User login

Prescription cascade more likely after CCBs than other hypertension meds

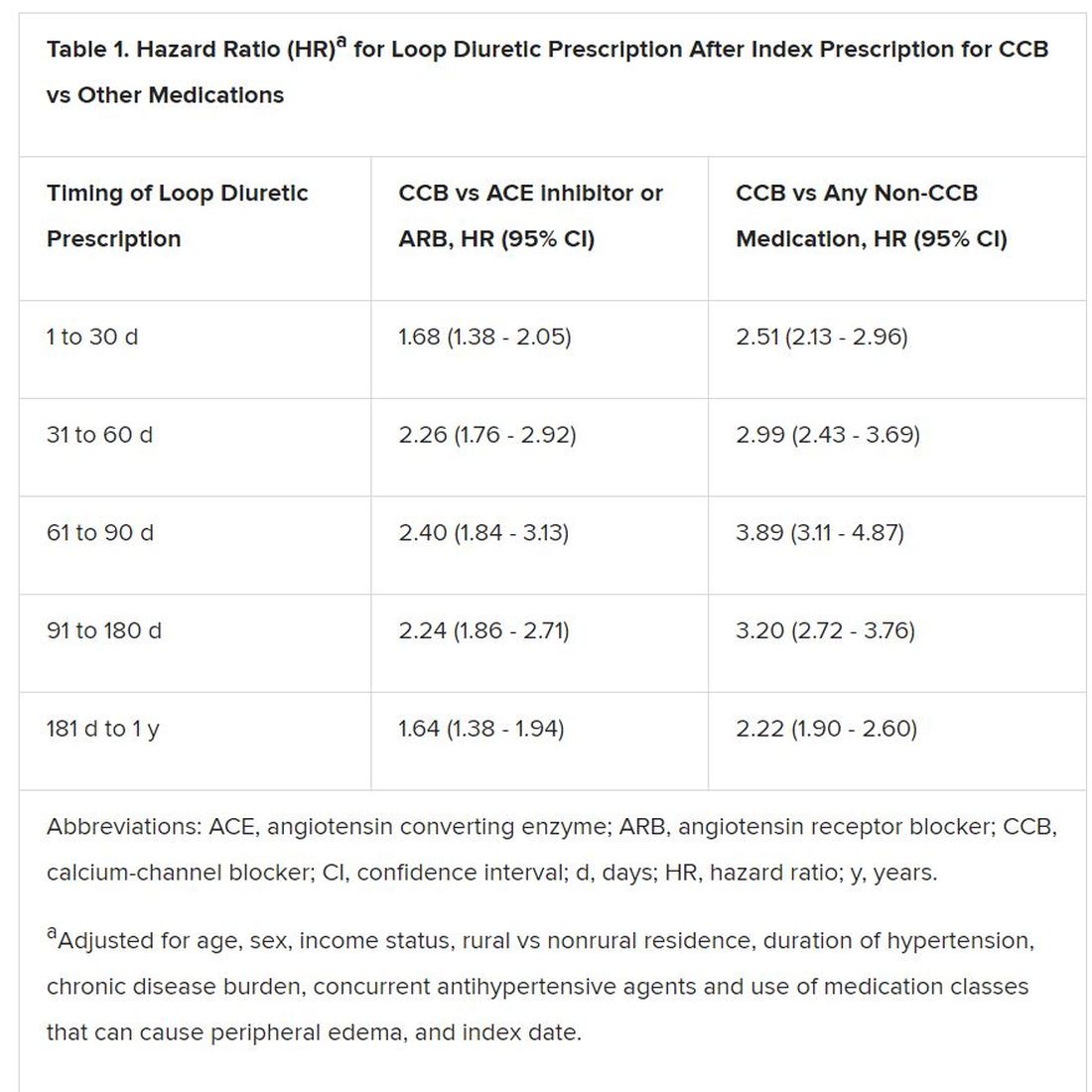

Elderly adults with hypertension who are newly prescribed a calcium-channel blocker (CCB), compared to other antihypertensive agents, are at least twice as likely to be given a loop diuretic over the following months, a large cohort study suggests.

The likelihood remained elevated for as long as a year after the start of a CCB and was more pronounced when comparing CCBs to any other kind of medication.

“Our findings suggest that many older adults who begin taking a CCB may subsequently experience a prescribing cascade” when loop diuretics are prescribed for peripheral edema, a known CCB adverse effect, that is misinterpreted as a new medical condition, Rachel D. Savage, PhD, Women’s College Hospital, Toronto, Canada, told theheart.org/Medscape Cardiology.

Edema caused by CCBs is caused by fluid redistribution, not overload, and “treating euvolemic individuals with a diuretic places them at increased risk of overdiuresis, leading to falls, urinary incontinence, acute kidney injury, electrolyte imbalances, and a cascade of other downstream consequences to which older adults are especially vulnerable,” explain Savage and coauthors of the analysis published online February 24 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

However, 1.4% of the cohort had been prescribed a loop diuretic, and 4.5% had been given any diuretic within 90 days after the start of CCBs. The corresponding rates were 0.7% and 3.4%, respectively, for patients who had started on ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) rather than a CCB.

Also, Savage observed, “the likelihood of being prescribed a loop diuretic following initiation of a CCB changed over time and was greatest 61 to 90 days postinitiation.” At that point, it was increased 2.4 times compared with initiation of an ACE inhibitor or an ARB in an adjusted analysis and increased almost 4 times compared with starting on any non-CCB agent.

Importantly, the actual prevalence of peripheral edema among those started on CCBs, ACE inhibitors, ARBs, or any non-CCB medication was not available in the data sets.

However, “the main message for clinicians is to consider medication side effects as a potential cause for new symptoms when patients present. We also encourage patients to ask prescribers about whether new symptoms could be caused by a medication,” senior author Lisa M. McCarthy, PharmD, told theheart.org/Medscape Cardiology.

“If a patient experiences peripheral edema while taking a CCB, we would encourage clinicians to consider whether the calcium-channel blocker is still necessary, whether it could be discontinued or the dose reduced, or whether the patient can be switched to another therapy,” she said.

Based on the current analysis, if the rate of CCB-induced peripheral edema is assumed to be 10%, which is consistent with the literature, then “potentially 7% to 14% of people who develop edema while taking a calcium channel blocker may then receive a loop diuretic,” an accompanying editorial notes.

“Patients with polypharmacy are at heightened risk of being exposed to [a] series of prescribing cascades if their current use of medications is not carefully discussed before the decision to add a new antihypertensive,” observe Timothy S. Anderson, MD, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts, and Michael A. Steinman, MD, San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center and University of California, San Francisco.

“The initial prescribing cascade can set off many other negative consequences, including adverse drug events, potentially avoidable diagnostic testing, and hospitalizations,” the editorialists caution.

“Identifying prescribing cascades and their consequences is an important step to stem the tide of polypharmacy and inform deprescribing efforts.”

The analysis was based on administrative data from almost 340,000 adults in the community aged 66 years or older with hypertension and new drug prescriptions over 5 years ending in September 2016, the report notes. Their mean age was 74.5 years and 56.5% were women.

The data set included 41,086 patients who were newly prescribed a CCB; 66,494 who were newly prescribed an ACE inhibitor or ARB; and 231,439 newly prescribed any medication other than a CCB. The prescribed CCB was amlodipine in 79.6% of patients.

Although loop diuretics could possibly have been prescribed sometimes as a second-tier antihypertensive in the absence of peripheral edema, “we made efforts, through the design of our study, to limit this where possible,” Savage said in an interview.

For example, the focus was on loop diuretics, which aren’t generally recommended for blood-pressure lowering. Also, patients with heart failure and those with a recent history of diuretic or other antihypertensive medication use had been excluded, she said.

“As such, our cohort comprised individuals with new-onset or milder hypertension for whom diuretics would unlikely to be prescribed as part of guideline-based hypertension management.”

Although amlodipine was the most commonly prescribed CCB, the potential for a prescribing cascade seemed to be a class effect and to apply at a range of dosages.

That was unexpected, McCarthy observed, because “peripheral edema occurs more commonly in people taking dihydropyridine CCBs, like amlodipine, compared to non–dihydropyridine CCBs, such as verapamil and diltiazem.”

Savage, McCarthy, their coauthors, and the editorialists have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Elderly adults with hypertension who are newly prescribed a calcium-channel blocker (CCB), compared to other antihypertensive agents, are at least twice as likely to be given a loop diuretic over the following months, a large cohort study suggests.

The likelihood remained elevated for as long as a year after the start of a CCB and was more pronounced when comparing CCBs to any other kind of medication.

“Our findings suggest that many older adults who begin taking a CCB may subsequently experience a prescribing cascade” when loop diuretics are prescribed for peripheral edema, a known CCB adverse effect, that is misinterpreted as a new medical condition, Rachel D. Savage, PhD, Women’s College Hospital, Toronto, Canada, told theheart.org/Medscape Cardiology.

Edema caused by CCBs is caused by fluid redistribution, not overload, and “treating euvolemic individuals with a diuretic places them at increased risk of overdiuresis, leading to falls, urinary incontinence, acute kidney injury, electrolyte imbalances, and a cascade of other downstream consequences to which older adults are especially vulnerable,” explain Savage and coauthors of the analysis published online February 24 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

However, 1.4% of the cohort had been prescribed a loop diuretic, and 4.5% had been given any diuretic within 90 days after the start of CCBs. The corresponding rates were 0.7% and 3.4%, respectively, for patients who had started on ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) rather than a CCB.

Also, Savage observed, “the likelihood of being prescribed a loop diuretic following initiation of a CCB changed over time and was greatest 61 to 90 days postinitiation.” At that point, it was increased 2.4 times compared with initiation of an ACE inhibitor or an ARB in an adjusted analysis and increased almost 4 times compared with starting on any non-CCB agent.

Importantly, the actual prevalence of peripheral edema among those started on CCBs, ACE inhibitors, ARBs, or any non-CCB medication was not available in the data sets.

However, “the main message for clinicians is to consider medication side effects as a potential cause for new symptoms when patients present. We also encourage patients to ask prescribers about whether new symptoms could be caused by a medication,” senior author Lisa M. McCarthy, PharmD, told theheart.org/Medscape Cardiology.

“If a patient experiences peripheral edema while taking a CCB, we would encourage clinicians to consider whether the calcium-channel blocker is still necessary, whether it could be discontinued or the dose reduced, or whether the patient can be switched to another therapy,” she said.

Based on the current analysis, if the rate of CCB-induced peripheral edema is assumed to be 10%, which is consistent with the literature, then “potentially 7% to 14% of people who develop edema while taking a calcium channel blocker may then receive a loop diuretic,” an accompanying editorial notes.

“Patients with polypharmacy are at heightened risk of being exposed to [a] series of prescribing cascades if their current use of medications is not carefully discussed before the decision to add a new antihypertensive,” observe Timothy S. Anderson, MD, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts, and Michael A. Steinman, MD, San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center and University of California, San Francisco.

“The initial prescribing cascade can set off many other negative consequences, including adverse drug events, potentially avoidable diagnostic testing, and hospitalizations,” the editorialists caution.

“Identifying prescribing cascades and their consequences is an important step to stem the tide of polypharmacy and inform deprescribing efforts.”

The analysis was based on administrative data from almost 340,000 adults in the community aged 66 years or older with hypertension and new drug prescriptions over 5 years ending in September 2016, the report notes. Their mean age was 74.5 years and 56.5% were women.

The data set included 41,086 patients who were newly prescribed a CCB; 66,494 who were newly prescribed an ACE inhibitor or ARB; and 231,439 newly prescribed any medication other than a CCB. The prescribed CCB was amlodipine in 79.6% of patients.

Although loop diuretics could possibly have been prescribed sometimes as a second-tier antihypertensive in the absence of peripheral edema, “we made efforts, through the design of our study, to limit this where possible,” Savage said in an interview.

For example, the focus was on loop diuretics, which aren’t generally recommended for blood-pressure lowering. Also, patients with heart failure and those with a recent history of diuretic or other antihypertensive medication use had been excluded, she said.

“As such, our cohort comprised individuals with new-onset or milder hypertension for whom diuretics would unlikely to be prescribed as part of guideline-based hypertension management.”

Although amlodipine was the most commonly prescribed CCB, the potential for a prescribing cascade seemed to be a class effect and to apply at a range of dosages.

That was unexpected, McCarthy observed, because “peripheral edema occurs more commonly in people taking dihydropyridine CCBs, like amlodipine, compared to non–dihydropyridine CCBs, such as verapamil and diltiazem.”

Savage, McCarthy, their coauthors, and the editorialists have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Elderly adults with hypertension who are newly prescribed a calcium-channel blocker (CCB), compared to other antihypertensive agents, are at least twice as likely to be given a loop diuretic over the following months, a large cohort study suggests.

The likelihood remained elevated for as long as a year after the start of a CCB and was more pronounced when comparing CCBs to any other kind of medication.

“Our findings suggest that many older adults who begin taking a CCB may subsequently experience a prescribing cascade” when loop diuretics are prescribed for peripheral edema, a known CCB adverse effect, that is misinterpreted as a new medical condition, Rachel D. Savage, PhD, Women’s College Hospital, Toronto, Canada, told theheart.org/Medscape Cardiology.

Edema caused by CCBs is caused by fluid redistribution, not overload, and “treating euvolemic individuals with a diuretic places them at increased risk of overdiuresis, leading to falls, urinary incontinence, acute kidney injury, electrolyte imbalances, and a cascade of other downstream consequences to which older adults are especially vulnerable,” explain Savage and coauthors of the analysis published online February 24 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

However, 1.4% of the cohort had been prescribed a loop diuretic, and 4.5% had been given any diuretic within 90 days after the start of CCBs. The corresponding rates were 0.7% and 3.4%, respectively, for patients who had started on ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) rather than a CCB.

Also, Savage observed, “the likelihood of being prescribed a loop diuretic following initiation of a CCB changed over time and was greatest 61 to 90 days postinitiation.” At that point, it was increased 2.4 times compared with initiation of an ACE inhibitor or an ARB in an adjusted analysis and increased almost 4 times compared with starting on any non-CCB agent.

Importantly, the actual prevalence of peripheral edema among those started on CCBs, ACE inhibitors, ARBs, or any non-CCB medication was not available in the data sets.

However, “the main message for clinicians is to consider medication side effects as a potential cause for new symptoms when patients present. We also encourage patients to ask prescribers about whether new symptoms could be caused by a medication,” senior author Lisa M. McCarthy, PharmD, told theheart.org/Medscape Cardiology.

“If a patient experiences peripheral edema while taking a CCB, we would encourage clinicians to consider whether the calcium-channel blocker is still necessary, whether it could be discontinued or the dose reduced, or whether the patient can be switched to another therapy,” she said.

Based on the current analysis, if the rate of CCB-induced peripheral edema is assumed to be 10%, which is consistent with the literature, then “potentially 7% to 14% of people who develop edema while taking a calcium channel blocker may then receive a loop diuretic,” an accompanying editorial notes.

“Patients with polypharmacy are at heightened risk of being exposed to [a] series of prescribing cascades if their current use of medications is not carefully discussed before the decision to add a new antihypertensive,” observe Timothy S. Anderson, MD, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts, and Michael A. Steinman, MD, San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center and University of California, San Francisco.

“The initial prescribing cascade can set off many other negative consequences, including adverse drug events, potentially avoidable diagnostic testing, and hospitalizations,” the editorialists caution.

“Identifying prescribing cascades and their consequences is an important step to stem the tide of polypharmacy and inform deprescribing efforts.”

The analysis was based on administrative data from almost 340,000 adults in the community aged 66 years or older with hypertension and new drug prescriptions over 5 years ending in September 2016, the report notes. Their mean age was 74.5 years and 56.5% were women.

The data set included 41,086 patients who were newly prescribed a CCB; 66,494 who were newly prescribed an ACE inhibitor or ARB; and 231,439 newly prescribed any medication other than a CCB. The prescribed CCB was amlodipine in 79.6% of patients.

Although loop diuretics could possibly have been prescribed sometimes as a second-tier antihypertensive in the absence of peripheral edema, “we made efforts, through the design of our study, to limit this where possible,” Savage said in an interview.

For example, the focus was on loop diuretics, which aren’t generally recommended for blood-pressure lowering. Also, patients with heart failure and those with a recent history of diuretic or other antihypertensive medication use had been excluded, she said.

“As such, our cohort comprised individuals with new-onset or milder hypertension for whom diuretics would unlikely to be prescribed as part of guideline-based hypertension management.”

Although amlodipine was the most commonly prescribed CCB, the potential for a prescribing cascade seemed to be a class effect and to apply at a range of dosages.

That was unexpected, McCarthy observed, because “peripheral edema occurs more commonly in people taking dihydropyridine CCBs, like amlodipine, compared to non–dihydropyridine CCBs, such as verapamil and diltiazem.”

Savage, McCarthy, their coauthors, and the editorialists have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Varied nightly bedtime, sleep duration linked to CVD risk

People who frequently alter the amount of sleep and time they go to bed each night are twofold more likely to develop cardiovascular disease, independent of traditional CVD risk factors, new research suggests.

Prior studies have focused on shift workers because night shift work will influence circadian rhythm and increase CVD risk. But it is increasingly recognized that circadian disruption may occur outside of shift work and accumulate over time, particularly given modern lifestyle factors such as increased use of mobile devices and television at night, said study coauthor Tianyi Huang, ScD, MSc, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts.

“Even if they tend to go to sleep at certain times, by following that lifestyle or behavior, it can interfere with their planned sleep timing,” he said.

“One thing that surprised me in this sample is that about one third of participants have irregular sleep patterns that can put them at increased risk of cardiovascular disease. So I think the prevalence is higher than expected,” Huang added.

As reported today in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, the investigators used data from 7-day wrist actigraphy, 1 night of at-home polysomnography, and sleep questionnaires to assess sleep duration and sleep-onset timing among 1,992 Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis () participants, aged 45 to 84 years, who were free of CVD and prospectively followed for a me MESA dian of 4.9 years.

A total of 786 patients (39.5%) had sleep duration standard deviation (SD) > 90 minutes and 510 (25.6%) had sleep-onset timing SD > 90 minutes.

During follow-up, there were 111 incident CVD events, including myocardial infarction, coronary heart disease death, stroke, and other coronary events.

Compared with people who had less than 1 hour of variation in sleep duration, the risk for incident CVD was 9% higher for people whose sleep duration varied 61 to 90 minutes (hazard ratio [HR], 1.09; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.62 - 1.92), even after controlling for a variety of cardiovascular and sleep-related risk factors such as body mass index, systolic blood pressure, smoking status, total cholesterol, average sleep duration, insomnia symptoms, and sleep apnea.

Moreover, the adjusted CVD risk was substantially increased with 91 to 120 minutes of variation (HR, 1.59; 95% CI, 0.91 - 2.76) and more than 120 minutes of variation in sleep duration (HR, 2.14; 95% CI, 1.24 - 3.68).

Every 1-hour increase in sleep duration SD was associated with 36% higher CVD risk (95% CI; 1.07 - 1.73).

Compared with people with no more than a half hour of variation in nightly bedtimes, the adjusted hazard ratios for CVD were 1.16 (95% CI, 0.64 - 2.13), 1.52 (95% CI, 0.81 - 2.88), and 2.11 (95% CI, 1.13 - 3.91) when bedtimes varied by 31 to 60 minutes, 61 to 90 minutes, and more than 90 minutes.

For every 1-hour increase in sleep-onset timing SD, the risk of CVD was 18% higher (95% CI; 1.06 - 1.31).

“The results are similar for the regularity of sleep timing and the regularity of sleep duration, which means that both can contribute to circadian disruption and then lead to development of cardiovascular disease,” Huang said.

This is an important article and signals how sleep is an important marker and possibly a mediator of cardiovascular risk, said Harlan Krumholz, MD, of Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut, who was not involved with the study.

“What I like about this is it’s a nice longitudinal, epidemiologic study with not just self-report, but sensor-detected sleep, that has been correlated with well-curated and adjudicated outcomes to give us a strong sense of this association,” he told theheart.org/Medscape Cardiology. “And also, that it goes beyond just the duration — they combine the duration and timing in order to give a fuller picture of sleep.”

Nevertheless, Krumholz said researchers are only at the beginning of being able to quantify the various dimensions of sleep and the degree to which sleep is a reflection of underlying physiologic issues, or whether patients are having erratic sleep patterns that are having a toxic effect on their overall health.

Questions also remain about the mechanism behind the association, whether the increased risk is universal or more harmful for some people, and the best way to measure factors during sleep that can most comprehensively and precisely predict risk.

“As we get more information flowing in from sensors, I think we will begin to develop more sophisticated approaches toward understanding risk, and it will be accompanied by other studies that will help us understand whether, again, this is a reflection of other processes that we should be paying attention to or whether it is a cause of disease and risk,” Krumholz said.

Subgroup analyses suggested positive associations between irregular sleep and CVD in African Americans, Hispanics, and Chinese Americans but not in whites. This could be because sleep irregularity, both timing and duration, was substantially higher in minorities, especially African Americans, but may also be as a result of chance because the study sample is relatively small, Huang explained.

The authors note that the overall findings are biologically plausible because of their previous work linking sleep irregularity with metabolic risk factors that predispose to atherosclerosis, such as obesity, diabetes, and hypertension. Participants with irregular sleep tended to have worse baseline cardiometabolic profiles, but this only explained a small portion of the associations between sleep irregularity and CVD, they note.

Other possible explanations include circadian clock genes, such as clock, per2 and bmal1, which have been shown experimentally to control a broad range of cardiovascular functions, from blood pressure and endothelial functions to vascular thrombosis and cardiac remodeling.

Irregular sleep may also influence the rhythms of the autonomic nervous system, and behavioral rhythms with regard to timing and/or amount of eating or exercise.

Further research is needed to understand the mechanisms driving the associations, the impact of sleep irregularity on individual CVD outcomes, and to determine whether a 7-day SD of more than 90 minutes for either sleep duration or sleep-onset timing can be used clinically as a threshold target for promoting cardiometabolically healthy sleep, Huang said.

“When providers communicate with their patients regarding strategies for CVD prevention, usually they focus on healthy diet and physical activity; and even when they talk about sleep, they talk about whether they have good sleep quality or sufficient sleep,” he said. “But one thing they should provide is advice regarding sleep regularity and [they should] recommend their patients follow a regular sleep pattern for the purpose of cardiovascular prevention.”

In a related editorial, Olaf Oldenburg, MD, Luderus-Kliniken Münster, Clemenshospital, Münster, Germany, and Jens Spiesshoefer, MD, Institute of Life Sciences, Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna, Pisa, Italy, write that the observed independent association between sleep irregularity and CVD “is a particularly striking finding given that impaired circadian rhythm is likely to be much more prevalent than the extreme example of shift work.”

They call on researchers to utilize big data to facilitate understanding of the association and say it is essential to test whether experimental data support the hypothesis that altered circadian rhythms would translate into unfavorable changes in 24-hour sympathovagal and neurohormonal balance, and ultimately CVD.

The present study “will, and should, stimulate much needed additional research on the association between sleep and CVD that may offer novel approaches to help improve the prognosis and daily symptom burden of patients with CVD, and might make sleep itself a therapeutic target in CVD,” the editorialists conclude.

This research was supported by contracts from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), and by grants from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The MESA Sleep Study was supported by an NHLBI grant. Huang was supported by a career development grant from the National Institutes of Health.

Krumholz and Oldenburg have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Spiesshoefer is supported by grants from the Else-Kröner-Fresenius Stiftung, the Innovative Medical Research program at the University of Münster, and Deutsche Herzstiftung; and by young investigator research support from Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna Pisa. He also has received travel grants and lecture honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim and Chiesi.

Source: J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Mar 2. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.12.054.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

People who frequently alter the amount of sleep and time they go to bed each night are twofold more likely to develop cardiovascular disease, independent of traditional CVD risk factors, new research suggests.

Prior studies have focused on shift workers because night shift work will influence circadian rhythm and increase CVD risk. But it is increasingly recognized that circadian disruption may occur outside of shift work and accumulate over time, particularly given modern lifestyle factors such as increased use of mobile devices and television at night, said study coauthor Tianyi Huang, ScD, MSc, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts.

“Even if they tend to go to sleep at certain times, by following that lifestyle or behavior, it can interfere with their planned sleep timing,” he said.

“One thing that surprised me in this sample is that about one third of participants have irregular sleep patterns that can put them at increased risk of cardiovascular disease. So I think the prevalence is higher than expected,” Huang added.

As reported today in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, the investigators used data from 7-day wrist actigraphy, 1 night of at-home polysomnography, and sleep questionnaires to assess sleep duration and sleep-onset timing among 1,992 Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis () participants, aged 45 to 84 years, who were free of CVD and prospectively followed for a me MESA dian of 4.9 years.

A total of 786 patients (39.5%) had sleep duration standard deviation (SD) > 90 minutes and 510 (25.6%) had sleep-onset timing SD > 90 minutes.

During follow-up, there were 111 incident CVD events, including myocardial infarction, coronary heart disease death, stroke, and other coronary events.

Compared with people who had less than 1 hour of variation in sleep duration, the risk for incident CVD was 9% higher for people whose sleep duration varied 61 to 90 minutes (hazard ratio [HR], 1.09; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.62 - 1.92), even after controlling for a variety of cardiovascular and sleep-related risk factors such as body mass index, systolic blood pressure, smoking status, total cholesterol, average sleep duration, insomnia symptoms, and sleep apnea.

Moreover, the adjusted CVD risk was substantially increased with 91 to 120 minutes of variation (HR, 1.59; 95% CI, 0.91 - 2.76) and more than 120 minutes of variation in sleep duration (HR, 2.14; 95% CI, 1.24 - 3.68).

Every 1-hour increase in sleep duration SD was associated with 36% higher CVD risk (95% CI; 1.07 - 1.73).

Compared with people with no more than a half hour of variation in nightly bedtimes, the adjusted hazard ratios for CVD were 1.16 (95% CI, 0.64 - 2.13), 1.52 (95% CI, 0.81 - 2.88), and 2.11 (95% CI, 1.13 - 3.91) when bedtimes varied by 31 to 60 minutes, 61 to 90 minutes, and more than 90 minutes.

For every 1-hour increase in sleep-onset timing SD, the risk of CVD was 18% higher (95% CI; 1.06 - 1.31).

“The results are similar for the regularity of sleep timing and the regularity of sleep duration, which means that both can contribute to circadian disruption and then lead to development of cardiovascular disease,” Huang said.

This is an important article and signals how sleep is an important marker and possibly a mediator of cardiovascular risk, said Harlan Krumholz, MD, of Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut, who was not involved with the study.

“What I like about this is it’s a nice longitudinal, epidemiologic study with not just self-report, but sensor-detected sleep, that has been correlated with well-curated and adjudicated outcomes to give us a strong sense of this association,” he told theheart.org/Medscape Cardiology. “And also, that it goes beyond just the duration — they combine the duration and timing in order to give a fuller picture of sleep.”

Nevertheless, Krumholz said researchers are only at the beginning of being able to quantify the various dimensions of sleep and the degree to which sleep is a reflection of underlying physiologic issues, or whether patients are having erratic sleep patterns that are having a toxic effect on their overall health.

Questions also remain about the mechanism behind the association, whether the increased risk is universal or more harmful for some people, and the best way to measure factors during sleep that can most comprehensively and precisely predict risk.

“As we get more information flowing in from sensors, I think we will begin to develop more sophisticated approaches toward understanding risk, and it will be accompanied by other studies that will help us understand whether, again, this is a reflection of other processes that we should be paying attention to or whether it is a cause of disease and risk,” Krumholz said.

Subgroup analyses suggested positive associations between irregular sleep and CVD in African Americans, Hispanics, and Chinese Americans but not in whites. This could be because sleep irregularity, both timing and duration, was substantially higher in minorities, especially African Americans, but may also be as a result of chance because the study sample is relatively small, Huang explained.

The authors note that the overall findings are biologically plausible because of their previous work linking sleep irregularity with metabolic risk factors that predispose to atherosclerosis, such as obesity, diabetes, and hypertension. Participants with irregular sleep tended to have worse baseline cardiometabolic profiles, but this only explained a small portion of the associations between sleep irregularity and CVD, they note.

Other possible explanations include circadian clock genes, such as clock, per2 and bmal1, which have been shown experimentally to control a broad range of cardiovascular functions, from blood pressure and endothelial functions to vascular thrombosis and cardiac remodeling.

Irregular sleep may also influence the rhythms of the autonomic nervous system, and behavioral rhythms with regard to timing and/or amount of eating or exercise.

Further research is needed to understand the mechanisms driving the associations, the impact of sleep irregularity on individual CVD outcomes, and to determine whether a 7-day SD of more than 90 minutes for either sleep duration or sleep-onset timing can be used clinically as a threshold target for promoting cardiometabolically healthy sleep, Huang said.

“When providers communicate with their patients regarding strategies for CVD prevention, usually they focus on healthy diet and physical activity; and even when they talk about sleep, they talk about whether they have good sleep quality or sufficient sleep,” he said. “But one thing they should provide is advice regarding sleep regularity and [they should] recommend their patients follow a regular sleep pattern for the purpose of cardiovascular prevention.”

In a related editorial, Olaf Oldenburg, MD, Luderus-Kliniken Münster, Clemenshospital, Münster, Germany, and Jens Spiesshoefer, MD, Institute of Life Sciences, Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna, Pisa, Italy, write that the observed independent association between sleep irregularity and CVD “is a particularly striking finding given that impaired circadian rhythm is likely to be much more prevalent than the extreme example of shift work.”

They call on researchers to utilize big data to facilitate understanding of the association and say it is essential to test whether experimental data support the hypothesis that altered circadian rhythms would translate into unfavorable changes in 24-hour sympathovagal and neurohormonal balance, and ultimately CVD.

The present study “will, and should, stimulate much needed additional research on the association between sleep and CVD that may offer novel approaches to help improve the prognosis and daily symptom burden of patients with CVD, and might make sleep itself a therapeutic target in CVD,” the editorialists conclude.

This research was supported by contracts from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), and by grants from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The MESA Sleep Study was supported by an NHLBI grant. Huang was supported by a career development grant from the National Institutes of Health.

Krumholz and Oldenburg have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Spiesshoefer is supported by grants from the Else-Kröner-Fresenius Stiftung, the Innovative Medical Research program at the University of Münster, and Deutsche Herzstiftung; and by young investigator research support from Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna Pisa. He also has received travel grants and lecture honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim and Chiesi.

Source: J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Mar 2. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.12.054.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

People who frequently alter the amount of sleep and time they go to bed each night are twofold more likely to develop cardiovascular disease, independent of traditional CVD risk factors, new research suggests.

Prior studies have focused on shift workers because night shift work will influence circadian rhythm and increase CVD risk. But it is increasingly recognized that circadian disruption may occur outside of shift work and accumulate over time, particularly given modern lifestyle factors such as increased use of mobile devices and television at night, said study coauthor Tianyi Huang, ScD, MSc, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts.

“Even if they tend to go to sleep at certain times, by following that lifestyle or behavior, it can interfere with their planned sleep timing,” he said.

“One thing that surprised me in this sample is that about one third of participants have irregular sleep patterns that can put them at increased risk of cardiovascular disease. So I think the prevalence is higher than expected,” Huang added.

As reported today in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, the investigators used data from 7-day wrist actigraphy, 1 night of at-home polysomnography, and sleep questionnaires to assess sleep duration and sleep-onset timing among 1,992 Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis () participants, aged 45 to 84 years, who were free of CVD and prospectively followed for a me MESA dian of 4.9 years.

A total of 786 patients (39.5%) had sleep duration standard deviation (SD) > 90 minutes and 510 (25.6%) had sleep-onset timing SD > 90 minutes.

During follow-up, there were 111 incident CVD events, including myocardial infarction, coronary heart disease death, stroke, and other coronary events.

Compared with people who had less than 1 hour of variation in sleep duration, the risk for incident CVD was 9% higher for people whose sleep duration varied 61 to 90 minutes (hazard ratio [HR], 1.09; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.62 - 1.92), even after controlling for a variety of cardiovascular and sleep-related risk factors such as body mass index, systolic blood pressure, smoking status, total cholesterol, average sleep duration, insomnia symptoms, and sleep apnea.

Moreover, the adjusted CVD risk was substantially increased with 91 to 120 minutes of variation (HR, 1.59; 95% CI, 0.91 - 2.76) and more than 120 minutes of variation in sleep duration (HR, 2.14; 95% CI, 1.24 - 3.68).

Every 1-hour increase in sleep duration SD was associated with 36% higher CVD risk (95% CI; 1.07 - 1.73).

Compared with people with no more than a half hour of variation in nightly bedtimes, the adjusted hazard ratios for CVD were 1.16 (95% CI, 0.64 - 2.13), 1.52 (95% CI, 0.81 - 2.88), and 2.11 (95% CI, 1.13 - 3.91) when bedtimes varied by 31 to 60 minutes, 61 to 90 minutes, and more than 90 minutes.

For every 1-hour increase in sleep-onset timing SD, the risk of CVD was 18% higher (95% CI; 1.06 - 1.31).

“The results are similar for the regularity of sleep timing and the regularity of sleep duration, which means that both can contribute to circadian disruption and then lead to development of cardiovascular disease,” Huang said.

This is an important article and signals how sleep is an important marker and possibly a mediator of cardiovascular risk, said Harlan Krumholz, MD, of Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut, who was not involved with the study.

“What I like about this is it’s a nice longitudinal, epidemiologic study with not just self-report, but sensor-detected sleep, that has been correlated with well-curated and adjudicated outcomes to give us a strong sense of this association,” he told theheart.org/Medscape Cardiology. “And also, that it goes beyond just the duration — they combine the duration and timing in order to give a fuller picture of sleep.”

Nevertheless, Krumholz said researchers are only at the beginning of being able to quantify the various dimensions of sleep and the degree to which sleep is a reflection of underlying physiologic issues, or whether patients are having erratic sleep patterns that are having a toxic effect on their overall health.

Questions also remain about the mechanism behind the association, whether the increased risk is universal or more harmful for some people, and the best way to measure factors during sleep that can most comprehensively and precisely predict risk.

“As we get more information flowing in from sensors, I think we will begin to develop more sophisticated approaches toward understanding risk, and it will be accompanied by other studies that will help us understand whether, again, this is a reflection of other processes that we should be paying attention to or whether it is a cause of disease and risk,” Krumholz said.

Subgroup analyses suggested positive associations between irregular sleep and CVD in African Americans, Hispanics, and Chinese Americans but not in whites. This could be because sleep irregularity, both timing and duration, was substantially higher in minorities, especially African Americans, but may also be as a result of chance because the study sample is relatively small, Huang explained.

The authors note that the overall findings are biologically plausible because of their previous work linking sleep irregularity with metabolic risk factors that predispose to atherosclerosis, such as obesity, diabetes, and hypertension. Participants with irregular sleep tended to have worse baseline cardiometabolic profiles, but this only explained a small portion of the associations between sleep irregularity and CVD, they note.

Other possible explanations include circadian clock genes, such as clock, per2 and bmal1, which have been shown experimentally to control a broad range of cardiovascular functions, from blood pressure and endothelial functions to vascular thrombosis and cardiac remodeling.

Irregular sleep may also influence the rhythms of the autonomic nervous system, and behavioral rhythms with regard to timing and/or amount of eating or exercise.

Further research is needed to understand the mechanisms driving the associations, the impact of sleep irregularity on individual CVD outcomes, and to determine whether a 7-day SD of more than 90 minutes for either sleep duration or sleep-onset timing can be used clinically as a threshold target for promoting cardiometabolically healthy sleep, Huang said.

“When providers communicate with their patients regarding strategies for CVD prevention, usually they focus on healthy diet and physical activity; and even when they talk about sleep, they talk about whether they have good sleep quality or sufficient sleep,” he said. “But one thing they should provide is advice regarding sleep regularity and [they should] recommend their patients follow a regular sleep pattern for the purpose of cardiovascular prevention.”

In a related editorial, Olaf Oldenburg, MD, Luderus-Kliniken Münster, Clemenshospital, Münster, Germany, and Jens Spiesshoefer, MD, Institute of Life Sciences, Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna, Pisa, Italy, write that the observed independent association between sleep irregularity and CVD “is a particularly striking finding given that impaired circadian rhythm is likely to be much more prevalent than the extreme example of shift work.”

They call on researchers to utilize big data to facilitate understanding of the association and say it is essential to test whether experimental data support the hypothesis that altered circadian rhythms would translate into unfavorable changes in 24-hour sympathovagal and neurohormonal balance, and ultimately CVD.

The present study “will, and should, stimulate much needed additional research on the association between sleep and CVD that may offer novel approaches to help improve the prognosis and daily symptom burden of patients with CVD, and might make sleep itself a therapeutic target in CVD,” the editorialists conclude.

This research was supported by contracts from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), and by grants from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The MESA Sleep Study was supported by an NHLBI grant. Huang was supported by a career development grant from the National Institutes of Health.

Krumholz and Oldenburg have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Spiesshoefer is supported by grants from the Else-Kröner-Fresenius Stiftung, the Innovative Medical Research program at the University of Münster, and Deutsche Herzstiftung; and by young investigator research support from Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna Pisa. He also has received travel grants and lecture honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim and Chiesi.

Source: J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Mar 2. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.12.054.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Transradial access gains converts among U.S. interventional neurologists

LOS ANGELES –

“It’s growing dramatically in U.S. practice. It may be hype, but there is big excitement. We are still in an assessment mode, but the adoption rate has been high,” Raul G. Nogueira, MD, said in an interview during the International Stroke Conference sponsored by the American Heart Association. “The big advantage [of transradial catheterization entry] is elimination of groin complications, some of which can be pretty bad. Is it safe for the brain? It’s probably okay, but that needs more study,” said Dr. Nogueira, professor of neurology at Emory University and director of the Neurovascular Service at the Grady Marcus Stroke and Neuroscience Center in Atlanta.

His uncertainty stems from the more difficult route taken to advance a catheter from the wrist into brain vessels, a maneuver that requires significant manipulation of the catheter tip, unlike the path from the right radial artery into the heart’s arteries, a “straight shot,” he explained. To reach the brain’s vasculature, the tip must execute a spin “that may scrape small emboli from the arch or arteries, so we need to look at this a little more carefully.” Ideally in a prospective, randomized study, he said. “We need to see whether the burden of [magnetic resonance] lesions is any higher when you go through the radial [artery].”

Some of the first-reported, large-scale U.S. experiences using a radial-artery approach for various neurovascular procedures, including a few thrombectomy cases, came in a series of 1,272 patients treated at any of four U.S. centers during July 2018 to June 2019, a period when the neurovascular staffs at all four centers transitioned from primarily using femoral-artery access to using radial access as their default mode. During the 12-month transition period, overall use of radial access at all four centers rose from roughly a quarter of all neurovascular interventions during July to September 2018 to closer to 80% by April to June 2019, Eyad Almallouhi, MD, reported at the conference.

During the entire 12 months, the operators ran up a 94% rate of successfully completed procedures using radial access, a rate that rose from about 88% during the first quarter to roughly 95% success during the fourth quarter tracked, said Dr. Almallouhi, a neurologist at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. The rate of crossover from what began as a transradial procedure but switched to transfemoral was just under 6% overall, with a nearly 14% crossover rate during the first quarter that then dropped to around 5% for the rest of the transition year. Crossovers for interventional procedures throughout the study year occurred at a 12% rate, while crossovers for diagnostic procedures occurred at a 5% clip throughout the entire year.

None of the transradial patients had a major access-site complication, and minor complications occurred in less than 2% of the patients, including 11 with a forearm hematoma, 6 with forearm pain, and 5 with oozing at their access site. The absence of any major access-site complications among the transradial-access patients in this series contrasts with a recent report of a 1.7% rate of major complications secondary to femoral-artery access for mechanical thrombectomy in a combined analysis of data from seven published studies that included 660 thrombectomy procedures (Am J Neuroradiol. 2019 Feb. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A6423). The other three centers that participated in the study Dr. Almallouhi presented were the University of Miami, Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, and the University of Pittsburgh.

Of the 1,272 total procedures studied, 83% were diagnostic procedures, which had an overall 95% success rate, and 17% were interventional procedures, which had a success rate of 89%. The interventional transradial procedures included 62 primary coilings of aneurysms, 44 stent-assisted aneurysm coilings, 40 patients who underwent a flow diversion, 21 balloon-assisted aneurysm coilings, and 24 patients who underwent stroke thrombectomy.

The size of the devices commonly used for thrombectomy are often too large to allow for radial-artery access, noted Dr. Nogueira. For urgent interventions like thrombectomy “we use balloon-guided catheters that are large-bore and don’t fit well in the radial,” he said, although thrombectomy via the radial artery without a balloon-guided catheter is possible for clots located in the basilar artery. Last year, researchers in Germany reported using a balloon-guided catheter to perform mechanical thrombectomy via the radial artery (Interv Neuroradiol. 2019 Oct 1;25[5]:508-10). But it’s a different story for elective, diagnostic procedures. “I have moved most of these to transradial,” Dr. Nogueira said. He and his coauthors summarized the case for transradial access for cerebral angiography in a recent review; in addition to enhanced safety they cited other advantages including improved patient satisfaction and reduced cost because of a shorter length of stay (Interv Cardiol Clin. 2020 Jan;9[1]:75-86).

Despite his enthusiasm and the enthusiasm of other neurointerventionalists for the transradial approach, other stroke neurologists have been more cautious and slower to shift away from the femoral approach. “Our experience has been that for most cases it’s a bit more challenging to access the cervical vessels from the radial artery than from the traditional femoral approach. For arches with complex anatomy, however, the transradial approach can be of benefit in some cases, depending on the angles that need to be traversed,” commented Jeremy Payne, MD, director of the Banner Center for Neurovascular Medicine and medical director of the Banner—University Medical Center Phoenix Comprehensive Stroke Program. Dr. Payne highlighted that, while he is not an interventionalist himself, he and his interventional staff have regularly discussed the transradial option.

“In the cardiology literature the radial approach has been very successful, with better overall safety than the traditional femoral approach. Largely this seems to do with the anatomy of the aortic arch. It’s simply a more direct approach to the coronaries via the right radial artery; getting the wire into the correct vessel is significantly more difficult the more acute the angle it has to traverse,” such as when the target is an intracerebral vessel, Dr. Payne said in an interview.

“Our experience in the past 6 months has been about 25% transradial for some of our procedures, mainly diagnostic angiograms. We don’t find any difference in safety, however, as our transfemoral procedures are already very safe. One of the benefits of a transradial approach has been that a closure device may not be needed, with fewer vascular complications at the access site, such as fistula formation. We use ultrasound for access, and have not seen a difference in those approaches at all so far. One might argue that using ultrasound to establish access would slow us down, but so far our fastest case start-to-recanalization time in an acute stroke this year was 6 minutes, so speed does not appear to be a limiting issue. Another concern overall for transradial access is the potential limitation in the tools we may be able to deploy, given the smaller size of the vessel. It is reassuring [in the report from Dr. Almallouhi] that a variety of cases were successfully completed via this approach. However, fewer than 2% of their cases [24 patients] were apparently emergent, acute strokes, lending no specific support to that context. I do not expect that to change based on this paper,” Dr. Payne concluded.

“It is not clear to me that transradial neurointervention will change much. We have excellent safety data for the femoral approach, a proven track record of efficacy, and for most patients it seems to afford a somewhat wider range of tools that can be deployed, with simpler anatomy for accessing the cervical vessels in most arches. It is reassuring that the results reported by Dr. Almallouhi did not suggest negative outcomes, and as such I suspect the transradial approach at least gives us an additional option in a minority of patients. We have seen in the past 5-10 years an explosion of tools for the endovascular treatment of stroke; transradial access represents another potential strategy that appears so far to be safe,” Dr. Payne said.

Drs. Nogueira, Almallouhi, and Payne had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Almallouhi E et al. Stroke. 2020 Feb;51(suppl 1):A64.

LOS ANGELES –

“It’s growing dramatically in U.S. practice. It may be hype, but there is big excitement. We are still in an assessment mode, but the adoption rate has been high,” Raul G. Nogueira, MD, said in an interview during the International Stroke Conference sponsored by the American Heart Association. “The big advantage [of transradial catheterization entry] is elimination of groin complications, some of which can be pretty bad. Is it safe for the brain? It’s probably okay, but that needs more study,” said Dr. Nogueira, professor of neurology at Emory University and director of the Neurovascular Service at the Grady Marcus Stroke and Neuroscience Center in Atlanta.

His uncertainty stems from the more difficult route taken to advance a catheter from the wrist into brain vessels, a maneuver that requires significant manipulation of the catheter tip, unlike the path from the right radial artery into the heart’s arteries, a “straight shot,” he explained. To reach the brain’s vasculature, the tip must execute a spin “that may scrape small emboli from the arch or arteries, so we need to look at this a little more carefully.” Ideally in a prospective, randomized study, he said. “We need to see whether the burden of [magnetic resonance] lesions is any higher when you go through the radial [artery].”

Some of the first-reported, large-scale U.S. experiences using a radial-artery approach for various neurovascular procedures, including a few thrombectomy cases, came in a series of 1,272 patients treated at any of four U.S. centers during July 2018 to June 2019, a period when the neurovascular staffs at all four centers transitioned from primarily using femoral-artery access to using radial access as their default mode. During the 12-month transition period, overall use of radial access at all four centers rose from roughly a quarter of all neurovascular interventions during July to September 2018 to closer to 80% by April to June 2019, Eyad Almallouhi, MD, reported at the conference.

During the entire 12 months, the operators ran up a 94% rate of successfully completed procedures using radial access, a rate that rose from about 88% during the first quarter to roughly 95% success during the fourth quarter tracked, said Dr. Almallouhi, a neurologist at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. The rate of crossover from what began as a transradial procedure but switched to transfemoral was just under 6% overall, with a nearly 14% crossover rate during the first quarter that then dropped to around 5% for the rest of the transition year. Crossovers for interventional procedures throughout the study year occurred at a 12% rate, while crossovers for diagnostic procedures occurred at a 5% clip throughout the entire year.

None of the transradial patients had a major access-site complication, and minor complications occurred in less than 2% of the patients, including 11 with a forearm hematoma, 6 with forearm pain, and 5 with oozing at their access site. The absence of any major access-site complications among the transradial-access patients in this series contrasts with a recent report of a 1.7% rate of major complications secondary to femoral-artery access for mechanical thrombectomy in a combined analysis of data from seven published studies that included 660 thrombectomy procedures (Am J Neuroradiol. 2019 Feb. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A6423). The other three centers that participated in the study Dr. Almallouhi presented were the University of Miami, Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, and the University of Pittsburgh.

Of the 1,272 total procedures studied, 83% were diagnostic procedures, which had an overall 95% success rate, and 17% were interventional procedures, which had a success rate of 89%. The interventional transradial procedures included 62 primary coilings of aneurysms, 44 stent-assisted aneurysm coilings, 40 patients who underwent a flow diversion, 21 balloon-assisted aneurysm coilings, and 24 patients who underwent stroke thrombectomy.

The size of the devices commonly used for thrombectomy are often too large to allow for radial-artery access, noted Dr. Nogueira. For urgent interventions like thrombectomy “we use balloon-guided catheters that are large-bore and don’t fit well in the radial,” he said, although thrombectomy via the radial artery without a balloon-guided catheter is possible for clots located in the basilar artery. Last year, researchers in Germany reported using a balloon-guided catheter to perform mechanical thrombectomy via the radial artery (Interv Neuroradiol. 2019 Oct 1;25[5]:508-10). But it’s a different story for elective, diagnostic procedures. “I have moved most of these to transradial,” Dr. Nogueira said. He and his coauthors summarized the case for transradial access for cerebral angiography in a recent review; in addition to enhanced safety they cited other advantages including improved patient satisfaction and reduced cost because of a shorter length of stay (Interv Cardiol Clin. 2020 Jan;9[1]:75-86).

Despite his enthusiasm and the enthusiasm of other neurointerventionalists for the transradial approach, other stroke neurologists have been more cautious and slower to shift away from the femoral approach. “Our experience has been that for most cases it’s a bit more challenging to access the cervical vessels from the radial artery than from the traditional femoral approach. For arches with complex anatomy, however, the transradial approach can be of benefit in some cases, depending on the angles that need to be traversed,” commented Jeremy Payne, MD, director of the Banner Center for Neurovascular Medicine and medical director of the Banner—University Medical Center Phoenix Comprehensive Stroke Program. Dr. Payne highlighted that, while he is not an interventionalist himself, he and his interventional staff have regularly discussed the transradial option.

“In the cardiology literature the radial approach has been very successful, with better overall safety than the traditional femoral approach. Largely this seems to do with the anatomy of the aortic arch. It’s simply a more direct approach to the coronaries via the right radial artery; getting the wire into the correct vessel is significantly more difficult the more acute the angle it has to traverse,” such as when the target is an intracerebral vessel, Dr. Payne said in an interview.

“Our experience in the past 6 months has been about 25% transradial for some of our procedures, mainly diagnostic angiograms. We don’t find any difference in safety, however, as our transfemoral procedures are already very safe. One of the benefits of a transradial approach has been that a closure device may not be needed, with fewer vascular complications at the access site, such as fistula formation. We use ultrasound for access, and have not seen a difference in those approaches at all so far. One might argue that using ultrasound to establish access would slow us down, but so far our fastest case start-to-recanalization time in an acute stroke this year was 6 minutes, so speed does not appear to be a limiting issue. Another concern overall for transradial access is the potential limitation in the tools we may be able to deploy, given the smaller size of the vessel. It is reassuring [in the report from Dr. Almallouhi] that a variety of cases were successfully completed via this approach. However, fewer than 2% of their cases [24 patients] were apparently emergent, acute strokes, lending no specific support to that context. I do not expect that to change based on this paper,” Dr. Payne concluded.

“It is not clear to me that transradial neurointervention will change much. We have excellent safety data for the femoral approach, a proven track record of efficacy, and for most patients it seems to afford a somewhat wider range of tools that can be deployed, with simpler anatomy for accessing the cervical vessels in most arches. It is reassuring that the results reported by Dr. Almallouhi did not suggest negative outcomes, and as such I suspect the transradial approach at least gives us an additional option in a minority of patients. We have seen in the past 5-10 years an explosion of tools for the endovascular treatment of stroke; transradial access represents another potential strategy that appears so far to be safe,” Dr. Payne said.

Drs. Nogueira, Almallouhi, and Payne had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Almallouhi E et al. Stroke. 2020 Feb;51(suppl 1):A64.

LOS ANGELES –

“It’s growing dramatically in U.S. practice. It may be hype, but there is big excitement. We are still in an assessment mode, but the adoption rate has been high,” Raul G. Nogueira, MD, said in an interview during the International Stroke Conference sponsored by the American Heart Association. “The big advantage [of transradial catheterization entry] is elimination of groin complications, some of which can be pretty bad. Is it safe for the brain? It’s probably okay, but that needs more study,” said Dr. Nogueira, professor of neurology at Emory University and director of the Neurovascular Service at the Grady Marcus Stroke and Neuroscience Center in Atlanta.

His uncertainty stems from the more difficult route taken to advance a catheter from the wrist into brain vessels, a maneuver that requires significant manipulation of the catheter tip, unlike the path from the right radial artery into the heart’s arteries, a “straight shot,” he explained. To reach the brain’s vasculature, the tip must execute a spin “that may scrape small emboli from the arch or arteries, so we need to look at this a little more carefully.” Ideally in a prospective, randomized study, he said. “We need to see whether the burden of [magnetic resonance] lesions is any higher when you go through the radial [artery].”

Some of the first-reported, large-scale U.S. experiences using a radial-artery approach for various neurovascular procedures, including a few thrombectomy cases, came in a series of 1,272 patients treated at any of four U.S. centers during July 2018 to June 2019, a period when the neurovascular staffs at all four centers transitioned from primarily using femoral-artery access to using radial access as their default mode. During the 12-month transition period, overall use of radial access at all four centers rose from roughly a quarter of all neurovascular interventions during July to September 2018 to closer to 80% by April to June 2019, Eyad Almallouhi, MD, reported at the conference.

During the entire 12 months, the operators ran up a 94% rate of successfully completed procedures using radial access, a rate that rose from about 88% during the first quarter to roughly 95% success during the fourth quarter tracked, said Dr. Almallouhi, a neurologist at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. The rate of crossover from what began as a transradial procedure but switched to transfemoral was just under 6% overall, with a nearly 14% crossover rate during the first quarter that then dropped to around 5% for the rest of the transition year. Crossovers for interventional procedures throughout the study year occurred at a 12% rate, while crossovers for diagnostic procedures occurred at a 5% clip throughout the entire year.

None of the transradial patients had a major access-site complication, and minor complications occurred in less than 2% of the patients, including 11 with a forearm hematoma, 6 with forearm pain, and 5 with oozing at their access site. The absence of any major access-site complications among the transradial-access patients in this series contrasts with a recent report of a 1.7% rate of major complications secondary to femoral-artery access for mechanical thrombectomy in a combined analysis of data from seven published studies that included 660 thrombectomy procedures (Am J Neuroradiol. 2019 Feb. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A6423). The other three centers that participated in the study Dr. Almallouhi presented were the University of Miami, Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, and the University of Pittsburgh.

Of the 1,272 total procedures studied, 83% were diagnostic procedures, which had an overall 95% success rate, and 17% were interventional procedures, which had a success rate of 89%. The interventional transradial procedures included 62 primary coilings of aneurysms, 44 stent-assisted aneurysm coilings, 40 patients who underwent a flow diversion, 21 balloon-assisted aneurysm coilings, and 24 patients who underwent stroke thrombectomy.

The size of the devices commonly used for thrombectomy are often too large to allow for radial-artery access, noted Dr. Nogueira. For urgent interventions like thrombectomy “we use balloon-guided catheters that are large-bore and don’t fit well in the radial,” he said, although thrombectomy via the radial artery without a balloon-guided catheter is possible for clots located in the basilar artery. Last year, researchers in Germany reported using a balloon-guided catheter to perform mechanical thrombectomy via the radial artery (Interv Neuroradiol. 2019 Oct 1;25[5]:508-10). But it’s a different story for elective, diagnostic procedures. “I have moved most of these to transradial,” Dr. Nogueira said. He and his coauthors summarized the case for transradial access for cerebral angiography in a recent review; in addition to enhanced safety they cited other advantages including improved patient satisfaction and reduced cost because of a shorter length of stay (Interv Cardiol Clin. 2020 Jan;9[1]:75-86).

Despite his enthusiasm and the enthusiasm of other neurointerventionalists for the transradial approach, other stroke neurologists have been more cautious and slower to shift away from the femoral approach. “Our experience has been that for most cases it’s a bit more challenging to access the cervical vessels from the radial artery than from the traditional femoral approach. For arches with complex anatomy, however, the transradial approach can be of benefit in some cases, depending on the angles that need to be traversed,” commented Jeremy Payne, MD, director of the Banner Center for Neurovascular Medicine and medical director of the Banner—University Medical Center Phoenix Comprehensive Stroke Program. Dr. Payne highlighted that, while he is not an interventionalist himself, he and his interventional staff have regularly discussed the transradial option.

“In the cardiology literature the radial approach has been very successful, with better overall safety than the traditional femoral approach. Largely this seems to do with the anatomy of the aortic arch. It’s simply a more direct approach to the coronaries via the right radial artery; getting the wire into the correct vessel is significantly more difficult the more acute the angle it has to traverse,” such as when the target is an intracerebral vessel, Dr. Payne said in an interview.

“Our experience in the past 6 months has been about 25% transradial for some of our procedures, mainly diagnostic angiograms. We don’t find any difference in safety, however, as our transfemoral procedures are already very safe. One of the benefits of a transradial approach has been that a closure device may not be needed, with fewer vascular complications at the access site, such as fistula formation. We use ultrasound for access, and have not seen a difference in those approaches at all so far. One might argue that using ultrasound to establish access would slow us down, but so far our fastest case start-to-recanalization time in an acute stroke this year was 6 minutes, so speed does not appear to be a limiting issue. Another concern overall for transradial access is the potential limitation in the tools we may be able to deploy, given the smaller size of the vessel. It is reassuring [in the report from Dr. Almallouhi] that a variety of cases were successfully completed via this approach. However, fewer than 2% of their cases [24 patients] were apparently emergent, acute strokes, lending no specific support to that context. I do not expect that to change based on this paper,” Dr. Payne concluded.

“It is not clear to me that transradial neurointervention will change much. We have excellent safety data for the femoral approach, a proven track record of efficacy, and for most patients it seems to afford a somewhat wider range of tools that can be deployed, with simpler anatomy for accessing the cervical vessels in most arches. It is reassuring that the results reported by Dr. Almallouhi did not suggest negative outcomes, and as such I suspect the transradial approach at least gives us an additional option in a minority of patients. We have seen in the past 5-10 years an explosion of tools for the endovascular treatment of stroke; transradial access represents another potential strategy that appears so far to be safe,” Dr. Payne said.

Drs. Nogueira, Almallouhi, and Payne had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Almallouhi E et al. Stroke. 2020 Feb;51(suppl 1):A64.

REPORTING FROM ISC 2020

5-year-old boy • behavioral issues • elevated ALT and AST levels • Dx?

THE CASE

A 5-year-old boy was brought into his primary care clinic by his mother, who expressed concern about her son’s increasing impulsiveness, aggression, and difficulty staying on task at preschool and at home. The child’s medical history was unremarkable, and he was taking no medications. The family history was negative for hepatic or metabolic disease and positive for attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD; father).

The child’s growth was normal. His physical exam was remarkable for a liver edge 1 cm below his costal margin. No Kayser-Fleischer rings were present.

Screening included a complete metabolic panel. Notable results included an alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level of 208 U/dL (normal range, < 30 U/dL), an aspartate transaminase (AST) level of 125 U/dL (normal range, 10-34 U/dL), and an alkaline phosphatase (ALP) of 470 U/dL (normal range, 93-309 U/dL). Subsequent repeat laboratory testing confirmed these elevations (ALT, 248 U/dL; AST, 137 U/dL; ALP, 462 U/dL). Ceruloplasmin levels were low (11 mg/dL; normal range, 18-35 mg/dL), and 24-hour urinary copper was not obtainable. Prothrombin/partial thromboplastin time, ammonia, lactate, total and direct bilirubin, and gamma-glutamyltransferase levels were normal.

Further evaluation included abdominal ultrasound and brain magnetic resonance imaging, both of which yielded normal results. Testing for Epstein-Barr virus; cytomegalovirus; hepatitis A, B, and C titers; and antinuclear, anti-smooth muscle, and anti–liver-kidney microsomal antibodies was negative.

THE DIAGNOSIS

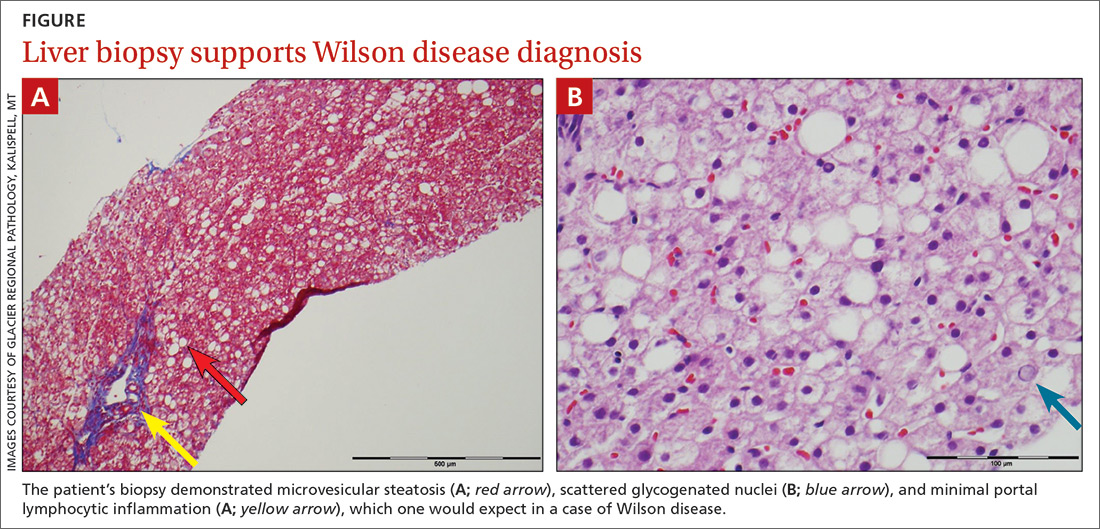

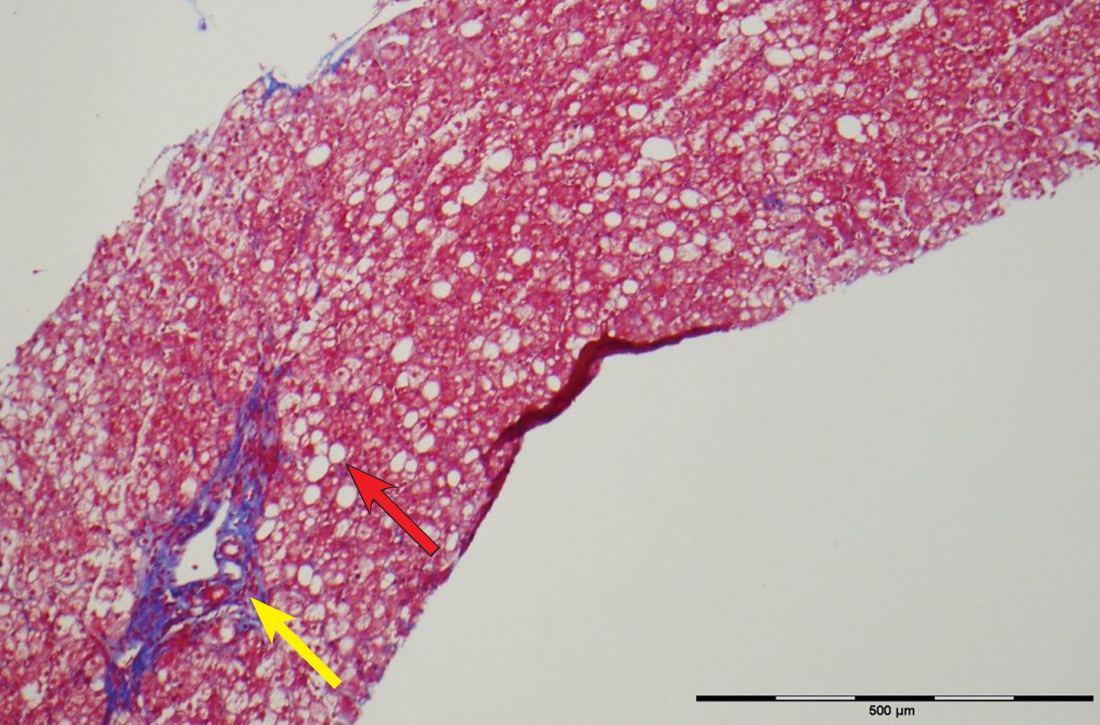

The patient’s low ceruloplasmin prompted referral to Pediatric Gastroenterology for consultation and liver biopsy due to concern for Wilson disease. Biopsy results were consistent with, and quantitative liver copper confirmatory for, this diagnosis (FIGURE).

Genetic testing for mutations in the ATP7B gene was performed on the patient, his mother, and his siblings (his father was unavailable). The patient, his mother, and his sister were all positive for His1069Gln mutation; only the patient was positive for a 3990_3993 del mutation (his half-brother was negative for both mutations). The presence of 2 different mutant alleles for the ATP7B gene, one on each chromosome—the common substitution mutation, His1069Gln, in exon 14 and a 3990_3993 del TTAT mutation in exon 19—qualified the patient as a compound heterozygote.

The 3990_3993 del TTAT mutation—which to our knowledge has not been previously reported—produced a translational frame shift and premature stop codon. As others have pointed out, frame shift and missense mutations produce a more severe phenotype.1

Continue to: Further testing was prompted...

Further testing was prompted by a report suggesting that codon 129 mutations of the human prion gene (HPG) influence Wilson disease.2 Compared with patients who are heterozygous (M129V) or homozygous (V129V) for valine, those who are homozygous for methionine (M129M) have delayed symptom onset.2 Our patient was heterozygous (M129V). It is interesting to speculate that HPG heterozygosity, combined with a mutation causing a stop codon, predisposed our patient to more rapid accumulation of copper and earlier age of onset.

DISCUSSION

Wilson disease is an inherited disorder of copper metabolism.3 An inherent difficulty in its recognition, diagnosis, and management is its rarity: global prevalence is estimated as 1/30,000, although this varies by geographic location.1 In contrast, ADHD has a prevalence of 7.2%,4 making it 2400 times more prevalent than Wilson disease. Furthermore, abnormal liver function tests are common in children; the differential diagnosis includes etiologies such as infection (both viral and nonviral), immune-mediated inflammatory disease, drug toxicity (iatrogenic or medication-induced), anatomic abnormalities, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.5

Wilson disease is remarkable, however, for being easily treatable if detected and devastating if not. Although liver abnormalities often improve with treatment, delayed diagnosis and management significantly impact neurologic recovery: An 18-month delay results in 38% of patients continuing to have major neurologic disabilities.6 Untreated, Wilson disease may be fatal within 5 years of development of neurologic symptoms.7 Thus, it has been suggested that evaluation for Wilson disease be considered in any child older than 1 year who presents with unexplained liver disease, including asymptomatic elevations of serum transaminases.8

Mutations in ATP7B on chromosome 13 are responsible for the pathology of Wilson disease9; more than 250 mutations have been identified, including substitutions, deletions, and missense mutations.10 Affected patients may be compound heterozygotes11 and/or may possess new mutations, as seen in our patient.

Although copper absorption is normal, impaired excretion causes toxic accumulation in affected organs. ATP7B’s product, ATPase 2, regulates copper excretion, as well as copper binding to apoceruloplasmin to form the carrier protein ceruloplasmin. An ATP7B abnormality would prevent the latter—making ceruloplasmin a useful screening biomarker and a reliable marker for Wilson disease by age 1 year.8

Continue to: Hepatic and neurocognitive effects

Hepatic and neurocognitive effects. Excess copper in hepatocytes causes oxidative damage and release of copper into the circulation, with accumulation in susceptible organs (eg, brain, kidneys). Hepatocyte apoptosis is accelerated by copper’s negative effect on inhibitor of apoptosis protein.12,13 Renal tubular damage leads to Fanconi syndrome,14 in which substances such as glucose, phosphates, and potassium are excreted in urine rather than absorbed into the bloodstream by the kidneys. Excess copper deposition in the Descemet membrane may lead to Kayser-Fleisher ring formation.15 In the brain, copper deposition may occur in the lenticular nuclei,3 as well as in the thalamus, subthalamus, brainstem, and frontal cortex—resulting in extrapyramidal, cerebral, and mild cerebellar symptoms.6

Cognitive impairment, which may be subtle, includes increased impulsivity, impaired judgment, apathy, poor decision making, decreased attention, increased lability, slowed thinking, and memory loss.6 Behavioral manifestations include changes in school or work performance and outbursts mimicking ADHD12,16,17 as well as paranoia, depression, and bizarre behaviors.16,18 Neuropsychiatric abnormalities include personality changes, pseudoparkinsonism, dyskinesia/dysarthria, and ataxia/tremor. Younger patients with psychiatric symptoms may be labelled with depression, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, bipolar disorder, or antisocial disorder.6,16,18

Hepatic disease manifestations range from asymptomatic elevations in AST/ALT to acute hepatitis, mimicking infectious processes. Cirrhosis is the end result of untreated Wilson disease, with liver transplantation required if end-stage liver disease results. Rarely, patients present in fulminant hepatic failure, with death occurring if emergent liver transplantation is not performed.6,8,10

Of note, before age 10, > 80% of patients with Wilson disease present with hepatic symptoms; those ages 10 to 18 often manifest psychiatric changes.17 Kayser-Fleisher rings are common in patients with neurologic manifestations but less so in those who have hepatic presentations or are presymptomatic.6,15

Effective disease-mitigating treatment is indicated and available for both symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals and includes the copper chelators D-penicillamine (starting dose, 150-300 mg/d with a gradual weekly increase to 20 mg/kg/d) and trientine hydrochloride (a heavy metal chelating compound; starting dose, 20 mg/kg/d to a maximum of 1000 mg/d in young adults). Adverse effects of D-penicillamine include cutaneous eruptions, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, proteinuria, and a lupus-like syndrome; therefore, trientine is increasingly being used as first-line therapy.8

Continue to: For asymptomatic...

For asymptomatic patients who have had effective chelation therapy and proven de-coppering, zinc salts are a useful follow-on therapy. Zinc’s proposed mechanism of action is induction of metallothionein in enterocytes, which promotes copper trapping and eventual excretion into the lumen. Importantly, treatment for Wilson disease is lifelong and monitoring of compliance is essential.8

Our 5-year-old patient was started on oral trientine at 20 mg/kg/d and a low copper diet. In response to this initial treatment, the patient’s liver function tests (LFTs) normalized, and he was switched to 25 mg tid of a zinc chelate, with continuation of the low copper diet. His LFTs have remained normal, although his urine copper levels are still elevated. He continues to be monitored periodically with LFTs and measurement of urine copper levels. He is also being treated for ADHD, as his presenting behavioral abnormalities suggestive of ADHD have not resolved.

THE TAKEAWAY

Although children presenting with symptoms consistent with ADHD often have ADHD, as was true in this case, it is important to consider other diagnoses. Unexplained elevations of liver function test values in children older than 1 year should prompt screening for Wilson disease.5,8 Additionally, other family members should be evaluated; if they have the disease, treatment should be started by age 2 years, even if the patient is asymptomatic.

In our patient’s case, routine screening saved the day. The complete metabolic panel revealed elevated ALT and AST levels, prompting further evaluation. Without this testing, his diagnosis likely would have been delayed, leading to progressive liver and central nervous system disease. With early identification and treatment, it is possible to stop the progression of Wilson disease.

CORRESPONDENCE