User login

Suicidal, violent, and treatment-resistant

CASE Violent, then catatonic

Mr. T, age 52, has a long history of schizoaffective disorder, depressed type; several suicide attempts; and violent episodes. He is admitted to a mental health rehabilitation center under a forensic commitment.

Several years earlier, Mr. T had been charged with first-degree attempted murder, assault with a deadly weapon, and abuse of a dependent/geriatric adult after allegedly stabbing his mother in the upper chest and neck. At that time, Mr. T was not in psychiatric treatment and was drinking heavily. He had become obsessed with John F. Kennedy’s assassination and believed the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), not Lee Harvey Oswald, was responsible. He feared the CIA wanted to kill him because of his knowledge, and he heard voices from his television he believed were threatening him. He acquired knives for self-protection. When his mother arrived at his apartment to take him to a psychiatric appointment, he believed she was conspiring with the CIA and attacked her. Mr. T’s mother survived her injuries. He was taken to the county jail, where psychiatric staff noted that Mr. T was psychotic.

The court found Mr. T incompetent to stand trial and sent him to a state hospital for psychiatric treatment and competency restoration. After 3 years, he was declared unable to be restored because of repeated decompensations, placed on a conservatorship, and sent back to county jail.

In the jail, Mr. T began to show signs of catatonia. He refused medications, food, and water, and became mute. He was admitted to a medical center after a 45-minute episode that appeared similar to a seizure; however, all laboratory evaluations were within normal limits, head CT was negative, and an EEG was unremarkable.

Mr. T’s catatonic state gradually resolved with increasing dosages of lorazepam, as well as clozapine. He showed improved mobility and oral intake. A month later, his train of thought was rambling and difficult to follow, circumstantial, and perseverating. However, at times he could be directed and respond to questions in a linear and logical fashion. Lorazepam was tapered, discontinued, and replaced with gabapentin because Mr. T viewed taking lorazepam as a threat to his sobriety.

Recently, Mr. T was transferred to our mental health rehabilitation center, where he expresses that he is grateful to be in a therapeutic environment. Upon admission, his medication regimen consists of clozapine, 300 mg by mouth at bedtime, duloxetine, 60 mg/d by mouth, gabapentin 600 mg by mouth 3 times a day, and docusate sodium, 250 mg/d by mouth. Our team has a discussion about the growing recognition of the pro-inflammatory state present in many patients who experience serious mental illness and the importance of augmenting standard evidence-based psychopharmacotherapy with agents that have neuroprotective properties.1,2 We offer Mr. T

[polldaddy:10375843]

The authors’ observations

Several studies have found that acute psychosis is associated with an inflammatory state, and interleukin-6 (IL-6) is a crucial biomarker. A recent meta-analysis of serum cytokines in patients with schizophrenia found that IL-6 levels were significantly increased among acutely ill patients compared with controls.3 IL-6 levels significantly decreased after treating acute episodes of schizophrenia.3 Further, levels of peripheral IL-6 mRNA levels in individuals with schizophrenia are directly correlated with severity of positive symptoms.4

Continue to: A meta-analyis reported...

A meta-analysis reported that tumor necrosis factor-alpha and IL-6 are elevated during acute psychosis3; however, IL-6 normalized with treatment, whereas tumor necrosis factor-alpha did not. This means that IL-6 is a more clinically meaningful biomarker to help gauge treatment response.

EVALUATION Elevated markers of inflammation

Laboratory testing reveals that Mr. T’s IL-6 level is 56.64 pg/mL, which is significantly elevated (reference range: 0.31 to 5.00 pg/mL). After reviewing the IL-6 results with Mr. T and explaining that there is “too much inflammation” in his brain, he agrees to take minocycline and complete follow-up IL-6 level tests to monitor his progress during treatment.

HISTORY Alcohol abuse, treatment resistance

According to Mr. T’s mother, he had met all developmental milestones and graduated from high school with plans to enter culinary school. At age 20, Mr. T began to experience psychotic symptoms, telling family members that he was being followed by FBI agents and was receiving messages from televisions. He began drinking heavily and was arrested twice for driving under the influence. In his mid-20s, he attempted suicide by overdose after his father died. Mr. T required inpatient hospitalization nearly every year thereafter. His mother, a registered nurse, was significantly involved in his care and carefully documented his treatment history.

Mr. T has had numerous medication trials, including oral and long-acting injectable risperidone, olanzapine, aripiprazole, ziprasidone, lithium, gabapentin, buspirone, quetiapine, trazodone, bupropion, and paroxetine. None of these medications were effective.

In his mid-40s, Mr. T attempted suicide by wandering into traffic and being struck by a motor vehicle. A year later, he attempted suicide by driving his car at high speed into a concrete highway median. Mr. T told first responders that he was “possessed,” and a demonic entity “forced” him to crash his car. He begged law enforcement officers at the scene to give him a gun so he could shoot himself.

Continue to: Mr. T entered an intensive outpatient treatment program...

Mr. T entered an intensive outpatient treatment program and was switched from long-acting injectable risperidone to oral aripiprazole. After taking aripiprazole for several weeks, he began to gamble compulsively at a nearby casino. Frustrated by the lack of response to psychotropic medications and his idiosyncratic response to aripiprazole, he stopped psychiatric treatment, relapsed to alcohol use, and isolated himself in his apartment shortly before stabbing his mother.

EVALUATION Pharmacogenomics testing

At the mental health rehabilitation center, Mr. T agrees to undergo pharmacogenomics testing, which suggests that he will have a normal response to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and is unlikely to experience adverse reactions. He does not carry the 2 alleles that place him at higher risk of serious dermatologic reactions when taking certain mood stabilizers. He is heterozygous for the C677T allele polymorphism in the MTHFR gene that is associated with reduced folic acid metabolism, moderately decreased serum folate levels, and moderately increased homocysteine levels. On the pharmacokinetic genes tested, Mr. T has the normal metabolism genotype on 5 of 6 cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes; he has the ultrarapid metabolizer genotype on CYP1A2. He also has normal activity and intermediate metabolizer phenotype on the 2 UGT enzymes tested, which are responsible for the glucuronidation process, a major part of phase II metabolism.

Based on these results, Mr. T’s clozapine dosage is decreased by 50% (from 300 to 150 mg/d) and he is started on fluvoxamine, 50 mg/d, because it is a strong inhibitor of CYP1A2. The reduced conversion of clozapine to norclozapine results in an average serum clozapine level of 527 ng/mL (a level of 350 ng/mL is usually therapeutic in patients with schizophrenia) and norclozapine level of 140 ng/mL (clozapine:norclozapine ratio = 3.8), which is to be expected because fluvoxamine can increase serum clozapine levels.

Due to accumulating evidence in the literature suggesting that latent infections in the CNS play a role in serious mental illnesses such as schizophrenia, Mr. T undergoes further laboratory testing.

[polldaddy:10375845]

The authors’ observations

Mr. T tested positive for TG and CMV and negative for HSV-1. We were aware of accumulating evidence that latent infections in the CNS play a role in serious mental illnesses such as schizophrenia, specifically TG5—a parasite transmitted by cats—and CMV and HSV-1,6 which are transmitted by humans. The theory that TG infection could be a factor in schizophrenia emerged in the 1990s but only in recent years received mainstream scientific attention. Toxoplasma gondii, the infectious parasite that causes toxoplasmosis, infects more than 30 million people in the United States; however, most individuals are asymptomatic because of the body’s immune response to the parasite.7

Continue to: A study of 162 individuals...

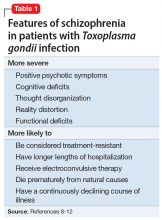

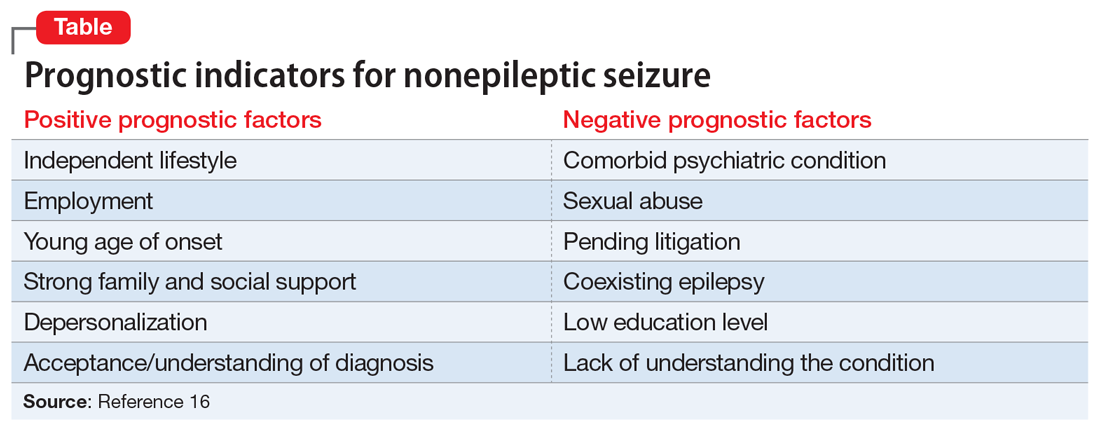

A study of 162 individuals with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depressive disorder found that this immunologic profile is associated with suicide attempts,8 which is consistent with Mr. T’s history. Research suggests that individuals with schizophrenia who have latent TG infection have a more severe form of the illness compared with patients without the infection.9-12 Many of these factors were present in Mr. T’s case (Table 18-12).

TREATMENT Improvement, then setback

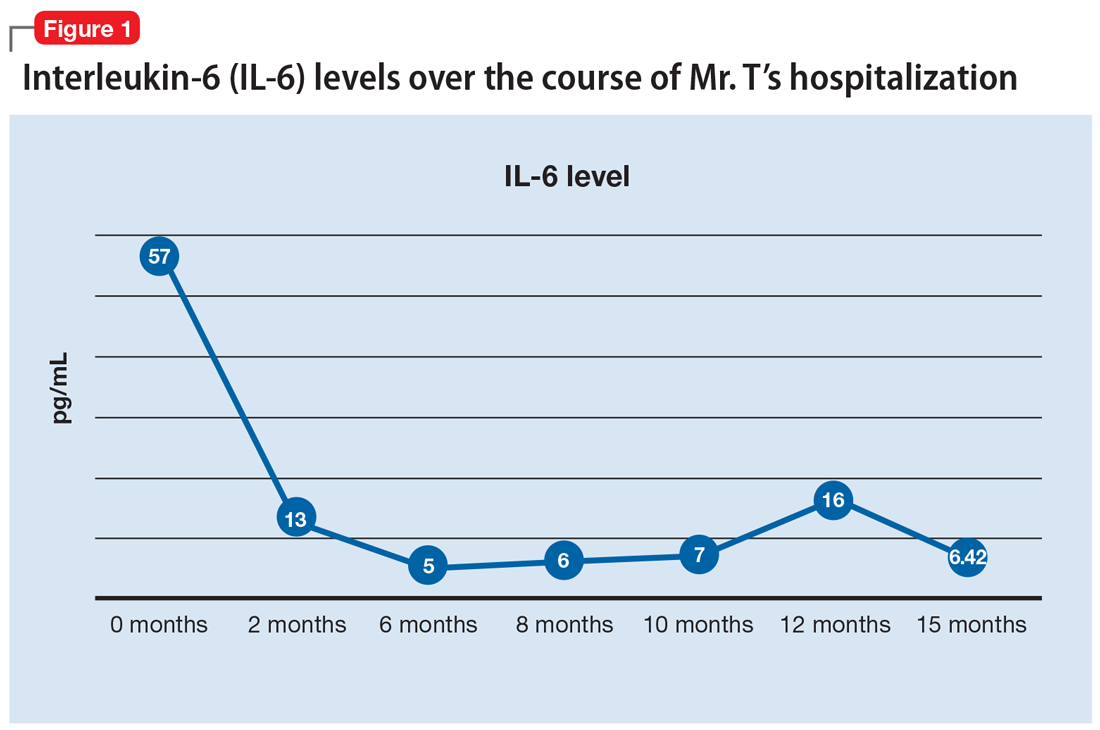

Mr. T’s medication regimen at the rehabilitation center includes clozapine, 100 mg/d; minocycline, 200 mg/d; fluvoxamine, 200 mg/d; and N-acetylcysteine, 1,200 mg/d. N-acetylcysteine is an antioxidant that could ease negative symptoms of schizophrenia by reducing oxidative stress caused by free radicals.13 Mr. T makes slow but steady improvement, and his IL-6 levels drop steadily (Figure 1).

After 6 months in the rehabilitation center, Mr. T no longer experiences catatonic symptoms and is able to participate in the therapeutic program. He is permitted to leave the facility on day passes with family members. However, approximately every 8 weeks, he continues to cycle through periods of intense anxiety, perseverates on topics, and exhibits fragmented thinking and speech. During these episodes, he has difficulty receiving and processing information.

During one of these periods, Mr. T eats 4 oleander leaves he gathered while on day pass outside of the facility. After he experiences stomach pain, nausea, and vomiting, he informs nursing staff that he ate oleander. He is brought to the emergency department, receives activated charcoal and a digoxin antidote, and is placed on continuous electrocardiogram monitoring. When asked why he made the suicide attempt, he said “I realized things will never be the same because of what happened. I felt trapped.” He later expresses regret and wants to return to the mental health rehabilitation center.

At the facility, Mr. T agrees to take 2 more agents—valproic acid and ginger root extract—that specifically target latent toxoplasmosis infection before pursuing electroconvulsive therapy. We offer valproic acid because it inhibits replication of TG in an in vitro model.14 Mr. T is started on extended-release valproic acid, 1,500 mg/d, which results in a therapeutic serum level of 74.8 µg/mL.

Continue to: Additionally, Mr. T expresses interest...

Additionally, Mr. T expresses interest in taking “natural” agents in addition to psychotropics. After reviewing the quality of available ginger root extract products, Mr. T is started on a supplement that contains 22.4 mg of gingerols and 6.7 mg of shogaols, titrated to 4 capsules twice daily.

The authors’ observations

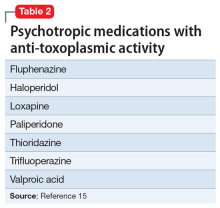

A retrospective cross-sectional analysis reported that patients with bipolar disorder who received medications with anti-toxoplasmic activity (Table 215), specifically valproic acid, had significantly fewer lifetime depressive episodes compared with patients who received medications without anti-toxoplasmic activity.15

Alternative medicine options

Research has demonstrated the beneficial effects of Chinese herbal plants for toxoplasmosis16,17 and ginger root extract has potent anti-toxoplasmic activity. A mouse model found that ginger root extract (Zingiber officinale) reduced the number of TG-infected cells by suppressing activation of apoptotic proteins the parasite induces, which prevents programmed cell death.18

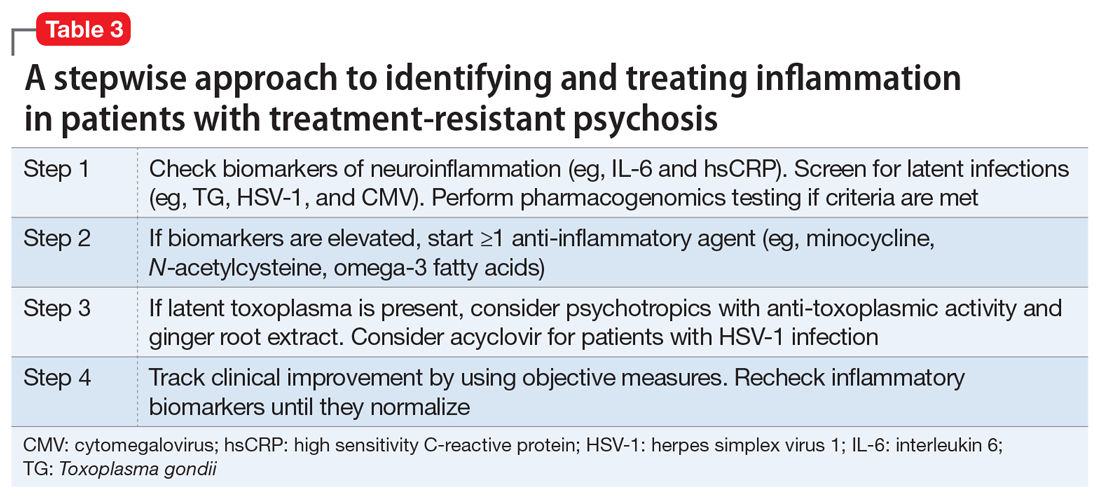

Table 3 presents a stepwise approach to identifying and treating inflammation in patients with treatment-resistant psychosis.

OUTCOME Immune response, improvement

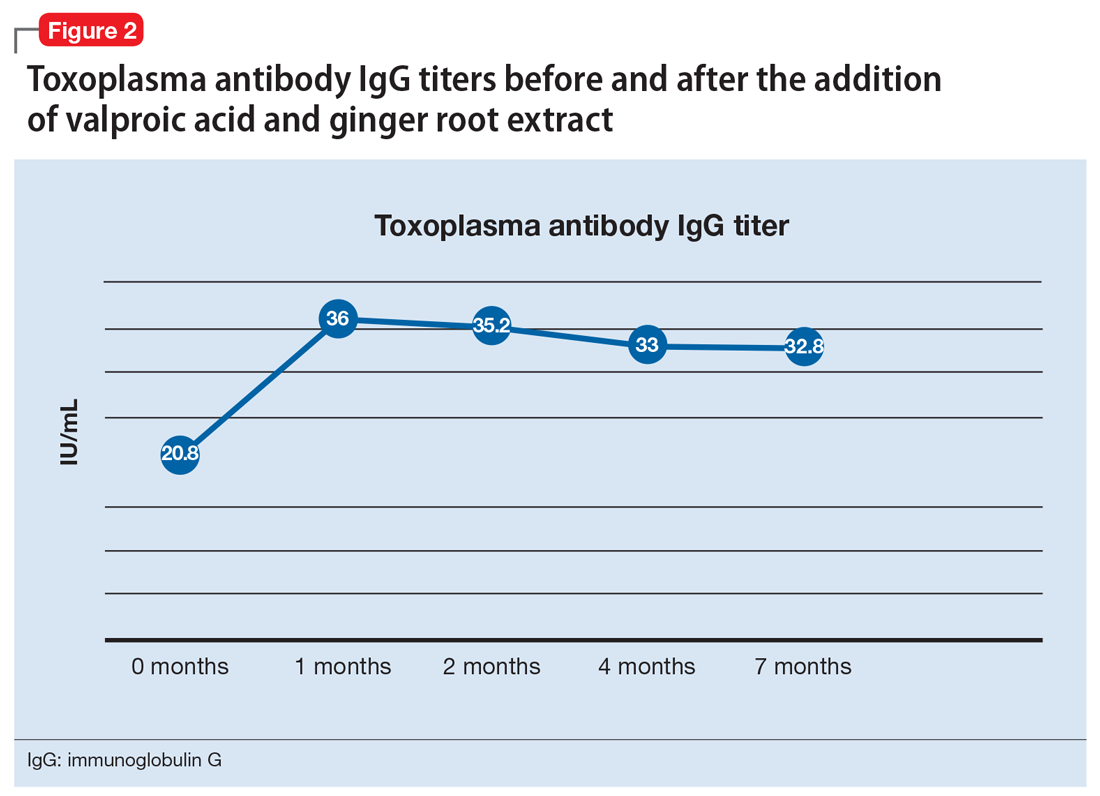

One month after the valproic acid and ginger root extract therapy is initiated, Mr. T’s toxoplasma antibody immunoglobulin G increases by 15.2 IU/mL, indicating that his immune system is mounting an enhanced response against the parasite (Figure 2). Mr. T continues to make progress while receiving the new regimen of clozapine, minocycline, valproic acid, and ginger root extract. He no longer cycles into periods of intense anxiety, perseverative thought, and fragmented thought and speech. He participates meaningfully in weekly psychotherapy and hopes to live independently and obtain gainful employment.

The District Attorney’s office dismisses his criminal charges, and Mr. T is discharged to a less restrictive level of care.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Several studies have shown that neuroinflammation increases the severity of mental illness. Consider adjunct anti-inflammatory agents for patients who have elevated levels of inflammatory biomarkers and for whom standard treatment approaches do not adequately control psychiatric symptoms. Also consider testing for the presence of latent infections in the CNS, which could reveal the underlying cause of treatment resistance or the genesis of disabling psychiatric symptoms.

Related Resources

- Fond G, Macgregor A, Tamouza R, et al. Comparative analysis of anti-toxoplasmic activity of antipsychotic drugs and valproate. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2014;264(2):179-183.

- Hamdani N, Daban-Huard C, Lajnef M, et al. Cognitive deterioration among bipolar disorder patients infected by Toxoplasma gondii is correlated to interleukin 6 levels. J Affect Disord. 2015;179:161-166.

- Monroe JM, Buckley PF, Miller BJ. Meta-analysis of antitoxoplasma gondii IgM antibodies in acute psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41(4):989-998.

Drug Brand Names

Acyclovir • Zovirax

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Buspirone • Buspar

Clozapine • Clozaril

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Fluphenazine • Prolixin

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Haloperidol • Haldol

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lorazepam • Ativan

Loxapine • Loxitane

Minocycline • Minocin

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Paliperidone • Invega

Paroxetine • Paxil

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal, Risperdal Consta

Thioridazine • Mellaril

Trifluoperazine • Stelazine

Trazodone • Desyrel

Valproic acid • Depakote

Ziprasidone • Geodon

1. Koola MM, Raines JK, Hamilton RG, et al. Can anti-inflammatory medications improve symptoms and reduce mortality in schizophrenia? Current Psychiatry. 2016;15(5):52-57.

2. Nasrallah HA. Are you neuroprotecting your patients? 10 Adjunctive therapies to consider. Current Psychiatry. 2016;15(12):12-14.

3. Goldsmith DR, Rapaport MH, Miller BJ. A meta-analysis of blood cytokine network alterations in psychiatric patients: comparisons between schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21(12):1696-1709.

4. Chase KA, Cone JJ, Rosen C, et al. The value of interleukin 6 as a peripheral diagnostic marker in schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:152.

5. Torrey EF, Bartko JJ, Lun ZR, et al. Antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii in patients with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33(3):729-736.

6. Shirts BH, Prasad KM, Pogue-Geile MF, et al. Antibodies to cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex virus 1 associated with cognitive function in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2008;106(2-3):268-274.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parasites - Toxoplasmosis (Toxoplasma infection). https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/toxoplasmosis/index.html. Accessed February 26, 2019.

8. Dickerson F, Wilcox HC, Adamos M, et al. Suicide attempts and markers of immune response in individuals with serious mental illness. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;87:37-43.

9. Celik T, Kartalci S, Aytas O, et al. Association between latent toxoplasmosis and clinical course of schizophrenia - continuous course of the disease is characteristic for Toxoplasma gondii-infected patients. Folia Parasitol (Praha). 2015;62. doi: 10.14411/fp.2015.015.

10. Dickerson F, Boronow J, Stallings C, et al. Toxoplasma gondii in individuals with schizophrenia: association with clinical and demographic factors and with mortality. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33(3):737-740.

11. Esshili A, Thabet S, Jemli A, et al. Toxoplasma gondii infection in schizophrenia and associated clinical features. Psychiatry Res. 2016;245:327-332.

12. Holub D, Flegr J, Dragomirecka E, et al. Differences in onset of disease and severity of psychopathology between toxoplasmosis-related and toxoplasmosis-unrelated schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2013;127(3):227-238.

13. Chen AT, Chibnall JT, Nasrallah HA. Placebo-controlled augmentation trials of the antioxidant NAC in schizophrenia: a review. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2016;28(3):190-196.

14. Jones-Brando L, Torrey EF, Yolken R. Drugs used in the treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder inhibit the replication of Toxoplasma gondii. Schizophr Res. 2003;62(3):237-244.

15. Fond G, Boyer L, Gaman A, et al. Treatment with anti-toxoplasmic activity (TATA) for toxoplasma positive patients with bipolar disorders or schizophrenia: a cross-sectional study. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;63:58-64.

16. Wei HX, Wei SS, Lindsay DS, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the efficacy of anti-Toxoplasma gondii medicines in humans. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0138204.

17. Zhuo XH, Sun HC, Huang B, et al. Evaluation of potential anti-toxoplasmosis efficiency of combined traditional herbs in a mouse model. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2017;18(6):453-461.

18. Choi WH, Jiang MH, Chu JP. Antiparasitic effects of Zingiber officinale (Ginger) extract against Toxoplasma gondii. Journal of Applied Biomedicine. 2013;11:15-26.

CASE Violent, then catatonic

Mr. T, age 52, has a long history of schizoaffective disorder, depressed type; several suicide attempts; and violent episodes. He is admitted to a mental health rehabilitation center under a forensic commitment.

Several years earlier, Mr. T had been charged with first-degree attempted murder, assault with a deadly weapon, and abuse of a dependent/geriatric adult after allegedly stabbing his mother in the upper chest and neck. At that time, Mr. T was not in psychiatric treatment and was drinking heavily. He had become obsessed with John F. Kennedy’s assassination and believed the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), not Lee Harvey Oswald, was responsible. He feared the CIA wanted to kill him because of his knowledge, and he heard voices from his television he believed were threatening him. He acquired knives for self-protection. When his mother arrived at his apartment to take him to a psychiatric appointment, he believed she was conspiring with the CIA and attacked her. Mr. T’s mother survived her injuries. He was taken to the county jail, where psychiatric staff noted that Mr. T was psychotic.

The court found Mr. T incompetent to stand trial and sent him to a state hospital for psychiatric treatment and competency restoration. After 3 years, he was declared unable to be restored because of repeated decompensations, placed on a conservatorship, and sent back to county jail.

In the jail, Mr. T began to show signs of catatonia. He refused medications, food, and water, and became mute. He was admitted to a medical center after a 45-minute episode that appeared similar to a seizure; however, all laboratory evaluations were within normal limits, head CT was negative, and an EEG was unremarkable.

Mr. T’s catatonic state gradually resolved with increasing dosages of lorazepam, as well as clozapine. He showed improved mobility and oral intake. A month later, his train of thought was rambling and difficult to follow, circumstantial, and perseverating. However, at times he could be directed and respond to questions in a linear and logical fashion. Lorazepam was tapered, discontinued, and replaced with gabapentin because Mr. T viewed taking lorazepam as a threat to his sobriety.

Recently, Mr. T was transferred to our mental health rehabilitation center, where he expresses that he is grateful to be in a therapeutic environment. Upon admission, his medication regimen consists of clozapine, 300 mg by mouth at bedtime, duloxetine, 60 mg/d by mouth, gabapentin 600 mg by mouth 3 times a day, and docusate sodium, 250 mg/d by mouth. Our team has a discussion about the growing recognition of the pro-inflammatory state present in many patients who experience serious mental illness and the importance of augmenting standard evidence-based psychopharmacotherapy with agents that have neuroprotective properties.1,2 We offer Mr. T

[polldaddy:10375843]

The authors’ observations

Several studies have found that acute psychosis is associated with an inflammatory state, and interleukin-6 (IL-6) is a crucial biomarker. A recent meta-analysis of serum cytokines in patients with schizophrenia found that IL-6 levels were significantly increased among acutely ill patients compared with controls.3 IL-6 levels significantly decreased after treating acute episodes of schizophrenia.3 Further, levels of peripheral IL-6 mRNA levels in individuals with schizophrenia are directly correlated with severity of positive symptoms.4

Continue to: A meta-analyis reported...

A meta-analysis reported that tumor necrosis factor-alpha and IL-6 are elevated during acute psychosis3; however, IL-6 normalized with treatment, whereas tumor necrosis factor-alpha did not. This means that IL-6 is a more clinically meaningful biomarker to help gauge treatment response.

EVALUATION Elevated markers of inflammation

Laboratory testing reveals that Mr. T’s IL-6 level is 56.64 pg/mL, which is significantly elevated (reference range: 0.31 to 5.00 pg/mL). After reviewing the IL-6 results with Mr. T and explaining that there is “too much inflammation” in his brain, he agrees to take minocycline and complete follow-up IL-6 level tests to monitor his progress during treatment.

HISTORY Alcohol abuse, treatment resistance

According to Mr. T’s mother, he had met all developmental milestones and graduated from high school with plans to enter culinary school. At age 20, Mr. T began to experience psychotic symptoms, telling family members that he was being followed by FBI agents and was receiving messages from televisions. He began drinking heavily and was arrested twice for driving under the influence. In his mid-20s, he attempted suicide by overdose after his father died. Mr. T required inpatient hospitalization nearly every year thereafter. His mother, a registered nurse, was significantly involved in his care and carefully documented his treatment history.

Mr. T has had numerous medication trials, including oral and long-acting injectable risperidone, olanzapine, aripiprazole, ziprasidone, lithium, gabapentin, buspirone, quetiapine, trazodone, bupropion, and paroxetine. None of these medications were effective.

In his mid-40s, Mr. T attempted suicide by wandering into traffic and being struck by a motor vehicle. A year later, he attempted suicide by driving his car at high speed into a concrete highway median. Mr. T told first responders that he was “possessed,” and a demonic entity “forced” him to crash his car. He begged law enforcement officers at the scene to give him a gun so he could shoot himself.

Continue to: Mr. T entered an intensive outpatient treatment program...

Mr. T entered an intensive outpatient treatment program and was switched from long-acting injectable risperidone to oral aripiprazole. After taking aripiprazole for several weeks, he began to gamble compulsively at a nearby casino. Frustrated by the lack of response to psychotropic medications and his idiosyncratic response to aripiprazole, he stopped psychiatric treatment, relapsed to alcohol use, and isolated himself in his apartment shortly before stabbing his mother.

EVALUATION Pharmacogenomics testing

At the mental health rehabilitation center, Mr. T agrees to undergo pharmacogenomics testing, which suggests that he will have a normal response to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and is unlikely to experience adverse reactions. He does not carry the 2 alleles that place him at higher risk of serious dermatologic reactions when taking certain mood stabilizers. He is heterozygous for the C677T allele polymorphism in the MTHFR gene that is associated with reduced folic acid metabolism, moderately decreased serum folate levels, and moderately increased homocysteine levels. On the pharmacokinetic genes tested, Mr. T has the normal metabolism genotype on 5 of 6 cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes; he has the ultrarapid metabolizer genotype on CYP1A2. He also has normal activity and intermediate metabolizer phenotype on the 2 UGT enzymes tested, which are responsible for the glucuronidation process, a major part of phase II metabolism.

Based on these results, Mr. T’s clozapine dosage is decreased by 50% (from 300 to 150 mg/d) and he is started on fluvoxamine, 50 mg/d, because it is a strong inhibitor of CYP1A2. The reduced conversion of clozapine to norclozapine results in an average serum clozapine level of 527 ng/mL (a level of 350 ng/mL is usually therapeutic in patients with schizophrenia) and norclozapine level of 140 ng/mL (clozapine:norclozapine ratio = 3.8), which is to be expected because fluvoxamine can increase serum clozapine levels.

Due to accumulating evidence in the literature suggesting that latent infections in the CNS play a role in serious mental illnesses such as schizophrenia, Mr. T undergoes further laboratory testing.

[polldaddy:10375845]

The authors’ observations

Mr. T tested positive for TG and CMV and negative for HSV-1. We were aware of accumulating evidence that latent infections in the CNS play a role in serious mental illnesses such as schizophrenia, specifically TG5—a parasite transmitted by cats—and CMV and HSV-1,6 which are transmitted by humans. The theory that TG infection could be a factor in schizophrenia emerged in the 1990s but only in recent years received mainstream scientific attention. Toxoplasma gondii, the infectious parasite that causes toxoplasmosis, infects more than 30 million people in the United States; however, most individuals are asymptomatic because of the body’s immune response to the parasite.7

Continue to: A study of 162 individuals...

A study of 162 individuals with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depressive disorder found that this immunologic profile is associated with suicide attempts,8 which is consistent with Mr. T’s history. Research suggests that individuals with schizophrenia who have latent TG infection have a more severe form of the illness compared with patients without the infection.9-12 Many of these factors were present in Mr. T’s case (Table 18-12).

TREATMENT Improvement, then setback

Mr. T’s medication regimen at the rehabilitation center includes clozapine, 100 mg/d; minocycline, 200 mg/d; fluvoxamine, 200 mg/d; and N-acetylcysteine, 1,200 mg/d. N-acetylcysteine is an antioxidant that could ease negative symptoms of schizophrenia by reducing oxidative stress caused by free radicals.13 Mr. T makes slow but steady improvement, and his IL-6 levels drop steadily (Figure 1).

After 6 months in the rehabilitation center, Mr. T no longer experiences catatonic symptoms and is able to participate in the therapeutic program. He is permitted to leave the facility on day passes with family members. However, approximately every 8 weeks, he continues to cycle through periods of intense anxiety, perseverates on topics, and exhibits fragmented thinking and speech. During these episodes, he has difficulty receiving and processing information.

During one of these periods, Mr. T eats 4 oleander leaves he gathered while on day pass outside of the facility. After he experiences stomach pain, nausea, and vomiting, he informs nursing staff that he ate oleander. He is brought to the emergency department, receives activated charcoal and a digoxin antidote, and is placed on continuous electrocardiogram monitoring. When asked why he made the suicide attempt, he said “I realized things will never be the same because of what happened. I felt trapped.” He later expresses regret and wants to return to the mental health rehabilitation center.

At the facility, Mr. T agrees to take 2 more agents—valproic acid and ginger root extract—that specifically target latent toxoplasmosis infection before pursuing electroconvulsive therapy. We offer valproic acid because it inhibits replication of TG in an in vitro model.14 Mr. T is started on extended-release valproic acid, 1,500 mg/d, which results in a therapeutic serum level of 74.8 µg/mL.

Continue to: Additionally, Mr. T expresses interest...

Additionally, Mr. T expresses interest in taking “natural” agents in addition to psychotropics. After reviewing the quality of available ginger root extract products, Mr. T is started on a supplement that contains 22.4 mg of gingerols and 6.7 mg of shogaols, titrated to 4 capsules twice daily.

The authors’ observations

A retrospective cross-sectional analysis reported that patients with bipolar disorder who received medications with anti-toxoplasmic activity (Table 215), specifically valproic acid, had significantly fewer lifetime depressive episodes compared with patients who received medications without anti-toxoplasmic activity.15

Alternative medicine options

Research has demonstrated the beneficial effects of Chinese herbal plants for toxoplasmosis16,17 and ginger root extract has potent anti-toxoplasmic activity. A mouse model found that ginger root extract (Zingiber officinale) reduced the number of TG-infected cells by suppressing activation of apoptotic proteins the parasite induces, which prevents programmed cell death.18

Table 3 presents a stepwise approach to identifying and treating inflammation in patients with treatment-resistant psychosis.

OUTCOME Immune response, improvement

One month after the valproic acid and ginger root extract therapy is initiated, Mr. T’s toxoplasma antibody immunoglobulin G increases by 15.2 IU/mL, indicating that his immune system is mounting an enhanced response against the parasite (Figure 2). Mr. T continues to make progress while receiving the new regimen of clozapine, minocycline, valproic acid, and ginger root extract. He no longer cycles into periods of intense anxiety, perseverative thought, and fragmented thought and speech. He participates meaningfully in weekly psychotherapy and hopes to live independently and obtain gainful employment.

The District Attorney’s office dismisses his criminal charges, and Mr. T is discharged to a less restrictive level of care.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Several studies have shown that neuroinflammation increases the severity of mental illness. Consider adjunct anti-inflammatory agents for patients who have elevated levels of inflammatory biomarkers and for whom standard treatment approaches do not adequately control psychiatric symptoms. Also consider testing for the presence of latent infections in the CNS, which could reveal the underlying cause of treatment resistance or the genesis of disabling psychiatric symptoms.

Related Resources

- Fond G, Macgregor A, Tamouza R, et al. Comparative analysis of anti-toxoplasmic activity of antipsychotic drugs and valproate. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2014;264(2):179-183.

- Hamdani N, Daban-Huard C, Lajnef M, et al. Cognitive deterioration among bipolar disorder patients infected by Toxoplasma gondii is correlated to interleukin 6 levels. J Affect Disord. 2015;179:161-166.

- Monroe JM, Buckley PF, Miller BJ. Meta-analysis of antitoxoplasma gondii IgM antibodies in acute psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41(4):989-998.

Drug Brand Names

Acyclovir • Zovirax

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Buspirone • Buspar

Clozapine • Clozaril

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Fluphenazine • Prolixin

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Haloperidol • Haldol

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lorazepam • Ativan

Loxapine • Loxitane

Minocycline • Minocin

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Paliperidone • Invega

Paroxetine • Paxil

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal, Risperdal Consta

Thioridazine • Mellaril

Trifluoperazine • Stelazine

Trazodone • Desyrel

Valproic acid • Depakote

Ziprasidone • Geodon

CASE Violent, then catatonic

Mr. T, age 52, has a long history of schizoaffective disorder, depressed type; several suicide attempts; and violent episodes. He is admitted to a mental health rehabilitation center under a forensic commitment.

Several years earlier, Mr. T had been charged with first-degree attempted murder, assault with a deadly weapon, and abuse of a dependent/geriatric adult after allegedly stabbing his mother in the upper chest and neck. At that time, Mr. T was not in psychiatric treatment and was drinking heavily. He had become obsessed with John F. Kennedy’s assassination and believed the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), not Lee Harvey Oswald, was responsible. He feared the CIA wanted to kill him because of his knowledge, and he heard voices from his television he believed were threatening him. He acquired knives for self-protection. When his mother arrived at his apartment to take him to a psychiatric appointment, he believed she was conspiring with the CIA and attacked her. Mr. T’s mother survived her injuries. He was taken to the county jail, where psychiatric staff noted that Mr. T was psychotic.

The court found Mr. T incompetent to stand trial and sent him to a state hospital for psychiatric treatment and competency restoration. After 3 years, he was declared unable to be restored because of repeated decompensations, placed on a conservatorship, and sent back to county jail.

In the jail, Mr. T began to show signs of catatonia. He refused medications, food, and water, and became mute. He was admitted to a medical center after a 45-minute episode that appeared similar to a seizure; however, all laboratory evaluations were within normal limits, head CT was negative, and an EEG was unremarkable.

Mr. T’s catatonic state gradually resolved with increasing dosages of lorazepam, as well as clozapine. He showed improved mobility and oral intake. A month later, his train of thought was rambling and difficult to follow, circumstantial, and perseverating. However, at times he could be directed and respond to questions in a linear and logical fashion. Lorazepam was tapered, discontinued, and replaced with gabapentin because Mr. T viewed taking lorazepam as a threat to his sobriety.

Recently, Mr. T was transferred to our mental health rehabilitation center, where he expresses that he is grateful to be in a therapeutic environment. Upon admission, his medication regimen consists of clozapine, 300 mg by mouth at bedtime, duloxetine, 60 mg/d by mouth, gabapentin 600 mg by mouth 3 times a day, and docusate sodium, 250 mg/d by mouth. Our team has a discussion about the growing recognition of the pro-inflammatory state present in many patients who experience serious mental illness and the importance of augmenting standard evidence-based psychopharmacotherapy with agents that have neuroprotective properties.1,2 We offer Mr. T

[polldaddy:10375843]

The authors’ observations

Several studies have found that acute psychosis is associated with an inflammatory state, and interleukin-6 (IL-6) is a crucial biomarker. A recent meta-analysis of serum cytokines in patients with schizophrenia found that IL-6 levels were significantly increased among acutely ill patients compared with controls.3 IL-6 levels significantly decreased after treating acute episodes of schizophrenia.3 Further, levels of peripheral IL-6 mRNA levels in individuals with schizophrenia are directly correlated with severity of positive symptoms.4

Continue to: A meta-analyis reported...

A meta-analysis reported that tumor necrosis factor-alpha and IL-6 are elevated during acute psychosis3; however, IL-6 normalized with treatment, whereas tumor necrosis factor-alpha did not. This means that IL-6 is a more clinically meaningful biomarker to help gauge treatment response.

EVALUATION Elevated markers of inflammation

Laboratory testing reveals that Mr. T’s IL-6 level is 56.64 pg/mL, which is significantly elevated (reference range: 0.31 to 5.00 pg/mL). After reviewing the IL-6 results with Mr. T and explaining that there is “too much inflammation” in his brain, he agrees to take minocycline and complete follow-up IL-6 level tests to monitor his progress during treatment.

HISTORY Alcohol abuse, treatment resistance

According to Mr. T’s mother, he had met all developmental milestones and graduated from high school with plans to enter culinary school. At age 20, Mr. T began to experience psychotic symptoms, telling family members that he was being followed by FBI agents and was receiving messages from televisions. He began drinking heavily and was arrested twice for driving under the influence. In his mid-20s, he attempted suicide by overdose after his father died. Mr. T required inpatient hospitalization nearly every year thereafter. His mother, a registered nurse, was significantly involved in his care and carefully documented his treatment history.

Mr. T has had numerous medication trials, including oral and long-acting injectable risperidone, olanzapine, aripiprazole, ziprasidone, lithium, gabapentin, buspirone, quetiapine, trazodone, bupropion, and paroxetine. None of these medications were effective.

In his mid-40s, Mr. T attempted suicide by wandering into traffic and being struck by a motor vehicle. A year later, he attempted suicide by driving his car at high speed into a concrete highway median. Mr. T told first responders that he was “possessed,” and a demonic entity “forced” him to crash his car. He begged law enforcement officers at the scene to give him a gun so he could shoot himself.

Continue to: Mr. T entered an intensive outpatient treatment program...

Mr. T entered an intensive outpatient treatment program and was switched from long-acting injectable risperidone to oral aripiprazole. After taking aripiprazole for several weeks, he began to gamble compulsively at a nearby casino. Frustrated by the lack of response to psychotropic medications and his idiosyncratic response to aripiprazole, he stopped psychiatric treatment, relapsed to alcohol use, and isolated himself in his apartment shortly before stabbing his mother.

EVALUATION Pharmacogenomics testing

At the mental health rehabilitation center, Mr. T agrees to undergo pharmacogenomics testing, which suggests that he will have a normal response to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and is unlikely to experience adverse reactions. He does not carry the 2 alleles that place him at higher risk of serious dermatologic reactions when taking certain mood stabilizers. He is heterozygous for the C677T allele polymorphism in the MTHFR gene that is associated with reduced folic acid metabolism, moderately decreased serum folate levels, and moderately increased homocysteine levels. On the pharmacokinetic genes tested, Mr. T has the normal metabolism genotype on 5 of 6 cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes; he has the ultrarapid metabolizer genotype on CYP1A2. He also has normal activity and intermediate metabolizer phenotype on the 2 UGT enzymes tested, which are responsible for the glucuronidation process, a major part of phase II metabolism.

Based on these results, Mr. T’s clozapine dosage is decreased by 50% (from 300 to 150 mg/d) and he is started on fluvoxamine, 50 mg/d, because it is a strong inhibitor of CYP1A2. The reduced conversion of clozapine to norclozapine results in an average serum clozapine level of 527 ng/mL (a level of 350 ng/mL is usually therapeutic in patients with schizophrenia) and norclozapine level of 140 ng/mL (clozapine:norclozapine ratio = 3.8), which is to be expected because fluvoxamine can increase serum clozapine levels.

Due to accumulating evidence in the literature suggesting that latent infections in the CNS play a role in serious mental illnesses such as schizophrenia, Mr. T undergoes further laboratory testing.

[polldaddy:10375845]

The authors’ observations

Mr. T tested positive for TG and CMV and negative for HSV-1. We were aware of accumulating evidence that latent infections in the CNS play a role in serious mental illnesses such as schizophrenia, specifically TG5—a parasite transmitted by cats—and CMV and HSV-1,6 which are transmitted by humans. The theory that TG infection could be a factor in schizophrenia emerged in the 1990s but only in recent years received mainstream scientific attention. Toxoplasma gondii, the infectious parasite that causes toxoplasmosis, infects more than 30 million people in the United States; however, most individuals are asymptomatic because of the body’s immune response to the parasite.7

Continue to: A study of 162 individuals...

A study of 162 individuals with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depressive disorder found that this immunologic profile is associated with suicide attempts,8 which is consistent with Mr. T’s history. Research suggests that individuals with schizophrenia who have latent TG infection have a more severe form of the illness compared with patients without the infection.9-12 Many of these factors were present in Mr. T’s case (Table 18-12).

TREATMENT Improvement, then setback

Mr. T’s medication regimen at the rehabilitation center includes clozapine, 100 mg/d; minocycline, 200 mg/d; fluvoxamine, 200 mg/d; and N-acetylcysteine, 1,200 mg/d. N-acetylcysteine is an antioxidant that could ease negative symptoms of schizophrenia by reducing oxidative stress caused by free radicals.13 Mr. T makes slow but steady improvement, and his IL-6 levels drop steadily (Figure 1).

After 6 months in the rehabilitation center, Mr. T no longer experiences catatonic symptoms and is able to participate in the therapeutic program. He is permitted to leave the facility on day passes with family members. However, approximately every 8 weeks, he continues to cycle through periods of intense anxiety, perseverates on topics, and exhibits fragmented thinking and speech. During these episodes, he has difficulty receiving and processing information.

During one of these periods, Mr. T eats 4 oleander leaves he gathered while on day pass outside of the facility. After he experiences stomach pain, nausea, and vomiting, he informs nursing staff that he ate oleander. He is brought to the emergency department, receives activated charcoal and a digoxin antidote, and is placed on continuous electrocardiogram monitoring. When asked why he made the suicide attempt, he said “I realized things will never be the same because of what happened. I felt trapped.” He later expresses regret and wants to return to the mental health rehabilitation center.

At the facility, Mr. T agrees to take 2 more agents—valproic acid and ginger root extract—that specifically target latent toxoplasmosis infection before pursuing electroconvulsive therapy. We offer valproic acid because it inhibits replication of TG in an in vitro model.14 Mr. T is started on extended-release valproic acid, 1,500 mg/d, which results in a therapeutic serum level of 74.8 µg/mL.

Continue to: Additionally, Mr. T expresses interest...

Additionally, Mr. T expresses interest in taking “natural” agents in addition to psychotropics. After reviewing the quality of available ginger root extract products, Mr. T is started on a supplement that contains 22.4 mg of gingerols and 6.7 mg of shogaols, titrated to 4 capsules twice daily.

The authors’ observations

A retrospective cross-sectional analysis reported that patients with bipolar disorder who received medications with anti-toxoplasmic activity (Table 215), specifically valproic acid, had significantly fewer lifetime depressive episodes compared with patients who received medications without anti-toxoplasmic activity.15

Alternative medicine options

Research has demonstrated the beneficial effects of Chinese herbal plants for toxoplasmosis16,17 and ginger root extract has potent anti-toxoplasmic activity. A mouse model found that ginger root extract (Zingiber officinale) reduced the number of TG-infected cells by suppressing activation of apoptotic proteins the parasite induces, which prevents programmed cell death.18

Table 3 presents a stepwise approach to identifying and treating inflammation in patients with treatment-resistant psychosis.

OUTCOME Immune response, improvement

One month after the valproic acid and ginger root extract therapy is initiated, Mr. T’s toxoplasma antibody immunoglobulin G increases by 15.2 IU/mL, indicating that his immune system is mounting an enhanced response against the parasite (Figure 2). Mr. T continues to make progress while receiving the new regimen of clozapine, minocycline, valproic acid, and ginger root extract. He no longer cycles into periods of intense anxiety, perseverative thought, and fragmented thought and speech. He participates meaningfully in weekly psychotherapy and hopes to live independently and obtain gainful employment.

The District Attorney’s office dismisses his criminal charges, and Mr. T is discharged to a less restrictive level of care.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Several studies have shown that neuroinflammation increases the severity of mental illness. Consider adjunct anti-inflammatory agents for patients who have elevated levels of inflammatory biomarkers and for whom standard treatment approaches do not adequately control psychiatric symptoms. Also consider testing for the presence of latent infections in the CNS, which could reveal the underlying cause of treatment resistance or the genesis of disabling psychiatric symptoms.

Related Resources

- Fond G, Macgregor A, Tamouza R, et al. Comparative analysis of anti-toxoplasmic activity of antipsychotic drugs and valproate. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2014;264(2):179-183.

- Hamdani N, Daban-Huard C, Lajnef M, et al. Cognitive deterioration among bipolar disorder patients infected by Toxoplasma gondii is correlated to interleukin 6 levels. J Affect Disord. 2015;179:161-166.

- Monroe JM, Buckley PF, Miller BJ. Meta-analysis of antitoxoplasma gondii IgM antibodies in acute psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41(4):989-998.

Drug Brand Names

Acyclovir • Zovirax

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Buspirone • Buspar

Clozapine • Clozaril

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Fluphenazine • Prolixin

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Haloperidol • Haldol

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lorazepam • Ativan

Loxapine • Loxitane

Minocycline • Minocin

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Paliperidone • Invega

Paroxetine • Paxil

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal, Risperdal Consta

Thioridazine • Mellaril

Trifluoperazine • Stelazine

Trazodone • Desyrel

Valproic acid • Depakote

Ziprasidone • Geodon

1. Koola MM, Raines JK, Hamilton RG, et al. Can anti-inflammatory medications improve symptoms and reduce mortality in schizophrenia? Current Psychiatry. 2016;15(5):52-57.

2. Nasrallah HA. Are you neuroprotecting your patients? 10 Adjunctive therapies to consider. Current Psychiatry. 2016;15(12):12-14.

3. Goldsmith DR, Rapaport MH, Miller BJ. A meta-analysis of blood cytokine network alterations in psychiatric patients: comparisons between schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21(12):1696-1709.

4. Chase KA, Cone JJ, Rosen C, et al. The value of interleukin 6 as a peripheral diagnostic marker in schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:152.

5. Torrey EF, Bartko JJ, Lun ZR, et al. Antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii in patients with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33(3):729-736.

6. Shirts BH, Prasad KM, Pogue-Geile MF, et al. Antibodies to cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex virus 1 associated with cognitive function in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2008;106(2-3):268-274.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parasites - Toxoplasmosis (Toxoplasma infection). https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/toxoplasmosis/index.html. Accessed February 26, 2019.

8. Dickerson F, Wilcox HC, Adamos M, et al. Suicide attempts and markers of immune response in individuals with serious mental illness. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;87:37-43.

9. Celik T, Kartalci S, Aytas O, et al. Association between latent toxoplasmosis and clinical course of schizophrenia - continuous course of the disease is characteristic for Toxoplasma gondii-infected patients. Folia Parasitol (Praha). 2015;62. doi: 10.14411/fp.2015.015.

10. Dickerson F, Boronow J, Stallings C, et al. Toxoplasma gondii in individuals with schizophrenia: association with clinical and demographic factors and with mortality. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33(3):737-740.

11. Esshili A, Thabet S, Jemli A, et al. Toxoplasma gondii infection in schizophrenia and associated clinical features. Psychiatry Res. 2016;245:327-332.

12. Holub D, Flegr J, Dragomirecka E, et al. Differences in onset of disease and severity of psychopathology between toxoplasmosis-related and toxoplasmosis-unrelated schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2013;127(3):227-238.

13. Chen AT, Chibnall JT, Nasrallah HA. Placebo-controlled augmentation trials of the antioxidant NAC in schizophrenia: a review. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2016;28(3):190-196.

14. Jones-Brando L, Torrey EF, Yolken R. Drugs used in the treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder inhibit the replication of Toxoplasma gondii. Schizophr Res. 2003;62(3):237-244.

15. Fond G, Boyer L, Gaman A, et al. Treatment with anti-toxoplasmic activity (TATA) for toxoplasma positive patients with bipolar disorders or schizophrenia: a cross-sectional study. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;63:58-64.

16. Wei HX, Wei SS, Lindsay DS, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the efficacy of anti-Toxoplasma gondii medicines in humans. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0138204.

17. Zhuo XH, Sun HC, Huang B, et al. Evaluation of potential anti-toxoplasmosis efficiency of combined traditional herbs in a mouse model. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2017;18(6):453-461.

18. Choi WH, Jiang MH, Chu JP. Antiparasitic effects of Zingiber officinale (Ginger) extract against Toxoplasma gondii. Journal of Applied Biomedicine. 2013;11:15-26.

1. Koola MM, Raines JK, Hamilton RG, et al. Can anti-inflammatory medications improve symptoms and reduce mortality in schizophrenia? Current Psychiatry. 2016;15(5):52-57.

2. Nasrallah HA. Are you neuroprotecting your patients? 10 Adjunctive therapies to consider. Current Psychiatry. 2016;15(12):12-14.

3. Goldsmith DR, Rapaport MH, Miller BJ. A meta-analysis of blood cytokine network alterations in psychiatric patients: comparisons between schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21(12):1696-1709.

4. Chase KA, Cone JJ, Rosen C, et al. The value of interleukin 6 as a peripheral diagnostic marker in schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:152.

5. Torrey EF, Bartko JJ, Lun ZR, et al. Antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii in patients with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33(3):729-736.

6. Shirts BH, Prasad KM, Pogue-Geile MF, et al. Antibodies to cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex virus 1 associated with cognitive function in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2008;106(2-3):268-274.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parasites - Toxoplasmosis (Toxoplasma infection). https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/toxoplasmosis/index.html. Accessed February 26, 2019.

8. Dickerson F, Wilcox HC, Adamos M, et al. Suicide attempts and markers of immune response in individuals with serious mental illness. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;87:37-43.

9. Celik T, Kartalci S, Aytas O, et al. Association between latent toxoplasmosis and clinical course of schizophrenia - continuous course of the disease is characteristic for Toxoplasma gondii-infected patients. Folia Parasitol (Praha). 2015;62. doi: 10.14411/fp.2015.015.

10. Dickerson F, Boronow J, Stallings C, et al. Toxoplasma gondii in individuals with schizophrenia: association with clinical and demographic factors and with mortality. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33(3):737-740.

11. Esshili A, Thabet S, Jemli A, et al. Toxoplasma gondii infection in schizophrenia and associated clinical features. Psychiatry Res. 2016;245:327-332.

12. Holub D, Flegr J, Dragomirecka E, et al. Differences in onset of disease and severity of psychopathology between toxoplasmosis-related and toxoplasmosis-unrelated schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2013;127(3):227-238.

13. Chen AT, Chibnall JT, Nasrallah HA. Placebo-controlled augmentation trials of the antioxidant NAC in schizophrenia: a review. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2016;28(3):190-196.

14. Jones-Brando L, Torrey EF, Yolken R. Drugs used in the treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder inhibit the replication of Toxoplasma gondii. Schizophr Res. 2003;62(3):237-244.

15. Fond G, Boyer L, Gaman A, et al. Treatment with anti-toxoplasmic activity (TATA) for toxoplasma positive patients with bipolar disorders or schizophrenia: a cross-sectional study. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;63:58-64.

16. Wei HX, Wei SS, Lindsay DS, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the efficacy of anti-Toxoplasma gondii medicines in humans. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0138204.

17. Zhuo XH, Sun HC, Huang B, et al. Evaluation of potential anti-toxoplasmosis efficiency of combined traditional herbs in a mouse model. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2017;18(6):453-461.

18. Choi WH, Jiang MH, Chu JP. Antiparasitic effects of Zingiber officinale (Ginger) extract against Toxoplasma gondii. Journal of Applied Biomedicine. 2013;11:15-26.

Beyond ‘selfies’: An epidemic of acquired narcissism

Narcissism has an evil reputation. But is it justified? A modicum of narcissism is actually healthy. It can bolster self-confidence, assertiveness, and success in business and in the sociobiology of mating. Perhaps that’s why narcissism as a trait has a survival value from an evolutionary perspective.

Taking an excessive number of “selfies” with a smartphone is probably the most common and relatively benign form of mild narcissism (and not in DSM-5, yet). Narcissistic personality disorder (NPD), with a prevalence of 1%, is on the extreme end of the narcissism continuum. It has become tainted with such an intensely negative halo that it has become a despised trait, an insult, and even a vile epithet, like a 4-letter word. But as psychiatrists and other mental health professionals, we clinically relate to patients with NPD as being afflicted with a serious neuropsychiatric disorder, not as despicable individuals. Many people outside the mental health profession abhor persons with NPD because of their gargantuan hubris, insufferable selfishness, self-aggrandizement, emotional abuse of others, and irremediable vanity. Narcissistic personality disorder deprives its sufferers of the prosocial capacity for empathy, which leads them to belittle others or treat competent individuals with disdain, never as equals. They also seem to be incapable of experiencing shame as they inflate their self-importance and megalomania at the expense of those they degrade. They cannot tolerate any success by others because it threatens to overshadow their own exaggerated achievements. They can be mercilessly harsh towards their underlings. They are incapable of fostering warm, long-term loving relationships, where bidirectional respect is essential. Their lives often are replete with brief, broken-up relationships because they emotionally, physically, or sexually abuse their intimate partners.

Primary NPD has been shown in twin studies to be highly genetic, and more strongly heritable than 17 other personality dimensions.1 It is also resistant to any effective psychotherapeutic, pharmacologic, or somatic treatments. This is particularly relevant given the proclivity of individuals with NPD to experience a crushing disappointment, commonly known as “narcissistic injury,” following a real or imagined failure. This could lead to a painful depression or an outburst of “narcissistic rage” directed at anyone perceived as undermining them, and may even lead to violent behavior.2

Apart from heritable narcissism, there is also another form of narcissism that can develop in some individuals following life events. That hazardous condition, known as “acquired narcissism,” is most often associated with achieving the coveted status of an exalted celebrity. At risk for this acquired personality affliction are famous actors, singers, movie directors, TV anchors, or politicians (although some politicians are natural-born narcissists, driven to seek the powers of public office), and less frequently physicians (perhaps because the practice of medicine is not done in front of spectators) or scientists (because research, no matter how momentous, rarely procures the glamour or public adulation of the entertainment industry). The ardent fans of those “celebs” shower them with such intense attention and adulation that it malignantly transforms previously “normal” individuals into narcissists who start believing they are indeed “very special” and superior to the rest of us mortals (especially as their earning power balloons into the millions after growing up with humble social or economic roots).

Social media has become a catalyst for acquired narcissism, with millions of followers on Twitter, Facebook, or YouTube. Cable TV also caters to politicians, some of whom morph into narcissists, intoxicated with their newfound eminence and stature among their partisan followers, and become genuinely convinced that they have supreme power or influence over the masses. They get carried away with their own exaggerated self-importance as oracles of the “truth,” regardless of how extreme their views may be. Celebrity, politics, social media, and cable TV have converged into a combustible mix, a crucible for acquired narcissism.

An interesting feature of acquired narcissism is “collective narcissism,” in which celebrities coalesce to consolidate their imagined superhuman attributes that go beyond the technical skills of their professions such as acting, singing, sports, or politics. Thus, entertainers or star athletes believe they can enunciate radical statements about contemporary social, political, or environmental issues (at both ends of the debate) as though their artistic success renders them wise arbiters of the truth. What complicates matters is their delirious fans, who revere and mimic whatever their idols say (and their fashion or their tattoos), which further intensifies the grandiosity and megalomania of acquired narcissism. Celebrity triggers mindless idolatry, fueling the narcissism of individuals who are blessed (or cursed?) with runaway personal success. Neuroscientists should conduct research into how the brain is neurobiologically altered by fame, but there are many more urgent questions that demand their attention. It would be important to know if it is reversible or enduring, even as fame inevitably dims.

Continue to: The pursuit of wealth and fame...

The pursuit of wealth and fame is widely prevalent and can be healthy if it is not all-consuming. But if achieved beyond the aspirer’s wildest dreams, he/she may reach an inflection point conducive to a pathologic degree of acquired narcissism. That’s what the French refer to as “les risques du métier” (ie, occupational hazard). I recall reading about celebrities who became enraged when a policeman “dared” to stop their car for some driving violation, confronting the officer with “Do you know who I am?” That question may be a clinical biomarker of acquired narcissism.

Interestingly, several years ago, when the American Psychiatry Association last revised the DSM—sometimes referred to as the “bible” of psychiatric nosology—it came close to dropping NPD from its listed disorders, but then reverted and kept it as one of the 275 diagnostic categories included in DSM-5.3 Had the NPD diagnosis been discarded, one wonders if the mythical god of narcissism would have suffered a transcendental “narcissistic injury”…

1. Livesley WJ, Jang KL, Jackson DN, et al. Genetic and environmental contributions to dimensions of personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(12):1826-1831

2. Malmquist CP. Homicide: a psychiatric perspective. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2006:181-182.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Narcissism has an evil reputation. But is it justified? A modicum of narcissism is actually healthy. It can bolster self-confidence, assertiveness, and success in business and in the sociobiology of mating. Perhaps that’s why narcissism as a trait has a survival value from an evolutionary perspective.

Taking an excessive number of “selfies” with a smartphone is probably the most common and relatively benign form of mild narcissism (and not in DSM-5, yet). Narcissistic personality disorder (NPD), with a prevalence of 1%, is on the extreme end of the narcissism continuum. It has become tainted with such an intensely negative halo that it has become a despised trait, an insult, and even a vile epithet, like a 4-letter word. But as psychiatrists and other mental health professionals, we clinically relate to patients with NPD as being afflicted with a serious neuropsychiatric disorder, not as despicable individuals. Many people outside the mental health profession abhor persons with NPD because of their gargantuan hubris, insufferable selfishness, self-aggrandizement, emotional abuse of others, and irremediable vanity. Narcissistic personality disorder deprives its sufferers of the prosocial capacity for empathy, which leads them to belittle others or treat competent individuals with disdain, never as equals. They also seem to be incapable of experiencing shame as they inflate their self-importance and megalomania at the expense of those they degrade. They cannot tolerate any success by others because it threatens to overshadow their own exaggerated achievements. They can be mercilessly harsh towards their underlings. They are incapable of fostering warm, long-term loving relationships, where bidirectional respect is essential. Their lives often are replete with brief, broken-up relationships because they emotionally, physically, or sexually abuse their intimate partners.

Primary NPD has been shown in twin studies to be highly genetic, and more strongly heritable than 17 other personality dimensions.1 It is also resistant to any effective psychotherapeutic, pharmacologic, or somatic treatments. This is particularly relevant given the proclivity of individuals with NPD to experience a crushing disappointment, commonly known as “narcissistic injury,” following a real or imagined failure. This could lead to a painful depression or an outburst of “narcissistic rage” directed at anyone perceived as undermining them, and may even lead to violent behavior.2

Apart from heritable narcissism, there is also another form of narcissism that can develop in some individuals following life events. That hazardous condition, known as “acquired narcissism,” is most often associated with achieving the coveted status of an exalted celebrity. At risk for this acquired personality affliction are famous actors, singers, movie directors, TV anchors, or politicians (although some politicians are natural-born narcissists, driven to seek the powers of public office), and less frequently physicians (perhaps because the practice of medicine is not done in front of spectators) or scientists (because research, no matter how momentous, rarely procures the glamour or public adulation of the entertainment industry). The ardent fans of those “celebs” shower them with such intense attention and adulation that it malignantly transforms previously “normal” individuals into narcissists who start believing they are indeed “very special” and superior to the rest of us mortals (especially as their earning power balloons into the millions after growing up with humble social or economic roots).

Social media has become a catalyst for acquired narcissism, with millions of followers on Twitter, Facebook, or YouTube. Cable TV also caters to politicians, some of whom morph into narcissists, intoxicated with their newfound eminence and stature among their partisan followers, and become genuinely convinced that they have supreme power or influence over the masses. They get carried away with their own exaggerated self-importance as oracles of the “truth,” regardless of how extreme their views may be. Celebrity, politics, social media, and cable TV have converged into a combustible mix, a crucible for acquired narcissism.

An interesting feature of acquired narcissism is “collective narcissism,” in which celebrities coalesce to consolidate their imagined superhuman attributes that go beyond the technical skills of their professions such as acting, singing, sports, or politics. Thus, entertainers or star athletes believe they can enunciate radical statements about contemporary social, political, or environmental issues (at both ends of the debate) as though their artistic success renders them wise arbiters of the truth. What complicates matters is their delirious fans, who revere and mimic whatever their idols say (and their fashion or their tattoos), which further intensifies the grandiosity and megalomania of acquired narcissism. Celebrity triggers mindless idolatry, fueling the narcissism of individuals who are blessed (or cursed?) with runaway personal success. Neuroscientists should conduct research into how the brain is neurobiologically altered by fame, but there are many more urgent questions that demand their attention. It would be important to know if it is reversible or enduring, even as fame inevitably dims.

Continue to: The pursuit of wealth and fame...

The pursuit of wealth and fame is widely prevalent and can be healthy if it is not all-consuming. But if achieved beyond the aspirer’s wildest dreams, he/she may reach an inflection point conducive to a pathologic degree of acquired narcissism. That’s what the French refer to as “les risques du métier” (ie, occupational hazard). I recall reading about celebrities who became enraged when a policeman “dared” to stop their car for some driving violation, confronting the officer with “Do you know who I am?” That question may be a clinical biomarker of acquired narcissism.

Interestingly, several years ago, when the American Psychiatry Association last revised the DSM—sometimes referred to as the “bible” of psychiatric nosology—it came close to dropping NPD from its listed disorders, but then reverted and kept it as one of the 275 diagnostic categories included in DSM-5.3 Had the NPD diagnosis been discarded, one wonders if the mythical god of narcissism would have suffered a transcendental “narcissistic injury”…

Narcissism has an evil reputation. But is it justified? A modicum of narcissism is actually healthy. It can bolster self-confidence, assertiveness, and success in business and in the sociobiology of mating. Perhaps that’s why narcissism as a trait has a survival value from an evolutionary perspective.

Taking an excessive number of “selfies” with a smartphone is probably the most common and relatively benign form of mild narcissism (and not in DSM-5, yet). Narcissistic personality disorder (NPD), with a prevalence of 1%, is on the extreme end of the narcissism continuum. It has become tainted with such an intensely negative halo that it has become a despised trait, an insult, and even a vile epithet, like a 4-letter word. But as psychiatrists and other mental health professionals, we clinically relate to patients with NPD as being afflicted with a serious neuropsychiatric disorder, not as despicable individuals. Many people outside the mental health profession abhor persons with NPD because of their gargantuan hubris, insufferable selfishness, self-aggrandizement, emotional abuse of others, and irremediable vanity. Narcissistic personality disorder deprives its sufferers of the prosocial capacity for empathy, which leads them to belittle others or treat competent individuals with disdain, never as equals. They also seem to be incapable of experiencing shame as they inflate their self-importance and megalomania at the expense of those they degrade. They cannot tolerate any success by others because it threatens to overshadow their own exaggerated achievements. They can be mercilessly harsh towards their underlings. They are incapable of fostering warm, long-term loving relationships, where bidirectional respect is essential. Their lives often are replete with brief, broken-up relationships because they emotionally, physically, or sexually abuse their intimate partners.

Primary NPD has been shown in twin studies to be highly genetic, and more strongly heritable than 17 other personality dimensions.1 It is also resistant to any effective psychotherapeutic, pharmacologic, or somatic treatments. This is particularly relevant given the proclivity of individuals with NPD to experience a crushing disappointment, commonly known as “narcissistic injury,” following a real or imagined failure. This could lead to a painful depression or an outburst of “narcissistic rage” directed at anyone perceived as undermining them, and may even lead to violent behavior.2

Apart from heritable narcissism, there is also another form of narcissism that can develop in some individuals following life events. That hazardous condition, known as “acquired narcissism,” is most often associated with achieving the coveted status of an exalted celebrity. At risk for this acquired personality affliction are famous actors, singers, movie directors, TV anchors, or politicians (although some politicians are natural-born narcissists, driven to seek the powers of public office), and less frequently physicians (perhaps because the practice of medicine is not done in front of spectators) or scientists (because research, no matter how momentous, rarely procures the glamour or public adulation of the entertainment industry). The ardent fans of those “celebs” shower them with such intense attention and adulation that it malignantly transforms previously “normal” individuals into narcissists who start believing they are indeed “very special” and superior to the rest of us mortals (especially as their earning power balloons into the millions after growing up with humble social or economic roots).

Social media has become a catalyst for acquired narcissism, with millions of followers on Twitter, Facebook, or YouTube. Cable TV also caters to politicians, some of whom morph into narcissists, intoxicated with their newfound eminence and stature among their partisan followers, and become genuinely convinced that they have supreme power or influence over the masses. They get carried away with their own exaggerated self-importance as oracles of the “truth,” regardless of how extreme their views may be. Celebrity, politics, social media, and cable TV have converged into a combustible mix, a crucible for acquired narcissism.

An interesting feature of acquired narcissism is “collective narcissism,” in which celebrities coalesce to consolidate their imagined superhuman attributes that go beyond the technical skills of their professions such as acting, singing, sports, or politics. Thus, entertainers or star athletes believe they can enunciate radical statements about contemporary social, political, or environmental issues (at both ends of the debate) as though their artistic success renders them wise arbiters of the truth. What complicates matters is their delirious fans, who revere and mimic whatever their idols say (and their fashion or their tattoos), which further intensifies the grandiosity and megalomania of acquired narcissism. Celebrity triggers mindless idolatry, fueling the narcissism of individuals who are blessed (or cursed?) with runaway personal success. Neuroscientists should conduct research into how the brain is neurobiologically altered by fame, but there are many more urgent questions that demand their attention. It would be important to know if it is reversible or enduring, even as fame inevitably dims.

Continue to: The pursuit of wealth and fame...

The pursuit of wealth and fame is widely prevalent and can be healthy if it is not all-consuming. But if achieved beyond the aspirer’s wildest dreams, he/she may reach an inflection point conducive to a pathologic degree of acquired narcissism. That’s what the French refer to as “les risques du métier” (ie, occupational hazard). I recall reading about celebrities who became enraged when a policeman “dared” to stop their car for some driving violation, confronting the officer with “Do you know who I am?” That question may be a clinical biomarker of acquired narcissism.

Interestingly, several years ago, when the American Psychiatry Association last revised the DSM—sometimes referred to as the “bible” of psychiatric nosology—it came close to dropping NPD from its listed disorders, but then reverted and kept it as one of the 275 diagnostic categories included in DSM-5.3 Had the NPD diagnosis been discarded, one wonders if the mythical god of narcissism would have suffered a transcendental “narcissistic injury”…

1. Livesley WJ, Jang KL, Jackson DN, et al. Genetic and environmental contributions to dimensions of personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(12):1826-1831

2. Malmquist CP. Homicide: a psychiatric perspective. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2006:181-182.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

1. Livesley WJ, Jang KL, Jackson DN, et al. Genetic and environmental contributions to dimensions of personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(12):1826-1831

2. Malmquist CP. Homicide: a psychiatric perspective. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2006:181-182.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Backlash against using rating scales

I strongly disagree with the editorial by Ahmed A. Aboraya, MD, DrPH, and Henry A. Nasrallah, MD, (“It’s time to implement measurement-based care in psychiatric practice,” From the Editor,

We do not have much more to lose before it’s a checklist, vital signs, and a script. I now refer to our profession as “McMedicine.” If you don’t have what is on the menu, you cannot get served. Diseases are rarely treated, symptoms are treated. This is not the profession of medicine. We are not fixing much; we are mostly providing consumers for pharmaceutical companies.

Few psychiatric disorders have been subjected to more measurement than depression. Quite a while ago, someone tried to compare depression scales. They correlated scale scores with the results of evaluations by board-certified psychiatrists. The best scale was a single question: “Are you depressed?” This had been included as a control. Can you do better?

Furthermore, the “paper and numbers” people can’t wait to get an “objective” wrench to tighten the screws and apply the principles of the industrial revolution to squeeze more money out of the system. They will find some way to turn patients into standardized products.

John L. Schenkel, MD

Retired psychiatrist

Peru, NY

With the use of an electronic medical record, what should be a simple 1-page note is transformed into a 5-page note of details. Doctors no longer attend to their patients but rather to their computers. Has this raised consciousness—the most important metric, according to Dr. David Hawkins? I doubt it.

In the words of my great professor, Dr. James Gustafson, I will continue to start my interview with what concerns the patient. Most of the time, they implicitly know.

Our focus should instead be on bringing down the cost of health care. This is what angers our patients most, and yet we do not make it a priority.

Psychiatrist

Glenbeigh Hospital

Rock Creek, Ohio

Signature Health

Ashtabula, Ohio

Behavioral Wellness Group

Mentor, Ohio

Continue to: The authors respond

The authors respond

We appreciate Drs. Schenkel’s and Primc’s comments on our editorial regarding measurement-based care (MBC). However, MBC will not increase the workload of psychiatrists; rather, it will streamline the evaluation of patients and measure the severity of their symptoms or adverse effects as well as the degree of their improvement. The proper use of scales with the appropriate patient populations may actually help clinicians to reduce the extensive amount of details that go into medical records.

The following quote, an excerpt from another article we wrote on MBC,1 speaks to Dr. Primc’s concerns:

“…measures in psychiatry could be considered the equivalent of a thermometer and a stethoscope to a physician.

Ahmed A. Aboraya, MD, DrPH

Assistant Professor

Department of Behavioral Medicine and Psychiatry

Chief of Psychiatry

Sharpe Hospital West Virginia University

Weston, West Virginia

Henry A. Nasrallah, MD

Professor of Psychiatry, Neurology, and Neuroscience

Medical Director: Neuropsychiatry

Director, Schizophrenia and Neuropsychiatry Programs

University of Cincinnati College of Medicine

Cincinnati, Ohio

Professor Emeritus, Saint Louis University

St. Louis, Missouri

Reference

1. Aboraya A, Nasrallah HA, Elswick DE, et al. Measurement-based care in psychiatry-past, present, and future. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2018;15(11-12):13-26.

I strongly disagree with the editorial by Ahmed A. Aboraya, MD, DrPH, and Henry A. Nasrallah, MD, (“It’s time to implement measurement-based care in psychiatric practice,” From the Editor,