User login

PPI-fracture link can’t be ruled out

PHILADELPHIA – While a potential effect can’t be ruled out, the evidence to date is inconsistent in terms of whether proton pump inhibitors increase risk of osteoporotic fractures, an expert said at the Digestive Diseases: New Advances conference jointly provided by Rutgers and Global Academy for Medical Education.

“These associations are possible,” said David C. Metz, MD, professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

However, Dr. Metz cautioned attendees to “be cognizant of the limitations of epidemiological data,” and highlighted a recent randomized, double-blind trial he recently published with colleagues showing a lack of proton pump inhibitors (PPI) effect on bone homeostasis in healthy, postmenopausal women.

Taking all the evidence into consideration, Dr. Metz recommended judicious use of PPIs: “Don’t deny therapy because of concerns about long-term side effects. If the patient deserves the drug, they work. Use the lowest effective long-term maintenance dose, depending on the indication.”

Dr. Metz was senior author on a frequently cited 2006 report in JAMA linking long-term PPI therapy to increased hip fracture risk, particularly when given at high doses. That study “opened up a cottage industry” of researchers examining positive or negative associations with PPI therapy, he said.

In a 2016 meta-analysis including 18 studies, investigators reported in Osteoporosis International that PPIs “modestly increased” risk of hip fracture (relative risk, 1.26; 95% confidence interval, 1.16-1.36), along with similar risk increases for spine or any-site fracture. However, many of the studies incorporated into that analysis did not conclusively associate PPIs with fractures, according to Dr. Metz.

Moreover, there had been no randomized, prospective, double-blind trials on the subject published until this month, according to Dr. Metz, when he and his coauthors reported in Gastroenterology that dexlansoprazole and esomeprazole did not affect bone homeostasis in healthy, postmenopausal women. The randomized, 26-week study, mandated by the Food and Drug Administration to evaluate long-term PPI risks, was “essentially a negative study,” Dr. Metz said in his presentation.

“I think it gives us comfort in knowing to use the drug appropriately when indicated,” he said.

In the randomized study, there were no significant differences between the PPI and placebo groups in bone mineral density, parathyroid hormone levels, serum or urine levels of minerals, or calcium absorption. There were significant increases in markers of bone turnover in women receiving PPIs versus women receiving placebo, but the levels remained within the normal limits, according to the investigators.

Nevertheless, he said that clinicians do need to be mindful of a potential risk of fracture associated with PPIs, even if studies to date are inconclusive. “I don’t think that PPIs really have a biological explanation yet at this point as to why they may make your parents a little bit more fracturable, if you happen to be a postmenopausal female who’s at risk for that.”

Dr. Metz reported receiving grant/research support from AAA, Ipsen, Lexicon, and Wren Laboratories, consulting for Takeda, and serving as a board member for the North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society. The study was funded by Takeda, which was responsible for and sponsored the study design, data collection, data interpretation, and writing of the manuscript appearing in Gastroenterology.

This news organization and Global Academy for Medical Education are owned by the same parent company.

PHILADELPHIA – While a potential effect can’t be ruled out, the evidence to date is inconsistent in terms of whether proton pump inhibitors increase risk of osteoporotic fractures, an expert said at the Digestive Diseases: New Advances conference jointly provided by Rutgers and Global Academy for Medical Education.

“These associations are possible,” said David C. Metz, MD, professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

However, Dr. Metz cautioned attendees to “be cognizant of the limitations of epidemiological data,” and highlighted a recent randomized, double-blind trial he recently published with colleagues showing a lack of proton pump inhibitors (PPI) effect on bone homeostasis in healthy, postmenopausal women.

Taking all the evidence into consideration, Dr. Metz recommended judicious use of PPIs: “Don’t deny therapy because of concerns about long-term side effects. If the patient deserves the drug, they work. Use the lowest effective long-term maintenance dose, depending on the indication.”

Dr. Metz was senior author on a frequently cited 2006 report in JAMA linking long-term PPI therapy to increased hip fracture risk, particularly when given at high doses. That study “opened up a cottage industry” of researchers examining positive or negative associations with PPI therapy, he said.

In a 2016 meta-analysis including 18 studies, investigators reported in Osteoporosis International that PPIs “modestly increased” risk of hip fracture (relative risk, 1.26; 95% confidence interval, 1.16-1.36), along with similar risk increases for spine or any-site fracture. However, many of the studies incorporated into that analysis did not conclusively associate PPIs with fractures, according to Dr. Metz.

Moreover, there had been no randomized, prospective, double-blind trials on the subject published until this month, according to Dr. Metz, when he and his coauthors reported in Gastroenterology that dexlansoprazole and esomeprazole did not affect bone homeostasis in healthy, postmenopausal women. The randomized, 26-week study, mandated by the Food and Drug Administration to evaluate long-term PPI risks, was “essentially a negative study,” Dr. Metz said in his presentation.

“I think it gives us comfort in knowing to use the drug appropriately when indicated,” he said.

In the randomized study, there were no significant differences between the PPI and placebo groups in bone mineral density, parathyroid hormone levels, serum or urine levels of minerals, or calcium absorption. There were significant increases in markers of bone turnover in women receiving PPIs versus women receiving placebo, but the levels remained within the normal limits, according to the investigators.

Nevertheless, he said that clinicians do need to be mindful of a potential risk of fracture associated with PPIs, even if studies to date are inconclusive. “I don’t think that PPIs really have a biological explanation yet at this point as to why they may make your parents a little bit more fracturable, if you happen to be a postmenopausal female who’s at risk for that.”

Dr. Metz reported receiving grant/research support from AAA, Ipsen, Lexicon, and Wren Laboratories, consulting for Takeda, and serving as a board member for the North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society. The study was funded by Takeda, which was responsible for and sponsored the study design, data collection, data interpretation, and writing of the manuscript appearing in Gastroenterology.

This news organization and Global Academy for Medical Education are owned by the same parent company.

PHILADELPHIA – While a potential effect can’t be ruled out, the evidence to date is inconsistent in terms of whether proton pump inhibitors increase risk of osteoporotic fractures, an expert said at the Digestive Diseases: New Advances conference jointly provided by Rutgers and Global Academy for Medical Education.

“These associations are possible,” said David C. Metz, MD, professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

However, Dr. Metz cautioned attendees to “be cognizant of the limitations of epidemiological data,” and highlighted a recent randomized, double-blind trial he recently published with colleagues showing a lack of proton pump inhibitors (PPI) effect on bone homeostasis in healthy, postmenopausal women.

Taking all the evidence into consideration, Dr. Metz recommended judicious use of PPIs: “Don’t deny therapy because of concerns about long-term side effects. If the patient deserves the drug, they work. Use the lowest effective long-term maintenance dose, depending on the indication.”

Dr. Metz was senior author on a frequently cited 2006 report in JAMA linking long-term PPI therapy to increased hip fracture risk, particularly when given at high doses. That study “opened up a cottage industry” of researchers examining positive or negative associations with PPI therapy, he said.

In a 2016 meta-analysis including 18 studies, investigators reported in Osteoporosis International that PPIs “modestly increased” risk of hip fracture (relative risk, 1.26; 95% confidence interval, 1.16-1.36), along with similar risk increases for spine or any-site fracture. However, many of the studies incorporated into that analysis did not conclusively associate PPIs with fractures, according to Dr. Metz.

Moreover, there had been no randomized, prospective, double-blind trials on the subject published until this month, according to Dr. Metz, when he and his coauthors reported in Gastroenterology that dexlansoprazole and esomeprazole did not affect bone homeostasis in healthy, postmenopausal women. The randomized, 26-week study, mandated by the Food and Drug Administration to evaluate long-term PPI risks, was “essentially a negative study,” Dr. Metz said in his presentation.

“I think it gives us comfort in knowing to use the drug appropriately when indicated,” he said.

In the randomized study, there were no significant differences between the PPI and placebo groups in bone mineral density, parathyroid hormone levels, serum or urine levels of minerals, or calcium absorption. There were significant increases in markers of bone turnover in women receiving PPIs versus women receiving placebo, but the levels remained within the normal limits, according to the investigators.

Nevertheless, he said that clinicians do need to be mindful of a potential risk of fracture associated with PPIs, even if studies to date are inconclusive. “I don’t think that PPIs really have a biological explanation yet at this point as to why they may make your parents a little bit more fracturable, if you happen to be a postmenopausal female who’s at risk for that.”

Dr. Metz reported receiving grant/research support from AAA, Ipsen, Lexicon, and Wren Laboratories, consulting for Takeda, and serving as a board member for the North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society. The study was funded by Takeda, which was responsible for and sponsored the study design, data collection, data interpretation, and writing of the manuscript appearing in Gastroenterology.

This news organization and Global Academy for Medical Education are owned by the same parent company.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM DIGESTIVE DISEASES: NEW ADVANCES

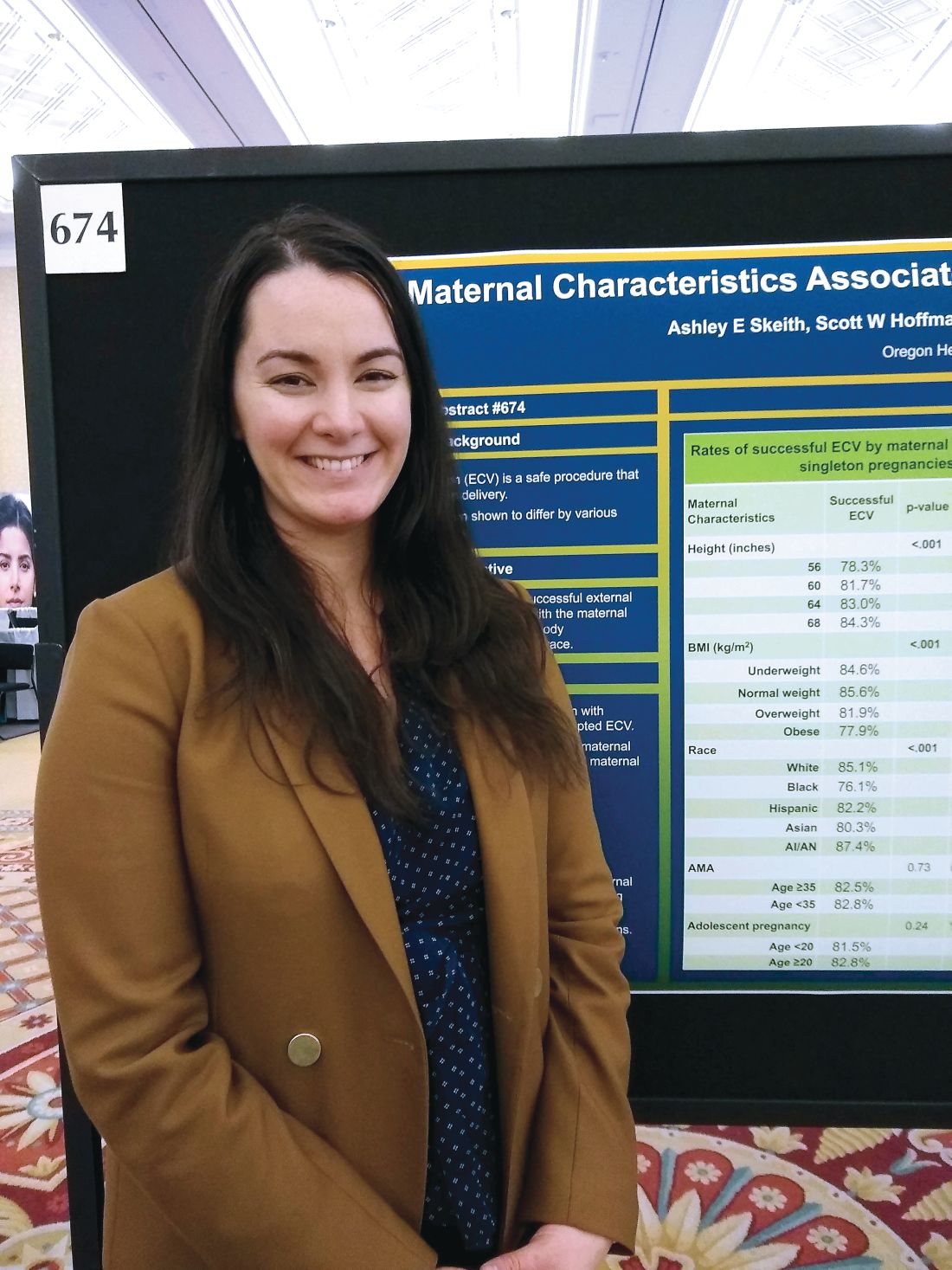

Successful external cephalic version more likely in taller, leaner women

LAS VEGAS – according to data shared in a poster session at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Race/ethnicity also had an impact on the likelihood that external cephalic version (ECV) would be successful.

In an interview, first author Ashley E. Skeith, a medical student at Oregon Health and Sciences University, Portland, said that various characteristics of a pregnancy may affect the success of ECV, but it wasn’t known which maternal characteristics might be associated with greater success of the maneuver.

She and her collaborators found that rates of success were high overall, but that 84% of women 68 inches or taller had successful ECVs, compared with 78% of women less than 60 inches tall. Rates were 82% and 83% for women 60-64 inches and 64-68 inches tall, respectively (adjusted odds ratio, 1.03; P less than .001).

The retrospective cohort study used data from 18,896 women who had singleton, breech, term gestations for whom ECV was attempted. Variables extracted from the medical record included maternal age, height, race, and prepregnancy body mass index (BMI).

For analysis, maternal BMI was grouped into four categories: underweight (BMI, less than 18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (BMI, 18.5-24.9 kg/m2), overweight (BMI, 25-29 kg/m2), and obese (BMI, greater than 30 kg/m2).

Women who were normal weight had the highest likelihood of a successful ECV, at 86%, followed by underweight women at 85%. Women who were overweight and obese had lower success rates, at 82% and 78%, respectively (aOR, 0.86; P less than .001).

Compared with white women, black women had an aOR of 0.60 for successful ECV (P less than .001). The aOR for successful ECV for Asian women was 0.71; for Hispanic women, the aOR was 0.82. American Indian and Alaska Native women were slightly more likely to have successful ECV than white women, but the difference was not significant after statistical adjustment.

Neither advanced maternal age (greater than 35 years) nor adolescent pregnancy were associated with decreased likelihood of successful ECV.

Potential confounders included maternal education level and insurance status, how much weight was gained during pregnancy, whether an epidural was administered, and whether the mother had diabetes. Multivariable regression analysis adjusted for these variables, said Ms. Skeith.

“External cephalic version is a safe procedure that reduces risk of cesarean delivery,” wrote Ms. Skeith and her colleagues. “Though fetal positioning and analgesia have been considered in the prediction of ECV success, [these] data [suggest] that maternal stature and race/ethnicity could be incorporated into potential prediction tools.”

Ms. Skeith reported no outside sources of funding or conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Skeith AE et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Jan;220(1):S445-7, Abstract 674.

LAS VEGAS – according to data shared in a poster session at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Race/ethnicity also had an impact on the likelihood that external cephalic version (ECV) would be successful.

In an interview, first author Ashley E. Skeith, a medical student at Oregon Health and Sciences University, Portland, said that various characteristics of a pregnancy may affect the success of ECV, but it wasn’t known which maternal characteristics might be associated with greater success of the maneuver.

She and her collaborators found that rates of success were high overall, but that 84% of women 68 inches or taller had successful ECVs, compared with 78% of women less than 60 inches tall. Rates were 82% and 83% for women 60-64 inches and 64-68 inches tall, respectively (adjusted odds ratio, 1.03; P less than .001).

The retrospective cohort study used data from 18,896 women who had singleton, breech, term gestations for whom ECV was attempted. Variables extracted from the medical record included maternal age, height, race, and prepregnancy body mass index (BMI).

For analysis, maternal BMI was grouped into four categories: underweight (BMI, less than 18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (BMI, 18.5-24.9 kg/m2), overweight (BMI, 25-29 kg/m2), and obese (BMI, greater than 30 kg/m2).

Women who were normal weight had the highest likelihood of a successful ECV, at 86%, followed by underweight women at 85%. Women who were overweight and obese had lower success rates, at 82% and 78%, respectively (aOR, 0.86; P less than .001).

Compared with white women, black women had an aOR of 0.60 for successful ECV (P less than .001). The aOR for successful ECV for Asian women was 0.71; for Hispanic women, the aOR was 0.82. American Indian and Alaska Native women were slightly more likely to have successful ECV than white women, but the difference was not significant after statistical adjustment.

Neither advanced maternal age (greater than 35 years) nor adolescent pregnancy were associated with decreased likelihood of successful ECV.

Potential confounders included maternal education level and insurance status, how much weight was gained during pregnancy, whether an epidural was administered, and whether the mother had diabetes. Multivariable regression analysis adjusted for these variables, said Ms. Skeith.

“External cephalic version is a safe procedure that reduces risk of cesarean delivery,” wrote Ms. Skeith and her colleagues. “Though fetal positioning and analgesia have been considered in the prediction of ECV success, [these] data [suggest] that maternal stature and race/ethnicity could be incorporated into potential prediction tools.”

Ms. Skeith reported no outside sources of funding or conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Skeith AE et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Jan;220(1):S445-7, Abstract 674.

LAS VEGAS – according to data shared in a poster session at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Race/ethnicity also had an impact on the likelihood that external cephalic version (ECV) would be successful.

In an interview, first author Ashley E. Skeith, a medical student at Oregon Health and Sciences University, Portland, said that various characteristics of a pregnancy may affect the success of ECV, but it wasn’t known which maternal characteristics might be associated with greater success of the maneuver.

She and her collaborators found that rates of success were high overall, but that 84% of women 68 inches or taller had successful ECVs, compared with 78% of women less than 60 inches tall. Rates were 82% and 83% for women 60-64 inches and 64-68 inches tall, respectively (adjusted odds ratio, 1.03; P less than .001).

The retrospective cohort study used data from 18,896 women who had singleton, breech, term gestations for whom ECV was attempted. Variables extracted from the medical record included maternal age, height, race, and prepregnancy body mass index (BMI).

For analysis, maternal BMI was grouped into four categories: underweight (BMI, less than 18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (BMI, 18.5-24.9 kg/m2), overweight (BMI, 25-29 kg/m2), and obese (BMI, greater than 30 kg/m2).

Women who were normal weight had the highest likelihood of a successful ECV, at 86%, followed by underweight women at 85%. Women who were overweight and obese had lower success rates, at 82% and 78%, respectively (aOR, 0.86; P less than .001).

Compared with white women, black women had an aOR of 0.60 for successful ECV (P less than .001). The aOR for successful ECV for Asian women was 0.71; for Hispanic women, the aOR was 0.82. American Indian and Alaska Native women were slightly more likely to have successful ECV than white women, but the difference was not significant after statistical adjustment.

Neither advanced maternal age (greater than 35 years) nor adolescent pregnancy were associated with decreased likelihood of successful ECV.

Potential confounders included maternal education level and insurance status, how much weight was gained during pregnancy, whether an epidural was administered, and whether the mother had diabetes. Multivariable regression analysis adjusted for these variables, said Ms. Skeith.

“External cephalic version is a safe procedure that reduces risk of cesarean delivery,” wrote Ms. Skeith and her colleagues. “Though fetal positioning and analgesia have been considered in the prediction of ECV success, [these] data [suggest] that maternal stature and race/ethnicity could be incorporated into potential prediction tools.”

Ms. Skeith reported no outside sources of funding or conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Skeith AE et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Jan;220(1):S445-7, Abstract 674.

REPORTING FROM THE PREGNANCY MEETING

Optical coherence tomography emerging as a promising biomarker for MS

DALLAS – Optical coherence tomography (OCT) has emerged as a promising biomarker in multiple sclerosis.

Thanks to OCT, clinicians are gaining an improved understanding of how MS affects certain eye structures. An optical analogue of ultrasound B mode imaging, OCT achieves a resolution of about 3-6 microns with commercially available devices. “That allows us to quantify the layers of the retina with quite a degree of accuracy,” Shiv Saidha, MD, said at ACTRIMS Forum 2019, the meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

At postmortem, up to 99% of MS patients have demyelinated plaques in their optic nerves. “This implies that optic neuropathy is an ubiquitous phenomenon as part of the MS disease process,” said Dr. Saidha, a neurologist at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. “The prevailing hypothesis is that there is demyelination or axonal transection related to acute inflammation that occurs within the optic nerve. There’s a retrograde degeneration of its constituent axons, and that results in thinning of the inner retinal nerve fiber layer as well as the neuronal derivative of this layer called the ganglion cell layer. In addition to neurodegenerative mechanisms in the retina, there is also perivascular inflammation, called retinal periphlebitis, which we know occurs in about 20% of MS patients. At postmortem, there are also activate microglia present within the retina of MS patients.”

One of the principal findings of OCT in MS to date is that the retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) and ganglion cell plus inner plexiform layer (GCIP) thinning reflects MS-related optic nerve neurodegeneration. In addition, RNFL and GCIP thinning occur after optic neuritis and also as part of the MS disease course in eyes without a history of optic neuritis. “RNFL and GCIP thinning in MS are clinically relevant and correlate with visual function, global disability, and brain atrophy,” Dr. Saidha said. Researchers have also found that rates of GCIP thinning are accelerated in MS patients exhibiting clinical and/or radiological disease activity and are altered by disease-modifying therapies, and that increased inner nuclear layer (INL) thickness correlates with T2 lesion volume and predicts clinical and radiological disease activity. “In numerous trials of putatively neuroprotective and restorative treatments, we see OCT incorporated more and more, either as a secondary or a primary outcome,” he said.

Predicting disability and brain atrophy

In a study expected to be appear in a forthcoming issue of the Annals of Translational and Clinical Neurology, colleagues of Dr. Saidha found that OCT derived retinal layer measurements and visual function predict disability at 10 years in patients with MS. The researchers used an earlier generation, lower quality OCT device to examine tertiles of total macular volume, “an old, nonspecific composite measure of all of the retinal components,” he explained. “Even with inferior technology, a single measurement at a point in time not only could predict the change in EDSS [Expanded Disability Status Scale] scores from baseline to 10 years, but the accumulation of meaningful disability.”

In an earlier study, Dr. Saidha and his colleagues conducted a 4-year study of OCT and MRI in MS (Ann Neurol 2015; 78[5]:801-13). It consisted of six monthly spectral domain OCT scans (including automated intra-retinal segmentation) and baseline and annual 3 T brain MRI (including substructure volumetrics). Patients with ocular relapses (optic neuritis) during the study were excluded. The researchers correlated individual-specific rates of change in retinal and brain measurements, adjusting for age, sex, disease duration, and optic neuritis history. They found that cerebral volume fraction (analogous to whole brain volume) “had a decent correlation between rates of GCIP atrophy and rates of whole brain volume loss,” he said. “That was predominately driven by cortical gray matter atrophy.”

Measuring effects of disease-modifying therapies

What about the effects of disease-modifying therapies? According to Dr. Saidha, there has been a paucity of studies assessing the effects of DMTs on retinal layer thickness, and they are limited by small patient numbers, cross-sectional design, and/or short periods of observation. In a retrospective analysis, he and his associates examined the effects of treatments in relapsing-remitting MS patients at his center who underwent OCT (Neurology. 2017;88[6]:525-32). Over a mean 3 years of follow-up, they examined the effects of glatiramer acetate (Copaxone), natalizumab (Tysabri), and interferon beta-1a subcutaneously (Rebif) and intramuscularly (Avonex). They adjusted for gap time, which is the interval between when a patient started a treatment and when they started to undergo retinal observation with OCT. “This is to try to account for some of the biological changes that might have occurred during that period of time,” he explained. The researchers observed that rates of GCIP atrophy as well as other retinal measures were significantly lower in people treated with natalizumab, relative to all other DMTs. “What I found fascinating was the rate of GCIP atrophy of those on natalizumab was basically the same as healthy controls,” Dr. Saidha said. “It didn’t differ.”

Retinal inflammation and treatment’s impact

Significant inflammation in the unmyelinated retina may inform clinicians about other aspects of MS, he continued. For example, retinal periphlebitis occurs in about 20% of MS patients and may be a marker of CNS inflammation. In addition, intermediate uveitis occurs in about 16% of MS patients, and postmortem studies reveal retinal inflammation with microglia. Specifically, macular microcystoid changes occur in the eyes of about 5% of MS patients and may represent a breakdown of the blood-retinal barrier and inflammation. “Since it’s a dynamic process, increased thickness of the INL in the absence of visible microcystoid changes might occur,” Dr. Saidha said. “We found that baseline INL thickness is predictive of clinico-radiologic disease activity.”

In a separate analysis of 108 MS patients and 40 healthy controls, German researchers evaluated the impact of DMTs on INL volume (Brain. 2016;11[1]:2855-63). They found that higher baseline INL volume correlated with new T2 and GAD lesions over 1 year. The reduction in INL volume was significantly associated with reduced activity, and overall, DMTs reduced INL volume over 6 months. Patients who were not treated, or who were treated and did not achieve NEDA-3 (no evidence of disease activity) did not show reductions in INL volume. They concluded that INL volume might be a novel outcome of DMT treatment.

Finding prognostic and diagnostic biomarkers

In an ongoing multisite study, Dr. Saidha and his colleagues are assessing the use of OCT in patients with progressive MS (including 186 patients from Johns Hopkins), and also determining if OCT changes differ over time between relapsing-remitting MS and different subtypes of progressive MS. So far, they have found that progressive MS is associated with accelerated inner and in particular outer layer retinal atrophy. “Although this is a decent-sized cohort, at this stage I’m not sure I would definitively say that these novel retinal biomarkers have utility specific to progressive MS, but I’m very excited about it,” he said. “The goal is to take a much deeper look at this.”

Findings from a large collaborative IMSVISUAL inter-eye asymmetry study showed that peripapillary RNFL and ganglion cell–inner plexiform layer inter-eye differences of 5 microns, respectively, were optimal for identifying patients with prior unilateral optic neuritis in the MS cohort. “In the future, the possibility of using OCT to identify subclinical optic neuropathy so we can define when a lesion is present in the optic nerve has huge diagnostic implications for MS, because the optic nerve is not currently recognized as a lesion site in current MS diagnostic criteria,” Dr. Saidha said.

Dr. Saidha disclosed that he has served on scientific advisory boards for Biogen, Genzyme, Genentech, EMD Serono, and Novartis. He has also received consulting fees from JuneBrain LLC and is the site investigator of a trial sponsored by MedDay Pharmaceuticals.

DALLAS – Optical coherence tomography (OCT) has emerged as a promising biomarker in multiple sclerosis.

Thanks to OCT, clinicians are gaining an improved understanding of how MS affects certain eye structures. An optical analogue of ultrasound B mode imaging, OCT achieves a resolution of about 3-6 microns with commercially available devices. “That allows us to quantify the layers of the retina with quite a degree of accuracy,” Shiv Saidha, MD, said at ACTRIMS Forum 2019, the meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

At postmortem, up to 99% of MS patients have demyelinated plaques in their optic nerves. “This implies that optic neuropathy is an ubiquitous phenomenon as part of the MS disease process,” said Dr. Saidha, a neurologist at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. “The prevailing hypothesis is that there is demyelination or axonal transection related to acute inflammation that occurs within the optic nerve. There’s a retrograde degeneration of its constituent axons, and that results in thinning of the inner retinal nerve fiber layer as well as the neuronal derivative of this layer called the ganglion cell layer. In addition to neurodegenerative mechanisms in the retina, there is also perivascular inflammation, called retinal periphlebitis, which we know occurs in about 20% of MS patients. At postmortem, there are also activate microglia present within the retina of MS patients.”

One of the principal findings of OCT in MS to date is that the retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) and ganglion cell plus inner plexiform layer (GCIP) thinning reflects MS-related optic nerve neurodegeneration. In addition, RNFL and GCIP thinning occur after optic neuritis and also as part of the MS disease course in eyes without a history of optic neuritis. “RNFL and GCIP thinning in MS are clinically relevant and correlate with visual function, global disability, and brain atrophy,” Dr. Saidha said. Researchers have also found that rates of GCIP thinning are accelerated in MS patients exhibiting clinical and/or radiological disease activity and are altered by disease-modifying therapies, and that increased inner nuclear layer (INL) thickness correlates with T2 lesion volume and predicts clinical and radiological disease activity. “In numerous trials of putatively neuroprotective and restorative treatments, we see OCT incorporated more and more, either as a secondary or a primary outcome,” he said.

Predicting disability and brain atrophy

In a study expected to be appear in a forthcoming issue of the Annals of Translational and Clinical Neurology, colleagues of Dr. Saidha found that OCT derived retinal layer measurements and visual function predict disability at 10 years in patients with MS. The researchers used an earlier generation, lower quality OCT device to examine tertiles of total macular volume, “an old, nonspecific composite measure of all of the retinal components,” he explained. “Even with inferior technology, a single measurement at a point in time not only could predict the change in EDSS [Expanded Disability Status Scale] scores from baseline to 10 years, but the accumulation of meaningful disability.”

In an earlier study, Dr. Saidha and his colleagues conducted a 4-year study of OCT and MRI in MS (Ann Neurol 2015; 78[5]:801-13). It consisted of six monthly spectral domain OCT scans (including automated intra-retinal segmentation) and baseline and annual 3 T brain MRI (including substructure volumetrics). Patients with ocular relapses (optic neuritis) during the study were excluded. The researchers correlated individual-specific rates of change in retinal and brain measurements, adjusting for age, sex, disease duration, and optic neuritis history. They found that cerebral volume fraction (analogous to whole brain volume) “had a decent correlation between rates of GCIP atrophy and rates of whole brain volume loss,” he said. “That was predominately driven by cortical gray matter atrophy.”

Measuring effects of disease-modifying therapies

What about the effects of disease-modifying therapies? According to Dr. Saidha, there has been a paucity of studies assessing the effects of DMTs on retinal layer thickness, and they are limited by small patient numbers, cross-sectional design, and/or short periods of observation. In a retrospective analysis, he and his associates examined the effects of treatments in relapsing-remitting MS patients at his center who underwent OCT (Neurology. 2017;88[6]:525-32). Over a mean 3 years of follow-up, they examined the effects of glatiramer acetate (Copaxone), natalizumab (Tysabri), and interferon beta-1a subcutaneously (Rebif) and intramuscularly (Avonex). They adjusted for gap time, which is the interval between when a patient started a treatment and when they started to undergo retinal observation with OCT. “This is to try to account for some of the biological changes that might have occurred during that period of time,” he explained. The researchers observed that rates of GCIP atrophy as well as other retinal measures were significantly lower in people treated with natalizumab, relative to all other DMTs. “What I found fascinating was the rate of GCIP atrophy of those on natalizumab was basically the same as healthy controls,” Dr. Saidha said. “It didn’t differ.”

Retinal inflammation and treatment’s impact

Significant inflammation in the unmyelinated retina may inform clinicians about other aspects of MS, he continued. For example, retinal periphlebitis occurs in about 20% of MS patients and may be a marker of CNS inflammation. In addition, intermediate uveitis occurs in about 16% of MS patients, and postmortem studies reveal retinal inflammation with microglia. Specifically, macular microcystoid changes occur in the eyes of about 5% of MS patients and may represent a breakdown of the blood-retinal barrier and inflammation. “Since it’s a dynamic process, increased thickness of the INL in the absence of visible microcystoid changes might occur,” Dr. Saidha said. “We found that baseline INL thickness is predictive of clinico-radiologic disease activity.”

In a separate analysis of 108 MS patients and 40 healthy controls, German researchers evaluated the impact of DMTs on INL volume (Brain. 2016;11[1]:2855-63). They found that higher baseline INL volume correlated with new T2 and GAD lesions over 1 year. The reduction in INL volume was significantly associated with reduced activity, and overall, DMTs reduced INL volume over 6 months. Patients who were not treated, or who were treated and did not achieve NEDA-3 (no evidence of disease activity) did not show reductions in INL volume. They concluded that INL volume might be a novel outcome of DMT treatment.

Finding prognostic and diagnostic biomarkers

In an ongoing multisite study, Dr. Saidha and his colleagues are assessing the use of OCT in patients with progressive MS (including 186 patients from Johns Hopkins), and also determining if OCT changes differ over time between relapsing-remitting MS and different subtypes of progressive MS. So far, they have found that progressive MS is associated with accelerated inner and in particular outer layer retinal atrophy. “Although this is a decent-sized cohort, at this stage I’m not sure I would definitively say that these novel retinal biomarkers have utility specific to progressive MS, but I’m very excited about it,” he said. “The goal is to take a much deeper look at this.”

Findings from a large collaborative IMSVISUAL inter-eye asymmetry study showed that peripapillary RNFL and ganglion cell–inner plexiform layer inter-eye differences of 5 microns, respectively, were optimal for identifying patients with prior unilateral optic neuritis in the MS cohort. “In the future, the possibility of using OCT to identify subclinical optic neuropathy so we can define when a lesion is present in the optic nerve has huge diagnostic implications for MS, because the optic nerve is not currently recognized as a lesion site in current MS diagnostic criteria,” Dr. Saidha said.

Dr. Saidha disclosed that he has served on scientific advisory boards for Biogen, Genzyme, Genentech, EMD Serono, and Novartis. He has also received consulting fees from JuneBrain LLC and is the site investigator of a trial sponsored by MedDay Pharmaceuticals.

DALLAS – Optical coherence tomography (OCT) has emerged as a promising biomarker in multiple sclerosis.

Thanks to OCT, clinicians are gaining an improved understanding of how MS affects certain eye structures. An optical analogue of ultrasound B mode imaging, OCT achieves a resolution of about 3-6 microns with commercially available devices. “That allows us to quantify the layers of the retina with quite a degree of accuracy,” Shiv Saidha, MD, said at ACTRIMS Forum 2019, the meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

At postmortem, up to 99% of MS patients have demyelinated plaques in their optic nerves. “This implies that optic neuropathy is an ubiquitous phenomenon as part of the MS disease process,” said Dr. Saidha, a neurologist at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. “The prevailing hypothesis is that there is demyelination or axonal transection related to acute inflammation that occurs within the optic nerve. There’s a retrograde degeneration of its constituent axons, and that results in thinning of the inner retinal nerve fiber layer as well as the neuronal derivative of this layer called the ganglion cell layer. In addition to neurodegenerative mechanisms in the retina, there is also perivascular inflammation, called retinal periphlebitis, which we know occurs in about 20% of MS patients. At postmortem, there are also activate microglia present within the retina of MS patients.”

One of the principal findings of OCT in MS to date is that the retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) and ganglion cell plus inner plexiform layer (GCIP) thinning reflects MS-related optic nerve neurodegeneration. In addition, RNFL and GCIP thinning occur after optic neuritis and also as part of the MS disease course in eyes without a history of optic neuritis. “RNFL and GCIP thinning in MS are clinically relevant and correlate with visual function, global disability, and brain atrophy,” Dr. Saidha said. Researchers have also found that rates of GCIP thinning are accelerated in MS patients exhibiting clinical and/or radiological disease activity and are altered by disease-modifying therapies, and that increased inner nuclear layer (INL) thickness correlates with T2 lesion volume and predicts clinical and radiological disease activity. “In numerous trials of putatively neuroprotective and restorative treatments, we see OCT incorporated more and more, either as a secondary or a primary outcome,” he said.

Predicting disability and brain atrophy

In a study expected to be appear in a forthcoming issue of the Annals of Translational and Clinical Neurology, colleagues of Dr. Saidha found that OCT derived retinal layer measurements and visual function predict disability at 10 years in patients with MS. The researchers used an earlier generation, lower quality OCT device to examine tertiles of total macular volume, “an old, nonspecific composite measure of all of the retinal components,” he explained. “Even with inferior technology, a single measurement at a point in time not only could predict the change in EDSS [Expanded Disability Status Scale] scores from baseline to 10 years, but the accumulation of meaningful disability.”

In an earlier study, Dr. Saidha and his colleagues conducted a 4-year study of OCT and MRI in MS (Ann Neurol 2015; 78[5]:801-13). It consisted of six monthly spectral domain OCT scans (including automated intra-retinal segmentation) and baseline and annual 3 T brain MRI (including substructure volumetrics). Patients with ocular relapses (optic neuritis) during the study were excluded. The researchers correlated individual-specific rates of change in retinal and brain measurements, adjusting for age, sex, disease duration, and optic neuritis history. They found that cerebral volume fraction (analogous to whole brain volume) “had a decent correlation between rates of GCIP atrophy and rates of whole brain volume loss,” he said. “That was predominately driven by cortical gray matter atrophy.”

Measuring effects of disease-modifying therapies

What about the effects of disease-modifying therapies? According to Dr. Saidha, there has been a paucity of studies assessing the effects of DMTs on retinal layer thickness, and they are limited by small patient numbers, cross-sectional design, and/or short periods of observation. In a retrospective analysis, he and his associates examined the effects of treatments in relapsing-remitting MS patients at his center who underwent OCT (Neurology. 2017;88[6]:525-32). Over a mean 3 years of follow-up, they examined the effects of glatiramer acetate (Copaxone), natalizumab (Tysabri), and interferon beta-1a subcutaneously (Rebif) and intramuscularly (Avonex). They adjusted for gap time, which is the interval between when a patient started a treatment and when they started to undergo retinal observation with OCT. “This is to try to account for some of the biological changes that might have occurred during that period of time,” he explained. The researchers observed that rates of GCIP atrophy as well as other retinal measures were significantly lower in people treated with natalizumab, relative to all other DMTs. “What I found fascinating was the rate of GCIP atrophy of those on natalizumab was basically the same as healthy controls,” Dr. Saidha said. “It didn’t differ.”

Retinal inflammation and treatment’s impact

Significant inflammation in the unmyelinated retina may inform clinicians about other aspects of MS, he continued. For example, retinal periphlebitis occurs in about 20% of MS patients and may be a marker of CNS inflammation. In addition, intermediate uveitis occurs in about 16% of MS patients, and postmortem studies reveal retinal inflammation with microglia. Specifically, macular microcystoid changes occur in the eyes of about 5% of MS patients and may represent a breakdown of the blood-retinal barrier and inflammation. “Since it’s a dynamic process, increased thickness of the INL in the absence of visible microcystoid changes might occur,” Dr. Saidha said. “We found that baseline INL thickness is predictive of clinico-radiologic disease activity.”

In a separate analysis of 108 MS patients and 40 healthy controls, German researchers evaluated the impact of DMTs on INL volume (Brain. 2016;11[1]:2855-63). They found that higher baseline INL volume correlated with new T2 and GAD lesions over 1 year. The reduction in INL volume was significantly associated with reduced activity, and overall, DMTs reduced INL volume over 6 months. Patients who were not treated, or who were treated and did not achieve NEDA-3 (no evidence of disease activity) did not show reductions in INL volume. They concluded that INL volume might be a novel outcome of DMT treatment.

Finding prognostic and diagnostic biomarkers

In an ongoing multisite study, Dr. Saidha and his colleagues are assessing the use of OCT in patients with progressive MS (including 186 patients from Johns Hopkins), and also determining if OCT changes differ over time between relapsing-remitting MS and different subtypes of progressive MS. So far, they have found that progressive MS is associated with accelerated inner and in particular outer layer retinal atrophy. “Although this is a decent-sized cohort, at this stage I’m not sure I would definitively say that these novel retinal biomarkers have utility specific to progressive MS, but I’m very excited about it,” he said. “The goal is to take a much deeper look at this.”

Findings from a large collaborative IMSVISUAL inter-eye asymmetry study showed that peripapillary RNFL and ganglion cell–inner plexiform layer inter-eye differences of 5 microns, respectively, were optimal for identifying patients with prior unilateral optic neuritis in the MS cohort. “In the future, the possibility of using OCT to identify subclinical optic neuropathy so we can define when a lesion is present in the optic nerve has huge diagnostic implications for MS, because the optic nerve is not currently recognized as a lesion site in current MS diagnostic criteria,” Dr. Saidha said.

Dr. Saidha disclosed that he has served on scientific advisory boards for Biogen, Genzyme, Genentech, EMD Serono, and Novartis. He has also received consulting fees from JuneBrain LLC and is the site investigator of a trial sponsored by MedDay Pharmaceuticals.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ACTRIMS FORUM 2019

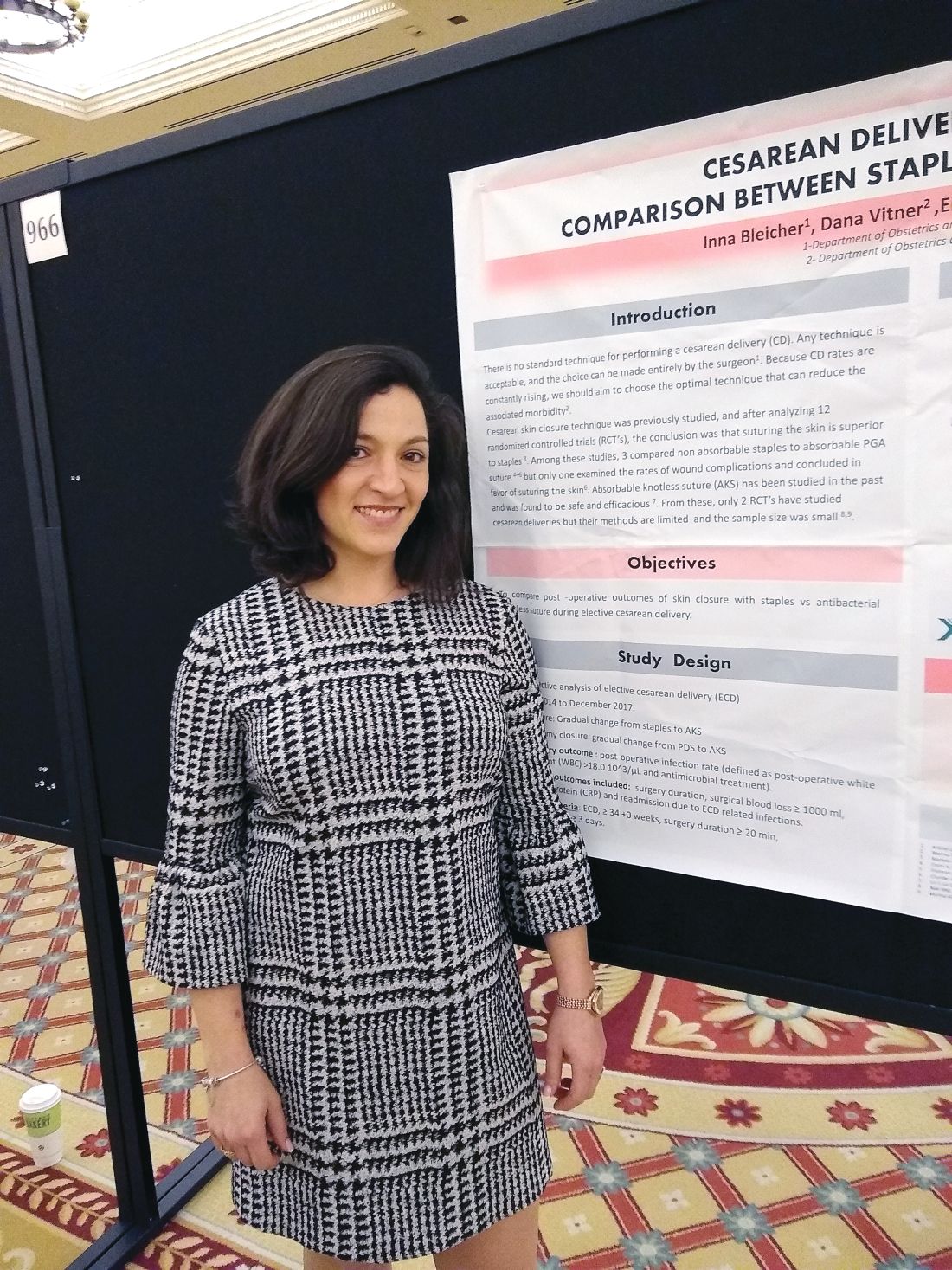

Knotless, absorbable sutures best staples for postcesarean skin closure

LAS VEGAS – compared with staples, in a single-site, retrospective study.

For women whose skin incisions were closed with knotless sutures, mean surgical time was 38 minutes; for women who received a staple closure, mean surgical time was 44 minutes (P less than .001). Also, fewer women whose incisions were closed with knotless sutures experienced surgical bleeding greater than 1,000 mL, compared with those who received staples (0.3% vs. 3.0%; P less than .001).

Two previous randomized, controlled trials comparing knotless sutures with staples for skin closure after cesarean delivery were small and had methodological limitations, Inna Bleicher, MD, said in an interview during a poster session at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Dr. Bleicher and her colleagues reviewed records from 2,173 elective cesarean deliveries over a period of 4 years. Absorbable, antibacterial, knotless sutures were used for closure for 1,172 women, while staples were used for the remaining 1,001 women.

Over the study period, Dr. Bleicher noted that there was a gradual transition from the use of staples to absorbable, knotless sutures, which also were increasingly used for the hysterotomy closure. She added that, in conversation with peers at Bnai-Zion Medical Center, Haifa, Israel, where she practices as an ob.gyn, she’s found that physicians find the sutures easy and quick to use, because the sutures are double ended, allowing the possibility for two operators to work together in wound closure.

The study’s primary outcome measure was the rate of postoperative infection, defined as postoperative white blood count greater than 18,000 per microliter and antimicrobial treatment. Secondary outcome measures included C-reactive protein levels, hospital readmission for infection related to the delivery, duration of surgery, and surgical blood loss estimated at 1,000 mL or more.

A higher proportion of women in the staple closure group than the knotless suture group required postsurgical antibiotic treatment (11% vs. 10%), but this difference didn’t reach statistical significance (P = .243).

There were no significant differences in the groups in terms of maternal age (about 32 years), or gestational age at delivery (about 39 weeks).

“Our results suggest that cesarean scar skin closure with antibacterial knotless sutures did not increase, and may even reduce, the rates of postoperative infection, morbidity, surgical blood loss, and may shorten operation time,” wrote Dr. Bleicher and her colleagues.

Dr. Bleicher reported no outside sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bleicher I et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Jan. 220;1:S622, Abstract 966.

LAS VEGAS – compared with staples, in a single-site, retrospective study.

For women whose skin incisions were closed with knotless sutures, mean surgical time was 38 minutes; for women who received a staple closure, mean surgical time was 44 minutes (P less than .001). Also, fewer women whose incisions were closed with knotless sutures experienced surgical bleeding greater than 1,000 mL, compared with those who received staples (0.3% vs. 3.0%; P less than .001).

Two previous randomized, controlled trials comparing knotless sutures with staples for skin closure after cesarean delivery were small and had methodological limitations, Inna Bleicher, MD, said in an interview during a poster session at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Dr. Bleicher and her colleagues reviewed records from 2,173 elective cesarean deliveries over a period of 4 years. Absorbable, antibacterial, knotless sutures were used for closure for 1,172 women, while staples were used for the remaining 1,001 women.

Over the study period, Dr. Bleicher noted that there was a gradual transition from the use of staples to absorbable, knotless sutures, which also were increasingly used for the hysterotomy closure. She added that, in conversation with peers at Bnai-Zion Medical Center, Haifa, Israel, where she practices as an ob.gyn, she’s found that physicians find the sutures easy and quick to use, because the sutures are double ended, allowing the possibility for two operators to work together in wound closure.

The study’s primary outcome measure was the rate of postoperative infection, defined as postoperative white blood count greater than 18,000 per microliter and antimicrobial treatment. Secondary outcome measures included C-reactive protein levels, hospital readmission for infection related to the delivery, duration of surgery, and surgical blood loss estimated at 1,000 mL or more.

A higher proportion of women in the staple closure group than the knotless suture group required postsurgical antibiotic treatment (11% vs. 10%), but this difference didn’t reach statistical significance (P = .243).

There were no significant differences in the groups in terms of maternal age (about 32 years), or gestational age at delivery (about 39 weeks).

“Our results suggest that cesarean scar skin closure with antibacterial knotless sutures did not increase, and may even reduce, the rates of postoperative infection, morbidity, surgical blood loss, and may shorten operation time,” wrote Dr. Bleicher and her colleagues.

Dr. Bleicher reported no outside sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bleicher I et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Jan. 220;1:S622, Abstract 966.

LAS VEGAS – compared with staples, in a single-site, retrospective study.

For women whose skin incisions were closed with knotless sutures, mean surgical time was 38 minutes; for women who received a staple closure, mean surgical time was 44 minutes (P less than .001). Also, fewer women whose incisions were closed with knotless sutures experienced surgical bleeding greater than 1,000 mL, compared with those who received staples (0.3% vs. 3.0%; P less than .001).

Two previous randomized, controlled trials comparing knotless sutures with staples for skin closure after cesarean delivery were small and had methodological limitations, Inna Bleicher, MD, said in an interview during a poster session at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Dr. Bleicher and her colleagues reviewed records from 2,173 elective cesarean deliveries over a period of 4 years. Absorbable, antibacterial, knotless sutures were used for closure for 1,172 women, while staples were used for the remaining 1,001 women.

Over the study period, Dr. Bleicher noted that there was a gradual transition from the use of staples to absorbable, knotless sutures, which also were increasingly used for the hysterotomy closure. She added that, in conversation with peers at Bnai-Zion Medical Center, Haifa, Israel, where she practices as an ob.gyn, she’s found that physicians find the sutures easy and quick to use, because the sutures are double ended, allowing the possibility for two operators to work together in wound closure.

The study’s primary outcome measure was the rate of postoperative infection, defined as postoperative white blood count greater than 18,000 per microliter and antimicrobial treatment. Secondary outcome measures included C-reactive protein levels, hospital readmission for infection related to the delivery, duration of surgery, and surgical blood loss estimated at 1,000 mL or more.

A higher proportion of women in the staple closure group than the knotless suture group required postsurgical antibiotic treatment (11% vs. 10%), but this difference didn’t reach statistical significance (P = .243).

There were no significant differences in the groups in terms of maternal age (about 32 years), or gestational age at delivery (about 39 weeks).

“Our results suggest that cesarean scar skin closure with antibacterial knotless sutures did not increase, and may even reduce, the rates of postoperative infection, morbidity, surgical blood loss, and may shorten operation time,” wrote Dr. Bleicher and her colleagues.

Dr. Bleicher reported no outside sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bleicher I et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Jan. 220;1:S622, Abstract 966.

REPORTING FROM THE PREGNANCY MEETING

Sexuality throughout life: Stephen Levine

Dr. Levine, professor of psychiatry at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, checked in from the 2018 AACP Encore meeting in Las Vegas. And later, Dr. RK discusses bipolar disorder in part I of her new series.

Dr. Levine, professor of psychiatry at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, checked in from the 2018 AACP Encore meeting in Las Vegas. And later, Dr. RK discusses bipolar disorder in part I of her new series.

Dr. Levine, professor of psychiatry at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, checked in from the 2018 AACP Encore meeting in Las Vegas. And later, Dr. RK discusses bipolar disorder in part I of her new series.

Prurigo Pigmentosa Induced by Ketosis: Resolution Through Dietary Modification

To the Editor:

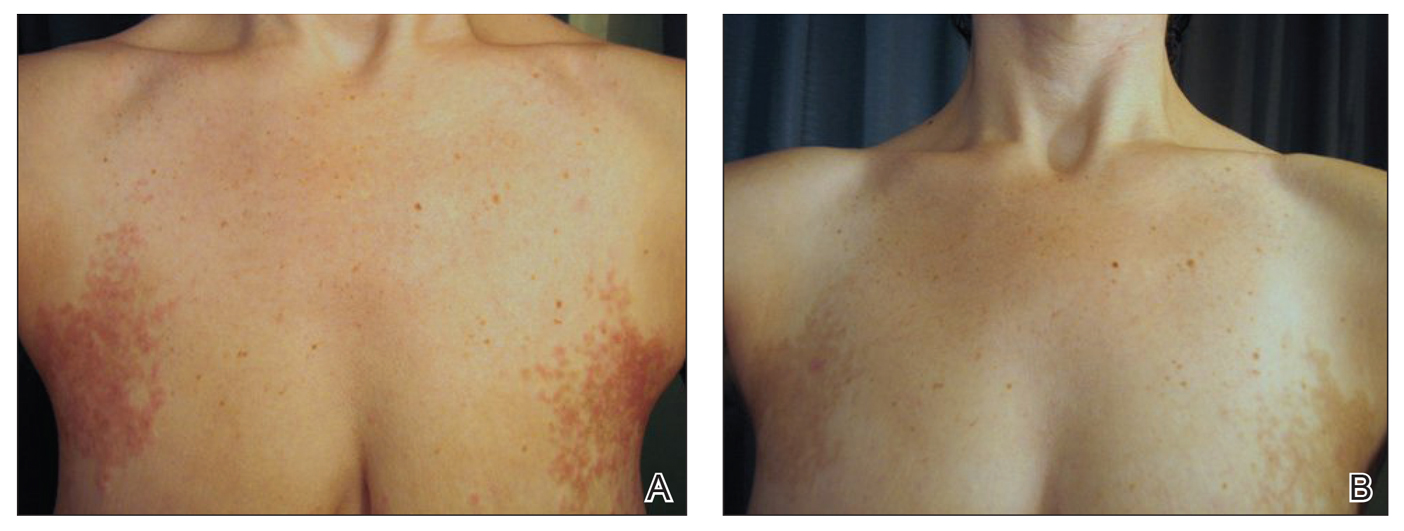

A 40-year-old white woman presented with a waxing and waning erythematous pruritic rash on the chest, back, and axillae of 3 years’ duration. The appearance of the rash coincided with an intentional weight loss of more than 100 lb, achieved through various diets, most recently a Paleolithic (paleo) diet that was high in protein; low in carbohydrates; and specifically restricted dairy, cereal grains, refined sugars, processed foods, white potatoes, salt, refined oils, and legumes.1 The patient had been monitoring blood glucose and ketone levels. Prior to presentation, she received various treatments including clotrimazole cream and topical steroids with no improvement.

On physical examination, there were scaly, pink-red, reticulated papules and plaques coexisting with tan reticulated patches that were symmetrically distributed on the central back, lateral and central chest (Figure 1A), breasts, and inframammary areas. During the most severe flare-up, the blood ketones measured 1 mmol/L. There was no relevant medical history. She was of Spanish and Italian descent.

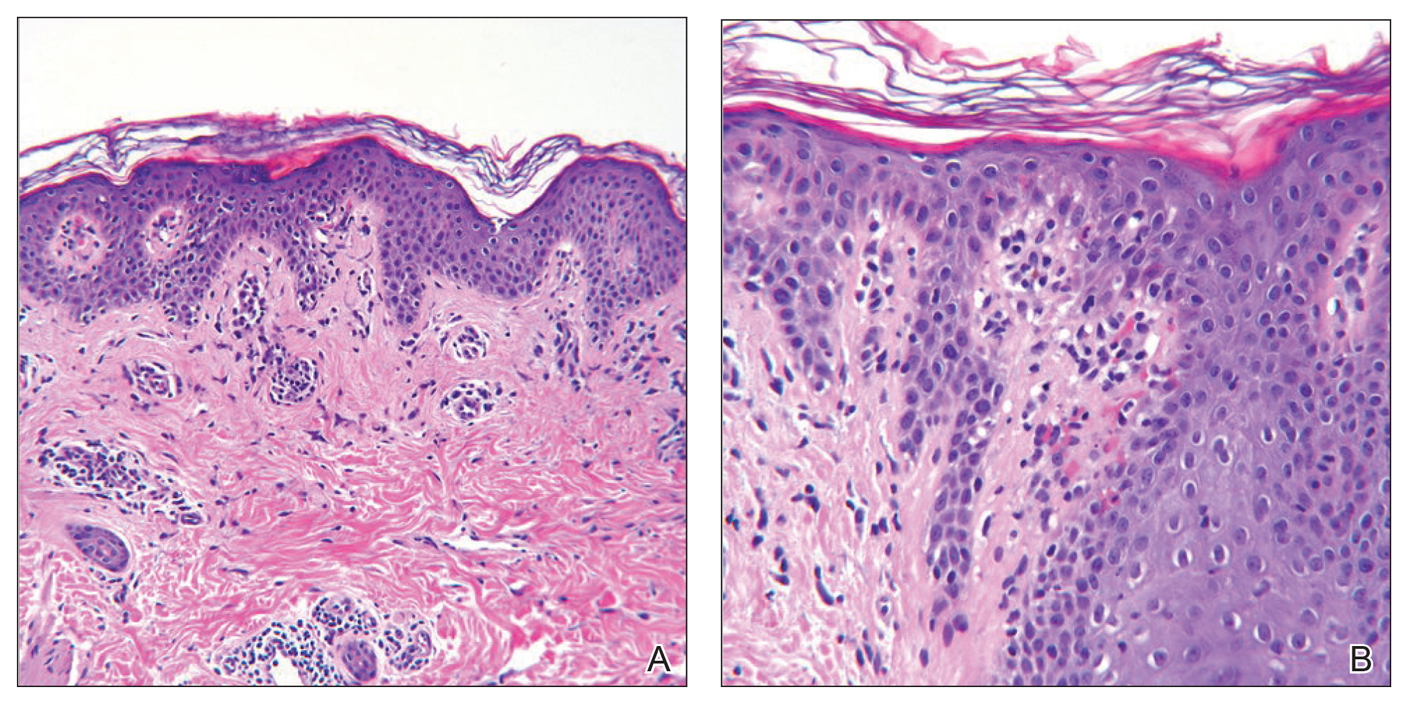

Histologic sections showed a sparse infiltrate of lymphocytes surrounding superficial dermal vessels and a mildly acanthotic epidermis with a focally parakeratotic stratum corneum (Figure 2A). Pigmentary incontinence and subtle interface changes were apparent, including rare necrotic keratinocytes (Figure 2B). No eosinophils or neutrophils were present.

After the initial presentation, carbohydrates were added back into her diet and both the ketosis and eruption remarkably resolved. When carbohydrate restriction was rechallenged, she again entered ketosis (0.5 mmol/L), followed by subsequent recurrence of the pruritic lesions. With re-introduction of carbohydrates, the eruption and ketosis once more resolved, leaving only postinflammatory reticulated hyperpigmentation (Figure 1B). Based on the clinical presentation, supportive histopathologic findings, and interesting response to ketones and diet modification, the patient was diagnosed with prurigo pigmentosa (PP).

Prurigo pigmentosa is a rare inflammatory dermatosis that was initially described in 1971 as “a peculiar pruriginous dermatosis with gross reticular pigmentation” by Nagashima et al.2 Prurigo pigmentosa is most frequently diagnosed in Japan, and since its discovery, it has been reported in more than 300 cases worldwide.2-4

Fewer than 50 non-Japanese cases have been reported, with the possibility of an additional ethnic predisposition among the Turkish and Sicilian populations, though only 6 cases have been reported in the United States.3-6 Prurigo pigmentosa tends to occur in the spring and summer months and is most common among young females, with a mean age of 24 years. The typical lesions of PP are symmetrically distributed on the trunk with a tendency to localize on the upper back, nape of the neck, and intermammary and inframammary regions. Eruptions have been reported to occur on additional areas; however, mucus membranes are always spared.6

Individual lesions differ in appearance depending on the stage of presentation and are categorized as early, fully developed, resolving, and late lesions.6 Pruritic macules and papules are present early in the disease state and resolve into crusted and/or scaly papules followed by pigmented macules. Early lesions tend to be intensely pruritic with signs of excoriation, while resolving lesions lack symptoms. Lesions last approximately 1 week but tend to reappear at the site where they were previously present, which allows for lesions of different ages to coexist, appearing in a reticular arrangement with hyperpigmented mottling lasting from a few weeks to months.6

Just as the clinical picture transpires rapidly within 1 week, so do the histopathologic findings.6 Early lesions are categorized by a superficial perivascular and interstitial infiltrate of neutrophils, spongiosis, ballooning, and necrotic keratinocytes. These early lesions are present for less than 48 hours, and these histopathologic findings are diagnostic of PP. Within 2 days, lymphocytes predominate in the dermal infiltrate, and a patchy lichenoid aspect is established in the fully developed lesion along with reticular and vacuolar alterations. Late lesions show a parakeratotic and hyperpigmented epidermis with melanophages present in the papillary and reticular dermis. At this last stage, the histopathologic features of PP are indistinguishable from any other disease that results in postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, making diagnosis difficult.6

A variety of therapeutic options are used in the treatment of PP, with the most effective agents being oral antibiotics including dapsone, minocycline, and doxycycline, all of which limit the local tissue inflammatory response and cytotoxic effects. Topical and systemic antihistamines as well as corticosteroids are ineffective and have not been shown to prevent the postinflammatory reticular pigmentation.6-10

Various underlying factors have been associated with PP, including friction, heat, sunlight, sweating, allergic contact sensitization, and ketosis due to nutritional deficiency or diabetes mellitus; however; the exact etiology remains ambiguous.2-7 The association with ketosis and nutrition is of particular interest in this case. Onset of PP has been reported to coincide with dieting, fasting, weight loss, anorexia nervosa, and diabetes mellitus.3,6-9 Roughly 50 patients with PP had ketosis subsequent to these metabolic disturbances.3,6-10 As of now, the only reported correlation between ketosis and PP is that upon diet modification, lesions resolved following ketone normalization, as was observed in our patient.3,6-8 Reports of PP in diabetic patients while in ketoacidosis describe resolution of lesions with insulin administration.6-9 The pathophysiology of ketosis and its association with PP is unclear; however, the similarities seen in the immune response of PP and that stimulated by ketosis may expose an associated mechanism.

Ketosis is a temporary condition characterized by elevated serum ketones that are used as an alternative energy source when blood glucose is low or insulin is deficient.11 The most common causes of ketosis are the physiologic responses to fasting, prolonged exercise, or a high-protein/low-carbohydrate diet, though pathologic causes include insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, alcoholism, and salicylate overdose.11 In healthy individuals, blood ketone levels rarely approach 0.5 mmol/L. Prolonged fasting or restricting intake of carbohydrates to less than 40 g daily can induce mild ketosis that resolves with re-introduction of carbohydrates.11

Ketone bodies pass from the circulating blood into tissues or remain near the blood vessels, inducing cytotoxic effects and perivascular inflammation.10,11 Increased ketone bodies have been shown to upregulate intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) and leukocyte function-associated antigen 1 (LFA-1), a phenomenon also seen in lesional keratinocytes of PP.12,13 Teraki et al13 observed that epidermal keratinocytes exhibited increased expression of ICAM-1 as well as intense expression of LFA-1 on dermal and epidermotropic leukocytes, which was thought to be due to cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Not only do increased ketone bodies upregulate ICAM-1 and LFA-1, but they also are involved in increasing many proinflammatory mediators that may be capable of inducing the response seen in PP keratinocytes.12,13

Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 is important in initiating cellular interactions in the immune response and is the ligand for LFA-1 found on most leukocytes.14 Increased ICAM-1/LFA-1 interaction is thought to be the major pathway by which leukocytes are able to attach to keratinocytes and endothelial cells, allowing for leukocyte tissue migration and specific immunologic reactions, including leukocyte-mediated cytotoxicity. Interestingly, glucocorticoids are ineffective in reducing the expression of ICAM-1 in cultured keratinocytes.14 This connection between ketosis and inflammation that results in leukocyte migration and ultimately keratinocyte cytotoxicity may well be fundamental to the pathophysiology of PP and may provide a possible explanation for the ineffectiveness of corticosteroid treatment.

Middleton and Norris15 observed that individual keratinocyte strains show considerable variability in ICAM-1 expression that was found to be attributable to genetic polymorphisms. The presence of a particular polymorphism affecting ICAM-1 expression on human keratinocytes may explain the apparent ethnogeographic predisposition of PP as well as the ease at which ICAM-1 is expressed in the presence of ketones.

We describe a case of a 40-year-old white woman who was diagnosed with PP that was prompted by a 100-lb weight loss and self-induced ketosis while following a paleo diet with carbohydrate restriction. Successful treatment was attained through diet modification alone. This interesting case was another instance in which the pathophysiology of PP was attributed to ketosis. Because not all patients that are in ketosis have PP, larger prospective cohort studies are needed to further elucidate the association of PP and ketosis.

- What is the paleo diet? The Paleo Diet website. http://thepaleodiet.com/the-paleo-diet-premise. Accessed March 9, 2019.

- Nagashima M, Ohshiro A, Shimizu N. A peculiar pruriginous dermatosis with gross reticular pigmentation [in Japanese]. Japanese J Dermatol. 1971;81:38-39.

- Michaels JD, Hoss E, DiCaudo DJ, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa after a strict ketogenic diet [published online December 30, 2013]. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:248-251.

- Baykal C, Buyukbabani N, Akinturk S, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: not an uncommon disease in the Turkish population. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1164-1168.

- Whang T, Kirkorian Y, Krishtul A, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: report of two cases in the United States and review of the literature. Dermatology Online J. 2011;17:2.

- Böer A, Ackerman AB. Prurigo Pigmentosa (Nagashima Disease): Textbook and Atlas of a Distinctive Inflammatory Disease of the Skin. New York, NY: Ardor Scribendi Ltd; 2004.

- Teraki Y, Teraki E, Kawashima M, at al. Ketosis is involved in the origin of prurigo pigmentosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:509-511.

- Oh YJ, Lee MH. Prurigo pigmentosa: a clinicopathologic study of 16 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;26:1149-1153.

- Yokozeki M, Watanabe J, Hotsubo T, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa disappeared following improvement of diabetic ketosis by insulin. J Dermatol. 2003;30:257-258.

- Kim JK, Chung WK, Chang SE, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: clinicopathological study and analysis of 50 cases in Korea. J Dermatol. 2012;39:891-897.

- VanItallie TB, Nufert TH. Ketones: metabolism’s ugly duckling. Annu Rev Nutr. 2003;61:327-341.

- Rains JL, Jain SK. Hyperketonemia increases monocyte adhesion to endothelial cells and is mediated by LFA-1 expression in monocytes and ICAM-1 expression in endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;301:e298-e306.

- Teraki Y, Shiohara T, Nagashima M, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: role of ICAM-1 in the localization of the eruption. Br J Dermatol. 1991;125:360-363.

- Kashihara-Sawami M, Norris DA. The state of differentiation of cultured human keratinocytes determines the level of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) expression induced by gamma interferon. J Invest Dermatol. 1992;98:741-747.

- Middleton MH, Norris DA. Cytokine-induced ICAM-1 expression in human keratinocytes is highly variable in keratinocyte strains from different donors. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;104:489-496.

To the Editor:

A 40-year-old white woman presented with a waxing and waning erythematous pruritic rash on the chest, back, and axillae of 3 years’ duration. The appearance of the rash coincided with an intentional weight loss of more than 100 lb, achieved through various diets, most recently a Paleolithic (paleo) diet that was high in protein; low in carbohydrates; and specifically restricted dairy, cereal grains, refined sugars, processed foods, white potatoes, salt, refined oils, and legumes.1 The patient had been monitoring blood glucose and ketone levels. Prior to presentation, she received various treatments including clotrimazole cream and topical steroids with no improvement.

On physical examination, there were scaly, pink-red, reticulated papules and plaques coexisting with tan reticulated patches that were symmetrically distributed on the central back, lateral and central chest (Figure 1A), breasts, and inframammary areas. During the most severe flare-up, the blood ketones measured 1 mmol/L. There was no relevant medical history. She was of Spanish and Italian descent.

Histologic sections showed a sparse infiltrate of lymphocytes surrounding superficial dermal vessels and a mildly acanthotic epidermis with a focally parakeratotic stratum corneum (Figure 2A). Pigmentary incontinence and subtle interface changes were apparent, including rare necrotic keratinocytes (Figure 2B). No eosinophils or neutrophils were present.

After the initial presentation, carbohydrates were added back into her diet and both the ketosis and eruption remarkably resolved. When carbohydrate restriction was rechallenged, she again entered ketosis (0.5 mmol/L), followed by subsequent recurrence of the pruritic lesions. With re-introduction of carbohydrates, the eruption and ketosis once more resolved, leaving only postinflammatory reticulated hyperpigmentation (Figure 1B). Based on the clinical presentation, supportive histopathologic findings, and interesting response to ketones and diet modification, the patient was diagnosed with prurigo pigmentosa (PP).

Prurigo pigmentosa is a rare inflammatory dermatosis that was initially described in 1971 as “a peculiar pruriginous dermatosis with gross reticular pigmentation” by Nagashima et al.2 Prurigo pigmentosa is most frequently diagnosed in Japan, and since its discovery, it has been reported in more than 300 cases worldwide.2-4

Fewer than 50 non-Japanese cases have been reported, with the possibility of an additional ethnic predisposition among the Turkish and Sicilian populations, though only 6 cases have been reported in the United States.3-6 Prurigo pigmentosa tends to occur in the spring and summer months and is most common among young females, with a mean age of 24 years. The typical lesions of PP are symmetrically distributed on the trunk with a tendency to localize on the upper back, nape of the neck, and intermammary and inframammary regions. Eruptions have been reported to occur on additional areas; however, mucus membranes are always spared.6

Individual lesions differ in appearance depending on the stage of presentation and are categorized as early, fully developed, resolving, and late lesions.6 Pruritic macules and papules are present early in the disease state and resolve into crusted and/or scaly papules followed by pigmented macules. Early lesions tend to be intensely pruritic with signs of excoriation, while resolving lesions lack symptoms. Lesions last approximately 1 week but tend to reappear at the site where they were previously present, which allows for lesions of different ages to coexist, appearing in a reticular arrangement with hyperpigmented mottling lasting from a few weeks to months.6

Just as the clinical picture transpires rapidly within 1 week, so do the histopathologic findings.6 Early lesions are categorized by a superficial perivascular and interstitial infiltrate of neutrophils, spongiosis, ballooning, and necrotic keratinocytes. These early lesions are present for less than 48 hours, and these histopathologic findings are diagnostic of PP. Within 2 days, lymphocytes predominate in the dermal infiltrate, and a patchy lichenoid aspect is established in the fully developed lesion along with reticular and vacuolar alterations. Late lesions show a parakeratotic and hyperpigmented epidermis with melanophages present in the papillary and reticular dermis. At this last stage, the histopathologic features of PP are indistinguishable from any other disease that results in postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, making diagnosis difficult.6

A variety of therapeutic options are used in the treatment of PP, with the most effective agents being oral antibiotics including dapsone, minocycline, and doxycycline, all of which limit the local tissue inflammatory response and cytotoxic effects. Topical and systemic antihistamines as well as corticosteroids are ineffective and have not been shown to prevent the postinflammatory reticular pigmentation.6-10

Various underlying factors have been associated with PP, including friction, heat, sunlight, sweating, allergic contact sensitization, and ketosis due to nutritional deficiency or diabetes mellitus; however; the exact etiology remains ambiguous.2-7 The association with ketosis and nutrition is of particular interest in this case. Onset of PP has been reported to coincide with dieting, fasting, weight loss, anorexia nervosa, and diabetes mellitus.3,6-9 Roughly 50 patients with PP had ketosis subsequent to these metabolic disturbances.3,6-10 As of now, the only reported correlation between ketosis and PP is that upon diet modification, lesions resolved following ketone normalization, as was observed in our patient.3,6-8 Reports of PP in diabetic patients while in ketoacidosis describe resolution of lesions with insulin administration.6-9 The pathophysiology of ketosis and its association with PP is unclear; however, the similarities seen in the immune response of PP and that stimulated by ketosis may expose an associated mechanism.

Ketosis is a temporary condition characterized by elevated serum ketones that are used as an alternative energy source when blood glucose is low or insulin is deficient.11 The most common causes of ketosis are the physiologic responses to fasting, prolonged exercise, or a high-protein/low-carbohydrate diet, though pathologic causes include insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, alcoholism, and salicylate overdose.11 In healthy individuals, blood ketone levels rarely approach 0.5 mmol/L. Prolonged fasting or restricting intake of carbohydrates to less than 40 g daily can induce mild ketosis that resolves with re-introduction of carbohydrates.11

Ketone bodies pass from the circulating blood into tissues or remain near the blood vessels, inducing cytotoxic effects and perivascular inflammation.10,11 Increased ketone bodies have been shown to upregulate intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) and leukocyte function-associated antigen 1 (LFA-1), a phenomenon also seen in lesional keratinocytes of PP.12,13 Teraki et al13 observed that epidermal keratinocytes exhibited increased expression of ICAM-1 as well as intense expression of LFA-1 on dermal and epidermotropic leukocytes, which was thought to be due to cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Not only do increased ketone bodies upregulate ICAM-1 and LFA-1, but they also are involved in increasing many proinflammatory mediators that may be capable of inducing the response seen in PP keratinocytes.12,13

Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 is important in initiating cellular interactions in the immune response and is the ligand for LFA-1 found on most leukocytes.14 Increased ICAM-1/LFA-1 interaction is thought to be the major pathway by which leukocytes are able to attach to keratinocytes and endothelial cells, allowing for leukocyte tissue migration and specific immunologic reactions, including leukocyte-mediated cytotoxicity. Interestingly, glucocorticoids are ineffective in reducing the expression of ICAM-1 in cultured keratinocytes.14 This connection between ketosis and inflammation that results in leukocyte migration and ultimately keratinocyte cytotoxicity may well be fundamental to the pathophysiology of PP and may provide a possible explanation for the ineffectiveness of corticosteroid treatment.

Middleton and Norris15 observed that individual keratinocyte strains show considerable variability in ICAM-1 expression that was found to be attributable to genetic polymorphisms. The presence of a particular polymorphism affecting ICAM-1 expression on human keratinocytes may explain the apparent ethnogeographic predisposition of PP as well as the ease at which ICAM-1 is expressed in the presence of ketones.

We describe a case of a 40-year-old white woman who was diagnosed with PP that was prompted by a 100-lb weight loss and self-induced ketosis while following a paleo diet with carbohydrate restriction. Successful treatment was attained through diet modification alone. This interesting case was another instance in which the pathophysiology of PP was attributed to ketosis. Because not all patients that are in ketosis have PP, larger prospective cohort studies are needed to further elucidate the association of PP and ketosis.

To the Editor:

A 40-year-old white woman presented with a waxing and waning erythematous pruritic rash on the chest, back, and axillae of 3 years’ duration. The appearance of the rash coincided with an intentional weight loss of more than 100 lb, achieved through various diets, most recently a Paleolithic (paleo) diet that was high in protein; low in carbohydrates; and specifically restricted dairy, cereal grains, refined sugars, processed foods, white potatoes, salt, refined oils, and legumes.1 The patient had been monitoring blood glucose and ketone levels. Prior to presentation, she received various treatments including clotrimazole cream and topical steroids with no improvement.

On physical examination, there were scaly, pink-red, reticulated papules and plaques coexisting with tan reticulated patches that were symmetrically distributed on the central back, lateral and central chest (Figure 1A), breasts, and inframammary areas. During the most severe flare-up, the blood ketones measured 1 mmol/L. There was no relevant medical history. She was of Spanish and Italian descent.

Histologic sections showed a sparse infiltrate of lymphocytes surrounding superficial dermal vessels and a mildly acanthotic epidermis with a focally parakeratotic stratum corneum (Figure 2A). Pigmentary incontinence and subtle interface changes were apparent, including rare necrotic keratinocytes (Figure 2B). No eosinophils or neutrophils were present.

After the initial presentation, carbohydrates were added back into her diet and both the ketosis and eruption remarkably resolved. When carbohydrate restriction was rechallenged, she again entered ketosis (0.5 mmol/L), followed by subsequent recurrence of the pruritic lesions. With re-introduction of carbohydrates, the eruption and ketosis once more resolved, leaving only postinflammatory reticulated hyperpigmentation (Figure 1B). Based on the clinical presentation, supportive histopathologic findings, and interesting response to ketones and diet modification, the patient was diagnosed with prurigo pigmentosa (PP).

Prurigo pigmentosa is a rare inflammatory dermatosis that was initially described in 1971 as “a peculiar pruriginous dermatosis with gross reticular pigmentation” by Nagashima et al.2 Prurigo pigmentosa is most frequently diagnosed in Japan, and since its discovery, it has been reported in more than 300 cases worldwide.2-4

Fewer than 50 non-Japanese cases have been reported, with the possibility of an additional ethnic predisposition among the Turkish and Sicilian populations, though only 6 cases have been reported in the United States.3-6 Prurigo pigmentosa tends to occur in the spring and summer months and is most common among young females, with a mean age of 24 years. The typical lesions of PP are symmetrically distributed on the trunk with a tendency to localize on the upper back, nape of the neck, and intermammary and inframammary regions. Eruptions have been reported to occur on additional areas; however, mucus membranes are always spared.6

Individual lesions differ in appearance depending on the stage of presentation and are categorized as early, fully developed, resolving, and late lesions.6 Pruritic macules and papules are present early in the disease state and resolve into crusted and/or scaly papules followed by pigmented macules. Early lesions tend to be intensely pruritic with signs of excoriation, while resolving lesions lack symptoms. Lesions last approximately 1 week but tend to reappear at the site where they were previously present, which allows for lesions of different ages to coexist, appearing in a reticular arrangement with hyperpigmented mottling lasting from a few weeks to months.6