User login

Guideline: Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia

A new guideline has been published to update the 2007 guidelines for the management of adults with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP).

The practice guideline was jointly written by an ad hoc committee of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. CAP refers to a pneumonia infection that was acquired by a patient in his or her community. Decisions about which antibiotics to use to treat this kind of infection are based on risk factors for resistant organisms and the severity of illness.

Pathogens

Traditionally, CAP is caused by common bacterial pathogens that include Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Legionella species, Chlamydia pneumonia, and Moraxella catarrhalis. Risk factors for multidrug resistant pathogens such as methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa include previous infection with MRSA or P. aeruginosa, recent hospitalization, and requiring parenteral antibiotics in the last 90 days.

Defining severe community-acquired pneumonia

The health care–associated pneumonia, or HCAP, classification should no longer be used to determine empiric treatment. The recommendations for which antibiotics to use are linked to the severity of illness. Previously the site of treatment drove antibiotic selection, but since decision about the site of care can be affected by many considerations, the guidelines recommend using the CAP severity criteria. Severe CAP includes either one major or at least three minor criteria.

Major criteria are:

- Septic shock requiring vasopressors.

- Respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation.

Minor criteria are:

- Respiratory rate greater than or equal to 30 breaths/min.

- Ratio of arterial O2 partial pressure to fractional inspired O2 less than or equal to 250.

- Multilobar infiltrates.

- Confusion/disorientation.

- Uremia (blood urea nitrogen level greater than or equal to 20 mg/dL).

- Leukopenia (white blood cell count less than 4,000 cells/mcL).

- Thrombocytopenia (platelet count less than 100,000 mcL)

- Hypothermia (core temperature less than 36º C).

- Hypotension requiring aggressive fluid resuscitation.

Management and diagnostic testing

Clinicians should use the Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) and clinical judgment to guide the site of treatment for patients. Gram stain, sputum, and blood culture should not be routinely obtained in an outpatient setting. Legionella antigen should not be routinely obtained unless indicated by epidemiological factors. During influenza season, a rapid influenza assay, preferably a nucleic acid amplification test, should be obtained to help guide treatment.

For patients with severe CAP or risk factors for MRSA or P. aeruginosa, gram stain and culture and Legionella antigen should be obtained to manage antibiotic choices. Also, blood cultures should be obtained for these patients.

Empiric antibiotic therapy should be initiated based on clinical judgment and radiographic confirmation of CAP. Serum procalcitonin should not be used to assess initiation of antibiotic therapy.

Empiric antibiotic therapy

Healthy adults without comorbidities should be treated with monotherapy of either:

- Amoxicillin 1 g three times daily.

- OR doxycycline 100 mg twice daily.

- OR a macrolide (azithromycin 500 mg on first day then 250 mg daily or clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily or clarithromycin extended release 1,000 mg daily) only in areas with pneumococcal resistance to macrolides less than 25%.

Adults with comorbidities such as chronic heart, lung, liver, or renal disease; diabetes mellitus; alcoholism; malignancy; or asplenia should be treated with:

- Amoxicillin/clavulanate 500 mg/125 mg three times daily, or amoxicillin/ clavulanate 875 mg/125 mg twice daily, or 2,000 mg/125 mg twice daily, or a cephalosporin (cefpodoxime 200 mg twice daily or cefuroxime 500 mg twice daily); and a macrolide (azithromycin 500 mg on first day then 250 mg daily, clarithromycin [500 mg twice daily or extended release 1,000 mg once daily]), or doxycycline 100 mg twice daily. (Some experts recommend that the first dose of doxycycline should be 200 mg.)

- OR monotherapy with respiratory fluoroquinolone (levofloxacin 750 mg daily, moxifloxacin 400 mg daily, or gemifloxacin 320 mg daily).

Inpatient pneumonia that is not severe, without risk factors for resistant organisms should be treated with:

- Beta-lactam (ampicillin 1 sulbactam 1.5-3 g every 6 h, cefotaxime 1-2 g every 8 h, ceftriaxone 1-2 g daily, or ceftaroline 600 mg every 12 h) and a macrolide (azithromycin 500 mg daily or clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily).

- OR monotherapy with a respiratory fluoroquinolone (levofloxacin 750 mg daily, moxifloxacin 400 mg daily).

If there is a contraindication for the use of both a macrolide and a fluoroquinolone, then doxycycline can be used instead.

Severe inpatient pneumonia without risk factors for resistant organisms should be treated with combination therapy of either (agents and doses the same as above):

- Beta-lactam and macrolide.

- OR fluoroquinolone and beta-lactam.

It is recommended to not routinely add anaerobic coverage for suspected aspiration pneumonia unless lung abscess or empyema is suspected. Clinicians should identify risk factors for MRSA or P. aeruginosa before adding additional agents.

Duration of antibiotic therapy is determined by the patient achieving clinical stability with no less than 5 days of antibiotics. In adults with symptom resolution within 5-7 days, no additional follow-up chest imaging is recommended. If patients test positive for influenza, then anti-influenza treatment such as oseltamivir should be used in addition to antibiotics regardless of length of influenza symptoms before presentation.

The bottom line

CAP treatment should be based on severity of illness and risk factors for resistant organisms. Blood and sputum cultures are recommended only for patients with severe pneumonia. There have been important changes in the recommendations for antibiotic treatment of CAP, with high-dose amoxicillin recommended for most patients with CAP who are treated as outpatients. Patients who exhibit clinical stability should be treated for at least 5 days and do not require follow up imaging studies.

For a podcast of this guideline, go to iTunes and download the Infectious Diseases Society of America guideline podcast.

Reference

Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. An official clinical practice guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019 Oct 1;200(7):e45-e67.

Tina Chuong, DO, is a second-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health.

A new guideline has been published to update the 2007 guidelines for the management of adults with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP).

The practice guideline was jointly written by an ad hoc committee of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. CAP refers to a pneumonia infection that was acquired by a patient in his or her community. Decisions about which antibiotics to use to treat this kind of infection are based on risk factors for resistant organisms and the severity of illness.

Pathogens

Traditionally, CAP is caused by common bacterial pathogens that include Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Legionella species, Chlamydia pneumonia, and Moraxella catarrhalis. Risk factors for multidrug resistant pathogens such as methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa include previous infection with MRSA or P. aeruginosa, recent hospitalization, and requiring parenteral antibiotics in the last 90 days.

Defining severe community-acquired pneumonia

The health care–associated pneumonia, or HCAP, classification should no longer be used to determine empiric treatment. The recommendations for which antibiotics to use are linked to the severity of illness. Previously the site of treatment drove antibiotic selection, but since decision about the site of care can be affected by many considerations, the guidelines recommend using the CAP severity criteria. Severe CAP includes either one major or at least three minor criteria.

Major criteria are:

- Septic shock requiring vasopressors.

- Respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation.

Minor criteria are:

- Respiratory rate greater than or equal to 30 breaths/min.

- Ratio of arterial O2 partial pressure to fractional inspired O2 less than or equal to 250.

- Multilobar infiltrates.

- Confusion/disorientation.

- Uremia (blood urea nitrogen level greater than or equal to 20 mg/dL).

- Leukopenia (white blood cell count less than 4,000 cells/mcL).

- Thrombocytopenia (platelet count less than 100,000 mcL)

- Hypothermia (core temperature less than 36º C).

- Hypotension requiring aggressive fluid resuscitation.

Management and diagnostic testing

Clinicians should use the Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) and clinical judgment to guide the site of treatment for patients. Gram stain, sputum, and blood culture should not be routinely obtained in an outpatient setting. Legionella antigen should not be routinely obtained unless indicated by epidemiological factors. During influenza season, a rapid influenza assay, preferably a nucleic acid amplification test, should be obtained to help guide treatment.

For patients with severe CAP or risk factors for MRSA or P. aeruginosa, gram stain and culture and Legionella antigen should be obtained to manage antibiotic choices. Also, blood cultures should be obtained for these patients.

Empiric antibiotic therapy should be initiated based on clinical judgment and radiographic confirmation of CAP. Serum procalcitonin should not be used to assess initiation of antibiotic therapy.

Empiric antibiotic therapy

Healthy adults without comorbidities should be treated with monotherapy of either:

- Amoxicillin 1 g three times daily.

- OR doxycycline 100 mg twice daily.

- OR a macrolide (azithromycin 500 mg on first day then 250 mg daily or clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily or clarithromycin extended release 1,000 mg daily) only in areas with pneumococcal resistance to macrolides less than 25%.

Adults with comorbidities such as chronic heart, lung, liver, or renal disease; diabetes mellitus; alcoholism; malignancy; or asplenia should be treated with:

- Amoxicillin/clavulanate 500 mg/125 mg three times daily, or amoxicillin/ clavulanate 875 mg/125 mg twice daily, or 2,000 mg/125 mg twice daily, or a cephalosporin (cefpodoxime 200 mg twice daily or cefuroxime 500 mg twice daily); and a macrolide (azithromycin 500 mg on first day then 250 mg daily, clarithromycin [500 mg twice daily or extended release 1,000 mg once daily]), or doxycycline 100 mg twice daily. (Some experts recommend that the first dose of doxycycline should be 200 mg.)

- OR monotherapy with respiratory fluoroquinolone (levofloxacin 750 mg daily, moxifloxacin 400 mg daily, or gemifloxacin 320 mg daily).

Inpatient pneumonia that is not severe, without risk factors for resistant organisms should be treated with:

- Beta-lactam (ampicillin 1 sulbactam 1.5-3 g every 6 h, cefotaxime 1-2 g every 8 h, ceftriaxone 1-2 g daily, or ceftaroline 600 mg every 12 h) and a macrolide (azithromycin 500 mg daily or clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily).

- OR monotherapy with a respiratory fluoroquinolone (levofloxacin 750 mg daily, moxifloxacin 400 mg daily).

If there is a contraindication for the use of both a macrolide and a fluoroquinolone, then doxycycline can be used instead.

Severe inpatient pneumonia without risk factors for resistant organisms should be treated with combination therapy of either (agents and doses the same as above):

- Beta-lactam and macrolide.

- OR fluoroquinolone and beta-lactam.

It is recommended to not routinely add anaerobic coverage for suspected aspiration pneumonia unless lung abscess or empyema is suspected. Clinicians should identify risk factors for MRSA or P. aeruginosa before adding additional agents.

Duration of antibiotic therapy is determined by the patient achieving clinical stability with no less than 5 days of antibiotics. In adults with symptom resolution within 5-7 days, no additional follow-up chest imaging is recommended. If patients test positive for influenza, then anti-influenza treatment such as oseltamivir should be used in addition to antibiotics regardless of length of influenza symptoms before presentation.

The bottom line

CAP treatment should be based on severity of illness and risk factors for resistant organisms. Blood and sputum cultures are recommended only for patients with severe pneumonia. There have been important changes in the recommendations for antibiotic treatment of CAP, with high-dose amoxicillin recommended for most patients with CAP who are treated as outpatients. Patients who exhibit clinical stability should be treated for at least 5 days and do not require follow up imaging studies.

For a podcast of this guideline, go to iTunes and download the Infectious Diseases Society of America guideline podcast.

Reference

Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. An official clinical practice guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019 Oct 1;200(7):e45-e67.

Tina Chuong, DO, is a second-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health.

A new guideline has been published to update the 2007 guidelines for the management of adults with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP).

The practice guideline was jointly written by an ad hoc committee of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. CAP refers to a pneumonia infection that was acquired by a patient in his or her community. Decisions about which antibiotics to use to treat this kind of infection are based on risk factors for resistant organisms and the severity of illness.

Pathogens

Traditionally, CAP is caused by common bacterial pathogens that include Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Legionella species, Chlamydia pneumonia, and Moraxella catarrhalis. Risk factors for multidrug resistant pathogens such as methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa include previous infection with MRSA or P. aeruginosa, recent hospitalization, and requiring parenteral antibiotics in the last 90 days.

Defining severe community-acquired pneumonia

The health care–associated pneumonia, or HCAP, classification should no longer be used to determine empiric treatment. The recommendations for which antibiotics to use are linked to the severity of illness. Previously the site of treatment drove antibiotic selection, but since decision about the site of care can be affected by many considerations, the guidelines recommend using the CAP severity criteria. Severe CAP includes either one major or at least three minor criteria.

Major criteria are:

- Septic shock requiring vasopressors.

- Respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation.

Minor criteria are:

- Respiratory rate greater than or equal to 30 breaths/min.

- Ratio of arterial O2 partial pressure to fractional inspired O2 less than or equal to 250.

- Multilobar infiltrates.

- Confusion/disorientation.

- Uremia (blood urea nitrogen level greater than or equal to 20 mg/dL).

- Leukopenia (white blood cell count less than 4,000 cells/mcL).

- Thrombocytopenia (platelet count less than 100,000 mcL)

- Hypothermia (core temperature less than 36º C).

- Hypotension requiring aggressive fluid resuscitation.

Management and diagnostic testing

Clinicians should use the Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) and clinical judgment to guide the site of treatment for patients. Gram stain, sputum, and blood culture should not be routinely obtained in an outpatient setting. Legionella antigen should not be routinely obtained unless indicated by epidemiological factors. During influenza season, a rapid influenza assay, preferably a nucleic acid amplification test, should be obtained to help guide treatment.

For patients with severe CAP or risk factors for MRSA or P. aeruginosa, gram stain and culture and Legionella antigen should be obtained to manage antibiotic choices. Also, blood cultures should be obtained for these patients.

Empiric antibiotic therapy should be initiated based on clinical judgment and radiographic confirmation of CAP. Serum procalcitonin should not be used to assess initiation of antibiotic therapy.

Empiric antibiotic therapy

Healthy adults without comorbidities should be treated with monotherapy of either:

- Amoxicillin 1 g three times daily.

- OR doxycycline 100 mg twice daily.

- OR a macrolide (azithromycin 500 mg on first day then 250 mg daily or clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily or clarithromycin extended release 1,000 mg daily) only in areas with pneumococcal resistance to macrolides less than 25%.

Adults with comorbidities such as chronic heart, lung, liver, or renal disease; diabetes mellitus; alcoholism; malignancy; or asplenia should be treated with:

- Amoxicillin/clavulanate 500 mg/125 mg three times daily, or amoxicillin/ clavulanate 875 mg/125 mg twice daily, or 2,000 mg/125 mg twice daily, or a cephalosporin (cefpodoxime 200 mg twice daily or cefuroxime 500 mg twice daily); and a macrolide (azithromycin 500 mg on first day then 250 mg daily, clarithromycin [500 mg twice daily or extended release 1,000 mg once daily]), or doxycycline 100 mg twice daily. (Some experts recommend that the first dose of doxycycline should be 200 mg.)

- OR monotherapy with respiratory fluoroquinolone (levofloxacin 750 mg daily, moxifloxacin 400 mg daily, or gemifloxacin 320 mg daily).

Inpatient pneumonia that is not severe, without risk factors for resistant organisms should be treated with:

- Beta-lactam (ampicillin 1 sulbactam 1.5-3 g every 6 h, cefotaxime 1-2 g every 8 h, ceftriaxone 1-2 g daily, or ceftaroline 600 mg every 12 h) and a macrolide (azithromycin 500 mg daily or clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily).

- OR monotherapy with a respiratory fluoroquinolone (levofloxacin 750 mg daily, moxifloxacin 400 mg daily).

If there is a contraindication for the use of both a macrolide and a fluoroquinolone, then doxycycline can be used instead.

Severe inpatient pneumonia without risk factors for resistant organisms should be treated with combination therapy of either (agents and doses the same as above):

- Beta-lactam and macrolide.

- OR fluoroquinolone and beta-lactam.

It is recommended to not routinely add anaerobic coverage for suspected aspiration pneumonia unless lung abscess or empyema is suspected. Clinicians should identify risk factors for MRSA or P. aeruginosa before adding additional agents.

Duration of antibiotic therapy is determined by the patient achieving clinical stability with no less than 5 days of antibiotics. In adults with symptom resolution within 5-7 days, no additional follow-up chest imaging is recommended. If patients test positive for influenza, then anti-influenza treatment such as oseltamivir should be used in addition to antibiotics regardless of length of influenza symptoms before presentation.

The bottom line

CAP treatment should be based on severity of illness and risk factors for resistant organisms. Blood and sputum cultures are recommended only for patients with severe pneumonia. There have been important changes in the recommendations for antibiotic treatment of CAP, with high-dose amoxicillin recommended for most patients with CAP who are treated as outpatients. Patients who exhibit clinical stability should be treated for at least 5 days and do not require follow up imaging studies.

For a podcast of this guideline, go to iTunes and download the Infectious Diseases Society of America guideline podcast.

Reference

Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. An official clinical practice guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019 Oct 1;200(7):e45-e67.

Tina Chuong, DO, is a second-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health.

Elagolix is effective second-tier treatment for endometriosis-associated dysmenorrhea

PHILADELPHIA – Charles E. Miller, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine.

Although clinicians need prior authorization and evidence of treatment failure before prescribing Elagolix, the drug is a viable option as a second-tier treatment for patients with endometriosis-associated dysmenorrhea, said Dr. Miller, director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital in Park Ridge, Ill. “We have a drug that is very effective, that has a very low adverse event profile, and is tolerated by the vast majority of our patients.”

First-line options

NSAIDs are first-line treatment for endometriosis-related dysmenorrhea, with acetaminophen used in cases where NSAIDs are contraindicated or cause side effects such as gastrointestinal issues. Hormonal contraceptives also can be used as first-line treatment, divided into estrogen/progestin and progestin-only options that can be combined. Evidence from the literature has shown oral pills decrease pain, compared with placebo, but the decrease is not dose dependent, said Dr. Miller.

“We also know that if you use it continuously or prolonged, we find that there is going to be greater success with dysmenorrhea, and that ultimately you would use a higher-dose pill because of the greater risk of breakthrough when using a lesser dose in a continuous fashion,” he said. “Obviously if you’re not having menses, you’re not going to have dysmenorrhea.”

Other estrogen/progestin hormonal contraception such as the vaginal ring or transdermal patch also have been shown to decrease dysmenorrhea from endometriosis, with one study showing a reduction from 17% to 6% in moderate to severe dysmenorrhea in patients using the vaginal ring, compared with patients receiving oral contraceptives. In a separate randomized, controlled trial, “dysmenorrhea was more common in patch users, so it doesn’t appear that the patch is quite as effective in terms of reducing dysmenorrhea,” said Dr. Miller (JAMA. 2001 May 9. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.18.2347).

Compared with combination hormone therapy, there has been less research conducted on progestin-only hormone contraceptives on reducing dysmenorrhea from endometriosis. For example, there is little evidence for depot medroxyprogesterone acetate in reducing dysmenorrhea, but rather with it causing amenorrhea; one study showed a 50% amenorrhea rate at 1 year. “The disadvantage, however, in our infertile population is ultimately getting the menses back,” said Dr. Miller.

IUDs using levonorgestrel appear comparable with gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists in reducing endometriosis-related pain; in one study, most women treated with either of these had visual analogue scores of less than 3 at 6 months of treatment. Between 68% and 75% of women with dysmenorrhea who receive an implantable contraceptive device with etonogestrel report decreased pain, and one meta-analysis reported 75% of women had “complete resolution of dysmenorrhea.” Concerning progestin-only pills, they can be used for endometriosis-related dysmenorrhea, but they are “problematic in that there’s a lot of breakthrough bleeding, and often times that is associated with pain,” said Dr. Miller.

Second-tier options

Injectable GnRH agonists are effective options as second-tier treatments for endometriosis-related dysmenorrhea, but patients are at risk of developing postmenopausal symptoms such as hot flashes, insomnia, spotting, and decreased libido. “One advantage to that is, over the years and particularly something that I’ve done with my endometriosis-related dysmenorrhea, is to utilize add-back with these patients,” said Dr. Miller, who noted that patients on 2.5 mg of norethindrone acetate and 0.5 mg of ethinyl estradiol“do very well” with that combination of add-back therapy.

Elagolix is the most recent second-tier treatment option for these patients, and was studied in the Elaris EM-I and Elaris EM-II trials in a once-daily dose of 150 mg and a twice-daily dose of 200 mg. In Elaris EM-1, 76% of patients in the 200-mg elagolix group had a clinical response, compared with 46% in the 150-mg group and 20% in the placebo group (N Engl J Med. 2017 Jul 6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1700089). However, patients should not be on elagolix at 200 mg for more than 6 months, while patients receiving elagolix at 150 mg can stay on the treatment for up to 2 years.

Patients taking elagolix also showed postmenopausal symptoms, with 24% in the 150-mg group and 46% in the 200-mg group experiencing hot flashes, compared with 9% of patients in the placebo group. While 6% of patients in the 150-mg group and 10% in the 200-mg group discontinued because of adverse events, 1% and 3% of patients in the 150-mg and 200-mg group discontinued because of hot flashes or night sweats, respectively. “Symptoms are well tolerated, far different than in comparison with leuprolide acetate and GnRH agonists,” said Dr. Miller.

There also is a benefit to how patients recover from bone mineral density (BMD) changes after remaining on elagolix, Dr. Miller noted. In patients who received elagolix for 12 months at doses of 150 mg and 200 mg, there was an increase in lumbar spine BMD recovered 6 months after discontinuation, with patients in the 150-mg group experiencing a recovery close to baseline BMD levels. Among patients who discontinued treatment, there also was a quick resumption in menses for both groups: 87% of patients in the 150 mg group and 88% of patients in the 200-mg group who discontinued treatment after 6 months had resumed menses by 2 months after discontinuation, while 95% of patients in the 150-mg and 91% in the 200-mg group who discontinued after 12 months resumed menses by 2 months after discontinuation.

Dr. Miller reported relationships with AbbVie, Allergan, Blue Seas Med Spa, Espiner Medical, Gynesonics, Halt Medical, Hologic, Karl Storz, Medtronic, and Richard Wolf in the form of consultancies, grants, speakers’ bureau appointments, stock options, royalties, and ownership interests.

PHILADELPHIA – Charles E. Miller, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine.

Although clinicians need prior authorization and evidence of treatment failure before prescribing Elagolix, the drug is a viable option as a second-tier treatment for patients with endometriosis-associated dysmenorrhea, said Dr. Miller, director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital in Park Ridge, Ill. “We have a drug that is very effective, that has a very low adverse event profile, and is tolerated by the vast majority of our patients.”

First-line options

NSAIDs are first-line treatment for endometriosis-related dysmenorrhea, with acetaminophen used in cases where NSAIDs are contraindicated or cause side effects such as gastrointestinal issues. Hormonal contraceptives also can be used as first-line treatment, divided into estrogen/progestin and progestin-only options that can be combined. Evidence from the literature has shown oral pills decrease pain, compared with placebo, but the decrease is not dose dependent, said Dr. Miller.

“We also know that if you use it continuously or prolonged, we find that there is going to be greater success with dysmenorrhea, and that ultimately you would use a higher-dose pill because of the greater risk of breakthrough when using a lesser dose in a continuous fashion,” he said. “Obviously if you’re not having menses, you’re not going to have dysmenorrhea.”

Other estrogen/progestin hormonal contraception such as the vaginal ring or transdermal patch also have been shown to decrease dysmenorrhea from endometriosis, with one study showing a reduction from 17% to 6% in moderate to severe dysmenorrhea in patients using the vaginal ring, compared with patients receiving oral contraceptives. In a separate randomized, controlled trial, “dysmenorrhea was more common in patch users, so it doesn’t appear that the patch is quite as effective in terms of reducing dysmenorrhea,” said Dr. Miller (JAMA. 2001 May 9. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.18.2347).

Compared with combination hormone therapy, there has been less research conducted on progestin-only hormone contraceptives on reducing dysmenorrhea from endometriosis. For example, there is little evidence for depot medroxyprogesterone acetate in reducing dysmenorrhea, but rather with it causing amenorrhea; one study showed a 50% amenorrhea rate at 1 year. “The disadvantage, however, in our infertile population is ultimately getting the menses back,” said Dr. Miller.

IUDs using levonorgestrel appear comparable with gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists in reducing endometriosis-related pain; in one study, most women treated with either of these had visual analogue scores of less than 3 at 6 months of treatment. Between 68% and 75% of women with dysmenorrhea who receive an implantable contraceptive device with etonogestrel report decreased pain, and one meta-analysis reported 75% of women had “complete resolution of dysmenorrhea.” Concerning progestin-only pills, they can be used for endometriosis-related dysmenorrhea, but they are “problematic in that there’s a lot of breakthrough bleeding, and often times that is associated with pain,” said Dr. Miller.

Second-tier options

Injectable GnRH agonists are effective options as second-tier treatments for endometriosis-related dysmenorrhea, but patients are at risk of developing postmenopausal symptoms such as hot flashes, insomnia, spotting, and decreased libido. “One advantage to that is, over the years and particularly something that I’ve done with my endometriosis-related dysmenorrhea, is to utilize add-back with these patients,” said Dr. Miller, who noted that patients on 2.5 mg of norethindrone acetate and 0.5 mg of ethinyl estradiol“do very well” with that combination of add-back therapy.

Elagolix is the most recent second-tier treatment option for these patients, and was studied in the Elaris EM-I and Elaris EM-II trials in a once-daily dose of 150 mg and a twice-daily dose of 200 mg. In Elaris EM-1, 76% of patients in the 200-mg elagolix group had a clinical response, compared with 46% in the 150-mg group and 20% in the placebo group (N Engl J Med. 2017 Jul 6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1700089). However, patients should not be on elagolix at 200 mg for more than 6 months, while patients receiving elagolix at 150 mg can stay on the treatment for up to 2 years.

Patients taking elagolix also showed postmenopausal symptoms, with 24% in the 150-mg group and 46% in the 200-mg group experiencing hot flashes, compared with 9% of patients in the placebo group. While 6% of patients in the 150-mg group and 10% in the 200-mg group discontinued because of adverse events, 1% and 3% of patients in the 150-mg and 200-mg group discontinued because of hot flashes or night sweats, respectively. “Symptoms are well tolerated, far different than in comparison with leuprolide acetate and GnRH agonists,” said Dr. Miller.

There also is a benefit to how patients recover from bone mineral density (BMD) changes after remaining on elagolix, Dr. Miller noted. In patients who received elagolix for 12 months at doses of 150 mg and 200 mg, there was an increase in lumbar spine BMD recovered 6 months after discontinuation, with patients in the 150-mg group experiencing a recovery close to baseline BMD levels. Among patients who discontinued treatment, there also was a quick resumption in menses for both groups: 87% of patients in the 150 mg group and 88% of patients in the 200-mg group who discontinued treatment after 6 months had resumed menses by 2 months after discontinuation, while 95% of patients in the 150-mg and 91% in the 200-mg group who discontinued after 12 months resumed menses by 2 months after discontinuation.

Dr. Miller reported relationships with AbbVie, Allergan, Blue Seas Med Spa, Espiner Medical, Gynesonics, Halt Medical, Hologic, Karl Storz, Medtronic, and Richard Wolf in the form of consultancies, grants, speakers’ bureau appointments, stock options, royalties, and ownership interests.

PHILADELPHIA – Charles E. Miller, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine.

Although clinicians need prior authorization and evidence of treatment failure before prescribing Elagolix, the drug is a viable option as a second-tier treatment for patients with endometriosis-associated dysmenorrhea, said Dr. Miller, director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital in Park Ridge, Ill. “We have a drug that is very effective, that has a very low adverse event profile, and is tolerated by the vast majority of our patients.”

First-line options

NSAIDs are first-line treatment for endometriosis-related dysmenorrhea, with acetaminophen used in cases where NSAIDs are contraindicated or cause side effects such as gastrointestinal issues. Hormonal contraceptives also can be used as first-line treatment, divided into estrogen/progestin and progestin-only options that can be combined. Evidence from the literature has shown oral pills decrease pain, compared with placebo, but the decrease is not dose dependent, said Dr. Miller.

“We also know that if you use it continuously or prolonged, we find that there is going to be greater success with dysmenorrhea, and that ultimately you would use a higher-dose pill because of the greater risk of breakthrough when using a lesser dose in a continuous fashion,” he said. “Obviously if you’re not having menses, you’re not going to have dysmenorrhea.”

Other estrogen/progestin hormonal contraception such as the vaginal ring or transdermal patch also have been shown to decrease dysmenorrhea from endometriosis, with one study showing a reduction from 17% to 6% in moderate to severe dysmenorrhea in patients using the vaginal ring, compared with patients receiving oral contraceptives. In a separate randomized, controlled trial, “dysmenorrhea was more common in patch users, so it doesn’t appear that the patch is quite as effective in terms of reducing dysmenorrhea,” said Dr. Miller (JAMA. 2001 May 9. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.18.2347).

Compared with combination hormone therapy, there has been less research conducted on progestin-only hormone contraceptives on reducing dysmenorrhea from endometriosis. For example, there is little evidence for depot medroxyprogesterone acetate in reducing dysmenorrhea, but rather with it causing amenorrhea; one study showed a 50% amenorrhea rate at 1 year. “The disadvantage, however, in our infertile population is ultimately getting the menses back,” said Dr. Miller.

IUDs using levonorgestrel appear comparable with gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists in reducing endometriosis-related pain; in one study, most women treated with either of these had visual analogue scores of less than 3 at 6 months of treatment. Between 68% and 75% of women with dysmenorrhea who receive an implantable contraceptive device with etonogestrel report decreased pain, and one meta-analysis reported 75% of women had “complete resolution of dysmenorrhea.” Concerning progestin-only pills, they can be used for endometriosis-related dysmenorrhea, but they are “problematic in that there’s a lot of breakthrough bleeding, and often times that is associated with pain,” said Dr. Miller.

Second-tier options

Injectable GnRH agonists are effective options as second-tier treatments for endometriosis-related dysmenorrhea, but patients are at risk of developing postmenopausal symptoms such as hot flashes, insomnia, spotting, and decreased libido. “One advantage to that is, over the years and particularly something that I’ve done with my endometriosis-related dysmenorrhea, is to utilize add-back with these patients,” said Dr. Miller, who noted that patients on 2.5 mg of norethindrone acetate and 0.5 mg of ethinyl estradiol“do very well” with that combination of add-back therapy.

Elagolix is the most recent second-tier treatment option for these patients, and was studied in the Elaris EM-I and Elaris EM-II trials in a once-daily dose of 150 mg and a twice-daily dose of 200 mg. In Elaris EM-1, 76% of patients in the 200-mg elagolix group had a clinical response, compared with 46% in the 150-mg group and 20% in the placebo group (N Engl J Med. 2017 Jul 6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1700089). However, patients should not be on elagolix at 200 mg for more than 6 months, while patients receiving elagolix at 150 mg can stay on the treatment for up to 2 years.

Patients taking elagolix also showed postmenopausal symptoms, with 24% in the 150-mg group and 46% in the 200-mg group experiencing hot flashes, compared with 9% of patients in the placebo group. While 6% of patients in the 150-mg group and 10% in the 200-mg group discontinued because of adverse events, 1% and 3% of patients in the 150-mg and 200-mg group discontinued because of hot flashes or night sweats, respectively. “Symptoms are well tolerated, far different than in comparison with leuprolide acetate and GnRH agonists,” said Dr. Miller.

There also is a benefit to how patients recover from bone mineral density (BMD) changes after remaining on elagolix, Dr. Miller noted. In patients who received elagolix for 12 months at doses of 150 mg and 200 mg, there was an increase in lumbar spine BMD recovered 6 months after discontinuation, with patients in the 150-mg group experiencing a recovery close to baseline BMD levels. Among patients who discontinued treatment, there also was a quick resumption in menses for both groups: 87% of patients in the 150 mg group and 88% of patients in the 200-mg group who discontinued treatment after 6 months had resumed menses by 2 months after discontinuation, while 95% of patients in the 150-mg and 91% in the 200-mg group who discontinued after 12 months resumed menses by 2 months after discontinuation.

Dr. Miller reported relationships with AbbVie, Allergan, Blue Seas Med Spa, Espiner Medical, Gynesonics, Halt Medical, Hologic, Karl Storz, Medtronic, and Richard Wolf in the form of consultancies, grants, speakers’ bureau appointments, stock options, royalties, and ownership interests.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ASRM 2019

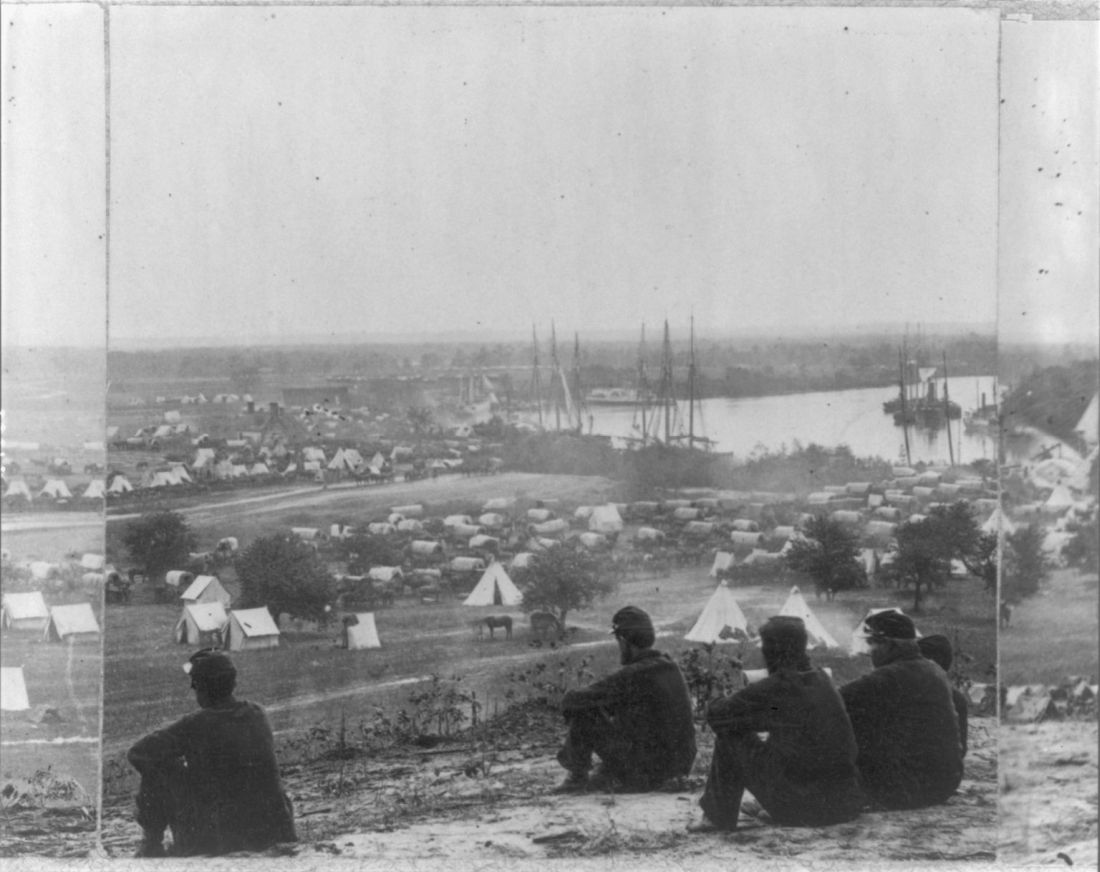

ID Blog: The waters of death

Diseases of the American Civil War, Part I

If cleanliness is next to godliness, then the average soldier in the American Civil War lived just down the street from hell. In a land at war, before the formal tenets of germ theory had spread beyond the confines of Louis Pasteur’s laboratory in France, the lack of basic hygiene, both cultural and situational, coupled to an almost complete lack of curative therapies created an appalling death toll. Waterborne diseases in particular spared neither general nor private, and neither doctor nor nurse.

“Of all the adversities that Union and Confederate soldiers confronted, none was more deadly or more prevalent than contaminated water,” according to Jeffrey S. Sartin, MD, in his survey of Civil War diseases.1

The Union Army records list 1,765,000 cases of diarrhea or dysentery with 45,000 deaths and 149,000 cases of typhoid fever with 35,000 deaths. Add to these the 1,316,000 cases of malaria (borne by mosquitoes breeding in the waters) with its 10,000 deaths, and it is easy to see how the battlefield itself took second place in service to the grim reaper. (Overall, there were roughly two deaths from disease for every one from wounds.)

The chief waterborne plague, infectious diarrhea – including bacterial, amoebic, and other parasites – as well as cholera and typhoid, was an all-year-long problem, and, with the typical wry humor of soldiers, these maladies were given popular names, including the “Tennessee trots” and the “Virginia quick-step.”

Unsanitary conditions in the camps were primarily to blame, and this problem of sanitation was obvious to many observers at the time.

Despite a lack of knowledge of germ theory, doctors were fully aware of the relationship of unsanitary conditions to disease, even if they ascribed the link to miasmas or particles of filth.

Hospitals, which were under more strict control than the regular army camps, were meticulous about the placement of latrines and about keeping high standards of cleanliness among the patients, including routine washing. However, this was insufficient for complete protection, because what passed for clean in the absence of the knowledge of bacterial contamination was often totally ineffective. As one Civil War surgeon stated: “We operated in old bloodstained and often pus-stained coats, we used undisinfected instruments from undisinfected plush-lined cases. If a sponge (if they had sponges) or instrument fell on the floor it was washed and squeezed in a basin of water and used as if it was clean.”2

Overall, efforts at what passed for sanitation remained a constant goal and constant struggle in the field.

After the First Battle of Bull Run, Women’s Central Association of Relief President Henry W. Bellows met with Secretary of War Simon Cameron to discuss the abysmal sanitary conditions witnessed by WCAR volunteers. This meeting led to the creation of what would become the U.S. Sanitary Commission, which was approved by President Abraham Lincoln on June 13, 1861.

The U.S. Sanitary Commission served as a means for funneling civilian assistance to the military, with volunteers providing assistance in the organization of military hospitals and camps and aiding in the transportation of the wounded. However, despite these efforts, the setup of army camps and the behavior of the soldiers were not often directed toward proper sanitation. “The principal causes of disease, however, in our camps were the same that we have always to deplore and find it so difficult to remedy, simply because citizens suddenly called to the field cannot comprehend that men in masses require the attention of their officers to enforce certain hygienic conditions without which health cannot be preserved.”3

Breaches of sanitation were common in the confines of the camps, despite regulations designed to protect the soldiers. According to one U.S. Army surgeon of the time: “Especially [needed] was policing of the latrines. The trench is generally too shallow, the daily covering ... with dirt is entirely neglected. Large numbers of the men will not use the sinks [latrines], ... but instead every clump of bushes, every fence border in the vicinity.” Another pointed out that, after the Battle of Seven Pines, “the only water was infiltrated with the decaying animal matter of the battlefield.” Commenting on the placement of latrines in one encampment, another surgeon described how “the sink [latrine] is the ground in the vicinity, which slopes down to the stream, from which all water from the camp is obtained.”4

Treatment for diarrhea and dysentery was varied. Opiates were one of the most common treatments for diarrhea, whether in an alcohol solution as laudanum or in pill form, with belladonna being used to treat intestinal cramps, according to Glenna R. Schroeder-Lein in her book “The Encyclopedia of Civil War Medicine.” However, useless or damaging treatments were also prescribed, including the use of calomel (a mercury compound), turpentine, castor oil, and quinine.5

Acute diarrhea and dysentery illnesses occurred in at least 641/1,000 troops per year in the Union army. And even though the death rate was comparatively low (20/1,000 cases), it frequently led to chronic diarrhea, which was responsible for 288 deaths per 1,000 cases, and was the third highest cause of medical discharge after gunshot wounds and tuberculosis, according to Ms. Schroeder-Lein.

Although the American Civil War was the last major conflict before the spread of the knowledge of germ theory, the struggle to prevent the spread of waterborne diseases under wartime conditions remains ongoing. Hygiene is difficult under conditions of abject poverty and especially under conditions of armed conflict, and until the era of curative antibiotics there was no recourse.

Antibiotics are not the final solution for antibiotic resistance in intestinal disease pathogens, as outlined in a recent CDC report, is an increasing problem.6 For example, nontyphoidal Salmonella causes an estimated 1.35 million infections, 26,500 hospitalizations, and 420 deaths each year in the United States, with 16% of strains being resistant to at least one essential antibiotic. On a global scale, according to the World Health Organization, poor sanitation causes up to 432,000 diarrheal deaths annually and is linked to the transmission of other diseases like cholera, dysentery, typhoid, hepatitis A, and polio.7

With regard to actual epidemics, the world is only a hygienic crisis away from a major outbreak of dysentery (the last occurring between 1969 and 1972, when 20,000 people in Central America died), according to researchers who have detected antibiotic resistance in all but 1% of circulating Shigella dysenteriae strains surveyed since the 1990s. “This bacterium is still in circulation, and could be responsible for future epidemics if conditions should prove favorable – such as a large gathering of people without access to drinking water or treatment of human waste,” wrote François-Xavier Weill of the Pasteur Institute’s Enteric Bacterial Pathogens Unit.8

References

1. Sartin JS. Clin Infec Dis. 1993;16:580-4. (Correction published in 2002).

2. Civil War Battlefield Surgery. eHistory. The Ohio State University.

3. “Myths About Antiseptics and Camp Life – George Wunderlich,” published online Oct. 11, 2011. http://civilwarscholars.com/2011/10/myths-about-antiseptics-and-camp-life-george-wunderlich/

4. Dorwart BB. “Death is in the Breeze: Disease during the American Civil War” (The National Museum of the American Civil War Press, 2009).

5. Glenna R, Schroeder-Lein GR. “The Encyclopedia of Civil War Medicine” (New York: M. E. Sharpe, 2008).

6. “Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States 2019” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

7. “New report exposes horror of working conditions for millions of sanitation workers in the developing world,” World Health Organization. 2019 Nov 14.

8. Grant B. Origins of Dysentery. The Scientist. Published online March 22, 2016.

Mark Lesney is the managing editor of MDedge.com/IDPractioner. He has a PhD in plant virology and a PhD in the history of science, with a focus on the history of biotechnology and medicine. He has served as an adjunct assistant professor of the department of biochemistry and molecular & cellular biology at Georgetown University, Washington.

Diseases of the American Civil War, Part I

Diseases of the American Civil War, Part I

If cleanliness is next to godliness, then the average soldier in the American Civil War lived just down the street from hell. In a land at war, before the formal tenets of germ theory had spread beyond the confines of Louis Pasteur’s laboratory in France, the lack of basic hygiene, both cultural and situational, coupled to an almost complete lack of curative therapies created an appalling death toll. Waterborne diseases in particular spared neither general nor private, and neither doctor nor nurse.

“Of all the adversities that Union and Confederate soldiers confronted, none was more deadly or more prevalent than contaminated water,” according to Jeffrey S. Sartin, MD, in his survey of Civil War diseases.1

The Union Army records list 1,765,000 cases of diarrhea or dysentery with 45,000 deaths and 149,000 cases of typhoid fever with 35,000 deaths. Add to these the 1,316,000 cases of malaria (borne by mosquitoes breeding in the waters) with its 10,000 deaths, and it is easy to see how the battlefield itself took second place in service to the grim reaper. (Overall, there were roughly two deaths from disease for every one from wounds.)

The chief waterborne plague, infectious diarrhea – including bacterial, amoebic, and other parasites – as well as cholera and typhoid, was an all-year-long problem, and, with the typical wry humor of soldiers, these maladies were given popular names, including the “Tennessee trots” and the “Virginia quick-step.”

Unsanitary conditions in the camps were primarily to blame, and this problem of sanitation was obvious to many observers at the time.

Despite a lack of knowledge of germ theory, doctors were fully aware of the relationship of unsanitary conditions to disease, even if they ascribed the link to miasmas or particles of filth.

Hospitals, which were under more strict control than the regular army camps, were meticulous about the placement of latrines and about keeping high standards of cleanliness among the patients, including routine washing. However, this was insufficient for complete protection, because what passed for clean in the absence of the knowledge of bacterial contamination was often totally ineffective. As one Civil War surgeon stated: “We operated in old bloodstained and often pus-stained coats, we used undisinfected instruments from undisinfected plush-lined cases. If a sponge (if they had sponges) or instrument fell on the floor it was washed and squeezed in a basin of water and used as if it was clean.”2

Overall, efforts at what passed for sanitation remained a constant goal and constant struggle in the field.

After the First Battle of Bull Run, Women’s Central Association of Relief President Henry W. Bellows met with Secretary of War Simon Cameron to discuss the abysmal sanitary conditions witnessed by WCAR volunteers. This meeting led to the creation of what would become the U.S. Sanitary Commission, which was approved by President Abraham Lincoln on June 13, 1861.

The U.S. Sanitary Commission served as a means for funneling civilian assistance to the military, with volunteers providing assistance in the organization of military hospitals and camps and aiding in the transportation of the wounded. However, despite these efforts, the setup of army camps and the behavior of the soldiers were not often directed toward proper sanitation. “The principal causes of disease, however, in our camps were the same that we have always to deplore and find it so difficult to remedy, simply because citizens suddenly called to the field cannot comprehend that men in masses require the attention of their officers to enforce certain hygienic conditions without which health cannot be preserved.”3

Breaches of sanitation were common in the confines of the camps, despite regulations designed to protect the soldiers. According to one U.S. Army surgeon of the time: “Especially [needed] was policing of the latrines. The trench is generally too shallow, the daily covering ... with dirt is entirely neglected. Large numbers of the men will not use the sinks [latrines], ... but instead every clump of bushes, every fence border in the vicinity.” Another pointed out that, after the Battle of Seven Pines, “the only water was infiltrated with the decaying animal matter of the battlefield.” Commenting on the placement of latrines in one encampment, another surgeon described how “the sink [latrine] is the ground in the vicinity, which slopes down to the stream, from which all water from the camp is obtained.”4

Treatment for diarrhea and dysentery was varied. Opiates were one of the most common treatments for diarrhea, whether in an alcohol solution as laudanum or in pill form, with belladonna being used to treat intestinal cramps, according to Glenna R. Schroeder-Lein in her book “The Encyclopedia of Civil War Medicine.” However, useless or damaging treatments were also prescribed, including the use of calomel (a mercury compound), turpentine, castor oil, and quinine.5

Acute diarrhea and dysentery illnesses occurred in at least 641/1,000 troops per year in the Union army. And even though the death rate was comparatively low (20/1,000 cases), it frequently led to chronic diarrhea, which was responsible for 288 deaths per 1,000 cases, and was the third highest cause of medical discharge after gunshot wounds and tuberculosis, according to Ms. Schroeder-Lein.

Although the American Civil War was the last major conflict before the spread of the knowledge of germ theory, the struggle to prevent the spread of waterborne diseases under wartime conditions remains ongoing. Hygiene is difficult under conditions of abject poverty and especially under conditions of armed conflict, and until the era of curative antibiotics there was no recourse.

Antibiotics are not the final solution for antibiotic resistance in intestinal disease pathogens, as outlined in a recent CDC report, is an increasing problem.6 For example, nontyphoidal Salmonella causes an estimated 1.35 million infections, 26,500 hospitalizations, and 420 deaths each year in the United States, with 16% of strains being resistant to at least one essential antibiotic. On a global scale, according to the World Health Organization, poor sanitation causes up to 432,000 diarrheal deaths annually and is linked to the transmission of other diseases like cholera, dysentery, typhoid, hepatitis A, and polio.7

With regard to actual epidemics, the world is only a hygienic crisis away from a major outbreak of dysentery (the last occurring between 1969 and 1972, when 20,000 people in Central America died), according to researchers who have detected antibiotic resistance in all but 1% of circulating Shigella dysenteriae strains surveyed since the 1990s. “This bacterium is still in circulation, and could be responsible for future epidemics if conditions should prove favorable – such as a large gathering of people without access to drinking water or treatment of human waste,” wrote François-Xavier Weill of the Pasteur Institute’s Enteric Bacterial Pathogens Unit.8

References

1. Sartin JS. Clin Infec Dis. 1993;16:580-4. (Correction published in 2002).

2. Civil War Battlefield Surgery. eHistory. The Ohio State University.

3. “Myths About Antiseptics and Camp Life – George Wunderlich,” published online Oct. 11, 2011. http://civilwarscholars.com/2011/10/myths-about-antiseptics-and-camp-life-george-wunderlich/

4. Dorwart BB. “Death is in the Breeze: Disease during the American Civil War” (The National Museum of the American Civil War Press, 2009).

5. Glenna R, Schroeder-Lein GR. “The Encyclopedia of Civil War Medicine” (New York: M. E. Sharpe, 2008).

6. “Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States 2019” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

7. “New report exposes horror of working conditions for millions of sanitation workers in the developing world,” World Health Organization. 2019 Nov 14.

8. Grant B. Origins of Dysentery. The Scientist. Published online March 22, 2016.

Mark Lesney is the managing editor of MDedge.com/IDPractioner. He has a PhD in plant virology and a PhD in the history of science, with a focus on the history of biotechnology and medicine. He has served as an adjunct assistant professor of the department of biochemistry and molecular & cellular biology at Georgetown University, Washington.

If cleanliness is next to godliness, then the average soldier in the American Civil War lived just down the street from hell. In a land at war, before the formal tenets of germ theory had spread beyond the confines of Louis Pasteur’s laboratory in France, the lack of basic hygiene, both cultural and situational, coupled to an almost complete lack of curative therapies created an appalling death toll. Waterborne diseases in particular spared neither general nor private, and neither doctor nor nurse.

“Of all the adversities that Union and Confederate soldiers confronted, none was more deadly or more prevalent than contaminated water,” according to Jeffrey S. Sartin, MD, in his survey of Civil War diseases.1

The Union Army records list 1,765,000 cases of diarrhea or dysentery with 45,000 deaths and 149,000 cases of typhoid fever with 35,000 deaths. Add to these the 1,316,000 cases of malaria (borne by mosquitoes breeding in the waters) with its 10,000 deaths, and it is easy to see how the battlefield itself took second place in service to the grim reaper. (Overall, there were roughly two deaths from disease for every one from wounds.)

The chief waterborne plague, infectious diarrhea – including bacterial, amoebic, and other parasites – as well as cholera and typhoid, was an all-year-long problem, and, with the typical wry humor of soldiers, these maladies were given popular names, including the “Tennessee trots” and the “Virginia quick-step.”

Unsanitary conditions in the camps were primarily to blame, and this problem of sanitation was obvious to many observers at the time.

Despite a lack of knowledge of germ theory, doctors were fully aware of the relationship of unsanitary conditions to disease, even if they ascribed the link to miasmas or particles of filth.

Hospitals, which were under more strict control than the regular army camps, were meticulous about the placement of latrines and about keeping high standards of cleanliness among the patients, including routine washing. However, this was insufficient for complete protection, because what passed for clean in the absence of the knowledge of bacterial contamination was often totally ineffective. As one Civil War surgeon stated: “We operated in old bloodstained and often pus-stained coats, we used undisinfected instruments from undisinfected plush-lined cases. If a sponge (if they had sponges) or instrument fell on the floor it was washed and squeezed in a basin of water and used as if it was clean.”2

Overall, efforts at what passed for sanitation remained a constant goal and constant struggle in the field.

After the First Battle of Bull Run, Women’s Central Association of Relief President Henry W. Bellows met with Secretary of War Simon Cameron to discuss the abysmal sanitary conditions witnessed by WCAR volunteers. This meeting led to the creation of what would become the U.S. Sanitary Commission, which was approved by President Abraham Lincoln on June 13, 1861.

The U.S. Sanitary Commission served as a means for funneling civilian assistance to the military, with volunteers providing assistance in the organization of military hospitals and camps and aiding in the transportation of the wounded. However, despite these efforts, the setup of army camps and the behavior of the soldiers were not often directed toward proper sanitation. “The principal causes of disease, however, in our camps were the same that we have always to deplore and find it so difficult to remedy, simply because citizens suddenly called to the field cannot comprehend that men in masses require the attention of their officers to enforce certain hygienic conditions without which health cannot be preserved.”3

Breaches of sanitation were common in the confines of the camps, despite regulations designed to protect the soldiers. According to one U.S. Army surgeon of the time: “Especially [needed] was policing of the latrines. The trench is generally too shallow, the daily covering ... with dirt is entirely neglected. Large numbers of the men will not use the sinks [latrines], ... but instead every clump of bushes, every fence border in the vicinity.” Another pointed out that, after the Battle of Seven Pines, “the only water was infiltrated with the decaying animal matter of the battlefield.” Commenting on the placement of latrines in one encampment, another surgeon described how “the sink [latrine] is the ground in the vicinity, which slopes down to the stream, from which all water from the camp is obtained.”4

Treatment for diarrhea and dysentery was varied. Opiates were one of the most common treatments for diarrhea, whether in an alcohol solution as laudanum or in pill form, with belladonna being used to treat intestinal cramps, according to Glenna R. Schroeder-Lein in her book “The Encyclopedia of Civil War Medicine.” However, useless or damaging treatments were also prescribed, including the use of calomel (a mercury compound), turpentine, castor oil, and quinine.5

Acute diarrhea and dysentery illnesses occurred in at least 641/1,000 troops per year in the Union army. And even though the death rate was comparatively low (20/1,000 cases), it frequently led to chronic diarrhea, which was responsible for 288 deaths per 1,000 cases, and was the third highest cause of medical discharge after gunshot wounds and tuberculosis, according to Ms. Schroeder-Lein.

Although the American Civil War was the last major conflict before the spread of the knowledge of germ theory, the struggle to prevent the spread of waterborne diseases under wartime conditions remains ongoing. Hygiene is difficult under conditions of abject poverty and especially under conditions of armed conflict, and until the era of curative antibiotics there was no recourse.

Antibiotics are not the final solution for antibiotic resistance in intestinal disease pathogens, as outlined in a recent CDC report, is an increasing problem.6 For example, nontyphoidal Salmonella causes an estimated 1.35 million infections, 26,500 hospitalizations, and 420 deaths each year in the United States, with 16% of strains being resistant to at least one essential antibiotic. On a global scale, according to the World Health Organization, poor sanitation causes up to 432,000 diarrheal deaths annually and is linked to the transmission of other diseases like cholera, dysentery, typhoid, hepatitis A, and polio.7

With regard to actual epidemics, the world is only a hygienic crisis away from a major outbreak of dysentery (the last occurring between 1969 and 1972, when 20,000 people in Central America died), according to researchers who have detected antibiotic resistance in all but 1% of circulating Shigella dysenteriae strains surveyed since the 1990s. “This bacterium is still in circulation, and could be responsible for future epidemics if conditions should prove favorable – such as a large gathering of people without access to drinking water or treatment of human waste,” wrote François-Xavier Weill of the Pasteur Institute’s Enteric Bacterial Pathogens Unit.8

References

1. Sartin JS. Clin Infec Dis. 1993;16:580-4. (Correction published in 2002).

2. Civil War Battlefield Surgery. eHistory. The Ohio State University.

3. “Myths About Antiseptics and Camp Life – George Wunderlich,” published online Oct. 11, 2011. http://civilwarscholars.com/2011/10/myths-about-antiseptics-and-camp-life-george-wunderlich/

4. Dorwart BB. “Death is in the Breeze: Disease during the American Civil War” (The National Museum of the American Civil War Press, 2009).

5. Glenna R, Schroeder-Lein GR. “The Encyclopedia of Civil War Medicine” (New York: M. E. Sharpe, 2008).

6. “Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States 2019” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

7. “New report exposes horror of working conditions for millions of sanitation workers in the developing world,” World Health Organization. 2019 Nov 14.

8. Grant B. Origins of Dysentery. The Scientist. Published online March 22, 2016.

Mark Lesney is the managing editor of MDedge.com/IDPractioner. He has a PhD in plant virology and a PhD in the history of science, with a focus on the history of biotechnology and medicine. He has served as an adjunct assistant professor of the department of biochemistry and molecular & cellular biology at Georgetown University, Washington.

SPIRIT-H2H results confirm superiority of ixekizumab over adalimumab for PsA

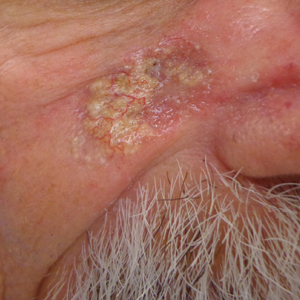

ATLANTA – Ixekizumab (Taltz) provided significantly greater improvement in joint and skin symptoms, compared with adalimumab (Humira), in biologic-naive patients with active psoriatic arthritis (PsA), according to final 52-week safety and efficacy results from the randomized SPIRIT-H2H study.

The high-affinity monoclonal antibody against interleukin-17A also performed at least as well as the tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–inhibitor adalimumab across multiple PsA domains and regardless of methotrexate use, Josef Smolen, MD, reported during a late-breaking abstract session at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Multiple biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARDs) are available for the treatment of PsA, but few studies have directly compared their efficacy and safety, said Dr. Smolen of the Medical University of Vienna. He noted that the SPIRIT-H2H study aimed to compare ixekizumab and adalimumab and also to address “one of the most clinically relevant questions for clinicians,” which relates to the efficacy of bDMARDs with and without concomitant methotrexate.

Ixekizumab is approved for adults with active PsA and moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, but TNF inhibitors like adalimumab have long been considered the gold standard for PsA treatment, he explained.

Of 283 patients with PsA randomized to receive ixekizumab and 283 randomized to receive adalimumab, 87% and 84%, respectively, completed week 52 of the head-to-head, open-label study comparing the bDMARDs. Treatment with ixekizumab achieved the primary endpoint of simultaneous improvement of 50% on ACR response criteria (ACR50) and 100% on the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI100) in 39% of patients, which was significantly higher than the rate of 26% with adalimumab, Dr. Smolen said.

Ixekizumab also performed at least as well as adalimumab for the secondary outcome measures of ACR50 response (50% in both groups) and PASI100 response (64% vs. 41%), as well as for all other outcomes measures, including multiple musculoskeletal PsA domains, he said.

“Remarkably ... at 1 year, more than one-third of the patients achieved an ACR70 in both groups, and half of the patients achieved an ACR50,” he added, noting that the ACR100 responses were in line with previous investigations.

Stratification by methotrexate use showed that the simultaneous ACR50 and PASI100 response rates were improved with ixekizumab versus adalimumab both in users and nonusers of methotrexate (39% vs. 30% and 40% vs. 20%, respectively). This finding highlights the ongoing debate about whether TNF inhibitors should or should not be used with methotrexate for PsA.

“This study was not adequately powered to say that, but there is some indication, and I think that this is food for thought for future further analysis because the data in the literature are discrepant in this respect,” Dr. Smolen said.

In non-methotrexate users in SPIRIT-H2H, the ACR20 responses were 53% with ixekinumab vs. 40% with adalimumab, ACR50 responses were 72% vs. 60%, and ACR70 responses were 41% vs. 27%, respectively, he said noting that the difference for ACR70 was statistically significant, and that the ACR70 response with ixekinumab was about the same as the ACR50 for adalimumab.

As for ACR20, ACR50, and ACR70 responses in methotrexate users, “the lines criss-crossed” early on, he said, but all were “slightly superior” with adalimumab than with ixekizumab at 52 weeks (75% vs. 68%, 56% vs. 48%, and 39% vs. 32%, respectively).

Study participants had a mean age of 48 years and had active PsA with at least 3/66 tender joints, at least 3/68 swollen joints, at least 3% psoriasis body surface area involvement, no prior treatment with bDMARDs, and prior inadequate response to one or more conventional synthetic DMARDs. Treatment was dosed according to drug labeling through 52 weeks.

The safety profiles of both agents were consistent with previous reports; treatment-emergent adverse events occurred in 73.9% of ixekizumab and 68.6% of adalimumab patients, and serious adverse events occurred in 4.2% and 12.4%, respectively.

“On the other hand, ixekizumab had more injection site reactions: 11% vs. close to 4%,” he said, noting that 4.2% of the ixekizumab patients and 7.4% of the adalimumab patients discontinued treatment because of adverse events. No deaths occurred in either group.

As reported previously in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, ixekizumab was superior to adalimumab for simultaneous achievement of ACR50 and PASI100 at 24 weeks, and these final 52-week results confirm those results, he said.

The study was funded by Eli Lilly, which markets ixekizumab. Dr. Smolen reported research grants and/or honoraria from Eli Lilly and AbbVie, which markets adalimumab, as well as many other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Smolen J et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10), Abstract L20.

ATLANTA – Ixekizumab (Taltz) provided significantly greater improvement in joint and skin symptoms, compared with adalimumab (Humira), in biologic-naive patients with active psoriatic arthritis (PsA), according to final 52-week safety and efficacy results from the randomized SPIRIT-H2H study.

The high-affinity monoclonal antibody against interleukin-17A also performed at least as well as the tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–inhibitor adalimumab across multiple PsA domains and regardless of methotrexate use, Josef Smolen, MD, reported during a late-breaking abstract session at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Multiple biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARDs) are available for the treatment of PsA, but few studies have directly compared their efficacy and safety, said Dr. Smolen of the Medical University of Vienna. He noted that the SPIRIT-H2H study aimed to compare ixekizumab and adalimumab and also to address “one of the most clinically relevant questions for clinicians,” which relates to the efficacy of bDMARDs with and without concomitant methotrexate.

Ixekizumab is approved for adults with active PsA and moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, but TNF inhibitors like adalimumab have long been considered the gold standard for PsA treatment, he explained.

Of 283 patients with PsA randomized to receive ixekizumab and 283 randomized to receive adalimumab, 87% and 84%, respectively, completed week 52 of the head-to-head, open-label study comparing the bDMARDs. Treatment with ixekizumab achieved the primary endpoint of simultaneous improvement of 50% on ACR response criteria (ACR50) and 100% on the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI100) in 39% of patients, which was significantly higher than the rate of 26% with adalimumab, Dr. Smolen said.

Ixekizumab also performed at least as well as adalimumab for the secondary outcome measures of ACR50 response (50% in both groups) and PASI100 response (64% vs. 41%), as well as for all other outcomes measures, including multiple musculoskeletal PsA domains, he said.

“Remarkably ... at 1 year, more than one-third of the patients achieved an ACR70 in both groups, and half of the patients achieved an ACR50,” he added, noting that the ACR100 responses were in line with previous investigations.

Stratification by methotrexate use showed that the simultaneous ACR50 and PASI100 response rates were improved with ixekizumab versus adalimumab both in users and nonusers of methotrexate (39% vs. 30% and 40% vs. 20%, respectively). This finding highlights the ongoing debate about whether TNF inhibitors should or should not be used with methotrexate for PsA.

“This study was not adequately powered to say that, but there is some indication, and I think that this is food for thought for future further analysis because the data in the literature are discrepant in this respect,” Dr. Smolen said.

In non-methotrexate users in SPIRIT-H2H, the ACR20 responses were 53% with ixekinumab vs. 40% with adalimumab, ACR50 responses were 72% vs. 60%, and ACR70 responses were 41% vs. 27%, respectively, he said noting that the difference for ACR70 was statistically significant, and that the ACR70 response with ixekinumab was about the same as the ACR50 for adalimumab.

As for ACR20, ACR50, and ACR70 responses in methotrexate users, “the lines criss-crossed” early on, he said, but all were “slightly superior” with adalimumab than with ixekizumab at 52 weeks (75% vs. 68%, 56% vs. 48%, and 39% vs. 32%, respectively).

Study participants had a mean age of 48 years and had active PsA with at least 3/66 tender joints, at least 3/68 swollen joints, at least 3% psoriasis body surface area involvement, no prior treatment with bDMARDs, and prior inadequate response to one or more conventional synthetic DMARDs. Treatment was dosed according to drug labeling through 52 weeks.

The safety profiles of both agents were consistent with previous reports; treatment-emergent adverse events occurred in 73.9% of ixekizumab and 68.6% of adalimumab patients, and serious adverse events occurred in 4.2% and 12.4%, respectively.

“On the other hand, ixekizumab had more injection site reactions: 11% vs. close to 4%,” he said, noting that 4.2% of the ixekizumab patients and 7.4% of the adalimumab patients discontinued treatment because of adverse events. No deaths occurred in either group.

As reported previously in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, ixekizumab was superior to adalimumab for simultaneous achievement of ACR50 and PASI100 at 24 weeks, and these final 52-week results confirm those results, he said.

The study was funded by Eli Lilly, which markets ixekizumab. Dr. Smolen reported research grants and/or honoraria from Eli Lilly and AbbVie, which markets adalimumab, as well as many other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Smolen J et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10), Abstract L20.

ATLANTA – Ixekizumab (Taltz) provided significantly greater improvement in joint and skin symptoms, compared with adalimumab (Humira), in biologic-naive patients with active psoriatic arthritis (PsA), according to final 52-week safety and efficacy results from the randomized SPIRIT-H2H study.

The high-affinity monoclonal antibody against interleukin-17A also performed at least as well as the tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–inhibitor adalimumab across multiple PsA domains and regardless of methotrexate use, Josef Smolen, MD, reported during a late-breaking abstract session at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Multiple biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARDs) are available for the treatment of PsA, but few studies have directly compared their efficacy and safety, said Dr. Smolen of the Medical University of Vienna. He noted that the SPIRIT-H2H study aimed to compare ixekizumab and adalimumab and also to address “one of the most clinically relevant questions for clinicians,” which relates to the efficacy of bDMARDs with and without concomitant methotrexate.

Ixekizumab is approved for adults with active PsA and moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, but TNF inhibitors like adalimumab have long been considered the gold standard for PsA treatment, he explained.

Of 283 patients with PsA randomized to receive ixekizumab and 283 randomized to receive adalimumab, 87% and 84%, respectively, completed week 52 of the head-to-head, open-label study comparing the bDMARDs. Treatment with ixekizumab achieved the primary endpoint of simultaneous improvement of 50% on ACR response criteria (ACR50) and 100% on the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI100) in 39% of patients, which was significantly higher than the rate of 26% with adalimumab, Dr. Smolen said.

Ixekizumab also performed at least as well as adalimumab for the secondary outcome measures of ACR50 response (50% in both groups) and PASI100 response (64% vs. 41%), as well as for all other outcomes measures, including multiple musculoskeletal PsA domains, he said.

“Remarkably ... at 1 year, more than one-third of the patients achieved an ACR70 in both groups, and half of the patients achieved an ACR50,” he added, noting that the ACR100 responses were in line with previous investigations.

Stratification by methotrexate use showed that the simultaneous ACR50 and PASI100 response rates were improved with ixekizumab versus adalimumab both in users and nonusers of methotrexate (39% vs. 30% and 40% vs. 20%, respectively). This finding highlights the ongoing debate about whether TNF inhibitors should or should not be used with methotrexate for PsA.

“This study was not adequately powered to say that, but there is some indication, and I think that this is food for thought for future further analysis because the data in the literature are discrepant in this respect,” Dr. Smolen said.

In non-methotrexate users in SPIRIT-H2H, the ACR20 responses were 53% with ixekinumab vs. 40% with adalimumab, ACR50 responses were 72% vs. 60%, and ACR70 responses were 41% vs. 27%, respectively, he said noting that the difference for ACR70 was statistically significant, and that the ACR70 response with ixekinumab was about the same as the ACR50 for adalimumab.

As for ACR20, ACR50, and ACR70 responses in methotrexate users, “the lines criss-crossed” early on, he said, but all were “slightly superior” with adalimumab than with ixekizumab at 52 weeks (75% vs. 68%, 56% vs. 48%, and 39% vs. 32%, respectively).