User login

Cutaneous Gummatous Tuberculosis in a Kidney Transplant Patient

Case Report

A 60-year-old Cambodian woman presented with recurrent fever (temperature, up to 38.8°C) 7 months after receiving a kidney transplant secondary to polycystic kidney disease. Fever was attributed to recurrent pyelonephritis of the native kidneys while on mycophenolate mofetil, tacrolimus, and prednisone. As a result, she underwent a bilateral native nephrectomy and was found to have peritoneal nodules. Pathology of both native kidneys and peritoneal tissue revealed caseating granulomas and acid-fast bacilli (AFB) diagnostic for kidney and peritoneal tuberculosis (TB). She had no history of TB, and a TB skin test (purified protein derivative [PPD]) upon entering the United States from Cambodia a decade earlier was negative. Additionally, her pretransplantation PPD was negative.

Treatment with isoniazid, ethambutol, pyrazinamide, and levofloxacin was initiated immediately upon diagnosis, and all of her immunosuppressive medications—mycophenolate mofetil, tacrolimus, and prednisone—were discontinued. Her symptoms subsided within 1 week, and she was discharged from the hospital. Over the next 2 months, her immunosuppressive medications were restarted, and her TB medications were periodically discontinued by the Tuberculosis Control Program at the Department of Health (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) due to severe thrombocytopenia. During this time, she was closely monitored twice weekly in the clinic with blood draws performed weekly.

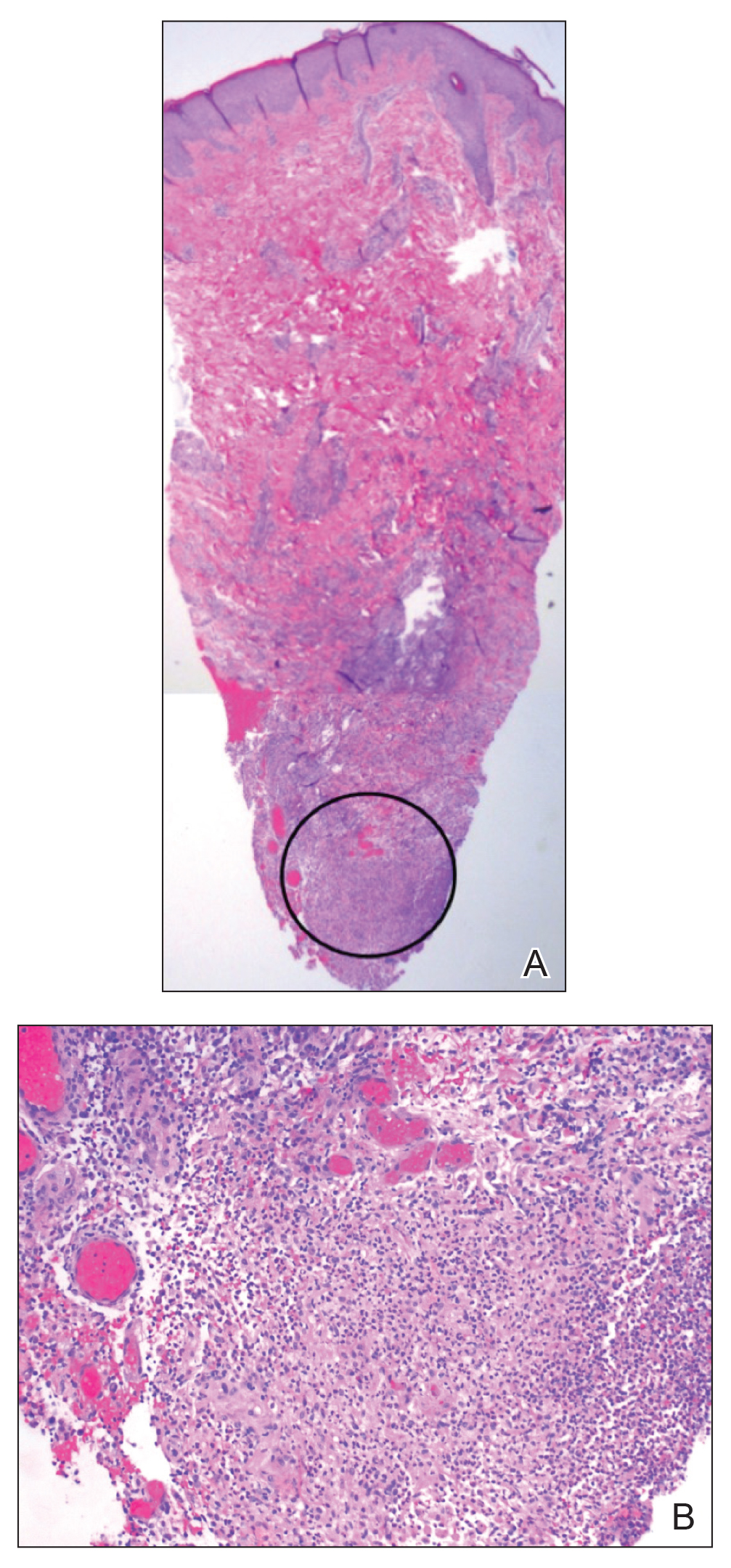

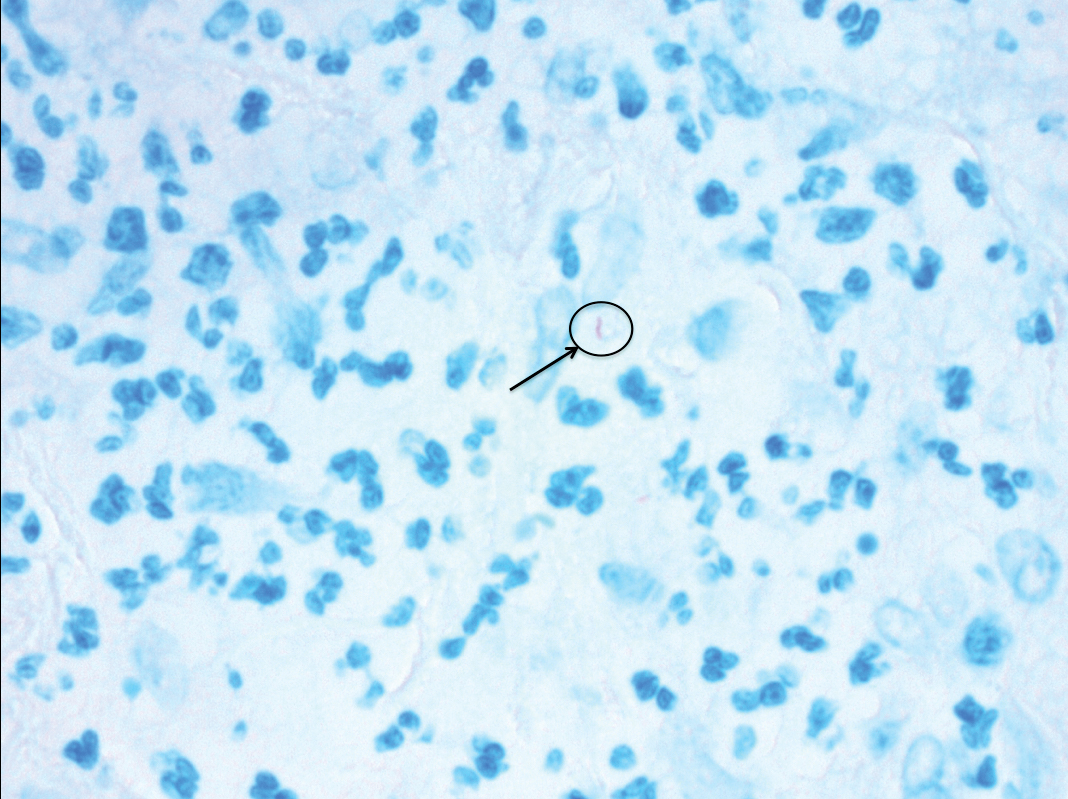

Approximately 10 weeks after initiation of treatment, she noted recurrent subjective fever (temperature, up to 38.8°C) and painful lesions on the right side of the flank, left breast, and left arm of 3 days’ duration. Physical examination revealed a warm, dull red, tender nodule on the right side of the flank (Figure 1) and subcutaneous nodules with no overlying skin changes on the left breast and left arm. A biopsy of the lesion on the right side of the flank was performed, which resulted in substantial purulent drainage. Histologic analysis showed an inflammatory infiltrate within the deep dermis composed of neutrophils, macrophages, and giant cells, indicative of suppurative granulomatous dermatitis (Figure 2). Ziehl-Neelsen stain demonstrated rare AFB within the cytoplasm of macrophages, suggestive of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection (Figure 3). A repeat chest radiograph was normal.

Based on the patient’s history and clinical presentation, she was continued on isoniazid, ethambutol, and levofloxacin, with complete resolution of symptoms and cutaneous lesions. Over the subsequent 2 months, the therapy was modified to rifabutin, pyrazinamide, and levofloxacin, and subsequently pyrazinamide was stopped. A subsequent biopsy of the left breast and histologic analysis indicated that the specimen was benign; stains for AFB were negative. Currently, both the fever and skin lesions have completely resolved, and she remains on anti-TB therapy.

Comment

Clinical Presentation

Cutaneous TB is an uncommon manifestation of TB that can occur either exogenously or endogenously.1 It tends to occur primarily in previously infected TB patients through hematogenous, lymphatic, or contiguous spread.2 Due to their immunocompromised state, solid organ transplant recipients have an increased incidence of primary and reactivated latent TB reported to be 20 to 74 times greater than the general population.3,4 One report stated the total incidence of posttransplant TB as 0.48% in the West and 11.8% in endemic regions such as India.5 The occurrence of cutaneous TB is rare among solid organ transplant recipients.1 On average, a diagnosis of latent TB is made 9 months after transplantation because of the opportunistic nature of M tuberculosis in an immunosuppressed environment.6

TB Subtypes

Cutaneous TB can be in the form of localized disease (eg, primary tuberculous chancre, TB verrucosa cutis, lupus vulgaris, smear-negative scrofuloderma), disseminated disease (eg, disseminated TB, TB gumma, orificial TB, miliary cutaneous TB), or tuberculids (eg, papulonecrotic tuberculid, lichen scrofulosorum, erythema induratum).7 Due to the pustular epithelioid cell granulomas and AFB positivity of the involved cutaneous lesions, our patient’s TB can be classified as a metastatic TB abscess or gummatous TB.7

Metastatic TB abscess, an uncommon subtype of cutaneous TB, generally is only seen in malnourished children and notably immunocompromised individuals.2,8,9 In these individuals, systemic failure of cell-mediated immunity enables M tuberculosis to hematogenously infect various organs of the body, resulting in alternative forms of TB, such as gummatous-type TB.10 One study reported that of the 0.1% of dermatology patients presenting with cutaneous TB, only 5.4% of these individuals had the rarer gummatous form.7 These metastatic TB abscesses begin as a single or multiple nontender subcutaneous nodule(s), which breaks down and softens to form a draining sinus abscess.2,8,9 Abscesses are most commonly seen on the trunk and extremities; however, they can be found nearly anywhere on the body.8 The pathology of cutaneous TB lesions demonstrates caseating necrosis with epithelioid and giant cells forming a surrounding rim.9

Diagnosis

Diagnosis may be difficult because of the vast number of dermatologic conditions that resemble cutaneous TB, including mycoses, sarcoidosis, leishmaniasis, leprosy, syphilis, other non-TB mycobacteria, and Wegener granulomatosis.9 Thus, confirmatory diagnosis is made via clinical presentation, detailed history and physical examination, and laboratory tests.11 These tests include the Mantoux tuberculin skin test (PPD or TST) or IFN-γ release assays (QuantiFERON-TB Gold test), identification of AFB on skin biopsy, and isolation of M tuberculosis from tissue culture or polymerase chain reaction.11

At-Risk Populations

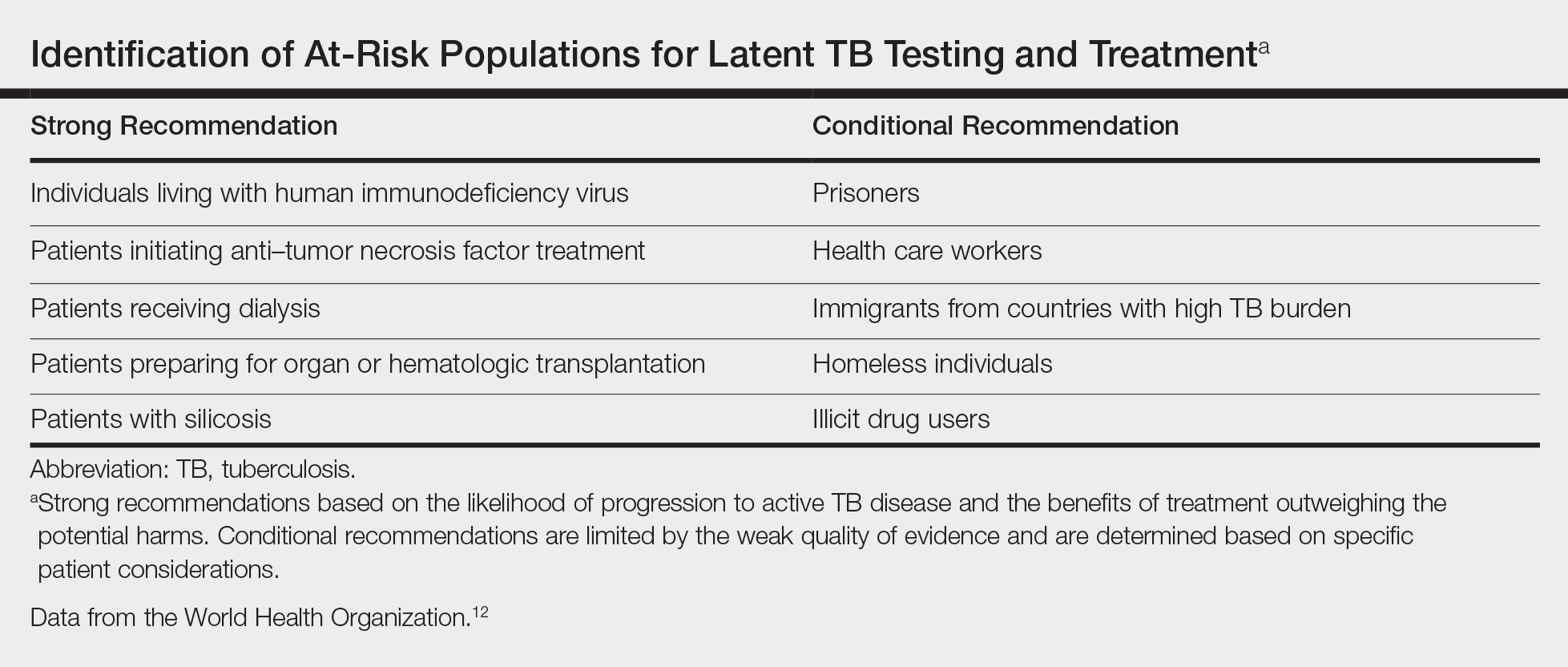

The recommendation for the identification of at-risk populations for latent TB testing and treatment have been clearly defined by the World Health Organization (Table).12 Our patient met 2 of these criteria: she had been preparing for organ transplantation and was from a country with high TB burden. Such at-risk patients should be tested for a latent TB infection with either IFN-γ release assays or PPD.12

Treatment

The recommended treatment of active TB in transplant recipients is based on randomized trials in immunocompetent hosts, and thus the same as that used by the general population.16 This anti-TB regimen includes the use of 4 drugs—typically rifampicin, isoniazid, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide—for a 6-month duration.11 Unfortunately, the management of TB in an immunocompromised patient is more challenging due to the potential side effects and drug interactions.

Finally, thrombocytopenia is an infrequent, life-threatening complication that can be acquired by immunocompromised patients on anti-TB therapy.17 Drug-induced thrombocytopenia can be caused by a variety of medications, including rifampicin, isoniazid, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide. Diagnosis of drug-induced thrombocytopenia can be confirmed only after discontinuation of the suspected drug and subsequent resolution of the thrombocytopenia.17 Our patient initially became thrombocytopenic while taking isoniazid, ethambutol, pyrazinamide, and levofloxacin. However, her platelet levels improved once the pyrazinamide was discontinued, thereby suggesting pyrazinamide-induced thrombocytopenia.

Conclusion

The risk for infectious disease reactivation in an immunocompromised patient undergoing transplant surgery is notable. Our findings emphasize the value of a comprehensive pretransplant evaluation, vigilance even when test results appear negative, and treatment of latent TB within this population.16,18,19 Furthermore, this case illustrates a noteworthy example of a rare form of cutaneous TB, which should be considered and included in the differential for cutaneous lesions in an immunosuppressed patient.

- Sakhuja V, Jha V, Varma PP, et al. The high incidence of tuberculosis among renal transplant recipients in India. Transplantation. 1996;61:211-215.

- Frankel A, Penrose C, Emer J. Cutaneous tuberculosis: a practical case report and review for the dermatologist. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2009;2:19-27.

- Schultz V, Marroni CA, Amorim CS, et al. Risk factors for hepatotoxicity in solid organ transplants recipients being treated for tuberculosis. Transplant Proc. 2014;46:3606-3610.

- Tabarsi P, Farshidpour M, Marjani M, et al. Mycobacterial infection and the impact of rifabutin treatment in organ transplant recipients: a single-center study. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2015;26:6-11.

- Rathi M, Gundlapalli S, Ramachandran R, et al. A rare case of cytomegalovirus, scedosporium apiospermum and mycobacterium tuberculosis in a renal transplant recipient. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:259.

- Hickey MD, Quan DJ, Chin-Hong PV, et al. Use of rifabutin for the treatment of a latent tuberculosis infection in a patient after solid organ transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2013;19:457-461.

- Kumar B, Muralidhar S. Cutaneous tuberculosis: a twenty-year prospective study. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 1999;3:494-500.

- Dekeyzer S, Moerman F, Callens S, et al. Cutaneous metastatic tuberculous abscess in patient with cervico-mediastinal lymphatic tuberculosis. Acta Clin Belg. 2013;68:34-36.

- Ko M, Wu C, Chiu H. Tuberculous gumma (cutaneous metastatic tuberculous abscess). Dermatol Sinica. 2005;23:27-31.

- Steger JW, Barrett TL. Cutaneous tuberculosis. In: James WD, ed. Textbook of Military Medicine: Military Dermatology. Washington, DC: Borden Institute; 1994:355-389.

- Santos JB, Figueiredo AR, Ferraz CE, et al. Cutaneous tuberculosis: diagnosis, histopathology and treatment - part II. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:545-555.

- Guidelines on the Management of Latent Tuberculosis Infection. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2015.

- Targeted tuberculin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. This official statement of the American Thoracic Society was adopted by the ATS Board of Directors, July 1999. This is a Joint Statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). This statement was endorsed by the Council of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. (IDSA), September 1999, and the sections of this statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(4 pt 2):S221-S247.

- Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Am J Transplant. 2004;4(suppl 10):37-41.

- Aguado JM, Torre-Cisneros J, Fortún J, et al. Tuberculosis in solid-organ transplant recipients: consensus statement of the group for the study of infection in transplant recipients (GESITRA) of the Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:1276-1284.

- Blumberg HM, Burman WJ, Chaisson RE, et al; American Thoracic Society, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Infectious Diseases Society. American Thoracic Society/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Infectious Diseases Society of America: treatment of tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:603-662.

- Kant S, Verma SK, Gupta V, et al. Pyrazinamide induced thrombocytopenia. Indian J Pharmacol. 2010;42:108-109.

- Screening for tuberculosis and tuberculosis infection in high-risk populations. recommendations of the Advisory Council for the Elimination of Tuberculosis. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1995;44:19-34.

- Fischer SA, Avery RK; AST Infectious Disease Community of Practice. Screening of donor and recipient prior to solid organ transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(suppl 4):S7-S18.

Case Report

A 60-year-old Cambodian woman presented with recurrent fever (temperature, up to 38.8°C) 7 months after receiving a kidney transplant secondary to polycystic kidney disease. Fever was attributed to recurrent pyelonephritis of the native kidneys while on mycophenolate mofetil, tacrolimus, and prednisone. As a result, she underwent a bilateral native nephrectomy and was found to have peritoneal nodules. Pathology of both native kidneys and peritoneal tissue revealed caseating granulomas and acid-fast bacilli (AFB) diagnostic for kidney and peritoneal tuberculosis (TB). She had no history of TB, and a TB skin test (purified protein derivative [PPD]) upon entering the United States from Cambodia a decade earlier was negative. Additionally, her pretransplantation PPD was negative.

Treatment with isoniazid, ethambutol, pyrazinamide, and levofloxacin was initiated immediately upon diagnosis, and all of her immunosuppressive medications—mycophenolate mofetil, tacrolimus, and prednisone—were discontinued. Her symptoms subsided within 1 week, and she was discharged from the hospital. Over the next 2 months, her immunosuppressive medications were restarted, and her TB medications were periodically discontinued by the Tuberculosis Control Program at the Department of Health (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) due to severe thrombocytopenia. During this time, she was closely monitored twice weekly in the clinic with blood draws performed weekly.

Approximately 10 weeks after initiation of treatment, she noted recurrent subjective fever (temperature, up to 38.8°C) and painful lesions on the right side of the flank, left breast, and left arm of 3 days’ duration. Physical examination revealed a warm, dull red, tender nodule on the right side of the flank (Figure 1) and subcutaneous nodules with no overlying skin changes on the left breast and left arm. A biopsy of the lesion on the right side of the flank was performed, which resulted in substantial purulent drainage. Histologic analysis showed an inflammatory infiltrate within the deep dermis composed of neutrophils, macrophages, and giant cells, indicative of suppurative granulomatous dermatitis (Figure 2). Ziehl-Neelsen stain demonstrated rare AFB within the cytoplasm of macrophages, suggestive of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection (Figure 3). A repeat chest radiograph was normal.

Based on the patient’s history and clinical presentation, she was continued on isoniazid, ethambutol, and levofloxacin, with complete resolution of symptoms and cutaneous lesions. Over the subsequent 2 months, the therapy was modified to rifabutin, pyrazinamide, and levofloxacin, and subsequently pyrazinamide was stopped. A subsequent biopsy of the left breast and histologic analysis indicated that the specimen was benign; stains for AFB were negative. Currently, both the fever and skin lesions have completely resolved, and she remains on anti-TB therapy.

Comment

Clinical Presentation

Cutaneous TB is an uncommon manifestation of TB that can occur either exogenously or endogenously.1 It tends to occur primarily in previously infected TB patients through hematogenous, lymphatic, or contiguous spread.2 Due to their immunocompromised state, solid organ transplant recipients have an increased incidence of primary and reactivated latent TB reported to be 20 to 74 times greater than the general population.3,4 One report stated the total incidence of posttransplant TB as 0.48% in the West and 11.8% in endemic regions such as India.5 The occurrence of cutaneous TB is rare among solid organ transplant recipients.1 On average, a diagnosis of latent TB is made 9 months after transplantation because of the opportunistic nature of M tuberculosis in an immunosuppressed environment.6

TB Subtypes

Cutaneous TB can be in the form of localized disease (eg, primary tuberculous chancre, TB verrucosa cutis, lupus vulgaris, smear-negative scrofuloderma), disseminated disease (eg, disseminated TB, TB gumma, orificial TB, miliary cutaneous TB), or tuberculids (eg, papulonecrotic tuberculid, lichen scrofulosorum, erythema induratum).7 Due to the pustular epithelioid cell granulomas and AFB positivity of the involved cutaneous lesions, our patient’s TB can be classified as a metastatic TB abscess or gummatous TB.7

Metastatic TB abscess, an uncommon subtype of cutaneous TB, generally is only seen in malnourished children and notably immunocompromised individuals.2,8,9 In these individuals, systemic failure of cell-mediated immunity enables M tuberculosis to hematogenously infect various organs of the body, resulting in alternative forms of TB, such as gummatous-type TB.10 One study reported that of the 0.1% of dermatology patients presenting with cutaneous TB, only 5.4% of these individuals had the rarer gummatous form.7 These metastatic TB abscesses begin as a single or multiple nontender subcutaneous nodule(s), which breaks down and softens to form a draining sinus abscess.2,8,9 Abscesses are most commonly seen on the trunk and extremities; however, they can be found nearly anywhere on the body.8 The pathology of cutaneous TB lesions demonstrates caseating necrosis with epithelioid and giant cells forming a surrounding rim.9

Diagnosis

Diagnosis may be difficult because of the vast number of dermatologic conditions that resemble cutaneous TB, including mycoses, sarcoidosis, leishmaniasis, leprosy, syphilis, other non-TB mycobacteria, and Wegener granulomatosis.9 Thus, confirmatory diagnosis is made via clinical presentation, detailed history and physical examination, and laboratory tests.11 These tests include the Mantoux tuberculin skin test (PPD or TST) or IFN-γ release assays (QuantiFERON-TB Gold test), identification of AFB on skin biopsy, and isolation of M tuberculosis from tissue culture or polymerase chain reaction.11

At-Risk Populations

The recommendation for the identification of at-risk populations for latent TB testing and treatment have been clearly defined by the World Health Organization (Table).12 Our patient met 2 of these criteria: she had been preparing for organ transplantation and was from a country with high TB burden. Such at-risk patients should be tested for a latent TB infection with either IFN-γ release assays or PPD.12

Treatment

The recommended treatment of active TB in transplant recipients is based on randomized trials in immunocompetent hosts, and thus the same as that used by the general population.16 This anti-TB regimen includes the use of 4 drugs—typically rifampicin, isoniazid, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide—for a 6-month duration.11 Unfortunately, the management of TB in an immunocompromised patient is more challenging due to the potential side effects and drug interactions.

Finally, thrombocytopenia is an infrequent, life-threatening complication that can be acquired by immunocompromised patients on anti-TB therapy.17 Drug-induced thrombocytopenia can be caused by a variety of medications, including rifampicin, isoniazid, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide. Diagnosis of drug-induced thrombocytopenia can be confirmed only after discontinuation of the suspected drug and subsequent resolution of the thrombocytopenia.17 Our patient initially became thrombocytopenic while taking isoniazid, ethambutol, pyrazinamide, and levofloxacin. However, her platelet levels improved once the pyrazinamide was discontinued, thereby suggesting pyrazinamide-induced thrombocytopenia.

Conclusion

The risk for infectious disease reactivation in an immunocompromised patient undergoing transplant surgery is notable. Our findings emphasize the value of a comprehensive pretransplant evaluation, vigilance even when test results appear negative, and treatment of latent TB within this population.16,18,19 Furthermore, this case illustrates a noteworthy example of a rare form of cutaneous TB, which should be considered and included in the differential for cutaneous lesions in an immunosuppressed patient.

Case Report

A 60-year-old Cambodian woman presented with recurrent fever (temperature, up to 38.8°C) 7 months after receiving a kidney transplant secondary to polycystic kidney disease. Fever was attributed to recurrent pyelonephritis of the native kidneys while on mycophenolate mofetil, tacrolimus, and prednisone. As a result, she underwent a bilateral native nephrectomy and was found to have peritoneal nodules. Pathology of both native kidneys and peritoneal tissue revealed caseating granulomas and acid-fast bacilli (AFB) diagnostic for kidney and peritoneal tuberculosis (TB). She had no history of TB, and a TB skin test (purified protein derivative [PPD]) upon entering the United States from Cambodia a decade earlier was negative. Additionally, her pretransplantation PPD was negative.

Treatment with isoniazid, ethambutol, pyrazinamide, and levofloxacin was initiated immediately upon diagnosis, and all of her immunosuppressive medications—mycophenolate mofetil, tacrolimus, and prednisone—were discontinued. Her symptoms subsided within 1 week, and she was discharged from the hospital. Over the next 2 months, her immunosuppressive medications were restarted, and her TB medications were periodically discontinued by the Tuberculosis Control Program at the Department of Health (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) due to severe thrombocytopenia. During this time, she was closely monitored twice weekly in the clinic with blood draws performed weekly.

Approximately 10 weeks after initiation of treatment, she noted recurrent subjective fever (temperature, up to 38.8°C) and painful lesions on the right side of the flank, left breast, and left arm of 3 days’ duration. Physical examination revealed a warm, dull red, tender nodule on the right side of the flank (Figure 1) and subcutaneous nodules with no overlying skin changes on the left breast and left arm. A biopsy of the lesion on the right side of the flank was performed, which resulted in substantial purulent drainage. Histologic analysis showed an inflammatory infiltrate within the deep dermis composed of neutrophils, macrophages, and giant cells, indicative of suppurative granulomatous dermatitis (Figure 2). Ziehl-Neelsen stain demonstrated rare AFB within the cytoplasm of macrophages, suggestive of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection (Figure 3). A repeat chest radiograph was normal.

Based on the patient’s history and clinical presentation, she was continued on isoniazid, ethambutol, and levofloxacin, with complete resolution of symptoms and cutaneous lesions. Over the subsequent 2 months, the therapy was modified to rifabutin, pyrazinamide, and levofloxacin, and subsequently pyrazinamide was stopped. A subsequent biopsy of the left breast and histologic analysis indicated that the specimen was benign; stains for AFB were negative. Currently, both the fever and skin lesions have completely resolved, and she remains on anti-TB therapy.

Comment

Clinical Presentation

Cutaneous TB is an uncommon manifestation of TB that can occur either exogenously or endogenously.1 It tends to occur primarily in previously infected TB patients through hematogenous, lymphatic, or contiguous spread.2 Due to their immunocompromised state, solid organ transplant recipients have an increased incidence of primary and reactivated latent TB reported to be 20 to 74 times greater than the general population.3,4 One report stated the total incidence of posttransplant TB as 0.48% in the West and 11.8% in endemic regions such as India.5 The occurrence of cutaneous TB is rare among solid organ transplant recipients.1 On average, a diagnosis of latent TB is made 9 months after transplantation because of the opportunistic nature of M tuberculosis in an immunosuppressed environment.6

TB Subtypes

Cutaneous TB can be in the form of localized disease (eg, primary tuberculous chancre, TB verrucosa cutis, lupus vulgaris, smear-negative scrofuloderma), disseminated disease (eg, disseminated TB, TB gumma, orificial TB, miliary cutaneous TB), or tuberculids (eg, papulonecrotic tuberculid, lichen scrofulosorum, erythema induratum).7 Due to the pustular epithelioid cell granulomas and AFB positivity of the involved cutaneous lesions, our patient’s TB can be classified as a metastatic TB abscess or gummatous TB.7

Metastatic TB abscess, an uncommon subtype of cutaneous TB, generally is only seen in malnourished children and notably immunocompromised individuals.2,8,9 In these individuals, systemic failure of cell-mediated immunity enables M tuberculosis to hematogenously infect various organs of the body, resulting in alternative forms of TB, such as gummatous-type TB.10 One study reported that of the 0.1% of dermatology patients presenting with cutaneous TB, only 5.4% of these individuals had the rarer gummatous form.7 These metastatic TB abscesses begin as a single or multiple nontender subcutaneous nodule(s), which breaks down and softens to form a draining sinus abscess.2,8,9 Abscesses are most commonly seen on the trunk and extremities; however, they can be found nearly anywhere on the body.8 The pathology of cutaneous TB lesions demonstrates caseating necrosis with epithelioid and giant cells forming a surrounding rim.9

Diagnosis

Diagnosis may be difficult because of the vast number of dermatologic conditions that resemble cutaneous TB, including mycoses, sarcoidosis, leishmaniasis, leprosy, syphilis, other non-TB mycobacteria, and Wegener granulomatosis.9 Thus, confirmatory diagnosis is made via clinical presentation, detailed history and physical examination, and laboratory tests.11 These tests include the Mantoux tuberculin skin test (PPD or TST) or IFN-γ release assays (QuantiFERON-TB Gold test), identification of AFB on skin biopsy, and isolation of M tuberculosis from tissue culture or polymerase chain reaction.11

At-Risk Populations

The recommendation for the identification of at-risk populations for latent TB testing and treatment have been clearly defined by the World Health Organization (Table).12 Our patient met 2 of these criteria: she had been preparing for organ transplantation and was from a country with high TB burden. Such at-risk patients should be tested for a latent TB infection with either IFN-γ release assays or PPD.12

Treatment

The recommended treatment of active TB in transplant recipients is based on randomized trials in immunocompetent hosts, and thus the same as that used by the general population.16 This anti-TB regimen includes the use of 4 drugs—typically rifampicin, isoniazid, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide—for a 6-month duration.11 Unfortunately, the management of TB in an immunocompromised patient is more challenging due to the potential side effects and drug interactions.

Finally, thrombocytopenia is an infrequent, life-threatening complication that can be acquired by immunocompromised patients on anti-TB therapy.17 Drug-induced thrombocytopenia can be caused by a variety of medications, including rifampicin, isoniazid, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide. Diagnosis of drug-induced thrombocytopenia can be confirmed only after discontinuation of the suspected drug and subsequent resolution of the thrombocytopenia.17 Our patient initially became thrombocytopenic while taking isoniazid, ethambutol, pyrazinamide, and levofloxacin. However, her platelet levels improved once the pyrazinamide was discontinued, thereby suggesting pyrazinamide-induced thrombocytopenia.

Conclusion

The risk for infectious disease reactivation in an immunocompromised patient undergoing transplant surgery is notable. Our findings emphasize the value of a comprehensive pretransplant evaluation, vigilance even when test results appear negative, and treatment of latent TB within this population.16,18,19 Furthermore, this case illustrates a noteworthy example of a rare form of cutaneous TB, which should be considered and included in the differential for cutaneous lesions in an immunosuppressed patient.

- Sakhuja V, Jha V, Varma PP, et al. The high incidence of tuberculosis among renal transplant recipients in India. Transplantation. 1996;61:211-215.

- Frankel A, Penrose C, Emer J. Cutaneous tuberculosis: a practical case report and review for the dermatologist. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2009;2:19-27.

- Schultz V, Marroni CA, Amorim CS, et al. Risk factors for hepatotoxicity in solid organ transplants recipients being treated for tuberculosis. Transplant Proc. 2014;46:3606-3610.

- Tabarsi P, Farshidpour M, Marjani M, et al. Mycobacterial infection and the impact of rifabutin treatment in organ transplant recipients: a single-center study. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2015;26:6-11.

- Rathi M, Gundlapalli S, Ramachandran R, et al. A rare case of cytomegalovirus, scedosporium apiospermum and mycobacterium tuberculosis in a renal transplant recipient. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:259.

- Hickey MD, Quan DJ, Chin-Hong PV, et al. Use of rifabutin for the treatment of a latent tuberculosis infection in a patient after solid organ transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2013;19:457-461.

- Kumar B, Muralidhar S. Cutaneous tuberculosis: a twenty-year prospective study. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 1999;3:494-500.

- Dekeyzer S, Moerman F, Callens S, et al. Cutaneous metastatic tuberculous abscess in patient with cervico-mediastinal lymphatic tuberculosis. Acta Clin Belg. 2013;68:34-36.

- Ko M, Wu C, Chiu H. Tuberculous gumma (cutaneous metastatic tuberculous abscess). Dermatol Sinica. 2005;23:27-31.

- Steger JW, Barrett TL. Cutaneous tuberculosis. In: James WD, ed. Textbook of Military Medicine: Military Dermatology. Washington, DC: Borden Institute; 1994:355-389.

- Santos JB, Figueiredo AR, Ferraz CE, et al. Cutaneous tuberculosis: diagnosis, histopathology and treatment - part II. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:545-555.

- Guidelines on the Management of Latent Tuberculosis Infection. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2015.

- Targeted tuberculin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. This official statement of the American Thoracic Society was adopted by the ATS Board of Directors, July 1999. This is a Joint Statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). This statement was endorsed by the Council of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. (IDSA), September 1999, and the sections of this statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(4 pt 2):S221-S247.

- Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Am J Transplant. 2004;4(suppl 10):37-41.

- Aguado JM, Torre-Cisneros J, Fortún J, et al. Tuberculosis in solid-organ transplant recipients: consensus statement of the group for the study of infection in transplant recipients (GESITRA) of the Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:1276-1284.

- Blumberg HM, Burman WJ, Chaisson RE, et al; American Thoracic Society, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Infectious Diseases Society. American Thoracic Society/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Infectious Diseases Society of America: treatment of tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:603-662.

- Kant S, Verma SK, Gupta V, et al. Pyrazinamide induced thrombocytopenia. Indian J Pharmacol. 2010;42:108-109.

- Screening for tuberculosis and tuberculosis infection in high-risk populations. recommendations of the Advisory Council for the Elimination of Tuberculosis. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1995;44:19-34.

- Fischer SA, Avery RK; AST Infectious Disease Community of Practice. Screening of donor and recipient prior to solid organ transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(suppl 4):S7-S18.

- Sakhuja V, Jha V, Varma PP, et al. The high incidence of tuberculosis among renal transplant recipients in India. Transplantation. 1996;61:211-215.

- Frankel A, Penrose C, Emer J. Cutaneous tuberculosis: a practical case report and review for the dermatologist. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2009;2:19-27.

- Schultz V, Marroni CA, Amorim CS, et al. Risk factors for hepatotoxicity in solid organ transplants recipients being treated for tuberculosis. Transplant Proc. 2014;46:3606-3610.

- Tabarsi P, Farshidpour M, Marjani M, et al. Mycobacterial infection and the impact of rifabutin treatment in organ transplant recipients: a single-center study. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2015;26:6-11.

- Rathi M, Gundlapalli S, Ramachandran R, et al. A rare case of cytomegalovirus, scedosporium apiospermum and mycobacterium tuberculosis in a renal transplant recipient. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:259.

- Hickey MD, Quan DJ, Chin-Hong PV, et al. Use of rifabutin for the treatment of a latent tuberculosis infection in a patient after solid organ transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2013;19:457-461.

- Kumar B, Muralidhar S. Cutaneous tuberculosis: a twenty-year prospective study. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 1999;3:494-500.

- Dekeyzer S, Moerman F, Callens S, et al. Cutaneous metastatic tuberculous abscess in patient with cervico-mediastinal lymphatic tuberculosis. Acta Clin Belg. 2013;68:34-36.

- Ko M, Wu C, Chiu H. Tuberculous gumma (cutaneous metastatic tuberculous abscess). Dermatol Sinica. 2005;23:27-31.

- Steger JW, Barrett TL. Cutaneous tuberculosis. In: James WD, ed. Textbook of Military Medicine: Military Dermatology. Washington, DC: Borden Institute; 1994:355-389.

- Santos JB, Figueiredo AR, Ferraz CE, et al. Cutaneous tuberculosis: diagnosis, histopathology and treatment - part II. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:545-555.

- Guidelines on the Management of Latent Tuberculosis Infection. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2015.

- Targeted tuberculin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. This official statement of the American Thoracic Society was adopted by the ATS Board of Directors, July 1999. This is a Joint Statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). This statement was endorsed by the Council of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. (IDSA), September 1999, and the sections of this statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(4 pt 2):S221-S247.

- Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Am J Transplant. 2004;4(suppl 10):37-41.

- Aguado JM, Torre-Cisneros J, Fortún J, et al. Tuberculosis in solid-organ transplant recipients: consensus statement of the group for the study of infection in transplant recipients (GESITRA) of the Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:1276-1284.

- Blumberg HM, Burman WJ, Chaisson RE, et al; American Thoracic Society, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Infectious Diseases Society. American Thoracic Society/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Infectious Diseases Society of America: treatment of tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:603-662.

- Kant S, Verma SK, Gupta V, et al. Pyrazinamide induced thrombocytopenia. Indian J Pharmacol. 2010;42:108-109.

- Screening for tuberculosis and tuberculosis infection in high-risk populations. recommendations of the Advisory Council for the Elimination of Tuberculosis. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1995;44:19-34.

- Fischer SA, Avery RK; AST Infectious Disease Community of Practice. Screening of donor and recipient prior to solid organ transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(suppl 4):S7-S18.

Practice Points

- Transplant patients are at increased risk for infection given their immunosuppressed state.

- Although rare, cutaneous tuberculosis should be considered in the differential for cutaneous lesions in an immunosuppressed patient.

Annular Atrophic Plaques on the Forearm

Sarcoidosis is a systemic noncaseating granulomatous disease of unknown etiology. The skin is the second most common location for disease manifestation following the lungs.1 Cutaneous sarcoidosis is present in 35% of patients with sarcoidosis and may be further subtyped by its morphologic characteristics (eg, hyperpigmented, papular, nodular, atrophic, ulcerative, psoriasiform). Cutaneous sarcoidosis has an increased tendency to occur at areas of prior injury such as surgeries or tattoos.2 Although sarcoidosis affects all races and sexes, it is more prevalent in women and in the black population.3

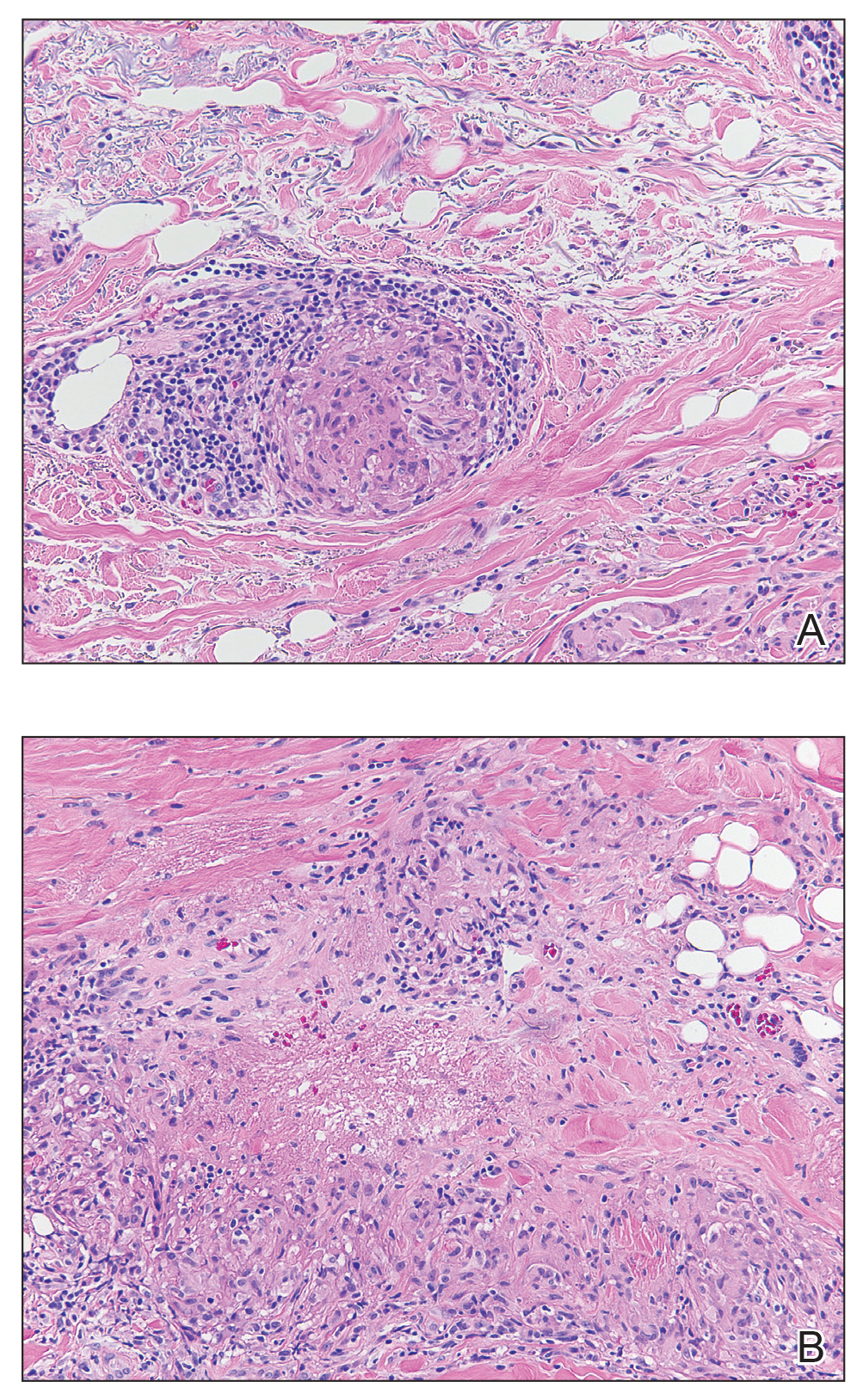

The clinical presentation of sarcoidosis is difficult due to its morphologic variation, allowing for a wide differential diagnosis. With our patient’s presentation of atrophic plaques, the differential diagnosis included granuloma annulare, necrobiosis lipoidica, tumid lupus erythematosus, leprosy, and sarcoidosis; however, biopsy is required for definitive diagnosis. The characteristic histopathology for cutaneous sarcoidosis includes noncaseating granulomas (Figure, A) composed of epithelioid histiocytes with giant cells surrounded by a lymphocytic infiltrate. Noncaseating granulomas are considered specific to sarcoidosis and are present in 71% to 89% of biopsied lesions.4 Interestingly, our patient presented with a rare subtype of atrophic ulcerative cutaneous sarcoidosis, necrobiosis lipoidica–like sarcoidosis, which is more common in females and in the black population. It is characterized by pink to violaceous plaques with depressed centers and prominent necrotizing granuloma (Figure, B) on histopathology. In a small case series, all 3 patients with necrobiosis lipoidica–like sarcoidosis were female and had systemic involvement at the time of diagnosis.5

Sarcoidosis typically is a systemic disease with only a limited number of cases presenting with isolated cutaneous findings. Therefore, patients require a systemic evaluation, which may include a chest radiograph, complete blood cell count, ophthalmologic examinations, thyroid testing, and vitamin D monitoring, as well as an echocardiogram and electrocardiogram.2

Treatment is guided by the severity of disease. For isolated cutaneous lesions, topical or intralesional high-potency steroids have been shown to be effective.6,7 Several studies also have shown phototherapy and laser therapy as well as surgical excision to be beneficial.8-10 Once cutaneous lesions become disfiguring or systemic involvement is found, systemic corticosteroids or other immunomodulatory medications may be warranted.11 Our patient was started on intralesional and topical high-potency steroids, which failed, and she was transitioned to methotrexate and adalimumab. Unfortunately, even with advanced therapies, our patient did not have notableresolution of the lesions.

- Mañá J, Marcoval J. Skin manifestations of sarcoidosis. Presse Med. 2012;41 (6, pt 2): E355-E374.

- Wanat KA, Rosenbach M. Cutaneous sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med.2015; 36:685-702.

- Baughman RP, Teirstein AS, Judson MA, et al. Clinical characteristics ofpatients in a case control study of sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(10, pt 1):1885-1889.

- Ball NJ, Kho GT, Martinka M. The histologic spectrum of cutaneous sarcoidosis: a study of twenty-eight cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2004; 31:160-168.

- Mendoza V, Vahid B, Kozic H, et al. Clinical and pathologic manifestations of necrobiosis lipoidica-like skin involvement in sarcoidosis. Joint Bone Spine. 2007; 74:647-649.

- Khatri KA, Chotzen VA, Burrall BA. Lupus pernio: successful treatment with a potent topical corticosteroid. Arch Dermatol. 1995; 131:617-618.

- Singh SK, Singh S, Pandey SS. Cutaneous sarcoidosis without systemic involvement: response to intralesional corticosteroid. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1996; 62:273-274.

- Karrer S, Abels C, Wimmershoff MB, et al. Successful treatment of cutaneous sarcoidosis using topical photodynamic therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2002; 138:581-584.

- Mahnke N, Medve-koenigs K, Berneburg M, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidosis treated with medium-dose UVA1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004; 50:978-979.

- Frederiksen LG, Jørgensen K. Sarcoidosis of the nose treated with laser surgery. Rhinology. 1996; 34:245-246.

- Baughman RP, Lower EE. Evidence-based therapy for cutaneous sarcoidosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007; 25:334-340.

Sarcoidosis is a systemic noncaseating granulomatous disease of unknown etiology. The skin is the second most common location for disease manifestation following the lungs.1 Cutaneous sarcoidosis is present in 35% of patients with sarcoidosis and may be further subtyped by its morphologic characteristics (eg, hyperpigmented, papular, nodular, atrophic, ulcerative, psoriasiform). Cutaneous sarcoidosis has an increased tendency to occur at areas of prior injury such as surgeries or tattoos.2 Although sarcoidosis affects all races and sexes, it is more prevalent in women and in the black population.3

The clinical presentation of sarcoidosis is difficult due to its morphologic variation, allowing for a wide differential diagnosis. With our patient’s presentation of atrophic plaques, the differential diagnosis included granuloma annulare, necrobiosis lipoidica, tumid lupus erythematosus, leprosy, and sarcoidosis; however, biopsy is required for definitive diagnosis. The characteristic histopathology for cutaneous sarcoidosis includes noncaseating granulomas (Figure, A) composed of epithelioid histiocytes with giant cells surrounded by a lymphocytic infiltrate. Noncaseating granulomas are considered specific to sarcoidosis and are present in 71% to 89% of biopsied lesions.4 Interestingly, our patient presented with a rare subtype of atrophic ulcerative cutaneous sarcoidosis, necrobiosis lipoidica–like sarcoidosis, which is more common in females and in the black population. It is characterized by pink to violaceous plaques with depressed centers and prominent necrotizing granuloma (Figure, B) on histopathology. In a small case series, all 3 patients with necrobiosis lipoidica–like sarcoidosis were female and had systemic involvement at the time of diagnosis.5

Sarcoidosis typically is a systemic disease with only a limited number of cases presenting with isolated cutaneous findings. Therefore, patients require a systemic evaluation, which may include a chest radiograph, complete blood cell count, ophthalmologic examinations, thyroid testing, and vitamin D monitoring, as well as an echocardiogram and electrocardiogram.2

Treatment is guided by the severity of disease. For isolated cutaneous lesions, topical or intralesional high-potency steroids have been shown to be effective.6,7 Several studies also have shown phototherapy and laser therapy as well as surgical excision to be beneficial.8-10 Once cutaneous lesions become disfiguring or systemic involvement is found, systemic corticosteroids or other immunomodulatory medications may be warranted.11 Our patient was started on intralesional and topical high-potency steroids, which failed, and she was transitioned to methotrexate and adalimumab. Unfortunately, even with advanced therapies, our patient did not have notableresolution of the lesions.

Sarcoidosis is a systemic noncaseating granulomatous disease of unknown etiology. The skin is the second most common location for disease manifestation following the lungs.1 Cutaneous sarcoidosis is present in 35% of patients with sarcoidosis and may be further subtyped by its morphologic characteristics (eg, hyperpigmented, papular, nodular, atrophic, ulcerative, psoriasiform). Cutaneous sarcoidosis has an increased tendency to occur at areas of prior injury such as surgeries or tattoos.2 Although sarcoidosis affects all races and sexes, it is more prevalent in women and in the black population.3

The clinical presentation of sarcoidosis is difficult due to its morphologic variation, allowing for a wide differential diagnosis. With our patient’s presentation of atrophic plaques, the differential diagnosis included granuloma annulare, necrobiosis lipoidica, tumid lupus erythematosus, leprosy, and sarcoidosis; however, biopsy is required for definitive diagnosis. The characteristic histopathology for cutaneous sarcoidosis includes noncaseating granulomas (Figure, A) composed of epithelioid histiocytes with giant cells surrounded by a lymphocytic infiltrate. Noncaseating granulomas are considered specific to sarcoidosis and are present in 71% to 89% of biopsied lesions.4 Interestingly, our patient presented with a rare subtype of atrophic ulcerative cutaneous sarcoidosis, necrobiosis lipoidica–like sarcoidosis, which is more common in females and in the black population. It is characterized by pink to violaceous plaques with depressed centers and prominent necrotizing granuloma (Figure, B) on histopathology. In a small case series, all 3 patients with necrobiosis lipoidica–like sarcoidosis were female and had systemic involvement at the time of diagnosis.5

Sarcoidosis typically is a systemic disease with only a limited number of cases presenting with isolated cutaneous findings. Therefore, patients require a systemic evaluation, which may include a chest radiograph, complete blood cell count, ophthalmologic examinations, thyroid testing, and vitamin D monitoring, as well as an echocardiogram and electrocardiogram.2

Treatment is guided by the severity of disease. For isolated cutaneous lesions, topical or intralesional high-potency steroids have been shown to be effective.6,7 Several studies also have shown phototherapy and laser therapy as well as surgical excision to be beneficial.8-10 Once cutaneous lesions become disfiguring or systemic involvement is found, systemic corticosteroids or other immunomodulatory medications may be warranted.11 Our patient was started on intralesional and topical high-potency steroids, which failed, and she was transitioned to methotrexate and adalimumab. Unfortunately, even with advanced therapies, our patient did not have notableresolution of the lesions.

- Mañá J, Marcoval J. Skin manifestations of sarcoidosis. Presse Med. 2012;41 (6, pt 2): E355-E374.

- Wanat KA, Rosenbach M. Cutaneous sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med.2015; 36:685-702.

- Baughman RP, Teirstein AS, Judson MA, et al. Clinical characteristics ofpatients in a case control study of sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(10, pt 1):1885-1889.

- Ball NJ, Kho GT, Martinka M. The histologic spectrum of cutaneous sarcoidosis: a study of twenty-eight cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2004; 31:160-168.

- Mendoza V, Vahid B, Kozic H, et al. Clinical and pathologic manifestations of necrobiosis lipoidica-like skin involvement in sarcoidosis. Joint Bone Spine. 2007; 74:647-649.

- Khatri KA, Chotzen VA, Burrall BA. Lupus pernio: successful treatment with a potent topical corticosteroid. Arch Dermatol. 1995; 131:617-618.

- Singh SK, Singh S, Pandey SS. Cutaneous sarcoidosis without systemic involvement: response to intralesional corticosteroid. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1996; 62:273-274.

- Karrer S, Abels C, Wimmershoff MB, et al. Successful treatment of cutaneous sarcoidosis using topical photodynamic therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2002; 138:581-584.

- Mahnke N, Medve-koenigs K, Berneburg M, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidosis treated with medium-dose UVA1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004; 50:978-979.

- Frederiksen LG, Jørgensen K. Sarcoidosis of the nose treated with laser surgery. Rhinology. 1996; 34:245-246.

- Baughman RP, Lower EE. Evidence-based therapy for cutaneous sarcoidosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007; 25:334-340.

- Mañá J, Marcoval J. Skin manifestations of sarcoidosis. Presse Med. 2012;41 (6, pt 2): E355-E374.

- Wanat KA, Rosenbach M. Cutaneous sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med.2015; 36:685-702.

- Baughman RP, Teirstein AS, Judson MA, et al. Clinical characteristics ofpatients in a case control study of sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(10, pt 1):1885-1889.

- Ball NJ, Kho GT, Martinka M. The histologic spectrum of cutaneous sarcoidosis: a study of twenty-eight cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2004; 31:160-168.

- Mendoza V, Vahid B, Kozic H, et al. Clinical and pathologic manifestations of necrobiosis lipoidica-like skin involvement in sarcoidosis. Joint Bone Spine. 2007; 74:647-649.

- Khatri KA, Chotzen VA, Burrall BA. Lupus pernio: successful treatment with a potent topical corticosteroid. Arch Dermatol. 1995; 131:617-618.

- Singh SK, Singh S, Pandey SS. Cutaneous sarcoidosis without systemic involvement: response to intralesional corticosteroid. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1996; 62:273-274.

- Karrer S, Abels C, Wimmershoff MB, et al. Successful treatment of cutaneous sarcoidosis using topical photodynamic therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2002; 138:581-584.

- Mahnke N, Medve-koenigs K, Berneburg M, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidosis treated with medium-dose UVA1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004; 50:978-979.

- Frederiksen LG, Jørgensen K. Sarcoidosis of the nose treated with laser surgery. Rhinology. 1996; 34:245-246.

- Baughman RP, Lower EE. Evidence-based therapy for cutaneous sarcoidosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007; 25:334-340.

A 57-year-old woman presented with several lesions on the left extensor forearm of 10 years’ duration. A single annular indurated lesion with central atrophy initially developed near a prior surgical site. The lesions were pruritic with no associated pain or bleeding. Over 5 years, similar lesions had developed extending up the arm. No benefit was seen with low-potency topical steroid application. Biopsy for histopathologic examination was performed to confirm the diagnosis.

Attitudes of Women Toward the Gynecologic Examination

Novel biomarker could predict resistance to palbociclib

, according to a gene expression analysis.

Nicholas C. Turner, MD, PhD, of Royal Marsden Hospital and Institute of Cancer Research in London, and his colleagues used a gene expression panel to detect biomarkers related to the efficacy of palbociclib plus fulvestrant in patients with endocrine-pretreated metastatic breast cancer.

“No predictive biomarkers have been identified in randomized trials of CDK4/6 inhibitors,” the researchers wrote in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Study participants were randomly assigned to receive either combination palbociclib and fulvestrant (n = 194) or placebo and fulvestrant (n = 108). The primary analysis was completed using data from the PALOMA-3 trial, which included 10 genes selected from a panel search of 2,534 genes.

The association between level of gene expression and efficacy of palbociclib combination therapy was evaluated by way of advanced statistical analysis.

After analysis, the efficacy of palbociclib was found to be reduced with high levels of cyclin E1 mRNA expression compared with low levels (median PFS palbociclib arm, 7.6 vs. 14.1 months; placebo arm, 4.0 vs. 4.8 months; P = .00238).

“These data suggest that CCNE1 mRNA expression may be associated with the benefit from palbociclib in early-stage breast cancer,” they wrote.

The authors acknowledged that one key limitation of the study was that the biomarkers identified may not be relevant to other CDK4/6 inhibitor combinations.

“Additional methodologic and clinical validations are warranted to elucidate the role of CCNE1 mRNA expression as a biomarker of CDK4/6 inhibitor therapy,” they concluded.

The study was supported by Pfizer. The authors reported financial interests with AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Genentech, Novartis, Pfizer, and others.

SOURCE: Turner NC et al. J Clin Oncol. 2019 Feb 26. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.00925.

, according to a gene expression analysis.

Nicholas C. Turner, MD, PhD, of Royal Marsden Hospital and Institute of Cancer Research in London, and his colleagues used a gene expression panel to detect biomarkers related to the efficacy of palbociclib plus fulvestrant in patients with endocrine-pretreated metastatic breast cancer.

“No predictive biomarkers have been identified in randomized trials of CDK4/6 inhibitors,” the researchers wrote in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Study participants were randomly assigned to receive either combination palbociclib and fulvestrant (n = 194) or placebo and fulvestrant (n = 108). The primary analysis was completed using data from the PALOMA-3 trial, which included 10 genes selected from a panel search of 2,534 genes.

The association between level of gene expression and efficacy of palbociclib combination therapy was evaluated by way of advanced statistical analysis.

After analysis, the efficacy of palbociclib was found to be reduced with high levels of cyclin E1 mRNA expression compared with low levels (median PFS palbociclib arm, 7.6 vs. 14.1 months; placebo arm, 4.0 vs. 4.8 months; P = .00238).

“These data suggest that CCNE1 mRNA expression may be associated with the benefit from palbociclib in early-stage breast cancer,” they wrote.

The authors acknowledged that one key limitation of the study was that the biomarkers identified may not be relevant to other CDK4/6 inhibitor combinations.

“Additional methodologic and clinical validations are warranted to elucidate the role of CCNE1 mRNA expression as a biomarker of CDK4/6 inhibitor therapy,” they concluded.

The study was supported by Pfizer. The authors reported financial interests with AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Genentech, Novartis, Pfizer, and others.

SOURCE: Turner NC et al. J Clin Oncol. 2019 Feb 26. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.00925.

, according to a gene expression analysis.

Nicholas C. Turner, MD, PhD, of Royal Marsden Hospital and Institute of Cancer Research in London, and his colleagues used a gene expression panel to detect biomarkers related to the efficacy of palbociclib plus fulvestrant in patients with endocrine-pretreated metastatic breast cancer.

“No predictive biomarkers have been identified in randomized trials of CDK4/6 inhibitors,” the researchers wrote in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Study participants were randomly assigned to receive either combination palbociclib and fulvestrant (n = 194) or placebo and fulvestrant (n = 108). The primary analysis was completed using data from the PALOMA-3 trial, which included 10 genes selected from a panel search of 2,534 genes.

The association between level of gene expression and efficacy of palbociclib combination therapy was evaluated by way of advanced statistical analysis.

After analysis, the efficacy of palbociclib was found to be reduced with high levels of cyclin E1 mRNA expression compared with low levels (median PFS palbociclib arm, 7.6 vs. 14.1 months; placebo arm, 4.0 vs. 4.8 months; P = .00238).

“These data suggest that CCNE1 mRNA expression may be associated with the benefit from palbociclib in early-stage breast cancer,” they wrote.

The authors acknowledged that one key limitation of the study was that the biomarkers identified may not be relevant to other CDK4/6 inhibitor combinations.

“Additional methodologic and clinical validations are warranted to elucidate the role of CCNE1 mRNA expression as a biomarker of CDK4/6 inhibitor therapy,” they concluded.

The study was supported by Pfizer. The authors reported financial interests with AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Genentech, Novartis, Pfizer, and others.

SOURCE: Turner NC et al. J Clin Oncol. 2019 Feb 26. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.00925.

FROM JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

The dangers of dog walking

The estimated number of fractures associated with walking a leashed dog was 4,396 in 2017 among those aged 65 years and older, compared with 1,671 in 2004, which is a significant increase, Kevin Pirruccio of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and his associates wrote in JAMA Surgery.

Over the entire study period, 2004-2017, almost 79% of all fractures occurred in women and 67% of all patients were treated in the emergency department and released. The most common injury was hip fracture (17.3%), although upper-extremity fractures were more common (52.1%) than those of the lower extremities (29.4%), trunk (10.1%), or head and neck (7.3%), the investigators reported.

“For older adults – especially those living alone and with decreased bone mineral density – the risks associated with walking leashed dogs merit consideration. Even one such injury could result in a potentially lethal hip fracture, lifelong complications, or loss of independence,” they wrote.

The retrospective, cross-sectional analysis involved the Consumer Product Safety Commission’s National Electronic Injury Surveillance System database, which includes approximately 100 hospital emergency departments. The investigators did not report any conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Pirruccio K et al. JAMA Surg. 2019 Mar 6. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.0061.

The estimated number of fractures associated with walking a leashed dog was 4,396 in 2017 among those aged 65 years and older, compared with 1,671 in 2004, which is a significant increase, Kevin Pirruccio of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and his associates wrote in JAMA Surgery.

Over the entire study period, 2004-2017, almost 79% of all fractures occurred in women and 67% of all patients were treated in the emergency department and released. The most common injury was hip fracture (17.3%), although upper-extremity fractures were more common (52.1%) than those of the lower extremities (29.4%), trunk (10.1%), or head and neck (7.3%), the investigators reported.

“For older adults – especially those living alone and with decreased bone mineral density – the risks associated with walking leashed dogs merit consideration. Even one such injury could result in a potentially lethal hip fracture, lifelong complications, or loss of independence,” they wrote.

The retrospective, cross-sectional analysis involved the Consumer Product Safety Commission’s National Electronic Injury Surveillance System database, which includes approximately 100 hospital emergency departments. The investigators did not report any conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Pirruccio K et al. JAMA Surg. 2019 Mar 6. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.0061.

The estimated number of fractures associated with walking a leashed dog was 4,396 in 2017 among those aged 65 years and older, compared with 1,671 in 2004, which is a significant increase, Kevin Pirruccio of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and his associates wrote in JAMA Surgery.

Over the entire study period, 2004-2017, almost 79% of all fractures occurred in women and 67% of all patients were treated in the emergency department and released. The most common injury was hip fracture (17.3%), although upper-extremity fractures were more common (52.1%) than those of the lower extremities (29.4%), trunk (10.1%), or head and neck (7.3%), the investigators reported.

“For older adults – especially those living alone and with decreased bone mineral density – the risks associated with walking leashed dogs merit consideration. Even one such injury could result in a potentially lethal hip fracture, lifelong complications, or loss of independence,” they wrote.

The retrospective, cross-sectional analysis involved the Consumer Product Safety Commission’s National Electronic Injury Surveillance System database, which includes approximately 100 hospital emergency departments. The investigators did not report any conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Pirruccio K et al. JAMA Surg. 2019 Mar 6. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.0061.

FROM JAMA SURGERY

FDA urges caution with robotic devices in cancer surgery

A new safety communication from the Food and Drug Administration on the use of robotically assisted surgical devices for mastectomy and other cancer-related surgeries in women encourages physician-patient dialogue and suggests that, moving forward, data on specific oncologic outcomes – not only perioperative and short-term outcomes – are key.

The FDA is “warning patients and providers that the use of robotically assisted surgical devices for any cancer-related surgery has not been granted marketing authorization by the agency, and therefore the survival benefits to patients when compared to traditional surgery have not been established,” Terri Cornelison, MD, PhD, assistant director for the health of women in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in a statement.

The safety communication focuses on women and calls attention specifically to robotically-assisted mastectomy and hysterectomy for early cervical cancers. It says there is “limited, preliminary evidence that the use of robotically-assisted surgical devices for treatment or prevention of cancers that primarily (breast) or exclusively (cervical) affect women may be associated with diminished long-term survival.”

The FDA cited a multicenter randomized trial that found that minimally invasive radical hysterectomy in women with cervical cancer (laparoscopic and robotically assisted) was associated with a lower rate of long-term survival compared with open surgery (N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1895-1904).

The communication does not refer to any other specific studies. Regarding current evidence on robotically-assisted mastectomies, the FDA safety communication says simply that safety and effectiveness have not been established and that the agency is “aware of scientific literature and media publications describing surgeons and hospital systems that use robotically-assisted surgical devices for mastectomy.”

Robotically-assisted mastectomy

Walton Taylor, MD, president of the American Society of Breast Surgeons and a surgeon with Texas Health Physicians Group in Dallas, said that the FDA’s concern is valid. “I really hope that robotic surgery turns out to be good [for mastectomy]. It’s awesome technology that can be great for patients,” he said. “But we have to gather real data that shows that long-term and short-term outcomes – from a cancer standpoint – are as good as with the open procedure ... that there aren’t negative unintended consequences.”

Right now, Dr. Taylor said, robotic mastectomy “is not commonplace by any means.”

The technique for robotic nipple-sparing mastectomy (NSM) was first described by Antonio Toesca, MD, of the European Institute of Oncology in Milan (Ann Surg. 2017;266[2]:e28-e30).

In an editorial published recently in Annals of Surgical Oncology, Jesse C. Selber, MD, MPH, of the department of plastic surgery at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, described the technique as a “natural next step in the evolution of minimally invasive breast surgery that has the potential to mitigate the challenges associated with traditional NSM” (Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26[1]:10-11). Robotic nipple-sparing mastectomy is catching on in Europe” with very promising early results, he wrote.

At least a couple of practices promoted their performance of robotic mastectomy last year. Northwell Health, a large network of hospitals, outpatient facilities, and physicians in New York, announced in March 2018 that Neil Tanna, MD, and Alan Kadison, MD, of the divisions of plastic and reconstructive surgery and surgical oncology, respectively, had performed the first robotic nipple-sparing mastectomy and breast reconstructive surgery in the United States. Their patient carried the BRCA gene and had a preventive mastectomy at Northwell Health’s Long Island Jewish Medical Center.

In October 2018, a surgeon in Tinton Falls, N.J., Stephen Chagares, MD, announced that he had performed the first robotic nipple-sparing mastectomy with reconstruction in a patient with breast cancer at Monmouth Medical Center. His press release described a 3-cm incision “to the side of the breast, tucked neatly behind the armpit.” Both Dr. Chagares and Dr. Tanna had traveled to Milan to train with Dr. Toesca, according to the press releases.

Both of these cases – as well as a decision by Monmouth Medical Center in December 2018 to suspend the surgery pending further review – were mentioned in a letter submitted to the FDA in mid-December by Hooman Noorchashm, MD, PhD, a Philadelphia cardiothoracic surgeon-turned-patient-advocate whose wife Amy Josephine Reed, MD, PhD, died of uterine cancer in May 2017 following a laparoscopic hysterectomy performed with a power morcellator.

In his complaint, Dr. Noorchashm urged the agency to issue a warning about the “potentially dangerous/premature application” of robotic mastectomy for the treatment of breast cancer or BRCA carrier status outside the setting of randomized controlled trials with primary cancer–related outcomes metrics or an investigational device exemption from the FDA. (Receipt of the letter was acknowledged by the Allegation of Regulatory Misconduct Branch of the FDA several days later.)

In an interview, Dr. Noorchashm said he wants to see a regulatory framework that doesn’t allow 510(k) devices (devices requiring a premarket notification to the FDA) to modify an existing standard of care without having been shown to have noninferior primary outcomes. When devices are used in the diagnosis or treatment of cancerous or potentially cancerous tissue, he said, this means primary oncologic outcomes must be shown to be noninferior.

“When you have 510(k) devices able to inject themselves and affect existing standards of care without any sort of clinical trial requirement, you get the standard of care changing without any outcomes data to back it up,” he said. “That’s what happened with the power morcellator. Physicians started using it without any sort of prospective data, level 1 outcomes data, and it dramatically changed the conduct of hysterectomies.”

In its safety communication, the FDA encourages the establishment of patient registries to gather data on robotically-assisted surgical devices for all uses, including the prevention and treatment of cancer. It also says that while the agency’s evaluation of the devices has generally focused on complication rates at 30 days, the FDA “anticipates” that their use in the prevention or treatment of cancer “would be supported by specific clinical outcomes, such as local cancer recurrence, disease-free survival, or overall survival at time periods much longer than 30 days.”

The American Society of Breast Surgeons has a Nipple Sparing Mastectomy Registry that is collecting oncologic outcomes as well as aesthetic outcomes and other metrics on 2,000 patients. “In the last year or two, we’ve seen nipple-sparing mastectomy become much more commonplace,” said Dr. Taylor. Thus far, the registry does not include robotic procedures, but “if there were interest in a registry specifically for robotic nipple-sparing mastectomy, we would do it in a heartbeat.”

Gynecologic oncology surgery

The randomized controlled study on radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer that caught the FDA’s attention reported lower rates of disease-free survival at 4.5 years with minimally invasive surgery than with open abdominal surgery (86% versus 96.5%) and lower rates of overall survival at 3 years.

The phase 3 multicenter Laparoscopic Approach to Cervical Cancer trial recruited more than 600 women with stage IA1, IA2, or IB1 cervical cancer. Most (91.9%) had IB1 disease and either squamous-cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, or adenosquamous carcinoma. Differences in the outcomes remained after adjustment for age, body mass index, disease stage, lymphovascular invasion, and lymph-node involvement. The findings led to early termination of the study.

The study did not single out robotically-assisted surgery. It was a two-arm study and was “not powered to analyze laparoscopy versus robotics,” lead author Pedro T. Ramirez, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, said in an interview. “But based on our numbers, we saw no difference [in outcomes] between the two groups.” Of the patients who underwent minimally invasive surgery, 84.4% underwent laparoscopy and 15.6% underwent robot-assisted surgery.

The study, funded by MD Anderson and Medtronic, has been criticized for potential design and conduct issues. Outside experts pointed out that the study involved extremely small numbers of patients at each of the 33 participating centers, and that cancer recurrences were clustered at 14 of these centers. It’s important to appreciate, Dr. Ramirez said in the interview, that the majority of patients were accrued in these 14 centers.

In its safety communication, the FDA noted that other researchers have reported no statistically significant difference in long-term survival when open and minimally invasive approaches to radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer have been compared.

Asked to comment on the FDA’s safety communication, Dwight D. Im, MD, who leads the National Institute of Robotic Surgery at Mercy in Baltimore, said in an e-mail that “while robotic surgery may advance into new areas, such as mastectomy and cancer prevention, more research must be done and this should be part of any conversation between gyn-surgeons who are experienced in the realm of robotic surgery, and their patients.”

Regarding the treatment of cervical cancer, “I think it is safe to say that most gynecologic oncologists now offer only open laparotomies until we have more data comparing open to minimally invasive (laparoscopic and robotic) approaches,” he said.

The FDA said in a briefing document accompanying the safety communication that it has received a “small number of medical device reports of patient injury when [robotically-assisted surgical devices] are used in cancer-related procedures.”

According to the FDA spokesperson, 5 of 32 medical device reports received between January 2016 and December 2018 describe patients who underwent hysterectomy and experienced metastases afterward. It does not appear that any of the 5 cases were a direct result of a system error or device malfunction, and the complications described in the reports are not unique to robotically-assisted surgical devices, the spokesperson said.

The safety communication “reflects the agency’s commitment to enhancing the oversight of device safety as part of our Medical Device Action Plan, as well as the agency’s ongoing commitment to advancing women’s health.”

Dr. Taylor reported that he has no current financial disclosures. Dr. Ramirez reported to the New England Journal of Medicine that he had no relevant disclosures. Dr. Im reported that he is a speaker for Intuitive Surgical, which manufacturers the da Vinci Surgical System, as well as for Conmed and Ethicon.

A new safety communication from the Food and Drug Administration on the use of robotically assisted surgical devices for mastectomy and other cancer-related surgeries in women encourages physician-patient dialogue and suggests that, moving forward, data on specific oncologic outcomes – not only perioperative and short-term outcomes – are key.

The FDA is “warning patients and providers that the use of robotically assisted surgical devices for any cancer-related surgery has not been granted marketing authorization by the agency, and therefore the survival benefits to patients when compared to traditional surgery have not been established,” Terri Cornelison, MD, PhD, assistant director for the health of women in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in a statement.

The safety communication focuses on women and calls attention specifically to robotically-assisted mastectomy and hysterectomy for early cervical cancers. It says there is “limited, preliminary evidence that the use of robotically-assisted surgical devices for treatment or prevention of cancers that primarily (breast) or exclusively (cervical) affect women may be associated with diminished long-term survival.”

The FDA cited a multicenter randomized trial that found that minimally invasive radical hysterectomy in women with cervical cancer (laparoscopic and robotically assisted) was associated with a lower rate of long-term survival compared with open surgery (N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1895-1904).

The communication does not refer to any other specific studies. Regarding current evidence on robotically-assisted mastectomies, the FDA safety communication says simply that safety and effectiveness have not been established and that the agency is “aware of scientific literature and media publications describing surgeons and hospital systems that use robotically-assisted surgical devices for mastectomy.”

Robotically-assisted mastectomy

Walton Taylor, MD, president of the American Society of Breast Surgeons and a surgeon with Texas Health Physicians Group in Dallas, said that the FDA’s concern is valid. “I really hope that robotic surgery turns out to be good [for mastectomy]. It’s awesome technology that can be great for patients,” he said. “But we have to gather real data that shows that long-term and short-term outcomes – from a cancer standpoint – are as good as with the open procedure ... that there aren’t negative unintended consequences.”

Right now, Dr. Taylor said, robotic mastectomy “is not commonplace by any means.”

The technique for robotic nipple-sparing mastectomy (NSM) was first described by Antonio Toesca, MD, of the European Institute of Oncology in Milan (Ann Surg. 2017;266[2]:e28-e30).

In an editorial published recently in Annals of Surgical Oncology, Jesse C. Selber, MD, MPH, of the department of plastic surgery at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, described the technique as a “natural next step in the evolution of minimally invasive breast surgery that has the potential to mitigate the challenges associated with traditional NSM” (Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26[1]:10-11). Robotic nipple-sparing mastectomy is catching on in Europe” with very promising early results, he wrote.

At least a couple of practices promoted their performance of robotic mastectomy last year. Northwell Health, a large network of hospitals, outpatient facilities, and physicians in New York, announced in March 2018 that Neil Tanna, MD, and Alan Kadison, MD, of the divisions of plastic and reconstructive surgery and surgical oncology, respectively, had performed the first robotic nipple-sparing mastectomy and breast reconstructive surgery in the United States. Their patient carried the BRCA gene and had a preventive mastectomy at Northwell Health’s Long Island Jewish Medical Center.

In October 2018, a surgeon in Tinton Falls, N.J., Stephen Chagares, MD, announced that he had performed the first robotic nipple-sparing mastectomy with reconstruction in a patient with breast cancer at Monmouth Medical Center. His press release described a 3-cm incision “to the side of the breast, tucked neatly behind the armpit.” Both Dr. Chagares and Dr. Tanna had traveled to Milan to train with Dr. Toesca, according to the press releases.

Both of these cases – as well as a decision by Monmouth Medical Center in December 2018 to suspend the surgery pending further review – were mentioned in a letter submitted to the FDA in mid-December by Hooman Noorchashm, MD, PhD, a Philadelphia cardiothoracic surgeon-turned-patient-advocate whose wife Amy Josephine Reed, MD, PhD, died of uterine cancer in May 2017 following a laparoscopic hysterectomy performed with a power morcellator.

In his complaint, Dr. Noorchashm urged the agency to issue a warning about the “potentially dangerous/premature application” of robotic mastectomy for the treatment of breast cancer or BRCA carrier status outside the setting of randomized controlled trials with primary cancer–related outcomes metrics or an investigational device exemption from the FDA. (Receipt of the letter was acknowledged by the Allegation of Regulatory Misconduct Branch of the FDA several days later.)

In an interview, Dr. Noorchashm said he wants to see a regulatory framework that doesn’t allow 510(k) devices (devices requiring a premarket notification to the FDA) to modify an existing standard of care without having been shown to have noninferior primary outcomes. When devices are used in the diagnosis or treatment of cancerous or potentially cancerous tissue, he said, this means primary oncologic outcomes must be shown to be noninferior.

“When you have 510(k) devices able to inject themselves and affect existing standards of care without any sort of clinical trial requirement, you get the standard of care changing without any outcomes data to back it up,” he said. “That’s what happened with the power morcellator. Physicians started using it without any sort of prospective data, level 1 outcomes data, and it dramatically changed the conduct of hysterectomies.”

In its safety communication, the FDA encourages the establishment of patient registries to gather data on robotically-assisted surgical devices for all uses, including the prevention and treatment of cancer. It also says that while the agency’s evaluation of the devices has generally focused on complication rates at 30 days, the FDA “anticipates” that their use in the prevention or treatment of cancer “would be supported by specific clinical outcomes, such as local cancer recurrence, disease-free survival, or overall survival at time periods much longer than 30 days.”

The American Society of Breast Surgeons has a Nipple Sparing Mastectomy Registry that is collecting oncologic outcomes as well as aesthetic outcomes and other metrics on 2,000 patients. “In the last year or two, we’ve seen nipple-sparing mastectomy become much more commonplace,” said Dr. Taylor. Thus far, the registry does not include robotic procedures, but “if there were interest in a registry specifically for robotic nipple-sparing mastectomy, we would do it in a heartbeat.”

Gynecologic oncology surgery

The randomized controlled study on radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer that caught the FDA’s attention reported lower rates of disease-free survival at 4.5 years with minimally invasive surgery than with open abdominal surgery (86% versus 96.5%) and lower rates of overall survival at 3 years.

The phase 3 multicenter Laparoscopic Approach to Cervical Cancer trial recruited more than 600 women with stage IA1, IA2, or IB1 cervical cancer. Most (91.9%) had IB1 disease and either squamous-cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, or adenosquamous carcinoma. Differences in the outcomes remained after adjustment for age, body mass index, disease stage, lymphovascular invasion, and lymph-node involvement. The findings led to early termination of the study.

The study did not single out robotically-assisted surgery. It was a two-arm study and was “not powered to analyze laparoscopy versus robotics,” lead author Pedro T. Ramirez, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, said in an interview. “But based on our numbers, we saw no difference [in outcomes] between the two groups.” Of the patients who underwent minimally invasive surgery, 84.4% underwent laparoscopy and 15.6% underwent robot-assisted surgery.

The study, funded by MD Anderson and Medtronic, has been criticized for potential design and conduct issues. Outside experts pointed out that the study involved extremely small numbers of patients at each of the 33 participating centers, and that cancer recurrences were clustered at 14 of these centers. It’s important to appreciate, Dr. Ramirez said in the interview, that the majority of patients were accrued in these 14 centers.