User login

Hospitalists and PTs: Building strong relationships

Optimizing discharge disposition and longitudinal recovery

Sanctimonious, self-righteous, discharge saboteurs. These are just a few descriptors I’ve heard hospitalists use to describe my physical therapy (PT) colleagues.

These charged comments come mostly after a hospitalist reads therapy notes and encounters a contradiction to their chosen discharge location for a patient.

I recently met with hospitalists from four different hospitals. They echoed the frustrations of their physician colleagues across the country. The PTs they work with write “the patient requires 24-hour supervision and 3 hours of therapy a day,” or “the patient is unsafe to go home and needs continued therapy at an inpatient rehabilitation center.” The hospitalists in turn want to know “If I discharge the patient home am I liable if the patient falls or has some other negative outcome?” The frustration hospitalists experience is palpable and understandable as their attempts to support a home recovery are often contradicted.

Outside the four walls

The transition from fee-for-service to value-based care now calls upon hospitalists to be innovators in managing patients in alternative payment models, such as accountable care organizations, bundled payment programs, and Medicare Advantage plans. Each model looks to support a home recovery whenever possible and prevent readmissions.

Case managers for Medicare Advantage programs routinely review PT notes to inform hospital discharge disposition and post-acute authorization for skilled nursing facility (SNF) admissions and days in SNF. Hospitalists, working with care managers, can follow suit to succeed in alternative payment models. They have the advantage of in-person access to PT colleagues for elaboration and push-back as necessary. For hospitalists, working collaboratively with PTs is crucial to improving the value of care provided as patients transition beyond the four walls of the hospital.

The evolution of PT in acute care

Prior to diagnosis-related groups (DRGs), PTs were profit centers for hospitals – rehabilitation departments were well staffed and easily accommodated consults and requests for mobility.

With the advent of DRGs, physical therapy became a cost center, and rehabilitation staffs were reduced. PTs became overextended, were less available for consultations for mobilization, and patients suffered the deleterious effects of immobility. With reduced staffing and a rush to get patients out of the hospital, acute PT practice morphed into evaluating functional status and determining discharge destination.

Now, as members of an aligned health care team, PTs need to facilitate a safe home discharge whenever possible and determine what skilled services a patient needs post-acute stay, not where they should receive them.

Discharge disposition and longitudinal recovery

PTs, as experts in function, have a series of “special tests” at their disposal beyond pain, range of motion, and strength assessments. These include: Activity Measure for Post-Acute Care (AM-PAC) or “6-Clicks” Mobility Score, Timed Up and Go, Six-Minute Walk Test, Tinetti, Berg Balance Scale, Modified Barthel Index, Five Times Chair Rise, and Thirty-Second Chair Rise. These are all objective measures of function that can be used to inform discharge disposition and guide longitudinal recovery.

To elaborate on one tool, the 6-Clicks Mobility Score is a validated test that allows PTs to assess basic mobility.1,2 It rates six functional tasks (hence 6 clicks) that include: turning over in bed, moving from lying to sitting, moving to/from bed to chair, transitioning from sitting to standing from a chair, walking in a hospital room, and climbing three to five steps. These functional tasks are scored based on the amount of assistance needed. The scores, in turn, have been shown to support discharge destination planning.1 In addition to informing discharge destination decisions, hospitalists and the rest of the health care team can use 6-Clicks to estimate prolonged hospital stays, readmissions, and emergency department (ED) visits.3

Of course, discharge disposition is influenced by many factors in addition to functional status. Hospitalists are the obvious choice to lead the health care team in interpreting relevant data and test results, and to communicate these results to patients and caregivers so together they can decide the most appropriate discharge destination.

I envision a conversation between a fully informed hospitalist and a patient as follows: “Based on your past history, your living situation, all of your test results including labs, x-rays and the functional tests performed by your PT, your potential for a full recovery is good. You have a moderate decline in function with a high likelihood of returning home in the next 7-10 days. I recommend you go to a SNF for high-intensity rehabilitation for 7 days and that the SNF order PT and OT twice a day and walks with nursing every evening.”

This fully informed conversation can only take place if hospitalists are provided clear, concise documentation, including results of objective functional testing, by their physical therapy colleagues.

In conclusion, PTs working in the acute setting need to use validated tests to objectively assess function and educate their hospitalist colleagues on the meaning of these tests. Hospitalists in turn can incorporate these assessments into a discussion of discharge disposition and longitudinal recovery with patients. In this way, hospitalists and physical therapists can work together to achieve patient-centered, high-value care during and following a hospitalization.

Ms. Tammany is SVP of clinical strategy & innovation for Remedy Partners, Norwalk, Conn.

References

1. Jette DU et al. AM-PAC “6-Clicks” functional assessment scores predict acute care hospital discharge destination. Phys Ther. 2014 Sep;94(9):1252-61.

2. Jette DU et al. Validity of the AM-PAC “6-Clicks” inpatient daily activity and basic mobility short forms. Phys Ther. 2014 Mar;94(3):379-91.

3. Menendez ME et al. Does “6-Clicks” Day 1 Postoperative Mobility Score Predict Discharge Disposition After Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasties?” J Arthroplasty. 2016 Sep;31(9):1916-20.

Optimizing discharge disposition and longitudinal recovery

Optimizing discharge disposition and longitudinal recovery

Sanctimonious, self-righteous, discharge saboteurs. These are just a few descriptors I’ve heard hospitalists use to describe my physical therapy (PT) colleagues.

These charged comments come mostly after a hospitalist reads therapy notes and encounters a contradiction to their chosen discharge location for a patient.

I recently met with hospitalists from four different hospitals. They echoed the frustrations of their physician colleagues across the country. The PTs they work with write “the patient requires 24-hour supervision and 3 hours of therapy a day,” or “the patient is unsafe to go home and needs continued therapy at an inpatient rehabilitation center.” The hospitalists in turn want to know “If I discharge the patient home am I liable if the patient falls or has some other negative outcome?” The frustration hospitalists experience is palpable and understandable as their attempts to support a home recovery are often contradicted.

Outside the four walls

The transition from fee-for-service to value-based care now calls upon hospitalists to be innovators in managing patients in alternative payment models, such as accountable care organizations, bundled payment programs, and Medicare Advantage plans. Each model looks to support a home recovery whenever possible and prevent readmissions.

Case managers for Medicare Advantage programs routinely review PT notes to inform hospital discharge disposition and post-acute authorization for skilled nursing facility (SNF) admissions and days in SNF. Hospitalists, working with care managers, can follow suit to succeed in alternative payment models. They have the advantage of in-person access to PT colleagues for elaboration and push-back as necessary. For hospitalists, working collaboratively with PTs is crucial to improving the value of care provided as patients transition beyond the four walls of the hospital.

The evolution of PT in acute care

Prior to diagnosis-related groups (DRGs), PTs were profit centers for hospitals – rehabilitation departments were well staffed and easily accommodated consults and requests for mobility.

With the advent of DRGs, physical therapy became a cost center, and rehabilitation staffs were reduced. PTs became overextended, were less available for consultations for mobilization, and patients suffered the deleterious effects of immobility. With reduced staffing and a rush to get patients out of the hospital, acute PT practice morphed into evaluating functional status and determining discharge destination.

Now, as members of an aligned health care team, PTs need to facilitate a safe home discharge whenever possible and determine what skilled services a patient needs post-acute stay, not where they should receive them.

Discharge disposition and longitudinal recovery

PTs, as experts in function, have a series of “special tests” at their disposal beyond pain, range of motion, and strength assessments. These include: Activity Measure for Post-Acute Care (AM-PAC) or “6-Clicks” Mobility Score, Timed Up and Go, Six-Minute Walk Test, Tinetti, Berg Balance Scale, Modified Barthel Index, Five Times Chair Rise, and Thirty-Second Chair Rise. These are all objective measures of function that can be used to inform discharge disposition and guide longitudinal recovery.

To elaborate on one tool, the 6-Clicks Mobility Score is a validated test that allows PTs to assess basic mobility.1,2 It rates six functional tasks (hence 6 clicks) that include: turning over in bed, moving from lying to sitting, moving to/from bed to chair, transitioning from sitting to standing from a chair, walking in a hospital room, and climbing three to five steps. These functional tasks are scored based on the amount of assistance needed. The scores, in turn, have been shown to support discharge destination planning.1 In addition to informing discharge destination decisions, hospitalists and the rest of the health care team can use 6-Clicks to estimate prolonged hospital stays, readmissions, and emergency department (ED) visits.3

Of course, discharge disposition is influenced by many factors in addition to functional status. Hospitalists are the obvious choice to lead the health care team in interpreting relevant data and test results, and to communicate these results to patients and caregivers so together they can decide the most appropriate discharge destination.

I envision a conversation between a fully informed hospitalist and a patient as follows: “Based on your past history, your living situation, all of your test results including labs, x-rays and the functional tests performed by your PT, your potential for a full recovery is good. You have a moderate decline in function with a high likelihood of returning home in the next 7-10 days. I recommend you go to a SNF for high-intensity rehabilitation for 7 days and that the SNF order PT and OT twice a day and walks with nursing every evening.”

This fully informed conversation can only take place if hospitalists are provided clear, concise documentation, including results of objective functional testing, by their physical therapy colleagues.

In conclusion, PTs working in the acute setting need to use validated tests to objectively assess function and educate their hospitalist colleagues on the meaning of these tests. Hospitalists in turn can incorporate these assessments into a discussion of discharge disposition and longitudinal recovery with patients. In this way, hospitalists and physical therapists can work together to achieve patient-centered, high-value care during and following a hospitalization.

Ms. Tammany is SVP of clinical strategy & innovation for Remedy Partners, Norwalk, Conn.

References

1. Jette DU et al. AM-PAC “6-Clicks” functional assessment scores predict acute care hospital discharge destination. Phys Ther. 2014 Sep;94(9):1252-61.

2. Jette DU et al. Validity of the AM-PAC “6-Clicks” inpatient daily activity and basic mobility short forms. Phys Ther. 2014 Mar;94(3):379-91.

3. Menendez ME et al. Does “6-Clicks” Day 1 Postoperative Mobility Score Predict Discharge Disposition After Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasties?” J Arthroplasty. 2016 Sep;31(9):1916-20.

Sanctimonious, self-righteous, discharge saboteurs. These are just a few descriptors I’ve heard hospitalists use to describe my physical therapy (PT) colleagues.

These charged comments come mostly after a hospitalist reads therapy notes and encounters a contradiction to their chosen discharge location for a patient.

I recently met with hospitalists from four different hospitals. They echoed the frustrations of their physician colleagues across the country. The PTs they work with write “the patient requires 24-hour supervision and 3 hours of therapy a day,” or “the patient is unsafe to go home and needs continued therapy at an inpatient rehabilitation center.” The hospitalists in turn want to know “If I discharge the patient home am I liable if the patient falls or has some other negative outcome?” The frustration hospitalists experience is palpable and understandable as their attempts to support a home recovery are often contradicted.

Outside the four walls

The transition from fee-for-service to value-based care now calls upon hospitalists to be innovators in managing patients in alternative payment models, such as accountable care organizations, bundled payment programs, and Medicare Advantage plans. Each model looks to support a home recovery whenever possible and prevent readmissions.

Case managers for Medicare Advantage programs routinely review PT notes to inform hospital discharge disposition and post-acute authorization for skilled nursing facility (SNF) admissions and days in SNF. Hospitalists, working with care managers, can follow suit to succeed in alternative payment models. They have the advantage of in-person access to PT colleagues for elaboration and push-back as necessary. For hospitalists, working collaboratively with PTs is crucial to improving the value of care provided as patients transition beyond the four walls of the hospital.

The evolution of PT in acute care

Prior to diagnosis-related groups (DRGs), PTs were profit centers for hospitals – rehabilitation departments were well staffed and easily accommodated consults and requests for mobility.

With the advent of DRGs, physical therapy became a cost center, and rehabilitation staffs were reduced. PTs became overextended, were less available for consultations for mobilization, and patients suffered the deleterious effects of immobility. With reduced staffing and a rush to get patients out of the hospital, acute PT practice morphed into evaluating functional status and determining discharge destination.

Now, as members of an aligned health care team, PTs need to facilitate a safe home discharge whenever possible and determine what skilled services a patient needs post-acute stay, not where they should receive them.

Discharge disposition and longitudinal recovery

PTs, as experts in function, have a series of “special tests” at their disposal beyond pain, range of motion, and strength assessments. These include: Activity Measure for Post-Acute Care (AM-PAC) or “6-Clicks” Mobility Score, Timed Up and Go, Six-Minute Walk Test, Tinetti, Berg Balance Scale, Modified Barthel Index, Five Times Chair Rise, and Thirty-Second Chair Rise. These are all objective measures of function that can be used to inform discharge disposition and guide longitudinal recovery.

To elaborate on one tool, the 6-Clicks Mobility Score is a validated test that allows PTs to assess basic mobility.1,2 It rates six functional tasks (hence 6 clicks) that include: turning over in bed, moving from lying to sitting, moving to/from bed to chair, transitioning from sitting to standing from a chair, walking in a hospital room, and climbing three to five steps. These functional tasks are scored based on the amount of assistance needed. The scores, in turn, have been shown to support discharge destination planning.1 In addition to informing discharge destination decisions, hospitalists and the rest of the health care team can use 6-Clicks to estimate prolonged hospital stays, readmissions, and emergency department (ED) visits.3

Of course, discharge disposition is influenced by many factors in addition to functional status. Hospitalists are the obvious choice to lead the health care team in interpreting relevant data and test results, and to communicate these results to patients and caregivers so together they can decide the most appropriate discharge destination.

I envision a conversation between a fully informed hospitalist and a patient as follows: “Based on your past history, your living situation, all of your test results including labs, x-rays and the functional tests performed by your PT, your potential for a full recovery is good. You have a moderate decline in function with a high likelihood of returning home in the next 7-10 days. I recommend you go to a SNF for high-intensity rehabilitation for 7 days and that the SNF order PT and OT twice a day and walks with nursing every evening.”

This fully informed conversation can only take place if hospitalists are provided clear, concise documentation, including results of objective functional testing, by their physical therapy colleagues.

In conclusion, PTs working in the acute setting need to use validated tests to objectively assess function and educate their hospitalist colleagues on the meaning of these tests. Hospitalists in turn can incorporate these assessments into a discussion of discharge disposition and longitudinal recovery with patients. In this way, hospitalists and physical therapists can work together to achieve patient-centered, high-value care during and following a hospitalization.

Ms. Tammany is SVP of clinical strategy & innovation for Remedy Partners, Norwalk, Conn.

References

1. Jette DU et al. AM-PAC “6-Clicks” functional assessment scores predict acute care hospital discharge destination. Phys Ther. 2014 Sep;94(9):1252-61.

2. Jette DU et al. Validity of the AM-PAC “6-Clicks” inpatient daily activity and basic mobility short forms. Phys Ther. 2014 Mar;94(3):379-91.

3. Menendez ME et al. Does “6-Clicks” Day 1 Postoperative Mobility Score Predict Discharge Disposition After Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasties?” J Arthroplasty. 2016 Sep;31(9):1916-20.

Abstinence by moderate drinkers improves their AFib

NEW ORLEANS – Abstinence from alcohol on the part of moderate drinkers with atrial fibrillation resulted in clinically meaningful improvement in their arrhythmia in the randomized controlled Alcohol-AF trial, Aleksandr Voskoboinik, MBBS, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

The benefits of abstinence included significant reductions in the AFib recurrence rate, total AFib burden, and symptom severity. And the payoff extended beyond the arrhythmia: The abstinent group also averaged a 12–mm Hg drop in systolic blood pressure and dropped 3 kg of body weight over the course of the 6-month trial, added Dr. Voskoboinik, a cardiologist at the Baker Heart & Diabetes Institute at the University of Melbourne.

“We would conclude that significant reduction in alcohol intake should be considered as part of the lifestyle intervention in moderate drinkers with AFib,” he said.

Some physicians already advise alcohol abstinence for moderate drinkers with AFib, but until now such recommendations were not evidence based. Instead, the guidance was based on extrapolation from the well-established harmful effects of heavy drinking and binge drinking on AFib as well as epidemiologic studies.

“We wanted to provide some evidence base for physicians to say, ‘If I have motivated patients, here’s what’s potentially achievable,’” he explained.

The key word here is “motivated.” Conducting the Alcohol-AF trial made clear that many moderate drinkers with AFib enjoy their beverages more than they hate having their arrhythmia. Indeed, out of 697 moderate-drinking patients with paroxysmal or persistent AFib who were deemed good candidates and were approached about study participation, more than 500 were excluded because they were flat out unwilling to consider abstinence. After Dr. Voskoboinik and his coinvestigators shortened the planned trial duration from 12 months to 6 because so many recruits were unwilling to abstain for a full year, 140 of the initial 697 patients were randomized to abstinence or continuation of their usual consumption. Thirty percent of them had previously undergone AFib ablation.

The Alcohol-AF study was a multicenter, prospective, open-label study conducted at six Australian hospitals. All subjects underwent comprehensive rhythm monitoring via an implantable loop recorder or an existing pacemaker. Twice daily they triggered the AliveCor mobile phone app together with Holter monitoring. Patients assigned to abstinence were counseled to abstain completely, got written and verbal advice to help with compliance, and had contact with the investigators on a monthly basis. They also underwent urine testing to monitor compliance. All study participants kept a weekly alcohol intake diary, reviewed monthly by investigators.

Participants averaged 17 standard drinks per week at enrollment. Two-thirds were primarily wine drinkers. At the 6-month mark, patients in the abstinence arm averaged two drinks per week, for an 88% reduction from baseline, and 43 of the 70, or 61%, had remained completely abstinent. The control arm averaged a 20% reduction in weekly consumption.

One of the two co-primary endpoints was recurrent AFib episodes lasting for at least 30 seconds. The rate was 53% in the abstinence group and 73% in controls. The time to first recurrence averaged 118 days in the abstinence group, compared to 86 days in controls, for a 37% prolongation through abstinence.

The other primary endpoint was total AFib burden. During the 6-month study, the abstinence group spent a mean of 5.6% of their time in AFib, compared to 8.2% in controls. The median times were 0.5% and 1.2%.

In a multivariate analysis, neither AFib type, duration, history of AFib ablation, age, nor gender predicted AFib recurrence. In fact, the only significant predictor was alcohol abstinence, which conferred a 48% reduction in risk.

Symptom severity, a secondary endpoint, showed an impressive between-group difference at follow-up. Ten percent of patients in the abstinence group had moderate or severe symptoms at follow-up as assessed via the European Heart Rhythm Association score of atrial fibrillation, compared to 32% of controls, for an absolute 22% difference. And 90% of the abstinence group had no or mild symptoms, as did 68% of controls. Nine percent of the abstinence group had an AFib-related hospitalization, as did 20% of controls.

Cardiac MRI, performed in all subjects, showed that the abstinence group experienced a significant reduction in left atrial area, from 29.5 cm2 at baseline to 27.1 cm2 at follow-up. They also experienced significant improvement in left atrial mechanical function, with their left atrial emptying fraction climbing from 42% to 50%.

The 3-kg weight loss from a baseline of 90 kg in the abstinent group represented a 0.7 kg/m2 reduction in body mass index.

In terms of the likely mechanism of benefit of alcohol abstinence in moderate drinkers, Dr. Voskoboinik noted that he and his colleagues recently demonstrated that regular moderate alcohol consumption, but not mild intake, is associated with potentially explanatory atrial electrical and structural changes, including conduction slowing, lower global bipolar atrial voltage, and an increase in complex atrial potentials (Heart Rhythm. 2019 Feb;16[2]:251-9).

Alcohol has been shown to be linked with AFib through multiple mechanisms. Alcohol has adverse effects on the atrial substrate, including promotion of left atrial remodeling, dilation, and fibrosis via oxidative stress, and alcohol has a contributory role in hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea. Alcohol can act as an acute trigger of AFib through binge drinking – the holiday heart syndrome – which causes autonomic changes, electrolyte abnormalities, and electrophysiologic effects, he continued.

Epidemiologic evidence in support of the notion that moderate drinking increases the risk of AFib includes a Swedish meta-analysis of seven prospective studies comprising 12,554 patients with AFib. The researchers concluded that the relative risk of AFib rose by about 8% with each drink per day, compared with the risk of a reference group composed of current drinkers at a rate of less than one drink per week (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014 Jul 22;64[3]:281-9).

Although discussants were wowed by the 61% complete abstinence rate in the trial, Dr. Voskoboinik cautioned that the study participants were a highly motivated subset of the universe of moderate drinkers with AFib. And even so, “It was an incredibly challenging study to run,” he said.

“I think lifestyle change is a challenge, and with alcohol particularly so, because alcohol is so ubiquitous in our society. I think the important key message for us as physicians is to take an alcohol history and have a discussion with the patient. And we now have some data to show them. But at the end of the day, it’s up to the patient in conjunction with the physician,” he observed.

Discussant Annabelle S. Volgman, MD, noted that 85% of study participants were men, and because of important differences in AFib between men and women, she doesn’t consider the findings applicable to women.

“You need to redo the study in women,” advised Dr. Volgman, professor of medicine at Rush University, Chicago, and director of the Rush Heart Center for Women.

She suggested that an interventional trial such as this one is a great opportunity to utilize wearable device technology, such as the Apple Watch, which can detect irregular pulse rhythms as demonstrated in the Apple Heart Study. This technology is especially popular with younger individuals.

“A lot of young men and women drink a lot of alcohol,” Dr. Volgman noted.

“That’s a great idea. It gets around a problem with AliveCor, which can miss episodes while you’re sleeping,” Dr. Voskoboinik replied.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding the investigator-initiated and -funded Alcohol-AF trial.

SOURCE: Voskoboinik A. ACC 19, Session 413-08.

NEW ORLEANS – Abstinence from alcohol on the part of moderate drinkers with atrial fibrillation resulted in clinically meaningful improvement in their arrhythmia in the randomized controlled Alcohol-AF trial, Aleksandr Voskoboinik, MBBS, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

The benefits of abstinence included significant reductions in the AFib recurrence rate, total AFib burden, and symptom severity. And the payoff extended beyond the arrhythmia: The abstinent group also averaged a 12–mm Hg drop in systolic blood pressure and dropped 3 kg of body weight over the course of the 6-month trial, added Dr. Voskoboinik, a cardiologist at the Baker Heart & Diabetes Institute at the University of Melbourne.

“We would conclude that significant reduction in alcohol intake should be considered as part of the lifestyle intervention in moderate drinkers with AFib,” he said.

Some physicians already advise alcohol abstinence for moderate drinkers with AFib, but until now such recommendations were not evidence based. Instead, the guidance was based on extrapolation from the well-established harmful effects of heavy drinking and binge drinking on AFib as well as epidemiologic studies.

“We wanted to provide some evidence base for physicians to say, ‘If I have motivated patients, here’s what’s potentially achievable,’” he explained.

The key word here is “motivated.” Conducting the Alcohol-AF trial made clear that many moderate drinkers with AFib enjoy their beverages more than they hate having their arrhythmia. Indeed, out of 697 moderate-drinking patients with paroxysmal or persistent AFib who were deemed good candidates and were approached about study participation, more than 500 were excluded because they were flat out unwilling to consider abstinence. After Dr. Voskoboinik and his coinvestigators shortened the planned trial duration from 12 months to 6 because so many recruits were unwilling to abstain for a full year, 140 of the initial 697 patients were randomized to abstinence or continuation of their usual consumption. Thirty percent of them had previously undergone AFib ablation.

The Alcohol-AF study was a multicenter, prospective, open-label study conducted at six Australian hospitals. All subjects underwent comprehensive rhythm monitoring via an implantable loop recorder or an existing pacemaker. Twice daily they triggered the AliveCor mobile phone app together with Holter monitoring. Patients assigned to abstinence were counseled to abstain completely, got written and verbal advice to help with compliance, and had contact with the investigators on a monthly basis. They also underwent urine testing to monitor compliance. All study participants kept a weekly alcohol intake diary, reviewed monthly by investigators.

Participants averaged 17 standard drinks per week at enrollment. Two-thirds were primarily wine drinkers. At the 6-month mark, patients in the abstinence arm averaged two drinks per week, for an 88% reduction from baseline, and 43 of the 70, or 61%, had remained completely abstinent. The control arm averaged a 20% reduction in weekly consumption.

One of the two co-primary endpoints was recurrent AFib episodes lasting for at least 30 seconds. The rate was 53% in the abstinence group and 73% in controls. The time to first recurrence averaged 118 days in the abstinence group, compared to 86 days in controls, for a 37% prolongation through abstinence.

The other primary endpoint was total AFib burden. During the 6-month study, the abstinence group spent a mean of 5.6% of their time in AFib, compared to 8.2% in controls. The median times were 0.5% and 1.2%.

In a multivariate analysis, neither AFib type, duration, history of AFib ablation, age, nor gender predicted AFib recurrence. In fact, the only significant predictor was alcohol abstinence, which conferred a 48% reduction in risk.

Symptom severity, a secondary endpoint, showed an impressive between-group difference at follow-up. Ten percent of patients in the abstinence group had moderate or severe symptoms at follow-up as assessed via the European Heart Rhythm Association score of atrial fibrillation, compared to 32% of controls, for an absolute 22% difference. And 90% of the abstinence group had no or mild symptoms, as did 68% of controls. Nine percent of the abstinence group had an AFib-related hospitalization, as did 20% of controls.

Cardiac MRI, performed in all subjects, showed that the abstinence group experienced a significant reduction in left atrial area, from 29.5 cm2 at baseline to 27.1 cm2 at follow-up. They also experienced significant improvement in left atrial mechanical function, with their left atrial emptying fraction climbing from 42% to 50%.

The 3-kg weight loss from a baseline of 90 kg in the abstinent group represented a 0.7 kg/m2 reduction in body mass index.

In terms of the likely mechanism of benefit of alcohol abstinence in moderate drinkers, Dr. Voskoboinik noted that he and his colleagues recently demonstrated that regular moderate alcohol consumption, but not mild intake, is associated with potentially explanatory atrial electrical and structural changes, including conduction slowing, lower global bipolar atrial voltage, and an increase in complex atrial potentials (Heart Rhythm. 2019 Feb;16[2]:251-9).

Alcohol has been shown to be linked with AFib through multiple mechanisms. Alcohol has adverse effects on the atrial substrate, including promotion of left atrial remodeling, dilation, and fibrosis via oxidative stress, and alcohol has a contributory role in hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea. Alcohol can act as an acute trigger of AFib through binge drinking – the holiday heart syndrome – which causes autonomic changes, electrolyte abnormalities, and electrophysiologic effects, he continued.

Epidemiologic evidence in support of the notion that moderate drinking increases the risk of AFib includes a Swedish meta-analysis of seven prospective studies comprising 12,554 patients with AFib. The researchers concluded that the relative risk of AFib rose by about 8% with each drink per day, compared with the risk of a reference group composed of current drinkers at a rate of less than one drink per week (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014 Jul 22;64[3]:281-9).

Although discussants were wowed by the 61% complete abstinence rate in the trial, Dr. Voskoboinik cautioned that the study participants were a highly motivated subset of the universe of moderate drinkers with AFib. And even so, “It was an incredibly challenging study to run,” he said.

“I think lifestyle change is a challenge, and with alcohol particularly so, because alcohol is so ubiquitous in our society. I think the important key message for us as physicians is to take an alcohol history and have a discussion with the patient. And we now have some data to show them. But at the end of the day, it’s up to the patient in conjunction with the physician,” he observed.

Discussant Annabelle S. Volgman, MD, noted that 85% of study participants were men, and because of important differences in AFib between men and women, she doesn’t consider the findings applicable to women.

“You need to redo the study in women,” advised Dr. Volgman, professor of medicine at Rush University, Chicago, and director of the Rush Heart Center for Women.

She suggested that an interventional trial such as this one is a great opportunity to utilize wearable device technology, such as the Apple Watch, which can detect irregular pulse rhythms as demonstrated in the Apple Heart Study. This technology is especially popular with younger individuals.

“A lot of young men and women drink a lot of alcohol,” Dr. Volgman noted.

“That’s a great idea. It gets around a problem with AliveCor, which can miss episodes while you’re sleeping,” Dr. Voskoboinik replied.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding the investigator-initiated and -funded Alcohol-AF trial.

SOURCE: Voskoboinik A. ACC 19, Session 413-08.

NEW ORLEANS – Abstinence from alcohol on the part of moderate drinkers with atrial fibrillation resulted in clinically meaningful improvement in their arrhythmia in the randomized controlled Alcohol-AF trial, Aleksandr Voskoboinik, MBBS, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

The benefits of abstinence included significant reductions in the AFib recurrence rate, total AFib burden, and symptom severity. And the payoff extended beyond the arrhythmia: The abstinent group also averaged a 12–mm Hg drop in systolic blood pressure and dropped 3 kg of body weight over the course of the 6-month trial, added Dr. Voskoboinik, a cardiologist at the Baker Heart & Diabetes Institute at the University of Melbourne.

“We would conclude that significant reduction in alcohol intake should be considered as part of the lifestyle intervention in moderate drinkers with AFib,” he said.

Some physicians already advise alcohol abstinence for moderate drinkers with AFib, but until now such recommendations were not evidence based. Instead, the guidance was based on extrapolation from the well-established harmful effects of heavy drinking and binge drinking on AFib as well as epidemiologic studies.

“We wanted to provide some evidence base for physicians to say, ‘If I have motivated patients, here’s what’s potentially achievable,’” he explained.

The key word here is “motivated.” Conducting the Alcohol-AF trial made clear that many moderate drinkers with AFib enjoy their beverages more than they hate having their arrhythmia. Indeed, out of 697 moderate-drinking patients with paroxysmal or persistent AFib who were deemed good candidates and were approached about study participation, more than 500 were excluded because they were flat out unwilling to consider abstinence. After Dr. Voskoboinik and his coinvestigators shortened the planned trial duration from 12 months to 6 because so many recruits were unwilling to abstain for a full year, 140 of the initial 697 patients were randomized to abstinence or continuation of their usual consumption. Thirty percent of them had previously undergone AFib ablation.

The Alcohol-AF study was a multicenter, prospective, open-label study conducted at six Australian hospitals. All subjects underwent comprehensive rhythm monitoring via an implantable loop recorder or an existing pacemaker. Twice daily they triggered the AliveCor mobile phone app together with Holter monitoring. Patients assigned to abstinence were counseled to abstain completely, got written and verbal advice to help with compliance, and had contact with the investigators on a monthly basis. They also underwent urine testing to monitor compliance. All study participants kept a weekly alcohol intake diary, reviewed monthly by investigators.

Participants averaged 17 standard drinks per week at enrollment. Two-thirds were primarily wine drinkers. At the 6-month mark, patients in the abstinence arm averaged two drinks per week, for an 88% reduction from baseline, and 43 of the 70, or 61%, had remained completely abstinent. The control arm averaged a 20% reduction in weekly consumption.

One of the two co-primary endpoints was recurrent AFib episodes lasting for at least 30 seconds. The rate was 53% in the abstinence group and 73% in controls. The time to first recurrence averaged 118 days in the abstinence group, compared to 86 days in controls, for a 37% prolongation through abstinence.

The other primary endpoint was total AFib burden. During the 6-month study, the abstinence group spent a mean of 5.6% of their time in AFib, compared to 8.2% in controls. The median times were 0.5% and 1.2%.

In a multivariate analysis, neither AFib type, duration, history of AFib ablation, age, nor gender predicted AFib recurrence. In fact, the only significant predictor was alcohol abstinence, which conferred a 48% reduction in risk.

Symptom severity, a secondary endpoint, showed an impressive between-group difference at follow-up. Ten percent of patients in the abstinence group had moderate or severe symptoms at follow-up as assessed via the European Heart Rhythm Association score of atrial fibrillation, compared to 32% of controls, for an absolute 22% difference. And 90% of the abstinence group had no or mild symptoms, as did 68% of controls. Nine percent of the abstinence group had an AFib-related hospitalization, as did 20% of controls.

Cardiac MRI, performed in all subjects, showed that the abstinence group experienced a significant reduction in left atrial area, from 29.5 cm2 at baseline to 27.1 cm2 at follow-up. They also experienced significant improvement in left atrial mechanical function, with their left atrial emptying fraction climbing from 42% to 50%.

The 3-kg weight loss from a baseline of 90 kg in the abstinent group represented a 0.7 kg/m2 reduction in body mass index.

In terms of the likely mechanism of benefit of alcohol abstinence in moderate drinkers, Dr. Voskoboinik noted that he and his colleagues recently demonstrated that regular moderate alcohol consumption, but not mild intake, is associated with potentially explanatory atrial electrical and structural changes, including conduction slowing, lower global bipolar atrial voltage, and an increase in complex atrial potentials (Heart Rhythm. 2019 Feb;16[2]:251-9).

Alcohol has been shown to be linked with AFib through multiple mechanisms. Alcohol has adverse effects on the atrial substrate, including promotion of left atrial remodeling, dilation, and fibrosis via oxidative stress, and alcohol has a contributory role in hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea. Alcohol can act as an acute trigger of AFib through binge drinking – the holiday heart syndrome – which causes autonomic changes, electrolyte abnormalities, and electrophysiologic effects, he continued.

Epidemiologic evidence in support of the notion that moderate drinking increases the risk of AFib includes a Swedish meta-analysis of seven prospective studies comprising 12,554 patients with AFib. The researchers concluded that the relative risk of AFib rose by about 8% with each drink per day, compared with the risk of a reference group composed of current drinkers at a rate of less than one drink per week (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014 Jul 22;64[3]:281-9).

Although discussants were wowed by the 61% complete abstinence rate in the trial, Dr. Voskoboinik cautioned that the study participants were a highly motivated subset of the universe of moderate drinkers with AFib. And even so, “It was an incredibly challenging study to run,” he said.

“I think lifestyle change is a challenge, and with alcohol particularly so, because alcohol is so ubiquitous in our society. I think the important key message for us as physicians is to take an alcohol history and have a discussion with the patient. And we now have some data to show them. But at the end of the day, it’s up to the patient in conjunction with the physician,” he observed.

Discussant Annabelle S. Volgman, MD, noted that 85% of study participants were men, and because of important differences in AFib between men and women, she doesn’t consider the findings applicable to women.

“You need to redo the study in women,” advised Dr. Volgman, professor of medicine at Rush University, Chicago, and director of the Rush Heart Center for Women.

She suggested that an interventional trial such as this one is a great opportunity to utilize wearable device technology, such as the Apple Watch, which can detect irregular pulse rhythms as demonstrated in the Apple Heart Study. This technology is especially popular with younger individuals.

“A lot of young men and women drink a lot of alcohol,” Dr. Volgman noted.

“That’s a great idea. It gets around a problem with AliveCor, which can miss episodes while you’re sleeping,” Dr. Voskoboinik replied.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding the investigator-initiated and -funded Alcohol-AF trial.

SOURCE: Voskoboinik A. ACC 19, Session 413-08.

REPORTING FROM ACC 19

Biogen, Eisai discontinue aducanumab Alzheimer’s trials

Biogen and Eisai have announced that they are discontinuing the ENGAGE and EMERGE trials, which were designed to test the efficacy and safety of aducanumab in patients with mild cognitive impairment caused by Alzheimer’s disease and mild Alzheimer’s disease dementia.

The phase 3, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trials were canceled not because of safety concerns but because of a futility analysis conducted by an independent data monitoring committee that indicated the drug would not meet the trials’ primary endpoint, which was the slowing of cognitive and functional impairment as measured by changes in Clinical Dementia Rating–Sum of Boxes score, compared with placebo.

In addition to ENGAGE and EMERGE, the phase 2 EVOLVE safety study and the long-term extension of the phase 1b PRIME study have also been canceled. Data from the ENGAGE and EMERGE trials will be presented at future medical meetings.

Aducanumab is a human monoclonal antibody derived from B cells collected from healthy elderly subjects with no cognitive decline or those with unusually slow cognitive decline through Neurimmune’s technology platform called Reverse Translational Medicine. It was granted Fast Track designation by the Food and Drug Administration.

“This disappointing news confirms the complexity of treating Alzheimer’s disease and the need to further advance knowledge in neuroscience. We are incredibly grateful to all the Alzheimer’s disease patients, their families, and the investigators who participated in the trials and contributed greatly to this research,” Michel Vounatsos, CEO at Biogen, said in a press release.

Biogen and Eisai have announced that they are discontinuing the ENGAGE and EMERGE trials, which were designed to test the efficacy and safety of aducanumab in patients with mild cognitive impairment caused by Alzheimer’s disease and mild Alzheimer’s disease dementia.

The phase 3, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trials were canceled not because of safety concerns but because of a futility analysis conducted by an independent data monitoring committee that indicated the drug would not meet the trials’ primary endpoint, which was the slowing of cognitive and functional impairment as measured by changes in Clinical Dementia Rating–Sum of Boxes score, compared with placebo.

In addition to ENGAGE and EMERGE, the phase 2 EVOLVE safety study and the long-term extension of the phase 1b PRIME study have also been canceled. Data from the ENGAGE and EMERGE trials will be presented at future medical meetings.

Aducanumab is a human monoclonal antibody derived from B cells collected from healthy elderly subjects with no cognitive decline or those with unusually slow cognitive decline through Neurimmune’s technology platform called Reverse Translational Medicine. It was granted Fast Track designation by the Food and Drug Administration.

“This disappointing news confirms the complexity of treating Alzheimer’s disease and the need to further advance knowledge in neuroscience. We are incredibly grateful to all the Alzheimer’s disease patients, their families, and the investigators who participated in the trials and contributed greatly to this research,” Michel Vounatsos, CEO at Biogen, said in a press release.

Biogen and Eisai have announced that they are discontinuing the ENGAGE and EMERGE trials, which were designed to test the efficacy and safety of aducanumab in patients with mild cognitive impairment caused by Alzheimer’s disease and mild Alzheimer’s disease dementia.

The phase 3, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trials were canceled not because of safety concerns but because of a futility analysis conducted by an independent data monitoring committee that indicated the drug would not meet the trials’ primary endpoint, which was the slowing of cognitive and functional impairment as measured by changes in Clinical Dementia Rating–Sum of Boxes score, compared with placebo.

In addition to ENGAGE and EMERGE, the phase 2 EVOLVE safety study and the long-term extension of the phase 1b PRIME study have also been canceled. Data from the ENGAGE and EMERGE trials will be presented at future medical meetings.

Aducanumab is a human monoclonal antibody derived from B cells collected from healthy elderly subjects with no cognitive decline or those with unusually slow cognitive decline through Neurimmune’s technology platform called Reverse Translational Medicine. It was granted Fast Track designation by the Food and Drug Administration.

“This disappointing news confirms the complexity of treating Alzheimer’s disease and the need to further advance knowledge in neuroscience. We are incredibly grateful to all the Alzheimer’s disease patients, their families, and the investigators who participated in the trials and contributed greatly to this research,” Michel Vounatsos, CEO at Biogen, said in a press release.

Wedding dermatology

Planning a wedding doesn’t just involve decisions on venues, vows, guests, food, and décor, but also on the betrothed couple’s appearance. Memories and photographs from this day last a lifetime, so it is understandable that people may want to and feel pressured to look their best on this important day – which along with the pressures of planning a wedding, can lead to unnecessary stress, increased cortisol, and unexpected acne and other skin issues.

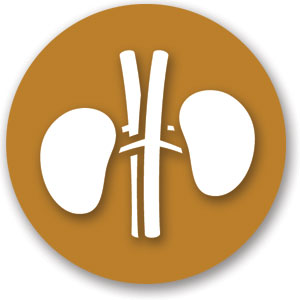

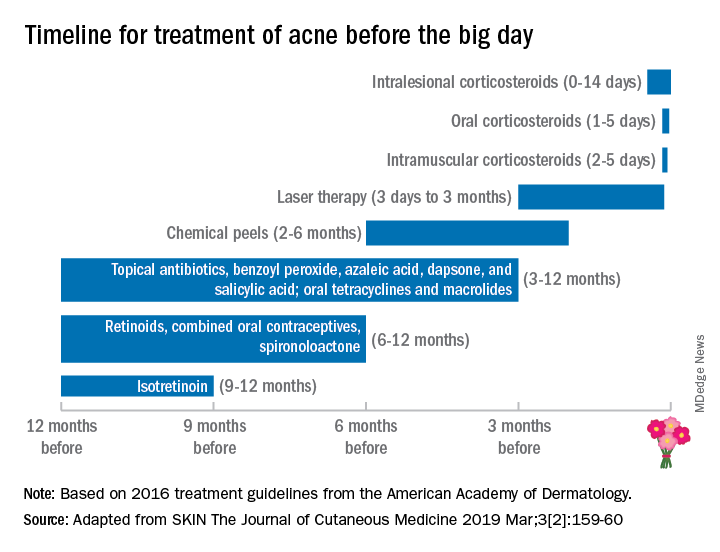

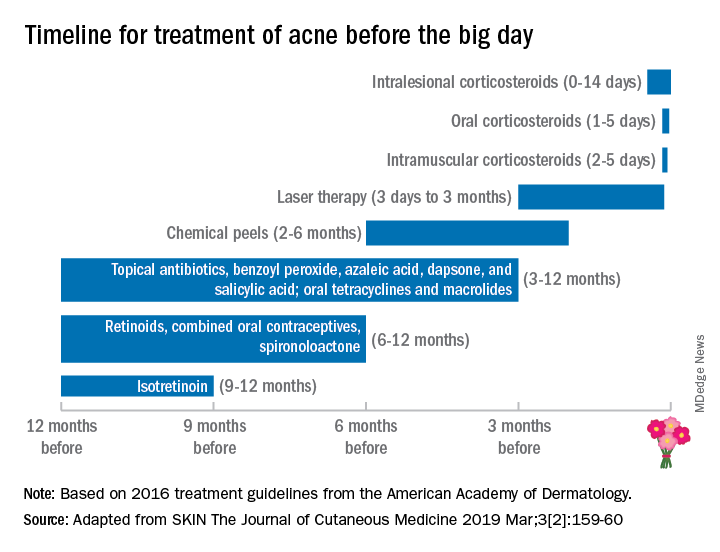

Because of a complete absence of wedding skin recommendations in the dermatology literature, Winklemann R et al. recently published a paper titled “Wedding Dermatology: A proposed timeline to optimize skin clearance and the avoidance of a true dermatologic emergency” (SKIN The Journal of Cutaneous Medicine 2019 Mar;3[2]:159-60). He focused on acne, using the American Academy of Dermatology acne treatment guidelines and expert opinion, they point out that other than intralesional corticosteroids (which take 0-14 days to have an effect), the majority of acne treatments require at least 3-12 months to achieve clearance or improvement.

This proposed treatment timeline makes sense given that skin cell turnover on the face takes about 6-8 weeks; therefore, it may take that long for acne lesions to resolve or for treatment to have an effect.

Besides acne treatment, cosmetic treatments also have varying healing times and may require multiple sessions with time in between treatments for optimal results. For instance, treatment of photoaging with intense pulsed light or nonablative fractionated resurfacing may require three to six treatments, typically spaced 1 month apart.

Botulinum toxin treatments may take up to 2 weeks to kick in fully, then last 3-4 months. While the lead time for botulinum toxin to kick in is relatively short, I advise people not to get their first botulinum toxin 2 weeks before their wedding. Sometimes, having this treatment 4-6 weeks prior to the wedding date provides enough time for botulinum toxin to kick in – and to start wearing off to the point that the patient has the desired cosmetic effect, but still has some movement for the desired emotional facial expressions on the wedding day. Some patients also may require touch-ups, optimally at the 2-week window, once the botulinum toxin effect has fully kicked in.

With any injectable, there may be bruising and swelling that can take a week or so to heal, even when the bruises are treated with pulse dye laser used to make bruises resolve more quickly. Even a facial may result in blemishes that take a few days to 1-2 weeks to heal, especially with extractions. As such, a facial, especially a hydrafacial, may be beneficial before one’s wedding, but I would recommend having them done at least once or twice to assess an individual’s recovery time (if any) prior to the actual wedding date.

Treatment needs will vary considerably depending on the patient’s baseline skin health. As dermatologists, our patients depend greatly on us to help them look and feel their best, especially during a time when they are about to embark on a new journey like marriage. Patients need to be given realistic treatment options and time frames to achieve their goals. Whether the goal is treating acne or acne scars, starting or fine-tuning cosmetic treatments, or deciding on a skin-care regimen, the bottom line is making an appointment with the dermatologist early – 6-12 months in advance, if possible – to figure out the right plan.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at dermnews@mdedge.com. They had no relevant disclosures.

Planning a wedding doesn’t just involve decisions on venues, vows, guests, food, and décor, but also on the betrothed couple’s appearance. Memories and photographs from this day last a lifetime, so it is understandable that people may want to and feel pressured to look their best on this important day – which along with the pressures of planning a wedding, can lead to unnecessary stress, increased cortisol, and unexpected acne and other skin issues.

Because of a complete absence of wedding skin recommendations in the dermatology literature, Winklemann R et al. recently published a paper titled “Wedding Dermatology: A proposed timeline to optimize skin clearance and the avoidance of a true dermatologic emergency” (SKIN The Journal of Cutaneous Medicine 2019 Mar;3[2]:159-60). He focused on acne, using the American Academy of Dermatology acne treatment guidelines and expert opinion, they point out that other than intralesional corticosteroids (which take 0-14 days to have an effect), the majority of acne treatments require at least 3-12 months to achieve clearance or improvement.

This proposed treatment timeline makes sense given that skin cell turnover on the face takes about 6-8 weeks; therefore, it may take that long for acne lesions to resolve or for treatment to have an effect.

Besides acne treatment, cosmetic treatments also have varying healing times and may require multiple sessions with time in between treatments for optimal results. For instance, treatment of photoaging with intense pulsed light or nonablative fractionated resurfacing may require three to six treatments, typically spaced 1 month apart.

Botulinum toxin treatments may take up to 2 weeks to kick in fully, then last 3-4 months. While the lead time for botulinum toxin to kick in is relatively short, I advise people not to get their first botulinum toxin 2 weeks before their wedding. Sometimes, having this treatment 4-6 weeks prior to the wedding date provides enough time for botulinum toxin to kick in – and to start wearing off to the point that the patient has the desired cosmetic effect, but still has some movement for the desired emotional facial expressions on the wedding day. Some patients also may require touch-ups, optimally at the 2-week window, once the botulinum toxin effect has fully kicked in.

With any injectable, there may be bruising and swelling that can take a week or so to heal, even when the bruises are treated with pulse dye laser used to make bruises resolve more quickly. Even a facial may result in blemishes that take a few days to 1-2 weeks to heal, especially with extractions. As such, a facial, especially a hydrafacial, may be beneficial before one’s wedding, but I would recommend having them done at least once or twice to assess an individual’s recovery time (if any) prior to the actual wedding date.

Treatment needs will vary considerably depending on the patient’s baseline skin health. As dermatologists, our patients depend greatly on us to help them look and feel their best, especially during a time when they are about to embark on a new journey like marriage. Patients need to be given realistic treatment options and time frames to achieve their goals. Whether the goal is treating acne or acne scars, starting or fine-tuning cosmetic treatments, or deciding on a skin-care regimen, the bottom line is making an appointment with the dermatologist early – 6-12 months in advance, if possible – to figure out the right plan.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at dermnews@mdedge.com. They had no relevant disclosures.

Planning a wedding doesn’t just involve decisions on venues, vows, guests, food, and décor, but also on the betrothed couple’s appearance. Memories and photographs from this day last a lifetime, so it is understandable that people may want to and feel pressured to look their best on this important day – which along with the pressures of planning a wedding, can lead to unnecessary stress, increased cortisol, and unexpected acne and other skin issues.

Because of a complete absence of wedding skin recommendations in the dermatology literature, Winklemann R et al. recently published a paper titled “Wedding Dermatology: A proposed timeline to optimize skin clearance and the avoidance of a true dermatologic emergency” (SKIN The Journal of Cutaneous Medicine 2019 Mar;3[2]:159-60). He focused on acne, using the American Academy of Dermatology acne treatment guidelines and expert opinion, they point out that other than intralesional corticosteroids (which take 0-14 days to have an effect), the majority of acne treatments require at least 3-12 months to achieve clearance or improvement.

This proposed treatment timeline makes sense given that skin cell turnover on the face takes about 6-8 weeks; therefore, it may take that long for acne lesions to resolve or for treatment to have an effect.

Besides acne treatment, cosmetic treatments also have varying healing times and may require multiple sessions with time in between treatments for optimal results. For instance, treatment of photoaging with intense pulsed light or nonablative fractionated resurfacing may require three to six treatments, typically spaced 1 month apart.

Botulinum toxin treatments may take up to 2 weeks to kick in fully, then last 3-4 months. While the lead time for botulinum toxin to kick in is relatively short, I advise people not to get their first botulinum toxin 2 weeks before their wedding. Sometimes, having this treatment 4-6 weeks prior to the wedding date provides enough time for botulinum toxin to kick in – and to start wearing off to the point that the patient has the desired cosmetic effect, but still has some movement for the desired emotional facial expressions on the wedding day. Some patients also may require touch-ups, optimally at the 2-week window, once the botulinum toxin effect has fully kicked in.

With any injectable, there may be bruising and swelling that can take a week or so to heal, even when the bruises are treated with pulse dye laser used to make bruises resolve more quickly. Even a facial may result in blemishes that take a few days to 1-2 weeks to heal, especially with extractions. As such, a facial, especially a hydrafacial, may be beneficial before one’s wedding, but I would recommend having them done at least once or twice to assess an individual’s recovery time (if any) prior to the actual wedding date.

Treatment needs will vary considerably depending on the patient’s baseline skin health. As dermatologists, our patients depend greatly on us to help them look and feel their best, especially during a time when they are about to embark on a new journey like marriage. Patients need to be given realistic treatment options and time frames to achieve their goals. Whether the goal is treating acne or acne scars, starting or fine-tuning cosmetic treatments, or deciding on a skin-care regimen, the bottom line is making an appointment with the dermatologist early – 6-12 months in advance, if possible – to figure out the right plan.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at dermnews@mdedge.com. They had no relevant disclosures.

High survival in relapsed FL after primary radiotherapy

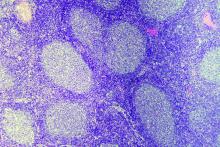

The prognosis post relapse following primary radiotherapy was found to be excellent for patients with localized follicular lymphoma (FL), according to a retrospective analysis.

But patients who experienced early relapse – at 1 year or less after diagnosis – had significantly worse survival.

While primary radiotherapy may be curative for localized FL, about 30%-50% of patients will relapse and optimal salvage therapy is not well defined, Michael S. Binkley, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, and his colleagues wrote in the International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics.

The researchers retrospectively studied 512 patients with localized FL using data from multiple centers under the direction of the International Lymphoma Radiation Oncology Group (ILROG). Clinical information was collected, including method of detection, age at relapse, location of recurrence, and response to salvage therapy.

The team defined disease recurrence as lymphoma nonresponsive to primary radiotherapy inside of the prescribed dose volume, which included having no radiographic or clinical response within 6 months of initial radiotherapy treatment.

With a median follow-up of 52 months, Dr. Binkley and his colleagues found that 29.1% of patients developed relapsed lymphoma at a median 23 months (range, 1-143 months) following primary radiotherapy.

The team reported that the 3-year overall survival rate was 91.4% for patients with lymphoma recurrence after primary radiotherapy. In total, 16 deaths occurred during follow-up: eight were lymphoma specific deaths, three were from other causes, and in five patients the cause was unknown.

Of the 149 cases of relapsed lymphoma, 93 were indolent. There were also three cases of FL grade 3B/not otherwise specified and 18 cases of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. In 35 patients who relapsed, biopsies were not performed.

“The excellent prognosis observed for this relapse cohort emphasizes that primary radiation for localized follicular lymphoma is an excellent treatment option,” the researchers wrote.

When the researchers examined survival based on the time of relapse, they found that overall survival was “significantly worse” for patients who had relapsed 12 months or less after the date of diagnosis, at 88.7%, compared with all others at 95.8% (P = .01).

They found no difference in overall survival between patients who received immediate salvage treatment, compared with observation after relapse (P = .28). There was also no significant difference in survival between patients who relapsed in 1 year or less but underwent immediate treatment, compared to early relapsed patients who were observed (log-rank P = .34).

“[A]ny decision to offer treatment at time of relapse must be weighed with the risk of acute and late adverse effects. Greater than 60% of patients in our cohort with indolent recurrence who underwent salvage treatment received rituximab, likely contributing to the excellent outcomes,” the researchers wrote. “However, nearly 60% of patients with indolent recurrence who were observed did not have disease progression nor [did they] receive treatment within 3 years.”

The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Binkley MS et al. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2019 Mar 8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2019.03.004.

The prognosis post relapse following primary radiotherapy was found to be excellent for patients with localized follicular lymphoma (FL), according to a retrospective analysis.

But patients who experienced early relapse – at 1 year or less after diagnosis – had significantly worse survival.

While primary radiotherapy may be curative for localized FL, about 30%-50% of patients will relapse and optimal salvage therapy is not well defined, Michael S. Binkley, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, and his colleagues wrote in the International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics.

The researchers retrospectively studied 512 patients with localized FL using data from multiple centers under the direction of the International Lymphoma Radiation Oncology Group (ILROG). Clinical information was collected, including method of detection, age at relapse, location of recurrence, and response to salvage therapy.

The team defined disease recurrence as lymphoma nonresponsive to primary radiotherapy inside of the prescribed dose volume, which included having no radiographic or clinical response within 6 months of initial radiotherapy treatment.

With a median follow-up of 52 months, Dr. Binkley and his colleagues found that 29.1% of patients developed relapsed lymphoma at a median 23 months (range, 1-143 months) following primary radiotherapy.

The team reported that the 3-year overall survival rate was 91.4% for patients with lymphoma recurrence after primary radiotherapy. In total, 16 deaths occurred during follow-up: eight were lymphoma specific deaths, three were from other causes, and in five patients the cause was unknown.

Of the 149 cases of relapsed lymphoma, 93 were indolent. There were also three cases of FL grade 3B/not otherwise specified and 18 cases of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. In 35 patients who relapsed, biopsies were not performed.

“The excellent prognosis observed for this relapse cohort emphasizes that primary radiation for localized follicular lymphoma is an excellent treatment option,” the researchers wrote.

When the researchers examined survival based on the time of relapse, they found that overall survival was “significantly worse” for patients who had relapsed 12 months or less after the date of diagnosis, at 88.7%, compared with all others at 95.8% (P = .01).

They found no difference in overall survival between patients who received immediate salvage treatment, compared with observation after relapse (P = .28). There was also no significant difference in survival between patients who relapsed in 1 year or less but underwent immediate treatment, compared to early relapsed patients who were observed (log-rank P = .34).

“[A]ny decision to offer treatment at time of relapse must be weighed with the risk of acute and late adverse effects. Greater than 60% of patients in our cohort with indolent recurrence who underwent salvage treatment received rituximab, likely contributing to the excellent outcomes,” the researchers wrote. “However, nearly 60% of patients with indolent recurrence who were observed did not have disease progression nor [did they] receive treatment within 3 years.”

The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Binkley MS et al. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2019 Mar 8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2019.03.004.

The prognosis post relapse following primary radiotherapy was found to be excellent for patients with localized follicular lymphoma (FL), according to a retrospective analysis.

But patients who experienced early relapse – at 1 year or less after diagnosis – had significantly worse survival.

While primary radiotherapy may be curative for localized FL, about 30%-50% of patients will relapse and optimal salvage therapy is not well defined, Michael S. Binkley, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, and his colleagues wrote in the International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics.

The researchers retrospectively studied 512 patients with localized FL using data from multiple centers under the direction of the International Lymphoma Radiation Oncology Group (ILROG). Clinical information was collected, including method of detection, age at relapse, location of recurrence, and response to salvage therapy.

The team defined disease recurrence as lymphoma nonresponsive to primary radiotherapy inside of the prescribed dose volume, which included having no radiographic or clinical response within 6 months of initial radiotherapy treatment.

With a median follow-up of 52 months, Dr. Binkley and his colleagues found that 29.1% of patients developed relapsed lymphoma at a median 23 months (range, 1-143 months) following primary radiotherapy.

The team reported that the 3-year overall survival rate was 91.4% for patients with lymphoma recurrence after primary radiotherapy. In total, 16 deaths occurred during follow-up: eight were lymphoma specific deaths, three were from other causes, and in five patients the cause was unknown.

Of the 149 cases of relapsed lymphoma, 93 were indolent. There were also three cases of FL grade 3B/not otherwise specified and 18 cases of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. In 35 patients who relapsed, biopsies were not performed.

“The excellent prognosis observed for this relapse cohort emphasizes that primary radiation for localized follicular lymphoma is an excellent treatment option,” the researchers wrote.

When the researchers examined survival based on the time of relapse, they found that overall survival was “significantly worse” for patients who had relapsed 12 months or less after the date of diagnosis, at 88.7%, compared with all others at 95.8% (P = .01).

They found no difference in overall survival between patients who received immediate salvage treatment, compared with observation after relapse (P = .28). There was also no significant difference in survival between patients who relapsed in 1 year or less but underwent immediate treatment, compared to early relapsed patients who were observed (log-rank P = .34).

“[A]ny decision to offer treatment at time of relapse must be weighed with the risk of acute and late adverse effects. Greater than 60% of patients in our cohort with indolent recurrence who underwent salvage treatment received rituximab, likely contributing to the excellent outcomes,” the researchers wrote. “However, nearly 60% of patients with indolent recurrence who were observed did not have disease progression nor [did they] receive treatment within 3 years.”

The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Binkley MS et al. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2019 Mar 8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2019.03.004.

FROM THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RADIATION ONCOLOGY, BIOLOGY, PHYSICS

Sleepless democracy, space herpes, and the F-bomb diet

Sleep: the key to democracy?

You might need to lie down for this one. Insufficient sleep could be affecting the very institutions and behaviors that keep society from crumbling.

Lack of sleep is proven to affect “private” behaviors, like working, but a new study has shown that exhaustion also has consequences on a national scale. Sleeping less negatively affects the “social behaviors that hold society and democracy together,” according to the study’s authors.

Willingness to vote, donate to charities, and sign petitions decreased in sleep-deprived participants. Although that last one is iffy – is anyone really willing to sign a petition, regardless of sleep intake? One thing to glean from this study is, if you’re holding a clipboard, let the most tired-looking people keep walking.

Perhaps we should start a petition to make the day before Election Day a national napping holiday.

I hear you knocking, but you can’t come in

LOTME takes you to the ends of the earth for this edition of Bacteria vs. the World. Let’s go to our correspondent, Danielle Kang, on the International Space Station.

Hi, this is Briny Baird in Berlin, Germany. The space station’s extreme environment weakens astronauts’ immune systems, but it has the opposite effect on bacteria, as Elisabeth Grohmann, PhD, of Beuth University of Applied Sciences explains.

“The bacteria [astronauts] carry become hardier – developing thick protective coatings and resistance to antibiotics – and more vigorous, multiplying and metabolizing faster.”

This is, as scientists put it, bad. To prevent an on-board bacterial bacchanal, Dr. Grohmann and her associates covered a vital piece of ISS equipment, the toilet door, with a new coating containing “silver and ruthenium, conditioned by a vitamin derivative.” After 19 months in space, the coated section of the door had 80% fewer bacteria on it than an uncoated control surface.

With long-term missions to Mars being considered, it should be safer for astronauts and their toilet doors to … go where no one has gone before. Back to the studio.

The F-bomb diet

You might think vulgarities and Homo sapiens have been an inseparable pair since the first human bashed her thumb while chipping stones into spearheads to add meat to her diet. You’d probably be right – except for blue-tinged language built on the consonant foundations of the letters F and V.

New linguistics research finds that those $#%*! letters, like truckers and Marine gunnery sergeants, are relatively modern developments. As humans moved away from finger-harming hunting and gathering and toward finger-harming farming, they developed a taste for softer foods. And their speech picked up “labiodentals” such as F and V – which are sounds made when we touch our lower lips to our upper teeth. Half the world’s languages are now riddled with soft-food profanities, er, labiodentals.

Next on the linguists’ research list: Does the paleo diet lead to the dropping of fewer F-bombs?

Herpes! In space!

Viruses can never let bacteria have all the fun. Where there’s an immune system weakened by radiation and microgravity, rest assured, our old friend the herpes virus will be waiting for us.

Yes, it looks like frequent bathroom trips won’t be the only issue future Dr. McCoys will be treating. According to a study published in Frontiers in Microbiology, four of the eight herpes viruses were discovered in the saliva and urine of more than half of the hundred or so astronauts who had samples analyzed during spaceflight.

The good news is that only six astronauts actually had symptoms emerge, all of which were minor. The bad news is that the strength, frequency, and duration of viral shedding through urine and saliva increased as more time was spent in space. Also, only one of the herpes varieties found has a vaccine. The rest will just have to be treated as symptoms emerge.

We’ll just hope Captain Kirk doesn’t come down with a case of mononucleosis while fighting the Klingons. Damn it, Jim, I’m a doctor, not a miracle worker!

Sleep: the key to democracy?

You might need to lie down for this one. Insufficient sleep could be affecting the very institutions and behaviors that keep society from crumbling.

Lack of sleep is proven to affect “private” behaviors, like working, but a new study has shown that exhaustion also has consequences on a national scale. Sleeping less negatively affects the “social behaviors that hold society and democracy together,” according to the study’s authors.

Willingness to vote, donate to charities, and sign petitions decreased in sleep-deprived participants. Although that last one is iffy – is anyone really willing to sign a petition, regardless of sleep intake? One thing to glean from this study is, if you’re holding a clipboard, let the most tired-looking people keep walking.

Perhaps we should start a petition to make the day before Election Day a national napping holiday.

I hear you knocking, but you can’t come in

LOTME takes you to the ends of the earth for this edition of Bacteria vs. the World. Let’s go to our correspondent, Danielle Kang, on the International Space Station.

Hi, this is Briny Baird in Berlin, Germany. The space station’s extreme environment weakens astronauts’ immune systems, but it has the opposite effect on bacteria, as Elisabeth Grohmann, PhD, of Beuth University of Applied Sciences explains.

“The bacteria [astronauts] carry become hardier – developing thick protective coatings and resistance to antibiotics – and more vigorous, multiplying and metabolizing faster.”

This is, as scientists put it, bad. To prevent an on-board bacterial bacchanal, Dr. Grohmann and her associates covered a vital piece of ISS equipment, the toilet door, with a new coating containing “silver and ruthenium, conditioned by a vitamin derivative.” After 19 months in space, the coated section of the door had 80% fewer bacteria on it than an uncoated control surface.

With long-term missions to Mars being considered, it should be safer for astronauts and their toilet doors to … go where no one has gone before. Back to the studio.

The F-bomb diet

You might think vulgarities and Homo sapiens have been an inseparable pair since the first human bashed her thumb while chipping stones into spearheads to add meat to her diet. You’d probably be right – except for blue-tinged language built on the consonant foundations of the letters F and V.

New linguistics research finds that those $#%*! letters, like truckers and Marine gunnery sergeants, are relatively modern developments. As humans moved away from finger-harming hunting and gathering and toward finger-harming farming, they developed a taste for softer foods. And their speech picked up “labiodentals” such as F and V – which are sounds made when we touch our lower lips to our upper teeth. Half the world’s languages are now riddled with soft-food profanities, er, labiodentals.

Next on the linguists’ research list: Does the paleo diet lead to the dropping of fewer F-bombs?

Herpes! In space!

Viruses can never let bacteria have all the fun. Where there’s an immune system weakened by radiation and microgravity, rest assured, our old friend the herpes virus will be waiting for us.

Yes, it looks like frequent bathroom trips won’t be the only issue future Dr. McCoys will be treating. According to a study published in Frontiers in Microbiology, four of the eight herpes viruses were discovered in the saliva and urine of more than half of the hundred or so astronauts who had samples analyzed during spaceflight.

The good news is that only six astronauts actually had symptoms emerge, all of which were minor. The bad news is that the strength, frequency, and duration of viral shedding through urine and saliva increased as more time was spent in space. Also, only one of the herpes varieties found has a vaccine. The rest will just have to be treated as symptoms emerge.

We’ll just hope Captain Kirk doesn’t come down with a case of mononucleosis while fighting the Klingons. Damn it, Jim, I’m a doctor, not a miracle worker!

Sleep: the key to democracy?

You might need to lie down for this one. Insufficient sleep could be affecting the very institutions and behaviors that keep society from crumbling.

Lack of sleep is proven to affect “private” behaviors, like working, but a new study has shown that exhaustion also has consequences on a national scale. Sleeping less negatively affects the “social behaviors that hold society and democracy together,” according to the study’s authors.

Willingness to vote, donate to charities, and sign petitions decreased in sleep-deprived participants. Although that last one is iffy – is anyone really willing to sign a petition, regardless of sleep intake? One thing to glean from this study is, if you’re holding a clipboard, let the most tired-looking people keep walking.

Perhaps we should start a petition to make the day before Election Day a national napping holiday.

I hear you knocking, but you can’t come in

LOTME takes you to the ends of the earth for this edition of Bacteria vs. the World. Let’s go to our correspondent, Danielle Kang, on the International Space Station.