User login

Cerebral small vessel disease progression linked to MCI in hypertensive patients

Patients with hypertension who show substantial progression of cerebral small vessel disease over time have sixfold higher odds of developing mild cognitive impairment than do those without signs of progression on brain MRI, new research has found.

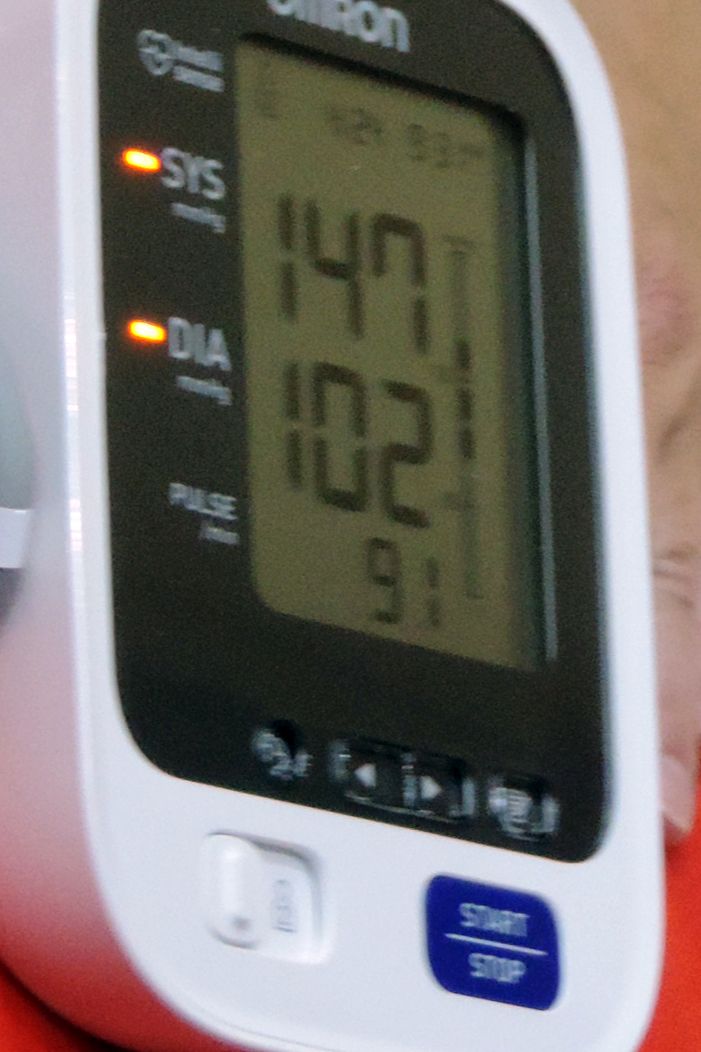

The results, published online Jan. 4 in Hypertension, come from a longitudinal, population-based study of 976 patients with hypertension but with no history of dementia or clinical stroke. Participants underwent a vascular risk assessment, brain MRI, cognitive evaluation, and blood sampling at baseline, and 345 patients were also retested after a mean of nearly 4 years.

Researchers saw significant sixfold higher odds of developing incident mild cognitive impairment (MCI) among individuals who showed marked progression of periventricular white matter hyperintensities – an imaging hallmark of cerebral small vessel disease – compared with individuals who did not show any progression (odds ratio = 6.184; 95% confidence interval, 1.506-25.370; P = .011).

Patients with greater progression of periventricular white matter hyperintensities also showed significantly greater decreases in global cognition scores – both in total DRS-2 Z-score and executive function Z-score – when compared against individuals without white matter hyperintensity progression.

“As MCI is one of the most important risk factors in the development of dementia, future research should investigate the mechanisms by which PVH [periventricular white matter hyperintensities] trigger cognitive impairment and the clinical utility of its assessment,” wrote Joan Jiménez-Balado of Vall d’Hebron Research Institute, Barcelona, and his associates.

However, deep white matter hyperintensity progression – as opposed to periventricular – was not linked to cognitive changes, except in the case of bilateral occipital deep white matter hyperintensity changes, which were linked to a significant worsening in the attention Z-score.

The authors noted that the different impacts of periventricular versus deep white matter hyperintensities may relate to a number of factors. The first was that deep white matter hyperintensities disrupt cortico-cortical connections but periventricular ones are more likely to affect long cortico-subcortical association fibers, which “would be an important variable to determine the impaired networks involved in cognition.”

They also suggested that periventricular and deep white matter hyperintensities may affect different neuromodulator systems; the periventricular white matter could be closer to ascending cholinergic bundles that may play a role in vascular cognitive impairment.

Periventricular white matter hyperintensities may also accelerate the deposition of amyloid because of their association with venous collagenosis, which is linked to ischemia and disruptions of the interstitial fluid circulation.

“On the other hand, [deep white matter hyperintensity] may be more related to hypoperfusion, as deep areas are particularly vulnerable to low [blood pressure],” the authors wrote, while stressing that the pathophysiology of white matter hyperintensities is not fully understood, so further research is needed.

Overall, the 345 patients with follow-up data had a median age of 65 years at baseline and mean blood pressure of 143/78.2 mm Hg at baseline and 146.5/75 mm Hg at follow-up. White matter hyperintensity changes occurred periventricularly in 22% and in deep white matter in 48%. The researchers saw new infarcts in 6.1% of patients, and 5.5% had incident cerebral microbleeds. While incident cerebral microbleeds were significantly associated with declines in the attention Z-score, they did not affect other cognitive functions, and incidental infarcts were also not associated with cognitive changes.

Baseline blood pressure and average blood pressure during follow-up were not associated with changes in cardiac small vessel disease lesions. However, diastolic – but not systolic – blood pressure at baseline and follow-up was positively correlated with total, attention, and executive function DRS-2 Z-scores at follow-up.

Three-quarters of patients showed cognitive changes associated with normal aging both at baseline and follow-up, 9.1% had stable MCI, and 9.1% of patients had incident MCI. However, 6.6% of subjects reverted back to normal aging after having MCI at baseline.

The authors noted that they did not examine markers of neurodegeneration, such as tau or amyloid-beta, which could also be linked to hypertension and cerebral small vessel disease lesions.

The study was supported by Instituto de Salud Carlos III, AGAUR (Agency for Management of University and Research Grants), the Secretary of Universities and Research of the Department of Economy and Knowledge, and the European Regional Development Fund. The authors said they have no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Jiménez-Balado J et al. Hypertension. 2019 Jan 4. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.12090

Patients with hypertension who show substantial progression of cerebral small vessel disease over time have sixfold higher odds of developing mild cognitive impairment than do those without signs of progression on brain MRI, new research has found.

The results, published online Jan. 4 in Hypertension, come from a longitudinal, population-based study of 976 patients with hypertension but with no history of dementia or clinical stroke. Participants underwent a vascular risk assessment, brain MRI, cognitive evaluation, and blood sampling at baseline, and 345 patients were also retested after a mean of nearly 4 years.

Researchers saw significant sixfold higher odds of developing incident mild cognitive impairment (MCI) among individuals who showed marked progression of periventricular white matter hyperintensities – an imaging hallmark of cerebral small vessel disease – compared with individuals who did not show any progression (odds ratio = 6.184; 95% confidence interval, 1.506-25.370; P = .011).

Patients with greater progression of periventricular white matter hyperintensities also showed significantly greater decreases in global cognition scores – both in total DRS-2 Z-score and executive function Z-score – when compared against individuals without white matter hyperintensity progression.

“As MCI is one of the most important risk factors in the development of dementia, future research should investigate the mechanisms by which PVH [periventricular white matter hyperintensities] trigger cognitive impairment and the clinical utility of its assessment,” wrote Joan Jiménez-Balado of Vall d’Hebron Research Institute, Barcelona, and his associates.

However, deep white matter hyperintensity progression – as opposed to periventricular – was not linked to cognitive changes, except in the case of bilateral occipital deep white matter hyperintensity changes, which were linked to a significant worsening in the attention Z-score.

The authors noted that the different impacts of periventricular versus deep white matter hyperintensities may relate to a number of factors. The first was that deep white matter hyperintensities disrupt cortico-cortical connections but periventricular ones are more likely to affect long cortico-subcortical association fibers, which “would be an important variable to determine the impaired networks involved in cognition.”

They also suggested that periventricular and deep white matter hyperintensities may affect different neuromodulator systems; the periventricular white matter could be closer to ascending cholinergic bundles that may play a role in vascular cognitive impairment.

Periventricular white matter hyperintensities may also accelerate the deposition of amyloid because of their association with venous collagenosis, which is linked to ischemia and disruptions of the interstitial fluid circulation.

“On the other hand, [deep white matter hyperintensity] may be more related to hypoperfusion, as deep areas are particularly vulnerable to low [blood pressure],” the authors wrote, while stressing that the pathophysiology of white matter hyperintensities is not fully understood, so further research is needed.

Overall, the 345 patients with follow-up data had a median age of 65 years at baseline and mean blood pressure of 143/78.2 mm Hg at baseline and 146.5/75 mm Hg at follow-up. White matter hyperintensity changes occurred periventricularly in 22% and in deep white matter in 48%. The researchers saw new infarcts in 6.1% of patients, and 5.5% had incident cerebral microbleeds. While incident cerebral microbleeds were significantly associated with declines in the attention Z-score, they did not affect other cognitive functions, and incidental infarcts were also not associated with cognitive changes.

Baseline blood pressure and average blood pressure during follow-up were not associated with changes in cardiac small vessel disease lesions. However, diastolic – but not systolic – blood pressure at baseline and follow-up was positively correlated with total, attention, and executive function DRS-2 Z-scores at follow-up.

Three-quarters of patients showed cognitive changes associated with normal aging both at baseline and follow-up, 9.1% had stable MCI, and 9.1% of patients had incident MCI. However, 6.6% of subjects reverted back to normal aging after having MCI at baseline.

The authors noted that they did not examine markers of neurodegeneration, such as tau or amyloid-beta, which could also be linked to hypertension and cerebral small vessel disease lesions.

The study was supported by Instituto de Salud Carlos III, AGAUR (Agency for Management of University and Research Grants), the Secretary of Universities and Research of the Department of Economy and Knowledge, and the European Regional Development Fund. The authors said they have no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Jiménez-Balado J et al. Hypertension. 2019 Jan 4. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.12090

Patients with hypertension who show substantial progression of cerebral small vessel disease over time have sixfold higher odds of developing mild cognitive impairment than do those without signs of progression on brain MRI, new research has found.

The results, published online Jan. 4 in Hypertension, come from a longitudinal, population-based study of 976 patients with hypertension but with no history of dementia or clinical stroke. Participants underwent a vascular risk assessment, brain MRI, cognitive evaluation, and blood sampling at baseline, and 345 patients were also retested after a mean of nearly 4 years.

Researchers saw significant sixfold higher odds of developing incident mild cognitive impairment (MCI) among individuals who showed marked progression of periventricular white matter hyperintensities – an imaging hallmark of cerebral small vessel disease – compared with individuals who did not show any progression (odds ratio = 6.184; 95% confidence interval, 1.506-25.370; P = .011).

Patients with greater progression of periventricular white matter hyperintensities also showed significantly greater decreases in global cognition scores – both in total DRS-2 Z-score and executive function Z-score – when compared against individuals without white matter hyperintensity progression.

“As MCI is one of the most important risk factors in the development of dementia, future research should investigate the mechanisms by which PVH [periventricular white matter hyperintensities] trigger cognitive impairment and the clinical utility of its assessment,” wrote Joan Jiménez-Balado of Vall d’Hebron Research Institute, Barcelona, and his associates.

However, deep white matter hyperintensity progression – as opposed to periventricular – was not linked to cognitive changes, except in the case of bilateral occipital deep white matter hyperintensity changes, which were linked to a significant worsening in the attention Z-score.

The authors noted that the different impacts of periventricular versus deep white matter hyperintensities may relate to a number of factors. The first was that deep white matter hyperintensities disrupt cortico-cortical connections but periventricular ones are more likely to affect long cortico-subcortical association fibers, which “would be an important variable to determine the impaired networks involved in cognition.”

They also suggested that periventricular and deep white matter hyperintensities may affect different neuromodulator systems; the periventricular white matter could be closer to ascending cholinergic bundles that may play a role in vascular cognitive impairment.

Periventricular white matter hyperintensities may also accelerate the deposition of amyloid because of their association with venous collagenosis, which is linked to ischemia and disruptions of the interstitial fluid circulation.

“On the other hand, [deep white matter hyperintensity] may be more related to hypoperfusion, as deep areas are particularly vulnerable to low [blood pressure],” the authors wrote, while stressing that the pathophysiology of white matter hyperintensities is not fully understood, so further research is needed.

Overall, the 345 patients with follow-up data had a median age of 65 years at baseline and mean blood pressure of 143/78.2 mm Hg at baseline and 146.5/75 mm Hg at follow-up. White matter hyperintensity changes occurred periventricularly in 22% and in deep white matter in 48%. The researchers saw new infarcts in 6.1% of patients, and 5.5% had incident cerebral microbleeds. While incident cerebral microbleeds were significantly associated with declines in the attention Z-score, they did not affect other cognitive functions, and incidental infarcts were also not associated with cognitive changes.

Baseline blood pressure and average blood pressure during follow-up were not associated with changes in cardiac small vessel disease lesions. However, diastolic – but not systolic – blood pressure at baseline and follow-up was positively correlated with total, attention, and executive function DRS-2 Z-scores at follow-up.

Three-quarters of patients showed cognitive changes associated with normal aging both at baseline and follow-up, 9.1% had stable MCI, and 9.1% of patients had incident MCI. However, 6.6% of subjects reverted back to normal aging after having MCI at baseline.

The authors noted that they did not examine markers of neurodegeneration, such as tau or amyloid-beta, which could also be linked to hypertension and cerebral small vessel disease lesions.

The study was supported by Instituto de Salud Carlos III, AGAUR (Agency for Management of University and Research Grants), the Secretary of Universities and Research of the Department of Economy and Knowledge, and the European Regional Development Fund. The authors said they have no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Jiménez-Balado J et al. Hypertension. 2019 Jan 4. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.12090

FROM HYPERTENSION

Key clinical point: Cerebral small vessel disease changes are associated with the development of mild cognitive impairment in hypertensive patients.

Major finding: Periventricular white matter hyperintensities in patients with hypertension were associated with sixfold higher odds of mild cognitive impairment.

Study details: A longitudinal, population-based study of 345 patients with hypertension.

Disclosures: The study was supported by Instituto de Salud Carlos III, AGAUR (Agency for Management of University and Research Grants), the Secretary of Universities and Research of the Department of Economy and Knowledge, and the European Regional Development Fund. The authors said they have no conflicts of interest.

Source: Jiménez-Balado J et al. Hypertension. 2019 Jan 4. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.12090.

Aspirin and Omega-3 fatty acids fail

Also today, New data reveal that college students are at greater risk of meningococcal B infection, children who survive Hodgkin lymphoma face a massive increased risk for second cancers down the road, and the 2018/19 flu season shows high activity in nine states.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Also today, New data reveal that college students are at greater risk of meningococcal B infection, children who survive Hodgkin lymphoma face a massive increased risk for second cancers down the road, and the 2018/19 flu season shows high activity in nine states.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Also today, New data reveal that college students are at greater risk of meningococcal B infection, children who survive Hodgkin lymphoma face a massive increased risk for second cancers down the road, and the 2018/19 flu season shows high activity in nine states.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Raymond Barfield Part I

Now, he joins the Postcall Podcast to discuss why he’s back, what he’s working on to prevent burnout, and how he wants to remake pre-med education. You can read more from Dr. Barfield’s story here.

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Now, he joins the Postcall Podcast to discuss why he’s back, what he’s working on to prevent burnout, and how he wants to remake pre-med education. You can read more from Dr. Barfield’s story here.

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Now, he joins the Postcall Podcast to discuss why he’s back, what he’s working on to prevent burnout, and how he wants to remake pre-med education. You can read more from Dr. Barfield’s story here.

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

How Often Are Staring Spells Seizures?

Investigators review cases at a new-onset seizure clinic.

CHICAGO—About half of staring spells referred to a new-onset seizure (NOS) clinic turn out to be epileptic seizures, according to a retrospective chart review presented at the 47th Annual Meeting of the Child Neurology Society.

Children with nonepileptic staring were younger and more likely to have developmental delay, compared with children with epileptic staring, said Seunghyo Kim, MD, Visiting Associate Professor of Pediatrics at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, and his colleagues

A Common Reason for Referral

Staring spells are common in children and a frequent reason for referral to NOS clinics, the investigators said. Staring spells may be generalized absence seizures, focal seizures, or nonepileptic events. Few studies, however, have examined patients who newly present to a neurology clinic with the chief complaint of staring spells.

To evaluate the clinical and demographic features of children who present with staring spells to a regional NOS clinic, the researchers reviewed charts from 2,818 patients who visited a children’s hospital between September 22, 2015, and March 19, 2018. The investigators identified 189 patients with staring spells.

They excluded 48 cases where staring was accompanied by or followed by generalized tonic-clonic seizures or other motor seizures. In addition, they excluded 16 cases of established epilepsy and four cases of provoked seizures, including febrile seizures.

The final study population included 121 cases. About 48% of these patients with staring spells were African American, and 38% were white. Patients’ mean age at first visit to the NOS clinic was 6, and mean age at staring spell onset was 5.2.

Fifty-nine patients (49%) had epileptic staring episodes, and 62 patients (51%) had nonepileptic events.

Continue to: Approximately 50% were referred by an emergency department...

Approximately 50% were referred by an emergency department, 48% by a primary care physician, and 2% by an urgent care clinic. Of the 62 cases that turned out to be nonepileptic events, about 61% were referred by primary care physicians.

MRI Findings in Patients With Focal Seizures

On average, patients with nonepileptic staring were younger at the initial clinic presentation and at staring spell onset. Patients with nonepileptic staring had an average age of 4.8 at their initial visit, whereas patients with focal seizures had an average age of 6.3. Patients with absence seizures had an average age of 8.3.

Patients with nonepileptic events were more likely to have developmental delay (approximately 35%) versus patients with focal seizures (23%) or absence seizures (8%).

Absence epilepsy was diagnosed in 24 patients (20%), and focal epilepsy in 35 patients (29%).

Of the 59 cases of epileptic staring, 46% (n = 27) were classified as syndromic; 36% (n = 21) had childhood absence epilepsy, and 5% (n = 3) had juvenile absence epilepsy. In addition, there was one case each of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy with hippocampal sclerosis, Panayiotopoulos syndrome, and generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures.

About one-third of patients received MRI, and seven patients had etiologically relevant findings (eg, brain tumor, malformation of cortical development, and periventricular leukomalacia). All of the patients with abnormal MRIs had focal seizures.

“An NOS clinic ... can provide rapid, accurate diagnoses for staring spells,” said Dr. Kim. “This is important, as children with nonepileptic events should not be given the diagnosis of epilepsy, and their events should not be treated with seizure medications. Similarly, children who have epileptic seizures require accurate diagnosis, as the treatment depends on the seizure type.”

Investigators review cases at a new-onset seizure clinic.

Investigators review cases at a new-onset seizure clinic.

CHICAGO—About half of staring spells referred to a new-onset seizure (NOS) clinic turn out to be epileptic seizures, according to a retrospective chart review presented at the 47th Annual Meeting of the Child Neurology Society.

Children with nonepileptic staring were younger and more likely to have developmental delay, compared with children with epileptic staring, said Seunghyo Kim, MD, Visiting Associate Professor of Pediatrics at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, and his colleagues

A Common Reason for Referral

Staring spells are common in children and a frequent reason for referral to NOS clinics, the investigators said. Staring spells may be generalized absence seizures, focal seizures, or nonepileptic events. Few studies, however, have examined patients who newly present to a neurology clinic with the chief complaint of staring spells.

To evaluate the clinical and demographic features of children who present with staring spells to a regional NOS clinic, the researchers reviewed charts from 2,818 patients who visited a children’s hospital between September 22, 2015, and March 19, 2018. The investigators identified 189 patients with staring spells.

They excluded 48 cases where staring was accompanied by or followed by generalized tonic-clonic seizures or other motor seizures. In addition, they excluded 16 cases of established epilepsy and four cases of provoked seizures, including febrile seizures.

The final study population included 121 cases. About 48% of these patients with staring spells were African American, and 38% were white. Patients’ mean age at first visit to the NOS clinic was 6, and mean age at staring spell onset was 5.2.

Fifty-nine patients (49%) had epileptic staring episodes, and 62 patients (51%) had nonepileptic events.

Continue to: Approximately 50% were referred by an emergency department...

Approximately 50% were referred by an emergency department, 48% by a primary care physician, and 2% by an urgent care clinic. Of the 62 cases that turned out to be nonepileptic events, about 61% were referred by primary care physicians.

MRI Findings in Patients With Focal Seizures

On average, patients with nonepileptic staring were younger at the initial clinic presentation and at staring spell onset. Patients with nonepileptic staring had an average age of 4.8 at their initial visit, whereas patients with focal seizures had an average age of 6.3. Patients with absence seizures had an average age of 8.3.

Patients with nonepileptic events were more likely to have developmental delay (approximately 35%) versus patients with focal seizures (23%) or absence seizures (8%).

Absence epilepsy was diagnosed in 24 patients (20%), and focal epilepsy in 35 patients (29%).

Of the 59 cases of epileptic staring, 46% (n = 27) were classified as syndromic; 36% (n = 21) had childhood absence epilepsy, and 5% (n = 3) had juvenile absence epilepsy. In addition, there was one case each of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy with hippocampal sclerosis, Panayiotopoulos syndrome, and generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures.

About one-third of patients received MRI, and seven patients had etiologically relevant findings (eg, brain tumor, malformation of cortical development, and periventricular leukomalacia). All of the patients with abnormal MRIs had focal seizures.

“An NOS clinic ... can provide rapid, accurate diagnoses for staring spells,” said Dr. Kim. “This is important, as children with nonepileptic events should not be given the diagnosis of epilepsy, and their events should not be treated with seizure medications. Similarly, children who have epileptic seizures require accurate diagnosis, as the treatment depends on the seizure type.”

CHICAGO—About half of staring spells referred to a new-onset seizure (NOS) clinic turn out to be epileptic seizures, according to a retrospective chart review presented at the 47th Annual Meeting of the Child Neurology Society.

Children with nonepileptic staring were younger and more likely to have developmental delay, compared with children with epileptic staring, said Seunghyo Kim, MD, Visiting Associate Professor of Pediatrics at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, and his colleagues

A Common Reason for Referral

Staring spells are common in children and a frequent reason for referral to NOS clinics, the investigators said. Staring spells may be generalized absence seizures, focal seizures, or nonepileptic events. Few studies, however, have examined patients who newly present to a neurology clinic with the chief complaint of staring spells.

To evaluate the clinical and demographic features of children who present with staring spells to a regional NOS clinic, the researchers reviewed charts from 2,818 patients who visited a children’s hospital between September 22, 2015, and March 19, 2018. The investigators identified 189 patients with staring spells.

They excluded 48 cases where staring was accompanied by or followed by generalized tonic-clonic seizures or other motor seizures. In addition, they excluded 16 cases of established epilepsy and four cases of provoked seizures, including febrile seizures.

The final study population included 121 cases. About 48% of these patients with staring spells were African American, and 38% were white. Patients’ mean age at first visit to the NOS clinic was 6, and mean age at staring spell onset was 5.2.

Fifty-nine patients (49%) had epileptic staring episodes, and 62 patients (51%) had nonepileptic events.

Continue to: Approximately 50% were referred by an emergency department...

Approximately 50% were referred by an emergency department, 48% by a primary care physician, and 2% by an urgent care clinic. Of the 62 cases that turned out to be nonepileptic events, about 61% were referred by primary care physicians.

MRI Findings in Patients With Focal Seizures

On average, patients with nonepileptic staring were younger at the initial clinic presentation and at staring spell onset. Patients with nonepileptic staring had an average age of 4.8 at their initial visit, whereas patients with focal seizures had an average age of 6.3. Patients with absence seizures had an average age of 8.3.

Patients with nonepileptic events were more likely to have developmental delay (approximately 35%) versus patients with focal seizures (23%) or absence seizures (8%).

Absence epilepsy was diagnosed in 24 patients (20%), and focal epilepsy in 35 patients (29%).

Of the 59 cases of epileptic staring, 46% (n = 27) were classified as syndromic; 36% (n = 21) had childhood absence epilepsy, and 5% (n = 3) had juvenile absence epilepsy. In addition, there was one case each of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy with hippocampal sclerosis, Panayiotopoulos syndrome, and generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures.

About one-third of patients received MRI, and seven patients had etiologically relevant findings (eg, brain tumor, malformation of cortical development, and periventricular leukomalacia). All of the patients with abnormal MRIs had focal seizures.

“An NOS clinic ... can provide rapid, accurate diagnoses for staring spells,” said Dr. Kim. “This is important, as children with nonepileptic events should not be given the diagnosis of epilepsy, and their events should not be treated with seizure medications. Similarly, children who have epileptic seizures require accurate diagnosis, as the treatment depends on the seizure type.”

Survey Identifies Variations in Management of Pediatric Posttraumatic Headache

Findings highlight a need to establish best evidence-based practices, researchers say.

CHICAGO—Child neurologists differ in their approach to diagnosing and managing posttraumatic headache, according to survey results presented at the 47th Annual Meeting of the Child Neurology Society.

For example, practice differs as to when posttraumatic headaches are considered persistent and when to recommend preventive therapy.

“As there are no established guidelines on management of posttraumatic headache, it is not surprising that diagnosis and management vary considerably,” said Rachel Pearson, MD, a child neurology resident at Children’s Hospital of Orange County in Orange, California, and colleagues. “Further studies are needed to define the best evidence-based practices for pediatric posttraumatic headache.”

Research indicates that about 7% of children ages 3 to 17 experience a significant head injury, and headache is the most common postconcussive symptom. Headache persists at three months in as much as 43% of cases, according to current studies. To better understand the current clinical practices of child neurologists in the diagnosis and treatment of posttraumatic headache, Dr. Pearson and colleagues sent all active, nonresident members of the Child Neurology Society a link to an online survey. The survey covered diagnosis, management, and return-to-play guidelines. Ninety-five members responded to the survey.

Persistence Threshold: Four Weeks or Three Months?

Although 39% of respondents reported that they always use ICHD diagnostic criteria to diagnose posttraumatic headache, and 31% sometimes use ICHD criteria, “only 19% of respondents correctly defined persistent posttraumatic headache per ICHD diagnostic criteria” as lasting more than three months, the researchers said. “The largest number of participants considered posttraumatic headache to be persistent at four weeks,” they said. “This may have implications for when prophylactic headache medications are considered.”

More than 90% recommend NSAIDs as abortive therapy. One-third consider starting preventive headache therapy within one month, and one-third between one and two months.

The most commonly used preventive medications are amitriptyline and nortriptyline (93.7%) and topiramate (71.6%). Amitriptyline and nortriptyline may be widely used because they “can also address other postconcussive symptoms, such as sleep or mood disturbance,” the investigators noted.

Treatment Options

In addition, 59% of providers use vitamins and supplements (eg, magnesium, riboflavin, melatonin, and CoQ10) as preventive treatments. “These are considered generally safe and have few adverse effects,” and “families may prefer these treatment options as they are perceived as ‘natural,’” Dr. Pearson and colleagues said. More than half of respondents use nonmedicinal therapies such as physical therapy, pain-focused cognitive behavioral therapy, and biofeedback.

Thirty-eight percent use injection-based therapies (eg, nerve blocks, botulinum toxin, and trigger point injections), and 14% of providers administer injections themselves.

One-third of respondents recommend cognitive and physical rest for one to three days, followed by a progressive return to activities, consistent with evidence-based recommendations. Approximately one-third advise patients to rest for seven to 14 days before returning to play.

“As a whole, these findings can guide additional research in this area and serve as a platform on which to base future randomized controlled trials,” said Dr. Pearson and colleagues.

—Jake Remaly

Suggested Reading

Blume HK, Vavilala MS, Jaffe KM, et al. Headache after pediatric traumatic brain injury: a cohort study. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):e31-e39.

Blume HK. Headaches after concussion in pediatrics: a review. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2015;19(9):42.

Choe MC, Blume HK. Pediatric posttraumatic headache: a review. J Child Neurol. 2016;31(1): 76-85.

Findings highlight a need to establish best evidence-based practices, researchers say.

Findings highlight a need to establish best evidence-based practices, researchers say.

CHICAGO—Child neurologists differ in their approach to diagnosing and managing posttraumatic headache, according to survey results presented at the 47th Annual Meeting of the Child Neurology Society.

For example, practice differs as to when posttraumatic headaches are considered persistent and when to recommend preventive therapy.

“As there are no established guidelines on management of posttraumatic headache, it is not surprising that diagnosis and management vary considerably,” said Rachel Pearson, MD, a child neurology resident at Children’s Hospital of Orange County in Orange, California, and colleagues. “Further studies are needed to define the best evidence-based practices for pediatric posttraumatic headache.”

Research indicates that about 7% of children ages 3 to 17 experience a significant head injury, and headache is the most common postconcussive symptom. Headache persists at three months in as much as 43% of cases, according to current studies. To better understand the current clinical practices of child neurologists in the diagnosis and treatment of posttraumatic headache, Dr. Pearson and colleagues sent all active, nonresident members of the Child Neurology Society a link to an online survey. The survey covered diagnosis, management, and return-to-play guidelines. Ninety-five members responded to the survey.

Persistence Threshold: Four Weeks or Three Months?

Although 39% of respondents reported that they always use ICHD diagnostic criteria to diagnose posttraumatic headache, and 31% sometimes use ICHD criteria, “only 19% of respondents correctly defined persistent posttraumatic headache per ICHD diagnostic criteria” as lasting more than three months, the researchers said. “The largest number of participants considered posttraumatic headache to be persistent at four weeks,” they said. “This may have implications for when prophylactic headache medications are considered.”

More than 90% recommend NSAIDs as abortive therapy. One-third consider starting preventive headache therapy within one month, and one-third between one and two months.

The most commonly used preventive medications are amitriptyline and nortriptyline (93.7%) and topiramate (71.6%). Amitriptyline and nortriptyline may be widely used because they “can also address other postconcussive symptoms, such as sleep or mood disturbance,” the investigators noted.

Treatment Options

In addition, 59% of providers use vitamins and supplements (eg, magnesium, riboflavin, melatonin, and CoQ10) as preventive treatments. “These are considered generally safe and have few adverse effects,” and “families may prefer these treatment options as they are perceived as ‘natural,’” Dr. Pearson and colleagues said. More than half of respondents use nonmedicinal therapies such as physical therapy, pain-focused cognitive behavioral therapy, and biofeedback.

Thirty-eight percent use injection-based therapies (eg, nerve blocks, botulinum toxin, and trigger point injections), and 14% of providers administer injections themselves.

One-third of respondents recommend cognitive and physical rest for one to three days, followed by a progressive return to activities, consistent with evidence-based recommendations. Approximately one-third advise patients to rest for seven to 14 days before returning to play.

“As a whole, these findings can guide additional research in this area and serve as a platform on which to base future randomized controlled trials,” said Dr. Pearson and colleagues.

—Jake Remaly

Suggested Reading

Blume HK, Vavilala MS, Jaffe KM, et al. Headache after pediatric traumatic brain injury: a cohort study. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):e31-e39.

Blume HK. Headaches after concussion in pediatrics: a review. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2015;19(9):42.

Choe MC, Blume HK. Pediatric posttraumatic headache: a review. J Child Neurol. 2016;31(1): 76-85.

CHICAGO—Child neurologists differ in their approach to diagnosing and managing posttraumatic headache, according to survey results presented at the 47th Annual Meeting of the Child Neurology Society.

For example, practice differs as to when posttraumatic headaches are considered persistent and when to recommend preventive therapy.

“As there are no established guidelines on management of posttraumatic headache, it is not surprising that diagnosis and management vary considerably,” said Rachel Pearson, MD, a child neurology resident at Children’s Hospital of Orange County in Orange, California, and colleagues. “Further studies are needed to define the best evidence-based practices for pediatric posttraumatic headache.”

Research indicates that about 7% of children ages 3 to 17 experience a significant head injury, and headache is the most common postconcussive symptom. Headache persists at three months in as much as 43% of cases, according to current studies. To better understand the current clinical practices of child neurologists in the diagnosis and treatment of posttraumatic headache, Dr. Pearson and colleagues sent all active, nonresident members of the Child Neurology Society a link to an online survey. The survey covered diagnosis, management, and return-to-play guidelines. Ninety-five members responded to the survey.

Persistence Threshold: Four Weeks or Three Months?

Although 39% of respondents reported that they always use ICHD diagnostic criteria to diagnose posttraumatic headache, and 31% sometimes use ICHD criteria, “only 19% of respondents correctly defined persistent posttraumatic headache per ICHD diagnostic criteria” as lasting more than three months, the researchers said. “The largest number of participants considered posttraumatic headache to be persistent at four weeks,” they said. “This may have implications for when prophylactic headache medications are considered.”

More than 90% recommend NSAIDs as abortive therapy. One-third consider starting preventive headache therapy within one month, and one-third between one and two months.

The most commonly used preventive medications are amitriptyline and nortriptyline (93.7%) and topiramate (71.6%). Amitriptyline and nortriptyline may be widely used because they “can also address other postconcussive symptoms, such as sleep or mood disturbance,” the investigators noted.

Treatment Options

In addition, 59% of providers use vitamins and supplements (eg, magnesium, riboflavin, melatonin, and CoQ10) as preventive treatments. “These are considered generally safe and have few adverse effects,” and “families may prefer these treatment options as they are perceived as ‘natural,’” Dr. Pearson and colleagues said. More than half of respondents use nonmedicinal therapies such as physical therapy, pain-focused cognitive behavioral therapy, and biofeedback.

Thirty-eight percent use injection-based therapies (eg, nerve blocks, botulinum toxin, and trigger point injections), and 14% of providers administer injections themselves.

One-third of respondents recommend cognitive and physical rest for one to three days, followed by a progressive return to activities, consistent with evidence-based recommendations. Approximately one-third advise patients to rest for seven to 14 days before returning to play.

“As a whole, these findings can guide additional research in this area and serve as a platform on which to base future randomized controlled trials,” said Dr. Pearson and colleagues.

—Jake Remaly

Suggested Reading

Blume HK, Vavilala MS, Jaffe KM, et al. Headache after pediatric traumatic brain injury: a cohort study. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):e31-e39.

Blume HK. Headaches after concussion in pediatrics: a review. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2015;19(9):42.

Choe MC, Blume HK. Pediatric posttraumatic headache: a review. J Child Neurol. 2016;31(1): 76-85.

CMT provides survival benefit in young HL patients

Combined modality therapy (CMT) can improve survival in young patients with early stage Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), according to research published in JAMA Oncology.

In a retrospective study, researchers compared chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy—CMT—to chemotherapy alone in more than 5,600 HL patients age 21 and younger.

There was a significant improvement in 5-year overall survival (OS) among patients who received CMT.

The treatment appeared particularly beneficial for adolescents and young adults as well as patients with low-risk disease.

However, the researchers observed a nearly 25% decrease in the use of CMT over the period studied.

“Nationwide, there has been a notable decrease in combined modality therapy, especially in clinical trials, many of which are designed to avoid this strategy,” said Rahul Parikh, MD, of Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey in New Brunswick.

“This form of treatment has shown to be effective, with event-free survival rates greater than 80% and overall survival rates greater than 95%. The question then becomes, ‘does treatment benefit outweigh the risk of long-term side effects?”

With this in mind, Dr. Parikh and his colleagues compared CMT to chemotherapy alone using data from the National Cancer Database spanning the period from 2004 to 2015.

The researchers analyzed 5,657 patients with stage I/II classical HL who had a mean age of 17.1.

Roughly half of patients received CMT (50.3%, n=2845), and the other half received chemotherapy alone (49.7%, n=2812).

The median radiotherapy dose was 21.0 Gy, and the most common modality was photon therapy (59.0%).

Patients who received CMT were significantly more likely to be younger than 16 (P<0.001), be male (P<0.001), have stage II disease (P=0.02), and have private health insurance (P=0.002).

Results

The median follow-up was 5.1 years.

The 5-year OS was 94.5% for patients who received chemotherapy alone and 97.3% for patients treated with CMT.

CMT was significantly associated with improved OS in both univariate (hazard ratio [HR]=0.58, P<0.001) and multivariate analyses (HR=0.57, P<0.001).

In a sensitivity analysis, the researchers found the greatest benefits of CMT were in adolescents and young adults (age 14 and older, adjusted HR=0.47) and patients with low-risk disease (stage I-IIA, adjusted HR=0.59).

The researchers noted that this study was limited by their inability to control for unreported prognostic factors, such as the number of nodal sites and bulk of disease.

Another limitation was the duration of follow-up, which did not allow the researchers to fully assess secondary late effects of CMT and their potential impact on survival.

Still, Dr. Parikh said this study demonstrates a survival benefit for young HL patients treated with CMT.

“With that, physicians should be encouraged to discuss combined modality therapy as one of the many treatment options [for young HL patients],” he said.

“Investigators may also consider designing future clinical trials for this population to include combined modality therapy as a standard arm with the inclusion of interim treatment response assessment (PET scans, etc.). And as multiple disparities to the use of combined modality therapy have been identified through this work, future studies should address improving access to care for all pediatric patients.”

Dr. Parikh and his colleagues declared no conflicts of interest for the current study.

Combined modality therapy (CMT) can improve survival in young patients with early stage Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), according to research published in JAMA Oncology.

In a retrospective study, researchers compared chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy—CMT—to chemotherapy alone in more than 5,600 HL patients age 21 and younger.

There was a significant improvement in 5-year overall survival (OS) among patients who received CMT.

The treatment appeared particularly beneficial for adolescents and young adults as well as patients with low-risk disease.

However, the researchers observed a nearly 25% decrease in the use of CMT over the period studied.

“Nationwide, there has been a notable decrease in combined modality therapy, especially in clinical trials, many of which are designed to avoid this strategy,” said Rahul Parikh, MD, of Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey in New Brunswick.

“This form of treatment has shown to be effective, with event-free survival rates greater than 80% and overall survival rates greater than 95%. The question then becomes, ‘does treatment benefit outweigh the risk of long-term side effects?”

With this in mind, Dr. Parikh and his colleagues compared CMT to chemotherapy alone using data from the National Cancer Database spanning the period from 2004 to 2015.

The researchers analyzed 5,657 patients with stage I/II classical HL who had a mean age of 17.1.

Roughly half of patients received CMT (50.3%, n=2845), and the other half received chemotherapy alone (49.7%, n=2812).

The median radiotherapy dose was 21.0 Gy, and the most common modality was photon therapy (59.0%).

Patients who received CMT were significantly more likely to be younger than 16 (P<0.001), be male (P<0.001), have stage II disease (P=0.02), and have private health insurance (P=0.002).

Results

The median follow-up was 5.1 years.

The 5-year OS was 94.5% for patients who received chemotherapy alone and 97.3% for patients treated with CMT.

CMT was significantly associated with improved OS in both univariate (hazard ratio [HR]=0.58, P<0.001) and multivariate analyses (HR=0.57, P<0.001).

In a sensitivity analysis, the researchers found the greatest benefits of CMT were in adolescents and young adults (age 14 and older, adjusted HR=0.47) and patients with low-risk disease (stage I-IIA, adjusted HR=0.59).

The researchers noted that this study was limited by their inability to control for unreported prognostic factors, such as the number of nodal sites and bulk of disease.

Another limitation was the duration of follow-up, which did not allow the researchers to fully assess secondary late effects of CMT and their potential impact on survival.

Still, Dr. Parikh said this study demonstrates a survival benefit for young HL patients treated with CMT.

“With that, physicians should be encouraged to discuss combined modality therapy as one of the many treatment options [for young HL patients],” he said.

“Investigators may also consider designing future clinical trials for this population to include combined modality therapy as a standard arm with the inclusion of interim treatment response assessment (PET scans, etc.). And as multiple disparities to the use of combined modality therapy have been identified through this work, future studies should address improving access to care for all pediatric patients.”

Dr. Parikh and his colleagues declared no conflicts of interest for the current study.

Combined modality therapy (CMT) can improve survival in young patients with early stage Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), according to research published in JAMA Oncology.

In a retrospective study, researchers compared chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy—CMT—to chemotherapy alone in more than 5,600 HL patients age 21 and younger.

There was a significant improvement in 5-year overall survival (OS) among patients who received CMT.

The treatment appeared particularly beneficial for adolescents and young adults as well as patients with low-risk disease.

However, the researchers observed a nearly 25% decrease in the use of CMT over the period studied.

“Nationwide, there has been a notable decrease in combined modality therapy, especially in clinical trials, many of which are designed to avoid this strategy,” said Rahul Parikh, MD, of Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey in New Brunswick.

“This form of treatment has shown to be effective, with event-free survival rates greater than 80% and overall survival rates greater than 95%. The question then becomes, ‘does treatment benefit outweigh the risk of long-term side effects?”

With this in mind, Dr. Parikh and his colleagues compared CMT to chemotherapy alone using data from the National Cancer Database spanning the period from 2004 to 2015.

The researchers analyzed 5,657 patients with stage I/II classical HL who had a mean age of 17.1.

Roughly half of patients received CMT (50.3%, n=2845), and the other half received chemotherapy alone (49.7%, n=2812).

The median radiotherapy dose was 21.0 Gy, and the most common modality was photon therapy (59.0%).

Patients who received CMT were significantly more likely to be younger than 16 (P<0.001), be male (P<0.001), have stage II disease (P=0.02), and have private health insurance (P=0.002).

Results

The median follow-up was 5.1 years.

The 5-year OS was 94.5% for patients who received chemotherapy alone and 97.3% for patients treated with CMT.

CMT was significantly associated with improved OS in both univariate (hazard ratio [HR]=0.58, P<0.001) and multivariate analyses (HR=0.57, P<0.001).

In a sensitivity analysis, the researchers found the greatest benefits of CMT were in adolescents and young adults (age 14 and older, adjusted HR=0.47) and patients with low-risk disease (stage I-IIA, adjusted HR=0.59).

The researchers noted that this study was limited by their inability to control for unreported prognostic factors, such as the number of nodal sites and bulk of disease.

Another limitation was the duration of follow-up, which did not allow the researchers to fully assess secondary late effects of CMT and their potential impact on survival.

Still, Dr. Parikh said this study demonstrates a survival benefit for young HL patients treated with CMT.

“With that, physicians should be encouraged to discuss combined modality therapy as one of the many treatment options [for young HL patients],” he said.

“Investigators may also consider designing future clinical trials for this population to include combined modality therapy as a standard arm with the inclusion of interim treatment response assessment (PET scans, etc.). And as multiple disparities to the use of combined modality therapy have been identified through this work, future studies should address improving access to care for all pediatric patients.”

Dr. Parikh and his colleagues declared no conflicts of interest for the current study.

Chemo for solid tumors and risk of tMDS/AML

Chemotherapy for solid tumors is associated with an increased risk of therapy-related myelodysplastic syndromes or acute myeloid leukemia (tMDS/AML), according to a retrospective analysis.

Long-term, population-based cohort data showed the risk of tMDS/AML was significantly elevated after chemotherapy for 22 solid tumor types.

The relative risk of tMDS/AML was 1.5- to 39.0-fold greater among patients treated for these tumors than among the general population.

Lindsay M. Morton, PhD, of the National Institutes of Health in Rockville, Maryland, and her colleagues reported these findings in JAMA Oncology.

“We undertook an investigation to quantify tMDS/AML risks after chemotherapy for solid tumors in the modern treatment era, 2000-2014, using United States cancer registry data from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program,” the investigators wrote.

They retrospectively analyzed data from 1619 patients with tMDS/AML who were diagnosed with an initial primary solid tumor from 2000 to 2013.

Patients were given initial chemotherapy and lived for at least 1 year after treatment. Subsequently, Dr. Morton and her colleagues linked patient database records with Medicare insurance claim information to confirm the accuracy of chemotherapy data.

“Because registry data do not include treatment details, we used an alternative database to provide descriptive information on population-based patterns of chemotherapeutic drug use,” the investigators noted.

The team found the risk of developing tMDS/AML was significantly increased following chemotherapy administration for 22 of 23 solid tumor types, excluding colon cancer.

The standardized incidence ratio (SIR) for tMDS/AML ranged from 1.5 to 39.0, and the excess absolute risk (EAR) ranged from 1.4 to 23.6 cases per 10,000 person-years.

SIRs were greatest in patients who received chemotherapy for malignancy of the bone (SIR=39.0, EAR=23.6), testis (SIR, 12.3, EAR=4.4), soft tissue (SIR=10.4, EAR=12.6), fallopian tube (SIR=8.7, EAR=16.0), small cell lung (SIR=8.1, EAR=19.9), peritoneum (SIR=7.5, EAR=15.8), brain or central nervous system (SIR=7.2, EAR=6.0), and ovary (SIR=5.8, EAR=8.2).

The investigators also found that patients who were given chemotherapy at a young age had the highest risk of developing tMDS/AML.

“For patients treated with chemotherapy at the present time, approximately three-quarters of tMDS/AML cases expected to occur within the next 5 years will be attributable to chemotherapy,” the investigators said.

They acknowledged a key limitation of this study was the limited data on patient-specific chemotherapy and dosing information. Given these limitations, Dr. Morton and her colleagues said, “the exact magnitude of our risk estimates, including the proportions of excess cases, should therefore be interpreted cautiously.”

This study was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, and the California Department of Public Health. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Chemotherapy for solid tumors is associated with an increased risk of therapy-related myelodysplastic syndromes or acute myeloid leukemia (tMDS/AML), according to a retrospective analysis.

Long-term, population-based cohort data showed the risk of tMDS/AML was significantly elevated after chemotherapy for 22 solid tumor types.

The relative risk of tMDS/AML was 1.5- to 39.0-fold greater among patients treated for these tumors than among the general population.

Lindsay M. Morton, PhD, of the National Institutes of Health in Rockville, Maryland, and her colleagues reported these findings in JAMA Oncology.

“We undertook an investigation to quantify tMDS/AML risks after chemotherapy for solid tumors in the modern treatment era, 2000-2014, using United States cancer registry data from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program,” the investigators wrote.

They retrospectively analyzed data from 1619 patients with tMDS/AML who were diagnosed with an initial primary solid tumor from 2000 to 2013.

Patients were given initial chemotherapy and lived for at least 1 year after treatment. Subsequently, Dr. Morton and her colleagues linked patient database records with Medicare insurance claim information to confirm the accuracy of chemotherapy data.

“Because registry data do not include treatment details, we used an alternative database to provide descriptive information on population-based patterns of chemotherapeutic drug use,” the investigators noted.

The team found the risk of developing tMDS/AML was significantly increased following chemotherapy administration for 22 of 23 solid tumor types, excluding colon cancer.

The standardized incidence ratio (SIR) for tMDS/AML ranged from 1.5 to 39.0, and the excess absolute risk (EAR) ranged from 1.4 to 23.6 cases per 10,000 person-years.

SIRs were greatest in patients who received chemotherapy for malignancy of the bone (SIR=39.0, EAR=23.6), testis (SIR, 12.3, EAR=4.4), soft tissue (SIR=10.4, EAR=12.6), fallopian tube (SIR=8.7, EAR=16.0), small cell lung (SIR=8.1, EAR=19.9), peritoneum (SIR=7.5, EAR=15.8), brain or central nervous system (SIR=7.2, EAR=6.0), and ovary (SIR=5.8, EAR=8.2).

The investigators also found that patients who were given chemotherapy at a young age had the highest risk of developing tMDS/AML.

“For patients treated with chemotherapy at the present time, approximately three-quarters of tMDS/AML cases expected to occur within the next 5 years will be attributable to chemotherapy,” the investigators said.

They acknowledged a key limitation of this study was the limited data on patient-specific chemotherapy and dosing information. Given these limitations, Dr. Morton and her colleagues said, “the exact magnitude of our risk estimates, including the proportions of excess cases, should therefore be interpreted cautiously.”

This study was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, and the California Department of Public Health. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Chemotherapy for solid tumors is associated with an increased risk of therapy-related myelodysplastic syndromes or acute myeloid leukemia (tMDS/AML), according to a retrospective analysis.

Long-term, population-based cohort data showed the risk of tMDS/AML was significantly elevated after chemotherapy for 22 solid tumor types.

The relative risk of tMDS/AML was 1.5- to 39.0-fold greater among patients treated for these tumors than among the general population.

Lindsay M. Morton, PhD, of the National Institutes of Health in Rockville, Maryland, and her colleagues reported these findings in JAMA Oncology.

“We undertook an investigation to quantify tMDS/AML risks after chemotherapy for solid tumors in the modern treatment era, 2000-2014, using United States cancer registry data from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program,” the investigators wrote.

They retrospectively analyzed data from 1619 patients with tMDS/AML who were diagnosed with an initial primary solid tumor from 2000 to 2013.

Patients were given initial chemotherapy and lived for at least 1 year after treatment. Subsequently, Dr. Morton and her colleagues linked patient database records with Medicare insurance claim information to confirm the accuracy of chemotherapy data.

“Because registry data do not include treatment details, we used an alternative database to provide descriptive information on population-based patterns of chemotherapeutic drug use,” the investigators noted.

The team found the risk of developing tMDS/AML was significantly increased following chemotherapy administration for 22 of 23 solid tumor types, excluding colon cancer.

The standardized incidence ratio (SIR) for tMDS/AML ranged from 1.5 to 39.0, and the excess absolute risk (EAR) ranged from 1.4 to 23.6 cases per 10,000 person-years.

SIRs were greatest in patients who received chemotherapy for malignancy of the bone (SIR=39.0, EAR=23.6), testis (SIR, 12.3, EAR=4.4), soft tissue (SIR=10.4, EAR=12.6), fallopian tube (SIR=8.7, EAR=16.0), small cell lung (SIR=8.1, EAR=19.9), peritoneum (SIR=7.5, EAR=15.8), brain or central nervous system (SIR=7.2, EAR=6.0), and ovary (SIR=5.8, EAR=8.2).

The investigators also found that patients who were given chemotherapy at a young age had the highest risk of developing tMDS/AML.

“For patients treated with chemotherapy at the present time, approximately three-quarters of tMDS/AML cases expected to occur within the next 5 years will be attributable to chemotherapy,” the investigators said.

They acknowledged a key limitation of this study was the limited data on patient-specific chemotherapy and dosing information. Given these limitations, Dr. Morton and her colleagues said, “the exact magnitude of our risk estimates, including the proportions of excess cases, should therefore be interpreted cautiously.”

This study was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, and the California Department of Public Health. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Commentary: Improving transgender education for medical students

Despite clinical practice guidelines,1,2 the lack of informed providers remains the greatest barrier to optimal transgender medical care, notable even with improvement with regard to other barriers to care.3 Barriers accessing appropriate care play a significant role in the persistent health disparities experienced by transgender individuals, such as increased rates of certain cancers, substance abuse, mental health concerns, infections, and chronic diseases.

In the United States, transgender people make up an estimated 0.6% of the population.4 Transgender individuals have unique health needs. However, when surveyed, most members of the medical community report that they are not adequately trained to address those needs.5 There is a need for health care providers to be comfortable treating, as well as versed in the health needs of, transgender patients. Physicians and medical students report having knowledge gaps in transgender health care because of insufficient education and exposure.

For medical students, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) launched a guide for medical schools in 2014 regarding the integration of LGBT-related curricula. Still, in a survey of 4,262 medical students from 170 medical schools in Canada and the United States, 67% of students rated their LGBT-related curriculum as “very poor,” “poor,” or “fair.”6

Data that are transgender specific are scarce. In a transgender medicine education–specific survey done among 365 Canadian medical students attending English-language medical schools, only 24% of them reported that transgender health was proficiently taught and only 6% reported feeling sufficiently knowledgeable to care for transgender individuals.7 Additionally, a survey among 341 United States medical students at a single institution reported that knowledge of transgender health lagged behind knowledge of other LGB health.8

Park et al. reported on the expanded Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM) transgender medical education model which supplemented the AAMC framework with evidence based, transgender-specific medical–education integrated throughout the medical curriculum.9 Beyond the AAMC-suggested program, first-year BUSM students in physiology learn about the biologic evidence for gender identity.10 In the following year, BUSM students are taught both the classic treatment regimens and monitoring requirements for transgender hormone therapy as part of the standard endocrinology curriculum.11 Following the first 2 years, students reported a significant increase in willingness to care for transgender patients and a 67% decrease in discomfort with providing care to transgender patients.

However, the relative comfort with transgender-specific care still lagged behind the comfort for LGB care in general. In 2014, BUSM expanded its transgender programming further to include an experiential component with a clinical elective for 4th-year medical students.9 The transgender medicine elective included direct patient care experiences with transgender individuals in adult primary care, pediatrics, endocrinology, and surgery. Direct patient contact has been demonstrated to facilitate greater confidence in providing transgender medical care for other medical trainees.12

A mechanism for the national adoption of the BUSM approach should be instituted for all medical schools. Such a move could easily result in a significant improvement in reported comfort among students. After that, the goal should be to leverage opportunities to mandate experiential components in transgender medical education.

While aspects of health care for transgender individuals have improved significantly, education among healthcare providers still lags and remains the largest barrier to care for transgender individuals. With the identified transgender population continuing to expand, the gap remains large in the production and training of sufficient numbers of providers proficient in transgender care. Although data for effectiveness are only short term, several interventions among medical students have been shown to be effective and seem logical to adopt universally.

Dr. Safer is executive director, Center for Transgender Medicine and Surgery, Mount Sinai Health System and Icahn School of Medicine, New York.

References

1. Coleman E et al. Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people, Version 7. Int J Transgend. 2012;13:165.

2. Hembree WC et al. Endocrine treatment of gender-dysphoric/gender-incongruent persons: An Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102:3869-903.

3. Safer JD et al. Barriers to healthcare for transgender individuals. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2016;23:168-71.

4. Flores AR et al. How many adults identify as transgender in the United States? The Williams Institute. 2017 Jun. Los Angeles, Calif. (Accessed on Oct. 30, 2018).

5. Irwig MS. Transgender care by endocrinologists in the United States. Endocr Pract. 2016 Jul;22:832-6.

6. White W et al. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patient care: Medical students’ preparedness and comfort. Teach Learn Med. 2015 Jul 9;27:254-63.

7. Chan B et al. Gaps in transgender medicine content identified among Canadian medical school curricula. Transgend Health. 2016 Jul 1;1:142-50.

8. Liang JJ et al. Observed deficiencies in medical student knowledge of transgender and intersex health. Endocr Pract. 2017 Aug;23:897-906.

9. Park JA et al. Clinical exposure to transgender medicine improves students’ preparedness above levels seen with didactic teaching alone: A key addition to the Boston University model for teaching transgender healthcare. Transgend Health. 2018 Jan 1;3:10-6.

10. Eriksson SE et al. Evidence-based curricular content improves student knowledge and changes attitudes towards transgender medicine. Endocr Pract. 2016 Jul;22:837-41.

11. Safer JD et al. A simple curriculum content change increased medical student comfort with transgender medicine. Endocr Pract. 2013 Jul-Aug;19:633-7.

12. Morrison SD et al. Transgender-related education in plastic surgery and urology residency programs. J Grad Med Educ. 2017 Apr;9:178-83.

Despite clinical practice guidelines,1,2 the lack of informed providers remains the greatest barrier to optimal transgender medical care, notable even with improvement with regard to other barriers to care.3 Barriers accessing appropriate care play a significant role in the persistent health disparities experienced by transgender individuals, such as increased rates of certain cancers, substance abuse, mental health concerns, infections, and chronic diseases.

In the United States, transgender people make up an estimated 0.6% of the population.4 Transgender individuals have unique health needs. However, when surveyed, most members of the medical community report that they are not adequately trained to address those needs.5 There is a need for health care providers to be comfortable treating, as well as versed in the health needs of, transgender patients. Physicians and medical students report having knowledge gaps in transgender health care because of insufficient education and exposure.

For medical students, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) launched a guide for medical schools in 2014 regarding the integration of LGBT-related curricula. Still, in a survey of 4,262 medical students from 170 medical schools in Canada and the United States, 67% of students rated their LGBT-related curriculum as “very poor,” “poor,” or “fair.”6

Data that are transgender specific are scarce. In a transgender medicine education–specific survey done among 365 Canadian medical students attending English-language medical schools, only 24% of them reported that transgender health was proficiently taught and only 6% reported feeling sufficiently knowledgeable to care for transgender individuals.7 Additionally, a survey among 341 United States medical students at a single institution reported that knowledge of transgender health lagged behind knowledge of other LGB health.8

Park et al. reported on the expanded Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM) transgender medical education model which supplemented the AAMC framework with evidence based, transgender-specific medical–education integrated throughout the medical curriculum.9 Beyond the AAMC-suggested program, first-year BUSM students in physiology learn about the biologic evidence for gender identity.10 In the following year, BUSM students are taught both the classic treatment regimens and monitoring requirements for transgender hormone therapy as part of the standard endocrinology curriculum.11 Following the first 2 years, students reported a significant increase in willingness to care for transgender patients and a 67% decrease in discomfort with providing care to transgender patients.

However, the relative comfort with transgender-specific care still lagged behind the comfort for LGB care in general. In 2014, BUSM expanded its transgender programming further to include an experiential component with a clinical elective for 4th-year medical students.9 The transgender medicine elective included direct patient care experiences with transgender individuals in adult primary care, pediatrics, endocrinology, and surgery. Direct patient contact has been demonstrated to facilitate greater confidence in providing transgender medical care for other medical trainees.12

A mechanism for the national adoption of the BUSM approach should be instituted for all medical schools. Such a move could easily result in a significant improvement in reported comfort among students. After that, the goal should be to leverage opportunities to mandate experiential components in transgender medical education.

While aspects of health care for transgender individuals have improved significantly, education among healthcare providers still lags and remains the largest barrier to care for transgender individuals. With the identified transgender population continuing to expand, the gap remains large in the production and training of sufficient numbers of providers proficient in transgender care. Although data for effectiveness are only short term, several interventions among medical students have been shown to be effective and seem logical to adopt universally.

Dr. Safer is executive director, Center for Transgender Medicine and Surgery, Mount Sinai Health System and Icahn School of Medicine, New York.

References

1. Coleman E et al. Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people, Version 7. Int J Transgend. 2012;13:165.

2. Hembree WC et al. Endocrine treatment of gender-dysphoric/gender-incongruent persons: An Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102:3869-903.

3. Safer JD et al. Barriers to healthcare for transgender individuals. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2016;23:168-71.

4. Flores AR et al. How many adults identify as transgender in the United States? The Williams Institute. 2017 Jun. Los Angeles, Calif. (Accessed on Oct. 30, 2018).

5. Irwig MS. Transgender care by endocrinologists in the United States. Endocr Pract. 2016 Jul;22:832-6.

6. White W et al. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patient care: Medical students’ preparedness and comfort. Teach Learn Med. 2015 Jul 9;27:254-63.

7. Chan B et al. Gaps in transgender medicine content identified among Canadian medical school curricula. Transgend Health. 2016 Jul 1;1:142-50.

8. Liang JJ et al. Observed deficiencies in medical student knowledge of transgender and intersex health. Endocr Pract. 2017 Aug;23:897-906.

9. Park JA et al. Clinical exposure to transgender medicine improves students’ preparedness above levels seen with didactic teaching alone: A key addition to the Boston University model for teaching transgender healthcare. Transgend Health. 2018 Jan 1;3:10-6.

10. Eriksson SE et al. Evidence-based curricular content improves student knowledge and changes attitudes towards transgender medicine. Endocr Pract. 2016 Jul;22:837-41.

11. Safer JD et al. A simple curriculum content change increased medical student comfort with transgender medicine. Endocr Pract. 2013 Jul-Aug;19:633-7.

12. Morrison SD et al. Transgender-related education in plastic surgery and urology residency programs. J Grad Med Educ. 2017 Apr;9:178-83.

Despite clinical practice guidelines,1,2 the lack of informed providers remains the greatest barrier to optimal transgender medical care, notable even with improvement with regard to other barriers to care.3 Barriers accessing appropriate care play a significant role in the persistent health disparities experienced by transgender individuals, such as increased rates of certain cancers, substance abuse, mental health concerns, infections, and chronic diseases.

In the United States, transgender people make up an estimated 0.6% of the population.4 Transgender individuals have unique health needs. However, when surveyed, most members of the medical community report that they are not adequately trained to address those needs.5 There is a need for health care providers to be comfortable treating, as well as versed in the health needs of, transgender patients. Physicians and medical students report having knowledge gaps in transgender health care because of insufficient education and exposure.

For medical students, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) launched a guide for medical schools in 2014 regarding the integration of LGBT-related curricula. Still, in a survey of 4,262 medical students from 170 medical schools in Canada and the United States, 67% of students rated their LGBT-related curriculum as “very poor,” “poor,” or “fair.”6

Data that are transgender specific are scarce. In a transgender medicine education–specific survey done among 365 Canadian medical students attending English-language medical schools, only 24% of them reported that transgender health was proficiently taught and only 6% reported feeling sufficiently knowledgeable to care for transgender individuals.7 Additionally, a survey among 341 United States medical students at a single institution reported that knowledge of transgender health lagged behind knowledge of other LGB health.8

Park et al. reported on the expanded Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM) transgender medical education model which supplemented the AAMC framework with evidence based, transgender-specific medical–education integrated throughout the medical curriculum.9 Beyond the AAMC-suggested program, first-year BUSM students in physiology learn about the biologic evidence for gender identity.10 In the following year, BUSM students are taught both the classic treatment regimens and monitoring requirements for transgender hormone therapy as part of the standard endocrinology curriculum.11 Following the first 2 years, students reported a significant increase in willingness to care for transgender patients and a 67% decrease in discomfort with providing care to transgender patients.

However, the relative comfort with transgender-specific care still lagged behind the comfort for LGB care in general. In 2014, BUSM expanded its transgender programming further to include an experiential component with a clinical elective for 4th-year medical students.9 The transgender medicine elective included direct patient care experiences with transgender individuals in adult primary care, pediatrics, endocrinology, and surgery. Direct patient contact has been demonstrated to facilitate greater confidence in providing transgender medical care for other medical trainees.12

A mechanism for the national adoption of the BUSM approach should be instituted for all medical schools. Such a move could easily result in a significant improvement in reported comfort among students. After that, the goal should be to leverage opportunities to mandate experiential components in transgender medical education.

While aspects of health care for transgender individuals have improved significantly, education among healthcare providers still lags and remains the largest barrier to care for transgender individuals. With the identified transgender population continuing to expand, the gap remains large in the production and training of sufficient numbers of providers proficient in transgender care. Although data for effectiveness are only short term, several interventions among medical students have been shown to be effective and seem logical to adopt universally.

Dr. Safer is executive director, Center for Transgender Medicine and Surgery, Mount Sinai Health System and Icahn School of Medicine, New York.

References

1. Coleman E et al. Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people, Version 7. Int J Transgend. 2012;13:165.

2. Hembree WC et al. Endocrine treatment of gender-dysphoric/gender-incongruent persons: An Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102:3869-903.

3. Safer JD et al. Barriers to healthcare for transgender individuals. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2016;23:168-71.

4. Flores AR et al. How many adults identify as transgender in the United States? The Williams Institute. 2017 Jun. Los Angeles, Calif. (Accessed on Oct. 30, 2018).