User login

Evaluate liability risks in prescribing

Dear Dr. Mossman,

I prescribed topiramate for Mr. B, a patient with no history of kidney stones. Many months later he developed back pain. During the medical workup for a possible kidney stone, Mr. B and I revisited the risk of kidney stones with topiramate, which we had discussed at the beginning of therapy. Mr. B was adamantly opposed to stopping topiramate, even if he had a kidney stone. Testing revealed that Mr. B did not have a stone, but I wasn’t sure how to proceed. I worried that I might be found liable if Mr. B stayed on topiramate and did develop a kidney stone.—Submitted by Dr. A

When a patient develops a medical problem from a drug you prescribed, it is natural to feel responsible—after all, your treatment caused the adverse event. But did you commit malpractice? To answer this, let’s review the concept of “medical negligence.”

Malpractice law applies legal principles of negligence to professional conduct.1 The elements of a negligence case (Table 1) can be summarized as “breach of duty causing damages.” Therefore, when you wonder whether possible harm to a patient might be considered malpractice, ask yourself, “Did I breach my professional duty?”

Physicians have a duty to practice within their specialty’s standard of care, and if they do this, they should not be held liable even if their treatments cause adverse effects. Each jurisdiction defines the standard of care differently, but the general expectation is “that physicians acting within the ambit of their professional work will exercise the skill, knowledge, and care normally possessed and exercised by other members of their profession…in the relevant medical community.”1

It’s impossible to describe all the skills, knowledge, and care a psychiatrist normally employs when prescribing a drug, but elements of good practice include reasonable efforts to:

- make an appropriate diagnosis

- offer appropriate treatment

- monitor effects of treatment.

Further, treatment should occur only when a patient gives informed consent. Let’s examine each of these elements as they apply to Dr. A and Mr. B.

- Submit your malpractice-related questions to Dr. Mossman at douglas.mossman@dowdenhealth.com.

- Include your name, address, and practice location. If your question is chosen for publication, your name can be withheld by request.

- All readers who submit questions will be included in quarterly drawings for a $50 gift certificate for Professional Risk Management Services, Inc’s online market-place of risk management publications and resources (www.prms.com).

Table 1

Elements of a successful negligence case

|

| Source: Reference 1 |

Appropriate assessment

Despite the availability of guidelines for psychiatric evaluation,2,3 it is tough to summarize everything psychiatrists do when assessing patients. But—focusing on Dr. A’s question—it is reasonable to ask: Did the psychiatric evaluation provide reasonably good evidence that Mr. B had a condition that topiramate might alleviate? Mr. B’s strong desire to keep taking the drug suggests that the answer is “yes.”

Dr. A also should consider potential interactions between topiramate and any other medications that Mr. B is taking. A prudent clinician must judge whether the potential benefit of topiramate for Mr. B outweighs the risk of adverse effects. If Mr. B actually had developed a kidney stone, Dr. A might seek a nephrologist’s advice about how to minimize the risk of recurrence.

Appropriate treatment

Topiramate is FDA-approved only for treating seizures and for prophylaxis against migraine headaches. However, FDA approval limits only how pharmaceutical companies can promote a medication.4 Physicians may prescribe drugs for unapproved “off-label” uses, and doing so is accepted medical practice. Peer-reviewed publications support using topiramate to treat agitation,5 alcohol dependence,6 binge-eating disorder,7 and other conditions that psychiatrists often manage. A tendency to promote weight loss has made topiramate an attractive add-on medication for patients whose weight problems are causing other health difficulties.8

Assuming that Mr. B is taking topiramate for an off-label purpose, an appropriate question to ask is, “Does professional literature support use of topiramate in Mr. B’s circumstances?” Also, given everything known about Mr. B up to this point, is topiramate a good treatment choice?

Appropriate monitoring

As every clinician knows, medications can cause problems. Monitoring topiramate therapy involves periodic lab testing and assessment of effectiveness. Dr. A should feel reasonably sure that Mr. B—assisted by a family member or close friend, if necessary—can and will cooperate with monitoring requirements. Dr. A also should verify that Mr. B can grasp and follow instructions designed to avert complications—such as ample hydration to reduce risk of nephrolithiasis—and will promptly address problems if they occur.

Informed consent

Informed consent is especially important when a patient receives a treatment that has a known risk. Although the Physician’s Desk Reference does not list previous kidney stones as a contraindication to topiramate therapy, it urges caution under these circumstances.4 Therefore, if Dr. A wishes to prescribe topiramate for a patient with a history of kidney stone, the patient should meaningfully collaborate in the treatment decision.

Informed consent for treatment requires that patients not feel coerced by the doctor or setting and have the mental capacity or competence to give consent. Under the conceptualization developed by Appelbaum and Grisso,9 competent patients can:

- express a consistent choice

- understand medical information provided to them

- appreciate how this information applies to them and their condition

- reason logically about treatment.

What information should patients receive before giving consent? The legal standard varies, but in most U.S. jurisdictions, patients “are entitled to material information about the nature of any proposed medical procedure. For example, patients are entitled to information about the risks of the procedure, its necessity, and alternate procedures that might be preferable.”1 Topiramate’s manufacturer instructs physicians to question and warn patients about the risk of kidney stones—which Dr. A did in Mr. B’s case. When you prescribe a drug off-label, you may want to tell patients this, but explain why the drug is appropriate nonetheless.

Table 2

Evaluating a patient’s capacity to consent to treatment

| Is this patient able to? | Questions to ask |

|---|---|

| Express a clear treatment preference | What treatment have you chosen? |

| Understand basic information communicated by caregivers | Can you tell me in your own words about your condition and the treatment options I have told you about? |

| Appreciate his or her medical condition and how information about treatment applies | What do you think is wrong with your health now? Do you think you need some kind of treatment? What do you think treatment will do for you? |

| Reason logically when choosing treatment options | Why did you choose this treatment? Why is it better than your other treatment options? |

| Source: Adapted and reprinted with permission from Appelbaum PS. Assessment of patients’ competence to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med 2007;357:1834-40 | |

1. Dobbs DB. The law of torts. St. Paul, MN: West Group; 2000:269.

2. King RA. Practice parameters for the psychiatric assessment of children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997;36(10 suppl):4S-20S.

3. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for psychiatric evaluation of adults. Am J Psychiatry 1995;152(11 suppl):63-80.

4. Physicians’ Desk Reference. 62 ed. Montvale, NJ: Thomson Healthcare Inc.; 2007.

5. Guay DR. Newer antiepileptic drugs in the management of agitation/aggression in patients with dementia or developmental disability. Consult Pharm 2007;22:1004-34.

6. Johnson BA, Rosenthal N, Capece JA, et al. Topiramate for Alcoholism Advisory Board; Topiramate for Alcoholism Study Group. Topiramate for treating alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;298:1641-51.

7. McElroy SL, Arnold LM, Shapira NA, et al. Topiramate in the treatment of binge eating disorder associated with obesity: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 2003;160:255-61.

8. Kirov G, Tredget J. Add-on topiramate reduces weight in overweight patients with affective disorders: a clinical case series. BMC Psychiatry 2005;5(1):19.-

9. Appelbaum PS, Grisso T. Assessing patients’ capacities to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med 1988;319:1635-8.

10. Appelbaum PS. Assessment of patients’ competence to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med 2007;357:1834-40.

Dear Dr. Mossman,

I prescribed topiramate for Mr. B, a patient with no history of kidney stones. Many months later he developed back pain. During the medical workup for a possible kidney stone, Mr. B and I revisited the risk of kidney stones with topiramate, which we had discussed at the beginning of therapy. Mr. B was adamantly opposed to stopping topiramate, even if he had a kidney stone. Testing revealed that Mr. B did not have a stone, but I wasn’t sure how to proceed. I worried that I might be found liable if Mr. B stayed on topiramate and did develop a kidney stone.—Submitted by Dr. A

When a patient develops a medical problem from a drug you prescribed, it is natural to feel responsible—after all, your treatment caused the adverse event. But did you commit malpractice? To answer this, let’s review the concept of “medical negligence.”

Malpractice law applies legal principles of negligence to professional conduct.1 The elements of a negligence case (Table 1) can be summarized as “breach of duty causing damages.” Therefore, when you wonder whether possible harm to a patient might be considered malpractice, ask yourself, “Did I breach my professional duty?”

Physicians have a duty to practice within their specialty’s standard of care, and if they do this, they should not be held liable even if their treatments cause adverse effects. Each jurisdiction defines the standard of care differently, but the general expectation is “that physicians acting within the ambit of their professional work will exercise the skill, knowledge, and care normally possessed and exercised by other members of their profession…in the relevant medical community.”1

It’s impossible to describe all the skills, knowledge, and care a psychiatrist normally employs when prescribing a drug, but elements of good practice include reasonable efforts to:

- make an appropriate diagnosis

- offer appropriate treatment

- monitor effects of treatment.

Further, treatment should occur only when a patient gives informed consent. Let’s examine each of these elements as they apply to Dr. A and Mr. B.

- Submit your malpractice-related questions to Dr. Mossman at douglas.mossman@dowdenhealth.com.

- Include your name, address, and practice location. If your question is chosen for publication, your name can be withheld by request.

- All readers who submit questions will be included in quarterly drawings for a $50 gift certificate for Professional Risk Management Services, Inc’s online market-place of risk management publications and resources (www.prms.com).

Table 1

Elements of a successful negligence case

|

| Source: Reference 1 |

Appropriate assessment

Despite the availability of guidelines for psychiatric evaluation,2,3 it is tough to summarize everything psychiatrists do when assessing patients. But—focusing on Dr. A’s question—it is reasonable to ask: Did the psychiatric evaluation provide reasonably good evidence that Mr. B had a condition that topiramate might alleviate? Mr. B’s strong desire to keep taking the drug suggests that the answer is “yes.”

Dr. A also should consider potential interactions between topiramate and any other medications that Mr. B is taking. A prudent clinician must judge whether the potential benefit of topiramate for Mr. B outweighs the risk of adverse effects. If Mr. B actually had developed a kidney stone, Dr. A might seek a nephrologist’s advice about how to minimize the risk of recurrence.

Appropriate treatment

Topiramate is FDA-approved only for treating seizures and for prophylaxis against migraine headaches. However, FDA approval limits only how pharmaceutical companies can promote a medication.4 Physicians may prescribe drugs for unapproved “off-label” uses, and doing so is accepted medical practice. Peer-reviewed publications support using topiramate to treat agitation,5 alcohol dependence,6 binge-eating disorder,7 and other conditions that psychiatrists often manage. A tendency to promote weight loss has made topiramate an attractive add-on medication for patients whose weight problems are causing other health difficulties.8

Assuming that Mr. B is taking topiramate for an off-label purpose, an appropriate question to ask is, “Does professional literature support use of topiramate in Mr. B’s circumstances?” Also, given everything known about Mr. B up to this point, is topiramate a good treatment choice?

Appropriate monitoring

As every clinician knows, medications can cause problems. Monitoring topiramate therapy involves periodic lab testing and assessment of effectiveness. Dr. A should feel reasonably sure that Mr. B—assisted by a family member or close friend, if necessary—can and will cooperate with monitoring requirements. Dr. A also should verify that Mr. B can grasp and follow instructions designed to avert complications—such as ample hydration to reduce risk of nephrolithiasis—and will promptly address problems if they occur.

Informed consent

Informed consent is especially important when a patient receives a treatment that has a known risk. Although the Physician’s Desk Reference does not list previous kidney stones as a contraindication to topiramate therapy, it urges caution under these circumstances.4 Therefore, if Dr. A wishes to prescribe topiramate for a patient with a history of kidney stone, the patient should meaningfully collaborate in the treatment decision.

Informed consent for treatment requires that patients not feel coerced by the doctor or setting and have the mental capacity or competence to give consent. Under the conceptualization developed by Appelbaum and Grisso,9 competent patients can:

- express a consistent choice

- understand medical information provided to them

- appreciate how this information applies to them and their condition

- reason logically about treatment.

What information should patients receive before giving consent? The legal standard varies, but in most U.S. jurisdictions, patients “are entitled to material information about the nature of any proposed medical procedure. For example, patients are entitled to information about the risks of the procedure, its necessity, and alternate procedures that might be preferable.”1 Topiramate’s manufacturer instructs physicians to question and warn patients about the risk of kidney stones—which Dr. A did in Mr. B’s case. When you prescribe a drug off-label, you may want to tell patients this, but explain why the drug is appropriate nonetheless.

Table 2

Evaluating a patient’s capacity to consent to treatment

| Is this patient able to? | Questions to ask |

|---|---|

| Express a clear treatment preference | What treatment have you chosen? |

| Understand basic information communicated by caregivers | Can you tell me in your own words about your condition and the treatment options I have told you about? |

| Appreciate his or her medical condition and how information about treatment applies | What do you think is wrong with your health now? Do you think you need some kind of treatment? What do you think treatment will do for you? |

| Reason logically when choosing treatment options | Why did you choose this treatment? Why is it better than your other treatment options? |

| Source: Adapted and reprinted with permission from Appelbaum PS. Assessment of patients’ competence to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med 2007;357:1834-40 | |

Dear Dr. Mossman,

I prescribed topiramate for Mr. B, a patient with no history of kidney stones. Many months later he developed back pain. During the medical workup for a possible kidney stone, Mr. B and I revisited the risk of kidney stones with topiramate, which we had discussed at the beginning of therapy. Mr. B was adamantly opposed to stopping topiramate, even if he had a kidney stone. Testing revealed that Mr. B did not have a stone, but I wasn’t sure how to proceed. I worried that I might be found liable if Mr. B stayed on topiramate and did develop a kidney stone.—Submitted by Dr. A

When a patient develops a medical problem from a drug you prescribed, it is natural to feel responsible—after all, your treatment caused the adverse event. But did you commit malpractice? To answer this, let’s review the concept of “medical negligence.”

Malpractice law applies legal principles of negligence to professional conduct.1 The elements of a negligence case (Table 1) can be summarized as “breach of duty causing damages.” Therefore, when you wonder whether possible harm to a patient might be considered malpractice, ask yourself, “Did I breach my professional duty?”

Physicians have a duty to practice within their specialty’s standard of care, and if they do this, they should not be held liable even if their treatments cause adverse effects. Each jurisdiction defines the standard of care differently, but the general expectation is “that physicians acting within the ambit of their professional work will exercise the skill, knowledge, and care normally possessed and exercised by other members of their profession…in the relevant medical community.”1

It’s impossible to describe all the skills, knowledge, and care a psychiatrist normally employs when prescribing a drug, but elements of good practice include reasonable efforts to:

- make an appropriate diagnosis

- offer appropriate treatment

- monitor effects of treatment.

Further, treatment should occur only when a patient gives informed consent. Let’s examine each of these elements as they apply to Dr. A and Mr. B.

- Submit your malpractice-related questions to Dr. Mossman at douglas.mossman@dowdenhealth.com.

- Include your name, address, and practice location. If your question is chosen for publication, your name can be withheld by request.

- All readers who submit questions will be included in quarterly drawings for a $50 gift certificate for Professional Risk Management Services, Inc’s online market-place of risk management publications and resources (www.prms.com).

Table 1

Elements of a successful negligence case

|

| Source: Reference 1 |

Appropriate assessment

Despite the availability of guidelines for psychiatric evaluation,2,3 it is tough to summarize everything psychiatrists do when assessing patients. But—focusing on Dr. A’s question—it is reasonable to ask: Did the psychiatric evaluation provide reasonably good evidence that Mr. B had a condition that topiramate might alleviate? Mr. B’s strong desire to keep taking the drug suggests that the answer is “yes.”

Dr. A also should consider potential interactions between topiramate and any other medications that Mr. B is taking. A prudent clinician must judge whether the potential benefit of topiramate for Mr. B outweighs the risk of adverse effects. If Mr. B actually had developed a kidney stone, Dr. A might seek a nephrologist’s advice about how to minimize the risk of recurrence.

Appropriate treatment

Topiramate is FDA-approved only for treating seizures and for prophylaxis against migraine headaches. However, FDA approval limits only how pharmaceutical companies can promote a medication.4 Physicians may prescribe drugs for unapproved “off-label” uses, and doing so is accepted medical practice. Peer-reviewed publications support using topiramate to treat agitation,5 alcohol dependence,6 binge-eating disorder,7 and other conditions that psychiatrists often manage. A tendency to promote weight loss has made topiramate an attractive add-on medication for patients whose weight problems are causing other health difficulties.8

Assuming that Mr. B is taking topiramate for an off-label purpose, an appropriate question to ask is, “Does professional literature support use of topiramate in Mr. B’s circumstances?” Also, given everything known about Mr. B up to this point, is topiramate a good treatment choice?

Appropriate monitoring

As every clinician knows, medications can cause problems. Monitoring topiramate therapy involves periodic lab testing and assessment of effectiveness. Dr. A should feel reasonably sure that Mr. B—assisted by a family member or close friend, if necessary—can and will cooperate with monitoring requirements. Dr. A also should verify that Mr. B can grasp and follow instructions designed to avert complications—such as ample hydration to reduce risk of nephrolithiasis—and will promptly address problems if they occur.

Informed consent

Informed consent is especially important when a patient receives a treatment that has a known risk. Although the Physician’s Desk Reference does not list previous kidney stones as a contraindication to topiramate therapy, it urges caution under these circumstances.4 Therefore, if Dr. A wishes to prescribe topiramate for a patient with a history of kidney stone, the patient should meaningfully collaborate in the treatment decision.

Informed consent for treatment requires that patients not feel coerced by the doctor or setting and have the mental capacity or competence to give consent. Under the conceptualization developed by Appelbaum and Grisso,9 competent patients can:

- express a consistent choice

- understand medical information provided to them

- appreciate how this information applies to them and their condition

- reason logically about treatment.

What information should patients receive before giving consent? The legal standard varies, but in most U.S. jurisdictions, patients “are entitled to material information about the nature of any proposed medical procedure. For example, patients are entitled to information about the risks of the procedure, its necessity, and alternate procedures that might be preferable.”1 Topiramate’s manufacturer instructs physicians to question and warn patients about the risk of kidney stones—which Dr. A did in Mr. B’s case. When you prescribe a drug off-label, you may want to tell patients this, but explain why the drug is appropriate nonetheless.

Table 2

Evaluating a patient’s capacity to consent to treatment

| Is this patient able to? | Questions to ask |

|---|---|

| Express a clear treatment preference | What treatment have you chosen? |

| Understand basic information communicated by caregivers | Can you tell me in your own words about your condition and the treatment options I have told you about? |

| Appreciate his or her medical condition and how information about treatment applies | What do you think is wrong with your health now? Do you think you need some kind of treatment? What do you think treatment will do for you? |

| Reason logically when choosing treatment options | Why did you choose this treatment? Why is it better than your other treatment options? |

| Source: Adapted and reprinted with permission from Appelbaum PS. Assessment of patients’ competence to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med 2007;357:1834-40 | |

1. Dobbs DB. The law of torts. St. Paul, MN: West Group; 2000:269.

2. King RA. Practice parameters for the psychiatric assessment of children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997;36(10 suppl):4S-20S.

3. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for psychiatric evaluation of adults. Am J Psychiatry 1995;152(11 suppl):63-80.

4. Physicians’ Desk Reference. 62 ed. Montvale, NJ: Thomson Healthcare Inc.; 2007.

5. Guay DR. Newer antiepileptic drugs in the management of agitation/aggression in patients with dementia or developmental disability. Consult Pharm 2007;22:1004-34.

6. Johnson BA, Rosenthal N, Capece JA, et al. Topiramate for Alcoholism Advisory Board; Topiramate for Alcoholism Study Group. Topiramate for treating alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;298:1641-51.

7. McElroy SL, Arnold LM, Shapira NA, et al. Topiramate in the treatment of binge eating disorder associated with obesity: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 2003;160:255-61.

8. Kirov G, Tredget J. Add-on topiramate reduces weight in overweight patients with affective disorders: a clinical case series. BMC Psychiatry 2005;5(1):19.-

9. Appelbaum PS, Grisso T. Assessing patients’ capacities to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med 1988;319:1635-8.

10. Appelbaum PS. Assessment of patients’ competence to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med 2007;357:1834-40.

1. Dobbs DB. The law of torts. St. Paul, MN: West Group; 2000:269.

2. King RA. Practice parameters for the psychiatric assessment of children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997;36(10 suppl):4S-20S.

3. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for psychiatric evaluation of adults. Am J Psychiatry 1995;152(11 suppl):63-80.

4. Physicians’ Desk Reference. 62 ed. Montvale, NJ: Thomson Healthcare Inc.; 2007.

5. Guay DR. Newer antiepileptic drugs in the management of agitation/aggression in patients with dementia or developmental disability. Consult Pharm 2007;22:1004-34.

6. Johnson BA, Rosenthal N, Capece JA, et al. Topiramate for Alcoholism Advisory Board; Topiramate for Alcoholism Study Group. Topiramate for treating alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;298:1641-51.

7. McElroy SL, Arnold LM, Shapira NA, et al. Topiramate in the treatment of binge eating disorder associated with obesity: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 2003;160:255-61.

8. Kirov G, Tredget J. Add-on topiramate reduces weight in overweight patients with affective disorders: a clinical case series. BMC Psychiatry 2005;5(1):19.-

9. Appelbaum PS, Grisso T. Assessing patients’ capacities to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med 1988;319:1635-8.

10. Appelbaum PS. Assessment of patients’ competence to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med 2007;357:1834-40.

Heparin contaminant identified

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has identified the structure and source of the contaminant found in lots of heparin.

The contaminant, which has been linked to severe allergic reactions and deaths, was found in crude lots of heparin at a Chinese processing plant. The substance has been identified as over-sulfated chondroitin sulfate.

Researchers initially had difficulty identifying the contaminant because it is so similar to heparin. Over-sulfated chondroitin sulfate has approximately the same molecular weight as heparin, and both materials belong to the class of molecules known as glucosaminoglycans (GAGs).

It is still unknown whether the over-sulfated chondroitin sulfate was a byproduct of the heparin production process or if it was intentionally added to the active pharmaceutical ingredient.

After learning about the source of the over-sulfated chondroitin sulfate, the FDA issued a border alert that requires all finished heparin, as well as heparin source material, to be tested before it is allowed into the US. Five heparin manufacturers, companies that supply most of the heparin used in this country, have agreed to conduct the tests.

Janet Woodcock, MD, director of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said the agency would test heparin products made by companies that cannot conduct the testing themselves. Any product that is not tested or fails the tests will be destroyed.

Scientific Protein Laboratories is the company that supplied crude heparin from the Changzhou plant in China to the biopharmaceutical company Baxter. Scientific Protein Laboratories has said it is cooperating with the FDA, and the Changzhou plant is not currently producing heparin.

In addition to the new testing instituted at the US borders, the FDA said heparin testing is now being conducted worldwide. Germany and Japan are among the countries that have started testing.

Germany recalled heparin last week after a cluster of about 100 serious allergic reactions, including hypotension and anaphylaxis. Japan has also recalled heparin but has not reported any adverse events linked to heparin injections.

Both Scientific Protein Laboratories and Baxter have conducted massive voluntary recalls of heparin products. Since Baxter recalled all of its heparin vials, there have been no additional deaths.

Last week, the FDA received 785 reports of adverse events associated with heparin. Those reports included 46 deaths, but Dr Woodcock said only 19 were related to the allergic profile associated with the Baxter heparin.

Baxter has said it cannot confirm that heparin has caused any fatalities as a result of an allergic reaction. The company said there are 4 cases in which patients received Baxter heparin and suffered an allergic-type reaction to the drug.

Baxter also said there is not yet enough medical data available to draw a firm conclusion that the reaction caused death. In each of these cases, the patient had multiple underlying complex medical conditions. Three of the 4 patients had undergone, or were in the process of undergoing, invasive cardiac surgery.

The heparin saga began January 17 of this year, when Baxter recalled the first batch of heparin after receiving reports of the allergic reactions. Recalls of the drug have continued since that time.

The FDA released the news of the contaminant’s source March 14 and the discovery of its structure March 19. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has identified the structure and source of the contaminant found in lots of heparin.

The contaminant, which has been linked to severe allergic reactions and deaths, was found in crude lots of heparin at a Chinese processing plant. The substance has been identified as over-sulfated chondroitin sulfate.

Researchers initially had difficulty identifying the contaminant because it is so similar to heparin. Over-sulfated chondroitin sulfate has approximately the same molecular weight as heparin, and both materials belong to the class of molecules known as glucosaminoglycans (GAGs).

It is still unknown whether the over-sulfated chondroitin sulfate was a byproduct of the heparin production process or if it was intentionally added to the active pharmaceutical ingredient.

After learning about the source of the over-sulfated chondroitin sulfate, the FDA issued a border alert that requires all finished heparin, as well as heparin source material, to be tested before it is allowed into the US. Five heparin manufacturers, companies that supply most of the heparin used in this country, have agreed to conduct the tests.

Janet Woodcock, MD, director of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said the agency would test heparin products made by companies that cannot conduct the testing themselves. Any product that is not tested or fails the tests will be destroyed.

Scientific Protein Laboratories is the company that supplied crude heparin from the Changzhou plant in China to the biopharmaceutical company Baxter. Scientific Protein Laboratories has said it is cooperating with the FDA, and the Changzhou plant is not currently producing heparin.

In addition to the new testing instituted at the US borders, the FDA said heparin testing is now being conducted worldwide. Germany and Japan are among the countries that have started testing.

Germany recalled heparin last week after a cluster of about 100 serious allergic reactions, including hypotension and anaphylaxis. Japan has also recalled heparin but has not reported any adverse events linked to heparin injections.

Both Scientific Protein Laboratories and Baxter have conducted massive voluntary recalls of heparin products. Since Baxter recalled all of its heparin vials, there have been no additional deaths.

Last week, the FDA received 785 reports of adverse events associated with heparin. Those reports included 46 deaths, but Dr Woodcock said only 19 were related to the allergic profile associated with the Baxter heparin.

Baxter has said it cannot confirm that heparin has caused any fatalities as a result of an allergic reaction. The company said there are 4 cases in which patients received Baxter heparin and suffered an allergic-type reaction to the drug.

Baxter also said there is not yet enough medical data available to draw a firm conclusion that the reaction caused death. In each of these cases, the patient had multiple underlying complex medical conditions. Three of the 4 patients had undergone, or were in the process of undergoing, invasive cardiac surgery.

The heparin saga began January 17 of this year, when Baxter recalled the first batch of heparin after receiving reports of the allergic reactions. Recalls of the drug have continued since that time.

The FDA released the news of the contaminant’s source March 14 and the discovery of its structure March 19. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has identified the structure and source of the contaminant found in lots of heparin.

The contaminant, which has been linked to severe allergic reactions and deaths, was found in crude lots of heparin at a Chinese processing plant. The substance has been identified as over-sulfated chondroitin sulfate.

Researchers initially had difficulty identifying the contaminant because it is so similar to heparin. Over-sulfated chondroitin sulfate has approximately the same molecular weight as heparin, and both materials belong to the class of molecules known as glucosaminoglycans (GAGs).

It is still unknown whether the over-sulfated chondroitin sulfate was a byproduct of the heparin production process or if it was intentionally added to the active pharmaceutical ingredient.

After learning about the source of the over-sulfated chondroitin sulfate, the FDA issued a border alert that requires all finished heparin, as well as heparin source material, to be tested before it is allowed into the US. Five heparin manufacturers, companies that supply most of the heparin used in this country, have agreed to conduct the tests.

Janet Woodcock, MD, director of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said the agency would test heparin products made by companies that cannot conduct the testing themselves. Any product that is not tested or fails the tests will be destroyed.

Scientific Protein Laboratories is the company that supplied crude heparin from the Changzhou plant in China to the biopharmaceutical company Baxter. Scientific Protein Laboratories has said it is cooperating with the FDA, and the Changzhou plant is not currently producing heparin.

In addition to the new testing instituted at the US borders, the FDA said heparin testing is now being conducted worldwide. Germany and Japan are among the countries that have started testing.

Germany recalled heparin last week after a cluster of about 100 serious allergic reactions, including hypotension and anaphylaxis. Japan has also recalled heparin but has not reported any adverse events linked to heparin injections.

Both Scientific Protein Laboratories and Baxter have conducted massive voluntary recalls of heparin products. Since Baxter recalled all of its heparin vials, there have been no additional deaths.

Last week, the FDA received 785 reports of adverse events associated with heparin. Those reports included 46 deaths, but Dr Woodcock said only 19 were related to the allergic profile associated with the Baxter heparin.

Baxter has said it cannot confirm that heparin has caused any fatalities as a result of an allergic reaction. The company said there are 4 cases in which patients received Baxter heparin and suffered an allergic-type reaction to the drug.

Baxter also said there is not yet enough medical data available to draw a firm conclusion that the reaction caused death. In each of these cases, the patient had multiple underlying complex medical conditions. Three of the 4 patients had undergone, or were in the process of undergoing, invasive cardiac surgery.

The heparin saga began January 17 of this year, when Baxter recalled the first batch of heparin after receiving reports of the allergic reactions. Recalls of the drug have continued since that time.

The FDA released the news of the contaminant’s source March 14 and the discovery of its structure March 19. ![]()

Proceedings of the 2nd Heart-Brain Summit

Supplement Editor:

Marc S. Penn, MD, PhD

Contents*†

Introduction: Heart-brain medicine: Update 2007

Marc S. Penn, MD, PhD, and Earl E. Bakken, MD, HonC, (3) SciDHon

Depression in coronary artery disease: Does treatment help?

Peter A. Shapiro, MD

Case study in heart-brain interplay: A 53-year-old woman recovering from mitral valve repair

Thomas D. Callahan, IV, MD; Ubaid Khokhar, MD; Leo Pozuelo, MD; and James B. Young, MD

Emotional predictors and behavioral triggers of acute coronary syndrome

Karina W. Davidson, PhD

Impacts of depression and emotional distress on cardiac disease

Wei Jiang, MD

Inflammation as a link between brain injury and heart damage: The model of subarachnoid hemorrhage

Hazem Antar Mashaly, MD, and J. Javier Provencio, MD

Biofeedback: An overview in the context of heart-brain medicine

Michael G. McKee, PhD

Biofeedback therapy in cardiovascular disease: Rationale and research overview

Christine S. Moravec, PhD

Helping children and adults with hypnosis and biofeedback

Karen Olness, MD

Clinical hypnosis for reduction of atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass graft surgery

Roberto Novoa, MD, and Tracy Hammonds, BA

Depression and coronary heart disease: Association and implications for treatment

James A. Blumenthal, PhD

Cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction in patients with movement disorders

Benjamin L. Walter, MD

Deep brain stimulation: How does it work?

Jerrold L. Vitek, MD, PhD

Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy: Impact, mechanisms, and prevention

Lara Jehi, MD, and Imad M. Najm, MD

Evaluating brain function in patients with disorders of consciousness

Tristan Bekinschtein, PhD, and Facundo Manes, MD

Preconditioning paradigms and pathways in the brain

Karl B. Shpargel; Walid Jalabi, PhD; Yongming Jin; Alisher Dadabayev, MD; Marc S. Penn, MD, PhD,

and Bruce D. Trapp, PhD

Post-stroke exercise rehabilitation:What we know about retraining the motor system and how it may apply to retraining the heart

Andreas Luft, MD; Richard Macko, MD; Larry Forrester, PhD; Andrew Goldberg, MD; and Daniel F. Hanley, MD

Hippocampal volume change in the Alzheimer Disease Cholesterol-Lowering Treatment trial

D. Larry Sparks, PhD; Susan K. Lemieux, PhD; Marc W. Haut, PhD; Leslie C. Baxter, PhD; Sterling C. Johnson, PhD; Lisa M. Sparks, BS; Hemalatha Sampath, BSEE; Jean E. Lopez, RN; Marwan H. Sabbagh, MD; and Donald J. Connor, PhD

Heart-brain interactions in cardiac arrhythmias: Role of the autonomic nervous system

Douglas P. Zipes, MD

Insular Alzheimer disease pathology and the psychometric correlates of mortality

Donald R. Royall, MD

Poster abstracts

* These proceedings represent the large majority of presentations at the 2nd Heart-Brain Summit, but five Summit presentations were not able to be captured for publication here.

† Articles in these proceedings were either submitted as manuscripts by the Summit faculty or developed by the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine staff from transcripts of audiotaped Summit presentations and then revised and approved by the Summit faculty.

Supplement Editor:

Marc S. Penn, MD, PhD

Contents*†

Introduction: Heart-brain medicine: Update 2007

Marc S. Penn, MD, PhD, and Earl E. Bakken, MD, HonC, (3) SciDHon

Depression in coronary artery disease: Does treatment help?

Peter A. Shapiro, MD

Case study in heart-brain interplay: A 53-year-old woman recovering from mitral valve repair

Thomas D. Callahan, IV, MD; Ubaid Khokhar, MD; Leo Pozuelo, MD; and James B. Young, MD

Emotional predictors and behavioral triggers of acute coronary syndrome

Karina W. Davidson, PhD

Impacts of depression and emotional distress on cardiac disease

Wei Jiang, MD

Inflammation as a link between brain injury and heart damage: The model of subarachnoid hemorrhage

Hazem Antar Mashaly, MD, and J. Javier Provencio, MD

Biofeedback: An overview in the context of heart-brain medicine

Michael G. McKee, PhD

Biofeedback therapy in cardiovascular disease: Rationale and research overview

Christine S. Moravec, PhD

Helping children and adults with hypnosis and biofeedback

Karen Olness, MD

Clinical hypnosis for reduction of atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass graft surgery

Roberto Novoa, MD, and Tracy Hammonds, BA

Depression and coronary heart disease: Association and implications for treatment

James A. Blumenthal, PhD

Cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction in patients with movement disorders

Benjamin L. Walter, MD

Deep brain stimulation: How does it work?

Jerrold L. Vitek, MD, PhD

Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy: Impact, mechanisms, and prevention

Lara Jehi, MD, and Imad M. Najm, MD

Evaluating brain function in patients with disorders of consciousness

Tristan Bekinschtein, PhD, and Facundo Manes, MD

Preconditioning paradigms and pathways in the brain

Karl B. Shpargel; Walid Jalabi, PhD; Yongming Jin; Alisher Dadabayev, MD; Marc S. Penn, MD, PhD,

and Bruce D. Trapp, PhD

Post-stroke exercise rehabilitation:What we know about retraining the motor system and how it may apply to retraining the heart

Andreas Luft, MD; Richard Macko, MD; Larry Forrester, PhD; Andrew Goldberg, MD; and Daniel F. Hanley, MD

Hippocampal volume change in the Alzheimer Disease Cholesterol-Lowering Treatment trial

D. Larry Sparks, PhD; Susan K. Lemieux, PhD; Marc W. Haut, PhD; Leslie C. Baxter, PhD; Sterling C. Johnson, PhD; Lisa M. Sparks, BS; Hemalatha Sampath, BSEE; Jean E. Lopez, RN; Marwan H. Sabbagh, MD; and Donald J. Connor, PhD

Heart-brain interactions in cardiac arrhythmias: Role of the autonomic nervous system

Douglas P. Zipes, MD

Insular Alzheimer disease pathology and the psychometric correlates of mortality

Donald R. Royall, MD

Poster abstracts

* These proceedings represent the large majority of presentations at the 2nd Heart-Brain Summit, but five Summit presentations were not able to be captured for publication here.

† Articles in these proceedings were either submitted as manuscripts by the Summit faculty or developed by the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine staff from transcripts of audiotaped Summit presentations and then revised and approved by the Summit faculty.

Supplement Editor:

Marc S. Penn, MD, PhD

Contents*†

Introduction: Heart-brain medicine: Update 2007

Marc S. Penn, MD, PhD, and Earl E. Bakken, MD, HonC, (3) SciDHon

Depression in coronary artery disease: Does treatment help?

Peter A. Shapiro, MD

Case study in heart-brain interplay: A 53-year-old woman recovering from mitral valve repair

Thomas D. Callahan, IV, MD; Ubaid Khokhar, MD; Leo Pozuelo, MD; and James B. Young, MD

Emotional predictors and behavioral triggers of acute coronary syndrome

Karina W. Davidson, PhD

Impacts of depression and emotional distress on cardiac disease

Wei Jiang, MD

Inflammation as a link between brain injury and heart damage: The model of subarachnoid hemorrhage

Hazem Antar Mashaly, MD, and J. Javier Provencio, MD

Biofeedback: An overview in the context of heart-brain medicine

Michael G. McKee, PhD

Biofeedback therapy in cardiovascular disease: Rationale and research overview

Christine S. Moravec, PhD

Helping children and adults with hypnosis and biofeedback

Karen Olness, MD

Clinical hypnosis for reduction of atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass graft surgery

Roberto Novoa, MD, and Tracy Hammonds, BA

Depression and coronary heart disease: Association and implications for treatment

James A. Blumenthal, PhD

Cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction in patients with movement disorders

Benjamin L. Walter, MD

Deep brain stimulation: How does it work?

Jerrold L. Vitek, MD, PhD

Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy: Impact, mechanisms, and prevention

Lara Jehi, MD, and Imad M. Najm, MD

Evaluating brain function in patients with disorders of consciousness

Tristan Bekinschtein, PhD, and Facundo Manes, MD

Preconditioning paradigms and pathways in the brain

Karl B. Shpargel; Walid Jalabi, PhD; Yongming Jin; Alisher Dadabayev, MD; Marc S. Penn, MD, PhD,

and Bruce D. Trapp, PhD

Post-stroke exercise rehabilitation:What we know about retraining the motor system and how it may apply to retraining the heart

Andreas Luft, MD; Richard Macko, MD; Larry Forrester, PhD; Andrew Goldberg, MD; and Daniel F. Hanley, MD

Hippocampal volume change in the Alzheimer Disease Cholesterol-Lowering Treatment trial

D. Larry Sparks, PhD; Susan K. Lemieux, PhD; Marc W. Haut, PhD; Leslie C. Baxter, PhD; Sterling C. Johnson, PhD; Lisa M. Sparks, BS; Hemalatha Sampath, BSEE; Jean E. Lopez, RN; Marwan H. Sabbagh, MD; and Donald J. Connor, PhD

Heart-brain interactions in cardiac arrhythmias: Role of the autonomic nervous system

Douglas P. Zipes, MD

Insular Alzheimer disease pathology and the psychometric correlates of mortality

Donald R. Royall, MD

Poster abstracts

* These proceedings represent the large majority of presentations at the 2nd Heart-Brain Summit, but five Summit presentations were not able to be captured for publication here.

† Articles in these proceedings were either submitted as manuscripts by the Summit faculty or developed by the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine staff from transcripts of audiotaped Summit presentations and then revised and approved by the Summit faculty.

Post-stroke exercise rehabilitation: What we know about retraining the motor system and how it may apply to retraining the heart

Ideally, rehabilitation following a stroke that leads to functional deficit will result in a rapid return to normal function. In the real world, however, a rapid improvement in function is rarely achieved. Between 80% and 90% of stroke survivors have a motor deficit, with impairments in walking being the most common motor deficits.1 Most stroke survivors have a diminished fitness reserve that is stable and resistant to routine rehabilitative interventions. Recent research has begun to assess the value of exercise and other modalities of training during this period of stability to improve function long after cessation of other therapeutic interventions. This article will review this research and provide insight into those issues in post-stroke rehabilitation that remain to be addressed and may affect heart and brain physiology.

STROKE REDUCES AEROBIC CAPACITY

At all ages, the fitness level of stroke survivors, as measured by maximum oxygen consumption, is reduced by approximately 50% below that of an age-matched normal population. In a study comparing peak oxygen consumption during treadmill walking between stroke survivors and age-matched sedentary controls, we found that the stroke participants had an approximately 50% lower level of peak fitness relative to the control subjects.2 During treadmill walking at self-selected speeds, the stroke volunteers used 75% of their functional capacity, compared with 27% for the age-matched healthy controls. Furthermore, compared with the controls, the stroke subjects demonstrated a poorer economy of gait that required greater oxygen consumption to sustain their self-selected walking speeds.

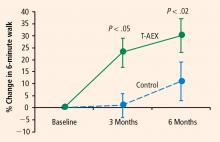

CLINICAL TRIALS OF POST-STROKE EXERCISE REHABILITATION

In light of the efficacy of treadmill exercise in cardiac rehabilitation, we are evaluating whether treadmill exercise can similarly improve fitness, endurance, and walking velocity in stroke survivors. We have completed 6 months of treadmill training in two separate cohorts that show highly consistent results in terms of improved walking abilities in hemiparetic stroke subjects.3,4 A third cohort is in progress to confirm these findings and examine the effects of intensity on the functional benefits5 and mechanisms6 underlying the effects of treadmill training.

Treadmill exercise results in functional benefits and improved glucose metabolism

The first cohort was a before-and-after comparison of stable stroke survivors who underwent a three-times-weekly treadmill exercise program for 6 months.3 Peak exercise capacity testing (VO2peak) revealed functional benefits with minimal cardiac and injury risk compared with baseline, demonstrating the feasibility and safety of treadmill exercise therapy in stroke-impaired adults.

Potential mechanisms for the benefits

These findings raise the question of whether these beneficial effects of treadmill exercise are attributable to muscle training effects, cardiopulmonary circulatory training effects, or perhaps neural mechanisms involving economy of gait movements and neuroplasticity of the motor system.

This question is being examined in our third cohort, now under investigation. This cohort will evaluate the effects of treadmill exercise on 32 chronically disabled stroke survivors in a single-center study design that is randomizing 64 subjects to 6 months of three-times-weekly treadmill training or conventional physiotherapy.6 Similar to our prior studies, subjects are randomized at least 6 months after their index stroke; this lengthy interval is deliberate because subjects are considered to be in a “plateau” phase of recovery, as they have previously completed rehabilitative therapy.

Activation will be measured in five prespecified “regions of interest”: the precentral gyrus, the postcentral gyrus, the supplementary motor area, the midbrain, and the cerebellum (anterior/posterior lobes). Difference activation maps of post-training minus pretraining fMRIs of paretic knee movement across all patients undergoing treadmill therapy will then be analyzed. The control group, which will receive dose-matched stretching activity from physical therapy, can be contrasted by comparing the patterns of pre/post differences in each region. This will allow for assessment of increased regional activation in the brain that should be specific to the treadmill training intervention. Furthermore, if a specifically localized regional activation difference is found, then individual fMRI and VO2 training responses (VO2peak, increase in walking speeds) can be correlated to further assess the relationship between regional activation and magnitude of functional response to the treadmill intervention.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Central control of walking

Control of gait in animals is mediated by the cortex, brainstem/cerebellum,9,10 and spinal cord—the so-called cervical gait and lumbar gait pattern-generating areas of the spinal cord. In humans, cortical and spinal gait pattern areas are thought to be major regulatory centers of ambulation. Whether the cortical areas influence ambulatory recovery mediated by exercise training or whether the recruitment of spinal gait areas is needed to improve motor control after stroke is not known in humans. We will test the hypothesis that the recruitment of cortical and/or subcortical areas is relevant to some or all of the exercise-induced neuroplasticity response to treadmill rehabilitation. If a consistent pattern of brain regional activation is associated with an improvement in walking ability, this finding will suggest potential brain targets for neurally directed rehabilitation interventions. If brain targets for rehabilitation produce viable therapeutic improvement in walking and cardiocirculatory performance (such as VO2), this will be further evidence of heart-brain interactions.

Future research directions

Studies to date demonstrate that long-term treadmill exercise affects both the brain and cardiac physiology. This has holistic implications for the function of the whole person as well. Yet several pressing issues continue to confront researchers in post-stroke rehabilitation. One is the optimal therapeutic target and the intensity of the rehabilitative effort. Is this improvement solely a response of muscle and cardiac tissue to exercise, or is it possible that improved neuromotor control is a critical component to a major recovery of walking function? Furthermore, the most efficacious elements of rehabilitative therapy are not known. Should treadmill training be high- or low-intensity, and should it be accompanied by strength training, agility and flexibility activities, or other elements directed at reacquisition of finer degrees of gait-related motor training and neuropsychological input, as achieved by tai-chi or yoga? Another issue is the proper dose of rehabilitative therapy, which has barely been explored, although recent preliminary work suggests that the response is dose-dependent. Finally, predictors of response have not been established because the mechanisms of therapy and surrogate markers for early response are not well understood.

Our future research plans are to assess whether a better understanding of neural targets for rehabilitative treatment will be a fruitful avenue to improve recovery. Additionally, this plan will assess whether fMRI can serve as a surrogate marker of recovery by offering a noninvasive means to measure response to rehabilitation.

- Mayo NE, Wood-Dauphinee S, Ahmed S, et al. Disablement following stroke. Disabil Rehabil 1999; 21:258–268.

- Michael K, Macko RF. Ambulatory activity intensity profiles, fitness, and fatigue in chronic stroke. Top Stroke Rehabil 2007; 14:5–12.

- Macko RF, Smith GV, Dobrovolny CL, Sorkin JD, Goldberg AP, Silver KH. Treadmill training improves fitness reserve in chronic stroke patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2001; 82:879–884.

- Macko RF, Ivey FM, Forrester LW, et al. Treadmill exercise rehabilitation improves ambulatory function and cardiovascular fitness in patients with chronic stroke. A randomized, controlled trial. Stroke 2005; 36:2206–2211.

- Ivey FM, Ryan AS, Hafer-Macko CE, Goldberg AP, Macko RF. Treadmill aerobic training improves glucose tolerance and indices of insulin sensitivity in disabled stroke survivors: a preliminary report. Stroke 2007; 38:2752–2758.

- Luft AR, Macko R, Forrester L, Villagra F, Hanley D. Subcortical reorganization induced by aerobic locomotor training in chronic stroke survivors [abstract]. Poster presented at: Annual Meeting of the Society for Neuroscience; November 15, 2005; Washington, DC.

- Luft AR, Smith GV, Forrester L, et al. Comparing brain activation associated with isolated upper and lower limb movement across corresponding joints. Hum Brain Mapping 2002; 17:131–140.

- Luft AR, Forrester L, Macko RF, et al. Brain activation of lower extremity movement in chronically impaired stroke survivors. Neuroimage 2005; 26:184–194.

- Lawrence DG, Kuypers HG. The functional organization of the motor system in the monkey. I. The effects of bilateral pyramidal lesions. Brain 1968; 91:1–14.

- Lawrence DG, Kuypers HG. The functional organization of the motor system in the monkey. II. The effects of lesions of the descending brain-stem pathways. Brain 1968; 91:15–36.

Ideally, rehabilitation following a stroke that leads to functional deficit will result in a rapid return to normal function. In the real world, however, a rapid improvement in function is rarely achieved. Between 80% and 90% of stroke survivors have a motor deficit, with impairments in walking being the most common motor deficits.1 Most stroke survivors have a diminished fitness reserve that is stable and resistant to routine rehabilitative interventions. Recent research has begun to assess the value of exercise and other modalities of training during this period of stability to improve function long after cessation of other therapeutic interventions. This article will review this research and provide insight into those issues in post-stroke rehabilitation that remain to be addressed and may affect heart and brain physiology.

STROKE REDUCES AEROBIC CAPACITY

At all ages, the fitness level of stroke survivors, as measured by maximum oxygen consumption, is reduced by approximately 50% below that of an age-matched normal population. In a study comparing peak oxygen consumption during treadmill walking between stroke survivors and age-matched sedentary controls, we found that the stroke participants had an approximately 50% lower level of peak fitness relative to the control subjects.2 During treadmill walking at self-selected speeds, the stroke volunteers used 75% of their functional capacity, compared with 27% for the age-matched healthy controls. Furthermore, compared with the controls, the stroke subjects demonstrated a poorer economy of gait that required greater oxygen consumption to sustain their self-selected walking speeds.

CLINICAL TRIALS OF POST-STROKE EXERCISE REHABILITATION

In light of the efficacy of treadmill exercise in cardiac rehabilitation, we are evaluating whether treadmill exercise can similarly improve fitness, endurance, and walking velocity in stroke survivors. We have completed 6 months of treadmill training in two separate cohorts that show highly consistent results in terms of improved walking abilities in hemiparetic stroke subjects.3,4 A third cohort is in progress to confirm these findings and examine the effects of intensity on the functional benefits5 and mechanisms6 underlying the effects of treadmill training.

Treadmill exercise results in functional benefits and improved glucose metabolism

The first cohort was a before-and-after comparison of stable stroke survivors who underwent a three-times-weekly treadmill exercise program for 6 months.3 Peak exercise capacity testing (VO2peak) revealed functional benefits with minimal cardiac and injury risk compared with baseline, demonstrating the feasibility and safety of treadmill exercise therapy in stroke-impaired adults.

Potential mechanisms for the benefits

These findings raise the question of whether these beneficial effects of treadmill exercise are attributable to muscle training effects, cardiopulmonary circulatory training effects, or perhaps neural mechanisms involving economy of gait movements and neuroplasticity of the motor system.

This question is being examined in our third cohort, now under investigation. This cohort will evaluate the effects of treadmill exercise on 32 chronically disabled stroke survivors in a single-center study design that is randomizing 64 subjects to 6 months of three-times-weekly treadmill training or conventional physiotherapy.6 Similar to our prior studies, subjects are randomized at least 6 months after their index stroke; this lengthy interval is deliberate because subjects are considered to be in a “plateau” phase of recovery, as they have previously completed rehabilitative therapy.

Activation will be measured in five prespecified “regions of interest”: the precentral gyrus, the postcentral gyrus, the supplementary motor area, the midbrain, and the cerebellum (anterior/posterior lobes). Difference activation maps of post-training minus pretraining fMRIs of paretic knee movement across all patients undergoing treadmill therapy will then be analyzed. The control group, which will receive dose-matched stretching activity from physical therapy, can be contrasted by comparing the patterns of pre/post differences in each region. This will allow for assessment of increased regional activation in the brain that should be specific to the treadmill training intervention. Furthermore, if a specifically localized regional activation difference is found, then individual fMRI and VO2 training responses (VO2peak, increase in walking speeds) can be correlated to further assess the relationship between regional activation and magnitude of functional response to the treadmill intervention.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Central control of walking

Control of gait in animals is mediated by the cortex, brainstem/cerebellum,9,10 and spinal cord—the so-called cervical gait and lumbar gait pattern-generating areas of the spinal cord. In humans, cortical and spinal gait pattern areas are thought to be major regulatory centers of ambulation. Whether the cortical areas influence ambulatory recovery mediated by exercise training or whether the recruitment of spinal gait areas is needed to improve motor control after stroke is not known in humans. We will test the hypothesis that the recruitment of cortical and/or subcortical areas is relevant to some or all of the exercise-induced neuroplasticity response to treadmill rehabilitation. If a consistent pattern of brain regional activation is associated with an improvement in walking ability, this finding will suggest potential brain targets for neurally directed rehabilitation interventions. If brain targets for rehabilitation produce viable therapeutic improvement in walking and cardiocirculatory performance (such as VO2), this will be further evidence of heart-brain interactions.

Future research directions

Studies to date demonstrate that long-term treadmill exercise affects both the brain and cardiac physiology. This has holistic implications for the function of the whole person as well. Yet several pressing issues continue to confront researchers in post-stroke rehabilitation. One is the optimal therapeutic target and the intensity of the rehabilitative effort. Is this improvement solely a response of muscle and cardiac tissue to exercise, or is it possible that improved neuromotor control is a critical component to a major recovery of walking function? Furthermore, the most efficacious elements of rehabilitative therapy are not known. Should treadmill training be high- or low-intensity, and should it be accompanied by strength training, agility and flexibility activities, or other elements directed at reacquisition of finer degrees of gait-related motor training and neuropsychological input, as achieved by tai-chi or yoga? Another issue is the proper dose of rehabilitative therapy, which has barely been explored, although recent preliminary work suggests that the response is dose-dependent. Finally, predictors of response have not been established because the mechanisms of therapy and surrogate markers for early response are not well understood.

Our future research plans are to assess whether a better understanding of neural targets for rehabilitative treatment will be a fruitful avenue to improve recovery. Additionally, this plan will assess whether fMRI can serve as a surrogate marker of recovery by offering a noninvasive means to measure response to rehabilitation.

Ideally, rehabilitation following a stroke that leads to functional deficit will result in a rapid return to normal function. In the real world, however, a rapid improvement in function is rarely achieved. Between 80% and 90% of stroke survivors have a motor deficit, with impairments in walking being the most common motor deficits.1 Most stroke survivors have a diminished fitness reserve that is stable and resistant to routine rehabilitative interventions. Recent research has begun to assess the value of exercise and other modalities of training during this period of stability to improve function long after cessation of other therapeutic interventions. This article will review this research and provide insight into those issues in post-stroke rehabilitation that remain to be addressed and may affect heart and brain physiology.

STROKE REDUCES AEROBIC CAPACITY

At all ages, the fitness level of stroke survivors, as measured by maximum oxygen consumption, is reduced by approximately 50% below that of an age-matched normal population. In a study comparing peak oxygen consumption during treadmill walking between stroke survivors and age-matched sedentary controls, we found that the stroke participants had an approximately 50% lower level of peak fitness relative to the control subjects.2 During treadmill walking at self-selected speeds, the stroke volunteers used 75% of their functional capacity, compared with 27% for the age-matched healthy controls. Furthermore, compared with the controls, the stroke subjects demonstrated a poorer economy of gait that required greater oxygen consumption to sustain their self-selected walking speeds.

CLINICAL TRIALS OF POST-STROKE EXERCISE REHABILITATION

In light of the efficacy of treadmill exercise in cardiac rehabilitation, we are evaluating whether treadmill exercise can similarly improve fitness, endurance, and walking velocity in stroke survivors. We have completed 6 months of treadmill training in two separate cohorts that show highly consistent results in terms of improved walking abilities in hemiparetic stroke subjects.3,4 A third cohort is in progress to confirm these findings and examine the effects of intensity on the functional benefits5 and mechanisms6 underlying the effects of treadmill training.

Treadmill exercise results in functional benefits and improved glucose metabolism

The first cohort was a before-and-after comparison of stable stroke survivors who underwent a three-times-weekly treadmill exercise program for 6 months.3 Peak exercise capacity testing (VO2peak) revealed functional benefits with minimal cardiac and injury risk compared with baseline, demonstrating the feasibility and safety of treadmill exercise therapy in stroke-impaired adults.

Potential mechanisms for the benefits

These findings raise the question of whether these beneficial effects of treadmill exercise are attributable to muscle training effects, cardiopulmonary circulatory training effects, or perhaps neural mechanisms involving economy of gait movements and neuroplasticity of the motor system.

This question is being examined in our third cohort, now under investigation. This cohort will evaluate the effects of treadmill exercise on 32 chronically disabled stroke survivors in a single-center study design that is randomizing 64 subjects to 6 months of three-times-weekly treadmill training or conventional physiotherapy.6 Similar to our prior studies, subjects are randomized at least 6 months after their index stroke; this lengthy interval is deliberate because subjects are considered to be in a “plateau” phase of recovery, as they have previously completed rehabilitative therapy.

Activation will be measured in five prespecified “regions of interest”: the precentral gyrus, the postcentral gyrus, the supplementary motor area, the midbrain, and the cerebellum (anterior/posterior lobes). Difference activation maps of post-training minus pretraining fMRIs of paretic knee movement across all patients undergoing treadmill therapy will then be analyzed. The control group, which will receive dose-matched stretching activity from physical therapy, can be contrasted by comparing the patterns of pre/post differences in each region. This will allow for assessment of increased regional activation in the brain that should be specific to the treadmill training intervention. Furthermore, if a specifically localized regional activation difference is found, then individual fMRI and VO2 training responses (VO2peak, increase in walking speeds) can be correlated to further assess the relationship between regional activation and magnitude of functional response to the treadmill intervention.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Central control of walking

Control of gait in animals is mediated by the cortex, brainstem/cerebellum,9,10 and spinal cord—the so-called cervical gait and lumbar gait pattern-generating areas of the spinal cord. In humans, cortical and spinal gait pattern areas are thought to be major regulatory centers of ambulation. Whether the cortical areas influence ambulatory recovery mediated by exercise training or whether the recruitment of spinal gait areas is needed to improve motor control after stroke is not known in humans. We will test the hypothesis that the recruitment of cortical and/or subcortical areas is relevant to some or all of the exercise-induced neuroplasticity response to treadmill rehabilitation. If a consistent pattern of brain regional activation is associated with an improvement in walking ability, this finding will suggest potential brain targets for neurally directed rehabilitation interventions. If brain targets for rehabilitation produce viable therapeutic improvement in walking and cardiocirculatory performance (such as VO2), this will be further evidence of heart-brain interactions.

Future research directions

Studies to date demonstrate that long-term treadmill exercise affects both the brain and cardiac physiology. This has holistic implications for the function of the whole person as well. Yet several pressing issues continue to confront researchers in post-stroke rehabilitation. One is the optimal therapeutic target and the intensity of the rehabilitative effort. Is this improvement solely a response of muscle and cardiac tissue to exercise, or is it possible that improved neuromotor control is a critical component to a major recovery of walking function? Furthermore, the most efficacious elements of rehabilitative therapy are not known. Should treadmill training be high- or low-intensity, and should it be accompanied by strength training, agility and flexibility activities, or other elements directed at reacquisition of finer degrees of gait-related motor training and neuropsychological input, as achieved by tai-chi or yoga? Another issue is the proper dose of rehabilitative therapy, which has barely been explored, although recent preliminary work suggests that the response is dose-dependent. Finally, predictors of response have not been established because the mechanisms of therapy and surrogate markers for early response are not well understood.

Our future research plans are to assess whether a better understanding of neural targets for rehabilitative treatment will be a fruitful avenue to improve recovery. Additionally, this plan will assess whether fMRI can serve as a surrogate marker of recovery by offering a noninvasive means to measure response to rehabilitation.

- Mayo NE, Wood-Dauphinee S, Ahmed S, et al. Disablement following stroke. Disabil Rehabil 1999; 21:258–268.

- Michael K, Macko RF. Ambulatory activity intensity profiles, fitness, and fatigue in chronic stroke. Top Stroke Rehabil 2007; 14:5–12.

- Macko RF, Smith GV, Dobrovolny CL, Sorkin JD, Goldberg AP, Silver KH. Treadmill training improves fitness reserve in chronic stroke patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2001; 82:879–884.

- Macko RF, Ivey FM, Forrester LW, et al. Treadmill exercise rehabilitation improves ambulatory function and cardiovascular fitness in patients with chronic stroke. A randomized, controlled trial. Stroke 2005; 36:2206–2211.

- Ivey FM, Ryan AS, Hafer-Macko CE, Goldberg AP, Macko RF. Treadmill aerobic training improves glucose tolerance and indices of insulin sensitivity in disabled stroke survivors: a preliminary report. Stroke 2007; 38:2752–2758.

- Luft AR, Macko R, Forrester L, Villagra F, Hanley D. Subcortical reorganization induced by aerobic locomotor training in chronic stroke survivors [abstract]. Poster presented at: Annual Meeting of the Society for Neuroscience; November 15, 2005; Washington, DC.

- Luft AR, Smith GV, Forrester L, et al. Comparing brain activation associated with isolated upper and lower limb movement across corresponding joints. Hum Brain Mapping 2002; 17:131–140.

- Luft AR, Forrester L, Macko RF, et al. Brain activation of lower extremity movement in chronically impaired stroke survivors. Neuroimage 2005; 26:184–194.

- Lawrence DG, Kuypers HG. The functional organization of the motor system in the monkey. I. The effects of bilateral pyramidal lesions. Brain 1968; 91:1–14.

- Lawrence DG, Kuypers HG. The functional organization of the motor system in the monkey. II. The effects of lesions of the descending brain-stem pathways. Brain 1968; 91:15–36.

- Mayo NE, Wood-Dauphinee S, Ahmed S, et al. Disablement following stroke. Disabil Rehabil 1999; 21:258–268.

- Michael K, Macko RF. Ambulatory activity intensity profiles, fitness, and fatigue in chronic stroke. Top Stroke Rehabil 2007; 14:5–12.

- Macko RF, Smith GV, Dobrovolny CL, Sorkin JD, Goldberg AP, Silver KH. Treadmill training improves fitness reserve in chronic stroke patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2001; 82:879–884.

- Macko RF, Ivey FM, Forrester LW, et al. Treadmill exercise rehabilitation improves ambulatory function and cardiovascular fitness in patients with chronic stroke. A randomized, controlled trial. Stroke 2005; 36:2206–2211.

- Ivey FM, Ryan AS, Hafer-Macko CE, Goldberg AP, Macko RF. Treadmill aerobic training improves glucose tolerance and indices of insulin sensitivity in disabled stroke survivors: a preliminary report. Stroke 2007; 38:2752–2758.

- Luft AR, Macko R, Forrester L, Villagra F, Hanley D. Subcortical reorganization induced by aerobic locomotor training in chronic stroke survivors [abstract]. Poster presented at: Annual Meeting of the Society for Neuroscience; November 15, 2005; Washington, DC.

- Luft AR, Smith GV, Forrester L, et al. Comparing brain activation associated with isolated upper and lower limb movement across corresponding joints. Hum Brain Mapping 2002; 17:131–140.

- Luft AR, Forrester L, Macko RF, et al. Brain activation of lower extremity movement in chronically impaired stroke survivors. Neuroimage 2005; 26:184–194.

- Lawrence DG, Kuypers HG. The functional organization of the motor system in the monkey. I. The effects of bilateral pyramidal lesions. Brain 1968; 91:1–14.

- Lawrence DG, Kuypers HG. The functional organization of the motor system in the monkey. II. The effects of lesions of the descending brain-stem pathways. Brain 1968; 91:15–36.

Team Approach

Team Approach

Question: We work with a large orthopedic group. We would like to propose a more formal structure to this. We are interested in building business and partnerships. Do you know of any articles or references to support hospitalists doing this, or any sources to show the orthopedic group we can and would improve outcomes and their work life and workload?

Julie Lepzinski, director,

hospitalist medicine group,

Michigan

Dr. Hospitalist responds: I commend you and your hospitalist group for taking the initiative to develop a relationship with your orthopedics colleagues. Many hospitalist groups are exploring such relationships with not only orthopedists but also with other surgical and medical subspecialists.

As you mentioned, the opportunity exists to improve your group’s income and improve orthopedist work life. More importantly, there is a real opportunity to improve the medical care of patients admitted to the hospital primarily with orthopedic problems.

There are published data from an academic medical center on a hospitalist-orthopedics co-management model. Huddleston, et al., studied the effect of such a co-management model on the care of patients after elective hip and knee arthroplasty at the Mayo Clinic.1 They found that “the co-management medical hospitalist-orthopedic team model reduced minor postoperative complication rates with no statistically significant difference in length of stay or cost. The nurses and surgeons strongly preferred the co-management hospitalist model.”

This study would seem to support your notion that orthopedists may prefer the involvement of hospitalists in the care of their patients. Hospitalist involvement reduced minor complications (urinary tract infections, fever, electrolyte abnormalities). However, investigators did not find that hospitalist co-management reduced major postoperative complications (death, myocardial infarction, renal failure requiring hemodialysis) or intermediate ones (heart failure, pulmonary embolus, ileus, pneumonia).

Mayo Clinic hospitalists also studied the impact of a hospitalist-orthopedist co-management model of the care on elderly patients admitted to their hospital with hip fracture.2 Phy, et al., found that, “In elderly patients with hip fracture, a hospitalist model decreased time to surgery, time from surgery to dismissal and length of stay without adversely affecting inpatient deaths or 30-day readmission rates.” This study demonstrated that hospitalist co-management can decrease hospital length of stay in this population of patients.

We should recognize the obvious limitations of these studies. They were done at a single large academic institution with a largely Caucasian population at the turn of the century (2000-2001), early in the hospitalist movement. The hospitalist movement has matured, with approximately 20,000 hospitalists in the country. I hope we will soon see more robust data coming from multicenter trials that include a more diverse population of patients as well as a mix of community and academic institutions.

Start an HMG?

Question: We own a medical clinic in Arizona and are thinking of starting a hospitalist group as a separate business entity. Are you aware of any recommended reading or articles on how to start one, if it’s profitable, and in what shape or form? And most important--regarding the current trends and projections--I wonder if the need has changed, as most hospitals reduce their number of vendors.

Shawn Toloui, president and owner,

1st Care Medical Clinic,

Phoenix, Ariz.