User login

Does low-dose aspirin decrease a woman’s risk of ovarian cancer?

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Epidemiologic studies conducted in ovarian cancer suggest an association between chronic inflammation and incidence of disease.1 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) work to decrease inflammation through the inhibition of cyclo-oxygenase (COX). Therefore, anti-inflammatory agents such as NSAIDs have been proposed to play a role in the pathophysiology of ovarian cancer.

Previous studies of this association show conflicting data. The majority of these studies are retrospective, and those that are prospective do not include detailed data regarding dosing and frequency of ASA use.2-6

_

Details of the study

This study by Barnard and colleagues is a prospective cohort study evaluating a total of 205,498 women from 1980–2015 from 2 separate cohorts (the Nurses’ Health Study and the Nurses’ Health Study II). The primary outcome was “to evaluate whether regular aspirin or nonaspirin NSAID use and patterns of use are associated with lower ovarian cancer risk.” Analgesic use and data regarding covariates were obtained via self-reported questionnaires. Ovarian cancer diagnosis was confirmed via medical records.

Results demonstrated that current low-dose aspirin use was associated with a decreased risk of ovarian cancer (hazard ratio [HR], 0.77; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.61–0.96). This significance was not maintained upon further controlling for inflammatory factors (hypertension, autoimmune disease, inflammatory diet scores, smoking, etc) (HR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.69–1.26). Other significant findings included an increased risk of developing ovarian cancer with standard-dose ASA use of ≥5 years or standard-dose use at 6 to 9 tablets per week (HR, 1.77; 95% CI, 1.13–2.77 and HR, 2.00; 95% CI, 1.27–3.15, respectively). An increased risk of developing ovarian cancer also was found for >10-year use or use of >10 tablets per week of nonaspirin NSAIDs (HR, 2.00; 95% CI, 1.27–3.15 and HR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.02–1.79, respectively).

The authors concluded that there was a slight inverse association for low-dose aspirin and ovarian cancer risk and that standard aspirin or NSAID use actually may be associated with an increased risk of ovarian cancer.

Study strengths and weaknesses

This study has many strengths. It was a large prospective cohort investigation with adequate power to detect clinically significant differences. The authors collected detailed exposure data, which was novel. They also considered a latency period prior to the diagnosis of ovarian cancer during which a patient may increase their analgesic use in order to treat pain caused by the impending cancer.

However, the conclusions of the authors seem to be overstated in the setting of the data. Specifically, the deduction regarding a decreased risk of ovarian cancer with low-dose aspirin use given the loss of the statistical significance when controlling for pertinent cofounders. Further, the study authors did not evaluate adverse effects associated with low-dose aspirin use, which would be clinically applicable when determining whether the results from this study should become formal recommendations. Lastly, other important clinical factors, such as the presence of genetic mutations or endometriosis, were not considered, and these considerations would greatly affect results.

In the setting of previous large prospective studies that suggest no association between ASA use and ovarian cancer risk,4-6 data from this study are not compelling enough to recommend regular low-dose aspirin use to all women.

Based on these current data, there is insufficient evidence to suggest the use of low-dose aspirin for chemoprophylaxis of ovarian cancer. In order to suggest the use of a drug for prophylaxis the benefits must outweigh the risks, and in the case of NSAIDs, this has yet to be confirmed.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Poole EM, Lee IM, Ridker PM, et al. A prospective study of circulating C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor alpha receptor 2 levels and risk of ovarian cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178:1256-1264.

- Trabert B, Ness RB, Lo-Ciganic WH, et al. Aspirin, nonaspirin nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, and acetaminophen use and risk of invasive epithelial ovarian cancer: a pooled analysis in the Ovarian Cancer Association Consortium. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:djt431.

- Peres LC, Camacho F, Abbott SE, et al. Analgesic medication use and risk of epithelial ovarian cancer in African American women. Br J Cancer. 2016;114(7):819-825.

- Murphy MA, Trabert B, Yang HP, et al. Non-steroidal antiinflammatory drug use and ovarian cancer risk: findings from the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study and systematic review. Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23:1839-1852.

- Brasky TM, Liu J, White E, et al. Non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs and cancer risk in women: results from the Women’s Health Initiative. Int J Cancer. 2014;135:1869-1883.

- Lacey JV Jr, Sherman ME, Hartge P, et al. Medication use and risk of ovarian carcinoma: a prospective study. Int J Cancer. 2004;108:281-286.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Epidemiologic studies conducted in ovarian cancer suggest an association between chronic inflammation and incidence of disease.1 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) work to decrease inflammation through the inhibition of cyclo-oxygenase (COX). Therefore, anti-inflammatory agents such as NSAIDs have been proposed to play a role in the pathophysiology of ovarian cancer.

Previous studies of this association show conflicting data. The majority of these studies are retrospective, and those that are prospective do not include detailed data regarding dosing and frequency of ASA use.2-6

_

Details of the study

This study by Barnard and colleagues is a prospective cohort study evaluating a total of 205,498 women from 1980–2015 from 2 separate cohorts (the Nurses’ Health Study and the Nurses’ Health Study II). The primary outcome was “to evaluate whether regular aspirin or nonaspirin NSAID use and patterns of use are associated with lower ovarian cancer risk.” Analgesic use and data regarding covariates were obtained via self-reported questionnaires. Ovarian cancer diagnosis was confirmed via medical records.

Results demonstrated that current low-dose aspirin use was associated with a decreased risk of ovarian cancer (hazard ratio [HR], 0.77; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.61–0.96). This significance was not maintained upon further controlling for inflammatory factors (hypertension, autoimmune disease, inflammatory diet scores, smoking, etc) (HR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.69–1.26). Other significant findings included an increased risk of developing ovarian cancer with standard-dose ASA use of ≥5 years or standard-dose use at 6 to 9 tablets per week (HR, 1.77; 95% CI, 1.13–2.77 and HR, 2.00; 95% CI, 1.27–3.15, respectively). An increased risk of developing ovarian cancer also was found for >10-year use or use of >10 tablets per week of nonaspirin NSAIDs (HR, 2.00; 95% CI, 1.27–3.15 and HR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.02–1.79, respectively).

The authors concluded that there was a slight inverse association for low-dose aspirin and ovarian cancer risk and that standard aspirin or NSAID use actually may be associated with an increased risk of ovarian cancer.

Study strengths and weaknesses

This study has many strengths. It was a large prospective cohort investigation with adequate power to detect clinically significant differences. The authors collected detailed exposure data, which was novel. They also considered a latency period prior to the diagnosis of ovarian cancer during which a patient may increase their analgesic use in order to treat pain caused by the impending cancer.

However, the conclusions of the authors seem to be overstated in the setting of the data. Specifically, the deduction regarding a decreased risk of ovarian cancer with low-dose aspirin use given the loss of the statistical significance when controlling for pertinent cofounders. Further, the study authors did not evaluate adverse effects associated with low-dose aspirin use, which would be clinically applicable when determining whether the results from this study should become formal recommendations. Lastly, other important clinical factors, such as the presence of genetic mutations or endometriosis, were not considered, and these considerations would greatly affect results.

In the setting of previous large prospective studies that suggest no association between ASA use and ovarian cancer risk,4-6 data from this study are not compelling enough to recommend regular low-dose aspirin use to all women.

Based on these current data, there is insufficient evidence to suggest the use of low-dose aspirin for chemoprophylaxis of ovarian cancer. In order to suggest the use of a drug for prophylaxis the benefits must outweigh the risks, and in the case of NSAIDs, this has yet to be confirmed.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Epidemiologic studies conducted in ovarian cancer suggest an association between chronic inflammation and incidence of disease.1 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) work to decrease inflammation through the inhibition of cyclo-oxygenase (COX). Therefore, anti-inflammatory agents such as NSAIDs have been proposed to play a role in the pathophysiology of ovarian cancer.

Previous studies of this association show conflicting data. The majority of these studies are retrospective, and those that are prospective do not include detailed data regarding dosing and frequency of ASA use.2-6

_

Details of the study

This study by Barnard and colleagues is a prospective cohort study evaluating a total of 205,498 women from 1980–2015 from 2 separate cohorts (the Nurses’ Health Study and the Nurses’ Health Study II). The primary outcome was “to evaluate whether regular aspirin or nonaspirin NSAID use and patterns of use are associated with lower ovarian cancer risk.” Analgesic use and data regarding covariates were obtained via self-reported questionnaires. Ovarian cancer diagnosis was confirmed via medical records.

Results demonstrated that current low-dose aspirin use was associated with a decreased risk of ovarian cancer (hazard ratio [HR], 0.77; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.61–0.96). This significance was not maintained upon further controlling for inflammatory factors (hypertension, autoimmune disease, inflammatory diet scores, smoking, etc) (HR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.69–1.26). Other significant findings included an increased risk of developing ovarian cancer with standard-dose ASA use of ≥5 years or standard-dose use at 6 to 9 tablets per week (HR, 1.77; 95% CI, 1.13–2.77 and HR, 2.00; 95% CI, 1.27–3.15, respectively). An increased risk of developing ovarian cancer also was found for >10-year use or use of >10 tablets per week of nonaspirin NSAIDs (HR, 2.00; 95% CI, 1.27–3.15 and HR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.02–1.79, respectively).

The authors concluded that there was a slight inverse association for low-dose aspirin and ovarian cancer risk and that standard aspirin or NSAID use actually may be associated with an increased risk of ovarian cancer.

Study strengths and weaknesses

This study has many strengths. It was a large prospective cohort investigation with adequate power to detect clinically significant differences. The authors collected detailed exposure data, which was novel. They also considered a latency period prior to the diagnosis of ovarian cancer during which a patient may increase their analgesic use in order to treat pain caused by the impending cancer.

However, the conclusions of the authors seem to be overstated in the setting of the data. Specifically, the deduction regarding a decreased risk of ovarian cancer with low-dose aspirin use given the loss of the statistical significance when controlling for pertinent cofounders. Further, the study authors did not evaluate adverse effects associated with low-dose aspirin use, which would be clinically applicable when determining whether the results from this study should become formal recommendations. Lastly, other important clinical factors, such as the presence of genetic mutations or endometriosis, were not considered, and these considerations would greatly affect results.

In the setting of previous large prospective studies that suggest no association between ASA use and ovarian cancer risk,4-6 data from this study are not compelling enough to recommend regular low-dose aspirin use to all women.

Based on these current data, there is insufficient evidence to suggest the use of low-dose aspirin for chemoprophylaxis of ovarian cancer. In order to suggest the use of a drug for prophylaxis the benefits must outweigh the risks, and in the case of NSAIDs, this has yet to be confirmed.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Poole EM, Lee IM, Ridker PM, et al. A prospective study of circulating C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor alpha receptor 2 levels and risk of ovarian cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178:1256-1264.

- Trabert B, Ness RB, Lo-Ciganic WH, et al. Aspirin, nonaspirin nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, and acetaminophen use and risk of invasive epithelial ovarian cancer: a pooled analysis in the Ovarian Cancer Association Consortium. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:djt431.

- Peres LC, Camacho F, Abbott SE, et al. Analgesic medication use and risk of epithelial ovarian cancer in African American women. Br J Cancer. 2016;114(7):819-825.

- Murphy MA, Trabert B, Yang HP, et al. Non-steroidal antiinflammatory drug use and ovarian cancer risk: findings from the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study and systematic review. Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23:1839-1852.

- Brasky TM, Liu J, White E, et al. Non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs and cancer risk in women: results from the Women’s Health Initiative. Int J Cancer. 2014;135:1869-1883.

- Lacey JV Jr, Sherman ME, Hartge P, et al. Medication use and risk of ovarian carcinoma: a prospective study. Int J Cancer. 2004;108:281-286.

- Poole EM, Lee IM, Ridker PM, et al. A prospective study of circulating C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor alpha receptor 2 levels and risk of ovarian cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178:1256-1264.

- Trabert B, Ness RB, Lo-Ciganic WH, et al. Aspirin, nonaspirin nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, and acetaminophen use and risk of invasive epithelial ovarian cancer: a pooled analysis in the Ovarian Cancer Association Consortium. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:djt431.

- Peres LC, Camacho F, Abbott SE, et al. Analgesic medication use and risk of epithelial ovarian cancer in African American women. Br J Cancer. 2016;114(7):819-825.

- Murphy MA, Trabert B, Yang HP, et al. Non-steroidal antiinflammatory drug use and ovarian cancer risk: findings from the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study and systematic review. Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23:1839-1852.

- Brasky TM, Liu J, White E, et al. Non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs and cancer risk in women: results from the Women’s Health Initiative. Int J Cancer. 2014;135:1869-1883.

- Lacey JV Jr, Sherman ME, Hartge P, et al. Medication use and risk of ovarian carcinoma: a prospective study. Int J Cancer. 2004;108:281-286.

No boost in OS with addition of capecitabine for early TNBC

SAN ANTONIO – A phase 3 randomized controlled trial jointly conducted by GEICAM and CIBOMA is negative, showing that adding adjuvant capecitabine (Xeloda) to surgery and standard chemotherapy does not improve disease-free or overall survival in women with early-stage triple-negative breast cancer, reported lead investigator Miguel Martín, MD, PhD.

At the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, he discussed the overall findings and intriguing subgroup results suggesting that there was a benefit in women with tumors having the nonbasal phenotype. Dr. Martín also detailed implications in the context of the CREATE-X trial findings and the era of personalized medicine, and outlined next avenues of research.

The trial was supported by Roche, which also provided capecitabine. Dr. Martín disclosed that he has received speakers honoraria from Pfizer and Lilly; honoraria for participation in advisory boards from AstraZeneca, Novartis, Roche-Genentech, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, PharmaMar, Taiho Oncology, and Lilly; and research grants from Novartis and Roche.

SAN ANTONIO – A phase 3 randomized controlled trial jointly conducted by GEICAM and CIBOMA is negative, showing that adding adjuvant capecitabine (Xeloda) to surgery and standard chemotherapy does not improve disease-free or overall survival in women with early-stage triple-negative breast cancer, reported lead investigator Miguel Martín, MD, PhD.

At the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, he discussed the overall findings and intriguing subgroup results suggesting that there was a benefit in women with tumors having the nonbasal phenotype. Dr. Martín also detailed implications in the context of the CREATE-X trial findings and the era of personalized medicine, and outlined next avenues of research.

The trial was supported by Roche, which also provided capecitabine. Dr. Martín disclosed that he has received speakers honoraria from Pfizer and Lilly; honoraria for participation in advisory boards from AstraZeneca, Novartis, Roche-Genentech, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, PharmaMar, Taiho Oncology, and Lilly; and research grants from Novartis and Roche.

SAN ANTONIO – A phase 3 randomized controlled trial jointly conducted by GEICAM and CIBOMA is negative, showing that adding adjuvant capecitabine (Xeloda) to surgery and standard chemotherapy does not improve disease-free or overall survival in women with early-stage triple-negative breast cancer, reported lead investigator Miguel Martín, MD, PhD.

At the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, he discussed the overall findings and intriguing subgroup results suggesting that there was a benefit in women with tumors having the nonbasal phenotype. Dr. Martín also detailed implications in the context of the CREATE-X trial findings and the era of personalized medicine, and outlined next avenues of research.

The trial was supported by Roche, which also provided capecitabine. Dr. Martín disclosed that he has received speakers honoraria from Pfizer and Lilly; honoraria for participation in advisory boards from AstraZeneca, Novartis, Roche-Genentech, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, PharmaMar, Taiho Oncology, and Lilly; and research grants from Novartis and Roche.

REPORTING FROM SABCS 2018

Treatment Challenges When Headache Has Central and Peripheral Involvement

Diagnosis and treatment can be complicated when the headache history includes evidence of central and peripheral causes of pain.

ASHEVILLE, NC—Although neurologists tend to classify disorders as problems of either the CNS or the peripheral nervous system, patients with headache may have symptoms that indicate the involvement of both systems, according to an overview provided at the Eighth Annual Scientific Meeting of the Southern Headache Society. Research has revealed anatomic connections between extracranial and intracranial spaces that could contribute to the generation of headaches. Thus, the central and peripheral nervous systems “do not have to be two separate spaces and two separate pathologies,” said Pamela Blake, MD, Director of the Headache Center of Greater Heights in Houston.

Problems With Prevention and Acute Treatment

One patient presented to Dr. Blake with an eight-year history of throbbing headaches and constant pain and tightness in the neck and occiput. The pain radiated to her temples and forehead two to four times per week with accompanying photophobia, phonophobia, and nausea. The patient also had mild allodynia. The frontal pain and accompanying symptoms were consistent with episodic migraine, but the allodynia and pain in the neck and occiput were not, said Dr. Blake. A possible diagnosis was episodic migraine without aura with chronic tension-type headaches and neck pain, she added.

A 2017 study published in the Journal of Headache and Pain suggested that this headache type is problematic. Among 148 migraineurs, the researchers identified 100 patients who also had tension-type headache and chronic neck pain. Compared with healthy controls, these patients had less physical activity, less psychologic well-being, more perceived stress, and poorer self-rated health. Pain reduced these patients’ ability to perform physical activity, which could make treatment more difficult, according to the authors.

Patients with these symptoms have trigeminal and occipital pain. “These symptoms do not appear to be solely, or even primarily, central,” said Dr. Blake. The frontal pain responds to triptans, but the occipital pain, which is the more constant pain, does not. “Preventive medications do not work well in this population, and that’s why they have chronic headaches,” said Dr. Blake.

Physiologic and Pathophysiologic Mechanisms

Research by Schueler and colleagues suggested a potential physiologic explanation for combined central and peripheral involvement in headache. They applied a fluorescent tracer to proximally cut meningeal nerves in rat skulls and to distal branches of the spinosus nerve in human calvaria that was lined with dura mater. They observed that branches of the spinosus nerve travel “along the middle meningeal artery, supplying the dura, entering the cranial bone, and running through the calvarium,” said Dr. Blake. Branches of the spinosus nerve also “entered the tenderness junctions of the pericranial muscles, including in the neck.”

This work indicates a connection between intracranial and extracranial areas but does not shed light on the pathophysiology of a headache with central and peripheral symptoms, said Dr. Blake. In 2016, she and her colleagues took perivascular biopsies from healthy controls and subjects with chronic migraine and predominantly occipital headache. They found a significant increase in the expression of proinflammatory genes and a decrease in the expression of anti-inflammatory genes among migraineurs, compared with controls. “This was the first evidence of localized extracranial pathophysiology in chronic migraine,” said Dr. Blake.

This inflammation could result from compression of the occipital nerves. A 2013 study by Schmid et al found that progressive nerve compression results in chronic local and remote immune-mediated inflammation. Stress also can cause inflammation. “Many patients who present with occipital nerve compression headaches had the onset of their pain during a time of intense stress,” said Dr. Blake.

The Role of the Occipital Nerve

Occipital nerve compression headache is characterized by daily or near-daily pain in the distribution of the occipital nerve. Patients describe the pain as a tight, imploding pressure that sometimes radiates to frontal areas and becomes a throbbing pain. This headache rarely has a neuropathic component.

Allodynia is “almost a requirement of this diagnosis,” said Dr. Blake. The allodynia symptom checklist, however, does not capture it well in these patients because it focuses on pain in the trigeminal nerve distribution. Patients report that the back of the head is tender to the touch and that it hurts to rest the head on a pillow.

The cervical muscles compress the nerve and contribute to the symptoms as well. Patients often report that moving the head or neck exacerbates the pain. The headache also may have migrainous features. It takes skill and expertise to elicit an adequate history from these patients, said Dr. Blake. “Careful questioning is helpful. I often find … that a second visit is more helpful to obtain this history after reviewing the anatomy with the patient, reviewing this pathophysiology, and sending them back out to keep a careful log for two weeks.”

Nerve Blocks and Nerve Decompression

Occipital nerve blocks provide relief for these patients, but they may not be easy to administer. A large dorsal occipital nerve may be mistaken for the greater occipital nerve, for example. Physiologic abnormalities in some patients also can complicate this treatment.

Another effective treatment is nerve decompression surgery. Dr. Blake and colleagues conducted a retrospective review of patients who had undergone decompression of the greater occipital nerves at the point where they traverse the musculature of the posterior neck. The intervention provided complete relief for three to six years in one patient with new daily persistent headache and two patients with chronic posttraumatic headache. Two patients with chronic headache or migraine had partial relief. Surgery provided no relief for two patients with episodic migraine, one patient with chronic migraine, and one patient with chronic tension-type headache.

“In our experience, … 75% to 80% of patients experience a greater than 50% reduction in their headaches, measured by headache frequency and intensity,” said Dr. Blake. She and her colleagues compared outcomes between 18 chronic migraineurs with predominantly occipital pain who underwent surgical decompression of the occipital nerve and 23 patients who were referred for surgery but unable to receive it. In the surgical group, the number of predominantly occipital chronic migraine days per month decreased from 28.9 at baseline to 7.28 at a mean of 46 months later. The outcome in the control group did not change.

Correct patient selection “is the first, most important step” toward treatment success, said Dr. Blake. This process includes a preoperative psychologic evaluation that screens surgical candidates for somatic symptom disorder, mood disorders, a history of trauma, and catastrophizing. If indicated, neurologists may begin providing cognitive behavioral therapy or supportive psychotherapy before surgery. “We have a comprehensive program with postoperative management, including physical therapy and gradual taper of medications,” said Dr. Blake. Central migraine processes may contribute to headache in some of these patients. “Menstrual migraines are not going to go away with nerve decompression. Chronic migraine sometimes does not go away. This is a complex group of patients who definitely require a lot of follow-up.”

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Blake P, Nir RR, Perry CJ, Burstein R. Tracking patients with chronic occipital headache after occipital nerve decompression surgery: a case series. Cephalalgia. 2018 Sep 14 [Epub ahead of print].

Krøll LS, Hammarlund CS, Westergaard ML, et al. Level of physical activity, well-being, stress and self-rated health in persons with migraine and co-existing tension-type headache and neck pain. J Headache Pain. 2017;18(1):46. Perry CJ, Blake P, Buettner C, et al. Upregulation of inflammatory gene transcripts in periosteum of chronic migraineurs: implications for extracranial origin of headache. Ann Neurol. 2016;79(6):1000-1013.

Schmid AB, Coppieters MW, Ruitenberg MJ, McLachlan EM. Local and remote immune-mediated inflammation after mild peripheral nerve compression in rats. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2013;72(7):662-680.

Schueler M, Neuhuber WL, De Col R, Messlinger K. Innervation of rat and human dura mater and pericranial tissues in the parieto-temporal region by meningeal afferents. Headache. 2014;54(6):996-1009.

Diagnosis and treatment can be complicated when the headache history includes evidence of central and peripheral causes of pain.

Diagnosis and treatment can be complicated when the headache history includes evidence of central and peripheral causes of pain.

ASHEVILLE, NC—Although neurologists tend to classify disorders as problems of either the CNS or the peripheral nervous system, patients with headache may have symptoms that indicate the involvement of both systems, according to an overview provided at the Eighth Annual Scientific Meeting of the Southern Headache Society. Research has revealed anatomic connections between extracranial and intracranial spaces that could contribute to the generation of headaches. Thus, the central and peripheral nervous systems “do not have to be two separate spaces and two separate pathologies,” said Pamela Blake, MD, Director of the Headache Center of Greater Heights in Houston.

Problems With Prevention and Acute Treatment

One patient presented to Dr. Blake with an eight-year history of throbbing headaches and constant pain and tightness in the neck and occiput. The pain radiated to her temples and forehead two to four times per week with accompanying photophobia, phonophobia, and nausea. The patient also had mild allodynia. The frontal pain and accompanying symptoms were consistent with episodic migraine, but the allodynia and pain in the neck and occiput were not, said Dr. Blake. A possible diagnosis was episodic migraine without aura with chronic tension-type headaches and neck pain, she added.

A 2017 study published in the Journal of Headache and Pain suggested that this headache type is problematic. Among 148 migraineurs, the researchers identified 100 patients who also had tension-type headache and chronic neck pain. Compared with healthy controls, these patients had less physical activity, less psychologic well-being, more perceived stress, and poorer self-rated health. Pain reduced these patients’ ability to perform physical activity, which could make treatment more difficult, according to the authors.

Patients with these symptoms have trigeminal and occipital pain. “These symptoms do not appear to be solely, or even primarily, central,” said Dr. Blake. The frontal pain responds to triptans, but the occipital pain, which is the more constant pain, does not. “Preventive medications do not work well in this population, and that’s why they have chronic headaches,” said Dr. Blake.

Physiologic and Pathophysiologic Mechanisms

Research by Schueler and colleagues suggested a potential physiologic explanation for combined central and peripheral involvement in headache. They applied a fluorescent tracer to proximally cut meningeal nerves in rat skulls and to distal branches of the spinosus nerve in human calvaria that was lined with dura mater. They observed that branches of the spinosus nerve travel “along the middle meningeal artery, supplying the dura, entering the cranial bone, and running through the calvarium,” said Dr. Blake. Branches of the spinosus nerve also “entered the tenderness junctions of the pericranial muscles, including in the neck.”

This work indicates a connection between intracranial and extracranial areas but does not shed light on the pathophysiology of a headache with central and peripheral symptoms, said Dr. Blake. In 2016, she and her colleagues took perivascular biopsies from healthy controls and subjects with chronic migraine and predominantly occipital headache. They found a significant increase in the expression of proinflammatory genes and a decrease in the expression of anti-inflammatory genes among migraineurs, compared with controls. “This was the first evidence of localized extracranial pathophysiology in chronic migraine,” said Dr. Blake.

This inflammation could result from compression of the occipital nerves. A 2013 study by Schmid et al found that progressive nerve compression results in chronic local and remote immune-mediated inflammation. Stress also can cause inflammation. “Many patients who present with occipital nerve compression headaches had the onset of their pain during a time of intense stress,” said Dr. Blake.

The Role of the Occipital Nerve

Occipital nerve compression headache is characterized by daily or near-daily pain in the distribution of the occipital nerve. Patients describe the pain as a tight, imploding pressure that sometimes radiates to frontal areas and becomes a throbbing pain. This headache rarely has a neuropathic component.

Allodynia is “almost a requirement of this diagnosis,” said Dr. Blake. The allodynia symptom checklist, however, does not capture it well in these patients because it focuses on pain in the trigeminal nerve distribution. Patients report that the back of the head is tender to the touch and that it hurts to rest the head on a pillow.

The cervical muscles compress the nerve and contribute to the symptoms as well. Patients often report that moving the head or neck exacerbates the pain. The headache also may have migrainous features. It takes skill and expertise to elicit an adequate history from these patients, said Dr. Blake. “Careful questioning is helpful. I often find … that a second visit is more helpful to obtain this history after reviewing the anatomy with the patient, reviewing this pathophysiology, and sending them back out to keep a careful log for two weeks.”

Nerve Blocks and Nerve Decompression

Occipital nerve blocks provide relief for these patients, but they may not be easy to administer. A large dorsal occipital nerve may be mistaken for the greater occipital nerve, for example. Physiologic abnormalities in some patients also can complicate this treatment.

Another effective treatment is nerve decompression surgery. Dr. Blake and colleagues conducted a retrospective review of patients who had undergone decompression of the greater occipital nerves at the point where they traverse the musculature of the posterior neck. The intervention provided complete relief for three to six years in one patient with new daily persistent headache and two patients with chronic posttraumatic headache. Two patients with chronic headache or migraine had partial relief. Surgery provided no relief for two patients with episodic migraine, one patient with chronic migraine, and one patient with chronic tension-type headache.

“In our experience, … 75% to 80% of patients experience a greater than 50% reduction in their headaches, measured by headache frequency and intensity,” said Dr. Blake. She and her colleagues compared outcomes between 18 chronic migraineurs with predominantly occipital pain who underwent surgical decompression of the occipital nerve and 23 patients who were referred for surgery but unable to receive it. In the surgical group, the number of predominantly occipital chronic migraine days per month decreased from 28.9 at baseline to 7.28 at a mean of 46 months later. The outcome in the control group did not change.

Correct patient selection “is the first, most important step” toward treatment success, said Dr. Blake. This process includes a preoperative psychologic evaluation that screens surgical candidates for somatic symptom disorder, mood disorders, a history of trauma, and catastrophizing. If indicated, neurologists may begin providing cognitive behavioral therapy or supportive psychotherapy before surgery. “We have a comprehensive program with postoperative management, including physical therapy and gradual taper of medications,” said Dr. Blake. Central migraine processes may contribute to headache in some of these patients. “Menstrual migraines are not going to go away with nerve decompression. Chronic migraine sometimes does not go away. This is a complex group of patients who definitely require a lot of follow-up.”

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Blake P, Nir RR, Perry CJ, Burstein R. Tracking patients with chronic occipital headache after occipital nerve decompression surgery: a case series. Cephalalgia. 2018 Sep 14 [Epub ahead of print].

Krøll LS, Hammarlund CS, Westergaard ML, et al. Level of physical activity, well-being, stress and self-rated health in persons with migraine and co-existing tension-type headache and neck pain. J Headache Pain. 2017;18(1):46. Perry CJ, Blake P, Buettner C, et al. Upregulation of inflammatory gene transcripts in periosteum of chronic migraineurs: implications for extracranial origin of headache. Ann Neurol. 2016;79(6):1000-1013.

Schmid AB, Coppieters MW, Ruitenberg MJ, McLachlan EM. Local and remote immune-mediated inflammation after mild peripheral nerve compression in rats. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2013;72(7):662-680.

Schueler M, Neuhuber WL, De Col R, Messlinger K. Innervation of rat and human dura mater and pericranial tissues in the parieto-temporal region by meningeal afferents. Headache. 2014;54(6):996-1009.

ASHEVILLE, NC—Although neurologists tend to classify disorders as problems of either the CNS or the peripheral nervous system, patients with headache may have symptoms that indicate the involvement of both systems, according to an overview provided at the Eighth Annual Scientific Meeting of the Southern Headache Society. Research has revealed anatomic connections between extracranial and intracranial spaces that could contribute to the generation of headaches. Thus, the central and peripheral nervous systems “do not have to be two separate spaces and two separate pathologies,” said Pamela Blake, MD, Director of the Headache Center of Greater Heights in Houston.

Problems With Prevention and Acute Treatment

One patient presented to Dr. Blake with an eight-year history of throbbing headaches and constant pain and tightness in the neck and occiput. The pain radiated to her temples and forehead two to four times per week with accompanying photophobia, phonophobia, and nausea. The patient also had mild allodynia. The frontal pain and accompanying symptoms were consistent with episodic migraine, but the allodynia and pain in the neck and occiput were not, said Dr. Blake. A possible diagnosis was episodic migraine without aura with chronic tension-type headaches and neck pain, she added.

A 2017 study published in the Journal of Headache and Pain suggested that this headache type is problematic. Among 148 migraineurs, the researchers identified 100 patients who also had tension-type headache and chronic neck pain. Compared with healthy controls, these patients had less physical activity, less psychologic well-being, more perceived stress, and poorer self-rated health. Pain reduced these patients’ ability to perform physical activity, which could make treatment more difficult, according to the authors.

Patients with these symptoms have trigeminal and occipital pain. “These symptoms do not appear to be solely, or even primarily, central,” said Dr. Blake. The frontal pain responds to triptans, but the occipital pain, which is the more constant pain, does not. “Preventive medications do not work well in this population, and that’s why they have chronic headaches,” said Dr. Blake.

Physiologic and Pathophysiologic Mechanisms

Research by Schueler and colleagues suggested a potential physiologic explanation for combined central and peripheral involvement in headache. They applied a fluorescent tracer to proximally cut meningeal nerves in rat skulls and to distal branches of the spinosus nerve in human calvaria that was lined with dura mater. They observed that branches of the spinosus nerve travel “along the middle meningeal artery, supplying the dura, entering the cranial bone, and running through the calvarium,” said Dr. Blake. Branches of the spinosus nerve also “entered the tenderness junctions of the pericranial muscles, including in the neck.”

This work indicates a connection between intracranial and extracranial areas but does not shed light on the pathophysiology of a headache with central and peripheral symptoms, said Dr. Blake. In 2016, she and her colleagues took perivascular biopsies from healthy controls and subjects with chronic migraine and predominantly occipital headache. They found a significant increase in the expression of proinflammatory genes and a decrease in the expression of anti-inflammatory genes among migraineurs, compared with controls. “This was the first evidence of localized extracranial pathophysiology in chronic migraine,” said Dr. Blake.

This inflammation could result from compression of the occipital nerves. A 2013 study by Schmid et al found that progressive nerve compression results in chronic local and remote immune-mediated inflammation. Stress also can cause inflammation. “Many patients who present with occipital nerve compression headaches had the onset of their pain during a time of intense stress,” said Dr. Blake.

The Role of the Occipital Nerve

Occipital nerve compression headache is characterized by daily or near-daily pain in the distribution of the occipital nerve. Patients describe the pain as a tight, imploding pressure that sometimes radiates to frontal areas and becomes a throbbing pain. This headache rarely has a neuropathic component.

Allodynia is “almost a requirement of this diagnosis,” said Dr. Blake. The allodynia symptom checklist, however, does not capture it well in these patients because it focuses on pain in the trigeminal nerve distribution. Patients report that the back of the head is tender to the touch and that it hurts to rest the head on a pillow.

The cervical muscles compress the nerve and contribute to the symptoms as well. Patients often report that moving the head or neck exacerbates the pain. The headache also may have migrainous features. It takes skill and expertise to elicit an adequate history from these patients, said Dr. Blake. “Careful questioning is helpful. I often find … that a second visit is more helpful to obtain this history after reviewing the anatomy with the patient, reviewing this pathophysiology, and sending them back out to keep a careful log for two weeks.”

Nerve Blocks and Nerve Decompression

Occipital nerve blocks provide relief for these patients, but they may not be easy to administer. A large dorsal occipital nerve may be mistaken for the greater occipital nerve, for example. Physiologic abnormalities in some patients also can complicate this treatment.

Another effective treatment is nerve decompression surgery. Dr. Blake and colleagues conducted a retrospective review of patients who had undergone decompression of the greater occipital nerves at the point where they traverse the musculature of the posterior neck. The intervention provided complete relief for three to six years in one patient with new daily persistent headache and two patients with chronic posttraumatic headache. Two patients with chronic headache or migraine had partial relief. Surgery provided no relief for two patients with episodic migraine, one patient with chronic migraine, and one patient with chronic tension-type headache.

“In our experience, … 75% to 80% of patients experience a greater than 50% reduction in their headaches, measured by headache frequency and intensity,” said Dr. Blake. She and her colleagues compared outcomes between 18 chronic migraineurs with predominantly occipital pain who underwent surgical decompression of the occipital nerve and 23 patients who were referred for surgery but unable to receive it. In the surgical group, the number of predominantly occipital chronic migraine days per month decreased from 28.9 at baseline to 7.28 at a mean of 46 months later. The outcome in the control group did not change.

Correct patient selection “is the first, most important step” toward treatment success, said Dr. Blake. This process includes a preoperative psychologic evaluation that screens surgical candidates for somatic symptom disorder, mood disorders, a history of trauma, and catastrophizing. If indicated, neurologists may begin providing cognitive behavioral therapy or supportive psychotherapy before surgery. “We have a comprehensive program with postoperative management, including physical therapy and gradual taper of medications,” said Dr. Blake. Central migraine processes may contribute to headache in some of these patients. “Menstrual migraines are not going to go away with nerve decompression. Chronic migraine sometimes does not go away. This is a complex group of patients who definitely require a lot of follow-up.”

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Blake P, Nir RR, Perry CJ, Burstein R. Tracking patients with chronic occipital headache after occipital nerve decompression surgery: a case series. Cephalalgia. 2018 Sep 14 [Epub ahead of print].

Krøll LS, Hammarlund CS, Westergaard ML, et al. Level of physical activity, well-being, stress and self-rated health in persons with migraine and co-existing tension-type headache and neck pain. J Headache Pain. 2017;18(1):46. Perry CJ, Blake P, Buettner C, et al. Upregulation of inflammatory gene transcripts in periosteum of chronic migraineurs: implications for extracranial origin of headache. Ann Neurol. 2016;79(6):1000-1013.

Schmid AB, Coppieters MW, Ruitenberg MJ, McLachlan EM. Local and remote immune-mediated inflammation after mild peripheral nerve compression in rats. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2013;72(7):662-680.

Schueler M, Neuhuber WL, De Col R, Messlinger K. Innervation of rat and human dura mater and pericranial tissues in the parieto-temporal region by meningeal afferents. Headache. 2014;54(6):996-1009.

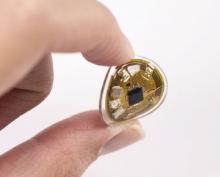

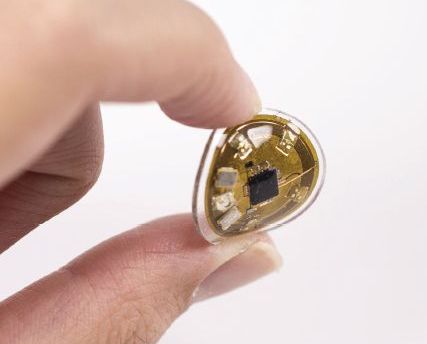

New devices can monitor personalized light exposure for radiation

, according to three studies of the millimeter-scale near-field communication (mm-NFC) devices.

“These studies highlight the differences between mm-NFC dosimeters and commercial devices in real-world, practical scenarios,” wrote lead author Seung Yun Heo of the department of biomedical engineering at the Center for Bio-Integrated Electronics at Northwestern University, Chicago, and her coauthors. “The former operate in continuous, uninterrupted modes, whereas the latter capture instantaneous values of intensity at preprogrammed intervals,”they noted. The study was published in Science Translational Medicine.

Separate studies to assess the performance of these “flexible” dosimeters took place in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and St. Petersburg, Fla. The Florida study included 13 healthy participants who wore skin-mounted mm-NFC ultraviolet A (UVA) dosimeters on the right back hand, left back hand, left inner arm, and left outer arm, plus a commercial dosimeter on the right wrist. The volunteers walked a 6.44-km path three times: a morning and subsequent afternoon stroll, plus an evening walk 4 days later. Four devices failed during the afternoon exercise, but otherwise, participants received data on their smartphones via the dosimeters at 30-minute intervals.

The Brazilian study was made up of nine healthy participants who wore mm-NFC UVA dosimeters on the thumbnail or the middle fingernail; commercial dosimeters were worn on the wrist of the ipsilateral side. These volunteers engaged in rooftop recreational activities that corresponded to solar zenith angles, along with showering and swimming with the use of soap and skin creams. All sensors remained functional over the 4 days of testing, and 14 of 20 devices remained adhered to the fingernail. Accumulated doses ranged widely, “as expected on the basis of the differences in behaviors,” the authors wrote. These observations imply highly variable UV-associated risks between participants, due not only to differences in Fitzpatrick skin types but also to individual behavior patterns,” they added.

The third study of mm-NFC blue light dosimeters comprised three newborns in an Urbana, Ill., neonatal ICU undergoing blue light phototherapy treatments. Nurses mounted dosimeters on the patients’ chests before phototherapy; an antenna underneath the incubator mattress transmitted continuous wireless measurements of blue intensity and dosage at 20-minute intervals for 20 hours.

The authors acknowledged that these devices and their designs have limitations, including a small detection area as compared to the surface area of a human body. The study’s results “represent localized measurements of exposure, whereas the sun irradiance profile across the body surface is not uniform and varies by position of the sun in the sky over the course of a day.” They recommended that future research could “create anatomic specific risk assessment of UV exposure” via multinodal sensing with UVA/UVB dosimeters on several parts of the body.

The Brazilian UV study was sponsored by La Roche Posay and L’Oreal California Research Center. Research was supported by the National Cancer Institute. Five of the authors reported commercial interests in the technology. Another author reported paid consultation for Aclaris Therapeutics.

SOURCE: Heo SY et al. Sci. Transl. Med. 2018 Dec 5. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aau1643.

, according to three studies of the millimeter-scale near-field communication (mm-NFC) devices.

“These studies highlight the differences between mm-NFC dosimeters and commercial devices in real-world, practical scenarios,” wrote lead author Seung Yun Heo of the department of biomedical engineering at the Center for Bio-Integrated Electronics at Northwestern University, Chicago, and her coauthors. “The former operate in continuous, uninterrupted modes, whereas the latter capture instantaneous values of intensity at preprogrammed intervals,”they noted. The study was published in Science Translational Medicine.

Separate studies to assess the performance of these “flexible” dosimeters took place in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and St. Petersburg, Fla. The Florida study included 13 healthy participants who wore skin-mounted mm-NFC ultraviolet A (UVA) dosimeters on the right back hand, left back hand, left inner arm, and left outer arm, plus a commercial dosimeter on the right wrist. The volunteers walked a 6.44-km path three times: a morning and subsequent afternoon stroll, plus an evening walk 4 days later. Four devices failed during the afternoon exercise, but otherwise, participants received data on their smartphones via the dosimeters at 30-minute intervals.

The Brazilian study was made up of nine healthy participants who wore mm-NFC UVA dosimeters on the thumbnail or the middle fingernail; commercial dosimeters were worn on the wrist of the ipsilateral side. These volunteers engaged in rooftop recreational activities that corresponded to solar zenith angles, along with showering and swimming with the use of soap and skin creams. All sensors remained functional over the 4 days of testing, and 14 of 20 devices remained adhered to the fingernail. Accumulated doses ranged widely, “as expected on the basis of the differences in behaviors,” the authors wrote. These observations imply highly variable UV-associated risks between participants, due not only to differences in Fitzpatrick skin types but also to individual behavior patterns,” they added.

The third study of mm-NFC blue light dosimeters comprised three newborns in an Urbana, Ill., neonatal ICU undergoing blue light phototherapy treatments. Nurses mounted dosimeters on the patients’ chests before phototherapy; an antenna underneath the incubator mattress transmitted continuous wireless measurements of blue intensity and dosage at 20-minute intervals for 20 hours.

The authors acknowledged that these devices and their designs have limitations, including a small detection area as compared to the surface area of a human body. The study’s results “represent localized measurements of exposure, whereas the sun irradiance profile across the body surface is not uniform and varies by position of the sun in the sky over the course of a day.” They recommended that future research could “create anatomic specific risk assessment of UV exposure” via multinodal sensing with UVA/UVB dosimeters on several parts of the body.

The Brazilian UV study was sponsored by La Roche Posay and L’Oreal California Research Center. Research was supported by the National Cancer Institute. Five of the authors reported commercial interests in the technology. Another author reported paid consultation for Aclaris Therapeutics.

SOURCE: Heo SY et al. Sci. Transl. Med. 2018 Dec 5. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aau1643.

, according to three studies of the millimeter-scale near-field communication (mm-NFC) devices.

“These studies highlight the differences between mm-NFC dosimeters and commercial devices in real-world, practical scenarios,” wrote lead author Seung Yun Heo of the department of biomedical engineering at the Center for Bio-Integrated Electronics at Northwestern University, Chicago, and her coauthors. “The former operate in continuous, uninterrupted modes, whereas the latter capture instantaneous values of intensity at preprogrammed intervals,”they noted. The study was published in Science Translational Medicine.

Separate studies to assess the performance of these “flexible” dosimeters took place in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and St. Petersburg, Fla. The Florida study included 13 healthy participants who wore skin-mounted mm-NFC ultraviolet A (UVA) dosimeters on the right back hand, left back hand, left inner arm, and left outer arm, plus a commercial dosimeter on the right wrist. The volunteers walked a 6.44-km path three times: a morning and subsequent afternoon stroll, plus an evening walk 4 days later. Four devices failed during the afternoon exercise, but otherwise, participants received data on their smartphones via the dosimeters at 30-minute intervals.

The Brazilian study was made up of nine healthy participants who wore mm-NFC UVA dosimeters on the thumbnail or the middle fingernail; commercial dosimeters were worn on the wrist of the ipsilateral side. These volunteers engaged in rooftop recreational activities that corresponded to solar zenith angles, along with showering and swimming with the use of soap and skin creams. All sensors remained functional over the 4 days of testing, and 14 of 20 devices remained adhered to the fingernail. Accumulated doses ranged widely, “as expected on the basis of the differences in behaviors,” the authors wrote. These observations imply highly variable UV-associated risks between participants, due not only to differences in Fitzpatrick skin types but also to individual behavior patterns,” they added.

The third study of mm-NFC blue light dosimeters comprised three newborns in an Urbana, Ill., neonatal ICU undergoing blue light phototherapy treatments. Nurses mounted dosimeters on the patients’ chests before phototherapy; an antenna underneath the incubator mattress transmitted continuous wireless measurements of blue intensity and dosage at 20-minute intervals for 20 hours.

The authors acknowledged that these devices and their designs have limitations, including a small detection area as compared to the surface area of a human body. The study’s results “represent localized measurements of exposure, whereas the sun irradiance profile across the body surface is not uniform and varies by position of the sun in the sky over the course of a day.” They recommended that future research could “create anatomic specific risk assessment of UV exposure” via multinodal sensing with UVA/UVB dosimeters on several parts of the body.

The Brazilian UV study was sponsored by La Roche Posay and L’Oreal California Research Center. Research was supported by the National Cancer Institute. Five of the authors reported commercial interests in the technology. Another author reported paid consultation for Aclaris Therapeutics.

SOURCE: Heo SY et al. Sci. Transl. Med. 2018 Dec 5. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aau1643.

FROM SCIENCE TRANSLATIONAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Newly designed flexible dosimeters can track personalized light exposure and electromagnetic radiation via wireless sensor technology.

Major finding: In one study, during four days of testing – including recreational activities, showering, and swimming—all mm-NFC UVA dosimeter sensors remained functional and 14 of 20 devices remained adhered to the fingernail.

Study details: Three studies of millimeter-scale near-field communication dosimeters, comprising healthy volunteers from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; St. Petersburg, Florida; and neonates undergoing blue light phototherapy treatments in an Urbana, Ill., neonatal ICU.

Disclosures: The UV study in Brazil, was sponsored by La Roche Posay and the L’Oreal California Research Center. Research was supported by the National Cancer Institute. Five of the authors reported commercial interests in the technology. Another author reported paid consultation for Aclaris Therapeutics.

Source: Heo SY et al. Sci. Transl. Med. 2018 Dec 5 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aau1643.

Anticoagulant choice, PPI cotherapy impact risk of upper GI bleeding

Patients receiving oral anticoagulant treatment had the lowest risk of gastrointestinal bleeding when taking apixaban, compared with rivaroxaban, dabigatran, and warfarin, according to a recent study.

Further, patients who received proton pump inhibitor (PPI) cotherapy had a lower overall risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, according to Wayne A. Ray, PhD, from the department of health policy at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., and his colleagues.

“These findings indicate the potential benefits of a gastrointestinal bleeding risk assessment before initiating anticoagulant treatment,” Dr. Ray and his colleagues wrote in their study, which was published in JAMA.

Dr. Ray and his colleagues performed a retrospective, population-based study of 1,643,123 Medicare beneficiaries (mean age, 76.4 years) who received 1,713,183 new episodes of oral anticoagulant treatment between January 2011 and September 2015. They analyzed how patients reacted to apixaban, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or warfarin both with and without PPI cotherapy.

Overall, the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding across 754,389 person-years without PPI therapy was 115 per 10,000 person-years (95% confidence interval, 112-118) in 7,119 patients. The researchers found the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding was highest in patients taking rivaroxaban (1,278 patients; 144 per 10,000 person-years; 95% CI, 136-152) and lowest when taking apixaban (279 patients; 120 per 10,000 person-years; incidence rate ratio, 1,97; 95% CI, 1.73-2.25), compared with dabigatran (629 patients; 120 per 10,000 person-years; IRR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.08-1.32) and warfarin (4,933 patients; 113 per 10,000 person-years; IRR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.19-1.35). There was a significantly lower incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding for apixaban, compared with warfarin (IRR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.57-0.73) and dabigatran (IRR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.52-0.70).

There was a lower overall incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding when receiving PPI cotherapy (264,447 person-years; 76 per 10,000 person-years), compared with patients who received anticoagulant treatment without PPI cotherapy (IRR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.62-0.69). This reduced incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding was also seen in patients receiving PPI cotherapy and taking apixaban (IRR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.52-0.85), dabigatran (IRR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.41-0.59), rivaroxaban (IRR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.68-0.84), and warfarin (IRR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.62-0.69).

The researchers noted that limitations in this study included potential misclassification of anticoagulant treatment, PPI cotherapy, and NSAIDs because of a reliance on filled prescription data; confounding by unmeasured factors such as aspirin exposure or Helicobacter pylori infection; and gastrointestinal bleeding being measured using a disease risk score.

This study was supported by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Ray WA et al. JAMA. 2018 Dec 4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.17242.

Patients receiving oral anticoagulant treatment had the lowest risk of gastrointestinal bleeding when taking apixaban, compared with rivaroxaban, dabigatran, and warfarin, according to a recent study.

Further, patients who received proton pump inhibitor (PPI) cotherapy had a lower overall risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, according to Wayne A. Ray, PhD, from the department of health policy at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., and his colleagues.

“These findings indicate the potential benefits of a gastrointestinal bleeding risk assessment before initiating anticoagulant treatment,” Dr. Ray and his colleagues wrote in their study, which was published in JAMA.

Dr. Ray and his colleagues performed a retrospective, population-based study of 1,643,123 Medicare beneficiaries (mean age, 76.4 years) who received 1,713,183 new episodes of oral anticoagulant treatment between January 2011 and September 2015. They analyzed how patients reacted to apixaban, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or warfarin both with and without PPI cotherapy.

Overall, the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding across 754,389 person-years without PPI therapy was 115 per 10,000 person-years (95% confidence interval, 112-118) in 7,119 patients. The researchers found the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding was highest in patients taking rivaroxaban (1,278 patients; 144 per 10,000 person-years; 95% CI, 136-152) and lowest when taking apixaban (279 patients; 120 per 10,000 person-years; incidence rate ratio, 1,97; 95% CI, 1.73-2.25), compared with dabigatran (629 patients; 120 per 10,000 person-years; IRR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.08-1.32) and warfarin (4,933 patients; 113 per 10,000 person-years; IRR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.19-1.35). There was a significantly lower incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding for apixaban, compared with warfarin (IRR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.57-0.73) and dabigatran (IRR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.52-0.70).

There was a lower overall incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding when receiving PPI cotherapy (264,447 person-years; 76 per 10,000 person-years), compared with patients who received anticoagulant treatment without PPI cotherapy (IRR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.62-0.69). This reduced incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding was also seen in patients receiving PPI cotherapy and taking apixaban (IRR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.52-0.85), dabigatran (IRR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.41-0.59), rivaroxaban (IRR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.68-0.84), and warfarin (IRR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.62-0.69).

The researchers noted that limitations in this study included potential misclassification of anticoagulant treatment, PPI cotherapy, and NSAIDs because of a reliance on filled prescription data; confounding by unmeasured factors such as aspirin exposure or Helicobacter pylori infection; and gastrointestinal bleeding being measured using a disease risk score.

This study was supported by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Ray WA et al. JAMA. 2018 Dec 4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.17242.

Patients receiving oral anticoagulant treatment had the lowest risk of gastrointestinal bleeding when taking apixaban, compared with rivaroxaban, dabigatran, and warfarin, according to a recent study.

Further, patients who received proton pump inhibitor (PPI) cotherapy had a lower overall risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, according to Wayne A. Ray, PhD, from the department of health policy at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., and his colleagues.

“These findings indicate the potential benefits of a gastrointestinal bleeding risk assessment before initiating anticoagulant treatment,” Dr. Ray and his colleagues wrote in their study, which was published in JAMA.

Dr. Ray and his colleagues performed a retrospective, population-based study of 1,643,123 Medicare beneficiaries (mean age, 76.4 years) who received 1,713,183 new episodes of oral anticoagulant treatment between January 2011 and September 2015. They analyzed how patients reacted to apixaban, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or warfarin both with and without PPI cotherapy.

Overall, the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding across 754,389 person-years without PPI therapy was 115 per 10,000 person-years (95% confidence interval, 112-118) in 7,119 patients. The researchers found the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding was highest in patients taking rivaroxaban (1,278 patients; 144 per 10,000 person-years; 95% CI, 136-152) and lowest when taking apixaban (279 patients; 120 per 10,000 person-years; incidence rate ratio, 1,97; 95% CI, 1.73-2.25), compared with dabigatran (629 patients; 120 per 10,000 person-years; IRR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.08-1.32) and warfarin (4,933 patients; 113 per 10,000 person-years; IRR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.19-1.35). There was a significantly lower incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding for apixaban, compared with warfarin (IRR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.57-0.73) and dabigatran (IRR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.52-0.70).

There was a lower overall incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding when receiving PPI cotherapy (264,447 person-years; 76 per 10,000 person-years), compared with patients who received anticoagulant treatment without PPI cotherapy (IRR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.62-0.69). This reduced incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding was also seen in patients receiving PPI cotherapy and taking apixaban (IRR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.52-0.85), dabigatran (IRR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.41-0.59), rivaroxaban (IRR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.68-0.84), and warfarin (IRR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.62-0.69).

The researchers noted that limitations in this study included potential misclassification of anticoagulant treatment, PPI cotherapy, and NSAIDs because of a reliance on filled prescription data; confounding by unmeasured factors such as aspirin exposure or Helicobacter pylori infection; and gastrointestinal bleeding being measured using a disease risk score.

This study was supported by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Ray WA et al. JAMA. 2018 Dec 4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.17242.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: In patients receiving oral anticoagulant treatment, risk of gastrointestinal bleeding was highest in patients taking rivaroxaban, lowest when taking apixaban, and there was a lower overall incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding when receiving proton pump inhibitor cotherapy.

Major finding: Per 10,000 person-years, the incidence rate of gastrointestinal bleeding was 144 for rivaroxaban, 73 for apixaban, 120 for dabigatran, and 113 for warfarin; there was a gastrointestinal bleeding incidence rate ratio of 0.66 for patients using protein pump inhibitor cotherapy.

Study details: A retrospective, population-based study of 1,643,123 Medicare beneficiaries who received oral anticoagulant treatment between January 2011 and September 2015.

Disclosures: This study was supported by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Source: Ray WA et al. JAMA. 2018 Dec 4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.17242.

ONC releases draft strategy on reducing EHR burden

A new federal proposal aims to move you away from the keyboard and back face-to-face with your patients.

The draft strategy from the Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT has three aims: to reduce the time and effort to record information in EHRs; to reduce the time and effort required to meet regulatory requirements; and to improve the functionality and ease of use of EHRs.

“This draft strategy includes recommendations that will allow physicians and other clinicians to provide effective care to their patients with a renewed sense of satisfaction for them and their patients,” Andrew Gettinger, MD, chief clinical officer at ONC, and Kate Goodrich, MD, chief medical officer at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, wrote in a recent blog post. “We are taking one more step toward improving the interoperability and usability of health information by establishing a goal, strategy, and recommendations to reduce regulatory and administrative burdens relating to the use of EHRs.”

To ease documentation burdens, the proposal seeks to “mitigate the EHR-related burden associated with a variety of administrative processes,” the draft strategy notes. “We are considering how reforming certain administrative requirements or optimizing out-of-date requirements for health IT–enabled health care provider work flows can reduce the burden of clinical documentation.”

Specifically, ONC proposes to reduce the overall regulatory burden, leverage data present in the electronic record to reduce the redocumentation, waive certain documentation requirements for participants in advanced alternative payment models (APMs), and promote standardized documentation for ordering and prior authorization.

To improve health IT usability, the draft strategy aims to “address how improvements in the design and use of health IT systems” can reduce burden and calls on clinicians, software developers, and other vendors to collaborate.

To do so, ONC recommends better alignment between EHR design and clinical work flow and making improvements to clinical decision support, as well as improving the presentation of clinical data within EHRs and clinical documentation functionality.

ONC also recommends standardizing basic clinical operations across all EHRs, designing EHR interfaces that are standard to health care delivery, and better integration of the EHR with the exam room.

The draft strategy also includes recommendations to help doctors better understand the financial requirements for successful implementation and optimize the log-in procedures to help reduce burden.

EHR reporting strategies “are designed to address many of the programmatic, technical, and operational challenges raised by stakeholders to reduce EHR-related burden associated with program reporting.”

ONC wants to simplify scoring for the “promoting interoperability” performance category in the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) track of the Quality Payment Program and improving other measures of health IT usage; applying additional data standards to make data access, extraction, and integration across multiple systems easier and less costly; and exploring alternate, less burdensome approaches to electronic quality measurement through pilot programs and reporting program incentives.

Finally, public health reporting strategies “look at a set of topics linked to federal, state, local, territorial, and tribal government policies and public health programs, with a specific focus on EPCS [electronic prescribing for controlled substances] and PDMPs [prescription drug monitoring programs]. Where EHR-related burden remains a key barrier to progress in these areas, there are several recommendations for how stakeholders can advance these burden reduction goals related to public health.”

In this area, ONC is recommending increasing adoption of e-prescribing of controlled substances with access to medication history to better inform prescribing of controlled substances, harmonizing reporting requirements across federally funded programs to streamline reporting requirements, and providing better guidance about HIPPA and federal confidentially requirements governing substance abuse disorder to better facilitate the electronic exchange of health information for patient care.

Comments on the report may be submitted electronically through Jan. 28, 2019.

A new federal proposal aims to move you away from the keyboard and back face-to-face with your patients.

The draft strategy from the Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT has three aims: to reduce the time and effort to record information in EHRs; to reduce the time and effort required to meet regulatory requirements; and to improve the functionality and ease of use of EHRs.

“This draft strategy includes recommendations that will allow physicians and other clinicians to provide effective care to their patients with a renewed sense of satisfaction for them and their patients,” Andrew Gettinger, MD, chief clinical officer at ONC, and Kate Goodrich, MD, chief medical officer at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, wrote in a recent blog post. “We are taking one more step toward improving the interoperability and usability of health information by establishing a goal, strategy, and recommendations to reduce regulatory and administrative burdens relating to the use of EHRs.”

To ease documentation burdens, the proposal seeks to “mitigate the EHR-related burden associated with a variety of administrative processes,” the draft strategy notes. “We are considering how reforming certain administrative requirements or optimizing out-of-date requirements for health IT–enabled health care provider work flows can reduce the burden of clinical documentation.”

Specifically, ONC proposes to reduce the overall regulatory burden, leverage data present in the electronic record to reduce the redocumentation, waive certain documentation requirements for participants in advanced alternative payment models (APMs), and promote standardized documentation for ordering and prior authorization.

To improve health IT usability, the draft strategy aims to “address how improvements in the design and use of health IT systems” can reduce burden and calls on clinicians, software developers, and other vendors to collaborate.

To do so, ONC recommends better alignment between EHR design and clinical work flow and making improvements to clinical decision support, as well as improving the presentation of clinical data within EHRs and clinical documentation functionality.

ONC also recommends standardizing basic clinical operations across all EHRs, designing EHR interfaces that are standard to health care delivery, and better integration of the EHR with the exam room.

The draft strategy also includes recommendations to help doctors better understand the financial requirements for successful implementation and optimize the log-in procedures to help reduce burden.

EHR reporting strategies “are designed to address many of the programmatic, technical, and operational challenges raised by stakeholders to reduce EHR-related burden associated with program reporting.”

ONC wants to simplify scoring for the “promoting interoperability” performance category in the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) track of the Quality Payment Program and improving other measures of health IT usage; applying additional data standards to make data access, extraction, and integration across multiple systems easier and less costly; and exploring alternate, less burdensome approaches to electronic quality measurement through pilot programs and reporting program incentives.

Finally, public health reporting strategies “look at a set of topics linked to federal, state, local, territorial, and tribal government policies and public health programs, with a specific focus on EPCS [electronic prescribing for controlled substances] and PDMPs [prescription drug monitoring programs]. Where EHR-related burden remains a key barrier to progress in these areas, there are several recommendations for how stakeholders can advance these burden reduction goals related to public health.”

In this area, ONC is recommending increasing adoption of e-prescribing of controlled substances with access to medication history to better inform prescribing of controlled substances, harmonizing reporting requirements across federally funded programs to streamline reporting requirements, and providing better guidance about HIPPA and federal confidentially requirements governing substance abuse disorder to better facilitate the electronic exchange of health information for patient care.

Comments on the report may be submitted electronically through Jan. 28, 2019.

A new federal proposal aims to move you away from the keyboard and back face-to-face with your patients.

The draft strategy from the Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT has three aims: to reduce the time and effort to record information in EHRs; to reduce the time and effort required to meet regulatory requirements; and to improve the functionality and ease of use of EHRs.

“This draft strategy includes recommendations that will allow physicians and other clinicians to provide effective care to their patients with a renewed sense of satisfaction for them and their patients,” Andrew Gettinger, MD, chief clinical officer at ONC, and Kate Goodrich, MD, chief medical officer at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, wrote in a recent blog post. “We are taking one more step toward improving the interoperability and usability of health information by establishing a goal, strategy, and recommendations to reduce regulatory and administrative burdens relating to the use of EHRs.”

To ease documentation burdens, the proposal seeks to “mitigate the EHR-related burden associated with a variety of administrative processes,” the draft strategy notes. “We are considering how reforming certain administrative requirements or optimizing out-of-date requirements for health IT–enabled health care provider work flows can reduce the burden of clinical documentation.”

Specifically, ONC proposes to reduce the overall regulatory burden, leverage data present in the electronic record to reduce the redocumentation, waive certain documentation requirements for participants in advanced alternative payment models (APMs), and promote standardized documentation for ordering and prior authorization.

To improve health IT usability, the draft strategy aims to “address how improvements in the design and use of health IT systems” can reduce burden and calls on clinicians, software developers, and other vendors to collaborate.

To do so, ONC recommends better alignment between EHR design and clinical work flow and making improvements to clinical decision support, as well as improving the presentation of clinical data within EHRs and clinical documentation functionality.

ONC also recommends standardizing basic clinical operations across all EHRs, designing EHR interfaces that are standard to health care delivery, and better integration of the EHR with the exam room.

The draft strategy also includes recommendations to help doctors better understand the financial requirements for successful implementation and optimize the log-in procedures to help reduce burden.

EHR reporting strategies “are designed to address many of the programmatic, technical, and operational challenges raised by stakeholders to reduce EHR-related burden associated with program reporting.”

ONC wants to simplify scoring for the “promoting interoperability” performance category in the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) track of the Quality Payment Program and improving other measures of health IT usage; applying additional data standards to make data access, extraction, and integration across multiple systems easier and less costly; and exploring alternate, less burdensome approaches to electronic quality measurement through pilot programs and reporting program incentives.