User login

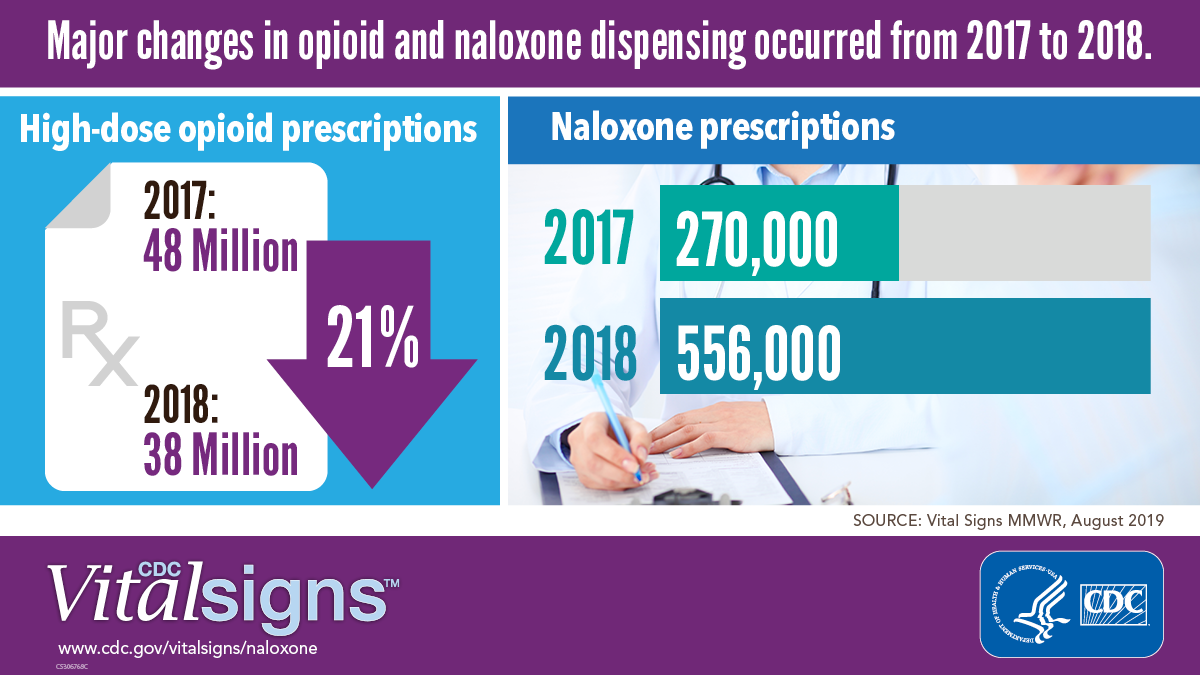

CDC finds that too little naloxone is dispensed

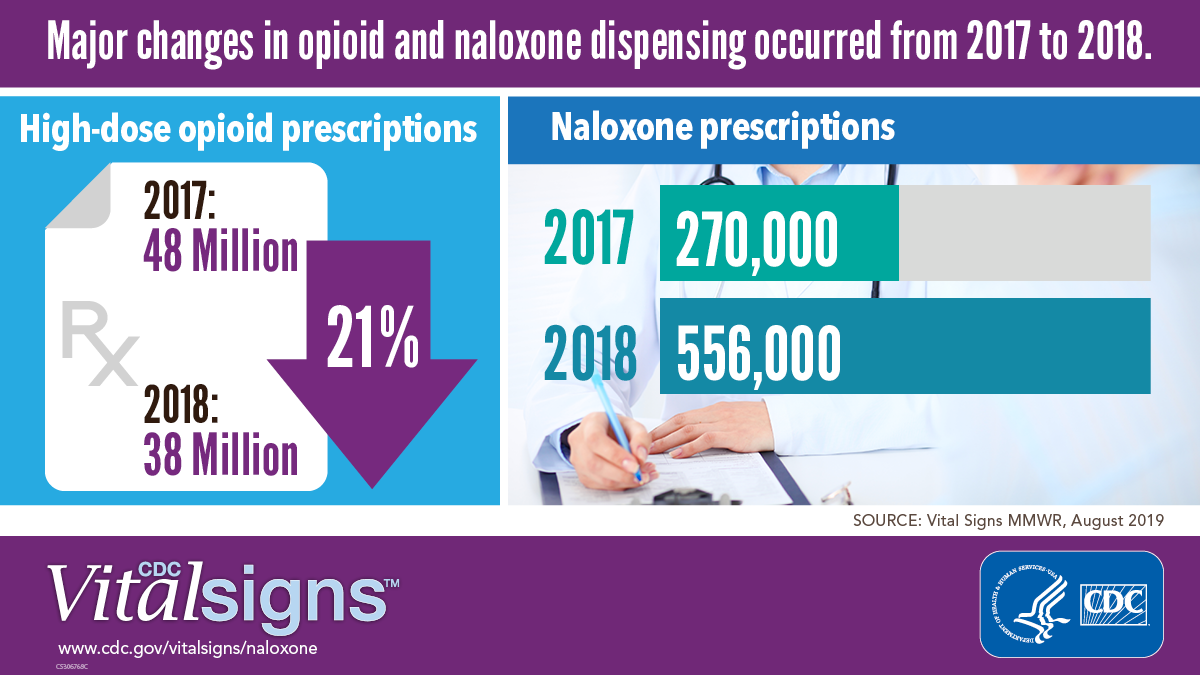

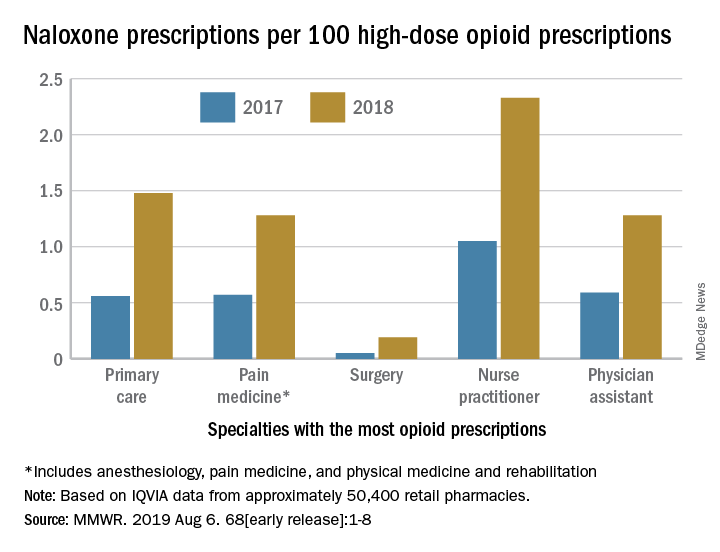

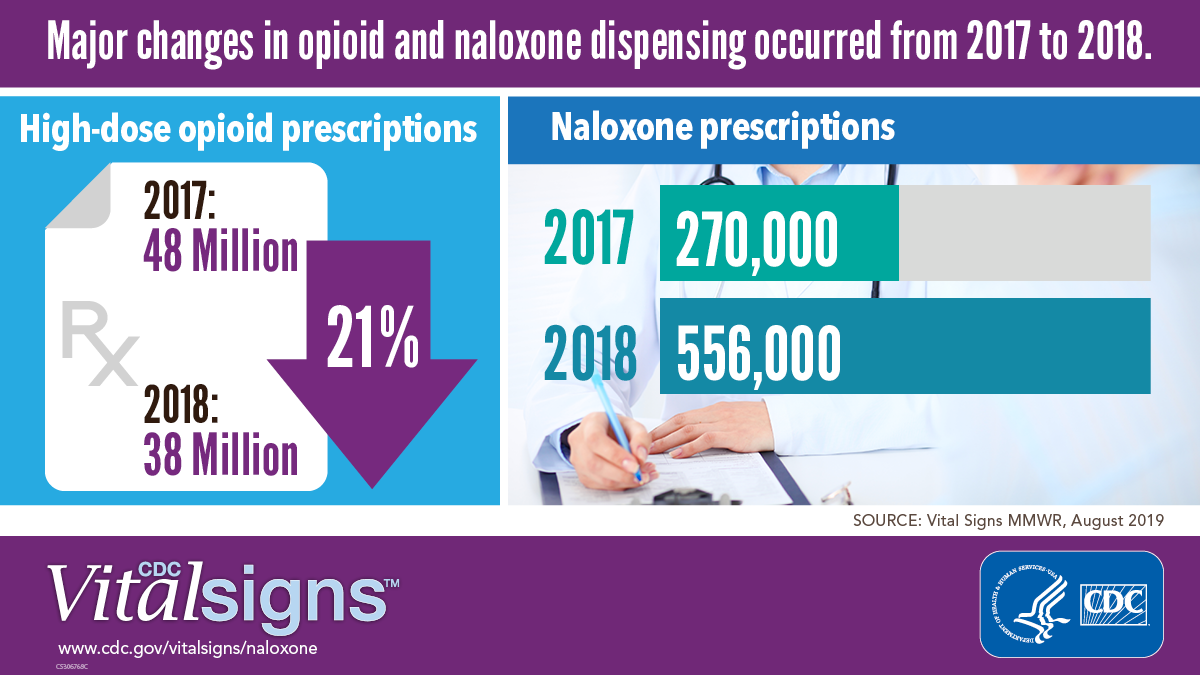

Although the CDC recommends that clinicians consider prescribing naloxone, which can reverse the effects of an opioid overdose, to patients who receive high-dose opioid prescriptions, one naloxone prescription was dispensed in 2018 for every 69 such patients, according to a Vital Signs investigation published Aug. 6 in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Approximately 9 million more naloxone prescriptions could have been dispensed in 2018 if every patient with a high-dose opioid prescription were offered the drug, according to the agency. In addition, the rate at which naloxone is dispensed varies significantly according to region.

“Thousands of Americans are alive today thanks to the use of naloxone,” said Alex M. Azar, secretary of Health and Human Services, in a press release. “Giving people a chance to survive an opioid overdose and safely enter recovery is one of the five key pillars of our HHS strategy for ending the overdose epidemic. With help from Congress, the private sector, state, and local governments and communities, targeted access to naloxone has expanded dramatically over the last several years, but today’s CDC report is a reminder that there is much more all of us need to do to save lives.”

Investigators examined retail pharmacy data

In 2017, 47,600 (67.8%) drug overdose deaths in the United States involved opioids. For decades, emergency medical service providers have administered naloxone to patients with suspected drug overdose. A major focus of public health initiatives intended to address the opioid overdose crisis has been to increase access to naloxone through clinician prescribing and pharmacy dispensing. The CDC recommends considering prescribing naloxone to patients with a history of overdose or substance use disorder, those receiving opioid dosages of 50 morphine milligram equivalents per day or greater (that is, high-dose prescriptions), and those who are using benzodiazepines concurrently.

Investigators at the CDC examined retail pharmacy data from IQVIA, a company that maintains information on prescriptions from approximately 50,400 retail pharmacies. They extracted data from 2012 through 2018 to analyze naloxone dispensing by region, urban versus rural status, prescriber specialty, and recipient characteristics (for example, age group, sex, out-of-pocket costs, and method of payment).

Dispensations doubled from 2017 to 2018

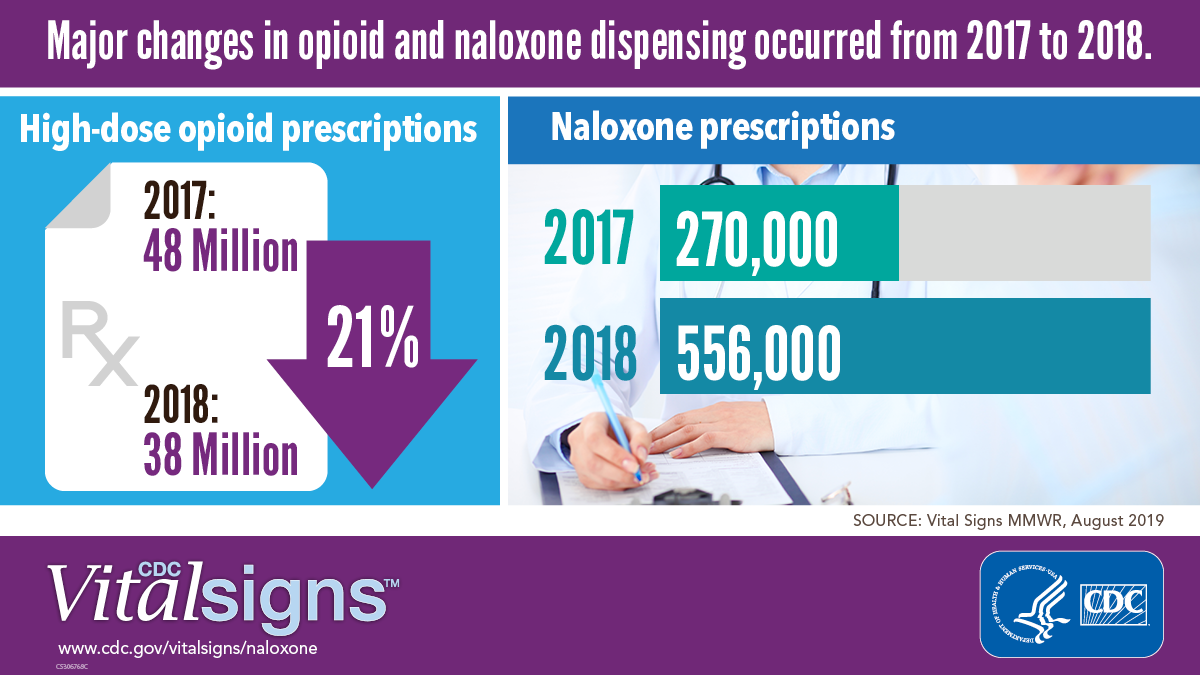

Naloxone dispensing from retail pharmacies increased from 0.4 prescriptions per 100,000 in 2012 to 170.2 prescriptions per 100,000 in 2018. From 2017 to 2018 alone, the number of prescriptions dispensed increased by 106%.

Despite consistency among state laws, naloxone dispensation varied by region. The average rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions ranged from 0.2 in the lowest quartile to 2.9 in the highest quartile. In 2018, the rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions ranged from 1.5 in metropolitan counties and 1.6 in the Northeast to 1.2 in rural counties and 1.3 in the Midwest. Rural counties were nearly three times more likely to be low-dispensing counties, compared with metropolitan counties.

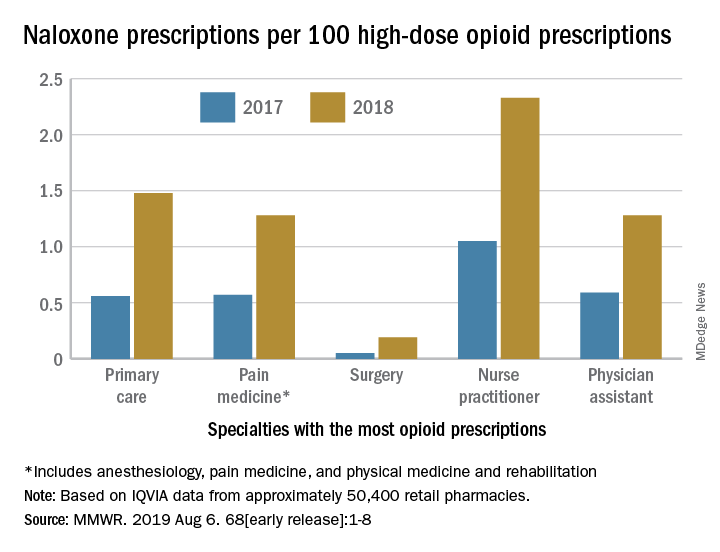

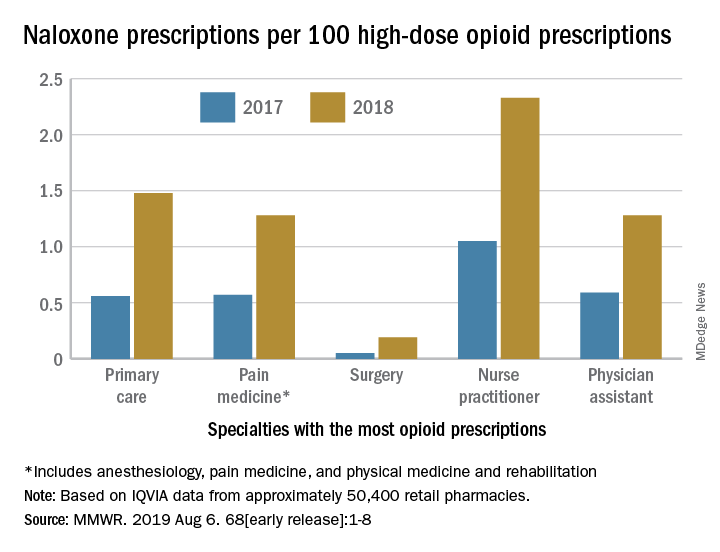

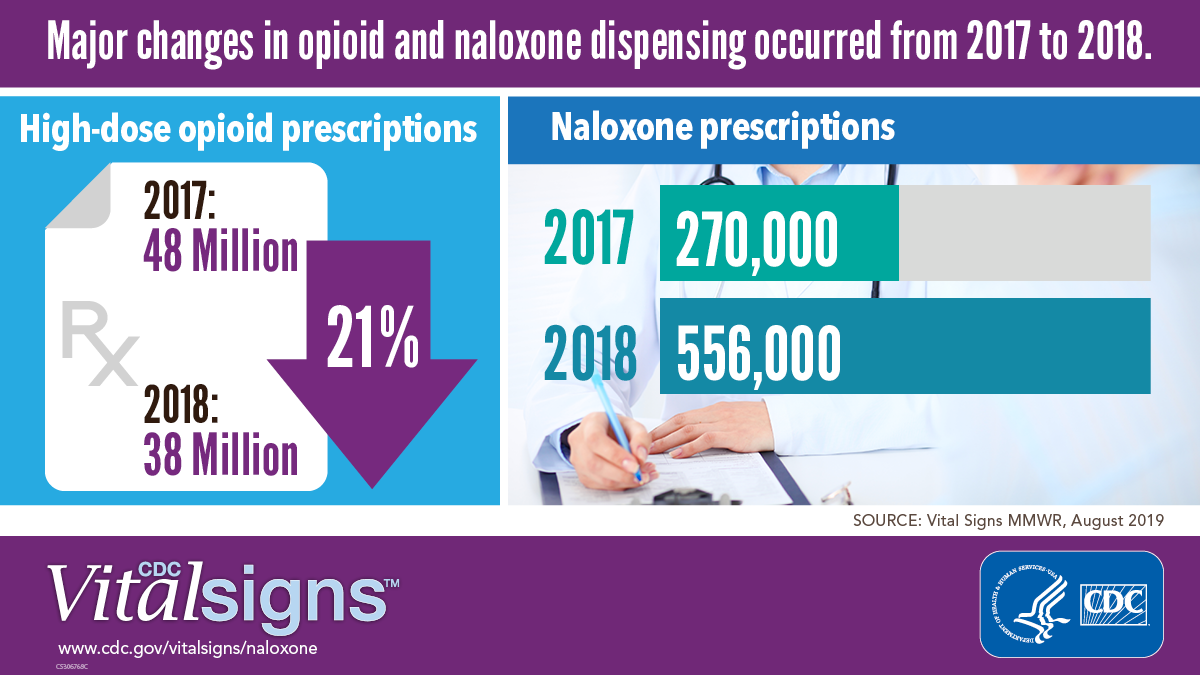

The rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions also varied by provider specialty. This rate was lowest among surgeons (0.2) and highest among psychiatrists (12.9).

Most naloxone prescriptions entailed out-of-pocket costs. About 71% of prescriptions paid for by Medicare entailed out-of-pocket costs, compared with 43.8% of prescriptions paid for by Medicaid, and 41.5% of prescriptions paid for by commercial insurance.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

More can be done

“It is clear from the data that there is still much needed education around the important role naloxone plays in reducing overdose deaths,” said Robert R. Redfield, MD, director of the CDC, in a press release. “The time is now to ensure all individuals who are prescribed high-dose opioids also receive naloxone as a potential life-saving intervention. As we aggressively confront what is the public health crisis of our time, CDC will continue to stress with health care providers the benefit of making this overdose-reversing medicine available to patients.”

“While we’ve seen these important increases [in naloxone prescriptions], we are not as far along as we’d like to be,” said Anne Schuchat, MD, principal deputy director of the CDC, during a press conference. “Cost is one of the issues, but I think awareness is another.” These data should prompt pharmacies to make sure that they stock naloxone and remind clinicians to consider naloxone when they prescribe opioids, she added. Patients and their family members should be aware of naloxone and ask their health care providers about it. “We’d really like to see the increase [in naloxone prescriptions] move much more rapidly,” she concluded.

The investigators disclosed no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Guy GP et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Aug 6.

Although the CDC recommends that clinicians consider prescribing naloxone, which can reverse the effects of an opioid overdose, to patients who receive high-dose opioid prescriptions, one naloxone prescription was dispensed in 2018 for every 69 such patients, according to a Vital Signs investigation published Aug. 6 in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Approximately 9 million more naloxone prescriptions could have been dispensed in 2018 if every patient with a high-dose opioid prescription were offered the drug, according to the agency. In addition, the rate at which naloxone is dispensed varies significantly according to region.

“Thousands of Americans are alive today thanks to the use of naloxone,” said Alex M. Azar, secretary of Health and Human Services, in a press release. “Giving people a chance to survive an opioid overdose and safely enter recovery is one of the five key pillars of our HHS strategy for ending the overdose epidemic. With help from Congress, the private sector, state, and local governments and communities, targeted access to naloxone has expanded dramatically over the last several years, but today’s CDC report is a reminder that there is much more all of us need to do to save lives.”

Investigators examined retail pharmacy data

In 2017, 47,600 (67.8%) drug overdose deaths in the United States involved opioids. For decades, emergency medical service providers have administered naloxone to patients with suspected drug overdose. A major focus of public health initiatives intended to address the opioid overdose crisis has been to increase access to naloxone through clinician prescribing and pharmacy dispensing. The CDC recommends considering prescribing naloxone to patients with a history of overdose or substance use disorder, those receiving opioid dosages of 50 morphine milligram equivalents per day or greater (that is, high-dose prescriptions), and those who are using benzodiazepines concurrently.

Investigators at the CDC examined retail pharmacy data from IQVIA, a company that maintains information on prescriptions from approximately 50,400 retail pharmacies. They extracted data from 2012 through 2018 to analyze naloxone dispensing by region, urban versus rural status, prescriber specialty, and recipient characteristics (for example, age group, sex, out-of-pocket costs, and method of payment).

Dispensations doubled from 2017 to 2018

Naloxone dispensing from retail pharmacies increased from 0.4 prescriptions per 100,000 in 2012 to 170.2 prescriptions per 100,000 in 2018. From 2017 to 2018 alone, the number of prescriptions dispensed increased by 106%.

Despite consistency among state laws, naloxone dispensation varied by region. The average rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions ranged from 0.2 in the lowest quartile to 2.9 in the highest quartile. In 2018, the rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions ranged from 1.5 in metropolitan counties and 1.6 in the Northeast to 1.2 in rural counties and 1.3 in the Midwest. Rural counties were nearly three times more likely to be low-dispensing counties, compared with metropolitan counties.

The rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions also varied by provider specialty. This rate was lowest among surgeons (0.2) and highest among psychiatrists (12.9).

Most naloxone prescriptions entailed out-of-pocket costs. About 71% of prescriptions paid for by Medicare entailed out-of-pocket costs, compared with 43.8% of prescriptions paid for by Medicaid, and 41.5% of prescriptions paid for by commercial insurance.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

More can be done

“It is clear from the data that there is still much needed education around the important role naloxone plays in reducing overdose deaths,” said Robert R. Redfield, MD, director of the CDC, in a press release. “The time is now to ensure all individuals who are prescribed high-dose opioids also receive naloxone as a potential life-saving intervention. As we aggressively confront what is the public health crisis of our time, CDC will continue to stress with health care providers the benefit of making this overdose-reversing medicine available to patients.”

“While we’ve seen these important increases [in naloxone prescriptions], we are not as far along as we’d like to be,” said Anne Schuchat, MD, principal deputy director of the CDC, during a press conference. “Cost is one of the issues, but I think awareness is another.” These data should prompt pharmacies to make sure that they stock naloxone and remind clinicians to consider naloxone when they prescribe opioids, she added. Patients and their family members should be aware of naloxone and ask their health care providers about it. “We’d really like to see the increase [in naloxone prescriptions] move much more rapidly,” she concluded.

The investigators disclosed no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Guy GP et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Aug 6.

Although the CDC recommends that clinicians consider prescribing naloxone, which can reverse the effects of an opioid overdose, to patients who receive high-dose opioid prescriptions, one naloxone prescription was dispensed in 2018 for every 69 such patients, according to a Vital Signs investigation published Aug. 6 in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Approximately 9 million more naloxone prescriptions could have been dispensed in 2018 if every patient with a high-dose opioid prescription were offered the drug, according to the agency. In addition, the rate at which naloxone is dispensed varies significantly according to region.

“Thousands of Americans are alive today thanks to the use of naloxone,” said Alex M. Azar, secretary of Health and Human Services, in a press release. “Giving people a chance to survive an opioid overdose and safely enter recovery is one of the five key pillars of our HHS strategy for ending the overdose epidemic. With help from Congress, the private sector, state, and local governments and communities, targeted access to naloxone has expanded dramatically over the last several years, but today’s CDC report is a reminder that there is much more all of us need to do to save lives.”

Investigators examined retail pharmacy data

In 2017, 47,600 (67.8%) drug overdose deaths in the United States involved opioids. For decades, emergency medical service providers have administered naloxone to patients with suspected drug overdose. A major focus of public health initiatives intended to address the opioid overdose crisis has been to increase access to naloxone through clinician prescribing and pharmacy dispensing. The CDC recommends considering prescribing naloxone to patients with a history of overdose or substance use disorder, those receiving opioid dosages of 50 morphine milligram equivalents per day or greater (that is, high-dose prescriptions), and those who are using benzodiazepines concurrently.

Investigators at the CDC examined retail pharmacy data from IQVIA, a company that maintains information on prescriptions from approximately 50,400 retail pharmacies. They extracted data from 2012 through 2018 to analyze naloxone dispensing by region, urban versus rural status, prescriber specialty, and recipient characteristics (for example, age group, sex, out-of-pocket costs, and method of payment).

Dispensations doubled from 2017 to 2018

Naloxone dispensing from retail pharmacies increased from 0.4 prescriptions per 100,000 in 2012 to 170.2 prescriptions per 100,000 in 2018. From 2017 to 2018 alone, the number of prescriptions dispensed increased by 106%.

Despite consistency among state laws, naloxone dispensation varied by region. The average rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions ranged from 0.2 in the lowest quartile to 2.9 in the highest quartile. In 2018, the rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions ranged from 1.5 in metropolitan counties and 1.6 in the Northeast to 1.2 in rural counties and 1.3 in the Midwest. Rural counties were nearly three times more likely to be low-dispensing counties, compared with metropolitan counties.

The rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions also varied by provider specialty. This rate was lowest among surgeons (0.2) and highest among psychiatrists (12.9).

Most naloxone prescriptions entailed out-of-pocket costs. About 71% of prescriptions paid for by Medicare entailed out-of-pocket costs, compared with 43.8% of prescriptions paid for by Medicaid, and 41.5% of prescriptions paid for by commercial insurance.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

More can be done

“It is clear from the data that there is still much needed education around the important role naloxone plays in reducing overdose deaths,” said Robert R. Redfield, MD, director of the CDC, in a press release. “The time is now to ensure all individuals who are prescribed high-dose opioids also receive naloxone as a potential life-saving intervention. As we aggressively confront what is the public health crisis of our time, CDC will continue to stress with health care providers the benefit of making this overdose-reversing medicine available to patients.”

“While we’ve seen these important increases [in naloxone prescriptions], we are not as far along as we’d like to be,” said Anne Schuchat, MD, principal deputy director of the CDC, during a press conference. “Cost is one of the issues, but I think awareness is another.” These data should prompt pharmacies to make sure that they stock naloxone and remind clinicians to consider naloxone when they prescribe opioids, she added. Patients and their family members should be aware of naloxone and ask their health care providers about it. “We’d really like to see the increase [in naloxone prescriptions] move much more rapidly,” she concluded.

The investigators disclosed no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Guy GP et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Aug 6.

FROM MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY WEEKLY REPORT

Preoperative tramadol fails to improve function after knee surgery

according to findings of a study based on pre- and postsurgery data.

Tramadol has become a popular choice for nonoperative knee pain relief because of its low potential for abuse and favorable safety profile, but its impact on postoperative outcomes when given before knee surgery has not been well studied, wrote Adam Driesman, MD, of the New York University Langone Orthopedic Hospital and colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of Arthroplasty, the researchers compared patient-reported outcomes (PRO) after total knee arthroplasty among 136 patients who received no opiates, 21 who received tramadol, and 42 who received other opiates. All patients who did not have preoperative and postoperative PRO scores were excluded

All patients received the same multimodal perioperative pain protocol, and all were placed on oxycodone postoperatively for maintenance and breakthrough pain as needed, with discharge prescriptions for acetaminophen/oxycodone combination (Percocet) for breakthrough pain.

Patients preoperative assessment using the Knee Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score Jr. (KOOS, JR.) were similar among the groups prior to surgery; baseline scores for the groups receiving either tramadol, no opiates, or other opiates were 49.95, 50.4, and 48.0, respectively. Demographics also were not significantly different among the groups.

At 3 months, the average KOOS, JR., score for the tramadol group (62.4) was significantly lower, compared with the other-opiate group (67.1) and treatment-naive group (70.1). In addition, patients in the tramadol group had the least change in scores on KOOS, JR., with an average of 12.5 points, compared with 19.1-point and 20.1-point improvements, respectively, in the alternate-opiate group and opiate-naive group.

The data expand on previous findings that patients given preoperative opioids had proportionally less postoperative pain relief than those not on opioids, the researchers said, but noted that they were surprised by the worse outcomes in the tramadol group given its demonstrated side-effect profile.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the retrospective design and relatively short follow-up period, as well as the inability to accurately determine outpatient medication use, not only of opioids, but of nonopioid postoperative pain medications that could have affected the results, the researchers said.

“However, given the conflicting evidence presented in this study and despite the 2013 American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons Clinical Practice Guidelines, it is recommended providers remain very conservative in their administration of outpatient narcotics including tramadol prior to surgery,” they concluded.

chestphysiciannews@chestnet.org

SOURCE: Driesman A et al. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34(8):1662-66.

according to findings of a study based on pre- and postsurgery data.

Tramadol has become a popular choice for nonoperative knee pain relief because of its low potential for abuse and favorable safety profile, but its impact on postoperative outcomes when given before knee surgery has not been well studied, wrote Adam Driesman, MD, of the New York University Langone Orthopedic Hospital and colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of Arthroplasty, the researchers compared patient-reported outcomes (PRO) after total knee arthroplasty among 136 patients who received no opiates, 21 who received tramadol, and 42 who received other opiates. All patients who did not have preoperative and postoperative PRO scores were excluded

All patients received the same multimodal perioperative pain protocol, and all were placed on oxycodone postoperatively for maintenance and breakthrough pain as needed, with discharge prescriptions for acetaminophen/oxycodone combination (Percocet) for breakthrough pain.

Patients preoperative assessment using the Knee Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score Jr. (KOOS, JR.) were similar among the groups prior to surgery; baseline scores for the groups receiving either tramadol, no opiates, or other opiates were 49.95, 50.4, and 48.0, respectively. Demographics also were not significantly different among the groups.

At 3 months, the average KOOS, JR., score for the tramadol group (62.4) was significantly lower, compared with the other-opiate group (67.1) and treatment-naive group (70.1). In addition, patients in the tramadol group had the least change in scores on KOOS, JR., with an average of 12.5 points, compared with 19.1-point and 20.1-point improvements, respectively, in the alternate-opiate group and opiate-naive group.

The data expand on previous findings that patients given preoperative opioids had proportionally less postoperative pain relief than those not on opioids, the researchers said, but noted that they were surprised by the worse outcomes in the tramadol group given its demonstrated side-effect profile.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the retrospective design and relatively short follow-up period, as well as the inability to accurately determine outpatient medication use, not only of opioids, but of nonopioid postoperative pain medications that could have affected the results, the researchers said.

“However, given the conflicting evidence presented in this study and despite the 2013 American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons Clinical Practice Guidelines, it is recommended providers remain very conservative in their administration of outpatient narcotics including tramadol prior to surgery,” they concluded.

chestphysiciannews@chestnet.org

SOURCE: Driesman A et al. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34(8):1662-66.

according to findings of a study based on pre- and postsurgery data.

Tramadol has become a popular choice for nonoperative knee pain relief because of its low potential for abuse and favorable safety profile, but its impact on postoperative outcomes when given before knee surgery has not been well studied, wrote Adam Driesman, MD, of the New York University Langone Orthopedic Hospital and colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of Arthroplasty, the researchers compared patient-reported outcomes (PRO) after total knee arthroplasty among 136 patients who received no opiates, 21 who received tramadol, and 42 who received other opiates. All patients who did not have preoperative and postoperative PRO scores were excluded

All patients received the same multimodal perioperative pain protocol, and all were placed on oxycodone postoperatively for maintenance and breakthrough pain as needed, with discharge prescriptions for acetaminophen/oxycodone combination (Percocet) for breakthrough pain.

Patients preoperative assessment using the Knee Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score Jr. (KOOS, JR.) were similar among the groups prior to surgery; baseline scores for the groups receiving either tramadol, no opiates, or other opiates were 49.95, 50.4, and 48.0, respectively. Demographics also were not significantly different among the groups.

At 3 months, the average KOOS, JR., score for the tramadol group (62.4) was significantly lower, compared with the other-opiate group (67.1) and treatment-naive group (70.1). In addition, patients in the tramadol group had the least change in scores on KOOS, JR., with an average of 12.5 points, compared with 19.1-point and 20.1-point improvements, respectively, in the alternate-opiate group and opiate-naive group.

The data expand on previous findings that patients given preoperative opioids had proportionally less postoperative pain relief than those not on opioids, the researchers said, but noted that they were surprised by the worse outcomes in the tramadol group given its demonstrated side-effect profile.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the retrospective design and relatively short follow-up period, as well as the inability to accurately determine outpatient medication use, not only of opioids, but of nonopioid postoperative pain medications that could have affected the results, the researchers said.

“However, given the conflicting evidence presented in this study and despite the 2013 American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons Clinical Practice Guidelines, it is recommended providers remain very conservative in their administration of outpatient narcotics including tramadol prior to surgery,” they concluded.

chestphysiciannews@chestnet.org

SOURCE: Driesman A et al. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34(8):1662-66.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF ARTHROPLASTY

Endoscopic duodenal mucosal resection found effective for some patients with T2D

Among patients with suboptimally controlled type 2 diabetes who use oral glucose-lowering medication, endoscopic duodenal mucosal resection (DMR) can be implemented safely and effectively, results from a multicenter, international, phase 2 study demonstrated.

“DMR elicited a substantial improvement in parameters of glycemia as well as a decrease in liver transaminase levels at 24 weeks, which was sustained at 12 months post procedure,” researchers led by Annieke C.G. van Baar, MD, wrote in a study published online in Gut. “These findings were also associated with an improvement in patients’ diabetes treatment satisfaction.”

For the study, Dr. van Baar, of the department of gastroenterology and hepatology at Amsterdam University Medical Center, and colleagues at seven clinical sites enrolled 46 patients with type 2 diabetes who were on stable glucose-lowering medication to undergo DMR. The procedure “involves circumferential hydrothermal ablation of the duodenal mucosa resulting in subsequent regeneration of the mucosa,” they wrote. “Before ablation, the mucosa is lifted with saline to protect the outer layers of the duodenum.” DMR was performed under either general anesthesia or deep sedation with propofol by a single endoscopist at each site with extensive experience in therapeutic upper GI endoscopy and guidewire management.

The mean age of the study participants was 55 years and 63% were male. Of the 46 patients, 37 (80%) underwent complete DMR and results were reported for 36 of them. A total of 24 patients had at least one adverse event related to DMR (52%), mostly GI symptoms such as diarrhea, abdominal pain, nausea, and oropharyngeal pain. Of these, 81% were mild. One serious adverse event was considered to be related to the procedure. “This concerned a patient with general malaise, mild fever, and increased C-reactive protein level on the first day after DMR,” the researchers wrote. “The mild fever resolved within 24 hours and [C-reactive protein] level normalized within 3 days.” No unanticipated adverse events were reported.

During follow-up measures taken 24 weeks after their DMR, hemoglobin A1c fell by a mean of 10 mmol/mol (P less than .001), fasting plasma glucose by 1.7 mmol/L (P less than .001), and the Homeostatic Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance improved significantly (P less than .001). In addition, the procedure conferred a moderate reduction in weight (a mean loss of 2.5 kg) and a decrease in hepatic transaminase levels. The effects were sustained at 12 months.

“While the majority of patients showed a durable glycemic response over 12 months, a minority exhibited less benefit from DMR and required additional glucose-lowering medication at 24 weeks,” the researchers wrote. “Of note, approximately two-thirds of the patients who required addition of antidiabetic medication in the latter phase of study had undergone insulin secretagogue medication withdrawal at screening. For future study, it may not be necessary to discontinue these medications before DMR, and this will allow an even more precise measure of DMR effect.”

Dr. van Baar and colleagues acknowledged certain limitations of the phase 2 study, including its open-label, uncontrolled design. “The results of this multicenter study need to be confirmed in a proper controlled study. Nevertheless, this study forms the requisite solid foundation for further research, and controlled studies are currently underway.”

The study was funded by Fractyl Laboratories. Dr. van Baar reported having no financial disclosures. Four of the study authors reported having financial relationships with numerous pharmaceutical and device companies.

SOURCE: van Baar ACG et al. Gut. 2019 Jul 22. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318349.

Among patients with suboptimally controlled type 2 diabetes who use oral glucose-lowering medication, endoscopic duodenal mucosal resection (DMR) can be implemented safely and effectively, results from a multicenter, international, phase 2 study demonstrated.

“DMR elicited a substantial improvement in parameters of glycemia as well as a decrease in liver transaminase levels at 24 weeks, which was sustained at 12 months post procedure,” researchers led by Annieke C.G. van Baar, MD, wrote in a study published online in Gut. “These findings were also associated with an improvement in patients’ diabetes treatment satisfaction.”

For the study, Dr. van Baar, of the department of gastroenterology and hepatology at Amsterdam University Medical Center, and colleagues at seven clinical sites enrolled 46 patients with type 2 diabetes who were on stable glucose-lowering medication to undergo DMR. The procedure “involves circumferential hydrothermal ablation of the duodenal mucosa resulting in subsequent regeneration of the mucosa,” they wrote. “Before ablation, the mucosa is lifted with saline to protect the outer layers of the duodenum.” DMR was performed under either general anesthesia or deep sedation with propofol by a single endoscopist at each site with extensive experience in therapeutic upper GI endoscopy and guidewire management.

The mean age of the study participants was 55 years and 63% were male. Of the 46 patients, 37 (80%) underwent complete DMR and results were reported for 36 of them. A total of 24 patients had at least one adverse event related to DMR (52%), mostly GI symptoms such as diarrhea, abdominal pain, nausea, and oropharyngeal pain. Of these, 81% were mild. One serious adverse event was considered to be related to the procedure. “This concerned a patient with general malaise, mild fever, and increased C-reactive protein level on the first day after DMR,” the researchers wrote. “The mild fever resolved within 24 hours and [C-reactive protein] level normalized within 3 days.” No unanticipated adverse events were reported.

During follow-up measures taken 24 weeks after their DMR, hemoglobin A1c fell by a mean of 10 mmol/mol (P less than .001), fasting plasma glucose by 1.7 mmol/L (P less than .001), and the Homeostatic Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance improved significantly (P less than .001). In addition, the procedure conferred a moderate reduction in weight (a mean loss of 2.5 kg) and a decrease in hepatic transaminase levels. The effects were sustained at 12 months.

“While the majority of patients showed a durable glycemic response over 12 months, a minority exhibited less benefit from DMR and required additional glucose-lowering medication at 24 weeks,” the researchers wrote. “Of note, approximately two-thirds of the patients who required addition of antidiabetic medication in the latter phase of study had undergone insulin secretagogue medication withdrawal at screening. For future study, it may not be necessary to discontinue these medications before DMR, and this will allow an even more precise measure of DMR effect.”

Dr. van Baar and colleagues acknowledged certain limitations of the phase 2 study, including its open-label, uncontrolled design. “The results of this multicenter study need to be confirmed in a proper controlled study. Nevertheless, this study forms the requisite solid foundation for further research, and controlled studies are currently underway.”

The study was funded by Fractyl Laboratories. Dr. van Baar reported having no financial disclosures. Four of the study authors reported having financial relationships with numerous pharmaceutical and device companies.

SOURCE: van Baar ACG et al. Gut. 2019 Jul 22. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318349.

Among patients with suboptimally controlled type 2 diabetes who use oral glucose-lowering medication, endoscopic duodenal mucosal resection (DMR) can be implemented safely and effectively, results from a multicenter, international, phase 2 study demonstrated.

“DMR elicited a substantial improvement in parameters of glycemia as well as a decrease in liver transaminase levels at 24 weeks, which was sustained at 12 months post procedure,” researchers led by Annieke C.G. van Baar, MD, wrote in a study published online in Gut. “These findings were also associated with an improvement in patients’ diabetes treatment satisfaction.”

For the study, Dr. van Baar, of the department of gastroenterology and hepatology at Amsterdam University Medical Center, and colleagues at seven clinical sites enrolled 46 patients with type 2 diabetes who were on stable glucose-lowering medication to undergo DMR. The procedure “involves circumferential hydrothermal ablation of the duodenal mucosa resulting in subsequent regeneration of the mucosa,” they wrote. “Before ablation, the mucosa is lifted with saline to protect the outer layers of the duodenum.” DMR was performed under either general anesthesia or deep sedation with propofol by a single endoscopist at each site with extensive experience in therapeutic upper GI endoscopy and guidewire management.

The mean age of the study participants was 55 years and 63% were male. Of the 46 patients, 37 (80%) underwent complete DMR and results were reported for 36 of them. A total of 24 patients had at least one adverse event related to DMR (52%), mostly GI symptoms such as diarrhea, abdominal pain, nausea, and oropharyngeal pain. Of these, 81% were mild. One serious adverse event was considered to be related to the procedure. “This concerned a patient with general malaise, mild fever, and increased C-reactive protein level on the first day after DMR,” the researchers wrote. “The mild fever resolved within 24 hours and [C-reactive protein] level normalized within 3 days.” No unanticipated adverse events were reported.

During follow-up measures taken 24 weeks after their DMR, hemoglobin A1c fell by a mean of 10 mmol/mol (P less than .001), fasting plasma glucose by 1.7 mmol/L (P less than .001), and the Homeostatic Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance improved significantly (P less than .001). In addition, the procedure conferred a moderate reduction in weight (a mean loss of 2.5 kg) and a decrease in hepatic transaminase levels. The effects were sustained at 12 months.

“While the majority of patients showed a durable glycemic response over 12 months, a minority exhibited less benefit from DMR and required additional glucose-lowering medication at 24 weeks,” the researchers wrote. “Of note, approximately two-thirds of the patients who required addition of antidiabetic medication in the latter phase of study had undergone insulin secretagogue medication withdrawal at screening. For future study, it may not be necessary to discontinue these medications before DMR, and this will allow an even more precise measure of DMR effect.”

Dr. van Baar and colleagues acknowledged certain limitations of the phase 2 study, including its open-label, uncontrolled design. “The results of this multicenter study need to be confirmed in a proper controlled study. Nevertheless, this study forms the requisite solid foundation for further research, and controlled studies are currently underway.”

The study was funded by Fractyl Laboratories. Dr. van Baar reported having no financial disclosures. Four of the study authors reported having financial relationships with numerous pharmaceutical and device companies.

SOURCE: van Baar ACG et al. Gut. 2019 Jul 22. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318349.

FROM GUT

Rubbery Nodule on the Face of an Infant

The Diagnosis: Juvenile Xanthogranuloma

Juvenile xanthogranuloma (JXG) was first described in 1905 by Adamson1 as solitary or multiple plaquiform or nodular lesions that are yellow to yellowish brown. In 1954, Helwig and Hackney2 coined the term juvenile xanthogranuloma to define this histiocytic cutaneous granulomatous tumor.

Juvenile xanthogranuloma is a rare dermatologic disorder that may be present at birth and primarily affects infants and young children. The benign lesions generally occur in the first 4 years of life, with a median age of onset of 2 years.3 Lesions range in size from millimeters to several centimeters in diameter.4 The skin of the head and neck is the most commonly involved site in JXG. The most frequent noncutaneous site of JXG involvement is the eye, particularly the iris, accounting for 0.4% of cases.5,6 Extracutaneous sites such as the heart, liver, lungs, spleen, oral cavity, and brain also may be involved.4

Most children with JXG are asymptomatic. Skin lesions present as well-demarcated, rubbery, tan-orange papules or nodules. They usually are solitary, and multiple nodules can increase the risk for extracutaneous involvement.4 A case series of patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 showed 14 of 77 (18%) patients examined in the first year of life presented with JXG or other non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis.7 The adult form of cutaneous xanthogranuloma often presents with severe bronchial asthma.8

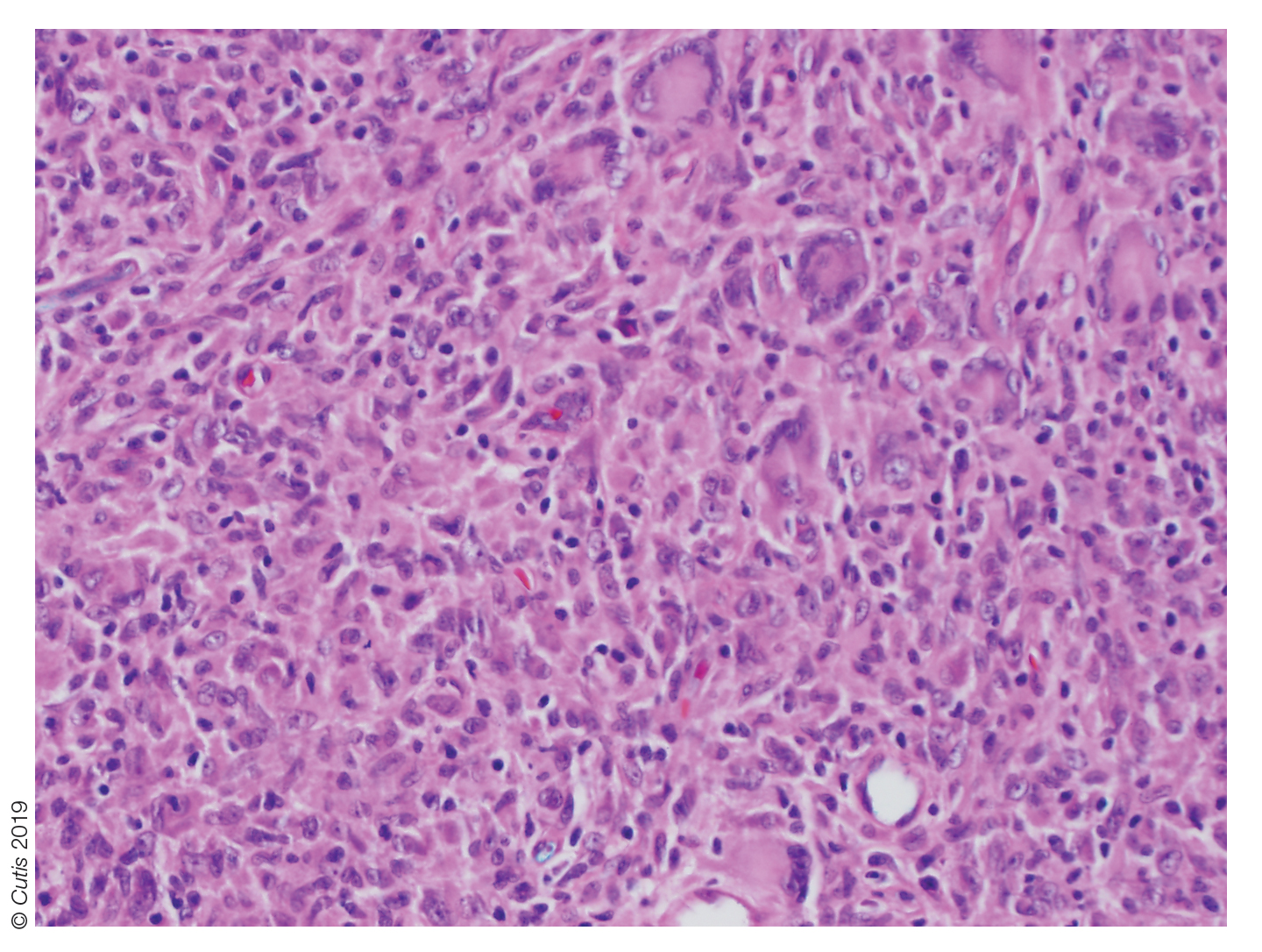

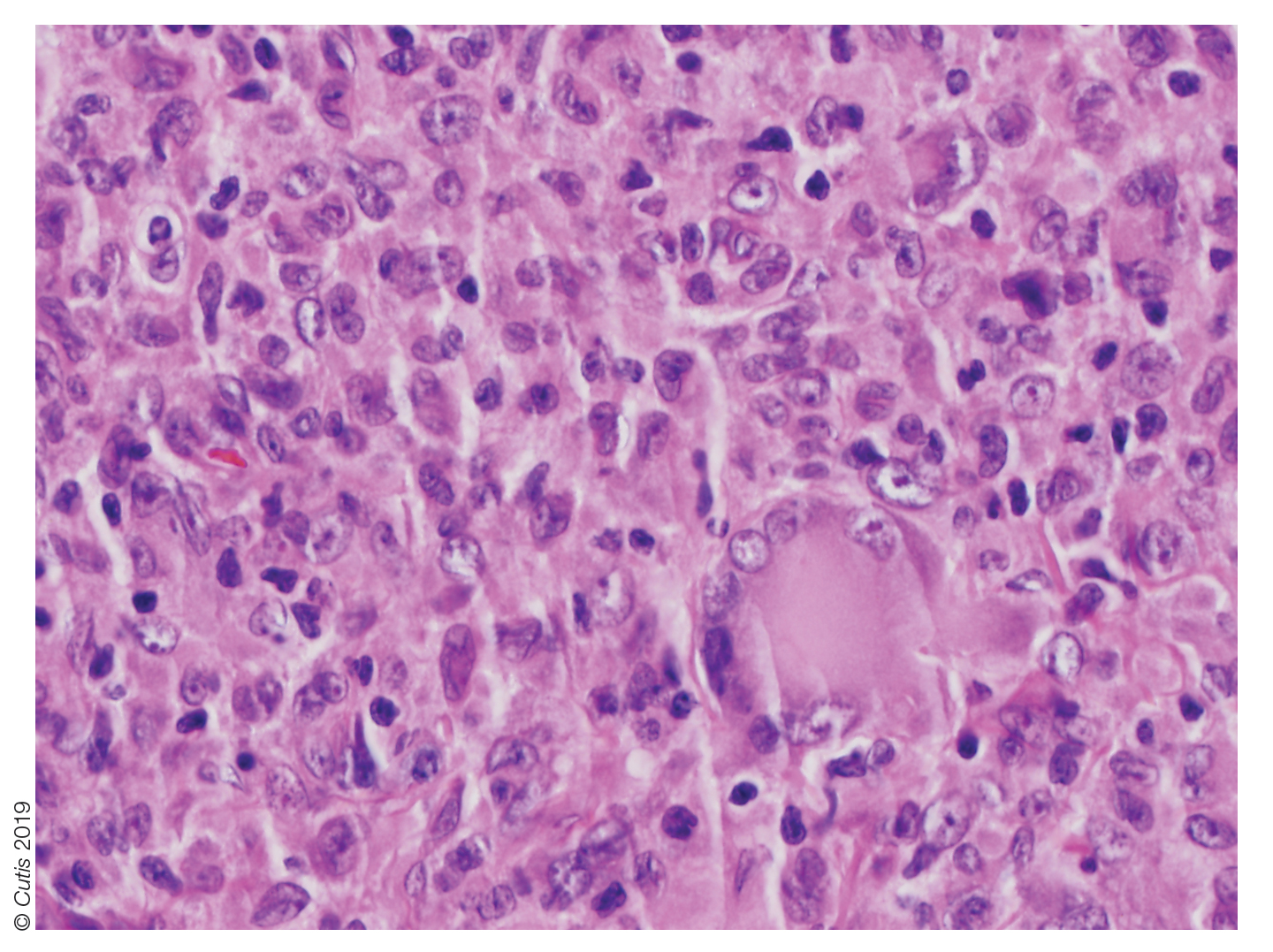

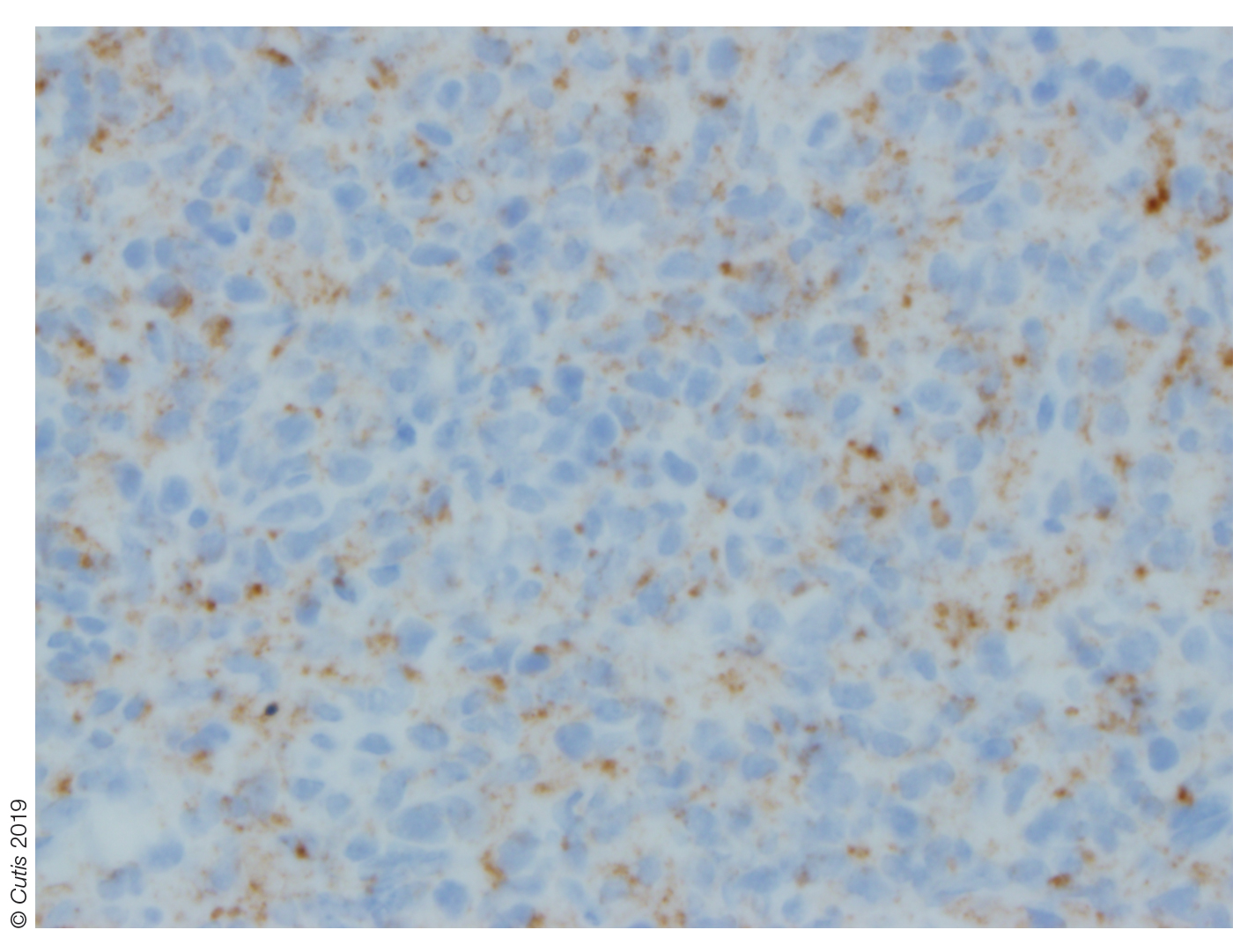

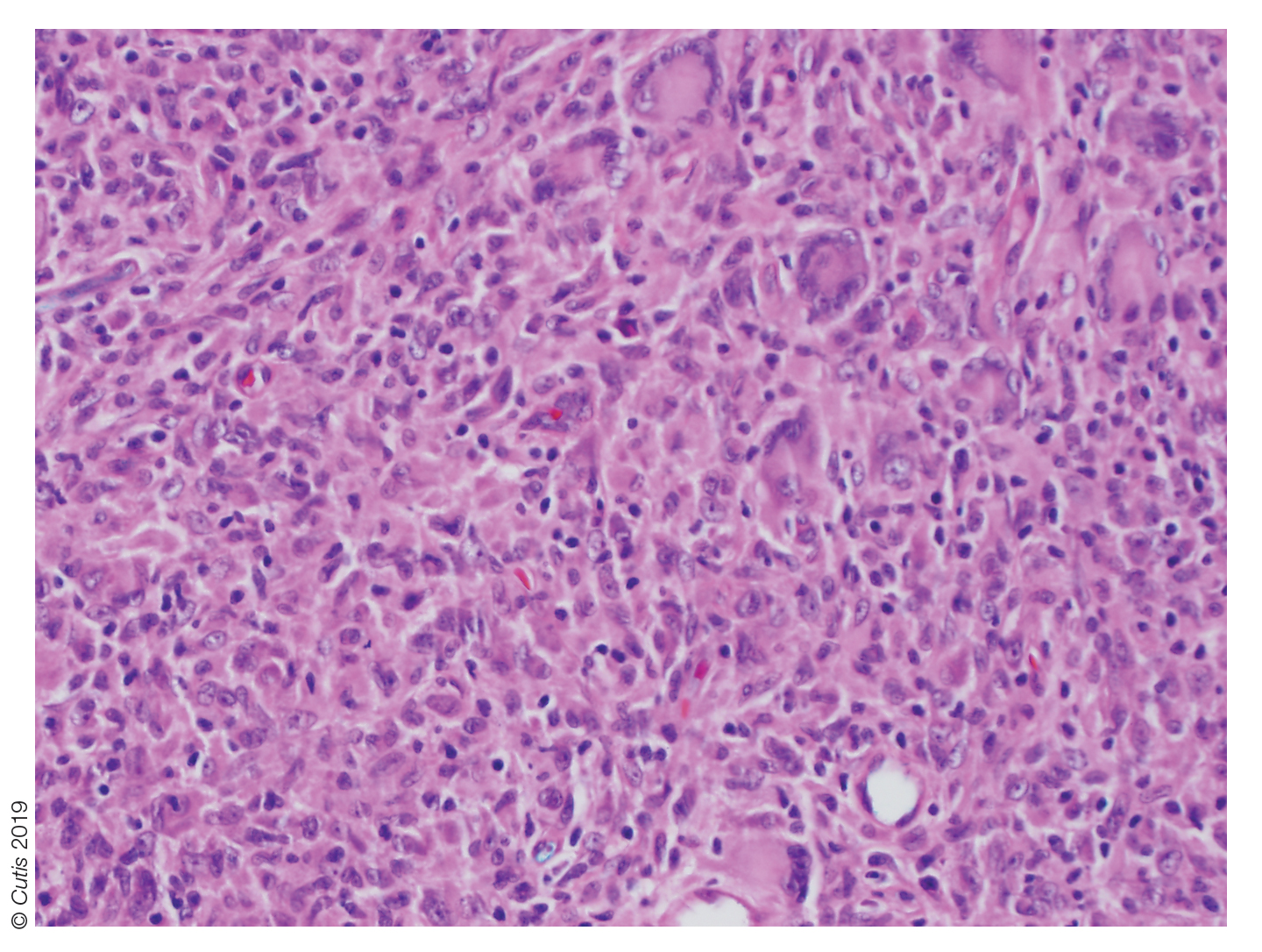

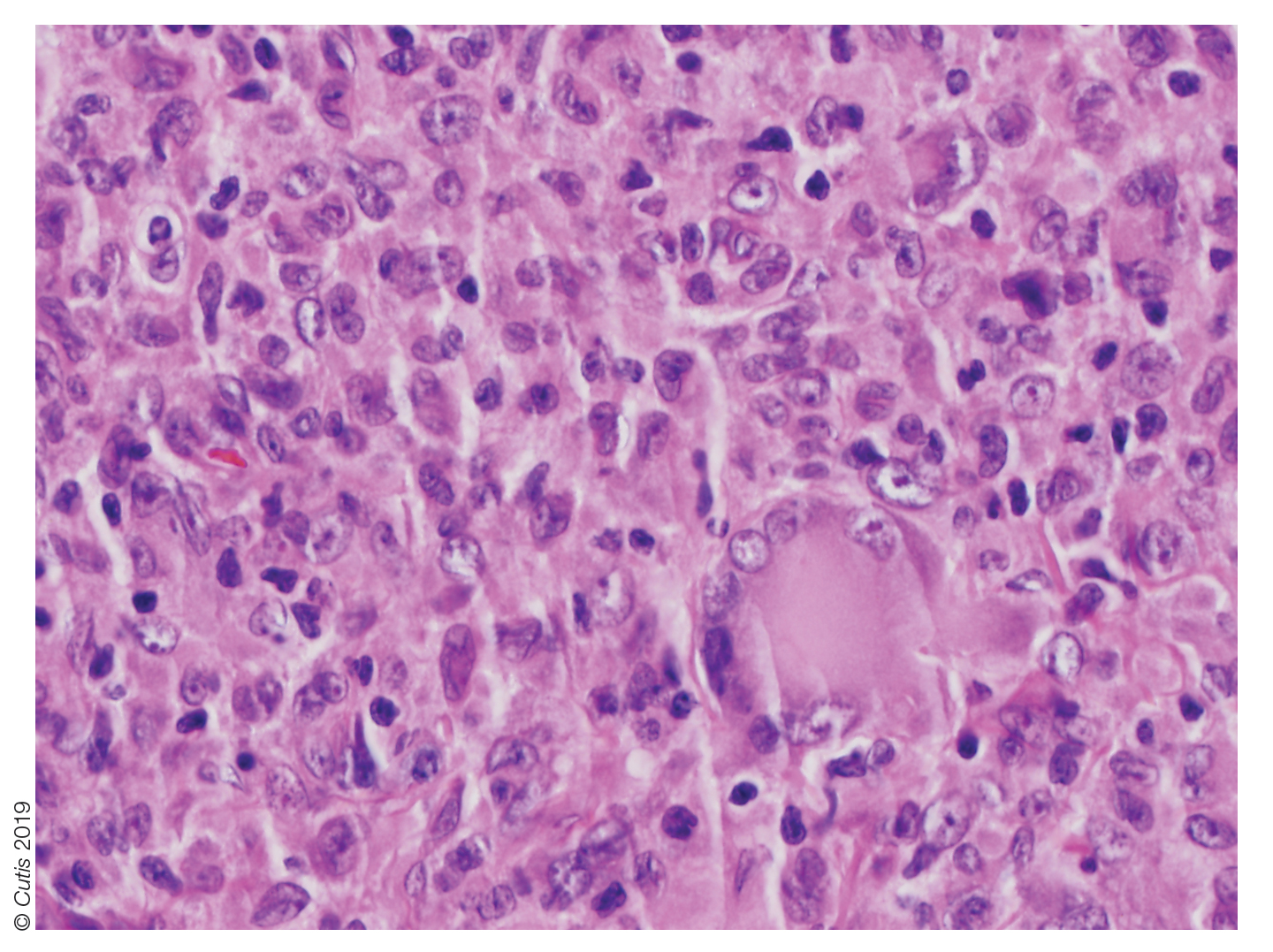

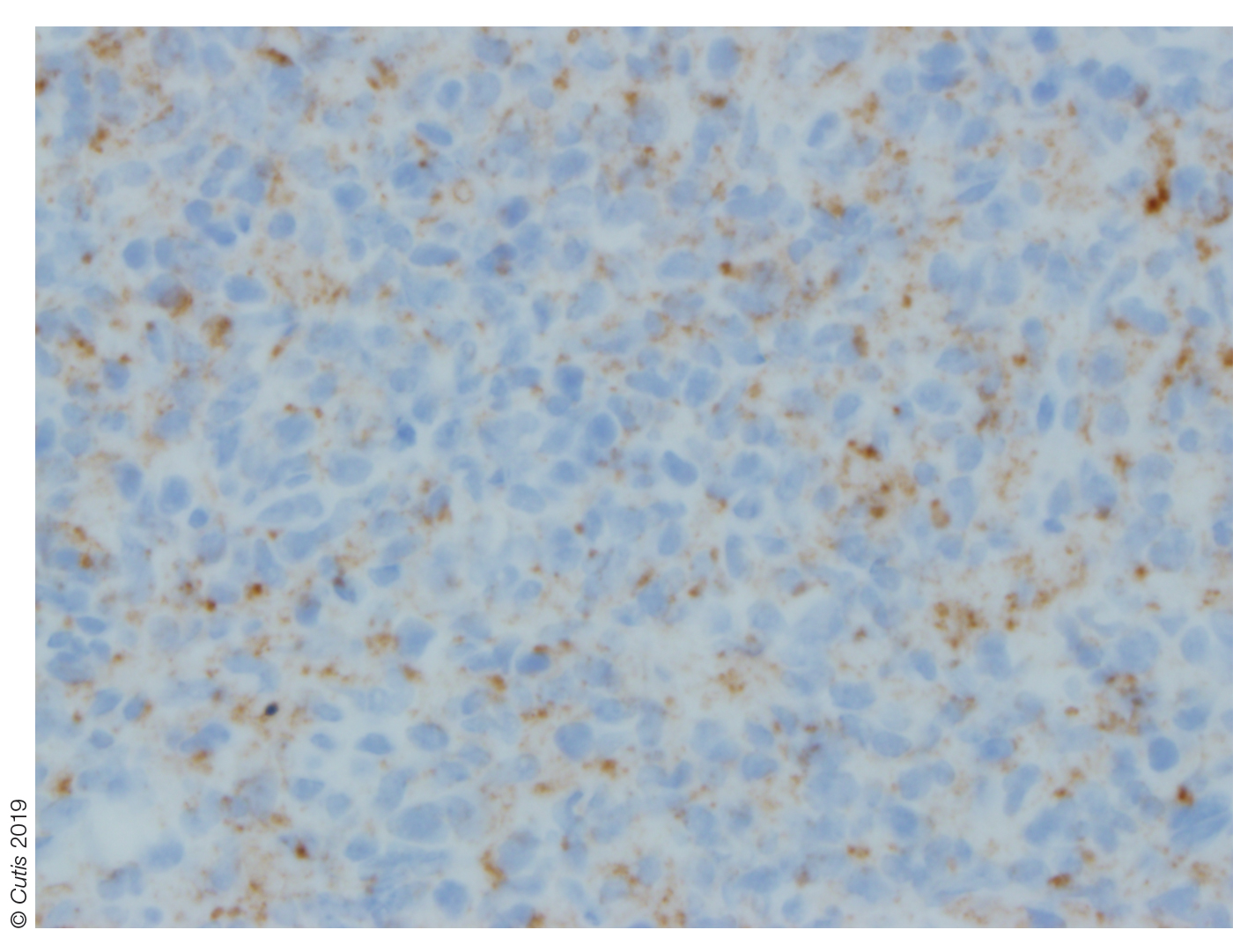

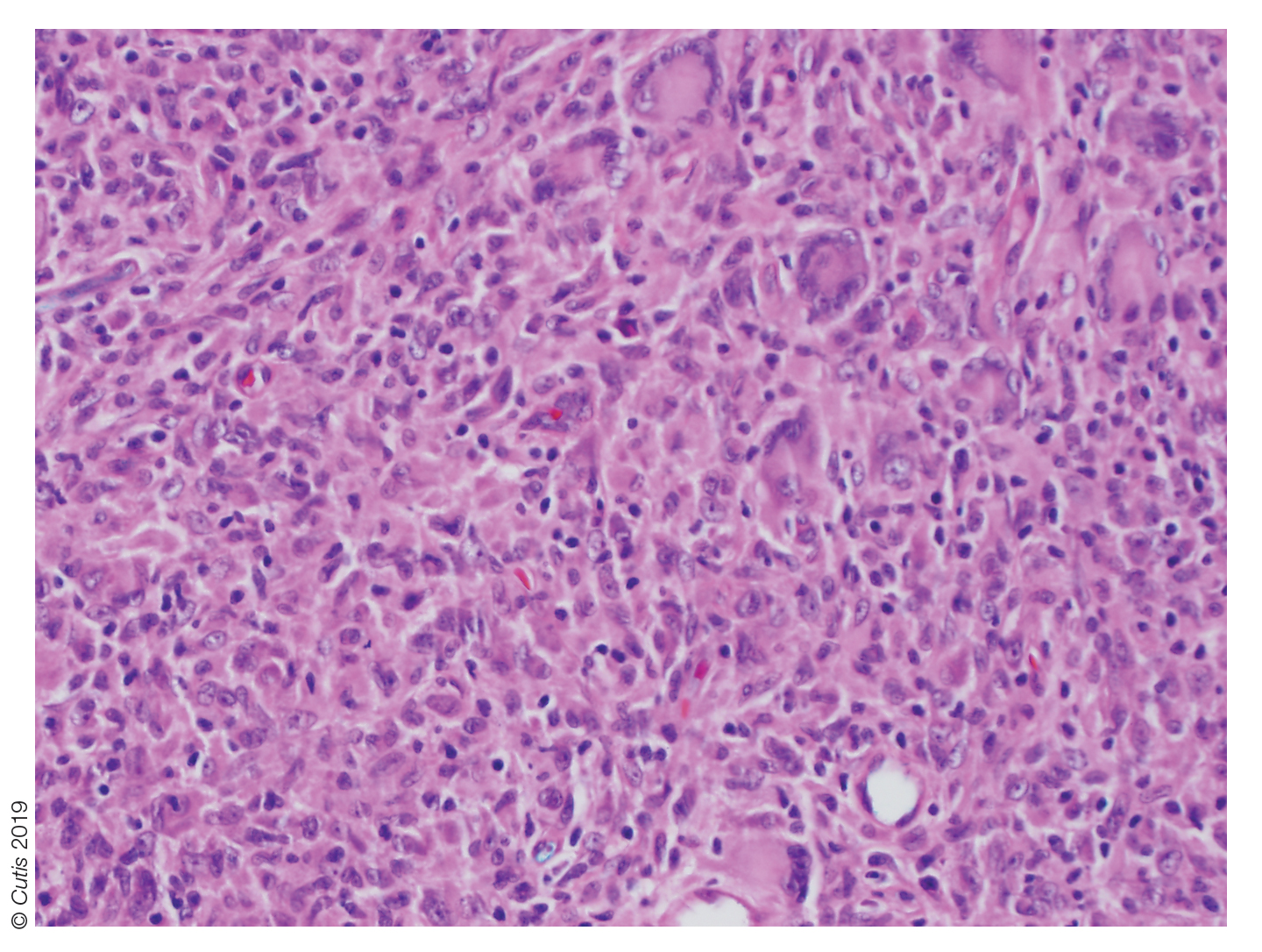

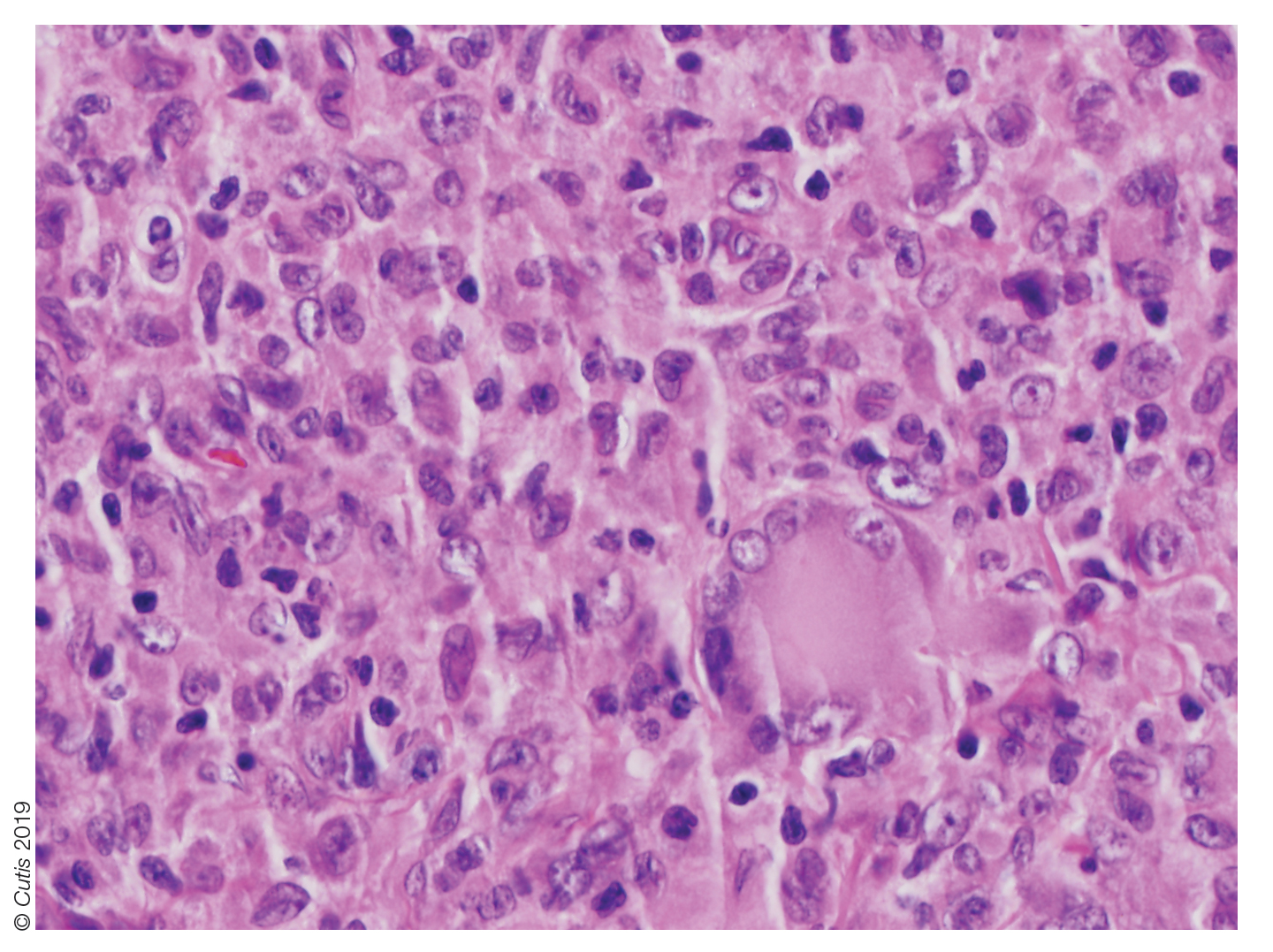

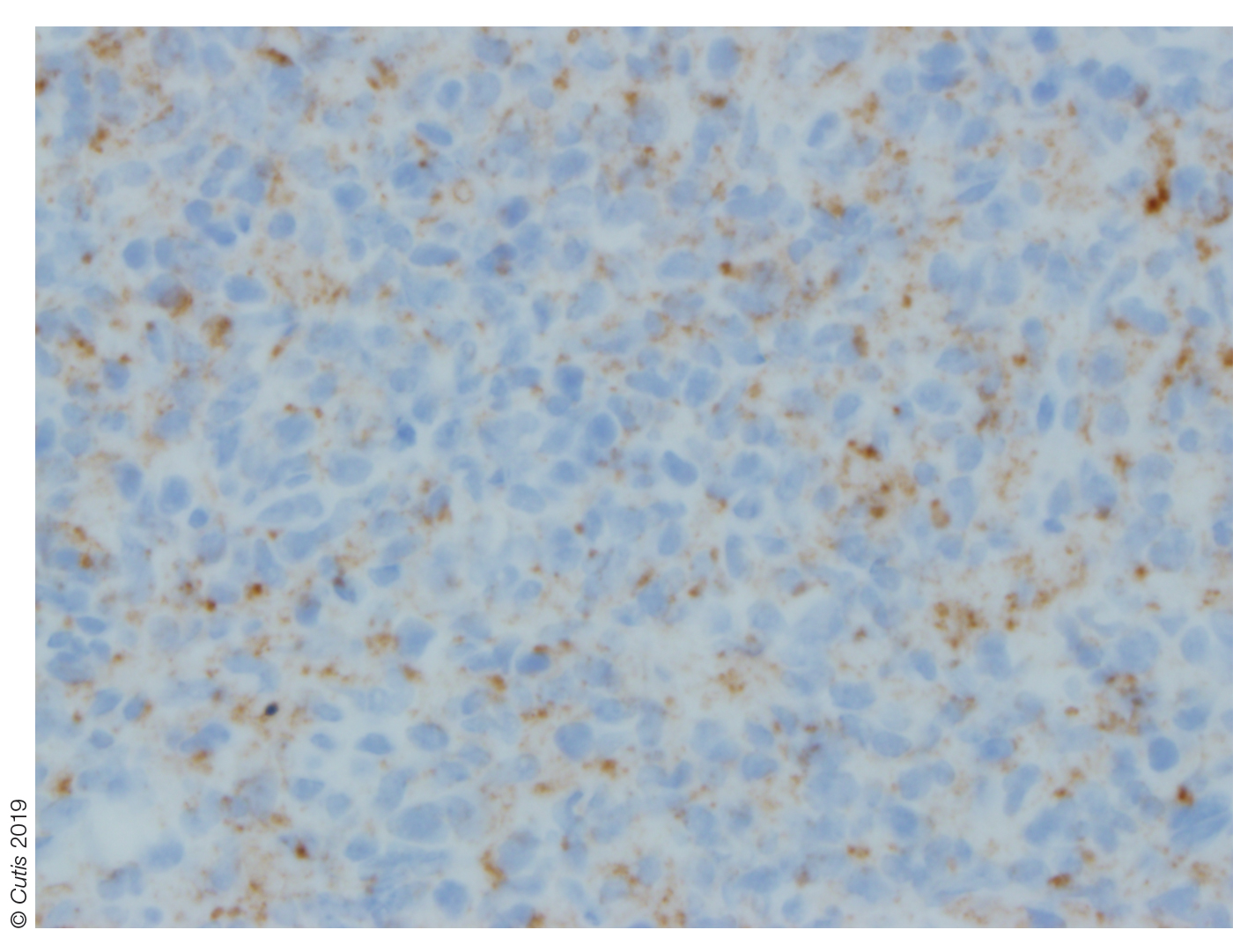

Histopathologic examination of a biopsy of the lesion typically demonstrates well-circumscribed nodules with dense infiltrates of polyhedral histiocytes with vaculoles.3-7 In 85% of cases, Touton giant cells are present.4,9 A prominent vascular network often is present, which was observed in our patient’s biopsy (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry typically is positive for CD14, CD68, CD163, fascin, and factor XIIIa.4,10 Classically, the cells are negative for S-100 and CD1a, which differentiates these lesions from Langerhans cell histiocytosis.4-7,10 Our patient demonstrated scattered S-100–positive cells representing background dendritic cells and macrophages (Figure 2). The remainder of the clinical, morphologic, and immunophenotypic findings were consistent with non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis, specifically JXG.

Biopsy should be performed in all cases, and basic laboratory test results such as a complete blood cell count and basic metabolic panel also are appropriate. Routine referral of all patients with cutaneous JXG for ophthalmologic evaluation is not recommended.11 Most patients with ocular involvement present with acute ocular concerns; asymptomatic eye involvement is rare. It is reasonable to consider referral to ophthalmology for patients younger than 2 years who present with multiple lesions, as they may have a higher risk for ocular involvement.11

Juvenile xanthogranuloma usually is a benign disorder with management involving observation, as the lesions typically involute spontaneously.3-7,9,10,12 Systemic or intralesional corticosteroids may be used for treatment in lesions that do not resolve. Ocular JXG refractory to steroid treatment has been managed in several cases with intravitreal bevacizumab.13 Additionally, surgical excision can be considered if malignancy is suspected, the lesion does not resolve with observation or steroid treatment, or the lesion is located near vital structures.4-7,9-13

Spitz nevus presents as a single dome-shaped papule, but histology shows a symmetrical proliferation of spindle and epithelioid cells. Trachoma can present in and around the eye as a follicular hypertrophy but most commonly is seen in the conjunctiva. Dermoid cysts present as solitary subcutaneous cystic lesions; histology demonstrates a lining of keratinizing squamous epithelium with the presence of pilosebaceous structures. Dermatofibroma appears as a tan to reddish-brown papule in an area of prior minor trauma; pathology demonstrates an acanthotic epidermis with an underlying zone of normal papillary dermis and unencapsulated lesions with spindle cells overlapping in fascicles and whorls at the periphery.

1. Adamson HG. Society intelligence: the Dermatological Society of

London. Br J Dermatol. 1905;17:222-223.

2. Helwig E, Hackney VC. Juvenile xanthogranuloma (nevoxanthoendothelioma).

Am J Pathol. 1954;30:625-626.

3. Farrugia EJ, Stephen AP, Raza SA. Juvenile xanthogranuloma of

temporal bone—a case report. J Laryngol Otol. 1997;111:63-65.

4. Cypel TK, Zuker RM. Juvenile xanthogranuloma: case report and review

of the literature. Can J Plast Surg. 2008;16:175-177.

5. Chang MW, Frieden IJ, Good W. The risk of intraocular juvenile

xanthogranuloma: survey of current practices and assessment of risk.

J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:445-449.

6. Zimmerman LE. Ocular lesions of juvenile xanthogranuloma.

nevoxanthoendothelioma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1965;60:1011-1035.

7. Cambiaghi S, Restano L, Caputo R. Juvenile xanthogranuloma associated

with neurofibromatosis 1: 14 patients without evidence of hematologic

malignancies. Pediatr Dermatol. 2004;21:97-101.

8. Stover DG, Alapati S, Regueira O, et al. Treatment of juvenile xanthogranuloma.

Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;51:130-133.

9. Dehner LP. Juvenile xanthogranulomas in the first two decades of life. a

clinicopathologic study of 174 cases with cutaneous and extracutaneous

manifestations. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:579-593.

10. Weitzman S, Jaffe R. Uncommon histiocytic disorders: the non-

Langerhans cell histiocytoses. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;45:256-264.

11. Chang MW, Frieden IJ, Good W. The risk of intraocular juvenile

xanthogranuloma: survey of current practices and assessment of risk.

J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:445.

12. Eggli KD, Caro P, Quioque T, et al. Juvenile xanthogranuloma: non-X

histiocytosis with systemic involvement. Pediatr Radiol. 1992;22:374-376.

13. Ashkenazy N, Henry CR, Abbey AM, et al. Successful treatment of juvenile

xanthogranuloma using bevacizumab. J AAPOS. 2014;18:295-297.

The Diagnosis: Juvenile Xanthogranuloma

Juvenile xanthogranuloma (JXG) was first described in 1905 by Adamson1 as solitary or multiple plaquiform or nodular lesions that are yellow to yellowish brown. In 1954, Helwig and Hackney2 coined the term juvenile xanthogranuloma to define this histiocytic cutaneous granulomatous tumor.

Juvenile xanthogranuloma is a rare dermatologic disorder that may be present at birth and primarily affects infants and young children. The benign lesions generally occur in the first 4 years of life, with a median age of onset of 2 years.3 Lesions range in size from millimeters to several centimeters in diameter.4 The skin of the head and neck is the most commonly involved site in JXG. The most frequent noncutaneous site of JXG involvement is the eye, particularly the iris, accounting for 0.4% of cases.5,6 Extracutaneous sites such as the heart, liver, lungs, spleen, oral cavity, and brain also may be involved.4

Most children with JXG are asymptomatic. Skin lesions present as well-demarcated, rubbery, tan-orange papules or nodules. They usually are solitary, and multiple nodules can increase the risk for extracutaneous involvement.4 A case series of patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 showed 14 of 77 (18%) patients examined in the first year of life presented with JXG or other non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis.7 The adult form of cutaneous xanthogranuloma often presents with severe bronchial asthma.8

Histopathologic examination of a biopsy of the lesion typically demonstrates well-circumscribed nodules with dense infiltrates of polyhedral histiocytes with vaculoles.3-7 In 85% of cases, Touton giant cells are present.4,9 A prominent vascular network often is present, which was observed in our patient’s biopsy (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry typically is positive for CD14, CD68, CD163, fascin, and factor XIIIa.4,10 Classically, the cells are negative for S-100 and CD1a, which differentiates these lesions from Langerhans cell histiocytosis.4-7,10 Our patient demonstrated scattered S-100–positive cells representing background dendritic cells and macrophages (Figure 2). The remainder of the clinical, morphologic, and immunophenotypic findings were consistent with non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis, specifically JXG.

Biopsy should be performed in all cases, and basic laboratory test results such as a complete blood cell count and basic metabolic panel also are appropriate. Routine referral of all patients with cutaneous JXG for ophthalmologic evaluation is not recommended.11 Most patients with ocular involvement present with acute ocular concerns; asymptomatic eye involvement is rare. It is reasonable to consider referral to ophthalmology for patients younger than 2 years who present with multiple lesions, as they may have a higher risk for ocular involvement.11

Juvenile xanthogranuloma usually is a benign disorder with management involving observation, as the lesions typically involute spontaneously.3-7,9,10,12 Systemic or intralesional corticosteroids may be used for treatment in lesions that do not resolve. Ocular JXG refractory to steroid treatment has been managed in several cases with intravitreal bevacizumab.13 Additionally, surgical excision can be considered if malignancy is suspected, the lesion does not resolve with observation or steroid treatment, or the lesion is located near vital structures.4-7,9-13

Spitz nevus presents as a single dome-shaped papule, but histology shows a symmetrical proliferation of spindle and epithelioid cells. Trachoma can present in and around the eye as a follicular hypertrophy but most commonly is seen in the conjunctiva. Dermoid cysts present as solitary subcutaneous cystic lesions; histology demonstrates a lining of keratinizing squamous epithelium with the presence of pilosebaceous structures. Dermatofibroma appears as a tan to reddish-brown papule in an area of prior minor trauma; pathology demonstrates an acanthotic epidermis with an underlying zone of normal papillary dermis and unencapsulated lesions with spindle cells overlapping in fascicles and whorls at the periphery.

The Diagnosis: Juvenile Xanthogranuloma

Juvenile xanthogranuloma (JXG) was first described in 1905 by Adamson1 as solitary or multiple plaquiform or nodular lesions that are yellow to yellowish brown. In 1954, Helwig and Hackney2 coined the term juvenile xanthogranuloma to define this histiocytic cutaneous granulomatous tumor.

Juvenile xanthogranuloma is a rare dermatologic disorder that may be present at birth and primarily affects infants and young children. The benign lesions generally occur in the first 4 years of life, with a median age of onset of 2 years.3 Lesions range in size from millimeters to several centimeters in diameter.4 The skin of the head and neck is the most commonly involved site in JXG. The most frequent noncutaneous site of JXG involvement is the eye, particularly the iris, accounting for 0.4% of cases.5,6 Extracutaneous sites such as the heart, liver, lungs, spleen, oral cavity, and brain also may be involved.4

Most children with JXG are asymptomatic. Skin lesions present as well-demarcated, rubbery, tan-orange papules or nodules. They usually are solitary, and multiple nodules can increase the risk for extracutaneous involvement.4 A case series of patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 showed 14 of 77 (18%) patients examined in the first year of life presented with JXG or other non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis.7 The adult form of cutaneous xanthogranuloma often presents with severe bronchial asthma.8

Histopathologic examination of a biopsy of the lesion typically demonstrates well-circumscribed nodules with dense infiltrates of polyhedral histiocytes with vaculoles.3-7 In 85% of cases, Touton giant cells are present.4,9 A prominent vascular network often is present, which was observed in our patient’s biopsy (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry typically is positive for CD14, CD68, CD163, fascin, and factor XIIIa.4,10 Classically, the cells are negative for S-100 and CD1a, which differentiates these lesions from Langerhans cell histiocytosis.4-7,10 Our patient demonstrated scattered S-100–positive cells representing background dendritic cells and macrophages (Figure 2). The remainder of the clinical, morphologic, and immunophenotypic findings were consistent with non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis, specifically JXG.

Biopsy should be performed in all cases, and basic laboratory test results such as a complete blood cell count and basic metabolic panel also are appropriate. Routine referral of all patients with cutaneous JXG for ophthalmologic evaluation is not recommended.11 Most patients with ocular involvement present with acute ocular concerns; asymptomatic eye involvement is rare. It is reasonable to consider referral to ophthalmology for patients younger than 2 years who present with multiple lesions, as they may have a higher risk for ocular involvement.11

Juvenile xanthogranuloma usually is a benign disorder with management involving observation, as the lesions typically involute spontaneously.3-7,9,10,12 Systemic or intralesional corticosteroids may be used for treatment in lesions that do not resolve. Ocular JXG refractory to steroid treatment has been managed in several cases with intravitreal bevacizumab.13 Additionally, surgical excision can be considered if malignancy is suspected, the lesion does not resolve with observation or steroid treatment, or the lesion is located near vital structures.4-7,9-13

Spitz nevus presents as a single dome-shaped papule, but histology shows a symmetrical proliferation of spindle and epithelioid cells. Trachoma can present in and around the eye as a follicular hypertrophy but most commonly is seen in the conjunctiva. Dermoid cysts present as solitary subcutaneous cystic lesions; histology demonstrates a lining of keratinizing squamous epithelium with the presence of pilosebaceous structures. Dermatofibroma appears as a tan to reddish-brown papule in an area of prior minor trauma; pathology demonstrates an acanthotic epidermis with an underlying zone of normal papillary dermis and unencapsulated lesions with spindle cells overlapping in fascicles and whorls at the periphery.

1. Adamson HG. Society intelligence: the Dermatological Society of

London. Br J Dermatol. 1905;17:222-223.

2. Helwig E, Hackney VC. Juvenile xanthogranuloma (nevoxanthoendothelioma).

Am J Pathol. 1954;30:625-626.

3. Farrugia EJ, Stephen AP, Raza SA. Juvenile xanthogranuloma of

temporal bone—a case report. J Laryngol Otol. 1997;111:63-65.

4. Cypel TK, Zuker RM. Juvenile xanthogranuloma: case report and review

of the literature. Can J Plast Surg. 2008;16:175-177.

5. Chang MW, Frieden IJ, Good W. The risk of intraocular juvenile

xanthogranuloma: survey of current practices and assessment of risk.

J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:445-449.

6. Zimmerman LE. Ocular lesions of juvenile xanthogranuloma.

nevoxanthoendothelioma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1965;60:1011-1035.

7. Cambiaghi S, Restano L, Caputo R. Juvenile xanthogranuloma associated

with neurofibromatosis 1: 14 patients without evidence of hematologic

malignancies. Pediatr Dermatol. 2004;21:97-101.

8. Stover DG, Alapati S, Regueira O, et al. Treatment of juvenile xanthogranuloma.

Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;51:130-133.

9. Dehner LP. Juvenile xanthogranulomas in the first two decades of life. a

clinicopathologic study of 174 cases with cutaneous and extracutaneous

manifestations. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:579-593.

10. Weitzman S, Jaffe R. Uncommon histiocytic disorders: the non-

Langerhans cell histiocytoses. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;45:256-264.

11. Chang MW, Frieden IJ, Good W. The risk of intraocular juvenile

xanthogranuloma: survey of current practices and assessment of risk.

J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:445.

12. Eggli KD, Caro P, Quioque T, et al. Juvenile xanthogranuloma: non-X

histiocytosis with systemic involvement. Pediatr Radiol. 1992;22:374-376.

13. Ashkenazy N, Henry CR, Abbey AM, et al. Successful treatment of juvenile

xanthogranuloma using bevacizumab. J AAPOS. 2014;18:295-297.

1. Adamson HG. Society intelligence: the Dermatological Society of

London. Br J Dermatol. 1905;17:222-223.

2. Helwig E, Hackney VC. Juvenile xanthogranuloma (nevoxanthoendothelioma).

Am J Pathol. 1954;30:625-626.

3. Farrugia EJ, Stephen AP, Raza SA. Juvenile xanthogranuloma of

temporal bone—a case report. J Laryngol Otol. 1997;111:63-65.

4. Cypel TK, Zuker RM. Juvenile xanthogranuloma: case report and review

of the literature. Can J Plast Surg. 2008;16:175-177.

5. Chang MW, Frieden IJ, Good W. The risk of intraocular juvenile

xanthogranuloma: survey of current practices and assessment of risk.

J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:445-449.

6. Zimmerman LE. Ocular lesions of juvenile xanthogranuloma.

nevoxanthoendothelioma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1965;60:1011-1035.

7. Cambiaghi S, Restano L, Caputo R. Juvenile xanthogranuloma associated

with neurofibromatosis 1: 14 patients without evidence of hematologic

malignancies. Pediatr Dermatol. 2004;21:97-101.

8. Stover DG, Alapati S, Regueira O, et al. Treatment of juvenile xanthogranuloma.

Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;51:130-133.

9. Dehner LP. Juvenile xanthogranulomas in the first two decades of life. a

clinicopathologic study of 174 cases with cutaneous and extracutaneous

manifestations. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:579-593.

10. Weitzman S, Jaffe R. Uncommon histiocytic disorders: the non-

Langerhans cell histiocytoses. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;45:256-264.

11. Chang MW, Frieden IJ, Good W. The risk of intraocular juvenile

xanthogranuloma: survey of current practices and assessment of risk.

J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:445.

12. Eggli KD, Caro P, Quioque T, et al. Juvenile xanthogranuloma: non-X

histiocytosis with systemic involvement. Pediatr Radiol. 1992;22:374-376.

13. Ashkenazy N, Henry CR, Abbey AM, et al. Successful treatment of juvenile

xanthogranuloma using bevacizumab. J AAPOS. 2014;18:295-297.

A 10-month-old girl presented with a facial nodule of 7 months’ duration that started as a small lesion. On physical examination, a single 10×10-mm, nontender, well-circumscribed, firm, freely mobile nodule was observed in the left infraorbital area. The patient was born full term at 37 weeks’ gestation via spontaneous vaginal delivery and had no other notable findings on physical examination. Excision was performed by an oculoplastic surgeon. Pathology revealed a relatively well-circumscribed, diffuse, dermal infiltrate of cells arranged in short fascicles and a storiform pattern. The cells had abundant clear to amphophilic cytoplasm, ovoid to reniform nuclei with vesicular chromatin and focal grooves, and diffuse CD68+ immunoreactivity, as well as scattered S-100–positive cells. The patient did well with the excision and no new lesions have developed.

IV fluid weaning unnecessary after gastroenteritis rehydration

SEATTLE – Intravenous fluids can simply be stopped after children with acute viral gastroenteritis are rehydrated in the hospital; there’s no need for a slow wean, according to a review at the Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, Hartford.

Researchers found that children leave the hospital hours sooner, with no ill effects. “This study suggests that slowly weaning IV fluids may not be necessary,” said lead investigator Danielle Klima, DO, a University of Connecticut pediatrics resident.

The team at Connecticut Children’s noticed that weaning practices after gastroenteritis rehydration varied widely on the pediatric floors, and appeared to be largely provider dependent, with “much subjective decision making.” The team wanted to see if it made a difference one way or the other, Dr. Klima said at Pediatric Hospital Medicine.

During respiratory season, “our pediatric floors are surging. Saving even a couple hours to get these kids out” quicker matters, she said, noting that it’s likely the first time the issue has been studied.

The team reviewed 153 children aged 2 months to 18 years, 95 of whom had IV fluids stopped once physicians deemed they were fluid resuscitated and ready for an oral feeding trial; the other 58 were weaned, with at least two reductions by half before final discontinuation.

There were no significant differences in age, gender, race, or insurance type between the two groups. The mean age was 2.6 years, and there were slightly more boys. The ED triage level was a mean of 3.2 points in both groups on a scale of 1-5, with 1 being the most urgent. Children with serious comorbidities, chronic diarrhea, feeding tubes, severe electrolyte abnormalities, or feeding problems were among those excluded.

Overall length of stay was 36 hours in the stop group versus 40.5 hours in the weaning group (P = .004). Children left the hospital about 6 hours after IV fluids were discontinued, versus 26 hours after weaning was started (P less than .001).

Electrolyte abnormalities on admission were more common in the weaning group (65% versus 57%), but not significantly so (P = .541). Electrolyte abnormalities were also more common at the end of fluid resuscitation in the weaning arm, but again not significantly (65% 42%, P = .077).

Fluid resuscitation needed to be restarted in 15 children in the stop group (16%), versus 11 (19%) in the wean arm (P = .459). One child in the stop group (1%) versus four (7%) who were weaned were readmitted to the hospital within a week for acute viral gastroenteritis (P = .067).

“I expected we were taking a more conservative weaning approach in younger infants,” but age didn’t seem to affect whether patients were weaned or not, Dr. Klima said.

With the results in hand, “our group is taking a closer look at exactly what we are doing,” perhaps with an eye toward standardization or even a randomized trial, she said.

She noted that weaning still makes sense for a fussy toddler who refuses to take anything by mouth.

There was no external funding, and Dr. Klima had no disclosures. The conference was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

SEATTLE – Intravenous fluids can simply be stopped after children with acute viral gastroenteritis are rehydrated in the hospital; there’s no need for a slow wean, according to a review at the Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, Hartford.

Researchers found that children leave the hospital hours sooner, with no ill effects. “This study suggests that slowly weaning IV fluids may not be necessary,” said lead investigator Danielle Klima, DO, a University of Connecticut pediatrics resident.

The team at Connecticut Children’s noticed that weaning practices after gastroenteritis rehydration varied widely on the pediatric floors, and appeared to be largely provider dependent, with “much subjective decision making.” The team wanted to see if it made a difference one way or the other, Dr. Klima said at Pediatric Hospital Medicine.

During respiratory season, “our pediatric floors are surging. Saving even a couple hours to get these kids out” quicker matters, she said, noting that it’s likely the first time the issue has been studied.

The team reviewed 153 children aged 2 months to 18 years, 95 of whom had IV fluids stopped once physicians deemed they were fluid resuscitated and ready for an oral feeding trial; the other 58 were weaned, with at least two reductions by half before final discontinuation.

There were no significant differences in age, gender, race, or insurance type between the two groups. The mean age was 2.6 years, and there were slightly more boys. The ED triage level was a mean of 3.2 points in both groups on a scale of 1-5, with 1 being the most urgent. Children with serious comorbidities, chronic diarrhea, feeding tubes, severe electrolyte abnormalities, or feeding problems were among those excluded.

Overall length of stay was 36 hours in the stop group versus 40.5 hours in the weaning group (P = .004). Children left the hospital about 6 hours after IV fluids were discontinued, versus 26 hours after weaning was started (P less than .001).

Electrolyte abnormalities on admission were more common in the weaning group (65% versus 57%), but not significantly so (P = .541). Electrolyte abnormalities were also more common at the end of fluid resuscitation in the weaning arm, but again not significantly (65% 42%, P = .077).

Fluid resuscitation needed to be restarted in 15 children in the stop group (16%), versus 11 (19%) in the wean arm (P = .459). One child in the stop group (1%) versus four (7%) who were weaned were readmitted to the hospital within a week for acute viral gastroenteritis (P = .067).

“I expected we were taking a more conservative weaning approach in younger infants,” but age didn’t seem to affect whether patients were weaned or not, Dr. Klima said.

With the results in hand, “our group is taking a closer look at exactly what we are doing,” perhaps with an eye toward standardization or even a randomized trial, she said.

She noted that weaning still makes sense for a fussy toddler who refuses to take anything by mouth.

There was no external funding, and Dr. Klima had no disclosures. The conference was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

SEATTLE – Intravenous fluids can simply be stopped after children with acute viral gastroenteritis are rehydrated in the hospital; there’s no need for a slow wean, according to a review at the Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, Hartford.

Researchers found that children leave the hospital hours sooner, with no ill effects. “This study suggests that slowly weaning IV fluids may not be necessary,” said lead investigator Danielle Klima, DO, a University of Connecticut pediatrics resident.

The team at Connecticut Children’s noticed that weaning practices after gastroenteritis rehydration varied widely on the pediatric floors, and appeared to be largely provider dependent, with “much subjective decision making.” The team wanted to see if it made a difference one way or the other, Dr. Klima said at Pediatric Hospital Medicine.

During respiratory season, “our pediatric floors are surging. Saving even a couple hours to get these kids out” quicker matters, she said, noting that it’s likely the first time the issue has been studied.

The team reviewed 153 children aged 2 months to 18 years, 95 of whom had IV fluids stopped once physicians deemed they were fluid resuscitated and ready for an oral feeding trial; the other 58 were weaned, with at least two reductions by half before final discontinuation.

There were no significant differences in age, gender, race, or insurance type between the two groups. The mean age was 2.6 years, and there were slightly more boys. The ED triage level was a mean of 3.2 points in both groups on a scale of 1-5, with 1 being the most urgent. Children with serious comorbidities, chronic diarrhea, feeding tubes, severe electrolyte abnormalities, or feeding problems were among those excluded.

Overall length of stay was 36 hours in the stop group versus 40.5 hours in the weaning group (P = .004). Children left the hospital about 6 hours after IV fluids were discontinued, versus 26 hours after weaning was started (P less than .001).

Electrolyte abnormalities on admission were more common in the weaning group (65% versus 57%), but not significantly so (P = .541). Electrolyte abnormalities were also more common at the end of fluid resuscitation in the weaning arm, but again not significantly (65% 42%, P = .077).

Fluid resuscitation needed to be restarted in 15 children in the stop group (16%), versus 11 (19%) in the wean arm (P = .459). One child in the stop group (1%) versus four (7%) who were weaned were readmitted to the hospital within a week for acute viral gastroenteritis (P = .067).

“I expected we were taking a more conservative weaning approach in younger infants,” but age didn’t seem to affect whether patients were weaned or not, Dr. Klima said.

With the results in hand, “our group is taking a closer look at exactly what we are doing,” perhaps with an eye toward standardization or even a randomized trial, she said.

She noted that weaning still makes sense for a fussy toddler who refuses to take anything by mouth.

There was no external funding, and Dr. Klima had no disclosures. The conference was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

REPORTING FROM PHM 2019

Are your patients ready for the transition to adult care?

AUSTIN, TEX. – All too often, children and adolescents stumble on their way to adult health care – if they make it at all.

In fact, data from an ongoing survey by the Department of Health & Human Services and the Health Resources and Services Administration indicate that only 40% of children with special health care needs aged 12-17 years receive the services necessary to make transitions to adult health care.

“Most fall off the proverbial cliff and do not engage with adult providers,” Cynthia Peacock, MD, said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. She recalled meeting with one individual who, after being a patient at the children’s hospital for 13 years, was told over the phone to transition to an adult provider with not so much as a promised letter of introduction being sent on. “She did not know about the adult health care culture, which is fractured in care, relies on the patient to be their own advocate, and wants patients to be able to do their visit in 10-15 minutes.”

Dr. Peacock, medical director of the Transition Medicine Clinic at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, described “Starting at age 12 is not too early,” she said. “It gives you time so that you can keep introducing the concept when that individual keeps coming back to see you, especially if it’s a chronic condition.”

She recommended that clinicians ask several questions to assess transition readiness of pediatric patients to adult care, including, Do you know your medications? Do you know how to take them? Do you know how to refill them? Do you know how to discuss them? Can you discuss your medical condition with the adult doctor? Can you call for a doctor’s appointment or get a prescription filled? “Adolescents are notorious for calling [the doctor’s office], and if they’re told they can’t make an appointment, that’s it; they stop right there,” Dr. Peacock said. “They don’t tend to problem solve. They don’t engage.”

Studies have suggested that the transfer of care is more likely to be successful if a formal transition program is in place to prepare the patient and to facilitate the change in health care providers. “There is a growing evidence base in the literature that skills training for young people with chronic illnesses can be associated with positive outcomes,” she said. “This can be as easy as telling the individual, ‘Do a book report about your condition. Talk to a friend. Tell a friend what your condition is. Or, do school science fair project and talk to your class about what you have.’ Get them past that uncomfortable feeling of having to talk about it.”

The earlier this happens, the better. “We know from research that if you get them to be their own [health care] advocate, that’s one less thing they have to do in the adult health care system,” she said. “They will move on to other things, such as getting a job or going to college.”

Dr. Peacock, who is board certified in pediatrics and internal medicine, added that providing adolescents with the option of being seen by professionals without their parents is considered best practice. “You could start by introducing the concept at age 12, but say at age 13, ‘I want to spend a minute with you alone without your parent. I want you to bring in questions that you want to ask me that you may not want to ask in front of your parents,’” she said. “I guarantee you that on that third visit the adolescent will ask you a question.”

Optimistic messaging is another component of effective planning. “You may see someone in your office with a disease that you know has high mortality and high morbidity, and you’re trying to help the family cope,” Dr. Peacock said. “That young person needs to be asked, ‘What are your plans for your future?’ Think about it: In 10 or 20 years when you’re transitioning that individual out of your health care system, what medical miracles have happened?” She recalled visiting with the mother of a patient with Down syndrome who had significant congenital heart disease. He was in his 30s and struggled to keep his behavior in check. “We were trying to develop a behavior plan, but his past care team had never put one in place for him,” Dr. Peacock said. “The mother looked at me and said, accusingly, ‘It’s your fault. It’s all of your doctors’ faults because they never told me that this would happen. They told me to take him home and spoil him because he would not be around at this age.’”

Effective transition handoffs are collaborative, she continued, with care plans built around what is likely to happen with the patient over time. “At Baylor College of Medicine, pediatric dermatologists follow patients for life, but I take over everything else adult care related,” Dr. Peacock said. “The pediatric dermatologist has me come over to the hospital when we’re talking about quality-of-life issues – about advance care, advanced directives, those types of things.”

She recommends not transferring care to an adult provider during pregnancy, hospitalization, during active disease, or during changes to a patient’s medical therapy. “When pediatricians call me from the hospital and they want an urgent transfer, I tell them, ‘Your emergency is not my urgency. Get everything ready; get them discharged. Get them followed up and back on their chronic care management, and I’ll be happy to do that transition for you,’ ” she said. “It’s also good to leave that door open for the adult provider to call you. Give them your cell phone number because it may be just one question, like, ‘Can you tell me why his liver enzymes are elevated? We can’t figure it out.’ ”

Dr. Peacock advises pediatric providers to develop processes within their own practice that facilitates transfer, “even if it just means sharing information with the adult provider at the end of the time you’re seeing that young adult. Know your systems and your resources. Get that medical summary done, even if it’s making the patient do the medical summary.” More information for clinicians and for patients and their families can be found at www.gottransition.org.

She reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

AUSTIN, TEX. – All too often, children and adolescents stumble on their way to adult health care – if they make it at all.

In fact, data from an ongoing survey by the Department of Health & Human Services and the Health Resources and Services Administration indicate that only 40% of children with special health care needs aged 12-17 years receive the services necessary to make transitions to adult health care.

“Most fall off the proverbial cliff and do not engage with adult providers,” Cynthia Peacock, MD, said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. She recalled meeting with one individual who, after being a patient at the children’s hospital for 13 years, was told over the phone to transition to an adult provider with not so much as a promised letter of introduction being sent on. “She did not know about the adult health care culture, which is fractured in care, relies on the patient to be their own advocate, and wants patients to be able to do their visit in 10-15 minutes.”

Dr. Peacock, medical director of the Transition Medicine Clinic at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, described “Starting at age 12 is not too early,” she said. “It gives you time so that you can keep introducing the concept when that individual keeps coming back to see you, especially if it’s a chronic condition.”

She recommended that clinicians ask several questions to assess transition readiness of pediatric patients to adult care, including, Do you know your medications? Do you know how to take them? Do you know how to refill them? Do you know how to discuss them? Can you discuss your medical condition with the adult doctor? Can you call for a doctor’s appointment or get a prescription filled? “Adolescents are notorious for calling [the doctor’s office], and if they’re told they can’t make an appointment, that’s it; they stop right there,” Dr. Peacock said. “They don’t tend to problem solve. They don’t engage.”

Studies have suggested that the transfer of care is more likely to be successful if a formal transition program is in place to prepare the patient and to facilitate the change in health care providers. “There is a growing evidence base in the literature that skills training for young people with chronic illnesses can be associated with positive outcomes,” she said. “This can be as easy as telling the individual, ‘Do a book report about your condition. Talk to a friend. Tell a friend what your condition is. Or, do school science fair project and talk to your class about what you have.’ Get them past that uncomfortable feeling of having to talk about it.”

The earlier this happens, the better. “We know from research that if you get them to be their own [health care] advocate, that’s one less thing they have to do in the adult health care system,” she said. “They will move on to other things, such as getting a job or going to college.”

Dr. Peacock, who is board certified in pediatrics and internal medicine, added that providing adolescents with the option of being seen by professionals without their parents is considered best practice. “You could start by introducing the concept at age 12, but say at age 13, ‘I want to spend a minute with you alone without your parent. I want you to bring in questions that you want to ask me that you may not want to ask in front of your parents,’” she said. “I guarantee you that on that third visit the adolescent will ask you a question.”

Optimistic messaging is another component of effective planning. “You may see someone in your office with a disease that you know has high mortality and high morbidity, and you’re trying to help the family cope,” Dr. Peacock said. “That young person needs to be asked, ‘What are your plans for your future?’ Think about it: In 10 or 20 years when you’re transitioning that individual out of your health care system, what medical miracles have happened?” She recalled visiting with the mother of a patient with Down syndrome who had significant congenital heart disease. He was in his 30s and struggled to keep his behavior in check. “We were trying to develop a behavior plan, but his past care team had never put one in place for him,” Dr. Peacock said. “The mother looked at me and said, accusingly, ‘It’s your fault. It’s all of your doctors’ faults because they never told me that this would happen. They told me to take him home and spoil him because he would not be around at this age.’”

Effective transition handoffs are collaborative, she continued, with care plans built around what is likely to happen with the patient over time. “At Baylor College of Medicine, pediatric dermatologists follow patients for life, but I take over everything else adult care related,” Dr. Peacock said. “The pediatric dermatologist has me come over to the hospital when we’re talking about quality-of-life issues – about advance care, advanced directives, those types of things.”

She recommends not transferring care to an adult provider during pregnancy, hospitalization, during active disease, or during changes to a patient’s medical therapy. “When pediatricians call me from the hospital and they want an urgent transfer, I tell them, ‘Your emergency is not my urgency. Get everything ready; get them discharged. Get them followed up and back on their chronic care management, and I’ll be happy to do that transition for you,’ ” she said. “It’s also good to leave that door open for the adult provider to call you. Give them your cell phone number because it may be just one question, like, ‘Can you tell me why his liver enzymes are elevated? We can’t figure it out.’ ”

Dr. Peacock advises pediatric providers to develop processes within their own practice that facilitates transfer, “even if it just means sharing information with the adult provider at the end of the time you’re seeing that young adult. Know your systems and your resources. Get that medical summary done, even if it’s making the patient do the medical summary.” More information for clinicians and for patients and their families can be found at www.gottransition.org.

She reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

AUSTIN, TEX. – All too often, children and adolescents stumble on their way to adult health care – if they make it at all.

In fact, data from an ongoing survey by the Department of Health & Human Services and the Health Resources and Services Administration indicate that only 40% of children with special health care needs aged 12-17 years receive the services necessary to make transitions to adult health care.

“Most fall off the proverbial cliff and do not engage with adult providers,” Cynthia Peacock, MD, said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. She recalled meeting with one individual who, after being a patient at the children’s hospital for 13 years, was told over the phone to transition to an adult provider with not so much as a promised letter of introduction being sent on. “She did not know about the adult health care culture, which is fractured in care, relies on the patient to be their own advocate, and wants patients to be able to do their visit in 10-15 minutes.”

Dr. Peacock, medical director of the Transition Medicine Clinic at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, described “Starting at age 12 is not too early,” she said. “It gives you time so that you can keep introducing the concept when that individual keeps coming back to see you, especially if it’s a chronic condition.”

She recommended that clinicians ask several questions to assess transition readiness of pediatric patients to adult care, including, Do you know your medications? Do you know how to take them? Do you know how to refill them? Do you know how to discuss them? Can you discuss your medical condition with the adult doctor? Can you call for a doctor’s appointment or get a prescription filled? “Adolescents are notorious for calling [the doctor’s office], and if they’re told they can’t make an appointment, that’s it; they stop right there,” Dr. Peacock said. “They don’t tend to problem solve. They don’t engage.”