User login

A longing for belonging

As I watched my grandson and his team warm up for their Saturday morning lacrosse game, a long parade of mostly purple-shirted adults and children of all ages began to weave its way around the periphery of the athletic field complex. A quick reading of the hand-lettered and machine-printed shirts made it clear that I was watching a charity walk for cystic fibrosis. There must have been several hundred walkers strolling by, laughing and chatting with one another. It lent a festive atmosphere to the park. I suspect that for most of the participants this was not their first fundraising event for cystic fibrosis.

The motley mix of marchers probably included several handfuls of parents of children with cystic fibrosis. I wonder how many of those parents realized how fortunate they were. Cystic fibrosis isn’t a great diagnosis. But at least it is a diagnosis, and with the diagnosis comes a community.

Reading a front-page article on DNA testing in a recent Wall Street Journal issue had primed me to reconsider how even an unfortunate diagnosis can be extremely valuable for a family (“The Unfulfilled Promise of DNA Testing,” by Amy Dockser Marcus, May 18, 2019).The focus of the article was on the confusion and disappointment that are the predictable consequences of our current inability to accurately correlate genetic code “mistakes” with phenotypic abnormalities. Of course there have been a few successes, but we aren’t even close to the promise that many have predicted in the wake of sequencing the human genome. The family featured in the article has a ridden roller coaster ride through two failed attributions of genetic syndromes that appeared to provide their now 8-year-old daughter with a diagnosis for her epilepsy and developmental delay.

In each case, the mother had searched out other families with children who shared the same genetic code errors. She formed support groups and created foundations to promote research for these rare disorders only to learn that her daughter didn’t really fit into the phenotype exhibited by the other children. As the article indicates this mother had “found a genetic home, only to feel that she no longer belonged.” She had made “intense friendships” and for “2 years, the community was her main emotional support.” Since the second diagnosis has evaporated, she has struggled with whether to remain with that community, having already left one behind. She has been encouraged to stay involved by another mother whose son does have the diagnosis. Understandably, she is still seeking the correct diagnosis, and I suspect will form or join a new community when she finds it.

We all want to belong to a community. And with that ticket comes the opportunity to share the frustrations and difficulties unique to children with that diagnosis, and the comfort that there are other people who look, behave, and feel the way we do. We hear repeatedly about the value of diversity and how wonderful it is to be all inclusive. And certainly we should continue to be as accepting as we can of people who are different. But the truth is that we will always fall short because we seem to be hardwired to notice what is different. And the power of the longing to belong is often stronger than our will to be inclusive.

The revolution that resulted in the disappearance of the label “mental retardation” and the widespread adoption of the diagnosis of autism are examples of how a community can form around a diagnosis. But not every child who is labeled as autistic will actually fit the diagnosis. Yet even a less-than-perfect attribution can provide a place where a family and a patient can feel that they belong.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

As I watched my grandson and his team warm up for their Saturday morning lacrosse game, a long parade of mostly purple-shirted adults and children of all ages began to weave its way around the periphery of the athletic field complex. A quick reading of the hand-lettered and machine-printed shirts made it clear that I was watching a charity walk for cystic fibrosis. There must have been several hundred walkers strolling by, laughing and chatting with one another. It lent a festive atmosphere to the park. I suspect that for most of the participants this was not their first fundraising event for cystic fibrosis.

The motley mix of marchers probably included several handfuls of parents of children with cystic fibrosis. I wonder how many of those parents realized how fortunate they were. Cystic fibrosis isn’t a great diagnosis. But at least it is a diagnosis, and with the diagnosis comes a community.

Reading a front-page article on DNA testing in a recent Wall Street Journal issue had primed me to reconsider how even an unfortunate diagnosis can be extremely valuable for a family (“The Unfulfilled Promise of DNA Testing,” by Amy Dockser Marcus, May 18, 2019).The focus of the article was on the confusion and disappointment that are the predictable consequences of our current inability to accurately correlate genetic code “mistakes” with phenotypic abnormalities. Of course there have been a few successes, but we aren’t even close to the promise that many have predicted in the wake of sequencing the human genome. The family featured in the article has a ridden roller coaster ride through two failed attributions of genetic syndromes that appeared to provide their now 8-year-old daughter with a diagnosis for her epilepsy and developmental delay.

In each case, the mother had searched out other families with children who shared the same genetic code errors. She formed support groups and created foundations to promote research for these rare disorders only to learn that her daughter didn’t really fit into the phenotype exhibited by the other children. As the article indicates this mother had “found a genetic home, only to feel that she no longer belonged.” She had made “intense friendships” and for “2 years, the community was her main emotional support.” Since the second diagnosis has evaporated, she has struggled with whether to remain with that community, having already left one behind. She has been encouraged to stay involved by another mother whose son does have the diagnosis. Understandably, she is still seeking the correct diagnosis, and I suspect will form or join a new community when she finds it.

We all want to belong to a community. And with that ticket comes the opportunity to share the frustrations and difficulties unique to children with that diagnosis, and the comfort that there are other people who look, behave, and feel the way we do. We hear repeatedly about the value of diversity and how wonderful it is to be all inclusive. And certainly we should continue to be as accepting as we can of people who are different. But the truth is that we will always fall short because we seem to be hardwired to notice what is different. And the power of the longing to belong is often stronger than our will to be inclusive.

The revolution that resulted in the disappearance of the label “mental retardation” and the widespread adoption of the diagnosis of autism are examples of how a community can form around a diagnosis. But not every child who is labeled as autistic will actually fit the diagnosis. Yet even a less-than-perfect attribution can provide a place where a family and a patient can feel that they belong.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

As I watched my grandson and his team warm up for their Saturday morning lacrosse game, a long parade of mostly purple-shirted adults and children of all ages began to weave its way around the periphery of the athletic field complex. A quick reading of the hand-lettered and machine-printed shirts made it clear that I was watching a charity walk for cystic fibrosis. There must have been several hundred walkers strolling by, laughing and chatting with one another. It lent a festive atmosphere to the park. I suspect that for most of the participants this was not their first fundraising event for cystic fibrosis.

The motley mix of marchers probably included several handfuls of parents of children with cystic fibrosis. I wonder how many of those parents realized how fortunate they were. Cystic fibrosis isn’t a great diagnosis. But at least it is a diagnosis, and with the diagnosis comes a community.

Reading a front-page article on DNA testing in a recent Wall Street Journal issue had primed me to reconsider how even an unfortunate diagnosis can be extremely valuable for a family (“The Unfulfilled Promise of DNA Testing,” by Amy Dockser Marcus, May 18, 2019).The focus of the article was on the confusion and disappointment that are the predictable consequences of our current inability to accurately correlate genetic code “mistakes” with phenotypic abnormalities. Of course there have been a few successes, but we aren’t even close to the promise that many have predicted in the wake of sequencing the human genome. The family featured in the article has a ridden roller coaster ride through two failed attributions of genetic syndromes that appeared to provide their now 8-year-old daughter with a diagnosis for her epilepsy and developmental delay.

In each case, the mother had searched out other families with children who shared the same genetic code errors. She formed support groups and created foundations to promote research for these rare disorders only to learn that her daughter didn’t really fit into the phenotype exhibited by the other children. As the article indicates this mother had “found a genetic home, only to feel that she no longer belonged.” She had made “intense friendships” and for “2 years, the community was her main emotional support.” Since the second diagnosis has evaporated, she has struggled with whether to remain with that community, having already left one behind. She has been encouraged to stay involved by another mother whose son does have the diagnosis. Understandably, she is still seeking the correct diagnosis, and I suspect will form or join a new community when she finds it.

We all want to belong to a community. And with that ticket comes the opportunity to share the frustrations and difficulties unique to children with that diagnosis, and the comfort that there are other people who look, behave, and feel the way we do. We hear repeatedly about the value of diversity and how wonderful it is to be all inclusive. And certainly we should continue to be as accepting as we can of people who are different. But the truth is that we will always fall short because we seem to be hardwired to notice what is different. And the power of the longing to belong is often stronger than our will to be inclusive.

The revolution that resulted in the disappearance of the label “mental retardation” and the widespread adoption of the diagnosis of autism are examples of how a community can form around a diagnosis. But not every child who is labeled as autistic will actually fit the diagnosis. Yet even a less-than-perfect attribution can provide a place where a family and a patient can feel that they belong.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

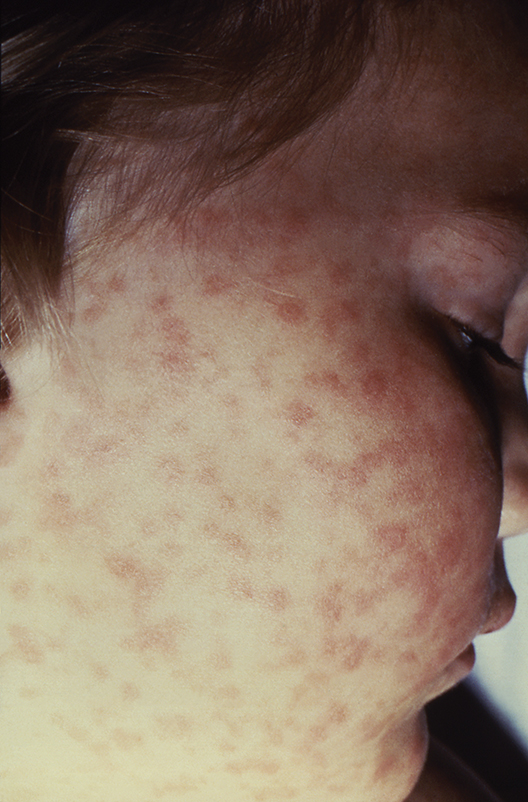

CDC creates interactive education module to improve RMSF recognition

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has created a first-of-its-kind interactive training module to help physicians both recognize and diagnose Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF).

A record number of cases of RMSF were reported to the CDC in 2017 (6,248, up from 4,269 in 2016), but less than 1% of those cases had sufficient laboratory evidence to be confirmed. The CDC education module includes scenarios based on real cases to aid providers in recognizing RMSF and differentiating it from similar diseases. CME is available for physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, veterinarians, nurses, epidemiologists, public health professionals, educators, and health communicators.

The disease initially presents with nonspecific symptoms such as fever, headache, or rash, but if left untreated, patients may require the amputation of fingers, toes, or limbs because of low blood flow; heart and lung specialty care; and ICU management. About 20% of untreated cases are fatal; half of these deaths occur within 8 days of initial presentation.

“Rocky Mountain spotted fever can be deadly if not treated early – yet cases often go unrecognized because the signs and symptoms are similar to those of many other diseases. With tickborne diseases on the rise in the U.S., this training will better equip health care providers to identify, diagnose, and treat this potentially fatal disease,” said CDC director Robert R. Redfield, MD.

Find the full press release on the CDC website.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has created a first-of-its-kind interactive training module to help physicians both recognize and diagnose Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF).

A record number of cases of RMSF were reported to the CDC in 2017 (6,248, up from 4,269 in 2016), but less than 1% of those cases had sufficient laboratory evidence to be confirmed. The CDC education module includes scenarios based on real cases to aid providers in recognizing RMSF and differentiating it from similar diseases. CME is available for physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, veterinarians, nurses, epidemiologists, public health professionals, educators, and health communicators.

The disease initially presents with nonspecific symptoms such as fever, headache, or rash, but if left untreated, patients may require the amputation of fingers, toes, or limbs because of low blood flow; heart and lung specialty care; and ICU management. About 20% of untreated cases are fatal; half of these deaths occur within 8 days of initial presentation.

“Rocky Mountain spotted fever can be deadly if not treated early – yet cases often go unrecognized because the signs and symptoms are similar to those of many other diseases. With tickborne diseases on the rise in the U.S., this training will better equip health care providers to identify, diagnose, and treat this potentially fatal disease,” said CDC director Robert R. Redfield, MD.

Find the full press release on the CDC website.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has created a first-of-its-kind interactive training module to help physicians both recognize and diagnose Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF).

A record number of cases of RMSF were reported to the CDC in 2017 (6,248, up from 4,269 in 2016), but less than 1% of those cases had sufficient laboratory evidence to be confirmed. The CDC education module includes scenarios based on real cases to aid providers in recognizing RMSF and differentiating it from similar diseases. CME is available for physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, veterinarians, nurses, epidemiologists, public health professionals, educators, and health communicators.

The disease initially presents with nonspecific symptoms such as fever, headache, or rash, but if left untreated, patients may require the amputation of fingers, toes, or limbs because of low blood flow; heart and lung specialty care; and ICU management. About 20% of untreated cases are fatal; half of these deaths occur within 8 days of initial presentation.

“Rocky Mountain spotted fever can be deadly if not treated early – yet cases often go unrecognized because the signs and symptoms are similar to those of many other diseases. With tickborne diseases on the rise in the U.S., this training will better equip health care providers to identify, diagnose, and treat this potentially fatal disease,” said CDC director Robert R. Redfield, MD.

Find the full press release on the CDC website.

Trial matches pediatric cancer patients to targeted therapies

Researchers have found they can screen pediatric cancer patients for genetic alterations and match those patients to appropriate targeted therapies.

Thus far, 24% of the patients screened have been matched and assigned to a treatment, and 10% have been enrolled on treatment protocols.

The patients were screened and matched as part of the National Cancer Institute–Children’s Oncology Group Pediatric MATCH (Molecular Analysis for Therapy Choice) trial.

Results from this trial are scheduled to be presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Donald Williams Parsons, MD, PhD, of Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Tex., presented some results at a press briefing in advance of the meeting. “[T]he last 10 years have been an incredible time in terms of learning more about the genetics and underlying molecular basis of both adult and pediatric cancers,” Dr. Parsons said.

He pointed out, however, that it is not yet known if this information will be useful in guiding the treatment of pediatric cancers. Specifically, how many pediatric patients can be matched to targeted therapies, and how effective will those therapies be?

The Pediatric MATCH trial (NCT03155620) was developed to answer these questions. Researchers plan to enroll at least 1,000 patients in this trial. Patients are eligible if they are 1-21 years of age and have refractory or recurrent solid tumors, non-Hodgkin lymphomas, or histiocytic disorders.

After patients are enrolled in the trial, their tumor samples undergo DNA and RNA sequencing, and the results are used to match each patient to a targeted therapy. At present, the trial can match patients to one of 10 drugs:

- larotrectinib (targeting NTRK fusions).

- erdafitinib (targeting FGFR1/2/3/4).

- tazemetostat (targeting EZH2 or members of the SWI/SNF complex).

- LY3023414 (targeting the PI3K/MTOR pathway).

- selumetinib (targeting the MAPK pathway).

- ensartinib (targeting ALK or ROS1).

- vemurafenib (targeting BRAF V600 mutations).

- olaparib (targeting defects in DNA damage repair).

- palbociclib (targeting alterations in cell cycle genes).

- ulixertinib (targeting MAPK pathway mutations).

Early results

From July 2017 through December 2018, 422 patients were enrolled in the trial. The patients had more than 60 different diagnoses, including brain tumors, sarcomas, neuroblastoma, renal and liver cancers, and other malignancies.

The researchers received tumor samples from 390 patients, attempted sequencing of 370 samples (95%), and completed sequencing of 357 samples (92%).

A treatment target was found in 112 (29%) patients, 95 (24%) of those patients were assigned to a treatment, and 39 (10%) were enrolled in a protocol. The median turnaround time from sample receipt to treatment assignment was 15 days.

“In addition to the sequencing being successful, the patients are being matched to the different treatments,” Dr. Parsons said. He added that the study is ongoing, so more of the matched and assigned patients will be enrolled in protocols in the future.

Dr. Parsons also presented results by tumor type. A targetable alteration was identified in 26% (67/255) of all non–central nervous system solid tumors, 13% (10/75) of osteosarcomas, 50% (18/36) of rhabdomyosarcomas, 21% (7/33) of Ewing sarcomas, 25% (9/36) of other sarcomas, 19% (5/26) of renal cancers, 16% (3/19) of carcinomas, 44% (8/18) of neuroblastomas, 43% (3/7) of liver cancers, and 29% (4/14) of “other” tumors.

Drilling down further, Dr. Parsons presented details on specific alterations in one cancer type: astrocytomas. Targetable alterations were found in 74% (29/39) of astrocytomas. This includes NF1 mutations (18%), BRAF V600E (15%), FGFR1 fusions/mutations (10%), BRAF fusions (10%), PIK3CA mutations (8%), NRAS/KRAS mutations (5%), and other alterations.

“Pretty remarkably, in this one diagnosis, there are patients who have been matched to nine of the ten different treatment arms,” Dr. Parsons said. “This study is allowing us to evaluate targeted therapies – specific types of investigational drugs – in patients with many different cancer types, some common, some very rare. So, hopefully, we can study these agents and identify signals of activity where some of these drugs may work for our patients.”

The Pediatric MATCH trial is sponsored by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Parsons has patents, royalties, and other intellectual property related to genes discovered through sequencing of several adult cancer types.

SOURCE: Parsons DW et al. ASCO 2019, Abstract 10011.

Researchers have found they can screen pediatric cancer patients for genetic alterations and match those patients to appropriate targeted therapies.

Thus far, 24% of the patients screened have been matched and assigned to a treatment, and 10% have been enrolled on treatment protocols.

The patients were screened and matched as part of the National Cancer Institute–Children’s Oncology Group Pediatric MATCH (Molecular Analysis for Therapy Choice) trial.

Results from this trial are scheduled to be presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Donald Williams Parsons, MD, PhD, of Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Tex., presented some results at a press briefing in advance of the meeting. “[T]he last 10 years have been an incredible time in terms of learning more about the genetics and underlying molecular basis of both adult and pediatric cancers,” Dr. Parsons said.

He pointed out, however, that it is not yet known if this information will be useful in guiding the treatment of pediatric cancers. Specifically, how many pediatric patients can be matched to targeted therapies, and how effective will those therapies be?

The Pediatric MATCH trial (NCT03155620) was developed to answer these questions. Researchers plan to enroll at least 1,000 patients in this trial. Patients are eligible if they are 1-21 years of age and have refractory or recurrent solid tumors, non-Hodgkin lymphomas, or histiocytic disorders.

After patients are enrolled in the trial, their tumor samples undergo DNA and RNA sequencing, and the results are used to match each patient to a targeted therapy. At present, the trial can match patients to one of 10 drugs:

- larotrectinib (targeting NTRK fusions).

- erdafitinib (targeting FGFR1/2/3/4).

- tazemetostat (targeting EZH2 or members of the SWI/SNF complex).

- LY3023414 (targeting the PI3K/MTOR pathway).

- selumetinib (targeting the MAPK pathway).

- ensartinib (targeting ALK or ROS1).

- vemurafenib (targeting BRAF V600 mutations).

- olaparib (targeting defects in DNA damage repair).

- palbociclib (targeting alterations in cell cycle genes).

- ulixertinib (targeting MAPK pathway mutations).

Early results

From July 2017 through December 2018, 422 patients were enrolled in the trial. The patients had more than 60 different diagnoses, including brain tumors, sarcomas, neuroblastoma, renal and liver cancers, and other malignancies.

The researchers received tumor samples from 390 patients, attempted sequencing of 370 samples (95%), and completed sequencing of 357 samples (92%).

A treatment target was found in 112 (29%) patients, 95 (24%) of those patients were assigned to a treatment, and 39 (10%) were enrolled in a protocol. The median turnaround time from sample receipt to treatment assignment was 15 days.

“In addition to the sequencing being successful, the patients are being matched to the different treatments,” Dr. Parsons said. He added that the study is ongoing, so more of the matched and assigned patients will be enrolled in protocols in the future.

Dr. Parsons also presented results by tumor type. A targetable alteration was identified in 26% (67/255) of all non–central nervous system solid tumors, 13% (10/75) of osteosarcomas, 50% (18/36) of rhabdomyosarcomas, 21% (7/33) of Ewing sarcomas, 25% (9/36) of other sarcomas, 19% (5/26) of renal cancers, 16% (3/19) of carcinomas, 44% (8/18) of neuroblastomas, 43% (3/7) of liver cancers, and 29% (4/14) of “other” tumors.

Drilling down further, Dr. Parsons presented details on specific alterations in one cancer type: astrocytomas. Targetable alterations were found in 74% (29/39) of astrocytomas. This includes NF1 mutations (18%), BRAF V600E (15%), FGFR1 fusions/mutations (10%), BRAF fusions (10%), PIK3CA mutations (8%), NRAS/KRAS mutations (5%), and other alterations.

“Pretty remarkably, in this one diagnosis, there are patients who have been matched to nine of the ten different treatment arms,” Dr. Parsons said. “This study is allowing us to evaluate targeted therapies – specific types of investigational drugs – in patients with many different cancer types, some common, some very rare. So, hopefully, we can study these agents and identify signals of activity where some of these drugs may work for our patients.”

The Pediatric MATCH trial is sponsored by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Parsons has patents, royalties, and other intellectual property related to genes discovered through sequencing of several adult cancer types.

SOURCE: Parsons DW et al. ASCO 2019, Abstract 10011.

Researchers have found they can screen pediatric cancer patients for genetic alterations and match those patients to appropriate targeted therapies.

Thus far, 24% of the patients screened have been matched and assigned to a treatment, and 10% have been enrolled on treatment protocols.

The patients were screened and matched as part of the National Cancer Institute–Children’s Oncology Group Pediatric MATCH (Molecular Analysis for Therapy Choice) trial.

Results from this trial are scheduled to be presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Donald Williams Parsons, MD, PhD, of Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Tex., presented some results at a press briefing in advance of the meeting. “[T]he last 10 years have been an incredible time in terms of learning more about the genetics and underlying molecular basis of both adult and pediatric cancers,” Dr. Parsons said.

He pointed out, however, that it is not yet known if this information will be useful in guiding the treatment of pediatric cancers. Specifically, how many pediatric patients can be matched to targeted therapies, and how effective will those therapies be?

The Pediatric MATCH trial (NCT03155620) was developed to answer these questions. Researchers plan to enroll at least 1,000 patients in this trial. Patients are eligible if they are 1-21 years of age and have refractory or recurrent solid tumors, non-Hodgkin lymphomas, or histiocytic disorders.

After patients are enrolled in the trial, their tumor samples undergo DNA and RNA sequencing, and the results are used to match each patient to a targeted therapy. At present, the trial can match patients to one of 10 drugs:

- larotrectinib (targeting NTRK fusions).

- erdafitinib (targeting FGFR1/2/3/4).

- tazemetostat (targeting EZH2 or members of the SWI/SNF complex).

- LY3023414 (targeting the PI3K/MTOR pathway).

- selumetinib (targeting the MAPK pathway).

- ensartinib (targeting ALK or ROS1).

- vemurafenib (targeting BRAF V600 mutations).

- olaparib (targeting defects in DNA damage repair).

- palbociclib (targeting alterations in cell cycle genes).

- ulixertinib (targeting MAPK pathway mutations).

Early results

From July 2017 through December 2018, 422 patients were enrolled in the trial. The patients had more than 60 different diagnoses, including brain tumors, sarcomas, neuroblastoma, renal and liver cancers, and other malignancies.

The researchers received tumor samples from 390 patients, attempted sequencing of 370 samples (95%), and completed sequencing of 357 samples (92%).

A treatment target was found in 112 (29%) patients, 95 (24%) of those patients were assigned to a treatment, and 39 (10%) were enrolled in a protocol. The median turnaround time from sample receipt to treatment assignment was 15 days.

“In addition to the sequencing being successful, the patients are being matched to the different treatments,” Dr. Parsons said. He added that the study is ongoing, so more of the matched and assigned patients will be enrolled in protocols in the future.

Dr. Parsons also presented results by tumor type. A targetable alteration was identified in 26% (67/255) of all non–central nervous system solid tumors, 13% (10/75) of osteosarcomas, 50% (18/36) of rhabdomyosarcomas, 21% (7/33) of Ewing sarcomas, 25% (9/36) of other sarcomas, 19% (5/26) of renal cancers, 16% (3/19) of carcinomas, 44% (8/18) of neuroblastomas, 43% (3/7) of liver cancers, and 29% (4/14) of “other” tumors.

Drilling down further, Dr. Parsons presented details on specific alterations in one cancer type: astrocytomas. Targetable alterations were found in 74% (29/39) of astrocytomas. This includes NF1 mutations (18%), BRAF V600E (15%), FGFR1 fusions/mutations (10%), BRAF fusions (10%), PIK3CA mutations (8%), NRAS/KRAS mutations (5%), and other alterations.

“Pretty remarkably, in this one diagnosis, there are patients who have been matched to nine of the ten different treatment arms,” Dr. Parsons said. “This study is allowing us to evaluate targeted therapies – specific types of investigational drugs – in patients with many different cancer types, some common, some very rare. So, hopefully, we can study these agents and identify signals of activity where some of these drugs may work for our patients.”

The Pediatric MATCH trial is sponsored by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Parsons has patents, royalties, and other intellectual property related to genes discovered through sequencing of several adult cancer types.

SOURCE: Parsons DW et al. ASCO 2019, Abstract 10011.

REPORTING FROM ASCO 2019

Proinflammatory diets up rheumatoid arthritis risk

BIRMINGHAM, ENGLAND – Proinflammatory diets are associated with increased C-reactive protein (CRP) and subsequent rheumatoid arthritis (RA), according to combined data from the European Prospective Investigation of Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) and Norfolk Arthritis Register (NOAR).

“There has always been a debate around this topic,” Max Yates, MBBS, PhD, said at the annual conference of the British Society for Rheumatology. “A quick online search will reveal a plethora of texts claiming to give definitive or the best advice for arthritis” and diet, he said, often from “questionable experts.”

“I think we’re all interested in diet,” observed Dr. Yates, of the University of East Anglia in Norwich (England), and “although the association between diet and arthritis is open to debate, previous studies have shown an association with those who have a lower intake of vitamin C and fiber.” The problem is one of credibility, he noted, so this was something that the NOAR investigators decided to look into with data from the Dietary Inflammatory Index (DII) collected from the EPIC cohort.

The DII is a literature-based, population-derived tool that has been used to determine the inflammatory potential of diet, Dr. Yates explained. Data show that inflammatory diets are is associated with increased levels of inflammatory markers including C-reactive protein (CRP) and interleukin (IL)-6. These diets include items such as trans and saturated fats, and fats from animal protein versus more anti-inflammatory items such as black tea, thyme, turmeric, and saffron.

“We are fortunate that NOAR is in the same geographic location as EPIC,” Dr. Yates said, and the two cohorts have been running alongside each other since the early 1990s. While NOAR has been collecting data on incident inflammatory polyarthritis since 1989, EPIC has been “intensively” collecting information on dietary and lifestyle factors and blood samples from its participants since 1993.

EPIC investigators have been “trailblazers” in recording of dietary data, Dr. Yates said. First using paper-based questionnaires and now smartphone apps that allow people to upload photos of what they are eating. Data are linked to both primary care practice and hospital records.

For the present study, data on 159 patients who participated in both NOAR and EPIC were used. Participants had RA according to the 2010 American College of Rheumatology criteria and had an average disease onset of 7 years after enrollment into NOAR and EPIC.

“Quite pleasingly, the dietary inflammatory index scores were associated with high-sensitivity CRP taken at baseline enrollment in 1993 to 1997, further validating the index again within another population,” Dr. Yates said.

Results showed that there was a significant association between the baseline DII score and subsequent development of RA, with an odds ratio of 1.90 comparing individuals with the highest and lowest DII scores (P less than .01).

When cases were matched by age, sex, and body mass index, however, there was only a trend for an association between inflammatory diets and RA onset. “We hope to identify more patients within EPIC to strengthen this association,” Dr. Yates said.

The results are consistent with data from the Nurses’ Health Study, Dr. Yates noted, adding that future research is needed to address whether dietary modification can demonstrate causality.

“Diet is one of the modifiable risk factors that we can use to tackle RA, and I think it’s about time we as a community take over this area and gave definitive advice.”

Dr. Yates presented the work on behalf of PhD student Ellie Sayer. Neither Dr. Yates nor Ms. Sayer had any conflicts of interests to disclose.

SOURCE: Sayer E et al. Rheumatology. 2019;58(suppl 3), Abstract 014.

BIRMINGHAM, ENGLAND – Proinflammatory diets are associated with increased C-reactive protein (CRP) and subsequent rheumatoid arthritis (RA), according to combined data from the European Prospective Investigation of Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) and Norfolk Arthritis Register (NOAR).

“There has always been a debate around this topic,” Max Yates, MBBS, PhD, said at the annual conference of the British Society for Rheumatology. “A quick online search will reveal a plethora of texts claiming to give definitive or the best advice for arthritis” and diet, he said, often from “questionable experts.”

“I think we’re all interested in diet,” observed Dr. Yates, of the University of East Anglia in Norwich (England), and “although the association between diet and arthritis is open to debate, previous studies have shown an association with those who have a lower intake of vitamin C and fiber.” The problem is one of credibility, he noted, so this was something that the NOAR investigators decided to look into with data from the Dietary Inflammatory Index (DII) collected from the EPIC cohort.

The DII is a literature-based, population-derived tool that has been used to determine the inflammatory potential of diet, Dr. Yates explained. Data show that inflammatory diets are is associated with increased levels of inflammatory markers including C-reactive protein (CRP) and interleukin (IL)-6. These diets include items such as trans and saturated fats, and fats from animal protein versus more anti-inflammatory items such as black tea, thyme, turmeric, and saffron.

“We are fortunate that NOAR is in the same geographic location as EPIC,” Dr. Yates said, and the two cohorts have been running alongside each other since the early 1990s. While NOAR has been collecting data on incident inflammatory polyarthritis since 1989, EPIC has been “intensively” collecting information on dietary and lifestyle factors and blood samples from its participants since 1993.

EPIC investigators have been “trailblazers” in recording of dietary data, Dr. Yates said. First using paper-based questionnaires and now smartphone apps that allow people to upload photos of what they are eating. Data are linked to both primary care practice and hospital records.

For the present study, data on 159 patients who participated in both NOAR and EPIC were used. Participants had RA according to the 2010 American College of Rheumatology criteria and had an average disease onset of 7 years after enrollment into NOAR and EPIC.

“Quite pleasingly, the dietary inflammatory index scores were associated with high-sensitivity CRP taken at baseline enrollment in 1993 to 1997, further validating the index again within another population,” Dr. Yates said.

Results showed that there was a significant association between the baseline DII score and subsequent development of RA, with an odds ratio of 1.90 comparing individuals with the highest and lowest DII scores (P less than .01).

When cases were matched by age, sex, and body mass index, however, there was only a trend for an association between inflammatory diets and RA onset. “We hope to identify more patients within EPIC to strengthen this association,” Dr. Yates said.

The results are consistent with data from the Nurses’ Health Study, Dr. Yates noted, adding that future research is needed to address whether dietary modification can demonstrate causality.

“Diet is one of the modifiable risk factors that we can use to tackle RA, and I think it’s about time we as a community take over this area and gave definitive advice.”

Dr. Yates presented the work on behalf of PhD student Ellie Sayer. Neither Dr. Yates nor Ms. Sayer had any conflicts of interests to disclose.

SOURCE: Sayer E et al. Rheumatology. 2019;58(suppl 3), Abstract 014.

BIRMINGHAM, ENGLAND – Proinflammatory diets are associated with increased C-reactive protein (CRP) and subsequent rheumatoid arthritis (RA), according to combined data from the European Prospective Investigation of Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) and Norfolk Arthritis Register (NOAR).

“There has always been a debate around this topic,” Max Yates, MBBS, PhD, said at the annual conference of the British Society for Rheumatology. “A quick online search will reveal a plethora of texts claiming to give definitive or the best advice for arthritis” and diet, he said, often from “questionable experts.”

“I think we’re all interested in diet,” observed Dr. Yates, of the University of East Anglia in Norwich (England), and “although the association between diet and arthritis is open to debate, previous studies have shown an association with those who have a lower intake of vitamin C and fiber.” The problem is one of credibility, he noted, so this was something that the NOAR investigators decided to look into with data from the Dietary Inflammatory Index (DII) collected from the EPIC cohort.

The DII is a literature-based, population-derived tool that has been used to determine the inflammatory potential of diet, Dr. Yates explained. Data show that inflammatory diets are is associated with increased levels of inflammatory markers including C-reactive protein (CRP) and interleukin (IL)-6. These diets include items such as trans and saturated fats, and fats from animal protein versus more anti-inflammatory items such as black tea, thyme, turmeric, and saffron.

“We are fortunate that NOAR is in the same geographic location as EPIC,” Dr. Yates said, and the two cohorts have been running alongside each other since the early 1990s. While NOAR has been collecting data on incident inflammatory polyarthritis since 1989, EPIC has been “intensively” collecting information on dietary and lifestyle factors and blood samples from its participants since 1993.

EPIC investigators have been “trailblazers” in recording of dietary data, Dr. Yates said. First using paper-based questionnaires and now smartphone apps that allow people to upload photos of what they are eating. Data are linked to both primary care practice and hospital records.

For the present study, data on 159 patients who participated in both NOAR and EPIC were used. Participants had RA according to the 2010 American College of Rheumatology criteria and had an average disease onset of 7 years after enrollment into NOAR and EPIC.

“Quite pleasingly, the dietary inflammatory index scores were associated with high-sensitivity CRP taken at baseline enrollment in 1993 to 1997, further validating the index again within another population,” Dr. Yates said.

Results showed that there was a significant association between the baseline DII score and subsequent development of RA, with an odds ratio of 1.90 comparing individuals with the highest and lowest DII scores (P less than .01).

When cases were matched by age, sex, and body mass index, however, there was only a trend for an association between inflammatory diets and RA onset. “We hope to identify more patients within EPIC to strengthen this association,” Dr. Yates said.

The results are consistent with data from the Nurses’ Health Study, Dr. Yates noted, adding that future research is needed to address whether dietary modification can demonstrate causality.

“Diet is one of the modifiable risk factors that we can use to tackle RA, and I think it’s about time we as a community take over this area and gave definitive advice.”

Dr. Yates presented the work on behalf of PhD student Ellie Sayer. Neither Dr. Yates nor Ms. Sayer had any conflicts of interests to disclose.

SOURCE: Sayer E et al. Rheumatology. 2019;58(suppl 3), Abstract 014.

REPORTING FROM BSR 2019

Warfarin found to increase adverse outcomes among patients with IPF

DALLAS – Warfarin appears to increase the risk of lung transplant or death for patients with fibrotic lung disease who need anticoagulation therapy, Christopher King, MD, said at the American Thoracic Society’s international conference.

Compared with direct oral anticoagulation (DOAC), warfarin doubled the risk of those outcomes, even after the researchers controlled for multiple morbidities that accompany the need for anticoagulation, said Dr. King, medical director of the transplant and advanced lung disease critical care program at Inova Fairfax (Va.) Hospital.

“The need for anticoagulation in patients with interstitial lung disease is already associated with an increased risk of death or transplant,” he said. Warfarin – but not oral anticoagulation – seems to increase that risk even more “no matter how you analyze it,” he said.

“We know now that fibrosis and coagulation are entwined, and there’s background epidemiologic data showing an increased incidence of venous thromboembolism and acute coronary syndrome in patients with pulmonary fibrosis. This suggests that a dysregulated coagulation cascade may play a role in the pathogenesis of fibrosis.”

The relationship has been explored for the last decade or so. Two recent meta-analyses came to similar conclusions.

In 2013, a 125-patient retrospective cohort study compared clinical characteristics and survival among patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) who received anticoagulant therapy with those who did not (Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2013 Aug 1;30[2]:121-7). Those who got the treatment had worse survival outcomes at 1 and 3 years than did those who received no therapy (84% vs. 53% and 89% vs. 64%, respectively).

In 2016, a post hoc analysis of three placebo-controlled studies determined that any anticoagulant use independently increased the risk of death among patients with IPF, compared with nonuse: 15.6% vs 6.3% all-cause mortality (Eur Respir J. 2016. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02087-2015).

But these investigations didn’t parse out the types of anticoagulation. Direct oral anticoagulation (DOAC) is much more common now, however, and Dr. King and colleagues wanted to find out how warfarin and DOAC compared.

They retrospectively analyzed data from the Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation’s database and compared the risk of lung transplant and death for patients on anticoagulation or no anticoagulation and for those receiving DOACs versus warfarin versus no anticoagulation.

The study comprised 1,918 patients, 91% of whom were not on anticoagulation therapy. The remaining 164 were either taking DOAC (n = 83) or warfarin (n = 81). Both of these groups were significantly older than those not on anticoagulation (70 vs. 67 years). As expected , they were significantly more likely to have cardiac arrhythmias, heart failure, or pulmonary embolism or deep vein thrombosis and significantly more likely to be on immunosuppressant therapy or steroids. Their diffusing capacity of lung for carbon dioxide was also significantly lower.

There were no significant lung disease–related differences in anticoagulation therapy, other than a trend toward more use among those with connective tissue disease–associated interstitial lung disease.

Over 2 years, the entire cohort experienced 110 deaths (5.7%), 52 transplants (2.7%), and 29 withdrawals (1.5%). Among patients with IPF, there were 80 deaths (6.7%), 43 transplants (3.6%) and 20 withdrawals (1.7%).

In an unadjusted analysis, anticoagulation more than doubled the risk of an event, compared with no anticoagulation (hazard ratio, 2.4). This was slightly attenuated, but still significant, in a multivariate model that controlled for age, gender, oxygen use, gastroesophageal reflux disease, obstructive sleep apnea, arrhythmia, cancer, heart failure, obesity, venous thromboembolism, and antifibrotics (HR, 1.88).

A second whole-cohort analysis looked at the survival ratios for both warfarin and DOAC, compared with no treatment. In the fully adjusted model, warfarin was associated with a significantly increased risk HR (2.28) but DOAC was not.

The investigators then examined risk in only patients with lung disease. Among those with IPF, the fully adjusted model showed that warfarin nearly tripled the risk of transplant or death (HR, 2.8), while DOAC had no significant effect.

The reason for this association remains unclear, Dr. King said. “Renal failure may be a big reason patients get warfarin instead of DOAC. It’s difficult to say whether these patients were frail or prone to bleeding. Even something like the care team not being as up to date with treatment could be affecting the numbers. And is it the direct effect of warfarin on fibrotic lung disease? Or maybe DOAC has some beneficial effect on pulmonary fibrosis? We don’t know.

“But what we can take away from this is that warfarin is associated with worse outcomes than DOAC in patients with IPF. It seems reasonable to use DOAC over warfarin if there’s no specific contraindication to DOAC. If you have a patient with pulmonary thrombosis who has indications for anticoagulation I would use DOAC, based on the evidence that we now have available.”

Dr. King had no disclosures.

DALLAS – Warfarin appears to increase the risk of lung transplant or death for patients with fibrotic lung disease who need anticoagulation therapy, Christopher King, MD, said at the American Thoracic Society’s international conference.

Compared with direct oral anticoagulation (DOAC), warfarin doubled the risk of those outcomes, even after the researchers controlled for multiple morbidities that accompany the need for anticoagulation, said Dr. King, medical director of the transplant and advanced lung disease critical care program at Inova Fairfax (Va.) Hospital.

“The need for anticoagulation in patients with interstitial lung disease is already associated with an increased risk of death or transplant,” he said. Warfarin – but not oral anticoagulation – seems to increase that risk even more “no matter how you analyze it,” he said.

“We know now that fibrosis and coagulation are entwined, and there’s background epidemiologic data showing an increased incidence of venous thromboembolism and acute coronary syndrome in patients with pulmonary fibrosis. This suggests that a dysregulated coagulation cascade may play a role in the pathogenesis of fibrosis.”

The relationship has been explored for the last decade or so. Two recent meta-analyses came to similar conclusions.

In 2013, a 125-patient retrospective cohort study compared clinical characteristics and survival among patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) who received anticoagulant therapy with those who did not (Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2013 Aug 1;30[2]:121-7). Those who got the treatment had worse survival outcomes at 1 and 3 years than did those who received no therapy (84% vs. 53% and 89% vs. 64%, respectively).

In 2016, a post hoc analysis of three placebo-controlled studies determined that any anticoagulant use independently increased the risk of death among patients with IPF, compared with nonuse: 15.6% vs 6.3% all-cause mortality (Eur Respir J. 2016. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02087-2015).

But these investigations didn’t parse out the types of anticoagulation. Direct oral anticoagulation (DOAC) is much more common now, however, and Dr. King and colleagues wanted to find out how warfarin and DOAC compared.

They retrospectively analyzed data from the Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation’s database and compared the risk of lung transplant and death for patients on anticoagulation or no anticoagulation and for those receiving DOACs versus warfarin versus no anticoagulation.

The study comprised 1,918 patients, 91% of whom were not on anticoagulation therapy. The remaining 164 were either taking DOAC (n = 83) or warfarin (n = 81). Both of these groups were significantly older than those not on anticoagulation (70 vs. 67 years). As expected , they were significantly more likely to have cardiac arrhythmias, heart failure, or pulmonary embolism or deep vein thrombosis and significantly more likely to be on immunosuppressant therapy or steroids. Their diffusing capacity of lung for carbon dioxide was also significantly lower.

There were no significant lung disease–related differences in anticoagulation therapy, other than a trend toward more use among those with connective tissue disease–associated interstitial lung disease.

Over 2 years, the entire cohort experienced 110 deaths (5.7%), 52 transplants (2.7%), and 29 withdrawals (1.5%). Among patients with IPF, there were 80 deaths (6.7%), 43 transplants (3.6%) and 20 withdrawals (1.7%).

In an unadjusted analysis, anticoagulation more than doubled the risk of an event, compared with no anticoagulation (hazard ratio, 2.4). This was slightly attenuated, but still significant, in a multivariate model that controlled for age, gender, oxygen use, gastroesophageal reflux disease, obstructive sleep apnea, arrhythmia, cancer, heart failure, obesity, venous thromboembolism, and antifibrotics (HR, 1.88).

A second whole-cohort analysis looked at the survival ratios for both warfarin and DOAC, compared with no treatment. In the fully adjusted model, warfarin was associated with a significantly increased risk HR (2.28) but DOAC was not.

The investigators then examined risk in only patients with lung disease. Among those with IPF, the fully adjusted model showed that warfarin nearly tripled the risk of transplant or death (HR, 2.8), while DOAC had no significant effect.

The reason for this association remains unclear, Dr. King said. “Renal failure may be a big reason patients get warfarin instead of DOAC. It’s difficult to say whether these patients were frail or prone to bleeding. Even something like the care team not being as up to date with treatment could be affecting the numbers. And is it the direct effect of warfarin on fibrotic lung disease? Or maybe DOAC has some beneficial effect on pulmonary fibrosis? We don’t know.

“But what we can take away from this is that warfarin is associated with worse outcomes than DOAC in patients with IPF. It seems reasonable to use DOAC over warfarin if there’s no specific contraindication to DOAC. If you have a patient with pulmonary thrombosis who has indications for anticoagulation I would use DOAC, based on the evidence that we now have available.”

Dr. King had no disclosures.

DALLAS – Warfarin appears to increase the risk of lung transplant or death for patients with fibrotic lung disease who need anticoagulation therapy, Christopher King, MD, said at the American Thoracic Society’s international conference.

Compared with direct oral anticoagulation (DOAC), warfarin doubled the risk of those outcomes, even after the researchers controlled for multiple morbidities that accompany the need for anticoagulation, said Dr. King, medical director of the transplant and advanced lung disease critical care program at Inova Fairfax (Va.) Hospital.

“The need for anticoagulation in patients with interstitial lung disease is already associated with an increased risk of death or transplant,” he said. Warfarin – but not oral anticoagulation – seems to increase that risk even more “no matter how you analyze it,” he said.

“We know now that fibrosis and coagulation are entwined, and there’s background epidemiologic data showing an increased incidence of venous thromboembolism and acute coronary syndrome in patients with pulmonary fibrosis. This suggests that a dysregulated coagulation cascade may play a role in the pathogenesis of fibrosis.”

The relationship has been explored for the last decade or so. Two recent meta-analyses came to similar conclusions.

In 2013, a 125-patient retrospective cohort study compared clinical characteristics and survival among patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) who received anticoagulant therapy with those who did not (Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2013 Aug 1;30[2]:121-7). Those who got the treatment had worse survival outcomes at 1 and 3 years than did those who received no therapy (84% vs. 53% and 89% vs. 64%, respectively).

In 2016, a post hoc analysis of three placebo-controlled studies determined that any anticoagulant use independently increased the risk of death among patients with IPF, compared with nonuse: 15.6% vs 6.3% all-cause mortality (Eur Respir J. 2016. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02087-2015).

But these investigations didn’t parse out the types of anticoagulation. Direct oral anticoagulation (DOAC) is much more common now, however, and Dr. King and colleagues wanted to find out how warfarin and DOAC compared.

They retrospectively analyzed data from the Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation’s database and compared the risk of lung transplant and death for patients on anticoagulation or no anticoagulation and for those receiving DOACs versus warfarin versus no anticoagulation.

The study comprised 1,918 patients, 91% of whom were not on anticoagulation therapy. The remaining 164 were either taking DOAC (n = 83) or warfarin (n = 81). Both of these groups were significantly older than those not on anticoagulation (70 vs. 67 years). As expected , they were significantly more likely to have cardiac arrhythmias, heart failure, or pulmonary embolism or deep vein thrombosis and significantly more likely to be on immunosuppressant therapy or steroids. Their diffusing capacity of lung for carbon dioxide was also significantly lower.

There were no significant lung disease–related differences in anticoagulation therapy, other than a trend toward more use among those with connective tissue disease–associated interstitial lung disease.

Over 2 years, the entire cohort experienced 110 deaths (5.7%), 52 transplants (2.7%), and 29 withdrawals (1.5%). Among patients with IPF, there were 80 deaths (6.7%), 43 transplants (3.6%) and 20 withdrawals (1.7%).

In an unadjusted analysis, anticoagulation more than doubled the risk of an event, compared with no anticoagulation (hazard ratio, 2.4). This was slightly attenuated, but still significant, in a multivariate model that controlled for age, gender, oxygen use, gastroesophageal reflux disease, obstructive sleep apnea, arrhythmia, cancer, heart failure, obesity, venous thromboembolism, and antifibrotics (HR, 1.88).

A second whole-cohort analysis looked at the survival ratios for both warfarin and DOAC, compared with no treatment. In the fully adjusted model, warfarin was associated with a significantly increased risk HR (2.28) but DOAC was not.

The investigators then examined risk in only patients with lung disease. Among those with IPF, the fully adjusted model showed that warfarin nearly tripled the risk of transplant or death (HR, 2.8), while DOAC had no significant effect.

The reason for this association remains unclear, Dr. King said. “Renal failure may be a big reason patients get warfarin instead of DOAC. It’s difficult to say whether these patients were frail or prone to bleeding. Even something like the care team not being as up to date with treatment could be affecting the numbers. And is it the direct effect of warfarin on fibrotic lung disease? Or maybe DOAC has some beneficial effect on pulmonary fibrosis? We don’t know.

“But what we can take away from this is that warfarin is associated with worse outcomes than DOAC in patients with IPF. It seems reasonable to use DOAC over warfarin if there’s no specific contraindication to DOAC. If you have a patient with pulmonary thrombosis who has indications for anticoagulation I would use DOAC, based on the evidence that we now have available.”

Dr. King had no disclosures.

REPORTING FROM ATS 2019

MS patients pay big price for breaks from DMT

SEATTLE – Patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) who stopped taking their disease-modifying therapy (DMT) for more than 60 days had significantly higher rates of relapse, hospitalization, emergency department visits and outpatient visits, a new study finds. Their nonmedication health care costs were higher, too.

“This information will help to inform patients about downstream economic risks of being off therapy. This may also help to inform payers of the importance of making DMTs easily and quickly available to patients with MS to prevent greater costs of health care resource utilization down the road,” study lead author Jacqueline A. Nicholas, MD, MPH, a clinical neuroimmunologist at OhioHealth Multiple Sclerosis Center, said in an interview. She spoke prior to the presentation of the findings at the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers.

Dr. Nicholas and her colleagues launched their study to better understand the economic and medical impacts of lapses in oral DMT.

The researchers used a claims database to track 8,779 patients with MS during 2011-2015 who had at least one claim for an oral DMT drug. The subjects were aged 18-63; 15% had a drug lapse of more than 60 days. After propensity matching, the subjects in both groups – 60-day lapse or not – had a mean age of 44 years.

An analysis found that “lapses in oral DMT use led to increased relapses, increased health care utilization, and higher costs incurred by individuals with MS,” Dr. Nicholas said.

Over an 18-month follow-up period, those with drug lapses of more than 60 days had 28% more relapses than did the other subjects (mean 1.2 vs. 0.8; P less than .0001).

Those with lapses greater than 60 days also had 40% more hospitalizations (0.2 vs. 0.1; P = .0003), 25% more emergency department visits (0.6 vs. 0.5; P = .0098), and 22% more outpatient visits (6.2 vs. 4.8; P less than .0001).

Nonmedication costs were 25% higher among patients with a greater than 60-day lapse ($16,012 vs. $12,092; P = .0006).

Moving forward, the researchers wrote, “more research is needed to better understand the reasons for lapses in therapy and the impact of lapse timing and lapse duration on outcomes in patients with MS receiving once- or twice-daily oral [disease-modifying drugs].”

The researchers noted that they don’t have information about the reasons why patients lapsed. They added that the information comes mainly from commercial insurers.

EMD Serono, a division of Merck KGaA, provided funding for the study. Dr. Nicholas disclosed grant support from EMD Serono, and two other study authors are employees of the company. Another two authors worked for a consulting firm that received funding from EMD Serono to conduct the study.

SEATTLE – Patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) who stopped taking their disease-modifying therapy (DMT) for more than 60 days had significantly higher rates of relapse, hospitalization, emergency department visits and outpatient visits, a new study finds. Their nonmedication health care costs were higher, too.

“This information will help to inform patients about downstream economic risks of being off therapy. This may also help to inform payers of the importance of making DMTs easily and quickly available to patients with MS to prevent greater costs of health care resource utilization down the road,” study lead author Jacqueline A. Nicholas, MD, MPH, a clinical neuroimmunologist at OhioHealth Multiple Sclerosis Center, said in an interview. She spoke prior to the presentation of the findings at the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers.

Dr. Nicholas and her colleagues launched their study to better understand the economic and medical impacts of lapses in oral DMT.

The researchers used a claims database to track 8,779 patients with MS during 2011-2015 who had at least one claim for an oral DMT drug. The subjects were aged 18-63; 15% had a drug lapse of more than 60 days. After propensity matching, the subjects in both groups – 60-day lapse or not – had a mean age of 44 years.

An analysis found that “lapses in oral DMT use led to increased relapses, increased health care utilization, and higher costs incurred by individuals with MS,” Dr. Nicholas said.

Over an 18-month follow-up period, those with drug lapses of more than 60 days had 28% more relapses than did the other subjects (mean 1.2 vs. 0.8; P less than .0001).

Those with lapses greater than 60 days also had 40% more hospitalizations (0.2 vs. 0.1; P = .0003), 25% more emergency department visits (0.6 vs. 0.5; P = .0098), and 22% more outpatient visits (6.2 vs. 4.8; P less than .0001).

Nonmedication costs were 25% higher among patients with a greater than 60-day lapse ($16,012 vs. $12,092; P = .0006).

Moving forward, the researchers wrote, “more research is needed to better understand the reasons for lapses in therapy and the impact of lapse timing and lapse duration on outcomes in patients with MS receiving once- or twice-daily oral [disease-modifying drugs].”

The researchers noted that they don’t have information about the reasons why patients lapsed. They added that the information comes mainly from commercial insurers.

EMD Serono, a division of Merck KGaA, provided funding for the study. Dr. Nicholas disclosed grant support from EMD Serono, and two other study authors are employees of the company. Another two authors worked for a consulting firm that received funding from EMD Serono to conduct the study.

SEATTLE – Patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) who stopped taking their disease-modifying therapy (DMT) for more than 60 days had significantly higher rates of relapse, hospitalization, emergency department visits and outpatient visits, a new study finds. Their nonmedication health care costs were higher, too.

“This information will help to inform patients about downstream economic risks of being off therapy. This may also help to inform payers of the importance of making DMTs easily and quickly available to patients with MS to prevent greater costs of health care resource utilization down the road,” study lead author Jacqueline A. Nicholas, MD, MPH, a clinical neuroimmunologist at OhioHealth Multiple Sclerosis Center, said in an interview. She spoke prior to the presentation of the findings at the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers.

Dr. Nicholas and her colleagues launched their study to better understand the economic and medical impacts of lapses in oral DMT.

The researchers used a claims database to track 8,779 patients with MS during 2011-2015 who had at least one claim for an oral DMT drug. The subjects were aged 18-63; 15% had a drug lapse of more than 60 days. After propensity matching, the subjects in both groups – 60-day lapse or not – had a mean age of 44 years.

An analysis found that “lapses in oral DMT use led to increased relapses, increased health care utilization, and higher costs incurred by individuals with MS,” Dr. Nicholas said.

Over an 18-month follow-up period, those with drug lapses of more than 60 days had 28% more relapses than did the other subjects (mean 1.2 vs. 0.8; P less than .0001).

Those with lapses greater than 60 days also had 40% more hospitalizations (0.2 vs. 0.1; P = .0003), 25% more emergency department visits (0.6 vs. 0.5; P = .0098), and 22% more outpatient visits (6.2 vs. 4.8; P less than .0001).

Nonmedication costs were 25% higher among patients with a greater than 60-day lapse ($16,012 vs. $12,092; P = .0006).

Moving forward, the researchers wrote, “more research is needed to better understand the reasons for lapses in therapy and the impact of lapse timing and lapse duration on outcomes in patients with MS receiving once- or twice-daily oral [disease-modifying drugs].”

The researchers noted that they don’t have information about the reasons why patients lapsed. They added that the information comes mainly from commercial insurers.

EMD Serono, a division of Merck KGaA, provided funding for the study. Dr. Nicholas disclosed grant support from EMD Serono, and two other study authors are employees of the company. Another two authors worked for a consulting firm that received funding from EMD Serono to conduct the study.

REPORTING FROM CMSC 2019

Evidence lacking in treatments for pain in MS

SEATTLE – When it comes to pain in patients with multiple sclerosis, two pain specialists offered this advice: Mind the gap. While pain is a major burden in MS, there’s a huge hole in research about the best treatments. That means medical professionals and patients can only rely on a few signposts for navigation.

But the medical literature does offer glimmers of insight into drug treatments, said Brett R. Stacey, MD, and Pamela Stitzlein Davies, MS, ARNP, FAANP, both of the University of Washington, Seattle, in presentations at the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers.

An estimated 44%-66% of patients with MS report pain. Their experiences are similar to those of other patients with pain, Dr. Stacey said, although there are some exceptions. Trigeminal neuralgia is not uncommon in patients with MS, and level of pain fluctuates markedly in MS patients.

“There are no [Food and Drug Administration]–approved drugs specifically for painful MS. There are few clinical trials and no first-line evidence about first-choice medicine,” Dr. Stacey said. As a result, he said, all drug options are off-label.

Based on his experience, the best first-line options for pain in MS appear to be the antidepressants duloxetine (Cymbalta), venlafaxine (Effexor), nortriptyline (Pamelor), desipramine (Norpramin), and amitriptyline, as well as the nerve pain drugs pregabalin (Lyrica) and gabapentin.

In regard to antidepressants, “most patients you give these medications to are not going to have a meaningful response. None of them are typically a home run” for pain in MS, Dr. Stacey said.

Duloxetine, he added, is expensive even as a generic, and nausea is possible within the first few days. It’s time to try something else if nausea sticks around for 5 days, he said.

However, there is a special benefit for duloxetine, he said: “For lower back pain, nothing is better. But that doesn’t mean the evidence is fantastic.”

Gabapentin, he said, “is relatively benign in terms of serious adverse effects,” although significant weight gain is possible. “It does not work for pain that doesn’t have a sensitization element. A lot of people throw gabapentin at things for which it will never work.”

Pregabalin, on the other hand, “can be potentially effective when other things like gabapentin and tricyclics have failed,” he said.

Second-line treatments include the lidocaine patch, tramadol, and the capsaicin 8% patch (Qutenza). And third-line treatments include botulinum toxin A and opioids.

Ms. Davies, who focused her presentation on opioids and pain in MS, agreed about the appropriate role of opioids. “They should be considered third-line, fourth-line, fifth-line, further down,” she said. “There’s a limited role for them in pain related to MS,” she said, specifically in regard to neuropathic pain.

There’s very little research into opioids in MS, she added, and their role is limited by side effects and the possibility of overdose.

Another option is low-dose naltrexone (Revia, Vivitrol), a drug used to treat alcohol and drug dependence. “Here in our clinic, patient after patient asks about naltrexone for everything,” Dr. Stacey said.

The treatment requires the use of a compounding pharmacy, he said, and evidence in MS consists of small studies with mixed results.

Dr. Stacey also addressed trigeminal neuralgia, which affects an estimated 5%-10% of patients with MS. For this condition, he said, “everything works less well in MS patients than non-MS patients.” Drug treatments include the seizure/nerve pain medication carbamazepine (Equetro, Carbatrol, Tegretol) and the seizure medication oxcarbazepine (Oxtellar, Trileptal), he said. Surgery is also an option.

SEATTLE – When it comes to pain in patients with multiple sclerosis, two pain specialists offered this advice: Mind the gap. While pain is a major burden in MS, there’s a huge hole in research about the best treatments. That means medical professionals and patients can only rely on a few signposts for navigation.

But the medical literature does offer glimmers of insight into drug treatments, said Brett R. Stacey, MD, and Pamela Stitzlein Davies, MS, ARNP, FAANP, both of the University of Washington, Seattle, in presentations at the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers.

An estimated 44%-66% of patients with MS report pain. Their experiences are similar to those of other patients with pain, Dr. Stacey said, although there are some exceptions. Trigeminal neuralgia is not uncommon in patients with MS, and level of pain fluctuates markedly in MS patients.

“There are no [Food and Drug Administration]–approved drugs specifically for painful MS. There are few clinical trials and no first-line evidence about first-choice medicine,” Dr. Stacey said. As a result, he said, all drug options are off-label.

Based on his experience, the best first-line options for pain in MS appear to be the antidepressants duloxetine (Cymbalta), venlafaxine (Effexor), nortriptyline (Pamelor), desipramine (Norpramin), and amitriptyline, as well as the nerve pain drugs pregabalin (Lyrica) and gabapentin.

In regard to antidepressants, “most patients you give these medications to are not going to have a meaningful response. None of them are typically a home run” for pain in MS, Dr. Stacey said.

Duloxetine, he added, is expensive even as a generic, and nausea is possible within the first few days. It’s time to try something else if nausea sticks around for 5 days, he said.

However, there is a special benefit for duloxetine, he said: “For lower back pain, nothing is better. But that doesn’t mean the evidence is fantastic.”

Gabapentin, he said, “is relatively benign in terms of serious adverse effects,” although significant weight gain is possible. “It does not work for pain that doesn’t have a sensitization element. A lot of people throw gabapentin at things for which it will never work.”

Pregabalin, on the other hand, “can be potentially effective when other things like gabapentin and tricyclics have failed,” he said.

Second-line treatments include the lidocaine patch, tramadol, and the capsaicin 8% patch (Qutenza). And third-line treatments include botulinum toxin A and opioids.

Ms. Davies, who focused her presentation on opioids and pain in MS, agreed about the appropriate role of opioids. “They should be considered third-line, fourth-line, fifth-line, further down,” she said. “There’s a limited role for them in pain related to MS,” she said, specifically in regard to neuropathic pain.

There’s very little research into opioids in MS, she added, and their role is limited by side effects and the possibility of overdose.

Another option is low-dose naltrexone (Revia, Vivitrol), a drug used to treat alcohol and drug dependence. “Here in our clinic, patient after patient asks about naltrexone for everything,” Dr. Stacey said.

The treatment requires the use of a compounding pharmacy, he said, and evidence in MS consists of small studies with mixed results.

Dr. Stacey also addressed trigeminal neuralgia, which affects an estimated 5%-10% of patients with MS. For this condition, he said, “everything works less well in MS patients than non-MS patients.” Drug treatments include the seizure/nerve pain medication carbamazepine (Equetro, Carbatrol, Tegretol) and the seizure medication oxcarbazepine (Oxtellar, Trileptal), he said. Surgery is also an option.

SEATTLE – When it comes to pain in patients with multiple sclerosis, two pain specialists offered this advice: Mind the gap. While pain is a major burden in MS, there’s a huge hole in research about the best treatments. That means medical professionals and patients can only rely on a few signposts for navigation.

But the medical literature does offer glimmers of insight into drug treatments, said Brett R. Stacey, MD, and Pamela Stitzlein Davies, MS, ARNP, FAANP, both of the University of Washington, Seattle, in presentations at the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers.

An estimated 44%-66% of patients with MS report pain. Their experiences are similar to those of other patients with pain, Dr. Stacey said, although there are some exceptions. Trigeminal neuralgia is not uncommon in patients with MS, and level of pain fluctuates markedly in MS patients.

“There are no [Food and Drug Administration]–approved drugs specifically for painful MS. There are few clinical trials and no first-line evidence about first-choice medicine,” Dr. Stacey said. As a result, he said, all drug options are off-label.

Based on his experience, the best first-line options for pain in MS appear to be the antidepressants duloxetine (Cymbalta), venlafaxine (Effexor), nortriptyline (Pamelor), desipramine (Norpramin), and amitriptyline, as well as the nerve pain drugs pregabalin (Lyrica) and gabapentin.

In regard to antidepressants, “most patients you give these medications to are not going to have a meaningful response. None of them are typically a home run” for pain in MS, Dr. Stacey said.

Duloxetine, he added, is expensive even as a generic, and nausea is possible within the first few days. It’s time to try something else if nausea sticks around for 5 days, he said.

However, there is a special benefit for duloxetine, he said: “For lower back pain, nothing is better. But that doesn’t mean the evidence is fantastic.”

Gabapentin, he said, “is relatively benign in terms of serious adverse effects,” although significant weight gain is possible. “It does not work for pain that doesn’t have a sensitization element. A lot of people throw gabapentin at things for which it will never work.”

Pregabalin, on the other hand, “can be potentially effective when other things like gabapentin and tricyclics have failed,” he said.

Second-line treatments include the lidocaine patch, tramadol, and the capsaicin 8% patch (Qutenza). And third-line treatments include botulinum toxin A and opioids.

Ms. Davies, who focused her presentation on opioids and pain in MS, agreed about the appropriate role of opioids. “They should be considered third-line, fourth-line, fifth-line, further down,” she said. “There’s a limited role for them in pain related to MS,” she said, specifically in regard to neuropathic pain.

There’s very little research into opioids in MS, she added, and their role is limited by side effects and the possibility of overdose.

Another option is low-dose naltrexone (Revia, Vivitrol), a drug used to treat alcohol and drug dependence. “Here in our clinic, patient after patient asks about naltrexone for everything,” Dr. Stacey said.

The treatment requires the use of a compounding pharmacy, he said, and evidence in MS consists of small studies with mixed results.

Dr. Stacey also addressed trigeminal neuralgia, which affects an estimated 5%-10% of patients with MS. For this condition, he said, “everything works less well in MS patients than non-MS patients.” Drug treatments include the seizure/nerve pain medication carbamazepine (Equetro, Carbatrol, Tegretol) and the seizure medication oxcarbazepine (Oxtellar, Trileptal), he said. Surgery is also an option.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM CMSC 2019

Which interventions can treat cognitive fatigue?

SEATTLE – Cognitive fatigue in patients with neurologic disease is a common problem with few objectively studied treatments, according to a systematic review presented at the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers., the review authors said.

One other objective trial found that Fampridine-SR (Ampyra) did not reduce cognitive fatigue in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS).

The researchers screened for studies across various neurologic conditions, and found that both trials were in patients with MS, “suggesting that more emphasis is given to this issue in this population,” said review author Alyssa Lindsay-Brown, a researcher at Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, and her collaborators. “This review highlighted the paucity of interventions designed to target objectively measured cognitive fatigability and demonstrates the need for further research in this area.”

Investigators have examined self-reported fatigue in patients with neurologic disease, but objective cognitive fatigability, the inability to maintain optimal task performance during a sustained cognitive task, is not well understood, and the best approach to treating cognitive fatigue is unclear, said Ms. Lindsay-Brown and colleagues. To determine how researchers objectively measure cognitive fatigability and summarize currently available treatments, they conducted a systematic literature review.