User login

Incidental Asymptomatic Fibular Stress Fractures Presenting as Varus Knee Osteoarthritis: A Case Report

ABSTRACT

Stress fractures are often missed, especially in unusual clinical settings. We report on 2 patients who presented to our orthopedic surgery clinic with incidental findings of asymptomatic proximal fibular tension side stress fractures in severe longstanding varus osteoarthritic knees. Initial plain films demonstrated an expansile deformity of the proximal fibular shaft, and differential diagnosis included a healed or healing fracture versus possible neoplasm. Magnetic resonance imaging with and without gadolinium was utilized to rule out the latter prior to planned total knee arthroplasty.

Continue to: The proximal fibula...

The proximal fibula is a rare site for stress fractures, with most of these fractures occurring in military recruits.1 To the authors’ knowledge, there has been only 1 documented case of a proximal fibular stress fracture in patients with severe osteoarthritis (OA) and fixed varus deformity, which mimicked L5 radiculopathy.2 We are not aware of any reports of asymptomatic tension-side fibular stress fractures in varus knees. In our 2 cases, the patients were indicated for total knee arthroplasty (TKA) for varus degenerative joint disease after failing nonoperative treatment; however, further work-up was justified to rule out neoplasm after plain films revealed expansile deformities of the proximal fibular shaft. Each patient subsequently underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with and without gadolinium contrast, which demonstrated a healed and healing proximal fibular stress fracture. Magnetic resonance imaging is rarely indicated in the evaluation of degenerative joint disease, and stress fractures about a varus knee generally occur on the compression side of the tibia and are symptomatic.3-7 The patients provided informed written consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

CASE REPORT

The first patient was a 77-year-old male who presented with longstanding knee pain, left greater than right, exacerbated by weight-bearing activities. The patient had no improvement with physical therapy or anti-inflammatory medication. He denied any history of trauma, weakness, paresthesias, or a recent increase in activity. The patient also denied any fevers, chills, night sweats, or other constitutional symptoms. On physical examination, the patient had an antalgic gait and limited range of motion bilaterally. Examination of his right lower extremity demonstrated a fixed 5° varus deformity. No distinct point tenderness was noted.

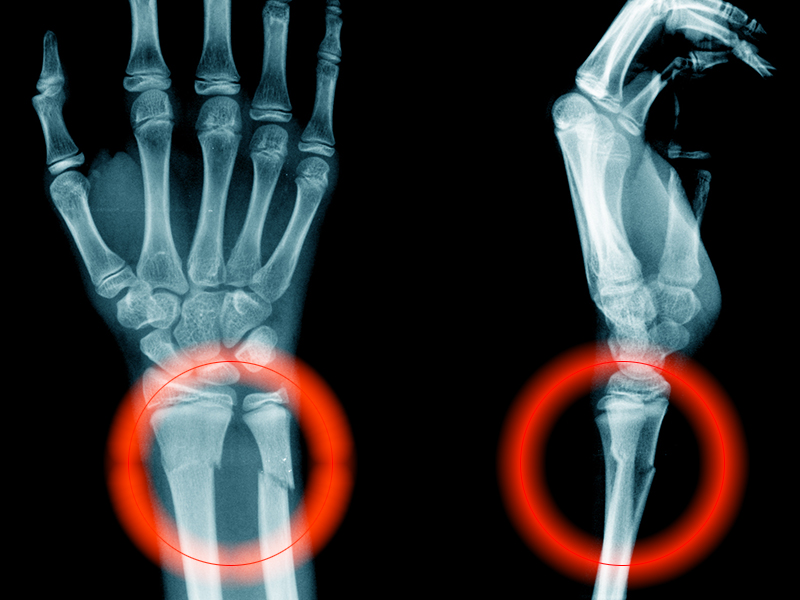

Radiographs of the right knee demonstrated varus deformity and tricompartmental degenerative changes with severe medial joint space narrowing. An expansile deformity of the proximal right fibular shaft was also noted (Figure 1), which was not present on the films 2 years earlier (Figure 2). The absence of this deformity on previous imaging raised the suspicion of a tumor. An MRI with and without gadolinium, which was obtained to rule out a neoplastic process, showed an old, healed proximal fibular shaft fracture with chronic periosteal reaction (Figure 3). There was no marrow edema to suggest acute injury and no neoplastic lesion. He was reassured regarding the benign findings and was scheduled for a left TKA, as his pain was more severe on the left knee. The patient’s stress fracture healed without complications, and he underwent a successful left TKA. He returned approximately 6 months after his procedure with worsening right knee pain and underwent a successful TKA on the right knee as well.

The second patient was a 67-year-old male with longstanding bilateral knee pain, right greater than left, with no antecedent trauma. He denied a history of increased activity, or weakness or paresthesias. He denied any fevers, chills, night sweats, or other constitutional symptoms. One year prior to presentation at our clinic, he had received corticosteroid injections and hyaluronic acid, without relief. The patient also had a history with another surgeon of arthroscopy 1 year earlier and subchondroplasty 3 years before presentation to our clinic. On physical examination, the patient’s right knee displayed a fixed 7° varus deformity with decreased range of motion, effusion, and diffuse crepitus. Further examination revealed tenderness to palpation of the proximal fibula.

Radiographs of the right knee showed degenerative joint disease with varus deformity and medial compartment joint space narrowing. They also demonstrated an expansile deformity of mixed lucency and sclerosis involving the proximal right fibular shaft (Figure 4). Although these findings appeared to be consistent with a stress fracture, their appearance was also suspicious for a neoplasm. To rule out malignancy, an MRI with and without gadolinium was obtained that revealed a healing stress fracture of the proximal fibula (Figure 5). The patient was reassured, and plans were made to proceed with a TKA. The patient’s stress fracture healed without complications, and he underwent successful right TKA. Radiographs from the patient’s 8-week follow-up showed a healed fibular stress fracture (Figure 6).

Continue to: DISCUSSION

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first report of incidental tension-side stress fractures in varus osteoarthritic knees. Stress fractures have been classified into 2 groups, fatigue fractures and insufficiency fractures. Fatigue fractures occur when abnormal stress is applied to normal bones, and insufficiency fractures result when normal stress is applied to abnormal bones.8 Stress fractures can also be classified into risk categories based on which bone is involved and the loading of the bone.9 Sites loaded in tension have increased risk of nonunion, progression to complete fracture, and reoccurrence compared with sites loaded in compression.9 Stress fractures of the fibula occur rarely, and when present, they are more commonly observed in the distal fibula in athletes and military recruits.1 Stress fractures occur rarely in patients with primary OA, and when present in this setting, obesity and malalignment are the contributing factors.3 Neither patient was obese in our case (body mass index of 27 and 28, respectively), but significant varus deformity was present in both patients. Stress fractures occurring near the knee in the setting of a varus deformity generally occur on the compression side of the tibia and are symptomatic.3-7

Regarding malalignment, Cheung and colleagues10 reported about a case of an elderly female with OA of the knee with valgus deformity that initially developed a proximal fibular stress fracture followed by a proximal tibial stress fracture. However, both of our patients had varus deformities. Mullaji and Shetty3 documented stress fractures in 34 patients with OA, a majority with varus deformities, but did not report any isolated proximal fibular stress fractures. Manish and colleagues2 reported the only documented case of an isolated proximal fibular stress fracture in a patient with osteoarthritic varus deformity. The patient presented initially with pain and paresthesias of the lower thigh and leg consistent with an L5 radiculopathy. They believed that the varus deformity and the repetitive contraction of the lateral knee muscles put increased shear forces on the fibula leading to the stress fracture. Our patients did not present with any radicular symptoms, a history of acute worsening pain, or an increased activity concerning for a stress fracture. Instead, our patients presented with progressively worsening knee pain typical of severe OA and incidental findings on imaging of tension-side fibular stress fractures. An MRI with and without gadolinium confirmed the diagnosis of a healed fracture in our first patient and a healing fracture in our second patient.

CONCLUSION

Although exceedingly rare in osteoarthritic varus knees, we presented 2 cases of MRI-confirmed proximal fibular stress fractures in this report. As demonstrated, patients may present with symptoms of OA or radicular symptoms as described by Manish and colleagues.2 Presentation may also include an expansile lesion on imaging, prompting a differential diagnosis that includes a neoplasm. If present in the setting of an osteoarthritic varus knee, stress fractures of the proximal fibula should heal with conservative treatment and not affect the plan or outcome of TKA.

- Devas MB, Sweetnam R. Stress fractures of the fibula; a review of fifty cases in athletes. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1956;38-B(4):818-829.

- Manish KK, Agnivesh T, Pramod PS, Samir SD. Isolated proximal fibular stress fracture in osteoarthritis knee presenting as L5 radiculopathy. J Orthop Case Reports. 2015;5(3):75-77. doi:10.13107/jocr.2250-0685.315.

- Mullaji A, Shetty G. Total knee arthroplasty for arthritic knees with tibiofibular stress fractures: classification and treatment guidelines. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25(2):295-301. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2008.11.012.

- Sourlas I, Papachristou G, Pilichou A, Giannoudis PV, Efstathopoulos N, Nikolaou VS. Proximal tibial stress fractures associated with primary degenerative knee osteoarthritis. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2009;38(3):120-124

- Demir B, Gursu S, Oke R, Ozturk K, Sahin V. Proximal tibia stress fracture caused by severe arthrosis of the knee with varus deformity. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2009;38(9):457-459.

- Satku K, Kumar VP, Pho RW. Stress fractures of the tibia in osteoarthritis of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1987;69(2):309-311. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.69B2.3818767.

- Martin LM, Bourne RB, Rorabeck CH. Stress fractures associated with osteoarthritis of the knee. A report of three cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988;70(5):771-774.

- Hong SH, Chu IT. Stress fracture of the proximal fibula in military recruits. Clin Orthop Surg. 2009;1(3):161-164. doi:10.4055/cios.2009.1.3.161

- Knapik JJ, Reynolds K, Hoedebecke KL. Stress fractures: Etiology, epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. J Spec Oper Med. 17(2):120-130.

- Cheung MHS, Lee M-F, Lui TH. Insufficiency fracture of the proximal fibula and then tibia: A case report. J Orthop Surg. 2013;21(1):103-105. doi:10.1177/230949901302100126

ABSTRACT

Stress fractures are often missed, especially in unusual clinical settings. We report on 2 patients who presented to our orthopedic surgery clinic with incidental findings of asymptomatic proximal fibular tension side stress fractures in severe longstanding varus osteoarthritic knees. Initial plain films demonstrated an expansile deformity of the proximal fibular shaft, and differential diagnosis included a healed or healing fracture versus possible neoplasm. Magnetic resonance imaging with and without gadolinium was utilized to rule out the latter prior to planned total knee arthroplasty.

Continue to: The proximal fibula...

The proximal fibula is a rare site for stress fractures, with most of these fractures occurring in military recruits.1 To the authors’ knowledge, there has been only 1 documented case of a proximal fibular stress fracture in patients with severe osteoarthritis (OA) and fixed varus deformity, which mimicked L5 radiculopathy.2 We are not aware of any reports of asymptomatic tension-side fibular stress fractures in varus knees. In our 2 cases, the patients were indicated for total knee arthroplasty (TKA) for varus degenerative joint disease after failing nonoperative treatment; however, further work-up was justified to rule out neoplasm after plain films revealed expansile deformities of the proximal fibular shaft. Each patient subsequently underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with and without gadolinium contrast, which demonstrated a healed and healing proximal fibular stress fracture. Magnetic resonance imaging is rarely indicated in the evaluation of degenerative joint disease, and stress fractures about a varus knee generally occur on the compression side of the tibia and are symptomatic.3-7 The patients provided informed written consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

CASE REPORT

The first patient was a 77-year-old male who presented with longstanding knee pain, left greater than right, exacerbated by weight-bearing activities. The patient had no improvement with physical therapy or anti-inflammatory medication. He denied any history of trauma, weakness, paresthesias, or a recent increase in activity. The patient also denied any fevers, chills, night sweats, or other constitutional symptoms. On physical examination, the patient had an antalgic gait and limited range of motion bilaterally. Examination of his right lower extremity demonstrated a fixed 5° varus deformity. No distinct point tenderness was noted.

Radiographs of the right knee demonstrated varus deformity and tricompartmental degenerative changes with severe medial joint space narrowing. An expansile deformity of the proximal right fibular shaft was also noted (Figure 1), which was not present on the films 2 years earlier (Figure 2). The absence of this deformity on previous imaging raised the suspicion of a tumor. An MRI with and without gadolinium, which was obtained to rule out a neoplastic process, showed an old, healed proximal fibular shaft fracture with chronic periosteal reaction (Figure 3). There was no marrow edema to suggest acute injury and no neoplastic lesion. He was reassured regarding the benign findings and was scheduled for a left TKA, as his pain was more severe on the left knee. The patient’s stress fracture healed without complications, and he underwent a successful left TKA. He returned approximately 6 months after his procedure with worsening right knee pain and underwent a successful TKA on the right knee as well.

The second patient was a 67-year-old male with longstanding bilateral knee pain, right greater than left, with no antecedent trauma. He denied a history of increased activity, or weakness or paresthesias. He denied any fevers, chills, night sweats, or other constitutional symptoms. One year prior to presentation at our clinic, he had received corticosteroid injections and hyaluronic acid, without relief. The patient also had a history with another surgeon of arthroscopy 1 year earlier and subchondroplasty 3 years before presentation to our clinic. On physical examination, the patient’s right knee displayed a fixed 7° varus deformity with decreased range of motion, effusion, and diffuse crepitus. Further examination revealed tenderness to palpation of the proximal fibula.

Radiographs of the right knee showed degenerative joint disease with varus deformity and medial compartment joint space narrowing. They also demonstrated an expansile deformity of mixed lucency and sclerosis involving the proximal right fibular shaft (Figure 4). Although these findings appeared to be consistent with a stress fracture, their appearance was also suspicious for a neoplasm. To rule out malignancy, an MRI with and without gadolinium was obtained that revealed a healing stress fracture of the proximal fibula (Figure 5). The patient was reassured, and plans were made to proceed with a TKA. The patient’s stress fracture healed without complications, and he underwent successful right TKA. Radiographs from the patient’s 8-week follow-up showed a healed fibular stress fracture (Figure 6).

Continue to: DISCUSSION

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first report of incidental tension-side stress fractures in varus osteoarthritic knees. Stress fractures have been classified into 2 groups, fatigue fractures and insufficiency fractures. Fatigue fractures occur when abnormal stress is applied to normal bones, and insufficiency fractures result when normal stress is applied to abnormal bones.8 Stress fractures can also be classified into risk categories based on which bone is involved and the loading of the bone.9 Sites loaded in tension have increased risk of nonunion, progression to complete fracture, and reoccurrence compared with sites loaded in compression.9 Stress fractures of the fibula occur rarely, and when present, they are more commonly observed in the distal fibula in athletes and military recruits.1 Stress fractures occur rarely in patients with primary OA, and when present in this setting, obesity and malalignment are the contributing factors.3 Neither patient was obese in our case (body mass index of 27 and 28, respectively), but significant varus deformity was present in both patients. Stress fractures occurring near the knee in the setting of a varus deformity generally occur on the compression side of the tibia and are symptomatic.3-7

Regarding malalignment, Cheung and colleagues10 reported about a case of an elderly female with OA of the knee with valgus deformity that initially developed a proximal fibular stress fracture followed by a proximal tibial stress fracture. However, both of our patients had varus deformities. Mullaji and Shetty3 documented stress fractures in 34 patients with OA, a majority with varus deformities, but did not report any isolated proximal fibular stress fractures. Manish and colleagues2 reported the only documented case of an isolated proximal fibular stress fracture in a patient with osteoarthritic varus deformity. The patient presented initially with pain and paresthesias of the lower thigh and leg consistent with an L5 radiculopathy. They believed that the varus deformity and the repetitive contraction of the lateral knee muscles put increased shear forces on the fibula leading to the stress fracture. Our patients did not present with any radicular symptoms, a history of acute worsening pain, or an increased activity concerning for a stress fracture. Instead, our patients presented with progressively worsening knee pain typical of severe OA and incidental findings on imaging of tension-side fibular stress fractures. An MRI with and without gadolinium confirmed the diagnosis of a healed fracture in our first patient and a healing fracture in our second patient.

CONCLUSION

Although exceedingly rare in osteoarthritic varus knees, we presented 2 cases of MRI-confirmed proximal fibular stress fractures in this report. As demonstrated, patients may present with symptoms of OA or radicular symptoms as described by Manish and colleagues.2 Presentation may also include an expansile lesion on imaging, prompting a differential diagnosis that includes a neoplasm. If present in the setting of an osteoarthritic varus knee, stress fractures of the proximal fibula should heal with conservative treatment and not affect the plan or outcome of TKA.

ABSTRACT

Stress fractures are often missed, especially in unusual clinical settings. We report on 2 patients who presented to our orthopedic surgery clinic with incidental findings of asymptomatic proximal fibular tension side stress fractures in severe longstanding varus osteoarthritic knees. Initial plain films demonstrated an expansile deformity of the proximal fibular shaft, and differential diagnosis included a healed or healing fracture versus possible neoplasm. Magnetic resonance imaging with and without gadolinium was utilized to rule out the latter prior to planned total knee arthroplasty.

Continue to: The proximal fibula...

The proximal fibula is a rare site for stress fractures, with most of these fractures occurring in military recruits.1 To the authors’ knowledge, there has been only 1 documented case of a proximal fibular stress fracture in patients with severe osteoarthritis (OA) and fixed varus deformity, which mimicked L5 radiculopathy.2 We are not aware of any reports of asymptomatic tension-side fibular stress fractures in varus knees. In our 2 cases, the patients were indicated for total knee arthroplasty (TKA) for varus degenerative joint disease after failing nonoperative treatment; however, further work-up was justified to rule out neoplasm after plain films revealed expansile deformities of the proximal fibular shaft. Each patient subsequently underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with and without gadolinium contrast, which demonstrated a healed and healing proximal fibular stress fracture. Magnetic resonance imaging is rarely indicated in the evaluation of degenerative joint disease, and stress fractures about a varus knee generally occur on the compression side of the tibia and are symptomatic.3-7 The patients provided informed written consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

CASE REPORT

The first patient was a 77-year-old male who presented with longstanding knee pain, left greater than right, exacerbated by weight-bearing activities. The patient had no improvement with physical therapy or anti-inflammatory medication. He denied any history of trauma, weakness, paresthesias, or a recent increase in activity. The patient also denied any fevers, chills, night sweats, or other constitutional symptoms. On physical examination, the patient had an antalgic gait and limited range of motion bilaterally. Examination of his right lower extremity demonstrated a fixed 5° varus deformity. No distinct point tenderness was noted.

Radiographs of the right knee demonstrated varus deformity and tricompartmental degenerative changes with severe medial joint space narrowing. An expansile deformity of the proximal right fibular shaft was also noted (Figure 1), which was not present on the films 2 years earlier (Figure 2). The absence of this deformity on previous imaging raised the suspicion of a tumor. An MRI with and without gadolinium, which was obtained to rule out a neoplastic process, showed an old, healed proximal fibular shaft fracture with chronic periosteal reaction (Figure 3). There was no marrow edema to suggest acute injury and no neoplastic lesion. He was reassured regarding the benign findings and was scheduled for a left TKA, as his pain was more severe on the left knee. The patient’s stress fracture healed without complications, and he underwent a successful left TKA. He returned approximately 6 months after his procedure with worsening right knee pain and underwent a successful TKA on the right knee as well.

The second patient was a 67-year-old male with longstanding bilateral knee pain, right greater than left, with no antecedent trauma. He denied a history of increased activity, or weakness or paresthesias. He denied any fevers, chills, night sweats, or other constitutional symptoms. One year prior to presentation at our clinic, he had received corticosteroid injections and hyaluronic acid, without relief. The patient also had a history with another surgeon of arthroscopy 1 year earlier and subchondroplasty 3 years before presentation to our clinic. On physical examination, the patient’s right knee displayed a fixed 7° varus deformity with decreased range of motion, effusion, and diffuse crepitus. Further examination revealed tenderness to palpation of the proximal fibula.

Radiographs of the right knee showed degenerative joint disease with varus deformity and medial compartment joint space narrowing. They also demonstrated an expansile deformity of mixed lucency and sclerosis involving the proximal right fibular shaft (Figure 4). Although these findings appeared to be consistent with a stress fracture, their appearance was also suspicious for a neoplasm. To rule out malignancy, an MRI with and without gadolinium was obtained that revealed a healing stress fracture of the proximal fibula (Figure 5). The patient was reassured, and plans were made to proceed with a TKA. The patient’s stress fracture healed without complications, and he underwent successful right TKA. Radiographs from the patient’s 8-week follow-up showed a healed fibular stress fracture (Figure 6).

Continue to: DISCUSSION

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first report of incidental tension-side stress fractures in varus osteoarthritic knees. Stress fractures have been classified into 2 groups, fatigue fractures and insufficiency fractures. Fatigue fractures occur when abnormal stress is applied to normal bones, and insufficiency fractures result when normal stress is applied to abnormal bones.8 Stress fractures can also be classified into risk categories based on which bone is involved and the loading of the bone.9 Sites loaded in tension have increased risk of nonunion, progression to complete fracture, and reoccurrence compared with sites loaded in compression.9 Stress fractures of the fibula occur rarely, and when present, they are more commonly observed in the distal fibula in athletes and military recruits.1 Stress fractures occur rarely in patients with primary OA, and when present in this setting, obesity and malalignment are the contributing factors.3 Neither patient was obese in our case (body mass index of 27 and 28, respectively), but significant varus deformity was present in both patients. Stress fractures occurring near the knee in the setting of a varus deformity generally occur on the compression side of the tibia and are symptomatic.3-7

Regarding malalignment, Cheung and colleagues10 reported about a case of an elderly female with OA of the knee with valgus deformity that initially developed a proximal fibular stress fracture followed by a proximal tibial stress fracture. However, both of our patients had varus deformities. Mullaji and Shetty3 documented stress fractures in 34 patients with OA, a majority with varus deformities, but did not report any isolated proximal fibular stress fractures. Manish and colleagues2 reported the only documented case of an isolated proximal fibular stress fracture in a patient with osteoarthritic varus deformity. The patient presented initially with pain and paresthesias of the lower thigh and leg consistent with an L5 radiculopathy. They believed that the varus deformity and the repetitive contraction of the lateral knee muscles put increased shear forces on the fibula leading to the stress fracture. Our patients did not present with any radicular symptoms, a history of acute worsening pain, or an increased activity concerning for a stress fracture. Instead, our patients presented with progressively worsening knee pain typical of severe OA and incidental findings on imaging of tension-side fibular stress fractures. An MRI with and without gadolinium confirmed the diagnosis of a healed fracture in our first patient and a healing fracture in our second patient.

CONCLUSION

Although exceedingly rare in osteoarthritic varus knees, we presented 2 cases of MRI-confirmed proximal fibular stress fractures in this report. As demonstrated, patients may present with symptoms of OA or radicular symptoms as described by Manish and colleagues.2 Presentation may also include an expansile lesion on imaging, prompting a differential diagnosis that includes a neoplasm. If present in the setting of an osteoarthritic varus knee, stress fractures of the proximal fibula should heal with conservative treatment and not affect the plan or outcome of TKA.

- Devas MB, Sweetnam R. Stress fractures of the fibula; a review of fifty cases in athletes. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1956;38-B(4):818-829.

- Manish KK, Agnivesh T, Pramod PS, Samir SD. Isolated proximal fibular stress fracture in osteoarthritis knee presenting as L5 radiculopathy. J Orthop Case Reports. 2015;5(3):75-77. doi:10.13107/jocr.2250-0685.315.

- Mullaji A, Shetty G. Total knee arthroplasty for arthritic knees with tibiofibular stress fractures: classification and treatment guidelines. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25(2):295-301. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2008.11.012.

- Sourlas I, Papachristou G, Pilichou A, Giannoudis PV, Efstathopoulos N, Nikolaou VS. Proximal tibial stress fractures associated with primary degenerative knee osteoarthritis. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2009;38(3):120-124

- Demir B, Gursu S, Oke R, Ozturk K, Sahin V. Proximal tibia stress fracture caused by severe arthrosis of the knee with varus deformity. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2009;38(9):457-459.

- Satku K, Kumar VP, Pho RW. Stress fractures of the tibia in osteoarthritis of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1987;69(2):309-311. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.69B2.3818767.

- Martin LM, Bourne RB, Rorabeck CH. Stress fractures associated with osteoarthritis of the knee. A report of three cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988;70(5):771-774.

- Hong SH, Chu IT. Stress fracture of the proximal fibula in military recruits. Clin Orthop Surg. 2009;1(3):161-164. doi:10.4055/cios.2009.1.3.161

- Knapik JJ, Reynolds K, Hoedebecke KL. Stress fractures: Etiology, epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. J Spec Oper Med. 17(2):120-130.

- Cheung MHS, Lee M-F, Lui TH. Insufficiency fracture of the proximal fibula and then tibia: A case report. J Orthop Surg. 2013;21(1):103-105. doi:10.1177/230949901302100126

- Devas MB, Sweetnam R. Stress fractures of the fibula; a review of fifty cases in athletes. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1956;38-B(4):818-829.

- Manish KK, Agnivesh T, Pramod PS, Samir SD. Isolated proximal fibular stress fracture in osteoarthritis knee presenting as L5 radiculopathy. J Orthop Case Reports. 2015;5(3):75-77. doi:10.13107/jocr.2250-0685.315.

- Mullaji A, Shetty G. Total knee arthroplasty for arthritic knees with tibiofibular stress fractures: classification and treatment guidelines. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25(2):295-301. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2008.11.012.

- Sourlas I, Papachristou G, Pilichou A, Giannoudis PV, Efstathopoulos N, Nikolaou VS. Proximal tibial stress fractures associated with primary degenerative knee osteoarthritis. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2009;38(3):120-124

- Demir B, Gursu S, Oke R, Ozturk K, Sahin V. Proximal tibia stress fracture caused by severe arthrosis of the knee with varus deformity. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2009;38(9):457-459.

- Satku K, Kumar VP, Pho RW. Stress fractures of the tibia in osteoarthritis of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1987;69(2):309-311. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.69B2.3818767.

- Martin LM, Bourne RB, Rorabeck CH. Stress fractures associated with osteoarthritis of the knee. A report of three cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988;70(5):771-774.

- Hong SH, Chu IT. Stress fracture of the proximal fibula in military recruits. Clin Orthop Surg. 2009;1(3):161-164. doi:10.4055/cios.2009.1.3.161

- Knapik JJ, Reynolds K, Hoedebecke KL. Stress fractures: Etiology, epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. J Spec Oper Med. 17(2):120-130.

- Cheung MHS, Lee M-F, Lui TH. Insufficiency fracture of the proximal fibula and then tibia: A case report. J Orthop Surg. 2013;21(1):103-105. doi:10.1177/230949901302100126

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Proximal fibular stress fractures in patients with primary osteoarthritis and fixed varus deformity have rarely been reported.

- Stress fractures occurring near the knee in the setting of a varus deformity generally occur on the compression side of the tibia and are symptomatic.

- Proximal fibular stress fractures may present as an incidental finding of an expansile deformity on plain films in patients with varus osteoarthritic knees.

- Magnetic resonance imaging is rarely indicated in the evaluation of degenerative joint disease; however, it was justified in our case to rule out neoplasm.

- When present in the setting of an osteoarthritic varus knee, stress fractures of the proximal fibula should heal with conservative treatment and should not affect the plan or outcome of TKA.

To prevent fractures, treating only women with osteoporosis is not enough

The conventional bone mineral density threshold for initiating treatment to prevent fragility fractures is a T-score of less than -2.5 (the World Health Organization criteria for osteoporosis).1 However, most fractures experienced by postmenopausal women occur not in osteoporotic women but in those with low bone mass (osteopenia).2

Investigators in New Zealand recently published the results of a randomized controlled trial they conducted to determine the efficacy of zoledronate (zoledronic acid) in preventing fractures in postmenopausal women.3 They enrolled women age 65 years or older with osteopenia of the hip and randomly assigned the participants to 4 intravenous infusions of 5 mg zoledronic acid or placebo at 18-month intervals for 6 years.

Zoledronic acid reduced fracture risk

The trial included 2,000 postmenopausal women (mean age at baseline, 71 years; 94% European ethnicity) with a T-score of -1.0 to -2.5 at either the total hip or the femoral neck on either side. Both hips were assessed. The women received either zoledronic acid treatment or placebo in a 1:1 ratio. Candidates were excluded if they regularly used bone-active drugs in the previous year.

Fragility fractures were noted in 190 women in the placebo group and in 122 women treated with zoledronic acid (hazard ratio [HR], 0.63; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.50–0.79, P<.001). The number of women that would need to be treated to prevent the occurrence of a fracture in 1 woman was 15.

Compared with placebo, zoledronic acid also lowered the risk of nonvertebral, symptomatic, and vertebral fractures as well as height loss (P≤.003 for these 4 comparisons). Relatively few adverse events occurred with zoledronic acid treatment. No atypical femoral fractures or cases of osteonecrosis of the jaw occurred in either group.

Trial closes the knowledge gap regarding treatment thresholds

This trial’s findings underscore the importance of age as a risk factor for fragility fracture and clarify that pharmacologic treatment is appropriate not only for women with osteoporosis but also for older postmenopausal women with osteopenia.

As the authors point out, administration of zoledronic acid less often than annually can be highly effective in preventing fractures; they recommend future trials of administration of this intravenous bisphosphonate at intervals less frequent than 18 months. Although the absence of atypical femoral fractures or cases of osteonecrosis of the jaw is reassuring, the authors note that their trial was underpowered to assess these uncommon events.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- World Health Organization. WHO Scientific Group on the assessment of osteoporosis at primary health care level. Summary meeting report, Brussels, Belgium, 5-7 May 2004. https://www. who.int/chp/topics/Osteoporosis.pdf. Accessed November 19, 2018.

- Siris ES, Chen YT, Abbott TA, et al. Bone mineral density thresholds for pharmacological intervention to prevent fractures. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1108-1112.

- Reid IR, Horne AM, Mihov B, et al. Fracture prevention with zoledronate in older women with osteopenia. N Engl J Med. 2018. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1808082.

The conventional bone mineral density threshold for initiating treatment to prevent fragility fractures is a T-score of less than -2.5 (the World Health Organization criteria for osteoporosis).1 However, most fractures experienced by postmenopausal women occur not in osteoporotic women but in those with low bone mass (osteopenia).2

Investigators in New Zealand recently published the results of a randomized controlled trial they conducted to determine the efficacy of zoledronate (zoledronic acid) in preventing fractures in postmenopausal women.3 They enrolled women age 65 years or older with osteopenia of the hip and randomly assigned the participants to 4 intravenous infusions of 5 mg zoledronic acid or placebo at 18-month intervals for 6 years.

Zoledronic acid reduced fracture risk

The trial included 2,000 postmenopausal women (mean age at baseline, 71 years; 94% European ethnicity) with a T-score of -1.0 to -2.5 at either the total hip or the femoral neck on either side. Both hips were assessed. The women received either zoledronic acid treatment or placebo in a 1:1 ratio. Candidates were excluded if they regularly used bone-active drugs in the previous year.

Fragility fractures were noted in 190 women in the placebo group and in 122 women treated with zoledronic acid (hazard ratio [HR], 0.63; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.50–0.79, P<.001). The number of women that would need to be treated to prevent the occurrence of a fracture in 1 woman was 15.

Compared with placebo, zoledronic acid also lowered the risk of nonvertebral, symptomatic, and vertebral fractures as well as height loss (P≤.003 for these 4 comparisons). Relatively few adverse events occurred with zoledronic acid treatment. No atypical femoral fractures or cases of osteonecrosis of the jaw occurred in either group.

Trial closes the knowledge gap regarding treatment thresholds

This trial’s findings underscore the importance of age as a risk factor for fragility fracture and clarify that pharmacologic treatment is appropriate not only for women with osteoporosis but also for older postmenopausal women with osteopenia.

As the authors point out, administration of zoledronic acid less often than annually can be highly effective in preventing fractures; they recommend future trials of administration of this intravenous bisphosphonate at intervals less frequent than 18 months. Although the absence of atypical femoral fractures or cases of osteonecrosis of the jaw is reassuring, the authors note that their trial was underpowered to assess these uncommon events.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

The conventional bone mineral density threshold for initiating treatment to prevent fragility fractures is a T-score of less than -2.5 (the World Health Organization criteria for osteoporosis).1 However, most fractures experienced by postmenopausal women occur not in osteoporotic women but in those with low bone mass (osteopenia).2

Investigators in New Zealand recently published the results of a randomized controlled trial they conducted to determine the efficacy of zoledronate (zoledronic acid) in preventing fractures in postmenopausal women.3 They enrolled women age 65 years or older with osteopenia of the hip and randomly assigned the participants to 4 intravenous infusions of 5 mg zoledronic acid or placebo at 18-month intervals for 6 years.

Zoledronic acid reduced fracture risk

The trial included 2,000 postmenopausal women (mean age at baseline, 71 years; 94% European ethnicity) with a T-score of -1.0 to -2.5 at either the total hip or the femoral neck on either side. Both hips were assessed. The women received either zoledronic acid treatment or placebo in a 1:1 ratio. Candidates were excluded if they regularly used bone-active drugs in the previous year.

Fragility fractures were noted in 190 women in the placebo group and in 122 women treated with zoledronic acid (hazard ratio [HR], 0.63; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.50–0.79, P<.001). The number of women that would need to be treated to prevent the occurrence of a fracture in 1 woman was 15.

Compared with placebo, zoledronic acid also lowered the risk of nonvertebral, symptomatic, and vertebral fractures as well as height loss (P≤.003 for these 4 comparisons). Relatively few adverse events occurred with zoledronic acid treatment. No atypical femoral fractures or cases of osteonecrosis of the jaw occurred in either group.

Trial closes the knowledge gap regarding treatment thresholds

This trial’s findings underscore the importance of age as a risk factor for fragility fracture and clarify that pharmacologic treatment is appropriate not only for women with osteoporosis but also for older postmenopausal women with osteopenia.

As the authors point out, administration of zoledronic acid less often than annually can be highly effective in preventing fractures; they recommend future trials of administration of this intravenous bisphosphonate at intervals less frequent than 18 months. Although the absence of atypical femoral fractures or cases of osteonecrosis of the jaw is reassuring, the authors note that their trial was underpowered to assess these uncommon events.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- World Health Organization. WHO Scientific Group on the assessment of osteoporosis at primary health care level. Summary meeting report, Brussels, Belgium, 5-7 May 2004. https://www. who.int/chp/topics/Osteoporosis.pdf. Accessed November 19, 2018.

- Siris ES, Chen YT, Abbott TA, et al. Bone mineral density thresholds for pharmacological intervention to prevent fractures. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1108-1112.

- Reid IR, Horne AM, Mihov B, et al. Fracture prevention with zoledronate in older women with osteopenia. N Engl J Med. 2018. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1808082.

- World Health Organization. WHO Scientific Group on the assessment of osteoporosis at primary health care level. Summary meeting report, Brussels, Belgium, 5-7 May 2004. https://www. who.int/chp/topics/Osteoporosis.pdf. Accessed November 19, 2018.

- Siris ES, Chen YT, Abbott TA, et al. Bone mineral density thresholds for pharmacological intervention to prevent fractures. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1108-1112.

- Reid IR, Horne AM, Mihov B, et al. Fracture prevention with zoledronate in older women with osteopenia. N Engl J Med. 2018. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1808082.

LCAR-B38M CAR T therapy appears durable in myeloma

SAN DIEGO – The chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy LCAR-B38M is in the race for approval in multiple myeloma following encouraging phase 1 results reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

In the LEGEND-2 phase 1/2 open study of 57 patients with advanced relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma treated with the investigational CAR T therapy, the overall response rate was 88% and the complete response rate was 74%. Among 42 patients who achieved complete response, 39 (68%) were negative for minimal residual disease (MRD).

With a median follow-up of 12 months, the median duration of response was 16 months and progression-free survival was 15 months. But in patients who achieved MRD-negative complete response, the median progression-free survival was extended to 24 months.

Pyrexia and cytokine release syndrome were reported in 90% or more of patients. Thrombocytopenia and leukopenia were reported in nearly half of patients.

The phase 1 study was conducted by researchers from the Second Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University in Xi’an, China. The B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA)–directed CAR T-cell therapy is being jointly developed by Nanjing Legend Biotech and Janssen. A phase 2 study is currently being planned in China for LCAR-B38M. In parallel, Janssen and Legend are enrolling patients in a phase 1b/2 trial of the agent (also known as JNJ-68284528) in the United States.

The therapy joins a growing field of anti-BCMA CAR T-cell agents with promising initial trial results, including bb2121.

In a video interview at ASH, Sen Zhuang, MD, PhD, vice president of oncology clinical development at Janssen Research & Development, said this class of CAR T agents offers the potential for “very long remissions” and possibly even a “cure” for myeloma.

The LEGEND-2 study is sponsored by Nanjing Legend Biotech and two of the investigators reported employment with the company.

SAN DIEGO – The chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy LCAR-B38M is in the race for approval in multiple myeloma following encouraging phase 1 results reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

In the LEGEND-2 phase 1/2 open study of 57 patients with advanced relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma treated with the investigational CAR T therapy, the overall response rate was 88% and the complete response rate was 74%. Among 42 patients who achieved complete response, 39 (68%) were negative for minimal residual disease (MRD).

With a median follow-up of 12 months, the median duration of response was 16 months and progression-free survival was 15 months. But in patients who achieved MRD-negative complete response, the median progression-free survival was extended to 24 months.

Pyrexia and cytokine release syndrome were reported in 90% or more of patients. Thrombocytopenia and leukopenia were reported in nearly half of patients.

The phase 1 study was conducted by researchers from the Second Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University in Xi’an, China. The B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA)–directed CAR T-cell therapy is being jointly developed by Nanjing Legend Biotech and Janssen. A phase 2 study is currently being planned in China for LCAR-B38M. In parallel, Janssen and Legend are enrolling patients in a phase 1b/2 trial of the agent (also known as JNJ-68284528) in the United States.

The therapy joins a growing field of anti-BCMA CAR T-cell agents with promising initial trial results, including bb2121.

In a video interview at ASH, Sen Zhuang, MD, PhD, vice president of oncology clinical development at Janssen Research & Development, said this class of CAR T agents offers the potential for “very long remissions” and possibly even a “cure” for myeloma.

The LEGEND-2 study is sponsored by Nanjing Legend Biotech and two of the investigators reported employment with the company.

SAN DIEGO – The chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy LCAR-B38M is in the race for approval in multiple myeloma following encouraging phase 1 results reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

In the LEGEND-2 phase 1/2 open study of 57 patients with advanced relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma treated with the investigational CAR T therapy, the overall response rate was 88% and the complete response rate was 74%. Among 42 patients who achieved complete response, 39 (68%) were negative for minimal residual disease (MRD).

With a median follow-up of 12 months, the median duration of response was 16 months and progression-free survival was 15 months. But in patients who achieved MRD-negative complete response, the median progression-free survival was extended to 24 months.

Pyrexia and cytokine release syndrome were reported in 90% or more of patients. Thrombocytopenia and leukopenia were reported in nearly half of patients.

The phase 1 study was conducted by researchers from the Second Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University in Xi’an, China. The B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA)–directed CAR T-cell therapy is being jointly developed by Nanjing Legend Biotech and Janssen. A phase 2 study is currently being planned in China for LCAR-B38M. In parallel, Janssen and Legend are enrolling patients in a phase 1b/2 trial of the agent (also known as JNJ-68284528) in the United States.

The therapy joins a growing field of anti-BCMA CAR T-cell agents with promising initial trial results, including bb2121.

In a video interview at ASH, Sen Zhuang, MD, PhD, vice president of oncology clinical development at Janssen Research & Development, said this class of CAR T agents offers the potential for “very long remissions” and possibly even a “cure” for myeloma.

The LEGEND-2 study is sponsored by Nanjing Legend Biotech and two of the investigators reported employment with the company.

REPORTING FROM ASH 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The complete response rate was 74% with median progression-free survival of 15 months.

Study details: A phase 1/2 study of 57 patients with advanced relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma.

Disclosures: The study is sponsored by Nanjing Legend Biotech. Two of the investigators reported employment with the company.

PD-L1 expression best predicts response to atezolizumab + nab-paclitaxel for mTNBC

SAN ANTONIO – in patients with untreated metastatic triple-negative breast cancer, according to exploratory efficacy analyses of data from the phase 3 IMpassion130 trial.

The analyses of data for the 902 patients randomized to receive the PD-L1 inhibitor atezolizumab (Tecentriq) plus nanoparticle albumin-bound (nab)–paclitaxel or placebo plus nab-palcitaxel for the study also showed consistency between local and central estrogen-receptor, progesterone-receptor, and human epidermal growth factor–receptor 2 testing, Leisha A. Emens, MD, reported at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

“IMpassion130 is the first phase 3 study to demonstrate a benefit from [atezolizumab + nab-paclitaxel] in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (mTNBC),” said Dr. Emens, professor of medicine in hematology/oncology, coleader of the Hillman Cancer Immunology and Immunotherapy Program, and director of translational immunotherapy for the Women’s Cancer Research Center at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

She explained that progression-free survival (PFS) was significantly better in PD-L1–positive mTNBC patients treated with the atezolizumab + nab-paclitaxel, than in those who received placebo + nab-paclitaxel (hazard ratios in the intent-to-treat population, 0.8 and 0.62, respectively).

At the first interim overall survival analysis, a clinically meaningful improvement in OS was seen in PD-L1–positive patients in the treatment group (HR, 0.62; median OS improvement from 15.5 months with placebo to 25 months), she added.

In exploratory analyses, Dr. Emens and her colleagues sought to evaluate whether preexisting immune biology is associated with clinical benefit from atezolizumab + nab-paclitaxel, as has been demonstrated in studies of other agents that target the PD-1 pathway in other cancer types of cancer. They also assessed BRCA 1/2 mutation status as a biomarker for response.

“In patients enrolled on the IMpassion130 trial we found that PD-L1 in triple-negative breast cancer was expressed primarily on tumor-infiltrating immune cells,” she said. “In contrast to this, we found a very low rate of PD-L1 expression specifically on tumor cells across the patient population.”

Looking at both of those biomarkers together showed that a majority of patients with expression of PD-L1 on tumor cells were included in the PD-L1 immune cell–positive population, with only 2% having PD-L1 expression exclusively on their tumor cells.

Data previously reported at the European Society for Medical Oncology and published in the New England Journal of Medicine showed a PFS benefit, as well as a clinically meaningful improvement in OS of nearly 10 months, specifically in patients with PD-L1 immune cell–positive lesions treated with atezolizumab + nab-paclitaxel, she noted.

“In data presented for the first time today you can see that PD-L1–negative patients derive no overall survival benefit as there was no treatment effect with this therapy combination,” she said.

A trend was seen toward an association between immune cell positivity and poor prognosis, but this was not statistically significant, she said.

“Taken together, these data definitively show that PD-L1 immune cell positivity is predictive of both progression-free and overall survival benefit with atezolizumab + nab-paclitaxel,” she said.

She and her colleagues also looked at the level of PD-L1 expression in immune cells to assess whether there is a threshold that might be required.

“As long as there was a PD-L1 expression level of 1% or more in the immune cells, there was a significant progression-free and overall survival benefit for patients treated with atezolizumab + nab-paclitaxel. This suggests that this expression of over 1% will represent a threshold for identifying those patients who are likely to benefit from this combination,” she said.

Further assessment by CD8 T-cell status showed that patients who had CD8-positive T cells but who were PD-L1 immune cell negative had no benefit from atezolizumab + nab-paclitaxel, whereas those who were positive for both CD8 and PD-L1 expression on their immune cells derived significant PFS and OS benefit (HR, 0.89 and 0.77, respectively).

“So patients with CD8-positive tumors derive clinical benefit only if their tumors are also PD-L1-positive,” she said.

Similarly, no clinical benefit was seen in patients with stromal tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL)–positive tumors but who were PD-L1-negative, whereas those with stromal TIL-positive PD-L1–positive tumors derived significant PFS and OS benefit (HRs, 0.99 and 1.53, respectively), and this was also seen in the 15% of evaluable patients who had BRCA mutations.

“In patients who were BRCA mutated, but who were PD-L1 immune cell negative, there was no association of progression-free survival or an overall survival benefit [with atezolizumab + nab-paclitaxel]. In contrast, in patients who were BRCA mutated but PD-L1 immune cell positive ... there was an association with progression-free survival and a trend toward overall survival,” she said, noting that while the BRCA mutation findings are limited by small numbers, “they do show that mutations in BRCA and PD-L1 expression in immune cells are independent biomarkers; patients with BRCA1 or 2 mutations derive clinical benefit only if their tumors are also PD-L1 positive.”

“In this phase 3 IMpassion130 study, PD-L1 expression on immune cells is a predictive biomarker for selecting patients who benefit clinically during first-line treatment with atezolizumab + nab-paclitaxel for metastatic triple-negative breast cancer,” she concluded, adding that “patients with newly diagnosed metastatic and unresectable locally advanced triple-negative breast cancer should be routinely tested for their PD-L1 immune cell status to determine if they might benefit from the combination of atezolizumab + nab-paclitaxel.

IMpassion130 was sponsored by Hoffman-La Roche. Dr. Emens reported receiving royalties and consulting fees from several companies. She has contracts with Roche/Genentech, Corvus, AstraZeneca, and EMD Serono, and ownership in Molecuvax. She receives other support from DSMB and Syndax, and has received grants from Aduro Biotech, Merck, Maxcyte, and the Breast Cancer Research Foundation. She also reported serving as a member of the Food and Drug Administration Advisory Committee on Tissue, Cell, and Gene Therapies, and is a member of the board of directors for the Society of Immunotherapy for Cancer.

SOURCE: Emens L et al. SABCS 2018, Abstract GS1-04.

SAN ANTONIO – in patients with untreated metastatic triple-negative breast cancer, according to exploratory efficacy analyses of data from the phase 3 IMpassion130 trial.

The analyses of data for the 902 patients randomized to receive the PD-L1 inhibitor atezolizumab (Tecentriq) plus nanoparticle albumin-bound (nab)–paclitaxel or placebo plus nab-palcitaxel for the study also showed consistency between local and central estrogen-receptor, progesterone-receptor, and human epidermal growth factor–receptor 2 testing, Leisha A. Emens, MD, reported at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

“IMpassion130 is the first phase 3 study to demonstrate a benefit from [atezolizumab + nab-paclitaxel] in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (mTNBC),” said Dr. Emens, professor of medicine in hematology/oncology, coleader of the Hillman Cancer Immunology and Immunotherapy Program, and director of translational immunotherapy for the Women’s Cancer Research Center at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

She explained that progression-free survival (PFS) was significantly better in PD-L1–positive mTNBC patients treated with the atezolizumab + nab-paclitaxel, than in those who received placebo + nab-paclitaxel (hazard ratios in the intent-to-treat population, 0.8 and 0.62, respectively).

At the first interim overall survival analysis, a clinically meaningful improvement in OS was seen in PD-L1–positive patients in the treatment group (HR, 0.62; median OS improvement from 15.5 months with placebo to 25 months), she added.

In exploratory analyses, Dr. Emens and her colleagues sought to evaluate whether preexisting immune biology is associated with clinical benefit from atezolizumab + nab-paclitaxel, as has been demonstrated in studies of other agents that target the PD-1 pathway in other cancer types of cancer. They also assessed BRCA 1/2 mutation status as a biomarker for response.

“In patients enrolled on the IMpassion130 trial we found that PD-L1 in triple-negative breast cancer was expressed primarily on tumor-infiltrating immune cells,” she said. “In contrast to this, we found a very low rate of PD-L1 expression specifically on tumor cells across the patient population.”

Looking at both of those biomarkers together showed that a majority of patients with expression of PD-L1 on tumor cells were included in the PD-L1 immune cell–positive population, with only 2% having PD-L1 expression exclusively on their tumor cells.

Data previously reported at the European Society for Medical Oncology and published in the New England Journal of Medicine showed a PFS benefit, as well as a clinically meaningful improvement in OS of nearly 10 months, specifically in patients with PD-L1 immune cell–positive lesions treated with atezolizumab + nab-paclitaxel, she noted.

“In data presented for the first time today you can see that PD-L1–negative patients derive no overall survival benefit as there was no treatment effect with this therapy combination,” she said.

A trend was seen toward an association between immune cell positivity and poor prognosis, but this was not statistically significant, she said.

“Taken together, these data definitively show that PD-L1 immune cell positivity is predictive of both progression-free and overall survival benefit with atezolizumab + nab-paclitaxel,” she said.

She and her colleagues also looked at the level of PD-L1 expression in immune cells to assess whether there is a threshold that might be required.

“As long as there was a PD-L1 expression level of 1% or more in the immune cells, there was a significant progression-free and overall survival benefit for patients treated with atezolizumab + nab-paclitaxel. This suggests that this expression of over 1% will represent a threshold for identifying those patients who are likely to benefit from this combination,” she said.

Further assessment by CD8 T-cell status showed that patients who had CD8-positive T cells but who were PD-L1 immune cell negative had no benefit from atezolizumab + nab-paclitaxel, whereas those who were positive for both CD8 and PD-L1 expression on their immune cells derived significant PFS and OS benefit (HR, 0.89 and 0.77, respectively).

“So patients with CD8-positive tumors derive clinical benefit only if their tumors are also PD-L1-positive,” she said.

Similarly, no clinical benefit was seen in patients with stromal tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL)–positive tumors but who were PD-L1-negative, whereas those with stromal TIL-positive PD-L1–positive tumors derived significant PFS and OS benefit (HRs, 0.99 and 1.53, respectively), and this was also seen in the 15% of evaluable patients who had BRCA mutations.

“In patients who were BRCA mutated, but who were PD-L1 immune cell negative, there was no association of progression-free survival or an overall survival benefit [with atezolizumab + nab-paclitaxel]. In contrast, in patients who were BRCA mutated but PD-L1 immune cell positive ... there was an association with progression-free survival and a trend toward overall survival,” she said, noting that while the BRCA mutation findings are limited by small numbers, “they do show that mutations in BRCA and PD-L1 expression in immune cells are independent biomarkers; patients with BRCA1 or 2 mutations derive clinical benefit only if their tumors are also PD-L1 positive.”

“In this phase 3 IMpassion130 study, PD-L1 expression on immune cells is a predictive biomarker for selecting patients who benefit clinically during first-line treatment with atezolizumab + nab-paclitaxel for metastatic triple-negative breast cancer,” she concluded, adding that “patients with newly diagnosed metastatic and unresectable locally advanced triple-negative breast cancer should be routinely tested for their PD-L1 immune cell status to determine if they might benefit from the combination of atezolizumab + nab-paclitaxel.

IMpassion130 was sponsored by Hoffman-La Roche. Dr. Emens reported receiving royalties and consulting fees from several companies. She has contracts with Roche/Genentech, Corvus, AstraZeneca, and EMD Serono, and ownership in Molecuvax. She receives other support from DSMB and Syndax, and has received grants from Aduro Biotech, Merck, Maxcyte, and the Breast Cancer Research Foundation. She also reported serving as a member of the Food and Drug Administration Advisory Committee on Tissue, Cell, and Gene Therapies, and is a member of the board of directors for the Society of Immunotherapy for Cancer.

SOURCE: Emens L et al. SABCS 2018, Abstract GS1-04.

SAN ANTONIO – in patients with untreated metastatic triple-negative breast cancer, according to exploratory efficacy analyses of data from the phase 3 IMpassion130 trial.

The analyses of data for the 902 patients randomized to receive the PD-L1 inhibitor atezolizumab (Tecentriq) plus nanoparticle albumin-bound (nab)–paclitaxel or placebo plus nab-palcitaxel for the study also showed consistency between local and central estrogen-receptor, progesterone-receptor, and human epidermal growth factor–receptor 2 testing, Leisha A. Emens, MD, reported at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

“IMpassion130 is the first phase 3 study to demonstrate a benefit from [atezolizumab + nab-paclitaxel] in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (mTNBC),” said Dr. Emens, professor of medicine in hematology/oncology, coleader of the Hillman Cancer Immunology and Immunotherapy Program, and director of translational immunotherapy for the Women’s Cancer Research Center at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

She explained that progression-free survival (PFS) was significantly better in PD-L1–positive mTNBC patients treated with the atezolizumab + nab-paclitaxel, than in those who received placebo + nab-paclitaxel (hazard ratios in the intent-to-treat population, 0.8 and 0.62, respectively).

At the first interim overall survival analysis, a clinically meaningful improvement in OS was seen in PD-L1–positive patients in the treatment group (HR, 0.62; median OS improvement from 15.5 months with placebo to 25 months), she added.

In exploratory analyses, Dr. Emens and her colleagues sought to evaluate whether preexisting immune biology is associated with clinical benefit from atezolizumab + nab-paclitaxel, as has been demonstrated in studies of other agents that target the PD-1 pathway in other cancer types of cancer. They also assessed BRCA 1/2 mutation status as a biomarker for response.

“In patients enrolled on the IMpassion130 trial we found that PD-L1 in triple-negative breast cancer was expressed primarily on tumor-infiltrating immune cells,” she said. “In contrast to this, we found a very low rate of PD-L1 expression specifically on tumor cells across the patient population.”

Looking at both of those biomarkers together showed that a majority of patients with expression of PD-L1 on tumor cells were included in the PD-L1 immune cell–positive population, with only 2% having PD-L1 expression exclusively on their tumor cells.

Data previously reported at the European Society for Medical Oncology and published in the New England Journal of Medicine showed a PFS benefit, as well as a clinically meaningful improvement in OS of nearly 10 months, specifically in patients with PD-L1 immune cell–positive lesions treated with atezolizumab + nab-paclitaxel, she noted.

“In data presented for the first time today you can see that PD-L1–negative patients derive no overall survival benefit as there was no treatment effect with this therapy combination,” she said.

A trend was seen toward an association between immune cell positivity and poor prognosis, but this was not statistically significant, she said.

“Taken together, these data definitively show that PD-L1 immune cell positivity is predictive of both progression-free and overall survival benefit with atezolizumab + nab-paclitaxel,” she said.

She and her colleagues also looked at the level of PD-L1 expression in immune cells to assess whether there is a threshold that might be required.

“As long as there was a PD-L1 expression level of 1% or more in the immune cells, there was a significant progression-free and overall survival benefit for patients treated with atezolizumab + nab-paclitaxel. This suggests that this expression of over 1% will represent a threshold for identifying those patients who are likely to benefit from this combination,” she said.

Further assessment by CD8 T-cell status showed that patients who had CD8-positive T cells but who were PD-L1 immune cell negative had no benefit from atezolizumab + nab-paclitaxel, whereas those who were positive for both CD8 and PD-L1 expression on their immune cells derived significant PFS and OS benefit (HR, 0.89 and 0.77, respectively).

“So patients with CD8-positive tumors derive clinical benefit only if their tumors are also PD-L1-positive,” she said.

Similarly, no clinical benefit was seen in patients with stromal tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL)–positive tumors but who were PD-L1-negative, whereas those with stromal TIL-positive PD-L1–positive tumors derived significant PFS and OS benefit (HRs, 0.99 and 1.53, respectively), and this was also seen in the 15% of evaluable patients who had BRCA mutations.

“In patients who were BRCA mutated, but who were PD-L1 immune cell negative, there was no association of progression-free survival or an overall survival benefit [with atezolizumab + nab-paclitaxel]. In contrast, in patients who were BRCA mutated but PD-L1 immune cell positive ... there was an association with progression-free survival and a trend toward overall survival,” she said, noting that while the BRCA mutation findings are limited by small numbers, “they do show that mutations in BRCA and PD-L1 expression in immune cells are independent biomarkers; patients with BRCA1 or 2 mutations derive clinical benefit only if their tumors are also PD-L1 positive.”

“In this phase 3 IMpassion130 study, PD-L1 expression on immune cells is a predictive biomarker for selecting patients who benefit clinically during first-line treatment with atezolizumab + nab-paclitaxel for metastatic triple-negative breast cancer,” she concluded, adding that “patients with newly diagnosed metastatic and unresectable locally advanced triple-negative breast cancer should be routinely tested for their PD-L1 immune cell status to determine if they might benefit from the combination of atezolizumab + nab-paclitaxel.

IMpassion130 was sponsored by Hoffman-La Roche. Dr. Emens reported receiving royalties and consulting fees from several companies. She has contracts with Roche/Genentech, Corvus, AstraZeneca, and EMD Serono, and ownership in Molecuvax. She receives other support from DSMB and Syndax, and has received grants from Aduro Biotech, Merck, Maxcyte, and the Breast Cancer Research Foundation. She also reported serving as a member of the Food and Drug Administration Advisory Committee on Tissue, Cell, and Gene Therapies, and is a member of the board of directors for the Society of Immunotherapy for Cancer.

SOURCE: Emens L et al. SABCS 2018, Abstract GS1-04.

REPORTING FROM SABCS 2018

Key clinical point: Treatment-naive mTNBC patients should be tested for PD-L1 expression as a biomarker of potential benefit from atezolizumab + nab-paclitaxel.

Major finding: PD-L1 expression of at least 1% confers a significant PFS and OS benefit in patients treated with atezolizumab + nab-paclitaxel.

Study details: Exploratory efficacy analyses of a phase 3 study of 902 patients.

Disclosures: IMpassion130 was sponsored by Hoffman-La Roche. Dr. Emens reported receiving royalties from and consulting fees from several companies. She has contracts with Roche/Genentech, Corvus, AstraZeneca, and EMD Serono, and ownership in Molecuvax. She receives other support from DSMB and Syndax, and has received grants from Aduro Biotech, Merck, Maxcyte, and the Breast Cancer Research Foundation. She also reported serving as a member of the FDA Advisory Committee on Tissue, Cell, and Gene Therapies, and is a member of the board of directors for the Society of Immunotherapy for Cancer.

Source: Emens L et al. SABCS 2018, Abstract GS1-04.

Ice Pack–Induced Perniosis: A Rare and Underrecognized Association

Perniosis, or chilblain, is characterized by localized, tender, erythematous skin lesions that occur as an abnormal reaction to exposure to cold and damp conditions. Although the lesions favor the distal extremities, perniosis may present anywhere on the body. Lesions can develop within hours to days following exposure to temperature less than 10°C or damp environments with greater than 60% humidity.1 Acute cases may lead to pruritus and tenderness, whereas chronic cases may involve lesions that blister or ulcerate and can take weeks to heal. We report an unusual case of erythematous plaques arising on the buttocks of a 73-year-old woman using ice pack treatments for chronic low back pain.

Case Report

A 73-year-old woman presented with recurrent tender lesions on the buttocks of 5 years’ duration. Her medical history was remarkable for hypertension, hypothyroidism, and lumbar spinal fusion surgery 5 years prior. Physical examination revealed indurated erythematous plaques with areas of erosions on the left buttock with some involvement of the right buttock (Figure 1).

After a trial of oral valacyclovir for presumed herpes simplex infection provided no relief, a punch biopsy of the left buttock was performed, which revealed a cell-poor interface dermatitis with superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrates (Figure 2). Perieccrine lymphocytes were present in a small portion of the reticular dermis (Figure 3). The patient revealed she had been sitting on ice packs for several hours daily since the lumbar spinal fusion surgery 5 years prior to alleviate chronic low back pain.

Based on the clinicopathologic correlation, a diagnosis of perniosis secondary to ice pack therapy was made. An evaluation for concomitant or underlying connective tissue disease (CTD) including a complete blood cell count with sedimentation rate, antinuclear antibodies (ANAs), serum protein electrophoresis, and serum levels of cryoglobulins and complement components was unremarkable. Our patient was treated with simple analgesia and was encouraged to avoid direct contact with ice packs for extended periods of time. Because of her low back pain, she continued to use ice packs but readjusted them sporadically and decreased frequency of use. She had complete resolution of the lesions at 6-month follow-up.

Comment

Perniosis is a self-limited condition, manifesting as erythematous plaques or nodules following exposure to cold and damp conditions. It was first reported in 1902 by Hochsinger2 as tender submental plaques occurring in children after exposure to cold weather. Since then, reports of perniosis have been described in equestrians and long-distance cyclists as well as in the context of other outdoor activities.3-5 In all cases, patients developed perniosis at sites of exposure to cold or damp conditions.

Perniosis arising in patients using ice pack therapy is a rare and recent phenomenon, with only 3 other known reported cases.6,7 In all cases, including ours, patients reported treating chronic low back pain with ice packs for more than 2 hours per day. Clinical presentations included erythematous to purpuric plaques with ulceration on the lower back or buttocks that reoccurred with subsequent use of ice packs. No concomitant CTD was reported.6

Much controversy exists as to whether idiopathic perniosis (IP) increases susceptibility to acquiring an autoimmune disease or if IP is a form of CTD that follows a more indolent course.8 In a prospective study of 33 patients with underlying IP, no patients developed lupus erythematosus (LE), with a median follow-up of 38 months.9 A study by Crowson and Magro8 revealed that 18 of 39 patients with perniotic lesions had an associated systemic disease including LE, human immunodeficiency virus, viral hepatitis, rheumatoid arthritis, cryofibrinogenemia, hypergammaglobulinemia, iritis, or Crohn disease. Of the 21 other patients who had no underlying CTD or systemic disease, 10 had a positive ANA test but no systemic symptoms; therefore, all 21 of these patients were classified as cases of IP.8

Cutaneous biopsy to distinguish between IP and autoimmune perniosis remains controversial; perniotic lesions and discoid LE share histopathologic features,9 as was evident with our case, which demonstrated overlapping findings of vacuolar change with superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphoid infiltrates. Typical features of IP include thrombosed capillaries in the papillary dermis and lymphocytic exocytosis localized to the acrosyringia, whereas secondary perniosis has superficial and deep perivascular and perieccrine lymphocytic infiltrates with vascular thrombosis in the reticular dermis. Vascular ectasia, dermal mucinosis, basement membrane zone thickening, and erythrocyte extravasation are not reliable and may be seen in both cases.8 One study revealed the only significant difference between both entities was the perieccrine distribution of lymphocytic infiltrate in cases of IP (P=.007), whereas an absence of perieccrine involvement was noted in autoimmune cases.9

Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) may help differentiate IP from autoimmune perniosis. In a prospective study by Viguier et al,9 6 of 9 patients with IP had negative DIF and 3 had slight nonspecific C3 immunoreactivity of dermal vessels. Conversely, in patients with autoimmune perniosis, positive DIF with the lupus band test was seen in 3 of 7 patients, all who had a positive ANA test9; however, positive ANA levels also were reported in patients with autoimmune perniosis but negative DIF, suggesting that DIF lacks specificity in diagnosing autoimmune perniosis.

Although histopathologic findings bear similarities to LE, there are no guidelines to suggest for or against laboratory testing for CTD in patients presenting with perniosis. Some investigators have suggested that any patient with clinical features suggestive of perniosis should undergo laboratory evaluation including a complete blood cell count and assessment for antibodies to Ro, ANA, rheumatoid factor, cryofibrinogens, and antiphospholipid antibodies.9 Serum protein electrophoresis and immunofixation electrophoresis may be done to exclude monoclonal gammopathy.

For idiopathic cases, treatment is aimed at limiting or removing cold exposure. Patients should be advised regarding the use of long-term ice pack use and the potential development of perniosis. For chronic perniosis lasting beyond several weeks, a combination of a slow taper of oral prednisone, hydroxychloroquine, and quinacrine has been successful in patients with persistent lesions despite making environmental modifications.3 Intralesional triamcinolone acetonide and nifedipine also have been effective in perniotic hand lesions.10

Conclusion

We report a rare case of perniosis on the buttocks that arose in a patient who utilized ice packs for treatment of chronic low back pain. Ice pack–induced perniosis may be an underreported entity. Histopathologic examination is nondescript, as overlapping features of perniosis and LE have been observed with no underlying CTD present. Correlation with patient history and clinical examination is paramount in diagnosis and management.

- Praminik T, Jha AK, Ghimire A. A retrospective study of cases with chilblains (perniosis) in Out Patient Department of Dermatology, Nepal Medical College and Teaching Hospital (NMCTH). Nepal Med Coll J. 2011;13:190-192.

- Hochsinger C. Acute perniosis in submental region of child [in German]. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd. 1902;1:323-327.

- Stewart CL, Adler DJ, Jacobson A, et al. Equestrian perniosis: a report of 2 cases and a review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:237-240.

- Neal AJ, Jarman AM, Bennett TG. Perniosis in a long-distance cyclist crossing Mongolia. J Travel Med. 2012;19:66-68.

- Price RD, Murdoch DR. Perniosis (chilblains) of the thigh: report of five cases including four following river crossings. High Alt Met Biol. 2001;2:535-538.

- West SA, McCalmont TH, North JP. Ice-pack dermatosis: a cold-induced dermatitis with similarities to cold panniculitis and perniosis that histopathologically resembles lupus. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1314-1318.

- Haber JS, Ker KJ, Werth VP, et al. Ice‐pack dermatosis: a diagnositic pitfall for dermatopathologists that mimics lupus erythematosus. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:1-4.

- Crowson AN, Magro CM. Idiopathic perniosis and its mimics: a clinical and histological study of 38 cases. Hum Pathol. 1997;28:478-484.

- Viguier M, Pinguier L, Cavelier-Balloy B, et al. Clinical and histopathologic features and immunologic variables in patients with severe chilblains. a study of the relationship to lupus erythematosus. Medicine. 2001;80:180-188.

- Patra AK, Das AL, Ramadasan P. Diltiazem vs. nifedipine in chilblains: a clinical trial. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2003;69:209-211.

Perniosis, or chilblain, is characterized by localized, tender, erythematous skin lesions that occur as an abnormal reaction to exposure to cold and damp conditions. Although the lesions favor the distal extremities, perniosis may present anywhere on the body. Lesions can develop within hours to days following exposure to temperature less than 10°C or damp environments with greater than 60% humidity.1 Acute cases may lead to pruritus and tenderness, whereas chronic cases may involve lesions that blister or ulcerate and can take weeks to heal. We report an unusual case of erythematous plaques arising on the buttocks of a 73-year-old woman using ice pack treatments for chronic low back pain.

Case Report

A 73-year-old woman presented with recurrent tender lesions on the buttocks of 5 years’ duration. Her medical history was remarkable for hypertension, hypothyroidism, and lumbar spinal fusion surgery 5 years prior. Physical examination revealed indurated erythematous plaques with areas of erosions on the left buttock with some involvement of the right buttock (Figure 1).