User login

Does screening by primary care providers effectively detect melanoma and other skin cancers?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

No trials have directly assessed skin cancer morbidity associated with physician visual skin screening. A 2018 ecologic cohort study found no difference in melanoma mortality in a population undergoing a national screening program, although screening was associated with 41% more diagnoses of skin cancer.1 A 2012 cohort study found a reduction in melanoma mortality over 7 years associated with a population-based visual skin cancer screening program compared with similar populations that didn’t undergo specific screening.2 At 12-year follow-up, however, there was no longer a difference in mortality.

Primary care visual screening doesn’t decrease melanoma mortality

German researchers trained 1673 non-dermatologists (64% of general practitioners, obstetrician-gynecologists, and urologists in that region of Germany) and 116 dermatologists (98% in the region) to recognize skin cancer through whole-body visual inspection.1 They recruited and screened 360,000 adults (19% of the population older than 20 years; 74% women) and followed age- and sex-adjusted melanoma mortality over the next 10 years. Non-dermatologists performed most screening exams (77%); 37% of screened positive patients were lost to follow-up.

Melanoma mortality ultimately didn’t change in the screened region, compared with populations in other European countries without national screening programs. Screening detected approximately half of melanoma cases (585/1169) in the region and was associated with 41% greater detection of skin cancers compared with other countries.

Researchers recorded age-adjusted increases in incidence per 100,000 of melanoma from 14.2 (95% confidence interval [CI], 13.3-15.1) to 18 (95% CI, 16.6-19.4), melanoma in situ from 5.8 (95% CI, 5.2-6.4) to 8.5 (95% CI, 7.5-9.5), squamous cell carcinoma from 11.2 (95% CI, 10.6-11.8) to 12.9 (95% CI, 12.0-13.8), and basal cell carcinoma from 60.5 (95% CI, 59.0-62.1) to 78.4 (95% CI, 75.9-80.8).

Visual screening by primary care providers vs screening by dermatologists

A cohort study of 16,383 Australian adults found that visual screening by primary care physicians detected melanoma over 3 years with a sensitivity of 40.2% (95% CIs not supplied) and specificity of 86.1% (95% CI, 85.6-86.6%; positive predictive value = 1.4%).3

A second cohort study, enrolling 7436 adults, that evaluated visual screening by dermatologists and plastic surgeons over 2 years found a sensitivity for melanoma of 49% (95% CI, 34.4-63.7%) and a specificity of 97.6% (95% CI, 97.2-97.9%) with a positive predictive value of 11.9% (95% CI, 7.8-17.2%).4

Visual screening more often detects thinner melanomas

A 3-year case-control study (3762 cases, 3824 controls) that examined the association between visual skin screening by a physician (type of physician not specified) and thickness of melanomas detected found that thin melanomas (≤ 0.75 mm) were more common among screened patients compared with unscreened patients (odds ratio [OR] = 1.38; 95% CI, 1.22-1.56) and thicker melanomas (≥ 0.75 mm) were less common (OR = 0.86; 95% CI, 0.75-0.98).5

Continue to: A systematic review...

A systematic review of 8 observational cohort studies with a total of 200,000 patients found a consistent linear increase in melanoma mortality with increasing tumor thickness.6 The largest study (68,495 patients), which compared melanoma mortality for thinner (< 1 mm) and thicker lesions, reported risk ratios of 2.89 for lesion thicknesses of 1.01 to 2 mm (95% CI, 2.62-3.18); 4.69 for thicknesses of 2.01 to 4 mm (95% CI, 4.24-5.02); and 5.71 for thicknesses > 4 mm (95% CI, 5.10-6.39).

The downside of visual screening: False-positives

The 2012 cohort study, which reported outcomes from 16,000 biopsies performed following visual screening exams, found that 28 biopsies were performed for each diagnosis of melanoma and 9 to 10 biopsies for each basal cell carcinoma.2 Diagnosis rates (number of skin biopsies performed for each case of cancer diagnosed) were equal in men and women for both types of cancer. However, researchers observed more biopsies for each diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma in women than men (56 vs 28 biopsies per case).

Younger patients underwent more biopsies than older patients for each diagnosis of skin cancer. Women 20 to 34 years of age underwent more biopsies than women 65 years or older for each diagnosis of melanoma (19 additional excisions) and basal cell carcinoma (134 additional excisions). Women 35 to 49 years of age underwent 565 more biopsies for each diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma than women 65 years or older. Similar patterns applied to men 20 to 34 years of age compared with men 65 years or older (24 additional biopsies per melanoma, 109 per basal cell carcinoma, and 898 per squamous cell carcinoma).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The US Preventive Services Task Force recommendations, based on a systematic review of mostly cohort studies, state that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of clinician visual skin cancer screening.7,8

The American Academy of Dermatology states that skin cancer screening can save lives and supports research on the benefits and harms of screening in the primary care setting.9

Continue to: Editor's Takeaway

Editor’s Takeaway

Skin cancer screening by primary care physicians is associated with increased detection of skin cancers, including melanomas—even though we have no confirmation that it changes melanoma mortality. It is unclear what the appropriate rate of false-positive screening tests should be, but wider adoption of noninvasive diagnostic techniques such as dermoscopy might reduce unwarranted biopsies.

1. Kaiser M, Schiller J, Schreckenberger C. The effectiveness of a population-based skin cancer screening program: evidence from Germany. Eur J Health Econ. 2018:19:355-367.

2. Waldmann A, Nolte S, Weinstock MA, et al. Skin cancer screening participation and impact on melanoma incidence in Germany—an observational study on incidence trends in regions with and without population-based screening. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:970-974.

3. Aitken JF, Janda M, Elwood M, et al. Clinical outcomes from skin screening clinics within a community-based melanoma screening program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006:54:105-114.

4. Fritschi L, Dye SA, Katris P. Validity of melanoma diagnosis in a community-based screening program. Am J Epidemiol. 2006:164:385-390.

5. Aitken JF, Elwood M, Baade PD, et al. Clinical whole-body skin examination reduces the incidence of thick melanomas. Int J Cancer. 2010:126:450-458.

6. Wernli KJ, Henrikson NB, Morrison CC, et al. Screening for Skin Cancer in Adults: An Updated Systematic Evidence Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2016. Evidence Synthesis 137.

7. Waldmann A, Nolte S, Geller AC, et al. Frequency of excisions and yields of malignant skin tumors in a population-based screening intervention of 360,288 whole-body examinations. Arch Dermatol. 2012:148:903-910.

8. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Skin Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2016;316:429-435.

9. Torres A. AAD statement on USPSTF recommendation on skin cancer screening. July 2016. https://www.aad.org/media/news-releases/aad-statement-on-uspstf 26. Accessed May 2018.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

No trials have directly assessed skin cancer morbidity associated with physician visual skin screening. A 2018 ecologic cohort study found no difference in melanoma mortality in a population undergoing a national screening program, although screening was associated with 41% more diagnoses of skin cancer.1 A 2012 cohort study found a reduction in melanoma mortality over 7 years associated with a population-based visual skin cancer screening program compared with similar populations that didn’t undergo specific screening.2 At 12-year follow-up, however, there was no longer a difference in mortality.

Primary care visual screening doesn’t decrease melanoma mortality

German researchers trained 1673 non-dermatologists (64% of general practitioners, obstetrician-gynecologists, and urologists in that region of Germany) and 116 dermatologists (98% in the region) to recognize skin cancer through whole-body visual inspection.1 They recruited and screened 360,000 adults (19% of the population older than 20 years; 74% women) and followed age- and sex-adjusted melanoma mortality over the next 10 years. Non-dermatologists performed most screening exams (77%); 37% of screened positive patients were lost to follow-up.

Melanoma mortality ultimately didn’t change in the screened region, compared with populations in other European countries without national screening programs. Screening detected approximately half of melanoma cases (585/1169) in the region and was associated with 41% greater detection of skin cancers compared with other countries.

Researchers recorded age-adjusted increases in incidence per 100,000 of melanoma from 14.2 (95% confidence interval [CI], 13.3-15.1) to 18 (95% CI, 16.6-19.4), melanoma in situ from 5.8 (95% CI, 5.2-6.4) to 8.5 (95% CI, 7.5-9.5), squamous cell carcinoma from 11.2 (95% CI, 10.6-11.8) to 12.9 (95% CI, 12.0-13.8), and basal cell carcinoma from 60.5 (95% CI, 59.0-62.1) to 78.4 (95% CI, 75.9-80.8).

Visual screening by primary care providers vs screening by dermatologists

A cohort study of 16,383 Australian adults found that visual screening by primary care physicians detected melanoma over 3 years with a sensitivity of 40.2% (95% CIs not supplied) and specificity of 86.1% (95% CI, 85.6-86.6%; positive predictive value = 1.4%).3

A second cohort study, enrolling 7436 adults, that evaluated visual screening by dermatologists and plastic surgeons over 2 years found a sensitivity for melanoma of 49% (95% CI, 34.4-63.7%) and a specificity of 97.6% (95% CI, 97.2-97.9%) with a positive predictive value of 11.9% (95% CI, 7.8-17.2%).4

Visual screening more often detects thinner melanomas

A 3-year case-control study (3762 cases, 3824 controls) that examined the association between visual skin screening by a physician (type of physician not specified) and thickness of melanomas detected found that thin melanomas (≤ 0.75 mm) were more common among screened patients compared with unscreened patients (odds ratio [OR] = 1.38; 95% CI, 1.22-1.56) and thicker melanomas (≥ 0.75 mm) were less common (OR = 0.86; 95% CI, 0.75-0.98).5

Continue to: A systematic review...

A systematic review of 8 observational cohort studies with a total of 200,000 patients found a consistent linear increase in melanoma mortality with increasing tumor thickness.6 The largest study (68,495 patients), which compared melanoma mortality for thinner (< 1 mm) and thicker lesions, reported risk ratios of 2.89 for lesion thicknesses of 1.01 to 2 mm (95% CI, 2.62-3.18); 4.69 for thicknesses of 2.01 to 4 mm (95% CI, 4.24-5.02); and 5.71 for thicknesses > 4 mm (95% CI, 5.10-6.39).

The downside of visual screening: False-positives

The 2012 cohort study, which reported outcomes from 16,000 biopsies performed following visual screening exams, found that 28 biopsies were performed for each diagnosis of melanoma and 9 to 10 biopsies for each basal cell carcinoma.2 Diagnosis rates (number of skin biopsies performed for each case of cancer diagnosed) were equal in men and women for both types of cancer. However, researchers observed more biopsies for each diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma in women than men (56 vs 28 biopsies per case).

Younger patients underwent more biopsies than older patients for each diagnosis of skin cancer. Women 20 to 34 years of age underwent more biopsies than women 65 years or older for each diagnosis of melanoma (19 additional excisions) and basal cell carcinoma (134 additional excisions). Women 35 to 49 years of age underwent 565 more biopsies for each diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma than women 65 years or older. Similar patterns applied to men 20 to 34 years of age compared with men 65 years or older (24 additional biopsies per melanoma, 109 per basal cell carcinoma, and 898 per squamous cell carcinoma).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The US Preventive Services Task Force recommendations, based on a systematic review of mostly cohort studies, state that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of clinician visual skin cancer screening.7,8

The American Academy of Dermatology states that skin cancer screening can save lives and supports research on the benefits and harms of screening in the primary care setting.9

Continue to: Editor's Takeaway

Editor’s Takeaway

Skin cancer screening by primary care physicians is associated with increased detection of skin cancers, including melanomas—even though we have no confirmation that it changes melanoma mortality. It is unclear what the appropriate rate of false-positive screening tests should be, but wider adoption of noninvasive diagnostic techniques such as dermoscopy might reduce unwarranted biopsies.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

No trials have directly assessed skin cancer morbidity associated with physician visual skin screening. A 2018 ecologic cohort study found no difference in melanoma mortality in a population undergoing a national screening program, although screening was associated with 41% more diagnoses of skin cancer.1 A 2012 cohort study found a reduction in melanoma mortality over 7 years associated with a population-based visual skin cancer screening program compared with similar populations that didn’t undergo specific screening.2 At 12-year follow-up, however, there was no longer a difference in mortality.

Primary care visual screening doesn’t decrease melanoma mortality

German researchers trained 1673 non-dermatologists (64% of general practitioners, obstetrician-gynecologists, and urologists in that region of Germany) and 116 dermatologists (98% in the region) to recognize skin cancer through whole-body visual inspection.1 They recruited and screened 360,000 adults (19% of the population older than 20 years; 74% women) and followed age- and sex-adjusted melanoma mortality over the next 10 years. Non-dermatologists performed most screening exams (77%); 37% of screened positive patients were lost to follow-up.

Melanoma mortality ultimately didn’t change in the screened region, compared with populations in other European countries without national screening programs. Screening detected approximately half of melanoma cases (585/1169) in the region and was associated with 41% greater detection of skin cancers compared with other countries.

Researchers recorded age-adjusted increases in incidence per 100,000 of melanoma from 14.2 (95% confidence interval [CI], 13.3-15.1) to 18 (95% CI, 16.6-19.4), melanoma in situ from 5.8 (95% CI, 5.2-6.4) to 8.5 (95% CI, 7.5-9.5), squamous cell carcinoma from 11.2 (95% CI, 10.6-11.8) to 12.9 (95% CI, 12.0-13.8), and basal cell carcinoma from 60.5 (95% CI, 59.0-62.1) to 78.4 (95% CI, 75.9-80.8).

Visual screening by primary care providers vs screening by dermatologists

A cohort study of 16,383 Australian adults found that visual screening by primary care physicians detected melanoma over 3 years with a sensitivity of 40.2% (95% CIs not supplied) and specificity of 86.1% (95% CI, 85.6-86.6%; positive predictive value = 1.4%).3

A second cohort study, enrolling 7436 adults, that evaluated visual screening by dermatologists and plastic surgeons over 2 years found a sensitivity for melanoma of 49% (95% CI, 34.4-63.7%) and a specificity of 97.6% (95% CI, 97.2-97.9%) with a positive predictive value of 11.9% (95% CI, 7.8-17.2%).4

Visual screening more often detects thinner melanomas

A 3-year case-control study (3762 cases, 3824 controls) that examined the association between visual skin screening by a physician (type of physician not specified) and thickness of melanomas detected found that thin melanomas (≤ 0.75 mm) were more common among screened patients compared with unscreened patients (odds ratio [OR] = 1.38; 95% CI, 1.22-1.56) and thicker melanomas (≥ 0.75 mm) were less common (OR = 0.86; 95% CI, 0.75-0.98).5

Continue to: A systematic review...

A systematic review of 8 observational cohort studies with a total of 200,000 patients found a consistent linear increase in melanoma mortality with increasing tumor thickness.6 The largest study (68,495 patients), which compared melanoma mortality for thinner (< 1 mm) and thicker lesions, reported risk ratios of 2.89 for lesion thicknesses of 1.01 to 2 mm (95% CI, 2.62-3.18); 4.69 for thicknesses of 2.01 to 4 mm (95% CI, 4.24-5.02); and 5.71 for thicknesses > 4 mm (95% CI, 5.10-6.39).

The downside of visual screening: False-positives

The 2012 cohort study, which reported outcomes from 16,000 biopsies performed following visual screening exams, found that 28 biopsies were performed for each diagnosis of melanoma and 9 to 10 biopsies for each basal cell carcinoma.2 Diagnosis rates (number of skin biopsies performed for each case of cancer diagnosed) were equal in men and women for both types of cancer. However, researchers observed more biopsies for each diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma in women than men (56 vs 28 biopsies per case).

Younger patients underwent more biopsies than older patients for each diagnosis of skin cancer. Women 20 to 34 years of age underwent more biopsies than women 65 years or older for each diagnosis of melanoma (19 additional excisions) and basal cell carcinoma (134 additional excisions). Women 35 to 49 years of age underwent 565 more biopsies for each diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma than women 65 years or older. Similar patterns applied to men 20 to 34 years of age compared with men 65 years or older (24 additional biopsies per melanoma, 109 per basal cell carcinoma, and 898 per squamous cell carcinoma).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The US Preventive Services Task Force recommendations, based on a systematic review of mostly cohort studies, state that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of clinician visual skin cancer screening.7,8

The American Academy of Dermatology states that skin cancer screening can save lives and supports research on the benefits and harms of screening in the primary care setting.9

Continue to: Editor's Takeaway

Editor’s Takeaway

Skin cancer screening by primary care physicians is associated with increased detection of skin cancers, including melanomas—even though we have no confirmation that it changes melanoma mortality. It is unclear what the appropriate rate of false-positive screening tests should be, but wider adoption of noninvasive diagnostic techniques such as dermoscopy might reduce unwarranted biopsies.

1. Kaiser M, Schiller J, Schreckenberger C. The effectiveness of a population-based skin cancer screening program: evidence from Germany. Eur J Health Econ. 2018:19:355-367.

2. Waldmann A, Nolte S, Weinstock MA, et al. Skin cancer screening participation and impact on melanoma incidence in Germany—an observational study on incidence trends in regions with and without population-based screening. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:970-974.

3. Aitken JF, Janda M, Elwood M, et al. Clinical outcomes from skin screening clinics within a community-based melanoma screening program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006:54:105-114.

4. Fritschi L, Dye SA, Katris P. Validity of melanoma diagnosis in a community-based screening program. Am J Epidemiol. 2006:164:385-390.

5. Aitken JF, Elwood M, Baade PD, et al. Clinical whole-body skin examination reduces the incidence of thick melanomas. Int J Cancer. 2010:126:450-458.

6. Wernli KJ, Henrikson NB, Morrison CC, et al. Screening for Skin Cancer in Adults: An Updated Systematic Evidence Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2016. Evidence Synthesis 137.

7. Waldmann A, Nolte S, Geller AC, et al. Frequency of excisions and yields of malignant skin tumors in a population-based screening intervention of 360,288 whole-body examinations. Arch Dermatol. 2012:148:903-910.

8. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Skin Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2016;316:429-435.

9. Torres A. AAD statement on USPSTF recommendation on skin cancer screening. July 2016. https://www.aad.org/media/news-releases/aad-statement-on-uspstf 26. Accessed May 2018.

1. Kaiser M, Schiller J, Schreckenberger C. The effectiveness of a population-based skin cancer screening program: evidence from Germany. Eur J Health Econ. 2018:19:355-367.

2. Waldmann A, Nolte S, Weinstock MA, et al. Skin cancer screening participation and impact on melanoma incidence in Germany—an observational study on incidence trends in regions with and without population-based screening. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:970-974.

3. Aitken JF, Janda M, Elwood M, et al. Clinical outcomes from skin screening clinics within a community-based melanoma screening program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006:54:105-114.

4. Fritschi L, Dye SA, Katris P. Validity of melanoma diagnosis in a community-based screening program. Am J Epidemiol. 2006:164:385-390.

5. Aitken JF, Elwood M, Baade PD, et al. Clinical whole-body skin examination reduces the incidence of thick melanomas. Int J Cancer. 2010:126:450-458.

6. Wernli KJ, Henrikson NB, Morrison CC, et al. Screening for Skin Cancer in Adults: An Updated Systematic Evidence Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2016. Evidence Synthesis 137.

7. Waldmann A, Nolte S, Geller AC, et al. Frequency of excisions and yields of malignant skin tumors in a population-based screening intervention of 360,288 whole-body examinations. Arch Dermatol. 2012:148:903-910.

8. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Skin Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2016;316:429-435.

9. Torres A. AAD statement on USPSTF recommendation on skin cancer screening. July 2016. https://www.aad.org/media/news-releases/aad-statement-on-uspstf 26. Accessed May 2018.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Possibly. No trials have directly assessed detection of melanoma and other skin cancers by primary care providers.

Training a group comprised largely of primary care physicians to perform skin cancer screening was associated with a 41% increase in skin cancer diagnoses but no change in melanoma mortality.

Visual screening for melanoma by primary care physicians is 40% sensitive and 86% specific (compared with 49% and 98%, respectively, for dermatologists and plastic surgeons).

Melanomas found by visual screening are 38% more likely to be thin (≤ 0.75 mm) than melanomas discovered without screening, which correlates with improved outcomes.

Visual skin cancer screening overall is associated with false-positive rates as follows: 28 biopsies for each melanoma detected, 9 to 10 biopsies for each basal cell carcinoma, and 28 to 56 biopsies for squamous cell carcinoma. False-positive rates are higher for women—as much as double the rate for men—and younger patients—as much as 20-fold the rate for older patients (strength of recommendations for all foregoing statements: B, cohort studies).

DoD ‘Taking all Necessary Precautions’ Against COVID-19

In late February, a soldier stationed at Camp Carroll near Daegu, South Korea, was the first military member to test positive for the coronavirus (COVID-19). Before being diagnosed, he visited other areas, including Camp Walker in Daegu, according to a statement released by US Forces Korea. More than 75,000 troops are stationed in countries with virus outbreaks, including Japan, Italy, and Bahrain.

Military research laboratories are working “feverishly around the horn” to come up with a vaccine, Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Gen. Mark A. Milley said in a March 2, 2020, news conference. At the same conference, Defense Secretary Mark T. Esper, MD, said US Department of Defense (DoD) civilian and military leadership are working together to prepare for short-and long-term scenarios.

The US Northern Command is the “global integrator,” Esper said, with the DoD communicating regularly with operational commanders to assess how the virus might impact exercises and ongoing operations around the world. For example, a command post exercise in South Korea has been postponed; Exercise Cobra Gold in Thailand is continuing.

Commanders are taking all necessary precautions because the virus is unique to every situation and every location, Esper said: “We’re relying on them to make good judgments.”

He emphasized that commanders at all levels have the authority and guidance they need to operate. In a late February video teleconference, Esper had told commanders deployed overseas that he wanted them to give him a heads-up before making decisions related to protecting their troops, according to The New York Times.

The New York Times article cited an exchange in which Gen. Robert Abrams, commander of American forces in South Korea, where > 4,000 coronavirus cases have been confirmed, discussed his options to protect American military personnel against the virus. Esper said he wanted advance notice, according to an official briefed on the call and quoted in the Times article. Gen. Abrams said although he would try to give Sec. Esper advance warning, he might have to make urgent health decisions before receiving final approval from Washington.

In a statement responding to the Times article, Jonathan Hoffman, Assistant to the Secretary of Defense for Public Affairs, said the Secretary of Defense has given the Global Combatant Commanders the “clear and unequivocal authority” to take any and all actions necessary to ensure the health and safety of US service members, civilian DoD personnel, families, and dependents.

In the video teleconference, Hoffman said, Secretary Espers “directed commanders to take all force health protection measures, and to notify their chain of command when actions are taken so that DoD leadership can inform the interagency—including US Department of Health and Human Services, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Department of Homeland Security, the State Department, and the White House—and the American people.” Esper “explicitly did not direct them to ‘clear’ their force health decisions in advance,” Hoffman said. “[T]hat is a dangerous and inaccurate mischaracterization.”

In January, the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense released a memorandum on force health protection guidance for the coronavirus outbreak. The DoD, it says, will follow the CDC guidance and will “closely coordinate with interagency partners to ensure accurate and timely information is available.”

“An informed, common-sense approach minimizes the chances of getting sick,” military health officials say. But, “due to the dynamic nature of this outbreak,” people should frequently check the CDC website for additional updates. Related Military Health System information and links to the CDC are available at https://www.health.mil/News/In-the-Spotlight/Coronavirus.

The CDC provides a summary of its latest recommendations and DoD health care providers can access COVID-19–specific guidance, including information on evaluating “persons under investigation,” at https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/clinical-criteria.html.

Sec. Esper, in the Monday news conference, said, “My number-one priority remains to protect our forces and their families; second is to safeguard our mission capabilities and third [is] to support the interagency whole-of-government’s approach. We will continue to take all necessary precautions to ensure that our people are safe and able to continue their very important mission.”

In late February, a soldier stationed at Camp Carroll near Daegu, South Korea, was the first military member to test positive for the coronavirus (COVID-19). Before being diagnosed, he visited other areas, including Camp Walker in Daegu, according to a statement released by US Forces Korea. More than 75,000 troops are stationed in countries with virus outbreaks, including Japan, Italy, and Bahrain.

Military research laboratories are working “feverishly around the horn” to come up with a vaccine, Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Gen. Mark A. Milley said in a March 2, 2020, news conference. At the same conference, Defense Secretary Mark T. Esper, MD, said US Department of Defense (DoD) civilian and military leadership are working together to prepare for short-and long-term scenarios.

The US Northern Command is the “global integrator,” Esper said, with the DoD communicating regularly with operational commanders to assess how the virus might impact exercises and ongoing operations around the world. For example, a command post exercise in South Korea has been postponed; Exercise Cobra Gold in Thailand is continuing.

Commanders are taking all necessary precautions because the virus is unique to every situation and every location, Esper said: “We’re relying on them to make good judgments.”

He emphasized that commanders at all levels have the authority and guidance they need to operate. In a late February video teleconference, Esper had told commanders deployed overseas that he wanted them to give him a heads-up before making decisions related to protecting their troops, according to The New York Times.

The New York Times article cited an exchange in which Gen. Robert Abrams, commander of American forces in South Korea, where > 4,000 coronavirus cases have been confirmed, discussed his options to protect American military personnel against the virus. Esper said he wanted advance notice, according to an official briefed on the call and quoted in the Times article. Gen. Abrams said although he would try to give Sec. Esper advance warning, he might have to make urgent health decisions before receiving final approval from Washington.

In a statement responding to the Times article, Jonathan Hoffman, Assistant to the Secretary of Defense for Public Affairs, said the Secretary of Defense has given the Global Combatant Commanders the “clear and unequivocal authority” to take any and all actions necessary to ensure the health and safety of US service members, civilian DoD personnel, families, and dependents.

In the video teleconference, Hoffman said, Secretary Espers “directed commanders to take all force health protection measures, and to notify their chain of command when actions are taken so that DoD leadership can inform the interagency—including US Department of Health and Human Services, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Department of Homeland Security, the State Department, and the White House—and the American people.” Esper “explicitly did not direct them to ‘clear’ their force health decisions in advance,” Hoffman said. “[T]hat is a dangerous and inaccurate mischaracterization.”

In January, the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense released a memorandum on force health protection guidance for the coronavirus outbreak. The DoD, it says, will follow the CDC guidance and will “closely coordinate with interagency partners to ensure accurate and timely information is available.”

“An informed, common-sense approach minimizes the chances of getting sick,” military health officials say. But, “due to the dynamic nature of this outbreak,” people should frequently check the CDC website for additional updates. Related Military Health System information and links to the CDC are available at https://www.health.mil/News/In-the-Spotlight/Coronavirus.

The CDC provides a summary of its latest recommendations and DoD health care providers can access COVID-19–specific guidance, including information on evaluating “persons under investigation,” at https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/clinical-criteria.html.

Sec. Esper, in the Monday news conference, said, “My number-one priority remains to protect our forces and their families; second is to safeguard our mission capabilities and third [is] to support the interagency whole-of-government’s approach. We will continue to take all necessary precautions to ensure that our people are safe and able to continue their very important mission.”

In late February, a soldier stationed at Camp Carroll near Daegu, South Korea, was the first military member to test positive for the coronavirus (COVID-19). Before being diagnosed, he visited other areas, including Camp Walker in Daegu, according to a statement released by US Forces Korea. More than 75,000 troops are stationed in countries with virus outbreaks, including Japan, Italy, and Bahrain.

Military research laboratories are working “feverishly around the horn” to come up with a vaccine, Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Gen. Mark A. Milley said in a March 2, 2020, news conference. At the same conference, Defense Secretary Mark T. Esper, MD, said US Department of Defense (DoD) civilian and military leadership are working together to prepare for short-and long-term scenarios.

The US Northern Command is the “global integrator,” Esper said, with the DoD communicating regularly with operational commanders to assess how the virus might impact exercises and ongoing operations around the world. For example, a command post exercise in South Korea has been postponed; Exercise Cobra Gold in Thailand is continuing.

Commanders are taking all necessary precautions because the virus is unique to every situation and every location, Esper said: “We’re relying on them to make good judgments.”

He emphasized that commanders at all levels have the authority and guidance they need to operate. In a late February video teleconference, Esper had told commanders deployed overseas that he wanted them to give him a heads-up before making decisions related to protecting their troops, according to The New York Times.

The New York Times article cited an exchange in which Gen. Robert Abrams, commander of American forces in South Korea, where > 4,000 coronavirus cases have been confirmed, discussed his options to protect American military personnel against the virus. Esper said he wanted advance notice, according to an official briefed on the call and quoted in the Times article. Gen. Abrams said although he would try to give Sec. Esper advance warning, he might have to make urgent health decisions before receiving final approval from Washington.

In a statement responding to the Times article, Jonathan Hoffman, Assistant to the Secretary of Defense for Public Affairs, said the Secretary of Defense has given the Global Combatant Commanders the “clear and unequivocal authority” to take any and all actions necessary to ensure the health and safety of US service members, civilian DoD personnel, families, and dependents.

In the video teleconference, Hoffman said, Secretary Espers “directed commanders to take all force health protection measures, and to notify their chain of command when actions are taken so that DoD leadership can inform the interagency—including US Department of Health and Human Services, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Department of Homeland Security, the State Department, and the White House—and the American people.” Esper “explicitly did not direct them to ‘clear’ their force health decisions in advance,” Hoffman said. “[T]hat is a dangerous and inaccurate mischaracterization.”

In January, the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense released a memorandum on force health protection guidance for the coronavirus outbreak. The DoD, it says, will follow the CDC guidance and will “closely coordinate with interagency partners to ensure accurate and timely information is available.”

“An informed, common-sense approach minimizes the chances of getting sick,” military health officials say. But, “due to the dynamic nature of this outbreak,” people should frequently check the CDC website for additional updates. Related Military Health System information and links to the CDC are available at https://www.health.mil/News/In-the-Spotlight/Coronavirus.

The CDC provides a summary of its latest recommendations and DoD health care providers can access COVID-19–specific guidance, including information on evaluating “persons under investigation,” at https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/clinical-criteria.html.

Sec. Esper, in the Monday news conference, said, “My number-one priority remains to protect our forces and their families; second is to safeguard our mission capabilities and third [is] to support the interagency whole-of-government’s approach. We will continue to take all necessary precautions to ensure that our people are safe and able to continue their very important mission.”

Spiky Papules on the Dorsal Feet

The Diagnosis: Hyperkeratosis Lenticularis Perstans (Flegel Disease)

Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans, also known as Flegel disease, is a rare dermatosis first described by Flegel1 in 1958. This benign disorder is characterized by multiple asymptomatic 1- to 5-mm keratotic papules in a symmetric distribution favoring the dorsal aspects of the feet and distal extremities in adults. An autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern has been postulated, though many cases sporadically occur.2 The characteristic spiky papules typically appear during mid to late adulthood and tend to persist. Treatment options are lacking, with reports of partial or no response to topical calcipotriol, topical 5-fluorouracil, cryotherapy, and topical and oral retinoids.3,4

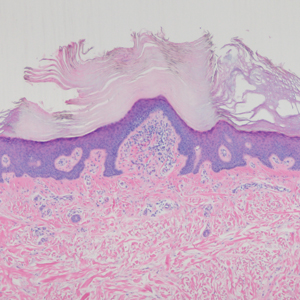

The histopathology of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans is distinct, showing a central discrete area of orthohyperkeratosis with patchy parakeratosis flanked by a normal stratum corneum. The underlying epidermis typically shows effacement of the rete ridge pattern with subtle basal zone vacuolization and rare necrotic keratinocytes with an underlying lichenoid infiltrate within the papillary dermis comprised of lymphomononuclear cells.

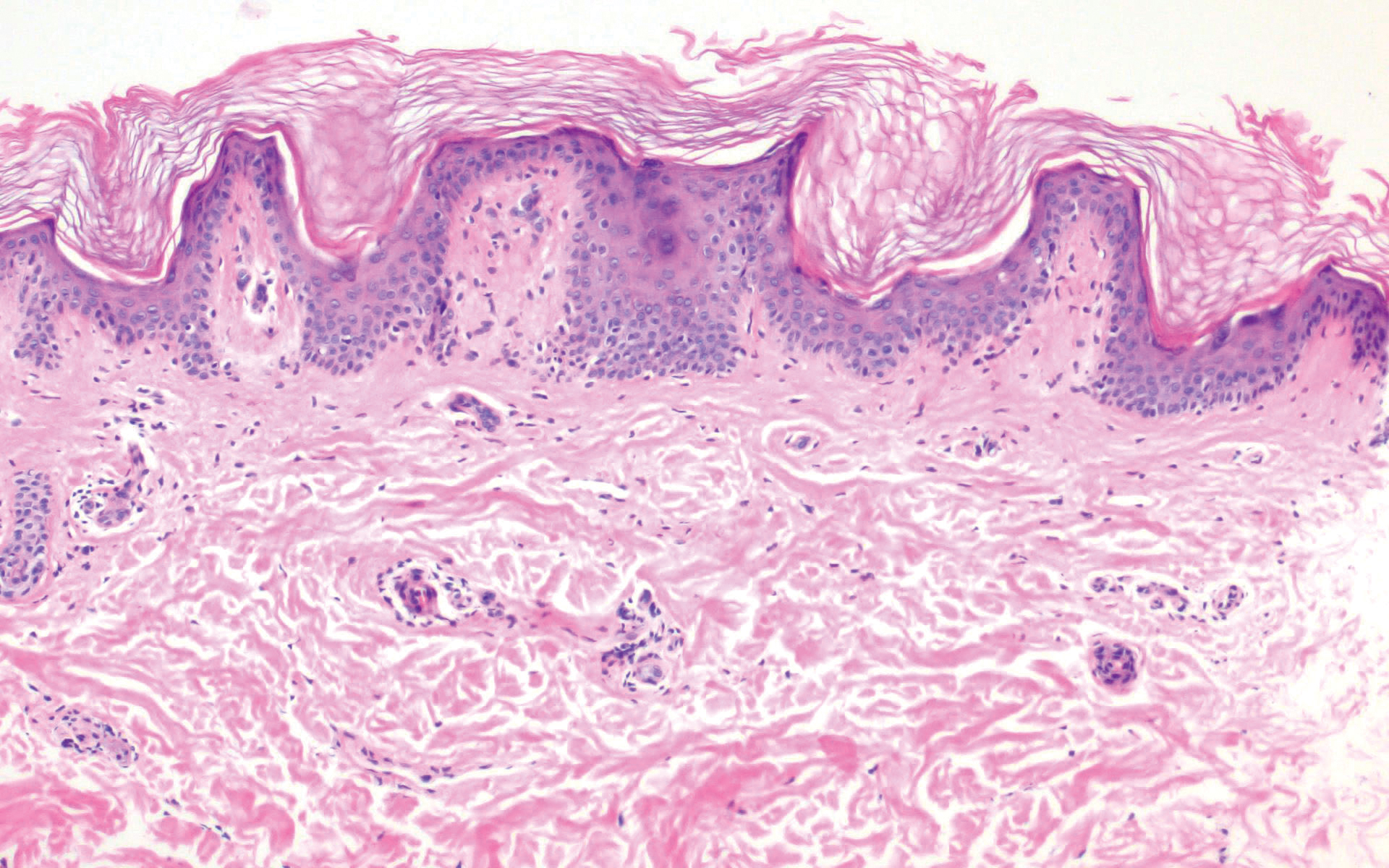

In contrast, punctate porokeratosis clinically tends to involve the palms and soles, though the arms and legs also may be involved. This entity tends to occur during adolescence. A raised hyperkeratotic papule clinically is present. Histopathologically, the epidermis has a cup-shaped depression filled with hyperkeratosis and a column of parakeratosis (coronoid lamellae)(Figure 1).

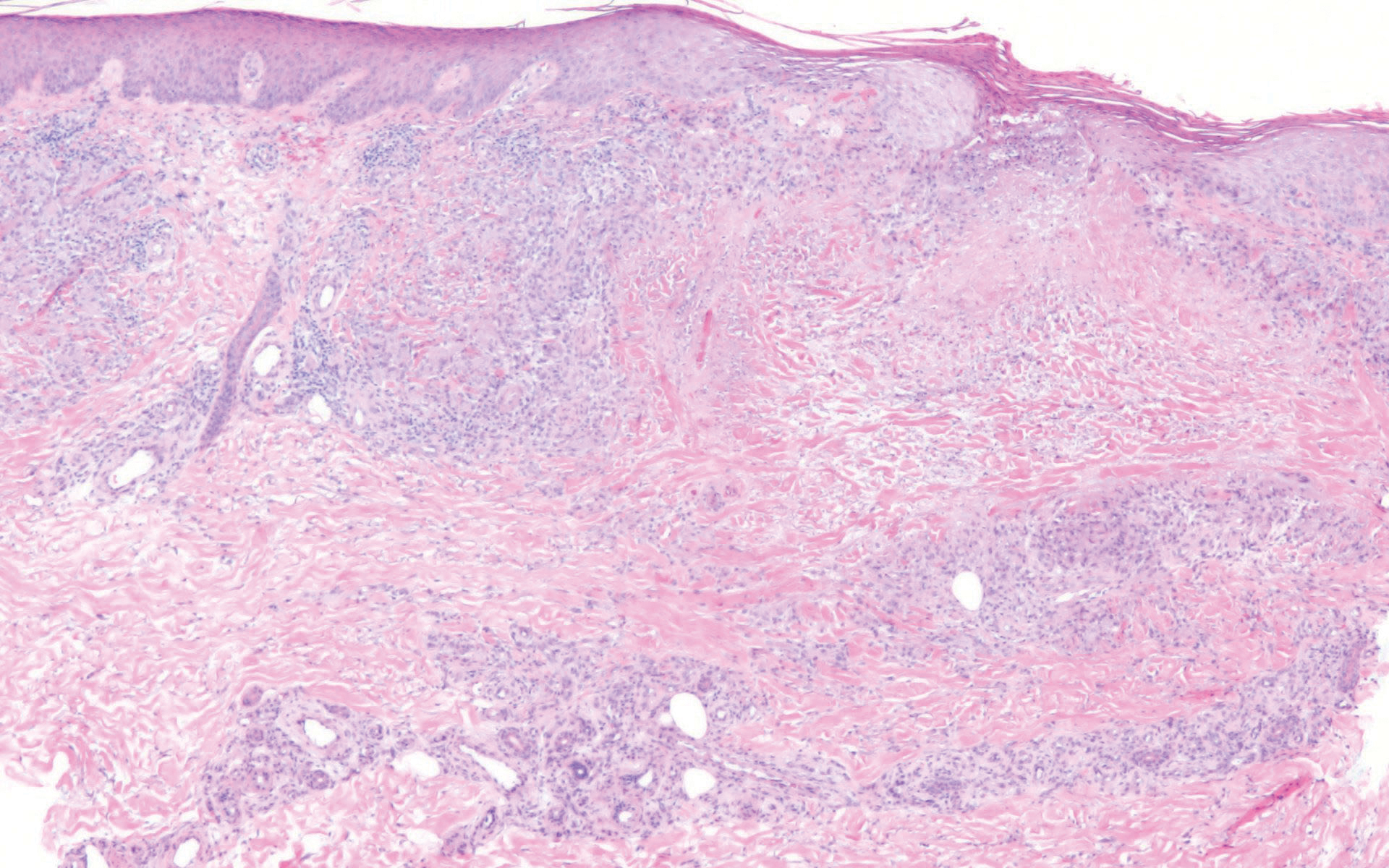

Acrokeratosis verruciformis of Hopf clinically appears on the dorsal aspects of the hands and feet as small warty papules in association with Darier disease. It typically presents during early childhood. Histopathology shows tiered hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and acanthosis (Figure 2).

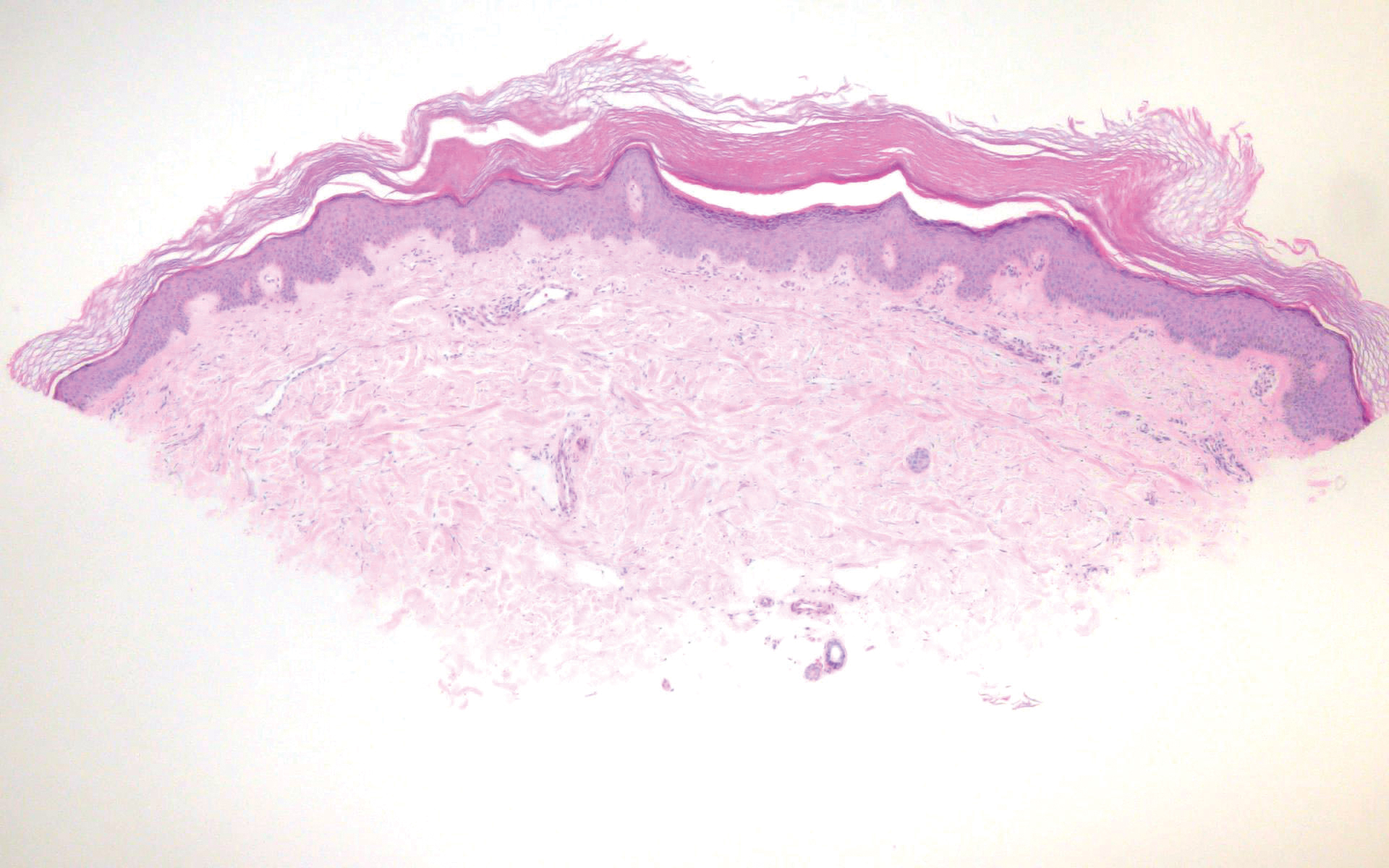

Perforating granuloma annulare presents on the dorsal aspects of the hands and fingers as scaly papules with either central umbilication or keratotic plugs. Histopathology shows transepidermal elimination of degenerated collagen (Figure 3).

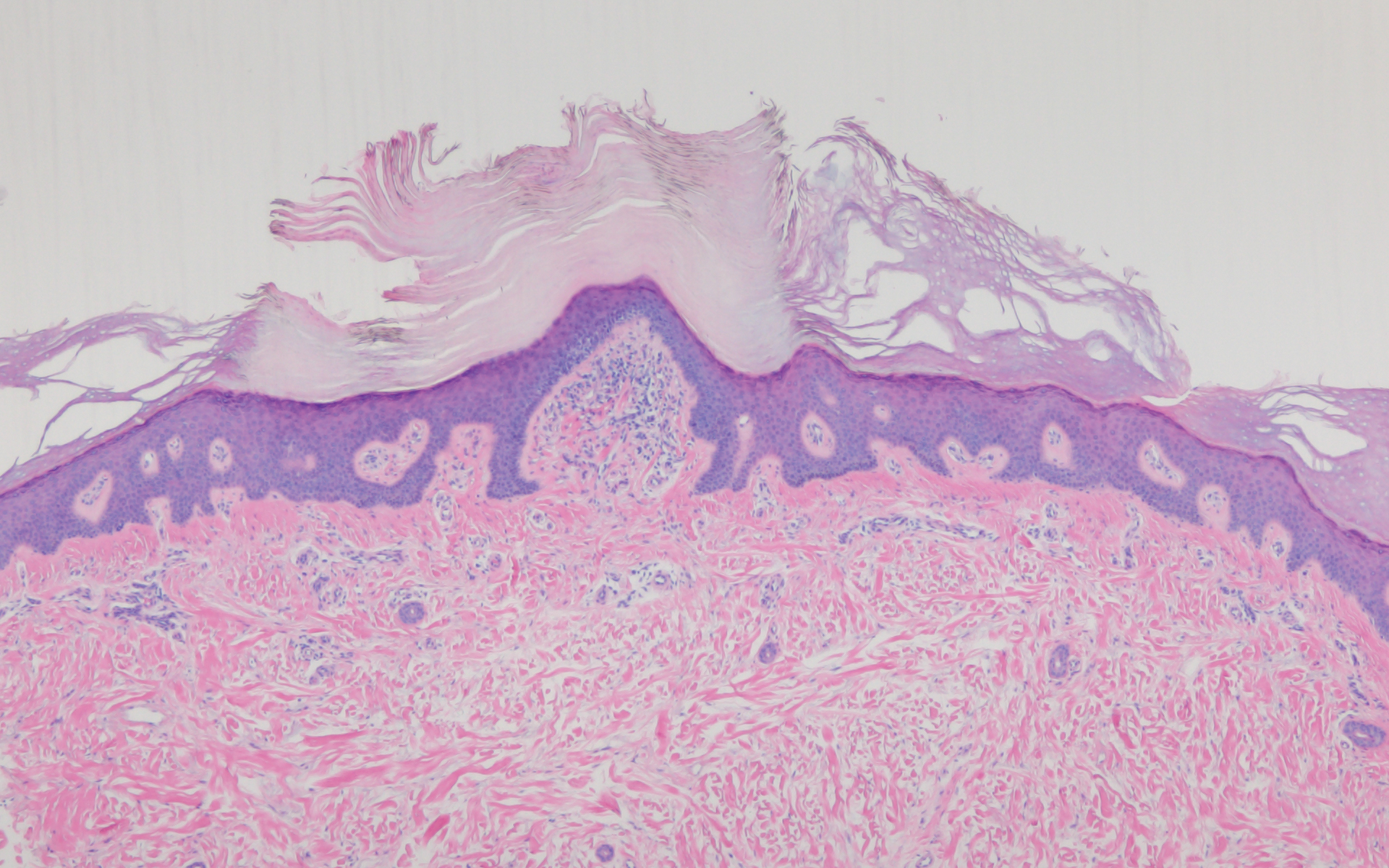

Stucco keratoses present on the dorsal aspects of the feet and ankles but are waxy smooth papules as opposed to hyperkeratotic spiky papules. Histologically, they are characterized by retention hyperkeratosis with lack of parakeratosis and regular acanthosis with a "string sign" indicating that the lesion extends to a uniform depth. (Figure 4).

- Flegel H. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Hautzarzt. 1958;9:363-364.

- Ando K, Hattori H, Yamauchi Y. Histopathological differences between early and old lesions of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:122-126.

- Langer K, Zonzits E, Konrad K. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). ultrastructural study of lesional and perilesional skin and therapeutic trial of topical tretinoin versus 5-fluorouracil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:812-816.

- Blaheta HJ, Metzler G, Rassner G, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease)--lack of response to treatment with tacalcitol and calcipotriol. Dermatology. 2001;202:255-258.

The Diagnosis: Hyperkeratosis Lenticularis Perstans (Flegel Disease)

Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans, also known as Flegel disease, is a rare dermatosis first described by Flegel1 in 1958. This benign disorder is characterized by multiple asymptomatic 1- to 5-mm keratotic papules in a symmetric distribution favoring the dorsal aspects of the feet and distal extremities in adults. An autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern has been postulated, though many cases sporadically occur.2 The characteristic spiky papules typically appear during mid to late adulthood and tend to persist. Treatment options are lacking, with reports of partial or no response to topical calcipotriol, topical 5-fluorouracil, cryotherapy, and topical and oral retinoids.3,4

The histopathology of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans is distinct, showing a central discrete area of orthohyperkeratosis with patchy parakeratosis flanked by a normal stratum corneum. The underlying epidermis typically shows effacement of the rete ridge pattern with subtle basal zone vacuolization and rare necrotic keratinocytes with an underlying lichenoid infiltrate within the papillary dermis comprised of lymphomononuclear cells.

In contrast, punctate porokeratosis clinically tends to involve the palms and soles, though the arms and legs also may be involved. This entity tends to occur during adolescence. A raised hyperkeratotic papule clinically is present. Histopathologically, the epidermis has a cup-shaped depression filled with hyperkeratosis and a column of parakeratosis (coronoid lamellae)(Figure 1).

Acrokeratosis verruciformis of Hopf clinically appears on the dorsal aspects of the hands and feet as small warty papules in association with Darier disease. It typically presents during early childhood. Histopathology shows tiered hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and acanthosis (Figure 2).

Perforating granuloma annulare presents on the dorsal aspects of the hands and fingers as scaly papules with either central umbilication or keratotic plugs. Histopathology shows transepidermal elimination of degenerated collagen (Figure 3).

Stucco keratoses present on the dorsal aspects of the feet and ankles but are waxy smooth papules as opposed to hyperkeratotic spiky papules. Histologically, they are characterized by retention hyperkeratosis with lack of parakeratosis and regular acanthosis with a "string sign" indicating that the lesion extends to a uniform depth. (Figure 4).

The Diagnosis: Hyperkeratosis Lenticularis Perstans (Flegel Disease)

Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans, also known as Flegel disease, is a rare dermatosis first described by Flegel1 in 1958. This benign disorder is characterized by multiple asymptomatic 1- to 5-mm keratotic papules in a symmetric distribution favoring the dorsal aspects of the feet and distal extremities in adults. An autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern has been postulated, though many cases sporadically occur.2 The characteristic spiky papules typically appear during mid to late adulthood and tend to persist. Treatment options are lacking, with reports of partial or no response to topical calcipotriol, topical 5-fluorouracil, cryotherapy, and topical and oral retinoids.3,4

The histopathology of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans is distinct, showing a central discrete area of orthohyperkeratosis with patchy parakeratosis flanked by a normal stratum corneum. The underlying epidermis typically shows effacement of the rete ridge pattern with subtle basal zone vacuolization and rare necrotic keratinocytes with an underlying lichenoid infiltrate within the papillary dermis comprised of lymphomononuclear cells.

In contrast, punctate porokeratosis clinically tends to involve the palms and soles, though the arms and legs also may be involved. This entity tends to occur during adolescence. A raised hyperkeratotic papule clinically is present. Histopathologically, the epidermis has a cup-shaped depression filled with hyperkeratosis and a column of parakeratosis (coronoid lamellae)(Figure 1).

Acrokeratosis verruciformis of Hopf clinically appears on the dorsal aspects of the hands and feet as small warty papules in association with Darier disease. It typically presents during early childhood. Histopathology shows tiered hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and acanthosis (Figure 2).

Perforating granuloma annulare presents on the dorsal aspects of the hands and fingers as scaly papules with either central umbilication or keratotic plugs. Histopathology shows transepidermal elimination of degenerated collagen (Figure 3).

Stucco keratoses present on the dorsal aspects of the feet and ankles but are waxy smooth papules as opposed to hyperkeratotic spiky papules. Histologically, they are characterized by retention hyperkeratosis with lack of parakeratosis and regular acanthosis with a "string sign" indicating that the lesion extends to a uniform depth. (Figure 4).

- Flegel H. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Hautzarzt. 1958;9:363-364.

- Ando K, Hattori H, Yamauchi Y. Histopathological differences between early and old lesions of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:122-126.

- Langer K, Zonzits E, Konrad K. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). ultrastructural study of lesional and perilesional skin and therapeutic trial of topical tretinoin versus 5-fluorouracil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:812-816.

- Blaheta HJ, Metzler G, Rassner G, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease)--lack of response to treatment with tacalcitol and calcipotriol. Dermatology. 2001;202:255-258.

- Flegel H. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Hautzarzt. 1958;9:363-364.

- Ando K, Hattori H, Yamauchi Y. Histopathological differences between early and old lesions of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:122-126.

- Langer K, Zonzits E, Konrad K. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). ultrastructural study of lesional and perilesional skin and therapeutic trial of topical tretinoin versus 5-fluorouracil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:812-816.

- Blaheta HJ, Metzler G, Rassner G, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease)--lack of response to treatment with tacalcitol and calcipotriol. Dermatology. 2001;202:255-258.

A 54-year-old man who was otherwise healthy presented with asymptomatic, discrete, rough, red-brown, hyperkeratotic papules on the dorsal aspects of the feet of several years' duration. The lesions spared the soles of the feet and hands. A diagnosis of eczema previously was made by his general practitioner, and he was using moisturizer. No prescription treatments were pursued, and no other rashes or lesions were noted on physical examination. A punch biopsy of a spiky papule was performed.

FDA rules to ban ESDs for self-injurious, aggressive behavior

The Food and Drug Administration has banned all electrical stimulation devices used for self-injurious or aggressive behavior because of an unreasonable risk of illness or injury. This marks only the third time the FDA has banned a medical device since it gained the authority to do so.

Electrical stimulation devices (ESDs) administer electric shocks through electrodes attached to the skin during self-injurious or aggressive behavior in an attempt to condition the patient to stop engaging in that behavior, according to the FDA press release. Current evidence indicates that use of these devices can lead to worsening of underlying symptoms, depression, anxiety, PTSD, pain, burns, and tissue damage; in contrast, evidence supporting their use is weak. In addition, many patients exposed to ESDs have intellectual or developmental disabilities and might not be able to adequately communicate their level of pain.

“Since ESDs were first marketed more than 20 years ago, we have gained a better understanding of the danger these devices present to public health. Through advancements in medical science, there are now more treatment options available to reduce or stop self-injurious or aggressive behavior, thus avoiding the substantial risk ESDs present,” William H. Maisel, MD, MPH, director of the Office of Product Evaluation and Quality in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in the release.

The ruling follows a 2016 proposal to ban ESDs from the marketplace; the proposed rule received more than 1,500 comments from stakeholders, such as parents of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, state agencies and their sister public-private organizations, the affected manufacturer and residential facility, some of the facility’s employees, and parents of individual residents, as well as from state and federal legislators and advocacy groups. Nearly all supported the ban.

The rule will go into effect 30 days after publication of the rule in the Federal Register, and compliance is required within 180 days.

The Food and Drug Administration has banned all electrical stimulation devices used for self-injurious or aggressive behavior because of an unreasonable risk of illness or injury. This marks only the third time the FDA has banned a medical device since it gained the authority to do so.

Electrical stimulation devices (ESDs) administer electric shocks through electrodes attached to the skin during self-injurious or aggressive behavior in an attempt to condition the patient to stop engaging in that behavior, according to the FDA press release. Current evidence indicates that use of these devices can lead to worsening of underlying symptoms, depression, anxiety, PTSD, pain, burns, and tissue damage; in contrast, evidence supporting their use is weak. In addition, many patients exposed to ESDs have intellectual or developmental disabilities and might not be able to adequately communicate their level of pain.

“Since ESDs were first marketed more than 20 years ago, we have gained a better understanding of the danger these devices present to public health. Through advancements in medical science, there are now more treatment options available to reduce or stop self-injurious or aggressive behavior, thus avoiding the substantial risk ESDs present,” William H. Maisel, MD, MPH, director of the Office of Product Evaluation and Quality in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in the release.

The ruling follows a 2016 proposal to ban ESDs from the marketplace; the proposed rule received more than 1,500 comments from stakeholders, such as parents of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, state agencies and their sister public-private organizations, the affected manufacturer and residential facility, some of the facility’s employees, and parents of individual residents, as well as from state and federal legislators and advocacy groups. Nearly all supported the ban.

The rule will go into effect 30 days after publication of the rule in the Federal Register, and compliance is required within 180 days.

The Food and Drug Administration has banned all electrical stimulation devices used for self-injurious or aggressive behavior because of an unreasonable risk of illness or injury. This marks only the third time the FDA has banned a medical device since it gained the authority to do so.

Electrical stimulation devices (ESDs) administer electric shocks through electrodes attached to the skin during self-injurious or aggressive behavior in an attempt to condition the patient to stop engaging in that behavior, according to the FDA press release. Current evidence indicates that use of these devices can lead to worsening of underlying symptoms, depression, anxiety, PTSD, pain, burns, and tissue damage; in contrast, evidence supporting their use is weak. In addition, many patients exposed to ESDs have intellectual or developmental disabilities and might not be able to adequately communicate their level of pain.

“Since ESDs were first marketed more than 20 years ago, we have gained a better understanding of the danger these devices present to public health. Through advancements in medical science, there are now more treatment options available to reduce or stop self-injurious or aggressive behavior, thus avoiding the substantial risk ESDs present,” William H. Maisel, MD, MPH, director of the Office of Product Evaluation and Quality in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in the release.

The ruling follows a 2016 proposal to ban ESDs from the marketplace; the proposed rule received more than 1,500 comments from stakeholders, such as parents of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, state agencies and their sister public-private organizations, the affected manufacturer and residential facility, some of the facility’s employees, and parents of individual residents, as well as from state and federal legislators and advocacy groups. Nearly all supported the ban.

The rule will go into effect 30 days after publication of the rule in the Federal Register, and compliance is required within 180 days.

Chronic anterior knee pain

A 14-year-old girl with an unremarkable medical history presented to the family medicine clinic with a 6-month history of right knee pain (episodic locking and anterior pain). Physical examination of the knee ligaments revealed that the knee was stable and pain-free in the frontal and sagittal planes. There was no intra-articular effusion, the joint spaces were not painful, and range of motion was normal.

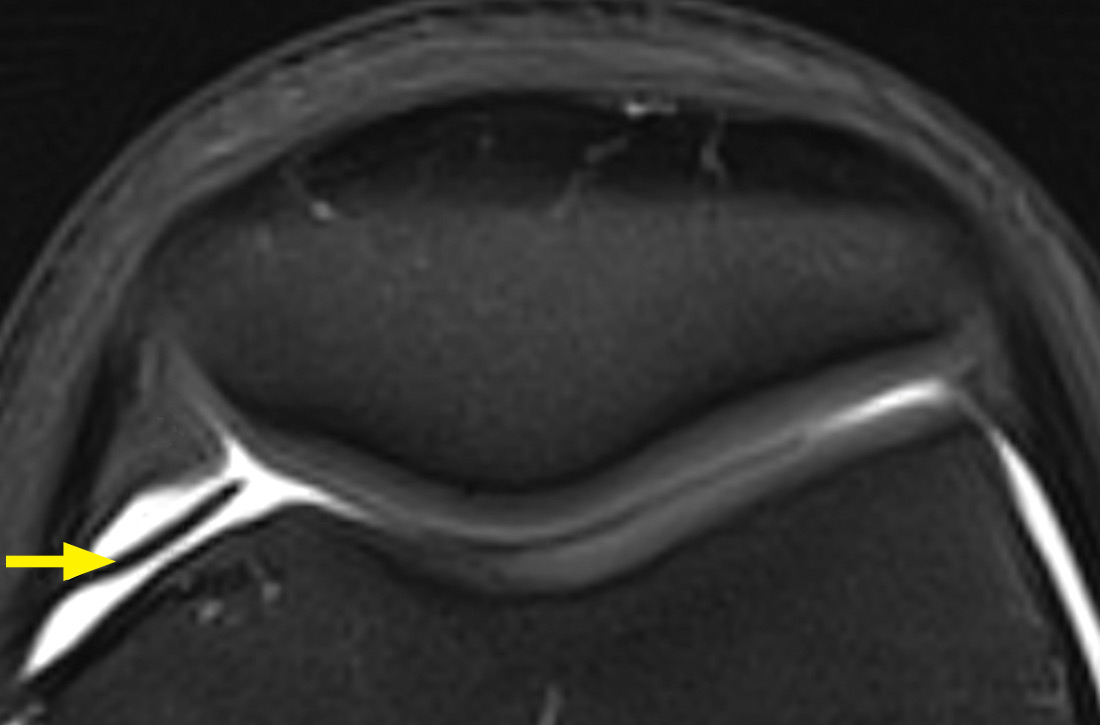

Palpation of the knee elicited pain, notably when the physician rolled his fingers over a “cord” above the internal parapatellar compartment. X-rays of the knee were normal. In light of the patient’s chronic pain, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed (FIGURE 1).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Synovial plica

The MRI with fat saturation revealed a symptomatic synovial plica between the patellar facet and the condyle (FIGURE 1, arrow). The normal x-ray findings had already ruled out osteochondritis dissecans of the femoral condyles, patellar abnormalities, and trochlear dysplasia; the MRI ruled out several additional items in the differential, such as damage to the meniscus, ligament, and/or cartilage.

The synovial plica is a normal structure that develops during the embryogenic phase; however, involution is incomplete in up to 50% of the population, resulting in persistent plicae.1 The plica is often located in a medial position but can occur lateral to, above, or below the knee cap. Although usually asymptomatic, the plica can become pathologic when irritation (eg, from repetitive motion) causes an inflammatory response.1

Synovial plica syndrome, as this condition is known, is a common cause of anterior knee pain in adolescents and athletes; incidence ranges from 3.8% to 5.5%.2 The patient often reports trauma (a direct impact to the knee) or participation in sports activities that require repeated flexion-extension of the knee.3

Presenting symptoms and MRI findings can unlock the diagnosis

The combination of anterior knee pain and a painful parapatellar “cord” on palpation is the most frequent diagnostic sign of synovial plica syndrome.1 Quadriceps wasting, intra-articular effusion, and reduced range of motion of the knee may also be observed.1,4 Some patients experience particularly disconcerting symptoms, such as knee locking, clicking, or instability.1

In most cases, MRI confirms the clinical diagnosis while ruling out other possible causes of the symptoms and associated pathologies.5 However, MRI may not reveal the plica if it is attached to the articular capsule or if there is no intra-articular effusion. Dynamic ultrasound might be of diagnostic value but is operator dependent.4

Continue to: If conservative treatment fails, consider surgical repair

If conservative treatment fails, consider surgical repair

Conservative treatment—a combination of analgesics, anti-inflammatories, and physiotherapy with vastus medialis strengthening and stretching—is the preferred first-line treatment, with a success rate of 40% to 60%.1 If conservative treatment fails, surgical treatment can be

Our patient underwent arthroscopic resection of the plica after 6 months of conservative treatment had failed (FIGURE 2). The patient was able to walk immediately after surgery. The outcome was favorable, since physiotherapy was no longer required 2 months after surgery.

CORRESPONDENCE

Céline Klein, MD, Service d’Orthopédie Pédiatrique, CHU Amiens, Groupe Hospitalier Sud, F-80054 Amiens cedex 1, France; celinekleinfr@yahoo.fr.

1. Camanho GL. Treatment of pathological synovial plicae of the knee. Clinics (Sao Paolo). 2010;65:247-250.

2. Ewing JW. Plica: pathologic or not? J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1993;1:117-121.

3. Patel DR, Villalobos A. Evaluation and management of knee pain in young athletes: overuse injuries of the knee. Transl Pediatr. 2017;6:190-198.

4. Paczesny Ł, Kruczyński J. Medial plica syndrome of the knee: diagnosis with dynamic sonography. Radiology. 2009;251:439-446.

5. Samim M, Smitaman E, Lawrence D, et al. MRI of anterior knee pain. Skeletal Radiol. 2014;43:875-893.

6. Weckström M, Niva MH, Lamminen A, et al. Arthroscopic resection of medial plica of the knee in young adults. Knee. 2010;17:103-107.

7. Kan H, Arai Y, Nakagawa S, et al. Characteristics of medial plica syndrome complicated with cartilage damage. Int Orthop. 2015;39:2489-2494.

A 14-year-old girl with an unremarkable medical history presented to the family medicine clinic with a 6-month history of right knee pain (episodic locking and anterior pain). Physical examination of the knee ligaments revealed that the knee was stable and pain-free in the frontal and sagittal planes. There was no intra-articular effusion, the joint spaces were not painful, and range of motion was normal.

Palpation of the knee elicited pain, notably when the physician rolled his fingers over a “cord” above the internal parapatellar compartment. X-rays of the knee were normal. In light of the patient’s chronic pain, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed (FIGURE 1).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Synovial plica

The MRI with fat saturation revealed a symptomatic synovial plica between the patellar facet and the condyle (FIGURE 1, arrow). The normal x-ray findings had already ruled out osteochondritis dissecans of the femoral condyles, patellar abnormalities, and trochlear dysplasia; the MRI ruled out several additional items in the differential, such as damage to the meniscus, ligament, and/or cartilage.

The synovial plica is a normal structure that develops during the embryogenic phase; however, involution is incomplete in up to 50% of the population, resulting in persistent plicae.1 The plica is often located in a medial position but can occur lateral to, above, or below the knee cap. Although usually asymptomatic, the plica can become pathologic when irritation (eg, from repetitive motion) causes an inflammatory response.1

Synovial plica syndrome, as this condition is known, is a common cause of anterior knee pain in adolescents and athletes; incidence ranges from 3.8% to 5.5%.2 The patient often reports trauma (a direct impact to the knee) or participation in sports activities that require repeated flexion-extension of the knee.3

Presenting symptoms and MRI findings can unlock the diagnosis

The combination of anterior knee pain and a painful parapatellar “cord” on palpation is the most frequent diagnostic sign of synovial plica syndrome.1 Quadriceps wasting, intra-articular effusion, and reduced range of motion of the knee may also be observed.1,4 Some patients experience particularly disconcerting symptoms, such as knee locking, clicking, or instability.1

In most cases, MRI confirms the clinical diagnosis while ruling out other possible causes of the symptoms and associated pathologies.5 However, MRI may not reveal the plica if it is attached to the articular capsule or if there is no intra-articular effusion. Dynamic ultrasound might be of diagnostic value but is operator dependent.4

Continue to: If conservative treatment fails, consider surgical repair

If conservative treatment fails, consider surgical repair

Conservative treatment—a combination of analgesics, anti-inflammatories, and physiotherapy with vastus medialis strengthening and stretching—is the preferred first-line treatment, with a success rate of 40% to 60%.1 If conservative treatment fails, surgical treatment can be

Our patient underwent arthroscopic resection of the plica after 6 months of conservative treatment had failed (FIGURE 2). The patient was able to walk immediately after surgery. The outcome was favorable, since physiotherapy was no longer required 2 months after surgery.

CORRESPONDENCE

Céline Klein, MD, Service d’Orthopédie Pédiatrique, CHU Amiens, Groupe Hospitalier Sud, F-80054 Amiens cedex 1, France; celinekleinfr@yahoo.fr.

A 14-year-old girl with an unremarkable medical history presented to the family medicine clinic with a 6-month history of right knee pain (episodic locking and anterior pain). Physical examination of the knee ligaments revealed that the knee was stable and pain-free in the frontal and sagittal planes. There was no intra-articular effusion, the joint spaces were not painful, and range of motion was normal.

Palpation of the knee elicited pain, notably when the physician rolled his fingers over a “cord” above the internal parapatellar compartment. X-rays of the knee were normal. In light of the patient’s chronic pain, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed (FIGURE 1).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Synovial plica

The MRI with fat saturation revealed a symptomatic synovial plica between the patellar facet and the condyle (FIGURE 1, arrow). The normal x-ray findings had already ruled out osteochondritis dissecans of the femoral condyles, patellar abnormalities, and trochlear dysplasia; the MRI ruled out several additional items in the differential, such as damage to the meniscus, ligament, and/or cartilage.

The synovial plica is a normal structure that develops during the embryogenic phase; however, involution is incomplete in up to 50% of the population, resulting in persistent plicae.1 The plica is often located in a medial position but can occur lateral to, above, or below the knee cap. Although usually asymptomatic, the plica can become pathologic when irritation (eg, from repetitive motion) causes an inflammatory response.1

Synovial plica syndrome, as this condition is known, is a common cause of anterior knee pain in adolescents and athletes; incidence ranges from 3.8% to 5.5%.2 The patient often reports trauma (a direct impact to the knee) or participation in sports activities that require repeated flexion-extension of the knee.3

Presenting symptoms and MRI findings can unlock the diagnosis

The combination of anterior knee pain and a painful parapatellar “cord” on palpation is the most frequent diagnostic sign of synovial plica syndrome.1 Quadriceps wasting, intra-articular effusion, and reduced range of motion of the knee may also be observed.1,4 Some patients experience particularly disconcerting symptoms, such as knee locking, clicking, or instability.1

In most cases, MRI confirms the clinical diagnosis while ruling out other possible causes of the symptoms and associated pathologies.5 However, MRI may not reveal the plica if it is attached to the articular capsule or if there is no intra-articular effusion. Dynamic ultrasound might be of diagnostic value but is operator dependent.4

Continue to: If conservative treatment fails, consider surgical repair

If conservative treatment fails, consider surgical repair

Conservative treatment—a combination of analgesics, anti-inflammatories, and physiotherapy with vastus medialis strengthening and stretching—is the preferred first-line treatment, with a success rate of 40% to 60%.1 If conservative treatment fails, surgical treatment can be

Our patient underwent arthroscopic resection of the plica after 6 months of conservative treatment had failed (FIGURE 2). The patient was able to walk immediately after surgery. The outcome was favorable, since physiotherapy was no longer required 2 months after surgery.

CORRESPONDENCE

Céline Klein, MD, Service d’Orthopédie Pédiatrique, CHU Amiens, Groupe Hospitalier Sud, F-80054 Amiens cedex 1, France; celinekleinfr@yahoo.fr.

1. Camanho GL. Treatment of pathological synovial plicae of the knee. Clinics (Sao Paolo). 2010;65:247-250.

2. Ewing JW. Plica: pathologic or not? J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1993;1:117-121.

3. Patel DR, Villalobos A. Evaluation and management of knee pain in young athletes: overuse injuries of the knee. Transl Pediatr. 2017;6:190-198.

4. Paczesny Ł, Kruczyński J. Medial plica syndrome of the knee: diagnosis with dynamic sonography. Radiology. 2009;251:439-446.

5. Samim M, Smitaman E, Lawrence D, et al. MRI of anterior knee pain. Skeletal Radiol. 2014;43:875-893.

6. Weckström M, Niva MH, Lamminen A, et al. Arthroscopic resection of medial plica of the knee in young adults. Knee. 2010;17:103-107.

7. Kan H, Arai Y, Nakagawa S, et al. Characteristics of medial plica syndrome complicated with cartilage damage. Int Orthop. 2015;39:2489-2494.

1. Camanho GL. Treatment of pathological synovial plicae of the knee. Clinics (Sao Paolo). 2010;65:247-250.

2. Ewing JW. Plica: pathologic or not? J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1993;1:117-121.

3. Patel DR, Villalobos A. Evaluation and management of knee pain in young athletes: overuse injuries of the knee. Transl Pediatr. 2017;6:190-198.

4. Paczesny Ł, Kruczyński J. Medial plica syndrome of the knee: diagnosis with dynamic sonography. Radiology. 2009;251:439-446.

5. Samim M, Smitaman E, Lawrence D, et al. MRI of anterior knee pain. Skeletal Radiol. 2014;43:875-893.

6. Weckström M, Niva MH, Lamminen A, et al. Arthroscopic resection of medial plica of the knee in young adults. Knee. 2010;17:103-107.

7. Kan H, Arai Y, Nakagawa S, et al. Characteristics of medial plica syndrome complicated with cartilage damage. Int Orthop. 2015;39:2489-2494.

Surgery for shoulder pain? Think twice

Shoulder pain is a very common presenting complaint in family physicians’ offices. Typically, a patient will have had minor trauma, such as a fall, or overuse from work or a recreational activity. Most of these patients have rotator cuff injuries, so we refer them to physical therapy or we prescribe a self-directed home exercise program and the problem gradually resolves. If the patient does not improve, however, should s(he) be referred for arthroscopic surgery? This answer, of course, is “it depends.”

In this issue of JFP, Onks et al provide an excellent review of conservative vs surgical management of rotator cuff tears. For complete or near complete tears in young people—especially athletes—arthroscopic surgery is the preferred approach. For partial tears, chronic tears, and for older folks like me, nonoperative management is the preferred approach. Surgery is reserved for those who do not improve with prolonged conservative management.

But what approach is best for the majority of people in whom shoulder pain is due to impingement syndrome, with or without a small rotator cuff tear? This question has been studied extensively and summarized in a recent Cochrane meta-analysis.1

The meta-analysis included 8 trials, with a total of 1062 participants with rotator cuff disease, all with subacromial impingement. “Compared with placebo, high-certainty evidence indicates that subacromial decompression provides no improvement in pain, shoulder function, or health-related quality of life up to one year, and probably no improvement in global success (moderate-certainty evidence).”1

A recently published guideline developed by doctors and patients for the treatment of shoulder pain gives a strong recommendation to avoid surgery for chronic shoulder pain due to impingement syndrome.2

Interestingly, research has shown that arthroscopic surgery for knee osteoarthritis and chronic meniscus tears is no better that conservative therapy.3,4 Similarly, surgery for chronic back pain due to degenerative disease (in the absence of spondylolisthesis) provides minimal, if any, improvement in pain and function.5 I see a pattern here.

When we talk to our patients who are contemplating these surgical procedures for these indications (except complete rotator cuff tears), we should advise them to have limited expectations or to avoid surgery altogether.

1. Karjalainen TV, Jain NB, Page CM, et al. Subacromial decompression surgery for rotator cuff disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;(1):CD005619. Epub January 17, 2019.

2. Vandvik PO, Lahdeoja T, Ardern C, et al. Subacromial decompression surgery for adults with shoulder pain: a clinical practice guideline. BMJ. 2019;364:1294.

3. Monk P, Garfjeld Roberts P, Palmer AJ, et al. The urgent need for evidence in arthroscopic meniscal surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45:965-973.

4. Kirkley A, Birmingham TB, Litchfield RB, et al. A randomized trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1097-1107.

5. Yavin D, Casha S, Wiebe S, et al. Lumbar fusion for degenerative disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurgery. 2017;80:701-715.

Shoulder pain is a very common presenting complaint in family physicians’ offices. Typically, a patient will have had minor trauma, such as a fall, or overuse from work or a recreational activity. Most of these patients have rotator cuff injuries, so we refer them to physical therapy or we prescribe a self-directed home exercise program and the problem gradually resolves. If the patient does not improve, however, should s(he) be referred for arthroscopic surgery? This answer, of course, is “it depends.”

In this issue of JFP, Onks et al provide an excellent review of conservative vs surgical management of rotator cuff tears. For complete or near complete tears in young people—especially athletes—arthroscopic surgery is the preferred approach. For partial tears, chronic tears, and for older folks like me, nonoperative management is the preferred approach. Surgery is reserved for those who do not improve with prolonged conservative management.

But what approach is best for the majority of people in whom shoulder pain is due to impingement syndrome, with or without a small rotator cuff tear? This question has been studied extensively and summarized in a recent Cochrane meta-analysis.1

The meta-analysis included 8 trials, with a total of 1062 participants with rotator cuff disease, all with subacromial impingement. “Compared with placebo, high-certainty evidence indicates that subacromial decompression provides no improvement in pain, shoulder function, or health-related quality of life up to one year, and probably no improvement in global success (moderate-certainty evidence).”1

A recently published guideline developed by doctors and patients for the treatment of shoulder pain gives a strong recommendation to avoid surgery for chronic shoulder pain due to impingement syndrome.2

Interestingly, research has shown that arthroscopic surgery for knee osteoarthritis and chronic meniscus tears is no better that conservative therapy.3,4 Similarly, surgery for chronic back pain due to degenerative disease (in the absence of spondylolisthesis) provides minimal, if any, improvement in pain and function.5 I see a pattern here.

When we talk to our patients who are contemplating these surgical procedures for these indications (except complete rotator cuff tears), we should advise them to have limited expectations or to avoid surgery altogether.

Shoulder pain is a very common presenting complaint in family physicians’ offices. Typically, a patient will have had minor trauma, such as a fall, or overuse from work or a recreational activity. Most of these patients have rotator cuff injuries, so we refer them to physical therapy or we prescribe a self-directed home exercise program and the problem gradually resolves. If the patient does not improve, however, should s(he) be referred for arthroscopic surgery? This answer, of course, is “it depends.”

In this issue of JFP, Onks et al provide an excellent review of conservative vs surgical management of rotator cuff tears. For complete or near complete tears in young people—especially athletes—arthroscopic surgery is the preferred approach. For partial tears, chronic tears, and for older folks like me, nonoperative management is the preferred approach. Surgery is reserved for those who do not improve with prolonged conservative management.

But what approach is best for the majority of people in whom shoulder pain is due to impingement syndrome, with or without a small rotator cuff tear? This question has been studied extensively and summarized in a recent Cochrane meta-analysis.1

The meta-analysis included 8 trials, with a total of 1062 participants with rotator cuff disease, all with subacromial impingement. “Compared with placebo, high-certainty evidence indicates that subacromial decompression provides no improvement in pain, shoulder function, or health-related quality of life up to one year, and probably no improvement in global success (moderate-certainty evidence).”1

A recently published guideline developed by doctors and patients for the treatment of shoulder pain gives a strong recommendation to avoid surgery for chronic shoulder pain due to impingement syndrome.2

Interestingly, research has shown that arthroscopic surgery for knee osteoarthritis and chronic meniscus tears is no better that conservative therapy.3,4 Similarly, surgery for chronic back pain due to degenerative disease (in the absence of spondylolisthesis) provides minimal, if any, improvement in pain and function.5 I see a pattern here.

When we talk to our patients who are contemplating these surgical procedures for these indications (except complete rotator cuff tears), we should advise them to have limited expectations or to avoid surgery altogether.

1. Karjalainen TV, Jain NB, Page CM, et al. Subacromial decompression surgery for rotator cuff disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;(1):CD005619. Epub January 17, 2019.

2. Vandvik PO, Lahdeoja T, Ardern C, et al. Subacromial decompression surgery for adults with shoulder pain: a clinical practice guideline. BMJ. 2019;364:1294.

3. Monk P, Garfjeld Roberts P, Palmer AJ, et al. The urgent need for evidence in arthroscopic meniscal surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45:965-973.

4. Kirkley A, Birmingham TB, Litchfield RB, et al. A randomized trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1097-1107.

5. Yavin D, Casha S, Wiebe S, et al. Lumbar fusion for degenerative disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurgery. 2017;80:701-715.

1. Karjalainen TV, Jain NB, Page CM, et al. Subacromial decompression surgery for rotator cuff disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;(1):CD005619. Epub January 17, 2019.

2. Vandvik PO, Lahdeoja T, Ardern C, et al. Subacromial decompression surgery for adults with shoulder pain: a clinical practice guideline. BMJ. 2019;364:1294.

3. Monk P, Garfjeld Roberts P, Palmer AJ, et al. The urgent need for evidence in arthroscopic meniscal surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45:965-973.

4. Kirkley A, Birmingham TB, Litchfield RB, et al. A randomized trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1097-1107.

5. Yavin D, Casha S, Wiebe S, et al. Lumbar fusion for degenerative disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurgery. 2017;80:701-715.

Recurrent Vesicles on the Palm

The Diagnosis: Herpes Simplex Virus Dermatitis

A swab of the lesions yielded negative varicella-zoster virus and herpes simplex virus (HSV) cultures, but polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was positive for HSV DNA. The patient was started on acyclovir, which resulted in resolution of the lesions.

Recurrent HSV dermatitis most frequently is encountered in the orolabial or genital regions. After primary infection, HSV is retrogradely taken up into the dorsal root ganglion and may be reactivated in the same dermatome upon stress induction, forming clustered vesicles that rupture to form painful erosions.1 Our patient's history of numerous recurrent episodes in the same area of the palm in the distribution of the median nerve suggests viral latency in the C5 through T1 dorsal root ganglia with reactivation rather than autoinoculation or external infection from another source. The incidence of HSV involving the hand has been estimated at 2.4 cases per 100,000 individuals per year, with finger, thumb, or palm/wrist involvement accounting for 67%, 22%, and 11% of cases, respectively.2 Of the palmar cases that have been reported, most have a positive history for genital or orolabial HSV infection.2-5