User login

Large Hemorrhagic Plaque With Central Crusting

The Diagnosis: Bullous/Hemorrhagic Lichen Sclerosus et Atrophicus

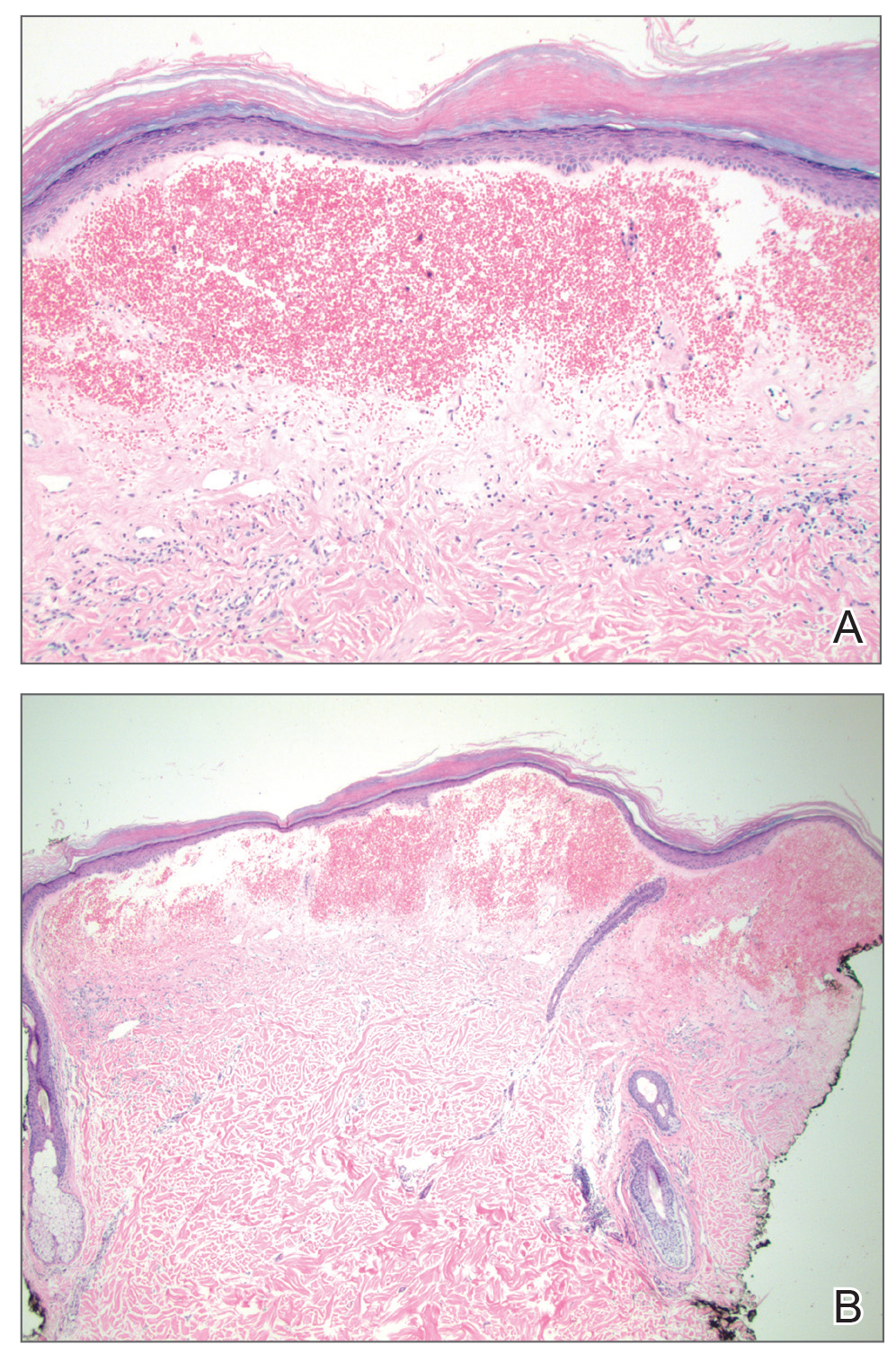

Histopathologic examination revealed hyperkeratosis of the stratum corneum and thinning of the epidermis (Figure). Subepidermal edema and hemorrhage in the papillary dermis were seen. There were dilated vessels beneath the edema in the reticular dermis, as well as perivascular, perifollicular, and interstitial lymphocytic inflammation. No cytologic atypia characteristic of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and angiosarcoma or large lymphatic channels characteristic of lymphangioma were noted. Based on clinicopathologic correlation, the diagnosis of the bullous/hemorrhagic form of lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LS&A) was made. The patient was treated with high-potency topical steroids with notable symptomatic improvement and rapid resolution of the hemorrhagic lesion.

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is a chronic inflammatory condition with a predilection for the anogenital region, though rare cases of extragenital involvement have been reported. It is seen in both sexes and across all age groups, with notably higher prevalence in females in the fifth and sixth decades of life.1,2 Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus can be difficult to diagnose, as these patients may present to a variety of specialists, may be embarrassed by the condition and reluctant for full evaluation, or may have asymptomatic lesions.2,3 Rare cases of isolated extragenital involvement and hemorrhagic or bullous lesions further complicate the diagnosis.1,2 Despite these difficulties, diagnosis is essential, as there is potential for cosmetically and functionally detrimental scarring as well as atrophy and development of overlying malignancies. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is not curable and rarely remits spontaneously, but appropriate treatment strategies can help control the symptoms of the condition as well as its most devastating sequelae.3

For females, classic LS&A is most common in theprepubertal, perimenopausal, or postmenopausal periods, commonly involving the vulva or perineum. Symptoms include pruritus, burning sensation, dysuria, dyspareunia, and labial stenosis, among others. For males, most cases involve the glans penis in prepubertal boys or middleaged men, and symptoms include pruritus, new-onset phimosis, decreased sensation, painful erections, dysuria, and urinary obstruction.1-3 An estimated 97% of patients have some form of genital involvement with only 2.5% showing isolated extragenital involvement, though the latter may be underdiagnosed, as this area is more likely to be asymptomatic.3-6 Extragenital LS&A most often involves the neck and shoulders. The classic appearance of LS&A includes shiny, white-red macules and papules that ultimately coalesce into atrophic plaques and can be accompanied by fissuring or scarring, especially in the genital area.2 There is an increased risk for SCC associated with genital LS&A.1

Bullous/hemorrhagic LS&A has been described as a rare phenotype. One case report cited an increased incidence of this subtype in patients with exclusively extragenital lesions, and the authors considered blister formation to be a characteristic feature of extragenital LS&A. The pathogenesis of blister formation and hemorrhage in LS&A is not completely understood, but trauma is thought to play a role due to decreased stress tolerance from atrophic skin.4 Furthermore, distortion of blood vessel architecture in LS&A has been described with loss of the capillary network and enlargement of vessels along the dermoepidermal junction, which also could play a role in hemorrhage. Differential diagnosis of the bullous/hemorrhagic type of LS&A includes bullous pemphigoid, bullous lichen planus, or bullous scleroderma.7 In our more exophytic hemorrhagic case, malignancies such as SCC or angiosarcoma also had to be considered. Unlike genital LS&A, extragenital LS&A including the bullous/hemorrhagic variant has not been linked to an increasedrisk for malignancy.1,5

The mainstay of treatment of all forms of LS&A is high-potency topical steroids, but topical retinoids, tacrolimus, and UVA phototherapy also have been used. Bullous/hemorrhagic lesions often resolve quickly with topical steroids, leaving behind more classic plaques in their place, which can be more refractory to treatment.5,7

- Meffert JJ, Davis BM, Grimwood RE. Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:393-416.

- Pugliese JM, Morey AF, Peterson AC. Lichen sclerosus: review of the literature and current recommendations for management. J Urol. 2007;178:2268-2276.

- Fistarol SK, Itin PH. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen sclerosus: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:27-47.

- Kimura A, Kambe N, Satoh T, et al. Follicular keratosis and bullous formation are typical signs of extragenital lichen sclerosus. J Dermatol. 2011;38:834-836.

- Khatu S, Vasani R. Isolated, localised extragenital bullous lichen sclerosus et atrophicus: a rare entity. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:409.

- Luzar B, Neil SM, Calonje E. Angiokeratoma-like changes in extragenital and genital lichen sclerosus. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:540-542.

- Lima RS, Maquine GA, Schettini AP, et al. Bullous and hemorrhagic lichen sclerosus—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90 (3 suppl 1):118-120.

The Diagnosis: Bullous/Hemorrhagic Lichen Sclerosus et Atrophicus

Histopathologic examination revealed hyperkeratosis of the stratum corneum and thinning of the epidermis (Figure). Subepidermal edema and hemorrhage in the papillary dermis were seen. There were dilated vessels beneath the edema in the reticular dermis, as well as perivascular, perifollicular, and interstitial lymphocytic inflammation. No cytologic atypia characteristic of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and angiosarcoma or large lymphatic channels characteristic of lymphangioma were noted. Based on clinicopathologic correlation, the diagnosis of the bullous/hemorrhagic form of lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LS&A) was made. The patient was treated with high-potency topical steroids with notable symptomatic improvement and rapid resolution of the hemorrhagic lesion.

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is a chronic inflammatory condition with a predilection for the anogenital region, though rare cases of extragenital involvement have been reported. It is seen in both sexes and across all age groups, with notably higher prevalence in females in the fifth and sixth decades of life.1,2 Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus can be difficult to diagnose, as these patients may present to a variety of specialists, may be embarrassed by the condition and reluctant for full evaluation, or may have asymptomatic lesions.2,3 Rare cases of isolated extragenital involvement and hemorrhagic or bullous lesions further complicate the diagnosis.1,2 Despite these difficulties, diagnosis is essential, as there is potential for cosmetically and functionally detrimental scarring as well as atrophy and development of overlying malignancies. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is not curable and rarely remits spontaneously, but appropriate treatment strategies can help control the symptoms of the condition as well as its most devastating sequelae.3

For females, classic LS&A is most common in theprepubertal, perimenopausal, or postmenopausal periods, commonly involving the vulva or perineum. Symptoms include pruritus, burning sensation, dysuria, dyspareunia, and labial stenosis, among others. For males, most cases involve the glans penis in prepubertal boys or middleaged men, and symptoms include pruritus, new-onset phimosis, decreased sensation, painful erections, dysuria, and urinary obstruction.1-3 An estimated 97% of patients have some form of genital involvement with only 2.5% showing isolated extragenital involvement, though the latter may be underdiagnosed, as this area is more likely to be asymptomatic.3-6 Extragenital LS&A most often involves the neck and shoulders. The classic appearance of LS&A includes shiny, white-red macules and papules that ultimately coalesce into atrophic plaques and can be accompanied by fissuring or scarring, especially in the genital area.2 There is an increased risk for SCC associated with genital LS&A.1

Bullous/hemorrhagic LS&A has been described as a rare phenotype. One case report cited an increased incidence of this subtype in patients with exclusively extragenital lesions, and the authors considered blister formation to be a characteristic feature of extragenital LS&A. The pathogenesis of blister formation and hemorrhage in LS&A is not completely understood, but trauma is thought to play a role due to decreased stress tolerance from atrophic skin.4 Furthermore, distortion of blood vessel architecture in LS&A has been described with loss of the capillary network and enlargement of vessels along the dermoepidermal junction, which also could play a role in hemorrhage. Differential diagnosis of the bullous/hemorrhagic type of LS&A includes bullous pemphigoid, bullous lichen planus, or bullous scleroderma.7 In our more exophytic hemorrhagic case, malignancies such as SCC or angiosarcoma also had to be considered. Unlike genital LS&A, extragenital LS&A including the bullous/hemorrhagic variant has not been linked to an increasedrisk for malignancy.1,5

The mainstay of treatment of all forms of LS&A is high-potency topical steroids, but topical retinoids, tacrolimus, and UVA phototherapy also have been used. Bullous/hemorrhagic lesions often resolve quickly with topical steroids, leaving behind more classic plaques in their place, which can be more refractory to treatment.5,7

The Diagnosis: Bullous/Hemorrhagic Lichen Sclerosus et Atrophicus

Histopathologic examination revealed hyperkeratosis of the stratum corneum and thinning of the epidermis (Figure). Subepidermal edema and hemorrhage in the papillary dermis were seen. There were dilated vessels beneath the edema in the reticular dermis, as well as perivascular, perifollicular, and interstitial lymphocytic inflammation. No cytologic atypia characteristic of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and angiosarcoma or large lymphatic channels characteristic of lymphangioma were noted. Based on clinicopathologic correlation, the diagnosis of the bullous/hemorrhagic form of lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LS&A) was made. The patient was treated with high-potency topical steroids with notable symptomatic improvement and rapid resolution of the hemorrhagic lesion.

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is a chronic inflammatory condition with a predilection for the anogenital region, though rare cases of extragenital involvement have been reported. It is seen in both sexes and across all age groups, with notably higher prevalence in females in the fifth and sixth decades of life.1,2 Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus can be difficult to diagnose, as these patients may present to a variety of specialists, may be embarrassed by the condition and reluctant for full evaluation, or may have asymptomatic lesions.2,3 Rare cases of isolated extragenital involvement and hemorrhagic or bullous lesions further complicate the diagnosis.1,2 Despite these difficulties, diagnosis is essential, as there is potential for cosmetically and functionally detrimental scarring as well as atrophy and development of overlying malignancies. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is not curable and rarely remits spontaneously, but appropriate treatment strategies can help control the symptoms of the condition as well as its most devastating sequelae.3

For females, classic LS&A is most common in theprepubertal, perimenopausal, or postmenopausal periods, commonly involving the vulva or perineum. Symptoms include pruritus, burning sensation, dysuria, dyspareunia, and labial stenosis, among others. For males, most cases involve the glans penis in prepubertal boys or middleaged men, and symptoms include pruritus, new-onset phimosis, decreased sensation, painful erections, dysuria, and urinary obstruction.1-3 An estimated 97% of patients have some form of genital involvement with only 2.5% showing isolated extragenital involvement, though the latter may be underdiagnosed, as this area is more likely to be asymptomatic.3-6 Extragenital LS&A most often involves the neck and shoulders. The classic appearance of LS&A includes shiny, white-red macules and papules that ultimately coalesce into atrophic plaques and can be accompanied by fissuring or scarring, especially in the genital area.2 There is an increased risk for SCC associated with genital LS&A.1

Bullous/hemorrhagic LS&A has been described as a rare phenotype. One case report cited an increased incidence of this subtype in patients with exclusively extragenital lesions, and the authors considered blister formation to be a characteristic feature of extragenital LS&A. The pathogenesis of blister formation and hemorrhage in LS&A is not completely understood, but trauma is thought to play a role due to decreased stress tolerance from atrophic skin.4 Furthermore, distortion of blood vessel architecture in LS&A has been described with loss of the capillary network and enlargement of vessels along the dermoepidermal junction, which also could play a role in hemorrhage. Differential diagnosis of the bullous/hemorrhagic type of LS&A includes bullous pemphigoid, bullous lichen planus, or bullous scleroderma.7 In our more exophytic hemorrhagic case, malignancies such as SCC or angiosarcoma also had to be considered. Unlike genital LS&A, extragenital LS&A including the bullous/hemorrhagic variant has not been linked to an increasedrisk for malignancy.1,5

The mainstay of treatment of all forms of LS&A is high-potency topical steroids, but topical retinoids, tacrolimus, and UVA phototherapy also have been used. Bullous/hemorrhagic lesions often resolve quickly with topical steroids, leaving behind more classic plaques in their place, which can be more refractory to treatment.5,7

- Meffert JJ, Davis BM, Grimwood RE. Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:393-416.

- Pugliese JM, Morey AF, Peterson AC. Lichen sclerosus: review of the literature and current recommendations for management. J Urol. 2007;178:2268-2276.

- Fistarol SK, Itin PH. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen sclerosus: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:27-47.

- Kimura A, Kambe N, Satoh T, et al. Follicular keratosis and bullous formation are typical signs of extragenital lichen sclerosus. J Dermatol. 2011;38:834-836.

- Khatu S, Vasani R. Isolated, localised extragenital bullous lichen sclerosus et atrophicus: a rare entity. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:409.

- Luzar B, Neil SM, Calonje E. Angiokeratoma-like changes in extragenital and genital lichen sclerosus. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:540-542.

- Lima RS, Maquine GA, Schettini AP, et al. Bullous and hemorrhagic lichen sclerosus—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90 (3 suppl 1):118-120.

- Meffert JJ, Davis BM, Grimwood RE. Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:393-416.

- Pugliese JM, Morey AF, Peterson AC. Lichen sclerosus: review of the literature and current recommendations for management. J Urol. 2007;178:2268-2276.

- Fistarol SK, Itin PH. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen sclerosus: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:27-47.

- Kimura A, Kambe N, Satoh T, et al. Follicular keratosis and bullous formation are typical signs of extragenital lichen sclerosus. J Dermatol. 2011;38:834-836.

- Khatu S, Vasani R. Isolated, localised extragenital bullous lichen sclerosus et atrophicus: a rare entity. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:409.

- Luzar B, Neil SM, Calonje E. Angiokeratoma-like changes in extragenital and genital lichen sclerosus. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:540-542.

- Lima RS, Maquine GA, Schettini AP, et al. Bullous and hemorrhagic lichen sclerosus—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90 (3 suppl 1):118-120.

A 54-year-old woman with no notable medical history was referred to dermatology by her primary care provider for evaluation of a hematoma on the posterior neck that had developed gradually over 5 months. The lesion initially was asymptomatic but more recently had started to be painful and bleed intermittently. The patient denied any personal or family history of skin cancer. Physical examination revealed a large hemorrhagic plaque on the left side of the posterior neck with central brown-yellow crusting. There were few smaller, white, thin, sclerotic plaques with crinkling atrophy at the periphery of and inferolateral to the lesion. A punch biopsy specimen was obtained from the hemorrhagic plaque.

Managing Postinflammatory Hyperpigmentation in Pediatric Patients With Skin of Color

Postnflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH) is an acquired hypermelanosis that can occur in children and adults following an inflammatory cutaneous disease or trauma. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation may last for months to even years. Although PIH may occur in all skin types, it is more common and presents with greater severity and intensity in individuals with skin of color. By the year 2050, 1 in 3 US residents is projected to be Hispanic.1 It is projected that by 2044, non-Hispanic white individuals (all ages) will make up less than 50% of the US population.2 Currently, the majority of the US residents younger than 18 years are minorities. The majority minority population in the United States already exists in those younger than 18 years and is predicted to occur in the adult population by 2044.2

Effective treatment options and management strategies for PIH in adults with skin of color have been described in the literature.3 Due to a paucity of research, the approach to management of PIH in children with skin of color has been based on clinical experience and lessons learned from adult patients. This article focuses on management of PIH in pediatric patients with skin of color, which includes black/African American, African-Caribbean, Hispanic, Asian, Pacific Islander, and American Indian individuals.

Underlying Inflammatory Dermatoses Resulting in PIH

There are numerous conditions that may result in PIH, including but not limited to atopic dermatitis (AD), acne, arthropod bites, and injuries to the skin. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation may have more of a psychological impact than the inciting disease or injury itself. The most important step in the approach to managing PIH is treating the underlying inflammatory condition that caused the pigmentation.

Parents/guardians may report a chief concern of dark spots, manchas (stains), blemishes, or stains on the skin, often with no mention of a coexisting inflammatory dermatosis. Parents/guardians of children with skin of color often have personally experienced PIH and may be determined to shield their children from similar angst associated with the condition. Although physicians may see just another pediatric patient with PIH, the child’s parents/guardians may see a condition that will be readily perceptible during major life events, such as the child’s prom or even his/her wedding day. Promptly diagnosing and instituting early treatment of inflammatory conditions associated with PIH may accelerate resolution and prevent worsening of the pigmentation.3

Select inflammatory dermatoses that are common in children with skin of color and may lead to PIH are highlighted below. Although this list is not comprehensive, the approach and management strategies should prompt creation of plans that keep PIH in mind when treating primary inflammatory skin diseases.

Atopic Dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis may induce PIH or hypopigmentation of the skin in children with skin of color. Developing a plan for AD flare prevention, as well as management of mild, moderate, and severe AD flares, is imperative in pediatric patients. Prevention plans should include gentle skin care, twice-daily application of emollients to the full body, and reduction of Staphylococcus aureus loads on the skin. The treatment action plan for mild to moderate flares may include topical corticosteroids, immunomodulators, and nonsteroidal agents. Treatment options for severe AD or patients who were unsuccessfully treated with other therapies may include phototherapy, biologics, and methotrexate, among others.4 Creating action plans for AD flares is a vital step in the prevention of PIH in patients with skin of color. Additionally, PIH should not be considered a sign of AD treatment failure.

Acne

Acne is a common skin disorder seen in patients with skin of color.5 A prospective observational study found that 34.3% of 683 children aged 9 to 14 years in a pediatric ambulatory clinic had acne.6 The number of preadolescents with acne is growing. Most cases are not associated with underlying endocrinopathy.7 With the growing population of children with skin of color in the United States along with the increasing childhood acne rate and subsequent inherent risk for hyperpigmentation, early acne interventions should be considered in pediatric acne patients with skin of color to reduce the impact of PIH in those at risk.

In a survey study of 313 adult acne patients with skin of color, 37.2% reported the presence of dark marks lasting 4 months or longer.5 Regardless of the severity of the acne, treatment should be initiated as tolerated in those with PIH. Adolescent acne patients with skin of color may develop PIH that is more severe and longer lasting than the acne itself.

The foundation for treatment of acne in adolescent skin of color patients is the same as those without skin of color, including topical retinoids, topical antibiotics, oral antibiotics, and isotretinoin when needed. Topical tretinoin, adapalene, azelaic acid, and tazarotene not only treat acne but also are a valuable part of the treatment armamentarium for PIH. Several studies in adults with skin of color have demonstrated improvement of PIH from the use of topical retinoids alone.8-10 Despite wanting to treat the acne aggressively, special guidance should be given to prevent retinoid dermatitis, which may lead to PIH.10 Demonstrating the application of the topical acne medications, discussing how to avoid potential side effects, and giving permission to skip applications, if needed, may empower families to make adjustments between visits to limit irritation that might prompt further PIH. Incorporating α-hydroxy acid–based cleansers, α-hydroxy acid–based chemical peels, or salicylic acid chemical peels may be warranted in the setting of intense PIH. Selecting treatments that not only help the inflammatory disease leading to the PIH but also can help improve the pigmentation are preferred; however, the risks and benefits have to be weighed because many treatments that work well for PIH also may cause irritation, leading to new or worsening PIH.

Arthropod Bites

Arthropod bites cause inflamed pruritic papules and nodules, and the resulting PIH in those with darker skin types may be quite dramatic. Parents/guardians should be instructed to have a low-potency topical corticosteroid on hand to use on bites for a few days when they appear, which will not only help with the inflammation associated with the bite but also will help decrease pruritus and subsequently skin injury from scratching. In homes with pets, checking animals routinely for fleas and other infestations is helpful. In the setting of repeated arthropod bites in the spring and summer, applying bug repellant with 10% to 30% DEET (N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide) on the child’s clothing and exposed body areas before playing outside or in the morning before school or camp may prevent some bites. There are DEET alternatives, such as picaridin, that may be used. Product instructions should be followed when using insect repellants in the pediatric population.11

PIH Management Strategies

Gentle Skin Care Routine

There are misconceptions that areas of hyperpigmentation on the skin are caused by dirt and that scrubbing the skin harder may help to lighten the affected areas. Parents/guardians may report that the child’s skin looks dirty or, in the setting of acne, view dirt as the cause of the skin condition, which may prompt the patient to scrub the skin and the friction further worsens the PIH. Use of daily gentle cleansers and moisturizers is advised to keep the skin moisturized and free of further potential irritation and dryness that may prompt scratching or flares of the underlying condition.

Photoprotection

During the treatment course for PIH, using sun protection is helpful to prevent further darkening of the PIH areas. Sun protection may be in the form of broad-spectrum sunscreen, hats, or sun-protective clothing. Patients should be encouraged to apply sunscreen daily and to reapply every 2 hours and after water-based activities.12 For pediatric and adolescent populations, practicing sun-protective behaviors before school or outdoor activities also should be advised, as many families only think about sun protection in the setting of sunny vacation activities. Research has demonstrated that individuals with skin of color may not realize that they can be affected by skin cancer,13 thus they may not have any experience selecting, applying, or regularly using sunscreens. Products that do not leave a white hue on the skin are suggested for adolescents who may be sensitive about their appearance following sunscreen application.

Skin Lightening Treatments

Although the most important therapy for PIH is to treat the underlying inflammatory conditions, some parents/guardians may desire additional options due to the extent of involvement of the PIH, its psychological impact on the child, or adverse effect on the child’s quality of life.14 In adolescents, incorporating an α-hydroxy acid–based cleanser, glycolic acid chemical peels, salicylic acid chemical peels, and topical cosmeceuticals may be warranted in the setting of intense PIH and acne. However, irritation may lead to further dyspigmentation.

Topical ammonium lactate 12% is lactic acid neutralized with ammonium hydroxide that is formulated as a lotion or a cream. It is used to hydrate dry skin and may decrease corneocyte cohesion.15 Topical ammonium lactate also has been used anecdotally for PIH on the body during periods of watchful waiting.

Topical hydroquinone, the gold standard for treating hyperpigmentation,3,16 is not approved in children, but some parents/guardians elect to utilize hydroquinone off label to accelerate the clearing of distressing PIH in adolescents. Careful consideration including a discussion of potential risks and alternatives (eg, watchful waiting) should be highlighted.

In the setting of chronic inflammatory conditions that recur and remit, potentially irritating topical treatments should be used only during periods when symptoms of inflammation such as itching or erythema are absent.

Conclusion

Despite the best management efforts, PIH in some patients with skin of color may be present for months to years. In the pediatric skin of color population, treatment of the underlying inflammatory condition, gentle skin care, use of photoprotection, and time may be all that is needed for PIH resolution. With their parent/guardians’ consent, adolescents distressed by PIH may decide to pursue more aggressive, potentially irritating treatments. Above all, the most important management in the setting of PIH is to treat the underlying inflammatory condition causing the PIH and set reasonable expectations. For challenging cases, pediatric dermatologists with special expertise in treating pediatric and adolescent patients with skin of color may be consulted.

- Broughton A. Minorities expected to be majority in 2050. CNN. August 13, 2008. Accessed January 2, 2019.

- Colby SL, Ortman JM. Projections of the Size and Composition of the US Population: 2014 to 2060. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2014. Current Population Reports, P25-1143. Published March 2015. Accessed January 23, 2019.

- Davis EC, Callender VD. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation: a review of the epidemiology, clinical features, and treatment options in skin of color. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3:20-31.

- Eichenfield LF, Ahluwalia J, Waldman A, et al. Current guidelines for the evaluation and management of atopic dermatitis: a comparison of the Joint Task Force Practice Parameter and American Academy of Dermatology guidelines. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(4S):S49-S57.

- Taylor SC, Cook-Bolden F, Rahman Z, et al. Acne vulgaris in skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(2 suppl):S98-S106.

- Napolitano M, Ruggiero G, Monfrecola G, et al. Acne prevalence in 9 to 14-year-old patients attending pediatric ambulatory clinics in Italy. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:1320-1323.

- Mancini AJ, Baldwin HE, Eichenfield LF. Acne life cycle: the spectrum of pediatric disease. Semin Cutan Med Surg 2011;30:2-5.

- Lowe NJ, Rizk D, Grimes P, et al. Azelaic acid 20% cream in the treatment of facial hyperpigmentation in darker-skinned patients. Clin Ther. 1998;20:945-959.

- Grimes P, Callender V. Tazarotene cream for postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and acne vulgaris in darker skin: a double-blind, randomized, vehicle-controlled study. Cutis. 2006;77:45-50.

- Bulengo-Ransby SM, Griffiths CE, Kimbrough-Green CK, et al. Topical tretinoin (retinoid acid) therapy for hyperpigmented lesions caused by inflammation of the skin in black patients. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1438-1443.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Choosing an insect repellent for your child. Healthy Children website. Updated July 18, 2018. Accessed January 8, 2019.

- Agbai ON, Buster K, Sanchez M, et al. Skin cancer and photoprotection in people of color: a review and recommendations for physicians and the public. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:312-317.

- Buster KJ, You Z, Fouad M, et al. Skin cancer risk perceptions: a comparison across ethnicity, age, education, gender, and income. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:771-779.

- Downie J. Help prevent and reverse post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation. Pract Dermatol Pediatr. May/June 2011:12-14. Accessed January 18, 2019.

- Ammonium lactate lotion 12% [package insert]. Bronx, New York: Perrigo New York, Inc; 2006.

- Grimes PE. Management of hyperpigmentation in darker racial ethnic groups. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009;28:77-85.

Postnflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH) is an acquired hypermelanosis that can occur in children and adults following an inflammatory cutaneous disease or trauma. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation may last for months to even years. Although PIH may occur in all skin types, it is more common and presents with greater severity and intensity in individuals with skin of color. By the year 2050, 1 in 3 US residents is projected to be Hispanic.1 It is projected that by 2044, non-Hispanic white individuals (all ages) will make up less than 50% of the US population.2 Currently, the majority of the US residents younger than 18 years are minorities. The majority minority population in the United States already exists in those younger than 18 years and is predicted to occur in the adult population by 2044.2

Effective treatment options and management strategies for PIH in adults with skin of color have been described in the literature.3 Due to a paucity of research, the approach to management of PIH in children with skin of color has been based on clinical experience and lessons learned from adult patients. This article focuses on management of PIH in pediatric patients with skin of color, which includes black/African American, African-Caribbean, Hispanic, Asian, Pacific Islander, and American Indian individuals.

Underlying Inflammatory Dermatoses Resulting in PIH

There are numerous conditions that may result in PIH, including but not limited to atopic dermatitis (AD), acne, arthropod bites, and injuries to the skin. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation may have more of a psychological impact than the inciting disease or injury itself. The most important step in the approach to managing PIH is treating the underlying inflammatory condition that caused the pigmentation.

Parents/guardians may report a chief concern of dark spots, manchas (stains), blemishes, or stains on the skin, often with no mention of a coexisting inflammatory dermatosis. Parents/guardians of children with skin of color often have personally experienced PIH and may be determined to shield their children from similar angst associated with the condition. Although physicians may see just another pediatric patient with PIH, the child’s parents/guardians may see a condition that will be readily perceptible during major life events, such as the child’s prom or even his/her wedding day. Promptly diagnosing and instituting early treatment of inflammatory conditions associated with PIH may accelerate resolution and prevent worsening of the pigmentation.3

Select inflammatory dermatoses that are common in children with skin of color and may lead to PIH are highlighted below. Although this list is not comprehensive, the approach and management strategies should prompt creation of plans that keep PIH in mind when treating primary inflammatory skin diseases.

Atopic Dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis may induce PIH or hypopigmentation of the skin in children with skin of color. Developing a plan for AD flare prevention, as well as management of mild, moderate, and severe AD flares, is imperative in pediatric patients. Prevention plans should include gentle skin care, twice-daily application of emollients to the full body, and reduction of Staphylococcus aureus loads on the skin. The treatment action plan for mild to moderate flares may include topical corticosteroids, immunomodulators, and nonsteroidal agents. Treatment options for severe AD or patients who were unsuccessfully treated with other therapies may include phototherapy, biologics, and methotrexate, among others.4 Creating action plans for AD flares is a vital step in the prevention of PIH in patients with skin of color. Additionally, PIH should not be considered a sign of AD treatment failure.

Acne

Acne is a common skin disorder seen in patients with skin of color.5 A prospective observational study found that 34.3% of 683 children aged 9 to 14 years in a pediatric ambulatory clinic had acne.6 The number of preadolescents with acne is growing. Most cases are not associated with underlying endocrinopathy.7 With the growing population of children with skin of color in the United States along with the increasing childhood acne rate and subsequent inherent risk for hyperpigmentation, early acne interventions should be considered in pediatric acne patients with skin of color to reduce the impact of PIH in those at risk.

In a survey study of 313 adult acne patients with skin of color, 37.2% reported the presence of dark marks lasting 4 months or longer.5 Regardless of the severity of the acne, treatment should be initiated as tolerated in those with PIH. Adolescent acne patients with skin of color may develop PIH that is more severe and longer lasting than the acne itself.

The foundation for treatment of acne in adolescent skin of color patients is the same as those without skin of color, including topical retinoids, topical antibiotics, oral antibiotics, and isotretinoin when needed. Topical tretinoin, adapalene, azelaic acid, and tazarotene not only treat acne but also are a valuable part of the treatment armamentarium for PIH. Several studies in adults with skin of color have demonstrated improvement of PIH from the use of topical retinoids alone.8-10 Despite wanting to treat the acne aggressively, special guidance should be given to prevent retinoid dermatitis, which may lead to PIH.10 Demonstrating the application of the topical acne medications, discussing how to avoid potential side effects, and giving permission to skip applications, if needed, may empower families to make adjustments between visits to limit irritation that might prompt further PIH. Incorporating α-hydroxy acid–based cleansers, α-hydroxy acid–based chemical peels, or salicylic acid chemical peels may be warranted in the setting of intense PIH. Selecting treatments that not only help the inflammatory disease leading to the PIH but also can help improve the pigmentation are preferred; however, the risks and benefits have to be weighed because many treatments that work well for PIH also may cause irritation, leading to new or worsening PIH.

Arthropod Bites

Arthropod bites cause inflamed pruritic papules and nodules, and the resulting PIH in those with darker skin types may be quite dramatic. Parents/guardians should be instructed to have a low-potency topical corticosteroid on hand to use on bites for a few days when they appear, which will not only help with the inflammation associated with the bite but also will help decrease pruritus and subsequently skin injury from scratching. In homes with pets, checking animals routinely for fleas and other infestations is helpful. In the setting of repeated arthropod bites in the spring and summer, applying bug repellant with 10% to 30% DEET (N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide) on the child’s clothing and exposed body areas before playing outside or in the morning before school or camp may prevent some bites. There are DEET alternatives, such as picaridin, that may be used. Product instructions should be followed when using insect repellants in the pediatric population.11

PIH Management Strategies

Gentle Skin Care Routine

There are misconceptions that areas of hyperpigmentation on the skin are caused by dirt and that scrubbing the skin harder may help to lighten the affected areas. Parents/guardians may report that the child’s skin looks dirty or, in the setting of acne, view dirt as the cause of the skin condition, which may prompt the patient to scrub the skin and the friction further worsens the PIH. Use of daily gentle cleansers and moisturizers is advised to keep the skin moisturized and free of further potential irritation and dryness that may prompt scratching or flares of the underlying condition.

Photoprotection

During the treatment course for PIH, using sun protection is helpful to prevent further darkening of the PIH areas. Sun protection may be in the form of broad-spectrum sunscreen, hats, or sun-protective clothing. Patients should be encouraged to apply sunscreen daily and to reapply every 2 hours and after water-based activities.12 For pediatric and adolescent populations, practicing sun-protective behaviors before school or outdoor activities also should be advised, as many families only think about sun protection in the setting of sunny vacation activities. Research has demonstrated that individuals with skin of color may not realize that they can be affected by skin cancer,13 thus they may not have any experience selecting, applying, or regularly using sunscreens. Products that do not leave a white hue on the skin are suggested for adolescents who may be sensitive about their appearance following sunscreen application.

Skin Lightening Treatments

Although the most important therapy for PIH is to treat the underlying inflammatory conditions, some parents/guardians may desire additional options due to the extent of involvement of the PIH, its psychological impact on the child, or adverse effect on the child’s quality of life.14 In adolescents, incorporating an α-hydroxy acid–based cleanser, glycolic acid chemical peels, salicylic acid chemical peels, and topical cosmeceuticals may be warranted in the setting of intense PIH and acne. However, irritation may lead to further dyspigmentation.

Topical ammonium lactate 12% is lactic acid neutralized with ammonium hydroxide that is formulated as a lotion or a cream. It is used to hydrate dry skin and may decrease corneocyte cohesion.15 Topical ammonium lactate also has been used anecdotally for PIH on the body during periods of watchful waiting.

Topical hydroquinone, the gold standard for treating hyperpigmentation,3,16 is not approved in children, but some parents/guardians elect to utilize hydroquinone off label to accelerate the clearing of distressing PIH in adolescents. Careful consideration including a discussion of potential risks and alternatives (eg, watchful waiting) should be highlighted.

In the setting of chronic inflammatory conditions that recur and remit, potentially irritating topical treatments should be used only during periods when symptoms of inflammation such as itching or erythema are absent.

Conclusion

Despite the best management efforts, PIH in some patients with skin of color may be present for months to years. In the pediatric skin of color population, treatment of the underlying inflammatory condition, gentle skin care, use of photoprotection, and time may be all that is needed for PIH resolution. With their parent/guardians’ consent, adolescents distressed by PIH may decide to pursue more aggressive, potentially irritating treatments. Above all, the most important management in the setting of PIH is to treat the underlying inflammatory condition causing the PIH and set reasonable expectations. For challenging cases, pediatric dermatologists with special expertise in treating pediatric and adolescent patients with skin of color may be consulted.

Postnflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH) is an acquired hypermelanosis that can occur in children and adults following an inflammatory cutaneous disease or trauma. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation may last for months to even years. Although PIH may occur in all skin types, it is more common and presents with greater severity and intensity in individuals with skin of color. By the year 2050, 1 in 3 US residents is projected to be Hispanic.1 It is projected that by 2044, non-Hispanic white individuals (all ages) will make up less than 50% of the US population.2 Currently, the majority of the US residents younger than 18 years are minorities. The majority minority population in the United States already exists in those younger than 18 years and is predicted to occur in the adult population by 2044.2

Effective treatment options and management strategies for PIH in adults with skin of color have been described in the literature.3 Due to a paucity of research, the approach to management of PIH in children with skin of color has been based on clinical experience and lessons learned from adult patients. This article focuses on management of PIH in pediatric patients with skin of color, which includes black/African American, African-Caribbean, Hispanic, Asian, Pacific Islander, and American Indian individuals.

Underlying Inflammatory Dermatoses Resulting in PIH

There are numerous conditions that may result in PIH, including but not limited to atopic dermatitis (AD), acne, arthropod bites, and injuries to the skin. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation may have more of a psychological impact than the inciting disease or injury itself. The most important step in the approach to managing PIH is treating the underlying inflammatory condition that caused the pigmentation.

Parents/guardians may report a chief concern of dark spots, manchas (stains), blemishes, or stains on the skin, often with no mention of a coexisting inflammatory dermatosis. Parents/guardians of children with skin of color often have personally experienced PIH and may be determined to shield their children from similar angst associated with the condition. Although physicians may see just another pediatric patient with PIH, the child’s parents/guardians may see a condition that will be readily perceptible during major life events, such as the child’s prom or even his/her wedding day. Promptly diagnosing and instituting early treatment of inflammatory conditions associated with PIH may accelerate resolution and prevent worsening of the pigmentation.3

Select inflammatory dermatoses that are common in children with skin of color and may lead to PIH are highlighted below. Although this list is not comprehensive, the approach and management strategies should prompt creation of plans that keep PIH in mind when treating primary inflammatory skin diseases.

Atopic Dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis may induce PIH or hypopigmentation of the skin in children with skin of color. Developing a plan for AD flare prevention, as well as management of mild, moderate, and severe AD flares, is imperative in pediatric patients. Prevention plans should include gentle skin care, twice-daily application of emollients to the full body, and reduction of Staphylococcus aureus loads on the skin. The treatment action plan for mild to moderate flares may include topical corticosteroids, immunomodulators, and nonsteroidal agents. Treatment options for severe AD or patients who were unsuccessfully treated with other therapies may include phototherapy, biologics, and methotrexate, among others.4 Creating action plans for AD flares is a vital step in the prevention of PIH in patients with skin of color. Additionally, PIH should not be considered a sign of AD treatment failure.

Acne

Acne is a common skin disorder seen in patients with skin of color.5 A prospective observational study found that 34.3% of 683 children aged 9 to 14 years in a pediatric ambulatory clinic had acne.6 The number of preadolescents with acne is growing. Most cases are not associated with underlying endocrinopathy.7 With the growing population of children with skin of color in the United States along with the increasing childhood acne rate and subsequent inherent risk for hyperpigmentation, early acne interventions should be considered in pediatric acne patients with skin of color to reduce the impact of PIH in those at risk.

In a survey study of 313 adult acne patients with skin of color, 37.2% reported the presence of dark marks lasting 4 months or longer.5 Regardless of the severity of the acne, treatment should be initiated as tolerated in those with PIH. Adolescent acne patients with skin of color may develop PIH that is more severe and longer lasting than the acne itself.

The foundation for treatment of acne in adolescent skin of color patients is the same as those without skin of color, including topical retinoids, topical antibiotics, oral antibiotics, and isotretinoin when needed. Topical tretinoin, adapalene, azelaic acid, and tazarotene not only treat acne but also are a valuable part of the treatment armamentarium for PIH. Several studies in adults with skin of color have demonstrated improvement of PIH from the use of topical retinoids alone.8-10 Despite wanting to treat the acne aggressively, special guidance should be given to prevent retinoid dermatitis, which may lead to PIH.10 Demonstrating the application of the topical acne medications, discussing how to avoid potential side effects, and giving permission to skip applications, if needed, may empower families to make adjustments between visits to limit irritation that might prompt further PIH. Incorporating α-hydroxy acid–based cleansers, α-hydroxy acid–based chemical peels, or salicylic acid chemical peels may be warranted in the setting of intense PIH. Selecting treatments that not only help the inflammatory disease leading to the PIH but also can help improve the pigmentation are preferred; however, the risks and benefits have to be weighed because many treatments that work well for PIH also may cause irritation, leading to new or worsening PIH.

Arthropod Bites

Arthropod bites cause inflamed pruritic papules and nodules, and the resulting PIH in those with darker skin types may be quite dramatic. Parents/guardians should be instructed to have a low-potency topical corticosteroid on hand to use on bites for a few days when they appear, which will not only help with the inflammation associated with the bite but also will help decrease pruritus and subsequently skin injury from scratching. In homes with pets, checking animals routinely for fleas and other infestations is helpful. In the setting of repeated arthropod bites in the spring and summer, applying bug repellant with 10% to 30% DEET (N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide) on the child’s clothing and exposed body areas before playing outside or in the morning before school or camp may prevent some bites. There are DEET alternatives, such as picaridin, that may be used. Product instructions should be followed when using insect repellants in the pediatric population.11

PIH Management Strategies

Gentle Skin Care Routine

There are misconceptions that areas of hyperpigmentation on the skin are caused by dirt and that scrubbing the skin harder may help to lighten the affected areas. Parents/guardians may report that the child’s skin looks dirty or, in the setting of acne, view dirt as the cause of the skin condition, which may prompt the patient to scrub the skin and the friction further worsens the PIH. Use of daily gentle cleansers and moisturizers is advised to keep the skin moisturized and free of further potential irritation and dryness that may prompt scratching or flares of the underlying condition.

Photoprotection

During the treatment course for PIH, using sun protection is helpful to prevent further darkening of the PIH areas. Sun protection may be in the form of broad-spectrum sunscreen, hats, or sun-protective clothing. Patients should be encouraged to apply sunscreen daily and to reapply every 2 hours and after water-based activities.12 For pediatric and adolescent populations, practicing sun-protective behaviors before school or outdoor activities also should be advised, as many families only think about sun protection in the setting of sunny vacation activities. Research has demonstrated that individuals with skin of color may not realize that they can be affected by skin cancer,13 thus they may not have any experience selecting, applying, or regularly using sunscreens. Products that do not leave a white hue on the skin are suggested for adolescents who may be sensitive about their appearance following sunscreen application.

Skin Lightening Treatments

Although the most important therapy for PIH is to treat the underlying inflammatory conditions, some parents/guardians may desire additional options due to the extent of involvement of the PIH, its psychological impact on the child, or adverse effect on the child’s quality of life.14 In adolescents, incorporating an α-hydroxy acid–based cleanser, glycolic acid chemical peels, salicylic acid chemical peels, and topical cosmeceuticals may be warranted in the setting of intense PIH and acne. However, irritation may lead to further dyspigmentation.

Topical ammonium lactate 12% is lactic acid neutralized with ammonium hydroxide that is formulated as a lotion or a cream. It is used to hydrate dry skin and may decrease corneocyte cohesion.15 Topical ammonium lactate also has been used anecdotally for PIH on the body during periods of watchful waiting.

Topical hydroquinone, the gold standard for treating hyperpigmentation,3,16 is not approved in children, but some parents/guardians elect to utilize hydroquinone off label to accelerate the clearing of distressing PIH in adolescents. Careful consideration including a discussion of potential risks and alternatives (eg, watchful waiting) should be highlighted.

In the setting of chronic inflammatory conditions that recur and remit, potentially irritating topical treatments should be used only during periods when symptoms of inflammation such as itching or erythema are absent.

Conclusion

Despite the best management efforts, PIH in some patients with skin of color may be present for months to years. In the pediatric skin of color population, treatment of the underlying inflammatory condition, gentle skin care, use of photoprotection, and time may be all that is needed for PIH resolution. With their parent/guardians’ consent, adolescents distressed by PIH may decide to pursue more aggressive, potentially irritating treatments. Above all, the most important management in the setting of PIH is to treat the underlying inflammatory condition causing the PIH and set reasonable expectations. For challenging cases, pediatric dermatologists with special expertise in treating pediatric and adolescent patients with skin of color may be consulted.

- Broughton A. Minorities expected to be majority in 2050. CNN. August 13, 2008. Accessed January 2, 2019.

- Colby SL, Ortman JM. Projections of the Size and Composition of the US Population: 2014 to 2060. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2014. Current Population Reports, P25-1143. Published March 2015. Accessed January 23, 2019.

- Davis EC, Callender VD. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation: a review of the epidemiology, clinical features, and treatment options in skin of color. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3:20-31.

- Eichenfield LF, Ahluwalia J, Waldman A, et al. Current guidelines for the evaluation and management of atopic dermatitis: a comparison of the Joint Task Force Practice Parameter and American Academy of Dermatology guidelines. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(4S):S49-S57.

- Taylor SC, Cook-Bolden F, Rahman Z, et al. Acne vulgaris in skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(2 suppl):S98-S106.

- Napolitano M, Ruggiero G, Monfrecola G, et al. Acne prevalence in 9 to 14-year-old patients attending pediatric ambulatory clinics in Italy. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:1320-1323.

- Mancini AJ, Baldwin HE, Eichenfield LF. Acne life cycle: the spectrum of pediatric disease. Semin Cutan Med Surg 2011;30:2-5.

- Lowe NJ, Rizk D, Grimes P, et al. Azelaic acid 20% cream in the treatment of facial hyperpigmentation in darker-skinned patients. Clin Ther. 1998;20:945-959.

- Grimes P, Callender V. Tazarotene cream for postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and acne vulgaris in darker skin: a double-blind, randomized, vehicle-controlled study. Cutis. 2006;77:45-50.

- Bulengo-Ransby SM, Griffiths CE, Kimbrough-Green CK, et al. Topical tretinoin (retinoid acid) therapy for hyperpigmented lesions caused by inflammation of the skin in black patients. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1438-1443.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Choosing an insect repellent for your child. Healthy Children website. Updated July 18, 2018. Accessed January 8, 2019.

- Agbai ON, Buster K, Sanchez M, et al. Skin cancer and photoprotection in people of color: a review and recommendations for physicians and the public. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:312-317.

- Buster KJ, You Z, Fouad M, et al. Skin cancer risk perceptions: a comparison across ethnicity, age, education, gender, and income. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:771-779.

- Downie J. Help prevent and reverse post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation. Pract Dermatol Pediatr. May/June 2011:12-14. Accessed January 18, 2019.

- Ammonium lactate lotion 12% [package insert]. Bronx, New York: Perrigo New York, Inc; 2006.

- Grimes PE. Management of hyperpigmentation in darker racial ethnic groups. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009;28:77-85.

- Broughton A. Minorities expected to be majority in 2050. CNN. August 13, 2008. Accessed January 2, 2019.

- Colby SL, Ortman JM. Projections of the Size and Composition of the US Population: 2014 to 2060. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2014. Current Population Reports, P25-1143. Published March 2015. Accessed January 23, 2019.

- Davis EC, Callender VD. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation: a review of the epidemiology, clinical features, and treatment options in skin of color. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3:20-31.

- Eichenfield LF, Ahluwalia J, Waldman A, et al. Current guidelines for the evaluation and management of atopic dermatitis: a comparison of the Joint Task Force Practice Parameter and American Academy of Dermatology guidelines. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(4S):S49-S57.

- Taylor SC, Cook-Bolden F, Rahman Z, et al. Acne vulgaris in skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(2 suppl):S98-S106.

- Napolitano M, Ruggiero G, Monfrecola G, et al. Acne prevalence in 9 to 14-year-old patients attending pediatric ambulatory clinics in Italy. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:1320-1323.

- Mancini AJ, Baldwin HE, Eichenfield LF. Acne life cycle: the spectrum of pediatric disease. Semin Cutan Med Surg 2011;30:2-5.

- Lowe NJ, Rizk D, Grimes P, et al. Azelaic acid 20% cream in the treatment of facial hyperpigmentation in darker-skinned patients. Clin Ther. 1998;20:945-959.

- Grimes P, Callender V. Tazarotene cream for postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and acne vulgaris in darker skin: a double-blind, randomized, vehicle-controlled study. Cutis. 2006;77:45-50.

- Bulengo-Ransby SM, Griffiths CE, Kimbrough-Green CK, et al. Topical tretinoin (retinoid acid) therapy for hyperpigmented lesions caused by inflammation of the skin in black patients. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1438-1443.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Choosing an insect repellent for your child. Healthy Children website. Updated July 18, 2018. Accessed January 8, 2019.

- Agbai ON, Buster K, Sanchez M, et al. Skin cancer and photoprotection in people of color: a review and recommendations for physicians and the public. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:312-317.

- Buster KJ, You Z, Fouad M, et al. Skin cancer risk perceptions: a comparison across ethnicity, age, education, gender, and income. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:771-779.

- Downie J. Help prevent and reverse post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation. Pract Dermatol Pediatr. May/June 2011:12-14. Accessed January 18, 2019.

- Ammonium lactate lotion 12% [package insert]. Bronx, New York: Perrigo New York, Inc; 2006.

- Grimes PE. Management of hyperpigmentation in darker racial ethnic groups. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009;28:77-85.

Practice Points

- The US population of children with skin of color is growing rapidly.

- Treating the underlying inflammatory dermatosis is the most important step in managing postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH); however, many pediatric PIH patients and their parents/guardians presenting with a chief concern of pigmentary changes are unaware of the associated inflammatory condition.

- When appropriate, choose treatments for the underlying inflammatory condition that can simultaneously improve any existing PIH. Gentle skin care, avoidance of rubbing and scrubbing the skin, and photoprotection are essential to halt worsening of PIH.

- Patients’ parents/guardians may consent to more aggressive PIH treatment in select cases (eg, emotional distress in adolescents).

Safety and Efficacy of Halobetasol Propionate Lotion 0.01% in the Treatment of Moderate to Severe Plaque Psoriasis: A Pooled Analysis of 2 Phase 3 Studies

Psoriasis is a chronic, immune-mediated, inflammatory disease affecting almost 2% of the population.1-3 It is characterized by patches of raised reddish skin covered by silvery-white scales. Most patients have limited disease (<5% body surface area [BSA] involvement) that can be managed with topical agents.4 Topical corticosteroids (TCSs) are considered first-line therapy for mild to moderate disease because of the inflammatory nature of the condition and often are used in conjunction with systemic agents in more severe psoriasis.4

As many as 20% to 30% of patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis have inadequate disease control.5 Several factors may affect patient outcomes; however, drug selection and patient adherence are important given the chronic nature of the disease. A survey of 1200 patients with psoriasis reported nonadherence rates of 73% with topical therapy.6 In addition, patients tend to apply less than the recommended dose or abandon treatment altogether if rapid improvement does not occur7,8; it is not uncommon for patients with psoriasis to mistakenly believe treatment will improve their condition within 1 to 2 weeks.9 Patient satisfaction with topical treatments is low, partly because of these false expectations and formulation issues. Treatments can be greasy and sticky, with unpleasant odors and the potential to stain clothes and linens.7,10 Safety concerns with TCSs also limit their consecutive use beyond 2 to 4 weeks, which is not ideal for a disease that requires a long-term management strategy.

A potent/superpotent TCS that is administered once daily and has a safety profile that affords longer-term, once-daily treatment in an aesthetically pleasing formulation would seem ideal. Herein, we investigate the safety and tolerability of a novel low-concentration (0.01%) lotion formulation of halobetasol propionate (HP), reporting on the pooled data from 2 phase 3 clinical studies in participants with moderate to severe psoriasis.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted 2 multicenter, double-blind, randomized, parallel-group phase 3 studies to assess the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of HP lotion 0.01% in participants with a clinical diagnosis of moderate to severe psoriasis with an investigator global assessment (IGA) score of 3 or 4 and an affected BSA of 3% to 12%. Participants were randomized (2:1) to receive HP lotion or vehicle applied topically to the affected area once daily for 8 weeks.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The studies included individuals of either sex aged 18 years or older. A target lesion was defined primarily to assess signs of psoriasis, measuring 16 to 100 cm2, with a score of 3 (moderate) or higher for 2 of 3 different psoriasis signs—erythema, plaque elevation, and scaling—and summed score of 8 or higher, with no sign scoring less than 2. Participants who had pustular psoriasis or used phototherapy, photochemotherapy, or systemic psoriasis therapy within the prior 4 weeks or biologics within the prior 3 months, or those who were diagnosed with skin conditions that would interfere with the interpretation of results were excluded from the studies.

Study Oversight

Participants provided written informed consent before study-related procedures were performed, and the protocol and consent were approved by institutional review boards or ethics committees at all investigational sites. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Efficacy Assessment

A 5-point scale ranging from 0 (clear) to 4 (severe) was used by the investigator at each study visit to assess the overall psoriasis severity of the treatable areas. Treatment success (the percentage of participants with at least a 2-grade improvement in baseline IGA score and a score of 0 [clear] or 1 [almost clear]) was evaluated at weeks 2, 4, 6, and 8, w

Signs of psoriasis at the target lesion were assessed at each visit using individual 5-point scales ranging from 0 (clear) to 4 (severe). Treatment success was defined as at least a 2-grade improvement from baseline score for each of the key signs—erythema, plaque elevation, and scaling—and reported at weeks 2, 4, 6, and 8, with a posttreatment follow-up at week 12.

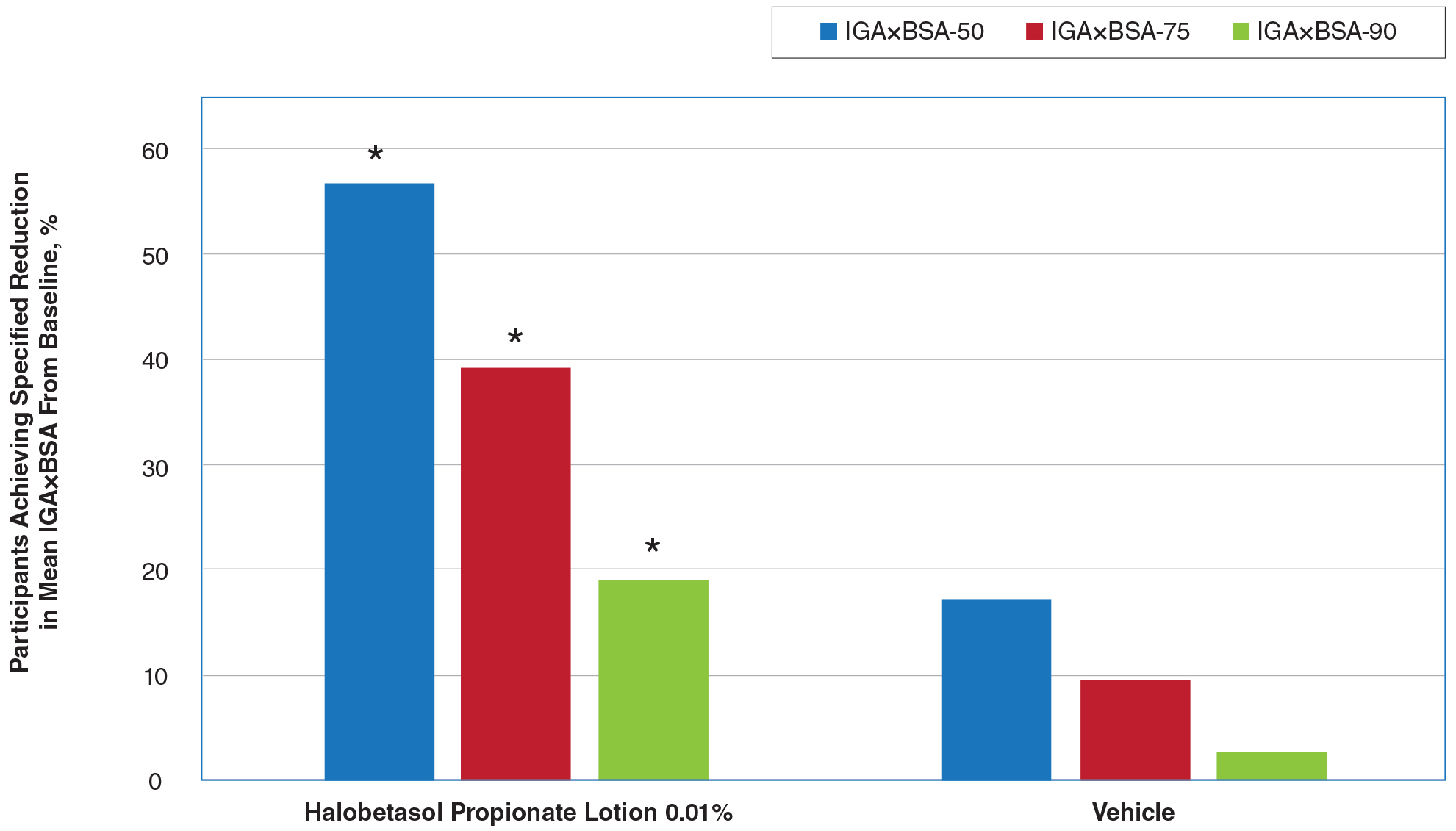

Affected BSA also was evaluated at each visit. In addition, an IGA×BSA composite score was calculated by multiplying the IGA by the BSA (range, 9–48 [eg, maximum IGA=4 and maximum BSA=12]) at each time point. The mean percentage change in IGA×BSA from baseline was calculated for each study visit. Additional end points included the achievement of a 50%, 75%, and 90% or greater reduction from baseline IGA×BSA score—IGA×BSA-50, IGA×BSA-75, and IGA×BSA-90—at week 8.

Safety Assessment

Safety evaluations including adverse events (AEs), local skin reactions (LSRs), vital signs, laboratory evaluations, and physical examinations were performed. Information on reported and observed AEs was obtained at each visit. Routine safety laboratory tests were performed at screening, week 4, and week 8. An abbreviated physical examination was performed at baseline, week 8 (end of treatment), and week 12 (end of study). Treatment areas also were examined by the investigator at baseline and each subsequent visit for the presence or absence of marked known drug-related AEs including skin atrophy, striae, telangiectasia, and folliculitis.

LSR Assessment

Local skin reactions such as itching, dryness, and burning/stinging were evaluated at each study visit using 4-point scales ranging from 0 (clear) to 3 (severe). Given the nature of the disease, the presence of LSRs and symptoms at baseline is commonplace, and as such, these evaluations identified both improvement and any emergent issues.

Statistical Analysis

The primary study goal was to assess differences in treatment efficacy between HP lotion and vehicle with respect to IGA. All statistical processing was performed using SAS unless otherwise stated; statistical tests were 2-sided and performed at the 0.05 level of significance. Markov Chain Monte Carlo multiple imputation was the primary method used to handle missing efficacy data. No imputations were made for missing safety data. All participants were randomized, and the dispensed study drug was included in the intention-to-treat analysis set. This analysis was considered primary for the evaluation of efficacy. Data were analyzed using Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel tests, stratified by analysis center.

Body surface area data were analyzed in a post hoc analysis of covariance with factors of treatment and analysis center and baseline BSA as a covariate. P values for comparisons of percentage change in IGA×BSA were derived from a Wilcoxon rank sum test. For IGA×BSA-50, IGA×BSA-75, and IGA×BSA-90, P values were derived from a Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test. Last observation carried forward was used to impute data for IGA and BSA through week 8 prior to analysis.

The primary safety analysis was conducted at week 8 using the safety analysis set, which included all participants who were randomized, received at least 1 confirmed dose of the study drug, and had at least 1 postbaseline safety assessment. Adverse events were recorded and classified using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA, Version 18.0). A post hoc Wilcoxon rank sum test was conducted to compare itching, dryness, and burning/stinging scores at week 8 for HP lotion versus vehicle.

RESULTS

Participant Disposition

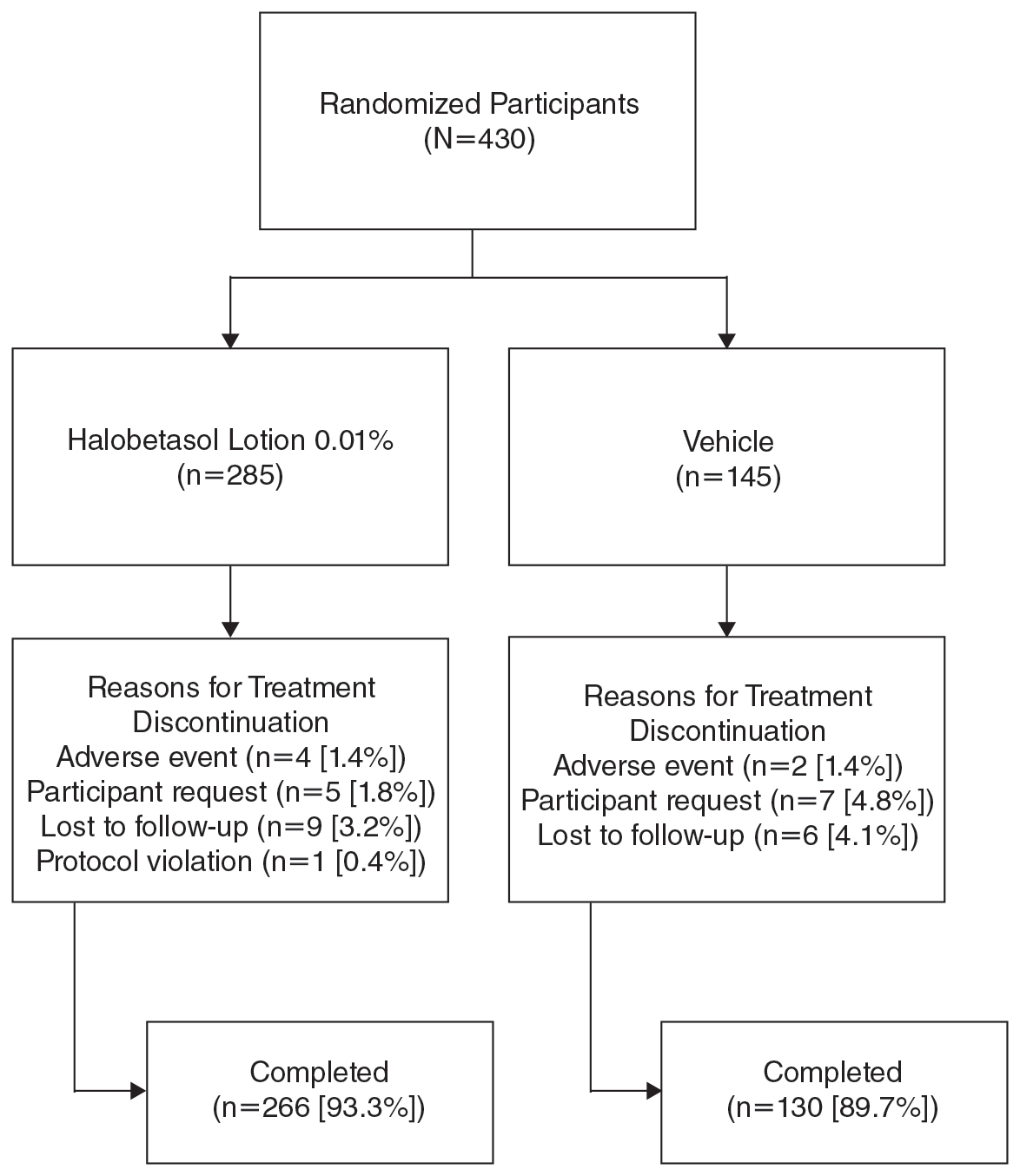

Overall, 430 participants were randomized (2:1) to HP lotion (n=285) or vehicle (n=145)(eFigure 1) and included in the intention-to-treat population. Across the 2 studies, 93.3% (n=266) of participants treated with HP lotion and 89.7% (n=130) of participants treated with vehicle completed treatment. The main reasons for study discontinuation with HP lotion were lost to follow-up (3.2%; n=9), participant request (1.8%; n=5), and AEs (1.4%; n=4). Participant request (4.8%; n=7), lost to follow-up (4.1%; n=6), and AEs (1.4%; n=2) also were the main reasons for treatment discontinuation in the vehicle arm.

A total of 426 participants were included in the safety population, with no postbaseline safety evaluation in 4 participants.

Baseline Participant Demographics

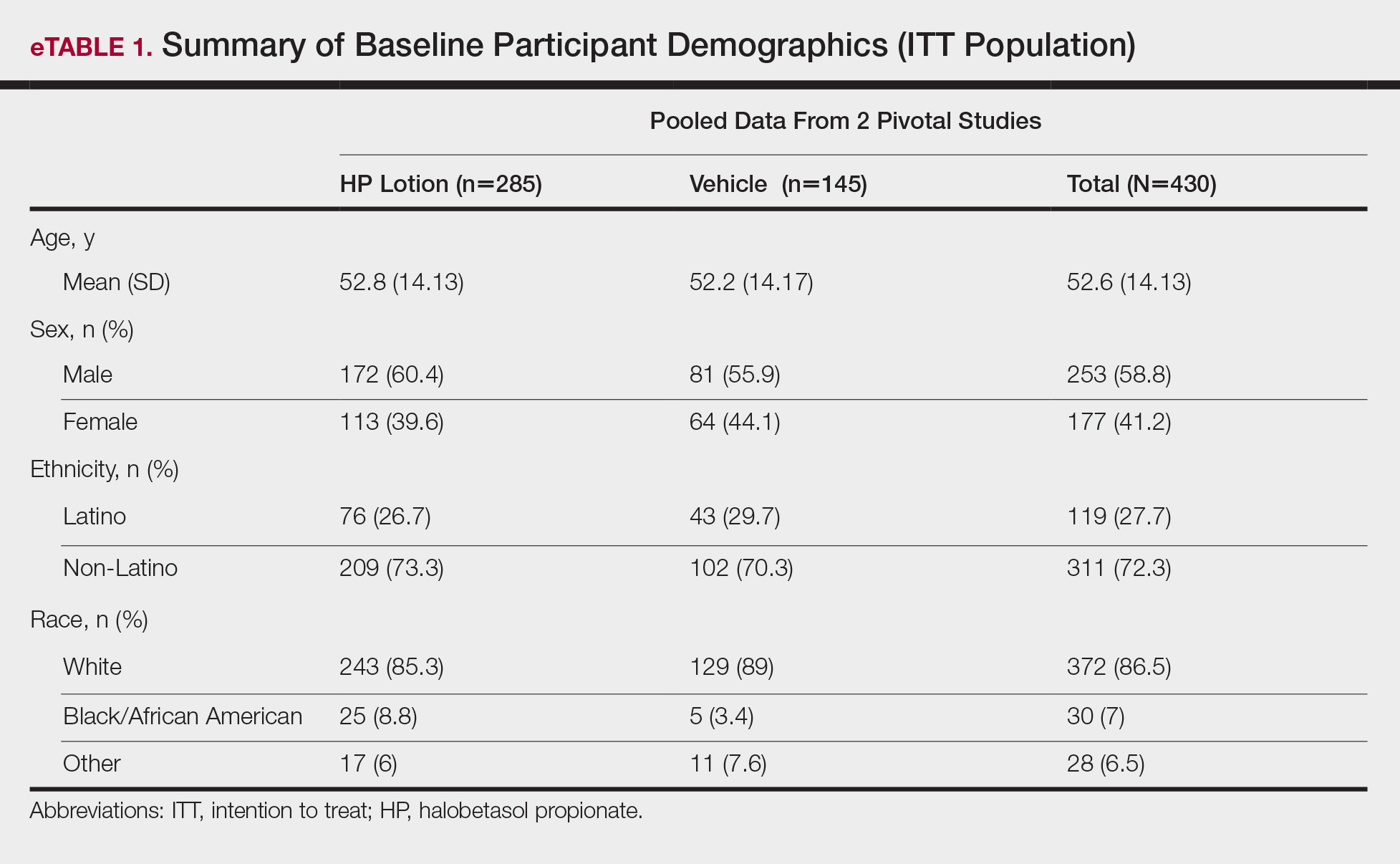

Demographic data were comparable across the 2 studies. The mean age (SD) was 52.6 (14.13) years. Overall, the majority of participants were male (58.8%; n=253) and white (86.5%; n=372)(eTable 1).

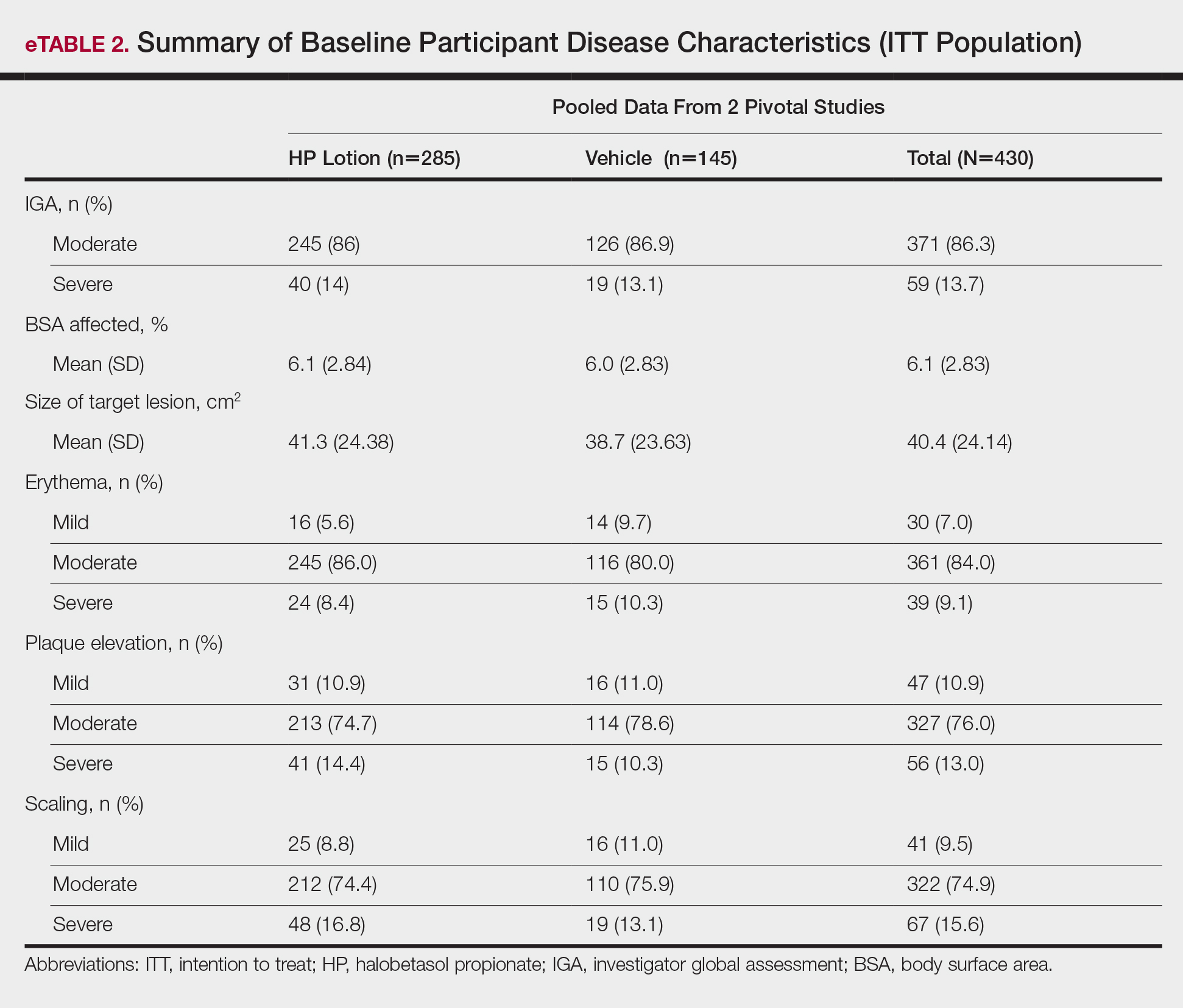

Baseline disease characteristics also were comparable across the treatment groups. Participants had moderate (86.3%; n=371) or severe (13.7%; n=59) disease, with a mean BSA (SD) of 6.1% (2.83) and mean size of target lesion (SD) of 40.4 cm2 (24.14). The majority of participants had moderate (erythema, 84.0%; plaque elevation, 76.0%; and scaling, 74.9%) or severe (erythema, 9.1%; plaque elevation, 13.0%; and scaling, 15.6%) signs of psoriasis at the target lesion site (eTable 2).

Efficacy Evaluation

IGA of Disease Severity

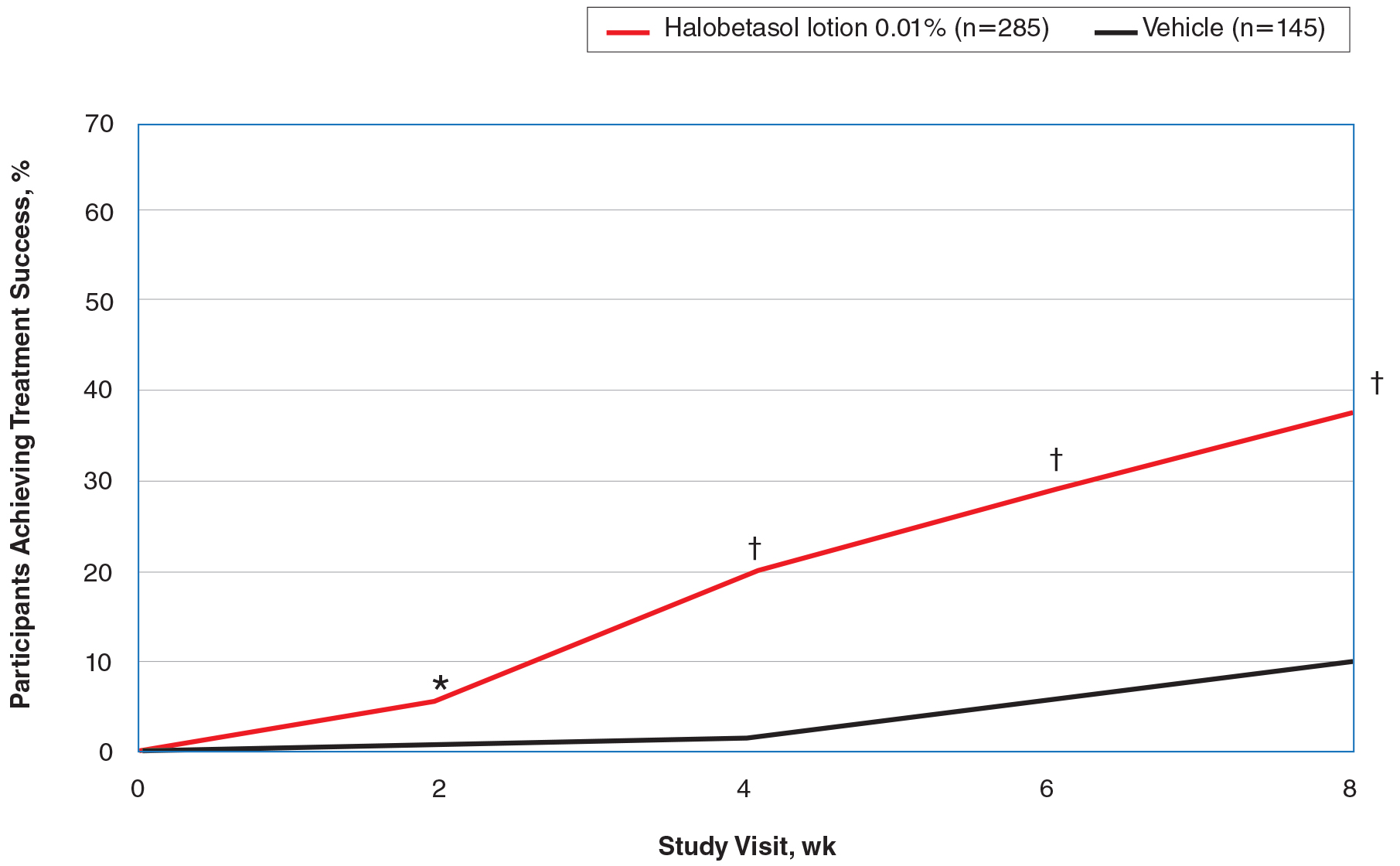

Halobetasol propionate lotion was consistently more effective than its vehicle in achieving treatment success (at least a 2-grade improvement in baseline IGA score and a score of 0 [clear] or 1 [almost clear]). Halobetasol propionate lotion demonstrated statistically significant superiority over vehicle as early as week 2 (P=.003). By week 8, 37.43% of participants in the HP lotion group achieved treatment success compared with 10.03% in the vehicle group (P<.001)(Figure 1).

Overall, 39% of participants who had moderate disease (IGA score, 3) at baseline were treatment successes with HP lotion at week 8 compared with 11.53% of participants treated with vehicle; 27.97% of participants with severe disease (IGA score, 4) were treatment successes, with at least a 3-grade improvement in IGA. No participants with severe psoriasis who were treated with vehicle achieved treatment success at week 8. Efficacy was similar in female and male participants, allowing for vehicle effects.

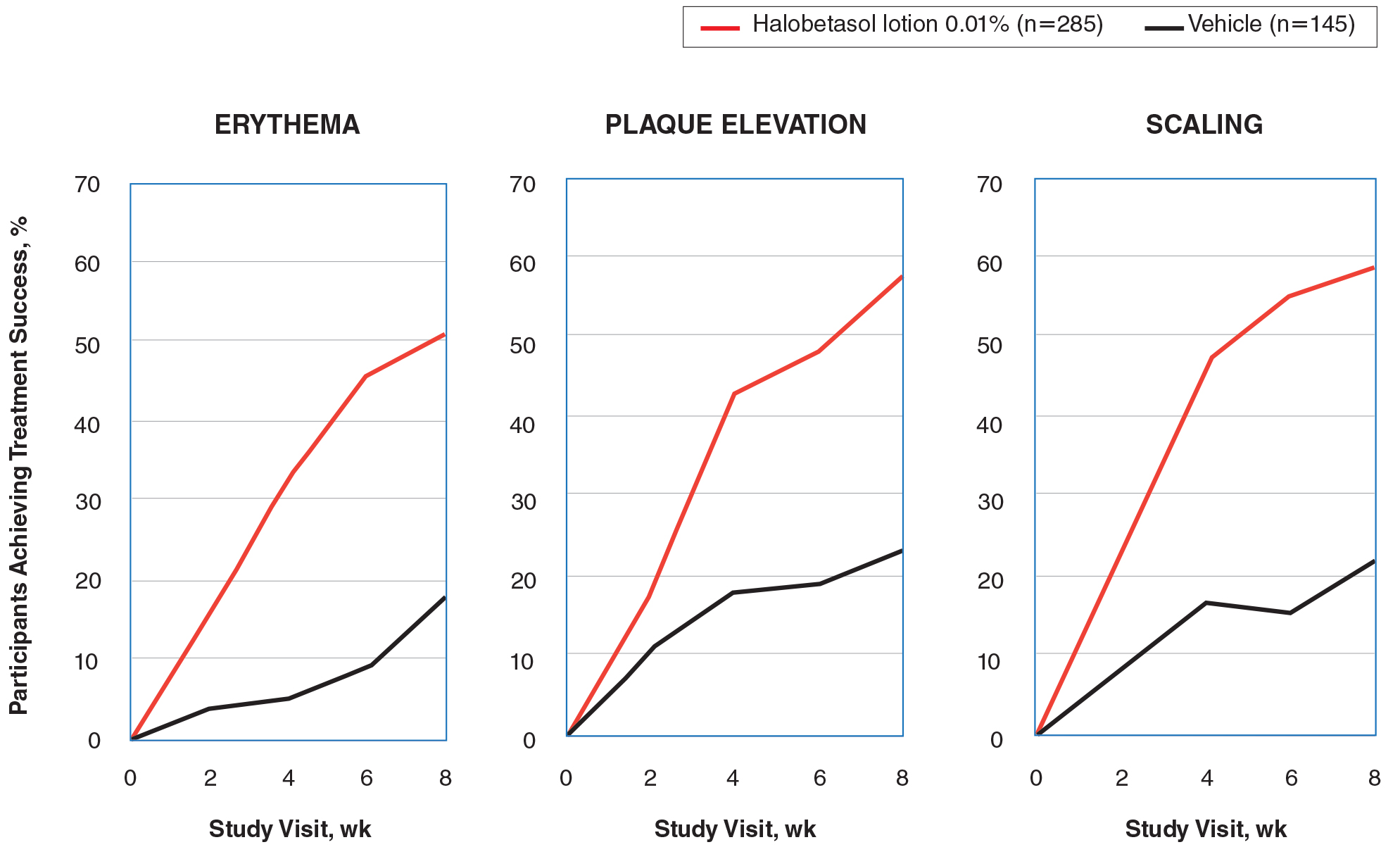

Severity of Signs of Psoriasis (Erythema, Plaque Elevation, and Scaling) at Target Lesion Site

Halobetasol propionate lotion was statistically superior to vehicle in reducing the psoriasis signs of erythema, plaque elevation, and scaling at the target lesion from week 2. At week 8, treatment success (at least a 2-grade improvement from baseline) was achieved by 51.48% (erythema), 57.64% (plaque elevation), and 58.98% (scaling) of participants compared with 17.85%, 23.61%, and 22.82%, respectively, with vehicle (all P<.001)(Figure 2).

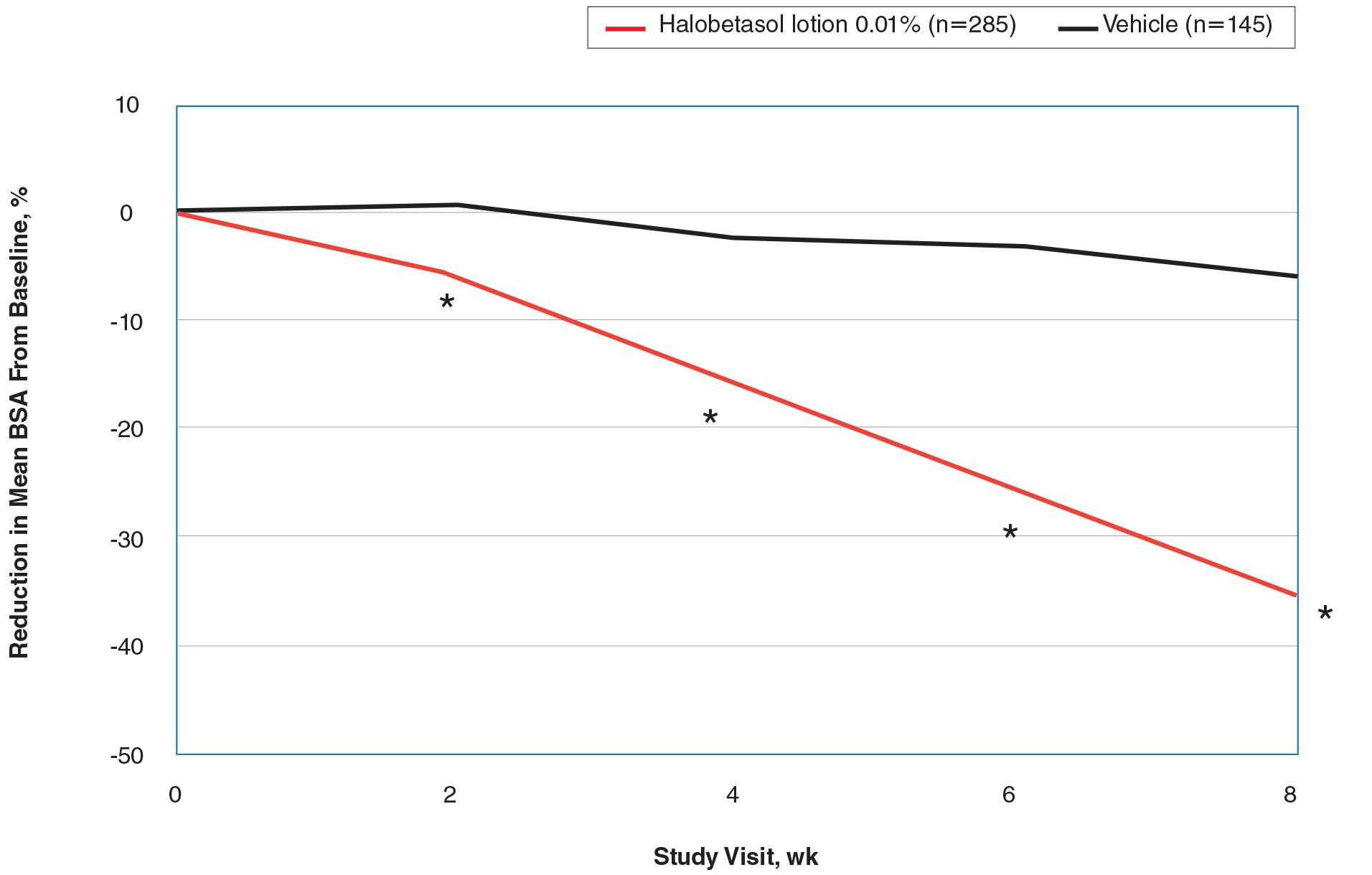

BSA Assessment

Halobetasol propionate lotion was statistically superior to vehicle in reducing BSA from week 2. At week 8 there was a 35.20% reduction in mean BSA for HP lotion compared to 5.85% for vehicle (P<.001)(eFigure 2).

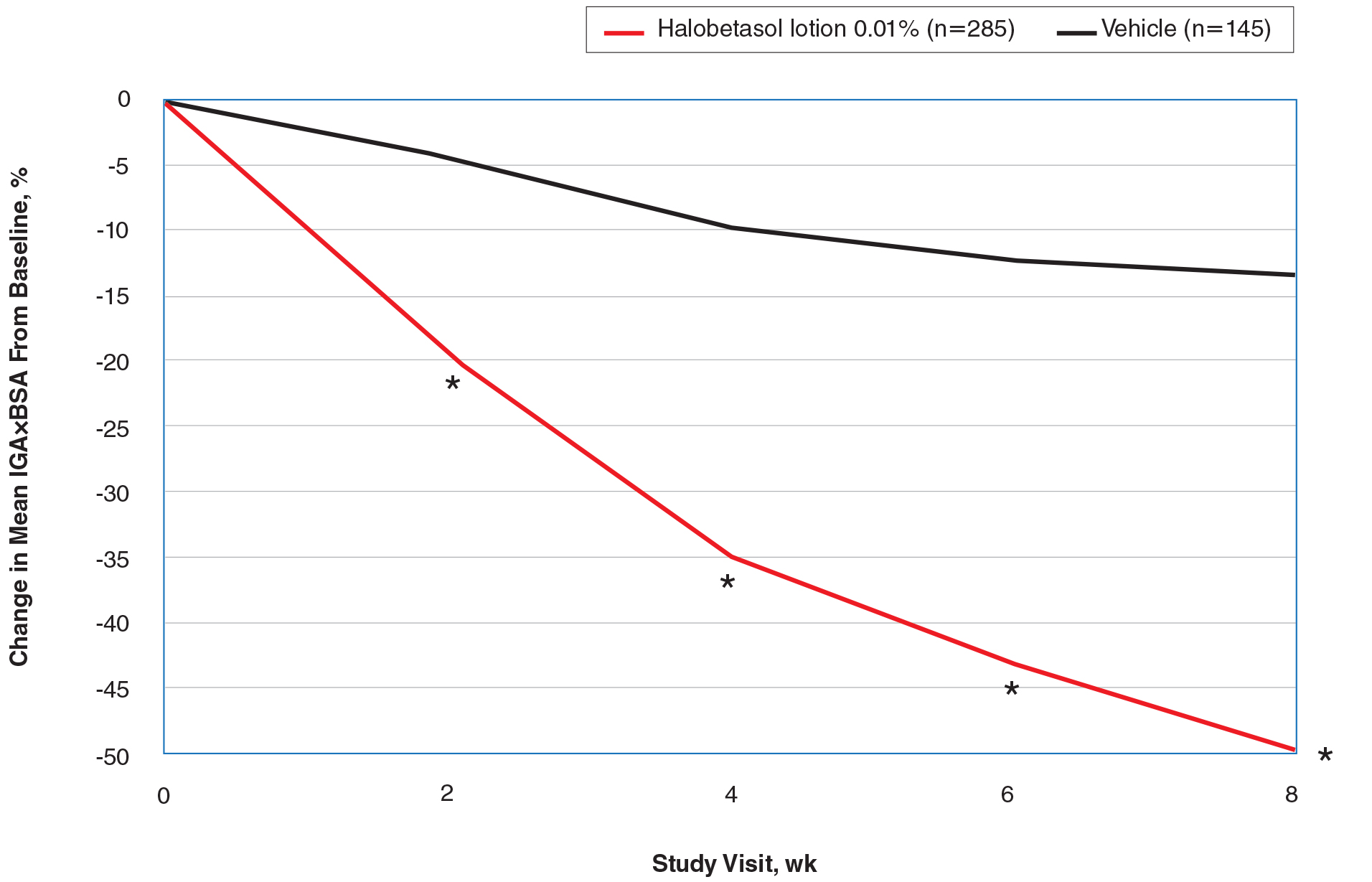

IGA×BSA Composite Score

At baseline, the mean IGA×BSA scores for HP lotion and vehicle were similar: 19.3 and 18.8, respectively. By week 8, the percentage change in mean IGA×BSA score with HP lotion was 49.44% compared to 13.35% with vehicle (P<.001). Differences were significant from week 2 (P<.001)(Figure 3).

By week 8, 56.8% of participants (n=162) treated with HP lotion had achieved a 50% or greater reduction in baseline IGA×BSA compared to 17.2% of participants treated with vehicle (P<.001). Reductions of IGA×BSA-75 and IGA×BSA-90 were achieved in 39.3% and 19.3% of participants treated with HP lotion, respectively, compared with 9.7% and 2.8% of participants treated with vehicle (both P<.001)(eFigure 3).

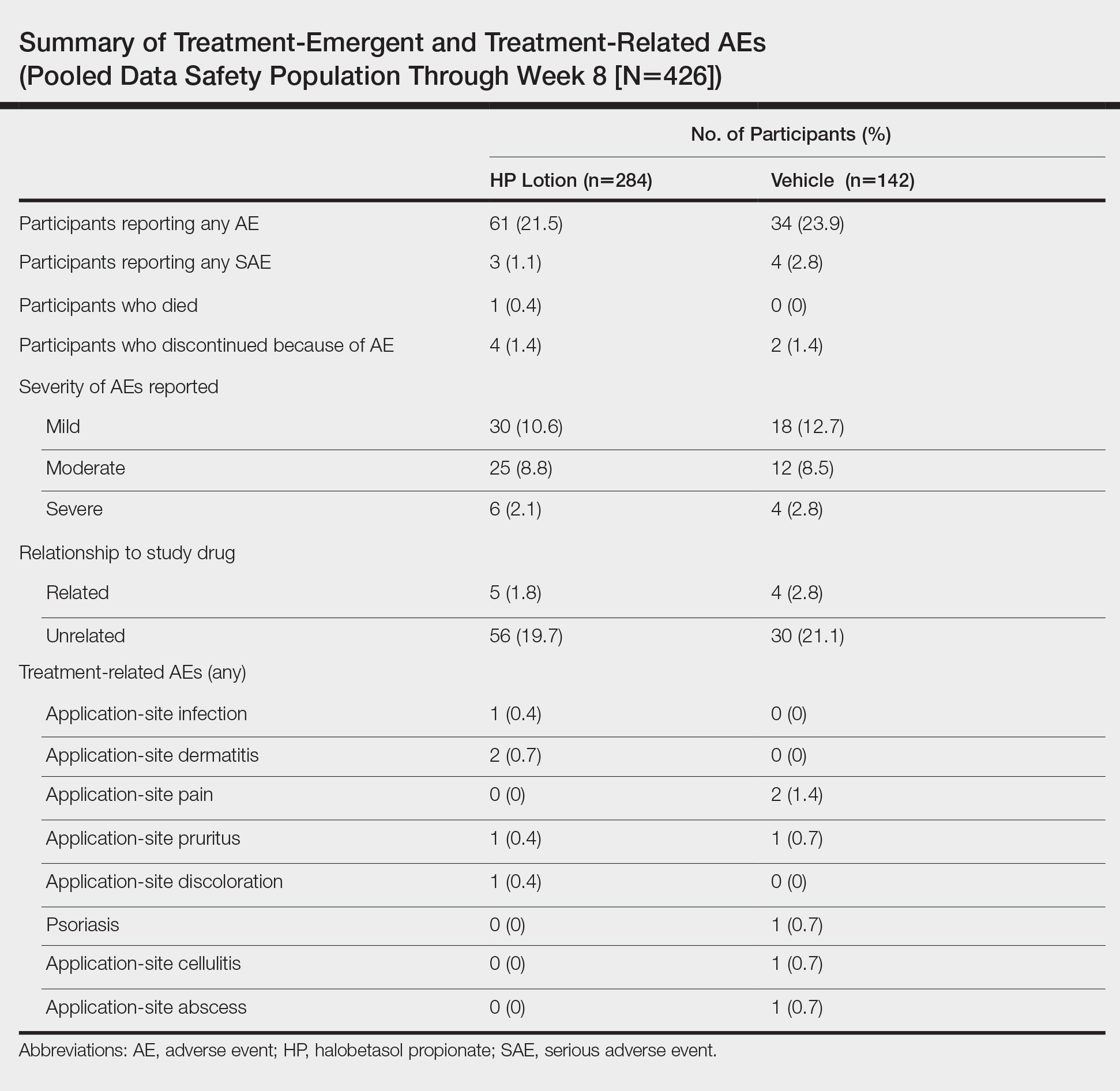

Safety Evaluation

Adverse event reports were low and similar between the active and vehicle groups. Overall, 61 participants (21.5%) treated with HP lotion reported AEs compared with 34 participants (23.9%) treated with vehicle (Table). The majority of participants treated with HP lotion (90.2%) had AEs that were mild or moderate. There was 1 AE of telangiectasia, not considered treatment related. There were 5 treatment-related AEs for HP lotion, all at the application site: dermatitis (0.7%; n=2), infection (0.4%; n=1), pruritus (0.4%; n=1), and discoloration (0.4%; n=1). There were no AE reports of skin atrophy or folliculitis.

Local Skin Reactions

Most LSRs at baseline were mild to moderate in severity. Itching was the most common, present in 76.8% of participants. Participant-reported burning/stinging was less common, reported by 40.6% of participants. Investigator-reported dryness was noted in 65.7% of participants. There was a rapid improvement in participant-reported itching as early as week 2 that was sustained to the end of the studies, with more gradual improvements in skin dryness and burning/stinging.

COMMENT

Plaque psoriasis is a chronic condition. The rationale behind the development of HP lotion 0.01% was to provide optimal topical treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis, allowing for the potential of prolonged use beyond the 2-week consecutive use normally applied to HP cream 0.05% in a light, once-daily, aesthetically pleasing lotion formulation that patients would prefer.

Treatment success was rapid and achieved in more than 37% of participants by week 8, with significant improvements in psoriasis signs and symptoms (erythema, plaque elevation, and scaling) compared with vehicle. However, IGA does not consider BSA involvement, a key aspect of disease severity,11,12 and improvements in psoriasis signs of erythema, plaque elevation, and scaling were only assessed at the target lesion. Recently, the product of the IGA and BSA involvement (IGA×BSA) has been proposed as a simple alternative for assessing response to therapy that has been consistently shown to be highly correlated with the psoriasis area and severity index.13-19 Halobetasol propionate lotion 0.01% achieved a 50% reduction in IGA×BSA score by week 8. This efficacy compares well with results reported with apremilast in patients with moderate plaque psoriasis.20

Achieving clinically meaningful outcomes is an important aspect of disease management, especially in psoriasis with its disease burden and detriment to quality of life. It has been suggested that achieving a 75% or greater reduction from baseline IGA×BSA score (IGA×BSA-75) is an appropriate clinical goal.20 In our investigation, IGA×BSA-75 was achieved by 39% of participants treated with HP lotion by week 8, which again compares favorably with 35% of participants in the apremilast study who achieved IGA×BSA-75 at week 16.20

Physicians continue to have long-term safety concerns with TCSs,4,11,12 participants remain concerned about the risk for skin thinning,13 and product labelling restricts HP cream 0.05% consecutive use to 2 weeks. In clinical experience, HP cream 0.05% is well tolerated, with potential local AEs similar to those experienced with other superpotent TCSs. In short-term clinical trials, local AEs at the site of application were reported in up to 13% of patients21-26; itching, burning, or stinging were the most common local AEs (reported in 4.4% of patients).27

There were minimal safety concerns in our 2 studies using an 8-week, once-daily treatment regimen with HP lotion 0.01%. Local AEs at the application site were reported in less than 1% of participants. Baseline itching, dryness, and burning/stinging all improved with treatment.

CONCLUSION

Halobetasol propionate lotion 0.01% provides rapid improvement in disease severity. Halobetasol propionate lotion was consistently more effective than vehicle in achieving treatment success; reducing the BSA affected by the disease; reducing erythema, plaque elevation, and scaling at the target lesion; and improving IGA×BSA score over 8 weeks, which is a realistic time frame to see improvement in psoriasis with a topical steroid. There were minimal safety concerns with prolonged use. Halobetasol propionate lotion may provide an effective and reasonable treatment option in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.

Acknowledgment

We thank Brian Bulley, MSc (Konic Limited, United Kingdom), for assistance with the preparation of this article. Ortho Dermatologics funded Mr. Bulley’s activities pertaining to this article.

- Gudjonsson JE, Elder JT. Psoriasis: epidemiology. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:535-546.

- Liu Y, Krueger JG, Bowcock AM. Psoriasis: genetic associations and immune system changes. Genes Immun. 2007;8:1-12.

- Nestle FO, Kaplan DH, Barker J. Psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:496-509.

- Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. section 3. guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:643-659.

- Alinia H, Moradi Tuchayi S, Smith JA, et al. Long-term adherence to topical psoriasis treatment can be abysmal: a 1-year randomized intervention study using objective electronic adherence monitoring. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:759-764.

- Young M, Aldredge L, Parker P. Psoriasis for the primary care practitioner. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2017;29:157-178.

- Devaux S, Castela A, Archier E, et al. Adherence to topical treatment in psoriasis: a systematic literature review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26(suppl 3):61-67.

- Ersser SJ, Cowdell FC, Latter SM, et al. Self-management experiences in adults with mild-moderate psoriasis: an exploratory study and implications for improved support. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:1044-1049.

- Choi CW, Kim BR, Ohn J, et al. The advantage of cyclosporine A and methotrexate rotational therapy in long-term systemic treatment for chronic plaque psoriasis in a real world practice. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29:55-60.

- Callis Duffin K, Yeung H, Takeshita J, et al. Patient satisfaction with treatments for moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis in clinical practice. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:672-680.

- Spuls PI, Lecluse LL, Poulsen ML, et al. How good are clinical severity and outcome measures for psoriasis? quantitative evaluation in a systematic review. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:933-943.

- Menter A, Gottlieb A, Feldman SR, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 1. overview of psoriasis and guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:826-850.

- Bozek A, Reich A. The reliability of three psoriasis assessment tools: psoriasis area severity index, body surface area and physician global assessment. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2017;26:851-856.

- Walsh JA, McFadden M, Woodcock J, et al. Product of the Physician Global Assessment and body surface area: a simple static measure of psoriasis severity in a longitudinal cohort. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:931-937.

- Paul C, Cather J, Gooderham M, et al. Efficacy and safety of apremilast, an oral phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis over 52 weeks: a phase III, randomized, controlled trial (ESTEEM 2). Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:1387-1399.

- Duffin KC, Papp KA, Bagel J, et al. Evaluation of the Physician Global Assessment and body surface area composite tool for assessing psoriasis response to apremilast therapy: results from ESTEEM 1 and ESTEEM 2. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:147-153.

- Chiesa Fuxench ZC, Callis DK, Siegel M, et al. Validity of the Simple Measure for Assessing Psoriasis Activity (S-MAPA) for objectively evaluating disease severity in patients with plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:868-870.

- Walsh J. Comparative assessment of PASI and variations of PGA×BSA as measures of psoriasis severity in a clinical trial of moderate to severe psoriasis [poster 1830]. Presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology; March 20-24, 2015; San Francisco, CA.

- Gottlieb AB, Merola JF, Chen R, et al. Assessing clinical response and defining minimal disease activity in plaque psoriasis with the Physician Global Assessment and body surface area (PGA×BSA) composite tool: An analysis of apremilast phase 3 ESTEEM data. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:1178-1180.

- Strober B, Bagel J, Lebwohl M, et al. Efficacy and safety of apremilast in patients with moderate plaque psoriasis with lower BSA: week 16 results from the UNVEIL study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:801-808.