User login

New RSV vaccine immunogenicity improved with protein engineering

Development of an effective respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccine is feasible using a new technology that can contribute to development of other vaccines as well, according to results of a proof-of-concept study in Science.

The new method of protein engineering preserves the RSV antigen protein’s prefusion structure, including the epitope, thereby inducing antibodies that better “match,” and neutralize, the actual pathogen.

“Protein-based RSV vaccines have had a particularly complicated history, especially those in which the primary immunogen has been the fusion (F) glycoprotein, which exists in two major conformational states: prefusion (pre-F) and postfusion (post-F),” lead author Michelle Crank, MD, of the Vaccine Research Center at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in Bethesda, Md., and her colleagues explained in the paper.

Since the failure of the whole-inactivated RSV vaccine in the 1960s, researchers have focused on F subunit vaccine candidates, but these contain only post-F or “structurally undefined” F protein.

“Although the products are immunogenic, a substantial proportion of antibodies elicited are non- or poorly neutralizing, and field trials have shown no or minimal efficacy,” the authors wrote.

But now researchers have an “atomic-level understanding of F conformational states, antigenic sites, and the specificity of the human B cell repertoire and serum antibody response to infection.” Having developed a way to engineer proteins to retain the F protein’s prefusion conformation, the researchers developed the DS-Cav1 vaccine with an F protein from RSV subtype A.

In their phase 1, randomized, open-label clinical trial, the researchers tested the safety, tolerability and immunogenicity of DS-Cav1. The trial involved 90 healthy adults, aged 18-50, who had no abnormal findings in clinical lab tests, their medical history, or a physical exam.

The participants received two intramuscular doses, 12 weeks apart, of either 50 mcg, 150 mcg or 500 mcg of the vaccine. In each of these dosage groups, half the participants received a vaccine with 0.5 mcg of alum as an adjuvant, and half received a vaccine without any adjuvants. Each of the six randomized dosage-adjuvant groups had 15 participants.

The investigators report on safety and immunogenicity through 28 days after the first vaccine dose among the first 40 participants enrolled, each randomly assigned into four groups of 10 for the 50 mcg and 150 mcg doses with and without the adjuvant. Their primary immunogenicity endpoint was neutralizing activity from the vaccine.

Neutralizing activity with RSV A was seven times higher with 50 mcg and 12-15 times higher with 150 mcg at week 4 than at baseline (P less than .001).

“These increases in neutralizing activity were higher than those previously reported for F protein subunit vaccines and exceeded the threefold increase in neutralization reported after experimental human challenge with RSV,” the authors noted. Neutralization levels remained 5-10 times higher than baseline at week 12 (P less than .001).

Even with RSV B, neutralizing activity from DS-Cav1 was 4-6 times greater with 50 mcg and 9 times greater with 150 mcg, both with and without alum (P less than .001).

“The boost in neutralizing activity to subtype B after a single immunization with a subtype A–based F vaccine reflected the high conservation of F between subtypes and suggested that multiple prior infections by both RSV A and B subtypes establishes a broad preexisting B-cell repertoire,” the authors wrote.

The adjuvant had no clinically significant effect on immunogenicity, and no serious adverse events occurred in the groups.

The findings reveal that DS-Cav1 induces antibodies far more functionally effective than seen in previous RSV vaccines while opening the door to using similar techniques with other vaccines, the authors wrote. “We are now entering an era of vaccinology in which new technologies provide avenues to define the structural basis of antigenicity and to rapidly isolate and characterize human monoclonal antibodies,” the researchers wrote, marking “a step toward a future of precision vaccines.”

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Several of the study authors are inventors on patents for stabilizing the RSV F protein.

Development of an effective respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccine is feasible using a new technology that can contribute to development of other vaccines as well, according to results of a proof-of-concept study in Science.

The new method of protein engineering preserves the RSV antigen protein’s prefusion structure, including the epitope, thereby inducing antibodies that better “match,” and neutralize, the actual pathogen.

“Protein-based RSV vaccines have had a particularly complicated history, especially those in which the primary immunogen has been the fusion (F) glycoprotein, which exists in two major conformational states: prefusion (pre-F) and postfusion (post-F),” lead author Michelle Crank, MD, of the Vaccine Research Center at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in Bethesda, Md., and her colleagues explained in the paper.

Since the failure of the whole-inactivated RSV vaccine in the 1960s, researchers have focused on F subunit vaccine candidates, but these contain only post-F or “structurally undefined” F protein.

“Although the products are immunogenic, a substantial proportion of antibodies elicited are non- or poorly neutralizing, and field trials have shown no or minimal efficacy,” the authors wrote.

But now researchers have an “atomic-level understanding of F conformational states, antigenic sites, and the specificity of the human B cell repertoire and serum antibody response to infection.” Having developed a way to engineer proteins to retain the F protein’s prefusion conformation, the researchers developed the DS-Cav1 vaccine with an F protein from RSV subtype A.

In their phase 1, randomized, open-label clinical trial, the researchers tested the safety, tolerability and immunogenicity of DS-Cav1. The trial involved 90 healthy adults, aged 18-50, who had no abnormal findings in clinical lab tests, their medical history, or a physical exam.

The participants received two intramuscular doses, 12 weeks apart, of either 50 mcg, 150 mcg or 500 mcg of the vaccine. In each of these dosage groups, half the participants received a vaccine with 0.5 mcg of alum as an adjuvant, and half received a vaccine without any adjuvants. Each of the six randomized dosage-adjuvant groups had 15 participants.

The investigators report on safety and immunogenicity through 28 days after the first vaccine dose among the first 40 participants enrolled, each randomly assigned into four groups of 10 for the 50 mcg and 150 mcg doses with and without the adjuvant. Their primary immunogenicity endpoint was neutralizing activity from the vaccine.

Neutralizing activity with RSV A was seven times higher with 50 mcg and 12-15 times higher with 150 mcg at week 4 than at baseline (P less than .001).

“These increases in neutralizing activity were higher than those previously reported for F protein subunit vaccines and exceeded the threefold increase in neutralization reported after experimental human challenge with RSV,” the authors noted. Neutralization levels remained 5-10 times higher than baseline at week 12 (P less than .001).

Even with RSV B, neutralizing activity from DS-Cav1 was 4-6 times greater with 50 mcg and 9 times greater with 150 mcg, both with and without alum (P less than .001).

“The boost in neutralizing activity to subtype B after a single immunization with a subtype A–based F vaccine reflected the high conservation of F between subtypes and suggested that multiple prior infections by both RSV A and B subtypes establishes a broad preexisting B-cell repertoire,” the authors wrote.

The adjuvant had no clinically significant effect on immunogenicity, and no serious adverse events occurred in the groups.

The findings reveal that DS-Cav1 induces antibodies far more functionally effective than seen in previous RSV vaccines while opening the door to using similar techniques with other vaccines, the authors wrote. “We are now entering an era of vaccinology in which new technologies provide avenues to define the structural basis of antigenicity and to rapidly isolate and characterize human monoclonal antibodies,” the researchers wrote, marking “a step toward a future of precision vaccines.”

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Several of the study authors are inventors on patents for stabilizing the RSV F protein.

Development of an effective respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccine is feasible using a new technology that can contribute to development of other vaccines as well, according to results of a proof-of-concept study in Science.

The new method of protein engineering preserves the RSV antigen protein’s prefusion structure, including the epitope, thereby inducing antibodies that better “match,” and neutralize, the actual pathogen.

“Protein-based RSV vaccines have had a particularly complicated history, especially those in which the primary immunogen has been the fusion (F) glycoprotein, which exists in two major conformational states: prefusion (pre-F) and postfusion (post-F),” lead author Michelle Crank, MD, of the Vaccine Research Center at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in Bethesda, Md., and her colleagues explained in the paper.

Since the failure of the whole-inactivated RSV vaccine in the 1960s, researchers have focused on F subunit vaccine candidates, but these contain only post-F or “structurally undefined” F protein.

“Although the products are immunogenic, a substantial proportion of antibodies elicited are non- or poorly neutralizing, and field trials have shown no or minimal efficacy,” the authors wrote.

But now researchers have an “atomic-level understanding of F conformational states, antigenic sites, and the specificity of the human B cell repertoire and serum antibody response to infection.” Having developed a way to engineer proteins to retain the F protein’s prefusion conformation, the researchers developed the DS-Cav1 vaccine with an F protein from RSV subtype A.

In their phase 1, randomized, open-label clinical trial, the researchers tested the safety, tolerability and immunogenicity of DS-Cav1. The trial involved 90 healthy adults, aged 18-50, who had no abnormal findings in clinical lab tests, their medical history, or a physical exam.

The participants received two intramuscular doses, 12 weeks apart, of either 50 mcg, 150 mcg or 500 mcg of the vaccine. In each of these dosage groups, half the participants received a vaccine with 0.5 mcg of alum as an adjuvant, and half received a vaccine without any adjuvants. Each of the six randomized dosage-adjuvant groups had 15 participants.

The investigators report on safety and immunogenicity through 28 days after the first vaccine dose among the first 40 participants enrolled, each randomly assigned into four groups of 10 for the 50 mcg and 150 mcg doses with and without the adjuvant. Their primary immunogenicity endpoint was neutralizing activity from the vaccine.

Neutralizing activity with RSV A was seven times higher with 50 mcg and 12-15 times higher with 150 mcg at week 4 than at baseline (P less than .001).

“These increases in neutralizing activity were higher than those previously reported for F protein subunit vaccines and exceeded the threefold increase in neutralization reported after experimental human challenge with RSV,” the authors noted. Neutralization levels remained 5-10 times higher than baseline at week 12 (P less than .001).

Even with RSV B, neutralizing activity from DS-Cav1 was 4-6 times greater with 50 mcg and 9 times greater with 150 mcg, both with and without alum (P less than .001).

“The boost in neutralizing activity to subtype B after a single immunization with a subtype A–based F vaccine reflected the high conservation of F between subtypes and suggested that multiple prior infections by both RSV A and B subtypes establishes a broad preexisting B-cell repertoire,” the authors wrote.

The adjuvant had no clinically significant effect on immunogenicity, and no serious adverse events occurred in the groups.

The findings reveal that DS-Cav1 induces antibodies far more functionally effective than seen in previous RSV vaccines while opening the door to using similar techniques with other vaccines, the authors wrote. “We are now entering an era of vaccinology in which new technologies provide avenues to define the structural basis of antigenicity and to rapidly isolate and characterize human monoclonal antibodies,” the researchers wrote, marking “a step toward a future of precision vaccines.”

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Several of the study authors are inventors on patents for stabilizing the RSV F protein.

FROM SCIENCE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Epitope-neutralizing activity is 5-10 times greater 12 weeks after baseline with a 50 mcg or 150 mcg with and without alum adjuvant.

Study details: The findings are based on a prespecified interim analysis of 90 healthy adult participants in a phase 1, randomized, trial of DS-Cav1.

Disclosures: The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Several authors are inventors on patents for stabilizing the RSV F protein.

Source: Crank MC et al. Science. 2019;365(6452):505-9.

Sepsis survivors’ persistent immunosuppression raises mortality risk

readmission after discharge, and mortality, according to a study published in JAMA Network Open.

“Individuals with persistent biomarkers of inflammation and immunosuppression had a higher risk of readmission and death due to cardiovascular disease and cancer compared with those with normal circulating biomarkers,” Sachin Yende, MD, of the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System and the University of Pittsburgh and colleagues wrote in their study. “Our findings suggest that long-term immunomodulation strategies should be explored in patients hospitalized with sepsis.”

Dr. Yende and colleagues performed a multicenter, prospective cohort study of 483 patients who were hospitalized for sepsis at 12 different sites between January 2012 and May 2017. They measured inflammation using interleukin-6, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), and soluble programmed death-ligand 1 (sPD-L1); hemostasis using plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 and D-dimer; and endothelial dysfunction using intercellular adhesion molecule 1, vascular cell adhesion molecule 1, and E-selectin. The patients included were mean age 60.5 years, 54.9% were male, the mean Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score was 4.2, and a total of 376 patients (77.8%) had one or more chronic diseases.

Overall, there were 485 readmissions in 205 patients (42.5%). The mortality rate was 43 patients (8.9%) at 3 months, 56 patients (11.6%) at 6 months, and 85 patients (17.6%) at 12 months. At 3 months, 23 patients (25.8%) had elevated hs-CRP levels, which increased to 26 patients (30.2%) at 6 months and 40 patients (44.9%) at 12 months. sPD-L1 levels were elevated in 45 patients (46.4%) at 3 months, but the number of patients with elevated sPD-L1 did not appear to significantly increase at 6 months (40 patients; 44.9%) or 12 months (44 patients; 49.4%).

From these results, researchers developed a phenotype of hyperinflammation and immunosuppression that consisted of 326 of 477 (68.3%) patients with high hs-CRP and elevated sPD-L1 levels. Patients with this phenotype of hyperinflammation and immunosuppression had more than eight times the risk of 1-year mortality (odds ratio, 8.26; 95% confidence interval, 3.45-21.69; P less than .001) and more than five times the risk of readmission or mortality at 6 months related to cardiovascular disease (hazard ratio, 5.07; 95% CI, 1.18-21.84; P = .02) or cancer (hazard ratio, 5.15; 95% CI, 1.25-21.18; P = .02), compared with patients who had normal hs-CRP and sPD-L1 levels. This hyperinflammation and immunosuppression phenotype also was associated with greater risk of 6-month all-cause readmission or mortality (HR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.10-2.13; P = .01), compared with patients who had the normal phenotype.

“The persistence of hyperinflammation in a large number of sepsis survivors and the increased risk of cardiovascular events among these patients may explain the association between infection and cardiovascular disease in a prior study,” the authors said. “Although prior trials tested immunomodulation strategies during only the early phase of hospitalization for sepsis, immunomodulation may be needed after hospital discharge,” and suggest points of future study for patients who survive sepsis and develop long-term sequelae.

This study was funded by grants from National Institutes of Health and resources from the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System. The authors reported personal and institutional relationships in the form of personal fees, grants, and patents for Alung Technologies, Atox Bio, Bayer AG, Beckman Coulter, BristolMyers Squibb, Ferring, NIH, Roche, Selepressin, and the University of Pittsburgh.

SOURCE: Yende S et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Aug 7. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.8686.

readmission after discharge, and mortality, according to a study published in JAMA Network Open.

“Individuals with persistent biomarkers of inflammation and immunosuppression had a higher risk of readmission and death due to cardiovascular disease and cancer compared with those with normal circulating biomarkers,” Sachin Yende, MD, of the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System and the University of Pittsburgh and colleagues wrote in their study. “Our findings suggest that long-term immunomodulation strategies should be explored in patients hospitalized with sepsis.”

Dr. Yende and colleagues performed a multicenter, prospective cohort study of 483 patients who were hospitalized for sepsis at 12 different sites between January 2012 and May 2017. They measured inflammation using interleukin-6, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), and soluble programmed death-ligand 1 (sPD-L1); hemostasis using plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 and D-dimer; and endothelial dysfunction using intercellular adhesion molecule 1, vascular cell adhesion molecule 1, and E-selectin. The patients included were mean age 60.5 years, 54.9% were male, the mean Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score was 4.2, and a total of 376 patients (77.8%) had one or more chronic diseases.

Overall, there were 485 readmissions in 205 patients (42.5%). The mortality rate was 43 patients (8.9%) at 3 months, 56 patients (11.6%) at 6 months, and 85 patients (17.6%) at 12 months. At 3 months, 23 patients (25.8%) had elevated hs-CRP levels, which increased to 26 patients (30.2%) at 6 months and 40 patients (44.9%) at 12 months. sPD-L1 levels were elevated in 45 patients (46.4%) at 3 months, but the number of patients with elevated sPD-L1 did not appear to significantly increase at 6 months (40 patients; 44.9%) or 12 months (44 patients; 49.4%).

From these results, researchers developed a phenotype of hyperinflammation and immunosuppression that consisted of 326 of 477 (68.3%) patients with high hs-CRP and elevated sPD-L1 levels. Patients with this phenotype of hyperinflammation and immunosuppression had more than eight times the risk of 1-year mortality (odds ratio, 8.26; 95% confidence interval, 3.45-21.69; P less than .001) and more than five times the risk of readmission or mortality at 6 months related to cardiovascular disease (hazard ratio, 5.07; 95% CI, 1.18-21.84; P = .02) or cancer (hazard ratio, 5.15; 95% CI, 1.25-21.18; P = .02), compared with patients who had normal hs-CRP and sPD-L1 levels. This hyperinflammation and immunosuppression phenotype also was associated with greater risk of 6-month all-cause readmission or mortality (HR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.10-2.13; P = .01), compared with patients who had the normal phenotype.

“The persistence of hyperinflammation in a large number of sepsis survivors and the increased risk of cardiovascular events among these patients may explain the association between infection and cardiovascular disease in a prior study,” the authors said. “Although prior trials tested immunomodulation strategies during only the early phase of hospitalization for sepsis, immunomodulation may be needed after hospital discharge,” and suggest points of future study for patients who survive sepsis and develop long-term sequelae.

This study was funded by grants from National Institutes of Health and resources from the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System. The authors reported personal and institutional relationships in the form of personal fees, grants, and patents for Alung Technologies, Atox Bio, Bayer AG, Beckman Coulter, BristolMyers Squibb, Ferring, NIH, Roche, Selepressin, and the University of Pittsburgh.

SOURCE: Yende S et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Aug 7. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.8686.

readmission after discharge, and mortality, according to a study published in JAMA Network Open.

“Individuals with persistent biomarkers of inflammation and immunosuppression had a higher risk of readmission and death due to cardiovascular disease and cancer compared with those with normal circulating biomarkers,” Sachin Yende, MD, of the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System and the University of Pittsburgh and colleagues wrote in their study. “Our findings suggest that long-term immunomodulation strategies should be explored in patients hospitalized with sepsis.”

Dr. Yende and colleagues performed a multicenter, prospective cohort study of 483 patients who were hospitalized for sepsis at 12 different sites between January 2012 and May 2017. They measured inflammation using interleukin-6, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), and soluble programmed death-ligand 1 (sPD-L1); hemostasis using plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 and D-dimer; and endothelial dysfunction using intercellular adhesion molecule 1, vascular cell adhesion molecule 1, and E-selectin. The patients included were mean age 60.5 years, 54.9% were male, the mean Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score was 4.2, and a total of 376 patients (77.8%) had one or more chronic diseases.

Overall, there were 485 readmissions in 205 patients (42.5%). The mortality rate was 43 patients (8.9%) at 3 months, 56 patients (11.6%) at 6 months, and 85 patients (17.6%) at 12 months. At 3 months, 23 patients (25.8%) had elevated hs-CRP levels, which increased to 26 patients (30.2%) at 6 months and 40 patients (44.9%) at 12 months. sPD-L1 levels were elevated in 45 patients (46.4%) at 3 months, but the number of patients with elevated sPD-L1 did not appear to significantly increase at 6 months (40 patients; 44.9%) or 12 months (44 patients; 49.4%).

From these results, researchers developed a phenotype of hyperinflammation and immunosuppression that consisted of 326 of 477 (68.3%) patients with high hs-CRP and elevated sPD-L1 levels. Patients with this phenotype of hyperinflammation and immunosuppression had more than eight times the risk of 1-year mortality (odds ratio, 8.26; 95% confidence interval, 3.45-21.69; P less than .001) and more than five times the risk of readmission or mortality at 6 months related to cardiovascular disease (hazard ratio, 5.07; 95% CI, 1.18-21.84; P = .02) or cancer (hazard ratio, 5.15; 95% CI, 1.25-21.18; P = .02), compared with patients who had normal hs-CRP and sPD-L1 levels. This hyperinflammation and immunosuppression phenotype also was associated with greater risk of 6-month all-cause readmission or mortality (HR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.10-2.13; P = .01), compared with patients who had the normal phenotype.

“The persistence of hyperinflammation in a large number of sepsis survivors and the increased risk of cardiovascular events among these patients may explain the association between infection and cardiovascular disease in a prior study,” the authors said. “Although prior trials tested immunomodulation strategies during only the early phase of hospitalization for sepsis, immunomodulation may be needed after hospital discharge,” and suggest points of future study for patients who survive sepsis and develop long-term sequelae.

This study was funded by grants from National Institutes of Health and resources from the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System. The authors reported personal and institutional relationships in the form of personal fees, grants, and patents for Alung Technologies, Atox Bio, Bayer AG, Beckman Coulter, BristolMyers Squibb, Ferring, NIH, Roche, Selepressin, and the University of Pittsburgh.

SOURCE: Yende S et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Aug 7. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.8686.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Key clinical point: Markers of inflammation and immunosuppression persist in over two-thirds of patients hospitalized for sepsis, which could explain worsened outcomes and mortality up to 1 year after hospitalization.

Major finding: Patients with signs of hyperinflammation and immunosuppression had significantly increased mortality after 1 year and were significantly more likely to be readmitted or die because of cardiovascular disease or cancer.

Study details: A prospective cohort study of 483 patients who were hospitalized because of sepsis at 12 different centers between January 2012 and May 2017.

Disclosures: This study was funded by grants from National Institutes of Health and resources from the Veterans Affairs Pittsburgh Healthcare System. The authors reported personal and institutional relationships in the form of personal fees, grants, and patents for Alung Technologies, Atox Bio, Bayer AG, Beckman Coulter, BristolMyers Squibb, Ferring, NIH, Roche, Selepressin, and the University of Pittsburgh.

Source: Yende S et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Aug 7. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.8686.

Smartphone mind control, wasp gyn remedy, and seagull stare downs

Don’t put THAT THERE!

As a doctor, you’ve probably thought, “I can’t believe I have to tell them this” more than once. Warnings that you think are common sense – please don’t try that home remedy, please don’t put that there, please don’t eat that anymore.

Well, here’s a new one for all doctors with female patients out there: Please don’t put a ground-up wasp’s nest into your vagina.

An intrepid ob.gyn. with a large Internet following found that someone has been selling oak galls online as vaginal medicine. Oak galls are little bumps that grow on a tree after the gall wasp lays its larvae. Fun insect-plant behavior! Very bad to put inside your body in any way!

One would think you don’t need to warn patients that tree/wasp paste is not the correct medicine to use on an episiotomy cut, as the Etsy seller suggested.

But with Gwyneth Paltrow out there trying to convince people that purposeful bee stings, healing stickers, and goat milk cleanses are all valid health tips, sometimes the obvious things just need to be spelled out.

Eye of the seagull

Rising up/Back on the beach/Did my time, made my sandwich

Went to the kitchen/Now I’m back on the street

Just a man and his will to surviiiiiiiiiive

It’s the eye of the seagull/It’s the thrill of the fight

Research shows you have to stare them down

When a seagull eyes your sandwich/Don’t let it have a bite

Don’t give in to the eye of the seagull.

That’s just a little ditty for you to sing this summer while enjoying your time on the sand, surrounded by those greedy flying sandwich thieves. Research out of the University of Exeter, England, suggests that staring down approaching seagulls can actually slow them down or even completely deter them from attempting to steal your snacks.

Perhaps the seagulls don’t like being watched while they commit their crimes? Maybe they can’t stand the shame of it all.

Whatever the reason, if you’re assaulted by a flock of seagulls this summer (the birds, not the band), try engaging in a staring contest to keep your food safe.

A gut microbe with a rye smile

Rye is not exactly a huge deal here in the good old U.S. of A., but rye bread happens to be the national food of Finland. So when the Finns say something about rye, it pays to listen.

Investigators at the University of Eastern Finland used metabolomics – which, we discovered the hard way, is the “analysis of metabolites in a biological specimen” and not the Finnish word for a “financial system based on rye bread” – to examine the effects of rye sourdough on the gut microbes of mice and an in vitro gastrointestinal model that mimicked the function of the human gut.

Many compounds found in rye sourdough, such as branched-chain amino acids and amino acid–containing small peptides known to have an impact on insulin metabolism, are processed by gut bacteria before getting absorbed into the body.

The gut microbes of mice fed rye sourdough also produce derivatives of trimethylglycine known as betaine, and at least one of these derivatives reduces the need for oxygen in heart muscle cells, which may protect the heart from ischemia or possibly even enhance its performance, the investigators said.

“The major role played by gut microbes in human health has become more and more evident over the past decades, and this is why gut microbes should be taken very good care of. It’s a good idea to avoid unnecessary antibiotics and feed gut microbes with optimal food, such as rye,” researcher Ville M. Koistinen said in a written statement.

The bottom line? A rye-filled gut microbe is a happy gut microbe. And this comes from Finland, the nation that gave the world “pantsdrunk,” so it must be true. On behalf of the Finns, you’re welcome, world.

This is your brain on smartphones

Hey. Hey, you. Do you want some scientists to install a small device in your brain that uses light and drugs to control your neurons and can be controlled externally by a smartphone? No?

Sounds like a terrible idea only fit for a cheesy science fiction dystopia, you say? Too bad, because a group of researchers from South Korea and the University of Colorado already have invented such a device.

To be fair, their study, published in Nature Biomedical Engineering, is relatively free of nefariousness. The device is meant to be used to search for brain diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, as well as disorders such as depression, addiction, and pain.

The researchers say that their device is superior to current diagnostic technology available – which uses a similar drug/light combo but is bulkier, stationary, and causes long-term brain damage – because it can be used long term and outside the lab and – we’re sorry – but we’re straying back into dystopia here.

Okay, let’s try again. To test their device, the researchers conducted an animal study and found that, by manipulating the behavior of one animal using the drug/light combo from behind their smartphones, they could influence the behavior of the entire group.

Did we say that the study was relatively free of nefariousness? Sorry about that. At this point, we wouldn’t be surprised if the whole thing was bankrolled by a couple of genetically engineered lab mice from Acme Labs bent on world domination.

Don’t put THAT THERE!

As a doctor, you’ve probably thought, “I can’t believe I have to tell them this” more than once. Warnings that you think are common sense – please don’t try that home remedy, please don’t put that there, please don’t eat that anymore.

Well, here’s a new one for all doctors with female patients out there: Please don’t put a ground-up wasp’s nest into your vagina.

An intrepid ob.gyn. with a large Internet following found that someone has been selling oak galls online as vaginal medicine. Oak galls are little bumps that grow on a tree after the gall wasp lays its larvae. Fun insect-plant behavior! Very bad to put inside your body in any way!

One would think you don’t need to warn patients that tree/wasp paste is not the correct medicine to use on an episiotomy cut, as the Etsy seller suggested.

But with Gwyneth Paltrow out there trying to convince people that purposeful bee stings, healing stickers, and goat milk cleanses are all valid health tips, sometimes the obvious things just need to be spelled out.

Eye of the seagull

Rising up/Back on the beach/Did my time, made my sandwich

Went to the kitchen/Now I’m back on the street

Just a man and his will to surviiiiiiiiiive

It’s the eye of the seagull/It’s the thrill of the fight

Research shows you have to stare them down

When a seagull eyes your sandwich/Don’t let it have a bite

Don’t give in to the eye of the seagull.

That’s just a little ditty for you to sing this summer while enjoying your time on the sand, surrounded by those greedy flying sandwich thieves. Research out of the University of Exeter, England, suggests that staring down approaching seagulls can actually slow them down or even completely deter them from attempting to steal your snacks.

Perhaps the seagulls don’t like being watched while they commit their crimes? Maybe they can’t stand the shame of it all.

Whatever the reason, if you’re assaulted by a flock of seagulls this summer (the birds, not the band), try engaging in a staring contest to keep your food safe.

A gut microbe with a rye smile

Rye is not exactly a huge deal here in the good old U.S. of A., but rye bread happens to be the national food of Finland. So when the Finns say something about rye, it pays to listen.

Investigators at the University of Eastern Finland used metabolomics – which, we discovered the hard way, is the “analysis of metabolites in a biological specimen” and not the Finnish word for a “financial system based on rye bread” – to examine the effects of rye sourdough on the gut microbes of mice and an in vitro gastrointestinal model that mimicked the function of the human gut.

Many compounds found in rye sourdough, such as branched-chain amino acids and amino acid–containing small peptides known to have an impact on insulin metabolism, are processed by gut bacteria before getting absorbed into the body.

The gut microbes of mice fed rye sourdough also produce derivatives of trimethylglycine known as betaine, and at least one of these derivatives reduces the need for oxygen in heart muscle cells, which may protect the heart from ischemia or possibly even enhance its performance, the investigators said.

“The major role played by gut microbes in human health has become more and more evident over the past decades, and this is why gut microbes should be taken very good care of. It’s a good idea to avoid unnecessary antibiotics and feed gut microbes with optimal food, such as rye,” researcher Ville M. Koistinen said in a written statement.

The bottom line? A rye-filled gut microbe is a happy gut microbe. And this comes from Finland, the nation that gave the world “pantsdrunk,” so it must be true. On behalf of the Finns, you’re welcome, world.

This is your brain on smartphones

Hey. Hey, you. Do you want some scientists to install a small device in your brain that uses light and drugs to control your neurons and can be controlled externally by a smartphone? No?

Sounds like a terrible idea only fit for a cheesy science fiction dystopia, you say? Too bad, because a group of researchers from South Korea and the University of Colorado already have invented such a device.

To be fair, their study, published in Nature Biomedical Engineering, is relatively free of nefariousness. The device is meant to be used to search for brain diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, as well as disorders such as depression, addiction, and pain.

The researchers say that their device is superior to current diagnostic technology available – which uses a similar drug/light combo but is bulkier, stationary, and causes long-term brain damage – because it can be used long term and outside the lab and – we’re sorry – but we’re straying back into dystopia here.

Okay, let’s try again. To test their device, the researchers conducted an animal study and found that, by manipulating the behavior of one animal using the drug/light combo from behind their smartphones, they could influence the behavior of the entire group.

Did we say that the study was relatively free of nefariousness? Sorry about that. At this point, we wouldn’t be surprised if the whole thing was bankrolled by a couple of genetically engineered lab mice from Acme Labs bent on world domination.

Don’t put THAT THERE!

As a doctor, you’ve probably thought, “I can’t believe I have to tell them this” more than once. Warnings that you think are common sense – please don’t try that home remedy, please don’t put that there, please don’t eat that anymore.

Well, here’s a new one for all doctors with female patients out there: Please don’t put a ground-up wasp’s nest into your vagina.

An intrepid ob.gyn. with a large Internet following found that someone has been selling oak galls online as vaginal medicine. Oak galls are little bumps that grow on a tree after the gall wasp lays its larvae. Fun insect-plant behavior! Very bad to put inside your body in any way!

One would think you don’t need to warn patients that tree/wasp paste is not the correct medicine to use on an episiotomy cut, as the Etsy seller suggested.

But with Gwyneth Paltrow out there trying to convince people that purposeful bee stings, healing stickers, and goat milk cleanses are all valid health tips, sometimes the obvious things just need to be spelled out.

Eye of the seagull

Rising up/Back on the beach/Did my time, made my sandwich

Went to the kitchen/Now I’m back on the street

Just a man and his will to surviiiiiiiiiive

It’s the eye of the seagull/It’s the thrill of the fight

Research shows you have to stare them down

When a seagull eyes your sandwich/Don’t let it have a bite

Don’t give in to the eye of the seagull.

That’s just a little ditty for you to sing this summer while enjoying your time on the sand, surrounded by those greedy flying sandwich thieves. Research out of the University of Exeter, England, suggests that staring down approaching seagulls can actually slow them down or even completely deter them from attempting to steal your snacks.

Perhaps the seagulls don’t like being watched while they commit their crimes? Maybe they can’t stand the shame of it all.

Whatever the reason, if you’re assaulted by a flock of seagulls this summer (the birds, not the band), try engaging in a staring contest to keep your food safe.

A gut microbe with a rye smile

Rye is not exactly a huge deal here in the good old U.S. of A., but rye bread happens to be the national food of Finland. So when the Finns say something about rye, it pays to listen.

Investigators at the University of Eastern Finland used metabolomics – which, we discovered the hard way, is the “analysis of metabolites in a biological specimen” and not the Finnish word for a “financial system based on rye bread” – to examine the effects of rye sourdough on the gut microbes of mice and an in vitro gastrointestinal model that mimicked the function of the human gut.

Many compounds found in rye sourdough, such as branched-chain amino acids and amino acid–containing small peptides known to have an impact on insulin metabolism, are processed by gut bacteria before getting absorbed into the body.

The gut microbes of mice fed rye sourdough also produce derivatives of trimethylglycine known as betaine, and at least one of these derivatives reduces the need for oxygen in heart muscle cells, which may protect the heart from ischemia or possibly even enhance its performance, the investigators said.

“The major role played by gut microbes in human health has become more and more evident over the past decades, and this is why gut microbes should be taken very good care of. It’s a good idea to avoid unnecessary antibiotics and feed gut microbes with optimal food, such as rye,” researcher Ville M. Koistinen said in a written statement.

The bottom line? A rye-filled gut microbe is a happy gut microbe. And this comes from Finland, the nation that gave the world “pantsdrunk,” so it must be true. On behalf of the Finns, you’re welcome, world.

This is your brain on smartphones

Hey. Hey, you. Do you want some scientists to install a small device in your brain that uses light and drugs to control your neurons and can be controlled externally by a smartphone? No?

Sounds like a terrible idea only fit for a cheesy science fiction dystopia, you say? Too bad, because a group of researchers from South Korea and the University of Colorado already have invented such a device.

To be fair, their study, published in Nature Biomedical Engineering, is relatively free of nefariousness. The device is meant to be used to search for brain diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, as well as disorders such as depression, addiction, and pain.

The researchers say that their device is superior to current diagnostic technology available – which uses a similar drug/light combo but is bulkier, stationary, and causes long-term brain damage – because it can be used long term and outside the lab and – we’re sorry – but we’re straying back into dystopia here.

Okay, let’s try again. To test their device, the researchers conducted an animal study and found that, by manipulating the behavior of one animal using the drug/light combo from behind their smartphones, they could influence the behavior of the entire group.

Did we say that the study was relatively free of nefariousness? Sorry about that. At this point, we wouldn’t be surprised if the whole thing was bankrolled by a couple of genetically engineered lab mice from Acme Labs bent on world domination.

Use of Mobile Messaging System for Self-Management of Chemotherapy Symptoms in Patients with Advanced Cancer (FULL)

Cancer and cancer-related treatment can cause a myriad of adverse effects.1,2 Early identification and management of these symptoms is paramount to the success of cancer treatment completion; however, clinic and telephonic strategies for addressing symptoms often result in delays in care.1 New strategies for patient engagement in the management of cancer and treatment-related symptoms are needed.

The use of online self-management tools can result in improvement in symptoms, reduce cancer symptom distress, improve quality-of-life, and improve medication adherence.3-9 A meta-analysis concluded that online interventions showed promise, but optimizing interventions would require additional research.10 Another meta-analysis found that online self-management was effective in managing several symptoms.11 An e-health method of collecting patient self-reported symptoms has been found to be acceptable to patients and feasible for use.12-14 We postulated that a mobile text messaging strategy may be an effective modality for augmenting symptom management for cancer patients in real time.

In the US Departmant of Veterans Affairs (VA), “Annie,” a self-care tool utilizing a text-messaging system has been implemented. Annie was developed modeling “Flo,” a messaging system in the United Kingdom that has been used for case management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure, stress incontinence, asthma, as a medication reminder tool, and to provide support for weight loss or post-operatively.15-17 Using Annie in the US, veterans have the ability to receive and track health information. Use of the Annie program has demonstrated improved continuous positive airway pressure monitor utilization in veterans with traumatic brain injury.18 Other uses within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) include assisting patients with anger management, liver disease, anxiety, asthma, diabetes, HIV, hypertension, weight loss, and smoking cessation.

Methods

The Hematology/Oncology division of the Minneapolis VA Healthcare System (MVAHCS) is a tertiary care facility that administers about 260 new chemotherapy regimens annually. The MVAHCS interdisciplinary hematology/oncology group initiated a quality improvement project to determine the feasibility, acceptability, and experience of tailoring the Annie tool for self-management of cancer symptoms. The group consisted of 2 physicians, 3 advanced practice registered nurses, 1 physician assistant, 2 registered nurses, and 2 Annie program team members.

We first created a symptom management pilot protocol as a result of multidisciplinary team discussions. Examples of discussion points for consideration included, but were not limited to, timing of texts, amount of information to ask for and provide, what potential symptoms to consider, and which patient population to pilot first.

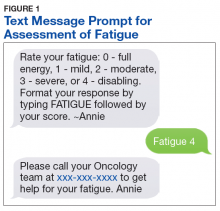

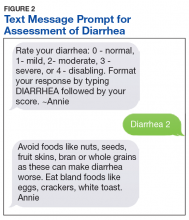

The initial protocol was agreed upon and is as follows: Patients were sent text messages twice daily Monday through Friday, and asked to rate 2 symptoms per day, using a severity scale of 0 to 4 (absent, mild, moderate, severe, or disabling): nausea/vomiting, mouth sores, fatigue (Figure 1), trouble breathing, appetite, constipation, diarrhea (Figure 2), numbness/tingling, pain. In addition, patients were asked whether they had had a fever or not. Based on their response to the symptom inquiries, the patient received an automated text response. The text may have provided positive affirmation that they were doing well, given them advice for home management, referred them to an educational hyperlink, asked them to call a direct number to the clinic, or instructed them to report directly to the emergency department (ED). Patients could input a particular symptom on any day, even if they were not specifically asked about that symptom on that day. Patients also were instructed to text, only if it was not an inconvenience to them, as we wanted the intervention to be helpful and not a burden.

Results

Through screening new patient consults or those referred for chemotherapy education, 15 male veterans enrolled in the symptom monitoring program over an 8 month period. There were additional patients who were not offered the program or chose not to participate; often due to not having texting capabilities on their phone or not liking the texting feature. The majority of those who participated in the program (n = 14) were enrolled at the start of Cycle 1; the other patient was enrolled at the start of Cycle 2. Patients were enrolled an average of 89 days (range 8-204). Average response rate was 84.2% (range 30-100%).

Although symptoms were not reviewed in real time, we reviewed responses to determine the utilization of the instructions given for the program. No veteran had 0 symptoms reported. There were numerous occurrences of a score of 1 or 2. Many of these patients had baseline symptoms due to their underlying cancer. A score of 3 or 4 on the system prompted the patient to call the clinic or go to the ED. Seven patients (some with multiple occurrences) were prompted to call; only 4 of these made the follow-up call to the clinic. All were offered a same day visit, but each declined. Only 1 patient reported a symptom on a day not prompted for that symptom. Symptoms that were reported are listed in order of frequency: fatigue, appetite loss, numbness, pain, mouth sore, and breathing difficulty. There were no visits to the ED.

Program Evaluation

An evaluation was conducted 30 to 60 days after program enrollment. We elicited feedback to determine who was reading and responding to the text message: the patient, a family member, or a caregiver; whether they found the prompts helpful and took action; how they felt about the number of texts; if they felt the program was helpful; and any other feedback that would improve the program. In general, the patients (8) answered the texts independently. In 4 cases, the spouse answered the texts, and 3 patients answered the texts together with their spouses. Most patients (11) found the amount of texting to be “just right.” However, 3 found it to be too many texts and 1 didn’t find the amount of texting to be enough.

Three veterans did not have enough symptoms to feel the program was of benefit to them, but they did feel it would have been helpful if they had been more symptomatic. One veteran recalled taking loperamide as needed, as a result of prompting. No veterans felt as though the texting feature was difficult to use; and overall, were very positive about the program. Several appreciated receiving messages that validated when they were doing well, and they felt empowered by self-management. One of the spouses was a registered nurse and found the information too basic to be of use.

Discussion

Initial evaluation of the program via survey found no technology challenges. Patients have been very positive about the program including ease of use, appreciation of messages that validated when they were doing well, empowerment of self-management, and some utilization of the texting advice for symptom management. Educational hyperlinks for constipation, fatigue, diarrhea, and nausea/vomiting were added after this evaluation, and patients felt that these additions provided a higher level of education.

Staff time for this intervention was minimal. A nurse navigator offered the texting program to the patient during chemotherapy education, along with some instructions, which generally took about 5 minutes. One of the Annie program staff enrolled the patient. From that point forward, this was a self-management tool, beyond checking to ensure that the patient was successful in starting the program and evaluating use for the purposes of this quality improvement project. This self-management tool did not replace any other mechanism that a patient would normally have in our department for seeking help for symptoms. The MVAHSC typical process for symptom management is to have patients call a 24/7 nurse line. If the triage nurse feels the symptoms are related to the patient’s cancer or cancer treatment, they are referred to the physician assistant who is assigned to take those calls and has the option to see the patient the same day. Patients could continue to call the nurse line or speak with providers at the next appointment at their discretion.

Conclusion

Although Annie has the option of using either text messaging or a mobile application, this project only utilized text messaging. The study by Basch and colleagues was the closest randomized trial we could identify to compare to our quality improvement intervention.5 The 2 main, distinct differences were that Basch and colleagues utilized online monitoring; and nurses were utilized to screen and intervene on responses, as appropriate.

The ability of our program to text patients without the use of an application or tablet, may enable more patients to participate due to ease of use. There would be no increased in expected workload for clinical staff, and may lead to decreased call burden. Since our program is automated, while still providing patients with the option to call and speak with a staff member as needed, this is a cost-effective, first-line option for symptom management for those experiencing cancer-related symptoms. We believe this text messaging tool can have system wide use and benefit throughout the VHA.

1. Bruera E, Dev R. Overview of managing common non-pain symptoms in palliative care. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-managing-common-non-pain-symptoms-in-palliative-care. Updated June 12, 2019. Accessed July 18, 2019.

2. Pirschel C. The crucial role of symptom management in cancer care. https://voice.ons.org/news-and-views/the-crucial-role-of-symptom-management-in-cancer-care. Published December 14, 2017. Accessed July 18, 2019.

3. Adam R, Burton CD, Bond CM, de Bruin M, Murchie P. Can patient-reported measurements of pain be used to improve cancer pain management? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2017;7(4):373-382.

4. Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, et al. Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(6):557-565.

5. Berry DL, Blonquist TM, Patel RA, Halpenny B, McReynolds J. Exposure to a patient-centered, Web-based intervention for managing cancer symptom and quality of life issues: Impact on symptom distress. J Med Internet Res. 2015;3(7):e136.

6. Kolb NA, Smith AG, Singleton JR, et al. Chemotherapy-related neuropathic symptom management: a randomized trial of an automated symptom-monitoring system paired with nurse practitioner follow-up. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(5):1607-1615

7. Kamdar MM, Centi AJ, Fischer N, Jetwani K. A randomized controlled trial of a novel artificial-intelligence based smartphone application to optimize the management of cancer-related pain. Presented at: 2018 Palliative and Supportive Care in Oncology Symposium; November 16-17, 2018; San Diego, CA.

8. Mooney KH, Beck SL, Wong B, et al. Automated home monitoring and management of patient-reported symptoms during chemotherapy: results of the symptom care at home RCT. Cancer Med. 2017;6(3):537-546.

9. Spoelstra SL, Given CW, Sikorskii A, et al. Proof of concept of a mobile health short message service text message intervention that promotes adherence to oral anticancer agent medications: a randomized controlled trial. Telemed J E Health. 2016;22(6):497-506.

10. Fridriksdottir N, Gunnarsdottir S, Zoëga S, Ingadottir B, Hafsteinsdottir EJG. Effects of web-based interventions on cancer patients’ symptoms: review of randomized trials. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(2):3370-351.

11. Kim AR, Park HA. Web-based self-management support intervention for cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2015;216:142-147.

12. Girgis A, Durcinoska I, Levesque JV, et al; PROMPT-Care Program Group. eHealth system for collecting and utilizing patient reported outcome measures for personalized treatment and care (PROMPT-Care) among cancer patients: mixed methods approach to evaluate feasibility and acceptability. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(10):e330.

13. Moradian S, Krzyzanowska MK, Maguire R, et al. Usability evaluation of a mobile phone-based system for remote monitoring and management of chemotherapy-related side effects in cancer patients: Mixed methods study. JMIR Cancer. 2018;4(2): e10932.

14. Voruganti T, Grunfeld E, Jamieson T, et al. My team of care study: a pilot randomized controlled trial of a web-based communication tool for collaborative care in patients with advanced cancer. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(7):e219.

15. The Health Foundation. Overview of Florence simple telehealth text messaging system. https://www.health.org.uk/article/overview-of-the-florence-simple-telehealth-text-messaging-system. Accessed July 31, 2019.

16. Bragg DD, Edis H, Clark S, Parsons SL, Perumpalath B…Maxwell-Armstrong CA. Development of a telehealth monitoring service after colorectal surgery: a feasibility study. 2017;9(9):193-199.

17. O’Connell P. Annie-the VA’s self-care game changer. http://www.simple.uk.net/home/blog/blogcontent/annie-thevasself-caregamechanger. Published April 21, 2016. Accessed August 2, 2019.

18. Kataria L, Sundahl, C, Skalina L, et al. Text message reminders and intensive education improves positive airway pressure compliance and cognition in veterans with traumatic brain injury and obstructive sleep apnea: ANNIE pilot study (P1.097). Neurology, 2018; 90(suppl 15):P1.097.

Cancer and cancer-related treatment can cause a myriad of adverse effects.1,2 Early identification and management of these symptoms is paramount to the success of cancer treatment completion; however, clinic and telephonic strategies for addressing symptoms often result in delays in care.1 New strategies for patient engagement in the management of cancer and treatment-related symptoms are needed.

The use of online self-management tools can result in improvement in symptoms, reduce cancer symptom distress, improve quality-of-life, and improve medication adherence.3-9 A meta-analysis concluded that online interventions showed promise, but optimizing interventions would require additional research.10 Another meta-analysis found that online self-management was effective in managing several symptoms.11 An e-health method of collecting patient self-reported symptoms has been found to be acceptable to patients and feasible for use.12-14 We postulated that a mobile text messaging strategy may be an effective modality for augmenting symptom management for cancer patients in real time.

In the US Departmant of Veterans Affairs (VA), “Annie,” a self-care tool utilizing a text-messaging system has been implemented. Annie was developed modeling “Flo,” a messaging system in the United Kingdom that has been used for case management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure, stress incontinence, asthma, as a medication reminder tool, and to provide support for weight loss or post-operatively.15-17 Using Annie in the US, veterans have the ability to receive and track health information. Use of the Annie program has demonstrated improved continuous positive airway pressure monitor utilization in veterans with traumatic brain injury.18 Other uses within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) include assisting patients with anger management, liver disease, anxiety, asthma, diabetes, HIV, hypertension, weight loss, and smoking cessation.

Methods

The Hematology/Oncology division of the Minneapolis VA Healthcare System (MVAHCS) is a tertiary care facility that administers about 260 new chemotherapy regimens annually. The MVAHCS interdisciplinary hematology/oncology group initiated a quality improvement project to determine the feasibility, acceptability, and experience of tailoring the Annie tool for self-management of cancer symptoms. The group consisted of 2 physicians, 3 advanced practice registered nurses, 1 physician assistant, 2 registered nurses, and 2 Annie program team members.

We first created a symptom management pilot protocol as a result of multidisciplinary team discussions. Examples of discussion points for consideration included, but were not limited to, timing of texts, amount of information to ask for and provide, what potential symptoms to consider, and which patient population to pilot first.

The initial protocol was agreed upon and is as follows: Patients were sent text messages twice daily Monday through Friday, and asked to rate 2 symptoms per day, using a severity scale of 0 to 4 (absent, mild, moderate, severe, or disabling): nausea/vomiting, mouth sores, fatigue (Figure 1), trouble breathing, appetite, constipation, diarrhea (Figure 2), numbness/tingling, pain. In addition, patients were asked whether they had had a fever or not. Based on their response to the symptom inquiries, the patient received an automated text response. The text may have provided positive affirmation that they were doing well, given them advice for home management, referred them to an educational hyperlink, asked them to call a direct number to the clinic, or instructed them to report directly to the emergency department (ED). Patients could input a particular symptom on any day, even if they were not specifically asked about that symptom on that day. Patients also were instructed to text, only if it was not an inconvenience to them, as we wanted the intervention to be helpful and not a burden.

Results

Through screening new patient consults or those referred for chemotherapy education, 15 male veterans enrolled in the symptom monitoring program over an 8 month period. There were additional patients who were not offered the program or chose not to participate; often due to not having texting capabilities on their phone or not liking the texting feature. The majority of those who participated in the program (n = 14) were enrolled at the start of Cycle 1; the other patient was enrolled at the start of Cycle 2. Patients were enrolled an average of 89 days (range 8-204). Average response rate was 84.2% (range 30-100%).

Although symptoms were not reviewed in real time, we reviewed responses to determine the utilization of the instructions given for the program. No veteran had 0 symptoms reported. There were numerous occurrences of a score of 1 or 2. Many of these patients had baseline symptoms due to their underlying cancer. A score of 3 or 4 on the system prompted the patient to call the clinic or go to the ED. Seven patients (some with multiple occurrences) were prompted to call; only 4 of these made the follow-up call to the clinic. All were offered a same day visit, but each declined. Only 1 patient reported a symptom on a day not prompted for that symptom. Symptoms that were reported are listed in order of frequency: fatigue, appetite loss, numbness, pain, mouth sore, and breathing difficulty. There were no visits to the ED.

Program Evaluation

An evaluation was conducted 30 to 60 days after program enrollment. We elicited feedback to determine who was reading and responding to the text message: the patient, a family member, or a caregiver; whether they found the prompts helpful and took action; how they felt about the number of texts; if they felt the program was helpful; and any other feedback that would improve the program. In general, the patients (8) answered the texts independently. In 4 cases, the spouse answered the texts, and 3 patients answered the texts together with their spouses. Most patients (11) found the amount of texting to be “just right.” However, 3 found it to be too many texts and 1 didn’t find the amount of texting to be enough.

Three veterans did not have enough symptoms to feel the program was of benefit to them, but they did feel it would have been helpful if they had been more symptomatic. One veteran recalled taking loperamide as needed, as a result of prompting. No veterans felt as though the texting feature was difficult to use; and overall, were very positive about the program. Several appreciated receiving messages that validated when they were doing well, and they felt empowered by self-management. One of the spouses was a registered nurse and found the information too basic to be of use.

Discussion

Initial evaluation of the program via survey found no technology challenges. Patients have been very positive about the program including ease of use, appreciation of messages that validated when they were doing well, empowerment of self-management, and some utilization of the texting advice for symptom management. Educational hyperlinks for constipation, fatigue, diarrhea, and nausea/vomiting were added after this evaluation, and patients felt that these additions provided a higher level of education.

Staff time for this intervention was minimal. A nurse navigator offered the texting program to the patient during chemotherapy education, along with some instructions, which generally took about 5 minutes. One of the Annie program staff enrolled the patient. From that point forward, this was a self-management tool, beyond checking to ensure that the patient was successful in starting the program and evaluating use for the purposes of this quality improvement project. This self-management tool did not replace any other mechanism that a patient would normally have in our department for seeking help for symptoms. The MVAHSC typical process for symptom management is to have patients call a 24/7 nurse line. If the triage nurse feels the symptoms are related to the patient’s cancer or cancer treatment, they are referred to the physician assistant who is assigned to take those calls and has the option to see the patient the same day. Patients could continue to call the nurse line or speak with providers at the next appointment at their discretion.

Conclusion

Although Annie has the option of using either text messaging or a mobile application, this project only utilized text messaging. The study by Basch and colleagues was the closest randomized trial we could identify to compare to our quality improvement intervention.5 The 2 main, distinct differences were that Basch and colleagues utilized online monitoring; and nurses were utilized to screen and intervene on responses, as appropriate.

The ability of our program to text patients without the use of an application or tablet, may enable more patients to participate due to ease of use. There would be no increased in expected workload for clinical staff, and may lead to decreased call burden. Since our program is automated, while still providing patients with the option to call and speak with a staff member as needed, this is a cost-effective, first-line option for symptom management for those experiencing cancer-related symptoms. We believe this text messaging tool can have system wide use and benefit throughout the VHA.

Cancer and cancer-related treatment can cause a myriad of adverse effects.1,2 Early identification and management of these symptoms is paramount to the success of cancer treatment completion; however, clinic and telephonic strategies for addressing symptoms often result in delays in care.1 New strategies for patient engagement in the management of cancer and treatment-related symptoms are needed.

The use of online self-management tools can result in improvement in symptoms, reduce cancer symptom distress, improve quality-of-life, and improve medication adherence.3-9 A meta-analysis concluded that online interventions showed promise, but optimizing interventions would require additional research.10 Another meta-analysis found that online self-management was effective in managing several symptoms.11 An e-health method of collecting patient self-reported symptoms has been found to be acceptable to patients and feasible for use.12-14 We postulated that a mobile text messaging strategy may be an effective modality for augmenting symptom management for cancer patients in real time.

In the US Departmant of Veterans Affairs (VA), “Annie,” a self-care tool utilizing a text-messaging system has been implemented. Annie was developed modeling “Flo,” a messaging system in the United Kingdom that has been used for case management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure, stress incontinence, asthma, as a medication reminder tool, and to provide support for weight loss or post-operatively.15-17 Using Annie in the US, veterans have the ability to receive and track health information. Use of the Annie program has demonstrated improved continuous positive airway pressure monitor utilization in veterans with traumatic brain injury.18 Other uses within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) include assisting patients with anger management, liver disease, anxiety, asthma, diabetes, HIV, hypertension, weight loss, and smoking cessation.

Methods

The Hematology/Oncology division of the Minneapolis VA Healthcare System (MVAHCS) is a tertiary care facility that administers about 260 new chemotherapy regimens annually. The MVAHCS interdisciplinary hematology/oncology group initiated a quality improvement project to determine the feasibility, acceptability, and experience of tailoring the Annie tool for self-management of cancer symptoms. The group consisted of 2 physicians, 3 advanced practice registered nurses, 1 physician assistant, 2 registered nurses, and 2 Annie program team members.

We first created a symptom management pilot protocol as a result of multidisciplinary team discussions. Examples of discussion points for consideration included, but were not limited to, timing of texts, amount of information to ask for and provide, what potential symptoms to consider, and which patient population to pilot first.

The initial protocol was agreed upon and is as follows: Patients were sent text messages twice daily Monday through Friday, and asked to rate 2 symptoms per day, using a severity scale of 0 to 4 (absent, mild, moderate, severe, or disabling): nausea/vomiting, mouth sores, fatigue (Figure 1), trouble breathing, appetite, constipation, diarrhea (Figure 2), numbness/tingling, pain. In addition, patients were asked whether they had had a fever or not. Based on their response to the symptom inquiries, the patient received an automated text response. The text may have provided positive affirmation that they were doing well, given them advice for home management, referred them to an educational hyperlink, asked them to call a direct number to the clinic, or instructed them to report directly to the emergency department (ED). Patients could input a particular symptom on any day, even if they were not specifically asked about that symptom on that day. Patients also were instructed to text, only if it was not an inconvenience to them, as we wanted the intervention to be helpful and not a burden.

Results

Through screening new patient consults or those referred for chemotherapy education, 15 male veterans enrolled in the symptom monitoring program over an 8 month period. There were additional patients who were not offered the program or chose not to participate; often due to not having texting capabilities on their phone or not liking the texting feature. The majority of those who participated in the program (n = 14) were enrolled at the start of Cycle 1; the other patient was enrolled at the start of Cycle 2. Patients were enrolled an average of 89 days (range 8-204). Average response rate was 84.2% (range 30-100%).

Although symptoms were not reviewed in real time, we reviewed responses to determine the utilization of the instructions given for the program. No veteran had 0 symptoms reported. There were numerous occurrences of a score of 1 or 2. Many of these patients had baseline symptoms due to their underlying cancer. A score of 3 or 4 on the system prompted the patient to call the clinic or go to the ED. Seven patients (some with multiple occurrences) were prompted to call; only 4 of these made the follow-up call to the clinic. All were offered a same day visit, but each declined. Only 1 patient reported a symptom on a day not prompted for that symptom. Symptoms that were reported are listed in order of frequency: fatigue, appetite loss, numbness, pain, mouth sore, and breathing difficulty. There were no visits to the ED.

Program Evaluation

An evaluation was conducted 30 to 60 days after program enrollment. We elicited feedback to determine who was reading and responding to the text message: the patient, a family member, or a caregiver; whether they found the prompts helpful and took action; how they felt about the number of texts; if they felt the program was helpful; and any other feedback that would improve the program. In general, the patients (8) answered the texts independently. In 4 cases, the spouse answered the texts, and 3 patients answered the texts together with their spouses. Most patients (11) found the amount of texting to be “just right.” However, 3 found it to be too many texts and 1 didn’t find the amount of texting to be enough.

Three veterans did not have enough symptoms to feel the program was of benefit to them, but they did feel it would have been helpful if they had been more symptomatic. One veteran recalled taking loperamide as needed, as a result of prompting. No veterans felt as though the texting feature was difficult to use; and overall, were very positive about the program. Several appreciated receiving messages that validated when they were doing well, and they felt empowered by self-management. One of the spouses was a registered nurse and found the information too basic to be of use.

Discussion

Initial evaluation of the program via survey found no technology challenges. Patients have been very positive about the program including ease of use, appreciation of messages that validated when they were doing well, empowerment of self-management, and some utilization of the texting advice for symptom management. Educational hyperlinks for constipation, fatigue, diarrhea, and nausea/vomiting were added after this evaluation, and patients felt that these additions provided a higher level of education.

Staff time for this intervention was minimal. A nurse navigator offered the texting program to the patient during chemotherapy education, along with some instructions, which generally took about 5 minutes. One of the Annie program staff enrolled the patient. From that point forward, this was a self-management tool, beyond checking to ensure that the patient was successful in starting the program and evaluating use for the purposes of this quality improvement project. This self-management tool did not replace any other mechanism that a patient would normally have in our department for seeking help for symptoms. The MVAHSC typical process for symptom management is to have patients call a 24/7 nurse line. If the triage nurse feels the symptoms are related to the patient’s cancer or cancer treatment, they are referred to the physician assistant who is assigned to take those calls and has the option to see the patient the same day. Patients could continue to call the nurse line or speak with providers at the next appointment at their discretion.

Conclusion

Although Annie has the option of using either text messaging or a mobile application, this project only utilized text messaging. The study by Basch and colleagues was the closest randomized trial we could identify to compare to our quality improvement intervention.5 The 2 main, distinct differences were that Basch and colleagues utilized online monitoring; and nurses were utilized to screen and intervene on responses, as appropriate.

The ability of our program to text patients without the use of an application or tablet, may enable more patients to participate due to ease of use. There would be no increased in expected workload for clinical staff, and may lead to decreased call burden. Since our program is automated, while still providing patients with the option to call and speak with a staff member as needed, this is a cost-effective, first-line option for symptom management for those experiencing cancer-related symptoms. We believe this text messaging tool can have system wide use and benefit throughout the VHA.

1. Bruera E, Dev R. Overview of managing common non-pain symptoms in palliative care. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-managing-common-non-pain-symptoms-in-palliative-care. Updated June 12, 2019. Accessed July 18, 2019.

2. Pirschel C. The crucial role of symptom management in cancer care. https://voice.ons.org/news-and-views/the-crucial-role-of-symptom-management-in-cancer-care. Published December 14, 2017. Accessed July 18, 2019.

3. Adam R, Burton CD, Bond CM, de Bruin M, Murchie P. Can patient-reported measurements of pain be used to improve cancer pain management? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2017;7(4):373-382.

4. Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, et al. Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(6):557-565.

5. Berry DL, Blonquist TM, Patel RA, Halpenny B, McReynolds J. Exposure to a patient-centered, Web-based intervention for managing cancer symptom and quality of life issues: Impact on symptom distress. J Med Internet Res. 2015;3(7):e136.

6. Kolb NA, Smith AG, Singleton JR, et al. Chemotherapy-related neuropathic symptom management: a randomized trial of an automated symptom-monitoring system paired with nurse practitioner follow-up. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(5):1607-1615

7. Kamdar MM, Centi AJ, Fischer N, Jetwani K. A randomized controlled trial of a novel artificial-intelligence based smartphone application to optimize the management of cancer-related pain. Presented at: 2018 Palliative and Supportive Care in Oncology Symposium; November 16-17, 2018; San Diego, CA.

8. Mooney KH, Beck SL, Wong B, et al. Automated home monitoring and management of patient-reported symptoms during chemotherapy: results of the symptom care at home RCT. Cancer Med. 2017;6(3):537-546.

9. Spoelstra SL, Given CW, Sikorskii A, et al. Proof of concept of a mobile health short message service text message intervention that promotes adherence to oral anticancer agent medications: a randomized controlled trial. Telemed J E Health. 2016;22(6):497-506.

10. Fridriksdottir N, Gunnarsdottir S, Zoëga S, Ingadottir B, Hafsteinsdottir EJG. Effects of web-based interventions on cancer patients’ symptoms: review of randomized trials. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(2):3370-351.

11. Kim AR, Park HA. Web-based self-management support intervention for cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2015;216:142-147.

12. Girgis A, Durcinoska I, Levesque JV, et al; PROMPT-Care Program Group. eHealth system for collecting and utilizing patient reported outcome measures for personalized treatment and care (PROMPT-Care) among cancer patients: mixed methods approach to evaluate feasibility and acceptability. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(10):e330.

13. Moradian S, Krzyzanowska MK, Maguire R, et al. Usability evaluation of a mobile phone-based system for remote monitoring and management of chemotherapy-related side effects in cancer patients: Mixed methods study. JMIR Cancer. 2018;4(2): e10932.

14. Voruganti T, Grunfeld E, Jamieson T, et al. My team of care study: a pilot randomized controlled trial of a web-based communication tool for collaborative care in patients with advanced cancer. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(7):e219.

15. The Health Foundation. Overview of Florence simple telehealth text messaging system. https://www.health.org.uk/article/overview-of-the-florence-simple-telehealth-text-messaging-system. Accessed July 31, 2019.

16. Bragg DD, Edis H, Clark S, Parsons SL, Perumpalath B…Maxwell-Armstrong CA. Development of a telehealth monitoring service after colorectal surgery: a feasibility study. 2017;9(9):193-199.

17. O’Connell P. Annie-the VA’s self-care game changer. http://www.simple.uk.net/home/blog/blogcontent/annie-thevasself-caregamechanger. Published April 21, 2016. Accessed August 2, 2019.