User login

MSBase study validates therapy for relapse in secondary progressive MS

An observational cohort study of a prospective international database of patients with multiple sclerosis has reported that medical therapy can reduce disability progression in patients with active secondary progressive MS (SPMS) who are prone to inflammatory relapses.

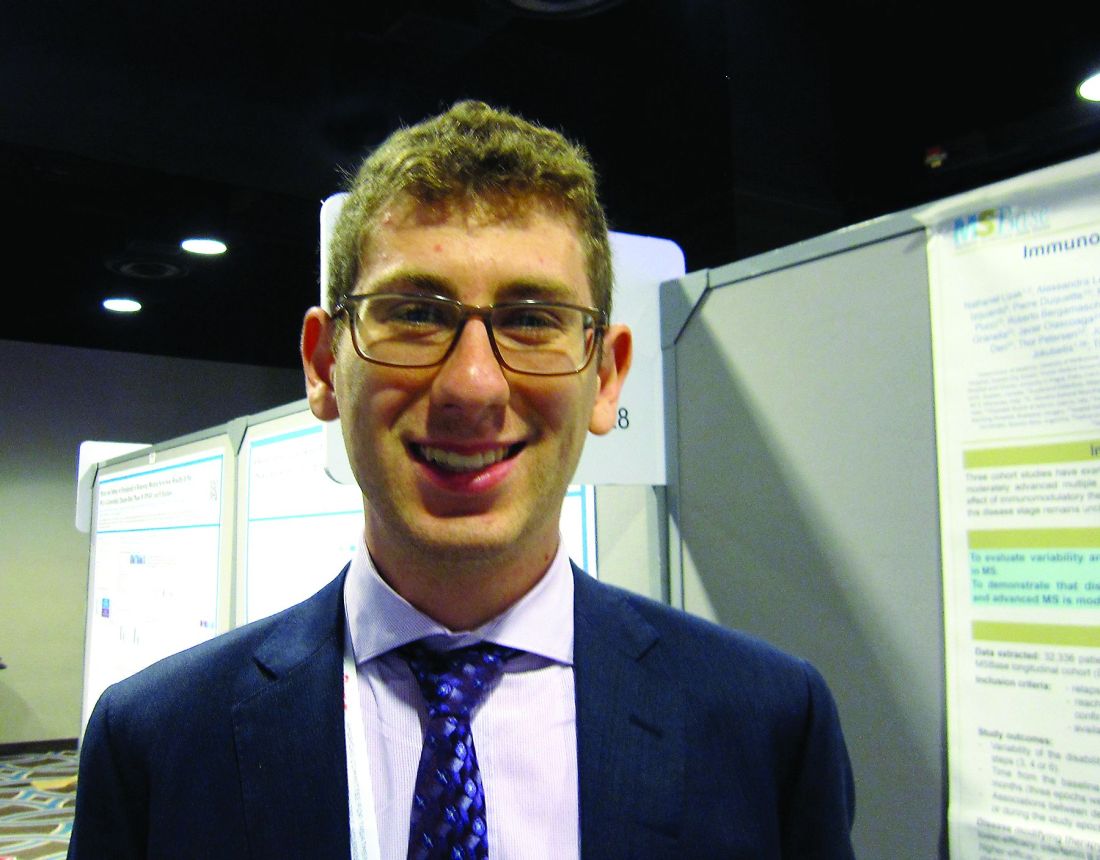

The international researchers, led by Nathanial Lizak, MMBS, of the University of Melbourne, conducted the cohort study of 1,621 patients with SPMS from the MSBase international registry, which prospectively collected the information from 1995 to 2018. Their findings were published in JAMA Neurology.

“ wrote Dr. Lizak and colleagues of the MSBase Study Group.

Therapy’s impact on disease progression

To ensure that they had timely data on the early disease course of all study patients, they researchers only included patients whose diagnosis and first documented Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score were no more than 24 months apart. At SPMS conversion, 1,494 patients had an EDSS score of less than 7 (on a scale of 0-10); during the follow-up period, 267 of them (17.9%) crossed over the threshold of 7.

Dr. Lizak and colleagues noted that early treatment during relapsing remitting MS didn’t impact outcomes after SPMS conversion.

For evaluating the MS Severity Score (MSSS), the study split the cohort into three groups depending on the efficacy of therapy: low-efficacy treatments, mostly consisting of interferon-beta and glatiramer acetate; medium-efficacy treatments, mostly fingolimod and dimethyl fumarate; and high-efficacy treatments, predominately natalizumab and mitoxantrone.

The MSSS progression slope in the cohort had an average reduction of 0.02 points per year. “For patients who experienced superimposed relapses during SPMS, a reduced MSSS progression slope during SPMS was observed among those who received disease-modifying therapies for a greater proportion of time during SPMS,” Dr. Lizak and colleagues wrote.

MSSS progression slope reduction was more pronounced in the medium- and high-efficacy groups, with a reduction of beta 0.22 (P = .06) and 0.034 (P = .002), respectively.

“Based on our models, the level of disability in patients with active SPMS who are continuously treated with high-efficacy immunotherapies would progress more slowly in comparison with the general population with MS by a mean (standard deviation) of 1.56 (4.60) deciles over 10 years,” Dr. Lizak and colleagues wrote.

While the researchers cited a number of studies that didn’t support immunotherapy for SPMS, they also did cite the EXPAND trial to support treatment with siponimod in SPMS patients (Lancet. 2018;391:1263-73). The ASCEND trial of natalizumab enrolled a largely relapse-free cohort and found no link between treatment and disability progression in SPMS (Lancet Neurol. 2018;17:405-15), and a previous report by the MSBase Study Group found no benefit of therapy when adjusted for SPMS relapse rates (Neurology. 2017;89:1050-9).

“Together with the present study, the existing data converge on the suggestion that relapses during SPMS provide a therapeutic target and a marker of future response to immunotherapy during SPMS,” Dr. Lizak and colleagues wrote.

Challenging dogma

Commenting on the research, Mark Freedman, HBSc, MSc, MD, said that the MSBase study makes an important contribution to the literature on management of SPMS. “Up until this point we’ve been basing our assumptions on secondary progressive MS on natural history studies, which are actually quite old, dating back 20-30 years.” Dr. Freedman is senior scientist in the Neuroscience Program at the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute and professor of medicine in neurology at the University of Ottawa.

He said “the most damaging” of those studies was by the late Christian Confavreaux, MD, and colleagues in Lyon, France (N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1430-8), that reported relapses didn’t alter the progression of disability. “In other words, once you’re in EDSS of 4, it’s a runaway train; it doesn’t matter what you do,” Dr. Freedman said.

“That was kind of dogma for years,” he said. “The reason this publication is important is because it’s suggesting that’s not the case.” In other words, the MSBase cohort study is validating what neurologists have been doing in the real world for years: treating patients with SPMS who have relapses.

Dr Lizak reported receiving travel compensation from Merck outside the scope of the study. His coauthors reported numerous financial relationships.

SOURCE: Lizak N et al. JAMA Neurol. 2020 Jul 27. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.2453

An observational cohort study of a prospective international database of patients with multiple sclerosis has reported that medical therapy can reduce disability progression in patients with active secondary progressive MS (SPMS) who are prone to inflammatory relapses.

The international researchers, led by Nathanial Lizak, MMBS, of the University of Melbourne, conducted the cohort study of 1,621 patients with SPMS from the MSBase international registry, which prospectively collected the information from 1995 to 2018. Their findings were published in JAMA Neurology.

“ wrote Dr. Lizak and colleagues of the MSBase Study Group.

Therapy’s impact on disease progression

To ensure that they had timely data on the early disease course of all study patients, they researchers only included patients whose diagnosis and first documented Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score were no more than 24 months apart. At SPMS conversion, 1,494 patients had an EDSS score of less than 7 (on a scale of 0-10); during the follow-up period, 267 of them (17.9%) crossed over the threshold of 7.

Dr. Lizak and colleagues noted that early treatment during relapsing remitting MS didn’t impact outcomes after SPMS conversion.

For evaluating the MS Severity Score (MSSS), the study split the cohort into three groups depending on the efficacy of therapy: low-efficacy treatments, mostly consisting of interferon-beta and glatiramer acetate; medium-efficacy treatments, mostly fingolimod and dimethyl fumarate; and high-efficacy treatments, predominately natalizumab and mitoxantrone.

The MSSS progression slope in the cohort had an average reduction of 0.02 points per year. “For patients who experienced superimposed relapses during SPMS, a reduced MSSS progression slope during SPMS was observed among those who received disease-modifying therapies for a greater proportion of time during SPMS,” Dr. Lizak and colleagues wrote.

MSSS progression slope reduction was more pronounced in the medium- and high-efficacy groups, with a reduction of beta 0.22 (P = .06) and 0.034 (P = .002), respectively.

“Based on our models, the level of disability in patients with active SPMS who are continuously treated with high-efficacy immunotherapies would progress more slowly in comparison with the general population with MS by a mean (standard deviation) of 1.56 (4.60) deciles over 10 years,” Dr. Lizak and colleagues wrote.

While the researchers cited a number of studies that didn’t support immunotherapy for SPMS, they also did cite the EXPAND trial to support treatment with siponimod in SPMS patients (Lancet. 2018;391:1263-73). The ASCEND trial of natalizumab enrolled a largely relapse-free cohort and found no link between treatment and disability progression in SPMS (Lancet Neurol. 2018;17:405-15), and a previous report by the MSBase Study Group found no benefit of therapy when adjusted for SPMS relapse rates (Neurology. 2017;89:1050-9).

“Together with the present study, the existing data converge on the suggestion that relapses during SPMS provide a therapeutic target and a marker of future response to immunotherapy during SPMS,” Dr. Lizak and colleagues wrote.

Challenging dogma

Commenting on the research, Mark Freedman, HBSc, MSc, MD, said that the MSBase study makes an important contribution to the literature on management of SPMS. “Up until this point we’ve been basing our assumptions on secondary progressive MS on natural history studies, which are actually quite old, dating back 20-30 years.” Dr. Freedman is senior scientist in the Neuroscience Program at the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute and professor of medicine in neurology at the University of Ottawa.

He said “the most damaging” of those studies was by the late Christian Confavreaux, MD, and colleagues in Lyon, France (N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1430-8), that reported relapses didn’t alter the progression of disability. “In other words, once you’re in EDSS of 4, it’s a runaway train; it doesn’t matter what you do,” Dr. Freedman said.

“That was kind of dogma for years,” he said. “The reason this publication is important is because it’s suggesting that’s not the case.” In other words, the MSBase cohort study is validating what neurologists have been doing in the real world for years: treating patients with SPMS who have relapses.

Dr Lizak reported receiving travel compensation from Merck outside the scope of the study. His coauthors reported numerous financial relationships.

SOURCE: Lizak N et al. JAMA Neurol. 2020 Jul 27. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.2453

An observational cohort study of a prospective international database of patients with multiple sclerosis has reported that medical therapy can reduce disability progression in patients with active secondary progressive MS (SPMS) who are prone to inflammatory relapses.

The international researchers, led by Nathanial Lizak, MMBS, of the University of Melbourne, conducted the cohort study of 1,621 patients with SPMS from the MSBase international registry, which prospectively collected the information from 1995 to 2018. Their findings were published in JAMA Neurology.

“ wrote Dr. Lizak and colleagues of the MSBase Study Group.

Therapy’s impact on disease progression

To ensure that they had timely data on the early disease course of all study patients, they researchers only included patients whose diagnosis and first documented Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score were no more than 24 months apart. At SPMS conversion, 1,494 patients had an EDSS score of less than 7 (on a scale of 0-10); during the follow-up period, 267 of them (17.9%) crossed over the threshold of 7.

Dr. Lizak and colleagues noted that early treatment during relapsing remitting MS didn’t impact outcomes after SPMS conversion.

For evaluating the MS Severity Score (MSSS), the study split the cohort into three groups depending on the efficacy of therapy: low-efficacy treatments, mostly consisting of interferon-beta and glatiramer acetate; medium-efficacy treatments, mostly fingolimod and dimethyl fumarate; and high-efficacy treatments, predominately natalizumab and mitoxantrone.

The MSSS progression slope in the cohort had an average reduction of 0.02 points per year. “For patients who experienced superimposed relapses during SPMS, a reduced MSSS progression slope during SPMS was observed among those who received disease-modifying therapies for a greater proportion of time during SPMS,” Dr. Lizak and colleagues wrote.

MSSS progression slope reduction was more pronounced in the medium- and high-efficacy groups, with a reduction of beta 0.22 (P = .06) and 0.034 (P = .002), respectively.

“Based on our models, the level of disability in patients with active SPMS who are continuously treated with high-efficacy immunotherapies would progress more slowly in comparison with the general population with MS by a mean (standard deviation) of 1.56 (4.60) deciles over 10 years,” Dr. Lizak and colleagues wrote.

While the researchers cited a number of studies that didn’t support immunotherapy for SPMS, they also did cite the EXPAND trial to support treatment with siponimod in SPMS patients (Lancet. 2018;391:1263-73). The ASCEND trial of natalizumab enrolled a largely relapse-free cohort and found no link between treatment and disability progression in SPMS (Lancet Neurol. 2018;17:405-15), and a previous report by the MSBase Study Group found no benefit of therapy when adjusted for SPMS relapse rates (Neurology. 2017;89:1050-9).

“Together with the present study, the existing data converge on the suggestion that relapses during SPMS provide a therapeutic target and a marker of future response to immunotherapy during SPMS,” Dr. Lizak and colleagues wrote.

Challenging dogma

Commenting on the research, Mark Freedman, HBSc, MSc, MD, said that the MSBase study makes an important contribution to the literature on management of SPMS. “Up until this point we’ve been basing our assumptions on secondary progressive MS on natural history studies, which are actually quite old, dating back 20-30 years.” Dr. Freedman is senior scientist in the Neuroscience Program at the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute and professor of medicine in neurology at the University of Ottawa.

He said “the most damaging” of those studies was by the late Christian Confavreaux, MD, and colleagues in Lyon, France (N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1430-8), that reported relapses didn’t alter the progression of disability. “In other words, once you’re in EDSS of 4, it’s a runaway train; it doesn’t matter what you do,” Dr. Freedman said.

“That was kind of dogma for years,” he said. “The reason this publication is important is because it’s suggesting that’s not the case.” In other words, the MSBase cohort study is validating what neurologists have been doing in the real world for years: treating patients with SPMS who have relapses.

Dr Lizak reported receiving travel compensation from Merck outside the scope of the study. His coauthors reported numerous financial relationships.

SOURCE: Lizak N et al. JAMA Neurol. 2020 Jul 27. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.2453

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

All NSAIDs raise post-MI risk but some are safer than others: Next chapter

Patients on antithrombotics after an acute MI will face a greater risk for bleeding and secondary cardiovascular (CV) events if they start taking any nonaspirin NSAID, confirms a large observational study.

Like other research before it, the new study suggests those risks will be much lower for some nonaspirin NSAIDs than others. But it may also challenge at least some conventional thinking about the safety of these drugs, and is based solely on a large cohort in South Korea, a group for which such NSAID data has been in short supply.

“It was intriguing that our study presented better safety profiles with celecoxib and meloxicam versus other subtypes of NSAIDs,” noted the report, published online July 27 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Most of the NSAIDs included in the analysis, “including naproxen, conferred a significantly higher risk for cardiovascular and bleeding events, compared with celecoxib and meloxicam,” wrote the authors, led by Dong Oh Kang, MD, Korea University Guro Hospital, Seoul, South Korea.

A main contribution of the study “is the thorough and comprehensive evaluation of the Korean population by use of the nationwide prescription claims database that reflects real-world clinical practice,” senior author Cheol Ung Choi, MD, PhD, of the same institution, said in an interview.

“Because we included the largest number of patients of any comparable clinical studies on NSAID treatment after MI thus far, our study may allow the generalizability of the adverse events of NSAIDs to all patients by constituting global evidence encompassing different population groups,” Dr. Choi said.

The analysis has limitations along with its strengths, the authors acknowledged, including its observational design and potential for confounding not addressed in statistical adjustments.

Observers of the study concurred, but some cited evidence pointing to such confounding that is serious enough to question the entire study’s validity.

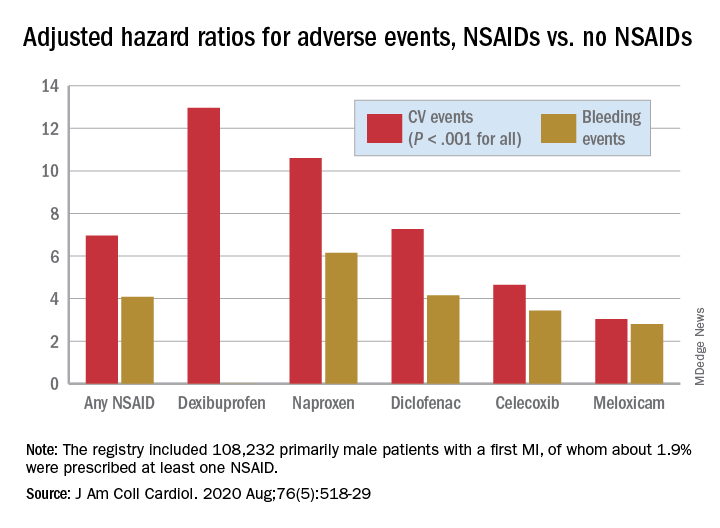

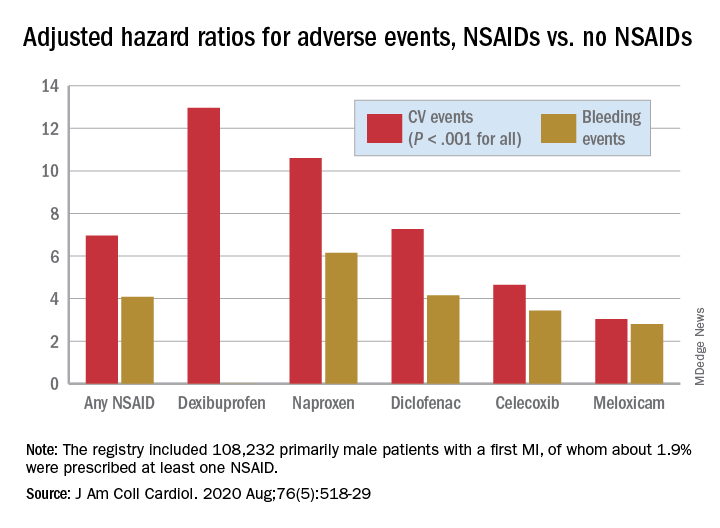

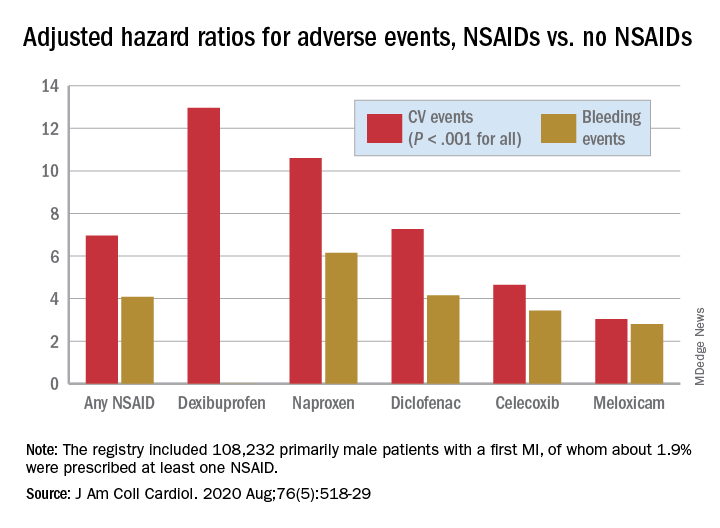

Among the cohort of more than 100,000 patients followed for an average of about 2.3 years after their MI, the adjusted risk of thromboembolic CV events went up almost 7 times for those who took any NSAID for at least 4 consecutive weeks, compared with those who didn’t take NSAIDs, based on prescription records.

Their adjusted risk of bleeding events – which included gastrointestinal, intracranial, respiratory, or urinary tract bleeding or posthemorrhagic anemia, the group writes – was increased 300%.

There was wide variance in the adjusted hazard ratios for outcomes by type of NSAID. The risk of CV events climbed from a low of about 3 with meloxicam and almost 5 for celecoxib to more than 10 and 12 for naproxen and dexibuprofen, respectively.

The hazard ratios for bleeding ranged from about 3 for both meloxicam and celecoxib to more than 6 for naproxen.

Of note, celecoxib and meloxicam both preferentially target the cyclooxygenase type 2 (COX-2) pathway, and naproxen among NSAIDs once had a reputation for relative cardiac safety, although subsequent studies have challenged that notion.

“On the basis of the contemporary guidelines, NSAID treatment should be limited as much as possible after MI; however, our data suggest that celecoxib and meloxicam could be considered possible alternative choices in patients with MI when NSAID prescription is unavoidable,” the group wrote.

They acknowledged some limitations of the analysis, including an observational design and the possibility of unidentified confounders; that mortality outcomes were not available from the National Health Insurance Service database used in the study; and that the 2009-2013 span for the data didn’t allow consideration of more contemporary antiplatelet agents and direct oral anticoagulants.

Also, NSAID use was based on prescriptions without regard to over-the-counter usage. Although use of over-the-counter NSAIDs is common in Korea, “most MI patients in Korea are prescribed most medications, including NSAIDs, in the hospital. So I think that usage of over-the-counter NSAIDs did not change the results,” Dr. Choi said.

“This study breaks new ground by demonstrating cardiovascular safety of meloxicam (and not only of celecoxib), probably because of its higher COX-2 selectivity,” wrote the authors of an accompanying editorial, Juan J. Badimon, PhD, and Carlos G. Santos-Gallego, MD, both of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

Notably, “this paper rejects the cardiovascular safety of naproxen, which had been suggested classically and in the previous Danish data, but that was not evident in this study.” The finding is consistent with the PRECISION trial, in which both bleeding and CV risk were increased with naproxen versus other NSAIDs, observed Dr. Badimon and Dr. Santos-Gallego.

They agreed with the authors in recommending that, “although NSAID treatment should be avoided in patients with MI, if the use of NSAIDs is inevitable due to comorbidities, the prescription of celecoxib and meloxicam could be considered as alternative options.”

But, “as no study is perfect, this article also presents some limitations,” the editorial agreed, citing some of the same issues noted by Dr. Kang and associates, along with potential confounding by indication and the lack of “clinical information to adjust (e.g., angiographic features, left ventricular function).”

“There’s undoubtedly residual confounding,” James M. Brophy, MD, PhD, a pharmacoepidemiologist at McGill University, Montreal, said in an interview.

The 400%-900% relative risks for CV events “are just too far in left field, compared to everything else we know,” he said. “There has never been a class of drugs that have shown this sort of magnitude of effect for adverse events.”

Even in PRECISION with its more than 24,000 high-coronary-risk patients randomized and followed for 5 years, Dr. Brophy observed, relative risks for the different NSAIDs varied by an order of magnitude of only 1-2.

“You should be interpreting things in the context of what is already known,” Dr. Brophy said. “The only conclusion I would draw is the paper is fatally flawed.”

The registry included 108,232 primarily male patients followed from their first diagnosed MI for CV and bleeding events. About 1.9% were prescribed at least one NSAID for 4 or more consecutive weeks during the follow-up period averaging 2.3 years, the group reported.

The most frequently prescribed NSAID was diclofenac, at about 72% of prescribed NSAIDs in the analysis for CV events and about 69% in the bleeding-event analysis.

Adding any NSAID to post-MI antithrombotic therapy led to an adjusted HR of 6.96 (P < .001) for CV events and 4.08 (P < .001) for bleeding events, compared with no NSAID treatment.

The 88% of the cohort who were on dual-antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel showed very nearly the same risk increases for both endpoints.

Further studies are needed to confirm the results “and ensure their generalizability to other populations,” Dr. Choi said. They should be validated especially using the claims data bases of countries near Korea, “such as Japan and Taiwan, to examine the reproducibility of the results in similar ethnic populations.”

That the study focused on a cohort in Korea is a strength, contended the authors as well as Dr. Badimon and Dr. Santos-Gallego, given “that most data about NSAIDs were extracted from Western populations, but the risk of thrombosis/bleeding post-MI varies according to ethnicity,” according to the editorial

Dr. Brophy agreed, but doubted that ethnic differences are responsible for variation in relative risks between the current results and other studies. “There are pharmacogenomic differences between different ethnicities as to how they activate these drugs. But I suspect that sort of difference is really minor. Maybe it leads to a 2% or a 5% difference in risks.”

Dr. Kang and associates, Dr. Badimon, Dr. Santos-Gallego, and Dr. Brophy disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients on antithrombotics after an acute MI will face a greater risk for bleeding and secondary cardiovascular (CV) events if they start taking any nonaspirin NSAID, confirms a large observational study.

Like other research before it, the new study suggests those risks will be much lower for some nonaspirin NSAIDs than others. But it may also challenge at least some conventional thinking about the safety of these drugs, and is based solely on a large cohort in South Korea, a group for which such NSAID data has been in short supply.

“It was intriguing that our study presented better safety profiles with celecoxib and meloxicam versus other subtypes of NSAIDs,” noted the report, published online July 27 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Most of the NSAIDs included in the analysis, “including naproxen, conferred a significantly higher risk for cardiovascular and bleeding events, compared with celecoxib and meloxicam,” wrote the authors, led by Dong Oh Kang, MD, Korea University Guro Hospital, Seoul, South Korea.

A main contribution of the study “is the thorough and comprehensive evaluation of the Korean population by use of the nationwide prescription claims database that reflects real-world clinical practice,” senior author Cheol Ung Choi, MD, PhD, of the same institution, said in an interview.

“Because we included the largest number of patients of any comparable clinical studies on NSAID treatment after MI thus far, our study may allow the generalizability of the adverse events of NSAIDs to all patients by constituting global evidence encompassing different population groups,” Dr. Choi said.

The analysis has limitations along with its strengths, the authors acknowledged, including its observational design and potential for confounding not addressed in statistical adjustments.

Observers of the study concurred, but some cited evidence pointing to such confounding that is serious enough to question the entire study’s validity.

Among the cohort of more than 100,000 patients followed for an average of about 2.3 years after their MI, the adjusted risk of thromboembolic CV events went up almost 7 times for those who took any NSAID for at least 4 consecutive weeks, compared with those who didn’t take NSAIDs, based on prescription records.

Their adjusted risk of bleeding events – which included gastrointestinal, intracranial, respiratory, or urinary tract bleeding or posthemorrhagic anemia, the group writes – was increased 300%.

There was wide variance in the adjusted hazard ratios for outcomes by type of NSAID. The risk of CV events climbed from a low of about 3 with meloxicam and almost 5 for celecoxib to more than 10 and 12 for naproxen and dexibuprofen, respectively.

The hazard ratios for bleeding ranged from about 3 for both meloxicam and celecoxib to more than 6 for naproxen.

Of note, celecoxib and meloxicam both preferentially target the cyclooxygenase type 2 (COX-2) pathway, and naproxen among NSAIDs once had a reputation for relative cardiac safety, although subsequent studies have challenged that notion.

“On the basis of the contemporary guidelines, NSAID treatment should be limited as much as possible after MI; however, our data suggest that celecoxib and meloxicam could be considered possible alternative choices in patients with MI when NSAID prescription is unavoidable,” the group wrote.

They acknowledged some limitations of the analysis, including an observational design and the possibility of unidentified confounders; that mortality outcomes were not available from the National Health Insurance Service database used in the study; and that the 2009-2013 span for the data didn’t allow consideration of more contemporary antiplatelet agents and direct oral anticoagulants.

Also, NSAID use was based on prescriptions without regard to over-the-counter usage. Although use of over-the-counter NSAIDs is common in Korea, “most MI patients in Korea are prescribed most medications, including NSAIDs, in the hospital. So I think that usage of over-the-counter NSAIDs did not change the results,” Dr. Choi said.

“This study breaks new ground by demonstrating cardiovascular safety of meloxicam (and not only of celecoxib), probably because of its higher COX-2 selectivity,” wrote the authors of an accompanying editorial, Juan J. Badimon, PhD, and Carlos G. Santos-Gallego, MD, both of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

Notably, “this paper rejects the cardiovascular safety of naproxen, which had been suggested classically and in the previous Danish data, but that was not evident in this study.” The finding is consistent with the PRECISION trial, in which both bleeding and CV risk were increased with naproxen versus other NSAIDs, observed Dr. Badimon and Dr. Santos-Gallego.

They agreed with the authors in recommending that, “although NSAID treatment should be avoided in patients with MI, if the use of NSAIDs is inevitable due to comorbidities, the prescription of celecoxib and meloxicam could be considered as alternative options.”

But, “as no study is perfect, this article also presents some limitations,” the editorial agreed, citing some of the same issues noted by Dr. Kang and associates, along with potential confounding by indication and the lack of “clinical information to adjust (e.g., angiographic features, left ventricular function).”

“There’s undoubtedly residual confounding,” James M. Brophy, MD, PhD, a pharmacoepidemiologist at McGill University, Montreal, said in an interview.

The 400%-900% relative risks for CV events “are just too far in left field, compared to everything else we know,” he said. “There has never been a class of drugs that have shown this sort of magnitude of effect for adverse events.”

Even in PRECISION with its more than 24,000 high-coronary-risk patients randomized and followed for 5 years, Dr. Brophy observed, relative risks for the different NSAIDs varied by an order of magnitude of only 1-2.

“You should be interpreting things in the context of what is already known,” Dr. Brophy said. “The only conclusion I would draw is the paper is fatally flawed.”

The registry included 108,232 primarily male patients followed from their first diagnosed MI for CV and bleeding events. About 1.9% were prescribed at least one NSAID for 4 or more consecutive weeks during the follow-up period averaging 2.3 years, the group reported.

The most frequently prescribed NSAID was diclofenac, at about 72% of prescribed NSAIDs in the analysis for CV events and about 69% in the bleeding-event analysis.

Adding any NSAID to post-MI antithrombotic therapy led to an adjusted HR of 6.96 (P < .001) for CV events and 4.08 (P < .001) for bleeding events, compared with no NSAID treatment.

The 88% of the cohort who were on dual-antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel showed very nearly the same risk increases for both endpoints.

Further studies are needed to confirm the results “and ensure their generalizability to other populations,” Dr. Choi said. They should be validated especially using the claims data bases of countries near Korea, “such as Japan and Taiwan, to examine the reproducibility of the results in similar ethnic populations.”

That the study focused on a cohort in Korea is a strength, contended the authors as well as Dr. Badimon and Dr. Santos-Gallego, given “that most data about NSAIDs were extracted from Western populations, but the risk of thrombosis/bleeding post-MI varies according to ethnicity,” according to the editorial

Dr. Brophy agreed, but doubted that ethnic differences are responsible for variation in relative risks between the current results and other studies. “There are pharmacogenomic differences between different ethnicities as to how they activate these drugs. But I suspect that sort of difference is really minor. Maybe it leads to a 2% or a 5% difference in risks.”

Dr. Kang and associates, Dr. Badimon, Dr. Santos-Gallego, and Dr. Brophy disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients on antithrombotics after an acute MI will face a greater risk for bleeding and secondary cardiovascular (CV) events if they start taking any nonaspirin NSAID, confirms a large observational study.

Like other research before it, the new study suggests those risks will be much lower for some nonaspirin NSAIDs than others. But it may also challenge at least some conventional thinking about the safety of these drugs, and is based solely on a large cohort in South Korea, a group for which such NSAID data has been in short supply.

“It was intriguing that our study presented better safety profiles with celecoxib and meloxicam versus other subtypes of NSAIDs,” noted the report, published online July 27 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Most of the NSAIDs included in the analysis, “including naproxen, conferred a significantly higher risk for cardiovascular and bleeding events, compared with celecoxib and meloxicam,” wrote the authors, led by Dong Oh Kang, MD, Korea University Guro Hospital, Seoul, South Korea.

A main contribution of the study “is the thorough and comprehensive evaluation of the Korean population by use of the nationwide prescription claims database that reflects real-world clinical practice,” senior author Cheol Ung Choi, MD, PhD, of the same institution, said in an interview.

“Because we included the largest number of patients of any comparable clinical studies on NSAID treatment after MI thus far, our study may allow the generalizability of the adverse events of NSAIDs to all patients by constituting global evidence encompassing different population groups,” Dr. Choi said.

The analysis has limitations along with its strengths, the authors acknowledged, including its observational design and potential for confounding not addressed in statistical adjustments.

Observers of the study concurred, but some cited evidence pointing to such confounding that is serious enough to question the entire study’s validity.

Among the cohort of more than 100,000 patients followed for an average of about 2.3 years after their MI, the adjusted risk of thromboembolic CV events went up almost 7 times for those who took any NSAID for at least 4 consecutive weeks, compared with those who didn’t take NSAIDs, based on prescription records.

Their adjusted risk of bleeding events – which included gastrointestinal, intracranial, respiratory, or urinary tract bleeding or posthemorrhagic anemia, the group writes – was increased 300%.

There was wide variance in the adjusted hazard ratios for outcomes by type of NSAID. The risk of CV events climbed from a low of about 3 with meloxicam and almost 5 for celecoxib to more than 10 and 12 for naproxen and dexibuprofen, respectively.

The hazard ratios for bleeding ranged from about 3 for both meloxicam and celecoxib to more than 6 for naproxen.

Of note, celecoxib and meloxicam both preferentially target the cyclooxygenase type 2 (COX-2) pathway, and naproxen among NSAIDs once had a reputation for relative cardiac safety, although subsequent studies have challenged that notion.

“On the basis of the contemporary guidelines, NSAID treatment should be limited as much as possible after MI; however, our data suggest that celecoxib and meloxicam could be considered possible alternative choices in patients with MI when NSAID prescription is unavoidable,” the group wrote.

They acknowledged some limitations of the analysis, including an observational design and the possibility of unidentified confounders; that mortality outcomes were not available from the National Health Insurance Service database used in the study; and that the 2009-2013 span for the data didn’t allow consideration of more contemporary antiplatelet agents and direct oral anticoagulants.

Also, NSAID use was based on prescriptions without regard to over-the-counter usage. Although use of over-the-counter NSAIDs is common in Korea, “most MI patients in Korea are prescribed most medications, including NSAIDs, in the hospital. So I think that usage of over-the-counter NSAIDs did not change the results,” Dr. Choi said.

“This study breaks new ground by demonstrating cardiovascular safety of meloxicam (and not only of celecoxib), probably because of its higher COX-2 selectivity,” wrote the authors of an accompanying editorial, Juan J. Badimon, PhD, and Carlos G. Santos-Gallego, MD, both of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

Notably, “this paper rejects the cardiovascular safety of naproxen, which had been suggested classically and in the previous Danish data, but that was not evident in this study.” The finding is consistent with the PRECISION trial, in which both bleeding and CV risk were increased with naproxen versus other NSAIDs, observed Dr. Badimon and Dr. Santos-Gallego.

They agreed with the authors in recommending that, “although NSAID treatment should be avoided in patients with MI, if the use of NSAIDs is inevitable due to comorbidities, the prescription of celecoxib and meloxicam could be considered as alternative options.”

But, “as no study is perfect, this article also presents some limitations,” the editorial agreed, citing some of the same issues noted by Dr. Kang and associates, along with potential confounding by indication and the lack of “clinical information to adjust (e.g., angiographic features, left ventricular function).”

“There’s undoubtedly residual confounding,” James M. Brophy, MD, PhD, a pharmacoepidemiologist at McGill University, Montreal, said in an interview.

The 400%-900% relative risks for CV events “are just too far in left field, compared to everything else we know,” he said. “There has never been a class of drugs that have shown this sort of magnitude of effect for adverse events.”

Even in PRECISION with its more than 24,000 high-coronary-risk patients randomized and followed for 5 years, Dr. Brophy observed, relative risks for the different NSAIDs varied by an order of magnitude of only 1-2.

“You should be interpreting things in the context of what is already known,” Dr. Brophy said. “The only conclusion I would draw is the paper is fatally flawed.”

The registry included 108,232 primarily male patients followed from their first diagnosed MI for CV and bleeding events. About 1.9% were prescribed at least one NSAID for 4 or more consecutive weeks during the follow-up period averaging 2.3 years, the group reported.

The most frequently prescribed NSAID was diclofenac, at about 72% of prescribed NSAIDs in the analysis for CV events and about 69% in the bleeding-event analysis.

Adding any NSAID to post-MI antithrombotic therapy led to an adjusted HR of 6.96 (P < .001) for CV events and 4.08 (P < .001) for bleeding events, compared with no NSAID treatment.

The 88% of the cohort who were on dual-antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel showed very nearly the same risk increases for both endpoints.

Further studies are needed to confirm the results “and ensure their generalizability to other populations,” Dr. Choi said. They should be validated especially using the claims data bases of countries near Korea, “such as Japan and Taiwan, to examine the reproducibility of the results in similar ethnic populations.”

That the study focused on a cohort in Korea is a strength, contended the authors as well as Dr. Badimon and Dr. Santos-Gallego, given “that most data about NSAIDs were extracted from Western populations, but the risk of thrombosis/bleeding post-MI varies according to ethnicity,” according to the editorial

Dr. Brophy agreed, but doubted that ethnic differences are responsible for variation in relative risks between the current results and other studies. “There are pharmacogenomic differences between different ethnicities as to how they activate these drugs. But I suspect that sort of difference is really minor. Maybe it leads to a 2% or a 5% difference in risks.”

Dr. Kang and associates, Dr. Badimon, Dr. Santos-Gallego, and Dr. Brophy disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Study finds no link between platelet count, surgery bleed risk in cirrhosis

The findings raise questions about current recommendations that call for transfusing platelet concentrates to reduce bleeding risk during surgery in cirrhosis patients with extremely low platelet counts, Gian Marco Podda, MD, PhD, said at the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis virtual congress.

The overall rate of perioperative bleeding was 8.9% in 996 patients who underwent excision of hepatocellular carcinoma by resection (42%) or radiofrequency ablation (58%) without platelet transfusion between 1998 and 2018. The rates were slightly higher among 65 patients with platelet count of fewer than 50 × 109/L indicating severe thrombocytopenia, and in 292 patients with counts of 50-100 × 109/L, indicating moderate thrombocytopenia (10.8% and 10.2%, respectively), compared with those with a platelet count of higher than 100 × 109/L (8.1%), but the differences were not statistically significant, said Dr. Podda of the University of Milan (Italy).

The corresponding rates among those who underwent radiofrequency ablation were 8.6%, 5.9%, and 5%, and among those who underwent resection, they were 18.8%, 17.7%, and 15.9%.

On multivariate analysis, factors associated with an increased incidence of major bleeding were low hemoglobin level (odds ratio, 0.57), age over 65 years (OR, 1.19), aspartate aminotransferase level greater than twice the upper limit of normal (OR, 2.12), hepatitis B or C cirrhosis versus cryptogenic cirrhosis (OR, 0.08), and resection versus radiofrequency ablation (OR, 3.74), he noted. Logistic regression analysis showed no significant association between platelet count and major bleeding events.

Mortality, a secondary outcome measure, was significantly higher among those with moderate or severe thrombocytopenia (rate of 5.5% for each), compared with those with mild or no thrombocytopenia (2.4%), Dr. Podda said.

Factors associated with mortality on multivariate analysis were severe liver dysfunction as demonstrated by Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score of 10 or greater versus less than 10 (OR, 3.13) and Child-Pugh B and C score versus Child-Pugh A score (OR, 16.72), advanced tumor status as measured by Barcelona-Clínic Liver Cancer staging greater than A4 versus A1 (OR, 5.78), major bleeding (OR, 4.59), and resection versus radiofrequency ablation (OR, 3.31).

“Low platelet count was associated with an increased risk of mortality at 3 months. However, this association disappeared at the multivariate analysis, which took into account markers of severity of liver cirrhosis,” he said.

Dr. Podda and his colleagues conducted the study in light of a recommendation from a consensus conference of the Italian Association for the Study of Liver Disease and the Italian Society of Internal Medicine that called for increasing platelet count by platelet transfusions in patients with cirrhosis who undergo an invasive procedure and who have a platelet count lower than 50 × 109/L.

“This recommendation mostly stemmed from consideration of biological plausibility prospects rather than being based on hard experimental evidence,” he explained, noting that such severe thrombocytopenia affects about 10% of patients with liver cirrhosis.

Based on the findings of this study, the practice is not supported, he concluded.

Dr. Podda reported honoraria from Sanofi, Boehringer Ingelheim.

SOURCE: Ronca V et al. ISTH 2020, Abstract OC 13.4.

The findings raise questions about current recommendations that call for transfusing platelet concentrates to reduce bleeding risk during surgery in cirrhosis patients with extremely low platelet counts, Gian Marco Podda, MD, PhD, said at the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis virtual congress.

The overall rate of perioperative bleeding was 8.9% in 996 patients who underwent excision of hepatocellular carcinoma by resection (42%) or radiofrequency ablation (58%) without platelet transfusion between 1998 and 2018. The rates were slightly higher among 65 patients with platelet count of fewer than 50 × 109/L indicating severe thrombocytopenia, and in 292 patients with counts of 50-100 × 109/L, indicating moderate thrombocytopenia (10.8% and 10.2%, respectively), compared with those with a platelet count of higher than 100 × 109/L (8.1%), but the differences were not statistically significant, said Dr. Podda of the University of Milan (Italy).

The corresponding rates among those who underwent radiofrequency ablation were 8.6%, 5.9%, and 5%, and among those who underwent resection, they were 18.8%, 17.7%, and 15.9%.

On multivariate analysis, factors associated with an increased incidence of major bleeding were low hemoglobin level (odds ratio, 0.57), age over 65 years (OR, 1.19), aspartate aminotransferase level greater than twice the upper limit of normal (OR, 2.12), hepatitis B or C cirrhosis versus cryptogenic cirrhosis (OR, 0.08), and resection versus radiofrequency ablation (OR, 3.74), he noted. Logistic regression analysis showed no significant association between platelet count and major bleeding events.

Mortality, a secondary outcome measure, was significantly higher among those with moderate or severe thrombocytopenia (rate of 5.5% for each), compared with those with mild or no thrombocytopenia (2.4%), Dr. Podda said.

Factors associated with mortality on multivariate analysis were severe liver dysfunction as demonstrated by Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score of 10 or greater versus less than 10 (OR, 3.13) and Child-Pugh B and C score versus Child-Pugh A score (OR, 16.72), advanced tumor status as measured by Barcelona-Clínic Liver Cancer staging greater than A4 versus A1 (OR, 5.78), major bleeding (OR, 4.59), and resection versus radiofrequency ablation (OR, 3.31).

“Low platelet count was associated with an increased risk of mortality at 3 months. However, this association disappeared at the multivariate analysis, which took into account markers of severity of liver cirrhosis,” he said.

Dr. Podda and his colleagues conducted the study in light of a recommendation from a consensus conference of the Italian Association for the Study of Liver Disease and the Italian Society of Internal Medicine that called for increasing platelet count by platelet transfusions in patients with cirrhosis who undergo an invasive procedure and who have a platelet count lower than 50 × 109/L.

“This recommendation mostly stemmed from consideration of biological plausibility prospects rather than being based on hard experimental evidence,” he explained, noting that such severe thrombocytopenia affects about 10% of patients with liver cirrhosis.

Based on the findings of this study, the practice is not supported, he concluded.

Dr. Podda reported honoraria from Sanofi, Boehringer Ingelheim.

SOURCE: Ronca V et al. ISTH 2020, Abstract OC 13.4.

The findings raise questions about current recommendations that call for transfusing platelet concentrates to reduce bleeding risk during surgery in cirrhosis patients with extremely low platelet counts, Gian Marco Podda, MD, PhD, said at the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis virtual congress.

The overall rate of perioperative bleeding was 8.9% in 996 patients who underwent excision of hepatocellular carcinoma by resection (42%) or radiofrequency ablation (58%) without platelet transfusion between 1998 and 2018. The rates were slightly higher among 65 patients with platelet count of fewer than 50 × 109/L indicating severe thrombocytopenia, and in 292 patients with counts of 50-100 × 109/L, indicating moderate thrombocytopenia (10.8% and 10.2%, respectively), compared with those with a platelet count of higher than 100 × 109/L (8.1%), but the differences were not statistically significant, said Dr. Podda of the University of Milan (Italy).

The corresponding rates among those who underwent radiofrequency ablation were 8.6%, 5.9%, and 5%, and among those who underwent resection, they were 18.8%, 17.7%, and 15.9%.

On multivariate analysis, factors associated with an increased incidence of major bleeding were low hemoglobin level (odds ratio, 0.57), age over 65 years (OR, 1.19), aspartate aminotransferase level greater than twice the upper limit of normal (OR, 2.12), hepatitis B or C cirrhosis versus cryptogenic cirrhosis (OR, 0.08), and resection versus radiofrequency ablation (OR, 3.74), he noted. Logistic regression analysis showed no significant association between platelet count and major bleeding events.

Mortality, a secondary outcome measure, was significantly higher among those with moderate or severe thrombocytopenia (rate of 5.5% for each), compared with those with mild or no thrombocytopenia (2.4%), Dr. Podda said.

Factors associated with mortality on multivariate analysis were severe liver dysfunction as demonstrated by Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score of 10 or greater versus less than 10 (OR, 3.13) and Child-Pugh B and C score versus Child-Pugh A score (OR, 16.72), advanced tumor status as measured by Barcelona-Clínic Liver Cancer staging greater than A4 versus A1 (OR, 5.78), major bleeding (OR, 4.59), and resection versus radiofrequency ablation (OR, 3.31).

“Low platelet count was associated with an increased risk of mortality at 3 months. However, this association disappeared at the multivariate analysis, which took into account markers of severity of liver cirrhosis,” he said.

Dr. Podda and his colleagues conducted the study in light of a recommendation from a consensus conference of the Italian Association for the Study of Liver Disease and the Italian Society of Internal Medicine that called for increasing platelet count by platelet transfusions in patients with cirrhosis who undergo an invasive procedure and who have a platelet count lower than 50 × 109/L.

“This recommendation mostly stemmed from consideration of biological plausibility prospects rather than being based on hard experimental evidence,” he explained, noting that such severe thrombocytopenia affects about 10% of patients with liver cirrhosis.

Based on the findings of this study, the practice is not supported, he concluded.

Dr. Podda reported honoraria from Sanofi, Boehringer Ingelheim.

SOURCE: Ronca V et al. ISTH 2020, Abstract OC 13.4.

REPORTING FROM THE 2020 ISTH CONGRESS

Anti-CD8a, anti-IL-17A antibodies improved immune disruption in mice with history of NASH

Changes in a variety of T cells in the liver and visceral adipose tissue play a key role in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, according to the results of a murine study.

Mikhaïl A. Van Herck, of the University of Antwerp (Belgium), and associates fed 8-week old mice a high-fat, high-fructose diet for 20 weeks, and then switched the mice to standard mouse chow for 12 weeks. The high-fat, high-fructose diet induced the metabolic syndrome and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), accompanied by shifts in T cells. Interleukin-17–producing (Th17 cells increased in the liver, visceral adipose tissue, and blood, while regulatory T cells decreased in visceral adipose tissue, and cytotoxic T (Tc) cells rose in visceral adipose tissue while dropping in the blood and spleen.

These are “important immune disruptions,” the researchers wrote in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “In particular, visceral adipose tissue Tc cells are critically involved in NASH pathogenesis, linking adipose tissue inflammation to liver disease.”

After the mice were switched from the high-fat, high-fructose diet to standard mouse chow, their body weight, body fat, and plasma cholesterol significantly decreased and their glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity improved to resemble the metrics of mice fed standard mouse chow throughout the study. Mice who underwent diet reversal also had significantly decreased liver weight and levels of plasma ALT, compared with mice that remained on the high-fat, high-fructose diet. Diet reversal also improved liver histology (nonalcoholic fatty liver disease activity scores), compared with the high-fat, high-fructose diet, the researchers wrote. “Importantly, the NASH was not significantly different between diet-reversal mice and mice fed the control diet for 32 weeks.”

Genetic tests supported these findings. On multiplex RNA analysis, hepatic expression of Acta2, Col1a1, and Col1a3 reverted to normal with diet reversal, indicating a normalization of hepatic collagen. Hepatic expression of the metabolic genes Ppara, Pparg, and Fgf21 also returned to normal, while visceral adipose tissue showed a decrease in Lep and Fgf21 expression and resolution of adipocyte hypertrophy.

However, diet reversal did not reverse inflammatory changes in T-cell subsets. Administering anti-CD8a antibodies after diet reversal decreased Tc cells in all tissue types that were tested, signifying “a biochemical and histologic attenuation of the high-fat, high-fructose diet-induced NASH,” the investigators wrote. Treating the mice with antibodies targeting IL-17A did not attenuate NASH but did reduce hepatic inflammation.

The fact that “the most pronounced effect” on NASH resulted from correcting immune disruption in visceral adipose tissue underscored “the immense importance of adipose tissue inflammation in [NASH] pathogenesis,” the researchers wrote. The finding that diet reversal alone did not reverse inflammation in hepatic or visceral adipose tissue “challeng[es] our current understanding of the reversibility of NASH and other obesity-related conditions.” They called for studies of underlying mechanisms as part of “the search for a medical treatment for NASH.”

Funders included the University Research Fund, University of Antwerp, and Research Foundation Flanders. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest except that one coinvestigator is the chief science officer at Biocellvia, which performed some histologic analyses.

SOURCE: Van Herck MA et al. Cell Molec Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Apr 20. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2020.04.010.

The trajectory of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is a public health watershed moment in gastroenterology and hepatology causing unparalleled morbidity, mortality, and societal costs. This study by Van Herck et al. advances our understanding of just how important a two-pronged environmental and biologic approach is to turn the NASH tide. The authors demonstrate that both dietary environmental exposure and biologic tissue-specific T-cell responses are involved in NASH pathogenesis, and that targeting one part of the equation is insufficient to fully mitigate disease. They observed that mice with more severe diet-induced NASH had more Th17 cells in the liver and visceral adipose tissue and more cytotoxic T cells in VAT. Conversely, there were fewer VAT T-regulatory cells in mice with more liver inflammation. The major novelty of this study is that simply changing the diet to a metabolically healthier and weight-reducing diet failed to correct T-cell dysregulation. Only T cell–directed therapies improved this abnormality.

Rotonya M. Carr, MD, is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. She is a hepatologist, director of the liver metabolism and fatty liver program, and codirector of the human metabolic tissue resource. Dr. Carr receives research and salary support from Intercept Pharmaceuticals.

The trajectory of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is a public health watershed moment in gastroenterology and hepatology causing unparalleled morbidity, mortality, and societal costs. This study by Van Herck et al. advances our understanding of just how important a two-pronged environmental and biologic approach is to turn the NASH tide. The authors demonstrate that both dietary environmental exposure and biologic tissue-specific T-cell responses are involved in NASH pathogenesis, and that targeting one part of the equation is insufficient to fully mitigate disease. They observed that mice with more severe diet-induced NASH had more Th17 cells in the liver and visceral adipose tissue and more cytotoxic T cells in VAT. Conversely, there were fewer VAT T-regulatory cells in mice with more liver inflammation. The major novelty of this study is that simply changing the diet to a metabolically healthier and weight-reducing diet failed to correct T-cell dysregulation. Only T cell–directed therapies improved this abnormality.

Rotonya M. Carr, MD, is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. She is a hepatologist, director of the liver metabolism and fatty liver program, and codirector of the human metabolic tissue resource. Dr. Carr receives research and salary support from Intercept Pharmaceuticals.

The trajectory of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is a public health watershed moment in gastroenterology and hepatology causing unparalleled morbidity, mortality, and societal costs. This study by Van Herck et al. advances our understanding of just how important a two-pronged environmental and biologic approach is to turn the NASH tide. The authors demonstrate that both dietary environmental exposure and biologic tissue-specific T-cell responses are involved in NASH pathogenesis, and that targeting one part of the equation is insufficient to fully mitigate disease. They observed that mice with more severe diet-induced NASH had more Th17 cells in the liver and visceral adipose tissue and more cytotoxic T cells in VAT. Conversely, there were fewer VAT T-regulatory cells in mice with more liver inflammation. The major novelty of this study is that simply changing the diet to a metabolically healthier and weight-reducing diet failed to correct T-cell dysregulation. Only T cell–directed therapies improved this abnormality.

Rotonya M. Carr, MD, is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. She is a hepatologist, director of the liver metabolism and fatty liver program, and codirector of the human metabolic tissue resource. Dr. Carr receives research and salary support from Intercept Pharmaceuticals.

Changes in a variety of T cells in the liver and visceral adipose tissue play a key role in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, according to the results of a murine study.

Mikhaïl A. Van Herck, of the University of Antwerp (Belgium), and associates fed 8-week old mice a high-fat, high-fructose diet for 20 weeks, and then switched the mice to standard mouse chow for 12 weeks. The high-fat, high-fructose diet induced the metabolic syndrome and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), accompanied by shifts in T cells. Interleukin-17–producing (Th17 cells increased in the liver, visceral adipose tissue, and blood, while regulatory T cells decreased in visceral adipose tissue, and cytotoxic T (Tc) cells rose in visceral adipose tissue while dropping in the blood and spleen.

These are “important immune disruptions,” the researchers wrote in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “In particular, visceral adipose tissue Tc cells are critically involved in NASH pathogenesis, linking adipose tissue inflammation to liver disease.”

After the mice were switched from the high-fat, high-fructose diet to standard mouse chow, their body weight, body fat, and plasma cholesterol significantly decreased and their glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity improved to resemble the metrics of mice fed standard mouse chow throughout the study. Mice who underwent diet reversal also had significantly decreased liver weight and levels of plasma ALT, compared with mice that remained on the high-fat, high-fructose diet. Diet reversal also improved liver histology (nonalcoholic fatty liver disease activity scores), compared with the high-fat, high-fructose diet, the researchers wrote. “Importantly, the NASH was not significantly different between diet-reversal mice and mice fed the control diet for 32 weeks.”

Genetic tests supported these findings. On multiplex RNA analysis, hepatic expression of Acta2, Col1a1, and Col1a3 reverted to normal with diet reversal, indicating a normalization of hepatic collagen. Hepatic expression of the metabolic genes Ppara, Pparg, and Fgf21 also returned to normal, while visceral adipose tissue showed a decrease in Lep and Fgf21 expression and resolution of adipocyte hypertrophy.

However, diet reversal did not reverse inflammatory changes in T-cell subsets. Administering anti-CD8a antibodies after diet reversal decreased Tc cells in all tissue types that were tested, signifying “a biochemical and histologic attenuation of the high-fat, high-fructose diet-induced NASH,” the investigators wrote. Treating the mice with antibodies targeting IL-17A did not attenuate NASH but did reduce hepatic inflammation.

The fact that “the most pronounced effect” on NASH resulted from correcting immune disruption in visceral adipose tissue underscored “the immense importance of adipose tissue inflammation in [NASH] pathogenesis,” the researchers wrote. The finding that diet reversal alone did not reverse inflammation in hepatic or visceral adipose tissue “challeng[es] our current understanding of the reversibility of NASH and other obesity-related conditions.” They called for studies of underlying mechanisms as part of “the search for a medical treatment for NASH.”

Funders included the University Research Fund, University of Antwerp, and Research Foundation Flanders. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest except that one coinvestigator is the chief science officer at Biocellvia, which performed some histologic analyses.

SOURCE: Van Herck MA et al. Cell Molec Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Apr 20. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2020.04.010.

Changes in a variety of T cells in the liver and visceral adipose tissue play a key role in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, according to the results of a murine study.

Mikhaïl A. Van Herck, of the University of Antwerp (Belgium), and associates fed 8-week old mice a high-fat, high-fructose diet for 20 weeks, and then switched the mice to standard mouse chow for 12 weeks. The high-fat, high-fructose diet induced the metabolic syndrome and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), accompanied by shifts in T cells. Interleukin-17–producing (Th17 cells increased in the liver, visceral adipose tissue, and blood, while regulatory T cells decreased in visceral adipose tissue, and cytotoxic T (Tc) cells rose in visceral adipose tissue while dropping in the blood and spleen.

These are “important immune disruptions,” the researchers wrote in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “In particular, visceral adipose tissue Tc cells are critically involved in NASH pathogenesis, linking adipose tissue inflammation to liver disease.”

After the mice were switched from the high-fat, high-fructose diet to standard mouse chow, their body weight, body fat, and plasma cholesterol significantly decreased and their glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity improved to resemble the metrics of mice fed standard mouse chow throughout the study. Mice who underwent diet reversal also had significantly decreased liver weight and levels of plasma ALT, compared with mice that remained on the high-fat, high-fructose diet. Diet reversal also improved liver histology (nonalcoholic fatty liver disease activity scores), compared with the high-fat, high-fructose diet, the researchers wrote. “Importantly, the NASH was not significantly different between diet-reversal mice and mice fed the control diet for 32 weeks.”

Genetic tests supported these findings. On multiplex RNA analysis, hepatic expression of Acta2, Col1a1, and Col1a3 reverted to normal with diet reversal, indicating a normalization of hepatic collagen. Hepatic expression of the metabolic genes Ppara, Pparg, and Fgf21 also returned to normal, while visceral adipose tissue showed a decrease in Lep and Fgf21 expression and resolution of adipocyte hypertrophy.

However, diet reversal did not reverse inflammatory changes in T-cell subsets. Administering anti-CD8a antibodies after diet reversal decreased Tc cells in all tissue types that were tested, signifying “a biochemical and histologic attenuation of the high-fat, high-fructose diet-induced NASH,” the investigators wrote. Treating the mice with antibodies targeting IL-17A did not attenuate NASH but did reduce hepatic inflammation.

The fact that “the most pronounced effect” on NASH resulted from correcting immune disruption in visceral adipose tissue underscored “the immense importance of adipose tissue inflammation in [NASH] pathogenesis,” the researchers wrote. The finding that diet reversal alone did not reverse inflammation in hepatic or visceral adipose tissue “challeng[es] our current understanding of the reversibility of NASH and other obesity-related conditions.” They called for studies of underlying mechanisms as part of “the search for a medical treatment for NASH.”

Funders included the University Research Fund, University of Antwerp, and Research Foundation Flanders. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest except that one coinvestigator is the chief science officer at Biocellvia, which performed some histologic analyses.

SOURCE: Van Herck MA et al. Cell Molec Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Apr 20. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2020.04.010.

FROM CELLULAR AND MOLECULAR GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Exploring cannabis use by older adults

Older Americans – people aged 65 or older – make up 15% of the U.S. population, according to the Census Bureau. By the end of this decade, or the year 2030, this proportion will increase to 21% – and all “baby boomers,” those born between 1946 and 1964, will be older than 65.1 Those demographic developments are occurring alongside a change in societal, legal, and public attitudes on cannabis.

Liberalization of cannabis laws across the United States allows for ever easier access to medicinal and recreational cannabis. Traditionally, cannabis use, its effects, and related considerations in the adolescent and young adult populations have commanded significant research attention. Cannabis use in older adults, however, is not as well studied.2 An exploration of trends in cannabis use by older adults and potential impact in terms of health is timely and important.

According to data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, cannabis use in adults aged 65 years and older appears to have been increasing steadily over the past 2 decades. Use among this group rose from 0.4% in 2006 and 2007, to 2.9% in 2015 and 2016.2 And, most recently, use climbed from 3.7% in 2017 to 4.2% in 2018.2

Cannabis use also has risen among other adults. For those aged 50-64, cannabis use increased from 2.8% in 2006-2007 to 4.8% in 2012-2013.2,3 Meanwhile, from 2015 to 2016, that number increased to 9.0%.3,4

Past-year cannabis use in the groups of those aged 50-64 and those aged 65 and older appears to be higher in individuals with mental health problems, alcohol use disorder, and nicotine dependence.5,6 Being male and being unmarried appear to be correlated with past-year cannabis use. Multimorbidity does not appear to be associated with past-year cannabis use. Those using cannabis tend to be long-term users and have first use at a much younger age, typically before age 21.

Older adults use cannabis for both recreational and perceived medical benefits. Arthritis, chronic back pain, anxiety, depression, relaxation, stress reduction, and enhancement in terms of creativity are all purported reasons for use. However, there is limited to no evidence for the efficacy of cannabis in helping with those conditions and purposes. Clinical trials have shown that cannabis can be beneficial in managing pain and nausea, but those trials have not been conducted in older adults.7,8

There is a real risk of cannabis use having a negative impact on the health of older adults. To begin with, the cannabis consumed today is significantly higher in potency than the cannabis that baby boomers were introduced to in their youth. The higher potency, combined with an age-related decline in function experienced by some older adults, makes them vulnerable to its known side effects, such as anxiety, dry mouth, tachycardia, high blood pressure, palpitations, wheezing, confusion, and dizziness.

Cannabis use is reported to bring a fourfold increase in cardiac events within the first hour of ingestion.9 Cognitive decline and memory impairment are well known adverse effects of cannabis use. Research has shown significant self-reported cognitive decline in older adults in relation to cannabis use.Cannabis metabolites are known to have an effect on cytochrome P450 enzymes, affecting the metabolism of medication, and increasing the susceptibility of older adults who use cannabis to adverse effects of polypharmacy. Finally, as research on emergency department visits by older adults shows, cannabis use can increase the risk of injury among this cohort.

As in the United States, cannabis use among older adults in Canada has increased significantly. The percentage of older adults who use cannabis in the Canadian province of Ontario, for example, reportedly doubled from 2005 to 2015. In response to this increase, and in anticipation of a rise in problematic use of cannabis and cannabis use disorder in older adults, the Canadian Coalition for Seniors’ Mental Health (through financial support from Substance Use and Addictions Program of Health Canada) has created guidelines on the prevention, assessment, and management of cannabis use disorder in older adults.

In the absence of a set of guidelines specific to the United States, the recommendations made by the coalition should be helpful in the care of older Americans. Among other recommendations, the guidelines highlight the needs for primary care physicians to build a better knowledge base around the use of cannabis in older adults, to screen older adults for cannabis use, and to educate older adults and their families about the risk of cannabis use.9

Cannabis use is increasingly popular among older adults10 for both medicinal and recreational purposes. Research and data supporting its medical benefits are limited, and the potential of harm from its use among older adults is present and significant. Importantly, many older adults who use marijuana have co-occurring mental health issues and substance use disorder(s).

Often, our older patients learn about benefits and harms of cannabis from friends and the Internet rather than from physicians and other clinicians.9 We must do our part to make sure that older patients understand the potential negative health impact that cannabis can have on their health. Physicians should screen older adults for marijuana use. Building a better knowledge base around changing trends and views in/on the use and accessibility of cannabis will help physicians better address cannabis use in older adults.

Mr. Kaleka is a medical student in the class of 2021 at Central Michigan University College of Medicine, Mount Pleasant. He has no disclosures. Mr. Kaleka would like to thank his mentor, Furhut Janssen, DO, for her continued guidance and support in research on mental health in vulnerable populations.

References

1. Vespa J et al. Demographic turning points for the United States: Population projections for 2020 to 2060. Current Population Reports. Washington: U.S. Census Bureau. 2020 Feb.

2. Han BH et al. Addiction. 2016 Oct 21. doi: 10.1111/add.13670.

3. Han BH and Palamar JJ. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018 Oct;191:374-81.

4. Han BH and Palamar JJ. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 Feb 4;180(4):609-11.

5. Choi NG et al. Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2018;44(2):215-23.

6. Reynolds IR et al. J Am Griatr Soc. 2018 Nov;66(11):2167-71.

7. Ahmed AIA et al. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014 Feb;62(2):410-1.

8. Lum HD et al. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2019 Jan-Dec;5:2333721419843707.

9. Bertram JR et al. Can Geriatr J. 2020 Mar;23(1):135-42.

10. Baumbusch J and Yip IS. Clin Gerontol. 2020 Mar 29;1-7.

Older Americans – people aged 65 or older – make up 15% of the U.S. population, according to the Census Bureau. By the end of this decade, or the year 2030, this proportion will increase to 21% – and all “baby boomers,” those born between 1946 and 1964, will be older than 65.1 Those demographic developments are occurring alongside a change in societal, legal, and public attitudes on cannabis.

Liberalization of cannabis laws across the United States allows for ever easier access to medicinal and recreational cannabis. Traditionally, cannabis use, its effects, and related considerations in the adolescent and young adult populations have commanded significant research attention. Cannabis use in older adults, however, is not as well studied.2 An exploration of trends in cannabis use by older adults and potential impact in terms of health is timely and important.

According to data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, cannabis use in adults aged 65 years and older appears to have been increasing steadily over the past 2 decades. Use among this group rose from 0.4% in 2006 and 2007, to 2.9% in 2015 and 2016.2 And, most recently, use climbed from 3.7% in 2017 to 4.2% in 2018.2

Cannabis use also has risen among other adults. For those aged 50-64, cannabis use increased from 2.8% in 2006-2007 to 4.8% in 2012-2013.2,3 Meanwhile, from 2015 to 2016, that number increased to 9.0%.3,4

Past-year cannabis use in the groups of those aged 50-64 and those aged 65 and older appears to be higher in individuals with mental health problems, alcohol use disorder, and nicotine dependence.5,6 Being male and being unmarried appear to be correlated with past-year cannabis use. Multimorbidity does not appear to be associated with past-year cannabis use. Those using cannabis tend to be long-term users and have first use at a much younger age, typically before age 21.

Older adults use cannabis for both recreational and perceived medical benefits. Arthritis, chronic back pain, anxiety, depression, relaxation, stress reduction, and enhancement in terms of creativity are all purported reasons for use. However, there is limited to no evidence for the efficacy of cannabis in helping with those conditions and purposes. Clinical trials have shown that cannabis can be beneficial in managing pain and nausea, but those trials have not been conducted in older adults.7,8

There is a real risk of cannabis use having a negative impact on the health of older adults. To begin with, the cannabis consumed today is significantly higher in potency than the cannabis that baby boomers were introduced to in their youth. The higher potency, combined with an age-related decline in function experienced by some older adults, makes them vulnerable to its known side effects, such as anxiety, dry mouth, tachycardia, high blood pressure, palpitations, wheezing, confusion, and dizziness.

Cannabis use is reported to bring a fourfold increase in cardiac events within the first hour of ingestion.9 Cognitive decline and memory impairment are well known adverse effects of cannabis use. Research has shown significant self-reported cognitive decline in older adults in relation to cannabis use.Cannabis metabolites are known to have an effect on cytochrome P450 enzymes, affecting the metabolism of medication, and increasing the susceptibility of older adults who use cannabis to adverse effects of polypharmacy. Finally, as research on emergency department visits by older adults shows, cannabis use can increase the risk of injury among this cohort.

As in the United States, cannabis use among older adults in Canada has increased significantly. The percentage of older adults who use cannabis in the Canadian province of Ontario, for example, reportedly doubled from 2005 to 2015. In response to this increase, and in anticipation of a rise in problematic use of cannabis and cannabis use disorder in older adults, the Canadian Coalition for Seniors’ Mental Health (through financial support from Substance Use and Addictions Program of Health Canada) has created guidelines on the prevention, assessment, and management of cannabis use disorder in older adults.

In the absence of a set of guidelines specific to the United States, the recommendations made by the coalition should be helpful in the care of older Americans. Among other recommendations, the guidelines highlight the needs for primary care physicians to build a better knowledge base around the use of cannabis in older adults, to screen older adults for cannabis use, and to educate older adults and their families about the risk of cannabis use.9

Cannabis use is increasingly popular among older adults10 for both medicinal and recreational purposes. Research and data supporting its medical benefits are limited, and the potential of harm from its use among older adults is present and significant. Importantly, many older adults who use marijuana have co-occurring mental health issues and substance use disorder(s).

Often, our older patients learn about benefits and harms of cannabis from friends and the Internet rather than from physicians and other clinicians.9 We must do our part to make sure that older patients understand the potential negative health impact that cannabis can have on their health. Physicians should screen older adults for marijuana use. Building a better knowledge base around changing trends and views in/on the use and accessibility of cannabis will help physicians better address cannabis use in older adults.

Mr. Kaleka is a medical student in the class of 2021 at Central Michigan University College of Medicine, Mount Pleasant. He has no disclosures. Mr. Kaleka would like to thank his mentor, Furhut Janssen, DO, for her continued guidance and support in research on mental health in vulnerable populations.

References

1. Vespa J et al. Demographic turning points for the United States: Population projections for 2020 to 2060. Current Population Reports. Washington: U.S. Census Bureau. 2020 Feb.

2. Han BH et al. Addiction. 2016 Oct 21. doi: 10.1111/add.13670.

3. Han BH and Palamar JJ. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018 Oct;191:374-81.

4. Han BH and Palamar JJ. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 Feb 4;180(4):609-11.

5. Choi NG et al. Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2018;44(2):215-23.

6. Reynolds IR et al. J Am Griatr Soc. 2018 Nov;66(11):2167-71.

7. Ahmed AIA et al. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014 Feb;62(2):410-1.

8. Lum HD et al. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2019 Jan-Dec;5:2333721419843707.

9. Bertram JR et al. Can Geriatr J. 2020 Mar;23(1):135-42.

10. Baumbusch J and Yip IS. Clin Gerontol. 2020 Mar 29;1-7.

Older Americans – people aged 65 or older – make up 15% of the U.S. population, according to the Census Bureau. By the end of this decade, or the year 2030, this proportion will increase to 21% – and all “baby boomers,” those born between 1946 and 1964, will be older than 65.1 Those demographic developments are occurring alongside a change in societal, legal, and public attitudes on cannabis.

Liberalization of cannabis laws across the United States allows for ever easier access to medicinal and recreational cannabis. Traditionally, cannabis use, its effects, and related considerations in the adolescent and young adult populations have commanded significant research attention. Cannabis use in older adults, however, is not as well studied.2 An exploration of trends in cannabis use by older adults and potential impact in terms of health is timely and important.

According to data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, cannabis use in adults aged 65 years and older appears to have been increasing steadily over the past 2 decades. Use among this group rose from 0.4% in 2006 and 2007, to 2.9% in 2015 and 2016.2 And, most recently, use climbed from 3.7% in 2017 to 4.2% in 2018.2

Cannabis use also has risen among other adults. For those aged 50-64, cannabis use increased from 2.8% in 2006-2007 to 4.8% in 2012-2013.2,3 Meanwhile, from 2015 to 2016, that number increased to 9.0%.3,4