User login

Screen all adults for hepatitis C, says USPSTF

Adults aged 18-79 years should be screened for hepatitis C virus infection, according to an updated grade B recommendation from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

Cases of acute hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection have spiked in the last decade, in part because of increased use of injection drugs and in part because of better surveillance, Douglas K. Owens, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, and colleagues wrote in the recommendation statement published in JAMA.

The recommendation applies to all asymptomatic adults aged 18-79 years without known liver disease, and expands on the 2013 recommendation to screen adults born between 1945 and 1965. The grade B designation means that the task force concluded with moderate certainty that HCV screening for adults aged 18-79 years had “substantial net benefit.”

The recommendations are based on an evidence report including 8 randomized, controlled trials, 48 other treatment studies, and 33 cohort studies published through February 2019 for a total of 179,230 individuals.

The screening is a one-time procedure for most adults, according to the task force, but clinicians should periodically screen individuals at increased risk, such as those with a past or current history of injection drug use. In addition, clinicians should consider screening individuals at increased risk who are above or below the recommended age range.

Although the task force identified no direct evidence on the benefit of screening for HCV infection in asymptomatic adults, a notable finding was that the newer direct-acting antiviral (DAA) regimens are sufficiently effective to support the expanded screening recommendation, they said. However, clinicians should inform patients that screening is voluntary and conducted only with the patient’s knowledge. Clinicians should educate patients about hepatitis C and give them an opportunity to ask questions and to make a decision about screening, according to the task force.

In the evidence report, a total of 49 studies including 10,181 individuals showed DAA treatment associated with pooled sustained virologic response rates greater than 95% across all virus genotypes, and a short-term serious adverse event rate of 1.9%. In addition, sustained virologic response following an antiviral therapy was associated with a reduction in risk of all-cause mortality (pooled hazard ratio 0.40) and of hepatocellular carcinoma (pooled HR 0.29) compared with cases of no sustained virologic response.

The evidence report findings were limited by several factors, including the relatively small number of randomized trials involving current DAA treatments, limited data on baseline symptoms, limited data on adolescents, and limited evidence on potential long-term harms of DAA therapy, noted Richard Chou, MD, of Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, and colleagues. However, new pooled evidence “indicates that SVR rates with currently recommended all-oral DAA regimens are substantially higher (more than 95%) than with interferon-based therapies evaluated in the prior review (68%-78%),” they said.

Several editorials were published concurrently with the recommendation.

In an editorial published in JAMA, Camilla S. Graham, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and Stacey Trooskin, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, wrote that the new recommendation reflects changes in hepatitis C virus management.

“With the approvals of sofosbuvir and simeprevir in 2013, patients with hepatitis C, a chronic viral illness associated with the deaths of more U.S. patients than the next 60 reportable infectious diseases combined, including HIV and tuberculosis, could expect a greater than 90% rate of achieving sustained virologic response (SVR, defined as undetectable HCV levels 12 weeks or longer after treatment completion, which is consistent with virologic cure of HCV infection) following 12 weeks of treatment,” they said.

These medications are effective but expensive; however, the combination of the availability of generic medications and the ongoing opioid epidemic in the United States are important contributors to the expanded recommendations, which “are welcome,” and may help meeting WHO 2030 targets for reducing new HCV infections, they said.

Dr. Graham disclosed personal fees from UpToDate. Dr. Trooskin disclosed grants from Gilead Sciences and personal fees from Merck, AbbVie, and Gilead Sciences.

In an editorial published in JAMA Internal Medicine, Jennifer C. Price, MD, and Danielle Brandman, MD, both of the University of California, San Francisco, wrote that “the advancements in HCV diagnosis and treatment have been extraordinary,” but that the new recommendation does not go far enough. “Implementation of HCV screening and linkage to treatment requires large-scale coordinated efforts, innovation, and resources. For example, point-of-care HCV RNA testing would enable scale-up of HCV screening and confirmatory testing among individuals at greatest risk of HCV infection,” they said. “Additionally, barriers remain between diagnosis and treatment, such as access to a health care provider who can treat HCV and authorization to receive affordable DAAs,” they noted. “Although the USPSTF HCV screening recommendation is a step forward for controlling HCV infection in the U.S., it will take a coordinated and funded effort to ensure that the anticipated benefits are realized,” they concluded.

Dr. Price disclosed research funding from Gilead Sciences and Merck. Dr. Brandman disclosed research funding from Gilead Sciences, Pfizer, Conatus, Allergan, and Grifols, as well as personal fees from Alnylam.

In an editorial published in JAMA Network Open, Eli S. Rosenberg, PhD, of the University at Albany (N.Y.) School of Public Health, and Joshua A. Barocas, MD, of Boston University, emphasized the need to change the stigma surrounding HCV infection in the United States.

“Given the changing epidemiology of HCV infection, new public health priorities, advancements in treatment, and unmet diagnostic needs, it is wise to periodically reevaluate screening recommendations to ensure that they are maximally addressing these areas and patients’ individual needs,” they said. “The Affordable Care Act requires private insurers and Medicaid to cover preventive services recommended by the USPSTF with a grade of A or B with no cost sharing (i.e., no deductible or copayment),” they noted. Although the new recommendation for one-time screening will likely identify more cases, improve outcomes, and reduce deaths, the editorialists cautioned that “one-time screening should not be interpreted like catch-up vaccinations, whereby we immunize someone at any age for hepatitis B virus, for example, and they are then immunized for the remainder of their life,” and that reassessments are needed, especially for younger adults.

In addition, they emphasized the need to reduce the stigma surrounding HCV and allow for recommendations based on risk, rather than age. “We have forced the USPSTF to adopt age-based screening recommendations because we, as a society, have created a culture in which we have stigmatized these behaviors and we, as practitioners, have proven to be inadequate at eliciting HCV risk behaviors,” they said. “Our responsibility as a society and practice community is to address structural and individual factors that limit our ability to most precisely address the needs of our patients and truly move toward HCV elimination,” they concluded.

The USPSTF is supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The task force researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCES: Owens DK et al. JAMA. 2020 Mar 2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1123; Chou R et al. JAMA. 2020 Mar 2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.20788; Graham CS, Trooskin S. JAMA. 2020 Mar 2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.22313; Price JC and Brandman D. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 Mar 2. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.7334; Rosenberg ES, Barocas JA. JAMA Network Open. 2020 Mar 2. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.0538.

Use AGA patient education to help your patients better understand HCV, including their risk and treatment options, at https://www.gastro.org/

Adults aged 18-79 years should be screened for hepatitis C virus infection, according to an updated grade B recommendation from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

Cases of acute hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection have spiked in the last decade, in part because of increased use of injection drugs and in part because of better surveillance, Douglas K. Owens, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, and colleagues wrote in the recommendation statement published in JAMA.

The recommendation applies to all asymptomatic adults aged 18-79 years without known liver disease, and expands on the 2013 recommendation to screen adults born between 1945 and 1965. The grade B designation means that the task force concluded with moderate certainty that HCV screening for adults aged 18-79 years had “substantial net benefit.”

The recommendations are based on an evidence report including 8 randomized, controlled trials, 48 other treatment studies, and 33 cohort studies published through February 2019 for a total of 179,230 individuals.

The screening is a one-time procedure for most adults, according to the task force, but clinicians should periodically screen individuals at increased risk, such as those with a past or current history of injection drug use. In addition, clinicians should consider screening individuals at increased risk who are above or below the recommended age range.

Although the task force identified no direct evidence on the benefit of screening for HCV infection in asymptomatic adults, a notable finding was that the newer direct-acting antiviral (DAA) regimens are sufficiently effective to support the expanded screening recommendation, they said. However, clinicians should inform patients that screening is voluntary and conducted only with the patient’s knowledge. Clinicians should educate patients about hepatitis C and give them an opportunity to ask questions and to make a decision about screening, according to the task force.

In the evidence report, a total of 49 studies including 10,181 individuals showed DAA treatment associated with pooled sustained virologic response rates greater than 95% across all virus genotypes, and a short-term serious adverse event rate of 1.9%. In addition, sustained virologic response following an antiviral therapy was associated with a reduction in risk of all-cause mortality (pooled hazard ratio 0.40) and of hepatocellular carcinoma (pooled HR 0.29) compared with cases of no sustained virologic response.

The evidence report findings were limited by several factors, including the relatively small number of randomized trials involving current DAA treatments, limited data on baseline symptoms, limited data on adolescents, and limited evidence on potential long-term harms of DAA therapy, noted Richard Chou, MD, of Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, and colleagues. However, new pooled evidence “indicates that SVR rates with currently recommended all-oral DAA regimens are substantially higher (more than 95%) than with interferon-based therapies evaluated in the prior review (68%-78%),” they said.

Several editorials were published concurrently with the recommendation.

In an editorial published in JAMA, Camilla S. Graham, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and Stacey Trooskin, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, wrote that the new recommendation reflects changes in hepatitis C virus management.

“With the approvals of sofosbuvir and simeprevir in 2013, patients with hepatitis C, a chronic viral illness associated with the deaths of more U.S. patients than the next 60 reportable infectious diseases combined, including HIV and tuberculosis, could expect a greater than 90% rate of achieving sustained virologic response (SVR, defined as undetectable HCV levels 12 weeks or longer after treatment completion, which is consistent with virologic cure of HCV infection) following 12 weeks of treatment,” they said.

These medications are effective but expensive; however, the combination of the availability of generic medications and the ongoing opioid epidemic in the United States are important contributors to the expanded recommendations, which “are welcome,” and may help meeting WHO 2030 targets for reducing new HCV infections, they said.

Dr. Graham disclosed personal fees from UpToDate. Dr. Trooskin disclosed grants from Gilead Sciences and personal fees from Merck, AbbVie, and Gilead Sciences.

In an editorial published in JAMA Internal Medicine, Jennifer C. Price, MD, and Danielle Brandman, MD, both of the University of California, San Francisco, wrote that “the advancements in HCV diagnosis and treatment have been extraordinary,” but that the new recommendation does not go far enough. “Implementation of HCV screening and linkage to treatment requires large-scale coordinated efforts, innovation, and resources. For example, point-of-care HCV RNA testing would enable scale-up of HCV screening and confirmatory testing among individuals at greatest risk of HCV infection,” they said. “Additionally, barriers remain between diagnosis and treatment, such as access to a health care provider who can treat HCV and authorization to receive affordable DAAs,” they noted. “Although the USPSTF HCV screening recommendation is a step forward for controlling HCV infection in the U.S., it will take a coordinated and funded effort to ensure that the anticipated benefits are realized,” they concluded.

Dr. Price disclosed research funding from Gilead Sciences and Merck. Dr. Brandman disclosed research funding from Gilead Sciences, Pfizer, Conatus, Allergan, and Grifols, as well as personal fees from Alnylam.

In an editorial published in JAMA Network Open, Eli S. Rosenberg, PhD, of the University at Albany (N.Y.) School of Public Health, and Joshua A. Barocas, MD, of Boston University, emphasized the need to change the stigma surrounding HCV infection in the United States.

“Given the changing epidemiology of HCV infection, new public health priorities, advancements in treatment, and unmet diagnostic needs, it is wise to periodically reevaluate screening recommendations to ensure that they are maximally addressing these areas and patients’ individual needs,” they said. “The Affordable Care Act requires private insurers and Medicaid to cover preventive services recommended by the USPSTF with a grade of A or B with no cost sharing (i.e., no deductible or copayment),” they noted. Although the new recommendation for one-time screening will likely identify more cases, improve outcomes, and reduce deaths, the editorialists cautioned that “one-time screening should not be interpreted like catch-up vaccinations, whereby we immunize someone at any age for hepatitis B virus, for example, and they are then immunized for the remainder of their life,” and that reassessments are needed, especially for younger adults.

In addition, they emphasized the need to reduce the stigma surrounding HCV and allow for recommendations based on risk, rather than age. “We have forced the USPSTF to adopt age-based screening recommendations because we, as a society, have created a culture in which we have stigmatized these behaviors and we, as practitioners, have proven to be inadequate at eliciting HCV risk behaviors,” they said. “Our responsibility as a society and practice community is to address structural and individual factors that limit our ability to most precisely address the needs of our patients and truly move toward HCV elimination,” they concluded.

The USPSTF is supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The task force researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCES: Owens DK et al. JAMA. 2020 Mar 2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1123; Chou R et al. JAMA. 2020 Mar 2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.20788; Graham CS, Trooskin S. JAMA. 2020 Mar 2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.22313; Price JC and Brandman D. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 Mar 2. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.7334; Rosenberg ES, Barocas JA. JAMA Network Open. 2020 Mar 2. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.0538.

Use AGA patient education to help your patients better understand HCV, including their risk and treatment options, at https://www.gastro.org/

Adults aged 18-79 years should be screened for hepatitis C virus infection, according to an updated grade B recommendation from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

Cases of acute hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection have spiked in the last decade, in part because of increased use of injection drugs and in part because of better surveillance, Douglas K. Owens, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, and colleagues wrote in the recommendation statement published in JAMA.

The recommendation applies to all asymptomatic adults aged 18-79 years without known liver disease, and expands on the 2013 recommendation to screen adults born between 1945 and 1965. The grade B designation means that the task force concluded with moderate certainty that HCV screening for adults aged 18-79 years had “substantial net benefit.”

The recommendations are based on an evidence report including 8 randomized, controlled trials, 48 other treatment studies, and 33 cohort studies published through February 2019 for a total of 179,230 individuals.

The screening is a one-time procedure for most adults, according to the task force, but clinicians should periodically screen individuals at increased risk, such as those with a past or current history of injection drug use. In addition, clinicians should consider screening individuals at increased risk who are above or below the recommended age range.

Although the task force identified no direct evidence on the benefit of screening for HCV infection in asymptomatic adults, a notable finding was that the newer direct-acting antiviral (DAA) regimens are sufficiently effective to support the expanded screening recommendation, they said. However, clinicians should inform patients that screening is voluntary and conducted only with the patient’s knowledge. Clinicians should educate patients about hepatitis C and give them an opportunity to ask questions and to make a decision about screening, according to the task force.

In the evidence report, a total of 49 studies including 10,181 individuals showed DAA treatment associated with pooled sustained virologic response rates greater than 95% across all virus genotypes, and a short-term serious adverse event rate of 1.9%. In addition, sustained virologic response following an antiviral therapy was associated with a reduction in risk of all-cause mortality (pooled hazard ratio 0.40) and of hepatocellular carcinoma (pooled HR 0.29) compared with cases of no sustained virologic response.

The evidence report findings were limited by several factors, including the relatively small number of randomized trials involving current DAA treatments, limited data on baseline symptoms, limited data on adolescents, and limited evidence on potential long-term harms of DAA therapy, noted Richard Chou, MD, of Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, and colleagues. However, new pooled evidence “indicates that SVR rates with currently recommended all-oral DAA regimens are substantially higher (more than 95%) than with interferon-based therapies evaluated in the prior review (68%-78%),” they said.

Several editorials were published concurrently with the recommendation.

In an editorial published in JAMA, Camilla S. Graham, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and Stacey Trooskin, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, wrote that the new recommendation reflects changes in hepatitis C virus management.

“With the approvals of sofosbuvir and simeprevir in 2013, patients with hepatitis C, a chronic viral illness associated with the deaths of more U.S. patients than the next 60 reportable infectious diseases combined, including HIV and tuberculosis, could expect a greater than 90% rate of achieving sustained virologic response (SVR, defined as undetectable HCV levels 12 weeks or longer after treatment completion, which is consistent with virologic cure of HCV infection) following 12 weeks of treatment,” they said.

These medications are effective but expensive; however, the combination of the availability of generic medications and the ongoing opioid epidemic in the United States are important contributors to the expanded recommendations, which “are welcome,” and may help meeting WHO 2030 targets for reducing new HCV infections, they said.

Dr. Graham disclosed personal fees from UpToDate. Dr. Trooskin disclosed grants from Gilead Sciences and personal fees from Merck, AbbVie, and Gilead Sciences.

In an editorial published in JAMA Internal Medicine, Jennifer C. Price, MD, and Danielle Brandman, MD, both of the University of California, San Francisco, wrote that “the advancements in HCV diagnosis and treatment have been extraordinary,” but that the new recommendation does not go far enough. “Implementation of HCV screening and linkage to treatment requires large-scale coordinated efforts, innovation, and resources. For example, point-of-care HCV RNA testing would enable scale-up of HCV screening and confirmatory testing among individuals at greatest risk of HCV infection,” they said. “Additionally, barriers remain between diagnosis and treatment, such as access to a health care provider who can treat HCV and authorization to receive affordable DAAs,” they noted. “Although the USPSTF HCV screening recommendation is a step forward for controlling HCV infection in the U.S., it will take a coordinated and funded effort to ensure that the anticipated benefits are realized,” they concluded.

Dr. Price disclosed research funding from Gilead Sciences and Merck. Dr. Brandman disclosed research funding from Gilead Sciences, Pfizer, Conatus, Allergan, and Grifols, as well as personal fees from Alnylam.

In an editorial published in JAMA Network Open, Eli S. Rosenberg, PhD, of the University at Albany (N.Y.) School of Public Health, and Joshua A. Barocas, MD, of Boston University, emphasized the need to change the stigma surrounding HCV infection in the United States.

“Given the changing epidemiology of HCV infection, new public health priorities, advancements in treatment, and unmet diagnostic needs, it is wise to periodically reevaluate screening recommendations to ensure that they are maximally addressing these areas and patients’ individual needs,” they said. “The Affordable Care Act requires private insurers and Medicaid to cover preventive services recommended by the USPSTF with a grade of A or B with no cost sharing (i.e., no deductible or copayment),” they noted. Although the new recommendation for one-time screening will likely identify more cases, improve outcomes, and reduce deaths, the editorialists cautioned that “one-time screening should not be interpreted like catch-up vaccinations, whereby we immunize someone at any age for hepatitis B virus, for example, and they are then immunized for the remainder of their life,” and that reassessments are needed, especially for younger adults.

In addition, they emphasized the need to reduce the stigma surrounding HCV and allow for recommendations based on risk, rather than age. “We have forced the USPSTF to adopt age-based screening recommendations because we, as a society, have created a culture in which we have stigmatized these behaviors and we, as practitioners, have proven to be inadequate at eliciting HCV risk behaviors,” they said. “Our responsibility as a society and practice community is to address structural and individual factors that limit our ability to most precisely address the needs of our patients and truly move toward HCV elimination,” they concluded.

The USPSTF is supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The task force researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCES: Owens DK et al. JAMA. 2020 Mar 2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1123; Chou R et al. JAMA. 2020 Mar 2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.20788; Graham CS, Trooskin S. JAMA. 2020 Mar 2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.22313; Price JC and Brandman D. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 Mar 2. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.7334; Rosenberg ES, Barocas JA. JAMA Network Open. 2020 Mar 2. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.0538.

Use AGA patient education to help your patients better understand HCV, including their risk and treatment options, at https://www.gastro.org/

FROM JAMA

Upcoming vaccine may offset surge in polio subtypes

Although wild poliovirus type 3 has not been detected globally for 7 years, the number of wild type 1 cases increased from 33 in 2018 to 173 in 2019. In response, a modified oral vaccine is being developed, according to Stephen Cochi, MD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Center for Global Health.

Several factors, including a Taliban ban on house-to-house vaccination in Afghanistan and a delay of large-scale vaccinations in Pakistan contributed to the surge in polio infections, Dr. Cochi said in a presentation at the February meeting of the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).

In addition, circulating vaccine-derived polioviruses (cVDPV) outbreaks have occurred in multiple countries including sub-Saharan Africa, China, Pakistan, and the Philippines. These outbreaks threaten the success of the bivalent oral polio vaccine introduced in April 2016 in 155 countries, Dr. Cochi said.

Outbreaks tend to occur just outside targeted areas for campaigns, caused by decreasing population immunity, he said.

The novel OPV2 (nOPV2) is a genetic modification of the existing OPV2 vaccine designed to improve genetic stability, Dr. Cochi explained. The modifications would “decrease the risk of seeding new cVDPVs and the risk of vaccine-associated paralytic poliomyelitis (VAPP),” he said.

The Emergency Use Listing (EUL) was developed by the World Health Organization in response to the Ebola virus outbreak in 2014-2016 and is the fastest way to obtain regulatory review and approval of drug products, said Dr. Cochi.

A pilot plant has been established in Indonesia, and upon EUL approval, 4-8 million doses of the nOPV2 should be available for use in the second quarter of 2020, he concluded.

Dr. Cochi had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

Although wild poliovirus type 3 has not been detected globally for 7 years, the number of wild type 1 cases increased from 33 in 2018 to 173 in 2019. In response, a modified oral vaccine is being developed, according to Stephen Cochi, MD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Center for Global Health.

Several factors, including a Taliban ban on house-to-house vaccination in Afghanistan and a delay of large-scale vaccinations in Pakistan contributed to the surge in polio infections, Dr. Cochi said in a presentation at the February meeting of the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).

In addition, circulating vaccine-derived polioviruses (cVDPV) outbreaks have occurred in multiple countries including sub-Saharan Africa, China, Pakistan, and the Philippines. These outbreaks threaten the success of the bivalent oral polio vaccine introduced in April 2016 in 155 countries, Dr. Cochi said.

Outbreaks tend to occur just outside targeted areas for campaigns, caused by decreasing population immunity, he said.

The novel OPV2 (nOPV2) is a genetic modification of the existing OPV2 vaccine designed to improve genetic stability, Dr. Cochi explained. The modifications would “decrease the risk of seeding new cVDPVs and the risk of vaccine-associated paralytic poliomyelitis (VAPP),” he said.

The Emergency Use Listing (EUL) was developed by the World Health Organization in response to the Ebola virus outbreak in 2014-2016 and is the fastest way to obtain regulatory review and approval of drug products, said Dr. Cochi.

A pilot plant has been established in Indonesia, and upon EUL approval, 4-8 million doses of the nOPV2 should be available for use in the second quarter of 2020, he concluded.

Dr. Cochi had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

Although wild poliovirus type 3 has not been detected globally for 7 years, the number of wild type 1 cases increased from 33 in 2018 to 173 in 2019. In response, a modified oral vaccine is being developed, according to Stephen Cochi, MD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Center for Global Health.

Several factors, including a Taliban ban on house-to-house vaccination in Afghanistan and a delay of large-scale vaccinations in Pakistan contributed to the surge in polio infections, Dr. Cochi said in a presentation at the February meeting of the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).

In addition, circulating vaccine-derived polioviruses (cVDPV) outbreaks have occurred in multiple countries including sub-Saharan Africa, China, Pakistan, and the Philippines. These outbreaks threaten the success of the bivalent oral polio vaccine introduced in April 2016 in 155 countries, Dr. Cochi said.

Outbreaks tend to occur just outside targeted areas for campaigns, caused by decreasing population immunity, he said.

The novel OPV2 (nOPV2) is a genetic modification of the existing OPV2 vaccine designed to improve genetic stability, Dr. Cochi explained. The modifications would “decrease the risk of seeding new cVDPVs and the risk of vaccine-associated paralytic poliomyelitis (VAPP),” he said.

The Emergency Use Listing (EUL) was developed by the World Health Organization in response to the Ebola virus outbreak in 2014-2016 and is the fastest way to obtain regulatory review and approval of drug products, said Dr. Cochi.

A pilot plant has been established in Indonesia, and upon EUL approval, 4-8 million doses of the nOPV2 should be available for use in the second quarter of 2020, he concluded.

Dr. Cochi had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM AN ACIP MEETING

ERAS protocol for cesarean delivery reduces opioid usage

GRAPEVINE, TEX. – An enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) pathway for cesarean delivery decreased postoperative opioid usage by 62% in one health care organization, researchers reported at the Pregnancy Meeting. The protocol incorporates a stepwise approach to pain control with no scheduled postoperative opioids.

Abington Jefferson Health, which includes two hospitals in Pennsylvania, implemented an ERAS pathway for all cesarean deliveries in October 2018. Kathryn Ruymann, MD, said at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Dr. Ruymann is an obstetrics and gynecology resident at Abington Jefferson Health.

Prior to the ERAS protocol, 99%-100% of patients took an opioid during the postoperative period. “With ERAS, 26% of patients never took an opioid during the postop period,” Dr. Ruymann and her associates reported. “Pain scores decreased with ERAS for postoperative days 1-3 and remained unchanged on day 4.”

One in 300 opioid-naive patients who receives opioids after cesarean delivery becomes a persistent user, one study has shown (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Sep; 215(3):353.e1-18). “ERAS pathways integrate evidence-based interventions before, during, and after surgery to optimize outcomes, specifically to decrease postoperative opioid use,” the researchers said.

While other surgical fields have adopted ERAS pathways, more research is needed in obstetrics, said Dr. Ruymann. More than 4,500 women deliver at Abington Jefferson Health each year, and about a third undergo cesarean deliveries.

The organization’s ERAS pathway incorporates preoperative education, fasting guidelines, and intraoperative analgesia, nausea prophylaxis, and antimicrobial therapy. Under the new protocol, postoperative analgesia includes scheduled administration of nonopioid medications, including celecoxib and acetaminophen. In addition, patients may take 5-10 mg of oxycodone orally every 4 hours as needed, and hydromorphone 0.4 mg IV as needed may be used for refractory pain. In addition, patients should resume eating as soon as tolerated and be out of bed within 4 hours after surgery, according to the protocol. Postoperative management of pruritus and instructions on how to wean off opioids at home are among the other elements of the enhanced recovery plan.

To examine postoperative opioid usage before and after implementation of the ERAS pathway, the investigators conducted a retrospective cohort study of 316 women who underwent cesarean delivery 3 months before the start of the ERAS pathway and 267 who underwent cesarean delivery 3 months after. The researchers used an application developed in Qlik Sense, a data analytics platform, to calculate opioid usage.

Mean postoperative opioid use decreased by 62%. The reduction in opioid use remained 8 months after starting the ERAS pathway.

“An ERAS pathway for [cesarean delivery] decreases postoperative opioid usage by integrating a multimodal stepwise approach to pain control and recovery,” the researchers said. “Standardized order sets and departmentwide education were crucial in the success of ERAS. Additional research is needed to evaluate the impact of unique components of ERAS in order to optimize this pathway.”

The researchers had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Ruymann K et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jan;222(1):S212, Abstract 315.

GRAPEVINE, TEX. – An enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) pathway for cesarean delivery decreased postoperative opioid usage by 62% in one health care organization, researchers reported at the Pregnancy Meeting. The protocol incorporates a stepwise approach to pain control with no scheduled postoperative opioids.

Abington Jefferson Health, which includes two hospitals in Pennsylvania, implemented an ERAS pathway for all cesarean deliveries in October 2018. Kathryn Ruymann, MD, said at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Dr. Ruymann is an obstetrics and gynecology resident at Abington Jefferson Health.

Prior to the ERAS protocol, 99%-100% of patients took an opioid during the postoperative period. “With ERAS, 26% of patients never took an opioid during the postop period,” Dr. Ruymann and her associates reported. “Pain scores decreased with ERAS for postoperative days 1-3 and remained unchanged on day 4.”

One in 300 opioid-naive patients who receives opioids after cesarean delivery becomes a persistent user, one study has shown (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Sep; 215(3):353.e1-18). “ERAS pathways integrate evidence-based interventions before, during, and after surgery to optimize outcomes, specifically to decrease postoperative opioid use,” the researchers said.

While other surgical fields have adopted ERAS pathways, more research is needed in obstetrics, said Dr. Ruymann. More than 4,500 women deliver at Abington Jefferson Health each year, and about a third undergo cesarean deliveries.

The organization’s ERAS pathway incorporates preoperative education, fasting guidelines, and intraoperative analgesia, nausea prophylaxis, and antimicrobial therapy. Under the new protocol, postoperative analgesia includes scheduled administration of nonopioid medications, including celecoxib and acetaminophen. In addition, patients may take 5-10 mg of oxycodone orally every 4 hours as needed, and hydromorphone 0.4 mg IV as needed may be used for refractory pain. In addition, patients should resume eating as soon as tolerated and be out of bed within 4 hours after surgery, according to the protocol. Postoperative management of pruritus and instructions on how to wean off opioids at home are among the other elements of the enhanced recovery plan.

To examine postoperative opioid usage before and after implementation of the ERAS pathway, the investigators conducted a retrospective cohort study of 316 women who underwent cesarean delivery 3 months before the start of the ERAS pathway and 267 who underwent cesarean delivery 3 months after. The researchers used an application developed in Qlik Sense, a data analytics platform, to calculate opioid usage.

Mean postoperative opioid use decreased by 62%. The reduction in opioid use remained 8 months after starting the ERAS pathway.

“An ERAS pathway for [cesarean delivery] decreases postoperative opioid usage by integrating a multimodal stepwise approach to pain control and recovery,” the researchers said. “Standardized order sets and departmentwide education were crucial in the success of ERAS. Additional research is needed to evaluate the impact of unique components of ERAS in order to optimize this pathway.”

The researchers had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Ruymann K et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jan;222(1):S212, Abstract 315.

GRAPEVINE, TEX. – An enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) pathway for cesarean delivery decreased postoperative opioid usage by 62% in one health care organization, researchers reported at the Pregnancy Meeting. The protocol incorporates a stepwise approach to pain control with no scheduled postoperative opioids.

Abington Jefferson Health, which includes two hospitals in Pennsylvania, implemented an ERAS pathway for all cesarean deliveries in October 2018. Kathryn Ruymann, MD, said at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Dr. Ruymann is an obstetrics and gynecology resident at Abington Jefferson Health.

Prior to the ERAS protocol, 99%-100% of patients took an opioid during the postoperative period. “With ERAS, 26% of patients never took an opioid during the postop period,” Dr. Ruymann and her associates reported. “Pain scores decreased with ERAS for postoperative days 1-3 and remained unchanged on day 4.”

One in 300 opioid-naive patients who receives opioids after cesarean delivery becomes a persistent user, one study has shown (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Sep; 215(3):353.e1-18). “ERAS pathways integrate evidence-based interventions before, during, and after surgery to optimize outcomes, specifically to decrease postoperative opioid use,” the researchers said.

While other surgical fields have adopted ERAS pathways, more research is needed in obstetrics, said Dr. Ruymann. More than 4,500 women deliver at Abington Jefferson Health each year, and about a third undergo cesarean deliveries.

The organization’s ERAS pathway incorporates preoperative education, fasting guidelines, and intraoperative analgesia, nausea prophylaxis, and antimicrobial therapy. Under the new protocol, postoperative analgesia includes scheduled administration of nonopioid medications, including celecoxib and acetaminophen. In addition, patients may take 5-10 mg of oxycodone orally every 4 hours as needed, and hydromorphone 0.4 mg IV as needed may be used for refractory pain. In addition, patients should resume eating as soon as tolerated and be out of bed within 4 hours after surgery, according to the protocol. Postoperative management of pruritus and instructions on how to wean off opioids at home are among the other elements of the enhanced recovery plan.

To examine postoperative opioid usage before and after implementation of the ERAS pathway, the investigators conducted a retrospective cohort study of 316 women who underwent cesarean delivery 3 months before the start of the ERAS pathway and 267 who underwent cesarean delivery 3 months after. The researchers used an application developed in Qlik Sense, a data analytics platform, to calculate opioid usage.

Mean postoperative opioid use decreased by 62%. The reduction in opioid use remained 8 months after starting the ERAS pathway.

“An ERAS pathway for [cesarean delivery] decreases postoperative opioid usage by integrating a multimodal stepwise approach to pain control and recovery,” the researchers said. “Standardized order sets and departmentwide education were crucial in the success of ERAS. Additional research is needed to evaluate the impact of unique components of ERAS in order to optimize this pathway.”

The researchers had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Ruymann K et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jan;222(1):S212, Abstract 315.

REPORTING FROM THE PREGNANCY MEETING

ACIP vaccination update

Every year the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) updates the recommended immunization schedules for children/adolescents and adults on the Web site of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/index.html). The schedules for 2020 reflect additions and changes adopted by ACIP in 2019 and are discussed in this Practice Alert.

Hepatitis A: New directives on homelessness, HIV, and vaccine catch-up

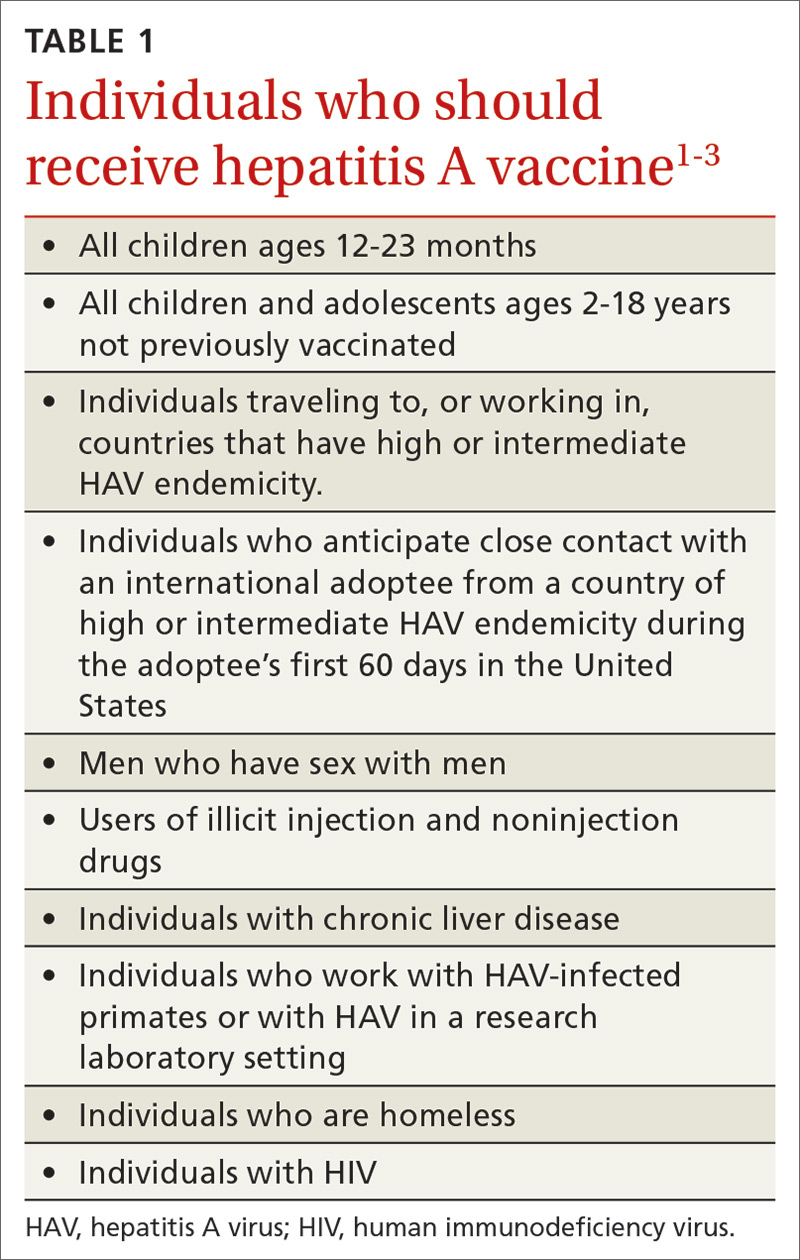

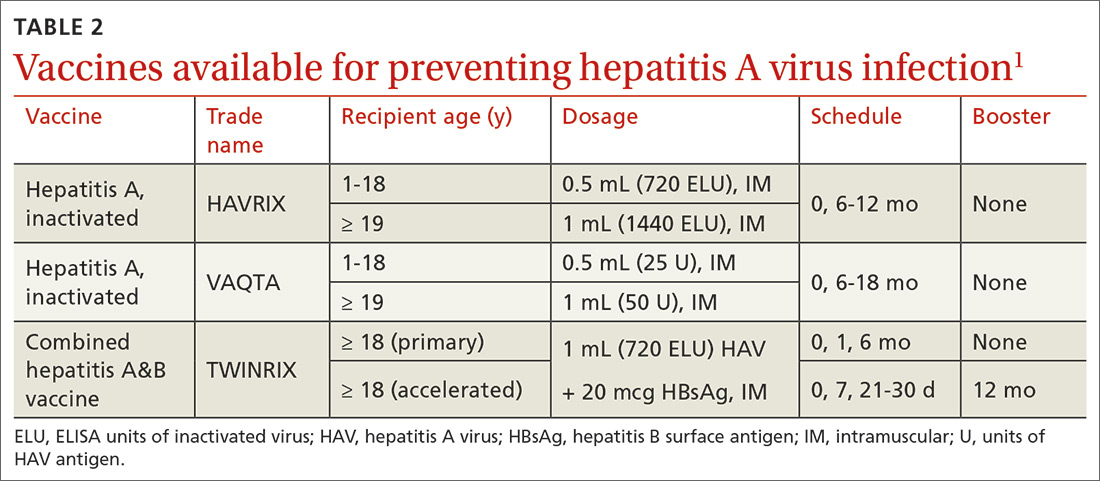

Hepatitis A (HepA) vaccination is recommended for children ages 12 to 23 months, and for those at increased risk for hepatitis A virus (HAV) infection or for complications from HAV infection (TABLE 1).1-3 Routine vaccination is either 2 doses of HepA given 6 months apart or a 3-dose schedule of combined hepatitis A and B vaccine (Twinrix). Vaccines licensed in the United States for the prevention of HAV infection are listed in TABLE 2.1

ACIP recently added homeless individuals to the list of those who should receive HepA vaccine.4 This step was taken in response to numerous outbreaks among those who are homeless or who use illicit drugs. These outbreaks have increased rates of HAV infection overall as well as rates of hospitalization (71%) and death (3%) among those infected.5 Concern about a homeless individual’s ability to complete a 2- or 3-dose series should not preclude initiating HepA vaccination; even 1 dose achieves protective immunity in 94% to 100% of those who have intact immune systems.2

At its June 2019 meeting, ACIP made 2 other additions to its recommendations regarding HepA vaccination.1 First, those infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are now among the individuals who should receive HepA vaccine. Those who are HIV-positive and ≥ 1 year old were recommended for HepA vaccination because they often have one of the other risks for HAV infection and have higher rates of complications and prolonged infections if they contract HAV.1 Second, catch-up HepA vaccination is indicated for children and adolescents ages 2 through 18 years who have not been previously vaccinated.1Also at the June 2019 meeting, the safety of HepA vaccination during pregnancy was confirmed. ACIP recommends HepA vaccine for any pregnant woman not previously vaccinated who is at risk for HAV infection or for a severe outcome from HAV infection.1

Japanese encephalitis: Vaccination can be accelerated

Japanese encephalitis (JE) is a serious mosquito-borne vaccine-preventable infection endemic to most of Asia and parts of the western Pacific. Most travelers to countries with endemic JE are at low risk of infection. But risk increases with prolonged visits to these areas and particularly during the JE virus transmission season (summer/fall in temperate areas; year-round in tropical climates). Risk is also heightened by traveling to, or living in, rural Asian areas, by participating in extensive outdoor activities, and by staying in accommodations without air-conditioning, screens, or bed nets.6

The only JE vaccine licensed in the United States is JE-VC (Ixiaro), manufactured by Valneva Austria GmbH. It is approved for use in children ≥ 2 months and adults. It requires a 2-dose series with 28 days between doses, and a booster after 1 year. ACIP recently approved an accelerated schedule for adults ages 18 to 65 years that allows the second dose to be administered as early as 7 days after the first. A full description of the epidemiology of JE and ACIP recommendations regarding JE-VC were published in July 2019.6

Meningococcal B vaccine booster doses recommended

Meningococcal B (MenB) vaccine is recommended for individuals ≥ 10 years old who are at increased risk of meningococcal infection, including those with complement deficiency, complement inhibitor use, or asplenia; microbiologists; and individuals exposed during an outbreak.7 It is also recommended for those ages 16 to 23 years who desire vaccination after individual clinical decision making.8

Continue to: Two MenB vaccines...

Two MenB vaccines are available in the United States: MenB-FHbp (Trumenba, Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, Inc.) and MenB-4C (Bexsero, GlaxoSmithKline). Either MenB vaccine can be used; however, they are not interchangeable and the same product must be used for all doses an individual receives. MenB-FHbp is licensed as a 3-dose series given at 0, 1-2, and 6 months, or as a 2-dose series given at 0 and 6 months. ACIP recommends the 3-dose schedule for individuals at increased risk for meningococcal disease or for use during community outbreaks of serogroup B meningococcal disease.9 For healthy adolescents who are not at increased risk for meningococcal disease, ACIP recommends using the 2-dose schedule of MenB-FHbp.9 MenB-4C is licensed as a 2-dose series, with doses administered at least 1 month apart.

At the June 2019 meeting, ACIP voted to recommend a MenB booster dose for those who are still at increased risk 1 year following completion of a MenB primary series, followed by booster doses every 2 to 3 years thereafter for as long as increased risk remains. This recommendation was made because of a rapid waning of immunity following the primary series and subsequent booster doses. A booster dose was not recommended for those who choose to be vaccinated after clinical decision making unless they are exposed during an outbreak and it has been at least a year since they received the primary series. An interval of 6 months for the booster can be considered, depending on the outbreak situation.10

A new DTaP product, and substituting Tdap for Td is approved

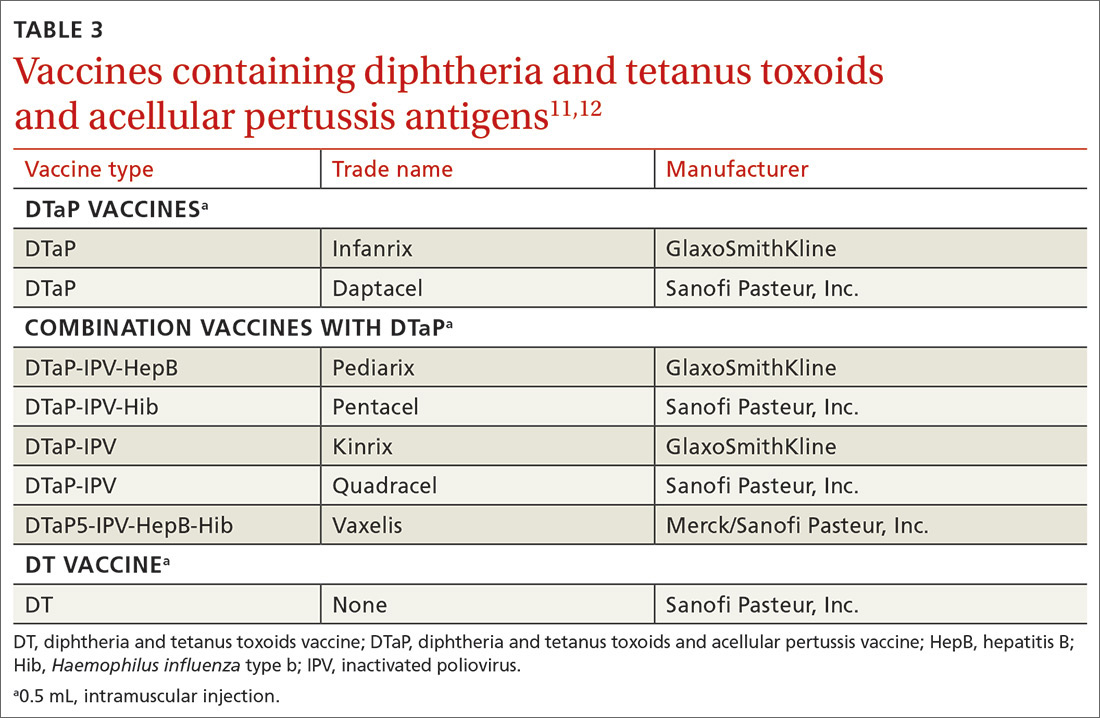

Diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis vaccine (DTaP) is recommended for children as a 3-dose primary series (2, 4, 6 months) followed by 2 booster doses (at 15-18 months and at 4-6 years). These 3 antigens are available as DTaP products solely or as part of vaccines that combine other antigens with DTaP (TABLE 3).11,12 In addition, as a joint venture between Merck and Sanofi Pasteur, a new pediatric hexavalent vaccine containing DTaP5, polio, Haemophilus influenzae type b, and hepatitis B antigens is now available to be given at ages 2, 4, and 6 months.12

Tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine is recommended for adolescents ages 11 to 12 years.11 It is also recommended once for adults who have not previously received it. The exception to the single Tdap dose for adults is during pregnancy; it is recommended as a single dose during each pregnancy regardless of the previous number of Tdap doses received.11

Td is recommended every 10 years after Tdap given at ages 11 to 12, for protection against tetanus and diphtheria. Tdap can be substituted for one of these decennial Td boosters. Tdap can also be substituted for Td for tetanus prophylaxis after a patient sustains a wound.11 The recommended single dose of Tdap for adolescents/adults also can be administered as part of a catch-up 3-dose Td series in previously unvaccinated adolescents and adults.

Continue to: It has become common...

It has become common practice throughout the country to substitute Tdap for Td when Td is indicated, even if Tdap has been received previously. ACIP looked at the safety of repeated doses of Tdap and found no safety concerns. For practicality, ACIP voted to recommend either Td or Tdap for these situations: the decennial booster, when tetanus prophylaxis is indicated in wound management, and when catch-up is needed in previously unvaccinated or inadequately vaccinated individuals who are 7 years of age and older. The resulting increase in the number of Tdap doses is not expected to have a major impact on the incidence of pertussis.13

Additional recommendations

Recommendations for preventing influenza in the 2019-2020 season are discussed in a previous Practice Alert.14

In 2019, ACIP also changed a previous recommendation on the routine use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) in adults ≥ 65 years. The new recommendation, covered in another Practice Alert, states that PCV13 should be used in immunocompetent adults ≥ 65 years only after individual clinical decision making.15

ACIP also changed its recommendations pertaining to human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine. Catch-up vaccination is now recommended for all individuals through age 26 years. Previously catch up was recommended only for women and for men who have sex with men. And, even though use of HPV vaccine has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for adults ages 27 to 45 years, ACIP did not recommend its routine use in this age group but instead recommended it only after individual clinical decision making.16,17

1. Nelson N. Hepatitis A vaccine. Presentation to the ACIP; June 27, 2019. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2019-06/Hepatitis-2-Nelson-508.pdf. Accessed February 24, 2020.

2. Fiore AE, Wasley A, Bell BP; Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Prevention of hepatitis A through active or passive immunization: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(No. RR-7):1-23.

3. CDC. Prevention of hepatitis A through active or passive immunization. MMWR Wkly. 2006;55:1-23.

4. Doshani M, Weng M, Moore KL, et al. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for use of hepatitis A vaccine for persons experiencing homelessness. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:153-156.

5. Foster M, Ramachandran S, Myatt K, et al. Hepatitis A virus outbreaks associated with drug use and homelessness—California, Kentucky, Michigan, and Utah, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1208-1210.

6. Hills SL, Walter EB, Atmar RL, et al. Japanese encephalitis vaccine: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2019;68:1-33.

7. CDC. Meningococcal vaccination: what everyone should know. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/mening/public/index.html. Accessed February 24, 2020.

8. MacNeil JR, Rubin L, Folaranmi T, et al. Use of seroproup B meningococcal vaccine in adolescents and young adults: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015; 64:1171-1176.

9. Patton M, Stephens D, Moore K, et al. Updated recommendations for use of MenB-FHbp seropgroup B meningococcal vaccine—Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:509-513.

10. Mbaeyi S. Serogroup B Meningococcal vaccine booster doses. Presentation to ACIP; June 27, 2019. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2019-06/Meningococcal-2-Mbaeyi-508.pdf. Accessed February 24, 2020.

11. Liang JL, Tiwari T, Moro P, et al. Prevention of pertussis, tetanus, and diphtheria with vaccines in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2018;67(No. RR-2):1-44.

12. Lee A. Immunogenicity and safety of DTaP5-IPV-HepB-Hib (Vaxelis™), a pediatric hexavalent combination vaccine. Presentation to the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; February 2019. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2019-02/Combo-vaccine-2-Lee-508.pdf. Accessed February 24, 2020.

13. Havers F. Tdap and Td: summary of work group considerations and proposed policy options. Presentation to ACIP; October 23, 2019. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2019-10/Pertussis-03-Havers-508.pdf. Accessed February 24, 2020.

14. Campos-Outcalt D. Influenza update. J Fam Pract. 2019;68:456-458.

15. Campos-Outcalt D. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine update. J Fam Pract. 2019;68:564-566.

16. Meites E, Szilagyi PG, Chesson HW, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination for adults: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019; 68:698–702.

17. Campos-Outcalt D. ACIP issues 2 new recs on HPV vaccine [audio]. J Fam Pract. September 2019. www.mdedge.com/familymedicine/article/205784/vaccines/acip-issues-2-new-recs-hpv-vaccination. Accessed February 24, 2020.

Every year the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) updates the recommended immunization schedules for children/adolescents and adults on the Web site of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/index.html). The schedules for 2020 reflect additions and changes adopted by ACIP in 2019 and are discussed in this Practice Alert.

Hepatitis A: New directives on homelessness, HIV, and vaccine catch-up

Hepatitis A (HepA) vaccination is recommended for children ages 12 to 23 months, and for those at increased risk for hepatitis A virus (HAV) infection or for complications from HAV infection (TABLE 1).1-3 Routine vaccination is either 2 doses of HepA given 6 months apart or a 3-dose schedule of combined hepatitis A and B vaccine (Twinrix). Vaccines licensed in the United States for the prevention of HAV infection are listed in TABLE 2.1

ACIP recently added homeless individuals to the list of those who should receive HepA vaccine.4 This step was taken in response to numerous outbreaks among those who are homeless or who use illicit drugs. These outbreaks have increased rates of HAV infection overall as well as rates of hospitalization (71%) and death (3%) among those infected.5 Concern about a homeless individual’s ability to complete a 2- or 3-dose series should not preclude initiating HepA vaccination; even 1 dose achieves protective immunity in 94% to 100% of those who have intact immune systems.2

At its June 2019 meeting, ACIP made 2 other additions to its recommendations regarding HepA vaccination.1 First, those infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are now among the individuals who should receive HepA vaccine. Those who are HIV-positive and ≥ 1 year old were recommended for HepA vaccination because they often have one of the other risks for HAV infection and have higher rates of complications and prolonged infections if they contract HAV.1 Second, catch-up HepA vaccination is indicated for children and adolescents ages 2 through 18 years who have not been previously vaccinated.1Also at the June 2019 meeting, the safety of HepA vaccination during pregnancy was confirmed. ACIP recommends HepA vaccine for any pregnant woman not previously vaccinated who is at risk for HAV infection or for a severe outcome from HAV infection.1

Japanese encephalitis: Vaccination can be accelerated

Japanese encephalitis (JE) is a serious mosquito-borne vaccine-preventable infection endemic to most of Asia and parts of the western Pacific. Most travelers to countries with endemic JE are at low risk of infection. But risk increases with prolonged visits to these areas and particularly during the JE virus transmission season (summer/fall in temperate areas; year-round in tropical climates). Risk is also heightened by traveling to, or living in, rural Asian areas, by participating in extensive outdoor activities, and by staying in accommodations without air-conditioning, screens, or bed nets.6

The only JE vaccine licensed in the United States is JE-VC (Ixiaro), manufactured by Valneva Austria GmbH. It is approved for use in children ≥ 2 months and adults. It requires a 2-dose series with 28 days between doses, and a booster after 1 year. ACIP recently approved an accelerated schedule for adults ages 18 to 65 years that allows the second dose to be administered as early as 7 days after the first. A full description of the epidemiology of JE and ACIP recommendations regarding JE-VC were published in July 2019.6

Meningococcal B vaccine booster doses recommended

Meningococcal B (MenB) vaccine is recommended for individuals ≥ 10 years old who are at increased risk of meningococcal infection, including those with complement deficiency, complement inhibitor use, or asplenia; microbiologists; and individuals exposed during an outbreak.7 It is also recommended for those ages 16 to 23 years who desire vaccination after individual clinical decision making.8

Continue to: Two MenB vaccines...

Two MenB vaccines are available in the United States: MenB-FHbp (Trumenba, Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, Inc.) and MenB-4C (Bexsero, GlaxoSmithKline). Either MenB vaccine can be used; however, they are not interchangeable and the same product must be used for all doses an individual receives. MenB-FHbp is licensed as a 3-dose series given at 0, 1-2, and 6 months, or as a 2-dose series given at 0 and 6 months. ACIP recommends the 3-dose schedule for individuals at increased risk for meningococcal disease or for use during community outbreaks of serogroup B meningococcal disease.9 For healthy adolescents who are not at increased risk for meningococcal disease, ACIP recommends using the 2-dose schedule of MenB-FHbp.9 MenB-4C is licensed as a 2-dose series, with doses administered at least 1 month apart.

At the June 2019 meeting, ACIP voted to recommend a MenB booster dose for those who are still at increased risk 1 year following completion of a MenB primary series, followed by booster doses every 2 to 3 years thereafter for as long as increased risk remains. This recommendation was made because of a rapid waning of immunity following the primary series and subsequent booster doses. A booster dose was not recommended for those who choose to be vaccinated after clinical decision making unless they are exposed during an outbreak and it has been at least a year since they received the primary series. An interval of 6 months for the booster can be considered, depending on the outbreak situation.10

A new DTaP product, and substituting Tdap for Td is approved

Diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis vaccine (DTaP) is recommended for children as a 3-dose primary series (2, 4, 6 months) followed by 2 booster doses (at 15-18 months and at 4-6 years). These 3 antigens are available as DTaP products solely or as part of vaccines that combine other antigens with DTaP (TABLE 3).11,12 In addition, as a joint venture between Merck and Sanofi Pasteur, a new pediatric hexavalent vaccine containing DTaP5, polio, Haemophilus influenzae type b, and hepatitis B antigens is now available to be given at ages 2, 4, and 6 months.12

Tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine is recommended for adolescents ages 11 to 12 years.11 It is also recommended once for adults who have not previously received it. The exception to the single Tdap dose for adults is during pregnancy; it is recommended as a single dose during each pregnancy regardless of the previous number of Tdap doses received.11

Td is recommended every 10 years after Tdap given at ages 11 to 12, for protection against tetanus and diphtheria. Tdap can be substituted for one of these decennial Td boosters. Tdap can also be substituted for Td for tetanus prophylaxis after a patient sustains a wound.11 The recommended single dose of Tdap for adolescents/adults also can be administered as part of a catch-up 3-dose Td series in previously unvaccinated adolescents and adults.

Continue to: It has become common...

It has become common practice throughout the country to substitute Tdap for Td when Td is indicated, even if Tdap has been received previously. ACIP looked at the safety of repeated doses of Tdap and found no safety concerns. For practicality, ACIP voted to recommend either Td or Tdap for these situations: the decennial booster, when tetanus prophylaxis is indicated in wound management, and when catch-up is needed in previously unvaccinated or inadequately vaccinated individuals who are 7 years of age and older. The resulting increase in the number of Tdap doses is not expected to have a major impact on the incidence of pertussis.13

Additional recommendations

Recommendations for preventing influenza in the 2019-2020 season are discussed in a previous Practice Alert.14

In 2019, ACIP also changed a previous recommendation on the routine use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) in adults ≥ 65 years. The new recommendation, covered in another Practice Alert, states that PCV13 should be used in immunocompetent adults ≥ 65 years only after individual clinical decision making.15

ACIP also changed its recommendations pertaining to human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine. Catch-up vaccination is now recommended for all individuals through age 26 years. Previously catch up was recommended only for women and for men who have sex with men. And, even though use of HPV vaccine has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for adults ages 27 to 45 years, ACIP did not recommend its routine use in this age group but instead recommended it only after individual clinical decision making.16,17

Every year the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) updates the recommended immunization schedules for children/adolescents and adults on the Web site of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/index.html). The schedules for 2020 reflect additions and changes adopted by ACIP in 2019 and are discussed in this Practice Alert.

Hepatitis A: New directives on homelessness, HIV, and vaccine catch-up

Hepatitis A (HepA) vaccination is recommended for children ages 12 to 23 months, and for those at increased risk for hepatitis A virus (HAV) infection or for complications from HAV infection (TABLE 1).1-3 Routine vaccination is either 2 doses of HepA given 6 months apart or a 3-dose schedule of combined hepatitis A and B vaccine (Twinrix). Vaccines licensed in the United States for the prevention of HAV infection are listed in TABLE 2.1

ACIP recently added homeless individuals to the list of those who should receive HepA vaccine.4 This step was taken in response to numerous outbreaks among those who are homeless or who use illicit drugs. These outbreaks have increased rates of HAV infection overall as well as rates of hospitalization (71%) and death (3%) among those infected.5 Concern about a homeless individual’s ability to complete a 2- or 3-dose series should not preclude initiating HepA vaccination; even 1 dose achieves protective immunity in 94% to 100% of those who have intact immune systems.2

At its June 2019 meeting, ACIP made 2 other additions to its recommendations regarding HepA vaccination.1 First, those infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are now among the individuals who should receive HepA vaccine. Those who are HIV-positive and ≥ 1 year old were recommended for HepA vaccination because they often have one of the other risks for HAV infection and have higher rates of complications and prolonged infections if they contract HAV.1 Second, catch-up HepA vaccination is indicated for children and adolescents ages 2 through 18 years who have not been previously vaccinated.1Also at the June 2019 meeting, the safety of HepA vaccination during pregnancy was confirmed. ACIP recommends HepA vaccine for any pregnant woman not previously vaccinated who is at risk for HAV infection or for a severe outcome from HAV infection.1

Japanese encephalitis: Vaccination can be accelerated

Japanese encephalitis (JE) is a serious mosquito-borne vaccine-preventable infection endemic to most of Asia and parts of the western Pacific. Most travelers to countries with endemic JE are at low risk of infection. But risk increases with prolonged visits to these areas and particularly during the JE virus transmission season (summer/fall in temperate areas; year-round in tropical climates). Risk is also heightened by traveling to, or living in, rural Asian areas, by participating in extensive outdoor activities, and by staying in accommodations without air-conditioning, screens, or bed nets.6

The only JE vaccine licensed in the United States is JE-VC (Ixiaro), manufactured by Valneva Austria GmbH. It is approved for use in children ≥ 2 months and adults. It requires a 2-dose series with 28 days between doses, and a booster after 1 year. ACIP recently approved an accelerated schedule for adults ages 18 to 65 years that allows the second dose to be administered as early as 7 days after the first. A full description of the epidemiology of JE and ACIP recommendations regarding JE-VC were published in July 2019.6

Meningococcal B vaccine booster doses recommended

Meningococcal B (MenB) vaccine is recommended for individuals ≥ 10 years old who are at increased risk of meningococcal infection, including those with complement deficiency, complement inhibitor use, or asplenia; microbiologists; and individuals exposed during an outbreak.7 It is also recommended for those ages 16 to 23 years who desire vaccination after individual clinical decision making.8

Continue to: Two MenB vaccines...

Two MenB vaccines are available in the United States: MenB-FHbp (Trumenba, Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, Inc.) and MenB-4C (Bexsero, GlaxoSmithKline). Either MenB vaccine can be used; however, they are not interchangeable and the same product must be used for all doses an individual receives. MenB-FHbp is licensed as a 3-dose series given at 0, 1-2, and 6 months, or as a 2-dose series given at 0 and 6 months. ACIP recommends the 3-dose schedule for individuals at increased risk for meningococcal disease or for use during community outbreaks of serogroup B meningococcal disease.9 For healthy adolescents who are not at increased risk for meningococcal disease, ACIP recommends using the 2-dose schedule of MenB-FHbp.9 MenB-4C is licensed as a 2-dose series, with doses administered at least 1 month apart.

At the June 2019 meeting, ACIP voted to recommend a MenB booster dose for those who are still at increased risk 1 year following completion of a MenB primary series, followed by booster doses every 2 to 3 years thereafter for as long as increased risk remains. This recommendation was made because of a rapid waning of immunity following the primary series and subsequent booster doses. A booster dose was not recommended for those who choose to be vaccinated after clinical decision making unless they are exposed during an outbreak and it has been at least a year since they received the primary series. An interval of 6 months for the booster can be considered, depending on the outbreak situation.10

A new DTaP product, and substituting Tdap for Td is approved

Diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis vaccine (DTaP) is recommended for children as a 3-dose primary series (2, 4, 6 months) followed by 2 booster doses (at 15-18 months and at 4-6 years). These 3 antigens are available as DTaP products solely or as part of vaccines that combine other antigens with DTaP (TABLE 3).11,12 In addition, as a joint venture between Merck and Sanofi Pasteur, a new pediatric hexavalent vaccine containing DTaP5, polio, Haemophilus influenzae type b, and hepatitis B antigens is now available to be given at ages 2, 4, and 6 months.12

Tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine is recommended for adolescents ages 11 to 12 years.11 It is also recommended once for adults who have not previously received it. The exception to the single Tdap dose for adults is during pregnancy; it is recommended as a single dose during each pregnancy regardless of the previous number of Tdap doses received.11

Td is recommended every 10 years after Tdap given at ages 11 to 12, for protection against tetanus and diphtheria. Tdap can be substituted for one of these decennial Td boosters. Tdap can also be substituted for Td for tetanus prophylaxis after a patient sustains a wound.11 The recommended single dose of Tdap for adolescents/adults also can be administered as part of a catch-up 3-dose Td series in previously unvaccinated adolescents and adults.

Continue to: It has become common...

It has become common practice throughout the country to substitute Tdap for Td when Td is indicated, even if Tdap has been received previously. ACIP looked at the safety of repeated doses of Tdap and found no safety concerns. For practicality, ACIP voted to recommend either Td or Tdap for these situations: the decennial booster, when tetanus prophylaxis is indicated in wound management, and when catch-up is needed in previously unvaccinated or inadequately vaccinated individuals who are 7 years of age and older. The resulting increase in the number of Tdap doses is not expected to have a major impact on the incidence of pertussis.13

Additional recommendations

Recommendations for preventing influenza in the 2019-2020 season are discussed in a previous Practice Alert.14

In 2019, ACIP also changed a previous recommendation on the routine use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) in adults ≥ 65 years. The new recommendation, covered in another Practice Alert, states that PCV13 should be used in immunocompetent adults ≥ 65 years only after individual clinical decision making.15

ACIP also changed its recommendations pertaining to human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine. Catch-up vaccination is now recommended for all individuals through age 26 years. Previously catch up was recommended only for women and for men who have sex with men. And, even though use of HPV vaccine has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for adults ages 27 to 45 years, ACIP did not recommend its routine use in this age group but instead recommended it only after individual clinical decision making.16,17

1. Nelson N. Hepatitis A vaccine. Presentation to the ACIP; June 27, 2019. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2019-06/Hepatitis-2-Nelson-508.pdf. Accessed February 24, 2020.

2. Fiore AE, Wasley A, Bell BP; Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Prevention of hepatitis A through active or passive immunization: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(No. RR-7):1-23.

3. CDC. Prevention of hepatitis A through active or passive immunization. MMWR Wkly. 2006;55:1-23.

4. Doshani M, Weng M, Moore KL, et al. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for use of hepatitis A vaccine for persons experiencing homelessness. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:153-156.

5. Foster M, Ramachandran S, Myatt K, et al. Hepatitis A virus outbreaks associated with drug use and homelessness—California, Kentucky, Michigan, and Utah, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1208-1210.

6. Hills SL, Walter EB, Atmar RL, et al. Japanese encephalitis vaccine: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2019;68:1-33.

7. CDC. Meningococcal vaccination: what everyone should know. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/mening/public/index.html. Accessed February 24, 2020.

8. MacNeil JR, Rubin L, Folaranmi T, et al. Use of seroproup B meningococcal vaccine in adolescents and young adults: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015; 64:1171-1176.

9. Patton M, Stephens D, Moore K, et al. Updated recommendations for use of MenB-FHbp seropgroup B meningococcal vaccine—Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:509-513.

10. Mbaeyi S. Serogroup B Meningococcal vaccine booster doses. Presentation to ACIP; June 27, 2019. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2019-06/Meningococcal-2-Mbaeyi-508.pdf. Accessed February 24, 2020.

11. Liang JL, Tiwari T, Moro P, et al. Prevention of pertussis, tetanus, and diphtheria with vaccines in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2018;67(No. RR-2):1-44.

12. Lee A. Immunogenicity and safety of DTaP5-IPV-HepB-Hib (Vaxelis™), a pediatric hexavalent combination vaccine. Presentation to the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; February 2019. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2019-02/Combo-vaccine-2-Lee-508.pdf. Accessed February 24, 2020.

13. Havers F. Tdap and Td: summary of work group considerations and proposed policy options. Presentation to ACIP; October 23, 2019. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2019-10/Pertussis-03-Havers-508.pdf. Accessed February 24, 2020.

14. Campos-Outcalt D. Influenza update. J Fam Pract. 2019;68:456-458.

15. Campos-Outcalt D. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine update. J Fam Pract. 2019;68:564-566.

16. Meites E, Szilagyi PG, Chesson HW, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination for adults: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019; 68:698–702.

17. Campos-Outcalt D. ACIP issues 2 new recs on HPV vaccine [audio]. J Fam Pract. September 2019. www.mdedge.com/familymedicine/article/205784/vaccines/acip-issues-2-new-recs-hpv-vaccination. Accessed February 24, 2020.

1. Nelson N. Hepatitis A vaccine. Presentation to the ACIP; June 27, 2019. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2019-06/Hepatitis-2-Nelson-508.pdf. Accessed February 24, 2020.

2. Fiore AE, Wasley A, Bell BP; Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Prevention of hepatitis A through active or passive immunization: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(No. RR-7):1-23.

3. CDC. Prevention of hepatitis A through active or passive immunization. MMWR Wkly. 2006;55:1-23.

4. Doshani M, Weng M, Moore KL, et al. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for use of hepatitis A vaccine for persons experiencing homelessness. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:153-156.

5. Foster M, Ramachandran S, Myatt K, et al. Hepatitis A virus outbreaks associated with drug use and homelessness—California, Kentucky, Michigan, and Utah, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1208-1210.

6. Hills SL, Walter EB, Atmar RL, et al. Japanese encephalitis vaccine: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2019;68:1-33.

7. CDC. Meningococcal vaccination: what everyone should know. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/mening/public/index.html. Accessed February 24, 2020.

8. MacNeil JR, Rubin L, Folaranmi T, et al. Use of seroproup B meningococcal vaccine in adolescents and young adults: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015; 64:1171-1176.

9. Patton M, Stephens D, Moore K, et al. Updated recommendations for use of MenB-FHbp seropgroup B meningococcal vaccine—Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:509-513.

10. Mbaeyi S. Serogroup B Meningococcal vaccine booster doses. Presentation to ACIP; June 27, 2019. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2019-06/Meningococcal-2-Mbaeyi-508.pdf. Accessed February 24, 2020.

11. Liang JL, Tiwari T, Moro P, et al. Prevention of pertussis, tetanus, and diphtheria with vaccines in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2018;67(No. RR-2):1-44.

12. Lee A. Immunogenicity and safety of DTaP5-IPV-HepB-Hib (Vaxelis™), a pediatric hexavalent combination vaccine. Presentation to the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; February 2019. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2019-02/Combo-vaccine-2-Lee-508.pdf. Accessed February 24, 2020.

13. Havers F. Tdap and Td: summary of work group considerations and proposed policy options. Presentation to ACIP; October 23, 2019. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2019-10/Pertussis-03-Havers-508.pdf. Accessed February 24, 2020.

14. Campos-Outcalt D. Influenza update. J Fam Pract. 2019;68:456-458.

15. Campos-Outcalt D. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine update. J Fam Pract. 2019;68:564-566.

16. Meites E, Szilagyi PG, Chesson HW, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination for adults: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019; 68:698–702.

17. Campos-Outcalt D. ACIP issues 2 new recs on HPV vaccine [audio]. J Fam Pract. September 2019. www.mdedge.com/familymedicine/article/205784/vaccines/acip-issues-2-new-recs-hpv-vaccination. Accessed February 24, 2020.

Dengue vaccine deemed acceptable by most doctors, fewer parents

Adults are interested in a dengue vaccine for themselves and their children, and physicians recognize that dengue is a public health problem, according to data from parents and physicians in Puerto Rico. Most doctors, but fewer parents, found the idea of protecting children with Dengue vaccine acceptable.

Lack of detailed information about the vaccine is the greatest barrier to parents’ consent to vaccination, noted Ines Esquilin, MD, of the University of Puerto Rico, San Juan, in a presentation at the February meeting of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).

The ACIP dengue vaccines work group reviewed data from 102 physicians in Puerto Rico, 82% of which were pediatricians, regarding potential dengue vaccination. Overall, 98% said they considered dengue a significant public health problem in Puerto Rico, and 73% said they would recommend the dengue vaccine to patients if a laboratory test with acceptable specificity were available. Among the physicians who said they would not recommend the vaccine, the most common reason (71%) was concern about the risks of vaccinating individuals with false-positive tests.

The availability of a test that can be performed in the medical office and avoid repeat visits is a major factor in the feasibility of dengue vaccination, Dr. Esquilin said.

The ACIP dengue vaccines work group also sought public opinion on the acceptability of a generic dengue vaccine through focus group sessions with parents of children aged 9-16 years in Puerto Rico, said Dr. Esquilin.

Approximately one-third of the parents said they were willing to vaccinate their children, one-third were unwilling, and one-third were unsure. The most commonly identified barriers to vaccination included lack of information or inconsistent information about the vaccine, high cost/lack of insurance coverage, time-consuming lab test to confirm infection, side effects, potential for false-positive lab results, and low vaccine effectiveness.

Motivating factors for vaccination included correct information about the vaccine, desire to prevent infection, lab-confirmed positive test, support from public health organizations, the presence of a dengue epidemic, and educational forums.