User login

Pembrolizumab/lenvatinib active against urothelial carcinoma

SAN FRANCISCO – A combination of a targeted therapy and an immune checkpoint inhibitor showed promising activity against advanced urothelial cancer in early data from a phase 1b/2 study.

In a cohort of 20 patients with urothelial carcinoma who were enrolled in a larger clinical trial testing the combination of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) lenvatinib (Lenvima) and the checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab (Keytruda) against urinary tract and other solid malignancies, 5 had an objective response to the combination, including one complete and four partial responses, for an objective response rate of 25%, reported Nicholas J. Vogelzang, MD, from Comprehensive Cancers Centers of Nevada in Las Vegas.

“This response rate warrants further investigation. The lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab combination will be studied in a phase 3 trial in urothelial carcinoma,” he said at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) - Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC): Clinical Immuno-Oncology Symposium.

Dr. Vogelzang noted that urothelial carcinomas account for more than 90% of all bladder cancers. Pembrolizumab monotherapy is approved for treatment of patients with urothelial carcinoma who are ineligible for cisplatin and whose tumors have a combined positive score (CPS) for programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) of 10 or greater or who are ineligible for platinum-based chemotherapy regimens and, in the second line, for advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma.

Lenvatinib, a multikinase inhibitor, is approved as monotherapy for radioiodine-refractory differentiated thyroid cancer, unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma, and in combination with everolimus for advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC) after one year of antiangiogenic therapy.

Dr. Vogelzang reported results of the urothelial cancer cohort from a multicohort study testing the combination.

Twenty patients with histologically confirmed metastatic urothelial cancer were enrolled. The patients all had no more than two prior systemic regimens, good performance status, and a life expectancy of at least 12 weeks. The patients received oral lenvatinib 20 mg daily and pembrolizumab 200 mg intravenously every 21 days. The median patient age was 72 years. The cohort included 14 men and six women.

The objective response rate (ORR) at 24 weeks, the primary endpoint, was 25%, comprising one complete and four partial responses. Nine patients had stable disease, two had disease progression, and four were not evaluable for efficacy. The results were identical according to immune-related Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1 and modified RECIST version 1.1. Of the 16 evaluable patients, 12 experienced tumor-size reductions from baseline.

“Although there were five objective responses, there were an additional seven patients or more who had minor regressions of disease – clearly an active regimen,” Dr. Vogelzang said. Four of the patients, including one with a PD-L1–positive tumor and three with PD-L1–negative tumors were still alive, with the longest survival past 80 weeks since the start of therapy. The majority of patients, however, had no objective response or disease progression within about 20 weeks.

After a median follow-up of 11.7 months, the median progression-free survival (PFS) was 5.4 months, and the 12-month PFS rate was 26%.

In all, 18 of the 20 patients (90%) experienced a treatment-related adverse event of any grade, 10 had grade 3 or 4 events, and 6 had serious adverse events including one death from gastrointestinal hemorrhage that Dr. Vogelzang said appeared to be related to lenvatinib. A total of four patients (20%) had a treatment-related event leading to withdrawal or discontinuation, seven had a dose reduction, and 12 had an interruption in therapy, primarily of lenvatinib. The most common toxicities were proteinuria, diarrhea, hypertension, fatigue, hypothyroidism, decreased appetite with nausea, pancreatitis with increased lipase, skin rash, vomiting, and dry mouth.

In addition to the planned phase 3 trial of the combination in urothelial carcinoma, lenvatinib/pembrolizumab is also being studied for the treatment of RCC.

The study was supported by Eisai and Merck Sharp & Dohme. Dr. Vogelzang disclosed financial relationships with Caris Life Sciences, Pfizer, Up to Date, AstraZeneca, MedImmune, and other companies. Five coauthors are employees of Merck or Esai.

SOURCE: Vogelzang NJ et al. ASCO-SITC, Abstract 11.

SAN FRANCISCO – A combination of a targeted therapy and an immune checkpoint inhibitor showed promising activity against advanced urothelial cancer in early data from a phase 1b/2 study.

In a cohort of 20 patients with urothelial carcinoma who were enrolled in a larger clinical trial testing the combination of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) lenvatinib (Lenvima) and the checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab (Keytruda) against urinary tract and other solid malignancies, 5 had an objective response to the combination, including one complete and four partial responses, for an objective response rate of 25%, reported Nicholas J. Vogelzang, MD, from Comprehensive Cancers Centers of Nevada in Las Vegas.

“This response rate warrants further investigation. The lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab combination will be studied in a phase 3 trial in urothelial carcinoma,” he said at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) - Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC): Clinical Immuno-Oncology Symposium.

Dr. Vogelzang noted that urothelial carcinomas account for more than 90% of all bladder cancers. Pembrolizumab monotherapy is approved for treatment of patients with urothelial carcinoma who are ineligible for cisplatin and whose tumors have a combined positive score (CPS) for programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) of 10 or greater or who are ineligible for platinum-based chemotherapy regimens and, in the second line, for advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma.

Lenvatinib, a multikinase inhibitor, is approved as monotherapy for radioiodine-refractory differentiated thyroid cancer, unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma, and in combination with everolimus for advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC) after one year of antiangiogenic therapy.

Dr. Vogelzang reported results of the urothelial cancer cohort from a multicohort study testing the combination.

Twenty patients with histologically confirmed metastatic urothelial cancer were enrolled. The patients all had no more than two prior systemic regimens, good performance status, and a life expectancy of at least 12 weeks. The patients received oral lenvatinib 20 mg daily and pembrolizumab 200 mg intravenously every 21 days. The median patient age was 72 years. The cohort included 14 men and six women.

The objective response rate (ORR) at 24 weeks, the primary endpoint, was 25%, comprising one complete and four partial responses. Nine patients had stable disease, two had disease progression, and four were not evaluable for efficacy. The results were identical according to immune-related Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1 and modified RECIST version 1.1. Of the 16 evaluable patients, 12 experienced tumor-size reductions from baseline.

“Although there were five objective responses, there were an additional seven patients or more who had minor regressions of disease – clearly an active regimen,” Dr. Vogelzang said. Four of the patients, including one with a PD-L1–positive tumor and three with PD-L1–negative tumors were still alive, with the longest survival past 80 weeks since the start of therapy. The majority of patients, however, had no objective response or disease progression within about 20 weeks.

After a median follow-up of 11.7 months, the median progression-free survival (PFS) was 5.4 months, and the 12-month PFS rate was 26%.

In all, 18 of the 20 patients (90%) experienced a treatment-related adverse event of any grade, 10 had grade 3 or 4 events, and 6 had serious adverse events including one death from gastrointestinal hemorrhage that Dr. Vogelzang said appeared to be related to lenvatinib. A total of four patients (20%) had a treatment-related event leading to withdrawal or discontinuation, seven had a dose reduction, and 12 had an interruption in therapy, primarily of lenvatinib. The most common toxicities were proteinuria, diarrhea, hypertension, fatigue, hypothyroidism, decreased appetite with nausea, pancreatitis with increased lipase, skin rash, vomiting, and dry mouth.

In addition to the planned phase 3 trial of the combination in urothelial carcinoma, lenvatinib/pembrolizumab is also being studied for the treatment of RCC.

The study was supported by Eisai and Merck Sharp & Dohme. Dr. Vogelzang disclosed financial relationships with Caris Life Sciences, Pfizer, Up to Date, AstraZeneca, MedImmune, and other companies. Five coauthors are employees of Merck or Esai.

SOURCE: Vogelzang NJ et al. ASCO-SITC, Abstract 11.

SAN FRANCISCO – A combination of a targeted therapy and an immune checkpoint inhibitor showed promising activity against advanced urothelial cancer in early data from a phase 1b/2 study.

In a cohort of 20 patients with urothelial carcinoma who were enrolled in a larger clinical trial testing the combination of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) lenvatinib (Lenvima) and the checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab (Keytruda) against urinary tract and other solid malignancies, 5 had an objective response to the combination, including one complete and four partial responses, for an objective response rate of 25%, reported Nicholas J. Vogelzang, MD, from Comprehensive Cancers Centers of Nevada in Las Vegas.

“This response rate warrants further investigation. The lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab combination will be studied in a phase 3 trial in urothelial carcinoma,” he said at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) - Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC): Clinical Immuno-Oncology Symposium.

Dr. Vogelzang noted that urothelial carcinomas account for more than 90% of all bladder cancers. Pembrolizumab monotherapy is approved for treatment of patients with urothelial carcinoma who are ineligible for cisplatin and whose tumors have a combined positive score (CPS) for programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) of 10 or greater or who are ineligible for platinum-based chemotherapy regimens and, in the second line, for advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma.

Lenvatinib, a multikinase inhibitor, is approved as monotherapy for radioiodine-refractory differentiated thyroid cancer, unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma, and in combination with everolimus for advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC) after one year of antiangiogenic therapy.

Dr. Vogelzang reported results of the urothelial cancer cohort from a multicohort study testing the combination.

Twenty patients with histologically confirmed metastatic urothelial cancer were enrolled. The patients all had no more than two prior systemic regimens, good performance status, and a life expectancy of at least 12 weeks. The patients received oral lenvatinib 20 mg daily and pembrolizumab 200 mg intravenously every 21 days. The median patient age was 72 years. The cohort included 14 men and six women.

The objective response rate (ORR) at 24 weeks, the primary endpoint, was 25%, comprising one complete and four partial responses. Nine patients had stable disease, two had disease progression, and four were not evaluable for efficacy. The results were identical according to immune-related Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1 and modified RECIST version 1.1. Of the 16 evaluable patients, 12 experienced tumor-size reductions from baseline.

“Although there were five objective responses, there were an additional seven patients or more who had minor regressions of disease – clearly an active regimen,” Dr. Vogelzang said. Four of the patients, including one with a PD-L1–positive tumor and three with PD-L1–negative tumors were still alive, with the longest survival past 80 weeks since the start of therapy. The majority of patients, however, had no objective response or disease progression within about 20 weeks.

After a median follow-up of 11.7 months, the median progression-free survival (PFS) was 5.4 months, and the 12-month PFS rate was 26%.

In all, 18 of the 20 patients (90%) experienced a treatment-related adverse event of any grade, 10 had grade 3 or 4 events, and 6 had serious adverse events including one death from gastrointestinal hemorrhage that Dr. Vogelzang said appeared to be related to lenvatinib. A total of four patients (20%) had a treatment-related event leading to withdrawal or discontinuation, seven had a dose reduction, and 12 had an interruption in therapy, primarily of lenvatinib. The most common toxicities were proteinuria, diarrhea, hypertension, fatigue, hypothyroidism, decreased appetite with nausea, pancreatitis with increased lipase, skin rash, vomiting, and dry mouth.

In addition to the planned phase 3 trial of the combination in urothelial carcinoma, lenvatinib/pembrolizumab is also being studied for the treatment of RCC.

The study was supported by Eisai and Merck Sharp & Dohme. Dr. Vogelzang disclosed financial relationships with Caris Life Sciences, Pfizer, Up to Date, AstraZeneca, MedImmune, and other companies. Five coauthors are employees of Merck or Esai.

SOURCE: Vogelzang NJ et al. ASCO-SITC, Abstract 11.

REPORTING FROM ASCO-SITC

Distinct features found in young-onset CRC

Young-onset colorectal cancer (CRC) has distinct clinical and molecular features, compared with disease diagnosed later in life, according to investigators who conducted a review that included more than 36,000 patients.

investigators said. Conversely, those younger patients were less likely to have BRAF V600 mutations than were patients 50 years old and older, the investigators reported in the journal Cancer.

Very young patients were more likely to have signet ring histology and less likely to have adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) mutations, according to senior study author Jonathan M. Loree, MD, and his coinvestigators at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

“We need to appreciate that there are unique biologic subtypes within young patients that may affect how their cancers behave and may require a personalized approach to treatment,” Dr. Loree said in a press statement. “Going forward, special clinical consideration should be given to, and further scientific investigations should be performed for, both very young patients with colorectal cancer and those with predisposing medical conditions.”

The incidence of young-onset CRC has increased 1%-3% annually in recent years, Dr. Loree and colleagues wrote in their report.

Although smaller studies have characterized molecular features of CRC in younger patients, there has so far been no comprehensive molecular characterization of these patients, they added. Accordingly, the investigators conducted a retrospective analysis that included more than 36,000 patients in four different patient cohorts.

Patients under 50 years more likely had synchronous metastases (P = .009), more likely had primary tumors in the distal colon and rectum (P less than .0001), and were more likely to be MSI-high (P = .038), compared with their older counterparts, Dr. Loree and coauthors reported.

BRAF V600 mutations were infrequent in patients under 30 years of age, at a prevalence of 4% or less, increasing to a high of 13% in patients aged 70 years or older (P less than 0.001), investigators also reported.

Very young patients, or those aged 18-29 years, had a higher prevalence of signet ring histology, compared with the other age groups (P = .0003), and they had a nearly fivefold increased odds of signet ring histology compared with patients in the 30-49 year age range, investigators wrote.

There were also considerably fewer APC mutations in the patients younger than 30 years, compared with older patients in the young-onset CRC group, with an odds ratio of 0.56 (95% confidence interval, 0.35-0.90; P = .015).

Hispanic patients were significantly overrepresented in the under-30-years age group (P = .0015), according to the report.

For patients under 50 years who also had inflammatory bowel disease, odds of mucinous or signet ring histology were higher (OR, 5.54; 95% CI, 2.24-13.74; P = .0004), and odds of APC mutations were lower (OR, 0.24; 95% CI, 0.07-0.75; P = .019), compared with younger patients with no such predisposing conditions.

“These notable differences in very young patients with CRC and those with predisposing conditions highlight that early-onset CRC has unique subsets within the population of patients younger than 50 years,” Dr. Loree and coauthors concluded.

Support to investigators in the study came from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, and the MD Anderson Colorectal Cancer Moon Shot Program. One coinvestigator reported disclosures related to Roche, Genentech, EMD Serono, Merck, Karyopharm, Amal, Navire, Symphogen, Holystone, Biocartis, Amgen, and Novartis.

SOURCE: Willauer AN et al. Cancer. 2019 Mar 11. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31994

Young-onset colorectal cancer (CRC) has distinct clinical and molecular features, compared with disease diagnosed later in life, according to investigators who conducted a review that included more than 36,000 patients.

investigators said. Conversely, those younger patients were less likely to have BRAF V600 mutations than were patients 50 years old and older, the investigators reported in the journal Cancer.

Very young patients were more likely to have signet ring histology and less likely to have adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) mutations, according to senior study author Jonathan M. Loree, MD, and his coinvestigators at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

“We need to appreciate that there are unique biologic subtypes within young patients that may affect how their cancers behave and may require a personalized approach to treatment,” Dr. Loree said in a press statement. “Going forward, special clinical consideration should be given to, and further scientific investigations should be performed for, both very young patients with colorectal cancer and those with predisposing medical conditions.”

The incidence of young-onset CRC has increased 1%-3% annually in recent years, Dr. Loree and colleagues wrote in their report.

Although smaller studies have characterized molecular features of CRC in younger patients, there has so far been no comprehensive molecular characterization of these patients, they added. Accordingly, the investigators conducted a retrospective analysis that included more than 36,000 patients in four different patient cohorts.

Patients under 50 years more likely had synchronous metastases (P = .009), more likely had primary tumors in the distal colon and rectum (P less than .0001), and were more likely to be MSI-high (P = .038), compared with their older counterparts, Dr. Loree and coauthors reported.

BRAF V600 mutations were infrequent in patients under 30 years of age, at a prevalence of 4% or less, increasing to a high of 13% in patients aged 70 years or older (P less than 0.001), investigators also reported.

Very young patients, or those aged 18-29 years, had a higher prevalence of signet ring histology, compared with the other age groups (P = .0003), and they had a nearly fivefold increased odds of signet ring histology compared with patients in the 30-49 year age range, investigators wrote.

There were also considerably fewer APC mutations in the patients younger than 30 years, compared with older patients in the young-onset CRC group, with an odds ratio of 0.56 (95% confidence interval, 0.35-0.90; P = .015).

Hispanic patients were significantly overrepresented in the under-30-years age group (P = .0015), according to the report.

For patients under 50 years who also had inflammatory bowel disease, odds of mucinous or signet ring histology were higher (OR, 5.54; 95% CI, 2.24-13.74; P = .0004), and odds of APC mutations were lower (OR, 0.24; 95% CI, 0.07-0.75; P = .019), compared with younger patients with no such predisposing conditions.

“These notable differences in very young patients with CRC and those with predisposing conditions highlight that early-onset CRC has unique subsets within the population of patients younger than 50 years,” Dr. Loree and coauthors concluded.

Support to investigators in the study came from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, and the MD Anderson Colorectal Cancer Moon Shot Program. One coinvestigator reported disclosures related to Roche, Genentech, EMD Serono, Merck, Karyopharm, Amal, Navire, Symphogen, Holystone, Biocartis, Amgen, and Novartis.

SOURCE: Willauer AN et al. Cancer. 2019 Mar 11. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31994

Young-onset colorectal cancer (CRC) has distinct clinical and molecular features, compared with disease diagnosed later in life, according to investigators who conducted a review that included more than 36,000 patients.

investigators said. Conversely, those younger patients were less likely to have BRAF V600 mutations than were patients 50 years old and older, the investigators reported in the journal Cancer.

Very young patients were more likely to have signet ring histology and less likely to have adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) mutations, according to senior study author Jonathan M. Loree, MD, and his coinvestigators at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

“We need to appreciate that there are unique biologic subtypes within young patients that may affect how their cancers behave and may require a personalized approach to treatment,” Dr. Loree said in a press statement. “Going forward, special clinical consideration should be given to, and further scientific investigations should be performed for, both very young patients with colorectal cancer and those with predisposing medical conditions.”

The incidence of young-onset CRC has increased 1%-3% annually in recent years, Dr. Loree and colleagues wrote in their report.

Although smaller studies have characterized molecular features of CRC in younger patients, there has so far been no comprehensive molecular characterization of these patients, they added. Accordingly, the investigators conducted a retrospective analysis that included more than 36,000 patients in four different patient cohorts.

Patients under 50 years more likely had synchronous metastases (P = .009), more likely had primary tumors in the distal colon and rectum (P less than .0001), and were more likely to be MSI-high (P = .038), compared with their older counterparts, Dr. Loree and coauthors reported.

BRAF V600 mutations were infrequent in patients under 30 years of age, at a prevalence of 4% or less, increasing to a high of 13% in patients aged 70 years or older (P less than 0.001), investigators also reported.

Very young patients, or those aged 18-29 years, had a higher prevalence of signet ring histology, compared with the other age groups (P = .0003), and they had a nearly fivefold increased odds of signet ring histology compared with patients in the 30-49 year age range, investigators wrote.

There were also considerably fewer APC mutations in the patients younger than 30 years, compared with older patients in the young-onset CRC group, with an odds ratio of 0.56 (95% confidence interval, 0.35-0.90; P = .015).

Hispanic patients were significantly overrepresented in the under-30-years age group (P = .0015), according to the report.

For patients under 50 years who also had inflammatory bowel disease, odds of mucinous or signet ring histology were higher (OR, 5.54; 95% CI, 2.24-13.74; P = .0004), and odds of APC mutations were lower (OR, 0.24; 95% CI, 0.07-0.75; P = .019), compared with younger patients with no such predisposing conditions.

“These notable differences in very young patients with CRC and those with predisposing conditions highlight that early-onset CRC has unique subsets within the population of patients younger than 50 years,” Dr. Loree and coauthors concluded.

Support to investigators in the study came from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, and the MD Anderson Colorectal Cancer Moon Shot Program. One coinvestigator reported disclosures related to Roche, Genentech, EMD Serono, Merck, Karyopharm, Amal, Navire, Symphogen, Holystone, Biocartis, Amgen, and Novartis.

SOURCE: Willauer AN et al. Cancer. 2019 Mar 11. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31994

FROM CANCER

Antenatal steroids for preterm birth is cost effective

Administering antenatal corticosteroids to pregnant women at high risk for preterm birth was a cost-effective intervention that improved infant respiratory outcomes, according to a new study.

“This intervention has a potential cost saving in the United States of approximately $100 million dollars annually from the benefit in the immediate neonatal outcome alone,” Cynthia Gyamfi-Bannerman, MD, of Columbia University, New York, and her associates reported in JAMA Pediatrics. “Because late preterm birth comprises a large proportion of all preterm births, our findings have the potential for a large influence on public health.”

The researchers conducted a retrospective secondary analysis of the randomized Antenatal Late Preterm Steroids (ALPS) clinical trial October 2010 to February 2015. The trial enrolled randomly assigned antenatal administration of betamethasone or placebo to women pregnant with a singleton and at high risk for preterm birth while between 34 weeks, 6 days, and 36 weeks, 0 days, of gestation.

Antenatal corticosteroid administration was regarded as effective if a newborn did not require treatment in the first 72 hours for respiratory distress or illness. Treatment could include “continuous positive airway pressure or high-flow nasal cannula for 2 hours or more, supplemental oxygen with a fraction of inspired oxygen of 30% or more for 4 hours or more, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation or mechanical ventilation,” Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman and her associates wrote.

To tally the costs, the researchers used Medicaid rates to estimate the total in 2015 U.S. dollars for betamethasone, outpatient visits or inpatient stays to administer it, and all direct newborn care costs, including neonatal ICU daily costs stratified by respiratory illness severity. Betamethasone administration included an initial 12-mg intramuscular dose followed by another after 24 hours if the infant had not been delivered.

“Because therapy often persists for longer than this 72-hour duration, we measured costs through hospital discharge,” the authors wrote. “The analysis took the perspective of a third-party payer in which we included direct medical costs and associated overhead accruing to hospitals and medical payers for the care of enrolled patients and their infants.”

Among 2,821 mothers not lost to follow-up during the secondary analysis, 1,426 received betamethasone and 1,395 received placebo. For mothers who received betamethasone antenatally, the total mean cost was $4,681 per mother-infant pair. Total mean cost for those in the placebo group was $5,379 per pair, resulting in a significant mean $698 savings (P = .02). Respiratory morbidity was 2.9% lower in infants whose mothers received antenatal corticosteroid treatment.

“Thus, because the treated group had lower costs and this strategy was more effective, administration of betamethasone to women at risk for late preterm birth was judged to be a dominant strategy, which is defined as one in which costs are lower and effectiveness is higher than a comparator (incremental cost-effectiveness ratio [ICER], −23 986),” Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman and her associates reported. ICER is defined as the difference in mean total cost per patient in the betamethasone and placebo arms divided by the difference in the effectiveness.

Study limitations were an inability to estimate costs according to quality-adjusted life years or to include families’/caregivers’ costs.

SOURCE: Gyamfi-Bannerman C. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Mar 11. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.0032.

Administering antenatal corticosteroids to pregnant women at high risk for preterm birth was a cost-effective intervention that improved infant respiratory outcomes, according to a new study.

“This intervention has a potential cost saving in the United States of approximately $100 million dollars annually from the benefit in the immediate neonatal outcome alone,” Cynthia Gyamfi-Bannerman, MD, of Columbia University, New York, and her associates reported in JAMA Pediatrics. “Because late preterm birth comprises a large proportion of all preterm births, our findings have the potential for a large influence on public health.”

The researchers conducted a retrospective secondary analysis of the randomized Antenatal Late Preterm Steroids (ALPS) clinical trial October 2010 to February 2015. The trial enrolled randomly assigned antenatal administration of betamethasone or placebo to women pregnant with a singleton and at high risk for preterm birth while between 34 weeks, 6 days, and 36 weeks, 0 days, of gestation.

Antenatal corticosteroid administration was regarded as effective if a newborn did not require treatment in the first 72 hours for respiratory distress or illness. Treatment could include “continuous positive airway pressure or high-flow nasal cannula for 2 hours or more, supplemental oxygen with a fraction of inspired oxygen of 30% or more for 4 hours or more, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation or mechanical ventilation,” Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman and her associates wrote.

To tally the costs, the researchers used Medicaid rates to estimate the total in 2015 U.S. dollars for betamethasone, outpatient visits or inpatient stays to administer it, and all direct newborn care costs, including neonatal ICU daily costs stratified by respiratory illness severity. Betamethasone administration included an initial 12-mg intramuscular dose followed by another after 24 hours if the infant had not been delivered.

“Because therapy often persists for longer than this 72-hour duration, we measured costs through hospital discharge,” the authors wrote. “The analysis took the perspective of a third-party payer in which we included direct medical costs and associated overhead accruing to hospitals and medical payers for the care of enrolled patients and their infants.”

Among 2,821 mothers not lost to follow-up during the secondary analysis, 1,426 received betamethasone and 1,395 received placebo. For mothers who received betamethasone antenatally, the total mean cost was $4,681 per mother-infant pair. Total mean cost for those in the placebo group was $5,379 per pair, resulting in a significant mean $698 savings (P = .02). Respiratory morbidity was 2.9% lower in infants whose mothers received antenatal corticosteroid treatment.

“Thus, because the treated group had lower costs and this strategy was more effective, administration of betamethasone to women at risk for late preterm birth was judged to be a dominant strategy, which is defined as one in which costs are lower and effectiveness is higher than a comparator (incremental cost-effectiveness ratio [ICER], −23 986),” Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman and her associates reported. ICER is defined as the difference in mean total cost per patient in the betamethasone and placebo arms divided by the difference in the effectiveness.

Study limitations were an inability to estimate costs according to quality-adjusted life years or to include families’/caregivers’ costs.

SOURCE: Gyamfi-Bannerman C. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Mar 11. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.0032.

Administering antenatal corticosteroids to pregnant women at high risk for preterm birth was a cost-effective intervention that improved infant respiratory outcomes, according to a new study.

“This intervention has a potential cost saving in the United States of approximately $100 million dollars annually from the benefit in the immediate neonatal outcome alone,” Cynthia Gyamfi-Bannerman, MD, of Columbia University, New York, and her associates reported in JAMA Pediatrics. “Because late preterm birth comprises a large proportion of all preterm births, our findings have the potential for a large influence on public health.”

The researchers conducted a retrospective secondary analysis of the randomized Antenatal Late Preterm Steroids (ALPS) clinical trial October 2010 to February 2015. The trial enrolled randomly assigned antenatal administration of betamethasone or placebo to women pregnant with a singleton and at high risk for preterm birth while between 34 weeks, 6 days, and 36 weeks, 0 days, of gestation.

Antenatal corticosteroid administration was regarded as effective if a newborn did not require treatment in the first 72 hours for respiratory distress or illness. Treatment could include “continuous positive airway pressure or high-flow nasal cannula for 2 hours or more, supplemental oxygen with a fraction of inspired oxygen of 30% or more for 4 hours or more, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation or mechanical ventilation,” Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman and her associates wrote.

To tally the costs, the researchers used Medicaid rates to estimate the total in 2015 U.S. dollars for betamethasone, outpatient visits or inpatient stays to administer it, and all direct newborn care costs, including neonatal ICU daily costs stratified by respiratory illness severity. Betamethasone administration included an initial 12-mg intramuscular dose followed by another after 24 hours if the infant had not been delivered.

“Because therapy often persists for longer than this 72-hour duration, we measured costs through hospital discharge,” the authors wrote. “The analysis took the perspective of a third-party payer in which we included direct medical costs and associated overhead accruing to hospitals and medical payers for the care of enrolled patients and their infants.”

Among 2,821 mothers not lost to follow-up during the secondary analysis, 1,426 received betamethasone and 1,395 received placebo. For mothers who received betamethasone antenatally, the total mean cost was $4,681 per mother-infant pair. Total mean cost for those in the placebo group was $5,379 per pair, resulting in a significant mean $698 savings (P = .02). Respiratory morbidity was 2.9% lower in infants whose mothers received antenatal corticosteroid treatment.

“Thus, because the treated group had lower costs and this strategy was more effective, administration of betamethasone to women at risk for late preterm birth was judged to be a dominant strategy, which is defined as one in which costs are lower and effectiveness is higher than a comparator (incremental cost-effectiveness ratio [ICER], −23 986),” Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman and her associates reported. ICER is defined as the difference in mean total cost per patient in the betamethasone and placebo arms divided by the difference in the effectiveness.

Study limitations were an inability to estimate costs according to quality-adjusted life years or to include families’/caregivers’ costs.

SOURCE: Gyamfi-Bannerman C. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Mar 11. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.0032.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Daily aspirin associated with lower risk of COPD flareup

Daily aspirin use could reduce the risk of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, new data suggest.

Researchers reported the outcomes of an observational cohort study of 1,698 individuals with COPD, 45% of whom said they were taking daily aspirin at baseline. Their findings were published in Chest.

After a median follow up of 2.7 years, aspirin users had an overall 22% lower incidence of acute COPD exacerbations compared with nonusers. This was largely accounted for by a 25% reduction in moderate exacerbations, but there was no significant difference between aspirin users and nonusers in severe exacerbations.

A similar pattern was seen after just 1 year of follow-up, with an overall 30% reduction in the incidence of exacerbations, a 37% reduction in moderate exacerbations, but no significant reduction in severe exacerbations.

“Though aspirin use has previously been linked with reduced mortality risk in patients with COPD, to our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the association of daily aspirin use with respiratory morbidity in COPD,” wrote Ashraf Fawzy, MD, of the division of pulmonary and critical care medicine at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and his coauthors.

The association between aspirin use and reduced incidence of exacerbations was stronger among individuals with chronic bronchitis, which prompted the authors to suggest that future studies of aspirin in COPD should focus on participants with chronic bronchitis.

However, the association was not affected by COPD severity, emphysema presence or severity, or cardiometabolic phenotype.

Aspirin users reported better respiratory-specific quality of life than that of nonusers, including 34% lower odds of reporting moderate to severe dyspnea, and better baseline COPD health status.

“Findings of this study add to the existing literature by highlighting that aspirin use is also associated with reduced respiratory morbidity across several domains – including exacerbation risk, quality of life, and dyspnea – factors related to patient well-being and healthcare utilization,” the authors wrote.

Aspirin users were more likely to be white, male, and obese, and less likely to be smokers. They had better lung function but more cardiovascular comorbidities at baseline, although the aspirin users and nonusers were matched on baseline characteristics.

Speculating on the mechanisms by which aspirin might impact COPD exacerbations, the authors noted that the drug has both systemic and local pulmonary mechanisms of action.

For example, a pathway that results in elevated levels of a urinary metabolite in patients with COPD is irreversibly blocked by aspirin. Aspirin also attenuates the elevation of inflammatory markers interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein, which are part of the inflammatory phenotype of COPD. Aspirin has been shown to reduce proinflammatory cytokines in the lung.

The authors did note that aspirin use was self-reported, so they did not have data on dosage or duration of use.

The National Institutes of Health funded the study. Six authors declared advisory board positions, research support, and other funding from the pharmaceutical sector. One author was also a founder of a company commercializing lung image analysis software. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Fawzy A et al. Chest. 2019 Mar;155(3): 519-27. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.11.028.

Daily aspirin use could reduce the risk of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, new data suggest.

Researchers reported the outcomes of an observational cohort study of 1,698 individuals with COPD, 45% of whom said they were taking daily aspirin at baseline. Their findings were published in Chest.

After a median follow up of 2.7 years, aspirin users had an overall 22% lower incidence of acute COPD exacerbations compared with nonusers. This was largely accounted for by a 25% reduction in moderate exacerbations, but there was no significant difference between aspirin users and nonusers in severe exacerbations.

A similar pattern was seen after just 1 year of follow-up, with an overall 30% reduction in the incidence of exacerbations, a 37% reduction in moderate exacerbations, but no significant reduction in severe exacerbations.

“Though aspirin use has previously been linked with reduced mortality risk in patients with COPD, to our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the association of daily aspirin use with respiratory morbidity in COPD,” wrote Ashraf Fawzy, MD, of the division of pulmonary and critical care medicine at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and his coauthors.

The association between aspirin use and reduced incidence of exacerbations was stronger among individuals with chronic bronchitis, which prompted the authors to suggest that future studies of aspirin in COPD should focus on participants with chronic bronchitis.

However, the association was not affected by COPD severity, emphysema presence or severity, or cardiometabolic phenotype.

Aspirin users reported better respiratory-specific quality of life than that of nonusers, including 34% lower odds of reporting moderate to severe dyspnea, and better baseline COPD health status.

“Findings of this study add to the existing literature by highlighting that aspirin use is also associated with reduced respiratory morbidity across several domains – including exacerbation risk, quality of life, and dyspnea – factors related to patient well-being and healthcare utilization,” the authors wrote.

Aspirin users were more likely to be white, male, and obese, and less likely to be smokers. They had better lung function but more cardiovascular comorbidities at baseline, although the aspirin users and nonusers were matched on baseline characteristics.

Speculating on the mechanisms by which aspirin might impact COPD exacerbations, the authors noted that the drug has both systemic and local pulmonary mechanisms of action.

For example, a pathway that results in elevated levels of a urinary metabolite in patients with COPD is irreversibly blocked by aspirin. Aspirin also attenuates the elevation of inflammatory markers interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein, which are part of the inflammatory phenotype of COPD. Aspirin has been shown to reduce proinflammatory cytokines in the lung.

The authors did note that aspirin use was self-reported, so they did not have data on dosage or duration of use.

The National Institutes of Health funded the study. Six authors declared advisory board positions, research support, and other funding from the pharmaceutical sector. One author was also a founder of a company commercializing lung image analysis software. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Fawzy A et al. Chest. 2019 Mar;155(3): 519-27. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.11.028.

Daily aspirin use could reduce the risk of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, new data suggest.

Researchers reported the outcomes of an observational cohort study of 1,698 individuals with COPD, 45% of whom said they were taking daily aspirin at baseline. Their findings were published in Chest.

After a median follow up of 2.7 years, aspirin users had an overall 22% lower incidence of acute COPD exacerbations compared with nonusers. This was largely accounted for by a 25% reduction in moderate exacerbations, but there was no significant difference between aspirin users and nonusers in severe exacerbations.

A similar pattern was seen after just 1 year of follow-up, with an overall 30% reduction in the incidence of exacerbations, a 37% reduction in moderate exacerbations, but no significant reduction in severe exacerbations.

“Though aspirin use has previously been linked with reduced mortality risk in patients with COPD, to our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the association of daily aspirin use with respiratory morbidity in COPD,” wrote Ashraf Fawzy, MD, of the division of pulmonary and critical care medicine at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and his coauthors.

The association between aspirin use and reduced incidence of exacerbations was stronger among individuals with chronic bronchitis, which prompted the authors to suggest that future studies of aspirin in COPD should focus on participants with chronic bronchitis.

However, the association was not affected by COPD severity, emphysema presence or severity, or cardiometabolic phenotype.

Aspirin users reported better respiratory-specific quality of life than that of nonusers, including 34% lower odds of reporting moderate to severe dyspnea, and better baseline COPD health status.

“Findings of this study add to the existing literature by highlighting that aspirin use is also associated with reduced respiratory morbidity across several domains – including exacerbation risk, quality of life, and dyspnea – factors related to patient well-being and healthcare utilization,” the authors wrote.

Aspirin users were more likely to be white, male, and obese, and less likely to be smokers. They had better lung function but more cardiovascular comorbidities at baseline, although the aspirin users and nonusers were matched on baseline characteristics.

Speculating on the mechanisms by which aspirin might impact COPD exacerbations, the authors noted that the drug has both systemic and local pulmonary mechanisms of action.

For example, a pathway that results in elevated levels of a urinary metabolite in patients with COPD is irreversibly blocked by aspirin. Aspirin also attenuates the elevation of inflammatory markers interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein, which are part of the inflammatory phenotype of COPD. Aspirin has been shown to reduce proinflammatory cytokines in the lung.

The authors did note that aspirin use was self-reported, so they did not have data on dosage or duration of use.

The National Institutes of Health funded the study. Six authors declared advisory board positions, research support, and other funding from the pharmaceutical sector. One author was also a founder of a company commercializing lung image analysis software. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Fawzy A et al. Chest. 2019 Mar;155(3): 519-27. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.11.028.

FROM CHEST

Bariatric surgery leads to less improvement in black patients

“Per this analysis, there are significant racial disparities in perioperative outcomes, weight loss, and quality of life after bariatric surgery,” wrote lead author Michael H. Wood, MD, of Wayne State University, Detroit, and his coauthors, adding that, “while biological differences may explain some of the disparity in outcomes, environmental, social, and behavioral factors likely play a role.” The study was published online in JAMA Surgery.

This study reviewed data from 14,210 participants in the Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative (MBSC), a state-wide consortium and clinical registry of bariatric surgery patients. Matching cohorts were established for black (n = 7,105) and white (n = 7,105) patients who underwent a primary bariatric operation (Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, or adjustable gastric banding) between June 2006 and January 2017. The only significant differences between cohorts – clarified as “never more than 1 or 2 percentage points” – were in regard to income brackets and procedure type.

At 30-day follow-up, the rate of overall complications was higher in black patients (628, 8.8%) than in white patients (481, 6.8%; adjusted odds ratio, 1.33; 95% confidence interval, 1.17-1.51; P = .02), as was the length of stay (mean, 2.2 days vs. 1.9 days; aOR, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.20-0.40; P less than .001). Black patients also had a higher rate of both ED visits (541 [11.6%] vs. 826 [7.6%]; aOR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.43-1.79; P less than .001) and readmissions (414 [5.8%] vs. 245 [3.5%]; aOR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.47-2.03; P less than .001).

In addition, at 1-year follow-up, black patients had a lower mean weight loss (32.0 kg vs. 38.3 kg; P less than .001) and percentage of total weight loss (26% vs. 29%; P less than .001) compared with white patients. And though black patients were more likely than white patients to report a high quality of life before surgery (2,672 [49.5%] vs. 2,354 [41.4%]; P less than .001), they were less likely to do so 1 year afterward (1,379 [87.2%] vs. 2,133 [90.4%]; P = .002).

The coauthors acknowledged the limitations of their study, including potential unmeasured factors between cohorts such as disease duration or severity. They also noted that a wider time horizon than 30 days post surgery could have altered the results, although “serious adverse events and resource use tend to be highest within the first month after surgery, and we anticipate that this effect would have been negligible.”

The study was funded by Blue Cross Blue Shield Michigan/Blue Care Network. Dr. Wood reported no conflicts of interest. Three of his coauthors reported receiving salary support from Blue Cross Blue Shield Michigan/Blue Care Network for their work with the MBSC, and one other coauthor reported receiving an honorarium for being the MBSC’s executive committee chair.

SOURCE: Wood MH et al. JAMA Surg. 2019 Mar 6. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.0029.

The well-documented disparities between black and white patients after bariatric surgery are brought back to the forefront via to this study from Wood et al., according to Brian Hodgens, MD, and Kenric M. Murayama, MD, of the University of Hawaii, Honolulu.

Some of the findings hint at the cultural differences that permeate the time before and after a surgery like this: In particular, they highlighted how black patients were more likely to report good or very good quality of life before surgery but less likely after. This could be related to a “difference in perceptions of obesity by black patients,” where they are more hesitant to pursue the surgery than their white counterparts, Dr. Hodgens and Dr. Murayama wrote.

More work is needed, they added, but “this study and others like it can better equip practicing bariatric surgeons to educate themselves and patients on expectations before and after bariatric surgery.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial ( JAMA Surg. 2019 Mar 6. doi: 1 0.1001/jamasurg.2019.0067 ). Dr. Murayama reported receiving personal fees from Medtronic outside the submitted work.

The well-documented disparities between black and white patients after bariatric surgery are brought back to the forefront via to this study from Wood et al., according to Brian Hodgens, MD, and Kenric M. Murayama, MD, of the University of Hawaii, Honolulu.

Some of the findings hint at the cultural differences that permeate the time before and after a surgery like this: In particular, they highlighted how black patients were more likely to report good or very good quality of life before surgery but less likely after. This could be related to a “difference in perceptions of obesity by black patients,” where they are more hesitant to pursue the surgery than their white counterparts, Dr. Hodgens and Dr. Murayama wrote.

More work is needed, they added, but “this study and others like it can better equip practicing bariatric surgeons to educate themselves and patients on expectations before and after bariatric surgery.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial ( JAMA Surg. 2019 Mar 6. doi: 1 0.1001/jamasurg.2019.0067 ). Dr. Murayama reported receiving personal fees from Medtronic outside the submitted work.

The well-documented disparities between black and white patients after bariatric surgery are brought back to the forefront via to this study from Wood et al., according to Brian Hodgens, MD, and Kenric M. Murayama, MD, of the University of Hawaii, Honolulu.

Some of the findings hint at the cultural differences that permeate the time before and after a surgery like this: In particular, they highlighted how black patients were more likely to report good or very good quality of life before surgery but less likely after. This could be related to a “difference in perceptions of obesity by black patients,” where they are more hesitant to pursue the surgery than their white counterparts, Dr. Hodgens and Dr. Murayama wrote.

More work is needed, they added, but “this study and others like it can better equip practicing bariatric surgeons to educate themselves and patients on expectations before and after bariatric surgery.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial ( JAMA Surg. 2019 Mar 6. doi: 1 0.1001/jamasurg.2019.0067 ). Dr. Murayama reported receiving personal fees from Medtronic outside the submitted work.

“Per this analysis, there are significant racial disparities in perioperative outcomes, weight loss, and quality of life after bariatric surgery,” wrote lead author Michael H. Wood, MD, of Wayne State University, Detroit, and his coauthors, adding that, “while biological differences may explain some of the disparity in outcomes, environmental, social, and behavioral factors likely play a role.” The study was published online in JAMA Surgery.

This study reviewed data from 14,210 participants in the Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative (MBSC), a state-wide consortium and clinical registry of bariatric surgery patients. Matching cohorts were established for black (n = 7,105) and white (n = 7,105) patients who underwent a primary bariatric operation (Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, or adjustable gastric banding) between June 2006 and January 2017. The only significant differences between cohorts – clarified as “never more than 1 or 2 percentage points” – were in regard to income brackets and procedure type.

At 30-day follow-up, the rate of overall complications was higher in black patients (628, 8.8%) than in white patients (481, 6.8%; adjusted odds ratio, 1.33; 95% confidence interval, 1.17-1.51; P = .02), as was the length of stay (mean, 2.2 days vs. 1.9 days; aOR, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.20-0.40; P less than .001). Black patients also had a higher rate of both ED visits (541 [11.6%] vs. 826 [7.6%]; aOR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.43-1.79; P less than .001) and readmissions (414 [5.8%] vs. 245 [3.5%]; aOR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.47-2.03; P less than .001).

In addition, at 1-year follow-up, black patients had a lower mean weight loss (32.0 kg vs. 38.3 kg; P less than .001) and percentage of total weight loss (26% vs. 29%; P less than .001) compared with white patients. And though black patients were more likely than white patients to report a high quality of life before surgery (2,672 [49.5%] vs. 2,354 [41.4%]; P less than .001), they were less likely to do so 1 year afterward (1,379 [87.2%] vs. 2,133 [90.4%]; P = .002).

The coauthors acknowledged the limitations of their study, including potential unmeasured factors between cohorts such as disease duration or severity. They also noted that a wider time horizon than 30 days post surgery could have altered the results, although “serious adverse events and resource use tend to be highest within the first month after surgery, and we anticipate that this effect would have been negligible.”

The study was funded by Blue Cross Blue Shield Michigan/Blue Care Network. Dr. Wood reported no conflicts of interest. Three of his coauthors reported receiving salary support from Blue Cross Blue Shield Michigan/Blue Care Network for their work with the MBSC, and one other coauthor reported receiving an honorarium for being the MBSC’s executive committee chair.

SOURCE: Wood MH et al. JAMA Surg. 2019 Mar 6. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.0029.

“Per this analysis, there are significant racial disparities in perioperative outcomes, weight loss, and quality of life after bariatric surgery,” wrote lead author Michael H. Wood, MD, of Wayne State University, Detroit, and his coauthors, adding that, “while biological differences may explain some of the disparity in outcomes, environmental, social, and behavioral factors likely play a role.” The study was published online in JAMA Surgery.

This study reviewed data from 14,210 participants in the Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative (MBSC), a state-wide consortium and clinical registry of bariatric surgery patients. Matching cohorts were established for black (n = 7,105) and white (n = 7,105) patients who underwent a primary bariatric operation (Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, or adjustable gastric banding) between June 2006 and January 2017. The only significant differences between cohorts – clarified as “never more than 1 or 2 percentage points” – were in regard to income brackets and procedure type.

At 30-day follow-up, the rate of overall complications was higher in black patients (628, 8.8%) than in white patients (481, 6.8%; adjusted odds ratio, 1.33; 95% confidence interval, 1.17-1.51; P = .02), as was the length of stay (mean, 2.2 days vs. 1.9 days; aOR, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.20-0.40; P less than .001). Black patients also had a higher rate of both ED visits (541 [11.6%] vs. 826 [7.6%]; aOR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.43-1.79; P less than .001) and readmissions (414 [5.8%] vs. 245 [3.5%]; aOR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.47-2.03; P less than .001).

In addition, at 1-year follow-up, black patients had a lower mean weight loss (32.0 kg vs. 38.3 kg; P less than .001) and percentage of total weight loss (26% vs. 29%; P less than .001) compared with white patients. And though black patients were more likely than white patients to report a high quality of life before surgery (2,672 [49.5%] vs. 2,354 [41.4%]; P less than .001), they were less likely to do so 1 year afterward (1,379 [87.2%] vs. 2,133 [90.4%]; P = .002).

The coauthors acknowledged the limitations of their study, including potential unmeasured factors between cohorts such as disease duration or severity. They also noted that a wider time horizon than 30 days post surgery could have altered the results, although “serious adverse events and resource use tend to be highest within the first month after surgery, and we anticipate that this effect would have been negligible.”

The study was funded by Blue Cross Blue Shield Michigan/Blue Care Network. Dr. Wood reported no conflicts of interest. Three of his coauthors reported receiving salary support from Blue Cross Blue Shield Michigan/Blue Care Network for their work with the MBSC, and one other coauthor reported receiving an honorarium for being the MBSC’s executive committee chair.

SOURCE: Wood MH et al. JAMA Surg. 2019 Mar 6. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.0029.

FROM JAMA SURGERY

Peer-Review Transparency

Federal health care providers live under a microscope, so it seems only fair that we at Fed Pract honor that reality and open ourselves up to scrutiny as well.1 We hope that by shedding light on our peer-review process and manuscript acceptance rate, we will not only highlight our accomplishments, but identify areas for improvement.

Free access to Fed Pract content has always been our priority. While many journals charge authors or readers, Fed Pract has been and will remain free for readers and authors.2 Advertising enables the journal to support this free model of publishing, but we take care to ensure that advertisements do not influence content in any way. Our advertising policy can be found at www.mdedge.com/fedprac/page/advertising.

In January 2019, Fed Pract placed > 400 peer-reviewed articles published since January 2015 in the PubMed Central (PMC) database (ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc). The full text of these and all future Fed Pract peer-reviewed articles will be available at PMC (no registration required), and the citations also will be included in PubMed. We hope that this process will make it even easier for anyone to access our authors’ works.

In 2018 about 36,000 federal health care providers (HCPs) received hard copies of this journal. The print journal is free, but circulation is limited to HCPs who work at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), US Department of Defense (DoD), and the US Public Health Service (PHS). The mdedge.com/fedprac website, which includes every article published since 2003, had 1.4 million page views in 2018. After reading 3 online articles, readers in the US are asked to complete a simple registration form to help us better customize the reader experience. In some cases, international readers may be asked to pay for access to articles online; however, any VA, DoD, or PHS officer stationed overseas can contact the editorial staff (fedprac@mdedge.com) to ensure that they can access the articles for free.

In 2018 the journal received 164 manuscripts and published 94 articles written by 357 different federal HCPs. The 164 manuscript submissions represented a 45% growth over previous years. Not surprisingly, the increased rate of submissions began shortly after the May 2018 announcement that journal articles would be included in PMC. Most of those articles (83%) were submitted unsolicited.

Fed Pract has always prided itself on being an early promoter of interdisciplinary health care professional publications. Nearly half of its listed authors were physicians (48%), while pharmacists made up the next largest cohort (18%). There were smaller numbers of PhDs, nurses, social workers, and physical therapists. The majority were written by HCPs affiliated with the VA (95% of articles and 93% of authors), and no articles in 2018 were written by PHS officers. Physicians comprise about two-thirds of the audience, while pharmacists make up 17% and nurses 9%. PHS and DoD HCPs make up 19% of the Fed Pract audience, suggesting that the journal needs to do more work to encourage these HCPs to contribute articles to the journal.3

Articles published in 2018 covered a broad range of topics from “Anesthesia Care Practice Models in the VHA” and “Army Behavioral Health System” to “Vitreous Hemorrhage in the Setting of a Vascular Loop” and “A Workforce Assessment of VA Home-Based Primary Care Pharmacists.” Categorizing the articles is a challenge. Few health care topics fit neatly into a single topic or specialty. This is especially true in federal health care where much of the care is delivered by multidisciplinary patient-centered medical homes or patient aligned care teams. Nevertheless, a few broad outlines can be discerned. Articles were roughly split between primary care and hospital-based and/or specialty care topics; one-quarter of the articles were case studies or case series articles, and about 20% were editorials or opinion columns. Nineteen articles dealt explicitly with chronic conditions, and 10 articles focused on mental health care.

Peer reviewers are an essential part of the process. Reviewers are blinded to the identityof the authors, ensuring fairness and reducing potential conflicts of interest. We are extremely grateful to each and every reviewer for the time and energy they contribute to the journal. Peer reviewers do not get nearly enough recognition for their important work. In 2018 Fed Pract invited 1,205 reviewers for 164 manuscript submissions and 94 manuscript revisions. More than 200 different reviewers submitted 487 reviews with a median (SD) of 2 reviews (1.8) and a range of 1 to 10. The top 20 reviewers completed 134 reviews with a median (SD) of 6 reviews (1.2). The results stand in contrast to some journals that must offer many invitations per review and depend on a small number of reviewers.1,4-6

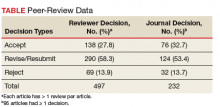

The reviewers recommended to reject 14% and to revise 26% of the articles, which is a much lower rejection rate than many other journals (Table).4

These data suggest that Fed Pract and its peer-review process is on a sound foundation but needs to make improvements. Moving into 2019, the journal expects that an increasing number of submissions will require a higher rejection rate. Moreover, we will need to do a better job reaching out to underrepresented portions of our audience. To decrease the time to publication for accepted manuscripts, in 2019 we will publish more articles online ahead of the print publication as we strive to improve the experience for authors, reviewers, readers, and the entire Fed Pract audience.

None of this work can be done without our small and dedicated staff. I would like to thank Managing Editor Joyce Brody who sent out each and every one of those reviewer invitations, Deputy Editor Robert Fee, who manages the special issues, Web Editor Teraya Smith, who runs our entire digital operation, and of course, Editor in Chief Cynthia Geppert, who oversees it all. Finally, it is important that you let us know how we are doing and whether we are meeting your needs. Visit mdedge.com/fedprac to take the readership survey or reach out to me at rpaul@mdedge.com.

1. Geppert CMA. Caring under a microscope. Fed Pract. 2018;35(7):6-7.

2. Smith R. Peer review: a flawed process at the heart of science and journals. J R Soc Med. 2006;99(4):178-182.

3. BPA Worldwide. Federal Practitioner brand report for the 6 month period ending June 2018. https://www.frontlinemedcom.com/wp-content/uploads/FEDPRAC_BPA.pdf. Updated June 2018. Accessed March 5, 2019.

4. Fontanarosa PB, Bauchner H, Golub RM. Thank you to JAMA authors, peer reviewers, and readers. JAMA. 2017;317(8):812-813.

5. Publons, Clarivate Analytics. 2018 global state of peer review. https://publons.com/static/Publons-Global-State-Of-Peer-Review-2018.pdf. Published September 2018. Accessed March 5, 2019.

6. Malcom D. It’s time we fix the peer review system. Am J Pharm Educ. 2018;82(5):7144.

Federal health care providers live under a microscope, so it seems only fair that we at Fed Pract honor that reality and open ourselves up to scrutiny as well.1 We hope that by shedding light on our peer-review process and manuscript acceptance rate, we will not only highlight our accomplishments, but identify areas for improvement.

Free access to Fed Pract content has always been our priority. While many journals charge authors or readers, Fed Pract has been and will remain free for readers and authors.2 Advertising enables the journal to support this free model of publishing, but we take care to ensure that advertisements do not influence content in any way. Our advertising policy can be found at www.mdedge.com/fedprac/page/advertising.

In January 2019, Fed Pract placed > 400 peer-reviewed articles published since January 2015 in the PubMed Central (PMC) database (ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc). The full text of these and all future Fed Pract peer-reviewed articles will be available at PMC (no registration required), and the citations also will be included in PubMed. We hope that this process will make it even easier for anyone to access our authors’ works.

In 2018 about 36,000 federal health care providers (HCPs) received hard copies of this journal. The print journal is free, but circulation is limited to HCPs who work at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), US Department of Defense (DoD), and the US Public Health Service (PHS). The mdedge.com/fedprac website, which includes every article published since 2003, had 1.4 million page views in 2018. After reading 3 online articles, readers in the US are asked to complete a simple registration form to help us better customize the reader experience. In some cases, international readers may be asked to pay for access to articles online; however, any VA, DoD, or PHS officer stationed overseas can contact the editorial staff (fedprac@mdedge.com) to ensure that they can access the articles for free.

In 2018 the journal received 164 manuscripts and published 94 articles written by 357 different federal HCPs. The 164 manuscript submissions represented a 45% growth over previous years. Not surprisingly, the increased rate of submissions began shortly after the May 2018 announcement that journal articles would be included in PMC. Most of those articles (83%) were submitted unsolicited.

Fed Pract has always prided itself on being an early promoter of interdisciplinary health care professional publications. Nearly half of its listed authors were physicians (48%), while pharmacists made up the next largest cohort (18%). There were smaller numbers of PhDs, nurses, social workers, and physical therapists. The majority were written by HCPs affiliated with the VA (95% of articles and 93% of authors), and no articles in 2018 were written by PHS officers. Physicians comprise about two-thirds of the audience, while pharmacists make up 17% and nurses 9%. PHS and DoD HCPs make up 19% of the Fed Pract audience, suggesting that the journal needs to do more work to encourage these HCPs to contribute articles to the journal.3

Articles published in 2018 covered a broad range of topics from “Anesthesia Care Practice Models in the VHA” and “Army Behavioral Health System” to “Vitreous Hemorrhage in the Setting of a Vascular Loop” and “A Workforce Assessment of VA Home-Based Primary Care Pharmacists.” Categorizing the articles is a challenge. Few health care topics fit neatly into a single topic or specialty. This is especially true in federal health care where much of the care is delivered by multidisciplinary patient-centered medical homes or patient aligned care teams. Nevertheless, a few broad outlines can be discerned. Articles were roughly split between primary care and hospital-based and/or specialty care topics; one-quarter of the articles were case studies or case series articles, and about 20% were editorials or opinion columns. Nineteen articles dealt explicitly with chronic conditions, and 10 articles focused on mental health care.

Peer reviewers are an essential part of the process. Reviewers are blinded to the identityof the authors, ensuring fairness and reducing potential conflicts of interest. We are extremely grateful to each and every reviewer for the time and energy they contribute to the journal. Peer reviewers do not get nearly enough recognition for their important work. In 2018 Fed Pract invited 1,205 reviewers for 164 manuscript submissions and 94 manuscript revisions. More than 200 different reviewers submitted 487 reviews with a median (SD) of 2 reviews (1.8) and a range of 1 to 10. The top 20 reviewers completed 134 reviews with a median (SD) of 6 reviews (1.2). The results stand in contrast to some journals that must offer many invitations per review and depend on a small number of reviewers.1,4-6

The reviewers recommended to reject 14% and to revise 26% of the articles, which is a much lower rejection rate than many other journals (Table).4

These data suggest that Fed Pract and its peer-review process is on a sound foundation but needs to make improvements. Moving into 2019, the journal expects that an increasing number of submissions will require a higher rejection rate. Moreover, we will need to do a better job reaching out to underrepresented portions of our audience. To decrease the time to publication for accepted manuscripts, in 2019 we will publish more articles online ahead of the print publication as we strive to improve the experience for authors, reviewers, readers, and the entire Fed Pract audience.

None of this work can be done without our small and dedicated staff. I would like to thank Managing Editor Joyce Brody who sent out each and every one of those reviewer invitations, Deputy Editor Robert Fee, who manages the special issues, Web Editor Teraya Smith, who runs our entire digital operation, and of course, Editor in Chief Cynthia Geppert, who oversees it all. Finally, it is important that you let us know how we are doing and whether we are meeting your needs. Visit mdedge.com/fedprac to take the readership survey or reach out to me at rpaul@mdedge.com.

Federal health care providers live under a microscope, so it seems only fair that we at Fed Pract honor that reality and open ourselves up to scrutiny as well.1 We hope that by shedding light on our peer-review process and manuscript acceptance rate, we will not only highlight our accomplishments, but identify areas for improvement.

Free access to Fed Pract content has always been our priority. While many journals charge authors or readers, Fed Pract has been and will remain free for readers and authors.2 Advertising enables the journal to support this free model of publishing, but we take care to ensure that advertisements do not influence content in any way. Our advertising policy can be found at www.mdedge.com/fedprac/page/advertising.

In January 2019, Fed Pract placed > 400 peer-reviewed articles published since January 2015 in the PubMed Central (PMC) database (ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc). The full text of these and all future Fed Pract peer-reviewed articles will be available at PMC (no registration required), and the citations also will be included in PubMed. We hope that this process will make it even easier for anyone to access our authors’ works.

In 2018 about 36,000 federal health care providers (HCPs) received hard copies of this journal. The print journal is free, but circulation is limited to HCPs who work at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), US Department of Defense (DoD), and the US Public Health Service (PHS). The mdedge.com/fedprac website, which includes every article published since 2003, had 1.4 million page views in 2018. After reading 3 online articles, readers in the US are asked to complete a simple registration form to help us better customize the reader experience. In some cases, international readers may be asked to pay for access to articles online; however, any VA, DoD, or PHS officer stationed overseas can contact the editorial staff (fedprac@mdedge.com) to ensure that they can access the articles for free.

In 2018 the journal received 164 manuscripts and published 94 articles written by 357 different federal HCPs. The 164 manuscript submissions represented a 45% growth over previous years. Not surprisingly, the increased rate of submissions began shortly after the May 2018 announcement that journal articles would be included in PMC. Most of those articles (83%) were submitted unsolicited.

Fed Pract has always prided itself on being an early promoter of interdisciplinary health care professional publications. Nearly half of its listed authors were physicians (48%), while pharmacists made up the next largest cohort (18%). There were smaller numbers of PhDs, nurses, social workers, and physical therapists. The majority were written by HCPs affiliated with the VA (95% of articles and 93% of authors), and no articles in 2018 were written by PHS officers. Physicians comprise about two-thirds of the audience, while pharmacists make up 17% and nurses 9%. PHS and DoD HCPs make up 19% of the Fed Pract audience, suggesting that the journal needs to do more work to encourage these HCPs to contribute articles to the journal.3

Articles published in 2018 covered a broad range of topics from “Anesthesia Care Practice Models in the VHA” and “Army Behavioral Health System” to “Vitreous Hemorrhage in the Setting of a Vascular Loop” and “A Workforce Assessment of VA Home-Based Primary Care Pharmacists.” Categorizing the articles is a challenge. Few health care topics fit neatly into a single topic or specialty. This is especially true in federal health care where much of the care is delivered by multidisciplinary patient-centered medical homes or patient aligned care teams. Nevertheless, a few broad outlines can be discerned. Articles were roughly split between primary care and hospital-based and/or specialty care topics; one-quarter of the articles were case studies or case series articles, and about 20% were editorials or opinion columns. Nineteen articles dealt explicitly with chronic conditions, and 10 articles focused on mental health care.

Peer reviewers are an essential part of the process. Reviewers are blinded to the identityof the authors, ensuring fairness and reducing potential conflicts of interest. We are extremely grateful to each and every reviewer for the time and energy they contribute to the journal. Peer reviewers do not get nearly enough recognition for their important work. In 2018 Fed Pract invited 1,205 reviewers for 164 manuscript submissions and 94 manuscript revisions. More than 200 different reviewers submitted 487 reviews with a median (SD) of 2 reviews (1.8) and a range of 1 to 10. The top 20 reviewers completed 134 reviews with a median (SD) of 6 reviews (1.2). The results stand in contrast to some journals that must offer many invitations per review and depend on a small number of reviewers.1,4-6

The reviewers recommended to reject 14% and to revise 26% of the articles, which is a much lower rejection rate than many other journals (Table).4

These data suggest that Fed Pract and its peer-review process is on a sound foundation but needs to make improvements. Moving into 2019, the journal expects that an increasing number of submissions will require a higher rejection rate. Moreover, we will need to do a better job reaching out to underrepresented portions of our audience. To decrease the time to publication for accepted manuscripts, in 2019 we will publish more articles online ahead of the print publication as we strive to improve the experience for authors, reviewers, readers, and the entire Fed Pract audience.

None of this work can be done without our small and dedicated staff. I would like to thank Managing Editor Joyce Brody who sent out each and every one of those reviewer invitations, Deputy Editor Robert Fee, who manages the special issues, Web Editor Teraya Smith, who runs our entire digital operation, and of course, Editor in Chief Cynthia Geppert, who oversees it all. Finally, it is important that you let us know how we are doing and whether we are meeting your needs. Visit mdedge.com/fedprac to take the readership survey or reach out to me at rpaul@mdedge.com.

1. Geppert CMA. Caring under a microscope. Fed Pract. 2018;35(7):6-7.

2. Smith R. Peer review: a flawed process at the heart of science and journals. J R Soc Med. 2006;99(4):178-182.

3. BPA Worldwide. Federal Practitioner brand report for the 6 month period ending June 2018. https://www.frontlinemedcom.com/wp-content/uploads/FEDPRAC_BPA.pdf. Updated June 2018. Accessed March 5, 2019.

4. Fontanarosa PB, Bauchner H, Golub RM. Thank you to JAMA authors, peer reviewers, and readers. JAMA. 2017;317(8):812-813.

5. Publons, Clarivate Analytics. 2018 global state of peer review. https://publons.com/static/Publons-Global-State-Of-Peer-Review-2018.pdf. Published September 2018. Accessed March 5, 2019.

6. Malcom D. It’s time we fix the peer review system. Am J Pharm Educ. 2018;82(5):7144.

1. Geppert CMA. Caring under a microscope. Fed Pract. 2018;35(7):6-7.

2. Smith R. Peer review: a flawed process at the heart of science and journals. J R Soc Med. 2006;99(4):178-182.

3. BPA Worldwide. Federal Practitioner brand report for the 6 month period ending June 2018. https://www.frontlinemedcom.com/wp-content/uploads/FEDPRAC_BPA.pdf. Updated June 2018. Accessed March 5, 2019.

4. Fontanarosa PB, Bauchner H, Golub RM. Thank you to JAMA authors, peer reviewers, and readers. JAMA. 2017;317(8):812-813.

5. Publons, Clarivate Analytics. 2018 global state of peer review. https://publons.com/static/Publons-Global-State-Of-Peer-Review-2018.pdf. Published September 2018. Accessed March 5, 2019.