User login

Measuring Restrictive Lung Disease Severity Using FEV1 vs TLC

Respiratory diseases have varied clinical presentations and are classified as restrictive, obstructive, mixed, or normal. Restrictive lung diseases have reduced lung volumes, either due to an alteration in lung parenchyma or a disease of the pleura, chest wall, or neuromuscular apparatus. If caused by parenchymal lung disease, restrictive lung disorders are accompanied by reduced gas transfer, which may be portrayed clinically by desaturation after exercise. Based on anatomical structures, the causes of lung volume reduction may be intrinsic or extrinsic. Intrinsic causes correspond to diseases of the lung parenchyma, such as idiopathic fibrotic diseases, connective-tissue diseases, drug-induced lung diseases, and other primary diseases of the lungs. Extrinsic causes refer to disorders outside the lungs or extra-pulmonary diseases such as neuromuscular and nonmuscular diseases of the chest wall.1 For example, obesity and myasthenia gravis can cause restrictive lung diseases, one through mechanical interference of lung expansion and the other through neuromuscular impedance of thoracic cage expansion. All these diseases eventually result in lung restriction, impaired lung function, and respiratory failure. This heterogenicity of disease makes establishing a single severity criterion difficult.

Laboratory testing, imaging studies, and examinations are important for determining the pulmonary disease and its course and progression. The pulmonary function test (PFT), which consists of multiple procedures that are performed depending on the information needed, has been an essential tool in practice for the pulmonologist. The PFT includes spirometry, lung volume measurement, respiratory muscle strength, diffusion capacity, and a broncho-provocation test. Each test has a particular role in assisting the diagnosis and/or follow-up of the patient. Spirometry is frequently used due to its range of dynamic physiological parameters, ease of use, and accessibility. It is used for the diagnosis of pulmonary symptoms, in the assessment of disability, and preoperatory evaluation, including lung resection surgery, assisting in the diagnosis, monitoring, and therapy response of pulmonary diseases.

A systematic approach to PFT interpretation is recommended by several societies, such as the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS).2 The pulmonary function test results must be reproducible and meet established standards to ensure reliable and consistent clinical outcomes. A restrictive respiratory disease is defined by a decrease in total lung capacity (TLC) (< 5% of predicted value) and a normal forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio.2 Although other findings—such as a decrease in vital capacity—should prompt an investigation into whether the patient has a possible restrictive respiratory disease, the sole presence of this parameter is not definitive or diagnostic of a restrictive impairment.2-4 The assessment of severity is typically determined by TLC. Unfortunately, the severity of a restrictive respiratory disease and the degree of patient discomfort do not always correlate when utilizing just TLC. Pulmonary sarcoidosis, for example, is a granulomatous lung disease with a restrictive PFT pattern and a disease burden that may vary over time. Having a more consistent method of grading the severity of the restrictive lung disease may help guide treatment. The modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) scale, a 5-point dyspnea scale, is widely used in assessing the severity of dyspnea in various respiratory conditions, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), where its scores have been associated with patient mortality.1,5 The goal of this study was to document the associations between objective parameters obtained through PFT and other variables, with an established measurement of dyspnea to assess the severity grade of restrictive lung diseases.

Methods

This retrospective record review at the Veterans Affairs Caribbean Healthcare System (VACHS) in San Juan, Puerto Rico, wasconducted using the Veterans Health Information Systems and Technology Architecture to identify patients with a PFT, including spirometry, that indicated a restrictive ventilator pattern based on the current ATS/ERS Task Force on Lung Function Testing.2 Patients were included if they were aged ≥ 21 years, PFT with TLC ≤ 80% predicted, mMRC score documented on PFT, and documented diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO). Patients were excluded if their FEV1/vital capacity (VC) was < 70% predicted using the largest VC, or no mMRC score was available. All patients meeting the inclusion criteria were considered regardless of comorbidities.

The PFT results of all adult patients, including those performed between June 1, 2013, and January 6, 2016, were submitted to spirometry, and lung volume measurements were analyzed. Sociodemographic information was collected, including sex, ethnicity, age, height, weight, and basal metabolic index. Other data found in PFTs, such as smoking status, smoking in packs/year, mMRC score, predicted TLC value, imaging present (chest X-ray, computed tomography), and hospitalizations and exacerbations within 1 year were collected. In addition, we examined the predicted values for FEV1, DLCO, and DLCO/VA (calculated using the Ayer equation), FVC (calculated using the Knudson equation), expiratory reserve volume, inspiratory VC, and slow VC. PaO2, PaCO2, and Alveolar-arterial gradients also were collected.6-9 Information about heart failure status was gathered through medical evaluation of notes and cardiac studies. All categorical variables were correlated with Spearman analysis and quantitative variables with average percentages. P values were calculated with analysis of variance.

Results

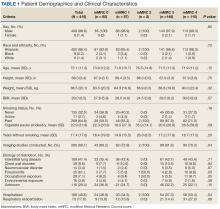

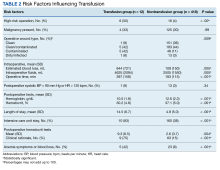

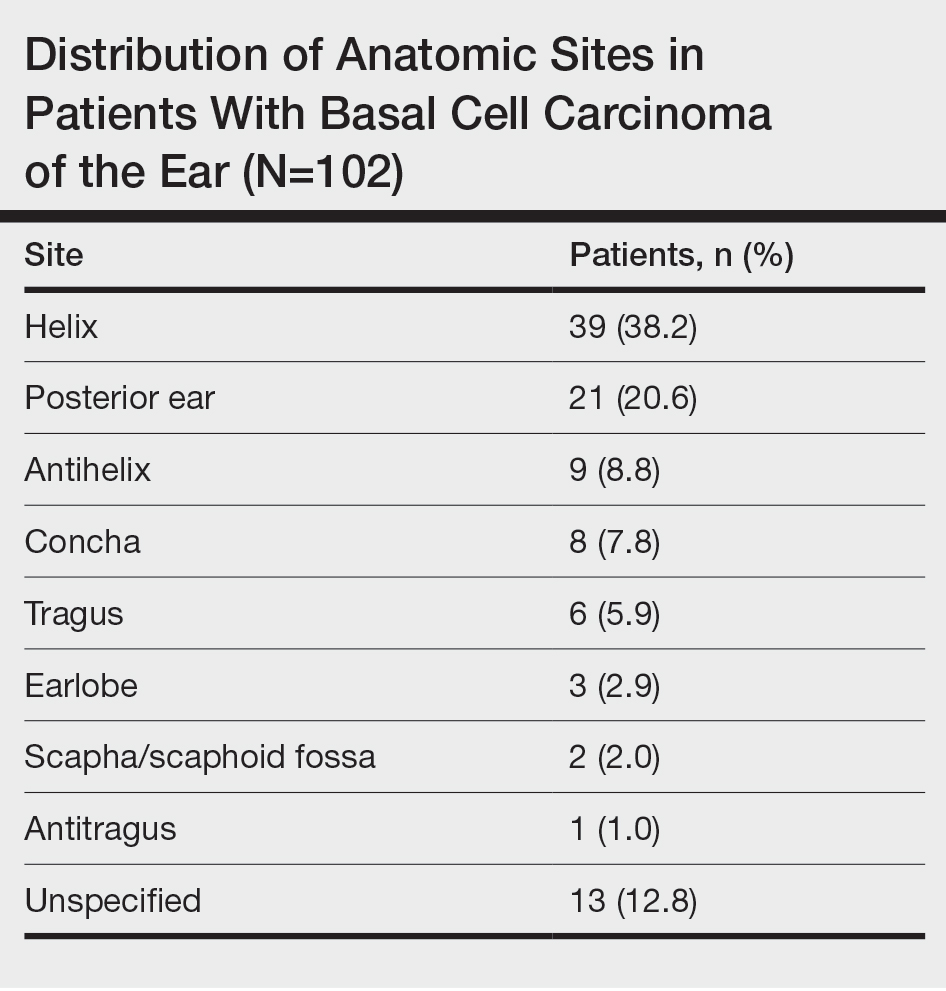

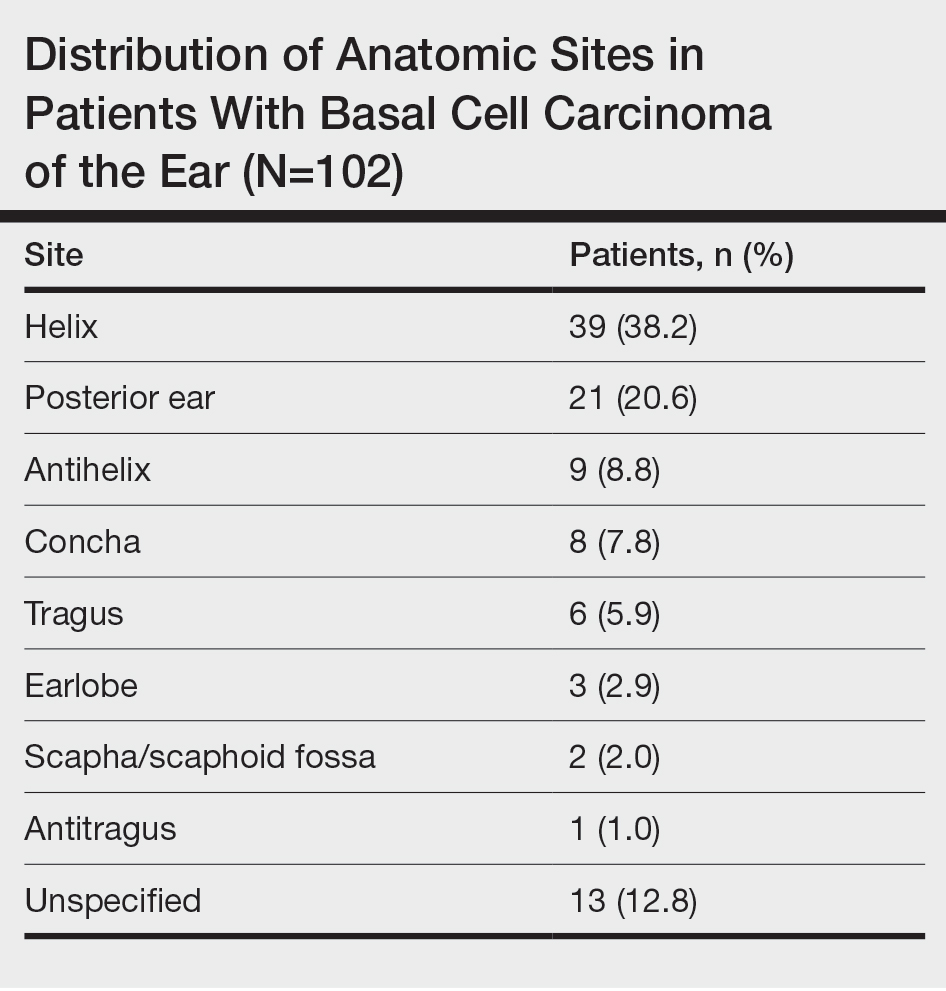

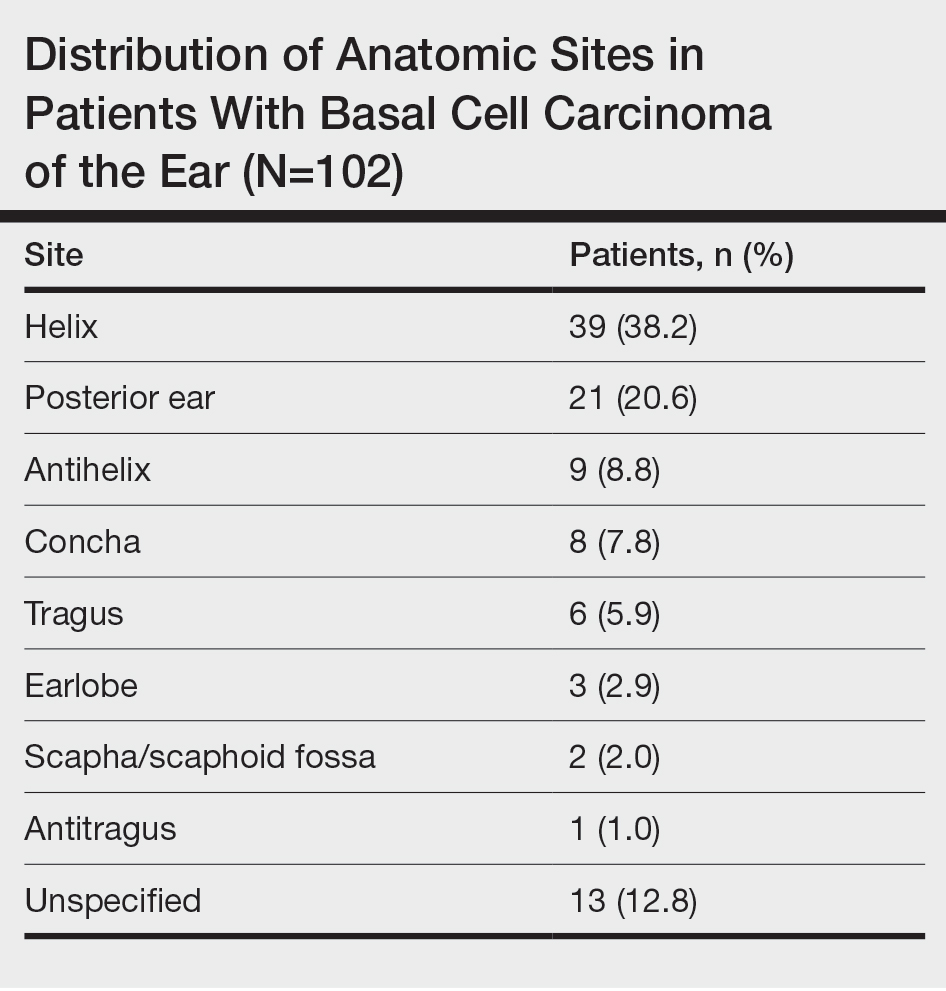

Of 6461 VACHS patient records reviewed, 415 met the inclusion criteria. Patients were divided according to their mMRC score: 65 had mMRC score of 0, 87 had an mMRC score of 1, 2 had an mMRC score of 2, 146 had an mMRC of 3, and 115 had an mMRC score of 4. The population was primarily male (98.6%) and of Hispanic ethnicity (96.4%), with a mean age of 72 years (Table 1). Most patients (n = 269, 64.0%) were prior smokers, while 135 patients (32.5%) had never smoked, and 11 (2.7%) were current smokers. At baseline, 169 patients (41.4%) had interstitial lung disease, 39 (9.6%) had chest wall disorders, 29 (7.1%) had occupational exposure, 25 (6.1%) had pneumonitis, and 14 (3.4%) had neuromuscular disorders.

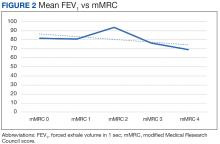

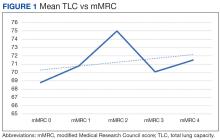

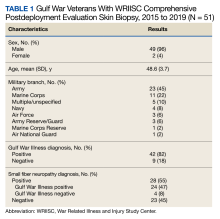

There was a statistically significant relationship between mMRC score and hospitalization and FEV1 but not TLC (Table 2). As mMRC increased, so did hospitalizations: a total of 168 patients (40.5%) were hospitalized; 24 patients (36.9%) had an mMRC score of 0, 30 patients (34.0%) had an mMRC score of 1, 2 patients (100%) had an mMRC score of 2, 54 patients (37.0%) had an mMRC score of 3, and 58 patients (50.0%) had an mMRC score of 4 (P = .04). Mean (SD) TLC values increased as mMRC scores increased. Mean (SD) TLC was 70.5% (33.0) for the entire population; 68.8% (7.2) for patients with an mMRC score of 0, 70.8% (5.8) for patients with an mMRC score of 1, 75.0% (1.4) for patients with an mMRC score of 2, 70.1% (7.2) for patients with an mMRC score of 3, and 71.5% (62.1) for patients with an mMRC score of 4 (P = .10) (Figure 1). There was an associated decrease in mean (SD) FEV1 with mMRC. Mean (SD) FEV1 was 76.2% (18.9) for the entire population; 81.7% (19.3) for patients with an mMRC score of 0, 80.9% (18) for patients with an mMRC score of 1, 93.5% (34.6) for patients with an mMRC score of 2, 76.2% (17.1) for patients with an mMRC score of 3, and 69.2% (19.4) for patients with an mMRC score of 4; (P < .001) (Figure 2).

The correlation between mMRC and FEV1 (r = 0.25, P < .001) was stronger than the correlation between mMRC and TLC (r = 0.15, P < .001). The correlations for DLCO (P < .001), DLCO/VA (P < .001), hemoglobin (P < .02), and PaO2 (P < .001) were all statistically significant (P < .005), but with no strong identifiable trend.

Discussion

The patient population of this study was primarily older males of Hispanic ethnicity with a history of smoking. There was no association between body mass index or smoking status with worsening dyspnea as measured with mMRC scores. We observed no significant correlation between mMRC scores and various factors such as comorbidities including heart conditions, and epidemiological factors like the etiology of lung disease, including both intrinsic and extrinsic causes. This lack of association was anticipated, as restrictive lung diseases in our study predominantly arose from intrinsic pulmonary etiologies, such as interstitial lung disease. A difference between more hospitalizations and worsening dyspnea was identified. There was a slightly higher correlation between FEV1 and mMRC scores when compared with TLC and mMRC scores concerning worsening dyspnea, which could indicate that the use of FEV1 should be preferred over previous recommendations to use TLC.10 Other guidelines have utilized exercise capacity via the 6-minute walk test as a marker of severity with spirometry values and found that DLCO was correlated with severity.11

The latest ERS/ATS guidelines recommend z scores for grading the severity of obstructive lung diseases but do not recommend them for the diagnosis of restrictive lung diseases.12 A z score encompasses diverse variables (eg, age, sex, and ethnicity) to provide more uniform and consistent results. Other studies have been done to relate z scores to other spirometry variables with restrictive lung disease. One such study indicates the potential benefit of using FVC alone to grade restrictive lung diseases.13 There continues to be great diversity in the interpretation of pulmonary function tests, and we believe the information gathered can provide valuable insight for managing patients with restrictive lung diseases.

Limitations

Only 2 patients reported an mMRC score of 2 in our study. This may have affected statistical outcomes. It also may reveal possible deficits in the efficacy of patient education on the mMRC scale. This study was also limited by its small sample size, single center location, and the distribution of patients that reported an mMRC favored either low or high values. The patients in this study, who were all veterans, may not be representative of other patient populations.

Conclusions

There continue to be few factors associated with the physiological severity of the defective oxygen delivery and reported dyspnea of a patient with restrictive lung disease that allows for an accurate, repeatable grading of severity. Using FEV1 instead of TLC to determine the severity of a restrictive lung disease should be reconsidered. We could not find any other strong correlation among other factors studied. Further research should be conducted to continue looking for variables that more accurately depict patient dyspnea in restrictive lung disease.

Acknowledgments

This study is based upon work supported by the Veterans Affairs Caribbean Healthcare System in San Juan, Puerto Rico, and is the result of work supported by Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine service, with resources and the use of its facilities.

1. Hegewald MJ, Crapo RO. Pulmonary function testing. In: Broaddus VC, Ernst JD, King Jr TE, eds. Murray and Nadel’s Textbook of Respiratory Medicine. 5th ed. Saunders; 2010:522-553.

2. Pellegrino R, Viegi G, Brusasco V, et al. Interpretative strategies for lung function tests. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(5):948-968. doi:10.1183/09031936.05.00035205

3. Rabe KF, Beghé B, Luppi F, Fabbri LM. Update in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease 2006. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(12):1222-1232. doi:10.1164/rccm.200704-586UP

4. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Spirometry for health care providers Accessed April 30, 2024. https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/GOLD_Spirometry_2010.pdf

5. Mannino DM, Holguin F, Pavlin BI, Ferdinands JM. Risk factors for prevalence of and mortality related to restriction on spirometry: findings from the First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and follow-up. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2005;9(6):613-621.

6. Knudson RJ, Lebowitz MD, Holberg CJ, Burrows B. Changes in the normal maximal expiratory flow-volume curve with growth and aging. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983;127(6):725-734. doi:10.1164/arrd.1983.127.6.725

7. Knudson RJ, Burrows B, Lebowitz MD. The maximal expiratory flow-volume curve: its use in the detection of ventilatory abnormalities in a population study. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1976;114(5):871-879. doi:10.1164/arrd.1976.114.5.871

8. Knudson RJ, Lebowitz MD, Burton AP, Knudson DE. The closing volume test: evaluation of nitrogen and bolus methods in a random population. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1977;115(3):423-434. doi:10.1164/arrd.1977.115.3.423

9. Ayers LN, Ginsberg ML, Fein J, Wasserman K. Diffusing capacity, specific diffusing capacity and interpretation of diffusion defects. West J Med. 1975;123(4):255-264.

10. Lung function testing: selection of reference values and interpretative strategies. American Thoracic Society. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;144(5):1202-1218. doi:10.1164/ajrccm/144.5.1202

11. Larson J, Wrzos K, Corazalla E, Wang Q, Kim HJ, Cho RJ. Should FEV1 be used to grade restrictive impairment? A single-center comparison of lung function parameters to 6-minute walk test in patients with restrictive lung disease. HSOA J Pulm Med Respir Res. 2023;9:082. doi:10.24966/PMRR-0177/100082

12. Stanojevic S, Kaminsky DA, Miller MR, et al. ERS/ATS technical standard on interpretive strategies for routine lung function tests. Eur Respir J. 2022;60(1):2101499. Published 2022 Jul 13. doi:10.1183/13993003.01499-2021

13. Myrberg T, Lindberg A, Eriksson B, et al. Restrictive spirometry versus restrictive lung function using the GLI reference values. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2022;42(3):181-189. doi:10.1111/cpf.12745

Respiratory diseases have varied clinical presentations and are classified as restrictive, obstructive, mixed, or normal. Restrictive lung diseases have reduced lung volumes, either due to an alteration in lung parenchyma or a disease of the pleura, chest wall, or neuromuscular apparatus. If caused by parenchymal lung disease, restrictive lung disorders are accompanied by reduced gas transfer, which may be portrayed clinically by desaturation after exercise. Based on anatomical structures, the causes of lung volume reduction may be intrinsic or extrinsic. Intrinsic causes correspond to diseases of the lung parenchyma, such as idiopathic fibrotic diseases, connective-tissue diseases, drug-induced lung diseases, and other primary diseases of the lungs. Extrinsic causes refer to disorders outside the lungs or extra-pulmonary diseases such as neuromuscular and nonmuscular diseases of the chest wall.1 For example, obesity and myasthenia gravis can cause restrictive lung diseases, one through mechanical interference of lung expansion and the other through neuromuscular impedance of thoracic cage expansion. All these diseases eventually result in lung restriction, impaired lung function, and respiratory failure. This heterogenicity of disease makes establishing a single severity criterion difficult.

Laboratory testing, imaging studies, and examinations are important for determining the pulmonary disease and its course and progression. The pulmonary function test (PFT), which consists of multiple procedures that are performed depending on the information needed, has been an essential tool in practice for the pulmonologist. The PFT includes spirometry, lung volume measurement, respiratory muscle strength, diffusion capacity, and a broncho-provocation test. Each test has a particular role in assisting the diagnosis and/or follow-up of the patient. Spirometry is frequently used due to its range of dynamic physiological parameters, ease of use, and accessibility. It is used for the diagnosis of pulmonary symptoms, in the assessment of disability, and preoperatory evaluation, including lung resection surgery, assisting in the diagnosis, monitoring, and therapy response of pulmonary diseases.

A systematic approach to PFT interpretation is recommended by several societies, such as the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS).2 The pulmonary function test results must be reproducible and meet established standards to ensure reliable and consistent clinical outcomes. A restrictive respiratory disease is defined by a decrease in total lung capacity (TLC) (< 5% of predicted value) and a normal forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio.2 Although other findings—such as a decrease in vital capacity—should prompt an investigation into whether the patient has a possible restrictive respiratory disease, the sole presence of this parameter is not definitive or diagnostic of a restrictive impairment.2-4 The assessment of severity is typically determined by TLC. Unfortunately, the severity of a restrictive respiratory disease and the degree of patient discomfort do not always correlate when utilizing just TLC. Pulmonary sarcoidosis, for example, is a granulomatous lung disease with a restrictive PFT pattern and a disease burden that may vary over time. Having a more consistent method of grading the severity of the restrictive lung disease may help guide treatment. The modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) scale, a 5-point dyspnea scale, is widely used in assessing the severity of dyspnea in various respiratory conditions, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), where its scores have been associated with patient mortality.1,5 The goal of this study was to document the associations between objective parameters obtained through PFT and other variables, with an established measurement of dyspnea to assess the severity grade of restrictive lung diseases.

Methods

This retrospective record review at the Veterans Affairs Caribbean Healthcare System (VACHS) in San Juan, Puerto Rico, wasconducted using the Veterans Health Information Systems and Technology Architecture to identify patients with a PFT, including spirometry, that indicated a restrictive ventilator pattern based on the current ATS/ERS Task Force on Lung Function Testing.2 Patients were included if they were aged ≥ 21 years, PFT with TLC ≤ 80% predicted, mMRC score documented on PFT, and documented diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO). Patients were excluded if their FEV1/vital capacity (VC) was < 70% predicted using the largest VC, or no mMRC score was available. All patients meeting the inclusion criteria were considered regardless of comorbidities.

The PFT results of all adult patients, including those performed between June 1, 2013, and January 6, 2016, were submitted to spirometry, and lung volume measurements were analyzed. Sociodemographic information was collected, including sex, ethnicity, age, height, weight, and basal metabolic index. Other data found in PFTs, such as smoking status, smoking in packs/year, mMRC score, predicted TLC value, imaging present (chest X-ray, computed tomography), and hospitalizations and exacerbations within 1 year were collected. In addition, we examined the predicted values for FEV1, DLCO, and DLCO/VA (calculated using the Ayer equation), FVC (calculated using the Knudson equation), expiratory reserve volume, inspiratory VC, and slow VC. PaO2, PaCO2, and Alveolar-arterial gradients also were collected.6-9 Information about heart failure status was gathered through medical evaluation of notes and cardiac studies. All categorical variables were correlated with Spearman analysis and quantitative variables with average percentages. P values were calculated with analysis of variance.

Results

Of 6461 VACHS patient records reviewed, 415 met the inclusion criteria. Patients were divided according to their mMRC score: 65 had mMRC score of 0, 87 had an mMRC score of 1, 2 had an mMRC score of 2, 146 had an mMRC of 3, and 115 had an mMRC score of 4. The population was primarily male (98.6%) and of Hispanic ethnicity (96.4%), with a mean age of 72 years (Table 1). Most patients (n = 269, 64.0%) were prior smokers, while 135 patients (32.5%) had never smoked, and 11 (2.7%) were current smokers. At baseline, 169 patients (41.4%) had interstitial lung disease, 39 (9.6%) had chest wall disorders, 29 (7.1%) had occupational exposure, 25 (6.1%) had pneumonitis, and 14 (3.4%) had neuromuscular disorders.

There was a statistically significant relationship between mMRC score and hospitalization and FEV1 but not TLC (Table 2). As mMRC increased, so did hospitalizations: a total of 168 patients (40.5%) were hospitalized; 24 patients (36.9%) had an mMRC score of 0, 30 patients (34.0%) had an mMRC score of 1, 2 patients (100%) had an mMRC score of 2, 54 patients (37.0%) had an mMRC score of 3, and 58 patients (50.0%) had an mMRC score of 4 (P = .04). Mean (SD) TLC values increased as mMRC scores increased. Mean (SD) TLC was 70.5% (33.0) for the entire population; 68.8% (7.2) for patients with an mMRC score of 0, 70.8% (5.8) for patients with an mMRC score of 1, 75.0% (1.4) for patients with an mMRC score of 2, 70.1% (7.2) for patients with an mMRC score of 3, and 71.5% (62.1) for patients with an mMRC score of 4 (P = .10) (Figure 1). There was an associated decrease in mean (SD) FEV1 with mMRC. Mean (SD) FEV1 was 76.2% (18.9) for the entire population; 81.7% (19.3) for patients with an mMRC score of 0, 80.9% (18) for patients with an mMRC score of 1, 93.5% (34.6) for patients with an mMRC score of 2, 76.2% (17.1) for patients with an mMRC score of 3, and 69.2% (19.4) for patients with an mMRC score of 4; (P < .001) (Figure 2).

The correlation between mMRC and FEV1 (r = 0.25, P < .001) was stronger than the correlation between mMRC and TLC (r = 0.15, P < .001). The correlations for DLCO (P < .001), DLCO/VA (P < .001), hemoglobin (P < .02), and PaO2 (P < .001) were all statistically significant (P < .005), but with no strong identifiable trend.

Discussion

The patient population of this study was primarily older males of Hispanic ethnicity with a history of smoking. There was no association between body mass index or smoking status with worsening dyspnea as measured with mMRC scores. We observed no significant correlation between mMRC scores and various factors such as comorbidities including heart conditions, and epidemiological factors like the etiology of lung disease, including both intrinsic and extrinsic causes. This lack of association was anticipated, as restrictive lung diseases in our study predominantly arose from intrinsic pulmonary etiologies, such as interstitial lung disease. A difference between more hospitalizations and worsening dyspnea was identified. There was a slightly higher correlation between FEV1 and mMRC scores when compared with TLC and mMRC scores concerning worsening dyspnea, which could indicate that the use of FEV1 should be preferred over previous recommendations to use TLC.10 Other guidelines have utilized exercise capacity via the 6-minute walk test as a marker of severity with spirometry values and found that DLCO was correlated with severity.11

The latest ERS/ATS guidelines recommend z scores for grading the severity of obstructive lung diseases but do not recommend them for the diagnosis of restrictive lung diseases.12 A z score encompasses diverse variables (eg, age, sex, and ethnicity) to provide more uniform and consistent results. Other studies have been done to relate z scores to other spirometry variables with restrictive lung disease. One such study indicates the potential benefit of using FVC alone to grade restrictive lung diseases.13 There continues to be great diversity in the interpretation of pulmonary function tests, and we believe the information gathered can provide valuable insight for managing patients with restrictive lung diseases.

Limitations

Only 2 patients reported an mMRC score of 2 in our study. This may have affected statistical outcomes. It also may reveal possible deficits in the efficacy of patient education on the mMRC scale. This study was also limited by its small sample size, single center location, and the distribution of patients that reported an mMRC favored either low or high values. The patients in this study, who were all veterans, may not be representative of other patient populations.

Conclusions

There continue to be few factors associated with the physiological severity of the defective oxygen delivery and reported dyspnea of a patient with restrictive lung disease that allows for an accurate, repeatable grading of severity. Using FEV1 instead of TLC to determine the severity of a restrictive lung disease should be reconsidered. We could not find any other strong correlation among other factors studied. Further research should be conducted to continue looking for variables that more accurately depict patient dyspnea in restrictive lung disease.

Acknowledgments

This study is based upon work supported by the Veterans Affairs Caribbean Healthcare System in San Juan, Puerto Rico, and is the result of work supported by Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine service, with resources and the use of its facilities.

Respiratory diseases have varied clinical presentations and are classified as restrictive, obstructive, mixed, or normal. Restrictive lung diseases have reduced lung volumes, either due to an alteration in lung parenchyma or a disease of the pleura, chest wall, or neuromuscular apparatus. If caused by parenchymal lung disease, restrictive lung disorders are accompanied by reduced gas transfer, which may be portrayed clinically by desaturation after exercise. Based on anatomical structures, the causes of lung volume reduction may be intrinsic or extrinsic. Intrinsic causes correspond to diseases of the lung parenchyma, such as idiopathic fibrotic diseases, connective-tissue diseases, drug-induced lung diseases, and other primary diseases of the lungs. Extrinsic causes refer to disorders outside the lungs or extra-pulmonary diseases such as neuromuscular and nonmuscular diseases of the chest wall.1 For example, obesity and myasthenia gravis can cause restrictive lung diseases, one through mechanical interference of lung expansion and the other through neuromuscular impedance of thoracic cage expansion. All these diseases eventually result in lung restriction, impaired lung function, and respiratory failure. This heterogenicity of disease makes establishing a single severity criterion difficult.

Laboratory testing, imaging studies, and examinations are important for determining the pulmonary disease and its course and progression. The pulmonary function test (PFT), which consists of multiple procedures that are performed depending on the information needed, has been an essential tool in practice for the pulmonologist. The PFT includes spirometry, lung volume measurement, respiratory muscle strength, diffusion capacity, and a broncho-provocation test. Each test has a particular role in assisting the diagnosis and/or follow-up of the patient. Spirometry is frequently used due to its range of dynamic physiological parameters, ease of use, and accessibility. It is used for the diagnosis of pulmonary symptoms, in the assessment of disability, and preoperatory evaluation, including lung resection surgery, assisting in the diagnosis, monitoring, and therapy response of pulmonary diseases.

A systematic approach to PFT interpretation is recommended by several societies, such as the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS).2 The pulmonary function test results must be reproducible and meet established standards to ensure reliable and consistent clinical outcomes. A restrictive respiratory disease is defined by a decrease in total lung capacity (TLC) (< 5% of predicted value) and a normal forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio.2 Although other findings—such as a decrease in vital capacity—should prompt an investigation into whether the patient has a possible restrictive respiratory disease, the sole presence of this parameter is not definitive or diagnostic of a restrictive impairment.2-4 The assessment of severity is typically determined by TLC. Unfortunately, the severity of a restrictive respiratory disease and the degree of patient discomfort do not always correlate when utilizing just TLC. Pulmonary sarcoidosis, for example, is a granulomatous lung disease with a restrictive PFT pattern and a disease burden that may vary over time. Having a more consistent method of grading the severity of the restrictive lung disease may help guide treatment. The modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) scale, a 5-point dyspnea scale, is widely used in assessing the severity of dyspnea in various respiratory conditions, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), where its scores have been associated with patient mortality.1,5 The goal of this study was to document the associations between objective parameters obtained through PFT and other variables, with an established measurement of dyspnea to assess the severity grade of restrictive lung diseases.

Methods

This retrospective record review at the Veterans Affairs Caribbean Healthcare System (VACHS) in San Juan, Puerto Rico, wasconducted using the Veterans Health Information Systems and Technology Architecture to identify patients with a PFT, including spirometry, that indicated a restrictive ventilator pattern based on the current ATS/ERS Task Force on Lung Function Testing.2 Patients were included if they were aged ≥ 21 years, PFT with TLC ≤ 80% predicted, mMRC score documented on PFT, and documented diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO). Patients were excluded if their FEV1/vital capacity (VC) was < 70% predicted using the largest VC, or no mMRC score was available. All patients meeting the inclusion criteria were considered regardless of comorbidities.

The PFT results of all adult patients, including those performed between June 1, 2013, and January 6, 2016, were submitted to spirometry, and lung volume measurements were analyzed. Sociodemographic information was collected, including sex, ethnicity, age, height, weight, and basal metabolic index. Other data found in PFTs, such as smoking status, smoking in packs/year, mMRC score, predicted TLC value, imaging present (chest X-ray, computed tomography), and hospitalizations and exacerbations within 1 year were collected. In addition, we examined the predicted values for FEV1, DLCO, and DLCO/VA (calculated using the Ayer equation), FVC (calculated using the Knudson equation), expiratory reserve volume, inspiratory VC, and slow VC. PaO2, PaCO2, and Alveolar-arterial gradients also were collected.6-9 Information about heart failure status was gathered through medical evaluation of notes and cardiac studies. All categorical variables were correlated with Spearman analysis and quantitative variables with average percentages. P values were calculated with analysis of variance.

Results

Of 6461 VACHS patient records reviewed, 415 met the inclusion criteria. Patients were divided according to their mMRC score: 65 had mMRC score of 0, 87 had an mMRC score of 1, 2 had an mMRC score of 2, 146 had an mMRC of 3, and 115 had an mMRC score of 4. The population was primarily male (98.6%) and of Hispanic ethnicity (96.4%), with a mean age of 72 years (Table 1). Most patients (n = 269, 64.0%) were prior smokers, while 135 patients (32.5%) had never smoked, and 11 (2.7%) were current smokers. At baseline, 169 patients (41.4%) had interstitial lung disease, 39 (9.6%) had chest wall disorders, 29 (7.1%) had occupational exposure, 25 (6.1%) had pneumonitis, and 14 (3.4%) had neuromuscular disorders.

There was a statistically significant relationship between mMRC score and hospitalization and FEV1 but not TLC (Table 2). As mMRC increased, so did hospitalizations: a total of 168 patients (40.5%) were hospitalized; 24 patients (36.9%) had an mMRC score of 0, 30 patients (34.0%) had an mMRC score of 1, 2 patients (100%) had an mMRC score of 2, 54 patients (37.0%) had an mMRC score of 3, and 58 patients (50.0%) had an mMRC score of 4 (P = .04). Mean (SD) TLC values increased as mMRC scores increased. Mean (SD) TLC was 70.5% (33.0) for the entire population; 68.8% (7.2) for patients with an mMRC score of 0, 70.8% (5.8) for patients with an mMRC score of 1, 75.0% (1.4) for patients with an mMRC score of 2, 70.1% (7.2) for patients with an mMRC score of 3, and 71.5% (62.1) for patients with an mMRC score of 4 (P = .10) (Figure 1). There was an associated decrease in mean (SD) FEV1 with mMRC. Mean (SD) FEV1 was 76.2% (18.9) for the entire population; 81.7% (19.3) for patients with an mMRC score of 0, 80.9% (18) for patients with an mMRC score of 1, 93.5% (34.6) for patients with an mMRC score of 2, 76.2% (17.1) for patients with an mMRC score of 3, and 69.2% (19.4) for patients with an mMRC score of 4; (P < .001) (Figure 2).

The correlation between mMRC and FEV1 (r = 0.25, P < .001) was stronger than the correlation between mMRC and TLC (r = 0.15, P < .001). The correlations for DLCO (P < .001), DLCO/VA (P < .001), hemoglobin (P < .02), and PaO2 (P < .001) were all statistically significant (P < .005), but with no strong identifiable trend.

Discussion

The patient population of this study was primarily older males of Hispanic ethnicity with a history of smoking. There was no association between body mass index or smoking status with worsening dyspnea as measured with mMRC scores. We observed no significant correlation between mMRC scores and various factors such as comorbidities including heart conditions, and epidemiological factors like the etiology of lung disease, including both intrinsic and extrinsic causes. This lack of association was anticipated, as restrictive lung diseases in our study predominantly arose from intrinsic pulmonary etiologies, such as interstitial lung disease. A difference between more hospitalizations and worsening dyspnea was identified. There was a slightly higher correlation between FEV1 and mMRC scores when compared with TLC and mMRC scores concerning worsening dyspnea, which could indicate that the use of FEV1 should be preferred over previous recommendations to use TLC.10 Other guidelines have utilized exercise capacity via the 6-minute walk test as a marker of severity with spirometry values and found that DLCO was correlated with severity.11

The latest ERS/ATS guidelines recommend z scores for grading the severity of obstructive lung diseases but do not recommend them for the diagnosis of restrictive lung diseases.12 A z score encompasses diverse variables (eg, age, sex, and ethnicity) to provide more uniform and consistent results. Other studies have been done to relate z scores to other spirometry variables with restrictive lung disease. One such study indicates the potential benefit of using FVC alone to grade restrictive lung diseases.13 There continues to be great diversity in the interpretation of pulmonary function tests, and we believe the information gathered can provide valuable insight for managing patients with restrictive lung diseases.

Limitations

Only 2 patients reported an mMRC score of 2 in our study. This may have affected statistical outcomes. It also may reveal possible deficits in the efficacy of patient education on the mMRC scale. This study was also limited by its small sample size, single center location, and the distribution of patients that reported an mMRC favored either low or high values. The patients in this study, who were all veterans, may not be representative of other patient populations.

Conclusions

There continue to be few factors associated with the physiological severity of the defective oxygen delivery and reported dyspnea of a patient with restrictive lung disease that allows for an accurate, repeatable grading of severity. Using FEV1 instead of TLC to determine the severity of a restrictive lung disease should be reconsidered. We could not find any other strong correlation among other factors studied. Further research should be conducted to continue looking for variables that more accurately depict patient dyspnea in restrictive lung disease.

Acknowledgments

This study is based upon work supported by the Veterans Affairs Caribbean Healthcare System in San Juan, Puerto Rico, and is the result of work supported by Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine service, with resources and the use of its facilities.

1. Hegewald MJ, Crapo RO. Pulmonary function testing. In: Broaddus VC, Ernst JD, King Jr TE, eds. Murray and Nadel’s Textbook of Respiratory Medicine. 5th ed. Saunders; 2010:522-553.

2. Pellegrino R, Viegi G, Brusasco V, et al. Interpretative strategies for lung function tests. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(5):948-968. doi:10.1183/09031936.05.00035205

3. Rabe KF, Beghé B, Luppi F, Fabbri LM. Update in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease 2006. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(12):1222-1232. doi:10.1164/rccm.200704-586UP

4. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Spirometry for health care providers Accessed April 30, 2024. https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/GOLD_Spirometry_2010.pdf

5. Mannino DM, Holguin F, Pavlin BI, Ferdinands JM. Risk factors for prevalence of and mortality related to restriction on spirometry: findings from the First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and follow-up. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2005;9(6):613-621.

6. Knudson RJ, Lebowitz MD, Holberg CJ, Burrows B. Changes in the normal maximal expiratory flow-volume curve with growth and aging. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983;127(6):725-734. doi:10.1164/arrd.1983.127.6.725

7. Knudson RJ, Burrows B, Lebowitz MD. The maximal expiratory flow-volume curve: its use in the detection of ventilatory abnormalities in a population study. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1976;114(5):871-879. doi:10.1164/arrd.1976.114.5.871

8. Knudson RJ, Lebowitz MD, Burton AP, Knudson DE. The closing volume test: evaluation of nitrogen and bolus methods in a random population. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1977;115(3):423-434. doi:10.1164/arrd.1977.115.3.423

9. Ayers LN, Ginsberg ML, Fein J, Wasserman K. Diffusing capacity, specific diffusing capacity and interpretation of diffusion defects. West J Med. 1975;123(4):255-264.

10. Lung function testing: selection of reference values and interpretative strategies. American Thoracic Society. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;144(5):1202-1218. doi:10.1164/ajrccm/144.5.1202

11. Larson J, Wrzos K, Corazalla E, Wang Q, Kim HJ, Cho RJ. Should FEV1 be used to grade restrictive impairment? A single-center comparison of lung function parameters to 6-minute walk test in patients with restrictive lung disease. HSOA J Pulm Med Respir Res. 2023;9:082. doi:10.24966/PMRR-0177/100082

12. Stanojevic S, Kaminsky DA, Miller MR, et al. ERS/ATS technical standard on interpretive strategies for routine lung function tests. Eur Respir J. 2022;60(1):2101499. Published 2022 Jul 13. doi:10.1183/13993003.01499-2021

13. Myrberg T, Lindberg A, Eriksson B, et al. Restrictive spirometry versus restrictive lung function using the GLI reference values. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2022;42(3):181-189. doi:10.1111/cpf.12745

1. Hegewald MJ, Crapo RO. Pulmonary function testing. In: Broaddus VC, Ernst JD, King Jr TE, eds. Murray and Nadel’s Textbook of Respiratory Medicine. 5th ed. Saunders; 2010:522-553.

2. Pellegrino R, Viegi G, Brusasco V, et al. Interpretative strategies for lung function tests. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(5):948-968. doi:10.1183/09031936.05.00035205

3. Rabe KF, Beghé B, Luppi F, Fabbri LM. Update in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease 2006. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(12):1222-1232. doi:10.1164/rccm.200704-586UP

4. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Spirometry for health care providers Accessed April 30, 2024. https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/GOLD_Spirometry_2010.pdf

5. Mannino DM, Holguin F, Pavlin BI, Ferdinands JM. Risk factors for prevalence of and mortality related to restriction on spirometry: findings from the First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and follow-up. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2005;9(6):613-621.

6. Knudson RJ, Lebowitz MD, Holberg CJ, Burrows B. Changes in the normal maximal expiratory flow-volume curve with growth and aging. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983;127(6):725-734. doi:10.1164/arrd.1983.127.6.725

7. Knudson RJ, Burrows B, Lebowitz MD. The maximal expiratory flow-volume curve: its use in the detection of ventilatory abnormalities in a population study. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1976;114(5):871-879. doi:10.1164/arrd.1976.114.5.871

8. Knudson RJ, Lebowitz MD, Burton AP, Knudson DE. The closing volume test: evaluation of nitrogen and bolus methods in a random population. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1977;115(3):423-434. doi:10.1164/arrd.1977.115.3.423

9. Ayers LN, Ginsberg ML, Fein J, Wasserman K. Diffusing capacity, specific diffusing capacity and interpretation of diffusion defects. West J Med. 1975;123(4):255-264.

10. Lung function testing: selection of reference values and interpretative strategies. American Thoracic Society. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;144(5):1202-1218. doi:10.1164/ajrccm/144.5.1202

11. Larson J, Wrzos K, Corazalla E, Wang Q, Kim HJ, Cho RJ. Should FEV1 be used to grade restrictive impairment? A single-center comparison of lung function parameters to 6-minute walk test in patients with restrictive lung disease. HSOA J Pulm Med Respir Res. 2023;9:082. doi:10.24966/PMRR-0177/100082

12. Stanojevic S, Kaminsky DA, Miller MR, et al. ERS/ATS technical standard on interpretive strategies for routine lung function tests. Eur Respir J. 2022;60(1):2101499. Published 2022 Jul 13. doi:10.1183/13993003.01499-2021

13. Myrberg T, Lindberg A, Eriksson B, et al. Restrictive spirometry versus restrictive lung function using the GLI reference values. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2022;42(3):181-189. doi:10.1111/cpf.12745

Long-Term Assessment of Weight Loss Medications in a Veteran Population

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) classifies individuals with a body mass index (BMI) of 25 to 29.9as overweight and those with a BMI > 30 as obese (obesity classes: I, BMI 30 to 34.9; II, BMI 35 to 39.9; and III, BMI ≥ 40).1 In 2011, the CDC estimated that 27.4% of adults in the United States were obese; less than a decade later, that number increased to 31.9%.1 In that same period, the percentage of adults in Indiana classified as obese increased from 30.8% to 36.8%.1 About 1 in 14 individuals in the US have class III obesity and 86% of veterans are either overweight or obese.2

High medical expenses can likely be attributed to the long-term health consequences of obesity. Compared to those with a healthy weight, individuals who are overweight or obese are at an increased risk for high blood pressure, high low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, high triglyceride levels, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), coronary heart disease, stroke, gallbladder disease, osteoarthritis, sleep apnea, cancer, mental health disorders, body pain, low quality of life, and death.3 Many of these conditions lead to increased health care needs, medication needs, hospitalizations, and overall health care system use.

Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of obesity have been produced by the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and The Obesity Society; the Endocrine Society; the American Diabetes Association; and the US Departments of Veterans Affairs (VA) and Defense. Each follows a general algorithm to manage and prevent adverse effects (AEs) related to obesity. General practice is to assess a patient for elevated BMI (> 25), implement intense lifestyle modifications including calorie restriction and exercise, reassess for a maintained 5% to 10% weight loss for cardiovascular benefits, and potentially assess for pharmacological or surgical intervention to assist in weight loss.2,4-6

While some weight loss medications (eg, phentermine/topiramate, naltrexone/bupropion, orlistat, and lorcaserin) tend to have unfavorable AEs or mixed efficacy, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) have provided new options.7-10 Lorcaserin, for example, was removed from the market in 2020 due to its association with cancer risks.11 The GLP-1RAs liraglutide and semaglutide received US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for weight loss in 2014 and 2021, respectively.12,13 GLP-1RAs have shown the greatest efficacy and benefits in reducing hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c); they are the preferred agents for patients who qualify for pharmacologic intervention for weight loss, especially those with T2DM. However, these studies have not evaluated the long-term outcomes of using these medications for weight loss and may not reflect the veteran population.14,15

At Veteran Health Indiana (VHI), clinicians may use several weight loss medications for patients to achieve 5% to 10% weight loss. The medications most often used include liraglutide, phentermine/topiramate, naltrexone/bupropion, orlistat, and phentermine alone. However, more research is needed to determine which weight loss medication is the most beneficial for veterans, particularly following FDA approval of GLP-1RAs. At VHI, phentermine/topiramate is the preferred first-line agent unless patients have contraindications for use, in which case naltrexone/bupropion is recommended. These are considered first-line due to their ease of use in pill form, lower cost, and comparable weight loss to the GLP-1 medication class.2 However, for patients with prediabetes, T2DM, BMI > 40, or BMI > 35 with specific comorbid conditions, liraglutide is preferred because of its beneficial effects for both weight loss and blood glucose control.2

This study aimed to expand on the 2021 Hood and colleagues study that examined total weight loss and weight loss as a percentage of baseline weight in patients with obesity at 3, 6, 12, and > 12 months of pharmacologic therapy by extending the time frame to 48 months.16 This study excluded semaglutide because few patients were prescribed the medication for weight loss during the study.

METHODS

We conducted a single-center, retrospective chart review of patients prescribed weight loss medications at VHI. A patient list was generated based on prescription fills from June 1, 2017, to July 31, 2021. Data were obtained from the Computerized Patient Record System; patients were not contacted. This study was approved by the Indiana University Health Institutional Review Board and VHI Research and Development Committee.

At the time of this study, liraglutide, phentermine/topiramate, naltrexone/bupropion, orlistat, and phentermine alone were available at VHI for patients who met the clinical criteria for use. All patients must have been enrolled in dietary and lifestyle management programs, including the VA MOVE! program, to be approved for these medications. After the MOVE! orientation, patients could participate in group or individual 12-week programs that included weigh-ins, goal-setting strategies, meal planning, and habit modification support. If patients could not meet in person, phone and other telehealth opportunities were available.

Patients were included in the study if they were aged ≥ 18 years, received a prescription for any of the 5 available medications for weight loss during the enrollment period, and were on the medication for ≥ 6 consecutive months. Patients were excluded if they received a prescription, were treated outside the VA system, or were pregnant. The primary indication for the included medication was not weight loss; the primary indication for the GLP-1RA was T2DM, or the weight loss was attributed to another disease. Adherence was not a measured outcome of this study; if patients were filling the medication, it was assumed they were taking it. Data were collected for each instance of medication use; as a result, a few patients were included more than once. Data collection for a failed medication ended when failure was documented. New data points began when new medication was prescribed; all data were per medication, not per patient. This allowed us to account for medication failure and provide accurate weight loss results based on medication choice within VHI.

Primary outcomes included total weight loss and weight loss as a percentage ofbaseline weight during the study period at 3, 6, 12, 24, 36, and 48 months of therapy. Secondary outcomes included the percentage of patients who lost 5% to 10% of their body weight from baseline; the percentage of patients who maintained ≥ 5% weight loss from baseline to 12, 24, 36, and 48 months if maintained on medication for that duration; duration of medication treatment in weeks; medication discontinuation rate; reason for medication discontinuation; enrollment in the MOVE! clinic and the time enrolled; percentage of patients with a BMI of 18 to 24.9 at the end of the study; and change in HbA1c at 3, 6, 12, 24, 36, and 48 months.

Demographic data included race, age, sex, baseline weight, height, baseline BMI, and comorbid conditions (collected based on the most recent primary care clinical note before initiating medication). Medication data collected included medications used to manage comorbidities. Data related to weight management medication included prescribing clinic, maintenance dose of medication, duration of medication during the study period, the reason for medication discontinuation, or bariatric surgery intervention if applicable.

Basic descriptive statistics were used to characterize study participants. For continuous data, analysis of variance tests were used; if those results were not normal, then nonparametric tests were used, followed by pairwise tests between medication groups if the overall test was significant using the Fisher significant differences test. For nominal data, χ2 or Fisher exact tests were used. For comparisons of primary and secondary outcomes, if the analyses needed to include adjustment for confounding variables, analysis of covariance was used for continuous data. A 2-sided 5% significance level was used for all tests.

RESULTS

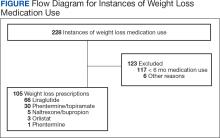

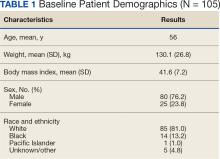

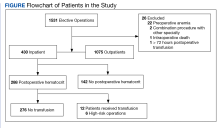

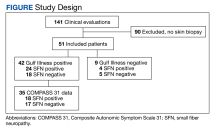

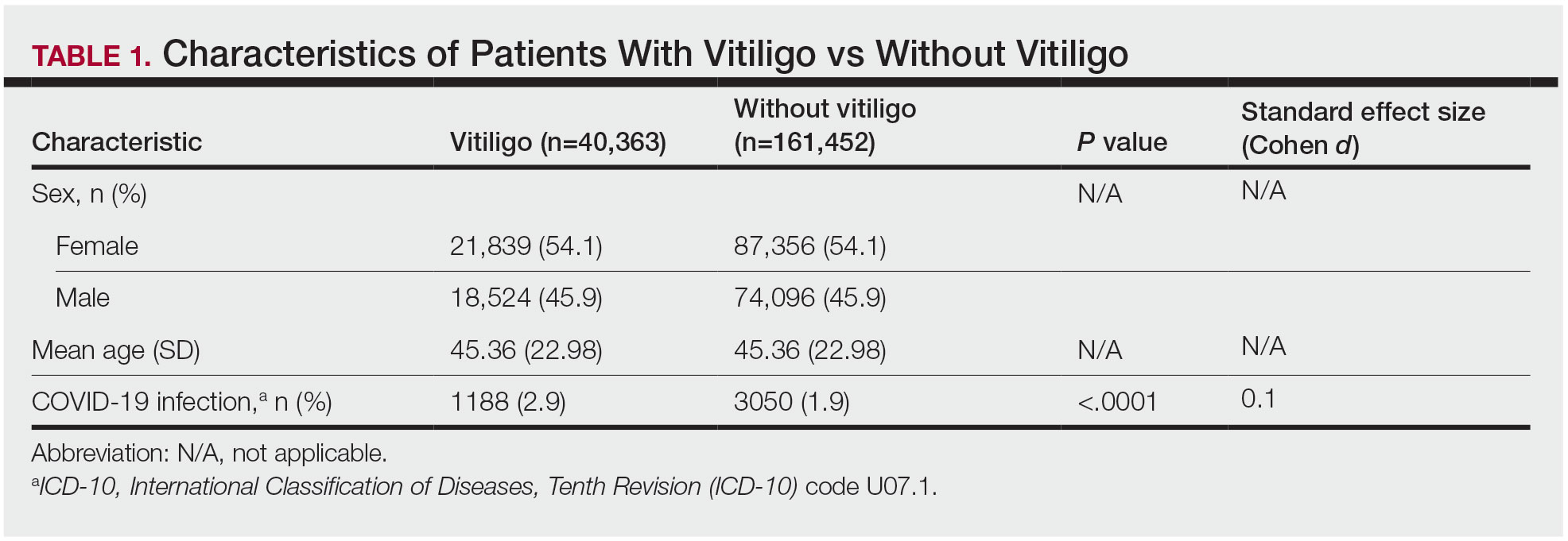

A total of 228 instances of medication use were identified based on prescription fills; 123 did not meet inclusion criteria (117 for < 6 consecutive months of medication use) (Figure). The study included 105 participants with a mean age of 56 years; 80 were male (76.2%), and 85 identified as White race (81.0%). Mean (SD) weight was 130.1 kg (26.8) and BMI was 41.6 (7.2). The most common comorbid disease states among patients included hypertension, dyslipidemia, obstructive sleep apnea, and T2DM (Table 1). The baseline characteristics were comparable to those of Hood and colleagues.16

Most patients at VHI started on liraglutide (63%) or phentermine/topiramate (28%). For primary and secondary outcomes, statistics were calculated to determine whether the results were statistically significant for comparing the liraglutide and phentermine/topiramate subgroups. Sample sizes were too small for statistical analysis for bupropion/naltrexone, phentermine, and orlistat.

Primary Outcomes

The mean (SD) weight of participants dropped 8.1% from 130.1 kg to 119.5 kg over the patient-specific duration of weight management medication therapy for an absolute difference of 10.6 kg (9.7). Duration of individual medication use varied from 6 to 48 months. Weight loss was recorded at 6, 12, 24, 36, and 48 months of weight management therapy. Patient weight was not recorded after the medication was discontinued.

When classified by medication choice, the mean change in weight over the duration of the study was −23.9 kg for 2 patients using orlistat, −10.2 kg for 46 patients using liraglutide, −11.0 kg for 25 patients using phentermine/topiramate, -7.4 kg for 1 patient using phentermine, and -13.0 kg for 4 patients using naltrexone/bupropion. Patients without a weight documented at the end of their therapy or at the conclusion of the data collection period were not included in the total weight loss at the end of therapy. There were 78 documented instances of weight loss at the end of therapy (Table 2).

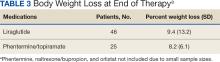

Body weight loss percentage was recorded at 6, 12, 24, 36, and 48 months of weight management therapy. The mean (SD) body weight loss percentage over the duration of the study was 9.2% (11.2). When classified by medication choice, the mean percentage of body weight loss was 16.8% for 2 patients using orlistat, 9.4% for 46 patients using liraglutide, 8.2% for 25 patients using phentermine/topiramate, 6.0% for 1 patient using phentermine alone, and 10.6% for 4 patients using naltrexone/bupropion (Table 3).

Secondary Outcomes

While none of the secondary outcomes were statistically significant, the results of this study suggest that both medications may contribute to weight loss in many patients included in this study. Almost two-thirds of the included patients analyzed lost ≥ 5% of weight from baseline while taking weight management medication. Sixty-six patients (63%) lost ≥ 5% of body weight at any time during the data collection period. When stratified by liraglutide and phentermine/topiramate, 41 patients (63%) taking liraglutide and 20 patients (67%) taking phentermine/topiramate lost ≥ 5% of weight from baseline. Of the 66 patients who lost ≥ 5% of body weight from baseline, 36 (55%) lost ≥ 10% of body weight from baseline at any time during the data collection period.

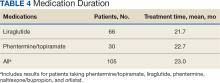

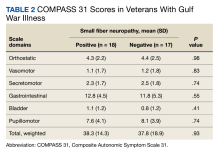

The mean (SD) duration for weight management medication use was 23 months (14.9). Phentermine/topiramate was tolerated longer than liraglutide: 22.7 months vs 21.7 months, respectively (Table 4).

The average overall documented medication discontinuation rate was 35.2%. Reasons for discontinuation included 21 patient-elected discontinuations, 8 patients no longer met criteria for use, 4 medications were no longer indicated, and 4 patients experienced AEs. It is unknown whether weight management medication was discontinued or not in 18 patients (17.2%).

DISCUSSION

This study evaluated the use and outcomes of weight loss medications over a longer period (up to 48 months) than what was previously studied among patients at VHI (12 months). The study aimed to better understand the long-term effect of weight loss medications, determine which medication had better long-term outcomes, and examine the reasons for medication discontinuation.

The results of this study displayed some similarities and differences compared with the Hood and colleagues study.16 Both yielded similar results for 5% of body weight loss and 10% of body weight loss. The largest difference was mean weight loss over the study period. In this study, patients lost a mean 10.6 kg over the course of weight loss medication use compared to 15.8 kg found by Hood and colleagues.16 A reason patients in the current study lost less weight overall could be the difference in time frames. The current study encompassed the COVID-19 pandemic, meaning fewer overall in-person patient appointments, which led to patients being lost to follow-up, missing weigh-ins during the time period, and gaps in care. For some patients, the pandemic possibly contributed to depression, missed medication doses, and a more sedentary lifestyle, leading to more weight gain.17 Telemedicine services at VHI expanded during the pandemic in an attempt to increase patient monitoring and counseling. It is unclear whether this expansion was enough to replace the in-person contact necessary to promote a healthy lifestyle.

VA pharmacists now care for patients through telehealth and are more involved in weight loss management. Since the conclusion of the Hood and colleagues study and start of this research, 2 pharmacists at VHI have been assigned to follow patients for obesity management to help with adherence to medication and lifestyle changes, management of AEs, dispense logistics, interventions for medications that may cause weight gain, and case management of glycemic control and weight loss with GLP-1RAs. Care management by pharmacists at VHI helps improve the logistics of titratable orders and save money by improving the use of high-cost items like GLP-1RAs. VA clinical pharmacy practitioners already monitor GLP-1RAs for patients with T2DM, so they are prepared to educate and assist patients with these medications.

It is important to continue developing a standardized process for weight loss medication management across the VA to improve the quality of patient care and optimize prescription outcomes. VA facilities differ in how weight loss management care is delivered and the level at which pharmacists are involved. Given the high rate of obesity among patients at the VA, the advent of new prescription options for weight loss, and the high cost associated with these medications, there has been increased attention to obesity care. Some Veterans Integrated Service Networks are forming a weight management community of practice groups to create standard operating procedures and algorithms to standardize care. Developing consistent processes is necessary to improve weight loss and patient care for veterans regardless where they receive treatment.

Limitations

The data used in this study were dependent on clinician documentation. Because of a lack of documentation in many instances, it was difficult to determine the full efficacy of the medications studied due to missing weight recordings. The lack of documentation made it difficult to determine whether patients were enrolled and active in the MOVE! program. It is required that patients enroll in MOVE! to obtain medications, but many did not have any follow-up MOVE! visits after initially obtaining their weight loss medication.

In this study, differences in the outcomes of patients with and without T2DM were not compared. It is the VA standard of care to prefer liraglutide over phentermine/topiramate in patients with T2DM or prediabetes.2 This makes it difficult to assess whether phentermine/topiramate or liraglutide is more effective for weight loss in patients with T2DM. Weight gain after the discontinuation of weight loss medications was not assessed. Collecting this data may help determine whether a certain weight loss medication is less likely to cause rebound weight gain when discontinued.

Other limitations to this study consisted of excluding patients who discontinued therapy within 6 months, small sample sizes on some medications, and lack of data on adherence. Adherence was based on medication refills, which means that if a patient refilled the medication, it was assumed they were taking it. This is not always the case, and while accurate data on adherence is difficult to gather, it can impact how results may be interpreted. These additional limitations make it difficult to accurately determine the efficacy of the medications in this study.

CONCLUSIONS

This study found similar outcomes to what has been observed in larger clinical trials regarding weight loss medications. Nevertheless, there was a lack of accurate clinical documentation for most patients, which limits the conclusions. This lack of documentation potentially led to inaccurate results. It revealed that many patients at VHI did not uniformly receive consistent follow-up after starting a weight loss medication during the study period. With more standardized processes implemented at VA facilities, increased pharmacist involvement in weight loss medication management, and increased use of established telehealth services, patients could have the opportunity for closer follow-up that may lead to better weight loss outcomes. With these changes, there is more reason for additional studies to be conducted to assess follow-up, medication management, and weight loss overall.

1. Overweight & obesity. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated September 21, 2023. Accessed April 23, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/index.html

2. US Department of Defense, US Department of Veterans Affairs. The Management of Adult Overweight and Obesity Working Group. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Adult Overweight and Obesity. Updated July 2020. Accessed April 23, 2024. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/CD/obesity/VADoDObesityCPGFinal5087242020.pdf

3. Health effects of overweight and obesity. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated September 24, 2022. Accessed April 23, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/effects/index.html

4. Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 Pt B):2985-3023. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.004

5. Apovian CM, Aronne LJ, Bessesen DH, et al. Pharmacological management of obesity: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(2):342-362. doi:10.1210/jc.2014-3415

6. American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 3. Prevention or delay of type 2 diabetes and associated comorbidities: standards of medical care in diabetes-2022. Diabetes Care. 2022;45(Suppl 1):S39-S45. doi:10.2337/dc22-S003

7. Phentermine and topiramate extended-release. Package insert. Vivus, Inc; 2012. Accessed April 23, 2024. https://qsymia.com/patient/include/media/pdf/prescribing-information.pdf

8. Naltrexone and bupropion extended-release. Package insert. Orexigen Therapeutics, Inc; 2014. Accessed April 23, 2024. https://contrave.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Contrave-label-113023.pdf

9. Orlistat. Package insert. Roche Laboratories, Inc; 2009. Accessed April 23, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2009/020766s026lbl.pdf

10. Lorcaserin. Package insert. Arena Pharmaceuticals; 2012. Accessed April 23, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2012/022529lbl.pdf

11. FDA requests the withdrawal of the weight-loss drug Belviq, Belviq XR (lorcaserin) from the market. News release. US Food & Drug Administration. February 13, 2020. Accessed April 23, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-requests-withdrawal-weight-loss-drug-belviq-belviq-xr-lorcaserin-market

12. Saxenda Injection (Liraglutide [rDNA origin]). Novo Nordisk, Inc. October 1, 2015. Accessed April 23, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2014/206321Orig1s000TOC.cfm

13. FDA approves new drug treatment for chronic weight management, first since 2014. News release. US Food & Drug Administration. June 4, 2021. Accessed April 23, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-new-drug-treatment-chronic-weight-management-first-2014

14. Pi-Sunyer X, Astrup A, Fujioka K, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of 3.0 mg of liraglutide in weight management. New Engl J Med. 2015;373:11-22. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1411892

15. Wilding JPH, Batterham RL, Calanna S, et al. Once-weekly semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity. New Engl J Med 2021;384:989-1002. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2032183

16. Hood SR, Berkeley AW, Moore EA. Evaluation of pharmacologic interventions for weight management in a veteran population. Fed Pract. 2021;38(5):220-226. doi:10.12788/fp.0117

17. Melamed OC, Selby P, Taylor VH. Mental health and obesity during the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr Obes Rep. 2022;11(1):23-31. doi:10.1007/s13679-021-00466-6

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) classifies individuals with a body mass index (BMI) of 25 to 29.9as overweight and those with a BMI > 30 as obese (obesity classes: I, BMI 30 to 34.9; II, BMI 35 to 39.9; and III, BMI ≥ 40).1 In 2011, the CDC estimated that 27.4% of adults in the United States were obese; less than a decade later, that number increased to 31.9%.1 In that same period, the percentage of adults in Indiana classified as obese increased from 30.8% to 36.8%.1 About 1 in 14 individuals in the US have class III obesity and 86% of veterans are either overweight or obese.2

High medical expenses can likely be attributed to the long-term health consequences of obesity. Compared to those with a healthy weight, individuals who are overweight or obese are at an increased risk for high blood pressure, high low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, high triglyceride levels, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), coronary heart disease, stroke, gallbladder disease, osteoarthritis, sleep apnea, cancer, mental health disorders, body pain, low quality of life, and death.3 Many of these conditions lead to increased health care needs, medication needs, hospitalizations, and overall health care system use.

Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of obesity have been produced by the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and The Obesity Society; the Endocrine Society; the American Diabetes Association; and the US Departments of Veterans Affairs (VA) and Defense. Each follows a general algorithm to manage and prevent adverse effects (AEs) related to obesity. General practice is to assess a patient for elevated BMI (> 25), implement intense lifestyle modifications including calorie restriction and exercise, reassess for a maintained 5% to 10% weight loss for cardiovascular benefits, and potentially assess for pharmacological or surgical intervention to assist in weight loss.2,4-6

While some weight loss medications (eg, phentermine/topiramate, naltrexone/bupropion, orlistat, and lorcaserin) tend to have unfavorable AEs or mixed efficacy, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) have provided new options.7-10 Lorcaserin, for example, was removed from the market in 2020 due to its association with cancer risks.11 The GLP-1RAs liraglutide and semaglutide received US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for weight loss in 2014 and 2021, respectively.12,13 GLP-1RAs have shown the greatest efficacy and benefits in reducing hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c); they are the preferred agents for patients who qualify for pharmacologic intervention for weight loss, especially those with T2DM. However, these studies have not evaluated the long-term outcomes of using these medications for weight loss and may not reflect the veteran population.14,15

At Veteran Health Indiana (VHI), clinicians may use several weight loss medications for patients to achieve 5% to 10% weight loss. The medications most often used include liraglutide, phentermine/topiramate, naltrexone/bupropion, orlistat, and phentermine alone. However, more research is needed to determine which weight loss medication is the most beneficial for veterans, particularly following FDA approval of GLP-1RAs. At VHI, phentermine/topiramate is the preferred first-line agent unless patients have contraindications for use, in which case naltrexone/bupropion is recommended. These are considered first-line due to their ease of use in pill form, lower cost, and comparable weight loss to the GLP-1 medication class.2 However, for patients with prediabetes, T2DM, BMI > 40, or BMI > 35 with specific comorbid conditions, liraglutide is preferred because of its beneficial effects for both weight loss and blood glucose control.2

This study aimed to expand on the 2021 Hood and colleagues study that examined total weight loss and weight loss as a percentage of baseline weight in patients with obesity at 3, 6, 12, and > 12 months of pharmacologic therapy by extending the time frame to 48 months.16 This study excluded semaglutide because few patients were prescribed the medication for weight loss during the study.

METHODS

We conducted a single-center, retrospective chart review of patients prescribed weight loss medications at VHI. A patient list was generated based on prescription fills from June 1, 2017, to July 31, 2021. Data were obtained from the Computerized Patient Record System; patients were not contacted. This study was approved by the Indiana University Health Institutional Review Board and VHI Research and Development Committee.

At the time of this study, liraglutide, phentermine/topiramate, naltrexone/bupropion, orlistat, and phentermine alone were available at VHI for patients who met the clinical criteria for use. All patients must have been enrolled in dietary and lifestyle management programs, including the VA MOVE! program, to be approved for these medications. After the MOVE! orientation, patients could participate in group or individual 12-week programs that included weigh-ins, goal-setting strategies, meal planning, and habit modification support. If patients could not meet in person, phone and other telehealth opportunities were available.

Patients were included in the study if they were aged ≥ 18 years, received a prescription for any of the 5 available medications for weight loss during the enrollment period, and were on the medication for ≥ 6 consecutive months. Patients were excluded if they received a prescription, were treated outside the VA system, or were pregnant. The primary indication for the included medication was not weight loss; the primary indication for the GLP-1RA was T2DM, or the weight loss was attributed to another disease. Adherence was not a measured outcome of this study; if patients were filling the medication, it was assumed they were taking it. Data were collected for each instance of medication use; as a result, a few patients were included more than once. Data collection for a failed medication ended when failure was documented. New data points began when new medication was prescribed; all data were per medication, not per patient. This allowed us to account for medication failure and provide accurate weight loss results based on medication choice within VHI.

Primary outcomes included total weight loss and weight loss as a percentage ofbaseline weight during the study period at 3, 6, 12, 24, 36, and 48 months of therapy. Secondary outcomes included the percentage of patients who lost 5% to 10% of their body weight from baseline; the percentage of patients who maintained ≥ 5% weight loss from baseline to 12, 24, 36, and 48 months if maintained on medication for that duration; duration of medication treatment in weeks; medication discontinuation rate; reason for medication discontinuation; enrollment in the MOVE! clinic and the time enrolled; percentage of patients with a BMI of 18 to 24.9 at the end of the study; and change in HbA1c at 3, 6, 12, 24, 36, and 48 months.

Demographic data included race, age, sex, baseline weight, height, baseline BMI, and comorbid conditions (collected based on the most recent primary care clinical note before initiating medication). Medication data collected included medications used to manage comorbidities. Data related to weight management medication included prescribing clinic, maintenance dose of medication, duration of medication during the study period, the reason for medication discontinuation, or bariatric surgery intervention if applicable.

Basic descriptive statistics were used to characterize study participants. For continuous data, analysis of variance tests were used; if those results were not normal, then nonparametric tests were used, followed by pairwise tests between medication groups if the overall test was significant using the Fisher significant differences test. For nominal data, χ2 or Fisher exact tests were used. For comparisons of primary and secondary outcomes, if the analyses needed to include adjustment for confounding variables, analysis of covariance was used for continuous data. A 2-sided 5% significance level was used for all tests.

RESULTS

A total of 228 instances of medication use were identified based on prescription fills; 123 did not meet inclusion criteria (117 for < 6 consecutive months of medication use) (Figure). The study included 105 participants with a mean age of 56 years; 80 were male (76.2%), and 85 identified as White race (81.0%). Mean (SD) weight was 130.1 kg (26.8) and BMI was 41.6 (7.2). The most common comorbid disease states among patients included hypertension, dyslipidemia, obstructive sleep apnea, and T2DM (Table 1). The baseline characteristics were comparable to those of Hood and colleagues.16

Most patients at VHI started on liraglutide (63%) or phentermine/topiramate (28%). For primary and secondary outcomes, statistics were calculated to determine whether the results were statistically significant for comparing the liraglutide and phentermine/topiramate subgroups. Sample sizes were too small for statistical analysis for bupropion/naltrexone, phentermine, and orlistat.

Primary Outcomes

The mean (SD) weight of participants dropped 8.1% from 130.1 kg to 119.5 kg over the patient-specific duration of weight management medication therapy for an absolute difference of 10.6 kg (9.7). Duration of individual medication use varied from 6 to 48 months. Weight loss was recorded at 6, 12, 24, 36, and 48 months of weight management therapy. Patient weight was not recorded after the medication was discontinued.

When classified by medication choice, the mean change in weight over the duration of the study was −23.9 kg for 2 patients using orlistat, −10.2 kg for 46 patients using liraglutide, −11.0 kg for 25 patients using phentermine/topiramate, -7.4 kg for 1 patient using phentermine, and -13.0 kg for 4 patients using naltrexone/bupropion. Patients without a weight documented at the end of their therapy or at the conclusion of the data collection period were not included in the total weight loss at the end of therapy. There were 78 documented instances of weight loss at the end of therapy (Table 2).

Body weight loss percentage was recorded at 6, 12, 24, 36, and 48 months of weight management therapy. The mean (SD) body weight loss percentage over the duration of the study was 9.2% (11.2). When classified by medication choice, the mean percentage of body weight loss was 16.8% for 2 patients using orlistat, 9.4% for 46 patients using liraglutide, 8.2% for 25 patients using phentermine/topiramate, 6.0% for 1 patient using phentermine alone, and 10.6% for 4 patients using naltrexone/bupropion (Table 3).

Secondary Outcomes

While none of the secondary outcomes were statistically significant, the results of this study suggest that both medications may contribute to weight loss in many patients included in this study. Almost two-thirds of the included patients analyzed lost ≥ 5% of weight from baseline while taking weight management medication. Sixty-six patients (63%) lost ≥ 5% of body weight at any time during the data collection period. When stratified by liraglutide and phentermine/topiramate, 41 patients (63%) taking liraglutide and 20 patients (67%) taking phentermine/topiramate lost ≥ 5% of weight from baseline. Of the 66 patients who lost ≥ 5% of body weight from baseline, 36 (55%) lost ≥ 10% of body weight from baseline at any time during the data collection period.

The mean (SD) duration for weight management medication use was 23 months (14.9). Phentermine/topiramate was tolerated longer than liraglutide: 22.7 months vs 21.7 months, respectively (Table 4).

The average overall documented medication discontinuation rate was 35.2%. Reasons for discontinuation included 21 patient-elected discontinuations, 8 patients no longer met criteria for use, 4 medications were no longer indicated, and 4 patients experienced AEs. It is unknown whether weight management medication was discontinued or not in 18 patients (17.2%).

DISCUSSION

This study evaluated the use and outcomes of weight loss medications over a longer period (up to 48 months) than what was previously studied among patients at VHI (12 months). The study aimed to better understand the long-term effect of weight loss medications, determine which medication had better long-term outcomes, and examine the reasons for medication discontinuation.

The results of this study displayed some similarities and differences compared with the Hood and colleagues study.16 Both yielded similar results for 5% of body weight loss and 10% of body weight loss. The largest difference was mean weight loss over the study period. In this study, patients lost a mean 10.6 kg over the course of weight loss medication use compared to 15.8 kg found by Hood and colleagues.16 A reason patients in the current study lost less weight overall could be the difference in time frames. The current study encompassed the COVID-19 pandemic, meaning fewer overall in-person patient appointments, which led to patients being lost to follow-up, missing weigh-ins during the time period, and gaps in care. For some patients, the pandemic possibly contributed to depression, missed medication doses, and a more sedentary lifestyle, leading to more weight gain.17 Telemedicine services at VHI expanded during the pandemic in an attempt to increase patient monitoring and counseling. It is unclear whether this expansion was enough to replace the in-person contact necessary to promote a healthy lifestyle.

VA pharmacists now care for patients through telehealth and are more involved in weight loss management. Since the conclusion of the Hood and colleagues study and start of this research, 2 pharmacists at VHI have been assigned to follow patients for obesity management to help with adherence to medication and lifestyle changes, management of AEs, dispense logistics, interventions for medications that may cause weight gain, and case management of glycemic control and weight loss with GLP-1RAs. Care management by pharmacists at VHI helps improve the logistics of titratable orders and save money by improving the use of high-cost items like GLP-1RAs. VA clinical pharmacy practitioners already monitor GLP-1RAs for patients with T2DM, so they are prepared to educate and assist patients with these medications.