User login

Semen cryopreservation viable for young transgender patients in small study

as transgender women, according to results of a small retrospective cohort study.

The lack of data on this topic, however, makes it difficult to determine how long an individual must be off gender-affirming therapy before spermatogenesis resumes, if it resumes, and what the long-term effects of gender-affirming therapy are.

“This information is critical to address as part of a multidisciplinary fertility discussion with youth and their guardians so that an informed decision can be made regarding fertility preservation use,” wrote Emily P. Barnard, DO, of UPMC Magee-Womens Hospital in Pittsburgh and her associates.

The researchers retrospectively collected data on transgender patients who sought fertility preservation between 2015 and 2018.

The 11 white transgender women (sex assigned male at birth) who followed up on adolescent medicine or pediatric endocrinology referrals for fertility preservation received their consultations between ages 16 and 24, with 19 years having been the median age at which they occurred. Gender dysphoria onset happened at a median age of 12 for the patients, who were evaluated for it at a median age of 17.

All but one patient submitted at least one semen sample, and eight ultimately cryopreserved their semen.

The eight samples from gender-affirming therapy–naive patients had abnormal morphology, with the median morphology having been 6% versus the normal range of greater than 13.0%. Otherwise, the samples collected were normal, but the authors noted that established semen analysis parameters don’t exist for adolescents and young adults.

All eight patients who had their semen cryopreserved, began gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist therapy after cryopreservation, and four of those patients concurrently began taking estradiol.

One patient had already been taking intramuscular leuprolide acetate every 6 months and discontinued it to attempt fertility preservation. Spermatogenesis returned after 5 months of azoospermia, albeit with abnormal morphology (9%).

Another patient had been taking spironolactone and estradiol for 26 months before ceasing therapy to attempt fertility preservation. She remained azoospermic 4 months after stopping therapy and then moved forward with an orchiectomy.

“For many transgender patients, the potential need to discontinue GnRH agonist or gender-affirming therapy to allow for resumption of spermatogenesis may be a significant barrier to pursuing fertility preservation because cessation of therapy may result in exacerbation of gender dysphoria and progression of undesired male secondary sex characteristics,” the researchers wrote. “For individuals for whom this risk is not acceptable or if azoospermia is noted on semen analysis, there are several alternate options, including electroejaculation, testicular sperm extraction, and testicular tissue cryopreservation,” they continued. Electroejaculation with a transrectal probe is an option particularly for those who cannot masturbate or feel uncomfortable doing so, the authors explained.

For those who have not previously received gender-affirming therapy, the fertility preservation “process can be completed quickly, with collections occurring every 2 to 3 days to preserve several samples before initiating GnRH agonist or gender-affirming therapy,” they concluded.

SOURCE: Barnard EP et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Aug 5. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3943.

The lack of long-term data on various gender-affirming medical interventions, particularly hormone therapies, for transgender adolescents and young adults has led professional medical organizations to recommend patients receive fertility counseling before beginning any such therapies.

Yet few data exist on fertility preservation either. The study by Barnard et al. is the first to examine semen cryopreservation outcomes in adolescents and young adults assigned male at birth and asserting a female gender identity.

“There is often urgency to start medical affirming interventions (MAI) among transgender and gender-diverse adolescents and young adults (TGD-AYA) due to gender dysphoria and related psychological sequelae,” wrote Jason Rafferty, MD, MPH, in an accompanying editorial. “However, starting MAI immediately and delaying fertility services may lead to increased overall morbidity for some patients.”

Although multiple professional organizations recommend fertility counseling before MAI initiation, many transgender patients are not following this advice. Dr. Rafferty noted one study found only 20% of TGD-AYA discussed fertility with their physicians before beginning MAI, and only 13% discussed possible effects of MAI on fertility – yet 60% wanted to learn more.

“Barnard et al. review data suggesting TGD-AYA have low interest in fertility services, but many TGD-AYA questioned whether this may later change,” Dr. Rafferty wrote. “After starting MAIs, TGD-AYA report being more emotionally capable of considering future parenting because of increasing comfort with their bodies and romantic relationships.”

Various barriers also exist for TGD-AYA interested in fertility services, such as cost, lack of insurance coverage, low availability of services, increased dysphoria from the procedures, stereotypes, stigma, and interest in starting MAI as soon as possible.

“Under a reproductive justice framework, autonomy around family planning is a right that should not be limited by structural or systemic barriers,” Dr. Rafferty wrote. “Overall, there is a clinical and ethical imperative to better understand and provide access to fertility services for TGD-AYA.”

Jason Rafferty, MD, MPH, is a pediatrician and child psychiatrist who practices at the gender and sexuality clinic in Riverside and at the Adolescent Healthcare Center at Hasbro Children’s Hospital in Providence, R.I. His comments are summarized from an accompanying editorial (Pediatrics 2019 Aug 5. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2000).

The lack of long-term data on various gender-affirming medical interventions, particularly hormone therapies, for transgender adolescents and young adults has led professional medical organizations to recommend patients receive fertility counseling before beginning any such therapies.

Yet few data exist on fertility preservation either. The study by Barnard et al. is the first to examine semen cryopreservation outcomes in adolescents and young adults assigned male at birth and asserting a female gender identity.

“There is often urgency to start medical affirming interventions (MAI) among transgender and gender-diverse adolescents and young adults (TGD-AYA) due to gender dysphoria and related psychological sequelae,” wrote Jason Rafferty, MD, MPH, in an accompanying editorial. “However, starting MAI immediately and delaying fertility services may lead to increased overall morbidity for some patients.”

Although multiple professional organizations recommend fertility counseling before MAI initiation, many transgender patients are not following this advice. Dr. Rafferty noted one study found only 20% of TGD-AYA discussed fertility with their physicians before beginning MAI, and only 13% discussed possible effects of MAI on fertility – yet 60% wanted to learn more.

“Barnard et al. review data suggesting TGD-AYA have low interest in fertility services, but many TGD-AYA questioned whether this may later change,” Dr. Rafferty wrote. “After starting MAIs, TGD-AYA report being more emotionally capable of considering future parenting because of increasing comfort with their bodies and romantic relationships.”

Various barriers also exist for TGD-AYA interested in fertility services, such as cost, lack of insurance coverage, low availability of services, increased dysphoria from the procedures, stereotypes, stigma, and interest in starting MAI as soon as possible.

“Under a reproductive justice framework, autonomy around family planning is a right that should not be limited by structural or systemic barriers,” Dr. Rafferty wrote. “Overall, there is a clinical and ethical imperative to better understand and provide access to fertility services for TGD-AYA.”

Jason Rafferty, MD, MPH, is a pediatrician and child psychiatrist who practices at the gender and sexuality clinic in Riverside and at the Adolescent Healthcare Center at Hasbro Children’s Hospital in Providence, R.I. His comments are summarized from an accompanying editorial (Pediatrics 2019 Aug 5. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2000).

The lack of long-term data on various gender-affirming medical interventions, particularly hormone therapies, for transgender adolescents and young adults has led professional medical organizations to recommend patients receive fertility counseling before beginning any such therapies.

Yet few data exist on fertility preservation either. The study by Barnard et al. is the first to examine semen cryopreservation outcomes in adolescents and young adults assigned male at birth and asserting a female gender identity.

“There is often urgency to start medical affirming interventions (MAI) among transgender and gender-diverse adolescents and young adults (TGD-AYA) due to gender dysphoria and related psychological sequelae,” wrote Jason Rafferty, MD, MPH, in an accompanying editorial. “However, starting MAI immediately and delaying fertility services may lead to increased overall morbidity for some patients.”

Although multiple professional organizations recommend fertility counseling before MAI initiation, many transgender patients are not following this advice. Dr. Rafferty noted one study found only 20% of TGD-AYA discussed fertility with their physicians before beginning MAI, and only 13% discussed possible effects of MAI on fertility – yet 60% wanted to learn more.

“Barnard et al. review data suggesting TGD-AYA have low interest in fertility services, but many TGD-AYA questioned whether this may later change,” Dr. Rafferty wrote. “After starting MAIs, TGD-AYA report being more emotionally capable of considering future parenting because of increasing comfort with their bodies and romantic relationships.”

Various barriers also exist for TGD-AYA interested in fertility services, such as cost, lack of insurance coverage, low availability of services, increased dysphoria from the procedures, stereotypes, stigma, and interest in starting MAI as soon as possible.

“Under a reproductive justice framework, autonomy around family planning is a right that should not be limited by structural or systemic barriers,” Dr. Rafferty wrote. “Overall, there is a clinical and ethical imperative to better understand and provide access to fertility services for TGD-AYA.”

Jason Rafferty, MD, MPH, is a pediatrician and child psychiatrist who practices at the gender and sexuality clinic in Riverside and at the Adolescent Healthcare Center at Hasbro Children’s Hospital in Providence, R.I. His comments are summarized from an accompanying editorial (Pediatrics 2019 Aug 5. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2000).

as transgender women, according to results of a small retrospective cohort study.

The lack of data on this topic, however, makes it difficult to determine how long an individual must be off gender-affirming therapy before spermatogenesis resumes, if it resumes, and what the long-term effects of gender-affirming therapy are.

“This information is critical to address as part of a multidisciplinary fertility discussion with youth and their guardians so that an informed decision can be made regarding fertility preservation use,” wrote Emily P. Barnard, DO, of UPMC Magee-Womens Hospital in Pittsburgh and her associates.

The researchers retrospectively collected data on transgender patients who sought fertility preservation between 2015 and 2018.

The 11 white transgender women (sex assigned male at birth) who followed up on adolescent medicine or pediatric endocrinology referrals for fertility preservation received their consultations between ages 16 and 24, with 19 years having been the median age at which they occurred. Gender dysphoria onset happened at a median age of 12 for the patients, who were evaluated for it at a median age of 17.

All but one patient submitted at least one semen sample, and eight ultimately cryopreserved their semen.

The eight samples from gender-affirming therapy–naive patients had abnormal morphology, with the median morphology having been 6% versus the normal range of greater than 13.0%. Otherwise, the samples collected were normal, but the authors noted that established semen analysis parameters don’t exist for adolescents and young adults.

All eight patients who had their semen cryopreserved, began gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist therapy after cryopreservation, and four of those patients concurrently began taking estradiol.

One patient had already been taking intramuscular leuprolide acetate every 6 months and discontinued it to attempt fertility preservation. Spermatogenesis returned after 5 months of azoospermia, albeit with abnormal morphology (9%).

Another patient had been taking spironolactone and estradiol for 26 months before ceasing therapy to attempt fertility preservation. She remained azoospermic 4 months after stopping therapy and then moved forward with an orchiectomy.

“For many transgender patients, the potential need to discontinue GnRH agonist or gender-affirming therapy to allow for resumption of spermatogenesis may be a significant barrier to pursuing fertility preservation because cessation of therapy may result in exacerbation of gender dysphoria and progression of undesired male secondary sex characteristics,” the researchers wrote. “For individuals for whom this risk is not acceptable or if azoospermia is noted on semen analysis, there are several alternate options, including electroejaculation, testicular sperm extraction, and testicular tissue cryopreservation,” they continued. Electroejaculation with a transrectal probe is an option particularly for those who cannot masturbate or feel uncomfortable doing so, the authors explained.

For those who have not previously received gender-affirming therapy, the fertility preservation “process can be completed quickly, with collections occurring every 2 to 3 days to preserve several samples before initiating GnRH agonist or gender-affirming therapy,” they concluded.

SOURCE: Barnard EP et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Aug 5. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3943.

as transgender women, according to results of a small retrospective cohort study.

The lack of data on this topic, however, makes it difficult to determine how long an individual must be off gender-affirming therapy before spermatogenesis resumes, if it resumes, and what the long-term effects of gender-affirming therapy are.

“This information is critical to address as part of a multidisciplinary fertility discussion with youth and their guardians so that an informed decision can be made regarding fertility preservation use,” wrote Emily P. Barnard, DO, of UPMC Magee-Womens Hospital in Pittsburgh and her associates.

The researchers retrospectively collected data on transgender patients who sought fertility preservation between 2015 and 2018.

The 11 white transgender women (sex assigned male at birth) who followed up on adolescent medicine or pediatric endocrinology referrals for fertility preservation received their consultations between ages 16 and 24, with 19 years having been the median age at which they occurred. Gender dysphoria onset happened at a median age of 12 for the patients, who were evaluated for it at a median age of 17.

All but one patient submitted at least one semen sample, and eight ultimately cryopreserved their semen.

The eight samples from gender-affirming therapy–naive patients had abnormal morphology, with the median morphology having been 6% versus the normal range of greater than 13.0%. Otherwise, the samples collected were normal, but the authors noted that established semen analysis parameters don’t exist for adolescents and young adults.

All eight patients who had their semen cryopreserved, began gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist therapy after cryopreservation, and four of those patients concurrently began taking estradiol.

One patient had already been taking intramuscular leuprolide acetate every 6 months and discontinued it to attempt fertility preservation. Spermatogenesis returned after 5 months of azoospermia, albeit with abnormal morphology (9%).

Another patient had been taking spironolactone and estradiol for 26 months before ceasing therapy to attempt fertility preservation. She remained azoospermic 4 months after stopping therapy and then moved forward with an orchiectomy.

“For many transgender patients, the potential need to discontinue GnRH agonist or gender-affirming therapy to allow for resumption of spermatogenesis may be a significant barrier to pursuing fertility preservation because cessation of therapy may result in exacerbation of gender dysphoria and progression of undesired male secondary sex characteristics,” the researchers wrote. “For individuals for whom this risk is not acceptable or if azoospermia is noted on semen analysis, there are several alternate options, including electroejaculation, testicular sperm extraction, and testicular tissue cryopreservation,” they continued. Electroejaculation with a transrectal probe is an option particularly for those who cannot masturbate or feel uncomfortable doing so, the authors explained.

For those who have not previously received gender-affirming therapy, the fertility preservation “process can be completed quickly, with collections occurring every 2 to 3 days to preserve several samples before initiating GnRH agonist or gender-affirming therapy,” they concluded.

SOURCE: Barnard EP et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Aug 5. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3943.

FROM PEDIATRICS

COPD adds complexity to shared decision making for LDCT lung cancer screening

research suggests.

Jonathan M. Iaccarino, MD, of the pulmonary center at the Boston University, and coauthors reported the results of a secondary analysis of patient-level outcomes from 75,138 low-dose CT (LDCT) scans in 26,453 participants in the National Lung Screening Trial (Chest 2019 Jul 5. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.06.016).

Currently, LDCT screening is recommended annually for high-risk smokers aged 55-80 years. The National Lung Screening Trial showed that this screening achieved a 20% relative reduction in lung cancer mortality and 6.7% relative reduction in overall mortality in this group. The guidelines stress the importance of shared decision making, with discussion of the risks and benefits of screening.

Dr. Iaccarino and colleagues point out that decision aids for shared decision making need to include important baseline characteristics, such as the presence of COPD, as these can complicate the risk and benefit analysis.

In this study, they found that 14.2% of LDCT scans performed led to a subsequent diagnostic study and 1.5% resulted in an invasive procedure. In addition, 0.3% of scans resulted in a procedure-related complication, and in 89 cases (0.1%), this procedure-related complication was serious.

At the patient level, nearly one-third (30.5%) received a diagnostic study, 4.2% underwent an invasive procedure – 41% of whom ultimately were found not to have lung cancer – 0.9% had a procedure-related complication, and 0.3% had a serious procedure related complication. Furthermore, among those who experienced a serious complication, 12.5% were found not to have lung cancer.

“Our study analyzes cumulative outcomes at the level of the individual patient over the three years of LDCT screening during the NLST, showing higher rates of diagnostic procedures, invasive procedures, complications and serious complications than apparent when data is presented at the level of the individual test,” the authors wrote.

The 4,632 participants with COPD were significantly more likely to undergo diagnostic studies (36.2%), have an invasive procedure (6%), experience a procedure-related complication (1.5%) and experience a serious procedure-related complication (0.6%) than were participants without COPD. However, they also had a significantly higher incidence of lung cancer diagnosis than did participants without COPD (6.1% vs. 3.6%).

“While most decision aids note the risks of screening may be increased in those with COPD, our study helps quantify these increased risks as well as the increased likelihood of a lung cancer diagnosis, a critical advance given that providing personalized (rather than generic) information results in more accurate risk perception and more informed choices among individuals considering screening,” the authors wrote. “With the significant change in the balance of benefits and risks of screening in patients with COPD, it is critical to adjust the shared decision-making discussions accordingly.”

They also noted that other comorbidities, such as heart disease, vascular disease, and other lung diseases, would likely affect the balance of risk and benefit of LDCT screening, and that there was a need for further exploration of screening in these patients.

Noting the study’s limitations, the authors pointed that their analysis focused on outcomes that were not the primary outcomes of the National Lung Screening trial, and that they relied on self-reported COPD diagnoses.

The study was supported by the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the Charles A. King Trust, and Edith Nourse Rogers Memorial Veterans Hospital. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Iaccarino JM et al. CHEST 2019 Jul 5. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.06.016.

research suggests.

Jonathan M. Iaccarino, MD, of the pulmonary center at the Boston University, and coauthors reported the results of a secondary analysis of patient-level outcomes from 75,138 low-dose CT (LDCT) scans in 26,453 participants in the National Lung Screening Trial (Chest 2019 Jul 5. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.06.016).

Currently, LDCT screening is recommended annually for high-risk smokers aged 55-80 years. The National Lung Screening Trial showed that this screening achieved a 20% relative reduction in lung cancer mortality and 6.7% relative reduction in overall mortality in this group. The guidelines stress the importance of shared decision making, with discussion of the risks and benefits of screening.

Dr. Iaccarino and colleagues point out that decision aids for shared decision making need to include important baseline characteristics, such as the presence of COPD, as these can complicate the risk and benefit analysis.

In this study, they found that 14.2% of LDCT scans performed led to a subsequent diagnostic study and 1.5% resulted in an invasive procedure. In addition, 0.3% of scans resulted in a procedure-related complication, and in 89 cases (0.1%), this procedure-related complication was serious.

At the patient level, nearly one-third (30.5%) received a diagnostic study, 4.2% underwent an invasive procedure – 41% of whom ultimately were found not to have lung cancer – 0.9% had a procedure-related complication, and 0.3% had a serious procedure related complication. Furthermore, among those who experienced a serious complication, 12.5% were found not to have lung cancer.

“Our study analyzes cumulative outcomes at the level of the individual patient over the three years of LDCT screening during the NLST, showing higher rates of diagnostic procedures, invasive procedures, complications and serious complications than apparent when data is presented at the level of the individual test,” the authors wrote.

The 4,632 participants with COPD were significantly more likely to undergo diagnostic studies (36.2%), have an invasive procedure (6%), experience a procedure-related complication (1.5%) and experience a serious procedure-related complication (0.6%) than were participants without COPD. However, they also had a significantly higher incidence of lung cancer diagnosis than did participants without COPD (6.1% vs. 3.6%).

“While most decision aids note the risks of screening may be increased in those with COPD, our study helps quantify these increased risks as well as the increased likelihood of a lung cancer diagnosis, a critical advance given that providing personalized (rather than generic) information results in more accurate risk perception and more informed choices among individuals considering screening,” the authors wrote. “With the significant change in the balance of benefits and risks of screening in patients with COPD, it is critical to adjust the shared decision-making discussions accordingly.”

They also noted that other comorbidities, such as heart disease, vascular disease, and other lung diseases, would likely affect the balance of risk and benefit of LDCT screening, and that there was a need for further exploration of screening in these patients.

Noting the study’s limitations, the authors pointed that their analysis focused on outcomes that were not the primary outcomes of the National Lung Screening trial, and that they relied on self-reported COPD diagnoses.

The study was supported by the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the Charles A. King Trust, and Edith Nourse Rogers Memorial Veterans Hospital. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Iaccarino JM et al. CHEST 2019 Jul 5. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.06.016.

research suggests.

Jonathan M. Iaccarino, MD, of the pulmonary center at the Boston University, and coauthors reported the results of a secondary analysis of patient-level outcomes from 75,138 low-dose CT (LDCT) scans in 26,453 participants in the National Lung Screening Trial (Chest 2019 Jul 5. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.06.016).

Currently, LDCT screening is recommended annually for high-risk smokers aged 55-80 years. The National Lung Screening Trial showed that this screening achieved a 20% relative reduction in lung cancer mortality and 6.7% relative reduction in overall mortality in this group. The guidelines stress the importance of shared decision making, with discussion of the risks and benefits of screening.

Dr. Iaccarino and colleagues point out that decision aids for shared decision making need to include important baseline characteristics, such as the presence of COPD, as these can complicate the risk and benefit analysis.

In this study, they found that 14.2% of LDCT scans performed led to a subsequent diagnostic study and 1.5% resulted in an invasive procedure. In addition, 0.3% of scans resulted in a procedure-related complication, and in 89 cases (0.1%), this procedure-related complication was serious.

At the patient level, nearly one-third (30.5%) received a diagnostic study, 4.2% underwent an invasive procedure – 41% of whom ultimately were found not to have lung cancer – 0.9% had a procedure-related complication, and 0.3% had a serious procedure related complication. Furthermore, among those who experienced a serious complication, 12.5% were found not to have lung cancer.

“Our study analyzes cumulative outcomes at the level of the individual patient over the three years of LDCT screening during the NLST, showing higher rates of diagnostic procedures, invasive procedures, complications and serious complications than apparent when data is presented at the level of the individual test,” the authors wrote.

The 4,632 participants with COPD were significantly more likely to undergo diagnostic studies (36.2%), have an invasive procedure (6%), experience a procedure-related complication (1.5%) and experience a serious procedure-related complication (0.6%) than were participants without COPD. However, they also had a significantly higher incidence of lung cancer diagnosis than did participants without COPD (6.1% vs. 3.6%).

“While most decision aids note the risks of screening may be increased in those with COPD, our study helps quantify these increased risks as well as the increased likelihood of a lung cancer diagnosis, a critical advance given that providing personalized (rather than generic) information results in more accurate risk perception and more informed choices among individuals considering screening,” the authors wrote. “With the significant change in the balance of benefits and risks of screening in patients with COPD, it is critical to adjust the shared decision-making discussions accordingly.”

They also noted that other comorbidities, such as heart disease, vascular disease, and other lung diseases, would likely affect the balance of risk and benefit of LDCT screening, and that there was a need for further exploration of screening in these patients.

Noting the study’s limitations, the authors pointed that their analysis focused on outcomes that were not the primary outcomes of the National Lung Screening trial, and that they relied on self-reported COPD diagnoses.

The study was supported by the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the Charles A. King Trust, and Edith Nourse Rogers Memorial Veterans Hospital. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Iaccarino JM et al. CHEST 2019 Jul 5. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.06.016.

FROM CHEST

Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors: Management of Advanced Disease

Most advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are due to a recurrence of localized disease, with only a small minority presenting with metastatic disease.1 Compared with chemotherapy, tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have significantly improved the natural history of the disease, with median overall survival (OS) increasing from less than 1 year to about 5 years and approximately 1 in 5 patients achieving long-term survival.2 In addition, newer drugs in development and in clinical trials appear promising and have the potential to improve outcomes even further. This article reviews current evidence on options for treating metastatic or recurrent GISTs and GISTs that have progressed following initial therapy. The evaluation and diagnosis of GIST along with management of localized disease are reviewed in a separate article.

Case Presentation

A 64-year-old African American man underwent surgical resection of a 10-cm gastric mass, which pathology reported was positive for CD117, DOG1, and CD34 and negative for smooth muscle actin and S-100, consistent with a diagnosis of GIST. There were 10 mitoses per 50 HPF, and there was no intraoperative or intraperitoneal tumor rupture. The patient was treated with adjuvant imatinib, which was discontinued after 3 years due to grade 2 myalgias, periorbital edema, and macrocytic anemia. Surveillance included office visits every 3 to 6 months and a contrast CT abdomen and pelvis every 6 months. For the past 5 years, he has not had any clinical or radiographic evidence of disease recurrence. New imaging reveals multiple liver metastases and peritoneal implants. He feels fatigued and has lost about 10 lb since his last visit. He is 5 years out from his initial diagnosis and 2 years out from last receiving imatinib. His original tumor harbored a KIT exon 11 deletion.

What treatment should you recommend now?

Imatinib for Advanced GISTs

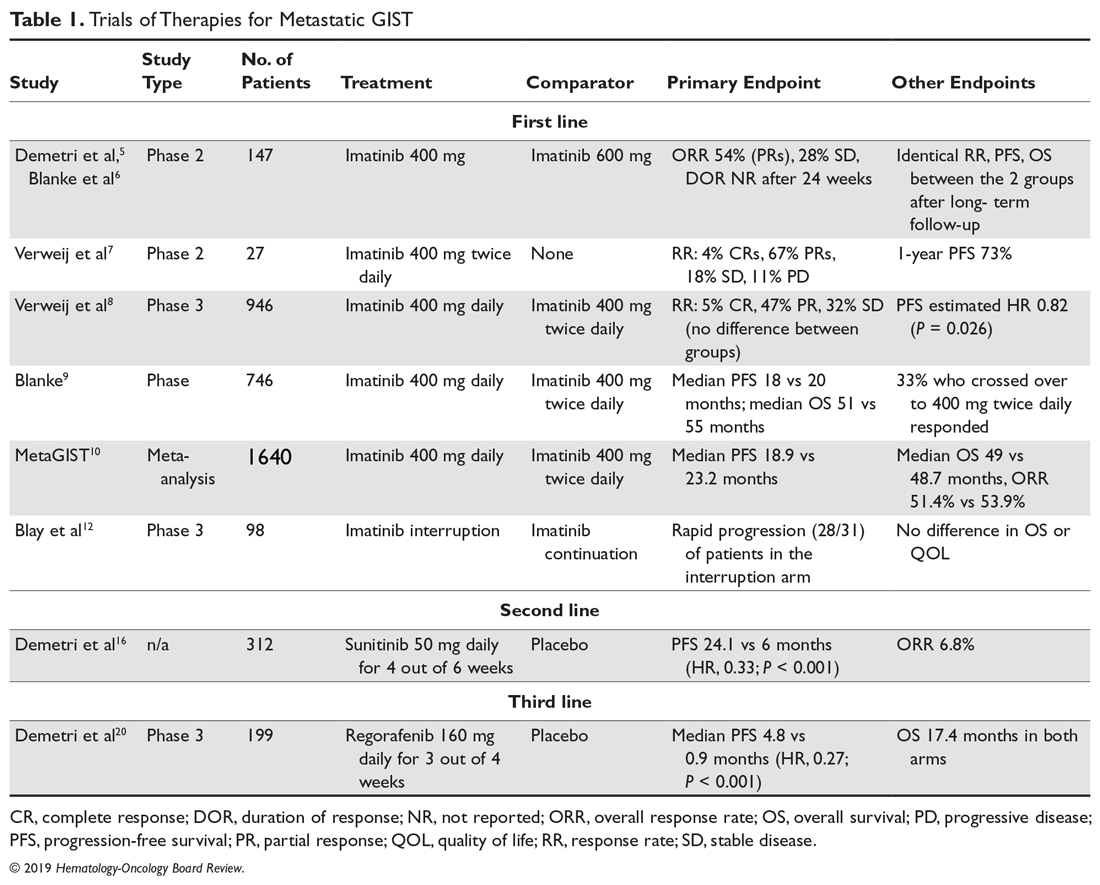

Before the first report of the efficacy of imatinib for metastatic GISTs in 2002, patients with advanced unresectable or metastatic GISTs were routinely treated with doxorubicin-based chemotherapy regimens, which were largely ineffective, with response rates (RRs) of around 5% and a median overall survival (OS) of less than 1 year.3,4 In 2002 a landmark phase 2 study revealed imatinib’s significant efficacy profile in advanced or metastatic GISTs, resulting in its approval by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).5 In this study, 147 patients with CD117-positive GISTs were randomly assigned to receive daily imatinib 400 mg or 600 mg for up to 36 months. The RRs were similar between the 2 groups (68.5% vs 67.6%), with a median time to response of 12 weeks and median duration of response of 118 days. Results of this study were much more favorable when compared to doxorubicin, rendering imatinib the new standard of care for advanced GISTs. A long-term follow-up of this study after a median of 63 months confirmed near identical RRs, progression-free survival (PFS), and median survival of 57 months among the 2 groups.6

Imatinib Daily Dosing

Although 400 mg of daily imatinib proved to be efficacious, it was unclear if a dose-response relationship existed for imatinib. An EORTC phase 2 study demonstrated a benefit of using a higher dose of imatinib at 400 mg twice daily, producing a RR of 71% (4% complete , 67% partial) and 1-year PFS of 73%, which appeared favorable compared with once-daily dosing and set the framework for larger phase 3 studies.7 Two phase 3 studies compared imatinib 400 mg once daily versus twice daily (until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity) among patients with CD117-positive advanced or metastatic GISTs. These studies were eventually combined into a meta-analysis (metaGIST) to compare RR, PFS and OS between the treatment groups. Both studies allowed cross-over to the 800 mg dose for patients who progressed on 400 mg daily.

The first study, conducted jointly by the EORTC, Italian Sarcoma Group, and Australasian Gastro-Intestinal Trials Group (EU-AUS),8 randomly assigned 946 patients to 400 mg once daily or twice daily. There were no differences in response rates between the groups, but the twice-daily group had a predicted 18% reduction in the hazard for progression compared with the once-daily group (estimated HR, 0.82; P = 0.026), which came at the expense of greater toxicities warranting dose reductions (60%) and treatment interruptions (64%). Cross-over to high-dose imatinib was feasible and safe, producing a partial response in 2%, stable disease in 27%, and a median PFS of 81 days. The second study was an intergroup study conducted jointly by SWOG, CALGB, NCI-C, and ECOG (S0033, US-CDN), with a nearly identical study design as the EU-AUS trial.9 The trial enrolled 746 patients. After a median follow up of 4.5 years, the median PFS and OS were not statistically different (18 vs 20 months and 55 vs 51 months, respectively). There were also no differences in response rates. One third of patients initially placed on the once-daily arm who crossed over after progression achieved a treatment response or stable disease.

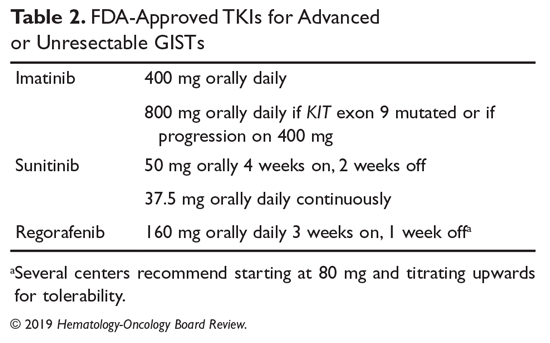

The combined EU-AUS and US-CDN analysis (metaGIST) included 1640 patients with a median age of 60 years and 58% of whom were men; 818 and 822 patients were assigned to the 400 mg and 800 mg total daily doses, respectively.10 The median follow-up was 37.5 months. There were no differences in OS (49 vs 48.7 months), median PFS (18.9 vs 23.2 months), or overall response rates (51.4% vs 53.9%). Patients who had crossed over (n = 347) to the 800 mg total daily dose arm had a 7.7-month average PFS while on the higher daily dose. An analysis was performed on 377 patients in the EU-AUS trial assessing the impact of mutational status on clinical outcomes among imatinib-treated patients. KIT exon 9 activating mutations were found to be a significant independent prognostic factor for death when compared with KIT exon 11 mutations. However, the adverse prognostic value of KIT exon 9 mutations was partially overcome with higher doses of imatinib, as those who received 800 mg total had a significantly better PFS, with a 61% relative risk reduction, than those who received 400 mg. Altogether, it was concluded that imatinib 400 mg once daily should be the standard-of-care first-line treatment for advanced or metastatic GISTs, unless a KIT exon 9 mutation is present, in which case imatinib 800 mg should be considered, if 400 mg is well tolerated. In addition, patients treated with frontline imatinib at 400 mg once daily, if tolerated well, should be considered for imatinib 800 mg upon progression of disease.

Despite there being problems with secondary resistance, significant progress has occurred in the treatment of metastatic disease over a short period of time. Prior to 2000, median OS for patients with metastatic GISTs was 9 months. With the introduction of imatinib and other TKIs, the median OS has increased to 5 years, with an estimated 10-year OS rate of approximately 20%.2

Imatinib Interruption

Since at this point, imatinib was a well-established standard of care for advanced GISTs, it was questioned whether imatinib therapy could be interrupted. At this time, treatment interruption in a stop-and-go fashion was deemed feasible in other metastatic solid tumors such as colorectal cancer (OPTIMOX1).11 The BFR French trial showed that stopping imatinib therapy in patients who had a response or stable disease after 1, 3, or 5 years was generally followed by relatively rapid tumor progression (approximately 50% of patients within 6 months), even when tumors were previously removed.12 Therefore, it is recommended that treatment in the metastatic setting should be continued indefinitely, unless there is disease progression. Hence, unlike with colorectal cancer or chronic myelogenous leukemia, as of now there is no role for imatinib interruption in metastatic GISTs.

Case Continued

The patient is started on imatinib 400 mg daily, and overall he tolerates therapy well. Interval CT imaging reveals a treatment response. Two years later, imaging reveals an increase in the tumor size and density with a new nodule present within a preexisting mass. There are no clinical trials in the area.

What defines tumor progression?

Disease Progression

When GISTs are responding to treatment, on imaging the tumors can become more cystic and less dense but with an increase in size. In addition, tumor progression may not always be associated with increased size—increased density of the tumor or a nodule within a mass that may indicate progression. If CT imaging is equivocal for progression, positron emission tomography (PET) can play a role in identifying true progression. It is critically important that tumor size and density are carefully assessed when performing interval imaging. Of note, radiofrequency ablation, cryotherapy, or chemoembolization can be used for symptomatic liver metastases or oligometastatic disease. When evaluating for progression, one needs to ask patients about compliance (ie, maintaining dose intensity related to side effects of therapy as well as the financial burden of treatment—copay toxicity).

What are mechanisms of secondary imatinib resistance?

Imatinib resistance can be subtle in patients with GISTs, manifesting with new nodular, enhancing foci enclosed within a preexisting mass (resistant clonal nodule), or can be clinically or radiographically overt.13 Imatinib resistance occurs through multiple mechanisms including acquisition of secondary activating KIT mutations in the intracellular ATP-binding domain (exons 13 and 14) and the activation loop (exons 17 and 18).14

What are the treatment options for this patient?

Second-line Therapy

Sunitinib malate is a multitargeted TKI that not only targets c-Kit and PDGFRA, but also has anti-angiogenic activity through inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor receptors (VEGFR). Sunitinib gained FDA approval for the second-line treatment of advanced GISTs based on an international double-blind trial that randomized 312 patients with imatinib-resistant metastatic GISTs in a 2:1 fashion to receive sunitinib 50 mg daily for 4 weeks on and 2 weeks off or placebo.15,16 The trial was unblinded early at the planned interim analysis, which revealed a marked benefit, producing a 66% reduction in the hazard risk of progression (27.3 vs 6.4 weeks, HR, 0.33; P < 0.001). The most common treatment-related adverse events were fatigue, diarrhea, skin discoloration, nausea, and hand-foot syndrome. Another open-label phase 2 study assessed a continuous dosing schema of sunitinib 37.5 mg daily, which has been shown to be effective with less toxicity.17 Among the 60 patients enrolled, the primary endpoint of clinical benefit rate at 24 weeks was reached in 53%, which consisted of 13% partial responses and 40% stable disease. Most toxicities were grade 1 or 2 and easily manageable through standard interventions. This has been recommended as an alternative to the initial scheduled regimen.18 Part of sunitinib’s success is its activity against GISTs harboring secondary KIT exon 13 and 14 mutations, and possibly its anti-angiogenic activity.19 Sunitinib is particularly efficacious among GISTs harboring KIT exon 9 mutations.

Third-line Therapy

Patients who have progressed on prior imatinib and sunitinib can receive third-line regorafenib, a multi-TKI that differs chemically from sorafenib by a fluorouracil group (fluoro-sorafenib). FDA approval of regorafenib was based on the phase 3 GRID (GIST Regorafenib In progressive Disease) multicenter international trial.20 This trial randomly assigned 199 patients in a 2:1 fashion to receive regorafenib 160 mg daily for 21 days out of 28-day cycles plus best supportive care (BSC) versus placebo plus BSC. Cross-over was allowed. Regorafenib significantly reduced the hazard risk of progression by 73% compared with placebo (4.8 vs 0.9 months; HR, 0.27; P < 0.001). There was no difference in OS, which may be because of cross-over (median OS, 17.4 months in both arms). As a result, regorafenib is now considered standard third-line treatment for patients with metastatic GISTs. It has a less favorable toxicity profile than imatinib, with hand-foot syndrome, transaminitis, hypertension and fatigue being the most common treatment toxicities. In order to avoid noncompliance, it is recommended to start at 80 mg and carefully titrate upwards to the 160 mg dose.

A list of landmark studies for advanced GISTs is provided in Table 1.

A summary of FDA-approved drugs for treating GISTs is provided in Table 2.

Clinical Trials

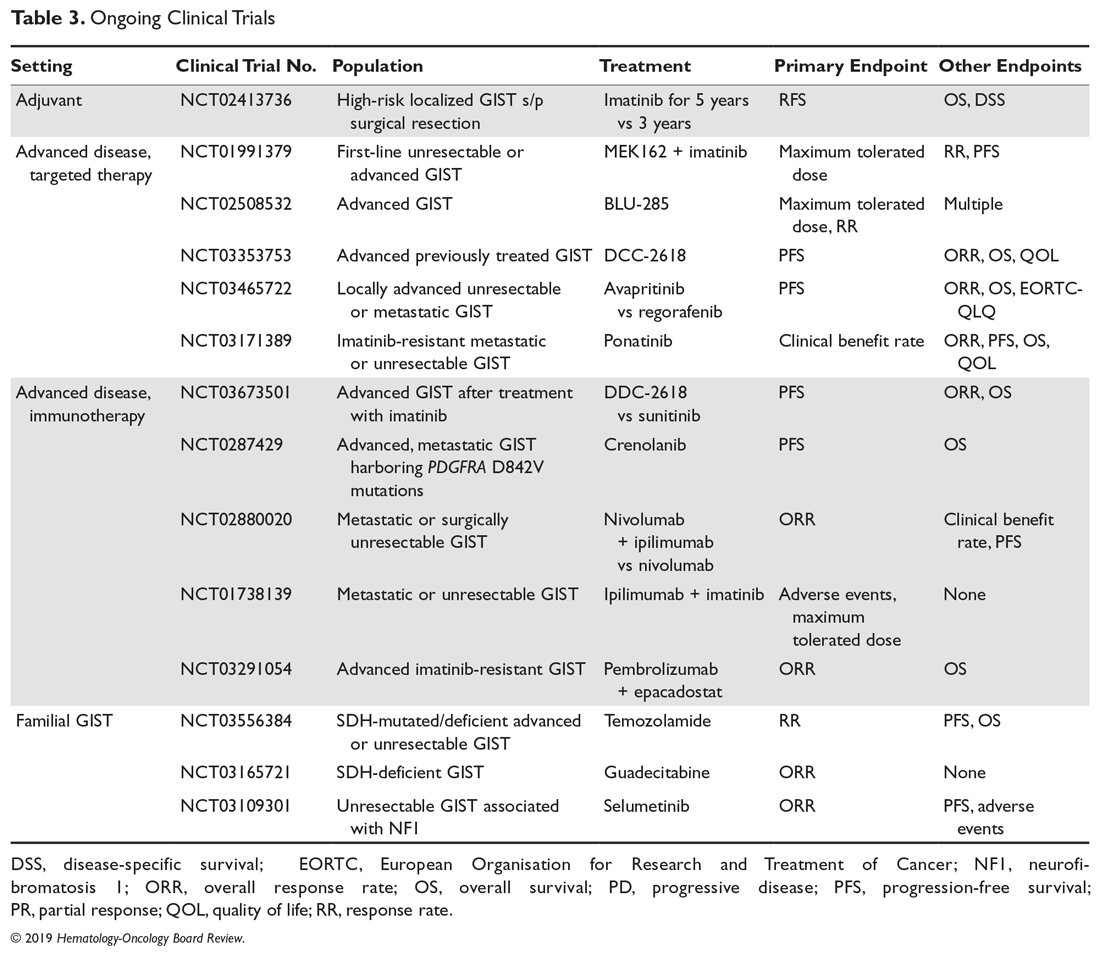

Clinical trial enrollment should be considered for all patients with advanced or unresectable GISTs throughout their treatment continuum. Owing to significant advances in genomic profiling through next-generation sequencing, multiple driver mutations have recently been identified, and targeted therapies are being explored in clinical trials.21 For example, the neurotrophic receptor tyrosine kinase (NTRK) gene appears to be mutated in a small number of advanced GISTs, and these can respond to the highly selective TRK inhibitor larotrectinib.22 Additionally, ongoing studies are assessing immunotherapies for sporadic GISTs and treatment for familial GISTs (Table 3). Some notable studies include those assessing the efficacy of agents that target KIT and PDGFR secondary mutations, including avapritinib (BLU-285) and DCC-2618, MEK inhibitors, and the multi-kinase inhibitor crenolanib for GISTs harboring the imatinib-resistant PDGFRA D842V mutation. There are also studies utilizing checkpoint inhibitors alone or in combination with imatinib.

Case Conclusion

Given the patient’s progression on imatinib, he is started on second-line sunitinib malate. He experiences grade 1 fatigue and hand-foot syndrome, which are managed supportively. After he has been on sunitinib for approximately 8 months, his disease progresses. He subsequently undergoes genomic profiling of his tumor and starts BLU-285 on a clinical trial.

Key Points

- For advanced and metastatic disease, TKIs have substantially improved the prognosis of KIT mutated GISTs, with 3 FDA-approved drugs: imatinib, sunitinib, and regorafenib. Imatinib 400 mg is the standard-of-care frontline therapy for locally advanced, unresectable, or metastatic imatinib-sensitive GISTs. If a patient has a KIT exon 9 mutation and 400 mg is well-tolerated, increasing to 800 mg is recommended. Imatinib should be continued indefinitely unless there is intolerance, a specific patient request for interruption, or progression of disease.

- When there is progression of disease in a patient with a sensitive mutation on 400 mg of imatinib, the dose can be increased to 800 mg.

- For patients who are imatinib-intolerant or have progression, standard second line is sunitinib.

- For patients who further progress or are sunitinib-intolerant, regorafenib is the standard third-line treatment.

- There needs to be close attention to side effects, drug and food interactions, and patient copay costs in order to maintain patient compliance while on TKI therapy.

- There are still major limitations in the systemic treatment of GISTs marked by their inherent genetic heterogeneity and secondary resistance. Continued translational and clinical research is needed in order to improve treatment for patients who develop secondary resistance or who have less common primary resistant mutations. Patients are encouraged to participate in clinical trials of new therapies.

Summary

GISTs are the most common mesenchymal tumors of the GI tract. They comprise an expanding landscape of tumors that are heterogenous in terms of natural history, mutations, and response to systemic treatments. The mainstay of treatment for localized GISTs is surgical resection followed by at least 3-years of adjuvant imatinib for patients with high-risk features who are imatinib-sensitive. Patients with GISTs harboring resistance mutations such as PDGFRA D842V or with SDH-deficient or NF1-associated GISTs should not receive adjuvant imatinib. Patients with more advanced GISTs and/or in difficult to resect sites harboring a sensitive mutation can be considered for neoadjuvant imatinib. Those with metastatic GISTs can receive first-, second-, and third-line imatinib, sunitinib, or regorafenib, respectively. Clinical trial enrollment should be encouraged for patients whose GISTs harbor primary imatinib-resistant mutations, and those with advanced or unresectable GISTs with secondary resistance.

1. Ma GL, Murphy JD, Martinez ME et al. Epidemiology of gastrointestinal stromal tumors in the era of histology codes: results of a population-based study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24:298-302.

2. Heinrich MC, Rankin C, Blanke CD, et al. Correlation of long-term results of imatinib in advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors with next-generation sequencing results: analysis of phase 3 SWOG Intergroup Trial S0033. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:944-952.

3. DeMatteo RP, Lewis JJ, Leung D, et al. Two hundred gastrointestinal stromal tumors recurrence patterns and prognostic factors for survival. Ann Surg. 2000;231:51-58.

4. Goss GA, Merriam P, Manola J, et al. Clinical and pathological characteristics of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST). Prog Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2000;19:599a.

5. Demetri GD, von Mehren M, Blanke CD, et al. Efficacy and safety of imatinib mesylate in advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors. N Engl J Med. 2002; 347:472-480.

6. Blanke CD, Demetri GD, von Mehren M, et al. Long-term results from a randomized phase ii trial of standard- versus higher-dose imatinib mesylate for patients with unresectable or metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors expressing KIT. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:620-625.

7. Verweij J, van Oosterom A, Blay JY, et al. Imatinib mesylate (STI-571 Glivec, Gleevac) is an active agent for gastrointestinal stromal tumours, but does not yield responses in other soft-tissue sarcomas that are unselected for a molecular target. Results from an EORTC Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group phase II study. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:2006-2011.

8. Verweij J, Casali PG, Zalcberg J, et al. Progression-free survival in gastrointestinal stromal tumours with high-dose imatinib: randomized trial. Lancet. 2004;364:1127-1134.

9. Blanke CD, Rankin C, Demetri GD, et al. Phase III randomized, intergroup trial assessing imatinib mesylate at two dose levels in patients with unresectable or metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors expressing the kit receptor tyrosine kinase: S0033. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:626-632.

10. Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor Meta-Analysis Group (MetaGIST). Comparison of two doses of imatinib for the treatment of unresectable or metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a meta-analysis of 1,640 patients. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1247-1253.

11. Tournigand C, Cervantes A, Figer A, et al. OPTIMOX1: a randomized study of FOLFOX4 or FOLFOX7 with oxaliplatin in a stop-and-Go fashion in advanced colorectal cancer –a GERCOR study. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:394-400.

12. Blay JV, Cesne AL, Ray-Coquard I, et al. Prospective multicentric randomized phase iii study of imatinib in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors comparing interruption versus continuation of treatment beyond 1 year: The French Sarcoma Group. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1107-1113.

13. Desai J, Shankar S, Heinrich MC, et al. Clonal evolution of resistance to imatinib in patients with metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(18 Pt 1): 5398-5405.

14. Gramza AW, Corless CL, Heinrich MC. Resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitors in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:7510-7518.

15. Sutent (sunitinib malate) [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer Labs; 2017.

16. Demetri GD, van Oosterom AT, Garrett CR, et al. Efficacy and safety of sunitinib in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumour after failure of imatinib: a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;368:1329-1338.

17. George S, Blay JY, Casali PG, et al. Clinical evaluation of continuous daily dosing of sunitinib malate in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumour after imatinib failure. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:1959-1968.

18. Brennan MF, Antonescu CR, Maki RG. Management of Soft Tissue Sarcomas. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2013.

19. Heinrich MC, Maki RG, Corless CL, et al. Primary and secondary kinase genotypes correlate with the biological and clinical activity of sunitinib in imatinib-resistant gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5352-5359.

20. Demetri GD, Reichardt P, Kang YK, et al. Efficacy and safety of regorafenib for advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumours after failure of imatinib and sunitinib (GRID): an international, multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013;381:295-302.

21. Wilky BA, Villalobos VM. Emerging role for precision therapy through next-generation sequencing for sarcomas. JCO Precision Oncology. 2018;2:1-4.

22. Drilon A, Laetsch TW, Kummar S, et al. Efficacy of larotrectinib in trk fusion-positive cancers in adults and children. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:731-739.

Most advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are due to a recurrence of localized disease, with only a small minority presenting with metastatic disease.1 Compared with chemotherapy, tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have significantly improved the natural history of the disease, with median overall survival (OS) increasing from less than 1 year to about 5 years and approximately 1 in 5 patients achieving long-term survival.2 In addition, newer drugs in development and in clinical trials appear promising and have the potential to improve outcomes even further. This article reviews current evidence on options for treating metastatic or recurrent GISTs and GISTs that have progressed following initial therapy. The evaluation and diagnosis of GIST along with management of localized disease are reviewed in a separate article.

Case Presentation

A 64-year-old African American man underwent surgical resection of a 10-cm gastric mass, which pathology reported was positive for CD117, DOG1, and CD34 and negative for smooth muscle actin and S-100, consistent with a diagnosis of GIST. There were 10 mitoses per 50 HPF, and there was no intraoperative or intraperitoneal tumor rupture. The patient was treated with adjuvant imatinib, which was discontinued after 3 years due to grade 2 myalgias, periorbital edema, and macrocytic anemia. Surveillance included office visits every 3 to 6 months and a contrast CT abdomen and pelvis every 6 months. For the past 5 years, he has not had any clinical or radiographic evidence of disease recurrence. New imaging reveals multiple liver metastases and peritoneal implants. He feels fatigued and has lost about 10 lb since his last visit. He is 5 years out from his initial diagnosis and 2 years out from last receiving imatinib. His original tumor harbored a KIT exon 11 deletion.

What treatment should you recommend now?

Imatinib for Advanced GISTs

Before the first report of the efficacy of imatinib for metastatic GISTs in 2002, patients with advanced unresectable or metastatic GISTs were routinely treated with doxorubicin-based chemotherapy regimens, which were largely ineffective, with response rates (RRs) of around 5% and a median overall survival (OS) of less than 1 year.3,4 In 2002 a landmark phase 2 study revealed imatinib’s significant efficacy profile in advanced or metastatic GISTs, resulting in its approval by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).5 In this study, 147 patients with CD117-positive GISTs were randomly assigned to receive daily imatinib 400 mg or 600 mg for up to 36 months. The RRs were similar between the 2 groups (68.5% vs 67.6%), with a median time to response of 12 weeks and median duration of response of 118 days. Results of this study were much more favorable when compared to doxorubicin, rendering imatinib the new standard of care for advanced GISTs. A long-term follow-up of this study after a median of 63 months confirmed near identical RRs, progression-free survival (PFS), and median survival of 57 months among the 2 groups.6

Imatinib Daily Dosing

Although 400 mg of daily imatinib proved to be efficacious, it was unclear if a dose-response relationship existed for imatinib. An EORTC phase 2 study demonstrated a benefit of using a higher dose of imatinib at 400 mg twice daily, producing a RR of 71% (4% complete , 67% partial) and 1-year PFS of 73%, which appeared favorable compared with once-daily dosing and set the framework for larger phase 3 studies.7 Two phase 3 studies compared imatinib 400 mg once daily versus twice daily (until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity) among patients with CD117-positive advanced or metastatic GISTs. These studies were eventually combined into a meta-analysis (metaGIST) to compare RR, PFS and OS between the treatment groups. Both studies allowed cross-over to the 800 mg dose for patients who progressed on 400 mg daily.

The first study, conducted jointly by the EORTC, Italian Sarcoma Group, and Australasian Gastro-Intestinal Trials Group (EU-AUS),8 randomly assigned 946 patients to 400 mg once daily or twice daily. There were no differences in response rates between the groups, but the twice-daily group had a predicted 18% reduction in the hazard for progression compared with the once-daily group (estimated HR, 0.82; P = 0.026), which came at the expense of greater toxicities warranting dose reductions (60%) and treatment interruptions (64%). Cross-over to high-dose imatinib was feasible and safe, producing a partial response in 2%, stable disease in 27%, and a median PFS of 81 days. The second study was an intergroup study conducted jointly by SWOG, CALGB, NCI-C, and ECOG (S0033, US-CDN), with a nearly identical study design as the EU-AUS trial.9 The trial enrolled 746 patients. After a median follow up of 4.5 years, the median PFS and OS were not statistically different (18 vs 20 months and 55 vs 51 months, respectively). There were also no differences in response rates. One third of patients initially placed on the once-daily arm who crossed over after progression achieved a treatment response or stable disease.

The combined EU-AUS and US-CDN analysis (metaGIST) included 1640 patients with a median age of 60 years and 58% of whom were men; 818 and 822 patients were assigned to the 400 mg and 800 mg total daily doses, respectively.10 The median follow-up was 37.5 months. There were no differences in OS (49 vs 48.7 months), median PFS (18.9 vs 23.2 months), or overall response rates (51.4% vs 53.9%). Patients who had crossed over (n = 347) to the 800 mg total daily dose arm had a 7.7-month average PFS while on the higher daily dose. An analysis was performed on 377 patients in the EU-AUS trial assessing the impact of mutational status on clinical outcomes among imatinib-treated patients. KIT exon 9 activating mutations were found to be a significant independent prognostic factor for death when compared with KIT exon 11 mutations. However, the adverse prognostic value of KIT exon 9 mutations was partially overcome with higher doses of imatinib, as those who received 800 mg total had a significantly better PFS, with a 61% relative risk reduction, than those who received 400 mg. Altogether, it was concluded that imatinib 400 mg once daily should be the standard-of-care first-line treatment for advanced or metastatic GISTs, unless a KIT exon 9 mutation is present, in which case imatinib 800 mg should be considered, if 400 mg is well tolerated. In addition, patients treated with frontline imatinib at 400 mg once daily, if tolerated well, should be considered for imatinib 800 mg upon progression of disease.

Despite there being problems with secondary resistance, significant progress has occurred in the treatment of metastatic disease over a short period of time. Prior to 2000, median OS for patients with metastatic GISTs was 9 months. With the introduction of imatinib and other TKIs, the median OS has increased to 5 years, with an estimated 10-year OS rate of approximately 20%.2

Imatinib Interruption

Since at this point, imatinib was a well-established standard of care for advanced GISTs, it was questioned whether imatinib therapy could be interrupted. At this time, treatment interruption in a stop-and-go fashion was deemed feasible in other metastatic solid tumors such as colorectal cancer (OPTIMOX1).11 The BFR French trial showed that stopping imatinib therapy in patients who had a response or stable disease after 1, 3, or 5 years was generally followed by relatively rapid tumor progression (approximately 50% of patients within 6 months), even when tumors were previously removed.12 Therefore, it is recommended that treatment in the metastatic setting should be continued indefinitely, unless there is disease progression. Hence, unlike with colorectal cancer or chronic myelogenous leukemia, as of now there is no role for imatinib interruption in metastatic GISTs.

Case Continued

The patient is started on imatinib 400 mg daily, and overall he tolerates therapy well. Interval CT imaging reveals a treatment response. Two years later, imaging reveals an increase in the tumor size and density with a new nodule present within a preexisting mass. There are no clinical trials in the area.

What defines tumor progression?

Disease Progression

When GISTs are responding to treatment, on imaging the tumors can become more cystic and less dense but with an increase in size. In addition, tumor progression may not always be associated with increased size—increased density of the tumor or a nodule within a mass that may indicate progression. If CT imaging is equivocal for progression, positron emission tomography (PET) can play a role in identifying true progression. It is critically important that tumor size and density are carefully assessed when performing interval imaging. Of note, radiofrequency ablation, cryotherapy, or chemoembolization can be used for symptomatic liver metastases or oligometastatic disease. When evaluating for progression, one needs to ask patients about compliance (ie, maintaining dose intensity related to side effects of therapy as well as the financial burden of treatment—copay toxicity).

What are mechanisms of secondary imatinib resistance?

Imatinib resistance can be subtle in patients with GISTs, manifesting with new nodular, enhancing foci enclosed within a preexisting mass (resistant clonal nodule), or can be clinically or radiographically overt.13 Imatinib resistance occurs through multiple mechanisms including acquisition of secondary activating KIT mutations in the intracellular ATP-binding domain (exons 13 and 14) and the activation loop (exons 17 and 18).14

What are the treatment options for this patient?

Second-line Therapy

Sunitinib malate is a multitargeted TKI that not only targets c-Kit and PDGFRA, but also has anti-angiogenic activity through inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor receptors (VEGFR). Sunitinib gained FDA approval for the second-line treatment of advanced GISTs based on an international double-blind trial that randomized 312 patients with imatinib-resistant metastatic GISTs in a 2:1 fashion to receive sunitinib 50 mg daily for 4 weeks on and 2 weeks off or placebo.15,16 The trial was unblinded early at the planned interim analysis, which revealed a marked benefit, producing a 66% reduction in the hazard risk of progression (27.3 vs 6.4 weeks, HR, 0.33; P < 0.001). The most common treatment-related adverse events were fatigue, diarrhea, skin discoloration, nausea, and hand-foot syndrome. Another open-label phase 2 study assessed a continuous dosing schema of sunitinib 37.5 mg daily, which has been shown to be effective with less toxicity.17 Among the 60 patients enrolled, the primary endpoint of clinical benefit rate at 24 weeks was reached in 53%, which consisted of 13% partial responses and 40% stable disease. Most toxicities were grade 1 or 2 and easily manageable through standard interventions. This has been recommended as an alternative to the initial scheduled regimen.18 Part of sunitinib’s success is its activity against GISTs harboring secondary KIT exon 13 and 14 mutations, and possibly its anti-angiogenic activity.19 Sunitinib is particularly efficacious among GISTs harboring KIT exon 9 mutations.

Third-line Therapy

Patients who have progressed on prior imatinib and sunitinib can receive third-line regorafenib, a multi-TKI that differs chemically from sorafenib by a fluorouracil group (fluoro-sorafenib). FDA approval of regorafenib was based on the phase 3 GRID (GIST Regorafenib In progressive Disease) multicenter international trial.20 This trial randomly assigned 199 patients in a 2:1 fashion to receive regorafenib 160 mg daily for 21 days out of 28-day cycles plus best supportive care (BSC) versus placebo plus BSC. Cross-over was allowed. Regorafenib significantly reduced the hazard risk of progression by 73% compared with placebo (4.8 vs 0.9 months; HR, 0.27; P < 0.001). There was no difference in OS, which may be because of cross-over (median OS, 17.4 months in both arms). As a result, regorafenib is now considered standard third-line treatment for patients with metastatic GISTs. It has a less favorable toxicity profile than imatinib, with hand-foot syndrome, transaminitis, hypertension and fatigue being the most common treatment toxicities. In order to avoid noncompliance, it is recommended to start at 80 mg and carefully titrate upwards to the 160 mg dose.

A list of landmark studies for advanced GISTs is provided in Table 1.

A summary of FDA-approved drugs for treating GISTs is provided in Table 2.

Clinical Trials

Clinical trial enrollment should be considered for all patients with advanced or unresectable GISTs throughout their treatment continuum. Owing to significant advances in genomic profiling through next-generation sequencing, multiple driver mutations have recently been identified, and targeted therapies are being explored in clinical trials.21 For example, the neurotrophic receptor tyrosine kinase (NTRK) gene appears to be mutated in a small number of advanced GISTs, and these can respond to the highly selective TRK inhibitor larotrectinib.22 Additionally, ongoing studies are assessing immunotherapies for sporadic GISTs and treatment for familial GISTs (Table 3). Some notable studies include those assessing the efficacy of agents that target KIT and PDGFR secondary mutations, including avapritinib (BLU-285) and DCC-2618, MEK inhibitors, and the multi-kinase inhibitor crenolanib for GISTs harboring the imatinib-resistant PDGFRA D842V mutation. There are also studies utilizing checkpoint inhibitors alone or in combination with imatinib.

Case Conclusion

Given the patient’s progression on imatinib, he is started on second-line sunitinib malate. He experiences grade 1 fatigue and hand-foot syndrome, which are managed supportively. After he has been on sunitinib for approximately 8 months, his disease progresses. He subsequently undergoes genomic profiling of his tumor and starts BLU-285 on a clinical trial.

Key Points

- For advanced and metastatic disease, TKIs have substantially improved the prognosis of KIT mutated GISTs, with 3 FDA-approved drugs: imatinib, sunitinib, and regorafenib. Imatinib 400 mg is the standard-of-care frontline therapy for locally advanced, unresectable, or metastatic imatinib-sensitive GISTs. If a patient has a KIT exon 9 mutation and 400 mg is well-tolerated, increasing to 800 mg is recommended. Imatinib should be continued indefinitely unless there is intolerance, a specific patient request for interruption, or progression of disease.

- When there is progression of disease in a patient with a sensitive mutation on 400 mg of imatinib, the dose can be increased to 800 mg.

- For patients who are imatinib-intolerant or have progression, standard second line is sunitinib.

- For patients who further progress or are sunitinib-intolerant, regorafenib is the standard third-line treatment.

- There needs to be close attention to side effects, drug and food interactions, and patient copay costs in order to maintain patient compliance while on TKI therapy.

- There are still major limitations in the systemic treatment of GISTs marked by their inherent genetic heterogeneity and secondary resistance. Continued translational and clinical research is needed in order to improve treatment for patients who develop secondary resistance or who have less common primary resistant mutations. Patients are encouraged to participate in clinical trials of new therapies.

Summary

GISTs are the most common mesenchymal tumors of the GI tract. They comprise an expanding landscape of tumors that are heterogenous in terms of natural history, mutations, and response to systemic treatments. The mainstay of treatment for localized GISTs is surgical resection followed by at least 3-years of adjuvant imatinib for patients with high-risk features who are imatinib-sensitive. Patients with GISTs harboring resistance mutations such as PDGFRA D842V or with SDH-deficient or NF1-associated GISTs should not receive adjuvant imatinib. Patients with more advanced GISTs and/or in difficult to resect sites harboring a sensitive mutation can be considered for neoadjuvant imatinib. Those with metastatic GISTs can receive first-, second-, and third-line imatinib, sunitinib, or regorafenib, respectively. Clinical trial enrollment should be encouraged for patients whose GISTs harbor primary imatinib-resistant mutations, and those with advanced or unresectable GISTs with secondary resistance.

Most advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are due to a recurrence of localized disease, with only a small minority presenting with metastatic disease.1 Compared with chemotherapy, tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have significantly improved the natural history of the disease, with median overall survival (OS) increasing from less than 1 year to about 5 years and approximately 1 in 5 patients achieving long-term survival.2 In addition, newer drugs in development and in clinical trials appear promising and have the potential to improve outcomes even further. This article reviews current evidence on options for treating metastatic or recurrent GISTs and GISTs that have progressed following initial therapy. The evaluation and diagnosis of GIST along with management of localized disease are reviewed in a separate article.

Case Presentation

A 64-year-old African American man underwent surgical resection of a 10-cm gastric mass, which pathology reported was positive for CD117, DOG1, and CD34 and negative for smooth muscle actin and S-100, consistent with a diagnosis of GIST. There were 10 mitoses per 50 HPF, and there was no intraoperative or intraperitoneal tumor rupture. The patient was treated with adjuvant imatinib, which was discontinued after 3 years due to grade 2 myalgias, periorbital edema, and macrocytic anemia. Surveillance included office visits every 3 to 6 months and a contrast CT abdomen and pelvis every 6 months. For the past 5 years, he has not had any clinical or radiographic evidence of disease recurrence. New imaging reveals multiple liver metastases and peritoneal implants. He feels fatigued and has lost about 10 lb since his last visit. He is 5 years out from his initial diagnosis and 2 years out from last receiving imatinib. His original tumor harbored a KIT exon 11 deletion.

What treatment should you recommend now?

Imatinib for Advanced GISTs

Before the first report of the efficacy of imatinib for metastatic GISTs in 2002, patients with advanced unresectable or metastatic GISTs were routinely treated with doxorubicin-based chemotherapy regimens, which were largely ineffective, with response rates (RRs) of around 5% and a median overall survival (OS) of less than 1 year.3,4 In 2002 a landmark phase 2 study revealed imatinib’s significant efficacy profile in advanced or metastatic GISTs, resulting in its approval by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).5 In this study, 147 patients with CD117-positive GISTs were randomly assigned to receive daily imatinib 400 mg or 600 mg for up to 36 months. The RRs were similar between the 2 groups (68.5% vs 67.6%), with a median time to response of 12 weeks and median duration of response of 118 days. Results of this study were much more favorable when compared to doxorubicin, rendering imatinib the new standard of care for advanced GISTs. A long-term follow-up of this study after a median of 63 months confirmed near identical RRs, progression-free survival (PFS), and median survival of 57 months among the 2 groups.6

Imatinib Daily Dosing

Although 400 mg of daily imatinib proved to be efficacious, it was unclear if a dose-response relationship existed for imatinib. An EORTC phase 2 study demonstrated a benefit of using a higher dose of imatinib at 400 mg twice daily, producing a RR of 71% (4% complete , 67% partial) and 1-year PFS of 73%, which appeared favorable compared with once-daily dosing and set the framework for larger phase 3 studies.7 Two phase 3 studies compared imatinib 400 mg once daily versus twice daily (until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity) among patients with CD117-positive advanced or metastatic GISTs. These studies were eventually combined into a meta-analysis (metaGIST) to compare RR, PFS and OS between the treatment groups. Both studies allowed cross-over to the 800 mg dose for patients who progressed on 400 mg daily.

The first study, conducted jointly by the EORTC, Italian Sarcoma Group, and Australasian Gastro-Intestinal Trials Group (EU-AUS),8 randomly assigned 946 patients to 400 mg once daily or twice daily. There were no differences in response rates between the groups, but the twice-daily group had a predicted 18% reduction in the hazard for progression compared with the once-daily group (estimated HR, 0.82; P = 0.026), which came at the expense of greater toxicities warranting dose reductions (60%) and treatment interruptions (64%). Cross-over to high-dose imatinib was feasible and safe, producing a partial response in 2%, stable disease in 27%, and a median PFS of 81 days. The second study was an intergroup study conducted jointly by SWOG, CALGB, NCI-C, and ECOG (S0033, US-CDN), with a nearly identical study design as the EU-AUS trial.9 The trial enrolled 746 patients. After a median follow up of 4.5 years, the median PFS and OS were not statistically different (18 vs 20 months and 55 vs 51 months, respectively). There were also no differences in response rates. One third of patients initially placed on the once-daily arm who crossed over after progression achieved a treatment response or stable disease.

The combined EU-AUS and US-CDN analysis (metaGIST) included 1640 patients with a median age of 60 years and 58% of whom were men; 818 and 822 patients were assigned to the 400 mg and 800 mg total daily doses, respectively.10 The median follow-up was 37.5 months. There were no differences in OS (49 vs 48.7 months), median PFS (18.9 vs 23.2 months), or overall response rates (51.4% vs 53.9%). Patients who had crossed over (n = 347) to the 800 mg total daily dose arm had a 7.7-month average PFS while on the higher daily dose. An analysis was performed on 377 patients in the EU-AUS trial assessing the impact of mutational status on clinical outcomes among imatinib-treated patients. KIT exon 9 activating mutations were found to be a significant independent prognostic factor for death when compared with KIT exon 11 mutations. However, the adverse prognostic value of KIT exon 9 mutations was partially overcome with higher doses of imatinib, as those who received 800 mg total had a significantly better PFS, with a 61% relative risk reduction, than those who received 400 mg. Altogether, it was concluded that imatinib 400 mg once daily should be the standard-of-care first-line treatment for advanced or metastatic GISTs, unless a KIT exon 9 mutation is present, in which case imatinib 800 mg should be considered, if 400 mg is well tolerated. In addition, patients treated with frontline imatinib at 400 mg once daily, if tolerated well, should be considered for imatinib 800 mg upon progression of disease.

Despite there being problems with secondary resistance, significant progress has occurred in the treatment of metastatic disease over a short period of time. Prior to 2000, median OS for patients with metastatic GISTs was 9 months. With the introduction of imatinib and other TKIs, the median OS has increased to 5 years, with an estimated 10-year OS rate of approximately 20%.2

Imatinib Interruption

Since at this point, imatinib was a well-established standard of care for advanced GISTs, it was questioned whether imatinib therapy could be interrupted. At this time, treatment interruption in a stop-and-go fashion was deemed feasible in other metastatic solid tumors such as colorectal cancer (OPTIMOX1).11 The BFR French trial showed that stopping imatinib therapy in patients who had a response or stable disease after 1, 3, or 5 years was generally followed by relatively rapid tumor progression (approximately 50% of patients within 6 months), even when tumors were previously removed.12 Therefore, it is recommended that treatment in the metastatic setting should be continued indefinitely, unless there is disease progression. Hence, unlike with colorectal cancer or chronic myelogenous leukemia, as of now there is no role for imatinib interruption in metastatic GISTs.

Case Continued

The patient is started on imatinib 400 mg daily, and overall he tolerates therapy well. Interval CT imaging reveals a treatment response. Two years later, imaging reveals an increase in the tumor size and density with a new nodule present within a preexisting mass. There are no clinical trials in the area.

What defines tumor progression?

Disease Progression

When GISTs are responding to treatment, on imaging the tumors can become more cystic and less dense but with an increase in size. In addition, tumor progression may not always be associated with increased size—increased density of the tumor or a nodule within a mass that may indicate progression. If CT imaging is equivocal for progression, positron emission tomography (PET) can play a role in identifying true progression. It is critically important that tumor size and density are carefully assessed when performing interval imaging. Of note, radiofrequency ablation, cryotherapy, or chemoembolization can be used for symptomatic liver metastases or oligometastatic disease. When evaluating for progression, one needs to ask patients about compliance (ie, maintaining dose intensity related to side effects of therapy as well as the financial burden of treatment—copay toxicity).

What are mechanisms of secondary imatinib resistance?

Imatinib resistance can be subtle in patients with GISTs, manifesting with new nodular, enhancing foci enclosed within a preexisting mass (resistant clonal nodule), or can be clinically or radiographically overt.13 Imatinib resistance occurs through multiple mechanisms including acquisition of secondary activating KIT mutations in the intracellular ATP-binding domain (exons 13 and 14) and the activation loop (exons 17 and 18).14

What are the treatment options for this patient?

Second-line Therapy

Sunitinib malate is a multitargeted TKI that not only targets c-Kit and PDGFRA, but also has anti-angiogenic activity through inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor receptors (VEGFR). Sunitinib gained FDA approval for the second-line treatment of advanced GISTs based on an international double-blind trial that randomized 312 patients with imatinib-resistant metastatic GISTs in a 2:1 fashion to receive sunitinib 50 mg daily for 4 weeks on and 2 weeks off or placebo.15,16 The trial was unblinded early at the planned interim analysis, which revealed a marked benefit, producing a 66% reduction in the hazard risk of progression (27.3 vs 6.4 weeks, HR, 0.33; P < 0.001). The most common treatment-related adverse events were fatigue, diarrhea, skin discoloration, nausea, and hand-foot syndrome. Another open-label phase 2 study assessed a continuous dosing schema of sunitinib 37.5 mg daily, which has been shown to be effective with less toxicity.17 Among the 60 patients enrolled, the primary endpoint of clinical benefit rate at 24 weeks was reached in 53%, which consisted of 13% partial responses and 40% stable disease. Most toxicities were grade 1 or 2 and easily manageable through standard interventions. This has been recommended as an alternative to the initial scheduled regimen.18 Part of sunitinib’s success is its activity against GISTs harboring secondary KIT exon 13 and 14 mutations, and possibly its anti-angiogenic activity.19 Sunitinib is particularly efficacious among GISTs harboring KIT exon 9 mutations.

Third-line Therapy