User login

Early pregnancy loss and abortion: Medical management is safe, effective

NASHVILLE, TENN. – Medical management of abortion and early pregnancy loss is best achieved with both mifepristone and misoprostol, according to Sarah W. Prager, MD.

First-trimester procedures account for about 90% of elective abortions, with about two-thirds of those occurring before 8 weeks of gestation and 80% occurring in the first 10 weeks – and therefore considered eligible for medical management, Dr. Prager, director of the Family Planning Division and Family Planning Fellowship at the University of Washington, Seattle, said at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

“We estimate that it’s approximately 31% of all abortions that are done using medication, but it’s about 45% of those eligible by gestational age,” she noted.

The alternative is uterine aspiration, and in the absence of a clear contraindication, patient preference should determine management choice, she said.

The same is true for early pregnancy loss (spontaneous abortion), which is the most common complication of early pregnancy, occurring in about 20% of clinically recognized pregnancies.

“That means that there are about 1 million spontaneous abortions happening annually in the United States, and about 80% of those are in the first trimester,” Dr. Prager said.

Expectant management is an additional option for managing early pregnancy loss, she noted.

Candidates

Medical management is appropriate for patients who are undergoing elective abortion at up to about 70 days of gestation or with pregnancy loss in the first trimester.

“They should have stable vital signs, no evidence of infection, no allergies to the medications being used, no serious social or medical problems,” Dr. Prager said, explaining that “a shared decision making process” is important for patients with extreme anxiety or homelessness/lack of stable housing, for example, in order to make sure that medical management is a good option.

“While she definitely gets to have the final say, unless there is a real medical contraindication, it definitely should be part of that decision making,” Dr. Prager said, adding that adequate counseling and acceptance by the patient of the risks and side effects also are imperative.

Protocol

The most effective evidence-based treatment protocol for elective abortion through day 70 of gestation includes a 200-mg oral dose of mifepristone, followed 24-72 hours later with at-home buccal or vaginal administration of an 800-mcg dose of misoprostol, with follow up within 1-2 weeks, Dr. Prager said, citing a 2010 Cochrane review.

The Food and Drug Administration–approved protocol, which was updated in April 2016, adheres closely to those findings, except that it calls for misoprostol within 48 hours of mifepristone dosing. Optional repeat dosing of misoprostol is allowed, as well, she noted.

Buccal or vaginal administration of misoprostol is preferable to oral and sublingual administration because while the latter approaches provide more rapid onset, the former approaches provide significantly better sustained action over a 5-hour period of time.

“And by not having that big peak at the beginning, it actually decreases the side effects that women experience with the misoprostol medication,” she said.

Misoprostol can also be given alone for early pregnancy loss management – also at a dose of 800 mcg buccally or vaginally – with repeat dosing at 12-24 hours for incomplete abortion. However, new data suggest that, before about 63 days of gestation, giving two doses 3 hours apart is slightly more effective. That approach can also be repeated if necessary, Dr. Prager said.

Pain management is an important part of treatment, as both miscarriage and medication abortion can range from uncomfortable to extremely painful, depending on the patient, her prior obstetric experience, and her life experiences.

“I recommend talking to all your patients about pain management. For most people, just using some type of NSAID is probably going to be sufficient,” she said, noting that some women will require a narcotic.

Antiemetic medication may also be necessary, as some women will experience nausea and vomiting.

Complications and intervention

Major complications are rare with medical management of first-trimester abortion and early pregnancy loss, but can include ongoing pregnancy, which is infrequent but possible; incomplete abortion, which is easily managed; and allergic reactions, which are “extremely rare,” Dr. Prager said.

Hemorrhage can occur, but isn’t common and usually is at a level that doesn’t require blood transfusion. “But it does require somebody to come in, potentially needing uterine aspiration or sometimes just a second dose of misoprostol,” she said.

Serious infections are “extraordinarily uncommon,” with an actual risk of infectious death of 0.5 per 100,000, and therefore antibiotic prophylaxis is not recommended.

“This is not to say that there can’t be serious infectious problems with medication abortion, and actually also with spontaneous abortion ... but it’s extremely rare,” Dr. Prager said, adding that “there are also consequences to giving everybody antibiotics if they are not necessary. I, personally, am way more afraid of antibiotic resistance these days than I am about preventing an infection from an medication abortion.”

Intervention is necessary in certain situations, including when the gestational sac remains and when the patient continues to have clinical symptoms or has developed clinical symptoms, she said.

“Does she now show signs of infection? Is she bleeding very heavily or [is she] extremely uncomfortable with cramping? Those are all really great reasons to intervene,” she said.

Sometimes patients just prefer to switch to an alternative method of management, particularly in cases of early pregnancy loss when medical management has “not been successful after some period of time,” Dr. Prager added.

Outcomes

Studies have shown that the success rates with a single dose of 400-800 mcg of misoprostol range from 25% to 88%, and with repeat dosing for incomplete abortion at 24 hours, the success rate improves to between 80% and 88%. The success rate with placebo is 16%-60%; this indicates that “some miscarriages just happen expectantly,” Dr. Prager explained.

“We already knew that ... and that’s why expectant management is an option with early pregnancy loss,” she said, adding that expectant management works about 50% of the time – “if you wait long enough.”

However, success rates with medical management depend on the type of miscarriage; the rate is close to 100% with incomplete abortion, but for other types, such as anembryonic pregnancy or fetal demise, it is slightly less effective at about 87%, Dr. Prager noted.

When mifepristone and misoprostol are both used, success rates for early pregnancy loss range from 52% to 84% in observational trials and using nonstandard doses, and between 90% and 93% with standard dosing.

Other recent data, which led to a 2016 “reaffirmation” of an ACOG practice bulletin on medical management of first-trimester abortion, show an 83% success rate with the combination therapy in anembryonic pregnancies, and a 25% reduction in the need for further intervention (N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2161-70).

“So it really was significantly more effective to be using that addition of the mifepristone,” she said. “My take-home message about this is that, if mifepristone is something that you have easily available to you at your clinical site, absolutely use it, because it creates better outcomes for your patients. However, if it’s not available to you ... it is still perfectly reasonable for patients to choose medication management of their early pregnancy loss and use misoprostol only.

“It is effective enough, and that is just part of your informed consent.”

Postabortion care

Postmiscarriage care is important and involves several components, Dr. Prager said.

- RhoGAM treatment. The use of RhoGAM to prevent Rh immunization has been routine, but data increasingly suggest this is not necessary, and in some countries it is not given at all, particularly at 8 or fewer weeks of gestation and sometimes even during the whole first trimester for early pregnancy loss. “That is not common practice yet in the United States; I’m not recommending at this time that everybody change their practice ... but I will say that there are some really interesting studies going on right now in the United States that are looking specifically at this, and I think we may, within the next 10 years or so, change this practice of giving RhoGAM at all gestational ages,” she said.

- Counseling about bleeding. Light to moderate bleeding after abortion is common for about 2 weeks after abortion, with normal menses returning between 4 and 8 weeks, and typically around 6 weeks. “I usually ask patients to come back and see me if they have not had what seems to be a normal period to them 8 weeks following their completed process,” Dr. Prager said.

- Counseling about human chorionic gonadotropin levels. It is also helpful to inform patients that human chorionic gonadotropin may remain present for about 2-4 weeks after completed abortion, resulting in a positive pregnancy test during that time. A positive test at 4 weeks may still be normal, but warrants evaluation to determine why the patient is testing positive.

- Counseling about conception timing. Data do not support delaying repeat pregnancy after abortion. Studies show no difference in the ability to conceive or in pregnancy outcomes among women who conceive without delay after early pregnancy loss and in those who wait at least 3 months. “So what I now tell women is ‘when you’re emotionally ready to start trying to get pregnant again, it’s perfectly medically acceptable to do so. There’s no biologic reason why you have to wait,’ ” she said.

- Contraception initiation. Contraception, including IUDs, can be initiated right away after elective or spontaneous abortion. However, for IUD insertion after medical abortion, it is important to first use ultrasound to confirm complete abortion, Dr. Prager said.

- Grief counseling. This may be appropriate in cases of early pregnancy loss and for elective abortions. “Both groups of people may need some counseling, may be experiencing grief around this process – and they may not be,” she said. “I think we just need to be sensitive about asking our patients what their needs might be around this.”

Future directions

The future of medical management for first trimester abortion may involve “demedicalization,” Dr. Prager said.

“There are many papers coming out now about clinic versus home use of mifepristone,” she said, explaining that home use would require removing the FDA’s Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy restriction that requires that the drug be dispensed in a clinic by a physician or physician extender.

Studies are also looking at prescriptions, pharmacist provision of mifepristone, and mailing of medications to women in rural areas.

Another area of research beyond these “really creative ways of using these medications” is whether medical management is effective beyond 10 weeks. A study that will soon be published is looking at mifepristone and two doses of misoprostol at 11 weeks, she noted.

“I think from pregnancy diagnosis through at least week 10 – soon we will see potentially week 11 – medical abortion techniques are safe, they’re effective, and they’re extremely well accepted by patients,” she said. “Also ... a diverse group of clinicians can be trained to offer medical abortion and provide back-up so that access can be improved.”

Dr. Prager reported having no financial disclosures.

NASHVILLE, TENN. – Medical management of abortion and early pregnancy loss is best achieved with both mifepristone and misoprostol, according to Sarah W. Prager, MD.

First-trimester procedures account for about 90% of elective abortions, with about two-thirds of those occurring before 8 weeks of gestation and 80% occurring in the first 10 weeks – and therefore considered eligible for medical management, Dr. Prager, director of the Family Planning Division and Family Planning Fellowship at the University of Washington, Seattle, said at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

“We estimate that it’s approximately 31% of all abortions that are done using medication, but it’s about 45% of those eligible by gestational age,” she noted.

The alternative is uterine aspiration, and in the absence of a clear contraindication, patient preference should determine management choice, she said.

The same is true for early pregnancy loss (spontaneous abortion), which is the most common complication of early pregnancy, occurring in about 20% of clinically recognized pregnancies.

“That means that there are about 1 million spontaneous abortions happening annually in the United States, and about 80% of those are in the first trimester,” Dr. Prager said.

Expectant management is an additional option for managing early pregnancy loss, she noted.

Candidates

Medical management is appropriate for patients who are undergoing elective abortion at up to about 70 days of gestation or with pregnancy loss in the first trimester.

“They should have stable vital signs, no evidence of infection, no allergies to the medications being used, no serious social or medical problems,” Dr. Prager said, explaining that “a shared decision making process” is important for patients with extreme anxiety or homelessness/lack of stable housing, for example, in order to make sure that medical management is a good option.

“While she definitely gets to have the final say, unless there is a real medical contraindication, it definitely should be part of that decision making,” Dr. Prager said, adding that adequate counseling and acceptance by the patient of the risks and side effects also are imperative.

Protocol

The most effective evidence-based treatment protocol for elective abortion through day 70 of gestation includes a 200-mg oral dose of mifepristone, followed 24-72 hours later with at-home buccal or vaginal administration of an 800-mcg dose of misoprostol, with follow up within 1-2 weeks, Dr. Prager said, citing a 2010 Cochrane review.

The Food and Drug Administration–approved protocol, which was updated in April 2016, adheres closely to those findings, except that it calls for misoprostol within 48 hours of mifepristone dosing. Optional repeat dosing of misoprostol is allowed, as well, she noted.

Buccal or vaginal administration of misoprostol is preferable to oral and sublingual administration because while the latter approaches provide more rapid onset, the former approaches provide significantly better sustained action over a 5-hour period of time.

“And by not having that big peak at the beginning, it actually decreases the side effects that women experience with the misoprostol medication,” she said.

Misoprostol can also be given alone for early pregnancy loss management – also at a dose of 800 mcg buccally or vaginally – with repeat dosing at 12-24 hours for incomplete abortion. However, new data suggest that, before about 63 days of gestation, giving two doses 3 hours apart is slightly more effective. That approach can also be repeated if necessary, Dr. Prager said.

Pain management is an important part of treatment, as both miscarriage and medication abortion can range from uncomfortable to extremely painful, depending on the patient, her prior obstetric experience, and her life experiences.

“I recommend talking to all your patients about pain management. For most people, just using some type of NSAID is probably going to be sufficient,” she said, noting that some women will require a narcotic.

Antiemetic medication may also be necessary, as some women will experience nausea and vomiting.

Complications and intervention

Major complications are rare with medical management of first-trimester abortion and early pregnancy loss, but can include ongoing pregnancy, which is infrequent but possible; incomplete abortion, which is easily managed; and allergic reactions, which are “extremely rare,” Dr. Prager said.

Hemorrhage can occur, but isn’t common and usually is at a level that doesn’t require blood transfusion. “But it does require somebody to come in, potentially needing uterine aspiration or sometimes just a second dose of misoprostol,” she said.

Serious infections are “extraordinarily uncommon,” with an actual risk of infectious death of 0.5 per 100,000, and therefore antibiotic prophylaxis is not recommended.

“This is not to say that there can’t be serious infectious problems with medication abortion, and actually also with spontaneous abortion ... but it’s extremely rare,” Dr. Prager said, adding that “there are also consequences to giving everybody antibiotics if they are not necessary. I, personally, am way more afraid of antibiotic resistance these days than I am about preventing an infection from an medication abortion.”

Intervention is necessary in certain situations, including when the gestational sac remains and when the patient continues to have clinical symptoms or has developed clinical symptoms, she said.

“Does she now show signs of infection? Is she bleeding very heavily or [is she] extremely uncomfortable with cramping? Those are all really great reasons to intervene,” she said.

Sometimes patients just prefer to switch to an alternative method of management, particularly in cases of early pregnancy loss when medical management has “not been successful after some period of time,” Dr. Prager added.

Outcomes

Studies have shown that the success rates with a single dose of 400-800 mcg of misoprostol range from 25% to 88%, and with repeat dosing for incomplete abortion at 24 hours, the success rate improves to between 80% and 88%. The success rate with placebo is 16%-60%; this indicates that “some miscarriages just happen expectantly,” Dr. Prager explained.

“We already knew that ... and that’s why expectant management is an option with early pregnancy loss,” she said, adding that expectant management works about 50% of the time – “if you wait long enough.”

However, success rates with medical management depend on the type of miscarriage; the rate is close to 100% with incomplete abortion, but for other types, such as anembryonic pregnancy or fetal demise, it is slightly less effective at about 87%, Dr. Prager noted.

When mifepristone and misoprostol are both used, success rates for early pregnancy loss range from 52% to 84% in observational trials and using nonstandard doses, and between 90% and 93% with standard dosing.

Other recent data, which led to a 2016 “reaffirmation” of an ACOG practice bulletin on medical management of first-trimester abortion, show an 83% success rate with the combination therapy in anembryonic pregnancies, and a 25% reduction in the need for further intervention (N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2161-70).

“So it really was significantly more effective to be using that addition of the mifepristone,” she said. “My take-home message about this is that, if mifepristone is something that you have easily available to you at your clinical site, absolutely use it, because it creates better outcomes for your patients. However, if it’s not available to you ... it is still perfectly reasonable for patients to choose medication management of their early pregnancy loss and use misoprostol only.

“It is effective enough, and that is just part of your informed consent.”

Postabortion care

Postmiscarriage care is important and involves several components, Dr. Prager said.

- RhoGAM treatment. The use of RhoGAM to prevent Rh immunization has been routine, but data increasingly suggest this is not necessary, and in some countries it is not given at all, particularly at 8 or fewer weeks of gestation and sometimes even during the whole first trimester for early pregnancy loss. “That is not common practice yet in the United States; I’m not recommending at this time that everybody change their practice ... but I will say that there are some really interesting studies going on right now in the United States that are looking specifically at this, and I think we may, within the next 10 years or so, change this practice of giving RhoGAM at all gestational ages,” she said.

- Counseling about bleeding. Light to moderate bleeding after abortion is common for about 2 weeks after abortion, with normal menses returning between 4 and 8 weeks, and typically around 6 weeks. “I usually ask patients to come back and see me if they have not had what seems to be a normal period to them 8 weeks following their completed process,” Dr. Prager said.

- Counseling about human chorionic gonadotropin levels. It is also helpful to inform patients that human chorionic gonadotropin may remain present for about 2-4 weeks after completed abortion, resulting in a positive pregnancy test during that time. A positive test at 4 weeks may still be normal, but warrants evaluation to determine why the patient is testing positive.

- Counseling about conception timing. Data do not support delaying repeat pregnancy after abortion. Studies show no difference in the ability to conceive or in pregnancy outcomes among women who conceive without delay after early pregnancy loss and in those who wait at least 3 months. “So what I now tell women is ‘when you’re emotionally ready to start trying to get pregnant again, it’s perfectly medically acceptable to do so. There’s no biologic reason why you have to wait,’ ” she said.

- Contraception initiation. Contraception, including IUDs, can be initiated right away after elective or spontaneous abortion. However, for IUD insertion after medical abortion, it is important to first use ultrasound to confirm complete abortion, Dr. Prager said.

- Grief counseling. This may be appropriate in cases of early pregnancy loss and for elective abortions. “Both groups of people may need some counseling, may be experiencing grief around this process – and they may not be,” she said. “I think we just need to be sensitive about asking our patients what their needs might be around this.”

Future directions

The future of medical management for first trimester abortion may involve “demedicalization,” Dr. Prager said.

“There are many papers coming out now about clinic versus home use of mifepristone,” she said, explaining that home use would require removing the FDA’s Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy restriction that requires that the drug be dispensed in a clinic by a physician or physician extender.

Studies are also looking at prescriptions, pharmacist provision of mifepristone, and mailing of medications to women in rural areas.

Another area of research beyond these “really creative ways of using these medications” is whether medical management is effective beyond 10 weeks. A study that will soon be published is looking at mifepristone and two doses of misoprostol at 11 weeks, she noted.

“I think from pregnancy diagnosis through at least week 10 – soon we will see potentially week 11 – medical abortion techniques are safe, they’re effective, and they’re extremely well accepted by patients,” she said. “Also ... a diverse group of clinicians can be trained to offer medical abortion and provide back-up so that access can be improved.”

Dr. Prager reported having no financial disclosures.

NASHVILLE, TENN. – Medical management of abortion and early pregnancy loss is best achieved with both mifepristone and misoprostol, according to Sarah W. Prager, MD.

First-trimester procedures account for about 90% of elective abortions, with about two-thirds of those occurring before 8 weeks of gestation and 80% occurring in the first 10 weeks – and therefore considered eligible for medical management, Dr. Prager, director of the Family Planning Division and Family Planning Fellowship at the University of Washington, Seattle, said at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

“We estimate that it’s approximately 31% of all abortions that are done using medication, but it’s about 45% of those eligible by gestational age,” she noted.

The alternative is uterine aspiration, and in the absence of a clear contraindication, patient preference should determine management choice, she said.

The same is true for early pregnancy loss (spontaneous abortion), which is the most common complication of early pregnancy, occurring in about 20% of clinically recognized pregnancies.

“That means that there are about 1 million spontaneous abortions happening annually in the United States, and about 80% of those are in the first trimester,” Dr. Prager said.

Expectant management is an additional option for managing early pregnancy loss, she noted.

Candidates

Medical management is appropriate for patients who are undergoing elective abortion at up to about 70 days of gestation or with pregnancy loss in the first trimester.

“They should have stable vital signs, no evidence of infection, no allergies to the medications being used, no serious social or medical problems,” Dr. Prager said, explaining that “a shared decision making process” is important for patients with extreme anxiety or homelessness/lack of stable housing, for example, in order to make sure that medical management is a good option.

“While she definitely gets to have the final say, unless there is a real medical contraindication, it definitely should be part of that decision making,” Dr. Prager said, adding that adequate counseling and acceptance by the patient of the risks and side effects also are imperative.

Protocol

The most effective evidence-based treatment protocol for elective abortion through day 70 of gestation includes a 200-mg oral dose of mifepristone, followed 24-72 hours later with at-home buccal or vaginal administration of an 800-mcg dose of misoprostol, with follow up within 1-2 weeks, Dr. Prager said, citing a 2010 Cochrane review.

The Food and Drug Administration–approved protocol, which was updated in April 2016, adheres closely to those findings, except that it calls for misoprostol within 48 hours of mifepristone dosing. Optional repeat dosing of misoprostol is allowed, as well, she noted.

Buccal or vaginal administration of misoprostol is preferable to oral and sublingual administration because while the latter approaches provide more rapid onset, the former approaches provide significantly better sustained action over a 5-hour period of time.

“And by not having that big peak at the beginning, it actually decreases the side effects that women experience with the misoprostol medication,” she said.

Misoprostol can also be given alone for early pregnancy loss management – also at a dose of 800 mcg buccally or vaginally – with repeat dosing at 12-24 hours for incomplete abortion. However, new data suggest that, before about 63 days of gestation, giving two doses 3 hours apart is slightly more effective. That approach can also be repeated if necessary, Dr. Prager said.

Pain management is an important part of treatment, as both miscarriage and medication abortion can range from uncomfortable to extremely painful, depending on the patient, her prior obstetric experience, and her life experiences.

“I recommend talking to all your patients about pain management. For most people, just using some type of NSAID is probably going to be sufficient,” she said, noting that some women will require a narcotic.

Antiemetic medication may also be necessary, as some women will experience nausea and vomiting.

Complications and intervention

Major complications are rare with medical management of first-trimester abortion and early pregnancy loss, but can include ongoing pregnancy, which is infrequent but possible; incomplete abortion, which is easily managed; and allergic reactions, which are “extremely rare,” Dr. Prager said.

Hemorrhage can occur, but isn’t common and usually is at a level that doesn’t require blood transfusion. “But it does require somebody to come in, potentially needing uterine aspiration or sometimes just a second dose of misoprostol,” she said.

Serious infections are “extraordinarily uncommon,” with an actual risk of infectious death of 0.5 per 100,000, and therefore antibiotic prophylaxis is not recommended.

“This is not to say that there can’t be serious infectious problems with medication abortion, and actually also with spontaneous abortion ... but it’s extremely rare,” Dr. Prager said, adding that “there are also consequences to giving everybody antibiotics if they are not necessary. I, personally, am way more afraid of antibiotic resistance these days than I am about preventing an infection from an medication abortion.”

Intervention is necessary in certain situations, including when the gestational sac remains and when the patient continues to have clinical symptoms or has developed clinical symptoms, she said.

“Does she now show signs of infection? Is she bleeding very heavily or [is she] extremely uncomfortable with cramping? Those are all really great reasons to intervene,” she said.

Sometimes patients just prefer to switch to an alternative method of management, particularly in cases of early pregnancy loss when medical management has “not been successful after some period of time,” Dr. Prager added.

Outcomes

Studies have shown that the success rates with a single dose of 400-800 mcg of misoprostol range from 25% to 88%, and with repeat dosing for incomplete abortion at 24 hours, the success rate improves to between 80% and 88%. The success rate with placebo is 16%-60%; this indicates that “some miscarriages just happen expectantly,” Dr. Prager explained.

“We already knew that ... and that’s why expectant management is an option with early pregnancy loss,” she said, adding that expectant management works about 50% of the time – “if you wait long enough.”

However, success rates with medical management depend on the type of miscarriage; the rate is close to 100% with incomplete abortion, but for other types, such as anembryonic pregnancy or fetal demise, it is slightly less effective at about 87%, Dr. Prager noted.

When mifepristone and misoprostol are both used, success rates for early pregnancy loss range from 52% to 84% in observational trials and using nonstandard doses, and between 90% and 93% with standard dosing.

Other recent data, which led to a 2016 “reaffirmation” of an ACOG practice bulletin on medical management of first-trimester abortion, show an 83% success rate with the combination therapy in anembryonic pregnancies, and a 25% reduction in the need for further intervention (N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2161-70).

“So it really was significantly more effective to be using that addition of the mifepristone,” she said. “My take-home message about this is that, if mifepristone is something that you have easily available to you at your clinical site, absolutely use it, because it creates better outcomes for your patients. However, if it’s not available to you ... it is still perfectly reasonable for patients to choose medication management of their early pregnancy loss and use misoprostol only.

“It is effective enough, and that is just part of your informed consent.”

Postabortion care

Postmiscarriage care is important and involves several components, Dr. Prager said.

- RhoGAM treatment. The use of RhoGAM to prevent Rh immunization has been routine, but data increasingly suggest this is not necessary, and in some countries it is not given at all, particularly at 8 or fewer weeks of gestation and sometimes even during the whole first trimester for early pregnancy loss. “That is not common practice yet in the United States; I’m not recommending at this time that everybody change their practice ... but I will say that there are some really interesting studies going on right now in the United States that are looking specifically at this, and I think we may, within the next 10 years or so, change this practice of giving RhoGAM at all gestational ages,” she said.

- Counseling about bleeding. Light to moderate bleeding after abortion is common for about 2 weeks after abortion, with normal menses returning between 4 and 8 weeks, and typically around 6 weeks. “I usually ask patients to come back and see me if they have not had what seems to be a normal period to them 8 weeks following their completed process,” Dr. Prager said.

- Counseling about human chorionic gonadotropin levels. It is also helpful to inform patients that human chorionic gonadotropin may remain present for about 2-4 weeks after completed abortion, resulting in a positive pregnancy test during that time. A positive test at 4 weeks may still be normal, but warrants evaluation to determine why the patient is testing positive.

- Counseling about conception timing. Data do not support delaying repeat pregnancy after abortion. Studies show no difference in the ability to conceive or in pregnancy outcomes among women who conceive without delay after early pregnancy loss and in those who wait at least 3 months. “So what I now tell women is ‘when you’re emotionally ready to start trying to get pregnant again, it’s perfectly medically acceptable to do so. There’s no biologic reason why you have to wait,’ ” she said.

- Contraception initiation. Contraception, including IUDs, can be initiated right away after elective or spontaneous abortion. However, for IUD insertion after medical abortion, it is important to first use ultrasound to confirm complete abortion, Dr. Prager said.

- Grief counseling. This may be appropriate in cases of early pregnancy loss and for elective abortions. “Both groups of people may need some counseling, may be experiencing grief around this process – and they may not be,” she said. “I think we just need to be sensitive about asking our patients what their needs might be around this.”

Future directions

The future of medical management for first trimester abortion may involve “demedicalization,” Dr. Prager said.

“There are many papers coming out now about clinic versus home use of mifepristone,” she said, explaining that home use would require removing the FDA’s Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy restriction that requires that the drug be dispensed in a clinic by a physician or physician extender.

Studies are also looking at prescriptions, pharmacist provision of mifepristone, and mailing of medications to women in rural areas.

Another area of research beyond these “really creative ways of using these medications” is whether medical management is effective beyond 10 weeks. A study that will soon be published is looking at mifepristone and two doses of misoprostol at 11 weeks, she noted.

“I think from pregnancy diagnosis through at least week 10 – soon we will see potentially week 11 – medical abortion techniques are safe, they’re effective, and they’re extremely well accepted by patients,” she said. “Also ... a diverse group of clinicians can be trained to offer medical abortion and provide back-up so that access can be improved.”

Dr. Prager reported having no financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ACOG 2019

Dr. Carl Bell always asked the hard questions

Carl C. Bell, MD, started his career by asking the hard questions that no one dared to ask. His curiosity, courage, and compassion for all communities would lead him to impact the world in ways that few psychiatrists could ever imagine.

His accomplishments were many and far-reaching, dating back over 4 decades of service and research. He was a prolific author and researcher, having written more than 400 books, chapters, and articles. His research covered a lot of ground, but four critical areas of focus were childhood trauma, violence prevention, criminal justice reform, and most recently, fetal alcohol spectrum disorders.

The word “visionary” is frequently overused. But when we apply it to Dr. Carl Bell, the word does not do him justice. If you take a closer look at all four of those areas, you can see a common thread: What are the elements of a society that can tear communities apart?

When I look at Dr. Bell’s research, I see a man with a dedicated vision to addressing each of those elements in systematic way, and a determination to bring the results of that research into his Southside Chicago community in numerous ways, including by serving as president and CEO of the Community Mental Health Council, and as director of the Institute for Juvenile Research at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Dr. Bell was a leader for his patients as well as for black psychiatrists. He was a founding member of Black Psychiatrists of America and served as a mentor in some way to the vast majority of black psychiatrists currently practicing in the country. As a black male psychiatrist, I saw Dr. Bell as a source of inspiration in my career and the standard by which I measured myself. I’m not talking about awards or accomplishments, as Dr. Bell has countless accolades, including most recently, being presented this year with the American Psychiatric Association’s Adolph Meyer Award for Lifetime Achievement in Psychiatric Research and the National Medical Association’s Scroll of Merit. I am referring to Dr. Bell’s willingness to walk away from something he thought was wrong.

For every accolade he won or prestigious committee he served on, I would wager that he declined or stepped way from just as many. Dr. Bell’s character and vision for psychiatry in general, and the mental health of African American communities specifically, would not allow him to pay lip service to agendas that were self-serving, and did not push the field and communities forward.

During his service as an editorial advisory board member for Clinical Psychiatry News, Dr. Bell could always be relied upon to offer an insightful perspective to any discussion, ranging from violence prevention to the social determinants of health and their role in fetal alcohol spectrum disorders.

What I will remember most about Dr. Bell is his strong character. My guess is that he was never shy about stating the truth to a patient or a president of the United States. He possessed the intellect to back up any of his views while also having the humility of a dedicated community psychiatrist who worked for no other reason than to serve his patients.

When I first met Dr. Bell, he was giving a grand rounds at the George Washington University department of psychiatry. He was wearing a hat during the lecture and a belt with the Superman logo. I thought to myself, “Whoa, this is a different type of guy,” then I sat and listened to the talk, and was utterly astounded by his intellect, humor, honesty, and passion for his patients. I had never heard a psychiatrist speak with a combination of such command and approachability, and again, I thought to myself, “Whoa, this is a different type of guy.”

Little did I know that Dr. Bell and I would end up serving together on the editorial board of CPN. I loved seeing Dr. Bell, and catching up and gleaning from his wisdom. I was very humbled by how generous Dr. Bell was with his time and the extent to which he would make himself available as a mentor. During a CPN board meeting, we were trying to come up with a mantra that would capture the mission of the new MDedge Psychiatry website. Dr. Bell (in a hat, of course) let everyone else talk, and then, in a calm voice, said: “We ask the hard questions.” As editor in chief of MDedge Psychiatry, I knew this had to be the mantra. It was aspirational, gave us an identity, and held our feet to the fire – to always ask hard questions in the service of patients and readers. I looked forward to discussing the evolution of the site, seeing him at meetings and conferences, brainstorming the implications of new advances in the field, and simply walking down the street and laughing.

Those events will never occur again, because Carl left us on Thursday, Aug 1. Carl has left us with a legacy of work that we are still coming to appreciate. He left us with a mandate to pursue the truth and make an impact in our communities. He taught black psychiatrists what it meant to stand up unapologetically for your community and society. As I reflect on the scope of his life, I have one last hard question for Carl: “Why did you have to leave us so soon?”

Dr. Norris is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at George Washington University, Washington. He also serves as assistant dean of student affairs at the university, and medical director of psychiatric and behavioral sciences at GWU Hospital. Dr. Norris also is host of the MDedge Psychcast.

Carl C. Bell, MD, started his career by asking the hard questions that no one dared to ask. His curiosity, courage, and compassion for all communities would lead him to impact the world in ways that few psychiatrists could ever imagine.

His accomplishments were many and far-reaching, dating back over 4 decades of service and research. He was a prolific author and researcher, having written more than 400 books, chapters, and articles. His research covered a lot of ground, but four critical areas of focus were childhood trauma, violence prevention, criminal justice reform, and most recently, fetal alcohol spectrum disorders.

The word “visionary” is frequently overused. But when we apply it to Dr. Carl Bell, the word does not do him justice. If you take a closer look at all four of those areas, you can see a common thread: What are the elements of a society that can tear communities apart?

When I look at Dr. Bell’s research, I see a man with a dedicated vision to addressing each of those elements in systematic way, and a determination to bring the results of that research into his Southside Chicago community in numerous ways, including by serving as president and CEO of the Community Mental Health Council, and as director of the Institute for Juvenile Research at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Dr. Bell was a leader for his patients as well as for black psychiatrists. He was a founding member of Black Psychiatrists of America and served as a mentor in some way to the vast majority of black psychiatrists currently practicing in the country. As a black male psychiatrist, I saw Dr. Bell as a source of inspiration in my career and the standard by which I measured myself. I’m not talking about awards or accomplishments, as Dr. Bell has countless accolades, including most recently, being presented this year with the American Psychiatric Association’s Adolph Meyer Award for Lifetime Achievement in Psychiatric Research and the National Medical Association’s Scroll of Merit. I am referring to Dr. Bell’s willingness to walk away from something he thought was wrong.

For every accolade he won or prestigious committee he served on, I would wager that he declined or stepped way from just as many. Dr. Bell’s character and vision for psychiatry in general, and the mental health of African American communities specifically, would not allow him to pay lip service to agendas that were self-serving, and did not push the field and communities forward.

During his service as an editorial advisory board member for Clinical Psychiatry News, Dr. Bell could always be relied upon to offer an insightful perspective to any discussion, ranging from violence prevention to the social determinants of health and their role in fetal alcohol spectrum disorders.

What I will remember most about Dr. Bell is his strong character. My guess is that he was never shy about stating the truth to a patient or a president of the United States. He possessed the intellect to back up any of his views while also having the humility of a dedicated community psychiatrist who worked for no other reason than to serve his patients.

When I first met Dr. Bell, he was giving a grand rounds at the George Washington University department of psychiatry. He was wearing a hat during the lecture and a belt with the Superman logo. I thought to myself, “Whoa, this is a different type of guy,” then I sat and listened to the talk, and was utterly astounded by his intellect, humor, honesty, and passion for his patients. I had never heard a psychiatrist speak with a combination of such command and approachability, and again, I thought to myself, “Whoa, this is a different type of guy.”

Little did I know that Dr. Bell and I would end up serving together on the editorial board of CPN. I loved seeing Dr. Bell, and catching up and gleaning from his wisdom. I was very humbled by how generous Dr. Bell was with his time and the extent to which he would make himself available as a mentor. During a CPN board meeting, we were trying to come up with a mantra that would capture the mission of the new MDedge Psychiatry website. Dr. Bell (in a hat, of course) let everyone else talk, and then, in a calm voice, said: “We ask the hard questions.” As editor in chief of MDedge Psychiatry, I knew this had to be the mantra. It was aspirational, gave us an identity, and held our feet to the fire – to always ask hard questions in the service of patients and readers. I looked forward to discussing the evolution of the site, seeing him at meetings and conferences, brainstorming the implications of new advances in the field, and simply walking down the street and laughing.

Those events will never occur again, because Carl left us on Thursday, Aug 1. Carl has left us with a legacy of work that we are still coming to appreciate. He left us with a mandate to pursue the truth and make an impact in our communities. He taught black psychiatrists what it meant to stand up unapologetically for your community and society. As I reflect on the scope of his life, I have one last hard question for Carl: “Why did you have to leave us so soon?”

Dr. Norris is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at George Washington University, Washington. He also serves as assistant dean of student affairs at the university, and medical director of psychiatric and behavioral sciences at GWU Hospital. Dr. Norris also is host of the MDedge Psychcast.

Carl C. Bell, MD, started his career by asking the hard questions that no one dared to ask. His curiosity, courage, and compassion for all communities would lead him to impact the world in ways that few psychiatrists could ever imagine.

His accomplishments were many and far-reaching, dating back over 4 decades of service and research. He was a prolific author and researcher, having written more than 400 books, chapters, and articles. His research covered a lot of ground, but four critical areas of focus were childhood trauma, violence prevention, criminal justice reform, and most recently, fetal alcohol spectrum disorders.

The word “visionary” is frequently overused. But when we apply it to Dr. Carl Bell, the word does not do him justice. If you take a closer look at all four of those areas, you can see a common thread: What are the elements of a society that can tear communities apart?

When I look at Dr. Bell’s research, I see a man with a dedicated vision to addressing each of those elements in systematic way, and a determination to bring the results of that research into his Southside Chicago community in numerous ways, including by serving as president and CEO of the Community Mental Health Council, and as director of the Institute for Juvenile Research at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Dr. Bell was a leader for his patients as well as for black psychiatrists. He was a founding member of Black Psychiatrists of America and served as a mentor in some way to the vast majority of black psychiatrists currently practicing in the country. As a black male psychiatrist, I saw Dr. Bell as a source of inspiration in my career and the standard by which I measured myself. I’m not talking about awards or accomplishments, as Dr. Bell has countless accolades, including most recently, being presented this year with the American Psychiatric Association’s Adolph Meyer Award for Lifetime Achievement in Psychiatric Research and the National Medical Association’s Scroll of Merit. I am referring to Dr. Bell’s willingness to walk away from something he thought was wrong.

For every accolade he won or prestigious committee he served on, I would wager that he declined or stepped way from just as many. Dr. Bell’s character and vision for psychiatry in general, and the mental health of African American communities specifically, would not allow him to pay lip service to agendas that were self-serving, and did not push the field and communities forward.

During his service as an editorial advisory board member for Clinical Psychiatry News, Dr. Bell could always be relied upon to offer an insightful perspective to any discussion, ranging from violence prevention to the social determinants of health and their role in fetal alcohol spectrum disorders.

What I will remember most about Dr. Bell is his strong character. My guess is that he was never shy about stating the truth to a patient or a president of the United States. He possessed the intellect to back up any of his views while also having the humility of a dedicated community psychiatrist who worked for no other reason than to serve his patients.

When I first met Dr. Bell, he was giving a grand rounds at the George Washington University department of psychiatry. He was wearing a hat during the lecture and a belt with the Superman logo. I thought to myself, “Whoa, this is a different type of guy,” then I sat and listened to the talk, and was utterly astounded by his intellect, humor, honesty, and passion for his patients. I had never heard a psychiatrist speak with a combination of such command and approachability, and again, I thought to myself, “Whoa, this is a different type of guy.”

Little did I know that Dr. Bell and I would end up serving together on the editorial board of CPN. I loved seeing Dr. Bell, and catching up and gleaning from his wisdom. I was very humbled by how generous Dr. Bell was with his time and the extent to which he would make himself available as a mentor. During a CPN board meeting, we were trying to come up with a mantra that would capture the mission of the new MDedge Psychiatry website. Dr. Bell (in a hat, of course) let everyone else talk, and then, in a calm voice, said: “We ask the hard questions.” As editor in chief of MDedge Psychiatry, I knew this had to be the mantra. It was aspirational, gave us an identity, and held our feet to the fire – to always ask hard questions in the service of patients and readers. I looked forward to discussing the evolution of the site, seeing him at meetings and conferences, brainstorming the implications of new advances in the field, and simply walking down the street and laughing.

Those events will never occur again, because Carl left us on Thursday, Aug 1. Carl has left us with a legacy of work that we are still coming to appreciate. He left us with a mandate to pursue the truth and make an impact in our communities. He taught black psychiatrists what it meant to stand up unapologetically for your community and society. As I reflect on the scope of his life, I have one last hard question for Carl: “Why did you have to leave us so soon?”

Dr. Norris is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at George Washington University, Washington. He also serves as assistant dean of student affairs at the university, and medical director of psychiatric and behavioral sciences at GWU Hospital. Dr. Norris also is host of the MDedge Psychcast.

2019 Update on female sexual dysfunction

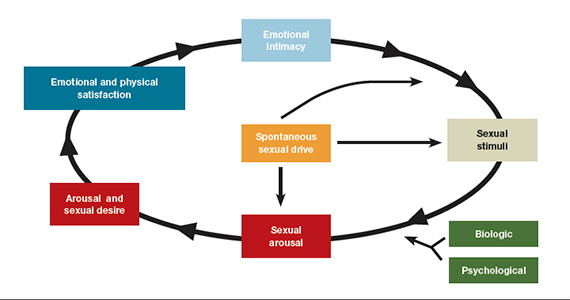

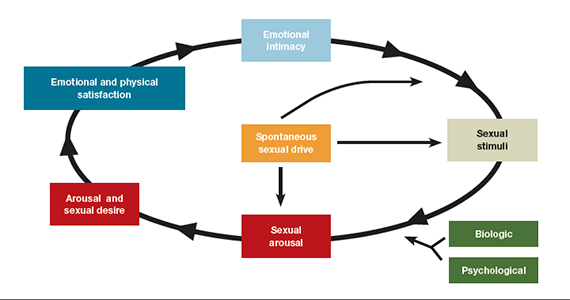

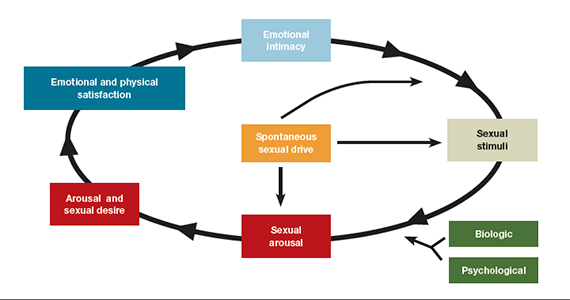

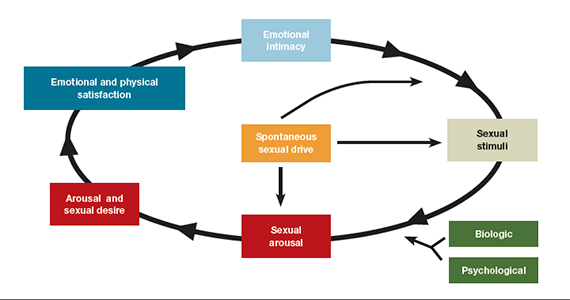

Hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) is the most prevalent sexual health problem in women of all ages, with population-based studies showing that about 36% to 39% of women report low sexual desire, and 8% to 10% meet the diagnostic criteria of low sexual desire and associated distress.1,2 An expanded definition of HSDD may include3:

- lack of motivation for sexual activity (reduced or absent spontaneous desire or responsive desire to erotic cues and stimulation; inability to maintain desire or interest through sexual activity)

- loss of desire to initiate or participate in sexual activity (including avoiding situations that could lead to sexual activity) combined with significant personal distress (frustration, loss, sadness, worry) (FIGURE).4

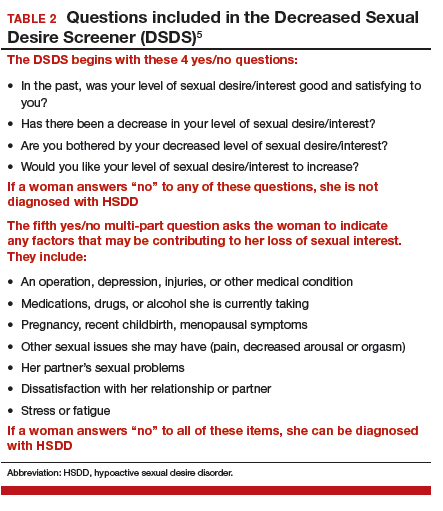

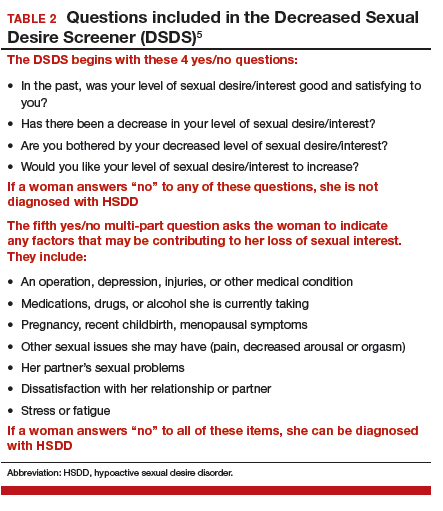

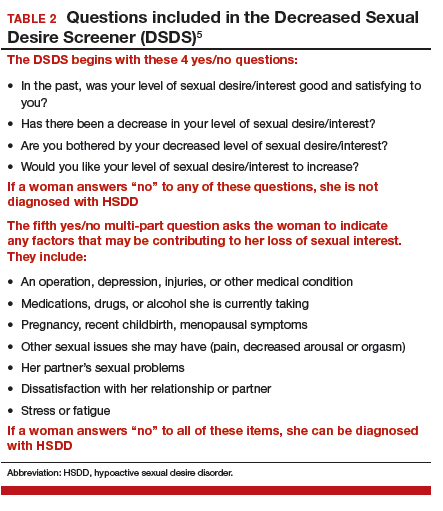

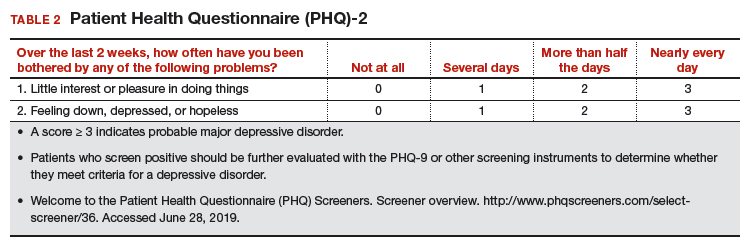

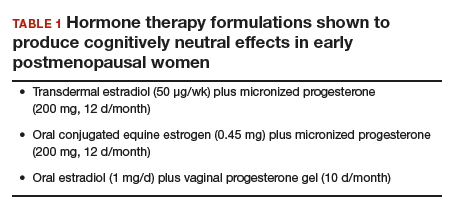

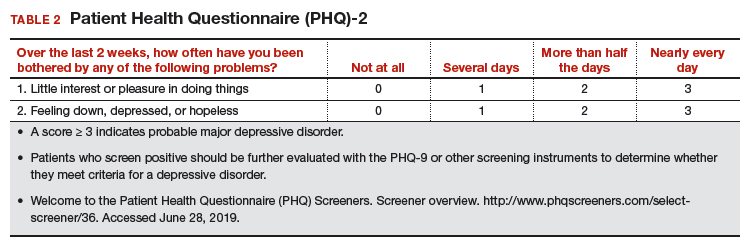

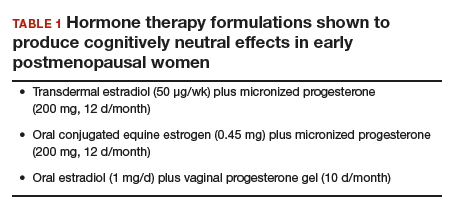

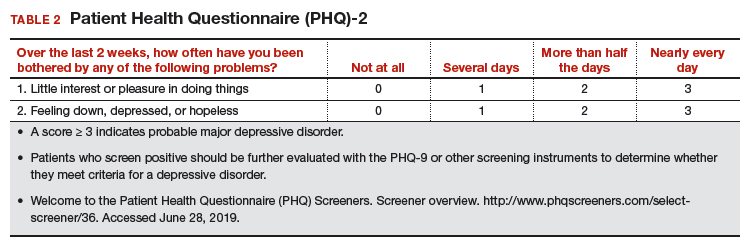

Despite the high prevalence of HSDD, patients often are uncomfortable and reluctant to voice concerns about low sexual desire to their ObGyn. Further, clinicians may feel ill equipped to diagnose and treat patients with HSDD. ObGyns, however, are well positioned to initiate a general discussion about sexual concerns with patients and use screening tools, such as the Decreased Sexual Desire Screener (DSDS), to facilitate a discussion and clarify a diagnosis of generalized acquired HSDD (TABLES 1 and 2).5 Helpful guidance on HSDD is available from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health.6-8

Importantly, clinicians have a new treatment option they can offer to patients with HSDD. Bremelanotide was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on June 21, 2019, to treat acquired, generalized HSDD in premenopausal women. Up until this approval, flibanserin (approved in 2015) was the only drug FDA approved for the treatment of HSDD.

Assessing and treating HSDD today can be likened to managing depression 30 years ago, before selective serotonin receptor inhibitors were available. ObGyns would refer patients with depression to other health care providers, or not even ask patients about depressive symptoms because we had so little to offer. Once safe and effective antidepressants became available, knowing we could provide pharmacologic options made inquiring about depressive symptoms and the use of screening tools more readily incorporated into standard clinical practice. Depression is now recognized as a medical condition with biologic underpinnings, just like HSDD, and treatment options are available for both disorders.

For this Update, I had the opportunity to discuss the clinical trial experience with bremelanotide for HSDD with Dr. Sheryl Kingsberg, including efficacy and safety, dosage and administration, contraindications, and adverse events. She also details an ideal patient for treatment with bremelanotide, and we review pertinent aspects of flibanserin for comparative purposes.

Bremelanotide: A new therapeutic option

According to the product labeling for bremelanotide, the drug is indicated for the treatment of premenopausal women with acquired, generalized HSDD (low sexual desire that causes marked distress or interpersonal difficulty).9 This means that the HSDD developed in a woman who previously did not have problems with sexual desire, and that it occurred regardless of the type of stimulation, situation, or partner. In addition, the HSDD should not result from a coexisting medical or psychiatric condition, problems with the relationship, or the effects of a medication or drug substance.

Flibanserin also is indicated for the treatment of premenopausal women with HSDD. While both bremelanotide and flibanserin have indications only for premenopausal women, 2 studies of flibanserin in postmenopausal women have been published.10,11 Results from these studies in naturally menopausal women suggest that flibanserin may be efficacious in this population, with improvement in sexual desire, reduced distress associated with low desire, and improvement in the number of satisfying sexual events (SSEs).

No trials of bremelanotide in postmenopausal women have been published, but since this drug acts on central nervous system receptors, as does flibanserin, it may have similar effectiveness in postmenopausal women as well.

Continue to: Clinical trials show bremelanotide improves desire, reduces distress...

Clinical trials show bremelanotide improves desire, reduces distress

Two phase 3 clinical trials, dubbed the Reconnect studies, demonstrated that, compared with placebo, bremelanotide was associated with statistically significant improvements in sexual desire and levels of distress regarding sexual desire.

The 2 identical, randomized, placebo-controlled multicenter trials included 1,247 premenopausal women with HSDD of at least 6 months' duration.9,12 Bremelanotide 1.75 mg (or placebo) was self-administered subcutaneously with an autoinjector on an as-desired basis. The 24-week double-blind treatment period was followed by a 52-week open-label extension study.

The co-primary efficacy end points were the change from baseline to end-of-study (week 24 of the double-blind treatment period) in the 1) Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) desire domain score and 2) feeling bothered by low sexual desire as measured by Question 13 on the Female Sexual Distress Scale (FSDS). An increase in the FSFI desire domain score over time denotes improvement in sexual desire, while a decrease in the FSDS Question 13 score over time indicates improvement in the level of distress associated with low sexual desire.

In the 2 clinical studies, the mean change from baseline (SD) in the FSFI desire domain score, which ranged from 1.2 to 6.0 at study outset (higher scores indicate greater desire), was:

- study 1: 0.5 (1.1) in the bremelanotide-treated women and 0.2 (1.0) in the placebo-treated women (P = .0002)

- study 2: 0.6 (1.0) in the bremelanotide group versus 0.2 (0.9) in the placebo group (P<.0001).

For FSDS Question 13, for which the score range was 0 to 4 (higher scores indicate greater bother), the mean change from baseline score was:

- study 1: -0.7 (1.2) in the bremelanotide-treated group compared with -0.4 (1.1) in the placebo-treated group (P<.0001)

- study 2: -0.7 (1.1) in the bremelanotide group and -0.4 (1.1) in the placebo group (P = .0053).

It should be noted that, in the past, SSEs were used as a primary end point in clinical studies. However, we have shifted from SSEs to desire and distress as an end point because SSEs have little to do with desire. Women worry about and are distressed by the fact that they no longer have sexual appetite. They no longer "want to want" even though their body will be responsive and they can have an orgasm. That is exemplified by the woman in our case scenario (see box, page 18), who very much wants the experience of being able to anticipate with pleasure the idea of having an enjoyable connection with her partner.

Continue to: Physiologic target: The melanocortin receptor...

Physiologic target: The melanocortin receptor

Bremelanotide's theorized mechanism of action is that it works to rebalance neurotransmitters that are implicated in causing HSDD, acting as an agonist on the melanocortin receptor to promote dopamine release and allow women to perceive sexual cues as rewarding. They can then respond to those cues the way they used to and therefore experience desire. Flibanserin has affinity for serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine [5-HT]) receptors, with agonist and antagonist activity, as well as moderate antagonist activity on some dopamine receptors.

The bottom line is that we now have treatments to address the underlying biologic aspect of HSDD, which is a biopsychosocial disorder. Again, this has parallels to depression and its biologic mechanism, for which we have effective treatments.

Dosing is an as-needed injection

Unlike the daily nighttime oral dose required with flibanserin, bremelanotide is a 1.75-mg dose administered as a subcutaneous injection (in either the thigh or the abdomen) with a pen-like autoinjector, on an as-needed basis. It should be administered at least 45 minutes before anticipated sexual activity. That is a benefit for many women who do not want to take a daily pill when they know that their "desire to desire" may be once per week or once every other week.

Regarding the drug delivery mode, nobody dropped out of the bremelanotide clinical trials because of having to take an injection with an autoinjector, which employs a very thin needle and is virtually painless. A small number of bremelanotide-treated women, about 13%, had injection site reactions (compared with 8% in the placebo group), which is common with subcutaneous injection. Even in the phase 2 clinical trial, in which a syringe was used to administer the drug, no participants discontinued the study because of the injection mode.

There are no clear pharmacokinetic data on how long bremelanotide's effects last, but it may be anywhere from 8 to 16 hours. Patients should not take more than 1 dose within 24 hours--but since the effect may last up to 16 hours that should not be a problem--and use of more than 8 doses per month is not recommended.

While bremelanotide improves desire, certainly better than placebo, there is also some peripheral improvement in arousal, although women in the trials had only HSDD. We do not know whether bremelanotide would treat arousal disorder, but it will help women with or without arousal difficulties associated with their HSDD, as shown in a subgroup analysis in the trials.13

Counsel patients on treatment potentialities

Clinicians should be aware of several precautions with bremelanotide use.

Blood pressure increases. After each dose of bremelanotide, transient increases in blood pressure (6 mm Hg in systolic and 3 mm Hg in diastolic blood pressure) and reductions in heart rate (up to 5 beats per minute) occur; these measurements return to baseline usually within 12 hours postdose.9 When you think about whether having sexual desire will increase blood pressure, this may be physiologic. It is similar to walking up a flight of stairs.

The drug is not recommended, however, for use in patients at high risk for cardiovascular disease, and it is contraindicated in women with uncontrolled hypertension or known cardiovascular disease. Blood pressure should be well controlled before bremelanotide is initiated--use of antihypertensive agents is not contraindicated with bremelanotide as the drugs do not interact.

Clinicians are not required to participate in a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program to prescribe bremelanotide as they are with flibanserin (because of the increased risk of severe hypotension and syncope due to flibanserin's interaction with alcohol).

Drug interactions. Bremelanotide is a melanocortin receptor agonist--a unique compound. Antidepressants, other psychoactive medications, and oral contraceptives are not contraindicated with bremelanotide as there are no known interactions. Alcohol use also is not a contraindication or caution, in contrast to flibanserin. (In April, the FDA issued a labeling change order for flibanserin, specifying that alcohol does not have to be avoided completely when taking flibanserin, but that women should discontinue drinking alcohol at least 2 hours before taking the drug at bedtime, or skip the flibanserin dose that evening.14) Bremelanotide may slow gastric emptying, though, so when a patient is taking oral drugs that require threshold concentrations for efficacy, such as antibiotics, they should avoid bremelanotide. In addition, some drugs, such as indomethacin, may have a delayed onset of action with concomitant bremelanotide use.9

Importantly, patients should avoid using bremelanotide if they are taking an oral naltrexone product for treatment of alcohol or opioid addiction, because bremelanotide may decrease systemic exposure of oral naltrexone. That would potentially lead to naltrexone treatment failure and its consequences.9

Skin pigmentation changes. Hyperpigmentation occurred with bremelanotide use on the face, gingiva, and breasts, as reported in the clinical trials, in 1% of treated patients who received up to 8 doses per month, compared with no such occurrences in placebo-treated patients. In addition, 38% of patients who received bremelanotide daily for 8 days developed focal hyperpigmentation. It was not confirmed in all patients whether the hyperpigmentation resolved. Women with dark skin were more likely to develop hyperpigmentation.9

Common adverse reactions. The most common adverse reactions with bremelanotide treatment are nausea, flushing, injection site reactions, and headache, with most events being mild to moderate in intensity. In the clinical trials, 40% of the bremelanotide-treated women experienced nausea (compared with 1% of placebo-treated women), with most occurrences being mild; for most participants nausea improved with the second dose. Women had nausea that either went away or was intermittent, or it was mild enough that the drug benefits outweighed the tolerability costs--of women who experienced nausea, 92% continued in the trial, and 8% dropped out because of nausea.9

The following scenario describes the experience of HSDD in one of Dr. Kingsberg's patients.

CASE Woman avoids sex because of low desire; marriage is suffering

A 40-year-old woman, Sandra, who has been married for 19 years and has fraternal twins aged 8, presented to the behavioral medicine clinic with distressing symptoms of low sexual desire. For several years into the marriage the patient experienced excellent sex drive. After 6 to 7 years, she noticed that her desire had declined and that she was starting to avoid sex. She was irritated when her husband initiated sex, and she would make excuses as to why it was not the right time.

Her husband felt hurt, frustrated, and rejected. The couple was close to divorce because he was angry and resentful. Sandra recognized there was a problem but did not know how to fix it. She could not understand why her interest had waned since she still loved her husband and considered him objectively very attractive.

Sandra came to see Dr. Kingsberg at the behavioral medicine clinic. Using the 5-item validated diagnostic tool called the Decreased Sexual Desire Screener, Dr. Kingsberg diagnosed hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD), a term Sandra had never heard of and did not know was a condition. The patient was relieved to know that she was one of several million women affected by HSDD and that the problem was not just that she was a "bad wife" or that she had some kind of psychological block. She emphasized how much she loved her husband and how she wanted desperately to "want to want desire," as she recalled feeling previously.

Sandra was treated with counseling and psychotherapy in which we addressed the relationship issues, the avoidance of sex, the comfort with being sexual, and the recognition that responsive desire can be helpful (as she was able to have arousal and orgasm and have a satisfying sexual event). The issue was that she had no motivation to seek out sex and had no interest in experiencing that pleasure. In subsequent couple's therapy, the husband recognized that his wife was not intentionally rejecting him, but that she had a real medical condition.

Although Sandra's relationship was now more stable and she and her husband were both working toward finding a solution to Sandra's loss of desire, she was still very distressed by her lack of desire. Sandra tried flibanserin for 3 months but unfortunately did not respond. Sandra heard about the recent approval of bremelanotide and is looking forward to the drug being available so that she can try it.

Final considerations

Asking patients about sexual function and using sexual function screening tools can help clinicians identify patients with the decreased sexual desire and associated distress characteristic of HSDD. ObGyns are the appropriate clinicians to treat these women and soon will have 2 pharmacologic options--bremelanotide (anticipated to be available in Fall 2019) and flibanserin--to offer patients with this biopsychosocial disorder that can adversely impact well-being and quality of life. Clinicians should individualize treatment, which may include psychotherapeutic counseling, and counsel patients on appropriate drug use and potential adverse effects.

AMAG Pharmaceuticals, Inc. has announced that they will have a copay assistance program for bremelanotide, where the first prescription of four autoinjectors will be a $0 copay, followed by a $99 copay or less for refills.15

- Shifren JL, Monz BU, Russo PA, et al. Sexual problems and distress in United States women: prevalence and correlates. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:970-978.

- West SL, D'Aloisio AA, Agans RP, et al. Prevalence of low sexual desire and hypoactive sexual desire disorder in a nationally representative sample of US women. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1441-1449.

- Parish SJ, Goldstein AT, Goldstein SW, et al. Toward a more evidence-based nosology and nomenclature for female sexual dysfunctions: part II. J Sex Med. 2016;13:1888-1906.

- Basson R. Using a different model for female sexual response to address women's problematic low sexual desire. J Sex Marital Ther. 2001;27:395-403.

- Clayton AH, Goldfischer ER, Goldstein I, et al. Validation of the Decreased Sexual Desire Screener (DSDS): a brief diagnostic instrument for generalized acquired female hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD). J Sex Med. 2009;6:730-738.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin no. 213: Female sexual dysfunction. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:e1-e18.

- Goldstein I, Kim NN, Clayton AH, et al. Hypoactive sexual desire disorder: International Society for the Study of Women's Sexual Health (ISSWSH) expert consensus panel review. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:114-128.

- Clayton AH, Goldstein I, Kim NN, et al. The International Society for the Study of Women's Sexual Health process of care for management of hypoactive sexual desire disorder in women. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018;93:467-487.

- Vyleesi [package insert]. Waltham, MA: AMAG Pharmaceuticals; 2019.

- Simon JA, Kingsberg SA, Shumel B, et al. Efficacy and safety of flibanserin in postmenopausal women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder: results of the SNOWDROP trial. Menopause. 2014;21;633-640.

- Portman DJ, Brown L, Yuan, et al. Flibanserin in postmenopausal women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder: results of the PLUMERIA study. J Sex Med. 2017;14:834-842.

- Kingsberg SA, Clayton AH, Portman D, et al. Bremelanotide for the treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder: two randomized phase 3 trials. Obstet Gynecol. Forthcoming.

- Clayton AH, Lucas J, Jordon R, et al. Efficacy of the Investigational drug bremelanotide in the Reconnect studies. Poster presented at: 30th ECNP Congress of Applied and Translational Neuroscience; September 2-5, 2017, Paris, France.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA orders important safety labeling changes for Addyi [press release]. April 11, 2019. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-orders-important-safety-labeling-changes-addyi. Accessed July 17, 2019.

- Vyleesi website (https://vyleesipro.com). Accessed August 5, 2019.

Hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) is the most prevalent sexual health problem in women of all ages, with population-based studies showing that about 36% to 39% of women report low sexual desire, and 8% to 10% meet the diagnostic criteria of low sexual desire and associated distress.1,2 An expanded definition of HSDD may include3:

- lack of motivation for sexual activity (reduced or absent spontaneous desire or responsive desire to erotic cues and stimulation; inability to maintain desire or interest through sexual activity)

- loss of desire to initiate or participate in sexual activity (including avoiding situations that could lead to sexual activity) combined with significant personal distress (frustration, loss, sadness, worry) (FIGURE).4

Despite the high prevalence of HSDD, patients often are uncomfortable and reluctant to voice concerns about low sexual desire to their ObGyn. Further, clinicians may feel ill equipped to diagnose and treat patients with HSDD. ObGyns, however, are well positioned to initiate a general discussion about sexual concerns with patients and use screening tools, such as the Decreased Sexual Desire Screener (DSDS), to facilitate a discussion and clarify a diagnosis of generalized acquired HSDD (TABLES 1 and 2).5 Helpful guidance on HSDD is available from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health.6-8

Importantly, clinicians have a new treatment option they can offer to patients with HSDD. Bremelanotide was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on June 21, 2019, to treat acquired, generalized HSDD in premenopausal women. Up until this approval, flibanserin (approved in 2015) was the only drug FDA approved for the treatment of HSDD.

Assessing and treating HSDD today can be likened to managing depression 30 years ago, before selective serotonin receptor inhibitors were available. ObGyns would refer patients with depression to other health care providers, or not even ask patients about depressive symptoms because we had so little to offer. Once safe and effective antidepressants became available, knowing we could provide pharmacologic options made inquiring about depressive symptoms and the use of screening tools more readily incorporated into standard clinical practice. Depression is now recognized as a medical condition with biologic underpinnings, just like HSDD, and treatment options are available for both disorders.

For this Update, I had the opportunity to discuss the clinical trial experience with bremelanotide for HSDD with Dr. Sheryl Kingsberg, including efficacy and safety, dosage and administration, contraindications, and adverse events. She also details an ideal patient for treatment with bremelanotide, and we review pertinent aspects of flibanserin for comparative purposes.

Bremelanotide: A new therapeutic option

According to the product labeling for bremelanotide, the drug is indicated for the treatment of premenopausal women with acquired, generalized HSDD (low sexual desire that causes marked distress or interpersonal difficulty).9 This means that the HSDD developed in a woman who previously did not have problems with sexual desire, and that it occurred regardless of the type of stimulation, situation, or partner. In addition, the HSDD should not result from a coexisting medical or psychiatric condition, problems with the relationship, or the effects of a medication or drug substance.

Flibanserin also is indicated for the treatment of premenopausal women with HSDD. While both bremelanotide and flibanserin have indications only for premenopausal women, 2 studies of flibanserin in postmenopausal women have been published.10,11 Results from these studies in naturally menopausal women suggest that flibanserin may be efficacious in this population, with improvement in sexual desire, reduced distress associated with low desire, and improvement in the number of satisfying sexual events (SSEs).

No trials of bremelanotide in postmenopausal women have been published, but since this drug acts on central nervous system receptors, as does flibanserin, it may have similar effectiveness in postmenopausal women as well.

Continue to: Clinical trials show bremelanotide improves desire, reduces distress...

Clinical trials show bremelanotide improves desire, reduces distress

Two phase 3 clinical trials, dubbed the Reconnect studies, demonstrated that, compared with placebo, bremelanotide was associated with statistically significant improvements in sexual desire and levels of distress regarding sexual desire.

The 2 identical, randomized, placebo-controlled multicenter trials included 1,247 premenopausal women with HSDD of at least 6 months' duration.9,12 Bremelanotide 1.75 mg (or placebo) was self-administered subcutaneously with an autoinjector on an as-desired basis. The 24-week double-blind treatment period was followed by a 52-week open-label extension study.

The co-primary efficacy end points were the change from baseline to end-of-study (week 24 of the double-blind treatment period) in the 1) Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) desire domain score and 2) feeling bothered by low sexual desire as measured by Question 13 on the Female Sexual Distress Scale (FSDS). An increase in the FSFI desire domain score over time denotes improvement in sexual desire, while a decrease in the FSDS Question 13 score over time indicates improvement in the level of distress associated with low sexual desire.

In the 2 clinical studies, the mean change from baseline (SD) in the FSFI desire domain score, which ranged from 1.2 to 6.0 at study outset (higher scores indicate greater desire), was:

- study 1: 0.5 (1.1) in the bremelanotide-treated women and 0.2 (1.0) in the placebo-treated women (P = .0002)

- study 2: 0.6 (1.0) in the bremelanotide group versus 0.2 (0.9) in the placebo group (P<.0001).

For FSDS Question 13, for which the score range was 0 to 4 (higher scores indicate greater bother), the mean change from baseline score was:

- study 1: -0.7 (1.2) in the bremelanotide-treated group compared with -0.4 (1.1) in the placebo-treated group (P<.0001)

- study 2: -0.7 (1.1) in the bremelanotide group and -0.4 (1.1) in the placebo group (P = .0053).

It should be noted that, in the past, SSEs were used as a primary end point in clinical studies. However, we have shifted from SSEs to desire and distress as an end point because SSEs have little to do with desire. Women worry about and are distressed by the fact that they no longer have sexual appetite. They no longer "want to want" even though their body will be responsive and they can have an orgasm. That is exemplified by the woman in our case scenario (see box, page 18), who very much wants the experience of being able to anticipate with pleasure the idea of having an enjoyable connection with her partner.

Continue to: Physiologic target: The melanocortin receptor...

Physiologic target: The melanocortin receptor