are sent and know the rules for allowable and excluded services.

FCA is an old law that was first enacted in 1863. It imposes liability for submitting a payment demand to the federal government where there is actual or constructive knowledge that the claim is false. Intent to defraud is not a required element but knowing or showing reckless disregard of the truth is. However, an error that is negligently committed is insufficient to constitute a violation. Penalties include treble damages, costs and attorney fees, and fines of $11,000 per false claim, as well as possible imprisonment and criminal fines. A so-called whistle-blower may file a lawsuit on behalf of the government and is entitled to a percentage of any recoveries. Whistle-blowers may be current or ex-business partners, hospital or office staff, patients, or competitors. The fact that a claim results from a kickback or is made in violation of the Stark law (discussed below) may also render it fraudulent, thus creating additional liability under FCA.

HHS-OIG, as well as the Department of Justice, discloses named cases of statutory violations on their websites. A few random 2019 examples include a New York licensed doctor was convicted of nine counts in connection with Oxycodone and Fentanyl diversion scheme; a Newton, Mass., geriatrician agreed to pay $680,000 to resolve allegations that he violated the False Claims Act by submitting inflated claims to Medicare and the Massachusetts Medicaid program (MassHealth) for care rendered to nursing home patients; and two Clermont, Fla., ophthalmologists agreed to pay a combined total of $157,312.32 to resolve allegations that they violated FCA by knowingly billing the government for mutually exclusive eyelid repair surgeries.

Anti-Kickback Statute (AKS)

AKS (42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7b[b]) is a criminal law that prohibits the knowing and willful payment of “remuneration” to induce or reward patient referrals or the generation of business involving any item or service payable by federal health care programs. Remuneration includes anything of value and can take many forms besides cash, such as free rent, lavish travel, and excessive compensation for medical directorships or consultancies. Rewarding a referral source may be acceptable in some industries, but is a crime in federal health care programs.

Moreover, the statute covers both the payers of kickbacks (those who offer or pay remuneration) and the recipients of kickbacks. Each party’s intent is a key element of their liability under AKS. Physicians who pay or accept kickbacks face penalties of up to $50,000 per kickback plus three times the amount of the remuneration and criminal prosecution. As an example, a Tulsa, Okla., doctor earlier this year agreed to pay the government $84,666.42 for allegedly accepting illegal kickback payments from a pharmacy, and in another case, a marketer agreed to pay nearly $340,000 for receiving kickbacks in exchange for prescription referrals.

A physician is an attractive target for kickback schemes. The kickback prohibition applies to all sources, even patients. For example, where the Medicare and Medicaid programs require patients to be responsible for copays for services, the health care provider is generally required to collect that money from the patients. Advertising the forgiveness of copayments or routinely waiving these copays would violate AKS. However, one may waive a copayment when a patient cannot afford to pay one or is uninsured. AKS also imposes civil monetary penalties on physicians who offer remuneration to Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries to influence them to use their services. Note that the government does not need to prove patient harm or financial loss to show that a violation has occurred, and physicians can be guilty even if they rendered services that are medically necessary.

There are so-called safe harbors that protect certain payment and business practices from running afoul of AKS. The rules and requirements are complex, and require full understanding and strict adherence.4

Physician Self-Referral Law

The Physician Self-Referral Law (42 U.S.C. § 1395nn), commonly referred to as the Stark law, prohibits physicians from referring patients to receive “designated health services” payable by Medicare or Medicaid from entities with which the physician or an immediate family member has a financial relationship, unless an exception applies. Financial relationships include both ownership/investment interests and compensation arrangements. A partial list of “designated health services” includes services related to clinical laboratory, physical therapy, radiology, parenteral and enteral supplies, prosthetic devices and supplies, home health care outpatient prescription drugs, and inpatient and outpatient hospital services. This list is not meant to be an exhaustive one.

Stark is a strict liability statute, which means proof of specific intent to violate the law is not required. The law prohibits the submission, or causing the submission, of claims in violation of the law’s restrictions on referrals. Penalties for physicians who violate the Stark law include fines, as well as exclusion from participation in federal health care programs. Like AKS, Stark law features its own safe harbors.

Dr. Tan is professor emeritus of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii, Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. Some materials may have been discussed in earlier columns. For additional information, readers may contact the author at siang@hawaii.edu.

References

1. HHS Office of Inspector General. About OIG. https://oig.hhs.gov/about-oig/about-us/index.asp

2. HHS Office of Inspector General. OIG most wanted fugitives.

3. HHS Office of Inspector General. “Physician education training materials.” A roadmap for new physicians: Avoiding Medicare and Medicaid fraud and abuse.

4. HHS Office of Inspector General. Safe harbor regulations.

Question: Which one of the following statements is incorrect?

A. Office of Inspector General (OIG) is a federal agency of Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) that investigates statutory violations of health care fraud and abuse.

B. The three main legal minefields for physicians are false claims, kickbacks, and self-referrals.

C. Jail terms are part of the penalties provided by law.

D. OIG is also responsible for excluding violators from participating in Medicare/Medicaid programs, as well as curtailing a physician’s license to practice.

E. A private citizen can file a qui tam lawsuit against an errant practitioner or health care entity for fraud and abuse.

Answer: D. Health care fraud, waste, and abuse consume some 10% of federal health expenditures despite well-established laws that attempt to prevent and reduce such losses. The Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) Office of Inspector General, as well as the Department of Justice and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services are charged with enforcing these and other laws like the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act. Their web pages, referenced throughout this article, contain a wealth of information for the practitioner.

The term “Office of Inspector General” (OIG) refers to the oversight division of a federal or state agency charged with identifying and investigating fraud, waste, abuse, and mismanagement within that department or agency. There are currently 73 separate federal offices of inspectors general, which employ armed and unarmed criminal investigators, auditors, forensic auditors called “audigators,” and a variety of other specialists. An Act of Congress in 1976 established the first OIG under HHS. Besides being the first, HHS-OIG is also the largest, with a staff of approximately 1,600. A majority of resources goes toward the oversight of Medicare and Medicaid, as well as programs under other HHS institutions such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institutes of Health, and the Food and Drug Administration.1

HHS-OIG has the authority to seek civil monetary penalties, assessments, and exclusion against an individual or entity based on a wide variety of prohibited conduct affecting federal health care programs. Stiff penalties are regularly assessed against violators, and jail terms are not uncommon; however, it has no direct jurisdictions over physician licensure or nonfederal programs. The government maintains a pictorial list of its most wanted health care fugitives2 and provides an excellent set of Physician Education Training Materials on its website.3

False Claims Act (FCA)

In the health care arena, violation of FCA (31 U.S.C. §§3729-3733) is the foremost infraction. False claims by physicians can include billing for noncovered services such as experimental treatments, double billing, billing the government as the primary payer, or regularly waiving deductibles and copayments, as well as quality of care issues and unnecessary services. Wrongdoing also includes knowingly using another patient’s name for purposes of, say, federal drug coverage, billing for no-shows, and misrepresenting the diagnosis to justify services, as well as other claims. In the modern doctor’s office, the EMR enables easy check-offs on a preprinted form as documentation of actual work done. However, fraud is implicated if the information is deliberately misleading such as for purposes of upcoding. Importantly, physicians are liable for the actions of their office staff, so it is prudent to oversee and supervise all such activities. Naturally, one should document all claims that are sent and know the rules for allowable and excluded services.

FCA is an old law that was first enacted in 1863. It imposes liability for submitting a payment demand to the federal government where there is actual or constructive knowledge that the claim is false. Intent to defraud is not a required element but knowing or showing reckless disregard of the truth is. However, an error that is negligently committed is insufficient to constitute a violation. Penalties include treble damages, costs and attorney fees, and fines of $11,000 per false claim, as well as possible imprisonment and criminal fines. A so-called whistle-blower may file a lawsuit on behalf of the government and is entitled to a percentage of any recoveries. Whistle-blowers may be current or ex-business partners, hospital or office staff, patients, or competitors. The fact that a claim results from a kickback or is made in violation of the Stark law (discussed below) may also render it fraudulent, thus creating additional liability under FCA.

HHS-OIG, as well as the Department of Justice, discloses named cases of statutory violations on their websites. A few random 2019 examples include a New York licensed doctor was convicted of nine counts in connection with Oxycodone and Fentanyl diversion scheme; a Newton, Mass., geriatrician agreed to pay $680,000 to resolve allegations that he violated the False Claims Act by submitting inflated claims to Medicare and the Massachusetts Medicaid program (MassHealth) for care rendered to nursing home patients; and two Clermont, Fla., ophthalmologists agreed to pay a combined total of $157,312.32 to resolve allegations that they violated FCA by knowingly billing the government for mutually exclusive eyelid repair surgeries.

Anti-Kickback Statute (AKS)

AKS (42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7b[b]) is a criminal law that prohibits the knowing and willful payment of “remuneration” to induce or reward patient referrals or the generation of business involving any item or service payable by federal health care programs. Remuneration includes anything of value and can take many forms besides cash, such as free rent, lavish travel, and excessive compensation for medical directorships or consultancies. Rewarding a referral source may be acceptable in some industries, but is a crime in federal health care programs.

Moreover, the statute covers both the payers of kickbacks (those who offer or pay remuneration) and the recipients of kickbacks. Each party’s intent is a key element of their liability under AKS. Physicians who pay or accept kickbacks face penalties of up to $50,000 per kickback plus three times the amount of the remuneration and criminal prosecution. As an example, a Tulsa, Okla., doctor earlier this year agreed to pay the government $84,666.42 for allegedly accepting illegal kickback payments from a pharmacy, and in another case, a marketer agreed to pay nearly $340,000 for receiving kickbacks in exchange for prescription referrals.

A physician is an attractive target for kickback schemes. The kickback prohibition applies to all sources, even patients. For example, where the Medicare and Medicaid programs require patients to be responsible for copays for services, the health care provider is generally required to collect that money from the patients. Advertising the forgiveness of copayments or routinely waiving these copays would violate AKS. However, one may waive a copayment when a patient cannot afford to pay one or is uninsured. AKS also imposes civil monetary penalties on physicians who offer remuneration to Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries to influence them to use their services. Note that the government does not need to prove patient harm or financial loss to show that a violation has occurred, and physicians can be guilty even if they rendered services that are medically necessary.

There are so-called safe harbors that protect certain payment and business practices from running afoul of AKS. The rules and requirements are complex, and require full understanding and strict adherence.4

Physician Self-Referral Law

The Physician Self-Referral Law (42 U.S.C. § 1395nn), commonly referred to as the Stark law, prohibits physicians from referring patients to receive “designated health services” payable by Medicare or Medicaid from entities with which the physician or an immediate family member has a financial relationship, unless an exception applies. Financial relationships include both ownership/investment interests and compensation arrangements. A partial list of “designated health services” includes services related to clinical laboratory, physical therapy, radiology, parenteral and enteral supplies, prosthetic devices and supplies, home health care outpatient prescription drugs, and inpatient and outpatient hospital services. This list is not meant to be an exhaustive one.

Stark is a strict liability statute, which means proof of specific intent to violate the law is not required. The law prohibits the submission, or causing the submission, of claims in violation of the law’s restrictions on referrals. Penalties for physicians who violate the Stark law include fines, as well as exclusion from participation in federal health care programs. Like AKS, Stark law features its own safe harbors.

Dr. Tan is professor emeritus of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii, Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. Some materials may have been discussed in earlier columns. For additional information, readers may contact the author at siang@hawaii.edu.

References

1. HHS Office of Inspector General. About OIG. https://oig.hhs.gov/about-oig/about-us/index.asp

2. HHS Office of Inspector General. OIG most wanted fugitives.

3. HHS Office of Inspector General. “Physician education training materials.” A roadmap for new physicians: Avoiding Medicare and Medicaid fraud and abuse.

4. HHS Office of Inspector General. Safe harbor regulations.

Question: Which one of the following statements is incorrect?

A. Office of Inspector General (OIG) is a federal agency of Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) that investigates statutory violations of health care fraud and abuse.

B. The three main legal minefields for physicians are false claims, kickbacks, and self-referrals.

C. Jail terms are part of the penalties provided by law.

D. OIG is also responsible for excluding violators from participating in Medicare/Medicaid programs, as well as curtailing a physician’s license to practice.

E. A private citizen can file a qui tam lawsuit against an errant practitioner or health care entity for fraud and abuse.

Answer: D. Health care fraud, waste, and abuse consume some 10% of federal health expenditures despite well-established laws that attempt to prevent and reduce such losses. The Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) Office of Inspector General, as well as the Department of Justice and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services are charged with enforcing these and other laws like the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act. Their web pages, referenced throughout this article, contain a wealth of information for the practitioner.

The term “Office of Inspector General” (OIG) refers to the oversight division of a federal or state agency charged with identifying and investigating fraud, waste, abuse, and mismanagement within that department or agency. There are currently 73 separate federal offices of inspectors general, which employ armed and unarmed criminal investigators, auditors, forensic auditors called “audigators,” and a variety of other specialists. An Act of Congress in 1976 established the first OIG under HHS. Besides being the first, HHS-OIG is also the largest, with a staff of approximately 1,600. A majority of resources goes toward the oversight of Medicare and Medicaid, as well as programs under other HHS institutions such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institutes of Health, and the Food and Drug Administration.1

HHS-OIG has the authority to seek civil monetary penalties, assessments, and exclusion against an individual or entity based on a wide variety of prohibited conduct affecting federal health care programs. Stiff penalties are regularly assessed against violators, and jail terms are not uncommon; however, it has no direct jurisdictions over physician licensure or nonfederal programs. The government maintains a pictorial list of its most wanted health care fugitives2 and provides an excellent set of Physician Education Training Materials on its website.3

False Claims Act (FCA)

In the health care arena, violation of FCA (31 U.S.C. §§3729-3733) is the foremost infraction. False claims by physicians can include billing for noncovered services such as experimental treatments, double billing, billing the government as the primary payer, or regularly waiving deductibles and copayments, as well as quality of care issues and unnecessary services. Wrongdoing also includes knowingly using another patient’s name for purposes of, say, federal drug coverage, billing for no-shows, and misrepresenting the diagnosis to justify services, as well as other claims. In the modern doctor’s office, the EMR enables easy check-offs on a preprinted form as documentation of actual work done. However, fraud is implicated if the information is deliberately misleading such as for purposes of upcoding. Importantly, physicians are liable for the actions of their office staff, so it is prudent to oversee and supervise all such activities. Naturally, one should document all claims that are sent and know the rules for allowable and excluded services.

FCA is an old law that was first enacted in 1863. It imposes liability for submitting a payment demand to the federal government where there is actual or constructive knowledge that the claim is false. Intent to defraud is not a required element but knowing or showing reckless disregard of the truth is. However, an error that is negligently committed is insufficient to constitute a violation. Penalties include treble damages, costs and attorney fees, and fines of $11,000 per false claim, as well as possible imprisonment and criminal fines. A so-called whistle-blower may file a lawsuit on behalf of the government and is entitled to a percentage of any recoveries. Whistle-blowers may be current or ex-business partners, hospital or office staff, patients, or competitors. The fact that a claim results from a kickback or is made in violation of the Stark law (discussed below) may also render it fraudulent, thus creating additional liability under FCA.

HHS-OIG, as well as the Department of Justice, discloses named cases of statutory violations on their websites. A few random 2019 examples include a New York licensed doctor was convicted of nine counts in connection with Oxycodone and Fentanyl diversion scheme; a Newton, Mass., geriatrician agreed to pay $680,000 to resolve allegations that he violated the False Claims Act by submitting inflated claims to Medicare and the Massachusetts Medicaid program (MassHealth) for care rendered to nursing home patients; and two Clermont, Fla., ophthalmologists agreed to pay a combined total of $157,312.32 to resolve allegations that they violated FCA by knowingly billing the government for mutually exclusive eyelid repair surgeries.

Anti-Kickback Statute (AKS)

AKS (42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7b[b]) is a criminal law that prohibits the knowing and willful payment of “remuneration” to induce or reward patient referrals or the generation of business involving any item or service payable by federal health care programs. Remuneration includes anything of value and can take many forms besides cash, such as free rent, lavish travel, and excessive compensation for medical directorships or consultancies. Rewarding a referral source may be acceptable in some industries, but is a crime in federal health care programs.

Moreover, the statute covers both the payers of kickbacks (those who offer or pay remuneration) and the recipients of kickbacks. Each party’s intent is a key element of their liability under AKS. Physicians who pay or accept kickbacks face penalties of up to $50,000 per kickback plus three times the amount of the remuneration and criminal prosecution. As an example, a Tulsa, Okla., doctor earlier this year agreed to pay the government $84,666.42 for allegedly accepting illegal kickback payments from a pharmacy, and in another case, a marketer agreed to pay nearly $340,000 for receiving kickbacks in exchange for prescription referrals.

A physician is an attractive target for kickback schemes. The kickback prohibition applies to all sources, even patients. For example, where the Medicare and Medicaid programs require patients to be responsible for copays for services, the health care provider is generally required to collect that money from the patients. Advertising the forgiveness of copayments or routinely waiving these copays would violate AKS. However, one may waive a copayment when a patient cannot afford to pay one or is uninsured. AKS also imposes civil monetary penalties on physicians who offer remuneration to Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries to influence them to use their services. Note that the government does not need to prove patient harm or financial loss to show that a violation has occurred, and physicians can be guilty even if they rendered services that are medically necessary.

There are so-called safe harbors that protect certain payment and business practices from running afoul of AKS. The rules and requirements are complex, and require full understanding and strict adherence.4

Physician Self-Referral Law

The Physician Self-Referral Law (42 U.S.C. § 1395nn), commonly referred to as the Stark law, prohibits physicians from referring patients to receive “designated health services” payable by Medicare or Medicaid from entities with which the physician or an immediate family member has a financial relationship, unless an exception applies. Financial relationships include both ownership/investment interests and compensation arrangements. A partial list of “designated health services” includes services related to clinical laboratory, physical therapy, radiology, parenteral and enteral supplies, prosthetic devices and supplies, home health care outpatient prescription drugs, and inpatient and outpatient hospital services. This list is not meant to be an exhaustive one.

Stark is a strict liability statute, which means proof of specific intent to violate the law is not required. The law prohibits the submission, or causing the submission, of claims in violation of the law’s restrictions on referrals. Penalties for physicians who violate the Stark law include fines, as well as exclusion from participation in federal health care programs. Like AKS, Stark law features its own safe harbors.

Dr. Tan is professor emeritus of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii, Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. Some materials may have been discussed in earlier columns. For additional information, readers may contact the author at siang@hawaii.edu.

References

1. HHS Office of Inspector General. About OIG. https://oig.hhs.gov/about-oig/about-us/index.asp

2. HHS Office of Inspector General. OIG most wanted fugitives.

3. HHS Office of Inspector General. “Physician education training materials.” A roadmap for new physicians: Avoiding Medicare and Medicaid fraud and abuse.

4. HHS Office of Inspector General. Safe harbor regulations.

Antecedent Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia May Be Associated With More Aggressive Mycosis Fungoides

To the Editor:

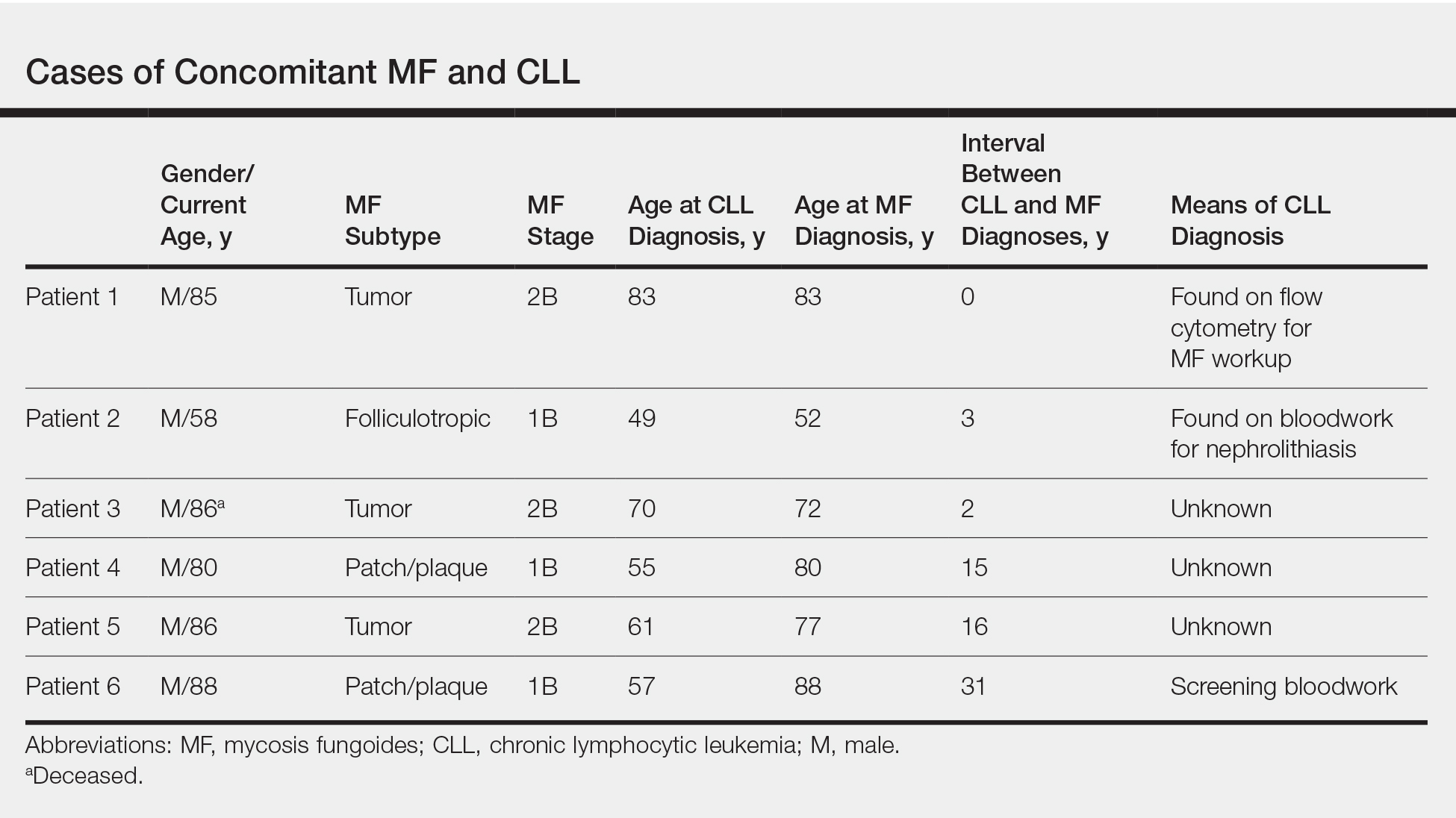

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is the most common form of primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. It has been associated with increased risk for other visceral and hematologic malignancies.1 Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is one of the most common hematologic malignancies. In the United States, a patient’s lifetime risk for CLL is 0.6%. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia often is diagnosed as an incidental finding and typically is not detrimental to a patient’s health. Six cases of MF with antecedent or concomitant CLL were identified in a cohort of patients treated at the University of Minnesota (Minneapolis, Minnesota) from 2005 to 2017 (Table).

All 6 patients were male, with a mean age of 80.5 years. The mean age at CLL diagnosis was 62.5 years, while the mean age at MF diagnosis was 75.3 years. Three patients were younger than 60 years when their CLL was diagnosed: 49, 55, and 57 years. Notably, 4 patients had more aggressive types of MF: 3 with tumor-stage disease, and 1 with folliculotropic MF. Five patients were diagnosed with CLL before their MF was diagnosed (mean, 13.4 years prior; range, 3–31 years), and 1 was diagnosed as part of the initial MF workup.

Given the frequency of both MF and CLL, the co-occurrence of these diseases is not surprising, as other case reports and a larger case series have described the relationship between MF and malignancy.2 It is possible that CLL patients are more likely to be diagnosed with MF because of their regular hematology/oncology follow-up; however, none of our patients were referred from hematology/oncology to dermatology. Alternatively, patients with MF may be more likely to be diagnosed with CLL because of repeated bloodwork performed for diagnosis and screening, which occurred in only 1 of 6 cases. Most of the other patients were diagnosed with MF more than a decade after being diagnosed with CLL.

Does having CLL make patients more likely to develop MF? It is known that patients with CLL may experience immunodeficiency secondary to immune dysregulation, making them more susceptible to infection and secondary malignancies.3 Of our 6 cases, 4 had aggressive or advanced forms of MF, which is similar to the findings of Chang et al.2 In their report, of 8 patients with MF, 2 had tumor-stage disease and 2 had erythrodermic MF. They determined that these patients had worse overall survival.2 Our data corroborate the finding that patients with CLL may develop more severe MF, which leads to the conclusion that patients diagnosed with CLL before, concomitantly, or after their diagnosis of MF should be closely monitored. It is notable that patients with more advanced disease tend to be older at the time of diagnosis and that patients who are diagnosed at 57 years or older have been found to have worse disease-specific survival.4,5

This report is limited by the small sample size (6 cases), but it serves to draw attention to the phenomenon of co-occurrence of MF and CLL, and the concern that patients with CLL may develop more aggressive MF.

- Huang KP, Weinstock MA, Clarke CA, et al. Second lymphomas and other malignant neoplasms in patients with mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:45-50.

- Chang MB, Weaver AL, Brewer JD. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: clinical characteristics, temporal relationships, and survival data in a series of 14 patients at Mayo Clinic. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:966-970.

- Hamblin AD, Hamblin TJ. The immunodeficiency of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br Med Bull. 2008;87:49-62.

- Kim YH, Liu HL, Mraz-Gernhard S, et al. Long-term outcome of 525 patients with mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome: clinical prognostic factors and risk for disease progression. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:857-866.

- Agar NS, Wedgeworth E, Crichton S, et al. Survival outcomes and prognostic factors in mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome: validation of the revised International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas/European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer staging proposal. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4730-4739.

To the Editor:

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is the most common form of primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. It has been associated with increased risk for other visceral and hematologic malignancies.1 Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is one of the most common hematologic malignancies. In the United States, a patient’s lifetime risk for CLL is 0.6%. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia often is diagnosed as an incidental finding and typically is not detrimental to a patient’s health. Six cases of MF with antecedent or concomitant CLL were identified in a cohort of patients treated at the University of Minnesota (Minneapolis, Minnesota) from 2005 to 2017 (Table).

All 6 patients were male, with a mean age of 80.5 years. The mean age at CLL diagnosis was 62.5 years, while the mean age at MF diagnosis was 75.3 years. Three patients were younger than 60 years when their CLL was diagnosed: 49, 55, and 57 years. Notably, 4 patients had more aggressive types of MF: 3 with tumor-stage disease, and 1 with folliculotropic MF. Five patients were diagnosed with CLL before their MF was diagnosed (mean, 13.4 years prior; range, 3–31 years), and 1 was diagnosed as part of the initial MF workup.

Given the frequency of both MF and CLL, the co-occurrence of these diseases is not surprising, as other case reports and a larger case series have described the relationship between MF and malignancy.2 It is possible that CLL patients are more likely to be diagnosed with MF because of their regular hematology/oncology follow-up; however, none of our patients were referred from hematology/oncology to dermatology. Alternatively, patients with MF may be more likely to be diagnosed with CLL because of repeated bloodwork performed for diagnosis and screening, which occurred in only 1 of 6 cases. Most of the other patients were diagnosed with MF more than a decade after being diagnosed with CLL.

Does having CLL make patients more likely to develop MF? It is known that patients with CLL may experience immunodeficiency secondary to immune dysregulation, making them more susceptible to infection and secondary malignancies.3 Of our 6 cases, 4 had aggressive or advanced forms of MF, which is similar to the findings of Chang et al.2 In their report, of 8 patients with MF, 2 had tumor-stage disease and 2 had erythrodermic MF. They determined that these patients had worse overall survival.2 Our data corroborate the finding that patients with CLL may develop more severe MF, which leads to the conclusion that patients diagnosed with CLL before, concomitantly, or after their diagnosis of MF should be closely monitored. It is notable that patients with more advanced disease tend to be older at the time of diagnosis and that patients who are diagnosed at 57 years or older have been found to have worse disease-specific survival.4,5

This report is limited by the small sample size (6 cases), but it serves to draw attention to the phenomenon of co-occurrence of MF and CLL, and the concern that patients with CLL may develop more aggressive MF.

To the Editor:

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is the most common form of primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. It has been associated with increased risk for other visceral and hematologic malignancies.1 Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is one of the most common hematologic malignancies. In the United States, a patient’s lifetime risk for CLL is 0.6%. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia often is diagnosed as an incidental finding and typically is not detrimental to a patient’s health. Six cases of MF with antecedent or concomitant CLL were identified in a cohort of patients treated at the University of Minnesota (Minneapolis, Minnesota) from 2005 to 2017 (Table).

All 6 patients were male, with a mean age of 80.5 years. The mean age at CLL diagnosis was 62.5 years, while the mean age at MF diagnosis was 75.3 years. Three patients were younger than 60 years when their CLL was diagnosed: 49, 55, and 57 years. Notably, 4 patients had more aggressive types of MF: 3 with tumor-stage disease, and 1 with folliculotropic MF. Five patients were diagnosed with CLL before their MF was diagnosed (mean, 13.4 years prior; range, 3–31 years), and 1 was diagnosed as part of the initial MF workup.

Given the frequency of both MF and CLL, the co-occurrence of these diseases is not surprising, as other case reports and a larger case series have described the relationship between MF and malignancy.2 It is possible that CLL patients are more likely to be diagnosed with MF because of their regular hematology/oncology follow-up; however, none of our patients were referred from hematology/oncology to dermatology. Alternatively, patients with MF may be more likely to be diagnosed with CLL because of repeated bloodwork performed for diagnosis and screening, which occurred in only 1 of 6 cases. Most of the other patients were diagnosed with MF more than a decade after being diagnosed with CLL.

Does having CLL make patients more likely to develop MF? It is known that patients with CLL may experience immunodeficiency secondary to immune dysregulation, making them more susceptible to infection and secondary malignancies.3 Of our 6 cases, 4 had aggressive or advanced forms of MF, which is similar to the findings of Chang et al.2 In their report, of 8 patients with MF, 2 had tumor-stage disease and 2 had erythrodermic MF. They determined that these patients had worse overall survival.2 Our data corroborate the finding that patients with CLL may develop more severe MF, which leads to the conclusion that patients diagnosed with CLL before, concomitantly, or after their diagnosis of MF should be closely monitored. It is notable that patients with more advanced disease tend to be older at the time of diagnosis and that patients who are diagnosed at 57 years or older have been found to have worse disease-specific survival.4,5

This report is limited by the small sample size (6 cases), but it serves to draw attention to the phenomenon of co-occurrence of MF and CLL, and the concern that patients with CLL may develop more aggressive MF.

- Huang KP, Weinstock MA, Clarke CA, et al. Second lymphomas and other malignant neoplasms in patients with mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:45-50.

- Chang MB, Weaver AL, Brewer JD. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: clinical characteristics, temporal relationships, and survival data in a series of 14 patients at Mayo Clinic. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:966-970.

- Hamblin AD, Hamblin TJ. The immunodeficiency of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br Med Bull. 2008;87:49-62.

- Kim YH, Liu HL, Mraz-Gernhard S, et al. Long-term outcome of 525 patients with mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome: clinical prognostic factors and risk for disease progression. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:857-866.

- Agar NS, Wedgeworth E, Crichton S, et al. Survival outcomes and prognostic factors in mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome: validation of the revised International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas/European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer staging proposal. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4730-4739.

- Huang KP, Weinstock MA, Clarke CA, et al. Second lymphomas and other malignant neoplasms in patients with mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:45-50.

- Chang MB, Weaver AL, Brewer JD. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: clinical characteristics, temporal relationships, and survival data in a series of 14 patients at Mayo Clinic. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:966-970.

- Hamblin AD, Hamblin TJ. The immunodeficiency of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br Med Bull. 2008;87:49-62.

- Kim YH, Liu HL, Mraz-Gernhard S, et al. Long-term outcome of 525 patients with mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome: clinical prognostic factors and risk for disease progression. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:857-866.

- Agar NS, Wedgeworth E, Crichton S, et al. Survival outcomes and prognostic factors in mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome: validation of the revised International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas/European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer staging proposal. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4730-4739.

Practice Points

- Patients with mycosis fungoides (MF) are at increased risk for second hematologic malignancies, including chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

- Anecdotal information suggests that patients with CLL prior to developing MF may have more severe phenotypes of MF.

Over half of NASH patients have improvement in liver fibrosis after bariatric surgery

BOSTON – For almost half of patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), bariatric surgery does not resolve severe fibrosis, even after significant weight loss and resolution of multiple metabolic comorbidities, according to investigators.

Still, bariatric surgery was highly effective at improving liver histology in patients without severe fibrosis, reported lead author Raluca Pais, MD, of Sorbonne University, Paris, and colleagues.

“There are many targeted agents for NASH at this time, but their response rate is limited to less than 30%,” Dr. Pais said in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. “In very selective patients, bariatric surgery is a very attractive therapeutic option, as it promotes massive weight loss and sustained improvement in metabolic comorbidities, which are concomitant with very high rates of hepatic histological improvement in most but not all patients.” Despite the known benefits of bariatric surgery, histologic outcomes have been minimally studied, Dr. Pais said, which prompted the present trial.

The investigators began by analyzing data from 868 patients with NASH who underwent bariatric surgery with perioperative liver biopsy between 2004 and 2014. Of these patients, 181 had advanced NASH, a diagnosis that was subclassified by severe fibrosis (F3 or F4) or high activity (steatosis, activity, and fibrosis score of 3-4 with F0-2). Out of the 181 patients with advanced NASH, 65 consented to follow-up liver biopsy, which was conducted a mean of 6 years after surgery. Among these patients, 53 had undergone gastric bypass surgery, while 12 had undergone sleeve gastrectomy.

Almost one-third (29%) of the 65 patients who underwent bariatric surgery had normal livers at follow-up biopsy. Among the 35 patients who had severe fibrosis at baseline, slightly more than half (54%) had resolution of severe fibrosis. In contrast, resolution of high activity occurred in almost all affected patients (97%).

While the findings highlighted some of the benefits associated with bariatric surgery, Dr. Pais emphasized the other side of the coin; many patients did not have resolution of severe fibrosis, even years after surgery. Specifically, 45% of patients had persistent severe fibrosis at follow-up biopsy, despite improvements in comorbidities. On average, these patients lost 23% of their baseline body weight, and two-thirds of the group achieved normal ALT and resolution of NASH. Many also had improvements in insulin resistance and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease activity scores. These findings suggest that changes in severe fibrosis occur independently of many other improvements, Dr. Pais said.

Although multiple comorbidities were not correlated with changes in severe fibrosis, several other predictors were identified. Compared with patients who had resolution of severe fibrosis, nonresponders were typically older (56 vs. 49 years), more often had persistent diabetes (79% vs. 50%), and generally had shorter time between surgery and follow-up biopsy (4.2 vs. 7.5 years). Compared with nonresponders, responders were more likely to have undergone gastric bypass surgery (100% vs. 69%), suggesting that this procedure was more effective at resolving severe fibrosis than sleeve gastrectomy.

During the question-and-answer session following the presentation, multiple conference attendees suggested that the title of the study, “Persistence of severe liver fibrosis despite substantial weight loss with bariatric surgery,” was unnecessarily negative, when in fact the study offered strong support for bariatric surgery.

“This is wonderful data that shows surgery is very effective,” one attendee said.

“This is really positive data,” said another. “I mean, you’ve got reversal of advanced fibrosis in half of the population by the time you follow up for several years, so I would say this is really, very positive data.”

The investigators disclosed relationships with Allergan, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk, and others.

*This story was updated on November 15, 2019.

SOURCE: Pais R et al. The Liver Meeting 2019, Abstract 66.

BOSTON – For almost half of patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), bariatric surgery does not resolve severe fibrosis, even after significant weight loss and resolution of multiple metabolic comorbidities, according to investigators.

Still, bariatric surgery was highly effective at improving liver histology in patients without severe fibrosis, reported lead author Raluca Pais, MD, of Sorbonne University, Paris, and colleagues.

“There are many targeted agents for NASH at this time, but their response rate is limited to less than 30%,” Dr. Pais said in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. “In very selective patients, bariatric surgery is a very attractive therapeutic option, as it promotes massive weight loss and sustained improvement in metabolic comorbidities, which are concomitant with very high rates of hepatic histological improvement in most but not all patients.” Despite the known benefits of bariatric surgery, histologic outcomes have been minimally studied, Dr. Pais said, which prompted the present trial.

The investigators began by analyzing data from 868 patients with NASH who underwent bariatric surgery with perioperative liver biopsy between 2004 and 2014. Of these patients, 181 had advanced NASH, a diagnosis that was subclassified by severe fibrosis (F3 or F4) or high activity (steatosis, activity, and fibrosis score of 3-4 with F0-2). Out of the 181 patients with advanced NASH, 65 consented to follow-up liver biopsy, which was conducted a mean of 6 years after surgery. Among these patients, 53 had undergone gastric bypass surgery, while 12 had undergone sleeve gastrectomy.

Almost one-third (29%) of the 65 patients who underwent bariatric surgery had normal livers at follow-up biopsy. Among the 35 patients who had severe fibrosis at baseline, slightly more than half (54%) had resolution of severe fibrosis. In contrast, resolution of high activity occurred in almost all affected patients (97%).

While the findings highlighted some of the benefits associated with bariatric surgery, Dr. Pais emphasized the other side of the coin; many patients did not have resolution of severe fibrosis, even years after surgery. Specifically, 45% of patients had persistent severe fibrosis at follow-up biopsy, despite improvements in comorbidities. On average, these patients lost 23% of their baseline body weight, and two-thirds of the group achieved normal ALT and resolution of NASH. Many also had improvements in insulin resistance and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease activity scores. These findings suggest that changes in severe fibrosis occur independently of many other improvements, Dr. Pais said.

Although multiple comorbidities were not correlated with changes in severe fibrosis, several other predictors were identified. Compared with patients who had resolution of severe fibrosis, nonresponders were typically older (56 vs. 49 years), more often had persistent diabetes (79% vs. 50%), and generally had shorter time between surgery and follow-up biopsy (4.2 vs. 7.5 years). Compared with nonresponders, responders were more likely to have undergone gastric bypass surgery (100% vs. 69%), suggesting that this procedure was more effective at resolving severe fibrosis than sleeve gastrectomy.

During the question-and-answer session following the presentation, multiple conference attendees suggested that the title of the study, “Persistence of severe liver fibrosis despite substantial weight loss with bariatric surgery,” was unnecessarily negative, when in fact the study offered strong support for bariatric surgery.

“This is wonderful data that shows surgery is very effective,” one attendee said.

“This is really positive data,” said another. “I mean, you’ve got reversal of advanced fibrosis in half of the population by the time you follow up for several years, so I would say this is really, very positive data.”

The investigators disclosed relationships with Allergan, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk, and others.

*This story was updated on November 15, 2019.

SOURCE: Pais R et al. The Liver Meeting 2019, Abstract 66.

BOSTON – For almost half of patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), bariatric surgery does not resolve severe fibrosis, even after significant weight loss and resolution of multiple metabolic comorbidities, according to investigators.

Still, bariatric surgery was highly effective at improving liver histology in patients without severe fibrosis, reported lead author Raluca Pais, MD, of Sorbonne University, Paris, and colleagues.

“There are many targeted agents for NASH at this time, but their response rate is limited to less than 30%,” Dr. Pais said in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. “In very selective patients, bariatric surgery is a very attractive therapeutic option, as it promotes massive weight loss and sustained improvement in metabolic comorbidities, which are concomitant with very high rates of hepatic histological improvement in most but not all patients.” Despite the known benefits of bariatric surgery, histologic outcomes have been minimally studied, Dr. Pais said, which prompted the present trial.

The investigators began by analyzing data from 868 patients with NASH who underwent bariatric surgery with perioperative liver biopsy between 2004 and 2014. Of these patients, 181 had advanced NASH, a diagnosis that was subclassified by severe fibrosis (F3 or F4) or high activity (steatosis, activity, and fibrosis score of 3-4 with F0-2). Out of the 181 patients with advanced NASH, 65 consented to follow-up liver biopsy, which was conducted a mean of 6 years after surgery. Among these patients, 53 had undergone gastric bypass surgery, while 12 had undergone sleeve gastrectomy.

Almost one-third (29%) of the 65 patients who underwent bariatric surgery had normal livers at follow-up biopsy. Among the 35 patients who had severe fibrosis at baseline, slightly more than half (54%) had resolution of severe fibrosis. In contrast, resolution of high activity occurred in almost all affected patients (97%).

While the findings highlighted some of the benefits associated with bariatric surgery, Dr. Pais emphasized the other side of the coin; many patients did not have resolution of severe fibrosis, even years after surgery. Specifically, 45% of patients had persistent severe fibrosis at follow-up biopsy, despite improvements in comorbidities. On average, these patients lost 23% of their baseline body weight, and two-thirds of the group achieved normal ALT and resolution of NASH. Many also had improvements in insulin resistance and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease activity scores. These findings suggest that changes in severe fibrosis occur independently of many other improvements, Dr. Pais said.

Although multiple comorbidities were not correlated with changes in severe fibrosis, several other predictors were identified. Compared with patients who had resolution of severe fibrosis, nonresponders were typically older (56 vs. 49 years), more often had persistent diabetes (79% vs. 50%), and generally had shorter time between surgery and follow-up biopsy (4.2 vs. 7.5 years). Compared with nonresponders, responders were more likely to have undergone gastric bypass surgery (100% vs. 69%), suggesting that this procedure was more effective at resolving severe fibrosis than sleeve gastrectomy.

During the question-and-answer session following the presentation, multiple conference attendees suggested that the title of the study, “Persistence of severe liver fibrosis despite substantial weight loss with bariatric surgery,” was unnecessarily negative, when in fact the study offered strong support for bariatric surgery.

“This is wonderful data that shows surgery is very effective,” one attendee said.

“This is really positive data,” said another. “I mean, you’ve got reversal of advanced fibrosis in half of the population by the time you follow up for several years, so I would say this is really, very positive data.”

The investigators disclosed relationships with Allergan, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk, and others.

*This story was updated on November 15, 2019.

SOURCE: Pais R et al. The Liver Meeting 2019, Abstract 66.

REPORTING FROM THE LIVER MEETING 2019