User login

When is electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) indicated?

Know the general work-up and contraindications

Case

A 56-year-old female comes to the hospitalist service for presumed sepsis with acute renal insufficiency. She has a history of steadily progressive Parkinson’s disease. Vital signs show a temperature of 104° F; heart rate,135; BP, 100/70; respiratory rate, 20; oxygen saturation, 100% on room air. She is rigid on exam with creatine kinase, 2450 IU/L, and serum creatinine, 2.2. History reveals the patient’s levodopa was increased to 1,200 mg/day recently, then stopped by the family after she became paranoid. A diagnosis of neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) is made.

Background

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) has been the gold standard for treatment of refractory psychiatric disease for decades. While it has proven beneficial for both medical and psychiatric disorders, it remains surrounded in controversy. Additionally, there is a significant degree of discomfort among nonpsychiatric providers on when to consider ECT, as well as how to evaluate the patient and manage their comorbidities before and during the procedure1.

Hospitalists should be familiar with the relative contraindications and general work-up for ECT, which can expedite both psychiatric and anesthesia evaluations and minimize adverse outcomes.

While the mechanism of action still is not known, ECT exerts a variety of effects in the brain and periphery. The dominant theory is that ECT increases neurotransmitter activity throughout the brain. Studies have shown increased GABA transmission, normalized glutamate transmission, and resetting of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis, as well as activation of downstream signal transduction pathways leading to increased synaptic connectivity in the brain. Many of ECT’s results may be caused by combinations of the above mechanisms2.

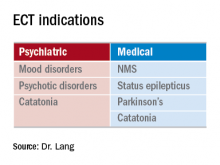

ECT principally is indicated for refractory mood and psychotic disorders. These include schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depression. ECT-responsive patients typically have failed multiple appropriate medication trials and often have prolonged hospitalizations. What is less known are the medical indications for this procedure. Examples include Parkinson’s disease (especially with on/off phenomenon), status epilepticus, and neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Additionally, ECT has been shown to be beneficial for slow-to-resolve delirium and catatonia (regardless of etiology).

A psychiatrist also may take into consideration factors such as past response to ECT or the level of urgency to the patient’s presentation. A general work-up includes basic comprehensive metabolic panel, complete blood count, chest x-ray, EKG, and other testing based on history, physical, and past medical history.

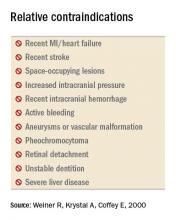

While there are no absolute contraindications to ECT, several relative contraindications exist. These include recent MI or stroke (generally within the last 30 days), increased intracranial pressure, active bleeding (especially from the central nervous system), retinal detachment, and unstable dentition. Apart from making sure the technique is medically indicated, an ECT consultant also evaluates the medical comorbidities. The patient may require treatment, such as removal of unstable dentition prior to the procedure, if clinical urgency does not preclude a delay.

Select patients require more detailed consultation prior to the onset of anesthesia. Examples would include patients with pseudocholinesterase deficiency, myasthenia gravis, or pregnancy. Pregnancy often is considered a contraindication, but ECT has no notable effect on labor & delivery, fetal injury, or development. It would be a preferred modality over medications, especially in unstable mothers during the first trimester. ECT exerts little effect on the fetus, as the amount of current that actually gets to the fetus is negligible6.

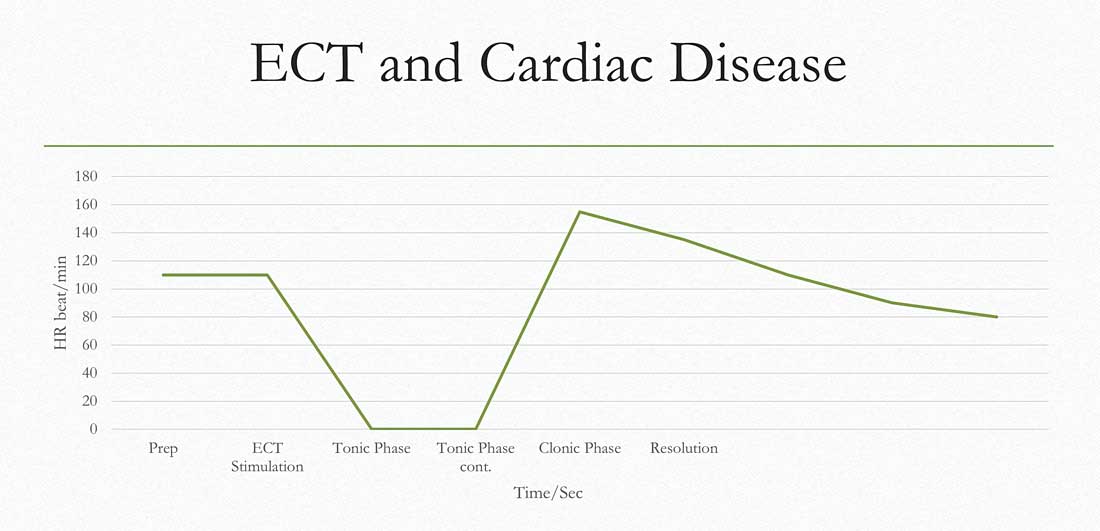

Outside the central nervous system, ECT exerts the most influence over the cardiovascular system. During the tonic phase of a seizure, increased vagal tone can depress the heart rate to asystole in some patients (see chart below). This may last for 3-4 seconds until the clonic phase occurs (with a noradrenergic surge), whereupon the heart rate can accelerate to the 140s. Unless unstable cardiac disease is present, patients typically tolerate this extremely well without any adverse sequela7. Studies involving patients who have severe aortic stenosis and pacemakers/defibrillators show overall excellent tolerability8,9.

Medications can have an impact on the onset, quality, and duration of seizures. Thus, a careful medication review is needed. A consultant will look first for medications such as benzodiazepines or anticonvulsants that would raise the seizure threshold. Ideally, the medications would be stopped, but if not feasible, they can be held the night before (or the day before in the case of such long half-life agents as diazepam) to minimize their impact.

As for anticonvulsants, the doses can be reduced, along with modest increases in energy settings to facilitate seizure. If used for mood stabilization only, one could consider stopping them completely, but this is usually not required (it is not recommended to stop them if used for epilepsy). Lithium can lead to prolonged neuromuscular blockade, prolonged seizures, or postictal delirium. However, discontinuation of lithium also has a risk-benefit consideration, so usually, doses are reduced and/or decreased doses of neuromuscular blockade are employed. Theophylline can induce extended seizures or status epilepticus so it is usually held prior to ECT.

Back to the case

Given the patient’s severe Parkinson’s disease and concurrent NMS, ECT was initiated. By the second treatment, fever and tachycardia resolved. By the sixth treatment, all NMS symptoms and associated paranoia had completely resolved and her Parkinson’s disease rating scale score went from 142 to 42. Her levodopa dose was reduced from 1,200 to 300 mg/day. She remained stable for years afterward.

Bottom line

ECT is both effective and well tolerated in patients who have received appropriate medical evaluation.

Dr. Lang is clinical associate professor in the departments of psychiatry and internal medicine and director of the electroconvulsive therapy and transcranial magnetic stimulation programs at East Carolina University, Greenville, N.C.

Key points

- ECT is indicated for psychotic and depressive disorders, with high efficacy and rapid response.

- ECT also has proven benefits for NMS, catatonia, delirium, status epilepticus, and Parkinson’s disease.

- Evaluation and focused treatment of relative contraindications maximizes both safety and tolerability of ECT.

References

1. Weiner R et al. “Electroconvulsive therapy in the medical & neurologic patient” in A Stoudemire, BS Fogel & D Greenberg (eds) Psychiatric Care of the Medical Patient, 2nd ed., New York, Oxford Univ Press. 2000:419-28. (Second edition is out of print.)

2. Baghai T et al. Electroconvulsive therapy and its different indications. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. Mar 2008;10(1):105-17.

3. Ozer F et al. Electroconvulsive therapy in drug-induced psychiatric states and neuroleptic malignant syndrome. J ECT. 2005 Jun;21(2):125-7.

4. Taylor S. Electroconvulsive therapy: A review of history, patient selection, technique, and medication management. South Med J. 2007 May;100(5):494-8.

5. The Practice of Electroconvulsive Therapy, 2nd edition. A Task Force Report of the American Psychiatric Association. 2001. pp. 84-85.

6. Miller LJ. Use of electroconvulsive therapy during pregnancy. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1994 May;45(5):444-50.

7. Miller R et al. ECT: Physiologic Effects. Miller’s Anesthesia. 7th Edition. 2009.

8. Mueller PS et al. The Safety of electroconvulsive therapy in patients with severe aortic stenosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007 Nov;82(11):1360-3.

9. Dolenc TJ et al. Electroconvulsive therapy in patients with cardiac pacemakers & implantable cardioverter defibrillators. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2004 Sep;27(9):1257-63.

Suggested readings

The practice of electroconvulsive therapy: Recommendations for treatment, training, and privileging (A Task Force Report of the American Psychiatric Association), 2nd Edition. APA Publishing. 2001.

Weiner R et al. “Electroconvulsive therapy in the medical & neurologic patient” in A Stoudemire, BS Fogel & D Greenberg (eds) Psychiatric Care of the Medical Patient, 2nd ed., New York, Oxford Univ Press. 2000:419-28. (Second edition is out of print.)

Rosenquist P et al. Charting the course of electroconvulsive therapy: Where have we been and where are we headed? J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2016 Dec 1;54(12):39-43.

QUIZ

1. All of the following are indications for ECT except?

A. Schizophrenia.

B. Panic attacks.

C. Bipolar mania.

D. Catatonia.

Answer: B. Panic attacks. ECT is not effective for anxiety disorders including panic, generalized anxiety, PTSD, or OCD.

2. The most commonly accepted mechanism of action for ECT is?

A. Reduction in glutamate levels.

B. Altering signal transduction pathways.

C. Increased neurotransmitter activity.

D. Increased cerebral blood flow.

Answer: C. Increased neurotransmitter activity. There are data to support all, but neurotransmitter flow is most accepted thus far.

3. Which of the following is a common side effect of ECT?

A. Bronchospasm.

B. Diarrhea.

C. Delirium.

D. Visual changes.

Answer: C. Delirium. The rest are rare or not noted.

4. Which of the following is a relative contraindication for ECT?

A. Pregnancy.

B. Epilepsy.

C. Advanced age.

D. Increased intracranial pressure.

Answer: D. Increased intracranial pressure.

Know the general work-up and contraindications

Know the general work-up and contraindications

Case

A 56-year-old female comes to the hospitalist service for presumed sepsis with acute renal insufficiency. She has a history of steadily progressive Parkinson’s disease. Vital signs show a temperature of 104° F; heart rate,135; BP, 100/70; respiratory rate, 20; oxygen saturation, 100% on room air. She is rigid on exam with creatine kinase, 2450 IU/L, and serum creatinine, 2.2. History reveals the patient’s levodopa was increased to 1,200 mg/day recently, then stopped by the family after she became paranoid. A diagnosis of neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) is made.

Background

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) has been the gold standard for treatment of refractory psychiatric disease for decades. While it has proven beneficial for both medical and psychiatric disorders, it remains surrounded in controversy. Additionally, there is a significant degree of discomfort among nonpsychiatric providers on when to consider ECT, as well as how to evaluate the patient and manage their comorbidities before and during the procedure1.

Hospitalists should be familiar with the relative contraindications and general work-up for ECT, which can expedite both psychiatric and anesthesia evaluations and minimize adverse outcomes.

While the mechanism of action still is not known, ECT exerts a variety of effects in the brain and periphery. The dominant theory is that ECT increases neurotransmitter activity throughout the brain. Studies have shown increased GABA transmission, normalized glutamate transmission, and resetting of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis, as well as activation of downstream signal transduction pathways leading to increased synaptic connectivity in the brain. Many of ECT’s results may be caused by combinations of the above mechanisms2.

ECT principally is indicated for refractory mood and psychotic disorders. These include schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depression. ECT-responsive patients typically have failed multiple appropriate medication trials and often have prolonged hospitalizations. What is less known are the medical indications for this procedure. Examples include Parkinson’s disease (especially with on/off phenomenon), status epilepticus, and neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Additionally, ECT has been shown to be beneficial for slow-to-resolve delirium and catatonia (regardless of etiology).

A psychiatrist also may take into consideration factors such as past response to ECT or the level of urgency to the patient’s presentation. A general work-up includes basic comprehensive metabolic panel, complete blood count, chest x-ray, EKG, and other testing based on history, physical, and past medical history.

While there are no absolute contraindications to ECT, several relative contraindications exist. These include recent MI or stroke (generally within the last 30 days), increased intracranial pressure, active bleeding (especially from the central nervous system), retinal detachment, and unstable dentition. Apart from making sure the technique is medically indicated, an ECT consultant also evaluates the medical comorbidities. The patient may require treatment, such as removal of unstable dentition prior to the procedure, if clinical urgency does not preclude a delay.

Select patients require more detailed consultation prior to the onset of anesthesia. Examples would include patients with pseudocholinesterase deficiency, myasthenia gravis, or pregnancy. Pregnancy often is considered a contraindication, but ECT has no notable effect on labor & delivery, fetal injury, or development. It would be a preferred modality over medications, especially in unstable mothers during the first trimester. ECT exerts little effect on the fetus, as the amount of current that actually gets to the fetus is negligible6.

Outside the central nervous system, ECT exerts the most influence over the cardiovascular system. During the tonic phase of a seizure, increased vagal tone can depress the heart rate to asystole in some patients (see chart below). This may last for 3-4 seconds until the clonic phase occurs (with a noradrenergic surge), whereupon the heart rate can accelerate to the 140s. Unless unstable cardiac disease is present, patients typically tolerate this extremely well without any adverse sequela7. Studies involving patients who have severe aortic stenosis and pacemakers/defibrillators show overall excellent tolerability8,9.

Medications can have an impact on the onset, quality, and duration of seizures. Thus, a careful medication review is needed. A consultant will look first for medications such as benzodiazepines or anticonvulsants that would raise the seizure threshold. Ideally, the medications would be stopped, but if not feasible, they can be held the night before (or the day before in the case of such long half-life agents as diazepam) to minimize their impact.

As for anticonvulsants, the doses can be reduced, along with modest increases in energy settings to facilitate seizure. If used for mood stabilization only, one could consider stopping them completely, but this is usually not required (it is not recommended to stop them if used for epilepsy). Lithium can lead to prolonged neuromuscular blockade, prolonged seizures, or postictal delirium. However, discontinuation of lithium also has a risk-benefit consideration, so usually, doses are reduced and/or decreased doses of neuromuscular blockade are employed. Theophylline can induce extended seizures or status epilepticus so it is usually held prior to ECT.

Back to the case

Given the patient’s severe Parkinson’s disease and concurrent NMS, ECT was initiated. By the second treatment, fever and tachycardia resolved. By the sixth treatment, all NMS symptoms and associated paranoia had completely resolved and her Parkinson’s disease rating scale score went from 142 to 42. Her levodopa dose was reduced from 1,200 to 300 mg/day. She remained stable for years afterward.

Bottom line

ECT is both effective and well tolerated in patients who have received appropriate medical evaluation.

Dr. Lang is clinical associate professor in the departments of psychiatry and internal medicine and director of the electroconvulsive therapy and transcranial magnetic stimulation programs at East Carolina University, Greenville, N.C.

Key points

- ECT is indicated for psychotic and depressive disorders, with high efficacy and rapid response.

- ECT also has proven benefits for NMS, catatonia, delirium, status epilepticus, and Parkinson’s disease.

- Evaluation and focused treatment of relative contraindications maximizes both safety and tolerability of ECT.

References

1. Weiner R et al. “Electroconvulsive therapy in the medical & neurologic patient” in A Stoudemire, BS Fogel & D Greenberg (eds) Psychiatric Care of the Medical Patient, 2nd ed., New York, Oxford Univ Press. 2000:419-28. (Second edition is out of print.)

2. Baghai T et al. Electroconvulsive therapy and its different indications. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. Mar 2008;10(1):105-17.

3. Ozer F et al. Electroconvulsive therapy in drug-induced psychiatric states and neuroleptic malignant syndrome. J ECT. 2005 Jun;21(2):125-7.

4. Taylor S. Electroconvulsive therapy: A review of history, patient selection, technique, and medication management. South Med J. 2007 May;100(5):494-8.

5. The Practice of Electroconvulsive Therapy, 2nd edition. A Task Force Report of the American Psychiatric Association. 2001. pp. 84-85.

6. Miller LJ. Use of electroconvulsive therapy during pregnancy. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1994 May;45(5):444-50.

7. Miller R et al. ECT: Physiologic Effects. Miller’s Anesthesia. 7th Edition. 2009.

8. Mueller PS et al. The Safety of electroconvulsive therapy in patients with severe aortic stenosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007 Nov;82(11):1360-3.

9. Dolenc TJ et al. Electroconvulsive therapy in patients with cardiac pacemakers & implantable cardioverter defibrillators. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2004 Sep;27(9):1257-63.

Suggested readings

The practice of electroconvulsive therapy: Recommendations for treatment, training, and privileging (A Task Force Report of the American Psychiatric Association), 2nd Edition. APA Publishing. 2001.

Weiner R et al. “Electroconvulsive therapy in the medical & neurologic patient” in A Stoudemire, BS Fogel & D Greenberg (eds) Psychiatric Care of the Medical Patient, 2nd ed., New York, Oxford Univ Press. 2000:419-28. (Second edition is out of print.)

Rosenquist P et al. Charting the course of electroconvulsive therapy: Where have we been and where are we headed? J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2016 Dec 1;54(12):39-43.

QUIZ

1. All of the following are indications for ECT except?

A. Schizophrenia.

B. Panic attacks.

C. Bipolar mania.

D. Catatonia.

Answer: B. Panic attacks. ECT is not effective for anxiety disorders including panic, generalized anxiety, PTSD, or OCD.

2. The most commonly accepted mechanism of action for ECT is?

A. Reduction in glutamate levels.

B. Altering signal transduction pathways.

C. Increased neurotransmitter activity.

D. Increased cerebral blood flow.

Answer: C. Increased neurotransmitter activity. There are data to support all, but neurotransmitter flow is most accepted thus far.

3. Which of the following is a common side effect of ECT?

A. Bronchospasm.

B. Diarrhea.

C. Delirium.

D. Visual changes.

Answer: C. Delirium. The rest are rare or not noted.

4. Which of the following is a relative contraindication for ECT?

A. Pregnancy.

B. Epilepsy.

C. Advanced age.

D. Increased intracranial pressure.

Answer: D. Increased intracranial pressure.

Case

A 56-year-old female comes to the hospitalist service for presumed sepsis with acute renal insufficiency. She has a history of steadily progressive Parkinson’s disease. Vital signs show a temperature of 104° F; heart rate,135; BP, 100/70; respiratory rate, 20; oxygen saturation, 100% on room air. She is rigid on exam with creatine kinase, 2450 IU/L, and serum creatinine, 2.2. History reveals the patient’s levodopa was increased to 1,200 mg/day recently, then stopped by the family after she became paranoid. A diagnosis of neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) is made.

Background

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) has been the gold standard for treatment of refractory psychiatric disease for decades. While it has proven beneficial for both medical and psychiatric disorders, it remains surrounded in controversy. Additionally, there is a significant degree of discomfort among nonpsychiatric providers on when to consider ECT, as well as how to evaluate the patient and manage their comorbidities before and during the procedure1.

Hospitalists should be familiar with the relative contraindications and general work-up for ECT, which can expedite both psychiatric and anesthesia evaluations and minimize adverse outcomes.

While the mechanism of action still is not known, ECT exerts a variety of effects in the brain and periphery. The dominant theory is that ECT increases neurotransmitter activity throughout the brain. Studies have shown increased GABA transmission, normalized glutamate transmission, and resetting of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis, as well as activation of downstream signal transduction pathways leading to increased synaptic connectivity in the brain. Many of ECT’s results may be caused by combinations of the above mechanisms2.

ECT principally is indicated for refractory mood and psychotic disorders. These include schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depression. ECT-responsive patients typically have failed multiple appropriate medication trials and often have prolonged hospitalizations. What is less known are the medical indications for this procedure. Examples include Parkinson’s disease (especially with on/off phenomenon), status epilepticus, and neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Additionally, ECT has been shown to be beneficial for slow-to-resolve delirium and catatonia (regardless of etiology).

A psychiatrist also may take into consideration factors such as past response to ECT or the level of urgency to the patient’s presentation. A general work-up includes basic comprehensive metabolic panel, complete blood count, chest x-ray, EKG, and other testing based on history, physical, and past medical history.

While there are no absolute contraindications to ECT, several relative contraindications exist. These include recent MI or stroke (generally within the last 30 days), increased intracranial pressure, active bleeding (especially from the central nervous system), retinal detachment, and unstable dentition. Apart from making sure the technique is medically indicated, an ECT consultant also evaluates the medical comorbidities. The patient may require treatment, such as removal of unstable dentition prior to the procedure, if clinical urgency does not preclude a delay.

Select patients require more detailed consultation prior to the onset of anesthesia. Examples would include patients with pseudocholinesterase deficiency, myasthenia gravis, or pregnancy. Pregnancy often is considered a contraindication, but ECT has no notable effect on labor & delivery, fetal injury, or development. It would be a preferred modality over medications, especially in unstable mothers during the first trimester. ECT exerts little effect on the fetus, as the amount of current that actually gets to the fetus is negligible6.

Outside the central nervous system, ECT exerts the most influence over the cardiovascular system. During the tonic phase of a seizure, increased vagal tone can depress the heart rate to asystole in some patients (see chart below). This may last for 3-4 seconds until the clonic phase occurs (with a noradrenergic surge), whereupon the heart rate can accelerate to the 140s. Unless unstable cardiac disease is present, patients typically tolerate this extremely well without any adverse sequela7. Studies involving patients who have severe aortic stenosis and pacemakers/defibrillators show overall excellent tolerability8,9.

Medications can have an impact on the onset, quality, and duration of seizures. Thus, a careful medication review is needed. A consultant will look first for medications such as benzodiazepines or anticonvulsants that would raise the seizure threshold. Ideally, the medications would be stopped, but if not feasible, they can be held the night before (or the day before in the case of such long half-life agents as diazepam) to minimize their impact.

As for anticonvulsants, the doses can be reduced, along with modest increases in energy settings to facilitate seizure. If used for mood stabilization only, one could consider stopping them completely, but this is usually not required (it is not recommended to stop them if used for epilepsy). Lithium can lead to prolonged neuromuscular blockade, prolonged seizures, or postictal delirium. However, discontinuation of lithium also has a risk-benefit consideration, so usually, doses are reduced and/or decreased doses of neuromuscular blockade are employed. Theophylline can induce extended seizures or status epilepticus so it is usually held prior to ECT.

Back to the case

Given the patient’s severe Parkinson’s disease and concurrent NMS, ECT was initiated. By the second treatment, fever and tachycardia resolved. By the sixth treatment, all NMS symptoms and associated paranoia had completely resolved and her Parkinson’s disease rating scale score went from 142 to 42. Her levodopa dose was reduced from 1,200 to 300 mg/day. She remained stable for years afterward.

Bottom line

ECT is both effective and well tolerated in patients who have received appropriate medical evaluation.

Dr. Lang is clinical associate professor in the departments of psychiatry and internal medicine and director of the electroconvulsive therapy and transcranial magnetic stimulation programs at East Carolina University, Greenville, N.C.

Key points

- ECT is indicated for psychotic and depressive disorders, with high efficacy and rapid response.

- ECT also has proven benefits for NMS, catatonia, delirium, status epilepticus, and Parkinson’s disease.

- Evaluation and focused treatment of relative contraindications maximizes both safety and tolerability of ECT.

References

1. Weiner R et al. “Electroconvulsive therapy in the medical & neurologic patient” in A Stoudemire, BS Fogel & D Greenberg (eds) Psychiatric Care of the Medical Patient, 2nd ed., New York, Oxford Univ Press. 2000:419-28. (Second edition is out of print.)

2. Baghai T et al. Electroconvulsive therapy and its different indications. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. Mar 2008;10(1):105-17.

3. Ozer F et al. Electroconvulsive therapy in drug-induced psychiatric states and neuroleptic malignant syndrome. J ECT. 2005 Jun;21(2):125-7.

4. Taylor S. Electroconvulsive therapy: A review of history, patient selection, technique, and medication management. South Med J. 2007 May;100(5):494-8.

5. The Practice of Electroconvulsive Therapy, 2nd edition. A Task Force Report of the American Psychiatric Association. 2001. pp. 84-85.

6. Miller LJ. Use of electroconvulsive therapy during pregnancy. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1994 May;45(5):444-50.

7. Miller R et al. ECT: Physiologic Effects. Miller’s Anesthesia. 7th Edition. 2009.

8. Mueller PS et al. The Safety of electroconvulsive therapy in patients with severe aortic stenosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007 Nov;82(11):1360-3.

9. Dolenc TJ et al. Electroconvulsive therapy in patients with cardiac pacemakers & implantable cardioverter defibrillators. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2004 Sep;27(9):1257-63.

Suggested readings

The practice of electroconvulsive therapy: Recommendations for treatment, training, and privileging (A Task Force Report of the American Psychiatric Association), 2nd Edition. APA Publishing. 2001.

Weiner R et al. “Electroconvulsive therapy in the medical & neurologic patient” in A Stoudemire, BS Fogel & D Greenberg (eds) Psychiatric Care of the Medical Patient, 2nd ed., New York, Oxford Univ Press. 2000:419-28. (Second edition is out of print.)

Rosenquist P et al. Charting the course of electroconvulsive therapy: Where have we been and where are we headed? J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2016 Dec 1;54(12):39-43.

QUIZ

1. All of the following are indications for ECT except?

A. Schizophrenia.

B. Panic attacks.

C. Bipolar mania.

D. Catatonia.

Answer: B. Panic attacks. ECT is not effective for anxiety disorders including panic, generalized anxiety, PTSD, or OCD.

2. The most commonly accepted mechanism of action for ECT is?

A. Reduction in glutamate levels.

B. Altering signal transduction pathways.

C. Increased neurotransmitter activity.

D. Increased cerebral blood flow.

Answer: C. Increased neurotransmitter activity. There are data to support all, but neurotransmitter flow is most accepted thus far.

3. Which of the following is a common side effect of ECT?

A. Bronchospasm.

B. Diarrhea.

C. Delirium.

D. Visual changes.

Answer: C. Delirium. The rest are rare or not noted.

4. Which of the following is a relative contraindication for ECT?

A. Pregnancy.

B. Epilepsy.

C. Advanced age.

D. Increased intracranial pressure.

Answer: D. Increased intracranial pressure.

FDA: Faulty hematology analyzers face class I recall

The Food and Drug Administration is alerting laboratories and providers to a class I recall on Beckman Coulter hematology analyzers because of the potential for inaccurate platelet count results.

A class I recall indicates reasonable probability of serious adverse health consequences or death associated with use, according to the FDA.

The recall is related to the devices’ platelet analyzing function; among other uses, these devices help assess patients fitness for surgery, so a faulty reading on platelet counts could result in increased risk for life-threatening bleeding during a procedure in patients who have unidentified severe thrombocytopenia, according to a statement from the agency.

“Because this may cause serious injury, or even death, to a patient, we are urging health care professionals to be aware of the potential for inaccurate diagnostic results with these analyzers and to take appropriate actions including the use of alternative diagnostic testing or confirming analyzer results with manual scanning or estimate of platelets,” Tim Stenzel, MD, PhD, director of the Office of In Vitro Diagnostics and Radiological Health in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in the statement.

The recall applies to the UniCel DxH 800 Coulter Cellular Analysis System, UniCel DxH 600 Coulter Cellular Analysis System, and UniCel DxH 900 Coulter Cellular Analysis System. The faulty devices were first identified in 2018, and the manufacturer released an urgent medical device correction letter at that time. The company has more recently released a software patch for the devices, but the FDA has not yet assessed whether it resolves the problem. The agency has released detailed actions and recommendations related to these devices.

At this time, the FDA is unaware of any serious adverse events that have been directly linked to these devices, but the agency recommends that any events be reported through its MedWatch reporting system.

The Food and Drug Administration is alerting laboratories and providers to a class I recall on Beckman Coulter hematology analyzers because of the potential for inaccurate platelet count results.

A class I recall indicates reasonable probability of serious adverse health consequences or death associated with use, according to the FDA.

The recall is related to the devices’ platelet analyzing function; among other uses, these devices help assess patients fitness for surgery, so a faulty reading on platelet counts could result in increased risk for life-threatening bleeding during a procedure in patients who have unidentified severe thrombocytopenia, according to a statement from the agency.

“Because this may cause serious injury, or even death, to a patient, we are urging health care professionals to be aware of the potential for inaccurate diagnostic results with these analyzers and to take appropriate actions including the use of alternative diagnostic testing or confirming analyzer results with manual scanning or estimate of platelets,” Tim Stenzel, MD, PhD, director of the Office of In Vitro Diagnostics and Radiological Health in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in the statement.

The recall applies to the UniCel DxH 800 Coulter Cellular Analysis System, UniCel DxH 600 Coulter Cellular Analysis System, and UniCel DxH 900 Coulter Cellular Analysis System. The faulty devices were first identified in 2018, and the manufacturer released an urgent medical device correction letter at that time. The company has more recently released a software patch for the devices, but the FDA has not yet assessed whether it resolves the problem. The agency has released detailed actions and recommendations related to these devices.

At this time, the FDA is unaware of any serious adverse events that have been directly linked to these devices, but the agency recommends that any events be reported through its MedWatch reporting system.

The Food and Drug Administration is alerting laboratories and providers to a class I recall on Beckman Coulter hematology analyzers because of the potential for inaccurate platelet count results.

A class I recall indicates reasonable probability of serious adverse health consequences or death associated with use, according to the FDA.

The recall is related to the devices’ platelet analyzing function; among other uses, these devices help assess patients fitness for surgery, so a faulty reading on platelet counts could result in increased risk for life-threatening bleeding during a procedure in patients who have unidentified severe thrombocytopenia, according to a statement from the agency.

“Because this may cause serious injury, or even death, to a patient, we are urging health care professionals to be aware of the potential for inaccurate diagnostic results with these analyzers and to take appropriate actions including the use of alternative diagnostic testing or confirming analyzer results with manual scanning or estimate of platelets,” Tim Stenzel, MD, PhD, director of the Office of In Vitro Diagnostics and Radiological Health in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in the statement.

The recall applies to the UniCel DxH 800 Coulter Cellular Analysis System, UniCel DxH 600 Coulter Cellular Analysis System, and UniCel DxH 900 Coulter Cellular Analysis System. The faulty devices were first identified in 2018, and the manufacturer released an urgent medical device correction letter at that time. The company has more recently released a software patch for the devices, but the FDA has not yet assessed whether it resolves the problem. The agency has released detailed actions and recommendations related to these devices.

At this time, the FDA is unaware of any serious adverse events that have been directly linked to these devices, but the agency recommends that any events be reported through its MedWatch reporting system.

Sometimes You Should Order Another Test

On August 7, 2012, a 44-year-old electrical engineer sustained a knee injury. He initially sought treatment at an emergency department (ED) in Indiana, where he lived, and was released with a splint on his leg.

On August 9, the patient presented to an Illinois medical clinic. He was seen by a physician who referred the patient to another physician at the clinic for evaluation for surgery. The procedure, to repair ruptured ligaments in the patient’s left knee, was scheduled for August 16.

After returning home, the patient called the first physician with complaints that his splinted left knee, calf, and leg felt hot. The physician sent approval for the patient to undergo Doppler imaging of his left leg at a hospital in Indiana. The Doppler was performed on August 10, and the results were sent to the referring physician. The imaging was negative for any abnormalities.

On the morning of August 13, the patient presented to the Illinois medical clinic for presurgical clearance. The examination was performed by an NP, and then the patient had a presurgical consultation with the surgeon. The patient allegedly reported to the NP and the surgeon that he had continuing pain, swelling, and heat sensation in his left leg. Relying on the Doppler performed a few days earlier, the surgeon told the patient that these symptoms were related to the knee trauma he had sustained. No additional Doppler imaging was ordered.

On August 16, the patient was anesthetized in preparation for surgery and soon thereafter suffered a pulmonary embolism (PE) when a deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in his left leg detached and traveled to his lung. He went into pulmonary arrest, coded, and was declared brain dead within hours of arriving for surgery.

The decedent left behind a wife and 2 daughters, ages 12 and 14. His wife, as the administrator of her husband’s estate, sued the NP and her employer. The 2 orthopedic physicians, a treating cardiologist, and their employer were named as respondents in discovery. The physicians’ employer was ultimately added as a defendant, along with the NP’s employer. Prior to trial, the 3 physicians and the NP were dismissed from the case. The matter proceeded against the 2 employing organizations.

The estate alleged that the NP and operating surgeon/physician, each as agents of their respective employers, failed to order a second Doppler image of the decedent’s left leg during presurgical clearance procedures and in the 4 days leading up to the surgery. The estate alleged that a second Doppler was needed because the decedent had complaints that were consistent with DVT—such as continuing pain, swelling, and heat sensation—in his left leg at the August 13 visit. The estate argued that the failure to order a second Doppler led to a failure to diagnose the DVT from which the decedent was suffering symptoms. The estate alleged that the earlier Doppler was performed too soon after the decedent’s injury to show a DVT, as DVTs do not develop immediately after trauma but grow and spread over time.

Continue to: While pain, swelling, and warmth...

While pain, swelling, and warmth/heat sensation are symptoms that accompany trauma, the estate asserted that these are also symptoms of a DVT and that the surgeon, as a reasonable orthopedic physician, should have tested the decedent for a DVT on August 13, on the morning of the surgery, or any day in between and that he also should have ordered a hematologic consult. The estate’s orthopedic surgery expert testified that the surgeon violated the standard of care by failing to appreciate the symptoms and risk factors the decedent was experiencing. The expert testified that the decedent had 4 of 5 high-risk factors for a DVT: Although there was no family history of DVT, the decedent had sustained leg trauma, he was older than 40, his leg was immobilized, and he was considered obese (BMI > 30).

The same orthopedist further opined that a Doppler performed on August 13 more likely than not would have shown the DVT, and the August 16 knee surgery would have been delayed until it was treated. He added that the failure to perform a second Doppler before surgery constituted negligence that caused the decedent’s death. The estate’s hematology expert testified that the decedent was a candidate for prophylactic anticoagulation on August 13 and, if a Doppler had been performed, the need for such medication would have been discovered.

The defense argued that the decedent’s signs and symptoms did not change following the Doppler on August 10 and, therefore, there was no reason for the surgeon to order a second Doppler prior to performing surgery. The defense further argued that the NP, in the scope of her practice, was not allowed to order a Doppler, knew that the surgeon would be seeing the decedent during the same visit, and could rely on the surgeon to order the necessary presurgical tests. The defense’s orthopedics expert testified that, unless there was an increase in signs and/or symptoms, the standard of care did not require the surgeon to order another Doppler. The expert further testified that the surgeon did not place the decedent on a presurgical anticoagulant because this would have increased his risk for bleeding. The defense’s hematology expert testified that there was no guarantee an anticoagulant would have prevented the PE because of the large size of the clot. He further stated that the decedent was not a candidate for prophylactic anticoagulants prior to surgery because the Doppler was negative for clotting, and there was no increase in his symptoms after the Doppler was performed.

The estate’s NP expert testified that, while performing the presurgical clearance, the defendant NP failed to obtain the Doppler history or a full description of the patient’s symptoms (which resulted from a DVT) and failed to order a Doppler. The defense’s NP expert testified that, based on the defendant NP’s testimony, she was not allowed to order a Doppler, and that, as an NP, she would have had a document in her credentials setting forth what she can and cannot recommend. Since such a document was not produced, this could not be determined, she opined.

VERDICT

After an 11-day trial and 2.5 hours of deliberation, the jury found in favor of the plaintiff estate. The jury found the NP’s employer not liable but the physicians’ employer responsible. Damages totaling $5,511,567 were awarded to the estate.

Continue to: COMMENTARY

COMMENTARY

If the Grim Reaper had an Employee of the Month plaque, DVT would proudly see its name etched thereon about 8 months of the year. Missed bleeding takes second place (muttering under its breath, promising to “up its game” next year). You may think the pathophysiology is boring. DVTs don’t care. They just kill.

While these comments may seem flip, the intention is not to minimize the threat posed by DVTs but rather to underscore it. DVT/PE is one of the most missed clinical entities giving rise to litigation; it is legally problematic because its development is often foreseeable. There is a clear setup (eg, surgery or immobilization) and a disease process that is easily understood by even lay people. Jurors understand the concept of a “clot”—if you aren’t moving much, you are apt to get a “clog” and if the clog is discovered and “dissolved” the threat goes away, but if it “breaks loose” it could kill. Jurors need not understand highbrow concepts such as the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system or the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis; it is a clog. This is common sense; during deliberations, jurors will reason that if they “get it,” why couldn’t you?

To add insult to (endothelial) injury, DVT and PE are generally curable; most patients recover fully with proper treatment. Plaintiff’s counsel can trot out the tried-and-true argument: “If a simple, painless ultrasound test had been done, [the patient] would be having dinner with his family tonight.” Furthermore, affected patients are apt to be on the younger side, with a lengthy employment life ahead of them—potentially giving rise to substantial loss-of-earnings damages.

In the case presented here, we are told that the decedent complained of “continuing pain, swelling, and heat sensation” when he saw both an NP and a surgeon for presurgical clearance. We do not know if his leg was examined, but if it had been, the positive and negative findings likely would have been discussed in the case synopsis. It appears the NP and the surgeon saw the leg in the immobilizer and decided to rely on the previous negative Doppler.

First, let’s address the diagnosis of DVT: We should all realize that Homan’s sign sucks. You have permission to elicit Homan’s sign if you are in a museum for antiquated medicine (where other artifacts include AZT monotherapy, bite-and-swallow nifedipine for hypertensive urgency, and meperidine for sphincter of Oddi spasm). Everywhere else on the planet, Homan’s sign has always been bad and is certainly not the standard of care. If you are still attempting to elicit Homan’s sign—cut it out. It is the 1970s leisure suit in your closet: never was any good, never is going to be. Declutter your clinical test arsenal and KonMari Homan’s sign straight to the junk pile.

Continue to: A diagnostic tool...

A diagnostic tool that works better is the Wells’ Criteria, which operates on a points system (with 3-8 points indicating high probability of DVT, 1-2 points indicating moderate probability, and less than 1 point indicating low probability).1 Patients are assessed according to the following criteria:

- Paralysis, paresis, or recent orthopedic casting of lower extremity (1 pt)

- Recently bedridden (> 3 d) or major surgery within past 4 weeks (1 pt)

- Localized tenderness in deep vein system (1 pt)

- Swelling of entire leg (1 pt)

- Calf swelling 3 cm greater than other leg (measured 10 cm below the tibial tuberosity) (1 pt)

- Pitting edema greater in the symptomatic leg (1 pt)

- Collateral nonvaricose superficial veins (1 pt)

- Active cancer or cancer treated within 6 months (1 pt)

- Alternative diagnosis more likely than DVT (Baker cyst, cellulitis, muscle damage, superficial venous thrombosis, postphlebitic syndrome, inguinal lymphadenopathy, external venous compression) (–2 pts).1

Moving through the Wells’ score system, we don’t have enough clinical data input for this patient. We do know he had leg pain and possibly swelling (1 pt). His knee was immobilized (albeit without plaster) (1 pt). We don’t know how “bedridden” he was. I’ll argue we should not deduct for “an alternative diagnosis more likely” because the decedent injured his knee and we can expect knee pain and knee swelling, not symptoms and findings involving the entire leg. So this patient would score at least 1 point, possibly 2, and thus be stratified as “moderate probability.”

There was an initial suspicion of DVT in this patient, and a Doppler was ordered on August 10. The patient’s symptoms persisted. However, in light of the negative Doppler results, the continued symptoms were attributed to the knee derangement and not a DVT.

Which brings us to the first malpractice trap: reliance on a prior negative study to rule out a dynamic condition. For any condition that can evolve, do not hesitate to order a repeat test when needed. DVT is a dynamic process; given the right clinical setup (in this case, immobility and ongoing/increasing symptoms), a clinician should not be bashful about ordering a follow-up study. As providers, we recognize the static nature of certain studies and have no reservations about ordering serial complete blood counts or a repeat chest film. Yet we are more reluctant to order repeat studies for equally dynamic disease processes—even when they are required by the standard of care. Here, reliance on a 3-day-old Doppler was problematic. Don’t rely on an old study if the disease under suspicion evolves rapidly.

The second trap: Do not allow yourself to be scolded (or engage in self-scolding) if a correctly ordered test is negative. A clinical decision is correct if it is based on science and in the interest of safeguarding the patient. Don’t buy into the trap that your decision needs to be validated by a positive result. Here, the persisting or worsening leg pain with entire leg swelling warranted a new study—even if the result was expected to be negative.

Continue to: When your decision to order...

When your decision to order such a test is challenged, my favorite rhetorical defense is “Those are some pretty big dice to roll.” That is what you are doing if you skip a test that should be ordered. The bounceback kid with a prior negative lumbar puncture, who now appears toxic, needs a repeat tap. Why? Because you cannot afford to miss meningitis—that would be a risky roll of the dice.

One final point about this case: The NP argued “she was not allowed to order a Doppler” and her NP expert made the argument that “she would have had a document in her credentials setting forth what she can and cannot recommend.” The expert testified she could not find such a document and “could not determine” whether the defendant NP could “recommend” that test. I don’t fault the tactical decision to use this argument, in this case, when the surgeon also saw the patient on the same day. However, we should all recognize this will not normally work. A clinician cannot credibly argue she is not “credentialed” to recommend a course of action she can’t presently deliver.

Consider a clinician employed in an urgent care center without direct access to order CT. She evaluates an 80-year-old woman on warfarin who slipped and struck her head on a marble table. The standard of care requires a CT scan (likely several) to rule out an intracranial bleed. The urgent care clinician cannot send the patient away and later claim she was “not credentialed” to recommend CT imaging to rule out an intracranial bleed. As a matter of the standard of care, our hypothetical clinician would be duty bound to advise the patient of the risk for bleeding and then take steps to arrange for that care—even though she is not in a position to personally deliver it.

IN SUMMARY

Protect your patients from evolving cases by ordering updated tests. Do not be afraid of a negative result. Instead, fear the Reaper; keep him away from your patients. Let him get his “more cowbell” somewhere else.

1. Wells PS, Anderson DR, Bormanis J, et al. Value of assessment of pretest probability of deep-vein thrombosis in clinical management. Lancet. 1997;350(9094):1795-1798.

On August 7, 2012, a 44-year-old electrical engineer sustained a knee injury. He initially sought treatment at an emergency department (ED) in Indiana, where he lived, and was released with a splint on his leg.

On August 9, the patient presented to an Illinois medical clinic. He was seen by a physician who referred the patient to another physician at the clinic for evaluation for surgery. The procedure, to repair ruptured ligaments in the patient’s left knee, was scheduled for August 16.

After returning home, the patient called the first physician with complaints that his splinted left knee, calf, and leg felt hot. The physician sent approval for the patient to undergo Doppler imaging of his left leg at a hospital in Indiana. The Doppler was performed on August 10, and the results were sent to the referring physician. The imaging was negative for any abnormalities.

On the morning of August 13, the patient presented to the Illinois medical clinic for presurgical clearance. The examination was performed by an NP, and then the patient had a presurgical consultation with the surgeon. The patient allegedly reported to the NP and the surgeon that he had continuing pain, swelling, and heat sensation in his left leg. Relying on the Doppler performed a few days earlier, the surgeon told the patient that these symptoms were related to the knee trauma he had sustained. No additional Doppler imaging was ordered.

On August 16, the patient was anesthetized in preparation for surgery and soon thereafter suffered a pulmonary embolism (PE) when a deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in his left leg detached and traveled to his lung. He went into pulmonary arrest, coded, and was declared brain dead within hours of arriving for surgery.

The decedent left behind a wife and 2 daughters, ages 12 and 14. His wife, as the administrator of her husband’s estate, sued the NP and her employer. The 2 orthopedic physicians, a treating cardiologist, and their employer were named as respondents in discovery. The physicians’ employer was ultimately added as a defendant, along with the NP’s employer. Prior to trial, the 3 physicians and the NP were dismissed from the case. The matter proceeded against the 2 employing organizations.

The estate alleged that the NP and operating surgeon/physician, each as agents of their respective employers, failed to order a second Doppler image of the decedent’s left leg during presurgical clearance procedures and in the 4 days leading up to the surgery. The estate alleged that a second Doppler was needed because the decedent had complaints that were consistent with DVT—such as continuing pain, swelling, and heat sensation—in his left leg at the August 13 visit. The estate argued that the failure to order a second Doppler led to a failure to diagnose the DVT from which the decedent was suffering symptoms. The estate alleged that the earlier Doppler was performed too soon after the decedent’s injury to show a DVT, as DVTs do not develop immediately after trauma but grow and spread over time.

Continue to: While pain, swelling, and warmth...

While pain, swelling, and warmth/heat sensation are symptoms that accompany trauma, the estate asserted that these are also symptoms of a DVT and that the surgeon, as a reasonable orthopedic physician, should have tested the decedent for a DVT on August 13, on the morning of the surgery, or any day in between and that he also should have ordered a hematologic consult. The estate’s orthopedic surgery expert testified that the surgeon violated the standard of care by failing to appreciate the symptoms and risk factors the decedent was experiencing. The expert testified that the decedent had 4 of 5 high-risk factors for a DVT: Although there was no family history of DVT, the decedent had sustained leg trauma, he was older than 40, his leg was immobilized, and he was considered obese (BMI > 30).

The same orthopedist further opined that a Doppler performed on August 13 more likely than not would have shown the DVT, and the August 16 knee surgery would have been delayed until it was treated. He added that the failure to perform a second Doppler before surgery constituted negligence that caused the decedent’s death. The estate’s hematology expert testified that the decedent was a candidate for prophylactic anticoagulation on August 13 and, if a Doppler had been performed, the need for such medication would have been discovered.

The defense argued that the decedent’s signs and symptoms did not change following the Doppler on August 10 and, therefore, there was no reason for the surgeon to order a second Doppler prior to performing surgery. The defense further argued that the NP, in the scope of her practice, was not allowed to order a Doppler, knew that the surgeon would be seeing the decedent during the same visit, and could rely on the surgeon to order the necessary presurgical tests. The defense’s orthopedics expert testified that, unless there was an increase in signs and/or symptoms, the standard of care did not require the surgeon to order another Doppler. The expert further testified that the surgeon did not place the decedent on a presurgical anticoagulant because this would have increased his risk for bleeding. The defense’s hematology expert testified that there was no guarantee an anticoagulant would have prevented the PE because of the large size of the clot. He further stated that the decedent was not a candidate for prophylactic anticoagulants prior to surgery because the Doppler was negative for clotting, and there was no increase in his symptoms after the Doppler was performed.

The estate’s NP expert testified that, while performing the presurgical clearance, the defendant NP failed to obtain the Doppler history or a full description of the patient’s symptoms (which resulted from a DVT) and failed to order a Doppler. The defense’s NP expert testified that, based on the defendant NP’s testimony, she was not allowed to order a Doppler, and that, as an NP, she would have had a document in her credentials setting forth what she can and cannot recommend. Since such a document was not produced, this could not be determined, she opined.

VERDICT

After an 11-day trial and 2.5 hours of deliberation, the jury found in favor of the plaintiff estate. The jury found the NP’s employer not liable but the physicians’ employer responsible. Damages totaling $5,511,567 were awarded to the estate.

Continue to: COMMENTARY

COMMENTARY

If the Grim Reaper had an Employee of the Month plaque, DVT would proudly see its name etched thereon about 8 months of the year. Missed bleeding takes second place (muttering under its breath, promising to “up its game” next year). You may think the pathophysiology is boring. DVTs don’t care. They just kill.

While these comments may seem flip, the intention is not to minimize the threat posed by DVTs but rather to underscore it. DVT/PE is one of the most missed clinical entities giving rise to litigation; it is legally problematic because its development is often foreseeable. There is a clear setup (eg, surgery or immobilization) and a disease process that is easily understood by even lay people. Jurors understand the concept of a “clot”—if you aren’t moving much, you are apt to get a “clog” and if the clog is discovered and “dissolved” the threat goes away, but if it “breaks loose” it could kill. Jurors need not understand highbrow concepts such as the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system or the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis; it is a clog. This is common sense; during deliberations, jurors will reason that if they “get it,” why couldn’t you?

To add insult to (endothelial) injury, DVT and PE are generally curable; most patients recover fully with proper treatment. Plaintiff’s counsel can trot out the tried-and-true argument: “If a simple, painless ultrasound test had been done, [the patient] would be having dinner with his family tonight.” Furthermore, affected patients are apt to be on the younger side, with a lengthy employment life ahead of them—potentially giving rise to substantial loss-of-earnings damages.

In the case presented here, we are told that the decedent complained of “continuing pain, swelling, and heat sensation” when he saw both an NP and a surgeon for presurgical clearance. We do not know if his leg was examined, but if it had been, the positive and negative findings likely would have been discussed in the case synopsis. It appears the NP and the surgeon saw the leg in the immobilizer and decided to rely on the previous negative Doppler.

First, let’s address the diagnosis of DVT: We should all realize that Homan’s sign sucks. You have permission to elicit Homan’s sign if you are in a museum for antiquated medicine (where other artifacts include AZT monotherapy, bite-and-swallow nifedipine for hypertensive urgency, and meperidine for sphincter of Oddi spasm). Everywhere else on the planet, Homan’s sign has always been bad and is certainly not the standard of care. If you are still attempting to elicit Homan’s sign—cut it out. It is the 1970s leisure suit in your closet: never was any good, never is going to be. Declutter your clinical test arsenal and KonMari Homan’s sign straight to the junk pile.

Continue to: A diagnostic tool...

A diagnostic tool that works better is the Wells’ Criteria, which operates on a points system (with 3-8 points indicating high probability of DVT, 1-2 points indicating moderate probability, and less than 1 point indicating low probability).1 Patients are assessed according to the following criteria:

- Paralysis, paresis, or recent orthopedic casting of lower extremity (1 pt)

- Recently bedridden (> 3 d) or major surgery within past 4 weeks (1 pt)

- Localized tenderness in deep vein system (1 pt)

- Swelling of entire leg (1 pt)

- Calf swelling 3 cm greater than other leg (measured 10 cm below the tibial tuberosity) (1 pt)

- Pitting edema greater in the symptomatic leg (1 pt)

- Collateral nonvaricose superficial veins (1 pt)

- Active cancer or cancer treated within 6 months (1 pt)

- Alternative diagnosis more likely than DVT (Baker cyst, cellulitis, muscle damage, superficial venous thrombosis, postphlebitic syndrome, inguinal lymphadenopathy, external venous compression) (–2 pts).1

Moving through the Wells’ score system, we don’t have enough clinical data input for this patient. We do know he had leg pain and possibly swelling (1 pt). His knee was immobilized (albeit without plaster) (1 pt). We don’t know how “bedridden” he was. I’ll argue we should not deduct for “an alternative diagnosis more likely” because the decedent injured his knee and we can expect knee pain and knee swelling, not symptoms and findings involving the entire leg. So this patient would score at least 1 point, possibly 2, and thus be stratified as “moderate probability.”

There was an initial suspicion of DVT in this patient, and a Doppler was ordered on August 10. The patient’s symptoms persisted. However, in light of the negative Doppler results, the continued symptoms were attributed to the knee derangement and not a DVT.

Which brings us to the first malpractice trap: reliance on a prior negative study to rule out a dynamic condition. For any condition that can evolve, do not hesitate to order a repeat test when needed. DVT is a dynamic process; given the right clinical setup (in this case, immobility and ongoing/increasing symptoms), a clinician should not be bashful about ordering a follow-up study. As providers, we recognize the static nature of certain studies and have no reservations about ordering serial complete blood counts or a repeat chest film. Yet we are more reluctant to order repeat studies for equally dynamic disease processes—even when they are required by the standard of care. Here, reliance on a 3-day-old Doppler was problematic. Don’t rely on an old study if the disease under suspicion evolves rapidly.

The second trap: Do not allow yourself to be scolded (or engage in self-scolding) if a correctly ordered test is negative. A clinical decision is correct if it is based on science and in the interest of safeguarding the patient. Don’t buy into the trap that your decision needs to be validated by a positive result. Here, the persisting or worsening leg pain with entire leg swelling warranted a new study—even if the result was expected to be negative.

Continue to: When your decision to order...

When your decision to order such a test is challenged, my favorite rhetorical defense is “Those are some pretty big dice to roll.” That is what you are doing if you skip a test that should be ordered. The bounceback kid with a prior negative lumbar puncture, who now appears toxic, needs a repeat tap. Why? Because you cannot afford to miss meningitis—that would be a risky roll of the dice.

One final point about this case: The NP argued “she was not allowed to order a Doppler” and her NP expert made the argument that “she would have had a document in her credentials setting forth what she can and cannot recommend.” The expert testified she could not find such a document and “could not determine” whether the defendant NP could “recommend” that test. I don’t fault the tactical decision to use this argument, in this case, when the surgeon also saw the patient on the same day. However, we should all recognize this will not normally work. A clinician cannot credibly argue she is not “credentialed” to recommend a course of action she can’t presently deliver.

Consider a clinician employed in an urgent care center without direct access to order CT. She evaluates an 80-year-old woman on warfarin who slipped and struck her head on a marble table. The standard of care requires a CT scan (likely several) to rule out an intracranial bleed. The urgent care clinician cannot send the patient away and later claim she was “not credentialed” to recommend CT imaging to rule out an intracranial bleed. As a matter of the standard of care, our hypothetical clinician would be duty bound to advise the patient of the risk for bleeding and then take steps to arrange for that care—even though she is not in a position to personally deliver it.

IN SUMMARY

Protect your patients from evolving cases by ordering updated tests. Do not be afraid of a negative result. Instead, fear the Reaper; keep him away from your patients. Let him get his “more cowbell” somewhere else.

On August 7, 2012, a 44-year-old electrical engineer sustained a knee injury. He initially sought treatment at an emergency department (ED) in Indiana, where he lived, and was released with a splint on his leg.

On August 9, the patient presented to an Illinois medical clinic. He was seen by a physician who referred the patient to another physician at the clinic for evaluation for surgery. The procedure, to repair ruptured ligaments in the patient’s left knee, was scheduled for August 16.

After returning home, the patient called the first physician with complaints that his splinted left knee, calf, and leg felt hot. The physician sent approval for the patient to undergo Doppler imaging of his left leg at a hospital in Indiana. The Doppler was performed on August 10, and the results were sent to the referring physician. The imaging was negative for any abnormalities.

On the morning of August 13, the patient presented to the Illinois medical clinic for presurgical clearance. The examination was performed by an NP, and then the patient had a presurgical consultation with the surgeon. The patient allegedly reported to the NP and the surgeon that he had continuing pain, swelling, and heat sensation in his left leg. Relying on the Doppler performed a few days earlier, the surgeon told the patient that these symptoms were related to the knee trauma he had sustained. No additional Doppler imaging was ordered.

On August 16, the patient was anesthetized in preparation for surgery and soon thereafter suffered a pulmonary embolism (PE) when a deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in his left leg detached and traveled to his lung. He went into pulmonary arrest, coded, and was declared brain dead within hours of arriving for surgery.

The decedent left behind a wife and 2 daughters, ages 12 and 14. His wife, as the administrator of her husband’s estate, sued the NP and her employer. The 2 orthopedic physicians, a treating cardiologist, and their employer were named as respondents in discovery. The physicians’ employer was ultimately added as a defendant, along with the NP’s employer. Prior to trial, the 3 physicians and the NP were dismissed from the case. The matter proceeded against the 2 employing organizations.

The estate alleged that the NP and operating surgeon/physician, each as agents of their respective employers, failed to order a second Doppler image of the decedent’s left leg during presurgical clearance procedures and in the 4 days leading up to the surgery. The estate alleged that a second Doppler was needed because the decedent had complaints that were consistent with DVT—such as continuing pain, swelling, and heat sensation—in his left leg at the August 13 visit. The estate argued that the failure to order a second Doppler led to a failure to diagnose the DVT from which the decedent was suffering symptoms. The estate alleged that the earlier Doppler was performed too soon after the decedent’s injury to show a DVT, as DVTs do not develop immediately after trauma but grow and spread over time.

Continue to: While pain, swelling, and warmth...

While pain, swelling, and warmth/heat sensation are symptoms that accompany trauma, the estate asserted that these are also symptoms of a DVT and that the surgeon, as a reasonable orthopedic physician, should have tested the decedent for a DVT on August 13, on the morning of the surgery, or any day in between and that he also should have ordered a hematologic consult. The estate’s orthopedic surgery expert testified that the surgeon violated the standard of care by failing to appreciate the symptoms and risk factors the decedent was experiencing. The expert testified that the decedent had 4 of 5 high-risk factors for a DVT: Although there was no family history of DVT, the decedent had sustained leg trauma, he was older than 40, his leg was immobilized, and he was considered obese (BMI > 30).

The same orthopedist further opined that a Doppler performed on August 13 more likely than not would have shown the DVT, and the August 16 knee surgery would have been delayed until it was treated. He added that the failure to perform a second Doppler before surgery constituted negligence that caused the decedent’s death. The estate’s hematology expert testified that the decedent was a candidate for prophylactic anticoagulation on August 13 and, if a Doppler had been performed, the need for such medication would have been discovered.

The defense argued that the decedent’s signs and symptoms did not change following the Doppler on August 10 and, therefore, there was no reason for the surgeon to order a second Doppler prior to performing surgery. The defense further argued that the NP, in the scope of her practice, was not allowed to order a Doppler, knew that the surgeon would be seeing the decedent during the same visit, and could rely on the surgeon to order the necessary presurgical tests. The defense’s orthopedics expert testified that, unless there was an increase in signs and/or symptoms, the standard of care did not require the surgeon to order another Doppler. The expert further testified that the surgeon did not place the decedent on a presurgical anticoagulant because this would have increased his risk for bleeding. The defense’s hematology expert testified that there was no guarantee an anticoagulant would have prevented the PE because of the large size of the clot. He further stated that the decedent was not a candidate for prophylactic anticoagulants prior to surgery because the Doppler was negative for clotting, and there was no increase in his symptoms after the Doppler was performed.

The estate’s NP expert testified that, while performing the presurgical clearance, the defendant NP failed to obtain the Doppler history or a full description of the patient’s symptoms (which resulted from a DVT) and failed to order a Doppler. The defense’s NP expert testified that, based on the defendant NP’s testimony, she was not allowed to order a Doppler, and that, as an NP, she would have had a document in her credentials setting forth what she can and cannot recommend. Since such a document was not produced, this could not be determined, she opined.

VERDICT

After an 11-day trial and 2.5 hours of deliberation, the jury found in favor of the plaintiff estate. The jury found the NP’s employer not liable but the physicians’ employer responsible. Damages totaling $5,511,567 were awarded to the estate.

Continue to: COMMENTARY

COMMENTARY

If the Grim Reaper had an Employee of the Month plaque, DVT would proudly see its name etched thereon about 8 months of the year. Missed bleeding takes second place (muttering under its breath, promising to “up its game” next year). You may think the pathophysiology is boring. DVTs don’t care. They just kill.

While these comments may seem flip, the intention is not to minimize the threat posed by DVTs but rather to underscore it. DVT/PE is one of the most missed clinical entities giving rise to litigation; it is legally problematic because its development is often foreseeable. There is a clear setup (eg, surgery or immobilization) and a disease process that is easily understood by even lay people. Jurors understand the concept of a “clot”—if you aren’t moving much, you are apt to get a “clog” and if the clog is discovered and “dissolved” the threat goes away, but if it “breaks loose” it could kill. Jurors need not understand highbrow concepts such as the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system or the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis; it is a clog. This is common sense; during deliberations, jurors will reason that if they “get it,” why couldn’t you?

To add insult to (endothelial) injury, DVT and PE are generally curable; most patients recover fully with proper treatment. Plaintiff’s counsel can trot out the tried-and-true argument: “If a simple, painless ultrasound test had been done, [the patient] would be having dinner with his family tonight.” Furthermore, affected patients are apt to be on the younger side, with a lengthy employment life ahead of them—potentially giving rise to substantial loss-of-earnings damages.

In the case presented here, we are told that the decedent complained of “continuing pain, swelling, and heat sensation” when he saw both an NP and a surgeon for presurgical clearance. We do not know if his leg was examined, but if it had been, the positive and negative findings likely would have been discussed in the case synopsis. It appears the NP and the surgeon saw the leg in the immobilizer and decided to rely on the previous negative Doppler.

First, let’s address the diagnosis of DVT: We should all realize that Homan’s sign sucks. You have permission to elicit Homan’s sign if you are in a museum for antiquated medicine (where other artifacts include AZT monotherapy, bite-and-swallow nifedipine for hypertensive urgency, and meperidine for sphincter of Oddi spasm). Everywhere else on the planet, Homan’s sign has always been bad and is certainly not the standard of care. If you are still attempting to elicit Homan’s sign—cut it out. It is the 1970s leisure suit in your closet: never was any good, never is going to be. Declutter your clinical test arsenal and KonMari Homan’s sign straight to the junk pile.

Continue to: A diagnostic tool...

A diagnostic tool that works better is the Wells’ Criteria, which operates on a points system (with 3-8 points indicating high probability of DVT, 1-2 points indicating moderate probability, and less than 1 point indicating low probability).1 Patients are assessed according to the following criteria:

- Paralysis, paresis, or recent orthopedic casting of lower extremity (1 pt)

- Recently bedridden (> 3 d) or major surgery within past 4 weeks (1 pt)

- Localized tenderness in deep vein system (1 pt)

- Swelling of entire leg (1 pt)

- Calf swelling 3 cm greater than other leg (measured 10 cm below the tibial tuberosity) (1 pt)

- Pitting edema greater in the symptomatic leg (1 pt)

- Collateral nonvaricose superficial veins (1 pt)

- Active cancer or cancer treated within 6 months (1 pt)

- Alternative diagnosis more likely than DVT (Baker cyst, cellulitis, muscle damage, superficial venous thrombosis, postphlebitic syndrome, inguinal lymphadenopathy, external venous compression) (–2 pts).1

Moving through the Wells’ score system, we don’t have enough clinical data input for this patient. We do know he had leg pain and possibly swelling (1 pt). His knee was immobilized (albeit without plaster) (1 pt). We don’t know how “bedridden” he was. I’ll argue we should not deduct for “an alternative diagnosis more likely” because the decedent injured his knee and we can expect knee pain and knee swelling, not symptoms and findings involving the entire leg. So this patient would score at least 1 point, possibly 2, and thus be stratified as “moderate probability.”

There was an initial suspicion of DVT in this patient, and a Doppler was ordered on August 10. The patient’s symptoms persisted. However, in light of the negative Doppler results, the continued symptoms were attributed to the knee derangement and not a DVT.

Which brings us to the first malpractice trap: reliance on a prior negative study to rule out a dynamic condition. For any condition that can evolve, do not hesitate to order a repeat test when needed. DVT is a dynamic process; given the right clinical setup (in this case, immobility and ongoing/increasing symptoms), a clinician should not be bashful about ordering a follow-up study. As providers, we recognize the static nature of certain studies and have no reservations about ordering serial complete blood counts or a repeat chest film. Yet we are more reluctant to order repeat studies for equally dynamic disease processes—even when they are required by the standard of care. Here, reliance on a 3-day-old Doppler was problematic. Don’t rely on an old study if the disease under suspicion evolves rapidly.

The second trap: Do not allow yourself to be scolded (or engage in self-scolding) if a correctly ordered test is negative. A clinical decision is correct if it is based on science and in the interest of safeguarding the patient. Don’t buy into the trap that your decision needs to be validated by a positive result. Here, the persisting or worsening leg pain with entire leg swelling warranted a new study—even if the result was expected to be negative.

Continue to: When your decision to order...

When your decision to order such a test is challenged, my favorite rhetorical defense is “Those are some pretty big dice to roll.” That is what you are doing if you skip a test that should be ordered. The bounceback kid with a prior negative lumbar puncture, who now appears toxic, needs a repeat tap. Why? Because you cannot afford to miss meningitis—that would be a risky roll of the dice.

One final point about this case: The NP argued “she was not allowed to order a Doppler” and her NP expert made the argument that “she would have had a document in her credentials setting forth what she can and cannot recommend.” The expert testified she could not find such a document and “could not determine” whether the defendant NP could “recommend” that test. I don’t fault the tactical decision to use this argument, in this case, when the surgeon also saw the patient on the same day. However, we should all recognize this will not normally work. A clinician cannot credibly argue she is not “credentialed” to recommend a course of action she can’t presently deliver.

Consider a clinician employed in an urgent care center without direct access to order CT. She evaluates an 80-year-old woman on warfarin who slipped and struck her head on a marble table. The standard of care requires a CT scan (likely several) to rule out an intracranial bleed. The urgent care clinician cannot send the patient away and later claim she was “not credentialed” to recommend CT imaging to rule out an intracranial bleed. As a matter of the standard of care, our hypothetical clinician would be duty bound to advise the patient of the risk for bleeding and then take steps to arrange for that care—even though she is not in a position to personally deliver it.

IN SUMMARY