User login

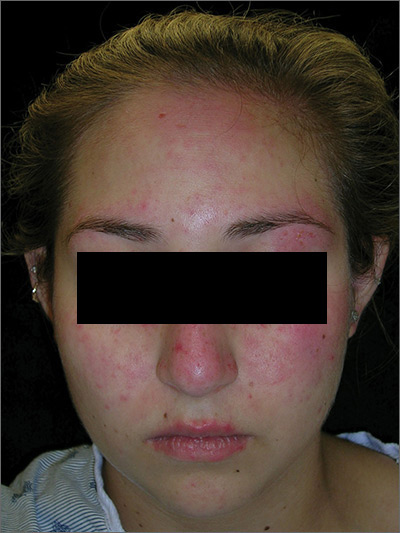

Rash on face, chest, upper arms, and thighs

The FP suspected acute systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) with an acute cutaneous component. Laboratory testing showed a very high level of antinuclear antibodies. The patient was referred to Rheumatology and Dermatology. The dermatologist was available for a phone consult and suggested starting the patient on prednisone 60 mg/d as the Medrol Dosepak that the patient previously received had insufficient prednisolone for this severe flare of acute cutaneous lupus.

Although the classic description of acute SLE involves a butterfly rash, the rash of acute cutaneous lupus can include other areas of the face and body. As was seen in this case, the nasolabial fold tends to be spared and there are often skin erosions and crusting.

Based on the patient’s lab tests and symptoms, the dermatologist determined that the patient met the criteria for SLE. The patient was started on hydroxychloroquine 400 mg/d. The plan was to taper the patient’s prednisone slowly. By the following week, her skin and fatigue were much improved.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Pye A, Mayeaux EJ, Mishra V, et al. Lupus. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1183-1193.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

The FP suspected acute systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) with an acute cutaneous component. Laboratory testing showed a very high level of antinuclear antibodies. The patient was referred to Rheumatology and Dermatology. The dermatologist was available for a phone consult and suggested starting the patient on prednisone 60 mg/d as the Medrol Dosepak that the patient previously received had insufficient prednisolone for this severe flare of acute cutaneous lupus.

Although the classic description of acute SLE involves a butterfly rash, the rash of acute cutaneous lupus can include other areas of the face and body. As was seen in this case, the nasolabial fold tends to be spared and there are often skin erosions and crusting.

Based on the patient’s lab tests and symptoms, the dermatologist determined that the patient met the criteria for SLE. The patient was started on hydroxychloroquine 400 mg/d. The plan was to taper the patient’s prednisone slowly. By the following week, her skin and fatigue were much improved.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Pye A, Mayeaux EJ, Mishra V, et al. Lupus. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1183-1193.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

The FP suspected acute systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) with an acute cutaneous component. Laboratory testing showed a very high level of antinuclear antibodies. The patient was referred to Rheumatology and Dermatology. The dermatologist was available for a phone consult and suggested starting the patient on prednisone 60 mg/d as the Medrol Dosepak that the patient previously received had insufficient prednisolone for this severe flare of acute cutaneous lupus.

Although the classic description of acute SLE involves a butterfly rash, the rash of acute cutaneous lupus can include other areas of the face and body. As was seen in this case, the nasolabial fold tends to be spared and there are often skin erosions and crusting.

Based on the patient’s lab tests and symptoms, the dermatologist determined that the patient met the criteria for SLE. The patient was started on hydroxychloroquine 400 mg/d. The plan was to taper the patient’s prednisone slowly. By the following week, her skin and fatigue were much improved.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Pye A, Mayeaux EJ, Mishra V, et al. Lupus. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1183-1193.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

Post-Ebola mortality five times higher than general population

Survivors of the 2013-2016 Ebola epidemic in West Africa had lingering health effects of the disease. These patients had a much greater mortality in the first year after discharge, compared with the general population. Among those survivors who died, the majority appear to have expired because of renal failure, according to the results of an assessment the by the Guinean national survivors’ monitoring program.

The Surveillance Active en Ceinture obtained data on 1,130 (89%) of survivors of Ebola virus disease who were discharged from Ebola treatment units in Guinea. Compared with the general Guinean population, survivors of Ebola virus showed a five times increased risk of mortality within a year of follow-up after discharge, according to a survey of patients’ medical records and patients’ relatives, reported researchers Mory Keita, MD, and colleagues.

After 1 year, the difference in mortality between Ebola survivors and the general population had disappeared, according to the study published online in the Lancet Infectious Diseases.

A total of 59 deaths were reported among the discharged survivors available for follow-up. Renal failure was the assumed cause in 37 (63%) of these patients based on a description of reported anuria. The exact date of death was unknown for 43 of the 59 deaths. Of the 16 initial survivors for whom an exact date of death was available, 5 died within a month of discharge from Ebola treatment units, an additional 3 died within 3 months of discharge, 4 died 3-12 months after discharge, and 4 died more than a year after discharge (up to 21 months).

Age and area of residence (urban vs. nonurban area) were independently and significantly associated with mortality, with patients of older age (55 years or greater) and those from nonurban areas being at greater risk. Patient sex was not associated with survival.

Those survivors who were hospitalized for 12 days or more had more than double the risk of death than did those hospitalized less than 12 days, which was a statistically significant association.

“Survivors’ monitoring programs should be strengthened and should not focus exclusively on testing of bodily fluids,” the authors advised. “Furthermore, our study provides preliminary evidence that survivors hospitalized for longer than 12 days with Ebola virus disease could be at particularly high risk of mortality and should be specifically targeted, and perhaps also evidence that renal function should be monitored,” Dr. Keita and colleagues concluded.

The study was funded by the World Health Organization, International Medical Corps, and the Guinean Red Cross. The authors reported that they had no conflicts

SOURCE: Keita M et al. Lancet Infect Dis 2019 Sept 4. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30313-5.

Survivors of the 2013-2016 Ebola epidemic in West Africa had lingering health effects of the disease. These patients had a much greater mortality in the first year after discharge, compared with the general population. Among those survivors who died, the majority appear to have expired because of renal failure, according to the results of an assessment the by the Guinean national survivors’ monitoring program.

The Surveillance Active en Ceinture obtained data on 1,130 (89%) of survivors of Ebola virus disease who were discharged from Ebola treatment units in Guinea. Compared with the general Guinean population, survivors of Ebola virus showed a five times increased risk of mortality within a year of follow-up after discharge, according to a survey of patients’ medical records and patients’ relatives, reported researchers Mory Keita, MD, and colleagues.

After 1 year, the difference in mortality between Ebola survivors and the general population had disappeared, according to the study published online in the Lancet Infectious Diseases.

A total of 59 deaths were reported among the discharged survivors available for follow-up. Renal failure was the assumed cause in 37 (63%) of these patients based on a description of reported anuria. The exact date of death was unknown for 43 of the 59 deaths. Of the 16 initial survivors for whom an exact date of death was available, 5 died within a month of discharge from Ebola treatment units, an additional 3 died within 3 months of discharge, 4 died 3-12 months after discharge, and 4 died more than a year after discharge (up to 21 months).

Age and area of residence (urban vs. nonurban area) were independently and significantly associated with mortality, with patients of older age (55 years or greater) and those from nonurban areas being at greater risk. Patient sex was not associated with survival.

Those survivors who were hospitalized for 12 days or more had more than double the risk of death than did those hospitalized less than 12 days, which was a statistically significant association.

“Survivors’ monitoring programs should be strengthened and should not focus exclusively on testing of bodily fluids,” the authors advised. “Furthermore, our study provides preliminary evidence that survivors hospitalized for longer than 12 days with Ebola virus disease could be at particularly high risk of mortality and should be specifically targeted, and perhaps also evidence that renal function should be monitored,” Dr. Keita and colleagues concluded.

The study was funded by the World Health Organization, International Medical Corps, and the Guinean Red Cross. The authors reported that they had no conflicts

SOURCE: Keita M et al. Lancet Infect Dis 2019 Sept 4. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30313-5.

Survivors of the 2013-2016 Ebola epidemic in West Africa had lingering health effects of the disease. These patients had a much greater mortality in the first year after discharge, compared with the general population. Among those survivors who died, the majority appear to have expired because of renal failure, according to the results of an assessment the by the Guinean national survivors’ monitoring program.

The Surveillance Active en Ceinture obtained data on 1,130 (89%) of survivors of Ebola virus disease who were discharged from Ebola treatment units in Guinea. Compared with the general Guinean population, survivors of Ebola virus showed a five times increased risk of mortality within a year of follow-up after discharge, according to a survey of patients’ medical records and patients’ relatives, reported researchers Mory Keita, MD, and colleagues.

After 1 year, the difference in mortality between Ebola survivors and the general population had disappeared, according to the study published online in the Lancet Infectious Diseases.

A total of 59 deaths were reported among the discharged survivors available for follow-up. Renal failure was the assumed cause in 37 (63%) of these patients based on a description of reported anuria. The exact date of death was unknown for 43 of the 59 deaths. Of the 16 initial survivors for whom an exact date of death was available, 5 died within a month of discharge from Ebola treatment units, an additional 3 died within 3 months of discharge, 4 died 3-12 months after discharge, and 4 died more than a year after discharge (up to 21 months).

Age and area of residence (urban vs. nonurban area) were independently and significantly associated with mortality, with patients of older age (55 years or greater) and those from nonurban areas being at greater risk. Patient sex was not associated with survival.

Those survivors who were hospitalized for 12 days or more had more than double the risk of death than did those hospitalized less than 12 days, which was a statistically significant association.

“Survivors’ monitoring programs should be strengthened and should not focus exclusively on testing of bodily fluids,” the authors advised. “Furthermore, our study provides preliminary evidence that survivors hospitalized for longer than 12 days with Ebola virus disease could be at particularly high risk of mortality and should be specifically targeted, and perhaps also evidence that renal function should be monitored,” Dr. Keita and colleagues concluded.

The study was funded by the World Health Organization, International Medical Corps, and the Guinean Red Cross. The authors reported that they had no conflicts

SOURCE: Keita M et al. Lancet Infect Dis 2019 Sept 4. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30313-5.

FROM THE LANCET INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Key clinical point: Renal failure was the assumed cause of death in 63% of the survivors based on reported anuria.

Major finding:

Study details: A postdischarge survey of 1,130 (89%) of the Ebola survivors and their relations in Guinea.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the World Health Organization, International Medical Corps, and the Guinean Red Cross. The authors reported that they had no conflicts.

Source: Keita M et al. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019 Sept 4. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30313-5.

New report cites mental health challenges faced by separated immigrant children

Care providers encountered significant challenges when addressing the mental health needs of unaccompanied immigrant children in federal custody, including overwhelming caseloads and the deteriorating mental health of some patients, according to a new report by the Office of Inspector General (OIG).

In the report, released Sept. 3, the OIG outlined findings from its analysis of 45 Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) facilities between August and September 2018. The U.S. Department of Health & Human Services ORR is the legal custodian of unaccompanied immigrant children in its care who have no parent or legal guardian available. This includes children who arrive in the United States unaccompanied and children who are separated from their parents or guardians by immigration authorities after arriving in the country.

For the analysis, OIG investigators collected data from interviews with mental health clinicians, medical coordinators, facility leadership, and ORR federal field specialists at the 45 selected facilities.

Investigators recorded numerous serious challenges experienced by providers when attempting to provide mental health care to the children. Namely, they cited overwhelming patient caseloads, and difficulty accessing external mental health clinicians and referring children to providers within ORR’s network, according to the OIG’s report.

Mental health clinicians reported that the high caseloads hurt their ability to build rapport with young patients – and allowed less time for counseling and less frequent sessions for children with greater needs. The heavy caseloads were generated by heightened immigration enforcement beginning in 2017, and the separation of many more families at the border and more children being placed in federal custody, according to the report.

In addition, providers reported challenges when addressing the mental health needs of children who had experienced significant trauma before coming into federal custody. This included trauma that occurred while the children lived in the countries of origin, trauma during their journey to the United States, and trauma upon their arrival in the United States.

Separation from parents and a chaotic reunification process added to the trauma that children had already experienced, providers reported, and put extreme pressure on facility staff. Separated children exhibited “more fear, feelings of abandonment, and posttraumatic stress than did children who were not separated,” according to the findings. Separated children also experienced elevated feelings of anxiety and loss as a consequence of unexpected separation from loved ones.

Also, facilities reported that longer lengths of stay resulted in deteriorating mental health for some children and increased demands on staff. Facilities reported that children who stayed in federal custody for longer periods experienced more stress, anxiety, and behavioral issues. According to the facilities, the longer stays resulted in higher levels of defiance, hopelessness, and frustration among children – in addition to more instances of self-harm and suicidal ideation.

It is not surprising that the OIG study reflects that mental health services at facilities for unaccompanied minors are understaffed, undertrained, and overwhelmed, said Craig L. Katz, MD, a clinical professor of psychiatry at Mount Sinai in New York.

“In some sense, this can probably be said for most of the U.S. and definitely the world when it comes to child mental health services,” Dr. Katz said in an interview. “But, what’s especially tough to stomach about this shortfall at these facilities is that they encompass an immensely high-risk population – an inevitably highly, if not multiply traumatized population of children who lack primary caregivers.”

Dr. Katz was coinvestigator of a recent study that assessed the mental health of children held at a U.S. immigration detention center through the Parent-Report Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. Among the 425 children evaluated, many demonstrated elevated scores for emotional problems, peer problems, and total difficulties, according to the June 2018 study, published in Social Science & Medicine (2019 Jun; 230:303-8). Younger children (aged 4-8 years) demonstrated more difficulties associated with conduct, hyperactivity, and total difficulties, compared with older children, the study found.

Children who had been forcibly separated from their mothers demonstrated significantly more emotional problems and total difficulties, compared with those who had never been separated. Of 150 children who completed the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Reaction Index, 17% had a probable diagnosis of PTSD, results found.

Dr. Katz said the OIG reached the same basic conclusion as his quantitative study – that separated minors appear to have even greater mental health problems than do fellow unaccompanied minors.

“In our study, we found that children in family detention had greater mental health problems than [did] American community samples but that formerly separated children who had been reunited with their mothers had even more health problems than their fellow detainees,” Dr. Katz said. “Something about being separated per U.S. policy was especially pernicious, which we knew in our hearts; but now in this study and ours, we know empirically.”

As long as the United States continues to detain children, the psychological harm created by such detainments is likely to continue, said Kim A. Baranowski, PhD, a psychologist and lecturer at Columbia University in New York. At a minimum, unaccompanied minors should have access to highly trained licensed clinicians who can respond to their immediate mental health needs within the initial hours and days following their arrival in the United States, and such children should be released rapidly from government custody and reunited with their families, said Dr. Baranowski, a coauthor of the Social Science & Medicine study.

“We need to effectively support their integration into the community, and connect children and their families with linguistically, culturally, and developmentally appropriate trauma-informed pro bono treatment services that respond to their experiences” of premigration, migration, and postmigration stressors, “as well as potential exposure to trauma,” she said in an interview.

The OIG issued several recommendations for practical steps that ORR can take to assist facilities and better provide mental health care to immigrant children in federal custody. The agency advised that the ORR should provide facilities with evidence-based guidance on addressing trauma in short-term therapy and that the ORR also should develop strategies for overcoming challenges to hiring and retaining qualified mental health clinicians.

The Office of Inspector General also suggested that facilities consider maximum caseloads for individual clinicians. Finally, the OIG recommends that ORR address gaps in options for children who require more specialized treatment and that the office take reasonable steps to minimize the length of time that children remain in custody.

agallegos@mdedge.com

*This article was updated 9/5/2019.

Care providers encountered significant challenges when addressing the mental health needs of unaccompanied immigrant children in federal custody, including overwhelming caseloads and the deteriorating mental health of some patients, according to a new report by the Office of Inspector General (OIG).

In the report, released Sept. 3, the OIG outlined findings from its analysis of 45 Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) facilities between August and September 2018. The U.S. Department of Health & Human Services ORR is the legal custodian of unaccompanied immigrant children in its care who have no parent or legal guardian available. This includes children who arrive in the United States unaccompanied and children who are separated from their parents or guardians by immigration authorities after arriving in the country.

For the analysis, OIG investigators collected data from interviews with mental health clinicians, medical coordinators, facility leadership, and ORR federal field specialists at the 45 selected facilities.

Investigators recorded numerous serious challenges experienced by providers when attempting to provide mental health care to the children. Namely, they cited overwhelming patient caseloads, and difficulty accessing external mental health clinicians and referring children to providers within ORR’s network, according to the OIG’s report.

Mental health clinicians reported that the high caseloads hurt their ability to build rapport with young patients – and allowed less time for counseling and less frequent sessions for children with greater needs. The heavy caseloads were generated by heightened immigration enforcement beginning in 2017, and the separation of many more families at the border and more children being placed in federal custody, according to the report.

In addition, providers reported challenges when addressing the mental health needs of children who had experienced significant trauma before coming into federal custody. This included trauma that occurred while the children lived in the countries of origin, trauma during their journey to the United States, and trauma upon their arrival in the United States.

Separation from parents and a chaotic reunification process added to the trauma that children had already experienced, providers reported, and put extreme pressure on facility staff. Separated children exhibited “more fear, feelings of abandonment, and posttraumatic stress than did children who were not separated,” according to the findings. Separated children also experienced elevated feelings of anxiety and loss as a consequence of unexpected separation from loved ones.

Also, facilities reported that longer lengths of stay resulted in deteriorating mental health for some children and increased demands on staff. Facilities reported that children who stayed in federal custody for longer periods experienced more stress, anxiety, and behavioral issues. According to the facilities, the longer stays resulted in higher levels of defiance, hopelessness, and frustration among children – in addition to more instances of self-harm and suicidal ideation.

It is not surprising that the OIG study reflects that mental health services at facilities for unaccompanied minors are understaffed, undertrained, and overwhelmed, said Craig L. Katz, MD, a clinical professor of psychiatry at Mount Sinai in New York.

“In some sense, this can probably be said for most of the U.S. and definitely the world when it comes to child mental health services,” Dr. Katz said in an interview. “But, what’s especially tough to stomach about this shortfall at these facilities is that they encompass an immensely high-risk population – an inevitably highly, if not multiply traumatized population of children who lack primary caregivers.”

Dr. Katz was coinvestigator of a recent study that assessed the mental health of children held at a U.S. immigration detention center through the Parent-Report Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. Among the 425 children evaluated, many demonstrated elevated scores for emotional problems, peer problems, and total difficulties, according to the June 2018 study, published in Social Science & Medicine (2019 Jun; 230:303-8). Younger children (aged 4-8 years) demonstrated more difficulties associated with conduct, hyperactivity, and total difficulties, compared with older children, the study found.

Children who had been forcibly separated from their mothers demonstrated significantly more emotional problems and total difficulties, compared with those who had never been separated. Of 150 children who completed the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Reaction Index, 17% had a probable diagnosis of PTSD, results found.

Dr. Katz said the OIG reached the same basic conclusion as his quantitative study – that separated minors appear to have even greater mental health problems than do fellow unaccompanied minors.

“In our study, we found that children in family detention had greater mental health problems than [did] American community samples but that formerly separated children who had been reunited with their mothers had even more health problems than their fellow detainees,” Dr. Katz said. “Something about being separated per U.S. policy was especially pernicious, which we knew in our hearts; but now in this study and ours, we know empirically.”

As long as the United States continues to detain children, the psychological harm created by such detainments is likely to continue, said Kim A. Baranowski, PhD, a psychologist and lecturer at Columbia University in New York. At a minimum, unaccompanied minors should have access to highly trained licensed clinicians who can respond to their immediate mental health needs within the initial hours and days following their arrival in the United States, and such children should be released rapidly from government custody and reunited with their families, said Dr. Baranowski, a coauthor of the Social Science & Medicine study.

“We need to effectively support their integration into the community, and connect children and their families with linguistically, culturally, and developmentally appropriate trauma-informed pro bono treatment services that respond to their experiences” of premigration, migration, and postmigration stressors, “as well as potential exposure to trauma,” she said in an interview.

The OIG issued several recommendations for practical steps that ORR can take to assist facilities and better provide mental health care to immigrant children in federal custody. The agency advised that the ORR should provide facilities with evidence-based guidance on addressing trauma in short-term therapy and that the ORR also should develop strategies for overcoming challenges to hiring and retaining qualified mental health clinicians.

The Office of Inspector General also suggested that facilities consider maximum caseloads for individual clinicians. Finally, the OIG recommends that ORR address gaps in options for children who require more specialized treatment and that the office take reasonable steps to minimize the length of time that children remain in custody.

agallegos@mdedge.com

*This article was updated 9/5/2019.

Care providers encountered significant challenges when addressing the mental health needs of unaccompanied immigrant children in federal custody, including overwhelming caseloads and the deteriorating mental health of some patients, according to a new report by the Office of Inspector General (OIG).

In the report, released Sept. 3, the OIG outlined findings from its analysis of 45 Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) facilities between August and September 2018. The U.S. Department of Health & Human Services ORR is the legal custodian of unaccompanied immigrant children in its care who have no parent or legal guardian available. This includes children who arrive in the United States unaccompanied and children who are separated from their parents or guardians by immigration authorities after arriving in the country.

For the analysis, OIG investigators collected data from interviews with mental health clinicians, medical coordinators, facility leadership, and ORR federal field specialists at the 45 selected facilities.

Investigators recorded numerous serious challenges experienced by providers when attempting to provide mental health care to the children. Namely, they cited overwhelming patient caseloads, and difficulty accessing external mental health clinicians and referring children to providers within ORR’s network, according to the OIG’s report.

Mental health clinicians reported that the high caseloads hurt their ability to build rapport with young patients – and allowed less time for counseling and less frequent sessions for children with greater needs. The heavy caseloads were generated by heightened immigration enforcement beginning in 2017, and the separation of many more families at the border and more children being placed in federal custody, according to the report.

In addition, providers reported challenges when addressing the mental health needs of children who had experienced significant trauma before coming into federal custody. This included trauma that occurred while the children lived in the countries of origin, trauma during their journey to the United States, and trauma upon their arrival in the United States.

Separation from parents and a chaotic reunification process added to the trauma that children had already experienced, providers reported, and put extreme pressure on facility staff. Separated children exhibited “more fear, feelings of abandonment, and posttraumatic stress than did children who were not separated,” according to the findings. Separated children also experienced elevated feelings of anxiety and loss as a consequence of unexpected separation from loved ones.

Also, facilities reported that longer lengths of stay resulted in deteriorating mental health for some children and increased demands on staff. Facilities reported that children who stayed in federal custody for longer periods experienced more stress, anxiety, and behavioral issues. According to the facilities, the longer stays resulted in higher levels of defiance, hopelessness, and frustration among children – in addition to more instances of self-harm and suicidal ideation.

It is not surprising that the OIG study reflects that mental health services at facilities for unaccompanied minors are understaffed, undertrained, and overwhelmed, said Craig L. Katz, MD, a clinical professor of psychiatry at Mount Sinai in New York.

“In some sense, this can probably be said for most of the U.S. and definitely the world when it comes to child mental health services,” Dr. Katz said in an interview. “But, what’s especially tough to stomach about this shortfall at these facilities is that they encompass an immensely high-risk population – an inevitably highly, if not multiply traumatized population of children who lack primary caregivers.”

Dr. Katz was coinvestigator of a recent study that assessed the mental health of children held at a U.S. immigration detention center through the Parent-Report Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. Among the 425 children evaluated, many demonstrated elevated scores for emotional problems, peer problems, and total difficulties, according to the June 2018 study, published in Social Science & Medicine (2019 Jun; 230:303-8). Younger children (aged 4-8 years) demonstrated more difficulties associated with conduct, hyperactivity, and total difficulties, compared with older children, the study found.

Children who had been forcibly separated from their mothers demonstrated significantly more emotional problems and total difficulties, compared with those who had never been separated. Of 150 children who completed the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Reaction Index, 17% had a probable diagnosis of PTSD, results found.

Dr. Katz said the OIG reached the same basic conclusion as his quantitative study – that separated minors appear to have even greater mental health problems than do fellow unaccompanied minors.

“In our study, we found that children in family detention had greater mental health problems than [did] American community samples but that formerly separated children who had been reunited with their mothers had even more health problems than their fellow detainees,” Dr. Katz said. “Something about being separated per U.S. policy was especially pernicious, which we knew in our hearts; but now in this study and ours, we know empirically.”

As long as the United States continues to detain children, the psychological harm created by such detainments is likely to continue, said Kim A. Baranowski, PhD, a psychologist and lecturer at Columbia University in New York. At a minimum, unaccompanied minors should have access to highly trained licensed clinicians who can respond to their immediate mental health needs within the initial hours and days following their arrival in the United States, and such children should be released rapidly from government custody and reunited with their families, said Dr. Baranowski, a coauthor of the Social Science & Medicine study.

“We need to effectively support their integration into the community, and connect children and their families with linguistically, culturally, and developmentally appropriate trauma-informed pro bono treatment services that respond to their experiences” of premigration, migration, and postmigration stressors, “as well as potential exposure to trauma,” she said in an interview.

The OIG issued several recommendations for practical steps that ORR can take to assist facilities and better provide mental health care to immigrant children in federal custody. The agency advised that the ORR should provide facilities with evidence-based guidance on addressing trauma in short-term therapy and that the ORR also should develop strategies for overcoming challenges to hiring and retaining qualified mental health clinicians.

The Office of Inspector General also suggested that facilities consider maximum caseloads for individual clinicians. Finally, the OIG recommends that ORR address gaps in options for children who require more specialized treatment and that the office take reasonable steps to minimize the length of time that children remain in custody.

agallegos@mdedge.com

*This article was updated 9/5/2019.

CDC, SAMHSA commit $1.8 billion to combat opioid crisis

More financial reinforcements are arriving in the battle against the opioid crisis, with the Trump administration promising more than $1.8 billion in new funds to help states address the crisis.

Speaking at a Sept. 4 press conference announcing the funding, President Donald Trump said the money will be used “to increase access to medication and medication-assisted treatment and mental health resources, which are critical for ending homelessness and getting people the help they deserve.” The president added that the grants also will help state and local governments obtain high-quality, comprehensive data.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention will provide more than $900 million in new funding over the next 3 years to “advance the understanding of the opioid overdose epidemic and to scale-up prevention and response activities,” the Department of Health & Human Services said in a statement announcing the funding.

“This money will help states and local communities track overdose data and develop strategies that save lives,” HHS Secretary Alex Azar said during the press conference.

He noted that, when the Trump administration began, overdose data were published with a 12-month lag. That lag has since shortened to 6 months. One of the goals with the new funding is to bring data publishing as close to real time as possible.

Separately, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration awarded $932 million to all 50 states as part of its State Opioid Response grants, which “provide flexible funding to state governments to support prevention, treatment, and recovery services in the ways that meet the needs of their state,” according to the HHS statement.

That flexibility “can mean everything from expanding the use of medication-assisted treatment in criminal justice settings or in rural areas via telemedicine, to youth-focused community-based prevention efforts,” Secretary Azar explained. The funds can also support employment coaching and naloxone distribution, he added.

More financial reinforcements are arriving in the battle against the opioid crisis, with the Trump administration promising more than $1.8 billion in new funds to help states address the crisis.

Speaking at a Sept. 4 press conference announcing the funding, President Donald Trump said the money will be used “to increase access to medication and medication-assisted treatment and mental health resources, which are critical for ending homelessness and getting people the help they deserve.” The president added that the grants also will help state and local governments obtain high-quality, comprehensive data.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention will provide more than $900 million in new funding over the next 3 years to “advance the understanding of the opioid overdose epidemic and to scale-up prevention and response activities,” the Department of Health & Human Services said in a statement announcing the funding.

“This money will help states and local communities track overdose data and develop strategies that save lives,” HHS Secretary Alex Azar said during the press conference.

He noted that, when the Trump administration began, overdose data were published with a 12-month lag. That lag has since shortened to 6 months. One of the goals with the new funding is to bring data publishing as close to real time as possible.

Separately, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration awarded $932 million to all 50 states as part of its State Opioid Response grants, which “provide flexible funding to state governments to support prevention, treatment, and recovery services in the ways that meet the needs of their state,” according to the HHS statement.

That flexibility “can mean everything from expanding the use of medication-assisted treatment in criminal justice settings or in rural areas via telemedicine, to youth-focused community-based prevention efforts,” Secretary Azar explained. The funds can also support employment coaching and naloxone distribution, he added.

More financial reinforcements are arriving in the battle against the opioid crisis, with the Trump administration promising more than $1.8 billion in new funds to help states address the crisis.

Speaking at a Sept. 4 press conference announcing the funding, President Donald Trump said the money will be used “to increase access to medication and medication-assisted treatment and mental health resources, which are critical for ending homelessness and getting people the help they deserve.” The president added that the grants also will help state and local governments obtain high-quality, comprehensive data.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention will provide more than $900 million in new funding over the next 3 years to “advance the understanding of the opioid overdose epidemic and to scale-up prevention and response activities,” the Department of Health & Human Services said in a statement announcing the funding.

“This money will help states and local communities track overdose data and develop strategies that save lives,” HHS Secretary Alex Azar said during the press conference.

He noted that, when the Trump administration began, overdose data were published with a 12-month lag. That lag has since shortened to 6 months. One of the goals with the new funding is to bring data publishing as close to real time as possible.

Separately, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration awarded $932 million to all 50 states as part of its State Opioid Response grants, which “provide flexible funding to state governments to support prevention, treatment, and recovery services in the ways that meet the needs of their state,” according to the HHS statement.

That flexibility “can mean everything from expanding the use of medication-assisted treatment in criminal justice settings or in rural areas via telemedicine, to youth-focused community-based prevention efforts,” Secretary Azar explained. The funds can also support employment coaching and naloxone distribution, he added.

SAGE-217 shows reduction in depression with no safety concerns

A new oral antidepressant that targets the gamma-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptors in the brain has been found to achieve a reduction in symptoms in adult patients with moderate to severe major depressive disorder, with no serious safety signals, results of a double-blind, phase 2 trial show.

The study involved 89 participants with major depression, excluding those with a history of treatment-resistant depression, who were randomized either to a once-daily dose of 30 mg of SAGE-217, a synthetic neurosteroid that acts as a positive allosteric modulator of GABAA receptors, or placebo for 14 days. Thirty-six of the 45 patients in the SAGE-217 group were black, as were 28 of the 44 patients in the placebo group, reported Handan Gunduz-Bruce, MD, of Sage Therapeutics and coauthors. Their study was published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“One hypothesis for the mechanism of depression implicates deficits in gamma-aminobutyric acid and downstream alterations in monoaminergic neurotransmission,” wrote Dr. Gunduz-Bruce and coauthors. “Preclinical studies have shown that the naturally occurring neurosteroid allopregnanolone is a positive allosteric modulator of synaptic and extrasynaptic GABAA receptors that affects both phasic and tonic inhibition of neurons.”

At day 15 of the study, there was a significantly greater mean change from baseline in Hamilton Depression Rating Scale scores in the treatment group, compared with the placebo group (–17.4 vs. –10.3, P less than .001), and 79% of participants in the treatment arm showed a greater than 50% reduction in depression scores, compared with 41% of the placebo group.

At day 28, 62% of the treatment group and 46% of the placebo group had a reduction of more than 50% from baseline depression scores.

No serious or severe adverse events were seen in either group, and the most common adverse events in the SAGE-217 group included headache (18%), dizziness (11%), and nausea (11%). One patient in the treatment arm also reported euphoria.

The authors commented that somnolence and sedation were expected adverse events, based on the pharmacological properties of SAGE-217.

Six patients in the treatment arm also had dose reductions as a result of adverse events. Two patients in the SAGE-217 arm stopped treatment because they met prespecified criteria for discontinuation; the investigators reported nausea, dizziness, and headache in one patient, and increased levels of alkaline phosphatase, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and gamma-glutamyltransferase in the other. However, the second patient had shown mildly elevated values of these at baseline, was asymptomatic throughout the trial, and the patient’s values returned to baseline or near-baseline after stopping treatment.

About one-quarter of both the SAGE-217 and placebo groups were receiving antidepressant treatment at baseline (27% and 23% respectively), with the duration of prior treatment ranging from 2 to 48 months. Investigators also gave three patients in the treatment arm and 11 in the placebo arm concomitant antidepressants during the follow-up period.

The small sample size and limited racial diversity among the participants were cited as limitations.

The study was supported by SAGE-217 manufacturer Sage Therapeutics. Ten authors were employees or directors of Sage Therapeutics, with stock options and patent interests. Three authors declared grants, personal fees, or advisory board positions with the pharmaceutical sector, including from Sage, and one also declared interest in a range of patents outside the study. One author had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Gunduz-Bruce H et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 5;381:903-11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1815981.

Glutamate modulators, such as ketamine, recently have been found to achieve a rapid reduction in depressive symptoms – often within 24 hours. This is a significant development given that most existing antidepressants do not work quickly, and time is critical for patients with suicidal ideation.

This trial of SAGE-217 also shows a more rapid clinical response than is typical of existing antidepressants. However, the absence of a significant difference between the treatment and placebo arm in change of depression scores from baseline to day 28 suggests that the drug should be administered for longer than 14 days. It is also important to note that the trial excluded patients with treatment-resistant depression.

Emil F. Coccaro, MD, is affiliated with the department of psychiatry and behavioral neuroscience at the University of Chicago. These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 5;381:980-1. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1907638). Dr. Coccaro declared grants from the National Institutes of Health and personal fees or stock options in the pharmaceutical sector.

Glutamate modulators, such as ketamine, recently have been found to achieve a rapid reduction in depressive symptoms – often within 24 hours. This is a significant development given that most existing antidepressants do not work quickly, and time is critical for patients with suicidal ideation.

This trial of SAGE-217 also shows a more rapid clinical response than is typical of existing antidepressants. However, the absence of a significant difference between the treatment and placebo arm in change of depression scores from baseline to day 28 suggests that the drug should be administered for longer than 14 days. It is also important to note that the trial excluded patients with treatment-resistant depression.

Emil F. Coccaro, MD, is affiliated with the department of psychiatry and behavioral neuroscience at the University of Chicago. These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 5;381:980-1. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1907638). Dr. Coccaro declared grants from the National Institutes of Health and personal fees or stock options in the pharmaceutical sector.

Glutamate modulators, such as ketamine, recently have been found to achieve a rapid reduction in depressive symptoms – often within 24 hours. This is a significant development given that most existing antidepressants do not work quickly, and time is critical for patients with suicidal ideation.

This trial of SAGE-217 also shows a more rapid clinical response than is typical of existing antidepressants. However, the absence of a significant difference between the treatment and placebo arm in change of depression scores from baseline to day 28 suggests that the drug should be administered for longer than 14 days. It is also important to note that the trial excluded patients with treatment-resistant depression.

Emil F. Coccaro, MD, is affiliated with the department of psychiatry and behavioral neuroscience at the University of Chicago. These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 5;381:980-1. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1907638). Dr. Coccaro declared grants from the National Institutes of Health and personal fees or stock options in the pharmaceutical sector.

A new oral antidepressant that targets the gamma-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptors in the brain has been found to achieve a reduction in symptoms in adult patients with moderate to severe major depressive disorder, with no serious safety signals, results of a double-blind, phase 2 trial show.

The study involved 89 participants with major depression, excluding those with a history of treatment-resistant depression, who were randomized either to a once-daily dose of 30 mg of SAGE-217, a synthetic neurosteroid that acts as a positive allosteric modulator of GABAA receptors, or placebo for 14 days. Thirty-six of the 45 patients in the SAGE-217 group were black, as were 28 of the 44 patients in the placebo group, reported Handan Gunduz-Bruce, MD, of Sage Therapeutics and coauthors. Their study was published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“One hypothesis for the mechanism of depression implicates deficits in gamma-aminobutyric acid and downstream alterations in monoaminergic neurotransmission,” wrote Dr. Gunduz-Bruce and coauthors. “Preclinical studies have shown that the naturally occurring neurosteroid allopregnanolone is a positive allosteric modulator of synaptic and extrasynaptic GABAA receptors that affects both phasic and tonic inhibition of neurons.”

At day 15 of the study, there was a significantly greater mean change from baseline in Hamilton Depression Rating Scale scores in the treatment group, compared with the placebo group (–17.4 vs. –10.3, P less than .001), and 79% of participants in the treatment arm showed a greater than 50% reduction in depression scores, compared with 41% of the placebo group.

At day 28, 62% of the treatment group and 46% of the placebo group had a reduction of more than 50% from baseline depression scores.

No serious or severe adverse events were seen in either group, and the most common adverse events in the SAGE-217 group included headache (18%), dizziness (11%), and nausea (11%). One patient in the treatment arm also reported euphoria.

The authors commented that somnolence and sedation were expected adverse events, based on the pharmacological properties of SAGE-217.

Six patients in the treatment arm also had dose reductions as a result of adverse events. Two patients in the SAGE-217 arm stopped treatment because they met prespecified criteria for discontinuation; the investigators reported nausea, dizziness, and headache in one patient, and increased levels of alkaline phosphatase, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and gamma-glutamyltransferase in the other. However, the second patient had shown mildly elevated values of these at baseline, was asymptomatic throughout the trial, and the patient’s values returned to baseline or near-baseline after stopping treatment.

About one-quarter of both the SAGE-217 and placebo groups were receiving antidepressant treatment at baseline (27% and 23% respectively), with the duration of prior treatment ranging from 2 to 48 months. Investigators also gave three patients in the treatment arm and 11 in the placebo arm concomitant antidepressants during the follow-up period.

The small sample size and limited racial diversity among the participants were cited as limitations.

The study was supported by SAGE-217 manufacturer Sage Therapeutics. Ten authors were employees or directors of Sage Therapeutics, with stock options and patent interests. Three authors declared grants, personal fees, or advisory board positions with the pharmaceutical sector, including from Sage, and one also declared interest in a range of patents outside the study. One author had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Gunduz-Bruce H et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 5;381:903-11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1815981.

A new oral antidepressant that targets the gamma-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptors in the brain has been found to achieve a reduction in symptoms in adult patients with moderate to severe major depressive disorder, with no serious safety signals, results of a double-blind, phase 2 trial show.

The study involved 89 participants with major depression, excluding those with a history of treatment-resistant depression, who were randomized either to a once-daily dose of 30 mg of SAGE-217, a synthetic neurosteroid that acts as a positive allosteric modulator of GABAA receptors, or placebo for 14 days. Thirty-six of the 45 patients in the SAGE-217 group were black, as were 28 of the 44 patients in the placebo group, reported Handan Gunduz-Bruce, MD, of Sage Therapeutics and coauthors. Their study was published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“One hypothesis for the mechanism of depression implicates deficits in gamma-aminobutyric acid and downstream alterations in monoaminergic neurotransmission,” wrote Dr. Gunduz-Bruce and coauthors. “Preclinical studies have shown that the naturally occurring neurosteroid allopregnanolone is a positive allosteric modulator of synaptic and extrasynaptic GABAA receptors that affects both phasic and tonic inhibition of neurons.”

At day 15 of the study, there was a significantly greater mean change from baseline in Hamilton Depression Rating Scale scores in the treatment group, compared with the placebo group (–17.4 vs. –10.3, P less than .001), and 79% of participants in the treatment arm showed a greater than 50% reduction in depression scores, compared with 41% of the placebo group.

At day 28, 62% of the treatment group and 46% of the placebo group had a reduction of more than 50% from baseline depression scores.

No serious or severe adverse events were seen in either group, and the most common adverse events in the SAGE-217 group included headache (18%), dizziness (11%), and nausea (11%). One patient in the treatment arm also reported euphoria.

The authors commented that somnolence and sedation were expected adverse events, based on the pharmacological properties of SAGE-217.

Six patients in the treatment arm also had dose reductions as a result of adverse events. Two patients in the SAGE-217 arm stopped treatment because they met prespecified criteria for discontinuation; the investigators reported nausea, dizziness, and headache in one patient, and increased levels of alkaline phosphatase, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and gamma-glutamyltransferase in the other. However, the second patient had shown mildly elevated values of these at baseline, was asymptomatic throughout the trial, and the patient’s values returned to baseline or near-baseline after stopping treatment.

About one-quarter of both the SAGE-217 and placebo groups were receiving antidepressant treatment at baseline (27% and 23% respectively), with the duration of prior treatment ranging from 2 to 48 months. Investigators also gave three patients in the treatment arm and 11 in the placebo arm concomitant antidepressants during the follow-up period.

The small sample size and limited racial diversity among the participants were cited as limitations.

The study was supported by SAGE-217 manufacturer Sage Therapeutics. Ten authors were employees or directors of Sage Therapeutics, with stock options and patent interests. Three authors declared grants, personal fees, or advisory board positions with the pharmaceutical sector, including from Sage, and one also declared interest in a range of patents outside the study. One author had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Gunduz-Bruce H et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 5;381:903-11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1815981.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Taking SAGE-217 – a new oral antidepressant – for 14 days leads to reductions in depressive symptoms at day 15.

Major finding: Treatment with SAGE-217 was associated with significantly greater improvements in depression scores, compared with placebo.

Study details: Phase 2, randomized, placebo-controlled trial in 89 patients with major depression.

Disclosures: The study was supported by SAGE-217 manufacturer Sage Therapeutics. Ten authors were employees or directors of Sage Therapeutics, with stock options and patent interests. Three authors declared grants, personal fees, or advisory board positions with the pharmaceutical sector, including from Sage, and one also declared interest in a range of patents outside the study. One author had no disclosures.

Source: Gunduz-Bruce H et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 5;381:903-11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1815981.

Mitapivat elicits positive response in pyruvate kinase deficiency

Mitapivat showed positive safety and efficacy outcomes in patients with pyruvate kinase deficiency, according to results from a phase 2 trial.

After 24 weeks of treatment, the therapy was associated with a rapid rise in hemoglobin levels in 50% of study participants, while the majority of toxicities reported were transient and low grade.

“The primary objective of this study was to assess the safety and side-effect profile of mitapivat administration in patients with pyruvate kinase deficiency,” wrote Rachael F. Grace, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School, Boston, and coinvestigators. The findings were published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The uncontrolled study included 52 adults with pyruvate kinase deficiency who were not undergoing regular transfusions.

The median age at baseline was 34 years (range, 18-61 years), 62% of patients were male, and the median baseline hemoglobin level was 8.9 g/dL (range, 6.5-12.3 g/dL). In addition, 73% and 83% of patients had previously undergone cholecystectomy and splenectomy, respectively.

Study patients received oral mitapivat at 50 mg or 300 mg twice weekly for a total of 24 weeks. Eligible participants were subsequently enrolled into an extension phase that continued to monitor safety.

At 24 weeks, the team reported that 26 patients – 50% – experienced a greater than 1.0-g/dL rise in hemoglobin levels, with a maximum mean increase of 3.4 g/dL (range, 1.1-5.8 g/dL). The first rise of greater than 1.0 g/dL was observed after a median duration of 10 days (range, 7-187 days).

Of the 26 patients, 20 had an increase from baseline of more than 1.0 g/dL at more than half of the assessment during the core study period. That met the definition for hemoglobin response, according to the researchers.

“The hemoglobin response was maintained in the 19 patients who were continuing to be treated in the extension phase, all of whom had at least 21.6 months of treatment,” they wrote.

With respect to safety, the majority of adverse events were of low severity (grade 1-2) and transient in nature, with most resolving within 7 days. The most frequently reported toxicities in the core period and extension phase were headache (46%), insomnia (42%), and nausea (40%). The most serious reported toxicities were pharyngitis (4%) and hemolytic anemia (4%).

“Patient-reported quality of life was not assessed in this phase 2 safety study, although such outcome measures are being evaluated in the ongoing phase 3 trials,” Dr. Grace and colleagues wrote. “This study establishes proof of concept for a molecular therapy targeting the underlying enzymatic defect of a hereditary enzymopathy,” they concluded.

Agios Pharmaceuticals funded the study. Dr. Grace reported research funding from and consulting for Agios, and several authors reported employment, consulting, or research funding with the company.

SOURCE: Grace RF et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:933-44.

Mitapivat showed positive safety and efficacy outcomes in patients with pyruvate kinase deficiency, according to results from a phase 2 trial.

After 24 weeks of treatment, the therapy was associated with a rapid rise in hemoglobin levels in 50% of study participants, while the majority of toxicities reported were transient and low grade.

“The primary objective of this study was to assess the safety and side-effect profile of mitapivat administration in patients with pyruvate kinase deficiency,” wrote Rachael F. Grace, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School, Boston, and coinvestigators. The findings were published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The uncontrolled study included 52 adults with pyruvate kinase deficiency who were not undergoing regular transfusions.

The median age at baseline was 34 years (range, 18-61 years), 62% of patients were male, and the median baseline hemoglobin level was 8.9 g/dL (range, 6.5-12.3 g/dL). In addition, 73% and 83% of patients had previously undergone cholecystectomy and splenectomy, respectively.

Study patients received oral mitapivat at 50 mg or 300 mg twice weekly for a total of 24 weeks. Eligible participants were subsequently enrolled into an extension phase that continued to monitor safety.

At 24 weeks, the team reported that 26 patients – 50% – experienced a greater than 1.0-g/dL rise in hemoglobin levels, with a maximum mean increase of 3.4 g/dL (range, 1.1-5.8 g/dL). The first rise of greater than 1.0 g/dL was observed after a median duration of 10 days (range, 7-187 days).

Of the 26 patients, 20 had an increase from baseline of more than 1.0 g/dL at more than half of the assessment during the core study period. That met the definition for hemoglobin response, according to the researchers.

“The hemoglobin response was maintained in the 19 patients who were continuing to be treated in the extension phase, all of whom had at least 21.6 months of treatment,” they wrote.

With respect to safety, the majority of adverse events were of low severity (grade 1-2) and transient in nature, with most resolving within 7 days. The most frequently reported toxicities in the core period and extension phase were headache (46%), insomnia (42%), and nausea (40%). The most serious reported toxicities were pharyngitis (4%) and hemolytic anemia (4%).

“Patient-reported quality of life was not assessed in this phase 2 safety study, although such outcome measures are being evaluated in the ongoing phase 3 trials,” Dr. Grace and colleagues wrote. “This study establishes proof of concept for a molecular therapy targeting the underlying enzymatic defect of a hereditary enzymopathy,” they concluded.

Agios Pharmaceuticals funded the study. Dr. Grace reported research funding from and consulting for Agios, and several authors reported employment, consulting, or research funding with the company.

SOURCE: Grace RF et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:933-44.

Mitapivat showed positive safety and efficacy outcomes in patients with pyruvate kinase deficiency, according to results from a phase 2 trial.

After 24 weeks of treatment, the therapy was associated with a rapid rise in hemoglobin levels in 50% of study participants, while the majority of toxicities reported were transient and low grade.

“The primary objective of this study was to assess the safety and side-effect profile of mitapivat administration in patients with pyruvate kinase deficiency,” wrote Rachael F. Grace, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School, Boston, and coinvestigators. The findings were published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The uncontrolled study included 52 adults with pyruvate kinase deficiency who were not undergoing regular transfusions.

The median age at baseline was 34 years (range, 18-61 years), 62% of patients were male, and the median baseline hemoglobin level was 8.9 g/dL (range, 6.5-12.3 g/dL). In addition, 73% and 83% of patients had previously undergone cholecystectomy and splenectomy, respectively.

Study patients received oral mitapivat at 50 mg or 300 mg twice weekly for a total of 24 weeks. Eligible participants were subsequently enrolled into an extension phase that continued to monitor safety.

At 24 weeks, the team reported that 26 patients – 50% – experienced a greater than 1.0-g/dL rise in hemoglobin levels, with a maximum mean increase of 3.4 g/dL (range, 1.1-5.8 g/dL). The first rise of greater than 1.0 g/dL was observed after a median duration of 10 days (range, 7-187 days).

Of the 26 patients, 20 had an increase from baseline of more than 1.0 g/dL at more than half of the assessment during the core study period. That met the definition for hemoglobin response, according to the researchers.

“The hemoglobin response was maintained in the 19 patients who were continuing to be treated in the extension phase, all of whom had at least 21.6 months of treatment,” they wrote.

With respect to safety, the majority of adverse events were of low severity (grade 1-2) and transient in nature, with most resolving within 7 days. The most frequently reported toxicities in the core period and extension phase were headache (46%), insomnia (42%), and nausea (40%). The most serious reported toxicities were pharyngitis (4%) and hemolytic anemia (4%).

“Patient-reported quality of life was not assessed in this phase 2 safety study, although such outcome measures are being evaluated in the ongoing phase 3 trials,” Dr. Grace and colleagues wrote. “This study establishes proof of concept for a molecular therapy targeting the underlying enzymatic defect of a hereditary enzymopathy,” they concluded.

Agios Pharmaceuticals funded the study. Dr. Grace reported research funding from and consulting for Agios, and several authors reported employment, consulting, or research funding with the company.

SOURCE: Grace RF et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:933-44.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Major finding: At 24 weeks, 50% of patients experienced a greater than 1.0-g/dL rise in hemoglobin levels, with a maximum mean increase of 3.4 g/dL (range, 1.1-5.8 g/dL).

Study details: A phase 2 study of 52 patients with pyruvate kinase deficiency.

Disclosures: Agios Pharmaceuticals funded the study. Dr. Grace reported research funding from and consulting for Agios, and several authors reported employment, consulting, or research funding with the company.

Source: Grace RF et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:933-44.

Embryologic development of the external genitalia as it relates to vaginoplasty for the transgender woman

Women with epilepsy: 5 clinical pearls for contraception and preconception counseling

In 2015, 1.2% of the US population was estimated to have active epilepsy.1 For neurologists, key goals in the treatment of epilepsy include: controlling seizures, minimizing adverse effects of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) and optimizing quality of life. For obstetrician-gynecologists, women with epilepsy (WWE) have unique contraceptive, preconception, and obstetric needs that require highly specialized approaches to care. Here, I highlight 5 care points that are important to keep in mind when counseling WWE.

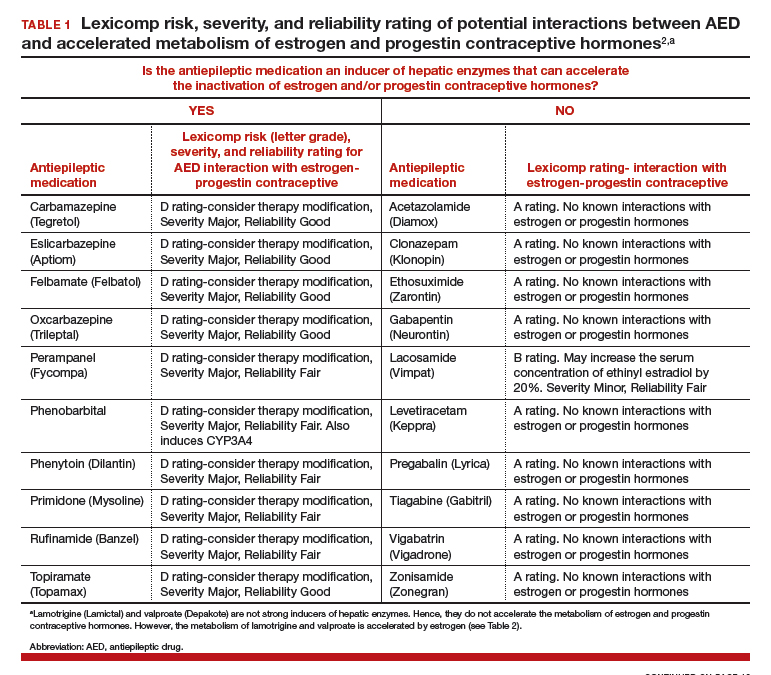

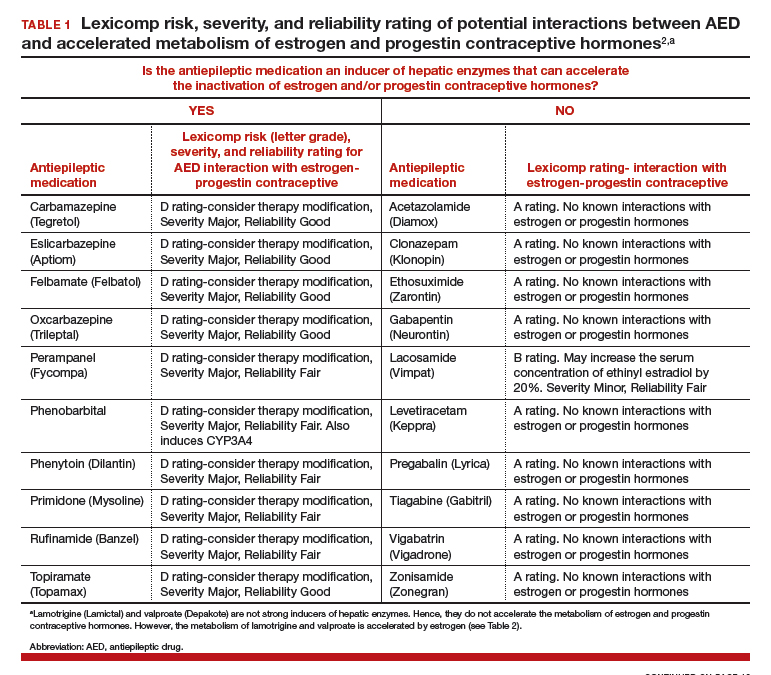

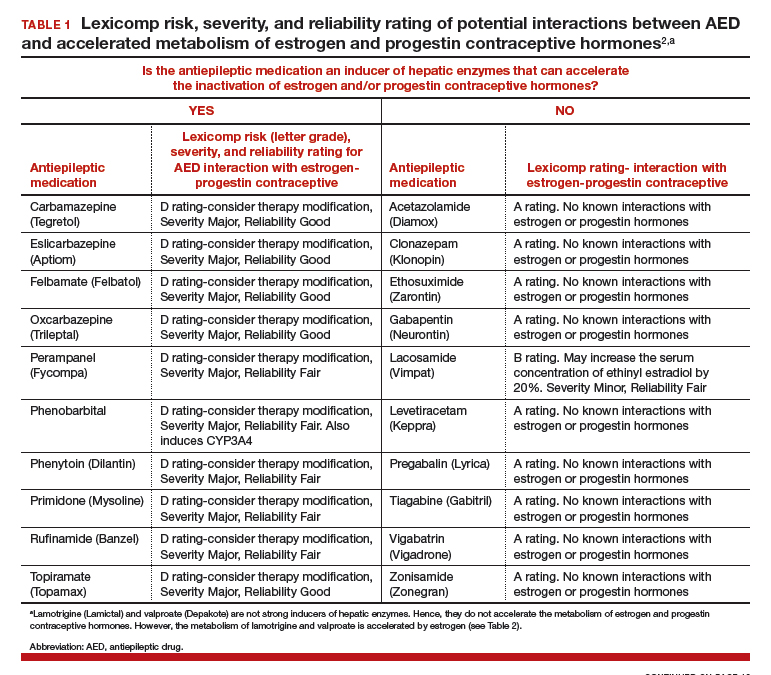

1. Enzyme-inducing AEDs reduce the effectiveness of estrogen-progestin and some progestin contraceptives.

AEDs can induce hepatic enzymes that accelerate steroid hormone metabolism, producing clinically important reductions in bioavailable steroid hormone concentration (TABLE 1). According to Lexicomp, AEDs that are inducers of hepatic enzymes that metabolize steroid hormones include: carbamazepine (Tegretol), eslicarbazepine (Aptiom), felbamate (Felbatol), oxcarbazepine (Trileptal), perampanel (Fycompa), phenobarbital, phenytoin (Dilantin), primidone (Mysoline), rufinamide (Banzel), and topiramate (Topamax) (at dosages >200 mg daily). According to Lexicomp, the following AEDs do not cause clinically significant changes in hepatic enzymes that metabolize steroid hormones: acetazolamide (Diamox), clonazepam (Klonopin), ethosuximide (Zarontin), gabapentin (Neurontin), lacosamide (Vimpat), levetiracetam (Keppra), pregabalin (Lyrica), tiagabine (Gabitril), vigabatrin (Vigadrone), and zonisamide (Zonegran).2,3 In addition, lamotrigine (Lamictal) and valproate (Depakote) do not significantly influence the metabolism of contraceptive steroids,4,5 but contraceptive steroids significantly influence their metabolism (TABLE 2).

For WWE taking an AED that accelerates steroid hormone metabolism, estrogen-progestin contraceptive failure is common. In a survey of 111 WWE taking both an oral contraceptive and an AED, 27 reported becoming pregnant while taking the oral contraceptive.6 Carbamazepine, a strong inducer of hepatic enzymes, was the most frequently used AED in this sample.

Many studies report that carbamazepine accelerates the metabolisms of estrogen and progestins and reduces contraceptive efficacy. For example, in one study 20 healthy women were administered an ethinyl estradiol (20 µg)-levonorgestrel (100 µg) contraceptive, and randomly assigned to either receive carbamazepine 600 mg daily or a placebo pill.7 In this study, based on serum progesterone measurements, 5 of 10 women in the carbamazepine group ovulated, compared with 1 of 10 women in the placebo group. Women taking carbamazepine had integrated serum ethinyl estradiol and levonorgestrel concentrations approximately 45% lower than women taking placebo.7 Other studies also report that carbamazepine accelerates steroid hormone metabolism and reduces the circulating concentration of ethinyl estradiol, norethindrone, and levonorgestrel by about 50%.5,8

WWE taking an AED that induces hepatic enzymes should be counseled to use a copper or levonorgestrel (LNG) intrauterine device (IUD) or depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) for contraception.9 WWE taking AEDs that do not induce hepatic enzymes can be offered the full array of contraceptive options, as outlined in Table 1. Occasionally, a WWE taking an AED that is an inducer of hepatic enzymes may strongly prefer to use an estrogen-progestin contraceptive and decline the preferred option of using an IUD or DMPA. If an estrogen-progestin contraceptive is to be prescribed, safeguards to reduce the risk of pregnancy include:

- prescribe a contraceptive with ≥35 µg of ethinyl estradiol

- prescribe a contraceptive with the highest dose of progestin with a long half-life (drospirenone, desogestrel, levonorgestrel)

- consider continuous hormonal contraception rather than 4 or 7 days off hormones and

- recommend use of a barrier contraceptive in addition to the hormonal contraceptive.

The effectiveness of levonorgestrel emergency contraception may also be reduced in WWE taking an enzyme-inducing AED. In these cases, some experts recommend a regimen of two doses of levonorgestrel 1.5 mg, separated by 12 hours.10 The effectiveness of progestin subdermal contraceptives may be reduced in women taking phenytoin. In one study of 9 WWE using a progestin subdermal implant, phenytoin reduced the circulating levonorgestrel level by approximately 40%.11

Continue to: 2. Do not use lamotrigine with cyclic estrogen-progestin contraceptives...

2. Do not use lamotrigine with cyclic estrogen-progestin contraceptives.

Estrogens, but not progestins, are known to reduce the serum concentration of lamotrigine by about 50%.12,13 This is a clinically significant pharmacologic interaction. Consequently, when a cyclic estrogen-progestin contraceptive is prescribed to a woman taking lamotrigine, oscillation in lamotrigine serum concentration can occur. When the woman is taking estrogen-containing pills, lamotrigine levels decrease, which increases the risk of seizure. When the woman is not taking the estrogen-containing pills, lamotrigine levels increase, possibly causing such adverse effects as nausea and vomiting. If a woman taking lamotrigine insists on using an estrogen-progestin contraceptive, the medication should be prescribed in a continuous regimen and the neurologist alerted so that they can increase the dose of lamotrigine and intensify their monitoring of lamotrigine levels. Lamotrigine does not change the metabolism of ethinyl estradiol and has minimal impact on the metabolism of levonorgestrel.4

3. Estrogen-progestin contraceptives require valproate dosage adjustment.

A few studies report that estrogen-progestin contraceptives accelerate the metabolism of valproate and reduce circulating valproate concentration,14,15 as noted in Table 2.In one study, estrogen-progestin contraceptive was associated with 18% and 29% decreases in total and unbound valproate concentrations, respectively.14 Valproate may induce polycystic ovary syndrome in women.16 Therefore, it is common that valproate and an estrogen-progestin contraceptive are co-prescribed. In these situations, the neurologist should be alerted prior to prescribing an estrogen-progestin contraceptive to WWE taking valproate so that dosage adjustment may occur, if indicated. Valproate does not appear to change the metabolism of ethinyl estradiol or levonorgestrel.5

4. Preconception counseling: Before conception consider using an AED with low teratogenicity.

Valproate is a potent teratogen, and consideration should be given to discontinuing valproate prior to conception. In a study of 1,788 pregnancies exposed to valproate, the risk of a major congenital malformation was 10% for valproate monotherapy, 11.3% for valproate combined with lamotrigine, and 11.7% for valproate combined with another AED, but not lamotrigine.17 At a valproate dose of ≥1,500 mg daily, the risk of major malformation was 24% for valproate monotherapy, 31% for valproate plus lamotrigine, and 19% for valproate plus another AED, but not lamotrigine.17 Valproate is reported to be associated with the following major congenital malformations: spina bifida, ventricular and atrial septal defects, pulmonary valve atresia, hypoplastic left heart syndrome, cleft palate, anorectal atresia, and hypospadias.18

In a study of 7,555 pregnancies in women using a single AED, the risk of major congenital anomalies varied greatly among the AEDs, including: valproate (10.3%), phenobarbital (6.5%), phenytoin (6.4%), carbamazepine (5.5%), topiramate (3.9%), oxcarbazepine (3.0%), lamotrigine (2.9%), and levetiracetam (2.8%).19 For WWE considering pregnancy, many experts recommend use of lamotrigine, levetiracetam, or oxcarbazepine to minimize the risk of fetal anomalies.

Continue to: 5. Folic acid...

5. Folic acid: Although the optimal dose for WWE taking an AED and planning to become pregnant is unknown, a high dose is reasonable.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that women planning pregnancy take 0.4 mg of folic acid daily, starting at least 1 month before pregnancy and continuing through at least the 12th week of gestation.20 ACOG also recommends that women at high risk of a neural tube defect should take 4 mg of folic acid daily. WWE taking a teratogenic AED are known to be at increased risk for fetal malformations, including neural tube defects. Should these women take 4 mg of folic acid daily? ACOG notes that, for women taking valproate, the benefit of high-dose folic acid (4 mg daily) has not been definitively proven,21 and guidelines from the American Academy of Neurology do not recommend high-dose folic acid for women receiving AEDs.22 Hence, ACOG does not recommend that WWE taking an AED take high-dose folic acid.

By contrast, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (RCOG) recommends that all WWE planning a pregnancy take folic acid 5 mg daily, initiated 3 months before conception and continued through the first trimester of pregnancy.23 The RCOG notes that among WWE taking an AED, intelligence quotient is greater in children whose mothers took folic acid during pregnancy.24 Given the potential benefit of folic acid on long-term outcomes and the known safety of folic acid, it is reasonable to recommend high-dose folic acid for WWE.

Final takeaways

Surveys consistently report that WWE have a low-level of awareness about the interaction between AEDs and hormonal contraceptives and the teratogenicity of AEDs. For example, in a survey of 2,000 WWE, 45% who were taking an enzyme-inducing AED and an estrogen-progestin oral contraceptive reported that they had not been warned about the potential interaction between the medications.25 Surprisingly, surveys of neurologists and obstetrician-gynecologists also report that there is a low level of awareness about the interaction between AEDs and hormonal contraceptives.26 When providing contraceptive counseling for WWE, prioritize the use of a copper or levonorgestrel IUD. When providing preconception counseling for WWE, educate the patient about the high teratogenicity of valproate and the lower risk of malformations associated with the use of lamotrigine, levetiracetam, and oxcarbazepine.

For most women with epilepsy, maintaining a valid driver's license is important for completion of daily life tasks. Most states require that a patient with seizures be seizure-free for 6 to 12 months to operate a motor vehicle. Estrogen-containing hormonal contraceptives can reduce the concentration of some AEDs, such as lamotrigine. Hence, it is important that the patient be aware of this interaction and that the primary neurologist be alerted if an estrogen-containing contraceptive is prescribed to a woman taking lamotrigine or valproate. Specific state laws related to epilepsy and driving are available at the Epilepsy Foundation website (https://www.epilepsy.com/driving-laws).

- Zack MM, Kobau R. National and state estimates of the numbers of adults and children with active epilepsy - United States 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:821-825.

- Lexicomp. https://www.wolterskluwercdi.com/lexicomp-online/. Accessed August 16, 2019.

- Reimers A, Brodtkorb E, Sabers A. Interactions between hormonal contraception and antiepileptic drugs: clinical and mechanistic considerations. Seizure. 2015;28:66-70.