User login

Is chest radiography routinely needed after thoracentesis?

No. After thoracentesis, chest radiography or another lung imaging study should be done only if pneumothorax is suspected, if thoracentesis requires more than 1 attempt, if the patient is on mechanical ventilation or has pre-existing lung disease, or if a large volume (> 1,500 mL) of fluid is removed. Radiography is also usually not necessary after diagnostic thoracentesis in a patient breathing spontaneously. In most cases, pneumothorax found incidentally after thoracentesis does not require decompression and can be managed supportively.

WHAT ARE THE RISKS OF THORACENTESIS?

Thoracentesis is a minimally invasive procedure usually performed at the bedside that involves insertion of a needle into the pleural cavity for drainage of fluid.1 Diagnostic thoracentesis should be done in most cases of a new pleural effusion unless the effusion is small and with a clear diagnosis, or in cases of typical heart failure.

Therapeutic thoracentesis, often called large-volume thoracentesis, aims to improve symptoms such as dyspnea attributed to the pleural effusion by removing at least 1 L of pleural fluid. The presence of active respiratory symptoms and suspicion of infected pleural effusion should lead to thoracentesis as soon as possible.

Complications of thoracentesis may be benign, such as pain and anxiety associated with the procedure and external bleeding at the site of needle insertion. Pneumothorax is the most common serious procedural complication and the principal reason to order postprocedural chest radiography.1 Less common complications include hemothorax, re-expansion pulmonary edema, infection, subdiaphragmatic organ puncture, and procedure-related death. Bleeding complications and hemothorax are rare even in patients with underlying coagulopathy.2

Point-of-care pleural ultrasonography is now considered the standard of care to guide optimal needle location for the procedure and to exclude other conditions that can mimic pleural effusion on chest radiography, such as lung consolidation and atelectasis.3 High proficiency in the use of preprocedural point-of-care ultrasonography reduces the rate of procedural complications, though it does not eliminate the risk entirely.3,4

Factors associated with higher rates of complications include lack of operator proficiency, poor understanding of the anatomy, poor patient positioning, poor patient cooperation with the procedure, lack of availability of bedside ultrasonography, and drainage of more than 1,500 mL of fluid. Addressing these factors has been shown to decrease the risk of pneumothorax and infection.1–5

HOW OFTEN DOES PNEUMOTHORAX OCCUR AFTER THORACENTESIS?

Several early studies have examined the incidence of pneumothorax after thoracentesis. Lack of ultrasonography use likely explains a higher incidence of complications in early studies: rates of pneumothorax after thoracentesis without ultrasonographic guidance ranged from 5.2% to 26%.6,7

Gervais et al8 analyzed thoracentesis with ultrasonographic guidance in 434 patients, 92 of whom were intubated, and reported that pneumothorax occurred in 10 patients, of whom 6 were intubated. Two of the intubated patients required chest tubes. Other studies have confirmed the low incidence of pneumothorax in patients undergoing thoracentesis, with rates such as 0.61%,1 5%,9 and 4%.10

The major predictor of postprocedural pneumothorax was the presence of symptoms such as chest pain and dyspnea. No intervention was necessary for most cases of pneumothorax in asymptomatic patients. The more widespread use of procedural ultrasonography may explain some discrepancies between the early5,6 and more recent studies.1,8–10

Several studies have demonstrated that postprocedural radiography is unnecessary unless a complication is suspected based on the patient’s symptoms or the need to demonstrate lung re-expansion.1,4,9,10 Clinical suspicion and the patient’s symptoms are the major predictors of procedure-related pneumothorax requiring treatment with a chest tube. Otherwise, incidentally discovered pneumothorax can usually be observed and managed supportively.

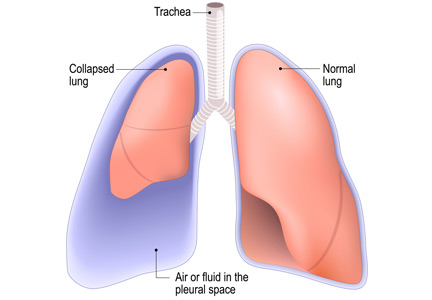

WHAT MECHANISMS UNDERLIE POSTPROCEDURAL PNEUMOTHORAX?

Major causes of pneumothorax in patients undergoing thoracentesis are direct puncture during needle or catheter insertion, the introduction of air through the needle or catheter into the pleural cavity, and the inability of the ipsilateral lung to fully expand after drainage of a large volume of fluid, known as pneumothorax ex vacuo.5

Pneumothorax ex vacuo may be seen in patients with medical conditions such as endobronchial obstruction, pleural scarring from long-standing pleural effusion, and lung malignancy, all of which can impair the lung’s ability to expand after removal of a large volume of pleural fluid. It is believed that transient parenchymal pleural fistulae form if the lung cannot expand, causing air leakage into the pleural cavity.5,8,9 Pleural manometry to monitor changes in pleural pressure and elastance can decrease the rates of pneumothorax ex vacuo in patients with the above risk factors.5

WHEN IS RADIOGRAPHY INDICATED AFTER THORACENTESIS?

Current literature suggests that imaging to evaluate for postprocedural complications should be done if there is suspicion of a complication, if thoracentesis required multiple attempts, if the procedure caused aspiration of air, if the patient has advanced lung disease, if the patient is scheduled to undergo thoracic radiation, if the patient is on mechanical ventilation, and after therapeutic thoracentesis if a large volume of fluid is removed.1–10 Routine chest radiography after thoracentesis is not supported in the literature in the absence of these risk factors.

Some practitioners order chest imaging after therapeutic thoracentesis to assess for residual pleural fluid and for visualization of other abnormalities previously hidden by pleural effusion, rather than simply to exclude postprocedural pneumothorax. Alternatively, postprocedural bedside pleural ultrasonography with recording of images can be done to assess for complications and residual pleural fluid volume without exposing the patient to radiation.11

Needle decompression and chest tube insertion should be considered in patients with tension pneumothorax, large pneumothorax (distance from the chest wall to the visceral pleural line of at least 2 cm), mechanical ventilation, progressing pneumothorax, and symptoms.

KEY POINTS

- Pneumothorax is a rare complication of thoracentesis when performed by a skilled operator using ultrasonographic guidance.

- Mechanisms behind the occurrence of pneumothorax are direct lung puncture, introduction of air into the pleural cavity, and pneumothorax ex vacuo.

- In asymptomatic patients, pneumothorax after thoracentesis rarely requires intervention beyond supportive care and close observation.

- Factors such as multiple thoracentesis attempts, symptoms, clinical suspicion, air aspiration during thoracentesis, presence of previous lung disease, and removal of a large volume of fluid may require postprocedural lung imaging (eg, bedside ultrasonography, radiography).

- Ault MJ, Rosen BT, Scher J, Feinglass J, Barsuk JH. Thoracentesis outcomes: a 12-year experience. Thorax 2015; 70(2):127–132. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-206114

- Hibbert RM, Atwell TD, Lekah A, et al. Safety of ultrasound-guided thoracentesis in patients with abnormal preprocedural coagulation parameters. Chest 2013; 144(2):456–463. doi:10.1378/chest.12-2374

- Barnes TW, Morgenthaler TI, Olson EJ, Hesley GK, Decker PA, Ryu JH. Sonographically guided thoracentesis and rate of pneumothorax. J Clin Ultrasound 2005; 33(9):442–446. doi:10.1002/jcu.20163

- Gordon CE, Feller-Kopman D, Balk EM, Smetana GW. Pneumothorax following thoracentesis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 2010; 170(4):332–339. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.548

- Heidecker J, Huggins JT, Sahn SA, Doelken P. Pathophysiology of pneumothorax following ultrasound-guided thoracentesis. Chest 2006; 130(4):1173–1184. doi:10.1016/S0012-3692(15)51155-0

- Brandstetter RD, Karetzky M, Rastogi R, Lolis JD. Pneumothorax after thoracentesis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Heart Lung 1994; 23(1):67–70. pmid:8150647

- Doyle JJ, Hnatiuk OW, Torrington KG, Slade AR, Howard RS. Necessity of routine chest roentgenography after thoracentesis. Ann Intern Med 1996; 124(9):816–820. pmid:8610950

- Gervais DA, Petersein A, Lee MJ, Hahn PF, Saini S, Mueller PR. US-guided thoracentesis: requirement for postprocedure chest radiography in patients who receive mechanical ventilation versus patients who breathe spontaneously. Radiology 1997; 204(2):503–506. doi:10.1148/radiology.204.2.9240544

- Capizzi SA, Prakash UB. Chest roentgenography after outpatient thoracentesis. Mayo Clin Proc 1998; 73(10):948–950. doi:10.4065/73.10.948

- Alemán C, Alegre J, Armadans L, et al. The value of chest roentgenography in the diagnosis of pneumothorax after thoracentesis. Am J Med 1999; 107(4):340–343. pmid:10527035

- Lichtenstein D. Lung ultrasound in the critically ill. Curr Opin Crit Care 2014; 20(3):315–322. doi:10.1097/MCC.0000000000000096

No. After thoracentesis, chest radiography or another lung imaging study should be done only if pneumothorax is suspected, if thoracentesis requires more than 1 attempt, if the patient is on mechanical ventilation or has pre-existing lung disease, or if a large volume (> 1,500 mL) of fluid is removed. Radiography is also usually not necessary after diagnostic thoracentesis in a patient breathing spontaneously. In most cases, pneumothorax found incidentally after thoracentesis does not require decompression and can be managed supportively.

WHAT ARE THE RISKS OF THORACENTESIS?

Thoracentesis is a minimally invasive procedure usually performed at the bedside that involves insertion of a needle into the pleural cavity for drainage of fluid.1 Diagnostic thoracentesis should be done in most cases of a new pleural effusion unless the effusion is small and with a clear diagnosis, or in cases of typical heart failure.

Therapeutic thoracentesis, often called large-volume thoracentesis, aims to improve symptoms such as dyspnea attributed to the pleural effusion by removing at least 1 L of pleural fluid. The presence of active respiratory symptoms and suspicion of infected pleural effusion should lead to thoracentesis as soon as possible.

Complications of thoracentesis may be benign, such as pain and anxiety associated with the procedure and external bleeding at the site of needle insertion. Pneumothorax is the most common serious procedural complication and the principal reason to order postprocedural chest radiography.1 Less common complications include hemothorax, re-expansion pulmonary edema, infection, subdiaphragmatic organ puncture, and procedure-related death. Bleeding complications and hemothorax are rare even in patients with underlying coagulopathy.2

Point-of-care pleural ultrasonography is now considered the standard of care to guide optimal needle location for the procedure and to exclude other conditions that can mimic pleural effusion on chest radiography, such as lung consolidation and atelectasis.3 High proficiency in the use of preprocedural point-of-care ultrasonography reduces the rate of procedural complications, though it does not eliminate the risk entirely.3,4

Factors associated with higher rates of complications include lack of operator proficiency, poor understanding of the anatomy, poor patient positioning, poor patient cooperation with the procedure, lack of availability of bedside ultrasonography, and drainage of more than 1,500 mL of fluid. Addressing these factors has been shown to decrease the risk of pneumothorax and infection.1–5

HOW OFTEN DOES PNEUMOTHORAX OCCUR AFTER THORACENTESIS?

Several early studies have examined the incidence of pneumothorax after thoracentesis. Lack of ultrasonography use likely explains a higher incidence of complications in early studies: rates of pneumothorax after thoracentesis without ultrasonographic guidance ranged from 5.2% to 26%.6,7

Gervais et al8 analyzed thoracentesis with ultrasonographic guidance in 434 patients, 92 of whom were intubated, and reported that pneumothorax occurred in 10 patients, of whom 6 were intubated. Two of the intubated patients required chest tubes. Other studies have confirmed the low incidence of pneumothorax in patients undergoing thoracentesis, with rates such as 0.61%,1 5%,9 and 4%.10

The major predictor of postprocedural pneumothorax was the presence of symptoms such as chest pain and dyspnea. No intervention was necessary for most cases of pneumothorax in asymptomatic patients. The more widespread use of procedural ultrasonography may explain some discrepancies between the early5,6 and more recent studies.1,8–10

Several studies have demonstrated that postprocedural radiography is unnecessary unless a complication is suspected based on the patient’s symptoms or the need to demonstrate lung re-expansion.1,4,9,10 Clinical suspicion and the patient’s symptoms are the major predictors of procedure-related pneumothorax requiring treatment with a chest tube. Otherwise, incidentally discovered pneumothorax can usually be observed and managed supportively.

WHAT MECHANISMS UNDERLIE POSTPROCEDURAL PNEUMOTHORAX?

Major causes of pneumothorax in patients undergoing thoracentesis are direct puncture during needle or catheter insertion, the introduction of air through the needle or catheter into the pleural cavity, and the inability of the ipsilateral lung to fully expand after drainage of a large volume of fluid, known as pneumothorax ex vacuo.5

Pneumothorax ex vacuo may be seen in patients with medical conditions such as endobronchial obstruction, pleural scarring from long-standing pleural effusion, and lung malignancy, all of which can impair the lung’s ability to expand after removal of a large volume of pleural fluid. It is believed that transient parenchymal pleural fistulae form if the lung cannot expand, causing air leakage into the pleural cavity.5,8,9 Pleural manometry to monitor changes in pleural pressure and elastance can decrease the rates of pneumothorax ex vacuo in patients with the above risk factors.5

WHEN IS RADIOGRAPHY INDICATED AFTER THORACENTESIS?

Current literature suggests that imaging to evaluate for postprocedural complications should be done if there is suspicion of a complication, if thoracentesis required multiple attempts, if the procedure caused aspiration of air, if the patient has advanced lung disease, if the patient is scheduled to undergo thoracic radiation, if the patient is on mechanical ventilation, and after therapeutic thoracentesis if a large volume of fluid is removed.1–10 Routine chest radiography after thoracentesis is not supported in the literature in the absence of these risk factors.

Some practitioners order chest imaging after therapeutic thoracentesis to assess for residual pleural fluid and for visualization of other abnormalities previously hidden by pleural effusion, rather than simply to exclude postprocedural pneumothorax. Alternatively, postprocedural bedside pleural ultrasonography with recording of images can be done to assess for complications and residual pleural fluid volume without exposing the patient to radiation.11

Needle decompression and chest tube insertion should be considered in patients with tension pneumothorax, large pneumothorax (distance from the chest wall to the visceral pleural line of at least 2 cm), mechanical ventilation, progressing pneumothorax, and symptoms.

KEY POINTS

- Pneumothorax is a rare complication of thoracentesis when performed by a skilled operator using ultrasonographic guidance.

- Mechanisms behind the occurrence of pneumothorax are direct lung puncture, introduction of air into the pleural cavity, and pneumothorax ex vacuo.

- In asymptomatic patients, pneumothorax after thoracentesis rarely requires intervention beyond supportive care and close observation.

- Factors such as multiple thoracentesis attempts, symptoms, clinical suspicion, air aspiration during thoracentesis, presence of previous lung disease, and removal of a large volume of fluid may require postprocedural lung imaging (eg, bedside ultrasonography, radiography).

No. After thoracentesis, chest radiography or another lung imaging study should be done only if pneumothorax is suspected, if thoracentesis requires more than 1 attempt, if the patient is on mechanical ventilation or has pre-existing lung disease, or if a large volume (> 1,500 mL) of fluid is removed. Radiography is also usually not necessary after diagnostic thoracentesis in a patient breathing spontaneously. In most cases, pneumothorax found incidentally after thoracentesis does not require decompression and can be managed supportively.

WHAT ARE THE RISKS OF THORACENTESIS?

Thoracentesis is a minimally invasive procedure usually performed at the bedside that involves insertion of a needle into the pleural cavity for drainage of fluid.1 Diagnostic thoracentesis should be done in most cases of a new pleural effusion unless the effusion is small and with a clear diagnosis, or in cases of typical heart failure.

Therapeutic thoracentesis, often called large-volume thoracentesis, aims to improve symptoms such as dyspnea attributed to the pleural effusion by removing at least 1 L of pleural fluid. The presence of active respiratory symptoms and suspicion of infected pleural effusion should lead to thoracentesis as soon as possible.

Complications of thoracentesis may be benign, such as pain and anxiety associated with the procedure and external bleeding at the site of needle insertion. Pneumothorax is the most common serious procedural complication and the principal reason to order postprocedural chest radiography.1 Less common complications include hemothorax, re-expansion pulmonary edema, infection, subdiaphragmatic organ puncture, and procedure-related death. Bleeding complications and hemothorax are rare even in patients with underlying coagulopathy.2

Point-of-care pleural ultrasonography is now considered the standard of care to guide optimal needle location for the procedure and to exclude other conditions that can mimic pleural effusion on chest radiography, such as lung consolidation and atelectasis.3 High proficiency in the use of preprocedural point-of-care ultrasonography reduces the rate of procedural complications, though it does not eliminate the risk entirely.3,4

Factors associated with higher rates of complications include lack of operator proficiency, poor understanding of the anatomy, poor patient positioning, poor patient cooperation with the procedure, lack of availability of bedside ultrasonography, and drainage of more than 1,500 mL of fluid. Addressing these factors has been shown to decrease the risk of pneumothorax and infection.1–5

HOW OFTEN DOES PNEUMOTHORAX OCCUR AFTER THORACENTESIS?

Several early studies have examined the incidence of pneumothorax after thoracentesis. Lack of ultrasonography use likely explains a higher incidence of complications in early studies: rates of pneumothorax after thoracentesis without ultrasonographic guidance ranged from 5.2% to 26%.6,7

Gervais et al8 analyzed thoracentesis with ultrasonographic guidance in 434 patients, 92 of whom were intubated, and reported that pneumothorax occurred in 10 patients, of whom 6 were intubated. Two of the intubated patients required chest tubes. Other studies have confirmed the low incidence of pneumothorax in patients undergoing thoracentesis, with rates such as 0.61%,1 5%,9 and 4%.10

The major predictor of postprocedural pneumothorax was the presence of symptoms such as chest pain and dyspnea. No intervention was necessary for most cases of pneumothorax in asymptomatic patients. The more widespread use of procedural ultrasonography may explain some discrepancies between the early5,6 and more recent studies.1,8–10

Several studies have demonstrated that postprocedural radiography is unnecessary unless a complication is suspected based on the patient’s symptoms or the need to demonstrate lung re-expansion.1,4,9,10 Clinical suspicion and the patient’s symptoms are the major predictors of procedure-related pneumothorax requiring treatment with a chest tube. Otherwise, incidentally discovered pneumothorax can usually be observed and managed supportively.

WHAT MECHANISMS UNDERLIE POSTPROCEDURAL PNEUMOTHORAX?

Major causes of pneumothorax in patients undergoing thoracentesis are direct puncture during needle or catheter insertion, the introduction of air through the needle or catheter into the pleural cavity, and the inability of the ipsilateral lung to fully expand after drainage of a large volume of fluid, known as pneumothorax ex vacuo.5

Pneumothorax ex vacuo may be seen in patients with medical conditions such as endobronchial obstruction, pleural scarring from long-standing pleural effusion, and lung malignancy, all of which can impair the lung’s ability to expand after removal of a large volume of pleural fluid. It is believed that transient parenchymal pleural fistulae form if the lung cannot expand, causing air leakage into the pleural cavity.5,8,9 Pleural manometry to monitor changes in pleural pressure and elastance can decrease the rates of pneumothorax ex vacuo in patients with the above risk factors.5

WHEN IS RADIOGRAPHY INDICATED AFTER THORACENTESIS?

Current literature suggests that imaging to evaluate for postprocedural complications should be done if there is suspicion of a complication, if thoracentesis required multiple attempts, if the procedure caused aspiration of air, if the patient has advanced lung disease, if the patient is scheduled to undergo thoracic radiation, if the patient is on mechanical ventilation, and after therapeutic thoracentesis if a large volume of fluid is removed.1–10 Routine chest radiography after thoracentesis is not supported in the literature in the absence of these risk factors.

Some practitioners order chest imaging after therapeutic thoracentesis to assess for residual pleural fluid and for visualization of other abnormalities previously hidden by pleural effusion, rather than simply to exclude postprocedural pneumothorax. Alternatively, postprocedural bedside pleural ultrasonography with recording of images can be done to assess for complications and residual pleural fluid volume without exposing the patient to radiation.11

Needle decompression and chest tube insertion should be considered in patients with tension pneumothorax, large pneumothorax (distance from the chest wall to the visceral pleural line of at least 2 cm), mechanical ventilation, progressing pneumothorax, and symptoms.

KEY POINTS

- Pneumothorax is a rare complication of thoracentesis when performed by a skilled operator using ultrasonographic guidance.

- Mechanisms behind the occurrence of pneumothorax are direct lung puncture, introduction of air into the pleural cavity, and pneumothorax ex vacuo.

- In asymptomatic patients, pneumothorax after thoracentesis rarely requires intervention beyond supportive care and close observation.

- Factors such as multiple thoracentesis attempts, symptoms, clinical suspicion, air aspiration during thoracentesis, presence of previous lung disease, and removal of a large volume of fluid may require postprocedural lung imaging (eg, bedside ultrasonography, radiography).

- Ault MJ, Rosen BT, Scher J, Feinglass J, Barsuk JH. Thoracentesis outcomes: a 12-year experience. Thorax 2015; 70(2):127–132. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-206114

- Hibbert RM, Atwell TD, Lekah A, et al. Safety of ultrasound-guided thoracentesis in patients with abnormal preprocedural coagulation parameters. Chest 2013; 144(2):456–463. doi:10.1378/chest.12-2374

- Barnes TW, Morgenthaler TI, Olson EJ, Hesley GK, Decker PA, Ryu JH. Sonographically guided thoracentesis and rate of pneumothorax. J Clin Ultrasound 2005; 33(9):442–446. doi:10.1002/jcu.20163

- Gordon CE, Feller-Kopman D, Balk EM, Smetana GW. Pneumothorax following thoracentesis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 2010; 170(4):332–339. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.548

- Heidecker J, Huggins JT, Sahn SA, Doelken P. Pathophysiology of pneumothorax following ultrasound-guided thoracentesis. Chest 2006; 130(4):1173–1184. doi:10.1016/S0012-3692(15)51155-0

- Brandstetter RD, Karetzky M, Rastogi R, Lolis JD. Pneumothorax after thoracentesis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Heart Lung 1994; 23(1):67–70. pmid:8150647

- Doyle JJ, Hnatiuk OW, Torrington KG, Slade AR, Howard RS. Necessity of routine chest roentgenography after thoracentesis. Ann Intern Med 1996; 124(9):816–820. pmid:8610950

- Gervais DA, Petersein A, Lee MJ, Hahn PF, Saini S, Mueller PR. US-guided thoracentesis: requirement for postprocedure chest radiography in patients who receive mechanical ventilation versus patients who breathe spontaneously. Radiology 1997; 204(2):503–506. doi:10.1148/radiology.204.2.9240544

- Capizzi SA, Prakash UB. Chest roentgenography after outpatient thoracentesis. Mayo Clin Proc 1998; 73(10):948–950. doi:10.4065/73.10.948

- Alemán C, Alegre J, Armadans L, et al. The value of chest roentgenography in the diagnosis of pneumothorax after thoracentesis. Am J Med 1999; 107(4):340–343. pmid:10527035

- Lichtenstein D. Lung ultrasound in the critically ill. Curr Opin Crit Care 2014; 20(3):315–322. doi:10.1097/MCC.0000000000000096

- Ault MJ, Rosen BT, Scher J, Feinglass J, Barsuk JH. Thoracentesis outcomes: a 12-year experience. Thorax 2015; 70(2):127–132. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-206114

- Hibbert RM, Atwell TD, Lekah A, et al. Safety of ultrasound-guided thoracentesis in patients with abnormal preprocedural coagulation parameters. Chest 2013; 144(2):456–463. doi:10.1378/chest.12-2374

- Barnes TW, Morgenthaler TI, Olson EJ, Hesley GK, Decker PA, Ryu JH. Sonographically guided thoracentesis and rate of pneumothorax. J Clin Ultrasound 2005; 33(9):442–446. doi:10.1002/jcu.20163

- Gordon CE, Feller-Kopman D, Balk EM, Smetana GW. Pneumothorax following thoracentesis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 2010; 170(4):332–339. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.548

- Heidecker J, Huggins JT, Sahn SA, Doelken P. Pathophysiology of pneumothorax following ultrasound-guided thoracentesis. Chest 2006; 130(4):1173–1184. doi:10.1016/S0012-3692(15)51155-0

- Brandstetter RD, Karetzky M, Rastogi R, Lolis JD. Pneumothorax after thoracentesis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Heart Lung 1994; 23(1):67–70. pmid:8150647

- Doyle JJ, Hnatiuk OW, Torrington KG, Slade AR, Howard RS. Necessity of routine chest roentgenography after thoracentesis. Ann Intern Med 1996; 124(9):816–820. pmid:8610950

- Gervais DA, Petersein A, Lee MJ, Hahn PF, Saini S, Mueller PR. US-guided thoracentesis: requirement for postprocedure chest radiography in patients who receive mechanical ventilation versus patients who breathe spontaneously. Radiology 1997; 204(2):503–506. doi:10.1148/radiology.204.2.9240544

- Capizzi SA, Prakash UB. Chest roentgenography after outpatient thoracentesis. Mayo Clin Proc 1998; 73(10):948–950. doi:10.4065/73.10.948

- Alemán C, Alegre J, Armadans L, et al. The value of chest roentgenography in the diagnosis of pneumothorax after thoracentesis. Am J Med 1999; 107(4):340–343. pmid:10527035

- Lichtenstein D. Lung ultrasound in the critically ill. Curr Opin Crit Care 2014; 20(3):315–322. doi:10.1097/MCC.0000000000000096

A 69-year-old woman with double vision and lower-extremity weakness

A 69-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital with double vision, weakness in the lower extremities, sensory loss, pain, and falls. Her symptoms started with sudden onset of horizontal diplopia 6 weeks before, followed by gradually worsening lower-extremity weakness, as well as ataxia and patchy and bilateral radicular burning leg pain more pronounced on the right. Her medical history included narcolepsy, obstructive sleep apnea, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and bilateral knee replacements for osteoarthritis.

Neurologic examination showed inability to abduct the right eye, bilateral hip flexion weakness, decreased pinprick response, decreased proprioception, and diminished muscle stretch reflexes in the lower extremities. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain without contrast and magnetic resonance angiography of the brain and carotid arteries showed no evidence of acute stroke. No abnormalities were noted on electrocardiography and echocardiography.

A diagnosis of idiopathic peripheral neuropathy was made, and outpatient physical therapy was recommended. Over the subsequent 2 weeks, her condition declined to the point where she needed a walker. She continued to have worsening leg weakness with falls, prompting hospital readmission.

INITIAL EVALUATION

In addition to her diplopia and weakness, she said she had lost 15 pounds since the onset of symptoms and had experienced symptoms suggesting urinary retention.

Physical examination

Her temperature was 37°C (98.6°F), heart rate 79 beats per minute, blood pressure 117/86 mm Hg, respiratory rate 14 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation 98% on room air. Examination of the head, neck, heart, lung, abdomen, lymph nodes, and extremities yielded nothing remarkable except for chronic venous changes in the lower extremities.

The neurologic examination showed incomplete lateral gaze bilaterally (cranial nerve VI dysfunction). Strength in the upper extremities was normal. In the legs, the Medical Research Council scale score for proximal muscle strength was 2 to 3 out of 5, and for distal muscles 3 to 4 out of 5, with the right side worse than the left and flexors and extensors affected equally. Muscle stretch reflexes were absent in both lower extremities and the left upper extremity, but intact in the right upper extremity. No abnormal corticospinal tract reflexes were elicited.

Sensory testing revealed diminished pin-prick perception in a length-dependent fashion in the lower extremities, reduced 50% compared with the hands. Gait could not be assessed due to weakness.

Initial laboratory testing

Results of initial laboratory tests—complete blood cell count, complete metabolic panel, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and hemoglobin A1c—were unremarkable.

FURTHER EVALUATION AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

1. Which of the following is the most likely diagnosis at this point?

- Cerebral infarction

- Guillain-Barré syndrome

- Progressive polyneuropathy

- Transverse myelitis

- Polyradiculopathy

In the absence of definitive diagnostic tests, all of the above options were considered in the differential diagnosis for this patient.

Cerebral infarction

Although acute-onset diplopia can be explained by brainstem stroke involving cranial nerve nuclei or their projections, the onset of diplopia with progressive bilateral lower-extremity weakness makes stroke unlikely. Flaccid paralysis, areflexia of the lower extremities, and sensory involvement can also be caused by acute anterior spinal artery occlusion leading to spinal cord infarction; however, the deficits are usually maximal at onset.

Guillain-Barré syndrome

The combination of acute-subacute progressive ascending weakness, sensory involvement, and diminished or absent reflexes is typical of Guillain-Barré syndrome. Cranial nerve involvement can overlap with the more typical features of the syndrome. However, most patients reach the nadir of their disease by 4 weeks after initial symptom onset, even without treatment.1 This patient’s condition continued to worsen over 8 weeks. In addition, the asymmetric lower-extremity weakness and sparing of the arms are atypical for Guillain-Barré syndrome.

Given the progression of symptoms, chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy is also a consideration, typically presenting as a relapsing or progressive neuropathy in proximal and distal muscles and worsening over at least an 8-week period.2

The initial workup for Guillain-Barré syndrome or chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy includes lumbar puncture to assess for albuminocytologic dissociation (elevated protein with normal white blood cell count) in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and electromyography (EMG) to assess for neurophysiologic evidence of peripheral nerve demyelination. In Miller-Fisher syndrome, a rare variant of Guillain-Barré syndrome characterized by ataxia, ophthalmoparesis, and areflexia, serum ganglioside antibodies to GQ1b are found in over 90% of patients.3,4 Although MRI of the spine is not necessary to diagnose Guillain-Barré syndrome, it is often done to exclude other causes of lower-extremity weakness such as spinal cord or cauda equina compression that would require urgent neurosurgical consultation. MRI can support the diagnosis of Guillain-Barré syndrome when it reveals enhancement of the spinal nerve roots or cauda equina.

Other polyneuropathies

Polyneuropathy is caused by a variety of diseases that affect the function of peripheral motor, sensory, or autonomic nerves. The differential diagnosis is broad and involves inflammatory diseases (including autoimmune and paraneoplastic causes), hereditary disorders, infection, toxicity, and ischemic and nutritional deficiencies.5 Polyneuropathy can present in a distal-predominant, generalized, or asymmetric pattern involving individual nerve trunks termed “mononeuropathy multiplex,” as in our patient’s presentation. The initial workup includes EMG and a battery of serologic tests. In cases of severe and progressive polyneuropathy, nerve biopsy can assess for the presence of vasculitis, amyloidosis, and paraprotein deposition.

Transverse myelitis

Transverse myelitis is an inflammatory myelopathy that usually presents with acute or subacute weakness of the upper extremities or lower extremities, or both, corresponding to the level of the lesion, hyperreflexia, bladder and bowel dysfunction, spinal level of sensory loss, and autonomic involvement.6 The differential diagnosis of acute myelopathy includes:

- Infection (eg, herpes simplex virus, West Nile virus, Lyme disease, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, human immunodeficiency virus)

- Systemic inflammatory disease (systemic lupus erythematosus, sarcoidosis, Sjögren syndrome, scleroderma, paraneoplastic syndrome)

- Central nervous system demyelinating disease (acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, multiple sclerosis, neuromyelitis optica)

- Vascular malformation (dural arteriovenous fistula)

- Compression due to tumor, bleeding, disc herniation, infection, or abscess.

The workup involves laboratory tests to exclude systemic inflammatory and infectious causes, as well as MRI of the spine with and without contrast to identify a causative lesion. Lumbar puncture and CSF analysis may show pleocytosis, elevated protein concentration, and increased intrathecal immunoglobulin G (IgG) index.7

Although our patient’s presentation with subacute lower-extremity weakness, sensory changes, and bladder dysfunction were consistent with transverse myelitis, her cranial nerve abnormalities would be atypical for it.

Polyradiculopathy

Polyradiculopathy has many possible causes. In the United States, the most common causes are lumbar spondylosis, lumbar canal stenosis, and diabetic polyradiculoneuropathy.

When multiple spinal segments are affected, leptomeningeal disease involving the arachnoid and pia mater should be considered. Causes include malignant invasion, inflammatory cell accumulation, and protein deposition, leading to patchy but widespread dysfunction of spinal nerve roots and cranial nerves. Specific causes are myriad and include carcinomatous meningitis,8 syphilis, tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, and paraproteinemias. CSF and MRI changes are often nonspecific, leading to the need for meningeal biopsy for diagnosis.

CASE CONTINUED

During her hospitalization, our patient developed acute right upper and lower facial weakness consistent with peripheral facial mononeuropathy. Bilateral lower-extremity weakness progressed to disabling paraparesis.

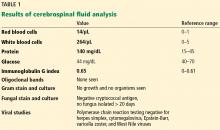

She underwent lumbar puncture and CSF analysis (Table 1). The most notable findings were significant pleocytosis (72% lymphocytic predominance), protein elevation, and elevated IgG index (indicative of elevated intrathecal immunoglobulin synthesis in the central nervous system). Viral, bacterial, and fungal studies were negative. Guillain-Barré syndrome, other polyneuropathies, and spinal cord infarction would not be expected with these CSF features.

Surface EMG demonstrated normal sensory responses, and needle EMG showed chronic and active motor axon loss in the L3 and S1 root distributions, suggesting polyradiculopathy without polyneuropathy. These findings would not be expected in typical acute transverse myelitis but could be seen with spinal cord infarction.

MRI of the entire spine with and without contrast showed cauda equina nerve root thickening and enhancement, especially involving the L5 and S1 roots (Figure 1). The spinal cord appeared normal. These findings further supported polyradiculopathy and a leptomeningeal process.

Further evaluation included chest radiography, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, hemoglobin A1c, human immunodeficiency virus testing, antinuclear antibody, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, extractable nuclear antibody, GQ1b antibody, serum and CSF paraneoplastic panels, levels of vitamin B1, B12, and B6, copper, and ceruloplasmin, and a screen for heavy metals. All results were within normal ranges.

ESTABLISHING THE DIAGNOSIS

Serum monoclonal protein analysis with immunofixation revealed IgM kappa monoclonal gammopathy with an IgM level of 1,570 (reference range 53–334 mg/dL) and M-spike 0.75 (0.00 mg/dL), serum free kappa light chains 61.1 (3.30–19.40 mg/L), lambda 9.3 (5.7–26.3 mg/L), and kappa-lambda ratio 6.57 (0.26–1.65).

2. Which is the best next step in this patient’s neurologic evaluation?

- Test CSF angiotensin-converting enzyme level

- CSF cytology

- Meningeal biopsy

- Peripheral nerve biopsy

Given the high suspicion for malignancy, CSF cytology was performed and showed increased numbers of mononuclear chronic inflammatory cells, including a mixture of lymphocytes and monocytes, favoring a reactive lymphoid pleocytosis. Flow cytometry indicated the presence of a monoclonal, CD5- and CD10- negative, B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder. The immunophenotypic findings were not specific for a single diagnosis. The differential diagnosis included marginal zone lymphoma and lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma.

3. Given the presence of serum IgM monoclonal gammopathy in this patient, which is the most likely diagnosis?

- Neurosarcoidosis

- Multiple myeloma

- Waldenström macroglobulinemia

- Carcinomatous meningitis

Study of bone marrow biopsy demonstrated limited bone marrow involvement (1%) by a lymphoproliferative disorder with plasmacytoid features, and DNA testing detected an MYD88 L265P mutation, reported to be present in 90% of patients with Waldenström macroglobulinemia.9 This finding confirmed the diagnosis of Waldenström macroglobulinemia with central nervous system involvement. Our patient began therapy with rituximab and methotrexate, which resulted in some improvement in strength, gait, and vision.

WALDENSTRÖM MACROGLOBULINEMIA AND BING-NEEL SYNDROME

Waldenström macroglobulinemia is a lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma associated with a monoclonal IgM protein.10 It is considered a paraproteinemic disorder, similar to multiple myeloma. The presenting symptoms and complications are related to direct tumor infiltration, hyperviscosity syndrome, and deposition of IgM in various tissues.11,12

Waldenström macroglobulinemia is usually indolent, and treatment is reserved for patients with symptoms.13,14 It includes rituximab, usually in combination with chemotherapy or other targeted agents.15,16

Paraneoplastic antibody-mediated polyneuropathy may occur in these patients. However, the pattern is usually symmetrical clinically, with demyelination on EMG, and is not associated with cranial nerve or meningeal involvement. Management with plasmapheresis, corticosteroids, and intravenous immunoglobulin has not been shown to be effective.17

Involvement of the central nervous system as a complication of Waldenström macroglobulinemia has been described as Bing-Neel syndrome. It can present as diffuse malignant cell infiltration of the leptomeningeal space, white matter, or spinal cord, or in a tumoral form presenting as intraparenchymal masses or nodular lesions. The distinction between the tumoral and diffuse forms is based primarily on imaging findings.18

In a report of 44 patients with Bing-Neel syndrome, 36% presented with the disorder as the initial manifestation of Waldenström macroglobulinemia.18 The primary presenting symptoms were imbalance and gait difficulty (48%) and cranial nerve involvement (36%), which presented as predominantly facial or oculomotor nerve palsy. Cauda equina syndrome with motor involvement (seen in our patient) occurred in 14% of patients. Other presenting symptoms included cognitive impairment, sensory deficits, headache, dysarthria, aphasia, and seizures.

LEARNING POINTS

The differential diagnosis for patients presenting with multifocal neurologic symptoms can be broad, and a systematic approach to the diagnosis is necessary. Localizing the lesion is important in determining the diagnosis for patients presenting with neurologic symptoms. The process of localization begins with taking the history, is further refined during the examination, and is confirmed with diagnostic studies. Atypical presentations of relatively common neurologic diseases such as Guillain-Barré syndrome, transverse myelitis, and peripheral polyneuropathy do occur, but uncommon diagnoses need to be considered when support for the initial diagnosis is lacking.

- Fokke C, van den Berg B, Drenthen J, Walgaard C, van Doorn PA, Jacobs BC. Diagnosis of Guillain-Barre syndrome and validation of Brighton criteria. Brain 2014; 137(Pt 1):33–43. doi:10.1093/brain/awt285

- Mathey EK, Park SB, Hughes RA, et al. Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy: from pathology to phenotype. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2015; 86(9):973–985. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2014-309697

- Chiba A, Kusunoki S, Obata H, Machinami R, Kanazawa I. Serum anti-GQ1b IgG antibody is associated with ophthalmoplegia in Miller Fisher syndrome and Guillain-Barré syndrome: clinical and immunohistochemical studies. Neurology 1993; 43(10):1911–1917. pmid:8413947

- Teener J. Miller Fisher’s syndrome. Semin Neurol 2012; 32(5):512–516. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1334470

- Watson JC, Dyck PJ. Peripheral neuropathy: a practical approach to diagnosis and symptom management. Mayo Clin Proc 2015; 90(7):940–951. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.05.004

- Greenberg BM. Treatment of acute transverse myelitis and its early complications. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2011; 17(4):733–743. doi:10.1212/01.CON.0000403792.36161.f5

- West TW. Transverse myelitis—a review of the presentation, diagnosis, and initial management. Discov Med 2013; 16(88):167–177. pmid:24099672

- Le Rhun E, Taillibert S, Chamberlain MC. Carcinomatous meningitis: leptomeningeal metastases in solid tumors. Surg Neurol Int 2013; 4(suppl 4):S265–S288. doi:10.4103/2152-7806.111304

- Treon SP, Xu L, Yang G, et al. MYD88 L265P somatic mutation in Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia. N Engl J Med 2012; 367(9):826–833. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1200710

- Owen RG, Treon SP, Al-Katib A, et al. Clinicopathological definition of Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia: consensus panel recommendations from the Second International Workshop on Waldenstrom’s Macroglobulinemia. Semin Oncol 2003; 30(2):110–115. doi:10.1053/sonc.2003.50082

- Björkholm M, Johansson E, Papamichael D, et al. Patterns of clinical presentation, treatment, and outcome in patients with Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia: a two-institution study. Semin Oncol 2003; 30(2):226–230. doi:10.1053/sonc.2003.50054

- Rison RA, Beydoun SR. Paraproteinemic neuropathy: a practical review. BMC Neurol 2016; 16:13. doi:10.1186/s12883-016-0532-4

- Kyle RA, Benson J, Larson D, et al. IgM monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and smoldering Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma 2009; 9(1):17–18. doi:10.3816/CLM.2009.n.002

- Kyle RA, Benson JT, Larson DR, et al. Progression in smoldering Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia: long-term results. Blood 2012; 119(19):4462–4466. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-10-384768

- Leblond V, Kastritis E, Advani R, et al. Treatment recommendations from the Eighth International Workshop on Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia. Blood 2016; 128(10):1321–1328. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-04-711234

- Kapoor P, Ansell SM, Fonseca R, et al. Diagnosis and management of Waldenström macroglobulinemia: Mayo stratification of macroglobulinemia and risk-adapted therapy (mSMART) guidelines 2016. JAMA Oncol 2017; 3(9):1257–1265. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5763

- D’Sa S, Kersten MJ, Castillo JJ, et al. Investigation and management of IgM and Waldenström-associated peripheral neuropathies: recommendations from the IWWM-8 consensus panel. Br J Haematol 2017; 176(5):728–742. doi:10.1111/bjh.14492

- Simon L, Fitsiori A, Lemal R, et al. Bing-Neel syndrome, a rare complication of Waldenström macroglobulinemia: analysis of 44 cases and review of the literature. A study on behalf of the French Innovative Leukemia Organization (FILO). Haematologica 2015; 100(12):1587–1594. doi:10.3324/haematol.2015.133744

A 69-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital with double vision, weakness in the lower extremities, sensory loss, pain, and falls. Her symptoms started with sudden onset of horizontal diplopia 6 weeks before, followed by gradually worsening lower-extremity weakness, as well as ataxia and patchy and bilateral radicular burning leg pain more pronounced on the right. Her medical history included narcolepsy, obstructive sleep apnea, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and bilateral knee replacements for osteoarthritis.

Neurologic examination showed inability to abduct the right eye, bilateral hip flexion weakness, decreased pinprick response, decreased proprioception, and diminished muscle stretch reflexes in the lower extremities. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain without contrast and magnetic resonance angiography of the brain and carotid arteries showed no evidence of acute stroke. No abnormalities were noted on electrocardiography and echocardiography.

A diagnosis of idiopathic peripheral neuropathy was made, and outpatient physical therapy was recommended. Over the subsequent 2 weeks, her condition declined to the point where she needed a walker. She continued to have worsening leg weakness with falls, prompting hospital readmission.

INITIAL EVALUATION

In addition to her diplopia and weakness, she said she had lost 15 pounds since the onset of symptoms and had experienced symptoms suggesting urinary retention.

Physical examination

Her temperature was 37°C (98.6°F), heart rate 79 beats per minute, blood pressure 117/86 mm Hg, respiratory rate 14 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation 98% on room air. Examination of the head, neck, heart, lung, abdomen, lymph nodes, and extremities yielded nothing remarkable except for chronic venous changes in the lower extremities.

The neurologic examination showed incomplete lateral gaze bilaterally (cranial nerve VI dysfunction). Strength in the upper extremities was normal. In the legs, the Medical Research Council scale score for proximal muscle strength was 2 to 3 out of 5, and for distal muscles 3 to 4 out of 5, with the right side worse than the left and flexors and extensors affected equally. Muscle stretch reflexes were absent in both lower extremities and the left upper extremity, but intact in the right upper extremity. No abnormal corticospinal tract reflexes were elicited.

Sensory testing revealed diminished pin-prick perception in a length-dependent fashion in the lower extremities, reduced 50% compared with the hands. Gait could not be assessed due to weakness.

Initial laboratory testing

Results of initial laboratory tests—complete blood cell count, complete metabolic panel, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and hemoglobin A1c—were unremarkable.

FURTHER EVALUATION AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

1. Which of the following is the most likely diagnosis at this point?

- Cerebral infarction

- Guillain-Barré syndrome

- Progressive polyneuropathy

- Transverse myelitis

- Polyradiculopathy

In the absence of definitive diagnostic tests, all of the above options were considered in the differential diagnosis for this patient.

Cerebral infarction

Although acute-onset diplopia can be explained by brainstem stroke involving cranial nerve nuclei or their projections, the onset of diplopia with progressive bilateral lower-extremity weakness makes stroke unlikely. Flaccid paralysis, areflexia of the lower extremities, and sensory involvement can also be caused by acute anterior spinal artery occlusion leading to spinal cord infarction; however, the deficits are usually maximal at onset.

Guillain-Barré syndrome

The combination of acute-subacute progressive ascending weakness, sensory involvement, and diminished or absent reflexes is typical of Guillain-Barré syndrome. Cranial nerve involvement can overlap with the more typical features of the syndrome. However, most patients reach the nadir of their disease by 4 weeks after initial symptom onset, even without treatment.1 This patient’s condition continued to worsen over 8 weeks. In addition, the asymmetric lower-extremity weakness and sparing of the arms are atypical for Guillain-Barré syndrome.

Given the progression of symptoms, chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy is also a consideration, typically presenting as a relapsing or progressive neuropathy in proximal and distal muscles and worsening over at least an 8-week period.2

The initial workup for Guillain-Barré syndrome or chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy includes lumbar puncture to assess for albuminocytologic dissociation (elevated protein with normal white blood cell count) in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and electromyography (EMG) to assess for neurophysiologic evidence of peripheral nerve demyelination. In Miller-Fisher syndrome, a rare variant of Guillain-Barré syndrome characterized by ataxia, ophthalmoparesis, and areflexia, serum ganglioside antibodies to GQ1b are found in over 90% of patients.3,4 Although MRI of the spine is not necessary to diagnose Guillain-Barré syndrome, it is often done to exclude other causes of lower-extremity weakness such as spinal cord or cauda equina compression that would require urgent neurosurgical consultation. MRI can support the diagnosis of Guillain-Barré syndrome when it reveals enhancement of the spinal nerve roots or cauda equina.

Other polyneuropathies

Polyneuropathy is caused by a variety of diseases that affect the function of peripheral motor, sensory, or autonomic nerves. The differential diagnosis is broad and involves inflammatory diseases (including autoimmune and paraneoplastic causes), hereditary disorders, infection, toxicity, and ischemic and nutritional deficiencies.5 Polyneuropathy can present in a distal-predominant, generalized, or asymmetric pattern involving individual nerve trunks termed “mononeuropathy multiplex,” as in our patient’s presentation. The initial workup includes EMG and a battery of serologic tests. In cases of severe and progressive polyneuropathy, nerve biopsy can assess for the presence of vasculitis, amyloidosis, and paraprotein deposition.

Transverse myelitis

Transverse myelitis is an inflammatory myelopathy that usually presents with acute or subacute weakness of the upper extremities or lower extremities, or both, corresponding to the level of the lesion, hyperreflexia, bladder and bowel dysfunction, spinal level of sensory loss, and autonomic involvement.6 The differential diagnosis of acute myelopathy includes:

- Infection (eg, herpes simplex virus, West Nile virus, Lyme disease, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, human immunodeficiency virus)

- Systemic inflammatory disease (systemic lupus erythematosus, sarcoidosis, Sjögren syndrome, scleroderma, paraneoplastic syndrome)

- Central nervous system demyelinating disease (acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, multiple sclerosis, neuromyelitis optica)

- Vascular malformation (dural arteriovenous fistula)

- Compression due to tumor, bleeding, disc herniation, infection, or abscess.

The workup involves laboratory tests to exclude systemic inflammatory and infectious causes, as well as MRI of the spine with and without contrast to identify a causative lesion. Lumbar puncture and CSF analysis may show pleocytosis, elevated protein concentration, and increased intrathecal immunoglobulin G (IgG) index.7

Although our patient’s presentation with subacute lower-extremity weakness, sensory changes, and bladder dysfunction were consistent with transverse myelitis, her cranial nerve abnormalities would be atypical for it.

Polyradiculopathy

Polyradiculopathy has many possible causes. In the United States, the most common causes are lumbar spondylosis, lumbar canal stenosis, and diabetic polyradiculoneuropathy.

When multiple spinal segments are affected, leptomeningeal disease involving the arachnoid and pia mater should be considered. Causes include malignant invasion, inflammatory cell accumulation, and protein deposition, leading to patchy but widespread dysfunction of spinal nerve roots and cranial nerves. Specific causes are myriad and include carcinomatous meningitis,8 syphilis, tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, and paraproteinemias. CSF and MRI changes are often nonspecific, leading to the need for meningeal biopsy for diagnosis.

CASE CONTINUED

During her hospitalization, our patient developed acute right upper and lower facial weakness consistent with peripheral facial mononeuropathy. Bilateral lower-extremity weakness progressed to disabling paraparesis.

She underwent lumbar puncture and CSF analysis (Table 1). The most notable findings were significant pleocytosis (72% lymphocytic predominance), protein elevation, and elevated IgG index (indicative of elevated intrathecal immunoglobulin synthesis in the central nervous system). Viral, bacterial, and fungal studies were negative. Guillain-Barré syndrome, other polyneuropathies, and spinal cord infarction would not be expected with these CSF features.

Surface EMG demonstrated normal sensory responses, and needle EMG showed chronic and active motor axon loss in the L3 and S1 root distributions, suggesting polyradiculopathy without polyneuropathy. These findings would not be expected in typical acute transverse myelitis but could be seen with spinal cord infarction.

MRI of the entire spine with and without contrast showed cauda equina nerve root thickening and enhancement, especially involving the L5 and S1 roots (Figure 1). The spinal cord appeared normal. These findings further supported polyradiculopathy and a leptomeningeal process.

Further evaluation included chest radiography, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, hemoglobin A1c, human immunodeficiency virus testing, antinuclear antibody, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, extractable nuclear antibody, GQ1b antibody, serum and CSF paraneoplastic panels, levels of vitamin B1, B12, and B6, copper, and ceruloplasmin, and a screen for heavy metals. All results were within normal ranges.

ESTABLISHING THE DIAGNOSIS

Serum monoclonal protein analysis with immunofixation revealed IgM kappa monoclonal gammopathy with an IgM level of 1,570 (reference range 53–334 mg/dL) and M-spike 0.75 (0.00 mg/dL), serum free kappa light chains 61.1 (3.30–19.40 mg/L), lambda 9.3 (5.7–26.3 mg/L), and kappa-lambda ratio 6.57 (0.26–1.65).

2. Which is the best next step in this patient’s neurologic evaluation?

- Test CSF angiotensin-converting enzyme level

- CSF cytology

- Meningeal biopsy

- Peripheral nerve biopsy

Given the high suspicion for malignancy, CSF cytology was performed and showed increased numbers of mononuclear chronic inflammatory cells, including a mixture of lymphocytes and monocytes, favoring a reactive lymphoid pleocytosis. Flow cytometry indicated the presence of a monoclonal, CD5- and CD10- negative, B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder. The immunophenotypic findings were not specific for a single diagnosis. The differential diagnosis included marginal zone lymphoma and lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma.

3. Given the presence of serum IgM monoclonal gammopathy in this patient, which is the most likely diagnosis?

- Neurosarcoidosis

- Multiple myeloma

- Waldenström macroglobulinemia

- Carcinomatous meningitis

Study of bone marrow biopsy demonstrated limited bone marrow involvement (1%) by a lymphoproliferative disorder with plasmacytoid features, and DNA testing detected an MYD88 L265P mutation, reported to be present in 90% of patients with Waldenström macroglobulinemia.9 This finding confirmed the diagnosis of Waldenström macroglobulinemia with central nervous system involvement. Our patient began therapy with rituximab and methotrexate, which resulted in some improvement in strength, gait, and vision.

WALDENSTRÖM MACROGLOBULINEMIA AND BING-NEEL SYNDROME

Waldenström macroglobulinemia is a lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma associated with a monoclonal IgM protein.10 It is considered a paraproteinemic disorder, similar to multiple myeloma. The presenting symptoms and complications are related to direct tumor infiltration, hyperviscosity syndrome, and deposition of IgM in various tissues.11,12

Waldenström macroglobulinemia is usually indolent, and treatment is reserved for patients with symptoms.13,14 It includes rituximab, usually in combination with chemotherapy or other targeted agents.15,16

Paraneoplastic antibody-mediated polyneuropathy may occur in these patients. However, the pattern is usually symmetrical clinically, with demyelination on EMG, and is not associated with cranial nerve or meningeal involvement. Management with plasmapheresis, corticosteroids, and intravenous immunoglobulin has not been shown to be effective.17

Involvement of the central nervous system as a complication of Waldenström macroglobulinemia has been described as Bing-Neel syndrome. It can present as diffuse malignant cell infiltration of the leptomeningeal space, white matter, or spinal cord, or in a tumoral form presenting as intraparenchymal masses or nodular lesions. The distinction between the tumoral and diffuse forms is based primarily on imaging findings.18

In a report of 44 patients with Bing-Neel syndrome, 36% presented with the disorder as the initial manifestation of Waldenström macroglobulinemia.18 The primary presenting symptoms were imbalance and gait difficulty (48%) and cranial nerve involvement (36%), which presented as predominantly facial or oculomotor nerve palsy. Cauda equina syndrome with motor involvement (seen in our patient) occurred in 14% of patients. Other presenting symptoms included cognitive impairment, sensory deficits, headache, dysarthria, aphasia, and seizures.

LEARNING POINTS

The differential diagnosis for patients presenting with multifocal neurologic symptoms can be broad, and a systematic approach to the diagnosis is necessary. Localizing the lesion is important in determining the diagnosis for patients presenting with neurologic symptoms. The process of localization begins with taking the history, is further refined during the examination, and is confirmed with diagnostic studies. Atypical presentations of relatively common neurologic diseases such as Guillain-Barré syndrome, transverse myelitis, and peripheral polyneuropathy do occur, but uncommon diagnoses need to be considered when support for the initial diagnosis is lacking.

A 69-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital with double vision, weakness in the lower extremities, sensory loss, pain, and falls. Her symptoms started with sudden onset of horizontal diplopia 6 weeks before, followed by gradually worsening lower-extremity weakness, as well as ataxia and patchy and bilateral radicular burning leg pain more pronounced on the right. Her medical history included narcolepsy, obstructive sleep apnea, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and bilateral knee replacements for osteoarthritis.

Neurologic examination showed inability to abduct the right eye, bilateral hip flexion weakness, decreased pinprick response, decreased proprioception, and diminished muscle stretch reflexes in the lower extremities. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain without contrast and magnetic resonance angiography of the brain and carotid arteries showed no evidence of acute stroke. No abnormalities were noted on electrocardiography and echocardiography.

A diagnosis of idiopathic peripheral neuropathy was made, and outpatient physical therapy was recommended. Over the subsequent 2 weeks, her condition declined to the point where she needed a walker. She continued to have worsening leg weakness with falls, prompting hospital readmission.

INITIAL EVALUATION

In addition to her diplopia and weakness, she said she had lost 15 pounds since the onset of symptoms and had experienced symptoms suggesting urinary retention.

Physical examination

Her temperature was 37°C (98.6°F), heart rate 79 beats per minute, blood pressure 117/86 mm Hg, respiratory rate 14 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation 98% on room air. Examination of the head, neck, heart, lung, abdomen, lymph nodes, and extremities yielded nothing remarkable except for chronic venous changes in the lower extremities.

The neurologic examination showed incomplete lateral gaze bilaterally (cranial nerve VI dysfunction). Strength in the upper extremities was normal. In the legs, the Medical Research Council scale score for proximal muscle strength was 2 to 3 out of 5, and for distal muscles 3 to 4 out of 5, with the right side worse than the left and flexors and extensors affected equally. Muscle stretch reflexes were absent in both lower extremities and the left upper extremity, but intact in the right upper extremity. No abnormal corticospinal tract reflexes were elicited.

Sensory testing revealed diminished pin-prick perception in a length-dependent fashion in the lower extremities, reduced 50% compared with the hands. Gait could not be assessed due to weakness.

Initial laboratory testing

Results of initial laboratory tests—complete blood cell count, complete metabolic panel, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and hemoglobin A1c—were unremarkable.

FURTHER EVALUATION AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

1. Which of the following is the most likely diagnosis at this point?

- Cerebral infarction

- Guillain-Barré syndrome

- Progressive polyneuropathy

- Transverse myelitis

- Polyradiculopathy

In the absence of definitive diagnostic tests, all of the above options were considered in the differential diagnosis for this patient.

Cerebral infarction

Although acute-onset diplopia can be explained by brainstem stroke involving cranial nerve nuclei or their projections, the onset of diplopia with progressive bilateral lower-extremity weakness makes stroke unlikely. Flaccid paralysis, areflexia of the lower extremities, and sensory involvement can also be caused by acute anterior spinal artery occlusion leading to spinal cord infarction; however, the deficits are usually maximal at onset.

Guillain-Barré syndrome

The combination of acute-subacute progressive ascending weakness, sensory involvement, and diminished or absent reflexes is typical of Guillain-Barré syndrome. Cranial nerve involvement can overlap with the more typical features of the syndrome. However, most patients reach the nadir of their disease by 4 weeks after initial symptom onset, even without treatment.1 This patient’s condition continued to worsen over 8 weeks. In addition, the asymmetric lower-extremity weakness and sparing of the arms are atypical for Guillain-Barré syndrome.

Given the progression of symptoms, chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy is also a consideration, typically presenting as a relapsing or progressive neuropathy in proximal and distal muscles and worsening over at least an 8-week period.2

The initial workup for Guillain-Barré syndrome or chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy includes lumbar puncture to assess for albuminocytologic dissociation (elevated protein with normal white blood cell count) in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and electromyography (EMG) to assess for neurophysiologic evidence of peripheral nerve demyelination. In Miller-Fisher syndrome, a rare variant of Guillain-Barré syndrome characterized by ataxia, ophthalmoparesis, and areflexia, serum ganglioside antibodies to GQ1b are found in over 90% of patients.3,4 Although MRI of the spine is not necessary to diagnose Guillain-Barré syndrome, it is often done to exclude other causes of lower-extremity weakness such as spinal cord or cauda equina compression that would require urgent neurosurgical consultation. MRI can support the diagnosis of Guillain-Barré syndrome when it reveals enhancement of the spinal nerve roots or cauda equina.

Other polyneuropathies

Polyneuropathy is caused by a variety of diseases that affect the function of peripheral motor, sensory, or autonomic nerves. The differential diagnosis is broad and involves inflammatory diseases (including autoimmune and paraneoplastic causes), hereditary disorders, infection, toxicity, and ischemic and nutritional deficiencies.5 Polyneuropathy can present in a distal-predominant, generalized, or asymmetric pattern involving individual nerve trunks termed “mononeuropathy multiplex,” as in our patient’s presentation. The initial workup includes EMG and a battery of serologic tests. In cases of severe and progressive polyneuropathy, nerve biopsy can assess for the presence of vasculitis, amyloidosis, and paraprotein deposition.

Transverse myelitis

Transverse myelitis is an inflammatory myelopathy that usually presents with acute or subacute weakness of the upper extremities or lower extremities, or both, corresponding to the level of the lesion, hyperreflexia, bladder and bowel dysfunction, spinal level of sensory loss, and autonomic involvement.6 The differential diagnosis of acute myelopathy includes:

- Infection (eg, herpes simplex virus, West Nile virus, Lyme disease, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, human immunodeficiency virus)

- Systemic inflammatory disease (systemic lupus erythematosus, sarcoidosis, Sjögren syndrome, scleroderma, paraneoplastic syndrome)

- Central nervous system demyelinating disease (acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, multiple sclerosis, neuromyelitis optica)

- Vascular malformation (dural arteriovenous fistula)

- Compression due to tumor, bleeding, disc herniation, infection, or abscess.

The workup involves laboratory tests to exclude systemic inflammatory and infectious causes, as well as MRI of the spine with and without contrast to identify a causative lesion. Lumbar puncture and CSF analysis may show pleocytosis, elevated protein concentration, and increased intrathecal immunoglobulin G (IgG) index.7

Although our patient’s presentation with subacute lower-extremity weakness, sensory changes, and bladder dysfunction were consistent with transverse myelitis, her cranial nerve abnormalities would be atypical for it.

Polyradiculopathy

Polyradiculopathy has many possible causes. In the United States, the most common causes are lumbar spondylosis, lumbar canal stenosis, and diabetic polyradiculoneuropathy.

When multiple spinal segments are affected, leptomeningeal disease involving the arachnoid and pia mater should be considered. Causes include malignant invasion, inflammatory cell accumulation, and protein deposition, leading to patchy but widespread dysfunction of spinal nerve roots and cranial nerves. Specific causes are myriad and include carcinomatous meningitis,8 syphilis, tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, and paraproteinemias. CSF and MRI changes are often nonspecific, leading to the need for meningeal biopsy for diagnosis.

CASE CONTINUED

During her hospitalization, our patient developed acute right upper and lower facial weakness consistent with peripheral facial mononeuropathy. Bilateral lower-extremity weakness progressed to disabling paraparesis.

She underwent lumbar puncture and CSF analysis (Table 1). The most notable findings were significant pleocytosis (72% lymphocytic predominance), protein elevation, and elevated IgG index (indicative of elevated intrathecal immunoglobulin synthesis in the central nervous system). Viral, bacterial, and fungal studies were negative. Guillain-Barré syndrome, other polyneuropathies, and spinal cord infarction would not be expected with these CSF features.

Surface EMG demonstrated normal sensory responses, and needle EMG showed chronic and active motor axon loss in the L3 and S1 root distributions, suggesting polyradiculopathy without polyneuropathy. These findings would not be expected in typical acute transverse myelitis but could be seen with spinal cord infarction.

MRI of the entire spine with and without contrast showed cauda equina nerve root thickening and enhancement, especially involving the L5 and S1 roots (Figure 1). The spinal cord appeared normal. These findings further supported polyradiculopathy and a leptomeningeal process.

Further evaluation included chest radiography, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, hemoglobin A1c, human immunodeficiency virus testing, antinuclear antibody, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, extractable nuclear antibody, GQ1b antibody, serum and CSF paraneoplastic panels, levels of vitamin B1, B12, and B6, copper, and ceruloplasmin, and a screen for heavy metals. All results were within normal ranges.

ESTABLISHING THE DIAGNOSIS

Serum monoclonal protein analysis with immunofixation revealed IgM kappa monoclonal gammopathy with an IgM level of 1,570 (reference range 53–334 mg/dL) and M-spike 0.75 (0.00 mg/dL), serum free kappa light chains 61.1 (3.30–19.40 mg/L), lambda 9.3 (5.7–26.3 mg/L), and kappa-lambda ratio 6.57 (0.26–1.65).

2. Which is the best next step in this patient’s neurologic evaluation?

- Test CSF angiotensin-converting enzyme level

- CSF cytology

- Meningeal biopsy

- Peripheral nerve biopsy

Given the high suspicion for malignancy, CSF cytology was performed and showed increased numbers of mononuclear chronic inflammatory cells, including a mixture of lymphocytes and monocytes, favoring a reactive lymphoid pleocytosis. Flow cytometry indicated the presence of a monoclonal, CD5- and CD10- negative, B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder. The immunophenotypic findings were not specific for a single diagnosis. The differential diagnosis included marginal zone lymphoma and lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma.

3. Given the presence of serum IgM monoclonal gammopathy in this patient, which is the most likely diagnosis?

- Neurosarcoidosis

- Multiple myeloma

- Waldenström macroglobulinemia

- Carcinomatous meningitis

Study of bone marrow biopsy demonstrated limited bone marrow involvement (1%) by a lymphoproliferative disorder with plasmacytoid features, and DNA testing detected an MYD88 L265P mutation, reported to be present in 90% of patients with Waldenström macroglobulinemia.9 This finding confirmed the diagnosis of Waldenström macroglobulinemia with central nervous system involvement. Our patient began therapy with rituximab and methotrexate, which resulted in some improvement in strength, gait, and vision.

WALDENSTRÖM MACROGLOBULINEMIA AND BING-NEEL SYNDROME

Waldenström macroglobulinemia is a lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma associated with a monoclonal IgM protein.10 It is considered a paraproteinemic disorder, similar to multiple myeloma. The presenting symptoms and complications are related to direct tumor infiltration, hyperviscosity syndrome, and deposition of IgM in various tissues.11,12

Waldenström macroglobulinemia is usually indolent, and treatment is reserved for patients with symptoms.13,14 It includes rituximab, usually in combination with chemotherapy or other targeted agents.15,16

Paraneoplastic antibody-mediated polyneuropathy may occur in these patients. However, the pattern is usually symmetrical clinically, with demyelination on EMG, and is not associated with cranial nerve or meningeal involvement. Management with plasmapheresis, corticosteroids, and intravenous immunoglobulin has not been shown to be effective.17

Involvement of the central nervous system as a complication of Waldenström macroglobulinemia has been described as Bing-Neel syndrome. It can present as diffuse malignant cell infiltration of the leptomeningeal space, white matter, or spinal cord, or in a tumoral form presenting as intraparenchymal masses or nodular lesions. The distinction between the tumoral and diffuse forms is based primarily on imaging findings.18

In a report of 44 patients with Bing-Neel syndrome, 36% presented with the disorder as the initial manifestation of Waldenström macroglobulinemia.18 The primary presenting symptoms were imbalance and gait difficulty (48%) and cranial nerve involvement (36%), which presented as predominantly facial or oculomotor nerve palsy. Cauda equina syndrome with motor involvement (seen in our patient) occurred in 14% of patients. Other presenting symptoms included cognitive impairment, sensory deficits, headache, dysarthria, aphasia, and seizures.

LEARNING POINTS

The differential diagnosis for patients presenting with multifocal neurologic symptoms can be broad, and a systematic approach to the diagnosis is necessary. Localizing the lesion is important in determining the diagnosis for patients presenting with neurologic symptoms. The process of localization begins with taking the history, is further refined during the examination, and is confirmed with diagnostic studies. Atypical presentations of relatively common neurologic diseases such as Guillain-Barré syndrome, transverse myelitis, and peripheral polyneuropathy do occur, but uncommon diagnoses need to be considered when support for the initial diagnosis is lacking.

- Fokke C, van den Berg B, Drenthen J, Walgaard C, van Doorn PA, Jacobs BC. Diagnosis of Guillain-Barre syndrome and validation of Brighton criteria. Brain 2014; 137(Pt 1):33–43. doi:10.1093/brain/awt285

- Mathey EK, Park SB, Hughes RA, et al. Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy: from pathology to phenotype. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2015; 86(9):973–985. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2014-309697

- Chiba A, Kusunoki S, Obata H, Machinami R, Kanazawa I. Serum anti-GQ1b IgG antibody is associated with ophthalmoplegia in Miller Fisher syndrome and Guillain-Barré syndrome: clinical and immunohistochemical studies. Neurology 1993; 43(10):1911–1917. pmid:8413947

- Teener J. Miller Fisher’s syndrome. Semin Neurol 2012; 32(5):512–516. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1334470

- Watson JC, Dyck PJ. Peripheral neuropathy: a practical approach to diagnosis and symptom management. Mayo Clin Proc 2015; 90(7):940–951. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.05.004

- Greenberg BM. Treatment of acute transverse myelitis and its early complications. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2011; 17(4):733–743. doi:10.1212/01.CON.0000403792.36161.f5

- West TW. Transverse myelitis—a review of the presentation, diagnosis, and initial management. Discov Med 2013; 16(88):167–177. pmid:24099672

- Le Rhun E, Taillibert S, Chamberlain MC. Carcinomatous meningitis: leptomeningeal metastases in solid tumors. Surg Neurol Int 2013; 4(suppl 4):S265–S288. doi:10.4103/2152-7806.111304

- Treon SP, Xu L, Yang G, et al. MYD88 L265P somatic mutation in Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia. N Engl J Med 2012; 367(9):826–833. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1200710

- Owen RG, Treon SP, Al-Katib A, et al. Clinicopathological definition of Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia: consensus panel recommendations from the Second International Workshop on Waldenstrom’s Macroglobulinemia. Semin Oncol 2003; 30(2):110–115. doi:10.1053/sonc.2003.50082

- Björkholm M, Johansson E, Papamichael D, et al. Patterns of clinical presentation, treatment, and outcome in patients with Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia: a two-institution study. Semin Oncol 2003; 30(2):226–230. doi:10.1053/sonc.2003.50054

- Rison RA, Beydoun SR. Paraproteinemic neuropathy: a practical review. BMC Neurol 2016; 16:13. doi:10.1186/s12883-016-0532-4

- Kyle RA, Benson J, Larson D, et al. IgM monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and smoldering Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma 2009; 9(1):17–18. doi:10.3816/CLM.2009.n.002

- Kyle RA, Benson JT, Larson DR, et al. Progression in smoldering Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia: long-term results. Blood 2012; 119(19):4462–4466. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-10-384768

- Leblond V, Kastritis E, Advani R, et al. Treatment recommendations from the Eighth International Workshop on Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia. Blood 2016; 128(10):1321–1328. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-04-711234

- Kapoor P, Ansell SM, Fonseca R, et al. Diagnosis and management of Waldenström macroglobulinemia: Mayo stratification of macroglobulinemia and risk-adapted therapy (mSMART) guidelines 2016. JAMA Oncol 2017; 3(9):1257–1265. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5763

- D’Sa S, Kersten MJ, Castillo JJ, et al. Investigation and management of IgM and Waldenström-associated peripheral neuropathies: recommendations from the IWWM-8 consensus panel. Br J Haematol 2017; 176(5):728–742. doi:10.1111/bjh.14492

- Simon L, Fitsiori A, Lemal R, et al. Bing-Neel syndrome, a rare complication of Waldenström macroglobulinemia: analysis of 44 cases and review of the literature. A study on behalf of the French Innovative Leukemia Organization (FILO). Haematologica 2015; 100(12):1587–1594. doi:10.3324/haematol.2015.133744