User login

Low-dose tamoxifen halves recurrence of breast intraepithelial neoplasia

SAN ANTONIO – New life for old medicine: Women aged under 75 years with breast intraepithelial neoplasms (IEN) who took tamoxifen for 3 years at a dose of 5 mg per day – one-fourth the standard dose – had a 50% reduction in risk of IEN recurrence and an even more remarkable 75% reduction in the risk of contralateral breast cancer, compared with women who took placebos in the TAMO1 study.

Despite concerns about the known side effects of tamoxifen, there were no significant differences in either the rate of endometrial cancer or of deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism between groups, and there was only a borderline increase in hot flashes among patients randomized to tamoxifen, reported Dr. Andrea De Censi, MD, from Ospedali Galliera in Genoa, Italy.

In a video interview, Dr. De Censi discusses how tamoxifen, a decades-old, inexpensive drug still offers real clinical benefit in day-to-day practice for patients with IEN.

The TAM01 study was supported by the Italian Ministry of Health, Italian Association for Cancer Research, and the Italian League Against Cancer. Dr. De Censi and his coauthors reported having no direct conflicts of interest.

SAN ANTONIO – New life for old medicine: Women aged under 75 years with breast intraepithelial neoplasms (IEN) who took tamoxifen for 3 years at a dose of 5 mg per day – one-fourth the standard dose – had a 50% reduction in risk of IEN recurrence and an even more remarkable 75% reduction in the risk of contralateral breast cancer, compared with women who took placebos in the TAMO1 study.

Despite concerns about the known side effects of tamoxifen, there were no significant differences in either the rate of endometrial cancer or of deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism between groups, and there was only a borderline increase in hot flashes among patients randomized to tamoxifen, reported Dr. Andrea De Censi, MD, from Ospedali Galliera in Genoa, Italy.

In a video interview, Dr. De Censi discusses how tamoxifen, a decades-old, inexpensive drug still offers real clinical benefit in day-to-day practice for patients with IEN.

The TAM01 study was supported by the Italian Ministry of Health, Italian Association for Cancer Research, and the Italian League Against Cancer. Dr. De Censi and his coauthors reported having no direct conflicts of interest.

SAN ANTONIO – New life for old medicine: Women aged under 75 years with breast intraepithelial neoplasms (IEN) who took tamoxifen for 3 years at a dose of 5 mg per day – one-fourth the standard dose – had a 50% reduction in risk of IEN recurrence and an even more remarkable 75% reduction in the risk of contralateral breast cancer, compared with women who took placebos in the TAMO1 study.

Despite concerns about the known side effects of tamoxifen, there were no significant differences in either the rate of endometrial cancer or of deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism between groups, and there was only a borderline increase in hot flashes among patients randomized to tamoxifen, reported Dr. Andrea De Censi, MD, from Ospedali Galliera in Genoa, Italy.

In a video interview, Dr. De Censi discusses how tamoxifen, a decades-old, inexpensive drug still offers real clinical benefit in day-to-day practice for patients with IEN.

The TAM01 study was supported by the Italian Ministry of Health, Italian Association for Cancer Research, and the Italian League Against Cancer. Dr. De Censi and his coauthors reported having no direct conflicts of interest.

REPORTING FROM SABCS 2018

Adjuvant capecitabine found disappointing in TNBC

SAN ANTONIO – Adjuvant capecitabine does not improve outcomes in women with early-stage triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) who have undergone resection and received standard chemotherapy, finds a phase 3, randomized, controlled trial jointly conducted by the Spanish GEICAM group and the Central and South American CIBOMA group. But the story may not end there.

Findings reported in a session and press conference at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium showed that, compared with observation, eight cycles of adjuvant capecitabine (Xeloda) reduced the 5-year risks of disease-free survival events and death by a nonsignificant relative 18% and 8%, respectively, among all 876 women randomized. However, the subgroup whose tumors had the nonbasal phenotype saw large significant benefits, with 47% and 58% relative reductions in these risks, respectively.

“The trial is formally negative,” commented lead investigator Miguel Martín, MD, PhD, head of the medical oncology service at Hospital Gregorio Marañón in Madrid. However, the observation arm fared better than expected. In addition, the trial had a very low–risk patient population, which may help explain why its findings differ somewhat from the more positive findings of the similar CREATE-X trial.

“Our data don’t speak against the CREATE-X study. My personal view is that capecitabine is useful for some TNBC patients,” Dr. Martin said. “Our study is not finished because we are going to look at the genomic characteristics of this group defined as non–basal-like because we want to know more about this subgroup. We are planning also to reproduce our subset in the CREATE-X trial to see if this is a real finding because we are in the era of personalized medicine.”

TNBC is a broad group defined only by negative findings for the main markers having available treatments, he elaborated. “So if we could define a subpopulation that actually benefited from capecitabine, this will be great for the patients.” Currently, conventional pathology does not routinely report on tumor basal phenotype, so all TNBC patients receive the same drugs. “This is a mistake. We should select the right drug for the right patient. Probably not all breast cancer patients are sensitive to the same drugs. But the fact is that we don’t have funding to run trials looking at that because this kind of trial is not interesting for pharma companies.”

“That’s an important message that triple-negative is really a big, very heterogeneous group,” agreed SABCS codirector and press conference moderator Carlos Arteaga, MD, director of the Harold C. Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center and associate dean of oncology programs at the University of Texas, Dallas.

Patients and clinicians alike are largely unaware of the presence of TNBC basal and nonbasal subtypes and their potential importance, he said. “We all need some education on that, us included. It’s a very, very heterogeneous group, it is one that is very challenging. We need to start by educating all of us that there is a need to do research on that. ... We have a duty to define this phenotype better.”

Study details

“TNBC is sensitive to chemotherapy, but a significant proportion of patients will eventually relapse after conventional anthracycline and taxane combinations, so we need new approaches to this population,” Dr. Martín noted.

The trial, joint GEICAM/2003-11 and CIBOMA/2004-01, was designed in 2004. Although no information about capecitabine in breast cancer was available at the time, the investigators selected this drug because it is non–cross-resistant with anthracyclines and taxanes.

About 55% of the patients randomized had node-negative disease and roughly 80% received adjuvant chemotherapy alone because neoadjuvant chemotherapy was generally not used 14 years ago, Dr. Martín noted.

After a median follow-up of 7.34 years, the 5-year disease-free survival rate—the trial’s primary endpoint—was 79.6% with capecitabine and 76.8% with observation, a nonsignificant difference in both unadjusted analysis (hazard ratio, 0.82; P = .136) and adjusted analysis (HR, 0.79; P = .082). The 5-year overall survival rate was 86.2% with capecitabine and 85.9% with observation, another nonsignificant difference (HR, 0.92; P = .623).

However, in subgroup analyses among the 248 patients with nonbasal disease, defined as immunohistochemically negative for both EGFR and CK5/6, capecitabine conferred a significant disease-free survival advantage (HR, 0.53; P = .02) and overall survival advantage (HR, 0.420; P = .007) relative to observation.

Interaction of basal/nonbasal phenotype with treatment was marginal for disease-free survival (P = .0694) and significant for overall survival (P = .0052).

In the nonbasal subgroup, the disease-free survival benefit of capecitabine was mainly driven by a reduction in distant recurrences, particularly in the liver and the brain.

Adjuvant capecitabine had tolerability that was “exactly as expected,” according to Dr. Martín. The median dose intensity was 86.3%, and 75.2% of patients completed all of the planned eight cycles.

The trial was supported by Roche, which also provided capecitabine. Dr. Martín reported receiving speaker’s honoraria from Pfizer and Eli Lilly; honoraria for participation in advisory boards from AstraZeneca, Novartis, Roche-Genentech, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, PharmaMar, Taiho Oncology, and Eli Lilly; and research grants from Novartis and Roche.

SOURCE: Martín M et al. SABCS 2018, Abstract GS2-04.

SAN ANTONIO – Adjuvant capecitabine does not improve outcomes in women with early-stage triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) who have undergone resection and received standard chemotherapy, finds a phase 3, randomized, controlled trial jointly conducted by the Spanish GEICAM group and the Central and South American CIBOMA group. But the story may not end there.

Findings reported in a session and press conference at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium showed that, compared with observation, eight cycles of adjuvant capecitabine (Xeloda) reduced the 5-year risks of disease-free survival events and death by a nonsignificant relative 18% and 8%, respectively, among all 876 women randomized. However, the subgroup whose tumors had the nonbasal phenotype saw large significant benefits, with 47% and 58% relative reductions in these risks, respectively.

“The trial is formally negative,” commented lead investigator Miguel Martín, MD, PhD, head of the medical oncology service at Hospital Gregorio Marañón in Madrid. However, the observation arm fared better than expected. In addition, the trial had a very low–risk patient population, which may help explain why its findings differ somewhat from the more positive findings of the similar CREATE-X trial.

“Our data don’t speak against the CREATE-X study. My personal view is that capecitabine is useful for some TNBC patients,” Dr. Martin said. “Our study is not finished because we are going to look at the genomic characteristics of this group defined as non–basal-like because we want to know more about this subgroup. We are planning also to reproduce our subset in the CREATE-X trial to see if this is a real finding because we are in the era of personalized medicine.”

TNBC is a broad group defined only by negative findings for the main markers having available treatments, he elaborated. “So if we could define a subpopulation that actually benefited from capecitabine, this will be great for the patients.” Currently, conventional pathology does not routinely report on tumor basal phenotype, so all TNBC patients receive the same drugs. “This is a mistake. We should select the right drug for the right patient. Probably not all breast cancer patients are sensitive to the same drugs. But the fact is that we don’t have funding to run trials looking at that because this kind of trial is not interesting for pharma companies.”

“That’s an important message that triple-negative is really a big, very heterogeneous group,” agreed SABCS codirector and press conference moderator Carlos Arteaga, MD, director of the Harold C. Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center and associate dean of oncology programs at the University of Texas, Dallas.

Patients and clinicians alike are largely unaware of the presence of TNBC basal and nonbasal subtypes and their potential importance, he said. “We all need some education on that, us included. It’s a very, very heterogeneous group, it is one that is very challenging. We need to start by educating all of us that there is a need to do research on that. ... We have a duty to define this phenotype better.”

Study details

“TNBC is sensitive to chemotherapy, but a significant proportion of patients will eventually relapse after conventional anthracycline and taxane combinations, so we need new approaches to this population,” Dr. Martín noted.

The trial, joint GEICAM/2003-11 and CIBOMA/2004-01, was designed in 2004. Although no information about capecitabine in breast cancer was available at the time, the investigators selected this drug because it is non–cross-resistant with anthracyclines and taxanes.

About 55% of the patients randomized had node-negative disease and roughly 80% received adjuvant chemotherapy alone because neoadjuvant chemotherapy was generally not used 14 years ago, Dr. Martín noted.

After a median follow-up of 7.34 years, the 5-year disease-free survival rate—the trial’s primary endpoint—was 79.6% with capecitabine and 76.8% with observation, a nonsignificant difference in both unadjusted analysis (hazard ratio, 0.82; P = .136) and adjusted analysis (HR, 0.79; P = .082). The 5-year overall survival rate was 86.2% with capecitabine and 85.9% with observation, another nonsignificant difference (HR, 0.92; P = .623).

However, in subgroup analyses among the 248 patients with nonbasal disease, defined as immunohistochemically negative for both EGFR and CK5/6, capecitabine conferred a significant disease-free survival advantage (HR, 0.53; P = .02) and overall survival advantage (HR, 0.420; P = .007) relative to observation.

Interaction of basal/nonbasal phenotype with treatment was marginal for disease-free survival (P = .0694) and significant for overall survival (P = .0052).

In the nonbasal subgroup, the disease-free survival benefit of capecitabine was mainly driven by a reduction in distant recurrences, particularly in the liver and the brain.

Adjuvant capecitabine had tolerability that was “exactly as expected,” according to Dr. Martín. The median dose intensity was 86.3%, and 75.2% of patients completed all of the planned eight cycles.

The trial was supported by Roche, which also provided capecitabine. Dr. Martín reported receiving speaker’s honoraria from Pfizer and Eli Lilly; honoraria for participation in advisory boards from AstraZeneca, Novartis, Roche-Genentech, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, PharmaMar, Taiho Oncology, and Eli Lilly; and research grants from Novartis and Roche.

SOURCE: Martín M et al. SABCS 2018, Abstract GS2-04.

SAN ANTONIO – Adjuvant capecitabine does not improve outcomes in women with early-stage triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) who have undergone resection and received standard chemotherapy, finds a phase 3, randomized, controlled trial jointly conducted by the Spanish GEICAM group and the Central and South American CIBOMA group. But the story may not end there.

Findings reported in a session and press conference at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium showed that, compared with observation, eight cycles of adjuvant capecitabine (Xeloda) reduced the 5-year risks of disease-free survival events and death by a nonsignificant relative 18% and 8%, respectively, among all 876 women randomized. However, the subgroup whose tumors had the nonbasal phenotype saw large significant benefits, with 47% and 58% relative reductions in these risks, respectively.

“The trial is formally negative,” commented lead investigator Miguel Martín, MD, PhD, head of the medical oncology service at Hospital Gregorio Marañón in Madrid. However, the observation arm fared better than expected. In addition, the trial had a very low–risk patient population, which may help explain why its findings differ somewhat from the more positive findings of the similar CREATE-X trial.

“Our data don’t speak against the CREATE-X study. My personal view is that capecitabine is useful for some TNBC patients,” Dr. Martin said. “Our study is not finished because we are going to look at the genomic characteristics of this group defined as non–basal-like because we want to know more about this subgroup. We are planning also to reproduce our subset in the CREATE-X trial to see if this is a real finding because we are in the era of personalized medicine.”

TNBC is a broad group defined only by negative findings for the main markers having available treatments, he elaborated. “So if we could define a subpopulation that actually benefited from capecitabine, this will be great for the patients.” Currently, conventional pathology does not routinely report on tumor basal phenotype, so all TNBC patients receive the same drugs. “This is a mistake. We should select the right drug for the right patient. Probably not all breast cancer patients are sensitive to the same drugs. But the fact is that we don’t have funding to run trials looking at that because this kind of trial is not interesting for pharma companies.”

“That’s an important message that triple-negative is really a big, very heterogeneous group,” agreed SABCS codirector and press conference moderator Carlos Arteaga, MD, director of the Harold C. Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center and associate dean of oncology programs at the University of Texas, Dallas.

Patients and clinicians alike are largely unaware of the presence of TNBC basal and nonbasal subtypes and their potential importance, he said. “We all need some education on that, us included. It’s a very, very heterogeneous group, it is one that is very challenging. We need to start by educating all of us that there is a need to do research on that. ... We have a duty to define this phenotype better.”

Study details

“TNBC is sensitive to chemotherapy, but a significant proportion of patients will eventually relapse after conventional anthracycline and taxane combinations, so we need new approaches to this population,” Dr. Martín noted.

The trial, joint GEICAM/2003-11 and CIBOMA/2004-01, was designed in 2004. Although no information about capecitabine in breast cancer was available at the time, the investigators selected this drug because it is non–cross-resistant with anthracyclines and taxanes.

About 55% of the patients randomized had node-negative disease and roughly 80% received adjuvant chemotherapy alone because neoadjuvant chemotherapy was generally not used 14 years ago, Dr. Martín noted.

After a median follow-up of 7.34 years, the 5-year disease-free survival rate—the trial’s primary endpoint—was 79.6% with capecitabine and 76.8% with observation, a nonsignificant difference in both unadjusted analysis (hazard ratio, 0.82; P = .136) and adjusted analysis (HR, 0.79; P = .082). The 5-year overall survival rate was 86.2% with capecitabine and 85.9% with observation, another nonsignificant difference (HR, 0.92; P = .623).

However, in subgroup analyses among the 248 patients with nonbasal disease, defined as immunohistochemically negative for both EGFR and CK5/6, capecitabine conferred a significant disease-free survival advantage (HR, 0.53; P = .02) and overall survival advantage (HR, 0.420; P = .007) relative to observation.

Interaction of basal/nonbasal phenotype with treatment was marginal for disease-free survival (P = .0694) and significant for overall survival (P = .0052).

In the nonbasal subgroup, the disease-free survival benefit of capecitabine was mainly driven by a reduction in distant recurrences, particularly in the liver and the brain.

Adjuvant capecitabine had tolerability that was “exactly as expected,” according to Dr. Martín. The median dose intensity was 86.3%, and 75.2% of patients completed all of the planned eight cycles.

The trial was supported by Roche, which also provided capecitabine. Dr. Martín reported receiving speaker’s honoraria from Pfizer and Eli Lilly; honoraria for participation in advisory boards from AstraZeneca, Novartis, Roche-Genentech, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, PharmaMar, Taiho Oncology, and Eli Lilly; and research grants from Novartis and Roche.

SOURCE: Martín M et al. SABCS 2018, Abstract GS2-04.

REPORTING FROM SABCS 2018

Key clinical point: Adjuvant capecitabine fails to improve outcomes in early-stage triple-negative breast cancer treated with surgery and standard chemotherapy.

Major finding: The 5-year disease-free survival rate was 79.6% with eight cycles of adjuvant capecitabine versus 76.8% with observation (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.79; P = .082).

Study details: A phase 3, randomized, controlled trial among 876 women with early-stage triple-negative breast cancer who had undergone surgery and received standard chemotherapy (joint GEICAM/2003-11 and CIBOMA/2004-01 trial).

Disclosures: The trial was supported by Roche, which also provided capecitabine. Dr. Martín reported receiving speaker’s honoraria from Pfizer and Eli Lilly; honoraria for participation in advisory boards from AstraZeneca, Novartis, Roche-Genentech, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, PharmaMar, Taiho Oncology, and Eli Lilly; and research grants from Novartis and Roche.

Source: Martín M et al. SABCS 2018, Abstract GS2-04.

Cost-conscious minimally invasive hysterectomy: A case illustration

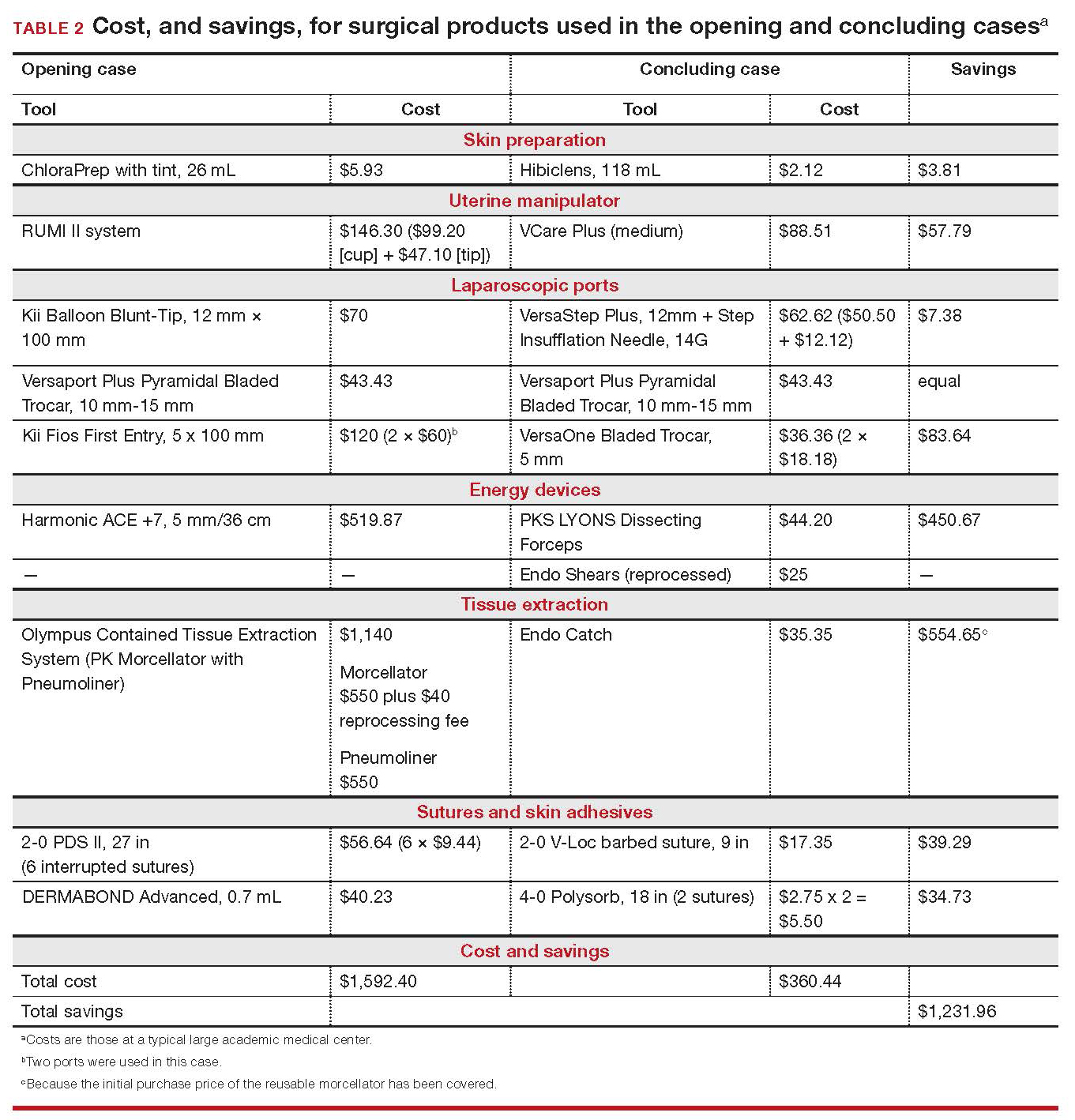

CASE Cost-conscious benign laparoscopic hysterectomy

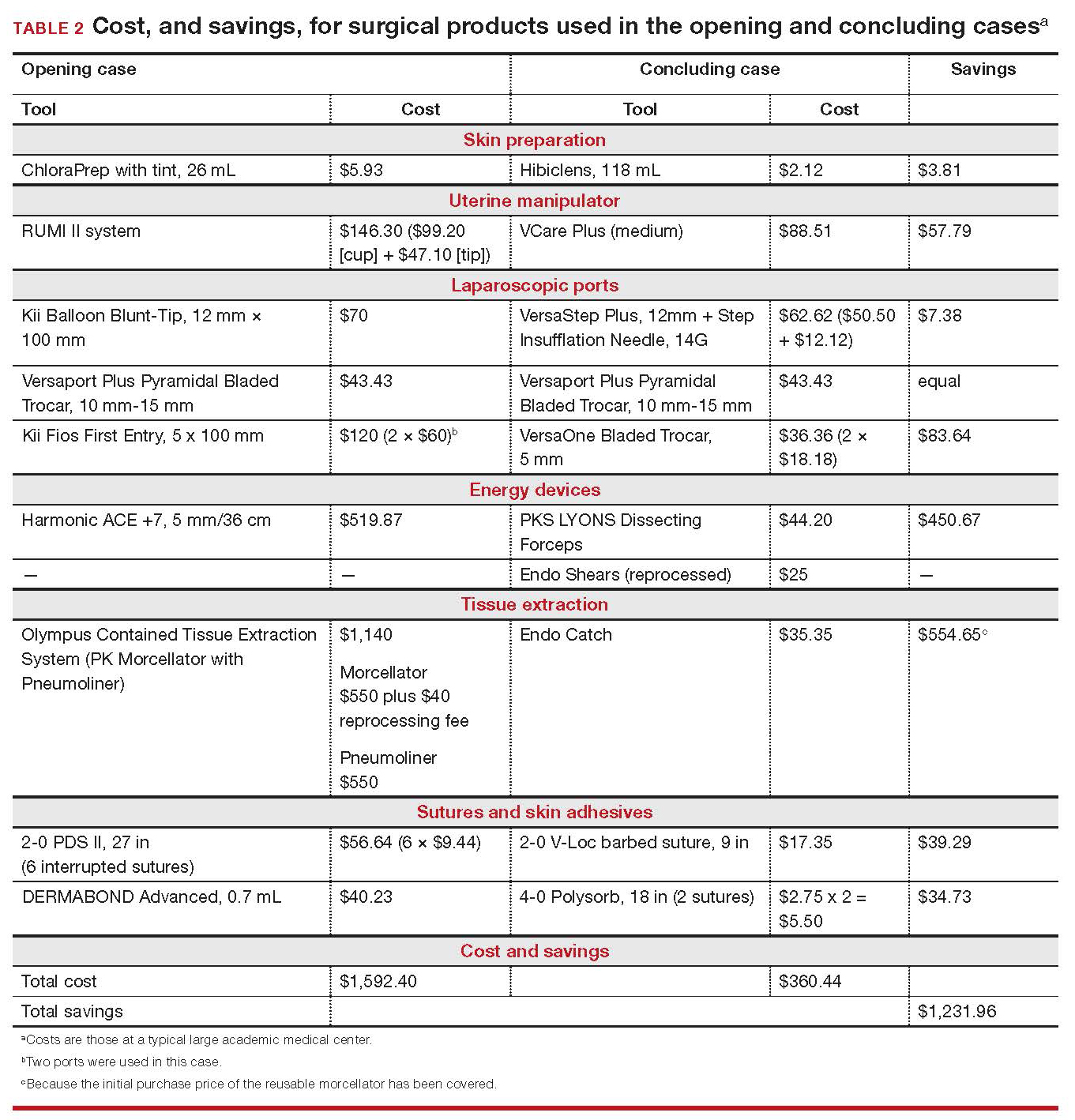

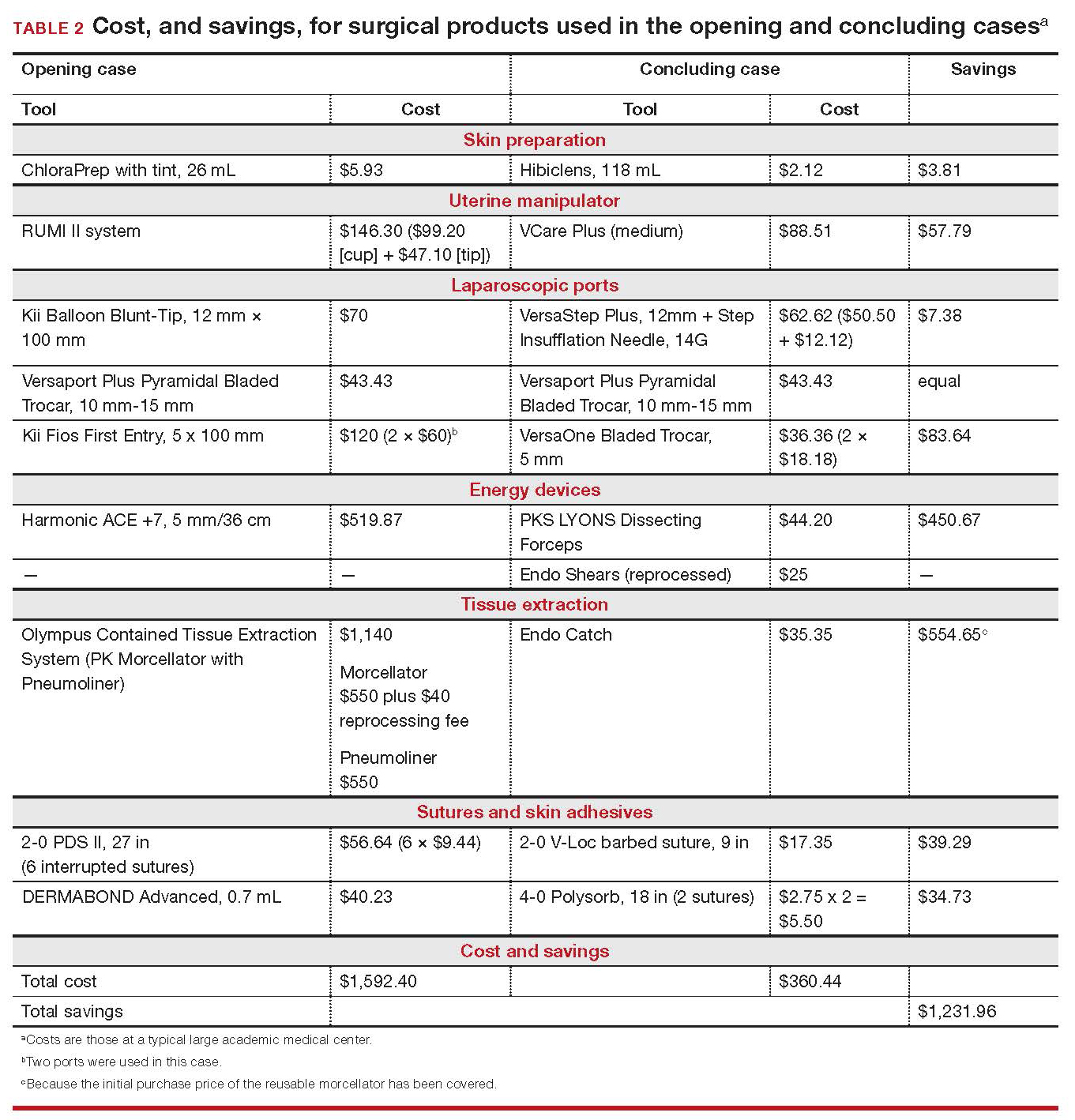

A 43-year-old woman undergoes laparoscopic hysterectomy for treatment of presumed benign uterine fibroids and menorrhagia. Once she is prepped with ChloraPrep with tint, a RUMI II uterine manipulator is placed. Laparoscopic ports include a Kii Balloon Blunt Tip system, a Versaport Plus Pyramidal Bladed Trocar, and 2 Kii Fios First Entry trocars.

The surgeon uses the Harmonic ACE +7 device (a purely ultrasonic device) to perform most of the procedure. The uterus is morcellated and removed using the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved Olympus Contained Tissue Extraction System, and the vaginal cuff is closed using a series of 2-0 PDS II sutures. Skin incisions are closed using Dermabond skin adhesive.

Total cost of the products used in this case: $1,592.40. Could different product choices have reduced this figure?

Health-care costs continue to rise faster than inflation: Total health-care expenditures account for approximately 18% of gross domestic product in the United States. Physicians therefore face increasing pressure to take cost into account in their care of patients.1 Cost-effectiveness and outcome quality continue to increase in importance as measures in many clinical trials that compare standard and alternative therapies. And women’s health—specifically, minimally invasive gynecologic surgery—invites such comparisons.

Overall, conventional laparoscopic gynecologic procedures tend to cost less than laparotomy, a consequence of shorter hospital stays, faster recovery, and fewer complications.2-5 What is not fully appreciated, however, is how choice of laparoscopic instrumentation and associated products affects surgical costs. In this article, which revisits and updates a 2013 OBG Management examination of cost-consciousness in the selection of equipment and supplies for minimally invasive gynecologic surgery,6 we review these costs in 2018. Our goal is to raise awareness of the role of cost in care among minimally invasive gynecologic surgeons.

In the sections that follow, we highlight several aspects of laparoscopic gynecologic surgery that can affect your selection of instruments and products, describing differences in cost as well as some distinctive characteristics of products. Note that our comparisons focus solely on cost—not on ease of utility, effectiveness, surgical technique, risk of complications, or any other assessment. Note also that numerous other instruments and devices are commercially available besides those we list.

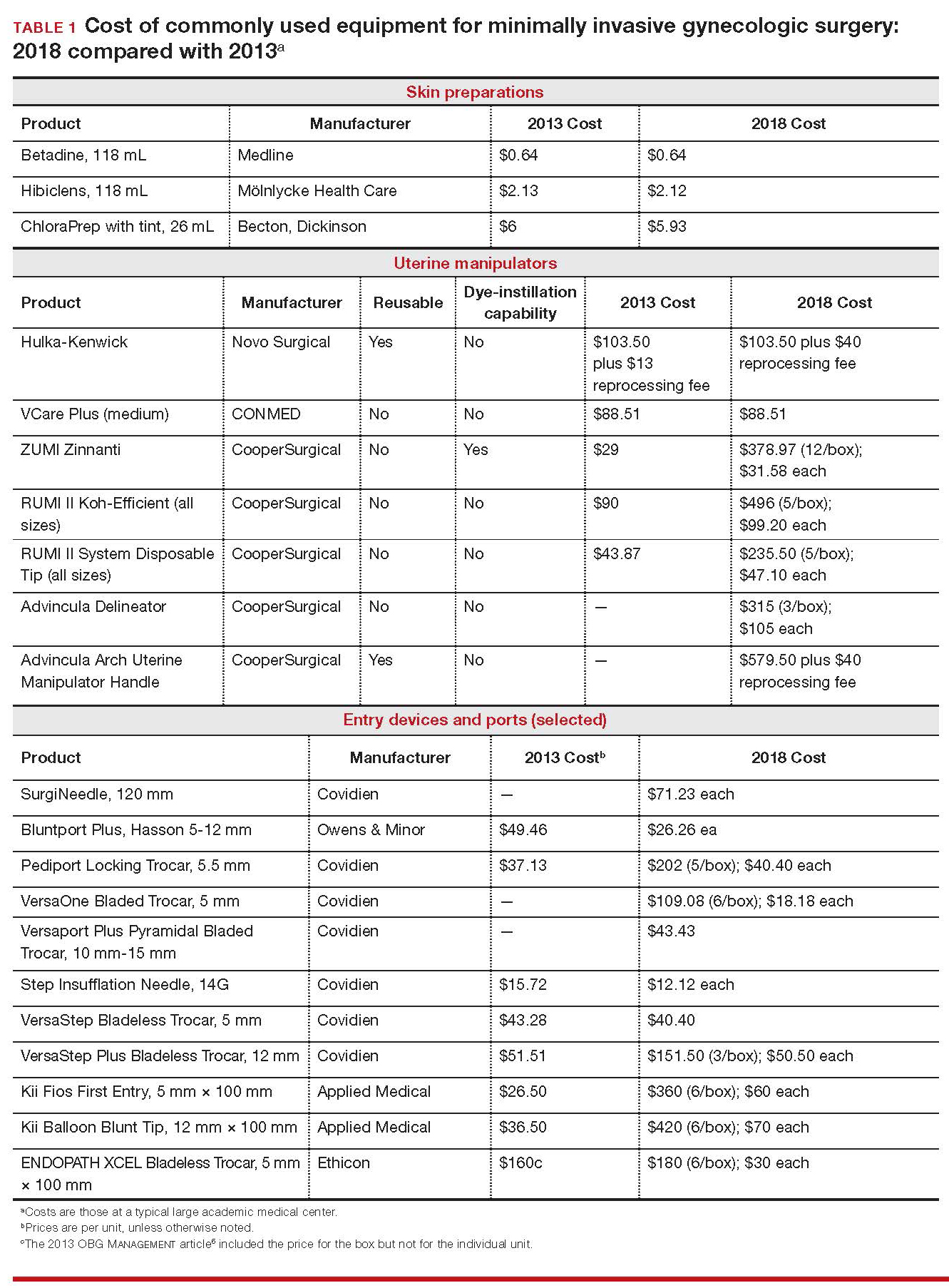

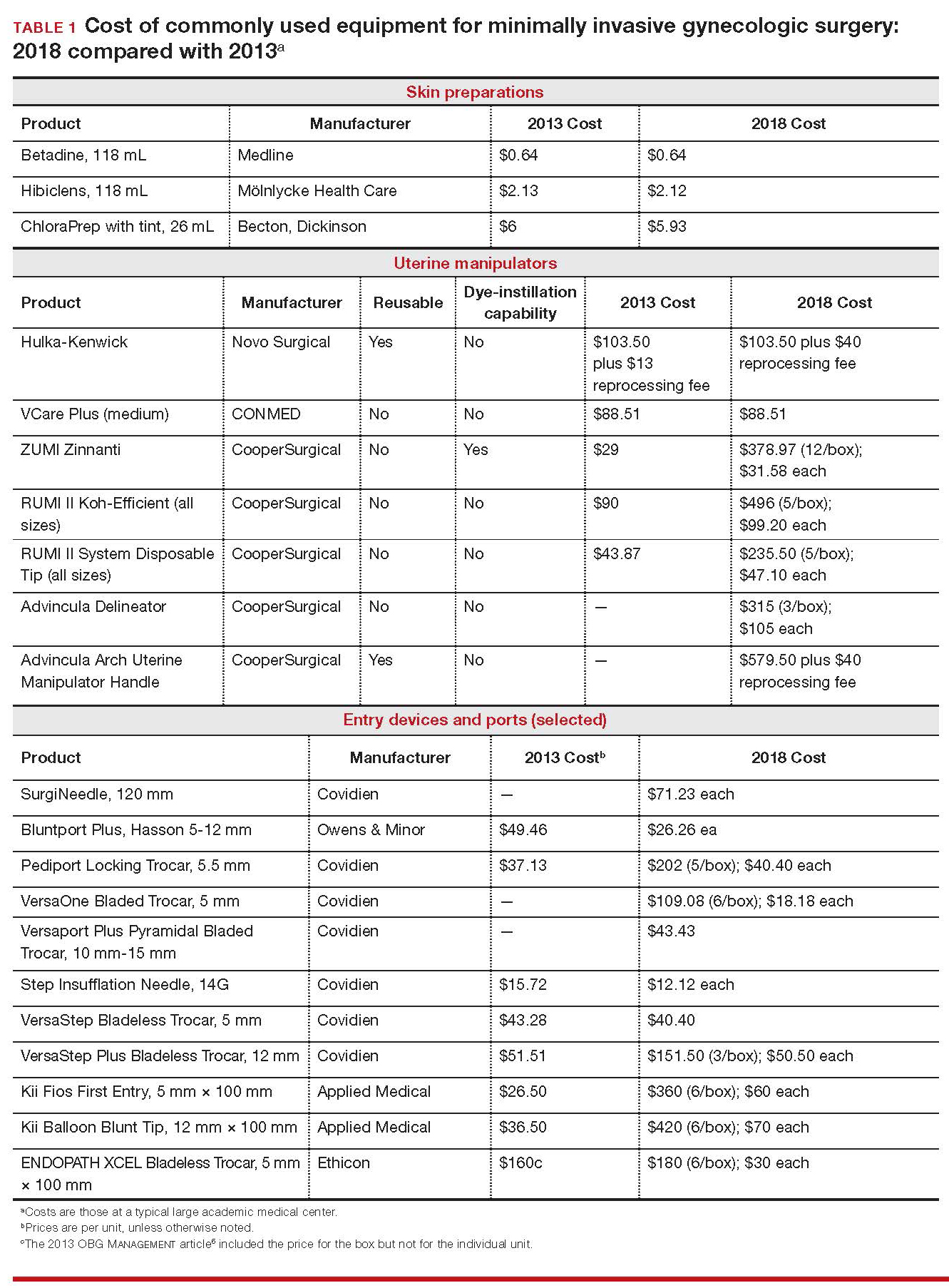

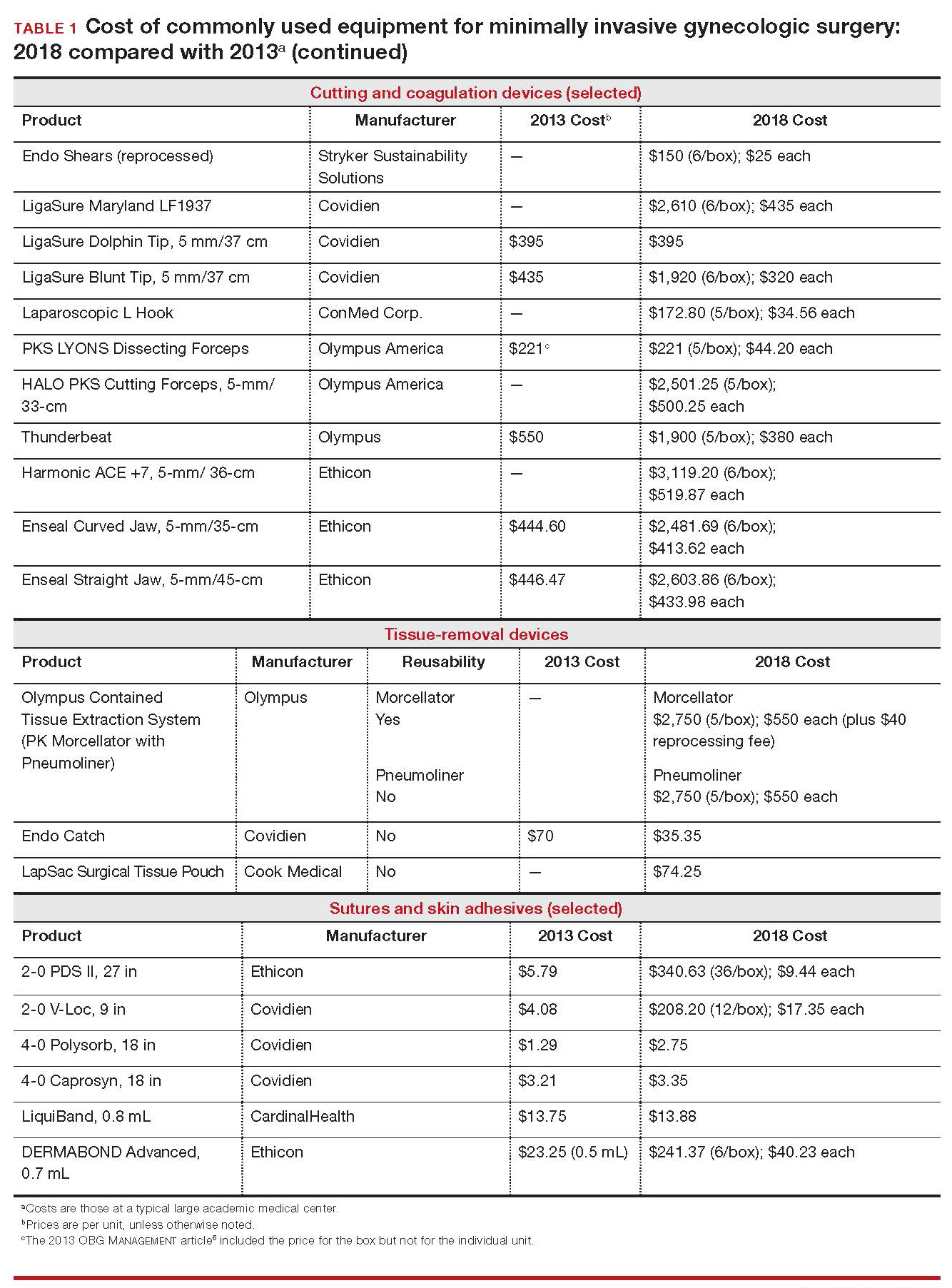

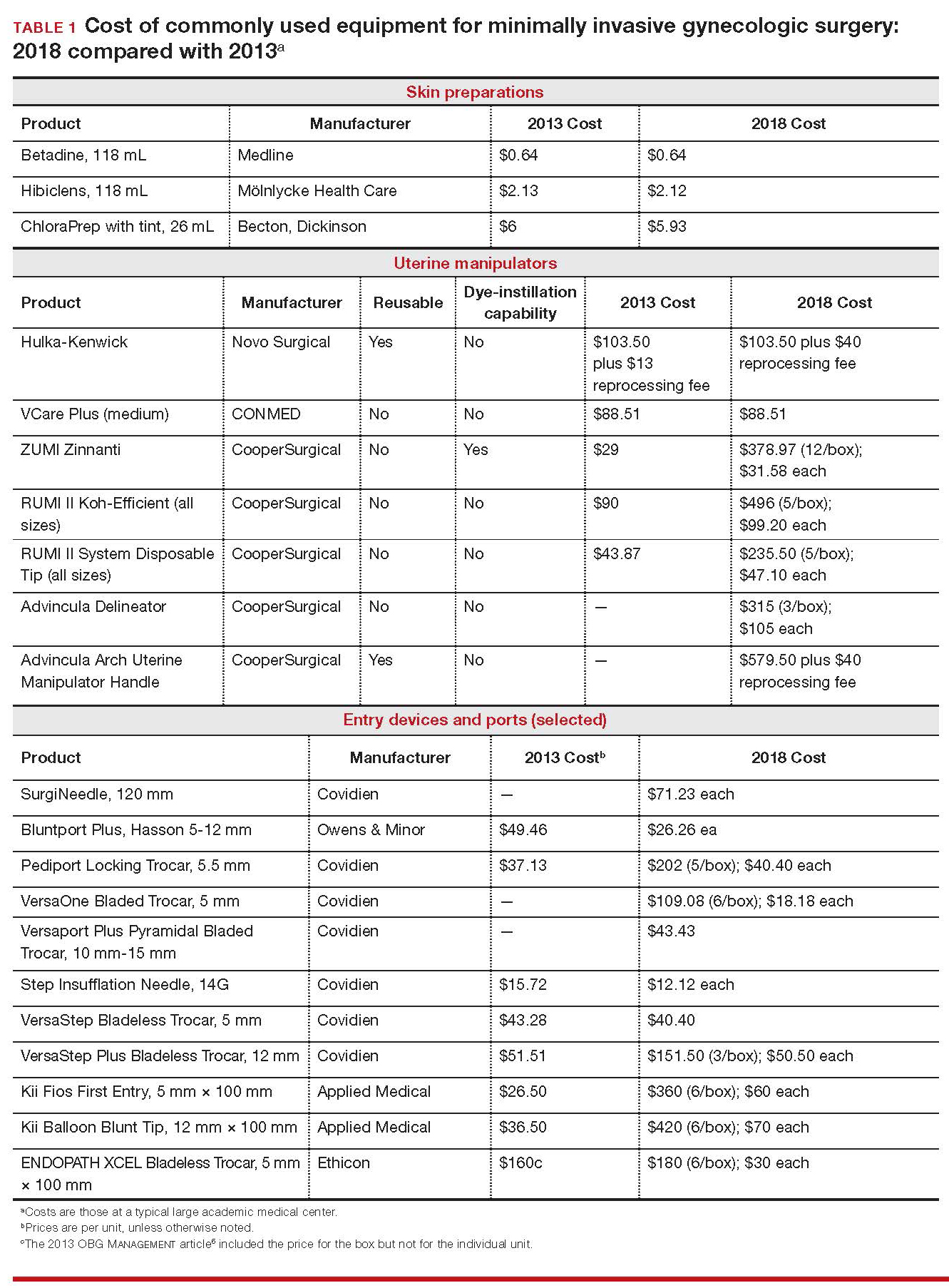

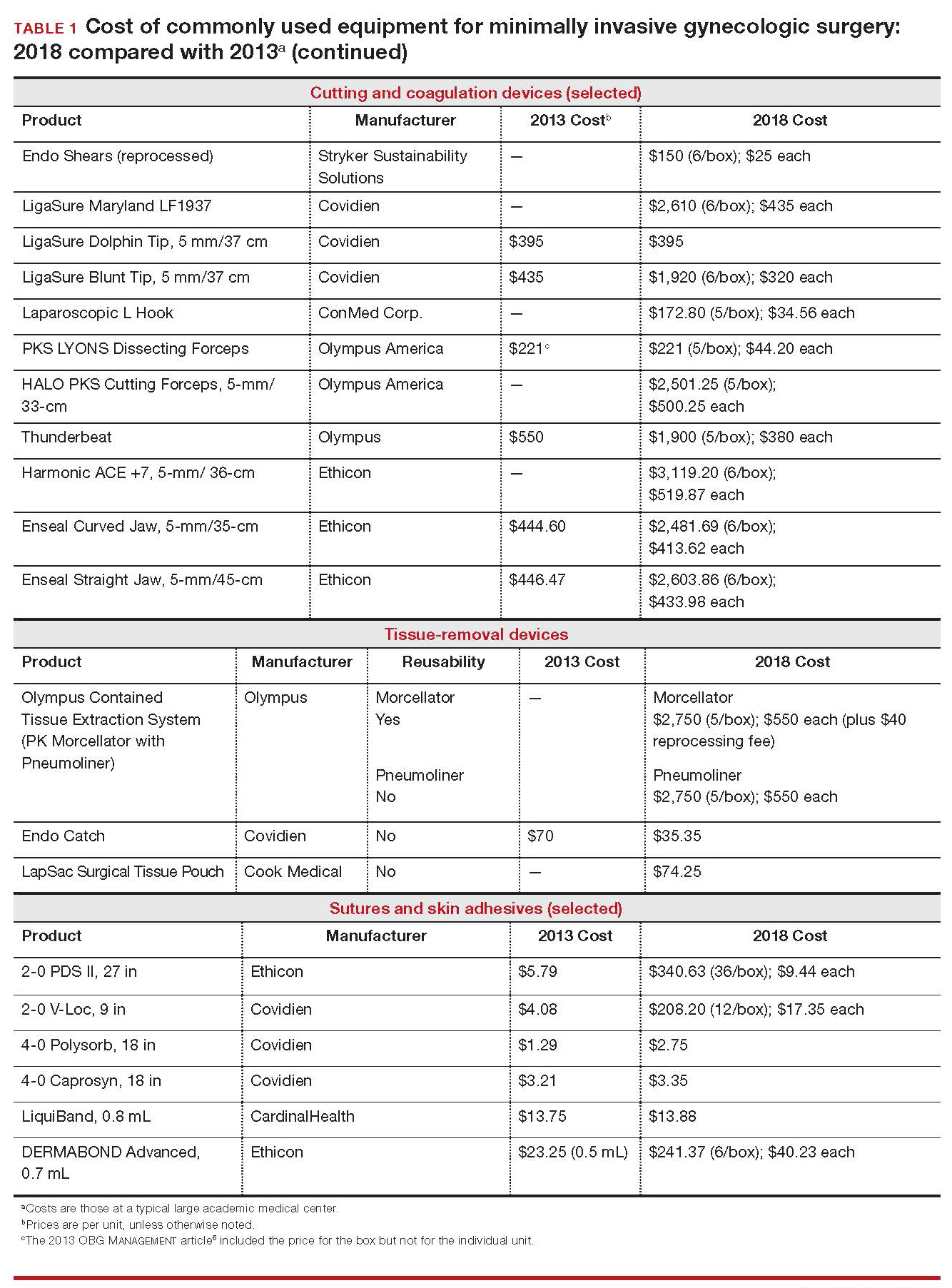

Importantly, 2013 and 2018 costs are included in TABLE 1. Unless otherwise noted, costs are per unit. Changes in manufacturers and material costs and technologic advances have contributed to some, but not all, of the changes in cost between 2013 and 2018.

Continue to: Variables to keep in mind

Variables to keep in mind

Even when taking cost into consideration, tailor your selection of instruments and supplies to your capabilities and comfort, as well as to the particular characteristics of the patient and the planned procedure. Also, remember that your institution might have arrangements with companies that supply minimally invasive instruments, and that such arrangements might limit your options, to some degree. Last, be aware that reprocessed ports and instruments are now available at a reduced cost. In short, we believe that it is crucial for surgeons to be cognizant of all products available to them prior to attending a surgical case.

Skin preparation and other preop considerations

Multiple preoperative skin preparations are available (TABLE 1). Traditionally, a povidone–iodine topical antiseptic, such as Betadine, has been used for skin and vaginal preparation prior to gynecologic surgery. Hibiclens and ChloraPrep are different combinations of chlorhexidine gluconate and isopropyl alcohol that act as broad-spectrum antiseptics.

ChloraPrep is applied with a wand-like applicator and contains a much higher concentration of isopropyl alcohol than Hibiclens (70% and 4%, respectively), rendering it more flammable. It also requires longer drying time before surgery can be started. Clear and tinted ChloraPrep formulations are available.

Continue to: Uterine manipulators

Uterine manipulators

Cannulation of the cervical canal allows for uterine manipulation, increasing intraoperative traction and exposure as well as visualization of the adnexae and peritoneal surfaces.

The Hulka-Kenwick is a reusable uterine manipulator that is fairly standard and easy to apply. Specialized, single-use manipulators also are available, including the Advincula Delineator and VCare Plus uterine manipulator/elevator. The VCare Plus manipulator consists of 2 opposing cups: one cup (available in 4 sizes, small to extra-large) fits around the cervix and defines the site for colpotomy; the other helps maintain pneumoperitoneum once a colpotomy is created.

The ZUMI (Zinnanti Uterine Manipulator Injector) is a rigid, curved shaft with an intrauterine balloon to help prevent expulsion. It also has an integrated injection channel to allow for intraoperative chromotubation.

The RUMI II System fits individual patient anatomy with various tip lengths and colpotomy cup sizes. The Advincula Arch Uterine Manipulator Handle is a reusable alternative to the articulating RUMI II and works with the RUMI II System Disposable Tip (TABLE 1).

Continue to: Entry style and ports

Entry style and ports

The peritoneal cavity can be entered using either a closed (Veress needle) or open (Hasson) technique.7,8 Closed entry might allow for quicker access to the peritoneal cavity. A 2015 Cochrane review of 46 randomized, controlled trials of 7,389 patients undergoing laparoscopy compared outcomes between laparoscopic entry techniques and found no difference in major vascular or visceral injury between closed and open techniques at the umbilicus.9 However, open entry was associated with a greater likelihood of successful entry into the peritoneal cavity.9

Left upper-quadrant (Palmer’s point) entry is another option when adhesions are anticipated or abnormal anatomy is encountered at the umbilicus.

In general, complications related to laparoscopic entry are rare in gynecologic surgery, ranging from 0.18% to 0.5% of cases in studies.8,10,11 A minimally invasive surgeon might prefer one entry technique over another but should be able to perform both methods competently and recognize when a particular technique is warranted.

--

Choosing a port

Laparoscopic ports usually range from 5 mm to 12 mm and can be fixed or variable in size.

The primary port, usually placed through the umbilicus, can be a standard, blunt, 10-mm (Bluntport Plus Hasson) port, or it can be specialized to ease entry of the port or stabilize the port once it is introduced through the skin incision.

Optical trocars have a transparent tip that allows the surgeon to visualize the abdominal wall entry layer by layer using a 0° laparoscope, sometimes after pneumoperitoneum is created with a Veress needle. Other specialized ports include those that have balloons or foam collars, or both, to secure the port without traditional stay sutures on the fascia and to minimize leakage of pneumoperitoneum.

Continue to: Accessory ports

Accessory ports

When choosing an accessory port type and size, it is important to anticipate which instruments and devices, such as an Endo Catch bag, suture, or needle, will need to pass through it. Also, know whether 5-mm and 10-mm laparoscopes are available, and anticipate whether a second port with insufflation capabilities will be required.

The Pediport Locking Trocar is a user-friendly, 5-mm bladed port that deploys a mushroom-shaped stabilizer to prevent dislodgement. The Versaport bladed trocar has a spring-loaded entry shield, which slides over the blade to protect it once the peritoneal cavity is entered.

VersaStep Bladeless Trocars are introduced after a Step Insufflation Needle has been inserted. These trocars create a smaller fascial defect than conventional bladed trocars for an equivalent cannula size (TABLE 1).

Cutting and coagulating

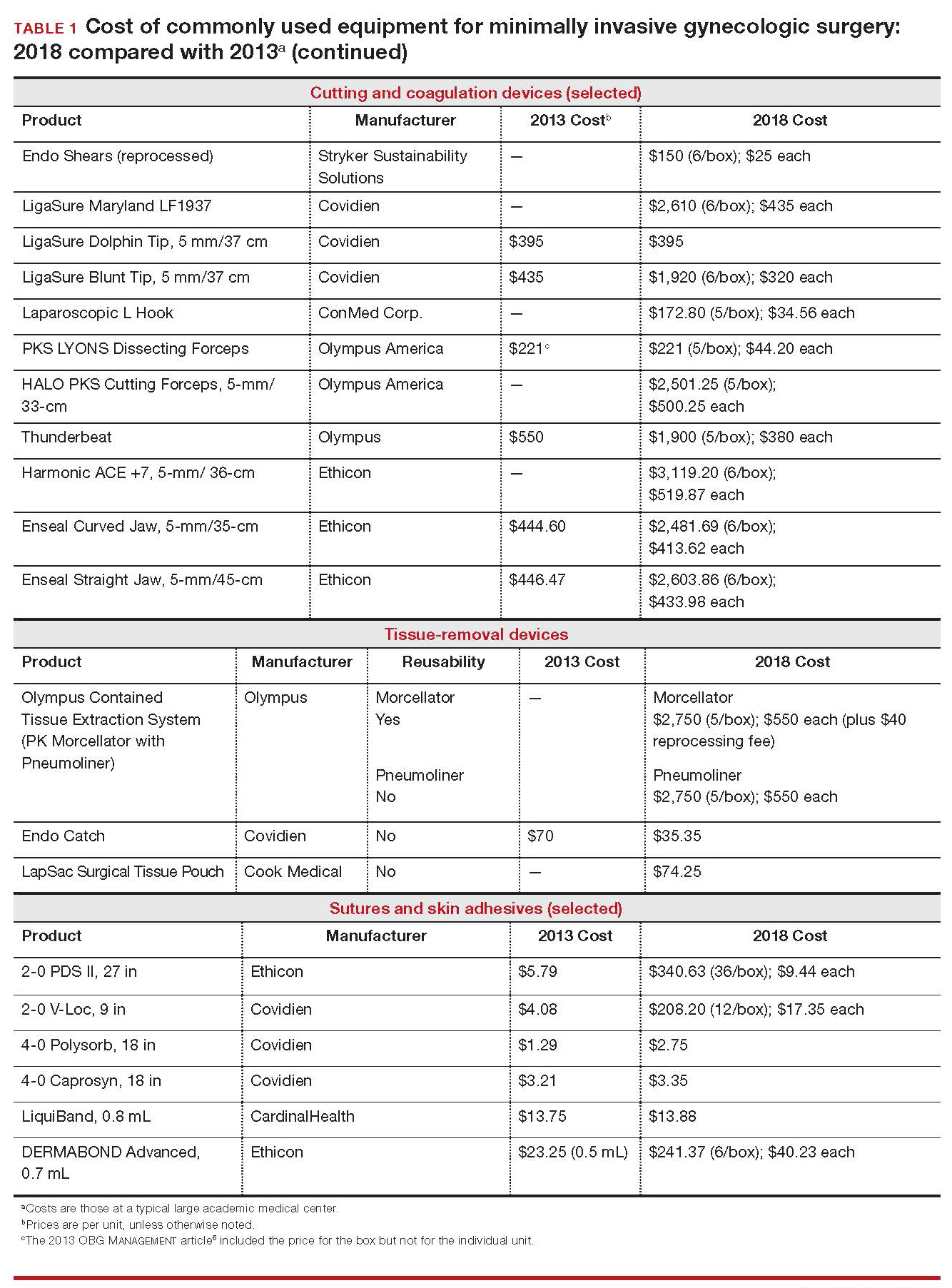

Both monopolar and bipolar electrosurgical techniques are commonly employed in gynecologic laparoscopy. A wide variety of disposable and reusable instruments are available for monopolar energy, such as scissors, a hook, and a spatula.

Bipolar devices also can be disposable or reusable. Although bipolar electrosurgery minimizes injury to surrounding tissues by containing the current within the jaws of the forceps, it cannot cut or seal large vessels. As a result, several advanced bipolar devices with sealing and transecting capabilities have emerged (the LigaSure line of devices, Enseal). Ultrasonic devices, such as the Harmonic ACE, also can coagulate and cut at lower temperatures by converting electrical energy to mechanical energy (TABLE 1).

Continue to: Suture material

Suture material

Aspects of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery that require the use of suture include, but are not limited to, closure of the vaginal cuff, oophoropexy, and reapproximation of the ovarian cortex after cystectomy. Synthetic and delayed absorbable sutures, such as PDS II, are used frequently. The barbed suture also has gained popularity because it anchors to tissue without the need for intracorporeal or extracorporeal knots (TABLE 1).

Tissue removal

Adnexae and pathologic tissue, such as dermoid cysts, can be removed intact from the peritoneal cavity using an Endo Catch Single Use Specimen Pouch, a polyurethane sac. Careful use, with placement of the ovary with the cyst into the pouch prior to cystectomy, can contain or prevent spillage outside the bag.

A large uterus that cannot be extracted through a colpotomy can be manually morcellated. Appropriate candidates can undergo power morcellation using an FDA-approved device. (TABLE 1), allowing for the removal of smaller pieces through a small laparoscopic incision or the colpotomy.

Issues surrounding morcellation continue to require that gynecologic surgeons understand FDA recommendations. In 2014, the FDA issued a safety communication that morcellation is “contraindicated in gynecologic surgery if tissue is known or suspected to be malignant; it is contraindicated for uterine tissue removal with presumed benign fibroids in perimenopausal women.”12 A black-box warning was issued that uterine tissue might contain unsuspected cancer.

A task force created by AAGL addressed key issues in this controversy.

AAGL then provided guidelines related to morcellation13:

- Do not use morcellate in the setting of known malignancy.

- Provide appropriate preoperative evaluation with up-to-date Pap smear screening and image analysis.

- Increasing age significantly increases the risk of leiomyosarcoma, especially in a postmenopausal woman.

- Fibroid growth is not a reliable sign of malignancy.

- Do not use a morcellator if the patient is at high risk for malignancy.

- If leiomyosarcoma is the presumed pathology, await the final pathology report before proceeding with hysterectomy.

- Concomitant use of a bag might mitigate the risk of tissue spread.

- Obtain informed consent before proceeding with morcellation.

Continue to: Skin closure

Skin closure

Final subcuticular closure can be accomplished using sutures or skin adhesive. Sutures can be synthetic, absorbable monofilament (Caprosyn), or synthetic, absorbable, braided multifilament (Polysorb).

Skin adhesive closes incisions quickly, avoids inflammation related to foreign bodies, and can ease patients’ concerns that sometimes arise when absorbable suture persists postoperatively (TABLE 1).

The impact of physician experience

Physician experience has been shown to reduce cost while maintaining quality of care.14 That was the conclusion of researchers who undertook a retrospective study, addressing cost and clinical outcomes, of senior and junior attending physicians who performed laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy on 120 patients. Studies such as these often lead to clinical pathways to facilitate cost-effective quality care.

--

CASE Same outcome at lower cost

The hypothetical 43-year-old patient in the opening case undergoes laparoscopic hysterectomy for treatment of uterine fibroids and menorrhagia. In this scenario, however, the surgeon makes the following product choices:

- The patient is prepped with Hibiclens.

- A VCare Plus uterine manipulator is placed.

- Laparoscopic ports include a VersaStep Plus Bladeless Trocar with Step Insufflation Needle; Versaport Plus Pyramidal Bladed Trocar; and 2 VersaOne Bladed trocars.

- The surgeon uses the PKS LYONS Dissecting Forceps and reprocessed Endo Shears to perform the hysterectomy.

- The uterus is enclosed in an Endo Catch bag and removed through the minilaparotomy site.

- The vaginal cuff is closed using 2-0 V-Loc barbed suture. Skin incisions are closed with 4-0 Polysorb, a polyglycolic acid absorbable suture.

The cost of this set of products? $360.44 or, roughly, $1,231.96 less than the set-up described in the case at the beginning of this article (TABLE 2).

Continue to: Summing up

Summing up

Here are key points to take away from this analysis and discussion:

- As third-party payers and hospitals continue to evaluate surgeons individually and compare procedures from surgeon to surgeon, reimbursement might be stratified—thereby favoring physicians who demonstrate both quality outcomes and cost containment.

- There are many ways a minimally invasive surgeon can implement cost-conscious choices that have little or no impact on the quality of outcome.

- Surgeons who are familiar with surgical instruments and models available at their institution are better prepared to make wise cost-conscious decisions. (See “Caregivers should keep cost in mind: Here’s why,” in the Web version of this article at https://www.mdedge.com/obgyn.)

- Cost is not the only indicator of value: The surgeon must know how to apply tools correctly and be familiar with their limitations, and should choose instruments and products for their safety and ease of use. More often than not, a surgeon’s training and personal experience define—and sometimes restrict—the choice of devices.

- Last, it makes sense to have instruments and devices readily available in the operating room at the start of a case, to avoid unnecessary surgical delays. However, we recommend that you refrain from opening these tools until they are required intraoperatively. It is possible that the case will require conversion to laparotomy or that, after direct visualization of the pathology, different ports or instruments are required.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Meredith Snook, MD, who was coauthor of the original 2013 article6 and Kathleen Riordan, BSN, RN, for assistance in gathering specific cost-related information for this article.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. National health expenditure projections 2017-2026: Forecast summary. www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems /Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData /Downloads/ForecastSummary.pdf. Accessed November 3, 2018.

- Vilos GA, Alshimmiri MM. Cost-benefit analysis of laparoscopic versus laparotomy salpingo-oophorectomy for benign tubo-ovarian disease. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1995;2(3):299-303.

- Gray DT, Thorburn J, Lundor P, et al. A cost-effectiveness study of a randomised trial of laparoscopy versus laparotomy for ectopic pregnancy. Lancet. 1995;345(8958):1139-1143.

- Chapron C, Fauconnier A, Goffinet F, et al. Laparoscopic surgery is not inherently dangerous for patients presenting with benign gynaecologic pathology. Results of a metaanalysis. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(5):1334-1342.

- Benezra V, Verma U, Whitted RW. Comparison of laparoscopy versus laparotomy for the surgical treatment of ovarian dermoid cysts. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2006;61(1): 20-21.

- Sanfilippo JS, Snook ML. Cost-conscious choices for minimally invasive gynecologic surgery. OBG Manag. 2013;25(11):40-41,44,46-48,72.

- Hasson HM. A modified instrument and method for laparoscopy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1971;110(6):886-887.

- Ott J, Jaeger-Lansky A, Poschalko G, et al. Entry techniques in gynecologic laparoscopy—a review. Gynecol Surg. 2012;9(2):139-146.

- Ahmad G, Gent D, Henderson D, et al. Laparoscopic entry techniques. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;8:CD006583.

- Hasson HM, Rotman C, Rana N, et al. Open laparoscopy: 29-year experience. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96(5 Pt 1):763-766.

- Schäfer M, Lauper M, Krähenbühl L. Trocar and Veress needle injuries during laparoscopy. Surg Endosc. 2001;15(3):275- 280.

- Immediately in effect guidance document: product labeling for laparoscopic power morcellators. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration Center for Devices and Radiological Health; November 25, 2014. www.fda.gov/downloads /MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance /GuidanceDocuments/UCM424123.pdf. Accessed November 3, 2018.

- Tissue Extraction Task Force Members. Morcellation during uterine tissue extraction: an update. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25(4):543-550.

- Chang WC, Li TC, Lin CC. The effect of physician experience on costs and clinical outcomes of laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy: a multivariate analysis. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2003;10(3):356-359.

CASE Cost-conscious benign laparoscopic hysterectomy

A 43-year-old woman undergoes laparoscopic hysterectomy for treatment of presumed benign uterine fibroids and menorrhagia. Once she is prepped with ChloraPrep with tint, a RUMI II uterine manipulator is placed. Laparoscopic ports include a Kii Balloon Blunt Tip system, a Versaport Plus Pyramidal Bladed Trocar, and 2 Kii Fios First Entry trocars.

The surgeon uses the Harmonic ACE +7 device (a purely ultrasonic device) to perform most of the procedure. The uterus is morcellated and removed using the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved Olympus Contained Tissue Extraction System, and the vaginal cuff is closed using a series of 2-0 PDS II sutures. Skin incisions are closed using Dermabond skin adhesive.

Total cost of the products used in this case: $1,592.40. Could different product choices have reduced this figure?

Health-care costs continue to rise faster than inflation: Total health-care expenditures account for approximately 18% of gross domestic product in the United States. Physicians therefore face increasing pressure to take cost into account in their care of patients.1 Cost-effectiveness and outcome quality continue to increase in importance as measures in many clinical trials that compare standard and alternative therapies. And women’s health—specifically, minimally invasive gynecologic surgery—invites such comparisons.

Overall, conventional laparoscopic gynecologic procedures tend to cost less than laparotomy, a consequence of shorter hospital stays, faster recovery, and fewer complications.2-5 What is not fully appreciated, however, is how choice of laparoscopic instrumentation and associated products affects surgical costs. In this article, which revisits and updates a 2013 OBG Management examination of cost-consciousness in the selection of equipment and supplies for minimally invasive gynecologic surgery,6 we review these costs in 2018. Our goal is to raise awareness of the role of cost in care among minimally invasive gynecologic surgeons.

In the sections that follow, we highlight several aspects of laparoscopic gynecologic surgery that can affect your selection of instruments and products, describing differences in cost as well as some distinctive characteristics of products. Note that our comparisons focus solely on cost—not on ease of utility, effectiveness, surgical technique, risk of complications, or any other assessment. Note also that numerous other instruments and devices are commercially available besides those we list.

Importantly, 2013 and 2018 costs are included in TABLE 1. Unless otherwise noted, costs are per unit. Changes in manufacturers and material costs and technologic advances have contributed to some, but not all, of the changes in cost between 2013 and 2018.

Continue to: Variables to keep in mind

Variables to keep in mind

Even when taking cost into consideration, tailor your selection of instruments and supplies to your capabilities and comfort, as well as to the particular characteristics of the patient and the planned procedure. Also, remember that your institution might have arrangements with companies that supply minimally invasive instruments, and that such arrangements might limit your options, to some degree. Last, be aware that reprocessed ports and instruments are now available at a reduced cost. In short, we believe that it is crucial for surgeons to be cognizant of all products available to them prior to attending a surgical case.

Skin preparation and other preop considerations

Multiple preoperative skin preparations are available (TABLE 1). Traditionally, a povidone–iodine topical antiseptic, such as Betadine, has been used for skin and vaginal preparation prior to gynecologic surgery. Hibiclens and ChloraPrep are different combinations of chlorhexidine gluconate and isopropyl alcohol that act as broad-spectrum antiseptics.

ChloraPrep is applied with a wand-like applicator and contains a much higher concentration of isopropyl alcohol than Hibiclens (70% and 4%, respectively), rendering it more flammable. It also requires longer drying time before surgery can be started. Clear and tinted ChloraPrep formulations are available.

Continue to: Uterine manipulators

Uterine manipulators

Cannulation of the cervical canal allows for uterine manipulation, increasing intraoperative traction and exposure as well as visualization of the adnexae and peritoneal surfaces.

The Hulka-Kenwick is a reusable uterine manipulator that is fairly standard and easy to apply. Specialized, single-use manipulators also are available, including the Advincula Delineator and VCare Plus uterine manipulator/elevator. The VCare Plus manipulator consists of 2 opposing cups: one cup (available in 4 sizes, small to extra-large) fits around the cervix and defines the site for colpotomy; the other helps maintain pneumoperitoneum once a colpotomy is created.

The ZUMI (Zinnanti Uterine Manipulator Injector) is a rigid, curved shaft with an intrauterine balloon to help prevent expulsion. It also has an integrated injection channel to allow for intraoperative chromotubation.

The RUMI II System fits individual patient anatomy with various tip lengths and colpotomy cup sizes. The Advincula Arch Uterine Manipulator Handle is a reusable alternative to the articulating RUMI II and works with the RUMI II System Disposable Tip (TABLE 1).

Continue to: Entry style and ports

Entry style and ports

The peritoneal cavity can be entered using either a closed (Veress needle) or open (Hasson) technique.7,8 Closed entry might allow for quicker access to the peritoneal cavity. A 2015 Cochrane review of 46 randomized, controlled trials of 7,389 patients undergoing laparoscopy compared outcomes between laparoscopic entry techniques and found no difference in major vascular or visceral injury between closed and open techniques at the umbilicus.9 However, open entry was associated with a greater likelihood of successful entry into the peritoneal cavity.9

Left upper-quadrant (Palmer’s point) entry is another option when adhesions are anticipated or abnormal anatomy is encountered at the umbilicus.

In general, complications related to laparoscopic entry are rare in gynecologic surgery, ranging from 0.18% to 0.5% of cases in studies.8,10,11 A minimally invasive surgeon might prefer one entry technique over another but should be able to perform both methods competently and recognize when a particular technique is warranted.

--

Choosing a port

Laparoscopic ports usually range from 5 mm to 12 mm and can be fixed or variable in size.

The primary port, usually placed through the umbilicus, can be a standard, blunt, 10-mm (Bluntport Plus Hasson) port, or it can be specialized to ease entry of the port or stabilize the port once it is introduced through the skin incision.

Optical trocars have a transparent tip that allows the surgeon to visualize the abdominal wall entry layer by layer using a 0° laparoscope, sometimes after pneumoperitoneum is created with a Veress needle. Other specialized ports include those that have balloons or foam collars, or both, to secure the port without traditional stay sutures on the fascia and to minimize leakage of pneumoperitoneum.

Continue to: Accessory ports

Accessory ports

When choosing an accessory port type and size, it is important to anticipate which instruments and devices, such as an Endo Catch bag, suture, or needle, will need to pass through it. Also, know whether 5-mm and 10-mm laparoscopes are available, and anticipate whether a second port with insufflation capabilities will be required.

The Pediport Locking Trocar is a user-friendly, 5-mm bladed port that deploys a mushroom-shaped stabilizer to prevent dislodgement. The Versaport bladed trocar has a spring-loaded entry shield, which slides over the blade to protect it once the peritoneal cavity is entered.

VersaStep Bladeless Trocars are introduced after a Step Insufflation Needle has been inserted. These trocars create a smaller fascial defect than conventional bladed trocars for an equivalent cannula size (TABLE 1).

Cutting and coagulating

Both monopolar and bipolar electrosurgical techniques are commonly employed in gynecologic laparoscopy. A wide variety of disposable and reusable instruments are available for monopolar energy, such as scissors, a hook, and a spatula.

Bipolar devices also can be disposable or reusable. Although bipolar electrosurgery minimizes injury to surrounding tissues by containing the current within the jaws of the forceps, it cannot cut or seal large vessels. As a result, several advanced bipolar devices with sealing and transecting capabilities have emerged (the LigaSure line of devices, Enseal). Ultrasonic devices, such as the Harmonic ACE, also can coagulate and cut at lower temperatures by converting electrical energy to mechanical energy (TABLE 1).

Continue to: Suture material

Suture material

Aspects of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery that require the use of suture include, but are not limited to, closure of the vaginal cuff, oophoropexy, and reapproximation of the ovarian cortex after cystectomy. Synthetic and delayed absorbable sutures, such as PDS II, are used frequently. The barbed suture also has gained popularity because it anchors to tissue without the need for intracorporeal or extracorporeal knots (TABLE 1).

Tissue removal

Adnexae and pathologic tissue, such as dermoid cysts, can be removed intact from the peritoneal cavity using an Endo Catch Single Use Specimen Pouch, a polyurethane sac. Careful use, with placement of the ovary with the cyst into the pouch prior to cystectomy, can contain or prevent spillage outside the bag.

A large uterus that cannot be extracted through a colpotomy can be manually morcellated. Appropriate candidates can undergo power morcellation using an FDA-approved device. (TABLE 1), allowing for the removal of smaller pieces through a small laparoscopic incision or the colpotomy.

Issues surrounding morcellation continue to require that gynecologic surgeons understand FDA recommendations. In 2014, the FDA issued a safety communication that morcellation is “contraindicated in gynecologic surgery if tissue is known or suspected to be malignant; it is contraindicated for uterine tissue removal with presumed benign fibroids in perimenopausal women.”12 A black-box warning was issued that uterine tissue might contain unsuspected cancer.

A task force created by AAGL addressed key issues in this controversy.

AAGL then provided guidelines related to morcellation13:

- Do not use morcellate in the setting of known malignancy.

- Provide appropriate preoperative evaluation with up-to-date Pap smear screening and image analysis.

- Increasing age significantly increases the risk of leiomyosarcoma, especially in a postmenopausal woman.

- Fibroid growth is not a reliable sign of malignancy.

- Do not use a morcellator if the patient is at high risk for malignancy.

- If leiomyosarcoma is the presumed pathology, await the final pathology report before proceeding with hysterectomy.

- Concomitant use of a bag might mitigate the risk of tissue spread.

- Obtain informed consent before proceeding with morcellation.

Continue to: Skin closure

Skin closure

Final subcuticular closure can be accomplished using sutures or skin adhesive. Sutures can be synthetic, absorbable monofilament (Caprosyn), or synthetic, absorbable, braided multifilament (Polysorb).

Skin adhesive closes incisions quickly, avoids inflammation related to foreign bodies, and can ease patients’ concerns that sometimes arise when absorbable suture persists postoperatively (TABLE 1).

The impact of physician experience

Physician experience has been shown to reduce cost while maintaining quality of care.14 That was the conclusion of researchers who undertook a retrospective study, addressing cost and clinical outcomes, of senior and junior attending physicians who performed laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy on 120 patients. Studies such as these often lead to clinical pathways to facilitate cost-effective quality care.

--

CASE Same outcome at lower cost

The hypothetical 43-year-old patient in the opening case undergoes laparoscopic hysterectomy for treatment of uterine fibroids and menorrhagia. In this scenario, however, the surgeon makes the following product choices:

- The patient is prepped with Hibiclens.

- A VCare Plus uterine manipulator is placed.

- Laparoscopic ports include a VersaStep Plus Bladeless Trocar with Step Insufflation Needle; Versaport Plus Pyramidal Bladed Trocar; and 2 VersaOne Bladed trocars.

- The surgeon uses the PKS LYONS Dissecting Forceps and reprocessed Endo Shears to perform the hysterectomy.

- The uterus is enclosed in an Endo Catch bag and removed through the minilaparotomy site.

- The vaginal cuff is closed using 2-0 V-Loc barbed suture. Skin incisions are closed with 4-0 Polysorb, a polyglycolic acid absorbable suture.

The cost of this set of products? $360.44 or, roughly, $1,231.96 less than the set-up described in the case at the beginning of this article (TABLE 2).

Continue to: Summing up

Summing up

Here are key points to take away from this analysis and discussion:

- As third-party payers and hospitals continue to evaluate surgeons individually and compare procedures from surgeon to surgeon, reimbursement might be stratified—thereby favoring physicians who demonstrate both quality outcomes and cost containment.

- There are many ways a minimally invasive surgeon can implement cost-conscious choices that have little or no impact on the quality of outcome.

- Surgeons who are familiar with surgical instruments and models available at their institution are better prepared to make wise cost-conscious decisions. (See “Caregivers should keep cost in mind: Here’s why,” in the Web version of this article at https://www.mdedge.com/obgyn.)

- Cost is not the only indicator of value: The surgeon must know how to apply tools correctly and be familiar with their limitations, and should choose instruments and products for their safety and ease of use. More often than not, a surgeon’s training and personal experience define—and sometimes restrict—the choice of devices.

- Last, it makes sense to have instruments and devices readily available in the operating room at the start of a case, to avoid unnecessary surgical delays. However, we recommend that you refrain from opening these tools until they are required intraoperatively. It is possible that the case will require conversion to laparotomy or that, after direct visualization of the pathology, different ports or instruments are required.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Meredith Snook, MD, who was coauthor of the original 2013 article6 and Kathleen Riordan, BSN, RN, for assistance in gathering specific cost-related information for this article.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

CASE Cost-conscious benign laparoscopic hysterectomy

A 43-year-old woman undergoes laparoscopic hysterectomy for treatment of presumed benign uterine fibroids and menorrhagia. Once she is prepped with ChloraPrep with tint, a RUMI II uterine manipulator is placed. Laparoscopic ports include a Kii Balloon Blunt Tip system, a Versaport Plus Pyramidal Bladed Trocar, and 2 Kii Fios First Entry trocars.

The surgeon uses the Harmonic ACE +7 device (a purely ultrasonic device) to perform most of the procedure. The uterus is morcellated and removed using the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved Olympus Contained Tissue Extraction System, and the vaginal cuff is closed using a series of 2-0 PDS II sutures. Skin incisions are closed using Dermabond skin adhesive.

Total cost of the products used in this case: $1,592.40. Could different product choices have reduced this figure?

Health-care costs continue to rise faster than inflation: Total health-care expenditures account for approximately 18% of gross domestic product in the United States. Physicians therefore face increasing pressure to take cost into account in their care of patients.1 Cost-effectiveness and outcome quality continue to increase in importance as measures in many clinical trials that compare standard and alternative therapies. And women’s health—specifically, minimally invasive gynecologic surgery—invites such comparisons.

Overall, conventional laparoscopic gynecologic procedures tend to cost less than laparotomy, a consequence of shorter hospital stays, faster recovery, and fewer complications.2-5 What is not fully appreciated, however, is how choice of laparoscopic instrumentation and associated products affects surgical costs. In this article, which revisits and updates a 2013 OBG Management examination of cost-consciousness in the selection of equipment and supplies for minimally invasive gynecologic surgery,6 we review these costs in 2018. Our goal is to raise awareness of the role of cost in care among minimally invasive gynecologic surgeons.

In the sections that follow, we highlight several aspects of laparoscopic gynecologic surgery that can affect your selection of instruments and products, describing differences in cost as well as some distinctive characteristics of products. Note that our comparisons focus solely on cost—not on ease of utility, effectiveness, surgical technique, risk of complications, or any other assessment. Note also that numerous other instruments and devices are commercially available besides those we list.

Importantly, 2013 and 2018 costs are included in TABLE 1. Unless otherwise noted, costs are per unit. Changes in manufacturers and material costs and technologic advances have contributed to some, but not all, of the changes in cost between 2013 and 2018.

Continue to: Variables to keep in mind

Variables to keep in mind

Even when taking cost into consideration, tailor your selection of instruments and supplies to your capabilities and comfort, as well as to the particular characteristics of the patient and the planned procedure. Also, remember that your institution might have arrangements with companies that supply minimally invasive instruments, and that such arrangements might limit your options, to some degree. Last, be aware that reprocessed ports and instruments are now available at a reduced cost. In short, we believe that it is crucial for surgeons to be cognizant of all products available to them prior to attending a surgical case.

Skin preparation and other preop considerations

Multiple preoperative skin preparations are available (TABLE 1). Traditionally, a povidone–iodine topical antiseptic, such as Betadine, has been used for skin and vaginal preparation prior to gynecologic surgery. Hibiclens and ChloraPrep are different combinations of chlorhexidine gluconate and isopropyl alcohol that act as broad-spectrum antiseptics.

ChloraPrep is applied with a wand-like applicator and contains a much higher concentration of isopropyl alcohol than Hibiclens (70% and 4%, respectively), rendering it more flammable. It also requires longer drying time before surgery can be started. Clear and tinted ChloraPrep formulations are available.

Continue to: Uterine manipulators

Uterine manipulators

Cannulation of the cervical canal allows for uterine manipulation, increasing intraoperative traction and exposure as well as visualization of the adnexae and peritoneal surfaces.

The Hulka-Kenwick is a reusable uterine manipulator that is fairly standard and easy to apply. Specialized, single-use manipulators also are available, including the Advincula Delineator and VCare Plus uterine manipulator/elevator. The VCare Plus manipulator consists of 2 opposing cups: one cup (available in 4 sizes, small to extra-large) fits around the cervix and defines the site for colpotomy; the other helps maintain pneumoperitoneum once a colpotomy is created.

The ZUMI (Zinnanti Uterine Manipulator Injector) is a rigid, curved shaft with an intrauterine balloon to help prevent expulsion. It also has an integrated injection channel to allow for intraoperative chromotubation.

The RUMI II System fits individual patient anatomy with various tip lengths and colpotomy cup sizes. The Advincula Arch Uterine Manipulator Handle is a reusable alternative to the articulating RUMI II and works with the RUMI II System Disposable Tip (TABLE 1).

Continue to: Entry style and ports

Entry style and ports

The peritoneal cavity can be entered using either a closed (Veress needle) or open (Hasson) technique.7,8 Closed entry might allow for quicker access to the peritoneal cavity. A 2015 Cochrane review of 46 randomized, controlled trials of 7,389 patients undergoing laparoscopy compared outcomes between laparoscopic entry techniques and found no difference in major vascular or visceral injury between closed and open techniques at the umbilicus.9 However, open entry was associated with a greater likelihood of successful entry into the peritoneal cavity.9

Left upper-quadrant (Palmer’s point) entry is another option when adhesions are anticipated or abnormal anatomy is encountered at the umbilicus.

In general, complications related to laparoscopic entry are rare in gynecologic surgery, ranging from 0.18% to 0.5% of cases in studies.8,10,11 A minimally invasive surgeon might prefer one entry technique over another but should be able to perform both methods competently and recognize when a particular technique is warranted.

--

Choosing a port

Laparoscopic ports usually range from 5 mm to 12 mm and can be fixed or variable in size.

The primary port, usually placed through the umbilicus, can be a standard, blunt, 10-mm (Bluntport Plus Hasson) port, or it can be specialized to ease entry of the port or stabilize the port once it is introduced through the skin incision.

Optical trocars have a transparent tip that allows the surgeon to visualize the abdominal wall entry layer by layer using a 0° laparoscope, sometimes after pneumoperitoneum is created with a Veress needle. Other specialized ports include those that have balloons or foam collars, or both, to secure the port without traditional stay sutures on the fascia and to minimize leakage of pneumoperitoneum.

Continue to: Accessory ports

Accessory ports

When choosing an accessory port type and size, it is important to anticipate which instruments and devices, such as an Endo Catch bag, suture, or needle, will need to pass through it. Also, know whether 5-mm and 10-mm laparoscopes are available, and anticipate whether a second port with insufflation capabilities will be required.

The Pediport Locking Trocar is a user-friendly, 5-mm bladed port that deploys a mushroom-shaped stabilizer to prevent dislodgement. The Versaport bladed trocar has a spring-loaded entry shield, which slides over the blade to protect it once the peritoneal cavity is entered.

VersaStep Bladeless Trocars are introduced after a Step Insufflation Needle has been inserted. These trocars create a smaller fascial defect than conventional bladed trocars for an equivalent cannula size (TABLE 1).

Cutting and coagulating

Both monopolar and bipolar electrosurgical techniques are commonly employed in gynecologic laparoscopy. A wide variety of disposable and reusable instruments are available for monopolar energy, such as scissors, a hook, and a spatula.

Bipolar devices also can be disposable or reusable. Although bipolar electrosurgery minimizes injury to surrounding tissues by containing the current within the jaws of the forceps, it cannot cut or seal large vessels. As a result, several advanced bipolar devices with sealing and transecting capabilities have emerged (the LigaSure line of devices, Enseal). Ultrasonic devices, such as the Harmonic ACE, also can coagulate and cut at lower temperatures by converting electrical energy to mechanical energy (TABLE 1).

Continue to: Suture material

Suture material

Aspects of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery that require the use of suture include, but are not limited to, closure of the vaginal cuff, oophoropexy, and reapproximation of the ovarian cortex after cystectomy. Synthetic and delayed absorbable sutures, such as PDS II, are used frequently. The barbed suture also has gained popularity because it anchors to tissue without the need for intracorporeal or extracorporeal knots (TABLE 1).

Tissue removal

Adnexae and pathologic tissue, such as dermoid cysts, can be removed intact from the peritoneal cavity using an Endo Catch Single Use Specimen Pouch, a polyurethane sac. Careful use, with placement of the ovary with the cyst into the pouch prior to cystectomy, can contain or prevent spillage outside the bag.

A large uterus that cannot be extracted through a colpotomy can be manually morcellated. Appropriate candidates can undergo power morcellation using an FDA-approved device. (TABLE 1), allowing for the removal of smaller pieces through a small laparoscopic incision or the colpotomy.

Issues surrounding morcellation continue to require that gynecologic surgeons understand FDA recommendations. In 2014, the FDA issued a safety communication that morcellation is “contraindicated in gynecologic surgery if tissue is known or suspected to be malignant; it is contraindicated for uterine tissue removal with presumed benign fibroids in perimenopausal women.”12 A black-box warning was issued that uterine tissue might contain unsuspected cancer.

A task force created by AAGL addressed key issues in this controversy.

AAGL then provided guidelines related to morcellation13:

- Do not use morcellate in the setting of known malignancy.

- Provide appropriate preoperative evaluation with up-to-date Pap smear screening and image analysis.

- Increasing age significantly increases the risk of leiomyosarcoma, especially in a postmenopausal woman.

- Fibroid growth is not a reliable sign of malignancy.

- Do not use a morcellator if the patient is at high risk for malignancy.

- If leiomyosarcoma is the presumed pathology, await the final pathology report before proceeding with hysterectomy.

- Concomitant use of a bag might mitigate the risk of tissue spread.

- Obtain informed consent before proceeding with morcellation.

Continue to: Skin closure

Skin closure

Final subcuticular closure can be accomplished using sutures or skin adhesive. Sutures can be synthetic, absorbable monofilament (Caprosyn), or synthetic, absorbable, braided multifilament (Polysorb).

Skin adhesive closes incisions quickly, avoids inflammation related to foreign bodies, and can ease patients’ concerns that sometimes arise when absorbable suture persists postoperatively (TABLE 1).

The impact of physician experience

Physician experience has been shown to reduce cost while maintaining quality of care.14 That was the conclusion of researchers who undertook a retrospective study, addressing cost and clinical outcomes, of senior and junior attending physicians who performed laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy on 120 patients. Studies such as these often lead to clinical pathways to facilitate cost-effective quality care.

--

CASE Same outcome at lower cost

The hypothetical 43-year-old patient in the opening case undergoes laparoscopic hysterectomy for treatment of uterine fibroids and menorrhagia. In this scenario, however, the surgeon makes the following product choices:

- The patient is prepped with Hibiclens.

- A VCare Plus uterine manipulator is placed.

- Laparoscopic ports include a VersaStep Plus Bladeless Trocar with Step Insufflation Needle; Versaport Plus Pyramidal Bladed Trocar; and 2 VersaOne Bladed trocars.

- The surgeon uses the PKS LYONS Dissecting Forceps and reprocessed Endo Shears to perform the hysterectomy.

- The uterus is enclosed in an Endo Catch bag and removed through the minilaparotomy site.

- The vaginal cuff is closed using 2-0 V-Loc barbed suture. Skin incisions are closed with 4-0 Polysorb, a polyglycolic acid absorbable suture.

The cost of this set of products? $360.44 or, roughly, $1,231.96 less than the set-up described in the case at the beginning of this article (TABLE 2).

Continue to: Summing up

Summing up

Here are key points to take away from this analysis and discussion:

- As third-party payers and hospitals continue to evaluate surgeons individually and compare procedures from surgeon to surgeon, reimbursement might be stratified—thereby favoring physicians who demonstrate both quality outcomes and cost containment.

- There are many ways a minimally invasive surgeon can implement cost-conscious choices that have little or no impact on the quality of outcome.

- Surgeons who are familiar with surgical instruments and models available at their institution are better prepared to make wise cost-conscious decisions. (See “Caregivers should keep cost in mind: Here’s why,” in the Web version of this article at https://www.mdedge.com/obgyn.)

- Cost is not the only indicator of value: The surgeon must know how to apply tools correctly and be familiar with their limitations, and should choose instruments and products for their safety and ease of use. More often than not, a surgeon’s training and personal experience define—and sometimes restrict—the choice of devices.

- Last, it makes sense to have instruments and devices readily available in the operating room at the start of a case, to avoid unnecessary surgical delays. However, we recommend that you refrain from opening these tools until they are required intraoperatively. It is possible that the case will require conversion to laparotomy or that, after direct visualization of the pathology, different ports or instruments are required.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Meredith Snook, MD, who was coauthor of the original 2013 article6 and Kathleen Riordan, BSN, RN, for assistance in gathering specific cost-related information for this article.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. National health expenditure projections 2017-2026: Forecast summary. www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems /Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData /Downloads/ForecastSummary.pdf. Accessed November 3, 2018.

- Vilos GA, Alshimmiri MM. Cost-benefit analysis of laparoscopic versus laparotomy salpingo-oophorectomy for benign tubo-ovarian disease. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1995;2(3):299-303.

- Gray DT, Thorburn J, Lundor P, et al. A cost-effectiveness study of a randomised trial of laparoscopy versus laparotomy for ectopic pregnancy. Lancet. 1995;345(8958):1139-1143.

- Chapron C, Fauconnier A, Goffinet F, et al. Laparoscopic surgery is not inherently dangerous for patients presenting with benign gynaecologic pathology. Results of a metaanalysis. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(5):1334-1342.

- Benezra V, Verma U, Whitted RW. Comparison of laparoscopy versus laparotomy for the surgical treatment of ovarian dermoid cysts. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2006;61(1): 20-21.

- Sanfilippo JS, Snook ML. Cost-conscious choices for minimally invasive gynecologic surgery. OBG Manag. 2013;25(11):40-41,44,46-48,72.

- Hasson HM. A modified instrument and method for laparoscopy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1971;110(6):886-887.

- Ott J, Jaeger-Lansky A, Poschalko G, et al. Entry techniques in gynecologic laparoscopy—a review. Gynecol Surg. 2012;9(2):139-146.

- Ahmad G, Gent D, Henderson D, et al. Laparoscopic entry techniques. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;8:CD006583.

- Hasson HM, Rotman C, Rana N, et al. Open laparoscopy: 29-year experience. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96(5 Pt 1):763-766.

- Schäfer M, Lauper M, Krähenbühl L. Trocar and Veress needle injuries during laparoscopy. Surg Endosc. 2001;15(3):275- 280.

- Immediately in effect guidance document: product labeling for laparoscopic power morcellators. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration Center for Devices and Radiological Health; November 25, 2014. www.fda.gov/downloads /MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance /GuidanceDocuments/UCM424123.pdf. Accessed November 3, 2018.

- Tissue Extraction Task Force Members. Morcellation during uterine tissue extraction: an update. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25(4):543-550.

- Chang WC, Li TC, Lin CC. The effect of physician experience on costs and clinical outcomes of laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy: a multivariate analysis. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2003;10(3):356-359.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. National health expenditure projections 2017-2026: Forecast summary. www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems /Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData /Downloads/ForecastSummary.pdf. Accessed November 3, 2018.

- Vilos GA, Alshimmiri MM. Cost-benefit analysis of laparoscopic versus laparotomy salpingo-oophorectomy for benign tubo-ovarian disease. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1995;2(3):299-303.

- Gray DT, Thorburn J, Lundor P, et al. A cost-effectiveness study of a randomised trial of laparoscopy versus laparotomy for ectopic pregnancy. Lancet. 1995;345(8958):1139-1143.

- Chapron C, Fauconnier A, Goffinet F, et al. Laparoscopic surgery is not inherently dangerous for patients presenting with benign gynaecologic pathology. Results of a metaanalysis. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(5):1334-1342.

- Benezra V, Verma U, Whitted RW. Comparison of laparoscopy versus laparotomy for the surgical treatment of ovarian dermoid cysts. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2006;61(1): 20-21.

- Sanfilippo JS, Snook ML. Cost-conscious choices for minimally invasive gynecologic surgery. OBG Manag. 2013;25(11):40-41,44,46-48,72.

- Hasson HM. A modified instrument and method for laparoscopy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1971;110(6):886-887.

- Ott J, Jaeger-Lansky A, Poschalko G, et al. Entry techniques in gynecologic laparoscopy—a review. Gynecol Surg. 2012;9(2):139-146.

- Ahmad G, Gent D, Henderson D, et al. Laparoscopic entry techniques. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;8:CD006583.

- Hasson HM, Rotman C, Rana N, et al. Open laparoscopy: 29-year experience. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96(5 Pt 1):763-766.

- Schäfer M, Lauper M, Krähenbühl L. Trocar and Veress needle injuries during laparoscopy. Surg Endosc. 2001;15(3):275- 280.

- Immediately in effect guidance document: product labeling for laparoscopic power morcellators. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration Center for Devices and Radiological Health; November 25, 2014. www.fda.gov/downloads /MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance /GuidanceDocuments/UCM424123.pdf. Accessed November 3, 2018.

- Tissue Extraction Task Force Members. Morcellation during uterine tissue extraction: an update. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25(4):543-550.

- Chang WC, Li TC, Lin CC. The effect of physician experience on costs and clinical outcomes of laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy: a multivariate analysis. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2003;10(3):356-359.

Epistaxis: A guide to assessment and management

Epistaxis is a common presenting complaint in family medicine. Successful treatment requires knowledge of nasal anatomy, possible causes, and a step-wise approach.

Epistaxis predominantly affects children between the ages of 2 and 10 years and older adults between the ages of 45 and 65.1-4 Many presentations are spontaneous and self-limiting; often all that is required is proper first aid. It is important, however, to recognize the signs and symptoms that are suggestive of more worrisome conditions.

Management of epistaxis requires good preparation, appropriate equipment, and adequate assistance. If any of these are lacking, prompt nasal packing followed by referral to an emergency department or ear, nose, and throat (ENT) service is recommended.

Anatomy of the nasal cavity

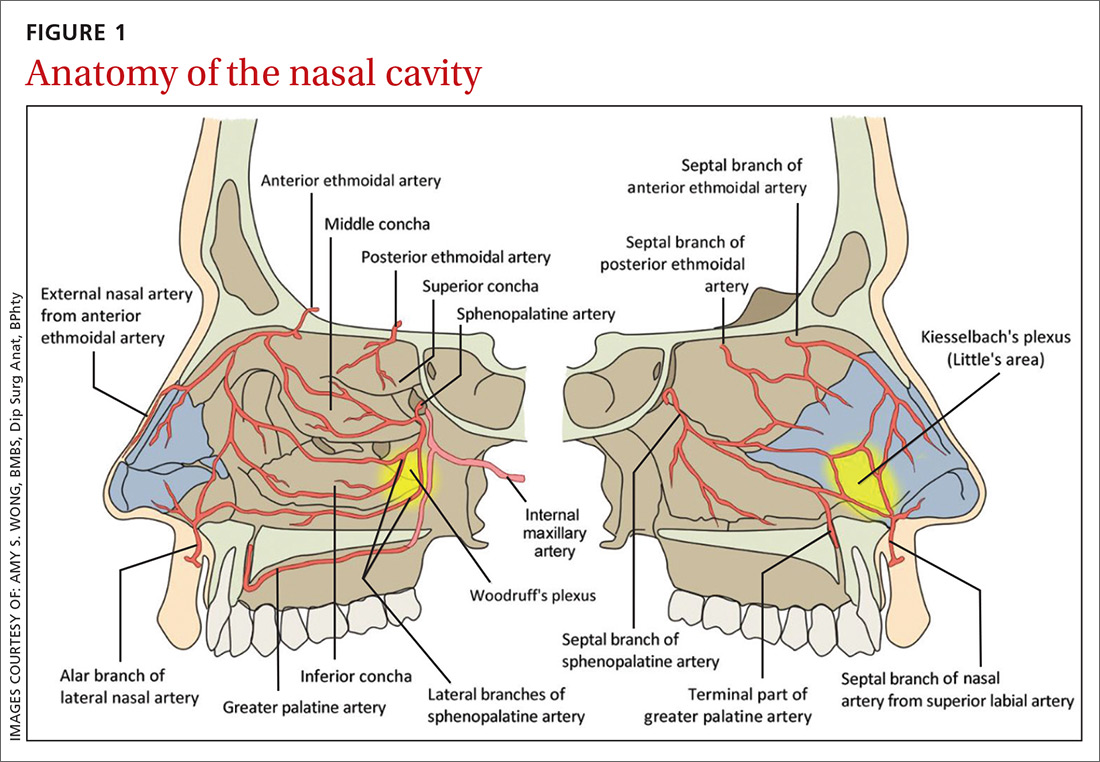

The nasal cavity has a rich and highly varied blood supply arising from the internal and external carotid arteries with multiple anastomoses and a crossover between the left and right arterial systems.2,4,5 The internal maxillary artery (IMAX) supplies 80% of the nasal vault.2 The sphenopalatine artery (SPA) supplies most of the nasal septum and the turbinates, while the greater palatine artery (GPA) supplies the floor of the nasal septum.3,5 The ethmoidal arteries course through the cribriform plate to supply the roof of the nasal cavity. The ethmoidal arteries communicates with branches of the SPA posteriorly and several branches anteriorly (FIGURE 1).

Kiesselbach’s plexus is a highly vascularized region of cartilaginous nasal septum anteroinferiorly that is also known as Little’s area. It is supplied by the SPA, GPA, superior labial artery, and ethmoidal arteries.5 Woodruff’s plexus is the richly vascularized posterior aspect of the nasal cavity primarily supplied by the SPA.3,5

Is the bleed anterior or posterior; primary or secondary?

Epistaxis is classified as anterior or posterior based on the arterial supply and the location of the bleed in relation to the piriform aperture.2,3 Anterior epistaxis occurs in >90% of patients and arises in Little’s area.6 Posterior epistaxis arises from Woodruff’s plexus in the posterior nasal septum or lateral nasal wall. It occurs in 5% to 10% of patients, is usually arterial in origin, and leads to a greater risk of airway compromise, aspiration, and difficulty in controlling the hemorrhage.2,6

Epistaxis can be classified further as primary or secondary hemorrhage. Primary epistaxis is idiopathic, spontaneous bleeds without any precipitants.2 Blood vessels within the nasal mucosa run superficially and are relatively unprotected. Damage to this mucosa and to vessel walls can result in bleeding.4 Spontaneous rupture of vessels may occur occasionally, during, say the Valsalva maneuver or when straining to lift heavy objects.4 Secondary epistaxis occurs when there is a clear and definite cause (eg trauma, anticoagulant use, or surgery).

Continue to: Numerous causes...

Numerous causes: From trauma to medications

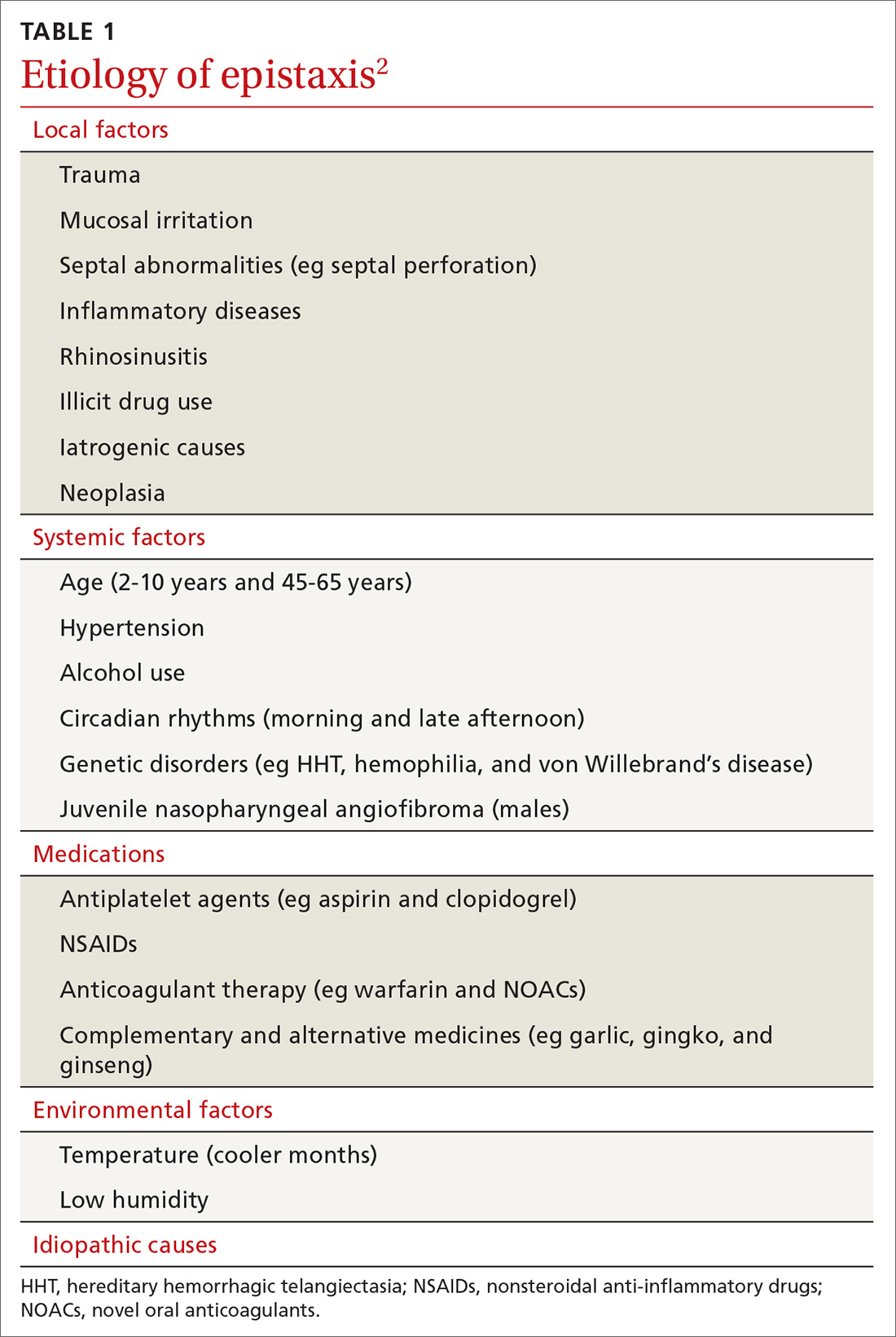

Epistaxis can be caused by local, systemic, or environmental factors; medications; or be idiopathic in nature (TABLE 12). It commonly arises due to self-inflicted trauma from nose picking, particularly in children; trauma to nasal bones or septum; and mucosal irritation from topical nasal drugs, such as corticosteroids and antihistamines. Other local factors include septal abnormalities, such as septal perforation, inflammatory diseases, rhinosinusitis, illicit drug use (eg cocaine), iatrogenic causes, and neoplasia.

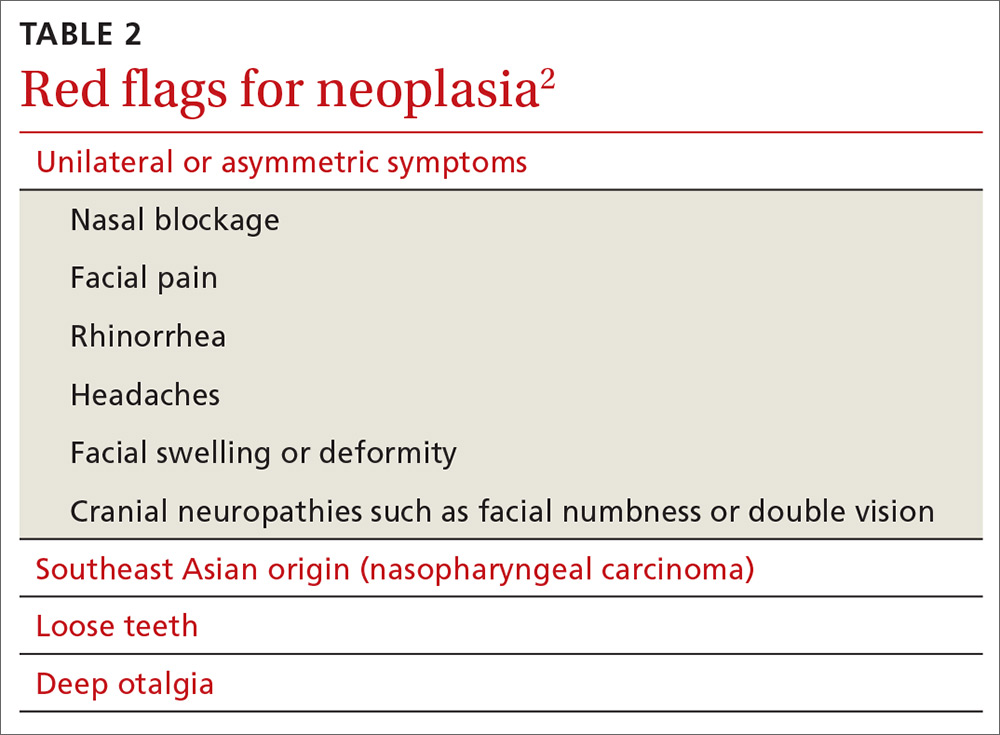

Red flags for neoplasia include unilateral or asymmetric symptoms, such as nasal blockage, facial pain, rhinorrhea, headaches, facial swelling or deformity, and cranial neuropathies (ie, facial numbness or double vision). Other red flags include Southeast Asian origin (nasopharyngeal carcinoma), loose maxillary teeth, and deep otalgia (TABLE 22). In adolescent males, it is important to consider juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma, a benign tumor that can bleed extensively.