User login

Prevalence and Postdischarge Outcomes Associated with Frailty in Medical Inpatients: Impact of Different Frailty Definitions

Frailty is associated with adverse outcomes in hospitalized patients, including longer length of stay, increased risk of institutionalization at discharge, and higher rates of readmissions or death postdischarge.1-4 Multiple tools have been developed to evaluate frailty and in an earlier study,4 we compared the three most common of these and demonstrated that the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS)5 was the most useful tool clinically as it was most strongly associated with adverse events in the first 30 days after discharge. However, it must be collected prospectively and requires contact with patients or proxies for the evaluator to assign the patient into one of nine categories depending on their disease state, mobility, cognition, and ability to perform instrumental and functional activities of daily living. Recently, a new score has been described which is based on an administrative data algorithm that assigns points to patients having any of 109 ICD-10 codes listed for their index hospitalization and all hospitalizations in the prior two years and can be generated retrospectively without trained observers.6 Although higher Hospital Frailty Risk Scores (HFRS) were associated with greater risk of postdischarge adverse events, the kappa when compared with the CFS was only 0.30 (95% CI 0.22-0.38) in that study.6 However, as the HFRS was developed and validated in patients aged ≥75 years within the UK National Health Service, the authors themselves recommended that it be evaluated in other healthcare systems, other populations, and with comparison to prospectively collected frailty data from cumulative deficit models such as the CFS.

The aim of this study was to compare frailty assessments using the CFS and the HFRS in a population of adult patients hospitalized on general medical wards in North America to determine the impact on prevalence estimates and prediction of outcomes within the first 30 days after hospital discharge (a timeframe highlighted in the Affordable Care Act and used by Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services as an important hospital quality indicator).

METHODS

As described previously,7 we performed a prospective cohort study of adults without cognitive impairment or life expectancy less than three months being discharged back to the community (not to long-term care facilities) from general medical wards in two teaching hospitals in Edmonton, Alberta, between October 2013 and November 2014. All patients provided signed consent, and the University of Alberta Health Research Ethics board (project ID Pro00036880) approved the study.

Trained observers assessed each patient’s frailty status within 24 hours of discharge based on the patient’s best status in the week prior to becoming ill with the reason for the index hospitalization. The research assistant classified patients into one of the following nine CFS categories: very fit, well, managing well, vulnerable, mildly frail (need help with at least one instrumental activities of daily living such as shopping, finances, meal preparation, or housework), moderately frail (need help with one or two activities of daily living such as bathing and dressing), severely frail (dependent for personal care), very severely frail (bedbound), and terminally ill. According to the CFS validation studies, the last five categories were defined as frail for the purposes of our analyses.

Independent of the trained observer’s assessments, we calculated the HFRS for each participant in our cohort by linking to Alberta administrative data holdings within the Alberta Health Services Data Integration and Measurement Reporting unit and examining all diagnostic codes for the index hospitalization and any other hospitalizations in the prior two years for the 109 ICD-10 codes listed in the original HFRS paper and used the same score cutpoints as they reported (HFRS <5 being low risk, 5-15 defined as intermediate risk, and >15 as high risk for frailty; scores ≥5 were defined as frail).6

All patients were followed after discharge by research personnel blinded to the patient’s frailty assessment. We used patient/caregiver self-report and the provincial electronic health record to collect information on all-cause readmissions or mortality within 30 days.

We have previously reported4,7 the association between frailty defined by the CFS and unplanned readmissions or death within 30 days of discharge but in this study, we examined the correlation between CFS-defined frailty and the HFRS score (classifying those with intermediate or high scores as frail) using chance-corrected kappa coefficients. We also compared the prognostic accuracy of both models for predicting death and/or unplanned readmissions within 30 days using the C statistic and the integrated discrimination improvement index and examined patients aged >65 years as a subgroup.8 We used SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) for analyses, with P values of <.05 considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Of the 499 patients in our original cohort,7 we could not link 10 to the administrative data to calculate HFRS, and thus this study sample is only 489 patients (mean age 64 years, 50% women, 52% older than 65 years, a mean of 4.9 comorbidities, and median length of stay five days).

Overall, 276 (56%) patients were deemed frail according to at least one assessment (214 [44%] on the HFRS [35% intermediate risk and 9% high risk] and 161 [33%] on the CFS), and 99 (20%) met both frailty definitions (Appendix Figure). Among the 252 patients aged >65 years, 66 (26%) met both frailty definitions and 166 (66%) were frail according to at least one assessment. Agreement between HFRS and the CFS (kappa 0.24, 95% CI 0.16-0.33) was poor. The CFS definition of frailty was 46% sensitive and 77% specific in classifying frail patients compared with HFRS-defined frailty.

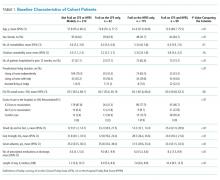

As we reported earlier,4 patients deemed frail were generally similar across scales in that they were older, had more comorbidities, more prescriptions, longer lengths of stay, and poorer quality of life than nonfrail patients (all P < .01, Table 1). However, patients classified as frail on the HFRS only but not meeting the CFS definition were younger, had higher quality of life, and despite a similar Charlson Score and number of comorbidities were much more likely to have been living independently prior to admission than those classified as frail on the CFS.

Death or unplanned readmission within 30 days occurred in 13.3% (65 patients), with most events being readmissions (62, 12.7%). HFRS-defined frail patients exhibited higher 30-day death/readmission rates (16% vs 11% for not frail, P = .08; 14% vs 11% in the elderly, P = .5), which was not statistically significantly different from the nonfrail patients even after adjusting for age and sex (aOR [adjusted odds ratio] 1.62, 95% CI 0.95-2.75 for all adults; aOR 1.24, 95% CI 0.58-2.63 for the elderly). CFS-defined frail patients had significantly higher 30-day readmission/death rates (19% vs 10% for not frail, aOR 2.53, 95% CI 1.40-4.57 for all adults and 21% vs 6% in the elderly, aOR 4.31, 95% CI 1.80-10.31).

Adding the HFRS results to the CFS-based predictive models added little new information, with an integrated discrimination improvement of only 0.009 that was not statistically significant (P = .09, Table 2). In fact, the HFRS was not an independent predictor of postdischarge outcomes after adjusting for age and sex. Although predictive models incorporating the CFS demonstrated the best C statistics, none of the models had high C statistics (ranging between 0.54 and 0.64 for all adults and between 0.55 and 0.68 for those aged >65 years). Even when the frailty definitions were examined as continuous variables, the C statistics were similar as for the dichotomized analyses (0.64 for CFS and 0.58 for HFRS) and the correlation between the two remained weak (Spearman’s correlation coefficient 0.34).

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated that the prevalence of frailty in patients being discharged from medical wards was high, with the HFRS (44%) being higher than the CFS (33%), and that only 46% of patients deemed frail on the HFRS were also deemed frail on the CFS. We confirm the report by the developers of the HFRS that there was poor correlation between the CFS cumulative deficit model and the administrative-data-based HFRS model in our cohort, even among those older than 65 years.

Previous studies have reported marked heterogeneity in prevalence estimates between different frailty instruments.2,9 For example, Aguayo et al. found that the prevalence of frailty in the English Longitudinal Study of Aging varied between 0.9% and 68% depending on which of the 35 frailty scales they tested were used, although the prevalence with comprehensive geriatric assessments (the gold standard) was 14.9% (and 15.3% on the CFS).9 Although frail patients are at higher risk for death and/or readmission after discharge, other investigators have also reported similar findings to ours that frailty-based risk models are surprisingly modest at predicting postdischarge readmission or death, with the C statistics ranging between 0.52 and 0.57, although the CFS appears to correlate best with the gold standard of comprehensive geriatric assessment.10-14 This is not surprising since the CFS is multidimensional and as a cumulative deficit model, it incorporates assessment of the patient’s underlying diseases, cognition, function, mobility, and mood in the assignment of their CFS level. Regardless, others15 have pointed out the need for studies such as ours to compare the validity of published frailty scales.

Despite our prospective cohort design and blinded endpoint ascertainment, there are some potential limitations to our study. First, we excluded long-term care residents and patients with foreshortened life expectancy – the frailest of the frail – from our analysis of 30-day outcomes, thereby potentially reducing the magnitude of the association between frailty and adverse outcomes. However, we were interested only in situations where clinicians were faced with equipoise about patient prognosis. Second, we assessed only 30-day readmissions or deaths and cannot comment on the impact of frailty definitions on other postdischarge outcomes (such as discharge locale or need for home care services) or other timeframes. Finally, although the association between the HFRS definition of frailty and the 30-day mortality/readmission was not statistically significant, the 95% confidence intervals were wide and thus we cannot definitively rule out a positive association.

In conclusion, considering that it had the strongest association with postdischarge outcomes and is the fastest and easiest to perform, the most useful of the frailty assessment tools for clinicians at the bedside still appears to be the CFS (both overall and in those patients who are elderly). However, for researchers who are analyzing data retrospectively or policy planners looking at health services data where the CFS was not collected, the HFRS holds promise for risk adjustment in population-level studies comparing processes and outcomes between hospitals.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Miriam Fradette, Debbie Boyko, Sara Belga, Darren Lau, Jenelle Pederson, and Sharry Kahlon for their important contributions in data acquisition in our original cohort study, as well as all the physicians rotating through the general internal medicine wards at the University of Alberta Hospital for their help in identifying the patients. We also thank Dr. Simon Conroy, MB ChB PhD, University of Leicester, UK, for his helpful comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. All authors had access to the data and played a role in writing and revising this manuscript.

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by an operating grant from Alberta Innovates - Health Solutions. F.A.M. holds the Chair in Cardiovascular Outcomes Research at the Mazankowski Heart Institute, University of Alberta. The authors have no affiliations or financial interests with any organization or entity with a financial interest in the contents of this manuscript.

1. Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 2013;381(9868):752-762. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62167-9. PubMed

2. Collard RM, Boter H, Schoevers RA, Oude Voshaar RC. Prevalence of frailty in community-dwelling older persons: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(8):1487-1492. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04054.x. PubMed

3. de Vries NM, Staal JB, van Ravensberg CD, Hobbelen JS, Olde Rikkert MG, Nijhuis-van der Sanden MW. Outcome instruments to measure frailty: a systematic review. Ageing Res Rev. 2011;10(1):104-114. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2010.09.001. PubMed

4. Belga S, Majumdar SR, Kahlon S, et al. Comparing three different measures of frailty in medical inpatients: multicenter prospective cohort study examining 30-day risk of readmission or death. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(8):556-562. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2607. PubMed

5. Rockwood K, Andrew M, Mintnitski A. A comparison of two approaches to measuring frailty in elerly people. J Gerontol. 2007;62(7):738-743. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.7.738. PubMed

6. Gilbert T, Neuburger J, Kraindler J, et al. Development and validation of a Hospital Frailty Risk Score focusing on older people in acute care settings using electronic hospital records: an observational study. Lancet. 2018;391(10132):1775-1782. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30668-8Get. PubMed

7. Kahlon S, Pederson J, Majumdar SR, et al. Association between frailty and 30-day outcomes after discharge from hospital. CMAJ. 2015;187(11):799-804. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.150100. PubMed

8. Pencina MJ, D’ Agostino RB, Vasan RS. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the roc curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat Med. 2008;27(2):157-172. doi: 10.1002/sim.2929.

9. Aguayo GA, Donneau A-F, Vaillant MT, et al. Agreement between 35 published frailty scores in the general population. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;186(4):420-434. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwx061. PubMed

10. Ritt M, Bollheimer LC, Siever CC, Gaßmann KG. Prediction of one-year mortality by five different frailty instruments: a comparative study in hospitalized geriatric patients. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2016;66:66-72. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2016.05.004. PubMed

11. Forti P, Rietti E, Pisacane N, Olivelli V, Maltoni B, Ravaglia G. A comparison of frailty indexes for prediction of adverse health outcomes in a elderly cohort. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;54(1):16-20. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2011.01.007. PubMed

12. Wou F, Gladman JR, Bradshaw L, Franklin M, Edmans J, Conroy SP. The predictive properties of frailty-rating scales in the acute medical unit. Age Ageing. 2013;42(6):776-781. doi: 10.1093/ageing/aft055. PubMed

13. Wallis SJ, Wall J, Biram RW, Romero-Ortuno R. Association of the clinical frailty scale with hospital outcomes. QJM. 2015;108(12):943-949. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcv066. PubMed

14. Harmand MGC, Meillon C, Bergua V, et al. Comparing the predictive value of three definitions of frailty: results from the Three-City Study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2017;72:153-163. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2017.06.005. PubMed

15. Bouillon K, Kivimaki M, Hamer M, et al. Measures of frailty in population-based studies: an overview. BMC Geriatrics. 2013;13(1):64. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-13-64. PubMed

Frailty is associated with adverse outcomes in hospitalized patients, including longer length of stay, increased risk of institutionalization at discharge, and higher rates of readmissions or death postdischarge.1-4 Multiple tools have been developed to evaluate frailty and in an earlier study,4 we compared the three most common of these and demonstrated that the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS)5 was the most useful tool clinically as it was most strongly associated with adverse events in the first 30 days after discharge. However, it must be collected prospectively and requires contact with patients or proxies for the evaluator to assign the patient into one of nine categories depending on their disease state, mobility, cognition, and ability to perform instrumental and functional activities of daily living. Recently, a new score has been described which is based on an administrative data algorithm that assigns points to patients having any of 109 ICD-10 codes listed for their index hospitalization and all hospitalizations in the prior two years and can be generated retrospectively without trained observers.6 Although higher Hospital Frailty Risk Scores (HFRS) were associated with greater risk of postdischarge adverse events, the kappa when compared with the CFS was only 0.30 (95% CI 0.22-0.38) in that study.6 However, as the HFRS was developed and validated in patients aged ≥75 years within the UK National Health Service, the authors themselves recommended that it be evaluated in other healthcare systems, other populations, and with comparison to prospectively collected frailty data from cumulative deficit models such as the CFS.

The aim of this study was to compare frailty assessments using the CFS and the HFRS in a population of adult patients hospitalized on general medical wards in North America to determine the impact on prevalence estimates and prediction of outcomes within the first 30 days after hospital discharge (a timeframe highlighted in the Affordable Care Act and used by Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services as an important hospital quality indicator).

METHODS

As described previously,7 we performed a prospective cohort study of adults without cognitive impairment or life expectancy less than three months being discharged back to the community (not to long-term care facilities) from general medical wards in two teaching hospitals in Edmonton, Alberta, between October 2013 and November 2014. All patients provided signed consent, and the University of Alberta Health Research Ethics board (project ID Pro00036880) approved the study.

Trained observers assessed each patient’s frailty status within 24 hours of discharge based on the patient’s best status in the week prior to becoming ill with the reason for the index hospitalization. The research assistant classified patients into one of the following nine CFS categories: very fit, well, managing well, vulnerable, mildly frail (need help with at least one instrumental activities of daily living such as shopping, finances, meal preparation, or housework), moderately frail (need help with one or two activities of daily living such as bathing and dressing), severely frail (dependent for personal care), very severely frail (bedbound), and terminally ill. According to the CFS validation studies, the last five categories were defined as frail for the purposes of our analyses.

Independent of the trained observer’s assessments, we calculated the HFRS for each participant in our cohort by linking to Alberta administrative data holdings within the Alberta Health Services Data Integration and Measurement Reporting unit and examining all diagnostic codes for the index hospitalization and any other hospitalizations in the prior two years for the 109 ICD-10 codes listed in the original HFRS paper and used the same score cutpoints as they reported (HFRS <5 being low risk, 5-15 defined as intermediate risk, and >15 as high risk for frailty; scores ≥5 were defined as frail).6

All patients were followed after discharge by research personnel blinded to the patient’s frailty assessment. We used patient/caregiver self-report and the provincial electronic health record to collect information on all-cause readmissions or mortality within 30 days.

We have previously reported4,7 the association between frailty defined by the CFS and unplanned readmissions or death within 30 days of discharge but in this study, we examined the correlation between CFS-defined frailty and the HFRS score (classifying those with intermediate or high scores as frail) using chance-corrected kappa coefficients. We also compared the prognostic accuracy of both models for predicting death and/or unplanned readmissions within 30 days using the C statistic and the integrated discrimination improvement index and examined patients aged >65 years as a subgroup.8 We used SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) for analyses, with P values of <.05 considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Of the 499 patients in our original cohort,7 we could not link 10 to the administrative data to calculate HFRS, and thus this study sample is only 489 patients (mean age 64 years, 50% women, 52% older than 65 years, a mean of 4.9 comorbidities, and median length of stay five days).

Overall, 276 (56%) patients were deemed frail according to at least one assessment (214 [44%] on the HFRS [35% intermediate risk and 9% high risk] and 161 [33%] on the CFS), and 99 (20%) met both frailty definitions (Appendix Figure). Among the 252 patients aged >65 years, 66 (26%) met both frailty definitions and 166 (66%) were frail according to at least one assessment. Agreement between HFRS and the CFS (kappa 0.24, 95% CI 0.16-0.33) was poor. The CFS definition of frailty was 46% sensitive and 77% specific in classifying frail patients compared with HFRS-defined frailty.

As we reported earlier,4 patients deemed frail were generally similar across scales in that they were older, had more comorbidities, more prescriptions, longer lengths of stay, and poorer quality of life than nonfrail patients (all P < .01, Table 1). However, patients classified as frail on the HFRS only but not meeting the CFS definition were younger, had higher quality of life, and despite a similar Charlson Score and number of comorbidities were much more likely to have been living independently prior to admission than those classified as frail on the CFS.

Death or unplanned readmission within 30 days occurred in 13.3% (65 patients), with most events being readmissions (62, 12.7%). HFRS-defined frail patients exhibited higher 30-day death/readmission rates (16% vs 11% for not frail, P = .08; 14% vs 11% in the elderly, P = .5), which was not statistically significantly different from the nonfrail patients even after adjusting for age and sex (aOR [adjusted odds ratio] 1.62, 95% CI 0.95-2.75 for all adults; aOR 1.24, 95% CI 0.58-2.63 for the elderly). CFS-defined frail patients had significantly higher 30-day readmission/death rates (19% vs 10% for not frail, aOR 2.53, 95% CI 1.40-4.57 for all adults and 21% vs 6% in the elderly, aOR 4.31, 95% CI 1.80-10.31).

Adding the HFRS results to the CFS-based predictive models added little new information, with an integrated discrimination improvement of only 0.009 that was not statistically significant (P = .09, Table 2). In fact, the HFRS was not an independent predictor of postdischarge outcomes after adjusting for age and sex. Although predictive models incorporating the CFS demonstrated the best C statistics, none of the models had high C statistics (ranging between 0.54 and 0.64 for all adults and between 0.55 and 0.68 for those aged >65 years). Even when the frailty definitions were examined as continuous variables, the C statistics were similar as for the dichotomized analyses (0.64 for CFS and 0.58 for HFRS) and the correlation between the two remained weak (Spearman’s correlation coefficient 0.34).

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated that the prevalence of frailty in patients being discharged from medical wards was high, with the HFRS (44%) being higher than the CFS (33%), and that only 46% of patients deemed frail on the HFRS were also deemed frail on the CFS. We confirm the report by the developers of the HFRS that there was poor correlation between the CFS cumulative deficit model and the administrative-data-based HFRS model in our cohort, even among those older than 65 years.

Previous studies have reported marked heterogeneity in prevalence estimates between different frailty instruments.2,9 For example, Aguayo et al. found that the prevalence of frailty in the English Longitudinal Study of Aging varied between 0.9% and 68% depending on which of the 35 frailty scales they tested were used, although the prevalence with comprehensive geriatric assessments (the gold standard) was 14.9% (and 15.3% on the CFS).9 Although frail patients are at higher risk for death and/or readmission after discharge, other investigators have also reported similar findings to ours that frailty-based risk models are surprisingly modest at predicting postdischarge readmission or death, with the C statistics ranging between 0.52 and 0.57, although the CFS appears to correlate best with the gold standard of comprehensive geriatric assessment.10-14 This is not surprising since the CFS is multidimensional and as a cumulative deficit model, it incorporates assessment of the patient’s underlying diseases, cognition, function, mobility, and mood in the assignment of their CFS level. Regardless, others15 have pointed out the need for studies such as ours to compare the validity of published frailty scales.

Despite our prospective cohort design and blinded endpoint ascertainment, there are some potential limitations to our study. First, we excluded long-term care residents and patients with foreshortened life expectancy – the frailest of the frail – from our analysis of 30-day outcomes, thereby potentially reducing the magnitude of the association between frailty and adverse outcomes. However, we were interested only in situations where clinicians were faced with equipoise about patient prognosis. Second, we assessed only 30-day readmissions or deaths and cannot comment on the impact of frailty definitions on other postdischarge outcomes (such as discharge locale or need for home care services) or other timeframes. Finally, although the association between the HFRS definition of frailty and the 30-day mortality/readmission was not statistically significant, the 95% confidence intervals were wide and thus we cannot definitively rule out a positive association.

In conclusion, considering that it had the strongest association with postdischarge outcomes and is the fastest and easiest to perform, the most useful of the frailty assessment tools for clinicians at the bedside still appears to be the CFS (both overall and in those patients who are elderly). However, for researchers who are analyzing data retrospectively or policy planners looking at health services data where the CFS was not collected, the HFRS holds promise for risk adjustment in population-level studies comparing processes and outcomes between hospitals.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Miriam Fradette, Debbie Boyko, Sara Belga, Darren Lau, Jenelle Pederson, and Sharry Kahlon for their important contributions in data acquisition in our original cohort study, as well as all the physicians rotating through the general internal medicine wards at the University of Alberta Hospital for their help in identifying the patients. We also thank Dr. Simon Conroy, MB ChB PhD, University of Leicester, UK, for his helpful comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. All authors had access to the data and played a role in writing and revising this manuscript.

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by an operating grant from Alberta Innovates - Health Solutions. F.A.M. holds the Chair in Cardiovascular Outcomes Research at the Mazankowski Heart Institute, University of Alberta. The authors have no affiliations or financial interests with any organization or entity with a financial interest in the contents of this manuscript.

Frailty is associated with adverse outcomes in hospitalized patients, including longer length of stay, increased risk of institutionalization at discharge, and higher rates of readmissions or death postdischarge.1-4 Multiple tools have been developed to evaluate frailty and in an earlier study,4 we compared the three most common of these and demonstrated that the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS)5 was the most useful tool clinically as it was most strongly associated with adverse events in the first 30 days after discharge. However, it must be collected prospectively and requires contact with patients or proxies for the evaluator to assign the patient into one of nine categories depending on their disease state, mobility, cognition, and ability to perform instrumental and functional activities of daily living. Recently, a new score has been described which is based on an administrative data algorithm that assigns points to patients having any of 109 ICD-10 codes listed for their index hospitalization and all hospitalizations in the prior two years and can be generated retrospectively without trained observers.6 Although higher Hospital Frailty Risk Scores (HFRS) were associated with greater risk of postdischarge adverse events, the kappa when compared with the CFS was only 0.30 (95% CI 0.22-0.38) in that study.6 However, as the HFRS was developed and validated in patients aged ≥75 years within the UK National Health Service, the authors themselves recommended that it be evaluated in other healthcare systems, other populations, and with comparison to prospectively collected frailty data from cumulative deficit models such as the CFS.

The aim of this study was to compare frailty assessments using the CFS and the HFRS in a population of adult patients hospitalized on general medical wards in North America to determine the impact on prevalence estimates and prediction of outcomes within the first 30 days after hospital discharge (a timeframe highlighted in the Affordable Care Act and used by Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services as an important hospital quality indicator).

METHODS

As described previously,7 we performed a prospective cohort study of adults without cognitive impairment or life expectancy less than three months being discharged back to the community (not to long-term care facilities) from general medical wards in two teaching hospitals in Edmonton, Alberta, between October 2013 and November 2014. All patients provided signed consent, and the University of Alberta Health Research Ethics board (project ID Pro00036880) approved the study.

Trained observers assessed each patient’s frailty status within 24 hours of discharge based on the patient’s best status in the week prior to becoming ill with the reason for the index hospitalization. The research assistant classified patients into one of the following nine CFS categories: very fit, well, managing well, vulnerable, mildly frail (need help with at least one instrumental activities of daily living such as shopping, finances, meal preparation, or housework), moderately frail (need help with one or two activities of daily living such as bathing and dressing), severely frail (dependent for personal care), very severely frail (bedbound), and terminally ill. According to the CFS validation studies, the last five categories were defined as frail for the purposes of our analyses.

Independent of the trained observer’s assessments, we calculated the HFRS for each participant in our cohort by linking to Alberta administrative data holdings within the Alberta Health Services Data Integration and Measurement Reporting unit and examining all diagnostic codes for the index hospitalization and any other hospitalizations in the prior two years for the 109 ICD-10 codes listed in the original HFRS paper and used the same score cutpoints as they reported (HFRS <5 being low risk, 5-15 defined as intermediate risk, and >15 as high risk for frailty; scores ≥5 were defined as frail).6

All patients were followed after discharge by research personnel blinded to the patient’s frailty assessment. We used patient/caregiver self-report and the provincial electronic health record to collect information on all-cause readmissions or mortality within 30 days.

We have previously reported4,7 the association between frailty defined by the CFS and unplanned readmissions or death within 30 days of discharge but in this study, we examined the correlation between CFS-defined frailty and the HFRS score (classifying those with intermediate or high scores as frail) using chance-corrected kappa coefficients. We also compared the prognostic accuracy of both models for predicting death and/or unplanned readmissions within 30 days using the C statistic and the integrated discrimination improvement index and examined patients aged >65 years as a subgroup.8 We used SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) for analyses, with P values of <.05 considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Of the 499 patients in our original cohort,7 we could not link 10 to the administrative data to calculate HFRS, and thus this study sample is only 489 patients (mean age 64 years, 50% women, 52% older than 65 years, a mean of 4.9 comorbidities, and median length of stay five days).

Overall, 276 (56%) patients were deemed frail according to at least one assessment (214 [44%] on the HFRS [35% intermediate risk and 9% high risk] and 161 [33%] on the CFS), and 99 (20%) met both frailty definitions (Appendix Figure). Among the 252 patients aged >65 years, 66 (26%) met both frailty definitions and 166 (66%) were frail according to at least one assessment. Agreement between HFRS and the CFS (kappa 0.24, 95% CI 0.16-0.33) was poor. The CFS definition of frailty was 46% sensitive and 77% specific in classifying frail patients compared with HFRS-defined frailty.

As we reported earlier,4 patients deemed frail were generally similar across scales in that they were older, had more comorbidities, more prescriptions, longer lengths of stay, and poorer quality of life than nonfrail patients (all P < .01, Table 1). However, patients classified as frail on the HFRS only but not meeting the CFS definition were younger, had higher quality of life, and despite a similar Charlson Score and number of comorbidities were much more likely to have been living independently prior to admission than those classified as frail on the CFS.

Death or unplanned readmission within 30 days occurred in 13.3% (65 patients), with most events being readmissions (62, 12.7%). HFRS-defined frail patients exhibited higher 30-day death/readmission rates (16% vs 11% for not frail, P = .08; 14% vs 11% in the elderly, P = .5), which was not statistically significantly different from the nonfrail patients even after adjusting for age and sex (aOR [adjusted odds ratio] 1.62, 95% CI 0.95-2.75 for all adults; aOR 1.24, 95% CI 0.58-2.63 for the elderly). CFS-defined frail patients had significantly higher 30-day readmission/death rates (19% vs 10% for not frail, aOR 2.53, 95% CI 1.40-4.57 for all adults and 21% vs 6% in the elderly, aOR 4.31, 95% CI 1.80-10.31).

Adding the HFRS results to the CFS-based predictive models added little new information, with an integrated discrimination improvement of only 0.009 that was not statistically significant (P = .09, Table 2). In fact, the HFRS was not an independent predictor of postdischarge outcomes after adjusting for age and sex. Although predictive models incorporating the CFS demonstrated the best C statistics, none of the models had high C statistics (ranging between 0.54 and 0.64 for all adults and between 0.55 and 0.68 for those aged >65 years). Even when the frailty definitions were examined as continuous variables, the C statistics were similar as for the dichotomized analyses (0.64 for CFS and 0.58 for HFRS) and the correlation between the two remained weak (Spearman’s correlation coefficient 0.34).

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated that the prevalence of frailty in patients being discharged from medical wards was high, with the HFRS (44%) being higher than the CFS (33%), and that only 46% of patients deemed frail on the HFRS were also deemed frail on the CFS. We confirm the report by the developers of the HFRS that there was poor correlation between the CFS cumulative deficit model and the administrative-data-based HFRS model in our cohort, even among those older than 65 years.

Previous studies have reported marked heterogeneity in prevalence estimates between different frailty instruments.2,9 For example, Aguayo et al. found that the prevalence of frailty in the English Longitudinal Study of Aging varied between 0.9% and 68% depending on which of the 35 frailty scales they tested were used, although the prevalence with comprehensive geriatric assessments (the gold standard) was 14.9% (and 15.3% on the CFS).9 Although frail patients are at higher risk for death and/or readmission after discharge, other investigators have also reported similar findings to ours that frailty-based risk models are surprisingly modest at predicting postdischarge readmission or death, with the C statistics ranging between 0.52 and 0.57, although the CFS appears to correlate best with the gold standard of comprehensive geriatric assessment.10-14 This is not surprising since the CFS is multidimensional and as a cumulative deficit model, it incorporates assessment of the patient’s underlying diseases, cognition, function, mobility, and mood in the assignment of their CFS level. Regardless, others15 have pointed out the need for studies such as ours to compare the validity of published frailty scales.

Despite our prospective cohort design and blinded endpoint ascertainment, there are some potential limitations to our study. First, we excluded long-term care residents and patients with foreshortened life expectancy – the frailest of the frail – from our analysis of 30-day outcomes, thereby potentially reducing the magnitude of the association between frailty and adverse outcomes. However, we were interested only in situations where clinicians were faced with equipoise about patient prognosis. Second, we assessed only 30-day readmissions or deaths and cannot comment on the impact of frailty definitions on other postdischarge outcomes (such as discharge locale or need for home care services) or other timeframes. Finally, although the association between the HFRS definition of frailty and the 30-day mortality/readmission was not statistically significant, the 95% confidence intervals were wide and thus we cannot definitively rule out a positive association.

In conclusion, considering that it had the strongest association with postdischarge outcomes and is the fastest and easiest to perform, the most useful of the frailty assessment tools for clinicians at the bedside still appears to be the CFS (both overall and in those patients who are elderly). However, for researchers who are analyzing data retrospectively or policy planners looking at health services data where the CFS was not collected, the HFRS holds promise for risk adjustment in population-level studies comparing processes and outcomes between hospitals.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Miriam Fradette, Debbie Boyko, Sara Belga, Darren Lau, Jenelle Pederson, and Sharry Kahlon for their important contributions in data acquisition in our original cohort study, as well as all the physicians rotating through the general internal medicine wards at the University of Alberta Hospital for their help in identifying the patients. We also thank Dr. Simon Conroy, MB ChB PhD, University of Leicester, UK, for his helpful comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. All authors had access to the data and played a role in writing and revising this manuscript.

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by an operating grant from Alberta Innovates - Health Solutions. F.A.M. holds the Chair in Cardiovascular Outcomes Research at the Mazankowski Heart Institute, University of Alberta. The authors have no affiliations or financial interests with any organization or entity with a financial interest in the contents of this manuscript.

1. Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 2013;381(9868):752-762. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62167-9. PubMed

2. Collard RM, Boter H, Schoevers RA, Oude Voshaar RC. Prevalence of frailty in community-dwelling older persons: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(8):1487-1492. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04054.x. PubMed

3. de Vries NM, Staal JB, van Ravensberg CD, Hobbelen JS, Olde Rikkert MG, Nijhuis-van der Sanden MW. Outcome instruments to measure frailty: a systematic review. Ageing Res Rev. 2011;10(1):104-114. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2010.09.001. PubMed

4. Belga S, Majumdar SR, Kahlon S, et al. Comparing three different measures of frailty in medical inpatients: multicenter prospective cohort study examining 30-day risk of readmission or death. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(8):556-562. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2607. PubMed

5. Rockwood K, Andrew M, Mintnitski A. A comparison of two approaches to measuring frailty in elerly people. J Gerontol. 2007;62(7):738-743. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.7.738. PubMed

6. Gilbert T, Neuburger J, Kraindler J, et al. Development and validation of a Hospital Frailty Risk Score focusing on older people in acute care settings using electronic hospital records: an observational study. Lancet. 2018;391(10132):1775-1782. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30668-8Get. PubMed

7. Kahlon S, Pederson J, Majumdar SR, et al. Association between frailty and 30-day outcomes after discharge from hospital. CMAJ. 2015;187(11):799-804. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.150100. PubMed

8. Pencina MJ, D’ Agostino RB, Vasan RS. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the roc curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat Med. 2008;27(2):157-172. doi: 10.1002/sim.2929.

9. Aguayo GA, Donneau A-F, Vaillant MT, et al. Agreement between 35 published frailty scores in the general population. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;186(4):420-434. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwx061. PubMed

10. Ritt M, Bollheimer LC, Siever CC, Gaßmann KG. Prediction of one-year mortality by five different frailty instruments: a comparative study in hospitalized geriatric patients. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2016;66:66-72. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2016.05.004. PubMed

11. Forti P, Rietti E, Pisacane N, Olivelli V, Maltoni B, Ravaglia G. A comparison of frailty indexes for prediction of adverse health outcomes in a elderly cohort. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;54(1):16-20. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2011.01.007. PubMed

12. Wou F, Gladman JR, Bradshaw L, Franklin M, Edmans J, Conroy SP. The predictive properties of frailty-rating scales in the acute medical unit. Age Ageing. 2013;42(6):776-781. doi: 10.1093/ageing/aft055. PubMed

13. Wallis SJ, Wall J, Biram RW, Romero-Ortuno R. Association of the clinical frailty scale with hospital outcomes. QJM. 2015;108(12):943-949. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcv066. PubMed

14. Harmand MGC, Meillon C, Bergua V, et al. Comparing the predictive value of three definitions of frailty: results from the Three-City Study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2017;72:153-163. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2017.06.005. PubMed

15. Bouillon K, Kivimaki M, Hamer M, et al. Measures of frailty in population-based studies: an overview. BMC Geriatrics. 2013;13(1):64. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-13-64. PubMed

1. Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 2013;381(9868):752-762. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62167-9. PubMed

2. Collard RM, Boter H, Schoevers RA, Oude Voshaar RC. Prevalence of frailty in community-dwelling older persons: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(8):1487-1492. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04054.x. PubMed

3. de Vries NM, Staal JB, van Ravensberg CD, Hobbelen JS, Olde Rikkert MG, Nijhuis-van der Sanden MW. Outcome instruments to measure frailty: a systematic review. Ageing Res Rev. 2011;10(1):104-114. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2010.09.001. PubMed

4. Belga S, Majumdar SR, Kahlon S, et al. Comparing three different measures of frailty in medical inpatients: multicenter prospective cohort study examining 30-day risk of readmission or death. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(8):556-562. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2607. PubMed

5. Rockwood K, Andrew M, Mintnitski A. A comparison of two approaches to measuring frailty in elerly people. J Gerontol. 2007;62(7):738-743. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.7.738. PubMed

6. Gilbert T, Neuburger J, Kraindler J, et al. Development and validation of a Hospital Frailty Risk Score focusing on older people in acute care settings using electronic hospital records: an observational study. Lancet. 2018;391(10132):1775-1782. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30668-8Get. PubMed

7. Kahlon S, Pederson J, Majumdar SR, et al. Association between frailty and 30-day outcomes after discharge from hospital. CMAJ. 2015;187(11):799-804. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.150100. PubMed

8. Pencina MJ, D’ Agostino RB, Vasan RS. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the roc curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat Med. 2008;27(2):157-172. doi: 10.1002/sim.2929.

9. Aguayo GA, Donneau A-F, Vaillant MT, et al. Agreement between 35 published frailty scores in the general population. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;186(4):420-434. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwx061. PubMed

10. Ritt M, Bollheimer LC, Siever CC, Gaßmann KG. Prediction of one-year mortality by five different frailty instruments: a comparative study in hospitalized geriatric patients. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2016;66:66-72. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2016.05.004. PubMed

11. Forti P, Rietti E, Pisacane N, Olivelli V, Maltoni B, Ravaglia G. A comparison of frailty indexes for prediction of adverse health outcomes in a elderly cohort. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;54(1):16-20. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2011.01.007. PubMed

12. Wou F, Gladman JR, Bradshaw L, Franklin M, Edmans J, Conroy SP. The predictive properties of frailty-rating scales in the acute medical unit. Age Ageing. 2013;42(6):776-781. doi: 10.1093/ageing/aft055. PubMed

13. Wallis SJ, Wall J, Biram RW, Romero-Ortuno R. Association of the clinical frailty scale with hospital outcomes. QJM. 2015;108(12):943-949. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcv066. PubMed

14. Harmand MGC, Meillon C, Bergua V, et al. Comparing the predictive value of three definitions of frailty: results from the Three-City Study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2017;72:153-163. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2017.06.005. PubMed

15. Bouillon K, Kivimaki M, Hamer M, et al. Measures of frailty in population-based studies: an overview. BMC Geriatrics. 2013;13(1):64. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-13-64. PubMed

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

Things We Do For No Reason: Failing to Question a Penicillin Allergy History

Inspired by the ABIM Foundation’s Choosing Wisely® campaign, the “Things We Do for No Reason” (TWDFNR) series reviews practices that have become common parts of hospital care but may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent “black and white” conclusions or clinical practice standards but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion.

CLINICAL SCENARIO

An 80-year-old male—with a past medical history significant for hypertension, atrial fibrillation, and type II diabetes mellitus—presented to the hospital with fevers, confusion, and urinary outflow tract difficulties. On exam, he was noted to have mild suprapubic tenderness with flank tenderness. Blood and urine cultures grew Enterococcus faecalis sensitive to ampicillin. Because of the patient’s listed penicillin (PCN) allergy, he was started on aztreonam and vancomycin instead of ampicillin.

WHY YOU MIGHT SIMPLY ACCEPT A PCN ALLERGY HISTORY

Ten percent of the population in the United States reports an allergy to penicillin and derivatives—one of the most commonly reported drug allergies.1 Allergic reactions to drugs are distinct immune reactions mediated by drug-specific immunoglobulin E (IgE) that are potentially life-threatening. Specifically these allergic reactions are called IgE-mediated, type 1 hypersensitivity reactions which are characterized by hives; itching; flushing; tissue swelling, especially in areas of the face and neck; bronchospasm; and gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, including cramping and diarrhea. Head and neck swelling can quickly result in airway compromise. Profound fluid extravasation and release of mediators from mast cells and basophils can rapidly drop blood pressure. Anaphylaxis requires rapid intervention to prevent severe complications and death. Given the life-threatening consequences of anaphylaxis, a cautious approach before administering PCN to PCN-allergic patients is mandatory.

WHY YOU SHOULD QUESTION A REPORTED PCN ALLERGY

While 10% of the adult population and 15% of hospitalized adults report PCN allergy, clinical studies suggest that 90% of all patients reporting a PCN allergy can tolerate PCN antibiotics.1-3 There are several reasons patients initially labeled as PCN allergic may later be able to tolerate this drug. First, patients can lose sensitivity to specific PCN IgE antibodies over time if PCN is avoided.4 Second, non-IgE-mediated immune reactions of skin or GI tract are often wrongly attributed to an IgE-mediated process from a concurrent medication (Table). For example, viral infections can cause exanthems or hives which may be mistaken for an antibiotic-associated IgE-meditated allergic reaction.6 These non-IgE skin reactions include severe manifestations including Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis or benign adverse reactions such as GI upset, dizziness, or diarrhea which are often misclassified as an allergy, and this error is perpetuated in the medical record. Third, patients may report a PCN allergy for themselves when a family member is possibly allergic.

PCN allergy has risen to the level of a public health issue as PCN-allergic patients are often relegated to second-line broad-spectrum antibiotics.7 This public health issue is exacerbated when patients with faux or resolved PCN allergy receive the same treatment. Patients labeled as PCN allergic—whether correctly or incorrectly—have poorer outcomes as noted by increased rates of serious infections and tend to have longer hospital stays.8-10 Treatment-related secondary infections from the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, such as Clostridiiodes difficile and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus, are identified more frequently in PCN-allergic patients.7 Additionally, pregnant women with PCN allergy, with or without group B streptococcus infections, have higher rates of cesarean sections and longer hospitalizations.11 The misuse and overuse of antibiotics, especially broad-spectrum medications, has led to resistant bacteria that are increasingly difficult to treat.7 Treating with the most narrow-spectrum antibiotic whenever possible is critical. Overall, failure to address and assess PCN allergy can result in treatment failures and unnecessary broad-spectrum antibiotic use.

WHEN YOU SHOULD BELIEVE A REPORTED PCN AND BETA-LACTAMS ALLERGY HISTORY

Avoid beta-lactams for patients with a reported allergy who are medically frail (eg, critically ill intensive care unit patients and those unable to communicate) or have a documented allergic reaction to a beta-lactam within five years. An estimated 50% of patients who had a documented true IgE-mediated allergic reaction within five years of a documented true allergic reaction remain allergic to PCN and are at risk for an allergic reaction with reexposure.1 PCN allergy evaluation with PCN skin testing (PST) and oral challenge in patients who had a reaction within five years have a higher risk of a fatal outcome with an oral challenge despite negative skin testing. PCN allergy evaluation is best handled on a case by case basis in this population.

WHAT YOU SHOULD DO INSTEAD

Obtain a thorough drug allergy history. If the history is not consistent with a personal history of an IgE-mediated reaction to PCN ever or if there is documentation that PCN was administered and tolerated since the reaction (eg, a dental prescription), a PCN or beta-lactam can be given. An exception to this rule are patients with a history of an allergic reaction to both a cephalosporin and a PCN—approach this as two separate allergies. Remove the PCN allergy if it is not consistent with the history of IgE-mediated reaction or the patient subsequently had tolerated a PCN/PCN derivative. Regarding the cephalosporin issue, patients are often allergic to a side chain of the cephalosporin and not to the beta-lactam ring. Patients should avoid the specific cephalosporin unless the history is also not consistent with an IgE-mediated reaction or the patient had subsequently tolerated this medication. An allergy evaluation can be useful to discern next steps for cephalosporin allergy. Once the antibiotic is administered and tolerated, the medical record should be updated as well to prevent future mislabeling.

If the symptoms associated with a reported history of a PCN allergy are unknown or consistent with an IgE-mediated reaction, or the patient has not been exposed to PCN since the allergic reaction, the patient should undergo PST followed by a supervised oral test dose to determine whether the allergy exists or persists. PCN allergy evaluation is a simple two-step process of PST followed by an oral challenge of amoxicillin. The use of PCN allergy testing as described is validated and safe.12 A negative skin prick and intradermal test have a negative predictive value that approaches 100%.12,13 Completing the final step—the oral challenge—eliminates concerns for false-negative testing results and patient fears. Additionally, once a patient has had negative skin testing and passed an oral challenge, he/she is not at increased risk of resensitization after PCN/PCN derivative use.14

Although the test takes one and a half hours on average, the benefits that follow are lifelong. Improving future management by disproving a reported allergy affects an individual patient’s clinical course globally, results in cost savings, and increases the use of narrow-spectrum antimicrobials. It is particularly important to test PCN-allergic patients preemptively who are at high risk of requiring PCN/PCN derivative antibiotics. High-risk patients include, but are not limited to, surgery, transplant, hematology/oncology, and immunosuppressed patients. Inpatients with PCN allergy have higher antibiotic costs—both for medications used during their hospitalization and also for discharge medications.15 A study by Macy and Contreras compared the cost of skin testing to money saved by shortening hospitalization days for 51,582 patients with PCN allergy.7 The cost for testing was $131.37 each (total of $6.7 million). The testing contributed to a $64 million savings for the three-year study period—savings that is 9.5 times larger than the cost of the evaluation.8 A smaller study that looked at cost-effectiveness of PST for 50 patients found an overall cost savings of $11,005 due to the antimicrobial choice alone ($297 per patient switched to a beta-lactam antibiotic).16

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Obtain a thorough drug allergy history as many “allergic reactions” can be removed by history alone. Update the medical record if you can confirm a patient has since tolerated PCN or a PCN derivative to which they were previously allergic. Offer a supervised oral challenge if the patient has any concerns.

- Perform PST if a patient has a PCN allergy listed in their chart and the allergy history is unclear. A negative skin test should be followed by a supervised oral challenge to PCN/PCN derivative if skin testing is negative.

- Test PCN-allergic patients preemptively who are at high risk of requiring PCN/PCN derivative antibiotics. High-risk patients include surgery, transplant, hematology/oncology, and immunosuppressed patients.

- Implement published protocols from allergists for healthcare systems that lack access to allergy physicians.

- Do not perform PST on patients with a history that is suggestive of a non-IgE-mediated allergic reaction. For these cases, patients are advised to avoid the medication. A supervised graded oral challenge can be considered on a case by case basis if the reaction was not a severe cutaneous adverse reaction syndrome, like SJS, and the benefit of using the medication outweighs the potential harm.

CONCLUSION

The patient, in this case, reported an allergic reaction to PCN over 50 years before this presentation. The reported reaction immediately after receiving IV PCN was a rash—a symptom concerning for an IgE-mediated reaction. Since the patient is well over 10 years from his allergic reaction and would benefit from a PCN derivative, PST testing should be pursued.

The patient passed his skin testing and an oral challenge dose of amoxicillin. With the PCN allergy removed from his chart, his medical team transitioned him from aztreonam and vancomycin to ampicillin. He was then discharged home on amoxicillin and informed that he might be safely treated with PCN/PCN derivatives in the future.

Given the rise in antimicrobial resistance and both the clinical implications and increased costs associated with PCN allergy, it is crucial to offer an allergy evaluation to patients identified as PCN allergic. Hospitalists play a crucial role in obtaining the initial history, determining if the patient has tolerated the antibiotic since the initial reaction, and identifying patients who may benefit from further evaluation for PCN allergy. In hospitals with PST available for inpatients, testing can be performed during the admission. Additionally, it is essential that allergists work with hospitalists and primary care physicians to provide seamless access to outpatient drug allergy evaluations (PST followed by oral challenge) to address the issue of PCN allergy before an acute need for a PCN/PCN derivative antibiotic in the hospital.

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason?” Share what you do in your practice and join in the conversation online by retweeting it on Twitter (#TWDFNR) and liking it on Facebook. We invite you to propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason” topics by e-mailing TWDFNR@hospitalmedicine.org.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This work is supported by the following NIH Grant: T-32 AI007062-39.

1. American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology, the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology, and the Joint Council of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Drug allergy: an updated practice parameter. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;105(4):259-273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2010.08.002.

2. American Academy of Allergy AI. Ten things physicians and patients should question Choosing Wisely, ABIM Foundation 2014. http://www.choosingwisely.org/clinician-lists/american-academy-allergy-asthma-immunlogy-non-beta-lactam-antibiotics-penicillin-allergy/. Accessed October 23, 2017.

3. Blumenthal KG, Wickner PG, Hurwitz S, et al. Tackling inpatient penicillin allergies: Assessing tools for antimicrobial stewardship. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140(1):154-161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2017.02.005.

4. Blanca M, Torres MJ, Garcia JJ, et al. Natural evolution of skin test sensitivity in patients allergic to beta-lactam antibiotics. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;103(5):918-924. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0091-6749(99)70439-2.

5. Duong TA Valeyrie-Allanore L, Wolkenstein P, Chosidow O. Severe cutaneous adverse reactions to drugs. Lancet. 2017;390(10106:1996-2011. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30378-6.

6. Gonzalez-Estrada A, Radojicic C. Penicillin allergy: a practical guide for clinicians. Cleve Clin J Med. 2015;82(5):295-300. https://doi.org/10.3949/ccjm.82a.14111.

7. Solensky R. Penicillin allergy as a public health measure. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(3):797-798. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2013.10.032.

8. Macy E, Contreras R. Health care use and serious infection prevalence associated with penicillin “allergy” in hospitalized patients: a cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(3):790-796. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2013.09.021.

9. Chen JR, Khan DA. Evaluation of penicillin allergy in the hospitalized patient: opportunities for antimicrobial stewardship. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2017;17(6):40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11882-017-0706-1.

10. Blumenthal KG, Wickner PG, Hurwitz S, et al. Tackling inpatient penicillin allergies: Assessing tools for antimicrobial stewardship. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140(1):154-161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2017.02.005.

11. Desai SH, Kaplan MS, Chen Q, Macy EM. Morbidity in pregnant women associated with unverified penicillin allergies, antibiotic use, and group B Streptococcus infections. Perm J. 2017;21. https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/16-080.

12. Macy E, Ngor EW. Safely diagnosing clinically significant penicillin allergy using only penicilloyl-poly-lysine, penicillin, and oral amoxicillin. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2013;1(3):258-263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2013.02.002.

13. Solensky R. The time for penicillin skin testing is here. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2013;1(3):264-265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2013.03.010.

14. Solensky R, Earl HS, Gruchalla RS. Lack of penicillin resensitization in patients with a history of penicillin allergy after receiving repeated penicillin courses. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(7):822-826.

15. Sade K, Holtzer I, Levo Y, Kivity S. The economic burden of antibiotic treatment of penicillin-allergic patients in internal medicine wards of a general tertiary care hospital. Clin Exp Allergy. 2003;33(4):501-506. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2222.2003.01638.x.

16. King EA, Challa S, Curtin P, Bielory L. Penicillin skin testing in hospitalized patients with beta-lactam allergies: effect on antibiotic selection and cost. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016;117(1):67-71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2016.04.021.

Inspired by the ABIM Foundation’s Choosing Wisely® campaign, the “Things We Do for No Reason” (TWDFNR) series reviews practices that have become common parts of hospital care but may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent “black and white” conclusions or clinical practice standards but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion.

CLINICAL SCENARIO

An 80-year-old male—with a past medical history significant for hypertension, atrial fibrillation, and type II diabetes mellitus—presented to the hospital with fevers, confusion, and urinary outflow tract difficulties. On exam, he was noted to have mild suprapubic tenderness with flank tenderness. Blood and urine cultures grew Enterococcus faecalis sensitive to ampicillin. Because of the patient’s listed penicillin (PCN) allergy, he was started on aztreonam and vancomycin instead of ampicillin.

WHY YOU MIGHT SIMPLY ACCEPT A PCN ALLERGY HISTORY

Ten percent of the population in the United States reports an allergy to penicillin and derivatives—one of the most commonly reported drug allergies.1 Allergic reactions to drugs are distinct immune reactions mediated by drug-specific immunoglobulin E (IgE) that are potentially life-threatening. Specifically these allergic reactions are called IgE-mediated, type 1 hypersensitivity reactions which are characterized by hives; itching; flushing; tissue swelling, especially in areas of the face and neck; bronchospasm; and gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, including cramping and diarrhea. Head and neck swelling can quickly result in airway compromise. Profound fluid extravasation and release of mediators from mast cells and basophils can rapidly drop blood pressure. Anaphylaxis requires rapid intervention to prevent severe complications and death. Given the life-threatening consequences of anaphylaxis, a cautious approach before administering PCN to PCN-allergic patients is mandatory.

WHY YOU SHOULD QUESTION A REPORTED PCN ALLERGY

While 10% of the adult population and 15% of hospitalized adults report PCN allergy, clinical studies suggest that 90% of all patients reporting a PCN allergy can tolerate PCN antibiotics.1-3 There are several reasons patients initially labeled as PCN allergic may later be able to tolerate this drug. First, patients can lose sensitivity to specific PCN IgE antibodies over time if PCN is avoided.4 Second, non-IgE-mediated immune reactions of skin or GI tract are often wrongly attributed to an IgE-mediated process from a concurrent medication (Table). For example, viral infections can cause exanthems or hives which may be mistaken for an antibiotic-associated IgE-meditated allergic reaction.6 These non-IgE skin reactions include severe manifestations including Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis or benign adverse reactions such as GI upset, dizziness, or diarrhea which are often misclassified as an allergy, and this error is perpetuated in the medical record. Third, patients may report a PCN allergy for themselves when a family member is possibly allergic.

PCN allergy has risen to the level of a public health issue as PCN-allergic patients are often relegated to second-line broad-spectrum antibiotics.7 This public health issue is exacerbated when patients with faux or resolved PCN allergy receive the same treatment. Patients labeled as PCN allergic—whether correctly or incorrectly—have poorer outcomes as noted by increased rates of serious infections and tend to have longer hospital stays.8-10 Treatment-related secondary infections from the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, such as Clostridiiodes difficile and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus, are identified more frequently in PCN-allergic patients.7 Additionally, pregnant women with PCN allergy, with or without group B streptococcus infections, have higher rates of cesarean sections and longer hospitalizations.11 The misuse and overuse of antibiotics, especially broad-spectrum medications, has led to resistant bacteria that are increasingly difficult to treat.7 Treating with the most narrow-spectrum antibiotic whenever possible is critical. Overall, failure to address and assess PCN allergy can result in treatment failures and unnecessary broad-spectrum antibiotic use.

WHEN YOU SHOULD BELIEVE A REPORTED PCN AND BETA-LACTAMS ALLERGY HISTORY

Avoid beta-lactams for patients with a reported allergy who are medically frail (eg, critically ill intensive care unit patients and those unable to communicate) or have a documented allergic reaction to a beta-lactam within five years. An estimated 50% of patients who had a documented true IgE-mediated allergic reaction within five years of a documented true allergic reaction remain allergic to PCN and are at risk for an allergic reaction with reexposure.1 PCN allergy evaluation with PCN skin testing (PST) and oral challenge in patients who had a reaction within five years have a higher risk of a fatal outcome with an oral challenge despite negative skin testing. PCN allergy evaluation is best handled on a case by case basis in this population.

WHAT YOU SHOULD DO INSTEAD

Obtain a thorough drug allergy history. If the history is not consistent with a personal history of an IgE-mediated reaction to PCN ever or if there is documentation that PCN was administered and tolerated since the reaction (eg, a dental prescription), a PCN or beta-lactam can be given. An exception to this rule are patients with a history of an allergic reaction to both a cephalosporin and a PCN—approach this as two separate allergies. Remove the PCN allergy if it is not consistent with the history of IgE-mediated reaction or the patient subsequently had tolerated a PCN/PCN derivative. Regarding the cephalosporin issue, patients are often allergic to a side chain of the cephalosporin and not to the beta-lactam ring. Patients should avoid the specific cephalosporin unless the history is also not consistent with an IgE-mediated reaction or the patient had subsequently tolerated this medication. An allergy evaluation can be useful to discern next steps for cephalosporin allergy. Once the antibiotic is administered and tolerated, the medical record should be updated as well to prevent future mislabeling.

If the symptoms associated with a reported history of a PCN allergy are unknown or consistent with an IgE-mediated reaction, or the patient has not been exposed to PCN since the allergic reaction, the patient should undergo PST followed by a supervised oral test dose to determine whether the allergy exists or persists. PCN allergy evaluation is a simple two-step process of PST followed by an oral challenge of amoxicillin. The use of PCN allergy testing as described is validated and safe.12 A negative skin prick and intradermal test have a negative predictive value that approaches 100%.12,13 Completing the final step—the oral challenge—eliminates concerns for false-negative testing results and patient fears. Additionally, once a patient has had negative skin testing and passed an oral challenge, he/she is not at increased risk of resensitization after PCN/PCN derivative use.14

Although the test takes one and a half hours on average, the benefits that follow are lifelong. Improving future management by disproving a reported allergy affects an individual patient’s clinical course globally, results in cost savings, and increases the use of narrow-spectrum antimicrobials. It is particularly important to test PCN-allergic patients preemptively who are at high risk of requiring PCN/PCN derivative antibiotics. High-risk patients include, but are not limited to, surgery, transplant, hematology/oncology, and immunosuppressed patients. Inpatients with PCN allergy have higher antibiotic costs—both for medications used during their hospitalization and also for discharge medications.15 A study by Macy and Contreras compared the cost of skin testing to money saved by shortening hospitalization days for 51,582 patients with PCN allergy.7 The cost for testing was $131.37 each (total of $6.7 million). The testing contributed to a $64 million savings for the three-year study period—savings that is 9.5 times larger than the cost of the evaluation.8 A smaller study that looked at cost-effectiveness of PST for 50 patients found an overall cost savings of $11,005 due to the antimicrobial choice alone ($297 per patient switched to a beta-lactam antibiotic).16

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Obtain a thorough drug allergy history as many “allergic reactions” can be removed by history alone. Update the medical record if you can confirm a patient has since tolerated PCN or a PCN derivative to which they were previously allergic. Offer a supervised oral challenge if the patient has any concerns.

- Perform PST if a patient has a PCN allergy listed in their chart and the allergy history is unclear. A negative skin test should be followed by a supervised oral challenge to PCN/PCN derivative if skin testing is negative.

- Test PCN-allergic patients preemptively who are at high risk of requiring PCN/PCN derivative antibiotics. High-risk patients include surgery, transplant, hematology/oncology, and immunosuppressed patients.

- Implement published protocols from allergists for healthcare systems that lack access to allergy physicians.

- Do not perform PST on patients with a history that is suggestive of a non-IgE-mediated allergic reaction. For these cases, patients are advised to avoid the medication. A supervised graded oral challenge can be considered on a case by case basis if the reaction was not a severe cutaneous adverse reaction syndrome, like SJS, and the benefit of using the medication outweighs the potential harm.

CONCLUSION

The patient, in this case, reported an allergic reaction to PCN over 50 years before this presentation. The reported reaction immediately after receiving IV PCN was a rash—a symptom concerning for an IgE-mediated reaction. Since the patient is well over 10 years from his allergic reaction and would benefit from a PCN derivative, PST testing should be pursued.

The patient passed his skin testing and an oral challenge dose of amoxicillin. With the PCN allergy removed from his chart, his medical team transitioned him from aztreonam and vancomycin to ampicillin. He was then discharged home on amoxicillin and informed that he might be safely treated with PCN/PCN derivatives in the future.

Given the rise in antimicrobial resistance and both the clinical implications and increased costs associated with PCN allergy, it is crucial to offer an allergy evaluation to patients identified as PCN allergic. Hospitalists play a crucial role in obtaining the initial history, determining if the patient has tolerated the antibiotic since the initial reaction, and identifying patients who may benefit from further evaluation for PCN allergy. In hospitals with PST available for inpatients, testing can be performed during the admission. Additionally, it is essential that allergists work with hospitalists and primary care physicians to provide seamless access to outpatient drug allergy evaluations (PST followed by oral challenge) to address the issue of PCN allergy before an acute need for a PCN/PCN derivative antibiotic in the hospital.

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason?” Share what you do in your practice and join in the conversation online by retweeting it on Twitter (#TWDFNR) and liking it on Facebook. We invite you to propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason” topics by e-mailing TWDFNR@hospitalmedicine.org.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This work is supported by the following NIH Grant: T-32 AI007062-39.

Inspired by the ABIM Foundation’s Choosing Wisely® campaign, the “Things We Do for No Reason” (TWDFNR) series reviews practices that have become common parts of hospital care but may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent “black and white” conclusions or clinical practice standards but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion.

CLINICAL SCENARIO

An 80-year-old male—with a past medical history significant for hypertension, atrial fibrillation, and type II diabetes mellitus—presented to the hospital with fevers, confusion, and urinary outflow tract difficulties. On exam, he was noted to have mild suprapubic tenderness with flank tenderness. Blood and urine cultures grew Enterococcus faecalis sensitive to ampicillin. Because of the patient’s listed penicillin (PCN) allergy, he was started on aztreonam and vancomycin instead of ampicillin.

WHY YOU MIGHT SIMPLY ACCEPT A PCN ALLERGY HISTORY

Ten percent of the population in the United States reports an allergy to penicillin and derivatives—one of the most commonly reported drug allergies.1 Allergic reactions to drugs are distinct immune reactions mediated by drug-specific immunoglobulin E (IgE) that are potentially life-threatening. Specifically these allergic reactions are called IgE-mediated, type 1 hypersensitivity reactions which are characterized by hives; itching; flushing; tissue swelling, especially in areas of the face and neck; bronchospasm; and gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, including cramping and diarrhea. Head and neck swelling can quickly result in airway compromise. Profound fluid extravasation and release of mediators from mast cells and basophils can rapidly drop blood pressure. Anaphylaxis requires rapid intervention to prevent severe complications and death. Given the life-threatening consequences of anaphylaxis, a cautious approach before administering PCN to PCN-allergic patients is mandatory.

WHY YOU SHOULD QUESTION A REPORTED PCN ALLERGY

While 10% of the adult population and 15% of hospitalized adults report PCN allergy, clinical studies suggest that 90% of all patients reporting a PCN allergy can tolerate PCN antibiotics.1-3 There are several reasons patients initially labeled as PCN allergic may later be able to tolerate this drug. First, patients can lose sensitivity to specific PCN IgE antibodies over time if PCN is avoided.4 Second, non-IgE-mediated immune reactions of skin or GI tract are often wrongly attributed to an IgE-mediated process from a concurrent medication (Table). For example, viral infections can cause exanthems or hives which may be mistaken for an antibiotic-associated IgE-meditated allergic reaction.6 These non-IgE skin reactions include severe manifestations including Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis or benign adverse reactions such as GI upset, dizziness, or diarrhea which are often misclassified as an allergy, and this error is perpetuated in the medical record. Third, patients may report a PCN allergy for themselves when a family member is possibly allergic.

PCN allergy has risen to the level of a public health issue as PCN-allergic patients are often relegated to second-line broad-spectrum antibiotics.7 This public health issue is exacerbated when patients with faux or resolved PCN allergy receive the same treatment. Patients labeled as PCN allergic—whether correctly or incorrectly—have poorer outcomes as noted by increased rates of serious infections and tend to have longer hospital stays.8-10 Treatment-related secondary infections from the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, such as Clostridiiodes difficile and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus, are identified more frequently in PCN-allergic patients.7 Additionally, pregnant women with PCN allergy, with or without group B streptococcus infections, have higher rates of cesarean sections and longer hospitalizations.11 The misuse and overuse of antibiotics, especially broad-spectrum medications, has led to resistant bacteria that are increasingly difficult to treat.7 Treating with the most narrow-spectrum antibiotic whenever possible is critical. Overall, failure to address and assess PCN allergy can result in treatment failures and unnecessary broad-spectrum antibiotic use.

WHEN YOU SHOULD BELIEVE A REPORTED PCN AND BETA-LACTAMS ALLERGY HISTORY