User login

Indwelling endoscopic biliary stents reduced risk of recurrent strictures in chronic pancreatitis

Sundeep Lakhtakia, MD, and colleagues reported in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy.

Patients with severe disease at baseline were more than twice as likely to develop a postprocedural stricture (odds ratio, 2.4). Longer baseline stricture length was less predictive, but it was still significantly associated with increased risk (OR, 1.2), according to Dr. Lakhtakia of the Asian Institute of Gastroenterology, Hyderabad, India, and coauthors.

The results indicate that indwelling biliary stenting is a reasonable and beneficial procedure for many of these patients, wrote Dr. Lakhtakia and coauthors.

“The major message to be taken from this study is that in patients with chronic [symptomatic] pancreatitis ... associated with benign biliary strictures, the single placement of a fully covered self-expanding metal stent for an intended indwell of 10-12 months allows more than 60% to remain free of symptoms up to 5 years later without additional intervention.”

The prospective nonrandomized study comprised 118 patients with chronic symptomatic pancreatitis and benign biliary strictures. All received a stent with removal scheduled for 10-12 months later. Patients were followed for 5 years. The primary endpoints were stricture resolution and freedom from recurrence at the end of follow-up.

Patients were a mean of 52 years old; most (83%) were male. At baseline, the mean total bilirubin was 1.4 mg/dL, and the mean alkaline phosphate level was 338.7 IU/L. Mean stricture length was 23.7 mm, but varied from 7.2 to 40 mm. Severe disease was present in 70%.

Among the cohort, five cases (4.2%) were considered treatment failures, with four lost to follow-up and one treated surgically for chronic pancreatitis progression. Another five experienced a spontaneous complete distal stent migration. The rest of the cohort (108) had their scheduled stent removal. At that time, 95 of the 118 experienced successful stent removal, without serious adverse events or the need for immediate replacement.

At 5 years, patients were reassessed, with the primary follow-up endpoint of stricture resolution. Secondary endpoints were time to stricture recurrence and/or changes in liver function tests. Overall, 79.7% (94) of the overall cohort showed stricture resolution at 5 years.

Among the 108 who had a successful removal, a longer time of stent indwell was associated with a decreased chance of recurrent placement. Among those with the longer indwell (median, 344 days), the risk reduction was 34% (OR, 0.66). Of the 94 patients with stricture resolution at stent removal, 77.4% remained stent free at 5 years.

At the end of follow-up, 56 patients had symptomatic data available. Most (53) had not experienced symptoms of biliary obstruction and/or cholestasis. The other three had been symptom free at 48 months but had incomplete or missing 5-year data.

By 5 years, 19 patients needed a new stent. Of these, 13 had symptoms of biliary obstruction.

About 23% of stented patients had a stent-related serious adverse event. These included cholangitis (9.3%), abdominal pain (5%), pancreatitis (3.4%), cholecystitis (2%), and cholestasis (1.7%).

About 80% of the 19 patients who had a stricture recurrence experienced a serious adverse event in the month before recurrent stent placement. The most common were cholangitis, cholestasis, abdominal pain, and cholelithiasis.

In a univariate analysis, recurrence risk was significantly associated with severe baseline disease and longer stricture length. The associations remained significant in the multivariate model.

“Strikingly, patients with initial stricture resolution at [stent] removal ... were very likely to have long-term stricture resolution” the authors noted.

Dr. Lakhtakia had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Lakhtakia S et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2019.08.037.

Sundeep Lakhtakia, MD, and colleagues reported in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy.

Patients with severe disease at baseline were more than twice as likely to develop a postprocedural stricture (odds ratio, 2.4). Longer baseline stricture length was less predictive, but it was still significantly associated with increased risk (OR, 1.2), according to Dr. Lakhtakia of the Asian Institute of Gastroenterology, Hyderabad, India, and coauthors.

The results indicate that indwelling biliary stenting is a reasonable and beneficial procedure for many of these patients, wrote Dr. Lakhtakia and coauthors.

“The major message to be taken from this study is that in patients with chronic [symptomatic] pancreatitis ... associated with benign biliary strictures, the single placement of a fully covered self-expanding metal stent for an intended indwell of 10-12 months allows more than 60% to remain free of symptoms up to 5 years later without additional intervention.”

The prospective nonrandomized study comprised 118 patients with chronic symptomatic pancreatitis and benign biliary strictures. All received a stent with removal scheduled for 10-12 months later. Patients were followed for 5 years. The primary endpoints were stricture resolution and freedom from recurrence at the end of follow-up.

Patients were a mean of 52 years old; most (83%) were male. At baseline, the mean total bilirubin was 1.4 mg/dL, and the mean alkaline phosphate level was 338.7 IU/L. Mean stricture length was 23.7 mm, but varied from 7.2 to 40 mm. Severe disease was present in 70%.

Among the cohort, five cases (4.2%) were considered treatment failures, with four lost to follow-up and one treated surgically for chronic pancreatitis progression. Another five experienced a spontaneous complete distal stent migration. The rest of the cohort (108) had their scheduled stent removal. At that time, 95 of the 118 experienced successful stent removal, without serious adverse events or the need for immediate replacement.

At 5 years, patients were reassessed, with the primary follow-up endpoint of stricture resolution. Secondary endpoints were time to stricture recurrence and/or changes in liver function tests. Overall, 79.7% (94) of the overall cohort showed stricture resolution at 5 years.

Among the 108 who had a successful removal, a longer time of stent indwell was associated with a decreased chance of recurrent placement. Among those with the longer indwell (median, 344 days), the risk reduction was 34% (OR, 0.66). Of the 94 patients with stricture resolution at stent removal, 77.4% remained stent free at 5 years.

At the end of follow-up, 56 patients had symptomatic data available. Most (53) had not experienced symptoms of biliary obstruction and/or cholestasis. The other three had been symptom free at 48 months but had incomplete or missing 5-year data.

By 5 years, 19 patients needed a new stent. Of these, 13 had symptoms of biliary obstruction.

About 23% of stented patients had a stent-related serious adverse event. These included cholangitis (9.3%), abdominal pain (5%), pancreatitis (3.4%), cholecystitis (2%), and cholestasis (1.7%).

About 80% of the 19 patients who had a stricture recurrence experienced a serious adverse event in the month before recurrent stent placement. The most common were cholangitis, cholestasis, abdominal pain, and cholelithiasis.

In a univariate analysis, recurrence risk was significantly associated with severe baseline disease and longer stricture length. The associations remained significant in the multivariate model.

“Strikingly, patients with initial stricture resolution at [stent] removal ... were very likely to have long-term stricture resolution” the authors noted.

Dr. Lakhtakia had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Lakhtakia S et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2019.08.037.

Sundeep Lakhtakia, MD, and colleagues reported in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy.

Patients with severe disease at baseline were more than twice as likely to develop a postprocedural stricture (odds ratio, 2.4). Longer baseline stricture length was less predictive, but it was still significantly associated with increased risk (OR, 1.2), according to Dr. Lakhtakia of the Asian Institute of Gastroenterology, Hyderabad, India, and coauthors.

The results indicate that indwelling biliary stenting is a reasonable and beneficial procedure for many of these patients, wrote Dr. Lakhtakia and coauthors.

“The major message to be taken from this study is that in patients with chronic [symptomatic] pancreatitis ... associated with benign biliary strictures, the single placement of a fully covered self-expanding metal stent for an intended indwell of 10-12 months allows more than 60% to remain free of symptoms up to 5 years later without additional intervention.”

The prospective nonrandomized study comprised 118 patients with chronic symptomatic pancreatitis and benign biliary strictures. All received a stent with removal scheduled for 10-12 months later. Patients were followed for 5 years. The primary endpoints were stricture resolution and freedom from recurrence at the end of follow-up.

Patients were a mean of 52 years old; most (83%) were male. At baseline, the mean total bilirubin was 1.4 mg/dL, and the mean alkaline phosphate level was 338.7 IU/L. Mean stricture length was 23.7 mm, but varied from 7.2 to 40 mm. Severe disease was present in 70%.

Among the cohort, five cases (4.2%) were considered treatment failures, with four lost to follow-up and one treated surgically for chronic pancreatitis progression. Another five experienced a spontaneous complete distal stent migration. The rest of the cohort (108) had their scheduled stent removal. At that time, 95 of the 118 experienced successful stent removal, without serious adverse events or the need for immediate replacement.

At 5 years, patients were reassessed, with the primary follow-up endpoint of stricture resolution. Secondary endpoints were time to stricture recurrence and/or changes in liver function tests. Overall, 79.7% (94) of the overall cohort showed stricture resolution at 5 years.

Among the 108 who had a successful removal, a longer time of stent indwell was associated with a decreased chance of recurrent placement. Among those with the longer indwell (median, 344 days), the risk reduction was 34% (OR, 0.66). Of the 94 patients with stricture resolution at stent removal, 77.4% remained stent free at 5 years.

At the end of follow-up, 56 patients had symptomatic data available. Most (53) had not experienced symptoms of biliary obstruction and/or cholestasis. The other three had been symptom free at 48 months but had incomplete or missing 5-year data.

By 5 years, 19 patients needed a new stent. Of these, 13 had symptoms of biliary obstruction.

About 23% of stented patients had a stent-related serious adverse event. These included cholangitis (9.3%), abdominal pain (5%), pancreatitis (3.4%), cholecystitis (2%), and cholestasis (1.7%).

About 80% of the 19 patients who had a stricture recurrence experienced a serious adverse event in the month before recurrent stent placement. The most common were cholangitis, cholestasis, abdominal pain, and cholelithiasis.

In a univariate analysis, recurrence risk was significantly associated with severe baseline disease and longer stricture length. The associations remained significant in the multivariate model.

“Strikingly, patients with initial stricture resolution at [stent] removal ... were very likely to have long-term stricture resolution” the authors noted.

Dr. Lakhtakia had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Lakhtakia S et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2019.08.037.

FROM GASTROINTESTINAL ENDOSCOPY

Genetic analysis highlights value of germline variants in MDS, AML

Germline DDX41 mutations were found to be relatively prevalent and showed favorable outcomes in a cohort of patients with myelodysplastic syndromes or acute myeloid leukemia, according to a genetic analysis.

The results demonstrate that systematic genetic testing for DDX41 mutations may aid in clinical decision making for adults with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) or acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

“We screened a large, unselected cohort of adult patients diagnosed with MDS/AML to analyze the biological and clinical features of DDX41-related myeloid malignancies,” wrote Marie Sébert, MD, PhD, of Hôpital Saint Louis in Paris and colleagues. The results were published in Blood.

The researchers used next-generation sequencing to analyze blood and bone marrow samples from 1,385 patients with MDS or AML to detect DDX41 mutations. A variant allele frequency of greater than 0.4 was regarded as indicative of a germline origin, and only specific variants (minor allele frequency of less than 0.01) were included.

The team analyzed various parameters relevant to DDX41-related myeloid disorders, including patient demographics, karyotyping, and treatment response rates, in addition to the prevalence of DDX41-related malignancies.

A total of 28 distinct germline DDX41 variants were detected among 43 unrelated patients. The researchers classified 21 of the variants as causal, with the rest being of unknown significance.

“We focused on the 33 patients having causal variants, representing 2.4% of our cohort,” they wrote.

The majority of patients with DDX41-related MDS/AML were male, with a median age of 69 years. Few patients (27%) had a family history of blood malignancies, while the majority of patients (85%) had a normal karyotype.

With respect to treatment, most high-risk patients received either azacitidine or intensive chemotherapy, with overall response rates of 73% and 100%, respectively. The median overall survival was 5.2 years.

There are currently no consensus recommendations on genetic counseling and follow-up of asymptomatic carriers and more studies are needed to refine clinical management and genetic counseling, the researchers wrote. “However, in our experience, DDX41-mutated patients frequently presented mild cytopenias years before overt hematological myeloid malignancy, suggesting that watchful surveillance would allow the detection of disease evolution.”

No funding sources were reported, and the authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Sébert M et al. Blood. 2019 Sep 4. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019000909.

Germline DDX41 mutations were found to be relatively prevalent and showed favorable outcomes in a cohort of patients with myelodysplastic syndromes or acute myeloid leukemia, according to a genetic analysis.

The results demonstrate that systematic genetic testing for DDX41 mutations may aid in clinical decision making for adults with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) or acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

“We screened a large, unselected cohort of adult patients diagnosed with MDS/AML to analyze the biological and clinical features of DDX41-related myeloid malignancies,” wrote Marie Sébert, MD, PhD, of Hôpital Saint Louis in Paris and colleagues. The results were published in Blood.

The researchers used next-generation sequencing to analyze blood and bone marrow samples from 1,385 patients with MDS or AML to detect DDX41 mutations. A variant allele frequency of greater than 0.4 was regarded as indicative of a germline origin, and only specific variants (minor allele frequency of less than 0.01) were included.

The team analyzed various parameters relevant to DDX41-related myeloid disorders, including patient demographics, karyotyping, and treatment response rates, in addition to the prevalence of DDX41-related malignancies.

A total of 28 distinct germline DDX41 variants were detected among 43 unrelated patients. The researchers classified 21 of the variants as causal, with the rest being of unknown significance.

“We focused on the 33 patients having causal variants, representing 2.4% of our cohort,” they wrote.

The majority of patients with DDX41-related MDS/AML were male, with a median age of 69 years. Few patients (27%) had a family history of blood malignancies, while the majority of patients (85%) had a normal karyotype.

With respect to treatment, most high-risk patients received either azacitidine or intensive chemotherapy, with overall response rates of 73% and 100%, respectively. The median overall survival was 5.2 years.

There are currently no consensus recommendations on genetic counseling and follow-up of asymptomatic carriers and more studies are needed to refine clinical management and genetic counseling, the researchers wrote. “However, in our experience, DDX41-mutated patients frequently presented mild cytopenias years before overt hematological myeloid malignancy, suggesting that watchful surveillance would allow the detection of disease evolution.”

No funding sources were reported, and the authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Sébert M et al. Blood. 2019 Sep 4. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019000909.

Germline DDX41 mutations were found to be relatively prevalent and showed favorable outcomes in a cohort of patients with myelodysplastic syndromes or acute myeloid leukemia, according to a genetic analysis.

The results demonstrate that systematic genetic testing for DDX41 mutations may aid in clinical decision making for adults with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) or acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

“We screened a large, unselected cohort of adult patients diagnosed with MDS/AML to analyze the biological and clinical features of DDX41-related myeloid malignancies,” wrote Marie Sébert, MD, PhD, of Hôpital Saint Louis in Paris and colleagues. The results were published in Blood.

The researchers used next-generation sequencing to analyze blood and bone marrow samples from 1,385 patients with MDS or AML to detect DDX41 mutations. A variant allele frequency of greater than 0.4 was regarded as indicative of a germline origin, and only specific variants (minor allele frequency of less than 0.01) were included.

The team analyzed various parameters relevant to DDX41-related myeloid disorders, including patient demographics, karyotyping, and treatment response rates, in addition to the prevalence of DDX41-related malignancies.

A total of 28 distinct germline DDX41 variants were detected among 43 unrelated patients. The researchers classified 21 of the variants as causal, with the rest being of unknown significance.

“We focused on the 33 patients having causal variants, representing 2.4% of our cohort,” they wrote.

The majority of patients with DDX41-related MDS/AML were male, with a median age of 69 years. Few patients (27%) had a family history of blood malignancies, while the majority of patients (85%) had a normal karyotype.

With respect to treatment, most high-risk patients received either azacitidine or intensive chemotherapy, with overall response rates of 73% and 100%, respectively. The median overall survival was 5.2 years.

There are currently no consensus recommendations on genetic counseling and follow-up of asymptomatic carriers and more studies are needed to refine clinical management and genetic counseling, the researchers wrote. “However, in our experience, DDX41-mutated patients frequently presented mild cytopenias years before overt hematological myeloid malignancy, suggesting that watchful surveillance would allow the detection of disease evolution.”

No funding sources were reported, and the authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Sébert M et al. Blood. 2019 Sep 4. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019000909.

FROM BLOOD

Juvenile dermatomyositis derails growth and pubertal development

Children with juvenile dermatomyositis showed significant growth failure and pubertal delay, based on data from a longitudinal cohort study.

“Both the inflammatory activity of this severe chronic rheumatic disease and the well-known side effects of corticosteroid treatment may interfere with normal growth and pubertal development of children,” wrote Ellen Nordal, MD, of the University Hospital of Northern Norway, Tromsø, and colleagues.

The goal in treating juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM) is to achieve inactive disease and prevent permanent damage, but long-term data on growth and puberty in JDM patients are limited, they wrote.

In a study published in Arthritis Care & Research, the investigators reviewed data from 196 children and followed them for 2 years. The patients were part of the Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organisation (PRINTO) observational cohort study.

Overall, the researchers identified growth failure, height deflection, and/or delayed puberty in 94 children (48%) at the last study visit.

Growth failure was present at baseline in 17% of girls and 10% of boys. Over the 2-year study period, height deflection increased to 25% of girls and 31% of boys, but this change was not significant. Height deflection was defined as a change in the height z score of less than –0.25 per year from baseline. However, body mass index increased significantly from baseline during the study.

Catch-up growth had occurred by the final study visit in some patients, based on parent-adjusted z scores over time. Girls with a disease duration of 12 months or more showed no catch-up growth at 2 years and had significantly lower parent-adjusted height z scores.

In addition, the researchers observed a delay in the onset of puberty (including pubertal tempo and menarche) in approximately 36% of both boys and girls. However, neither growth failure nor height deflection was significantly associated with delayed puberty in either sex.

“In follow-up, clinicians should therefore be aware of both the pubertal development and the growth of the child, assess the milestones of development, and ensure that the children reach as much as possible of their genetic potential,” the researchers wrote.

The study participants were younger than 18 years at study enrollment, and all were in an active disease phase, defined as needing to start or receive a major dose increase of corticosteroids and/or immunosuppressants. Patients were assessed at baseline, at 6 months and/or at 12 months, and during a final visit at approximately 26 months. During the study, approximately half of the participants (50.5%) received methotrexate, 30 (15.3%) received cyclosporine A, 10 (5.1%) received cyclophosphamide, and 27 (13.8%) received intravenous immunoglobulin.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the short follow-up period for assessing pubertal development and the inability to analyze any impact of corticosteroid use prior to the study, the researchers noted. However, “the overall frequency of growth failure was not significantly higher at the final study visit 2 years after baseline, indicating that the very high doses of corticosteroid treatment given during the study period is reasonably well tolerated with regards to growth,” they wrote. But monitoring remains essential, especially for children with previous growth failure or with disease onset early in pubertal development.

The study was supported by the European Union, Helse Nord Research grants, and by IRCCS Istituto Giannina Gaslini. Five authors of the study reported financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Nordal E et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2019 Sep 10. doi: 10.1002/acr.24065.

Children with juvenile dermatomyositis showed significant growth failure and pubertal delay, based on data from a longitudinal cohort study.

“Both the inflammatory activity of this severe chronic rheumatic disease and the well-known side effects of corticosteroid treatment may interfere with normal growth and pubertal development of children,” wrote Ellen Nordal, MD, of the University Hospital of Northern Norway, Tromsø, and colleagues.

The goal in treating juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM) is to achieve inactive disease and prevent permanent damage, but long-term data on growth and puberty in JDM patients are limited, they wrote.

In a study published in Arthritis Care & Research, the investigators reviewed data from 196 children and followed them for 2 years. The patients were part of the Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organisation (PRINTO) observational cohort study.

Overall, the researchers identified growth failure, height deflection, and/or delayed puberty in 94 children (48%) at the last study visit.

Growth failure was present at baseline in 17% of girls and 10% of boys. Over the 2-year study period, height deflection increased to 25% of girls and 31% of boys, but this change was not significant. Height deflection was defined as a change in the height z score of less than –0.25 per year from baseline. However, body mass index increased significantly from baseline during the study.

Catch-up growth had occurred by the final study visit in some patients, based on parent-adjusted z scores over time. Girls with a disease duration of 12 months or more showed no catch-up growth at 2 years and had significantly lower parent-adjusted height z scores.

In addition, the researchers observed a delay in the onset of puberty (including pubertal tempo and menarche) in approximately 36% of both boys and girls. However, neither growth failure nor height deflection was significantly associated with delayed puberty in either sex.

“In follow-up, clinicians should therefore be aware of both the pubertal development and the growth of the child, assess the milestones of development, and ensure that the children reach as much as possible of their genetic potential,” the researchers wrote.

The study participants were younger than 18 years at study enrollment, and all were in an active disease phase, defined as needing to start or receive a major dose increase of corticosteroids and/or immunosuppressants. Patients were assessed at baseline, at 6 months and/or at 12 months, and during a final visit at approximately 26 months. During the study, approximately half of the participants (50.5%) received methotrexate, 30 (15.3%) received cyclosporine A, 10 (5.1%) received cyclophosphamide, and 27 (13.8%) received intravenous immunoglobulin.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the short follow-up period for assessing pubertal development and the inability to analyze any impact of corticosteroid use prior to the study, the researchers noted. However, “the overall frequency of growth failure was not significantly higher at the final study visit 2 years after baseline, indicating that the very high doses of corticosteroid treatment given during the study period is reasonably well tolerated with regards to growth,” they wrote. But monitoring remains essential, especially for children with previous growth failure or with disease onset early in pubertal development.

The study was supported by the European Union, Helse Nord Research grants, and by IRCCS Istituto Giannina Gaslini. Five authors of the study reported financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Nordal E et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2019 Sep 10. doi: 10.1002/acr.24065.

Children with juvenile dermatomyositis showed significant growth failure and pubertal delay, based on data from a longitudinal cohort study.

“Both the inflammatory activity of this severe chronic rheumatic disease and the well-known side effects of corticosteroid treatment may interfere with normal growth and pubertal development of children,” wrote Ellen Nordal, MD, of the University Hospital of Northern Norway, Tromsø, and colleagues.

The goal in treating juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM) is to achieve inactive disease and prevent permanent damage, but long-term data on growth and puberty in JDM patients are limited, they wrote.

In a study published in Arthritis Care & Research, the investigators reviewed data from 196 children and followed them for 2 years. The patients were part of the Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organisation (PRINTO) observational cohort study.

Overall, the researchers identified growth failure, height deflection, and/or delayed puberty in 94 children (48%) at the last study visit.

Growth failure was present at baseline in 17% of girls and 10% of boys. Over the 2-year study period, height deflection increased to 25% of girls and 31% of boys, but this change was not significant. Height deflection was defined as a change in the height z score of less than –0.25 per year from baseline. However, body mass index increased significantly from baseline during the study.

Catch-up growth had occurred by the final study visit in some patients, based on parent-adjusted z scores over time. Girls with a disease duration of 12 months or more showed no catch-up growth at 2 years and had significantly lower parent-adjusted height z scores.

In addition, the researchers observed a delay in the onset of puberty (including pubertal tempo and menarche) in approximately 36% of both boys and girls. However, neither growth failure nor height deflection was significantly associated with delayed puberty in either sex.

“In follow-up, clinicians should therefore be aware of both the pubertal development and the growth of the child, assess the milestones of development, and ensure that the children reach as much as possible of their genetic potential,” the researchers wrote.

The study participants were younger than 18 years at study enrollment, and all were in an active disease phase, defined as needing to start or receive a major dose increase of corticosteroids and/or immunosuppressants. Patients were assessed at baseline, at 6 months and/or at 12 months, and during a final visit at approximately 26 months. During the study, approximately half of the participants (50.5%) received methotrexate, 30 (15.3%) received cyclosporine A, 10 (5.1%) received cyclophosphamide, and 27 (13.8%) received intravenous immunoglobulin.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the short follow-up period for assessing pubertal development and the inability to analyze any impact of corticosteroid use prior to the study, the researchers noted. However, “the overall frequency of growth failure was not significantly higher at the final study visit 2 years after baseline, indicating that the very high doses of corticosteroid treatment given during the study period is reasonably well tolerated with regards to growth,” they wrote. But monitoring remains essential, especially for children with previous growth failure or with disease onset early in pubertal development.

The study was supported by the European Union, Helse Nord Research grants, and by IRCCS Istituto Giannina Gaslini. Five authors of the study reported financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Nordal E et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2019 Sep 10. doi: 10.1002/acr.24065.

FROM ARTHRITIS CARE & RESEARCH

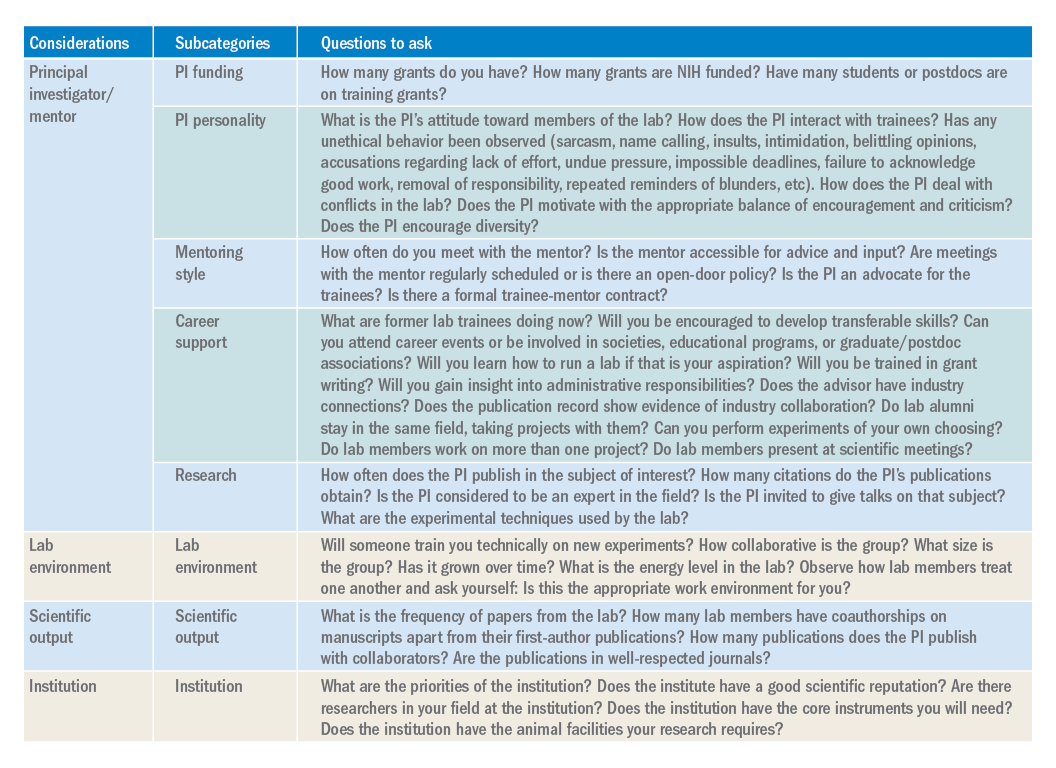

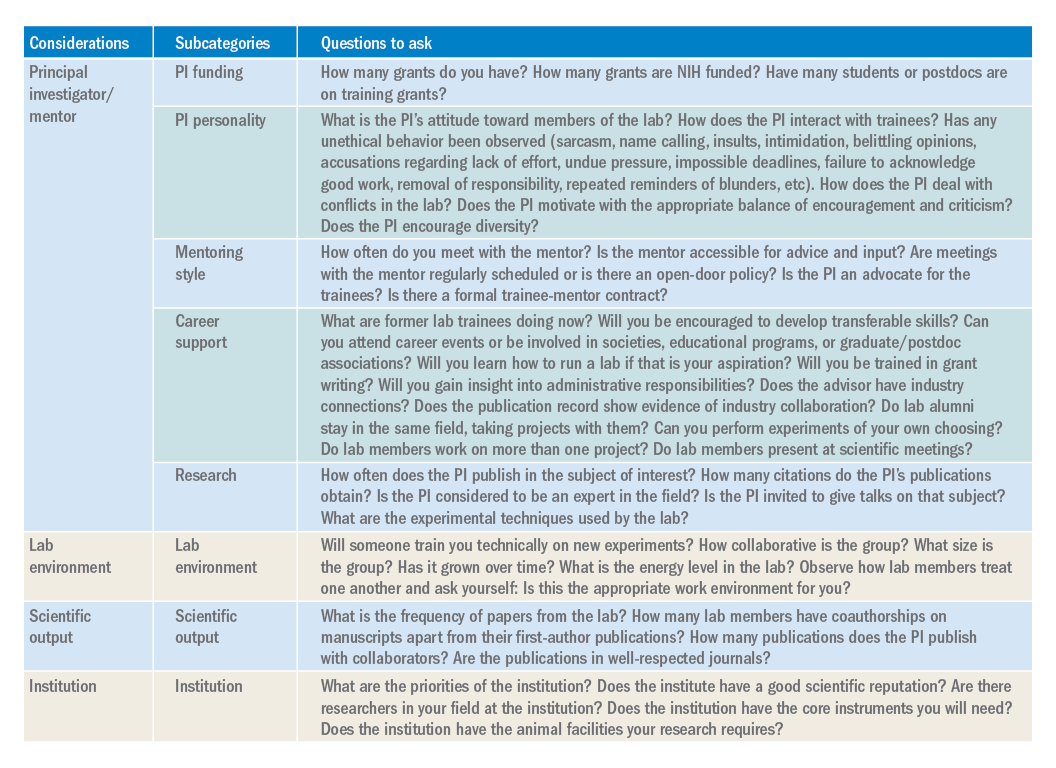

Not all labs are created equal: What to look for when searching for the right lab

Introduction

As researchers, we spend a substantial period of our careers as trainees in a lab. As graduate students or postdoctoral fellows, selecting the “right” lab has the potential to make a huge difference for your future career and your mental health. Although much of the decision is based on instinct, there is still some logic and reason that can be applied to ensure the choice is a good fit.

PI/mentor

PI funding. The history of funding and the funding of your specific project are important factors to consider. No matter how significant the scientific question, not having adequate funding can be paralyzing. For both graduate students and postdoctoral fellows, it is in your best interest to proactively inquire about the funding status of the lab. This can be accomplished using online reporters (such as NIH Reporter or Grantome) and asking the PI. It is equally important to identify which grant application/fellowship will fund your stipend and ensure that the funding is secure for 4-6 years.

PI personality. For better or for worse, the PI largely sets the tone for the lab. The personality of the PI can be a key determining factor in finding the right “fit” for a trainee. Ask your peers and current and past lab members about working with the PI. As you speak to lab members and alumni, don’t disregard warning signs of unethical behavior, bullying, or harassment. Even with the rise of movements such as the #MeTooSTEM, academic misconduct is hard to correct. It is far better to avoid these labs. If available, examine the PI’s social networks (LinkedIn, Twitter, Facebook, etc.) or read previously published interviews and look for the PI’s attitude toward its lab members.

Mentoring style. The NIH emphasizes mentorship in numerous funding mechanisms; thus, it isn’t surprising that selecting an appropriate mentor is paramount for a successful training experience. A lot of this decision requires information about you as a trainee. Reflect on what type of scientific mentor will be the best fit for your needs and honestly evaluate your own communication style, expectations, and final career goals. Ask questions of the PI and lab members to identify the mentoring style. Find a mentor who takes his or her responsibility to train you seriously and who genuinely cares about the well-being of the lab personnel. Good mentors advocate for their trainees inside and outside of the lab. A mentor’s vocal support of talented trainees can help propel them toward their career goals.

Career support. One of the most important questions you need to consider is whether your mentor can help you accomplish your career goals. Be prepared to have an honest conversation with the PI about your goals. The majority of PhD scientists will pursue careers outside of academia, so choose a mentor who supports diverse career paths. A mentor who is invested in your success will work with you to finish papers in a timely manner, encourage you to apply for awards and grants, aid in the identification of fruitful collaborations, help develop new skills, and expand your professional network. A good mentor will also ensure that you have freedom in your project to pursue your own scientific interests, and ultimately allow you to carve out a project for you to take with you when your training is complete.

Research. The research done in your lab will also factor into your decision. Especially if you are a postdoctoral fellow, this will be the field/subject/niche in which you will likely establish your career and expertise. If there is a field you want to pursue, identify mentors who have a publication record in that subject. Examine the PIs for publications, citations, and overall contributions to the field. If the PI in question is young, you may not find many citations of papers. However, you can identify the quality of the papers, the lab’s experimental techniques, and how often the PI is invited to give talks on that subject.

Lab environment

The composition of a lab can play a huge role in your overall productivity and mental well-being. Your coworkers will be the ones you interact with on a day-to-day basis. Your lab mates can be a huge asset in terms of mastering new techniques, collaborating on a project, or receiving helpful feedback. Thus, it is to your benefit to get along with your lab mates and to choose a lab that has people who you want to work with or don’t mind working with. The reality of postdoctoral training is that you will spend a large amount of time working in the lab, so choosing a lab that has an environment that fits your personality and desired workload and schedule is important. Considering the valuable contribution of lab members toward your research progression, you should give considerable weight to this factor when choosing a lab.

Scientific output

Although labs with high-impact publications are attractive, it is more important to consider the frequency with which a lab comes out with papers. Search Pubmed to obtain the complete publication roster of the PI. This output will give you an idea about the consistency and regularity of publications and overall lab productivity. When querying the lab’s publication list, check if the lab members have coauthorships on manuscripts apart from their first-author ones. It is desirable to be a coauthor on other manuscripts, as this will help increase your publication record. In addition, look for collaborators of the PI. These collaborations might benefit you by broadening your skill set and experience. Be intentional about reviewing the papers from the lab over the last 5 years. If you want to pursue academic research, you will want to be in a lab that publishes frequently in well-respected journals.

Institution

The institutional environment should also influence your decision. Top universities can attract some of the best researchers. Moreover, funding agencies examine the “Environment and Institutional Commitment” as one of the criteria for awarding grants. When choosing an institution, consider its priorities and ensure that it aligns with your priorities (i.e., research, undergraduate education, etc.). Consider the number of PIs conducting research in your field. These other labs may benefit your career development through collaborations, scientific discussions, letters of recommendation, career support, and feedback.

Conclusion

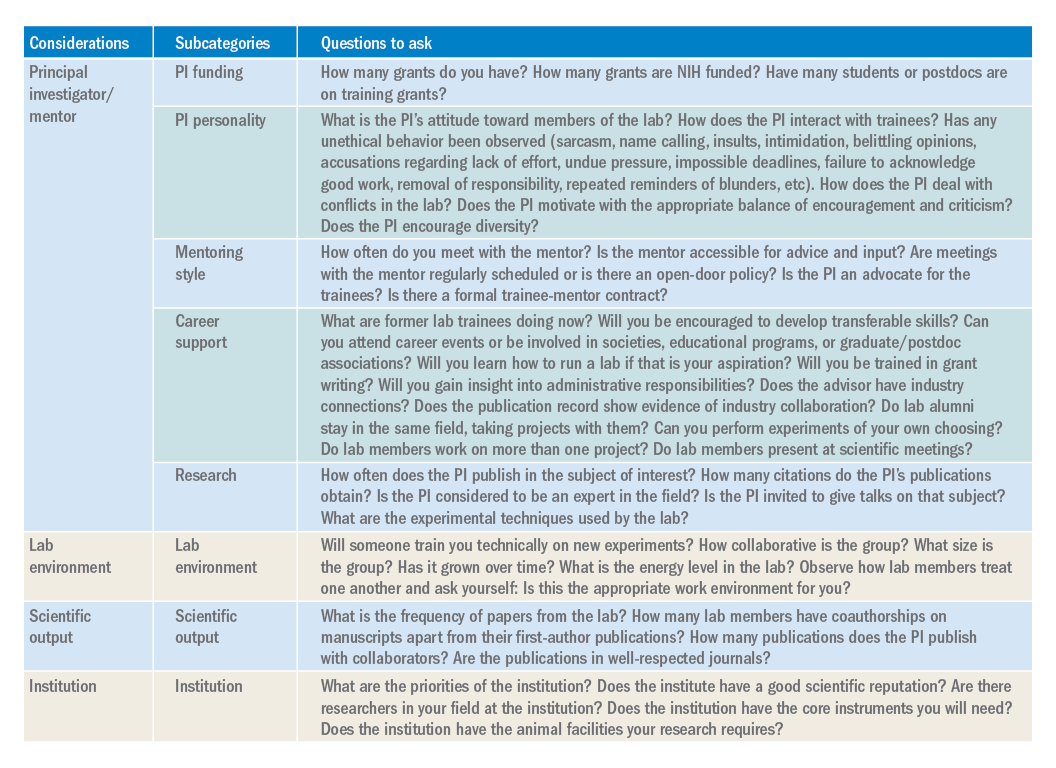

While there are certain key criteria that should be prioritized when choosing a lab, the path to finding (and joining) the right lab will vary from individual to individual. Gather data, ask questions, research what you can online (lab website, publication records, LinkedIn, ResearchGate, or Twitter), and be ready for the interview with a long list of written questions for the PI and lab members. One of the best ways to begin looking for a new lab is to ask your current mentor, committee members, peers, and others in your professional network for their suggestions. Table 1 has questions to keep in mind as you are searching for a lab. You will spend much of your time in the lab of your choosing, so choose wisely.

Dr. Engevik is an instructor in pathology and immunology, Baylor College of Medicine, Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston.

Introduction

As researchers, we spend a substantial period of our careers as trainees in a lab. As graduate students or postdoctoral fellows, selecting the “right” lab has the potential to make a huge difference for your future career and your mental health. Although much of the decision is based on instinct, there is still some logic and reason that can be applied to ensure the choice is a good fit.

PI/mentor

PI funding. The history of funding and the funding of your specific project are important factors to consider. No matter how significant the scientific question, not having adequate funding can be paralyzing. For both graduate students and postdoctoral fellows, it is in your best interest to proactively inquire about the funding status of the lab. This can be accomplished using online reporters (such as NIH Reporter or Grantome) and asking the PI. It is equally important to identify which grant application/fellowship will fund your stipend and ensure that the funding is secure for 4-6 years.

PI personality. For better or for worse, the PI largely sets the tone for the lab. The personality of the PI can be a key determining factor in finding the right “fit” for a trainee. Ask your peers and current and past lab members about working with the PI. As you speak to lab members and alumni, don’t disregard warning signs of unethical behavior, bullying, or harassment. Even with the rise of movements such as the #MeTooSTEM, academic misconduct is hard to correct. It is far better to avoid these labs. If available, examine the PI’s social networks (LinkedIn, Twitter, Facebook, etc.) or read previously published interviews and look for the PI’s attitude toward its lab members.

Mentoring style. The NIH emphasizes mentorship in numerous funding mechanisms; thus, it isn’t surprising that selecting an appropriate mentor is paramount for a successful training experience. A lot of this decision requires information about you as a trainee. Reflect on what type of scientific mentor will be the best fit for your needs and honestly evaluate your own communication style, expectations, and final career goals. Ask questions of the PI and lab members to identify the mentoring style. Find a mentor who takes his or her responsibility to train you seriously and who genuinely cares about the well-being of the lab personnel. Good mentors advocate for their trainees inside and outside of the lab. A mentor’s vocal support of talented trainees can help propel them toward their career goals.

Career support. One of the most important questions you need to consider is whether your mentor can help you accomplish your career goals. Be prepared to have an honest conversation with the PI about your goals. The majority of PhD scientists will pursue careers outside of academia, so choose a mentor who supports diverse career paths. A mentor who is invested in your success will work with you to finish papers in a timely manner, encourage you to apply for awards and grants, aid in the identification of fruitful collaborations, help develop new skills, and expand your professional network. A good mentor will also ensure that you have freedom in your project to pursue your own scientific interests, and ultimately allow you to carve out a project for you to take with you when your training is complete.

Research. The research done in your lab will also factor into your decision. Especially if you are a postdoctoral fellow, this will be the field/subject/niche in which you will likely establish your career and expertise. If there is a field you want to pursue, identify mentors who have a publication record in that subject. Examine the PIs for publications, citations, and overall contributions to the field. If the PI in question is young, you may not find many citations of papers. However, you can identify the quality of the papers, the lab’s experimental techniques, and how often the PI is invited to give talks on that subject.

Lab environment

The composition of a lab can play a huge role in your overall productivity and mental well-being. Your coworkers will be the ones you interact with on a day-to-day basis. Your lab mates can be a huge asset in terms of mastering new techniques, collaborating on a project, or receiving helpful feedback. Thus, it is to your benefit to get along with your lab mates and to choose a lab that has people who you want to work with or don’t mind working with. The reality of postdoctoral training is that you will spend a large amount of time working in the lab, so choosing a lab that has an environment that fits your personality and desired workload and schedule is important. Considering the valuable contribution of lab members toward your research progression, you should give considerable weight to this factor when choosing a lab.

Scientific output

Although labs with high-impact publications are attractive, it is more important to consider the frequency with which a lab comes out with papers. Search Pubmed to obtain the complete publication roster of the PI. This output will give you an idea about the consistency and regularity of publications and overall lab productivity. When querying the lab’s publication list, check if the lab members have coauthorships on manuscripts apart from their first-author ones. It is desirable to be a coauthor on other manuscripts, as this will help increase your publication record. In addition, look for collaborators of the PI. These collaborations might benefit you by broadening your skill set and experience. Be intentional about reviewing the papers from the lab over the last 5 years. If you want to pursue academic research, you will want to be in a lab that publishes frequently in well-respected journals.

Institution

The institutional environment should also influence your decision. Top universities can attract some of the best researchers. Moreover, funding agencies examine the “Environment and Institutional Commitment” as one of the criteria for awarding grants. When choosing an institution, consider its priorities and ensure that it aligns with your priorities (i.e., research, undergraduate education, etc.). Consider the number of PIs conducting research in your field. These other labs may benefit your career development through collaborations, scientific discussions, letters of recommendation, career support, and feedback.

Conclusion

While there are certain key criteria that should be prioritized when choosing a lab, the path to finding (and joining) the right lab will vary from individual to individual. Gather data, ask questions, research what you can online (lab website, publication records, LinkedIn, ResearchGate, or Twitter), and be ready for the interview with a long list of written questions for the PI and lab members. One of the best ways to begin looking for a new lab is to ask your current mentor, committee members, peers, and others in your professional network for their suggestions. Table 1 has questions to keep in mind as you are searching for a lab. You will spend much of your time in the lab of your choosing, so choose wisely.

Dr. Engevik is an instructor in pathology and immunology, Baylor College of Medicine, Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston.

Introduction

As researchers, we spend a substantial period of our careers as trainees in a lab. As graduate students or postdoctoral fellows, selecting the “right” lab has the potential to make a huge difference for your future career and your mental health. Although much of the decision is based on instinct, there is still some logic and reason that can be applied to ensure the choice is a good fit.

PI/mentor

PI funding. The history of funding and the funding of your specific project are important factors to consider. No matter how significant the scientific question, not having adequate funding can be paralyzing. For both graduate students and postdoctoral fellows, it is in your best interest to proactively inquire about the funding status of the lab. This can be accomplished using online reporters (such as NIH Reporter or Grantome) and asking the PI. It is equally important to identify which grant application/fellowship will fund your stipend and ensure that the funding is secure for 4-6 years.

PI personality. For better or for worse, the PI largely sets the tone for the lab. The personality of the PI can be a key determining factor in finding the right “fit” for a trainee. Ask your peers and current and past lab members about working with the PI. As you speak to lab members and alumni, don’t disregard warning signs of unethical behavior, bullying, or harassment. Even with the rise of movements such as the #MeTooSTEM, academic misconduct is hard to correct. It is far better to avoid these labs. If available, examine the PI’s social networks (LinkedIn, Twitter, Facebook, etc.) or read previously published interviews and look for the PI’s attitude toward its lab members.

Mentoring style. The NIH emphasizes mentorship in numerous funding mechanisms; thus, it isn’t surprising that selecting an appropriate mentor is paramount for a successful training experience. A lot of this decision requires information about you as a trainee. Reflect on what type of scientific mentor will be the best fit for your needs and honestly evaluate your own communication style, expectations, and final career goals. Ask questions of the PI and lab members to identify the mentoring style. Find a mentor who takes his or her responsibility to train you seriously and who genuinely cares about the well-being of the lab personnel. Good mentors advocate for their trainees inside and outside of the lab. A mentor’s vocal support of talented trainees can help propel them toward their career goals.

Career support. One of the most important questions you need to consider is whether your mentor can help you accomplish your career goals. Be prepared to have an honest conversation with the PI about your goals. The majority of PhD scientists will pursue careers outside of academia, so choose a mentor who supports diverse career paths. A mentor who is invested in your success will work with you to finish papers in a timely manner, encourage you to apply for awards and grants, aid in the identification of fruitful collaborations, help develop new skills, and expand your professional network. A good mentor will also ensure that you have freedom in your project to pursue your own scientific interests, and ultimately allow you to carve out a project for you to take with you when your training is complete.

Research. The research done in your lab will also factor into your decision. Especially if you are a postdoctoral fellow, this will be the field/subject/niche in which you will likely establish your career and expertise. If there is a field you want to pursue, identify mentors who have a publication record in that subject. Examine the PIs for publications, citations, and overall contributions to the field. If the PI in question is young, you may not find many citations of papers. However, you can identify the quality of the papers, the lab’s experimental techniques, and how often the PI is invited to give talks on that subject.

Lab environment

The composition of a lab can play a huge role in your overall productivity and mental well-being. Your coworkers will be the ones you interact with on a day-to-day basis. Your lab mates can be a huge asset in terms of mastering new techniques, collaborating on a project, or receiving helpful feedback. Thus, it is to your benefit to get along with your lab mates and to choose a lab that has people who you want to work with or don’t mind working with. The reality of postdoctoral training is that you will spend a large amount of time working in the lab, so choosing a lab that has an environment that fits your personality and desired workload and schedule is important. Considering the valuable contribution of lab members toward your research progression, you should give considerable weight to this factor when choosing a lab.

Scientific output

Although labs with high-impact publications are attractive, it is more important to consider the frequency with which a lab comes out with papers. Search Pubmed to obtain the complete publication roster of the PI. This output will give you an idea about the consistency and regularity of publications and overall lab productivity. When querying the lab’s publication list, check if the lab members have coauthorships on manuscripts apart from their first-author ones. It is desirable to be a coauthor on other manuscripts, as this will help increase your publication record. In addition, look for collaborators of the PI. These collaborations might benefit you by broadening your skill set and experience. Be intentional about reviewing the papers from the lab over the last 5 years. If you want to pursue academic research, you will want to be in a lab that publishes frequently in well-respected journals.

Institution

The institutional environment should also influence your decision. Top universities can attract some of the best researchers. Moreover, funding agencies examine the “Environment and Institutional Commitment” as one of the criteria for awarding grants. When choosing an institution, consider its priorities and ensure that it aligns with your priorities (i.e., research, undergraduate education, etc.). Consider the number of PIs conducting research in your field. These other labs may benefit your career development through collaborations, scientific discussions, letters of recommendation, career support, and feedback.

Conclusion

While there are certain key criteria that should be prioritized when choosing a lab, the path to finding (and joining) the right lab will vary from individual to individual. Gather data, ask questions, research what you can online (lab website, publication records, LinkedIn, ResearchGate, or Twitter), and be ready for the interview with a long list of written questions for the PI and lab members. One of the best ways to begin looking for a new lab is to ask your current mentor, committee members, peers, and others in your professional network for their suggestions. Table 1 has questions to keep in mind as you are searching for a lab. You will spend much of your time in the lab of your choosing, so choose wisely.

Dr. Engevik is an instructor in pathology and immunology, Baylor College of Medicine, Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston.

Three factors predict 6-month mortality in patients with DILI

Medical comorbidity burden is significantly associated with 6-month and overall mortality in individuals with suspected drug-induced liver injury (DILI). In addition,

Those are key findings from a study which set out to investigate the association between comorbidity burden and outcomes of patients with DILI and to develop a model to calculate risk of death within 6 months.

“Drug-induced liver injury is an important cause of liver-related morbidity and mortality that is likely under-recognized,” investigators led by Marwan S. Ghabril, MD, of the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at Indiana University, Indianapolis, wrote in a study published in Gastroenterology. “Its diagnosis depends on high index of suspicion, compatible temporal relationship, and thorough exclusion of competing etiologies. DILI by an implicated drug commonly occurs in patients with one or several comorbid conditions such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, renal disease, and malignancy. However, the impact of comorbidity burden on mortality in patients with suspected DILI has not been previously investigated.”

For the current analysis and model development, the researchers drew from 306 patients enrolled in the multicenter Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network Prospective Study at Indiana University between 2003 and 2017 (discovery cohort; Drug Saf. 2009;32:55-68). To validate their model, they used data from 247 patients who were enrolled in the same study at the University of North Carolina (validation cohort). The primary outcome of interest was mortality within 6 months of onset of liver injury.

The mean ages of the discovery and validation cohorts were 49 years and 51 years, respectively. Dr. Ghabril and colleagues found that 6-month mortality was 8.5% in the discovery cohort and 4.5% in the validation cohort. “The most common class of implicated agent was antimicrobials with no significant differences between groups,” they wrote. “However, herbal and dietary supplements were predominantly implicated in patients with none to mild comorbidity, while cardiovascular agents were predominantly implicated in patients with significant comorbidity.”

Among patients in the discovery cohort, the presence of significant comorbidities, defined as a Charlson Comorbidity Index score greater than 2, was independently associated with 6-month mortality (odds ratio, 5.22), as was model for end-stage liver disease score (OR, 1.11) and serum level of albumin at presentation (OR, 0.39). When the researchers created a morbidity risk model based on those three clinical variables, it performed well, identifying patients who died within 6 months with a C statistic value of 0.89 in the discovery cohort and 0.91 in the validation cohort. This spurred the development of a web-based risk calculator, which clinicians can access at http://gihep.com/calculators/hepatology/dili-cam/.

“Since DILI is not a unique cause of liver injury, it is conceivable that models incorporating comorbidity burden and severity of liver injury could prove useful in improving the prediction of mortality in a variety of liver injuries and diseases, and as such warrants further studies,” the researchers wrote.

The study was funded by grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Dr. Ghabril reported having no financial disclosures, but two coauthors reported having numerous financial ties to industry.

SOURCE: Ghabril M et al. Gastroenterology. 2019 Jul 11. doi: 10/1053/j.gastro.2019.07.006.

Medical comorbidity burden is significantly associated with 6-month and overall mortality in individuals with suspected drug-induced liver injury (DILI). In addition,

Those are key findings from a study which set out to investigate the association between comorbidity burden and outcomes of patients with DILI and to develop a model to calculate risk of death within 6 months.

“Drug-induced liver injury is an important cause of liver-related morbidity and mortality that is likely under-recognized,” investigators led by Marwan S. Ghabril, MD, of the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at Indiana University, Indianapolis, wrote in a study published in Gastroenterology. “Its diagnosis depends on high index of suspicion, compatible temporal relationship, and thorough exclusion of competing etiologies. DILI by an implicated drug commonly occurs in patients with one or several comorbid conditions such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, renal disease, and malignancy. However, the impact of comorbidity burden on mortality in patients with suspected DILI has not been previously investigated.”

For the current analysis and model development, the researchers drew from 306 patients enrolled in the multicenter Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network Prospective Study at Indiana University between 2003 and 2017 (discovery cohort; Drug Saf. 2009;32:55-68). To validate their model, they used data from 247 patients who were enrolled in the same study at the University of North Carolina (validation cohort). The primary outcome of interest was mortality within 6 months of onset of liver injury.

The mean ages of the discovery and validation cohorts were 49 years and 51 years, respectively. Dr. Ghabril and colleagues found that 6-month mortality was 8.5% in the discovery cohort and 4.5% in the validation cohort. “The most common class of implicated agent was antimicrobials with no significant differences between groups,” they wrote. “However, herbal and dietary supplements were predominantly implicated in patients with none to mild comorbidity, while cardiovascular agents were predominantly implicated in patients with significant comorbidity.”

Among patients in the discovery cohort, the presence of significant comorbidities, defined as a Charlson Comorbidity Index score greater than 2, was independently associated with 6-month mortality (odds ratio, 5.22), as was model for end-stage liver disease score (OR, 1.11) and serum level of albumin at presentation (OR, 0.39). When the researchers created a morbidity risk model based on those three clinical variables, it performed well, identifying patients who died within 6 months with a C statistic value of 0.89 in the discovery cohort and 0.91 in the validation cohort. This spurred the development of a web-based risk calculator, which clinicians can access at http://gihep.com/calculators/hepatology/dili-cam/.

“Since DILI is not a unique cause of liver injury, it is conceivable that models incorporating comorbidity burden and severity of liver injury could prove useful in improving the prediction of mortality in a variety of liver injuries and diseases, and as such warrants further studies,” the researchers wrote.

The study was funded by grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Dr. Ghabril reported having no financial disclosures, but two coauthors reported having numerous financial ties to industry.

SOURCE: Ghabril M et al. Gastroenterology. 2019 Jul 11. doi: 10/1053/j.gastro.2019.07.006.

Medical comorbidity burden is significantly associated with 6-month and overall mortality in individuals with suspected drug-induced liver injury (DILI). In addition,

Those are key findings from a study which set out to investigate the association between comorbidity burden and outcomes of patients with DILI and to develop a model to calculate risk of death within 6 months.

“Drug-induced liver injury is an important cause of liver-related morbidity and mortality that is likely under-recognized,” investigators led by Marwan S. Ghabril, MD, of the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at Indiana University, Indianapolis, wrote in a study published in Gastroenterology. “Its diagnosis depends on high index of suspicion, compatible temporal relationship, and thorough exclusion of competing etiologies. DILI by an implicated drug commonly occurs in patients with one or several comorbid conditions such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, renal disease, and malignancy. However, the impact of comorbidity burden on mortality in patients with suspected DILI has not been previously investigated.”

For the current analysis and model development, the researchers drew from 306 patients enrolled in the multicenter Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network Prospective Study at Indiana University between 2003 and 2017 (discovery cohort; Drug Saf. 2009;32:55-68). To validate their model, they used data from 247 patients who were enrolled in the same study at the University of North Carolina (validation cohort). The primary outcome of interest was mortality within 6 months of onset of liver injury.

The mean ages of the discovery and validation cohorts were 49 years and 51 years, respectively. Dr. Ghabril and colleagues found that 6-month mortality was 8.5% in the discovery cohort and 4.5% in the validation cohort. “The most common class of implicated agent was antimicrobials with no significant differences between groups,” they wrote. “However, herbal and dietary supplements were predominantly implicated in patients with none to mild comorbidity, while cardiovascular agents were predominantly implicated in patients with significant comorbidity.”

Among patients in the discovery cohort, the presence of significant comorbidities, defined as a Charlson Comorbidity Index score greater than 2, was independently associated with 6-month mortality (odds ratio, 5.22), as was model for end-stage liver disease score (OR, 1.11) and serum level of albumin at presentation (OR, 0.39). When the researchers created a morbidity risk model based on those three clinical variables, it performed well, identifying patients who died within 6 months with a C statistic value of 0.89 in the discovery cohort and 0.91 in the validation cohort. This spurred the development of a web-based risk calculator, which clinicians can access at http://gihep.com/calculators/hepatology/dili-cam/.

“Since DILI is not a unique cause of liver injury, it is conceivable that models incorporating comorbidity burden and severity of liver injury could prove useful in improving the prediction of mortality in a variety of liver injuries and diseases, and as such warrants further studies,” the researchers wrote.

The study was funded by grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Dr. Ghabril reported having no financial disclosures, but two coauthors reported having numerous financial ties to industry.

SOURCE: Ghabril M et al. Gastroenterology. 2019 Jul 11. doi: 10/1053/j.gastro.2019.07.006.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Australia’s rotavirus outbreak wasn’t caused by vaccine effectiveness decline

In 2017, the Australian state of New South Wales experienced an outbreak of rotavirus gastroenteritis in children despite a high level of rotavirus immunization. In a new study, researchers reported evidence that suggests a decline in vaccine effectiveness (VE) isn’t the cause, although they found that VE declines over time as children age.

“More analysis is required to investigate how novel or unusual strains ... interact with rotavirus vaccines and whether antigenic changes affect VE and challenge vaccination programs,” the study authors wrote in Pediatrics.

Researchers led by Julia E. Maguire, BSc, MSci(Epi), of Australia’s National Center for Immunization Research and the Australian National University, Canberra, launched the analysis in the wake of a 2017 outbreak of 2,319 rotavirus cases in New South Wales, a 210% increase over the rate in 2016. (The state, the largest in Australia, has about 7.5 million residents.)

The study authors tracked VE from 2010 to 2017 by analyzing 9,517 rotavirus cases in the state (50% male; median age, 5 years). Half weren’t eligible for rotavirus immunization because of their age; of the rest, 31% weren’t vaccinated.

Ms. Maguire and associates found that “In our study, two doses of RV1 [the Rotarix vaccine] was 73.7% effective in protecting children aged 6 months to 9 years against laboratory-confirmed rotavirus over our 8-year study period. Somewhat surprisingly in the 2017 outbreak year, a high two-dose VE of 88.4% in those aged 6-11 months was also observed.”

They added that “the median age of rotavirus cases has increased in Australia over the last 8 years from 3.9 years in 2010 to 7.1 years in 2017. Adults and older children born before the availability of vaccination in Australia are unimmunized and may have been less likely to have repeated subclinical infections because of reductions in virus circulation overall, resulting in less immune boosting.”

Going forward, the study authors wrote that “investigation of population-level VE in relation to rotavirus genotype data should continue in a range of settings to improve our understanding of rotavirus vaccines and the impact they have on disease across the age spectrum over time.”

In an accompanying commentary, Benjamin Lee, MD, and E. Ross Colgate, PhD, of the University of Vermont, Burlington, wrote that Australia’s adoption of rotavirus immunization in 2017 “with state-level implementation of either Rotarix or RotaTeq ... enabled a fascinating natural experiment of VE and strain selection.”

Pressure from vaccines “potentially enables the emergence of novel strains,” they wrote. “Despite this, large-scale strain replacement has not been demonstrated in rotaviruses, in contrast to the development of pneumococcal serotype replacement that was seen after pneumococcal conjugate vaccine introduction. Similarly, there has been no evidence of widespread vaccine escape due to antigenic drift or shift, as occurs with another important segmented RNA virus, influenza A.”

As Dr. Lee and Dr. Colgate noted, 100 million children worldwide remain unvaccinated against rotavirus, and more than 128,000 die because of rotavirus-associated gastroenteritis each year. “Improving vaccine access and coverage and solving the riddle of [oral rotavirus vaccine] underperformance in low-income countries are urgent priorities, which may ultimately require next-generation oral and/or parenteral vaccines, a number of which are under development and in clinical trials. In addition, because the emergence of novel strains of disease-causing pathogens is always a possibility, vigilance in rotavirus surveillance, including genotype assessment, should remain a priority for public health programs.”

The study was funded by Australia’s National Center for Immunization Research and Surveillance, which receives government funding. The Australian Rotavirus Surveillance Program is supported by government funding and the vaccine companies Commonwealth Serum Laboratories and GlaxoSmithKline. Ms. Maguire is supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship. One author is director of the Australian Rotavirus Surveillance Program, which received funding as above. The other study authors and the commentary authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCES: Maguire JE et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Sep 17. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1024; Lee B, Colgate ER. Pediatrics. 2019 Sep 17. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2426.

In 2017, the Australian state of New South Wales experienced an outbreak of rotavirus gastroenteritis in children despite a high level of rotavirus immunization. In a new study, researchers reported evidence that suggests a decline in vaccine effectiveness (VE) isn’t the cause, although they found that VE declines over time as children age.

“More analysis is required to investigate how novel or unusual strains ... interact with rotavirus vaccines and whether antigenic changes affect VE and challenge vaccination programs,” the study authors wrote in Pediatrics.

Researchers led by Julia E. Maguire, BSc, MSci(Epi), of Australia’s National Center for Immunization Research and the Australian National University, Canberra, launched the analysis in the wake of a 2017 outbreak of 2,319 rotavirus cases in New South Wales, a 210% increase over the rate in 2016. (The state, the largest in Australia, has about 7.5 million residents.)

The study authors tracked VE from 2010 to 2017 by analyzing 9,517 rotavirus cases in the state (50% male; median age, 5 years). Half weren’t eligible for rotavirus immunization because of their age; of the rest, 31% weren’t vaccinated.

Ms. Maguire and associates found that “In our study, two doses of RV1 [the Rotarix vaccine] was 73.7% effective in protecting children aged 6 months to 9 years against laboratory-confirmed rotavirus over our 8-year study period. Somewhat surprisingly in the 2017 outbreak year, a high two-dose VE of 88.4% in those aged 6-11 months was also observed.”

They added that “the median age of rotavirus cases has increased in Australia over the last 8 years from 3.9 years in 2010 to 7.1 years in 2017. Adults and older children born before the availability of vaccination in Australia are unimmunized and may have been less likely to have repeated subclinical infections because of reductions in virus circulation overall, resulting in less immune boosting.”

Going forward, the study authors wrote that “investigation of population-level VE in relation to rotavirus genotype data should continue in a range of settings to improve our understanding of rotavirus vaccines and the impact they have on disease across the age spectrum over time.”

In an accompanying commentary, Benjamin Lee, MD, and E. Ross Colgate, PhD, of the University of Vermont, Burlington, wrote that Australia’s adoption of rotavirus immunization in 2017 “with state-level implementation of either Rotarix or RotaTeq ... enabled a fascinating natural experiment of VE and strain selection.”

Pressure from vaccines “potentially enables the emergence of novel strains,” they wrote. “Despite this, large-scale strain replacement has not been demonstrated in rotaviruses, in contrast to the development of pneumococcal serotype replacement that was seen after pneumococcal conjugate vaccine introduction. Similarly, there has been no evidence of widespread vaccine escape due to antigenic drift or shift, as occurs with another important segmented RNA virus, influenza A.”

As Dr. Lee and Dr. Colgate noted, 100 million children worldwide remain unvaccinated against rotavirus, and more than 128,000 die because of rotavirus-associated gastroenteritis each year. “Improving vaccine access and coverage and solving the riddle of [oral rotavirus vaccine] underperformance in low-income countries are urgent priorities, which may ultimately require next-generation oral and/or parenteral vaccines, a number of which are under development and in clinical trials. In addition, because the emergence of novel strains of disease-causing pathogens is always a possibility, vigilance in rotavirus surveillance, including genotype assessment, should remain a priority for public health programs.”

The study was funded by Australia’s National Center for Immunization Research and Surveillance, which receives government funding. The Australian Rotavirus Surveillance Program is supported by government funding and the vaccine companies Commonwealth Serum Laboratories and GlaxoSmithKline. Ms. Maguire is supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship. One author is director of the Australian Rotavirus Surveillance Program, which received funding as above. The other study authors and the commentary authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCES: Maguire JE et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Sep 17. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1024; Lee B, Colgate ER. Pediatrics. 2019 Sep 17. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2426.

In 2017, the Australian state of New South Wales experienced an outbreak of rotavirus gastroenteritis in children despite a high level of rotavirus immunization. In a new study, researchers reported evidence that suggests a decline in vaccine effectiveness (VE) isn’t the cause, although they found that VE declines over time as children age.

“More analysis is required to investigate how novel or unusual strains ... interact with rotavirus vaccines and whether antigenic changes affect VE and challenge vaccination programs,” the study authors wrote in Pediatrics.

Researchers led by Julia E. Maguire, BSc, MSci(Epi), of Australia’s National Center for Immunization Research and the Australian National University, Canberra, launched the analysis in the wake of a 2017 outbreak of 2,319 rotavirus cases in New South Wales, a 210% increase over the rate in 2016. (The state, the largest in Australia, has about 7.5 million residents.)

The study authors tracked VE from 2010 to 2017 by analyzing 9,517 rotavirus cases in the state (50% male; median age, 5 years). Half weren’t eligible for rotavirus immunization because of their age; of the rest, 31% weren’t vaccinated.

Ms. Maguire and associates found that “In our study, two doses of RV1 [the Rotarix vaccine] was 73.7% effective in protecting children aged 6 months to 9 years against laboratory-confirmed rotavirus over our 8-year study period. Somewhat surprisingly in the 2017 outbreak year, a high two-dose VE of 88.4% in those aged 6-11 months was also observed.”

They added that “the median age of rotavirus cases has increased in Australia over the last 8 years from 3.9 years in 2010 to 7.1 years in 2017. Adults and older children born before the availability of vaccination in Australia are unimmunized and may have been less likely to have repeated subclinical infections because of reductions in virus circulation overall, resulting in less immune boosting.”

Going forward, the study authors wrote that “investigation of population-level VE in relation to rotavirus genotype data should continue in a range of settings to improve our understanding of rotavirus vaccines and the impact they have on disease across the age spectrum over time.”

In an accompanying commentary, Benjamin Lee, MD, and E. Ross Colgate, PhD, of the University of Vermont, Burlington, wrote that Australia’s adoption of rotavirus immunization in 2017 “with state-level implementation of either Rotarix or RotaTeq ... enabled a fascinating natural experiment of VE and strain selection.”

Pressure from vaccines “potentially enables the emergence of novel strains,” they wrote. “Despite this, large-scale strain replacement has not been demonstrated in rotaviruses, in contrast to the development of pneumococcal serotype replacement that was seen after pneumococcal conjugate vaccine introduction. Similarly, there has been no evidence of widespread vaccine escape due to antigenic drift or shift, as occurs with another important segmented RNA virus, influenza A.”

As Dr. Lee and Dr. Colgate noted, 100 million children worldwide remain unvaccinated against rotavirus, and more than 128,000 die because of rotavirus-associated gastroenteritis each year. “Improving vaccine access and coverage and solving the riddle of [oral rotavirus vaccine] underperformance in low-income countries are urgent priorities, which may ultimately require next-generation oral and/or parenteral vaccines, a number of which are under development and in clinical trials. In addition, because the emergence of novel strains of disease-causing pathogens is always a possibility, vigilance in rotavirus surveillance, including genotype assessment, should remain a priority for public health programs.”

The study was funded by Australia’s National Center for Immunization Research and Surveillance, which receives government funding. The Australian Rotavirus Surveillance Program is supported by government funding and the vaccine companies Commonwealth Serum Laboratories and GlaxoSmithKline. Ms. Maguire is supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship. One author is director of the Australian Rotavirus Surveillance Program, which received funding as above. The other study authors and the commentary authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCES: Maguire JE et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Sep 17. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1024; Lee B, Colgate ER. Pediatrics. 2019 Sep 17. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2426.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Laser treatment of basal cell carcinoma continues to be refined

SAN DIEGO – Using laser and light sources to treat nonaggressive basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is emerging as a promising treatment option, especially for those with multiple tumors and those who are poor surgical candidates, Arisa E. Ortiz, MD, said at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium.

“Topical therapies often result in recurrence, so there really is a need for an alternative [to surgery] that’s effective, efficient, and carries a low risk of side effects,” said Dr. Ortiz, who is director of laser and cosmetic dermatology at the University of California, San Diego,

“The prototypic feature of BCC is the presence of telangiectatic vessels,” she explained, and the postulated mechanism of action is selective photothermolysis of the tumor vasculature. “These vessels are slightly larger in caliber, compared with normal skin – 40 micrometers versus 15 micrometers – and more fragile. You can tailor your pulse duration to the size of the vessels. Theoretically, by targeting the vasculature then you get tumor regression with sparing of normal tissue.”

Initial studies of this approach have used the 595-nm pulsed-dye laser, which is well absorbed by oxyhemoglobin, but more recent studies have used the 1064-nm Nd:YAG to reach deep arterial vessels. In a prospective, open-label study, 10 patients with 13 BCCs less than 1.5 cm in diameter received one treatment with a 10-ms pulsed 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser delivered on the trunk or extremities at a fluence of 80-120 J/cm2 (Lasers Surg Med. 2015;47[2]:106-10). Dr. Ortiz and her colleagues observed a 92% clearance rate overall.