User login

When is it safe to resume anticoagulation in my patient with hemorrhagic stroke?

Balancing risk is critical to decision making

Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston

Case

A 75 year-old woman with a history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, heart failure and nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (CHA2DS2-VASc score, 8) on anticoagulation is admitted with weakness and dysarthria. Exam is notable for hypertension and right-sided hemiparesis. CT of the head shows an intraparenchymal hemorrhage in the left putamen. Her anticoagulation is reversed and blood pressure well controlled. She is discharged 12 days later.

Brief overview of the issue

Intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) is the second most common cause of stroke and is associated with high morbidity and mortality.1 It is estimated that 10%-15% of spontaneous ICH cases occur in patients on therapeutic anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation.2 As our population ages and more people develop atrial fibrillation, anticoagulation for primary or secondary prevention of embolic stroke also will likely increase, placing more people at risk for ICH. Even stringently controlled therapeutic international normalized ratios (INRs) between 2 and 3 may double the risk of ICH.3

Patients with ICH require close monitoring and treatment, including blood pressure control, reversal of anticoagulation, reduction of intracranial pressure and, at times, neurosurgery.4 Although anticoagulation is discontinued and reversed at the onset of ICH, no clear consensus exists as to when it is safe to resume it. Although anticoagulation decreases the risk of stroke/thromboembolism, it may also increase the amount of bleeding associated with the initial ICH or lead to its recurrence.

Factors that may contribute to rebleeding include uncontrolled hypertension, advanced age, time to resumption of anticoagulation, and lobar location of ICH (i.e., in cerebral cortex and/or underlying white matter).5 Traditionally, lobar ICH has high incidence of cerebral amyloid angiopathy and has been associated with higher bleeding rates than has deep ICH (i.e., involving the thalami, basal ganglia, cerebellum, or brainstem) where cerebral amyloid angiopathy is rare and ICH is usually from hypertensive vessel disease. However, in patients with active thromboembolic disease, high-risk atrial fibrillation, and mechanical valves, withholding anticoagulation could place them at high risk of stroke.

Two questions should be addressed in the case presented: Is it safe to restart therapeutic anticoagulation; and if so, what is the optimal time interval between ICH and reinitiation of anticoagulation?

Overview of the data

There is limited guidance from major professional societies regarding the reinitiation of anticoagulation and the optimal timing of safely resuming anticoagulation in patients with prior ICH.

Current European Stroke Organization guidelines provide no specific recommendations for anticoagulation resumption after ICH.7 The American Heart Association/American Stroke Association guideline has a class IIA (weak) recommendation to avoid anticoagulation in spontaneous lobar ICH and a class IIB (very weak) recommendation to consider resuming anticoagulation in nonlobar ICH on a case-by-case basis.4

Two recent meta-analyses have examined outcomes of resuming anticoagulation after ICH. In a meta-analysis of 5,300 patients with nonlobar ICH involving eight retrospective studies, Murthy et al. evaluated the risk of thromboembolic events (described as a composite outcome of MI and stroke) and the risk of recurrent ICH.8 They reported that resumption of therapeutic anticoagulation was associated with a decrease in the rate of thromboembolic events (6.7% vs. 17.6%; risk ratio, 0.35; 95% confidence interval, 0.25-0.45) with no significant change in the rate of repeat ICH (8.7% vs. 7.8%).

A second meta-analysis of three retrospective trials conducted by Biffi et al. examined anticoagulation resumption in 1,012 patients with ICH solely in the setting of thromboprophylaxis for nonvalvular atrial fibrillation.9 Reinitiation of anticoagulation after ICH was associated with decreased mortality (hazard ratio, 0.27; 95% CI, 0.19-0.40; P less than .0001), improved functional outcome (HR, 4.15; 95% CI, 2.92-5.90; P less than .0001), and reduction in all-cause stroke recurrence (HR 0.47; 95% CI, 0.36-0.64; P less than .0001). There was no significant difference in the rate of recurrent ICH when anticoagulation was resumed. Despite the notion that patients with cerebral amyloid angiopathy are at high risk of rebleeding, this positive association still held irrespective of lobar vs. nonlobar location of ICH.

Collectively, these studies suggest that resumption of anticoagulation may be effective in decreasing the rates of thromboembolism, as well as provide a functional and mortality benefit without increasing the risk of rebleeding, irrespective of the location of the bleed.

Less is known about the optimal timing of resumption of therapeutic anticoagulation, with data ranging from 72 hours to 30 weeks.10 The American Heart Association/American Stroke Association has a class IIB (very weak) recommendation to avoid anticoagulation for at least 4 weeks in patients without mechanical heart valves.4 The median time to resumption of therapeutic anticoagulation in aforementioned meta-analyses ranged from 10 to 44 days.8,9

A recent observational study of 2,619 ICH survivors explored the relationship between the timing of reinitiation of anticoagulation and the incidence of thrombotic events (defined as ischemic stroke or death because of MI or systemic arterial thromboembolism) and hemorrhagic events (defined as recurrent ICH or bleeding event leading to death) occurring at least 28 days after initial ICH in patients with atrial fibrillation.11

A decrease in thrombotic events was demonstrated if anticoagulation was started 4-16 weeks after ICH. However, when anticoagulation was started more than 16 weeks after ICH, no benefit was seen. Additionally, there was no significant difference in hemorrhagic events between men and women who resumed anticoagulation. In patients with high venous thromboembolism risk based on CHA2DS2-VASc score, resumption of anticoagulation was associated with a decreased predicted incidence of vascular death and nonfatal stroke, with the greatest benefit observed when anticoagulation was started at 7-8 weeks after ICH.

Unfortunately, published literature to date on anticoagulation after ICH is based entirely on retrospective studies – not randomized, controlled studies – making it more likely that anticoagulation would have been resumed in healthier patients, not those left debilitated by the ICH.

Furthermore, information on the location and size of the hemorrhages – which may serve as another confounding factor – often has not been reported. This is important since patients with smaller hemorrhages in less precarious areas also may be more likely to have resumption of anticoagulation. Another limitation of the current literature is that warfarin is the most common anticoagulant studied, with few studies involving the increasingly prescribed newer direct oral anticoagulants. It is also important to stress that a causal relationship between use of anticoagulants and certain outcomes or adverse effects following ICH may be more difficult to invoke in the absence of randomized controlled study designs.

Application of the data to our patient

Resumption of anticoagulation in our patient with ICH requires balancing the risk of hemorrhage expansion and recurrent ICH with the risk of thromboembolic disease.

Our patient is at higher risk of bleeding because of her advanced age, but adequate control of her blood pressure and nonlobar location of her ICH in the basal ganglia also may decrease her risk of recurrent ICH. Her high CHA2DS2-VASc score places her at high risk of thromboembolic event and stroke, making it more likely for reinitiation of anticoagulation to confer a mortality benefit.

Based on AHA guidelines,4 we should wait at least 4 weeks, or possibly wait until weeks 7-8 after ICH when the greatest benefit may be expected based on prediction models.11

Bottom line

It would likely be safe to resume anticoagulation 4-8 weeks after ICH in our patient.

Dr. Gibson, Dr. Restrepo, Dr. Sasidhara, and Dr. Manian are hospitalists at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

References

1. An SJ et al. Epidemiology, risk factors, and clinical features of intracerebral hemorrhage: An update. J Stroke. 2017 Jan;19:3-10.

2. Horstmann S et al. Intracerebral hemorrhage during anticoagulation with vitamin K antagonists: a consecutive observational study. J Neurol. 2013 Aug;260:2046-51.

3. Rosand J et al. The effect of warfarin and intensity of anticoagulation on outcome of intracerebral hemorrhage. Arch Intern Med. 2004 Apr 26;164:880-4.

4. Hemphill JC et al. Guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2015 Jul;46:2032-60.

5. Aguillar MI et al. Update in intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurohospitalist. 2011;1:148-59.

6. Hill MD et al. Rate of stroke recurrence in patients with primary intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2000;31:123-7.

7. Steiner T et al. European Stroke Organization (ESO) guidelines for the management of spontaneous cerebral hemorrhage. Int J Stroke. 2014;9:840-55.

8. Murthy SB et al. Restarting anticoagulation therapy after intracranial hemorrhage: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke. 2017 Jun;48:1594-600.

9. Biffi A et al. Oral anticoagulation and functional outcome after intracerebral hemorrhage. Ann Neurol. 2017 Nov;82:755-65.

10. Witt DM. What to do after the bleed: Resuming anticoagulation after major bleeding. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2016 Dec 2;206:620-4.

11. Pennlert J et al. Optimal timing of anticoagulant treatment after intracerebral hemorrhage in patients with atrial fibrillation. Stroke. 2017 Feb;48:314-20.

Key Points

- Robust scientific data on when to resume anticoagulation after ICH does not exist.

- Retrospective studies have shown that anticoagulation resumption after 4-8 weeks decreases the risk of thromboembolic events, decreases mortality, and improves functional status following ICH with no significant change in the risk of its recurrence.

- Prospective, randomized controlled trials are needed to explore risks/benefits of anticoagulation resumption and better define its optimal timing in relation to ICH.

Quiz

Which of the following is false regarding ICH?

A. Lobar ICHs are usually associated with cerebral amyloid angiopathy which are prone to bleeding.

B. Randomized, controlled studies have helped guide the decision as to when to resume anticoagulation in patients with ICH.

C. Current guidelines suggest deferring therapeutic anticoagulation for at least 4 weeks following ICH.

D. Resumption of anticoagulation after 4-8 weeks does not lead to increased risk of rebleeding in patients with prior ICH.

The false answer is B: Current recommendations regarding resumption of anticoagulation in patients with ICH are based solely on retrospective observational studies; there are no randomized, control trials to date.

A is true: In contrast to hypertensive vessel disease associated with deep ICH, lobar hemorrhages are usually associated with cerebral amyloid angiopathy, which are more prone to bleeding.

C is true: The AHA/ASA has a class IIB recommendation to avoid anticoagulation for at least 4 weeks after ICH in patients without mechanical heart valves.

D is true: Several studies have shown that resumption of anticoagulation 4-8 weeks after ICH does not increase the risk of rebleeding.

Balancing risk is critical to decision making

Balancing risk is critical to decision making

Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston

Case

A 75 year-old woman with a history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, heart failure and nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (CHA2DS2-VASc score, 8) on anticoagulation is admitted with weakness and dysarthria. Exam is notable for hypertension and right-sided hemiparesis. CT of the head shows an intraparenchymal hemorrhage in the left putamen. Her anticoagulation is reversed and blood pressure well controlled. She is discharged 12 days later.

Brief overview of the issue

Intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) is the second most common cause of stroke and is associated with high morbidity and mortality.1 It is estimated that 10%-15% of spontaneous ICH cases occur in patients on therapeutic anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation.2 As our population ages and more people develop atrial fibrillation, anticoagulation for primary or secondary prevention of embolic stroke also will likely increase, placing more people at risk for ICH. Even stringently controlled therapeutic international normalized ratios (INRs) between 2 and 3 may double the risk of ICH.3

Patients with ICH require close monitoring and treatment, including blood pressure control, reversal of anticoagulation, reduction of intracranial pressure and, at times, neurosurgery.4 Although anticoagulation is discontinued and reversed at the onset of ICH, no clear consensus exists as to when it is safe to resume it. Although anticoagulation decreases the risk of stroke/thromboembolism, it may also increase the amount of bleeding associated with the initial ICH or lead to its recurrence.

Factors that may contribute to rebleeding include uncontrolled hypertension, advanced age, time to resumption of anticoagulation, and lobar location of ICH (i.e., in cerebral cortex and/or underlying white matter).5 Traditionally, lobar ICH has high incidence of cerebral amyloid angiopathy and has been associated with higher bleeding rates than has deep ICH (i.e., involving the thalami, basal ganglia, cerebellum, or brainstem) where cerebral amyloid angiopathy is rare and ICH is usually from hypertensive vessel disease. However, in patients with active thromboembolic disease, high-risk atrial fibrillation, and mechanical valves, withholding anticoagulation could place them at high risk of stroke.

Two questions should be addressed in the case presented: Is it safe to restart therapeutic anticoagulation; and if so, what is the optimal time interval between ICH and reinitiation of anticoagulation?

Overview of the data

There is limited guidance from major professional societies regarding the reinitiation of anticoagulation and the optimal timing of safely resuming anticoagulation in patients with prior ICH.

Current European Stroke Organization guidelines provide no specific recommendations for anticoagulation resumption after ICH.7 The American Heart Association/American Stroke Association guideline has a class IIA (weak) recommendation to avoid anticoagulation in spontaneous lobar ICH and a class IIB (very weak) recommendation to consider resuming anticoagulation in nonlobar ICH on a case-by-case basis.4

Two recent meta-analyses have examined outcomes of resuming anticoagulation after ICH. In a meta-analysis of 5,300 patients with nonlobar ICH involving eight retrospective studies, Murthy et al. evaluated the risk of thromboembolic events (described as a composite outcome of MI and stroke) and the risk of recurrent ICH.8 They reported that resumption of therapeutic anticoagulation was associated with a decrease in the rate of thromboembolic events (6.7% vs. 17.6%; risk ratio, 0.35; 95% confidence interval, 0.25-0.45) with no significant change in the rate of repeat ICH (8.7% vs. 7.8%).

A second meta-analysis of three retrospective trials conducted by Biffi et al. examined anticoagulation resumption in 1,012 patients with ICH solely in the setting of thromboprophylaxis for nonvalvular atrial fibrillation.9 Reinitiation of anticoagulation after ICH was associated with decreased mortality (hazard ratio, 0.27; 95% CI, 0.19-0.40; P less than .0001), improved functional outcome (HR, 4.15; 95% CI, 2.92-5.90; P less than .0001), and reduction in all-cause stroke recurrence (HR 0.47; 95% CI, 0.36-0.64; P less than .0001). There was no significant difference in the rate of recurrent ICH when anticoagulation was resumed. Despite the notion that patients with cerebral amyloid angiopathy are at high risk of rebleeding, this positive association still held irrespective of lobar vs. nonlobar location of ICH.

Collectively, these studies suggest that resumption of anticoagulation may be effective in decreasing the rates of thromboembolism, as well as provide a functional and mortality benefit without increasing the risk of rebleeding, irrespective of the location of the bleed.

Less is known about the optimal timing of resumption of therapeutic anticoagulation, with data ranging from 72 hours to 30 weeks.10 The American Heart Association/American Stroke Association has a class IIB (very weak) recommendation to avoid anticoagulation for at least 4 weeks in patients without mechanical heart valves.4 The median time to resumption of therapeutic anticoagulation in aforementioned meta-analyses ranged from 10 to 44 days.8,9

A recent observational study of 2,619 ICH survivors explored the relationship between the timing of reinitiation of anticoagulation and the incidence of thrombotic events (defined as ischemic stroke or death because of MI or systemic arterial thromboembolism) and hemorrhagic events (defined as recurrent ICH or bleeding event leading to death) occurring at least 28 days after initial ICH in patients with atrial fibrillation.11

A decrease in thrombotic events was demonstrated if anticoagulation was started 4-16 weeks after ICH. However, when anticoagulation was started more than 16 weeks after ICH, no benefit was seen. Additionally, there was no significant difference in hemorrhagic events between men and women who resumed anticoagulation. In patients with high venous thromboembolism risk based on CHA2DS2-VASc score, resumption of anticoagulation was associated with a decreased predicted incidence of vascular death and nonfatal stroke, with the greatest benefit observed when anticoagulation was started at 7-8 weeks after ICH.

Unfortunately, published literature to date on anticoagulation after ICH is based entirely on retrospective studies – not randomized, controlled studies – making it more likely that anticoagulation would have been resumed in healthier patients, not those left debilitated by the ICH.

Furthermore, information on the location and size of the hemorrhages – which may serve as another confounding factor – often has not been reported. This is important since patients with smaller hemorrhages in less precarious areas also may be more likely to have resumption of anticoagulation. Another limitation of the current literature is that warfarin is the most common anticoagulant studied, with few studies involving the increasingly prescribed newer direct oral anticoagulants. It is also important to stress that a causal relationship between use of anticoagulants and certain outcomes or adverse effects following ICH may be more difficult to invoke in the absence of randomized controlled study designs.

Application of the data to our patient

Resumption of anticoagulation in our patient with ICH requires balancing the risk of hemorrhage expansion and recurrent ICH with the risk of thromboembolic disease.

Our patient is at higher risk of bleeding because of her advanced age, but adequate control of her blood pressure and nonlobar location of her ICH in the basal ganglia also may decrease her risk of recurrent ICH. Her high CHA2DS2-VASc score places her at high risk of thromboembolic event and stroke, making it more likely for reinitiation of anticoagulation to confer a mortality benefit.

Based on AHA guidelines,4 we should wait at least 4 weeks, or possibly wait until weeks 7-8 after ICH when the greatest benefit may be expected based on prediction models.11

Bottom line

It would likely be safe to resume anticoagulation 4-8 weeks after ICH in our patient.

Dr. Gibson, Dr. Restrepo, Dr. Sasidhara, and Dr. Manian are hospitalists at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

References

1. An SJ et al. Epidemiology, risk factors, and clinical features of intracerebral hemorrhage: An update. J Stroke. 2017 Jan;19:3-10.

2. Horstmann S et al. Intracerebral hemorrhage during anticoagulation with vitamin K antagonists: a consecutive observational study. J Neurol. 2013 Aug;260:2046-51.

3. Rosand J et al. The effect of warfarin and intensity of anticoagulation on outcome of intracerebral hemorrhage. Arch Intern Med. 2004 Apr 26;164:880-4.

4. Hemphill JC et al. Guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2015 Jul;46:2032-60.

5. Aguillar MI et al. Update in intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurohospitalist. 2011;1:148-59.

6. Hill MD et al. Rate of stroke recurrence in patients with primary intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2000;31:123-7.

7. Steiner T et al. European Stroke Organization (ESO) guidelines for the management of spontaneous cerebral hemorrhage. Int J Stroke. 2014;9:840-55.

8. Murthy SB et al. Restarting anticoagulation therapy after intracranial hemorrhage: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke. 2017 Jun;48:1594-600.

9. Biffi A et al. Oral anticoagulation and functional outcome after intracerebral hemorrhage. Ann Neurol. 2017 Nov;82:755-65.

10. Witt DM. What to do after the bleed: Resuming anticoagulation after major bleeding. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2016 Dec 2;206:620-4.

11. Pennlert J et al. Optimal timing of anticoagulant treatment after intracerebral hemorrhage in patients with atrial fibrillation. Stroke. 2017 Feb;48:314-20.

Key Points

- Robust scientific data on when to resume anticoagulation after ICH does not exist.

- Retrospective studies have shown that anticoagulation resumption after 4-8 weeks decreases the risk of thromboembolic events, decreases mortality, and improves functional status following ICH with no significant change in the risk of its recurrence.

- Prospective, randomized controlled trials are needed to explore risks/benefits of anticoagulation resumption and better define its optimal timing in relation to ICH.

Quiz

Which of the following is false regarding ICH?

A. Lobar ICHs are usually associated with cerebral amyloid angiopathy which are prone to bleeding.

B. Randomized, controlled studies have helped guide the decision as to when to resume anticoagulation in patients with ICH.

C. Current guidelines suggest deferring therapeutic anticoagulation for at least 4 weeks following ICH.

D. Resumption of anticoagulation after 4-8 weeks does not lead to increased risk of rebleeding in patients with prior ICH.

The false answer is B: Current recommendations regarding resumption of anticoagulation in patients with ICH are based solely on retrospective observational studies; there are no randomized, control trials to date.

A is true: In contrast to hypertensive vessel disease associated with deep ICH, lobar hemorrhages are usually associated with cerebral amyloid angiopathy, which are more prone to bleeding.

C is true: The AHA/ASA has a class IIB recommendation to avoid anticoagulation for at least 4 weeks after ICH in patients without mechanical heart valves.

D is true: Several studies have shown that resumption of anticoagulation 4-8 weeks after ICH does not increase the risk of rebleeding.

Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston

Case

A 75 year-old woman with a history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, heart failure and nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (CHA2DS2-VASc score, 8) on anticoagulation is admitted with weakness and dysarthria. Exam is notable for hypertension and right-sided hemiparesis. CT of the head shows an intraparenchymal hemorrhage in the left putamen. Her anticoagulation is reversed and blood pressure well controlled. She is discharged 12 days later.

Brief overview of the issue

Intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) is the second most common cause of stroke and is associated with high morbidity and mortality.1 It is estimated that 10%-15% of spontaneous ICH cases occur in patients on therapeutic anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation.2 As our population ages and more people develop atrial fibrillation, anticoagulation for primary or secondary prevention of embolic stroke also will likely increase, placing more people at risk for ICH. Even stringently controlled therapeutic international normalized ratios (INRs) between 2 and 3 may double the risk of ICH.3

Patients with ICH require close monitoring and treatment, including blood pressure control, reversal of anticoagulation, reduction of intracranial pressure and, at times, neurosurgery.4 Although anticoagulation is discontinued and reversed at the onset of ICH, no clear consensus exists as to when it is safe to resume it. Although anticoagulation decreases the risk of stroke/thromboembolism, it may also increase the amount of bleeding associated with the initial ICH or lead to its recurrence.

Factors that may contribute to rebleeding include uncontrolled hypertension, advanced age, time to resumption of anticoagulation, and lobar location of ICH (i.e., in cerebral cortex and/or underlying white matter).5 Traditionally, lobar ICH has high incidence of cerebral amyloid angiopathy and has been associated with higher bleeding rates than has deep ICH (i.e., involving the thalami, basal ganglia, cerebellum, or brainstem) where cerebral amyloid angiopathy is rare and ICH is usually from hypertensive vessel disease. However, in patients with active thromboembolic disease, high-risk atrial fibrillation, and mechanical valves, withholding anticoagulation could place them at high risk of stroke.

Two questions should be addressed in the case presented: Is it safe to restart therapeutic anticoagulation; and if so, what is the optimal time interval between ICH and reinitiation of anticoagulation?

Overview of the data

There is limited guidance from major professional societies regarding the reinitiation of anticoagulation and the optimal timing of safely resuming anticoagulation in patients with prior ICH.

Current European Stroke Organization guidelines provide no specific recommendations for anticoagulation resumption after ICH.7 The American Heart Association/American Stroke Association guideline has a class IIA (weak) recommendation to avoid anticoagulation in spontaneous lobar ICH and a class IIB (very weak) recommendation to consider resuming anticoagulation in nonlobar ICH on a case-by-case basis.4

Two recent meta-analyses have examined outcomes of resuming anticoagulation after ICH. In a meta-analysis of 5,300 patients with nonlobar ICH involving eight retrospective studies, Murthy et al. evaluated the risk of thromboembolic events (described as a composite outcome of MI and stroke) and the risk of recurrent ICH.8 They reported that resumption of therapeutic anticoagulation was associated with a decrease in the rate of thromboembolic events (6.7% vs. 17.6%; risk ratio, 0.35; 95% confidence interval, 0.25-0.45) with no significant change in the rate of repeat ICH (8.7% vs. 7.8%).

A second meta-analysis of three retrospective trials conducted by Biffi et al. examined anticoagulation resumption in 1,012 patients with ICH solely in the setting of thromboprophylaxis for nonvalvular atrial fibrillation.9 Reinitiation of anticoagulation after ICH was associated with decreased mortality (hazard ratio, 0.27; 95% CI, 0.19-0.40; P less than .0001), improved functional outcome (HR, 4.15; 95% CI, 2.92-5.90; P less than .0001), and reduction in all-cause stroke recurrence (HR 0.47; 95% CI, 0.36-0.64; P less than .0001). There was no significant difference in the rate of recurrent ICH when anticoagulation was resumed. Despite the notion that patients with cerebral amyloid angiopathy are at high risk of rebleeding, this positive association still held irrespective of lobar vs. nonlobar location of ICH.

Collectively, these studies suggest that resumption of anticoagulation may be effective in decreasing the rates of thromboembolism, as well as provide a functional and mortality benefit without increasing the risk of rebleeding, irrespective of the location of the bleed.

Less is known about the optimal timing of resumption of therapeutic anticoagulation, with data ranging from 72 hours to 30 weeks.10 The American Heart Association/American Stroke Association has a class IIB (very weak) recommendation to avoid anticoagulation for at least 4 weeks in patients without mechanical heart valves.4 The median time to resumption of therapeutic anticoagulation in aforementioned meta-analyses ranged from 10 to 44 days.8,9

A recent observational study of 2,619 ICH survivors explored the relationship between the timing of reinitiation of anticoagulation and the incidence of thrombotic events (defined as ischemic stroke or death because of MI or systemic arterial thromboembolism) and hemorrhagic events (defined as recurrent ICH or bleeding event leading to death) occurring at least 28 days after initial ICH in patients with atrial fibrillation.11

A decrease in thrombotic events was demonstrated if anticoagulation was started 4-16 weeks after ICH. However, when anticoagulation was started more than 16 weeks after ICH, no benefit was seen. Additionally, there was no significant difference in hemorrhagic events between men and women who resumed anticoagulation. In patients with high venous thromboembolism risk based on CHA2DS2-VASc score, resumption of anticoagulation was associated with a decreased predicted incidence of vascular death and nonfatal stroke, with the greatest benefit observed when anticoagulation was started at 7-8 weeks after ICH.

Unfortunately, published literature to date on anticoagulation after ICH is based entirely on retrospective studies – not randomized, controlled studies – making it more likely that anticoagulation would have been resumed in healthier patients, not those left debilitated by the ICH.

Furthermore, information on the location and size of the hemorrhages – which may serve as another confounding factor – often has not been reported. This is important since patients with smaller hemorrhages in less precarious areas also may be more likely to have resumption of anticoagulation. Another limitation of the current literature is that warfarin is the most common anticoagulant studied, with few studies involving the increasingly prescribed newer direct oral anticoagulants. It is also important to stress that a causal relationship between use of anticoagulants and certain outcomes or adverse effects following ICH may be more difficult to invoke in the absence of randomized controlled study designs.

Application of the data to our patient

Resumption of anticoagulation in our patient with ICH requires balancing the risk of hemorrhage expansion and recurrent ICH with the risk of thromboembolic disease.

Our patient is at higher risk of bleeding because of her advanced age, but adequate control of her blood pressure and nonlobar location of her ICH in the basal ganglia also may decrease her risk of recurrent ICH. Her high CHA2DS2-VASc score places her at high risk of thromboembolic event and stroke, making it more likely for reinitiation of anticoagulation to confer a mortality benefit.

Based on AHA guidelines,4 we should wait at least 4 weeks, or possibly wait until weeks 7-8 after ICH when the greatest benefit may be expected based on prediction models.11

Bottom line

It would likely be safe to resume anticoagulation 4-8 weeks after ICH in our patient.

Dr. Gibson, Dr. Restrepo, Dr. Sasidhara, and Dr. Manian are hospitalists at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

References

1. An SJ et al. Epidemiology, risk factors, and clinical features of intracerebral hemorrhage: An update. J Stroke. 2017 Jan;19:3-10.

2. Horstmann S et al. Intracerebral hemorrhage during anticoagulation with vitamin K antagonists: a consecutive observational study. J Neurol. 2013 Aug;260:2046-51.

3. Rosand J et al. The effect of warfarin and intensity of anticoagulation on outcome of intracerebral hemorrhage. Arch Intern Med. 2004 Apr 26;164:880-4.

4. Hemphill JC et al. Guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2015 Jul;46:2032-60.

5. Aguillar MI et al. Update in intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurohospitalist. 2011;1:148-59.

6. Hill MD et al. Rate of stroke recurrence in patients with primary intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2000;31:123-7.

7. Steiner T et al. European Stroke Organization (ESO) guidelines for the management of spontaneous cerebral hemorrhage. Int J Stroke. 2014;9:840-55.

8. Murthy SB et al. Restarting anticoagulation therapy after intracranial hemorrhage: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke. 2017 Jun;48:1594-600.

9. Biffi A et al. Oral anticoagulation and functional outcome after intracerebral hemorrhage. Ann Neurol. 2017 Nov;82:755-65.

10. Witt DM. What to do after the bleed: Resuming anticoagulation after major bleeding. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2016 Dec 2;206:620-4.

11. Pennlert J et al. Optimal timing of anticoagulant treatment after intracerebral hemorrhage in patients with atrial fibrillation. Stroke. 2017 Feb;48:314-20.

Key Points

- Robust scientific data on when to resume anticoagulation after ICH does not exist.

- Retrospective studies have shown that anticoagulation resumption after 4-8 weeks decreases the risk of thromboembolic events, decreases mortality, and improves functional status following ICH with no significant change in the risk of its recurrence.

- Prospective, randomized controlled trials are needed to explore risks/benefits of anticoagulation resumption and better define its optimal timing in relation to ICH.

Quiz

Which of the following is false regarding ICH?

A. Lobar ICHs are usually associated with cerebral amyloid angiopathy which are prone to bleeding.

B. Randomized, controlled studies have helped guide the decision as to when to resume anticoagulation in patients with ICH.

C. Current guidelines suggest deferring therapeutic anticoagulation for at least 4 weeks following ICH.

D. Resumption of anticoagulation after 4-8 weeks does not lead to increased risk of rebleeding in patients with prior ICH.

The false answer is B: Current recommendations regarding resumption of anticoagulation in patients with ICH are based solely on retrospective observational studies; there are no randomized, control trials to date.

A is true: In contrast to hypertensive vessel disease associated with deep ICH, lobar hemorrhages are usually associated with cerebral amyloid angiopathy, which are more prone to bleeding.

C is true: The AHA/ASA has a class IIB recommendation to avoid anticoagulation for at least 4 weeks after ICH in patients without mechanical heart valves.

D is true: Several studies have shown that resumption of anticoagulation 4-8 weeks after ICH does not increase the risk of rebleeding.

Medical advice prompts unneeded emergency visits by AF patients

BOSTON – Patients with atrial fibrillation who present to emergency departments, despite being asymptomatic, often go based on of their understanding of advice they had previously received from their physicians, according to results from a prospective study of 356 Canadian atrial arrhythmia patients seen in emergency settings.

One way to deal with potentially inappropriate emergency department use is to have concerned patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) record their heart rhythm data with a handheld device or watch, transfer the records to their smartphones, and transmit the information to a remote physician for interpretation and advice, Benedict M. Glover, MD, said at the annual International AF Symposium.

Dr. Glover and his associates are in the process of developing a prototype system of this design to address the need they identified in a recent registry of 356 patients with a primary diagnosis of AF who sought care in the emergency department (ED) of any of seven participating Canadian medical centers, including five academic centers and two community hospitals. The survey results showed that 71% of the patients were symptomatic and 29% were asymptomatic then they first presented to an emergency department.

Case reviews of the 356 patients showed that 152 (43%) came to the EDs for what were classified as inappropriate reasons. The most common cause by far of an inappropriate emergency presentation was prior medical advice the patient had received, cited in 62% of the inappropriate cases, compared with 9% of the appropriate cases, said Dr. Glover, an electrophysiologist at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto.

The inappropriate ED use by AF patients could be addressed in at least two ways, he said. One solution might be to give patients an alternative destination, so that instead of going to an emergency department they could go to an outpatient AF clinic. A second solution is to give patients a way to have their heart rhythm assessed remotely at the time of their concern. Dr. Glover said that his center had the staff capacity to deal with the potential influx of rhythm data from a pilot-sized program of remote heart-rhythm monitoring, but he conceded that scaling up to deal with the data that could come from the entire panel of AF patients managed by Sunnybrook physicians would be a huge challenge.

“The issue is what do we do with the data after we get it,” Dr. Glover said. “It’s a lot of information.”

Dr. Glover had no disclosures.

BOSTON – Patients with atrial fibrillation who present to emergency departments, despite being asymptomatic, often go based on of their understanding of advice they had previously received from their physicians, according to results from a prospective study of 356 Canadian atrial arrhythmia patients seen in emergency settings.

One way to deal with potentially inappropriate emergency department use is to have concerned patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) record their heart rhythm data with a handheld device or watch, transfer the records to their smartphones, and transmit the information to a remote physician for interpretation and advice, Benedict M. Glover, MD, said at the annual International AF Symposium.

Dr. Glover and his associates are in the process of developing a prototype system of this design to address the need they identified in a recent registry of 356 patients with a primary diagnosis of AF who sought care in the emergency department (ED) of any of seven participating Canadian medical centers, including five academic centers and two community hospitals. The survey results showed that 71% of the patients were symptomatic and 29% were asymptomatic then they first presented to an emergency department.

Case reviews of the 356 patients showed that 152 (43%) came to the EDs for what were classified as inappropriate reasons. The most common cause by far of an inappropriate emergency presentation was prior medical advice the patient had received, cited in 62% of the inappropriate cases, compared with 9% of the appropriate cases, said Dr. Glover, an electrophysiologist at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto.

The inappropriate ED use by AF patients could be addressed in at least two ways, he said. One solution might be to give patients an alternative destination, so that instead of going to an emergency department they could go to an outpatient AF clinic. A second solution is to give patients a way to have their heart rhythm assessed remotely at the time of their concern. Dr. Glover said that his center had the staff capacity to deal with the potential influx of rhythm data from a pilot-sized program of remote heart-rhythm monitoring, but he conceded that scaling up to deal with the data that could come from the entire panel of AF patients managed by Sunnybrook physicians would be a huge challenge.

“The issue is what do we do with the data after we get it,” Dr. Glover said. “It’s a lot of information.”

Dr. Glover had no disclosures.

BOSTON – Patients with atrial fibrillation who present to emergency departments, despite being asymptomatic, often go based on of their understanding of advice they had previously received from their physicians, according to results from a prospective study of 356 Canadian atrial arrhythmia patients seen in emergency settings.

One way to deal with potentially inappropriate emergency department use is to have concerned patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) record their heart rhythm data with a handheld device or watch, transfer the records to their smartphones, and transmit the information to a remote physician for interpretation and advice, Benedict M. Glover, MD, said at the annual International AF Symposium.

Dr. Glover and his associates are in the process of developing a prototype system of this design to address the need they identified in a recent registry of 356 patients with a primary diagnosis of AF who sought care in the emergency department (ED) of any of seven participating Canadian medical centers, including five academic centers and two community hospitals. The survey results showed that 71% of the patients were symptomatic and 29% were asymptomatic then they first presented to an emergency department.

Case reviews of the 356 patients showed that 152 (43%) came to the EDs for what were classified as inappropriate reasons. The most common cause by far of an inappropriate emergency presentation was prior medical advice the patient had received, cited in 62% of the inappropriate cases, compared with 9% of the appropriate cases, said Dr. Glover, an electrophysiologist at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto.

The inappropriate ED use by AF patients could be addressed in at least two ways, he said. One solution might be to give patients an alternative destination, so that instead of going to an emergency department they could go to an outpatient AF clinic. A second solution is to give patients a way to have their heart rhythm assessed remotely at the time of their concern. Dr. Glover said that his center had the staff capacity to deal with the potential influx of rhythm data from a pilot-sized program of remote heart-rhythm monitoring, but he conceded that scaling up to deal with the data that could come from the entire panel of AF patients managed by Sunnybrook physicians would be a huge challenge.

“The issue is what do we do with the data after we get it,” Dr. Glover said. “It’s a lot of information.”

Dr. Glover had no disclosures.

REPORTING FROM THE AF SYMPOSIUM 2019

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Among 152 AF patients who made an inappropriate ED visit, 62% cited their prior medical advice.

Study details: Prospective study of 356 AF patients who sought ED care at any of seven Canadian hospitals.

Disclosures: Dr. Glover had no disclosures.

New recall for CoaguChek test strips issued

According to a release, the Food and Drug Administration has identified this recall as Class I, which is the most serious type of recall and indicates that “use of these devices may cause serious injuries or death.”

These strips are used by patients taking warfarin to help determine the patients’ international normalized ratio, which doctors and patients then use to decide whether the dose is appropriate. Roche Diagnostics, the strips’ manufacturer, issued a recall in September 2018; the test strips distributed by Terrific Care and Medex, however, were not labeled or authorized for sale in the United States and were therefore not included in that original recall. According to the release, the strips in this recall, which was initiated Dec. 21, 2018, were purchased by Terrific Care and Medex from an unknown source and then distributed in the United States. On Jan. 28, 2019, Terrific Care sent an Urgent Medical Device Recall Notification Letter to customers.

The full recall is described on the FDA website.

According to a release, the Food and Drug Administration has identified this recall as Class I, which is the most serious type of recall and indicates that “use of these devices may cause serious injuries or death.”

These strips are used by patients taking warfarin to help determine the patients’ international normalized ratio, which doctors and patients then use to decide whether the dose is appropriate. Roche Diagnostics, the strips’ manufacturer, issued a recall in September 2018; the test strips distributed by Terrific Care and Medex, however, were not labeled or authorized for sale in the United States and were therefore not included in that original recall. According to the release, the strips in this recall, which was initiated Dec. 21, 2018, were purchased by Terrific Care and Medex from an unknown source and then distributed in the United States. On Jan. 28, 2019, Terrific Care sent an Urgent Medical Device Recall Notification Letter to customers.

The full recall is described on the FDA website.

According to a release, the Food and Drug Administration has identified this recall as Class I, which is the most serious type of recall and indicates that “use of these devices may cause serious injuries or death.”

These strips are used by patients taking warfarin to help determine the patients’ international normalized ratio, which doctors and patients then use to decide whether the dose is appropriate. Roche Diagnostics, the strips’ manufacturer, issued a recall in September 2018; the test strips distributed by Terrific Care and Medex, however, were not labeled or authorized for sale in the United States and were therefore not included in that original recall. According to the release, the strips in this recall, which was initiated Dec. 21, 2018, were purchased by Terrific Care and Medex from an unknown source and then distributed in the United States. On Jan. 28, 2019, Terrific Care sent an Urgent Medical Device Recall Notification Letter to customers.

The full recall is described on the FDA website.

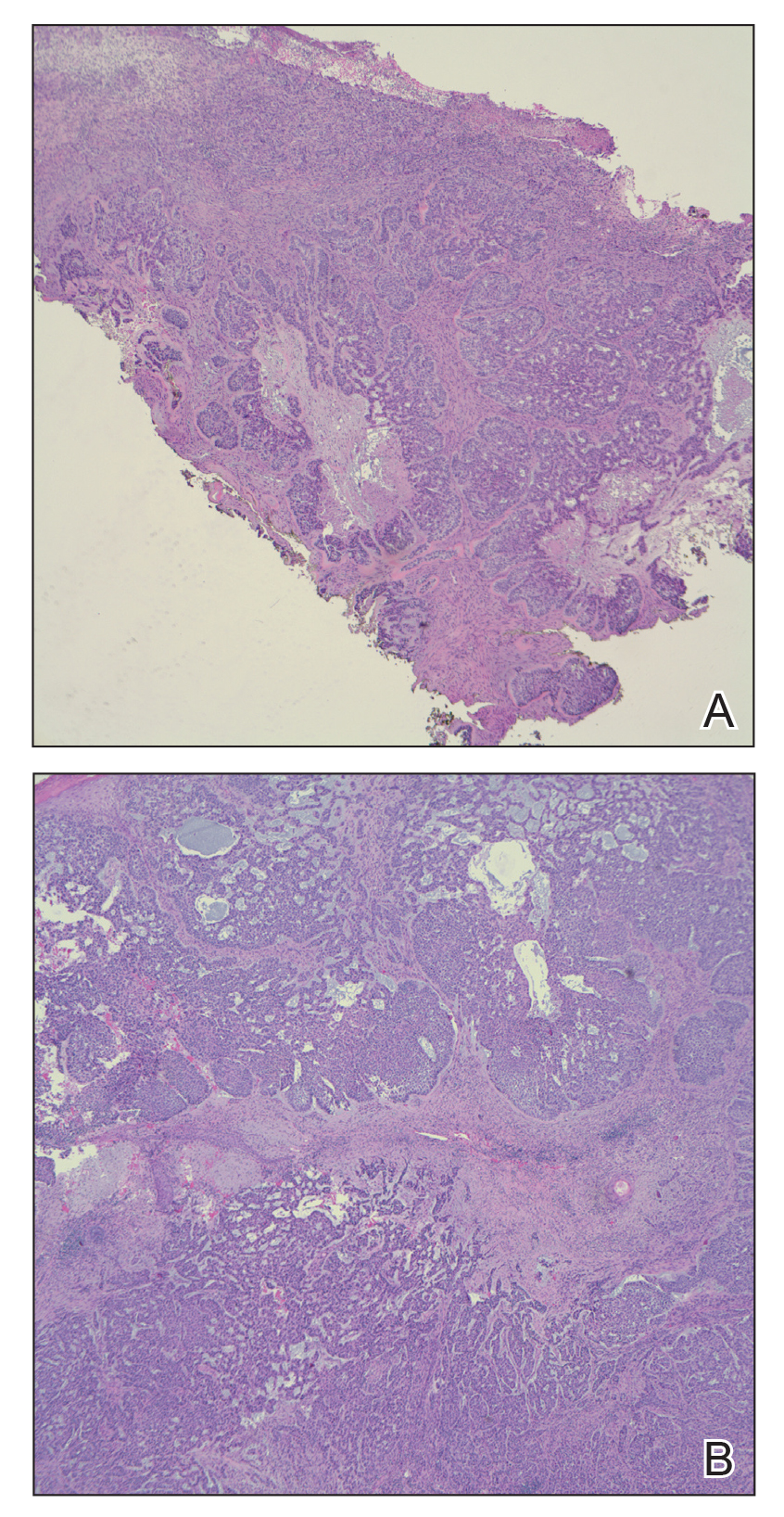

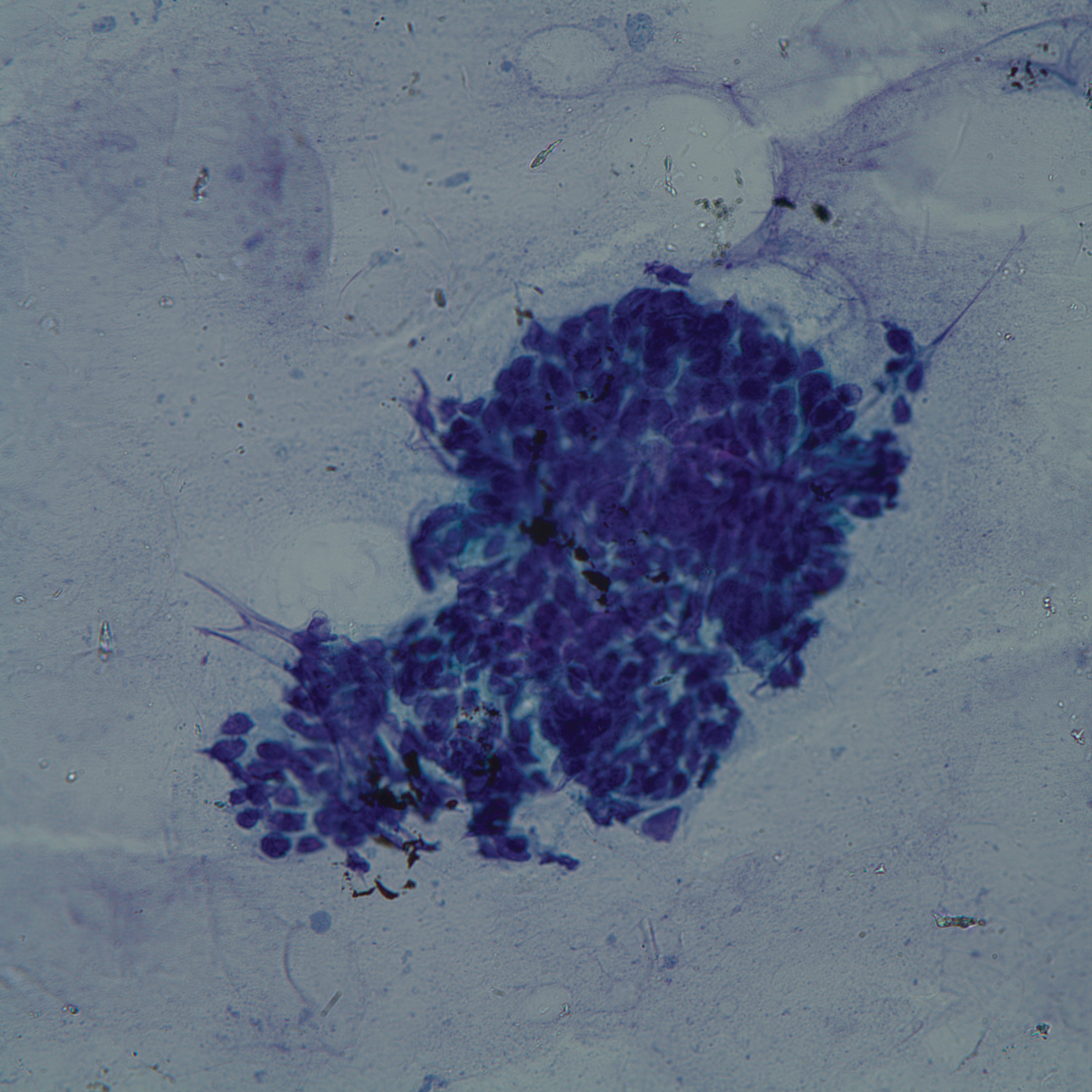

Combo emerges as bridge to transplant in rel/ref PTCL

LA JOLLA, CALIF. – The combination of duvelisib and romidepsin is active and can provide a bridge to transplant in relapsed or refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL), according to researchers.

In a phase 1 trial, duvelisib plus romidepsin produced an overall response rate (ORR) of 59% in patients with PTCL. Sixteen patients achieved a response, nine had a complete response (CR), and six complete responders went on to transplant.

“So we think that you can achieve remission deep enough to then move on to a potentially curative approach,” said study investigator Neha Mehta-Shah, MD, of Washington University in St. Louis.

She and her colleagues evaluated romidepsin plus duvelisib, as well as bortezomib plus duvelisib, in a phase 1 trial (NCT02783625) of patients with relapsed or refractory PTCL or cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL).

Dr. Mehta-Shah presented the results at the annual T-cell Lymphoma Forum.

She reported results in 80 patients – 51 with PTCL and 29 with CTCL. The patients’ median age was 64 years (range, 28-83), and 57% of the study population were men. Patients had received a median of 3 (range, 1-16) prior therapies, and 16% had received a prior transplant.

Treatment

Dr. Mehta-Shah noted that patients and providers could choose whether patients would receive romidepsin or bortezomib.

Patients in the romidepsin arm received romidepsin at 10 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15 of each 28-day cycle. Patients in the bortezomib arm received bortezomib at 1 mg/m2 on days 1, 4, 8, and 11 of each cycle.

Duvelisib dosing was escalated, so patients received duvelisib at 25 mg, 50 mg, or 75 mg twice daily.

In the bortezomib arm, there was one dose-limiting toxicity – grade 3 neutropenia – in a patient who received duvelisib at the 25-mg dose. There were no dose-limiting toxicities in the romidepsin arm.

The researchers determined that the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of duvelisib was 75 mg twice daily in the romidepsin arm and 25 mg twice daily in the bortezomib arm.

Lead-in phase

The study also had a lead-in phase during which patients could receive single-agent duvelisib.

“Because the original phase 1 study of duvelisib did not collect as many prospective tumor biopsies or on-treatment biopsies, we built into this study a lead-in phase so that we could characterize on-treatment biopsies to better understand mechanisms of response or resistance,” Dr. Mehta-Shah said.

Patients and providers could choose to be part of the lead-in phase, she noted. Patients who did not achieve a CR during this phase went on to receive either combination therapy, which was predetermined before the monotherapy began.

There were 14 patients who received duvelisib monotherapy at 75 mg twice daily. Four of them achieved a CR, and three had a partial response (PR). Ten patients went on to receive romidepsin as well. One of them achieved a CR, and three had a PR.

There were 12 patients who received duvelisib monotherapy at 25 mg twice daily. Three of them achieved a CR, and two had a PR. Nine patients went on to receive bortezomib as well. This combination produced one CR and two PRs.

Efficacy with romidepsin

Among all evaluable PTCL patients in the romidepsin arm, the ORR was 59% (16/27), and the CR rate was 33% (9/27).

Responses occurred in seven patients with PTCL not otherwise specified (NOS), six with angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL), one with hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma, one with aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma, and one with primary cutaneous PTCL.

CRs occurred in five patients with AITL and four with PTCL-NOS. Six patients who achieved a CR went on to transplant.

Among evaluable CTCL patients in the romidepsin arm, the ORR was 45% (5/11), and there were no CRs. Responses occurred in three patients with mycosis fungoides and two with Sézary syndrome.

The median progression-free survival was 5.41 months in CTCL patients and 6.72 months in PTCL patients.

Efficacy with bortezomib

Among evaluable PTCL patients in the bortezomib arm, the ORR was 44% (7/16), and the CR rate was 25% (4/16).

Responses occurred in three patients with AITL and four with PTCL-NOS. CRs occurred in two patients with each subtype.

Among evaluable CTCL patients in the bortezomib arm, the ORR was 27% (4/15), and there were no CRs. Responses occurred in one patient with mycosis fungoides and three with Sézary syndrome. One CTCL patient went on to transplant.

The median progression-free survival was 4.56 months among CTCL patients and 4.39 months in PTCL patients.

Safety

Dr. Mehta-Shah said both combinations were considered safe and well tolerated. However, there was a grade 5 adverse event (AE) – Stevens-Johnson syndrome – that occurred in the bortezomib arm and was considered possibly related to treatment.

Grade 3/4 AEs observed in the 31 patients treated at the MTD in the romidepsin arm were transaminase increase (n = 7), diarrhea (n = 6), hyponatremia (n = 4), neutrophil count decrease (n = 10), and platelet count decrease (n = 3).

Grade 3/4 AEs observed in the 23 patients treated at the MTD in the bortezomib arm were transaminase increase (n = 2) and neutrophil count decrease (n = 5).

Grade 3/4 transaminitis seemed to be more common among patients who received duvelisib alone during the lead-in phase, Dr. Mehta-Shah said.

Among patients treated at the MTD in the romidepsin arm, grade 3/4 transaminitis occurred in four patients treated during the lead-in phase and three who began receiving romidepsin and duvelisib together. In the bortezomib arm, grade 3/4 transaminitis occurred in two patients treated at the MTD, both of whom received duvelisib alone during the lead-in phase.

Based on these results, Dr. Mehta-Shah and her colleagues are planning to expand the romidepsin arm to an additional 25 patients. By testing the combination in more patients, the researchers hope to better understand the occurrence of transaminitis and assess the durability of response.

This study is supported by Verastem. Dr. Shah reported relationships with Celgene, Kyowa Kirin, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Verastem, and Genentech.

The T-cell Lymphoma Forum is held by Jonathan Wood & Associates, which is owned by the same company as this news organization.

LA JOLLA, CALIF. – The combination of duvelisib and romidepsin is active and can provide a bridge to transplant in relapsed or refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL), according to researchers.

In a phase 1 trial, duvelisib plus romidepsin produced an overall response rate (ORR) of 59% in patients with PTCL. Sixteen patients achieved a response, nine had a complete response (CR), and six complete responders went on to transplant.

“So we think that you can achieve remission deep enough to then move on to a potentially curative approach,” said study investigator Neha Mehta-Shah, MD, of Washington University in St. Louis.

She and her colleagues evaluated romidepsin plus duvelisib, as well as bortezomib plus duvelisib, in a phase 1 trial (NCT02783625) of patients with relapsed or refractory PTCL or cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL).

Dr. Mehta-Shah presented the results at the annual T-cell Lymphoma Forum.

She reported results in 80 patients – 51 with PTCL and 29 with CTCL. The patients’ median age was 64 years (range, 28-83), and 57% of the study population were men. Patients had received a median of 3 (range, 1-16) prior therapies, and 16% had received a prior transplant.

Treatment

Dr. Mehta-Shah noted that patients and providers could choose whether patients would receive romidepsin or bortezomib.

Patients in the romidepsin arm received romidepsin at 10 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15 of each 28-day cycle. Patients in the bortezomib arm received bortezomib at 1 mg/m2 on days 1, 4, 8, and 11 of each cycle.

Duvelisib dosing was escalated, so patients received duvelisib at 25 mg, 50 mg, or 75 mg twice daily.

In the bortezomib arm, there was one dose-limiting toxicity – grade 3 neutropenia – in a patient who received duvelisib at the 25-mg dose. There were no dose-limiting toxicities in the romidepsin arm.

The researchers determined that the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of duvelisib was 75 mg twice daily in the romidepsin arm and 25 mg twice daily in the bortezomib arm.

Lead-in phase

The study also had a lead-in phase during which patients could receive single-agent duvelisib.

“Because the original phase 1 study of duvelisib did not collect as many prospective tumor biopsies or on-treatment biopsies, we built into this study a lead-in phase so that we could characterize on-treatment biopsies to better understand mechanisms of response or resistance,” Dr. Mehta-Shah said.

Patients and providers could choose to be part of the lead-in phase, she noted. Patients who did not achieve a CR during this phase went on to receive either combination therapy, which was predetermined before the monotherapy began.

There were 14 patients who received duvelisib monotherapy at 75 mg twice daily. Four of them achieved a CR, and three had a partial response (PR). Ten patients went on to receive romidepsin as well. One of them achieved a CR, and three had a PR.

There were 12 patients who received duvelisib monotherapy at 25 mg twice daily. Three of them achieved a CR, and two had a PR. Nine patients went on to receive bortezomib as well. This combination produced one CR and two PRs.

Efficacy with romidepsin

Among all evaluable PTCL patients in the romidepsin arm, the ORR was 59% (16/27), and the CR rate was 33% (9/27).

Responses occurred in seven patients with PTCL not otherwise specified (NOS), six with angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL), one with hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma, one with aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma, and one with primary cutaneous PTCL.

CRs occurred in five patients with AITL and four with PTCL-NOS. Six patients who achieved a CR went on to transplant.

Among evaluable CTCL patients in the romidepsin arm, the ORR was 45% (5/11), and there were no CRs. Responses occurred in three patients with mycosis fungoides and two with Sézary syndrome.

The median progression-free survival was 5.41 months in CTCL patients and 6.72 months in PTCL patients.

Efficacy with bortezomib

Among evaluable PTCL patients in the bortezomib arm, the ORR was 44% (7/16), and the CR rate was 25% (4/16).

Responses occurred in three patients with AITL and four with PTCL-NOS. CRs occurred in two patients with each subtype.

Among evaluable CTCL patients in the bortezomib arm, the ORR was 27% (4/15), and there were no CRs. Responses occurred in one patient with mycosis fungoides and three with Sézary syndrome. One CTCL patient went on to transplant.

The median progression-free survival was 4.56 months among CTCL patients and 4.39 months in PTCL patients.

Safety

Dr. Mehta-Shah said both combinations were considered safe and well tolerated. However, there was a grade 5 adverse event (AE) – Stevens-Johnson syndrome – that occurred in the bortezomib arm and was considered possibly related to treatment.

Grade 3/4 AEs observed in the 31 patients treated at the MTD in the romidepsin arm were transaminase increase (n = 7), diarrhea (n = 6), hyponatremia (n = 4), neutrophil count decrease (n = 10), and platelet count decrease (n = 3).

Grade 3/4 AEs observed in the 23 patients treated at the MTD in the bortezomib arm were transaminase increase (n = 2) and neutrophil count decrease (n = 5).

Grade 3/4 transaminitis seemed to be more common among patients who received duvelisib alone during the lead-in phase, Dr. Mehta-Shah said.

Among patients treated at the MTD in the romidepsin arm, grade 3/4 transaminitis occurred in four patients treated during the lead-in phase and three who began receiving romidepsin and duvelisib together. In the bortezomib arm, grade 3/4 transaminitis occurred in two patients treated at the MTD, both of whom received duvelisib alone during the lead-in phase.

Based on these results, Dr. Mehta-Shah and her colleagues are planning to expand the romidepsin arm to an additional 25 patients. By testing the combination in more patients, the researchers hope to better understand the occurrence of transaminitis and assess the durability of response.

This study is supported by Verastem. Dr. Shah reported relationships with Celgene, Kyowa Kirin, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Verastem, and Genentech.

The T-cell Lymphoma Forum is held by Jonathan Wood & Associates, which is owned by the same company as this news organization.

LA JOLLA, CALIF. – The combination of duvelisib and romidepsin is active and can provide a bridge to transplant in relapsed or refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL), according to researchers.

In a phase 1 trial, duvelisib plus romidepsin produced an overall response rate (ORR) of 59% in patients with PTCL. Sixteen patients achieved a response, nine had a complete response (CR), and six complete responders went on to transplant.

“So we think that you can achieve remission deep enough to then move on to a potentially curative approach,” said study investigator Neha Mehta-Shah, MD, of Washington University in St. Louis.

She and her colleagues evaluated romidepsin plus duvelisib, as well as bortezomib plus duvelisib, in a phase 1 trial (NCT02783625) of patients with relapsed or refractory PTCL or cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL).

Dr. Mehta-Shah presented the results at the annual T-cell Lymphoma Forum.

She reported results in 80 patients – 51 with PTCL and 29 with CTCL. The patients’ median age was 64 years (range, 28-83), and 57% of the study population were men. Patients had received a median of 3 (range, 1-16) prior therapies, and 16% had received a prior transplant.

Treatment

Dr. Mehta-Shah noted that patients and providers could choose whether patients would receive romidepsin or bortezomib.

Patients in the romidepsin arm received romidepsin at 10 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15 of each 28-day cycle. Patients in the bortezomib arm received bortezomib at 1 mg/m2 on days 1, 4, 8, and 11 of each cycle.

Duvelisib dosing was escalated, so patients received duvelisib at 25 mg, 50 mg, or 75 mg twice daily.

In the bortezomib arm, there was one dose-limiting toxicity – grade 3 neutropenia – in a patient who received duvelisib at the 25-mg dose. There were no dose-limiting toxicities in the romidepsin arm.

The researchers determined that the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of duvelisib was 75 mg twice daily in the romidepsin arm and 25 mg twice daily in the bortezomib arm.

Lead-in phase

The study also had a lead-in phase during which patients could receive single-agent duvelisib.

“Because the original phase 1 study of duvelisib did not collect as many prospective tumor biopsies or on-treatment biopsies, we built into this study a lead-in phase so that we could characterize on-treatment biopsies to better understand mechanisms of response or resistance,” Dr. Mehta-Shah said.

Patients and providers could choose to be part of the lead-in phase, she noted. Patients who did not achieve a CR during this phase went on to receive either combination therapy, which was predetermined before the monotherapy began.

There were 14 patients who received duvelisib monotherapy at 75 mg twice daily. Four of them achieved a CR, and three had a partial response (PR). Ten patients went on to receive romidepsin as well. One of them achieved a CR, and three had a PR.

There were 12 patients who received duvelisib monotherapy at 25 mg twice daily. Three of them achieved a CR, and two had a PR. Nine patients went on to receive bortezomib as well. This combination produced one CR and two PRs.

Efficacy with romidepsin

Among all evaluable PTCL patients in the romidepsin arm, the ORR was 59% (16/27), and the CR rate was 33% (9/27).

Responses occurred in seven patients with PTCL not otherwise specified (NOS), six with angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL), one with hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma, one with aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma, and one with primary cutaneous PTCL.

CRs occurred in five patients with AITL and four with PTCL-NOS. Six patients who achieved a CR went on to transplant.

Among evaluable CTCL patients in the romidepsin arm, the ORR was 45% (5/11), and there were no CRs. Responses occurred in three patients with mycosis fungoides and two with Sézary syndrome.

The median progression-free survival was 5.41 months in CTCL patients and 6.72 months in PTCL patients.

Efficacy with bortezomib

Among evaluable PTCL patients in the bortezomib arm, the ORR was 44% (7/16), and the CR rate was 25% (4/16).

Responses occurred in three patients with AITL and four with PTCL-NOS. CRs occurred in two patients with each subtype.

Among evaluable CTCL patients in the bortezomib arm, the ORR was 27% (4/15), and there were no CRs. Responses occurred in one patient with mycosis fungoides and three with Sézary syndrome. One CTCL patient went on to transplant.

The median progression-free survival was 4.56 months among CTCL patients and 4.39 months in PTCL patients.

Safety

Dr. Mehta-Shah said both combinations were considered safe and well tolerated. However, there was a grade 5 adverse event (AE) – Stevens-Johnson syndrome – that occurred in the bortezomib arm and was considered possibly related to treatment.

Grade 3/4 AEs observed in the 31 patients treated at the MTD in the romidepsin arm were transaminase increase (n = 7), diarrhea (n = 6), hyponatremia (n = 4), neutrophil count decrease (n = 10), and platelet count decrease (n = 3).

Grade 3/4 AEs observed in the 23 patients treated at the MTD in the bortezomib arm were transaminase increase (n = 2) and neutrophil count decrease (n = 5).

Grade 3/4 transaminitis seemed to be more common among patients who received duvelisib alone during the lead-in phase, Dr. Mehta-Shah said.

Among patients treated at the MTD in the romidepsin arm, grade 3/4 transaminitis occurred in four patients treated during the lead-in phase and three who began receiving romidepsin and duvelisib together. In the bortezomib arm, grade 3/4 transaminitis occurred in two patients treated at the MTD, both of whom received duvelisib alone during the lead-in phase.

Based on these results, Dr. Mehta-Shah and her colleagues are planning to expand the romidepsin arm to an additional 25 patients. By testing the combination in more patients, the researchers hope to better understand the occurrence of transaminitis and assess the durability of response.

This study is supported by Verastem. Dr. Shah reported relationships with Celgene, Kyowa Kirin, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Verastem, and Genentech.

The T-cell Lymphoma Forum is held by Jonathan Wood & Associates, which is owned by the same company as this news organization.

REPORTING FROM TCLF 2019

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The overall response rate was 59%, and six of nine complete responders went on to transplant.

Study details: Phase 1 trial of 80 patients that included 27 evaluable PTCL patients who received romidepsin and duvelisib.

Disclosures: The study is supported by Verastem. Dr. Shah reported relationships with Celgene, Kyowa Kirin, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Verastem, and Genentech.

Rural pediatric patients face unique cancer care challenges

Rural families that live far from their child’s cancer center face unique challenges, particularly lost work and missed family activities, because of long drives and inadequate emergency care at local hospitals, a small study has found.

Lead author Emily B. Walling, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and her colleagues interviewed 18 caregivers with children who received treatment at St. Louis (Mo.) Children’s Hospital, an urban pediatric hospital. The caregivers lived in a rural area 2 or more hours’ driving distance from the hospital, and their children had received six or more treatments of chemotherapy and/or radiation at the cancer center. To be eligible, families had to have sought emergency care related to their child’s cancer diagnosis at least once in their local community. A total of 18 caregivers (12 mothers and 6 fathers) from 16 families were identified. The families answered questions focused on how the distance between home and hospital affected their child’s cancer treatment.

From the 18 interviews, investigators determined that top problems encountered by the rural families included poor emergent care at local hospitals, strain on family members because of extended travel time, and challenges in managing and coping with a pediatric diagnosis, according to the study published in the Journal of Oncology Practice.

In regards to emergency care, the families reported frustration with local emergency care providers who they felt did not take their concerns seriously. Parents also noted a lack of resources and training related to specialized care at local hospitals. Because of inadequacies at local hospitals, the caregivers reported delays in care, poor symptom management, incorrect procedures, inability to access central lines, and underappreciation of the child’s immunocompromised state, according to the study. The parents also reported that local hospital providers sometimes failed to follow the recommendations of oncology specialists at St. Louis Children’s Hospital and that other times there was redundant care between both health care centers.

Interviewees also described disruption to family members and guilt about missing important activities of other children because of long drives to the urban cancer center. Caregivers worried about missed school for children and separation from siblings. Families also reported financial burdens from missed work and increased costs associated with food, gas, and housing while away from home. In addition, inclement weather increased travel stress, as did treatment-related problems during the drive not easily managed in a vehicle.

Based on the interviews, investigators recommended steps to improve the care of rural pediatric cancer patients, including improved guidance to caregivers about unexpected trips to local hospitals, more outreach to local hospitals, and better medical visit coordination. If local hospitals are identified at diagnosis, communication between the local hospital and cancer center could be established early, study authors wrote. If deficiencies in care are discovered, local hospitals may be prompted to “stock materials or parents could be redirected to other hospitals at which they are routinely available,” authors suggested.

“This would foster collaboration between local physicians and specialists at the cancer-treating hospital, and thereby lower levels of frustration and increase parent’s trust of local providers,” authors wrote.

SOURCE: Walling EB et al. J Oncol Pract. 2019 Jan 31. doi: 10.1200/JOP.18.00115.

Rural families that live far from their child’s cancer center face unique challenges, particularly lost work and missed family activities, because of long drives and inadequate emergency care at local hospitals, a small study has found.

Lead author Emily B. Walling, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and her colleagues interviewed 18 caregivers with children who received treatment at St. Louis (Mo.) Children’s Hospital, an urban pediatric hospital. The caregivers lived in a rural area 2 or more hours’ driving distance from the hospital, and their children had received six or more treatments of chemotherapy and/or radiation at the cancer center. To be eligible, families had to have sought emergency care related to their child’s cancer diagnosis at least once in their local community. A total of 18 caregivers (12 mothers and 6 fathers) from 16 families were identified. The families answered questions focused on how the distance between home and hospital affected their child’s cancer treatment.

From the 18 interviews, investigators determined that top problems encountered by the rural families included poor emergent care at local hospitals, strain on family members because of extended travel time, and challenges in managing and coping with a pediatric diagnosis, according to the study published in the Journal of Oncology Practice.

In regards to emergency care, the families reported frustration with local emergency care providers who they felt did not take their concerns seriously. Parents also noted a lack of resources and training related to specialized care at local hospitals. Because of inadequacies at local hospitals, the caregivers reported delays in care, poor symptom management, incorrect procedures, inability to access central lines, and underappreciation of the child’s immunocompromised state, according to the study. The parents also reported that local hospital providers sometimes failed to follow the recommendations of oncology specialists at St. Louis Children’s Hospital and that other times there was redundant care between both health care centers.

Interviewees also described disruption to family members and guilt about missing important activities of other children because of long drives to the urban cancer center. Caregivers worried about missed school for children and separation from siblings. Families also reported financial burdens from missed work and increased costs associated with food, gas, and housing while away from home. In addition, inclement weather increased travel stress, as did treatment-related problems during the drive not easily managed in a vehicle.

Based on the interviews, investigators recommended steps to improve the care of rural pediatric cancer patients, including improved guidance to caregivers about unexpected trips to local hospitals, more outreach to local hospitals, and better medical visit coordination. If local hospitals are identified at diagnosis, communication between the local hospital and cancer center could be established early, study authors wrote. If deficiencies in care are discovered, local hospitals may be prompted to “stock materials or parents could be redirected to other hospitals at which they are routinely available,” authors suggested.

“This would foster collaboration between local physicians and specialists at the cancer-treating hospital, and thereby lower levels of frustration and increase parent’s trust of local providers,” authors wrote.

SOURCE: Walling EB et al. J Oncol Pract. 2019 Jan 31. doi: 10.1200/JOP.18.00115.

Rural families that live far from their child’s cancer center face unique challenges, particularly lost work and missed family activities, because of long drives and inadequate emergency care at local hospitals, a small study has found.

Lead author Emily B. Walling, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and her colleagues interviewed 18 caregivers with children who received treatment at St. Louis (Mo.) Children’s Hospital, an urban pediatric hospital. The caregivers lived in a rural area 2 or more hours’ driving distance from the hospital, and their children had received six or more treatments of chemotherapy and/or radiation at the cancer center. To be eligible, families had to have sought emergency care related to their child’s cancer diagnosis at least once in their local community. A total of 18 caregivers (12 mothers and 6 fathers) from 16 families were identified. The families answered questions focused on how the distance between home and hospital affected their child’s cancer treatment.

From the 18 interviews, investigators determined that top problems encountered by the rural families included poor emergent care at local hospitals, strain on family members because of extended travel time, and challenges in managing and coping with a pediatric diagnosis, according to the study published in the Journal of Oncology Practice.

In regards to emergency care, the families reported frustration with local emergency care providers who they felt did not take their concerns seriously. Parents also noted a lack of resources and training related to specialized care at local hospitals. Because of inadequacies at local hospitals, the caregivers reported delays in care, poor symptom management, incorrect procedures, inability to access central lines, and underappreciation of the child’s immunocompromised state, according to the study. The parents also reported that local hospital providers sometimes failed to follow the recommendations of oncology specialists at St. Louis Children’s Hospital and that other times there was redundant care between both health care centers.

Interviewees also described disruption to family members and guilt about missing important activities of other children because of long drives to the urban cancer center. Caregivers worried about missed school for children and separation from siblings. Families also reported financial burdens from missed work and increased costs associated with food, gas, and housing while away from home. In addition, inclement weather increased travel stress, as did treatment-related problems during the drive not easily managed in a vehicle.

Based on the interviews, investigators recommended steps to improve the care of rural pediatric cancer patients, including improved guidance to caregivers about unexpected trips to local hospitals, more outreach to local hospitals, and better medical visit coordination. If local hospitals are identified at diagnosis, communication between the local hospital and cancer center could be established early, study authors wrote. If deficiencies in care are discovered, local hospitals may be prompted to “stock materials or parents could be redirected to other hospitals at which they are routinely available,” authors suggested.

“This would foster collaboration between local physicians and specialists at the cancer-treating hospital, and thereby lower levels of frustration and increase parent’s trust of local providers,” authors wrote.

SOURCE: Walling EB et al. J Oncol Pract. 2019 Jan 31. doi: 10.1200/JOP.18.00115.

FROM JOURNAL OF ONCOLOGY PRACTICE

Key clinical point: Rural families of pediatric cancer patients experience unique burdens because of the distance between home and urban cancer center.

Major finding: Long drives to receive cancer care and inadequate emergency care at local community hospitals are primary challenges for rural families of pediatric cancer patients.

Study details: Interviews with 18 caregivers of pediatric cancer patients who received care at an urban children’s hospital.

Disclosures: No potential conflicts of interest were reported.

Source: Walling EB et al. J Oncol Pract. 2019 Jan 31. doi: 10.1200/JOP.18.00115.

Does the type of menopausal HT used increase the risk of venous thromboembolism?

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Vinogradova Y, Coupland C, Hippisley-Cox J. Use of hormone replacement therapy and risk of venous thromboembolism: nested case-control studies using the QResearch and CPRD databases. BMJ. 2019;364:k4810.

The Women’s Health Initiative trials, in which menopausal women were randomly assigned to treatment with oral CEE or placebo, found that statistically the largest risk associated with menopausal hormone therapy (HT) was increased VTE.1 Recently, investigators in the United Kingdom (UK) published results of their research aimed at determining the association between the risk of VTE and the use of different types of HT.2

Details of the study

Vinogradova and colleagues used 2 UK primary care research databases, QResearch and Clinical Practice Research Datalink, to identify cases of incident VTE in general practice records, hospital admissions, and mortality records. They identified 80,396 women (aged 40 to 79 years) diagnosed with VTE between 1998 and 2017 and 391,494 control women matched by age and general practice. The mean age of the case and control women was approximately 64 years; the great majority of women were white. Analyses were adjusted for smoking, body mass index (BMI), family history of VTE, and comorbidities associated with VTE.