User login

Caring for patients on probation or parole

Mr. A, age 35, presents to your outpatient community mental health practice. He has a history of psychosis that began in his late teens. Since then, his symptoms have included derogatory auditory hallucinations, a recurrent persecutory delusion that governmental agencies are tracking his movements, and intermittent disorganized speech. At age 30, Mr. A assaulted a stranger out of fear that the individual was a government agent. He was arrested and experienced a severe psychotic decompensation while awaiting trial. He was found incompetent to stand trial and sent to a state hospital for restoration.

After 6 months of treatment and observation, Mr. A was deemed competent to proceed and returned to jail. He was subsequently convicted of assault and sentenced to 7 years in prison. While in prison, he received regular mental health care with infrequent recurrence of minor psychotic symptoms. He was released on parole due to his good behavior, but as part of his conditions of parole, he was mandated to follow up with an outpatient mental health clinician.

After telling you the story of how he ended up in your office, Mr. A says he needs you to speak regularly with his parole officer to verify his attendance at appointments and to discuss any mental health concerns you may have. Since you have not worked with a patient on parole before, your mind is full of questions: What are the expectations regarding your communication with his parole officer? Could Mr. A return to prison if you express concerns about his mental health? What can you do to improve his chances of success in the community?

Given the high rates of mental illness among individuals incarcerated in the United States, it shouldn’t be surprising that there are similarly high rates of mental illness among those on supervised release from jails and prisons. Clinicians who work with patients on community release need to understand basic concepts related to probation and parole, and how to promote patients’ stability in the community to reduce recidivism and re-incarceration. The court may require individuals on probation or parole to adhere to certain conditions of release, which could include seeing a psychiatrist or psychotherapist, participating in substance abuse treatment, and/or taking psychotropic medication. The court usually closely monitors the probationer or parolee’s adherence, and noncompliance can be grounds for probation or parole violation and revocation.

This article reviews the concepts of probation and parole (Box1,2), describes the prevalence of mental illness among probationers and parolees, and discusses the unique challenges and opportunities psychiatrists and other mental health professionals face when working with individuals on community supervision.

Box

The US Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) defines probation as a “court-ordered period of correctional supervision in the community, generally as an alternative to incarceration.” Probation allows individuals to be released from jail to community supervision, with the potential for dismissal or lowering of charges if they adhere to the conditions of probation. Conditions of probation may include participating in substance abuse or mental health treatment programs, abstaining from drugs and alcohol, and avoiding contact with known felons. Failure to comply with conditions of probation can lead to re-incarceration and probation revocation.1 If probation is revoked, a probationer may be sentenced, potentially to prison, depending on the severity of the original offense.2

The BJS defines parole as “a period of conditional supervised release in the community following a term in state or federal prison.”2 Parole allows for the community supervision of individuals who have already been convicted of and sentenced to prison for a crime. Individuals may be released on parole if they demonstrate good behavior while incarcerated. Similar to probationers, parolees must adhere to the conditions of parole, and violation of these may lead to re-incarceration.1

As of December 31, 2016, there were more than 4.5 million adults on community supervision in the United States, representing 1 out of every 55 adults in the US population. Individuals on probation accounted for 81% of adults on community supervision. The number of people on community supervision has dropped continuously over the last decade, a trend driven by 2% annual decreases in the probation population. In contrast, the parolee population has continued to grow over time and was approximately 900,000 individuals at the end of 2016.2

Mental illness among probationers and parolees

Research on mental illness in people involved in the criminal justice system has largely focused on those who are incarcerated. Studies have documented high rates of severe mental illness (SMI), such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, among those who are incarcerated; some estimate the rates to be 3 times as high as those of community samples.3,4 In addition to SMI, substance use disorders and personality disorders (in particular, antisocial personality disorder) are common among people who are incarcerated.5,6

Comparatively little is known about mental illness among probationers and parolees, although presumably there would be a similarly high prevalence of SMI, substance use disorders, and other psychiatric disorders among this population. A 1997 Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) survey of approximately 3.4 million probationers found that 13.8% self-reported a mental or emotional condition and 8.2% self-reported a history of an “overnight stay in a mental hospital.”7 The BJS estimated that there were approximately 550,000 probationers with mental illness in the United States. The study’s author noted that probationers with mental illness were more likely to have a history of prior offenses and more likely to be violent recidivists. In terms of substance use, compared with other probationers, those with mental illness were more likely to report using drugs in the month before their most recent offense and at the time of the offense.7

Continue to: More recent research...

More recent research, although limited, has shed some light on the role of mental health services for individuals on probation and parole. In 2009, Crilly et al8 reported that 23% of probationers reported accessing mental health services within the past year. Other studies have found that probationer and parolee engagement in mental health care reduces the risk of recidivism.9,10 A 2011 study evaluated 100 individuals on probation and parole in 2 counties in a southeastern state. The authors found that 75% of participants reported that they needed counseling for a mental health concern in the past year, but that only approximately 30% of them actually sought help. Individuals reporting higher levels of posttraumatic stress disorder symptomatology or greater drug use before being on probation or parole were more likely to seek counseling in the past year.11

An alternative: Problem-solving courts

Problem-solving courts (PSCs) offer an alternative to standard probation and/or sentencing. Problem-solving courts are founded on the concept of therapeutic jurisprudence, which seeks to change “the behavior of litigants and [ensure] the future well-being of communities.”12 Types of PSCs include drug court (the most common type in the United States), domestic violence court, veterans court, and mental health court (MHC), among others.

An individual may choose a PSC over standard probation because participants usually receive more assistance in obtaining treatment and closer supervision with an emphasis on rehabilitation rather than incapacitation or retribution. The success of PSCs relies heavily on the judge, as he/she plays a pivotal role in developing relationships with the participants, considering therapeutic alternatives to “bad” behaviors, determining sanctions, and relying on community mental health partners to assist participants in complying with conditions of the court.13-15

Psychiatrists and other mental health clinicians should be aware of MHCs, which are a type of PSC that provides for the community supervision of individuals with mental illness. Mental health courts vary in terms of eligibility criteria. Some accept individuals who merely report a history of mental illness, whereas others have specific diagnostic requirements.16 Some accept individuals accused of minor violations such as ordinance violations or misdemeanor offenses, while others accept individuals accused of felonies. Like other PSCs, participation in an MHC is voluntary, and most require a participant to enter a guilty plea upon entry.17 Participants may choose to enter an MHC to avoid prison time or to reduce or expunge charges after completing the program. Many MHCs also assign a probation officer to follow the participant in the community, similar to a standard probation model. Participants are usually expected to engage in psychiatric treatment, including psychotherapy, substance abuse counseling, medication management, and other services. If they do not comply with these conditions, they face sanctions that could include jail “shock” time, enhanced supervision, or an increase in psychiatric services.

Outpatient mental health professionals play an integral role in MHCs. Depending on the model, he/she may be asked to communicate treatment recommendations, attend weekly meetings at the court, and provide suggestions for interventions when the participant relapses, recidivates, and/or decompensates psychiatrically. This collaborative model can work well and allow the clinician unique opportunities to educate the court and advocate for his/her patient. However, clinicians who participate in an MHC need to remain aware of the potential to become a de facto probation officer, and need to maintain appropriate boundaries and roles. They should ensure that the patient provides initial and ongoing consent for them to communicate with the court, and share their programmatic recommendations with the patient to preserve the therapeutic alliance.

Continue to: Challenges upon re-entering the community

Challenges upon re-entering the community

Individuals recently released from jail or prison face unique challenges when re-entering the community. An individual who has been incarcerated, particularly for months to years, has likely lost his/her job, housing, health insurance, and access to primary supports. People with mental illness with a history of incarceration have higher rates of homelessness, substance use disorders, and unemployment than those with no history of incarceration.7,18 For individuals with mental illness, these additional stressors lead to further psychiatric decompensation, recidivism, and overutilization of emergency and crisis services upon release from prison or jail. The loss of health insurance presents great challenges: when someone is incarcerated, his/her Medicaid is suspended or terminated.19 This can happen at any point during incarceration. In states that terminate rather than suspend Medicaid, former prisoners face even longer waits to re-establish access to needed health care.

The period immediately after release is a critical time for individuals to be linked with substance and mental health treatment. Binswanger et al20 found former prisoners were at highest risk of mortality in the 2 weeks following release from prison; the highest rates of death were from drug overdose, cardiovascular disease, homicide, and suicide. A subsequent study found that women were at increased risk of drug overdose and opioid-related deaths.21 One explanation for the increase in drug-related deaths is the loss of physiologic tolerance while incarcerated; however, a lack of treatment while incarcerated, high levels of stress upon re-entry, and poor linkage to aftercare also may be contributing factors. Among prisoners recently released from New York City jails, Lim et al22 found that those with a history of homelessness and previous incarceration had the highest rates of drug-related deaths and homicides in the first 2 weeks after release. Non-Hispanic white men had the highest risk of drug-related deaths and suicides. While the risk of death is greatest immediately after release, former prisoners face increased mortality from multiple causes for multiple years after release.20-22

Clinicians who work with recently released prisoners should be aware of these individuals’ risks and actively work with them and other members of the mental health team to ensure these patients have access to social services, employment training, housing, and substance use resources, including medication-assisted treatment. Patients with SMI should be considered for more intensive services, such as assertive community treatment (ACT) or even forensic ACT (FACT) services, given that FACTs have a modest impact in reducing recidivism.23

Knowing whether the patient is on probation or parole and the terms of his/her supervision can also be useful in creating and executing a collaborative treatment plan. The clinician can assist the patient in meeting conditions of probation/parole such as:

- creating a stable home plan with a permanent address

- planning routine check-ins with probation/parole officers, and

- keeping documentation of ongoing mental health and substance use treatment.

Being aware of other terms of supervision, such as abstaining from alcohol and drugs, or remaining in one’s jurisdiction, also can help the patient avoid technical violations and a return to jail or prison.

Continue to: How to best help patients on community supervision

How to best help patients on community supervision

There are some clinical recommendations when working with patients on community supervision. First, do not assume that someone who has been incarcerated has antisocial personality disorder. Behaviors primarily related to seeking or using drugs or survival-type crimes should not be considered “antisocial” without additional evidence of pervasive and persistent conduct demonstrating impulsivity, lack of empathy, dishonesty, or repeated disregard for social norms and others’ rights. To meet criteria for antisocial personality disorder, these behaviors must have begun during childhood or adolescence.

If a patient does meet criteria for antisocial personality disorder, remember that he/she may also have a psychotic, mood, substance use, or other disorder that could lead to a greater likelihood of violence, recidivism, or other poor outcomes if left untreated. Treating any co-occurring disorders could enhance the patient’s engagement with treatment. There is some evidence that certain psychotropic medications, su

In addition to promoting patients’ mental health, such efforts can prevent re-arrest and re-incarceration and make a lasting positive impact on patients’ lives.

CASE CONTINUED

Mr. A signs a release-of-information form and you call his parole officer. His parole officer states that he would like to speak with you every few months to check on Mr. A’s treatment adherence. Within a few months, you transition Mr. A from an oral antipsychotic medication to a long-acting injectable antipsychotic medication to manage his psychotic disorder. He presents on time each month to your clinic to receive the injection.

Five months later, Mr. A receives 2 weeks of “shock time” at the local county jail for “dropping a dirty urine” that was positive for cannabinoids at a meeting with his parole officer. During his time in jail, he receives no treatment and he misses his monthly long-acting injectable dose.

Continue to: Upon release...

Upon release, he demonstrates the recurrence of some mild persecutory fears and hallucinations, but you resume him on his prior treatment regimen, and he recovers.

You encourage the parole officer to notify you if Mr. A violates parole and is incarcerated so that you can speak with clinicians in the jail to ensure that Mr. A remains adequately treated while incarcerated.

In the coming years, you continue to work with Mr. A and his parole officer to manage his mental health condition and to navigate his parole requirements in order to reduce his risk of relapse and recidivism. After Mr. A completes his time on parole, you continue to see him for outpatient follow-up.

Bottom Line

Clinicians may provide psychiatric care to probationers and parolees in traditional outpatient settings or in collaboration with a mental health court (MHC) or forensic assertive community treatment team. It is crucial to be aware of the legal expectations of individuals on community supervision, as well as the unique mental health risks and challenges they face. You can help reduce probationers’ and parolees’ risk of relapse and recidivism and support their recovery in the community by engaging in collaborative treatment planning involving the patient, the court, and/or MHCs.

Related Resources

- Lamb HR. Weinberger LE. Understanding and treating offenders with serious mental illness in public sector mental health. Behav Sci Law. 2017;35(4):303-318.

- Worcester S. Mental illness and the criminal justice system: Reducing the risks. Clinical Psychiatry News. https://www.mdedge.com/psychiatry/article/173208/schizophrenia-other-psychotic-disorders/mental-illness-and-criminal. Published August 22, 2018.

1. Bureau of Justice Statistics. FAQ detail: What is the difference between probation and parole? U.S. Department of Justice. https://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=qa&iid=324. Accessed November 17, 2018.

2. Kaeble D. Probation and parole in the United States, 2016. U.S. Department of Justice. https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/ppus16.pdf. Published April 2018. Accessed April 23, 2019.

3. Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, et al. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617-627.

4. Diamond, P.M., et al., The prevalence of mental illness in prison. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2001;29(1):21-40.

5. MacDonald R, Kaba F, Rosner Z, et al. The Rikers Island hot spotters: defining the needs of the most frequently incarcerated. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(11):2262-2268.

6. Trestman RL, Ford J, Zhang W, et al. Current and lifetime psychiatric illness among inmates not identified as acutely mentally ill at intake in Connecticut’s jails. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35(4):490-500.

7. Ditton PM. Bureau of Justice Statistics special report: mental health and treatment of inmates and probationers. U.S. Department of Justice. https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/mhtip.pdf. Published July 1999. Accessed April 24, 2019.

8. Crilly JF, Caine ED, Lamberti JS, et al. Mental health services use and symptom prevalence in a cohort of adults on probation. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(4):542-544.

9. Herinckx HA, Swart SC, Ama SM, et al. Rearrest and linkage to mental health services among clients of the Clark County mental health court program. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(7):853-857.

10. Solomon P, Draine J, Marcus SC. Predicting incarceration of clients of a psychiatric probation and parole service. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(1):50-56.

11. Owens GP, Rogers SM, Whitesell AA. Use of mental health services and barriers to care for individuals on probation or parole. J Offender Rehabil. 2011;50(1):35-47.

12. Berman G, Feinblatt J. Problem‐solving courts: a brief primer. Law and Policy. 2001;23(2):126.

13. The Council of State Governments Justice Center. Mental health courts: a guide to research-informed policy and practice. U.S. Department of Justice. https://www.bja.gov/Publications/CSG_MHC_Research.pdf. Published 2009. Accessed November 22, 2018.

14. Landess J, Holoyda B. Mental health courts and forensic assertive community treatment teams as correctional diversion programs. Behav Sci Law. 2017;35(5-6):501-511.

15. Sammon KC. Therapeutic jurisprudence: an examination of problem‐solving justice in New York. Journal of Civil Rights and Economic Development. 2008;23:923.

16. Sarteschi CM, Vaughn MG, Kim, K. Assessing the effectiveness of mental health courts: a quantitative review. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2011;39(1):12-20.

17. Strong SM, Rantala RR. Census of problem-solving courts, 2012. U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Assistance. http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cpsc12.pdf. Revised October 12, 2016. Accessed April 24, 2019.

18. McGuire JF, Rosenheck RA. Criminal history as a prognostic indicator in the treatment of homeless people with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(1):42-48.

19. Families USA. Medicaid suspension policies for incarcerated people: a 50-state map. Families USA. https://familiesusa.org/product/medicaid-suspension-policies-incarcerated-people-50-state-map. Published July 2016. Accessed December 7, 2018.

20. Binswanger IA, Stern MF, Deyo RA, et al. Release from prison—a high risk of death for former inmates. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(2):157-165.

21. Binswanger IA, Blatchford PJ, Mueller SR, et al. Mortality after prison release: opioid overdose and other causes of death, risk factors, and time trends from 1999 to 2009. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(9):592-600.

22. Lim S, Seligson AL, Parvez FM, et al. Risks of drug-related death, suicide, and homicide during the immediate post-release period among people released from New York City Jails, 2001-2005. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175(6):519-526.

23. Cusack KJ, Morrissey JP, Cuddeback GS, et al. Criminal justice involvement, behavioral health service use, and costs of forensic assertive community treatment: a randomized trial. Community Ment Health J. 2010;46(4):356-363.

24. Felthous AR, Stanford MS. A proposed algorithm for the pharmacotherapy of impulsive aggression. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2015:43(4);456-467.

Mr. A, age 35, presents to your outpatient community mental health practice. He has a history of psychosis that began in his late teens. Since then, his symptoms have included derogatory auditory hallucinations, a recurrent persecutory delusion that governmental agencies are tracking his movements, and intermittent disorganized speech. At age 30, Mr. A assaulted a stranger out of fear that the individual was a government agent. He was arrested and experienced a severe psychotic decompensation while awaiting trial. He was found incompetent to stand trial and sent to a state hospital for restoration.

After 6 months of treatment and observation, Mr. A was deemed competent to proceed and returned to jail. He was subsequently convicted of assault and sentenced to 7 years in prison. While in prison, he received regular mental health care with infrequent recurrence of minor psychotic symptoms. He was released on parole due to his good behavior, but as part of his conditions of parole, he was mandated to follow up with an outpatient mental health clinician.

After telling you the story of how he ended up in your office, Mr. A says he needs you to speak regularly with his parole officer to verify his attendance at appointments and to discuss any mental health concerns you may have. Since you have not worked with a patient on parole before, your mind is full of questions: What are the expectations regarding your communication with his parole officer? Could Mr. A return to prison if you express concerns about his mental health? What can you do to improve his chances of success in the community?

Given the high rates of mental illness among individuals incarcerated in the United States, it shouldn’t be surprising that there are similarly high rates of mental illness among those on supervised release from jails and prisons. Clinicians who work with patients on community release need to understand basic concepts related to probation and parole, and how to promote patients’ stability in the community to reduce recidivism and re-incarceration. The court may require individuals on probation or parole to adhere to certain conditions of release, which could include seeing a psychiatrist or psychotherapist, participating in substance abuse treatment, and/or taking psychotropic medication. The court usually closely monitors the probationer or parolee’s adherence, and noncompliance can be grounds for probation or parole violation and revocation.

This article reviews the concepts of probation and parole (Box1,2), describes the prevalence of mental illness among probationers and parolees, and discusses the unique challenges and opportunities psychiatrists and other mental health professionals face when working with individuals on community supervision.

Box

The US Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) defines probation as a “court-ordered period of correctional supervision in the community, generally as an alternative to incarceration.” Probation allows individuals to be released from jail to community supervision, with the potential for dismissal or lowering of charges if they adhere to the conditions of probation. Conditions of probation may include participating in substance abuse or mental health treatment programs, abstaining from drugs and alcohol, and avoiding contact with known felons. Failure to comply with conditions of probation can lead to re-incarceration and probation revocation.1 If probation is revoked, a probationer may be sentenced, potentially to prison, depending on the severity of the original offense.2

The BJS defines parole as “a period of conditional supervised release in the community following a term in state or federal prison.”2 Parole allows for the community supervision of individuals who have already been convicted of and sentenced to prison for a crime. Individuals may be released on parole if they demonstrate good behavior while incarcerated. Similar to probationers, parolees must adhere to the conditions of parole, and violation of these may lead to re-incarceration.1

As of December 31, 2016, there were more than 4.5 million adults on community supervision in the United States, representing 1 out of every 55 adults in the US population. Individuals on probation accounted for 81% of adults on community supervision. The number of people on community supervision has dropped continuously over the last decade, a trend driven by 2% annual decreases in the probation population. In contrast, the parolee population has continued to grow over time and was approximately 900,000 individuals at the end of 2016.2

Mental illness among probationers and parolees

Research on mental illness in people involved in the criminal justice system has largely focused on those who are incarcerated. Studies have documented high rates of severe mental illness (SMI), such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, among those who are incarcerated; some estimate the rates to be 3 times as high as those of community samples.3,4 In addition to SMI, substance use disorders and personality disorders (in particular, antisocial personality disorder) are common among people who are incarcerated.5,6

Comparatively little is known about mental illness among probationers and parolees, although presumably there would be a similarly high prevalence of SMI, substance use disorders, and other psychiatric disorders among this population. A 1997 Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) survey of approximately 3.4 million probationers found that 13.8% self-reported a mental or emotional condition and 8.2% self-reported a history of an “overnight stay in a mental hospital.”7 The BJS estimated that there were approximately 550,000 probationers with mental illness in the United States. The study’s author noted that probationers with mental illness were more likely to have a history of prior offenses and more likely to be violent recidivists. In terms of substance use, compared with other probationers, those with mental illness were more likely to report using drugs in the month before their most recent offense and at the time of the offense.7

Continue to: More recent research...

More recent research, although limited, has shed some light on the role of mental health services for individuals on probation and parole. In 2009, Crilly et al8 reported that 23% of probationers reported accessing mental health services within the past year. Other studies have found that probationer and parolee engagement in mental health care reduces the risk of recidivism.9,10 A 2011 study evaluated 100 individuals on probation and parole in 2 counties in a southeastern state. The authors found that 75% of participants reported that they needed counseling for a mental health concern in the past year, but that only approximately 30% of them actually sought help. Individuals reporting higher levels of posttraumatic stress disorder symptomatology or greater drug use before being on probation or parole were more likely to seek counseling in the past year.11

An alternative: Problem-solving courts

Problem-solving courts (PSCs) offer an alternative to standard probation and/or sentencing. Problem-solving courts are founded on the concept of therapeutic jurisprudence, which seeks to change “the behavior of litigants and [ensure] the future well-being of communities.”12 Types of PSCs include drug court (the most common type in the United States), domestic violence court, veterans court, and mental health court (MHC), among others.

An individual may choose a PSC over standard probation because participants usually receive more assistance in obtaining treatment and closer supervision with an emphasis on rehabilitation rather than incapacitation or retribution. The success of PSCs relies heavily on the judge, as he/she plays a pivotal role in developing relationships with the participants, considering therapeutic alternatives to “bad” behaviors, determining sanctions, and relying on community mental health partners to assist participants in complying with conditions of the court.13-15

Psychiatrists and other mental health clinicians should be aware of MHCs, which are a type of PSC that provides for the community supervision of individuals with mental illness. Mental health courts vary in terms of eligibility criteria. Some accept individuals who merely report a history of mental illness, whereas others have specific diagnostic requirements.16 Some accept individuals accused of minor violations such as ordinance violations or misdemeanor offenses, while others accept individuals accused of felonies. Like other PSCs, participation in an MHC is voluntary, and most require a participant to enter a guilty plea upon entry.17 Participants may choose to enter an MHC to avoid prison time or to reduce or expunge charges after completing the program. Many MHCs also assign a probation officer to follow the participant in the community, similar to a standard probation model. Participants are usually expected to engage in psychiatric treatment, including psychotherapy, substance abuse counseling, medication management, and other services. If they do not comply with these conditions, they face sanctions that could include jail “shock” time, enhanced supervision, or an increase in psychiatric services.

Outpatient mental health professionals play an integral role in MHCs. Depending on the model, he/she may be asked to communicate treatment recommendations, attend weekly meetings at the court, and provide suggestions for interventions when the participant relapses, recidivates, and/or decompensates psychiatrically. This collaborative model can work well and allow the clinician unique opportunities to educate the court and advocate for his/her patient. However, clinicians who participate in an MHC need to remain aware of the potential to become a de facto probation officer, and need to maintain appropriate boundaries and roles. They should ensure that the patient provides initial and ongoing consent for them to communicate with the court, and share their programmatic recommendations with the patient to preserve the therapeutic alliance.

Continue to: Challenges upon re-entering the community

Challenges upon re-entering the community

Individuals recently released from jail or prison face unique challenges when re-entering the community. An individual who has been incarcerated, particularly for months to years, has likely lost his/her job, housing, health insurance, and access to primary supports. People with mental illness with a history of incarceration have higher rates of homelessness, substance use disorders, and unemployment than those with no history of incarceration.7,18 For individuals with mental illness, these additional stressors lead to further psychiatric decompensation, recidivism, and overutilization of emergency and crisis services upon release from prison or jail. The loss of health insurance presents great challenges: when someone is incarcerated, his/her Medicaid is suspended or terminated.19 This can happen at any point during incarceration. In states that terminate rather than suspend Medicaid, former prisoners face even longer waits to re-establish access to needed health care.

The period immediately after release is a critical time for individuals to be linked with substance and mental health treatment. Binswanger et al20 found former prisoners were at highest risk of mortality in the 2 weeks following release from prison; the highest rates of death were from drug overdose, cardiovascular disease, homicide, and suicide. A subsequent study found that women were at increased risk of drug overdose and opioid-related deaths.21 One explanation for the increase in drug-related deaths is the loss of physiologic tolerance while incarcerated; however, a lack of treatment while incarcerated, high levels of stress upon re-entry, and poor linkage to aftercare also may be contributing factors. Among prisoners recently released from New York City jails, Lim et al22 found that those with a history of homelessness and previous incarceration had the highest rates of drug-related deaths and homicides in the first 2 weeks after release. Non-Hispanic white men had the highest risk of drug-related deaths and suicides. While the risk of death is greatest immediately after release, former prisoners face increased mortality from multiple causes for multiple years after release.20-22

Clinicians who work with recently released prisoners should be aware of these individuals’ risks and actively work with them and other members of the mental health team to ensure these patients have access to social services, employment training, housing, and substance use resources, including medication-assisted treatment. Patients with SMI should be considered for more intensive services, such as assertive community treatment (ACT) or even forensic ACT (FACT) services, given that FACTs have a modest impact in reducing recidivism.23

Knowing whether the patient is on probation or parole and the terms of his/her supervision can also be useful in creating and executing a collaborative treatment plan. The clinician can assist the patient in meeting conditions of probation/parole such as:

- creating a stable home plan with a permanent address

- planning routine check-ins with probation/parole officers, and

- keeping documentation of ongoing mental health and substance use treatment.

Being aware of other terms of supervision, such as abstaining from alcohol and drugs, or remaining in one’s jurisdiction, also can help the patient avoid technical violations and a return to jail or prison.

Continue to: How to best help patients on community supervision

How to best help patients on community supervision

There are some clinical recommendations when working with patients on community supervision. First, do not assume that someone who has been incarcerated has antisocial personality disorder. Behaviors primarily related to seeking or using drugs or survival-type crimes should not be considered “antisocial” without additional evidence of pervasive and persistent conduct demonstrating impulsivity, lack of empathy, dishonesty, or repeated disregard for social norms and others’ rights. To meet criteria for antisocial personality disorder, these behaviors must have begun during childhood or adolescence.

If a patient does meet criteria for antisocial personality disorder, remember that he/she may also have a psychotic, mood, substance use, or other disorder that could lead to a greater likelihood of violence, recidivism, or other poor outcomes if left untreated. Treating any co-occurring disorders could enhance the patient’s engagement with treatment. There is some evidence that certain psychotropic medications, su

In addition to promoting patients’ mental health, such efforts can prevent re-arrest and re-incarceration and make a lasting positive impact on patients’ lives.

CASE CONTINUED

Mr. A signs a release-of-information form and you call his parole officer. His parole officer states that he would like to speak with you every few months to check on Mr. A’s treatment adherence. Within a few months, you transition Mr. A from an oral antipsychotic medication to a long-acting injectable antipsychotic medication to manage his psychotic disorder. He presents on time each month to your clinic to receive the injection.

Five months later, Mr. A receives 2 weeks of “shock time” at the local county jail for “dropping a dirty urine” that was positive for cannabinoids at a meeting with his parole officer. During his time in jail, he receives no treatment and he misses his monthly long-acting injectable dose.

Continue to: Upon release...

Upon release, he demonstrates the recurrence of some mild persecutory fears and hallucinations, but you resume him on his prior treatment regimen, and he recovers.

You encourage the parole officer to notify you if Mr. A violates parole and is incarcerated so that you can speak with clinicians in the jail to ensure that Mr. A remains adequately treated while incarcerated.

In the coming years, you continue to work with Mr. A and his parole officer to manage his mental health condition and to navigate his parole requirements in order to reduce his risk of relapse and recidivism. After Mr. A completes his time on parole, you continue to see him for outpatient follow-up.

Bottom Line

Clinicians may provide psychiatric care to probationers and parolees in traditional outpatient settings or in collaboration with a mental health court (MHC) or forensic assertive community treatment team. It is crucial to be aware of the legal expectations of individuals on community supervision, as well as the unique mental health risks and challenges they face. You can help reduce probationers’ and parolees’ risk of relapse and recidivism and support their recovery in the community by engaging in collaborative treatment planning involving the patient, the court, and/or MHCs.

Related Resources

- Lamb HR. Weinberger LE. Understanding and treating offenders with serious mental illness in public sector mental health. Behav Sci Law. 2017;35(4):303-318.

- Worcester S. Mental illness and the criminal justice system: Reducing the risks. Clinical Psychiatry News. https://www.mdedge.com/psychiatry/article/173208/schizophrenia-other-psychotic-disorders/mental-illness-and-criminal. Published August 22, 2018.

Mr. A, age 35, presents to your outpatient community mental health practice. He has a history of psychosis that began in his late teens. Since then, his symptoms have included derogatory auditory hallucinations, a recurrent persecutory delusion that governmental agencies are tracking his movements, and intermittent disorganized speech. At age 30, Mr. A assaulted a stranger out of fear that the individual was a government agent. He was arrested and experienced a severe psychotic decompensation while awaiting trial. He was found incompetent to stand trial and sent to a state hospital for restoration.

After 6 months of treatment and observation, Mr. A was deemed competent to proceed and returned to jail. He was subsequently convicted of assault and sentenced to 7 years in prison. While in prison, he received regular mental health care with infrequent recurrence of minor psychotic symptoms. He was released on parole due to his good behavior, but as part of his conditions of parole, he was mandated to follow up with an outpatient mental health clinician.

After telling you the story of how he ended up in your office, Mr. A says he needs you to speak regularly with his parole officer to verify his attendance at appointments and to discuss any mental health concerns you may have. Since you have not worked with a patient on parole before, your mind is full of questions: What are the expectations regarding your communication with his parole officer? Could Mr. A return to prison if you express concerns about his mental health? What can you do to improve his chances of success in the community?

Given the high rates of mental illness among individuals incarcerated in the United States, it shouldn’t be surprising that there are similarly high rates of mental illness among those on supervised release from jails and prisons. Clinicians who work with patients on community release need to understand basic concepts related to probation and parole, and how to promote patients’ stability in the community to reduce recidivism and re-incarceration. The court may require individuals on probation or parole to adhere to certain conditions of release, which could include seeing a psychiatrist or psychotherapist, participating in substance abuse treatment, and/or taking psychotropic medication. The court usually closely monitors the probationer or parolee’s adherence, and noncompliance can be grounds for probation or parole violation and revocation.

This article reviews the concepts of probation and parole (Box1,2), describes the prevalence of mental illness among probationers and parolees, and discusses the unique challenges and opportunities psychiatrists and other mental health professionals face when working with individuals on community supervision.

Box

The US Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) defines probation as a “court-ordered period of correctional supervision in the community, generally as an alternative to incarceration.” Probation allows individuals to be released from jail to community supervision, with the potential for dismissal or lowering of charges if they adhere to the conditions of probation. Conditions of probation may include participating in substance abuse or mental health treatment programs, abstaining from drugs and alcohol, and avoiding contact with known felons. Failure to comply with conditions of probation can lead to re-incarceration and probation revocation.1 If probation is revoked, a probationer may be sentenced, potentially to prison, depending on the severity of the original offense.2

The BJS defines parole as “a period of conditional supervised release in the community following a term in state or federal prison.”2 Parole allows for the community supervision of individuals who have already been convicted of and sentenced to prison for a crime. Individuals may be released on parole if they demonstrate good behavior while incarcerated. Similar to probationers, parolees must adhere to the conditions of parole, and violation of these may lead to re-incarceration.1

As of December 31, 2016, there were more than 4.5 million adults on community supervision in the United States, representing 1 out of every 55 adults in the US population. Individuals on probation accounted for 81% of adults on community supervision. The number of people on community supervision has dropped continuously over the last decade, a trend driven by 2% annual decreases in the probation population. In contrast, the parolee population has continued to grow over time and was approximately 900,000 individuals at the end of 2016.2

Mental illness among probationers and parolees

Research on mental illness in people involved in the criminal justice system has largely focused on those who are incarcerated. Studies have documented high rates of severe mental illness (SMI), such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, among those who are incarcerated; some estimate the rates to be 3 times as high as those of community samples.3,4 In addition to SMI, substance use disorders and personality disorders (in particular, antisocial personality disorder) are common among people who are incarcerated.5,6

Comparatively little is known about mental illness among probationers and parolees, although presumably there would be a similarly high prevalence of SMI, substance use disorders, and other psychiatric disorders among this population. A 1997 Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) survey of approximately 3.4 million probationers found that 13.8% self-reported a mental or emotional condition and 8.2% self-reported a history of an “overnight stay in a mental hospital.”7 The BJS estimated that there were approximately 550,000 probationers with mental illness in the United States. The study’s author noted that probationers with mental illness were more likely to have a history of prior offenses and more likely to be violent recidivists. In terms of substance use, compared with other probationers, those with mental illness were more likely to report using drugs in the month before their most recent offense and at the time of the offense.7

Continue to: More recent research...

More recent research, although limited, has shed some light on the role of mental health services for individuals on probation and parole. In 2009, Crilly et al8 reported that 23% of probationers reported accessing mental health services within the past year. Other studies have found that probationer and parolee engagement in mental health care reduces the risk of recidivism.9,10 A 2011 study evaluated 100 individuals on probation and parole in 2 counties in a southeastern state. The authors found that 75% of participants reported that they needed counseling for a mental health concern in the past year, but that only approximately 30% of them actually sought help. Individuals reporting higher levels of posttraumatic stress disorder symptomatology or greater drug use before being on probation or parole were more likely to seek counseling in the past year.11

An alternative: Problem-solving courts

Problem-solving courts (PSCs) offer an alternative to standard probation and/or sentencing. Problem-solving courts are founded on the concept of therapeutic jurisprudence, which seeks to change “the behavior of litigants and [ensure] the future well-being of communities.”12 Types of PSCs include drug court (the most common type in the United States), domestic violence court, veterans court, and mental health court (MHC), among others.

An individual may choose a PSC over standard probation because participants usually receive more assistance in obtaining treatment and closer supervision with an emphasis on rehabilitation rather than incapacitation or retribution. The success of PSCs relies heavily on the judge, as he/she plays a pivotal role in developing relationships with the participants, considering therapeutic alternatives to “bad” behaviors, determining sanctions, and relying on community mental health partners to assist participants in complying with conditions of the court.13-15

Psychiatrists and other mental health clinicians should be aware of MHCs, which are a type of PSC that provides for the community supervision of individuals with mental illness. Mental health courts vary in terms of eligibility criteria. Some accept individuals who merely report a history of mental illness, whereas others have specific diagnostic requirements.16 Some accept individuals accused of minor violations such as ordinance violations or misdemeanor offenses, while others accept individuals accused of felonies. Like other PSCs, participation in an MHC is voluntary, and most require a participant to enter a guilty plea upon entry.17 Participants may choose to enter an MHC to avoid prison time or to reduce or expunge charges after completing the program. Many MHCs also assign a probation officer to follow the participant in the community, similar to a standard probation model. Participants are usually expected to engage in psychiatric treatment, including psychotherapy, substance abuse counseling, medication management, and other services. If they do not comply with these conditions, they face sanctions that could include jail “shock” time, enhanced supervision, or an increase in psychiatric services.

Outpatient mental health professionals play an integral role in MHCs. Depending on the model, he/she may be asked to communicate treatment recommendations, attend weekly meetings at the court, and provide suggestions for interventions when the participant relapses, recidivates, and/or decompensates psychiatrically. This collaborative model can work well and allow the clinician unique opportunities to educate the court and advocate for his/her patient. However, clinicians who participate in an MHC need to remain aware of the potential to become a de facto probation officer, and need to maintain appropriate boundaries and roles. They should ensure that the patient provides initial and ongoing consent for them to communicate with the court, and share their programmatic recommendations with the patient to preserve the therapeutic alliance.

Continue to: Challenges upon re-entering the community

Challenges upon re-entering the community

Individuals recently released from jail or prison face unique challenges when re-entering the community. An individual who has been incarcerated, particularly for months to years, has likely lost his/her job, housing, health insurance, and access to primary supports. People with mental illness with a history of incarceration have higher rates of homelessness, substance use disorders, and unemployment than those with no history of incarceration.7,18 For individuals with mental illness, these additional stressors lead to further psychiatric decompensation, recidivism, and overutilization of emergency and crisis services upon release from prison or jail. The loss of health insurance presents great challenges: when someone is incarcerated, his/her Medicaid is suspended or terminated.19 This can happen at any point during incarceration. In states that terminate rather than suspend Medicaid, former prisoners face even longer waits to re-establish access to needed health care.

The period immediately after release is a critical time for individuals to be linked with substance and mental health treatment. Binswanger et al20 found former prisoners were at highest risk of mortality in the 2 weeks following release from prison; the highest rates of death were from drug overdose, cardiovascular disease, homicide, and suicide. A subsequent study found that women were at increased risk of drug overdose and opioid-related deaths.21 One explanation for the increase in drug-related deaths is the loss of physiologic tolerance while incarcerated; however, a lack of treatment while incarcerated, high levels of stress upon re-entry, and poor linkage to aftercare also may be contributing factors. Among prisoners recently released from New York City jails, Lim et al22 found that those with a history of homelessness and previous incarceration had the highest rates of drug-related deaths and homicides in the first 2 weeks after release. Non-Hispanic white men had the highest risk of drug-related deaths and suicides. While the risk of death is greatest immediately after release, former prisoners face increased mortality from multiple causes for multiple years after release.20-22

Clinicians who work with recently released prisoners should be aware of these individuals’ risks and actively work with them and other members of the mental health team to ensure these patients have access to social services, employment training, housing, and substance use resources, including medication-assisted treatment. Patients with SMI should be considered for more intensive services, such as assertive community treatment (ACT) or even forensic ACT (FACT) services, given that FACTs have a modest impact in reducing recidivism.23

Knowing whether the patient is on probation or parole and the terms of his/her supervision can also be useful in creating and executing a collaborative treatment plan. The clinician can assist the patient in meeting conditions of probation/parole such as:

- creating a stable home plan with a permanent address

- planning routine check-ins with probation/parole officers, and

- keeping documentation of ongoing mental health and substance use treatment.

Being aware of other terms of supervision, such as abstaining from alcohol and drugs, or remaining in one’s jurisdiction, also can help the patient avoid technical violations and a return to jail or prison.

Continue to: How to best help patients on community supervision

How to best help patients on community supervision

There are some clinical recommendations when working with patients on community supervision. First, do not assume that someone who has been incarcerated has antisocial personality disorder. Behaviors primarily related to seeking or using drugs or survival-type crimes should not be considered “antisocial” without additional evidence of pervasive and persistent conduct demonstrating impulsivity, lack of empathy, dishonesty, or repeated disregard for social norms and others’ rights. To meet criteria for antisocial personality disorder, these behaviors must have begun during childhood or adolescence.

If a patient does meet criteria for antisocial personality disorder, remember that he/she may also have a psychotic, mood, substance use, or other disorder that could lead to a greater likelihood of violence, recidivism, or other poor outcomes if left untreated. Treating any co-occurring disorders could enhance the patient’s engagement with treatment. There is some evidence that certain psychotropic medications, su

In addition to promoting patients’ mental health, such efforts can prevent re-arrest and re-incarceration and make a lasting positive impact on patients’ lives.

CASE CONTINUED

Mr. A signs a release-of-information form and you call his parole officer. His parole officer states that he would like to speak with you every few months to check on Mr. A’s treatment adherence. Within a few months, you transition Mr. A from an oral antipsychotic medication to a long-acting injectable antipsychotic medication to manage his psychotic disorder. He presents on time each month to your clinic to receive the injection.

Five months later, Mr. A receives 2 weeks of “shock time” at the local county jail for “dropping a dirty urine” that was positive for cannabinoids at a meeting with his parole officer. During his time in jail, he receives no treatment and he misses his monthly long-acting injectable dose.

Continue to: Upon release...

Upon release, he demonstrates the recurrence of some mild persecutory fears and hallucinations, but you resume him on his prior treatment regimen, and he recovers.

You encourage the parole officer to notify you if Mr. A violates parole and is incarcerated so that you can speak with clinicians in the jail to ensure that Mr. A remains adequately treated while incarcerated.

In the coming years, you continue to work with Mr. A and his parole officer to manage his mental health condition and to navigate his parole requirements in order to reduce his risk of relapse and recidivism. After Mr. A completes his time on parole, you continue to see him for outpatient follow-up.

Bottom Line

Clinicians may provide psychiatric care to probationers and parolees in traditional outpatient settings or in collaboration with a mental health court (MHC) or forensic assertive community treatment team. It is crucial to be aware of the legal expectations of individuals on community supervision, as well as the unique mental health risks and challenges they face. You can help reduce probationers’ and parolees’ risk of relapse and recidivism and support their recovery in the community by engaging in collaborative treatment planning involving the patient, the court, and/or MHCs.

Related Resources

- Lamb HR. Weinberger LE. Understanding and treating offenders with serious mental illness in public sector mental health. Behav Sci Law. 2017;35(4):303-318.

- Worcester S. Mental illness and the criminal justice system: Reducing the risks. Clinical Psychiatry News. https://www.mdedge.com/psychiatry/article/173208/schizophrenia-other-psychotic-disorders/mental-illness-and-criminal. Published August 22, 2018.

1. Bureau of Justice Statistics. FAQ detail: What is the difference between probation and parole? U.S. Department of Justice. https://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=qa&iid=324. Accessed November 17, 2018.

2. Kaeble D. Probation and parole in the United States, 2016. U.S. Department of Justice. https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/ppus16.pdf. Published April 2018. Accessed April 23, 2019.

3. Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, et al. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617-627.

4. Diamond, P.M., et al., The prevalence of mental illness in prison. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2001;29(1):21-40.

5. MacDonald R, Kaba F, Rosner Z, et al. The Rikers Island hot spotters: defining the needs of the most frequently incarcerated. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(11):2262-2268.

6. Trestman RL, Ford J, Zhang W, et al. Current and lifetime psychiatric illness among inmates not identified as acutely mentally ill at intake in Connecticut’s jails. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35(4):490-500.

7. Ditton PM. Bureau of Justice Statistics special report: mental health and treatment of inmates and probationers. U.S. Department of Justice. https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/mhtip.pdf. Published July 1999. Accessed April 24, 2019.

8. Crilly JF, Caine ED, Lamberti JS, et al. Mental health services use and symptom prevalence in a cohort of adults on probation. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(4):542-544.

9. Herinckx HA, Swart SC, Ama SM, et al. Rearrest and linkage to mental health services among clients of the Clark County mental health court program. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(7):853-857.

10. Solomon P, Draine J, Marcus SC. Predicting incarceration of clients of a psychiatric probation and parole service. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(1):50-56.

11. Owens GP, Rogers SM, Whitesell AA. Use of mental health services and barriers to care for individuals on probation or parole. J Offender Rehabil. 2011;50(1):35-47.

12. Berman G, Feinblatt J. Problem‐solving courts: a brief primer. Law and Policy. 2001;23(2):126.

13. The Council of State Governments Justice Center. Mental health courts: a guide to research-informed policy and practice. U.S. Department of Justice. https://www.bja.gov/Publications/CSG_MHC_Research.pdf. Published 2009. Accessed November 22, 2018.

14. Landess J, Holoyda B. Mental health courts and forensic assertive community treatment teams as correctional diversion programs. Behav Sci Law. 2017;35(5-6):501-511.

15. Sammon KC. Therapeutic jurisprudence: an examination of problem‐solving justice in New York. Journal of Civil Rights and Economic Development. 2008;23:923.

16. Sarteschi CM, Vaughn MG, Kim, K. Assessing the effectiveness of mental health courts: a quantitative review. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2011;39(1):12-20.

17. Strong SM, Rantala RR. Census of problem-solving courts, 2012. U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Assistance. http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cpsc12.pdf. Revised October 12, 2016. Accessed April 24, 2019.

18. McGuire JF, Rosenheck RA. Criminal history as a prognostic indicator in the treatment of homeless people with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(1):42-48.

19. Families USA. Medicaid suspension policies for incarcerated people: a 50-state map. Families USA. https://familiesusa.org/product/medicaid-suspension-policies-incarcerated-people-50-state-map. Published July 2016. Accessed December 7, 2018.

20. Binswanger IA, Stern MF, Deyo RA, et al. Release from prison—a high risk of death for former inmates. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(2):157-165.

21. Binswanger IA, Blatchford PJ, Mueller SR, et al. Mortality after prison release: opioid overdose and other causes of death, risk factors, and time trends from 1999 to 2009. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(9):592-600.

22. Lim S, Seligson AL, Parvez FM, et al. Risks of drug-related death, suicide, and homicide during the immediate post-release period among people released from New York City Jails, 2001-2005. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175(6):519-526.

23. Cusack KJ, Morrissey JP, Cuddeback GS, et al. Criminal justice involvement, behavioral health service use, and costs of forensic assertive community treatment: a randomized trial. Community Ment Health J. 2010;46(4):356-363.

24. Felthous AR, Stanford MS. A proposed algorithm for the pharmacotherapy of impulsive aggression. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2015:43(4);456-467.

1. Bureau of Justice Statistics. FAQ detail: What is the difference between probation and parole? U.S. Department of Justice. https://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=qa&iid=324. Accessed November 17, 2018.

2. Kaeble D. Probation and parole in the United States, 2016. U.S. Department of Justice. https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/ppus16.pdf. Published April 2018. Accessed April 23, 2019.

3. Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, et al. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617-627.

4. Diamond, P.M., et al., The prevalence of mental illness in prison. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2001;29(1):21-40.

5. MacDonald R, Kaba F, Rosner Z, et al. The Rikers Island hot spotters: defining the needs of the most frequently incarcerated. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(11):2262-2268.

6. Trestman RL, Ford J, Zhang W, et al. Current and lifetime psychiatric illness among inmates not identified as acutely mentally ill at intake in Connecticut’s jails. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35(4):490-500.

7. Ditton PM. Bureau of Justice Statistics special report: mental health and treatment of inmates and probationers. U.S. Department of Justice. https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/mhtip.pdf. Published July 1999. Accessed April 24, 2019.

8. Crilly JF, Caine ED, Lamberti JS, et al. Mental health services use and symptom prevalence in a cohort of adults on probation. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(4):542-544.

9. Herinckx HA, Swart SC, Ama SM, et al. Rearrest and linkage to mental health services among clients of the Clark County mental health court program. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(7):853-857.

10. Solomon P, Draine J, Marcus SC. Predicting incarceration of clients of a psychiatric probation and parole service. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(1):50-56.

11. Owens GP, Rogers SM, Whitesell AA. Use of mental health services and barriers to care for individuals on probation or parole. J Offender Rehabil. 2011;50(1):35-47.

12. Berman G, Feinblatt J. Problem‐solving courts: a brief primer. Law and Policy. 2001;23(2):126.

13. The Council of State Governments Justice Center. Mental health courts: a guide to research-informed policy and practice. U.S. Department of Justice. https://www.bja.gov/Publications/CSG_MHC_Research.pdf. Published 2009. Accessed November 22, 2018.

14. Landess J, Holoyda B. Mental health courts and forensic assertive community treatment teams as correctional diversion programs. Behav Sci Law. 2017;35(5-6):501-511.

15. Sammon KC. Therapeutic jurisprudence: an examination of problem‐solving justice in New York. Journal of Civil Rights and Economic Development. 2008;23:923.

16. Sarteschi CM, Vaughn MG, Kim, K. Assessing the effectiveness of mental health courts: a quantitative review. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2011;39(1):12-20.

17. Strong SM, Rantala RR. Census of problem-solving courts, 2012. U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Assistance. http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cpsc12.pdf. Revised October 12, 2016. Accessed April 24, 2019.

18. McGuire JF, Rosenheck RA. Criminal history as a prognostic indicator in the treatment of homeless people with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(1):42-48.

19. Families USA. Medicaid suspension policies for incarcerated people: a 50-state map. Families USA. https://familiesusa.org/product/medicaid-suspension-policies-incarcerated-people-50-state-map. Published July 2016. Accessed December 7, 2018.

20. Binswanger IA, Stern MF, Deyo RA, et al. Release from prison—a high risk of death for former inmates. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(2):157-165.

21. Binswanger IA, Blatchford PJ, Mueller SR, et al. Mortality after prison release: opioid overdose and other causes of death, risk factors, and time trends from 1999 to 2009. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(9):592-600.

22. Lim S, Seligson AL, Parvez FM, et al. Risks of drug-related death, suicide, and homicide during the immediate post-release period among people released from New York City Jails, 2001-2005. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175(6):519-526.

23. Cusack KJ, Morrissey JP, Cuddeback GS, et al. Criminal justice involvement, behavioral health service use, and costs of forensic assertive community treatment: a randomized trial. Community Ment Health J. 2010;46(4):356-363.

24. Felthous AR, Stanford MS. A proposed algorithm for the pharmacotherapy of impulsive aggression. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2015:43(4);456-467.

Agitation in children and adolescents: Diagnostic and treatment considerations

Managing agitation—verbal and/or motor restlessness that often is accompanied by irritability and a predisposition to aggression or violence—can be challenging in any patient, but particularly so in children and adolescents. In the United States, the prevalence of children and adolescents presenting to an emergency department (ED) for treatment of psychiatric symptoms, including agitation, has been on the rise.1,2

Similar to the multitude of causes of fever, agitation among children and adolescents has many possible causes.3 Because agitation can pose a risk for harm to others and/or self, it is important to manage it proactively. Other than studies that focus on agitation in pediatric anesthesia, there is a dearth of studies examining agitation and its treatment in children and adolescents. There is also a scarcity of training in the management of acute agitation in children and adolescents. In a 2017 survey of pediatric hospitalists and consultation-liaison psychiatrists at 38 academic children’s hospitals in North America, approximately 60% of respondents indicated that they had received no training in the evaluation or management of pediatric acute agitation.4 In addition, approximately 54% of participants said they did not screen for risk factors for pediatric agitation, even though 84% encountered the condition at least once a month, and as often as weekly.4

This article reviews evidence on the causes and treatments of agitation in children and adolescents. For the purposes of this review, child refers to a patient age 6 to 12, and adolescent refers to a patient age 13 to 17.

Identifying the cause

Addressing the underlying cause of agitation is essential. It’s also important to manage acute agitation while the underlying cause is being investigated in a way that does not jeopardize the patient’s emotional or physical safety.

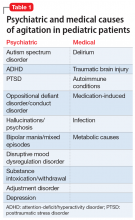

Agitation in children or teens can be due to psychiatric causes such as autism, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), or due to medical conditions such as delirium, traumatic brain injury, or other conditions (Table 1).

In a 2005 study of 194 children with agitation in a pediatric post-anesthesia care unit, pain (27%) and anxiety (25%) were found to be the most common causes of agitation.3 Anesthesia-related agitation was a less common cause (11%). Physiologic anomalies were found to be the underlying cause of agitation in only 3 children in this study, but were undiagnosed for a prolonged period in 2 of these 3 children, which highlights the importance of a thorough differential diagnosis in the management of agitation in children.3

Assessment of an agitated child should include a comprehensive history, physical exam, and laboratory testing as indicated. When a pediatric patient comes to the ED with a chief presentation of agitation, a thorough medical and psychiatric assessment should be performed. For patients with a history of psychiatric diagnoses, do not assume that the cause of agitation is psychiatric.

Continue to: Psychiatric causes

Psychiatric causes

Autism spectrum disorder. Children and teens with autism often feel overwhelmed due to transitions, changes, and/or sensory overload. This sensory overload may be in response to relatively subtle sensory stimuli, so it may not always be apparent to parents or others around them.

Research suggests that in general, the ability to cope effectively with emotions is difficult without optimal language development. Due to cognitive/language delays and a related lack of emotional attunement and limited skills in recognizing, expressing, or coping with emotions, difficult emotions in children and adolescents with autism can manifest as agitation.

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Children with ADHD may be at a higher risk for agitation, in part due to poor impulse control and limited coping skills. In addition, chronic negative feedback (from parents, teachers, or both) may contribute to low self-esteem, mood symptoms, defiance, and/or other behavioral difficulties. In addition to standard pharmacotherapy for ADHD, treatment involves parent behavior modification training. Setting firm yet empathic limits, “picking battles,” and implementing a developmentally appropriate behavioral plan to manage disruptive behavior in children or adolescents with ADHD can go a long way in helping to prevent the emergence of agitation.

Posttraumatic stress disorder. In some young children, new-onset, unexplained agitation may be the only sign of abuse or trauma. Children who have undergone trauma tend to experience confusion and distress. This may manifest as agitation or aggression, or other symptoms such as increased anxiety or nightmares.5 Trauma may be in the form of witnessing violence (domestic or other); experiencing physical, sexual, and/or emotional abuse; or witnessing/experiencing other significant threats to the safety of self and/or loved ones. Re-establishing (or establishing) a sense of psychological and physical safety is paramount in such patients.6 Psychotherapy is the first-line modality of treatment in children and adolescents with PTSD.6 In general, there is a scarcity of research on medication treatments for PTSD symptoms among children and adolescents.6

Oppositional defiant disorder/conduct disorder. Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) can be comorbid with ADHD. The diagnosis of ODD requires a pervasive pattern of anger, defiance, vindictiveness, and hostility, particularly towards authority figures. However, these symptoms need to be differentiated from the normal range of childhood behavior. Occasionally, children learn to cope maladaptively through disruptive behavior or agitation. Although a parent or caregiver may see this behavior as intentionally malevolent, in a child with limited coping skills (whether due to young age, developmental/cognitive/language/learning delays, or social communication deficits) or one who has witnessed frequent agitation or aggression in the family environment, agitation and disruptive behavior may be a maladaptive form of coping. Thus, diligence needs to be exercised in the diagnosis of ODD and in understanding the psychosocial factors affecting the child, particularly because impulsiveness and uncooperativeness on their own have been found to be linked to greater likelihood of prescription of psychotropic medications from multiple classes.7 Family-based interventions, particularly parent training, family therapy, and age-appropriate child skills training, are of prime importance in managing this condition.8 Research shows that a shortage of resources, system issues, and cultural roadblocks in implementing family-based psychosocial interventions also can contribute to the increased use of psychotropic medications for aggression in children and teens with ODD, conduct disorder, or ADHD.8 The astute clinician needs to be cognizant of this before prescribing.

Continue to: Hallucinations/psychosis

Hallucinations/psychosis. Hallucinations (whether from psychiatric or medical causes) are significantly associated with agitation.9 In particular, auditory command hallucinations have been linked to agitation. Command hallucinations in children and adolescents may be secondary to early-onset schizophrenia; however, this diagnosis is rare.10 Hallucinations can also be an adverse effect of amphetamine-based stimulant medications in children and adolescents. Visual hallucinations are most often a sign of an underlying medical disorder such as delirium, occipital lobe mass/infection, or drug intoxication or withdrawal. Hallucinations need to be distinguished from the normal, imaginative play of a young child.10

Bipolar mania. In adults, bipolar disorder is a primary psychiatric cause of agitation. In children and adolescents, the diagnosis of bipolar disorder can be complex and requires careful and nuanced history-taking. The risks of agitation are greater with bipolar disorder than with unipolar depression.11,12

Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder. Prior to DSM-5, many children and adolescents with chronic, non-episodic irritability and severe outbursts out of proportion to the situation or stimuli were given a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. These symptoms, in combination with other symptoms, are now considered part of disruptive mood dysregulation disorder when severe outbursts in a child or adolescent occur 3 to 4 times a week consistently, for at least 1 year. The diagnosis of disruptive mood dysregulation disorder requires ruling out other psychiatric and medical conditions, particularly ADHD.13

Substance intoxication/withdrawal. Intoxication or withdrawal from substances such as alcohol, stimulant medications, opioids, methamphetamines, and other agents can lead to agitation. This is more likely to occur among adolescents than children.14

Adjustment disorder. Parental divorce, especially if it is conflictual, or other life stressors, such as experiencing a move or frequent moves, may contribute to the development of agitation in children and adolescents.

Continue to: Depression

Depression. In children and adolescents, depression can manifest as anger or irritability, and occasionally as agitation.

Medical causes

Delirium. Refractory agitation is often a manifestation of delirium in children and adolescents.15 If unrecognized and untreated, delirium can be fatal.16 Therefore, it is imperative that clinicians routinely assess for delirium in any patient who presents with agitation.

Because a patient with delirium often presents with agitation and visual or auditory hallucinations, the medical team may tend to assume these symptoms are secondary to a psychiatric disorder. In this case, the role of the consultation-liaison psychiatrist is critical for guiding the medical team, particularly to continue a thorough exploration of underlying causes while avoiding polypharmacy. Noise, bright lights, frequent changes in nursing staff or caregivers, anticholinergic or benzodiazepine medications, and frequent changes in schedules should be avoided to prevent delirium from occurring or getting worse.17 A multidisciplinary team approach is key in identifying the underlying cause and managing delirium in pediatric patients.

Traumatic brain injury. Agitation may be a presenting symptom in youth with traumatic brain injury (TBI).18 Agitation may present often in the acute recovery phase.19 There is limited evidence on the efficacy and safety of pharmacotherapy for agitation in pediatric patients with TBI.18

Autoimmune conditions. In a study of 27 patients with

Continue to: Medication-induced/iatrogenic

Medication-induced/iatrogenic. Agitation can be an adverse effect of medications such as amantadine (often used for TBI),18 atypical antipsychotics,21 selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors.

Infection. Agitation can be a result of encephalitis, meningitis, or other infectious processes.22

Metabolic conditions. Hepatic or renal failure, diabetic ketoacidosis, and thyroid toxicosis may cause agitation in children or adolescents.22

Start with nonpharmacologic interventions

Few studies have examined de-escalation techniques in agitated children and adolescents. However, verbal de-escalation is generally viewed as the first-line technique for managing agitation in children and adolescents. When feasible, teaching and modeling developmentally appropriate stress management skills for children and teens can be a beneficial preventative strategy to reduce the incidence and worsening of agitation.23

Clinicians should refrain from using coercion.24 Coercion could harm the therapeutic alliance, thereby impeding assessment of the underlying causes of agitation, and can be particularly harmful for patients who have a history of trauma or abuse. Even in pediatric patients with no such history, coercion is discouraged due to its punitive connotations and potential to adversely impact a vulnerable child or teen.

Continue to: Establishing a therapeutic rapport...

Establishing a therapeutic rapport with the patient, when feasible, can facilitate smoother de-escalation by offering the patient an outlet to air his/her frustrations and emotions, and by helping the patient feel understood.24 To facilitate this, ensure that the patient’s basic comforts and needs are met, such as access to a warm bed, food, and safety.25

The psychiatrist’s role is to help uncover and address the underlying reason for the patient’s agony or distress. Once the child or adolescent has calmed, explore potential triggers or causes of the agitation.

There has been a significant move away from the use of restraints for managing agitation in children and adolescents.26 Restraints have a psychologically traumatizing effect,27 and have been linked to life-threatening injuries and death in children.24

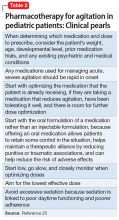

Pharmacotherapy: Proceed with caution