User login

Chronic anterior knee pain

A 14-year-old girl with an unremarkable medical history presented to the family medicine clinic with a 6-month history of right knee pain (episodic locking and anterior pain). Physical examination of the knee ligaments revealed that the knee was stable and pain-free in the frontal and sagittal planes. There was no intra-articular effusion, the joint spaces were not painful, and range of motion was normal.

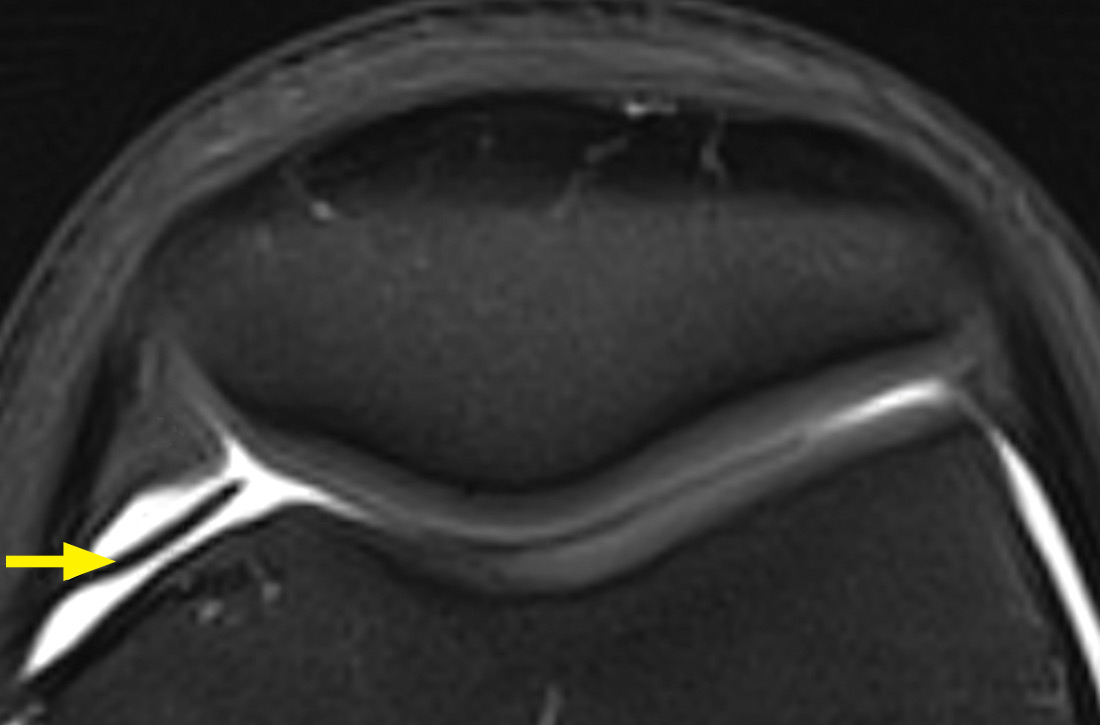

Palpation of the knee elicited pain, notably when the physician rolled his fingers over a “cord” above the internal parapatellar compartment. X-rays of the knee were normal. In light of the patient’s chronic pain, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed (FIGURE 1).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Synovial plica

The MRI with fat saturation revealed a symptomatic synovial plica between the patellar facet and the condyle (FIGURE 1, arrow). The normal x-ray findings had already ruled out osteochondritis dissecans of the femoral condyles, patellar abnormalities, and trochlear dysplasia; the MRI ruled out several additional items in the differential, such as damage to the meniscus, ligament, and/or cartilage.

The synovial plica is a normal structure that develops during the embryogenic phase; however, involution is incomplete in up to 50% of the population, resulting in persistent plicae.1 The plica is often located in a medial position but can occur lateral to, above, or below the knee cap. Although usually asymptomatic, the plica can become pathologic when irritation (eg, from repetitive motion) causes an inflammatory response.1

Synovial plica syndrome, as this condition is known, is a common cause of anterior knee pain in adolescents and athletes; incidence ranges from 3.8% to 5.5%.2 The patient often reports trauma (a direct impact to the knee) or participation in sports activities that require repeated flexion-extension of the knee.3

Presenting symptoms and MRI findings can unlock the diagnosis

The combination of anterior knee pain and a painful parapatellar “cord” on palpation is the most frequent diagnostic sign of synovial plica syndrome.1 Quadriceps wasting, intra-articular effusion, and reduced range of motion of the knee may also be observed.1,4 Some patients experience particularly disconcerting symptoms, such as knee locking, clicking, or instability.1

In most cases, MRI confirms the clinical diagnosis while ruling out other possible causes of the symptoms and associated pathologies.5 However, MRI may not reveal the plica if it is attached to the articular capsule or if there is no intra-articular effusion. Dynamic ultrasound might be of diagnostic value but is operator dependent.4

Continue to: If conservative treatment fails, consider surgical repair

If conservative treatment fails, consider surgical repair

Conservative treatment—a combination of analgesics, anti-inflammatories, and physiotherapy with vastus medialis strengthening and stretching—is the preferred first-line treatment, with a success rate of 40% to 60%.1 If conservative treatment fails, surgical treatment can be

Our patient underwent arthroscopic resection of the plica after 6 months of conservative treatment had failed (FIGURE 2). The patient was able to walk immediately after surgery. The outcome was favorable, since physiotherapy was no longer required 2 months after surgery.

CORRESPONDENCE

Céline Klein, MD, Service d’Orthopédie Pédiatrique, CHU Amiens, Groupe Hospitalier Sud, F-80054 Amiens cedex 1, France; celinekleinfr@yahoo.fr.

1. Camanho GL. Treatment of pathological synovial plicae of the knee. Clinics (Sao Paolo). 2010;65:247-250.

2. Ewing JW. Plica: pathologic or not? J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1993;1:117-121.

3. Patel DR, Villalobos A. Evaluation and management of knee pain in young athletes: overuse injuries of the knee. Transl Pediatr. 2017;6:190-198.

4. Paczesny Ł, Kruczyński J. Medial plica syndrome of the knee: diagnosis with dynamic sonography. Radiology. 2009;251:439-446.

5. Samim M, Smitaman E, Lawrence D, et al. MRI of anterior knee pain. Skeletal Radiol. 2014;43:875-893.

6. Weckström M, Niva MH, Lamminen A, et al. Arthroscopic resection of medial plica of the knee in young adults. Knee. 2010;17:103-107.

7. Kan H, Arai Y, Nakagawa S, et al. Characteristics of medial plica syndrome complicated with cartilage damage. Int Orthop. 2015;39:2489-2494.

A 14-year-old girl with an unremarkable medical history presented to the family medicine clinic with a 6-month history of right knee pain (episodic locking and anterior pain). Physical examination of the knee ligaments revealed that the knee was stable and pain-free in the frontal and sagittal planes. There was no intra-articular effusion, the joint spaces were not painful, and range of motion was normal.

Palpation of the knee elicited pain, notably when the physician rolled his fingers over a “cord” above the internal parapatellar compartment. X-rays of the knee were normal. In light of the patient’s chronic pain, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed (FIGURE 1).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Synovial plica

The MRI with fat saturation revealed a symptomatic synovial plica between the patellar facet and the condyle (FIGURE 1, arrow). The normal x-ray findings had already ruled out osteochondritis dissecans of the femoral condyles, patellar abnormalities, and trochlear dysplasia; the MRI ruled out several additional items in the differential, such as damage to the meniscus, ligament, and/or cartilage.

The synovial plica is a normal structure that develops during the embryogenic phase; however, involution is incomplete in up to 50% of the population, resulting in persistent plicae.1 The plica is often located in a medial position but can occur lateral to, above, or below the knee cap. Although usually asymptomatic, the plica can become pathologic when irritation (eg, from repetitive motion) causes an inflammatory response.1

Synovial plica syndrome, as this condition is known, is a common cause of anterior knee pain in adolescents and athletes; incidence ranges from 3.8% to 5.5%.2 The patient often reports trauma (a direct impact to the knee) or participation in sports activities that require repeated flexion-extension of the knee.3

Presenting symptoms and MRI findings can unlock the diagnosis

The combination of anterior knee pain and a painful parapatellar “cord” on palpation is the most frequent diagnostic sign of synovial plica syndrome.1 Quadriceps wasting, intra-articular effusion, and reduced range of motion of the knee may also be observed.1,4 Some patients experience particularly disconcerting symptoms, such as knee locking, clicking, or instability.1

In most cases, MRI confirms the clinical diagnosis while ruling out other possible causes of the symptoms and associated pathologies.5 However, MRI may not reveal the plica if it is attached to the articular capsule or if there is no intra-articular effusion. Dynamic ultrasound might be of diagnostic value but is operator dependent.4

Continue to: If conservative treatment fails, consider surgical repair

If conservative treatment fails, consider surgical repair

Conservative treatment—a combination of analgesics, anti-inflammatories, and physiotherapy with vastus medialis strengthening and stretching—is the preferred first-line treatment, with a success rate of 40% to 60%.1 If conservative treatment fails, surgical treatment can be

Our patient underwent arthroscopic resection of the plica after 6 months of conservative treatment had failed (FIGURE 2). The patient was able to walk immediately after surgery. The outcome was favorable, since physiotherapy was no longer required 2 months after surgery.

CORRESPONDENCE

Céline Klein, MD, Service d’Orthopédie Pédiatrique, CHU Amiens, Groupe Hospitalier Sud, F-80054 Amiens cedex 1, France; celinekleinfr@yahoo.fr.

A 14-year-old girl with an unremarkable medical history presented to the family medicine clinic with a 6-month history of right knee pain (episodic locking and anterior pain). Physical examination of the knee ligaments revealed that the knee was stable and pain-free in the frontal and sagittal planes. There was no intra-articular effusion, the joint spaces were not painful, and range of motion was normal.

Palpation of the knee elicited pain, notably when the physician rolled his fingers over a “cord” above the internal parapatellar compartment. X-rays of the knee were normal. In light of the patient’s chronic pain, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed (FIGURE 1).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Synovial plica

The MRI with fat saturation revealed a symptomatic synovial plica between the patellar facet and the condyle (FIGURE 1, arrow). The normal x-ray findings had already ruled out osteochondritis dissecans of the femoral condyles, patellar abnormalities, and trochlear dysplasia; the MRI ruled out several additional items in the differential, such as damage to the meniscus, ligament, and/or cartilage.

The synovial plica is a normal structure that develops during the embryogenic phase; however, involution is incomplete in up to 50% of the population, resulting in persistent plicae.1 The plica is often located in a medial position but can occur lateral to, above, or below the knee cap. Although usually asymptomatic, the plica can become pathologic when irritation (eg, from repetitive motion) causes an inflammatory response.1

Synovial plica syndrome, as this condition is known, is a common cause of anterior knee pain in adolescents and athletes; incidence ranges from 3.8% to 5.5%.2 The patient often reports trauma (a direct impact to the knee) or participation in sports activities that require repeated flexion-extension of the knee.3

Presenting symptoms and MRI findings can unlock the diagnosis

The combination of anterior knee pain and a painful parapatellar “cord” on palpation is the most frequent diagnostic sign of synovial plica syndrome.1 Quadriceps wasting, intra-articular effusion, and reduced range of motion of the knee may also be observed.1,4 Some patients experience particularly disconcerting symptoms, such as knee locking, clicking, or instability.1

In most cases, MRI confirms the clinical diagnosis while ruling out other possible causes of the symptoms and associated pathologies.5 However, MRI may not reveal the plica if it is attached to the articular capsule or if there is no intra-articular effusion. Dynamic ultrasound might be of diagnostic value but is operator dependent.4

Continue to: If conservative treatment fails, consider surgical repair

If conservative treatment fails, consider surgical repair

Conservative treatment—a combination of analgesics, anti-inflammatories, and physiotherapy with vastus medialis strengthening and stretching—is the preferred first-line treatment, with a success rate of 40% to 60%.1 If conservative treatment fails, surgical treatment can be

Our patient underwent arthroscopic resection of the plica after 6 months of conservative treatment had failed (FIGURE 2). The patient was able to walk immediately after surgery. The outcome was favorable, since physiotherapy was no longer required 2 months after surgery.

CORRESPONDENCE

Céline Klein, MD, Service d’Orthopédie Pédiatrique, CHU Amiens, Groupe Hospitalier Sud, F-80054 Amiens cedex 1, France; celinekleinfr@yahoo.fr.

1. Camanho GL. Treatment of pathological synovial plicae of the knee. Clinics (Sao Paolo). 2010;65:247-250.

2. Ewing JW. Plica: pathologic or not? J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1993;1:117-121.

3. Patel DR, Villalobos A. Evaluation and management of knee pain in young athletes: overuse injuries of the knee. Transl Pediatr. 2017;6:190-198.

4. Paczesny Ł, Kruczyński J. Medial plica syndrome of the knee: diagnosis with dynamic sonography. Radiology. 2009;251:439-446.

5. Samim M, Smitaman E, Lawrence D, et al. MRI of anterior knee pain. Skeletal Radiol. 2014;43:875-893.

6. Weckström M, Niva MH, Lamminen A, et al. Arthroscopic resection of medial plica of the knee in young adults. Knee. 2010;17:103-107.

7. Kan H, Arai Y, Nakagawa S, et al. Characteristics of medial plica syndrome complicated with cartilage damage. Int Orthop. 2015;39:2489-2494.

1. Camanho GL. Treatment of pathological synovial plicae of the knee. Clinics (Sao Paolo). 2010;65:247-250.

2. Ewing JW. Plica: pathologic or not? J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1993;1:117-121.

3. Patel DR, Villalobos A. Evaluation and management of knee pain in young athletes: overuse injuries of the knee. Transl Pediatr. 2017;6:190-198.

4. Paczesny Ł, Kruczyński J. Medial plica syndrome of the knee: diagnosis with dynamic sonography. Radiology. 2009;251:439-446.

5. Samim M, Smitaman E, Lawrence D, et al. MRI of anterior knee pain. Skeletal Radiol. 2014;43:875-893.

6. Weckström M, Niva MH, Lamminen A, et al. Arthroscopic resection of medial plica of the knee in young adults. Knee. 2010;17:103-107.

7. Kan H, Arai Y, Nakagawa S, et al. Characteristics of medial plica syndrome complicated with cartilage damage. Int Orthop. 2015;39:2489-2494.

Surgery for shoulder pain? Think twice

Shoulder pain is a very common presenting complaint in family physicians’ offices. Typically, a patient will have had minor trauma, such as a fall, or overuse from work or a recreational activity. Most of these patients have rotator cuff injuries, so we refer them to physical therapy or we prescribe a self-directed home exercise program and the problem gradually resolves. If the patient does not improve, however, should s(he) be referred for arthroscopic surgery? This answer, of course, is “it depends.”

In this issue of JFP, Onks et al provide an excellent review of conservative vs surgical management of rotator cuff tears. For complete or near complete tears in young people—especially athletes—arthroscopic surgery is the preferred approach. For partial tears, chronic tears, and for older folks like me, nonoperative management is the preferred approach. Surgery is reserved for those who do not improve with prolonged conservative management.

But what approach is best for the majority of people in whom shoulder pain is due to impingement syndrome, with or without a small rotator cuff tear? This question has been studied extensively and summarized in a recent Cochrane meta-analysis.1

The meta-analysis included 8 trials, with a total of 1062 participants with rotator cuff disease, all with subacromial impingement. “Compared with placebo, high-certainty evidence indicates that subacromial decompression provides no improvement in pain, shoulder function, or health-related quality of life up to one year, and probably no improvement in global success (moderate-certainty evidence).”1

A recently published guideline developed by doctors and patients for the treatment of shoulder pain gives a strong recommendation to avoid surgery for chronic shoulder pain due to impingement syndrome.2

Interestingly, research has shown that arthroscopic surgery for knee osteoarthritis and chronic meniscus tears is no better that conservative therapy.3,4 Similarly, surgery for chronic back pain due to degenerative disease (in the absence of spondylolisthesis) provides minimal, if any, improvement in pain and function.5 I see a pattern here.

When we talk to our patients who are contemplating these surgical procedures for these indications (except complete rotator cuff tears), we should advise them to have limited expectations or to avoid surgery altogether.

1. Karjalainen TV, Jain NB, Page CM, et al. Subacromial decompression surgery for rotator cuff disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;(1):CD005619. Epub January 17, 2019.

2. Vandvik PO, Lahdeoja T, Ardern C, et al. Subacromial decompression surgery for adults with shoulder pain: a clinical practice guideline. BMJ. 2019;364:1294.

3. Monk P, Garfjeld Roberts P, Palmer AJ, et al. The urgent need for evidence in arthroscopic meniscal surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45:965-973.

4. Kirkley A, Birmingham TB, Litchfield RB, et al. A randomized trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1097-1107.

5. Yavin D, Casha S, Wiebe S, et al. Lumbar fusion for degenerative disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurgery. 2017;80:701-715.

Shoulder pain is a very common presenting complaint in family physicians’ offices. Typically, a patient will have had minor trauma, such as a fall, or overuse from work or a recreational activity. Most of these patients have rotator cuff injuries, so we refer them to physical therapy or we prescribe a self-directed home exercise program and the problem gradually resolves. If the patient does not improve, however, should s(he) be referred for arthroscopic surgery? This answer, of course, is “it depends.”

In this issue of JFP, Onks et al provide an excellent review of conservative vs surgical management of rotator cuff tears. For complete or near complete tears in young people—especially athletes—arthroscopic surgery is the preferred approach. For partial tears, chronic tears, and for older folks like me, nonoperative management is the preferred approach. Surgery is reserved for those who do not improve with prolonged conservative management.

But what approach is best for the majority of people in whom shoulder pain is due to impingement syndrome, with or without a small rotator cuff tear? This question has been studied extensively and summarized in a recent Cochrane meta-analysis.1

The meta-analysis included 8 trials, with a total of 1062 participants with rotator cuff disease, all with subacromial impingement. “Compared with placebo, high-certainty evidence indicates that subacromial decompression provides no improvement in pain, shoulder function, or health-related quality of life up to one year, and probably no improvement in global success (moderate-certainty evidence).”1

A recently published guideline developed by doctors and patients for the treatment of shoulder pain gives a strong recommendation to avoid surgery for chronic shoulder pain due to impingement syndrome.2

Interestingly, research has shown that arthroscopic surgery for knee osteoarthritis and chronic meniscus tears is no better that conservative therapy.3,4 Similarly, surgery for chronic back pain due to degenerative disease (in the absence of spondylolisthesis) provides minimal, if any, improvement in pain and function.5 I see a pattern here.

When we talk to our patients who are contemplating these surgical procedures for these indications (except complete rotator cuff tears), we should advise them to have limited expectations or to avoid surgery altogether.

Shoulder pain is a very common presenting complaint in family physicians’ offices. Typically, a patient will have had minor trauma, such as a fall, or overuse from work or a recreational activity. Most of these patients have rotator cuff injuries, so we refer them to physical therapy or we prescribe a self-directed home exercise program and the problem gradually resolves. If the patient does not improve, however, should s(he) be referred for arthroscopic surgery? This answer, of course, is “it depends.”

In this issue of JFP, Onks et al provide an excellent review of conservative vs surgical management of rotator cuff tears. For complete or near complete tears in young people—especially athletes—arthroscopic surgery is the preferred approach. For partial tears, chronic tears, and for older folks like me, nonoperative management is the preferred approach. Surgery is reserved for those who do not improve with prolonged conservative management.

But what approach is best for the majority of people in whom shoulder pain is due to impingement syndrome, with or without a small rotator cuff tear? This question has been studied extensively and summarized in a recent Cochrane meta-analysis.1

The meta-analysis included 8 trials, with a total of 1062 participants with rotator cuff disease, all with subacromial impingement. “Compared with placebo, high-certainty evidence indicates that subacromial decompression provides no improvement in pain, shoulder function, or health-related quality of life up to one year, and probably no improvement in global success (moderate-certainty evidence).”1

A recently published guideline developed by doctors and patients for the treatment of shoulder pain gives a strong recommendation to avoid surgery for chronic shoulder pain due to impingement syndrome.2

Interestingly, research has shown that arthroscopic surgery for knee osteoarthritis and chronic meniscus tears is no better that conservative therapy.3,4 Similarly, surgery for chronic back pain due to degenerative disease (in the absence of spondylolisthesis) provides minimal, if any, improvement in pain and function.5 I see a pattern here.

When we talk to our patients who are contemplating these surgical procedures for these indications (except complete rotator cuff tears), we should advise them to have limited expectations or to avoid surgery altogether.

1. Karjalainen TV, Jain NB, Page CM, et al. Subacromial decompression surgery for rotator cuff disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;(1):CD005619. Epub January 17, 2019.

2. Vandvik PO, Lahdeoja T, Ardern C, et al. Subacromial decompression surgery for adults with shoulder pain: a clinical practice guideline. BMJ. 2019;364:1294.

3. Monk P, Garfjeld Roberts P, Palmer AJ, et al. The urgent need for evidence in arthroscopic meniscal surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45:965-973.

4. Kirkley A, Birmingham TB, Litchfield RB, et al. A randomized trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1097-1107.

5. Yavin D, Casha S, Wiebe S, et al. Lumbar fusion for degenerative disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurgery. 2017;80:701-715.

1. Karjalainen TV, Jain NB, Page CM, et al. Subacromial decompression surgery for rotator cuff disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;(1):CD005619. Epub January 17, 2019.

2. Vandvik PO, Lahdeoja T, Ardern C, et al. Subacromial decompression surgery for adults with shoulder pain: a clinical practice guideline. BMJ. 2019;364:1294.

3. Monk P, Garfjeld Roberts P, Palmer AJ, et al. The urgent need for evidence in arthroscopic meniscal surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45:965-973.

4. Kirkley A, Birmingham TB, Litchfield RB, et al. A randomized trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1097-1107.

5. Yavin D, Casha S, Wiebe S, et al. Lumbar fusion for degenerative disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurgery. 2017;80:701-715.

Recurrent Vesicles on the Palm

The Diagnosis: Herpes Simplex Virus Dermatitis

A swab of the lesions yielded negative varicella-zoster virus and herpes simplex virus (HSV) cultures, but polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was positive for HSV DNA. The patient was started on acyclovir, which resulted in resolution of the lesions.

Recurrent HSV dermatitis most frequently is encountered in the orolabial or genital regions. After primary infection, HSV is retrogradely taken up into the dorsal root ganglion and may be reactivated in the same dermatome upon stress induction, forming clustered vesicles that rupture to form painful erosions.1 Our patient's history of numerous recurrent episodes in the same area of the palm in the distribution of the median nerve suggests viral latency in the C5 through T1 dorsal root ganglia with reactivation rather than autoinoculation or external infection from another source. The incidence of HSV involving the hand has been estimated at 2.4 cases per 100,000 individuals per year, with finger, thumb, or palm/wrist involvement accounting for 67%, 22%, and 11% of cases, respectively.2 Of the palmar cases that have been reported, most have a positive history for genital or orolabial HSV infection.2-5

In cases of suspected HSV dermatitis with atypical presentations, diagnostic studies are of importance. Although viral culture is the diagnostic gold standard in active lesions, it has lower sensitivity in improperly handled specimens; cases of recurrent disease; and specimens from dried, crusted, or aged lesions,1 which helps to explain the negative culture result in our patient. Viral culture has been largely replaced in clinical practice by nucleic acid amplification tests using PCR, which is fast and type specific.6,7 The sensitivity of PCR approaches 100% when vesicles or wet ulcers are sampled, and PCR has better yields from dry ulcers or crusts compared to viral culture.6 However, because viral shedding is intermittent, a negative PCR result does not rule out HSV infection.8 Additional bedside diagnostic techniques include Tzanck smear, a rapid and inexpensive test in which lesions are scraped and stained with Giemsa, Wright, or Papanicolaou stains. Under light microscopy, multinucleated giant cells are seen in 60% to 75% of cases.9 This method, however, cannot distinguish HSV from varicella-zoster virus and must be followed by direct fluorescent antibody testing or immunohistochemistry for viral typing.1,9 Serologic testing also may be useful in patients who have a suspicious history for HSV infection but do not have lesions on physical examination to diagnose clinically or sample for PCR. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay testing can detect IgG starting 3 weeks after infection, and newer type-specific assays can distinguish between HSV types 1 and 2.6 In low-incidence populations, false positives from enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay can be seen and should be confirmed by western blot.6,7

Preferred treatment of HSV includes antiviral medications such as acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir. Regimens vary based on the site of infection, primary or recurrent nature of the infection, immune status of the patient, and whether or not viral suppression is desired to prevent recurrent outbreaks.7,10

Tinea manuum also may present with unilateral vesicles and erosions involving the palms11; however, it was less likely than HSV dermatitis in this patient presenting with a history of numerous recurrent episodes and without scaling on physical examination. Dyshidrotic eczema, contact dermatitis, and scabies are more characteristically pruritic rather than painful. Additionally, dyshidrotic eczema and scabies would be more likely to have symmetric involvement of the arms. Although vesicles are seen in both dyshidrotic eczema and HSV dermatitis, the vesicles of dyshidrotic eczema usually are noninflammatory compared to the painful vesicles on an erythematous base classically seen in HSV dermatitis.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Elizabeth Ergen, MD (Knoxville, Tennessee), for her assistance with this case.

- Fatahzadeh M, Schwartz RA. Human herpes simplex virus infections: epidemiology, pathogenesis, symptomatology, diagnosis, and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:737-763; quiz 764-766.

- Gill MJ, Arlette J, Buchan K. Herpes simplex virus infection of the hand. a profile of 79 cases. Am J Med. 1988;84:89-93.

- Widenfalk B, Wallin J. Recurrent herpes simplex virus infections in the adult hand. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 1988;22:177-180.

- Gill MJ, Arlette J, Buchan KA. Herpes simplex virus infection of the hand. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:111-116.

- Osio A, Fremont G, Petit A, et al. An unusual bipolar primary herpes simplex virus 1 infection. J Clin Virol. 2008;43:230-232.

- Gnann JW Jr, Whitley RJ. Clinical practice. genital herpes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:666-674.

- Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64:1-137.

- LeGoff J, Péré H, Bélec L. Diagnosis of genital herpes simplex virus infection in the clinical laboratory. Virol J. 2014;11:83.

- Downing C, Mendoza N, Sra K, et al. Human herpesviruses. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. China: Elsevier; 2018:1400-1424.

- WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee. WHO Guidelines for the Treatment of Genital Herpes Simplex Virus. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2016.

- Veraldi S, Schianchi R, Benzecry V, et al. Tinea manuum: a report of 18 cases observed in the metropolitan area of Milan and review of the literature. Mycoses. 2019;62:604-608.

The Diagnosis: Herpes Simplex Virus Dermatitis

A swab of the lesions yielded negative varicella-zoster virus and herpes simplex virus (HSV) cultures, but polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was positive for HSV DNA. The patient was started on acyclovir, which resulted in resolution of the lesions.

Recurrent HSV dermatitis most frequently is encountered in the orolabial or genital regions. After primary infection, HSV is retrogradely taken up into the dorsal root ganglion and may be reactivated in the same dermatome upon stress induction, forming clustered vesicles that rupture to form painful erosions.1 Our patient's history of numerous recurrent episodes in the same area of the palm in the distribution of the median nerve suggests viral latency in the C5 through T1 dorsal root ganglia with reactivation rather than autoinoculation or external infection from another source. The incidence of HSV involving the hand has been estimated at 2.4 cases per 100,000 individuals per year, with finger, thumb, or palm/wrist involvement accounting for 67%, 22%, and 11% of cases, respectively.2 Of the palmar cases that have been reported, most have a positive history for genital or orolabial HSV infection.2-5

In cases of suspected HSV dermatitis with atypical presentations, diagnostic studies are of importance. Although viral culture is the diagnostic gold standard in active lesions, it has lower sensitivity in improperly handled specimens; cases of recurrent disease; and specimens from dried, crusted, or aged lesions,1 which helps to explain the negative culture result in our patient. Viral culture has been largely replaced in clinical practice by nucleic acid amplification tests using PCR, which is fast and type specific.6,7 The sensitivity of PCR approaches 100% when vesicles or wet ulcers are sampled, and PCR has better yields from dry ulcers or crusts compared to viral culture.6 However, because viral shedding is intermittent, a negative PCR result does not rule out HSV infection.8 Additional bedside diagnostic techniques include Tzanck smear, a rapid and inexpensive test in which lesions are scraped and stained with Giemsa, Wright, or Papanicolaou stains. Under light microscopy, multinucleated giant cells are seen in 60% to 75% of cases.9 This method, however, cannot distinguish HSV from varicella-zoster virus and must be followed by direct fluorescent antibody testing or immunohistochemistry for viral typing.1,9 Serologic testing also may be useful in patients who have a suspicious history for HSV infection but do not have lesions on physical examination to diagnose clinically or sample for PCR. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay testing can detect IgG starting 3 weeks after infection, and newer type-specific assays can distinguish between HSV types 1 and 2.6 In low-incidence populations, false positives from enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay can be seen and should be confirmed by western blot.6,7

Preferred treatment of HSV includes antiviral medications such as acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir. Regimens vary based on the site of infection, primary or recurrent nature of the infection, immune status of the patient, and whether or not viral suppression is desired to prevent recurrent outbreaks.7,10

Tinea manuum also may present with unilateral vesicles and erosions involving the palms11; however, it was less likely than HSV dermatitis in this patient presenting with a history of numerous recurrent episodes and without scaling on physical examination. Dyshidrotic eczema, contact dermatitis, and scabies are more characteristically pruritic rather than painful. Additionally, dyshidrotic eczema and scabies would be more likely to have symmetric involvement of the arms. Although vesicles are seen in both dyshidrotic eczema and HSV dermatitis, the vesicles of dyshidrotic eczema usually are noninflammatory compared to the painful vesicles on an erythematous base classically seen in HSV dermatitis.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Elizabeth Ergen, MD (Knoxville, Tennessee), for her assistance with this case.

The Diagnosis: Herpes Simplex Virus Dermatitis

A swab of the lesions yielded negative varicella-zoster virus and herpes simplex virus (HSV) cultures, but polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was positive for HSV DNA. The patient was started on acyclovir, which resulted in resolution of the lesions.

Recurrent HSV dermatitis most frequently is encountered in the orolabial or genital regions. After primary infection, HSV is retrogradely taken up into the dorsal root ganglion and may be reactivated in the same dermatome upon stress induction, forming clustered vesicles that rupture to form painful erosions.1 Our patient's history of numerous recurrent episodes in the same area of the palm in the distribution of the median nerve suggests viral latency in the C5 through T1 dorsal root ganglia with reactivation rather than autoinoculation or external infection from another source. The incidence of HSV involving the hand has been estimated at 2.4 cases per 100,000 individuals per year, with finger, thumb, or palm/wrist involvement accounting for 67%, 22%, and 11% of cases, respectively.2 Of the palmar cases that have been reported, most have a positive history for genital or orolabial HSV infection.2-5

In cases of suspected HSV dermatitis with atypical presentations, diagnostic studies are of importance. Although viral culture is the diagnostic gold standard in active lesions, it has lower sensitivity in improperly handled specimens; cases of recurrent disease; and specimens from dried, crusted, or aged lesions,1 which helps to explain the negative culture result in our patient. Viral culture has been largely replaced in clinical practice by nucleic acid amplification tests using PCR, which is fast and type specific.6,7 The sensitivity of PCR approaches 100% when vesicles or wet ulcers are sampled, and PCR has better yields from dry ulcers or crusts compared to viral culture.6 However, because viral shedding is intermittent, a negative PCR result does not rule out HSV infection.8 Additional bedside diagnostic techniques include Tzanck smear, a rapid and inexpensive test in which lesions are scraped and stained with Giemsa, Wright, or Papanicolaou stains. Under light microscopy, multinucleated giant cells are seen in 60% to 75% of cases.9 This method, however, cannot distinguish HSV from varicella-zoster virus and must be followed by direct fluorescent antibody testing or immunohistochemistry for viral typing.1,9 Serologic testing also may be useful in patients who have a suspicious history for HSV infection but do not have lesions on physical examination to diagnose clinically or sample for PCR. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay testing can detect IgG starting 3 weeks after infection, and newer type-specific assays can distinguish between HSV types 1 and 2.6 In low-incidence populations, false positives from enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay can be seen and should be confirmed by western blot.6,7

Preferred treatment of HSV includes antiviral medications such as acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir. Regimens vary based on the site of infection, primary or recurrent nature of the infection, immune status of the patient, and whether or not viral suppression is desired to prevent recurrent outbreaks.7,10

Tinea manuum also may present with unilateral vesicles and erosions involving the palms11; however, it was less likely than HSV dermatitis in this patient presenting with a history of numerous recurrent episodes and without scaling on physical examination. Dyshidrotic eczema, contact dermatitis, and scabies are more characteristically pruritic rather than painful. Additionally, dyshidrotic eczema and scabies would be more likely to have symmetric involvement of the arms. Although vesicles are seen in both dyshidrotic eczema and HSV dermatitis, the vesicles of dyshidrotic eczema usually are noninflammatory compared to the painful vesicles on an erythematous base classically seen in HSV dermatitis.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Elizabeth Ergen, MD (Knoxville, Tennessee), for her assistance with this case.

- Fatahzadeh M, Schwartz RA. Human herpes simplex virus infections: epidemiology, pathogenesis, symptomatology, diagnosis, and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:737-763; quiz 764-766.

- Gill MJ, Arlette J, Buchan K. Herpes simplex virus infection of the hand. a profile of 79 cases. Am J Med. 1988;84:89-93.

- Widenfalk B, Wallin J. Recurrent herpes simplex virus infections in the adult hand. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 1988;22:177-180.

- Gill MJ, Arlette J, Buchan KA. Herpes simplex virus infection of the hand. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:111-116.

- Osio A, Fremont G, Petit A, et al. An unusual bipolar primary herpes simplex virus 1 infection. J Clin Virol. 2008;43:230-232.

- Gnann JW Jr, Whitley RJ. Clinical practice. genital herpes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:666-674.

- Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64:1-137.

- LeGoff J, Péré H, Bélec L. Diagnosis of genital herpes simplex virus infection in the clinical laboratory. Virol J. 2014;11:83.

- Downing C, Mendoza N, Sra K, et al. Human herpesviruses. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. China: Elsevier; 2018:1400-1424.

- WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee. WHO Guidelines for the Treatment of Genital Herpes Simplex Virus. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2016.

- Veraldi S, Schianchi R, Benzecry V, et al. Tinea manuum: a report of 18 cases observed in the metropolitan area of Milan and review of the literature. Mycoses. 2019;62:604-608.

- Fatahzadeh M, Schwartz RA. Human herpes simplex virus infections: epidemiology, pathogenesis, symptomatology, diagnosis, and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:737-763; quiz 764-766.

- Gill MJ, Arlette J, Buchan K. Herpes simplex virus infection of the hand. a profile of 79 cases. Am J Med. 1988;84:89-93.

- Widenfalk B, Wallin J. Recurrent herpes simplex virus infections in the adult hand. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 1988;22:177-180.

- Gill MJ, Arlette J, Buchan KA. Herpes simplex virus infection of the hand. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:111-116.

- Osio A, Fremont G, Petit A, et al. An unusual bipolar primary herpes simplex virus 1 infection. J Clin Virol. 2008;43:230-232.

- Gnann JW Jr, Whitley RJ. Clinical practice. genital herpes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:666-674.

- Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64:1-137.

- LeGoff J, Péré H, Bélec L. Diagnosis of genital herpes simplex virus infection in the clinical laboratory. Virol J. 2014;11:83.

- Downing C, Mendoza N, Sra K, et al. Human herpesviruses. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. China: Elsevier; 2018:1400-1424.

- WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee. WHO Guidelines for the Treatment of Genital Herpes Simplex Virus. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2016.

- Veraldi S, Schianchi R, Benzecry V, et al. Tinea manuum: a report of 18 cases observed in the metropolitan area of Milan and review of the literature. Mycoses. 2019;62:604-608.

A 54-year-old man presented to the emergency department with painful lesions at the base of the right palm that had progressed to include areas of erythema and warmth migrating proximally along the right forearm and distal right arm. He stated that similar lesions had occurred episodically in the same location approximately 100 times over the last 20 years. Each time, the lesions began as painful vesicles that he subsequently popped with a sewing needle. He denied any history of orolabial or genital herpes simplex virus infection. Physical examination revealed erythematous scattered papules with dry hemorrhagic crust over the base of the right palm with expressible serous fluid upon forceful pressure. Swelling, erythema, and warmth of the distal right forearm also were observed.

For a time, an old drug helps with PFS in a head and neck cancer

Everolimus, a safe, cheap and well-tolerated drug, prolonged progression-free survival (PFS) compared with placebo during the year patients with advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) were on it, a phase 2 study indicates.

However, once discontinued, the PFS advantage in favor of active therapy was no longer significant at 2 years, the same study suggests.

“The 5-year survival rate for advanced head and neck HPV [human papillomavirus]-negative smokers is dismal; hence the need for adjuvant therapy after a complete response to definitive therapy,” Cherie-Ann Nathan, MD, of Louisiana State University Health in Shreveport, Louisiana, said at the Multidisciplinary Head and Neck Cancer Symposium, sponsored by the American Society for Radiation Oncology.

“[Since] their survival rates have not changed in decades despite advances in surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy, these findings indicate that patients at high risk for tumor relapse could be given mTOR inhibitors to stall progression and keep any residual cancer cells from growing,” she added in a statement.

Advanced HNSCC

The investigator-initiated trial randomly assigned 28 patients with advanced HNSCC to everolimus 10 mg orally once daily or placebo for a maximum of 1 year or until disease progression, whichever came first.

Patients had stage IV HNSCC but had to be disease-free clinically and radiologically following definitive treatment with chemoradiation or surgery followed by chemoradiation. There was no difference in the type of definitive treatment received prior to the intervention between the two groups.

Adjuvant therapy was initiated between 8 and 16 weeks after completing definitive therapy.

If patients had HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer, they had to have a minimum of 10 pack-years of smoking history.

“The primary endpoint was PFS at 2 years; the secondary endpoint was toxicity,” Nathan observed.

Oral mucositis and leukopenia were common but only 7% of patients developed grade 3 mucositis or leukopenia.

Other grade 3 or greater toxicities were reported in 16 patients and were similar to the adverse events (AEs) noted in other trials with everolimus. Only two patients developed serious AEs possibly related to the drug.

At 1 year, 81% of patients on everolimus were disease-free compared with 57% of patients on placebo (P = .04), Nathan reported.

However, at 2 years, PFS – although continuing to favor those treated with adjuvant therapy – was no longer significant even though it was clear that during the year patients were receiving treatment, “there was a consistent, protective effect of everolimus,” Nathan suggested.

Special effect among TP53-mutated patients?

Targeted exon sequencing was also carried out, the results from which showed that TP53 was the most commonly mutated gene.

“As expected, HPV-negative tumors were more likely to be mutated for TP53,” Nathan observed. Approximately 80% of HPV-negative smoking-related HNSCC tumors carry the TP53 mutation.

Interestingly, survival rates were significantly higher in TP53-mutated patients treated with everolimus: 70% of the patients were still alive at 2 years compared with only 22% of placebo controls (P = .026), she said.

This is a surprising finding, Nathan suggested, as patients with TP53 mutations traditionally have worse survival than those without, suggesting that these patients in particular appear to benefit from adjuvant everolimus.

“Everolimus is used for patients with breast cancer or renal cell cancer for extended periods without major side effects and there is potential for patients with TP53-mutated head and neck disease to see a survival benefit as well,” Nathan speculated.

However, additional trials are needed to confirm the link between the TP53 mutation and survival and to assess the safety of keeping patients with HNSCC on an mTOR inhibitor for longer than 1 year.

The study was funded by Novartis. Nathan has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Everolimus, a safe, cheap and well-tolerated drug, prolonged progression-free survival (PFS) compared with placebo during the year patients with advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) were on it, a phase 2 study indicates.

However, once discontinued, the PFS advantage in favor of active therapy was no longer significant at 2 years, the same study suggests.

“The 5-year survival rate for advanced head and neck HPV [human papillomavirus]-negative smokers is dismal; hence the need for adjuvant therapy after a complete response to definitive therapy,” Cherie-Ann Nathan, MD, of Louisiana State University Health in Shreveport, Louisiana, said at the Multidisciplinary Head and Neck Cancer Symposium, sponsored by the American Society for Radiation Oncology.

“[Since] their survival rates have not changed in decades despite advances in surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy, these findings indicate that patients at high risk for tumor relapse could be given mTOR inhibitors to stall progression and keep any residual cancer cells from growing,” she added in a statement.

Advanced HNSCC

The investigator-initiated trial randomly assigned 28 patients with advanced HNSCC to everolimus 10 mg orally once daily or placebo for a maximum of 1 year or until disease progression, whichever came first.

Patients had stage IV HNSCC but had to be disease-free clinically and radiologically following definitive treatment with chemoradiation or surgery followed by chemoradiation. There was no difference in the type of definitive treatment received prior to the intervention between the two groups.

Adjuvant therapy was initiated between 8 and 16 weeks after completing definitive therapy.

If patients had HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer, they had to have a minimum of 10 pack-years of smoking history.

“The primary endpoint was PFS at 2 years; the secondary endpoint was toxicity,” Nathan observed.

Oral mucositis and leukopenia were common but only 7% of patients developed grade 3 mucositis or leukopenia.

Other grade 3 or greater toxicities were reported in 16 patients and were similar to the adverse events (AEs) noted in other trials with everolimus. Only two patients developed serious AEs possibly related to the drug.

At 1 year, 81% of patients on everolimus were disease-free compared with 57% of patients on placebo (P = .04), Nathan reported.

However, at 2 years, PFS – although continuing to favor those treated with adjuvant therapy – was no longer significant even though it was clear that during the year patients were receiving treatment, “there was a consistent, protective effect of everolimus,” Nathan suggested.

Special effect among TP53-mutated patients?

Targeted exon sequencing was also carried out, the results from which showed that TP53 was the most commonly mutated gene.

“As expected, HPV-negative tumors were more likely to be mutated for TP53,” Nathan observed. Approximately 80% of HPV-negative smoking-related HNSCC tumors carry the TP53 mutation.

Interestingly, survival rates were significantly higher in TP53-mutated patients treated with everolimus: 70% of the patients were still alive at 2 years compared with only 22% of placebo controls (P = .026), she said.

This is a surprising finding, Nathan suggested, as patients with TP53 mutations traditionally have worse survival than those without, suggesting that these patients in particular appear to benefit from adjuvant everolimus.

“Everolimus is used for patients with breast cancer or renal cell cancer for extended periods without major side effects and there is potential for patients with TP53-mutated head and neck disease to see a survival benefit as well,” Nathan speculated.

However, additional trials are needed to confirm the link between the TP53 mutation and survival and to assess the safety of keeping patients with HNSCC on an mTOR inhibitor for longer than 1 year.

The study was funded by Novartis. Nathan has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Everolimus, a safe, cheap and well-tolerated drug, prolonged progression-free survival (PFS) compared with placebo during the year patients with advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) were on it, a phase 2 study indicates.

However, once discontinued, the PFS advantage in favor of active therapy was no longer significant at 2 years, the same study suggests.

“The 5-year survival rate for advanced head and neck HPV [human papillomavirus]-negative smokers is dismal; hence the need for adjuvant therapy after a complete response to definitive therapy,” Cherie-Ann Nathan, MD, of Louisiana State University Health in Shreveport, Louisiana, said at the Multidisciplinary Head and Neck Cancer Symposium, sponsored by the American Society for Radiation Oncology.

“[Since] their survival rates have not changed in decades despite advances in surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy, these findings indicate that patients at high risk for tumor relapse could be given mTOR inhibitors to stall progression and keep any residual cancer cells from growing,” she added in a statement.

Advanced HNSCC

The investigator-initiated trial randomly assigned 28 patients with advanced HNSCC to everolimus 10 mg orally once daily or placebo for a maximum of 1 year or until disease progression, whichever came first.

Patients had stage IV HNSCC but had to be disease-free clinically and radiologically following definitive treatment with chemoradiation or surgery followed by chemoradiation. There was no difference in the type of definitive treatment received prior to the intervention between the two groups.

Adjuvant therapy was initiated between 8 and 16 weeks after completing definitive therapy.

If patients had HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer, they had to have a minimum of 10 pack-years of smoking history.

“The primary endpoint was PFS at 2 years; the secondary endpoint was toxicity,” Nathan observed.

Oral mucositis and leukopenia were common but only 7% of patients developed grade 3 mucositis or leukopenia.

Other grade 3 or greater toxicities were reported in 16 patients and were similar to the adverse events (AEs) noted in other trials with everolimus. Only two patients developed serious AEs possibly related to the drug.

At 1 year, 81% of patients on everolimus were disease-free compared with 57% of patients on placebo (P = .04), Nathan reported.

However, at 2 years, PFS – although continuing to favor those treated with adjuvant therapy – was no longer significant even though it was clear that during the year patients were receiving treatment, “there was a consistent, protective effect of everolimus,” Nathan suggested.

Special effect among TP53-mutated patients?

Targeted exon sequencing was also carried out, the results from which showed that TP53 was the most commonly mutated gene.

“As expected, HPV-negative tumors were more likely to be mutated for TP53,” Nathan observed. Approximately 80% of HPV-negative smoking-related HNSCC tumors carry the TP53 mutation.

Interestingly, survival rates were significantly higher in TP53-mutated patients treated with everolimus: 70% of the patients were still alive at 2 years compared with only 22% of placebo controls (P = .026), she said.

This is a surprising finding, Nathan suggested, as patients with TP53 mutations traditionally have worse survival than those without, suggesting that these patients in particular appear to benefit from adjuvant everolimus.

“Everolimus is used for patients with breast cancer or renal cell cancer for extended periods without major side effects and there is potential for patients with TP53-mutated head and neck disease to see a survival benefit as well,” Nathan speculated.

However, additional trials are needed to confirm the link between the TP53 mutation and survival and to assess the safety of keeping patients with HNSCC on an mTOR inhibitor for longer than 1 year.

The study was funded by Novartis. Nathan has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

REPORTING FROM HEAD AND NECK CANCERS SYMPOSIUM 2020

HM20 course director influenced by POCUS, global health

Dr. Benji Mathews praises mentors for his SHM roles

Benji K. Mathews, MD, SFHM, CLHM, is chief of hospital medicine at Regions Hospital in St. Paul, Minn., and director of point of care ultrasound (POCUS) for hospital medicine at HealthPartners. He is also the course director for the Society of Hospital Medicine’s 2020 Annual Conference (HM20), to be held April 16-18 in San Diego.

Dr. Mathews, an associate professor of medicine at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, is recognized by fellow hospitalists as a pioneer in the use of bedside ultrasound. In fact, his Certificate of Leadership in Hospital Medicine (CLHM) was completed with a focus on ultrasound in hospital medicine, and he is a Fellow in Diagnostic Safety through the Society to Improve Diagnosis in Medicine. “While a resident, I took an interest in the field of improving diagnosis and combined it with the 21st-century innovative tool of bedside ultrasound,” he said. “Now, I continue to teach clinicians, educators, and learners.”

In addition to his interest in POCUS and medical education, Dr. Mathews also has a passion for global health, rooted in a commitment to reducing health care disparities both locally and globally. He has worked with medical missions, nongovernmental organizations, and orphanages in Nepal, India, Bolivia, Honduras, and Costa Rica. This led him to complete the global health course at the University of Minnesota.

Dr. Mathews spent a few minutes with The Hospitalist to discuss his background and his new role of course director of the HM20 Annual Conference.

Can you describe your journey to becoming a hospitalist?

I’ve been a hospitalist for most of the last decade. I was fortunate to be a part of a great residency program at the University of Minnesota Medical School, which started a hospital medicine pathway that had several nationally recognized hospital medicine leaders as mentors. I was lucky to work with several of them through the HealthPartners organization in Saint Paul, and that developed in me a further desire to practice hospital medicine. The group and mentors provided opportunities to develop further niches in my practice, like bedside ultrasound.

How did you first get involved with SHM?

I entered SHM through the influence of mentors at HealthPartners, especially Burke Kealey, MD, SFHM, senior medical director for hospital specialties at HealthPartners Medical Group in Bloomington, Minn. and a past president of the Society, who encouraged me to participate on SHM committees. I eventually applied for the Annual Conference Committee, and somehow was accepted.

At that time, I was a community hospitalist among a lot of academic hospitalists. I thought that my voice could probably diversify the conversation, and bring the perspective of an early-career hospitalist to the discussion around educational offerings at the Annual Conference. I benefited from good mentorship on that committee, and with that experience I started getting involved with our local chapter in Minnesota. That was very important. I became our local chapter president and was able to combine my efforts with SHM nationally with our regional initiatives.

You have a particular interest in point-of-care ultrasound for hospitalists. How did that make its way into your involvement with SHM?

Point-of-care ultrasound and diagnostic error work really took off when I was a resident. My interest in that funneled naturally into the base curriculum of the Annual Conference, where once a year I could come together with 18 of my best hospitalist friends from across the nation to discuss curriculum. We talk about what content is applicable for frontline clinicians, what is right for early learners, and what innovations are coming in the future. Toward that last point, I was always involved as a judge or volunteer for the Research, Innovations and Clinical Vignettes – or RIV – competition at the Annual Conference. That’s the scientific abstract and poster competition at the conference. My interest grew to a point at which I decided to apply for one of the leadership roles in the RIV. I had the opportunity to serve as an Innovations Lead at RIV one year, and then chaired the overall RIV competition. Those opportunities helped me better understand the cutting-edge research that hospitalists should be aware of and which researchers and clinicians we should be in conversation with.

All these roles together have led me to my service as HM20 course director. I see myself as a lucky guy who has benefited from great mentorship, and I want to take advantage of my opportunities to serve.

We’ve been told that your elementary school–age children have learned to use ultrasound!

Well, they’ve learned how to use handheld ultrasound devices on each other. They’re able to find their siblings’ kidneys and hearts. I often show an image of this to encourage hospitalists that, if children can pick it up, highly educated providers can do the same and more.

To register for the Society of Hospital Medicine’s 2020 Annual Conference, please visit the HM20 Registration page.

Dr. Benji Mathews praises mentors for his SHM roles

Dr. Benji Mathews praises mentors for his SHM roles

Benji K. Mathews, MD, SFHM, CLHM, is chief of hospital medicine at Regions Hospital in St. Paul, Minn., and director of point of care ultrasound (POCUS) for hospital medicine at HealthPartners. He is also the course director for the Society of Hospital Medicine’s 2020 Annual Conference (HM20), to be held April 16-18 in San Diego.

Dr. Mathews, an associate professor of medicine at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, is recognized by fellow hospitalists as a pioneer in the use of bedside ultrasound. In fact, his Certificate of Leadership in Hospital Medicine (CLHM) was completed with a focus on ultrasound in hospital medicine, and he is a Fellow in Diagnostic Safety through the Society to Improve Diagnosis in Medicine. “While a resident, I took an interest in the field of improving diagnosis and combined it with the 21st-century innovative tool of bedside ultrasound,” he said. “Now, I continue to teach clinicians, educators, and learners.”

In addition to his interest in POCUS and medical education, Dr. Mathews also has a passion for global health, rooted in a commitment to reducing health care disparities both locally and globally. He has worked with medical missions, nongovernmental organizations, and orphanages in Nepal, India, Bolivia, Honduras, and Costa Rica. This led him to complete the global health course at the University of Minnesota.

Dr. Mathews spent a few minutes with The Hospitalist to discuss his background and his new role of course director of the HM20 Annual Conference.

Can you describe your journey to becoming a hospitalist?

I’ve been a hospitalist for most of the last decade. I was fortunate to be a part of a great residency program at the University of Minnesota Medical School, which started a hospital medicine pathway that had several nationally recognized hospital medicine leaders as mentors. I was lucky to work with several of them through the HealthPartners organization in Saint Paul, and that developed in me a further desire to practice hospital medicine. The group and mentors provided opportunities to develop further niches in my practice, like bedside ultrasound.

How did you first get involved with SHM?

I entered SHM through the influence of mentors at HealthPartners, especially Burke Kealey, MD, SFHM, senior medical director for hospital specialties at HealthPartners Medical Group in Bloomington, Minn. and a past president of the Society, who encouraged me to participate on SHM committees. I eventually applied for the Annual Conference Committee, and somehow was accepted.

At that time, I was a community hospitalist among a lot of academic hospitalists. I thought that my voice could probably diversify the conversation, and bring the perspective of an early-career hospitalist to the discussion around educational offerings at the Annual Conference. I benefited from good mentorship on that committee, and with that experience I started getting involved with our local chapter in Minnesota. That was very important. I became our local chapter president and was able to combine my efforts with SHM nationally with our regional initiatives.

You have a particular interest in point-of-care ultrasound for hospitalists. How did that make its way into your involvement with SHM?

Point-of-care ultrasound and diagnostic error work really took off when I was a resident. My interest in that funneled naturally into the base curriculum of the Annual Conference, where once a year I could come together with 18 of my best hospitalist friends from across the nation to discuss curriculum. We talk about what content is applicable for frontline clinicians, what is right for early learners, and what innovations are coming in the future. Toward that last point, I was always involved as a judge or volunteer for the Research, Innovations and Clinical Vignettes – or RIV – competition at the Annual Conference. That’s the scientific abstract and poster competition at the conference. My interest grew to a point at which I decided to apply for one of the leadership roles in the RIV. I had the opportunity to serve as an Innovations Lead at RIV one year, and then chaired the overall RIV competition. Those opportunities helped me better understand the cutting-edge research that hospitalists should be aware of and which researchers and clinicians we should be in conversation with.

All these roles together have led me to my service as HM20 course director. I see myself as a lucky guy who has benefited from great mentorship, and I want to take advantage of my opportunities to serve.

We’ve been told that your elementary school–age children have learned to use ultrasound!

Well, they’ve learned how to use handheld ultrasound devices on each other. They’re able to find their siblings’ kidneys and hearts. I often show an image of this to encourage hospitalists that, if children can pick it up, highly educated providers can do the same and more.

To register for the Society of Hospital Medicine’s 2020 Annual Conference, please visit the HM20 Registration page.

Benji K. Mathews, MD, SFHM, CLHM, is chief of hospital medicine at Regions Hospital in St. Paul, Minn., and director of point of care ultrasound (POCUS) for hospital medicine at HealthPartners. He is also the course director for the Society of Hospital Medicine’s 2020 Annual Conference (HM20), to be held April 16-18 in San Diego.

Dr. Mathews, an associate professor of medicine at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, is recognized by fellow hospitalists as a pioneer in the use of bedside ultrasound. In fact, his Certificate of Leadership in Hospital Medicine (CLHM) was completed with a focus on ultrasound in hospital medicine, and he is a Fellow in Diagnostic Safety through the Society to Improve Diagnosis in Medicine. “While a resident, I took an interest in the field of improving diagnosis and combined it with the 21st-century innovative tool of bedside ultrasound,” he said. “Now, I continue to teach clinicians, educators, and learners.”

In addition to his interest in POCUS and medical education, Dr. Mathews also has a passion for global health, rooted in a commitment to reducing health care disparities both locally and globally. He has worked with medical missions, nongovernmental organizations, and orphanages in Nepal, India, Bolivia, Honduras, and Costa Rica. This led him to complete the global health course at the University of Minnesota.

Dr. Mathews spent a few minutes with The Hospitalist to discuss his background and his new role of course director of the HM20 Annual Conference.

Can you describe your journey to becoming a hospitalist?

I’ve been a hospitalist for most of the last decade. I was fortunate to be a part of a great residency program at the University of Minnesota Medical School, which started a hospital medicine pathway that had several nationally recognized hospital medicine leaders as mentors. I was lucky to work with several of them through the HealthPartners organization in Saint Paul, and that developed in me a further desire to practice hospital medicine. The group and mentors provided opportunities to develop further niches in my practice, like bedside ultrasound.

How did you first get involved with SHM?

I entered SHM through the influence of mentors at HealthPartners, especially Burke Kealey, MD, SFHM, senior medical director for hospital specialties at HealthPartners Medical Group in Bloomington, Minn. and a past president of the Society, who encouraged me to participate on SHM committees. I eventually applied for the Annual Conference Committee, and somehow was accepted.

At that time, I was a community hospitalist among a lot of academic hospitalists. I thought that my voice could probably diversify the conversation, and bring the perspective of an early-career hospitalist to the discussion around educational offerings at the Annual Conference. I benefited from good mentorship on that committee, and with that experience I started getting involved with our local chapter in Minnesota. That was very important. I became our local chapter president and was able to combine my efforts with SHM nationally with our regional initiatives.

You have a particular interest in point-of-care ultrasound for hospitalists. How did that make its way into your involvement with SHM?

Point-of-care ultrasound and diagnostic error work really took off when I was a resident. My interest in that funneled naturally into the base curriculum of the Annual Conference, where once a year I could come together with 18 of my best hospitalist friends from across the nation to discuss curriculum. We talk about what content is applicable for frontline clinicians, what is right for early learners, and what innovations are coming in the future. Toward that last point, I was always involved as a judge or volunteer for the Research, Innovations and Clinical Vignettes – or RIV – competition at the Annual Conference. That’s the scientific abstract and poster competition at the conference. My interest grew to a point at which I decided to apply for one of the leadership roles in the RIV. I had the opportunity to serve as an Innovations Lead at RIV one year, and then chaired the overall RIV competition. Those opportunities helped me better understand the cutting-edge research that hospitalists should be aware of and which researchers and clinicians we should be in conversation with.

All these roles together have led me to my service as HM20 course director. I see myself as a lucky guy who has benefited from great mentorship, and I want to take advantage of my opportunities to serve.

We’ve been told that your elementary school–age children have learned to use ultrasound!

Well, they’ve learned how to use handheld ultrasound devices on each other. They’re able to find their siblings’ kidneys and hearts. I often show an image of this to encourage hospitalists that, if children can pick it up, highly educated providers can do the same and more.

To register for the Society of Hospital Medicine’s 2020 Annual Conference, please visit the HM20 Registration page.

RA magnifies fragility fracture risk in ESRD

MAUI, HAWAII – Comorbid rheumatoid arthritis is a force multiplier for fragility fracture risk in patients with end-stage renal disease, Renée Peterkin-McCalman, MD, reported at the 2020 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

“Patients with RA and ESRD are at substantially increased risk of osteoporotic fragility fractures compared to the overall population of ESRD patients. So fracture prevention prior to initiation of dialysis should be a focus of care in patients with RA,” said Dr. Peterkin-McCalman, a rheumatology fellow at the Medical College of Georgia, Augusta.

She presented a retrospective cohort study of 10,706 adults who initiated hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis for ESRD during 2005-2008, including 1,040 who also had RA. All subjects were drawn from the United States Renal Data System. The impetus for the study, Dr. Peterkin-McCalman explained in an interview, was that although prior studies have established that RA and ESRD are independent risk factors for osteoporotic fractures, the interplay between the two was previously unknown.

The risk of incident osteoporotic fractures during the first 3 years after going on renal dialysis was 14.7% in patients with ESRD only, vaulting to 25.6% in those with comorbid RA. Individuals with both RA and ESRD were at an adjusted 1.83-fold increased overall risk for new fragility fractures and at 1.85-fold increased risk for hip fracture, compared to those without RA.

Far and away the strongest risk factor for incident osteoporotic fractures in the group with RA plus ESRD was a history of a fracture sustained within 5 years prior to initiation of dialysis, with an associated 11.5-fold increased fracture risk overall and an 8.2-fold increased risk of hip fracture.

“The reason that’s important is we don’t really have any medications to reduce fracture risk once you get to ESRD. Of course, we have bisphosphonates and Prolia (denosumab) and things like that, but that’s in patients with milder CKD [chronic kidney disease] or no renal disease at all. So the goal is to identify the patients early who are at higher risk so that we can protect those bones before they get to ESRD and we have nothing left to treat them with,” she said.

In addition to a history of prevalent fracture prior to starting ESRD, the other risk factors for fracture in patients with ESRD and comorbid RA Dr. Peterkin-McCalman identified in her study included age greater than 50 years at the start of dialysis and female gender, which was associated with a twofold greater fracture risk than in men. Black patients with ESRD and RA were 64% less likely than whites to experience an incident fragility fracture. And the fracture risk was higher in patients on hemodialysis than with peritoneal dialysis.

Her study was supported by the Medical College of Georgia and a research grant from Dialysis Clinic Inc.

SOURCE: Peterkin-McCalman R et al. RWCS 2020.

MAUI, HAWAII – Comorbid rheumatoid arthritis is a force multiplier for fragility fracture risk in patients with end-stage renal disease, Renée Peterkin-McCalman, MD, reported at the 2020 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

“Patients with RA and ESRD are at substantially increased risk of osteoporotic fragility fractures compared to the overall population of ESRD patients. So fracture prevention prior to initiation of dialysis should be a focus of care in patients with RA,” said Dr. Peterkin-McCalman, a rheumatology fellow at the Medical College of Georgia, Augusta.

She presented a retrospective cohort study of 10,706 adults who initiated hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis for ESRD during 2005-2008, including 1,040 who also had RA. All subjects were drawn from the United States Renal Data System. The impetus for the study, Dr. Peterkin-McCalman explained in an interview, was that although prior studies have established that RA and ESRD are independent risk factors for osteoporotic fractures, the interplay between the two was previously unknown.

The risk of incident osteoporotic fractures during the first 3 years after going on renal dialysis was 14.7% in patients with ESRD only, vaulting to 25.6% in those with comorbid RA. Individuals with both RA and ESRD were at an adjusted 1.83-fold increased overall risk for new fragility fractures and at 1.85-fold increased risk for hip fracture, compared to those without RA.

Far and away the strongest risk factor for incident osteoporotic fractures in the group with RA plus ESRD was a history of a fracture sustained within 5 years prior to initiation of dialysis, with an associated 11.5-fold increased fracture risk overall and an 8.2-fold increased risk of hip fracture.

“The reason that’s important is we don’t really have any medications to reduce fracture risk once you get to ESRD. Of course, we have bisphosphonates and Prolia (denosumab) and things like that, but that’s in patients with milder CKD [chronic kidney disease] or no renal disease at all. So the goal is to identify the patients early who are at higher risk so that we can protect those bones before they get to ESRD and we have nothing left to treat them with,” she said.

In addition to a history of prevalent fracture prior to starting ESRD, the other risk factors for fracture in patients with ESRD and comorbid RA Dr. Peterkin-McCalman identified in her study included age greater than 50 years at the start of dialysis and female gender, which was associated with a twofold greater fracture risk than in men. Black patients with ESRD and RA were 64% less likely than whites to experience an incident fragility fracture. And the fracture risk was higher in patients on hemodialysis than with peritoneal dialysis.

Her study was supported by the Medical College of Georgia and a research grant from Dialysis Clinic Inc.

SOURCE: Peterkin-McCalman R et al. RWCS 2020.

MAUI, HAWAII – Comorbid rheumatoid arthritis is a force multiplier for fragility fracture risk in patients with end-stage renal disease, Renée Peterkin-McCalman, MD, reported at the 2020 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

“Patients with RA and ESRD are at substantially increased risk of osteoporotic fragility fractures compared to the overall population of ESRD patients. So fracture prevention prior to initiation of dialysis should be a focus of care in patients with RA,” said Dr. Peterkin-McCalman, a rheumatology fellow at the Medical College of Georgia, Augusta.

She presented a retrospective cohort study of 10,706 adults who initiated hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis for ESRD during 2005-2008, including 1,040 who also had RA. All subjects were drawn from the United States Renal Data System. The impetus for the study, Dr. Peterkin-McCalman explained in an interview, was that although prior studies have established that RA and ESRD are independent risk factors for osteoporotic fractures, the interplay between the two was previously unknown.

The risk of incident osteoporotic fractures during the first 3 years after going on renal dialysis was 14.7% in patients with ESRD only, vaulting to 25.6% in those with comorbid RA. Individuals with both RA and ESRD were at an adjusted 1.83-fold increased overall risk for new fragility fractures and at 1.85-fold increased risk for hip fracture, compared to those without RA.

Far and away the strongest risk factor for incident osteoporotic fractures in the group with RA plus ESRD was a history of a fracture sustained within 5 years prior to initiation of dialysis, with an associated 11.5-fold increased fracture risk overall and an 8.2-fold increased risk of hip fracture.

“The reason that’s important is we don’t really have any medications to reduce fracture risk once you get to ESRD. Of course, we have bisphosphonates and Prolia (denosumab) and things like that, but that’s in patients with milder CKD [chronic kidney disease] or no renal disease at all. So the goal is to identify the patients early who are at higher risk so that we can protect those bones before they get to ESRD and we have nothing left to treat them with,” she said.

In addition to a history of prevalent fracture prior to starting ESRD, the other risk factors for fracture in patients with ESRD and comorbid RA Dr. Peterkin-McCalman identified in her study included age greater than 50 years at the start of dialysis and female gender, which was associated with a twofold greater fracture risk than in men. Black patients with ESRD and RA were 64% less likely than whites to experience an incident fragility fracture. And the fracture risk was higher in patients on hemodialysis than with peritoneal dialysis.

Her study was supported by the Medical College of Georgia and a research grant from Dialysis Clinic Inc.

SOURCE: Peterkin-McCalman R et al. RWCS 2020.

REPORTING FROM RWCS 2020

Hospitalist profile: Ilaria Gadalla, DMSc, PA-C

Ilaria Gadalla, DMSc, PA-C, is a hospitalist at Treasure Coast Hospitalists in Port St. Lucie, Fla., and serves as the physician assistant department chair/program director at South University, West Palm Beach, Fla., where she supervises more than 40 PAs, medical directors, and administrative staff across the South University campuses.

Ms. Gadalla is the chair of SHM’s NP/PA Special Interest Group, which was integral in drafting the society’s recent white paper on NP/PA integration and optimization.

She says that she continuously drives innovative projects for NPs and PAs to demonstrate excellence in collaboration by working closely with C-suite administration to expand quality improvement and education efforts. A prime example is the optimal communication system that she developed within her first week as a hospitalist in the Port St. Lucie area. Nursing, ED, and pharmacy staff had difficulty contacting hospitalists since the electronic medical record would not reflect the assigned hospitalist. She developed a simple contact sheet that included the hospitalist team each day. This method is still in use today.

At what point in your life did you realize you wanted to be a physician assistant?