User login

Angiosarcoma Imitating a Morpheaform Basal Cell Carcinoma

To the Editor:

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common of the nonmelanoma skin cancers and is a highly curable skin growth.1,2 Conversely, angiosarcomas are aggressive vascular tumors of endothelial origin that classically appear as reddish purple patches or plaques that exhibit rapid growth and invasion.3 Sporadic cutaneous angiosarcomas are the most common type of this soft tissue tumor, occurring most often in the head and neck regions in men older than 70 years.4,5 Other types of angiosarcomas include those associated with radiation therapy and chronic lymphedema. Postradiation angiosarcomas have been most frequently reported after treatment of breast cancer and appear as infiltrative plaques over the irradiated area.4,5 Patients with chronic lymphedema, which most commonly is related to axillary lymph node dissection for breast cancer (90% of cases), may develop angiosarcoma presenting as a violaceous indurated plaque.5 Although angiosarcomas most often are seen with these distinct clinical characteristics, especially their violaceous color, they have been shown to mimic a few other skin disorders such as eczema and keratoacanthoma, but a limited number of cases of angiosarcoma mimicking BCC have been reported.1,6,7 We present a case of an elderly man with a unique presentation of a lesion that clinically appeared as a morpheaform BCC but was confirmed to be an angiosarcoma on histopathology.

A 75-year-old man was referred to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of a flesh-colored plaque on the face that initially had developed 2 years prior on the right central malar cheek. Computed tomography of the head and neck 1 year prior, which the patient reported was for workup of the lesion, was found to be negative; however, these medical records were not obtained for confirmation. The lesion had been stable in size and remained flesh colored until 6 months prior to the current presentation when it exhibited a rapid increase in size. An initial biopsy was performed 1 month prior to presentation by an outside dermatology office and had been read as an angiosarcoma.

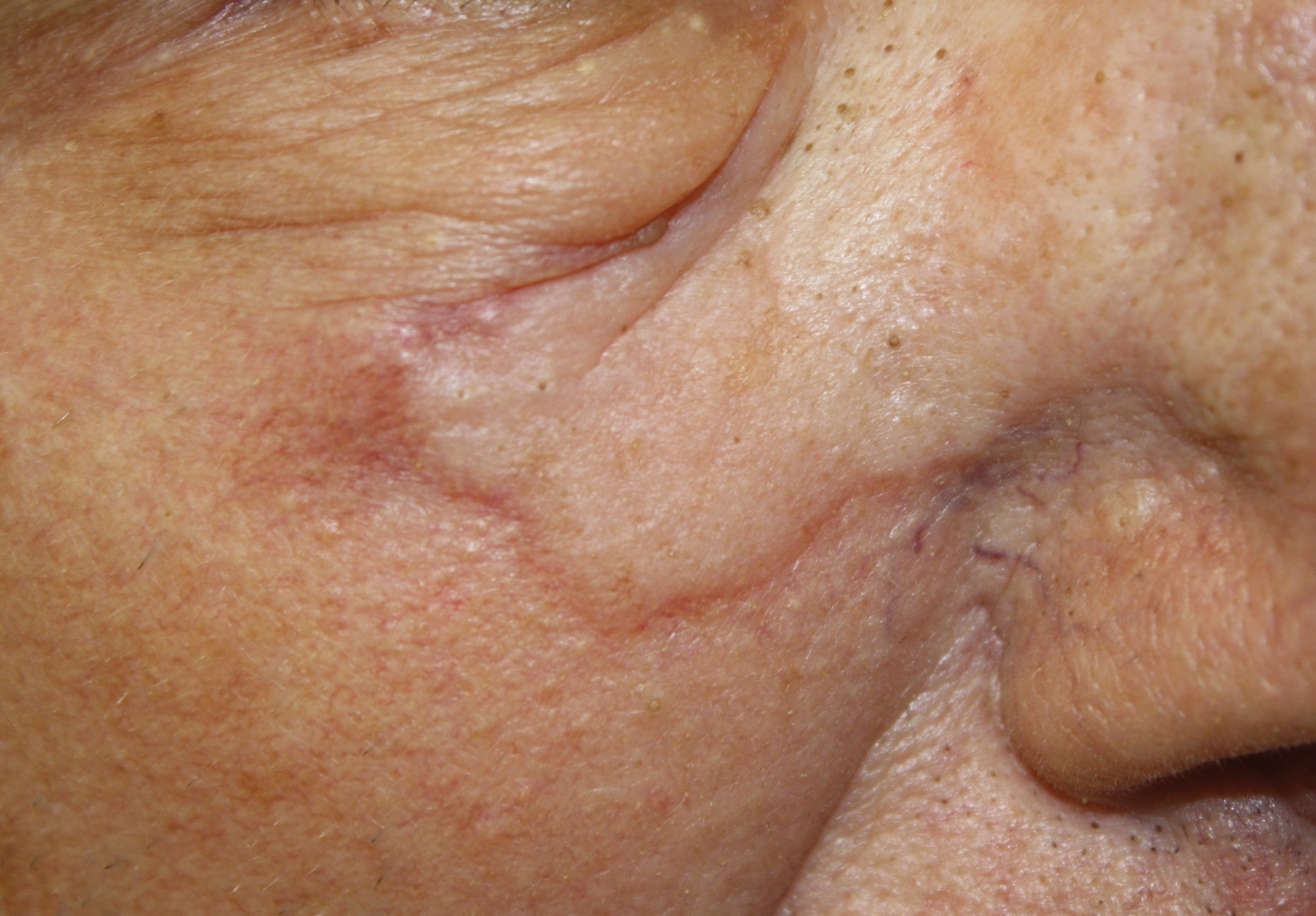

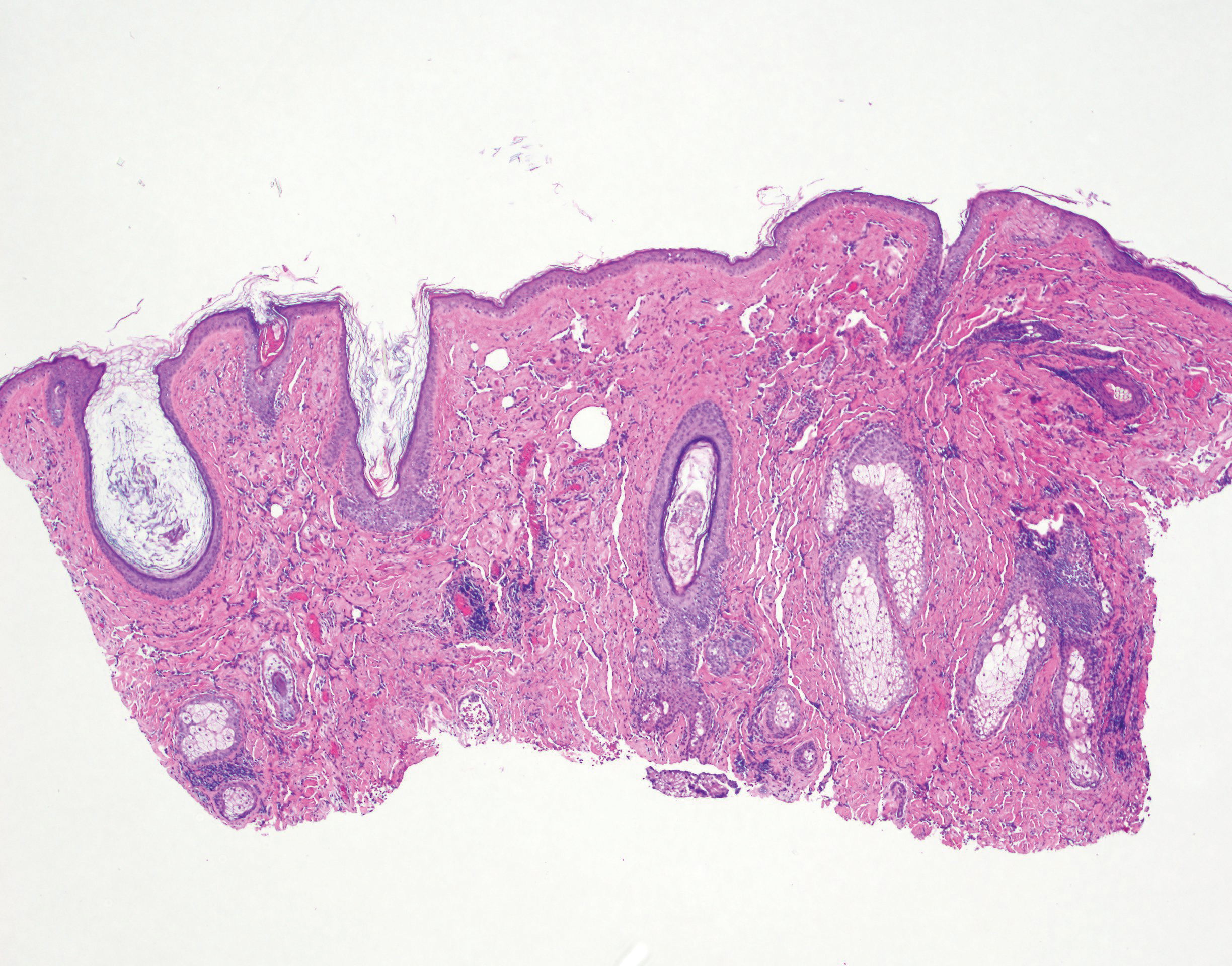

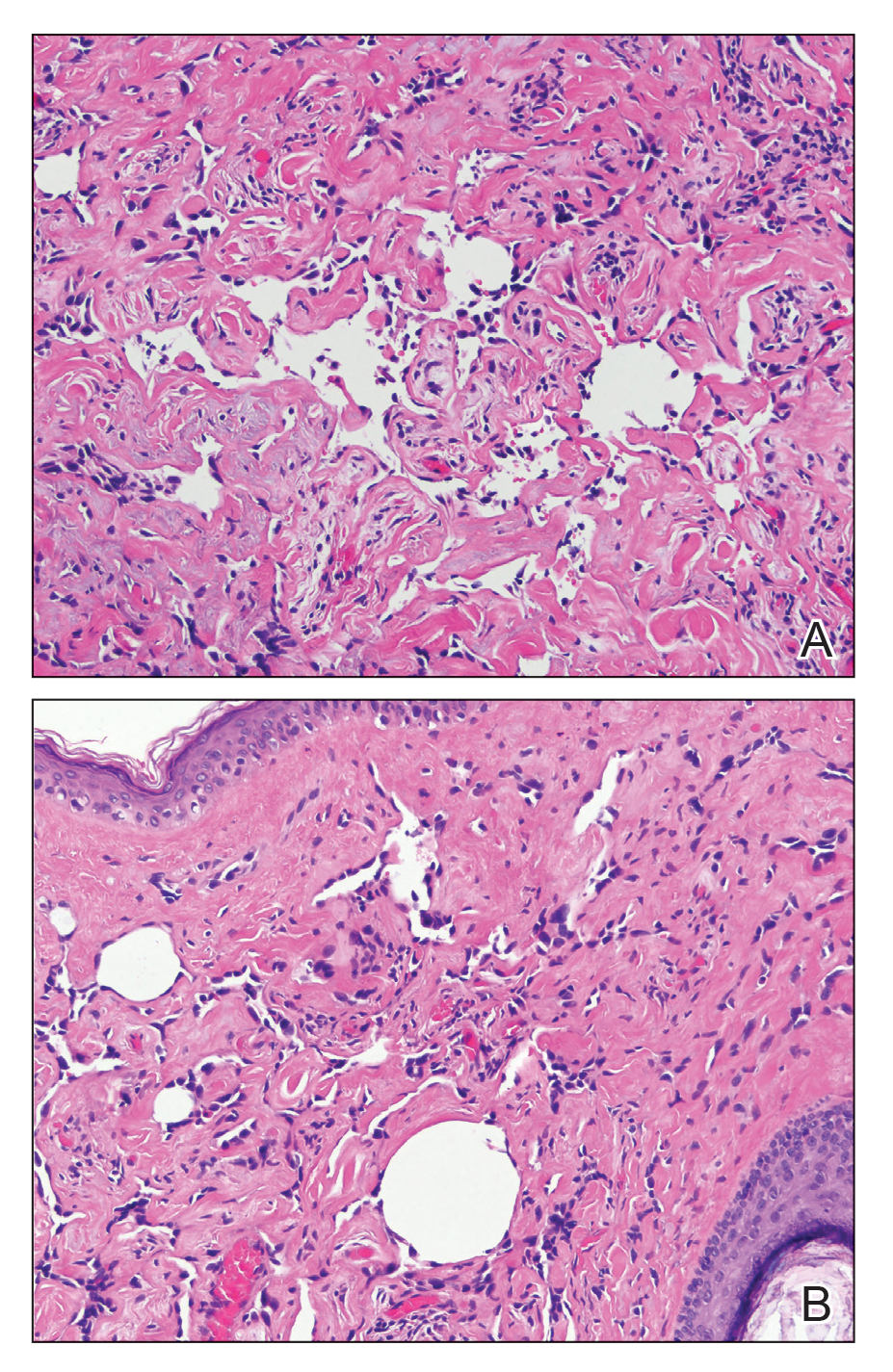

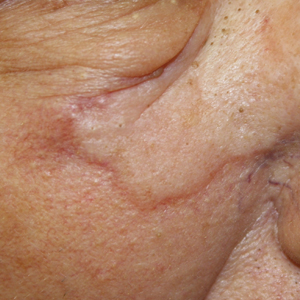

Physical examination revealed a 6-cm, flesh-colored, indurated, ill-defined plaque distributed on the right malar cheek below the eye and extending to the nasal bridge (Figure 1). There was no cervical or facial lymphadenopathy. The clinical features resembled a morpheaform BCC, and the lesion did not exhibit any reddish or purple color indicating it was of vascular origin. However, due to the prior histopathology report and recent rapid enlargement, a repeat sampling with a larger punch biopsy was performed, which confirmed the diagnosis of angiosarcoma. Histopathology demonstrated multiple atypical vascular channels lined by hyperchromatic cells extending from the upper dermis to the base of the biopsy site (Figure 2). Large, oval, atypical nuclei were present in multiple endothelial cells in the vascular channels, with some forming irregularly contoured and slitlike formations (Figure 3). Immunochemical staining was intensely and uniformly positive for CD31 and CD34, both endothelial markers. Diffuse positive staining with CD31 is considered to have high sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of angiosarcoma.4 Other pertinent staining demonstrated 2+ positivity for factor VIII and 1+ positivity for D2-40; CD45, AE1/AE3, S-100, and human herpesvirus 8 were negative, consistent with angiosarcoma. The patient was referred to radiation oncology and otolaryngology at our Multidisciplinary Head and Neck Oncology Center for further investigation of the extent of the disease and discussion of treatment. Computed tomography of the head and neck region at this time showed extensive disease extending into the medial canthal area without metastasis. Due to the extent of disease and facial location, he was not deemed a candidate for surgery. He was treated with 6 weeks of targeted radiation therapy with concurrent chemotherapy. He tolerated this treatment with minimal side effects and was found to be free from clinical disease 1 year after diagnosis. He was followed for 20 months by our Multidisciplinary Oncology Clinic without recurrence of his disease but was then lost to follow-up.

This case illustrates a rare presentation of an angiosarcoma clinically mimicking a BCC, which has been described in a small number of case reports and retrospective reviews. One study of 656 patients diagnosed with BCC based on clinical features revealed that 48 of these lesions were proven to be a BCC-mimicking lesion and only 1 was an angiosarcoma.1 Cutaneous lesions that appear on physical examination to be a highly curable BCC may not induce the same urgency for treatment as an angiosarcoma. Although the clinical presentation may mimic a morpheaform BCC, our case demonstrates that it is imperative to include angiosarcoma in the differential diagnosis and underscores the utility of tissue sampling. Angiosarcoma has a poor overall 5-year survival rate, and patients often are found to have multiple metastatic lesions at diagnosis. However, diagnosis prior to metastasis may improve prognosis.8

Our patient’s angiosarcoma did not exhibit metastasis at the time of diagnosis, and he was able to achieve a favorable outcome. However, the 5-year survival rate is only 40%, and close clinical monitoring after diagnosis is required.8 Including angiosarcoma in the differential diagnosis for our patient, particularly upon lesion appearance 2 years prior, may have resulted in diagnosis antecedent to local invasion, possibly providing more treatment options. Employing a higher index of clinical suspicion for angiosarcoma may lead to decreased mortality in other patients due to increased detection.

- Kim HS, Kim TW, Mun JH, et al. Basal cell carcinoma–mimicking lesions in Korean clinical settings. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:431-436.

- Christenson LJ, Borrowman TA, Vachon CM, et al. Incidence of basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas in a population younger than 40 years. JAMA. 2005;294:681-690.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz S, Gilchrest BA. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2012.

- Dosset LA, Harrington M, Cruse CW, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma. Curr Probl Cancer. 2015;39:258-263.

- North PE, Kincannon J. Vascular neoplasms and neoplastic-like proliferations. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1915-1942.

- Kong YL, Chandran NS, Goh SG, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the scalp mimicking a keratoacanthoma. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:18566.

- Trinh NQ, Rashed I, Hutchens KA, et al. Unusual clinical presentation of cutaneous angiosarcoma masquerading as eczema: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2013;2013:906426.

- Buehler D, Rice SR, Moody JS, et al. Angiosarcoma outcomes and prognostic factors. a 25-year single institution experience. Am J Clin Oncol. 2014;37:473-479.

To the Editor:

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common of the nonmelanoma skin cancers and is a highly curable skin growth.1,2 Conversely, angiosarcomas are aggressive vascular tumors of endothelial origin that classically appear as reddish purple patches or plaques that exhibit rapid growth and invasion.3 Sporadic cutaneous angiosarcomas are the most common type of this soft tissue tumor, occurring most often in the head and neck regions in men older than 70 years.4,5 Other types of angiosarcomas include those associated with radiation therapy and chronic lymphedema. Postradiation angiosarcomas have been most frequently reported after treatment of breast cancer and appear as infiltrative plaques over the irradiated area.4,5 Patients with chronic lymphedema, which most commonly is related to axillary lymph node dissection for breast cancer (90% of cases), may develop angiosarcoma presenting as a violaceous indurated plaque.5 Although angiosarcomas most often are seen with these distinct clinical characteristics, especially their violaceous color, they have been shown to mimic a few other skin disorders such as eczema and keratoacanthoma, but a limited number of cases of angiosarcoma mimicking BCC have been reported.1,6,7 We present a case of an elderly man with a unique presentation of a lesion that clinically appeared as a morpheaform BCC but was confirmed to be an angiosarcoma on histopathology.

A 75-year-old man was referred to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of a flesh-colored plaque on the face that initially had developed 2 years prior on the right central malar cheek. Computed tomography of the head and neck 1 year prior, which the patient reported was for workup of the lesion, was found to be negative; however, these medical records were not obtained for confirmation. The lesion had been stable in size and remained flesh colored until 6 months prior to the current presentation when it exhibited a rapid increase in size. An initial biopsy was performed 1 month prior to presentation by an outside dermatology office and had been read as an angiosarcoma.

Physical examination revealed a 6-cm, flesh-colored, indurated, ill-defined plaque distributed on the right malar cheek below the eye and extending to the nasal bridge (Figure 1). There was no cervical or facial lymphadenopathy. The clinical features resembled a morpheaform BCC, and the lesion did not exhibit any reddish or purple color indicating it was of vascular origin. However, due to the prior histopathology report and recent rapid enlargement, a repeat sampling with a larger punch biopsy was performed, which confirmed the diagnosis of angiosarcoma. Histopathology demonstrated multiple atypical vascular channels lined by hyperchromatic cells extending from the upper dermis to the base of the biopsy site (Figure 2). Large, oval, atypical nuclei were present in multiple endothelial cells in the vascular channels, with some forming irregularly contoured and slitlike formations (Figure 3). Immunochemical staining was intensely and uniformly positive for CD31 and CD34, both endothelial markers. Diffuse positive staining with CD31 is considered to have high sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of angiosarcoma.4 Other pertinent staining demonstrated 2+ positivity for factor VIII and 1+ positivity for D2-40; CD45, AE1/AE3, S-100, and human herpesvirus 8 were negative, consistent with angiosarcoma. The patient was referred to radiation oncology and otolaryngology at our Multidisciplinary Head and Neck Oncology Center for further investigation of the extent of the disease and discussion of treatment. Computed tomography of the head and neck region at this time showed extensive disease extending into the medial canthal area without metastasis. Due to the extent of disease and facial location, he was not deemed a candidate for surgery. He was treated with 6 weeks of targeted radiation therapy with concurrent chemotherapy. He tolerated this treatment with minimal side effects and was found to be free from clinical disease 1 year after diagnosis. He was followed for 20 months by our Multidisciplinary Oncology Clinic without recurrence of his disease but was then lost to follow-up.

This case illustrates a rare presentation of an angiosarcoma clinically mimicking a BCC, which has been described in a small number of case reports and retrospective reviews. One study of 656 patients diagnosed with BCC based on clinical features revealed that 48 of these lesions were proven to be a BCC-mimicking lesion and only 1 was an angiosarcoma.1 Cutaneous lesions that appear on physical examination to be a highly curable BCC may not induce the same urgency for treatment as an angiosarcoma. Although the clinical presentation may mimic a morpheaform BCC, our case demonstrates that it is imperative to include angiosarcoma in the differential diagnosis and underscores the utility of tissue sampling. Angiosarcoma has a poor overall 5-year survival rate, and patients often are found to have multiple metastatic lesions at diagnosis. However, diagnosis prior to metastasis may improve prognosis.8

Our patient’s angiosarcoma did not exhibit metastasis at the time of diagnosis, and he was able to achieve a favorable outcome. However, the 5-year survival rate is only 40%, and close clinical monitoring after diagnosis is required.8 Including angiosarcoma in the differential diagnosis for our patient, particularly upon lesion appearance 2 years prior, may have resulted in diagnosis antecedent to local invasion, possibly providing more treatment options. Employing a higher index of clinical suspicion for angiosarcoma may lead to decreased mortality in other patients due to increased detection.

To the Editor:

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common of the nonmelanoma skin cancers and is a highly curable skin growth.1,2 Conversely, angiosarcomas are aggressive vascular tumors of endothelial origin that classically appear as reddish purple patches or plaques that exhibit rapid growth and invasion.3 Sporadic cutaneous angiosarcomas are the most common type of this soft tissue tumor, occurring most often in the head and neck regions in men older than 70 years.4,5 Other types of angiosarcomas include those associated with radiation therapy and chronic lymphedema. Postradiation angiosarcomas have been most frequently reported after treatment of breast cancer and appear as infiltrative plaques over the irradiated area.4,5 Patients with chronic lymphedema, which most commonly is related to axillary lymph node dissection for breast cancer (90% of cases), may develop angiosarcoma presenting as a violaceous indurated plaque.5 Although angiosarcomas most often are seen with these distinct clinical characteristics, especially their violaceous color, they have been shown to mimic a few other skin disorders such as eczema and keratoacanthoma, but a limited number of cases of angiosarcoma mimicking BCC have been reported.1,6,7 We present a case of an elderly man with a unique presentation of a lesion that clinically appeared as a morpheaform BCC but was confirmed to be an angiosarcoma on histopathology.

A 75-year-old man was referred to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of a flesh-colored plaque on the face that initially had developed 2 years prior on the right central malar cheek. Computed tomography of the head and neck 1 year prior, which the patient reported was for workup of the lesion, was found to be negative; however, these medical records were not obtained for confirmation. The lesion had been stable in size and remained flesh colored until 6 months prior to the current presentation when it exhibited a rapid increase in size. An initial biopsy was performed 1 month prior to presentation by an outside dermatology office and had been read as an angiosarcoma.

Physical examination revealed a 6-cm, flesh-colored, indurated, ill-defined plaque distributed on the right malar cheek below the eye and extending to the nasal bridge (Figure 1). There was no cervical or facial lymphadenopathy. The clinical features resembled a morpheaform BCC, and the lesion did not exhibit any reddish or purple color indicating it was of vascular origin. However, due to the prior histopathology report and recent rapid enlargement, a repeat sampling with a larger punch biopsy was performed, which confirmed the diagnosis of angiosarcoma. Histopathology demonstrated multiple atypical vascular channels lined by hyperchromatic cells extending from the upper dermis to the base of the biopsy site (Figure 2). Large, oval, atypical nuclei were present in multiple endothelial cells in the vascular channels, with some forming irregularly contoured and slitlike formations (Figure 3). Immunochemical staining was intensely and uniformly positive for CD31 and CD34, both endothelial markers. Diffuse positive staining with CD31 is considered to have high sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of angiosarcoma.4 Other pertinent staining demonstrated 2+ positivity for factor VIII and 1+ positivity for D2-40; CD45, AE1/AE3, S-100, and human herpesvirus 8 were negative, consistent with angiosarcoma. The patient was referred to radiation oncology and otolaryngology at our Multidisciplinary Head and Neck Oncology Center for further investigation of the extent of the disease and discussion of treatment. Computed tomography of the head and neck region at this time showed extensive disease extending into the medial canthal area without metastasis. Due to the extent of disease and facial location, he was not deemed a candidate for surgery. He was treated with 6 weeks of targeted radiation therapy with concurrent chemotherapy. He tolerated this treatment with minimal side effects and was found to be free from clinical disease 1 year after diagnosis. He was followed for 20 months by our Multidisciplinary Oncology Clinic without recurrence of his disease but was then lost to follow-up.

This case illustrates a rare presentation of an angiosarcoma clinically mimicking a BCC, which has been described in a small number of case reports and retrospective reviews. One study of 656 patients diagnosed with BCC based on clinical features revealed that 48 of these lesions were proven to be a BCC-mimicking lesion and only 1 was an angiosarcoma.1 Cutaneous lesions that appear on physical examination to be a highly curable BCC may not induce the same urgency for treatment as an angiosarcoma. Although the clinical presentation may mimic a morpheaform BCC, our case demonstrates that it is imperative to include angiosarcoma in the differential diagnosis and underscores the utility of tissue sampling. Angiosarcoma has a poor overall 5-year survival rate, and patients often are found to have multiple metastatic lesions at diagnosis. However, diagnosis prior to metastasis may improve prognosis.8

Our patient’s angiosarcoma did not exhibit metastasis at the time of diagnosis, and he was able to achieve a favorable outcome. However, the 5-year survival rate is only 40%, and close clinical monitoring after diagnosis is required.8 Including angiosarcoma in the differential diagnosis for our patient, particularly upon lesion appearance 2 years prior, may have resulted in diagnosis antecedent to local invasion, possibly providing more treatment options. Employing a higher index of clinical suspicion for angiosarcoma may lead to decreased mortality in other patients due to increased detection.

- Kim HS, Kim TW, Mun JH, et al. Basal cell carcinoma–mimicking lesions in Korean clinical settings. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:431-436.

- Christenson LJ, Borrowman TA, Vachon CM, et al. Incidence of basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas in a population younger than 40 years. JAMA. 2005;294:681-690.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz S, Gilchrest BA. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2012.

- Dosset LA, Harrington M, Cruse CW, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma. Curr Probl Cancer. 2015;39:258-263.

- North PE, Kincannon J. Vascular neoplasms and neoplastic-like proliferations. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1915-1942.

- Kong YL, Chandran NS, Goh SG, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the scalp mimicking a keratoacanthoma. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:18566.

- Trinh NQ, Rashed I, Hutchens KA, et al. Unusual clinical presentation of cutaneous angiosarcoma masquerading as eczema: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2013;2013:906426.

- Buehler D, Rice SR, Moody JS, et al. Angiosarcoma outcomes and prognostic factors. a 25-year single institution experience. Am J Clin Oncol. 2014;37:473-479.

- Kim HS, Kim TW, Mun JH, et al. Basal cell carcinoma–mimicking lesions in Korean clinical settings. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:431-436.

- Christenson LJ, Borrowman TA, Vachon CM, et al. Incidence of basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas in a population younger than 40 years. JAMA. 2005;294:681-690.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz S, Gilchrest BA. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2012.

- Dosset LA, Harrington M, Cruse CW, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma. Curr Probl Cancer. 2015;39:258-263.

- North PE, Kincannon J. Vascular neoplasms and neoplastic-like proliferations. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1915-1942.

- Kong YL, Chandran NS, Goh SG, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the scalp mimicking a keratoacanthoma. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:18566.

- Trinh NQ, Rashed I, Hutchens KA, et al. Unusual clinical presentation of cutaneous angiosarcoma masquerading as eczema: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2013;2013:906426.

- Buehler D, Rice SR, Moody JS, et al. Angiosarcoma outcomes and prognostic factors. a 25-year single institution experience. Am J Clin Oncol. 2014;37:473-479.

Practice Points

- Angiosarcoma is an aggressive vascular tumor with a poor prognosis.

- Angiosarcomas can arise in the setting of chronic lymphedema or prior radiation therapy or can arise spontaneously.

- Classically, angiosarcoma presents as a violaceous patch or plaque but occasionally can exhibit atypical clinical features. Angiosarcomas should be considered on the differential for any changing plaque on the head or neck.

Sharp climb in weight gain after breast cancer diagnosis

Significant weight gain after a diagnosis of breast cancer may be a bigger problem than previously thought, and clinicians need to do more to help patients manage it, say the authors of a national survey conducted in Australia.

“We found that two-thirds of our respondents were currently overweight or obese,” report Carolyn Ee, MBBS, PhD, of the NICM Health Research Institute, Western Sydney University, Penrith, New South Wales, and colleagues.

“Because weight gain after breast cancer may lead to poorer outcomes, efforts to prevent and manage weight gain must be prioritized and accelerated particularly in the first year after diagnosis,” they comment.

Their article was published online February 20 in BMC Cancer.

The 60-item anonymous online survey was sent to 1835 members of the Breast Cancer Network Australia Review and Survey Group.

Although the response rate for the online survey was only 15%, most women reported a “high” level of concern about weight gain – and with good reason. The results showed that 64% of women gained an average of 9 kg (20 lb), and 17% gained >20 kg (44 lb).

In the 2-year period following a breast cancer diagnosis, the rate of overweight and obesity increased from 48% to 67%. The rate of obesity alone almost doubled, from 17% to 32%.

Overweight and obesity are strongly implicated in the development of breast cancer, the authors note. Weight gain after diagnosis is associated with morbidity and all-cause mortality and may increase the risk for breast cancer recurrence by 30% to 40%.

The survey, which also collected data from 26 women who were participants in online women’s health and breast cancer support groups, did not include information on quality of life and levels of distress. “Additional research in this area appears to be warranted,” the study authors suggest.

In a press statement, Ee noted that 77% of women reported that weight gain had occurred in the 12- to 18-month period after diagnosis. This could provide a “window of opportunity” for intervention, she said.

“Timing may be the key in helping women to manage weight after a diagnosis of breast cancer,” she added. “Cancer services and general practitioners play an important role in having early conversations with women and referring them to a team of qualified healthcare professionals such as dieticians and exercise physiologists with experience in cancer.”

Coauthor John Boyages, MBBS, PhD, a radiation oncologist at the Icon Cancer Center, Sydney Adventist Hospital, Wahroonga, emphasized that all women should be prescribed exercise after being diagnosed with breast cancer. “Prescribing a healthy lifestyle is just as important as prescribing tablets,” he said.

“As doctors, we really need to actively think about weight, nutrition, and exercise and advise about possible interventions. [Among patients with breast cancer,] weight gain adds to self-esteem problems, increases the risk of heart disease and other cancers, and several reports suggest it may affect prognosis and also increases the risk of lymphedema,” he added

“More effort needs to be geared to treating the whole body, as we know obesity is a risk factor for poorer outcomes when dealing with breast cancer,” commented Stephanie Bernik, MD, chief of breast service at Mount Sinai West and associate professor of surgery at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City. She was not involved in the study and was approached for comment.

Berwick also agreed that meeting with a nutritionist or receiving weight loss support is helpful for patients with cancer, but she added that not all cancer centers have the resources to provide these services.

Survey Details

Of 309 women who responded to the survey, complete data for pre- and post-diagnosis body mass index (BMI) were collected from 277 respondents, representing 15% of those surveyed.

Of these women, 254 had been diagnosed with stage I-III breast cancer; 33 had been diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ. The mean age of the patients was 59 years.

The results showed that for 20% of women, BMI increased from a healthy weight range at the time of diagnosis (BMI <25) to an unhealthy weight range (BMI >25). In addition, for 4.8% of patients, BMI increased from an overweight range (BMI 25 to <30) to obesity (BMI >30), and 60.7% reported an increase in BMI >1 kg/m2. Conversely, only a small proportion of women lost weight – 6% experienced a decrease of more than one BMI category.

Weight gain occurred within the first 2 years of diagnosis in 87% of women and within the first 12 months in 58%. In women who gained >10 kg (22 lb), 78% said they were highly concerned about it, as did 59% of women who gained >5 kg (11 lb).

Among all age groups (35 to 74 years), 69% experienced excess weight gain that was 0.48 kg higher each year compared with age-matched control persons who had not been diagnosed with breast cancer. Over 5 years, this represented an additional weight gain of 2 kg (5 lb) among women with breast cancer.

When approached for comment, Bernick agreed with the authors that these results should be interpreted with caution.

She pointed to the self-reporting bias and the fact that only 15% of women responded to the survey. “Perhaps it was only women who had gained weight who found it worthwhile reporting their experience with weight gain after a breast cancer diagnosis,” she suggested.

Even so, there are many reasons why weight gain during treatment for breast cancer presents a problem for women in the United States as well as Australia, Bernik told Medscape Medical News.

“Women undergoing chemotherapy may not have the energy to keep up with exercise regimens and may find eating food comforting,” she pointed out. “Because chemotherapy delivery and the after effects may take up a few days out of every 2 to 3 weeks, women have less time and energy to eat correctly or exercise. Furthermore, women sometimes get steroids while receiving chemotherapy, and this is known to drive up one’s appetite.”

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Significant weight gain after a diagnosis of breast cancer may be a bigger problem than previously thought, and clinicians need to do more to help patients manage it, say the authors of a national survey conducted in Australia.

“We found that two-thirds of our respondents were currently overweight or obese,” report Carolyn Ee, MBBS, PhD, of the NICM Health Research Institute, Western Sydney University, Penrith, New South Wales, and colleagues.

“Because weight gain after breast cancer may lead to poorer outcomes, efforts to prevent and manage weight gain must be prioritized and accelerated particularly in the first year after diagnosis,” they comment.

Their article was published online February 20 in BMC Cancer.

The 60-item anonymous online survey was sent to 1835 members of the Breast Cancer Network Australia Review and Survey Group.

Although the response rate for the online survey was only 15%, most women reported a “high” level of concern about weight gain – and with good reason. The results showed that 64% of women gained an average of 9 kg (20 lb), and 17% gained >20 kg (44 lb).

In the 2-year period following a breast cancer diagnosis, the rate of overweight and obesity increased from 48% to 67%. The rate of obesity alone almost doubled, from 17% to 32%.

Overweight and obesity are strongly implicated in the development of breast cancer, the authors note. Weight gain after diagnosis is associated with morbidity and all-cause mortality and may increase the risk for breast cancer recurrence by 30% to 40%.

The survey, which also collected data from 26 women who were participants in online women’s health and breast cancer support groups, did not include information on quality of life and levels of distress. “Additional research in this area appears to be warranted,” the study authors suggest.

In a press statement, Ee noted that 77% of women reported that weight gain had occurred in the 12- to 18-month period after diagnosis. This could provide a “window of opportunity” for intervention, she said.

“Timing may be the key in helping women to manage weight after a diagnosis of breast cancer,” she added. “Cancer services and general practitioners play an important role in having early conversations with women and referring them to a team of qualified healthcare professionals such as dieticians and exercise physiologists with experience in cancer.”

Coauthor John Boyages, MBBS, PhD, a radiation oncologist at the Icon Cancer Center, Sydney Adventist Hospital, Wahroonga, emphasized that all women should be prescribed exercise after being diagnosed with breast cancer. “Prescribing a healthy lifestyle is just as important as prescribing tablets,” he said.

“As doctors, we really need to actively think about weight, nutrition, and exercise and advise about possible interventions. [Among patients with breast cancer,] weight gain adds to self-esteem problems, increases the risk of heart disease and other cancers, and several reports suggest it may affect prognosis and also increases the risk of lymphedema,” he added

“More effort needs to be geared to treating the whole body, as we know obesity is a risk factor for poorer outcomes when dealing with breast cancer,” commented Stephanie Bernik, MD, chief of breast service at Mount Sinai West and associate professor of surgery at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City. She was not involved in the study and was approached for comment.

Berwick also agreed that meeting with a nutritionist or receiving weight loss support is helpful for patients with cancer, but she added that not all cancer centers have the resources to provide these services.

Survey Details

Of 309 women who responded to the survey, complete data for pre- and post-diagnosis body mass index (BMI) were collected from 277 respondents, representing 15% of those surveyed.

Of these women, 254 had been diagnosed with stage I-III breast cancer; 33 had been diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ. The mean age of the patients was 59 years.

The results showed that for 20% of women, BMI increased from a healthy weight range at the time of diagnosis (BMI <25) to an unhealthy weight range (BMI >25). In addition, for 4.8% of patients, BMI increased from an overweight range (BMI 25 to <30) to obesity (BMI >30), and 60.7% reported an increase in BMI >1 kg/m2. Conversely, only a small proportion of women lost weight – 6% experienced a decrease of more than one BMI category.

Weight gain occurred within the first 2 years of diagnosis in 87% of women and within the first 12 months in 58%. In women who gained >10 kg (22 lb), 78% said they were highly concerned about it, as did 59% of women who gained >5 kg (11 lb).

Among all age groups (35 to 74 years), 69% experienced excess weight gain that was 0.48 kg higher each year compared with age-matched control persons who had not been diagnosed with breast cancer. Over 5 years, this represented an additional weight gain of 2 kg (5 lb) among women with breast cancer.

When approached for comment, Bernick agreed with the authors that these results should be interpreted with caution.

She pointed to the self-reporting bias and the fact that only 15% of women responded to the survey. “Perhaps it was only women who had gained weight who found it worthwhile reporting their experience with weight gain after a breast cancer diagnosis,” she suggested.

Even so, there are many reasons why weight gain during treatment for breast cancer presents a problem for women in the United States as well as Australia, Bernik told Medscape Medical News.

“Women undergoing chemotherapy may not have the energy to keep up with exercise regimens and may find eating food comforting,” she pointed out. “Because chemotherapy delivery and the after effects may take up a few days out of every 2 to 3 weeks, women have less time and energy to eat correctly or exercise. Furthermore, women sometimes get steroids while receiving chemotherapy, and this is known to drive up one’s appetite.”

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Significant weight gain after a diagnosis of breast cancer may be a bigger problem than previously thought, and clinicians need to do more to help patients manage it, say the authors of a national survey conducted in Australia.

“We found that two-thirds of our respondents were currently overweight or obese,” report Carolyn Ee, MBBS, PhD, of the NICM Health Research Institute, Western Sydney University, Penrith, New South Wales, and colleagues.

“Because weight gain after breast cancer may lead to poorer outcomes, efforts to prevent and manage weight gain must be prioritized and accelerated particularly in the first year after diagnosis,” they comment.

Their article was published online February 20 in BMC Cancer.

The 60-item anonymous online survey was sent to 1835 members of the Breast Cancer Network Australia Review and Survey Group.

Although the response rate for the online survey was only 15%, most women reported a “high” level of concern about weight gain – and with good reason. The results showed that 64% of women gained an average of 9 kg (20 lb), and 17% gained >20 kg (44 lb).

In the 2-year period following a breast cancer diagnosis, the rate of overweight and obesity increased from 48% to 67%. The rate of obesity alone almost doubled, from 17% to 32%.

Overweight and obesity are strongly implicated in the development of breast cancer, the authors note. Weight gain after diagnosis is associated with morbidity and all-cause mortality and may increase the risk for breast cancer recurrence by 30% to 40%.

The survey, which also collected data from 26 women who were participants in online women’s health and breast cancer support groups, did not include information on quality of life and levels of distress. “Additional research in this area appears to be warranted,” the study authors suggest.

In a press statement, Ee noted that 77% of women reported that weight gain had occurred in the 12- to 18-month period after diagnosis. This could provide a “window of opportunity” for intervention, she said.

“Timing may be the key in helping women to manage weight after a diagnosis of breast cancer,” she added. “Cancer services and general practitioners play an important role in having early conversations with women and referring them to a team of qualified healthcare professionals such as dieticians and exercise physiologists with experience in cancer.”

Coauthor John Boyages, MBBS, PhD, a radiation oncologist at the Icon Cancer Center, Sydney Adventist Hospital, Wahroonga, emphasized that all women should be prescribed exercise after being diagnosed with breast cancer. “Prescribing a healthy lifestyle is just as important as prescribing tablets,” he said.

“As doctors, we really need to actively think about weight, nutrition, and exercise and advise about possible interventions. [Among patients with breast cancer,] weight gain adds to self-esteem problems, increases the risk of heart disease and other cancers, and several reports suggest it may affect prognosis and also increases the risk of lymphedema,” he added

“More effort needs to be geared to treating the whole body, as we know obesity is a risk factor for poorer outcomes when dealing with breast cancer,” commented Stephanie Bernik, MD, chief of breast service at Mount Sinai West and associate professor of surgery at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City. She was not involved in the study and was approached for comment.

Berwick also agreed that meeting with a nutritionist or receiving weight loss support is helpful for patients with cancer, but she added that not all cancer centers have the resources to provide these services.

Survey Details

Of 309 women who responded to the survey, complete data for pre- and post-diagnosis body mass index (BMI) were collected from 277 respondents, representing 15% of those surveyed.

Of these women, 254 had been diagnosed with stage I-III breast cancer; 33 had been diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ. The mean age of the patients was 59 years.

The results showed that for 20% of women, BMI increased from a healthy weight range at the time of diagnosis (BMI <25) to an unhealthy weight range (BMI >25). In addition, for 4.8% of patients, BMI increased from an overweight range (BMI 25 to <30) to obesity (BMI >30), and 60.7% reported an increase in BMI >1 kg/m2. Conversely, only a small proportion of women lost weight – 6% experienced a decrease of more than one BMI category.

Weight gain occurred within the first 2 years of diagnosis in 87% of women and within the first 12 months in 58%. In women who gained >10 kg (22 lb), 78% said they were highly concerned about it, as did 59% of women who gained >5 kg (11 lb).

Among all age groups (35 to 74 years), 69% experienced excess weight gain that was 0.48 kg higher each year compared with age-matched control persons who had not been diagnosed with breast cancer. Over 5 years, this represented an additional weight gain of 2 kg (5 lb) among women with breast cancer.

When approached for comment, Bernick agreed with the authors that these results should be interpreted with caution.

She pointed to the self-reporting bias and the fact that only 15% of women responded to the survey. “Perhaps it was only women who had gained weight who found it worthwhile reporting their experience with weight gain after a breast cancer diagnosis,” she suggested.

Even so, there are many reasons why weight gain during treatment for breast cancer presents a problem for women in the United States as well as Australia, Bernik told Medscape Medical News.

“Women undergoing chemotherapy may not have the energy to keep up with exercise regimens and may find eating food comforting,” she pointed out. “Because chemotherapy delivery and the after effects may take up a few days out of every 2 to 3 weeks, women have less time and energy to eat correctly or exercise. Furthermore, women sometimes get steroids while receiving chemotherapy, and this is known to drive up one’s appetite.”

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

‘Promising’ responses with preoperative immunotherapy in oral cavity cancer

Preoperative nivolumab, with or without ipilimumab, appeared safe and effective in a phase 2 trial of patients with oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma (OCSCC).

“We found that nivolumab, with or without ipilimumab, was feasible prior to surgery in patients with oral cavity cancers, with no delays in surgery observed,” said Jonathan D. Schoenfeld, MD, of the Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center in Boston.

“We did observe promising rates of volumetric and pathologic response, with near-complete and complete responses observed, particularly in the nivo-ipi arm.”

Dr. Schoenfeld presented these results at the Multidisciplinary Head and Neck Cancer Symposium, sponsored by the American Society for Radiation Oncology.

“The rationale behind evaluation of neoadjuvant immunotherapy is the potential of tumor downstaging, converting unresectable disease to resectable and inducing durable immunological memory as a result of exposure to the full breadth of tumor antigens preoperatively,” said Kartik Sehgal, MD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, who was not involved in this study.

“This randomized, phase 2 window study ... found that treatment with two neoadjuvant cycles of nivolumab alone or along with ipilimumab during the first cycle was feasible from an adverse events perspective and led to volumetric responses in approximately 50% of patients.”

Patients and treatment

The trial (NCT02919683) enrolled 30 patients with OCSCC, but 1 patient was excluded due to metastases at baseline. Patients had T2 (n = 20) or greater (n = 9) disease at baseline, and 58% of patients (n = 17) had node-positive disease.

The patients were randomized to two cycles of nivolumab (3 mg/kg) or nivolumab (3 mg/kg) plus ipilimumab (1 mg/kg with the first cycle). Patients underwent surgery 3-7 days after completing cycle 2.

In the nivolumab monotherapy arm (n = 14), the median age was 64.4 years (range, 39.1-81 years), and 71.4% of patients were men. Oral tongue was the primary tumor site in 50% of patients, and 50% of patients had stage IV disease.

In the nivolumab-ipilimumab arm (n = 15), the median age was 65.2 years (range, 32.5-78.4 years), and 53.3% of patients were men. Oral tongue was the primary tumor site in 60% of patients, and 73.3% of patients had stage IV disease.

Safety and tolerability

Six patients did not receive the full cycle 2 dose of immunotherapy, two in the nivolumab arm and four in the nivolumab-ipilimumab arm. This was most commonly due to an infusion reaction during cycle 2, Dr. Schoenfeld said.

There were no cases in which surgery was delayed. However, one patient did have surgery moved to an earlier date after cycle 1 because of concerns about progression.

There were three severe immune-related adverse events. In the nivolumab-ipilimumab arm, there was a case of grade 3 pneumonitis and a case of grade 3 colitis. Both of these events were reversible with treatment.

In the nivolumab monotherapy arm, one patient had grade 4 new-onset diabetes with diabetic ketoacidosis. This patient is still insulin dependent.

Perioperative adverse events in both arms included pulmonary embolism, postoperative hematoma, and flap failures (n = 2). One patient with flap failure also had a perioperative stroke, experienced progressive clinical decline, and ultimately died.

Response and survival

In the nivolumab monotherapy arm, 50% of patients (n = 7) had a volumetric response, and 8% (n = 1) had a pathologic complete response.

In the nivolumab-ipilimumab arm, 53% of patients (n = 8) had a volumetric response, and 20% (n = 3) had a pathologic complete response.

“In general, we found that our response metrics were concordant; that is, patients with volumetric responses tended more frequently to have pathologic responses,” Dr. Schoenfeld said. “There were a couple notable cases where there were volumetric increases and significant pathologic responses.”

To identify factors associated with response, Dr. Schoenfeld and colleagues performed correlative multiplex immunofluorescence on 21 patient specimens prior to treatment.

“We did not identify any differences in baseline levels of PD-L1 expression in tumor cells between the two arms,” Dr. Schoenfeld noted. “We found that CD4-positive T cells in the pretreatment specimens correlated with pathologic response [P = .016]. Interestingly, this association was only significant in patients treated with nivo-ipi [P = .008] but not nivolumab alone [P = .83].”

Ten patients went on to receive radiation, and nine received chemoradiation. One patient presented to the operating room but did not undergo surgery because he was thought to require total glossectomy. This patient received chemoradiotherapy, achieved a complete response, and is still disease free after more than 3 years of follow-up.

The median follow-up for the entire cohort was 14 months. At 12 months, the progression-free survival rate was 85%, and the overall survival rate was 89%.

Dr. Schoenfeld noted that this study was not powered to assess survival or to directly compare nivolumab monotherapy and nivolumab plus ipilimumab.

‘Encouraging’ results, but what’s next?

“We were very encouraged by the toxicity data ... [and] the impressive pathologic responses in both arms, but particularly in the nivo-ipi arm,” Dr. Schoenfeld said. “I think the real question is, ‘Does this translate into a significant progression-free or overall survival advantage?’ So I think that would be something worthy of further study.”

“These results are encouraging for management of patients with oral cavity cancers who remain at high risk for recurrence with the current standard of care but will need validation in larger prospective studies,” Dr. Sehgal noted. “Multiple clinical trials are currently ongoing to evaluate the role of neoadjuvant immunotherapy for disease-specific outcomes, notable being phase 2 NCT02296684 and phase 3 KEYNOTE-689 (NCT03765918) with pembrolizumab and phase 3 IMSTAR-HN (NCT03700905) with nivolumab alone or along with ipilimumab.”

The current study was funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Schoenfeld disclosed relationships with Bristol-Myers Squibb and other companies. Dr. Sehgal had no relevant conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Schoenfeld J et al. Head and Neck Cancers Symposium 2020, Abstract 1.

Preoperative nivolumab, with or without ipilimumab, appeared safe and effective in a phase 2 trial of patients with oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma (OCSCC).

“We found that nivolumab, with or without ipilimumab, was feasible prior to surgery in patients with oral cavity cancers, with no delays in surgery observed,” said Jonathan D. Schoenfeld, MD, of the Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center in Boston.

“We did observe promising rates of volumetric and pathologic response, with near-complete and complete responses observed, particularly in the nivo-ipi arm.”

Dr. Schoenfeld presented these results at the Multidisciplinary Head and Neck Cancer Symposium, sponsored by the American Society for Radiation Oncology.

“The rationale behind evaluation of neoadjuvant immunotherapy is the potential of tumor downstaging, converting unresectable disease to resectable and inducing durable immunological memory as a result of exposure to the full breadth of tumor antigens preoperatively,” said Kartik Sehgal, MD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, who was not involved in this study.

“This randomized, phase 2 window study ... found that treatment with two neoadjuvant cycles of nivolumab alone or along with ipilimumab during the first cycle was feasible from an adverse events perspective and led to volumetric responses in approximately 50% of patients.”

Patients and treatment

The trial (NCT02919683) enrolled 30 patients with OCSCC, but 1 patient was excluded due to metastases at baseline. Patients had T2 (n = 20) or greater (n = 9) disease at baseline, and 58% of patients (n = 17) had node-positive disease.

The patients were randomized to two cycles of nivolumab (3 mg/kg) or nivolumab (3 mg/kg) plus ipilimumab (1 mg/kg with the first cycle). Patients underwent surgery 3-7 days after completing cycle 2.

In the nivolumab monotherapy arm (n = 14), the median age was 64.4 years (range, 39.1-81 years), and 71.4% of patients were men. Oral tongue was the primary tumor site in 50% of patients, and 50% of patients had stage IV disease.

In the nivolumab-ipilimumab arm (n = 15), the median age was 65.2 years (range, 32.5-78.4 years), and 53.3% of patients were men. Oral tongue was the primary tumor site in 60% of patients, and 73.3% of patients had stage IV disease.

Safety and tolerability

Six patients did not receive the full cycle 2 dose of immunotherapy, two in the nivolumab arm and four in the nivolumab-ipilimumab arm. This was most commonly due to an infusion reaction during cycle 2, Dr. Schoenfeld said.

There were no cases in which surgery was delayed. However, one patient did have surgery moved to an earlier date after cycle 1 because of concerns about progression.

There were three severe immune-related adverse events. In the nivolumab-ipilimumab arm, there was a case of grade 3 pneumonitis and a case of grade 3 colitis. Both of these events were reversible with treatment.

In the nivolumab monotherapy arm, one patient had grade 4 new-onset diabetes with diabetic ketoacidosis. This patient is still insulin dependent.

Perioperative adverse events in both arms included pulmonary embolism, postoperative hematoma, and flap failures (n = 2). One patient with flap failure also had a perioperative stroke, experienced progressive clinical decline, and ultimately died.

Response and survival

In the nivolumab monotherapy arm, 50% of patients (n = 7) had a volumetric response, and 8% (n = 1) had a pathologic complete response.

In the nivolumab-ipilimumab arm, 53% of patients (n = 8) had a volumetric response, and 20% (n = 3) had a pathologic complete response.

“In general, we found that our response metrics were concordant; that is, patients with volumetric responses tended more frequently to have pathologic responses,” Dr. Schoenfeld said. “There were a couple notable cases where there were volumetric increases and significant pathologic responses.”

To identify factors associated with response, Dr. Schoenfeld and colleagues performed correlative multiplex immunofluorescence on 21 patient specimens prior to treatment.

“We did not identify any differences in baseline levels of PD-L1 expression in tumor cells between the two arms,” Dr. Schoenfeld noted. “We found that CD4-positive T cells in the pretreatment specimens correlated with pathologic response [P = .016]. Interestingly, this association was only significant in patients treated with nivo-ipi [P = .008] but not nivolumab alone [P = .83].”

Ten patients went on to receive radiation, and nine received chemoradiation. One patient presented to the operating room but did not undergo surgery because he was thought to require total glossectomy. This patient received chemoradiotherapy, achieved a complete response, and is still disease free after more than 3 years of follow-up.

The median follow-up for the entire cohort was 14 months. At 12 months, the progression-free survival rate was 85%, and the overall survival rate was 89%.

Dr. Schoenfeld noted that this study was not powered to assess survival or to directly compare nivolumab monotherapy and nivolumab plus ipilimumab.

‘Encouraging’ results, but what’s next?

“We were very encouraged by the toxicity data ... [and] the impressive pathologic responses in both arms, but particularly in the nivo-ipi arm,” Dr. Schoenfeld said. “I think the real question is, ‘Does this translate into a significant progression-free or overall survival advantage?’ So I think that would be something worthy of further study.”

“These results are encouraging for management of patients with oral cavity cancers who remain at high risk for recurrence with the current standard of care but will need validation in larger prospective studies,” Dr. Sehgal noted. “Multiple clinical trials are currently ongoing to evaluate the role of neoadjuvant immunotherapy for disease-specific outcomes, notable being phase 2 NCT02296684 and phase 3 KEYNOTE-689 (NCT03765918) with pembrolizumab and phase 3 IMSTAR-HN (NCT03700905) with nivolumab alone or along with ipilimumab.”

The current study was funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Schoenfeld disclosed relationships with Bristol-Myers Squibb and other companies. Dr. Sehgal had no relevant conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Schoenfeld J et al. Head and Neck Cancers Symposium 2020, Abstract 1.

Preoperative nivolumab, with or without ipilimumab, appeared safe and effective in a phase 2 trial of patients with oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma (OCSCC).

“We found that nivolumab, with or without ipilimumab, was feasible prior to surgery in patients with oral cavity cancers, with no delays in surgery observed,” said Jonathan D. Schoenfeld, MD, of the Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center in Boston.

“We did observe promising rates of volumetric and pathologic response, with near-complete and complete responses observed, particularly in the nivo-ipi arm.”

Dr. Schoenfeld presented these results at the Multidisciplinary Head and Neck Cancer Symposium, sponsored by the American Society for Radiation Oncology.

“The rationale behind evaluation of neoadjuvant immunotherapy is the potential of tumor downstaging, converting unresectable disease to resectable and inducing durable immunological memory as a result of exposure to the full breadth of tumor antigens preoperatively,” said Kartik Sehgal, MD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, who was not involved in this study.

“This randomized, phase 2 window study ... found that treatment with two neoadjuvant cycles of nivolumab alone or along with ipilimumab during the first cycle was feasible from an adverse events perspective and led to volumetric responses in approximately 50% of patients.”

Patients and treatment

The trial (NCT02919683) enrolled 30 patients with OCSCC, but 1 patient was excluded due to metastases at baseline. Patients had T2 (n = 20) or greater (n = 9) disease at baseline, and 58% of patients (n = 17) had node-positive disease.

The patients were randomized to two cycles of nivolumab (3 mg/kg) or nivolumab (3 mg/kg) plus ipilimumab (1 mg/kg with the first cycle). Patients underwent surgery 3-7 days after completing cycle 2.

In the nivolumab monotherapy arm (n = 14), the median age was 64.4 years (range, 39.1-81 years), and 71.4% of patients were men. Oral tongue was the primary tumor site in 50% of patients, and 50% of patients had stage IV disease.

In the nivolumab-ipilimumab arm (n = 15), the median age was 65.2 years (range, 32.5-78.4 years), and 53.3% of patients were men. Oral tongue was the primary tumor site in 60% of patients, and 73.3% of patients had stage IV disease.

Safety and tolerability

Six patients did not receive the full cycle 2 dose of immunotherapy, two in the nivolumab arm and four in the nivolumab-ipilimumab arm. This was most commonly due to an infusion reaction during cycle 2, Dr. Schoenfeld said.

There were no cases in which surgery was delayed. However, one patient did have surgery moved to an earlier date after cycle 1 because of concerns about progression.

There were three severe immune-related adverse events. In the nivolumab-ipilimumab arm, there was a case of grade 3 pneumonitis and a case of grade 3 colitis. Both of these events were reversible with treatment.

In the nivolumab monotherapy arm, one patient had grade 4 new-onset diabetes with diabetic ketoacidosis. This patient is still insulin dependent.

Perioperative adverse events in both arms included pulmonary embolism, postoperative hematoma, and flap failures (n = 2). One patient with flap failure also had a perioperative stroke, experienced progressive clinical decline, and ultimately died.

Response and survival

In the nivolumab monotherapy arm, 50% of patients (n = 7) had a volumetric response, and 8% (n = 1) had a pathologic complete response.

In the nivolumab-ipilimumab arm, 53% of patients (n = 8) had a volumetric response, and 20% (n = 3) had a pathologic complete response.

“In general, we found that our response metrics were concordant; that is, patients with volumetric responses tended more frequently to have pathologic responses,” Dr. Schoenfeld said. “There were a couple notable cases where there were volumetric increases and significant pathologic responses.”

To identify factors associated with response, Dr. Schoenfeld and colleagues performed correlative multiplex immunofluorescence on 21 patient specimens prior to treatment.

“We did not identify any differences in baseline levels of PD-L1 expression in tumor cells between the two arms,” Dr. Schoenfeld noted. “We found that CD4-positive T cells in the pretreatment specimens correlated with pathologic response [P = .016]. Interestingly, this association was only significant in patients treated with nivo-ipi [P = .008] but not nivolumab alone [P = .83].”

Ten patients went on to receive radiation, and nine received chemoradiation. One patient presented to the operating room but did not undergo surgery because he was thought to require total glossectomy. This patient received chemoradiotherapy, achieved a complete response, and is still disease free after more than 3 years of follow-up.

The median follow-up for the entire cohort was 14 months. At 12 months, the progression-free survival rate was 85%, and the overall survival rate was 89%.

Dr. Schoenfeld noted that this study was not powered to assess survival or to directly compare nivolumab monotherapy and nivolumab plus ipilimumab.

‘Encouraging’ results, but what’s next?

“We were very encouraged by the toxicity data ... [and] the impressive pathologic responses in both arms, but particularly in the nivo-ipi arm,” Dr. Schoenfeld said. “I think the real question is, ‘Does this translate into a significant progression-free or overall survival advantage?’ So I think that would be something worthy of further study.”

“These results are encouraging for management of patients with oral cavity cancers who remain at high risk for recurrence with the current standard of care but will need validation in larger prospective studies,” Dr. Sehgal noted. “Multiple clinical trials are currently ongoing to evaluate the role of neoadjuvant immunotherapy for disease-specific outcomes, notable being phase 2 NCT02296684 and phase 3 KEYNOTE-689 (NCT03765918) with pembrolizumab and phase 3 IMSTAR-HN (NCT03700905) with nivolumab alone or along with ipilimumab.”

The current study was funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Schoenfeld disclosed relationships with Bristol-Myers Squibb and other companies. Dr. Sehgal had no relevant conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Schoenfeld J et al. Head and Neck Cancers Symposium 2020, Abstract 1.

REPORTING FROM HEAD AND NECK CANCERS SYMPOSIUM 2020

Can this patient get IV contrast?

A 59-year-old man is admitted with abdominal pain. He has a history of pancreatitis. A contrast CT scan is ordered. He reports a history of severe shellfish allergy when the radiology tech checks him in for the procedure. You are paged regarding what to do:

A) Continue with scan as ordered.

B) Switch to MRI scan.

C) Switch to MRI scan with gadolinium.

D) Continue with CT with contrast, give dose of Solu-Medrol.

E) Continue with CT with contrast give IV diphenhydramine.

The correct answer here is A, This patient can receive his scan and receive contrast as ordered.

The mistaken thought was that shellfish contains iodine, so allergy to shellfish was likely to portend allergy to iodine.

Allergy to shellfish is caused by individual proteins that are definitely not in iodine-containing contrast.1 Beaty et al. studied the prevalence of the belief that allergy to shellfish is tied to iodine allergy in a survey given to 231 faculty radiologists and interventional cardiologists.2 Almost 70% responded that they inquire about seafood allergy before procedures that require iodine contrast, and 37% reported they would withhold the contrast or premedicate patients if they had a seafood allergy.

In a more recent study, Westermann-Clark and colleagues surveyed 252 health professionals before and after an educational intervention to dispel the myth of shellfish allergy and iodinated contrast reactions.3 Before the intervention, 66% of participants felt it was important to ask about shellfish allergies and 93% felt it was important to ask about iodine allergies; 26% responded that they would withhold iodinated contrast material in patients with a shellfish allergy, and 56% would withhold in patients with an iodine allergy. A total of 62% reported they would premedicate patients with a shellfish allergy and 75% would premedicate patients with an iodine allergy. The numbers declined dramatically after the educational intervention.

Patients who have seafood allergy have a higher rate of reactions to iodinated contrast, but not at a higher rate than do patients with other food allergies or asthma.4 Most radiology departments do not screen for other food allergies despite the fact these allergies have the same increased risk as for patients with a seafood/shellfish allergy. These patients are more allergic, and in general, are more likely to have reactions. The American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology recommends not routinely ordering low- or iso-osmolar radiocontrast media or pretreating with either antihistamines or steroids in patients with a history of seafood allergy.5

There is no evidence that iodine causes allergic reactions. It makes sense that iodine does not cause allergic reactions, as it is an essential component in the human body, in thyroid hormone and in amino acids.6 Patients with dermatitis following topical application of iodine preparations such as povidone-iodide are not reacting to the iodine.

Van Ketel and van den Berg patch-tested patients with a history of dermatitis after exposure to povidone-iodine.7 All patients reacted to patch testing with povidone-iodine, but none reacted to direct testing to iodine (0/5 with patch testing of potassium iodide and 0/3 with testing with iodine tincture).

Take home points:

- It is unnecessary and unhelpful to ask patients about seafood allergies before ordering radiologic studies involving contrast.

- Iodine allergy does not exist.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at dpaauw@uw.edu.

References

1. Narayan AK et al. Avoiding contrast-enhanced computed tomography scans in patients with shellfish allergies. J Hosp Med. 2016 Jun;11(6):435-7.

2. Beaty AD et al. Seafood allergy and radiocontrast media: Are physicians propagating a myth? Am J Med. 2008 Feb;121(2):158.e1-4.

3. Westermann-Clark E et al. Debunking myths about “allergy” to radiocontrast media in an academic institution. Postgrad Med. 2015 Apr;127(3):295-300.

4. Coakley FV and DM Panicek. Iodine allergy: An oyster without a pearl? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997 Oct;169(4):951-2.

5. American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology recommendations on low- or iso-osmolar radiocontrast media.

6. Schabelman E and M Witting. The relationship of radiocontrast, iodine, and seafood allergies: A medical myth exposed. J Emerg Med. 2010 Nov;39(5):701-7.

7. van Ketel WG and WH van den Berg. Sensitization to povidone-iodine. Dermatol Clin. 1990 Jan;8(1):107-9.

A 59-year-old man is admitted with abdominal pain. He has a history of pancreatitis. A contrast CT scan is ordered. He reports a history of severe shellfish allergy when the radiology tech checks him in for the procedure. You are paged regarding what to do:

A) Continue with scan as ordered.

B) Switch to MRI scan.

C) Switch to MRI scan with gadolinium.

D) Continue with CT with contrast, give dose of Solu-Medrol.

E) Continue with CT with contrast give IV diphenhydramine.

The correct answer here is A, This patient can receive his scan and receive contrast as ordered.

The mistaken thought was that shellfish contains iodine, so allergy to shellfish was likely to portend allergy to iodine.

Allergy to shellfish is caused by individual proteins that are definitely not in iodine-containing contrast.1 Beaty et al. studied the prevalence of the belief that allergy to shellfish is tied to iodine allergy in a survey given to 231 faculty radiologists and interventional cardiologists.2 Almost 70% responded that they inquire about seafood allergy before procedures that require iodine contrast, and 37% reported they would withhold the contrast or premedicate patients if they had a seafood allergy.

In a more recent study, Westermann-Clark and colleagues surveyed 252 health professionals before and after an educational intervention to dispel the myth of shellfish allergy and iodinated contrast reactions.3 Before the intervention, 66% of participants felt it was important to ask about shellfish allergies and 93% felt it was important to ask about iodine allergies; 26% responded that they would withhold iodinated contrast material in patients with a shellfish allergy, and 56% would withhold in patients with an iodine allergy. A total of 62% reported they would premedicate patients with a shellfish allergy and 75% would premedicate patients with an iodine allergy. The numbers declined dramatically after the educational intervention.

Patients who have seafood allergy have a higher rate of reactions to iodinated contrast, but not at a higher rate than do patients with other food allergies or asthma.4 Most radiology departments do not screen for other food allergies despite the fact these allergies have the same increased risk as for patients with a seafood/shellfish allergy. These patients are more allergic, and in general, are more likely to have reactions. The American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology recommends not routinely ordering low- or iso-osmolar radiocontrast media or pretreating with either antihistamines or steroids in patients with a history of seafood allergy.5

There is no evidence that iodine causes allergic reactions. It makes sense that iodine does not cause allergic reactions, as it is an essential component in the human body, in thyroid hormone and in amino acids.6 Patients with dermatitis following topical application of iodine preparations such as povidone-iodide are not reacting to the iodine.

Van Ketel and van den Berg patch-tested patients with a history of dermatitis after exposure to povidone-iodine.7 All patients reacted to patch testing with povidone-iodine, but none reacted to direct testing to iodine (0/5 with patch testing of potassium iodide and 0/3 with testing with iodine tincture).

Take home points:

- It is unnecessary and unhelpful to ask patients about seafood allergies before ordering radiologic studies involving contrast.

- Iodine allergy does not exist.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at dpaauw@uw.edu.

References

1. Narayan AK et al. Avoiding contrast-enhanced computed tomography scans in patients with shellfish allergies. J Hosp Med. 2016 Jun;11(6):435-7.

2. Beaty AD et al. Seafood allergy and radiocontrast media: Are physicians propagating a myth? Am J Med. 2008 Feb;121(2):158.e1-4.

3. Westermann-Clark E et al. Debunking myths about “allergy” to radiocontrast media in an academic institution. Postgrad Med. 2015 Apr;127(3):295-300.

4. Coakley FV and DM Panicek. Iodine allergy: An oyster without a pearl? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997 Oct;169(4):951-2.

5. American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology recommendations on low- or iso-osmolar radiocontrast media.

6. Schabelman E and M Witting. The relationship of radiocontrast, iodine, and seafood allergies: A medical myth exposed. J Emerg Med. 2010 Nov;39(5):701-7.

7. van Ketel WG and WH van den Berg. Sensitization to povidone-iodine. Dermatol Clin. 1990 Jan;8(1):107-9.

A 59-year-old man is admitted with abdominal pain. He has a history of pancreatitis. A contrast CT scan is ordered. He reports a history of severe shellfish allergy when the radiology tech checks him in for the procedure. You are paged regarding what to do:

A) Continue with scan as ordered.

B) Switch to MRI scan.

C) Switch to MRI scan with gadolinium.

D) Continue with CT with contrast, give dose of Solu-Medrol.

E) Continue with CT with contrast give IV diphenhydramine.

The correct answer here is A, This patient can receive his scan and receive contrast as ordered.

The mistaken thought was that shellfish contains iodine, so allergy to shellfish was likely to portend allergy to iodine.

Allergy to shellfish is caused by individual proteins that are definitely not in iodine-containing contrast.1 Beaty et al. studied the prevalence of the belief that allergy to shellfish is tied to iodine allergy in a survey given to 231 faculty radiologists and interventional cardiologists.2 Almost 70% responded that they inquire about seafood allergy before procedures that require iodine contrast, and 37% reported they would withhold the contrast or premedicate patients if they had a seafood allergy.

In a more recent study, Westermann-Clark and colleagues surveyed 252 health professionals before and after an educational intervention to dispel the myth of shellfish allergy and iodinated contrast reactions.3 Before the intervention, 66% of participants felt it was important to ask about shellfish allergies and 93% felt it was important to ask about iodine allergies; 26% responded that they would withhold iodinated contrast material in patients with a shellfish allergy, and 56% would withhold in patients with an iodine allergy. A total of 62% reported they would premedicate patients with a shellfish allergy and 75% would premedicate patients with an iodine allergy. The numbers declined dramatically after the educational intervention.

Patients who have seafood allergy have a higher rate of reactions to iodinated contrast, but not at a higher rate than do patients with other food allergies or asthma.4 Most radiology departments do not screen for other food allergies despite the fact these allergies have the same increased risk as for patients with a seafood/shellfish allergy. These patients are more allergic, and in general, are more likely to have reactions. The American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology recommends not routinely ordering low- or iso-osmolar radiocontrast media or pretreating with either antihistamines or steroids in patients with a history of seafood allergy.5

There is no evidence that iodine causes allergic reactions. It makes sense that iodine does not cause allergic reactions, as it is an essential component in the human body, in thyroid hormone and in amino acids.6 Patients with dermatitis following topical application of iodine preparations such as povidone-iodide are not reacting to the iodine.

Van Ketel and van den Berg patch-tested patients with a history of dermatitis after exposure to povidone-iodine.7 All patients reacted to patch testing with povidone-iodine, but none reacted to direct testing to iodine (0/5 with patch testing of potassium iodide and 0/3 with testing with iodine tincture).

Take home points:

- It is unnecessary and unhelpful to ask patients about seafood allergies before ordering radiologic studies involving contrast.

- Iodine allergy does not exist.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at dpaauw@uw.edu.

References

1. Narayan AK et al. Avoiding contrast-enhanced computed tomography scans in patients with shellfish allergies. J Hosp Med. 2016 Jun;11(6):435-7.

2. Beaty AD et al. Seafood allergy and radiocontrast media: Are physicians propagating a myth? Am J Med. 2008 Feb;121(2):158.e1-4.

3. Westermann-Clark E et al. Debunking myths about “allergy” to radiocontrast media in an academic institution. Postgrad Med. 2015 Apr;127(3):295-300.

4. Coakley FV and DM Panicek. Iodine allergy: An oyster without a pearl? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997 Oct;169(4):951-2.

5. American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology recommendations on low- or iso-osmolar radiocontrast media.

6. Schabelman E and M Witting. The relationship of radiocontrast, iodine, and seafood allergies: A medical myth exposed. J Emerg Med. 2010 Nov;39(5):701-7.

7. van Ketel WG and WH van den Berg. Sensitization to povidone-iodine. Dermatol Clin. 1990 Jan;8(1):107-9.

Mortality sevenfold higher post TAVR with severe kidney injury

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Acute kidney injury (AKI), a potentially modifiable risk factor in some cases, predicts increased mortality within the first year after transcatheter aortic valve transplantation (TAVR), according to an analysis of a U.S. registry presented at CRT 2020 sponsored by MedStar Heart & Vascular Institute.

“After adjustment, there are higher rates of all-cause mortality regardless of the severity of AKI,” reported Howard M. Julien, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Relative to the absence of AKI (stage 0), the hazard ratio for death at 1 year was more than threefold greater (HR, 3.26), even for those with stage 1 AKI. When unadjusted for covariates, it remained more than twice as high (HR, 2.67; P less than .001), Dr. Julien reported.

For stage 3 AKI, the unadjusted risk was more than nine times higher and remained roughly seven times greater after adjustment (HR, 7.04; P less than .001). Stage 2 AKI was linked with an adjusted risk of about the same magnitude.

Drawn from the National Cardiovascular TAVR Registry, which is maintained jointly by the Society of Thoracic Surgeons and the American College of Cardiology, data were analyzed on more than 100,000 TAVRs performed during 2012-2018. A subset of TAVRs performed between January 2016 and June 2018 served as a source of trends in what Dr. Julien described as the “modern era” of this procedure.

The incidence of AKI overall was about 10%, but rates were higher at the earliest time point in the analysis and fell modestly over the study period for all three stages. In a logistic regression analysis, the factors associated with the greatest odds ratio of developing AKI in patients following TAVR were conversion to open heart surgery (OR, 10.84, P less than .001), nonfemoral access (OR, 2.33; P less than .001), anemia (OR, 1.90; P less than .001), general versus moderate sedation (OR, 1.62; P less than .001), diabetes (OR, 1.61; P less than .001), and cardiogenic shock within 24 hours (OR, 1.60; P less than .023).

Other factors with a significant but lower relative risk association with AKI included a high contrast volume (OR, 1.004; P less than .001), use of a self-expanding valve (HR, 1.22; P = .009), severe lung disease (OR, 1.21; P = .043) and prior peripheral artery disease (HR, 1.20; P = .043).

“The message from these data is that there appears to be a cluster of patients who are unstable at the time of their procedure and are more likely to develop the most severe forms of AKI,” Dr. Julien reported.

The higher rate of AKI in patients who have diabetes is “not surprising,” but several of the factors associated with AKI are potentially modifiable. This includes choices in regard to sedation and arterial access. The value of modifying the amount of contrast is less clear, because the volume of contrast was no longer significant after an adjustment with multivariate analysis.

In fact, all of these factors require validation. Dr. Julien warned that neither the cause of AKI nor its temporal relationship to TAVR could be consistently determined from the registry data. In addition, retrospective analyses always include the potential for unrecognized residual confounders.

Still, these data are useful for drawing attention to the fact that AKI is a common complication of TAVR and one that is associated with adverse outcomes, including reduced survival at 1 year.

“The factors taken from these data might be useful to help identify patients who are at risk of the most severe forms of AKI and, hopefully, lead to prevention strategies that take these characteristics into consideration,” Dr. Julien said.

Dr. Julien reported no potential financial conflicts of interest.

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Acute kidney injury (AKI), a potentially modifiable risk factor in some cases, predicts increased mortality within the first year after transcatheter aortic valve transplantation (TAVR), according to an analysis of a U.S. registry presented at CRT 2020 sponsored by MedStar Heart & Vascular Institute.

“After adjustment, there are higher rates of all-cause mortality regardless of the severity of AKI,” reported Howard M. Julien, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Relative to the absence of AKI (stage 0), the hazard ratio for death at 1 year was more than threefold greater (HR, 3.26), even for those with stage 1 AKI. When unadjusted for covariates, it remained more than twice as high (HR, 2.67; P less than .001), Dr. Julien reported.

For stage 3 AKI, the unadjusted risk was more than nine times higher and remained roughly seven times greater after adjustment (HR, 7.04; P less than .001). Stage 2 AKI was linked with an adjusted risk of about the same magnitude.

Drawn from the National Cardiovascular TAVR Registry, which is maintained jointly by the Society of Thoracic Surgeons and the American College of Cardiology, data were analyzed on more than 100,000 TAVRs performed during 2012-2018. A subset of TAVRs performed between January 2016 and June 2018 served as a source of trends in what Dr. Julien described as the “modern era” of this procedure.