User login

Automated office BP readings best routine measures

Automated office blood pressure readings appear to be more accurate than routine office readings and BP readings in research settings, according to a recent systematic review and meta-analysis.

Based on the evidence, automated office BP (AOBP) readings should now be the preferred method of reading a patient’s BP in clinical practice despite initial reluctance to incorporate this technique over other methods, the researchers wrote in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“The existing evidence supports the use of AOBP to screen patients for possible hypertension in clinical practice, especially if one takes into account the white coat effect associated with current manual or oscillometric techniques for office BP measurement,” wrote Michael Roerecke, PhD, of the University of Toronto, and his colleagues.

Dr. Roerecke and his colleagues identified 31 articles with 9,279 participants (4,736 men, 4,543 women) where AOBP was compared with another method of BP reading, such as awake ambulatory, routine office, and research BP readings. The AOBP reading was performed with a fully automated oscillometric sphygmomanometer with the patient resting in a quiet area.

The researchers found systolic AOBP of 130 mm Hg was associated with significantly higher readings from routine office (mean difference, 14.5 mm Hg) or research BP readings (7.0 mm Hg), while participants had similar AOBP and awake ambulatory BP readings (0.3 mm Hg). All differences were statistically significant (P less than .001).

“If AOBP is to be used in clinical practice, readings must closely adhere to the procedures used in the AOBP studies in this meta-analysis, including multiple BP readings recorded with a fully automated oscillometric sphygmomanometer while the patient rests alone in a quiet place,” the researchers wrote.

Potential limitations of the study were the large statistical heterogeneity of the sample, though the researchers noted little clinical heterogeneity, and that most studies measured AOBP and awake ambulatory BP on the same day to limit differences in timing.

The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Roerecke M et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Feb 4. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6551.

Automated office blood pressure readings appear to be more accurate than routine office readings and BP readings in research settings, according to a recent systematic review and meta-analysis.

Based on the evidence, automated office BP (AOBP) readings should now be the preferred method of reading a patient’s BP in clinical practice despite initial reluctance to incorporate this technique over other methods, the researchers wrote in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“The existing evidence supports the use of AOBP to screen patients for possible hypertension in clinical practice, especially if one takes into account the white coat effect associated with current manual or oscillometric techniques for office BP measurement,” wrote Michael Roerecke, PhD, of the University of Toronto, and his colleagues.

Dr. Roerecke and his colleagues identified 31 articles with 9,279 participants (4,736 men, 4,543 women) where AOBP was compared with another method of BP reading, such as awake ambulatory, routine office, and research BP readings. The AOBP reading was performed with a fully automated oscillometric sphygmomanometer with the patient resting in a quiet area.

The researchers found systolic AOBP of 130 mm Hg was associated with significantly higher readings from routine office (mean difference, 14.5 mm Hg) or research BP readings (7.0 mm Hg), while participants had similar AOBP and awake ambulatory BP readings (0.3 mm Hg). All differences were statistically significant (P less than .001).

“If AOBP is to be used in clinical practice, readings must closely adhere to the procedures used in the AOBP studies in this meta-analysis, including multiple BP readings recorded with a fully automated oscillometric sphygmomanometer while the patient rests alone in a quiet place,” the researchers wrote.

Potential limitations of the study were the large statistical heterogeneity of the sample, though the researchers noted little clinical heterogeneity, and that most studies measured AOBP and awake ambulatory BP on the same day to limit differences in timing.

The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Roerecke M et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Feb 4. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6551.

Automated office blood pressure readings appear to be more accurate than routine office readings and BP readings in research settings, according to a recent systematic review and meta-analysis.

Based on the evidence, automated office BP (AOBP) readings should now be the preferred method of reading a patient’s BP in clinical practice despite initial reluctance to incorporate this technique over other methods, the researchers wrote in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“The existing evidence supports the use of AOBP to screen patients for possible hypertension in clinical practice, especially if one takes into account the white coat effect associated with current manual or oscillometric techniques for office BP measurement,” wrote Michael Roerecke, PhD, of the University of Toronto, and his colleagues.

Dr. Roerecke and his colleagues identified 31 articles with 9,279 participants (4,736 men, 4,543 women) where AOBP was compared with another method of BP reading, such as awake ambulatory, routine office, and research BP readings. The AOBP reading was performed with a fully automated oscillometric sphygmomanometer with the patient resting in a quiet area.

The researchers found systolic AOBP of 130 mm Hg was associated with significantly higher readings from routine office (mean difference, 14.5 mm Hg) or research BP readings (7.0 mm Hg), while participants had similar AOBP and awake ambulatory BP readings (0.3 mm Hg). All differences were statistically significant (P less than .001).

“If AOBP is to be used in clinical practice, readings must closely adhere to the procedures used in the AOBP studies in this meta-analysis, including multiple BP readings recorded with a fully automated oscillometric sphygmomanometer while the patient rests alone in a quiet place,” the researchers wrote.

Potential limitations of the study were the large statistical heterogeneity of the sample, though the researchers noted little clinical heterogeneity, and that most studies measured AOBP and awake ambulatory BP on the same day to limit differences in timing.

The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Roerecke M et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Feb 4. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6551.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Automated office BP readings are lower than those taken in routine office or research settings and are similar to awake ambulatory BP readings.

Major finding: The mean difference between automated office BP readings was 14.5 mm Hg, compared with routine office systolic BP, and 7.0 mm Hg, compared with research systolic BP readings.

Study details: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 31 articles with 9,279 patients comparing automated office BP readings with awake ambulatory, routine office, and research BP readings.

Disclosures: The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Source: Roerecke M et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Feb 4. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6551.

No increase in severe community-acquired pneumonia after PCV13

Despite concern about the rise of nonvaccine serotypes following widespread PCV13 immunization, cases of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) remain nearly as low as after initial implementation of the vaccine and severe cases have not risen at all.

This was the finding of a prospective time-series analysis study from eight French pediatric emergency departments between June 2009 and May 2017.

The 12,587 children with CAP enrolled in the study between June 2009 and May 2017 were all aged 15 years or younger and came from one of eight French pediatric EDs.

Pediatric pneumonia cases per 1,000 ED visits dropped 44% after PCV13 was implemented, a decrease from 6.3 to 3.5 cases of CAP per 1,000 pediatric visits from June 2011 to May 2014, with a slight but statistically significant increase to 3.8 cases of CAP per 1,000 pediatric visits from June 2014 to May 2017. However, there was no statistically significant increase in cases with pleural effusion, hospitalization, or high inflammatory biomarkers.

“These results contrast with the recent increase in frequency of invasive pneumococcal disease observed in several countries during the same period linked to serotype replacement beyond 5 years after PCV13 implementation,” reported Naïm Ouldali, MD, of the Association Clinique et Thérapeutique Infantile du Val-de-Marne in France, and associates. The report is in JAMA Pediatrics.

“This difference in the trends suggests different consequences of serotype replacement on pneumococcal CAP vs invasive pneumococcal disease,” they wrote. “The recent slight increase in the number of all CAP cases and virus involvement may reflect changes in the epidemiology of other pathogens and/or serotype replacement with less pathogenic serotypes.”

This latter point arose from discovering no dominant serotype during the study period. Of the 11 serotypes not covered by PCV13, none appeared in more than four cases.

“The implementation of PCV13 has led to the quasi-disappearance of the more invasive serotypes and increase in others in nasopharyngeal flora, which greatly reduces the frequency of the more severe forms of CAP, but could also play a role in the slight increase in frequency of the more benign forms,” the authors reported.

Among the study’s limitations was lack of a control group, precluding the ability to attribute findings to any changes in case reporting. And “participating physicians were encouraged to not change their practice, including test use, and no other potential interfering intervention.”

Funding sources for this study included the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Group of the French Pediatrics Society, Association Clinique et Thérapeutique Infantile du Val-de-Marne, the Foundation for Medical Research and a Pfizer Investigator Initiated Research grant.

Dr Ouldali has received grants from GlaxoSmithKline, and many of the authors have financial ties and/or have received non-financial support from AstraZeneca, Biocodex, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer and/or Sanofi Pasteur.

SOURCE: Ouldali N et al. JAMA Pediatrics. 2019 Feb 4. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.5273.

Despite concern about the rise of nonvaccine serotypes following widespread PCV13 immunization, cases of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) remain nearly as low as after initial implementation of the vaccine and severe cases have not risen at all.

This was the finding of a prospective time-series analysis study from eight French pediatric emergency departments between June 2009 and May 2017.

The 12,587 children with CAP enrolled in the study between June 2009 and May 2017 were all aged 15 years or younger and came from one of eight French pediatric EDs.

Pediatric pneumonia cases per 1,000 ED visits dropped 44% after PCV13 was implemented, a decrease from 6.3 to 3.5 cases of CAP per 1,000 pediatric visits from June 2011 to May 2014, with a slight but statistically significant increase to 3.8 cases of CAP per 1,000 pediatric visits from June 2014 to May 2017. However, there was no statistically significant increase in cases with pleural effusion, hospitalization, or high inflammatory biomarkers.

“These results contrast with the recent increase in frequency of invasive pneumococcal disease observed in several countries during the same period linked to serotype replacement beyond 5 years after PCV13 implementation,” reported Naïm Ouldali, MD, of the Association Clinique et Thérapeutique Infantile du Val-de-Marne in France, and associates. The report is in JAMA Pediatrics.

“This difference in the trends suggests different consequences of serotype replacement on pneumococcal CAP vs invasive pneumococcal disease,” they wrote. “The recent slight increase in the number of all CAP cases and virus involvement may reflect changes in the epidemiology of other pathogens and/or serotype replacement with less pathogenic serotypes.”

This latter point arose from discovering no dominant serotype during the study period. Of the 11 serotypes not covered by PCV13, none appeared in more than four cases.

“The implementation of PCV13 has led to the quasi-disappearance of the more invasive serotypes and increase in others in nasopharyngeal flora, which greatly reduces the frequency of the more severe forms of CAP, but could also play a role in the slight increase in frequency of the more benign forms,” the authors reported.

Among the study’s limitations was lack of a control group, precluding the ability to attribute findings to any changes in case reporting. And “participating physicians were encouraged to not change their practice, including test use, and no other potential interfering intervention.”

Funding sources for this study included the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Group of the French Pediatrics Society, Association Clinique et Thérapeutique Infantile du Val-de-Marne, the Foundation for Medical Research and a Pfizer Investigator Initiated Research grant.

Dr Ouldali has received grants from GlaxoSmithKline, and many of the authors have financial ties and/or have received non-financial support from AstraZeneca, Biocodex, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer and/or Sanofi Pasteur.

SOURCE: Ouldali N et al. JAMA Pediatrics. 2019 Feb 4. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.5273.

Despite concern about the rise of nonvaccine serotypes following widespread PCV13 immunization, cases of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) remain nearly as low as after initial implementation of the vaccine and severe cases have not risen at all.

This was the finding of a prospective time-series analysis study from eight French pediatric emergency departments between June 2009 and May 2017.

The 12,587 children with CAP enrolled in the study between June 2009 and May 2017 were all aged 15 years or younger and came from one of eight French pediatric EDs.

Pediatric pneumonia cases per 1,000 ED visits dropped 44% after PCV13 was implemented, a decrease from 6.3 to 3.5 cases of CAP per 1,000 pediatric visits from June 2011 to May 2014, with a slight but statistically significant increase to 3.8 cases of CAP per 1,000 pediatric visits from June 2014 to May 2017. However, there was no statistically significant increase in cases with pleural effusion, hospitalization, or high inflammatory biomarkers.

“These results contrast with the recent increase in frequency of invasive pneumococcal disease observed in several countries during the same period linked to serotype replacement beyond 5 years after PCV13 implementation,” reported Naïm Ouldali, MD, of the Association Clinique et Thérapeutique Infantile du Val-de-Marne in France, and associates. The report is in JAMA Pediatrics.

“This difference in the trends suggests different consequences of serotype replacement on pneumococcal CAP vs invasive pneumococcal disease,” they wrote. “The recent slight increase in the number of all CAP cases and virus involvement may reflect changes in the epidemiology of other pathogens and/or serotype replacement with less pathogenic serotypes.”

This latter point arose from discovering no dominant serotype during the study period. Of the 11 serotypes not covered by PCV13, none appeared in more than four cases.

“The implementation of PCV13 has led to the quasi-disappearance of the more invasive serotypes and increase in others in nasopharyngeal flora, which greatly reduces the frequency of the more severe forms of CAP, but could also play a role in the slight increase in frequency of the more benign forms,” the authors reported.

Among the study’s limitations was lack of a control group, precluding the ability to attribute findings to any changes in case reporting. And “participating physicians were encouraged to not change their practice, including test use, and no other potential interfering intervention.”

Funding sources for this study included the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Group of the French Pediatrics Society, Association Clinique et Thérapeutique Infantile du Val-de-Marne, the Foundation for Medical Research and a Pfizer Investigator Initiated Research grant.

Dr Ouldali has received grants from GlaxoSmithKline, and many of the authors have financial ties and/or have received non-financial support from AstraZeneca, Biocodex, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer and/or Sanofi Pasteur.

SOURCE: Ouldali N et al. JAMA Pediatrics. 2019 Feb 4. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.5273.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Pediatric community-acquired pneumonia cases dropped from 6.3 to 3.5 cases per 1,000 visits from 2010 to 2014 and increased to 3.8 cases per 1,000 visits in May 2017.

Study details: The findings are based on a prospective time series analysis of 12,587 pediatric pneumonia cases (under 15 years old) in eight French emergency departments from June 2009 to May 2017.

Disclosures: Funding sources for this study included the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Group of the French Pediatrics Society, Association Clinique et Thérapeutique Infantile du Val-de-Marne, the Foundation for Medical Research, and a Pfizer Investigator Initiated Research grant. Dr. Ouldali has received grants from GlaxoSmithKline, and many of the authors have financial ties and/or have received nonfinancial support from AstraZeneca, Biocodex, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, and/or Sanofi Pasteur.

Source: Ouldali N et al. JAMA Pediatrics. 2019 Feb 4. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.5273.

Acute pancreatitis, dealing with difficult people, and more

I’m very excited about the first issue of The New Gastroenterologist in 2019, which has some fantastic articles that I hope you will find interesting and useful. The In Focus feature this month covers acute pancreatitis, which is an incredibly important topic for all in our field. Amar Mandalia and Matthew DiMagno (University of Michigan) provide a comprehensive overview of the management of acute pancreatitis, including a review of the recent AGA guideline on this topic. This article can be found online, as well as in print in the February issue of GI & Hepatology News.

Rhonda Cole (Michael E. DeBakey VAMC/Baylor) addresses the important topic of how to deal with difficult people, and she provides some useful tips for situations that many of us struggle with. Also in this issue, Rishi Naik (Vanderbilt) and current Associate Editor of Gastroenterology John Inadomi (University of Washington) provide some tips on how to write an effective cover letter for a journal submission. Anna Duloy and Sachin Wani (University of Colorado) provide an overview of the current state of training in advanced endoscopy, which will be very helpful for all those considering a fellowship or incorporation of these procedures into their practices.

For those looking to pick the right private practice position, David Ramsay (Digestive Health Specialists, Winston-Salem, N.C.) provides some useful tips to help you find the job that will be the best fit. In prior issues of The New Gastroenterologist, there have been several articles discussing saving for retirement, but how about how to effectively save for your children’s education? To address that topic, Michael Clancy (Drexel) provides an informative overview of 529 college savings accounts.

Finally, Gyanprakash Ketwaroo (Baylor), Peter Liang (NYU Langone), Carol Brown, and Celena NuQuay (AGA) provide an overview of one of the most important and impactful initiatives from the AGA for the early career community – the AGA Regional Practice Skills Workshops. These workshops are a tremendous resource for early career GIs, and I would recommend that you check one out if you have not already had the opportunity.

If you’re interested in browsing older articles from The New Gastroenterologist, articles from previous issues can be found on our webpage. Also, we are always looking for new ideas and new contributors. If you have suggestions or are interested, please contact me at bryson.katona@uphs.upenn.edu or the managing editor, Ryan Farrell, at rfarrell@gastro.org

Sincerely,

Bryson W. Katona, MD, PhD

Editor in Chief

Dr. Katona is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

I’m very excited about the first issue of The New Gastroenterologist in 2019, which has some fantastic articles that I hope you will find interesting and useful. The In Focus feature this month covers acute pancreatitis, which is an incredibly important topic for all in our field. Amar Mandalia and Matthew DiMagno (University of Michigan) provide a comprehensive overview of the management of acute pancreatitis, including a review of the recent AGA guideline on this topic. This article can be found online, as well as in print in the February issue of GI & Hepatology News.

Rhonda Cole (Michael E. DeBakey VAMC/Baylor) addresses the important topic of how to deal with difficult people, and she provides some useful tips for situations that many of us struggle with. Also in this issue, Rishi Naik (Vanderbilt) and current Associate Editor of Gastroenterology John Inadomi (University of Washington) provide some tips on how to write an effective cover letter for a journal submission. Anna Duloy and Sachin Wani (University of Colorado) provide an overview of the current state of training in advanced endoscopy, which will be very helpful for all those considering a fellowship or incorporation of these procedures into their practices.

For those looking to pick the right private practice position, David Ramsay (Digestive Health Specialists, Winston-Salem, N.C.) provides some useful tips to help you find the job that will be the best fit. In prior issues of The New Gastroenterologist, there have been several articles discussing saving for retirement, but how about how to effectively save for your children’s education? To address that topic, Michael Clancy (Drexel) provides an informative overview of 529 college savings accounts.

Finally, Gyanprakash Ketwaroo (Baylor), Peter Liang (NYU Langone), Carol Brown, and Celena NuQuay (AGA) provide an overview of one of the most important and impactful initiatives from the AGA for the early career community – the AGA Regional Practice Skills Workshops. These workshops are a tremendous resource for early career GIs, and I would recommend that you check one out if you have not already had the opportunity.

If you’re interested in browsing older articles from The New Gastroenterologist, articles from previous issues can be found on our webpage. Also, we are always looking for new ideas and new contributors. If you have suggestions or are interested, please contact me at bryson.katona@uphs.upenn.edu or the managing editor, Ryan Farrell, at rfarrell@gastro.org

Sincerely,

Bryson W. Katona, MD, PhD

Editor in Chief

Dr. Katona is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

I’m very excited about the first issue of The New Gastroenterologist in 2019, which has some fantastic articles that I hope you will find interesting and useful. The In Focus feature this month covers acute pancreatitis, which is an incredibly important topic for all in our field. Amar Mandalia and Matthew DiMagno (University of Michigan) provide a comprehensive overview of the management of acute pancreatitis, including a review of the recent AGA guideline on this topic. This article can be found online, as well as in print in the February issue of GI & Hepatology News.

Rhonda Cole (Michael E. DeBakey VAMC/Baylor) addresses the important topic of how to deal with difficult people, and she provides some useful tips for situations that many of us struggle with. Also in this issue, Rishi Naik (Vanderbilt) and current Associate Editor of Gastroenterology John Inadomi (University of Washington) provide some tips on how to write an effective cover letter for a journal submission. Anna Duloy and Sachin Wani (University of Colorado) provide an overview of the current state of training in advanced endoscopy, which will be very helpful for all those considering a fellowship or incorporation of these procedures into their practices.

For those looking to pick the right private practice position, David Ramsay (Digestive Health Specialists, Winston-Salem, N.C.) provides some useful tips to help you find the job that will be the best fit. In prior issues of The New Gastroenterologist, there have been several articles discussing saving for retirement, but how about how to effectively save for your children’s education? To address that topic, Michael Clancy (Drexel) provides an informative overview of 529 college savings accounts.

Finally, Gyanprakash Ketwaroo (Baylor), Peter Liang (NYU Langone), Carol Brown, and Celena NuQuay (AGA) provide an overview of one of the most important and impactful initiatives from the AGA for the early career community – the AGA Regional Practice Skills Workshops. These workshops are a tremendous resource for early career GIs, and I would recommend that you check one out if you have not already had the opportunity.

If you’re interested in browsing older articles from The New Gastroenterologist, articles from previous issues can be found on our webpage. Also, we are always looking for new ideas and new contributors. If you have suggestions or are interested, please contact me at bryson.katona@uphs.upenn.edu or the managing editor, Ryan Farrell, at rfarrell@gastro.org

Sincerely,

Bryson W. Katona, MD, PhD

Editor in Chief

Dr. Katona is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Positive FIT test should prompt colonoscopy

Patients who test positive on a fecal immunochemical test (FIT), even after a recent colonoscopy, should be offered a repeat colonoscopy. That is the conclusion following a review of 2,228 subjects who were FIT positive, which revealed a greater risk of colorectal cancer (CRC) and advanced colorectal neoplasia (ACRN) the longer the gap since the last colonoscopy. The findings support the recommendations of the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on CRC Screening to offer repeat colonoscopies to FIT-positive patients, even if they recently underwent a colonoscopy.

That recommendation was based on low-quality supporting evidence, and there is currently little agreement about whether annual FIT should be performed along with colonoscopy.

The researchers set out to detect the frequency of CRC and ACRN among patients with a positive FIT test. They analyzed data from the National Cancer Screening Program in Korea, which offers an annual FIT for adults aged 50 years and older as an initial screening, followed by a colonoscopy in case of a positive result.

The researchers analyzed data from 52,376 individuals who underwent FIT at a single center in Korea during January 2013–July 2017. They excluded patients with a history of CRC or colorectal surgery, inflammatory bowel disease, or poor bowel preparation.

FIT-positive and FIT-negative patients were divided into three groups based on the length of time since their last colonoscopy: less than 3 years, 3-10 years, or more than 10 years or no colonoscopy.

Compared with FIT-negative subjects, FIT-positive individuals were more likely to be diagnosed with any colorectal neoplasia (61.3% vs. 51.8%; P less than .001), ACRN (20.0% vs. 10.3%; P less than .001), and CRC (5.0% vs. 1.9%; P less than .001).

A total of 6% of subjects had a positive FIT result, and data from 2,228 were analyzed after exclusions. They were compared with 6,135 participants who had negative FIT results but underwent a colonoscopy.

Of patients with a positive FIT result, 23.1% had a colonoscopy less than 3 years before, 19.2% had one 3-10 years prior, and 57.8% had a colonoscopy more than 10 years earlier or had never had one.

The more-than-10-year group had a higher frequency of colorectal neoplasia, ACRN, or CRC (26.0%) than did the 3-10-year group (12.6%), and the less-than-3-year group (10.9%; P less than .001 for all). A similar trend was seen for CRC: 7.2%, 1.6%, and 2.1%, respectively (P less than .001).

Of the 6,135 FIT-negative participants, 22.2% were in the less-than-3-years group, 28.9% 3-10 years, and 48.8% more-than-10 years-or-never group. The more-than-10-years group had a higher frequency of ACRN (14.7%) than did the 3-10-year group (0.4%) and the 0-3-year group (0.7%, P less than .001).

Among FIT-positive patients, the more-than-10-year group was at higher risk of ACRN diagnosis during follow-up colonoscopy than was the less-than-3-year group (adjusted OR, 3.63; 95% confidence interval, 2.48-5.31), but not compared with the 3-10-year group (aOR, 1.17; 95% CI, 0.71-1.93). The more-than-10-year group also was at greater risk of a CRC diagnosis than was the less-than-3-year group (aOR, 3.66; 95% CI, 1.74-7.73). There was no significant difference in CRC risk between the less-than-3-year group and the 3-10-year group (aOR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.17-1.93).

The authors suggest that CRC and ACRN found in patients who had a colonoscopy in the past 3 years are likely to be lesions that were missed in the previous exam, rather than new, fast-growing lesions. That suggests that FIT may help catch lesions that were missed during earlier screenings, though just 2.1% of the less-than-3-year group and 1.6% of the 3-10-year group were diagnosed with CRC, and 10.9% and 12.6% with ACRN, respectively.

The authors conclude that it may not be appropriate to offer interval FIT to all patients, since it can lead to unnecessary colonoscopies. They call for more research to determine which categories of patients are most likely to benefit from interval FIT.

SOURCE: Kim NH et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019 Jan 23. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2019.01.012.

Patients who test positive on a fecal immunochemical test (FIT), even after a recent colonoscopy, should be offered a repeat colonoscopy. That is the conclusion following a review of 2,228 subjects who were FIT positive, which revealed a greater risk of colorectal cancer (CRC) and advanced colorectal neoplasia (ACRN) the longer the gap since the last colonoscopy. The findings support the recommendations of the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on CRC Screening to offer repeat colonoscopies to FIT-positive patients, even if they recently underwent a colonoscopy.

That recommendation was based on low-quality supporting evidence, and there is currently little agreement about whether annual FIT should be performed along with colonoscopy.

The researchers set out to detect the frequency of CRC and ACRN among patients with a positive FIT test. They analyzed data from the National Cancer Screening Program in Korea, which offers an annual FIT for adults aged 50 years and older as an initial screening, followed by a colonoscopy in case of a positive result.

The researchers analyzed data from 52,376 individuals who underwent FIT at a single center in Korea during January 2013–July 2017. They excluded patients with a history of CRC or colorectal surgery, inflammatory bowel disease, or poor bowel preparation.

FIT-positive and FIT-negative patients were divided into three groups based on the length of time since their last colonoscopy: less than 3 years, 3-10 years, or more than 10 years or no colonoscopy.

Compared with FIT-negative subjects, FIT-positive individuals were more likely to be diagnosed with any colorectal neoplasia (61.3% vs. 51.8%; P less than .001), ACRN (20.0% vs. 10.3%; P less than .001), and CRC (5.0% vs. 1.9%; P less than .001).

A total of 6% of subjects had a positive FIT result, and data from 2,228 were analyzed after exclusions. They were compared with 6,135 participants who had negative FIT results but underwent a colonoscopy.

Of patients with a positive FIT result, 23.1% had a colonoscopy less than 3 years before, 19.2% had one 3-10 years prior, and 57.8% had a colonoscopy more than 10 years earlier or had never had one.

The more-than-10-year group had a higher frequency of colorectal neoplasia, ACRN, or CRC (26.0%) than did the 3-10-year group (12.6%), and the less-than-3-year group (10.9%; P less than .001 for all). A similar trend was seen for CRC: 7.2%, 1.6%, and 2.1%, respectively (P less than .001).

Of the 6,135 FIT-negative participants, 22.2% were in the less-than-3-years group, 28.9% 3-10 years, and 48.8% more-than-10 years-or-never group. The more-than-10-years group had a higher frequency of ACRN (14.7%) than did the 3-10-year group (0.4%) and the 0-3-year group (0.7%, P less than .001).

Among FIT-positive patients, the more-than-10-year group was at higher risk of ACRN diagnosis during follow-up colonoscopy than was the less-than-3-year group (adjusted OR, 3.63; 95% confidence interval, 2.48-5.31), but not compared with the 3-10-year group (aOR, 1.17; 95% CI, 0.71-1.93). The more-than-10-year group also was at greater risk of a CRC diagnosis than was the less-than-3-year group (aOR, 3.66; 95% CI, 1.74-7.73). There was no significant difference in CRC risk between the less-than-3-year group and the 3-10-year group (aOR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.17-1.93).

The authors suggest that CRC and ACRN found in patients who had a colonoscopy in the past 3 years are likely to be lesions that were missed in the previous exam, rather than new, fast-growing lesions. That suggests that FIT may help catch lesions that were missed during earlier screenings, though just 2.1% of the less-than-3-year group and 1.6% of the 3-10-year group were diagnosed with CRC, and 10.9% and 12.6% with ACRN, respectively.

The authors conclude that it may not be appropriate to offer interval FIT to all patients, since it can lead to unnecessary colonoscopies. They call for more research to determine which categories of patients are most likely to benefit from interval FIT.

SOURCE: Kim NH et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019 Jan 23. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2019.01.012.

Patients who test positive on a fecal immunochemical test (FIT), even after a recent colonoscopy, should be offered a repeat colonoscopy. That is the conclusion following a review of 2,228 subjects who were FIT positive, which revealed a greater risk of colorectal cancer (CRC) and advanced colorectal neoplasia (ACRN) the longer the gap since the last colonoscopy. The findings support the recommendations of the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on CRC Screening to offer repeat colonoscopies to FIT-positive patients, even if they recently underwent a colonoscopy.

That recommendation was based on low-quality supporting evidence, and there is currently little agreement about whether annual FIT should be performed along with colonoscopy.

The researchers set out to detect the frequency of CRC and ACRN among patients with a positive FIT test. They analyzed data from the National Cancer Screening Program in Korea, which offers an annual FIT for adults aged 50 years and older as an initial screening, followed by a colonoscopy in case of a positive result.

The researchers analyzed data from 52,376 individuals who underwent FIT at a single center in Korea during January 2013–July 2017. They excluded patients with a history of CRC or colorectal surgery, inflammatory bowel disease, or poor bowel preparation.

FIT-positive and FIT-negative patients were divided into three groups based on the length of time since their last colonoscopy: less than 3 years, 3-10 years, or more than 10 years or no colonoscopy.

Compared with FIT-negative subjects, FIT-positive individuals were more likely to be diagnosed with any colorectal neoplasia (61.3% vs. 51.8%; P less than .001), ACRN (20.0% vs. 10.3%; P less than .001), and CRC (5.0% vs. 1.9%; P less than .001).

A total of 6% of subjects had a positive FIT result, and data from 2,228 were analyzed after exclusions. They were compared with 6,135 participants who had negative FIT results but underwent a colonoscopy.

Of patients with a positive FIT result, 23.1% had a colonoscopy less than 3 years before, 19.2% had one 3-10 years prior, and 57.8% had a colonoscopy more than 10 years earlier or had never had one.

The more-than-10-year group had a higher frequency of colorectal neoplasia, ACRN, or CRC (26.0%) than did the 3-10-year group (12.6%), and the less-than-3-year group (10.9%; P less than .001 for all). A similar trend was seen for CRC: 7.2%, 1.6%, and 2.1%, respectively (P less than .001).

Of the 6,135 FIT-negative participants, 22.2% were in the less-than-3-years group, 28.9% 3-10 years, and 48.8% more-than-10 years-or-never group. The more-than-10-years group had a higher frequency of ACRN (14.7%) than did the 3-10-year group (0.4%) and the 0-3-year group (0.7%, P less than .001).

Among FIT-positive patients, the more-than-10-year group was at higher risk of ACRN diagnosis during follow-up colonoscopy than was the less-than-3-year group (adjusted OR, 3.63; 95% confidence interval, 2.48-5.31), but not compared with the 3-10-year group (aOR, 1.17; 95% CI, 0.71-1.93). The more-than-10-year group also was at greater risk of a CRC diagnosis than was the less-than-3-year group (aOR, 3.66; 95% CI, 1.74-7.73). There was no significant difference in CRC risk between the less-than-3-year group and the 3-10-year group (aOR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.17-1.93).

The authors suggest that CRC and ACRN found in patients who had a colonoscopy in the past 3 years are likely to be lesions that were missed in the previous exam, rather than new, fast-growing lesions. That suggests that FIT may help catch lesions that were missed during earlier screenings, though just 2.1% of the less-than-3-year group and 1.6% of the 3-10-year group were diagnosed with CRC, and 10.9% and 12.6% with ACRN, respectively.

The authors conclude that it may not be appropriate to offer interval FIT to all patients, since it can lead to unnecessary colonoscopies. They call for more research to determine which categories of patients are most likely to benefit from interval FIT.

SOURCE: Kim NH et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019 Jan 23. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2019.01.012.

FROM GASTROINTESTINAL ENDOSCOPY

Key clinical point: Positive findings are linked to greater CRC and advanced colorectal neoplasia risk.

Major finding: Regardless of time since last colonoscopy, CRC and ACRN frequencies were higher in FIT-positive subjects.

Study details: Retrospective analysis of 2,228 FIT-positive and 6,135 FIT-negative subjects

Disclosures: The study received no funding. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Kim NH et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019 Jan 23. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2019.01.012.

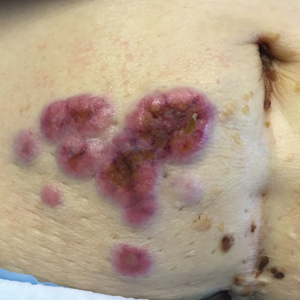

Erythematous Periumbilical Papules and Plaques

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Cancer

Further workup of patient 1 revealed an alkaline phosphatase level of 743 U/L (reference range, 30–120 U/L), total bilirubin level of 8.5 mg/dL (reference range, 0.3–1.2 mg/dL), and a white blood cell count of 14,000/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL). Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated cancer of unknown primary site that had metastasized to the colon, liver, and lungs. There was suspicion for potential colon cancer as the primary disease; however, based on the cutaneous findings, a skin biopsy was performed to confirm the diagnosis. Histology and immunohistochemistry revealed adenocarcinoma tumor cells positive for CDX2 (caudal type homeobox 2) and cytokeratin (CK) 7 with a subset positive for CK-20. The cells were negative for estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, mammaglobin, gross cystic disease fluid protein, and GATA3 (GATA binding protein 3). Immunohistochemistry was most consistent with pancreatic cancer. During palliative percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage placement, a liver biopsy confirmed the skin biopsy results.

Further workup of patient 2 revealed a white blood cell count of 13,000/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL). Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed metastatic disease to the lungs with a suspicion for colon cancer as the primary site. Biopsy of the skin lesion revealed a mucin-producing adenocarcinoma, and immunohistochemistry was positive for keratin (AE1/AE3), CK-20, and CDX2, consistent with metastatic colon carcinoma. Immunohistochemistry of the biopsied skin lesion was nonreactive for CK-7. The patient had a colonoscopy that revealed a fungating, partially obstructing, circumferential large mass in the ascending colon.

Metastasis to the skin from visceral malignancies is not uncommon and may represent the first evidence of widespread disease, particularly in breast cancer or mucosal cancers of the head and neck.1 Cutaneous metastasis of colon cancer is uncommon and cutaneous metastasis of pancreatic cancer is rare. Furthermore, nonumbilical sites are much more common than umbilical sites for cutaneous metastatic disease.2 Pancreatic cancer is estimated to be the origin of a cutaneous umbilical metastasis, frequently termed Sister Mary Joseph nodule, in 7% to 9% of cases; colon cancer is estimated to account for 13% to 15% of cases.3 Sister Mary Joseph nodule or sign refers to a nodule often bulging into the umbilicus, signifying metastasis from a

malignant cancer.

In a study of cutaneous metastases, 10% (42/420) of patients with metastatic disease had cutaneous metastasis; 0.48% (2/420) were due to pancreatic cancer and 4.3% (18/420) were due to colon cancer.4 In another review, 63 cases of cutaneous metastasis of pancreatic cancer were found, 43 of which were nonumbilical.2

On immunohistochemistry, CK-7 positivity is highly specific for pancreatic cancer.2 Cytokeratin 7 often is used in conjunction with CK-20 to differentiate various types of glandular tumors. CDX2 is a highly sensitive and specific marker for adenocarcinomas of intestinal origin.5 The negative estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, mammaglobin, gross cystic disease fluid protein, and GATA3 stains are useful in excluding breast cancer (patient 1 had history of breast cancer).

When cutaneous involvement is present in pancreatic cancer, the disease usually is widespread. Multiple studies have reported involvement of other organs with cutaneous metastasis at rates of 88.9%,6 90.3%,7 and 93.5%.2 However, early recognition of metastatic cancerous lesions can lead to earlier diagnosis and earlier palliative treatment, perhaps prolonging median survival time in patients. In a review of 63 patients with cutaneous metastatic pancreatic cancer, the authors found a median survival time of 5 months, with surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or a combination helping to improve survival time from a median of 3.0 to 8.3 months.2

The location of lesions and duration of disease in both patients was atypical for arthropod assault. Acyclovir-resistant herpes zoster rarely is reported outside of human immunodeficiency patients; in addition, there was a lack of clear dermatomal distribution. Although cutaneous Crohn disease can manifest as pink papules, it is rare and unlikely as a presenting symptom. Cutaneous sarcoidosis can take many different skin manifestations, and patients can have cutaneous involvement without systemic manifestation. In both patients, medical history was more indicative of metastatic cancer than the other options in the differential diagnosis.

Cutaneous metastasis from colon cancer and pancreatic cancer is rare, and the prognosis is poor in these cases; however, in the appropriate clinical scenario, especially in a patient with a history of cancer, sinister etiologies should be considered for firm red papules of the umbilicus. Skin biopsy coupled with immunohistochemical staining can assist in identifying the primary malignancy.

- Schwartz RA. Cutaneous metastatic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:161-165.

- Zhou HY, Wang XB, Gao F, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from pancreatic cancer: a case report and systematic review of the literature [published online October 10, 2014]. Oncol Lett. 2014;8:2654-2660.

- Galvañ VG. Sister Mary Joseph's nodule. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:410.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:228-236.

- Werling RW, Yaziji H, Bacchi CE, et al. CDX2, a highly sensitive and specific marker of adenocarcinomas of intestinal origin: an immnohistochemical survey of 476 primary and metastatic carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:303-310.

- Takeuchi H, Kawano T, Toda T, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a case report and a review of the literature. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:275-277.

- Horino K, Hiraoka T, Kanemitsu K, et al. Subcutaneous metastases after curative resection for pancreatic carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Pancreas. 1999;19:406-408.

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Cancer

Further workup of patient 1 revealed an alkaline phosphatase level of 743 U/L (reference range, 30–120 U/L), total bilirubin level of 8.5 mg/dL (reference range, 0.3–1.2 mg/dL), and a white blood cell count of 14,000/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL). Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated cancer of unknown primary site that had metastasized to the colon, liver, and lungs. There was suspicion for potential colon cancer as the primary disease; however, based on the cutaneous findings, a skin biopsy was performed to confirm the diagnosis. Histology and immunohistochemistry revealed adenocarcinoma tumor cells positive for CDX2 (caudal type homeobox 2) and cytokeratin (CK) 7 with a subset positive for CK-20. The cells were negative for estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, mammaglobin, gross cystic disease fluid protein, and GATA3 (GATA binding protein 3). Immunohistochemistry was most consistent with pancreatic cancer. During palliative percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage placement, a liver biopsy confirmed the skin biopsy results.

Further workup of patient 2 revealed a white blood cell count of 13,000/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL). Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed metastatic disease to the lungs with a suspicion for colon cancer as the primary site. Biopsy of the skin lesion revealed a mucin-producing adenocarcinoma, and immunohistochemistry was positive for keratin (AE1/AE3), CK-20, and CDX2, consistent with metastatic colon carcinoma. Immunohistochemistry of the biopsied skin lesion was nonreactive for CK-7. The patient had a colonoscopy that revealed a fungating, partially obstructing, circumferential large mass in the ascending colon.

Metastasis to the skin from visceral malignancies is not uncommon and may represent the first evidence of widespread disease, particularly in breast cancer or mucosal cancers of the head and neck.1 Cutaneous metastasis of colon cancer is uncommon and cutaneous metastasis of pancreatic cancer is rare. Furthermore, nonumbilical sites are much more common than umbilical sites for cutaneous metastatic disease.2 Pancreatic cancer is estimated to be the origin of a cutaneous umbilical metastasis, frequently termed Sister Mary Joseph nodule, in 7% to 9% of cases; colon cancer is estimated to account for 13% to 15% of cases.3 Sister Mary Joseph nodule or sign refers to a nodule often bulging into the umbilicus, signifying metastasis from a

malignant cancer.

In a study of cutaneous metastases, 10% (42/420) of patients with metastatic disease had cutaneous metastasis; 0.48% (2/420) were due to pancreatic cancer and 4.3% (18/420) were due to colon cancer.4 In another review, 63 cases of cutaneous metastasis of pancreatic cancer were found, 43 of which were nonumbilical.2

On immunohistochemistry, CK-7 positivity is highly specific for pancreatic cancer.2 Cytokeratin 7 often is used in conjunction with CK-20 to differentiate various types of glandular tumors. CDX2 is a highly sensitive and specific marker for adenocarcinomas of intestinal origin.5 The negative estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, mammaglobin, gross cystic disease fluid protein, and GATA3 stains are useful in excluding breast cancer (patient 1 had history of breast cancer).

When cutaneous involvement is present in pancreatic cancer, the disease usually is widespread. Multiple studies have reported involvement of other organs with cutaneous metastasis at rates of 88.9%,6 90.3%,7 and 93.5%.2 However, early recognition of metastatic cancerous lesions can lead to earlier diagnosis and earlier palliative treatment, perhaps prolonging median survival time in patients. In a review of 63 patients with cutaneous metastatic pancreatic cancer, the authors found a median survival time of 5 months, with surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or a combination helping to improve survival time from a median of 3.0 to 8.3 months.2

The location of lesions and duration of disease in both patients was atypical for arthropod assault. Acyclovir-resistant herpes zoster rarely is reported outside of human immunodeficiency patients; in addition, there was a lack of clear dermatomal distribution. Although cutaneous Crohn disease can manifest as pink papules, it is rare and unlikely as a presenting symptom. Cutaneous sarcoidosis can take many different skin manifestations, and patients can have cutaneous involvement without systemic manifestation. In both patients, medical history was more indicative of metastatic cancer than the other options in the differential diagnosis.

Cutaneous metastasis from colon cancer and pancreatic cancer is rare, and the prognosis is poor in these cases; however, in the appropriate clinical scenario, especially in a patient with a history of cancer, sinister etiologies should be considered for firm red papules of the umbilicus. Skin biopsy coupled with immunohistochemical staining can assist in identifying the primary malignancy.

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Cancer

Further workup of patient 1 revealed an alkaline phosphatase level of 743 U/L (reference range, 30–120 U/L), total bilirubin level of 8.5 mg/dL (reference range, 0.3–1.2 mg/dL), and a white blood cell count of 14,000/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL). Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated cancer of unknown primary site that had metastasized to the colon, liver, and lungs. There was suspicion for potential colon cancer as the primary disease; however, based on the cutaneous findings, a skin biopsy was performed to confirm the diagnosis. Histology and immunohistochemistry revealed adenocarcinoma tumor cells positive for CDX2 (caudal type homeobox 2) and cytokeratin (CK) 7 with a subset positive for CK-20. The cells were negative for estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, mammaglobin, gross cystic disease fluid protein, and GATA3 (GATA binding protein 3). Immunohistochemistry was most consistent with pancreatic cancer. During palliative percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage placement, a liver biopsy confirmed the skin biopsy results.

Further workup of patient 2 revealed a white blood cell count of 13,000/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL). Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed metastatic disease to the lungs with a suspicion for colon cancer as the primary site. Biopsy of the skin lesion revealed a mucin-producing adenocarcinoma, and immunohistochemistry was positive for keratin (AE1/AE3), CK-20, and CDX2, consistent with metastatic colon carcinoma. Immunohistochemistry of the biopsied skin lesion was nonreactive for CK-7. The patient had a colonoscopy that revealed a fungating, partially obstructing, circumferential large mass in the ascending colon.

Metastasis to the skin from visceral malignancies is not uncommon and may represent the first evidence of widespread disease, particularly in breast cancer or mucosal cancers of the head and neck.1 Cutaneous metastasis of colon cancer is uncommon and cutaneous metastasis of pancreatic cancer is rare. Furthermore, nonumbilical sites are much more common than umbilical sites for cutaneous metastatic disease.2 Pancreatic cancer is estimated to be the origin of a cutaneous umbilical metastasis, frequently termed Sister Mary Joseph nodule, in 7% to 9% of cases; colon cancer is estimated to account for 13% to 15% of cases.3 Sister Mary Joseph nodule or sign refers to a nodule often bulging into the umbilicus, signifying metastasis from a

malignant cancer.

In a study of cutaneous metastases, 10% (42/420) of patients with metastatic disease had cutaneous metastasis; 0.48% (2/420) were due to pancreatic cancer and 4.3% (18/420) were due to colon cancer.4 In another review, 63 cases of cutaneous metastasis of pancreatic cancer were found, 43 of which were nonumbilical.2

On immunohistochemistry, CK-7 positivity is highly specific for pancreatic cancer.2 Cytokeratin 7 often is used in conjunction with CK-20 to differentiate various types of glandular tumors. CDX2 is a highly sensitive and specific marker for adenocarcinomas of intestinal origin.5 The negative estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, mammaglobin, gross cystic disease fluid protein, and GATA3 stains are useful in excluding breast cancer (patient 1 had history of breast cancer).

When cutaneous involvement is present in pancreatic cancer, the disease usually is widespread. Multiple studies have reported involvement of other organs with cutaneous metastasis at rates of 88.9%,6 90.3%,7 and 93.5%.2 However, early recognition of metastatic cancerous lesions can lead to earlier diagnosis and earlier palliative treatment, perhaps prolonging median survival time in patients. In a review of 63 patients with cutaneous metastatic pancreatic cancer, the authors found a median survival time of 5 months, with surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or a combination helping to improve survival time from a median of 3.0 to 8.3 months.2

The location of lesions and duration of disease in both patients was atypical for arthropod assault. Acyclovir-resistant herpes zoster rarely is reported outside of human immunodeficiency patients; in addition, there was a lack of clear dermatomal distribution. Although cutaneous Crohn disease can manifest as pink papules, it is rare and unlikely as a presenting symptom. Cutaneous sarcoidosis can take many different skin manifestations, and patients can have cutaneous involvement without systemic manifestation. In both patients, medical history was more indicative of metastatic cancer than the other options in the differential diagnosis.

Cutaneous metastasis from colon cancer and pancreatic cancer is rare, and the prognosis is poor in these cases; however, in the appropriate clinical scenario, especially in a patient with a history of cancer, sinister etiologies should be considered for firm red papules of the umbilicus. Skin biopsy coupled with immunohistochemical staining can assist in identifying the primary malignancy.

- Schwartz RA. Cutaneous metastatic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:161-165.

- Zhou HY, Wang XB, Gao F, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from pancreatic cancer: a case report and systematic review of the literature [published online October 10, 2014]. Oncol Lett. 2014;8:2654-2660.

- Galvañ VG. Sister Mary Joseph's nodule. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:410.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:228-236.

- Werling RW, Yaziji H, Bacchi CE, et al. CDX2, a highly sensitive and specific marker of adenocarcinomas of intestinal origin: an immnohistochemical survey of 476 primary and metastatic carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:303-310.

- Takeuchi H, Kawano T, Toda T, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a case report and a review of the literature. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:275-277.

- Horino K, Hiraoka T, Kanemitsu K, et al. Subcutaneous metastases after curative resection for pancreatic carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Pancreas. 1999;19:406-408.

- Schwartz RA. Cutaneous metastatic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:161-165.

- Zhou HY, Wang XB, Gao F, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from pancreatic cancer: a case report and systematic review of the literature [published online October 10, 2014]. Oncol Lett. 2014;8:2654-2660.

- Galvañ VG. Sister Mary Joseph's nodule. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:410.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:228-236.

- Werling RW, Yaziji H, Bacchi CE, et al. CDX2, a highly sensitive and specific marker of adenocarcinomas of intestinal origin: an immnohistochemical survey of 476 primary and metastatic carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:303-310.

- Takeuchi H, Kawano T, Toda T, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a case report and a review of the literature. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:275-277.

- Horino K, Hiraoka T, Kanemitsu K, et al. Subcutaneous metastases after curative resection for pancreatic carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Pancreas. 1999;19:406-408.

A 75-year-old woman (patient 1) with a history of localized invasive ductal breast cancer treated definitively with lumpectomy and radiation therapy more than a decade ago presented to the emergency department with jaundice, abdominal pain, weakness, and multiple periumbilical pink-red papules (top) of 2 weeks’ duration. Prior to presentation, the skin lesions did not improve with 10 days of acyclovir treatment prescribed by her primary care physician for presumed herpes zoster.

An 86-year-old man (patient 2) with chronic lymphocytic leukemia treated with ibrutinib presented to the emergency department with jaundice, abdominal pain, weakness, and multiple pink periumbilical papules (bottom) of 6 weeks’ duration. Prior to presentation, the skin lesions did not improve with 21 days of valacyclovir treatment prescribed by his oncologist for presumed herpes zoster.

Newsletters for Our Trainees

The SVS is taking steps to provide more direct resources to our candidate members. To start, we’re sending newsletters that will keep these members, who are vital to our future, up-to-date on topics directly geared towards tomorrow’s vascular surgeons. The biweekly edition offers residents and students current information from the SVS, and the monthly edition addresses issues of importance to vascular trainees. Both newsletters will cover details on upcoming meetings and events — such as the Vascular Annual Meeting and the Vascular Research Initiatives Conference — awards and scholarships, open positions and much more. Subscribe to the newsletters and view past issues here.

The SVS is taking steps to provide more direct resources to our candidate members. To start, we’re sending newsletters that will keep these members, who are vital to our future, up-to-date on topics directly geared towards tomorrow’s vascular surgeons. The biweekly edition offers residents and students current information from the SVS, and the monthly edition addresses issues of importance to vascular trainees. Both newsletters will cover details on upcoming meetings and events — such as the Vascular Annual Meeting and the Vascular Research Initiatives Conference — awards and scholarships, open positions and much more. Subscribe to the newsletters and view past issues here.

The SVS is taking steps to provide more direct resources to our candidate members. To start, we’re sending newsletters that will keep these members, who are vital to our future, up-to-date on topics directly geared towards tomorrow’s vascular surgeons. The biweekly edition offers residents and students current information from the SVS, and the monthly edition addresses issues of importance to vascular trainees. Both newsletters will cover details on upcoming meetings and events — such as the Vascular Annual Meeting and the Vascular Research Initiatives Conference — awards and scholarships, open positions and much more. Subscribe to the newsletters and view past issues here.

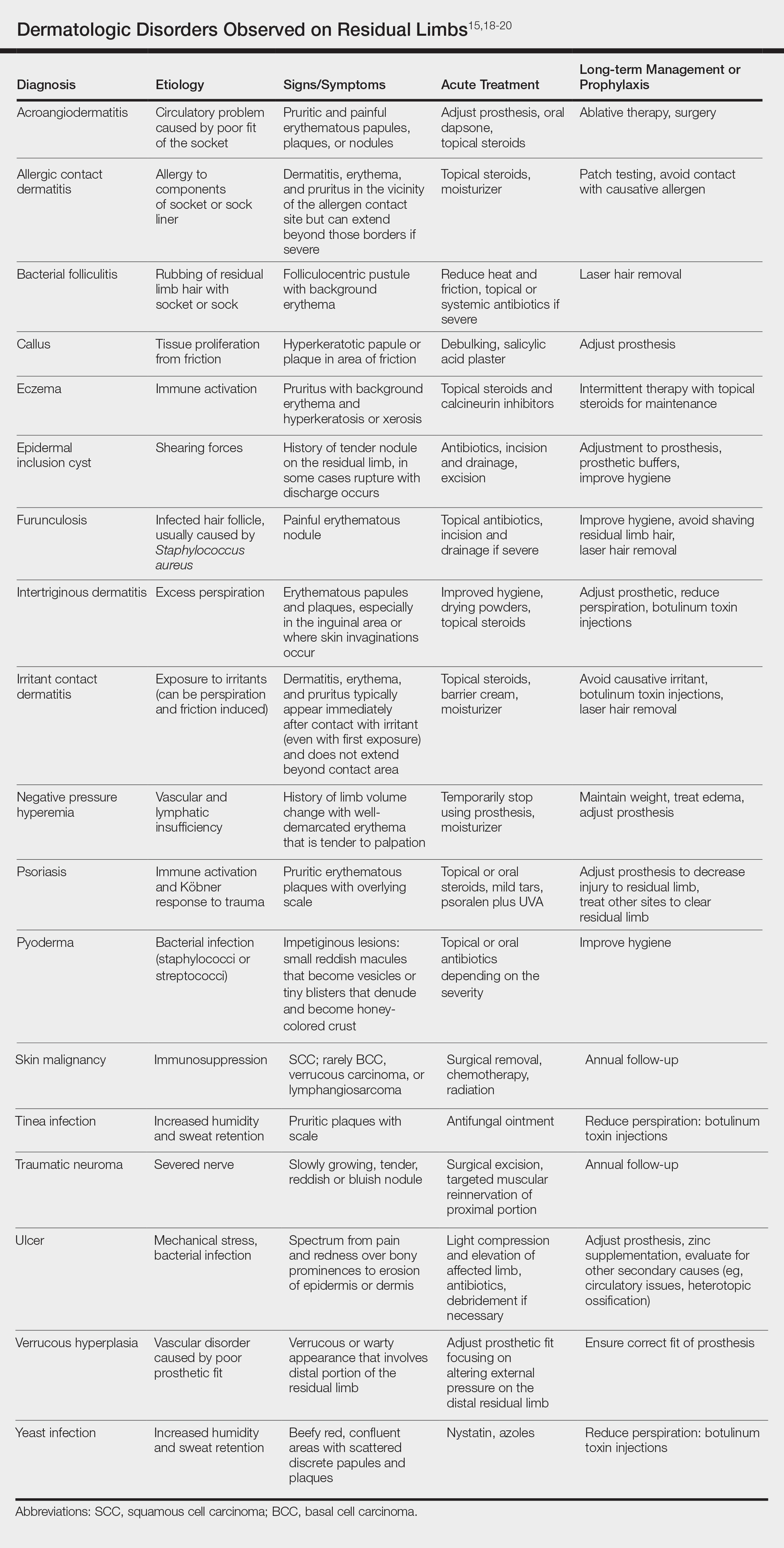

The Dermatologist’s Role in Amputee Skin Care

Limb amputation is a major life-changing event that markedly affects a patient’s quality of life as well as his/her ability to participate in activities of daily living. The most prevalent causes for amputation include vascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, trauma, and cancer, respectively.1,2 For amputees, maintaining prosthetic use is a major physical and psychological undertaking that benefits from a multidisciplinary team approach. Although individuals with lower limb amputations are disproportionately impacted by skin disease due to the increased mechanical forces exerted over the lower limbs, patients with upper limb amputations also develop dermatologic conditions secondary to wearing prostheses.

Approximately 185,000 amputations occur each year in the United States.3 Although amputations resulting from peripheral vascular disease or diabetes mellitus tend to occur in older individuals, amputations in younger patients usually occur from trauma.2 The US military has experienced increasing numbers of amputations from trauma due to the ongoing combat operations in the Middle East. Although improvements in body armor and tactical combat casualty care have reduced the number of preventable deaths, the number of casualties surviving with extremity injuries requiring amputation has increased.4,5 As of October 2017, 1705 US servicemembers underwent major limb amputations, with 1914 lower limb amputations and 302 upper limb amputations. These amputations mainly impacted men aged 21 to 29 years, but female servicemembers also were affected, and a small group of servicemembers had multiple amputations.6

One of the most common medical problems that amputees face during long-term care is skin disease, with approximately 75% of amputees using a lower limb prosthesis experiencing skin problems. In general, amputees experience nearly 65% more dermatologic concerns than the general population.7 In one study of 97 individuals with transfemoral amputations, some of the most common issues associated with socket prosthetics included heat and sweating in the prosthetic socket (72%) as well as sores and skin irritation from the socket (62%).8 Given the high incidence of skin disease on residual limbs, dermatologists are uniquely positioned to keep the amputee in his/her prosthesis and prevent prosthetic abandonment.

Complications Following Amputation

Although US military servicemembers who undergo amputations receive the very best prosthetic devices and rehabilitation resources, they still experience prosthesis abandonment.9 Despite the fact that prosthetic limbs and prosthesis technology have substantially improved over the last 2 decades, one study indicated that the high frequency of problems affecting tissue viability at residual limbs is due to the age-old problem of prosthetic fit.10 In patients with the most advanced prostheses, poor fit still results in mechanical damage to the skin, as the residual limb is exposed to unequal and shearing forces across the amputation site as well as high pressures that cause a vaso-occlusive effect.11,12 Issues with poor fit are especially important for more active patients, as they normally want to immediately return to their vigorous preinjury lifestyles. In these patients, even a properly fitting prosthetic may not be able to overcome the fact that the residual limb skin is not well suited for the mechanical forces generated by the prosthesis and the humid environment of the socket.1,13 Another complicating factor is the dynamic nature of the residual limb. Muscle atrophy, changes in gait, and weight gain or loss can lead to an ill-fitting prosthetic and subsequent skin breakdown.

There are many case reports and review articles describing the skin problems in amputees.1,14-17 The Table summarizes these conditions and outlines treatment options for each.15,18-20

Most skin diseases on residual limbs are the result of mechanical skin breakdown, inflammation, infection, or combinations of these processes. Overall, amputees with diabetes mellitus and peripheral vascular disease tend to have skin disease related to poor perfusion, whereas amputees who are active and healthy tend to have conditions related to mechanical stress.7,13,14,17,21,22 Bui et al17 reported ulcers, abscesses, and blisters as the most common skin conditions that occur at the site of residual limbs; however, other less common dermatologic disorders such as skin malignancies, verrucous hyperplasia and carcinoma, granulomatous cutaneous lesions, acroangiodermatitis, and bullous pemphigoid also are seen.23-26 Buikema and Meyerle15 hypothesize that these conditions, as well as the more common skin diseases, are partly from the amputation disrupting blood and lymphatic flow in the residual limb, which causes the site to act as an immunocompromised district that induces dysregulation of neuroimmune regulators.

It is important to note that skin disease on residual limbs is not just an acute problem. Long-term follow-up of 247 traumatic amputees from the Vietnam War showed that almost half of prosthesis users (48.2%) reported a skin problem in the preceding year, more than 38 years after the amputation. Additionally, one-quarter of these individuals experienced skin problems approximately 50% of the time, which unfortunately led to limited use or total abandonment of the prosthesis for the preceding year in 56% of the veterans surveyed.21

Other complications following amputation indirectly lead to skin problems. Heterotopic ossification, or the formation of bone at extraskeletal sites, has been observed in up to 65% of military amputees from recent operations in Iraq and Afghanistan.27,28 If symptomatic, heterotopic ossification can lead to poor prosthetic fit and subsequent skin breakdown. As a result, it has been reported that up to 40% of combat-related lower extremity amputations may require excision of heterotopic ossificiation.29

Amputation also can result in psychologic concerns that indirectly affect skin health. A systematic review by Mckechnie and John30 suggested that despite heterogeneity between studies, even using the lowest figures demonstrated the significance anxiety and depression play in the lives of traumatic amputees. If left untreated, these mental health issues can lead to poor residual limb hygiene and prosthetic maintenance due to reductions in the patient’s energy and motivation. Studies have shown that proper hygiene of residual limbs and silicone liners reduces associated skin problems.19,31

Role of the Dermatologist

Routine care and conservative management of amputee skin problems often are accomplished by prosthetists, primary care physicians, nurses, and physical therapists. In one study, more than 80% of the most common skin problems affecting amputees could be attributed to the prosthesis itself, which highlights the importance of the continued involvement of the prosthetist beyond the initial fitting period.13 However, when a skin problem becomes refractory to conservative management, referral to a dermatologist is prudent; therefore, the dermatologist is an integral member of the multidisciplinary team that provides care for amputees.

The dermatologist often is best positioned to diagnose skin diseases that result from wearing prostheses and is well versed in treatments for short-term and long-term management of skin disease on residual limbs. The dermatologist also can offer prophylactic treatments to decrease sweating and hair growth to prevent potential infections and subsequent skin breakdown. Additionally, proper education on self-care has been shown to decrease the amount of skin problems and increase functional status and quality of life for amputees.32,33 Dermatologists can assist with the patient education process as well as refer amputees to a useful resource from the Amputee Coalition website (www.amputee-coalition.org) to provide specific patient education on how to maintain skin on the residual limb to prevent skin disease.

Current Treatments and Future Directions

Skin disorders affecting residual limbs usually are conditions that dermatologists commonly encounter and are comfortable managing in general practice. Additionally, dermatologists routinely treat hyperhidrosis and conduct laser hair removal, both of which are effective prophylactic adjuncts for amputee skin health. There are a few treatments for reducing residual limb hyperhidrosis that are particularly useful. Although first-line treatment of residual limb hyperhidrosis often is topical aluminum chloride, it requires frequent application and often causes considerable skin irritation when applied to residual limbs. Alternatively, intradermal botulinum toxin has been shown to successfully reduce sweat production in individuals with residual limb hyperhidrosis and is well tolerated.34 A 2017 case report discussed the use of microwave thermal ablation of eccrine coils using a noninvasive 3-step hyperhidrosis treatment system on a bilateral below-the-knee amputee. The authors reported the patient tolerated the procedure well with decreased dermatitis and folliculitis, leading to his ability to wear a prosthetic for longer periods of time.35

Ablative fractional resurfacing with a CO2 laser is another key treatment modality central to amputees, more specifically to traumatic amputees. A CO2 laser can decrease skin tension and increase skin mobility associated with traumatic scars as well as decrease skin vulnerability to biofilms present in chronic wounds on residual limbs. It is believed that the pattern of injury caused by ablative fractional lasers disrupts biofilms and stimulates growth factor secretion and collagen remodeling through the concept of photomicrodebridement.36 The ablative fractional resurfacing approach to scar therapy and chronic wound debridement can result in less skin injury, allowing the amputee to continue rehabilitation and return more quickly to prosthetic use.37

One interesting area of research in amputee care involves the study of novel ways to increase the skin’s ability to adapt to mechanical stress and load bearing and accelerate wound healing on the residual limb. Multiple studies have identified collagen fibril enlargement as an important component of skin adaptation, and biomolecules such as decorin may enhance this process.38-40 The concept of increasing these biomolecules at the correct time during wound healing to strengthen the residual limb tissue currently is being studied.39

Another encouraging area of research is the involvement of fibroblasts in cutaneous wound healing and their role in determining the phenotype of residual limb skin in amputees. The clinical application of autologous fibroblasts is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for cosmetic use as a filler material and currently is under research for other applications, such as skin regeneration after surgery or manipulating skin characteristics to enhance the durability of residual limbs.41

Future preventative care of amputee skin may rely on tracking residual limb health before severe tissue injury occurs. For instance, Rink et al42 described an approach to monitor residual limb health using noninvasive imaging (eg, hyperspectral imaging, laser speckle imaging) and noninvasive probes that measure oxygenation, perfusion, skin barrier function, and skin hydration to the residual limb. Although these limb surveillance sensors would be employed by prosthetists, the dermatologist, as part of the multispecialty team, also could leverage the data for diagnosis and treatment considerations.

Final Thoughts

The dermatologist is an important member of the multidisciplinary team involved in the care of amputees. Skin disease is prevalent in amputees throughout their lives and often leads to abandonment of prostheses. Although current therapies and preventative treatments are for the most part successful, future research involving advanced technology to monitor skin health, increasing residual limb skin durability at the molecular level, and targeted laser therapies are promising. Through engagement and effective collaboration with the entire multidisciplinary team, dermatologists will have a considerable impact on amputee skin health.

- Dudek NL, Marks MB, Marshall SC, et al. Dermatologic conditions associated with use of a lower-extremity prosthesis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:659-663.

- Ziegler-Graham K, MacKenzie EJ, Ephraim PL, et al. Estimating the prevalence of limb loss in the United States: 2005 to 2050. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89:422-429.

- Kozak LJ. Ambulatory and Inpatient Procedures in the United States, 1995. Hyattsville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 1998.

- Epstein RA, Heinemann AW, McFarland LV. Quality of life for veterans and servicemembers with major traumatic limb loss from Vietnam and OIF/OEF conflicts. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2010;47:373-385.

- Dougherty AL, Mohrle CR, Galarneau MR, et al. Battlefield extremity injuries in Operation Iraqi Freedom. Injury. 2009;40:772-777.

- Farrokhi S, Perez K, Eskridge S, et al. Major deployment-related amputations of lower and upper limbs, active and reserve components, U.S. Armed Forces, 2001-2017. MSMR. 2018;25:10-16.

- Highsmith MJ, Highsmith JT. Identifying and managing skin issues with lower-limb prosthetic use. Amputee Coalition website. https://www.amputee-coalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/.../skin_issues_lower.pdf. Accessed January 4, 2019.

- Hagberg K, Brånemark R. Consequences of non-vascular trans-femoral amputation: a survey of quality of life, prosthetic use and problems. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2001;25:186-194.

- Gajewski D, Granville R. The United States Armed Forces Amputee Patient Care Program. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14(10 spec no):S183-S187.

- Butler K, Bowen C, Hughes AM, et al. A systematic review of the key factors affecting tissue viability and rehabilitation outcomes of the residual limb in lower extremity traumatic amputees. J Tissue Viability. 2014;23:81-93.

- Mak AF, Zhang M, Boone DA. State-of-the-art research in lower-limb prosthetic biomechanics-socket interface: a review. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2001;38:161-174.

- Silver-Thorn MB, Steege JW. A review of prosthetic interface stress investigations. J Rehabil Res Dev. 1996;33:253-266.

- Dudek NL, Marks MB, Marshall SC. Skin problems in an amputee clinic. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;85:424-429.

- Meulenbelt HE, Geertzen JH, Dijkstra PU, et al. Skin problems in lower limb amputees: an overview by case reports. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:147-155.

- Buikema KE, Meyerle JH. Amputation stump: privileged harbor for infections, tumors, and immune disorders. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:670-677.

- Highsmith JT, Highsmith MJ. Common skin pathology in LE prosthesis users. JAAPA. 2007;20:33-36, 47.

- Bui KM, Raugi GJ, Nguyen VQ, et al. Skin problems in individuals with lower-limb loss: literature review and proposed classification system. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2009;46:1085-1090.

- Levy SW. Skin Problems of the Amputee. St. Louis, MO: Warren H. Green Inc; 1983.

- Levy SW, Allende MF, Barnes GH. Skin problems of the leg amputee. Arch Dermatol. 1962;85:65-81.

- Dumanian GA, Potter BK, Mioton LM, et al. Targeted muscle reinnervation treats neuroma and phantom pain in major limb amputees: a randomized clinical trial [published October 26, 2018]. Ann Surg. 2018. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000003088.

- Yang NB, Garza LA, Foote CE, et al. High prevalence of stump dermatoses 38 years or more after amputation. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1283-1286.

- Meulenbelt HE, Geertzen JH, Jonkman MF, et al. Determinants of skin problems of the stump in lower-limb amputees. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90:74-81.

- Lin CH, Ma H, Chung MT, et al. Granulomatous cutaneous lesions associated with risperidone-induced hyperprolactinemia in an amputated upper limb: risperidone-induced cutaneous granulomas. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:75-78.

- Schwartz RA, Bagley MP, Janniger CK, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of a leg amputation stump. Dermatology. 1991;182:193-195.

- Reilly GD, Boulton AJ, Harrington CI. Stump pemphigoid: a new complication of the amputee. Br Med J. 1983;287:875-876.

- Turan H, Bas¸kan EB, Adim SB, et al. Acroangiodermatitis in a below-knee amputation stump: correspondence. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:560-561.

- Edwards DS, Kuhn KM, Potter BK, et al. Heterotopic ossification: a review of current understanding, treatment, and future. J Orthop Trauma. 2016;30(suppl 3):S27-S30.

- Potter BK, Burns TC, Lacap AP, et al. Heterotopic ossification following traumatic and combat-related amputations: prevalence, risk factors, and preliminary results of excision. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:476-486.

- Tintle SM, Shawen SB, Forsberg JA, et al. Reoperation after combat-related major lower extremity amputations. J Orthop Trauma. 2014;28:232-237.

- Mckechnie PS, John A. Anxiety and depression following traumatic limb amputation: a systematic review. Injury. 2014;45:1859-1866.

- Hachisuka K, Nakamura T, Ohmine S, et al. Hygiene problems of residual limb and silicone liners in transtibial amputees wearing the total surface bearing socket. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82:1286-1290.

- Pantera E, Pourtier-Piotte C, Bensoussan L, et al. Patient education after amputation: systematic review and experts’ opinions. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2014;57:143-158.

- Blum C, Ehrler S, Isner ME. Assessment of therapeutic education in 135 lower limb amputees. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2016;59:E161.

- Pasquina PF, Perry BN, Alphonso AL, et al. Residual limb hyperhidrosis and rimabotulinumtoxinB: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;97:659-664.e2.

- Mula KN, Winston J, Pace S, et al. Use of a microwave device for treatment of amputation residual limb hyperhidrosis. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:149-152.

- Shumaker PR, Kwan JM, Badiavas EV, et al. Rapid healing of scar-associated chronic wounds after ablative fractional resurfacing. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1289-1293.