User login

Methotrexate may affect joint erosions but not pain in patients with erosive hand OA

ATLANTA – , according to results from the small, prospective, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled ADEM trial.

“Our study failed to show the superiority of methotrexate over placebo on pain evolution, but our results on structural evolution and the presence of inflammatory parameters as predictors of erosive evolution in nonerosive diseases may lead us to discuss the place of methotrexate in early steps of the disease evolution, and underlines the importance of the part played by the interaction between synovitis and subchondral bone in erosive progression,” Christian Roux, MD, PhD, of the department of rheumatology at Côte d’Azur University, Nice, France, said in his presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Dr. Roux and colleagues enrolled 64 patients in the ADEM trial, where patients with symptomatic erosive hand osteoarthritis (EHOA) were randomized to receive 10 mg of methotrexate (MTX) per week or placebo. At 3 months, researchers assessed patients for pain using the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) score for hand pain, and secondary outcome measures at 12 months included VAS score for hand pain, radiographic progression using Verbruggen-Veys Anatomical Phase Score and Gent University Scoring System, and MRI.

Patients were included in the study if they were between 45 and 85 years old with a VAS pain score greater than 40, had failed classic therapeutics (acetaminophen, topical NSAIDs, and symptomatic slow-acting drugs), and had at least one erosive lesion. At baseline, the MTX and placebo groups were not significantly different with regard to gender (91% vs. 97% female), mean body mass index (24.6 kg/m2 vs. 24.2 kg/m2) and mean age (67.5 years vs. 64.9 years). Radiologic data showed joint loss, erosive, and erosive plus remodeling measurements were also similar between groups at baseline.

The mean VAS score for patients in the MTX group decreased from 65.7 at baseline to 48.2 at 3 months (–17.5; P = .07), compared with a decrease from 63.9 to 55.5 (–8.4; P = .002). At 12 months, VAS scores for patients in the MTX group decreased to 47.5, compared with a decrease in the placebo group to 48.2. However, the between-group differences for VAS scores were not significant at 3 months (P = .2) and at 12 months (P = .6).

“We have different hypotheses on the failure of our study on our main outcome, which was pain,” he said. “The first is a low-dose of methotrexate, and the second may be ... a placebo effect, which is very, very important in osteoarthritis.”

Dr. Roux noted the results from the ADEM trial were similar to a recent study in which 90 patients with hand OA were randomized to receive etanercept or placebo. At 24 weeks, there was no statistically significant difference between VAS pain in the etanercept group (between group difference, −5.7; 95% confidence interval, −15.9 to 4.5; P = .27) and the placebo groups, and at 1 year (between-group difference, –8.5; 95% CI, −18.6 to 1.6; P = .10), although the results favored patients receiving anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy (Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:1757-64. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213202).

With regard to the Verbruggen-Veys score, joint degradation was not significantly higher in the placebo group (29.4%), compared with the MTX group (7.7%), but there was a significantly higher number of erosive joints progressing to a remodeling phase in the MTX group (27.2%), compared with the placebo group (15.2%) at 12 months.

Dr. Roux said two factors are likely predictors of erosive disease based on data in ADEM: the level of interleukin-6 at baseline (odds ratio, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.03-1.06; P less than .0001), and joints with synovitis at baseline (OR, 4.7; 95% CI, 1.25-17.90; P = .02).

“Our study has several limitations, but we like to see our study as a pilot study,” he added, noting that a study analyzing bone turnover in patients with different doses of methotrexate and a longer disease duration is needed.

The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Ferraro S et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10), Abstract 1759.

ATLANTA – , according to results from the small, prospective, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled ADEM trial.

“Our study failed to show the superiority of methotrexate over placebo on pain evolution, but our results on structural evolution and the presence of inflammatory parameters as predictors of erosive evolution in nonerosive diseases may lead us to discuss the place of methotrexate in early steps of the disease evolution, and underlines the importance of the part played by the interaction between synovitis and subchondral bone in erosive progression,” Christian Roux, MD, PhD, of the department of rheumatology at Côte d’Azur University, Nice, France, said in his presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Dr. Roux and colleagues enrolled 64 patients in the ADEM trial, where patients with symptomatic erosive hand osteoarthritis (EHOA) were randomized to receive 10 mg of methotrexate (MTX) per week or placebo. At 3 months, researchers assessed patients for pain using the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) score for hand pain, and secondary outcome measures at 12 months included VAS score for hand pain, radiographic progression using Verbruggen-Veys Anatomical Phase Score and Gent University Scoring System, and MRI.

Patients were included in the study if they were between 45 and 85 years old with a VAS pain score greater than 40, had failed classic therapeutics (acetaminophen, topical NSAIDs, and symptomatic slow-acting drugs), and had at least one erosive lesion. At baseline, the MTX and placebo groups were not significantly different with regard to gender (91% vs. 97% female), mean body mass index (24.6 kg/m2 vs. 24.2 kg/m2) and mean age (67.5 years vs. 64.9 years). Radiologic data showed joint loss, erosive, and erosive plus remodeling measurements were also similar between groups at baseline.

The mean VAS score for patients in the MTX group decreased from 65.7 at baseline to 48.2 at 3 months (–17.5; P = .07), compared with a decrease from 63.9 to 55.5 (–8.4; P = .002). At 12 months, VAS scores for patients in the MTX group decreased to 47.5, compared with a decrease in the placebo group to 48.2. However, the between-group differences for VAS scores were not significant at 3 months (P = .2) and at 12 months (P = .6).

“We have different hypotheses on the failure of our study on our main outcome, which was pain,” he said. “The first is a low-dose of methotrexate, and the second may be ... a placebo effect, which is very, very important in osteoarthritis.”

Dr. Roux noted the results from the ADEM trial were similar to a recent study in which 90 patients with hand OA were randomized to receive etanercept or placebo. At 24 weeks, there was no statistically significant difference between VAS pain in the etanercept group (between group difference, −5.7; 95% confidence interval, −15.9 to 4.5; P = .27) and the placebo groups, and at 1 year (between-group difference, –8.5; 95% CI, −18.6 to 1.6; P = .10), although the results favored patients receiving anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy (Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:1757-64. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213202).

With regard to the Verbruggen-Veys score, joint degradation was not significantly higher in the placebo group (29.4%), compared with the MTX group (7.7%), but there was a significantly higher number of erosive joints progressing to a remodeling phase in the MTX group (27.2%), compared with the placebo group (15.2%) at 12 months.

Dr. Roux said two factors are likely predictors of erosive disease based on data in ADEM: the level of interleukin-6 at baseline (odds ratio, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.03-1.06; P less than .0001), and joints with synovitis at baseline (OR, 4.7; 95% CI, 1.25-17.90; P = .02).

“Our study has several limitations, but we like to see our study as a pilot study,” he added, noting that a study analyzing bone turnover in patients with different doses of methotrexate and a longer disease duration is needed.

The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Ferraro S et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10), Abstract 1759.

ATLANTA – , according to results from the small, prospective, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled ADEM trial.

“Our study failed to show the superiority of methotrexate over placebo on pain evolution, but our results on structural evolution and the presence of inflammatory parameters as predictors of erosive evolution in nonerosive diseases may lead us to discuss the place of methotrexate in early steps of the disease evolution, and underlines the importance of the part played by the interaction between synovitis and subchondral bone in erosive progression,” Christian Roux, MD, PhD, of the department of rheumatology at Côte d’Azur University, Nice, France, said in his presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Dr. Roux and colleagues enrolled 64 patients in the ADEM trial, where patients with symptomatic erosive hand osteoarthritis (EHOA) were randomized to receive 10 mg of methotrexate (MTX) per week or placebo. At 3 months, researchers assessed patients for pain using the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) score for hand pain, and secondary outcome measures at 12 months included VAS score for hand pain, radiographic progression using Verbruggen-Veys Anatomical Phase Score and Gent University Scoring System, and MRI.

Patients were included in the study if they were between 45 and 85 years old with a VAS pain score greater than 40, had failed classic therapeutics (acetaminophen, topical NSAIDs, and symptomatic slow-acting drugs), and had at least one erosive lesion. At baseline, the MTX and placebo groups were not significantly different with regard to gender (91% vs. 97% female), mean body mass index (24.6 kg/m2 vs. 24.2 kg/m2) and mean age (67.5 years vs. 64.9 years). Radiologic data showed joint loss, erosive, and erosive plus remodeling measurements were also similar between groups at baseline.

The mean VAS score for patients in the MTX group decreased from 65.7 at baseline to 48.2 at 3 months (–17.5; P = .07), compared with a decrease from 63.9 to 55.5 (–8.4; P = .002). At 12 months, VAS scores for patients in the MTX group decreased to 47.5, compared with a decrease in the placebo group to 48.2. However, the between-group differences for VAS scores were not significant at 3 months (P = .2) and at 12 months (P = .6).

“We have different hypotheses on the failure of our study on our main outcome, which was pain,” he said. “The first is a low-dose of methotrexate, and the second may be ... a placebo effect, which is very, very important in osteoarthritis.”

Dr. Roux noted the results from the ADEM trial were similar to a recent study in which 90 patients with hand OA were randomized to receive etanercept or placebo. At 24 weeks, there was no statistically significant difference between VAS pain in the etanercept group (between group difference, −5.7; 95% confidence interval, −15.9 to 4.5; P = .27) and the placebo groups, and at 1 year (between-group difference, –8.5; 95% CI, −18.6 to 1.6; P = .10), although the results favored patients receiving anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy (Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:1757-64. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213202).

With regard to the Verbruggen-Veys score, joint degradation was not significantly higher in the placebo group (29.4%), compared with the MTX group (7.7%), but there was a significantly higher number of erosive joints progressing to a remodeling phase in the MTX group (27.2%), compared with the placebo group (15.2%) at 12 months.

Dr. Roux said two factors are likely predictors of erosive disease based on data in ADEM: the level of interleukin-6 at baseline (odds ratio, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.03-1.06; P less than .0001), and joints with synovitis at baseline (OR, 4.7; 95% CI, 1.25-17.90; P = .02).

“Our study has several limitations, but we like to see our study as a pilot study,” he added, noting that a study analyzing bone turnover in patients with different doses of methotrexate and a longer disease duration is needed.

The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Ferraro S et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10), Abstract 1759.

REPORTING FROM ACR 2019

Unilateral Papules on the Face

The Diagnosis: Mosaic Tuberous Sclerosis

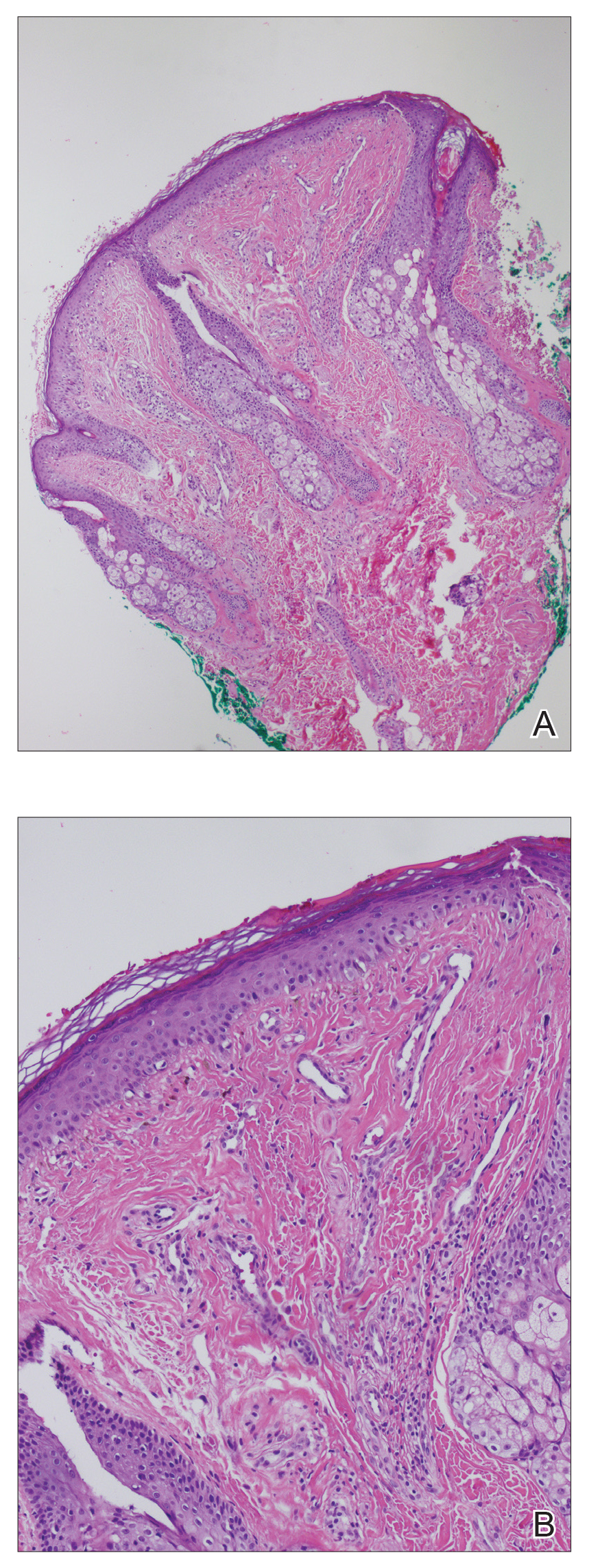

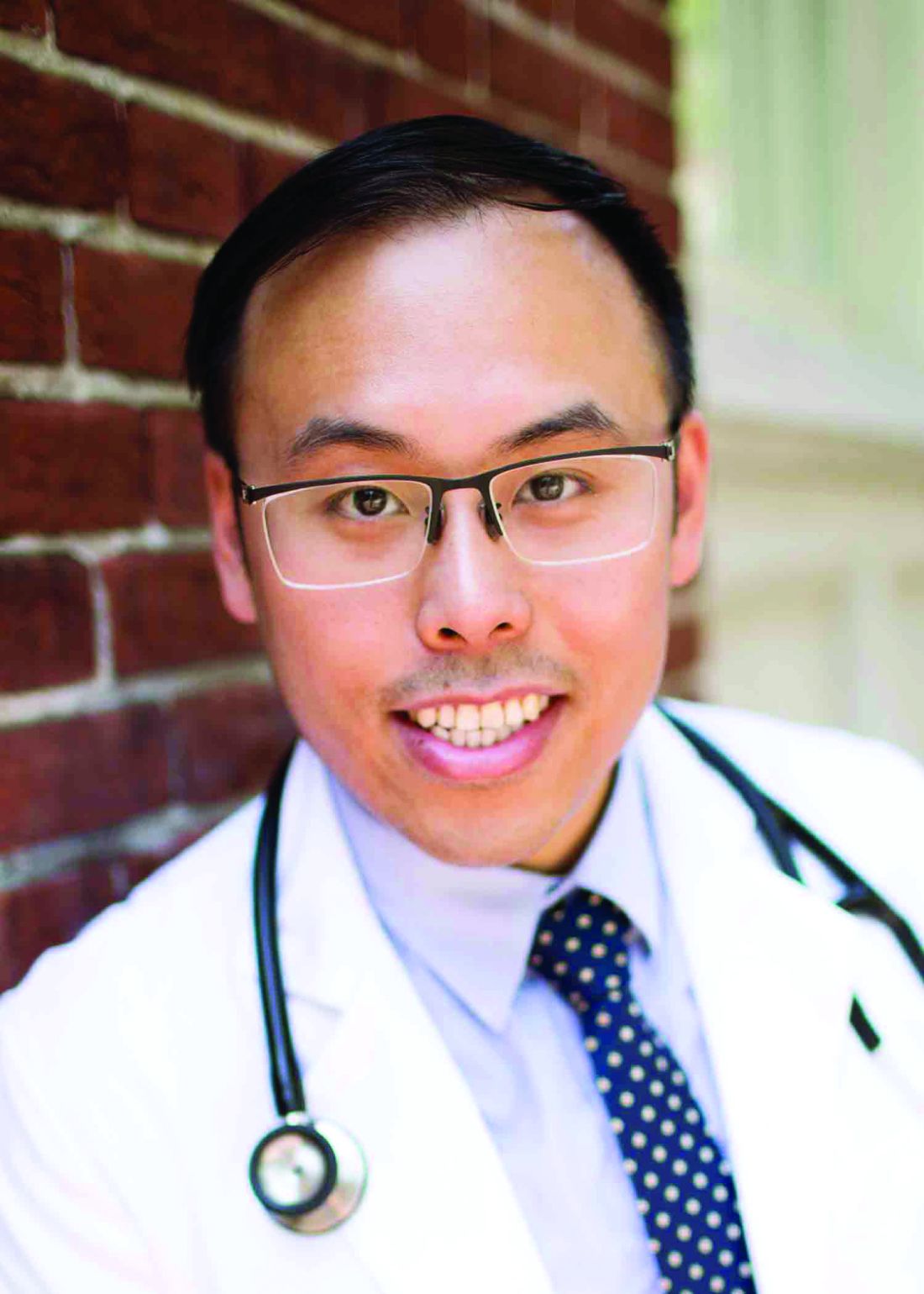

A punch biopsy of the facial lesion was stained with hematoxylin and eosin, which demonstrated spindled and stellate fibroblasts with dilated blood vessels (Figure), consistent with an angiofibroma. Given the clinical presentation and histologic findings, there was concern for a diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis (TSC). The patient was referred for genetic workup but tested negative for mutations of the TSC genes in the blood. Because the patient had only unilateral facial lesions, a possible cortical tuber, no other symptoms, and tested negative for TSC gene mutations, mosaic TSC was considered a likely diagnosis. Her facial lesions were treated with pulsed dye vascular laser therapy.

Tuberous sclerosis is an autosomal-dominant neurocutaneous disorder caused by inactivation of the genes TSC1 (encoding hamartin) and TSC2 (encoding tuberin). Mutation results in overactivation of the downstream mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway, resulting in abnormal cellular proliferation and hamartomas. These benign tumors can be found in nearly every organ, most often in the central nervous system and skin, and they provide for a highly variable presentation of the disease.1

Tuberous sclerosis affects 1 in 6000 to 10,000 live births and has a prevalence of 1 in 20,000 individuals. Of these individuals, 75% carry sporadic mutations, and 75% to 90% eventually test positive for a TSC gene mutation.2 Genetic mosaicism has been reported in 28% of cases affected by large deletions1 and as few as 1% of cases involving small mutations.3

The dermatologic manifestation of mosaic TSC most often includes unilateral angiofibromas, whereas in nonmosaic cases, angiofibromas cover both cheeks, the forehead, and the eyelids. The other skin lesions of TSC--shagreen patches, forehead plaques, hypomelanotic macules, and ungual fibromas--are seen less frequently.4-6 Additionally, neurologic disease in mosaic patients is notably milder, with 57% of mosaic patients found to have epilepsy compared to 91% of nonmosaic patients.7 Our patient had both unilateral facial angiofibromas and a cortical lesion suspicious for a tuber, prompting a suspected diagnosis of mosaic TSC.

The methods of diagnosis outlined by the International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group pose a challenge in diagnosing mosaic TSC. The clinical criteria require 2 major (eg, multiple angiofibromas, angiomyolipomas, a shagreen patch) and 1 minor feature (eg, dental enamel pit, renal cyst).2 However, case reports detailing unilateral facial angiofibromas have described patients with isolated dermatologic findings.5,6 Further, it has been demonstrated that genetic studies in mosaic TSC can be unreliable depending on the tissue sampled.8 Thus, for patients who have mosaic TSC, establishing a definitive diagnosis is not always possible and may rely solely on the clinical picture.

Considering the differential diagnosis, benign cephalic histiocytosis usually would present with small red-brown macules and papules symmetrically located on the head and neck. The lesions occur at a younger age, usually in the first year or two of life. Fibrofolliculomas present as multiple whitish, slightly larger papules found on the central face. They are a marker for Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome, which also is associated with spontaneous pneumothorax.

Agminated means clustering or grouping of lesions. Agminated melanocytic nevi and agminated Spitz nevi are clusters of nevi. These lesions can vary in size and color. They may be elevated or flat. Melanocytic nevi usually are tan-brown or black. Spitz nevi may be pink or pigmented brown or black. To definitively differentiate between these 2 diagnoses and this patient's diagnosis of angiofibroma, a biopsy is needed.

- Curatolo P, Moavero R, Roberto D, et al. Genotype/phenotype correlations in tuberous sclerosis complex. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2015;22:259-273.

- Northrup H, Krueger DA; International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group. Tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria update: recommendations of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference. Pediatr Neurol. 2013;49:243-254.

- Kwiatkowski DJ, Whittemore VH, Thiele EA. Tuberous Sclerosis Complex: Genes, Clinical Features and Therapeutics. Weinham, Germany: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011.

- Alshaiji JM, Spock CR, Connelly EA, et al. Facial angiofibromas in a mosaic pattern tuberous sclerosis: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:8.

- Gutte R, Khopkar U. Unilateral multiple facial angiofibromas: a case report with brief review of literature. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:159.

- Silvestre JF, Bañuls J, Ramón R, et al. Unilateral multiple facial angiofibromas: a mosaic form of TSC. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(1, pt 1):127-129.

- Kozlowski P, Roberts P, Dabora S, et al. Identification of 54 large deletions/duplications in TSC1 and TSC2 using MLPA, and genotype-phenotype correlations. Hum Genet. 2007;121:389-400.

- Kwiatkowska J, Wigowska-Sowinska J, Napierala D, et al. Mosaicism in TSC as a potential cause of the failure of molecular diagnosis. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:703-707.

The Diagnosis: Mosaic Tuberous Sclerosis

A punch biopsy of the facial lesion was stained with hematoxylin and eosin, which demonstrated spindled and stellate fibroblasts with dilated blood vessels (Figure), consistent with an angiofibroma. Given the clinical presentation and histologic findings, there was concern for a diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis (TSC). The patient was referred for genetic workup but tested negative for mutations of the TSC genes in the blood. Because the patient had only unilateral facial lesions, a possible cortical tuber, no other symptoms, and tested negative for TSC gene mutations, mosaic TSC was considered a likely diagnosis. Her facial lesions were treated with pulsed dye vascular laser therapy.

Tuberous sclerosis is an autosomal-dominant neurocutaneous disorder caused by inactivation of the genes TSC1 (encoding hamartin) and TSC2 (encoding tuberin). Mutation results in overactivation of the downstream mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway, resulting in abnormal cellular proliferation and hamartomas. These benign tumors can be found in nearly every organ, most often in the central nervous system and skin, and they provide for a highly variable presentation of the disease.1

Tuberous sclerosis affects 1 in 6000 to 10,000 live births and has a prevalence of 1 in 20,000 individuals. Of these individuals, 75% carry sporadic mutations, and 75% to 90% eventually test positive for a TSC gene mutation.2 Genetic mosaicism has been reported in 28% of cases affected by large deletions1 and as few as 1% of cases involving small mutations.3

The dermatologic manifestation of mosaic TSC most often includes unilateral angiofibromas, whereas in nonmosaic cases, angiofibromas cover both cheeks, the forehead, and the eyelids. The other skin lesions of TSC--shagreen patches, forehead plaques, hypomelanotic macules, and ungual fibromas--are seen less frequently.4-6 Additionally, neurologic disease in mosaic patients is notably milder, with 57% of mosaic patients found to have epilepsy compared to 91% of nonmosaic patients.7 Our patient had both unilateral facial angiofibromas and a cortical lesion suspicious for a tuber, prompting a suspected diagnosis of mosaic TSC.

The methods of diagnosis outlined by the International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group pose a challenge in diagnosing mosaic TSC. The clinical criteria require 2 major (eg, multiple angiofibromas, angiomyolipomas, a shagreen patch) and 1 minor feature (eg, dental enamel pit, renal cyst).2 However, case reports detailing unilateral facial angiofibromas have described patients with isolated dermatologic findings.5,6 Further, it has been demonstrated that genetic studies in mosaic TSC can be unreliable depending on the tissue sampled.8 Thus, for patients who have mosaic TSC, establishing a definitive diagnosis is not always possible and may rely solely on the clinical picture.

Considering the differential diagnosis, benign cephalic histiocytosis usually would present with small red-brown macules and papules symmetrically located on the head and neck. The lesions occur at a younger age, usually in the first year or two of life. Fibrofolliculomas present as multiple whitish, slightly larger papules found on the central face. They are a marker for Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome, which also is associated with spontaneous pneumothorax.

Agminated means clustering or grouping of lesions. Agminated melanocytic nevi and agminated Spitz nevi are clusters of nevi. These lesions can vary in size and color. They may be elevated or flat. Melanocytic nevi usually are tan-brown or black. Spitz nevi may be pink or pigmented brown or black. To definitively differentiate between these 2 diagnoses and this patient's diagnosis of angiofibroma, a biopsy is needed.

The Diagnosis: Mosaic Tuberous Sclerosis

A punch biopsy of the facial lesion was stained with hematoxylin and eosin, which demonstrated spindled and stellate fibroblasts with dilated blood vessels (Figure), consistent with an angiofibroma. Given the clinical presentation and histologic findings, there was concern for a diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis (TSC). The patient was referred for genetic workup but tested negative for mutations of the TSC genes in the blood. Because the patient had only unilateral facial lesions, a possible cortical tuber, no other symptoms, and tested negative for TSC gene mutations, mosaic TSC was considered a likely diagnosis. Her facial lesions were treated with pulsed dye vascular laser therapy.

Tuberous sclerosis is an autosomal-dominant neurocutaneous disorder caused by inactivation of the genes TSC1 (encoding hamartin) and TSC2 (encoding tuberin). Mutation results in overactivation of the downstream mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway, resulting in abnormal cellular proliferation and hamartomas. These benign tumors can be found in nearly every organ, most often in the central nervous system and skin, and they provide for a highly variable presentation of the disease.1

Tuberous sclerosis affects 1 in 6000 to 10,000 live births and has a prevalence of 1 in 20,000 individuals. Of these individuals, 75% carry sporadic mutations, and 75% to 90% eventually test positive for a TSC gene mutation.2 Genetic mosaicism has been reported in 28% of cases affected by large deletions1 and as few as 1% of cases involving small mutations.3

The dermatologic manifestation of mosaic TSC most often includes unilateral angiofibromas, whereas in nonmosaic cases, angiofibromas cover both cheeks, the forehead, and the eyelids. The other skin lesions of TSC--shagreen patches, forehead plaques, hypomelanotic macules, and ungual fibromas--are seen less frequently.4-6 Additionally, neurologic disease in mosaic patients is notably milder, with 57% of mosaic patients found to have epilepsy compared to 91% of nonmosaic patients.7 Our patient had both unilateral facial angiofibromas and a cortical lesion suspicious for a tuber, prompting a suspected diagnosis of mosaic TSC.

The methods of diagnosis outlined by the International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group pose a challenge in diagnosing mosaic TSC. The clinical criteria require 2 major (eg, multiple angiofibromas, angiomyolipomas, a shagreen patch) and 1 minor feature (eg, dental enamel pit, renal cyst).2 However, case reports detailing unilateral facial angiofibromas have described patients with isolated dermatologic findings.5,6 Further, it has been demonstrated that genetic studies in mosaic TSC can be unreliable depending on the tissue sampled.8 Thus, for patients who have mosaic TSC, establishing a definitive diagnosis is not always possible and may rely solely on the clinical picture.

Considering the differential diagnosis, benign cephalic histiocytosis usually would present with small red-brown macules and papules symmetrically located on the head and neck. The lesions occur at a younger age, usually in the first year or two of life. Fibrofolliculomas present as multiple whitish, slightly larger papules found on the central face. They are a marker for Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome, which also is associated with spontaneous pneumothorax.

Agminated means clustering or grouping of lesions. Agminated melanocytic nevi and agminated Spitz nevi are clusters of nevi. These lesions can vary in size and color. They may be elevated or flat. Melanocytic nevi usually are tan-brown or black. Spitz nevi may be pink or pigmented brown or black. To definitively differentiate between these 2 diagnoses and this patient's diagnosis of angiofibroma, a biopsy is needed.

- Curatolo P, Moavero R, Roberto D, et al. Genotype/phenotype correlations in tuberous sclerosis complex. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2015;22:259-273.

- Northrup H, Krueger DA; International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group. Tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria update: recommendations of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference. Pediatr Neurol. 2013;49:243-254.

- Kwiatkowski DJ, Whittemore VH, Thiele EA. Tuberous Sclerosis Complex: Genes, Clinical Features and Therapeutics. Weinham, Germany: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011.

- Alshaiji JM, Spock CR, Connelly EA, et al. Facial angiofibromas in a mosaic pattern tuberous sclerosis: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:8.

- Gutte R, Khopkar U. Unilateral multiple facial angiofibromas: a case report with brief review of literature. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:159.

- Silvestre JF, Bañuls J, Ramón R, et al. Unilateral multiple facial angiofibromas: a mosaic form of TSC. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(1, pt 1):127-129.

- Kozlowski P, Roberts P, Dabora S, et al. Identification of 54 large deletions/duplications in TSC1 and TSC2 using MLPA, and genotype-phenotype correlations. Hum Genet. 2007;121:389-400.

- Kwiatkowska J, Wigowska-Sowinska J, Napierala D, et al. Mosaicism in TSC as a potential cause of the failure of molecular diagnosis. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:703-707.

- Curatolo P, Moavero R, Roberto D, et al. Genotype/phenotype correlations in tuberous sclerosis complex. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2015;22:259-273.

- Northrup H, Krueger DA; International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group. Tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria update: recommendations of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference. Pediatr Neurol. 2013;49:243-254.

- Kwiatkowski DJ, Whittemore VH, Thiele EA. Tuberous Sclerosis Complex: Genes, Clinical Features and Therapeutics. Weinham, Germany: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011.

- Alshaiji JM, Spock CR, Connelly EA, et al. Facial angiofibromas in a mosaic pattern tuberous sclerosis: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:8.

- Gutte R, Khopkar U. Unilateral multiple facial angiofibromas: a case report with brief review of literature. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:159.

- Silvestre JF, Bañuls J, Ramón R, et al. Unilateral multiple facial angiofibromas: a mosaic form of TSC. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(1, pt 1):127-129.

- Kozlowski P, Roberts P, Dabora S, et al. Identification of 54 large deletions/duplications in TSC1 and TSC2 using MLPA, and genotype-phenotype correlations. Hum Genet. 2007;121:389-400.

- Kwiatkowska J, Wigowska-Sowinska J, Napierala D, et al. Mosaicism in TSC as a potential cause of the failure of molecular diagnosis. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:703-707.

An 18-year-old woman presented with a progressive appearance of firm, red-brown, asymptomatic, 1- to 3-mm, dome-shaped papules on the right cheek that developed over the course of 2 years. She had 10 lesions that covered a 2.2 ×4-cm area on the right medial cheek. No similar-appearing lesions were detectable on a full-body skin examination, and no periungual tumors, café au lait macules, or shagreen patches were noted. A full-body skin examination using a Wood lamp revealed 1 small hypopigmented macule on the right second finger. The patient had a history of treatment-refractory migraines; magnetic resonance imaging 5 years prior to the current presentation revealed a nonspecific lesion in the left parietal gyrus. There was no personal or family history of seizures, cognitive delay, kidney disease, or ocular disease. Punch biopsy of a facial lesion was performed for histopathologic correlation.

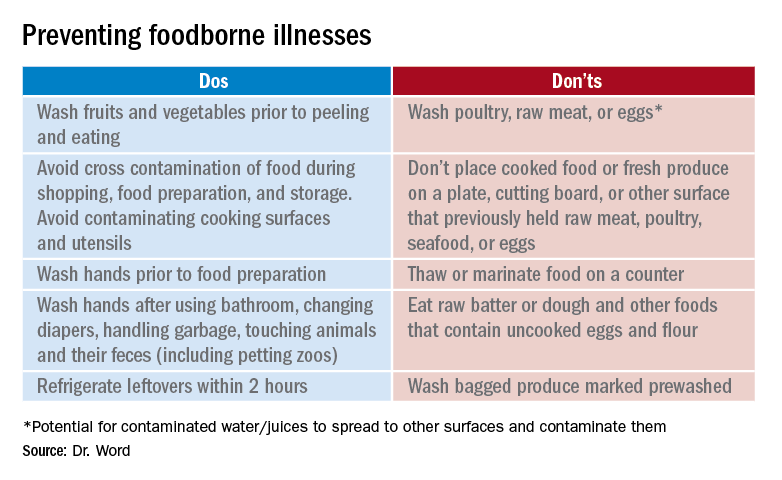

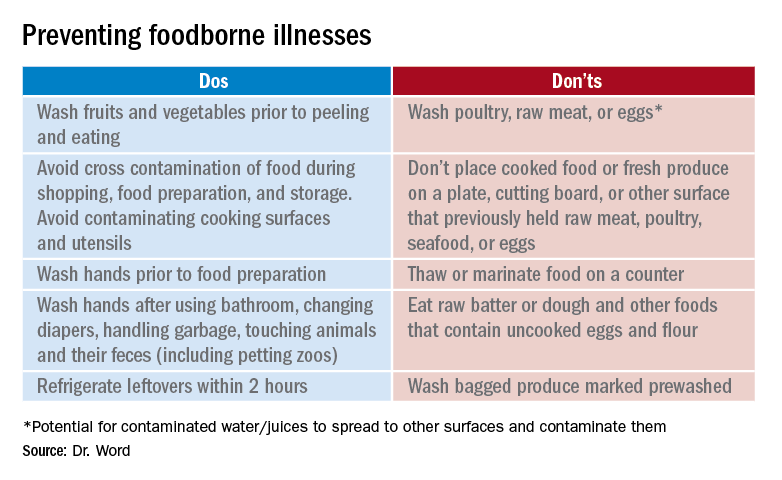

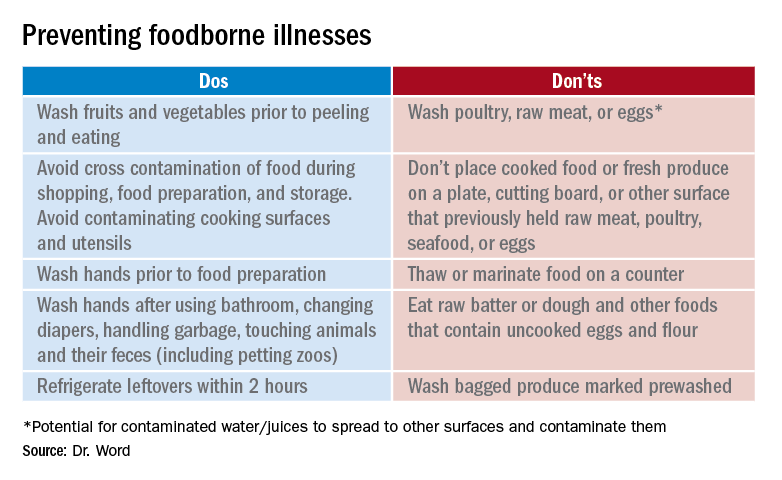

Don’t let a foodborne illness dampen the holiday season

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a foodborne disease occurs in one in six persons (48 million), resulting in 128,000 hospitalizations and 3,000 deaths annually in the United States. The Foodborne Active Surveillance Network (FoodNet) of the CDC’s Emerging Infections Program monitors cases of eight laboratory diagnosed infections from 10 U.S. sites (covering 15% of the U.S. population). Monitored organisms include Campylobacter, Cyclospora, Listeria, Salmonella, Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli (STEC), Shigella, Vibrio, and Yersinia. In 2018, FoodNet identified 25,606 cases of infection, 5,893 hospitalizations, and 120 deaths. The incidence of infection (cases/100,000) was highest for Campylobacter (20), Salmonella (18), STEC (6), Shigella (5), Vibrio (1), Yersinia (0.9), Cyclospora (0.7), and Listeria (0.3). How might these pathogens affect your patients? First, a quick review about the four more common infections. Treatment is beyond the scope of our discussion and you are referred to the 2018-2021 Red Book for assistance. The goal of this column is to prevent your patients from becoming a statistic this holiday season.

Campylobacter

It has been the most common infection reported in FoodNet since 2013. Clinically, patients present with fever, abdominal pain, and nonbloody diarrhea. However, bloody diarrhea maybe the only symptom in neonates and young infants. Abdominal pain can mimic acute appendicitis or intussusception. Bacteremia is rare but has been reported in the elderly and in some patients with underlying conditions. During convalescence, immunoreactive complications including Guillain-Barré syndrome, reactive arthritis, and erythema nodosum may occur. In patients with diarrhea, Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli are the most frequently isolated species.

Campylobacter is present in the intestinal tract of both domestic and wild birds and animals. Transmission is via consumption of contaminated food or water. Undercooked poultry, untreated water, and unpasteurized milk are the three main vehicles of transmission. Campylobacter can be isolated in stool and blood, however isolation from stool requires special media. Rehydration is the primary therapy. Use of azithromycin or erythromycin can shorten both the duration of symptoms and bacterial shedding.

Salmonella

Nontyphoidal salmonella (NTS) are responsible for a variety of infections including asymptomatic carriage, gastroenteritis, bacteremia, and serious focal infections. Gastroenteritis is the most common illness and is manifested as diarrhea, abdominal pain, and fever. If bacteremia occurs, up to 10% of patients will develop focal infections. Invasive disease occurs most frequently in infants, persons with hemoglobinopathies, immunosuppressive disorders, and malignancies. The genus Salmonella is divided into two species, S. enterica and S. bongori with S. enterica subspecies accounting for about half of culture-confirmed Salmonella isolates reported by public health laboratories.

Although infections are more common in the summer, infections can occur year-round. In 2018, the CDC investigated at least 15 food-related NTS outbreaks and 6 have been investigated so far in 2019. In industrialized countries, acquisition usually occurs from ingestion of poultry, eggs, and milk products. Infection also has been reported after animal contact and consumption of fresh produce, meats, and contaminated water. Ground beef is the source of the November 2019 outbreak of S. dublin. Diarrhea develops within 12-72 hours. Salmonella can be isolated from stool, blood, and urine. Treatment usually is not indicated for uncomplicated gastroenteritis. While benefit has not been proven, it is recommended for those at increased risk for developing invasive disease.

Shigella

Shigella is the classic cause of colonic or dysenteric diarrhea. Humans are the primary hosts but other primates can be infected. Transmission occurs through direct person-to-person spread, from ingestion of contaminated food and water, and contact with contaminated inanimate objects. Bacteria can survive up to 6 months in food and 30 days in water. As few as 10 organisms can initiate disease. Typically mucoid or bloody diarrhea with abdominal cramps and fever occurs 1-7 days following exposure. Isolation is from stool. Bacteremia is unusual. Therapy is recommended for severe disease.

Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli (STEC)

STEC causes hemorrhagic colitis, which can be complicated by hemolytic uremic syndrome. While E. coli O157:H7 is the serotype most often implicated, other serotypes can cause disease. STEC is shed in feces of cattle and other animals. Infection most often is associated with ingestion of undercooked ground beef, but outbreaks also have confirmed that contaminated leafy vegetables, drinking water, peanut butter, and unpasteurized milk have been the source. Symptoms usually develop 3 to 4 days after exposure. Stools initially may be nonbloody. Abdominal pain and bloody diarrhea occur over the next 2-3 days. Fever often is absent or low grade. Stools should be sent for culture and Shiga toxin for diagnosis. Antimicrobial treatment generally is not warranted if STEC is suspected or diagnosed.

Prevention

It seems so simple. Here are the basic guidelines:

- Clean. Wash hands and surfaces frequently.

- Separate. Separate raw meats and eggs from other foods.

- Cook. Cook all meats to the right temperature.

- Chill. Refrigerate food properly.

Finally, two comments about food poisoning:

Abrupt onset of nausea, vomiting and abdominal cramping due to staphylococcal food poisoning begins 30 minutes to 6 hours after ingestion of food contaminated by enterotoxigenic strains of Staphylococcus aureus which is usually introduced by a food preparer with a purulent lesion. Food left at room temperature allows bacteria to multiply and produce a heat stable toxin. Individuals with purulent lesions of the hands, face, eyes, or nose should not be involved with food preparation.

Clostridium perfringens is the second most common bacterial cause of food poisoning. Symptoms (watery diarrhea and cramping) begin 6-24 hours after ingestion of C. perfringens spores not killed during cooking, which now have multiplied in food left at room temperature that was inadequately reheated. Illness is caused by the production of enterotoxin in the intestine. Outbreaks occur most often in November and December.

This article was updated on 11/12/19.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Information sources

1. foodsafety.gov

2. cdc.gov/foodsafety

3. The United States Department of Agriculture Meat and Poultry Hotline: 888-674-6854

4. Appendix VII: Clinical syndromes associated with foodborne diseases, Red Book online, 31st ed. (Washington DC: Red Book online, 2018, pp. 1086-92).

5. Foodkeeper App available at the App store. Provides appropriate food storage information; food recalls also are available.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a foodborne disease occurs in one in six persons (48 million), resulting in 128,000 hospitalizations and 3,000 deaths annually in the United States. The Foodborne Active Surveillance Network (FoodNet) of the CDC’s Emerging Infections Program monitors cases of eight laboratory diagnosed infections from 10 U.S. sites (covering 15% of the U.S. population). Monitored organisms include Campylobacter, Cyclospora, Listeria, Salmonella, Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli (STEC), Shigella, Vibrio, and Yersinia. In 2018, FoodNet identified 25,606 cases of infection, 5,893 hospitalizations, and 120 deaths. The incidence of infection (cases/100,000) was highest for Campylobacter (20), Salmonella (18), STEC (6), Shigella (5), Vibrio (1), Yersinia (0.9), Cyclospora (0.7), and Listeria (0.3). How might these pathogens affect your patients? First, a quick review about the four more common infections. Treatment is beyond the scope of our discussion and you are referred to the 2018-2021 Red Book for assistance. The goal of this column is to prevent your patients from becoming a statistic this holiday season.

Campylobacter

It has been the most common infection reported in FoodNet since 2013. Clinically, patients present with fever, abdominal pain, and nonbloody diarrhea. However, bloody diarrhea maybe the only symptom in neonates and young infants. Abdominal pain can mimic acute appendicitis or intussusception. Bacteremia is rare but has been reported in the elderly and in some patients with underlying conditions. During convalescence, immunoreactive complications including Guillain-Barré syndrome, reactive arthritis, and erythema nodosum may occur. In patients with diarrhea, Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli are the most frequently isolated species.

Campylobacter is present in the intestinal tract of both domestic and wild birds and animals. Transmission is via consumption of contaminated food or water. Undercooked poultry, untreated water, and unpasteurized milk are the three main vehicles of transmission. Campylobacter can be isolated in stool and blood, however isolation from stool requires special media. Rehydration is the primary therapy. Use of azithromycin or erythromycin can shorten both the duration of symptoms and bacterial shedding.

Salmonella

Nontyphoidal salmonella (NTS) are responsible for a variety of infections including asymptomatic carriage, gastroenteritis, bacteremia, and serious focal infections. Gastroenteritis is the most common illness and is manifested as diarrhea, abdominal pain, and fever. If bacteremia occurs, up to 10% of patients will develop focal infections. Invasive disease occurs most frequently in infants, persons with hemoglobinopathies, immunosuppressive disorders, and malignancies. The genus Salmonella is divided into two species, S. enterica and S. bongori with S. enterica subspecies accounting for about half of culture-confirmed Salmonella isolates reported by public health laboratories.

Although infections are more common in the summer, infections can occur year-round. In 2018, the CDC investigated at least 15 food-related NTS outbreaks and 6 have been investigated so far in 2019. In industrialized countries, acquisition usually occurs from ingestion of poultry, eggs, and milk products. Infection also has been reported after animal contact and consumption of fresh produce, meats, and contaminated water. Ground beef is the source of the November 2019 outbreak of S. dublin. Diarrhea develops within 12-72 hours. Salmonella can be isolated from stool, blood, and urine. Treatment usually is not indicated for uncomplicated gastroenteritis. While benefit has not been proven, it is recommended for those at increased risk for developing invasive disease.

Shigella

Shigella is the classic cause of colonic or dysenteric diarrhea. Humans are the primary hosts but other primates can be infected. Transmission occurs through direct person-to-person spread, from ingestion of contaminated food and water, and contact with contaminated inanimate objects. Bacteria can survive up to 6 months in food and 30 days in water. As few as 10 organisms can initiate disease. Typically mucoid or bloody diarrhea with abdominal cramps and fever occurs 1-7 days following exposure. Isolation is from stool. Bacteremia is unusual. Therapy is recommended for severe disease.

Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli (STEC)

STEC causes hemorrhagic colitis, which can be complicated by hemolytic uremic syndrome. While E. coli O157:H7 is the serotype most often implicated, other serotypes can cause disease. STEC is shed in feces of cattle and other animals. Infection most often is associated with ingestion of undercooked ground beef, but outbreaks also have confirmed that contaminated leafy vegetables, drinking water, peanut butter, and unpasteurized milk have been the source. Symptoms usually develop 3 to 4 days after exposure. Stools initially may be nonbloody. Abdominal pain and bloody diarrhea occur over the next 2-3 days. Fever often is absent or low grade. Stools should be sent for culture and Shiga toxin for diagnosis. Antimicrobial treatment generally is not warranted if STEC is suspected or diagnosed.

Prevention

It seems so simple. Here are the basic guidelines:

- Clean. Wash hands and surfaces frequently.

- Separate. Separate raw meats and eggs from other foods.

- Cook. Cook all meats to the right temperature.

- Chill. Refrigerate food properly.

Finally, two comments about food poisoning:

Abrupt onset of nausea, vomiting and abdominal cramping due to staphylococcal food poisoning begins 30 minutes to 6 hours after ingestion of food contaminated by enterotoxigenic strains of Staphylococcus aureus which is usually introduced by a food preparer with a purulent lesion. Food left at room temperature allows bacteria to multiply and produce a heat stable toxin. Individuals with purulent lesions of the hands, face, eyes, or nose should not be involved with food preparation.

Clostridium perfringens is the second most common bacterial cause of food poisoning. Symptoms (watery diarrhea and cramping) begin 6-24 hours after ingestion of C. perfringens spores not killed during cooking, which now have multiplied in food left at room temperature that was inadequately reheated. Illness is caused by the production of enterotoxin in the intestine. Outbreaks occur most often in November and December.

This article was updated on 11/12/19.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Information sources

1. foodsafety.gov

2. cdc.gov/foodsafety

3. The United States Department of Agriculture Meat and Poultry Hotline: 888-674-6854

4. Appendix VII: Clinical syndromes associated with foodborne diseases, Red Book online, 31st ed. (Washington DC: Red Book online, 2018, pp. 1086-92).

5. Foodkeeper App available at the App store. Provides appropriate food storage information; food recalls also are available.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a foodborne disease occurs in one in six persons (48 million), resulting in 128,000 hospitalizations and 3,000 deaths annually in the United States. The Foodborne Active Surveillance Network (FoodNet) of the CDC’s Emerging Infections Program monitors cases of eight laboratory diagnosed infections from 10 U.S. sites (covering 15% of the U.S. population). Monitored organisms include Campylobacter, Cyclospora, Listeria, Salmonella, Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli (STEC), Shigella, Vibrio, and Yersinia. In 2018, FoodNet identified 25,606 cases of infection, 5,893 hospitalizations, and 120 deaths. The incidence of infection (cases/100,000) was highest for Campylobacter (20), Salmonella (18), STEC (6), Shigella (5), Vibrio (1), Yersinia (0.9), Cyclospora (0.7), and Listeria (0.3). How might these pathogens affect your patients? First, a quick review about the four more common infections. Treatment is beyond the scope of our discussion and you are referred to the 2018-2021 Red Book for assistance. The goal of this column is to prevent your patients from becoming a statistic this holiday season.

Campylobacter

It has been the most common infection reported in FoodNet since 2013. Clinically, patients present with fever, abdominal pain, and nonbloody diarrhea. However, bloody diarrhea maybe the only symptom in neonates and young infants. Abdominal pain can mimic acute appendicitis or intussusception. Bacteremia is rare but has been reported in the elderly and in some patients with underlying conditions. During convalescence, immunoreactive complications including Guillain-Barré syndrome, reactive arthritis, and erythema nodosum may occur. In patients with diarrhea, Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli are the most frequently isolated species.

Campylobacter is present in the intestinal tract of both domestic and wild birds and animals. Transmission is via consumption of contaminated food or water. Undercooked poultry, untreated water, and unpasteurized milk are the three main vehicles of transmission. Campylobacter can be isolated in stool and blood, however isolation from stool requires special media. Rehydration is the primary therapy. Use of azithromycin or erythromycin can shorten both the duration of symptoms and bacterial shedding.

Salmonella

Nontyphoidal salmonella (NTS) are responsible for a variety of infections including asymptomatic carriage, gastroenteritis, bacteremia, and serious focal infections. Gastroenteritis is the most common illness and is manifested as diarrhea, abdominal pain, and fever. If bacteremia occurs, up to 10% of patients will develop focal infections. Invasive disease occurs most frequently in infants, persons with hemoglobinopathies, immunosuppressive disorders, and malignancies. The genus Salmonella is divided into two species, S. enterica and S. bongori with S. enterica subspecies accounting for about half of culture-confirmed Salmonella isolates reported by public health laboratories.

Although infections are more common in the summer, infections can occur year-round. In 2018, the CDC investigated at least 15 food-related NTS outbreaks and 6 have been investigated so far in 2019. In industrialized countries, acquisition usually occurs from ingestion of poultry, eggs, and milk products. Infection also has been reported after animal contact and consumption of fresh produce, meats, and contaminated water. Ground beef is the source of the November 2019 outbreak of S. dublin. Diarrhea develops within 12-72 hours. Salmonella can be isolated from stool, blood, and urine. Treatment usually is not indicated for uncomplicated gastroenteritis. While benefit has not been proven, it is recommended for those at increased risk for developing invasive disease.

Shigella

Shigella is the classic cause of colonic or dysenteric diarrhea. Humans are the primary hosts but other primates can be infected. Transmission occurs through direct person-to-person spread, from ingestion of contaminated food and water, and contact with contaminated inanimate objects. Bacteria can survive up to 6 months in food and 30 days in water. As few as 10 organisms can initiate disease. Typically mucoid or bloody diarrhea with abdominal cramps and fever occurs 1-7 days following exposure. Isolation is from stool. Bacteremia is unusual. Therapy is recommended for severe disease.

Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli (STEC)

STEC causes hemorrhagic colitis, which can be complicated by hemolytic uremic syndrome. While E. coli O157:H7 is the serotype most often implicated, other serotypes can cause disease. STEC is shed in feces of cattle and other animals. Infection most often is associated with ingestion of undercooked ground beef, but outbreaks also have confirmed that contaminated leafy vegetables, drinking water, peanut butter, and unpasteurized milk have been the source. Symptoms usually develop 3 to 4 days after exposure. Stools initially may be nonbloody. Abdominal pain and bloody diarrhea occur over the next 2-3 days. Fever often is absent or low grade. Stools should be sent for culture and Shiga toxin for diagnosis. Antimicrobial treatment generally is not warranted if STEC is suspected or diagnosed.

Prevention

It seems so simple. Here are the basic guidelines:

- Clean. Wash hands and surfaces frequently.

- Separate. Separate raw meats and eggs from other foods.

- Cook. Cook all meats to the right temperature.

- Chill. Refrigerate food properly.

Finally, two comments about food poisoning:

Abrupt onset of nausea, vomiting and abdominal cramping due to staphylococcal food poisoning begins 30 minutes to 6 hours after ingestion of food contaminated by enterotoxigenic strains of Staphylococcus aureus which is usually introduced by a food preparer with a purulent lesion. Food left at room temperature allows bacteria to multiply and produce a heat stable toxin. Individuals with purulent lesions of the hands, face, eyes, or nose should not be involved with food preparation.

Clostridium perfringens is the second most common bacterial cause of food poisoning. Symptoms (watery diarrhea and cramping) begin 6-24 hours after ingestion of C. perfringens spores not killed during cooking, which now have multiplied in food left at room temperature that was inadequately reheated. Illness is caused by the production of enterotoxin in the intestine. Outbreaks occur most often in November and December.

This article was updated on 11/12/19.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Information sources

1. foodsafety.gov

2. cdc.gov/foodsafety

3. The United States Department of Agriculture Meat and Poultry Hotline: 888-674-6854

4. Appendix VII: Clinical syndromes associated with foodborne diseases, Red Book online, 31st ed. (Washington DC: Red Book online, 2018, pp. 1086-92).

5. Foodkeeper App available at the App store. Provides appropriate food storage information; food recalls also are available.

Smokers with PE have higher rate of hospital readmission

NEW ORLEANS – , according to a retrospective study.

The rate of readmission was significantly higher among patients with tobacco dependence, and tobacco dependence was independently associated with an increased risk of readmission.

“This is the first study to quantify the increased rate of hospital readmission due to smoking,” said study investigator Kam Sing Ho, MD, of Mount Sinai St. Luke’s and Mount Sinai West, New York.

Dr. Ho and colleagues described this study and its results in a poster presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

The researchers analyzed data on 168,891 hospital admissions of adults with PE, 34.2% of whom had tobacco dependence. Patients with and without tobacco dependence were propensity matched for baseline characteristics (n = 24,262 in each group).

The 30-day readmission rate was significantly higher in patients with tobacco dependence than in those without it – 11.0% and 8.9%, respectively (P less than .001). The most common reason for readmission in both groups was PE.

Dr. Ho said the higher readmission rate among patients with tobacco dependence might be explained by the fact that smokers have a higher level of fibrinogen, which may affect blood viscosity and contribute to thrombus formation (Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2005;2[1]:71-7).

The investigators also found that tobacco dependence was an independent predictor of readmission (hazard ratio, 1.43; P less than .001). And the mortality rate was significantly higher after readmission than after index admission – 6.27% and 3.15%, respectively (P less than .001).

The increased risk of readmission and death among smokers highlights the importance of smoking cessation services. Dr. Ho cited previous research suggesting these services are underused in the hospital setting (BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2014;3[1]:u204964.w2110).

“Given that smoking is a common phenomenon among patients admitted with pulmonary embolism, we suggest that more rigorous smoking cessation services are implemented prior to discharge for all active smokers,” Dr. Ho said. “[P]atients have the right to be informed on the benefits of smoking cessation and the autonomy to choose. Future research will focus on implementing inpatient smoking cessation at our hospital and its effect on local readmission rate, health resources utilization, and mortality.”

Dr. Ho has no relevant relationships to disclose.

SOURCE: Ho KS et al. CHEST 2019 October. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.08.1551.

NEW ORLEANS – , according to a retrospective study.

The rate of readmission was significantly higher among patients with tobacco dependence, and tobacco dependence was independently associated with an increased risk of readmission.

“This is the first study to quantify the increased rate of hospital readmission due to smoking,” said study investigator Kam Sing Ho, MD, of Mount Sinai St. Luke’s and Mount Sinai West, New York.

Dr. Ho and colleagues described this study and its results in a poster presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

The researchers analyzed data on 168,891 hospital admissions of adults with PE, 34.2% of whom had tobacco dependence. Patients with and without tobacco dependence were propensity matched for baseline characteristics (n = 24,262 in each group).

The 30-day readmission rate was significantly higher in patients with tobacco dependence than in those without it – 11.0% and 8.9%, respectively (P less than .001). The most common reason for readmission in both groups was PE.

Dr. Ho said the higher readmission rate among patients with tobacco dependence might be explained by the fact that smokers have a higher level of fibrinogen, which may affect blood viscosity and contribute to thrombus formation (Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2005;2[1]:71-7).

The investigators also found that tobacco dependence was an independent predictor of readmission (hazard ratio, 1.43; P less than .001). And the mortality rate was significantly higher after readmission than after index admission – 6.27% and 3.15%, respectively (P less than .001).

The increased risk of readmission and death among smokers highlights the importance of smoking cessation services. Dr. Ho cited previous research suggesting these services are underused in the hospital setting (BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2014;3[1]:u204964.w2110).

“Given that smoking is a common phenomenon among patients admitted with pulmonary embolism, we suggest that more rigorous smoking cessation services are implemented prior to discharge for all active smokers,” Dr. Ho said. “[P]atients have the right to be informed on the benefits of smoking cessation and the autonomy to choose. Future research will focus on implementing inpatient smoking cessation at our hospital and its effect on local readmission rate, health resources utilization, and mortality.”

Dr. Ho has no relevant relationships to disclose.

SOURCE: Ho KS et al. CHEST 2019 October. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.08.1551.

NEW ORLEANS – , according to a retrospective study.

The rate of readmission was significantly higher among patients with tobacco dependence, and tobacco dependence was independently associated with an increased risk of readmission.

“This is the first study to quantify the increased rate of hospital readmission due to smoking,” said study investigator Kam Sing Ho, MD, of Mount Sinai St. Luke’s and Mount Sinai West, New York.

Dr. Ho and colleagues described this study and its results in a poster presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

The researchers analyzed data on 168,891 hospital admissions of adults with PE, 34.2% of whom had tobacco dependence. Patients with and without tobacco dependence were propensity matched for baseline characteristics (n = 24,262 in each group).

The 30-day readmission rate was significantly higher in patients with tobacco dependence than in those without it – 11.0% and 8.9%, respectively (P less than .001). The most common reason for readmission in both groups was PE.

Dr. Ho said the higher readmission rate among patients with tobacco dependence might be explained by the fact that smokers have a higher level of fibrinogen, which may affect blood viscosity and contribute to thrombus formation (Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2005;2[1]:71-7).

The investigators also found that tobacco dependence was an independent predictor of readmission (hazard ratio, 1.43; P less than .001). And the mortality rate was significantly higher after readmission than after index admission – 6.27% and 3.15%, respectively (P less than .001).

The increased risk of readmission and death among smokers highlights the importance of smoking cessation services. Dr. Ho cited previous research suggesting these services are underused in the hospital setting (BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2014;3[1]:u204964.w2110).

“Given that smoking is a common phenomenon among patients admitted with pulmonary embolism, we suggest that more rigorous smoking cessation services are implemented prior to discharge for all active smokers,” Dr. Ho said. “[P]atients have the right to be informed on the benefits of smoking cessation and the autonomy to choose. Future research will focus on implementing inpatient smoking cessation at our hospital and its effect on local readmission rate, health resources utilization, and mortality.”

Dr. Ho has no relevant relationships to disclose.

SOURCE: Ho KS et al. CHEST 2019 October. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.08.1551.

REPORTING FROM CHEST 2019

Does tranexamic acid reduce mortality in women with postpartum hemorrhage?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2017 double-blind RCT that included 20,060 women with PPH from 21 countries (the WOMAN trial) found that the risk of maternal mortality was significantly lower among women who received tranexamic acid as part of their PPH treatment compared with placebo (1.5% [N = 155] vs 1.9% [N = 191]; P = .045; relative risk [RR] = 0.81; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.65-1; number needed to treat [NNT] = 250).1

Inclusion criteria were age 16 years or older, postpartum course complicated by hemorrhage of known or unknown etiology, and a case in which the clinician considered using tranexamic acid in addition to the standard of care. PPH was defined as > 500 mL blood loss after vaginal delivery, > 1000 mL blood loss after cesarean section, or blood loss sufficient to produce hemodynamic compromise.

Researchers randomized 10,051 women to the tranexamic acid group and 10,009 to the placebo group. Women in the experimental group received a 1-g IV injection of tranexamic acid over 10 to 20 minutes. A second dose was given if bleeding restarted after 30 minutes and within 24 hours of the first dose.

To reduce mortality give tranexamic acid promptly

Tranexamic acid reduced mortality most effectively compared with placebo when given within 3 hours of delivery (1.2% [N = 89] vs 1.7% [N = 127]; P = .008; RR = 0.69; 95% CI 0.52-0.91; NNT = 200). After 3 hours, no significant decrease in mortality occurred. No significant difference in effect was noted between vaginal and cesarean deliveries nor between uterine atony as the primary cause of hemorrhage and other causes.

Administering tranexamic acid didn’t reduce the composite primary endpoint of hysterectomy or death from all causes. Nor did it reduce the secondary endpoints of intrauterine tamponade, embolization, manual placental extraction, arterial ligation, blood transfusions, or number of units of packed red blood cells. The tranexamic acid group showed a significant decrease in cases of laparotomy for PPH (0.8% vs 1.3%; P = .002; RR = 0.64; 95% CI, 0.49-0.85; NNT = 200).

Women who received tranexamic acid vs placebo showed no significant difference in mortality from pulmonary embolism (0.1% [N = 10] vs 0.1% [N = 11]; P = .82; RR = .9; 95% CI, 0.38-2.13), organ failure ure (0.3% [N = 25] vs 0.2% [N = 18]; P = .29; RR = 1.38; 95% CI, 0.75-2.53), sepsis (0.2% [N = 15] vs 0.1% [N = 8]; P = .15; RR = 1.87; 95% CI, 0.79-4.4), eclampsia (0.02% [N = 2] vs 0.1% [N = 8]; P = .057; RR = .25; 95% CI, 0.05-1.17), or other causes (0.2% [N = 20] vs 0.2% [N = 20]; P = .99; RR = 0.99; 95% CI, 0.54-1.85).

Tranexamic acid doesn’t increase the risk of thromboembolism

A 2018 Cochrane review sought more broadly to determine the general effectiveness and safety of antifibrinolytic drugs in treating primary PPH.2 Of 15 RCTs identified, only 3 met the inclusion criteria for the review, 1 of which was the WOMAN trial (which contributed most of the data in the review). The other trials were a study conducted in France that recruited 152 women and a study of 200 women in Iran that contributed only 1 primary outcome—estimated blood loss—to the review. The former study didn’t report any maternal deaths, and the latter study didn’t look at maternal deaths. The Cochrane review concluded, based on data from the WOMAN trial, that IV tranexamic acid, if given as early as possible, reduced mortality from bleeding in women with primary PPH after both vaginal and cesarean delivery and didn’t increase the risk of thromboembolic events.2

Continue to: RECOMMENDATIONS

RECOMMENDATIONS

The newest practice guidelines on the management of postpartum hemorrhage published by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends considering tranexamic acid as an additional agent in managing PPH when initial standard-of-care treatments fail.3

Editor’s takeaway

The large international double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled trial provides convincing evidence that tranexamic acid should be administered readily in cases of PPH.

1. WOMAN Trial Collaborators. Effect of early tranexamic acid administration on mortality, hysterectomy, and other morbidities in women with post-partum haemorrhage (WOMAN): an international, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2105–2116.

2. Shakur H, Beaumont D, Pavord S, et al. Antifibrinolytic drugs for treating primary postpartum haemorrhage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;2:CD012964.

3. Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists). Practice Bulletin No. 183: Postpartum Hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e168-e186.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2017 double-blind RCT that included 20,060 women with PPH from 21 countries (the WOMAN trial) found that the risk of maternal mortality was significantly lower among women who received tranexamic acid as part of their PPH treatment compared with placebo (1.5% [N = 155] vs 1.9% [N = 191]; P = .045; relative risk [RR] = 0.81; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.65-1; number needed to treat [NNT] = 250).1

Inclusion criteria were age 16 years or older, postpartum course complicated by hemorrhage of known or unknown etiology, and a case in which the clinician considered using tranexamic acid in addition to the standard of care. PPH was defined as > 500 mL blood loss after vaginal delivery, > 1000 mL blood loss after cesarean section, or blood loss sufficient to produce hemodynamic compromise.

Researchers randomized 10,051 women to the tranexamic acid group and 10,009 to the placebo group. Women in the experimental group received a 1-g IV injection of tranexamic acid over 10 to 20 minutes. A second dose was given if bleeding restarted after 30 minutes and within 24 hours of the first dose.

To reduce mortality give tranexamic acid promptly

Tranexamic acid reduced mortality most effectively compared with placebo when given within 3 hours of delivery (1.2% [N = 89] vs 1.7% [N = 127]; P = .008; RR = 0.69; 95% CI 0.52-0.91; NNT = 200). After 3 hours, no significant decrease in mortality occurred. No significant difference in effect was noted between vaginal and cesarean deliveries nor between uterine atony as the primary cause of hemorrhage and other causes.

Administering tranexamic acid didn’t reduce the composite primary endpoint of hysterectomy or death from all causes. Nor did it reduce the secondary endpoints of intrauterine tamponade, embolization, manual placental extraction, arterial ligation, blood transfusions, or number of units of packed red blood cells. The tranexamic acid group showed a significant decrease in cases of laparotomy for PPH (0.8% vs 1.3%; P = .002; RR = 0.64; 95% CI, 0.49-0.85; NNT = 200).

Women who received tranexamic acid vs placebo showed no significant difference in mortality from pulmonary embolism (0.1% [N = 10] vs 0.1% [N = 11]; P = .82; RR = .9; 95% CI, 0.38-2.13), organ failure ure (0.3% [N = 25] vs 0.2% [N = 18]; P = .29; RR = 1.38; 95% CI, 0.75-2.53), sepsis (0.2% [N = 15] vs 0.1% [N = 8]; P = .15; RR = 1.87; 95% CI, 0.79-4.4), eclampsia (0.02% [N = 2] vs 0.1% [N = 8]; P = .057; RR = .25; 95% CI, 0.05-1.17), or other causes (0.2% [N = 20] vs 0.2% [N = 20]; P = .99; RR = 0.99; 95% CI, 0.54-1.85).

Tranexamic acid doesn’t increase the risk of thromboembolism

A 2018 Cochrane review sought more broadly to determine the general effectiveness and safety of antifibrinolytic drugs in treating primary PPH.2 Of 15 RCTs identified, only 3 met the inclusion criteria for the review, 1 of which was the WOMAN trial (which contributed most of the data in the review). The other trials were a study conducted in France that recruited 152 women and a study of 200 women in Iran that contributed only 1 primary outcome—estimated blood loss—to the review. The former study didn’t report any maternal deaths, and the latter study didn’t look at maternal deaths. The Cochrane review concluded, based on data from the WOMAN trial, that IV tranexamic acid, if given as early as possible, reduced mortality from bleeding in women with primary PPH after both vaginal and cesarean delivery and didn’t increase the risk of thromboembolic events.2

Continue to: RECOMMENDATIONS

RECOMMENDATIONS

The newest practice guidelines on the management of postpartum hemorrhage published by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends considering tranexamic acid as an additional agent in managing PPH when initial standard-of-care treatments fail.3

Editor’s takeaway

The large international double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled trial provides convincing evidence that tranexamic acid should be administered readily in cases of PPH.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2017 double-blind RCT that included 20,060 women with PPH from 21 countries (the WOMAN trial) found that the risk of maternal mortality was significantly lower among women who received tranexamic acid as part of their PPH treatment compared with placebo (1.5% [N = 155] vs 1.9% [N = 191]; P = .045; relative risk [RR] = 0.81; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.65-1; number needed to treat [NNT] = 250).1

Inclusion criteria were age 16 years or older, postpartum course complicated by hemorrhage of known or unknown etiology, and a case in which the clinician considered using tranexamic acid in addition to the standard of care. PPH was defined as > 500 mL blood loss after vaginal delivery, > 1000 mL blood loss after cesarean section, or blood loss sufficient to produce hemodynamic compromise.

Researchers randomized 10,051 women to the tranexamic acid group and 10,009 to the placebo group. Women in the experimental group received a 1-g IV injection of tranexamic acid over 10 to 20 minutes. A second dose was given if bleeding restarted after 30 minutes and within 24 hours of the first dose.

To reduce mortality give tranexamic acid promptly

Tranexamic acid reduced mortality most effectively compared with placebo when given within 3 hours of delivery (1.2% [N = 89] vs 1.7% [N = 127]; P = .008; RR = 0.69; 95% CI 0.52-0.91; NNT = 200). After 3 hours, no significant decrease in mortality occurred. No significant difference in effect was noted between vaginal and cesarean deliveries nor between uterine atony as the primary cause of hemorrhage and other causes.

Administering tranexamic acid didn’t reduce the composite primary endpoint of hysterectomy or death from all causes. Nor did it reduce the secondary endpoints of intrauterine tamponade, embolization, manual placental extraction, arterial ligation, blood transfusions, or number of units of packed red blood cells. The tranexamic acid group showed a significant decrease in cases of laparotomy for PPH (0.8% vs 1.3%; P = .002; RR = 0.64; 95% CI, 0.49-0.85; NNT = 200).

Women who received tranexamic acid vs placebo showed no significant difference in mortality from pulmonary embolism (0.1% [N = 10] vs 0.1% [N = 11]; P = .82; RR = .9; 95% CI, 0.38-2.13), organ failure ure (0.3% [N = 25] vs 0.2% [N = 18]; P = .29; RR = 1.38; 95% CI, 0.75-2.53), sepsis (0.2% [N = 15] vs 0.1% [N = 8]; P = .15; RR = 1.87; 95% CI, 0.79-4.4), eclampsia (0.02% [N = 2] vs 0.1% [N = 8]; P = .057; RR = .25; 95% CI, 0.05-1.17), or other causes (0.2% [N = 20] vs 0.2% [N = 20]; P = .99; RR = 0.99; 95% CI, 0.54-1.85).

Tranexamic acid doesn’t increase the risk of thromboembolism

A 2018 Cochrane review sought more broadly to determine the general effectiveness and safety of antifibrinolytic drugs in treating primary PPH.2 Of 15 RCTs identified, only 3 met the inclusion criteria for the review, 1 of which was the WOMAN trial (which contributed most of the data in the review). The other trials were a study conducted in France that recruited 152 women and a study of 200 women in Iran that contributed only 1 primary outcome—estimated blood loss—to the review. The former study didn’t report any maternal deaths, and the latter study didn’t look at maternal deaths. The Cochrane review concluded, based on data from the WOMAN trial, that IV tranexamic acid, if given as early as possible, reduced mortality from bleeding in women with primary PPH after both vaginal and cesarean delivery and didn’t increase the risk of thromboembolic events.2

Continue to: RECOMMENDATIONS

RECOMMENDATIONS

The newest practice guidelines on the management of postpartum hemorrhage published by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends considering tranexamic acid as an additional agent in managing PPH when initial standard-of-care treatments fail.3

Editor’s takeaway

The large international double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled trial provides convincing evidence that tranexamic acid should be administered readily in cases of PPH.

1. WOMAN Trial Collaborators. Effect of early tranexamic acid administration on mortality, hysterectomy, and other morbidities in women with post-partum haemorrhage (WOMAN): an international, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2105–2116.

2. Shakur H, Beaumont D, Pavord S, et al. Antifibrinolytic drugs for treating primary postpartum haemorrhage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;2:CD012964.

3. Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists). Practice Bulletin No. 183: Postpartum Hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e168-e186.

1. WOMAN Trial Collaborators. Effect of early tranexamic acid administration on mortality, hysterectomy, and other morbidities in women with post-partum haemorrhage (WOMAN): an international, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2105–2116.

2. Shakur H, Beaumont D, Pavord S, et al. Antifibrinolytic drugs for treating primary postpartum haemorrhage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;2:CD012964.

3. Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists). Practice Bulletin No. 183: Postpartum Hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e168-e186.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Yes. When used in conjunction with the standard of care, 1 g intravenous (IV) tranexamic acid given 1 to 3 hours after delivery is associated with a significant reduction in maternal mortality from postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) (strength of recommendation: A, randomized controlled trial [RCT] and Cochrane review).

No known significant risks are associated with the use of tranexamic acid to treat PPH.

5 Key Points on Dietary Counseling of Acne Patients

Molecule exhibits activity in heavily pretreated, HER2-positive solid tumors

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD – PRS-343, a 4-1BB/HER2 bispecific molecule, has demonstrated safety and antitumor activity in patients with heavily pretreated, HER2-positive solid tumors, an investigator reported at the annual meeting of the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer.

In a phase 1 trial of 18 evaluable patients, PRS-343 produced partial responses in 2 patients and enabled 8 patients to maintain stable disease. PRS-343 was considered well tolerated at all doses and schedules tested.

“PRS-343 is a bispecific construct targeting HER2 as well as 4-1BB,” said Geoffrey Y. Ku, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York. “The HER2 component of the molecule localizes it into the tumor microenvironment of any HER2-positive cells. If the density of the HER2 protein is high enough, that facilitates cross-linkage of 4-1BB.

“4-1BB is an immune agonist that’s present in activated T cells, and cross-linkage helps to improve T-cell exhaustion and is also critical for T-cell expansion. The idea is that, by localizing 4-1BB activation to the tumor microenvironment, we can avoid some of the systemic toxicities associated with naked 4-1BB antibodies,” Dr. Ku added.

The ongoing, phase 1 trial of PRS-343 (NCT03330561) has enrolled 53 patients with a range of HER2-positive malignancies. To be eligible, patients must have progressed on standard therapy or have a tumor for which no standard therapy is available.

The most common diagnosis among enrolled patients is gastroesophageal cancer (n = 19), followed by breast cancer (n = 14), gynecologic cancers (n = 6), colorectal cancer (n = 5), and other malignancies.

The patients’ median age at baseline was 61 years (range, 29-92 years), and a majority were female (62%). Most patients (79%) had received three or more prior lines of therapy, including anti-HER2 treatments. Breast cancer patients had received a median of four anti-HER2 treatments, and gastric cancer patients had received a median of two.

The patients have been treated with PRS-343 at 11 dose levels, ranging from 0.0005 mg/kg to 8 mg/kg, given every 3 weeks. The highest dose, 8 mg/kg, was also given every 2 weeks.

Treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) included infusion-related reactions (9%), fatigue (9%), chills (6%), flushing (6%), nausea (6%), diarrhea (6%), vomiting (5%), and noncardiac chest pain (4%).

“This was an extremely well-tolerated drug,” Dr. Ku said. “Out of 111 TRAEs, only a tiny proportion were grade 3, and toxicities mostly clustered around infusion-related reactions, constitutional symptoms, as well as gastrointestinal symptoms.”

Grade 3 TRAEs included infusion-related reactions (2%), fatigue (1%), flushing (3%), and noncardiac chest pain (1%). There were no grade 4-5 TRAEs.

At the data cutoff (Oct. 23, 2019), 18 patients were evaluable for a response at active dose levels (2.5 mg/kg, 5 mg/kg, and 8 mg/kg).

Two patients achieved a partial response, and eight had stable disease. “This translates to a response rate of 11% and a disease control rate of 55%,” Dr. Ku noted.

Both responders received PRS-343 at 8 mg/kg every 2 weeks. One of these patients had stage 4 gastric adenocarcinoma, and one had stage 4 gynecologic carcinoma.

Of the eight patients with stable disease, three received PRS-343 at 8 mg/kg every 2 weeks, two received 8 mg/kg every 3 weeks, one received the 5 mg/kg dose, and two received the 2.5 mg/kg dose.

Dr. Ku noted that the average time on treatment significantly increased in patients who received PRS-343 at 8 mg/kg every 2 weeks. Additionally, both responders and patients with stable disease had a “clear increase” in CD8+ T cells.

“[PRS-343] has demonstrated antitumor activity in heavily pretreated patients across multiple tumor types, and the treatment history, specifically the receipt of prior anti-HER2 therapy, indicates this is a 4-1BB-driven mechanism of action,” Dr. Ku said. “Based on these results, future studies are planned for continued development in defined HER2-positive indications.”

The current study is sponsored by Pieris Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Ku disclosed relationships with Arog Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Merck, Zymeworks, and Pieris Pharmaceuticals.

SOURCE: Ku GY et al. SITC 2019, Abstract O82.

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD – PRS-343, a 4-1BB/HER2 bispecific molecule, has demonstrated safety and antitumor activity in patients with heavily pretreated, HER2-positive solid tumors, an investigator reported at the annual meeting of the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer.

In a phase 1 trial of 18 evaluable patients, PRS-343 produced partial responses in 2 patients and enabled 8 patients to maintain stable disease. PRS-343 was considered well tolerated at all doses and schedules tested.

“PRS-343 is a bispecific construct targeting HER2 as well as 4-1BB,” said Geoffrey Y. Ku, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York. “The HER2 component of the molecule localizes it into the tumor microenvironment of any HER2-positive cells. If the density of the HER2 protein is high enough, that facilitates cross-linkage of 4-1BB.

“4-1BB is an immune agonist that’s present in activated T cells, and cross-linkage helps to improve T-cell exhaustion and is also critical for T-cell expansion. The idea is that, by localizing 4-1BB activation to the tumor microenvironment, we can avoid some of the systemic toxicities associated with naked 4-1BB antibodies,” Dr. Ku added.

The ongoing, phase 1 trial of PRS-343 (NCT03330561) has enrolled 53 patients with a range of HER2-positive malignancies. To be eligible, patients must have progressed on standard therapy or have a tumor for which no standard therapy is available.

The most common diagnosis among enrolled patients is gastroesophageal cancer (n = 19), followed by breast cancer (n = 14), gynecologic cancers (n = 6), colorectal cancer (n = 5), and other malignancies.