User login

Scars and color changes on face

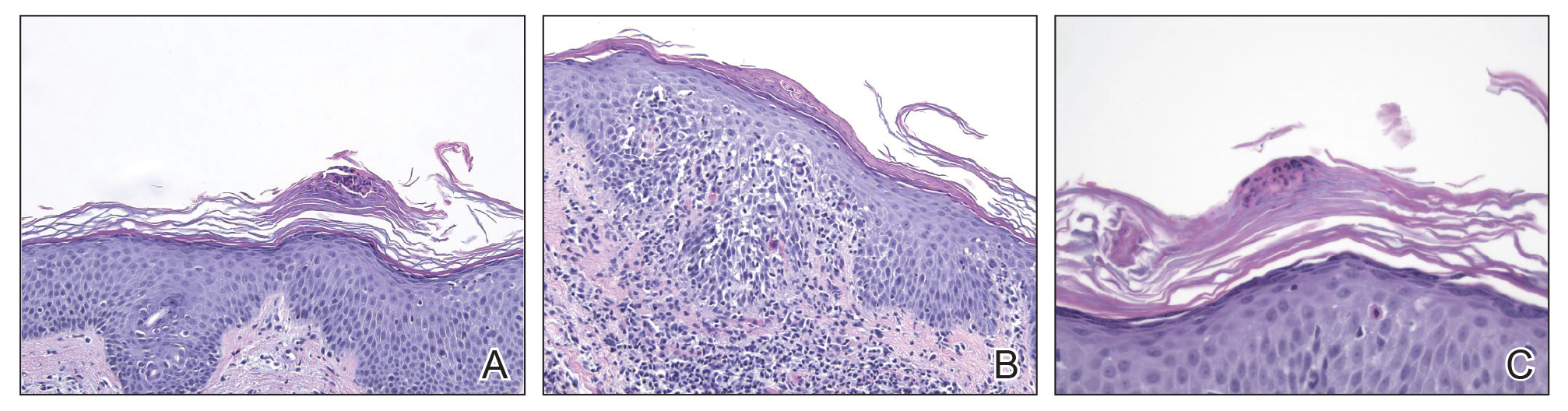

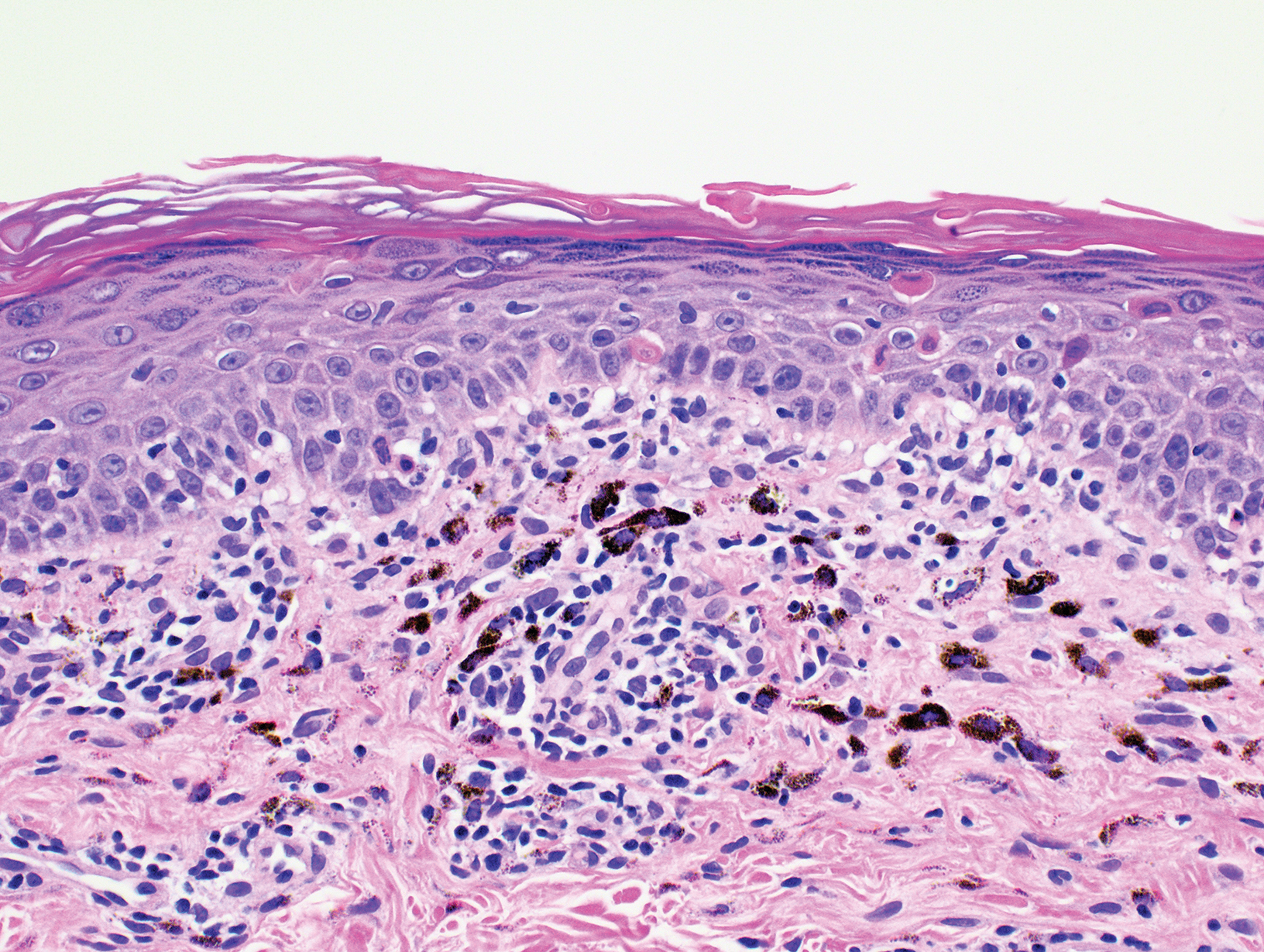

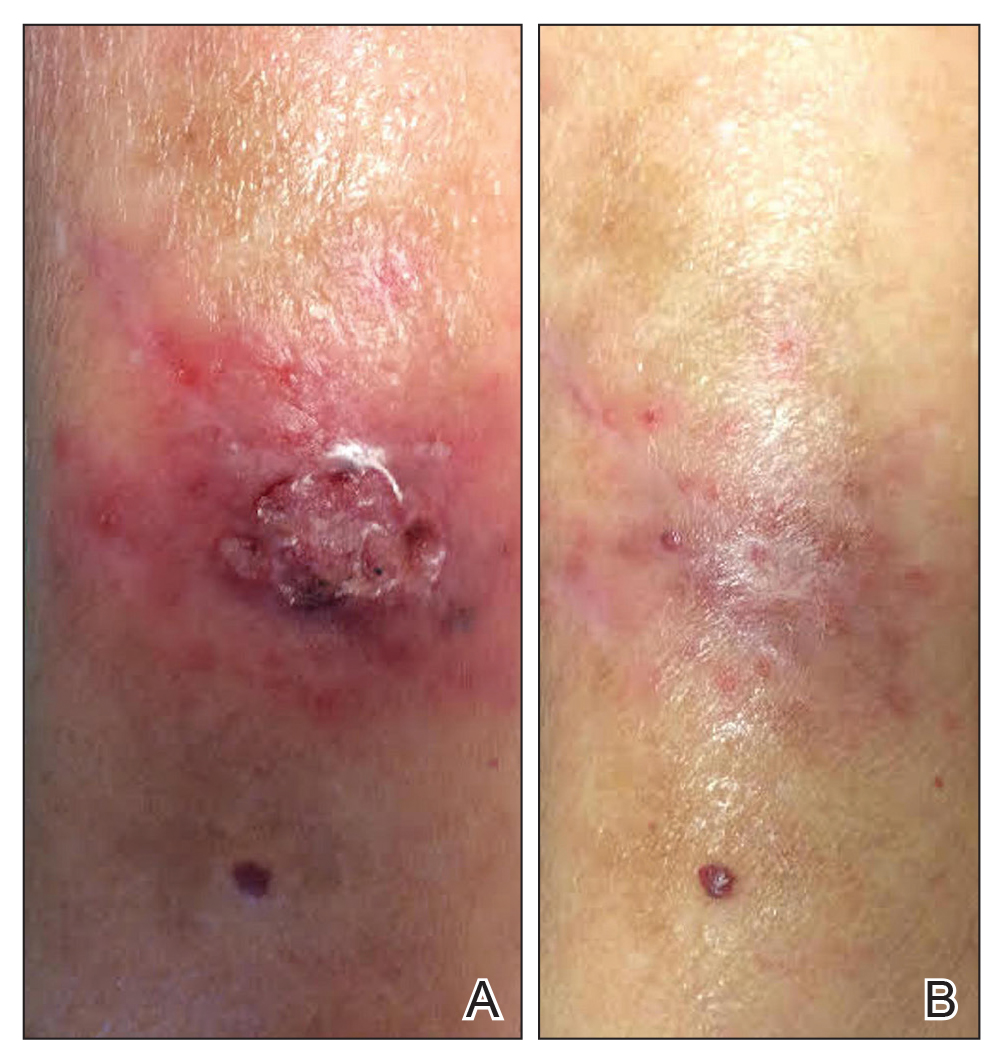

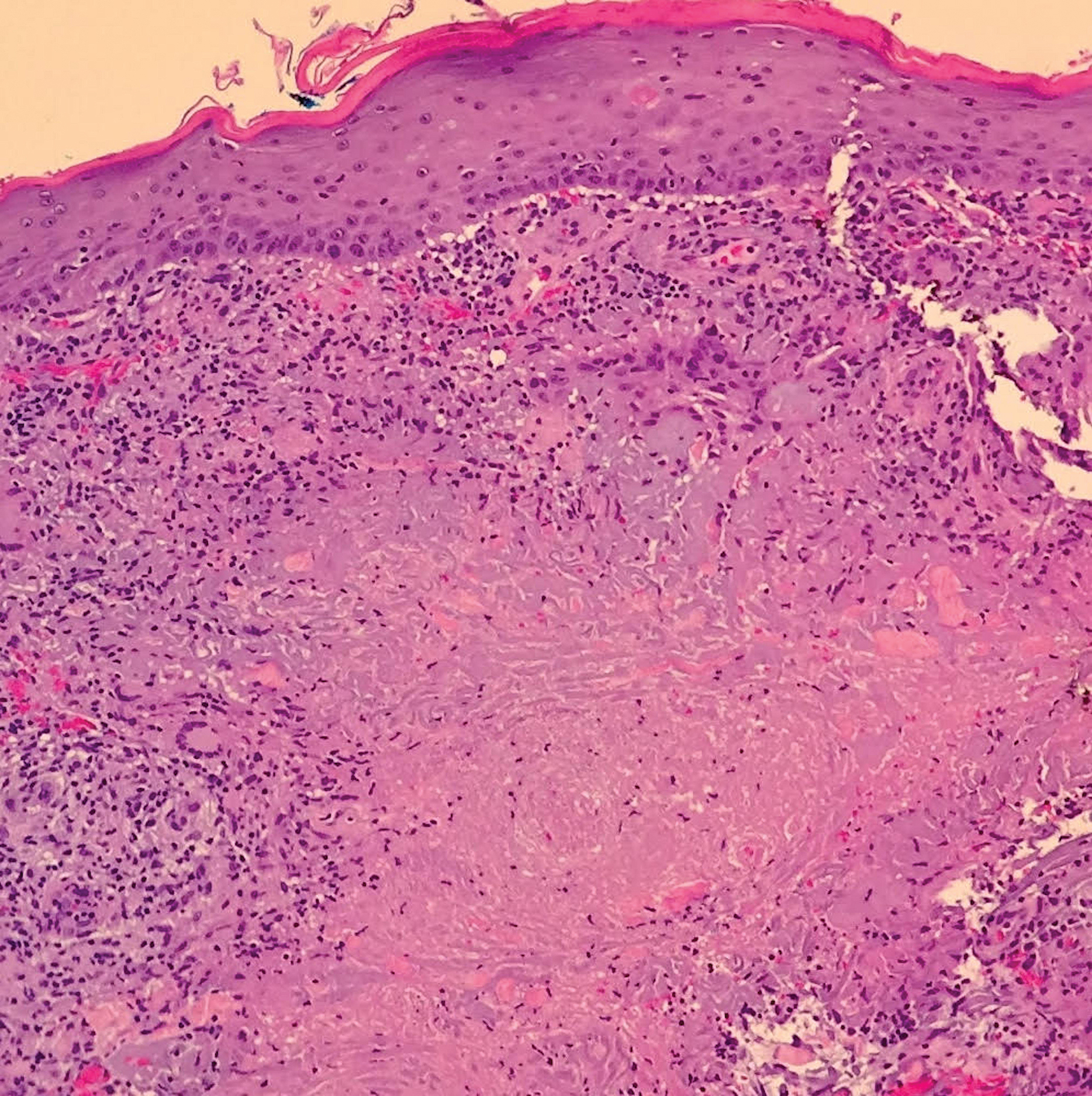

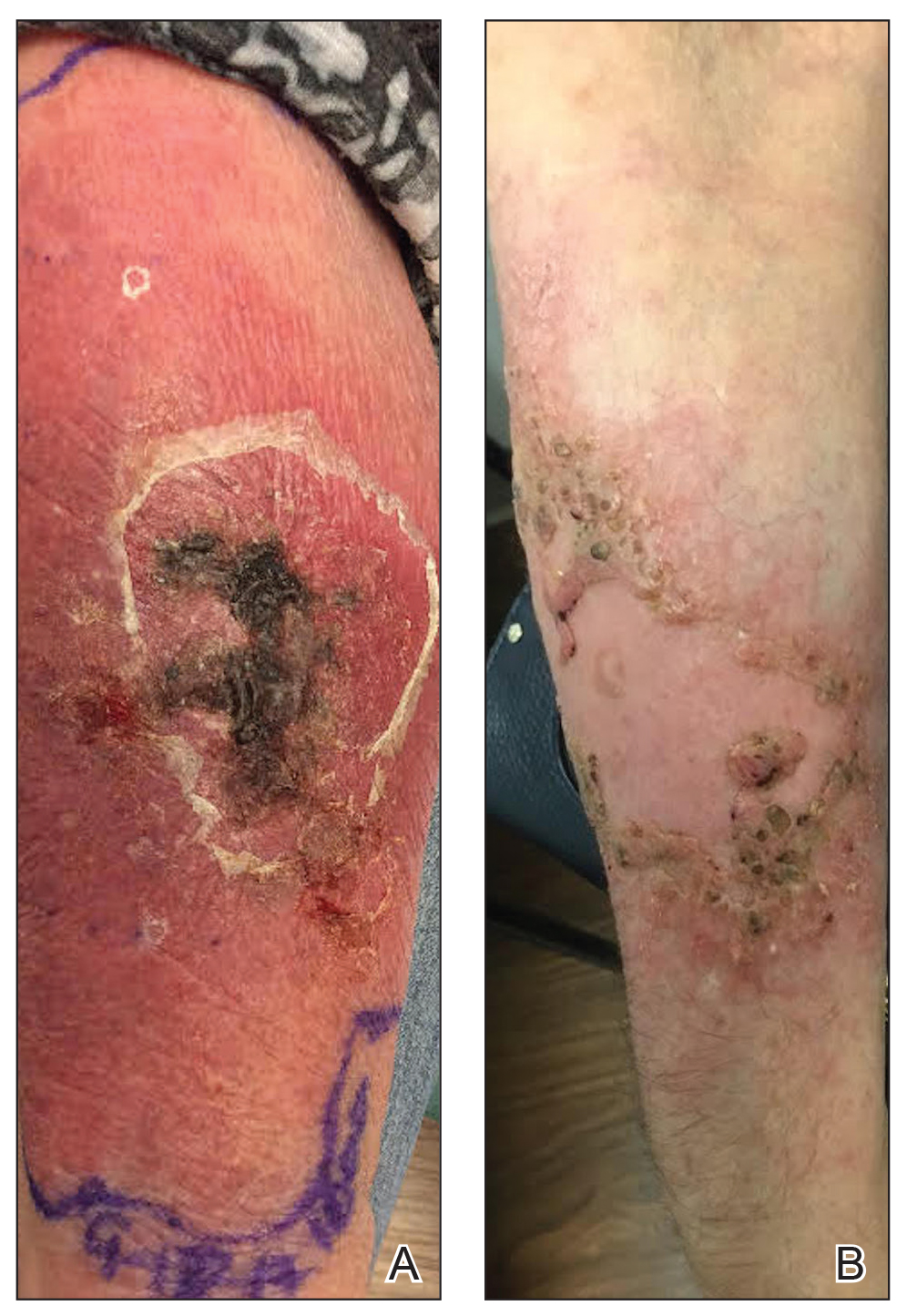

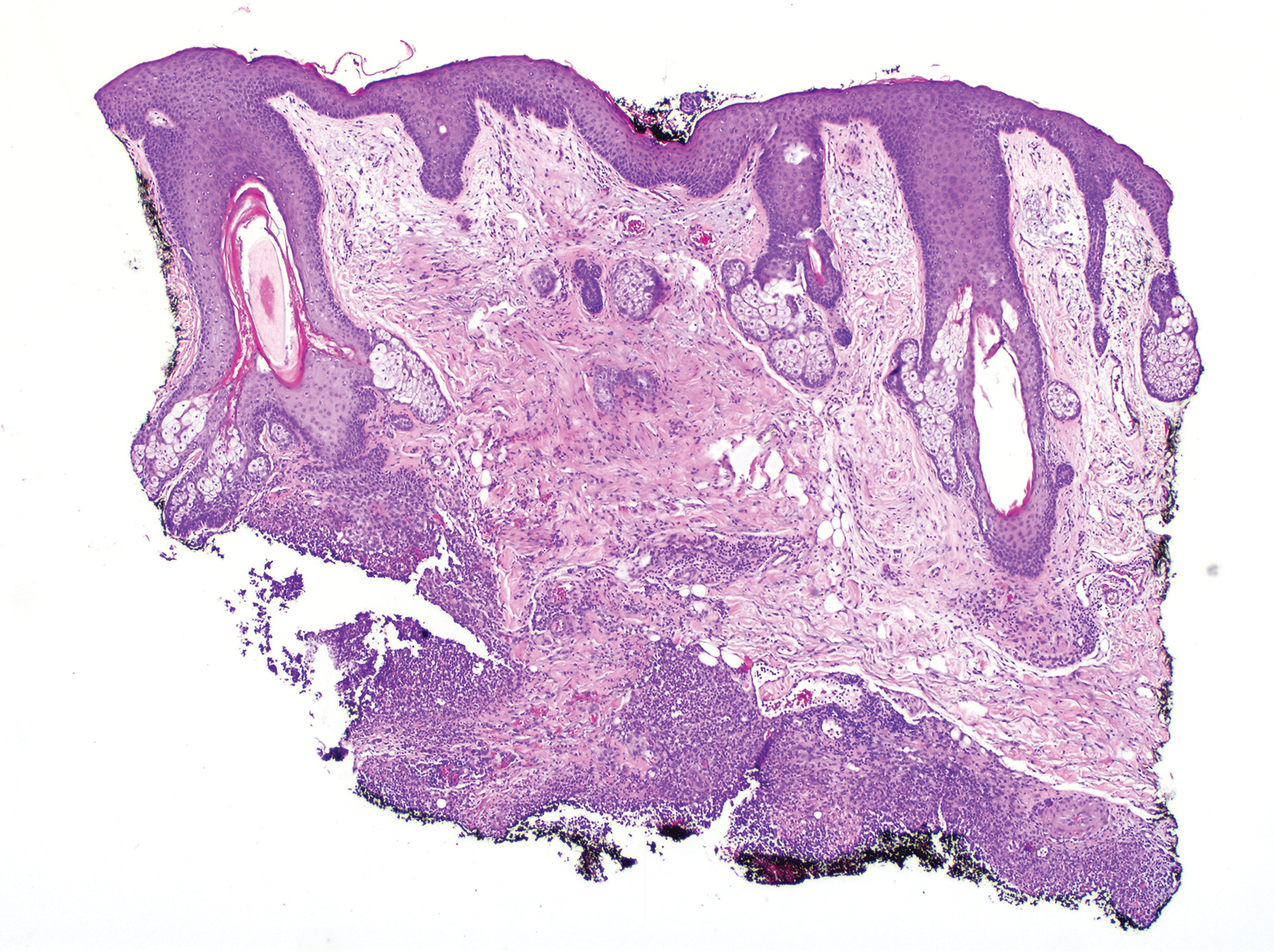

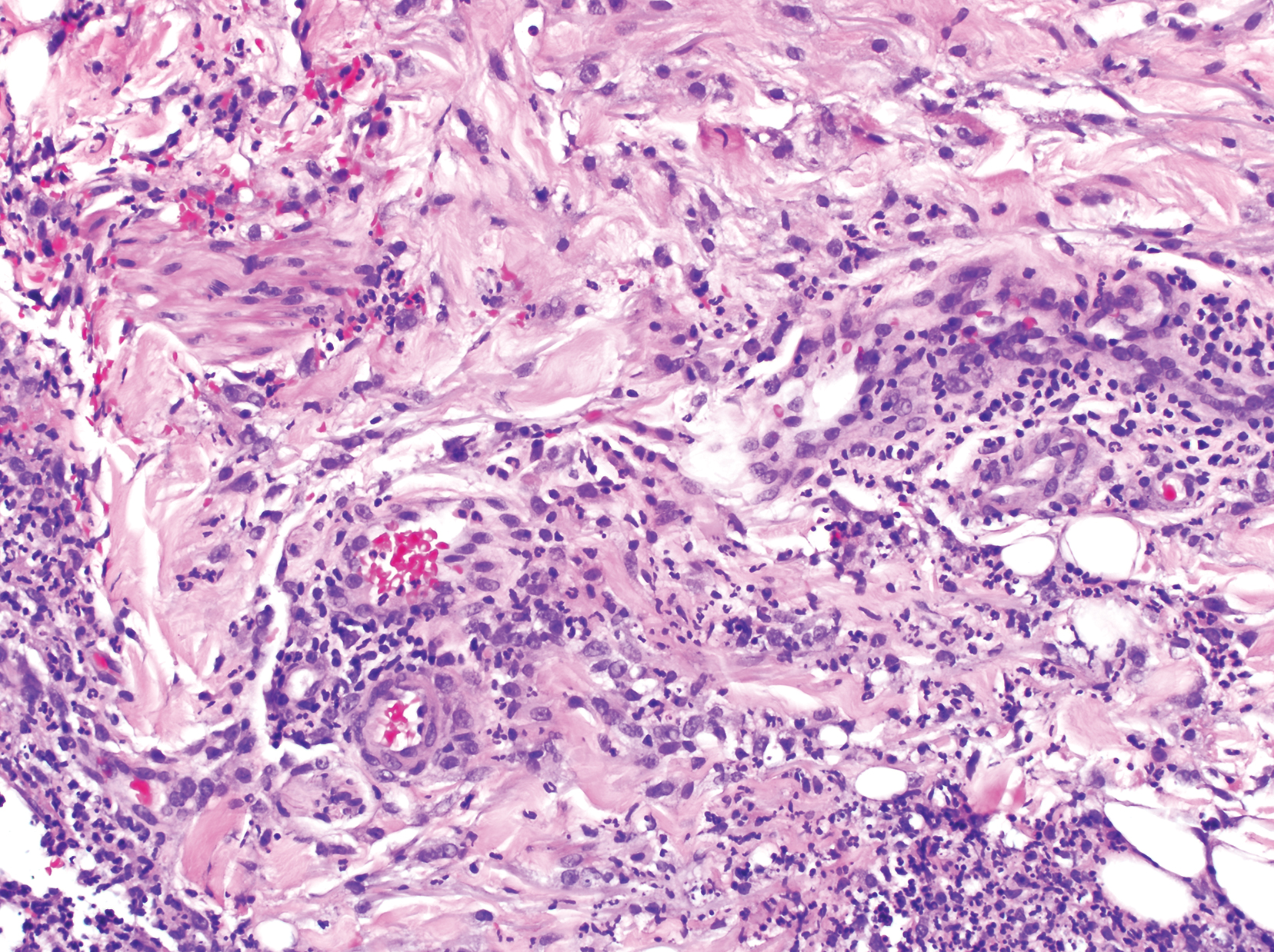

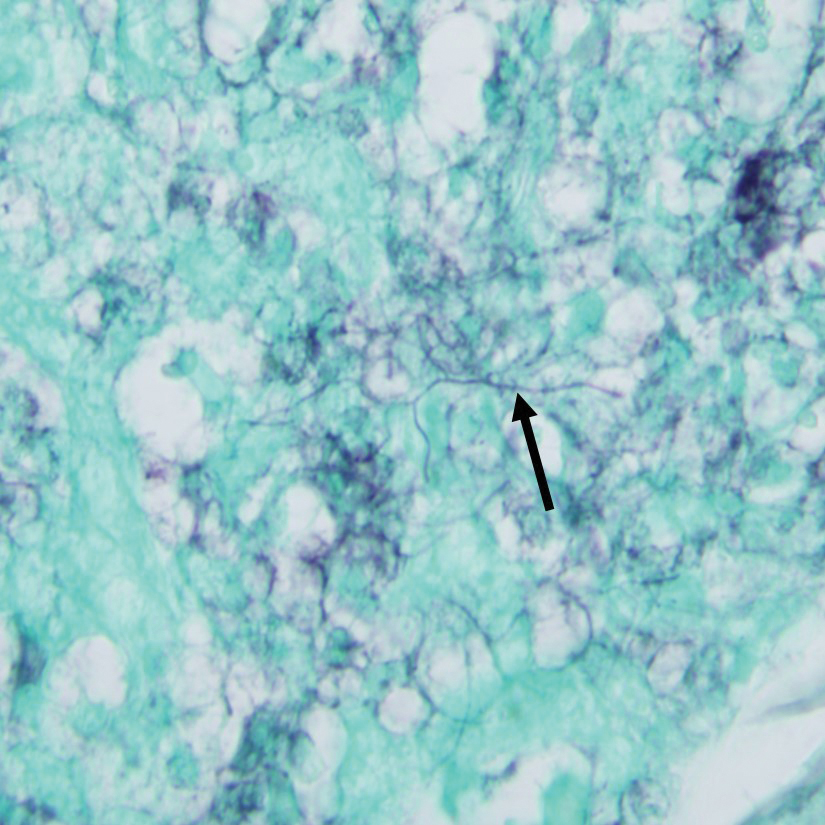

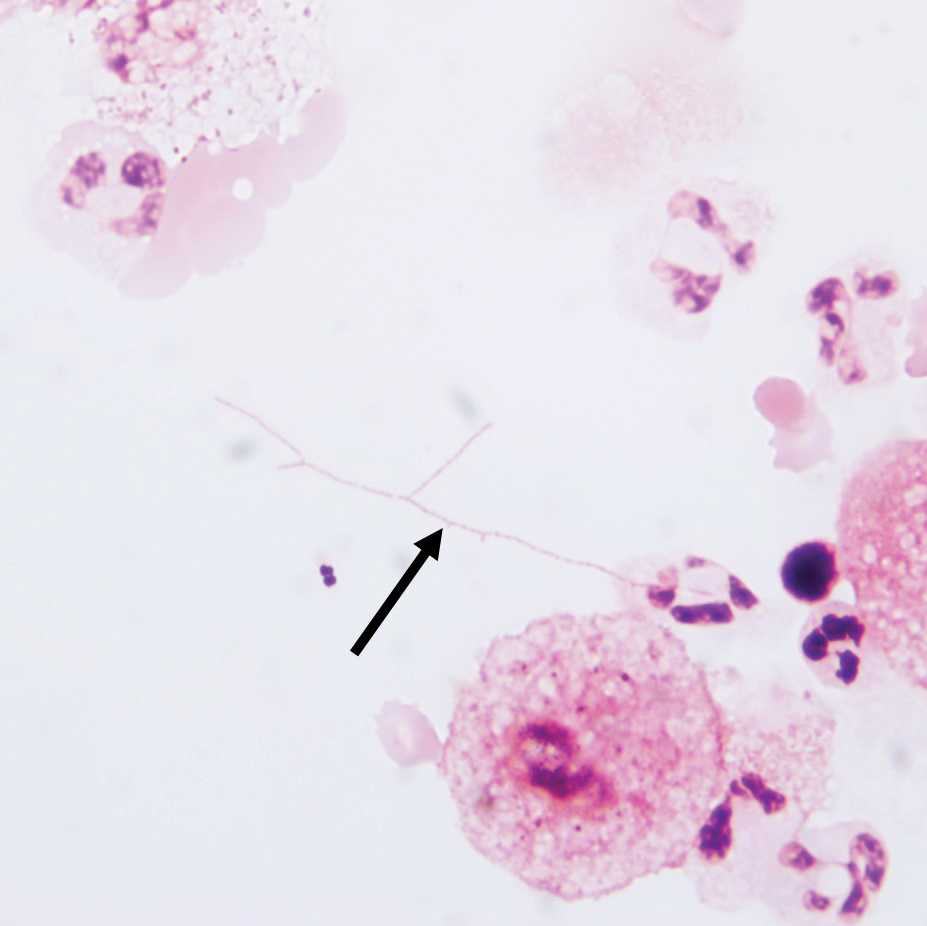

The FP recognized the scarring, skin atrophy, erythema and hyperpigmentation in the malar distribution as discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE). Upon examination, the FP noted similar patterns (with the addition of hypopigmentation) in the conchal bowls of both pinna. This was confirmatory for the DLE diagnosis (AKA chronic cutaneous lupus). (If in doubt, a 4-mm punch biopsy could be performed on the lesions of the face.) Without the lesions in the ears, sarcoidosis might have been considered as part of the differential diagnosis.

DLE lesions are characterized by discrete, erythematous, slightly infiltrated papules or plaques. Hypopigmentation develops in the central area and hyperpigmentation develops at the active border. Resolution of the active lesion results in atrophy and scarring.

In this case, the FP explained the diagnosis of DLE to the patient and ordered testing for antinuclear antibodies (ANA), a complete blood count, and comprehensive metabolic panel. All the labs were normal, and the ANA was negative, which confirmed that this was not a case of systemic lupus erythematosus. Patients with only DLE generally have negative or low-titer ANA titers.

DLE therapy includes corticosteroids (topical or intralesional) and oral antimalarials, such as hydroxychloroquine. The FP in this case started the patient on hydroxychloroquine 200 mg bid and topical triamcinolone 0.1% applied twice daily to the erythematous portions of the cheeks for 2 weeks. At the 2-week follow-up, the patient’s skin looked less red and inflamed and she was happy with the improved appearance of her skin. Patients on hydroxychloroquine need a baseline eye exam by an ophthalmologist and then yearly exams after 5 years of therapy to detect any retinal or visual field problems.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Pye A, Mayeaux, EJ, Mishra V, et al. Lupus. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1183-1193.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

The FP recognized the scarring, skin atrophy, erythema and hyperpigmentation in the malar distribution as discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE). Upon examination, the FP noted similar patterns (with the addition of hypopigmentation) in the conchal bowls of both pinna. This was confirmatory for the DLE diagnosis (AKA chronic cutaneous lupus). (If in doubt, a 4-mm punch biopsy could be performed on the lesions of the face.) Without the lesions in the ears, sarcoidosis might have been considered as part of the differential diagnosis.

DLE lesions are characterized by discrete, erythematous, slightly infiltrated papules or plaques. Hypopigmentation develops in the central area and hyperpigmentation develops at the active border. Resolution of the active lesion results in atrophy and scarring.

In this case, the FP explained the diagnosis of DLE to the patient and ordered testing for antinuclear antibodies (ANA), a complete blood count, and comprehensive metabolic panel. All the labs were normal, and the ANA was negative, which confirmed that this was not a case of systemic lupus erythematosus. Patients with only DLE generally have negative or low-titer ANA titers.

DLE therapy includes corticosteroids (topical or intralesional) and oral antimalarials, such as hydroxychloroquine. The FP in this case started the patient on hydroxychloroquine 200 mg bid and topical triamcinolone 0.1% applied twice daily to the erythematous portions of the cheeks for 2 weeks. At the 2-week follow-up, the patient’s skin looked less red and inflamed and she was happy with the improved appearance of her skin. Patients on hydroxychloroquine need a baseline eye exam by an ophthalmologist and then yearly exams after 5 years of therapy to detect any retinal or visual field problems.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Pye A, Mayeaux, EJ, Mishra V, et al. Lupus. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1183-1193.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

The FP recognized the scarring, skin atrophy, erythema and hyperpigmentation in the malar distribution as discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE). Upon examination, the FP noted similar patterns (with the addition of hypopigmentation) in the conchal bowls of both pinna. This was confirmatory for the DLE diagnosis (AKA chronic cutaneous lupus). (If in doubt, a 4-mm punch biopsy could be performed on the lesions of the face.) Without the lesions in the ears, sarcoidosis might have been considered as part of the differential diagnosis.

DLE lesions are characterized by discrete, erythematous, slightly infiltrated papules or plaques. Hypopigmentation develops in the central area and hyperpigmentation develops at the active border. Resolution of the active lesion results in atrophy and scarring.

In this case, the FP explained the diagnosis of DLE to the patient and ordered testing for antinuclear antibodies (ANA), a complete blood count, and comprehensive metabolic panel. All the labs were normal, and the ANA was negative, which confirmed that this was not a case of systemic lupus erythematosus. Patients with only DLE generally have negative or low-titer ANA titers.

DLE therapy includes corticosteroids (topical or intralesional) and oral antimalarials, such as hydroxychloroquine. The FP in this case started the patient on hydroxychloroquine 200 mg bid and topical triamcinolone 0.1% applied twice daily to the erythematous portions of the cheeks for 2 weeks. At the 2-week follow-up, the patient’s skin looked less red and inflamed and she was happy with the improved appearance of her skin. Patients on hydroxychloroquine need a baseline eye exam by an ophthalmologist and then yearly exams after 5 years of therapy to detect any retinal or visual field problems.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Pye A, Mayeaux, EJ, Mishra V, et al. Lupus. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1183-1193.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

IPD in children may be a signal of immunodeficiency

according to a systematic review published in JAMA Pediatrics.

Coen Butters, BMed, DCH, of the Royal Children’s Hospital in Melbourne, and coauthors wrote that, even with optimal vaccine coverage, there is still a group of children with increased susceptibility to invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD), and this could be a potential marker of primary immunodeficiency.

They conducted a systematic review of 17 studies of 6,002 children to examine the evidence on the incidence of primary immunodeficiency in children who presented with IPD but without any other risk factors or predisposing conditions.

Overall, the frequency of primary immunodeficiency in children presenting with IPD who did not have any other predisposing condition ranged from 1% to 26%.

One study of 162 children with IPD, which had an overall frequency of primary immunodeficiency of 10%, found that children older than 2 years were significantly more likely to have primary immunodeficiency than those aged under 2 years (26% vs. 3%; P less than .001).

Primary antibody deficiency was the most commonly diagnosed immunodeficiency in these children with IPD, accounting for 71% of cases. These deficiencies presented as hypogammaglobulinemia, specific pneumococcal antibody deficiency, X-linked agammaglobulinemia, and IgG2 deficiency.

The review also included four studies that looked at the frequency of mannose-binding lectin deficiency in 1,493 children with primary IPD. Two of these studies reported a prevalence of mannose-binding lectin deficiency ranging from 31% in children aged younger than 2 years to 41% in children younger than 1 year.

Five studies looked at the rate of primary immunodeficiency in children presenting with recurrent IPD. In addition to other predisposing conditions such as sickle cell disease, cancer, and anatomical breach in the blood-brain barrier, the three studies that screened for primary immunodeficiency found rates ranging from 10% to 67%. The most common conditions were complement deficiency, pneumococcal antibody deficiency, and a single case of TLR-signaling defect.

In a study of 162 children with primary IPD, screening for asplenia identified a single case of congenital asplenia. In another study of 2,498 cases of IPD, 22 patients had asplenia at presentation, half of whom died at presentation.

Dr. Butters and associates concluded that “this review’s findings suggests that existing data support the immune evaluation of children older than 2 years without a known predisposing condition who present with their first episode of Streptococcus pneumoniae meningitis, pneumonia, or recurrent IPD. Immune evaluation should include assessment for immunoglobulin deficiency, pneumococcal antibody deficiency, complement disorders, and asplenia.”

In an accompanying editorial, Stephen I. Pelton, MD, of the Maxwell Finland Laboratory for Infectious Diseases at Boston Medical Center, and coauthors wrote that in children with recurrent episodes of IPD caused by nonvaccine serotypes – particularly those aged over 5 years – evaluation for primary immunodeficiencies could uncover immune defects.

“Once identified, direct and indirect protection, penicillin prophylaxis, or a combination of these offers great potential for disease prevention and reduction of mortality and morbidity in children with [primary immunodeficiency],” they wrote.

No funding or conflicts of interest were declared for the study. Two of the editorialists declared research funding or honoraria from the pharmaceutical sector.

SOURCES: Butters C et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Sep 30. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.3203; Pelton SI et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Sep 30. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.3185.

according to a systematic review published in JAMA Pediatrics.

Coen Butters, BMed, DCH, of the Royal Children’s Hospital in Melbourne, and coauthors wrote that, even with optimal vaccine coverage, there is still a group of children with increased susceptibility to invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD), and this could be a potential marker of primary immunodeficiency.

They conducted a systematic review of 17 studies of 6,002 children to examine the evidence on the incidence of primary immunodeficiency in children who presented with IPD but without any other risk factors or predisposing conditions.

Overall, the frequency of primary immunodeficiency in children presenting with IPD who did not have any other predisposing condition ranged from 1% to 26%.

One study of 162 children with IPD, which had an overall frequency of primary immunodeficiency of 10%, found that children older than 2 years were significantly more likely to have primary immunodeficiency than those aged under 2 years (26% vs. 3%; P less than .001).

Primary antibody deficiency was the most commonly diagnosed immunodeficiency in these children with IPD, accounting for 71% of cases. These deficiencies presented as hypogammaglobulinemia, specific pneumococcal antibody deficiency, X-linked agammaglobulinemia, and IgG2 deficiency.

The review also included four studies that looked at the frequency of mannose-binding lectin deficiency in 1,493 children with primary IPD. Two of these studies reported a prevalence of mannose-binding lectin deficiency ranging from 31% in children aged younger than 2 years to 41% in children younger than 1 year.

Five studies looked at the rate of primary immunodeficiency in children presenting with recurrent IPD. In addition to other predisposing conditions such as sickle cell disease, cancer, and anatomical breach in the blood-brain barrier, the three studies that screened for primary immunodeficiency found rates ranging from 10% to 67%. The most common conditions were complement deficiency, pneumococcal antibody deficiency, and a single case of TLR-signaling defect.

In a study of 162 children with primary IPD, screening for asplenia identified a single case of congenital asplenia. In another study of 2,498 cases of IPD, 22 patients had asplenia at presentation, half of whom died at presentation.

Dr. Butters and associates concluded that “this review’s findings suggests that existing data support the immune evaluation of children older than 2 years without a known predisposing condition who present with their first episode of Streptococcus pneumoniae meningitis, pneumonia, or recurrent IPD. Immune evaluation should include assessment for immunoglobulin deficiency, pneumococcal antibody deficiency, complement disorders, and asplenia.”

In an accompanying editorial, Stephen I. Pelton, MD, of the Maxwell Finland Laboratory for Infectious Diseases at Boston Medical Center, and coauthors wrote that in children with recurrent episodes of IPD caused by nonvaccine serotypes – particularly those aged over 5 years – evaluation for primary immunodeficiencies could uncover immune defects.

“Once identified, direct and indirect protection, penicillin prophylaxis, or a combination of these offers great potential for disease prevention and reduction of mortality and morbidity in children with [primary immunodeficiency],” they wrote.

No funding or conflicts of interest were declared for the study. Two of the editorialists declared research funding or honoraria from the pharmaceutical sector.

SOURCES: Butters C et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Sep 30. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.3203; Pelton SI et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Sep 30. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.3185.

according to a systematic review published in JAMA Pediatrics.

Coen Butters, BMed, DCH, of the Royal Children’s Hospital in Melbourne, and coauthors wrote that, even with optimal vaccine coverage, there is still a group of children with increased susceptibility to invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD), and this could be a potential marker of primary immunodeficiency.

They conducted a systematic review of 17 studies of 6,002 children to examine the evidence on the incidence of primary immunodeficiency in children who presented with IPD but without any other risk factors or predisposing conditions.

Overall, the frequency of primary immunodeficiency in children presenting with IPD who did not have any other predisposing condition ranged from 1% to 26%.

One study of 162 children with IPD, which had an overall frequency of primary immunodeficiency of 10%, found that children older than 2 years were significantly more likely to have primary immunodeficiency than those aged under 2 years (26% vs. 3%; P less than .001).

Primary antibody deficiency was the most commonly diagnosed immunodeficiency in these children with IPD, accounting for 71% of cases. These deficiencies presented as hypogammaglobulinemia, specific pneumococcal antibody deficiency, X-linked agammaglobulinemia, and IgG2 deficiency.

The review also included four studies that looked at the frequency of mannose-binding lectin deficiency in 1,493 children with primary IPD. Two of these studies reported a prevalence of mannose-binding lectin deficiency ranging from 31% in children aged younger than 2 years to 41% in children younger than 1 year.

Five studies looked at the rate of primary immunodeficiency in children presenting with recurrent IPD. In addition to other predisposing conditions such as sickle cell disease, cancer, and anatomical breach in the blood-brain barrier, the three studies that screened for primary immunodeficiency found rates ranging from 10% to 67%. The most common conditions were complement deficiency, pneumococcal antibody deficiency, and a single case of TLR-signaling defect.

In a study of 162 children with primary IPD, screening for asplenia identified a single case of congenital asplenia. In another study of 2,498 cases of IPD, 22 patients had asplenia at presentation, half of whom died at presentation.

Dr. Butters and associates concluded that “this review’s findings suggests that existing data support the immune evaluation of children older than 2 years without a known predisposing condition who present with their first episode of Streptococcus pneumoniae meningitis, pneumonia, or recurrent IPD. Immune evaluation should include assessment for immunoglobulin deficiency, pneumococcal antibody deficiency, complement disorders, and asplenia.”

In an accompanying editorial, Stephen I. Pelton, MD, of the Maxwell Finland Laboratory for Infectious Diseases at Boston Medical Center, and coauthors wrote that in children with recurrent episodes of IPD caused by nonvaccine serotypes – particularly those aged over 5 years – evaluation for primary immunodeficiencies could uncover immune defects.

“Once identified, direct and indirect protection, penicillin prophylaxis, or a combination of these offers great potential for disease prevention and reduction of mortality and morbidity in children with [primary immunodeficiency],” they wrote.

No funding or conflicts of interest were declared for the study. Two of the editorialists declared research funding or honoraria from the pharmaceutical sector.

SOURCES: Butters C et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Sep 30. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.3203; Pelton SI et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Sep 30. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.3185.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Targeted agents vs. chemoimmunotherapy as first-line treatment of CLL

SAN FRANCISCO – Should targeted agents replace chemoimmunotherapy (CIT) as first-line treatment for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)? A recent debate suggests there’s no consensus.

William G. Wierda, MD, PhD, of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, and Jennifer R. Brown, MD, PhD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, debated the topic at the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Hematologic Malignancies Annual Congress.

Dr. Wierda argued that CLL patients should receive a BTK inhibitor or BCL2 inhibitor, with or without obinutuzumab, as first-line therapy because these targeted agents have been shown to provide better progression-free survival (PFS) than CIT, and the targeted therapies may prolong overall survival (OS) as well.

Dr. Brown countered that targeted agents don’t improve PFS for all CLL patients, improved PFS doesn’t always translate to improved OS, and targeted agents cost more than CIT.

No role for CIT as first-line treatment

“We have two approaches right now, with nonchemoimmunotherapy-based treatment,” Dr. Wierda said. “One approach, with small-molecule inhibitors, is to have a sustained and durable period of disease control, particularly with BTK inhibitors. The other strategy that has emerged is deep remissions with fixed-duration treatment with BCL2 small-molecule inhibitor-based therapy, which, I would argue, is better than being exposed to genotoxic chemoimmunotherapy.”

Dr. Wierda went on to explain that the BTK inhibitor ibrutinib has been shown to improve PFS, compared with CIT, in phase 3 trials.

In the iLLUMINATE trial, researchers compared ibrutinib plus obinutuzumab to chlorambucil plus obinutuzumab as first-line treatment in CLL. At a median follow-up of 31.3 months, the median PFS was not reached in the ibrutinib arm and was 19 months in the chlorambucil arm (P less than .0001; Lancet Oncol. 2019 Jan;20[1]:43-56).

In the A041202 study, researchers compared ibrutinib alone (Ib) or in combination with rituximab (Ib-R) to bendamustine plus rituximab (BR) in untreated, older patients with CLL. The 2-year PFS estimates were 74% in the BR arm, 87% in the Ib arm, and 88% in the Ib-R arm (P less than .001 for BR vs. Ib or Ib-R; N Engl J Med. 2018; 379:2517-28).

In the E1912 trial, researchers compared Ib-R to fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (FCR) in younger, untreated CLL patients. The 3-year PFS was 89.4% with Ib-R and 72.9% with FCR (P less than .001; N Engl J Med. 2019 Aug 1;381:432-43).

Dr. Wierda noted that the E1912 trial also showed superior OS with Ib-R. The 3-year OS rate was 98.8% with Ib-R and 91.5% with FCR (P less than .001). However, there was no significant difference in OS between the treatment arms in the A041202 trial or the iLLUMINATE trial.

“But I would argue that is, in part, because of short follow-up,” Dr. Wierda said. “The trials were all designed to look at progression-free survival, not overall survival. With longer follow-up, we may see differences in overall survival emerging.”

Dr. Wierda went on to say that fixed‐duration treatment with the BCL2 inhibitor venetoclax can improve PFS over CIT.

In the phase 3 CLL14 trial, researchers compared fixed-duration treatment with venetoclax plus obinutuzumab to chlorambucil plus obinutuzumab in previously untreated CLL patients with comorbidities. The estimated PFS at 2 years was 88.2% in the venetoclax group and 64.1% in the chlorambucil group (P less than .001; N Engl J Med. 2019; 380:2225-36).

“[There was] no difference in overall survival,” Dr. Wierda noted. “But, again, I would argue ... that follow-up is relatively limited. We may ultimately see a difference in overall survival.”

Based on these findings, Dr. Wierda made the following treatment recommendations:

- Any CLL patient with del(17p) or TP53 mutation, and older, unfit patients with unmutated IGHV should receive a BTK inhibitor, with or without obinutuzumab.

- All young, fit patients, and older, unfit patients with mutated IGHV should receive a BCL2 inhibitor plus obinutuzumab.

Dr. Wierda also noted that ibrutinib and venetoclax in combination have shown early promise for patients with previously untreated CLL (N Engl J Med. 2019; 380:2095-2103).

CIT still has a role as first-line treatment

Dr. Brown suggested that a PFS benefit may not be enough to recommend targeted agents over CIT. For one thing, the PFS benefit doesn’t apply to all patients, as the IGHV-mutated subgroup does equally well with CIT and targeted agents.

In the IGHV-mutated group from the E1912 trial, the 3-year PFS was 88% for patients who received Ib-R and those who received FCR (N Engl J Med. 2019 Aug 1;381:432-43). In the A041202 study, the 2-year PFS among IGHV-mutated patients was 87% in the BR arm, 86% in the Ib arm, and 88% in the Ib-R arm (N Engl J Med. 2018; 379:2517-28).

In the CLL14 trial, PFS rates were similar among IGHV-mutated patients who received chlorambucil plus obinutuzumab and IGHV-mutated or unmutated patients who received venetoclax and obinutuzumab (N Engl J Med. 2019; 380:2225-36).

Dr. Brown also noted that the overall improvement in PFS observed with ibrutinib and venetoclax doesn’t always translate to improved OS.

In the A041202 study, there was no significant difference in OS between the Ib, Ib-R, and BR arms (N Engl J Med. 2018; 379:2517-28). There was no significant difference in OS between the ibrutinib and chlorambucil arms in the iLLUMINATE trial (Lancet Oncol. 2019 Jan;20[1]:43-56). And there was no significant difference in OS between the venetoclax and chlorambucil arms in the CLL14 trial (N Engl J Med. 2019; 380:2225-36).

However, in the RESONATE-2 trial, ibrutinib provided an OS benefit over chlorambucil. The 2-year OS was 95% and 84%, respectively (P = .0145; Haematologica. Sept 2018;103:1502-10). Dr. Brown said the OS advantage in this study was due to the “very poor comparator of chlorambucil and very limited crossover.”

As Dr. Wierda mentioned, the OS rate was higher with Ib-R than with FCR in the E1912 trial. The 3-year OS rate was 98.8% and 91.5%, respectively (P less than .001; N Engl J Med. 2019 Aug 1;381:432-43). Dr. Brown noted, however, that there were few deaths in this study, and many of them “were not clearly related to the disease or its treatment.”

Dr. Brown also pointed out that FCR has been shown to have curative potential in IGHV-mutated CLL in both the FCR300 trial (Blood. 2016 127:303-9) and the CLL8 trial (Blood. 2016 127:208-15).

Another factor to consider is the greater cost of targeted agents. One analysis suggested the per-patient lifetime cost of CLL treatment in the United States will increase from $147,000 to $604,000 as targeted therapies overtake CIT as first-line treatment (J Clin Oncol. 2017 Jan 10;35[2]:166-174).

“Given all of the above, chemoimmunotherapy is going to remain part of the treatment repertoire for CLL,” Dr. Brown said. “It’s our only known potential cure for the fit, mutated patients ... and can also result in prolonged treatment-free intervals for patients who are older. As we manage CLL as a chronic disease over a lifetime, we need to continue to have this in our armamentarium.”

Specifically, Dr. Brown said CIT is appropriate for patients who don’t have del(17p) or mutated TP53. FCR should be given to young, fit patients with IGHV-mutated CLL, and FCR or BR should be given to older patients and young, fit patients with IGHV-unmutated CLL.

Dr. Brown and Dr. Wierda reported financial ties to multiple pharmaceutical companies, including makers of CLL treatments.

SAN FRANCISCO – Should targeted agents replace chemoimmunotherapy (CIT) as first-line treatment for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)? A recent debate suggests there’s no consensus.

William G. Wierda, MD, PhD, of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, and Jennifer R. Brown, MD, PhD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, debated the topic at the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Hematologic Malignancies Annual Congress.

Dr. Wierda argued that CLL patients should receive a BTK inhibitor or BCL2 inhibitor, with or without obinutuzumab, as first-line therapy because these targeted agents have been shown to provide better progression-free survival (PFS) than CIT, and the targeted therapies may prolong overall survival (OS) as well.

Dr. Brown countered that targeted agents don’t improve PFS for all CLL patients, improved PFS doesn’t always translate to improved OS, and targeted agents cost more than CIT.

No role for CIT as first-line treatment

“We have two approaches right now, with nonchemoimmunotherapy-based treatment,” Dr. Wierda said. “One approach, with small-molecule inhibitors, is to have a sustained and durable period of disease control, particularly with BTK inhibitors. The other strategy that has emerged is deep remissions with fixed-duration treatment with BCL2 small-molecule inhibitor-based therapy, which, I would argue, is better than being exposed to genotoxic chemoimmunotherapy.”

Dr. Wierda went on to explain that the BTK inhibitor ibrutinib has been shown to improve PFS, compared with CIT, in phase 3 trials.

In the iLLUMINATE trial, researchers compared ibrutinib plus obinutuzumab to chlorambucil plus obinutuzumab as first-line treatment in CLL. At a median follow-up of 31.3 months, the median PFS was not reached in the ibrutinib arm and was 19 months in the chlorambucil arm (P less than .0001; Lancet Oncol. 2019 Jan;20[1]:43-56).

In the A041202 study, researchers compared ibrutinib alone (Ib) or in combination with rituximab (Ib-R) to bendamustine plus rituximab (BR) in untreated, older patients with CLL. The 2-year PFS estimates were 74% in the BR arm, 87% in the Ib arm, and 88% in the Ib-R arm (P less than .001 for BR vs. Ib or Ib-R; N Engl J Med. 2018; 379:2517-28).

In the E1912 trial, researchers compared Ib-R to fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (FCR) in younger, untreated CLL patients. The 3-year PFS was 89.4% with Ib-R and 72.9% with FCR (P less than .001; N Engl J Med. 2019 Aug 1;381:432-43).

Dr. Wierda noted that the E1912 trial also showed superior OS with Ib-R. The 3-year OS rate was 98.8% with Ib-R and 91.5% with FCR (P less than .001). However, there was no significant difference in OS between the treatment arms in the A041202 trial or the iLLUMINATE trial.

“But I would argue that is, in part, because of short follow-up,” Dr. Wierda said. “The trials were all designed to look at progression-free survival, not overall survival. With longer follow-up, we may see differences in overall survival emerging.”

Dr. Wierda went on to say that fixed‐duration treatment with the BCL2 inhibitor venetoclax can improve PFS over CIT.

In the phase 3 CLL14 trial, researchers compared fixed-duration treatment with venetoclax plus obinutuzumab to chlorambucil plus obinutuzumab in previously untreated CLL patients with comorbidities. The estimated PFS at 2 years was 88.2% in the venetoclax group and 64.1% in the chlorambucil group (P less than .001; N Engl J Med. 2019; 380:2225-36).

“[There was] no difference in overall survival,” Dr. Wierda noted. “But, again, I would argue ... that follow-up is relatively limited. We may ultimately see a difference in overall survival.”

Based on these findings, Dr. Wierda made the following treatment recommendations:

- Any CLL patient with del(17p) or TP53 mutation, and older, unfit patients with unmutated IGHV should receive a BTK inhibitor, with or without obinutuzumab.

- All young, fit patients, and older, unfit patients with mutated IGHV should receive a BCL2 inhibitor plus obinutuzumab.

Dr. Wierda also noted that ibrutinib and venetoclax in combination have shown early promise for patients with previously untreated CLL (N Engl J Med. 2019; 380:2095-2103).

CIT still has a role as first-line treatment

Dr. Brown suggested that a PFS benefit may not be enough to recommend targeted agents over CIT. For one thing, the PFS benefit doesn’t apply to all patients, as the IGHV-mutated subgroup does equally well with CIT and targeted agents.

In the IGHV-mutated group from the E1912 trial, the 3-year PFS was 88% for patients who received Ib-R and those who received FCR (N Engl J Med. 2019 Aug 1;381:432-43). In the A041202 study, the 2-year PFS among IGHV-mutated patients was 87% in the BR arm, 86% in the Ib arm, and 88% in the Ib-R arm (N Engl J Med. 2018; 379:2517-28).

In the CLL14 trial, PFS rates were similar among IGHV-mutated patients who received chlorambucil plus obinutuzumab and IGHV-mutated or unmutated patients who received venetoclax and obinutuzumab (N Engl J Med. 2019; 380:2225-36).

Dr. Brown also noted that the overall improvement in PFS observed with ibrutinib and venetoclax doesn’t always translate to improved OS.

In the A041202 study, there was no significant difference in OS between the Ib, Ib-R, and BR arms (N Engl J Med. 2018; 379:2517-28). There was no significant difference in OS between the ibrutinib and chlorambucil arms in the iLLUMINATE trial (Lancet Oncol. 2019 Jan;20[1]:43-56). And there was no significant difference in OS between the venetoclax and chlorambucil arms in the CLL14 trial (N Engl J Med. 2019; 380:2225-36).

However, in the RESONATE-2 trial, ibrutinib provided an OS benefit over chlorambucil. The 2-year OS was 95% and 84%, respectively (P = .0145; Haematologica. Sept 2018;103:1502-10). Dr. Brown said the OS advantage in this study was due to the “very poor comparator of chlorambucil and very limited crossover.”

As Dr. Wierda mentioned, the OS rate was higher with Ib-R than with FCR in the E1912 trial. The 3-year OS rate was 98.8% and 91.5%, respectively (P less than .001; N Engl J Med. 2019 Aug 1;381:432-43). Dr. Brown noted, however, that there were few deaths in this study, and many of them “were not clearly related to the disease or its treatment.”

Dr. Brown also pointed out that FCR has been shown to have curative potential in IGHV-mutated CLL in both the FCR300 trial (Blood. 2016 127:303-9) and the CLL8 trial (Blood. 2016 127:208-15).

Another factor to consider is the greater cost of targeted agents. One analysis suggested the per-patient lifetime cost of CLL treatment in the United States will increase from $147,000 to $604,000 as targeted therapies overtake CIT as first-line treatment (J Clin Oncol. 2017 Jan 10;35[2]:166-174).

“Given all of the above, chemoimmunotherapy is going to remain part of the treatment repertoire for CLL,” Dr. Brown said. “It’s our only known potential cure for the fit, mutated patients ... and can also result in prolonged treatment-free intervals for patients who are older. As we manage CLL as a chronic disease over a lifetime, we need to continue to have this in our armamentarium.”

Specifically, Dr. Brown said CIT is appropriate for patients who don’t have del(17p) or mutated TP53. FCR should be given to young, fit patients with IGHV-mutated CLL, and FCR or BR should be given to older patients and young, fit patients with IGHV-unmutated CLL.

Dr. Brown and Dr. Wierda reported financial ties to multiple pharmaceutical companies, including makers of CLL treatments.

SAN FRANCISCO – Should targeted agents replace chemoimmunotherapy (CIT) as first-line treatment for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)? A recent debate suggests there’s no consensus.

William G. Wierda, MD, PhD, of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, and Jennifer R. Brown, MD, PhD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, debated the topic at the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Hematologic Malignancies Annual Congress.

Dr. Wierda argued that CLL patients should receive a BTK inhibitor or BCL2 inhibitor, with or without obinutuzumab, as first-line therapy because these targeted agents have been shown to provide better progression-free survival (PFS) than CIT, and the targeted therapies may prolong overall survival (OS) as well.

Dr. Brown countered that targeted agents don’t improve PFS for all CLL patients, improved PFS doesn’t always translate to improved OS, and targeted agents cost more than CIT.

No role for CIT as first-line treatment

“We have two approaches right now, with nonchemoimmunotherapy-based treatment,” Dr. Wierda said. “One approach, with small-molecule inhibitors, is to have a sustained and durable period of disease control, particularly with BTK inhibitors. The other strategy that has emerged is deep remissions with fixed-duration treatment with BCL2 small-molecule inhibitor-based therapy, which, I would argue, is better than being exposed to genotoxic chemoimmunotherapy.”

Dr. Wierda went on to explain that the BTK inhibitor ibrutinib has been shown to improve PFS, compared with CIT, in phase 3 trials.

In the iLLUMINATE trial, researchers compared ibrutinib plus obinutuzumab to chlorambucil plus obinutuzumab as first-line treatment in CLL. At a median follow-up of 31.3 months, the median PFS was not reached in the ibrutinib arm and was 19 months in the chlorambucil arm (P less than .0001; Lancet Oncol. 2019 Jan;20[1]:43-56).

In the A041202 study, researchers compared ibrutinib alone (Ib) or in combination with rituximab (Ib-R) to bendamustine plus rituximab (BR) in untreated, older patients with CLL. The 2-year PFS estimates were 74% in the BR arm, 87% in the Ib arm, and 88% in the Ib-R arm (P less than .001 for BR vs. Ib or Ib-R; N Engl J Med. 2018; 379:2517-28).

In the E1912 trial, researchers compared Ib-R to fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (FCR) in younger, untreated CLL patients. The 3-year PFS was 89.4% with Ib-R and 72.9% with FCR (P less than .001; N Engl J Med. 2019 Aug 1;381:432-43).

Dr. Wierda noted that the E1912 trial also showed superior OS with Ib-R. The 3-year OS rate was 98.8% with Ib-R and 91.5% with FCR (P less than .001). However, there was no significant difference in OS between the treatment arms in the A041202 trial or the iLLUMINATE trial.

“But I would argue that is, in part, because of short follow-up,” Dr. Wierda said. “The trials were all designed to look at progression-free survival, not overall survival. With longer follow-up, we may see differences in overall survival emerging.”

Dr. Wierda went on to say that fixed‐duration treatment with the BCL2 inhibitor venetoclax can improve PFS over CIT.

In the phase 3 CLL14 trial, researchers compared fixed-duration treatment with venetoclax plus obinutuzumab to chlorambucil plus obinutuzumab in previously untreated CLL patients with comorbidities. The estimated PFS at 2 years was 88.2% in the venetoclax group and 64.1% in the chlorambucil group (P less than .001; N Engl J Med. 2019; 380:2225-36).

“[There was] no difference in overall survival,” Dr. Wierda noted. “But, again, I would argue ... that follow-up is relatively limited. We may ultimately see a difference in overall survival.”

Based on these findings, Dr. Wierda made the following treatment recommendations:

- Any CLL patient with del(17p) or TP53 mutation, and older, unfit patients with unmutated IGHV should receive a BTK inhibitor, with or without obinutuzumab.

- All young, fit patients, and older, unfit patients with mutated IGHV should receive a BCL2 inhibitor plus obinutuzumab.

Dr. Wierda also noted that ibrutinib and venetoclax in combination have shown early promise for patients with previously untreated CLL (N Engl J Med. 2019; 380:2095-2103).

CIT still has a role as first-line treatment

Dr. Brown suggested that a PFS benefit may not be enough to recommend targeted agents over CIT. For one thing, the PFS benefit doesn’t apply to all patients, as the IGHV-mutated subgroup does equally well with CIT and targeted agents.

In the IGHV-mutated group from the E1912 trial, the 3-year PFS was 88% for patients who received Ib-R and those who received FCR (N Engl J Med. 2019 Aug 1;381:432-43). In the A041202 study, the 2-year PFS among IGHV-mutated patients was 87% in the BR arm, 86% in the Ib arm, and 88% in the Ib-R arm (N Engl J Med. 2018; 379:2517-28).

In the CLL14 trial, PFS rates were similar among IGHV-mutated patients who received chlorambucil plus obinutuzumab and IGHV-mutated or unmutated patients who received venetoclax and obinutuzumab (N Engl J Med. 2019; 380:2225-36).

Dr. Brown also noted that the overall improvement in PFS observed with ibrutinib and venetoclax doesn’t always translate to improved OS.

In the A041202 study, there was no significant difference in OS between the Ib, Ib-R, and BR arms (N Engl J Med. 2018; 379:2517-28). There was no significant difference in OS between the ibrutinib and chlorambucil arms in the iLLUMINATE trial (Lancet Oncol. 2019 Jan;20[1]:43-56). And there was no significant difference in OS between the venetoclax and chlorambucil arms in the CLL14 trial (N Engl J Med. 2019; 380:2225-36).

However, in the RESONATE-2 trial, ibrutinib provided an OS benefit over chlorambucil. The 2-year OS was 95% and 84%, respectively (P = .0145; Haematologica. Sept 2018;103:1502-10). Dr. Brown said the OS advantage in this study was due to the “very poor comparator of chlorambucil and very limited crossover.”

As Dr. Wierda mentioned, the OS rate was higher with Ib-R than with FCR in the E1912 trial. The 3-year OS rate was 98.8% and 91.5%, respectively (P less than .001; N Engl J Med. 2019 Aug 1;381:432-43). Dr. Brown noted, however, that there were few deaths in this study, and many of them “were not clearly related to the disease or its treatment.”

Dr. Brown also pointed out that FCR has been shown to have curative potential in IGHV-mutated CLL in both the FCR300 trial (Blood. 2016 127:303-9) and the CLL8 trial (Blood. 2016 127:208-15).

Another factor to consider is the greater cost of targeted agents. One analysis suggested the per-patient lifetime cost of CLL treatment in the United States will increase from $147,000 to $604,000 as targeted therapies overtake CIT as first-line treatment (J Clin Oncol. 2017 Jan 10;35[2]:166-174).

“Given all of the above, chemoimmunotherapy is going to remain part of the treatment repertoire for CLL,” Dr. Brown said. “It’s our only known potential cure for the fit, mutated patients ... and can also result in prolonged treatment-free intervals for patients who are older. As we manage CLL as a chronic disease over a lifetime, we need to continue to have this in our armamentarium.”

Specifically, Dr. Brown said CIT is appropriate for patients who don’t have del(17p) or mutated TP53. FCR should be given to young, fit patients with IGHV-mutated CLL, and FCR or BR should be given to older patients and young, fit patients with IGHV-unmutated CLL.

Dr. Brown and Dr. Wierda reported financial ties to multiple pharmaceutical companies, including makers of CLL treatments.

REPORTING FROM NCCN HEMATOLOGIC MALIGNANCIES

Novel cardiac troponin protocol rapidly rules out MI

PARIS – An accelerated rule-out pathway, reliant upon a single high-sensitivity cardiac troponin test upon presentation to the ED with suspected acute coronary syndrome, reduced length of stay and hospital admission rates without increasing cardiac events at 30 days or 1 year in a major Scottish study.

“We conclude that implementation of this early rule-out pathway is both effective and safe, and adoption of this pathway will have major benefits for patients and health care systems,” Nicholas L. Mills, MBChB, PhD, said in presenting the results of the HiSTORIC (High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin at Presentation to Rule Out Myocardial Infarction) trial at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Indeed, in the Unites States, where more than 20 million people per year present to EDs with suspected ACS, the 3.3-hour reduction in length of stay achieved in the HiSTORIC trial by implementing the accelerated rule-out pathway would add up to a $3.6 billion annual savings in bed occupancy alone, according to Dr. Mills, who is chair of cardiology at the University of Edinburgh.

The HiSTORIC pathway incorporates separate thresholds for risk stratification and diagnosis. This strategy is based on an accumulation of persuasive evidence that the major advantage of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin testing is to rule out MI, rather than to rule it in, Dr. Mills explained.

HiSTORIC was a 2-year, prospective, stepped-wedge, cluster-randomized, controlled trial including 31,492 consecutive patients with suspected ACS who presented to seven participating hospitals in Scotland. Patients were randomized, at the hospital level, to one of two management pathways. The control group got a standard guideline-recommended strategy involving high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I testing upon presentation and again 6-12 hours later, with MI being ruled out if the troponin levels were not above the 99th percentile.

In contrast, the novel early rule-out strategy worked as follows: If the patient presented with at least 2 hours of symptoms and the initial troponin I level was below 5 ng/L, then MI was ruled out and the patient was triaged straightaway for outpatient management. If the level was above the 99th percentile, the patient was admitted for serial testing to be done 6-12 hours after symptom onset. And for an intermediate test result – that is, a troponin level between 5 ng/L and the 99th percentile – patients remained in the ED for retesting 3 hours from the time of presentation, and were subsequently admitted only if their troponin level was rising.

Using the accelerated rule-out strategy, two-thirds of patients were quickly discharged from the ED on the basis of a troponin level below 5 ng/mL, and another 7% were ruled out for MI and discharged from the ED after a 3-hour stay on the basis of their second test.

The primary efficacy outcome was length of stay from initial presentation to the ED to discharge. The duration was 10.1 hours with the guideline-recommended pathway and 6.8 hours with the accelerated rule-out pathway, for a statistically significant and clinically meaningful 3.3-hour difference. Moreover, the proportion of patients discharged directly from the ED without hospital admission increased from 53% to 74%, a 57% jump.

The primary safety outcome was the rate of MI or cardiac death post discharge. The rates at 30 days and 1 year were 0.4% and 2.6%, respectively, in the standard-pathway group, compared with 0.3% and 1.8% with the early rule-out pathway. Those between-group differences favoring the accelerated rule-out pathway weren’t statistically significant, but they provided reassurance that the novel pathway was safe.

Of note, this was the first-ever randomized trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of an early rule-out pathway. Other rapid diagnostic pathways are largely based on observational experience and expert opinion, Dr. Mills said.

The assay utilized in the HiSTORIC trial was the Abbott Diagnostics Architect high sensitivity assay. The 5-ng/L threshold for early rule-out was chosen for the trial because an earlier study by Dr. Mills and coinvestigators showed that a level below that cutoff had a 99.6% negative predictive value for MI (Lancet. 2015 Dec 19;386[10012]:2481-8)

The early rule-out pathway was deliberately designed to be simple and pragmatic, according to the cardiologist. “One of the most remarkable observations in this trial was the adherence to the pathway. We prespecified three criteria to evaluate this and demonstrated adherence rates of 86%-92% for each of these criteria. This was despite the pathway being implemented in all consecutive patients at seven different hospitals and used by many hundreds of different clinicians.”

Discussant Hugo A. Katus, MD, called the HiSTORIC study “a really urgently needed and very well-conducted trial.”

“There were very consistently low MI and cardiac death rates at 30 days and 1 year. So this really works,” commented Dr. Katus, who is chief of internal medicine and director of the department of cardiovascular medicine at Heidelberg (Germany) University.

“Accelerated rule-out high-sensitivity cardiac troponin protocols are here to stay,” he declared.

However, Dr. Katus voiced a concern: “By early discharge as rule out, are other life-threatening conditions ignored?”

He raised this issue because of what he views as the substantial 1-year all-cause mortality and return-to-hospital rates of 5.8% and 39.2% in the standard-pathway group and 5.2% and 38.9% in the accelerated rule-out patients in HiSTORIC. An accelerated rule-out strategy should not prohibit a careful clinical work-up, he emphasized.

Dr. Mills discussed the results in a video interview.

The HiSTORIC trial was funded by the British Heart Foundation. Dr. Mills reported receiving research grants from Abbott Diagnostics and Siemens.

Simultaneous with Dr. Mills’ presentation of the HiSTORIC trial results at the ESC congress, an earlier study that formed the scientific basis for the investigators’ decision to employ distinct risk stratification and diagnostic thresholds for cardiac troponin testing was published online (Circulation. 2019 Sep 1. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.042866). The actual HiSTORIC trial results will be published later.

Dr. Katus reported holding a patent for a cardiac troponin T test and serving as a consultant to AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Novo Nordisk.

PARIS – An accelerated rule-out pathway, reliant upon a single high-sensitivity cardiac troponin test upon presentation to the ED with suspected acute coronary syndrome, reduced length of stay and hospital admission rates without increasing cardiac events at 30 days or 1 year in a major Scottish study.

“We conclude that implementation of this early rule-out pathway is both effective and safe, and adoption of this pathway will have major benefits for patients and health care systems,” Nicholas L. Mills, MBChB, PhD, said in presenting the results of the HiSTORIC (High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin at Presentation to Rule Out Myocardial Infarction) trial at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Indeed, in the Unites States, where more than 20 million people per year present to EDs with suspected ACS, the 3.3-hour reduction in length of stay achieved in the HiSTORIC trial by implementing the accelerated rule-out pathway would add up to a $3.6 billion annual savings in bed occupancy alone, according to Dr. Mills, who is chair of cardiology at the University of Edinburgh.

The HiSTORIC pathway incorporates separate thresholds for risk stratification and diagnosis. This strategy is based on an accumulation of persuasive evidence that the major advantage of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin testing is to rule out MI, rather than to rule it in, Dr. Mills explained.

HiSTORIC was a 2-year, prospective, stepped-wedge, cluster-randomized, controlled trial including 31,492 consecutive patients with suspected ACS who presented to seven participating hospitals in Scotland. Patients were randomized, at the hospital level, to one of two management pathways. The control group got a standard guideline-recommended strategy involving high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I testing upon presentation and again 6-12 hours later, with MI being ruled out if the troponin levels were not above the 99th percentile.

In contrast, the novel early rule-out strategy worked as follows: If the patient presented with at least 2 hours of symptoms and the initial troponin I level was below 5 ng/L, then MI was ruled out and the patient was triaged straightaway for outpatient management. If the level was above the 99th percentile, the patient was admitted for serial testing to be done 6-12 hours after symptom onset. And for an intermediate test result – that is, a troponin level between 5 ng/L and the 99th percentile – patients remained in the ED for retesting 3 hours from the time of presentation, and were subsequently admitted only if their troponin level was rising.

Using the accelerated rule-out strategy, two-thirds of patients were quickly discharged from the ED on the basis of a troponin level below 5 ng/mL, and another 7% were ruled out for MI and discharged from the ED after a 3-hour stay on the basis of their second test.

The primary efficacy outcome was length of stay from initial presentation to the ED to discharge. The duration was 10.1 hours with the guideline-recommended pathway and 6.8 hours with the accelerated rule-out pathway, for a statistically significant and clinically meaningful 3.3-hour difference. Moreover, the proportion of patients discharged directly from the ED without hospital admission increased from 53% to 74%, a 57% jump.

The primary safety outcome was the rate of MI or cardiac death post discharge. The rates at 30 days and 1 year were 0.4% and 2.6%, respectively, in the standard-pathway group, compared with 0.3% and 1.8% with the early rule-out pathway. Those between-group differences favoring the accelerated rule-out pathway weren’t statistically significant, but they provided reassurance that the novel pathway was safe.

Of note, this was the first-ever randomized trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of an early rule-out pathway. Other rapid diagnostic pathways are largely based on observational experience and expert opinion, Dr. Mills said.

The assay utilized in the HiSTORIC trial was the Abbott Diagnostics Architect high sensitivity assay. The 5-ng/L threshold for early rule-out was chosen for the trial because an earlier study by Dr. Mills and coinvestigators showed that a level below that cutoff had a 99.6% negative predictive value for MI (Lancet. 2015 Dec 19;386[10012]:2481-8)

The early rule-out pathway was deliberately designed to be simple and pragmatic, according to the cardiologist. “One of the most remarkable observations in this trial was the adherence to the pathway. We prespecified three criteria to evaluate this and demonstrated adherence rates of 86%-92% for each of these criteria. This was despite the pathway being implemented in all consecutive patients at seven different hospitals and used by many hundreds of different clinicians.”

Discussant Hugo A. Katus, MD, called the HiSTORIC study “a really urgently needed and very well-conducted trial.”

“There were very consistently low MI and cardiac death rates at 30 days and 1 year. So this really works,” commented Dr. Katus, who is chief of internal medicine and director of the department of cardiovascular medicine at Heidelberg (Germany) University.

“Accelerated rule-out high-sensitivity cardiac troponin protocols are here to stay,” he declared.

However, Dr. Katus voiced a concern: “By early discharge as rule out, are other life-threatening conditions ignored?”

He raised this issue because of what he views as the substantial 1-year all-cause mortality and return-to-hospital rates of 5.8% and 39.2% in the standard-pathway group and 5.2% and 38.9% in the accelerated rule-out patients in HiSTORIC. An accelerated rule-out strategy should not prohibit a careful clinical work-up, he emphasized.

Dr. Mills discussed the results in a video interview.

The HiSTORIC trial was funded by the British Heart Foundation. Dr. Mills reported receiving research grants from Abbott Diagnostics and Siemens.

Simultaneous with Dr. Mills’ presentation of the HiSTORIC trial results at the ESC congress, an earlier study that formed the scientific basis for the investigators’ decision to employ distinct risk stratification and diagnostic thresholds for cardiac troponin testing was published online (Circulation. 2019 Sep 1. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.042866). The actual HiSTORIC trial results will be published later.

Dr. Katus reported holding a patent for a cardiac troponin T test and serving as a consultant to AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Novo Nordisk.

PARIS – An accelerated rule-out pathway, reliant upon a single high-sensitivity cardiac troponin test upon presentation to the ED with suspected acute coronary syndrome, reduced length of stay and hospital admission rates without increasing cardiac events at 30 days or 1 year in a major Scottish study.

“We conclude that implementation of this early rule-out pathway is both effective and safe, and adoption of this pathway will have major benefits for patients and health care systems,” Nicholas L. Mills, MBChB, PhD, said in presenting the results of the HiSTORIC (High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin at Presentation to Rule Out Myocardial Infarction) trial at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Indeed, in the Unites States, where more than 20 million people per year present to EDs with suspected ACS, the 3.3-hour reduction in length of stay achieved in the HiSTORIC trial by implementing the accelerated rule-out pathway would add up to a $3.6 billion annual savings in bed occupancy alone, according to Dr. Mills, who is chair of cardiology at the University of Edinburgh.

The HiSTORIC pathway incorporates separate thresholds for risk stratification and diagnosis. This strategy is based on an accumulation of persuasive evidence that the major advantage of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin testing is to rule out MI, rather than to rule it in, Dr. Mills explained.

HiSTORIC was a 2-year, prospective, stepped-wedge, cluster-randomized, controlled trial including 31,492 consecutive patients with suspected ACS who presented to seven participating hospitals in Scotland. Patients were randomized, at the hospital level, to one of two management pathways. The control group got a standard guideline-recommended strategy involving high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I testing upon presentation and again 6-12 hours later, with MI being ruled out if the troponin levels were not above the 99th percentile.

In contrast, the novel early rule-out strategy worked as follows: If the patient presented with at least 2 hours of symptoms and the initial troponin I level was below 5 ng/L, then MI was ruled out and the patient was triaged straightaway for outpatient management. If the level was above the 99th percentile, the patient was admitted for serial testing to be done 6-12 hours after symptom onset. And for an intermediate test result – that is, a troponin level between 5 ng/L and the 99th percentile – patients remained in the ED for retesting 3 hours from the time of presentation, and were subsequently admitted only if their troponin level was rising.

Using the accelerated rule-out strategy, two-thirds of patients were quickly discharged from the ED on the basis of a troponin level below 5 ng/mL, and another 7% were ruled out for MI and discharged from the ED after a 3-hour stay on the basis of their second test.

The primary efficacy outcome was length of stay from initial presentation to the ED to discharge. The duration was 10.1 hours with the guideline-recommended pathway and 6.8 hours with the accelerated rule-out pathway, for a statistically significant and clinically meaningful 3.3-hour difference. Moreover, the proportion of patients discharged directly from the ED without hospital admission increased from 53% to 74%, a 57% jump.

The primary safety outcome was the rate of MI or cardiac death post discharge. The rates at 30 days and 1 year were 0.4% and 2.6%, respectively, in the standard-pathway group, compared with 0.3% and 1.8% with the early rule-out pathway. Those between-group differences favoring the accelerated rule-out pathway weren’t statistically significant, but they provided reassurance that the novel pathway was safe.

Of note, this was the first-ever randomized trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of an early rule-out pathway. Other rapid diagnostic pathways are largely based on observational experience and expert opinion, Dr. Mills said.

The assay utilized in the HiSTORIC trial was the Abbott Diagnostics Architect high sensitivity assay. The 5-ng/L threshold for early rule-out was chosen for the trial because an earlier study by Dr. Mills and coinvestigators showed that a level below that cutoff had a 99.6% negative predictive value for MI (Lancet. 2015 Dec 19;386[10012]:2481-8)

The early rule-out pathway was deliberately designed to be simple and pragmatic, according to the cardiologist. “One of the most remarkable observations in this trial was the adherence to the pathway. We prespecified three criteria to evaluate this and demonstrated adherence rates of 86%-92% for each of these criteria. This was despite the pathway being implemented in all consecutive patients at seven different hospitals and used by many hundreds of different clinicians.”

Discussant Hugo A. Katus, MD, called the HiSTORIC study “a really urgently needed and very well-conducted trial.”

“There were very consistently low MI and cardiac death rates at 30 days and 1 year. So this really works,” commented Dr. Katus, who is chief of internal medicine and director of the department of cardiovascular medicine at Heidelberg (Germany) University.

“Accelerated rule-out high-sensitivity cardiac troponin protocols are here to stay,” he declared.

However, Dr. Katus voiced a concern: “By early discharge as rule out, are other life-threatening conditions ignored?”

He raised this issue because of what he views as the substantial 1-year all-cause mortality and return-to-hospital rates of 5.8% and 39.2% in the standard-pathway group and 5.2% and 38.9% in the accelerated rule-out patients in HiSTORIC. An accelerated rule-out strategy should not prohibit a careful clinical work-up, he emphasized.

Dr. Mills discussed the results in a video interview.

The HiSTORIC trial was funded by the British Heart Foundation. Dr. Mills reported receiving research grants from Abbott Diagnostics and Siemens.

Simultaneous with Dr. Mills’ presentation of the HiSTORIC trial results at the ESC congress, an earlier study that formed the scientific basis for the investigators’ decision to employ distinct risk stratification and diagnostic thresholds for cardiac troponin testing was published online (Circulation. 2019 Sep 1. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.042866). The actual HiSTORIC trial results will be published later.

Dr. Katus reported holding a patent for a cardiac troponin T test and serving as a consultant to AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Novo Nordisk.

REPORTING FROM THE ESC CONGRESS 2019

Clinical Pharmacists Improve Patient Outcomes and Expand Access to Care

The US is in the midst of a chronic disease crisis. According to the latest published data available, 60% of Americans have at least 1 chronic condition, and 42% have ≥ 2 chronic conditions.1 Estimates by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) indicate a current shortfall of 13 800 primary care physicians and a projected escalation of that shortage to be between 14 800 and 49 300 physicians by the year 2030.2

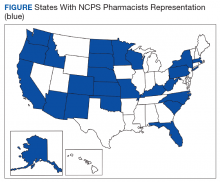

The US Public Health Service (USPHS) has used pharmacists since 1930 to provide direct patient care to underserved and vulnerable populations. Clinical pharmacists currently serve in direct patient care roles within the Indian Health Service (IHS), Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP), Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and the United States Coast Guard (USCG) in many states (Figure). These pharmacists play a vital role in improving access to care and delivering quality care by managing acute and chronic diseases in collaborative practice settings and pharmacist-managed clinics.

It has previously been reported that in the face of physician shortages and growing demand for primary health care providers, pharmacists are well-equipped and motivated to meet this demand.3 A review of the previous 2 years of outcomes reported by clinical pharmacists certified through the USPHS National Clinical Pharmacy Specialist (NCPS) Committee are presented to demonstrate the impact of pharmacists in advancing the health of the populations they serve and to showcase a model for ameliorating the ongoing physician shortage.

Background

The USPHS NCPS Committee serves to promote uniform competency among clinical pharmacists by establishing national standards for protocols, collaborative practice agreements (CPAs), credentialing and privileging of pharmacists, and by collecting, reviewing, and publishing health care outcomes. The committee, whose constituents include pharmacist and physician subject matter experts from across USPHS agencies, reviews applications and protocols and certifies pharmacists (civilian and uniformed) to recognize an advanced scope of practice in managing various diseases and optimizing medication therapy. NCPScertified pharmacists manage a wide spectrum of diseases, including coagulopathy, asthma, diabetes mellitus (DM), hepatitis C, HIV, hypertension, pain, seizure disorders, and tobacco use disorders.

Clinical pharmacists practicing chronic disease management establish a clinical service in collaboration with 1 or more physicians, physician assistants, or nurse practitioners. In this collaborative practice, the health care practitioner(s) refer patients to be managed by a pharmacist for specific medical needs, such as anticoagulation management, or for holistic medication- focused care (eg, cardiovascular risk reduction, DM management, HIV, hepatitis, or mental health). The pharmacist may order and interpret laboratory tests, check vital signs, perform a limited physical examination, and gather other pertinent information from the patient and the medical record in order to provide the best possible care to the patient.

Medications may be started, stopped, or adjusted, education is provided, and therapeutic lifestyle interventions may be recommended. The pharmacist-run clinic provides the patient more frequent interaction with a health care professional (pharmacist) and focused disease management. As a result, pharmacists increase access to care and allow the medical team to handle a larger panel of patients as the practitioner delegates specified diseases to the pharmacist- managed clinic(s). The number of NCPS-certified pharmacists grew 46% from 2012 (n = 230) to 2017 (n = 336), reflecting an evolution of pharmacists’ practice to better meet the need of patients across the nation.

Methods

The NCPS Committee requires NCPS pharmacists to report data annually from all patients referred for pharmacist management for specific diseases in which they have been certified. The data reflect the patient’s clinical outcome goal status at the time of referral as well as the same status at the end of the reporting period or on release from the pharmacist-run clinic. These data describe the impact prescribing pharmacists have on patients reaching clinical outcome goals acting as the team member specializing in the medication selection and dosing aspect of care.

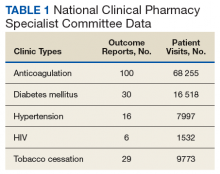

These records were reviewed for the fiscal year (FY) periods of October 1, 2015 to September 30, 2016 (FY 2016) and October 1, 2016 to September 30, 2017 (FY 2017). A systematic review of submitted reports resulted in 181 reports that included all requested data points for the disease as published here for FYs 2016 and 2017. These include 66 reports from FY 2016 and 115 reports from FY 2017; they cover 76 BOP and IHS facilities located across 24 states. Table 1 shows the number of outcome reports collected from 104 075 patient visits in pharmacist-run clinics in FYs 2016 and 2017.

Results

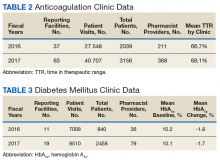

The following tables represent the standardized outcomes collected by NCPS-certified pharmacists providing direct patient care. Patients on anticoagulants (eg, warfarin) require special monitoring and education for drug interactions and adverse effects. NCPS-certified pharmacists were able to achieve a mean patient time in therapeutic range (TTR) of 67.6% (regardless of indication) over the 2 years (calculated per each facility by Rosendaal method of linear interpolation then combined in a weighted average per visit). The TTR produced by NCPS-certified pharmacists are consistent with Chest Guidelines and Expert Panel Report suggesting that TTR should be between 65% and 70%.4 Table 2 shows data from 100 reports with 68 255 patient visits for anticoagulation management.

DM management can be complex and time-intensive. NCPS data indicate pharmacist intervention resulted in a mean decrease in hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) of 1.8% from a baseline of 10.2% (decrease calculated per each facility then combined by weighted average per visit). Table 3 shows data from 30 reports with 16 518 patient visits for DM care.

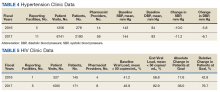

In addition to diet and exercise, medication management plays a vital role in managing hypertension. Patients managed by an NCPS-certified pharmacist experienced a mean decrease in blood pressure from 144/83 to 133/77, putting them in goal for both systolic and diastolic ranges (decrease calculated per each facility then combined by weighted average per visit). Table 4 shows data from 16 reports and 7997 patient visits for treatment of hypertension.

HIV viral suppression is vital in order to best manage patients with HIV and reduce the risk of transmission. Pharmacistled clinics have shown a 32.9% absolute improvement in patients at goal (viral load < 50 copies/mL), from a mean baseline of 46.0% to a mean final assessment of 71.6% of patients at goal (combined by weighted average visits). Table 5 shows data from 6 reports covering 1532 patient encounters for management of HIV.

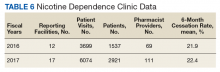

Nicotine dependence includes the use of cigarettes, cigars, pipe tobacco, chewing tobacco, and vaping products containing nicotine. NCPS-certified pharmacists have successfully helped patients improve their chance of quitting, with a 6-month quit rate of 22.2% (quit rate calculated per each facility then combined by weighted average by visits), which is higher than the national average of 9.4% as reported by the Centers for Disease and Control and Prevention. 5 Table 6 shows 29 reports covering 9773 patient visits for treatment of nicotine dependence.

Discussion

These data demonstrate the ability of advanced practice pharmacists in multiple locations within the federal sector to improve targeted clinical outcomes in patients with varying diseases. These results are strengthened by their varied origins as well as the improvements observed across the board. Limitations include the general lack of a comparable dataset, manual method of selfreporting by the individual facilities, and the relatively limited array of diseases reported. Although NCPS-certified pharmacists are currently providing care for patients with hepatitis C, asthma, seizure, pain and other diseases not reported here, there are insufficient data collected for FYs 2016 and 2017 to merit inclusion within this report.

Pharmacists are trusted, readily available medication experts. In a clinical role, NCPS-certified pharmacists have increased access to primary care services and demonstrated beneficial impact on important health outcomes as exhibited by the data reported above. Clinical pharmacy is a growing field, and NCPS has displayed continual growth in both the number of NCPS-certified pharmacists and the number of patient encounters performed by these providers. As more pharmacists in all settings collaborate with medical providers to offer high-quality clinical care, these providers will have more opportunity to delegate disease management. Continued reporting of clinical pharmacy outcomes is expected to increase confidence in pharmacists as primary care providers, increase utilization of pharmacy clinical services, and assist in easing the burden of primary care provider shortages across our nation.

Although these outcomes indicate demonstrable benefit in patient-centered outcomes, the need for ongoing assessment and continued improvement is not obviated. Future efforts may benefit from a comparison of alternative approaches to better facilitate the establishment of best practices. Alignment of clinical outcomes with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Electronic Clinical Quality Measures, where applicable, also may prove beneficial by automating the reporting process and thereby decreasing the burden of reporting as well as providing an avenue for standard comparison across multiple populations. Clinical pharmacy interventions have positive outcomes based on the NCPS model, and the NCPS Committee invites other clinical settings to report outcomes data with which to compare.

Conclusion

The NCPS Committee has documented positive outcomes of clinical pharmacy intervention and anticipates growth of the pharmacy profession as additional states and health systems recognize the capacity of the pharmacist to provide high-quality, multidisciplinary patient care. Clinical pharmacists are prepared to address critical health care needs as the US continues to face a PCP shortage.2 The NCPS Committee challenges those participating in clinical pharmacy practice to report outcomes to amplify this body of evidence.

Acknowledgments

NCPS-certified pharmacists provided the outcomes detailed in this report. For document review and edits: Federal Bureau of Prison Publication Review Workgroup; RADM Ty Bingham, USPHS; CAPT Cindy Gunderson, USPHS; CAPT Kevin Brooks, USPHS.

1. Buttorff C, Ruder T, Bauman M. Multiple Chronic Conditions in the United States. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corp; 2017.

2. Dall T, West T, Chakrabarti R, Reynolds R, Iacobucci W. The complexities of physician supply and demand: projections from 2016 to 2030, 2018 update. Association of American Medical Colleges. March 2018.

3. Giberson S, Yoder S, Lee MP. Improving patient and health system outcomes through advanced pharmacy practice. A report to the U.S. Surgeon General 2011. https://www .accp.com/docs/positions/misc/improving_patient_and _health_system_outcomes.pdf. Updated December 2011. Accessed September 11, 2019.

4. Lip G, Banerjee A, Boriani G, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for atrial fibrillation. CHEST guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2018;154(5):1121-1201.

5. Babb S, Marlarcher A, Schauer G, Asman K, Jamal A. Quitting smoking among adults—United States, 2000-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;65(52):1457-1464.

The US is in the midst of a chronic disease crisis. According to the latest published data available, 60% of Americans have at least 1 chronic condition, and 42% have ≥ 2 chronic conditions.1 Estimates by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) indicate a current shortfall of 13 800 primary care physicians and a projected escalation of that shortage to be between 14 800 and 49 300 physicians by the year 2030.2

The US Public Health Service (USPHS) has used pharmacists since 1930 to provide direct patient care to underserved and vulnerable populations. Clinical pharmacists currently serve in direct patient care roles within the Indian Health Service (IHS), Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP), Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and the United States Coast Guard (USCG) in many states (Figure). These pharmacists play a vital role in improving access to care and delivering quality care by managing acute and chronic diseases in collaborative practice settings and pharmacist-managed clinics.

It has previously been reported that in the face of physician shortages and growing demand for primary health care providers, pharmacists are well-equipped and motivated to meet this demand.3 A review of the previous 2 years of outcomes reported by clinical pharmacists certified through the USPHS National Clinical Pharmacy Specialist (NCPS) Committee are presented to demonstrate the impact of pharmacists in advancing the health of the populations they serve and to showcase a model for ameliorating the ongoing physician shortage.

Background

The USPHS NCPS Committee serves to promote uniform competency among clinical pharmacists by establishing national standards for protocols, collaborative practice agreements (CPAs), credentialing and privileging of pharmacists, and by collecting, reviewing, and publishing health care outcomes. The committee, whose constituents include pharmacist and physician subject matter experts from across USPHS agencies, reviews applications and protocols and certifies pharmacists (civilian and uniformed) to recognize an advanced scope of practice in managing various diseases and optimizing medication therapy. NCPScertified pharmacists manage a wide spectrum of diseases, including coagulopathy, asthma, diabetes mellitus (DM), hepatitis C, HIV, hypertension, pain, seizure disorders, and tobacco use disorders.

Clinical pharmacists practicing chronic disease management establish a clinical service in collaboration with 1 or more physicians, physician assistants, or nurse practitioners. In this collaborative practice, the health care practitioner(s) refer patients to be managed by a pharmacist for specific medical needs, such as anticoagulation management, or for holistic medication- focused care (eg, cardiovascular risk reduction, DM management, HIV, hepatitis, or mental health). The pharmacist may order and interpret laboratory tests, check vital signs, perform a limited physical examination, and gather other pertinent information from the patient and the medical record in order to provide the best possible care to the patient.

Medications may be started, stopped, or adjusted, education is provided, and therapeutic lifestyle interventions may be recommended. The pharmacist-run clinic provides the patient more frequent interaction with a health care professional (pharmacist) and focused disease management. As a result, pharmacists increase access to care and allow the medical team to handle a larger panel of patients as the practitioner delegates specified diseases to the pharmacist- managed clinic(s). The number of NCPS-certified pharmacists grew 46% from 2012 (n = 230) to 2017 (n = 336), reflecting an evolution of pharmacists’ practice to better meet the need of patients across the nation.

Methods

The NCPS Committee requires NCPS pharmacists to report data annually from all patients referred for pharmacist management for specific diseases in which they have been certified. The data reflect the patient’s clinical outcome goal status at the time of referral as well as the same status at the end of the reporting period or on release from the pharmacist-run clinic. These data describe the impact prescribing pharmacists have on patients reaching clinical outcome goals acting as the team member specializing in the medication selection and dosing aspect of care.

These records were reviewed for the fiscal year (FY) periods of October 1, 2015 to September 30, 2016 (FY 2016) and October 1, 2016 to September 30, 2017 (FY 2017). A systematic review of submitted reports resulted in 181 reports that included all requested data points for the disease as published here for FYs 2016 and 2017. These include 66 reports from FY 2016 and 115 reports from FY 2017; they cover 76 BOP and IHS facilities located across 24 states. Table 1 shows the number of outcome reports collected from 104 075 patient visits in pharmacist-run clinics in FYs 2016 and 2017.

Results

The following tables represent the standardized outcomes collected by NCPS-certified pharmacists providing direct patient care. Patients on anticoagulants (eg, warfarin) require special monitoring and education for drug interactions and adverse effects. NCPS-certified pharmacists were able to achieve a mean patient time in therapeutic range (TTR) of 67.6% (regardless of indication) over the 2 years (calculated per each facility by Rosendaal method of linear interpolation then combined in a weighted average per visit). The TTR produced by NCPS-certified pharmacists are consistent with Chest Guidelines and Expert Panel Report suggesting that TTR should be between 65% and 70%.4 Table 2 shows data from 100 reports with 68 255 patient visits for anticoagulation management.