User login

Bevacizumab-erlotinib combo falls short in EGFR-mutant advanced NSCLC

according to a multicenter, phase 2, randomized, controlled trial.

“The development of erlotinib as a first-line therapy was an important advance, but there was interest in improving the efficacy of erlotinib,” noted the investigators, led by Thomas E. Stinchcombe, MD, of the Duke Cancer Institute in Durham, N.C. Preclinical data suggested that adding an antiangiogenic agent could overcome resistance, and subgroup analyses of a phase 3 trial hinted at greater efficacy of this combination in patients with EGFR-mutant disease (Lancet. 2011;377:1846-54).

The new trial was conducted among 88 patients with previously untreated stage 4 EGFR-mutant NSCLC eligible to receive bevacizumab. Two-thirds had an EGFR exon 19 deletion.

The patients were assigned evenly to receive erlotinib (Tarceva), an EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor, either alone or in combination with bevacizumab (Avastin), an antibody directed against vascular endothelial growth factor.

Results reported in JAMA Oncology showed that, during a median follow-up of 33 months, median progression-free survival (PFS) – the trial’s primary endpoint – was 17.9 months with the combination and 13.5 months with erlotinib alone, a nonsignificant difference (hazard ratio, 0.81; P = .39).

There was also no significant difference between groups in objective response rate (81% vs. 83%; P = .81) and overall survival (median, 32.4 vs. 50.6 months; HR, 1.41; P = .33).

Relative to the erlotinib monotherapy group, the combination therapy group had higher rates of grade 3 or worse acneiform rash (26% vs. 16%), hypertension (40% vs. 20%), and proteinuria (12% vs. 0%), but a lower rate of grade 3 or worse diarrhea (9% vs. 13%).

“Our study, unlike previous randomized clinical trials, did not reveal a significant improvement in PFS with the combination of erlotinib and bevacizumab. ... One consideration is that our trial used investigator assessment of response and disease progression, whereas previous randomized trials used blinded independent radiologic review,” Dr. Stinchcombe and coinvestigators summarized.

“Future studies will investigate novel osimertinib [Tagrisso] combinations and molecular markers to identify patients most likely to experience disease progression with single-agent EGFR TKIs,” they concluded.

Dr. Stinchcombe reported no relevant conflicts of interest. The trial was supported by Genentech/Roche.

SOURCE: Stinchcombe TE et al. JAMA Oncol. 2019 Aug 8. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1847.

according to a multicenter, phase 2, randomized, controlled trial.

“The development of erlotinib as a first-line therapy was an important advance, but there was interest in improving the efficacy of erlotinib,” noted the investigators, led by Thomas E. Stinchcombe, MD, of the Duke Cancer Institute in Durham, N.C. Preclinical data suggested that adding an antiangiogenic agent could overcome resistance, and subgroup analyses of a phase 3 trial hinted at greater efficacy of this combination in patients with EGFR-mutant disease (Lancet. 2011;377:1846-54).

The new trial was conducted among 88 patients with previously untreated stage 4 EGFR-mutant NSCLC eligible to receive bevacizumab. Two-thirds had an EGFR exon 19 deletion.

The patients were assigned evenly to receive erlotinib (Tarceva), an EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor, either alone or in combination with bevacizumab (Avastin), an antibody directed against vascular endothelial growth factor.

Results reported in JAMA Oncology showed that, during a median follow-up of 33 months, median progression-free survival (PFS) – the trial’s primary endpoint – was 17.9 months with the combination and 13.5 months with erlotinib alone, a nonsignificant difference (hazard ratio, 0.81; P = .39).

There was also no significant difference between groups in objective response rate (81% vs. 83%; P = .81) and overall survival (median, 32.4 vs. 50.6 months; HR, 1.41; P = .33).

Relative to the erlotinib monotherapy group, the combination therapy group had higher rates of grade 3 or worse acneiform rash (26% vs. 16%), hypertension (40% vs. 20%), and proteinuria (12% vs. 0%), but a lower rate of grade 3 or worse diarrhea (9% vs. 13%).

“Our study, unlike previous randomized clinical trials, did not reveal a significant improvement in PFS with the combination of erlotinib and bevacizumab. ... One consideration is that our trial used investigator assessment of response and disease progression, whereas previous randomized trials used blinded independent radiologic review,” Dr. Stinchcombe and coinvestigators summarized.

“Future studies will investigate novel osimertinib [Tagrisso] combinations and molecular markers to identify patients most likely to experience disease progression with single-agent EGFR TKIs,” they concluded.

Dr. Stinchcombe reported no relevant conflicts of interest. The trial was supported by Genentech/Roche.

SOURCE: Stinchcombe TE et al. JAMA Oncol. 2019 Aug 8. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1847.

according to a multicenter, phase 2, randomized, controlled trial.

“The development of erlotinib as a first-line therapy was an important advance, but there was interest in improving the efficacy of erlotinib,” noted the investigators, led by Thomas E. Stinchcombe, MD, of the Duke Cancer Institute in Durham, N.C. Preclinical data suggested that adding an antiangiogenic agent could overcome resistance, and subgroup analyses of a phase 3 trial hinted at greater efficacy of this combination in patients with EGFR-mutant disease (Lancet. 2011;377:1846-54).

The new trial was conducted among 88 patients with previously untreated stage 4 EGFR-mutant NSCLC eligible to receive bevacizumab. Two-thirds had an EGFR exon 19 deletion.

The patients were assigned evenly to receive erlotinib (Tarceva), an EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor, either alone or in combination with bevacizumab (Avastin), an antibody directed against vascular endothelial growth factor.

Results reported in JAMA Oncology showed that, during a median follow-up of 33 months, median progression-free survival (PFS) – the trial’s primary endpoint – was 17.9 months with the combination and 13.5 months with erlotinib alone, a nonsignificant difference (hazard ratio, 0.81; P = .39).

There was also no significant difference between groups in objective response rate (81% vs. 83%; P = .81) and overall survival (median, 32.4 vs. 50.6 months; HR, 1.41; P = .33).

Relative to the erlotinib monotherapy group, the combination therapy group had higher rates of grade 3 or worse acneiform rash (26% vs. 16%), hypertension (40% vs. 20%), and proteinuria (12% vs. 0%), but a lower rate of grade 3 or worse diarrhea (9% vs. 13%).

“Our study, unlike previous randomized clinical trials, did not reveal a significant improvement in PFS with the combination of erlotinib and bevacizumab. ... One consideration is that our trial used investigator assessment of response and disease progression, whereas previous randomized trials used blinded independent radiologic review,” Dr. Stinchcombe and coinvestigators summarized.

“Future studies will investigate novel osimertinib [Tagrisso] combinations and molecular markers to identify patients most likely to experience disease progression with single-agent EGFR TKIs,” they concluded.

Dr. Stinchcombe reported no relevant conflicts of interest. The trial was supported by Genentech/Roche.

SOURCE: Stinchcombe TE et al. JAMA Oncol. 2019 Aug 8. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1847.

FROM JAMA ONCOLOGY

PROMIS tools provide useful data for managing rheumatology patients

LAKE BUENA VISTA, FLA. –

The PROMIS tools – which like most patient-reported outcome (PRO) measurement tools are designed to evaluate and monitor physical, mental, and social health – can be used both for the general population and for individuals living with chronic conditions, Dr. Curtis, professor of medicine in the division of clinical immunology and rheumatology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB), said at the annual meeting of the Florida Society of Rheumatology.

The tools take a deeper dive into various symptoms and their effects; for instance, with respect to physical health, they measure fatigue, physical function, sleep disturbance, pain intensity, and pain interference – the extent to which pain “messes your patient’s life up,” explained Dr. Curtis, who also is codirector of the UAB Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics Unit.

Additional physical health domains that PROs measure include dyspnea, gastrointestinal symptoms, pain behavior, pain quality, sexual function, and sleep-related impairment.

These are “things that, honestly, we don’t talk about much as a field, but absolutely affect patients with autoimmune diseases,” he said. “You know, sexual function – that doesn’t come up in my practice spontaneously very often, but there are ways you can quantify that, and for many patients that’s actually a big deal.”

The domains measured by PROMIS tools for mental health look at anxiety and depression, but also delve into alcohol use, anger, cognitive function, life satisfaction, self-efficacy for managing chronic conditions, substance use, and more. The domains for social health address ability to participate in social roles and activities, as well as companionship, satisfaction with social roles and activity, social isolation, and social support.

“You can’t go on a hike with friends [and] be far from a bathroom, because you have bad arthritis and you have Crohn’s disease. Well, that’s kind of an important thing that may or may not come up in your discussions about inflammatory arthritis associated with [inflammatory bowel disease],” he said.

Another example is a patient who is embarrassed attending social functions or wearing a swimsuit because of really bad psoriasis.

“These are the kinds of things that I’m suggesting you and I probably want to measure if we’re providing holistic care to rheumatology patients,” Dr. Curtis said.

The PROMIS tools provide a simple, user-friendly means for doing so in English, Spanish, and many other languages, he noted.

All the scales use the same 1-100 scoring range, which simplifies measurements. They are available for free by download and can be printed or used electronically for use in the office, at home, on the web, and via smartphone.

The NIH developed the PROMIS tools several years ago and validated them for multiple chronic disease populations, Dr. Curtis said, adding that the tools include multiple individual domains and overall “profiles” of varying lengths.

Most are fixed-length scales that are between 4 and 10 questions and can be completed within 30-60 seconds per scale, so several scales can be completed within 5-10 minutes.

However, some scales are longer and provide greater detail.

“The nice thing is that if you ask a few more questions you can get more precise information – there’s more of a floor and ceiling. You can detect people who do really well. You can distinguish between the marathon runners and the 5K-ers and the people who can walk 2 miles but aren’t going to run a race,” he explained.

Further, the PROMIS tools, like the 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36), are benchmarked against the U.S. adult population, allowing for assessment of how a specific drug or treatment “impacts your arthritis patient on a scale that would also be relevant for somebody who doesn’t have arthritis, they have diabetes.”

The metrics and scales are the same, and that can be helpful when trying to get a payer to pay for a particular drug, he said.

“None of these are rheumatology specific; this puts PROs into a language that can help rheumatology contend for the value of the care that we provide on a scale that would be relevant for any other chronic illness, even for nonrheumatology patients,” he explained.

In addition, minimally important differences (group mean change of about 2-3 units) and minimally clinical important differences for individuals (5 units) have been established.

“So we know what the numbers mean, and this is true for all of the scales,” he said.

PROMIS tools also include computer-adaptive testing (CAT) versions, which helps to personalize the scales to provide more precise information for a given patient and eliminate irrelevant information.

Of note, PROMIS health measures are among the data that can be tracked on a smartphone using Arthritis Power, an arthritis research registry developed with the help of a recent infrastructure grant awarded to the Center for Education and Research and Therapeutics of Musculoskeletal Disorders at UAB, Dr. Curtis said.

The measures were also shown in the AWARE study to track closely with other measures, including the Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI), and with patient improvement on therapy.

“So these PROMIS scores are tracking with things that you and I are familiar with ... and it looks like these scores are faithfully tracking, over time, patients getting better on therapies that we would expect them to,” he said. “I think this is additional validation – not just from the National Institutes of Health and a decade of research by lots of different groups, but in our own field – that these actually correlate with disease activity ... and that when you start an effective therapy like a [tumor necrosis factor inhibitor] they’re going to improve as you would anticipate.”

Dr. Curtis reported funding from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. He has also consulted for or received research grants from Amgen, AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, CORRONA, Lilly, Janssen, Myriad, Novartis, Roche, Pfizer, and Sanofi/Regeneron.

LAKE BUENA VISTA, FLA. –

The PROMIS tools – which like most patient-reported outcome (PRO) measurement tools are designed to evaluate and monitor physical, mental, and social health – can be used both for the general population and for individuals living with chronic conditions, Dr. Curtis, professor of medicine in the division of clinical immunology and rheumatology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB), said at the annual meeting of the Florida Society of Rheumatology.

The tools take a deeper dive into various symptoms and their effects; for instance, with respect to physical health, they measure fatigue, physical function, sleep disturbance, pain intensity, and pain interference – the extent to which pain “messes your patient’s life up,” explained Dr. Curtis, who also is codirector of the UAB Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics Unit.

Additional physical health domains that PROs measure include dyspnea, gastrointestinal symptoms, pain behavior, pain quality, sexual function, and sleep-related impairment.

These are “things that, honestly, we don’t talk about much as a field, but absolutely affect patients with autoimmune diseases,” he said. “You know, sexual function – that doesn’t come up in my practice spontaneously very often, but there are ways you can quantify that, and for many patients that’s actually a big deal.”

The domains measured by PROMIS tools for mental health look at anxiety and depression, but also delve into alcohol use, anger, cognitive function, life satisfaction, self-efficacy for managing chronic conditions, substance use, and more. The domains for social health address ability to participate in social roles and activities, as well as companionship, satisfaction with social roles and activity, social isolation, and social support.

“You can’t go on a hike with friends [and] be far from a bathroom, because you have bad arthritis and you have Crohn’s disease. Well, that’s kind of an important thing that may or may not come up in your discussions about inflammatory arthritis associated with [inflammatory bowel disease],” he said.

Another example is a patient who is embarrassed attending social functions or wearing a swimsuit because of really bad psoriasis.

“These are the kinds of things that I’m suggesting you and I probably want to measure if we’re providing holistic care to rheumatology patients,” Dr. Curtis said.

The PROMIS tools provide a simple, user-friendly means for doing so in English, Spanish, and many other languages, he noted.

All the scales use the same 1-100 scoring range, which simplifies measurements. They are available for free by download and can be printed or used electronically for use in the office, at home, on the web, and via smartphone.

The NIH developed the PROMIS tools several years ago and validated them for multiple chronic disease populations, Dr. Curtis said, adding that the tools include multiple individual domains and overall “profiles” of varying lengths.

Most are fixed-length scales that are between 4 and 10 questions and can be completed within 30-60 seconds per scale, so several scales can be completed within 5-10 minutes.

However, some scales are longer and provide greater detail.

“The nice thing is that if you ask a few more questions you can get more precise information – there’s more of a floor and ceiling. You can detect people who do really well. You can distinguish between the marathon runners and the 5K-ers and the people who can walk 2 miles but aren’t going to run a race,” he explained.

Further, the PROMIS tools, like the 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36), are benchmarked against the U.S. adult population, allowing for assessment of how a specific drug or treatment “impacts your arthritis patient on a scale that would also be relevant for somebody who doesn’t have arthritis, they have diabetes.”

The metrics and scales are the same, and that can be helpful when trying to get a payer to pay for a particular drug, he said.

“None of these are rheumatology specific; this puts PROs into a language that can help rheumatology contend for the value of the care that we provide on a scale that would be relevant for any other chronic illness, even for nonrheumatology patients,” he explained.

In addition, minimally important differences (group mean change of about 2-3 units) and minimally clinical important differences for individuals (5 units) have been established.

“So we know what the numbers mean, and this is true for all of the scales,” he said.

PROMIS tools also include computer-adaptive testing (CAT) versions, which helps to personalize the scales to provide more precise information for a given patient and eliminate irrelevant information.

Of note, PROMIS health measures are among the data that can be tracked on a smartphone using Arthritis Power, an arthritis research registry developed with the help of a recent infrastructure grant awarded to the Center for Education and Research and Therapeutics of Musculoskeletal Disorders at UAB, Dr. Curtis said.

The measures were also shown in the AWARE study to track closely with other measures, including the Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI), and with patient improvement on therapy.

“So these PROMIS scores are tracking with things that you and I are familiar with ... and it looks like these scores are faithfully tracking, over time, patients getting better on therapies that we would expect them to,” he said. “I think this is additional validation – not just from the National Institutes of Health and a decade of research by lots of different groups, but in our own field – that these actually correlate with disease activity ... and that when you start an effective therapy like a [tumor necrosis factor inhibitor] they’re going to improve as you would anticipate.”

Dr. Curtis reported funding from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. He has also consulted for or received research grants from Amgen, AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, CORRONA, Lilly, Janssen, Myriad, Novartis, Roche, Pfizer, and Sanofi/Regeneron.

LAKE BUENA VISTA, FLA. –

The PROMIS tools – which like most patient-reported outcome (PRO) measurement tools are designed to evaluate and monitor physical, mental, and social health – can be used both for the general population and for individuals living with chronic conditions, Dr. Curtis, professor of medicine in the division of clinical immunology and rheumatology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB), said at the annual meeting of the Florida Society of Rheumatology.

The tools take a deeper dive into various symptoms and their effects; for instance, with respect to physical health, they measure fatigue, physical function, sleep disturbance, pain intensity, and pain interference – the extent to which pain “messes your patient’s life up,” explained Dr. Curtis, who also is codirector of the UAB Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics Unit.

Additional physical health domains that PROs measure include dyspnea, gastrointestinal symptoms, pain behavior, pain quality, sexual function, and sleep-related impairment.

These are “things that, honestly, we don’t talk about much as a field, but absolutely affect patients with autoimmune diseases,” he said. “You know, sexual function – that doesn’t come up in my practice spontaneously very often, but there are ways you can quantify that, and for many patients that’s actually a big deal.”

The domains measured by PROMIS tools for mental health look at anxiety and depression, but also delve into alcohol use, anger, cognitive function, life satisfaction, self-efficacy for managing chronic conditions, substance use, and more. The domains for social health address ability to participate in social roles and activities, as well as companionship, satisfaction with social roles and activity, social isolation, and social support.

“You can’t go on a hike with friends [and] be far from a bathroom, because you have bad arthritis and you have Crohn’s disease. Well, that’s kind of an important thing that may or may not come up in your discussions about inflammatory arthritis associated with [inflammatory bowel disease],” he said.

Another example is a patient who is embarrassed attending social functions or wearing a swimsuit because of really bad psoriasis.

“These are the kinds of things that I’m suggesting you and I probably want to measure if we’re providing holistic care to rheumatology patients,” Dr. Curtis said.

The PROMIS tools provide a simple, user-friendly means for doing so in English, Spanish, and many other languages, he noted.

All the scales use the same 1-100 scoring range, which simplifies measurements. They are available for free by download and can be printed or used electronically for use in the office, at home, on the web, and via smartphone.

The NIH developed the PROMIS tools several years ago and validated them for multiple chronic disease populations, Dr. Curtis said, adding that the tools include multiple individual domains and overall “profiles” of varying lengths.

Most are fixed-length scales that are between 4 and 10 questions and can be completed within 30-60 seconds per scale, so several scales can be completed within 5-10 minutes.

However, some scales are longer and provide greater detail.

“The nice thing is that if you ask a few more questions you can get more precise information – there’s more of a floor and ceiling. You can detect people who do really well. You can distinguish between the marathon runners and the 5K-ers and the people who can walk 2 miles but aren’t going to run a race,” he explained.

Further, the PROMIS tools, like the 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36), are benchmarked against the U.S. adult population, allowing for assessment of how a specific drug or treatment “impacts your arthritis patient on a scale that would also be relevant for somebody who doesn’t have arthritis, they have diabetes.”

The metrics and scales are the same, and that can be helpful when trying to get a payer to pay for a particular drug, he said.

“None of these are rheumatology specific; this puts PROs into a language that can help rheumatology contend for the value of the care that we provide on a scale that would be relevant for any other chronic illness, even for nonrheumatology patients,” he explained.

In addition, minimally important differences (group mean change of about 2-3 units) and minimally clinical important differences for individuals (5 units) have been established.

“So we know what the numbers mean, and this is true for all of the scales,” he said.

PROMIS tools also include computer-adaptive testing (CAT) versions, which helps to personalize the scales to provide more precise information for a given patient and eliminate irrelevant information.

Of note, PROMIS health measures are among the data that can be tracked on a smartphone using Arthritis Power, an arthritis research registry developed with the help of a recent infrastructure grant awarded to the Center for Education and Research and Therapeutics of Musculoskeletal Disorders at UAB, Dr. Curtis said.

The measures were also shown in the AWARE study to track closely with other measures, including the Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI), and with patient improvement on therapy.

“So these PROMIS scores are tracking with things that you and I are familiar with ... and it looks like these scores are faithfully tracking, over time, patients getting better on therapies that we would expect them to,” he said. “I think this is additional validation – not just from the National Institutes of Health and a decade of research by lots of different groups, but in our own field – that these actually correlate with disease activity ... and that when you start an effective therapy like a [tumor necrosis factor inhibitor] they’re going to improve as you would anticipate.”

Dr. Curtis reported funding from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. He has also consulted for or received research grants from Amgen, AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, CORRONA, Lilly, Janssen, Myriad, Novartis, Roche, Pfizer, and Sanofi/Regeneron.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM FSR 2019

PTSD in the inpatient setting

A problem hiding in plain sight

“I need to get out of here! I haven’t gotten any sleep, my medications never come on time, and I feel like a pincushion. I am leaving NOW!” The commotion interrupts your intern’s meticulous presentation as your team quickly files into the room. You find a disheveled, visibly frustrated man tearing at his intravenous line, surrounded by his half-eaten breakfast and multiple urinals filled to various levels. His IV pump is beeping, and telemetry wires hang haphazardly off his chest.

Mr. Smith had been admitted for a heart failure exacerbation. You’d been making steady progress with diuresis but are now faced with a likely discharge against medical advice if you can’t defuse the situation.

As hospitalists, this scenario might feel eerily familiar. Perhaps Mr. Smith had enough of being in the hospital and just wanted to go home to see his dog, or maybe the food was not up to his standards.

However, his next line stops your team dead in its tracks. “I feel like I am in Vietnam all over again. I am tied up with all these wires and feel like a prisoner! Please let me go.” It turns out that Mr. Smith had a comorbidity that was overlooked during his initial intake: posttraumatic stress disorder.

Impact of PTSD

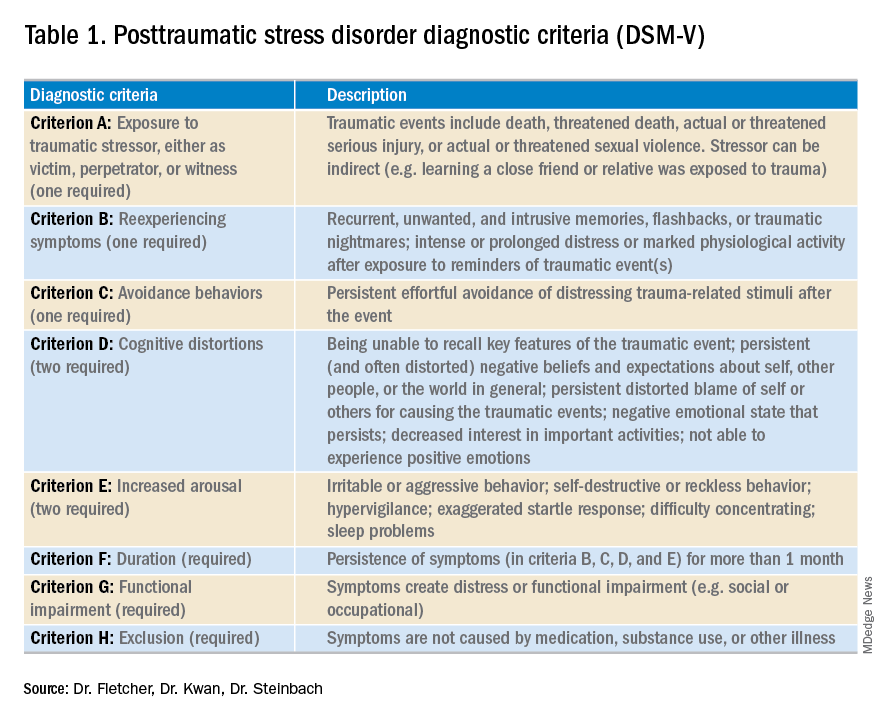

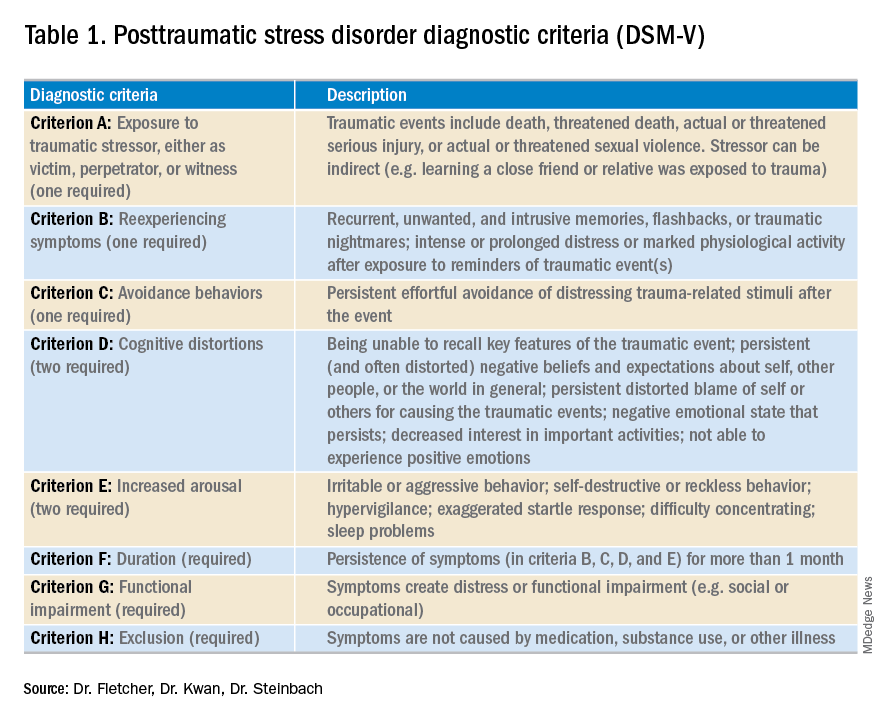

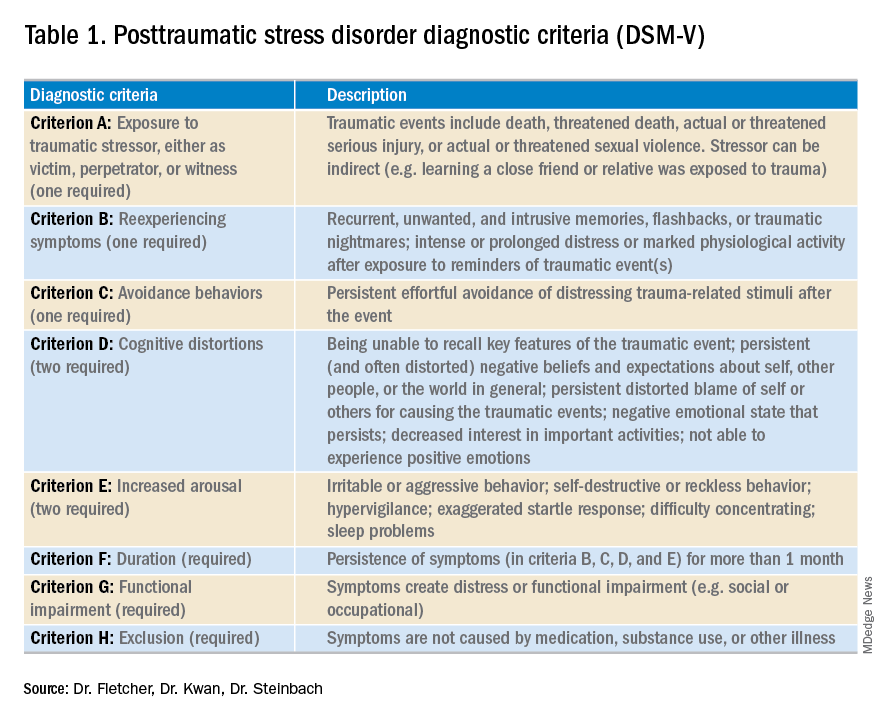

PTSD is a diagnosis characterized by intrusive recurrent thoughts, dreams, or flashbacks that follow exposure to a traumatic event or series of events (see Table 1). While more common among veterans (for example, Vietnam veterans have an estimated lifetime prevalence of PTSD of 30.9% for men and 26.9% for women),1 a national survey of U.S. households estimated the lifetime prevalence of PTSD among adult Americans to be 6.8%.2 PTSD is often underdiagnosed and underreported by patients in the outpatient setting, leading to underrecognition and undertreatment of these patients in the inpatient setting.

Although it may not be surprising that patients with PTSD use more mental health services, they are also more likely to use nonmental health services. In one study, total utilization of outpatient nonmental health services was 91% greater in veterans with PTSD, and these patients were three times more likely to be hospitalized than those without any mental health diagnoses.3 Additionally, they are likely to present later and stay longer when compared with patients without PTSD. One study estimated the cost of PTSD-related hospitalization in the United States from 2002 to 2011 as being $34.9 billion.4 Notably, close to 95% of hospitalizations in this study listed PTSD as a secondary rather than primary diagnosis, suggesting that the vast majority of these admitted patients are cared for by frontline providers who are not trained mental health professionals.

How PTSD manifests in the hospital

But, how exactly can the hospital environment contribute to decompensation of PTSD symptoms? Unfortunately, there is little empiric data to guide us. Based on what we do know of PTSD, we offer the following hypotheses.

Patients with PTSD may feel a loss of control or helplessness when admitted to the inpatient setting. For example, they cannot control when they receive their medications or when they get their meals. The act of showering or going outside requires approval. In addition, they might perceive they are being “ordered around” by staff and may be carted off to a study without knowing why the study is being done in the first place.

Triggers in the hospital environment may contribute to PTSD flares. Think about the loud, beeping IV pump that constantly goes off at random intervals, disrupting sleep. What about a blood draw in the early morning where the phlebotomist sticks a needle into the arm of a sleeping patient? Or the well-intentioned provider doing prerounds who wakes a sleeping patient with a shake of the shoulder or some other form of physical touch? The multidisciplinary team crowding around their hospital bed? For a patient suffering from PTSD, any of these could easily set off a cascade of escalating symptoms.

Knowing that these triggers exist, can anything be done to ameliorate their effects? We propose some practical suggestions for improving the hospital experience for patients with PTSD.

Strategies to combat PTSD in the inpatient setting

Perhaps the most practical place to start is with preserving sleep in hospitalized patients with PTSD. The majority of patients with PTSD have sleep disturbances, and interrupted sleep routines in these patients can exacerbate nightmares and underlying psychiatric issues.5 Therefore, we should strive to avoid unnecessary awakenings.

While this principle holds true for all hospitalized patients, it must be especially prioritized in patients with PTSD. Ask yourself these questions during your next admission: Must intravenous fluids run 24 hours a day, or could they be stopped at 6 p.m.? Are vital signs needed overnight? Could the last dose of furosemide occur at 4 p.m. to avoid nocturia?

Another strategy involves bedtime routines. Many of these patients may already follow a home sleep routine as part of their chronic PTSD management. To honor these habits in the hospital might mean that staff encourage turning the lights and the television off at a designated time. Additionally, the literature suggests music therapy can have a significant impact on enhanced sleep quality. When available, music therapy may reduce insomnia and decrease the amount of time prior to falling asleep.6

Other methods to counteract PTSD fall under the general principle of “trauma-informed care.” Trauma-informed care comprises practices promoting a culture of safety, empowerment, and healing.7 It is a mindful and sensitive approach that acknowledges the pervasive nature of trauma exposure, the reality of ongoing adverse effects in trauma survivors, and the fact that recovery is highly personal and complex.8

By definition, patients with PTSD have endured some traumatic event. Therefore, ideal care teams will ask patients about things that may trigger their anxiety and then work to mitigate them. For example, some patients with PTSD have a severe startle response when woken up by someone touching them. When patients feel that they can share their concerns with their care team and their team honors that observation by waking them in a different way, trust and control may be gained. This process of asking for patient guidance and adjusting accordingly is consistent with a trauma-informed care approach.9 A true trauma-informed care approach involves the entire practice environment but examining and adjusting our own behavior and assumptions are good places to start.

Summary of recommended treatments

Psychotherapy is preferable over pharmacotherapy, but both can be combined as needed. Individual trauma-focused psychotherapies utilizing a primary component of exposure and/or cognitive restructuring have strong evidence for effectiveness but are primarily outpatient based.

For pharmacologic treatment, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (for example, sertraline, paroxetine, or fluoxetine) and serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (for example, venlafaxine) monotherapy have strong evidence for effectiveness and can be started while inpatient. However, these medications typically take weeks to produce benefits. Recent trials studying prazosin, an alpha1-adrenergic receptor antagonist used to alleviate nightmares associated with PTSD, have demonstrated inefficacy or even harm,leading experts to caution against its use.10,11 Finally, benzodiazepine and atypical antipsychotic usage should be restricted and used as a last resort.12

In summary, PTSD is common among veterans and nonveterans. While hospitalists may rarely admit patients because of their PTSD, they will often take care of patients who have PTSD as a comorbidity. Therefore, understanding the basics of PTSD and how hospitalization may exacerbate its symptoms can meaningfully improve care for these patients.

Dr. Fletcher is a hospitalist at the Milwaukee Veterans Affairs Medical Center and Froedtert Hospital in Wauwatosa, Wis. She is professor of internal medicine and program director for the internal medicine residency program at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. She is also faculty mentor for the VA’s Chief Resident for Quality and Safety. Dr. Kwan is a hospitalist at the VA San Diego Healthcare System and is associate professor at the University of California, San Diego, in the division of hospital medicine. He serves as an associate clerkship director of both the internal medicine clerkship and the medicine subinternship. He is the chair of SHM’s Physicians in Training committee. Dr. Steinbach is chief of hospital medicine at the Atlanta VA Medical Center and assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Emory University, Atlanta.

References

1. Kang HK et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and chronic fatigue syndrome–like illness among Gulf War veterans: A population-based survey of 30,000 veterans. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(2):141-8.

2. Kessler RC et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005; 62(6):593-602.

3. Cohen BE et al. Mental health diagnoses and utilization of VA nonmental health medical services among returning Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(1):18-24.

4. Haviland MG et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder–related hospitalizations in the United States (2002-2011): Rates, co-occurring illnesses, suicidal ideation/self-harm, and hospital charges. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2016; 204(2):78-86.

5. Aurora RN et al. Best practice guide for the treatment of nightmare disorder in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2010;6(4):389-401.

6. Blanaru M et al. The effects of music relaxation and muscle relaxation techniques on sleep quality and emotional measures among individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder. Ment Illn. 2012;4(2):e13.

7. Tello M. (2018, Oct 16). Trauma-informed care: What it is, and why it’s important. Retrieved March 18, 2019, from https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/trauma-informed-care-what-it-is-and-why-its-important-2018101613562.

8. Harris M et al. Using trauma theory to design service systems. San Francisco: 2001.

9. Substance abuse and mental health services administration. SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. HHS publication no. SMA 14-4884. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014.

10. Raskind MA et al. Trial of prazosin for posttraumatic stress disorder in military veterans. N Engl J Med. 2018 Feb 8;378(6):507-7.

11. McCall WV et al. A pilot, randomized clinical trial of bedtime doses of prazosin versus placebo in suicidal posttraumatic stress disorder patients with nightmares. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2018 Dec;38(6):618-21.

12. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs/U.S. Department of Defense. Clinical practice guideline for the management of posttraumatic stress disorder and acute stress reaction 2017. Accessed February 18, 2019.

A problem hiding in plain sight

A problem hiding in plain sight

“I need to get out of here! I haven’t gotten any sleep, my medications never come on time, and I feel like a pincushion. I am leaving NOW!” The commotion interrupts your intern’s meticulous presentation as your team quickly files into the room. You find a disheveled, visibly frustrated man tearing at his intravenous line, surrounded by his half-eaten breakfast and multiple urinals filled to various levels. His IV pump is beeping, and telemetry wires hang haphazardly off his chest.

Mr. Smith had been admitted for a heart failure exacerbation. You’d been making steady progress with diuresis but are now faced with a likely discharge against medical advice if you can’t defuse the situation.

As hospitalists, this scenario might feel eerily familiar. Perhaps Mr. Smith had enough of being in the hospital and just wanted to go home to see his dog, or maybe the food was not up to his standards.

However, his next line stops your team dead in its tracks. “I feel like I am in Vietnam all over again. I am tied up with all these wires and feel like a prisoner! Please let me go.” It turns out that Mr. Smith had a comorbidity that was overlooked during his initial intake: posttraumatic stress disorder.

Impact of PTSD

PTSD is a diagnosis characterized by intrusive recurrent thoughts, dreams, or flashbacks that follow exposure to a traumatic event or series of events (see Table 1). While more common among veterans (for example, Vietnam veterans have an estimated lifetime prevalence of PTSD of 30.9% for men and 26.9% for women),1 a national survey of U.S. households estimated the lifetime prevalence of PTSD among adult Americans to be 6.8%.2 PTSD is often underdiagnosed and underreported by patients in the outpatient setting, leading to underrecognition and undertreatment of these patients in the inpatient setting.

Although it may not be surprising that patients with PTSD use more mental health services, they are also more likely to use nonmental health services. In one study, total utilization of outpatient nonmental health services was 91% greater in veterans with PTSD, and these patients were three times more likely to be hospitalized than those without any mental health diagnoses.3 Additionally, they are likely to present later and stay longer when compared with patients without PTSD. One study estimated the cost of PTSD-related hospitalization in the United States from 2002 to 2011 as being $34.9 billion.4 Notably, close to 95% of hospitalizations in this study listed PTSD as a secondary rather than primary diagnosis, suggesting that the vast majority of these admitted patients are cared for by frontline providers who are not trained mental health professionals.

How PTSD manifests in the hospital

But, how exactly can the hospital environment contribute to decompensation of PTSD symptoms? Unfortunately, there is little empiric data to guide us. Based on what we do know of PTSD, we offer the following hypotheses.

Patients with PTSD may feel a loss of control or helplessness when admitted to the inpatient setting. For example, they cannot control when they receive their medications or when they get their meals. The act of showering or going outside requires approval. In addition, they might perceive they are being “ordered around” by staff and may be carted off to a study without knowing why the study is being done in the first place.

Triggers in the hospital environment may contribute to PTSD flares. Think about the loud, beeping IV pump that constantly goes off at random intervals, disrupting sleep. What about a blood draw in the early morning where the phlebotomist sticks a needle into the arm of a sleeping patient? Or the well-intentioned provider doing prerounds who wakes a sleeping patient with a shake of the shoulder or some other form of physical touch? The multidisciplinary team crowding around their hospital bed? For a patient suffering from PTSD, any of these could easily set off a cascade of escalating symptoms.

Knowing that these triggers exist, can anything be done to ameliorate their effects? We propose some practical suggestions for improving the hospital experience for patients with PTSD.

Strategies to combat PTSD in the inpatient setting

Perhaps the most practical place to start is with preserving sleep in hospitalized patients with PTSD. The majority of patients with PTSD have sleep disturbances, and interrupted sleep routines in these patients can exacerbate nightmares and underlying psychiatric issues.5 Therefore, we should strive to avoid unnecessary awakenings.

While this principle holds true for all hospitalized patients, it must be especially prioritized in patients with PTSD. Ask yourself these questions during your next admission: Must intravenous fluids run 24 hours a day, or could they be stopped at 6 p.m.? Are vital signs needed overnight? Could the last dose of furosemide occur at 4 p.m. to avoid nocturia?

Another strategy involves bedtime routines. Many of these patients may already follow a home sleep routine as part of their chronic PTSD management. To honor these habits in the hospital might mean that staff encourage turning the lights and the television off at a designated time. Additionally, the literature suggests music therapy can have a significant impact on enhanced sleep quality. When available, music therapy may reduce insomnia and decrease the amount of time prior to falling asleep.6

Other methods to counteract PTSD fall under the general principle of “trauma-informed care.” Trauma-informed care comprises practices promoting a culture of safety, empowerment, and healing.7 It is a mindful and sensitive approach that acknowledges the pervasive nature of trauma exposure, the reality of ongoing adverse effects in trauma survivors, and the fact that recovery is highly personal and complex.8

By definition, patients with PTSD have endured some traumatic event. Therefore, ideal care teams will ask patients about things that may trigger their anxiety and then work to mitigate them. For example, some patients with PTSD have a severe startle response when woken up by someone touching them. When patients feel that they can share their concerns with their care team and their team honors that observation by waking them in a different way, trust and control may be gained. This process of asking for patient guidance and adjusting accordingly is consistent with a trauma-informed care approach.9 A true trauma-informed care approach involves the entire practice environment but examining and adjusting our own behavior and assumptions are good places to start.

Summary of recommended treatments

Psychotherapy is preferable over pharmacotherapy, but both can be combined as needed. Individual trauma-focused psychotherapies utilizing a primary component of exposure and/or cognitive restructuring have strong evidence for effectiveness but are primarily outpatient based.

For pharmacologic treatment, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (for example, sertraline, paroxetine, or fluoxetine) and serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (for example, venlafaxine) monotherapy have strong evidence for effectiveness and can be started while inpatient. However, these medications typically take weeks to produce benefits. Recent trials studying prazosin, an alpha1-adrenergic receptor antagonist used to alleviate nightmares associated with PTSD, have demonstrated inefficacy or even harm,leading experts to caution against its use.10,11 Finally, benzodiazepine and atypical antipsychotic usage should be restricted and used as a last resort.12

In summary, PTSD is common among veterans and nonveterans. While hospitalists may rarely admit patients because of their PTSD, they will often take care of patients who have PTSD as a comorbidity. Therefore, understanding the basics of PTSD and how hospitalization may exacerbate its symptoms can meaningfully improve care for these patients.

Dr. Fletcher is a hospitalist at the Milwaukee Veterans Affairs Medical Center and Froedtert Hospital in Wauwatosa, Wis. She is professor of internal medicine and program director for the internal medicine residency program at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. She is also faculty mentor for the VA’s Chief Resident for Quality and Safety. Dr. Kwan is a hospitalist at the VA San Diego Healthcare System and is associate professor at the University of California, San Diego, in the division of hospital medicine. He serves as an associate clerkship director of both the internal medicine clerkship and the medicine subinternship. He is the chair of SHM’s Physicians in Training committee. Dr. Steinbach is chief of hospital medicine at the Atlanta VA Medical Center and assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Emory University, Atlanta.

References

1. Kang HK et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and chronic fatigue syndrome–like illness among Gulf War veterans: A population-based survey of 30,000 veterans. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(2):141-8.

2. Kessler RC et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005; 62(6):593-602.

3. Cohen BE et al. Mental health diagnoses and utilization of VA nonmental health medical services among returning Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(1):18-24.

4. Haviland MG et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder–related hospitalizations in the United States (2002-2011): Rates, co-occurring illnesses, suicidal ideation/self-harm, and hospital charges. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2016; 204(2):78-86.

5. Aurora RN et al. Best practice guide for the treatment of nightmare disorder in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2010;6(4):389-401.

6. Blanaru M et al. The effects of music relaxation and muscle relaxation techniques on sleep quality and emotional measures among individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder. Ment Illn. 2012;4(2):e13.

7. Tello M. (2018, Oct 16). Trauma-informed care: What it is, and why it’s important. Retrieved March 18, 2019, from https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/trauma-informed-care-what-it-is-and-why-its-important-2018101613562.

8. Harris M et al. Using trauma theory to design service systems. San Francisco: 2001.

9. Substance abuse and mental health services administration. SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. HHS publication no. SMA 14-4884. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014.

10. Raskind MA et al. Trial of prazosin for posttraumatic stress disorder in military veterans. N Engl J Med. 2018 Feb 8;378(6):507-7.

11. McCall WV et al. A pilot, randomized clinical trial of bedtime doses of prazosin versus placebo in suicidal posttraumatic stress disorder patients with nightmares. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2018 Dec;38(6):618-21.

12. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs/U.S. Department of Defense. Clinical practice guideline for the management of posttraumatic stress disorder and acute stress reaction 2017. Accessed February 18, 2019.

“I need to get out of here! I haven’t gotten any sleep, my medications never come on time, and I feel like a pincushion. I am leaving NOW!” The commotion interrupts your intern’s meticulous presentation as your team quickly files into the room. You find a disheveled, visibly frustrated man tearing at his intravenous line, surrounded by his half-eaten breakfast and multiple urinals filled to various levels. His IV pump is beeping, and telemetry wires hang haphazardly off his chest.

Mr. Smith had been admitted for a heart failure exacerbation. You’d been making steady progress with diuresis but are now faced with a likely discharge against medical advice if you can’t defuse the situation.

As hospitalists, this scenario might feel eerily familiar. Perhaps Mr. Smith had enough of being in the hospital and just wanted to go home to see his dog, or maybe the food was not up to his standards.

However, his next line stops your team dead in its tracks. “I feel like I am in Vietnam all over again. I am tied up with all these wires and feel like a prisoner! Please let me go.” It turns out that Mr. Smith had a comorbidity that was overlooked during his initial intake: posttraumatic stress disorder.

Impact of PTSD

PTSD is a diagnosis characterized by intrusive recurrent thoughts, dreams, or flashbacks that follow exposure to a traumatic event or series of events (see Table 1). While more common among veterans (for example, Vietnam veterans have an estimated lifetime prevalence of PTSD of 30.9% for men and 26.9% for women),1 a national survey of U.S. households estimated the lifetime prevalence of PTSD among adult Americans to be 6.8%.2 PTSD is often underdiagnosed and underreported by patients in the outpatient setting, leading to underrecognition and undertreatment of these patients in the inpatient setting.

Although it may not be surprising that patients with PTSD use more mental health services, they are also more likely to use nonmental health services. In one study, total utilization of outpatient nonmental health services was 91% greater in veterans with PTSD, and these patients were three times more likely to be hospitalized than those without any mental health diagnoses.3 Additionally, they are likely to present later and stay longer when compared with patients without PTSD. One study estimated the cost of PTSD-related hospitalization in the United States from 2002 to 2011 as being $34.9 billion.4 Notably, close to 95% of hospitalizations in this study listed PTSD as a secondary rather than primary diagnosis, suggesting that the vast majority of these admitted patients are cared for by frontline providers who are not trained mental health professionals.

How PTSD manifests in the hospital

But, how exactly can the hospital environment contribute to decompensation of PTSD symptoms? Unfortunately, there is little empiric data to guide us. Based on what we do know of PTSD, we offer the following hypotheses.

Patients with PTSD may feel a loss of control or helplessness when admitted to the inpatient setting. For example, they cannot control when they receive their medications or when they get their meals. The act of showering or going outside requires approval. In addition, they might perceive they are being “ordered around” by staff and may be carted off to a study without knowing why the study is being done in the first place.

Triggers in the hospital environment may contribute to PTSD flares. Think about the loud, beeping IV pump that constantly goes off at random intervals, disrupting sleep. What about a blood draw in the early morning where the phlebotomist sticks a needle into the arm of a sleeping patient? Or the well-intentioned provider doing prerounds who wakes a sleeping patient with a shake of the shoulder or some other form of physical touch? The multidisciplinary team crowding around their hospital bed? For a patient suffering from PTSD, any of these could easily set off a cascade of escalating symptoms.

Knowing that these triggers exist, can anything be done to ameliorate their effects? We propose some practical suggestions for improving the hospital experience for patients with PTSD.

Strategies to combat PTSD in the inpatient setting

Perhaps the most practical place to start is with preserving sleep in hospitalized patients with PTSD. The majority of patients with PTSD have sleep disturbances, and interrupted sleep routines in these patients can exacerbate nightmares and underlying psychiatric issues.5 Therefore, we should strive to avoid unnecessary awakenings.

While this principle holds true for all hospitalized patients, it must be especially prioritized in patients with PTSD. Ask yourself these questions during your next admission: Must intravenous fluids run 24 hours a day, or could they be stopped at 6 p.m.? Are vital signs needed overnight? Could the last dose of furosemide occur at 4 p.m. to avoid nocturia?

Another strategy involves bedtime routines. Many of these patients may already follow a home sleep routine as part of their chronic PTSD management. To honor these habits in the hospital might mean that staff encourage turning the lights and the television off at a designated time. Additionally, the literature suggests music therapy can have a significant impact on enhanced sleep quality. When available, music therapy may reduce insomnia and decrease the amount of time prior to falling asleep.6

Other methods to counteract PTSD fall under the general principle of “trauma-informed care.” Trauma-informed care comprises practices promoting a culture of safety, empowerment, and healing.7 It is a mindful and sensitive approach that acknowledges the pervasive nature of trauma exposure, the reality of ongoing adverse effects in trauma survivors, and the fact that recovery is highly personal and complex.8

By definition, patients with PTSD have endured some traumatic event. Therefore, ideal care teams will ask patients about things that may trigger their anxiety and then work to mitigate them. For example, some patients with PTSD have a severe startle response when woken up by someone touching them. When patients feel that they can share their concerns with their care team and their team honors that observation by waking them in a different way, trust and control may be gained. This process of asking for patient guidance and adjusting accordingly is consistent with a trauma-informed care approach.9 A true trauma-informed care approach involves the entire practice environment but examining and adjusting our own behavior and assumptions are good places to start.

Summary of recommended treatments

Psychotherapy is preferable over pharmacotherapy, but both can be combined as needed. Individual trauma-focused psychotherapies utilizing a primary component of exposure and/or cognitive restructuring have strong evidence for effectiveness but are primarily outpatient based.

For pharmacologic treatment, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (for example, sertraline, paroxetine, or fluoxetine) and serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (for example, venlafaxine) monotherapy have strong evidence for effectiveness and can be started while inpatient. However, these medications typically take weeks to produce benefits. Recent trials studying prazosin, an alpha1-adrenergic receptor antagonist used to alleviate nightmares associated with PTSD, have demonstrated inefficacy or even harm,leading experts to caution against its use.10,11 Finally, benzodiazepine and atypical antipsychotic usage should be restricted and used as a last resort.12

In summary, PTSD is common among veterans and nonveterans. While hospitalists may rarely admit patients because of their PTSD, they will often take care of patients who have PTSD as a comorbidity. Therefore, understanding the basics of PTSD and how hospitalization may exacerbate its symptoms can meaningfully improve care for these patients.

Dr. Fletcher is a hospitalist at the Milwaukee Veterans Affairs Medical Center and Froedtert Hospital in Wauwatosa, Wis. She is professor of internal medicine and program director for the internal medicine residency program at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. She is also faculty mentor for the VA’s Chief Resident for Quality and Safety. Dr. Kwan is a hospitalist at the VA San Diego Healthcare System and is associate professor at the University of California, San Diego, in the division of hospital medicine. He serves as an associate clerkship director of both the internal medicine clerkship and the medicine subinternship. He is the chair of SHM’s Physicians in Training committee. Dr. Steinbach is chief of hospital medicine at the Atlanta VA Medical Center and assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Emory University, Atlanta.

References

1. Kang HK et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and chronic fatigue syndrome–like illness among Gulf War veterans: A population-based survey of 30,000 veterans. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(2):141-8.

2. Kessler RC et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005; 62(6):593-602.

3. Cohen BE et al. Mental health diagnoses and utilization of VA nonmental health medical services among returning Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(1):18-24.

4. Haviland MG et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder–related hospitalizations in the United States (2002-2011): Rates, co-occurring illnesses, suicidal ideation/self-harm, and hospital charges. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2016; 204(2):78-86.

5. Aurora RN et al. Best practice guide for the treatment of nightmare disorder in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2010;6(4):389-401.

6. Blanaru M et al. The effects of music relaxation and muscle relaxation techniques on sleep quality and emotional measures among individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder. Ment Illn. 2012;4(2):e13.

7. Tello M. (2018, Oct 16). Trauma-informed care: What it is, and why it’s important. Retrieved March 18, 2019, from https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/trauma-informed-care-what-it-is-and-why-its-important-2018101613562.

8. Harris M et al. Using trauma theory to design service systems. San Francisco: 2001.

9. Substance abuse and mental health services administration. SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. HHS publication no. SMA 14-4884. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014.

10. Raskind MA et al. Trial of prazosin for posttraumatic stress disorder in military veterans. N Engl J Med. 2018 Feb 8;378(6):507-7.

11. McCall WV et al. A pilot, randomized clinical trial of bedtime doses of prazosin versus placebo in suicidal posttraumatic stress disorder patients with nightmares. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2018 Dec;38(6):618-21.

12. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs/U.S. Department of Defense. Clinical practice guideline for the management of posttraumatic stress disorder and acute stress reaction 2017. Accessed February 18, 2019.

Apply for SVS Membership

The third membership deadline of 2019 is less than one month away on Sept. 1. SVS members enjoy many benefits such as SVSConnect, discounted pricing on publications and meeting registration, practice management resources and much more. Visit the membership page and start your application today. If you have any questions, please contact the SVS membership department at membership@vascularsociety.org.

The third membership deadline of 2019 is less than one month away on Sept. 1. SVS members enjoy many benefits such as SVSConnect, discounted pricing on publications and meeting registration, practice management resources and much more. Visit the membership page and start your application today. If you have any questions, please contact the SVS membership department at membership@vascularsociety.org.

The third membership deadline of 2019 is less than one month away on Sept. 1. SVS members enjoy many benefits such as SVSConnect, discounted pricing on publications and meeting registration, practice management resources and much more. Visit the membership page and start your application today. If you have any questions, please contact the SVS membership department at membership@vascularsociety.org.

Staying Awake to Evade Death

ANSWER

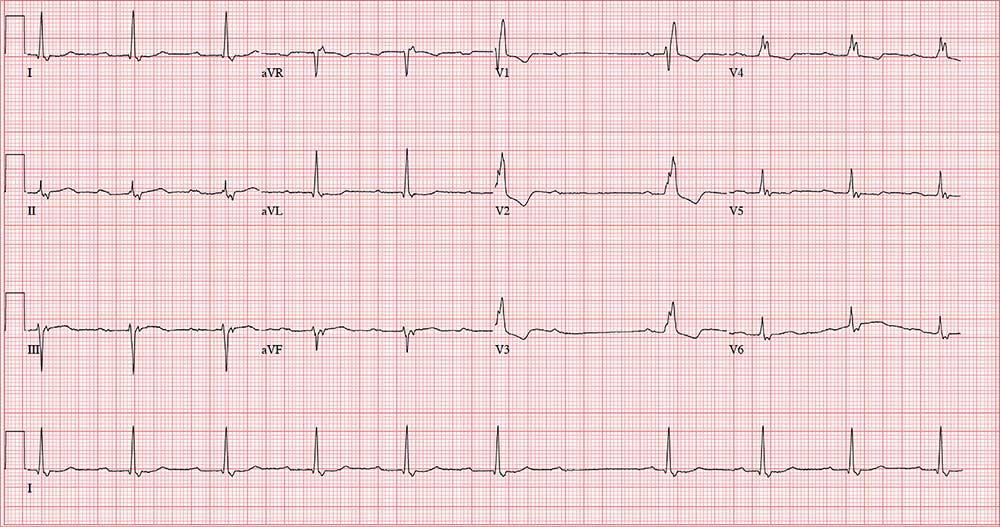

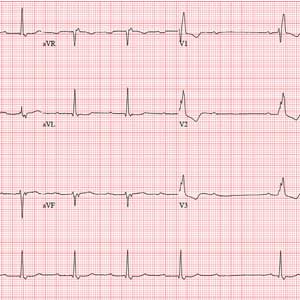

The correct answer includes sinus rhythm with second-degree atrioventricular (AV) block (Mobitz I) and a right bundle branch block (RBBB).

Sinus rhythm is evidenced by the consistent P-P intervals (best measured in the lead I rhythm strip). Mobitz I block is distinguished from Mobitz II block by the varying PR interval.

Remember that in Mobitz I (Wenckebach) block, the PR interval becomes progressively longer as the AV node fatigues, until there is blocked conduction between the atria and ventricles resulting in a P wave with no associated QRS complex. This is evident in the pause between the 6th and 7th QRS complexes. Notice also that the very next PR interval following the dropped QRS complex is much shorter than the PR interval immediately prior to that complex. In this example, the increasing PR interval before the pause is subtle compared to the PR intervals following the pause.

The skipped beats the patient feels are these pauses. Increased parasympathetic (vagal) activity occurs when a person is falling asleep, resulting in a reduction in heart rate and AV nodal conduction variability.

Finally, don’t forget the RBBB. It is indicated by a QRS duration > 120 ms, rSR’ complexes in precordial leads V1 to V3, and slurred S waves in leads I and aVF.

ANSWER

The correct answer includes sinus rhythm with second-degree atrioventricular (AV) block (Mobitz I) and a right bundle branch block (RBBB).

Sinus rhythm is evidenced by the consistent P-P intervals (best measured in the lead I rhythm strip). Mobitz I block is distinguished from Mobitz II block by the varying PR interval.

Remember that in Mobitz I (Wenckebach) block, the PR interval becomes progressively longer as the AV node fatigues, until there is blocked conduction between the atria and ventricles resulting in a P wave with no associated QRS complex. This is evident in the pause between the 6th and 7th QRS complexes. Notice also that the very next PR interval following the dropped QRS complex is much shorter than the PR interval immediately prior to that complex. In this example, the increasing PR interval before the pause is subtle compared to the PR intervals following the pause.

The skipped beats the patient feels are these pauses. Increased parasympathetic (vagal) activity occurs when a person is falling asleep, resulting in a reduction in heart rate and AV nodal conduction variability.

Finally, don’t forget the RBBB. It is indicated by a QRS duration > 120 ms, rSR’ complexes in precordial leads V1 to V3, and slurred S waves in leads I and aVF.

ANSWER

The correct answer includes sinus rhythm with second-degree atrioventricular (AV) block (Mobitz I) and a right bundle branch block (RBBB).

Sinus rhythm is evidenced by the consistent P-P intervals (best measured in the lead I rhythm strip). Mobitz I block is distinguished from Mobitz II block by the varying PR interval.

Remember that in Mobitz I (Wenckebach) block, the PR interval becomes progressively longer as the AV node fatigues, until there is blocked conduction between the atria and ventricles resulting in a P wave with no associated QRS complex. This is evident in the pause between the 6th and 7th QRS complexes. Notice also that the very next PR interval following the dropped QRS complex is much shorter than the PR interval immediately prior to that complex. In this example, the increasing PR interval before the pause is subtle compared to the PR intervals following the pause.

The skipped beats the patient feels are these pauses. Increased parasympathetic (vagal) activity occurs when a person is falling asleep, resulting in a reduction in heart rate and AV nodal conduction variability.

Finally, don’t forget the RBBB. It is indicated by a QRS duration > 120 ms, rSR’ complexes in precordial leads V1 to V3, and slurred S waves in leads I and aVF.

A 64-year-old man presents with a 6-month history of skipped heart beats. He says this occurs most often in the evenings, when he’s resting, and he has been awakened by it. He denies chest pain, dyspnea with exertion, syncope, or near-syncope. He has been otherwise asymptomatic from a cardiac and pulmonary standpoint.

However, he is increasingly concerned that his heart may “just stop beating” when he is asleep. When pressed further, he reveals he is afraid to go to sleep at night, knowing “my heart will start skipping beats and I’ll die!” He has discussed his fear of dying in his sleep with a psychologist, who told him that although he experiences fatigue and loss of energy and has recurrent thoughts of death, he does not meet DSM-5 criteria for major depressive disorder. The psychologist obtained an ECG and noticed pauses, which prompted referral of the patient to you.

Past medical history is remarkable for hypertension, cirrhosis, and osteoarthritis. Surgical history includes bilateral knee and left hip replacements. A screening colonoscopy 1 month ago yielded a diagnosis of stage 1 colorectal cancer.

The patient’s medication list includes hydrochlorothiazide and celecoxib. He is allergic to oxycodone (anaphylaxis).

The patient is divorced, which he attributes to his ongoing alcoholism. He drinks half a bottle of whiskey daily to “help with my nerves” and “get drunk enough to sleep.” He reports a lifetime of heavy drinking; he has tried Alcoholics Anonymous but kept dropping out to drink. He also smokes up to 1.5 packs/d of cigarettes. He has no children. He worked as a machinist in a factory but was laid off a year ago when the company downsized.

Family history is positive for alcoholism (father, 2 brothers) and hypothyroidism (mother).

Review of systems is positive for a chronic smoker’s cough, lower abdominal cramping following his colonoscopy, and arthritic pain in his wrists and ankles.

Vital signs include a blood pressure of 174/92 mm Hg; pulse, 74 beats/min; respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min; and O2 saturation, 97% on room air. His weight is 247 lb and his height, 69 in. His BMI is 36.5.

Physical exam reveals a somewhat disheveled male in no apparent distress. He wears corrective lenses and has tobacco stains on his mustache. His HEENT exam is surprisingly normal, and there is no evidence of rhinophyma. There is no jugular venous distention, thyromegaly, or lymphadenopathy. There are crackles and late expiratory wheezes in both lower lung fields.

The cardiac exam reveals a regular rate and rhythm of 74 beats/min, with no murmurs, rubs, or extra heart sounds. Peripheral pulses are strong and equal bilaterally. The abdomen is obese but nontender, and there are no palpable masses. There are surgical scars over both knees and the left hip. Arthritic changes are noticeable in the fingers on both hands. There are no neurologic deficits.

Through the electronic medical record, you access the ECG taken in the psychologist’s office. It shows a ventricular rate of 56 beats/min; no measurable PR interval; QRS duration, 144 ms; QT/QTc interval, 438/422 ms; P axis, 47°; R axis, –24°; and T axis, 55°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

State and federal efforts address rheumatology workforce issues

LAKE BUENA VISTA, FLA. – Workforce gaps loom large in rheumatology, but efforts on both the federal and state levels address the problem, according to the chair of the American College of Rheumatology’s Government Affairs Committee, Angus B. Worthing, MD.

“We have a workforce gap that’s growing in adult arthritis; demand is increasing, and supply is decreasing,” Dr. Worthing said during an update on the committee’s activities at the annual meeting of the Florida Society of Rheumatology.

A similar “grave discrepancy” plagues pediatric rheumatology, said Dr. Worthing, a partner in a private rheumatology practice in the Washington, D.C., area.

“But these are fundamentally different,” he said, explaining that there is an oversupply of applicants for adult rheumatology fellowship spots, whereas only half of the available spots in pediatric rheumatology are being filled.

“We’re unfortunately having to turn away highly qualified [adult rheumatology] applicants, because we don’t have enough money to fund fellowship positions in the United States; about 100 doctors a year who wanted to be rheumatologists are going into other specialties,” he said. “It’s a different problem in pediatric rheumatology where you spend 2-3 extra years to earn less money than you would as a general pediatrician.”

The American College of Rheumatology is working to “find those dollars,” to alleviate the problems, he said, encouraging those who are concerned about the workforce issues to consider investing in the Rheumatology Research Foundation, which is a “huge supporter of rheumatology fellowships.”

Another proposal involves loan repayment plans for health professionals who agree to work at least 2 years in pediatric medicine.

“There’s an active bill that you can send an e-mail on right now,” Dr. Worthing said.

The bill, titled the “Educating Medical Professionals and Optimizing Workforce Efficiency and Readiness [EMPOWER] for Health Act,” represents an effort on the federal level to increase access to pediatric medical subspecialists by increasing the number who practice in underserved areas.

“It was introduced the day after we spoke on the Hill in May to leaders about this [issue],” he said.

Another effort is underway in Georgia, where a legislator who has lupus is working with the ACR on legislation that would allow the state to repay up to $25,000 on loans for cognitive specialists who agree to work in the state for a period of time.

The ACR is also working to maintain Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) protections for recipients pursuing medical education, who could potentially help to alleviate the shortages, he noted.

The problem of workforce issues is multifaceted and it requires a multipronged approach, Dr. Worthing said.

“It will not be solved by the American College of Rheumatology alone; I think it will end up being solved by people on the ground working with their primary care physicians and referring doctors to try to close the gap and try to see patients when they’re needed,” he said.

Dr. Worthing reported having no disclosures.

LAKE BUENA VISTA, FLA. – Workforce gaps loom large in rheumatology, but efforts on both the federal and state levels address the problem, according to the chair of the American College of Rheumatology’s Government Affairs Committee, Angus B. Worthing, MD.

“We have a workforce gap that’s growing in adult arthritis; demand is increasing, and supply is decreasing,” Dr. Worthing said during an update on the committee’s activities at the annual meeting of the Florida Society of Rheumatology.

A similar “grave discrepancy” plagues pediatric rheumatology, said Dr. Worthing, a partner in a private rheumatology practice in the Washington, D.C., area.

“But these are fundamentally different,” he said, explaining that there is an oversupply of applicants for adult rheumatology fellowship spots, whereas only half of the available spots in pediatric rheumatology are being filled.

“We’re unfortunately having to turn away highly qualified [adult rheumatology] applicants, because we don’t have enough money to fund fellowship positions in the United States; about 100 doctors a year who wanted to be rheumatologists are going into other specialties,” he said. “It’s a different problem in pediatric rheumatology where you spend 2-3 extra years to earn less money than you would as a general pediatrician.”

The American College of Rheumatology is working to “find those dollars,” to alleviate the problems, he said, encouraging those who are concerned about the workforce issues to consider investing in the Rheumatology Research Foundation, which is a “huge supporter of rheumatology fellowships.”

Another proposal involves loan repayment plans for health professionals who agree to work at least 2 years in pediatric medicine.

“There’s an active bill that you can send an e-mail on right now,” Dr. Worthing said.

The bill, titled the “Educating Medical Professionals and Optimizing Workforce Efficiency and Readiness [EMPOWER] for Health Act,” represents an effort on the federal level to increase access to pediatric medical subspecialists by increasing the number who practice in underserved areas.

“It was introduced the day after we spoke on the Hill in May to leaders about this [issue],” he said.

Another effort is underway in Georgia, where a legislator who has lupus is working with the ACR on legislation that would allow the state to repay up to $25,000 on loans for cognitive specialists who agree to work in the state for a period of time.

The ACR is also working to maintain Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) protections for recipients pursuing medical education, who could potentially help to alleviate the shortages, he noted.

The problem of workforce issues is multifaceted and it requires a multipronged approach, Dr. Worthing said.

“It will not be solved by the American College of Rheumatology alone; I think it will end up being solved by people on the ground working with their primary care physicians and referring doctors to try to close the gap and try to see patients when they’re needed,” he said.

Dr. Worthing reported having no disclosures.

LAKE BUENA VISTA, FLA. – Workforce gaps loom large in rheumatology, but efforts on both the federal and state levels address the problem, according to the chair of the American College of Rheumatology’s Government Affairs Committee, Angus B. Worthing, MD.

“We have a workforce gap that’s growing in adult arthritis; demand is increasing, and supply is decreasing,” Dr. Worthing said during an update on the committee’s activities at the annual meeting of the Florida Society of Rheumatology.

A similar “grave discrepancy” plagues pediatric rheumatology, said Dr. Worthing, a partner in a private rheumatology practice in the Washington, D.C., area.

“But these are fundamentally different,” he said, explaining that there is an oversupply of applicants for adult rheumatology fellowship spots, whereas only half of the available spots in pediatric rheumatology are being filled.

“We’re unfortunately having to turn away highly qualified [adult rheumatology] applicants, because we don’t have enough money to fund fellowship positions in the United States; about 100 doctors a year who wanted to be rheumatologists are going into other specialties,” he said. “It’s a different problem in pediatric rheumatology where you spend 2-3 extra years to earn less money than you would as a general pediatrician.”

The American College of Rheumatology is working to “find those dollars,” to alleviate the problems, he said, encouraging those who are concerned about the workforce issues to consider investing in the Rheumatology Research Foundation, which is a “huge supporter of rheumatology fellowships.”

Another proposal involves loan repayment plans for health professionals who agree to work at least 2 years in pediatric medicine.

“There’s an active bill that you can send an e-mail on right now,” Dr. Worthing said.

The bill, titled the “Educating Medical Professionals and Optimizing Workforce Efficiency and Readiness [EMPOWER] for Health Act,” represents an effort on the federal level to increase access to pediatric medical subspecialists by increasing the number who practice in underserved areas.

“It was introduced the day after we spoke on the Hill in May to leaders about this [issue],” he said.

Another effort is underway in Georgia, where a legislator who has lupus is working with the ACR on legislation that would allow the state to repay up to $25,000 on loans for cognitive specialists who agree to work in the state for a period of time.

The ACR is also working to maintain Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) protections for recipients pursuing medical education, who could potentially help to alleviate the shortages, he noted.

The problem of workforce issues is multifaceted and it requires a multipronged approach, Dr. Worthing said.

“It will not be solved by the American College of Rheumatology alone; I think it will end up being solved by people on the ground working with their primary care physicians and referring doctors to try to close the gap and try to see patients when they’re needed,” he said.

Dr. Worthing reported having no disclosures.

REPORTING FROM FSR 2019

Immune-related toxicities, hospitalization common with checkpoint inhibitor therapy

, according to a retrospective cohort study.

In addition, the majority of the immune-related toxicities were high-grade events of grade 3 or higher (65%), necessitated multidisciplinary care (91%), and eventually improved or resolved (65%). The results highlight potential risk factors for hospitalizations due to immune-related toxicities in oncology patients.

“[We aimed to] characterize the spectrum of toxicities, management, and outcomes of hospitalizations for immune-related adverse events,” wrote Aanika Balaji, BS, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues. The findings were reported in the Journal of Oncology Practice.

The researchers studied 443 patients admitted to solid tumor oncology service at an oncology center over a period of 6-months. Of these, 100 patients had at any point received checkpoint inhibitor therapy.

The proportion of hospital admissions for patients with confirmed immune-related toxicities and associations between hospitalizations due to immune-related toxicity and patient characteristics were assessed by the team. Nearly half of the patients admitted with immune-related toxicities had thoracic or head and neck cancers.