User login

A solution for reducing referrals (and malpractice suits)

I agree with Dr. Hickner’s editorial “To refer—or not?” (J Fam Pract. 2019;68:8) that family physicians could manage about 30% of the patients they refer to specialists. Still, it’s worth noting that many referrals are motivated by the threat of unmerited malpractice suits. Until the medical liability system becomes less adversarial and unmerited suits are eliminated, all primary care doctors—not just family physicians—will continue to send patients to specialists—even when these physicians are themselves capable of treating such patients.

What might help mitigate malpractice suits? There could be benefit from oversight of health courts, which would be presided over by judges with special training in medical malpractice. Being nonadversarial, health courts would cut down on legal wrangling, settle suits, and get awards to patients quicker. They would also cut down on attorney and court fees, which account for almost half of the total amount spent on litigation. These courts wouldn’t completely eliminate unnecessary referrals to specialists, but they could help make a difference.

Edward Volpintesta, MD

Bethel, Conn

I agree with Dr. Hickner’s editorial “To refer—or not?” (J Fam Pract. 2019;68:8) that family physicians could manage about 30% of the patients they refer to specialists. Still, it’s worth noting that many referrals are motivated by the threat of unmerited malpractice suits. Until the medical liability system becomes less adversarial and unmerited suits are eliminated, all primary care doctors—not just family physicians—will continue to send patients to specialists—even when these physicians are themselves capable of treating such patients.

What might help mitigate malpractice suits? There could be benefit from oversight of health courts, which would be presided over by judges with special training in medical malpractice. Being nonadversarial, health courts would cut down on legal wrangling, settle suits, and get awards to patients quicker. They would also cut down on attorney and court fees, which account for almost half of the total amount spent on litigation. These courts wouldn’t completely eliminate unnecessary referrals to specialists, but they could help make a difference.

Edward Volpintesta, MD

Bethel, Conn

I agree with Dr. Hickner’s editorial “To refer—or not?” (J Fam Pract. 2019;68:8) that family physicians could manage about 30% of the patients they refer to specialists. Still, it’s worth noting that many referrals are motivated by the threat of unmerited malpractice suits. Until the medical liability system becomes less adversarial and unmerited suits are eliminated, all primary care doctors—not just family physicians—will continue to send patients to specialists—even when these physicians are themselves capable of treating such patients.

What might help mitigate malpractice suits? There could be benefit from oversight of health courts, which would be presided over by judges with special training in medical malpractice. Being nonadversarial, health courts would cut down on legal wrangling, settle suits, and get awards to patients quicker. They would also cut down on attorney and court fees, which account for almost half of the total amount spent on litigation. These courts wouldn’t completely eliminate unnecessary referrals to specialists, but they could help make a difference.

Edward Volpintesta, MD

Bethel, Conn

Acute hearing loss, tinnitus, and fullness in the left ear • Weber test lateralized to the right ear • Positive Rinne test and normal tympanometry • Dx?

THE CASE

A healthy 48-year-old man presented to our otolaryngology clinic with a 2-hour history of hearing loss, tinnitus, and fullness in the left ear. He denied any vertigo, nausea, vomiting, otalgia, or otorrhea. He had noticed signs of a possible upper respiratory infection, including a sore throat and headache, the day before his symptoms started. His medical history was unremarkable. He denied any history of otologic surgery, trauma, or vision problems, and he was not taking any medications.

The patient was afebrile on physical examination with a heart rate of 48 beats/min and blood pressure of 117/68 mm Hg. A Weber test performed using a 512-Hz tuning fork lateralized to the right ear. A Rinne test showed air conduction was louder than bone conduction in the affected left ear—a normal finding. Tympanometry and otoscopic examination showed the bilateral tympanic membranes were normal.

THE DIAGNOSIS

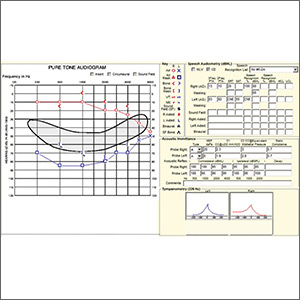

Pure tone audiometry showed severe sensorineural hearing loss in the left ear and a poor speech discrimination score. The Weber test confirmed the hearing loss was sensorineural and not conductive, ruling out a middle ear effusion. Additionally, the normal tympanogram made conductive hearing loss from a middle ear effusion or tympanic membrane perforation unlikely. The positive Rinne test was consistent with a diagnosis of idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss (SSNHL).

DISCUSSION

SSNHL is defined by hearing loss of more than 30 dB in at least 3 consecutive frequencies with acute onset of less than 72 hours.1,2 The most common symptoms include acute hearing loss, tinnitus, and fullness in the affected ear.1 The majority of cases of SSNHL are unilateral. The typical age of onset is in the fourth and fifth decades, occurring with equal distribution in both sexes.

Etiology.

Diagnosis. The initial evaluation should include an otoscopic examination, tuning fork tests, and pure tone audiometry.1-3 Weber and Rinne tests are essential when evaluating patients for unilateral hearing loss and determining the type of loss (ie, sensorineural vs conductive). The Weber test (ideally using a 512-Hz tuning fork) can detect either conductive or sensorineural hearing loss. In a normal Weber test, the patient should hear the vibration of the tuning fork equally in both ears. The tuning fork will be heard in both ears in conductive hearing loss but will only be heard in the unaffected hear if sensorineural hearing loss is present. So, for instance, if a patient has a perforation in the right tympanic membrane causing conductive hearing loss in the right hear, the tuning fork would be heard in both ears. If the patient has sensorineural hearing loss in the right ear, the tuning fork would only be heard in the left ear.

The Rinne test compares the perception of sound waves transmitted by air conduction vs bone conduction and serves as a rapid screen for conductive hearing loss.

Continue to: Magnetic resonance imaging...

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and brainstem with gadolinium contrast can reveal vascular events (thrombotic or hemorrhagic), demyelinating disorders, or retrocochlear lesions such as vestibular schwannoma and is indicated in all cases of suspected SSNHL.4,5

Treatment and management. The current standard of care for treatment of idiopathic SSNHL is systemic steroids.1,2 Although the gold standard currently is oral prednisolone or methylprednisolone (1 mg/kg/d for 10 to 14 days with a taper,1,2 the evidence for this regimen stems from a single placebo-controlled trial (N = 67) that demonstrated greater improvement in the steroid group compared with the placebo group (61% vs 32%).6 A Cochrane review and other systematic analyses have not demonstrated clear efficacy of corticosteroid treatment for the management of idiopathic SSNHL.7,8

Because of the potential systemic adverse effects associated with oral corticosteroids, intratympanic (IT) corticosteroids have been advocated as an alternative treatment option. A prospective, randomized, noninferiority trial comparing the efficacy of oral vs IT corticosteroids for idiopathic SSNHL found IT corticosteroids to be noninferior to systemic treatment.9 IT treatment also has been advocated as a rescue therapy for patients who do not respond to systemic treatment.10

A combination of oral and IT corticosteroids was investigated in a retrospective study analyzing multiple treatment modalities.10 Researchers first compared 122 patients receiving one of 3 treatments: (1) IT corticosteroids, (2) oral corticosteroids, and (3) combination treatment (IT + oral corticosteroids). There was no difference in hearing recovery among any of the treatments. Fifty-eight patients who were refractory to initial treatment were then included in a second analysis in which they were divided into those who received additional IT corticosteroids (salvage treatment) vs no treatment (control). There was no difference in hearing recovery between the 2 groups. The authors concluded that IT corticosteroids were as effective as oral treatment and that salvage IT treatment did not add any benefit.10

The American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) recently published guidelines on the diagnosis and management of SSNHL.11 The guidelines state that IT steroids should be considered in patients who cannot tolerate oral steroids, such as patients with diabetes. It is important to note, however, that the high cost of IT treatment (~$2000 for dexamethasone or methylprednisolone vs < $10 for oral prednisolone) is an issue that needs to be considered as health care costs continue to rise.

Continue to: Antivirals

Antivirals. Because an underlying viral etiology has been speculated as a potential cause of idiopathic SSNHL, antiviral agents such as valacyclovir or famciclovir also are potential treatment agents.12 Antiviral medications have minimal adverse effects and are relatively inexpensive, but the benefits have not yet been proven in randomized controlled trials,and they currently are not endorsed by the AAO-HNS in their guidelines for the management of SSNHL.11

Spontaneous recovery occurs in up to 40% of patients with idiopathic SSNHL. As many as 65% of those who experience recovery do so within 2 weeks of the onset of symptoms, regardless of treatment.1,2 Treatment beyond 2 weeks after onset of symptoms is unlikely to be of any benefit, although some otolaryngologists will treat for up to 6 weeks after the onset of hearing loss.

A substantial number of patients with SSNHL may not recover. Management of these patients begins with referral to an appropriate specialist to initiate counseling and lifestyle changes. Depending on the degree of hearing loss, audiologic rehabilitation may include use of a traditional or bone-anchored hearing aid or a frequency-modulation system.1,2,11 Tinnitus retraining therapy might be of benefit for patients with persistent tinnitus.11

Our patient. After a discussion of his treatment options, our patient decided on a combination of oral prednisolone (60 mg once daily for 9 days followed by a taper for 5 days) and intratympanic dexamethasone injections (1 mL [10 mg/mL] once weekly for 3 weeks).

The rationale for this approach was the minimal adverse effects associated with short-term (ie, days to 1–2 weeks) use of high-dose (ie, > 30 mg/d) corticosteroids. Although steroid therapy has been associated with adverse effects such as aseptic necrosis of the hip, these complications usually arise after longer periods (ie, months to years) of high-dose steroid therapy with a mean cumulative dose much higher than what was used in our patient.13

Continue to: Our patient...

Our patient noticed slight improvement within 48 hours of the initial onset of symptoms that continued for the next several weeks until full recovery was attained. An MRI performed 5 days after the onset of symptoms was negative for retrocochlear pathology.

THE TAKEAWAY

SSNHL is a medical emergency that requires prompt recognition and diagnosis. The steps in evaluating sudden hearing loss include: (1) appropriate history and physical examination (eg, otoscopic examination, tuning fork tests), (2) urgent audiometry to confirm hearing loss, (3) immediate referral to an otolaryngologist for further testing (eg, tympanometry, blood tests, MRI), and (4) initiation of treatment.

If a specific etiology is identified (eg, vestibular schwannoma), the patient should be referred to a specialist for appropriate treatment. If there is no identifiable cause (idiopathic SSNHL), the patient should be treated with oral and/or intratympanic steroids. Patients who do not recover following treatment should be offered audiologic rehabilitation.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sergio Huerta, MD, UT Southwestern Medical Center, 4500 S Lancaster Road #112L, Dallas, TX 75216; Sergio.Huerta@UTSouthwestern.edu

1. Schreiber BE, Agrup C, Haskard DO, et al. Sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Lancet. 2010;375:1203-1211.

2. Rauch SD. Clinical practice. Idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:833-840.

3. Paul BC, Roland JT Jr. An abnormal audiogram. JAMA. 2015;313:85-86.

4. Aarnisalo AA, Suoranta H, Ylikoski J. Magnetic resonance imaging findings in the auditory pathway of patients with sudden deafness. Otol Neurotol. 2004;25:245-249.

5. Cadoni G, Cianfoni A, Agostino S, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging findings in sudden sensorineural hearing loss. J Otolaryngol. 2006;35:310-316.

6. Wilson WR, Byl FM, Laird N. The efficacy of steroids in the treatment of idiopathic sudden hearing loss. A double-blind clinical study. Arch Otolaryngol. 1980;106:772-776.

7. Wei BPC, Stathopoulos D, O’Leary S. Steroids for idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003998.pub3.

8. Conlin AE, Parnes LS. Treatment of sudden sensorineural hearing loss: II. a meta-analysis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;133:582-586.

9. Rauch SD, Halpin CF, Antonelli PJ, et al. Oral vs intratympanic corticosteroid therapy for idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2011;305:2071-2079.

10. Lee KH, Ryu SH, Lee HM, et al. Is intratympanic dexamethasone injection effective for the treatment of idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss? J Audiol Otol. 2015;19:154-158.

11. Stachler RJ, Chandrasekhar SS, Archer SM, et al. Clinical practice guideline: sudden hearing loss. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;146(3 suppl):S1-S35.

12. Westerlaken BO, Stokroos RJ, Dhooge IJ, et al. Treatment of idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss with antiviral therapy: a prospective, randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2003;112:993-1000.

13. Nowak DA, Yeung J. Steroid-induced osteonecrosis in dermatology: a review [published online March 30, 2015]. J Cutan Med Surg. 2015;19:358-360.

THE CASE

A healthy 48-year-old man presented to our otolaryngology clinic with a 2-hour history of hearing loss, tinnitus, and fullness in the left ear. He denied any vertigo, nausea, vomiting, otalgia, or otorrhea. He had noticed signs of a possible upper respiratory infection, including a sore throat and headache, the day before his symptoms started. His medical history was unremarkable. He denied any history of otologic surgery, trauma, or vision problems, and he was not taking any medications.

The patient was afebrile on physical examination with a heart rate of 48 beats/min and blood pressure of 117/68 mm Hg. A Weber test performed using a 512-Hz tuning fork lateralized to the right ear. A Rinne test showed air conduction was louder than bone conduction in the affected left ear—a normal finding. Tympanometry and otoscopic examination showed the bilateral tympanic membranes were normal.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Pure tone audiometry showed severe sensorineural hearing loss in the left ear and a poor speech discrimination score. The Weber test confirmed the hearing loss was sensorineural and not conductive, ruling out a middle ear effusion. Additionally, the normal tympanogram made conductive hearing loss from a middle ear effusion or tympanic membrane perforation unlikely. The positive Rinne test was consistent with a diagnosis of idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss (SSNHL).

DISCUSSION

SSNHL is defined by hearing loss of more than 30 dB in at least 3 consecutive frequencies with acute onset of less than 72 hours.1,2 The most common symptoms include acute hearing loss, tinnitus, and fullness in the affected ear.1 The majority of cases of SSNHL are unilateral. The typical age of onset is in the fourth and fifth decades, occurring with equal distribution in both sexes.

Etiology.

Diagnosis. The initial evaluation should include an otoscopic examination, tuning fork tests, and pure tone audiometry.1-3 Weber and Rinne tests are essential when evaluating patients for unilateral hearing loss and determining the type of loss (ie, sensorineural vs conductive). The Weber test (ideally using a 512-Hz tuning fork) can detect either conductive or sensorineural hearing loss. In a normal Weber test, the patient should hear the vibration of the tuning fork equally in both ears. The tuning fork will be heard in both ears in conductive hearing loss but will only be heard in the unaffected hear if sensorineural hearing loss is present. So, for instance, if a patient has a perforation in the right tympanic membrane causing conductive hearing loss in the right hear, the tuning fork would be heard in both ears. If the patient has sensorineural hearing loss in the right ear, the tuning fork would only be heard in the left ear.

The Rinne test compares the perception of sound waves transmitted by air conduction vs bone conduction and serves as a rapid screen for conductive hearing loss.

Continue to: Magnetic resonance imaging...

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and brainstem with gadolinium contrast can reveal vascular events (thrombotic or hemorrhagic), demyelinating disorders, or retrocochlear lesions such as vestibular schwannoma and is indicated in all cases of suspected SSNHL.4,5

Treatment and management. The current standard of care for treatment of idiopathic SSNHL is systemic steroids.1,2 Although the gold standard currently is oral prednisolone or methylprednisolone (1 mg/kg/d for 10 to 14 days with a taper,1,2 the evidence for this regimen stems from a single placebo-controlled trial (N = 67) that demonstrated greater improvement in the steroid group compared with the placebo group (61% vs 32%).6 A Cochrane review and other systematic analyses have not demonstrated clear efficacy of corticosteroid treatment for the management of idiopathic SSNHL.7,8

Because of the potential systemic adverse effects associated with oral corticosteroids, intratympanic (IT) corticosteroids have been advocated as an alternative treatment option. A prospective, randomized, noninferiority trial comparing the efficacy of oral vs IT corticosteroids for idiopathic SSNHL found IT corticosteroids to be noninferior to systemic treatment.9 IT treatment also has been advocated as a rescue therapy for patients who do not respond to systemic treatment.10

A combination of oral and IT corticosteroids was investigated in a retrospective study analyzing multiple treatment modalities.10 Researchers first compared 122 patients receiving one of 3 treatments: (1) IT corticosteroids, (2) oral corticosteroids, and (3) combination treatment (IT + oral corticosteroids). There was no difference in hearing recovery among any of the treatments. Fifty-eight patients who were refractory to initial treatment were then included in a second analysis in which they were divided into those who received additional IT corticosteroids (salvage treatment) vs no treatment (control). There was no difference in hearing recovery between the 2 groups. The authors concluded that IT corticosteroids were as effective as oral treatment and that salvage IT treatment did not add any benefit.10

The American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) recently published guidelines on the diagnosis and management of SSNHL.11 The guidelines state that IT steroids should be considered in patients who cannot tolerate oral steroids, such as patients with diabetes. It is important to note, however, that the high cost of IT treatment (~$2000 for dexamethasone or methylprednisolone vs < $10 for oral prednisolone) is an issue that needs to be considered as health care costs continue to rise.

Continue to: Antivirals

Antivirals. Because an underlying viral etiology has been speculated as a potential cause of idiopathic SSNHL, antiviral agents such as valacyclovir or famciclovir also are potential treatment agents.12 Antiviral medications have minimal adverse effects and are relatively inexpensive, but the benefits have not yet been proven in randomized controlled trials,and they currently are not endorsed by the AAO-HNS in their guidelines for the management of SSNHL.11

Spontaneous recovery occurs in up to 40% of patients with idiopathic SSNHL. As many as 65% of those who experience recovery do so within 2 weeks of the onset of symptoms, regardless of treatment.1,2 Treatment beyond 2 weeks after onset of symptoms is unlikely to be of any benefit, although some otolaryngologists will treat for up to 6 weeks after the onset of hearing loss.

A substantial number of patients with SSNHL may not recover. Management of these patients begins with referral to an appropriate specialist to initiate counseling and lifestyle changes. Depending on the degree of hearing loss, audiologic rehabilitation may include use of a traditional or bone-anchored hearing aid or a frequency-modulation system.1,2,11 Tinnitus retraining therapy might be of benefit for patients with persistent tinnitus.11

Our patient. After a discussion of his treatment options, our patient decided on a combination of oral prednisolone (60 mg once daily for 9 days followed by a taper for 5 days) and intratympanic dexamethasone injections (1 mL [10 mg/mL] once weekly for 3 weeks).

The rationale for this approach was the minimal adverse effects associated with short-term (ie, days to 1–2 weeks) use of high-dose (ie, > 30 mg/d) corticosteroids. Although steroid therapy has been associated with adverse effects such as aseptic necrosis of the hip, these complications usually arise after longer periods (ie, months to years) of high-dose steroid therapy with a mean cumulative dose much higher than what was used in our patient.13

Continue to: Our patient...

Our patient noticed slight improvement within 48 hours of the initial onset of symptoms that continued for the next several weeks until full recovery was attained. An MRI performed 5 days after the onset of symptoms was negative for retrocochlear pathology.

THE TAKEAWAY

SSNHL is a medical emergency that requires prompt recognition and diagnosis. The steps in evaluating sudden hearing loss include: (1) appropriate history and physical examination (eg, otoscopic examination, tuning fork tests), (2) urgent audiometry to confirm hearing loss, (3) immediate referral to an otolaryngologist for further testing (eg, tympanometry, blood tests, MRI), and (4) initiation of treatment.

If a specific etiology is identified (eg, vestibular schwannoma), the patient should be referred to a specialist for appropriate treatment. If there is no identifiable cause (idiopathic SSNHL), the patient should be treated with oral and/or intratympanic steroids. Patients who do not recover following treatment should be offered audiologic rehabilitation.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sergio Huerta, MD, UT Southwestern Medical Center, 4500 S Lancaster Road #112L, Dallas, TX 75216; Sergio.Huerta@UTSouthwestern.edu

THE CASE

A healthy 48-year-old man presented to our otolaryngology clinic with a 2-hour history of hearing loss, tinnitus, and fullness in the left ear. He denied any vertigo, nausea, vomiting, otalgia, or otorrhea. He had noticed signs of a possible upper respiratory infection, including a sore throat and headache, the day before his symptoms started. His medical history was unremarkable. He denied any history of otologic surgery, trauma, or vision problems, and he was not taking any medications.

The patient was afebrile on physical examination with a heart rate of 48 beats/min and blood pressure of 117/68 mm Hg. A Weber test performed using a 512-Hz tuning fork lateralized to the right ear. A Rinne test showed air conduction was louder than bone conduction in the affected left ear—a normal finding. Tympanometry and otoscopic examination showed the bilateral tympanic membranes were normal.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Pure tone audiometry showed severe sensorineural hearing loss in the left ear and a poor speech discrimination score. The Weber test confirmed the hearing loss was sensorineural and not conductive, ruling out a middle ear effusion. Additionally, the normal tympanogram made conductive hearing loss from a middle ear effusion or tympanic membrane perforation unlikely. The positive Rinne test was consistent with a diagnosis of idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss (SSNHL).

DISCUSSION

SSNHL is defined by hearing loss of more than 30 dB in at least 3 consecutive frequencies with acute onset of less than 72 hours.1,2 The most common symptoms include acute hearing loss, tinnitus, and fullness in the affected ear.1 The majority of cases of SSNHL are unilateral. The typical age of onset is in the fourth and fifth decades, occurring with equal distribution in both sexes.

Etiology.

Diagnosis. The initial evaluation should include an otoscopic examination, tuning fork tests, and pure tone audiometry.1-3 Weber and Rinne tests are essential when evaluating patients for unilateral hearing loss and determining the type of loss (ie, sensorineural vs conductive). The Weber test (ideally using a 512-Hz tuning fork) can detect either conductive or sensorineural hearing loss. In a normal Weber test, the patient should hear the vibration of the tuning fork equally in both ears. The tuning fork will be heard in both ears in conductive hearing loss but will only be heard in the unaffected hear if sensorineural hearing loss is present. So, for instance, if a patient has a perforation in the right tympanic membrane causing conductive hearing loss in the right hear, the tuning fork would be heard in both ears. If the patient has sensorineural hearing loss in the right ear, the tuning fork would only be heard in the left ear.

The Rinne test compares the perception of sound waves transmitted by air conduction vs bone conduction and serves as a rapid screen for conductive hearing loss.

Continue to: Magnetic resonance imaging...

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and brainstem with gadolinium contrast can reveal vascular events (thrombotic or hemorrhagic), demyelinating disorders, or retrocochlear lesions such as vestibular schwannoma and is indicated in all cases of suspected SSNHL.4,5

Treatment and management. The current standard of care for treatment of idiopathic SSNHL is systemic steroids.1,2 Although the gold standard currently is oral prednisolone or methylprednisolone (1 mg/kg/d for 10 to 14 days with a taper,1,2 the evidence for this regimen stems from a single placebo-controlled trial (N = 67) that demonstrated greater improvement in the steroid group compared with the placebo group (61% vs 32%).6 A Cochrane review and other systematic analyses have not demonstrated clear efficacy of corticosteroid treatment for the management of idiopathic SSNHL.7,8

Because of the potential systemic adverse effects associated with oral corticosteroids, intratympanic (IT) corticosteroids have been advocated as an alternative treatment option. A prospective, randomized, noninferiority trial comparing the efficacy of oral vs IT corticosteroids for idiopathic SSNHL found IT corticosteroids to be noninferior to systemic treatment.9 IT treatment also has been advocated as a rescue therapy for patients who do not respond to systemic treatment.10

A combination of oral and IT corticosteroids was investigated in a retrospective study analyzing multiple treatment modalities.10 Researchers first compared 122 patients receiving one of 3 treatments: (1) IT corticosteroids, (2) oral corticosteroids, and (3) combination treatment (IT + oral corticosteroids). There was no difference in hearing recovery among any of the treatments. Fifty-eight patients who were refractory to initial treatment were then included in a second analysis in which they were divided into those who received additional IT corticosteroids (salvage treatment) vs no treatment (control). There was no difference in hearing recovery between the 2 groups. The authors concluded that IT corticosteroids were as effective as oral treatment and that salvage IT treatment did not add any benefit.10

The American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) recently published guidelines on the diagnosis and management of SSNHL.11 The guidelines state that IT steroids should be considered in patients who cannot tolerate oral steroids, such as patients with diabetes. It is important to note, however, that the high cost of IT treatment (~$2000 for dexamethasone or methylprednisolone vs < $10 for oral prednisolone) is an issue that needs to be considered as health care costs continue to rise.

Continue to: Antivirals

Antivirals. Because an underlying viral etiology has been speculated as a potential cause of idiopathic SSNHL, antiviral agents such as valacyclovir or famciclovir also are potential treatment agents.12 Antiviral medications have minimal adverse effects and are relatively inexpensive, but the benefits have not yet been proven in randomized controlled trials,and they currently are not endorsed by the AAO-HNS in their guidelines for the management of SSNHL.11

Spontaneous recovery occurs in up to 40% of patients with idiopathic SSNHL. As many as 65% of those who experience recovery do so within 2 weeks of the onset of symptoms, regardless of treatment.1,2 Treatment beyond 2 weeks after onset of symptoms is unlikely to be of any benefit, although some otolaryngologists will treat for up to 6 weeks after the onset of hearing loss.

A substantial number of patients with SSNHL may not recover. Management of these patients begins with referral to an appropriate specialist to initiate counseling and lifestyle changes. Depending on the degree of hearing loss, audiologic rehabilitation may include use of a traditional or bone-anchored hearing aid or a frequency-modulation system.1,2,11 Tinnitus retraining therapy might be of benefit for patients with persistent tinnitus.11

Our patient. After a discussion of his treatment options, our patient decided on a combination of oral prednisolone (60 mg once daily for 9 days followed by a taper for 5 days) and intratympanic dexamethasone injections (1 mL [10 mg/mL] once weekly for 3 weeks).

The rationale for this approach was the minimal adverse effects associated with short-term (ie, days to 1–2 weeks) use of high-dose (ie, > 30 mg/d) corticosteroids. Although steroid therapy has been associated with adverse effects such as aseptic necrosis of the hip, these complications usually arise after longer periods (ie, months to years) of high-dose steroid therapy with a mean cumulative dose much higher than what was used in our patient.13

Continue to: Our patient...

Our patient noticed slight improvement within 48 hours of the initial onset of symptoms that continued for the next several weeks until full recovery was attained. An MRI performed 5 days after the onset of symptoms was negative for retrocochlear pathology.

THE TAKEAWAY

SSNHL is a medical emergency that requires prompt recognition and diagnosis. The steps in evaluating sudden hearing loss include: (1) appropriate history and physical examination (eg, otoscopic examination, tuning fork tests), (2) urgent audiometry to confirm hearing loss, (3) immediate referral to an otolaryngologist for further testing (eg, tympanometry, blood tests, MRI), and (4) initiation of treatment.

If a specific etiology is identified (eg, vestibular schwannoma), the patient should be referred to a specialist for appropriate treatment. If there is no identifiable cause (idiopathic SSNHL), the patient should be treated with oral and/or intratympanic steroids. Patients who do not recover following treatment should be offered audiologic rehabilitation.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sergio Huerta, MD, UT Southwestern Medical Center, 4500 S Lancaster Road #112L, Dallas, TX 75216; Sergio.Huerta@UTSouthwestern.edu

1. Schreiber BE, Agrup C, Haskard DO, et al. Sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Lancet. 2010;375:1203-1211.

2. Rauch SD. Clinical practice. Idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:833-840.

3. Paul BC, Roland JT Jr. An abnormal audiogram. JAMA. 2015;313:85-86.

4. Aarnisalo AA, Suoranta H, Ylikoski J. Magnetic resonance imaging findings in the auditory pathway of patients with sudden deafness. Otol Neurotol. 2004;25:245-249.

5. Cadoni G, Cianfoni A, Agostino S, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging findings in sudden sensorineural hearing loss. J Otolaryngol. 2006;35:310-316.

6. Wilson WR, Byl FM, Laird N. The efficacy of steroids in the treatment of idiopathic sudden hearing loss. A double-blind clinical study. Arch Otolaryngol. 1980;106:772-776.

7. Wei BPC, Stathopoulos D, O’Leary S. Steroids for idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003998.pub3.

8. Conlin AE, Parnes LS. Treatment of sudden sensorineural hearing loss: II. a meta-analysis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;133:582-586.

9. Rauch SD, Halpin CF, Antonelli PJ, et al. Oral vs intratympanic corticosteroid therapy for idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2011;305:2071-2079.

10. Lee KH, Ryu SH, Lee HM, et al. Is intratympanic dexamethasone injection effective for the treatment of idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss? J Audiol Otol. 2015;19:154-158.

11. Stachler RJ, Chandrasekhar SS, Archer SM, et al. Clinical practice guideline: sudden hearing loss. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;146(3 suppl):S1-S35.

12. Westerlaken BO, Stokroos RJ, Dhooge IJ, et al. Treatment of idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss with antiviral therapy: a prospective, randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2003;112:993-1000.

13. Nowak DA, Yeung J. Steroid-induced osteonecrosis in dermatology: a review [published online March 30, 2015]. J Cutan Med Surg. 2015;19:358-360.

1. Schreiber BE, Agrup C, Haskard DO, et al. Sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Lancet. 2010;375:1203-1211.

2. Rauch SD. Clinical practice. Idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:833-840.

3. Paul BC, Roland JT Jr. An abnormal audiogram. JAMA. 2015;313:85-86.

4. Aarnisalo AA, Suoranta H, Ylikoski J. Magnetic resonance imaging findings in the auditory pathway of patients with sudden deafness. Otol Neurotol. 2004;25:245-249.

5. Cadoni G, Cianfoni A, Agostino S, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging findings in sudden sensorineural hearing loss. J Otolaryngol. 2006;35:310-316.

6. Wilson WR, Byl FM, Laird N. The efficacy of steroids in the treatment of idiopathic sudden hearing loss. A double-blind clinical study. Arch Otolaryngol. 1980;106:772-776.

7. Wei BPC, Stathopoulos D, O’Leary S. Steroids for idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003998.pub3.

8. Conlin AE, Parnes LS. Treatment of sudden sensorineural hearing loss: II. a meta-analysis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;133:582-586.

9. Rauch SD, Halpin CF, Antonelli PJ, et al. Oral vs intratympanic corticosteroid therapy for idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2011;305:2071-2079.

10. Lee KH, Ryu SH, Lee HM, et al. Is intratympanic dexamethasone injection effective for the treatment of idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss? J Audiol Otol. 2015;19:154-158.

11. Stachler RJ, Chandrasekhar SS, Archer SM, et al. Clinical practice guideline: sudden hearing loss. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;146(3 suppl):S1-S35.

12. Westerlaken BO, Stokroos RJ, Dhooge IJ, et al. Treatment of idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss with antiviral therapy: a prospective, randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2003;112:993-1000.

13. Nowak DA, Yeung J. Steroid-induced osteonecrosis in dermatology: a review [published online March 30, 2015]. J Cutan Med Surg. 2015;19:358-360.

Can unintended pregnancies be reduced by dispensing a year’s worth of hormonal contraception?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2013 systematic review studied the effect of dispensing a larger amount of pills on pregnancy rate, abortion rate, and overall cost to the health care system.1 Three of the 4 studies analyzed found lower rates of pregnancy and abortion, as well as lower cost despite increased pill wastage, in the groups that received more medication. The 1 study that didn’t show a significant difference between groups compared only short durations (1 vs 4 months).

The systematic review included a large retrospective cohort study from 2011 that examined public insurance data from more than 84,000 patients to compare pregnancy rates in women who were given a 1-year supply of oral contraceptives (12 or 13 packs) vs those given 1 or 3 packs at a time.2 The study found pregnancy rates of 2.9%, 3.3%, and 1.2% for 1, 3, and 12 or 13 months, respectively (P < .05; absolute risk reduction [ARR] = 1.7%; number needed to treat [NNT] = 59; relative risk reduction = 41%).

More pills lead to longer use of contraception

The systematic review also included a 2011 trial of 700 women starting oral contraceptives.3 It randomized them to receive a 7- or 3-month supply at their initial visit, then evaluated use of oral contraception at 6 months. All women were invited back for a 3-month follow-up visit, at which time the 3-month supply group would receive additional medication.

Fifty-one percent of the 7-month group were still using oral contraceptives at 6 months compared with 35% of the 3-month group (P < .001; NNT = 7). The contrast was starker for women younger than 18 years (49% vs 12%; NNT = 3). Notably, of the women who stopped using contraception, more in the 3-month group stopped because they ran out of medication (P = .02). Subjects in the 7-month group were more likely to have given birth and more likely to have 2 or more children.

A 2017 case study examined proposed legislation in California that required health plans to cover a 12-month supply of combined hormonal contraceptives.4 The California Health Benefits Review Program surveyed health insurers and reviewed contraception usage patterns. They found that, if the legislation passed, the state could expect a 30% reduction in unintended pregnancy (ARR = 2%; NNT = 50), resulting in 6000 fewer live births and 7000 fewer abortions per year.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use recommend prescribing or providing as much as a 1-year supply of combined hormonal contraceptives at the initial visit and each return visit.5

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) supports over-the-counter access to oral contraceptives, effectively allowing an unlimited supply.6

EDITOR’S TAKEAWAY

Adequate evidence of benefits and strong support from the CDC and ACOG should encourage us to offer 1-year supplies of combined oral contraceptives. Even though the higher-quality studies reviewed also showed a cost savings, up-front patient expense may remain a challenge.

1. Steenland MW, Rodriguez MI, Marchbanks PA, et al. How does the number of oral contraceptive pill packs dispensed or prescribed affect continuation and other measures of consistent and correct use? A systematic review. Contraception. 2013;87:605-610.

2. Foster DG, Hulett D, Bradsberry M, et al. Number of oral contraceptive pill packages dispensed and subsequent unintended pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:566-572.

3. White KO, Westhoff C. The effect of pack supply on oral contraceptive pill continuation: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:615-622.

4. McMenamin SB, Charles SA, Tabatabaeepour N, et al. Implications of dispensing self-administered hormonal contraceptives in a 1-year supply: a California case study. Contraception. 2017;95:449-451.

5. Curtis KM, Jatlaoui TC, Tepper NK, et al. U.S. Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-66.

6. Committee on Gynecologic Practice, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 544: Over-the-counter access to oral contraceptives. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:1527-1531.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2013 systematic review studied the effect of dispensing a larger amount of pills on pregnancy rate, abortion rate, and overall cost to the health care system.1 Three of the 4 studies analyzed found lower rates of pregnancy and abortion, as well as lower cost despite increased pill wastage, in the groups that received more medication. The 1 study that didn’t show a significant difference between groups compared only short durations (1 vs 4 months).

The systematic review included a large retrospective cohort study from 2011 that examined public insurance data from more than 84,000 patients to compare pregnancy rates in women who were given a 1-year supply of oral contraceptives (12 or 13 packs) vs those given 1 or 3 packs at a time.2 The study found pregnancy rates of 2.9%, 3.3%, and 1.2% for 1, 3, and 12 or 13 months, respectively (P < .05; absolute risk reduction [ARR] = 1.7%; number needed to treat [NNT] = 59; relative risk reduction = 41%).

More pills lead to longer use of contraception

The systematic review also included a 2011 trial of 700 women starting oral contraceptives.3 It randomized them to receive a 7- or 3-month supply at their initial visit, then evaluated use of oral contraception at 6 months. All women were invited back for a 3-month follow-up visit, at which time the 3-month supply group would receive additional medication.

Fifty-one percent of the 7-month group were still using oral contraceptives at 6 months compared with 35% of the 3-month group (P < .001; NNT = 7). The contrast was starker for women younger than 18 years (49% vs 12%; NNT = 3). Notably, of the women who stopped using contraception, more in the 3-month group stopped because they ran out of medication (P = .02). Subjects in the 7-month group were more likely to have given birth and more likely to have 2 or more children.

A 2017 case study examined proposed legislation in California that required health plans to cover a 12-month supply of combined hormonal contraceptives.4 The California Health Benefits Review Program surveyed health insurers and reviewed contraception usage patterns. They found that, if the legislation passed, the state could expect a 30% reduction in unintended pregnancy (ARR = 2%; NNT = 50), resulting in 6000 fewer live births and 7000 fewer abortions per year.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use recommend prescribing or providing as much as a 1-year supply of combined hormonal contraceptives at the initial visit and each return visit.5

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) supports over-the-counter access to oral contraceptives, effectively allowing an unlimited supply.6

EDITOR’S TAKEAWAY

Adequate evidence of benefits and strong support from the CDC and ACOG should encourage us to offer 1-year supplies of combined oral contraceptives. Even though the higher-quality studies reviewed also showed a cost savings, up-front patient expense may remain a challenge.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2013 systematic review studied the effect of dispensing a larger amount of pills on pregnancy rate, abortion rate, and overall cost to the health care system.1 Three of the 4 studies analyzed found lower rates of pregnancy and abortion, as well as lower cost despite increased pill wastage, in the groups that received more medication. The 1 study that didn’t show a significant difference between groups compared only short durations (1 vs 4 months).

The systematic review included a large retrospective cohort study from 2011 that examined public insurance data from more than 84,000 patients to compare pregnancy rates in women who were given a 1-year supply of oral contraceptives (12 or 13 packs) vs those given 1 or 3 packs at a time.2 The study found pregnancy rates of 2.9%, 3.3%, and 1.2% for 1, 3, and 12 or 13 months, respectively (P < .05; absolute risk reduction [ARR] = 1.7%; number needed to treat [NNT] = 59; relative risk reduction = 41%).

More pills lead to longer use of contraception

The systematic review also included a 2011 trial of 700 women starting oral contraceptives.3 It randomized them to receive a 7- or 3-month supply at their initial visit, then evaluated use of oral contraception at 6 months. All women were invited back for a 3-month follow-up visit, at which time the 3-month supply group would receive additional medication.

Fifty-one percent of the 7-month group were still using oral contraceptives at 6 months compared with 35% of the 3-month group (P < .001; NNT = 7). The contrast was starker for women younger than 18 years (49% vs 12%; NNT = 3). Notably, of the women who stopped using contraception, more in the 3-month group stopped because they ran out of medication (P = .02). Subjects in the 7-month group were more likely to have given birth and more likely to have 2 or more children.

A 2017 case study examined proposed legislation in California that required health plans to cover a 12-month supply of combined hormonal contraceptives.4 The California Health Benefits Review Program surveyed health insurers and reviewed contraception usage patterns. They found that, if the legislation passed, the state could expect a 30% reduction in unintended pregnancy (ARR = 2%; NNT = 50), resulting in 6000 fewer live births and 7000 fewer abortions per year.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use recommend prescribing or providing as much as a 1-year supply of combined hormonal contraceptives at the initial visit and each return visit.5

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) supports over-the-counter access to oral contraceptives, effectively allowing an unlimited supply.6

EDITOR’S TAKEAWAY

Adequate evidence of benefits and strong support from the CDC and ACOG should encourage us to offer 1-year supplies of combined oral contraceptives. Even though the higher-quality studies reviewed also showed a cost savings, up-front patient expense may remain a challenge.

1. Steenland MW, Rodriguez MI, Marchbanks PA, et al. How does the number of oral contraceptive pill packs dispensed or prescribed affect continuation and other measures of consistent and correct use? A systematic review. Contraception. 2013;87:605-610.

2. Foster DG, Hulett D, Bradsberry M, et al. Number of oral contraceptive pill packages dispensed and subsequent unintended pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:566-572.

3. White KO, Westhoff C. The effect of pack supply on oral contraceptive pill continuation: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:615-622.

4. McMenamin SB, Charles SA, Tabatabaeepour N, et al. Implications of dispensing self-administered hormonal contraceptives in a 1-year supply: a California case study. Contraception. 2017;95:449-451.

5. Curtis KM, Jatlaoui TC, Tepper NK, et al. U.S. Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-66.

6. Committee on Gynecologic Practice, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 544: Over-the-counter access to oral contraceptives. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:1527-1531.

1. Steenland MW, Rodriguez MI, Marchbanks PA, et al. How does the number of oral contraceptive pill packs dispensed or prescribed affect continuation and other measures of consistent and correct use? A systematic review. Contraception. 2013;87:605-610.

2. Foster DG, Hulett D, Bradsberry M, et al. Number of oral contraceptive pill packages dispensed and subsequent unintended pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:566-572.

3. White KO, Westhoff C. The effect of pack supply on oral contraceptive pill continuation: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:615-622.

4. McMenamin SB, Charles SA, Tabatabaeepour N, et al. Implications of dispensing self-administered hormonal contraceptives in a 1-year supply: a California case study. Contraception. 2017;95:449-451.

5. Curtis KM, Jatlaoui TC, Tepper NK, et al. U.S. Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-66.

6. Committee on Gynecologic Practice, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 544: Over-the-counter access to oral contraceptives. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:1527-1531.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Probably, although studies that looked directly at this outcome are limited. A systematic review showed that women who received a larger number of pills at one time were more likely to continue using combined hormonal contraception 7 to 15 months later (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, consistent evidence from 2 cohort studies and 1 randomized, controlled trial), which might be extrapolated to indicate lower unintended pregnancy rates.

One of the large retrospective cohort studies included in the review demonstrated a significantly lower rate of pregnancy among women who received 12 or 13 packs of oral contraceptives at an office visit compared with 1 or 3 packs (SOR: B, large retrospective cohort study).

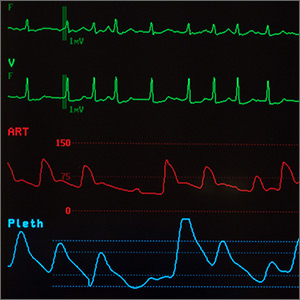

Do A-fib patients continue to benefit from vitamin K antagonists with advancing age?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A meta-analysis of 12 randomized trials of stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation (8932 patients, 63% male, mean age 72 years, 19.6% ≥ 80 years) examined outcomes of ischemic stroke, serious bleeding (systemic or intracranial hemorrhages requiring hospitalization, transfusion, or surgery) and cardiovascular events (ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, systemic emboli, and vascular death).1 Patients were randomized to oral anticoagulants (3430 patients), antiplatelet therapy (3531 patients), or no therapy (1971 patients).

Warfarin target international normalized ratios (INRs) ranged from 1.5 to 4.2. Previous stoke or transient ischemic attack varied across studies but averaged 22% (patient baseline characteristics were evenly distributed among all arms of all 12 studies, suggesting appropriate randomizations). Fifteen percent of patients had diabetes, 50% had hypertension, and 20% had congestive heart failure. They were followed for a mean of 2 years.

Overall, patients experienced 623 ischemic strokes, 289 serious bleeds, and 1210 cardiovascular events. After adjusting for treatment and covariates, age was independently associated with higher risk for each outcome. For every decade increase in age, the hazard ratio (HR) for ischemic stroke was 1.45 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.26-1.66); serious hemorrhage, 1.61 (95% CI, 1.47-1.77); and cardiovascular events, 1.43 (95% CI, 1.33-1.53).

Benefits of warfarin outweigh increased risk of hemorrhage

Treatment with vitamin K antagonists, compared with placebo, reduced ischemic strokes (HR = 0.36; 95% CI, 0.29-0.45) and cardiovascular events (HR = 0.59; 95% CI, 0.52-0.66) but increased the risk of serious hemorrhage (HR = 1.56; 95% CI, 1.03-2.37) in patients from 50 to 90 years of age. The benefits of decreased ischemic strokes and cardiovascular events consistently surpassed the increased risk of hemorrhage, however.

Across all age groups, the absolute risk reductions (ARRs) for ischemic stroke and cardiovascular events were 2% to 3% and 3% to 8%, respectively, whereas the absolute risk increase for serious hemorrhage was 0.5% to 1%. For those ages 70 to 75, for example, warfarin decreased the rate of ischemic stroke by 3% per year (number needed to treat [NNT] = 34; rates estimated from graphs) and the rate of cardiovascular events by 7% (NNT = 14) but increased the risk of serious hemorrhage by approximately 0.5% per year (number need to harm = 200).

Warfarin prevents major strokes more effectively than aspirin

A randomized open-label trial with blind assessment of endpoints, included in the meta-analysis, followed 973 patients older than 75 years (mean 81.5 years) with atrial fibrillation for 2 to 7 years.2 Researchers evaluated warfarin compared with aspirin for the outcomes of major stroke, arterial embolism, and intracranial hemorrhage. Major strokes comprised fatal or disabling strokes. Researchers excluded patients with minor strokes, rheumatic heart disease, a major nontraumatic hemorrhage within the previous 5 years, intracranial hemorrhage, peptic ulcer disease, esophageal varices, or a terminal illness.

Compared with aspirin, warfarin significantly reduced all primary events (ARR = 1.8% vs 3.8%; relative risk reduction [RRR] = 0.48; 95% CI, 0.28-0.80; NNT = 50). Warfarin decreased major strokes more than aspirin (21 vs 44 strokes; ARR = 1.8%; relative risk [RR] = 0.46; 95% CI, 0.26-0.79; NNT = 56) but didn’t alter the risk of hemorrhagic strokes (6 vs 5 absolute events, respectively; RRR = 1.15, 95% CI, 0.29-4.77) or other intracranial hemorrhages (2 vs 1 event, respectively; RR = 1.92; 95% CI, 0.10-113.3). Wide confidence intervals and the small number of hemorrhagic events suggest that the study wasn’t powered to detect a significant difference in hemorrhagic events.

Continue to: Large study finds net benefit for warfarin treatment

Large study finds net benefit for warfarin treatment

A retrospective cohort including all 182,678 Swedish Hospital Discharge Register patients with atrial fibrillation (260,000 patient-years) evaluated the net benefit of anticoagulation treatment decisions over an average of 1.5 years.3 The Swedish National Prescribed Drugs Registry, which includes all Swedish pharmacies, identified all patients who were prescribed warfarin during the study years of July 2005 through December 2008. The patients were divided into 2 groups, warfarin or no warfarin, and assigned risk scores using CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED.4,5

Researchers defined net benefit as the number of ischemic strokes avoided in patients taking warfarin, minus the number of excess intracranial bleeds. They assigned a weight of 1.5 to intracranial bleeds vs 1 for ischemic strokes to compensate for the generally more severe outcomes of intracranial bleeding.

Warfarin produced a net benefit at every CHA2DS2-VASc score greater than 0 (aggregate result of 3.9 fewer events per 100 patient-years; 95% CI, 3.8-4.1; NNT = 26). Kaplan-Meier composite plots of all-cause mortality, ischemic stroke, and intracranial bleeds showed a net benefit favoring warfarin use for all combinations of CHA2DS2-VASc greater than 0 (patients older than 65 years never have a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 0 because they’re assigned 1 point at ages 65 to 74 years and 2 points at 75 years and older) and HAS-BLED scores (all curves P < .00001).

Hazard ratios (HRs) of every combination of scores favored warfarin use (HRs ranged from 0.26-0.72; 95% CIs, less than 1 for all HRs; aggregate benefit at all risk scores: HR = 0.51; 95% CI, 0.50-0.52,). The risk of intracranial bleed, or any bleed, on warfarin at all risk strata was less than the corresponding risk of ischemic stroke (or thromboembolic event) without warfarin except among the lowest risk patients (CHA2DS2-VASc = 0). The difference between thromboses and hemorrhages increased as the CHA2DS2-VASc score increased. Of note, a smaller percentage of the highest risk patients were on warfarin.

EDITOR’S TAKEAWAY

We have solid evidence that, although the risks of systemic and intracranial bleeding from warfarin therapy in older patients with atrial fibrillation increase steadily with advancing age, so do the benefits in reduced ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, thrombotic emboli, and overall cardiovascular death. Most important, the benefits continue to outweigh the risks by a factor of 2 to 4, even in the oldest age groups.

1. van Walraven C, Hart R, et al. Effect of age on stroke prevention therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation. Stroke. 2009;40:1410-1416.

2. Mant J, Hobbs FD. Warfarin versus aspirin for stroke prevention in an elderly community population with atrial fibrillation (the Birmingham Atrial Fibrillation Treatment of the Aged Study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;370:493–503.

3. Friberg L, Rosenqvist M, Lip GY. Net clinical benefit of warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a report from the Swedish atrial fibrillation cohort study. Circulation. 2012;125:2298-2307.

4. Friberg L, Rosenqvist M, Lip G. Evaluation of risk stratification schemes for ischaemic stroke and bleeding in 182,678 patients with atrial fibrillation: the Swedish Atrial Fibrillation cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1500-1510.

5. Pisters R, Lane DA, Nieuwlaat R, et al. A novel user-friendly score (HAS-BLED) to assess 1-year risk of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation: The Euro Heart Survey. Chest. 2010;138:1093-1100.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A meta-analysis of 12 randomized trials of stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation (8932 patients, 63% male, mean age 72 years, 19.6% ≥ 80 years) examined outcomes of ischemic stroke, serious bleeding (systemic or intracranial hemorrhages requiring hospitalization, transfusion, or surgery) and cardiovascular events (ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, systemic emboli, and vascular death).1 Patients were randomized to oral anticoagulants (3430 patients), antiplatelet therapy (3531 patients), or no therapy (1971 patients).

Warfarin target international normalized ratios (INRs) ranged from 1.5 to 4.2. Previous stoke or transient ischemic attack varied across studies but averaged 22% (patient baseline characteristics were evenly distributed among all arms of all 12 studies, suggesting appropriate randomizations). Fifteen percent of patients had diabetes, 50% had hypertension, and 20% had congestive heart failure. They were followed for a mean of 2 years.

Overall, patients experienced 623 ischemic strokes, 289 serious bleeds, and 1210 cardiovascular events. After adjusting for treatment and covariates, age was independently associated with higher risk for each outcome. For every decade increase in age, the hazard ratio (HR) for ischemic stroke was 1.45 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.26-1.66); serious hemorrhage, 1.61 (95% CI, 1.47-1.77); and cardiovascular events, 1.43 (95% CI, 1.33-1.53).

Benefits of warfarin outweigh increased risk of hemorrhage

Treatment with vitamin K antagonists, compared with placebo, reduced ischemic strokes (HR = 0.36; 95% CI, 0.29-0.45) and cardiovascular events (HR = 0.59; 95% CI, 0.52-0.66) but increased the risk of serious hemorrhage (HR = 1.56; 95% CI, 1.03-2.37) in patients from 50 to 90 years of age. The benefits of decreased ischemic strokes and cardiovascular events consistently surpassed the increased risk of hemorrhage, however.

Across all age groups, the absolute risk reductions (ARRs) for ischemic stroke and cardiovascular events were 2% to 3% and 3% to 8%, respectively, whereas the absolute risk increase for serious hemorrhage was 0.5% to 1%. For those ages 70 to 75, for example, warfarin decreased the rate of ischemic stroke by 3% per year (number needed to treat [NNT] = 34; rates estimated from graphs) and the rate of cardiovascular events by 7% (NNT = 14) but increased the risk of serious hemorrhage by approximately 0.5% per year (number need to harm = 200).

Warfarin prevents major strokes more effectively than aspirin

A randomized open-label trial with blind assessment of endpoints, included in the meta-analysis, followed 973 patients older than 75 years (mean 81.5 years) with atrial fibrillation for 2 to 7 years.2 Researchers evaluated warfarin compared with aspirin for the outcomes of major stroke, arterial embolism, and intracranial hemorrhage. Major strokes comprised fatal or disabling strokes. Researchers excluded patients with minor strokes, rheumatic heart disease, a major nontraumatic hemorrhage within the previous 5 years, intracranial hemorrhage, peptic ulcer disease, esophageal varices, or a terminal illness.

Compared with aspirin, warfarin significantly reduced all primary events (ARR = 1.8% vs 3.8%; relative risk reduction [RRR] = 0.48; 95% CI, 0.28-0.80; NNT = 50). Warfarin decreased major strokes more than aspirin (21 vs 44 strokes; ARR = 1.8%; relative risk [RR] = 0.46; 95% CI, 0.26-0.79; NNT = 56) but didn’t alter the risk of hemorrhagic strokes (6 vs 5 absolute events, respectively; RRR = 1.15, 95% CI, 0.29-4.77) or other intracranial hemorrhages (2 vs 1 event, respectively; RR = 1.92; 95% CI, 0.10-113.3). Wide confidence intervals and the small number of hemorrhagic events suggest that the study wasn’t powered to detect a significant difference in hemorrhagic events.

Continue to: Large study finds net benefit for warfarin treatment

Large study finds net benefit for warfarin treatment

A retrospective cohort including all 182,678 Swedish Hospital Discharge Register patients with atrial fibrillation (260,000 patient-years) evaluated the net benefit of anticoagulation treatment decisions over an average of 1.5 years.3 The Swedish National Prescribed Drugs Registry, which includes all Swedish pharmacies, identified all patients who were prescribed warfarin during the study years of July 2005 through December 2008. The patients were divided into 2 groups, warfarin or no warfarin, and assigned risk scores using CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED.4,5

Researchers defined net benefit as the number of ischemic strokes avoided in patients taking warfarin, minus the number of excess intracranial bleeds. They assigned a weight of 1.5 to intracranial bleeds vs 1 for ischemic strokes to compensate for the generally more severe outcomes of intracranial bleeding.

Warfarin produced a net benefit at every CHA2DS2-VASc score greater than 0 (aggregate result of 3.9 fewer events per 100 patient-years; 95% CI, 3.8-4.1; NNT = 26). Kaplan-Meier composite plots of all-cause mortality, ischemic stroke, and intracranial bleeds showed a net benefit favoring warfarin use for all combinations of CHA2DS2-VASc greater than 0 (patients older than 65 years never have a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 0 because they’re assigned 1 point at ages 65 to 74 years and 2 points at 75 years and older) and HAS-BLED scores (all curves P < .00001).

Hazard ratios (HRs) of every combination of scores favored warfarin use (HRs ranged from 0.26-0.72; 95% CIs, less than 1 for all HRs; aggregate benefit at all risk scores: HR = 0.51; 95% CI, 0.50-0.52,). The risk of intracranial bleed, or any bleed, on warfarin at all risk strata was less than the corresponding risk of ischemic stroke (or thromboembolic event) without warfarin except among the lowest risk patients (CHA2DS2-VASc = 0). The difference between thromboses and hemorrhages increased as the CHA2DS2-VASc score increased. Of note, a smaller percentage of the highest risk patients were on warfarin.

EDITOR’S TAKEAWAY

We have solid evidence that, although the risks of systemic and intracranial bleeding from warfarin therapy in older patients with atrial fibrillation increase steadily with advancing age, so do the benefits in reduced ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, thrombotic emboli, and overall cardiovascular death. Most important, the benefits continue to outweigh the risks by a factor of 2 to 4, even in the oldest age groups.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A meta-analysis of 12 randomized trials of stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation (8932 patients, 63% male, mean age 72 years, 19.6% ≥ 80 years) examined outcomes of ischemic stroke, serious bleeding (systemic or intracranial hemorrhages requiring hospitalization, transfusion, or surgery) and cardiovascular events (ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, systemic emboli, and vascular death).1 Patients were randomized to oral anticoagulants (3430 patients), antiplatelet therapy (3531 patients), or no therapy (1971 patients).

Warfarin target international normalized ratios (INRs) ranged from 1.5 to 4.2. Previous stoke or transient ischemic attack varied across studies but averaged 22% (patient baseline characteristics were evenly distributed among all arms of all 12 studies, suggesting appropriate randomizations). Fifteen percent of patients had diabetes, 50% had hypertension, and 20% had congestive heart failure. They were followed for a mean of 2 years.

Overall, patients experienced 623 ischemic strokes, 289 serious bleeds, and 1210 cardiovascular events. After adjusting for treatment and covariates, age was independently associated with higher risk for each outcome. For every decade increase in age, the hazard ratio (HR) for ischemic stroke was 1.45 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.26-1.66); serious hemorrhage, 1.61 (95% CI, 1.47-1.77); and cardiovascular events, 1.43 (95% CI, 1.33-1.53).

Benefits of warfarin outweigh increased risk of hemorrhage

Treatment with vitamin K antagonists, compared with placebo, reduced ischemic strokes (HR = 0.36; 95% CI, 0.29-0.45) and cardiovascular events (HR = 0.59; 95% CI, 0.52-0.66) but increased the risk of serious hemorrhage (HR = 1.56; 95% CI, 1.03-2.37) in patients from 50 to 90 years of age. The benefits of decreased ischemic strokes and cardiovascular events consistently surpassed the increased risk of hemorrhage, however.

Across all age groups, the absolute risk reductions (ARRs) for ischemic stroke and cardiovascular events were 2% to 3% and 3% to 8%, respectively, whereas the absolute risk increase for serious hemorrhage was 0.5% to 1%. For those ages 70 to 75, for example, warfarin decreased the rate of ischemic stroke by 3% per year (number needed to treat [NNT] = 34; rates estimated from graphs) and the rate of cardiovascular events by 7% (NNT = 14) but increased the risk of serious hemorrhage by approximately 0.5% per year (number need to harm = 200).

Warfarin prevents major strokes more effectively than aspirin

A randomized open-label trial with blind assessment of endpoints, included in the meta-analysis, followed 973 patients older than 75 years (mean 81.5 years) with atrial fibrillation for 2 to 7 years.2 Researchers evaluated warfarin compared with aspirin for the outcomes of major stroke, arterial embolism, and intracranial hemorrhage. Major strokes comprised fatal or disabling strokes. Researchers excluded patients with minor strokes, rheumatic heart disease, a major nontraumatic hemorrhage within the previous 5 years, intracranial hemorrhage, peptic ulcer disease, esophageal varices, or a terminal illness.

Compared with aspirin, warfarin significantly reduced all primary events (ARR = 1.8% vs 3.8%; relative risk reduction [RRR] = 0.48; 95% CI, 0.28-0.80; NNT = 50). Warfarin decreased major strokes more than aspirin (21 vs 44 strokes; ARR = 1.8%; relative risk [RR] = 0.46; 95% CI, 0.26-0.79; NNT = 56) but didn’t alter the risk of hemorrhagic strokes (6 vs 5 absolute events, respectively; RRR = 1.15, 95% CI, 0.29-4.77) or other intracranial hemorrhages (2 vs 1 event, respectively; RR = 1.92; 95% CI, 0.10-113.3). Wide confidence intervals and the small number of hemorrhagic events suggest that the study wasn’t powered to detect a significant difference in hemorrhagic events.

Continue to: Large study finds net benefit for warfarin treatment

Large study finds net benefit for warfarin treatment

A retrospective cohort including all 182,678 Swedish Hospital Discharge Register patients with atrial fibrillation (260,000 patient-years) evaluated the net benefit of anticoagulation treatment decisions over an average of 1.5 years.3 The Swedish National Prescribed Drugs Registry, which includes all Swedish pharmacies, identified all patients who were prescribed warfarin during the study years of July 2005 through December 2008. The patients were divided into 2 groups, warfarin or no warfarin, and assigned risk scores using CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED.4,5

Researchers defined net benefit as the number of ischemic strokes avoided in patients taking warfarin, minus the number of excess intracranial bleeds. They assigned a weight of 1.5 to intracranial bleeds vs 1 for ischemic strokes to compensate for the generally more severe outcomes of intracranial bleeding.

Warfarin produced a net benefit at every CHA2DS2-VASc score greater than 0 (aggregate result of 3.9 fewer events per 100 patient-years; 95% CI, 3.8-4.1; NNT = 26). Kaplan-Meier composite plots of all-cause mortality, ischemic stroke, and intracranial bleeds showed a net benefit favoring warfarin use for all combinations of CHA2DS2-VASc greater than 0 (patients older than 65 years never have a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 0 because they’re assigned 1 point at ages 65 to 74 years and 2 points at 75 years and older) and HAS-BLED scores (all curves P < .00001).

Hazard ratios (HRs) of every combination of scores favored warfarin use (HRs ranged from 0.26-0.72; 95% CIs, less than 1 for all HRs; aggregate benefit at all risk scores: HR = 0.51; 95% CI, 0.50-0.52,). The risk of intracranial bleed, or any bleed, on warfarin at all risk strata was less than the corresponding risk of ischemic stroke (or thromboembolic event) without warfarin except among the lowest risk patients (CHA2DS2-VASc = 0). The difference between thromboses and hemorrhages increased as the CHA2DS2-VASc score increased. Of note, a smaller percentage of the highest risk patients were on warfarin.

EDITOR’S TAKEAWAY

We have solid evidence that, although the risks of systemic and intracranial bleeding from warfarin therapy in older patients with atrial fibrillation increase steadily with advancing age, so do the benefits in reduced ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, thrombotic emboli, and overall cardiovascular death. Most important, the benefits continue to outweigh the risks by a factor of 2 to 4, even in the oldest age groups.

1. van Walraven C, Hart R, et al. Effect of age on stroke prevention therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation. Stroke. 2009;40:1410-1416.

2. Mant J, Hobbs FD. Warfarin versus aspirin for stroke prevention in an elderly community population with atrial fibrillation (the Birmingham Atrial Fibrillation Treatment of the Aged Study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;370:493–503.

3. Friberg L, Rosenqvist M, Lip GY. Net clinical benefit of warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a report from the Swedish atrial fibrillation cohort study. Circulation. 2012;125:2298-2307.

4. Friberg L, Rosenqvist M, Lip G. Evaluation of risk stratification schemes for ischaemic stroke and bleeding in 182,678 patients with atrial fibrillation: the Swedish Atrial Fibrillation cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1500-1510.

5. Pisters R, Lane DA, Nieuwlaat R, et al. A novel user-friendly score (HAS-BLED) to assess 1-year risk of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation: The Euro Heart Survey. Chest. 2010;138:1093-1100.

1. van Walraven C, Hart R, et al. Effect of age on stroke prevention therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation. Stroke. 2009;40:1410-1416.

2. Mant J, Hobbs FD. Warfarin versus aspirin for stroke prevention in an elderly community population with atrial fibrillation (the Birmingham Atrial Fibrillation Treatment of the Aged Study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;370:493–503.

3. Friberg L, Rosenqvist M, Lip GY. Net clinical benefit of warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a report from the Swedish atrial fibrillation cohort study. Circulation. 2012;125:2298-2307.

4. Friberg L, Rosenqvist M, Lip G. Evaluation of risk stratification schemes for ischaemic stroke and bleeding in 182,678 patients with atrial fibrillation: the Swedish Atrial Fibrillation cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1500-1510.

5. Pisters R, Lane DA, Nieuwlaat R, et al. A novel user-friendly score (HAS-BLED) to assess 1-year risk of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation: The Euro Heart Survey. Chest. 2010;138:1093-1100.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Yes, patients with atrial fibrilla- tion who are between the ages of 50 and 90 years continue to benefit from vitamin K antagonist therapy (warfarin) (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [RCTs] and large cohorts). Regardless of age, warfarin produces a reduction in risk of thrombotic events that is 2- to 4-fold greater than the risk of hemorrhagic events.

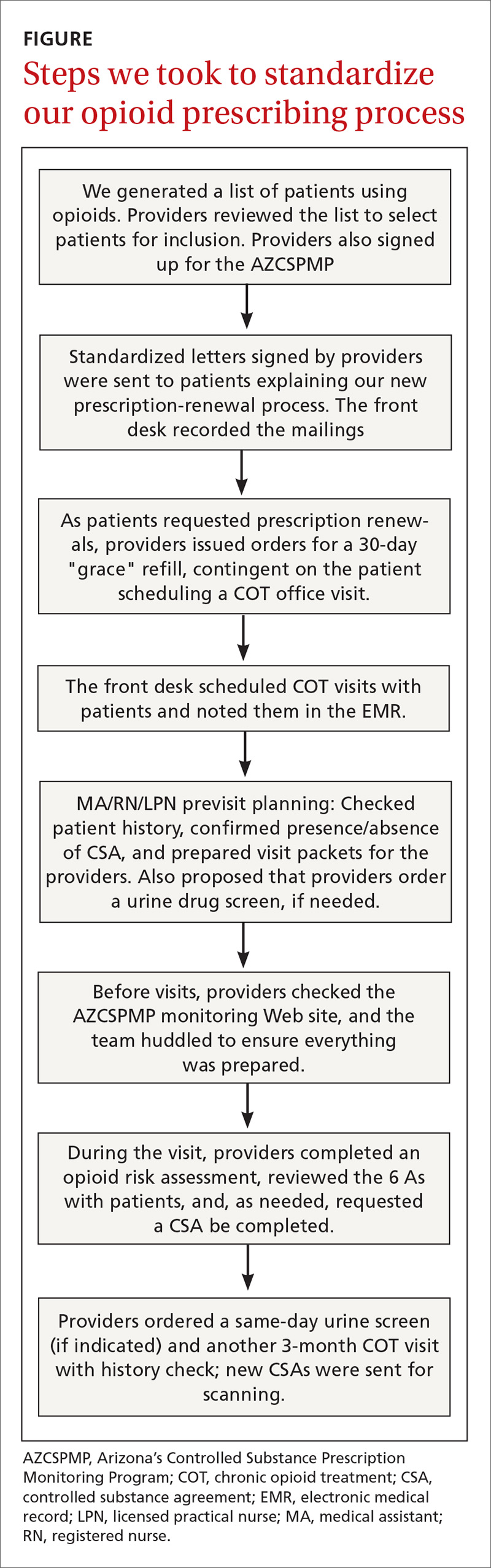

Facial swelling in an adolescent

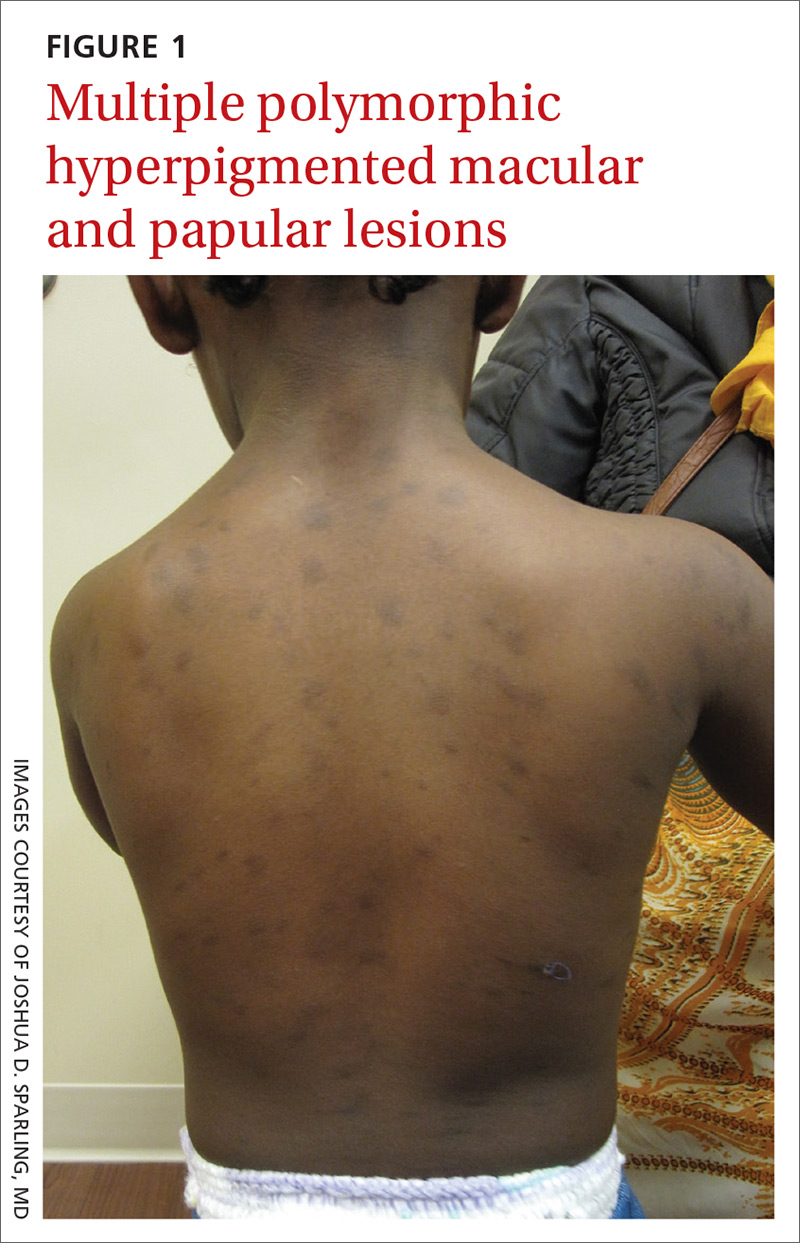

A 16-year-old boy sought care at a rural hospital in Panama for facial swelling that began 3 months earlier. He was seen by a family physician (RU) and a team of medical students who were there as part of a volunteer effort. The patient had difficulty opening his left eye. He denied fever and chills, and said he felt well—other than his inability to see out of his left eye. He denied any changes to his vision when he held the swollen eyelids open. The patient lived on a ranch far outside of town, and he walked down a mountain road alone for 6 hours with one eye swollen shut to present for treatment. The patient was not taking any medications and had not received any health care since his last vaccine several years ago. On physical exam, his vital signs were normal, and the swelling under his left eye was somewhat tender and slightly warm to the touch. There were no lesions on his trunk and the remainder of the exam was normal.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Nodulocystic acne

The family physician (FP) diagnosed severe inflammatory nodulocystic acne in this patient. He initially was concerned about possible cellulitis or an abscess, but his clinical experience suggested the swelling was secondary to severe inflammation and not a bacterial infection. The FP noted that the patient was afebrile and lacked systemic symptoms. In addition, the presence of open and closed comedones on the face, as well as the patient’s age and sex, supported the diagnosis of acne. No tests were performed; the diagnosis was made clinically.

A case of acne, or a bacterial infection?

The FP considered acne conglobata, acne fulminans, and a bacterial infection as other possible causes of the patient’s facial swelling.

Acne conglobata is a form of severe inflammatory cystic acne that affects the face, chest, and back. It is characterized by nodules, cysts, large open comedones, and interconnecting sinuses.1,2 Although this case of acne was severe, the young man did not have large open comedones or interconnecting sinus tracts. In addition, his trunk was unaffected.

Acne fulminans is a type of severe cystic acne with systemic symptoms, which is mainly seen in adolescent males. It may have a sudden onset and is characterized by ulcerated, nodular, and painful acne that bleeds, crusts, and results in severe scarring. Patients may present with fever, joint pain, and weight loss.1,2 Our patient did not have systemic symptoms despite the severe facial swelling.

Bacterial infections of the skin usually are caused by Staphylococcus aureus (S aureus) or Streptococcus pyogenes and can lead to cellulitis and/or abscess formation.3 This process was considered as a complication of the severe acne, but the clinical picture was consistent with severe inflammation rather than a bacterial superinfection.

Continue to: Treatment of choice includes prednisone and doxycycline

Treatment of choice includes prednisone and doxycycline

The FP knew that the severe inflammation and swelling needed to be treated with a systemic steroid, so he started the patient on prednisone 60 mg orally once daily at the time of presentation. Additionally, the FP prescribed doxycycline 100 mg bid to treat the inflammation and to cover a possible superinfection.

Doxycycline is the oral antibiotic of choice for inflammatory acne.2 It also is a good antibiotic for cutaneous methicillin-resistant S aureus infection.3 Although it is not the treatment of choice for a nonpurulent cellulitis, it is a good option for cellulitis with purulence.3

With the working diagnosis of severe inflammatory acne, it was expected that the prednisone and doxycycline would be effective. Treating with antibiotics alone (for fear of causing immunosuppression with steroids) would have likely been less effective. Since the patient lived 6 hours from the hospital by foot and was alone, he was admitted overnight for observation (with parental permission obtained over the phone).

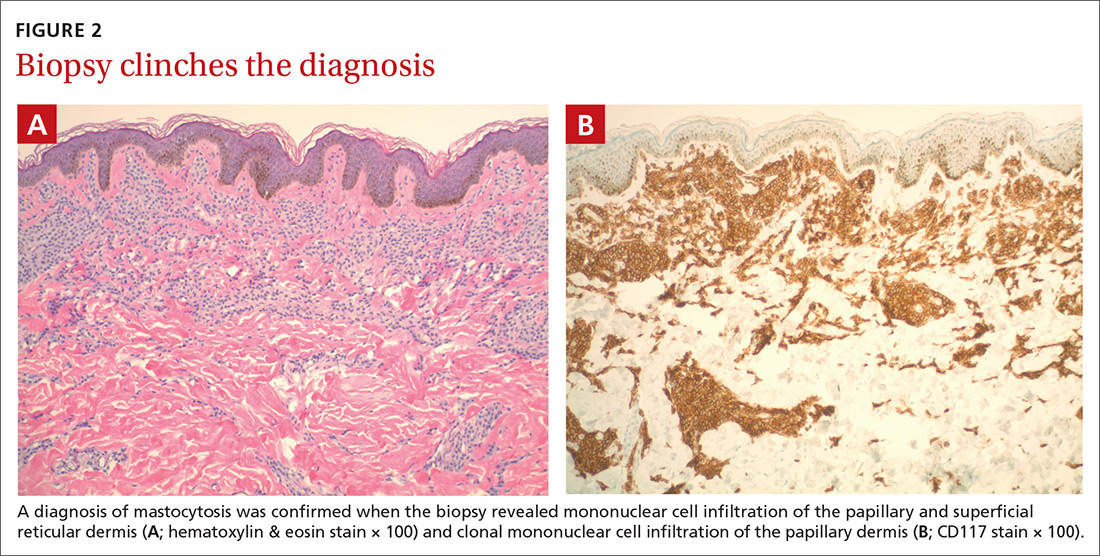

The patient’s condition improved overnight. Marked improvement in the swelling and inflammation was noted the following morning (FIGURES 2A and 2B). The patient was pleased with the results and was discharged to return home (transportation provided by the hospital) with directions on how to continue the oral prednisone and doxycycline. He was given 1 month of doxycycline to continue (100 mg bid) and enough oral prednisone to take 40 mg/d for 1 week and 20 mg/d for another week. He was given a follow-up appointment for 2 weeks to assess his acne and his ability to tolerate the medications.

He was warned to avoid the sun as much as possible, as doxycycline is photosensitizing, and to use a large hat and sunscreen when the sun could not be avoided. (Another option would have been to prescribe minocycline 100 mg bid because it is equally effective for acne with a lower risk for photosensitization.2)

Continue to: Access to medical care was limited

Access to medical care was limited. Although this patient was a good candidate for oral isotretinoin treatment, he did not have access to this medication in rural Panama. Managing his acne was challenging because of the severity of the case and the patient’s sun exposure in this tropical country. Access to the full range of topical anti-acne treatments also is limited in rural Panama, but fortunately his response to the initial oral medications was good.

The future plan at the follow-up visit consisted of continuing the doxycycline, stopping the prednisone, and adding topical benzoyl peroxide. The purpose of the benzoyl peroxide was to prevent bacterial resistance to the antibiotic.2

CORRESPONDENCE

Richard Usatine, MD, Skin Clinic, 903 W Martin Ave, Historic Building, San Antonio, TX 78207; usatine@uthscsa.edu