User login

Does vitamin D supplementation reduce asthma exacerbations?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

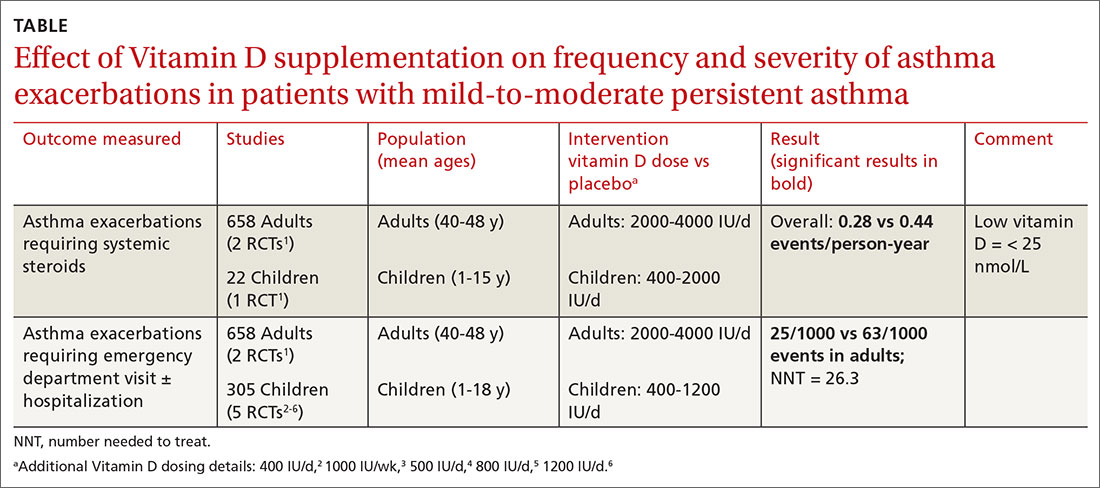

A Cochrane systematic review of vitamin D for managing asthma performed meta-analyses on RCTs that evaluated several outcomes.1 The review found improvement in the primary outcome of asthma exacerbations requiring systemic steroids, mainly in adult patients, and in the secondary outcomes of emergency department visits or hospitalization, in a mix of adults and children (TABLE1-6).

Most participants had mild-to-moderate asthma; trials lasted 4 to 12 months. Vitamin D dosage regimens varied, with a median daily dose of 900 IU/d (range, 400-4000 IU/d). Six RCTs were rated high-quality, and 1 had unclear risk of bias.

Supplementation reduced exacerbations in patients with low vitamin D levels

A subsequent (2017) systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating the primary outcome of exacerbations requiring steroids7 included another study8 (in addition to the 6 RCTs in the Cochrane review).

When researchers reanalyzed individual participant data from the trials in the Cochrane review, plus the additional RCT, to include baseline vitamin D levels, they found that vitamin D supplementation reduced exacerbations overall (NNT = 7.7) and in patients with low baseline vitamin D levels (25[OH] vitamin D < 25 nmol/L; 92 participants in 3 RCTs; NNT = 4.3) but not in patients with higher baseline levels (764 participants in 6 RCTs). Vitamin D supplementation reduced the asthma exacerbation rate in patients with low baseline vitamin D levels (0.19 vs 0.42 events per participant-year; P = .046).

Smaller benefit found on ED visits and hospitalizations

The Cochrane review, with 2 RCTs with adults (n = 658)1 and 5 RCTs with children (n = 305),2-6 evaluated whether Vitamin D reduced the need for emergency department visits and hospitalization with asthma exacerbations; they found a smaller benefit (NNT = 26.3).

Effects on FEV1, daily asthma symptoms, and serious adverse effects

Several RCTs included in the 2017 meta-analysis found no effect of vitamin D supplementation on FEV1, daily asthma symptoms (evaluated with the standardized Asthma Control Test Score), or reported serious adverse events.2-6,9,10 No deaths occurred in any trial.

Additional findings in children from lower-quality studies

A 2015 systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs evaluating vitamin D supplementation for children with asthma found11:

- moderate-quality evidence for decreased emergency department visits (1 RCT from India, 100 children ages 3 to 14 years, decrease not specified; P = .015);

- low-quality evidence for reduced exacerbations (6 RCTs [3 RCTs also in Cochrane review], 507 children ages 3 to 17 years; risk ratio = 0.41; 95% confidence interval, 0.27-0.63); and

- low-quality evidence for reduced standardized asthma symptom scores (6 RCTs [2 RCTs also in Cochrane review], 231 children ages 3 to 17 years; amount of reduction not listed; P = .01).

Continue to: RECOMMENDATIONS

RECOMMENDATIONS

No published guidelines discuss using vitamin D in managing asthma. An American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) summary of the Cochrane systematic review recommends that family physicians await further studies and updated guidelines before recommending vitamin D for patients with asthma.12 The AAFP also points out that the Endocrine Society has recommended vitamin D supplementation for adults (1500-2000 IU/d) and children (at least 1000 IU/d) at risk for deficiency.

Editor's takeaway

In the meta-analyses highlighted here, researchers evaluated asthma patients with a wide range of ages, baseline vitamin D levels, and vitamin D supplementation protocols. Although vitamin D reduced asthma exacerbations requiring steroids overall, the effect was driven by 3 studies of patients with low baseline vitamin D levels. As a result, disentangling who might benefit the most remains a challenge. The conservative course for now is to manage asthma according to current guidelines and supplement vitamin D in patients at risk for, or with known, deficiency.

, , , . Vitamin D for the management of asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;9:CD011511.

2. Jensen M, Mailhot G, Alos N, et al. Vitamin D intervention in preschoolers with viral-induced asthma (DIVA): a pilot randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2016;26:17:353.

, , , et al. Correlation of vitamin D with Foxp3 induction and steroid-sparing effect of immunotherapy in asthmatic children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;109:329-335.

, , , et al. Vitamin D supplementation in children may prevent asthma exacerbation triggered by acute respiratory infection. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:1294-1296.

, , , et al. Improved control of childhood asthma with low-dose, short-term vitamin D supplementation: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Allergy. 2016;71:1001-1009.

, , , et al. Randomized trial of vitamin D supplementation to prevent seasonal influenza A in school children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:1255-1260.

7. Joliffe DA, Greenberg L, Hooper RL, et al. Vitamin D supplementation to prevent asthma exacerbations: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet 2017;5:881-890.

8. Kerley CP, Hutchinson K, Cormical L, et al. Vitamin D3 for uncontrolled childhood asthma: a pilot study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2016;27:404-412.

, , , et al. Effect of vitamin D3 on asthma treatment failures in adults with symptomatic asthma and lower vitamin D levels: the VIDA randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311:2083-2091.

, , , et al. Double-blind multi-centre randomised controlled trial of vitamin D3 supplementation in adults with inhaled corticosteroid-treated asthma (ViDiAs). Thorax. 2015:70:451-457.

11. Riverin B, Maguire J, Li P. Vitamin D supplementation for childhood asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS One. 2015;10:e0136841.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A Cochrane systematic review of vitamin D for managing asthma performed meta-analyses on RCTs that evaluated several outcomes.1 The review found improvement in the primary outcome of asthma exacerbations requiring systemic steroids, mainly in adult patients, and in the secondary outcomes of emergency department visits or hospitalization, in a mix of adults and children (TABLE1-6).

Most participants had mild-to-moderate asthma; trials lasted 4 to 12 months. Vitamin D dosage regimens varied, with a median daily dose of 900 IU/d (range, 400-4000 IU/d). Six RCTs were rated high-quality, and 1 had unclear risk of bias.

Supplementation reduced exacerbations in patients with low vitamin D levels

A subsequent (2017) systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating the primary outcome of exacerbations requiring steroids7 included another study8 (in addition to the 6 RCTs in the Cochrane review).

When researchers reanalyzed individual participant data from the trials in the Cochrane review, plus the additional RCT, to include baseline vitamin D levels, they found that vitamin D supplementation reduced exacerbations overall (NNT = 7.7) and in patients with low baseline vitamin D levels (25[OH] vitamin D < 25 nmol/L; 92 participants in 3 RCTs; NNT = 4.3) but not in patients with higher baseline levels (764 participants in 6 RCTs). Vitamin D supplementation reduced the asthma exacerbation rate in patients with low baseline vitamin D levels (0.19 vs 0.42 events per participant-year; P = .046).

Smaller benefit found on ED visits and hospitalizations

The Cochrane review, with 2 RCTs with adults (n = 658)1 and 5 RCTs with children (n = 305),2-6 evaluated whether Vitamin D reduced the need for emergency department visits and hospitalization with asthma exacerbations; they found a smaller benefit (NNT = 26.3).

Effects on FEV1, daily asthma symptoms, and serious adverse effects

Several RCTs included in the 2017 meta-analysis found no effect of vitamin D supplementation on FEV1, daily asthma symptoms (evaluated with the standardized Asthma Control Test Score), or reported serious adverse events.2-6,9,10 No deaths occurred in any trial.

Additional findings in children from lower-quality studies

A 2015 systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs evaluating vitamin D supplementation for children with asthma found11:

- moderate-quality evidence for decreased emergency department visits (1 RCT from India, 100 children ages 3 to 14 years, decrease not specified; P = .015);

- low-quality evidence for reduced exacerbations (6 RCTs [3 RCTs also in Cochrane review], 507 children ages 3 to 17 years; risk ratio = 0.41; 95% confidence interval, 0.27-0.63); and

- low-quality evidence for reduced standardized asthma symptom scores (6 RCTs [2 RCTs also in Cochrane review], 231 children ages 3 to 17 years; amount of reduction not listed; P = .01).

Continue to: RECOMMENDATIONS

RECOMMENDATIONS

No published guidelines discuss using vitamin D in managing asthma. An American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) summary of the Cochrane systematic review recommends that family physicians await further studies and updated guidelines before recommending vitamin D for patients with asthma.12 The AAFP also points out that the Endocrine Society has recommended vitamin D supplementation for adults (1500-2000 IU/d) and children (at least 1000 IU/d) at risk for deficiency.

Editor's takeaway

In the meta-analyses highlighted here, researchers evaluated asthma patients with a wide range of ages, baseline vitamin D levels, and vitamin D supplementation protocols. Although vitamin D reduced asthma exacerbations requiring steroids overall, the effect was driven by 3 studies of patients with low baseline vitamin D levels. As a result, disentangling who might benefit the most remains a challenge. The conservative course for now is to manage asthma according to current guidelines and supplement vitamin D in patients at risk for, or with known, deficiency.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A Cochrane systematic review of vitamin D for managing asthma performed meta-analyses on RCTs that evaluated several outcomes.1 The review found improvement in the primary outcome of asthma exacerbations requiring systemic steroids, mainly in adult patients, and in the secondary outcomes of emergency department visits or hospitalization, in a mix of adults and children (TABLE1-6).

Most participants had mild-to-moderate asthma; trials lasted 4 to 12 months. Vitamin D dosage regimens varied, with a median daily dose of 900 IU/d (range, 400-4000 IU/d). Six RCTs were rated high-quality, and 1 had unclear risk of bias.

Supplementation reduced exacerbations in patients with low vitamin D levels

A subsequent (2017) systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating the primary outcome of exacerbations requiring steroids7 included another study8 (in addition to the 6 RCTs in the Cochrane review).

When researchers reanalyzed individual participant data from the trials in the Cochrane review, plus the additional RCT, to include baseline vitamin D levels, they found that vitamin D supplementation reduced exacerbations overall (NNT = 7.7) and in patients with low baseline vitamin D levels (25[OH] vitamin D < 25 nmol/L; 92 participants in 3 RCTs; NNT = 4.3) but not in patients with higher baseline levels (764 participants in 6 RCTs). Vitamin D supplementation reduced the asthma exacerbation rate in patients with low baseline vitamin D levels (0.19 vs 0.42 events per participant-year; P = .046).

Smaller benefit found on ED visits and hospitalizations

The Cochrane review, with 2 RCTs with adults (n = 658)1 and 5 RCTs with children (n = 305),2-6 evaluated whether Vitamin D reduced the need for emergency department visits and hospitalization with asthma exacerbations; they found a smaller benefit (NNT = 26.3).

Effects on FEV1, daily asthma symptoms, and serious adverse effects

Several RCTs included in the 2017 meta-analysis found no effect of vitamin D supplementation on FEV1, daily asthma symptoms (evaluated with the standardized Asthma Control Test Score), or reported serious adverse events.2-6,9,10 No deaths occurred in any trial.

Additional findings in children from lower-quality studies

A 2015 systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs evaluating vitamin D supplementation for children with asthma found11:

- moderate-quality evidence for decreased emergency department visits (1 RCT from India, 100 children ages 3 to 14 years, decrease not specified; P = .015);

- low-quality evidence for reduced exacerbations (6 RCTs [3 RCTs also in Cochrane review], 507 children ages 3 to 17 years; risk ratio = 0.41; 95% confidence interval, 0.27-0.63); and

- low-quality evidence for reduced standardized asthma symptom scores (6 RCTs [2 RCTs also in Cochrane review], 231 children ages 3 to 17 years; amount of reduction not listed; P = .01).

Continue to: RECOMMENDATIONS

RECOMMENDATIONS

No published guidelines discuss using vitamin D in managing asthma. An American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) summary of the Cochrane systematic review recommends that family physicians await further studies and updated guidelines before recommending vitamin D for patients with asthma.12 The AAFP also points out that the Endocrine Society has recommended vitamin D supplementation for adults (1500-2000 IU/d) and children (at least 1000 IU/d) at risk for deficiency.

Editor's takeaway

In the meta-analyses highlighted here, researchers evaluated asthma patients with a wide range of ages, baseline vitamin D levels, and vitamin D supplementation protocols. Although vitamin D reduced asthma exacerbations requiring steroids overall, the effect was driven by 3 studies of patients with low baseline vitamin D levels. As a result, disentangling who might benefit the most remains a challenge. The conservative course for now is to manage asthma according to current guidelines and supplement vitamin D in patients at risk for, or with known, deficiency.

, , , . Vitamin D for the management of asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;9:CD011511.

2. Jensen M, Mailhot G, Alos N, et al. Vitamin D intervention in preschoolers with viral-induced asthma (DIVA): a pilot randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2016;26:17:353.

, , , et al. Correlation of vitamin D with Foxp3 induction and steroid-sparing effect of immunotherapy in asthmatic children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;109:329-335.

, , , et al. Vitamin D supplementation in children may prevent asthma exacerbation triggered by acute respiratory infection. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:1294-1296.

, , , et al. Improved control of childhood asthma with low-dose, short-term vitamin D supplementation: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Allergy. 2016;71:1001-1009.

, , , et al. Randomized trial of vitamin D supplementation to prevent seasonal influenza A in school children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:1255-1260.

7. Joliffe DA, Greenberg L, Hooper RL, et al. Vitamin D supplementation to prevent asthma exacerbations: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet 2017;5:881-890.

8. Kerley CP, Hutchinson K, Cormical L, et al. Vitamin D3 for uncontrolled childhood asthma: a pilot study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2016;27:404-412.

, , , et al. Effect of vitamin D3 on asthma treatment failures in adults with symptomatic asthma and lower vitamin D levels: the VIDA randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311:2083-2091.

, , , et al. Double-blind multi-centre randomised controlled trial of vitamin D3 supplementation in adults with inhaled corticosteroid-treated asthma (ViDiAs). Thorax. 2015:70:451-457.

11. Riverin B, Maguire J, Li P. Vitamin D supplementation for childhood asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS One. 2015;10:e0136841.

, , , . Vitamin D for the management of asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;9:CD011511.

2. Jensen M, Mailhot G, Alos N, et al. Vitamin D intervention in preschoolers with viral-induced asthma (DIVA): a pilot randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2016;26:17:353.

, , , et al. Correlation of vitamin D with Foxp3 induction and steroid-sparing effect of immunotherapy in asthmatic children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;109:329-335.

, , , et al. Vitamin D supplementation in children may prevent asthma exacerbation triggered by acute respiratory infection. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:1294-1296.

, , , et al. Improved control of childhood asthma with low-dose, short-term vitamin D supplementation: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Allergy. 2016;71:1001-1009.

, , , et al. Randomized trial of vitamin D supplementation to prevent seasonal influenza A in school children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:1255-1260.

7. Joliffe DA, Greenberg L, Hooper RL, et al. Vitamin D supplementation to prevent asthma exacerbations: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet 2017;5:881-890.

8. Kerley CP, Hutchinson K, Cormical L, et al. Vitamin D3 for uncontrolled childhood asthma: a pilot study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2016;27:404-412.

, , , et al. Effect of vitamin D3 on asthma treatment failures in adults with symptomatic asthma and lower vitamin D levels: the VIDA randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311:2083-2091.

, , , et al. Double-blind multi-centre randomised controlled trial of vitamin D3 supplementation in adults with inhaled corticosteroid-treated asthma (ViDiAs). Thorax. 2015:70:451-457.

11. Riverin B, Maguire J, Li P. Vitamin D supplementation for childhood asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS One. 2015;10:e0136841.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Yes, to some extent it does, and primarily in patients with low vitamin D levels. Supplementation reduces asthma exacerbations requiring systemic steroids by 30% overall in adults and children with mild-to-moderate asthma (number needed to treat [NNT] = 7.7). The outcome is driven by the effect in patients with vitamin D levels < 25 nmol/L (NNT = 4.3), however; supplementation doesn’t decrease exacerbations in patients with higher levels. Supplementation also reduces, by a smaller amount (NNT = 26.3), the odds of exacerbations requiring emergency department care or hospitalization (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

In children, vitamin D supplementation may also reduce exacerbations and improve symptom scores (SOR: C, low-quality RCTs).

Vitamin D doesn’t improve forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) or standardized asthma control test scores. Also, it isn’t associated with serious adverse effects (SOR: A, meta-analysis of RCTs).

FDA approves olaparib/bevacizumab maintenance

The Food and Drug Administration has announced a new approved indication for olaparib (Lynparza) in adults with advanced epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer.

Olaparib is now FDA-approved for use in combination with bevacizumab as maintenance therapy in patients who responded to first-line platinum-based chemotherapy and whose cancer is homologous recombination deficiency positive, as defined by a deleterious or suspected deleterious BRCA mutation and/or genomic instability.

The FDA also approved the Myriad myChoice CDx test as a companion diagnostic for olaparib.

Trial results

The efficacy of olaparib and the myChoice CDx test were assessed in patients in the phase 3 PAOLA-1 trial (NCT02477644). The study enrolled patients with advanced high-grade epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer who had received first-line platinum-based chemotherapy and bevacizumab.

Patients were stratified by first-line treatment outcome and BRCA mutation status, as determined by prospective local testing. All available clinical samples were retrospectively tested with the Myriad myChoice CDx test.

The patients were randomized to receive olaparib at 300 mg orally twice daily in combination with bevacizumab at 15 mg/kg every 3 weeks (n = 537) or placebo plus bevacizumab (n = 269). Patients continued bevacizumab in the maintenance setting and started olaparib 3-9 weeks after their last chemotherapy dose. Olaparib could be continued for up to 2 years or until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

The median progression-free survival among the 387 patients with homologous recombination deficiency-positive tumors was 37.2 months in the olaparib arm and 17.7 months in the placebo arm (hazard ratio, 0.33), according to the prescribing information for olaparib.

Serious adverse events occurred in 31% of patients in the olaparib arm. The most common were hypertension (19%) and anemia (17%).

Dose interruptions from adverse events occurred in 54% of patients in the olaparib arm, and dose reductions from adverse events occurred in 41%.

The Food and Drug Administration has announced a new approved indication for olaparib (Lynparza) in adults with advanced epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer.

Olaparib is now FDA-approved for use in combination with bevacizumab as maintenance therapy in patients who responded to first-line platinum-based chemotherapy and whose cancer is homologous recombination deficiency positive, as defined by a deleterious or suspected deleterious BRCA mutation and/or genomic instability.

The FDA also approved the Myriad myChoice CDx test as a companion diagnostic for olaparib.

Trial results

The efficacy of olaparib and the myChoice CDx test were assessed in patients in the phase 3 PAOLA-1 trial (NCT02477644). The study enrolled patients with advanced high-grade epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer who had received first-line platinum-based chemotherapy and bevacizumab.

Patients were stratified by first-line treatment outcome and BRCA mutation status, as determined by prospective local testing. All available clinical samples were retrospectively tested with the Myriad myChoice CDx test.

The patients were randomized to receive olaparib at 300 mg orally twice daily in combination with bevacizumab at 15 mg/kg every 3 weeks (n = 537) or placebo plus bevacizumab (n = 269). Patients continued bevacizumab in the maintenance setting and started olaparib 3-9 weeks after their last chemotherapy dose. Olaparib could be continued for up to 2 years or until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

The median progression-free survival among the 387 patients with homologous recombination deficiency-positive tumors was 37.2 months in the olaparib arm and 17.7 months in the placebo arm (hazard ratio, 0.33), according to the prescribing information for olaparib.

Serious adverse events occurred in 31% of patients in the olaparib arm. The most common were hypertension (19%) and anemia (17%).

Dose interruptions from adverse events occurred in 54% of patients in the olaparib arm, and dose reductions from adverse events occurred in 41%.

The Food and Drug Administration has announced a new approved indication for olaparib (Lynparza) in adults with advanced epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer.

Olaparib is now FDA-approved for use in combination with bevacizumab as maintenance therapy in patients who responded to first-line platinum-based chemotherapy and whose cancer is homologous recombination deficiency positive, as defined by a deleterious or suspected deleterious BRCA mutation and/or genomic instability.

The FDA also approved the Myriad myChoice CDx test as a companion diagnostic for olaparib.

Trial results

The efficacy of olaparib and the myChoice CDx test were assessed in patients in the phase 3 PAOLA-1 trial (NCT02477644). The study enrolled patients with advanced high-grade epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer who had received first-line platinum-based chemotherapy and bevacizumab.

Patients were stratified by first-line treatment outcome and BRCA mutation status, as determined by prospective local testing. All available clinical samples were retrospectively tested with the Myriad myChoice CDx test.

The patients were randomized to receive olaparib at 300 mg orally twice daily in combination with bevacizumab at 15 mg/kg every 3 weeks (n = 537) or placebo plus bevacizumab (n = 269). Patients continued bevacizumab in the maintenance setting and started olaparib 3-9 weeks after their last chemotherapy dose. Olaparib could be continued for up to 2 years or until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

The median progression-free survival among the 387 patients with homologous recombination deficiency-positive tumors was 37.2 months in the olaparib arm and 17.7 months in the placebo arm (hazard ratio, 0.33), according to the prescribing information for olaparib.

Serious adverse events occurred in 31% of patients in the olaparib arm. The most common were hypertension (19%) and anemia (17%).

Dose interruptions from adverse events occurred in 54% of patients in the olaparib arm, and dose reductions from adverse events occurred in 41%.

Justices appear split over birth control mandate case

U.S. Supreme Court justices appear divided over whether the Trump administration acted properly when it expanded exemptions under the Affordable Care Act’s contraception mandate.

During oral arguments on May 6, the court expressed differing perspectives about the administration’s authority to allow for more exemptions under the health law’s birth control mandate and whether the expansions were reasonable. Justices heard the consolidated cases – Little Sisters of the Poor v. Pennsylvania and Trump v. Pennsylvania – by teleconference because of the COVID-19 pandemic. They are expected to make a decision by the summer.

Associate justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who participated in the telephone conference call from a hospital where she was recovering from a gallbladder condition, said the exemptions ignored the intent of Congress to provide women with comprehensive coverage through the ACA.

“The glaring feature of what the government has done in expanding this exemption is to toss to the winds entirely Congress’s instruction that women need and shall have seamless, no-cost, comprehensive coverage,” she said during oral arguments. “This leaves the women to hunt for other government programs that might cover them, and for those who are not covered by Medicaid or one of the other government programs, they can get contraceptive coverage only from paying out of their own pocket, which is exactly what Congress didn’t want to happen.”

Associate Justice Samuel Alito Jr., meanwhile, indicated that a lower court opinion that had blocked the exemptions from going forward conflicts with the Supreme Court’s ruling in a related case, Burwell v. Hobby Lobby.

“Explain to me why the Third Circuit’s analysis of the question of substantial burden is not squarely inconsistent with our reasoning in Hobby Lobby,” Associate Justice Alito said during oral arguments. “Hobby Lobby held that, if a person sincerely believes that it is immoral to perform an act that has the effect of enabling another person to commit an immoral act, a federal court does not have the right to say that this person is wrong on the question of moral complicity. That’s precisely the situation here. Reading the Third Circuit’s discussion of the substantial burden question, I wondered whether they had read that part of the Hobby Lobby decision.”

The dispute surrounding the ACA’s birth control mandate and the extent of exemptions afforded has gone on for a decade and has led to numerous legal challenges. The ACA initially required all employers to cover birth control for employees with no copayments, but exempted group health plans of religious employers. Those religious employers were primarily churches and other houses of worship. After a number of complaints and lawsuits, the Obama administration created a workaround for nonprofit religious employers not included in that exemption to opt out of the mandate. However, critics argued the process itself was a violation of their religious freedom.

The issue led to the case of Zubik v. Burwell, a legal challenge over the mandate exemption that went before the U.S. Supreme Court in March 2016. The issue was never resolved however, and in May 2016, the Supreme Court vacated the lower court rulings related to Zubik v. Burwell and remanded the case back to the four appeals courts that had originally ruled on the issue.

In 2018, the Trump administration announced new rules aimed at broadening exemptions to the ACA’s contraceptive mandate to entities that object to services covered by the mandate on the basis of “sincerely held religious beliefs.” A second rule allowed nonprofit organizations and small businesses that had nonreligious moral convictions against the mandate to opt out.

Thirteen states and the District of Columbia then sued the Trump administration over the rules, as well as Pennsylvania and New Jersey in a separate case. Little Sisters of the Poor, a religious nonprofit operating a home in Pittsburgh, intervened in the case as an aggrieved party. An appeal court temporarily barred the regulations from moving forward.

During oral arguments, Solicitor General for the Department of Justice Noel J. Francisco said the exemptions are lawful because they are authorized under a provision of the ACA as well as the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA).

“RFRA at the very least authorizes the religious exemption,” Mr. Francisco said during oral arguments.

Chief Deputy Attorney General for Pennsylvania Michael J. Fischer argued that the Trump administration’s moral and religious exemption rules rest on overly broad assertions of agency authority.

“First, the agencies twist a narrow delegation that allows the Health Resources and Services Administration to decide which preventive services insurers must cover under the Women’s Health Amendment into a grant of authority so broad it allows them to permit virtually any employer or college to opt out of providing contraceptive coverage entirely, including for reasons as amorphous as vaguely defined moral beliefs,” he said during oral arguments. “Second, the agencies claim that RFRA, a statute that limits government action, affirmatively authorizes them to permit employers to deny women their rights to contraceptive coverage even in the absence of a RFRA violation in the first place.”

U.S. Supreme Court justices appear divided over whether the Trump administration acted properly when it expanded exemptions under the Affordable Care Act’s contraception mandate.

During oral arguments on May 6, the court expressed differing perspectives about the administration’s authority to allow for more exemptions under the health law’s birth control mandate and whether the expansions were reasonable. Justices heard the consolidated cases – Little Sisters of the Poor v. Pennsylvania and Trump v. Pennsylvania – by teleconference because of the COVID-19 pandemic. They are expected to make a decision by the summer.

Associate justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who participated in the telephone conference call from a hospital where she was recovering from a gallbladder condition, said the exemptions ignored the intent of Congress to provide women with comprehensive coverage through the ACA.

“The glaring feature of what the government has done in expanding this exemption is to toss to the winds entirely Congress’s instruction that women need and shall have seamless, no-cost, comprehensive coverage,” she said during oral arguments. “This leaves the women to hunt for other government programs that might cover them, and for those who are not covered by Medicaid or one of the other government programs, they can get contraceptive coverage only from paying out of their own pocket, which is exactly what Congress didn’t want to happen.”

Associate Justice Samuel Alito Jr., meanwhile, indicated that a lower court opinion that had blocked the exemptions from going forward conflicts with the Supreme Court’s ruling in a related case, Burwell v. Hobby Lobby.

“Explain to me why the Third Circuit’s analysis of the question of substantial burden is not squarely inconsistent with our reasoning in Hobby Lobby,” Associate Justice Alito said during oral arguments. “Hobby Lobby held that, if a person sincerely believes that it is immoral to perform an act that has the effect of enabling another person to commit an immoral act, a federal court does not have the right to say that this person is wrong on the question of moral complicity. That’s precisely the situation here. Reading the Third Circuit’s discussion of the substantial burden question, I wondered whether they had read that part of the Hobby Lobby decision.”

The dispute surrounding the ACA’s birth control mandate and the extent of exemptions afforded has gone on for a decade and has led to numerous legal challenges. The ACA initially required all employers to cover birth control for employees with no copayments, but exempted group health plans of religious employers. Those religious employers were primarily churches and other houses of worship. After a number of complaints and lawsuits, the Obama administration created a workaround for nonprofit religious employers not included in that exemption to opt out of the mandate. However, critics argued the process itself was a violation of their religious freedom.

The issue led to the case of Zubik v. Burwell, a legal challenge over the mandate exemption that went before the U.S. Supreme Court in March 2016. The issue was never resolved however, and in May 2016, the Supreme Court vacated the lower court rulings related to Zubik v. Burwell and remanded the case back to the four appeals courts that had originally ruled on the issue.

In 2018, the Trump administration announced new rules aimed at broadening exemptions to the ACA’s contraceptive mandate to entities that object to services covered by the mandate on the basis of “sincerely held religious beliefs.” A second rule allowed nonprofit organizations and small businesses that had nonreligious moral convictions against the mandate to opt out.

Thirteen states and the District of Columbia then sued the Trump administration over the rules, as well as Pennsylvania and New Jersey in a separate case. Little Sisters of the Poor, a religious nonprofit operating a home in Pittsburgh, intervened in the case as an aggrieved party. An appeal court temporarily barred the regulations from moving forward.

During oral arguments, Solicitor General for the Department of Justice Noel J. Francisco said the exemptions are lawful because they are authorized under a provision of the ACA as well as the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA).

“RFRA at the very least authorizes the religious exemption,” Mr. Francisco said during oral arguments.

Chief Deputy Attorney General for Pennsylvania Michael J. Fischer argued that the Trump administration’s moral and religious exemption rules rest on overly broad assertions of agency authority.

“First, the agencies twist a narrow delegation that allows the Health Resources and Services Administration to decide which preventive services insurers must cover under the Women’s Health Amendment into a grant of authority so broad it allows them to permit virtually any employer or college to opt out of providing contraceptive coverage entirely, including for reasons as amorphous as vaguely defined moral beliefs,” he said during oral arguments. “Second, the agencies claim that RFRA, a statute that limits government action, affirmatively authorizes them to permit employers to deny women their rights to contraceptive coverage even in the absence of a RFRA violation in the first place.”

U.S. Supreme Court justices appear divided over whether the Trump administration acted properly when it expanded exemptions under the Affordable Care Act’s contraception mandate.

During oral arguments on May 6, the court expressed differing perspectives about the administration’s authority to allow for more exemptions under the health law’s birth control mandate and whether the expansions were reasonable. Justices heard the consolidated cases – Little Sisters of the Poor v. Pennsylvania and Trump v. Pennsylvania – by teleconference because of the COVID-19 pandemic. They are expected to make a decision by the summer.

Associate justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who participated in the telephone conference call from a hospital where she was recovering from a gallbladder condition, said the exemptions ignored the intent of Congress to provide women with comprehensive coverage through the ACA.

“The glaring feature of what the government has done in expanding this exemption is to toss to the winds entirely Congress’s instruction that women need and shall have seamless, no-cost, comprehensive coverage,” she said during oral arguments. “This leaves the women to hunt for other government programs that might cover them, and for those who are not covered by Medicaid or one of the other government programs, they can get contraceptive coverage only from paying out of their own pocket, which is exactly what Congress didn’t want to happen.”

Associate Justice Samuel Alito Jr., meanwhile, indicated that a lower court opinion that had blocked the exemptions from going forward conflicts with the Supreme Court’s ruling in a related case, Burwell v. Hobby Lobby.

“Explain to me why the Third Circuit’s analysis of the question of substantial burden is not squarely inconsistent with our reasoning in Hobby Lobby,” Associate Justice Alito said during oral arguments. “Hobby Lobby held that, if a person sincerely believes that it is immoral to perform an act that has the effect of enabling another person to commit an immoral act, a federal court does not have the right to say that this person is wrong on the question of moral complicity. That’s precisely the situation here. Reading the Third Circuit’s discussion of the substantial burden question, I wondered whether they had read that part of the Hobby Lobby decision.”

The dispute surrounding the ACA’s birth control mandate and the extent of exemptions afforded has gone on for a decade and has led to numerous legal challenges. The ACA initially required all employers to cover birth control for employees with no copayments, but exempted group health plans of religious employers. Those religious employers were primarily churches and other houses of worship. After a number of complaints and lawsuits, the Obama administration created a workaround for nonprofit religious employers not included in that exemption to opt out of the mandate. However, critics argued the process itself was a violation of their religious freedom.

The issue led to the case of Zubik v. Burwell, a legal challenge over the mandate exemption that went before the U.S. Supreme Court in March 2016. The issue was never resolved however, and in May 2016, the Supreme Court vacated the lower court rulings related to Zubik v. Burwell and remanded the case back to the four appeals courts that had originally ruled on the issue.

In 2018, the Trump administration announced new rules aimed at broadening exemptions to the ACA’s contraceptive mandate to entities that object to services covered by the mandate on the basis of “sincerely held religious beliefs.” A second rule allowed nonprofit organizations and small businesses that had nonreligious moral convictions against the mandate to opt out.

Thirteen states and the District of Columbia then sued the Trump administration over the rules, as well as Pennsylvania and New Jersey in a separate case. Little Sisters of the Poor, a religious nonprofit operating a home in Pittsburgh, intervened in the case as an aggrieved party. An appeal court temporarily barred the regulations from moving forward.

During oral arguments, Solicitor General for the Department of Justice Noel J. Francisco said the exemptions are lawful because they are authorized under a provision of the ACA as well as the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA).

“RFRA at the very least authorizes the religious exemption,” Mr. Francisco said during oral arguments.

Chief Deputy Attorney General for Pennsylvania Michael J. Fischer argued that the Trump administration’s moral and religious exemption rules rest on overly broad assertions of agency authority.

“First, the agencies twist a narrow delegation that allows the Health Resources and Services Administration to decide which preventive services insurers must cover under the Women’s Health Amendment into a grant of authority so broad it allows them to permit virtually any employer or college to opt out of providing contraceptive coverage entirely, including for reasons as amorphous as vaguely defined moral beliefs,” he said during oral arguments. “Second, the agencies claim that RFRA, a statute that limits government action, affirmatively authorizes them to permit employers to deny women their rights to contraceptive coverage even in the absence of a RFRA violation in the first place.”

Triple-antiviral combo speeds COVID-19 recovery

A triple-antiviral therapy regimen of interferon-beta1, lopinavir/ritonavir, and ribavirin shortened median time to COVID-19 viral negativity by 5 days in a small trial from Hong Kong.

In an open-label, randomized phase 2 trial in patients with mild or moderate COVID-19 infections, the median time to viral negativity by nasopharyngeal swab was 7 days for 86 patients assigned to receive a 14-day course of lopinavir 400 mg and ritonavir 100 mg every 12 hours, ribavirin 400 mg every 12 hours, and three doses of 8 million international units of interferon beta-1b on alternate days, compared with a median time to negativity of 12 days for patients treated with lopinavir/ritonavir alone (P = .0010), wrote Ivan Fan-Ngai Hung, MD, from Gleaneagles Hospital in Hong Kong, and colleagues.

“Triple-antiviral therapy with interferon beta-1b, lopinavir/ritonavir, and ribavirin were safe and superior to lopinavir/ritonavir alone in shortening virus shedding, alleviating symptoms, and facilitating discharge of patients with mild to moderate COVID-19,” they wrote in a study published online in The Lancet.

Patients who received the combination also had significantly shorter time to complete alleviation of symptoms as assessed by a National Early Warning Score 2 (NEWS2, a system for detecting clinical deterioration in patients with acute illnesses) score of 0 (4 vs. 8 days, respectively; hazard ratio 3.92, P < .0001), and to a Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score of 0 (3 vs. 8 days, HR 1.89, P = .041).

The median hospital stay was 9 days for patients treated with the combination, compared with 14.5 days for controls (HR 2.72, P = .016).

In most patients treated with the combination, SARS-CoV-2 viral load was effectively suppressed in all clinical specimens, including nasopharyngeal swabs, throat and posterior oropharyngeal saliva, and stool.

In addition, serum levels of interleukin 6 (IL-6) – an inflammatory cytokine implicated in the cytokine storm frequently seen in patients with severe COVID-19 infections – were significantly lower on treatment days 2, 6, and 8 in patients treated with the combination, compared with those treated with lopinavir/ritonavir alone.

“Our trial demonstrates that early treatment of mild to moderate COVID-19 with a triple combination of antiviral drugs may rapidly suppress the amount of virus in a patient’s body, relieve symptoms, and reduce the risk to health care workers by reducing the duration and quantity of viral shedding (when the virus is detectable and potentially transmissible). Furthermore, the treatment combination appeared safe and well tolerated by patients,” said lead investigator Professor Kwok-Yung Yuen from the University of Hong Kong, in a statement.

“Despite these encouraging findings,” he continued, “we must confirm in larger phase 3 trials that interferon beta-1b alone or in combination with other drugs is effective in patients with more severe illness (in whom the virus has had more time to replicate).”

Plausible rationale

Benjamin Medoff, MD, chief of the division of pulmonary and critical care medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview that the biologic rationale for the combination is plausible.

“I think this is a promising study that suggests that a regimen of interferon beta-1b, lopinavir/ritonavir, and ribavirin can shorten the duration of infection and improve symptoms in COVID-19 patients especially if started early in disease, in less than 7 days of symptom onset,” he said in reply to a request for expert analysis.

“The open-label nature and small size of the study limits the broad use of the regimen as noted by the authors, and it’s important to emphasize that the subjects enrolled did not have very severe disease (not in the ICU). However, the study does suggest that a larger truly randomized study is warranted,” he said.

AIDS drugs repurposed

Lopinavir/ritonavir is commonly used to treat HIV/AIDS throughout the world, and the investigators had previously reported that the antiviral agents combined with ribavirin reduced deaths and the need for intensive ventilator support among patients with SARS-CoV, the betacoronavirus that causes severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), and antivirals have shown in vitro activity against both SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, the closely related pathogen that causes Middle East respiratory syndrome.

“ However the viral load of SARS and MERS peaks at around day 7-10 after symptom onset, whereas the viral load of COVID-19 peaks at the time of presentation, similar to influenza. Experience from the treatment of patients with influenza who are admitted to hospital suggested that a combination of multiple antiviral drugs is more effective than single-drug treatments in this setting of patients with a high viral load at presentation,” the investigators wrote.

To test this, they enrolled adults patients admitted to one of six Hong Kong Hospitals for virologically confirmed COVID-19 infections from Feb. 10 through March 20, 2020.

A total of 86 patients were randomly assigned to the combination and 41 to lopinavir/ritonavir alone as controls, at doses described above.

Patients who entered the trial within less than 7 days of symptom onset received the triple combination, with interferon dosing adjusted according to the day that treatment started. Patients recruited 1 or 2 days after symptom onset received three doses of interferon, patients started on day 3 or 4 received two doses, and those started on days 5 or 6 received one interferon dose. Patients recruited 7 days or later from symptom onset did not receive interferon beta-1b because of its proinflammatory effects.

In post-hoc analysis by day of treatment initiation, clinical and virological outcomes (except stool samples) were superior in patients admitted less than 7 days after symptom onset for the 52 patients who received a least one interferon dose plus lopinavir/ritonavir and ribavirin, compared with 24 patients randomized to the control arm (lopinavir/ritonavir only). In contrast, among patients admitted and started on treatment at day 7 or later after symptom onset, there were no differences between those who received lopinavir/ritonavir alone or combined with ribavirin.

Adverse events were reported in 41 of 86 patients in the combination group and 20 of 41 patients in the control arm. The most common adverse events were diarrhea, occurring in 52 of all 127 patients, fever in 48, nausea in 43, and elevated alanine transaminase level in 18. The side effects generally resolved within 3 days of the start of treatments.

There were no serious adverse events reported in the combination group. One patient in the control group had impaired hepatic enzymes requiring discontinuation of treatment. No patients died during the study.

The study was funded by the Shaw Foundation, Richard and Carol Yu, May Tam Mak Mei Yin, and Sanming Project of Medicine. The authors and Dr. Medoff declared no competing interests.

SOURCE: Hung IFN et al. Lancet. 2020 May 8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31101-6.

A triple-antiviral therapy regimen of interferon-beta1, lopinavir/ritonavir, and ribavirin shortened median time to COVID-19 viral negativity by 5 days in a small trial from Hong Kong.

In an open-label, randomized phase 2 trial in patients with mild or moderate COVID-19 infections, the median time to viral negativity by nasopharyngeal swab was 7 days for 86 patients assigned to receive a 14-day course of lopinavir 400 mg and ritonavir 100 mg every 12 hours, ribavirin 400 mg every 12 hours, and three doses of 8 million international units of interferon beta-1b on alternate days, compared with a median time to negativity of 12 days for patients treated with lopinavir/ritonavir alone (P = .0010), wrote Ivan Fan-Ngai Hung, MD, from Gleaneagles Hospital in Hong Kong, and colleagues.

“Triple-antiviral therapy with interferon beta-1b, lopinavir/ritonavir, and ribavirin were safe and superior to lopinavir/ritonavir alone in shortening virus shedding, alleviating symptoms, and facilitating discharge of patients with mild to moderate COVID-19,” they wrote in a study published online in The Lancet.

Patients who received the combination also had significantly shorter time to complete alleviation of symptoms as assessed by a National Early Warning Score 2 (NEWS2, a system for detecting clinical deterioration in patients with acute illnesses) score of 0 (4 vs. 8 days, respectively; hazard ratio 3.92, P < .0001), and to a Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score of 0 (3 vs. 8 days, HR 1.89, P = .041).

The median hospital stay was 9 days for patients treated with the combination, compared with 14.5 days for controls (HR 2.72, P = .016).

In most patients treated with the combination, SARS-CoV-2 viral load was effectively suppressed in all clinical specimens, including nasopharyngeal swabs, throat and posterior oropharyngeal saliva, and stool.

In addition, serum levels of interleukin 6 (IL-6) – an inflammatory cytokine implicated in the cytokine storm frequently seen in patients with severe COVID-19 infections – were significantly lower on treatment days 2, 6, and 8 in patients treated with the combination, compared with those treated with lopinavir/ritonavir alone.

“Our trial demonstrates that early treatment of mild to moderate COVID-19 with a triple combination of antiviral drugs may rapidly suppress the amount of virus in a patient’s body, relieve symptoms, and reduce the risk to health care workers by reducing the duration and quantity of viral shedding (when the virus is detectable and potentially transmissible). Furthermore, the treatment combination appeared safe and well tolerated by patients,” said lead investigator Professor Kwok-Yung Yuen from the University of Hong Kong, in a statement.

“Despite these encouraging findings,” he continued, “we must confirm in larger phase 3 trials that interferon beta-1b alone or in combination with other drugs is effective in patients with more severe illness (in whom the virus has had more time to replicate).”

Plausible rationale

Benjamin Medoff, MD, chief of the division of pulmonary and critical care medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview that the biologic rationale for the combination is plausible.

“I think this is a promising study that suggests that a regimen of interferon beta-1b, lopinavir/ritonavir, and ribavirin can shorten the duration of infection and improve symptoms in COVID-19 patients especially if started early in disease, in less than 7 days of symptom onset,” he said in reply to a request for expert analysis.

“The open-label nature and small size of the study limits the broad use of the regimen as noted by the authors, and it’s important to emphasize that the subjects enrolled did not have very severe disease (not in the ICU). However, the study does suggest that a larger truly randomized study is warranted,” he said.

AIDS drugs repurposed

Lopinavir/ritonavir is commonly used to treat HIV/AIDS throughout the world, and the investigators had previously reported that the antiviral agents combined with ribavirin reduced deaths and the need for intensive ventilator support among patients with SARS-CoV, the betacoronavirus that causes severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), and antivirals have shown in vitro activity against both SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, the closely related pathogen that causes Middle East respiratory syndrome.

“ However the viral load of SARS and MERS peaks at around day 7-10 after symptom onset, whereas the viral load of COVID-19 peaks at the time of presentation, similar to influenza. Experience from the treatment of patients with influenza who are admitted to hospital suggested that a combination of multiple antiviral drugs is more effective than single-drug treatments in this setting of patients with a high viral load at presentation,” the investigators wrote.

To test this, they enrolled adults patients admitted to one of six Hong Kong Hospitals for virologically confirmed COVID-19 infections from Feb. 10 through March 20, 2020.

A total of 86 patients were randomly assigned to the combination and 41 to lopinavir/ritonavir alone as controls, at doses described above.

Patients who entered the trial within less than 7 days of symptom onset received the triple combination, with interferon dosing adjusted according to the day that treatment started. Patients recruited 1 or 2 days after symptom onset received three doses of interferon, patients started on day 3 or 4 received two doses, and those started on days 5 or 6 received one interferon dose. Patients recruited 7 days or later from symptom onset did not receive interferon beta-1b because of its proinflammatory effects.

In post-hoc analysis by day of treatment initiation, clinical and virological outcomes (except stool samples) were superior in patients admitted less than 7 days after symptom onset for the 52 patients who received a least one interferon dose plus lopinavir/ritonavir and ribavirin, compared with 24 patients randomized to the control arm (lopinavir/ritonavir only). In contrast, among patients admitted and started on treatment at day 7 or later after symptom onset, there were no differences between those who received lopinavir/ritonavir alone or combined with ribavirin.

Adverse events were reported in 41 of 86 patients in the combination group and 20 of 41 patients in the control arm. The most common adverse events were diarrhea, occurring in 52 of all 127 patients, fever in 48, nausea in 43, and elevated alanine transaminase level in 18. The side effects generally resolved within 3 days of the start of treatments.

There were no serious adverse events reported in the combination group. One patient in the control group had impaired hepatic enzymes requiring discontinuation of treatment. No patients died during the study.

The study was funded by the Shaw Foundation, Richard and Carol Yu, May Tam Mak Mei Yin, and Sanming Project of Medicine. The authors and Dr. Medoff declared no competing interests.

SOURCE: Hung IFN et al. Lancet. 2020 May 8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31101-6.

A triple-antiviral therapy regimen of interferon-beta1, lopinavir/ritonavir, and ribavirin shortened median time to COVID-19 viral negativity by 5 days in a small trial from Hong Kong.

In an open-label, randomized phase 2 trial in patients with mild or moderate COVID-19 infections, the median time to viral negativity by nasopharyngeal swab was 7 days for 86 patients assigned to receive a 14-day course of lopinavir 400 mg and ritonavir 100 mg every 12 hours, ribavirin 400 mg every 12 hours, and three doses of 8 million international units of interferon beta-1b on alternate days, compared with a median time to negativity of 12 days for patients treated with lopinavir/ritonavir alone (P = .0010), wrote Ivan Fan-Ngai Hung, MD, from Gleaneagles Hospital in Hong Kong, and colleagues.

“Triple-antiviral therapy with interferon beta-1b, lopinavir/ritonavir, and ribavirin were safe and superior to lopinavir/ritonavir alone in shortening virus shedding, alleviating symptoms, and facilitating discharge of patients with mild to moderate COVID-19,” they wrote in a study published online in The Lancet.

Patients who received the combination also had significantly shorter time to complete alleviation of symptoms as assessed by a National Early Warning Score 2 (NEWS2, a system for detecting clinical deterioration in patients with acute illnesses) score of 0 (4 vs. 8 days, respectively; hazard ratio 3.92, P < .0001), and to a Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score of 0 (3 vs. 8 days, HR 1.89, P = .041).

The median hospital stay was 9 days for patients treated with the combination, compared with 14.5 days for controls (HR 2.72, P = .016).

In most patients treated with the combination, SARS-CoV-2 viral load was effectively suppressed in all clinical specimens, including nasopharyngeal swabs, throat and posterior oropharyngeal saliva, and stool.

In addition, serum levels of interleukin 6 (IL-6) – an inflammatory cytokine implicated in the cytokine storm frequently seen in patients with severe COVID-19 infections – were significantly lower on treatment days 2, 6, and 8 in patients treated with the combination, compared with those treated with lopinavir/ritonavir alone.

“Our trial demonstrates that early treatment of mild to moderate COVID-19 with a triple combination of antiviral drugs may rapidly suppress the amount of virus in a patient’s body, relieve symptoms, and reduce the risk to health care workers by reducing the duration and quantity of viral shedding (when the virus is detectable and potentially transmissible). Furthermore, the treatment combination appeared safe and well tolerated by patients,” said lead investigator Professor Kwok-Yung Yuen from the University of Hong Kong, in a statement.

“Despite these encouraging findings,” he continued, “we must confirm in larger phase 3 trials that interferon beta-1b alone or in combination with other drugs is effective in patients with more severe illness (in whom the virus has had more time to replicate).”

Plausible rationale

Benjamin Medoff, MD, chief of the division of pulmonary and critical care medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview that the biologic rationale for the combination is plausible.

“I think this is a promising study that suggests that a regimen of interferon beta-1b, lopinavir/ritonavir, and ribavirin can shorten the duration of infection and improve symptoms in COVID-19 patients especially if started early in disease, in less than 7 days of symptom onset,” he said in reply to a request for expert analysis.

“The open-label nature and small size of the study limits the broad use of the regimen as noted by the authors, and it’s important to emphasize that the subjects enrolled did not have very severe disease (not in the ICU). However, the study does suggest that a larger truly randomized study is warranted,” he said.

AIDS drugs repurposed

Lopinavir/ritonavir is commonly used to treat HIV/AIDS throughout the world, and the investigators had previously reported that the antiviral agents combined with ribavirin reduced deaths and the need for intensive ventilator support among patients with SARS-CoV, the betacoronavirus that causes severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), and antivirals have shown in vitro activity against both SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, the closely related pathogen that causes Middle East respiratory syndrome.

“ However the viral load of SARS and MERS peaks at around day 7-10 after symptom onset, whereas the viral load of COVID-19 peaks at the time of presentation, similar to influenza. Experience from the treatment of patients with influenza who are admitted to hospital suggested that a combination of multiple antiviral drugs is more effective than single-drug treatments in this setting of patients with a high viral load at presentation,” the investigators wrote.

To test this, they enrolled adults patients admitted to one of six Hong Kong Hospitals for virologically confirmed COVID-19 infections from Feb. 10 through March 20, 2020.

A total of 86 patients were randomly assigned to the combination and 41 to lopinavir/ritonavir alone as controls, at doses described above.

Patients who entered the trial within less than 7 days of symptom onset received the triple combination, with interferon dosing adjusted according to the day that treatment started. Patients recruited 1 or 2 days after symptom onset received three doses of interferon, patients started on day 3 or 4 received two doses, and those started on days 5 or 6 received one interferon dose. Patients recruited 7 days or later from symptom onset did not receive interferon beta-1b because of its proinflammatory effects.

In post-hoc analysis by day of treatment initiation, clinical and virological outcomes (except stool samples) were superior in patients admitted less than 7 days after symptom onset for the 52 patients who received a least one interferon dose plus lopinavir/ritonavir and ribavirin, compared with 24 patients randomized to the control arm (lopinavir/ritonavir only). In contrast, among patients admitted and started on treatment at day 7 or later after symptom onset, there were no differences between those who received lopinavir/ritonavir alone or combined with ribavirin.

Adverse events were reported in 41 of 86 patients in the combination group and 20 of 41 patients in the control arm. The most common adverse events were diarrhea, occurring in 52 of all 127 patients, fever in 48, nausea in 43, and elevated alanine transaminase level in 18. The side effects generally resolved within 3 days of the start of treatments.

There were no serious adverse events reported in the combination group. One patient in the control group had impaired hepatic enzymes requiring discontinuation of treatment. No patients died during the study.

The study was funded by the Shaw Foundation, Richard and Carol Yu, May Tam Mak Mei Yin, and Sanming Project of Medicine. The authors and Dr. Medoff declared no competing interests.

SOURCE: Hung IFN et al. Lancet. 2020 May 8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31101-6.

FROM THE LANCET

Sun-damage selfies give kids motivation to protect skin

Photo-manipulated selfies can provide adolescents an influential window into the wrinkled, sun-damaged future that may be theirs if they’re not careful, a new study suggests.

In the study, researchers found that Brazilian teenagers, especially girls, were more likely to protect themselves from the sun if they got glimpses of how sun exposure could damage their faces. “The intervention used in this study was effective in convincing a substantial part of the students to take up regular sunscreen use and to examine their own skin regularly,” they wrote. “Moreover, these effects were maintained for at least half a year.”

The study, led by Titus J. Brinker, MD, of the department of dermatology, in the National Center for Tumor Diseases, German Cancer Research Center in Heidelberg, Germany, appeared online on May 6 in JAMA Dermatology (2020 May 6. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0511.

Dr. Brinker and colleagues launched the study in 2018 at eight public schools that serve grades 9-12 in Itaúna, a city in southeast Brazil, randomly assigning 1,573 students (52% girls, 48% boys; mean age, 16 years) to the intervention or control group.

Those in the intervention group attended seminars in which medical students showed them selfies of their classmates altered with a mobile phone app called Sunface, developed by Dr. Brinker.

The app, which takes the skin types of the subjects into account, was described by the Vice news site as “terrifying” in a 2018 article. It “could very well scare you into using sunscreen and wearing hats,” the author of that article wrote.

The app appeared to do just that – but not universally, according to the new study.

At 6 months, there was no change in sun protection habits in the control group. But among those remaining in the intervention group, the use of daily sunscreen significantly increased from 15% (110 of 734 students) during the 30 days prior to the survey, to 23% (139 of 607 students) at the 6-month follow-up (P less than .001), as did the percentage of those who performed at least one skin self-examination within the 6 months (25% to 49%; P less than .001). The students were slightly less likely to use tanning beds within the previous month (19% to 15%; P = .04); the researchers speculate that it’s easier to gain a new healthy habit than get rid of an old unhealthy one.

Girls were much more likely to change their habits than boys. The number needed to treat to reach the primary endpoint, daily sunscreen use, was 8 for girls and 31 for boys.

The researchers noted that the dropout rate was higher in the intervention group (17%) vs. the control group (6%). “The intervention may have led to strong adverse reactions in some students, leading to the observed higher dropout rate in the intervention group,” they wrote. Changes to the way the app is used could improve the dropout rate, but potentially hurt the intervention’s impact, they added.

In an accompanying editorial in JAMA Dermatology, two health intervention researchers wrote that “this work represents a needed shift toward scalable interventions that bring messaging to target populations using their preferred technology” (2020 May 6. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0510).

Referring to the finding that sunscreen use did not change much among the boys in the study, the authors, Sherry L. Pagoto, PhD, of the Institute for Collaborations on Health, Interventions, and Policy at the University of Connecticut, Storrs, and Alan C. Geller, MPH, RN, of the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, also noted that “teen boys have been largely resistant to traditional and nontraditional forms of sun safety education.”

“Teasing out sex differences is important,” they added, “because sun protection interventions woven into existing programs at pools, beaches, and sporting events might be more appealing and enduring for boys, particularly if the technology they regularly use is leveraged.”

Dr. Brinker disclosed receiving an award from La Fondation la Roche-Posay, which also provided support for the study which partially funded the study, for his research on the Sunface app. The University of Itaúna provided other study funding. Several other study authors had various disclosures. Dr. Pagoto disclosed consulting work and personal fees from Johnson & Johnson, unrelated to the topic of the commentary; Dr. Geller had no disclosures.

SOURCES: Brinker TJ et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 May 6. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0511; Pagoto SL and Geller AC. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 May 6. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0510.

Photo-manipulated selfies can provide adolescents an influential window into the wrinkled, sun-damaged future that may be theirs if they’re not careful, a new study suggests.

In the study, researchers found that Brazilian teenagers, especially girls, were more likely to protect themselves from the sun if they got glimpses of how sun exposure could damage their faces. “The intervention used in this study was effective in convincing a substantial part of the students to take up regular sunscreen use and to examine their own skin regularly,” they wrote. “Moreover, these effects were maintained for at least half a year.”

The study, led by Titus J. Brinker, MD, of the department of dermatology, in the National Center for Tumor Diseases, German Cancer Research Center in Heidelberg, Germany, appeared online on May 6 in JAMA Dermatology (2020 May 6. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0511.

Dr. Brinker and colleagues launched the study in 2018 at eight public schools that serve grades 9-12 in Itaúna, a city in southeast Brazil, randomly assigning 1,573 students (52% girls, 48% boys; mean age, 16 years) to the intervention or control group.

Those in the intervention group attended seminars in which medical students showed them selfies of their classmates altered with a mobile phone app called Sunface, developed by Dr. Brinker.

The app, which takes the skin types of the subjects into account, was described by the Vice news site as “terrifying” in a 2018 article. It “could very well scare you into using sunscreen and wearing hats,” the author of that article wrote.

The app appeared to do just that – but not universally, according to the new study.

At 6 months, there was no change in sun protection habits in the control group. But among those remaining in the intervention group, the use of daily sunscreen significantly increased from 15% (110 of 734 students) during the 30 days prior to the survey, to 23% (139 of 607 students) at the 6-month follow-up (P less than .001), as did the percentage of those who performed at least one skin self-examination within the 6 months (25% to 49%; P less than .001). The students were slightly less likely to use tanning beds within the previous month (19% to 15%; P = .04); the researchers speculate that it’s easier to gain a new healthy habit than get rid of an old unhealthy one.

Girls were much more likely to change their habits than boys. The number needed to treat to reach the primary endpoint, daily sunscreen use, was 8 for girls and 31 for boys.

The researchers noted that the dropout rate was higher in the intervention group (17%) vs. the control group (6%). “The intervention may have led to strong adverse reactions in some students, leading to the observed higher dropout rate in the intervention group,” they wrote. Changes to the way the app is used could improve the dropout rate, but potentially hurt the intervention’s impact, they added.

In an accompanying editorial in JAMA Dermatology, two health intervention researchers wrote that “this work represents a needed shift toward scalable interventions that bring messaging to target populations using their preferred technology” (2020 May 6. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0510).

Referring to the finding that sunscreen use did not change much among the boys in the study, the authors, Sherry L. Pagoto, PhD, of the Institute for Collaborations on Health, Interventions, and Policy at the University of Connecticut, Storrs, and Alan C. Geller, MPH, RN, of the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, also noted that “teen boys have been largely resistant to traditional and nontraditional forms of sun safety education.”

“Teasing out sex differences is important,” they added, “because sun protection interventions woven into existing programs at pools, beaches, and sporting events might be more appealing and enduring for boys, particularly if the technology they regularly use is leveraged.”

Dr. Brinker disclosed receiving an award from La Fondation la Roche-Posay, which also provided support for the study which partially funded the study, for his research on the Sunface app. The University of Itaúna provided other study funding. Several other study authors had various disclosures. Dr. Pagoto disclosed consulting work and personal fees from Johnson & Johnson, unrelated to the topic of the commentary; Dr. Geller had no disclosures.

SOURCES: Brinker TJ et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 May 6. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0511; Pagoto SL and Geller AC. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 May 6. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0510.

Photo-manipulated selfies can provide adolescents an influential window into the wrinkled, sun-damaged future that may be theirs if they’re not careful, a new study suggests.

In the study, researchers found that Brazilian teenagers, especially girls, were more likely to protect themselves from the sun if they got glimpses of how sun exposure could damage their faces. “The intervention used in this study was effective in convincing a substantial part of the students to take up regular sunscreen use and to examine their own skin regularly,” they wrote. “Moreover, these effects were maintained for at least half a year.”

The study, led by Titus J. Brinker, MD, of the department of dermatology, in the National Center for Tumor Diseases, German Cancer Research Center in Heidelberg, Germany, appeared online on May 6 in JAMA Dermatology (2020 May 6. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0511.

Dr. Brinker and colleagues launched the study in 2018 at eight public schools that serve grades 9-12 in Itaúna, a city in southeast Brazil, randomly assigning 1,573 students (52% girls, 48% boys; mean age, 16 years) to the intervention or control group.

Those in the intervention group attended seminars in which medical students showed them selfies of their classmates altered with a mobile phone app called Sunface, developed by Dr. Brinker.

The app, which takes the skin types of the subjects into account, was described by the Vice news site as “terrifying” in a 2018 article. It “could very well scare you into using sunscreen and wearing hats,” the author of that article wrote.

The app appeared to do just that – but not universally, according to the new study.

At 6 months, there was no change in sun protection habits in the control group. But among those remaining in the intervention group, the use of daily sunscreen significantly increased from 15% (110 of 734 students) during the 30 days prior to the survey, to 23% (139 of 607 students) at the 6-month follow-up (P less than .001), as did the percentage of those who performed at least one skin self-examination within the 6 months (25% to 49%; P less than .001). The students were slightly less likely to use tanning beds within the previous month (19% to 15%; P = .04); the researchers speculate that it’s easier to gain a new healthy habit than get rid of an old unhealthy one.

Girls were much more likely to change their habits than boys. The number needed to treat to reach the primary endpoint, daily sunscreen use, was 8 for girls and 31 for boys.

The researchers noted that the dropout rate was higher in the intervention group (17%) vs. the control group (6%). “The intervention may have led to strong adverse reactions in some students, leading to the observed higher dropout rate in the intervention group,” they wrote. Changes to the way the app is used could improve the dropout rate, but potentially hurt the intervention’s impact, they added.

In an accompanying editorial in JAMA Dermatology, two health intervention researchers wrote that “this work represents a needed shift toward scalable interventions that bring messaging to target populations using their preferred technology” (2020 May 6. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0510).

Referring to the finding that sunscreen use did not change much among the boys in the study, the authors, Sherry L. Pagoto, PhD, of the Institute for Collaborations on Health, Interventions, and Policy at the University of Connecticut, Storrs, and Alan C. Geller, MPH, RN, of the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, also noted that “teen boys have been largely resistant to traditional and nontraditional forms of sun safety education.”

“Teasing out sex differences is important,” they added, “because sun protection interventions woven into existing programs at pools, beaches, and sporting events might be more appealing and enduring for boys, particularly if the technology they regularly use is leveraged.”

Dr. Brinker disclosed receiving an award from La Fondation la Roche-Posay, which also provided support for the study which partially funded the study, for his research on the Sunface app. The University of Itaúna provided other study funding. Several other study authors had various disclosures. Dr. Pagoto disclosed consulting work and personal fees from Johnson & Johnson, unrelated to the topic of the commentary; Dr. Geller had no disclosures.

SOURCES: Brinker TJ et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 May 6. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0511; Pagoto SL and Geller AC. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 May 6. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0510.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

ASCO goes ahead online, as conference center is used as hospital

Traditionally at this time of year, everyone working in cancer turns their attention toward Chicago, and 40,000 or so travel to the city for the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

Not this year.

The McCormick Place convention center has been converted to a field hospital to cope with the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The cavernous meeting halls have been filled with makeshift wards with 750 acute care beds, as shown in a tweet from Toni Choueiri, MD, chief of genitourinary oncology at the Dana Farber Cancer Center in Boston.

But the annual meeting is still going ahead, having been transferred online.

“We have to remember that even though there’s a pandemic going on and people are dying every day from coronavirus, people are still dying every day from cancer,” Richard Schilsky, MD, PhD, chief medical officer at ASCO, told Medscape Medical News.

“This pandemic will end, but cancer will continue, and we need to be able to continue to get the most cutting edge scientific results out there to our members and our constituents so they can act on those results on behalf of their patients,” he said.

The ASCO Virtual Scientific Program will take place over the weekend of May 30-31.

“We’re certainly hoping that we’re going to deliver a program that features all of the most important science that would have been presented in person in Chicago,” Schilsky commented in an interview.

Most of the presentations will be prerecorded and then streamed, which “we hope will mitigate any of the technical glitches that could come from trying to do a live broadcast of the meeting,” he said.

There will be 250 oral and 2500 poster presentations in 24 disease-based and specialty tracks.

The majority of the abstracts will be released online on May 13. The majority of the on-demand content will be released on May 29. Some of the abstracts will be highlighted at ASCO press briefings and released on those two dates.